Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 02/02/01. The contractual start date was in October 2003. The draft report began editorial review in March 2012 and was accepted for publication in May 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Steve Halligan reports non-financial research and development evaluation work provided for iCAD Inc., which develops CAD for computed tomographic colonography. This author also provides expert witness testimony on matters relating to radiological diagnosis of colorectal cancer and holds patents/patent applications for computed tomography imaging technology (2010; International PCT no. PCT/GB2011/050448 ‘Apparatus and Method for Registering Medical Images Containing a Tubular Organ’). Wendy Atkin reports funds to support this work were also obtained from Imperial College London, London, UK.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Halligan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Along with lung cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the developed world, and around 1.2 million cases were diagnosed worldwide in 2008. 1 Roughly 40,000 new cases are reported in the UK each year2 and, with an ageing population, this number is increasing. Since 1 July 2000, the Department of Health has made recommendations that any patients with suspected cancer should be seen by a specialist within 2 weeks of referral from their general practitioner (GP). 3 This has led to the development of guidelines for referral of patients with suspected CRC, taking account of factors such as age (patients over 60 years are considered to be at increased risk) and symptoms including change in bowel habit, rectal bleeding and anaemia. 4 However, as these symptoms are non-specific and common in the general population, most patients who are investigated will not have the disease. 5,6 This places a considerable burden on diagnostic services and highlights the need for diagnostic tests that are not only sensitive and specific, but widely available, safe and acceptable to patients.

The currently established tests for examining the whole colon are colonoscopy and barium enema (BE). Colonoscopy is generally considered to be the most accurate examination for the detection of CRC and has the advantage of allowing biopsies to be taken in order to confirm the presence of cancer or other abnormalities within the bowel, and enabling the complete removal of precancerous polyps. However, colonoscopy is not without limitations. It is an invasive and technically demanding procedure and carries a small risk of serious adverse events, including bowel perforation and bleeding. 7 A study of 53,220 outpatients undergoing colonoscopy found that the risk of perforation and bleeding increased with age,8 yet older people constitute the majority of those with symptoms. Sedation is also usually required and this conveys additional risk. 9

Barium enema is safer than colonoscopy in elderly patients, but has been found in audits to miss a greater proportion of cancers in routine practice. 10 This has led to recommendations that its use be reduced. 11 However, for patients with a low index of suspicion for serious disease, avoidance of colonoscopy may be desirable, particularly in the elderly for whom the risks of sedation are greatest. BE is inexpensive, there is considerable experience with its use and it remains widely available, with an estimated 4 million procedures performed worldwide in 2009 (Mr Maurizio Franchini, Bracco International, 2009, personal communication).

Computed tomographic colonography (CTC) or ‘virtual colonoscopy’ is a relatively new health technology, potentially combining the sensitivity of colonoscopy with the safety of BE.

Existing research on the new technology

Computed tomographic colonography was first described in 1994. 12 The examination consists of a helical computed tomography (CT) scan of the cleansed and gas-distended large bowel, with evaluation of the resulting images by a radiologist. Complex image analysis techniques are used to aid interpretation, including three-dimensional (3D) rendering that simulates the colonoscopist’s endoluminal view of the colon.

Computed tomographic colonography has already received considerable attention in the context of CRC screening, as there is evidence that it is safer than colonoscopy13,14 and it does not require the patient to be sedated. It has a similar high sensitivity for cancer and large polyps in asymptomatic populations examined by experienced radiologists. 15–17 However, a role for symptomatic diagnosis has been relatively ignored.

One disadvantage of CTC when compared with colonoscopy is that it requires an additional endoscopic procedure to biopsy or remove any significant lesions detected, increasing inconvenience and cost. CTC may also detect small incidental lesions within the colon that are unlikely to be the cause of symptoms but which, once identified, will require endoscopic removal. Any patients with such lesions will not avoid colonoscopy and will need to undergo a second bowel preparation (unless colonoscopy can be performed on the same day, which is rare in normal clinical practice). However, the majority of patients having CTC will not need colonoscopy and there is evidence that CTC may be more acceptable to patients. 18–20

Because of its high sensitivity for CRC, it has been suggested that CTC should replace BE as an alternative to colonoscopy. 21 However, few studies have directly compared BE and CTC,22,23 and until now there have been no randomised trials. As a result, robust data to guide health policy have been lacking.

As CTC and colonoscopy have similar sensitivity for cancer and large polyps,15–17 the choice between these two procedures is likely to depend on other factors. For example, it is not known what proportion of patients presenting with symptoms of CRC require subsequent colonic investigation to verify findings at CTC, compared with colonoscopy. This is an important consideration if CTC is to be regarded as an alternative diagnostic test.

In the NHS it is possible that CTC will find a role in cancer detection in elderly patients, in whom the risks of colonoscopy-related adverse events (oversedation, colonic perforation) are greatest and the risks of exposure to ionising radiation less important. Unlike colonoscopy or BE, CTC can also image organs outside the colon, which may aid diagnosis in patients whose symptoms are extracolonic in origin. However, this also results in incidental findings24 with associated medical, psychological and financial consequences. If an extracolonic abnormality is identified it may prompt further investigation without any ultimate benefit to the patient, so careful evaluation is required. 25,26

We felt that such equipoise was the ideal point at which to conduct a trial,27 so that recommendations could be evidence based and any future implementation would be sensible, balanced and informed.

Objectives of the Special Interest Group in Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology trials

Our aim was to examine the diagnostic efficacy, acceptability and cost of CTC compared with BEs or colonoscopy, by carrying out two parallel randomised trials. In the trial of CTC compared with BEs, this comparison was based primarily on detection rates for significant neoplasia, whereas in the trial of CTC compared with colonoscopy, it was based on rates of referral for a confirmatory diagnostic procedure, because the similar sensitivities of CTC and colonoscopy would have made a trial powered on detection rates impractical (see Chapter 2, Sample size). We also compared other outcomes, including miss rates for CRC and rates of serious adverse events.

The acceptability to patients of CTC, BEs and colonoscopy was assessed by giving psychological questionnaires to a sample of participants in the study, documenting their experiences on the day after the test and at 3 months after the test (see Chapter 5).

Finally, an economic analysis was undertaken to estimate the costs and cost-effectiveness of the three procedures (see Chapter 6).

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The study consisted of two multicentre randomised trials (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number 95152621), conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. 28 Ethics approval was obtained from the Northern and Yorkshire Multi-Centre Ethics Committee in January 2004 and subsequently from all participating hospitals. The trial was supervised by an independent Data Monitoring Committee and a Trial Steering Committee. All patients gave informed written consent.

Patients with symptoms suggestive of CRC were initially seen in clinic and referred for either colonoscopy or a BE (the ‘default’ examinations) by the clinician seeing the patient, depending on whether they preferred radiological or endoscopic investigation in normal clinical practice for the particular patient in question. This decision depended on factors such as expectation of cancer, perceived frailty and locally available diagnostic resources. BEs and colonoscopy are not considered clinically equivalent in normal clinical practice. To design a three-way randomised controlled trial (RCT) of BE compared with colonoscopy compared with CTC would have been unethical because of a lack of equipoise between BE and CTC, and would have suffered from poor recruitment. As a result, the study was split into two separate trials: one for CTC compared with BE (the ‘BE trial’) and one for CTC compared with colonoscopy (the ‘colonoscopy trial’).

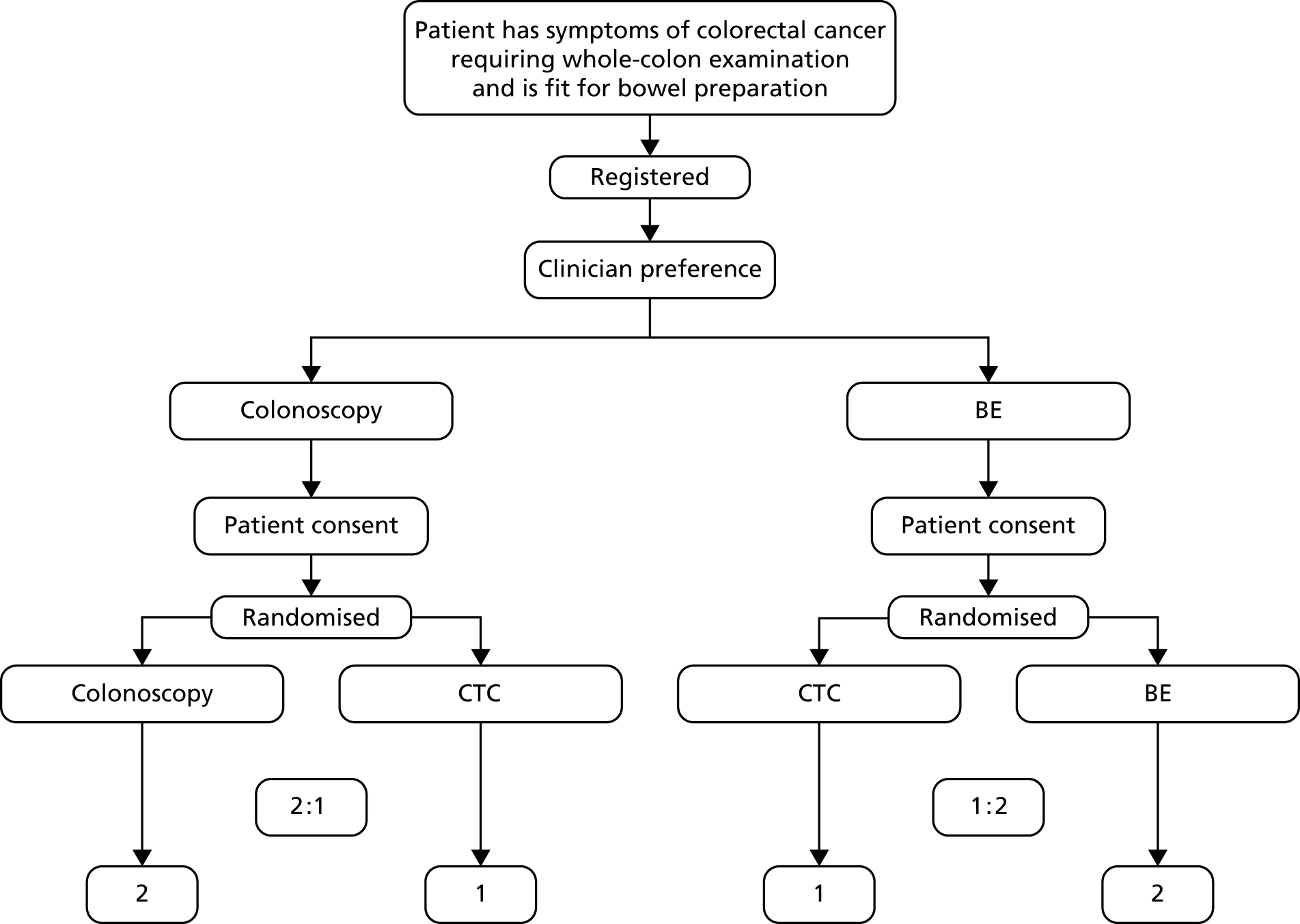

Within each trial, patients were randomised in a 2 : 1 ratio in favour of the ‘default’ whole-colon examination, in accordance with the algorithm shown in Figure 1. A 2 : 1 ratio was chosen in order to maximise recruitment within the constraints of provision for the new technology and the study was powered accordingly.

FIGURE 1.

Study design. Lower boxes refer to randomisation ratio numbers.

Centres

We recruited patients from 21 NHS hospitals in England. To increase generalisability, both teaching and general hospitals were included. Participating centres were expected to have an established and efficient fast-track referral system for patients with symptoms of CRC, usually an identifiable diagnostic clinic, to facilitate recruitment. Each centre had to have a named colorectal nurse specialist or researcher attached to the clinic who would take responsibility for recruitment. Centres were also required to nominate a lead clinician who would supervise the work of the colorectal nurse specialist and a lead radiologist [and a Special Interest Group in Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (SIGGAR) member] who was willing to undergo central training in CTC according to accreditation guidelines issued by the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) (see Computed tomographic colonography training). A final criterion for selection was agreement by the participating site that use of CTC as a primary diagnostic test would only be offered to eligible patients as part the trial.

Participating hospitals were chosen from interested centres via a ‘sham randomisation’ that identified centres likely to achieve a monthly recruitment target of at least 18 patients. 29 Over a 2-month period each centre was asked to identify patients who satisfied the trial eligibility criteria and to enter simple demographics (age, sex, symptoms, route of referral and type of whole-colon investigation requested) on a secure, password-protected online database. No patients were approached directly, but this ‘sham randomisation’ provided an estimate of how each centre might perform once the trial was in progress.

Participants

Following referral from their GP, suitable patients were identified from clinics and procedure waiting lists by the colorectal nurse specialist.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for the study if they were:

-

experiencing symptoms suggestive of CRC (this included both patients who fulfilled a 2-week wait criterion and those considered less urgent)

-

aged ≥ 55 years

-

clinically judged to need a whole-colon examination

-

clinically judged fit to undergo full bowel preparation

-

able to give fully informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Patients could not be included in the study if they had:

-

a known genetic predisposition to cancer, for example familial adenomatous polyposis or hereditary non-polyposis CRC

-

a known diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease

-

undergone a previous whole-colon examination in the past 6 months

-

been referred for whole-colon examination to follow up a previously diagnosed CRC.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

It became clear during piloting that many patients were being given a flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) examination prior to their randomised procedure. Excluding these patients would have made it difficult to recruit adequately to the study, as many hospitals make use of FS and this is likely to increase in future. Patients having FS were therefore eligible for the study if a strong clinical suspicion of right-sided cancer remained and if BE or colonoscopy would usually be the next test.

Interventions

Barium enema

Technical parameters

Exams were performed after full bowel preparation, with all centres using sodium picosulphate and magnesium citrate (Picolax®, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) as the primary laxative. An intravenous spasmolytic was administered routinely, usually 20 mg of hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan®, Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd) unless contraindicated. Air or carbon dioxide was used for insufflation. Digital fluoroscopic images of the double-contrasted colorectum were obtained to the caecum, supplemented by overcouch decubitus films. A minimum 512 × 512 matrix was required for all images.

Interpretation

Scans were interpreted by radiologists with a subspecialty interest in gastrointestinal (GI) radiology or by fully trained radiographic technicians. Radiologists had to be performing an average of three or more BEs each week in routine clinical practice and were required to have performed at least 50 enemas unaided. Radiographers had to have completed an accredited course in double-contrast BE techniques and since that time to have performed unaided an average of at least three enemas per week for at least 6 months. Radiographers’ practice had to be kept under regular audit.

Reporting

In total, 82 practitioners (including radiologists and fully trained radiographic technicians) interpreted BE scans in the study. Examinations could not be reported solely by a trainee radiologist without a subspecialty interest in GI radiology, so as to maintain parity with the CTC and colonoscopy groups. However, dual reporting was allowed, provided that one of the reporting clinicians fulfilled the criteria described above. In practice, all reports were either written or verified by a radiologist, except in a single centre, where dual reporting by senior radiographers was sometimes used. Radiologists or radiographers issued a report in accordance with normal clinical practice and completed a case report form (CRF) (see Appendix 1), which made it possible to capture additional information that would not routinely be mentioned in the report. Items recorded on the CRF included estimated size (mm) and location of detected lesions, the presence and site of diverticulosis, time taken for interpretation, technical difficulties (e.g. incontinence to barium or gas), quality of visualisation and any adverse events. Procedures were assessed as ‘very easy’, ‘quite easy’, ‘quite difficult’ or ‘very difficult’. The quality of the bowel preparation was rated as ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘adequate’ or ‘poor’. Visualisation of the six major large bowel segments (rectum, sigmoid, descending colon, transverse colon, ascending colon and caecum) was rated as ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘adequate’, ‘poor’ or ‘not seen’. The presence of diverticulosis in each segment was graded as ‘none’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’. If a polyp or cancer was visualised, confidence for its presence was rated as ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘adequate’ or ‘poor’.

Colonoscopy

Technical parameters

Colonoscopy was performed after full bowel preparation using video endoscopes. Sedation (usually 1–5 mg of midazolam) and analgesia (usually 50 µg of fentanyl or 25–50 mg of pethidine) were administered as judged clinically necessary. Examinations were carried out according to usual practice and any detected lesions were measured and either biopsied or excised where indicated.

Interpretation

A total of 217 gastroenterologists or colorectal surgeons who had satisfied criteria for competence performed colonoscopies in the study. After the trial obtained funding, the government announced three national training centres for endoscopy, one of which is the Wolfson Unit at St Mark’s Hospital in Harrow, UK, where the trial office was originally based. The aim of the national centres is to establish baseline and widespread competence in colonoscopy, and the training and accreditation procedures for the national centre were developed by trial collaborator Dr Brian Saunders. Assessment criteria for the GI endoscopists participating in the SIGGAR study were based on the accreditation procedures in place at the national training centres.

Reporting

A report was issued in line with normal clinical practice and an additional CRF completed, recording maximal diameter (mm) and location of detected lesions, information on any biopsies taken, presence and site of diverticulosis, depth of intubation and details of any adverse events. Procedures were assessed as ‘very easy’, ‘quite easy’, ‘quite difficult’ or ‘very difficult’. The quality of the bowel preparation was rated as ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘adequate’ or ‘poor’. The presence of diverticulosis in each segment was graded as ‘none’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’.

Computed tomographic colonography

Technical parameters

Computed tomographic colonography was performed in accordance with international guidelines for good practice,30,31 after full bowel preparation. Most centres used Picolax as the primary laxative, although one used macrogol (Klean-Prep®, Norgine Pharmaceuticals Ltd) and one used diatrizoate (Gastrografin®, Bayer Healthcare). In general, ‘dry’ preparations (e.g. Picolax) are better suited to CTC than wetter preparations, which are generally used for colonoscopy and can impair interpretation of CTC because lesions may be obscured by excess residual fluid. 32 Positive faecal tagging could be used if this was local practice or preferred. Examinations were performed following administration of intravenous spasmolytic, usually 20–40 mg of Buscopan, unless contraindicated. Insufflating gas could be either room air or carbon dioxide, according to local preference, and an automatic insufflator could be used. Intravenous contrast was administered at the discretion of the supervising radiologist, depending on local practice, their interpretation of the clinical circumstances of the patient and the probability that symptoms were due to extracolonic pathology.

Multidetector row machines were required, with a minimum capacity of four detector rows and individual slice collimation not exceeding 2.5 mm. A pitch that allowed abdominal coverage (40 cm) within a single breath hold (20 seconds at most) was used. Scans were usually obtained in two patient positions, normally prone and supine, but occasionally one of these plus lateral decubitus if the patient found it difficult to lie prone. In particularly frail patients, a single position could suffice if the supervising radiologist or CTC radiographer felt satisfied that distension was adequate to exclude a carcinoma.

Interpretation

In total, 46 radiologists registered by the Royal College of Radiologists and subspecialising in GI radiology interpreted CTC procedures in the trial. All were members of SIGGAR (now the British Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology), so as to reflect the type of radiologist likely to report CTC if implemented widely in UK practice (i.e. a subspecialist with an interest in GI imaging). All had prior experience of CTC, supplemented by a 2-day course for those who were judged to be relatively inexperienced (< 100 prior cases) and for more experienced radiologists who desired additional training (see Computed tomographic colonography training). The reading platform was determined by local preference but a minimum standard was primary analysis of the two-dimensional (2D) axial prone and supine CTC data sets, with volume-to-surface rendering for problem-solving. Visualisation software was provided [Voxar Colonscreen (Barco, Edinburgh, UK) and V3D (Viatronix, High Wycombe, UK)], but commercial alternatives were acceptable. Readers used 2D and 3D visualisation as required. Computer-assisted detection was also available (Medicsight PLC, London, UK). The primary focus was on identification/exclusion of significant colorectal neoplasia, defined as CRC or any polyp measuring ≥ 10 mm in maximal diameter, using electronic callipers on the 2D or 3D image, according to local preference.

Reporting

Radiologists issued a report and completed a CRF recording the same information as that for reporting BE examinations (see Barium Enema, Reporting). For CTC, the CRF included an additional section in which the radiologist could record details of extracolonic findings, including recommendations for any follow-up investigations that might be needed. Technical details of the scan were also recorded, including slice collimation (mm), number of detector rows, patient positioning (usually prone and supine), use of carbon dioxide or air for colon insufflation, use of mechanical insufflators, use of intravenous contrast or oral labelling, reading platform used and the proportion of 2D to 3D reading for interpretation.

Computed tomographic colonography training

Computed tomographic colonography is a new health technology with a steep learning curve. It is generally accepted that somewhere between 30 and 100 studies need to be analysed to achieve competence. In the UK, at the time recruitment began, relatively few radiologists possessed the requisite skills, although these skills are probably over-represented in the SIGGAR membership. ESGAR asked one of the present authors (SH) to formally assess the levels of training needed for competent CTC interpretation via a multicentre pan-European trial. 33 What is clear from the ESGAR study is that competence is variable and that some individuals can attain (and occasionally surpass) the median competence of very experienced readers after training on 50 endoscopically validated cases. Although many readers in the SIGGAR trial were very competent, it was clear from testing that others needed additional training, some of which was delivered by a 2-day course in June 2005 and some by one-to-one instruction at individual centres.

Recruitment

Suitable patients were identified from outpatient clinics and procedure waiting lists by the colorectal nurse specialist, who was responsible for checking the details of the referral and establishing that each patient met the trial entry criteria. Patients were then seen by the consulting physician, who assessed their need for a whole-colon examination and decided whether this should be a BE or colonoscopy. No patients could participate in the trial without the consultant’s consent. If consultant consent was given, the nurse specialist met the patient to explain the purpose of the study and describe the tests involved. Patient information sheets relating to the trial into which the patient was to be randomised (i.e. CTC vs. BE or CTC vs. colonoscopy) were given to the patient (see Appendix 2). All patients who wished to participate were given a consent form to complete. Patients recruited from outpatient departments were asked to complete the form in clinic, to ensure they could receive an appointment for their investigation on the day they were consented, and so would not be disadvantaged by having to return to the hospital to sign the form and arrange the procedure. For patients recruited from BE or colonoscopy waiting lists, the consent form and relevant patient information sheet were sent with an explanatory letter, inviting the patient to participate in the study. This was possible only if there was sufficient time for the consent form to be sent by post and returned, and (if necessary) for the patient’s procedure to be changed from a BE or colonoscopy to CTC, depending on the outcome of randomisation.

Once the consent form had been signed, the colorectal nurse specialist telephoned the trial office to randomise the patient. The patient’s name, sex, date of birth and the procedure for which they were originally referred (BE or colonoscopy) were recorded on the trial database and the randomised procedure was allocated and disclosed to the nurse specialist, who then booked the patient’s appointment. The trial office also sent an explanatory letter to the patient’s GP, informing them of the patient’s participation in the study.

Patients retained a copy of their consent form and the relevant patient information sheet and were given the telephone number of the trial office in case they had any further questions. They were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time, in which case the consent form would be destroyed by the nurse specialist and the patient allocated their original test.

Data collection

Demographic and baseline clinical information was collected on all potentially eligible patients, including those ultimately not randomised (the term ‘registered patients’ will be used here to refer to all patients who were registered as eligible for the trial but not subsequently randomised). Data at initial recruitment were recorded on a specially designed CRF (see Appendix 1), recording information such as the patient’s sex and date of birth, symptoms at presentation, urgency of the referral, details of the outpatient clinic, investigation requested and whether or not sigmoidoscopy was performed.

Details of the main trial procedures – BE, colonoscopy and CTC – were also recorded on CRFs, as were flexible sigmoidoscopies, surgical procedures and details of any outpatient appointments (see Appendix 1). Copies of the relevant radiology and endoscopy reports were also requested, along with copies of any pathology reports relating to endoscopy or surgery. Data on any other relevant procedures such as abdominal CT or gastroscopy were obtained by requesting a copy of the hospital report. Copies of patients’ discharge letters were also requested, to assist in determining their final diagnosis from the trial.

All documentation was collected by the local colorectal nurse specialist and sent to the trial office by post or fax. Forms were entered on a bespoke Oracle database (Oracle UK, Reading, UK) and any missing fields queried with the centre, to make the data as complete as possible.

Follow-up

After the randomised procedure, patients were referred for additional tests as judged clinically necessary, taking account of the patient’s status and symptoms, findings from the randomised procedure, and local policy. If cancer was detected by CTC or BE, options included referral for endoscopy and subsequent histological confirmation, or direct referral for staging examinations and/or surgery if the diagnosis of cancer was felt to be certain (which occurs more often in the case of CTC, as it has the capability to visualise the extramural extent of the cancer or to detect metastases outside the colon). Patients with lesions ≥ 10 mm at radiology exams were usually referred to endoscopy for excision and histological diagnosis. The decision to refer patients with smaller lesions was left to the clinician in charge, taking account of the patient’s age, wishes, nature of symptoms and the overall quality of the radiological examination. Further colonic investigation (usually endoscopy) was also requested where diagnostic uncertainty persisted following the randomised procedure, either owing to poor visualisation of one or more segments of the bowel, or when no cause for the patient’s symptoms had been found. Extracolonic lesions detected by CTC were also investigated if considered significant by the clinician in charge and details of these additional procedures were obtained.

If cancer was histologically confirmed at colonoscopy, patients could be referred directly for staging examinations and surgery. However, in cases for which lesions could not be histologically confirmed,if the examination was incomplete or if there was persistent clinical uncertainty, patients might be referred for additional tests.

If any adverse events occurred during or shortly after the randomised procedure, they could be reported by radiologists or endoscopists on the relevant trial CRF, or by patients themselves on a questionnaire completed the following day. Details of unplanned hospitalisations and deaths within 30 days of the randomised procedure were also collected, using hospital records and the NHS Information Centre (NHSIC), respectively. These were reviewed independently by a gastroenterologist, a radiologist and a surgeon, who each gave their opinion on whether or not the hospitalisation could be attributed to the patient’s randomised procedure (reviewers were blinded to the procedure type).

In order to identify any cancers missed by the trial procedures (including extracolonic cancers), all patients in the study were identified on the NHS Central Register (NHSCR) and details of new cancer diagnoses and deaths were obtained from NHSIC. Patients were also matched with national data from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) to reduce the time lag between cancer diagnosis and the time of notification. Cancers were confirmed using pathology and imaging reports obtained from the hospital where the cancer was diagnosed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome in the BE trial was the detection rate of CRC or large polyps (≥ 10 mm), confirmed histologically where possible. In a small number of cases, cancers were not confirmed histologically, for example because the presence of distant metastases was confirmed at CTC, or when staging scans showed the tumour to be unresectable. Secondary outcomes were referral rates for additional colonic investigation, time to diagnosis, miss rates for CRC, diagnoses of extracolonic cancer within 3 years, all-cause mortality and serious adverse events. Extracolonic findings at CTC were also analysed.

Evidence suggests that CTC and colonoscopy are similarly sensitive for the detection of cancer and polyps ≥ 10 mm,17 so a RCT powered on detection rates would be unfeasibly large (see Sample size). The primary outcome in the colonoscopy trial was therefore the proportion of patients undergoing additional colonic investigation following the randomised procedure, an important consideration if CTC is to become a suitable alternative to colonoscopy. Secondary outcomes were detection rates of CRC or large polyps, time to diagnosis, miss rates for CRC, other colorectal diagnoses, diagnoses of colonic and extracolonic cancer within 3 years, all-cause mortality and serious adverse events. Extracolonic findings at CTC were also analysed.

Sample size

In the BE trial, the sample size was initially calculated assuming a detection rate for cancers or large polyps of 15% for CTC and 10% for BE. With 2 : 1 randomisation in favour of BE, a sample size of 2160 gave 90% power to detect a significant difference in detection rates at 0.05 alpha (two-tailed). The 2 : 1 ratio was chosen so as not to overwhelm facilities for CTC and results in only a small loss of statistical power compared with the more usual 1 : 1 ratio.

In December 2005, an interim analysis performed for the external Data Monitoring Committee showed that the prevalence of significant neoplasia was lower than expected. It had been anticipated that this would differ between the two trials, as high-risk patients are more likely to be referred for colonoscopy (and, therefore, more likely to enter the colonoscopy than the BE trial). However, this difference was even larger than expected, with a prevalence of 12% in the colonoscopy trial and only 5% in the BE trial. The sample size, therefore, had to be increased and the power was dropped at the same time from 90% to the more conventional 80%. The revised calculation assumed detection rates for cancers and large polyps of 5% for BE and 7.5% for CTC. 34 With randomisation in a 2 : 1 ratio in favour of BE, a sample size of 3402 gave 80% power to detect a significant difference in detection rates at 0.05 alpha (two-tailed).

Powering the colonoscopy trial on detection rates would not have been practical. Assuming a detection rate of 15% for colonoscopy and a sensitivity of 93% for CTC relative to colonoscopy, with an inferiority margin equating to approximately 87% sensitivity, such a trial would require a total of 39,000 patients. The colonoscopy trial was, therefore, powered instead on the proportion of patients having additional colonic investigation following the randomised procedure. Assuming that symptomatic patients would need additional colonic tests in 20% of cases following CTC and 14% following colonoscopy, and with randomisation in a 2 : 1 ratio in favour of colonoscopy, a sample size of 2160 gave 90% power to detect a significant difference in referral rates at 0.05 alpha (two-tailed). However, as recruitment to the colonoscopy trial was proceeding at a lower rate than expected, it was decided to lower the power to 80% at the same time that this was done for the BE trial. Keeping all other assumptions as before, the new sample size required was 1430. The external Data Monitoring Committee approved all modifications.

Randomisation

The randomisation codes were generated by a programmer unconnected with the study and kept concealed until interventions were assigned. Randomisation was performed in blocks of six, stratified by centre, sex and diagnostic pathway (BE or colonoscopy). Details of the randomisation blocking, etc. were concealed from participating centres by excluding them from the study protocol for distribution.

Implementation

Once patients had agreed to take part in the study and signed the consent form, the colorectal nurse specialist contacted the trial office by telephone and gave the patient’s name, sex, date of birth and the procedure recommended by the clinician (BE or colonoscopy). These details were entered onto the trial database and the patient’s allocated test was then revealed.

Blinding

Given the nature of the interventions involved, there could be no blinding for either patients or medical staff.

Statistical methods

In the BE trial, both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were performed for the primary outcome. Intention-to-treat analyses considered the 2527 and 1277 patients randomised to BE and CTC, respectively, excluding those who withdrew consent. Per-protocol analyses considered the 2300 and 1206 patients who had their randomised procedure (BE and CTC respectively). Secondary outcomes were analysed only on a per-protocol basis, except for extracolonic cancers and overall mortality, which were analysed by intention to treat.

In the colonoscopy trial, both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were performed for the primary outcome, as well as for the secondary outcome of the detection rate of CRC or large polyps. All other secondary outcomes were analysed only on an intention-to-treat basis, except for CRC miss rates, adverse events and time to diagnosis, which were analysed by on a per-protocol basis. Intention-to-treat analyses considered the 1047 and 533 patients randomised to colonoscopy and CTC, respectively, excluding those who withdrew consent. Per-protocol analyses considered the 967 and 503 patients who had their randomised procedure (colonoscopy and CTC, respectively).

In patients who had FS prior to the randomised procedure, it was impossible to be certain whether or not the radiologist performing the randomised procedure was aware of the FS results. If any such lesions were seen again at the randomised procedure, we therefore had to assume that the radiologist was aware of the FS findings and these lesions were not counted as being detected at the randomised procedure. As a result, lesions found at sigmoidoscopy prior to randomisation were excluded from all analyses. Lesions found at FS between randomisation and the randomised procedure were included in the intention-to-treat analysis because these lesions were found in patients who were part of the randomised group, but were excluded from per-protocol analyses.

Detection rates were analysed on a per-patient basis, using the most advanced colonic lesion diagnosed. Lesions identified on successive procedures were matched based on size and location. The size measured at endoscopy was used as a reference standard unless it was unavailable or was exceeded by a measurement at pathology or surgery, in which case the latter was used. As in previous studies,15,16 lesions seen at randomised and subsequent procedures were considered to be the same if they were in the same or an adjacent colonic segment and the size was within 50% of the endoscopic measurement. For lesions not meeting these criteria, a consensus was reached by members of the research team.

When patients had a cancer or large polyp found during the trial, the date of diagnosis was defined as the date of the examination at which histological confirmation was first obtained (the date of first sighting on radiology was used for cancers that were not histologically confirmed). In the case of patients in whom no cancer or large polyp detected, the date of the final colonic examination was used (the date of the randomised procedure in patients with no subsequent referrals).

A CRC was defined as missed if it was identified through the NHSCR or the HES database within 36 months of randomisation but was not detected at the randomised procedure or mentioned in the patient’s final discharge letter.

Included extracolonic cancers were all reported primary malignant neoplasms, excluding CRCs [International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) site codes C18–C20] and non-melanoma malignant neoplasms of the skin (C44), diagnosed within 36 months of randomisation. The expected number of extracolonic cancers was calculated by applying age- and sex-specific cancer incidence rates for the general population to our cohort, having adjusted for reported mortality. Incidence rates were compared assuming a Poisson distribution.

Comparisons of categorical outcomes were made using Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Relative risks (RRs) or risk differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate differences between groups. RRs by age group (< 65 years and ≥ 65 years) and sex were illustrated using forest plots and tests of interaction (Mantel–Haenszel) were used to identify significant differences. Trial participants were randomised individually but we expected some natural clustering by centre. To check whether or not clustering by trial centre affected results, we also analysed the primary outcomes using random-effects logistic models allowing for heterogeneity in the outcome and intervention effects by centre (odds ratios were compared). All tests were two-tailed, with significance assigned at 5%. Analysis was performed using Stata 9.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Chapter 3 Results

This chapter contains information reprinted with permission from Elsevier, The Lancet, 2013, vol. 381, Halligan S, Wooldrage K, Dadswell E, Kralj-Hans I, von Wagner C, Edwards R, et al. Computed tomographic colonography versus barium enema for diagnosis of colorectal cancer or large polyps in symptomatic patients (SIGGAR): a multicentre randomised trial, pp. 1185–93;35 and The Lancet, 2013, vol. 381, Atkin W, Dadswell E, Wooldrage K, Kralj-Hans I, von Wagner C, Edwards R, et al. Computed tomographic colonography versus colonoscopy for diagnosis of colorectal cancer or large polyps in symptomatic patients (SIGGAR): a multicentre randomised clinical trial, pp. 1194–202. 36

Patient recruitment and randomisation

Patient recruitment began in March 2004 and was completed in December 2007, by which time the number of patients randomised in each trial had exceeded the target sample size. In total, 8484 patients were registered to the trial from 21 centres. Table 1 shows registration and randomisation by centre (centres ordered by date of joining the trial). The proportion of registered patients varied significantly by centre and may have been due to inadequate reporting of all eligible patients at some centres. In addition, centres relying heavily on recruitment from procedure waiting lists may have had lower rates of registration as they were only identifying patients who had already been referred for a whole-colon examination.

| Centre | Total registered | Registered only, excluded from randomisation | Randomised | Randomised within the BE vs. CTC trial | Randomised within the colonoscopy vs. CTC trial | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % of centre total | n | % of centre total | n | % of centre total | n | % of centre total | |

| St Mark’s | 1721 | 20 | 1012 | 59 | 709 | 41 | 216 | 13 | 493 | 29 |

| Birmingham | 441 | 5 | 25 | 6 | 416 | 94 | 310 | 70 | 106 | 24 |

| Bradford | 766 | 9 | 217 | 28 | 549 | 72 | 433 | 57 | 116 | 15 |

| Oldham | 454 | 5 | 270 | 59 | 184 | 41 | 151 | 33 | 33 | 7 |

| Portsmouth | 882 | 10 | 316 | 36 | 566 | 64 | 524 | 59 | 42 | 5 |

| Cornwall (Truro) | 536 | 6 | 73 | 14 | 463 | 86 | 366 | 68 | 97 | 18 |

| Lancaster | 451 | 5 | 84 | 19 | 367 | 81 | 358 | 79 | 9 | 2 |

| Nottingham City Hospital | 251 | 3 | 138 | 55 | 113 | 45 | 95 | 38 | 18 | 7 |

| Bath | 477 | 6 | 38 | 8 | 439 | 92 | 344 | 72 | 95 | 20 |

| Nottingham Queen’s Medical Centre | 410 | 5 | 186 | 45 | 224 | 55 | 210 | 51 | 14 | 3 |

| Crewe | 655 | 8 | 224 | 34 | 431 | 66 | 413 | 63 | 18 | 3 |

| Charing Cross | 256 | 3 | 115 | 45 | 141 | 55 | 5 | 2 | 136 | 53 |

| Plymouth | 250 | 3 | 16 | 6 | 234 | 94 | 33 | 13 | 201 | 80 |

| Hammersmith | 47 | 0.6 | 3 | 6 | 44 | 94 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 94 |

| Withington | 179 | 2 | 49 | 27 | 130 | 73 | 119 | 66 | 11 | 6 |

| Wythenshawe | 32 | 0.4 | 12 | 37 | 20 | 63 | 20 | 63 | 0 | 0 |

| Furness | 112 | 1 | 24 | 21 | 88 | 79 | 73 | 65 | 15 | 13 |

| Frimley Park | 59 | 0.7 | 18 | 31 | 41 | 69 | 17 | 29 | 24 | 41 |

| Oxford | 162 | 2 | 13 | 8 | 149 | 92 | 147 | 91 | 2 | 1 |

| Paddington (St Mary’s) | 271 | 3 | 164 | 61 | 107 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 107 | 39 |

| North Tees | 72 | 0.8 | 39 | 54 | 33 | 46 | 4 | 6 | 29 | 40 |

| Total | 8484 | 100 | 3036 | 36 | 5448 | 64 | 3838 | 45 | 1610 | 19 |

Baseline patient characteristics

Of the 8484 patients considered potentially eligible for the trial, 3036 were ultimately not randomised. Reasons why these patients were not included are given in Table 2. In most cases (72%), it was the clinician in charge of the patient’s care who made the decision not to enter the patient into the trial, usually because the clinician felt that a specific examination was needed and, therefore, could not allow the patient to be randomised. A smaller group of patients (7% of those excluded) met the eligibility criteria but were judged by the clinician to be unfit for a whole-colon examination. In 27% of cases it was the patient who declined consent, usually because they wanted to have a specific procedure, for example because they felt colonoscopy was too invasive or they were attracted by the possibility of extracolonic imaging at CTC.

| Reason | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Clinician reasons for declining consent | ||

| Colorectal or other cancer already diagnosed | ||

| CRC diagnosed | 56 | 1.8 |

| Other cancer diagnosed | 69 | 2.3 |

| Specific procedure requested | ||

| Colonoscopy | 731 | 24.1 |

| CT | 303 | 10.0 |

| FS | 230 | 7.6 |

| Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy | 218 | 7.2 |

| BE | 19 | 0.6 |

| Ultrasonography | 16 | 0.5 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 5 | 0.2 |

| Unknown | 39 | 1.3 |

| Clinical situation too urgent or waiting list too long | 52 | 1.7 |

| Patient unfit for whole-colon examination | 215 | 7.1 |

| Patient unable to give informed consent | 75 | 2.5 |

| No reason given | 148 | 4.9 |

| Total where clinician declined consent | 2176 | 71.7 |

| Patient reasons for declining consent | ||

| Patient wanted a specific procedure | ||

| Colonoscopy | 15 | 0.5 |

| CT | 3 | 0.1 |

| BE | 2 | 0.07 |

| Unknown | 128 | 4.2 |

| Patient did not want a specific procedure | ||

| CT as claustrophobic | 13 | 0.4 |

| CT for other reasons | 2 | 0.07 |

| Colonoscopy | 1 | 0.03 |

| BE | 1 | 0.03 |

| Patient had difficulty comprehending | 84 | 2.8 |

| Patient died before consent obtained | 2 | 0.07 |

| No reason given | 583 | 19.2 |

| Total where patient declined consent | 834 | 27.5 |

| Reason for exclusion unknown | 26 | 0.9 |

| Total excluded | 3036 | 100.0 |

Table 3 shows the baseline characteristics of patients in the BE trial compared with those patients who were not randomised in either trial. The proportion of women in the BE trial was significantly higher than in the non-randomised group. There was a significant difference in the age profile of the two groups, with patients in the BE trial being younger overall. There were also significant differences in all symptoms between the two groups, with patients in the BE trial more likely to present with a change in bowel habit or abdominal pain and less likely to present with rectal bleeding, anaemia or weight loss. The BE trial contained a significantly lower proportion of 2-week-wait patients than the non-randomised group.

| Randomised within BE vs. CTC trial (n = 3838) | Excluded from both BE vs. CTC trial and colonoscopy vs. CTC trial (n = 3036) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1483 | 39 | 1251 | 41 | 0.031 |

| Female | 2355 | 61 | 1785 | 59 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 55–64 | 1253 | 33 | 802 | 26 | < 0.001 |

| 65–74 | 1498 | 39 | 1045 | 34 | |

| 75–84 | 980 | 26 | 930 | 31 | |

| 85 + | 107 | 3 | 259 | 9 | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Change in bowel habit | 2909 | 76 | 1926 | 63 | < 0.001 |

| Harder, less frequent | 490 | 13 | 297 | 10 | |

| Looser, more frequent | 1557 | 41 | 1049 | 35 | |

| Variable frequency | 355 | 9 | 180 | 6 | |

| Unspecified | 507 | 13 | 400 | 13 | |

| Rectal bleeding | 1167 | 30 | 1169 | 39 | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 1235 | 32 | 574 | 19 | < 0.001 |

| Anaemia | 476 | 12 | 620 | 20 | < 0.001 |

| Weight loss | 523 | 14 | 500 | 16 | 0.001 |

| Other symptoms | 431 | 11 | 585 | 19 | < 0.001 |

| Route of referral | |||||

| Outpatient clinic | < 0.001 | ||||

| Colorectal surgical clinic | 2964 | 77 | 2733 | 90 | |

| Gastroenterology | 462 | 12 | 192 | 6 | |

| Geriatrics | 5 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.2 | |

| Other clinic type | 59 | 2 | 46 | 2 | |

| Unknown clinic type | 9 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.1 | |

| GP | 237 | 6 | 32 | 1 | |

| Other | 93 | 2 | 21 | 0.7 | |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Urgency of referral | |||||

| 2-week wait | 1682 | 44 | 1851 | 61 | < 0.001 |

| Urgent | 649 | 17 | 511 | 17 | |

| Soon | 484 | 13 | 179 | 6 | |

| Routine | 686 | 18 | 315 | 10 | |

| Not recorded | 337 | 9 | 180 | 6 | |

A comparison of the baseline characteristics of patients in the colonoscopy trial and those who were not randomised is given in Table 4. The colonoscopy trial had a significantly lower proportion of female patients than the non-randomised group. There was also a significant difference in the age of patients, with those in the colonoscopy trial being younger overall. The colonoscopy trial contained a higher proportion of patients presenting with a change in bowel habit, rectal bleeding, or abdominal pain and a lower proportion with anaemia. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with weight loss as one of the presenting symptoms.

| Randomised within colonoscopy vs. CTC trial (n = 1610) | Excluded from both BE vs. CTC trial and colonoscopy vs. CTC trial (n = 3036) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 729 | 45 | 1251 | 41 | 0.0075 |

| Female | 881 | 55 | 1785 | 59 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 55–64 | 609 | 38 | 802 | 26 | <0.001 |

| 65–74 | 576 | 36 | 1045 | 34 | |

| 75–84 | 372 | 23 | 930 | 31 | |

| 85 + | 53 | 3 | 259 | 9 | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Change in bowel habit | 1175 | 73 | 1926 | 63 | <0.001 |

| Harder, less frequent | 194 | 12 | 297 | 10 | |

| Looser, more frequent | 635 | 39 | 1049 | 35 | |

| Variable frequency | 182 | 11 | 180 | 6 | |

| Unspecified | 164 | 10 | 400 | 13 | |

| Rectal bleeding | 686 | 43 | 1169 | 39 | 0.0066 |

| Abdominal pain | 357 | 22 | 574 | 19 | 0.0081 |

| Anaemia | 208 | 13 | 620 | 20 | <0.001 |

| Weight loss | 240 | 15 | 500 | 16 | 0.17 |

| Other symptoms | 280 | 17 | 585 | 19 | 0.12 |

| Route of referral | |||||

| Outpatient clinic | <0.001 | ||||

| Colorectal surgical clinic | 1401 | 87 | 2733 | 90 | |

| Gastroenterology | 106 | 7 | 192 | 6 | |

| Geriatrics | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0.2 | |

| Other clinic type | 12 | 0.7 | 46 | 2 | |

| Unknown clinic type | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.1 | |

| GP | 62 | 4 | 32 | 1 | |

| Other | 29 | 2 | 21 | 0.7 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Urgency of referral | |||||

| 2-week wait | 963 | 60 | 1851 | 61 | <0.001 |

| Urgent | 333 | 21 | 511 | 17 | |

| Soon | 94 | 6 | 179 | 6 | |

| Routine | 105 | 7 | 315 | 10 | |

| Not recorded | 115 | 7 | 180 | 6 | |

Comparing patients randomised in the BE trial with those randomised in the colonoscopy trial (Table 5), patients in the BE trial were older and more likely to be female. They were less likely to present with rectal bleeding and more likely to present with abdominal pain and change in bowel habit. There was no significant difference between the two trials in the proportion of patients presenting with anaemia or weight loss.

| Randomised within BE vs. CTC trial (n = 3838) | Randomised within colonoscopy vs. CTC trial (n = 1610) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1483 | 39 | 729 | 45 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 2355 | 61 | 881 | 55 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 55–64 | 1253 | 33 | 609 | 38 | 0.001 |

| 65–74 | 1498 | 39 | 576 | 36 | |

| 75–84 | 980 | 26 | 372 | 23 | |

| 85 + | 107 | 3 | 53 | 3 | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Change in bowel habit | 2909 | 76 | 1175 | 73 | 0.029 |

| Harder, less frequent | 490 | 13 | 194 | 12 | |

| Looser, more frequent | 1557 | 41 | 635 | 39 | |

| Variable frequency | 355 | 9 | 182 | 11 | |

| Unspecified | 507 | 13 | 164 | 10 | |

| Rectal bleeding | 1167 | 30 | 686 | 43 | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 1235 | 32 | 357 | 22 | < 0.001 |

| Anaemia | 476 | 12 | 208 | 13 | 0.60 |

| Weight loss | 523 | 14 | 240 | 15 | 0.21 |

| Other symptoms | 431 | 11 | 280 | 17 | < 0.001 |

| Route of referral | |||||

| Outpatient clinic | < 0.001 | ||||

| Colorectal surgical clinic | 2964 | 77 | 1401 | 87 | |

| Gastroenterology | 462 | 12 | 106 | 7 | |

| Geriatrics | 5 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other clinic type | 59 | 2 | 12 | 0.7 | |

| Unknown clinic type | 9 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | |

| GP | 237 | 6 | 62 | 4 | |

| Other | 93 | 2 | 29 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Urgency of referral | |||||

| 2-week wait | 1682 | 44 | 963 | 60 | < 0.001 |

| Urgent | 649 | 17 | 333 | 21 | |

| Soon | 484 | 13 | 94 | 6 | |

| Routine | 686 | 18 | 105 | 7 | |

| Not recorded | 337 | 9 | 115 | 7 | |

Flexible sigmoidoscopies

Among randomised patients, the proportion of patients having FS before recruitment differed in the two groups, with the highest rate in the BE trial [25.1% (963/3838) vs. 9.1% (147/1610) for the colonoscopy trial; p < 0.0001]. This was probably as a result of variations in the use of FS between centres because the proportion of patients from each centre varied substantially between the two trials, as shown in Table 1.

Barium enema trial

Numbers analysed

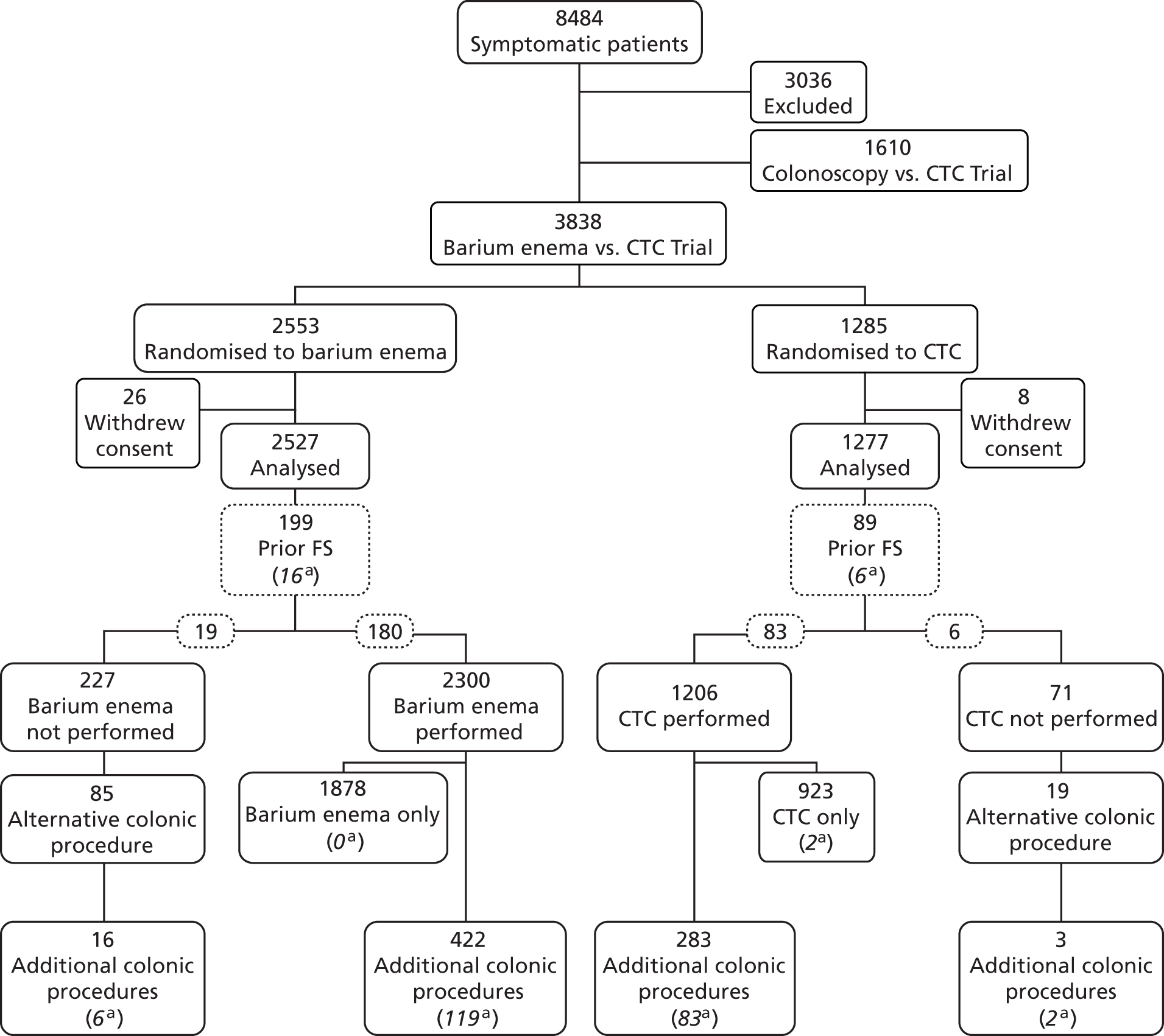

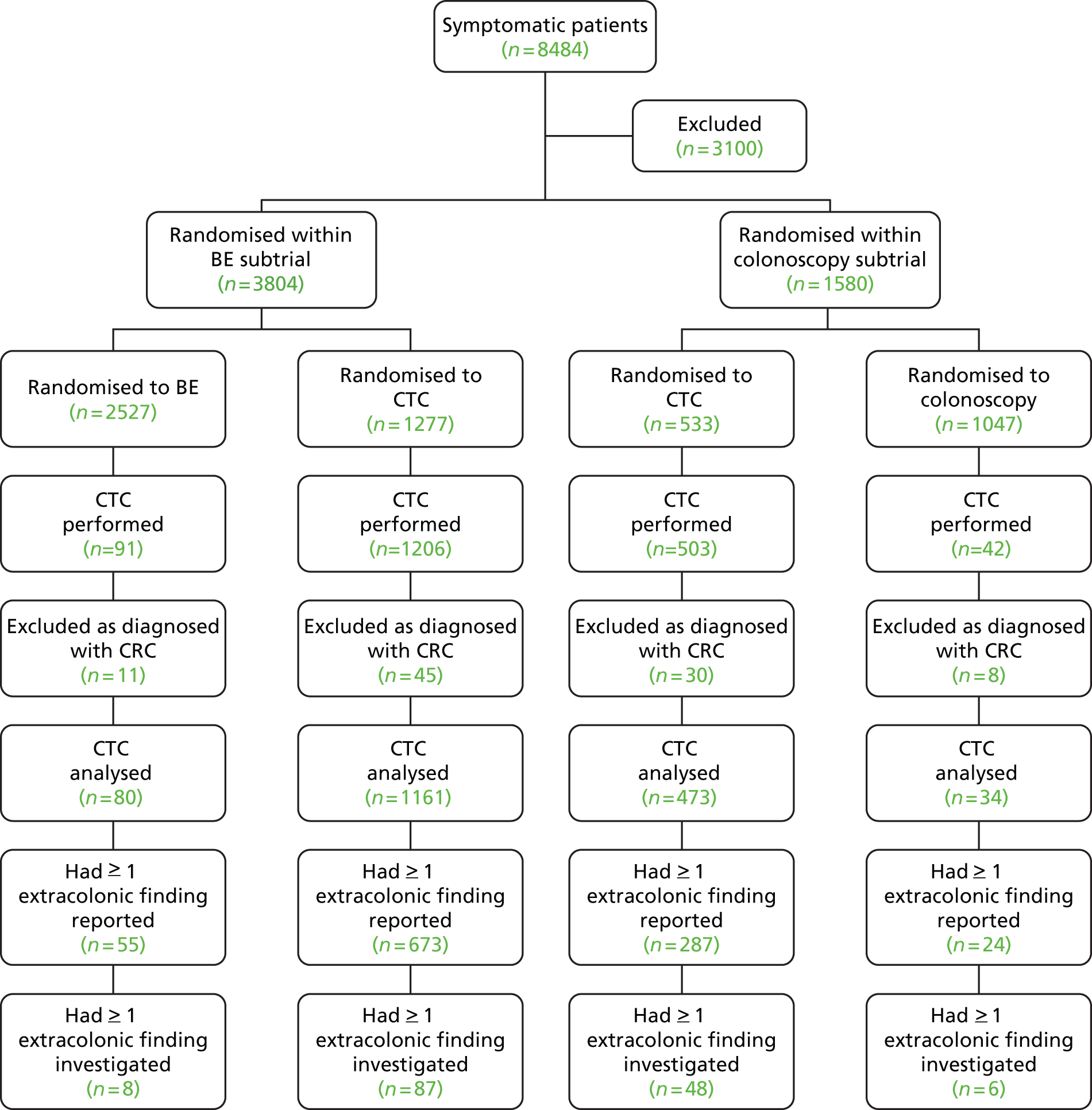

As seen in Figure 2, a total of 5448 patients were randomised in the study, with 1610 entering the colonoscopy trial and 3838 entering the BE trial, who were randomised between BE (n = 2553) and CTC (n = 1285). Thirty-four patients withdrew consent [26 (1%) in the BE and eight (1%) in the CTC arm], leaving 3804 for analysis (2527 BE and 1277 CTC). The proportion of patients withdrawing consent did not differ significantly between the two procedures.

FIGURE 2.

Participants’ progress through the BE vs. CTC trial and selected outcomes. a, Number of patients with cancers or large polyps diagnosed at that procedure.

Centres varied in the number of patients randomised to the BE trial [median 151, interquartile range (IQR) 33–358]. There were no significant differences in the demographic or clinical characteristics of patients randomised to BE or CTC (Table 6) (this is also true if patients who withdrew consent are included). The median age of patients was 69 years (IQR 62–75 years), and 61% were women. The most frequent presenting symptoms were change in bowel habit (76%), abdominal pain (32%) and rectal bleeding (30%); patients could report more than one symptom.

| Characteristic | Randomised to BE (n = 2527) | Randomised to CTC (n = 1277) | Total (n = 3804) | Excluded (n = 3036) | p-valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 983 | 39 | 490 | 38 | 1473 | 39 | 1251 | 41 | 0.0371 |

| Female | 1544 | 61 | 787 | 62 | 23311 | 61 | 1785 | 59 | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 55–64 | 826 | 33 | 416 | 33 | 1242 | 33 | 802 | 26 | < 0.0001 |

| 65–74 | 993 | 39 | 494 | 39 | 1487 | 39 | 1045 | 34 | |

| 75–84 | 640 | 25 | 330 | 26 | 970 | 25 | 930 | 31 | |

| 85 + | 68 | 3 | 37 | 3 | 105 | 3 | 259 | 9 | |

| Symptomsb | |||||||||

| Change in bowel habit | 1910 | 76 | 975 | 76 | 2885 | 76 | 1926 | 63 | < 0.0001 |

| Harder, less frequent | 321 | 13 | 166 | 13 | 490 | 13 | 297 | 10 | |

| Looser, more frequent | 1007 | 40 | 535 | 42 | 1557 | 41 | 1049 | 35 | |

| Variable frequency | 240 | 9 | 113 | 9 | 355 | 9 | 180 | 6 | |

| Unspecified | 342 | 14 | 161 | 13 | 507 | 13 | 400 | 13 | |

| Rectal bleeding | 767 | 30 | 388 | 30 | 1155 | 30 | 1169 | 39 | < 0.0001 |

| Abdominal pain | 819 | 32 | 406 | 32 | 1225 | 32 | 574 | 19 | < 0.0001 |

| Anaemia | 319 | 13 | 153 | 12 | 472 | 12 | 620 | 20 | < 0.0001 |

| Weight loss | 331 | 13 | 185 | 14 | 516 | 14 | 500 | 16 | 0.0008 |

| Other symptoms | 289 | 11 | 138 | 11 | 427 | 11 | 585 | 19 | < 0.0001 |

The number of patients who went on to have their randomised procedure is shown in Table 7, along with reasons why the procedure did not occur. A lower proportion of patients randomised to BE had their randomised procedure [91.0% (2300/2527) for BE vs. 94.4% (1206/1277) for CTC; p = 0.0002]. The main reason for this is that a larger proportion of patients were judged by the clinician to be unable to tolerate the examination (2.2%), which was rare for CTC (0.3%). There were also a substantial proportion of patients who did not want to have their randomised procedure, but this did not differ significantly between groups (3.2% for BE vs. 2.5% for CTC). Of those patients randomised to BE who did not have their assigned procedure, 37% (85/227) had an alternative procedure, usually CTC (62%, 53/85) or colonoscopy (21%, 18/85). Of those randomised to CTC who did not have their procedure, 27% (19/71) had an alternative examination usually BE (74%, 14/19) or colonoscopy (11%, 2/19).

| Status | BE (n = 2527) | CTC (n = 1277) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Occurrence of randomised procedure | |||||

| Occurred | 2300 | 91.0 | 1206 | 94.4 | 0.0002 |

| Did not occur | 227 | 9.0 | 71 | 5.6 | |

| Reasons did not occur | |||||

| Patient’s decision | |||||

| Patient refused randomised procedure | 81 | 3.2 | 32 | 2.5 | 0.27 |

| Patient did not attend scheduled procedure | 27 | 1.1 | 13 | 1.0 | |

| Total | 108 | 4.3 | 45 | 3.5 | |

| Medical decision | |||||

| Patient unable to tolerate randomised procedure | 55 | 2.2 | 4 | 0.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Finding at prior FS | 10 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Consultant requested alternative procedure | 29 | 1.0 | 11 | 0.9 | |

| Patient became too ill | 16 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Patient’s symptoms resolved | 4 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Patient died | 4 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Total | 118 | 4.7 | 23 | 1.8 | |

| Other reasons | |||||

| Equipment failure | 1 | 0.03 | 3 | 0.2 | 0.11 |

| Total | 1 | 0.03 | 3 | 0.2 | |

Prior FS was performed in 199 patients (7.9%) in the BE arm and 89 (7.0%) in the CTC arm (p = 0.32) (see Figure 2). The performance of prior FS did not affect the occurrence of the randomised procedure (91.3% in those who had prior FS, vs. 92.2% in those who did not; p = 0.58).

Performance of the examinations

A greater proportion of BE examinations were judged to be difficult to perform, with 24.1% (554/2300) rated as ‘quite’ or ‘very’ difficult, compared with 9.0% (109/1206) for CTC (p < 0.0001). Similarly, in a significantly higher proportion of BE examinations there was at least one segment that was not seen or for which the radiologist rated visualisation as ‘poor’: 22.3% (514/2300) for BE and 16.1% (194/1206) for CTC (p < 0.0001). In the left colon, there was no significant difference in the quality of visualisation between BE and CTC. However, poor visualisation in the right colon was more than twice as likely to be reported at BE (12.1%) as at CTC (4.9%) (p < 0.0001).

Outcomes

Detection of colorectal cancer and large polyps

Among 2527 patients randomised to BE, a CRC or large polyp was diagnosed in 141: in 119 following BE, in 16 at FS prior to BE and in six patients who had an alternative procedure (see Figure 2). Among 1277 patients randomised to CTC, a CRC or large polyp was diagnosed in 93: in 85 following CTC, in six at prior FS and in two patients having an alternative whole-colon investigation. The 141 lesions diagnosed in patients randomised to BE included 86 CRCs (including one carcinoid tumour and five non-pathologically confirmed cancers) and 55 large polyps (51 adenomas, two hyperplastic polyps, one juvenile polyp and a polyp ≥ 10 mm which was excised but not retrieved). The 93 lesions diagnosed in patients randomised to CTC included 47 CRCs (including two non-pathologically confirmed cancers) and 46 large polyps (41 adenomas, one hyperplastic polyp, one serrated adenoma and three polyps ≥ 10 mm which were excised but not retrieved). Analysing by intention to treat, the overall detection rate of CRC or large polyps was 7.3% (93/1277) in the CTC arm and 5.6% (141/2527) in the BE arm (p = 0.0390) (Table 8). The difference was mainly as a result of a higher detection rate of large polyps in the CTC arm (3.6% vs. 2.2%; p = 0.0098). There was no significant difference in detection rates of CRC (3.7% vs.3.4%; p = 0.66). Analysing per protocol, a cancer or large polyp was diagnosed in 7.0% (85/1206) of patients having CTC and 5.2% (119/2300) having a BE (p = 0.0243).

| Analysis | BE group | CTC group | Comparison of detection rates between procedures (CTC vs. BE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to treat | N = 2527 | N = 1277 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | RR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| CRC | 86b | 3.4 | 47c | 3.7 | 1.08 | 0.76 to 1.53 | 0.6600 |

| ≥ 10-mm polypd | 55e | 2.2 | 46f | 3.6 | 1.66 | 1.13 to 2.43 | 0.0098 |

| CRC or ≥ 10-mm polypd | 141b,e | 5.6 | 93c,f | 7.3 | 1.31 | 1.01 to 1.68 | 0.0390 |

| Per protocol | N = 2300 | N = 1206 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| CRC | 73b | 3.2 | 42c | 3.5 | 1.10 | 0.76 to 1.59 | 0.6300 |

| ≥ 10-mm polypd | 46e | 2.0 | 43f | 3.6 | 1.78 | 1.18 to 2.69 | 0.0051 |

| CRC or ≥ 10-mm polypd | 119b,e | 5.2 | 85c,f | 7.0 | 1.36 | 1.04 to 1.78 | 0.0243 |

The difference in detection rates between BE and CTC is probably due to the greater sensitivity of CTC for small lesions. BE and CTC have similar sensitivity for cancer, but most cancers in the trial were larger than 30 mm in size (Table 9). CTC was significantly better at detecting small lesions; the proportion of patients for whom the largest confirmed lesion was < 10 mm was 2.5% (58/2300) for BE and 4.3% for CTC (52/1206) (p = 0.0039) (see Table 9).

| Type of lesion and size | BE (N = 2300) | CTC (N = 1206) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| CRCs | ||||

| ≥ 30 mm | 62 | 2.7 | 33 | 2.7 |

| 20–29 mm | 9 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.5 |

| 15–19 mm | 1 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.08 |

| 10–14 mm | 1 | 0.04 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Total | 73 | 3.2 | 42 | 3.5 |

| Large polyps | ||||

| ≥ 30 mm | 7 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.6 |

| 20–29 mm | 5 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.5 |

| 15–19 mm | 13 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.7 |

| 10–14 mm | 21 | 0.9 | 21 | 1.7 |

| Total | 46 | 2.0 | 43 | 3.6 |

| Small polyps | ||||

| 6–9 mm | 16 | 0.7 | 15 | 1.2 |

| ≤ 5 mm | 42 | 1.8 | 37 | 3.1 |

| Total | 58 | 2.5 | 52 | 4.3 |

| No polyps or cancers detected | 2123 | 92.3 | 1069 | 88.6 |

Comparing results from models ignoring clustering to those controlling for clustering by trial centre showed that odds ratios were very similar in size and significance (Table 10).

| Analysis | No clustering | With clusteringa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Intention-to-treat analysis | 1.33 | 1.01 to 1.74 | 0.0390 | 1.44 | 1.04 to 2.01 | 0.0302 |

| Per-protocol analysis | 1.39 | 1.04 to 1.85 | 0.0243 | 1.47 | 1.01 to 2.14 | 0.0455 |

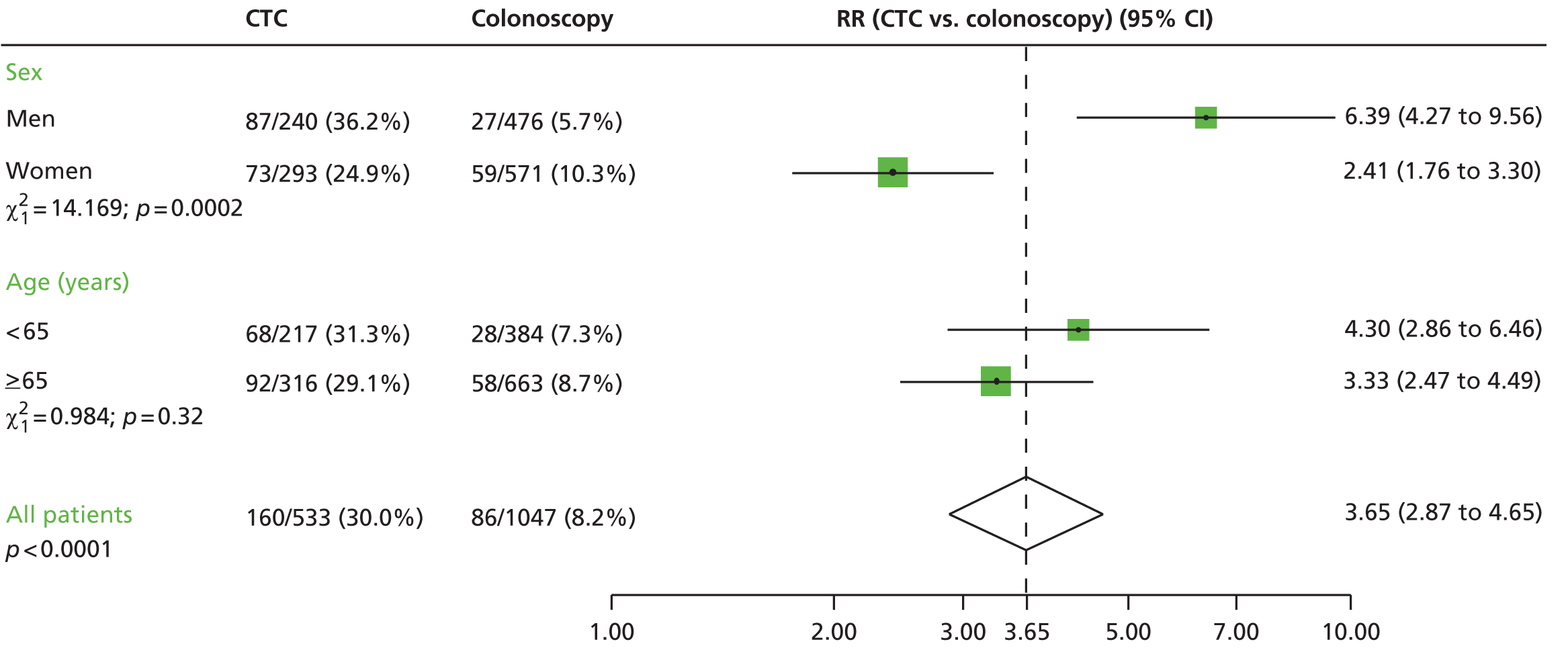

There was a significant difference by age in the relative detection rate following CTC compared with BE (p = 0.0159); in younger patients, the detection rate following CTC was double that for BE, whereas in older patients the RR did not differ from that found overall (age < 65 years: RR 2.32, 95% CI 1.36 to 3.94; age ≥ 65 years: RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.47) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference in relative detection rates between men and women (p = 0.66).

FIGURE 3.

Relative risks for CRC or large polyps (CTC vs. BE) by sex and age group in the BE vs. CTC trial.

Further colonic investigation

The proportion of patients undergoing a second colonic investigation was significantly higher in the CTC group [23.5% (283/1206)] than in the BE group [18.3% (422/2300); p = 0.0003] (Table 11 and see Figure 2). This was true whether the referral was for a suspected cancer or large polyp (11.0% vs. 7.5%; p = 0.0005) or for suspected smaller polyps (7.2% vs. 2.3%; p < 0.0001). Conversely, a lower proportion required further investigation because of an inadequate examination or clinical uncertainty (5.2% vs. 8.5%; p = 0.0005).

| Reason for referral | BE performed (N = 2300) | CTC performed (N = 1206) | Comparison of referral rates between procedures (CTC vs. BE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | RR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Cancer or large (≥ 10 mm) polyp suspected | |||||||

| Cancer | 86 | 3.7 | 68 | 5.6 | 0.0005 | ||

| Polyp ≥ 10 mm | 87 | 3.8 | 65 | 5.4 | |||

| Total with cancer or large (≥ 10 mm) polyp suspected | 173 | 7.5 | 133 | 11.0 | 1.47 | 1.18 to 1.82 | |

| Smaller polyp suspected | |||||||

| Polyp 8–9 mm | 18 | 0.8 | 18 | 1.5 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Polyp 6–7 mm | 12 | 0.5 | 34 | 2.8 | |||

| Polyp ≤ 5 mm | 24 | 1.0 | 35 | 2.9 | |||

| Total with smaller polyp suspected | 54 | 2.3 | 87 | 7.2 | 3.07 | 2.20 to 4.28 | |

| Clinical uncertainty (no polyps seen) | |||||||

| Inadequate examination | 116 | 5.0 | 34 | 2.8 | 0.56 | 0.38 to 0.81 | 0.0020 |

| Adequate examination | 79 | 3.4 | 29 | 2.4 | |||

| Total with clinical uncertainty | 195 | 8.5 | 63 | 5.2 | 0.62 | 0.47 to 0.81 | 0.0005 |

| Total having second procedure | 422 | 18.3 | 283 | 23.5 | 1.28 | 1.12 to 1.46 | 0.0003 |

Of the 422 patients referred following BE, 368 (87%) had colonoscopy (complete or limited as appropriate), 29 had a radiological procedure and 25 were referred straight to surgery. Of the 283 patients referred following CTC, 259 (91%) had colonoscopy, six had a radiological procedure and 18 were referred straight to surgery.

The probability of diagnosing a cancer or large polyp at a subsequent procedure (positive predictive value) was similar for patients referred because of findings at CTC or BE (29% vs. 28%, respectively) (Table 12). Among patients referred because of a suspected cancer or large polyp, the proportion in whom the lesion was confirmed was also similar for CTC and BE (56% vs. 62%). Of those referred because of smaller lesions at the randomised procedure, important end points were diagnosed in 10% referred after CTC (9/87; one cancer, eight polyps ≥ 10 mm) and 7% referred after BE (4/54; one cancer, three polyps ≥ 10 mm). Of 195 patients who had a second procedure because of clinical uncertainty after BE, four were found to have cancers and four had large polyps. No cancers or large polyps were detected in the 63 patients referred because of clinical uncertainty after CTC. Among patients not referred for an additional procedure, there remained a number of patients with incomplete or inadequate examinations: in BE 18.2% (341/1878) and in CTC 13.2% (122/923).

| Randomised procedure undertaken | BE | CTC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second colonic procedure undertaken | Lesions diagnosed at second procedure | Second colonic procedure undertaken | Lesions diagnosed at second procedure | |||||||||||

| CRC | Polyp ≥ 10 mmb | Cancer or polyps ≥ 10 mmb | CRC | Polyp ≥ 10 mmb | Cancer or polyps ≥ 10 mmb | |||||||||

| Reason for referral | N | n | % | n | % | n | % | N | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Cancer or large (≥ 10 mm) polyp suspected | ||||||||||||||

| Cancer | 86 | 64c | 74 | 7 | 8 | 71 | 83 | 68 | 36 | 53 | 2 | 3 | 38 | 56 |

| Polyp ≥ 10 mm | 87 | 4 | 5 | 32 | 37 | 36 | 41 | 65 | 3 | 5 | 33 | 51 | 36 | 55 |

| Total with cancer or large (≥ 10 mm) polyp suspected | 173 | 68c | 39 | 39 | 23 | 107 | 62 | 133 | 39 | 29 | 35 | 26 | 74 | 56 |

| Smaller polyp suspected | ||||||||||||||

| Polyp 8–9 mm | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 28 | 6 | 33 |

| Polyp 6–7 mm | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 |

| Polyp ≤ 5 mm | 24 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 4 | 17 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Total with smaller polyp suspected | 54 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 87 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Clinical uncertainty (no polyps seen) | ||||||||||||||

| Inadequate examination | 116 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adequate examination | 79 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total with clinical uncertainty | 195 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total having second procedure | 422 | 73c | 17 | 46 | 11 | 119 | 28 | 283 | 40 | 14 | 43 | 15 | 83 | 29 |

Time to diagnosis

Among patients who had their randomised procedure, the median time from the date of randomisation to the date of diagnosis was 23 days (IQR 14–40 days); the time was significantly longer for patients having CTC (n = 1206, median 28 days, IQR 16–47 days vs. BE n = 2300, median 21 days, IQR 14–37 days; p < 0.0001). The time to the randomised procedure was slightly longer for CTC (median 22 days, IQR 15–34 days vs. BE: median 18 days, IQR 12–28 days; p < 0.0001), but for subjects who had an additional referral after the randomised procedure there was no difference between procedures in the time from the randomised procedure to the second procedure [CTC (n = 283 patients) median 50 days, IQR 28–94 days vs. BE (n = 422 patients) median 49.5 days, IQR 27–94 days; p = 0.84]. For patients who had a diagnosis of cancer or a large polyp, the time to diagnosis for those having CTC was significantly longer [CTC (n = 93 patients) median 64 days, IQR 38–99 days vs. BE (n = 141 patients) median 47 days, IQR 30–72 days; p = 0.0045].

Extracolonic findings following computed tomographic colonography

At least one previously unknown extracolonic finding was reported in 58% (673/1161) of patients having CTC who did not have CRC diagnosed during the trial (patients with CRC were excluded from the analysis because it is not always possible to be sure that extracolonic findings are unrelated to the CRC and the presence of CRC will also influence the rate of subsequent investigation for extracolonic findings that are considered less important). Eighty-seven of these (7.5%) were referred for additional procedures, leading to diagnosis of extracolonic malignancy in 13 patients (Table 13). A more detailed analysis of extracolonic findings is given in Chapter 4.

| CTC (n = 1277) | BE (n = 2527) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Month of diagnosis | Found by CTC | Total | Month of diagnosis | Found by BE | |||||

| 1–12 | 13–24 | 25–36 | 1–12 | 13–24 | 25–36 | |||||

| All extracolonic cancersa | 78 | 28 | 31 | 19 | 11b | 131c | 66 | 37 | 28 | 4 |

| Person-years of follow-upd | 3663 | 1259 | 1219 | 1185 | 7275 | 2489 | 2424 | 2362 | ||

| Incidence (per 1000 person-years) | 21.3 | 22.2 | 25.4 | 16.0 | 18.0 | 26.5 | 15.3 | 11.9 | ||

| Cancer type (ICD-10) | ||||||||||

| Stomach (C16) | 2 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Small intestine (C17) | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Hepatobiliary system (C22, C24) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Pancreas (C25) | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Digestive organs, other and ill defined (C26) | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Bronchus and lung (C34) | 16 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 23 | 9 | 9 | 5 | |

| Mesothelial and soft tissue (C45, C46, C48) | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Breast (C50) | 14 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 14 | 6 | 5 | 3 | ||

| Cervix uteri (C53) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Ovary (C56) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| Prostate (C61) | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| Kidney (C64, C65) | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Bladder (C67) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Lymphoid or haematopoietic tissue (C81, C82, C83, C85, C90, C91, C92) | 7 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Primary site unknown (C80) | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Othere | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 14 | 6 | 2 | 6 | ||

Cancers diagnosed during 3 years’ follow-up

When analysis was performed in June 2012, registration was reported to be 97% complete for all cancers diagnosed until December 2010 (at which point all patients had been followed up for at least 36 months) and all deaths until December 2011 had been registered. By that time (median follow-up for deaths 5.4 years, IQR 4.7–6.0 years), 400 patients (15.8%) assigned to BE and patients 201 (15.7%) assigned to CTC patients had died (p = 0.94), and three patients (two BE and one CTC) who did not have their randomised procedure had been diagnosed with CRC. A further 12 CRCs were diagnosed following apparently normal BE (five distal – rectum or sigmoid colon – and seven proximal) and three following CTC (one distal and two proximal). In one of the CTC patients, a 6-mm caecal polyp was detected at CTC, but colonoscopy was not performed and a 12-mm caecal adenocarcinoma was diagnosed 28 months later. The miss rate among patients having their randomised procedure was, therefore, 6.7% for CTC (45 cancers diagnosed, of which three were missed) and 14.1% for BE (85 cancers diagnosed, of which 12 were missed) (difference –7.5%, 95% CI –17.8% to 2.9%; p = 0.21). Combining the two procedures, this gives a miss rate of 7.8% for distal cancers (6/77) and 17.0% for proximal cancers (9/53).

During the 3-year follow-up of the trial cohort, 78 primary extracolonic cancers were diagnosed in the CTC group and 131 in the BE group [21.3 per 1000 person-years in the CTC group vs. 18.0 per 1000 person-years in the BE group; incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.18, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.57; p = 0.24]. In the first year, rates of primary extracolonic cancer diagnosis in the trial cohort were nearly twice as high as expected (IRR 1.88, 95% CI 1.33 to 2.65; p = 0.0002), but rates did not differ significantly between the CTC and BE groups (IRR 0.84, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.30; p = 0.43). CTC detected 11 (39%) of the 28 extracolonic cancers that were diagnosed within the first year in the CTC group and BE detected 4 of 66 (6%).

Adverse events

An unplanned hospital admission within 30 days of the randomised procedure occurred in 14 patients following CTC and in 25 following a BE. Reasons for admission were reviewed independently by a gastroenterologist, radiologist and surgeon, who concluded that five were possibly attributable to the randomised procedure (reviewers were blinded to the procedure type). One patient was admitted directly after CTC with a possible perforation and was treated conservatively. Four hospitalisations occurred after a BE (reasons for admission were cardiac arrest, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding and patient collapsed after procedure). Three patients died within 30 days of a BE, one at 5 days (cardiac failure), one at 25 days (liver failure) and one at 28 days (perforated viscus), and one following CTC at 30 days (obstructive pulmonary disease).

Colonoscopy trial

Numbers analysed

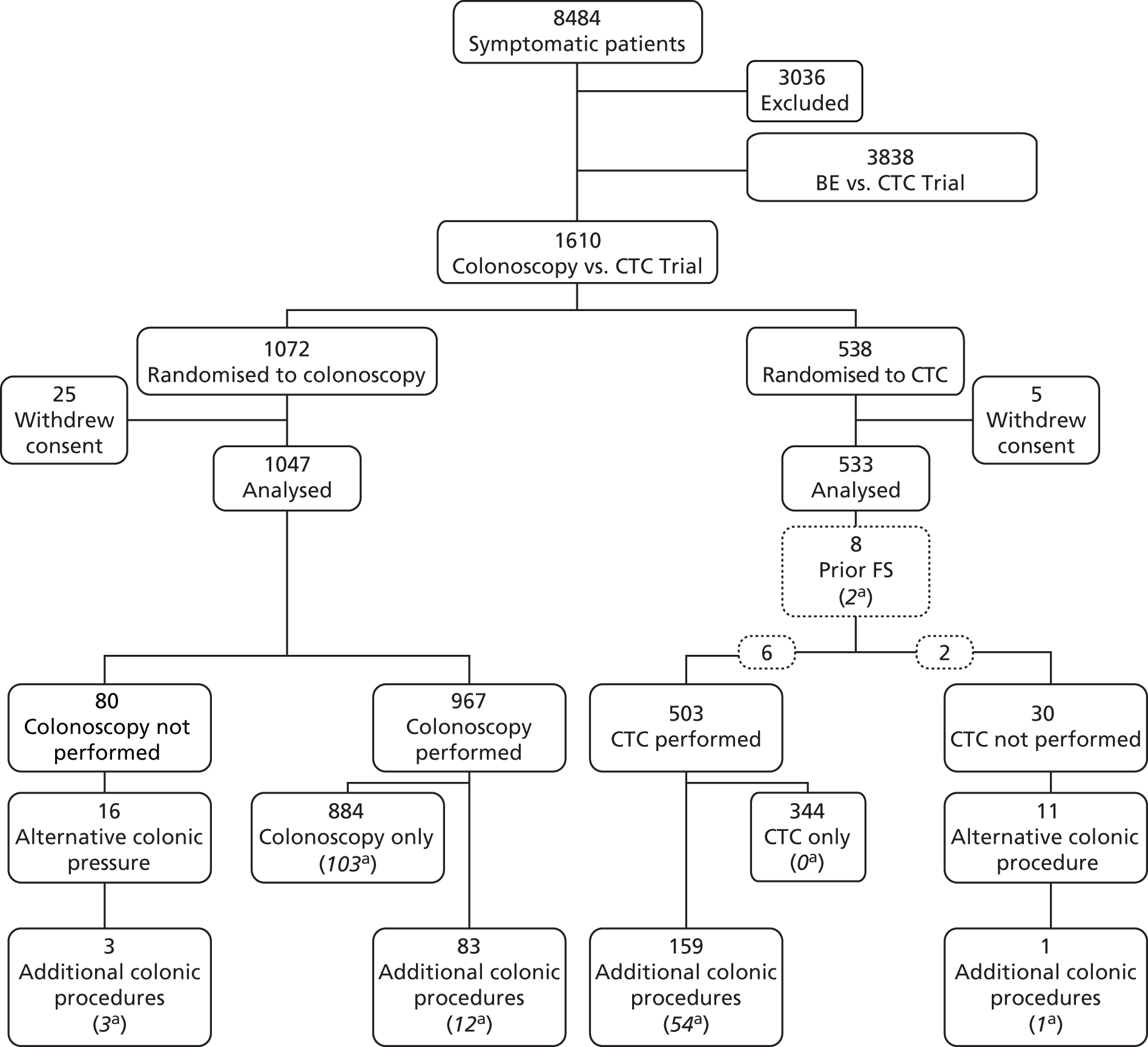

Of the 1610 patients in the colonoscopy trial, 1072 were randomised to colonoscopy and 538 to CTC. Thirty patients withdrew consent. The proportion of patients withdrawing consent differed between the two arms of the trial, just reaching the level of statistical significance [25 (2.3%) in the colonoscopy arm and 5 (0.9%) in the CTC arm; p = 0.0496].

The number of randomised patients at each site varied (median 37.5, IQR 16.5–106.5). There were no significant differences in the demographic or clinical characteristics of patients randomised to colonoscopy or CTC (Table 14). The median age of patients was 68 years (IQR 61–75 years) and 55% were women. The most frequent presenting symptoms were change in bowel habit (73%), rectal bleeding (43%) and abdominal pain (22%).

| Characteristic | Colonoscopy (N = 1047) | CTC (N = 533) | Total (N = 1580) | Trial participants excluded (N = 3036) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | p-valuea | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 476 | 45 | 240 | 45 | 716 | 45 | 1251 | 41 | 0.0074 |

| Female | 571 | 55 | 293 | 55 | 864 | 55 | 1785 | 59 | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 55–64 | 384 | 37 | 217 | 41 | 601 | 38 | 802 | 26 | <0.0001 |

| 65–74 | 377 | 36 | 186 | 35 | 563 | 36 | 1045 | 34 | |

| 75–84 | 253 | 24 | 113 | 21 | 366 | 23 | 930 | 31 | |

| 85 + | 33 | 3 | 17 | 3 | 50 | 3 | 259 | 9 | |

| Symptomsb | |||||||||

| Change in bowel habit | 772 | 74 | 383 | 72 | 1155 | 73 | 1926 | 63 | <0.0001 |

| Harder, less frequent | 126 | 12 | 66 | 12 | 192 | 12 | 297 | 10 | |

| Looser, more frequent | 410 | 39 | 214 | 40 | 624 | 39 | 1049 | 35 | |

| Variable | 124 | 12 | 54 | 10 | 178 | 11 | 180 | 6 | |

| Unspecified | 112 | 11 | 49 | 9 | 161 | 10 | 400 | 13 | |

| Rectal bleeding | 432 | 41 | 240 | 45 | 672 | 43 | 1169 | 39 | 0.0080 |

| Abdominal pain | 227 | 22 | 124 | 23 | 351 | 22 | 574 | 19 | 0.0077 |

| Anaemia | 140 | 13 | 60 | 11 | 200 | 13 | 620 | 20 | <0.0001 |

| Weight loss | 155 | 15 | 82 | 15 | 237 | 15 | 500 | 16 | 0.19 |

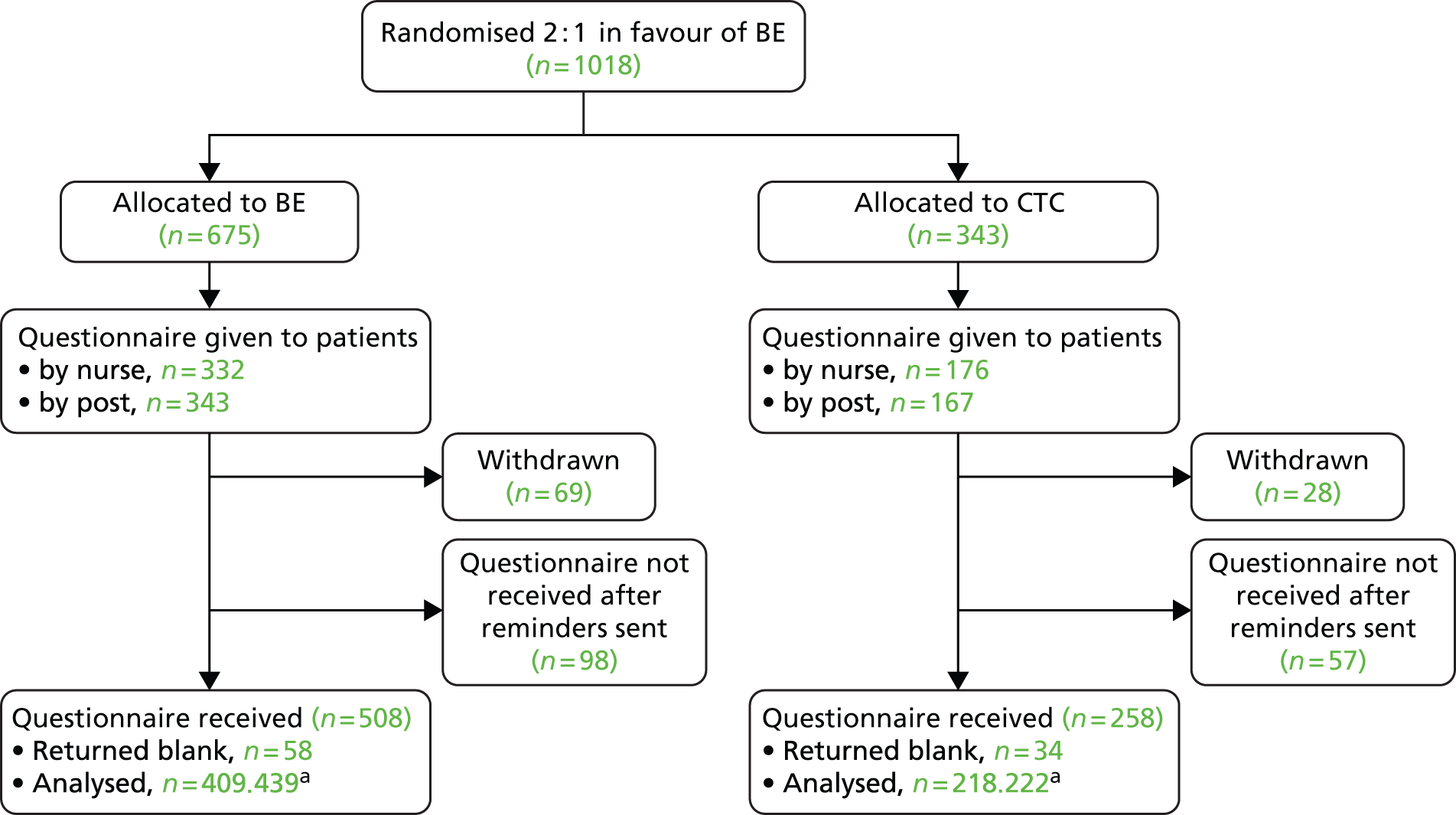

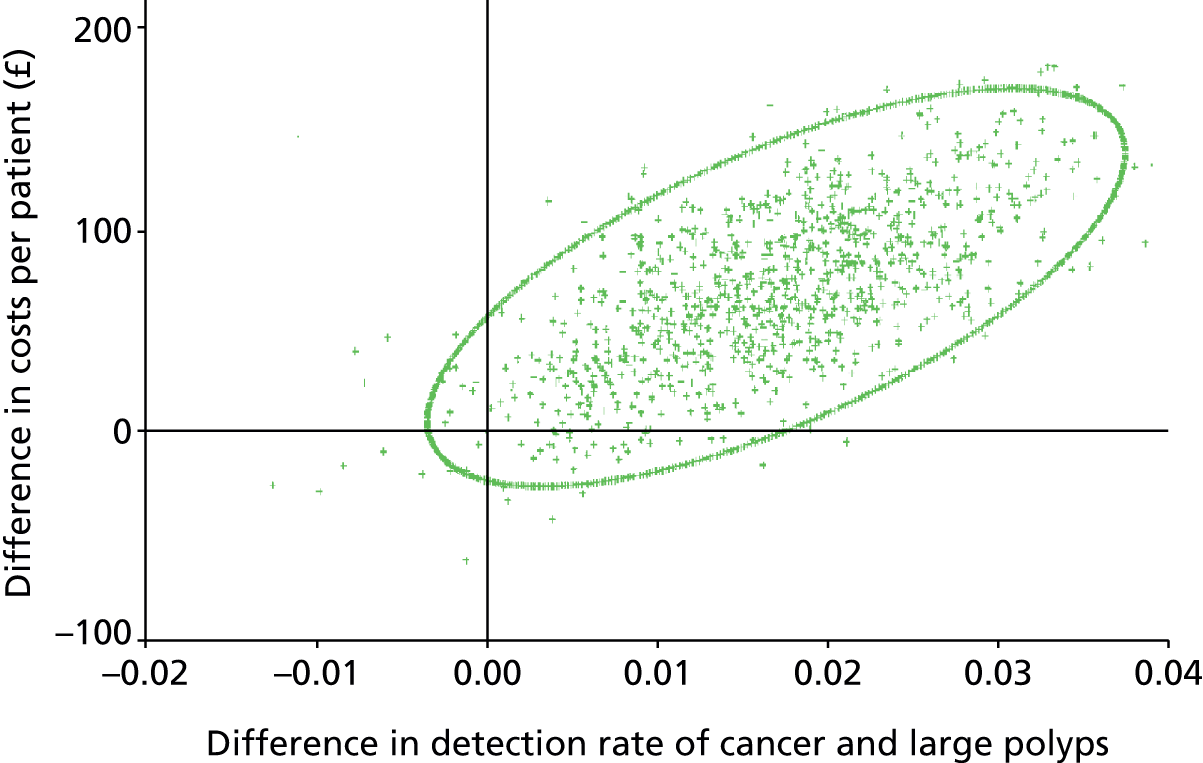

| Other symptoms | 172 | 16 | 102 | 19 | 274 | 17 | 585 | 19 | 0.11 |