Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/91/22. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The draft report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul McNamara stated the following conflicts of interest: received personal fees and consultancy payments for assisting in setting up a study on new antiviral for respiratory syncytial virus disease in the UK 2013–15 from Alios BioPharma; and received personal fees and honorarium for advisory board attendance to discuss new respiratory syncytial virus antivirals and vaccines in February 2014 from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Everard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Acute bronchiolitis is the most common reason for hospitalisation in infancy and childhood, with 1–3% of all infants being admitted to hospital during their first winter. 1–9 Common respiratory viruses infecting the lungs lead to severe difficulties in breathing by causing obstruction of the airways. 1–8,10–13 The age of peak incidence of babies admitted with this condition is between 1 and 6 months. 9 The acute illness is distressing for the infant and is associated with considerable stress for parents of an acutely unwell small infant.

The only intervention that has had a major impact on the survival of infants in the last 40 years of research is oxygen therapy, which has reduced mortality rates from around 20% to less than 1%. 14 Otherwise, current treatment consists of providing good supportive care until the infant recovers. 4,15,16 Admissions for bronchiolitis increased from 21,330 in 2004/5 to 33,472 in 2010/11,17 placing enormous strains on paediatric services and intensive care units (ICUs)4,8,18 which sometimes have to close because of the number of infants with acute bronchiolitis. 18–20 Despite many putative candidates, including antiviral agents, inhaled steroids and bronchodilators, no treatment other than oxygen therapy has been shown to have an impact on the course of the acute illness and an effective vaccine still appears some way off. The median duration of hospitalisation in the UK is around 3 days, which compares with a median of 1 day for all acute paediatric admissions. This relatively long duration of hospital stay combined with the large number of such infants admitted to hospital between November and March accounts for the substantial burden on hospital services resulting from the yearly winter epidemics.

At the time we were preparing the grant application for this project, a number of relatively small studies had suggested that nebulised hypertonic saline (HS) may reduce the duration of hospital stay for infants admitted with acute bronchiolitis. 21–24 A Cochrane review, published in 2008,25 undertook a systematic review of the literature, focusing on four trials which involved a total of 254 infants with acute viral bronchiolitis ,of whom 189 were inpatients and 65 patients were treated in the emergency department. The review concluded that ‘current evidence suggests nebulised 3% saline may significantly reduce the length of hospital stay and improve the clinical severity score in infants with acute viral bronchiolitis.’25 The conclusions do not go beyond suggesting that this intervention may have an impact because of the methodological limitations of the included studies and the potential for publication bias. The review noted that the conclusions are further limited by the small number of subjects included in each study and consequent low power; the different settings since inpatients and outpatients were included; and the failure to show a difference in some outcomes such as the failure to reduce hospitalisation in the outpatient groups. Despite these limitations, some hospitals in the UK had already adopted this approach to treatment by the time we started the SABRE (Saline in Acute Bronchiolitis RCT and Economic evaluation) trial. The subsequent development of the evidence base is discussed in Chapter 6, Strengths and weaknesses compared with earlier systematic reviews.

The suggested mode of action of HS is through an alteration in mucus rheology as a result of improved hydration and the breaking of ionic bonds within the mucus, leading to improvements in mucociliary clearance of secretions. 26,27 The observation that HS can increase ciliary beat frequency may further enhance clearance. 26 It is also suggested that this intervention reduces mucosal wall oedema through osmotic effects. There is good evidence that bronchoconstriction does not contribute significantly to the airways obstruction in infants with acute bronchiolitis, which explains why bronchodilators do not provide any benefit. 28–31 Instead, the obstruction appears to be in part because of oedema within the airway wall and, probably more importantly, accumulation of inflammatory exudates in the airways. Significant impairment of mucociliary clearance because of the shedding of ciliated cells compounds the problem and contributes to accumulation of secretions in the small airways. Hence an intervention leading to improvement in clearance of these secretions and reduced oedema of the airway wall may be of benefit in infants with acute bronchiolitis.

In contrast to these positive studies, a recent Canadian study based in an emergency department found no benefit when nebulised 3% HS was added to ‘usual care’,32 while a second study from Turkey,33 again involving non-hospitalised children, found that 3% HS offered no advantage over nebulised normal saline (NS) in addition to ‘usual’ care. In both cases the intervention was in addition to the use of bronchodilators. Understanding the differences between terminology for bronchiolitis used in North America and that used in the UK is key to understanding why these studies might be predicted to have a negative outcome and are not directly relevant to UK practice.

In North America, and a number of other countries, the term ‘acute bronchiolitis’ is generally used to describe an apparent viral infection in an infant or young child who is experiencing their first episode of wheeze. 2,5,34 In the UK, Australia and some northern European countries, the key feature of acute bronchiolitis is the presence of widespread crepitations on auscultations rather than wheeze, which may or may not be present. 2,4,34 In general, those patients with wheezing illnesses labelled as acute bronchiolitis are somewhat older (mean 9–15 months)35–37 than infants admitted in the UK with acute bronchiolitis, among whom the peak age for admissions is around 4 months of age. 35,38–41

The clinical phenotype of subjects included in a study has been shown to be important not just in the acute illness but in terms of subsequent morbidity, with those having the North American phenotype being much more likely to be subsequently shown to have asthma than those with acute bronchiolitis as defined in the UK, which is not associated with development of atopic asthma. 35,42

These subtle but very important differences in inclusion criteria are likely to explain some previous apparently contradictory results in this area. For example, some,36,37 but not all, studies assessing the possible efficacy of nebulised adrenaline in treating young children with acute bronchiolitis in North America have had a positive outcome, but when trialled in the UK and Australia nebulised adrenaline was found to be ineffective and was associated with potential side effects. 38,39 In contrast to experience with bronchodilators, it is possible that HS will be more effective in acute bronchiolitis as understood in the UK in that its putative modes of action would address the dominant mechanisms of airways obstruction in these patients, while it would be expected to have little or no effect in those with wheeze in whom there was significant bronchoconstriction. The studies from Canada and Turkey included children in an outpatient setting with an inclusion criterion of wheeze. Predictably, their mean age was significantly higher than that of the population admitted to UK units with ‘acute bronchiolitis’ and they represent a different phenotype, often referred to in the UK as wheezy bronchitis or virus-associated wheezing.

The observation that the greatest benefit from the use of nebulised HS appears to be in hospitalised infants with a similar age distribution (peak 2–6 months)28–30 to that seen in UK centres22–24 would support the potential of this approach in a well-defined UK population of infants admitted with acute bronchiolitis. Moreover, the mean duration of stay in the control group in all three studies was 3.5 days, again consistent with UK practice. The reduction in duration of inpatient stay in the three positive studies was 25–27%. 28–30

An inexpensive intervention that reduces length of hospital stay by 25% would be of considerable value to the NHS and is likely to have a significant impact on the levels of stress experienced by young parents with an acutely ill infant. Some paediatric units in the UK have already adopted this approach on the basis of the Cochrane review. However, it is possible that publication bias and poor study design has resulted in a false-positive outcome and, if this were the case, there is the potential for an ineffective therapy to creep into practice. Conversely, there is a significant risk that uncritical acceptance of the ambulatory studies may lead to discarding a potentially effective therapy through inclusion of a different patient population given the same clinical diagnosis.

In the light of the uncertainties surrounding this potential valuable therapy, it was essential to undertake an appropriately powered study in a clearly defined UK population to determine whether or not there is indeed reason for UK paediatric units to adopt this approach or if it should simply be added to the list of potential therapies known not to have a significant clinical impact. The importance of undertaking such a study had been recognised both by the Paediatric Respiratory Studies Group and by observers in countries with similar health-care systems and diagnostic criteria, such as Australia. 43

Research objectives

The purpose of the trial was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of nebulised HS in the treatment of acute bronchiolitis. The trial had one main objective and three secondary objectives.

Primary objective

The primary objective of the study was to assess whether or not the addition of nebulised 3% HS to usual supportive care resulted in a reduction in time to being declared fit for discharge.

Secondary objectives

-

Assessment of the impact of the intervention on other clinical outcomes and the quality of life of infants and carers at 28 days post randomisation.

-

Investigation of the impact on outcomes between those infants with human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection and those with acute bronchiolitis due to other causes, including other viruses (non-RSV).

-

Assessment of the economic impact of the intervention on both the NHS and parents at 28 days post randomisation.

Chapter 2 Methods

There are three sections to this chapter: The SABRE study methods, Health economic methods and Systematic review methods.

This report is concordant with the 2010 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. 44

The SABRE study methods

Trial design

The SABRE study was a multicentre, parallel-group randomised controlled trial (RCT), with a one-to-one allocation ratio and economic evaluation. It aimed to determine whether or not the addition of nebulised 3% HS to usual care resulted in significant (25%) reduction in the duration of hospitalisation of infants with acute bronchiolitis. Subjects were recruited from the paediatric wards and assessment units of the participating centres in England and Wales between October 2011 and December 2013. A table of changes made to the protocol over the course of the project is presented in Appendix 1.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

Substantial amendment 1

The primary outcome definition for fit for discharge was amended from 12 hours to 6 hours. After discussion with participating centres it was felt that 12 hours did not reflect current practice. This was agreed by the trial management group (TMG) and the chairperson of the trial steering committee (TSC). The time allowed to obtain full informed consent was also amended from 60 minutes to 90 minutes after agreement at a TMG that 90 minutes would be more practical in the clinical setting.

Minor amendment 3

It was clarified that ‘the saline will be discontinued once oxygen therapy has been discontinued’ as this had not been explicitly stated in the protocol previously. Clarification of one of the inclusion criteria was also provided, ‘Requiring supplemental oxygen therapy on admission’. Clarification of the wording for admissions to high-dependency unit (HDU)/ICU was provided, ‘Admission per se of a study participant to the HDU and/or ICU as a result of normal clinical diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis will be reported as an expected event not as [a serious adverse event]’.

Minor amendment 5

We further clarified when saline should be discontinued after discussion at a TMG meeting – the wording was amended from ‘the saline will be discontinued once oxygen therapy has been discontinued’ to ‘the saline will be discontinued once the “fit for discharge” criterion has been met – in air for 6 hours with oxygen saturations of at least 92% and feeding satisfactorily’.

Substantial amendment 6

The protocol was simplified to ensure that eligible babies who were admitted on oxygen were recruited within 90 minutes of admission. The web-based randomisation system was altered to request the time of admission in order to raise an alert if health professionals tried to randomise outside the 90-minute window.

Substantial amendment 7

Clarification of permitted medications for trial participants was provided, to reflect local practice and how these should be recorded. Inclusion criteria amended to clarify which staff can make ‘the decision to admit’ in order to begin the 90-minute consent/randomisation window.

Substantial amendment 8

The eligibility criteria for inclusion of patients in the trial were extended. Previously, in order for patients to be eligible for inclusion in the trial, they were required to be consented and randomised within 90 minutes of a decision to admit a patient to an inpatient ward. This amendment extended the time-based eligibility criteria to 4 hours. This change was proposed for two main reasons: first, a substantial number of included trial patients were retrospectively identified as protocol violations because of being randomised outside this 90-minute cut-off point (approximately 50 out of 172 patients randomised); and, second, there is no clinical rational basis for assuming that patients randomised in less than 90 minutes and patients randomised between 90 minutes and 4 hours are clinically different. Previous inpatient trials of saline in paediatric acute bronchiolitis have not included a strict time-based cut off for inclusion, as was operated in this study. This extension of eligibility was supported by the funder for the study [Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme] and it also had the support of the study sponsor.

Participants and eligibility criteria

The target population was infants less than 12 months of age admitted to hospital with a clinical diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis and requiring supplemental oxygen as part of routine supportive care. Subjects were recruited from paediatric wards and assessment units from the 10 participating centres between October 2011 and December 2013.

Inclusion criteria

-

Previously healthy infants less than 1 year of age.

-

Admitted to hospital with a clinical diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis, following the UK definition of an infant with an apparent viral respiratory tract infection associated with airways obstruction manifest by hyperinflation, tachypnoea and subcostal recession with widespread crepitations on auscultation. 4 Admission was defined as the point the paediatrician, or paediatric advanced nursing practitioner, made the decision to admit. (The perspective at the time was that advanced nursing practitioners were equivalent of specialty trainee 1 – specialty trainee 3/senior house officer).

-

Requiring supplemental oxygen therapy on admission (either the infant was already in oxygen or oxygen was recommended at the point of admission).

-

Consented and randomised within 4 hours of admission.

Exclusion criteria

-

Had wheezy bronchitis or asthma – children with an apparent viral respiratory infection and wheeze with no or only occasional crepitations.

-

Had gastro-oesophageal reflux (if investigated and diagnosed in hospital).

-

Had previous lower respiratory tract infections (which required assessment in hospital).

-

Had risk factors for severe disease (gestation of < 32 weeks, immunodeficiency, neurological and cardiac conditions, chronic lung disease).

-

Subjects for whom the carer’s English was not fluent and translational services were not available.

-

Required admission to HDUs or ICUs at the time of recruitment.

The principal ethical consideration was that the subject group were unable to provide their own consent, but this is an issue for all paediatric studies involving infants and young children. For this study there were no known risks associated with the intervention and the participating units were very familiar with the ethical challenges in this population.

There was a small chance that participants were involved in other research studies and this question was asked during the informed consent process. Patients for whom the investigating team felt that it would have been inappropriate to include them in the study were excluded on this basis.

Every effort was made to avoid protocol non-compliances caused by the randomisation of participants outside the time window (see Important changes to methods after trial commencement). Participating centres were asked to note the following:

-

In the case that the person consenting was called away in an emergency before randomising, the centre was not to then attempt to randomise the patient if this would take place outside 4 hours from admission.

-

Patients were not to be randomised without written consent. The randomisation system requested that randomising clinicians confirm that the parent/carer has provided consent for participation in the study.

Settings and locations where the data were collected

The data used in this study came from the following sources:

-

for patients who were eligible for randomisation into the study (including patients who were randomised):

-

patient recruitment form, which contained the age, sex and details regarding entry criteria

-

-

for patients who were randomised into the study:

-

randomisation schedule, which contained randomisation codes and allocated intervention group

-

case report form, which contained patient demographics, characteristics at presentation, investigations and events during treatment, assessment of ‘fit for discharge’, resource use and adverse events (AEs) over subsequent 28 days

-

post-discharge data collection forms, comprised of the symptom and health service utilisation diary.

-

Interventions

Infants were randomly allocated to either standard supportive care (control) or standard supportive care plus nebulised 3% HS solution (intervention) using a remote access, computer-generated allocation algorithm.

Three per cent HS is licensed as a medical device in the UK under the brand name MucoClear® (PARI GmbH, Starnberg, Germany) and is indicated for the mobilisation of secretions in the lower respiratory tract in patients with persistent mucus accumulation such as those with acute bronchiolitis or cystic fibrosis. It was presented as a 4-ml plastic ampoule for nebulisation and came in packs of 20 or 60. The product contained no preservatives and had an expiry date of 3 years from manufacture. The product was administered via the PARI Sprint nebuliser (PARI Medical Ltd, Surrey, UK). The dose was 4 ml every 6 hours, in accordance with previously published studies. It was administered by a nurse, with infants inhaling the aerosolised saline. The saline was discontinued once the fit for discharge criteria had been met – in air for 6 hours with oxygen saturations of at least 92% and feeding satisfactorily.

For the purpose of this trial, MucoClear® 3% was sourced by and dispensed locally from each site’s pharmacy department. Although this was not a clinical trial of a medicinal product and therefore not subject to the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004,45 the principal investigator in conjunction with his or her local pharmacy department ensured that the principles of good clinical practice (GCP) were applied to ensure robust accountability of the supply and administration of 3% HS.

Other medications

All concomitant medications were recorded. The use of antibiotics, saline nasal drops and HS given after an infant was declared fit for discharge was investigated in additional analyses to assess the impact of these possible confounding factors.

There is no proven drug therapy for the treatment of bronchiolitis. Antipyretics (paracetamol and/or ibuprofen) are recommended for pyrexia and pain management. Nappy rash cream, alginic acid, aluminium hydroxide, magnesium carbonate (Gaviscon®, Reckitt Benckiser), sodium chloride (Dioralyte, A Nattermann & Cie GmbH Cologne, Germany) and lactulose (and related generic medications) were permitted. Saline was continued if bronchiolitis remained the primary diagnosis. Antibiotics were permissible for suspected secondary bacterial infections (e.g. based on radiographic changes). It is routine clinical practice to discontinue antibiotics previously prescribed by general practitioners (GPs). Antibiotics are not recommended in any ‘bronchiolitis’ guideline, including the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) UK guideline,4 and published data have suggested their use has been associated with a significant level of AE with no discernible benefit.

Outcomes

Table 1 shows the timing of outcome assessments.

| Data collection time points | Before baseline | Baseline | Every 6 hours | After discharge | 28 days after randomisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility criteria applied by doctors | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Participant information sheet offered by nurses | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Informed consent by doctors or delegated nursing staff | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Baseline demographic data | – | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Randomisation | – | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Apply fit for discharge criteria | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| Diary – symptoms and health service utilisation | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| ITQoL | – | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Nurse telephone call to confirm diary and health service utilisation | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Safety assessments | – | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Ongoing monitoring | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Retrospective identification of additional AEs | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

Primary end point

The primary outcome was time to ‘fit for discharge’, and was taken as the period of time from randomisation to when the infant was judged to be feeding adequately (taking > 75% of usual intake orally) and had been in air with oxygen saturations of at least 92% for 6 hours, to reflect clinical practice. 4 An oxygen saturation level of less than 92% as the trigger for starting supplemental oxygen is conservative by US standards. 5 The reasons for choosing time to fit for discharge as the primary end point were twofold: first, its objectivity [actual length of stay (LoS) is influenced by policy, the timing of ward rounds and other features not directly related to bronchiolitis]; and, second, because of its direct relevance both to patients and to service providers.

Secondary end points

-

Actual time to discharge, from randomisation.

-

Admission to ICU/HDU.

-

The number of readmissions and the reasons for readmission within 28 days of randomisation.

-

Duration of respiratory symptoms post discharge and within 28 days of randomisation (see Appendix 2).

-

Health-care utilisation, after discharge and within 28 days of randomisation (see Appendix 2).

-

Infant and parental quality of life, using the Infant Toddler Quality of Life Questionnaire (ITQoL) at 28 days following randomisation. 46

-

AEs.

Fitness for discharge was assessed at baseline, then six times hourly until ‘fit for discharge’ criteria had been met. Research nurses recorded baseline demographic data, co-interventions and outcome data on the case report form. Research nurses also collected basic anonymised details (e.g. age, reason for admission) on all eligible patients to allow completion of a CONSORT flow chart. To assess worsening of condition since discharge and maximise completeness of data, research nurses telephoned parents/guardians approximately 14 days after randomisation. Non-responders after the 28 days were contacted by the research nurse and sent a further ITQoL if appropriate. The involvement of parents/guardians and infants ended at this point.

Readmission was defined as any readmission to hospital within 28 days of randomisation. These have been tabulated by study group and are further classified according to whether or not the readmission was related to the original bronchiolitis or was a new presenting complaint.

The ITQoL is a standardised quality-of-life questionnaire that has been validated for use in infants aged 2 months to 5 years. 46 The questionnaire was completed by a parent or guardian. It covered nine domains – six for the child and three for the parent – each of which was scored from 0 (worst health) to 100 (best health). It had been used successfully in a respiratory illness sample similar to this study, with a response rate of 79.7%. 46

Site trial staff and delegated NHS staff were responsible for recording all AEs that occurred during routine clinical care and making them known to the principal investigator. AEs were recorded on the case report form and database, but did not need to be reported by fax to the sponsor and Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU). AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported regularly in data reports to the oversight committees. Admission per se of a study participant to the HDU and/or ICU as a result of normal clinical diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis was reported as an expected event not as a SAE. The sponsor and CTRU were responsible for assessing the seriousness and reporting to relevant regulatory bodies, where appropriate.

Changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons

Substantial amendment 1

Protocol version 1 (28 June 2011) was amended to update the primary outcome definition for fit for discharge from 12 hours to 6 hours. After discussion with participating centres, it was felt that 12 hours did not reflect current practice. This was agreed by the TMG and TSC chairperson, and implemented in protocol version 0.1 (28 June 2011) before the start of recruitment. In addition, protocol version 4 (17 November 2011) was amended to provide further clarification of when the saline should be discontinued after discussion at a TMG meeting – the wording was amended from ‘the saline will be discontinued once oxygen therapy has been discontinued’ to ‘the saline will be discontinued once the “fit for discharge” criteria have been met – in air for 6 hours with oxygen saturations of at least 92% and feeding satisfactorily’.

Sample size

Based on the current mean time to discharge of around 3 days, we felt that a 25% reduction would be the minimum clinically significant effect, and this was the magnitude of the effect observed in previous studies. 47 As LoS varies considerably across different settings, we used UK Hospital Episode Statistics data as the basis of our sample size justification. Assuming a log-normal distribution, the standard deviation (SD) was estimated at 32 hours. While a similar, or smaller, SD was expected for our primary outcome measure, a slightly inflated SD of 46 hours was used because of uncertainties over its derivation here. In order to have 90% power to detect a 25% difference in time to meeting discharge criteria, the study needed 139 patients per group at a two-sided α-level of 5%. The dropout rate was thought to be negligible for the analysis of the primary outcome measure and therefore a conservative estimate of sample size was 150 patients per group. Overall, 10 centres recruited patients to the study. Targets of 25 participants for district general hospitals and 40 participants for teaching hospitals were set.

Explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines

The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) charter allowed the study to be stopped prematurely on the grounds of safety or futility based on recommendations from the DMEC or the funder. No formal interim analyses were planned for efficacy and consequently no adjustment was initially made for multiplicity. At the request of the DMEC, one interim analysis was subsequently undertaken in July 2012 to assess efficacy, in order to inform a funding extension decision necessitated by recruitment being slower than expected. An O’Brien–Fleming stopping rule was retrospectively employed in which superiority would be declared if statistical significance was demonstrated at the 1% level in the interim analysis or at the 4.5% level at the final analysis. 48 The DMEC had the authority to recommend that recruitment to the study should be terminated if the primary outcome (time to fitness for discharge) was significantly shorter in the saline group at the α = 1% level of statistical significance.

Method used to generate the random allocation sequence

A central web-based randomisation service delivered by the CTRU was used after patient eligibility and written consent were confirmed. Patients were randomly allocated via the online system to receive either (1) nebulised HS with usual care (n = 150) or (2) usual care (n = 150). The randomisation schedule was computer generated prior to the study by the CTRU Randomisation Service.

Type of randomisation; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size)

Participants were individually randomised using centralised, web-based randomisation system. Randomisation was conducted in randomly ordered blocks of size 2, 4 or 6, stratified by hospital.

Allocation concealment mechanism

The allocation schedule was concealed through the use of the centralised web-based randomisation service, which also allowed unblinding in the case of emergency. The randomisation sequence was not revealed to any person involved in patient recruitment. The data analysts were blind to treatment allocation until after the statistical analysis plan was finalised, the database locked and the data review completed. All unblinding (emergency and end of trial) would have been automatically logged by the CTRU randomisation system, which would have included the date, time and user responsible.

Sequence generation, enrolment and assignation

The randomisation sequence was computer generated and was not revealed to any person involved in patient recruitment. Recruitment was undertaken by GCP-trained trainee paediatricians, consultants or staff with equivalent training (e.g. GCP-trained paediatric nursing staff responsible for acute admissions). They approached parents/guardians to discuss the study at the point of first contact as soon as the infant had been identified as eligible for the study. Written information was then provided to parents/guardians willing to consider their infant taking part in the study. If agreed, written informed consent was obtained from the parents/guardians.

A flow chart detailing the consent and randomisation procedure can be found in Appendix 3. Owing to the acute nature of the condition, it was not possible to follow a usual time frame of at least 24 hours between receiving information and giving written informed consent. However, every opportunity was taken to ensure that parents/guardians fully understood the implications of taking part in our study. They were invited to ask questions and reflect prior to signing the informed consent document. No payment was offered to participants. The recruiter entered the participant’s details onto an online system and was asked the following:

-

to confirm written consent was received

-

to confirm the participant was in oxygen

-

to enter the time a paediatrician or paediatric advanced nursing practitioner made the decision to admit.

Participants were then randomly allocated via the online system to receive either (1) nebulised HS with usual care (n = 150) or (2) usual care (n = 150). The allocation was explained to participants by the hospital staff member obtaining consent.

Blinding

The study compared the intervention plus usual care with usual care alone, with no placebo. The use of placebo in this setting is ethically problematic as it would result in infants in the placebo arm receiving an intervention that may have a significant effect on outcome. The extra handling involved in nebulised therapy may have a deleterious effect, as has been shown to be associated with the increased handling associated with physiotherapy. 49 Similarly, the placebo agent may cause harm, as has been suggested in previous studies using nebulised distilled water, or may have an unexpected positive impact for an agent, such as NS. 32

The randomisation codes were stored electronically on the CTRU randomisation system. All other electronic data were held separately on the CTRU database system. Access to any data that would unblind the study was limited to members of the CTRU who were independent of the trial. All summaries presented to the DMEC were by treatment group. In order to maintain the blinding of the trial statistician, it was the responsibility of the CTRU to provide this by-treatment group information to the DMEC. No member of the study team had access to unblinded data sets or the unblinded reports until the final analyses.

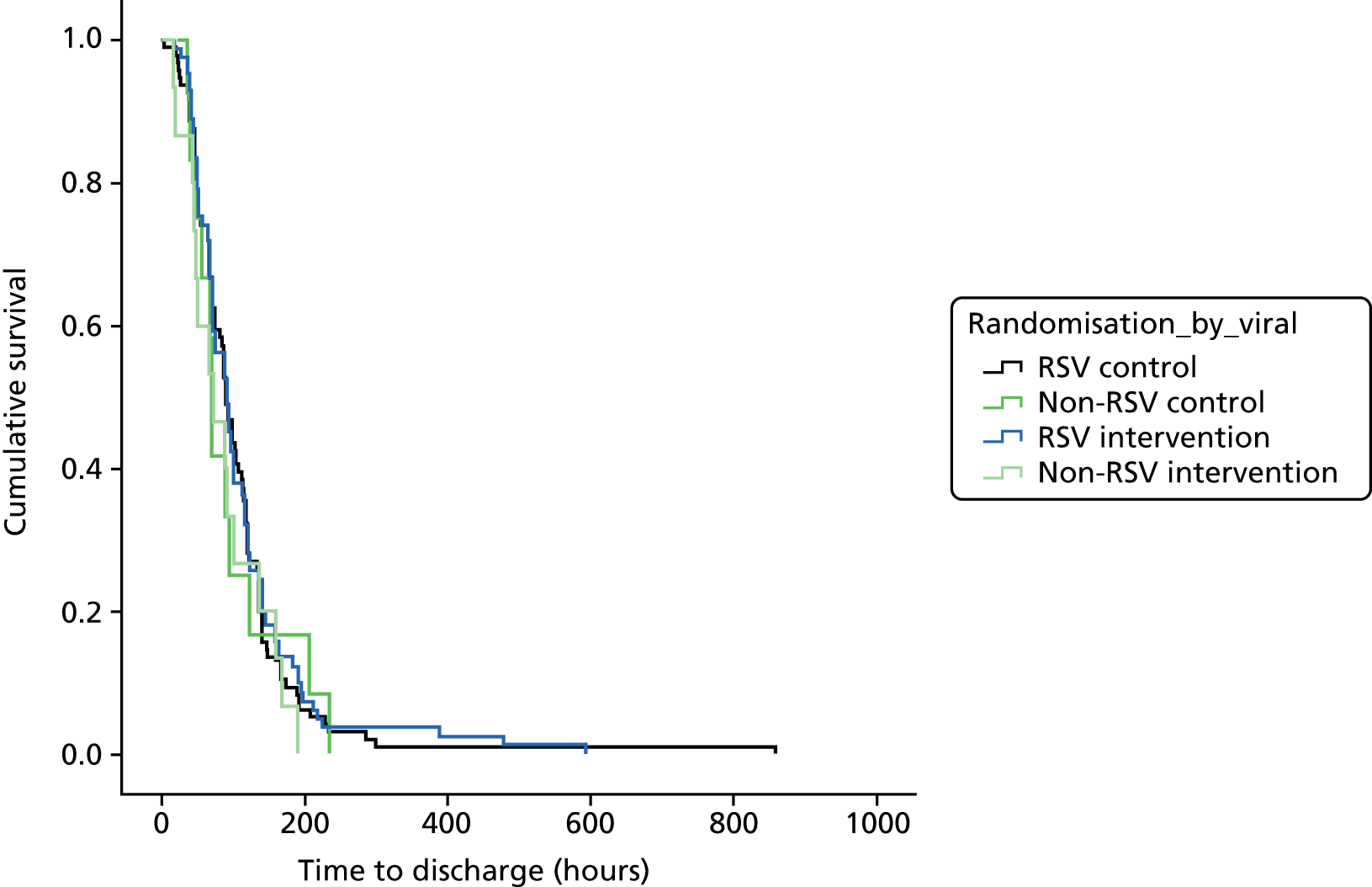

Statistical methods

The detailed statistical analysis plan can be found in Appendix 4. As time to being declared ready for discharge could be regarded as a survival time, initial differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test. In order to adjust for centre, a Cox proportional hazards regression model was used with centre fitted as a fixed effect (FE). One centre, Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust, randomised one patient: for the purposes of adjusting for centre, this patient was combined with those recruited from Doncaster and Bassetlaw Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, given the similarities that exist between these two geographically proximate populations in south Yorkshire. The proportionality of the hazards was assessed by examining the scatter of scaled Schoenfeld residuals against time. 50 This model was further extended by inclusion of viral status (RSV vs. non-RSV) to allow an examination of whether or not viral status had an impact on the effectiveness of treatment. In order to answer this question, the coefficient for the interaction between infection group (RSV vs. non-RSV) and treatment group was calculated together with its 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value. The collection of RSV test data was not a protocol requirement and such data were not collected at any particular centre except as part of routine practice.

The analysis of actual time to discharge was similar to the primary outcome measure, time to ‘fit to discharge’. Rates of admission to HDU/ICU and readmission rate within 28 days from randomisation were compared using Fisher’s exact test; although it is possible that children could be readmitted multiple times as a result of their single episode of bronchiolitis, it is much more likely that they will be readmitted just once. Thus, the percentage of children readmitted at least once was used for these analyses. In order to test the assumption that the results between groups differed according to RSV status, a logistic regression model was fitted and a coefficient for the interaction between infection group (RSV vs. non-RSV) and treatment group was calculated together with its 95% CIs and p-value. Each of the nine dimensions of the ITQoL used in this study was examined for differences between treatment groups, initially using a t-test. Where the assumptions underlying the t-test do not hold, a Mann–Whitney U-test was used.

It was originally envisaged that symptom duration would be analysed as a survival outcome. However, diary data were returned for only 108 individuals and, of these, data to 28 days were unavailable for almost one-quarter (25 out of 108: 1 at 15 days; 1 at 17 days; 1 at 18 days; 22 at 27 days) and almost one-quarter (24 out of 108) reported that they were still experiencing symptoms at 28 days. Although the majority of infants whose carers stopped sending in data before 28 days were no longer experiencing symptoms, because of the large amount of censoring at 28 days, we defined a new outcome variable that evaluated whether or not the patient was still experiencing symptoms at 28 days. This was analysed using the methods outlined above for binary outcomes.

The trial was originally designed to have a two-sided significance level of α = 5%. As a result of the aforementioned interim analysis, the significance threshold for the final analysis was changed to 4.5% in order to preserve the overall trial-wise significance level at 5%. All CIs remain two-sided 95% intervals. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Analysis populations

Four populations were used in the analyses:

-

all screened patients: patients who were screened for eligibility to the study, including those randomised

-

full analysis set (FAS): all randomised patients, with the following exclusions:

-

patients who had previously been randomised, in which case only data relating to the first admission were analysed

-

patients for whom no recorded informed consent was obtained from carers (oral or written)

-

patients whose carers withdrew consent before any study medications were given

-

patients whose carers withdrew consent retrospectively (i.e. requested that all the patient’s data were removed)

-

-

per protocol (PP): the subset of patients in the FAS who did not deviate from the protocol

-

safety: all randomised patients, with the exception of those for whom there was no recorded informed consent.

Summaries based on the FAS and PP populations were on an intention-to-treat basis, with patients assigned to the treatment group as originally randomised. Summaries based on the safety population analysed patients by the actual treatment received. Aside from RSV status (see Statistical methods) no other subgroup analyses were planned.

All outputs presented to the DMEC were based on the FAS population unless otherwise requested.

Patient and public involvement

Study design

At the grant application stage, meetings involving parents confirmed the impression that this disease, affecting very young babies, has a tremendous impact on parents and families. The handling required to administer the nebuliser may occasionally cause the infant to cry, but feedback from the parental involvement meetings indicated that parents do not find this unduly stressful and that parents were keen for their children to participate in the study. Parental involvement meetings identified that the ITQoL was by far the most relevant of the available quality of life instruments. This questionnaire also includes questions relating to the well-being of parents and, as such, allowed us to develop the grant application by removing the parental stress index from our secondary outcome measures.

Study oversight

The independent TSC contained a patient and public involvement representative throughout.

Health economic methods

Background

Nebulised HS is a relatively cheap intervention: approximately £50 for the nebuliser plus 12 doses of saline. Consequently, a large reduction in LoS is not required to suggest that the introduction of nebulised HS may be cost neutral or even cost saving. However, a broader economic evaluation that captures a wider set of costs and also includes patient outcomes is preferred. For example, if the intervention is not cost neutral, it may still be cost-effective once the value of patient health effects are also considered. Alternatively, the intervention may be cost-saving from the perspective of the hospital, but worse symptoms and more associated care following discharge may show the intervention not to be cost-effective.

Overview

A cost–utility analysis (CUA) was undertaken from the NHS perspective, with a time frame of 36 days post randomisation. The economic evaluation was originally designed to have a 28-day follow-up, but one patient in the study had a LoS of 35.7 days, so the time frame was extended to avoid censoring. A longer time frame was relevant, as there are no long-term sequelae associated with acute bronchiolitis. Given the difficulties of measuring utilities in the very young, the CUA was supplemented with a cost–consequences analysis (CCA) which considers the secondary clinical outcome measures alongside costs to allow a more qualitative assessment of cost-effectiveness.

Resource use

The main items of resource use collected were LoS by type of ward and number of readmissions. Nursing time was not included because, although nurse time is required to set up the equipment in the intervention group, increased monitoring time may be needed in patients who are not receiving active treatment. Consequently, a detailed observational study would be required to measure these costs in both arms. It was considered that any cost difference would be small, and inconsequential compared with any difference in LoS, and that calculating any difference would incur huge costs . Furthermore, if there were no difference in LoS, then clinical practice would not change based on small differences in nursing time.

Although other costs were also considered to be negligible in comparison with the inpatient costs, ease of data collection led us to collect data on the use of nebulised saline, concomitant medications and use of primary care services in the 28 days following discharge (e.g. GP or emergency department visits). Inpatient resource use was collected by staff using the same case report forms as those used for the clinical evaluation. Primary care resource use was collected using a patient diary, which was to be completed by the parent or guardian on a daily basis; tick boxes were available for GP contacts, NHS Direct, NHS walk-in centres, minor injury units and the emergency department.

Unit costs

All unit costs used were at 2012/13 price levels. Costs for a day in hospital were based on 2012–13 NHS Reference Costs, nebuliser costs were supplied by one of the participating hospitals, saline and medication costs were taken from the British National Formulary (BNF)51 and primary care costs were taken from NHS reference costs52 and the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care publication produced by the Personal Social Services Research Unit. 53 These are summarised in Table 2.

| Resource | Unit cost (2012/13), £ | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Nebuliser kits | 44 | Study hospital |

| Saline (4 ml) | 0.45 | BNF 65.51 3%, 6% and 7% solutions all have identical prices (£27 for 60 doses) |

| Inpatient day on ward | 547 | Derived from NHS reference costs.52 Activity-weighted average across all non-elective admissions relating to PA15B |

| Inpatient day on ICU | 1946 | Derived from NHS reference costs.52 Activity-weighted average across all paediatric intensive care categories, excluding ECMO/ECLS |

| Inpatient day on HDU | 1061 | Derived from NHS reference costs.52 Activity-weighted average across all paediatric high-dependency care categories |

| GP attendance | 45 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2013.53 Per-patient contact lasting 11.7 minutes, including direct care staff costs and costs of qualifications |

| NHS Direct | 25 | £24, 2010/11 prices.54 Inflated using Hospital and Community Health Care Pay and Prices Index53 |

| Walk-in centre | 41 | Derived from NHS reference costs.52 Activity-weighted average across service type 4, admitted and non-admitted. Category 1 investigation with category 3–4 treatment |

| Minor injuries unit | 88 | Derived from NHS reference costs.52 Activity-weighted average across service type 3, admitted and non-admitted. Category 1 investigation with category 3–4 treatment |

| Emergency department | 118 | Derived from NHS reference costs.52 Activity-weighted average across service types 1 and 2, admitted and non-admitted. Category 1 investigation with category 3–4 treatment |

The cost per day on a ward was derived using the NHS reference costs52 for an admission for paediatric acute bronchiolitis without complications (PA15B) and its associated number of bed-days. Separate costs per day for paediatric intensive care and high-dependency care are available directly from NHS reference costs. 52 The cost for paediatric acute bronchiolitis with complications or comorbidities (PA15A) was not considered relevant as our separate costing of paediatric intensive care and high-dependency care captures the costs of complications.

NHS Direct costs were taken from a report by the Medical Care Research Unit, which used a Department of Health contract value to derive a cost per call. 54 Emergency care unit costs (defined here as walk-in centres, minor injury units and emergency departments) relate to category 1 investigation (e.g. biochemistry) and category 3–4 treatment (e.g. oxygen).

Outcomes

For the CUA, it is usual for utilities to be calculated based on utility instruments, such as the EQ-5D, administered to patients. However, this is not possible for the participants in this trial, and even proxy completion by a parent would not be valid, as the descriptive systems of available utility instruments do not fit well with this patient group. Our original approach was to undertake a separate valuation study to estimate quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) losses related to hospitalisation and recovery and then apply these to the trial data. However, the National Institute for Health Research was not willing to fund this work, so we identified a published estimate relating to hospitalisation in paediatric populations that could be used. 55

Carroll et al. 55 estimated the utility decrement from full health during hospitalisation as 0.05 (with a standard error of 0.01) using the time trade-off technique. This then needs to be combined with the general population value for infants of the same age. The best method for combining comorbidities is considered to be through multiplication of the relevant values. 56 Following a search of the literature, the most relevant general population value using a paediatric utility instrument for the children recruited to the SABRE study was found to be a Health Utilities Index-II survey of 8-year-old Canadian children. The general population value in that study was 0.95 (compared with 0.82 for children of extremely low birthweight). 57 For the SABRE study, therefore, the non-hospitalised utility is 0.95 (taken from Saigal et al. 57), while the hospitalised utility is 0.9025 (calculated as the product of the Saigal et al. 57 and Carroll and Downs55 utility estimates).

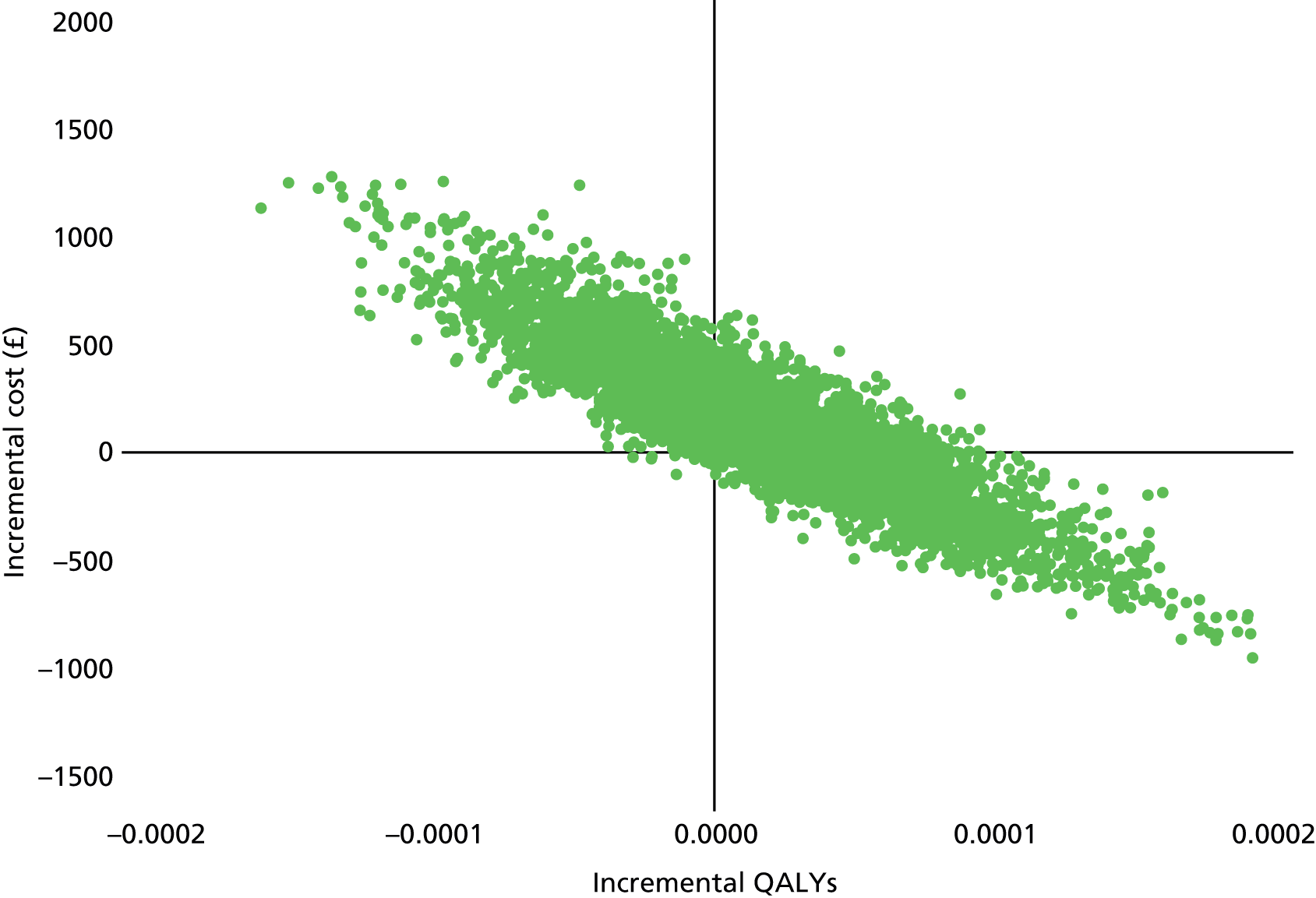

Analysis

Differences in costs and QALYs were assessed using non-parametric permutation t-tests that allow robust comparisons of the means in the presence of non-normal data. A permutation test samples from the observed data to calculate the correct distribution of the test statistic under the null hypothesis. Paired cost and QALY data were then bootstrapped with 5000 replications and plotted on the cost-effectiveness plane. The focus of the economic analysis was the resultant cost-effectiveness acceptability curve and the probability that the intervention will be cost-effective at £20,000 per QALY.

The main cost driver was expected to be hospital costs. Deterministic sensitivity analyses were planned for the cost per day on a ward, in intensive care and in high-dependency care. Alternative plausible unit costs to our preferred ward estimate of £547 are £558 per day (with the latter also including complicated admissions) and £425 (derived using excess bed-days costs for uncomplicated admissions). Alternative plausible unit costs to our preferred intensive and high-dependency care estimates of £1946 and £1061 are £1743 and £886, respectively (derived using only the basic care categories within each type of unit).

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis is undertaken through the bootstrapping procedure described previously, thereby incorporating the sampling uncertainty related to all clinical effects and resource use items. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis using distributions around unit costs and utility values is not routinely undertaken in economic evaluations alongside trials.

Where appropriate, missing data were to be imputed using multiple imputation. This assessment would be based on the degree of missingness and the mechanism by which missing data were generated (e.g. random or non-random).

Systematic review methods

Rationale

To produce an overview of the clinical effectiveness of HS for the treatment of inpatients with acute bronchiolitis.

Objective

The objective was to systematically review the evidence relating to the use of nebulised HS in young children, hospitalised for the treatment of acute bronchiolitis. The primary outcome of consideration was whether or not the use of this intervention resulted in a reduced hospital LoS.

Protocol and registration

The PROSPERO registration (registered 3 March 2014 and revised 18 December 2014) outlining the study review protocol can be found in Appendix 5.

Eligibility criteria

Types of participants

Studies involving children up to the age of 2 years who had been hospitalised as the result of an episode of acute bronchiolitis were considered for the review. Confirmation of the presence of RSV was not required for study inclusion as not all cases of bronchiolitis are a result of RSV, and therefore all cases of bronchiolitis regardless of organism have been included.

Types of interventions

Studies evaluating nebulised HS with or without an adjunct bronchodilator treatment given compared with NS or no intervention (control) were considered for the review. These pre-specified groups of studies were as follows:

-

nebulised HS alone versus NS

-

nebulised HS plus a bronchodilator (e.g. salbutamol) versus NS

-

nebulised HS plus a bronchodilator (e.g. salbutamol) versus NS plus same bronchodilator

-

nebulised HS alone or plus a bronchodilator (e.g. salbutamol) versus no intervention.

Groups were based on those that were pre-specified in the Cochrane systematic review carried out by Zhang and colleagues. 58

No restrictions were applied in terms of the concentration, dose or the way the intervention (HS) or control (NS with or without adjunct treatment) was administered in the trials. Studies in which HS was not the principal intervention under review were excluded.

Types of studies

Published and unpublished RCTs and quasi-randomised trials which had completed participant accrual were considered for inclusion. Quasi-randomised trials are those in which the allocation of intervention may not be completely random. Observational studies were excluded.

Only studies available in English were considered, as defined in the protocol. Nine potentially relevant studies in other languages with no English abstract or an unclear English abstract were excluded at the abstract review stage. 59–67 In addition, two studies in other languages were excluded at the full paper review stage. 68,69 The main database searches were performed from the start date of the database to January 2015.

Outcome measures

There were no eligibility restrictions based on outcomes reported. The systematic review’s primary outcome of interest is length of hospital stay calculated via the mean (SD) number of days (LoS) for each arm of each trial, a relevant and meaningful outcome. 70 Secondary outcomes of interest were (1) rate of readmission to hospital; (2) any AEs however described, but particularly tachycardia, hypertension, pallor, tremor, nausea, vomiting and acute urinary retention; and (3) final clinical severity scale (CSS) scores.

Information sources

The electronic databases searched included MEDLINE (via Ovid) (1946 to January 2015), EMBASE (1974 to January 2015), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) (2010 to January 2015) and Web of Science (2010 to January 2015). The full search strategy used in each database is listed in Appendix 6. No restrictions or limits (e.g. age, language and publication date) were applied to any of the databases other than Google Scholar and Web of Science, which were searched for articles from 2010 onwards, when the Cochrane Systematic review by Zhang and colleagues71 was last updated.

The following trial registries were searched, using the terms ‘bronchiolitis’ and ‘hypertonic saline’, to identify any unpublished data: ClinicalTrials.gov; UK Clinical Trials Gateway; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination databases (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, HTA Database); controlled-trials.com; centrewatch.com. The National Research Register was searched using the terms ‘bronchiolitis and ‘hypertonic saline’ on 5 March 2014, as the website could not be accessed when the searches were updated. We also hand-searched the journals Chest, Paediatrics and Journal of Paediatrics in January 2015 using the terms HS and bronchiolitis. The reference lists of all eligible trial publications were checked to identify any further published trials.

Search

A range of search strategies were employed, including pearl growing and checking reference lists. 72,73 Pearl growing involved identifying medical subject headings from articles identified from the previous systematic review,25 which were then combined with initial search terms and the searches rerun again. The final search strategy is outlined in Appendix 6. All searches were performed between January 2013 and January 2015. Any duplicated articles were removed from the final list prior to applying the eligibility criteria to the trials to select the studies of interest.

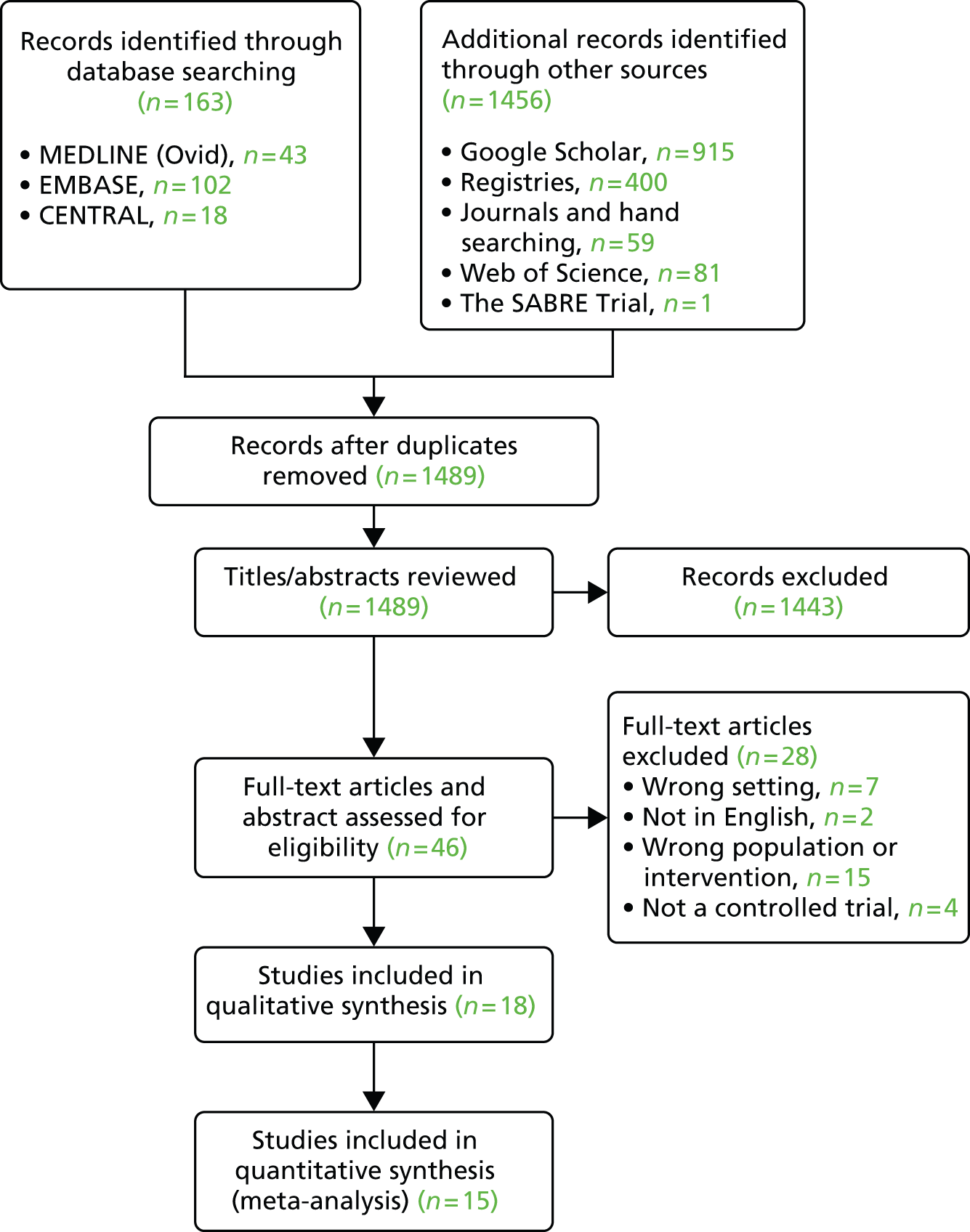

Study selection

After removal of duplicates, two researchers (CM and HC) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility; differences were resolved by discussion with DH and ME. If the abstract suggested eligibility, if no abstract was available for a particular citation or if the title was vague and unclear, the full paper was retrieved. Full papers were screened for eligibility in the same way.

Unsuccessful attempts were made to contact trial investigators of two unpublished studies74,75 to request additional unreported data. Although studies would not have been excluded based on the primary outcome, all but three of the studies were appropriate to be included in the meta-analysis of the primary outcome of interest, LoS.

Data collection process

The Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool76 was modified after piloting on one study of known eligibility. Details of the modified data extraction tool can be found in Appendix 6 and Table 3. CM and HC then used the modified tool independently to extract data. Attempts were made to contact study teams for missing data, particularly for five studies74,75,84,88,89 for which data were available only on ClinicalTrials.gov or in abstract form. Owing to the constraints in time, it was not possible to contact all the study authors for each of the items of missing data, for example risk of bias assessment.

| Main author | Country | Patient demographic (infant age, sex, other) | Total number randomised | Baseline imbalances reviewed? | Illness severity | At least 80% allocated followed up in final analysis? | Inclusion/exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giudice et al., 201277 | One centre: Italy | Children aged under 24 months, clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis | 109 | Yes: no significant differences | Severe; Wang et al.78 mean scores 8.8 (NS group) and 8.5 (HS group) | Yes: 106 of 109 patients followed up (97%) | Exclusion: pre-existing cardiac/pulmonary disease, premature birth (< 36 weeks), previous asthma diagnosis, initial oxygen saturation < 85% or respiratory distress requiring resuscitation |

| Inclusion: first episode of bronchiolitis, oxygen saturations of < 94% in room air, significant respiratory distress (Wang et al.78 CSS score) | |||||||

| Kuzik et al., 200724 | Three centres: one in the United Arab Emirates and two in Canada | Children aged under 18 months, diagnosed with bronchiolitis | 96 | Yes: no significant differences | Moderate severity; RDAI scale mean scores 8.1 (NS group) and 7.8 (HS group) | Yes: 100% included in ITT analysis | Exclusion: previous history of wheezing, cardiopulmonary disease or immunodeficiency, critical illness requiring admission to ICU, use of nebulised HS in last 12 hours or premature birth (< 34 weeks) |

| Inclusion: first episode of bronchiolitis | |||||||

| Tal et al., 200623 | Israel | Children aged up to 12 months, bronchiolitis | 44 | Yes: no significant differences | Moderate severity; baseline Wang et al.78 mean severity scores 7.6 (NS group) and 7.4 (HS group) | Yes: 41 of 44 patients (93%) | Exclusion: cardiac disease, chronic respiratory disease, previous wheezing episode, aged > 12 months, oxygen saturation < 85%, obtunded consciousness and/or progressive respiratory failure needing ventilation |

| Inclusion: clinical presentation of viral bronchiolitis that led to hospitalisation | |||||||

| Luo et al., 201079 | China | Children aged under 24 months (range 12–16.5 months), bronchiolitis | 93 | Yes: no significant differences | Mild to moderate; Wang et al.78 mean scores 5.7 (NS group) and 5.8 (HS group) | Yes: 100% included in final analysis | Exclusion: aged > 24 months, previous wheezing episode, chronic cardiac or pulmonary disease, immunodeficiency, accompanying respiratory failure, requiring mechanical ventilation, having intervention 12 hours before treatment, premature infants |

| Inclusion: first episode of viral bronchiolitis, mild to moderate bronchiolitis | |||||||

| Luo et al., 201180 | China | Children aged under 2 years, bronchiolitis | 126 | Yes: no significant differences | Moderate to severe; Wang et al.78 mean baseline scores 8.5 (NS group) and 8.8 (HS group) | Yes: 112 of 126 patients included in final analysis (89%) | Exclusion: age > 24 months, previous episode of wheezing, chronic cardiac and pulmonary disease, immunodeficiency, accompanying respiratory failure needing mechanical ventilation, inhaled 3% HS 12 hours before treatment, premature birth |

| Inclusion: infants aged < 24 months, first episode of wheezing, admitted to hospital for treatment of moderate to severe bronchiolitis | |||||||

| Mandelberg et al., 200322 | Israel | Children aged up to 12 months, bronchiolitis. Mean age 2.9 months (range 0.5–12 months) | 61 | Yes: no significant differences | Non-severe/moderate; Wang et al.78 mean scores 8.1 (NS group) and 8.29 (HS group) | Yes: 52 of 61 randomised included (85%) | Exclusion: cardiac or chronic respiratory disease, previous wheezing episode, saturation < 85% in room air, obtunded consciousness, progressive respiratory failure needing mechanical ventilation |

| Inclusion: viral bronchiolitis with temperature of > 38 °C leading to hospitalisation | |||||||

| Espelt, 201274 | Argentina | Children aged from 1 to 24 months, bronchiolitis | 100 | Insufficient evidence to say but similar numbers of each sex in each group | Moderate to severe (score of > 5) | Yes: 82 out of 100 randomised included (82%) | Exclusion: chronic respiratory or cardiovascular disease, respiratory failure |

| Inclusion: infants aged 1 to 24 months, first episode of bronchiolitis with CSS score of > 5 and O2 saturation of > 97% | |||||||

| Maheshkumar et al., 201381 | India | Children aged < 24 months: mean age 5.93 months (range 2–12 months). Enrolled within 24 hours of admission | 40 | Unclear: no baseline characteristics table provided | Mild to moderate severity); Wang et al.78 clinical scores between 4 and 8 | Yes: 100% included | Exclusion: pre-existing cardiac disease, previous wheezing episode, severe disease (score of > 8) needing mechanical ventilation, oxygen saturation < 85% on room air, cyanosis, obtunded consciousness and/or progressive respiratory failure |

| Inclusion: first episode of bronchiolitis, moderate distress | |||||||

| Sharma et al., 201382 | India | Children aged from 1 to 24 months | 250 | Yes: no significant differences | Moderate severity; Wang et al. clinical scores 3–6, median scores 6 (both groups) | Yes: 248 of 250 randomised included (99%) | Exclusions: obtunded consciousness, cardiac disease, chronic respiratory disease, previous wheezing episode, progressive respiratory distress needing respiratory support other than oxygen |

| Inclusion: first episode of acute bronchiolitis, hospitalised, CSS score of 3–6 | |||||||

| Al-Ansari et al., 201083 | Qatar | Children aged under 18 months diagnosed with acute bronchiolitis | 187 | Yes: ‘baseline characteristics before enrolment were similar in the three treatment arms’ | Moderate to severe bronchiolitis. BSS 5.77 (0.9% NS group) 6.16 (3% HS group) 5.65 (5% HS group) | Yes: 171 out of 187 included (91%) | Exclusion: < 34 weeks’ gestation, history of wheezing, steroid use within 48 hours, obtundation and progressive respiratory failure requiring ICU admission, apnoea within 24 hours, oxygen saturation < 85% in air, chronic lung disease, congenital heart disease, immunodeficiency |

| Inclusion: upper respiratory tract infection, wheezing and/or crackles on auscultation, BSS (> 4) | |||||||

| Nemsadze et al., 201384 | Georgia | Children aged 2–24 months with bronchiolitis | 42 | Yes: no significant differences | Mild to moderate (bronchiolitis clinical score) | Unclear – abstract only | Unclear – abstract only |

| Pandit et al., 201385 | One centre: India | Children aged 2–12 months diagnosed with acute bronchiolitis | 100 | Yes: no significant differences | Moderate/severe. Severity RDAI scale mean baseline scores 11.7 (NS group) and 12 (HS group) | Yes: 100% included | Exclusion: previous wheezing and respiratory distress, family history of asthma, atopy, congenital heart disease, ventilation as newborn infant, patients with shock, seizures, heart rate (> 180 beats per minute), respiratory rate (> 100 breaths per minute) and in respiratory failure, consolidation lung on radiograph |

| Inclusion: children age 2–12 months admitted with acute bronchiolitis | |||||||

| Teunissen et al., 201486 | 12 centres: the Netherlands | Children aged 0–24 months with viral bronchiolitis | 292 | Yes: no significant differences | Mild to moderate; Wang et al.78 mean scores at baseline 6.2 (0.9% NS group), 6.2 (3% HS group) and 6.2 (6% HS group) | Yes: 247 out of 292 analysed (85%) | Exclusion: excluded if Wang et al.78 score improved by at least two points after inhalation, congenital heart disease, chronic pre-existent lung disease, T-cell immunodeficiency, corticosteroid treatment and previous wheezing, eczema or food allergy |

| Inclusion: children aged 0–24 months admitted to hospital with viral bronchiolitis with a Wang et al.78 score of > 3 | |||||||

| Everard et al., 201487 | UK | Children aged up to 12 months with acute bronchiolitis | 317 | Yes: no significant differences | Severe bronchiolitis | Yes: 291 out of 317 included (92%) | Exclusion: wheezy bronchitis or asthma – children with an apparent viral respiratory infection and wheeze with no or occasional crepitations, reflux, previous lower respiratory tract infections (requiring assessment in hospital), risk factors for severe disease (< 32 weeks’ gestation, immunodeficiency, neurological and cardiac conditions, chronic lung disease), subjects where the carer’s English is not fluent and translational services are not available |

| Inclusion: previously healthy infants less than 1 year of age, admitted with acute bronchiolitis, consented and randomised within 4 hours of admission by a medical paediatrician | |||||||

| Silver, 201488 | USA | Children aged 0 to 12 months, with bronchiolitis | 227 | Yes: no significant differences | RDAI completed prior to first study treatment: mean 3.5 (NS group), 3.2 (HS group) | Yes: 190 out of 227 included (84%) | Exclusion: status asthmaticus, chronic cardiopulmonary disease, trisomy 21 and immunodeficiency or transplant recipient or neuromuscular disease. Admission directly to ICU, previous use of nebulised HS less than 12 hours prior to presentation and previous enrolment in the study in 72 hours prior to presentation |

| Inclusion: patients up to 12 months of age, admitted to hospital with bronchiolitis | |||||||

| Ozdogan et al., 201489 | Turkey | Infants aged 1 to 24 months, admitted with acute bronchiolitis | 69 | Yes: the demographic features were similar in each group | Respiratory assessment score, mild to moderate bronchiolitis | Unclear: abstract only | Exclusion: unclear – abstract only |

| Inclusion: infants 1–24 months of age admitted to hospital with acute bronchiolitis | |||||||

| Sosa-Bustamante, 201475 | Mexico | Children aged 2 to 24 months | Unclear: ClinicalTrials.gov only | Unclear: ClinicalTrials.gov only | Respiratory Distress Scale of the Sant Joan de Déu Hospital, moderate to severe bronchiolitis | Unclear: ClinicalTrials.gov only | Exclusion: subjects with history of previous wheezing, asthma, or who have received bronchodilator treatment before the present illness. Patients with chronic lung disease, heart disease, with congenital or acquired anatomic abnormalities of the airway |

| Inclusion: children aged 2–24 months, first episode of wheezing associated with respiratory distress, history of upper respiratory tract infections and evaluation of respiratory difficulty with the Respiratory Distress Scale of the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu from 6–16 at entry points | |||||||

| Ojha et al., 201490 | Nepal | Children aged 6 weeks to 24 months | 72 | Yes: baseline characteristic were comparable | Clinical scoring of respiratory distress of > 4. Mean scores at baseline 7.36 (0.9% NS group) and 8.08 (3% HS group) | Yes: 59 out of 72 included (82%) | Exclusion: previous episode of wheezing, chronic cardiac and pulmonary disease, immunodeficiency, respiratory failure, mechanical ventilation, inhaling nebulised 3% saline and salbutamol 12 hours before treatment, premature infants (less than 34 weeks), oxygen saturation < 85% on room air |

| Inclusion: children aged 6 weeks to 24 months presenting with bronchiolitis for the first time |

Data items

-

Study overview (country, year).

-

Participant characteristics (age, number randomised, baseline imbalances assessed by the authors in trials, withdrawals, % allocated completing follow-up, illness severity, eligibility).

-

Intervention and control group details (number randomised in each group, intervention details: duration, delivery, other drugs and compliance).

-

Outcomes data:

-

Continuous outcomes: LoS (mean LoS, SD and number of patients in each group, measured by who); CSS score (mean final CSS score, SD, number of patients for both groups).

-

AE data as available.

-

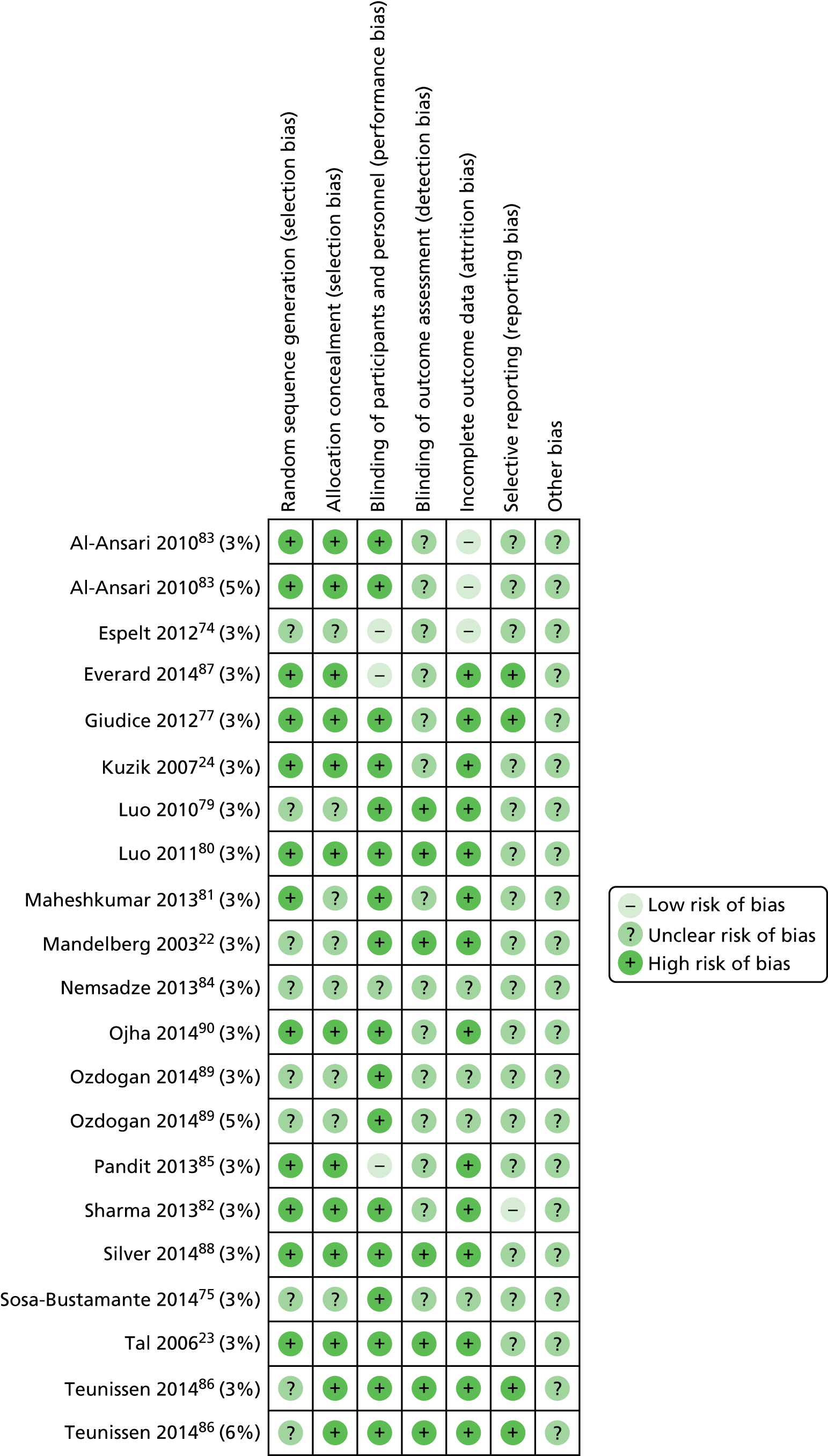

Risk of bias in individual studies

The Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool allows reported trial results to be differentiated from the methods used, with lower risk studies associated with more conservative effect estimates of risk. 91 CM and HC independently graded the quality of trials as ‘low’ where there is low risk, ‘high’ where there is high risk of bias or ‘unclear’ where the risk is unclear. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Risk of bias assessment was conducted at both study and outcome level. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,76 chapter 8.5.2, was used as a guide to make judgements on the methodological quality of the trials for the following domains of bias: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding, completeness of outcome data; and selective reporting. A supporting statement for each bias domain was extracted where a grade is given. Where an unclear grade is given, effort was made to obtain further information to categorise the trial by contacting the trial authors or searching for the study protocol to identify sources of reporting bias. Risk of bias data were entered into the Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan version 5.2, Cochrane, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) tool for analysis. Both a risk of bias graph and risk of bias summary were derived from the data and are reported in the results section.

Summary measures

All outcomes were continuous; the summary measure was the median difference and its associated 95% CI.

Synthesis of results

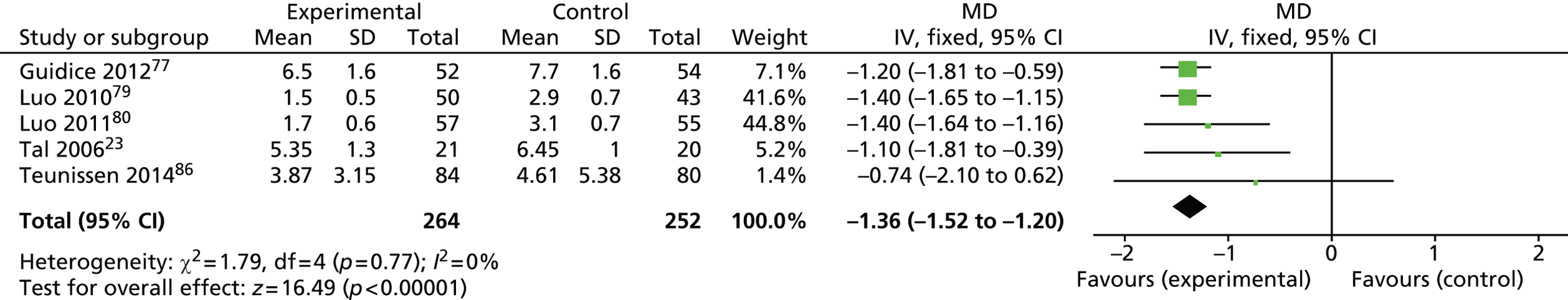

Analyses were undertaken using both RevMan version 5.2 and Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A FE model was used to combine (unstandardised) median differences between HS and the control. The FE model assumes that the LoS outcome would estimate the same effect size in each of the studies and weights studies according to their precision (standard error), which in turn relates to the sample size: the greater the sample size, the greater the weight assigned to the trial. 92 In addition, a second analysis was undertaken using the random-effects (RE) approach of DerSimonian and Laird,79 which incorporates the variability among trial estimates into the weighting of the trials.

Three-armed trials, which compared more than one concentration of HS with a control, were included in the review. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions recommends combining the active arms, but notes that heterogeneity can be better assessed by keeping dose arms separate. 76 As high levels of heterogeneity were identified in our review (see Chapter 5, Primary outcome: results and synthesis), this was the approach we adopted. To avoid double-counting of control patients, in three-arm trials control group numbers were divided by 2.

Mean final (post-treatment) CSS scores for participants in each arm of the trial were also extracted. A scoring system devised by Wang et al. 78 was used to assign CSS scores at baseline. Some of the studies reported a final CSS score for both the intervention and the control groups.

Data on AEs were synthesised narratively.

We used the I2-statistic to measure statistical heterogeneity with the following guidance on interpretation from the Cochrane Handbook:76

-

I2-statistic of 0–40% = heterogeneity may not be important

-

I2-statistic of 30–60% = may mean moderate heterogeneity

-

I2-statistic of 50–90% = may mean substantial heterogeneity

-

I2-statistic of 75–100% = considerable heterogeneity

-

Overlapping CIs are an indication of lower heterogeneity within the trials.

Forest plots also display the chi-squared test to test for statistical heterogeneity, with corresponding p-values at or below the threshold of 0.1 conventionally indicating a statistically significant heterogeneity. 70

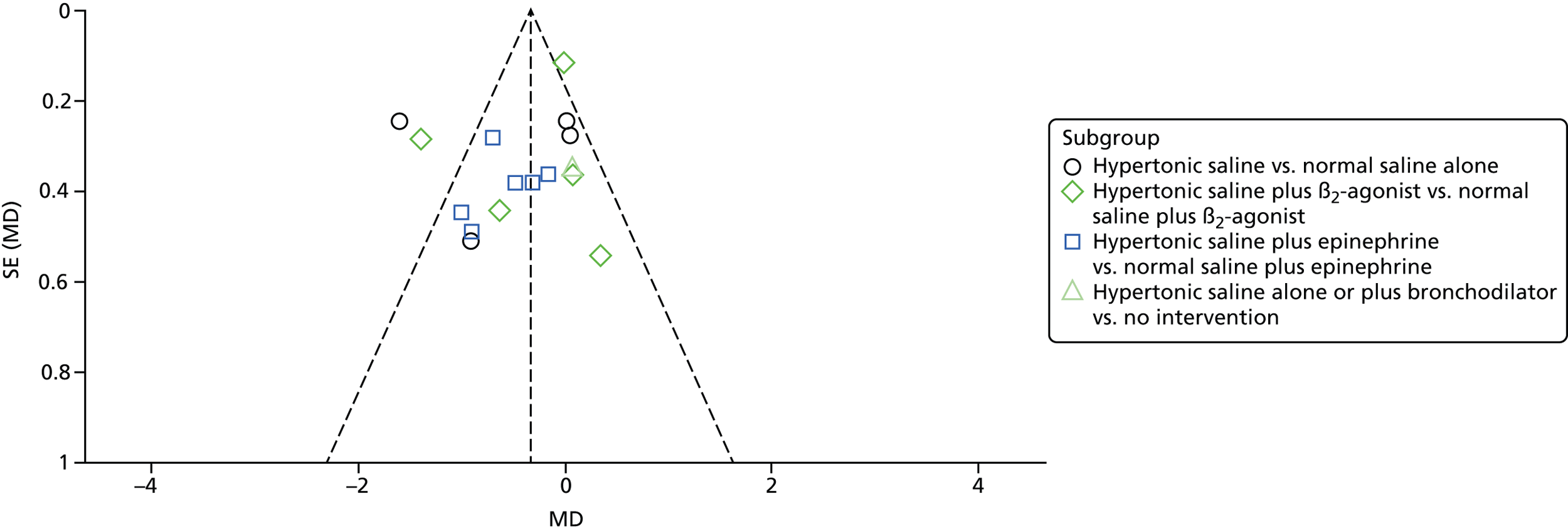

Risk of bias across studies

A funnel plot was generated to explore the possibility of publication bias in the primary outcome, LoS, for all trials. The main group was then split into subgroups to investigate reasons for heterogeneity.

Heterogeneity was explored by separating the group by comparator based on the following:

Intervention comparator:

-

nebulised HS alone versus NS alone (n = 4 trials)

-

nebulised HS plus a bronchodilator (e.g. salbutamol) versus NS alone (n = 0 trials)

-

nebulised HS plus a bronchodilator (e.g. salbutamol) versus NS plus same bronchodilator (n = 12 trials)

-

nebulised HS alone or plus a bronchodilator versus no treatment (n = 1 trial).

Further analyses were performed to separate the type of bronchodilator administered, for example beta-2 agonist compared with adrenaline. The subgroups for these are listed below:

-

nebulised HS alone versus NS alone (n = 4 trials)

-

nebulised HS plus a bronchodilator (e.g. salbutamol) versus NS alone (n = 0 trials)

-

NEBULISED HS plus a beta agonist versus NS plus same beta agonist (n = 7 trials)

-

nebulised HS plus adrenaline versus NS plus same adrenaline (n = 5 trials)

-

nebulised HS alone or plus a bronchodilator versus no treatment (n = 1 trial).

Outcome reporting bias arises from selectively picking outcome measures to report for the study based on the results achieved. 93 Smaller, lower-quality trials may in themselves introduce bias whereas larger, more expensive studies which may be more methodologically sound are more likely to be published even with negative results. 94 Using methods suggested by Dwan and colleagues,95 we also assessed the risk of outcome reporting bias.

Chapter 3 Trial results

Recruitment and participant flow

Participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment and were analysed for the primary outcome

Between 26 October 2011 and 23 December 2013, the trial recruited and randomised 317 participants, with 158 patients allocated to the nebulised 3% HS group and 159 allocated to usual care (Figures 1 and 2). There were five patients from the nebulised 3% HS group who did not receive the intended treatment. Of the 317 patients randomised, 26 of these patients were excluded because they were randomised when ineligible and for one patient primary outcome data were unavailable because their medical notes were lost; therefore, 290 patients were included in the primary outcome analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Participant recruitment curve.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram. ITT, intention to treat.

Losses and exclusions after randomisation

The number of post-randomisation exclusions together with the reason for exclusion is displayed in Table 4. Overall, 26 patients were excluded from the study: 16 from the intervention group and 10 from the control group.

| Post-randomisation exclusion reasons | Standard care plus (intervention group) | Standard care (control group) |

|---|---|---|

| Randomised outside the 4-hour recruitment window | 2 | 4 |

| Received HS prior to randomisation | 3 | 0 |

| Verbal consent was obtained prior to randomisation with written consent being obtained after randomisation | 3 | 0 |

| No decision to admit prior to randomisation | 1 | 0 |

| No recommendation for oxygen at the point of admission | 1 | 0 |

| Previously investigated and diagnosed in hospital with reflux | 1 | 0 |

| Previous lower respiratory tract infection requiring assessment in hospital | 4 | 6 |

| Patient’s study documentation was lost | 1 | 0 |

Of the 317 randomised patients, 26 were excluded, as described previously. Of the remaining 291 patients, five were not included in the PP analysis for the following reasons: four withdrew before receiving any HS/intervention and one patient’s medical notes were lost (therefore no treatment data were available). Of the remaining patients in the PP analysis, 32 withdrew from treatment having received at least one dose of HS and three withdrew from the study, two from the standard care group and one from the standard care plus intervention group.

Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up

The trial consisted of three recruitment seasons. The study recruited patients during winter 2011/12, winter 2012/13 and from October 2013 to December 2013. Patients were followed up for a period of 28 days after randomisation to collect data on readmissions, duration of respiratory symptoms post discharge, health-care utilisation post discharge and infant and parental quality of life.

Why the trial ended or was stopped

The trial closed to recruitment after reaching the accrual target on 23 December 2013.

Baseline data

Table 5 shows the characteristics of the recruited and non-recruited patients, the former being further subdivided according to whether or not the patient was subsequently excluded. There were no notable differences between these groups in terms of age or sex.

| Variable | Non-recruited | Recruited | ||