Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR128862. The contractual start date was in April 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in August 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Frederick Crocker et al. This work was produced by Frederick Crocker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Frederick Crocker et al.

Chapter 1 Background

There were 12.5 million people aged over 65 years in the UK in 2021 (19% of the population), and this number is expected to rise to 15 million (22%) over the following decade. 1,2 Similar growth is expected in most other developed countries, and more rapid population changes are anticipated in developing countries. In response to such demographic changes, policies and initiatives such as the World Health Organization’s Decade of Healthy Ageing emphasise healthy ageing – aiming to increase the number of years lived in good health and to optimise independence and quality of life in the presence of accumulating health conditions. 3,4 The concept of frailty can be used to distinguish between people who have remained in robust health, and those who have accumulated multiple long-term conditions, are at risk of losing independence and are likely to require health and social care resources. 5 In the UK, around 10% of people aged 65 years and over have frailty, rising to around 50% of people aged over 85 years6 and the additional annual cost to the healthcare system per person (in 2013–4) was approximately £550 for mild, £1200 for moderate and £2100 for severe frailty. This equates to a total additional financial cost of £5.6 billion per year across the UK. 7

Health, social care and third-sector organisations provide community services to support healthy ageing. A systematic review and meta-analysis summarised evidence from 89 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of complex interventions, published up to January 2005 and involving 97,984 participants, aiming to improve physical function and increase independence for community-dwelling older people. 8 The review reported that, in general, complex interventions provided in the community are effective in improving physical function and increasing independence in older people. While this result was encouraging, the review was unable to provide evidence to indicate which of the different service models or intervention components delivered within them were more effective. The review showed that services directed at older people after hospital discharge were significantly effective. It also showed that general untargeted services for older people were also significantly effective, whereas those targeted at older people with frailty were not. However, only one, ill-defined, service model (comprehensive geriatric assessment) was included in this subanalysis, and frailty was not operationalised using valid measurements. Policy-makers, commissioners and service providers require further information about the evidence of effectiveness of services and their components, and the effect that frailty has upon their effectiveness, to guide their decisions about exactly which complex community services for older people to commission and how they should be organised.

We have conducted such an evidence synthesis to update and expand the previous review. This updated meta-analysis includes additional studies of community-based services aiming to sustain the independence of older people in the community published since January 2005. By including information about the nature of the intervention components and the use of network meta-analysis (NMA), this updated review aimed to identify the most effective combinations of components or clusters of interventions. NMA extends traditional pairwise meta-analysis by incorporating evidence regarding the differential effects of multiple types of intervention. The review includes a formal evaluation of certainty in the available evidence. The impact of frailty has been examined in a meta regression analysis. Given the lack of a widely used taxonomy or classification of services or their components, this review has generated and applied a method to distinguish between intervention components and clusters of them.

Research questions and objectives

Research questions

-

Do community-based complex interventions to sustain independence in older people increase living at home, independence and health-related quality of life?

-

Do community-based complex interventions to sustain independence in older people reduce homecare usage, depression, loneliness, falls, hospitalisation, care-home placement, costs and mortality?

-

How should interventions be grouped for NMA?

-

What is the optimal configuration of community-based complex interventions to sustain independence in older people?

-

Do intervention effects differ by frailty level (robust, pre-frailty and frailty)?

Objectives

-

To identify RCTs and cluster RCTs (cRCTs) of community-based complex interventions to sustain independence in older people.

-

To synthesise evidence of their effectiveness for key outcomes (meta-analysis of study-level data).

-

To identify key intervention components and study-level frailty to inform groupings for NMA and meta regression.

-

To compare effectiveness of different intervention configurations (NMA).

-

To investigate the impact of frailty and pre-frailty (meta regression).

Chapter 2 Review methods

Design

Systematic review with NMA of trials evaluating community-based complex interventions to sustain independence in older people (mean age 65 years and over), compared with usual care or another complex intervention meeting our criteria, with follow-up for at least 24 weeks. We followed Cochrane methods,9 evaluated quality of evidence following Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) NMA guidance10 and reported the review in accordance with preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 and PRISMA NMA guidelines. 11 We prospectively registered the review on PROSPERO (CRD42019162195)12 and the protocol was published before analysis began. 13

Throughout the review we used monthly Project Management Group (PMG) meetings and the quarterly meetings of our established patient and public involvement (PPI) Frailty Oversight Group (FOG) to assure the relevance and appropriateness of day-to-day decisions and resolve disagreements between independent reviewers.

Health technologies being assessed

This review assessed community-based complex interventions for older people that were targeted at the individual and focused on sustaining their independence.

Complex interventions have been defined as interventions with several interacting components (intervention practices, structural elements and contextual factors). 14 They typically attempt to introduce new, or modify existing, patterns of collective action in healthcare or formal organisational settings, with an intention to lead to changed outcomes. 15 We used this definition of complex interventions to inform our eligibility criteria.

For this review, we defined sustaining independence to mean maintaining or improving independence in activities of daily living (washing, dressing, grooming, toileting, walking, preparing meals, doing housework, managing finances, assisting others, etc.), but not only one of these specific activities (e.g. walking only). This was a refinement made during the screening stage of our review, to ensure studies addressed this individually meaningful aim that is less interdependent on the wider healthcare context than other meanings (e.g. care home placement), and therefore more generalisable across trials.

Identification of studies

Information sources

Databases and trial registers

We searched the following databases from inception between 9 and 11 August 2021:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) Wiley (1992 to 11 August 2021)

-

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 6 August 2021)

-

Embase and Embase Classic Ovid (1947 to 6 August 2021)

-

CINAHL EBSCOhost (1972 to 9 August 2021)

-

APA PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to August Week 1, 2021).

We also searched trial registers from inception on 10 August 2021:

-

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; to 10 August 2021);

-

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (https://trialsearch.who.int; to 10 August 2021).

Other sources

We searched for additional reports of all included studies in the reference lists of their reports, by searching Google Scholar (scholar.google.co.uk) with the intervention name, project name and trial register number separately, and, if available, on the study’s website. We scanned the reference lists of included studies to identify potentially eligible trials not already identified (backward citation searching). We exhaustively continued backward citation searching and identification of additional reports, including for all reports and studies included in the review through these same processes.

Search strategy

Search strategies for the database and trial register searches were developed and tested through an iterative process by an experienced medical information specialist in consultation with the review team. The full search strategies for all databases and trial registers are available in Appendix 1, including for CINAHL in Table 23.

The search contained the following concepts:

-

Older people or frailty.

-

Home-based or community interventions.

-

RCT filter.

-

1 AND 2 AND 3.

Restrictions by publication status or language were not used.

Search terms were harvested by exploring three relevant systematic reviews and their included studies. 8,16,17 Their search strategies, as well as words and phrases in title, abstract and subject indexing were reviewed to find relevant search terms for inclusion. These terms were used to develop the initial draft search strategy. Extra search terms were found by reviewing results from that initial strategy. The PubMed PubReMiner (https://hgserver2.amc.nl/cgi-bin/miner/miner2.cgi) word frequency analysis tool was also used to find index terms and keyword terms for inclusion in the search strategy. For the concept ‘home-based or community interventions’, we included both broad and specific search terms as testing showed that this was necessary to capture all relevant interventions. We limited terms about geriatric nursing to community or home settings to increase the relevance of search results. Following testing, we also excluded some specific medical conditions in titles to increase the relevancy of the search results. For our MEDLINE search, we added the Cochrane Collaboration highly sensitive filter to identify randomised trials. 18 This was supplemented with a search filter developed to find Phase Three Trials not found by the Cochrane RCT filter. 19 For the Embase search, we used the filter for finding randomised trials in Embase developed by the Cochrane Collaboration. 20 For the PsycINFO search, we used a sensitive methodological search filter. 21 For the CINAHL search, we developed our own search strategy to identify randomised trials. The strategies were peer reviewed by another information specialist prior to execution using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist. 22

Study selection

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

Only RCTs and cRCTs were eligible. Where only one unit of randomisation (an individual or cluster) was allocated to an arm of a trial, we excluded the trial as the treatment effect is completely confounded with the unit. We accepted minimisation as a method of sequence generation, in keeping with Cochrane risk-of-bias (RoB) guidance. 23 We did not exclude variants of randomised trials such as stepped-wedge trials. Crossover and waiting-list designs were also eligible, but we only used outcome data from the pre-crossover period because it is likely that the older people’s independence evolves over time and that, were interventions to be effective at modifying outcomes such as activities of daily living (ADL), this would be a long-term modification whose effects may carry over into the subsequent period of the trial.

Types of participants

We included studies involving older people living at home (mean age of study participants 65 years or older). We excluded trials in residential/nursing homes. If not all participants were living at home, we only included the study if data could be extracted specifically for these participants.

Types of intervention

Aligned with our focus on community-based complex interventions, trials were considered eligible if:

-

the intervention was both initiated and mainly provided in the community

-

the intervention included two or more interacting components (intervention practices, structural elements and contextual factors)

-

the intervention was targeted at the individual person, with provision of appropriate specialist care

-

a focus of the intervention was sustaining (maintaining or improving) the person’s independence.

A broad range of interventions was eligible, differing in terms of how the service was organised and what was done to or for the older person. Our criterion of including two or more interacting components could be met in multiple ways. Eligible interventions could include multiple discrete practices, such as exercise sessions and nutritional advice. Alternatively, interventions could include one practice that interacted with other structural elements such as being reliant on general practice or other services; or interaction with contextual factors by being substantially tailored to the person’s physical and social environment such as ‘comprehensive geriatric assessment’24 or rehabilitation interventions.

Interventions that were not eligible for inclusion were those where:

-

the intervention was either not initiated, or not mainly provided, in the community, or neither for example interventions delivered in outpatient, day hospital, inpatient and intermediate (post-acute) care settings

-

the intervention included only one component (intervention practices, structural elements and contextual factors), for example, if any of the following were delivered as single component interventions: a drug; treadmill training; yoga; provision of information; cataract surgery for visual impairment; hearing aid for hearing impairment; medication-review; nutritional supplements

-

the intervention was not targeted at the individual person, with provision of appropriate specialist care for example general staff education (not training in a patient-level intervention), practice-level reorganisation, operational, managerial or information technology (IT) interventions, public health messages

-

the intervention was not focused on sustaining (maintaining or improving) independence; for example, we excluded interventions that primarily addressed cognitive deficits, mood disorders or both, unless they also aimed to improve overall independence

-

disease-focused case management of older people with specific long-term conditions; for example, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or depression

-

interventions in which the primary focus was fall prevention were excluded as the evidence base for fall prevention is well established including via NMA. 25 Nonetheless, falls were an additional outcome of this review.

Initially we intended to only include interventions for which sustaining independence was the main aim, but this was broadened as complex interventions were rarely described as having one main aim.

Comparators

Usual care, ‘placebo’ or attention control or a different complex intervention which met our criteria were eligible comparators.

Outcomes

Studies were only included where outcome data were measured at a minimum 24-week (approximately 6 months) time point. We included studies that met the above criteria whether or not they measured or reported our outcomes of interest (see below).

Study selection process

Records identified from the literature searches were imported to EndNote (vX9.3.3; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and duplicates were removed. The results were imported into the Rayyan web application (https://rayyan.qcri.org/) (January 2020 search) or Covidence web application (www.covidence.org/) (September 2020 and August 2021 updates). Two researchers independently assessed the title and abstract in each record. Where a record referred to a report of a potentially eligible study, we obtained the full text of the report. Two researchers independently assessed inclusion against our pre-specified criteria, resolving disagreements by consensus with guidance from the PMG. We contacted study authors if further information was required. In cases where there may have been more than one reason to exclude a report, two reviewers reached consensus on a primary reason for exclusion, selecting the first eligibility criterion in our list of eligibility criteria that they were certain was not met. Where studies appeared eligible and to have finished data collection but had not published any results, we contacted the authors to request completed study results. Translation was arranged if necessary throughout the selection process. We excluded as ‘ongoing’ studies that had not been completed, or had finished data collection within 12 months of August 2021 but for which we had no results. 26 The results of the study selection process were imported into and managed within EndNote.

Data collection process

Two independent researchers collected data using a piloted data collection form in a purpose-built database in Microsoft Access (v16.0; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Characteristics of included studies tables were produced from this database. The characteristics of excluded studies table was manually produced via our EndNote library.

Study-level data

We sought the following details for each study:

-

study report citations (i.e. authors, date and location of report)

-

sponsorship/funding source(s)

-

country

-

aims and rationale

-

type of RCT design – randomised by individual or cluster, parallel group or crossover. If cluster, level(s) of clustering

-

analysis details (e.g. intention to treat).

We also sought the following characteristics regarding their participants:

-

brief characterisation

-

inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

age (range and/or means)

-

gender percentages

-

frailty status (see Assessment of frailty)

-

health status

-

living arrangement

-

carer presence

-

ethnicity

-

total number of participants (and clusters) randomised into each group.

Trial arm (intervention) level data

-

number of participants allocated (and clusters where appropriate)

-

experimental nature of arm within the study (experimental/control).

Additionally, details of the intervention as specified by the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)27 were coded and summarised in NVivo (see Intervention grouping).

Outcomes of interest

We collected details of the outcomes measured by the included studies and sought to collect quantitative data and results on the following outcomes:

Main outcomes

-

Living at home.

-

Activities of daily living (personal/instrumental).

-

Hospitalisation.

-

Care-home placement.

-

Homecare services (non-healthcare professional) usage.

-

Costs.

-

Cost-effectiveness.

Additional outcomes

-

Health status/health-related quality of life.

-

Depression.

-

Loneliness.

-

Falls.

-

Mortality.

We worked with our PPI FOG to identify key outcomes, and prioritise them as ‘main’ or ‘additional’, from the perspective of older people. Originally (prior to analyses beginning) these outcomes were proposed as one primary outcome (living at home) with the others as secondary outcomes.

We sought binary data for living at home, homecare services usage, hospitalisation, care-home placement, falls and mortality; and continuous data for activities of daily living, homecare services usage, hospitalisation, costs, cost-effectiveness, health status, depression, loneliness and falls. We excluded bespoke metrics without evidence of evaluation of measurement properties, or metrics where significant problems with their use are recognised.

Specifically, for binary outcomes, we sought to extract the total number of participants in each intervention and control group, and the number of outcome events, alongside any reported effect measures and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), such as risk ratios (RRs) or odds ratios (ORs). For continuous outcomes, we sought to extract the total number of participants in each intervention and control group, the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the outcome in each group at baseline and at follow-up, and the mean and SD of the change score for each group. These estimates were extracted alongside any reported effect measures, such as the mean difference (MD) in final score or change score, or the ANCOVA (adjusted for baseline) result and a measure of variance such as the standard error. Where the above estimates were unavailable within publications, we attempted to recover these using alternate available information so as to avoid selection bias (e.g. using reported elements of the five-number summary, CIs, p-values, 2 × 2 contingency tables etc., to recover mean (SD) or ORs/RRs).

Where living at home was not a reported study outcome but care-home placement and mortality were, we calculated living at home as the remainder (not dead or living in a care home) where it was possible to do so without double-counting participants. Where care-home placement results related to all participants including those who had subsequently died, we could not disaggregate those who had died while living at home and so could not use these results.

Care-home placement as a standalone outcome was only included where it related to care-home residence at that time point, that is the figures excluded mortality during the period of reporting.

Time points

For all outcomes of interest, data were extracted and categorised for three time frames shown in Table 1.

| Label | Target time point | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Short term | 6 months | 24 weeks to 9 months |

| Medium term | 12 months | > 9 months to 18 months |

| Long term | 24 months | > 18 months |

Where more than one time point was reported for an outcome within a range specified above, we used the time point nearest to the target time point.

Because of the large number of outcomes and multiple time frames, we limited analyses of additional outcomes to the medium-term time frame only. We anticipated that the medium term would be of particular interest to commissioners and older people, would be most likely to allow sufficient time for effects to be realised but not washed out, and when most data would be available. We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses and meta regression for the medium-term time frame initially and to extend these to short- and long-term networks in the presence of significant findings.

Throughout the rest of the report we refer to results of interest, which we define here as reported data about a comparison between two arms of a trial for an outcome of interest in one of our analysis time frames.

Other outcomes

We listed all other outcomes measured by included studies but did not collect the results data.

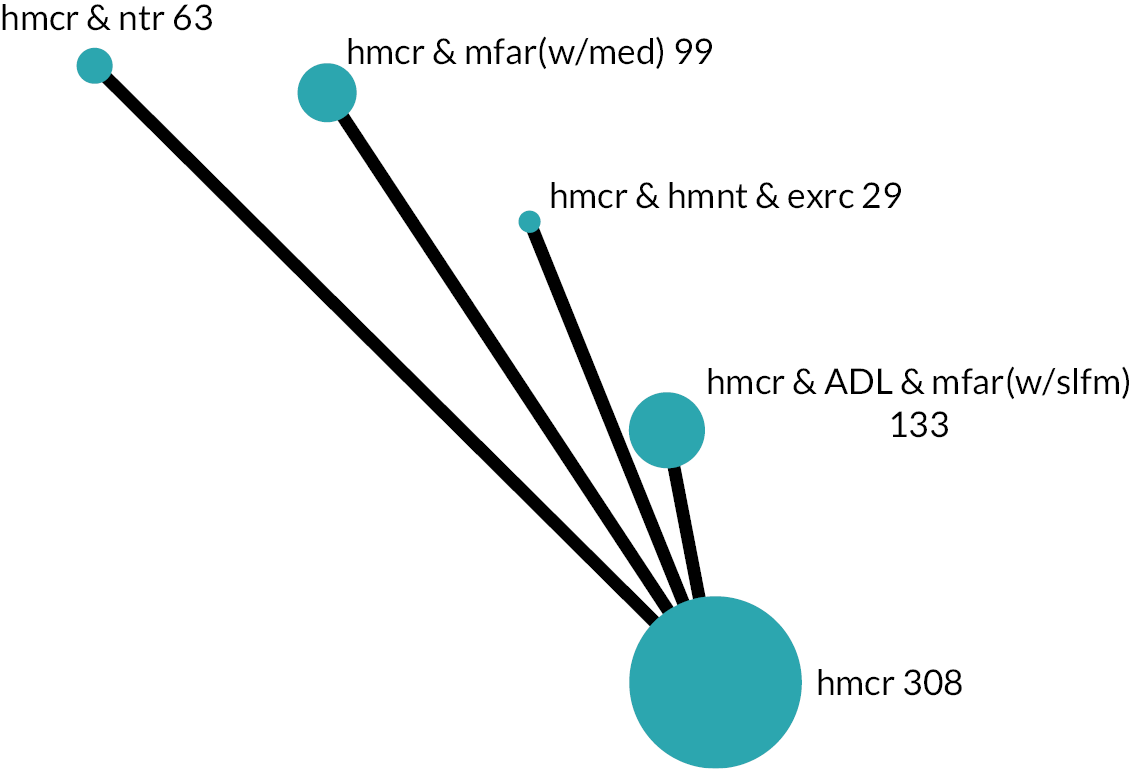

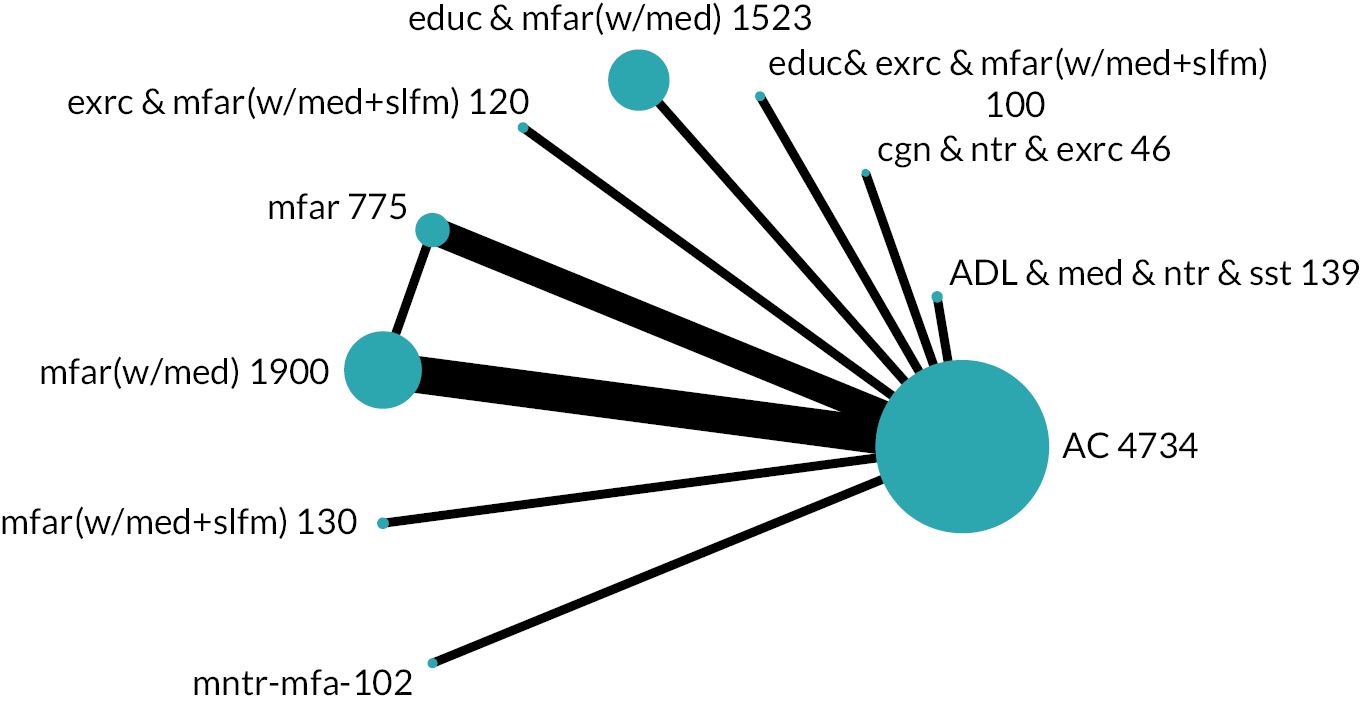

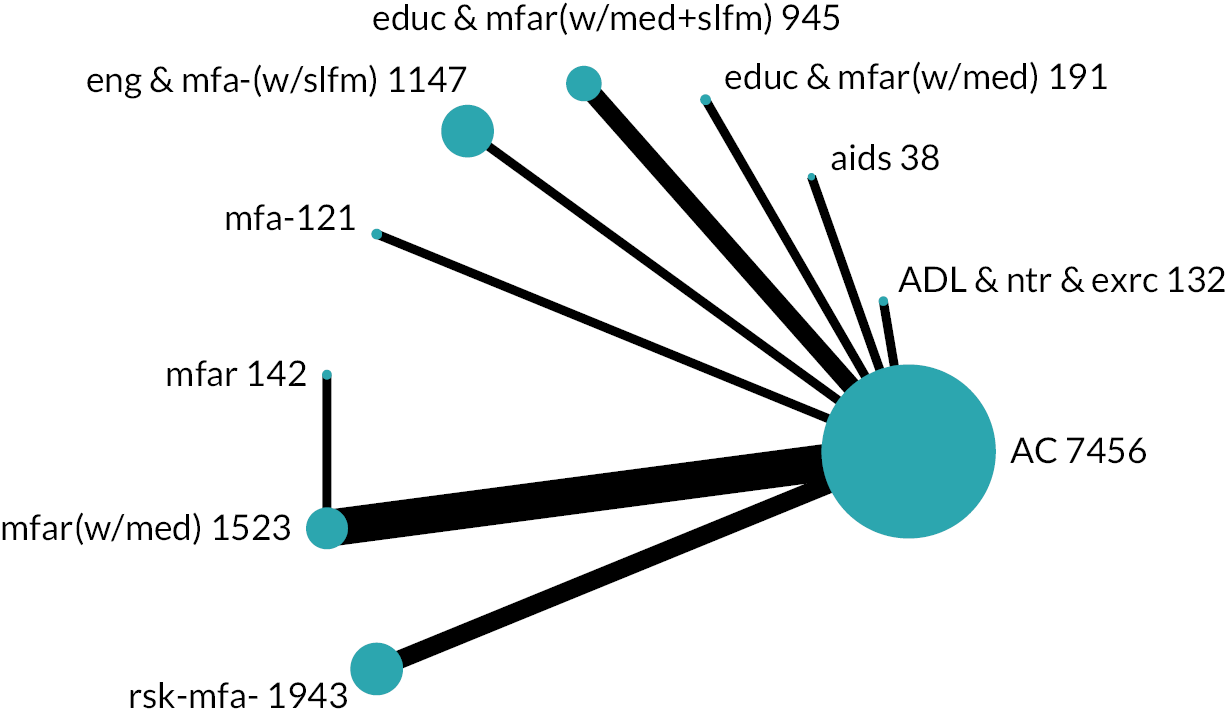

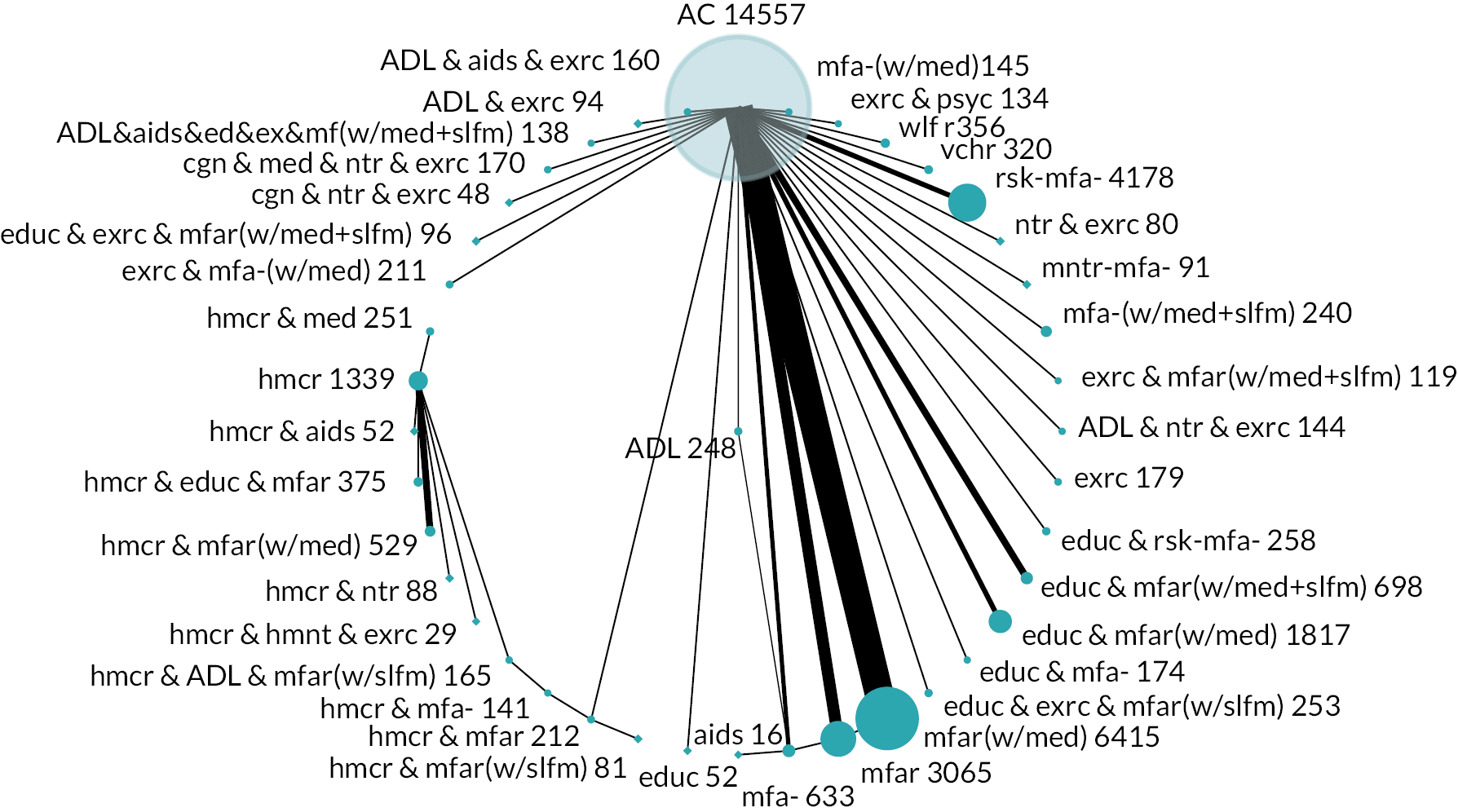

Intervention grouping

We grouped all eligible interventions (including comparators) in preparation for NMA in a three-stage process.

-

We used an extended version of the TIDieR framework to code and summarise reported interventions in NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Hawthorn East, VIC, Australia). 27 The TIDieR framework includes 12 key items (see Table 2). We added a further item regarding the organisational details of the intervention, such as the roles and responsibilities of the intervention providers, means of co-ordination, organisational boundaries and links and financial arrangements. One reviewer coded and summarised each intervention and at least one reviewer (TFC) assessed these and resolved any disagreements by consensus discussion. In the earlier stages, to improve consistency between reviewers, an additional reviewer made an assessment before it was assessed by TFC.

-

We categorised the coding using the principles of content analysis to inform provisional groupings. 28 This categorisation was also considered by at least two reviewers and disagreements were resolved by consensus, involving the PMG where necessary.

-

We developed initial intervention groupings with consideration for service organisation, care processes and specific patient care (e.g. exercise, ADL practice). Through internal discussions involving reviewers and the PMG, including reflections about existing frameworks,29,30 the practical restraints of what was reported and the diversity of interventions, we based our groups on the actions that were intended to be provided to all or almost all participants. These actions determined the components that we used to group an intervention. Interventions that were grouped together were compared and contrasted with subsequent refinement to coding, components and grouping. We presented our provisional groupings to experts including policy-makers, commissioners, older people and carers for open discussion. These led to further revision of our intervention groups and their descriptions (see Chapter 3, Results of the review for details). The intervention groups became the nodes in the NMA.

| TIDieR item | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Brief name | The brand name of the intervention (if any) and, if not descriptive, a short description. |

| 2. Why | Rationale, theory or goal of the elements essential to the intervention. |

| 3. What (materials) | The physical or informational materials used in the intervention, including those provided to participants or used in intervention delivery/training of intervention providers. |

| 4. What (procedures) | The procedures, activities and/or processes used in the intervention, including any enabling or support activities. |

| 5. Who provided | The expertise, background and any specific training given to each category of intervention provider. |

| 6. How | The modes of delivery (such as face-to-face or by some other mechanism) of the intervention, and whether it was provided individually or in a group. |

| 6b. How organised (additional item) | The roles and responsibilities of the intervention providers, means of co-ordination, organisational boundaries and links and financial arrangements. |

| 7. Where | The types of location where the intervention occurred, and any required infrastructure. |

| 8. When and how much | The amount and intensity of intervention delivered, including number of sessions, their schedule, duration and dose and the overall time frame in relation to triggering events. |

| 9. Tailoring | Details of any individual/group adaptations, personalisation or titration. |

| 10. Modifications | Details of any changes made to the intervention during the course of the study. |

| 11. How well (planned) | Strategies to achieve fidelity or adherence and planned assessment of fidelity. |

| 12. How well (actual) | Extent of intervention fidelity achieved. |

Assessment of frailty

We expected that a range of validated instruments and operationalised measures would be used to identify pre-frailty and frailty in included trial populations of some studies. Examples of such frailty measures include: the use of the Fried phenotype model, cumulative deficit frailty index (FI), the Tilburg Frailty Indicator, Groningen Frailty Indicator, Clinical Frailty Scale, Hebrew Rehabilitation Center for Aged Vulnerability Index, Vulnerable Elders Survey, Brief frailty measure derived from the Canadian Study of Health and Ageing or a formally produced Frailty Index. We classified the trial population in accordance with the frailty measure, so long as it was developed or validated according to the modern meaning of frailty (loss of biological reserves, failure of physiological mechanisms and vulnerability to experiencing adverse outcomes after minor stressor events) and not as a generic term for being old or disabled. We reported methods used for each study, including cutpoints for identification of pre-frailty and frailty.

We also expected that many studies would not formally have described study populations in terms of frailty. In such circumstances two reviewers with extensive clinical academic frailty expertise (AC and JG) independently used the well-validated phenotype model as a framework to categorise study-level frailty profile (robust; pre-frailty; frailty) of trial participants if the relevant variables were reported. 31 The model is based on five characteristics (weight loss; exhaustion; low energy expenditure; slow gait speed; low grip strength). Evidence of ≥ 3 indicates frailty, 1–2 pre-frailty and 0 robust. In the remaining studies where neither a recognised frailty measure nor the variables needed to apply the frailty phenotype categorisation were reported, the two reviewers independently attempted to classify the populations based on trial eligibility criteria and/or reported baseline characteristics closely linked to frailty including gait speed, hand grip strength, mobility, activity or disability levels. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

In categorising study level frailty, we recognised that trials included participants across different frailty categories, so as well as ‘robust’, ‘pre-frail’ and ‘frail’, our categories also included ‘robust and pre-frail’, ‘pre-frail and frail’ and ‘all’. Where we were not able to classify the population, we labelled it ‘unclassified’.

We planned for our main analysis of the impact of frailty to only include trials that were categorised according to a validated measure, with subsequent analyses including all categorised trials. However, we categorised insufficient trials according to a validated measure to enable this approach, so our analyses do not distinguish between the methods of categorisation.

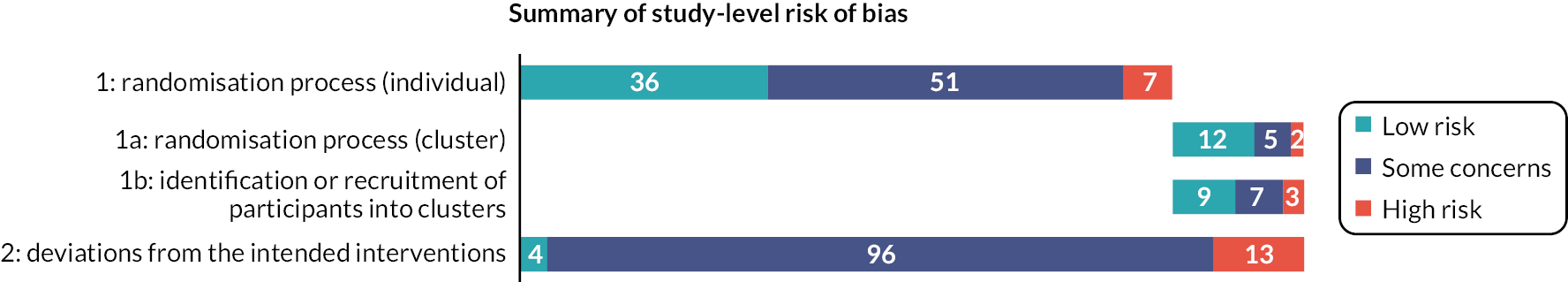

Risk-of-bias assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed RoB in each result of interest from each included study, using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2). 32,33 Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the reviewers or through discussion with the PMG. Our effect of interest was the effect of assignment to the intervention (‘intention-to-treat’ effect). For individually randomised studies, we assessed RoB in five domains:

-

bias arising from the randomisation process

-

bias due to deviations from intended interventions

-

bias due to missing outcome data

-

bias in measurement of the outcome

-

bias in selection of the reported result.

For cRCTs, we used the latest guidance34 to assess identification/recruitment bias, and the other issues such as loss of clusters detailed in section 23.2: Assessing RoB in cluster-randomised trials, of the Cochrane Handbook Version 6. 9 This assessment resulted in two domains of bias in place of domain 1: 1a, bias arising from the randomisation process, and 1b, bias arising from the identification or recruitment of participants. Other details were integrated within the same domains as for individually randomised trials.

For each domain, we made a judgement of high RoB, low RoB or some concerns. We used the signalling questions and algorithms and considered whether to override the result, recording our reasons and supporting evidence. For domain five, in the absence of a pre-specified analysis plan we judged the risk to be low when the result being assessed was very unlikely to have been selected on the basis of the results from multiple eligible outcome measurements or from multiple eligible analyses of the data.

For each assessed result of interest, we summarised our concerns and reached an overall risk-of-bias judgement that was at least as severe as the most severe domain risk. Although we considered whether to upgrade the severity where multiple domains were rated as some concerns (and none as high), we did not do so. We also judged whether a result at high RoB posed serious concerns (only one domain at high risk) or very serious concerns (more than one domain at high RoB or very serious concerns in relation to one domain). These judgements then fed into our GRADE assessment of RoB, consistent with GRADE and Cochrane recommendations regarding the association between RoB in individual results and the results of analyses. 35,36

We used the RoB 2 Excel tools (version 8 for individually randomised studies, version 3 for cluster-randomised studies, available from www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool) to manage our assessments and check consistency between reviewers. We resolved any disagreements by consensus. We imported these assessments into our Access database and presented domain level and overall judgements with a summary of the reasons any domain was not rated as low RoB.

Data synthesis

Summary measures

For each trial and each outcome separately, effect estimates and CIs that compared intervention and control groups were either extracted from the trial publication or calculated based on other reported information (e.g. number of outcome events and participants per group; mean and SD of follow-up scores, etc.). For continuous outcomes, we used standardised mean difference (SMD, specifically Hedges’ g) for outcomes with different measures for similar constructs (ADL, depression, self-evaluation of health status) across the trials. Where continuous outcome measures used a mix of measures favouring higher or lower values, the measures in one direction were reversed so that for a particular outcome, all trials measured improvement in outcome in the same direction.

For binary outcomes, we extracted or calculated RRs and ORs. For survival (time-to-event) outcomes, hazard (rate) ratios were extracted. Any details about non-proportional hazards were also extracted. Both adjusted and unadjusted results were extracted, though in practice unadjusted results were used in the synthesis due to a combination of heterogeneity in adjustment factors across studies and a sparsity of evidence to enable synthesis. Where effect estimates were calculated using 2 × 2 contingency tables which contained zero cells, a continuity correction of 0.5 was applied to all cells.

Effect estimates reported from cluster-randomised trials were included directly in cases where the original research had appropriately accounted for the clustered nature of the data in their analyses (e.g. multilevel modelling). Where studies were found to have ignored clustering in their analyses, we adjusted for this by reducing the sample size to the ‘effective sample size’ using the ‘design effect’ as a divisor for the original sample size. For stepped-wedge trials, we only included data from analyses that appropriately accounted for time trends.

Results of outcomes at all time points were recorded and placed into categories (around 6 months, 12 months and 24 months; see Table 1). We conducted meta-analysis separately for each of these three time frames for our main outcomes, and for the medium-term time frame for our additional outcomes as described in time points above.

For care-home placement and hospitalisation, our meta-analysis summarised the odds of this occurring for a participant, rather than counts, for example. We evaluated personal ADL and instrumental ADL as separate outcomes and did not additionally meta-analyse combined personal and instrumental ADL instruments. We did not combine all measures of health status due to differences in the underlying constructs. We chose to meta-analyse single global self-assessments of health status as it is readily interpretable and the most widely available measure. We tabulated results that we did not include in meta-analysis.

Methods of analysis

We meta-analysed the extracted effect estimates using modules within Stata, including metan, mvmeta and network. 37 Random-effects meta-analyses were conducted, to allow for potential between-study heterogeneity in each intervention effect. 38 Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation was used to fit all the models and 95% CIs were calculated using the Wald-based approach, but with inflated variances to account for uncertainty in the estimated variances, similar to the approach of Hartung–Knapp but using a normal approximation instead of a t-distribution. 39,40

Initially, for each outcome separately, we performed a separate meta-analysis for each type of intervention versus control, to provide summary effectiveness results based only on direct evidence. We summarised ORs for binary outcomes, and pooled (standardised) MDs for continuous outcomes. We found insufficient estimates to allow pooling of hazard ratios (HRs) for survival outcomes. We displayed forest plots, with study-specific estimates, CIs and percentage study weights, alongside the summary (pooled) meta-analysis estimates, 95% CI for the summary effect, and (if possible) a 95% prediction interval for the intervention effect in a new study similar to one of those included in the meta-analysis.

Heterogeneity was summarised by the estimate of between-study variance [tau (τ)], the proportion of the total variance due to between-study variance [I-squared (I2)] and 95% prediction intervals, as mentioned above.

Summary ORs were converted to a summary RR and multiple corresponding absolute intervention risks and risk differences; SMDs were re-expressed as the MD of a common measure of the outcome as described in Confidence in cumulative evidence.

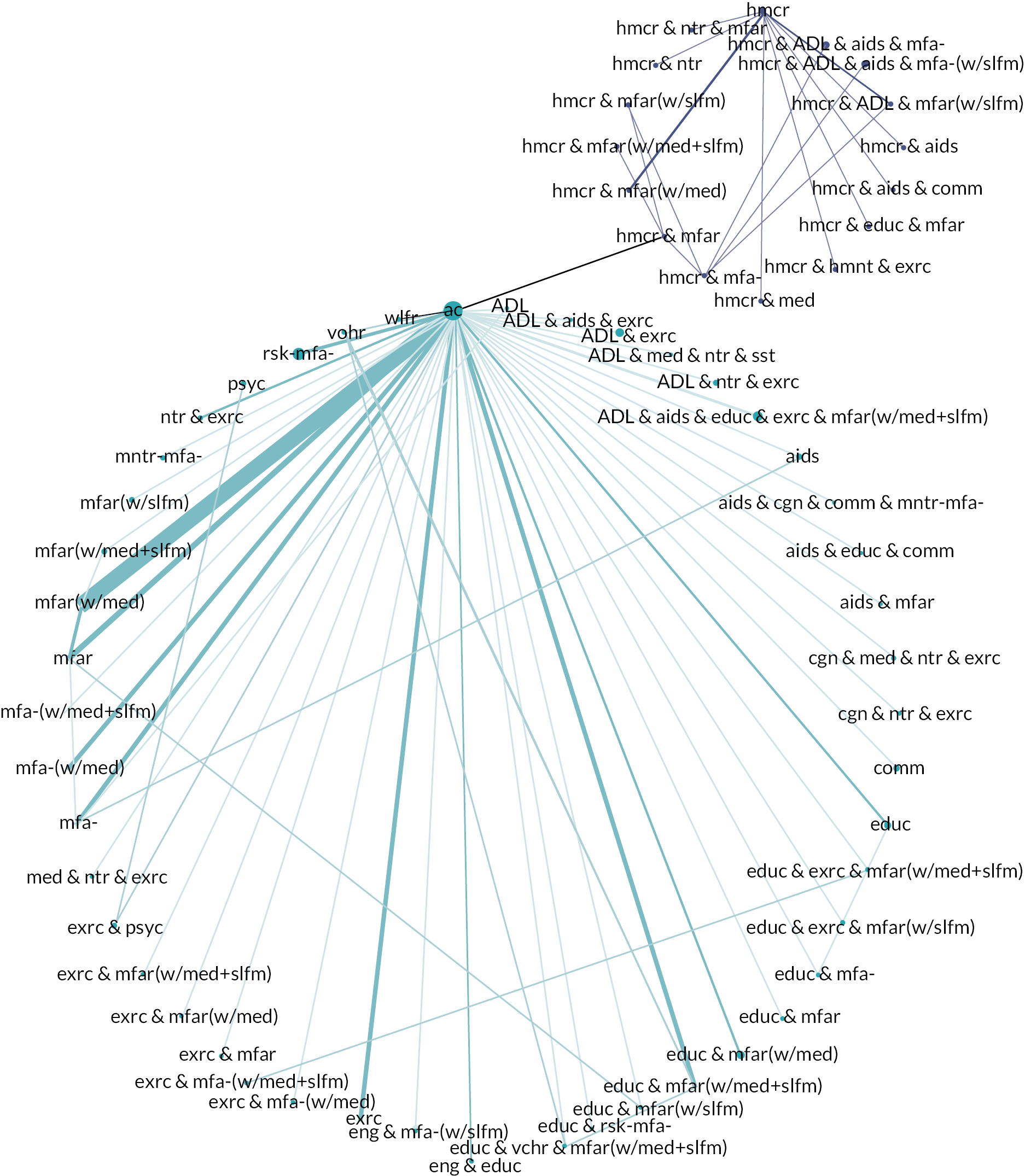

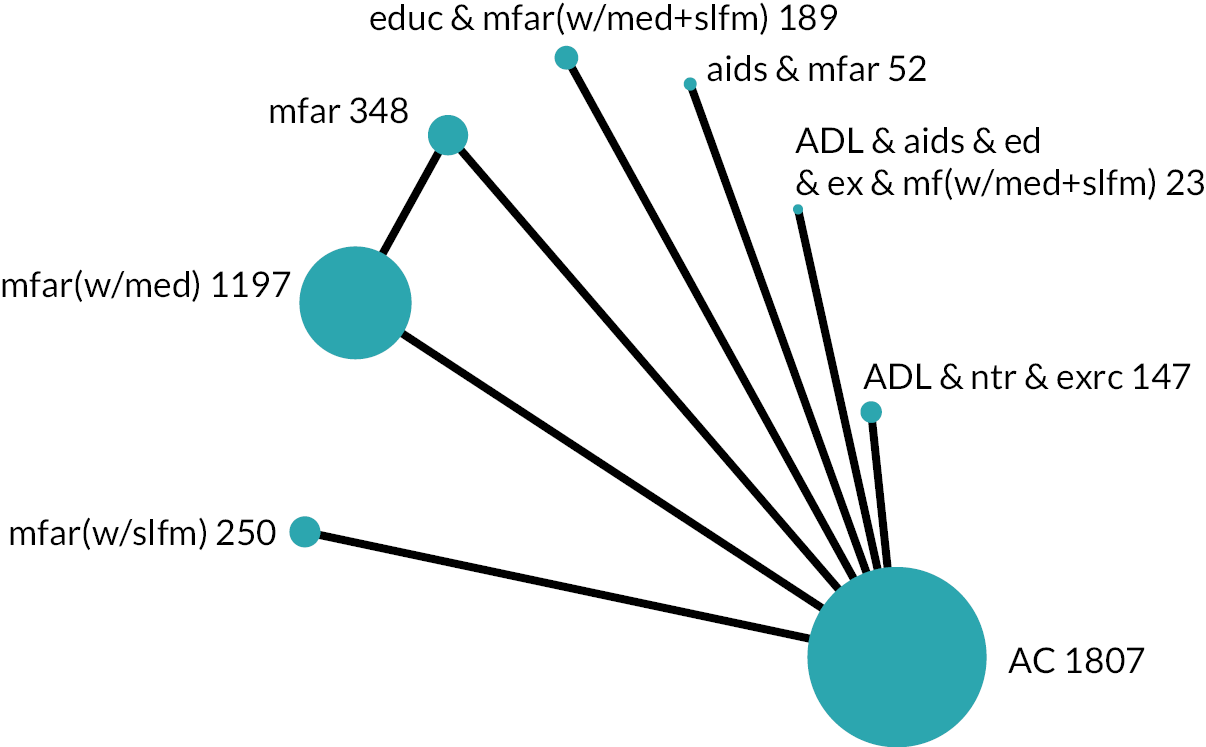

Network meta-analysis

A NMA was conducted (for each outcome and time frame separately), using a multivariate random-effects meta-analysis framework (where possible) via the network module in Stata using REML estimation. 37,41 This allowed both direct and indirect evidence to contribute towards each intervention effect (treatment contrast), via a consistency assumption. Where multiple studies were not available for any individual comparison (i.e. no degrees of freedom available to estimate heterogeneity) a common-effect model was fitted. The within-study correlation of multiple intervention effects from the same trial (i.e. in multigroup trials) was accounted for, and a common between-study variance assumed for all treatment contrasts in the network (thus implying a +0.5 between-study correlation for each pair of treatment effects). Summary (pooled) effect estimates for each pair of treatments in the network, with 95% CI, and (if possible) 95% prediction intervals were calculated. For binary outcomes, we chose to synthesise natural log-transformed ORs (ln ORs), as the OR is more portable across different baseline risks than the RR. 42

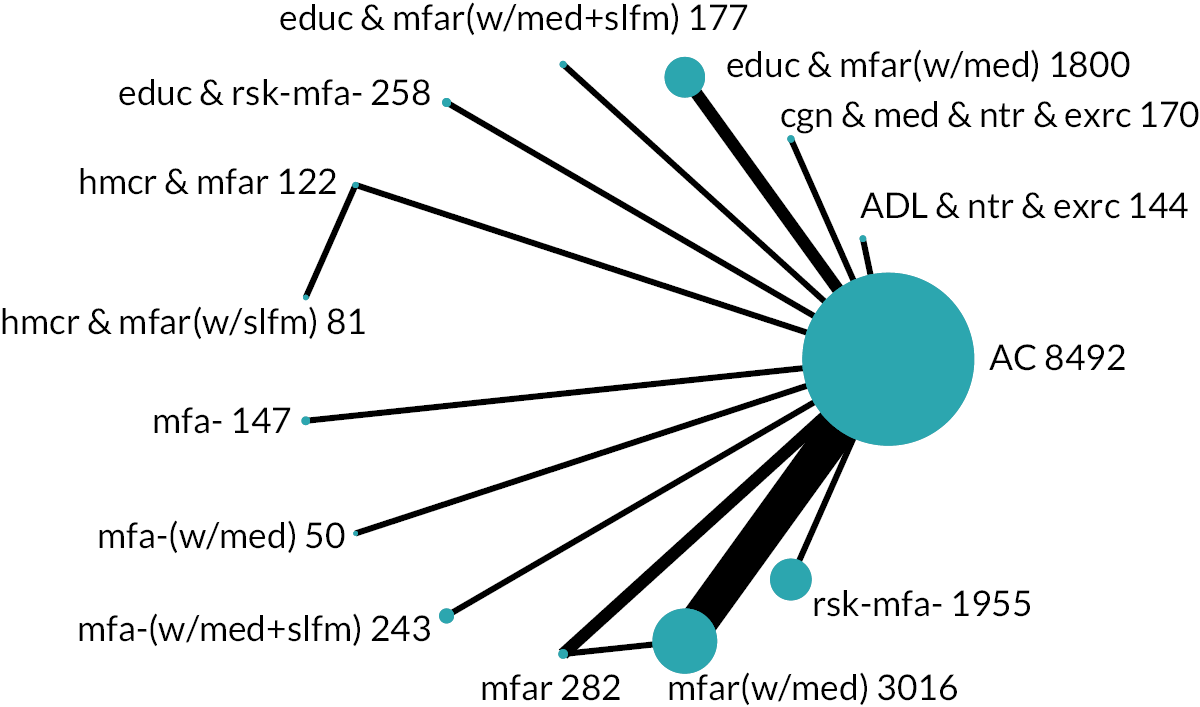

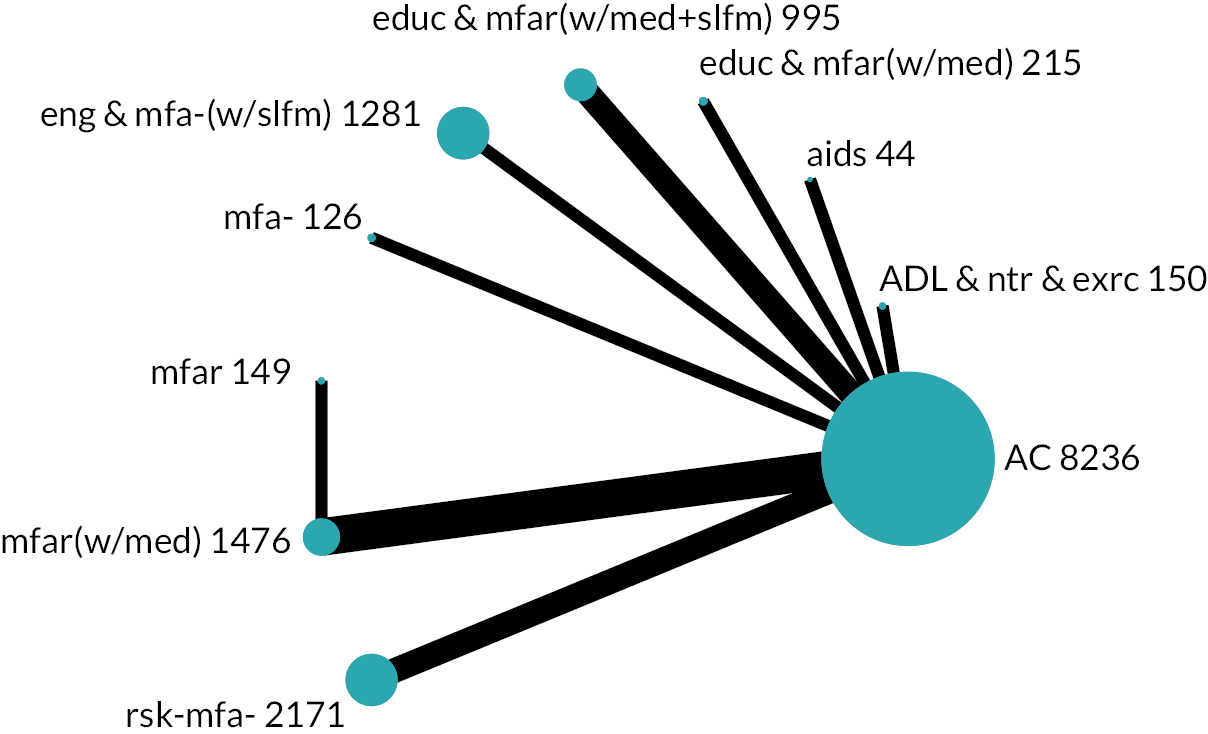

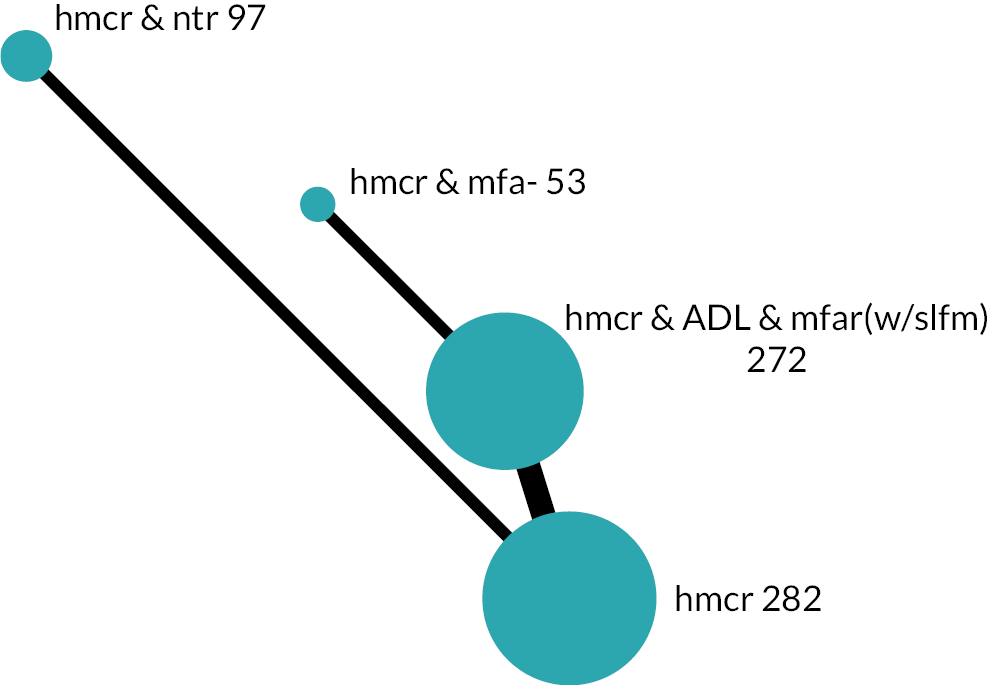

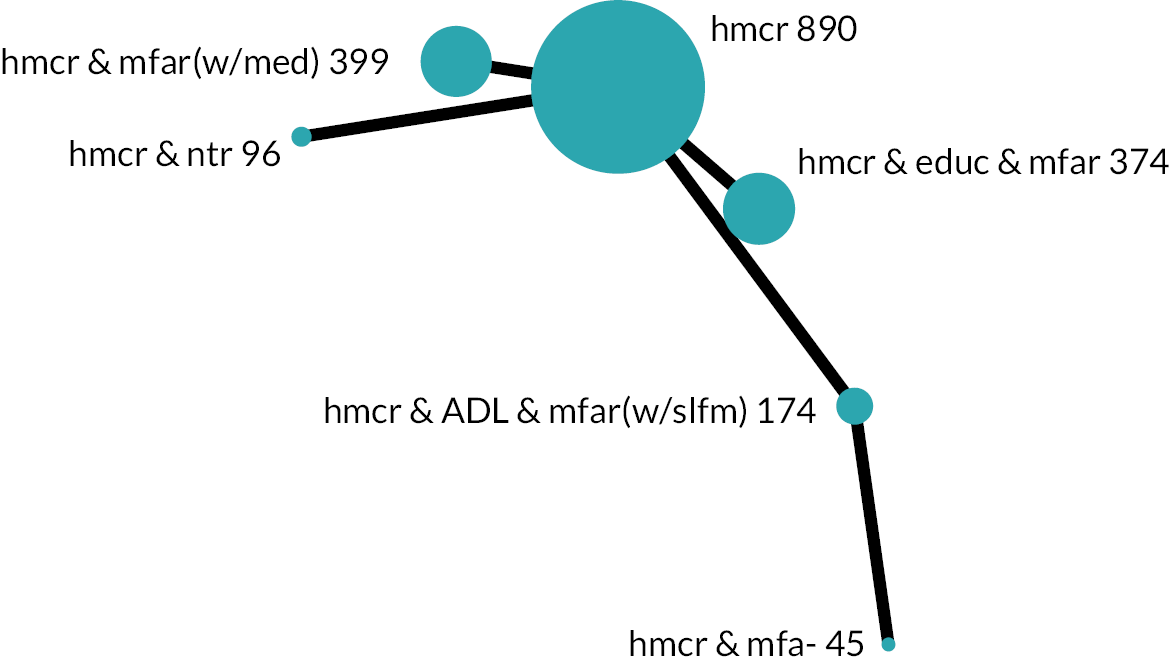

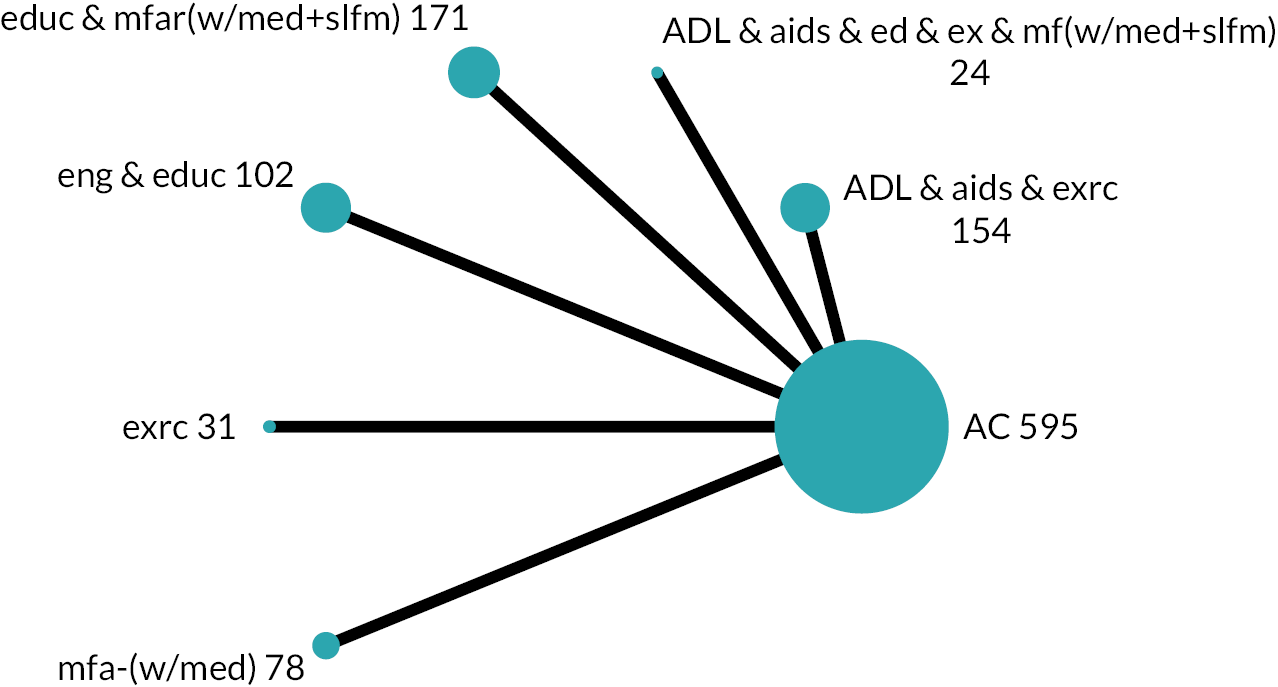

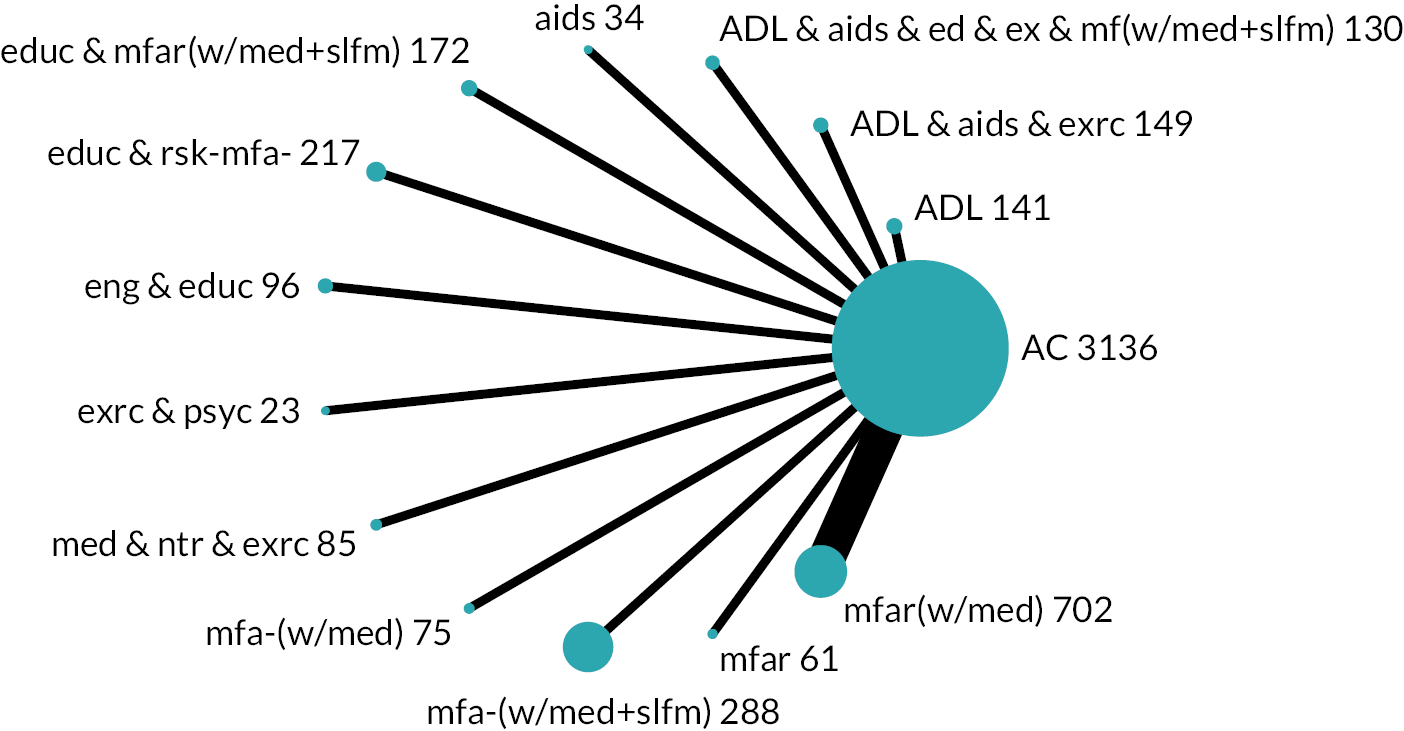

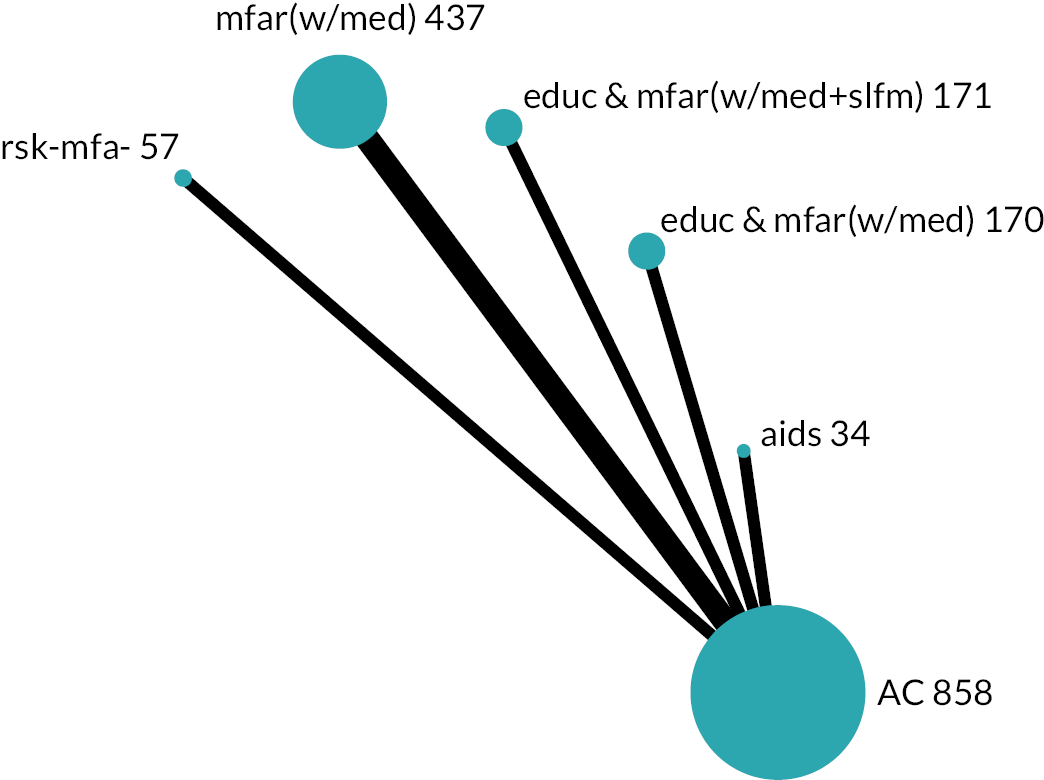

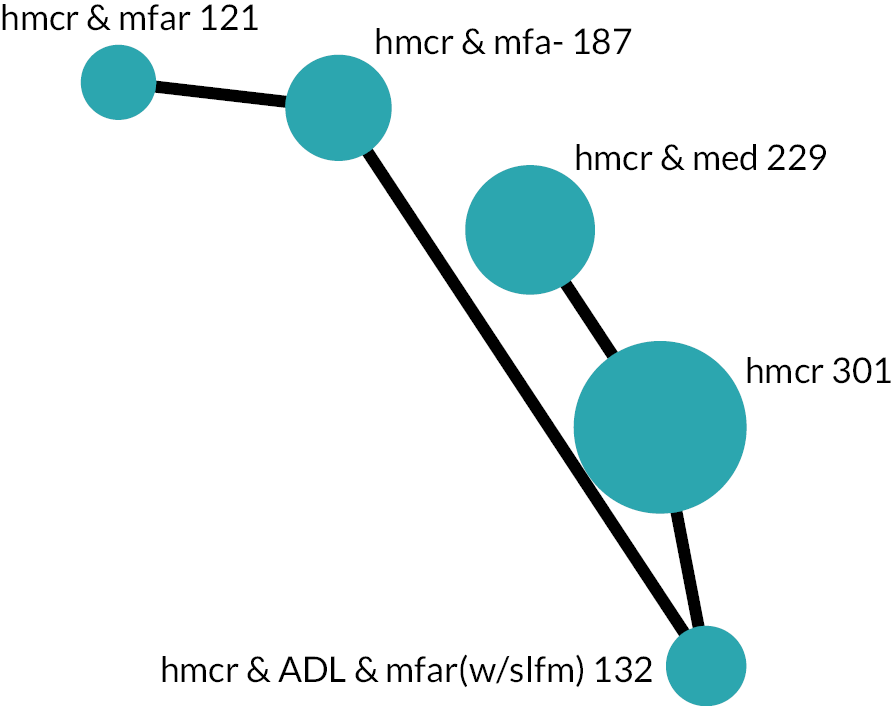

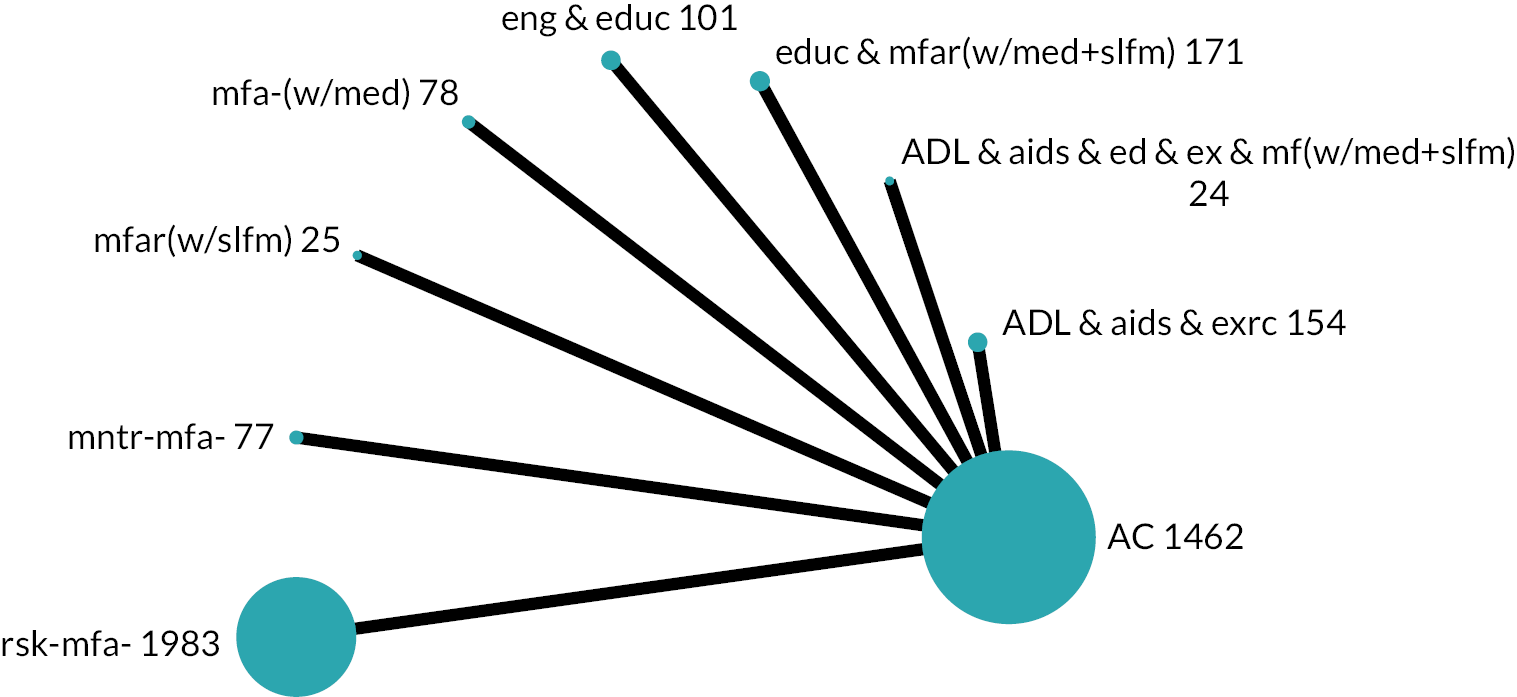

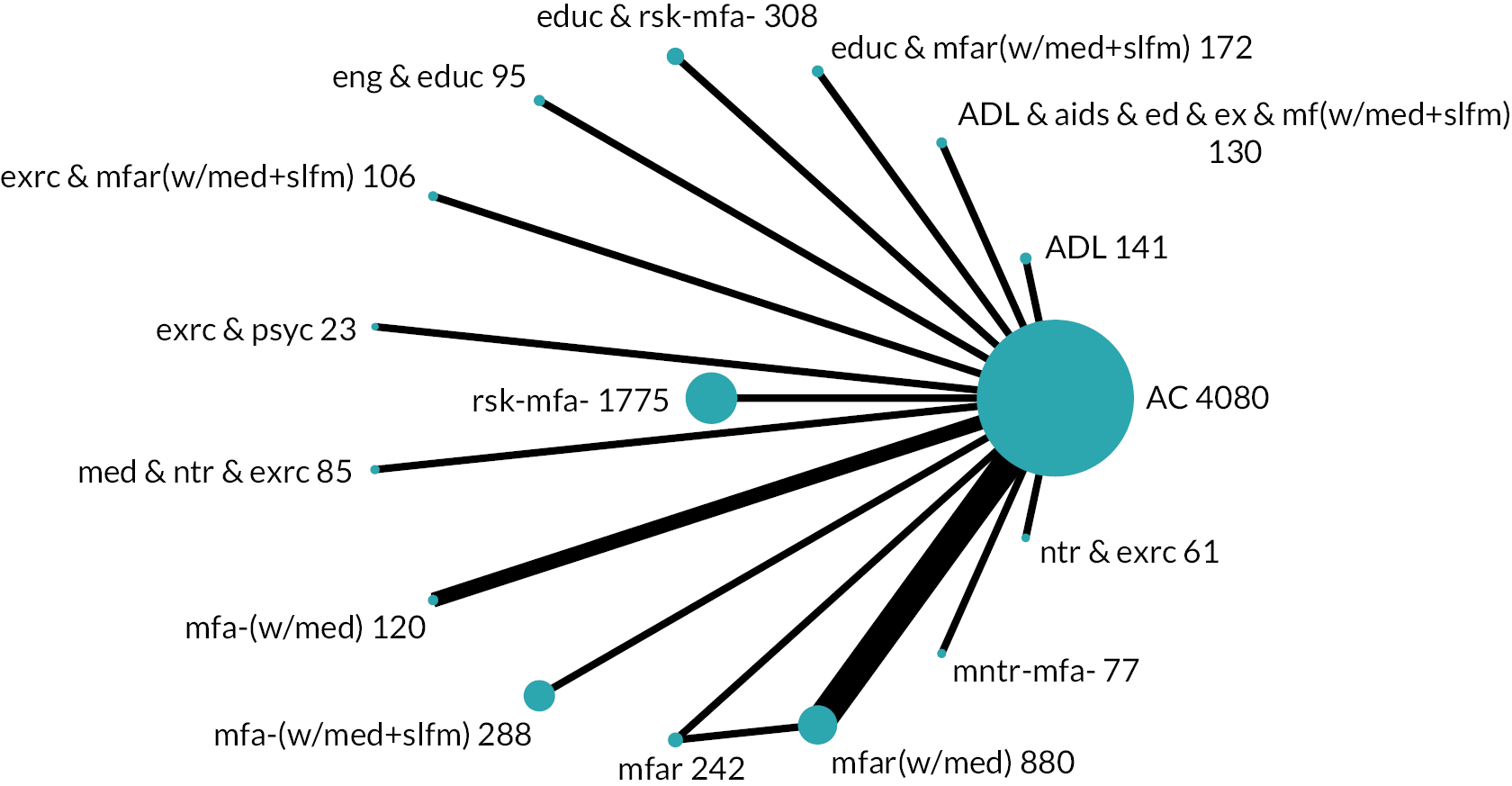

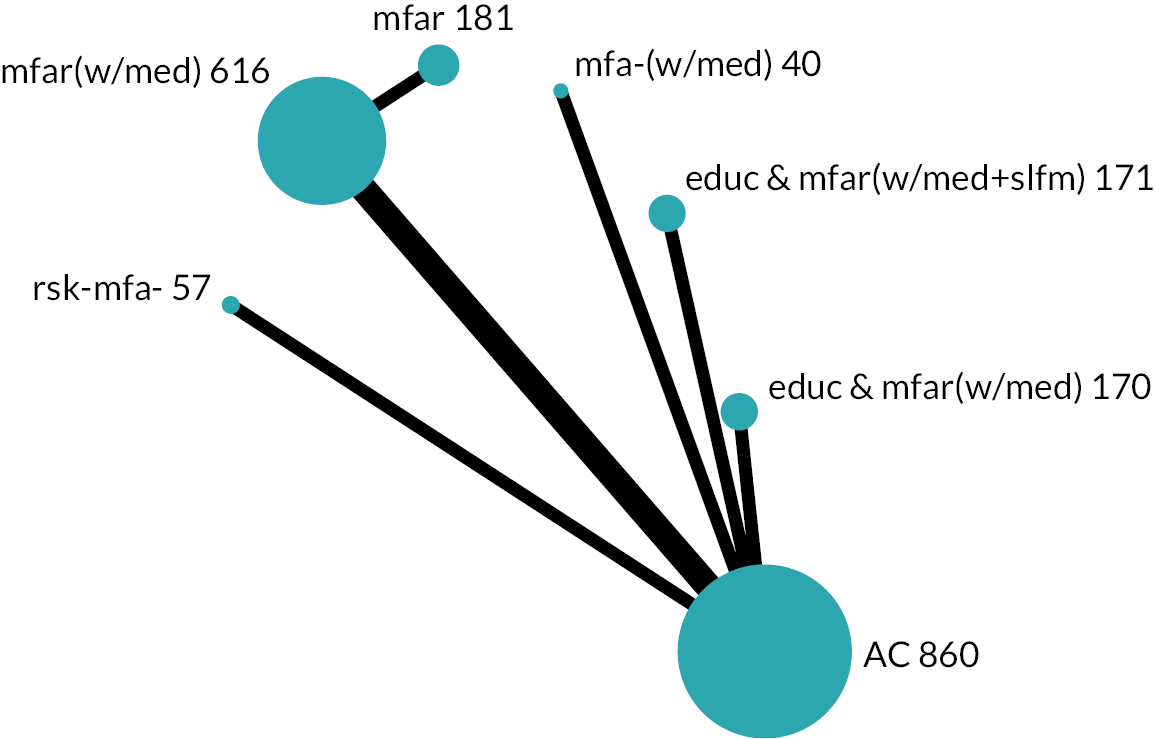

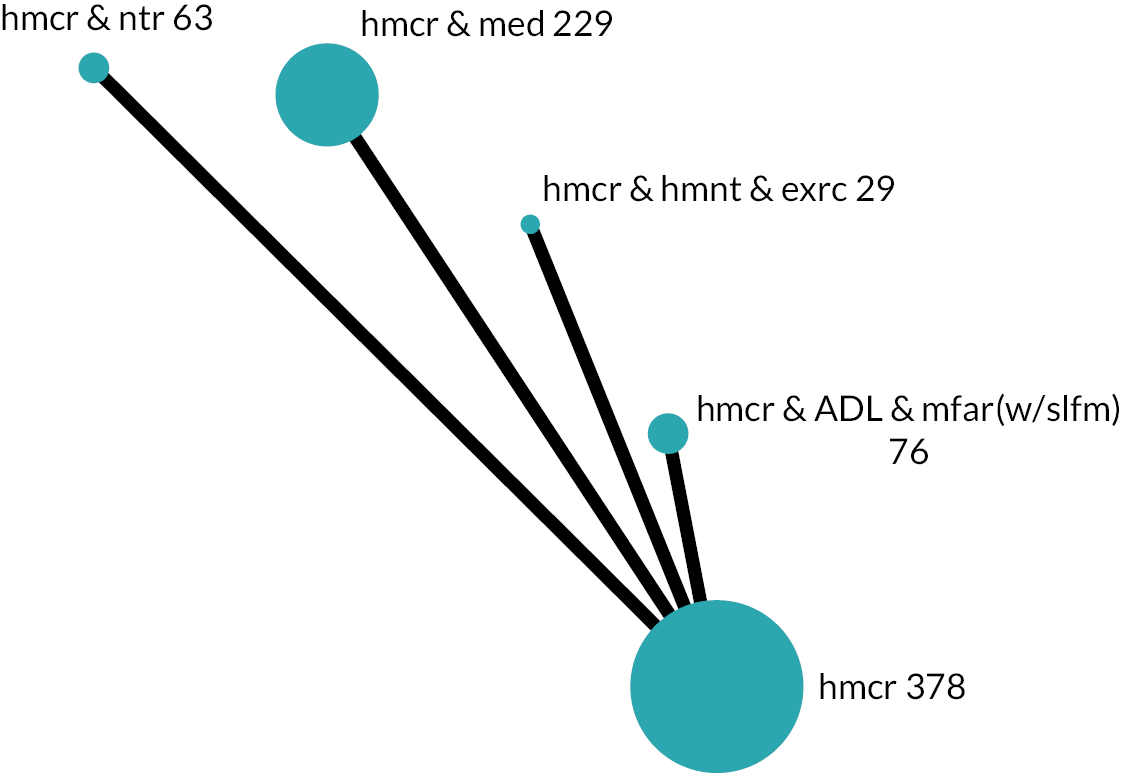

Based on the results, the ranking of intervention groups was calculated using resampling methods based on the (approximate) posterior distribution of treatment effect, and quantified by the probabilities of being ranked first, second, …, last, together with the mean rank and the Surface Under the Cumulative RAnking curve (SUCRA). Network diagrams, tables split between NMA and pairwise evidence and rankograms were used to graphically display the network set-up, results and rankings.

Certainty assessment

Assessment of inconsistency

The consistency assumption (that direct and indirect evidence were consistent with each other on average) was examined for each treatment comparison where there was direct and indirect evidence (seen as a closed loop within the network plot). This involved estimating direct and indirect evidence, and comparing the two using Wald tests, with a global test across all evidence indicating inconsistency if the p-value was < 0.05. Due to the low power associated with global tests, the node-splitting method of Dias et al. was also used to test for inconsistency separately between each treatment comparison, again p-values < 0.05 indicated the presence of inconsistency. 43,44 If evidence of inconsistency was found, explanations were sought and resolved. Where there were no closed loops in any individual network (i.e. no degrees of freedom to estimate inconsistency), the model was reduced to a so-called ‘consistency’ model whereby the inconsistency parameter in the model was set to zero for all comparisons under the assumption that consistency would hold.

Investigation of small-study effects

We planned that if there were 10 or more studies in a pairwise meta-analysis, funnel plots would be presented to investigate small-study effects (potentially caused by publication bias) and tests of asymmetry performed (Egger’s, Peter’s and Debray’s for continuous, binary and survival outcomes, respectively); however, no pairwise meta-analyses included 10 or more studies. If there were 10 or more studies in an NMA, ‘comparison-adjusted’ funnel plots comparing intervention with control were presented to investigate small-study effects, under the assumption that such effects would apply to the whole field. 45,46

Examination of frailty impact

Meta-analysis results were initially presented for all levels of frailty combined, then for frailty/pre-frailty where reported data permitted. Impact was further examined by extending the standard NMA to a network meta regression, with frailty/pre-frailty as a study-level categorical covariate allowing effects of frailty/pre-frailty to vary for each treatment effect, to quantify if intervention effects varied according to population-level frailty. Where possible, we kept the ‘all’ (robust, pre-fail and frail) category (or the lowest available category) as the reference to calculate the relative effect of frailty using meta regression.

As described above, we planned for our main analysis of the impact of frailty to only include trials that were categorised according to a validated measure, with subsequent analyses including all categorised trials. However, we categorised insufficient trials according to a validated measure to enable this approach, so our analyses do not distinguish between the methods of categorisation.

Additional analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted excluding results at the highest RoB (very serious concerns). We chose not to exclude all studies at high RoB while conducting risk-of-bias assessment, when it became apparent we would be able to conduct few sensitivity analyses using this approach. We planned to run additional sensitivity analyses to present results of more recent evaluations, restricted to trials in the last 15 years but decided not to given the volume of networks and their sparsity.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

We used the GRADE framework, adapted for NMA, to rate evidence quality of the results of our NMA. 10,36,47,48 We generated GRADE evidence profiles for our individual intervention groupings in comparison to a reference control for each outcome separately. We initially planned to use GRADE alone and subsequently planned to use the confidence in network meta-analysis (CINeMA) approach to inform our overall GRADE rating. 49 However, the CINeMA software produced errors for many of our analyses due to their sparseness and so we reverted to using GRADE.

As we included RCTs and cRCTs, the starting point was a high-quality evidence rating. We assessed the quality of direct and indirect treatment estimates separately and combined in NMA,48 with a focus on first-order loops for assessment of indirect treatment estimates. We assessed the domains of RoB, inconsistency (between-study heterogeneity), indirectness and publication bias (non-reporting bias) in the direct and indirect evidence, and additionally imprecision and incoherence (direct and indirect estimate inconsistency) for the combined network estimate. We made an overall judgement on whether the quality of evidence for an individual outcome warranted downgrading on the basis of study limitations in each of the domains, aligned with GRADE guidance. 36

For imprecision, we considered the 95% CI in relation to cut points for no effect and very small effect (positive and negative, see below). We also considered the ratio of the 95% CI limits for the OR, and whether the effective sample size was at least 800 for continuous outcomes or sufficient for 400 events for dichotomous outcomes, following the approach of Brignardello-Petersen et al. 47,50

Summary of findings tables were produced using a semi-automated workflow involving Microsoft Excel (v16.0; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Microsoft Word (v16.0; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) based on recommended formats. 35,51

We described interpretation of the evidence following recent guidance,52 providing an indication of size and direction if the evidence was not very low certainty. We used the terms ‘probably’ and ‘may’ to indicate moderate and low certainty, respectively. 52,53 Where the point estimate was large but the evidence was low certainty, we described only the direction in the text as we were not assessing certainty in the size of the estimate; in these cases, we described the size alongside the statistical summary.

For effect sizes expressed as SMD, we took 0.05 to be the lower bound for a very small effect, 0.16 to be a small effect, 0.38 to be a moderate effect, 0.76 to be a large effect and 1.2 and above to be a very large effect, based on empirical evidence of effect sizes in gerontological research. 54 We re-expressed SMDs as MDs using a pooled SD for a common measure of the outcome from the included studies. 35

We re-expressed ORs (and 95% CIs) as RRs using the median risk in the reference comparator arms, and as absolute effects (corresponding intervention risk and corresponding risk difference) for a high- and low-risk population, using the highest and lowest risk among the reference comparator arms with more than 100 participants as the assumed comparator risks. 35 By reference to other commonly used interventions in fields such as stroke prevention and hypertension, we noted that number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) for major outcomes was often between 50 and 100, and sometimes larger. 55–57 Based on this, we arbitrarily selected NNTB = 200 as a limit for important difference and used the corresponding risk difference for the high-risk population to define effect sizes as very small (5 per 1000), small (20 per 1000), moderate (40 per 1000), large (60 per 1000) or very large (100 or more per 1000).

Summary of economic evidence

Following the brief economic commentary framework recommended in the Cochrane Handbook, version 6,58 we extracted and summarised brief details of the analytic perspective, time horizon, evaluation type(s), main cost items, currency, price year, any reported details about discounting and sensitivity analysis, the principal findings which applied to this review’s time periods and outcomes of interest, and verbatim text of conclusions of each identified study. We then compared and contrasted the findings from similar interventions (classified in the same intervention group) and between different intervention groups, based on the conclusions of these studies.

We used the definitions stated in the ‘Glossary of Terms for Health Economics and Systematic Review’ from the Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group59 to classify the three full economic evaluation types60 – cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-utility analysis and cost–benefit analysis. We classified analysis of comparative costs for alternative interventions in monetary value of the resources used as cost analysis (partial economic evaluation). 58,61 We identified the cost item categories reported in each of these studies and used these to identify the evaluation perspective. The cost items were classified into four categories: health sector costs, other sector costs, patient and family costs and productivity impacts. 58,61 An evaluation that included the monetary expenses on health and/or social care was regarded as adopting a health and social care system perspective. If non-monetary, intangible resources for care or economic impacts associated with the intervention were also included in the total costs, for example informal care provided by family or friends, productivity loss, the evaluation perspective was classified as societal. Additionally, we extracted the intervention cost items if they were provided separately. We did not further assess the quality of the identified economic evaluations. 58

Chapter 3 Results of the review

Study selection

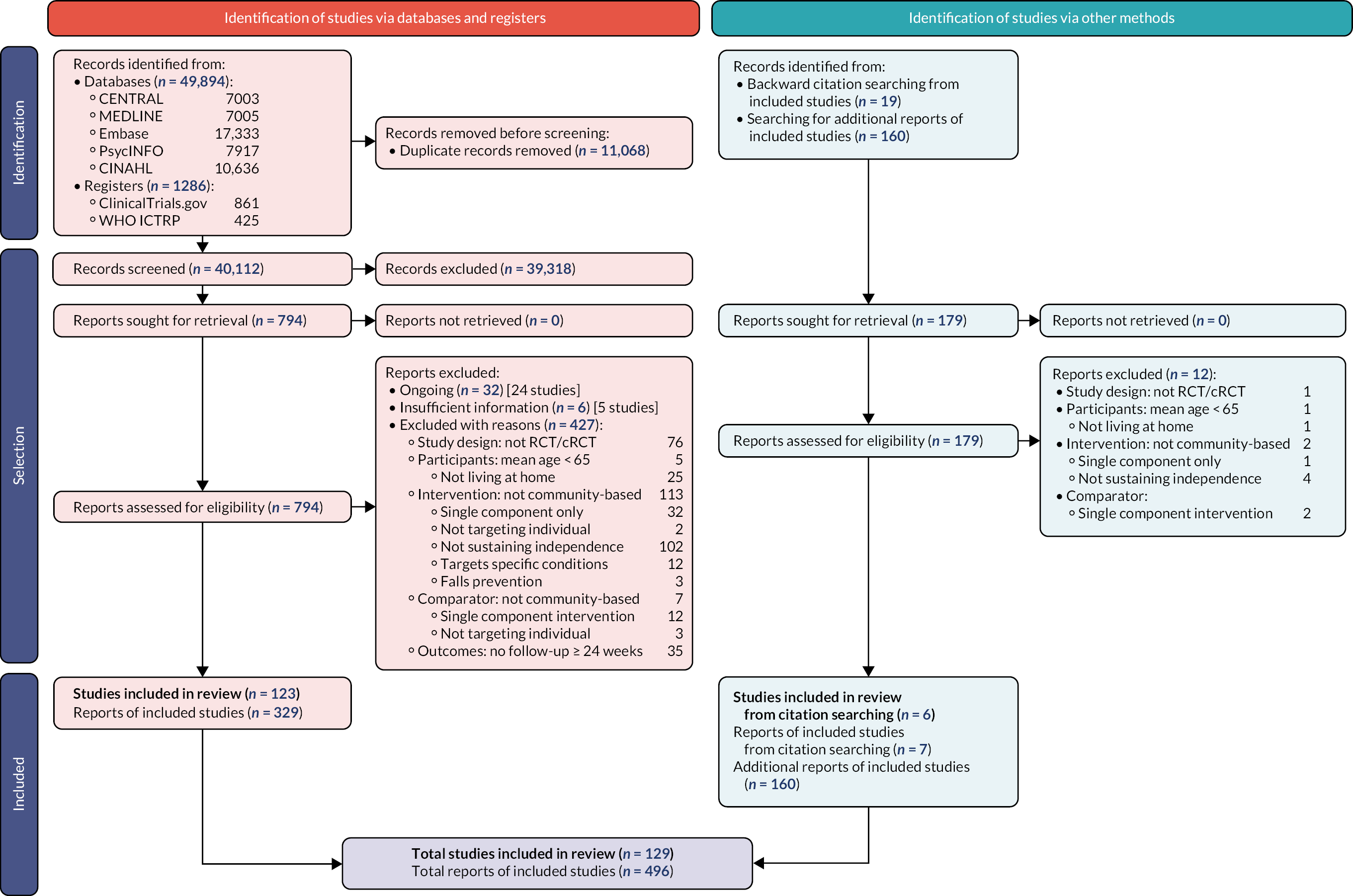

The results of the search and selection process are summarised in a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (see Figure 1). 62

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing identification, selection and inclusion of studies from databases, registers and other sources.

Results of the search and selection process

We found 49,894 records through database searches and 1286 records through trial register searches. After removal of 11,068 duplicates, we screened 40,112 records. We excluded 39,318 records through screening and sought, retrieved and reviewed the full text of the remaining 794 reports. Later, we identified and screened an additional 179 records by backward citation searching of included studies (n = 19) and from searching for additional reports of included studies (n = 160). In total, therefore, we assessed 973 reports for eligibility and excluded 477, finally including 129 studies63–191 consisting of 496 reports (see Figure 1): 123 studies from the electronic searches and six studies from the citation searches. Of these 129 studies, 113 provided results for the outcomes of interest and 90 contributed to the NMAs.

Excluded studies

Details of the studies excluded following assessment for eligibility are provided in Figure 1 above and Report Supplementary Material 2, and are summarised below. Additionally, a brief summary of the interventions excluded (where this was the reason for exclusion) is provided in Report Supplementary Material 2.

We excluded 24 studies192–215 (32 reports) as ongoing because the trial or the analyses were not completed and results were unavailable as of 31 August 2021, according to their respective trial register records. The collective total of their planned sample sizes is approximately n = 9218.

We had insufficient information to confirm the eligibility of five studies216–220 (six reports), despite attempts to contact the authors and searches for additional reports. For these studies, we only found trial register records, protocols or conference abstracts.

We assessed 439 reports as ineligible: 77 did not relate to a RCT or a cRCT; 32 had participants with a mean age < 65 (n = 6) or who were not living at home (n = 26); 271 were ineligible because of the intervention, which was not community based (n = 115), had a single component only (n = 33), did not target the individual (n = 2), did not aim to sustain independence (n = 106), targeted a specific condition (n = 12) or was for fall prevention (n = 3); 24 were ineligible because of the comparator, which was not community based (n = 7), was a single component intervention (n = 14), or did not target the individual (n = 3); and 35 were ineligible because there was no follow-up at 24 weeks or later.

Some excluded studies were part of a larger project from which other studies were included. These projects included PRevention in Older people – Assessment in GEneralists’ practices (PRO-AGE), Community Aging in Place – Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE) and Assessment of Services Promoting Independence and Recovery in Elders (ASPIRE). PRO-AGE consisted of three RCTs, two of which were eligible,104,164 while the third was ineligible as it was not delivered in a community setting. 221 This third study provided the baseline for a cohort, from which another eligible study was included. 151 We included two studies of the CAPABLE intervention166,167 but excluded a non-randomised study222 and a trial of two implementation strategies of the same intervention. 223 The ASPIRE project consisted of three RCTs, two of which were included146,147 while the third was ineligible because the intervention was partly delivered in residential care facilities. 224

Studies included in the review

Characteristics of included studies are provided as Report Supplementary Material 1; a summary is provided in Table 3.

| Study | Design | Enrolment began | Country | Population frailty | Enrolled | Interventions | Controls | Living at home | IADL | PADL | PADL & IADL | Hospitalisation | Homecare | Care-home placement | Cost | Cost-effectiveness | Health status | Depression | Loneliness | Falls | Mortality | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegria 201963,225,226 | RCT | 2015 | USA | P | 307 | exrc & psyc | ac | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Arthanat 201964,227,228 | RCT | >2005 | USA | U | 97 | comm | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | NC |

| Auvinen 202065,229–231 | RCT | 2015 | FIN | F | 512 | hmcr & med | hmcr | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Balaban 198866 | RCT | 1981 | USA | F | 198 | mfa-(w/med) | ac | – | – | ♦ | – | ▦ | – | ◌ | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Barenfeld 201867,232–235 | RCT | 2012 | SWE | all | 131 | educ | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ♦ | NC |

| Bernabei 199868,236,237 | RCT | 1995 | ITA | F | 200 | hmcr & mfar(w/med) | hmcr | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Bleijenberg 201669,238–246 | cRCT | 2010 | NLD | P,F | m:39; 3092 | rsk-mfa-; rsk-mfa- | ac | – | – | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | ◌ | ▦ | ◌ | ▦ | ♦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Blom 201670,245,247,248 | cRCT | 2009 | NLD | all | m:59; 1379 | mfa-(w/med + slfm) | ac | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | – | ♦ | NC |

| Borrows 201371 | RCT | 2008 | GBR | U | 36 | aids | mfa- | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Botjes 201372,249,250 | RCT | 2011 | NLD | U | 218 | mfa- | ac | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | NC |

| Bouman 200873,251–255 | RCT | 2002 | NLD | P,F | 330 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | ◌ | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | – | ♦ | NC |

| Brettschneider 201574,256–259 | RCT | 2007 | DEU | F | 336 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | ◌ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Cameron 201375,260–269 | RCT | 2008 | AUS | F | 241 | exrc & mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | – | – | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Carpenter 199076 | RCT | <2006 | GBR | all | 539 | rsk-mfa- | ac | ♦ | – | – | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | NC |

| Cesari 201477,270–275 | RCT | > 2005 | FRA | U | ? | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | – | NC |

| Challis 200478,276 | RCT | 1998 | GBR | F | 256 | mfar(w/med) | mfar | ♦ | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Clark 199779,277–281 | RCT | 1994 | USA | R,P | 361 | eng & educ | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | ♦ | – | – | ◌ | Mx |

| Clark 201280,282–287 | RCT | 2004 | USA | U | 460 | eng & educ | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Coleman 199981 | cRCT | < 2006 | USA | F | m:9; 169 | educ & mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | – | ◌ | ▦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Counsell 200782,288–292 | cRCT | 2002 | USA | U | m:164; 951 | educ & mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Cutchin 200983,293 | RCT | 2008 | USA | U | 110 | mfar | ac | – | – | – | ▦ | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | – | – | – | NC |

| Dalby 200084,294 | RCT | < 2006 | CAN | F | 142 | mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | – | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| de Craen 200685,295–297 | RCT | 2000 | NLD | all | 402 | mfa- | ac | – | – | – | ▦ | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ▦ | – | ♦ | NC |

| Dorresteijn 201686,298–301 | RCT | 2009 | NLD | U | 389 | ADL | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ◌ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Dupuy 201787,302 | RCT | > 2005 | FRA | P,F | 32 | hmcr & aids & comm | hmcr | – | ? | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NC |

| Fabacher 199488 | RCT | < 2006 | USA | all | 254 | mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | – | – | – | ◌ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Fairhall 201589,303,304 | RCT | 2013 | AUS | P | 230 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ◌ | NC |

| Faul 200990,305 | RCT | – | USA | R,P | 81 | educ & exrc & mfar(w/med + slfm); exrc & mfa-(w/med + slfm) | – | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | – | NC |

| Fernandez-Barres 201791,306,307 | RCT | 2010 | ESP | F | 173 | hmcr & ntr | hmcr | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Fischer 200992,308 | RCT | 2004 | DEU | all | 4224 | eng & mfa-(w/slfm) | ac | ♦ | – | – | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | ◌ | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ? |

| Ford 197193,309 | RCT | 1963 | USA | P,F | 300 | mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | ◌ | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Fox 199794 | RCT | 1994 | USA | all | 237 | mfar(w/med + slfm) | mfar(w/med) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NC |

| Fristedt 201995,310 | RCT | 2015 | SWE | F | 62 | hmcr & mfar(w/med) | hmcr | – | – | ◌ | – | ▦ | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Gene Huguet 201896 | RCT | 2016 | ESP | P | 200 | med & ntr & exrc | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NC |

| Gill 200297,311–314 | RCT | < 2006 | USA | P,F | 188 | ADL & exrc | ac | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Giné-Garriga 202098,315–325 | RCT | 2016 | EEE | R | 1360 | exrc | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | – | NC |

| Gitlin 200699,326–336 | RCT | 2003 | USA | P,F | 319 | ADL & aids & exrc | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | – | ◌ | ▦ | ▦ | – | ◌ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Grimmer 2013100,337 | RCT | 2014 | AUS | U | ? | mfa- | ac | – | – | ? | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | – | ? |

| Gustafson 2021101,338,339 | RCT | 2013 | USA | all | 390 | aids & educ & comm | ac | – | – | – | ▦ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | ▦ | ♦ | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | Mx |

| Gustafsson 2013102,232,340–347 | RCT | 2007 | SWE | all | 491 | educ & mfa-; educ | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ♦ | NC |

| Hall 1992103 | RCT | 1986 | CAN | F | 167 | hmcr & mfar(w/slfm) | hmcr & mfar | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | ♦ | ? |

| Harari 2008104,348–362 | RCT | 2000 | GBR | all | 2503 | mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | – | – | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ♦ | NC |

| Hattori 2019105,363 | RCT | 2018 | JPN | P,F | 375 | educ & mfar(w/slfm) | mfar | – | ◌ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Hay 1998106,364 | RCT | < 2006 | CAN | U | 619 | mfa- | ac; ac |

♦ | – | – | ▦ | ◌ | – | ♦ | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Hebert 2001107 | RCT | < 2006 | CAN | P,F | 503 | mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Henderson 2005108,365 | cRCT | 2002 | AUS | R | m:16; 167 | mfar | ac | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Hendriksen 1984109,366–368 | RCT | 1980 | DNK | all | 600 | mfar | ac | – | – | – | – | ♦ | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Hogg 2009110,369–373 | RCT | 2004 | CAN | U | 241 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Holland 2005111,374,375 | RCT | 2001 | USA | U | 504 | educ & exrc & mfar(w/slfm) | ac | – | – | ? | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Howel 2019112,376–378 | RCT | 2011 | GBR | all | 755 | wlfr | ac | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ◌ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Imhof 2012113,246 | RCT | 2008 | CHE | all | 461 | mfar | ac | ♦ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ▦ | ◌ | ♦ | – | – | – | ? | – | ◌ | ▦ | NC |

| Jing 2018114 | RCT | 2016 | CHN | F | 80 | psyc; exrc & psyc | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | ? |

| Jitapunkul 1998115 | RCT | 1993 | THA | U | 160 | rsk-mfa- | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | NC |

| Kerse 2014116,379–383 | cRCT | 2008 | NZL | P,F | m:60; 3893 | rsk-mfa- | ac | ♦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | ◌ | ▦ | ♦ | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| King 2012117,384–386 | cRCT | 2006 | NZL | P,F | m:21; 186 | hmcr & ADL & mfar(w/slfm) | hmcr | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | NC |

| Kono 2016118,387,388 | RCT | 2011 | JPN | P | 360 | mfar(w/med) | mfar | ♦ | ▦ | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | ♦ | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Kono 2004119 | RCT | 2000 | JPN | P,F | 119 | mfar | ac | ♦ | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Kono 2012120,389–391 | RCT | 2008 | JPN | P | 323 | mfar | mfar | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Kukkonen-Harjula 2017121,392–396 | RCT | 2014 | FIN | P,F | 300 | ADL & ntr & exrc | ac | ♦ | ◌ | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ♦ | NC |

| Lambotte 2018122,397–404 | RCT | 2017 | BEL | P,F | 871 | mfar | ac | – | – | ? | – | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NC |

| Leung 2004123,405 | RCT | 2000 | HKG | all | 260 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | – | – | ? | ▦ | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ? |

| Leveille 1998124,406,407 | RCT | 1995 | USA | U | 201 | educ & exrc & mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | – | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Lewin 2013125,408–410 | RCT | 2005 | AUS | F | 750 | hmcr & educ & mfar | hmcr | ♦ | ? | ? | – | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Liddle 1996126 | RCT | < 2006 | AUS | U | 105 | aids & mfar | ac | ♦ | – | ▦ | – | ◌ | ◌ | ♦ | – | – | ◌ | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Liimatta 2019127,411–413 | RCT | 2013 | FIN | R,P | 422 | exrc & mfa-(w/med) | ac | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Loh 2015128,414,415 | cRCT | 2014 | MYS | U | m:8; 256 | ntr & exrc | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | – | NC |

| Lood 2015129 | RCT | 2012 | SWE | R,P | 40 | educ | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | ? | – | – | NC |

| Mann J 2021130,416–420 | cRCT | 2018 | AUS | all | m:14; 92 | mfa-(w/med) | ac | – | – | ◌ | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | – | – | NC |

| Mann WC 1999131 | RCT | < 2006 | USA | F | 104 | hmcr & aids | hmcr | – | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Markle-Reid 2006132,421,422 | RCT | 2001 | CAN | F | 288 | hmcr & mfar(w/med + slfm) | hmcr & mfar | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | ◌ | ▦ | – | – | ◌ | NC |

| Melis 2008133,423–429 | RCT | 2003 | NLD | F | 155 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Meng 2005134,430–436 | RCT | 1998 | USA | F | 1786 | educ & vchr & mfar(w/med + slfm); educ & mfar(w/med + slfm); vchr |

ac | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Messens 2014135,437,438 | RCT | 2011 | EEE | P,F | 208 | aids & cgn & comm & mntr-mfa- | ac | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | NC |

| Metzelthin 2013136,245,439–444 | cRCT | 2009 | NLD | F | m:12; 346 | educ & mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | – | ◌ | ♦ | NC |

| Moll van Charante 2016137,445–455 | cRCT | 2006 | NLD | all | m:116; 3526 | educ & mfar(w/slfm) | ac | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Monteserin Nadal 2008138,456 | RCT | 2004 | ESP | all | 620 | educ & rsk-mfa- | ac | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | – | – | – | ◌ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Morey 2006139,457,458 | RCT | < 2006 | USA | all | 179 | exrc; exrc | exrc | – | – | ? | – | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | – | NC |

| Morey 2009140,459–462 | RCT | 2004 | USA | U | 400 | exrc | ac | – | – | – | ▦ | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | ♦ | NC |

| Morgan 2019141,463–465 | RCT | 2014 | GBR | P | 51 | exrc | ac | – | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Newbury 2001142,466 | RCT | 1998 | AUS | U | 100 | mfa-(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | – | – | ◌ | ♦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Newcomer 2004143,467,468 | RCT | 2001 | USA | U | 3079 | educ & mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | – | – | ♦ | – | ♦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ♦ | Mx |

| Ng 2015144,469,470 | RCT | 2009 | SGP | P,F | 246 | cgn & ntr & exrc | ac | – | – | – | – | ♦ | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Parsons J 2012145,471,472 | cRCT | 2007 | NZL | P,F | m:?; 205 | hmcr & mfar(w/slfm) | hmcr & mfa- | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Parsons M 2017146,473–476 | RCT | 2003 | NZL | F | 113 | hmcr & ADL & mfar(w/slfm) | hmcr & mfa- | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Parsons M 2012147,473–476 | cRCT | 2003 | NZL | F | m:55; 351 | hmcr & mfar | hmcr & mfa- | ▦ | ♦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ♦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Pathy 1992148 | RCT | < 2006 | GBR | all | 725 | rsk-mfa- | ac | – | – | – | ◌ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Phelan 2007149 | cRCT | 2002 | USA | all | m:31; 874 | mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | – | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Ploeg 201015.0,477 | RCT | 2004 | CAN | P,F | 719 | educ & mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | ? | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Profener 2016151,478–480 | RCT | 2007 | DEU | F | 553 | educ & mfar | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | NC |

| Rockwood 2000152,481 | RCT | < 2006 | CAN | F | 182 | mfa-(w/med) | ac | ▦ | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Romera-Liebana 2018153,482,483 | RCT | 2013 | ESP | P,F | 352 | cgn & med & ntr & exrc | ac | ♦ | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ♦ | NC |

| Rooijackers 2021154,484–488 | cRCT | 2017 | NLD | F | m:10; 264 | hmcr & ADL & mfar(w/slfm) | hmcr | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | – | – | ♦ | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | ♦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Rubenstein 2007155 | RCT | < 2006 | USA | F | 792 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | ◌ | – | – | – | ♦ | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Ryvicker 2011156,489 | cRCT | 2005 | USA | U | m:45; 3290 | hmcr & mfar | hmcr & mfar | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NC |

| Serra-Prat 2017157,490 | RCT | 2013 | ESP | P | 172 | ntr & exrc | ac | – | – | ♦ | – | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Shapiro 2002158 | RCT | 1998 | USA | F | 108 | hmcr & mfar | ac | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | ◌ | – | – | ? | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Sherman 2016159,491 | cRCT | 2006 | SWE | all | m:16; 583 | mfa-(w/med) | ac | – | – | – | ? | – | – | – | – | – | ? | – | ▦ | – | – | NC |

| Siemonsma 2018160,492,493 | RCT | 2009 | NLD | F | 155 | ADL | mfa- | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ◌ | ♦ | NC |

| Stewart 2005161,494,495 | RCT | 2000 | GBR | P,F | 321 | mfa- | mfa- | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Stuck 1995162,496–500 | RCT | 1988 | USA | all | 414 | educ & mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | ♦ | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ▦ | NC |

| Stuck 2000163,501–504 | RCT | 1993 | CHE | all | 791 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | – | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Stuck 2015164,359–362,505 | RCT | 2000 | CHE | R,P | 2284 | educ & mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | ♦ | – | – | – | ◌ | – | ♦ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ▦ | NC |

| Suijker 2016165,506–511 | cRCT | 2010 | NLD | F | m:24; 2283 | mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | ◌ | ◌ | ▦ | ▦ | – | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | NC |

| Szanton 2011166,512,513 | RCT | 2010 | USA | P,F | 40 | ADL & aids & educ & exrc & mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Szanton 2019167,512,514–523 | RCT | 2012 | USA | P,F | 300 | ADL & aids & educ & exrc & mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Takahashi 2012168,524–530 | RCT | 2009 | USA | F | 205 | mntr-mfa- | ac | – | – | ♦ | – | ♦ | – | – | ◌ | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | ♦ | Mx |

| Teut 2013169,531 | cRCT | 2009 | DEU | F | m:8; 58 | hmcr & hmnt & exrc | hmcr | – | ◌ | ♦ | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | ♦ | Mx |

| Thiel 2019170,532,533 | RCT | 2017 | DEU | F | ? | exrc & mfar(w/med) | ac | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | NC |

| Thomas 2007171 | RCT | 2001 | CAN | P,F | 520 | mfar(w/med); mfar(w/med) |

ac | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | ◌ | ? |

| Tomita 2007172 | RCT | < 2006 | USA | F | 124 | aids | ac | ♦ | ♦ | ◌ | – | ◌ | ◌ | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Tulloch 1979173 | RCT | 1972 | GBR | all | 339 | mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | – | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ? |

| Tuntland 2015174,534–536 | RCT | 2012 | NOR | U | 61 | hmcr & ADL & aids & mfa-(w/slfm) | hmcr & mfa- | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| van der Pols-Vijlbrief 2017175,537 | RCT | 2013 | NLD | F | 155 | hmcr & ntr & mfar | hmcr | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| van Dongen 2020176,538–541 | RCT | 2016 | NLD | all | 168 | ntr & exrc | ac | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | ▦ | – | – | – | – | Mx |

| van Heuvelen 2005177,542 | RCT | 2001 | NLD | P,F | 233 | exrc & psyc | ac | – | ♦ | ♦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | NC |

| van Hout 2010178,543,544 | RCT | 2002 | NLD | F | 658 | mfar(w/med) | ac | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | ♦ | – | ♦ | ◌ | – | ▦ | ◌ | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| van Leeuwen 2015179,545–549 | cRCT | 2010 | NLD | F | m:35; 1147 | mfar(w/med + slfm) | ac | – | ◌ | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | NC |

| van Lieshout 2018180,550 | RCT | 2011 | NLD | P,F | 710 | ADL & med & ntr & sst | ac | – | – | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | NC |

| van Rossum 1993181,551,552 | RCT | 1988 | NLD | all | 580 | mfar | ac | – | ? | ? | – | ♦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | NC |

| Vass 2005182,553–573 | cRCT | 1999 | DNK | all | m:34; 4060 | mfar(w/med) | mfar | – | – | – | – | ▦ | ◌ | ◌ | ▦ | ▦ | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Vetter 1984183 | RCT | 1980 | GBR | all | 1148 | mfar | ac | – | – | – | ◌ | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | ◌ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| von Bonsdorff 2008184,574–579 | RCT | 2003 | FIN | R | 632 | exrc | ac | – | ▦ | ? | – | ◌ | ▦ | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | ◌ | ? | – | ▦ | NC |

| Wallace 1998185,407 | RCT | < 2006 | USA | all | 100 | exrc & mfar | ac | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | NC |

| Walters 2017186,580,581 | RCT | 2015 | GBR | P | 51 | mfar(w/slfm) | ac | – | – | ♦ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | NC |

| Whitehead 2016187,582,583 | RCT | 2014 | GBR | F | 30 | hmcr & ADL & aids & mfa- | hmcr & mfa- | ◌ | ▦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ◌ | – | ▦ | – | – | ▦ | ▦ | NC |

| Williams 1992188,584 | RCT | < 2006 | GBR | all | 470 | mfar | mfa- | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Wolter 2013189,585–587 | cRCT | 2007 | DEU | F | m:69; 920 | hmcr & mfar(w/med) | hmcr | ♦ | ♦ | ▦ | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

| Wong 2019190,588–591 | RCT | 2016 | HKG | all | 540 | mfar(w/slfm) | ac | ♦ | ? | ◌ | – | ▦ | – | ♦ | ▦ | ▦ | ▦ | ◌ | – | – | ▦ | NC |

| Yamada 2003191 | RCT | 1999 | JPN | P,F | 368 | mfar(w/med) | ac | – | ◌ | – | – | ◌ | – | – | – | – | ▦ | – | – | – | ♦ | NC |

The 129 studies assigned 74,946 participants to an intervention, with a range of 30 to 4224 participants per study {mean 595, median [interquartile range (IQR)] 313 (168–582) participants from 126 studies; 3 studies missing data]. Most were individually randomised but 22 were cluster RCTs; these had a total of 845 clusters [mean 40, median (IQR) 31 (14–55), range 8 to 164 clusters, 1 study missing data}.

Context

The 129 studies enrolled participants between 1963 and 2018 and were published between 1971 and 2021. They took place in 23 countries or regions in four continents: predominantly Europe (64 studies) and North America (41 studies), the rest from Australasia (13 studies) and Asia (11 studies). The most common sources for recruitment were invitations via general practice or a primary care health centre, homecare services, service referrals, health insurance, selections from census or municipal records and community advertisement.

Participants

Sixty-one per cent of participants were women, reported in 123 studies. In 113 of these, most of the participants were women. Forty-six per cent of participants were living alone, reported in 77 studies. Three studies required a consented caregiver to participate with the participant. 82,91,171 Nineteen studies excluded participants with disabilities or who were dependent in activities of daily living. 86,97,99,101,104,108,114,119,124,135,140,141,156,157,164,170,184,185,190

Age

The pooled mean age of participants was 77.3 (SD 7.5) years, reported in 97 studies. Four studies had study populations aged 85 years or over on average (mean or median);74,95,102,113 only one study’s population was < 70 years on average (mean 68.4 years). 66 Most of the studies explicitly targeted older adults, except three where all adults were eligible. 66,71,174 A minimum age was either reported or an eligibility criterion in all but 8 studies: under 65 years in 20 studies (16–18 years: n = 3; 50 years: n = 3; 60 years: n = 14), 65–79 years in 90 studies (65–69 years: n = 46; 70–74 years: n = 20; 75–79 years: n = 24), 80 years or over in 5 studies,74,85,96,102,113 and 6 studies had criteria where minimum age differed in conjunction with ethnicity,116,145–147 medical condition143 or both. 130

Frailty

One-hundred and eight study populations were classified for frailty (21 were insufficiently described to be classified64,71,72,77,80,82,83,86,100,106,110,111,115,124,126,128,140,142,143,156,174): 31 included all frailty levels (robust, pre-frail and frail), 3 populations were robust, 5 were robust and pre-frail, 8 were pre-frail, 25 were pre-frail and frail and 36 were frail. The studies that had populations classified as ‘all’ typically had broad inclusion criteria, although some purposefully sampled multiple risk or frailty groups, and others were selective on health-related criteria but in a way that would include all frailty categories. Ninety-one populations were classified on the basis of characteristics and criteria, while 17 were classified on the basis of a validated measure, of which 2 were classified as all,102,176 4 as pre-frail,89,96,157,186 7 as pre-frail and frail69,121,122,135,144,153,180 and 4 as frail. 75,136,170,179

Excluded groups within included studies

Twelve studies reported on groups of participants which were ineligible for this review and have been excluded from all results. 70,98,103,106,114,121,126,144,149,160,177,183

Hall 1992103 and Siemonsma 2018160 reported about separately recruited, non-randomised observational control groups alongside their trial results, which were excluded from this review. Hay 1998106 and Liddle 1996126 identified participants with problems who were subsequently randomised but also reported on the non-randomised group without identified problems, which were excluded from this review. Similarly, Blom 201670 was a cRCT in which GPs were randomised and only a random subset of the participants with complex problems were intended to receive the intervention. However, they also described the participants without complex problems. Therefore, there were groups without complex problems in each arm and a group with complex problems in the intervention arm who were not individually randomised to receive the intervention, which were excluded from analyses in this review.

Kukkonen-Harjula 2017121 was effectively two parallel RCTs with the same intervention and control groups, one included older people with frailty and the other included older people with recent hip fracture. We only included the trial that recruited older people with frailty.

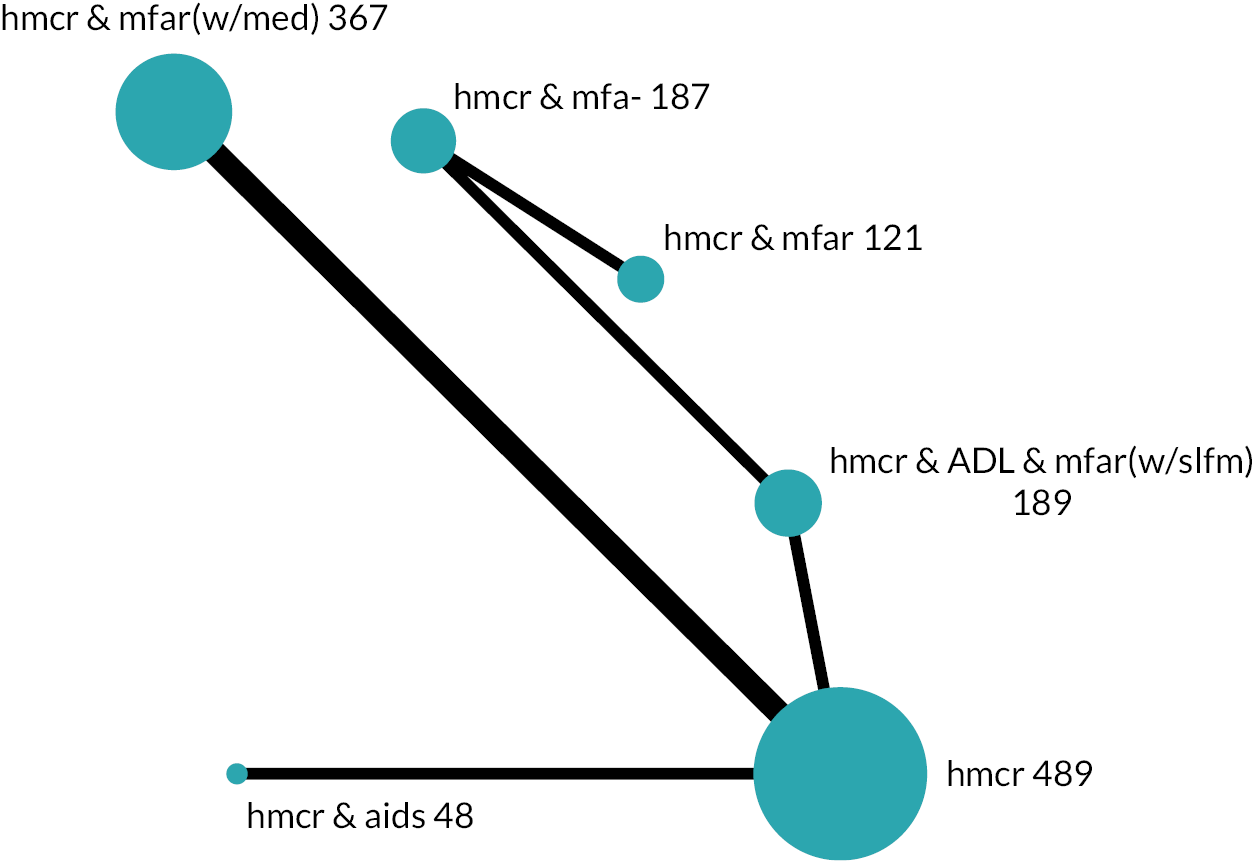

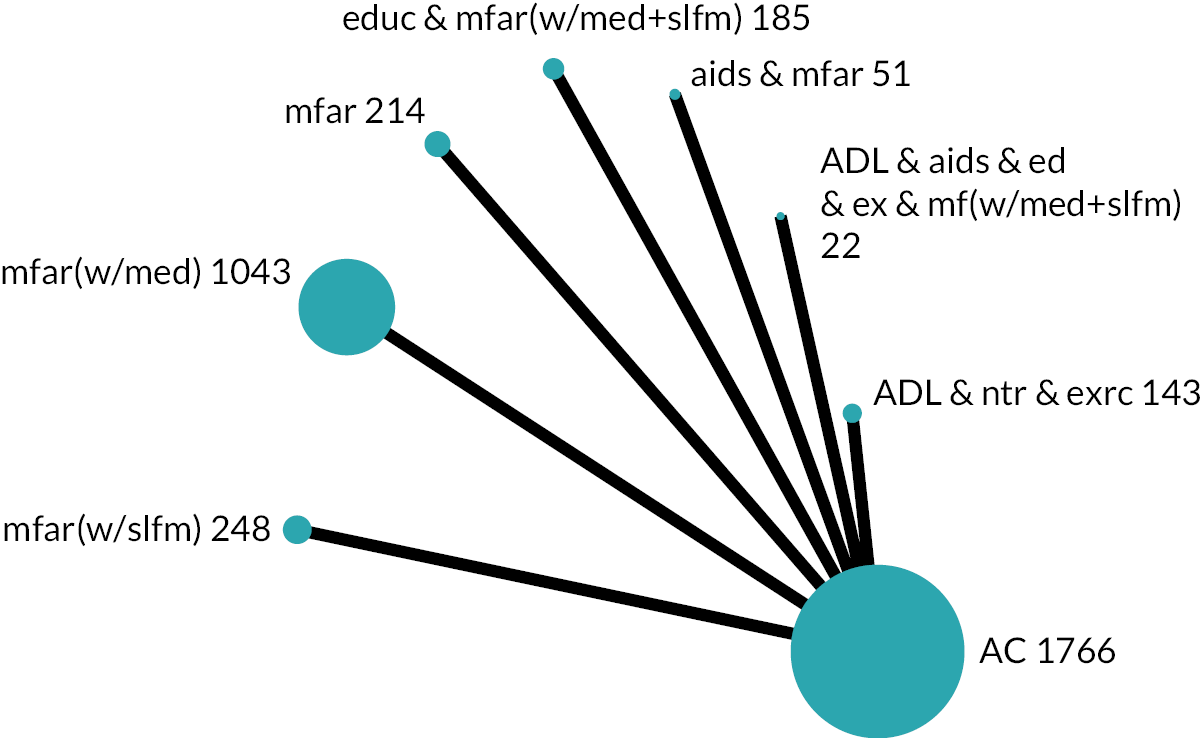

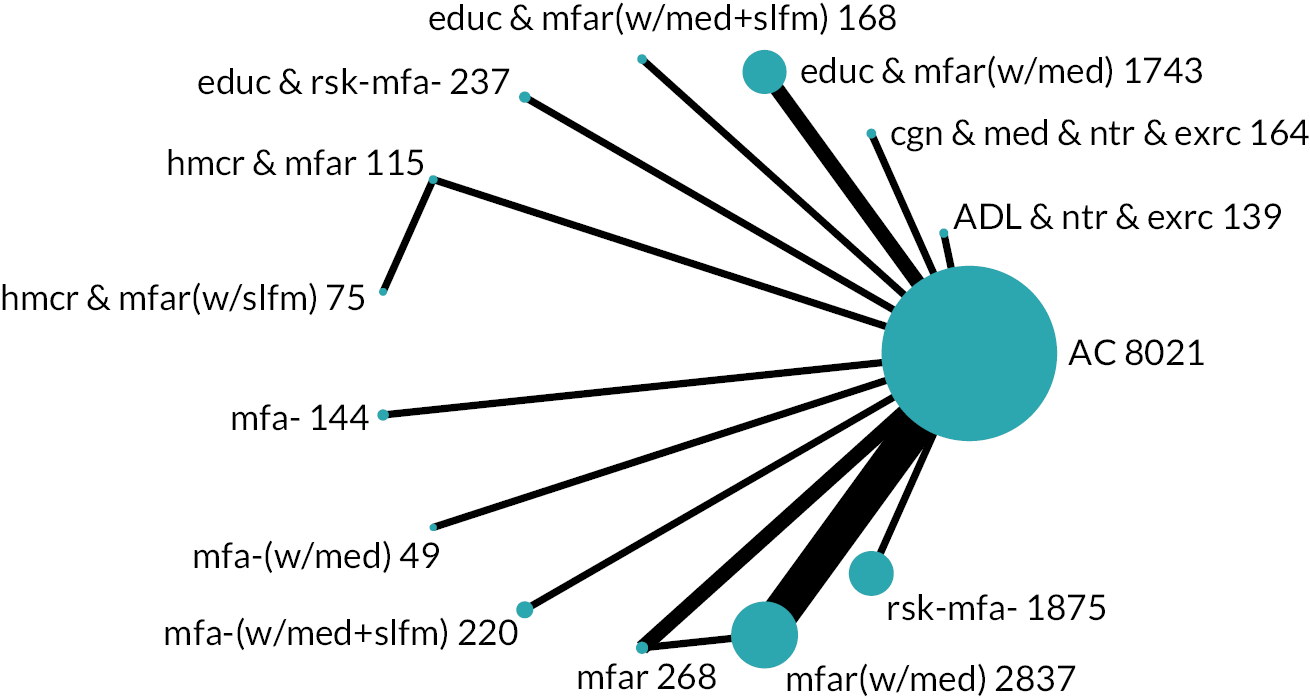

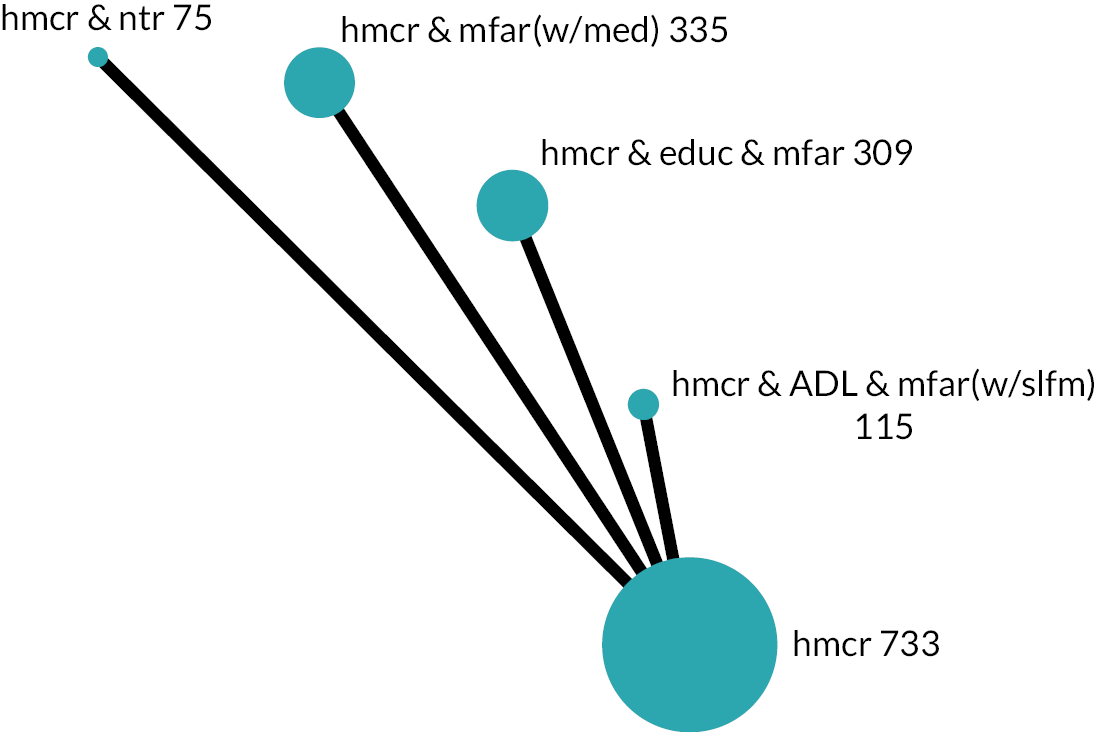

Seven intervention arms in four studies were excluded from this review because they were considered a single-component intervention: exercise referral scheme in Giné-Garriga 2020;98 Baduanjin training in Jing 2018;114 three arms of Ng 2015144 (nutrition supplementation, physical training and cognitive training); and two arms in van Heuvelen 2005177 (physical activity and psychological training).