Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/147/03. The contractual start date was in February 2014. The draft report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Sharples et al. This work was produced by Sharples et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Sharples et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background to the ETTAA study

Introduction

An estimated 1 in 10,000 patients per year is diagnosed with chronic thoracic aortic aneurysm (CTAA) of the arch or descending thoracic aorta. 1,2 Between 1999 and 2010, hospital admissions for thoracic aortic aneurysm increased from 4.4 to 9.0 per 100,000 inhabitants. 2

Normal aortic diameter varies by aortic segment, gender, age and body mass index (BMI). An aneurysm is defined as a dilatation to one and a half times the normal size of the vessel. Generally, in the arch or descending thoracic aorta (DTA), aneurysms of diameters of ≥ 4 cm are considered abnormal. Without treatment, aortic aneurysms can continue to expand, usually ‘silently’, giving no symptoms until the point of dissection (when the aortic wall tears) or rupture. Either of these events is immediately life-threatening, and survival depends on timely diagnosis and intervention. A study of Routine Hospital Episode Statistics of patients in England admitted with a new diagnosis of thoracic aortic aneurysm between 2004 and 2011 reported a 6-month mortality rate among treated patients of 17.7% and among untreated patients of 30%. 3

In an era of prevalent computerised tomography (CT) scanning, more cases of CTAA are being diagnosed early, offering the opportunity for planned intervention before any life-threatening event can occur. The Effective Treatments for Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms (ETTAA) study investigates the effectiveness of the current treatments available. This chapter outlines the nature of the condition and describes the available treatments and the evidence that currently guides clinical practice.

Pathology

Most aneurysms develop chronically, over several years. In the majority of patients, these are asymptomatic but occasionally they give rise to episodic chest or back pain. Severe pain or cardiovascular collapse may be a sign of rupture or dissection. Aneurysms can also occur acutely (i.e. within days) in the context of dissection of a normal-sized aorta, infection or trauma, but such situations fall outside the remit of this project.

Anatomical definitions and classifications

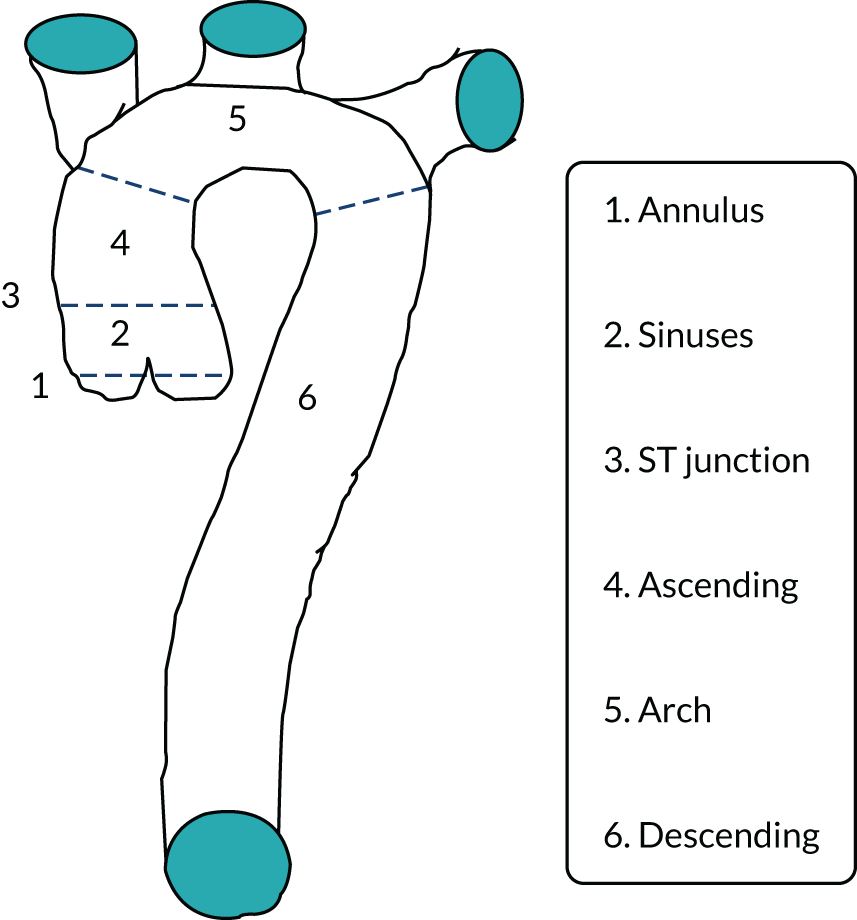

As shown in Figure 1, CTAAs are subdivided into ascending aortic, aortic arch and DTA aneurysms. Aneurysms may extend across both thoracic and abdominal segments, in which case they are classified as thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. The ETTAA study focuses on CTAAs of ≥ 4 cm in diameter in the arch, descending or thoracoabdominal aorta. Ascending aortic aneurysms are excluded because there is an established body of evidence supporting surgical repair, and no established endovascular treatment for comparison. 4

FIGURE 1.

Diagram illustrating sections of the thoracic aorta. ST, sinotubular.

Aneurysms do not always exhibit defined abrupt proximal and distal ends but instead have dilated aortic segments that extend into neighbouring segments. In some cases, most of the aorta or the entire aorta may be dilated to some degree, described as ectatic. Aneurysms in which the aorta has dilated evenly around its circumference are described as fusiform, whereas those in which the dilatation is predominantly on one side of the aorta are described as saccular. Thus, aortic dilatation can have diverse patterns, for various reasons. The different pathological features of the aneurysm influences treatment decisions and, therefore, patient outcomes.

Aetiology

Chronic thoracic aortic aneurysm occurs because the aortic wall is in some way abnormal and cannot withstand the normal stresses exerted by the blood pressure. In approximately 80% of CTAAs, the abnormality in the aortic wall is secondary to atherosclerotic plaques, which in turn are associated with smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and obesity. 5 In the remaining 20% of cases there is a genetic defect in some structural component of the aortic wall, so that it is weaker and dilates in response to normal stresses. Examples include mutated FBN1 (fibrillin 1 gene), causing Marfan syndrome, and mutated TGFBR2 (transforming growth factor beta receptor 2 gene), causing Loeys–Dietz syndrome. 6,7 The underlying cause of CTAA is important, as this can direct treatment. For example, in cases of genetically mediated aneurysm, current opinion is that the ‘normal’ aortic wall above and below the aneurysm, which are landing zones for the stent graft, will continue to dilate and lead to migration of the stent and endoleak, and so surgery is generally preferred. As individual genetic disorders are rare, we grouped them under the umbrella term ‘connective tissue disorders’ (CTDs).

Presentation and diagnosis

Most aneurysms of the arch or DTA are identified incidentally (on a scan for some other reason), or via screening if CTDs are suspected. Once an aneurysm is detected, monitoring of its progression requires repeated CT imaging or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which incurs radiation exposure and a significant cost. Longitudinal surveillance, although limited to small numbers of patients and studies,8,9 suggests that some aneurysms (whatever their size at diagnosis) appear quiescent, without growth for a prolonged period of time, whereas others progress precipitously. Genetic, acquired and pathological features may increase the rate of growth, but the evidence for this is sparse.

Management

Treatment options

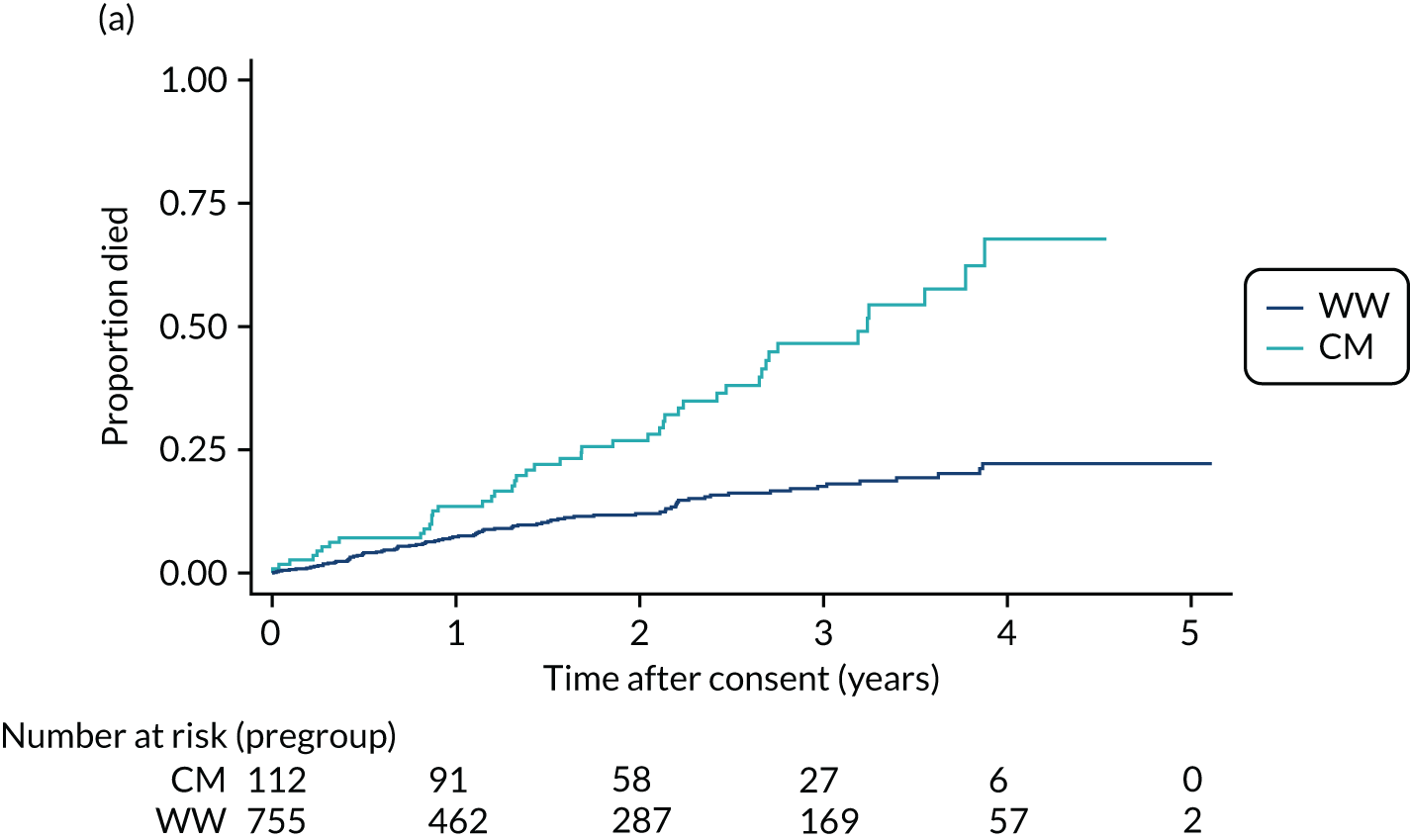

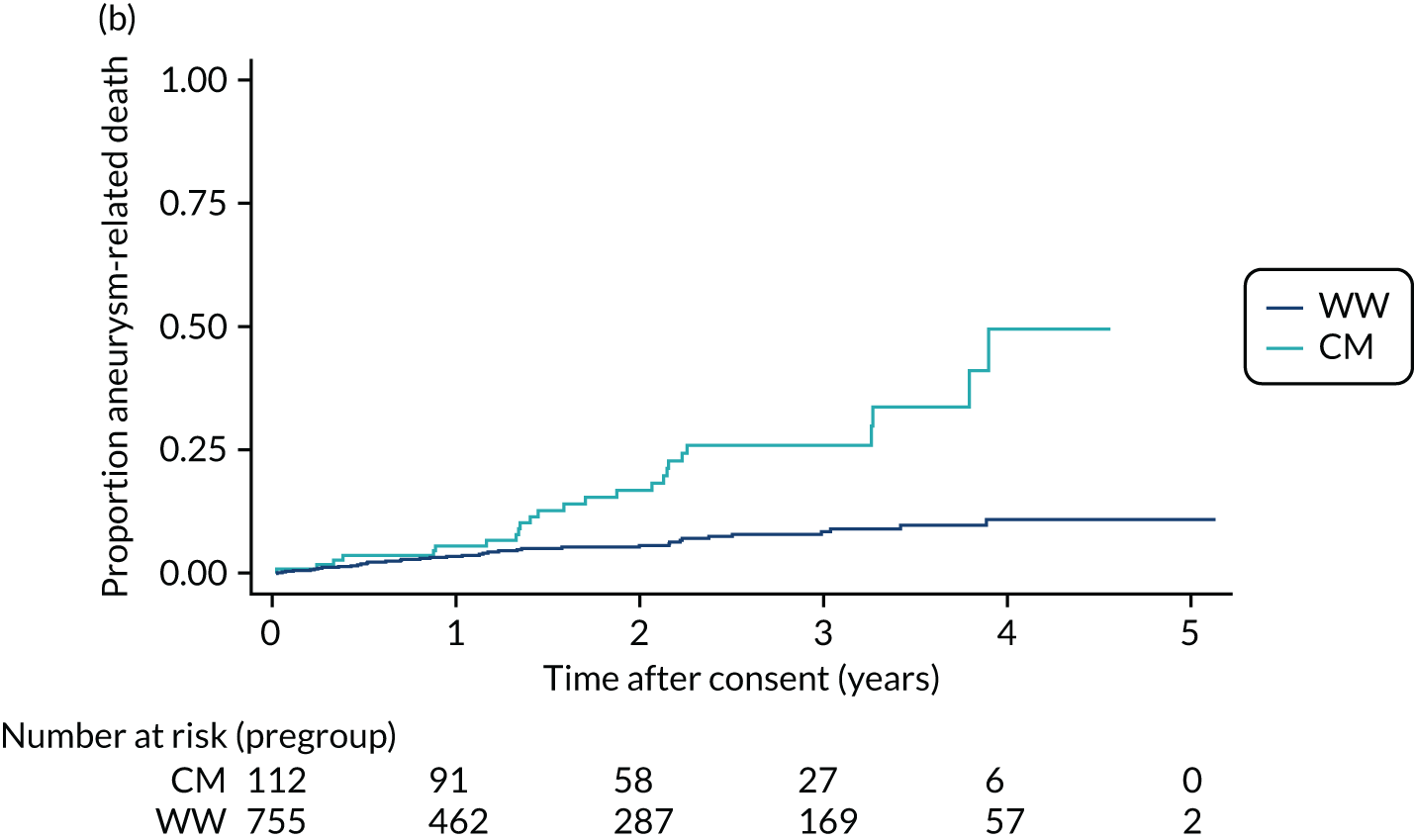

In the case of patients with smaller aneurysms, those who are less fit to undergo chest surgery or endovascular intervention or those who reject such interventions, treatment is confined to lifestyle modification advice (smoking cessation and dietary management) and medical management of hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension. In the ETTAA study, these non-intervention patients are described as either watchful waiting (WW) or conservative management (CM) patients (see Chapter 3). WW patients are monitored with serial (usually annual or biennial) CT or MRI scans with a view to future intervention should the aneurysm grow beyond the intervention threshold. CM patients either are considered to be at very high risk of life-threatening complications from intervention, despite having an aneurysm that is above the guideline thresholds for intervention, or have rejected potential interventions. In such patients aneurysm monitoring may decrease or stop altogether.

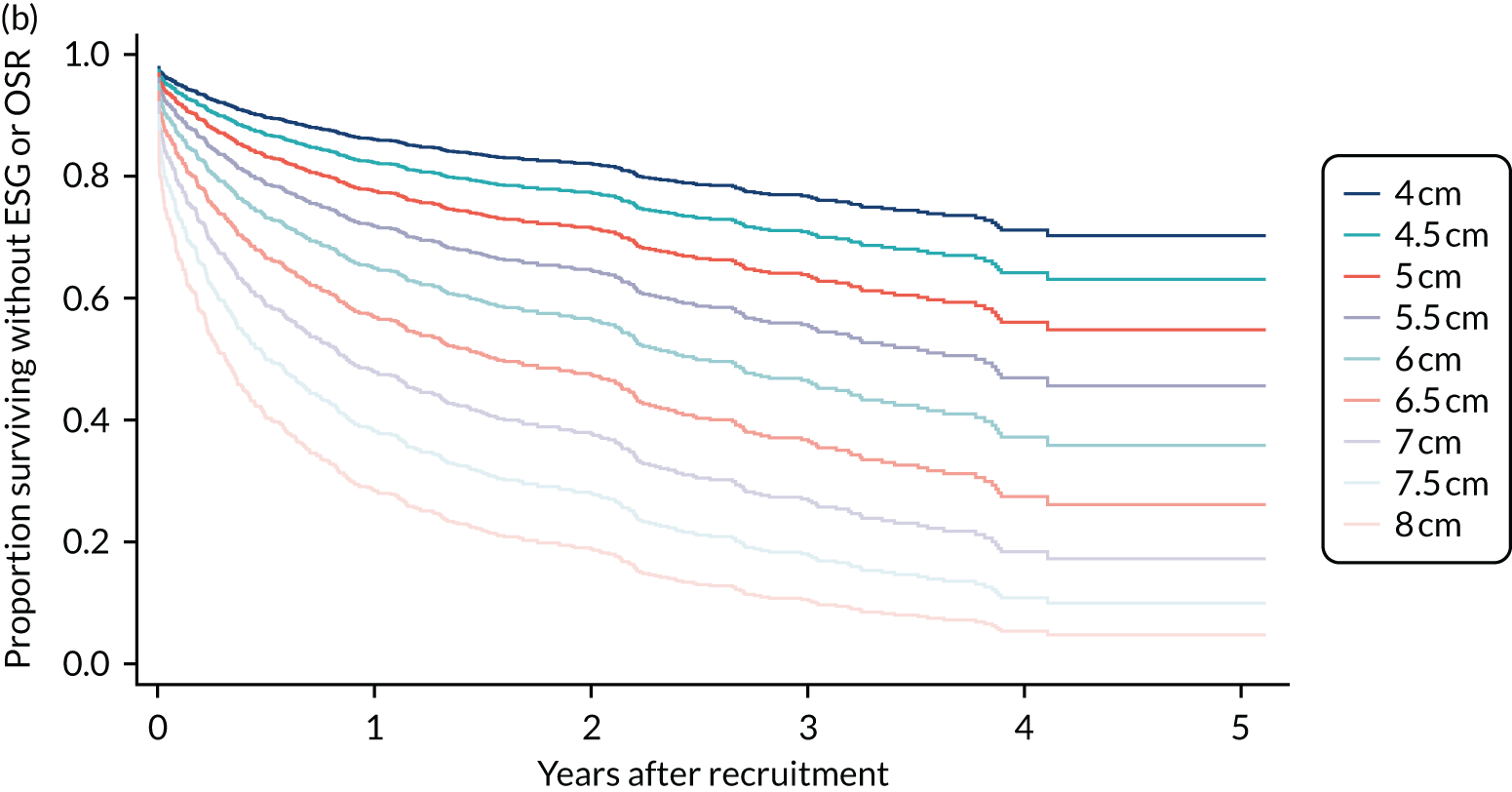

As aneurysms grow and the risk of fatal complications such as rupture or dissection increases, two main interventions are available: endovascular stent grafting (ESG) and open surgical repair (OSR). 10

Open surgical replacement describes procedures in which the chest cavity is opened in order to replace the diseased aortic segment, usually with woven prosthetic tube grafts. Most cases of OSR require cardiopulmonary bypass to support or reroute blood flow while the aorta is operated on. The arch and DTA give rise to important branch arteries to the head, neck, upper limbs and spine and so OSR carries a risk to these organs when the blood supply is interrupted. This risk is usually mitigated by the use of hypothermia and cardiopulmonary bypass. As the mainstay of treatment for CTAAs for over four decades, OSR has been demonstrated to reduce mortality and can be performed reproducibly in cardiac surgical centres. 11,12 Techniques have improved, but OSR still carries a risk of mortality of around 5% and of paraplegia of around 10%. 13

In ESG, a covered stent or frame (stent graft) is inserted into the arterial system at a peripheral access point (usually the femoral artery in the groin) and guided using X-rays to the aneurysm site. At the target segment, the stent springs open and fixes to the normal aorta above and below the aneurysm, so that the aneurysm is sealed and blood flows through the stent graft. The aneurysm outside the stent graft has no flowing blood and clots; thus, it is excluded from the circulation and the risk of rupture is very low. ESG for CTAAs is a more recent and less invasive technique, with reported risk of in-hospital mortality of 2–10%. It is technically feasible in many patients and excludes the aneurysm from the circulation, with shrinkage or stabilisation of the aneurysm sac in most cases, at least initially. Unfortunately, the procedure cannot be performed in all patients because it has specific anatomical requirements. It is resource intensive, as the stent grafts themselves are expensive, and it requires a hybrid theatre and an appropriate theatre team, but it does lead to a shorter length of stay and usually faster recovery. In the long term, patients who receive ESG need to be monitored as there may be leakage around/between stent components that requires urgent reintervention.

For some patients a hybrid procedure, including both stent components and surgical components, is necessary. For example, a minor surgical procedure may be completed in the patient’s neck to protect the cerebrovascular blood supply after arch stenting, thereby facilitating the endovascular placement of a stent into the arch of the aorta. When the ETTAA study began, these hybrids were most prevalent, and such patients were intended for the ESG arm, as the stent graft was considered (clinically) the predominant intervention. Alternatively, an endovascular stent may be placed into the DTA at the same time as the arch is replaced in an open surgical procedure. During the ETTAA study, these approaches became more prevalent when a hybrid graft became available. The hybrid graft is half surgical prosthesis–half stent and is inserted during open surgery, with the patient usually undergoing median sternotomy. In such cases the surgery is the predominant procedure, so these hybrid patients were placed in the OSR arm of the study.

Treatment decisions

Endovascular stent grafting and OSR are considered for arch/DTA aneurysms when the risk of rupture/dissection or death exceeds the risks associated with intervention. Risk of rupture is mostly determined by aneurysm size, measured using CT or MRI. 14,15

When the ETTAA study launched in 2014, clinical practice was informed by the 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for the diagnosis and management of thoracic aortic disease16 and the 2014 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases. 17 These guidelines were written by international panels of clinical experts, based on the available evidence. The American guidelines advised that operative treatment was reasonable for patients at low operative risk who had an arch aneurysm of > 5.5 cm in diameter. The level of evidence supporting this recommendation is classified as ‘B – multiple non-randomised studies of surgery versus conservative management’ in the hierarchy of evidence. 18 The European guidelines advised that an endovascular procedure ought to be considered in patients for whom it was technically feasible, but that, if surgery (OSR) were the only option, then it should be planned after the aortic diameter reached 6.0 cm. The level of evidence for the European guidelines was classified as ‘C – consensus of opinion of the experts and/or small studies, retrospective studies, registries’ in the hierarchy of evidence. 18 The main body of evidence considered by both committees came largely from data obtained from Yale University publications,19,20 alongside data from the American International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissections (IRAD) database21 and, to a lesser extent, the European German Registry for Acute Aortic Dissection Type A (GERAADA) data set22 and the International Aortic Arch Surgery Study Group's ARCH projects. 23 Analysis of the Yale registry of acute aortic dissections and ruptures indicated that the risk of life-threatening dissection or rupture dramatically increases at a diameter of 6 cm and outweighs the 5–10% risk of death, stroke or paralysis from procedural intervention. 19,20,23

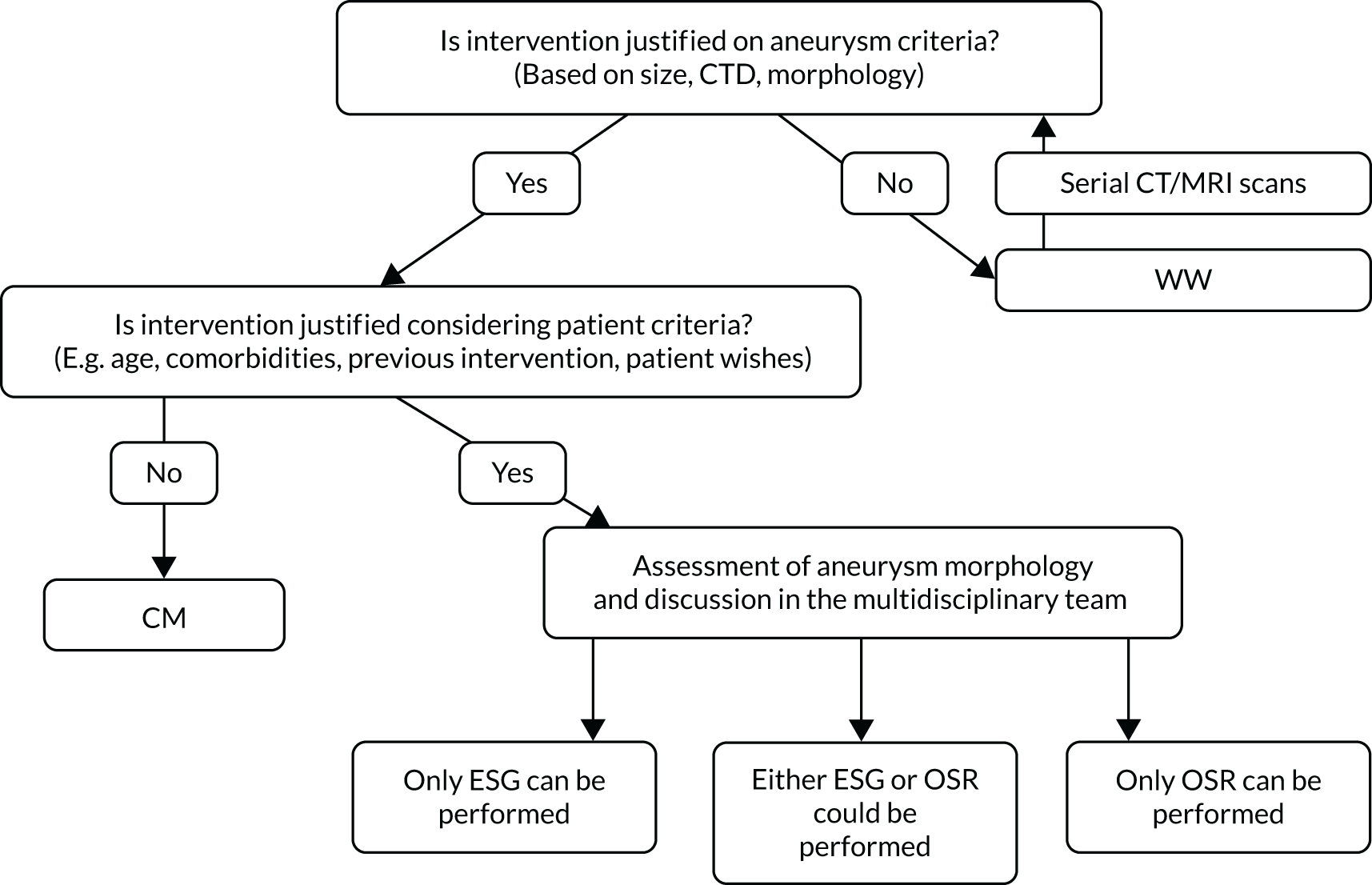

Taking the two guidelines together, and especially considering that many patients requiring arch surgery may not be considered at ‘low surgical risk’, the general practice in the UK in 2014 was to consider intervention with OSR or ESG when an arch/DTA aneurysm became > 6 cm in diameter. 16,17 Clinical opinion at the start of the ETTAA study is explored more comprehensively in Chapter 2, but it is useful to state here that the risks of intervention are influenced by a variety of factors and are different for every patient. At present, there are no national or international guidelines addressing patient selection for WW, CM, ESG or OSR. In the absence of such guidelines, specialist multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) play a key role in assessing the risk–benefit profile of each patient before recommending a treatment pathway (Figure 2). Ultimately, the choice of treatment is made by the patient after appropriate explanation and discussion.

FIGURE 2.

Multidisciplinary team decision-making process for treatment for CTAAs.

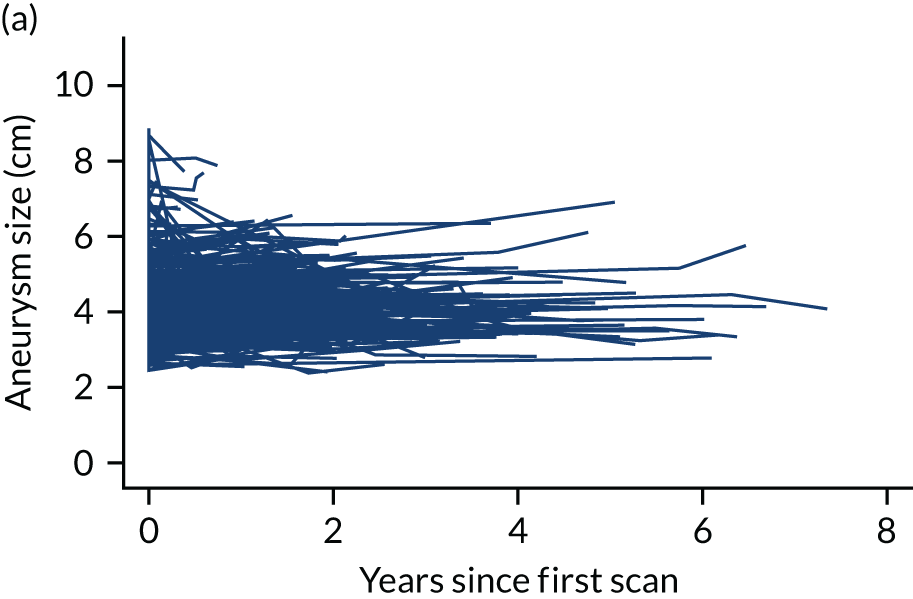

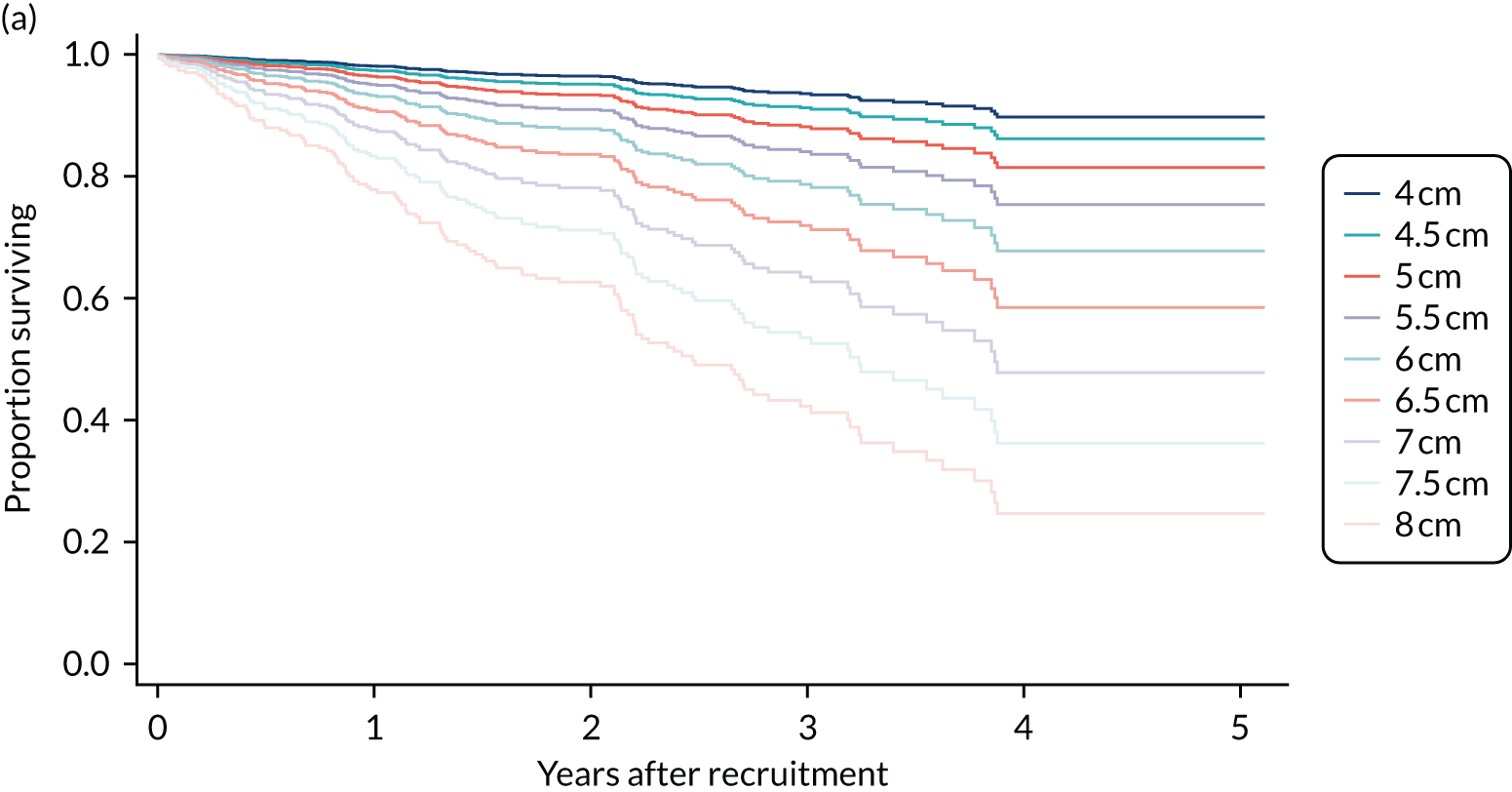

Natural history of arch/descending thoracic aorta aneurysms

To determine the benefits and effectiveness of intervention for arch/DTA aneurysms, it is necessary to understand what would happen without intervention. Unfortunately, contemporary studies of the natural history of CTAAs are rare. The most up-to-date analysis of this disease comes from the Yale registry and was published in 2015. 24 With aneurysms of > 6 cm in diameter, the Yale group suggests that the annual risks of dissection, rupture and death are 3.6%, 3.7% and 10.8%. 19 There is, however, increasing evidence that aneurysm diameter is not the only important predictor of risk; a 2011 review of the IRAD database showed that 60% of patients with arch/DTA dissections had aortic diameters of < 5.5 cm at the time of dissection, below the accepted threshold for intervention. 25 After aortic size, presence of CTDs and aneurysm growth rate have been associated with an increased risk of aortic dissection/rupture, along with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension and older age. All of these factors must be considered when judging the relative risks and benefits of management options.

Mean aortic arch growth rates have been reported in the range 0.09–0.56 cm per year, and mean DTA growth in the range 0.12–1.44 cm per year. Rare reports of regression of DTA aneurysms (up to 0.12 cm per year) were confined to cases of chronic dissection where thrombosis in the layers of the aortic wall accounted for the shrinkage. 26–28 Key factors that have been associated with aneurysm growth include aneurysm size, patency and size of the false lumen, number and location of tears around the arch, peak wall stress, comorbidities (hypertension, CTD, COPD), patient characteristics (age, sex, smoking history) and anticoagulant treatment. Owing to a lack of high-quality, consistently-recorded data, no large-scale multivariate regression analysis has been possible and no clear relationship between the risk factors and growth rate has emerged. 8 Two studies have generated prediction models for future aneurysm size using initial diameter and based on single-centre data; neither has been validated in a prospective clinical cohort. 29,30

Outcomes following intervention

Systematic review of outcomes

As part of the ETTAA study, a systematic review was conducted in January 2016 to assess the available evidence regarding the effectiveness of ESG compared with OSR for CTAA in the aortic arch or DTA. The review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42017054565)31 and details can be found in the published article. 32

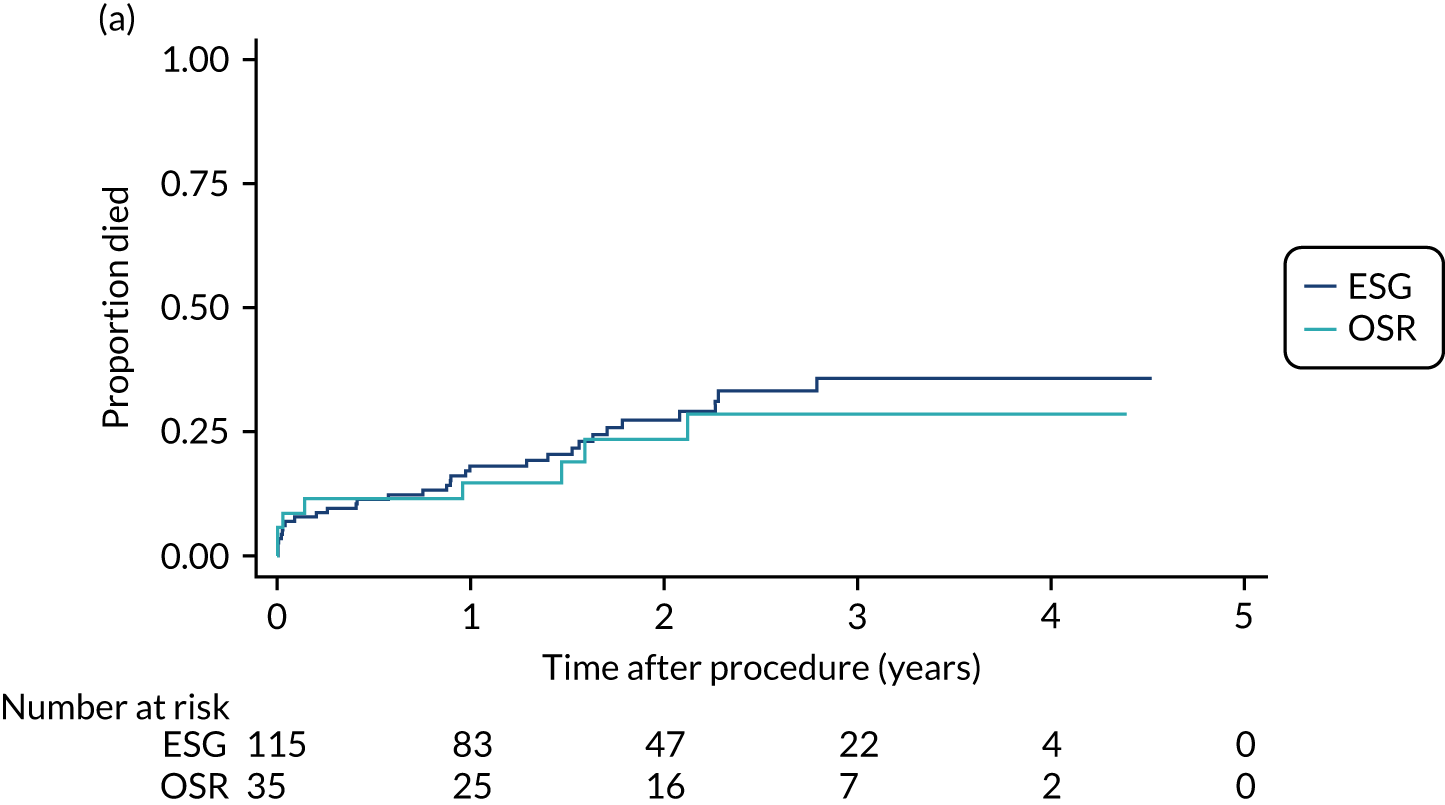

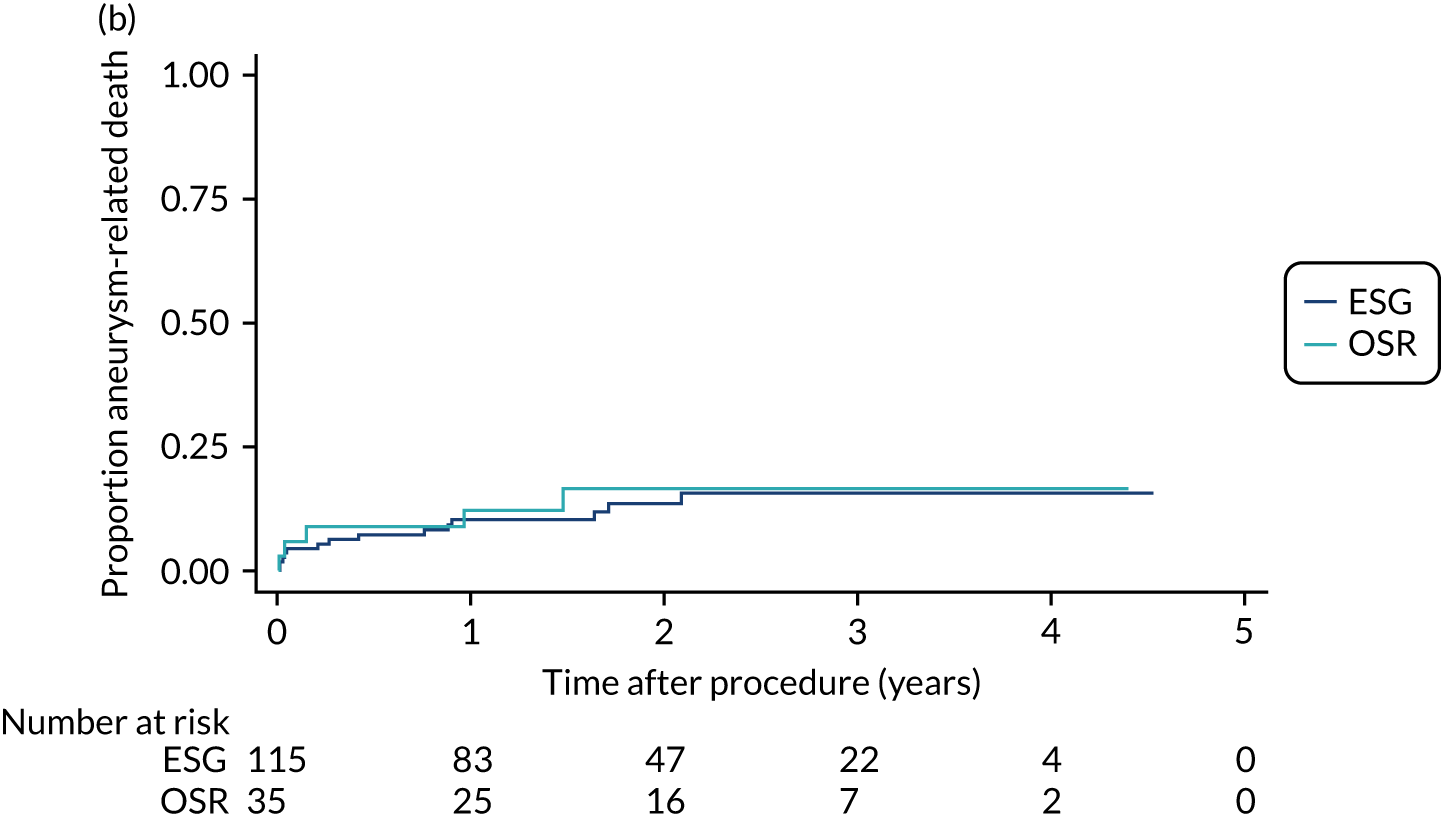

Briefly, no randomised studies comparing ESG and OSR have been published. Cohort studies and case–control studies matched on key outcomes were included if patients had elective treatment for arch/DTA aneurysms and some attempt had been made to adjust for selection bias. Five comparative cohort studies met the inclusion criteria, reporting a total of 3955 ESG and 21,197 OSR patients. In accordance with the ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions) tool,33 one study was judged to be at moderate risk of bias34 and the remaining four were judged to be at severe risk of bias because of the potential for confounding. 35–39 Early mortality rates (30 days or to discharge) ranged from 3.1% to 6.1% after ESG and from 1.5% to 20% after OSR, with extreme rates arising from small studies. The meta-analysis of unadjusted short-term all-cause mortality favoured ESG [odds ratio 0.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.55 to 0.1.03]. Adjusting for heterogeneity between small and large studies, the odds ratio did not change substantially (0.71, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.98). Meta-analysis of long-term all-cause mortality could not be carried out owing to differences in how results were reported. Overall, the long-term mortality was higher for ESG in larger studies and higher for OSR in smaller studies. For example, in von Allmen et al. ’s study36 of 618 patients, the hazard ratio (HR) for ESG relative to OSR up to 5 years, adjusting for age and sex, was 1.45 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.94; p = 0.013). Conversely, the Gore TAG study of 234 patients reported identical survival of 63% to 5 years for the two groups (log-rank p = 0.625),35 and the study of 28 patients by Piffaretti et al. 39 reported higher (non-significant) long-term survival with ESG. Freedom from reinterventions in the long-term also favoured OSR.

Overall, studies reporting short-term non-fatal complications suggested fewer events following ESG, although limited data prevented meta-analysis (Table 1). 35–39 However, Hughes et al. ’s 2014 study38 of 8967 patients reported lower odds of neurological complications (odds ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.86; p = 0.015), pulmonary complications (odds ratio 0.38, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.67; p = 0.001) and cardiac complications (odds ratio 0.24, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.37; p < 0.001) for ESG patients. The Gore TAG study35 reported a substantial endoleak rate for ESG patients of 8.5%.

| Complication | Number (%) of events | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gore TAG 200735 | Piffaretti et al. 200739 | Hughes et al. 201438 | ||||

| ESG group (N = 140) | OSR group (N = 94) | ESG group (N = 17) | OSR group (N = 11) | ESG group (N = 712) | OSR group (N = 8255) | |

| Neurological | ||||||

| Paraplegia/paraparesis | 4 (3) | 13 (14) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Cerebral vascular accident | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 2 (9) | 1 (12) | NR | NR |

| Neurological: unspecified | NR | NR | NR | NR | 20 (2.8) | 273 (3.3) |

| Respiratory | ||||||

| Respiratory failure | 5 (4) | 19 (20) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Pneumonia | NR | NR | 2 (12) | 3 (27) | NR | NR |

| Pulmonary: unspecified | NR | NR | NR | NR | 17 (2.4) | 462 (5.6) |

| Cardiac | ||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | NR | NR |

| Cardiac: unspecified | NR | NR | NR | NR | 28 (2.9) | 1252 (15.2) |

| Other | ||||||

| Endoleaks | 12 (8.5) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 20 (14) | 4 (4) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Although this systematic review was, to our knowledge, the first to consider evidence from non-randomised studies directly comparing ESG and OSR for treatment of elective arch/DTA aneurysms in CTAA patients, it identified increasingly dated evidence only, and this was limited by either small size or severe risk of bias. The conflicting evidence reinforced the need for updated evidence on UK practice and comparisons of short- and long-term outcomes of ESG and OSR.

Additional important studies reporting outcomes

Five relatively large, recent cohort studies40–44 reported clinical and cost outcomes but were not eligible for the systematic review because of the inclusion of a heterogeneous cohort. All five studies acknowledged important differences between ESG and OSR cohorts, which resulted in biased comparisons. ESG tended to be chosen for older patients with more comorbidity, many of whom may have been unsuitable for OSR. Despite this, the risk of death, paraplegia or other complications appeared to be lower after ESG than after OSR. Conversely, the need for reintervention was greater after ESG as a result of technical failures of the stent over time, and with each reintervention there was an added risk of complication owing to either the increased complexity of the procedure or the deteriorating health of the patient. One UK44 and one US41 study compared the costs of ESG against those of OSR procedures in the context of CTAAs. Both studies found open surgery to be more expensive by approximately US$6700 and £1650, but they considered in-hospital cost only, excluding reintervention. No formal economic evaluation has been performed. Therefore, there is a lack of economic data to guide decision-makers in allocating the scarce resources available.

Relationship with abdominal aortic aneurysms

Because aneurysms in the abdominal aorta are more prevalent, the evidence base for intervention with both endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) and open surgery is stronger for abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). In particular, the EVAR-1 randomised clinical trial (RCT) compared these techniques, initially showing a significant but short-lived benefit for the patients receiving EVAR. At the end of 15 years, the effect was reversed, with a significant advantage in overall survival for those who had received OSR, because of late complications and rupture in the EVAR group. Based on cost-effectiveness analysis of EVAR compared with open repair, draft guidelines for aneurysm repair from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), published in 2018,45 concluded that EVAR is not cost-effective and should not be used in fit or unfit patients with a non-ruptured aneurysm. After unprecedented stakeholder concern and intervention from NICE, the guidelines were revised and finally published. 46 The guidelines state that ‘where open surgical repair can’t be carried out – for example because of medical or anaesthetic risks – EVAR can be considered’46 (© NICE 2020 NICE Publishes its Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Available from www.nice.org.uk/news/article/nice-publishes-its-guideline-on-the-diagnosis-and-management-of-abdominal-aortic-aneurysms. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication). However, cost-effectiveness is clearly an increasingly important issue, given increasing health-care costs, and studies that attempt to find cost-effective improvements are needed.

The ETTAA study

Both ESG and OSR are effective in some patients with CTAAs, but both are associated with significant complications. Currently, there is no consensus on either best management strategy or timing of interventions and there are no UK-specific economic studies that assess outcomes beyond the chosen procedure. Further evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of ESG and OSR is needed, given the increasing demand for treatment (an ageing population with a rising prevalence of CTAAs)2 and limited NHS resources. The relatively low incidence of aneurysms in the thoracic aorta means that the feasibility of a trial is unclear. Therefore, the ETTAA study was designed as an observational study to document current practice in the management of CTAAs of the arch/DTA in the NHS, and to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the available treatment strategies, adjusting for selection bias.

Aims of the ETTAA study

The overall aims of the ETTAA study are to describe the pathways undertaken by current NHS patients who are diagnosed with CTAAs, to estimate the natural history of patients prior to endovascular or open surgical procedures and to compare clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness between the intervention groups.

Specifically, we aimed to answer the following questions:

-

Without procedural intervention for CTAAs, what is the risk of aneurysm growth, dissection, rupture, permanent neurological injury or death, and how does health-related quality of life (HRQoL) change over time?

-

If a patient receives ESG or OSR, what is the risk of dissection, rupture, permanent neurological injury or death?

-

What factors affect aneurysm growth pre intervention?

-

Can aneurysm- or patient-related predictors of treatment outcomes be determined?

-

What is the most cost-effective strategy in patients eligible for both ESG and OSR?

-

What further research is required?

The report is organised as follows. Chapter 2 reports a study of clinical expert opinion on the current management of CTAAs. Chapter 3 provides an overview of methods employed in the ETTAA study and a description of the resulting cohort. Chapters 4–7 describe the specific methods and results of the analysis of clinical and HRQoL outcomes (see Chapter 4), post-intervention clinical and HRQoL outcomes (see Chapter 5) and bias-adjusted clinical and HRQoL outcomes (see Chapter 6), and of the health economic analysis (see Chapter 7). Chapter 8 provides a discussion of the results and implications for service and future research.

Chapter 2 Expert clinical views at the start of the ETTAA study

Introduction

The ETTAA study was designed to identify the strengths and weaknesses of established practice. An integral consideration when comparing the outcomes in different treatment groups is how patients are selected for treatment. This chapter reports on a consensus study that aimed to understand how aneurysm features and patient characteristics influence treatment decisions in the UK. The main objective was to understand when there is clinician consensus regarding appropriate treatment methods for patients with CTAAs according to predefined criteria, what thresholds for intervention are commonly adopted and when clinicians are in equipoise between different treatment methods and, therefore, further research is required.

Methods

Preparation of resources

An initial design period involved production of study resources, including assembling an expert panel, defining clinical criteria and designing the study questionnaire. Thereafter, the consensus study was carried out in two rounds, combining features of both the Delphi survey technique and the nominal group technique. 47 The Delphi technique uses questionnaires and anonymised responses from experts to identify consensus where it exists. The nominal group technique allows further refinement of consensus in a face-to-face meeting of the panel (the nominal group), where experts discuss reasons for their decisions with the group and have the opportunity to revise their decision. The two rounds are described in greater detail below. The initial Delphi survey was conducted during autumn 2015 and the nominal group technique meeting was held in January 2016.

Assembling the expert panel

Invitations to form an expert panel were sent to cardiothoracic and vascular surgeons, cardiologists, interventional radiologists and anaesthesiologists who participated in thoracic aortic MDTs at 29 UK centres recruiting patients to the ETTAA study. These centres had already been identified as having significant experience in managing patients with arch, DTA and thoracoabdominal aneurysms during recruitment to the ETTAA study. Respondents were specialists who had expertise and significant experience in open or endovascular surgery, or both.

Defining case scenarios

Vascular and cardiothoracic surgeons in the ETTAA team compiled a list of patient and aneurysm factors that they considered influential in making treatment decisions regarding CTAAs. Initially, more than 20 factors were identified. However, to include all possible combinations of factors and levels would generate many millions of case scenarios (cases). Although these combinations (case scenarios) allow granularity of the information obtained by the consensus exercise, the elicitation of all combinations would result in fatigue/disengagement of members of the expert panel and so was not feasible. Thus, comorbidities related to the risk of surgical intervention or the operative fitness of the patient were included under the umbrella term of ‘high, medium or low risk of (open surgery) intervention’. After discussion, five characteristics with two to five levels remained (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Level |

|---|---|

| CTD | Present |

| Absent | |

| Aneurysm location | Aortic arch |

| DTA | |

| Thoracoabdominal aorta | |

| Age (years) | < 65 |

| 65–75 | |

| 76–85 | |

| > 85 | |

| Aneurysm size (maximum orthogonal diameter in cm) | < 5.0 |

| 5.1–6.0 | |

| 6.1–7.0 | |

| 7.1–8.0 | |

| > 8.0 | |

| Risk of open surgery | Low |

| Medium | |

| High |

Questionnaire design

A total of 360 case scenarios were developed in a factorial design of the attributes given in Table 2 and considered a good compromise between granularity and feasibility. These scenarios were grouped into six sections based on aneurysm location and presence or absence of CTD. The order in which experts completed the sections was randomised to minimise bias due to responder fatigue. The questionnaires were e-mailed to participants to be printed, completed and returned by post or e-mail.

Round 1: Delphi survey

For each clinical scenario, participants scored the ‘appropriateness’ of all four management options by indicating how strongly they considered each treatment option to be ‘appropriate’ on a scale of 1–9, where one represented ‘not at all appropriate’, five represented ‘just appropriate’ and nine represented ‘most appropriate’ (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for an example of a completed Delphi survey). Experts were guided to score for all four treatment methods for each clinical scenario and to avoid just marking the most ‘appropriate’. When an expert recorded ‘most appropriate’ for more than one management approach, this suggested equipoise for that expert.

When completing the scores, experts were asked to represent the opinion of their local multidisciplinary team as far as possible and to follow established definitions for clinical attributes. For each scenario, experts could assume that WW, CM, ESG and OSR were available, with no anatomical/morphological contraindications. ‘Hybrid’ interventions that included a component of conventional surgery as well as an endovascular stent graft were classified as OSR if they involved opening a body cavity (e.g. visceral artery bypass, re-implantation of innominate artery origin) and otherwise as endovascular repair (e.g. carotid to subclavian bypass through neck incision). No specific stipulations were given regarding methods of assessing the risk of intervention, but panel members were asked to follow local standard clinical practice.

Data analysis: round 1

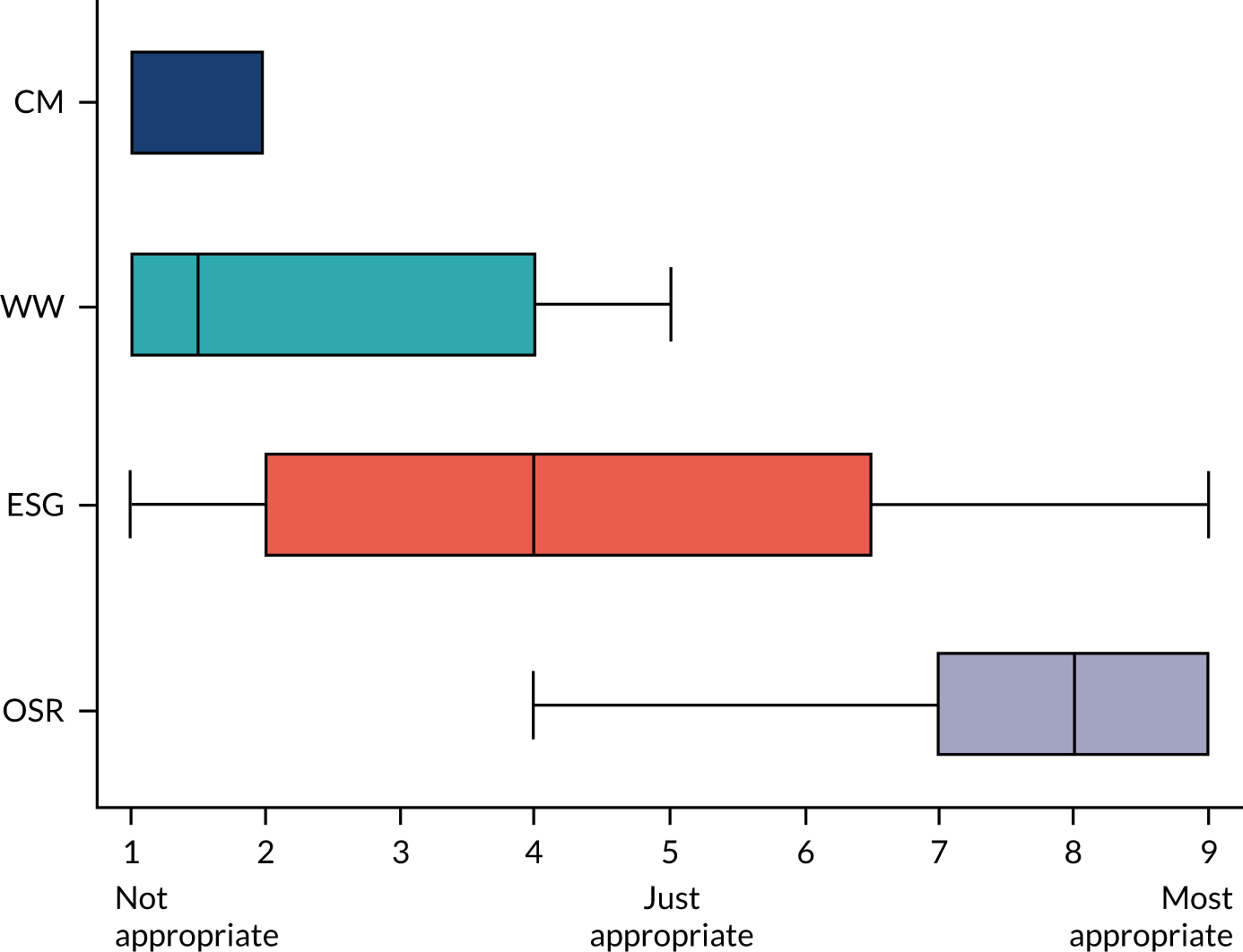

The anonymised results of round 1 were summarised as medians, interquartile ranges and whole ranges using box-and-whisker plots. For example, Figure 3 depicts the scoring for a clinical scenario with a median ‘appropriateness’ score of eight for OSR (range 4–9, interquartile range 7–9).

FIGURE 3.

Example of round 1 results for one clinical scenario: aneurysm size of 7.1–8 cm in diameter, in the aortic arch, in a patient with no connective tissue disorder, aged < 65 years and of low surgical risk.

To assess disagreement and appropriateness (and, thus, define consensus) the Research ANd Development (RAND)/University of California Los Angeles appropriateness method was used. 48 This considers the dispersion of individual scores and identifies scenarios in which expert responses are clustered at either end of the 9-point Likert scale, so that consensus is evident. Fitch et al. 48 argue that in cases when agreement is good, the distribution of responses should be narrow, and in cases where there is disagreement, the distribution should be wider. The width of the distribution is measured by the range between the 30th and 70th percentile, known as the interpercentile range (IPR). However, Fitch et al. 48 found that, in general, the IPR required for disagreement was smaller when responses were symmetrical than when they were asymmetrical, with respect to the middle of the distribution. To overcome this, they developed the asymmetry-adjusted IPR (IPRAS), which includes a correction factor for asymmetry. In this method, disagreement between experts is concluded for the ith scenario if the IPR > IPRAS for that scenario, or, conversely, IPR ≤ IPRAS indicates consensus. Clinical scenarios for which consensus was demonstrated in round 1 were noted and these were not taken into round 2.

Round 2: nominal group technique

Round 2 was completed at a face-to-face meeting of the expert panel moderated by one of the investigators (SRV). For each clinical scenario entering round 2, ‘appropriateness’ scores of the treatment options from round 1 were displayed as box-and-whisker plots, as demonstrated in Figure 3. The expert panel was given 60 seconds to study each summary, after which a brief discussion was held in which individual experts explained the reasons for their treatment choice. The role of the moderator was to clarify ambiguities, ensure a balanced discussion, give everyone a chance to express their opinion to the group and explore reasons for divergent views. It was decided prospectively that each expert would be given a maximum of 60 seconds of uninterrupted time to express opinions. Experts were concise, discussions were constructive and curtailment by the moderator was never required. After each discussion, individual experts were asked to select their single most ‘appropriate’ management strategy or to indicate more than one treatment method if there was equipoise between them.

Data analysis: round 2

In round 2 consensus was defined if the same management was chosen by ≥ 70% of participants; otherwise, there was no consensus. If there was no consensus, and ≥ 33% of participants thought that (the same) two management options were equally effective, equipoise about the choice of management was defined.

Results

Round 1: Delphi survey

Twenty experts from 13 centres returned round 1 scores. The expert panel consisted of an anaesthetist, an interventional radiologist, five cardiac surgeons and 13 vascular surgeons. Among the 360 scenarios considered, consensus was reached in 167 (46%) and the remaining 193 were discussed in round 2. The consensus achieved in round 1 was predominantly that WW was most appropriate for cases involving smaller aneurysms (< 6.0 cm in diameter), OSR was most appropriate for arch aneurysms in low-risk scenarios and ESG was most appropriate for DTA aneurysms in low- or medium-risk patients without CTDs.

Round 2: nominal group technique

Twelve experts, nine vascular surgeons and three cardiac surgeons took part in round 2, during which consensus was reached for a further 80 (22%) scenarios and equipoise between two different treatment modalities was noted for 34 (9%) scenarios, leaving neither consensus nor equipoise for a total of 79 scenarios (22%). Outcomes at the end of round 2 are presented in Tables 3 (aneurysms of ≤ 6.0 cm in diameter) and 4 (aneurysms of > 6.0 cm in diameter).

| Aneurysm site | Aneurysm size (cm) | Patient age (years) | No CTD | CTD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | Medium risk | High risk | Low risk | Medium risk | High risk | |||

| Aortic arch | < 5.0 | < 65 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW |

| 65–75 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | ||

| 75–85 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | ||

| > 85 | WW | No consensus | CM | WW | No consensus | CM | ||

| 5.1–6.0 | < 65 | WW | WW | WW | No consensus | No consensus | WW | |

| 65–75 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | ||

| 75–85 | WW | WW | WW | WW/OSR | WW | WW | ||

| > 85 | WW | WW | No consensus | OSR | OSR | WW | ||

| DTA | < 5.0 | < 65 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW |

| 65–75 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | ||

| 75–85 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | ||

| > 85 | No consensus | No consensus | CM | WW | CM | CM | ||

| 5.1–6.0 | < 65 | WW | WW | WW | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | |

| 65–75 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | ||

| 75–85 | WW | WW | WW | WW/OSR | WW/OSR | WW | ||

| > 85 | WW | WW | WW | WW/OSR | WW/OSR | WW | ||

| Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms | < 5.0 | < 65 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW |

| 65–75 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | ||

| 75–85 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | No consensus | ||

| > 85 | No consensus | CM | CM | WW | No consensus | CM | ||

| 5.1–6.0 | < 65 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | |

| 65–75 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW/CM | ||

| 75–85 | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | WW | ||

| > 85 | No consensus | No consensus | CM | WW/OSR | WW | CM | ||

| Aneurysm site | Aneurysm size (cm) | Patient age (years) | No CTD | CTD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | Medium risk | High risk | Low risk | Medium risk | High risk | |||

| Aortica arch | 6.1–7.0 | < 65 | No consensus | No consensus | CM | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus |

| 7.1–8.0 | OSR | No consensus | CM | OSR | No consensus | No consensus | ||

| > 8.0 | OSR | CM/ESG | CM | OSR | No consensus | ESG/OSR | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | 65–75 | OSR | ESG/OSR | No consensus | OSR | OSR | No consensus | |

| 7.1–8.0 | OSR | ESG/OSR | CM/ESG | OSR | ESG/OSR | CM/ESG | ||

| > 8.0 | OSR | ESG/OSR | CM | OSR | ESG/OSR | CM/ESG | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | 76–85 | OSR | OSR | No consensus | OSR | OSR | No consensus | |

| 7.1–8.0 | OSR | OSR | ESG | OSR | OSR | No consensus | ||

| > 8.0 | OSR | OSR | No consensus | OSR | OSR | No consensus | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | > 85 | OSR | OSR | No consensus | OSR | OSR | No consensus | |

| 7.1–8.0 | OSR | OSR | No consensus | OSR | OSR | No consensus | ||

| > 8.0 | OSR | OSR | ESG/OSR | OSR | OSR | ESG | ||

| DTA | 6.1–7.0 | < 65 | ESG | ESG | CM | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus |

| 7.1–8.0 | ESG | ESG | CM | ESG | No consensus | No consensus | ||

| > 8.0 | ESG | ESG | CM | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | 65–75 | ESG | ESG | No consensus | ESG | ESG | No consensus | |

| 7.1–8.0 | ESG | ESG | ESG | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | ||

| > 8.0 | ESG | ESG | ESG | No consensus | No consensus | CM/ESG | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | 76–85 | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG/OSR | ESG/OSR | ESG | |

| 7.1–8.0 | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG/OSR | ESG | ||

| > 8.0 | ESG | ESG | ESG | OSR | ESG/OSR | ESG | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | > 85 | ESG | ESG | ESG | OSR | OSR | ESG | |

| 7.1–8.0 | ESG | ESG | ESG | OSR | OSR | ESG | ||

| > 8.0 | ESG | ESG | ESG | OSR | ESG/OSR | ESG | ||

| Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms | 6.1–7.0 | < 65 | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus |

| 7.1–8.0 | No consensus | ESG | ESG | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | ||

| > 8.0 | No consensus | ESG | ESG | OSR | No consensus | No consensus | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | 65–75 | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | |

| 7.1–8.0 | ESG | ESG | CM | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | ||

| > 8.0 | ESG | ESG | CM/ESG | No consensus | No consensus | No consensus | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | 76–85 | ESG/OSR | ESG/OSR | ESG | OSR | OSR | No consensus | |

| 7.1–8.0 | ESG/OSR | ESG/OSR | ESG | OSR | OSR | No consensus | ||

| > 8.0 | ESG/OSR | ESG | ESG | OSR | OSR | No consensus | ||

| 6.1–7.0 | > 85 | No consensus | ESG/OSR | ESG | OSR | OSR | CM | |

| 7.1–8.0 | OSR | ESG/OSR | ESG | OSR | OSR | CM | ||

| > 8.0 | ESG/OSR | ESG/OSR | ESG | OSR | OSR | CM | ||

Aneurysms of ≤ 6.0 cm in diameter (144 scenarios; see Table 3)

Watchful waiting was generally the preferred management for patients with aneurysms of ≤ 6.0 cm in diameter (110/144, 76% scenarios), regardless of the presence of CTDs or the location of the aneurysm (arch, DTA or thoracoabdominal). Notable exceptions, mainly for older patients, were:

-

CM was preferred for most high surgical risk patients, aged > 85 years, for all aneurysm sites.

-

OSR was preferred for patients with CTDs, with arch aneurysm of 5.0–6.0 cm in diameter and > 85 years of age, if at low or medium surgical risk.

-

Equipoise was found between WW and OSR for older patients with CTDs and with low surgical risk and aneurysms of 5.1–6.0 cm in diameter.

No consensus was reported for 10% of the clinical scenarios in which aneurysms were of < 6.0 cm in diameter. This was mainly for low- to medium-risk patients aged > 85 years or patients with CTDs aged < 65 years.

Aneurysms of > 6.0 cm in diameter (see Table 4)

For patients with aneurysms of > 6.0 cm in diameter, clinical decisions were influenced by, in order, aneurysm site, surgical risk and age group, rather than by aneurysm size (see Table 4).

Aortic arch

In terms of aneurysms of > 6.0 cm in diameter experts favoured OSR over ESG in the arch, regardless of CTD status, for low- or medium-risk patients aged > 75 years, as well as for most low-risk patients aged ≤ 75 years. Clinicians were in equipoise between OSR and ESG for medium-risk patients aged 65–75 years with arch aneurysms of > 6.0 cm in diameter. There was uncertainty and a general lack of consensus about what to offer patients at high surgical risk, with the exception that experts generally preferred CM for high-risk non-CTD patients aged ≤ 75 years. There was also little consensus among experts on treatment for younger (aged < 65 years) patients at medium surgical risk (with or without CTD) or for younger low-risk patients with aneurysms of 6.1–7.0 cm in diameter.

Descending thoracic aorta

There was consensus that ESG should be offered to non-CTD patients with DTA aneurysms of > 6.0 cm in diameter. CM was recommended only for high-risk patients aged ≤ 65 years. There was little or no consensus on how to treat DTA aneurysms in CTD patients aged ≤ 75 years, although experts agreed that ESG should be recommended for older CTD patients at high operative risk. In general, for CTD patients, there was equipoise between ESG and OSR for those aged 75–85 years at medium surgical risk, and consensus for OSR for those aged > 85 years at low/medium surgical risk.

Thoracoabdominal aneurysms

There was no consensus on treatment for thoracoabdominal aneurysms of 6.1–7.0 cm in diameter for patients aged < 65 years, regardless of CTD status. For younger non-CTD patients (aged ≤ 75 years) with aneurysms of > 7.0 cm in diameter, ESG was often recommended, except for high-risk patients, for whom CM was considered. For older (aged > 75 years) non-CTD patients, ESG was supported for patients at high surgical risk, whereas both ESG and OSR were considered ‘appropriate’ for patients at low or medium surgical risk. For CTD patients aged ≤ 75 years, there was no consensus on ‘appropriate’ treatment. For older (aged > 75 years) CTD patients at low or medium risk, OSR was the treatment of choice, with the oldest high-risk patients considered suitable for CM.

Summary of findings

This chapter reports expert opinion among UK specialists regarding the most ‘appropriate’ management for 360 clinical scenarios relating to thoracic aortic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. Pathophysiology, natural history of disease, technical aspects relevant to open surgery and ESG are different between the aortic arch, DTA and thoracoabdominal aorta, so they need to be considered separately.

For patients with aneurysms of < 6.0 cm in diameter, there was clear consensus for WW in the majority of patient scenarios, including those in the arch and irrespective of the presence or absence of CTDs. This differs from ascending aortic aneurysms, for which the threshold for surgical intervention in CTD patients is lower (5.0 cm) than for non-CTD patients. This may reflect the fact that surgical repair of the ascending aorta can be offered with much lower operative risks than arch repair.

For larger aneurysms in the aortic arch, OSR was the treatment of choice in older patients provided that operative risk was acceptable, but there was little consensus among experts on the management of younger patients or high-risk patients. Aneurysms of the arch pose particular challenges for ESG as multiple cerebral emboli are associated with the use of endovascular stents and, therefore, there is a high risk of stroke. 49,50 Thus, OSR was preferred in the majority of cases where intervention was considered ‘appropriate’.

Conversely, there was consensus that ESG should be offered to patients with DTA aneurysms of > 6.0 cm in diameter. This is unsurprising given that the risk of paraplegia is significantly lower with ESG than with OSR and that the DTA procedure is more straightforward than ESG in the arch. Experts also recorded consensus for ESG for large aneurysms in the DTA in CTD patients at high operative risk, despite conventional ‘wisdom’ that implanting stents in the intrinsically weak aortic tissue of CTD patients should be avoided. 51–53

For the oldest patients, CTD played an influential role in decisions. Clinicians tended to prefer intervention for smaller aneurysms in patients with CTDs, possibly because of concerns that complications are seen with aneurysms of smaller diameters in this population. The presence of CTDs poses a particular threat to the durability of ESG, compared with absence of CTDs. 54 The consensus reflects a reluctance to use ESG in patients with CTD, particularly in younger and lower-risk cohorts. However, the anatomical features of the DTA conferred a consensus for ESG, even in the presence of CTDs, especially if operative risk was high.

Thoracoabdominal aneurysms are currently treated by ESG in anatomically suitable patients. 55 A consensus for the use of this technique was noted for patients without CTD, with OSR remaining the preferred choice in the majority with CTD.

Unsurprisingly, our findings are in line with recommendations in previously published guidelines,17 but they provide greater detail. They also reflect the importance of aneurysm diameter in the timing of intervention, the perceived benefits of endovascular techniques and the consequences of CTDs.

Our study has some methodological limitations. During study design, we could not identify an objective, widely understood measure of surgical risk. Decisions relied on each participant’s perception of surgical risk category, which may have differed between experts, particularly if they were from different centres or surgical specialties. The methods require us to categorise patient and aneurysm characteristics, but each patient and aneurysm repair might be considered unique, and we were not able to capture all important aspects affecting management decisions. In addition, we did not include aneurysm growth rate as an indication for operation because it would have greatly increased the number of clinical scenarios and growth cannot always be distinguished from random variation in aneurysm measurement. Although we drew participants from as wide a range as possible, all experts practised at UK NHS centres, and worked in multidisciplinary teams that included open surgical and endovascular expertise. Consensus was based on 12–20 participants who may not fully represent their local practice. Analysis of the empirical data from the ETTAA study will demonstrate how closely UK clinical practice aligns with the reported consensus in this study.

One reason for undertaking an early Delphi study was to identify patients for whom clinicians have equipoise between ESG and OSR. Perceived equipoise was found in only a few scenarios by our definition, although we stress that the study is based on practice reported by experts rather than on more objective data. The size of patient groups for which there is equipoise is also unclear. Chapters 3–7 report analysis of CTAA patient management in the NHS, both before and after undergoing a procedure.

Chapter 3 Cohort construction, data and study management and general methods

Introduction

In this chapter we describe the methods for constructing the ETTAA cohort and provide an overview of the design and analysis of planned work packages. The methods for each work package are described in greater detail in the relevant chapters. We also describe the main characteristics of recruited patients and their procedures. We stress here that the ETTAA study was designed as an observational study and we did not intervene in routine practice; rather, we describe management strategies and outcomes for existing patients. As with any observational study, biases can arise from measured and unmeasured confounders, informative dropouts, missing data and other selection strategies; our emphasis is on accommodating biases in the analysis as far as possible and on acknowledging residual bias in results where necessary.

Aims of the project overall

The overall aims of this project are to describe the pathways undertaken by current NHS patients who are diagnosed with CTAA, to compare outcomes between the main treatment groups using modern methods for addressing the biases inherent in non-randomised studies, and to provide inputs for a health economics model.

The specific questions are listed in Chapter 1, along with planned work.

To meet the aims of the ETTAA study, we had the following objectives:

-

to follow patients with CTAA, prospectively recording management, patient characteristics, clinical events, HRQoL and use of health and social services throughout the duration of the study

-

to quantify clinical outcomes in each management cohort (WW, CM, ESG, OSR) in terms of survival, clinical events and quality of life

-

to identify patient-specific or aneurysm-specific features that might predict poor outcome in each treatment group by risk-modelling methods

-

to estimate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of competing treatments to define optimal management strategies for patients in whom more than one treatment is considered appropriate.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Included patients were those aged ≥ 18 years presenting to an NHS hospital with an existing or a new CTAA in the arch or DTA of a diameter ≥ 4 cm (including aneurysms secondary to atherosclerotic degeneration, after acute dissection and secondary to aortopathy). Patients were eligible as long as they had not undergone intervention for the index aneurysm. If a patient had already received treatment for an aneurysm on a different part of the aorta (e.g. ascending, abdominal), then that patient was eligible. The arch was defined as between the brachiocephalic artery and the left subclavian artery. The DTA was defined as between the left subclavian artery and the coeliac axis. If the aneurysm of maximum diameter was located in the thoracoabdominal aorta (21 patients), then the patient was included if the index aneurysm in the DTA was ≥ 4 cm in diameter. If the DTA and arch both had aneurysms of the same size, the aortic arch was considered to be the location of the maximal aneurysm size.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to give written informed consent, were suffering from acute dissection or malperfusion syndromes (e.g. myocardial infarction, acute stroke or limb ischaemia) or had had a previous intervention for the same aneurysm.

Setting

All NHS hospitals that treat or manage patients with CTAA in a MDT setting or specialist clinic were eligible to participate in the study.

Patient and centre recruitment

Centres were recruited after completion of a feasibility questionnaire confirming that they treated patients with CTAA by ESG, OSR or both. In addition, hospitals that cared for patients using WW or CM were eligible to participate if they referred patients for intervention to a centre also participating in the ETTAA study. The initial intention was to recruit 8–10 large centres but, owing to slow recruitment, it became necessary to open the study to 30 hospitals.

Patient eligibility for the study was assessed either in a MDT setting or in a specialist clinic at participating centres. Eligible patients were enrolled, and consent to collect and retain the patient’s data was taken by local research personnel. Consent was obtained face to face or by post/telephone with the consent form posted to the research team.

Study groups

Patients were divided into four groups, depending on the planned management at the time of recruitment:

-

WW – patients with smaller aneurysms at low risk of rupture who were not expected to undergo a surgical or endovascular procedure as part of the current management plan, but for whom these interventions may be a future option should the aneurysm expand.

-

CM – patients with aneurysms of a size where risk of rupture is significant, who were not expected to undergo a surgical or endovascular procedure as part of the current or future management plan due to patient choice, comorbidities or procedural risk.

-

ESG – patients for whom the risks around intervention were considered lower than the risks of rupture, who were referred to a vascular surgeon for aneurysm repair.

-

OSR – patients for whom the risks around intervention were lower than the risks of rupture, who were referred to a cardiac surgeon for aneurysm repair.

During the study some patients transferred between groups, particularly from WW to active intervention (ESG or OSR), so that the final analysis was based on the numbers of patients in each group at end of the study period, with the exception of the analysis of aneurysm growth rates (see Chapter 4 for more details).

Management and interventions

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting patients with aneurysms considered ‘below threshold’ for intervention were treated with lifestyle modification advice (smoking cessation and dietary management) and medical management of hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension. Patients underwent surveillance of the aneurysm (by CT or MRI scans at intervals chosen by the local team) and MDT review (as per local practice).

Conservative management

Conservative management included lifestyle modification advice (smoking cessation and dietary management) and medical management of hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension. CM prohibited any endovascular or open surgical procedure. In this group, features of the aneurysm would have normally triggered intervention, but patient-related features (including comorbidities or patient choice) prohibited it; thus, CM is different from WW.

Endovascular stent grafting

Endovascular stent grafting included any endovascular repair of the aneurysm via transluminal introduction of a stent graft under X-ray guidance. It included any primary endovascular procedure comprising a combination of a conventional surgical component and a transluminal repair (described as a hybrid procedure in some publications). It was completed by a vascular surgeon or an interventional radiologist, usually in a ‘hybrid’ theatre equipped with an imaging scanner intensifier (with a fixed C-arm). It could also be performed in a catheter laboratory or surgical theatre with a mobile C-arm. It excluded open procedures via sternotomy or thoracotomy.

Open surgical replacement

Open surgical replacement comprised replacement of the aneurysmal aorta with a prosthetic conduit, requiring sternotomy or thoracotomy with circulatory support. OSR was completed in a surgical theatre by a cardiac or vascular surgeon. It also included cases where an adjacent segment of aorta was stabilised by implanting a stent at the time of surgery, through the surgical incision.

Hybrids

A hybrid treatment means that the intervention has both stent and surgical components (see Chapter 1 for examples). Where surgery involved only a minor incision, for example to guide stent placement, ESG was the predominant procedure, and these patients were included in the ESG group. Where the hybrid graft was half surgical prosthesis-half stent, inserted during open surgery involving median sternotomy, surgery was the predominant procedure and these patients were included in the OSR group.

Populations

Patient group allocation at recruitment

Once consented, patients took one of two typical pathways depending on whether or not an intervention had been planned and a date of procedure fixed. At recruitment, patients were assigned to CM by the recruiting centre if future management was not expected to involve an intervention, or to WW if future management could include an intervention but further imaging was to be completed before any procedure was planned. These patients entered a non-intervention period, during which baseline characteristics, medical history and HRQoL were recorded at the point of consent and at follow-up visits planned at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36 and 48 months while the patient remained in the non-intervention period. Each patient had either a CT or MRI scan to measure aneurysm size at baseline, and this was then repeated according to local management protocols, expected to occur approximately once per year.

Patients who had a known date of intervention at recruitment were assigned to the ESG or OSR group by the recruiting centre. For patients in the OSR or ESG group an additional assessment was undertaken at 1 month post intervention, with all other measurements taken at the same stages as for WW and CM patients. Procedure data, important complications, subsequent hospital admissions and serious adverse events (SAEs) were recorded by the participating centres as they occurred.

Crossover between groups

Owing to the observational nature of the study, patients switched groups according to local centre management protocols. Patients switching from WW to an intervention group were analysed as part of the non-intervention period up to the date of the procedure. Thereafter, patients entered a post-intervention period, with the timing of follow-up reset so that time zero was the date of the procedure to align with those who went straight to procedure.

Planned analyses

In accordance with the protocol, six work packages were planned to:

-

model aneurysm growth in WW and CM patients during the non-intervention period

-

quantify clinical outcomes within each treatment group (CM, ESG, OSR) and to assess the risk factors for each

-

compare propensity score-matched patients from each treatment group to estimate clinical effectiveness for patients in whom more than one treatment is appropriate

-

estimate cost-effectiveness of competing treatments to define optimal management strategies for patients in whom more than one treatment is considered appropriate

-

assess the subjective level of agreement among experts regarding best management for hypothetical patients using a RAND–Delphi exercise (see Chapter 2)

-

analyse aneurysm growth data from Yale University in collaboration with Professor John Elefteriades.

Amendments to the work packages

Work package 6 was not completed as initial analysis showed that the database included only 23 scans in 11 patients who satisfied the ETTAA study inclusion and exclusion criteria. This work package is not discussed further. For other work packages, aneurysm measurements were completed in sufficient numbers at only four locations (ascending, arch, descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal). Other locations are not reported in this monograph. See Report Supplementary Material 2 for a full list of protocol amendments and Report Supplementary Material 3 for a list of departures from the original protocol.

Outcomes

The primary and secondary outcomes for work packages 1–5 are listed briefly below with definitions.

-

Primary: aneurysm diameter in the aortic arch and DTA. Secondary: survival, time to intervention, clinical complications and HRQoL. Exploratory: aneurysm diameter in the ascending aorta and the thoracoabdominal aorta.

-

Primary: survival. Secondary: clinical complications, reinterventions, re-admission and HRQoL.

-

Primary: survival. Secondary: complications, reinterventions, re-admission, length of stay and HRQoL.

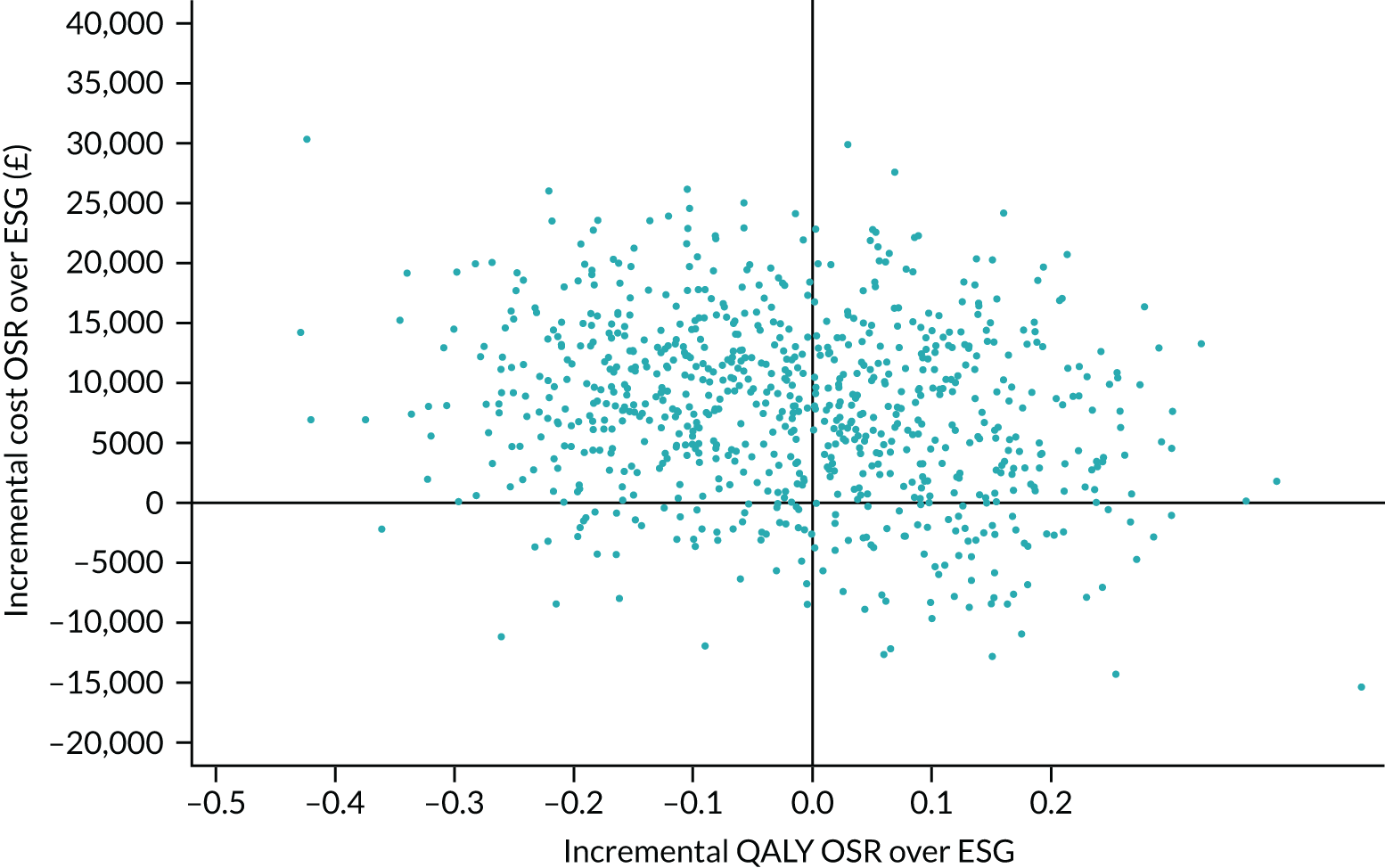

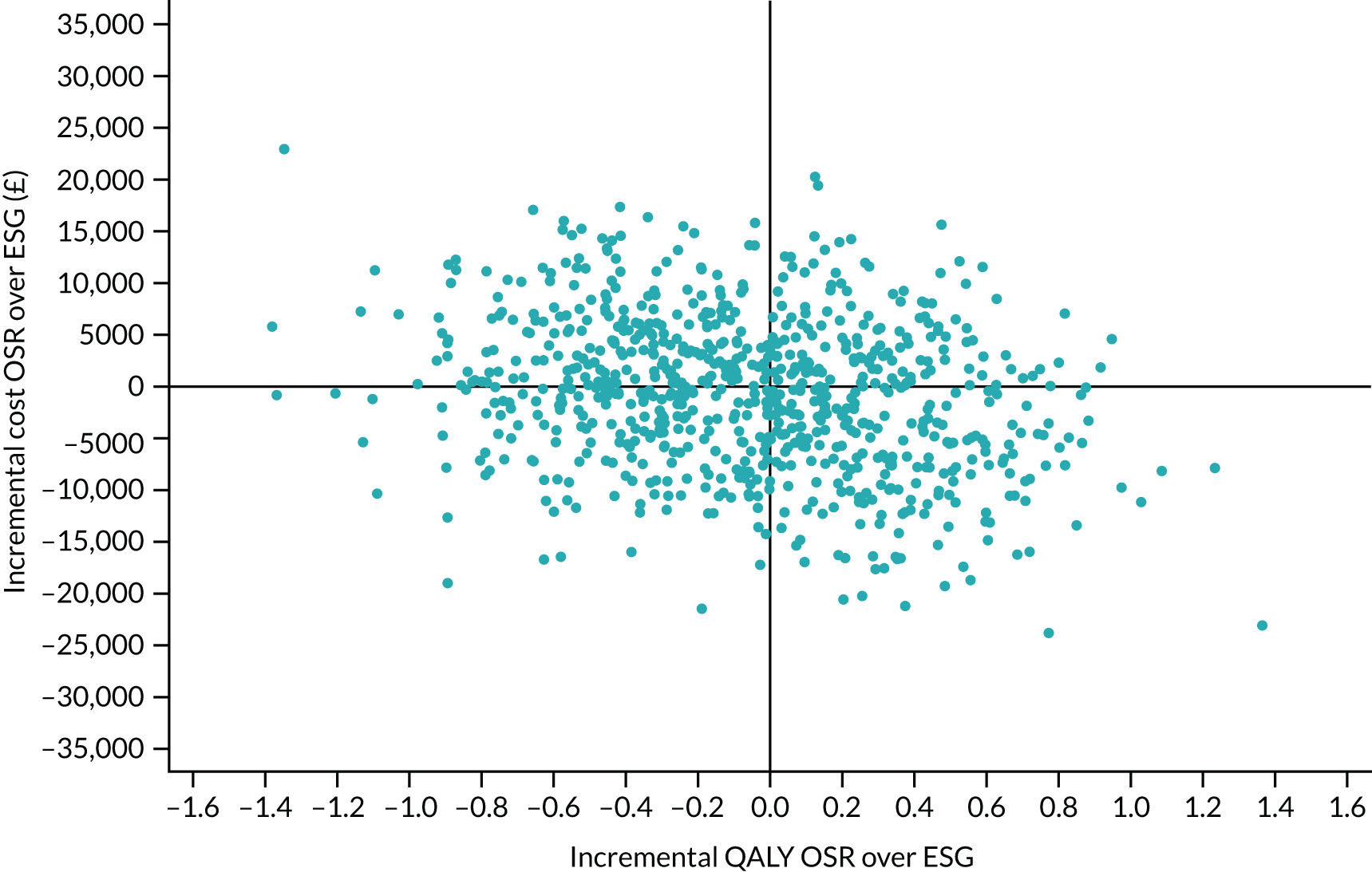

-

Primary: incremental cost per QALY gained. Secondary: HRQoL.

-

Primary: expert opinion on best treatment for any given theoretical patient scenario.

Definitions of outcome measurements

Aneurysm diameter

Study centres were asked to provide a copy of the chest CT or MRI radiological scan conducted closest to the time of recruitment to the ETTAA study (baseline scan) and the accompanying report needed to confirm that the patient had an eligible aneurysm of ≥ 4 cm in diameter. Centre co-ordinators were then asked to provide copies of any additional scans during patient follow-up. Note that all CT/MRI scans were conducted as part of routine care and, therefore, neither the timing of the scan nor the scan request itself was determined by participation in the ETTAA study. CT/MRI scans were anonymised and sent on DVD (digital versatile disc) to St George’s Hospital (London) or Royal Papworth Hospital Core Laboratory for the measurement of aortic diameters (in centimetres) to ensure that differences between multiple radiographers, hospitals and measurement techniques were minimised. In the original plan St George’s was to measure all scans but, owing to staffing issues, scans not analysed at the end of recruitment (30 June 2018) were transferred and analysed at Royal Papworth Hospital. A standard protocol was agreed and CT scan measurements at both centres were made using the same 3mensio (Pie Medical Imaging BV, Maastricht, the Netherlands) software (see Report Supplementary Material 4 for the scan measurement protocol). A total of five operators analysed CT scans [two at St George’s Hospital (n = 269 scans) and three at Royal Papworth Hospital (n = 1268 scans)]. All MRI scans were measured at Royal Papworth Hospital by two radiology consultants (n = 125). If neither core laboratory nor co-ordinating centre analysis was available, measurements were taken from the scan results provided by the participating hospital (n = 70). Although published evidence suggested that results from CT and MRI were comparable, statistical analyses of scan diameters were adjusted for scan modality. 56

Survival time in the non-intervention period

This was the time between the date of recruitment and the date of death or censoring. Patients were censored at date of the procedure or withdrawal or the last patient follow-up if any of these preceded death. The date and cause of death were reported by the participating centre.

Survival time in the intervention period

This was the time between the date of the procedure and the date of death or censoring. Patients were censored at withdrawal or on the date of the last post-procedure follow-up if this preceded death. The date and cause of death were reported by the participating centre.

Procedure-related data

For all interventions on the ascending, arch, DTA or thoracoabdominal aorta, the dates of admission, intervention and discharge, details of operative and postoperative care and clinical outcomes between admission and discharge were recorded by local centre staff from hospital medical records.

Time to intervention

This was the time interval between the date of recruitment and the date of the intervention.

Length of hospital stay for the index procedure

This was the interval in days between date of the index procedure and date of discharge from hospital or transfer to a non-hospital setting (e.g. a care home). This was separated into intensive care unit (ICU), high-dependency unit (HDU) and ward stay.

Clinical complications

All clinical complications related to the aneurysm or interventions were collected by centre staff from hospital records during the initial and follow-up hospital admissions, including myocardial infarctions, gastrointestinal, neurological or spinal events, thrombi, infections, vocal cord palsy and return to theatre, as well as requirement for cardiac support, prolonged ventilation and renal support. ESG complications were classified as access vessel injury, stent graft complication, endoleak, fistulae, aneurysm complication and other. In addition, the following were recorded: date of the event, theatre time, relationship to the procedure or treatment (not related, unlikely to be related, possibly related, probably related, definitely related), cause of event and management. Additional complications, which may arise outside the hospital, including vessel injury, endoleaks, aneurysm complications, stent graft complications and fistulae, were reported by participating centres. All complications were reviewed centrally by ETTAA clinicians (PS, SRL). Further details of complications are given in Appendix 1.

Readmissions to hospital

Readmissions after discharge were obtained by centre staff from hospital records. Information on dates of admission, days in ICU, HDU and ward, reason for admission, relationship to aneurysm or treatment and presenting symptoms were recorded. Further interventions on the ascending, arch, descending thoracic or thoracoabdominal aorta were also recorded.

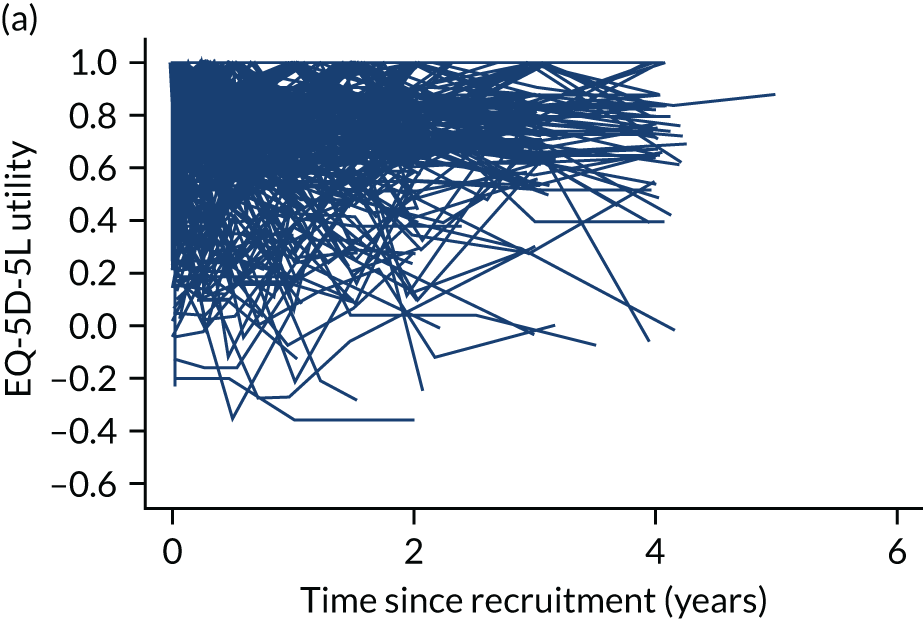

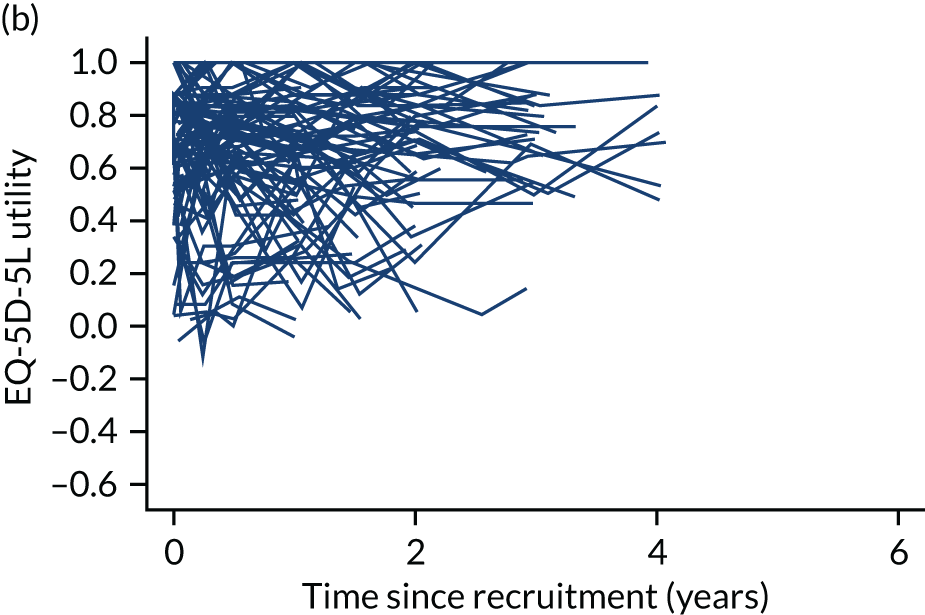

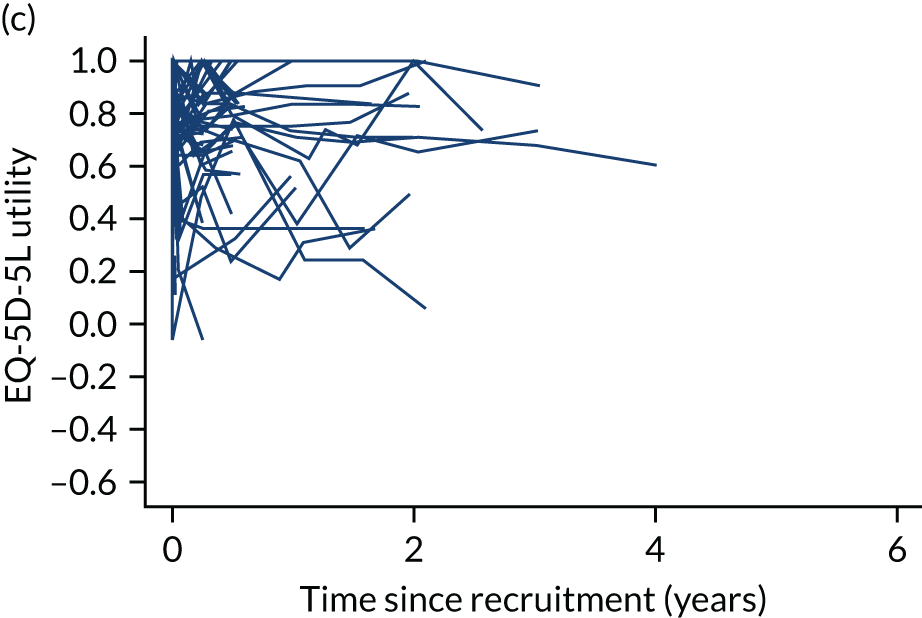

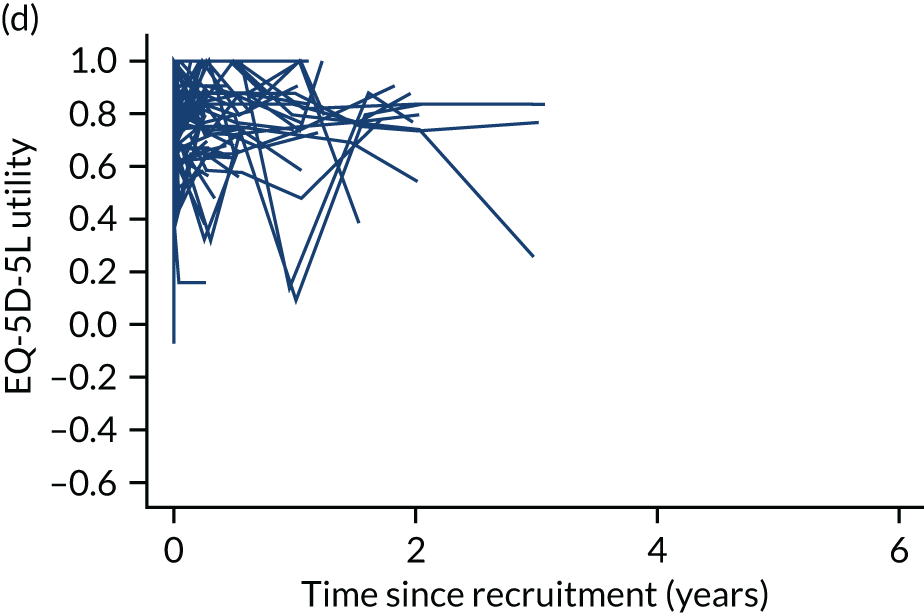

Health-related quality of life

The completion of the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) was scheduled at baseline, at 3, 6 and 12 months and annually thereafter pre intervention and at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months and annually thereafter post intervention. 57 EQ-5D-5L records mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression on a five-level Likert scale. Owing to varying times between recruitment and procedure, follow-up was not always synchronised with planned assessment times. See Chapters 4–7 for further details.

Quality-adjusted life-years

The results from the EQ-5D-5L were converted into health state utilities using UK population tariffs58 and used to estimate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) using the area-under-the-curve approach. QALYs at 12 months were estimated for patients who completed EQ-5D-5L score in the first year post intervention.

Resource use

Data on resource use from a UK NHS perspective were recorded for the procedure and any subsequent admissions to hospital for aneurysm-related or cardiac-related events. Other resource use was scheduled to be recorded at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 and 60 months post procedure for the use of primary care and Personal Social Services (PSS). Costs of health-care services were taken from standard sources such as NHS reference costs, Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) tariffs and manufacturer/supplier costs and from the centres themselves. See Chapter 7 for further details of health economic analyses.

Demographic and baseline variables collected

The baseline variables explored as predictors in modelling and for propensity score development are listed below.

Patient related

Sex, age, height, weight, BMI and smoking history.

Aneurysm related

Type of scan (CT or MRI), aneurysm diameter and location, and location of largest aneurysm.

Cardiovascular related

Diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes, left ventricular (LV) function, coronary artery disease, previous cardiac/aortic intervention, extracardiac arteriopathy, valvular heart disease, and medication (antihypertensive, anticoagulant, statin) at baseline and each follow-up visit.

Other markers of comorbidity

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification of heart disease and CTD. Serum creatinine and haemoglobin levels at baseline and follow-up visits, if recorded.

Operative risk related

Logistic EuroSCORE and formal/informal care (as a proxy for frailty).

Health-related quality of life

EQ-5D-5L score.

Data collection

At baseline, medical history was taken by research personnel to identify a patient’s eligibility. Procedure details and related complications, clinical outcome data and EQ-5D-5L questionnaires were collected prospectively until the study ended, either during hospital attendances or by post/telephone and from hospital databases.

Aneurysm imaging using CT or MRI was undertaken in accordance with local practice, and anonymised copies of scans from the time of diagnosis were sent to the study team.

For patients who transferred from WW to ESG or OSR, a reassignment form was completed at the time the clinical decision was made. Following reassignment, assessment visits were scheduled relative to the reassignment date. For patients waiting over 3 months for surgery, pre-procedure follow-up assessments were completed every 3 months.

Follow-up visits had to be conducted within the following windows:

-

1- and 3-month follow-up: ± 1 week

-

6-, 12-, 18- and 24-month follow-up: ± 2 weeks

-

36-, 48- and 60-month follow-up: ± 4 weeks.

Data were transferred into ETTAA’s electronic database by the local principal investigator (PI) or a delegated researcher.

Statistical methods

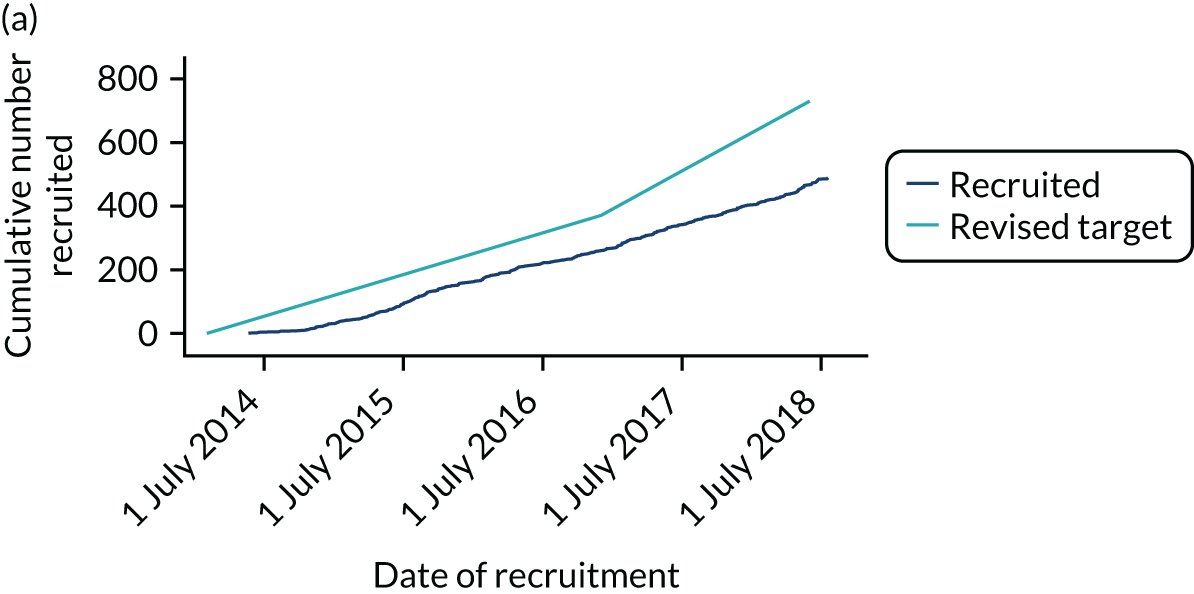

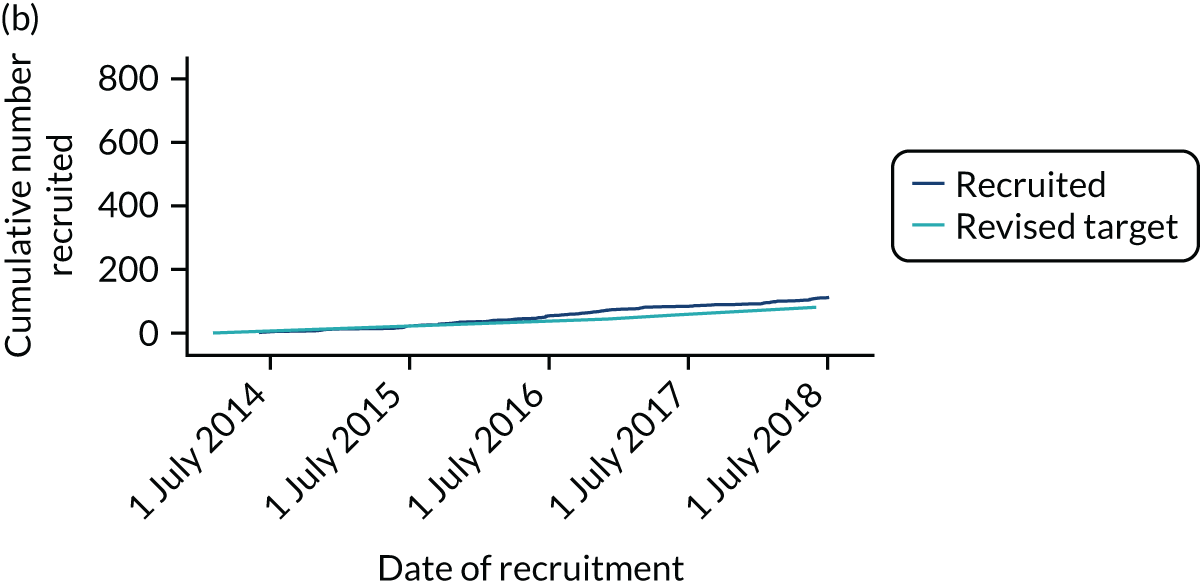

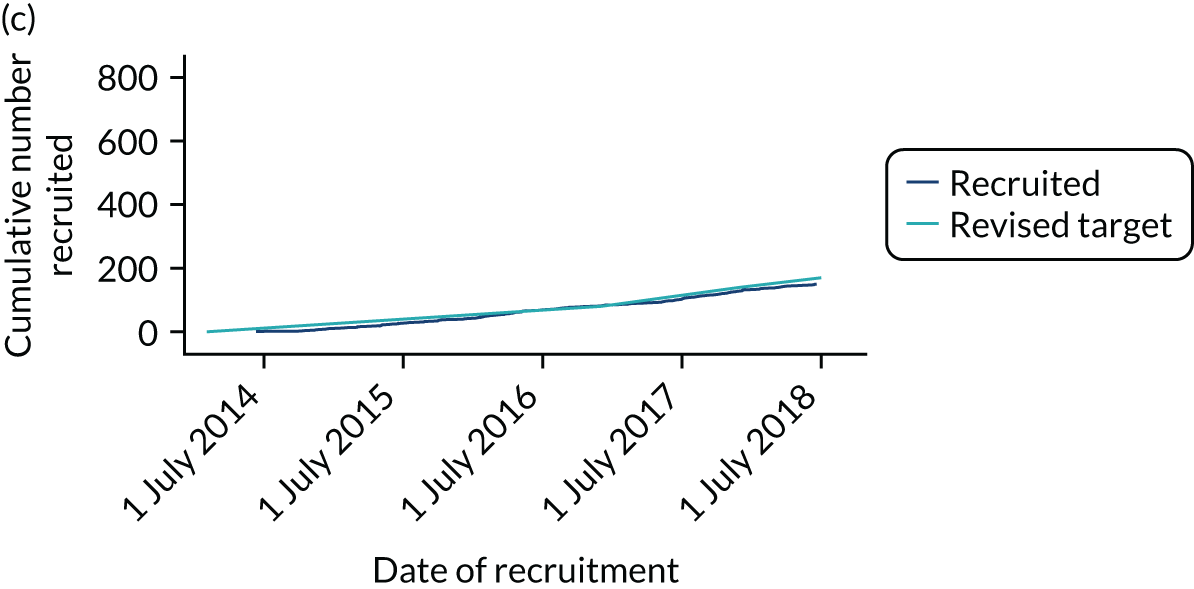

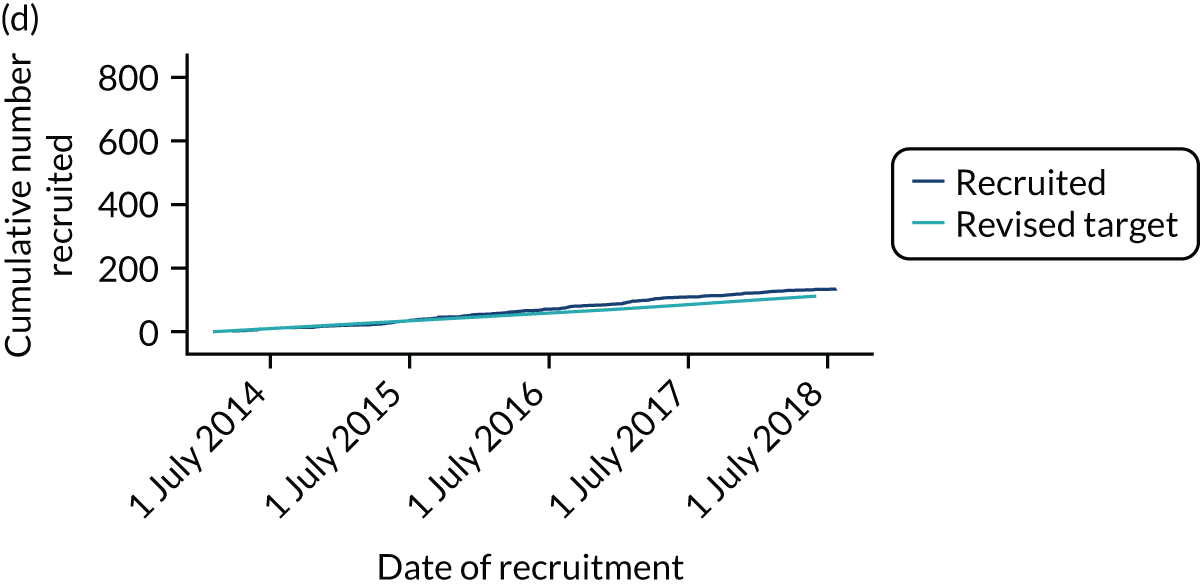

Original planned sample size and revision in October 2016

Although the ETTAA study was an observational study, we provided sample size estimates based on comparing survival between ESG and OSR. From UK registry data, 360 elective operations and stents were performed each year in the UK for arch and DTA aneurysms. 2 Based on log-rank tests, assuming proportional hazards and uninformative censoring, we calculated the smallest possible effect sizes that would be statistically significant at (two-sided) 5% error rate, with 80% power, assuming a fixed sample size and a range of predicted incidence of events in the OSR group.

Table 5 gives the range of the minimum HRs detectable for a given expected event incidence in OSR. The first set of estimates uses pre-study predictions of the final sample size (ESG, n = 293; OSR, n = 147). The second set uses October 2016 predictions of sample size (ESG, n = 170; OSR, n = 112). With these numbers, moderate to large effects (HR > 0.5) could be detected, providing that the event incidence (e.g. deaths) during the study in the OSR group was at least 30%.

| OSR group probability of observing an event during the study | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 45% | 40% | 35% | 30% | 25% | 20% | 15% | 10% | 5% | |

| HR based on original expected sample sizea | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.16 |

| HR based on revised expected sample sizeb | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.02 |

In response to requests from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), we also estimated the power of the study to detect the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in HRQoL. Assuming a MCID of 0.1 in the EuroQoL utility measure,59 with 5% significance and a sample size of 170 ESG and 112 OSR the power was > 90% for either two-sided t-test or Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney U-test (the latter would account for potential ceiling effects in HRQoL). The more sophisticated modelling methods to be used, adjusting for confounders, mean that 90% is a lower bound for power. Given this number of procedures, we expected 81 CM and 730 WW patients to be recruited during the study.

Data quality assurance

The assessment of data quality was complicated by the observational nature of the ETTAA study and the movement of patients between groups over time. Data completeness was assessed using summaries of individual case report forms (CRFs) returned. Data checks broadly followed recommendations in Kirkwood and Sterne. 60 Outliers in continuous variables were detected using ranges and plotting distributions within each group. Unresolved outliers that were extreme and separated from the distribution of a variable were removed and considered missing. Categorical variables were tabulated and unexpected values were queried with centres. Consistency checks between two or more variables were performed (e.g. bivariate plots, cross-tabulations). Dates were checked against planned timing assessments and interventions, as well as relative to other assessments in the same person. All queries were checked with centres and amended in the ETTAA database.

Data summaries

Detailed methods are provided in each chapter; here we give a brief overview of the descriptive methods. Throughout, variables were summarised as the total participants per group and overall, with means and standard deviations (SDs) if normally distributed, or median and interquartile range otherwise. Categorical data were presented as frequencies and proportion in each level. Time-to-event data were summarised as the actuarial survival probability or incidence during the non-intervention and post-intervention periods using Kaplan–Meier estimates. Post-intervention survival was also calculated separately for deaths within 30 days of an intervention. To assess whether or not patients allocated to different management groups were comparable, baseline variables were compared across the four groups using one-way analysis of variance, Pearson’s chi-squared test or a generalisation of Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. 61

Multiple-centre issues

For the analysis of aneurysm growth and HRQoL over time, clustering by centre was investigated using normal random effects in a three-level hierarchy (scan within patient within hospital) (see Chapter 4). For time-to-event outcomes in work package 1, gamma-distributed frailty terms for centres were investigated. For all other analyses, between-centre variation in outcomes could not be assessed owing to the small number of patients contributed by most centres.

Subgroup analysis

Sensitivity analysis included the subgroup of patients who were potentially suitable for both OSR and ESG (see Chapter 6).

Missing data

The extent of missing data per variable was quantified as the number of cases divided by the number of patients who were in the study at the point of assessment. All essential variables for work packages 1–3 are expected to be complete or to have low missing rates (< 8%). Variables for which > 25% of data were unavailable or missing were not used in modelling but were summarised and reported.

Missing data patterns were explored (e.g. monotonic, intermittent). Missing data mechanisms, missing at random (MAR) and missing completely at random (MCAR) were investigated using standard statistical tests (log-rank, Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, Pearson’s chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test) to assess the associations between missing variable status (yes/no) and outcomes. To inform imputation models, associations between pairs of covariates and predictors of missingness were assessed using correlations and other standard statistical tests. Missing covariates were analysed together irrespective of the reasons (death, withdrawal, loss to follow-up, test not completed). For the analysis of aneurysm growth and HRQoL (work packages 1 and 2), all patients with at least two measurements were included in random-effects models. No adjustment was made for missing measurements as estimates from such models are unbiased provided that the data are MAR conditional on the observed data. 62 For work packages 2 and 3, the analysis found little evidence against the hypothesis that data were MCAR (see Appendix 2), so the complete-case analysis is presented throughout. Sensitivity analysis assuming MAR used multiple imputation with chained equations (MICE). Imputation models included the outcome variable as well as all important covariates from exploratory analysis. Each imputation model performed predictive mean matching to impute missing data. Values were simulated for each missing variable and the resulting models were combined using Rubin’s rules. 63

Results

Recruitment

Centre recruitment

Between 24 March 2014 and 24 July 2018, 886 CTAA patients were recruited from 30 centres (see Appendix 3 for a list of participating centres). Studies covered the majority of England but did not recruit from the devolved nations (Figure 4). Although some centres specialised in either vascular or cardiac surgery, many centres recruited patients to all four management groups.

FIGURE 4.

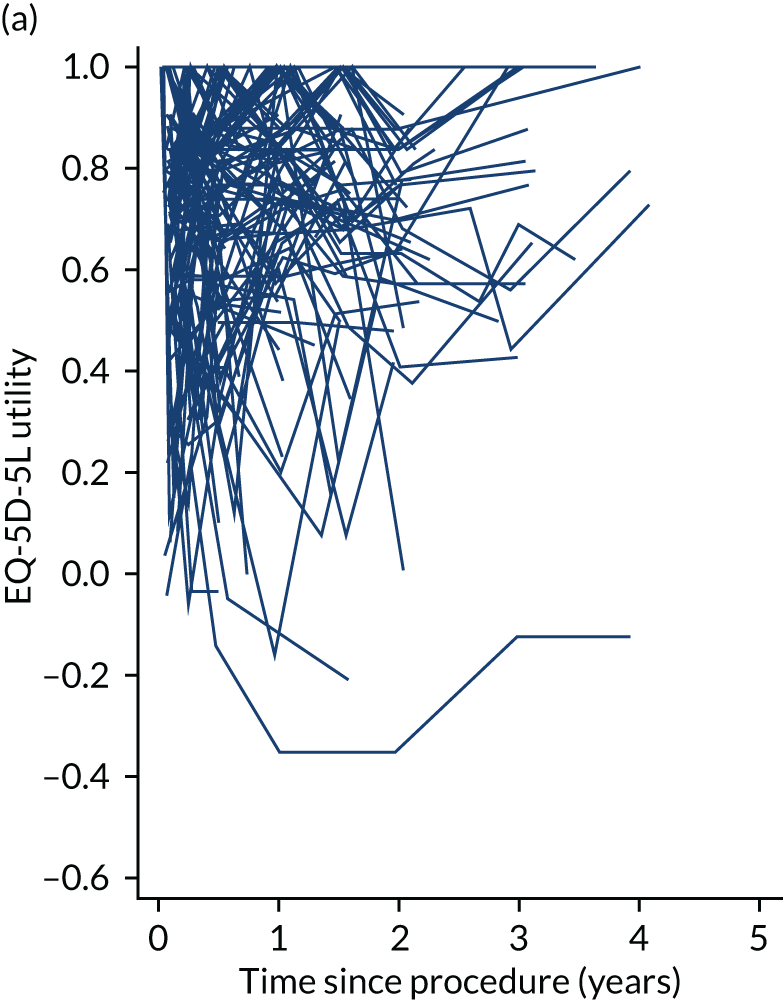

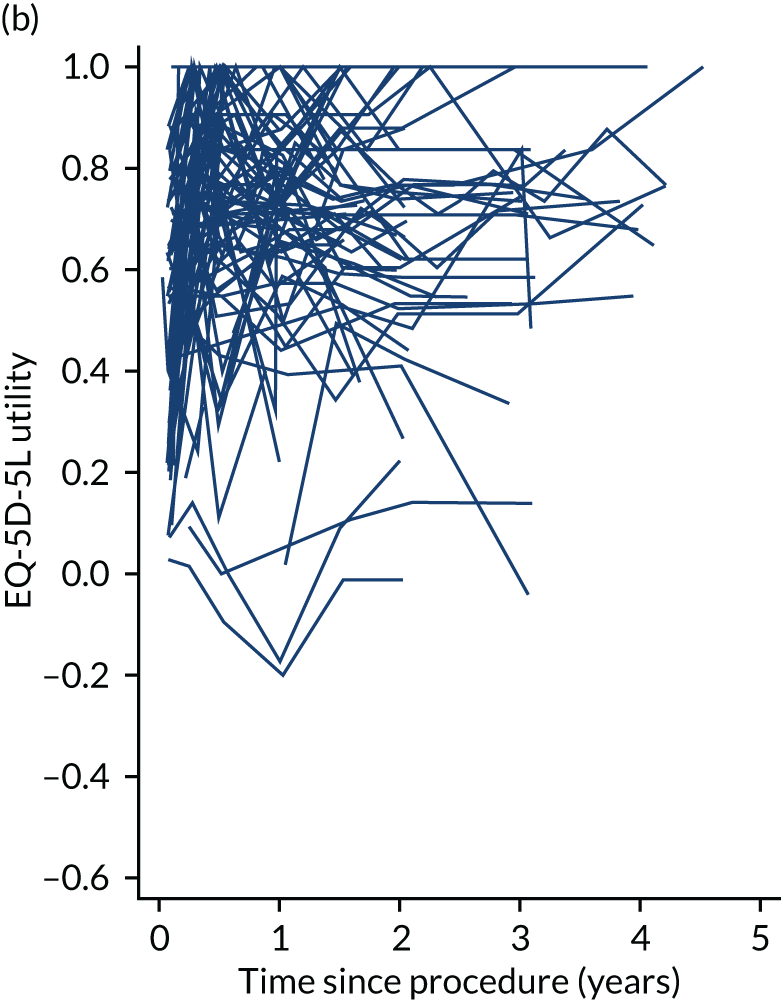

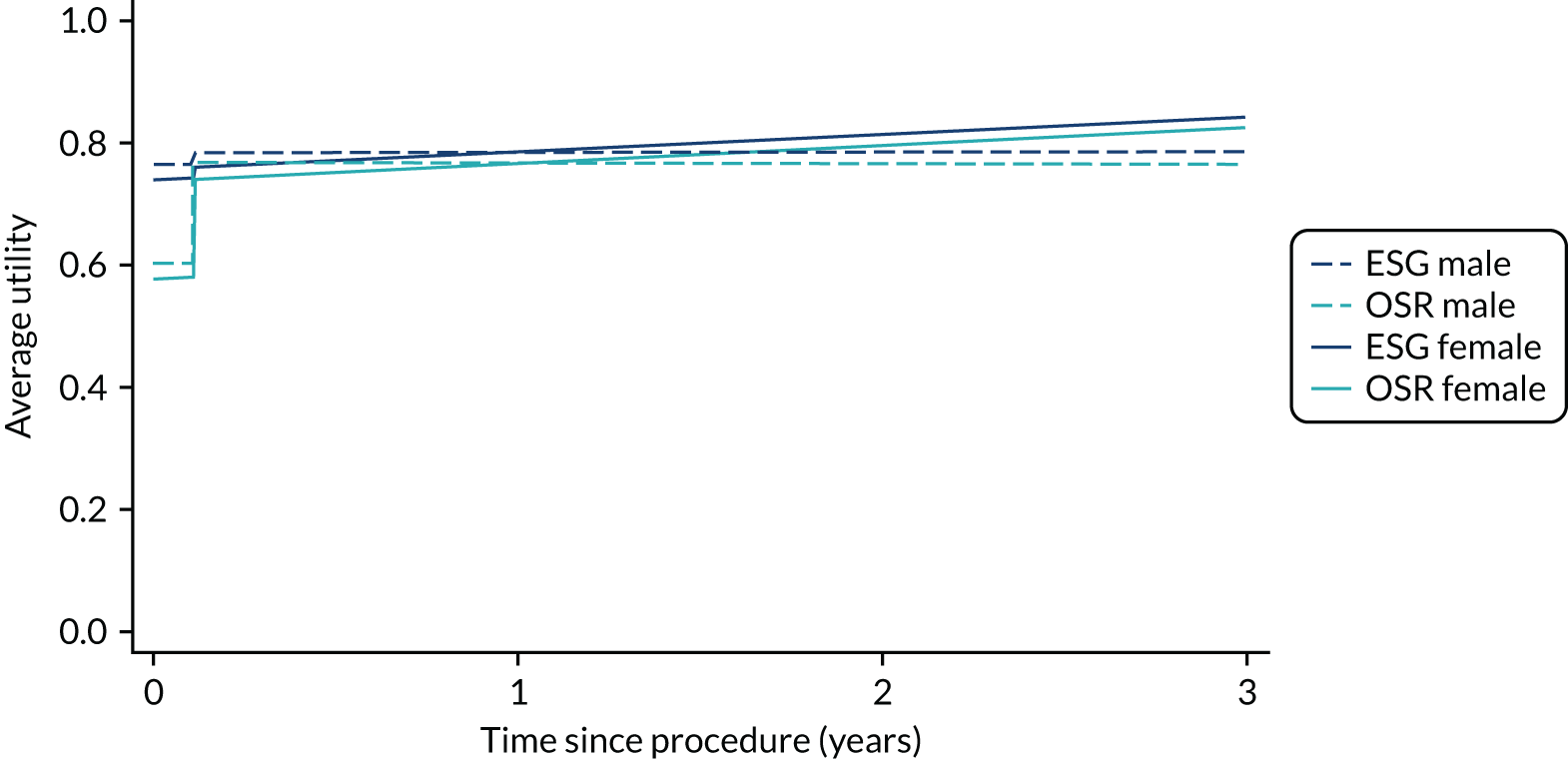

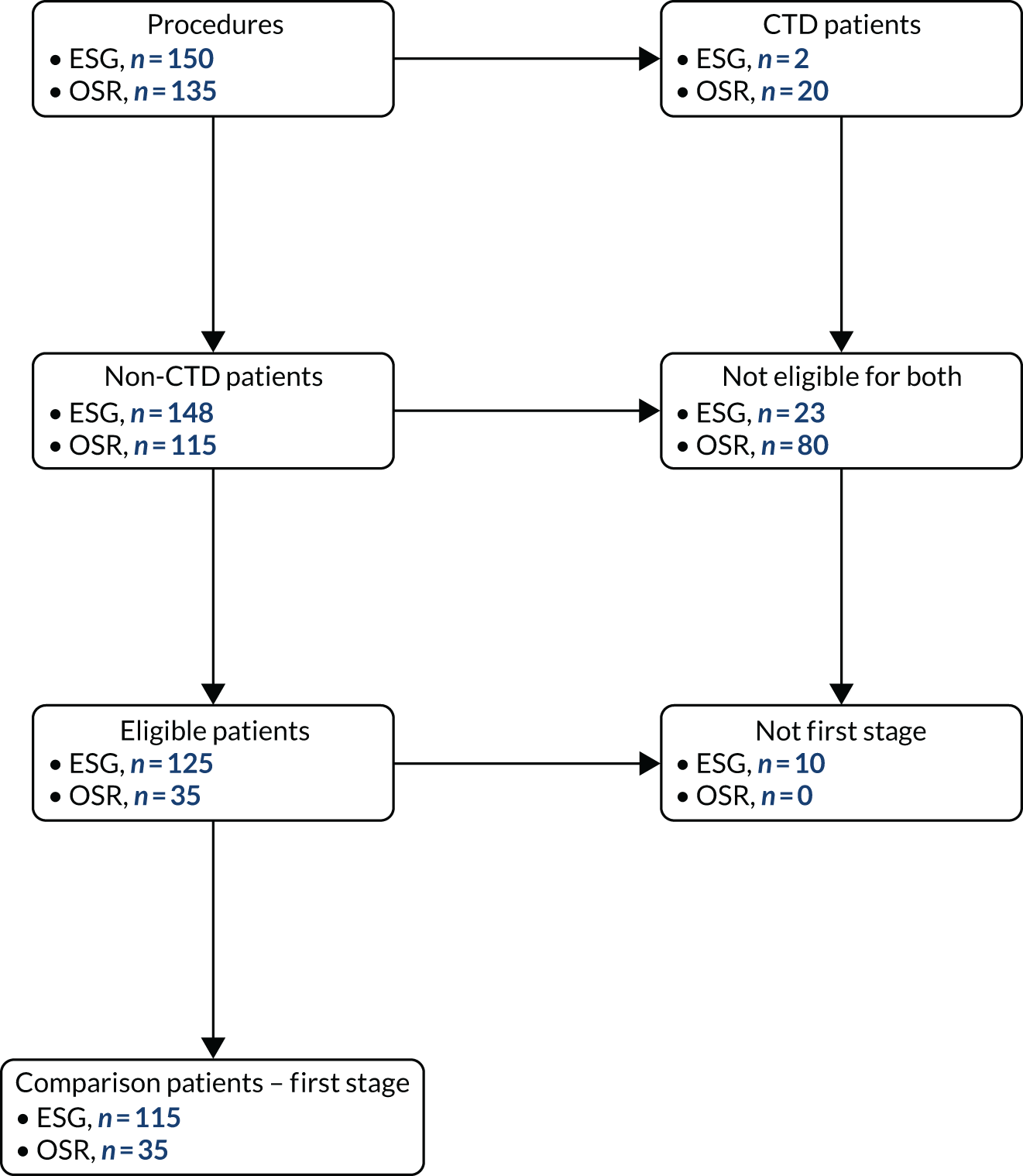

Locations of the 30 centres participating in the ETTAA study.