Notes

Article history

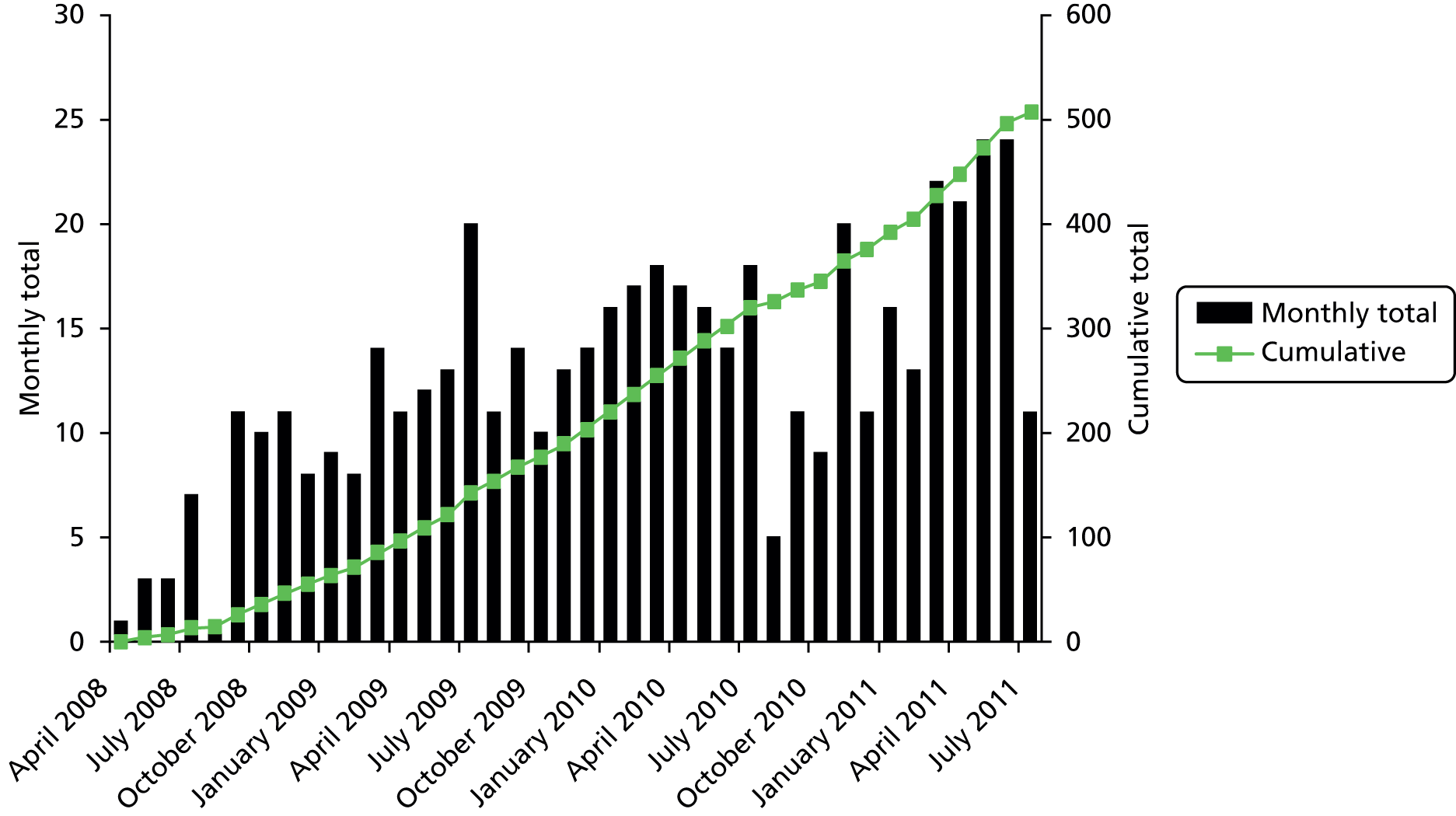

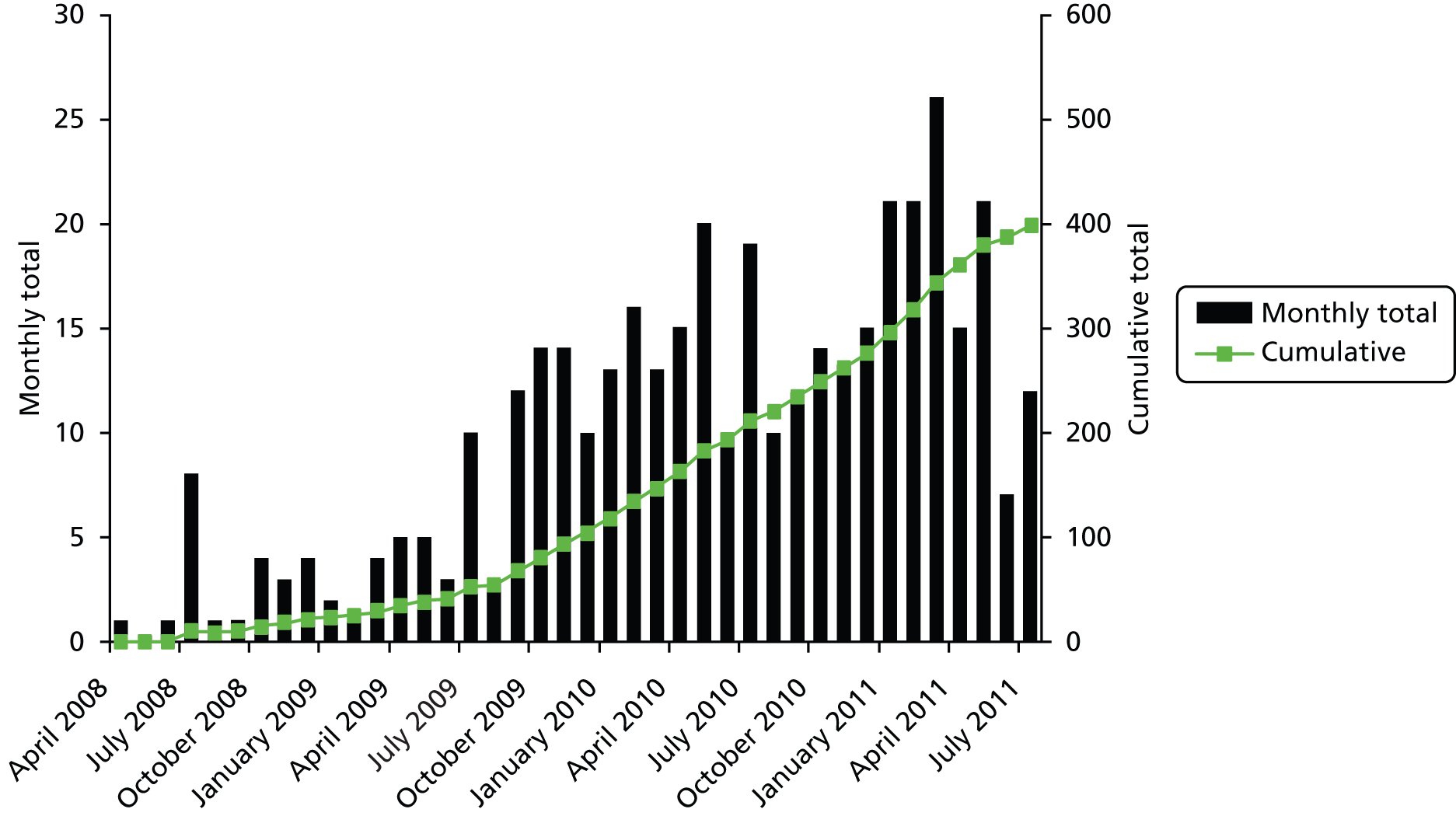

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/404/84. The contractual start date was in April 2008. The draft report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in February 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mr Clark reports receiving honoraria for training from Hologic and Ethicon, which make endoscopic instruments [Myosure (Hologic, Marlborough, MA, USA) and Versapoint (Gynecare, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA)] suitable for removing uterine pathologies such as polyps. Since completing the OPT Trial recruitment (but not before completing writing this report) he received £40,000 funding from Smith & Nephew to evaluate a product (TruClear) also suitable for removing uterine polyps and fibroids. Dr Smith reports grants from National Institute for Health Research Grants during the conduct of the study, and grants from Smith & Nephew outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Clark et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Definition of a uterine polyp

Uterine polyps are focal endometrial outgrowths that can occur anywhere within the uterine cavity. They contain a variable amount of glands, stroma and blood vessels, the relative amounts of which influence their visual appearance at hysteroscopy. Polyps may be soft and cystic or firm and fibrous; they may be pedunculated or sessile, single or multiple, and vary in size from small – with minimal uterine cavity distortion – to large, filling the whole cavity.

Aetiology of uterine polyps

Uterine polyps are composed of either functional and/or basal endometrium. They are typically a mixture of dense fibrous tissue (stroma), large and thick-walled vascular channels, and elongated glandular spaces of varying shapes1,2 which protrude into the uterine cavity. The underlying cause of uterine polyp formation remains unclear but is believed to be multifactorial. 3 They are thought to originate as focal areas of stromal and glandular overgrowth. This hyperplasia of the endometrium may occur within an area of mucosa that contains more hormonal receptors, thus making it more sensitive to oestrogenic stimulation. 4,5 The mechanism of uterine polyp development may differ according to menopausal status. In premenopausal women, a decrease in oestrogen and progesterone receptors within polyp stromal cells, although not the glandular component, has been found, which may make polyps less sensitive to cyclic hormonal changes. 6–8 Others have pointed to increased cell longevity, as a result of inhibition of apoptosis7,9 and biomarkers for altered gene expression have been documented within uterine polyps. 10,11

Diagnosis of uterine polyps

For many years the traditional method of diagnosing endometrial polyps was dilatation of the cervix and curettage of the endometrium [dilatation and curettage (D&C)]. However, this approach requires general anaesthesia, is associated with morbidity arising from uterine trauma, and has been shown to have limited diagnostic accuracy, because detecting and removing focal pathologies is notoriously problematic without direct visualisation. 12–15 The advent of convenient imaging of the uterine cavity using ultrasound or endoscopic technologies has largely replaced the D&C for endometrial evaluation; 16 when histological tissue samples are indicated, they can be obtained at the same time utilising blind, miniature outpatient biopsy devices17,18 or, in the case of hysteroscopy, guided biopsy. 19,20

Transvaginal ultrasound scan (TVS) is the least invasive outpatient test to evaluate the endometrium, as it avoids potentially painful instrumentation of the uterine cavity; the ultrasound probe simply sits within the top of the vagina. Uterine polyps typically appear as a hyperechoic lesion with or without cystic spaces, usually with regular contours and surrounded by a thin hyperechoic halo, or the polyp may appear as a non-specific endometrial thickening or focal mass within the endometrial cavity. TVS is often used as the first-line test for evaluating bleeding complaints because of its convenience and acceptability. 21 However, compared with saline infusion sonography (SIS), through which fluid is instilled to expand the uterine lumen and delineate the walls of the uterine cavity, or outpatient hysteroscopy (OPH), which directly visualises the inside of the uterus, TVS has poorer accuracy for diagnosing uterine polyps. 22,23 This is primarily because the sonographic findings are not specific to polyps, and other endometrial abnormalities – such as submucosal fibroids or endometrial irregularity – may have the same features, with the findings often subtle and easily overlooked especially for smaller polyps. 24 The development of ancillary technologies such as three-dimensional imaging and the use of colour or power Doppler may in time help improve the diagnostic accuracy of TVS for detecting focal pathologies within the uterus but evidence to date is lacking. 25,26

The gold standard investigative tools for diagnosing uterine polyps are SIS or OPH. Both tests have good accuracy for both detecting or excluding the presence of polyps within the uterus. 22,27–29 Although SIS is popular in some parts of Europe and North America, OPH is more widely practised in the UK and worldwide. This is because the skills of hysteroscopy are more widely attained by practising gynaecologists and it is safely practised30,31 but also because OPH allows convenient simultaneous removal of polyp (‘see and treat’),32 may be more cost-effective16 and appears to be preferred by women. 33,34 In contrast with OPH, SIS has the advantage of allowing assessment and visualisation of other pelvic structures, and visualisation of potential myometrial and adnexal abnormalities. 35

Prevalence and epidemiology of uterine polyps

The prevalence of uterine polyps in a general adult female population without abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is generally estimated to be around 10%. 32 Case series of asymptomatic women are generally small and estimates of prevalence imprecise; after TVS, uterine polyps were detected incidentally in 12% of premenopausal women36 and in 6–11% of infertile women without AUB. 37,38 In asymptomatic postmenopausal women, prevalences of 13%36 and 16%39 have been reported following investigation with ultrasound and hysteroscopy, respectively. However, they are found with increasing frequency in women undergoing investigation for problems with AUB (see Abnormal uterine bleeding and uterine polyps). In addition to AUB, risk factors for uterine polyp development are thought to include obesity, late menopause and the use of the partial oestrogen agonist tamoxifen. 36,40–42 The role of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on polyp formation is unclear, with some studies supporting an association36,40 and others not. 43,44

Clinical significance of uterine polyps

Once a uterine polyp has been diagnosed, the current clinical consensus is to remove it. 45 The rationale for this approach is based upon (1) a belief that uterine polyps are unlikely to spontaneously resolve; (2) a desire to alleviate AUB symptoms or optimise fertility; and (3) a need to exclude serious endometrial disease. 32

Natural history

The natural history of endometrial polyps is not fully understood. 46 A proportion of small polyps may regress naturally without treatment, but the majority persist; in one series of 45- to 50-year-old asymptomatic women, 27% of 31 polyps regressed spontaneously during a 1-year follow-up. Polyps that regressed tended to be smaller,47 in keeping with an earlier case series. 46

Oncogenesis

The pathogenesis and oncogenic potential of uterine polyps are unclear. However, the vast majority of uterine polyps are benign, and endometrial cancer originating within the polyp is a rare occurrence. Case series of varied populations report a cancer prevalence of approximately 0.5–3%. 48–55 Asymptomatic women are estimated to have a 4- to 10-fold reduced risk of malignancy compared with those women with AUB. 55,56 Outside of AUB, other risk factors for malignancy within uterine polyps appear to include increasing age, postmenopausal status, obesity, diabetes53–55 and an increased polyp diameter. 55,56 The use of tamoxifen appears to increase the risk of atypical hyperplasia and malignancy within uterine polyps. 41,57

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia (EH) is considered to be a premalignant condition58 and the prevalence within polyps ranges between 1% and 3%. 53–56 Non-atypical hyperplasia has been reported to be found in up to 13% of polyps,53 but the oncogenic potential of this condition is generally low. A systematic review of observational series evaluated the prevalence of premalignant and malignant disease within uterine polyps. It reported malignant tissue changes within endometrial polyps in 0–12.9% of included studies, and hyperplastic change in 0.2–23.8% of polyps. They found postmenopausal symptomatic women to have the highest risk of premalignant and malignant tissue changes. 59 A more recent review60 similarly found symptomatic women with AUB bleeding to be at higher risk of premalignancy or malignancy within a uterine polyp; they reported the prevalence of endometrial neoplasia within polyps in women with symptomatic bleeding as 4.2% (195/4697) compared with 2.2% (85/3941) for those without bleeding [relative risk (RR) 1.97; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.24 to 3.14]. Among symptomatic postmenopausal women with endometrial polyps, 4.5% (88 of 1968) had a malignant polyp in comparison with 1.5% (25/1654) of asymptomatic postmenopausal women (RR 3.36, 95% CI 1.45 to 7.80). The risk of premalignancy or malignancy within a uterine polyp was higher in symptomatic postmenopausal women (5.4%, 214/3946) compared with 1.7% (68/3997) in reproductive-aged women (RR 3.86, 95% CI 2.92 to 5.11).

Abnormal uterine bleeding

Abnormal uterine bleeding affects women of both reproductive (premenopausal women) and postreproductive (postmenopausal women) age. AUB is one of the four most common reasons for consulting a general practitioner (GP), and accounts for 70% of all referrals to hospital gynaecology clinics,61 making this complaint one of the commonest problems in gynaecology. A large proportion of health-care resources in both primary care and hospital settings are used up in managing this condition. 62

In premenopausal women, AUB manifests itself primarily as heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), which has been defined as ‘excessive menstrual blood loss which interferes with the woman’s physical, emotional, social and material quality of life, and which can occur alone or in combination with other symptoms’. 63 HMB affects one in five women of reproductive age, with 5% of women aged 30–49 years consulting their GP each year because of the condition. 64 The overall prevalence of HMB in England and Wales has been estimated at 1.5 million women. 65 Uterine bleeding may be unscheduled, however, occurring outside of the expected time of the menstrual period. This irregular ‘breakthrough’ bleeding is known as intermenstrual bleeding (IMB) and is also common; a recent survey within primary care found the 2-year cumulative incidence of IMB to be 24% (95% CI 21% to 27%). 66

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is also a common clinical problem in both general practice and secondary care (hospital settings). Women are most likely to present with PMB in the sixth decade of life, for which consultation rates in primary care are 14.3 per 1000 of the population. 67 PMB causes significant alarm and anxiety to women, who recognise vaginal bleeding after their periods have ceased as abnormal. Rapid referral to secondary care for investigation is indicated because between 5% and 10% of women with PMB will have endometrial cancer. 68 Postmenopausal women taking HRT may also develop problematic genital tract bleeding. Women taking sequential HRT regimens may present with either heavy scheduled bleeding or unscheduled, erratic bleeding, whereas women taking continuous, combined ‘no bleed’ HRT preparations present with unexpected bleeding, which is, by definition, unscheduled and abnormal. Similarly, women with breast cancer who are taking the partial oestrogen agonist tamoxifen may present with unscheduled bleeding. 69 Table 1 summarises the types of AUB.

| Bleeding type | Description |

|---|---|

| HMB | Excessive cyclical menstrual bleeding; menses may be frequent, prolonged or irregular |

| IMB | Intermittent or persistent episodes of bleeding that occur between normally timed menstrual periods; the bleeding may be of a regular and predictable or random, following no particular pattern |

| PMB | Any vaginal bleeding occurring after the menopause; in women taking exogenous hormones (HRT) bleeding may be heavy and scheduled (sequential ‘bleed’ HRT regimens) or unscheduled (sequential or continuous combined ‘no bleed’ preparations) |

Abnormal uterine bleeding and uterine polyps

The majority of women with symptomatic polyps present with AUB as described in the preceding section. With the advent of high-resolution pelvic ultrasound and hysteroscopic diagnosis, it has become clear that uterine polyps are highly prevalent during investigation of abnormal bleeding. The reported prevalence of endometrial polyps in general is considered to be between 20% and 30%,43,70,71 the variation reflecting the criteria used to define a polyp, the diagnostic test used, and the type of population studied. Although the prevalence of uterine polyps may be increased after the menopause,36 polyps are found commonly to affect both pre- and postmenopausal women across all age groups. 46 In recognition of the frequency in which uterine polyps are discovered in women of reproductive age, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) has recently accepted a new classification system for causes of AUB in the reproductive years, based on the acronym ‘PALM-COEIN’ with the ‘P’ denoting a ‘polyp’, i.e. describing AUB associated with the presence of uterine polyps. 72

The improved diagnostic accuracy, has led to the increased use of surgical intervention for the removal of polyps (‘polypectomy’), a procedure that is universally practised to resolve symptoms and to obtain tissue for histological examination. 45

Treatment of uterine polyps

Until recently, inpatient blind uterine curettage (D&C) under general anaesthetic has been the technique routinely used to perform uterine polypectomy. It involves wide dilatation of the cervix and the use of standard surgical polypectomy forceps to explore the uterine cavity. This technique is still used today, although most gynaecologists perform a hysteroscopy beforehand to locate the polyp to direct blind avulsion of the lesion followed by curettage. 45,73 Owing to the need for inpatient hospital admission and general anaesthesia, this approach is associated with heavy use of health-care resources, with over 25,000 inpatient procedures being performed during 2011–12 in the UK, a figure that was up by 4000 on the numbers from 1998 to 1999 confirming a trend towards an increase in the use of inpatient polypectomy [Department of Health (England), Hospital Episode Statistics – 2011/1274].

Expectant management

The observation that polyps are an incidental finding in around 5–15% of women,36–39 the majority of polyps are benign60,75 and some may naturally regress46,47 has led some to question whether removal of uterine polyps is necessary,76 and indeed removal may subject women to unnecessary morbidity and wastage of scarce health service resources. Two RCTs have addressed this issue, randomising women with AUB and uterine polyps to expectant management or surgical removal. 75,76 One trial76 failed to recruit women with PMB because neither doctors nor patients were in equipoise and so were unwilling to participate. This finding is consistent with postmenopausal women having a preference for hysteroscopic diagnosis and treatment when an abnormality is found. 73 The other RCT randomised 150 women with uterine polyps, of which 60% had AUB symptoms. Overall, no reduction in periodic blood loss was demonstrated at 6 months’ follow-up, but IMB symptoms were significantly improved. 75 The findings from this study are limited, given that it was restricted to premenopausal women, the sample size was small (only 60% of the population included were symptomatic), the presenting complaints were heterogeneous and the study length of follow-up was short.

Medical management

Medical management is widely adopted for the treatment of menstrual complaints and includes the use of hormonal contraceptives. Although some of these women may have undiagnosed uterine polyps, evidence for the use of medical therapy is lacking and not recommended. 63 Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues (‘GnRH-a’s) have been used prior to hysteroscopic resection of focal pathologies in premenopausal women77 but the costs and menopausal side effects are difficult to justify for the removal of uterine polyps. This is because polyps are successfully removed in the majority of cases without the need for adjunctive medical preparation, in contrast with submucous fibroids (SMFs). One small series evaluated different HRT regimens to see whether some have a reduced propensity to polyp formation. 78 The use of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) in women taking tamoxifen has been reported to reduce the incidence of endometrial polyps. 79

Surgical management: polypectomy

A UK national survey45 and two subsequent Dutch surveys80,81 confirmed that the vast majority of gynaecologists advocated surgical removal of polyps from the uterus after diagnosis with 854 of 918 (93%),45 455 of 553 (83%)80 and 411 of 585 (91%) respondents performing polypectomy. 81 In the UK, the predominant method for removal of uterine polyps was by blind avulsion or curettage, after hysteroscopic location of the focal lesion under general anaesthesia,45 whereas in the Netherlands removal under direct hysteroscopic vision under general or regional anaesthesia80,81 was the favoured approach.

Blind uterine polypectomy

Blind methods to retrieve focal intrauterine pathology included blind curettage of the endometrium or avulsion with polyp forceps. These approaches can be associated with potential uterine trauma, which can be unrecognised and lead to serious complications from intra-abdominal damage. 12,13 Failure to remove polyps and problems with incomplete removal are well recognised. 13–15,82–84

Hysteroscopic uterine polypectomy

Advances in hysteroscopic technology have enabled polyps to be removed under direct vision. Fine mechanical instruments, such a scissors, biopsy cups, forceps and snares can be used down a 5- or 7-French working channel of a rigid operative hysteroscope and the safety and feasibility of such approaches have been reported. 32,85–87 Potential drawbacks of mechanical instrumentation are the fragility of the instruments, limited manipulation, difficulty with cutting or avulsing large and fibrous pathology, and, in some instances, bleeding. 32,88

The adoption of electrosurgical technologies may help to overcome these difficulties. Large-diameter hysteroscopic resectoscopes that were developed originally to resect the endometrium for the treatment of HMB89 can also be used to resect focal pathologies, such as SMFs77,90 or polyps. 91,92 They have the advantage of speed and manipulation, but the large diameter of the instruments necessitates general anaesthesia, specialised skills are required93,94 and potential serious complications from fluid overload and inadvertent electrosurgical injury can occur. 95

In contrast with firm SMFs of myometrial origin, polyps are generally softer structures that are derived from the underlying endometrium. Thus, it has been recognised that smaller, less-traumatic electrosurgical instruments would suffice. A miniature bipolar electrosurgical system has been developed (Versapoint®, Gynecare, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) to cut away polyps and the safety, acceptability and feasibility of this approach has been reported. 96–98 However, retrieval of the tissue specimen from the uterine cavity can be problematic, and usually requires the additional use of mechanical instruments to effect. 32 Other technologies have been developed, including monopolar electrosurgical snares,86 and, more recently, morcellation technologies (TRUCLEAR™, Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA, USA) and Myosure (Hologic, Marlborough, MA, USA), which allow simultaneous tissue cutting and extraction. 99,100

Evidence for uterine polyp treatment in abnormal uterine bleeding

In 2006, our group published a systematic review of the efficacy of uterine polypectomy for the treatment of AUB. 87 The review included nine case series (534 patients) and a single controlled observational study comparing setting for the treatment of uterine polyps (58 patients). No randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were identified, or any studies on patient acceptability or cost-effectiveness. A summary of the evidence is given below:

-

Technique Uterine polypectomy was carried out under general anaesthesia utilising hysteroscopic or blind approaches in all studies, although local anaesthetic outpatient approaches were also used in three of these series. The hysteroscopic techniques under general anaesthesia involved use of large-size endoscopes that are associated with the need to perform wide cervical dilatation.

-

Setting A single, non-randomised comparative study of 58 women undertaken at the Birmingham Women’s Hospital97 showed that outpatient removal under local anaesthesia was no worse than inpatient, general anaesthetic treatment [14/18 (78%) vs. 14/16 (88%); p = 0.7], a result that could partly be explained by the possibility of type II error due to small sample size and lack of randomisation.

-

Alleviation of AUB All studies reported an improvement in symptoms of AUB following treatment (range 75–100%) at follow-up intervals of between 2 and 52 months.

-

Influence of type of AUB It was possible to stratify treatment outcome according to type of abnormal bleeding in only one small study of 45 women,101 which could not detect a difference between polypectomy for menstrual dysfunction or PMB (p = 0.2), again partly due to small sample size.

In summary, the evidence from this systematic review suggested that uterine polypectomy was a safe and technically successful procedure for the treatment of AUB. 87 However, randomised effectiveness data comparing treatment approaches or settings were non-existent, as were economic data to examine cost-effectiveness and qualitative data of patient acceptability and preference.

Systematic Review performed during the Outpatient versus inpatient Polyp Treatment Trial

For this report we have undertaken a systematic review of the effectiveness of uterine polypectomy, building on our previously published systematic review,87 using updated methodological advances in search strategies, quality assessment and statistical analysis. 102,103 The objective of the review was to systematically review the literature to evaluate the effectiveness of uterine polypectomy for the treatment of AUB. Our secondary aims were to establish if the type of AUB, setting or technique influenced outcome.

Methods

Search strategy

We performed searches on the general bibliographic databases MEDLINE (1950–2013), EMBASE (1980–2013) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1981–2013). Based on published advice, our search term combination for electronic databases was medical subject headings (MeSH) for polyps combined with word variants for endometrium (endometri* OR uter*) and surgical polypectomy (surgery OR curettage OR hysteroscopy OR polypectomy). Furthermore, all of the bibliographies of relevant studies were hand-searched to identify articles that were not captured by the electronic searches.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently selected articles in a two-stage process. First, abstracts obtained by either the electronic database searches or bibliography inspections were reviewed, and articles that could possibly fulfil the following criteria were selected for full text review.

Inclusion criteria

-

Population Women with intrauterine polyps and AUB.

-

Intervention Uterine polypectomy.

-

Outcome Relief of AUB symptoms.*

[*Measured in general terms, e.g. objective, semiobjective or subjective measures of change in AUB; normalisation of bleeding patterns; satisfaction with AUB outcome; change in quality-of-life scores from baseline.]

Once articles were selected both reviewers used specially designed data abstraction forms to collect data on the main outcome measure that was relief of AUB symptoms. Secondary outcomes included technical feasibility, complications and polyp histology. Differences in article and information selection were solved by deliberation. Where a consensus could not be found a third reviewer (TJC) made the final judgement. No language restrictions were applied and translation available where necessary.

The strength of agreement between reviewers taking into account the play of chance was computed using kappa statistic (agreement is considered good if > 0.6 and very good if > 0.8).

Type of study included

All relevant randomised controlled studies were included. Owing to the small number of RCTs, non-randomised studies including both prospective and retrospective observational studies were also included.

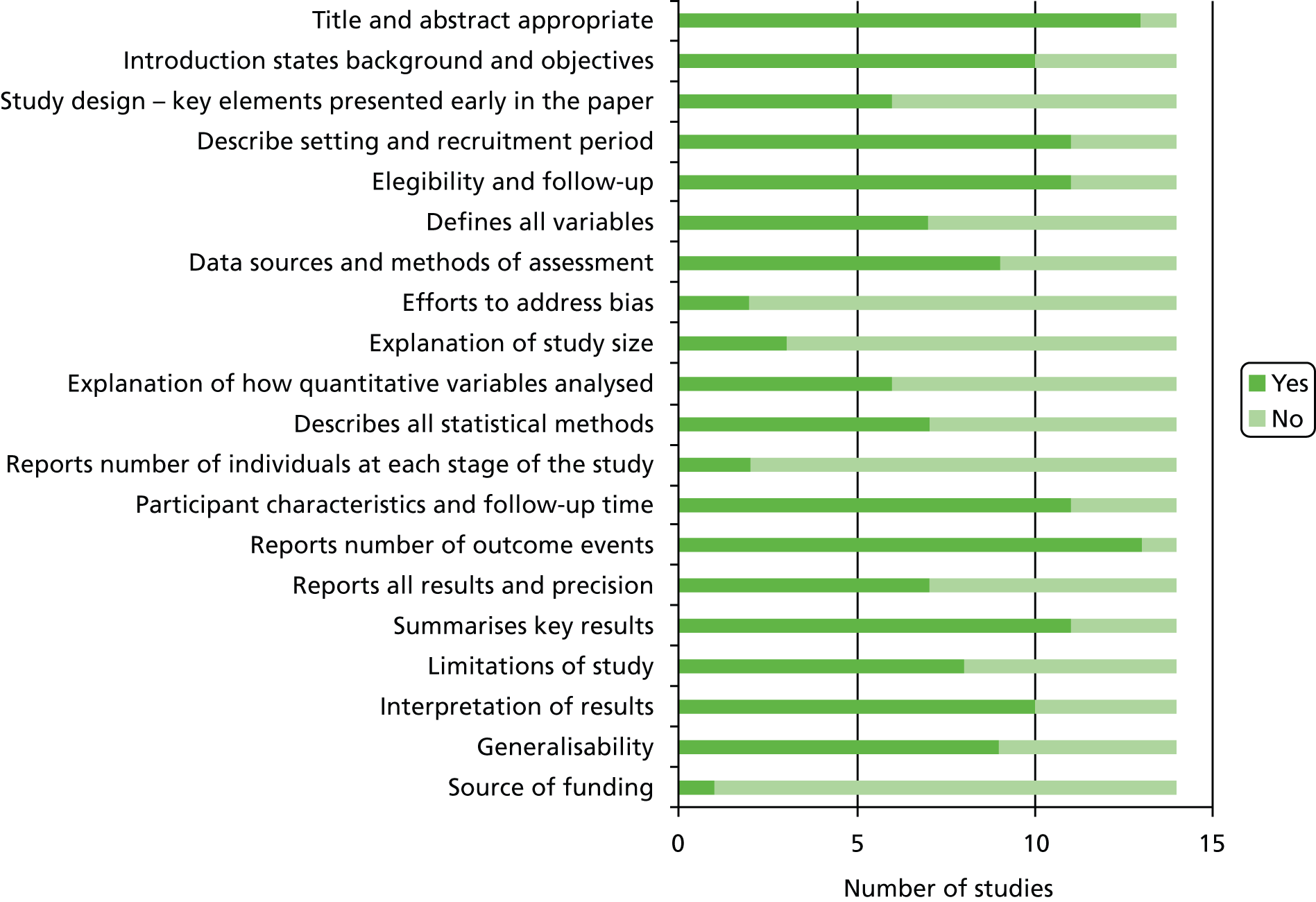

Study quality assessment

The 2007 STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist was used to assess the quality of the observational studies,104 whereas the Cochrane risk of bias tool checklist was used to assess the quality of the randomised controlled studies. 102 Two reviewers independently scrutinised the articles against each element of the relevant checklist.

Synthesis of results

Originally, in the absence of heterogeneity, data pooling and meta-analysis was planned. However, owing to a lack of controlled studies this could be performed for only inpatient treatment compared with outpatient treatment. All other extracted data were tabulated to allow qualitative analysis.

Results

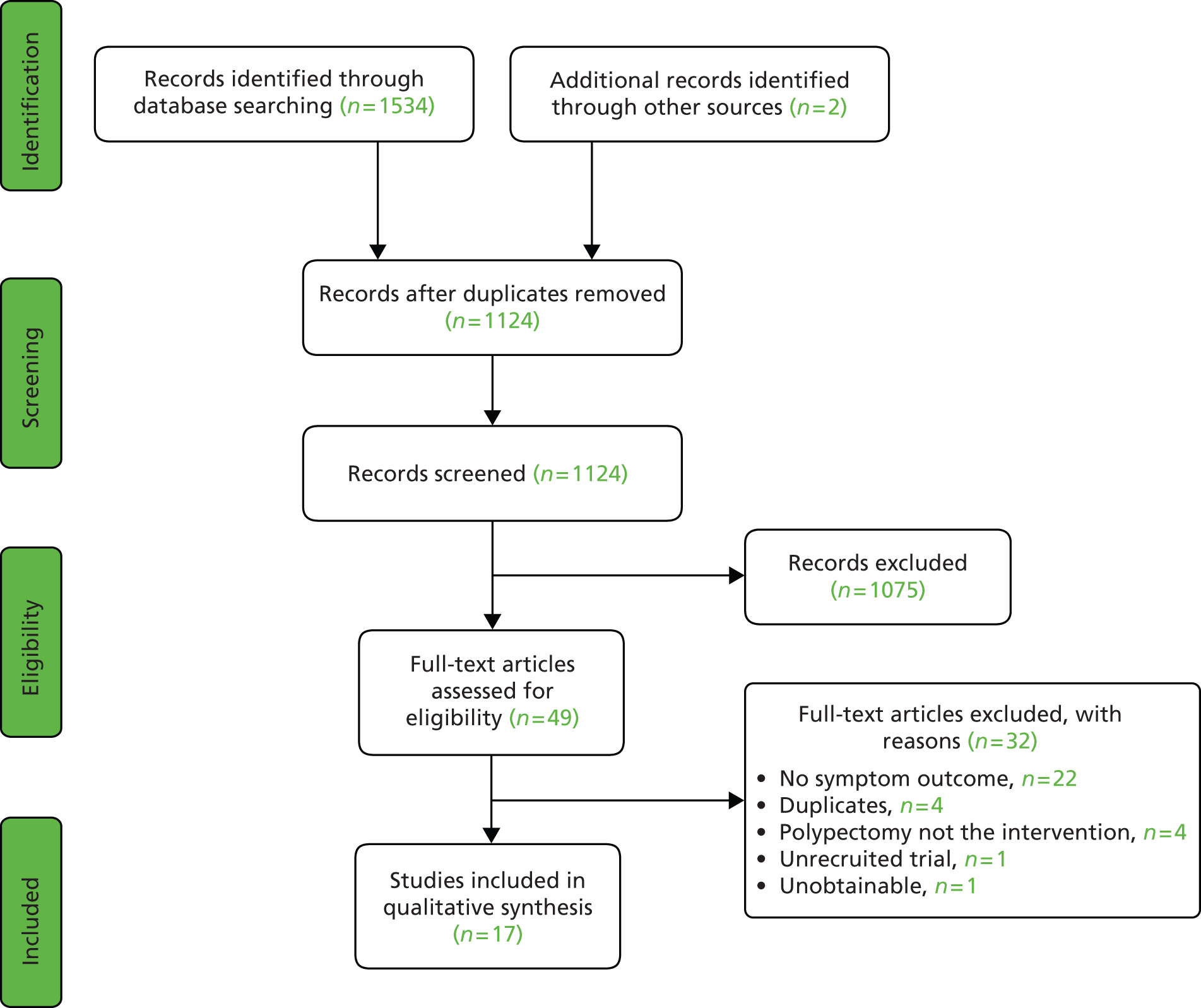

Results of search

From the electronic search we obtained 1122 citations and a further two from searching reference lists of relevant articles. At this stage 1075 citations were excluded, based on a review of the abstracts and titles. An attempt was made to retrieve the remaining 49 articles for further scrutiny. One article could not be retrieved either online or via The British Library. Review of these articles showed that 32 did not meet the selection criteria. The characteristics of the excluded articles105 are described in Figure 1. There was a high level of agreement between reviewers for which articles should be retrieved for further scrutiny (kappa agreement = 0.92; p ≤ 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Study selection process.

Included studies

The 17 studies23,75,91,97,101,105–114 (including TJ Clark, Birmingham Women’s Hospital, 2013, unpublished) that met our inclusion criteria enrolled a total of 1829 patients between 1989 and 2009. The population size ranged from 8 to 311, with only five studies having a population size of > 100. 12,16,21,22,29

Study quality and design

There were two randomised controlled studies: one comparing inpatient treatment with outpatient treatment (TJ Clark, unpublished), whereas the second compared polyp removal with observation for 6 months. 75 Of the remaining 15 observational studies, only two were controlled: one compared inpatient treatment with outpatient treatment97 and the second compared hysteroscopic morcellation to electrical resection. 105 The remaining 13 articles were uncontrolled observational studies. Only six of the studies were prospective, although the majority of the studies23,75,97,113,114 (plus TJ Clark, unpublished) collected the data consecutively (Figures 2 and 3; Table 2).

| Study author | Methodology, study design | Data collection | Patient Selection | Population: polyps and AUB | Follow-up (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Type (%) | |||||

| Clark TJ, unpublished | RCT | Prospective | Consecutive | 60 | Unspecified menstrual; PMB | 80 |

| Lieng et al.75 | RCT | Prospective | Consecutive | 150 | Intermenstrual (47); menorrhagia (13); irregular (8); discharge (7); asymptomatic (25) | 95 |

| AlHilli et al.105 | Controlled observational | Retrospective | Consecutive | 311 (IUM 139, HSR 172) | Menorrhagia (19.3%), menometrorrhagia (10.6%), PMB (44.4%) | 100 |

| Barisic et al.106 | Observational | Unreported | Unreported | 8 | Unspecified menstrual | 100 |

| Brooks et al.107 | Observational | Unreported | Unreported | 9 | Excessive menstrual | 89 |

| Clark et al.97 | Controlled observational | Prospective | Consecutive | 58 | Unspecified menstrual (10); PMB ± HRT (90) | 58 |

| Cravello et al.108 | Observational | Retrospective | Consecutive | 195 | Unspecified menstrual (60); PMB + HRT (12); tamoxifen (2); PMB (26) | 89 |

| Henriquez et al.109 | Observational | Retrospective | Consecutive | 56 | Unspecified | 100 |

| Nagele et al.101 | Observational | Unreported | Unreported | 33 | Excessive menstrual (47); IMB (13); PMB 40 | 100 |

| Pace et al.110 | Observational | Unreported | Consecutive | 87 | Unspecified menstrual/PMB (86); subfertility (14) | 87; 49 |

| Polena et al.111 | Observational | Retrospective | Consecutive | 367 | Menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, IMB | 83 |

| Preutthipan et al.91 | Observational | Retrospective | Unreported | 155 | Metrorrhagia (31), hypermenorrhea (29), IMB (19), menorrhagia (11) and menometrorrhagia (10) | 100 |

| Stamatellos et al.112 | Observational | Retrospective | Unreported | 83 | Unspecified | 100 |

| Timmermans et al.113 | Observational | Prospective | Consecutive | 49 | PMB | 100 |

| Towbin et al.114 | Observational | Prospective | Consecutive | 14 | Menorrhagia, metrorrhagia; postmenopausal | 100 |

| Tjarks et al.115 | Observational | Retrospective | Unreported | 34 | Unspecified menstrual (64); PMB (36) | 100 |

| Van Dongen et al.23 | Observational | Prospective | Consecutive | 21 | Menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, IMB | 90 |

Participant characteristics

One study looked exclusively at women suffering from PMB,113 seven studies looked at only women who were premenopausal23,75,106,107,109,111,112 and the remaining nine studies91,97,101,105,108,110,114,115 (plus TJ Clark, unpublished) examined mixed populations of women with AUB.

Interventions

When the operative technique was described, polypectomy was performed under direct vision (hysteroscopically) with the exception of two studies (Clark et al. 97 and TJ Clark, unpublished) that had inpatient arms in which blind avulsion was used. 97 There were a variety of techniques described for polyp removal under direct vision including: scissors, polyp forceps, morcellator devices and a variety of bipolar instruments (Table 3).

| Study author | Technique (%) | Anaesthesia (%) | Mean operation time | Polyps | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Mean size (range) | Histology (%) | ||||

| Clark TJ, unpublished | Outpatient = hysteroscopic; inpatient = blind | Outpatient = local (93), none (7); inpatient = general (100) | Outpatient (consultation time) 29 minutes; inpatient 24 minutes | NR | NR | NR |

| Lieng et al.75 | HSR or observation | General | NR | NR | 16.5 mm (SD 5.3) | EH (1.5); benign (98.5) |

| AlHilli et al.105 | HSR | General | NR | Single (65); multiple (35) | 2.1 cm | EH + ECA (7) |

| Barisic et al.106 | HSR | General | NR | Single (100) | (1.8–3 cm) | EH (13); benign (87) |

| Brooks et al.107 | HSR | General | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Clark et al.97 | Hysteroscopic (Versapoint) (50); or hysteroscopy + blind avulsion (50) | Local (50); general (50) | NR | NR | 0.9 cm | NR |

| Cravello et al.108 | HSR | General | 19 minutes | Single (90); multiple (10) | 1.4 cm (0.5–4 cm) | EH + A (1); benign (99) |

| Henriquez et al.109 | Hysteroscopic | General or spinal | NR | Single (62); multiple (39) | 17.5 mm (SD 8.3) | NR |

| Nagele et al.101 | HSR or mechanical excision (scissors) | Local (20); general (80%) | NR | Single; ‘some’ multiple | (1–5 cm) | EH + A (2); ECA (2); benign (96) |

| Pace et al.110 | HSR | General | 22 minutes | Single (86); multiple (14) | [< 1.5 cm (45%); > 1.5 cm (55%)] | EH (1); benign (99) |

| Polena et al.111 | HSR | General | NR | Single (81); multiple (19) | NR | ECA (0.05); benign (99.5) |

| Preutthipan et al.91 | HSR | General | 23.1 ± 4.7 minutes, micro scissors; 20.9 ± 3.9 minutes, grasping forceps; 25.2 ± 4.9 minutes, electric probe; 31.9 ± 8.3 minutes | Single (74) | 3.4 ± 0.9 cm premenopausal; 2.5 ± 0.8 cm postmenopausal | EH (3); benign (97) |

| Stamatellos et al.112 | HSR | General or none | NR | Single (41); multiple (59) same as polyp size data | < 1 cm [41]; > 1 cm [59] | NR |

| Timmermans et al.113 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Towbin et al.114 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Tjarks et al.115 | NR | General | NR | Single (88); multiple (12) | [< 1 cm (13%); > 1 cm (87%)] | NR |

| Van Dongen et al.23 | HSR | General or spinal | NR | Single (38.1); multiple (61.9) | 13.2 mm (SD 4.7) | NR |

Outcomes

There were large differences in the time of follow-up, ranging from 2 months110 to > 9 years91 (Table 4). Only two studies23,97 used a validated tool for measuring efficacy of polypectomy: both studies used a visual analogue scale (VAS). 23,97 The majority of studies defined the primary outcome as an improvement in symptoms of AUB as perceived by the patient. All of the studies23,75,91,97,101,105–115 (plus TJ Clark, unpublished) reported an improvement in symptoms from 60% to 100%. The study looking exclusively at postmenopausal patients presented a survival analysis curve. 113 The seven studies23,75,106,107,109,111,112 looking at premenopausal patients reported improvements in 60–100% of participants. The remaining nine studies91,97,101,105,108,110,114,115 (plus TJ Clark, unpublished) looking at mixed populations reported 65–100% symptomatic improvements. Two of these studies broke down recurrent AUB symptoms for those that were pre- and postmenopausal at treatment. 101,105 One of the studies101 found no significant difference in AUB at 1 year, although the numbers were small (27/34 premenopausal patients vs. 12/12 postmenopausal patients; p = 0.2). Although a larger study105 found that premenopausal women were more likely to have recurrence of symptoms [hazard ratio (HR) 2.42, 95% CI 1.42 to 4.11]. Another study109 broke down symptom outcome by types of AUB in premenopausal women; no differences in outcome were observed for those women complaining of HMB or IMB, although the study population was small (HR 1.29, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.73 and HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.09 to 1.76, respectively).

| Study author | Failure rate/complication rate | Outcome assessment (time) | Outcome measure | Treatment success (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark TJ, unpublished | Outpatient 2/1; inpatient 0/0 | Postal questionnaire (6 months) | Improvement in VAS | Outpatient 18/22 (82); 17/26 (65) inpatient |

| Lieng et al.75 | 0/1 | Postal questionnaire (6 months) | No gynaecological symptom | 68/75 (91) resection; 47/75 (63) observation |

| AlHilli et al.105 | NR | Clinical interview | Recurrence of AUB | 118/139 (85) IUM; 136/172 (79) HSR; 254/311 (81) both |

| Barisic et al.106 | NR/NR | NR (first three menstrual cycles) | Normalisation of AUB | 8/8 (100) |

| Brooks et al.107 | NR/0 | NR (> 3 months) | Improved vs. not improved | 7/8 (88) |

| Clark et al.97 | 0/0 | Postal questionnaire at 6 months | Better vs. not better; satisfied vs. not satisfied | Outpatient 11/12 (92); inpatient: 13/14 (93); outpatient: 14/18 (78); inpatient: 14/16 (88), 156/175 (89) |

| Cravello et al.108 | 0/2 | Telephone interview with patients or referring clinicians (NR) | Normalisation of AUB | 156/175 (89) |

| Henriquez et al.109 | NR | Review of clinical notes | Persistence of AUB requiring medical therapy or surgical intervention | 33/56 (60) 1 year |

| Nagele et al.101 | 0/0 | Clinical interview (3 months); postal questionnaire (5–52 months) | Short-term ‘cure’ of AUB; maintenance of ‘cure’ (no recurrence of AUB) | 44/49 (90); 38/49 (78) |

| Pace et al.110 | 0/1 | Clinical interview (2 months); clinical interview (12 months) | Normalisation of AUB (no ‘relapse’ of symptoms) | 85/87 (98);100 |

| Polena et al.111 | 1/4 (out of total population of 367) | Telephone interview and postal questionnaire | Normalisation of AUB | 91/97 (94) |

| Preutthipan et al.91 | NR/21 | Clinical interview 9 years 2 months | Normalisation of AUB | 144/155 (93) |

| Stamatellos et al.112 | NR/2 | Telephone interview or examination when indicated (3–18 months) | Normalisation of AUB | 76/83 (91) |

| Timmermans et al.113 | NR/NR | Patients self-reported symptoms | Recurrence of PMB | Survival curve |

| Towbin et al.114 | NR | Clinical interview | Recurrence of AUB | 14/14 (100) |

| Tjarks et al.115 | NR/NR | Telephone interview (5–24 months) | Menorrhagia score (scale 0–3); no. of days bleeding/month; satisfied vs. not satisfied | Significant reduction p < 0.05; significant reduction p < 0.05; 23/26 (88) |

| Van Dongen et al.23 | NR/NR | Questionnaire | Improvement of symptoms; menstrual chart score; VAS quality of life | 18/21 (86); improvement p < 0.001; improvement p < 0.001 |

The two studies (Clark et al. 97 plus TJ Clark, unpublished) comparing inpatient to outpatient treatment reported no difference in symptom improvement, although the study sizes were small: 11 of 12 (92%) after outpatient treatment compared with 13 of 14 (93%) after inpatient treatment,97 and 18 of 22 (82%) after outpatient treatment compared with 17 of 26 (65%) after inpatient uterine polypectomy (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.83). In both studies the outpatient polypectomies were performed under direct vision, whereas inpatient polypectomy was performed ‘blindly’.

There was one other controlled observational study105 and that compared mechanical polyp resection (using a morcellator) compared with electrical resection. Overall, 36 of 172 patients (21%) undergoing electrical resection and 21 of 139 patients (15%) undergoing intrauterine morcellation (IUM) reported recurrence of AUB.

The randomised controlled study comparing resection of polyps with observation for 6 months reported no difference in periodic blood loss using the pictorial blood assessment chart (PBAC) but did report a significant decrease in recurrence of gynaecological symptoms (e.g. IMB and vaginal discharge) in those women having polypectomy [7/75 patients (9.3%) vs. 28/75 control patients (37.3%); p < 0.001]. 75

Discussion

The evidence collated in this review supports the notion that removing uterine polyps is effective at improving symptoms of AUB. However, most of the evidence was derived from observational studies that reported high success rates, but, in general, the quality of the research was poor. The highest-quality studies, the two RCTs (Lieng et al. 75 and TJ Clark, unpublished) reported more modest improvements in symptoms. However, it was unclear whether menopausal status or exact the nature of the presenting AUB complaint influences treatment outcome.

The strengths of this review included the rigorous, systematic approach to literature searching; independent selection of studies and data abstraction in duplicate, and use of recommended study quality assessment tools. 102,104 The included studies were small, however, and many contained heterogeneous populations of women who were both pre- and postmenopausal. In addition, follow-up was often incomplete and short term, such that the strength of any clinical inference possible to draw is limited. Meta-analysis was precluded because of the observed heterogeneity within and between the study populations, as well as variation in follow-up and outcome assessment.

The majority of studies reported hysteroscopic polyp resection under direct vision. However, although hysteroscopic polypectomy is increasing in popularity, a large number of clinicians continue to use blind techniques, such as D&C, affecting the generalisability of the results presented in this review. 45,80,81 To better ascertain the effect of polyp removal on AUB we decided not to include data in which patients had concomitant or subsequent medical or surgical treatments, for example insertion of the LNG-IUS, which may also affect generalisability.

Larger randomised controlled studies are necessary to elucidate if certain groups of patients benefit more from uterine polypectomy. However, recruitment may be hampered by the unwillingness of both gynaecologists and patients to participate in placebo-controlled trials. 76 A further consideration is the increasing move to outpatient polypectomy observed in many units, driven by technological advances in instrumentation, patient expectation and scarcity of health-care resources. 32 Only two randomised studies were identified in this review. Large RCTs comparing conventional inpatient with novel outpatient approaches to polyp treatment are needed to identify best practice before opinion is solidified.

Current practice: surgical method and setting

Outpatient evaluation of the uterus for common gynaecological complaints is now commonplace and has superseded traditional inpatient admission for D&C under general anaesthesia. 21,116 Polyps are highly prevalent and being increasingly identified within the uterus in women presenting with AUB, whether it be HMB, IMB or PMB. 66,70,117–119 Recent technological advances in endoscopy have resulted in improved high-definition optical imaging and digital data capture. Moreover, hysteroscopy systems have become miniaturised, such that they are increasingly portable and easy to insert into the uterine cavity without the need for wide cervical dilatation and blind uterine exploration. Alongside these developments, miniature ancillary instrumentation has been developed, allowing precise targeting of focal pathologies, such as uterine polyps, using a variety of mechanical and electrosurgical equipment32,85–88,96–100 (see Surgical management: polypectomy). These developments have facilitated the concept of ‘see and treat’ hysteroscopy in a convenient outpatient setting. The approach obviates the need for general anaesthesia. Hysteroscopic intervention is not simply restricted to diagnosis, but when pathology amenable to treatment is identified then simultaneous treatment is carried out. 21,32,85,86,88

Despite these technological advances and the apparent safety, convenience and feasibility of outpatient intervention, as well as the high prevalence of uterine polyps associated with AUB, outpatient surgical removal of uterine polyps remains infrequently practised. As described above (see Surgical management: polypectomy), surgical polyp removal is universally practised in the UK45 and elsewhere, although the most prevalent technique differs between the UK and the Netherlands, two countries for which national surveys of practice pertaining to polyp treatment have been conducted. 45,80,81 In the UK the default method for removal of uterine polyps was by blind avulsion or curettage after hysteroscopic location of the focal lesion under general anaesthesia,45 whereas in the Netherlands it was removal under direct hysteroscopic vision under general or regional anaesthesia. 80,81

In 2001 in the UK, removal of polyps under direct vision using hysteroscopic techniques was generally restricted to those gynaecologists with an interest in endoscopic surgery, with such practice being more common in members of endoscopic societies. 45 Although outpatient removal of uterine polyps is possible using blind curettage and/or avulsion, techniques developed for surgery under general anaesthesia, such approaches are associated with increased uterine trauma and discomfort. 12–15,32,82–84 Thus, to set up an outpatient service, the ability to perform hysteroscopic polyp removal under direct vision is a prerequisite. Furthermore, the concomitant removal of focal uterine lesions under direct vision may allow for more complete removal and hence better symptomatic outcomes, in addition to the potential advantages to women and their doctors in terms of increased efficiency, convenience and choice.

Notwithstanding the observed differences in hysteroscopic and blind polyp treatment between the UK and the Netherlands, common to both countries was a propensity among gynaecologists to conduct uterine polypectomy as an inpatient under general anaesthesia. In the UK survey, 19% of respondents performed outpatient uterine polypectomy, but only half of these did so routinely. 45 In the Netherlands, 27% of respondents performed polypectomy in an outpatient setting, but those gynaecologists working in teaching hospitals were twice as likely to undertake such procedures than their colleagues who were practising within non-teaching institutions (39% vs. 19% respectively; p < 0.001). 80 It seems, therefore, that outpatient polypectomy is restricted to those gynaecologists, often working within teaching hospitals, with specific interests or skills in endoscopy. Given the high disease burden associated with uterine polyps,74 the ubiquity of polypectomy and the potential morbidity and resource use associated with inpatient surgery, this difference in practice is unsustainable. It is possible that practice has changed since these surveys were conducted a decade ago, but a subsequent follow-up Dutch survey published last year81 found no such change, confirming again that the vast majority of gynaecologists advocating surgical removal of polyps from the uterus did so using general anaesthesia. Those performing outpatient procedures were again twice as likely to be based within teaching hospitals (43% vs. 19%, respectively; p < 0.001). 81 Within the UK it is also likely that practice is much as it was a decade ago, and this contention is supported by the small proportion of UK centres approached to participate in the Outpatient versus inpatient Polyp Treatment (OPT) Trial who were eligible; the main reason for ineligibility being an absence of a therapeutic OPH service (TJ Clark, Birmingham Women’s Hospital, 2013, personal communication).

The reasons for variation in practice and persistence with inpatient surgical treatment under general anaesthesia are likely to be multiple. The absence of an established outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy service; no access to, or unfamiliarity with, equipment; lack of necessary surgical skills; and financial considerations restricting the development of new services are likely to play their part to a varying degree. As with any new health technologies, however, evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness is necessary once safety and feasibility of the intervention has been established. The lack of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness data is likely to be a key factor driving the current status quo.

Need for a large simple trial of outpatient uterine polypectomy compared with inpatient uterine polypectomy in abnormal uterine bleeding

Two systematic reviews59,87 (see Systematic review performed during the Outpatient versus inpatient Polyp Treatment Trial) provide evidence which suggests that uterine polypectomy is a safe and technically successful procedure for the treatment of AUB and results in an improvement in AUB symptoms. However, the quality of existing research is poor, introducing a substantial potential for bias, and no RCTs compare their impact upon patient symptoms and other patient-centred outcomes. On this latter point, qualitative data addressing patient factors are also fundamental considerations, such as patient preferences for choice of treatment setting as well as their tolerance and acceptability of interventional hysteroscopic procedures in an outpatient setting without general anaesthesia. OPH is known to be associated with discomfort and can induce anxiety. 32,120 Thus, practitioners and patient fears over inducing pain may also influence the continued use of inpatient admission to hospital and general anaesthesia. Moreover, the relative cost-effectiveness of outpatient polyp treatment (OPT) compared with traditional inpatient approaches remains unclear.

The limitations placed upon intrauterine surgery in the conscious outpatient, which include pain tolerance and problems with access or manipulation of miniature hysteroscopic equipment, may translate into reduced feasibility and poorer clinical outcomes. However, even if this were proven, the advantages to women of outpatient intervention in terms of safety, convenience and efficiency may outweigh any inferiority in clinical effectiveness. In addition to these considerations, the inflated cost of miniaturised technologically advanced equipment required for most outpatient procedures combined with the potential for poorer clinical outcomes may offset the efficiency of outpatient polypectomy, even when it is performed immediately following diagnosis at OPH – the ‘see and treat’ approach. Thus, outpatient polypectomy may remain an attractive and preferred treatment option, even if it were not much worse than, or ‘non-inferior to’, standard inpatient treatment.

In light of these considerations, the traditional RCT objective of establishing superiority of a new treatment, in this case outpatient polypectomy, was thought to be inappropriate. Establishing that outpatient treatment is not unacceptably worse than standard inpatient approaches requires a non-inferiority trial.

Thus further research in the form of an adequately powered RCT between treatment settings (outpatient vs. inpatient), stratified by type (i.e. pattern) of AUB, is required to assess the therapeutic role, patient acceptability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of uterine polypectomy in AUB both in the short and longer term. The need for such a trial was evident from publications25,32,87,121,122 and supported by UK consultant gynaecologists. Our national survey in 2001 indicated that 268 of 854 (31%) of gynaecologists performing uterine polypectomy were supportive of a trial comparing inpatient with outpatient uterine polypectomy. 45 This implies that the newer outpatient approach had been introduced in some centres without definite evidence but opinion regarding its use is not yet solidified (i.e. collective equipoise) making the need for a trial even more urgent. Furthermore, a recent practice guideline on the diagnosis and management of endometrial polyps produced by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) highlighted the ‘paucity of high-quality data in the subject area of endometrial polyps given the common occurrence of this pathology. The following considerations are proposed for future research: 1. Randomized trials of women with abnormal uterine bleeding to evaluate the clinical outcome of polypectomy and 2. Cost comparisons of different methods for hysteroscopic removal of polyps, including outpatient and outpatient locations’. 25

Assessing feasibility for a randomised controlled trial: the Outpatient versus inpatient Polyp Treatment pilot trial

In addition to systematically reviewing the medical literature87 and performing a national survey of practice,45 we undertook two primary clinical studies. The first was an observational cohort study to compare outpatient hysteroscopic polypectomy in the treatment of symptomatic endometrial polyps with inpatient management. 97 This study demonstrated that outpatient treatment was technically feasible and it had the potential to be efficacious and cost-effective. From this we launched an external pilot RCT of 60 patients in a single centre to assess the acceptability of randomisation to patients (TJ Clark, personal communication).

A short summary of the methods used and results are given below.

Objectives

-

To help us to optimise the trial design for a robust large scale, multicentre study with adequate statistical power to evaluate OPT reliably.

-

To demonstrate the acceptability of randomisation.

-

To establish standardised operating procedures for trial management, and piloted questionnaires and consent forms patients.

-

To inform the sample size of a larger study.

Methods

All women with AUB who are referred for a diagnostic OPH between January and July 2000 at the Birmingham Women’s Hospital were approached for consent to participate in this pilot trial. AUB was defined according to four categories: (1) PMB; (2) unscheduled bleeding while on HRT or tamoxifen for > 6 months; (3) IMB in women > 40 years old; and (4) excessive menstrual bleeding refractory to medical therapy. At OPH, those women with a benign uterine polyp [endometrial polyp or pedunculated (grade 0) fibroid] as described by Clark et al. ,32 were randomised to immediate outpatient polypectomy under local anaesthesia or delayed (within 3 months of randomisation) inpatient uterine polypectomy under general anaesthesia as a day case. Women were excluded if hysteroscopic features suggested a malignant lesion or when additional pelvic pathology necessitated hysterectomy. Inclusion and exclusion criteria, in full, are shown below.

Inclusion criteria

-

AUB requiring diagnostic hysteroscopy.

-

Finding of a benign polyp on diagnostic hysteroscopy.

-

No hysteroscopic features suspicious of malignancy.

-

Need for polypectomy or myomectomy.

Exclusion criteria

-

Hysteroscopic features suggesting malignant lesion.

-

Additional pathology necessitating hysterectomy.

Interventions

Outpatient uterine polypectomy was performed under direct hysteroscopic vision using Versapoint® spring tip bipolar electrodes (Gynecare, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) as previously described. 32,97 Inpatient uterine polypectomy was performed under general anaesthesia by traditional D&C, blind avulsion with or without prior localising hysteroscopy or under direct vision using an operative hysteroscope. In most instances, wide dilatation of the cervical canal was required to accommodate the larger diameter inpatient instruments within the uterus.

Outcomes

Patient completed outcomes, administered by postal questionnaire, were collected at baseline then at 3, 6 and 12 months post surgery. These consisted of:

-

Bleeding response: a 100-mm VAS to measure bleeding in the last month. The scale was anchored at each end by ‘none’ and ‘continuous’. For those women who expected bleeding (premenopausal and those on sequential HRT) we considered a 50% reduction from baseline in bleeding score as a ‘success’. For those women for whom no bleeding was expected (postmenopausal) we considered a score of 0–3 mm a ‘success’.

-

Disease-specific health-related quality of life (HRQL) was evaluated using the disease-specific Menorrhagia Multi-attribute Assessment Scale (MMAS). 123 Scores range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).

-

Generic HRQL using the generic EuroQol European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) instrument. 124 Scores range from –0.59 (worst) to 1.0 (best). Health thermometer scores range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).

-

Sexual satisfaction and functioning using the Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS). 125 Scores range from 0 (best) to 100 (worst).

Randomisation and blinding

Sixty women were randomised. The University of Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit provided third-party randomisation. For the randomisation sequence, variable block size in balanced groups was used to avoid any possibility of foreknowledge. Surgeons and patients could not be blinded in this study (to prevent performance bias and measurement bias) owing to the nature of the comparison, but randomisation was concealed such that the surgeons would be kept unaware of the patient’s group allocation until they had completed the diagnostic OPH, thereby preventing selection bias. In addition, the outcome assessments were conducted by self-administered questionnaires, avoiding possible bias arising from the influence of clinicians’ knowledge of patient’s group allocation at medical follow-up.

Statistical considerations

No formal sample size calculation was made. As many women as possible were randomised over the 6-month period; we considered this length of time to be long enough to achieve our stated objectives.

Summary statistics were produced to describe the demographics of the women randomised. No formal hypothesis testing was attempted on the outcome data, as with this size of sample we could not expect any statistically significant differences; this was not our objective here. Summary statistics for patient completed outcome measures at each time point are presented alongside estimates of uncertainty around point estimates: 95% two-sided CIs for RRs and mean differences between groups. Estimates of differences were adjusted for baseline using analysis of covariance. Analysis was by intention to treat (ITT).

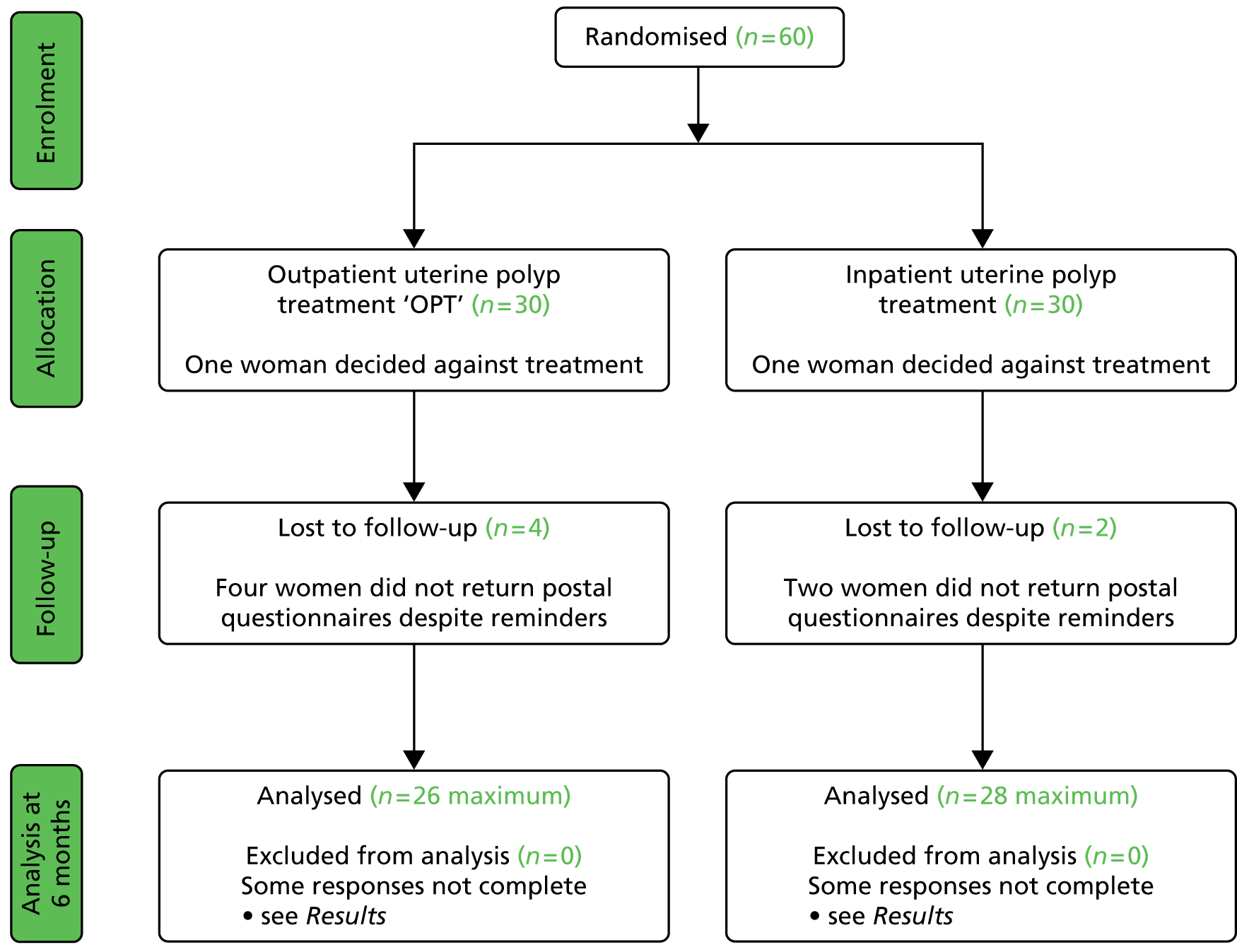

Summary of results

In total, 60 women were randomised to either inpatient or outpatient uterine polypectomy (Figure 4). The questionnaire response rate at 6 months was 54 of 60 (90%), although not all of the components of the questionnaire were always completed.

FIGURE 4.

Pilot OPT Trial profile.

The baseline characteristics of the women randomised are shown in Table 5. Some slight imbalance was seen in some of the parameters that would be expected in a study of this size.

| Patient characteristic | Outpatient (n = 30) | Inpatient (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 54 [7.8] | 57 [7.8] |

| Parity: | ||

| 0 | 3 (10) | 2 (7) |

| 1–3 | 20 (67) | 20 (67) |

| > 3 | 5 (16) | 6 (20) |

| Not reported | 2 (7) | 2 (6) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 21 (70) | 23 (77) |

| Other | 8 (27) | 5 (17) |

| Not reported | 1 (3) | 2 (7) |

| Sexually active | ||

| Yes | 17 (57) | 21 (70) |

| No | 12 (40) | 7 (23) |

| Not reported | 1 (3) | 2 (7) |

| AUB | ||

| Postmenopausal bleeding | 10 (33) | 9 (30) |

| Unscheduled bleeding on HRT | 13 (43) | 16 (53) |

| IMB | 5 (17) | 4 (13) |

| Excessive menstrual bleeding | 2 (7) | 1 (4) |

| Other uterine pathology | ||

| None | 30 (100) | 27 (90) |

| SMF | – | 1 (3) |

| Not reported | – | 2 (7) |

Bleeding response

Completed responses were available for 45 of 60 (75%) of the women randomised at 6 months. At this time point, successful bleeding response followed outpatient uterine polypectomy in 19/22 (86%) women, compared with 16/23 (69%) after inpatient uterine polypectomy at 6 months (Table 6). Similar proportions were seen at 1 year. Detailed VAS bleeding scores for those women who were expecting bleeding are detailed in Table 7.

| Time from treatment | Outpatient | Inpatient | RR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 13/19 (68%) | 13/22 (59%) | 1.16 (0.73 to 1.84) |

| 6 months | 19/22 (86%) | 16/23 (69%) | 1.24 (0.90 to 1.71) |

| 1 year | 19/24 (79%) | 15/22 (68%) | 1.16 (0.82 to 1.65) |

| Time of assessment | Outpatient, mean (SD) | Inpatient, mean (SD) | Difference between groups, 95% CIa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n = 8, 47.6 (33.5) | n = 11, 33.3 (25.6) | – |

| 3 months | n = 10, 22.7 (22.1) | n = 11, 24.9 (35.1) | 0.6 (–26.4 to 28.6) |

| 6 months | n = 11, 17.4 (25.2) | n = 12, 13.5 (22.6) | 3.8 (–15.5 to 23.2) |

| 1 year | n = 12, 21.3 (33.0) | n = 11, 19.1 (26.4) | 4.3 (–22.1 to 30.6) |

Quality of life

Results for the disease-specific (MMAS) and generic quality of life (EQ-5D) scores are given in Tables 8 and 9. Scores generally appeared to improve from baseline. Sexual satisfaction score are given in Table 10; no obvious increasing or decreasing trend was noted here. Low response rates were noted for the MMAS and sexual satisfaction questionnaires.

| Time of assessment | Outpatient, mean (SD) | Inpatient, mean (SD) | Difference between groups (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n = 6, 60.0 (28.9) | n = 5, 63.6 (22.3) | – |

| 3 months | n = 5, 68.5 (22.1) | n = 5, 65.3 (19.0) | 8.3 (–20.5 to 37.0) |

| 6 months | n = 6, 77.7 (17.9) | n = 5, 79.4 (26.2) | –2.2 (–31.5 to 27.0) |

| 1 year | n = 7, 76.0 (24.2) | n = 5, 73.6 (30.2) | 2.4 (–31.5 to 36.2) |

| Time of assessment | Outpatient, mean (SD) | Inpatient, mean (SD) | Difference between groups (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| EuroQoL EQ-5D | |||

| Baseline | n = 27, 0.75 (0.29) | n = 28, 0.78 (0.21) | – |

| 3 months | n = 25, 0.81 (0.31) | n = 26, 0.86 (0.18) | –0.04 (–0.14 to 0.07) |

| 6 months | n = 26, 0.86 (0.22) | n = 28, 0.88 (0.14) | –0.01 (–0.11 to 0.08) |

| 1 year | n = 27, 0.81 (0.29) | n = 27, 0.86 (0.18) | –0.04 (–0.16 to 0.08) |

| EuroQoL health thermometer | |||

| Baseline | n = 25, 78.1 (18.1) | n = 25, 77.5 (20.6) | – |

| 3 months | n = 23, 78.3 (16.5) | n = 26, 76.4 (18.9) | –0.2 (–9.9 to 9.5) |

| 6 months | n = 23, 80.7 (19.6) | n = 28, 79.0 (16.1) | 0.5 (–8.8 to 9.9) |

| 1 year | n = 26, 74.5 (23.0) | n = 28, 81.1 (15.7) | –3.9 (–14.5 to 6.7) |

| Time of assessment | Outpatient, mean (SD) | Inpatient, mean (SD) | Difference between groups, 95% CIa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n = 12, 17.8 (11.3) | n = 16, 23.6 (15.8) | – |

| 3 months | n = 8, 16.9 (13.4) | n = 12, 16.8 (14.5) | –2.8 (–14.2 to 8.5) |

| 6 months | n = 9, 19.8 (9.4) | n = 10, 21.4 (14.7) | –2.1 (–10.2 to 5.9) |

| 1 year | n = 12, 22.1 (17.0) | n = 11, 20.2 (14.8) | 0.4 (–5.3 to 6.1) |

Interpretation

The pilot RCT data demonstrated the acceptability of randomisation, as well as establishing standardised operating procedures for trial management, and piloted questionnaires and consent forms for patients. The accrual rate from a single centre convinced us of the feasibility of undertaking a multicentre trial, especially upon the background of a rapid increase in the provision of OPH facilities within the UK. 45

Impact on planning for a definitive trial

Although AUB may affect the sexual domain of life quality, the response to the ISS was low. This probably reflected the sensitive nature of the questions presented to women of all ages, some of whom may have felt them intrusive or irrelevant. Moreover, the cumulative burden of completing various outcome questionnaires may have been a disadvantage. In view of the low response rate and the concern that potentially inclusion of the ISS may compromise return of the primary outcome in the definitive trial, a decision was made to no longer include the ISS as one of the secondary outcome measures. The response rate to the condition-specific MMAS was also low. This was mainly because it is a condition-specific questionnaire designed for use in women with HMB. However, in the pilot study the MMAS was included within the self-completed outcome booklet that was sent to all women and was not restricted to the minority of women who actually presented with HMB. Consequently, the MMAS was considered irrelevant and ignored by the majority of participants. The use of disease-specific questionnaires, such as the MMAS, has been encouraged as an important and more sensitive patient-reported outcome in trials. 126,127 In light of this we planned to retain the MMAS in the multicentre trial but make it clear within the patient-reported outcome questionnaires that the MMAS should be completed by only those women with regular periods or hormone-induced withdrawal bleeds, even if their presenting complaint is unscheduled bleeding rather than HMB.

Participants found that understanding the concept of the VAS, as applied to amount of bleeding, was difficult. This reflected a lack of familiarity in providing responses on a continuous scale, especially as most women with AUB included in the pilot did not have HMB, so that the nature of the bleeding, not the amount of bleeding, was the primary concern. It was clear therefore that if we were to maintain the relevance and generalisability of our work in a future, larger-scale trial we would have to include all types of AUB found in association with uterine polyps (i.e. HMB, IMB and PMB) and measurement of the primary outcome – successful alleviation of AUB symptoms – needed to be revised.

This pilot RCT appeared to show that outpatient treatment was comparable to inpatient treatment in terms of symptomatic relief (86% vs. 69% respectively). However, given the difficulties with VAS score responses in this population as previously detailed we exercised caution in directly applying these proportions to inform the sample size of the definitive study. Furthermore, it should be noted that they were derived from a small population in a single specialist ambulatory tertiary referral centre. Uncontrolled series included in the original systematic review87 showed symptomatic relief in up to 100% of women treated as inpatients. The only controlled series included in the review reported an 80% vs. 90% satisfaction with treatment outcome in favour of inpatient treatment. Thus, all this evidence was used in combination to inform the sample size calculation for the proposed multicentre RCT.

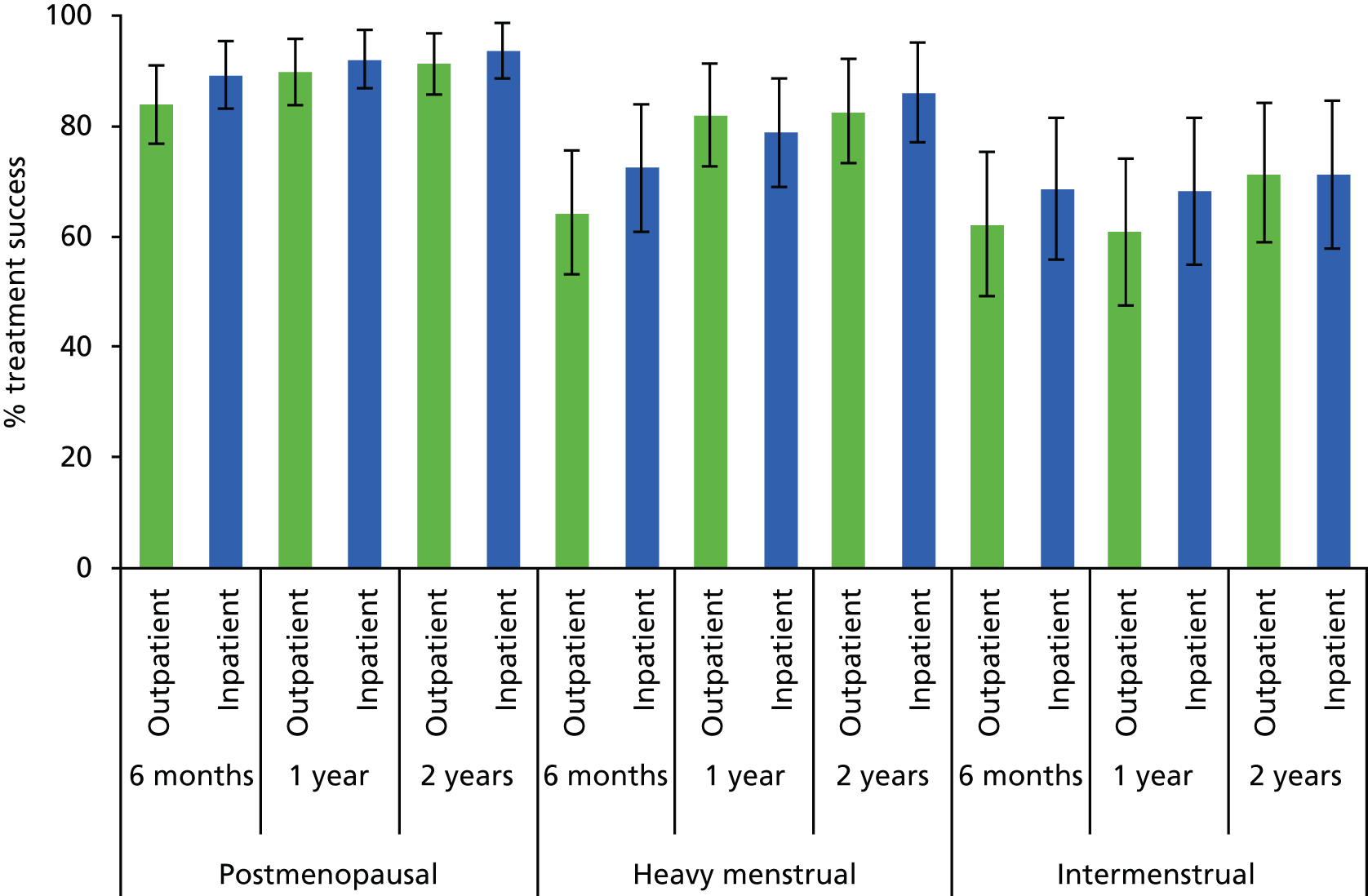

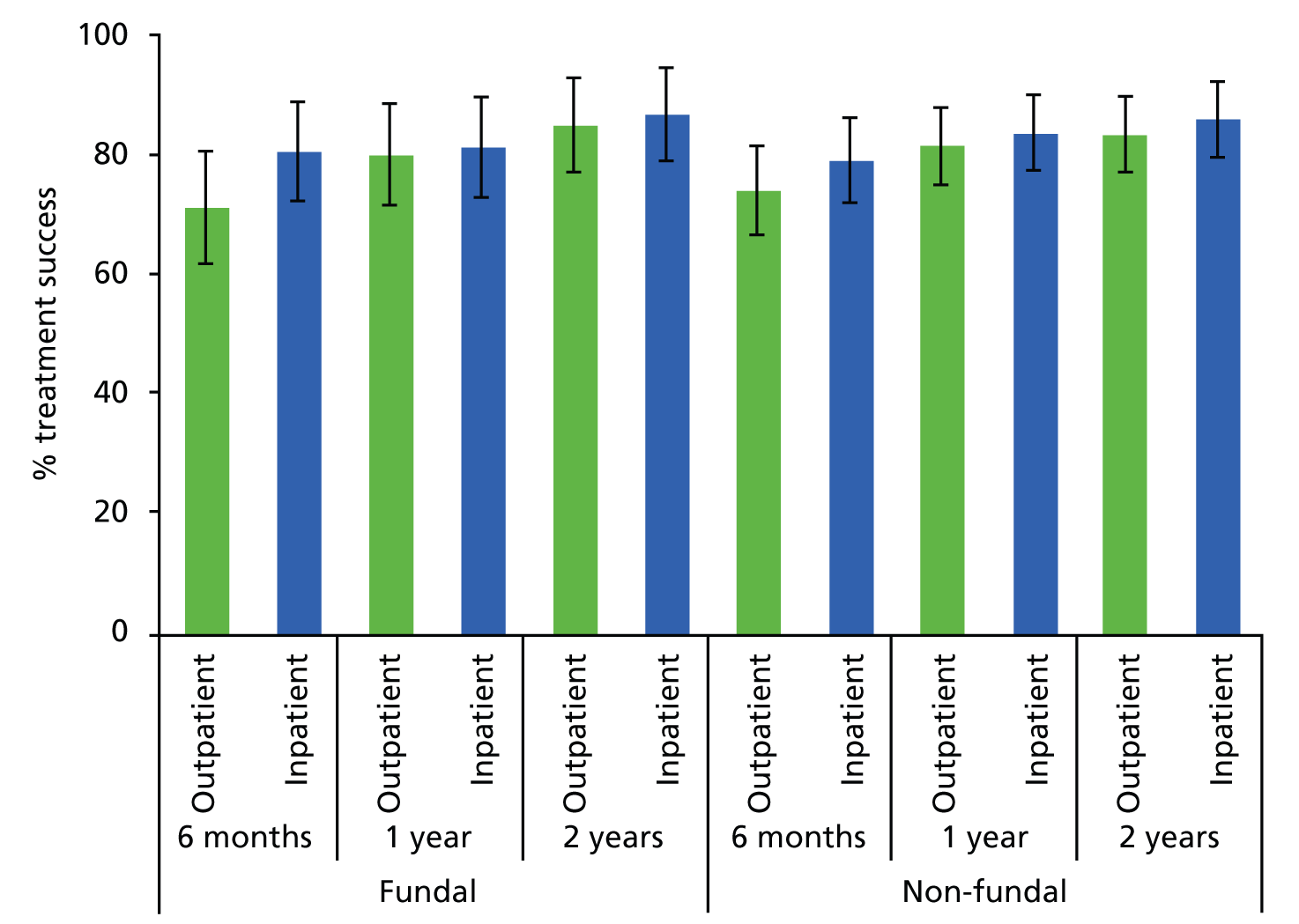

Clinical factors and prognosis

As outlined above (see Abnormal uterine bleeding), AUB comprises a number of complaints in women of both pre- and postreproductive age. Research to date is limited with regard to the impact of polypectomy upon the type of bleeding complaint: HMB, IMB or PMB. In addition, AUB and polyp formation may be affected by the use of exogenous sex steroid hormones found in HRT or the hormone partial agonist tamoxifen,36,40,41 commonly used in the treatment of breast cancer. Symptomatic outcomes may also be influenced by the location of the polyp within the uterus and its morphology. Fundally sited lesions can be harder to remove because the attachment to the uterine wall is less accessible. 32 Firmer fibrous lesions can be harder to cut through with mechanical instruments and retrieve from the uterine cavity via the narrow cervical canal. In contrast, softer glandular polyps may be more mobile and difficult to stabilise and detach but, because of their compressible consistency, they can be easier to extract from the uterine cavity. These variables were therefore identified a priori as potential prognostic factors.

Design implications for the substantive study

Although outpatient treatment of uterine polyps necessitates in most cases the use of innovative miniature endoscopic equipment, it is the treatment setting rather than the intervention itself that is novel. The limitations of outpatient polypectomy discussed previously could potentially result in reduced feasibility and poorer clinical outcomes. However, even if this were proven, the advantages to women of outpatient intervention in terms of safety, convenience and efficiency may outweigh any inferiority in clinical effectiveness. In addition to convenience, avoidance of inpatient stay and facilities may translate into substantially reduced costs to health services. Thus, outpatient polypectomy may remain an attractive and preferred treatment option, even if it were not much worse than, or ‘non-inferior to’, standard inpatient treatment.

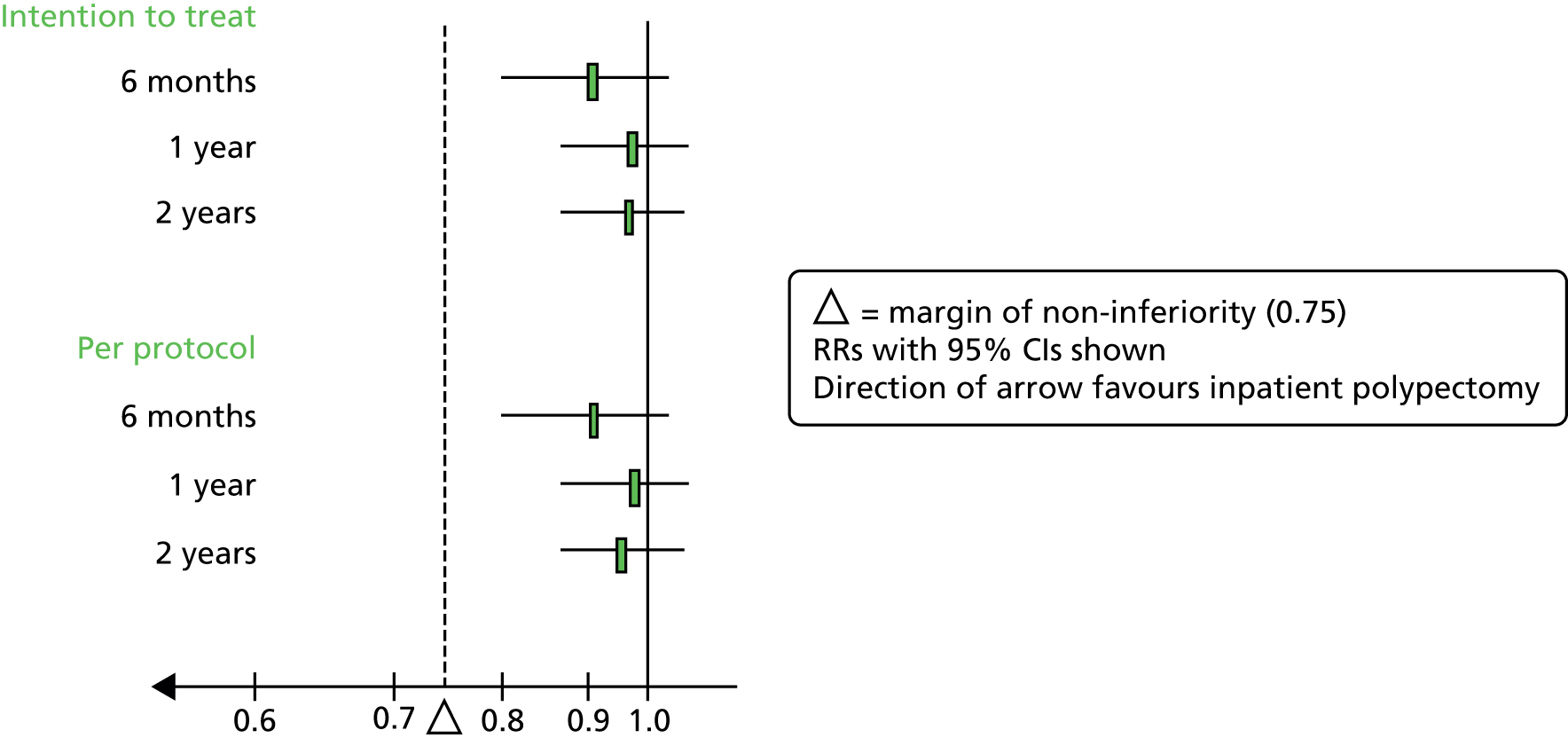

In light of these considerations, the traditional RCT objective of establishing superiority of a new treatment, in this case outpatient polypectomy, was thought to be inappropriate. We therefore framed our primary objective in terms of establishing that outpatient treatment was not unacceptably worse than standard inpatient approaches. Therefore, we designed a non-inferiority trial. Based upon our own experience and consultation with potential collaborating centres, we believed that outpatient would be the treatment of choice even if 25% fewer women (in relative terms) had alleviated symptoms at 6 months. Thus, the margin of non-inferiority was set at 0.75.

The pilot study did not formally collect data on the number of women declining randomisation on the basis of a preference for immediate outpatient treatment under local anaesthesia or delayed inpatient uterine polypectomy under general anaesthesia. However, experience suggested a substantial proportion expressed a strong preference for one or the other setting. Women choosing their treatment setting may tend to report more favourable outcomes, being empowered by having been part of the decision process, or conversely may have high expectations of success and be disappointed with a less-than-complete resolution of their symptoms. Given the potential for interaction between choice, or conversely lack of choice if randomised, and outcome, we planned a parallel patient preference study using the same outcome measures as the RCT.

Objectives of the Outpatient polyp treatment study

In undertaking the OPT study, we aimed to:

-

test the hypothesis that in women with AUB associated with benign uterine polyp(s), OPT achieved as good, or no more than 25% worse (in relative terms), alleviation of bleeding symptoms at 6 months, compared with standard inpatient treatment (principal objective)

-

test the hypothesis that response to uterine polyp treatment differed according to the pattern of AUB and menopausal status by three secondary analyses:

-

premenopausal women compared with postmenopausal women

-

IMB compared with excessive menstruation

-

postmenopausal women on HRT compared with those not on HRT

-

-

explore the variation in the effectiveness of outpatient polyp treatment compared with standard inpatient polyp treatment at different periods of follow-up (12 and 24 months)

-

assess patient acceptability and impact on HRQL

-

perform an economic evaluation for cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Methods of randomised controlled trial and preference study

Objectives

The objectives of the clinical trial and preference study were to:

-

test the hypothesis that in women with AUB associated with benign uterine polyp(s), OPT achieved as good, or no more than 25% worse (in relative terms), alleviation of bleeding symptoms compared with standard inpatient treatment at 6 months (principal objective)

-

test the hypothesis that response to uterine polyp treatment differed according to the pattern of AUB and menopausal status by three secondary analyses:

-

premenopausal women compared with postmenopausal women

-

IMB compared with excessive menstruation

-

postmenopausal women on HRT compared with those not on HRT

-

-

explore the variation in the effectiveness of OPT compared with standard inpatient polyp treatment at different periods of follow-up (12 and 24 months)

-

assess patient acceptability and impact on HRQL

-

investigate how treatment outcomes vary by choice.

Study design

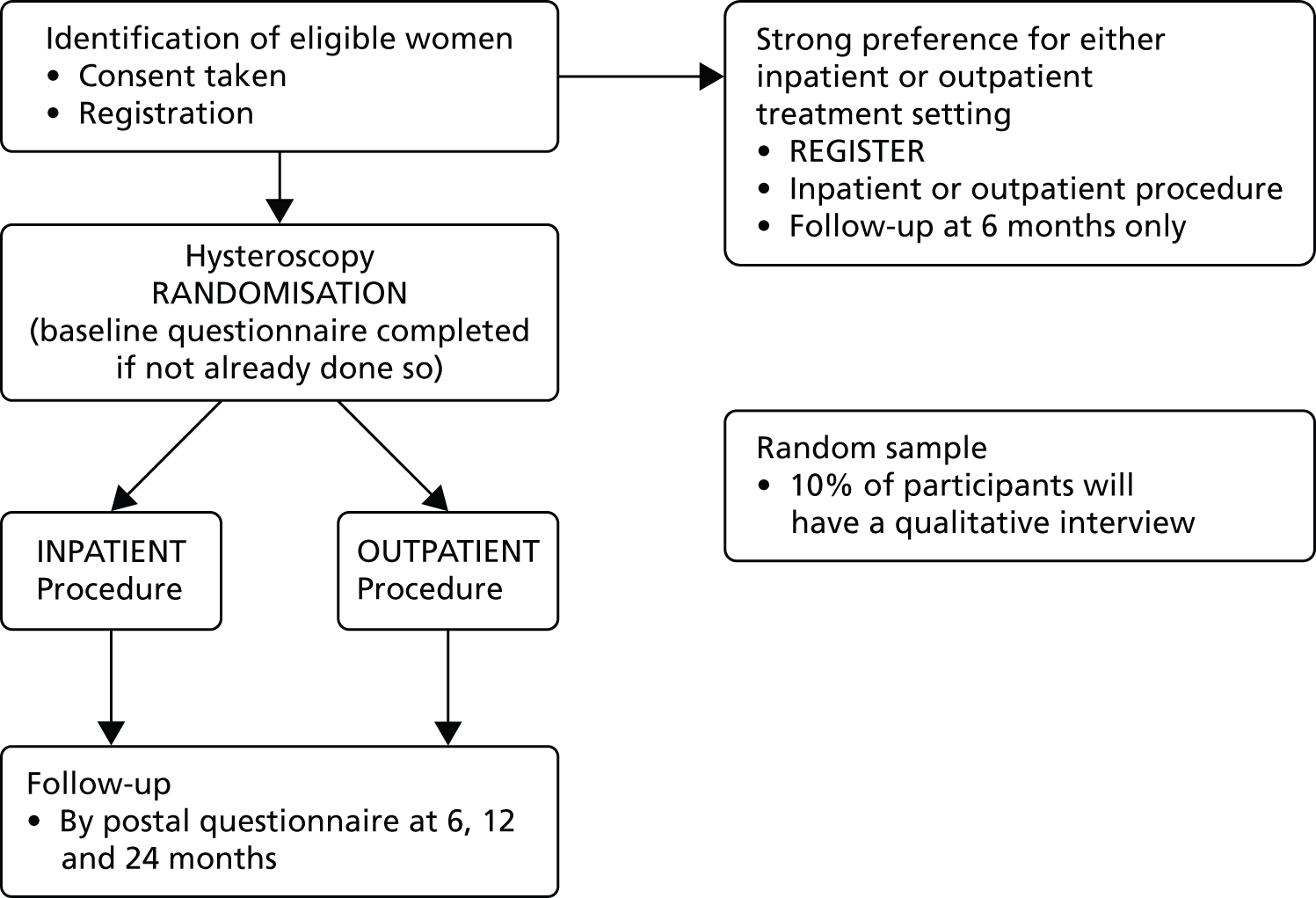

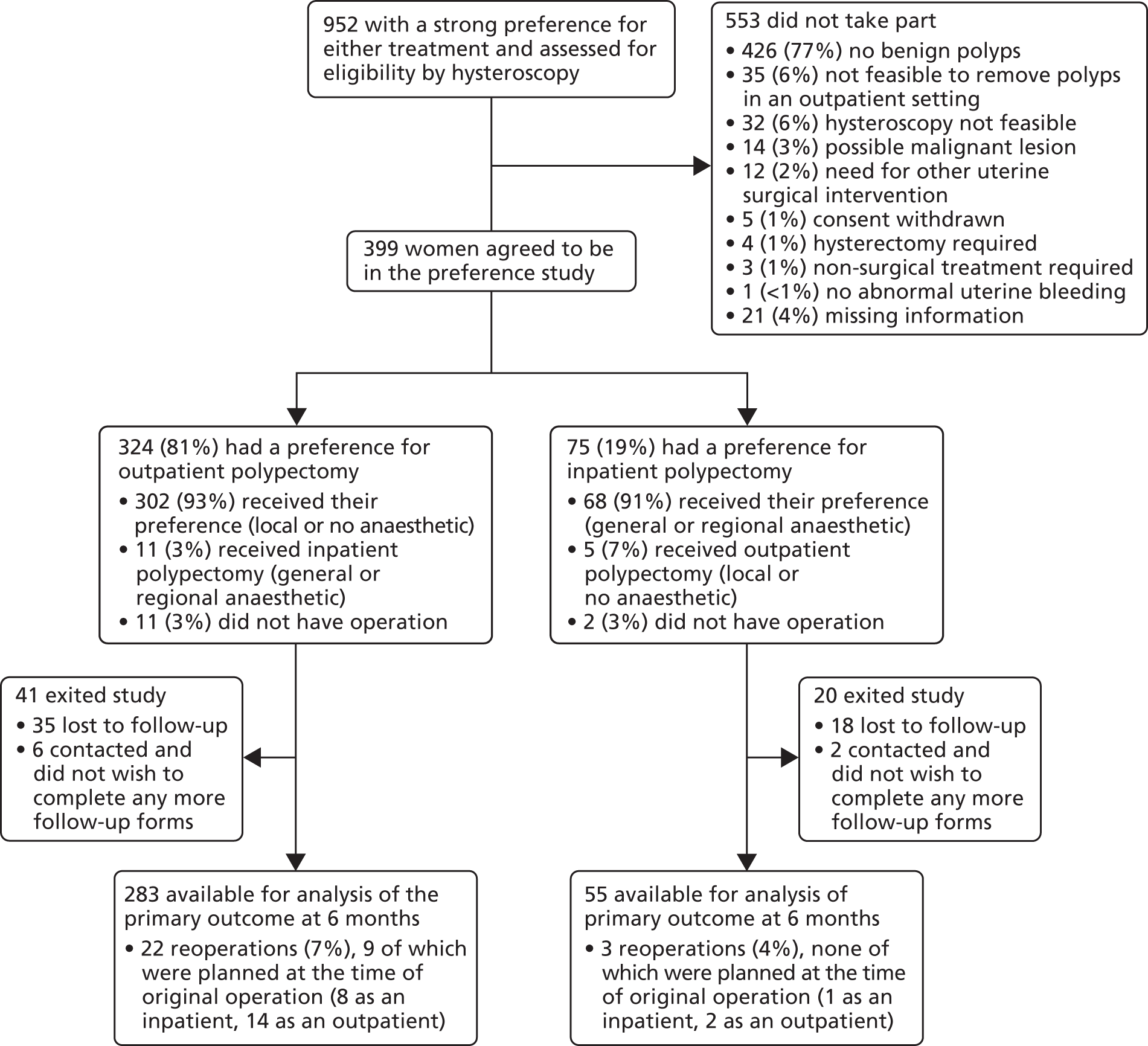

The OPT study (Figure 5) was designed as a pragmatic, multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial of outpatient polypectomy compared with inpatient polypectomy with a concurrent non-randomised cohort of women with a strong preference for treatment setting.

FIGURE 5.

Outpatient polyp treatment flow diagram.

Both the RCT and preference study had the same setting, structure and design, including outcome measures, although the preference study had a shorter follow-up length only up to 6 months; this was to encourage participation, as well as to minimise costs of longer-term follow-up.

Screening and consent prior to outpatient hysteroscopy

All women with AUB seen in hospital outpatient clinics and undergoing a diagnostic OPH were considered for the trial. The trial was introduced to them in the outpatient clinic and a comprehensive, evidence-based patient information sheet was provided, either at the first clinic visit or with the appointment letter for the hysteroscopy. Participant information sheets and consent forms were provided to each centre in English and other languages as appropriate to their local community.

Before the procedure, the women were given the chance to discuss the risks and benefits of uterine polypectomy in the outpatient setting using local anaesthesia and in the inpatient setting under general anaesthesia, the process of randomisation and the follow-up requirements with the consultant gynaecologist and/or gynaecology nurse. It was carefully explained that the final decision about eligibility would be taken during the hysteroscopic examination and would be dependent on the findings; therefore, consent was required before the procedure. Women were informed that the process of randomisation would prolong the diagnostic procedure time by up to 2 minutes. Women were also made aware that if the allocation was outpatient polypectomy then the procedure would be undertaken immediately in most instances and treatment would take an additional 10–15 minutes on average, whereas if the allocation was inpatient polypectomy, the diagnostic hysteroscope would be removed and she would be given another appointment for the inpatient procedure within 8 weeks. Women were also informed that only about one in four women will have a uterine polyp and therefore be eligible for the OPT Trial. Each woman appreciated that if a polyp was not found, appropriate treatment would be offered but she would not be recruited into the trial. In this case, the consent form, baseline questionnaire and randomisation form would be destroyed.

In centres at which a ‘see and treat’ outpatient approach was not used (i.e. outpatient as well as inpatient polypectomies were scheduled for a later date), discussion about participation into the OPT Trial and randomisation could take place after the diagnostic hysteroscopy in eligible women known to have uterine polyp.

Determining eligibility

All women with AUB who provided written informed consent to participate in the OPT study and satisfied the eligibility criteria were included. Those women consenting to the RCT were to be randomised following the diagnostic OPH procedure. Those consenting to participate in the preference study were treated according to their preference. The practitioner inspected the uterine cavity, according to their standard hysteroscopic protocol, to determine the presence of uterine polyp(s), absence of any excluding pathology and technical feasibility for outpatient polypectomy. For the purpose of the OPT Trial a uterine polyp was defined at diagnostic hysteroscopy as:

A discrete outgrowth of endometrium, attached by a pedicle, which moves with the flow of the distension medium.[32] Polyps may be pedunculated or sessile, single or multiple and vary in size (the variable amount of glands, stroma and blood vessels that constitute the polyp will influence their macroscopic appearance [i.e. glandulocystic polyps or firmer, more fibrous polyps (indistinguishable in some instances from grade 0 submucous fibroids)].

The following inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to assess eligibility.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 16 years.

-

AUB requiring diagnostic hysteroscopy.

-

Finding of a benign polyp or polyps (glandulocystic or pedunculated/grade 0 fibroid) on diagnostic hysteroscopy.

-

Feasible to remove polyp as an outpatient.

-

Need for polypectomy.

-

Ability to perform polypectomy within 8 weeks of diagnosis.

-

Baseline questionnaire completed prior to the hysteroscopy.

-

Written informed consent obtained prior to the hysteroscopy.

Exclusion criteria

-

Hysteroscopic features suggesting malignant lesion.

-

Need for other uterine surgical intervention (i.e. endometrial ablation, resection, myomectomy or hysterectomy).

-

Additional pathology necessitating hysterectomy.

Randomisation

If the woman was found to be eligible for the OPT Trial, the gynaecologist or member of his/her team obtained a randomised allocation during the hysteroscopic examination. Randomisation notepads were provided to investigators and used to collate the necessary information prior to randomisation. Participants were entered and randomised into the trial in a 1 : 1 ratio via a short telephone call to the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit, or by logging into a secure web-based randomisation system. To avoid any possibility of foreknowledge, the randomiser needed to provide the name and date of birth of the participant, and confirm the eligibility and stratification criteria, whereupon a randomised allocation was provided and a trial number allocated.

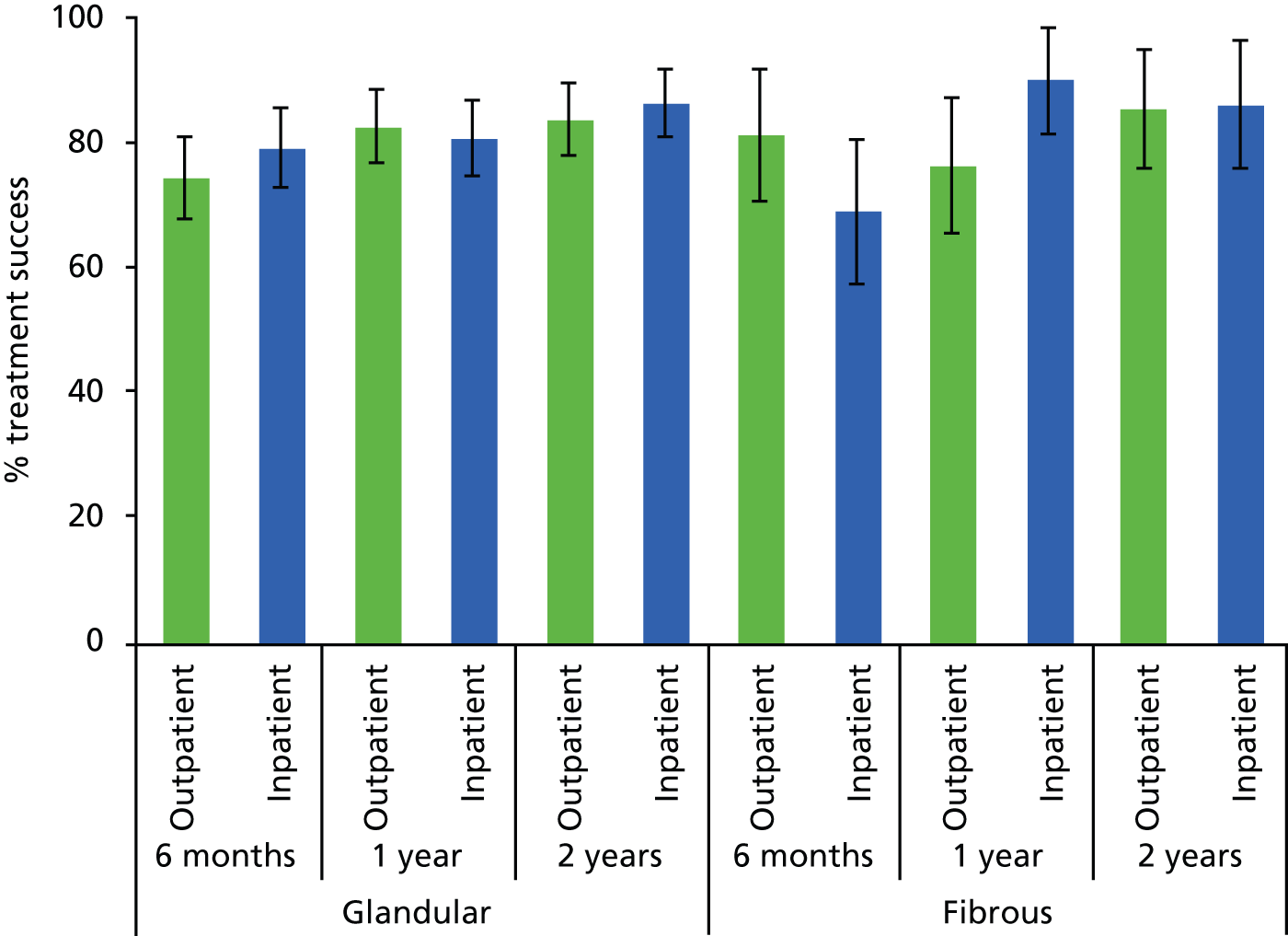

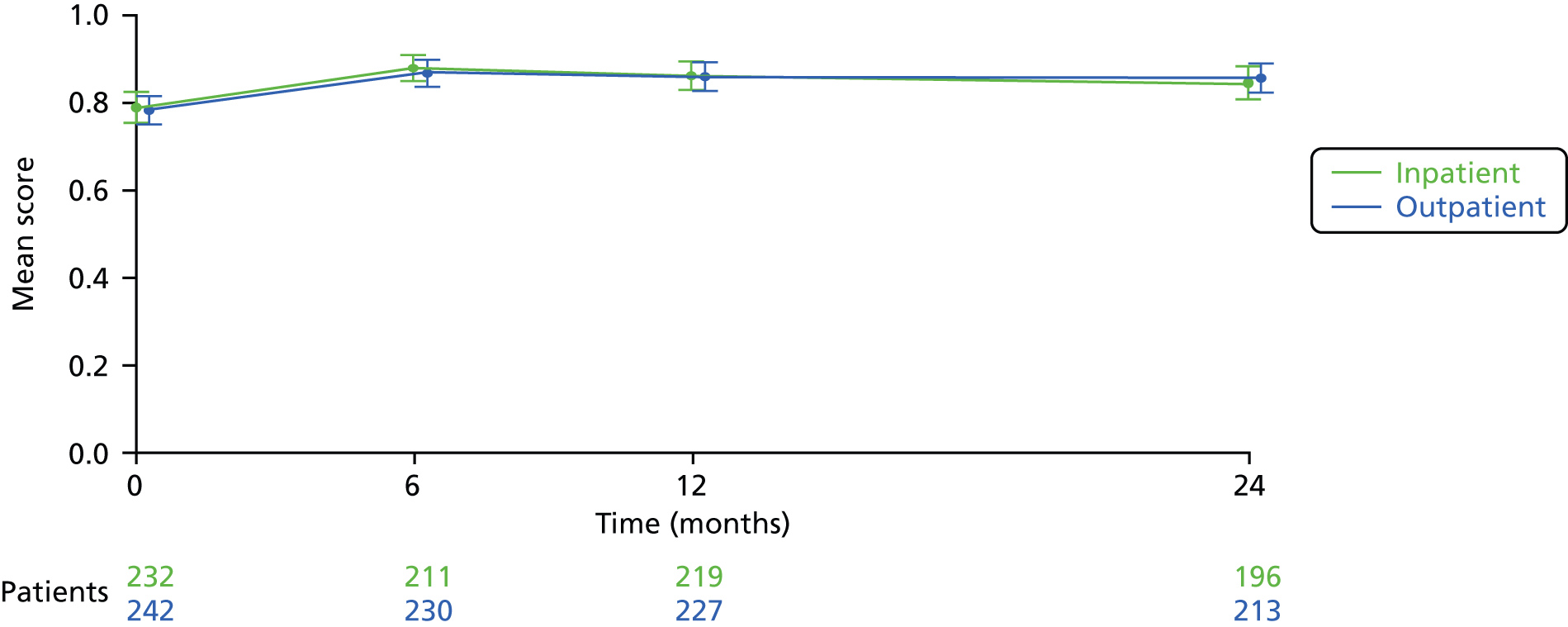

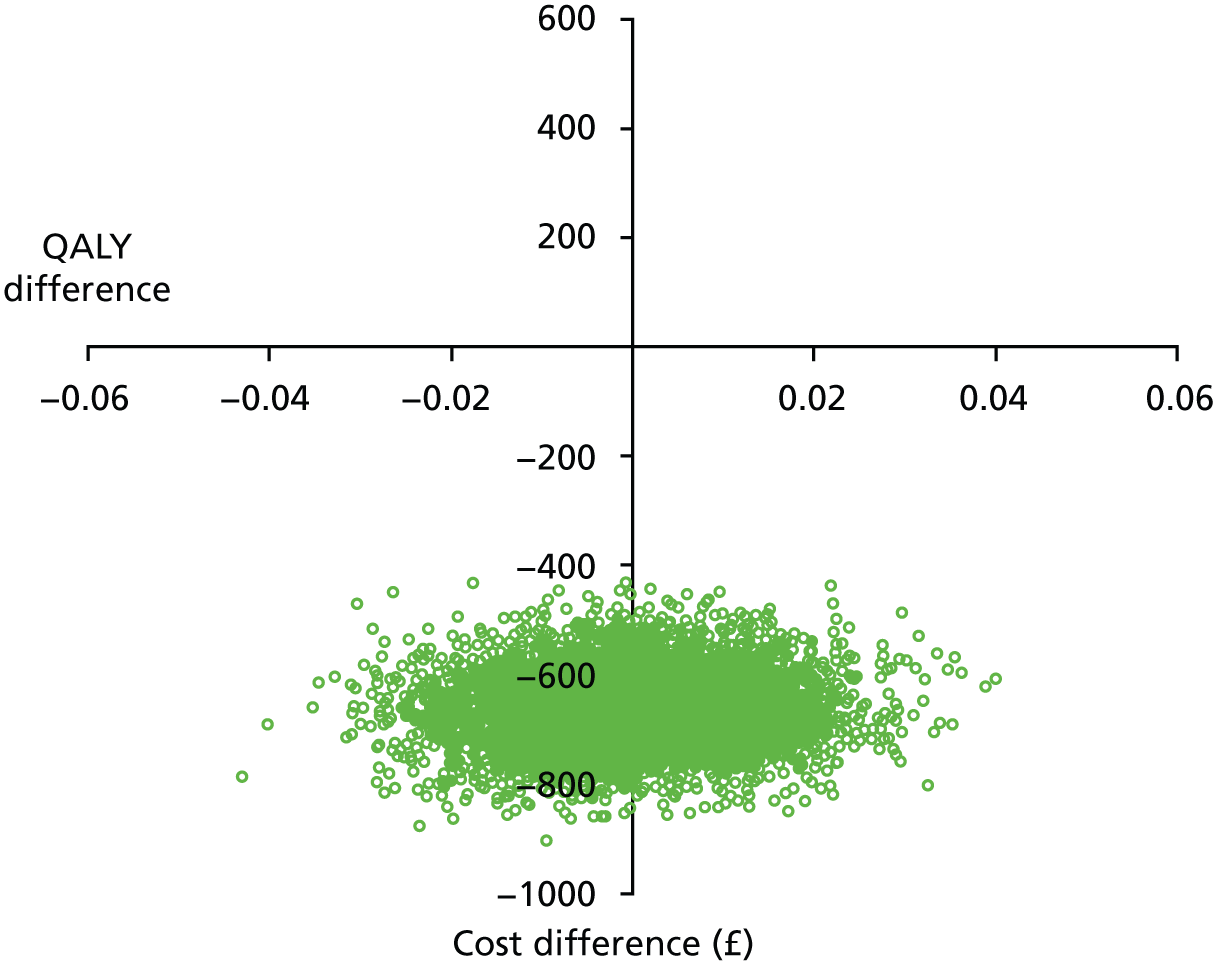

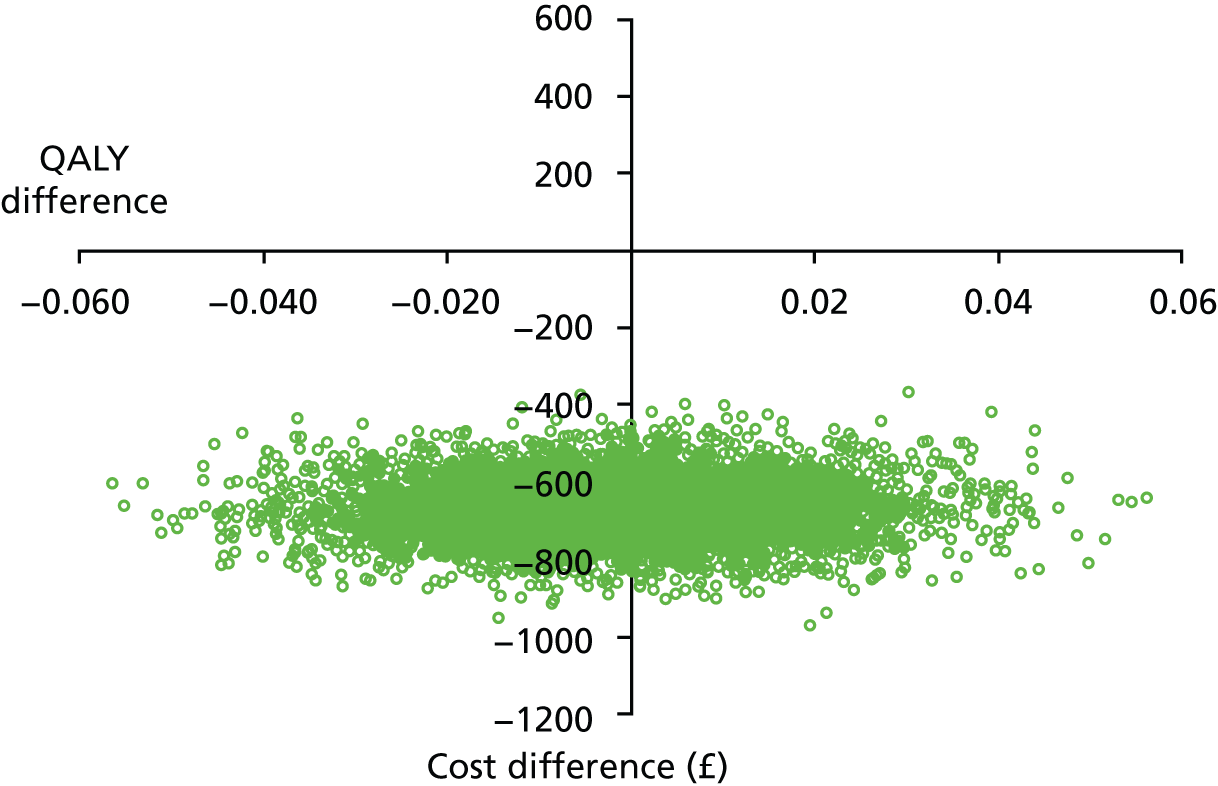

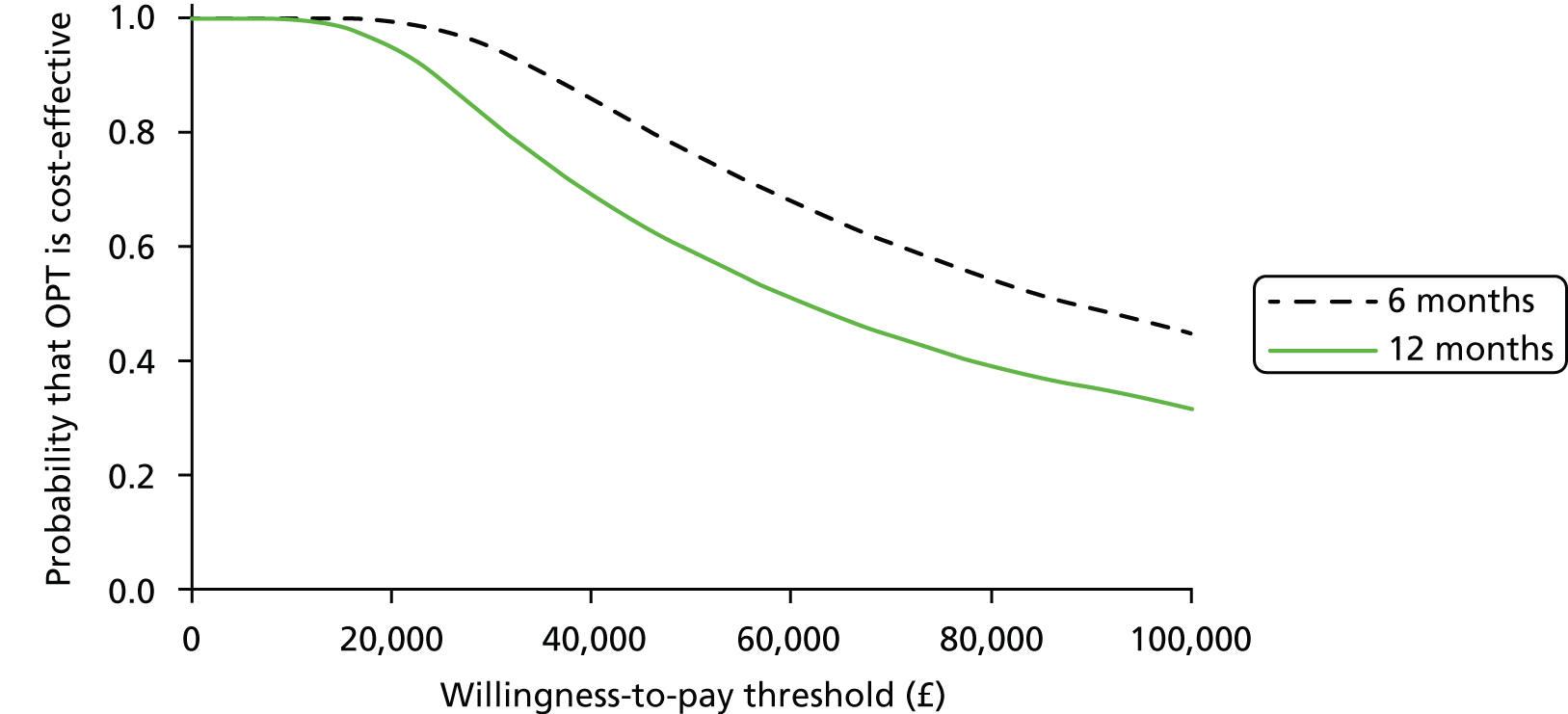

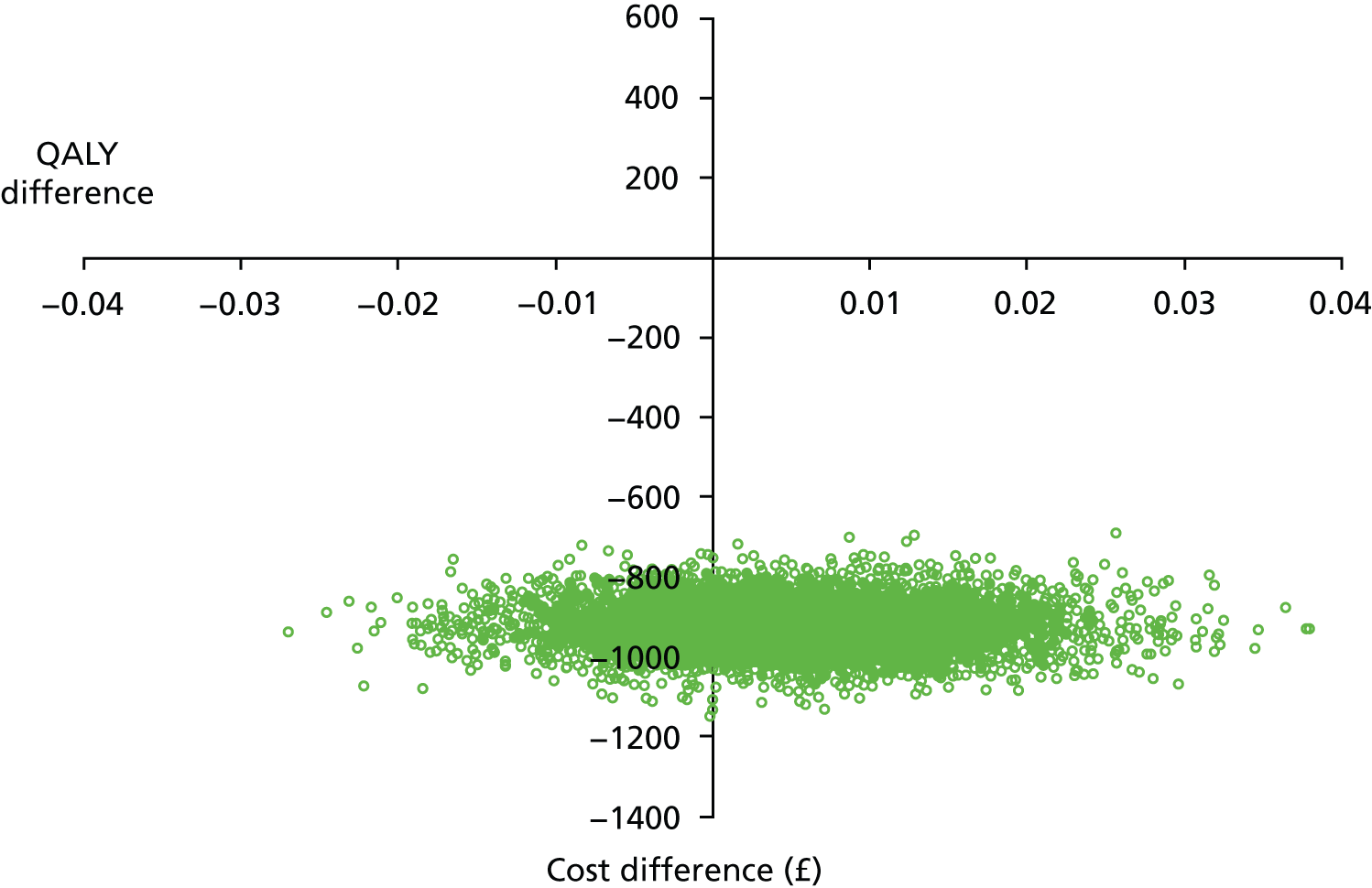

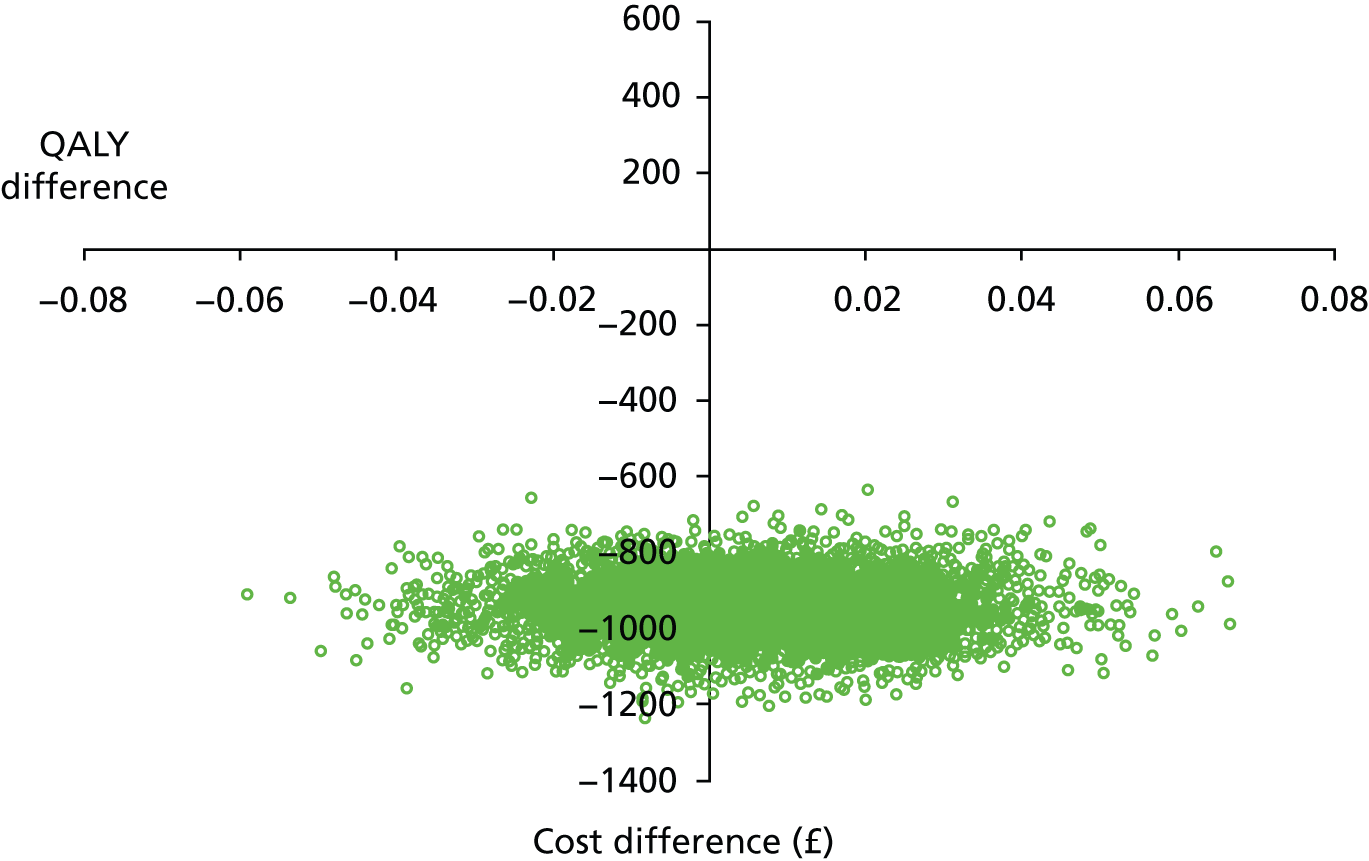

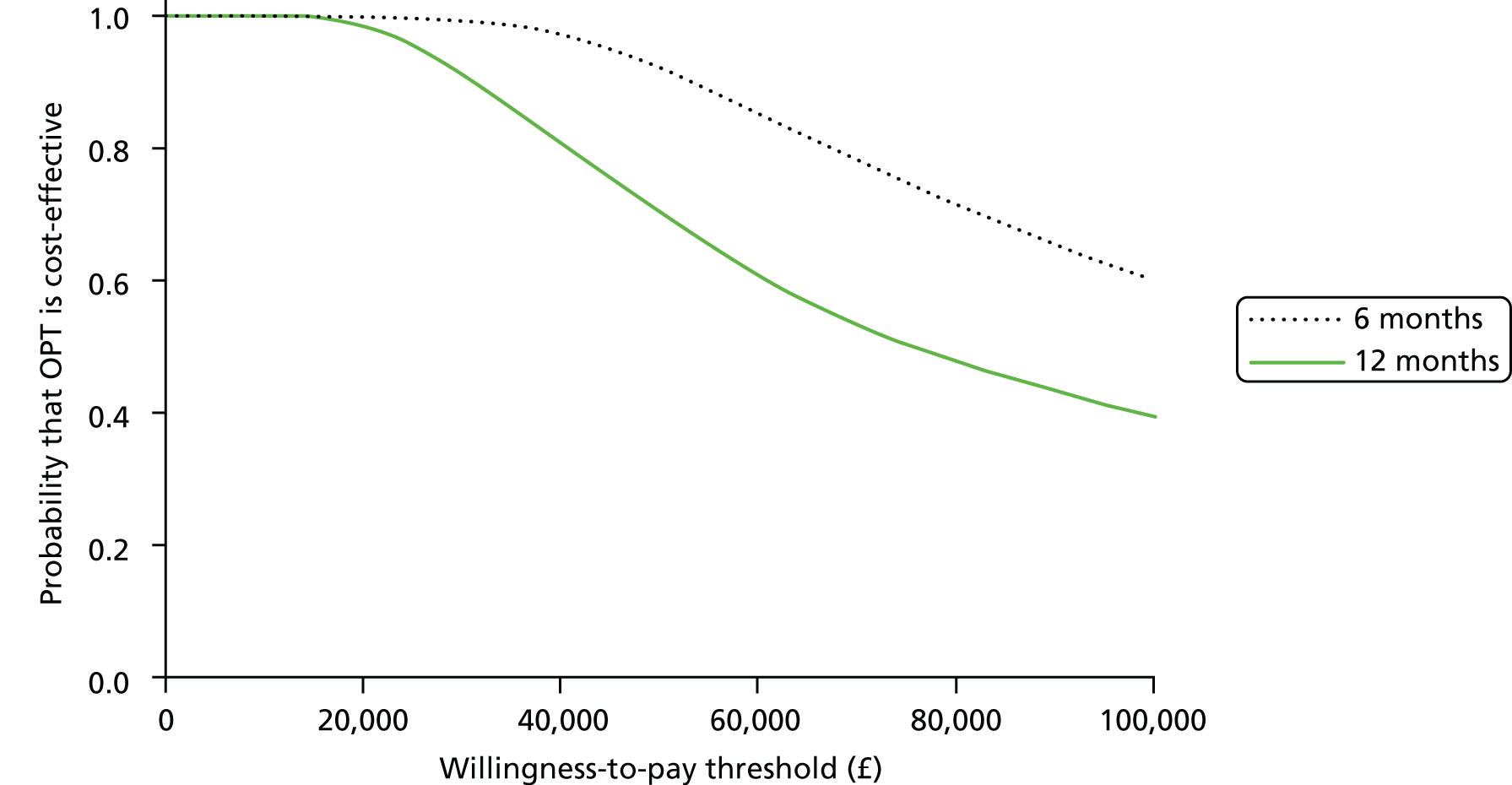

Women with strong preference for treatment setting