Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/134/02. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The draft report began editorial review in May 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Qureshi et al. This work was produced by Qureshi et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Qureshi et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is the commonest autosomal dominant disorder with around 1 in 250 individuals (0.4%) affected by the more common heterozygote form. 1,2 However, worldwide it is estimated that < 7% of those with the condition are currently identified. 3,4

Historic data from the time before effective lipid-lowering agents such as statins where available show that, if left untreated, individuals with FH have a dramatically higher risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), with a 100-fold increased mortality risk, than the general population. 5,6 CHD among people with FH can be very effectively prevented by high-intensity lipid-lowering treatment (LLT), with a 48% reduction in CHD mortality. 6 Moreover, 50% of their first-degree relatives and 25% of second-degree relatives will also have the condition and so benefit from intervention.

Improvement in the current low detection rate of FH is urgently needed. More effective cascade testing to identify affected relatives, especially younger relatives, and to initiate early statin treatment to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) will prevent and reduce premature mortality and long-term morbidity. Available service data highlight the major extent of the problem. National audits show that only around one affected relative is identified for each index case. 7

Current national guidelines recommend the early identification and management of patients with FH. Despite recommendations in the 2008 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,8 the Royal College of Physicians audit in 20109 indicated there were 15,341 FH adults and 1106 FH children known and under care in a UK lipid clinic, suggesting that up to 200,000 individuals with FH were not being treated according to guidelines and would be at elevated risk of CHD. 9

Identification in primary care remains poor and opportunistic. The most recent NICE guidelines advise primary care to search for patients with possible FH based on cholesterol levels. This is followed by referral to specialist care based on Simon Broome or Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN) criteria. 8 In specialist care, these patients are reassessed using these criteria, or modified versions [e.g. the Welsh-modified Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (WDLCN)10], and FH is confirmed using genetic testing. Subsequent cascade testing of relatives is also suboptimal, partly because of perceived barriers to specialists approaching relatives directly, particularly if the relatives live in different geographies. Moreover, people with FH are mainly managed by specialist care, despite the potential for greater management in primary care.

Existing cost-effectiveness analyses (UK and internationally) have explored whether or not specific protocols for cascading are cost-effective. 11–14 However, commissioners and policy-makers are uncertain about whether current cascade programmes represent the best value for money in practice. 15,16 They have questioned whether or not tighter criteria for cascading could offer better value for money, and whether or not service protocols could do more to maximise the number of relatives tested.

By using robust and multiple data sources and modelling a wide range of possible protocols for cascade testing, this study has identified the most cost-effective protocols for cascade testing for FH in UK clinical practice and the NHS.

The study used economic modelling to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of alternative cascade-testing protocols. Parameters to inform these models were derived from existing published literature and routinely available data in primary and specialist care. In this study, we originally proposed to collect data from three large regional FH services (Wessex, Scotland and Wales), with differing protocols for cascade testing.

The Welsh service, serving a population of 3.2 million since 2011 and co-funded by the British Heart Foundation (BHF), identifies new FH cases using the WDLCN criteria,10 including triglyceride levels. In the service, several modalities of identification are used, including specialist nurses accessing primary care records. Cascade testing of relatives is offered directly (initiated by the clinic/medical professionals) and indirectly (initiated by patients providing information to their family members).

The Wessex service, serving a population of 2.5 million, is one of the first BHF pilots (2014). Cases are identified through primary care-based FH co-ordinators using modified NICE Simon Broome referral criteria with higher LDL-C threshold (> 5.5 mmol/l) and taking account of triglyceride levels. 8 Cascade testing of relatives is usually through indirect contact.

The Scottish service protocol serves a population of 5.5 million since 2008. General practitioners (GPs) use NICE Simon Broome criteria for referring suspected index cases either directly for genetic testing or through a network of 17 lipid clinics. Patients with genetically confirmed FH are referred to genetic services for cascade testing, initially contacting relatives indirectly, but more recently using indirect and direct approaches.

Exploring and identifying the most cost-effective protocols and care pathways and wider implementation will be dependent on their acceptability to a range of stakeholders. Therefore, the experiences, views and attitudes of patients and family members, primary care and specialist health-care providers, and service commissioners are also explored.

Study aim

The aim was to identify the most cost-effective cascade-testing protocol for FH.

Study objectives

-

To determine the yield of cases, treatment patterns, and short- and long-term outcomes for FH patients through routine service data and by new linkage of national FH, primary and secondary care data sets.

-

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of alternative protocols for cascade testing using data from service protocols in three UK regions, the literature and linkage of national clinical databases.

-

To assess the acceptability of cascade-testing approaches to individuals and families with potential and confirmed FH, and health-care providers.

Objective 1 was addressed by developing an economic model that synthesises evidence on genetic testing to identify index cases and subsequent cascade testing, with evidence on the short- and long-term costs and benefits of identifying and managing FH cases. This was based on data from (1) cascade-testing services, (2) linking UK primary and secondary care data sets describing the management and outcomes of patients with FH (see objective 2) and (3) evidence from the literature and supplied by the Dutch FH service.

Objective 2 described treatment patterns and short- and long-term outcomes of FH patients, by linkage of national clinical databases. Data on cases managed in primary and secondary care were linked to data on LLT use and cholesterol response [from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and the Simon Broome FH Register)], and to cardiovascular disease (CVD) events [from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)] and mortality [from the Office for National Statistics (ONS)]. Furthermore, data on the yield of new FH index cases and patterns of contacting and testing of their relatives were captured from routine service data sets. Collectively, these provided a rich source of evidence from which to estimate the impact of identifying and managing relatives with FH, thereby providing more precise and robust parameters for the cost-effectiveness model.

Finally, objective 3 was addressed by qualitatively exploring acceptability, benefits and harms of cascade-testing approaches from patient, health-care practitioner and other stakeholder perspectives.

Modification to original protocol and structure of the report

As the project progressed, we adjusted the protocol to reflect the publication of new studies and data availability.

-

We concluded that a systematic review comparing outcomes among diagnosed patients with outcomes among undiagnosed patients was not required, given the publication of the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) consensus statement,17 which reviewed evidence from randomised controlled trials, observational studies and Mendelian randomisation studies. The statement concluded that CVD risk related to raised LDL-C increases over time,17 and, based on the meta-analysis of individual-level data from 28 randomised controlled trials on statin therapy, estimated that a 1-mmol/l reduction in LDL-C leads to a 22% reduction in CVD risk. 18

-

We concluded that a systematic review on the long-term benefits of LLT for paediatric patients was not required given the publication of recent systematic reviews on this topic. 19,20

-

We compared cascade protocols, including alternative ways to select index cases, to contact relatives and to test relatives; we did not compare policies that tested third-degree relatives because the service data did not differentiate between second-degree or more distant relatives to the index case.

-

Aligned with current NICE guidelines, we did not compare policies in which cascade to relatives started from an index in whom a FH mutation was not detected and their relatives are cascaded based on cholesterol alone, because the probability that index cases have an as yet undiscovered FH mutation is low,21 and the probability that relatives are affected is not clear.

-

For the cost-effectiveness model, we analysed the data from the CPRD cohort, a cohort of FH patients with linked NHS and mortality data. However, we were unable to analyse the Simon Broome cohort linked to routine NHS data sets on CVD events and mortality owing to delays with the provision and approval of these data for cost-effectiveness analysis. Furthermore, we applied for linkage of the Simon Broome cohort to the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) data set 2 months before the start of the study; despite repeated submissions and enquires, after 43 months there was still no progress. Following guidance from the external Study Steering Committee, we discontinued further pursuit of this linkage.

-

Our cost-effectiveness model assumes that diagnosis reduces LDL-C, as observed in the FH cohort, and links those reductions to CVD risk in the long term; it does not account for adherence to LLT explicitly, given the difficulty in linking adherence to changes in LDL-C over time, and its impact on CVD risk.

-

We informed the cost-effectiveness model using data from the Welsh and Wessex FH services. However, we could not use data from the Scottish FH service because it did not allow for the estimation of key parameters (e.g. index cases’ clinical scores, relationship between index cases and relatives).

-

Health resources involved in the cascade process were informed via a review of the literature and expert opinion, due to the lack of data on these in the Welsh, Wessex and Scottish data sets.

-

Given the small number of CVD events experienced by the CPRD cohort, we calculated the NHS cost of CVD events based on the literature, rather than conducting a costing analysis using the CPRD cohort data. This assumes that the costs of CVD events are generalised from a mixed population, a minority of which will have FH, to individuals with FH.

-

Stakeholders were closely involved in the development of the economic models (see Chapter 5). This group comprised consultant lipidologists, FH nurse specialists, public health physicians, commissioners, expert patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) representatives, and representatives from relevant charities (HEART UK and the BHF).

The study was completed by three research teams, and is presented accordingly in this report. The systematic reviews were led by the Nottingham team, with the diagnostic accuracy review undertaken by colleagues in Newcastle (see Chapter 2). The description of the included databases and primary epidemiological analysis was completed by the Nottingham team (see Chapters 3 and 4) Economic analyses of the CPRD database were completed by the York economic team (see Chapter 5, Economic analysis of the Clinical Practice Research Datalink database). The York team also completed a descriptive analysis of the PASS (PASS Software, Rijswijk, the Netherlands) Welsh and Wessex FH service data sets (see Section 8.3), and led the development of the two new economic models (see Chapter 5, Service data analysis, and Cost and health benefits of diagnosis of people with familial hypercholesterolaemia in the long term). Finally, the qualitative studies of patients and health professionals were led by the Nottingham qualitative research team (see Chapter 6).

Chapter 2 Systematic reviews

This chapter focuses on the systematic reviews that were proposed to supplement primary data available from clinical data sets to estimate parameters required for inputting into the economic model. The reviews were as follows:

-

effectiveness of cascade-testing protocols among relatives for FH

-

effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapies on LDL-C levels and CVD among adults

-

effectiveness of LLTs on LDL-C levels, and the impact of LDL-C levels on CVD and mortality among children with FH

-

diagnostic accuracy of clinical and biochemical criteria for identifying relatives of index cases with confirmed FH.

Review 1: effectiveness of cascade-testing protocols among relatives for familial hypercholesterolaemia

Introduction

The typical pathway for FH identification involves physicians, often the primary care provider, referring individuals with suspected FH to a specialist who confirms the diagnosis, often using genetic testing. The specialist will then arrange testing of relatives of confirmed FH cases, usually by the patient contacting the relatives themselves (indirect cascade testing). The exception could be testing children of affected parents, which may be done directly. In fact, the family are often traced to two or three generations. 8,22 Initially, this usually starts with the affected individuals’ children. 23 Internationally, most cascade testing starts with adult index patients and cascading testing to other relatives including children (‘forward cascade testing’). ‘Reverse’ cascade testing is also under consideration: starting identification from affected children. 24 However, despite being recognised as a cost-effective strategy,25 there are still many patients not being diagnosed, with one of the reasons being the relatively low yield, which could be related, partly, to using the indirect approach. The alternative approach to the indirect approach is direct cascade testing, whereby the genetic specialist contacts the relatives directly.

In 2019, a systematic review found that the proportion of cascade-tested relatives was higher with the direct approach;26 however, as this review did not synthesise the studies quantitatively, the magnitude of the differences between the approaches remains unclear. Therefore, we have performed a systematic review and a meta-analysis to quantify the yield of different approaches (direct, indirect, combination) for cascade testing for FH.

Materials and methods

The protocol for the systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42019125775). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines27 were adhered to throughout the conduct and reporting of the systematic review.

The systematic review encompasses relevant study designs, including controlled trials and epidemiological studies, which assessed the effectiveness of cascade testing for FH among relatives. Eligible participants were first- and second-degree relatives of index cases with confirmed FH, determined using a clinical diagnosis [i.e. Simon Broome,5 DLCN,3 make early diagnosis to prevent early death (MEDPED)28 or another criterion appropriate to the population being studied]; LDL-C levels, using age-specific cut-off points; or genetic diagnosis of mutation-positive cases. The protocol for cascade testing was the intervention of interest, which could be conducted via (1) a direct method of contact (whereby the relatives of the index case are contacted directly by the clinic, usually using personalised letters or telephone calls, once consent has been sought from the index case), (2) an indirect method of contact (whereby the index case acts as an intermediary by passing on personalised letters or information to their relatives) or (3) a choice of indirect or direct methods (or a combination of direct and indirect methods). The primary outcome measure was the proportion of relatives of the index cases tested out of those contacted, henceforth referred to as yield. Secondary outcome measures included the proportion of relatives of the index cases with confirmed FH out of those tested, the proportion of relatives of the index cases contacted out of those eligible, the proportion of relatives of the index cases who responded out of those contacted and the proportion of index cases who participated in cascade testing out of those genetically or clinically confirmed with FH.

Comprehensive literature searches of three databases [MEDLINE, from 1946 to May 2020; EMBASE, from 1980 to May 2020; and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), from 1966 to May 2020] were performed using a highly sensitive search strategy based on keywords and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms relating to the population (e.g. proband$, index patient$, relative$, family$, patient$) and intervention of interest (e.g. cascade, mass screening, contact tracing) (see Appendix 1 and Table 23, for the MEDLINE search strategy), and other publications were identified through contact with topic experts.

In addition, grey literature was identified from the following sources: the British Cardiovascular Society Annual Conference, the HEART UK Annual Scientific Conference, the European Human Genetics Conference and the EAS Congress, from dates of inception to March 2020, and through hand-searching the Atherosclerosis journal and the HEART UK (www.heartuk.org.uk/) and US Family Heart Foundation (https://thefhfoundation.org/) websites. No language restrictions were applied, and translations were sought when necessary.

Screening and study selection

Following the removal of duplicates, titles, abstracts and full texts of potentially eligible studies were screened independently by two authors (JLB and Ben Young/Kelly Eliman/CB). Disagreements regarding eligibility of a study were resolved through discussion with a third author (NQ). Reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage were documented.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A standardised form, developed by the authors and tailored to this review, was used for data extraction. Data relating to the study characteristics, the methods used, and primary and secondary outcomes were extracted independently by two authors (JLB and CB). When possible, the authors of any studies with missing data were contacted. Two authors (JLB and CB) independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the JBI Critical Appraisal tool. 29 Studies that scored ‘no’ for more than two of the questions were rated as having low methodological quality, high methodological quality was assigned when all the domains were rated as ‘yes’, and the remaining studies were rated as moderate. Discrepancies were discussed between authors, as needed.

Data synthesis and investigations of heterogeneity

For each study, we calculated raw proportions with 95% score-based confidence intervals (CIs) based on the appropriate numerator and denominator for each outcome measure. Variances of the raw proportions were stabilised before pooling using the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation30 to ensure studies that estimated proportions as 100% (standard error = 0) were not excluded from the analysis. The included studies presented outcome data for only one cascade protocol (direct, indirect or combination); therefore, no relative effect measures could be estimated. Thus, pooled proportions for the outcome measures overall and for each cascade protocol were estimated using a random-effects models whereby sufficient studies were included in the meta-analyses to allow for anticipated heterogeneity resulting from inherent biases within the studies. I2 was used to quantify inconsistency (heterogeneity). 31 Analyses were conducted in Stata® version 16.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The searches identified a total of 3742 studies. Following title and abstract screening, 217 studies were assessed for full-text screening (see Figure 1). At the full-text screening, 193 studies were excluded, related to ineligible study design (77 studies), ineligible or duplicate population (35 studies), ineligible or unclear intervention (62 studies) or ineligible outcome reporting (19 studies); therefore, 24 studies were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis32–55 (see Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow chart for systematic review of effectiveness of cascade-testing strategies.

| Study (first author and year) | Country | Number of confirmed index cases | Contact method | Format of cascade | Extent of cascading among relatives | FH diagnosis method for | Quality score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index cases | Relatives | |||||||

| Alver32 2019 | Estonia | 27 | Indirect | Forward | Second degree | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Andersen33 1997 | Denmark | 62 | Direct | Forward | Second degree | Clinical (study-specific) | Clinical (study-specific) | Moderate |

| Bell34 2015 | Australia | 100a | Both | Forward | Third degree | Genetic | Genetic | High |

| Bhatnagar35 2000 | England | 262 | Direct | Forward | First degree | Clinical (SB) | Clinical (SB) | Moderate |

| Breen36 2011 | England | 72 | Indirect | Forward | Not reported | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Chan37 2019 | Hong Kong | 64 | Indirect | Forward | Second degree | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Davis38 2016 | USA | 5 | Direct | Forward | First degree | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Descamps53 2021 | Belgium | 127 | Direct | Forward | Second degree | Clinical (DLCN) | Clinical (MEDPED/DLCN) | Moderate |

| Edwards39 2013 | Wales | 270 | Both | Forward | Not reported | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Ellis40 2019 | Spain | 755 | Direct | Forward | Not reported | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Hadfield41 2009 | England | 931 | Both | Forward | Not reported | Clinical (SB) | Clinical (SB) | Moderate |

| Jannes42 2015 | Brazil | 125 | Direct | Forward | Second degree | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Latkovskis43 2018 | Latvia | 140 | Indirect | Forward | First degree | Clinical (DLCN) | Clinical (DLCN) | High |

| Leren55 2008 | Norway | ≈1300 | Indirect | Forward | Not reported | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Marks44 2006 | England | 354 | Indirect | Forward | Not reported | Clinical (SB) | Clinical (MEDPED) | Moderate |

| Marteau45 2004 | England | 341 | Direct | Forward | Second degree | Clinical (SB) | Genetic or clinical (SB) | Moderate |

| Muir46 2010 | New Zealand | 76 | Direct | Forward | Not reported | Genetic | Genetic | Low |

| Neuner47 2020 | USA | 2 | Indirect | Forward | Not reported | Genetic | Genetic | Low |

| Raal54 2020 | South Africa | 252a,b | Direct | Forward | First degree | Genetic or clinical (not specified) | Genetic | Low |

| Setia48 2018 | India | 31 | Direct | Forward | Second degree | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Skovby52 1991 | Denmark | 17 | Direct | Reverse | Not reported | Clinical (study-specific) | Clinical (study-specific) | Moderate |

| Tilney49 2019 | Malta | 9 | Both | Forward | First degree | Clinical (DLCN) | Clinical (DLCN) | Moderate |

| Umans-Eckenhausen50 2001 | The Netherlands | 237a | Direct | Forward | Second degree | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

| Webster51 2019 | England | 215 | Both | Forward | Not reported | Genetic | Genetic | Moderate |

Of the 24 included studies, 16 were conducted in Europe (England,35,36,41,44,45,51 Wales,39 Belgium,53,56 Denmark,33,52 Latvia,43 the Netherlands,50 Norway,55 Spain,40 Malta49 and Estonia32), one in Australia,34 three in the Americas (the USA38,47 and Brazil42), one in New Zealand,46 two in Asia (India48 and Hong Kong37) and one in South Africa. 54 All studies used an observational design to assess the outcome measures. The average number of confirmed index cases enrolled in the studies was 242, with sample sizes ranging from 2 to approximately 1300 participants.

The direct method of contact was used in 12 studies,33,35,38,40,42,45,46,48,50,52–54 a further 7 studies used an indirect method,32,36,37,43,44,47,55 and the remaining 5 used a combination of direct and indirect methods. 34,39,41,49,51 Contact could be made via a range of approaches, including postal invitation, telephone, in person or a combination of approaches. Forward cascade testing was used in the majority of included studies (23 studies), with the remaining study using reverse cascade testing. 52 Fourteen of the included studies reported the extent of cascade: the majority (eight studies32,33,37,42,45,48,50,53) cascaded to second-degree relatives, with only five studies cascading to first-degree relatives35,38,43,49,54 and one study cascading to third-degree relatives. 34

The majority of included studies (14 studies32,34,36–40,42,46–48,50,51,55) confirmed FH diagnosis for the index cases using genetic testing; nine studies confirmed FH diagnosis for the index cases using clinical assessment based on Simon Broome (four studies35,41,44,45), DLCN (three studies43,49,53) or study-specific criteria (serum cholesterol of ≥ 8 mmol/l, LDL-C of ≥ 6 mmol/l and family history of hypercholesterolaemia;33 apolipoprotein B: apolipoprotein A-1 ratio > 97th centile or apolipoprotein B > 99th centile, LDL-C > 95th centile and no secondary causes for raised cholesterol52); and one study stated that diagnosis was based on either genetic or clinical criteria, but did not provide additional details. 54 For the relatives, genetic confirmation of FH was used in the majority of studies (15 studies32,34,36–40,42,46–48,50,51,55,57). A further eight studies used clinical assessment based on either Simon Broome,35,41 DLCN,43,49 MEDPED,44 a combination of DLCN and MEDPED,53 or study-specific criteria (serum cholesterol of ≥ 7 mmol/l;33 LDL-C > 95th centile52). The final study used genetic testing or clinical assessment based on Simon Broome criteria depending on which arm of the trial the index case had been randomised to. 45

For the 16 studies using genetic testing for confirmation of FH, testing of only the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene was performed in three studies,46,48,50 testing of the LDLR and apolipoprotein B-100 (APOB) genes was performed in two studies,45 testing of the LDLR, APOB and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) genes was performed in eight studies,32,34,37,38,40,42,47,51 and testing of the LDLR, APOB, PCSK9, and low-density lipoprotein receptor adaptor protein 1 (LDLRAP1) genes was performed in one study. 54 It was unclear what genes were tested in the remaining two studies. 36,39

The median number of new relatives with FH per known index case was 0.98 (range 0.15–8.6), with the largest medians seen in the studies using the indirect (median 1.39, range 0.22–8.60) and direct (median 1.27, range 0.15–3.86) testing strategies, compared with the combination approach (median 0.72, range 0.26–1.88); however, this is a crude analysis that does not consider the relative contribution of each study.

Quality assessment

The majority of studies were rated as having a moderate risk of bias; only three studies had a high methodological quality score34,43,53 and two studies were rated as having low methodological quality46,47 (see Table 1 and Appendix 1, and Table 24). The reasons for lower methodological quality were primarily related to less clarity regarding consecutive inclusion of participants (question 4) and incomplete inclusion of participants (question 5). Furthermore, many studies scored ‘no’ on clear reporting of the demographics (question 6, 10 studies) and clinical information of the participants (question 7, 10 studies).

Primary outcome measure

Proportion of relatives of index cases tested for familial hypercholesterolaemia of those contacted

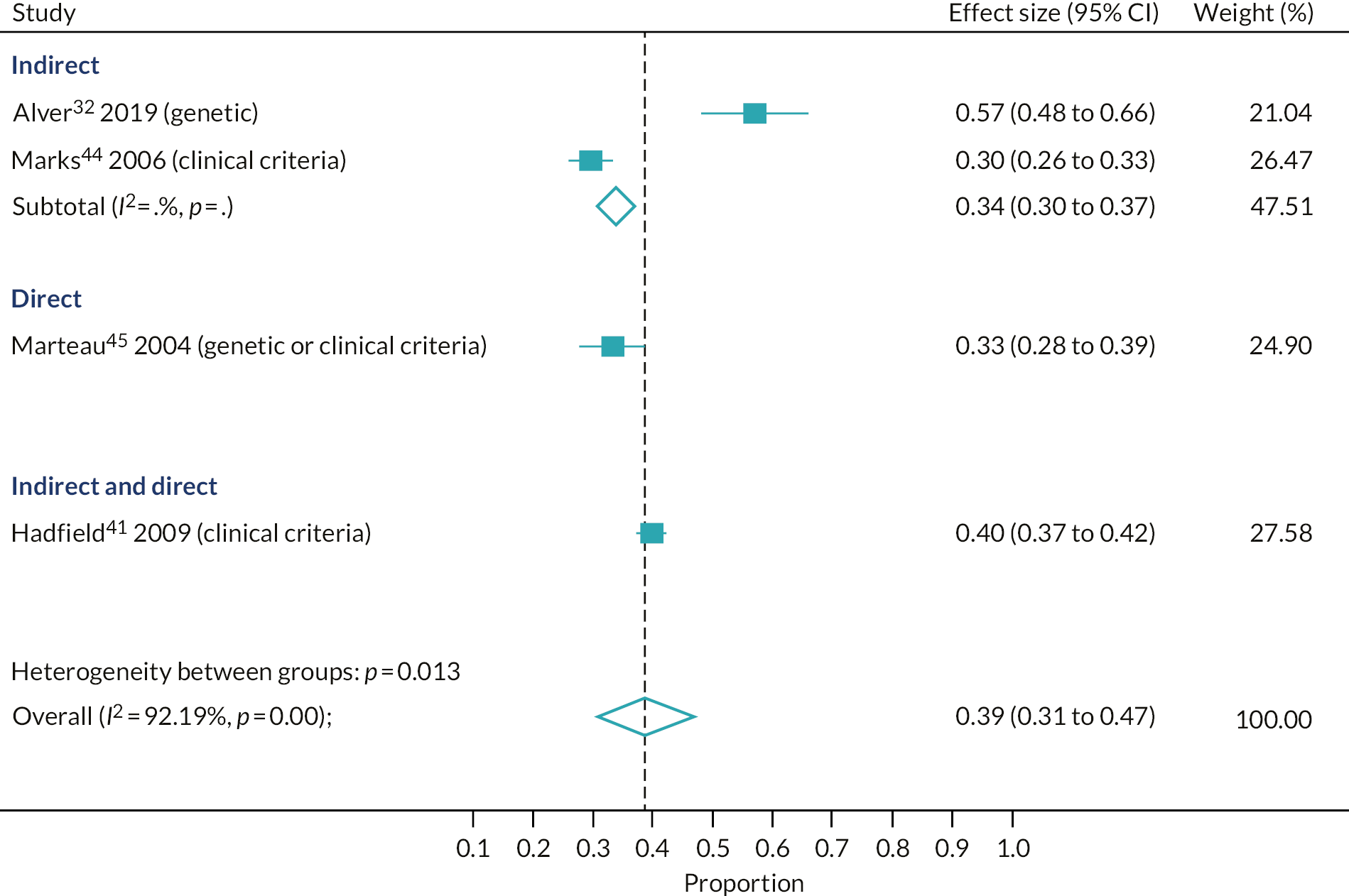

Four studies32,41,44,45 provided data to estimate the primary outcome. On average, 39% of relatives were tested for FH out of those contacted (95% CI 31% to 47%, four studies); however, the estimates varied significantly by the cascade approach used (p-value for subgroup differences, p = 0.01) (see Figure 2). The largest yield was seen in the study conducted in England that used a combination approach (40%, 95% CI 37% to 42%, one study); however, similar, but slightly lower, yields were seen for the direct and indirect strategies [direct: 33%, 95% CI 28% to 39% (one study, conducted in England); indirect: 34%, 95% CI 30% to 37% (two studies, conducted in England and Estonia)], although the results from the last two studies varied considerably (57%32 and 20%44).

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of relatives tested out of those contacted for FH cascade testing, by cascade approach.

Secondary outcome measures

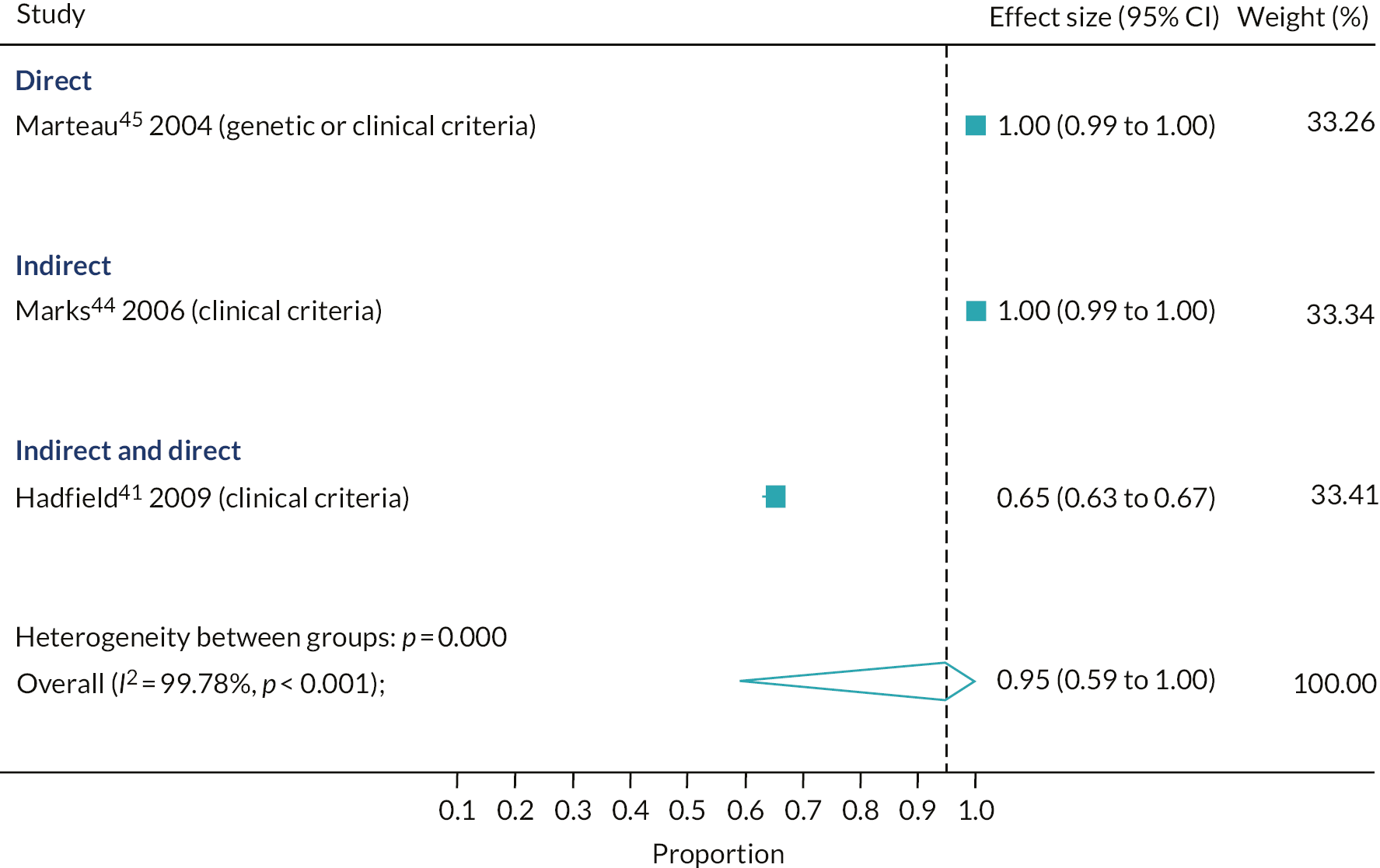

The proportion of relatives contacted for familial hypercholesterolaemia testing out of those eligible

Only three studies reported data to estimate the proportion of relatives contacted for FH testing out of those eligible. 41,44,45 For the studies that reported this outcome, on average, 95% of relatives were contacted out of those eligible (95% CI 59% to 100%, three studies). Using either a direct or an indirect approach resulted in all the relatives who were eligible for testing being contacted (direct: 100%, 95% CI 99% to 100%, one study; indirect: 100%, 95% CI 99% to 100%, one study) (see Figure 3). However, in the single study that used a combination of direct and indirect methods, a significantly lower proportion of relatives were contacted out of those eligible (65%, 95% CI 63% to 67%; p-value for subgroup differences, p < 0.001). However, in this study,41 only 26% of the index cases had a diagnosis of definite FH, with the remaining having a possible diagnosis of FH.

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of relatives contacted out of those eligible for FH cascade testing, by cascade approach.

The proportion of relatives who responded out of those contacted for familial hypercholesterolaemia testing

Three studies reported data on the proportion of relatives who responded to cascade screening out of those contacted;41,44,45 on average, 43% of relatives responded out of those contacted (95% CI 28% to 58%, three studies)

Using a combination of direct and indirect approaches yielded a significantly greater proportion of relatives responding out of those contacted (54%, 95% CI 51% to 56%, one study) than using either an indirect approach (31%, 95% CI 27% to 35%, one study) or a direct approach alone (45%, 95% CI 39% to 51%, one study) (p-value for subgroup difference, p < 0.001).

The proportion of relatives with confirmed familial hypercholesterolaemia of those tested

Twenty-one of the included studies reported data on the proportion of relatives confirmed as having FH out of the number of relatives tested (see Figure 4). On average, 47% of relatives were confirmed to have FH out of those tested (95% CI 42% to 52%, 21 studies). Contact strategies were found to produce similar pooled results (direct: 50%, 95% CI 41% to 58%, I2 = 97%, 10 studies; indirect: 45%, 95% CI 38% to 53%, I2 = 82%, 7 studies; combination: 43%, 95% CI 29% to 58%, I2 = 98, 4 studies; p-value for subgroup differences, p = 0.67).

FIGURE 4.

Proportion of relatives confirmed as having FH out of those tested, by cascade approach.

The proportion of index cases that participated in cascade testing out of those confirmed as having familial hypercholesterolaemia

Seventeen studies reported data on the proportion of index cases who participated in FH cascade testing out of those confirmed as having FH. On average, 89% of index cases participated in cascade testing out of those confirmed with a diagnosis of FH (95% CI 73% to 99%, 17 studies); however, the estimates varied significantly by the cascade approach used (p-value for subgroup differences, p < 0.001). The yield was highest using a direct approach (95%, 95% CI 83% to 100%, I2 = 98%, nine studies), a slightly lower yield was seen using an indirect approach (78%, 95% CI 46% to 99%, I2 = 99%, six studies), and the lowest yield was seen using a combination of direct and indirect approaches (60%, 95% CI 56% to 63%, two studies).

Conclusion

The review provides tentative support for the combination approach to cascade testing, whereby the index case determines which method is used to contact relatives. However, further evidence to support the combination approach requires experimental studies to compare the cascade approaches and/or interrogation of routine data sets and FH registers held on the cascade testing and the modality of contact with relatives.

Review 2: effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapies on low-density lipoprotein levels and cardiovascular disease among adults

An overview of reviews was conducted to assess the benefits of cholesterol-lowering therapies on LDL-C and CVD events in the general adult population and among adults with confirmed FH. Owing to the established evidence of the effectiveness of LLTs among people with FH,6 this review was limited to studies assessing the comparative effectiveness of active therapies with each other; thus, placebo and other non-active interventions were excluded. 27

Materials and methods

The protocol for the systematic review adhered to the PRISMA guidelines27 throughout, for both the conduct and the reporting of the review. Eligible participants were adults from the general population and adults with confirmed FH, determined using a clinical diagnosis (e.g. Simon Broome,5 DLCN,3 MEDPED28 or another criterion appropriate to the population being studied); LDL-C levels, with age-specific cut off points; or genetic diagnosis of mutation-positive cases. The eligible interventions and comparators were any licensed LLTs, including statins, ezetimibe, statins with ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, PCSK9 inhibitors with statins, PCSK9 inhibitors with statins and ezetimibe, or comparisons of different doses of the same treatment. Therefore, placebo or other non-active interventions were not eligible for inclusion as the comparator. The primary outcome measure was LDL-C levels, which could be reported as mean changes from baseline, mean percentage changes, or absolute level at follow-up. The study design included in this overview of reviews was systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials; however, we also included systematic reviews of observational cohort studies when there was a dearth of literature on adults with confirmed FH. We excluded studies that focused solely on index cases with homozygous FH.

Comprehensive literature searches of four databases [MEDLINE, from 1994 to June 2018; EMBASE, from 1994 to June 2018; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), from 1994 to June 2018; and CENTRAL, from 1994 to June 2018] were performed using a highly sensitive search strategy based on keywords and MeSH terms relating to the intervention of interest, outcome measures and study design (see Appendix 1 and Table 25, for the MEDLINE search strategy).

Screening and study selection

Following the removal of duplicates, titles, abstracts and full texts of potentially eligible studies were screened independently by two authors (JLB and Jacqueline Mhizha-Murira). Disagreements regarding eligibility of a study were resolved through discussion with a third author (NQ). Reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage were documented.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) critical appraisal tool58 was used by two reviewers (JLB and JMM) independently to assess the methodological quality of the included studies (e.g. the extent to which the systematic review had minimised the possibility of bias and reporting errors in its conduct) (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for scores on this critical appraisal tool).

Systematic reviews that gained scores of at least 12 on the AMSTAR critical appraisal tool were deemed to be of sufficient methodological quality to be included in the overview. Systematic reviews meeting the methodological quality threshold would have had their data extracted independently by two reviewers (JLB and JMM) using a standardised data extraction form.

Data synthesis and investigations of heterogeneity

A narrative synthesis of the included systematic reviews would have been conducted, whereby the findings from each systematic review would have been grouped based on interventions assessed. The findings would also have been tabulated to identify patterns and reported together with the number of studies that informed the outcome, the number of participants (from the included studies) and the heterogeneity of the results of included studies. When possible, the findings would have been translated using thematic or content analysis to identify areas of commonality between the results of the systematic reviews.

Results

The searches identified 2747 hits from MEDLINE, 1736 hits from EMBASE, 991 hits from CINAHL and 260 hits from CENTRAL, totalling 5734 hits. Following deduplication, 4829 hits were screened by title and abstract. Of the 214 papers identified for full-text screening, 14 papers59–72 were assessed for methodological quality (see Figure 5). The methodological quality of the 14 papers ranged from 1–11; thus, as none of the papers met the threshold of a score of at least 12, no papers were included in the overview of reviews.

FIGURE 5.

The PRISMA flow chart for the review of the effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapies.

Conclusion

The search did not identify any high-scoring systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness of head-to-head comparisons of cholesterol-lowering therapies for LDL-C and CVD events in the general adult population or among adults with confirmed FH.

Review 3: effectiveness of lipid-lowering treatments on low-density lipoprotein levels, and the impact of lipid-lowering treatments on low-density lipoprotein levels, cardiovascular disease and mortality among children with familial hypercholesterolaemia

We aimed to assess the effectiveness of LLTs on LDL-C levels and the association between LDL-C levels and CVD events and mortality among children with FH, using two systematic reviews. Two reviews, from 2016 and 2019, found good-quality evidence that LLT reduced LDL-C levels in children and young people. 19,20 However, no randomised controlled trial evidence was found on the direct effects among children of LLT on CVD events in adulthood or on the association between intermediate outcomes in childhood (e.g. atherosclerosis) and CVD events in adulthood. Given the difficulties of conducting these types of studies, we do not anticipate that additional studies will emerge in the next couple of years. Therefore, in the cost-effectiveness modelling, we linked LDL-C reductions to reductions in CVD risk later in life from the published literature based on adult data17 and we assumed that children and adolescents who are treated with LLT achieve the same LDL-C reductions as adults (see Chapter 5, Cost and health benefits of diagnosis of people with familial hypercholesterolaemia in the long term).

For these reasons, we did not consider a further review of paediatric cases to be a high priority and redirected resources to the newly proposed review 4.

Review 4: the diagnostic accuracy of clinical and biochemical criteria and scoring systems for the diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia among relatives

Background

Cascade testing consists of systematically testing individuals who are at risk of a hereditary disease. 73 Cascade testing has long been proposed to diagnose relatives of patients genetically or clinically confirmed to have FH (the initial patient is known as the index case) because, as the inheritance of heterozygote FH is autosomal dominant, the probability of having heterozygote FH is 50% for first-degree relatives, and 25% for second-degree relatives. 74–76 Cascade testing can be conducted with a genetic test for FH mutation or based on the relative’s clinical and biochemical characteristics (e.g. LDL-C level given their age and sex), or a combination of the two (e.g. using LDL-C level to triage relatives before the genetic test). An example of biochemical criteria is using LDL-C cut-off points specific to age and sex, which is recommended by Starr et al. 77 Similarly, the MEDPED criteria use cut-off points that are age-specific for both total cholesterol (TC) and LDL-C. 28

The 2008 NICE clinical guidelines (CGs) recommended cascade testing with a genetic test for relatives of index cases with FH who had an identified mutation and age- and sex-specific LDL-C criteria to diagnose relatives of probands with FH. 8 The 2017 update, however, recommends using only the genetic test to conduct cascade testing. This systematic review aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of clinical and biochemical characteristics, including LDL-C and TC, and clinical signs, for the diagnosis of FH among relatives of index case with confirmed FH to inform the parameters for the economic model.

Review method

The systematic review was conducted and reported according to the PRISMA guidelines. 78 The study protocol was published on PROSPERO (CRD42018117445).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all published and unpublished test-accuracy studies that reported the result of the index test with that of the reference standard, and for which the following criteria were met:

-

population – relative of index case with genetically confirmed FH

-

index test – use of one or more clinical or biochemical characteristics or a clinical scoring system based on these characteristics (e.g. LDL-C, TC)

-

reference standard – genetic confirmation for any mutation in three FH-causing genes (LDLR, APOB, PCSK9)

-

diagnosis of interest – heterozygote FH.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed in MEDLINE by an experienced information specialist in collaboration with the project team (see Appendix 1 and Table 26). We used a combination of thesaurus headings and terms from the title, abstract or keyword fields, and translated the searches to other databases as appropriate. The search was initially conducted in August 2018 and updated in February 2020. The searches were run from 1994, because of the introduction of a government-subsidised cascade-testing scheme in the Netherlands. 79 The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, CENTRAL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Science Citation Index (Web of Science). Grey literature was searched via websites of relevant organisations (e.g. FH Foundation, NICE guidelines). We checked the references of included studies. There were no restrictions by language, and translations were sought when necessary.

Study selection

Initially, titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (RK/Tumi Sotire/Dapo Ogunbayoa/Atefeh Mashayekhi) using a pilot study selection form based on the inclusion criteria for a random sample (10%) of the hits from the searches. The full texts of the potentially eligible studies were screened independently by two reviewers (RK/Tumi Sotire/Dapo Ogunbayoa/Atefeh Mashayekhi). Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the reviewers or using a third reviewer (NQ). 80

Data extraction and risk-of-bias assessment

Two reviewers (RK and Tumi Sotire) independently extracted data from the included studies based on the study methods and setting, index test, reference standard, sample size and participants’ characteristics. Included studies were assessed for risk of bias by two independent reviewers (RK and Tumi Sotire) using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies-2 (QUADAS-2). 81

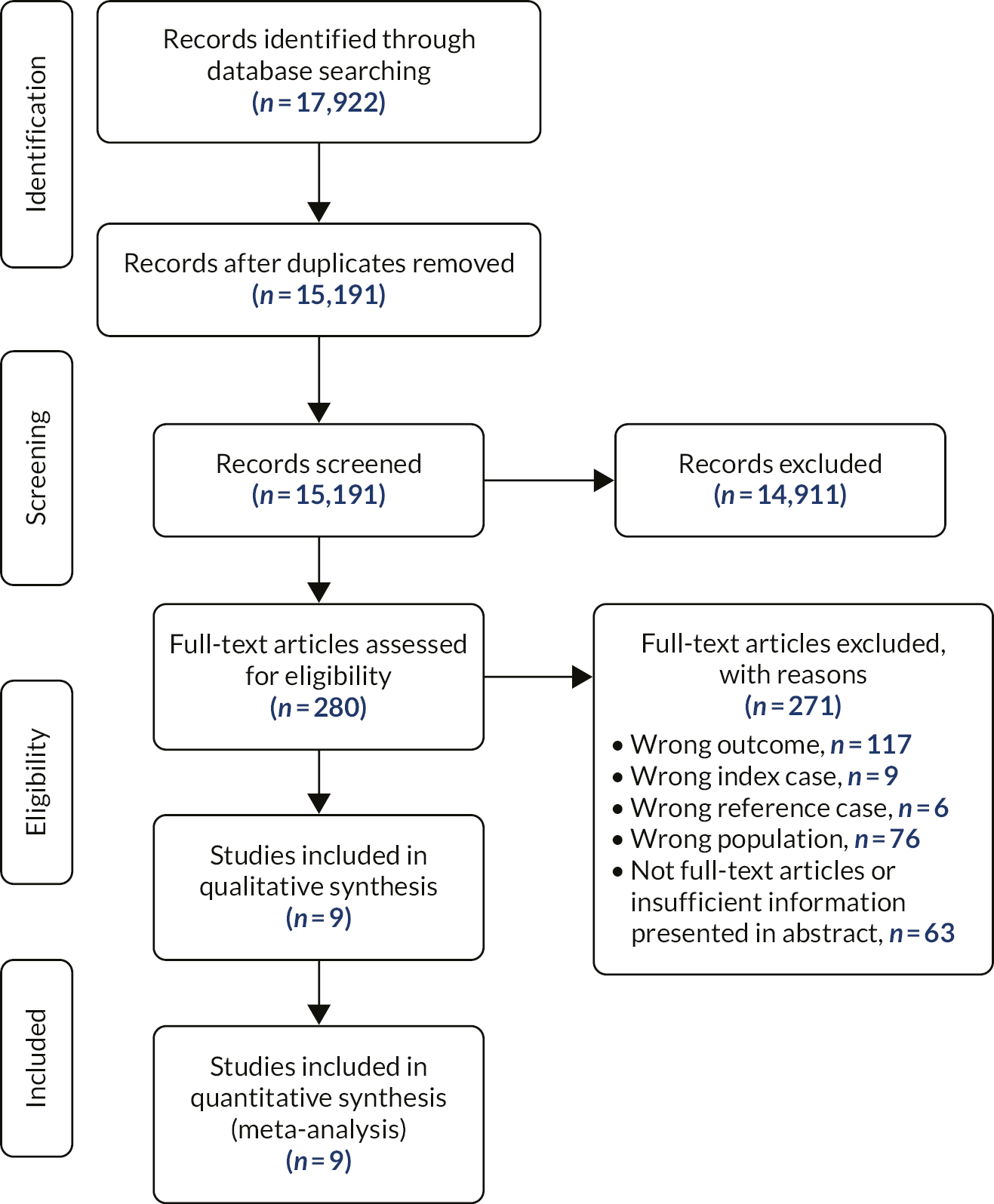

Results

After deduplication, 15,191 titles and abstracts were screened, 280 of which were screened at the full-text stage. Of these studies, 117 reported an ineligible outcome, 9 reported ineligible index cases, 6 reported ineligible reference standards, 76 reported an ineligible population, and 63 were not full-text articles or insufficient information was presented (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the review of the diagnostic accuracy of biochemical and clinical criteria among relatives.

Nine studies met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. 37,41,50,55,82–86 The studies were completed in the following countries: Australia,87 Denmark,41 Iceland,85 Japan,83 the Netherlands,41,82 Norway,41,50,55 South Africa86 and Vietnam. 84 Two studies used the same cohort of individuals; however, one assessed the diagnostic potential of TC50 and the other used LDL-C levels (Norwegian cohort). 41 None of the included studies used other index tests.

The nine studies included a total of 40,079 relatives, of whom 14,310 were diagnosed with FH. The number of index cases was 964 across five studies;37,55,84–86 this could not be determined for the remaining four studies. 41,50,82,83 Three studies enrolled only adults (mean age 40 years);55,82,83 one enrolled only children (mean age 13 years);37 two studies enrolled both adults and children,41,84 and three studies did not report the ages of relatives. 50,85,86 The extent of the cascade testing, in terms of the degree of relative, was unclear in the majority of studies (n = 5); however, only first-degree relatives were considered in two studies,37,41 and first- and second-degree relatives were considered in the remaining two studies. 50,83 Eight of the nine studies also collated triglyceride levels. Triglyceride levels among FH individuals were high in one study. 83

The index test used in four studies was LDL-C. 37,41,82,84 A further four studies used TC. 50,55,85 One study assessed both LDL-C and TC as the index test. 83 Starr et al. 77 compared the accuracy of their own age- and sex-specific cut-off points with that of the MEDPED criteria.

The five studies that used LDL-C as a diagnostic criterion reported varying cut-off values. 37,41,82–84 For example, Huijgen et al. 82 reported four statistical models with differing levels of genetic severity in a cohort from the Netherlands. Each analysis used a 90th percentile cut-off point, which is derived from the sample. Starr et al. 77 reported analyses for differing age and sex groups for three different countries (Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway), and presented the results of the MEDPED criteria for comparison. In each cohort, cut-off points varied from 3.01 mmol/l for males and 3.32 mmol/l for females (aged 15–24 years) to 4.31 mmol/l for males (aged 45–54 years) and 4.36 mmol/l for females (aged ≥ 55 years). The Netherlands and Norway cohorts included patients aged 0–14 years, which had cut-off points of 3.11 mmol/l and 3.37 mmol/l for males and females, respectively. 77 Similarly, Truong et al. 84 used different cut-off points for Vietnamese children (3.0 mmol/l) and adults (4.1 mmol/l). The same cut-off point was used for adults of Japanese origin. 83 The final study was conducted only with children, with a cut-off point of 3.5 mmol/l. 37

Five studies used TC as diagnostic criterion. 50,55,83,85,86 There were variations in cut-off values; however, one study, using a Norwegian cohort, did not report the cut-off values used. 55 In a Japanese cohort, a cut-off point of 5.8 mmol/l was assessed. 83 In a South African cohort, a cut-off point of 4.8 mmol/l (80th percentile of sample) was used. 86 The other two studies analysed the 90th and 95th percentiles of the samples, derived from Netherlands and Iceland cohorts, respectively. 50,85

Risk-of-bias overview

Regarding risk of bias, all studies had a low risk of bias for flow and timing; however, only four studies had a low risk of bias regarding the index test,50,55,82,86 whereas the remaining five studies were at either a high risk of bias37,83–85 or an unclear risk of bias41 owing to how the index test was conducted and interpreted. More specifically, in three of these studies, the threshold for the index test was not prespecified. 37,83,84 With regard to the reference standard, the majority of studies had a low risk of bias; however, one study had a high risk of bias related to the interpretation of the index test, because of a lack of prespecified thresholds and a lack of information regarding index test interpretation. 50 For patient selection, a low risk of bias was seen for eight studies; however, one study was rated as having a high risk of bias because of the lack of clarity regarding sampling technique, study design and whether or not any inappropriate exclusions took place. 83

Discussion

The aim of this review was to review the current evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of clinical and biochemical characteristics in identifying relatives with FH, compared with genetic identification. We found nine studies, all of which examined LDL-C and/or TC levels to diagnose FH among relatives of index cases, with one study assessing the diagnostic accuracy of both. 83 The studies varied in terms of geographical location, relatives’ ages, cut-off points (for LDL-C and TC levels) for diagnosis and quality. The small number of studies, coupled with substantial heterogeneity, means that clinical utility of these biochemical tests could not be determined.

Conclusion

Our systematic review on clinical and biochemical characteristics to diagnose FH among relatives of known index cases found nine studies on LDL-C and/or TC. However, the evidence on diagnostic accuracy and appropriate cut-off points for diagnosis was poor, owing to the paucity of studies and high heterogeneity, which we could not investigate quantitatively.

Summary of results and study limitations

The systematic review of the effectiveness of cascade-testing protocols among relatives was limited to four studies of limited quality. The combination approach, which allows the index case to decide how their relatives are contacted, appeared to result in a higher proportion of relatives tested than the direct or indirect approaches, which had similar yields. It was also noted in this study that only 26% of index cases had a definite diagnosis of FH, with the remaining having a probable diagnosis. 41 The UK study using a direct approach was a randomised controlled trial that compared routine clinical diagnosis plus genetic testing with routine clinical diagnosis alone among index cases and their relatives. 45 Therefore, the study design may have had an impact due to it being recruitment to a trial, whereas the participants recruited to the UK study using the indirect approach was part of a cascade-testing programme,44 and therefore probably more generalisable.

The limitations of this and a previous review26 predominantly related to the nature of the studies available. There were no within-study comparisons; therefore, we had to rely on comparing strategies across studies. Hence the differences in yield between the cascade-testing strategies were wholly ascribed to the contact method used. Only approximately half of the included studies reported the extent of cascading to other relatives; therefore, we were unable to explore whether there were differences in yields by cascade approach related to extent of cascading to other relatives. Owing to the limited evidence, particularly the lack of within-study comparison of modalities of contact, the data were not in a format that could be used to parameterise the economic model. However, the Welsh PASS data provided within-study comparison of the impact of the modality of contact (see Chapter 5, Service data analysis).

Although the search of relevant systematic reviews of the effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapies on LDL-C levels and CVD among adults identified 14 relevant systematic reviews, none of these met the methodological quality on the AMSTAR critical appraisal tool to be included in the review of reviews.

For the systematic review of the effectiveness of LLTs on LDL-C levels, and the impact of LLTs on LDL-C levels, CVD and mortality among children with FH, a preliminary scoping review identified two recent systematic reviews. 19,20 In particular, Lozano et al. 20 had indicated that there were no studies looking at the (long-term) relationship between LLT in children on CVD events in adulthood or at the association between intermediate outcomes in childhood (e.g. lipid concentrations, atherosclerosis) and CVD events in adulthood. We concluded, owing to the nature of these studies, that such data would not be available.

Finally, the systematic review evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of clinical and biochemical criteria and scoring systems for the diagnosis of FH among relatives found nine studies, all of which examined LDL-C and/or TC levels to diagnose FH among relatives of affected index cases, with one study assessing the diagnostic accuracy of both. The studies varied in terms of geographical location, relatives’ ages, cut-off points (i.e. LDL-C and TC levels) for diagnosis, and quality. The small number of studies, coupled with substantial heterogeneity, means that clinical utility of these biochemical tests could not be determined. However, the search included studies indicating that the Dutch national cascade screening programme for FH had relevant data for our research. 50 Therefore, we contacted the data controllers for this programme, who kindly provided aggregate data on the distributions of LDL-C levels among relatives tested for FH in the Dutch cascade screening programme, which we used to inform the cost-effectiveness analysis.

Chapter 3 Overview of database studies

Several databases were interrogated to identify treatment patterns among FH patients, and their outcomes. This includes a FH primary care data set (CPRD) and the Simon Broome FH specialist register. Both linked to secondary care HES data and national mortality data. Furthermore, yield of cases with FH cascade-testing approaches was to be identified through routine data captured from the Scottish, Welsh and Wessex FH services.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink

The CPRD is a large electronic database of UK patients’ anonymised primary care data. There are data from > 20 million patient lives, with > 5 million patients currently registered and active. It includes information on patient characteristics, clinical diagnoses, symptoms, laboratory test results, medication prescriptions and referrals. 88 Access to the data and ethics approval were granted by the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocol numbers 16_191R2, 18_143).

From CPRD GOLD, we identified all adults with FH in primary care, including those with documented FH diagnosis, and those with the clinical phenotype of definite FH using the Simon Broome or DLCN criteria. 8 Patients had at least one cholesterol measurement (TC or LDL-C) during the study period (1 January 1999 to 22 July 2016). For each patient with a clinical diagnosis of FH, we randomly identified three patients without FH and individually matched on age, sex and general practice. Those without FH (controls) had cholesterol testing done within 6 months of the start date of their matched FH case and no documented diagnosis of FH. All patients had to be registered in their general practice for at least 1 year before the start of follow-up and they were followed up until their first diagnosis of any cardiovascular outcome. Patients who did not develop CVD were followed up until date of death, transfer out of the practice or study end date, whichever occurred first.

There were 3,936,934 patients in the CPRD with records of either a TC or LDL-C measurement between 1 January 1999 and 22 July 2016. Of these, 14,097 patients had clinical FH, comprising 5152 with documented diagnosis of FH in the electronic health records and 8945 patients who had no documented FH diagnosis but had the clinical phenotype of FH based on the Simon Broome or DLCN diagnostic criteria for definite FH. Of the 5152 patients with a documented diagnosis of FH, 3182 had an eligible linkage to HES. For the epidemiological survival analysis, we utilised all patients regardless of linkage eligibility to HES (5152 documented diagnoses and 8945 patients who had a clinical phenotype and no documented diagnosis). 89,90

Simon Broome familial hypercholesterolaemia disease register

The Simon Broome FH Register comprises 3553 individuals with FH, recruited between 1 January 1980 and 20 December 2010, from 21 participating lipid clinics. Patients were invited to the registry after being referred by either their GPs or hospital specialists. The lipid clinics participating in the Simon Broome Register were in Glasgow, Manchester, Oxford and London.

Information recorded on registration to the Simon Broome Register included demographic and clinical characteristics, such as age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, past medical history, use of lipid-lowering, antihypertensive and diabetic treatments, and family history, and clinical examination findings, such as blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), tendon xanthomas, xanthelasma and arcus cornealis. 90 A fasting blood specimen taken at the registration visit determined serum TC, triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein. 6,88 Serum LDL-C concentrations were calculated using the Friedewald equation. 6 A diagnosis of definite FH was made if (1) TC concentration (either pre treatment or highest on treatment) was > 7.5 mmol/l in adults aged > 16 years or the LDL-C concentration was > 4.9 mmol/l, plus (2) the patient or a first- or second-degree relative had tendon xanthomas. A possible diagnosis of FH required (1) above, plus one of the following: family history of myocardial infarction before age 50 years in second-degree relative or before age 60 years in first-degree relative, or a family history of raised TC concentration above 7.5 mmol/l in a first- or second-degree relative. The presence of tendon xanthoma was determined by examination and palpation of the dorsum of the hands, elbows, pretibial tuberosities, dorsum of the feet and Achilles tendons by the physicians in the participating clinics. 6,88,91 Patients registered in the Simon Broome Register were linked with the NHS Central Register, which is part of the ONS, for ascertainment of death records including underlying cause and date of death, coded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). Because of the historical nature of the register, genetic testing for FH had been carried out among only the most recent recruits, with a mutation documented in 570 patients.

Hospital Episode Statistics and Office for National Statistics mortality statistics

The HES contain details on admissions, accident and emergency (A&E) attendances and outpatient appointments at NHS hospitals in England. HES data cover all NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in England and contain a wide range of information about individual patients, including clinical information about diagnoses and operations, patient information (age, sex, ethnicity), administrative data (dates, methods of admission, discharge) and geographical information (where patients are treated and the area in which they reside).

To explore long-term mortality and morbidity outcomes and effects of treatment, the two data sets (i.e. CPRD and Simon Broome Register) were subsequently linked to three HES data sets (HES Admitted Patient Care, HES Outpatient Care and HES A&E). In total, linkage to HES data sets was possible for 3182 CPRD patients with a clinical diagnosis of FH, and 2997 participants from the Simon Broome Register had a linked record to at least one of the HES data sets. HES Admitted Patient Care covered from March 1997 to April 2018, HES Outpatient Care covered from April 2003 to April 2018 and HES A&E covered from April 2007 to April 2018.

Linkages to HES and to ONS mortality records were approved by NHS Digital (Data Access Request Service reference number: NIC-115405) and the Confidentiality Advisory Group (reference number: 18/CAG/0007).

PASS Wales and Wessex Cascade Service Data

The Wales PASS database comprised 2618 index cases and 1205 relatives who have undergone FH genetic testing. These are patients who have been tested as part of the All Wales FH Service, which commenced in 2010. The data are held within NHS Wales and hosted by Cardiff and Vale University Health Board. PASS data were anonymised by the PASS data guardian (collaborator KH). Patients are from all health boards in Wales and those across English–Welsh border.

The English PASS database contains the Wessex data. These data comprise 1116 index cases and 501 relatives who have undergone FH genetic testing. The University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust is the data controller for the Wessex PASS data. The Wessex service covered the following CCGs: Fareham and Gosport, Isle of Wight, North and West Reading, North East Hampshire and Farnham, Newbury and District, North Hampshire, Portsmouth, South Eastern Hampshire, South Reading, Southampton, West Hampshire, and Wokingham.

In both the Wales and the Wessex services, index patients are entered into PASS when a referral is received for genetic testing by a FH nurse. This means that both data sets are made up of index patients with pathogenic variants, variants of uncertain significance (VUSs) and patients with no variants identified.

In both services, relatives were added to the pedigrees of index cases where a pathogenic variant is identified. In Wessex, the approach to contacting relatives for cascade testing is indirect, and in Wales the index patient is given a choice of either the direct or the indirect approach. When a relative is referred to cascade testing following direct contact or indirect contact via a letter, they are offered an appointment for genetic testing.

In Wales, segregation testing is offered to families when a VUS is identified in the index patient. This means that, in Wales, the relative data set also includes relatives’ VUS status. Segregation testing has resulted in the VUS of many families being reclassified to either pathogenic or benign. In Wessex, no segregation testing is offered to such families.

Prior to the study commencing, the level of completeness of the PASS clinical data was low. The study funded researchers to manually populate the clinical data both retrospectively and prospectively.

Quality control for mandatory data in PASS was managed by analysing data extractions for missing data. The study data were checked and validated before transferring to researchers, specifically the Welsh DLCN criteria score as it was found to be inaccurate sometimes.

A legacy of the study is that data entry for PASS has continued at a high level, with the FH nurses and FH administrative staff now populating all clinical and genetic data in PASS prospectively. Furthermore, as part of the study, a data extraction script was developed by Kate Haralambos and PASS software so that all the relevant data fields could be extracted in an anonymous format. This script, which took over 1 year to finalise, was vital for the study, but has also been found to be invaluable for future data extractions from PASS as part of evaluation of clinical care.

Scottish familial hypercholesterolaemia service data

The Scottish Lipid Forum, an informal network of 40 health-care professionals from across Scotland who are responsible for the diagnosis of FH and for the provision of care to FH patients (lipidologists, clinical geneticists, genetics counsellors, genetics and biochemistry laboratory scientists) created a sustainable, informally funded genetics cascade-testing programme for FH families in late 2008. Index cases were ascertained by secondary and primary care clinicians largely by the existing network of lipidologists from across Scotland using the Simon Broome criteria. Genetic testing of potential index cases is performed by the genetics laboratory funded by the Aberdeen NHS National Services Division.

NHS Grampian hosts the genetic database for FH screening and gene testing, Genetics Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) funded by NHS Scotland National Services Division. The data cover from 1995 to the first quarter of 2016. Test numbers were low prior to 2009. They then increased by about 250 per year to 2012, and were constant, at just below 1000 tests per year, from 2012 to 2015.

The secure de-identified NHS Safe Haven data linkage system was used to link the NHS Grampian LIMS FH database to NHS Scotland routine electronic data sets, such as National Records of Scotland for births and deaths, Prescribing Information System for dispensed prescriptions and Scottish Morbidity Records/hospital discharge data for cardiovascular outcomes. This was done by the indexing team at NHS National Services Scotland using a probabilistic approach based on Community Health Index numbers (unique patient identifiers). The study period was from 1981 to 2016.

Data access is via the Grampian Data Safe Haven, as the Scottish LIMS FH database and linked data are held by NHS Grampian and the Safe Haven. To comply with information governance procedures and preserve patients’ confidentiality, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidelines on human biobanks and genetic research databases are followed. The electronic Data Research and Innovation Service (eDRIS) provides pseudo-anonymised data extracts for researchers. Personal identifying information is removed and Community Health Index numbers are replaced by unique study numbers. The security of this process is maintained by different teams handling patient identifiers, study variables and the linkage. 92

This routine LIMS data set, which comprises partial dates of birth and death, sex, reason for test, VUS and mutation, along with linked national data sets, forms the baseline data set. This was further merged with NHS Grampian biochemistry data set (study period 1981–2016), which comprises all cholesterol measurements such as TC, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C and triglycerides, and test date. The total number of patients represented in the baseline data is made up of 4282 index cases and 1065 cascade cases. The data set has been updated since 2016.

Conclusion

The most comprehensive data sets for the cost-effectiveness analysis were the CPRD data set linked to HES and mortality data and the routine data set from the Wales and Wessex FH services, housed on the PASS server. The linked Simon Broome FH Register was also accessible for epidemiological analysis. As mentioned in Chapter 4, Summary of results and limitations, although the Scottish FH data were extracted from the safe haven, this data set did not provide appropriate data to parameterise the economic model. There was very limited recording of the ethnic origin of the FH patients in any of these data sets.

Chapter 4 Epidemiological analysis of longitudinal databases

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Iyen et al. 89 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Parts of this chapter have also been reproduced with permission from Iyen et al. 90 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Risk of cardiovascular disease among those with familial hypercholesterolaemia, from primary care records

Context

Although the association of FH with premature CHD is well known, the risk of atherosclerotic disease in other vascular regions among patients with FH is less clear, and evidence from previous studies is conflicting. 6,93–95 The work reported in this chapter sought to determine the CVD risk profile of patients with FH in the general population using longitudinal data from patients’ primary care electronic health records. We assessed the incidence and risks of CHD, stroke/transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) and peripheral vascular disease (PVD) among patients with clinical diagnoses of FH identified in primary care.

Research objective

The objective was to determine the CVD risk profile of patients with FH in the general population.

Methodology

We conducted a retrospective matched cohort study using data from the CPRD. For each patient with a clinical diagnosis of FH, we randomly identified three patients without FH and individually matched on age, sex and general practice. Those without FH had cholesterol testing done within 6 months of the start date of their matched FH case, no documented diagnosis of FH and no pre-existing CVD. Patients who had disease (Read) codes suggesting pre-existing CVD (CHD, stroke, TIA or PVD) prior to study entry were excluded.

Outcomes

Incident CVD was defined as any new clinical diagnosis of CHD, stroke/TIA or PVD. These were identified from patients’ primary care electronic health records during the study period, as were mortality and date of death. Disease codes used for CVD are shown Appendix 4.

Sample size calculation

Based on findings from previous research,96 we estimated a minimum hazard ratio (HR) of 1.2 for overall atherosclerotic CVD risk. To achieve this, a minimum total cohort size of 9450 individuals was required, with an expectation of 1265 CVD events at 90% power and significance level of 0.05 (two-sided test of significance).

Statistical analysis

Baseline descriptive analyses were performed for all patients in the cohort; results are represented as numbers and percentages, means and standard deviations (SDs), and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for categorical, normal continuous and non-normal continuous variables, respectively. Appropriate statistical tests, such as chi-squared tests, t-tests and analysis of variance tests, were used to assess differences between the groups of interest. The incidence rates of CVD were determined for FH and non-FH groups, presented per 1000 person-years at risk. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to derive HRs for the first onset of any CVD and, secondarily, HRs for the various major CVD subtypes (CHD, stroke/TIA and PVD) for patients with and patients without FH. Analyses were stratified on the matched variables and adjusted for individuals’ demographics, lifestyle factors, comorbidities and prescribed medication use, as listed previously. Confounder selection used the change-in-estimate criteria,97 and any covariate that changed the effect size of the univariate exposure–outcome model by 10% was considered an important confounder and included in the fully adjusted model. Statistical tests of the proportional hazards assumption found the Cox proportional hazards regression to be suitable for the analyses. For patients with missing or unrecorded categorical clinical variables, the common assumption was made that these individuals did not have the condition. Multiple imputation techniques98 were used to substitute missing lifestyle data when necessary. All analyses were performed using Stata SE15.

Results

There were 3,936,934 patients in the CPRD with records of either a TC or LDL-C measurement between 1 January 1999 and 22 July 2016. Of these, 14,097 patients had clinical FH and no prior history of CVD at baseline. This comprised 5152 patients with documented diagnosis of FH in the electronic health record, and 8945 patients who had no documented FH diagnosis but had the clinical phenotype of FH based on the Simon Broome or DLCN diagnostic criteria for definite FH. Of these identified patients, 53.3% were females, the mean age at the start of follow-up was 42 years and the mean BMI was 27.3 kg/m2. FH patients were matched with 42,506 non-FH patients. As individuals with and those without FH were matched on age and sex, the distribution of these characteristics were similar across both groups. The median follow-up time for both FH and non-FH patients was 13.8 years (IQR 8.4–17.7 years), and the average follow-up times for patients with and patients without FH were 174,950 and 588,470 person-years, respectively.

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and patients without FH are shown in Table 2. As expected, a significantly higher proportion of FH patients had a family history of premature CHD than non-FH patients (5.1% vs. 2.7%, respectively; p < 0.001), and more FH than non-FH patients were on lipid-lowering medication at the start of the study (19.1% vs. 4.7%, respectively; p < 0.001). Ethnicity records were missing for 85% of patients; for those for whom ethnicity was recorded, 80% were white. BMI records were available for 40% of patients, so multiple imputation with chained equations was used to estimate missing BMI values.

| Risk factor variable | FH patients (n = 14,097) | Non-FH patients (n = 42,506) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at start of study, mean (SD) | 42.5 (11.7) | 41.6 (12.5) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 6578 (46.7) | 19,843 (46.7) | |

| Female | 7519 (53.3) | 22,663 (53.3) | |

| Follow-up (years), median (IQR) | 12.4 (7.1–16.8) | 14.2 (8.8–17.8) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.8 (5.4) | 26.2 (5.6) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol misuse,a n (%) | 265 (1.9) | 712 (1.7) | 0.106 |

| Ever-smoked recordb (yes/no), n (%) | 11,518 (81.7) | 34,395 (80.9) | 0.038 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 783 (5.6) | 2393 (5.6) | 0.736 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 35 (0.3) | 120 (0.3) | 0.503 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 57 (0.4) | 127 (0.3) | 0.056 |

| Type 1 diabetes, n (%) | 60 (0.4) | 247 (0.6) | 0.029 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 311 (2.2) | 726 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Overweight/obesity, n (%) | 525 (3.7) | 1307 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis and/or other inflammatory diseases, n (%) | 100 (0.7) | 285 (0.7) | 0.626 |

| Family history of CHD, n (%) | 712 (5.1) | 1156 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| HIV, n (%) | 6 (0.04) | 16 (0.04) | 0.797 |

| Antipsychotic use, n (%) | 491 (3.5) | 1165 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| Oral corticosteroids, n (%) | 313 (2.2) | 920 (2.2) | 0.693 |

| Immunosuppressant drugs, n (%) | 315 (2.2) | 926 (2.2) | 0.694 |

| LLT,c n (%) | 2692 (19.1) | 2007 (4.7) | < 0.001 |

| Lipid profiled (mmol/l) | |||

| TC, mean (SD) | 9.30 (2.6) | 5.98 (1.6) | |

| LDL-C, mean (SD) | 5.72 (2.1) | 3.63 (1.1) | |

| Triglyceride, median (IQR) | 2.10 (1.3–3.5) | 1.30 (0.9–1.9) | |

| Statin potency, n (%) | |||

| Low | 57 (0.4) | 49 (0.1) | |

| Medium | 466 (3.3) | 384 (0.9) | |

| High | 447 (3.2) | 145 (0.3) | |

| Non-statin lipid-lowering medication, n (%) | 1722 (12.2) | 1429 (3.4) | |

For patients on statins or other cholesterol-lowering medication with known potency, the corrected levels of TC were estimated from observed levels, based on estimated percentage reduction in LDL-C with statins of different potencies. 99 As expected, the mean cholesterol concentration was significantly higher among those with FH [9.30 mmol/l (SD 0.02 mmol/l)] than among those without FH [5.98 mmol/l (SD 0.01 mmol/l)]. The median triglyceride concentrations in the FH and non-FH cohorts were 2.10 mmol/l (IQR 1.34–3.52 mmol/l) and 1.30 mmol/l (IQR 0.90–1.92 mmol/l), respectively. See Appendix 2 and Figure 18.

Cardiovascular disease outcomes

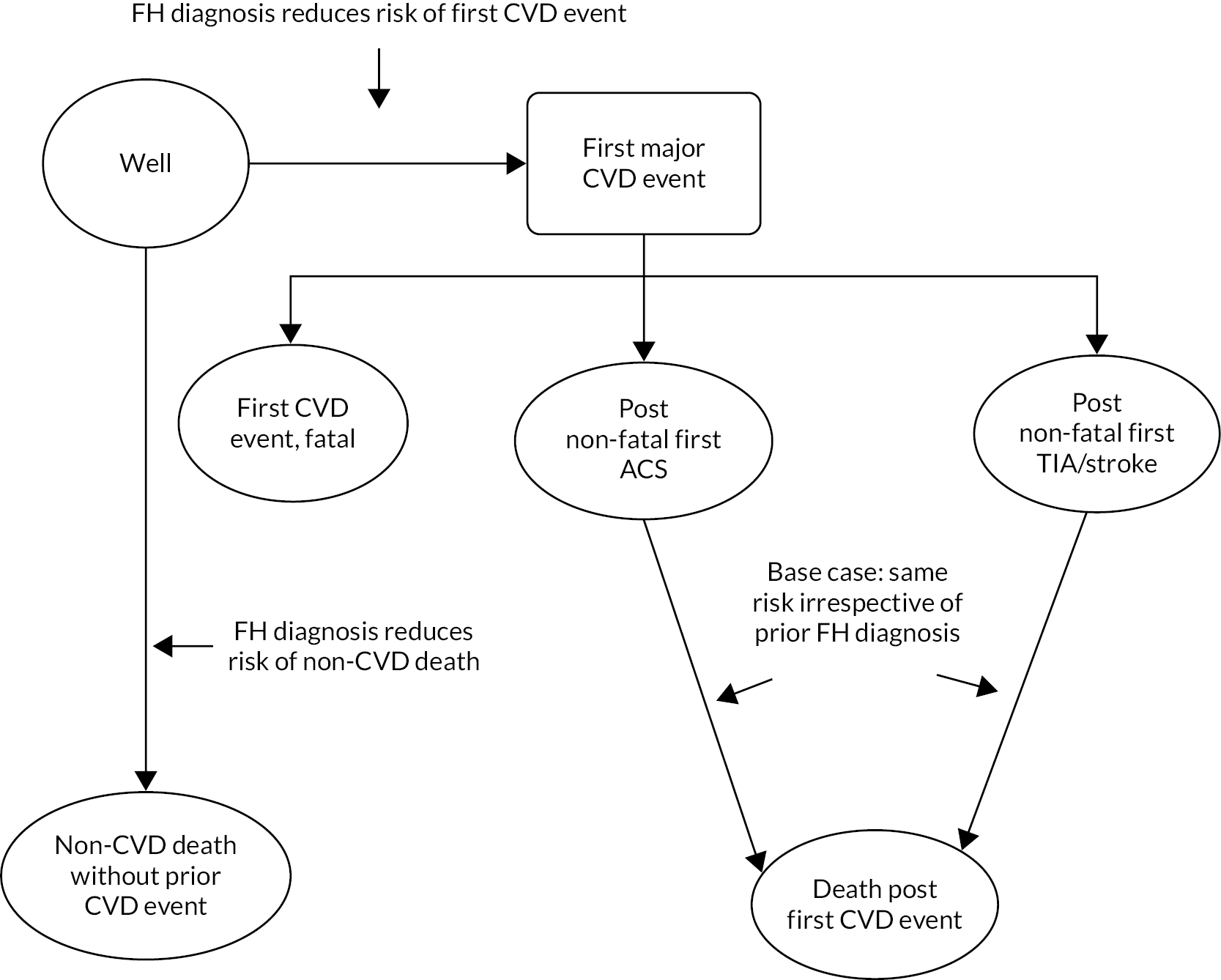

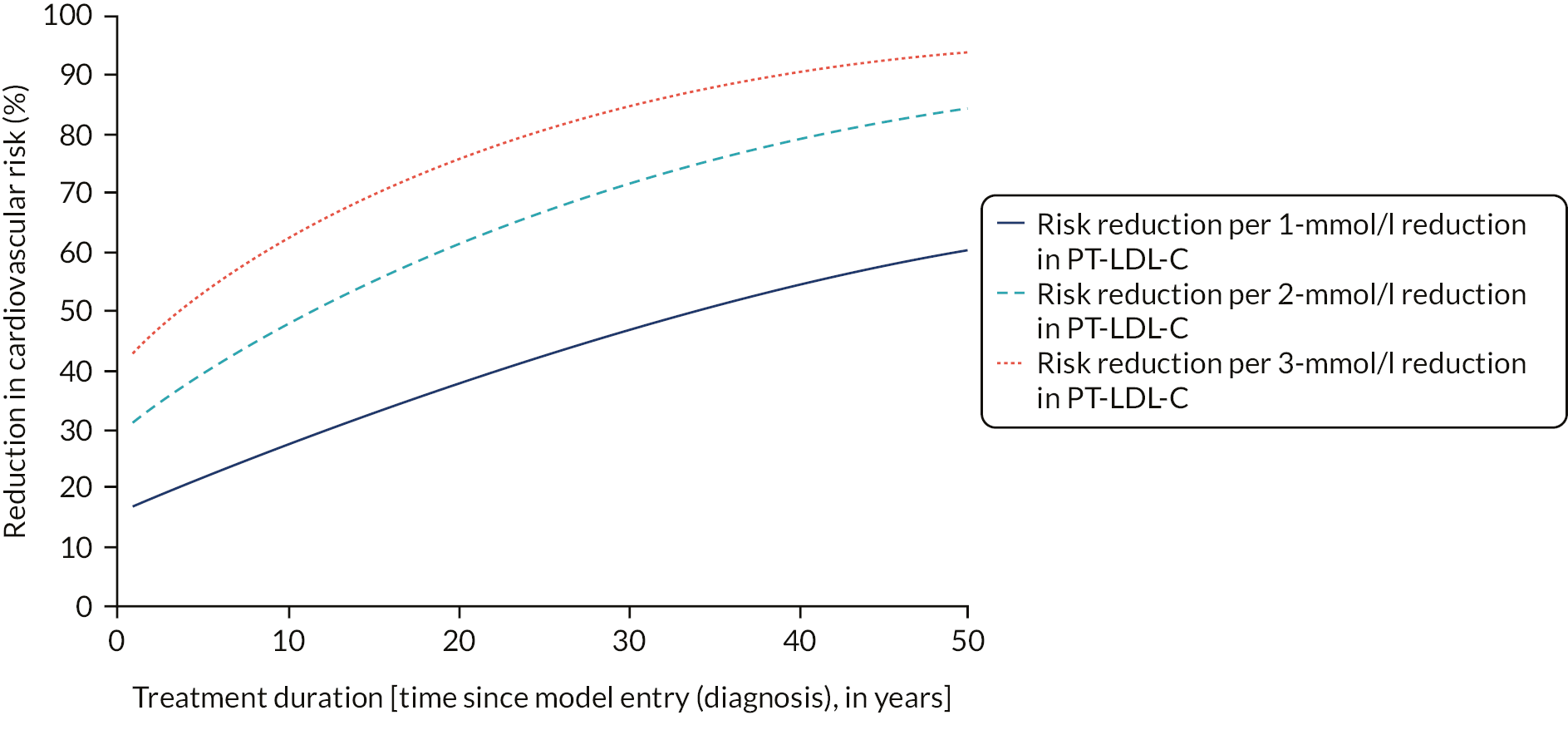

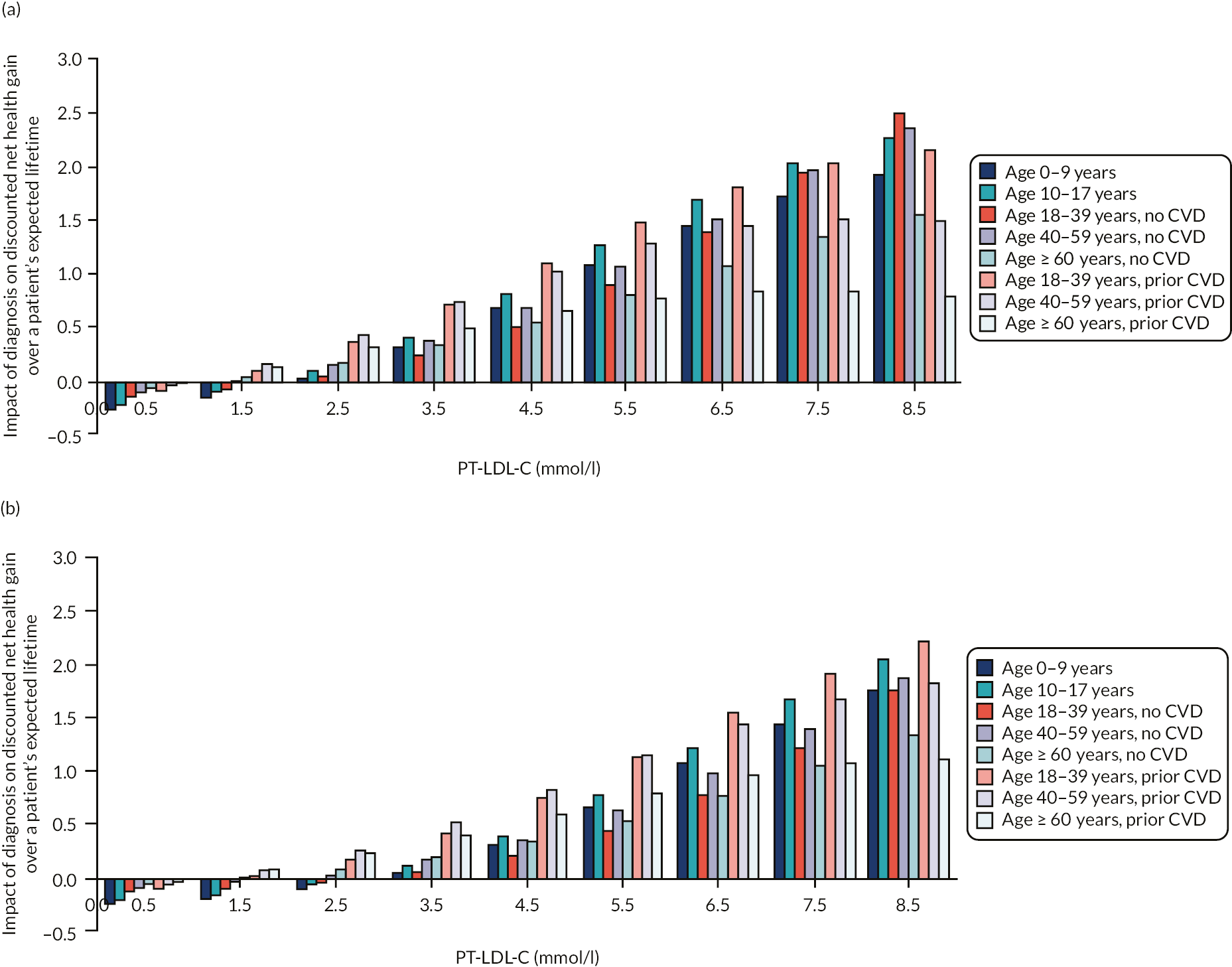

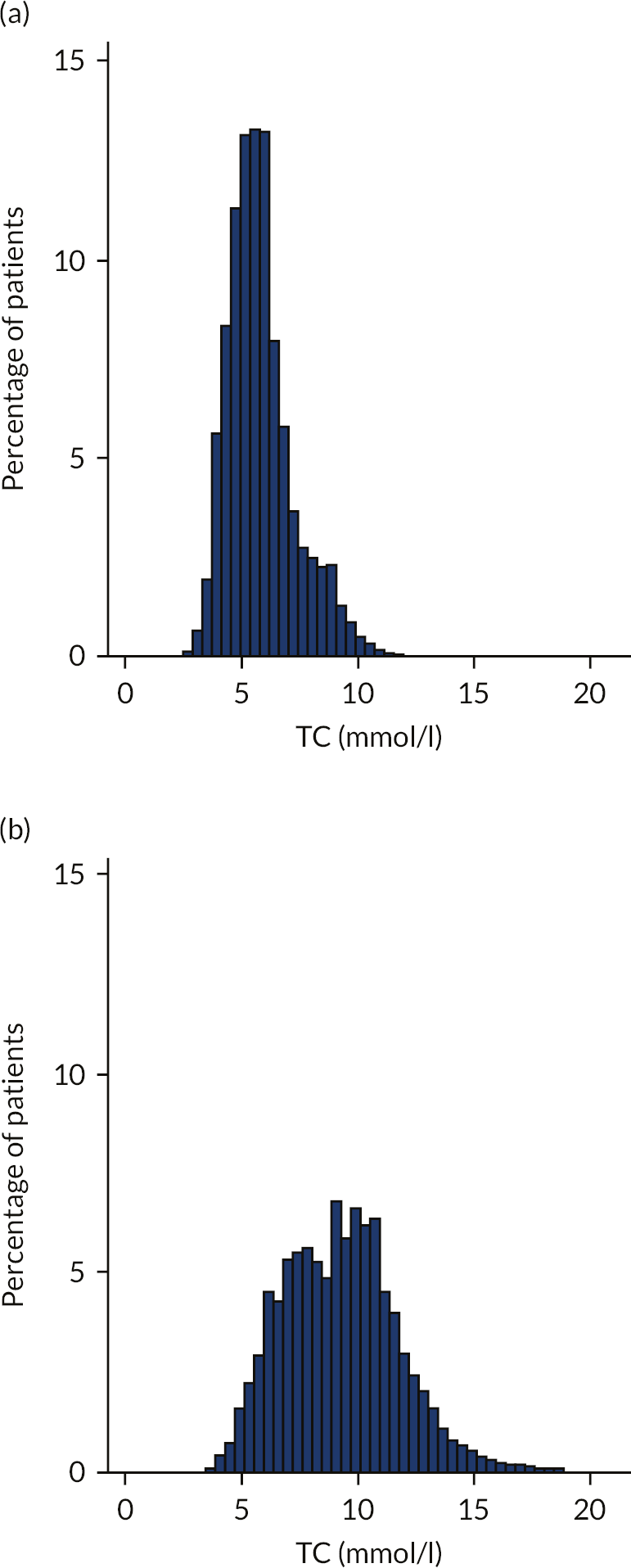

There was a total of 6202 incident cases of CVD (CHD, stroke, TIA or PVD) during the period of follow-up. These were identified in 31.7% of individuals with FH and in 4.1% of non-FH individuals. Comparing baseline characteristics of FH and non-FH patients, hypertension and atrial fibrillation were more prevalent among FH patients who developed CVD than among non-FH patients who developed CVD. Although more FH than non-FH patients with CVD had a history of smoking, the differences in prevalence of chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes were not statistically significant.