Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/43/05. The contractual start date was in May 2009. The draft report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Simon Gilbody is a Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board Member. Michael Barkham is a developer of the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure, which was used as a secondary outcome measure in the trial. Peter Bower reports personal fees from paid consultancy for the British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy, outside the submitted work. Karina Lovell is a Non-Executive Director for Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust and is paid a salary.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Littlewood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Depression

Depression is the most common mental health disorder in community settings and is estimated to become the second largest cause of global disability by 2020. 1 It is one of the most common reasons for consulting a general practitioner (GP), and is associated with significant personal and economic burden. 2

Psychological therapy for depression

Antidepressant medication is an important treatment option for depression; however, many patients and health-care professionals would like to access psychological therapy as an alternative or adjunct to medication. 3 A leading evidence-supported form of brief psychological therapy for people with depression is cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). 4,5 However, given that patient demand for CBT cannot be met from existing therapist resources,6 there is a need to increase patient access to psychological therapy. One potential way of achieving this might be the provision of CBT delivered via computer. 7 In recent years, a number of interactive programs have been developed which enable CBT to be delivered by computer. The provision of computerised CBT (cCBT) is now recommended in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines as an initial lower-intensity treatment for depression as part of a ‘stepped care’ approach in primary care. 5 cCBT, if shown to be effective, has the potential to expand the provision of psychological therapy in primary care and, as such, may represent an efficient and effective form of care for depression. 8

There are a number of interactive internet-based products that are available for those who decide to use (or commission the provision of) cCBT. Some of these cCBT products are commercially produced whereas others are free to use. 7 A number of commercial products have been marketed to bodies such as the NHS and have also been made available for patients to purchase directly. The free-to-use products have been developed by the public sector or by research institutes and can be accessed at no direct purchase cost to patients or health-care providers, although there may be costs associated with their support and use in the NHS.

Evidence for computerised cognitive behaviour therapy

Computerised CBT represents an alternative form of therapy delivery that has the potential to enhance access to psychological care. Existing research into cCBT has been summarised by Kaltenthaler and colleagues in their 2006 Health Technology Assessment (HTA) review of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. 6 With respect to depression, three commercially produced computerised packages available to the NHS were considered: Beating the Blues® (Ultrasis, London, UK), COPE and Overcoming Depression. Of these, only one, Beating the Blues, had been evaluated in a randomised controlled trial (RCT); the program was shown to be effective at reducing symptoms of depression. 7 However, this research was conducted by those who owned and held the intellectual copyright to Beating the Blues. Among internet-based free-to-use packages, only one, MoodGYM (National Institute for Mental Health Research, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia), has been evaluated in a randomised trial, which was also conducted by the package developers. 8 MoodGYM was found to be effective at reducing depressive symptomatology. 8 The overall conclusion of the HTA review was that ‘the efficacy but not effectiveness of Beating the Blues had been established in comparison with treatment as usual’. 6

Recommendations for further research on the effectiveness of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy

At the time of the commissioning and design of the REEACT (Randomised Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Acceptability of Computerised Therapy) trial, several caveats applied and specific recommendations for further research were made that are important with respect to the present trial.

-

Computerised CBT had been shown to be effective in the short term, but trials rarely examined the longer-term impact on depression compared with usual care. Trials with longer periods of follow-up are needed.

-

The cost-effectiveness of computerised packages is as yet unknown. More importantly, the cost-effectiveness from the perspective of the UK NHS has not been sufficiently established and the longer-term cost-effectiveness beyond the brief time horizon of existing trials is essentially unknown. This is important, as commercial packages (such as Beating the Blues) will need to be purchased by the NHS.

-

Existing trials are based on populations who have been referred to specialist cCBT services and are necessarily comfortable with information technology and willing to be offered computerised therapy as a treatment option. Computer-delivered CBT uses a computer rather than a trained CBT therapist, and the acceptability of the replacement of the therapist with a machine interface is largely unknown. Patients with depression might show a strong preference for or against computer therapy, and this might, in turn, be related to uptake and effectiveness. The acceptability and effectiveness of cCBT among patients who are representative of people treated for depression in NHS primary care services has not yet been established. There is, therefore, a need for pragmatic evaluations of cCBT based in UK primary care that examine real-world effectiveness and the issue of patient preference.

-

There are no trials of free-to-use cCBT packages versus pay-to-use cCBT packages. This is important, as the effectiveness of free-to-use cCBT would need to be comparable to pay-to-use CBT if it were to be a viable alternative within a stepped care pathway. 9

-

Evaluations of all the commercially available and free-to-use packages of cCBT have been conducted by researchers responsible for their development. Although this does not invalidate the results, it does raise concerns that a truly independent evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cCBT is needed to inform NHS decision-making. In their 2006 HTA report, Kaltenthaler and colleagues make this a core research recommendation and state that ‘Research needs to be carried out by independent researchers. It should be carried out by those who are not associated with commercial or product gains’. 6

The present trial was designed to address these recommendations. A subsequent meta-analysis has demonstrated that cCBT can be effective for depression, but there remains a need for longer-term pragmatic studies and evaluations by researchers other than the product developers. 10

The REEACT study represents a pragmatic evaluation of cCBT in a trial that is adequately controlled and has appropriate statistical power.

Research objectives

This was a fully randomised patient preference trial of usual GP care for depression versus the addition of one of two cCBT packages to usual GP care. The REEACT study included a concurrent economic and qualitative evaluation to meet the following specific aims:

-

to establish the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the addition of cCBT to usual GP care compared with usual GP care alone over a 2-year trial follow-up period

-

to establish the acceptability (to patients and health professionals) of cCBT

-

to establish the differential clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a free-to-use computerised package, in comparison with a commercial pay-to-use cCBT package over a 2-year and longer-term time horizon.

Some of this text has been reproduced from Gilbody et al. 11 © BMJ 2015. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The REEACT trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, open, three-armed parallel RCT with simple randomisation. The design included a fully randomised patient preference approach. 12 Participants with depression [defined as a score of ≥ 10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression severity instrument]13 were randomised (1 : 1 : 1) to receive:

-

a commercial pay-to-use cCBT program (Beating the Blues) plus usual GP care or

-

a free-to-use cCBT program (MoodGYM) plus usual GP care or

-

usual GP care alone.

Approvals obtained

The Leeds (East) Research Ethics Committee (REC) approved the study on 10 July 2008 and approved the substantial amendment to revise the trial design following advice from the funder on 22 September 2008 (see Chapter 3 for details of this substantial amendment). The details of the REC and Research and Development Department approvals are provided in Appendix 1. The trial was registered as ISRCTN91947481; EudraCT number 2007-007645-12; and UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio (UKCRN) identification number 4115.

Trial sites

The trial was conducted in nine UK sites. Five sites were involved from the commencement of the trial, and the remaining four sites were recruited throughout the duration of the trial. Details of the study sites are provided in Appendix 2.

Participant eligibility

People with depression were eligible to take part in the trial. Both prevalent and incident cases of depression were included.

Inclusion criteria

Potential participants were eligible for inclusion in the trial if they met the following criteria:

-

They met the inclusion threshold of a score of ≥ 10 on the PHQ-9 depression severity instrument. 13 This cut-off point is known to detect clinical depression (major depression) in a UK primary care population with sensitivity of 91.7% and specificity of 78.3%. 14

-

They were not currently in receipt of cCBT or specialist psychological therapy (including therapy from a psychologist), and were not currently under care from a local Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service.

-

They were aged 18 years or over.

Potential participants who met the above inclusion criteria were not excluded if:

-

They had a comorbid physical illness (such as diabetes).

-

They had a comorbid non-psychotic functional disorder (such as anxiety).

-

They were in receipt of antidepressant medication.

-

They had previous treatment experience of CBT.

Exclusion criteria

Potential participants were excluded if they met any one of the following criteria:

-

They were actively suicidal.

-

They were suffering a psychotic illness (as ascertained by the GP).

-

They had recently suffered bereavement (bereavement was classed as having lost a mother, father, partner, husband, wife, son or daughter in the last year).

-

They were depressed in the postnatal period (the postnatal period was classed as having had a baby in the last year).

-

They were suffering from psychotic depression (this decision was based on NICE guidance in which computerised therapy is not recommended for people with psychotic depression). 15

-

They had a primary diagnosis of alcohol or drug abuse.

-

They were not able to read and write in English.

Recruitment into the trial

All researchers participating in the study received training in all aspects of the trial including trial recruitment, eligibility criteria, trial protocol, adverse event reporting procedures, participant risk assessment and reporting procedures, trial database and trial documentation. Each researcher received a researcher manual detailing these procedures in order to standardise the running of the study across researchers and trial sites. All researchers also undertook Good Clinical Practice training.

Potential participants were referred to the trial through GP practices. All GP practices were provided with a GP practice manual. This provided details of key trial contacts and site information, information about cCBT and the trial intervention cCBT programs, a GP information sheet (see Appendix 3), and procedures and forms for recruiting participants via the various recruitment routes (described in Recruitment routes) and for reporting serious adverse events (SAEs). The manual also contained copies of trial documentation including the trial protocol, participant information sheet and patient consent form (see Appendix 4). GP practices were also provided with participant study information packs containing a study invitation/cover letter, a participant information sheet and a permission form for release of personal details (see Appendix 4).

In line with recommendations from a HTA-funded primary care depression trial by Peveler and colleagues,16 GP practices were reimbursed for the additional time involved in recruitment of patients to the trial via service support costs. An additional GP practice incentive was the use of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). 17 As the PHQ-9 was a validated assessment measure incentivised for the Depression 2 indicator in the QOF during the trial’s recruitment period, all GPs were provided with participants’ PHQ-9 scores at recruitment.

Recruitment routes

Potential participants were identified through one of four main recruitment routes:

General practitioner-initiated recruitment (direct referral)

General practitioners identified potential participants who presented with depression during patient consultations (both prevalent and incident cases of depression). GPs were asked to introduce the study to potential participants. For patients who were immediately interested in the trial, GPs completed a referral form stating that the patient matched the study criteria and provided the patient with a study cover letter and the participant information sheet. Patients were asked to complete a ‘permission for release of personal details form’ which included their contact details. The GP or a member of the GP practice staff would then fax the referral form and permission form to the local research team. For those patients who expressed a wish to consider the study over a longer period, GPs were asked to provide the patient with a study information pack which included an invitation letter explaining how to contact the research team. Patients interested in taking part in the study completed the ‘permission for release of personal details form’ and sent this back to the local research team. Patients were advised by their GP that they should expect to hear from a study researcher within 2 working days of the research team receiving their permission form.

Recruitment initiated by health professionals attached to a general practitioner practice (direct referral)

Practice-attached nurses and primary care mental health workers identified potential participants who presented with depression during patient visits. These health professionals were asked to introduce the study to potential participants and provide interested patients with the study information pack. They were also able to complete a referral form, ask patients to complete the ‘permission for release of personal details form’ and fax these forms to the local research team in the same way that a GP would. They would then notify the patient’s GP that a referral to the trial had been made.

Record screening (database screening)

General practitioner practice staff, with agreement from the lead research GP, reviewed patient records in accordance with a pre-specified protocol to identify a list of potential study participants (presenting prevalent cases of depression). This protocol contained a list of read codes which described a range of inclusion and exclusion criteria to search for over pre-specified time frames. GPs reviewed the list of potential participants and identified any patients who they felt were not suitable to take part in the trial. GP practices were supplied with study information packs to send out to potential participants on this list; alternatively, the GP could consider the patient for the trial at their next GP appointment. The frequency of these record searches was agreed between individual GP practices and the REEACT research team. Interested participants who received the study information pack in the post completed the ‘permission for release of personal details form’ and sent this back to the local research team.

Waiting room screening

Where a GP practice agreed, REEACT researchers would screen patients in the GP practice waiting room with a simple two-question screening instrument. 18 GPs were immediately notified of any patients who screened positive for possible depression so that the GP could consider introducing the study to them during their appointment. Although this recruitment route was available it was not implemented in any of the recruiting GP practices.

The number of participants recruited to the trial via direct referral and database screening recruitment routes is detailed in Appendix 5.

Researcher contact following trial referral

See Appendix 6 for a summary of participant involvement in the trial.

Following receipt of a completed ‘permission for release of personal details form’, the REEACT researcher would contact the patient to discuss the study and to pre-screen for eligibility using the PHQ-9 depression instrument. Initial contact was made within 1 or 2 working days of receiving the permission form, to allow the patient a minimum of 24 hours to read the information sheet and consider participation. If the patient scored ≥ 10 on the PHQ-9 during the pre-screen, the researcher arranged a face-to-face visit with the patient, at which the researcher would confirm the patient’s eligibility after obtaining written informed consent (part 1) by readministering the PHQ-9. If the patient scored ≥ 10 at this point, the researcher would obtain the patient’s written informed consent (part 2) to participate in the trial, administer the baseline measurements and ascertain treatment preference. The researcher would then ascertain and inform the patient of treatment allocation and make arrangements to initiate cCBT if this was the allocation. Arrangements would be made for the researcher to collect follow-up measures after 4 months. Following recruitment, participants’ GPs (and referrers, if the referrer was not their GP) were notified of the outcome of the referral, including treatment allocation and PHQ-9 score for participants who had been randomised to the study.

Baseline assessment

After written informed consent (parts 1 and 2) had been obtained, baseline data were collected on participants prior to randomisation using several self-report baseline questionnaires. The following data were collected.

Depression severity and symptomatology

Participants completed the PHQ-9 self-report questionnaire13 to confirm their eligibility to participate in the trial and to assess baseline depression severity and symptomatology.

Participants also completed a diagnostic gold standard lay-administered computer-based interview [Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised, (CIS-R)],19 which assesses depression severity and diagnosis and other common mental health disorders, such as anxiety, according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) criteria. 20

Biographical data

Participants completed a bespoke biographical questionnaire which recorded data on ethnicity, education, employment status, marital status, living arrangements, previous episodes of depression and treatment preference.

Ethnicity

The ethnicity of participants was recorded.

Education

Participants were asked to indicate their highest educational qualification.

Employment status

Information relating to participants’ current employment status was recorded. Participants who classed themselves as employed or self-employed indicated if they were currently off work sick because of their depression. Participants who described themselves as unemployed were asked to record the duration of their unemployment. Participants also indicated the type of position held in their most recent job.

Marital status

The marital status of participants was recorded.

Living arrangements

Married participants were asked to indicate if their spouse lived with them. The number of other people living with each participant, including the number of people under the age of 18 years, was recorded.

Previous episodes of depression

Whether or not participants had experienced a previous episode of depression for which they had sought help was recorded. Further information was recorded for those participants who indicated that they had experienced a previous episode of treated depression; this included the number of previous episodes of treated depression, if antidepressants had been prescribed, if participants had ever seen anyone for help with their depression other than their GP and, if so, who they had seen.

Treatment preference

The participant’s treatment preference was recorded on the biographical questionnaire (see Appendix 7) to allow us to explore the influence of patient preference prior to randomisation and the differential impact of preference on the relative effectiveness of cCBT versus usual GP care.

Generic and global mental health

Participants completed the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) questionnaire21,22 to assess their baseline generic and global mental health.

Health-related quality of life

Participants completed two self-report questionnaires to assess baseline health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and health-state utility. These were the Short Form questionnaire-36 items Health Survey® version 2 (SF-36v2)23,24 (QualityMetric Incorporated, Lincoln, RI, USA) and the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). 25,26

Resource use data

Participants completed an adapted version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)27 to assess baseline resource utilisation.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised 1 : 1 : 1 between the three trial arms: cCBT (Beating the Blues) plus usual GP care; cCBT (MoodGYM) plus usual GP care; and usual GP care alone. In view of the large number of participants to be recruited to the study, stratification by depression severity was not required. Randomisation was simple and, therefore, not restricted in any way. Simple randomisation reduces the risk of any possible subversion associated with restricted randomisation methods and has been shown to produce equally precise results28 as stratified randomisation, which improves treatment precision in trials with fewer than 50 participants. However, simple randomisation can lead to unequal group sizes by chance alone. To maintain allocation concealment, the generation of the randomisation sequence and subsequent treatment allocation were performed by an independent, secure, remote telephone or web-based randomisation service. The computerised randomisation sequence was checked periodically during the trial following standard operating procedures. Owing to the nature of the trial design and the intervention, it was not possible to conceal treatment allocation from either the participant or the REEACT researcher.

Sample size

We needed to know if cCBT represented a clinically effective addition to usual GP care and whether or not the free-to-use computerised program (MoodGYM) represented a less effective (non-inferior) choice of therapy for patients compared with the commercial pay-to-use computerised program (Beating the Blues). We therefore powered our trial both to capture any benefit of cCBT over usual GP care alone and to test the non-inferiority of free-to-use cCBT. We based our sample size calculation on the usual care arm of our own primary care trial of collaborative care for depression, where the proportion of patients responding to usual care was in the region of 0.6;29 a response rate similar to that found in a UK HTA trial of antidepressants in primary care16 and a US pragmatic depression trial. 30 We regarded a response rate of not more than 0.15 below this rate as being acceptable, given the additional care options that are available to patients who do not initially respond to cCBT within a stepped care framework. Our original sample size calculation of 600 participants (200 participants in each of the three arms) gave us in excess of 80% power to detect non-inferiority using the percentage success in both groups as 60%, with a non-inferiority margin of 15% and allowing for 25% attrition. However, the sample size was re-estimated as, despite better levels of recruitment than anticipated, levels of attrition were slightly higher than originally expected (see Chapter 3). In order to retain similar levels of power to detect non-inferiority between the free-to-use and commercial cCBT packages with 5% probability, while allowing for 35% attrition, 690 participants were recruited (230 participants in each of the three arms). The trial also retained 80% power to detect a difference of 15% between the usual GP care arm and either of the two cCBT arms using a conventional power analysis (α = 0.05; two-sided significance).

Trial interventions

Participants were randomised to receive a commercial pay-to-use cCBT program (Beating the Blues) plus usual GP care, a free-to-use cCBT program (MoodGYM) plus usual GP care, or usual GP care alone.

Experimental interventions

Participants randomised to either of the two intervention arms each received cCBT (Beating the Blues or MoodGYM) in addition to usual GP care. Given that this was a pragmatic trial design, we imposed no restrictions on usual GP care, including the use of antidepressant drugs or the addition of drug treatment to cCBT in the two intervention arms.

Location of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy access

In order to maximise participant accessibility and flexibility, while respecting the importance of patient choice, cCBT was offered in one of three locations, according to patient choice and local availability: (1) in the participant’s own home (if the participant already had a computer and a broadband connection at home); (2) in a central location close to the participant’s home – this could be in a psychotherapy department, a local library or a large GP practice (where a standalone computer in a private room operating on a weekly booking system would be provided); or (3) in the GP practice (provided the participant’s GP practice was able to provide a broadband-connected computer in a private room on a fixed weekly basis).

Telephone support calls

All participants in the two intervention arms were provided with support in the form of regular (weekly) telephone calls, conducted by telephone support staff. The purpose of these telephone calls was to provide participants with technical support with using the cCBT programs (such as how to access the cCBT programs and resetting passwords) and to encourage them to engage with the cCBT programs. The supportive telephone calls were not intended to offer any form of psychotherapy. The telephone support staff completed each of the two cCBT programs in order to familiarise themselves with the nature and content of these programs. As a way of ensuring standardisation of the telephone support calls, telephone support staff worked to specific and standardised instructions regarding what should be covered during each telephone call to ensure delivery of ‘support’ rather than ‘therapy’. Telephone support staff were provided with the skills required to respond to common questions which would inevitably arise during the telephone calls. The option of support e-mails was offered to those participants who specifically requested contact via e-mail or who found it difficult to respond to telephone calls. A record was made of all participant contacts, including a brief summary of the content of the contact and an estimate of the duration of the telephone calls. In order to supervise the telephone support staff, and as a means of ensuring quality control, the telephone calls were recorded. All participants were asked for their verbal informed consent to record each telephone call and participants were not excluded from the trial if they withheld their consent to the recording. Telephone support staff were aware that calls were being recorded, where participant consent had been given. Telephone support staff underwent regular supervision with the chief investigator or other senior study co-investigators.

Experimental group: Beating the Blues (pay-to-use computerised cognitive behaviour therapy program) plus usual general practitioner care

Beating the Blues (www.ultrasis.com) is an interactive, multimedia, cCBT program developed by Ultrasis comprising a 15-minute introductory video followed by eight therapy sessions of approximately 50 minutes’ duration each, with homework exercises between sessions. It was used via the internet. Beating the Blues has been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms of depression. 7 In addition, all participants were offered usual GP care, and no restrictions were placed on GPs in their ability to prescribe medication or refer participants to other forms of psychological therapy (including IAPT services).

Experimental group: MoodGYM (free-to-use computerised cognitive behaviour therapy program) plus usual general practitioner care

MoodGYM (http://moodgym.anu.edu.au) is a free-to-use, internet-based, interactive CBT program for depression developed and copyrighted at the National Institute for Mental Health Research of the Australian National University. It consists of five interactive modules of approximately 30–45 minutes’ duration, with revision of all aspects of the program in the sixth session. The program includes a personal workbook containing exercises and assessments, and ‘characters’ to represent patterns of ‘dysfunctional’ thinking, and provides patients with CBT techniques to overcome this. 31 MoodGYM has been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms of depression in a developer-led trial. 8 At the commencement of the study, MoodGYM was being used in the UK, with 20.5% of the registrants on MoodGYM being from the UK. In addition, all participants were offered usual GP care, and no restrictions were placed on GPs in their ability to prescribe medication or refer participants to other forms of psychological therapy (including IAPT services).

Control group: usual general practitioner care

Participants randomised to the control arm received usual care by their GP. In line with the overall pragmatic approach of the trial, we replicated ‘usual GP care’ by making no specific patient-level recommendation or requirement to alter usual GP care by participating in the trial. However, GPs were reminded of the existence of NICE guidance on the management of depression,15 including the prescription of antidepressants, where this is indicated. Participants in the control arm were given no specific encouragement to access cCBT but this remained an option if the GP chose to suggest this treatment or if it was offered in the context of a local IAPT service.

Participant follow-up

Participants were followed up at three time points following randomisation: 4 months, 12 months and 24 months. During the first 6 months of the trial follow-up period, participants completed their follow-up questionnaires with a REEACT researcher during face-to-face interviews or telephone interviews, according to participant preference. In order to improve follow-up rates, participants were later given the additional option of completing and returning follow-up questionnaires in the post (see Chapter 3). The participant information sheet was revised to reflect this additional method of follow-up completion, and participants already recruited to the trial were advised of this option and received a copy of the revised participant information sheet at their next scheduled follow-up. As a further means of improving our retention rates, participants received an unconditional £5 voucher with their follow-up as an acknowledgement for their taking part in the study and completing the questionnaires. The £5 voucher either accompanied their appointment letter for face-to-face or telephone interviews, or was sent along with postal questionnaires.

Trial completion

Participants were deemed to have exited the trial when:

-

The participant had completed the 24-month follow-up.

-

The participant wished to exit the trial fully.

-

The participant’s GP withdrew him or her from the trial.

-

The participant died.

Instead of withdrawing fully from the trial, participants had the option of:

-

withdrawing only from receiving the trial intervention (applicable only to participants randomised to receive either of the two cCBT programs).

Participants who elected to withdraw from the trial intervention (cCBT programs) and follow-ups were deemed to be full withdrawals (trial exit). REEACT researchers were able to indicate any change in the patient’s level of participation by registering this information on the trial database, which immediately notified the co-ordinating centre (University of York) of this change. REEACT researchers notified the patient’s GP when a participant elected to withdraw fully from the trial.

Measurement and verification of primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was depression severity and symptomatology as measured by the PHQ-913 questionnaire at 4 months. Participants completed the primary outcome measure during face-to-face interviews or telephone interviews with REEACT researchers, or as a postal questionnaire, according to their preference.

The PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire which records the core symptoms of depression based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. 32 Each item is rated on a scale of 0 to 3 based on the frequency of depressive symptoms (0 = ‘not at all’ to 3 = ‘nearly every day’). Scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of depression severity. It has the added advantage that it can be reliably administered over the telephone. 33

There are extensive US and non-US validation and sensitivity to change data using the PHQ-9. It has been validated in a UK primary care population14 and has become the instrument of choice in the management of depression in UK primary care, including monitoring symptom change,34,35 and in the fulfilment of QOF routine depression measurement. 36 It has also been shown to be sensitive to change over time. 37,38

Measurement and verification of secondary outcomes

A variety of disease-specific and generic outcome measures were administered to ascertain clinical effectiveness. Cost-effectiveness was determined by obtaining measures of HRQoL and resource utilisation using self-report questionnaires, along with objective data collection from participants’ GP medical records.

Outcome measures completed by participants were administered at each follow-up – 4 months, 12 months and 24 months – and were completed during face-to-face interviews or telephone interviews with REEACT researchers, or as a postal questionnaire, according to participant preference. Objective data from participants’ GP medical records were obtained after participants had completed their 24-month follow-up.

The following data were collected.

Depression severity and symptomatology

Participants completed the PHQ-913 self-report questionnaire to assess depression severity and symptomatology at each follow-up (see section on Measurement and verification of primary outcome for detailed information on this instrument).

Global and generic mental health

The CORE-OM21 questionnaire was completed by participants at each follow-up. The CORE-OM is a 34-item generic instrument which measures common mental health problems (including four items measuring depression), subjective well-being, functional capacity and risk. 21,22 It has been validated in a UK primary care population14 and is a widely used outcome measure for psychological therapies21,39 and in research. 40,41 It shows reliable sensitivity to change over time. 39

Health-related quality of life

Participants completed two generic questionnaires about their HRQoL (SF-36v2) and health-state utility (EQ-5D) at each follow-up in order to measure participants’ perceptions of health outcome during the study. Generic instruments of health status are useful for comparing different groups of participants, while also having a broad capacity for use in economic evaluations. Their generic nature also makes them potentially responsive to side effects or unforeseen effects of treatment.

Each participant’s perception of his or her general health was assessed using the SF-36v223,24 and the EQ-5D. 25,26 The SF-36v2 is a reliable and well-validated generic HRQoL measure. It has been validated for use in UK primary care42,43 and has been used as an outcome measure in a wide variety of patient groups, including patients with depression. 44 It measures health on eight dimensions covering functional status, well-being and overall evaluation of health, with scores ranging from 0 (worst HRQoL) to 100 (best HRQoL). It also yields two summary scores assessing physical and mental components, which have been shown to be reliable and valid measures of HRQoL. 45 It can also be used to generate a Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) score, which is a preference-based generic HRQoL measure suitable to be used as an outcome in economic evaluation. 46,47

The EQ-5D is a generic preference-based measure of health state that covers five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. 25 Patients indicate their health state by rating each dimension according to three possible levels of severity: no problems, some problems and major problems. This response will identify one among the 243 mutually exclusive health states defined by the combination of dimensions and levels, plus two additional health states referring to ‘death’ and ‘unconsciousness’, yielding a total of 245 health states. 26 HRQoL weights for these health states have been previously elicited by Dolan et al. 48 using a time trade-off technique from a representative sample of the UK population. A score of 1 represents perfect health and a score of 0 represents death. The EQ-5D has been validated in UK populations and has been used to measure HRQoL in patients with depression in primary care. 49–51

Resource use data

Information relating to participants’ resource utilisation was obtained via two measures: completion of a self-report questionnaire (an adapted CSRI) and objective data collection from GP medical records. Resource use data were used in the assessment of cost-effectiveness and allowed us to assess whether or not participants randomised to the two cCBT arms experienced differing levels of resource use from the usual GP care alone group. Given the significant overlap between the content of the adapted CSRI and service use data collected from GP medical records, preference was given to the use of GP record data to inform resource use, as GP records were considered the more consistent and reliable source of data. At the outset of the trial, the logistical issues of collecting data from GP medical records were not clear and so the adapted CSRI was retained and was planned to be used in the event of difficulties in accessing these records. In the final analysis, only resource data from GP medical records were used because of the high proportion of patients in whom service records were obtained and the degree of completeness.

Questionnaire data

The CSRI is a self-report questionnaire which asks participants about their use of health and social care services and employment. 27

Participants completed an adapted version of the CSRI at each follow-up (see Appendix 7). Participants were asked about their use of services in the previous 6 months (including inpatient and outpatient hospital services, community-based day services and primary and community care contacts) and whether or not they had incurred any additional costs associated with their depression in the previous 6 months (e.g. medication or drug costs, child-care costs, travel costs). Participants were asked about their current occupational status, including information about type of occupation, weekly hours worked, days absent from work and reason and duration for unemployment. Participants were also asked to record their use of any medication to help with their depression, including medication name, dose and duration taken (however, participants were asked this medication question only at the 24-month follow-up, as it was not included on previous versions of the questionnaire).

In addition, participants were asked to indicate their use of any cCBT since their last REEACT follow-up, allowing us to determine self-reported level of engagement with the two cCBT programs, or any other cCBT packages, for those participants randomised to the two intervention arms, and to examine whether or not participants in the control arm (usual GP care alone) made use of any cCBT packages. Participants were also asked to record their use of other self-help materials (such as self-help books for depression) since their last REEACT follow-up.

Data collected from general practitioner medical records

A range of data were obtained directly from participants’ GP medical records, provided participants had given their informed consent for us to access this information. Data were collected from 2 months before randomisation until the 24-month follow-up, or the date the participant was de-registered from his or her recruiting GP practice, if this occurred before their 24-month follow-up. The data were obtained across three time frames: (1) from 2 months before randomisation to the date of randomisation (representing a 2-month period); (2) from the date of randomisation to 12-month follow-up (‘year 1’, representing a 12-month period); and (3) from 12-month follow-up to 24-month follow-up (‘year 2’, representing a 12-month period).

Data were not collected for those participants who had withdrawn fully from the trial before completion of their 24-month follow-up (see section on Trial completion). Data were recorded by either REEACT researchers or GP practice staff using a data collection form.

Data were collected on the following.

General practitioner consultations

The number of consultations with a GP (including face-to-face, telephone and home consultations) was recorded. The number of these consultations that were clearly related to depression was also recorded.

Nurse appointments

The number of appointments with a practice nurse was recorded, along with the type of nurse seen, if known (e.g. practice nurse, treatment nurse, midwife, health-care assistant).

Health problems

Information about participants’ health problems was recorded. This included mental health problems (specifically depression and anxiety/panic), chronic illness (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, asthma), myocardial infarction, accident/life events (e.g. bereavement, divorce, birth of a baby), drug/alcohol disorders and any other health conditions.

Medication

Information about prescribed depression-related medication was recorded, including medication type, dosage, and prescription start and end dates. Medication type included antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, sleeping tablets and anxiety medication.

Referrals

General practitioner referrals were recorded. This included referrals to various mental health services [e.g. inhouse counsellor, community mental health teams (CMHTs), IAPT, psychologist and psychiatry services] and ‘other’ referrals for all other conditions. The date of referral was recorded, along with the number of sessions received for any mental health services accessed, if known.

Hospital stays

Hospital inpatient stays were recorded, including number of inpatient nights, area of specialty and reason for admission.

Hospital outpatient appointments

Hospital outpatient appointments were recorded, including the appointment date, specialty and reason.

Emergency contacts

The date and reason for visits to accident and emergency departments (for mental health concerns and ‘other’ concerns) and contacts made with out-of-hours services were recorded.

Adverse events

An adverse event was defined as ‘any undesirable clinical occurrence in a subject, whether it is considered to be caused by or related to treatment or not’.

Adverse events were identified during participant recruitment and follow-up by REEACT researchers or at any point during the participant’s involvement in the trial by the participant’s GP. In addition, participants completed a Health Events Questionnaire at each follow-up (see Appendix 7). This asked participants if they had experienced any health problems since their last follow-up, with particular reference to any problems or events that may be related to their depression. Participants were asked to describe their health problems, including when the problem or event happened. Adverse events were also identified via the adapted CSRI questionnaire, which was administered at each follow-up and asked participants about their use of inpatient hospital services during the previous 6 months.

Adverse events were categorised as serious or non-serious. A serious adverse event (SAE) was defined as an event that resulted in death, was life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalisation or prolonging of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, resulted in a congenital anomaly or birth defect or was deemed medically significant by the reporter.

Adverse events that were felt to be serious were reported to the trial co-ordinating team either by REEACT researchers or by the participant’s GP. The reporter was asked to complete a ‘serious adverse event/reaction form’ (see Appendix 7) for all those adverse events he or she judged to be serious, indicating why, in the reporter’s opinion, the event was considered to be serious and the relationship of the adverse event to treatment. Reporters were asked to report any SAEs to the trial co-ordinating team within 24 hours of the event occurring, or within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event. All adverse events judged to be serious were reviewed by at least two members of the Trial Management Group. SAEs felt to be related to treatment in some way were reviewed by the Data and Ethics Monitoring Committee (DMEC) and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). SAEs that were felt to be unrelated to treatment were reviewed by the DMEC and TSC at the next scheduled meeting.

The trial co-ordinating team regularly reviewed participant outputs reported on the Health Events Questionnaire. A SAE/reaction form was completed for any reported health problems/events considered to be serious and/or related to treatment. Health problems/events reported by participants that were felt to be non-serious by the trial co-ordinating team were reviewed by the DMEC and the TSC at the next scheduled meeting.

Statistical analysis of the REEACT clinical effectiveness data

All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, including all participants in the groups to which they were randomised. For superiority comparisons, two-sided significance tests at the 5% significance level were used. Analyses were conducted in Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Overview of analyses

All outcome measures were assessed separately among the following groups of participants:

-

Beating the Blues versus usual GP care alone (superiority)

-

MoodGYM versus usual GP care alone (superiority)

-

MoodGYM versus Beating the Blues (non-inferiority).

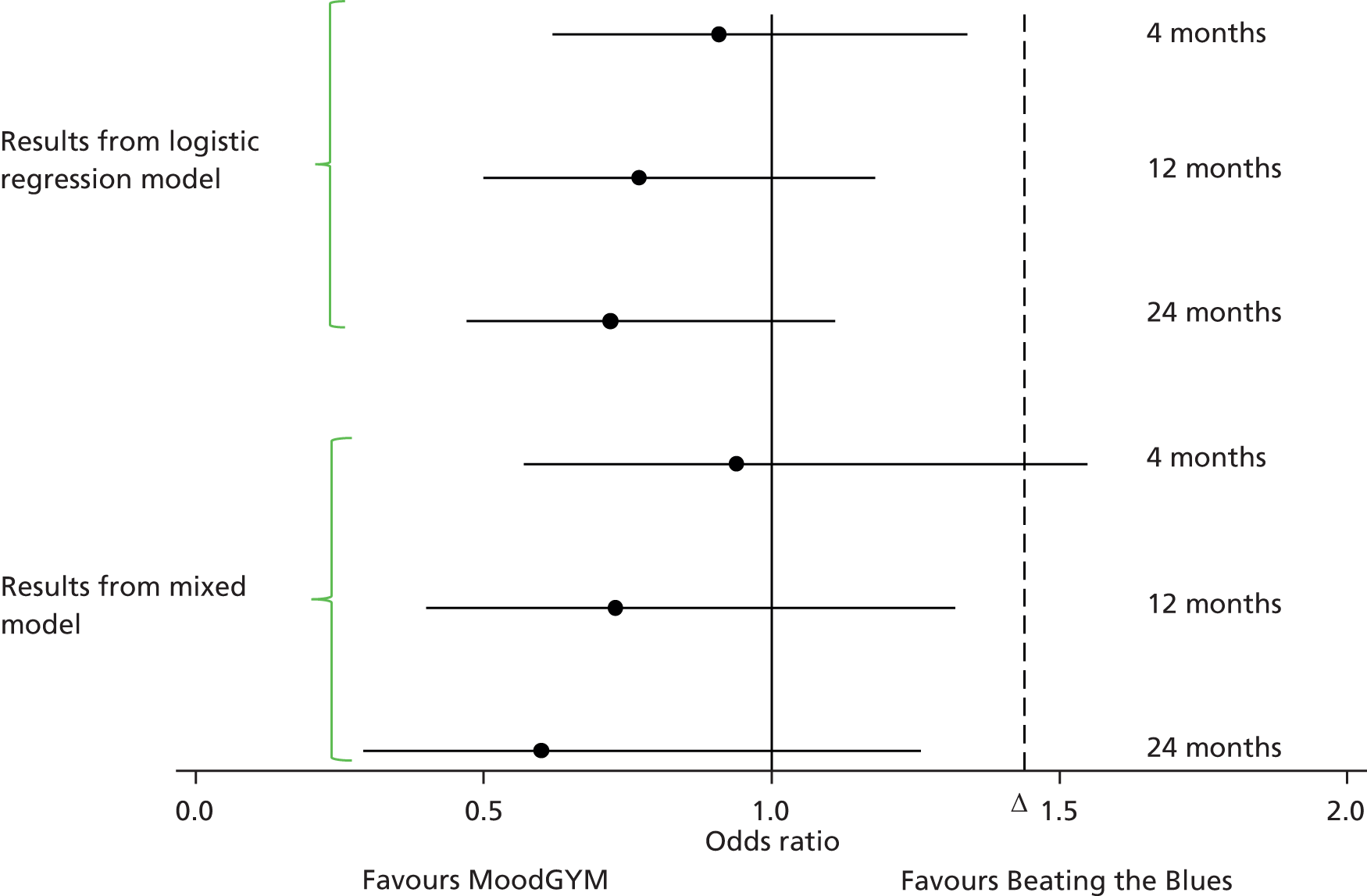

For each group comparison, similar analyses were applied depending on the type of comparison (superiority or non-inferiority) and the inclusion of potentially important covariates. It was aimed to minimise the number of models applied to each outcome to avoid issues arising from multiple comparisons. The non-inferiority comparison was undertaken only for the dichotomised PHQ-9 scores, with the primary outcome being at 4 months. To assess non-inferiority between Beating the Blues and MoodGYM, we computed two-sided 90% confidence intervals (CIs). Using this method, the free-to-use cCBT program MoodGYM was not inferior to the commercial pay-to-use cCBT program Beating the Blues at the 5% level if the upper boundary was below the pre-specified margin of non-inferiority [0.15 difference in proportions, which translated to 1.44 for the odds ratio (OR)].

Baseline data

All baseline data were summarised by treatment group and described descriptively. No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken. Continuous measures were reported as means and standard deviations (SDs; with medians and minimum and maximum values where appropriate), whereas the categorical data were reported as counts and percentages.

Primary analysis

The primary outcome was depression status at 4 months using a cut-off point of 10 on the PHQ-9. The PHQ-9 was scored if at least eight out of the nine questions were completed. If there was a missing response for one item, then the mean of the other eight responses was imputed. Groups were compared using a logistic regression model with adjustments for gender, age, baseline depression severity, depression duration and level of anxiety. From this model, we obtained ORs and corresponding 95% CIs.

Secondary analyses

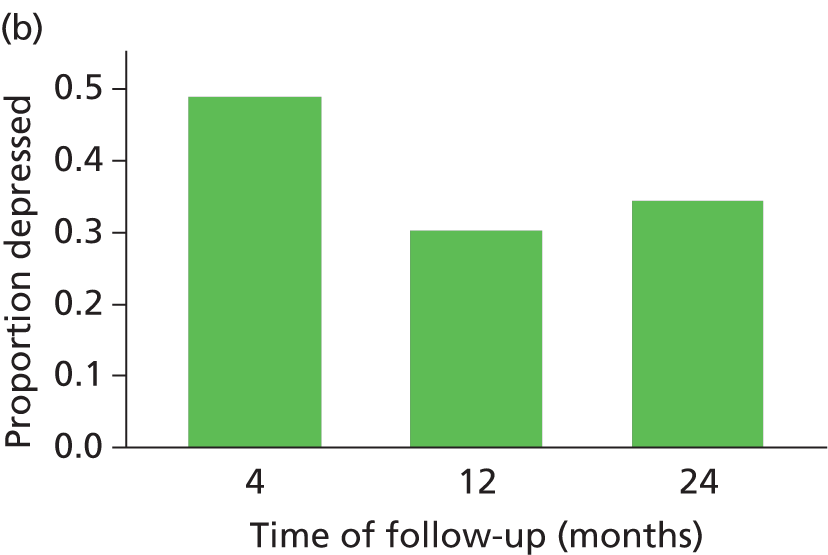

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 dichotomised

The primary analysis was repeated for the 12- and 24-month dichotomised PHQ-9 data using the same methods as described above. In addition, all time points were analysed in a single model rather than individual analyses at each time point, using a repeated measures multilevel logistic regression model. The outcome measures were the values at 4, 12 and 24 months, and baseline PHQ-9 score, age, gender, depression duration, level of anxiety, treatment group and time were included as fixed effects. The model also included an interaction between treatment and time. Participants were treated as random effects (to allow for clustering of data within individual participants). Different covariance patterns were calculated for the repeated measurements within participants: unstructured, independent, exchangeable and identity. Models were compared and the model with the smallest Akaike information criterion (AIC) value was selected for the final model for each comparison. Model assumptions for the final models were checked for all comparisons. Overall ORs and corresponding 95% (or 90% for non-inferiority) CIs and individual ORs at each time point (4, 12 and 24 months) were estimated from these models.

Subgroup analyses

An a priori subgroup analysis was performed for the dichotomised PHQ-9 scores at 4 months only. The primary analysis was repeated, including an interaction term between the baseline factor and treatment comparison as described in the previous section. As this study has not been powered to detect interactions, a statistical significance level of 10% (p < 0.10) was used. The subgroup analysis was based on baseline pre-randomised patient preference in relation to cCBT.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 continuous

The PHQ-9 outcome was also analysed in its continuous form using a repeated measures multilevel linear mixed model following a similar procedure to those outlined above for the dichotomised PHQ-9 scores. The model made adjustments for the same covariates.

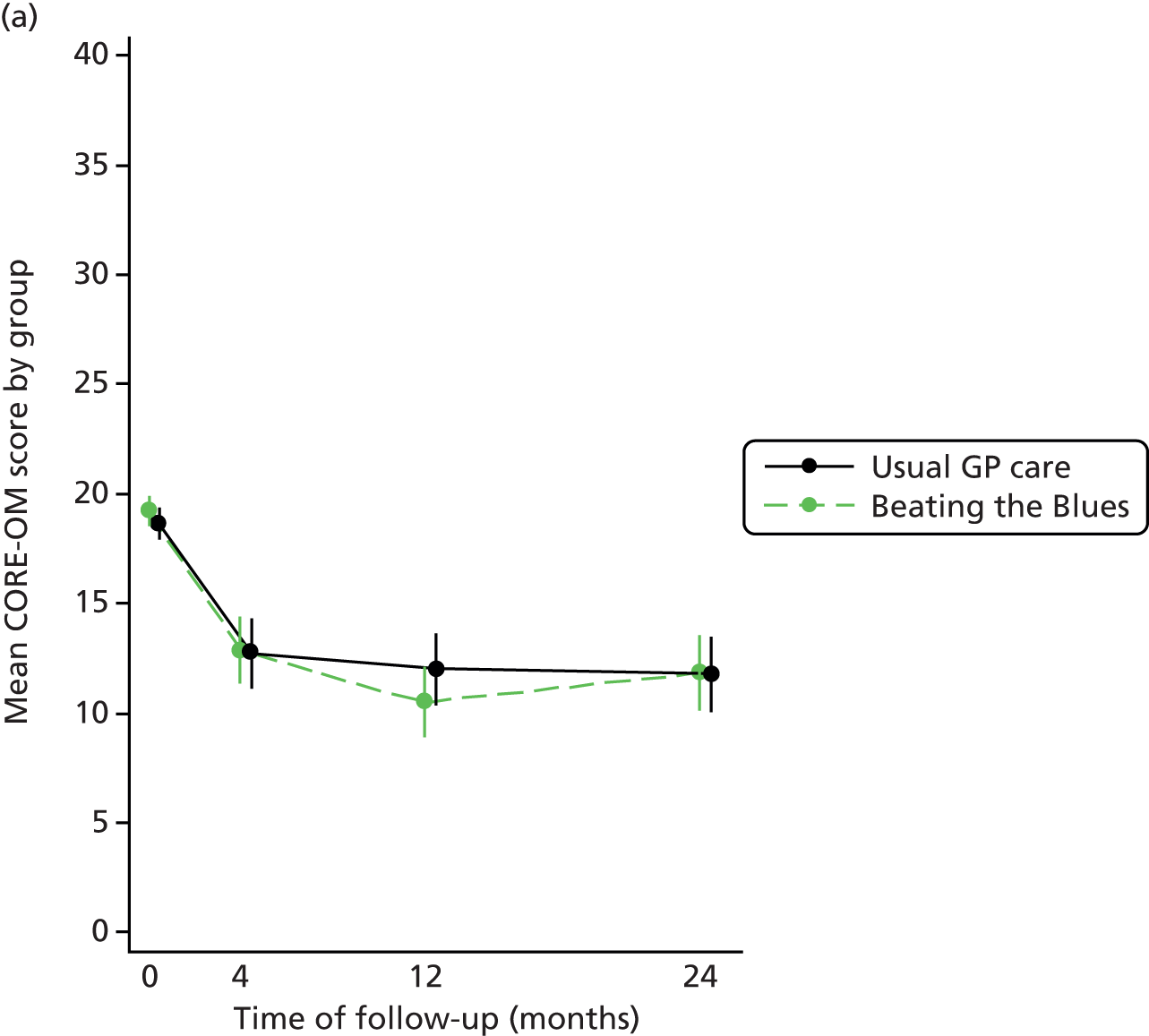

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure

The CORE-OM was analysed using a repeated measures multilevel linear mixed model following a similar procedure to that outlined above for the dichotomised PHQ-9 scores. The model adjusted for the same covariates but included the baseline CORE-OM score and not the baseline PHQ-9 score. If there was a missing response for no more than three items, then the overall score was still calculated by summing the valid responses and dividing by the number of valid responses.

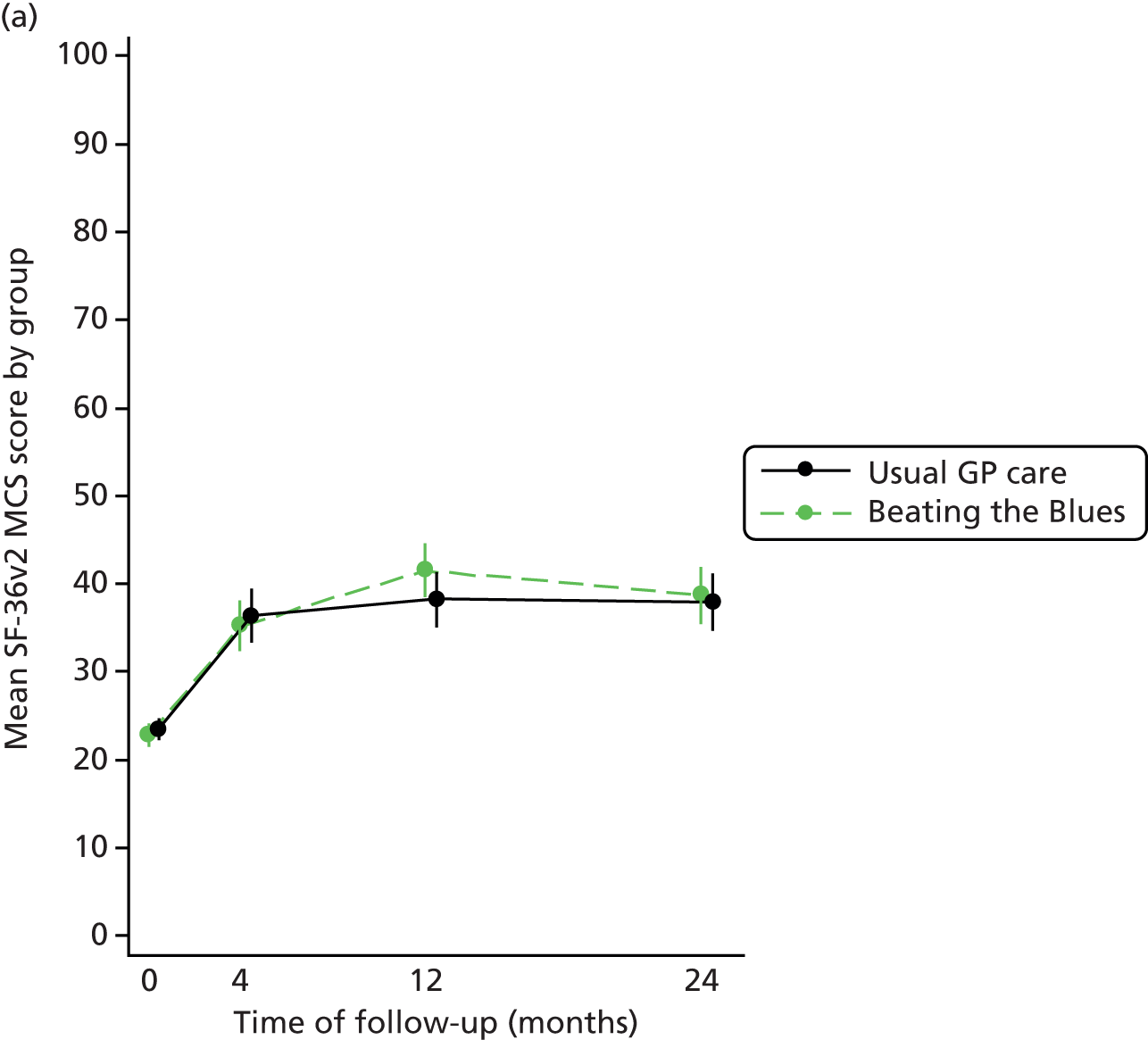

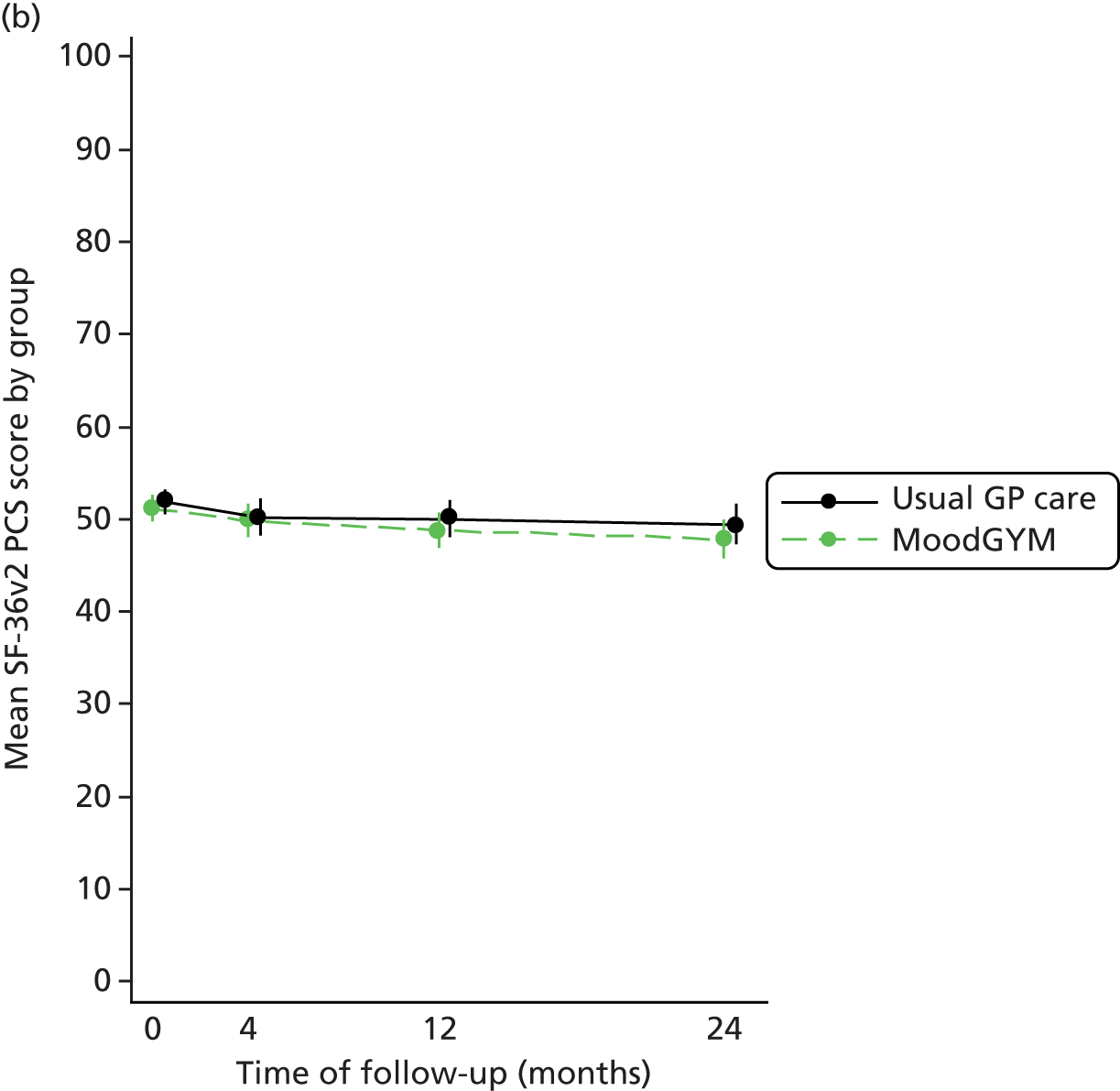

Short Form questionnaire-36 items Health Survey version 2

The HRQoL was measured using the SF-36v2 questionnaire at baseline and 4, 12 and 24 months. The scores for the individual SF-36v2 health components (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, role-emotional, vitality, social functioning and mental health) were summarised at each time point by group. For statistical analysis purposes, only the physical component summary (PCS) scores and mental component summary (MCS) scores were analysed to prevent problems caused by multiple testing. The SF-36v2 PCS and MCS scores were analysed using a repeated measures multilevel linear mixed model following a similar procedure to that outlined above for the dichotomised PHQ-9 scores. The model adjusted for the same covariates but included the baseline SF-36v2 score and not the baseline PHQ-9 score.

Adverse events

The number of adverse events and the number of participants experiencing those events were summarised overall and by group for non-serious adverse events (NSAEs) and SAEs separately. No statistical comparisons were undertaken.

Economic analysis of the REEACT cost-effectiveness data

Overview

A within-trial economic analysis was conducted to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of cCBT programs when added to usual GP care in patients with depression. Costs and health benefits expressed in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were estimated over a time horizon of 2 years for each treatment group. Incremental analyses of costs and QALYs were then performed to provide estimates of the incremental cost-effectiveness of a commercial pay-to-use cCBT program (Beating the Blues) plus usual GP care and a free-to-use cCBT program (MoodGYM) plus usual GP care compared with usual GP care alone. The analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis from the perspective of the UK NHS and Personal Social Services, in line with current UK guidelines for a cost-effectiveness analysis. 52 All costs were considered at a 2011–12 price base. Main analyses were conducted on multiply imputed data sets because of the presence of missing data in the trial. 53 A sensitivity analysis was performed to explore and quantify uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness results. The sensitivity analysis included: (1) scenario analyses testing different assumptions in terms of costs, HRQoL and missing data; and (2) a probabilistic sensitivity analysis. 54 Similar to the clinical analyses, a subgroup analysis was performed. The planned subgroup analysis aimed to assess the influence of participants’ treatment preference for treatment allocation on outcomes. Finally, exploratory analyses were conducted to integrate trial findings on a wider evidence base, and to include other psychological therapies as comparators in the cost-effectiveness analyses. All analyses were undertaken in Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Health-care resource use

Health-care resource use data were based on GP medical records. Data were collected for the following periods: 2 months prior to randomisation, from randomisation to 12 months after randomisation and from 12 to 24 months after randomisation. Use of health care was recorded for the following categories (see earlier section on Resource use data for a detailed description): GP visits (including telephone call appointments), including the number of GP contacts that were specifically related to depression; nurse visits (including telephone call appointments); out-of-hours GP services; hospital inpatient stays; hospital outpatient visits; other community services visits (including counsellors, psychologists, psychiatrists, CMHT and IAPT services); and depression-related medication (including antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, sleeping tablets and anxiety medication).

Costs

Costs were estimated in UK pounds sterling based on the financial year 2011–12. Unit costs were obtained from routinely published national cost sources, namely the British National Formulary,55 the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) Unit Costs of Health and Social Care56 and the NHS reference costs. 57 Costs accrued from 12 to 24 months were discounted at a 3.5% discount rate, in line with current UK guidance. 52

Appendix 8 provides sources and details of key unit costs. Total costs include the costs of cCBT, GP visits, nurse visits, out-of-hours GP services, hospital inpatient stays, outpatient visits, other community services and depression-related medication. Mental health services included visits to counsellors, psychologists, psychiatrists, CMHT and IAPT services.

Mean total costs were estimated per treatment group using regression analysis to control for patients’ covariates, including costs incurred in the 2 months prior to randomisation (henceforth referred to as baseline costs), and used as a primary outcome measure in the economic analysis.

An alternative costing scenario was considered, in which only costs related to depression were included in the cost analysis. Total depression-related costs included depression-related costs of GP and nurse visits, other community services attendances and depression-related medication costs. As depression-related nurse visits were not collected in this trial, this cost category was estimated by assuming that the proportion of nurse visit costs which were depression related was the same as for GP visits. Depression-related nurse visits costs per time period were estimated by applying to total nurse visits costs the ratio between mean depression-related GP visit costs and mean total GP visit costs. It was not possible to identify which hospital services costs were related to depression and, therefore, they were excluded entirely from the depression-related costs analysis.

Costs of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy

The costs associated with the provision of cCBT are shown in Table 1. These costs include the licence fee (applicable only to Beating the Blues) and the cost of support in the form of telephone calls to provide technical support and to encourage participants to engage with the computerised therapy. All costs related to the provision of cCBT were assumed to be incurred in the first year of follow-up.

| cCBT package | Licence fee cost per patient (£) | Support cost | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean duration (minutes) | Mean number of calls | Unit cost per hour (£) | Details | ||

| Beating the Blues | 50 | 6.2 | 0.2 | 21 | Based on clinical support worker nursing hour (Community – Band 2) |

| MoodGYM | Free software | 6.5 | 0.3 | 21 | |

The licence fee for Beating the Blues was obtained from the software website, and corresponds to £250 per five treatments. 58 The cost of the Beating the Blues licence per patient can be a maximum of £250 (if only one patient takes the treatment) and a minimum of £50 (if all five treatments are used by five patients). This is in contrast with a previous HTA report,6 where the cost of the Beating the Blues licence fee was a fixed cost per purchase at the GP practice level, with cost per patient depending on assumptions of the patient throughput at the practice. For the purpose of this evaluation, the cost of £50 per patient was used, as it was considered plausible that all five treatments permitted under each licence purchase were taken, given that the previous HTA estimated an annual patient throughput of 25 to 50 per practice. 6

The cost of telephone support calls was estimated based on mean duration and mean number of support calls recorded as part of the study and assuming the support was provided by a clinical support worker. The support calls aimed to provide technical support and to encourage participants to engage with the cCBT programs. In the REEACT trial, support was mostly provided by telephone support staff (grade 4).

Hardware and overhead costs associated with the provision of the computerised therapies at the GP practice were not included in the cost of any of the two interventions. Although the trial protocol allowed the use of the cCBT programs at the GP practice, only nine patients accessed the cCBT programs at their GP practice throughout the 2 years of trial follow-up. Therefore, it was assumed that use of the cCBT programs at the GP practice is likely to be minimal and that the exclusion of related costs was unlikely to affect the results of the cost-effectiveness analysis.

Health-related quality of life

The HRQoL was assessed using responses to the EQ-5D questionnaire applied at baseline, 4, 12 and 24 months. The EQ-5D is a generic preference-based measure of health state that covers five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) that can be rated according to three levels of severity to define unique health states. 25 HRQoL weights for these health states have been previously elicited by Dolan et al. 48 using a time trade-off technique from a representative sample of the UK population. A score of 1 represents perfect health and a score of 0 represents death.

The SF-6D was used as an alternative instrument to obtain estimates of HRQoL. SF-6D scores were estimated from responses to the SF-36v224,59 applied at baseline, 4, 12 and 24 months. The SF-6D instrument uses the participant’s responses to 11 items from the SF-36v2 to identify one health state from the 18,000 possible health states. Health states are defined by the different combinations of six attributes (physical functioning, role limitations, social functioning, pain, mental health and vitality) and four to six levels. 46,47 The classification score was based on standard gamble utility measurements on a representative sample of the UK population. 46,60

The EQ-5D scores were used to estimate patient-specific QALYs using the area under the curve method. 61 Mean QALYs measured by EQ-5D were estimated per treatment group using regression analysis to control for patients’ covariates, including baseline EQ-5D score,62 and were used as a primary outcome measure in the economic analysis. QALYs were also estimated using the SF-6D scores as an alternative to EQ-5D scores. Regression analysis was used in a similar way to estimate mean QALYs measured by SF-6D per treatment group, controlling for baseline SF-6D score and the same patient covariates as in the analysis with EQ-5D estimated QALYs. QALYs accrued from 12 to 24 months were discounted at a 3.5% discount rate, in line with current UK guidance. 52

Missing data

The existence of missing data is a common problem when economic evaluation relies on patient-level data. The use of complete case analysis not only can reduce the power of the analysis, but may also lead to biased estimates if there is an underlying relationship between missing values and any observed or unobserved variables, that is if values are not missing completely at random. 63 Available case analysis will only partially address the problem. Despite not reducing the power of the analysis like complete case analysis, in available case analysis sample size will vary across analysis, reducing comparability. 63

Alternative ways to deal with missing data include imputation techniques, where missing values are replaced by estimates based on observable variables. 63 Multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) was selected to handle missing data in this analysis. 53,64,65 This method’s central assumption is that data are missing at random, conditional on the values of observed variables in the data set and not on other unobserved variables. Another important feature of this method is that it allows incorporation of the uncertainty associated to the imputation method in the estimates that replace the missing values. 66

As complete case analysis requires stricter assumptions regarding the nature of missing data and is more likely to yield biased and less efficient estimates, and given the previously discussed advantages of multiple imputation, it was decided prior to the analysis that MICE would be used to handle missing data.

Multiple imputation by chained equations was performed for a total of 10 imputations (m), as previous research has suggested that three to five m are sufficient to provide adequate estimates but that increasing m improves efficiency. 67 EQ-5D and SF-6D scores were imputed at every follow-up time point (baseline, 4, 12 and 24 months), while costs were imputed for the same time intervals as resource use was collected (the 2 months prior to randomisation, from randomisation to 12 months, and from 12 to 24 months) for each resource use category that was collected on the trial. The independent variables specified in the imputation were baseline EQ-5D score, baseline SF-6D score, age, gender, anxiety level at baseline, depression level at baseline and depression duration at baseline.

Costs and utility scores distributions can accrue some difficulties to the analysis, as the former are bounded at 0 and tend to be positively skewed, whereas the latter are bounded between –0.594 and 1 for EQ-5D and between 0 and 1 for SF-6D. Failure to account for this while imputing the data sets can lead to predicting values that lie outside the bounds for each variable. To overcome this difficulty, predictive mean matching was used. In predictive mean matching, observed data are used to estimate a predictive model (using the MICE-specified covariates), but, instead of replacing missing values with the model predicted values, the nearest observed value is used to fill the missing value. Imputed values are, thus, sampled from values in the original data set and will not lie outside the bounds of the original data distribution. 66

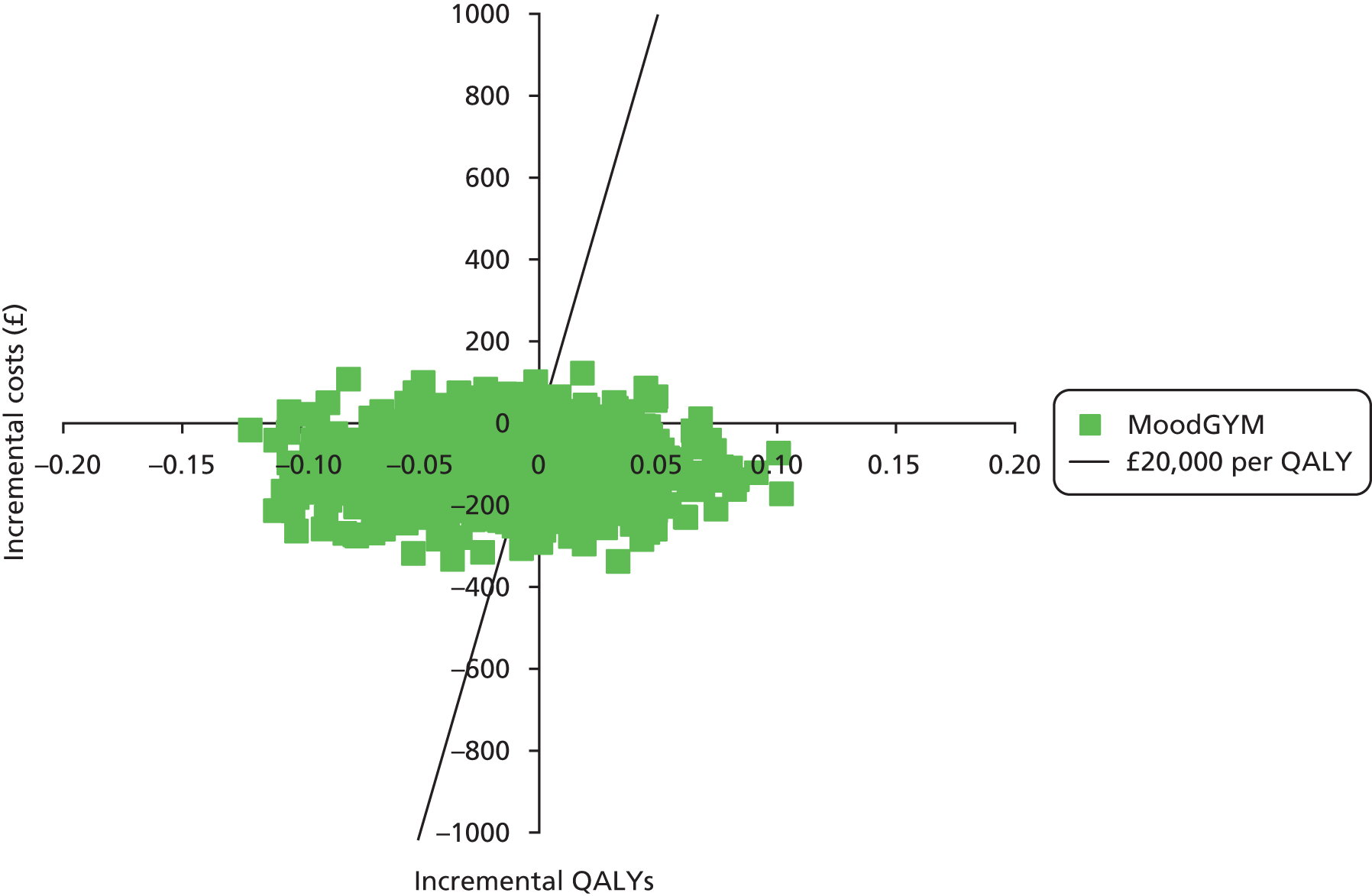

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The cost-effectiveness of the two cCBT programs, Beating the Blues and MoodGYM, when added to usual GP care in patients with depression, was assessed by comparing costs and QALYs in each cCBT treatment arm with costs and QALYs in the usual GP care alone arm, while controlling for baseline patient covariates. Costs and QALYs accrued from 12 to 24 months were discounted at a 3.5% discount rate, in line with current UK guidance. 52

All categories of health-care costs were included in the base-case analysis and QALYs estimated from EQ-5D scores were considered. Incremental estimates of costs and QALYs were obtained through regression methods, adjusting for the baseline characteristics of age, anxiety level, baseline depression severity, depression duration and gender (in accordance with the statistical analysis plan). Difference in QALYs measured by EQ-5D was also controlled for baseline EQ-5D, as it is likely to be a strong predictor of follow-up QALYs, and failure to adjust for this covariate may bias estimates in the presence of a EQ-5D baseline score imbalance between the treatment groups. 62 Similarly, differences in costs were also adjusted for baseline costs.

The regression model selected for the analysis of costs in the base case was a generalised linear model (GLM). This type of model was preferred to an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, as cost data tend to be heavily skewed and follow a non-normal distribution,68 which leads to violations of the OLS assumptions. GLM models impose a specific distribution function (F) on the dependent variable, to account for the relation between its mean and variance conditional on the covariates, and a link function (g(.)) to define the relationship between the mean (µi) and covariates (xji). 69 This allows the selection of a distribution that better fits cost data and enables issues with heteroscedasticity (i.e. non-constant variance of the error term in a regression) to be addressed, as mean and variance are modelled simultaneously. The model is described by the equation(1)g(µi)=β0+Σ1Jβjxji,yi∼F69,

where j is the total number of independent covariates in the model. For the analysis of costs (and also in subsequent scenario and subgroup analysis), a gamma family distribution was selected. Selection of the family distribution was based on the modified Park’s test70 performed on each imputed data set and complete case data set. An identity link function was selected, thus assuming an additive effect of covariates on costs. 69 The model was adjusted for the patient characteristics of age, gender, anxiety level at baseline, depression severity at baseline and depression duration at baseline. Adjustment was also made for baseline costs.

Incremental QALYs estimation was performed through OLS regression, as this method has been recommended for the estimation of QALYs in economic evaluation. 71 The distribution of QALYs was also inspected through histograms to assess distribution shape. QALYs distribution appeared to resemble normal distributions for both EQ-5D- and SF-6D-calculated QALYs (the latter used on scenario analyses). The regression model was adjusted for age, gender, anxiety level at baseline, depression severity at baseline and depression duration at baseline, as well as EQ-5D score at baseline (or the SF-6D score at baseline for the SF-6D scenario analysis).

Seemingly unrelated regressions (SURs; a bivariate regression model)72 of costs and QALYs were also considered as an alternative regression model to jointly estimate outcomes. In this bivariate model, incremental costs and QALYs were simultaneously estimated from two separate OLS regressions, assuming correlation between the error terms in each regression. The bivariate model was adjusted using the same covariates for costs and QALYs as in the main analysis. Although the bivariate approach allows the simultaneous estimation of costs and QALYs, and can increase the precision of estimates if there is a correlation between outcomes, it assumes an underlying normal distribution of error terms. 73 As the modified Park’s test suggested that a gamma distribution, rather than the normal distribution, is likely to provide a better fit for the error terms in the costs regression, SUR was not the preferred model.

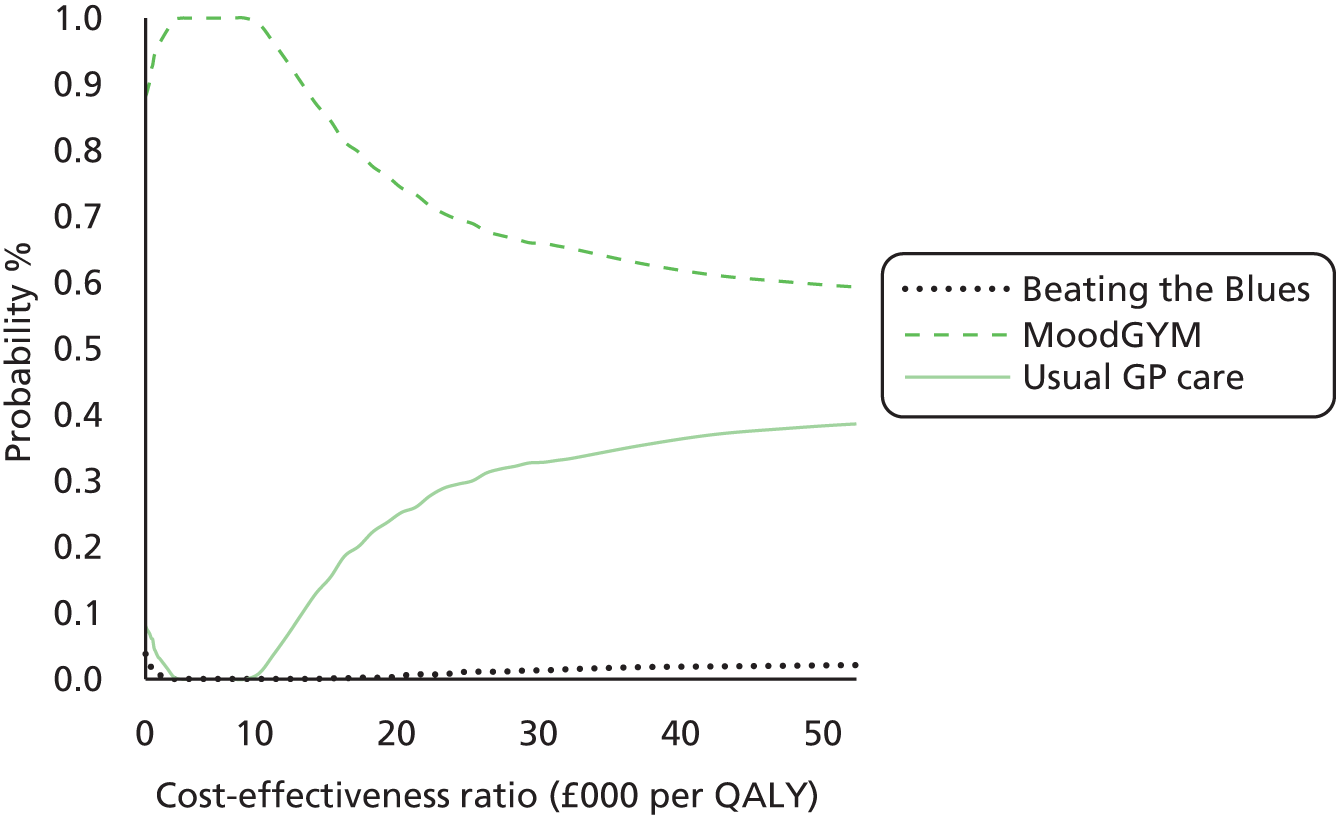

Standard decision rules74 were used to evaluate the incremental cost-effectiveness of the two cCBT programs, Beating the Blues and MoodGYM, when added to usual GP care, compared with GP usual care alone. An intervention that generates greater mean QALYs and lower mean costs can be considered dominant. Where no dominance arises, the interventions can be compared by calculating the ratio between incremental costs and QALYs to establish the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) between each cCBT intervention plus usual GP care and usual GP care alone. The cost-effectiveness of the interventions was assessed by comparing ICERs against a cost-effectiveness interval ranging from £20,000 to £30,000 per QALY, in line with NICE cost-effectiveness thresholds for the UK. 52

Uncertainty surrounding the decision was assessed using probabilistic sensitivity analysis and presented through cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) which graphically represent the probability of an intervention being cost-effective across a range of cost-effectiveness thresholds. 75 CEACs do not aim to identify which is the optimal strategy for a particular decision problem. 75 The estimation of probabilities of cost-effectiveness is nevertheless important to quantify the uncertainty surrounding the decision, and whether or not it is worth conducting further research to reduce this uncertainty. 75,76 In order to plot the CEAC, the variance–covariance matrices from the costs and QALYs regressions (one matrix for each, except in the SUR model) were extracted and the corresponding Cholesky decompositions used to obtain correlated draws from a multivariate normal distribution. 54 This approach is commonly used to ensure that parameters taken from a regression framework remain correlated when the probabilistic sensitivity analysis is performed (and CEACs are plotted), but it has the disadvantage of imposing normality on the sampling distribution.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by performing a number of alternative scenario analyses, where assumptions underlying the base-case analysis were varied. The aim of the sensitivity analyses was to assess the robustness of base-case results to alternative assumptions in terms of costs, HRQoL and nature of missing data. Table 2 illustrates which elements were varied in each scenario analysis.

| Scenario | Element | Base case | Variation for the sensitivity analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Source of HRQoL | EQ-5D instrument used to estimate QALYs | SF-6D instrument used to estimate QALYs |

| 2 | Costs | All cost categories included | Only depression-related costs included |

| 3 | Missing data | Data assumed to be missing at random; analysis therefore conducted on imputed data | Data assumed to be missing completely at random; therefore, analysis conducted on the complete case data |

| 4 | Missing data and source of HRQoL | Data assumed to be missing at random. EQ-5D instrument used to estimate QALYs | Data assumed to be missing completely at random; therefore, analysis conducted on the complete case data. SF-6D instrument used to estimate QALYs |

| 5 | Missing data and costs | Data assumed to be missing at random. All cost categories included | Data assumed to be missing completely at random; therefore, analysis conducted on the complete case data. Only depression-related costs included in the analysis |

The use of EQ-5D to measure HRQoL is recommended by NICE as part of the preferred base case for HTA52 and, therefore, EQ-5D-estimated QALYs were included in the base-case analysis. NICE also accepts the use of alternative instruments to measure HRQoL, such as the SF-6D, when EQ-5D-measured utilities are not available. 52 Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that, despite the convergence of measurements by EQ-5D and SF-6D, the two instruments are not interchangeable. 60 As the data collected in the REEACT trial allowed estimating QALYs as measured by SF-6D data, it was possible to explore in scenario 2 how sensitive the results of the base-case analysis were to the choice of HRQoL instrument. Similar to the base-case analysis, incremental QALYs were estimated through an OLS regression adjusted for age, gender, anxiety level at baseline, depression severity at baseline and depression duration at baseline, as well as SF-6D score at baseline.

In principle, only costs that differ as a result of the treatments being considered should be included, so as not to introduce additional variability in the analysis that will make relevant differences in costs more difficult to detect. 77 Nevertheless, the identification of which costs are relevant can be difficult, and it may be preferable to include a wider range of costs in the analysis. Uncertainty regarding which costs are relevant can be explored by testing the impact on cost-effectiveness analysis results of including a more restricted set of costs. In scenario 1, the categories of costs included in the estimation of total costs per treatment group was limited to those considered to be related to depression, that is depression-related GP and nurse visits, other community service attendances and depression-related medication. The regression model used to estimate incremental costs for scenario 2 was similar to the base case, that is, a GLM model with a gamma distribution and identity link function, adjusted for age, gender, anxiety level at baseline, depression level at baseline and depression duration at baseline. Adjustment was also made for baseline depression-related costs.