Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/01/20. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The draft report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elaine McColl received grants from Newcastle University, fees and expenses from the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Board and expenses for meeting attendance from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) panel during the course of the study. Luke Vale is a member of the NIHR PGfAR and the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Clarke et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Strabismus

Strabismus (sometimes referred to as ‘squint’) is a condition in which the eyes are misaligned, either constantly or intermittently. 1 Intermittent strabismus may progress to constant strabismus. Strabismus may have both socioeconomic and functional consequences for the affected individual. 2–4

The appearance of ocular misalignment may result in discrimination – in both interpersonal relations and employment – in adults,5 and in social exclusion and bullying in children. 6

The functional consequences of strabismus include impairment of three-dimensional (binocular) vision4 and amblyopia (lazy eye),7 which is impairment of visual acuity (VA) in one eye due to the effect, in this case, of ocular misalignment on visual development.

In 2011–12 there were 584,916 hospital appointments for children, between the ages of 0 and 9 years, in children’s eye outpatient departments, including orthoptic departments, in the UK (13% of total UK NHS outpatient appointments for this age group). 8 Ninety per cent of this workload is thought to relate to the management of strabismus and amblyopia. 9 In total, 6205 extraocular muscle surgeries were performed on children aged between 0 and 14 years during the same period.

The evidence base for the treatment of strabismus is poor, and this results in significant variation in the use of health-care resources, which is not easily explained and may not be clinically justified. 10

Intermittent exotropia

Intermittent exotropia [X(T)] is a common type of strabismus in which the eyes are intermittently in a divergent misalignment. 11,12

Intermittent exotropia is the commonest form of divergent strabismus in childhood13,14 and has been associated with later mental illness. 15 The usual age at onset of X(T) is between 12 and 24 months. 11,13 Three-dimensional vision for near viewing is usually within the age-related normal range but may deteriorate if the strabismus progresses from an intermittent to a constant misalignment. 16 X(T) is particularly common in Eastern Asia but is thought to be increasing in prevalence worldwide. 17

The NHS tariff rate for strabismus surgery is £800, and, together with around 100,000 clinic visits annually for review of patients with X(T) (at a tariff cost of £120 per new patient and £60 per review: estimated average new–review ratio of 1 : 8), the total cost to the NHS alone is almost £7.5M annually. With the inclusion of societal and family costs, the management of X(T) is costly.

The underlying cause of X(T) is unknown. The condition is diagnosed on the basis of a parental history of an intermittent ocular misalignment, which may be accompanied by closure of one eye, and on the demonstration of the potential of the eyes to adopt a divergent misalignment when binocular viewing is disrupted by covering one eye (cover test). 1

The frequency of the observed misalignment, or eye closure, and the ease with which the eyes realign following a cover test, is referred to as the control of the strabismus, and is used as clinical indicators of the severity of the condition. 18,19 Other measures of severity include the size of the ocular misalignment at near and distance viewing, and stereoacuity (a measure of three-dimensional vision). 20

Treatment is sought and recommended on the basis of concern about the appearance of the misalignment and the potential for disruption of normal visual development. 21

Treatment may be surgical (eye muscle surgery or botulinum toxin injection);22 non-surgical (glasses, patching, prisms, exercises);23 or a combination of the two. 24,25

Eye muscle surgery for X(T) aims to adjust the tension in the extraocular muscles such that the eyes are placed in a less divergent alignment. This can be achieved by weakening one or both lateral rectus muscles, either alone, or in combination with tightening of one medial rectus muscle.

Around 10–20% of children develop an intermittent or constant convergent strabismus following surgery for X(T), with some requiring further corrective procedures. 20,25,26

There are few data on the efficacy of non-surgical treatments for X(T) but, in general, they appear to be significantly less effective than eye muscle surgery. 24

A recently updated Cochrane review,27 specifically addressing the treatment of X(T), identified only one trial that was eligible for inclusion. This trial showed that unilateral surgery was more effective than bilateral surgery for correcting the basic type of X(T). No trials were identified comparing eye muscle surgery with watchful waiting or active monitoring.

The authors of the review concluded:

The available literature consists mainly of retrospective case reviews, which are difficult to reliably interpret and analyse. The one randomised trial included found unilateral surgery more effective than bilateral surgery for basic intermittent exotropia. However, across all identified studies, measures of severity and thus criteria for intervention are poorly validated, and there appear to be no reliable natural history data. There is therefore a pressing need for improved measures of severity, a better understanding of the natural history and carefully planned clinical trials of treatment to improve the evidence base for the management of this condition.

Another recent paper28 has commented:

To address controversies and improve the evidence base regarding surgical intervention of this condition, randomized controlled trials are needed and justified because the results indicate that it would be relatively safe to randomly allocate patients to groups who could receive differing treatments so as to determine optimum management strategies.

Evidence from randomised controlled trials of the treatment of X(T) is increasing. A randomised controlled trial assessing the relative benefits of different forms of eye muscle surgery is in progress29 and a trial comparing patching (occlusion) to observation has just been published. 30 Although the latter study provides some natural history data neither study addresses the utility of surgical treatment of X(T) per se.

The feasibility of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of strabismus treatment has been questioned.

A Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-sponsored systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening programmes for amblyopia and strabismus in children up to the age of 4–5 years31 commented, ‘RCTs into the efficacy, effectiveness and efficiency of strabismus treatment are unlikely to be feasible. Ethical considerations in study design prevent complete abstention of treatment, and decisions regarding treatment are often overridden by clinical need’.

We disagree with this statement, and do not see how the subject can make progress in establishing a robust evidence base without such studies.

A previous trial of deferred surgery for a different form of strabismus,32,33 infantile esotropia, demonstrates the potential for recruitment into RCTs of strabismus while highlighting some of the challenges that are inherent in this type of research. 34

We therefore proposed a study to determine the feasibility of a RCT of surgery compared with active monitoring for X(T).

Objectives

The specific objectives of the SamExo study (Surgery vs. Active Monitoring in Intermittent Exotropia), as stated in the original project description, were to:

-

determine whether or not participating centres are likely to recruit a sufficient number of patients to deliver the trial

-

determine whether or not recruited patients will stay within their allocated groups and complete follow-up in sufficient numbers to deliver the trial

-

develop a web-based trial management system to centralise and automate trial processes such as invitation, logging of replies, scheduling of appointments, confirmation of eligibility, randomisation and printing of letters

-

pilot the procedures involved in the trial, including recruitment (giving information and obtaining consent), randomisation, intervention (surgery), masking, and baseline and follow-up data collection

-

monitor potential bias by comparing the demographic and clinical status of patients retained with any withdrawing from the trial, and by comparing those who consent with those eligible but refusing to participate

-

identify through questionnaires and qualitative interviews, where possible, reasons why parents decline permission to participate

-

prepare a detailed protocol and application for funding for such a RCT (if findings from the pilot study indicate that a full-scale RCT is feasible).

Systematic review

The opportunity to apply for further funding for an associated project was offered once the trial was under way. Given the difficulty in synthesising the literature on X(T), and the lack of RCT data highlighted in the Cochrane review, a systematic review of non-randomised studies was proposed and funded, and the output of this work is included in this report.

Chapter 2 Systematic review

Background

Intermittent exotropia [X(T)] is a common form of childhood strabismus (squint) affecting approximately two out of every 100 children before the age of 3 years. 35 This particular ocular misalignment is characterised by an outwards deviation of the eye, which is not constant but is usually present initially on distance fixation or when the child is tired. 20 The natural history of X(T) is poorly understood: the ocular misalignment may worsen or deteriorate into constant exotropia, which adversely affects stereo vision; conversely the misalignment may resolve over time. 36 X(T) is also of concern for psychosocial reasons, as the cosmetic appearance might cause the child to develop social or psychological problems,2 which can impact into adult life, with effects on self-image, work and personal relationships. 37

A range of both conservative and surgical treatment options are available and include observation (watchful waiting), orthoptic exercises/vision therapy, occlusion therapy (patching), minus lens therapy (glasses) and surgery. 38 However, surgery is associated with possible adverse effects, including a risk of overcorrection, which may also adversely impact on stereoacuity. Evidence for the comparative effectiveness of treatment options is limited by the absence of RCT data,27 but there is a much larger literature of observational studies for the various interventions. As a consequence of the absence of robust and reliable effectiveness data on treatment options, and of uncertainty about the natural history of the condition, wide service variation exists (both nationally and internationally) in management of the condition.

Aim

The main aim of the review was to determine the effectiveness of surgical and non-surgical approaches as a means for managing X(T) in childhood. Secondary objectives were to (1) understand the circumstances under which particular interventions are most effective; (2) determine adverse effects associated with particular interventions; and (3) better understand the natural history of X(T).

Methods

The review was conducted following best practice guidelines for the design, conduct and reporting of systematic reviews. 39–41

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Participants

Studies that involved child participants aged up to 18 years were included. Studies including mixed populations (i.e. both adults and children) were eligible if they reported the results for children separately. To satisfy our inclusion criteria, the diagnosis was one of intermittent disease, rather than constant exotropia, and the type was either divergence excess or basic-type exotropia. Convergence insufficiency-type exotropia (misalignment primarily at near fixation) was excluded.

Interventions

A range of both surgical and non-surgical interventions were examined. As well as corrective surgery, we reviewed studies reporting on non-surgical interventions, including minus lenses, prisms, convergence exercises, occlusion therapy, onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®, Allergan) injections and watchful waiting (Box 1). We included studies that made a single comparison (e.g. unilateral vs. bilateral surgery) as well as studies reporting on the effectiveness of multiple therapies (e.g. surgery vs. BOTOX, vs. minus lenses vs. watchful waiting).

Surgery aims to prevent deterioration to constant exotropia, improve distance stereoacuity and improve appearance. 20 The following procedures are commonly offered:

Bilateral lateral rectus recessionThis surgical technique involves weakening of the lateral rectus muscles that control eye movement. Bilateral surgery is undertaken on both eyes, whereas unilateral lateral rectus recession involves one eye only.

Recession/resectionHorizontal rectus surgery (unilateral lateral rectus recession combined with medial rectus resection) is undertaken on the dominant or non-dominant eye to shift the muscular insertion points and alter the balance of forces on the globe. 42

Non-surgical interventions Botulinum toxinThe neurotoxin is used both diagnostically and therapeutically in the management of strabismus. Therapeutically it is used to temporarily paralyse the lateral rectus muscle leading to altered ocular alignment, which returns over time. 43,44

Overminus lensesOvercorrecting minus lenses aim to stimulate convergence of the eyes through the extra effort required to focus. 23

OcclusionOcclusion or patching aims to prevent development of abnormal adaptation to eyes being diverged. 42

Orthoptic exercisesThe objective of orthoptic exercises is to increase fusion, eliminate suppression and improve control in order to reduce the time during which the deviation is manifest. 45

ObservationGiven that the natural history of X(T) is unclear, observation or watchful waiting is another conservative option for management of X(T), particularly in cases of small-angle X(T). 42

Study designs

Given the paucity of high-level evidence in this area, we included RCTs, quasiexperimental studies and comparative observational studies (both prospective and retrospective studies, each with a comparator group). [Based on the Cochrane definition of cohort study as ‘A non-randomised (observational) study in which a defined group of people (the cohort) is followed over time. The outcomes of people in subsets of this cohort who received two or more different interventions are then compared’. This includes ‘routine database followed over time’ prospectively or retrospectively (source: http://bmg.cochrane.org/research-projectscochrane-risk-bias-tool). Accessed 17 December 2014] Case series (defined as chart reviews without a comparison group), qualitative studies and non-empirical, opinion pieces were excluded. Only studies with a follow-up period of at least 6 months were included.

Outcomes

Data on the following outcomes were extracted: angle of deviation, stereoacuity and control. We also sought to record quality of life (QoL) and patient-derived outcomes (e.g. acceptability and adherence), where possible, as well as data on adverse effects. The eligibility criteria used in the review are shown in Box 2.

Participants up to and including the age of 18 years. Where there was a mixed population of adults and children, a study was eligible only if it reported outcomes for children separately.

Divergence excess type [where the deviation is greater (by at least 10 PD at distance than at near], simulated divergence excess type [the deviation is initially greater at distance but after occlusion there is little difference between near and distance measurements (within 10 PD)] or basic type (the deviation is the same at both distance and near) X(T).

Follow-up for at least 6 months.

RCT, quasiexperimental or cohort study with a comparison group.

Exclusion criteriaPopulation aged > 18 years (or data not reported for children separately from adults).

Data unavailable for X(T) separately. In instances when the population included X(T) combined with constant exotropia (or other forms of strabismus), a study was eligible only if disaggregated data were reported for X(T).

Participants with convergence insufficiency type X(T) [the deviation is greater (by at least 10 PD) at near than at distance]. Studies were excluded if they reported outcomes for divergence excess and basic type combined with convergence insufficiency.

Studies with follow-up of < 6 months.

PD, prism dioptres.

Search strategy

We conducted systematic searches using the following databases (abbreviations, host sites and dates searched given in parentheses):

-

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to October week 3 2012)

-

EMBASE (Ovid, 1980 to October week 42 2012)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library via Wiley, issue 7 of 12 August 2012)

-

UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio (UKCRN, August 2012)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR, The Cochrane Library via Wiley, issue 7 of 12 August 2012)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE, The Cochrane Library via Wiley, issue 7 of 12 August 2012)

-

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA, The Cochrane Library via Wiley, issue 7 of 12 August 2012)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL, Ovid, 1981 to August 2012)

-

PsycINFO (Ovid, 1967 to August week 2 2012)

-

Science Citation Index (Web of Knowledge, 1970 to August 2012)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Web of Knowledge, 1990 to August 2012)

-

Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS, Virtual Health Library; 1982 to September 2012).

Initially a search was conducted which combined synonyms for exotropia with synonyms for under-18-year-olds. Subsequently, we decided to remove the age-related part of the search to capture studies in paediatric journals, which are less likely to specify in the title and abstract that they concern children, and the search was rerun in those databases in which age limits had been used. The search strategy was designed on MEDLINE (Ovid) and translated to other databases. Database-specific thesaurus terms [such as medical subject headings (MeSH)] were used as appropriate for each database. For an example search strategy designed for MEDLINE please see Appendix 1. We supplemented the electronic searches by hand-searching the bibliographies of all included studies for any additional related references, as well as searching the following key organisational websites:

-

Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology: www.arvo.org/ – searched meeting abstracts

-

American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus: www.aapos.org/

-

Royal College of Ophthalmologists: www.rcophth.ac.uk/ – searched 1st & 2nd World Congress of Paediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus

-

European Paediatric Ophthalmological Society: www.epos-focus.org/ – searched meetings

-

European Strabismological Association: www.esa-strabismology.com/

-

American Society of Certified Orthoptists: www.orthoptics.org/ – searched American Orthoptics Journal

-

American Academy of Ophthalmology: www.aao.org/

-

British Orthoptic Society: www.orthoptics.org.uk/.

We contacted key experts in the field for information about unpublished or in-progress studies and used relevant e-mail lists to issue a request for information about unpublished or ongoing studies that fit the eligibility criteria. We also manually searched the table of contents of key journals (including Journal of Vision; Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science) for the past 12 months to identify any papers not yet indexed. For two journals (British Orthoptic Journal and Australian Orthoptic Journal) that are not indexed on PubMed, we hand-searched the table of contents for the past 5 years.

References were managed using EndNote reference management software, version X6 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). Reasons for exclusion of studies at full paper sifting stage were recorded. Given the epidemiology of X(T)27 we did not exclude studies on the basis of language, country or publication date.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (FB and KJ) read the papers’ abstracts independently to consider whether or not the study met the eligibility criteria. Any studies deemed to be potentially relevant by either of the reviewers were sourced in full text and obtained for the second stage of the screening/sifting process. One reviewer (KJ) screened the full papers to exclude any obviously non-relevant papers (specifically letters, commentaries, reviews and qualitative studies); two reviewers (FB and KJ) then applied the eligibility criteria independently to determine inclusion in the review. If there was any disagreement regarding the eligibility of any of the research papers, the two reviewers met to discuss the ambiguous studies in order to come to a definitive decision on whether or not inclusion was warranted. In the situation of non-agreement, a third reviewer (MC or RT) provided input.

Strategy for dealing with foreign-language papers

To eliminate the prospect of language bias we used Google Translate to translate abstracts in order to apply our eligibility criteria. Where we remained unsure we recruited bilingual and multilingual postgraduate students and staff from our institution to support screening of foreign-language titles and abstracts. The process of data extraction of eligible foreign-language papers was then undertaken in collaboration with our bilingual and multilingual volunteers. For two of the papers (written in simplified Chinese) this was repeated with a second volunteer to enhance reliability of the process. This method enabled us to data extract and critically appraise the studies without having to translate the papers verbatim.

Data extraction

Dual independent data extraction was undertaken. To understand the conditions under which interventions are most successful, details around how the intervention was delivered (e.g. for surgical interventions we noted whether or not the aim of surgery was overcorrection), duration of treatment, length of follow-up, and completeness of follow-up, together with any additional contextual data, were recorded on the data extraction form (see Appendix 2). Likewise, detailed information on the study population was extracted to identify what intervention works for whom and at what time point (to include age, time after diagnosis and severity of misalignment). When data were missing or required clarification, we contacted the study authors for further details. We also contacted the study authors of any conference abstracts meeting the eligibility criteria.

Quality assessment

Each study was appraised for quality simultaneously alongside the data extraction process. We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs and for non-randomised studies we used a tool based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP46) instrument for cohort studies, which includes assessment of both internal and external validity with questions relating to selection bias, study design, confounding, data collection methods, dropout and intervention integrity (see Appendix 3). We neither calculated a quality score nor did we exclude studies on the basis of quality. Any differences in assessment were resolved through discussion between reviewers (KJ and FB) and, if necessary, with other members of the study team (MC and RT).

Data synthesis

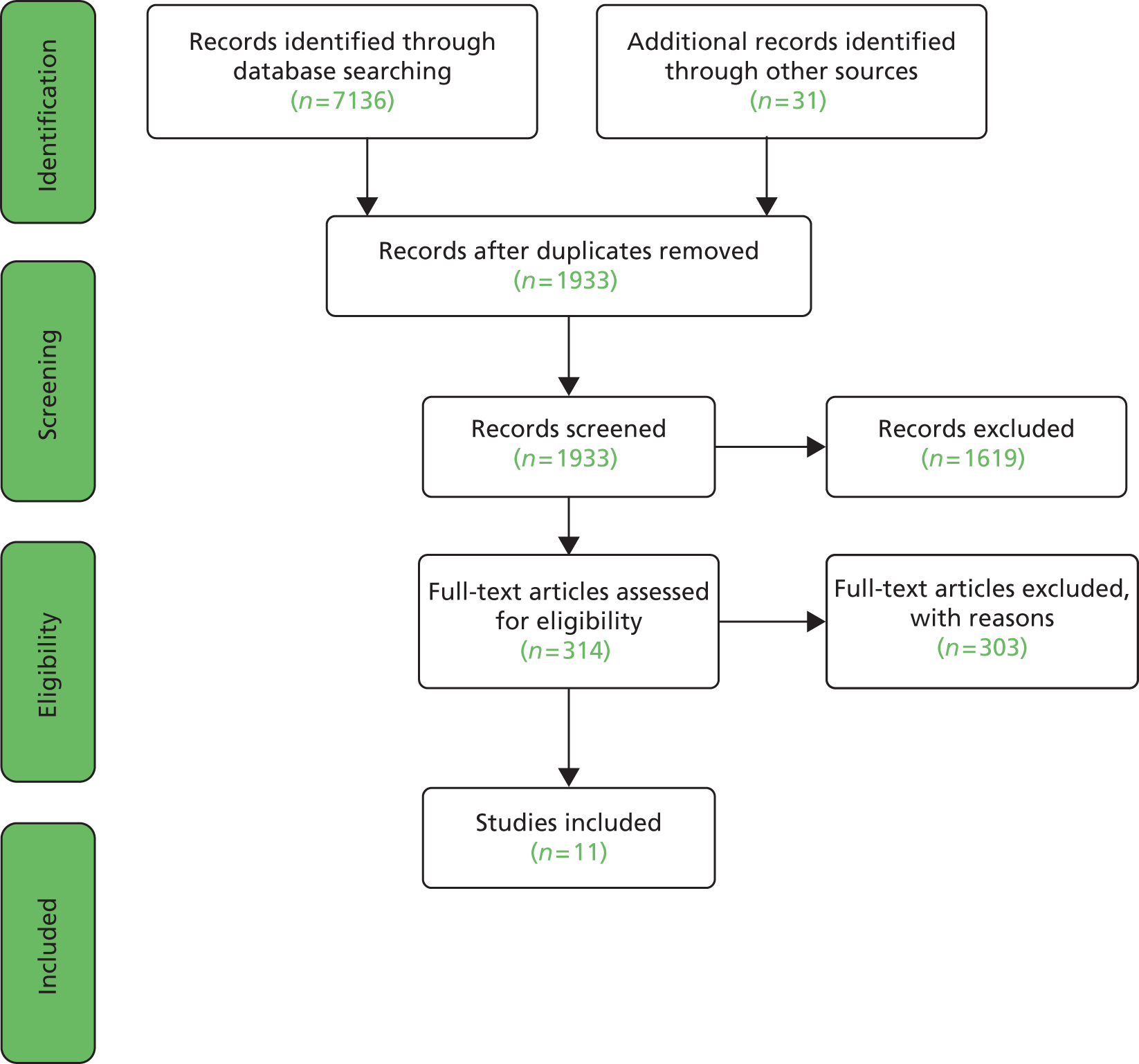

We used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidance and flow chart to support reporting41 (Figure 1). Studies can be pooled only if a number of studies are identified reporting the same primary outcome measure and there is sufficient homogeneity in terms of study design, intervention type and population. We were unable to synthesise any data quantitatively in the form of a meta-analysis due to high levels of study heterogeneity. Differences in study design, population, intervention and outcome measures precluded meta-analysis. In particular, there was a great deal of divergence in defining what constitutes a positive outcome. For example, change in angle of deviation versus with stereoacuity versus degree of control and how success was defined [e.g. deviation of > 20 prism dioptres (PD)] compared with deviation of < 10 PD, which is clearly likely to impact on comparable effectiveness between studies) and at what time point measurements were undertaken. Equally, there were differences in the study populations, for example some studies included only divergence excess type, whereas others grouped basic, true and simulated divergence excess types together.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of search process (based on PRISMA guidelines).

Because heterogeneity between studies precluded meta-analysis, we performed a narrative synthesis and report study findings separately by intervention type. In the narrative synthesis, we describe the main characteristics of the studies included, along with information about study quality and estimates of effect with relevant statistics. To avoid the introduction of bias into the narrative synthesis we have aimed to report the findings of each study judiciously and have made efforts to avoid inappropriate emphasis on any one particular study or author.

Findings

Description of studies

Electronic searches of 12 databases produced 7136 hits, which was reduced to 1902 after removal of duplicates. An additional 31 articles were retrieved through hand-searches, citation follow-up, discussion lists and key expert contact. On the basis of the abstract, these appeared to meet the eligibility criteria but all were excluded after review of the full text. A total of 314 papers were retrieved for full paper analysis but only 11 satisfied our eligibility criteria (see Appendix 4 for reasons for exclusion). 20,42,47–55 A further four conference abstracts were identified as potentially eligible on the basis of abstract alone,56–59 we wrote to the study authors for more information but received a response from the authors of only one of the papers stating that there was no comparison group.

Of the 11 studies that satisfied the inclusion criteria (Table 1), seven examined only surgical interventions,47,49–53,55 whereas four examined either surgery compared with non-surgical interventions or non-surgical interventions alone. 20,42,48,54 Non-surgical interventions included glasses, occlusion therapy, orthoptic exercises, prisms, BOTOX treatment, binocular vision therapy or observation only. Only 2 of the 11 studies were RCTs: one compared bilateral and unilateral surgery47 and the other examined the effectiveness of binocular vision training after surgery compared with no training. 48 The remaining nine studies were non-randomised observational studies involving a comparator group; the majority were retrospective with only two prospective studies. 20,54

| Study | Intervention and type of X(T) | Study design: follow-up | Type of X(T) and age | Final sample size | Outcomes | Summary findings | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buck 201220 | Non-surgical treatment only for X(T) (glasses and/or patches, exercises and/or prism); surgery (bilateral or unilateral) plus BOTOX or further surgery; observation only | Prospective cohort with comparison group; 2-year follow-up for non-surgical; 6 months for surgical | Basic, true divergence excess, simulated divergence excess Aged < 12 years |

n = 371 Observation, n = 195 Conservative intervention, n = 50 Surgery (in some cases plus conservative), n = 58 Surgery plus additional BOTOX or surgery, n = 5 |

Near and distance angle (APCT) Control (NCS61); stereoacuity (Frisby near stereoacuity test) |

Median change in near and distance angle (IQR): Surgery: near –9 (–18 to –1); distance –20 (–30 to –7) Non-surgical treatment: near 0 (–2 to 4); distance 0 (–5 to 0) Vision treatment only: near 0 (–4 to 5); distance 0 (–6 to 5) Observation: near 0 (–4 to 4); distance 0 (–7 to 5) Change in total NCS61 (% improved by ≥ 3): surgery 42%; non-surgical treatment 15%; vision treatment only 8%; observation 10% |

Overcorrection rate for surgery 21% (13/63) Overcorrection defined as the presence of a manifest esotropia (any amount) at 1/3 metre, 6 metres or both at 6 months post surgery |

| Chia 200649 | Surgery (BLR vs. R&R) | Retrospective cohort with comparison group; 1-year follow- up | X(T) with basic or divergence excess type and with divergent strabismus size between 25 and 50 PD; aged < 16 years | N = 118 BLR, n = 64; R&R, n = 54 |

Angle of deviation, success defined as X(T) < 10 PD | Authors report mixed results and conclude that their findings highlight a decline in success over time, resulting in only temporary improvement (with more exotropic drift over time (p = 0.01); subjects with basic type did worse than those with divergence excess at 1-year follow-up BLR: success 42.2%; residual exotropia 56.0%; consecutive ET 2.0% R&R: success 74.2%; residual exotropia 13.0%; consecutive ET 13.0% |

Consecutive esotropia (defined as any esotropia): R&R 13% (7/54), BLR 2% (1/64) |

| Choi 201250 | Surgery (BLR vs. R&R) | Retrospective cohort with comparison group; 24 months’ minimum follow-up |

Basic-type exotropia defined as distance deviation, within 10 PD of the near deviation Age: BLR 6.8 ± 3.4 years; R&R 7.2 ± 2.3 years |

N = 128 BLR, n = 55; R&R, n = 73 |

Angle of deviation (prism and alternate cover test and Krimsky test in some cases) Success was defined as esophoria/tropia ≤ 5 PD to exophoria/tropia ≤ 10 PD |

No statistically significant difference between the groups at 1 day, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year and 2 years postoperatively (p > 0.05); however, with regard to long-term follow-up, the final outcome at mean 3.8 years was significantly different between the groups, demonstrating a higher success rate in the BLR group than in the R&R group (58.2% vs. 27.4%; p < 0.01) | Overcorrection rate (defined as esophoria/tropia> 5 PD): BLR 3.6% (2/55), R&R 4.1% (3/73) |

| Figueira 200642 | Multiple groups: 1. S + Or/Oc; 2. S alone; 3. Or/Oc therapy; 4. O | Retrospective cohort with comparison group; Follow-up at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years and 5 years |

15 PD exodeviation for distance fixation Age (years) mean (SD): S + Or/Oc, 5.98 (2.45); S, 6.92 (3.68); Or/Oc, 4.41 (2.19); O, 4.57 (3.09) |

N = 150 S + Or/Oc, n = 48; S, n = 15; Or/Oc, n = 67; O, n = 20 |

Angle of deviation (mean, PD) Improvement/success was defined as orthophoria or < 10 PD esotropia/exotropia |

Surgery with preoperative orthoptic/occlusion Therapy had the highest success rates. Surgery with orthoptic/occlusion therapy was more effective in reducing exodeviation than surgery only Improvement of X(T) by intervention type in % (natural frequencies): Surgery + Or/Oc group: 6 months 87.50% (42/48); 1 year 85.70% (36/42); 2 years 83.33% (25/30); 5 years 84.62% (11/13) Surgery alone: 6 months 40.00% (6/15); 1 year 42.86% (6/14); 2 years 36.40% (4/11); 5 years 25.00% (1/4)Or/Oc alone: Overminus lenses: 6 months 15.38% (2/13); 1 year 16.67% (2/12); 2 years 11.11% (1/9); 5 years 0.00% (0/5) Occlusion alone: 6 months 6.00% (3/50); 1 year 8.57% (3/35); 2 years 5.26% (1/19); 5 years 0.00% (0/5) Observation alone: 6 months 5.00% (1/20); 1 year 5.26% (1/19); 2 years 9.09% (1/11); 5 years 33.33% (2/6) |

Limited data on over-correction rates One patient overcorrected by 20 PD |

| Kushner 199847 | Surgery (BLR vs. R&R) | RCT, 1-year follow-up (range 12–15 months) | Basic exotropia (randomised to R&R or BLR) Non-randomised simulated divergence excess group (received BLR) 3–18 years in all groups |

N = 36 R&R, n = 17; BLR, n = 19 |

Angle of deviation A satisfactory outcome was defined as between 10 PD of exophoria and 5 PD of esophoria |

R&R found to be more effective than BLR for basic type only: R&R: 14/17 (82%) satisfactory, 1 overcorrected, 2 undercorrected BLR: 10/19 (52%) satisfactory, 2 overcorrected, 7 undercorrected Significant difference (p < 0.2) between two types of surgery favouring R&R Simulated distance exotropia (n = 68): satisfactory 81% (55/68); overcorrected 4% (3/68); undercorrected 15% (10/68) Significant difference compared with basic type receiving BLR (p < 0.05) |

Overcorrection rate (defined as any amount of esotropia manifest or intermittent): BLR 11% (2/19), R&R 6% (1/17) |

| Lee 200151 | Surgery: BLR, vs. R&R | Retrospective cohort with comparison group; 1-year follow-up | Mixed X(T) type: 93 basic type; 10 pseudodivergence excess type 3–17 years with a mean age of 7.1 years |

n = 103 BLR, n = 46, R&R, n = 57 |

Motor alignment classified as follows: overcorrected by 11–20 PD (group I); overcorrected by 1–10 PD (group II); orthotropic (group III); undercorrected with an exotropia of 1–10 PD (group IV) | R&R: success 34/57 (59.6%); undercorrection 17/57 (29.8%); overcorrection 6/57 (10.5%) BLR: success 26/46 (56.5%); undercorrection 17/46 (37%); overcorrection 3/46 (6.5%) There were no significant differences in the success, undercorrection and overcorrection rates between the two surgical procedures after a 1-year postoperative period |

Overcorrection (as defined as > 5 PD esodeviation) BLR 0% (0/8), R&R 10.5% (6/57) |

| Lee 200752 | Surgery: Con or Aug | Retrospective cohort with comparison group; 6 months’ minimum follow-up | Basic type Age mean (SD): aug 8.0 ± 3.6 years; con 7.1 ± 3.9 years |

n = 107 Con = 41, aug = 66 Follow-up: con 21.3 ± 18.4 months (range 6–39 months); aug 23.3 ± 14.5 months (range 6–35) |

Angle of deviation Success defined as 8 PD of exophoria and 8 PD of esophoria |

Last follow-up: success (within 8 PD), significant difference (p = 0.01): con 43.9% (18/41); aug 68.2% (45/66) | Overcorrection rate (as defined as > 8 PD esotropia): con 2.4% (1/41); aug 1.5% (1/66) |

| Maruo 200153 | Surgery: BLR vs. R&R | Retrospective cohort with comparison group; maximum follow-up 4 years, ‘longer’ (mean 11.7 years, range 8–22 years) | No details of type of X(T) Aged < 15 years (no means or ranges given) |

BLR (n = 349); R&R (n = 298) One and four muscle procedures (n = 19) |

Angle of deviation Success defined as ≤ 20 PD heterotropia |

No statistically significant difference between the BLR and R&R techniques, but there is a trend towards the results favouring BLR (success rate 95.2% vs. 80% for R&R) | Overcorrection (as defined as > 5 PD esotropia): BLR 2.4% (5/210); R&R 0% (0/180) |

| aQiu 201048 | Binocular vision training | RCT; 1-year follow-up | No details of type Aged 5–16 years |

n = 121 Intervention n = 61; control n = 60 |

Angle of deviation (regression rate of eye position, defined as > 10 PD) | Regression rate (i.e. failure rates): intervention 7/61 (11.5%); control 21/60 (35%); p < 0.05 | No adverse effect data |

| aWu 200854 | BOTOX | Prospective cohort with comparison group; 6 months’ follow-up | No details of type Range 4–12 years BTXA mean 9.2 ± 2.14 years Surgery mean 7.03 ± 2.48 years |

N = 60 Surgery n = 30; BTXA n = 30 |

Eye alignment; binocular vision Definition of success (deviation must be within ±10 PD) |

After 6 months in the surgical group, 27 of 30 (90%) operations were successful, whereas in the BTXA group 23 of 30 (76.7%) cases were successful; of the seven less successful cases in the BTXA group, four reverted back after 6 months; where deviation was ≥ 20 PD, BTXA injections were repeated | BTXA: one child had diplopia which required patching; seven children had ptosis, six of seven patients improved after 1 month and all patients improved after 3 months Surgery: no adverse effects |

| aYuksel 199855 | Surgery: group 1 = R&R; group 2 = BLR | Retrospective cohort study with comparison group; mean follow-up 2.81 years, with a range of 6 months to 8 years | Basic type: mean (at surgery) 6.5 years; range 2–18 years | Unilateral n = 25; bilateral n = 30 | Deviation (cover and uncover test and prisms) Sensory fusion (Bagolini striated glasses and/or the Worth test) Stereopsis (TNO test and/or Lang stereoacuity test) Optimum outcome = orthotropia; good outcome = < 20 PD |

Immediate postoperative results favour asymmetrical surgery but at long-term follow-up there are no statistically significant differences between outcomes for either technique (p = 0.249) | Overcorrection rate (defined as any consecutive esotropia): R&R 8% (2/25); BLR 3% (1/30) |

Three of the included studies were non-English-language papers written in Chinese (simplified)48,54 and French. 55 Screening of titles and abstracts identified 122 foreign-language papers, of which 37 were reviewed at full-text stage. We collaborated with seven foreign language speakers [Chinese (two native speakers), French, German, Italian, Polish, Russian] to support the translation, data extraction and critical appraisal processes.

Characteristics of setting and participants

Four studies were conducted in Europe, the USA or Australia, whereas seven were conducted in Asian countries, which might be reflective of the epidemiology of X(T), specifically the observation that X(T) is more frequent in Asian populations and latitudes with greater exposure to sunlight. 27 Three studies were conducted in South Korea,50–52 two in China,48,54 one in the USA47 and one each in Australia,42 Belgium,55 Japan,53 Singapore49 and the UK. 20

There was some heterogeneity between studies in terms of the study population examined. Three studies20,49,51 included basic and divergence excess (simulated or true) types of X(T), whereas four studies47,50,52,55 included basic type only and four studies42,48,53,54 did not report on the type of X(T) examined. Only one study20 stated that their sample was recruited from multiple centres; the remainder were single-centre studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomised controlled trials

Two RCTs47,48 met our eligibility criteria: both were judged to have a high or unclear risk of bias in most areas according to the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Table 2). Both trials were unclear in their reporting of randomisation and allocation concealment procedures. One trial47 was judged to have a high risk of selection bias because the three groups were not assigned simultaneously and there were some inconsistencies in reporting of exclusion criteria (patients were also being recruited for two different trials concurrently). The methods in the other RCT48 were poorly reported, specifically with respect to techniques used for randomisation and allocation concealment. Detection bias was a concern in both trials, specifically around masking of outcome assessment. Where details of the intervention were unclear48 (i.e. duration of binocular vision training) we wrote to the study authors for further information but received no response. Both trials were judged to have low risk of bias with respect to attrition bias because one52 reported reasons for exclusions (albeit with uncertainty about the inclusion/exclusion of the patients from the other trial), and the other reported data for all participants at 1 year. 48

Non-randomised studies

Of the nine cohort studies with comparison groups,20,42,49–55 two of the studies20,54 were prospective (Table 3). A strength of the inception cohort study20 was that it recruited from multiple centres with a final sample size of 371 and a loss to follow-up of only 24%, whereas the other prospective cohort54 was a single-centre study and had a smaller sample (n = 60) and short follow-up period (6 months only), although it should be noted that there was no loss to follow-up in this study. Neither of the prospective studies used matched comparison groups. The remaining seven cohort studies42,49–53,55 were retrospective in design.

| Quality criterion | Buck 201220 | Chia 200649 | Choi 201250 | Figueira 200642 | Lee 200151 | Lee 200752 | Maruo 200153 | Wu 200854 | Yuksel 199855 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way (robust inclusion/exclusion criteria or consecutive recruitment)? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | N |

| Was the study prospective? | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N |

| Was the intervention conducted in an explicit and standardised manner (i.e. were guidelines or protocol for intervention described)? | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Was the outcome appropriately measured to minimise bias? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Did they identify important confounding factors (e.g. age at intervention, baseline angle of deviation)? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Did they adjust for confounding factors in the design and/or analysis where necessary? | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Were they followed up for at least 12 months? | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Are the authors’ conclusions substantiated by the reported data? | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

Of the nine non-randomised studies included,20,42,49–55 three used consecutive recruitment,42,50,52 one study20 identified cases prospectively from multiple cases according to well-defined inclusion criteria, and three studies49,51,53 identified cases retrospectively using well-defined inclusion criteria. In the remaining two studies54,55 details of how patients were recruited is either poorly described or unclear. In at least five of the studies there is a possibility of selection bias associated with determining which patient received which procedure, as many of the studies state that the choice of intervention was at the ophthalmologist’s or parents’ discretion. 20,42,49,50,54 With regard to the possibility of bias incorporated during exposure to the intervention, we assessed whether the interventions were carried out according to guidelines or a standardised protocol. Six studies42,50–53,55 included reference to a standardised protocol or guidelines to determine the amount of surgery performed. In one study it was stated that the amount of surgery was at the discretion of the operating surgeon,49 although this was unclear in two other studies. 20,54 Surgery was performed by three surgeons in one study,49 in six studies42,47,50–52,55 all procedures were performed by one surgeon, and in the remaining three studies48,53,54 details of who performed the surgery were not reported.

Differences in outcome assessment were considerable across the studies with a range of outcome measures being reported including motor alignment (angle of deviation), sensory function (stereopsis), control or a combination of the above. Of those studies reporting motor alignment as the primary outcome, one reported median change in deviation20 and the remainder42,47,49–55 reported success or improvement rates. However, ‘success’ or ‘improvement’ was variously defined so (leaving aside differences in study design, population and follow-up point at which outcomes were assessed) the studies were not suitable for pooling in a meta-synthesis. The diversity in definitions of success used is an important issue here, with some studies conceptualising a successful outcome as anything within 20 PD of orthotropia,53,55 whereas other authors operationalised a much stricter definition (e.g. ≤ 5 PD esophoria/-tropia to ≤ 10 PD exophoria/-tropia,47,50 and various definitions in between (e.g. deviation within ± 8 PD52 or deviation within ± 10 PD42,49,54). In terms of assessment of outcome measures, only one study50 reported carrying out measurements of the angle of deviation on three different occasions; in the remaining studies20,42,49,51–55 minimal detail was reported with regard to when outcomes were measured and how many times measurements were taken.

In two studies there were sparse42 or no data53 reported to assess the possibility of significant baseline differences between the intervention and control groups in terms of age and severity of X(T) at baseline, both of which are important confounding factors. Four studies51,52,54,55 reported no statistically significant differences between the intervention and comparison groups at study outset. However, two studies49,50 reported significant differences between the two groups at baseline, the former in initial angle of deviation and the latter in age, but no adjustments were made for these differences in their analyses.

Surgical interventions (one surgical technique versus another)

Of the seven studies examining the effectiveness of surgery, six compared symmetric with asymmetric surgery [bilateral lateral rectus recession (BLR) vs. unilateral recess resect]. 47,49–51,53,55 One study52 compared effectiveness between augmented and non-augmented forms of symmetric surgery. Only one of the surgical intervention studies47 was described as a RCT, the remainder were retrospective cohort studies with a comparison group.

Bilateral lateral rectus recession compared with unilateral recess resect

One RCT47 and five retrospective cohort studies49–51,53,55 reported on these surgical techniques. The RCT47 was conducted in children aged 3–18 years with basic type X(T), and compared unilateral recession/resection (R&R) (n = 17) with BLR (n = 19). A satisfactory outcome, measured 12 months after surgery, was defined as between 10 PD of exophoria and 5 PD of esophoria; stereoacuity was not assessed. The study47 reported a significantly higher proportion (p < 0.02) of patients with a satisfactory outcome in those receiving R&R procedures (82%,14/17) than in those receiving BLR (52%, 10/19) at least 12 months after surgery (range 12–15 months). The authors also compared their results to a non-randomised ‘control’ group of children with simulated distance exotropia (n = 68) who all received BLR surgery. Successful outcomes were observed in 81% of patients in the control group (55/68); overcorrection and undercorrection rates were 4% (3/68) and 15% (10/68) respectively. The results were significantly different to the patients with basic X(T) receiving BLR (p < 0.05) but similar to those receiving R&R. The study, however, was limited in several respects. First, there was a dearth of information about the randomisation procedures used, making it difficult to assess whether or not the method used to generate the allocation sequence would produce comparable groups and also whether or not the allocation sequence was concealed. Neither participant nor clinician was blinded to the intervention received. Likewise, outcome assessment was unblinded, with the clinician who performed surgery also measuring outcomes at 12 months (little detail is reported on how outcomes were measured, i.e. exact time point and number of measurements). It is noteworthy that the author excluded patients for whom he knew that, at the time of surgery, the referring physician would be conducting follow-up assessment. In addition patients, were excluded because they were enrolled in another in-progress RCT led by the author. The exclusion criteria used raise questions about the fidelity of the randomisation processes and actual study design used, and the possibility of selective reporting. The absence of clear and well-defined criteria for considering a patient for surgery (e.g. size of deviation, control of deviation) also introduces possible bias to the study findings. Finally, the sample size was also small (total n = 36) and the follow-up period may be insufficient to allow generalisability.

A retrospective cohort study49 (n = 118) of children aged < 16 years with either divergence excess or basic type X(T) compared the effectiveness of BLR with R&R undertaken by three different surgeons who determined the type and amount of surgery to achieve orthotropia. It should be noted that one surgeon had a strong preference for R&R, whereas the other two surgeons had a preference for BLR but would undertake R&R if there was a tendency for deviation in one eye or a strong near component. Outcomes were reported at 1 and 3 years postoperatively for both motor alignment (no reporting of number of measurements taken) and control (subjective assessment by an orthoptist). The study reported clear inclusion and exclusion criteria – patients were eligible if they had either basic or divergence excess type X(T) and a deviation of between 25 and 50 PD. A successful outcome was defined as X(T) ≤ 10 PD. At 12 months’ follow-up there was a statistically significant difference in the success rate of surgery between the two groups, with better outcomes in the group receiving the R&R procedure (74.2%) than in the group receiving BLR (42.2%; p < 0.001). However, the authors note that exotropic drift over time was greater in the R&R group, with a significant increase in the mean distance constant exotropia (XT) in the R&R group at 3 years’ postoperative follow-up (p = 0.01). There was no significant change in postoperative deviation for either distance or near measurements in the BLR group. It is noteworthy that the authors report significant differences between the two intervention groups, with the R&R group having a greater mean age (p = 0.052), a higher proportion of children with divergence excess-type X(T) (p = 0.0181) and a smaller mean angle of deviation (p = 0.0005) than the BLR group. These differences were not adjusted for in the analyses, which limits the generalisability of the findings. The authors acknowledge that the wide range in size of X(T) at baseline (up to 50 PD) might also affect interpretation of the study findings. Other limitations include the absence of clear guidelines for choice of surgical procedure (no standard protocol of tables for determining type or amount of surgery).

The comparison between R&R and BLR procedures was also examined in a retrospective study of 128 children. 50 Surgical outcomes were assessed in a cohort of children with basic-type X(T) and at least 2 years’ follow-up (mean 44.2 months for BLR and 47.8 months for R&R). Success was defined as esophoria/tropia ≤ 5 PD to exophoria/tropia ≤ 10 PD) measured on at least three occasions (this is the only study50 that explicitly reported measuring deviation on at least three occasions at baseline and follow-up). The authors found no difference between the two interventions at 2 years postoperatively; however after long-term follow-up (mean 3.8 years) the BLR procedure had a significantly higher success rate than R&R (58.2% vs. 27.4%; p < 0.01). One of the strengths of the study50 is the long follow-up period used, which identified greater recurrence in the R&R group (after mean 3.8 years’ follow-up, recurrence was 68.5% in the R&R group vs. 38.2% in the BLR group). However; it should be noted that ascertainment bias is an issue here, as patients with poorer outcomes might be more likely to be followed for longer. Equally, the inclusion criteria for this study50 were less rigid, with the inclusion of patients with a A or V pattern, dissociated vertical deviation or oblique muscle over-actions that did not require surgery. Further, there were statistically significant differences between the two surgical groups in terms of preoperative deviation and this potential confounding effect was not adjusted for in the analyses. The BLR group had a larger mean angle of deviation at baseline but, even so, had better success rates at longer-term follow-up. The findings are also limited by absence of data on sensory status, specifically stereopsis pre- or postoperatively.

The same surgical comparison was undertaken in a retrospective, single-centre study51 with a 1-year follow-up period. The population of 3- to 17-year-old children (n = 103) was mixed in terms of type of X(T), with 93 basic-type X(T) and 10 pseudodivergence excess-type X(T), and the aim of surgery was deliberate overcorrection. The authors reported no significant differences between the two intervention groups (BLR n = 46 and R&R n = 57) in terms of age or deviation at baseline. Success was defined as no more than 10 PD of exophoria or 5 PD of esophoria (sparse detail was included on how outcomes were measured). The authors reported no statistically significant differences in terms of success rate at 1-year follow-up between the two groups [BLR 56.5% (26/46) vs. R&R 59.6% (34/57); p > 0.05], and age and initial deviation had no significant effect on outcome (p > 0.05). The main objective of this particular study51 was to understand the relationship between motor alignment at day 1 and motor alignment at 1-year follow-up. The authors conclude that optimal results are produced with immediate postoperative overcorrection of 11–20 PD for BLR and 1–10 PD for R&R procedures. In terms of limitations of this study, there is a lack of detail on how choice of surgical procedure was determined, although it is stated that both procedures were performed by the same surgeon.

A large retrospective cohort study53 of children aged 15 years or younger (n = 666) explored long-term outcomes of BLR (n = 349) compared with R&R procedures (n = 298). The study53 reports a paucity of detail with respect to the baseline population, in particular type and severity of X(T); likewise, there is a dearth of information available on the specific protocol for outcome assessment. A further limitation is that the authors fail to explore (and take account of) baseline differences between the surgical groups in terms of age and size of initial deviation. The authors do include, however, guidelines for surgery. Comparative data are reported at 4 years’ follow-up for patients who initially showed orthotropia or minimicrotropia (defined as alignment within 4 PD of orthotropia) at 1 month postoperatively. Of the patients receiving BLR, 66.7% (140/210) retained orthotropia or minimicrotropia, whereas 32.8% who received R&R retained orthotropia or minimicrotropia (with more patients drifting towards exotropia in this group). A subset of 78 patients were followed for between 8 and 22 years but no comparative data for the two surgical techniques were reported. Restoration of normal appearance was also conceptualised as a key indicator of success, although there was no statistically significant difference between procedures in terms of success rates, with 95.2% of patients who received BLR achieving normal appearance compared with 80% of patients who received R&R achieving normal appearance. Caution should be applied when interpreting success outcomes, given that the definition of success is extremely broad (≤ 20 PD of heterotropia).

A retrospective cohort of children (aged 2–18 years) with basic-type X(T) also compared the R&R and BLR procedures. 55 Twenty-five children received R&R surgery on the non-fixating eye, whereas 30 children received BLR surgery; the groups were comparable (i.e. there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups) in terms of age, preoperative deviation and sensory results at baseline. The mean follow-up period was 2.81 years, with a range of 6 months to 8 years; there is limited information about how outcomes were assessed (e.g. use of repeat measurements). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of success rates at long-term follow-up (p = 0.249), with 52% of patients achieving an optimal or good outcome (defined as orthotropia or within ± 20 PD of orthotropia, respectively) in the BLR group compared with 57% achieving an optimal or good outcome in the R&R group. In terms of limitations the sample size is small and the findings should be interpreted in light of the retrospective study design.

In summary, the findings of the above studies (one RCT47 and five retrospective cohort studies49–51,53,55 with comparison groups) show that short-term outcomes tend to be better with the R&R procedure, but there is a suggestion of better long-term outcomes with BLR surgery. 47,49–51,53,55

Conventional recession/resection compared with augmented recession/resection

One study52 investigated the effectiveness of augmented surgery compared with conventional surgery, using the symmetric lateral rectus recession procedure that was assessed in a population of 107 children with basic-type X(T) followed for at least 6 months. Conventional surgery was conducted according to Parks formula, whereas augmented surgery was 1.5–2.5 mm more than a conventional lateral rectus recession. Success was defined as between 8 PD of exophoria and 8 PD or esophoria, and follow-up was 6–35 months in the augmented surgery group compared with 6–39 months in the conventional surgery group (sparse detail was included relating to outcome assessment). Conventional surgery was performed in 41 children (mean age 8 ± 3.6 years) and augmented surgery was performed in 66 children (mean age 7.1 ± 3.9 years). Comparison of success rates at the last follow-up visit demonstrated a statistically significant difference favouring augmented surgery (68.2% vs. 43.9%; p = 0.01). One of the key limitations of the study is that, although performed by the same surgeon, the two procedures were conducted at different time points, so, in effect, the control (conventional surgery) was recruited historically (both groups were recruited retrospectively but the control group was recruited earlier than the intervention group). That said, the groups were shown to be comparable, with no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of mean alignment at baseline (p = 0.23), mean age (p = 0.06) and mean length of follow-up period (p = 0.55). The authors also acknowledge that stricter success criteria might be required, with the recognition that patients with 8 PD of esophoria can complain of diplopia.

Non-surgical interventions

Surgery compared with non-surgical interventions

Four studies20,42,48,54 compared surgical and non-surgical interventions, two of which reported comparative findings on two interventions48,54 while the remaining two studies20,42 considered more than two interventions.

Surgery compared with BOTOX

One prospective cohort study54 investigated the effectiveness of treatment with attenuated botulinum strain A (BTXA) compared with surgery (including both unilateral and bilateral) in a population of children aged 4–12 years. No information about the type of X(T) was reported. The method of recruitment was non-randomised and outcomes were assessed at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months and 6 months post intervention. Success was defined as a deviation within ± 10 PD of orthotropia, although limited details relating to outcome assessment (e.g. number of measurements taken) was reported. Although the rate of successful corrections was lower in the BTXA group (23/30, 76.67%) in comparison with the group receiving surgery (27/30, 90.00%), the difference was not found to be statistically significant (p = 0.166). In the BTXA group the undercorrection rate was (7/30, 23.33%). Conversely, in the surgical group one case was undercorrected and two cases were overcorrected. The authors also reported complications for the BTXA group, with one case of double vision (requiring patching); the authors mention that double vision occurred for some of the other patients but not to the extent that it affected daily living; the authors do not state the proportion of patients who experienced these symptoms of double vision. In addition, seven cases of ptosis were reported, all of which resolved after 3 months.

Surgery alone compared with surgery plus binocular vision training

A RCT48 of children, aged 5–16 years, explored the effectiveness of binocular vision training after surgery for X(T). Patients were randomised to either the intervention group (n = 61), which involved a period of binocular vision training, which began 2 weeks post surgery, or the control group (n = 60), which received no training after surgery. Patients in the binocular vision training group completed exercises with red and blue glasses three times per day for a period of 20 minutes on each occasion. There is a dearth of detail regarding the intervention, in particular the period over which the exercises were undertaken and also the type of X(T) under investigation. The primary outcomes were recovery of binocular vision and regression/deterioration rate (defined as deviation of > ± 10 PD); both were assessed at 1 week post surgery and 12 months post follow-up. The authors conclude that binocular vision was better in the training group than the control at 12 months’ follow-up. Likewise the regression rate was worse in the control group than in the intervention, with 21/60 recessing in the control group (35%) compared with 7/61 (11.5%) in the intervention group; this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). These findings suggest that additional binocular vision training after surgery might improve outcomes.

Surgery compared with conservative interventions

Two studies20,42 considered surgery versus conservative interventions. Multiple intervention comparisons were explored in a prospective, multicentre cohort study of 371 children aged < 12 years. 20 Previously untreated basic, true and simulated divergence-excess types were included and children were followed for 2 years for each of the non-surgical interventions (n = 50), for observation (n = 195) and for treatment for reduced VA (n = 63), and 6 months postoperatively for the surgical intervention (n = 63). The non-surgical treatment group (n = 50) included the following interventions that aimed to improve control: spectacle lenses (n = 37); occlusion (n = 6); glasses and patching (n = 2); exercises (n = 4); and exercises and prism (n = 1). Outcomes assessed included change in angle of deviation (no detail of whether or not repeated measurements were used), control [Newcastle Control Score (NCS), which incorporates both objective and subjective components: high score = poor control; scores range from 0 to 961,62] and stereoacuity (Frisby Near Stereoacuity Test). The authors conclude that surgery was the only intervention associated with statistically significant improvements in angle of deviation (p < 0.001) and NCS61,62 (mean 60% reduction in both parental and clinic components). However, there was a risk of overcorrection (21% at 6 months) and additional surgery was required in 8% of children (5/63). Non-surgical interventions had no significant effect on angle of deviation, but significant small improvements in control were noted for the non-surgical intervention and observation groups (mean reductions of 20% and 13% in the clinic and parent components, respectively). Another key finding was that few children in the watchful-waiting group showed deterioration to constant exotropia (0.5%); however, follow-up was limited to 2 years. One of the strengths of this study20 is that children were recruited from 26 centres and loss to follow-up was not significant (with 81% of the original cohort being available for final follow-up). The authors also established that there were no significant differences between the final samples and those lost to follow-up. A possible weakness of this study is the absence of robust criteria/protocol for management decisions. However, the study was multicentre and the authors argue that treatment adopted was likely to reflect current practice at the centres involved. A second limitation surrounds comparison of the outcomes of surgery at 6 months compared with non-surgical intervention outcomes at 24 months, which the authors acknowledge may introduce bias in interpretation of the study findings.

A retrospective study of 150 children compared four different treatment options for X(T): (1) surgery only (BLR using recognised guidelines, n = 15); (2) surgery combined with orthoptic/occlusion therapy (n = 67); (3) orthoptic/occlusion therapy alone (48); and (4) observation (n = 20). 42 Within the orthoptic/occlusion group, treatment was divided into the following subgroups: convergence exercises, overminus lens therapy or occlusion therapy. For orthoptic/occlusion therapy before surgery, an additional intervention of preoperative diplopia awareness exercises was undertaken. Children, aged < 15 years, with an exodeviation of 15 PD for distance fixation were included and followed for a maximum of 5 years. Patients were not randomised to the intervention groups; the authors state that treatment method was ‘largely dependent on parent preference’, which might represent a source of bias. Success was defined as orthophoria or < 10 PD esotropia/exotropia (no reporting of protocol for assessment of angle of deviation), good stereoacuity (Lang stereotests) and cosmesis (parental subjective assessment). Comparison of change in deviation for each of the intervention groups revealed that surgery coupled with orthoptic/occlusion therapy produced the greatest mean reduction in exodeviation, the difference was significantly greater than with the other interventions at all follow-up time points (p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences in success rates between the subgroups of preoperative orthoptic/occlusion exercises. In terms of study limitations, the authors fail to explore the potential confounding effects of age and severity of X(T) at baseline. From baseline data it appears that the groups were not comparable in terms of mean age, sensory results and mean preoperative deviation, although no statistical assessment of difference across the intervention groups in terms of baseline characteristics is reported.

Adverse effects

Of the 11 included studies,20,42,47–55 1020,42,47,49–55 reported outcomes relating to adverse effects. Nine studies evaluating surgical interventions20,42,47,49–53,55 reported overcorrection rates, which ranged from 1.5%52 to 21%. 20 In four49–51,55 of six studies47,49–51,53,55 comparing BLR and R&R procedures, overcorrection rates were greater in the group undergoing the R&R procedure (overcorrection rates by individual study are shown in Table 1). One of the prospective cohort studies, which examined the effectiveness of BOTOX in comparison with surgery, found that some adverse effects were reported in the BOTOX group: diplopia (which required patching, in one patient) and ptosis (eyelid droop, in 7 of 30 patients – 23%) but these tended to resolve over time (6/7 cases improved after 1 month and all cases improved after 3 months. None of the remaining non-surgical interventions (overminus lenses; occlusion; orthoptic exercises; prisms) was associated with adverse outcomes. 20,42,48

Discussion

Summary of main results

Surgical intervention studies

The review revealed mixed findings when comparing R&R and BLR surgery, with two studies51,55 reporting equivocal results, two studies47,49 favouring R&R surgery, and two studies50,53 reporting more success with BLR surgery at long-term follow-up. R&R surgery produced more successful results, at least in the short term, with two studies47,49 reporting statistically significant results favouring R&R procedures. However, there are reservations around the stability of outcomes for R&R surgery in the long term, with studies49,50 suggesting greater exotropic drift over time. The BLR procedure produced better outcomes at long-term follow-up (at least 3 years) in two studies. 50,53 The reader should be aware that the study populations are different – we are not comparing like with like – some studies examine only basic-type X(T), whereas others include both basic and divergence excess types. Equally the follow-up point for measuring a successful outcome was defined differently, so these comparisons should be interpreted with caution. In terms of adverse effects, the rate of overcorrection was variously reported (range 1.552–21.00%20). The wide range in overcorrection rate is probably due to differences in the follow-up period between studies and the definition of overcorrection applied (e.g. strict definitions, i.e. any esotropia20 vs. looser definitions, e.g. esotropia > 8 PD52).

Non-surgical studies compared with surgical intervention studies

Only four studies20,42,48,54 meeting the design criteria (RCT, quasirandomised study or cohort study with comparison group) were located, each considered different interventions and comparison groups so it is difficult to synthesise results even tentatively. The prospective study comparing surgery, non-surgical interventions and observation found that surgery produced better outcomes in terms of motor alignment and control, but it was associated with a significant risk of overcorrection, with loss of near stereoacuity in some cases. 20 Importantly, the authors also conclude that watchful waiting is not associated with deterioration and progression to constant exotropia within the first 2 years after diagnosis. The RCT of vision training after surgery demonstrated more successful outcomes when compared with surgery alone. 48 The prospective study54 comparing treatment with BTXA with surgery found no statistically significant difference in success rates between the two procedures, but argued that BTXA represented a less invasive option when adverse effects (ptosis and diplopia) are only short lived. A retrospective study of multiple interventions reported orthoptic exercises or occlusion prior to surgery resulted in greater success when compared with surgery alone; there were no significant differences between the success rates of either orthoptic exercises or occlusion. 42

Quality of evidence

The body of evidence retrieved was limited in terms of size and quality. Only two RCTs47,48 were located, both of which had a risk of bias attributed to aspects of the study design (no masking of outcomes assessment and the possibility of selection bias). Both prospective cohort studies20,54 had comparison groups but neither was matched. The main sources of bias in the retrospective studies with comparison groups were small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, absence of a robust protocol for management or allocation to intervention groups, and limited adjustment for known confounders, such as age and initial deviation at baseline. But perhaps more important is the variability in outcome measures used and, specifically, the definition of success applied (e.g. broad vs. narrow thresholds to constitute success). These limitations were coupled with a paucity of detail on study methods, making it difficult to establish how interventions were undertaken (e.g. absence of guidelines or standardised protocol for surgery), how outcomes were assessed (e.g. lack of detail on specific tests used) and whether or not there were any differences between intervention groups at baseline (especially with regard to age and initial deviation).

Comparison with the existing evidence base

Commensurate with the conclusions of the earlier Cochrane review27 we found that there remains a need for further well-designed RCTs to examine questions of effectiveness for different management options of childhood X(T). Given the absence of high-quality evidence, the authors argue for prudence when considering management options given the potential to ‘do harm by correcting the appearance of misalignment but disrupting the ability to maintain binocular stereo vision’,27 p.10. A review of conservative treatment options for X(T)24 found that interventions such as minus lenses, anti-suppression occlusion and orthoptic exercises were effective both as an alternative, and as an adjunct, to surgery but they also highlighted a need for further research to understand the circumstances under which these management strategies were most successful, in particular dosage of antisuppression occlusion therapy. Similarly, a review of non-surgical interventions for X(T)45 underlined the dearth of well-designed intervention studies to examine questions of effectiveness. They highlighted the absence of consensus definitions of success as well as poor reporting of details around the actual intervention delivered and compliance with this. Our review supports each of these calls for further better-designed studies, consensus on outcome measures of success and improved reporting of interventions and outcomes.

Potential biases in the review process

The main limitation of this review is that we are reporting on effectiveness with suboptimal study design. The RCT is the design of choice when addressing questions of effectiveness. Owing to the absence of RCTs in this topic area, we have adopted a pragmatic approach, moving down the hierarchy of evidence to the next level when studies were available (i.e. cohort studies with a comparison group, both prospective and retrospective). By including non-randomised (observational) studies we are aware of the issue of selection bias due to the absence of robust methods of allocation (usually by clinician, which increases the risk of confounding by prognostic factors such as age or severity of the condition at baseline). 40 Far more case series were retrieved in the searches but, owing to the absence of a contemporaneous comparison group, we have excluded this study design. 63 The dearth of high-quality study designs, together with the considerable heterogeneity between studies in terms of population [i.e. type of X(T)], outcomes measured, definition of success and follow-up period used, precluded a meta-analysis that would be the ideal form of synthesis for a review of this nature.

We should also acknowledge that, although searches were conducted across multiple databases and supplemented by hand searches of non-indexed journals and contact with key experts in the field, it is possible that we may not have captured all relevant studies. That said, the search strategy was developed, piloted and refined by a highly experienced information researcher and efforts were made to contact key experts in the field using an established discussion list. In using these research findings, researchers and practitioners alike should be mindful that studies were retrieved using the search strategy presented in Appendix 1 and by applying the strict eligibility criteria set out in Box 2. We excluded studies if they did not report outcomes for children (up to 18 years) with X(T) (either basic or divergence excess types) separately. In other words, studies were excluded if they reported aggregated outcomes for exotropia generically (e.g. constant and intermittent mixed or for children and adults mixed). If time and resource constraints had allowed, we would ideally have contacted study authors of studies with mixed populations (adults and children; XT and X(T); convergence insufficiency type combined with divergence excess) to request disaggregated data.

One of the strengths of our review was the inclusion of foreign-language papers (n = 3), which is particularly important for the topic area given the epidemiology of X(T). 27 It should be noted, however, that the website and hand searches were conducted in English language only. Publication bias might also be an issue here, with studies presenting equivocal or non-significant results not being published.

The review has sought to address questions around effectiveness of interventions for X(T) in children. We included the best available level of evidence (mostly cohort studies with a comparison group) to examine intervention effectiveness. The study design used might not be the most appropriate to address our secondary objectives around the natural history of X(T) and adverse effects. Thus we recommend additional reviews to consider these questions. For example, a review of inception cohort studies would be most appropriate study design to consider evidence of adverse effects associated with different interventions for childhood X(T). Likewise, patient registry studies are suitable to explore the natural history of X(T) in children, observe disease progression and understand long-term outcomes.

Conclusions