Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/91/16. The contractual start date was in July 2011. The draft report began editorial review in June 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Steve Cunningham has the following potential competing interests: (1) current chair of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Bronchiolitis Guideline Group; (2) past chair of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network Bronchiolitis Guideline Group; (3) principal investigator for Alios Pharmaceuticals Phase 1 investigational medicine for treatment of infants with bronchiolitis; and (4) consultancy work on behalf of NHS Lothian for Ablynx Pharmaceuticals Phase 1 product development for treatment of infants with bronchiolitis.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Cunningham et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Bronchiolitis is a common self-limiting viral illness generally affecting children under 12 months of age. The illness is marked by acute inflammation of the mucous membranes of the nasal cavities (a coryzal illness) with a subsequent viral infection of the lower airway, associated with poor feeding, cough, increased work of breathing and hypoxaemia (low blood oxygen levels).

Normoxaemia and hypoxaemia

Normoxaemia is the range of oxygen levels within the blood of healthy individuals. An oxygen saturation of 94% or more is seen in 97.5% of the population up to 1500 m altitude, and 94% is commonly accepted as defining the lower limit of normoxaemia. 1

Hypoxaemia (an oxygen saturation of < 94%) is common, particularly in respiratory disease, and results from poor ventilation or perfusion or both.

Clinical approach to hypoxaemia in respiratory disease

Cyanosis has been a core clinical sign of hypoxaemia for over three centuries. With ready supply of supplemental oxygen from the 1950s, cyanosis was corrected during disease. The clinical availability of arterial pulse oximetry in the 1980s, becoming ubiquitous in the 1990s, has enabled clinicians to have a more finely tuned understanding of arterial oxygenation. This precision, however, has vexed clinicians about how to interpret safely small changes in oxygen saturation. Clinical cyanosis is distinguishable at approximately 85% oxygen saturation, so what is the clinical impact of increments in oxygen saturation between 85% and 94%? Since the early 1990s, clinicians have grown accustomed to interpreting changes in oxygen saturation without an evidence base on which to do so; in acute bronchiolitis the rate of admission to hospital would double when clinicians were provided with scenarios depicting only a 2% difference in oxygen saturation (from 94% to 92%). 2

Clinical response to supplemental oxygen in those with hypoxaemia

Supplemental oxygen is provided for both acute and chronic respiratory disease to treat hypoxaemia. There are different recommendations for oxygen saturation targets from which to supplement oxygen in developed and developing health-care settings. The evidence for recommendations is limited or absent.

In developed health-care settings, in adults with acute respiratory disease, it is recommended that a target oxygen saturation of 94–98% be maintained;3 however, supplemental oxygen has no effect on acute respiratory symptoms,4,5 and there is no evidence that it has any effect on duration of illness. Among adults with chronic respiratory disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), domiciliary oxygen supplementation confers a survival benefit on those who are severely hypoxaemic but not on those with mild or moderate hypoxia. 6 At the other end of the age spectrum, it has been found that preterm infants managed to a target oxygen saturation of 84–89% (median oxygen saturation attained 89%) were significantly more likely to die than those managed to a target oxygen saturation of 90–95% (median oxygen saturation attained 92%). 7 The small differences in median oxygen saturation observed in this study highlight the potential for significant health implications from minor variance of oxygen saturation in vulnerable populations.

In developing health-care settings, it is recommended that a target oxygen saturation of ≥ 90% be maintained in those with acute respiratory disease. 8 Provision of supplemental oxygen to meet this recommendation is associated with reduced mortality in children with acute respiratory infection. 9 The World Health Organization has recommended that the oxygen saturation target in acute respiratory infection be derived from expert interpretation of oxygen dissociation dynamics combined with a pragmatic wish to optimise resource allocation for maximal reduction of mortality in resource-poor settings. 10

Before the present study, there were no randomised studies assessing the role of oxygen supplementation in acute respiratory infection in children.

Hypoxaemia in acute viral bronchiolitis

One in five infants develops symptomatic bronchiolitis in the first year of life, and approximately 3% of all infants require hospital admission to receive supportive care,11 predominantly for help with feeding and to receive supplemental oxygen for hypoxaemia. Oxygen saturation below 92% leads to oxygen supplementation being provided in 70% of infants admitted to hospital with acute viral bronchiolitis. 12 In 57% of infants admitted to hospital, hypoxaemia will prolong length of stay after all issues have resolved (i.e. feeding). Length of stay for all infants with bronchiolitis is a mean of 72 hours, but in those requiring supplemental oxygen the mean is 96 hours. 12

Controversies in approach to hypoxaemia in bronchiolitis

Hypoxaemia is common in bronchiolitis; however, the majority of infants do not have clinical cyanosis. The controversies lie in how to address oxygen saturation values just below the limit of normoxaemia. Could there be clinical benefit from elevating oxygen saturation in this region to normoxaemia (as is suggested by adult recommendations for acute respiratory disease)? What harm may come from accepting oxygen saturation in this region during acute respiratory disease (because small changes in oxygen saturation targets cause significant harms in preterm infants)?

Since the early 1990s, the number of admissions to hospital with bronchiolitis have increased, while mortality from the condition has remained the same. 13 Death occurs in approximately 0.9% of hospital patients with bronchiolitis, mostly in those with pre-existing conditions. 14 Some have questioned whether or not the increase in admissions may be (in part) because of the increased use of oxygen saturation monitoring. 15

Two recent evidence-based guidelines have considered oxygen saturation in bronchiolitis. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guideline No. 9116 considered that, with no evidence available, current practice should prevail and infants should be considered ready for discharge once normoxaemia (oxygen saturation ≥ 94%) has been restored. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Guideline on Bronchiolitis,17 published in the same year, also accepted that there was no evidence but considered (by expert opinion of the group) that infants could be discharged home once they are clinically stable with an oxygen saturation ≥ 90%. The recommendation of an oxygen saturation at discharge below normal ranges has been controversial. 18 Since publication of these two evidence-based guidelines, there continues to be variation in practice and recommendations, possibly highlighting clinician uneasiness at the interpretation of oxygen saturation in sick infants. There are a variety of recommended oxygen saturation targets present within national guideline portals in the USA,19 the UK,20 Spain21 and Australia. 22 In addition, guidelines have recommended a lower target for starting supplemental oxygen than for stopping, typified by current guideline synthesis provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality at the US Department for Health and Human Services. 23 The clinical logic for the different targets to start and stop supplemental oxygen is not clear, particularly the lower oxygen saturation target for commencing supplemental oxygen at a time when infants are typically clinically less stable.

Potential health-care impact of clinical response to hypoxaemia in bronchiolitis

We performed a pilot study in 62 infants admitted to hospital with bronchiolitis who were provided with supplemental oxygen for low oxygen saturation. 24 Nursing observations noted oxygen saturation in air and amount of supplemental oxygen (if required) every 2 hours during the hospital stay. The median time for infants to improve from 90% to 94% oxygen saturation in air was 33 hours (stability for 4 hours at each level was required). In some infants, oxygen saturation was stable at ≥ 90% before feeding had been re-established. Taking feeding into account identified that a move from discharge at ≥ 94% saturation to ≥ 90% could facilitate discharge 22 hours earlier (30%) than currently is the case. If projected to the 70% of infants with bronchiolitis requiring oxygen during their admission, this would be equivalent to 18,434 bed-days per year gained for the UK NHS (an equivalent US value would be 95,608 bed-days per year). This represents substantial cost savings to the UK NHS, and, hence, assuming no significant cost increases through implementation of this changed regime and equal or improved health benefits, this would represent a highly cost-effective intervention.

There is a significant pressure to improve hospital logistics and costs associated with bronchiolitis. In the USA, an estimated 149,000 infants were admitted in 2002, for an average of 3.3 days, at a total cost of US$543M. Paediatric hospitals are logistically challenged each winter, particularly during the 6-week peak of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, as infants who are clinically stable remain in hospital for oxygen supplementation. In response, some centres now provide short-term supplemental oxygen at home, using primary care (USA)25 or secondary care home nursing teams (Australia). 26 The burden on primary care services and families of home oxygen is significant. 27 Studies have not provided a health-economic perspective on this service development. 28

Study aims

Bronchiolitis has no effective treatment. 16,17 Care is supportive to those who need it. In Scotland, approximately 2000 children under 12 months of age are admitted each year with bronchiolitis. 16 In the UK, in 2007, an estimated 28,728 infants under 12 months of age were admitted to hospital with bronchiolitis, similar to the number of all children (aged 0–14 years) admitted each year with acute asthma.

If the AAP recommendation of an oxygen saturation target of ≥ 90% were widely adopted and used as a target for both starting and stopping supplemental oxygen, this could reduce time in hospital for infants. To be acceptable to clinicians, however, the practice would need to be demonstrated to be safe, without clinical detriment and without undue additional burden on primary care or families caring for children at home during an earlier part of their illness. To answer this clinical question we performed a double-blind, randomised controlled, equivalence trial in children with acute viral bronchiolitis to determine whether or not a target oxygen saturation of ≥ 90% would be equivalent to ≥ 94% for resolution of illness and also to compare clinical, safety and parental outcomes.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a multicentre, parallel-group, double-blind, randomised controlled, equivalence trial conducted in the UK (eight sites). Infants were allocated 1 : 1 to trial intervention.

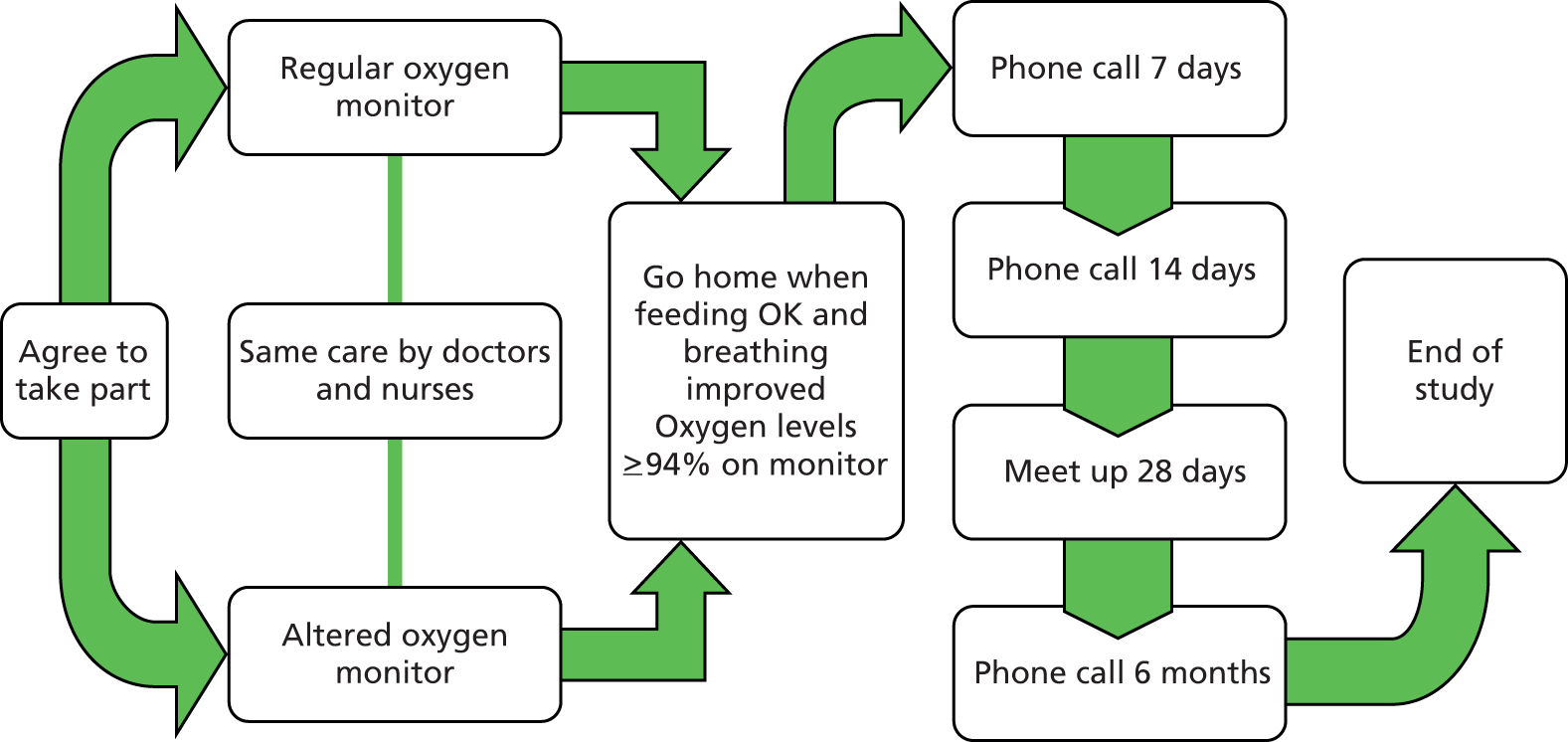

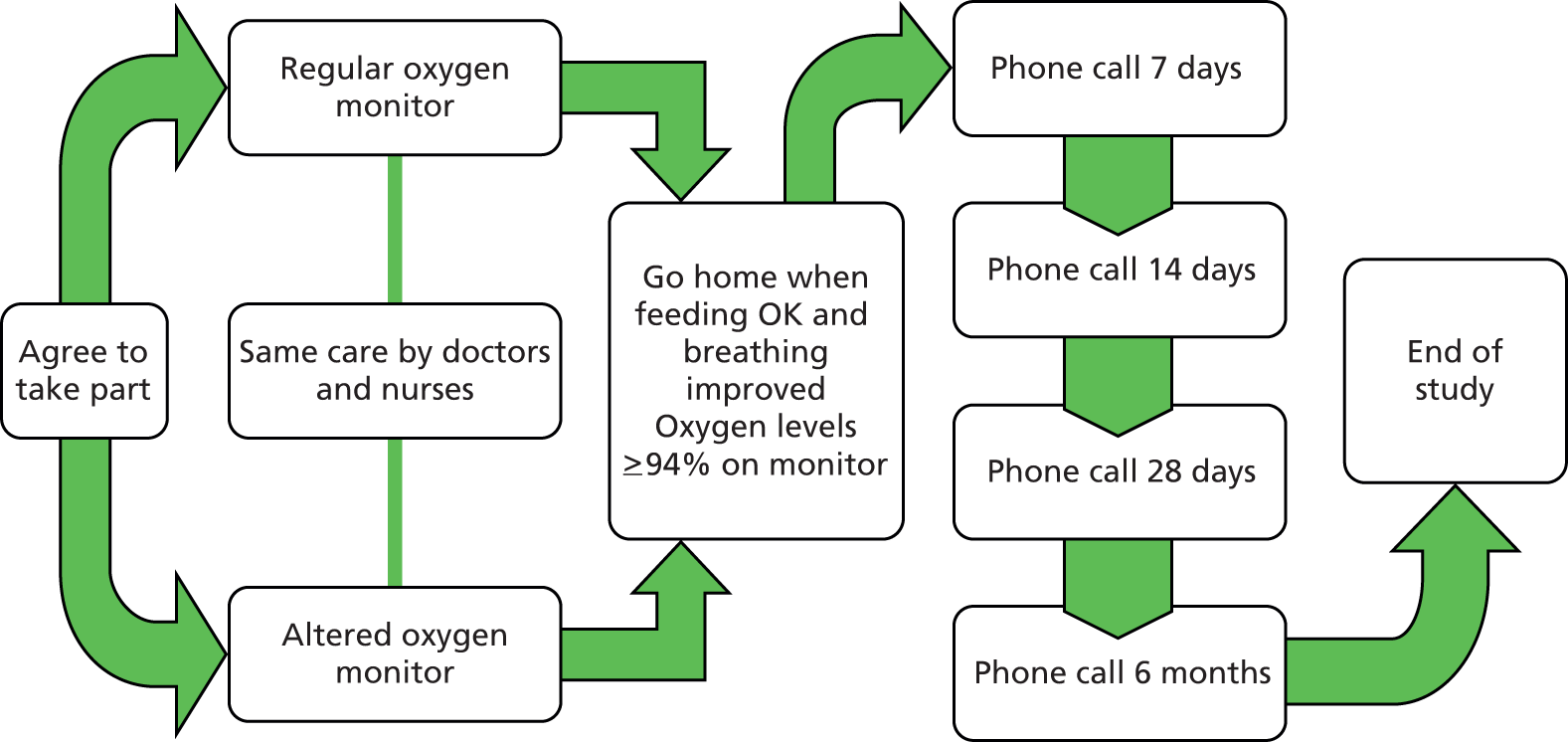

The trial was completed to the same methods throughout with one exception. In season 1, infants were met at 28 days for measurement of oxygen saturation. An unblinded review of the data by the independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) at the end of season 1 identified satisfactory oxygen saturation and no significant difference in oxygen saturation between groups. As a consequence, in season 2, there was no further measurement of oxygen saturation at day 28, and this meeting was replaced by a telephone call to parents to gather the same information that had previously been collected at the day-28 meeting.

Participants

Participants were infants aged ≥ 6 weeks and ≤ 12 months (corrected for prematurity) presenting to a participating hospital emergency department (ED)/acute assessment area (AAA) [either by general practitioner (GP) referral or by spontaneous attendance] who had a clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis (consistent with SIGN guideline No. 9116) made by acute receiving medical staff and who required admission to hospital for supportive care. The clinical decision to admit an infant with bronchiolitis prompted informed consent and randomisation to the study.

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used:

-

Inclusion criteria

-

Infants with a corrected age of ≥ 6 weeks and ≤ 12 months of age admitted to hospital with a clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis made by a medically qualified practitioner in ED/AAA.

-

-

Exclusion criteria

-

Preterm infant (< 37 weeks’ gestation) who received oxygen therapy in the previous 4 weeks.

-

Cyanosis/haemodynamically significant heart disease.

-

Cystic fibrosis or interstitial lung disease.

-

Documented immune function defect.

-

Direct admission to high-dependency unit (HDU)/paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) from ED/AAA.

-

Previously recruited to Bronchiolitis of Infancy Discharge Study (BIDS).

-

Infants were recruited only from 6 weeks of age, as infants below this age are often considered at higher risk and present more frequently with apnoea, often without significant desaturation. The generalisation of results to infants in this age group is covered in the discussion.

Identifying participants

The study aimed to recruit and randomise only during the historic peaks for bronchiolitis in two northern hemisphere winters. Infants who were eligible were identified by clinicians and research/specialist nurses in the ED/AAA. The clinical decision to admit an infant with bronchiolitis prompted consent for the study.

Settings and locations where the data were collected

The study took place in the ED/AAA and paediatric wards of eight paediatric hospitals in the UK (in Aberdeen, Bristol, Dundee, Edinburgh, Exeter, Glasgow, Kilmarnock and Truro). In season 1, randomisation was open from 3 October 2011 to 30 March 2012 in the five Scottish sites only. In season 2, randomisation was open from 1 October 2012 to 29 March 2013 in all eight sites.

Interventions

The intervention was to a randomly allocated standard or modified pulse oximeter. Therapeutic options for the treatment of acute viral bronchiolitis are very limited, and, in general, infants are admitted to hospital for supportive care only. 16,17 Supportive care includes feeding support (with nasal suction, nasogastric or intravenous fluids) and supplemental oxygen for oxygen desaturation. Oxygen saturation monitors are ubiquitous in the care of infants admitted to hospital with acute bronchiolitis and guide supplementation of oxygen and decision-making for discharge.

Eighty oxygen saturation monitors were provided by Masimo (Rad-8® with LNC 10 patient cable; Masimo Corporation Limited, CA, USA). Standard oximeters measured and displayed oxygen saturation in a standard way as usual care. The modified oximeters measured arterial oxygen saturation as per standard oximeters but manufacturer-altered internal algorithms provided a non-standard display: in the oxygen saturation measured range of 85–90%, the display was within the range of oxygen saturation of 85–94%. In this way infants with modified oximeters would appear to have a more rapid improvement with regard to oxygen requirement and, consequently, could stop supplemental oxygen at a displayed 94% oxygen saturation level when the actual oxygen saturation level was 90%. Figure 1 demonstrates the algorithmic relationship of measured (true) to displayed (altered) oxygen saturation. From a clinical perspective, study pulse oximeters were of identical appearance and function, identified only by a study number (Figure 2). In the study, infants received supplemental oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation of ≥ 94% (actual 90% on modified oximeters). As we expected that infants on modified oximeters might go home sooner, with an associated faster turnaround of oximeters, there were 43 standard oximeters and 37 modified oximeters in the oximeter pool.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted algorithm for modified oximetry (true vs. altered).

FIGURE 2.

Masimo Rad-8 study oximeter.

Infants remained on their study oximeter for the duration of their admission. Infants who suffered post-randomisation deterioration and required admission to a HDU/PICU were transferred to a standard non-study pulse oximeter during the HDU/PICU stay and recommenced on the same blinded study oximeter on transfer back to the ward for the remainder of their stay until discharge.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was equivalent time to no cough (collected by phone calls at follow-up). The primary outcome was assessed by the primary caregiver.

Secondary outcomes (admission questionnaires, clinical data, parental phone calls, home visit)

We were looking for equivalence between treatment groups in the following secondary outcomes:

-

time to re-established feeding (approximately 75% normal)

-

parental perspective of ‘time to back to normal’

-

oxygen saturation at 28 days post randomisation (season 1 only).

We were looking for a difference between treatment groups in the following secondary outcomes:

-

time to fit for discharge (oxygen saturation ≥ 94% for 4 hours including a period of sleep and adequate feeding at ≥ 75% usual)

-

time to discharge

-

health-care reattendance (primary care, ED, readmission)

-

change in anxiety score

-

time to return to work/usual activities for parent(s)/nursery for infants

-

family and societal costs incurred

-

health-care costs related to discharge time and subsequent health-care utilisation.

There were no major changes to trial outcomes following trial commencement. As above, oxygen saturation was measured at 28 days in season 1 with the agreement of the DMC when no significant differences were identified between the groups.

Measurements

Demographic information was collected by research nurses within 24 hours of admission. Data related to the hospital stay were collected progressively during the period of hospitalisation and at discharge.

Parents were contacted by the study team on four occasions, at 7, 14 and 28 days and at 6 months following randomisation. Standardised interview questions were asked to obtain study-related data. In season 1, infants and parents were met in person at 28 days for measurement of oxygen saturation and parents were asked day-28 information at this visit. In season 2, the same information was obtained by telephone call.

We could not identify a validated measure of parental anxiety during an acute illness of a child. The anxiety section of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was therefore used without the depression section (as the depression questions were not relevant). 29

Sample size

The sample size was determined for the primary outcome of time to resolution of cough following randomisation. An estimate of 544 participants was made by assuming that there would be no difference between the treatment groups, with a common standard deviation of 8.3 days. 30 The standard deviation of 8.3 days was calculated by dividing the interquartile range by 1.35. 31 This used a two-sided test (overall alpha 0.05), with power of 80% and limits of equivalence of 2 days (i.e. the difference between the two arms could be up to 2 days in either direction). To allow for skewness in the outcome measure, as well as any dropouts and non-compliance, the recruitment target was 600 infants. Every effort was made to minimise dropout and non-compliance.

There is no published evidence to support the limit of equivalence for cough resolution. We therefore sampled the expert opinion of consultant paediatricians who contribute to the general paediatric service at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh (and who provide clinical management of infants with bronchiolitis), and identified a variance of 2 days as being clinically meaningful with adequate safety. The same equivalence limit of 2 days in either direction was used for time to return to normal. For time to return to satisfactory feeding we used a typical infant feed interval of 4 hours as equivalence.

Although the number of infants admitted to these hospitals during the study would be more than 600, the sample size estimate included an allowance for infants with exclusion criteria, infants admitted on more than one occasion and parents who did not wish to participate (all exclusions estimated at 25%).

The epidemic and variable nature of seasonal bronchiolitis made it difficult to plan exact recruitment rates. The goal was to achieve recruitment of 75% of admissions, and centres provided monthly Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)-style infant outcome feedback32 to identify centre mismatch in recruitment rates and to enable re-evaluation and optimisation of study recruitment if poorer than expected. The chief investigator and trial manager, together with the principal investigator and lead clinical research facility nurse at each centre, held monthly teleconferences to discuss the project, problems encountered and difficulties in recruitment and to share experiences of how these issues may be addressed.

Following the outline proposal, we were asked to confirm that parents would, in principle, consent to a study as proposed. In a short survey carried out at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, in spring 2010, a group of parents whose infants had been admitted to or recently discharged from hospital with bronchiolitis were provided with the study scenario and asked if they would be willing for their infant to take part in the study. Fifteen parents were approached. The children of two parents were < 6 weeks of age at the time of admission and both parents said that they would decline to participate in the study because of their child’s age, confirming that a 6-week age minimum was reasonable. A further parent declined because their child had been admitted to hospital with bronchiolitis on numerous occasions. Of the remaining 12 parents, 11 said that they would have agreed to take part in the study (92% of those eligible), with one parent considering and requiring more information before making a decision.

Interim analyses and stopping guidelines

An independent DMC reviewed the efficacy and safety data after season 1. There were no safety concerns. A review of oxygen saturation data measured at 28 days revealed no differences, so these data were not collected for season 2.

The following criteria for stopping the trial were in the DMC charter (09.05.11 Version 1.0) (see Appendix 5):

The DMC should inform the Chair of the steering committee if, in their view:

(i) the results are likely to convince a broad range of clinicians, including those supporting the trial and the general clinical community, that one trial arm is clearly indicated or contraindicated, and there was a reasonable expectation that this new evidence would materially influence patient management; or

(ii) it becomes evident that no clear outcome would be obtained.

Randomisation

Sequence generation

Randomisation was by central internet-based secure password-protected randomisation database. Patient identifiers and some clinical details were entered to confirm eligibility (inclusion and exclusion criteria) and to prevent re-recruitment. The random allocation sequence was generated by the programmers at the Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit (ECTU).

Type of randomisation

Randomisation was by blocks of varying length (four and six) without stratification.

Allocation concealment mechanism

The person randomising the infant did not know the allocation until the infant was definitely enrolled into the study via the system.

Implementation

Infants were enrolled by clinicians and research/specialist nurses in the ED/AAA. Clinicians (mostly nursing staff) attached either a standard or a modified pulse oximeter in accordance with the computer-generated randomisation code. The administering clinician removed non-study oximeters from infants and, with an interval of 1 minute, reapplied the appropriate study oximeter, typically at a time when the infant was preparing to move between departments in the hospital (i.e. ED to a ward area).

Blinding

The monitors were identical in appearance and general function, with the exception of the study number (see Figure 2). All study staff involved in day-to-day running of the trial, hospital staff and parents were blind to study intervention and could not tell what the randomised group was from the study numbers on the machines. To further reduce the opportunity for accidental unblinding, study numbers on oximeters were changed in the period between season 1 and season 2. Those assessing outcomes were blind to the assigned intervention. The blind was not broken for any infant during the study.

Statistical methods

General statistical methods

All analyses were by intention to treat (ITT) unless otherwise specified. The ITT population included all infants randomised into the BIDS study. Infants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised, regardless of treatment received. Where a per-protocol analysis was performed, infants were analysed in the group of the treatment they actually received: any use of standard pulse oximeter versus any use of modified pulse oximeter. The group of infants in which no pulse oximeter was used were excluded from the per-protocol population. No infants received both types of oximeter. All applicable statistical tests were two-sided using a 5% significance level. Ninety-five per cent (two-sided) confidence intervals (CIs) were presented. The primary analysis was an unadjusted analysis. Where there were missing data for an outcome variable, in the first instance, those records were removed from any formal statistical analysis, unless otherwise specified.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the number of days from randomisation until resolution of cough. The difference in median number of days until cough resolution between the two treatment groups was estimated along with a 95% CI for the difference. The treatment arms were considered equivalent with respect to this outcome if this 95% CI lay entirely within the equivalence limits of ± 2 days. For the primary analysis, the difference between the medians and the 95% CI for this difference were estimated as described by Altman et al. 33 The large-sample formula for derivation of the confidence limits was used. The main primary outcome analysis was conducted on an ITT basis. A per-protocol analysis was also performed. The study would lead to firm conclusions only if the findings from the main analysis and the per-protocol analysis were in agreement.

Missing data

If a date of cough resolution was known, it was used. If it was known that the cough resolved but the precise date was unknown, a random value was chosen between the date that the cough was last known to be present and the date of the follow-up when it was found that the cough had stopped. The random value was chosen from infants in the same treatment group whose cough stopped in a similar time frame. If it was known that the cough had not resolved by 6 months, the date of cough was predicted by taking a random value from a uniform distribution capped from 180 days to 200 days (upper cap based on the observations by Shields and Thavagnanam34). If it was known that the cough had not stopped by the last follow-up but the infant was not followed to 6 months, then a random value was chosen from a uniform distribution with the lower cap pegged to the last known follow-up time (i.e. 7, 14 or 28 days) instead of 180 days. This process was repeated 100 times, and the analysis done on each data set. The mean values for the estimate of the median and the estimates of the CI limits were used. If 100 repetitions did not produce a stable estimate, then this number was to be increased, but this was not necessary. As a sensitivity analysis, a complete-case analysis was also done.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures were tested for a difference between the two arms of the trial.

For the outcome measures, the times, split by treatment group, were presented using a Kaplan–Meier plot. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the treatment effect: time from randomisation to (1) fit for discharge and (2) actual discharge for all infants admitted with acute viral bronchiolitis; (3) time to no supplemental oxygen; (4) time to readmission to hospital. We considered whether or not the season-1 data for Glasgow (Yorkhill) should be removed from the analysis of time to fit for discharge, as this variable was not recorded consistently at this centre in season 1. However, this made no difference to the results so these data were left in.

The results are presented at multiple time points, and due allowance would be made for this if any of them proved to be statistically significant. The effect of the intervention was estimated using binary logistic regression and reported as an adjusted odds ratio and 95% CI for the proportion of infants with at least one health-care reattendance (primary care, ED, hospital readmission) at days 7, 14 and 28 and at 6 months. The effect of the intervention was estimated using Poisson regression for the number of health-care reattendances (primary care, ED, hospital readmission) at days 7, 14 and 28 and at 6 months. The effect of the intervention was estimated using analysis of covariance models with the baseline score as a covariate for parental anxiety score (anxiety questions from HADS questionnaire at admission, at 7, 14 and 28 days’ follow-up and at 6 months’ follow-up).

For the outcome measures, the mean difference in times between the two trial arms was estimated from a normal linear model, and presented with a 95% CI: heart rate at discharge; respiratory rate at discharge.

We tested for equivalence between the two arms of the trial for the secondary outcome measures. The same method as the primary outcome was used for time in hours from randomisation to re-established feeding (equivalence limits of ± 4 hours), and time in days from randomisation to parental perspective of back to normal (equivalence limits of ± 2 days). For time to re-establish adequate feeding, no imputations for missing data were performed, as the data were recorded only at the end of discharge and they were almost complete. The difference in mean oxygen saturation measurements between the two trial arms was estimated with its corresponding 95% CI for awake oxygen saturation at 28 days after randomisation (equivalence limits of ± 1.0% oxygen saturation – season-1 data collection only).

Subgroup analyses

Primary outcome

The difference in median time from randomisation until resolution of cough between the two treatment groups was estimated along with a 95% CI for the difference, by subgroup, using the same method as for the primary outcome. As the two treatment groups were expected to be equivalent, subgroup analyses were unlikely to be informative, as qualitative subgroup effects were not expected. No formal analyses between subgroup comparisons were made, and the significance or non-significance of within-subgroup effects will not be discussed. The subgroups to be presented are length of illness prior to randomisation (0–3 days vs. ≥ 4 days), use of antibiotics before and/or during admission (any vs. none) and parental smoking (any vs. none).

Other outcomes

The effect of treatment allocation on time from randomisation to (1) fit for discharge and (2) actual discharge from hospital was evaluated separately in infants with/without an oxygen requirement during their stay. Formal evidence of a differential subgroup effect was based on the statistical significance of the regression coefficient for the interaction between treatment allocation and oxygen requirement.

Economic evaluation methods

Overview of economic evaluation

This trial investigated whether or not a 90% oxygen saturation discharge protocol (modified) is cost-effective compared with the standard 94% oxygen saturation discharge procedure. The research question the economic evaluation therefore addressed was: is the modified discharge procedure a cost-effective alternative to the standard discharge procedure? The economic evaluation measured the costs to the NHS and social care and combined this with the main outcome measure, time to cough resolution, within a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) framework. CEA is a form of economic evaluation in which both the costs and effects of two or more health interventions are compared, and the results report the incremental difference between the alternatives under consideration as an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The economic evaluation was undertaken alongside the trial, capturing individual resource-use data collected via economic data-collection questions integral to the trial forms. The analysis reported the incremental cost per reduction in time to cough resolution. The economic evaluation also took into consideration the seasonality of the disease by outlining the opportunity cost of hospital bed displacement during peak winter seasons. Individual patient-level data on outcomes and information on resource use were identified and measured during the trial and used in the economic evaluation.

Outcome measure for cost-effectiveness analysis

The primary endpoint in the trial is time to cough resolution (measured at 6 months). The economic evaluation used mean time to cough resolution, by measuring the area under the curve. 35,36 The area under the curve method permits comparison of the mean difference between treatment arms based on the entire survival curve, or in this case the entire time to cough resolution curve. 36,37 This is standard practice for an economic evaluation for determining the primary endpoint in time to event/survival analysis, where censored and skewed data are prevalent. The economic analysis considered the joint distribution of costs and effects. Therefore, the economic analysis used the mean time to cough resolution and accompanying standard errors for each arm of the trial to undertake probabilistic analysis, using bootstrapping38 to account for uncertainty around this primary outcome measure and how this affects the cost-effectiveness outcomes. The economic analysis explored the impact that baseline variables have on the mean time to cough resolution. It was hypothesised that variables such as sex, child gestation at birth, length of illness prior to onset, parental smoking status, antibiotics on arrival at accident and emergency (A&E), oxygen saturation and GP visits prior to onset might affect the time to cough resolution. In addition, the quality of life of parents was measured using the anxiety component of the HADS. 29

Resource use data collection

The base-case analysis was undertaken from the perspective of the UK NHS and personal social services. That is, the costs relevant to the economic analysis are those incurred by the NHS and social services. In a sensitivity analysis, the patient perspective was also incorporated, adding the costs incurred by the parent in terms of both financial costs (such as travel to and from hospital) and time lost from normal activities because of the illness.

There are five main resource categories of relevance: initial hospitalisation costs, medication, readmission costs, follow-up care and, in the sensitivity analysis, costs to parents. The base-case total cost (CT) is a function of the cost of hospital days (or hours) (Chosp), medication (Cmed), readmission (Creadmit) and any follow-up care (CFUcare). In the sensitivity analysis, the cost to parents is also included (Cparents). Equation 1 illustrates the main components of total cost.

Patient-level resource-use data were collected within trial, for example days (or hours) in an acute paediatric ward, days (or hours) in the HDU, tests and scans undertaken, medication prescribed, hospital readmissions and any additional follow-up care, that is GP appointments, referrals, etc. Parent time was also collected. Resource-use quantities and mean patient cost values are reported separately as per recent recommendations [Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) guidelines]. 39

Health-economic analysis methods

Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to carry out regression analysis exploring the effect that baseline variables have on the cost of each intervention, such as sex, child gestation at birth, length of illness prior to onset, parental smoking status and antibiotics on arrival at A&E. Potential non-normality in the cost data was explored and, if the cost data were found to be skewed, a generalised linear model (GLM) was employed. It was hypothesised that the cost data were likely to be highly skewed because of the very high costs associated with cases that are referred on to HDU or are readmitted. The GLM for cost regressions, described by Glick et al. ,40 was used in this case, and 95% CIs around the cost estimates were also calculated. 41 If, however, the cost data were found to be normally distributed, then standard parametric tests were used. In line with recent CHEERS guidelines,39 resource-use values, ranges references and probability distributions are reported for all resources. Mean values for the main categories of costs, as well as mean differences between the comparator groups (modified compared with standard), are reported.

Additional analyses were undertaken to explore the effect that baseline variables, such as sex, duration of illness before randomisation, parent smoking, GP visits prior to admission, had on the cost and time to cough resolution of each intervention. Potential non-normality in the cost and time to cough resolution data was explored and a GLM was employed. 40

Outcomes were analysed using multivariate logistic regression, adjusting for child age and sex, parental age left full-time education and heaviness of smoking index. 42 GLM regression was used for analysis of costs if they were skewed. GLM regression for cost was adjusted for treatment group, parental smoking and GP visits prior to admission. The other specified variables in the analysis plan (protocol) had no significant impact. A variety of families and various links for each family were investigated and tested using modified Park tests; gamma was found to be best fit, with a power link of –1. We ran GLM using gamma family and link power –1. GLM regression was used for the time-to-cough-resolution variable, given that the mean is skewed. GLM regression for time to cough resolution was adjusted for treatment group, season, sex, preterm birth, cost (total NHS cost), parental smoking, GP visits prior to admission and antibiotics prior to admission.

All within-trial analyses were performed using Stata version 12.

Unit costs

Unit cost information was combined with the resource-use data collected and the mean cost per patient per arm estimated. Valuing the resource use using the unit costs provided an estimate of the total cost for each resource. These were aggregated to estimate total patient costs within each arm, and the mean cost per patient per arm. The difference in average costs (and significance) between the two trial arms was estimated. All unit costs were collected in UK pounds sterling for the base year 2012/13. Cost information was collected from routine sources such as the British National Formulary (BNF) 63,43 Personal Social Services Research Unit44 and NHS Reference Costs. 45 Some unit costs were collected specifically from the trial/hospital financial records, such as the cost of specific lab tests that are not available on the BNF.

Handling missing cost and outcome data

Missing data were handled through the use of multiple imputation (for both cost and outcome data). The multiple imputation approach has been widely recommended by most experts in biomedical literature. 40 The key dependent variables used to base the imputations on were sex, child gestation at birth, length of illness prior to onset of cough, parental smoking status, antibiotics on arrival at A&E, oxygen saturation and number of GP visits prior to admission. Sensitivity analysis was undertaken to determine the influence of missing data at follow-up (resource-use data and primary outcome) on study conclusions, to assess the strength of association between time to cough resolution and ‘missingness’ (i.e. whether or not data are missing) and to allow for individual, sampling and imputation variation using multiple imputation.

Reporting and presenting of results

Appropriate consideration was given to the distribution of the cost and effect data in the economic evaluation. In order to explore the variation around the costs and effects generated by the trial data, stochastic variance around the cost–effect pairs was estimated using non-parametric bootstrapping methods. The incremental costs and the incremental benefits were reported within an ICER format where appropriate. The 95% CI for each ICER was estimated using Fieller’s theorem, a technique that includes any correlation between cost and outcome. 46 Sample uncertainty was explored using non-parametric bootstrapping to generate 1000 ICER values which are plotted on a cost-effectiveness plane in order to represent graphically uncertainty. 47 The result for the CEA was expressed in terms of positioning on the cost-effectiveness plane as well as translated into cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, indicating the likelihood that the results fall below any given cost-effectiveness ceiling ratio, where appropriate. Cost differences were reported between the arms as standard; however, in a departure from typical ‘treatment minus comparator’ differences for reporting purposes, the cost-effectiveness plane reported the differences as ‘standard minus modified’ to reflect the fact that this trial tested for equivalence in costs and effects.

Adjustment of timing of costs and benefits

Allowance for differential timing of costs and benefits was made using the recommended discount rate of 3.5% (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Methods Guidance). 48 Data within this trial were collected over two consecutive winter periods, and costs and benefits were estimated for the baseline year, 2012/13.

Sensitivity analyses

A detailed sensitivity analysis of key parameters was undertaken. In addition to this the patient perspective was incorporated to the analysis, adding the costs incurred by the parent (in terms of financial costs such as travel to and from hospital and time lost from normal activities because of the illness) to the NHS and social services costs.

Seasonality impacts

The economic analysis also took into consideration the seasonality of the disease and the economic impact of this with regard to availability of ward space/beds during peak hospital times. Information was collected on the type of ward in which patients were being cared for. It may be that during peak times infants have to be cared for in, say, surgical wards and this will have cost consequences. Further to this, the capacity of wards during such busy times was explored by obtaining hospital attendance information from the business managers at trial centres to allow a more precise costing (saving) in terms of opportunity cost of hospital stay as a result of bronchiolitis. This additional information will allow the economic analysis to provide further relevant policy implications for the potential hospital stay reductions arising through implementation of the 90% oxygen saturation protocol.

Publication policy

To safeguard the integrity of the trial, data from this study were not presented in public or submitted for publication without requesting comments and receiving agreement from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme. The success of the trial was dependent on the collaboration of many people. The results were, therefore, presented first to the trial local investigators. A summary of the results of the trial will be made available on the Scottish Children’s Research Network website (www.scotcrn.org) and the research sites can provide these to parents of participating children on request.

Organisation

A Trial Steering Committee (TSC; see Appendix 4) and a DMC were established (see Appendix 5). Day-to-day management of the trial was overseen by a Trial Management Group (see Appendix 6). Each participating centre identified a paediatric consultant as a principal investigator (see Acknowledgements). Each participating centre was reimbursed on a per-patient fee from the core trial grant. The Medicines for Children Research Network and/or local Comprehensive Local Research Networks supported research nursing time, and employed or reallocated a research nurse to support all aspects of the trial at the local centres.

Confidentiality

Patients were identified by their trial number to ensure confidentiality. However, as the main caregivers to the patients in the trial were contacted during the follow-up, the caregivers’ names and contact details were recorded on the data collection forms in addition to the allocated trial number. Stringent precautions were taken to ensure confidentiality of names and addresses at ECTU and the sites. The chief investigator and local investigators ensured conservation of records in areas to which access is restricted.

Audit

No audit of BIDS was carried out. The trial manager monitored all the sites at least once to verify that the site staff had sufficient knowledge of the trial protocol and procedures, that the site file was being properly maintained and that the site adhered to local requirements for consent.

Termination of the study

Before termination of recruitment, ECTU contacted all sites by telephone or e-mail in order to inform sites of the final date for recruitment. Once the recruitment period had expired, the internet-based randomisation database was disabled to prevent further recruitment. After all recruited patients had been followed up until 6 months after randomisation, a declaration of the end of trial form was sent to the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee. The following documents will be archived in each site file and kept for at least 10 years: original consent forms, data forms, trial-related documents and correspondence. The trial master files at ECTU will be archived for at least 10 years.

Funding

The costs for the study itself were covered by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme. See the Health Technology Assessment programme website for further project information. Clinical costs were met by the NHS under existing contracts.

Indemnity

If there was negligent harm during the clinical trial, then the NHS body owes a duty of care to the person harmed. NHS indemnity covers NHS staff, medical academic staff with honorary contracts and those conducting the trial. NHS indemnity does not offer no-fault compensation. The cosponsors were responsible for ensuring proper provision was made for insurance or indemnity to cover their liability and the liability of the chief investigator and staff.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow

A CONSORT diagram for recruitment is provided in Figure 3. In total, 615 infants were randomised in two seasons, meeting the recruitment target. Fifty-two per cent of eligible infants were randomised to the study, with 9% of parents declining to take part.

FIGURE 3.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram: seasons 1 and 2.

Study recruitment by country, centre and season is provided in Table 1, demonstrating no important differences in allocation of oximeters by centre or season.

| Parameter | Category | Allocated intervention | Overall, N = 615 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard pulse oximeter, n = 308 | Modified pulse oximeter, n = 307 | |||

| Distribution by country, n (%) | Scotland | 247 (80.2) | 260 (84.7) | 507 (82.4) |

| England | 61 (19.8) | 47 (15.3) | 108 (17.6) | |

| Distribution by centre, n (%)a | Aberdeen | 22 (7.1) | 22 (7.2) | 44 (7.2) |

| Dundee | 56 (18.2) | 54 (17.6) | 110 (17.9) | |

| Edinburgh | 100 (32.5) | 95 (30.9) | 195 (31.7) | |

| Glasgow | 45 (14.6) | 55 (17.9) | 100 (16.3) | |

| Kilmarnock | 24 (7.8) | 34 (11.1) | 58 (9.4) | |

| Bristol | 33 (10.7) | 26 (8.5) | 59 (9.6) | |

| Exeter | 14 (4.5) | 11 (3.6) | 25 (4.1) | |

| Truro | 14 (4.5) | 10 (3.3) | 24 (3.9) | |

| Distribution by season, n (%)b | 1 | 113 (36.7) | 112 (36.5) | 225 (36.6) |

| 2 | 195 (63.3) | 195 (63.5) | 390 (63.4) | |

Patient disposition and changes post randomisation

Tables 2 and 3 provide information on patient disposition. See Table 2 for the number of infants who reached the end of the study with > 90% of data [N = 584 (95%)]. Thirty-one infants did not reach 6-month follow-up: there were two deaths, one infant was withdrawn by the clinician, 21 infants were lost to follow-up and the parents declined further contact in another seven cases. Breakdown by group is provided in Table 2. Table 3 gives details of those in whom the primary outcome was directly obtained and the number in whom the primary outcome was estimated [standard care 43 (14.0%); modified care 38 (12.3%)].

| Parameter | Category | Allocated intervention | Overall, N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard pulse oximeter, n | Modified pulse oximeter, n | |||

| Reached end of studya | Reaching 6-month assessment | 293 | 291 | 584 |

| Reason not reached end of study | Deceased | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Withdrawn by clinician | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lost to follow-up | 8 | 13 | 21 | |

| Participant declined – no further contact | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| Parameter | Category | Allocated intervention | Overall, N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard pulse oximeter, n | Modified pulse oximeter, n | |||

| Patients in database | All patients | 309 | 308 | 617 |

| Not treated | Randomised in error | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Randomised and consented (ITT population) | Treated | 308 | 307 | 615 |

| In primary outcome | Data obtained | 296 | 293 | 589 |

| In primary outcome split by estimation | Yes | 43 | 39 | 82 |

| No | 253 | 254 | 507 | |

| Reason primary outcome not obtained | Deceased | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Withdrawn by clinician | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lost to follow-up | 7 | 12 | 19 | |

| Participant declined – no further contact | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

Protocol deviations and classification are provided in Table 4. There were similar numbers and categories in each group.

| Parameter | Category | Allocated intervention | Overall, N = 615 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard pulse oximeter, n = 308 | Modified pulse oximeter, n = 307 | |||

| Patients with a recorded deviation, n (%) | Yes | 34 (11.0) | 42 (13.7) | 76 (12.4) |

| No | 274 (89.0) | 265 (86.3) | 539 (87.6) | |

| Deviation categories (n)a | Attached late | 5 | 13 | 18 |

| Removed early | 15 | 9 | 24 | |

| Never attached | 6 | 9 | 15 | |

| Discharge criteria not met | 5 | 9 | 14 | |

| Other | 3 | 9 | 12 | |

Recruitment

Infants were recruited within two winter seasons. For the first season, recruitment was between 3 October 2011 and 30 March 2012 in the five Scottish sites only. For the second season, randomisation was from 1 October 2012 to 29 March 2013 in eight sites. The addition of three sites in south-west England was in response to a quieter RSV season than expected in season 1. An analysis of season-1 peak oximeter use enabled a redistribution of study oximeters across eight sites for season 2.

The trial completed recruitment on schedule and to target on 29 March 2013.

Baseline data

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are provided by group in Table 5. The modified care group had slightly fewer males and more preterm infants, though all other demographics and characteristics were similar.

| Parameter | Standard | Modified | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 308 | 307 | 615 |

| Age (weeks), median (IQR) | 21.3 (12.6–31.1) | 21.1 (11.1–32.0) | 21.3 (11.7–31.6) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 186 (60.4) | 166 (54.1) | 352 (57.2) |

| Preterm (< 37 weeks), n (%) | 28 (10.1) | 45 (16.1) | 73 (13.1) |

| Eczema, n (%) | 51 (16.7) | 44 (14.5) | 95 (15.6) |

| Food allergy, n (%) | 8 (2.6) | 11 (3.6) | 19 (3.1) |

| Household smoking, n (%) | 133 (43.9) | 130 (42.8) | 263 (43.3) |

| Siblings (≥ 1), n (%) | 221 (72.7) | 211 (69.4) | 432 (71.1) |

| Number of primary care attendances in previous 4 weeks, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (1–2) |

| Heart rate on arrival at ED, median (IQR) | 159 (146–173) | 158 (148–172) | 159 (147–172) |

| Respiratory rate on arrival at ED, median (IQR) | 50 (44–58) | 49 (42–58) | 50 (42–58) |

| Antibiotics on arrival at ED, n (%) | 24 (7.9) | 23 (7.6) | 47 (7.7) |

| Bronchodilator on arrival at ED, n (%) | 17 (5.6) | 16 (5.3) | 33 (5.4) |

| Length of illness (days) on arrival at ED, median (IQR) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) |

| Apnoea on arrival at ED, n (%) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 6 (1) |

| SpO2 on arrival at ED, median (IQR) | 95 (93–97) | 95 (93–97) | 95 (93–97) |

| SpO2 on arrival at ED ≤ 94%, n (%) | 121 (39.8) | 119 (39.3) | 240 (39.5) |

Virology test data

Laboratory virology testing was performed in 81.9% of infants, with near-patient testing in 40.0% of infants (Table 6). The proportion of infants who were RSV positive (either laboratory or near-patient testing) was 69.8% in the standard care group and 76.3% in the modified care group. Laboratory testing identified a positive result for a virus other than RSV in 27.2% of standard care infants and 22.0% of modified care infants.

| Parameter | Standard | Modified | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 308 | 307 | 615 |

| Laboratory virology testing | 250/302 (82.7) | 245/303 (80.9) | 495/605 (81.8) |

| Laboratory: any virus positive | 204/250 (81.6) | 217/245 (88.6) | 421/495 (85.1) |

| Laboratory: RSV positive | 167/250 (66.8) | 181/245 (73.9) | 348/495 (70.3) |

| Laboratory: non-RSV virus positive | 68/250 (27.2) | 54/245 (22.0) | 122/495 (24.6) |

| Near-patient testing | 121/305(39.7) | 122/303 (40.3) | 243/608 (40.0) |

| Near-patient testing: RSV positive (of those with result) | 79/101 (78.2) | 91/108 (84.3) | 170/209 (81.3) |

| RSV positive on laboratory or near-patient testing (of those with result) | 194/278 (69.8) | 213/279 (76.3) | 407/557 (72.9) |

Numbers analysed

The treatment offered versus allocated is given in Table 7. In eight instances the incorrect treatment was allocated (by staff attaching the wrong oximeter): in seven instances a modified oximeter was provided to an infant randomised to standard care and in one instance a standard oximeter was attached to an infant randomised to modified care. These infants are included in the group to which they were allocated as per ITT. In 44 instances treatment was interrupted, the majority per protocol during an admission to the HDU, with treatment restarted on discharge from the HDU.

| Parameter | Category | Allocated intervention | Overall, N = 615 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard pulse oximeter, n = 308 | Modified pulse oximeter, n = 307 | |||

| Treatment allocated, n (%) | Standard | 308 (100) | 0 | 308 (50.1) |

| Modified | 0 | 307 (100) | 307 (49.9) | |

| Treatment offered, n (%) | Standard | 307 (99.7) | 7 (2.3) | 314 (51.1) |

| Modified | 1 (0.3) | 300 (97.7) | 301 (48.9) | |

| Treatment given, n (%) | Standard | 301 (97.7) | 7 (2.3) | 308 (50.1) |

| Modified | 1 (0.3) | 291 (94.8) | 292 (47.5) | |

| Never treated | 6 (1.9) | 9 (2.9) | 15 (2.4) | |

| Treatment interrupted,a n (%) | Yes | 22 | 22 | 44 |

Protocol deviation

Seventy-six participants had a protocol deviation, 34 (11.0%) in the standard care group and 42 (13.7%) in the modified care group. The deviation categories are provided in Table 4 and are similar between groups.

Outcomes and estimation

Primary outcome

Our primary outcome was time to cough resolution (days) (Table 8). From the primary ITT analysis, the median time to no cough was 15.0 days in the standard care group and in the modified care group, with a median difference of 1.0 day (shorter for modified care). The upper and lower CIs for the median difference were –1 and 2 days. This interval falls within the prespecified equivalence limits of –2 to 2 days. We specified that perprotocol analysis must be in agreement with the ITT protocol for equivalence. In the per-protocol analysis, median difference in time to no cough was 0 days (95% CI –1 to 2 days). This interval falls within the prespecified equivalence limits of –2 to 2 days and is consistent with the ITT analysis. We performed a complete-case analysis for the ITT population, which showed very similar results (difference between groups of 0 days, 95% CI –1 to 2 days). The groups are considered equivalent for the primary outcome.

| Parameter | Standard care, median (IQR), n | Modified care, median (IQR), n | Median differencea | Upper and lower 95% CI | All, median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to cough resolution (days). Equivalence defined as ± 2 days | 15.0 (10.0–42.5), n = 296 | 15.0 (10.0–41.0), n = 293 | 1.0 | –1 to 2 | 15.0 (10.0–42.0) |

| Time feeding returned to ≥ 75% normal (hours). Equivalence defined as ± 4 hours | 24.1 (6.5–62.1), n = 304 | 19.5 (6.3–47.2), n = 296 | 2.7 | –0.3 to 7.0 | 21.8 (6.3–53.9) |

| Time to return to normal (days). Equivalence defined as ± 2 days | 12.0 (7.0–25.0), n = 296 | 11.0 (6.0–20.0), n = 293 | 1.0 | 0 to 3 | 11.0 (7.0–23.0) |

| Subgroup analyses | |||||

| Time to cough resolution: smoking household (days) | 15.0 (10.0–35.0), n = 129 | 13.0 (9.0–34.0), n = 125 | 1.0 | –2 to 3 | 14.0 (10.0–35.0) |

| Time to cough resolution: non-smoking household (days) | 15.5 (10.0–47.0), n = 166 | 16.0 (10.0–44.0), n = 168 | 0 | –2 to 2 | 16.0 (10.0–45.0) |

| Time to cough resolution: illness duration ≤ 3 days (days) | 13.0 (10.0–32.0), n = 143 | 14.0 (10.0–33.0), n = 134 | 0 | –2 to 2 | 14.0 (10.0–32.0) |

| Time to cough resolution: illness duration ≥ 4 days (days) | 18.0 (10.0–48.0), n = 153 | 16.0 (9.9–44.0), n = 157 | 1.0 | –1 to 3 | 17.0 (10.0–47.0) |

| Time to cough resolution: antibiotics yes (days) | 12.0 (9.0–65.0), n = 57 | 15.0 (10.0–43.0), n = 52 | 0 | –4 to 5 | 13.0 (10.0–55.0) |

| Time to cough resolution: antibiotics no (days) | 16.0 (10.0–39.0), n = 239 | 15.0 (9.0–40.0), n = 241 | 1 | –1 to 2 | 15.5 (10.0–39.5) |

Subgroup analysis of primary outcome

We specified an assessment of subgroups of the primary outcome for the number of days of illness prior to randomisation (would any effect be influenced by the degree of airway inflammation present?), household smoking (would an early discharge to a smoking household prolong symptoms?) and use of antibiotics. Between-subgroup comparisons did not show any evidence of a difference in the magnitude of the treatment effect between subgroups.

Secondary outcomes

Equivalence outcomes

Three further outcomes were assessed for equivalence: (1) time to return to adequate feeding (≥ 75% normal) in hospital, (2) time until parents considered that the infant was back to normal and (3) oxygen saturation measured at 28 days after randomisation.

Median time to return to adequate feeding was 24.1 hours in the standard care group and 19.5 hours in the modified care group. The median difference was 2.7 hours (95% CI –0.3 to 7.0 hours). This falls outside the prespecified equivalence limits of ± 4.0 hours, so we cannot infer equivalence. The 95% CI overlaps zero, so we cannot conclude that there is a difference either.

Figure 4 provides a survival curve for time to return to adequate feeding. A post-hoc analysis (Table 9) gave a hazard ratio of 1.22 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.44; p-value = 0.015), demonstrating some evidence that the modified care group returned to feeding faster than the modified care group, and the survival curve indicates that any difference between the groups was in the time period following the median time to return to adequate feeding. Thus, we have not proved equivalence. If any difference does exist, it goes in favour of the modified care group.

FIGURE 4.

Time to return to adequate feeding.

| Parameter | Standard care, median (IQR) | Modified care, median (IQR) | Hazard ratio estimate | Upper and lower 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time feeding returned to ≥ 75% normal | 24.1 (6.5–62.1) | 19.5 (6.3–47.2) | 1.22 | 1.04 to 1.44 | 0.015 |

| Time back to normal (days) | 12.0 (7.0–25.0) | 11.0 (6.0–20.0) | 1.19 | 1.01 to 1.41 | 0.043 |

Parents were asked in standardised telephone interviews when they considered their child had returned back to normal. This was a median of 12.0 days in the standard care group and 11.0 days in the modified care group. The median difference was 1.0 day (95% CI 0.0 days to 3.0 days). The 95% CI of the median difference fall outside the prespecified limits of ± 2 days and so we cannot infer equivalence. The 95% CI just touches zero, so there is some evidence that there was a small difference in favour of the modified care group.

Figure 5 provides a survival curve for time until parents considered their infant back to normal. A post-hoc analysis (see Table 9) gave a hazard ratio of 1.19 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.41; p-value = 0.043), providing some evidence that, in the parents’ perception, infants in the modified care group returned to normal faster than infants in the standard care group, and the survival curve indicates that any difference between the groups occurred after the median time it took for infants to return to normal. Thus, we have not proved equivalence. If any difference does exist, it is in favour of the modified care group. The benefit to the modified care group was not expected and is a modest overall difference.

FIGURE 5.

Time to return to normal (days).

These data were only collected for season 1, following unblinded review by the DMC at the end of the season. The median peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) value was 99% in both groups. At 28 days there was a mean absolute difference between the treatment groups in oxygen saturation of 0.11% (95% CI –0.35% to 0.57%). We prespecified equivalence limits of 1% in either direction. Oxygen saturation at 28 days was equivalent in the two groups.

Differences outcomes

Infants could be considered fit for discharge from hospital once they had achieved adequate feeding (≥ 75% normal) and had been observed to have stable oxygenation in air with continuous oxygen saturation monitoring for a period of hours including a period of sleep. Infants in the standard care group were fit for discharge at 44.2 hours, compared with 30.2 hours in the modified care group (Table 10). The hazard ratio was 1.46 (95% CI 1.23 to 1.73; p-value < 0.001) (Figure 6).

| Parameter | Standard care, median (IQR), n | Modified care, median (IQR), n | Hazard ratio estimate | 95% CI | All, median (IQR), n | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to fit for discharge (hours) | 44.2 (18.6–87.5), n = 283 | 30.2 (15.6–59.7), n = 276 | 1.46 | 1.23 to 1.73 | 38.4 (16.9–69.7), n = 559 | < 0.0001 |

| Time to actual discharge (hours) | 50.9 (23.1–93.4), n = 303 | 40.9 (21.8–67.3), n = 301 | 1.28 | 1.09 to 1.50 | 44.5 (22.2–78.4), n = 604 | 0.003 |

| Time to no further supplemental oxygen (hours) | 27.63 (0–68.1), n = 305 | 5.65 (0–32.4), n = 304 | 1.37 | 1.12 to 1.68 | 14.44 (0–54.5), n = 609 | 0.002 |

| Time to readmission to hospital (days) | 17 (7–22), n = 23 | 11 (2–21), n = 12 | 0.925 | 0.433 to 1.977 | 15 (3–22), n = 35 | 0.84 |

FIGURE 6.

Time to fit for discharge.

The time at which infants were actually discharged from hospital could be influenced by local practice and logistics. Infants in the standard care group were discharged after a median of 51.0 hours, compared with 40.9 hours in the modified care group (see Table 10). The hazard ratio was 1.28 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.50; p-value = 0.027) (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Time to discharge.

We measured the time from randomisation to the time that infants in each group last received supplemental oxygen prior to discharge. In the standard care group this was a median of 27.6 hours, and in the modified care group 5.7 hours (see Table 10). The hazard ratio was 1.37 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.68; p-value = 0.0021) (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Time to no supplemental oxygen.

There was no significant difference in time to readmission to hospital in those infants who were subsequently readmitted to hospital following discharge (see Table 10). Median difference was 0.9 days (95% CI 0.4 days to 2.0 days; p-value = 0.8410). Median duration of readmission was 3.0 days in both the modified and standard care groups.

Safety outcomes

It was expected that infants on modified oximeters would be managed on monitors that would report higher oxygen saturation than was actually the case and that reducing oxygen delivery could lead to an increase in the number of adverse events (AEs). It was also expected that infants on modified oximeters would be discharged home sooner than infants on standard monitors and that this might result in increased morbidity.

Deaths from bronchiolitis are infrequent, and we did not consider that the intervention would result in more deaths. Two deaths were recorded during the study period; both were in the standard care group and were unrelated to the study intervention.

The study did not recruit infants who were directly admitted to a high-dependency area at admission (n = 56; see Figure 3). There were eight HDU admissions (in eight infants) in the standard care group and 13 (in 12 infants) in the modified care group.

Tachycardia and tachypnoea are characteristic clinical features of infants admitted to hospital with bronchiolitis. We wished to determine if infants who were discharged home sooner in the course of their illness (as expected in the modified care group) had significantly higher heart and respiratory rates at discharge. Clinical observations of heart rate and respiratory rate were measured every 8 hours and the final measurement prior to discharge was used for discharge measurement. Contrary to expectation, there were no significant differences between standard and modified care groups in either heart rate (hazard ratio –1.16; p-value = 0.37) or respiratory rate (hazard ratio 0.09; p-value = 0.88) at discharge.

Readmission to hospital was reported as a serious adverse event (SAE) during the first 28 days following randomisation. In the first 7 days after randomisation there were eight readmissions to hospital in six infants in the standard care group and five readmissions in five infants in the modified care group. By 28 days there had been 26 readmissions in 23 infants in the standard care group and 12 readmissions in 12 infants in the modified care group. It was not expected that there would be fewer admissions in the modified care group, as this group was expected to be discharged sooner in the course of their illness than those in the standard care group. The absolute reduction of three readmissions (relative reduction 38%) at 7 days is not a clinically important difference, but an absolute difference of 14 readmissions (relative reduction 54%) at 28 days could be considered a clinically important difference (a 5% absolute reduction in readmission rate for infants in the modified care group).

An earlier discharge from hospital may have been associated with a greater number of contacts with health care after discharge. The numbers of heath-care contacts at 7, 14 and 28 days and at 6 months after randomisation were similar between groups (Table 11). There were no significant differences in the number of infants with a health-care contact at 7 days after randomisation (see Table 11). Infants in the modified care group did not experience a higher number of health-care contacts up to 6 months following randomisation.

| Parameter | Standard care | Modified care | All | Mean difference (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% Cl) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | 2 | 0 | 2 | – | – | – |

| High-dependency care (episodes) | 8 | 13 | 21 | – | – | – |

| Heart rate at discharge, median | 133 (IQR 122–144) | 135 (IQR 123–147) | 134 (IQR 122–145) | –1.16 (–3.70 to 1.37) | – | 0.37 |

| Respiratory rate at discharge, median | 38 (IQR 34–41) | 38 (IQR 34–42) | 38 (IQR 34–42) | 0.09 (–1.05 to 1.23) | – | 0.88 |

| Readmission to hospital within 7 days (episodes) | 8 | 5 | 13 | – | – | – |

| Readmission to hospital within 7 days (infants) | 6 | 5 | 11 | – | – | – |

| Readmission to hospital within 28 days (episodes) | 26 | 12 | 38 | – | – | – |

| Readmission to hospital within 28 days (infants) | 23 | 12 | 35 | – | – | – |

| Reattendance at health care within 7 days (episodes) | 41 | 43 | 84 | – | – | – |

| Reattendance at health care within 7 days (infants) | 39 (14.4%) (n = 270) | 34 (12.7%) (n = 267) | 73 (13.6%) (n = 537) | – | 0.98 (0.65 to 1.49) | 0.94 |

| Reattendance at health care within 14 days (episodes) | 92 (n = 270) | 88 (n = 267) | 180 (n = 537) | – | – | – |

| Reattendance at health care within 14 days (infants) | 76 (28.5%) (n = 267) | 70 (27.1%) (n = 258) | 146 (27.8%) (n = 525) | – | 1.07 (0.73 to 1.57) | 0.73 |

| Reattendance at health care within 28 days (episodes), n | 199 (n = 290) | 188 (n = 288) | 387 (n = 578) | – | – | – |

| Reattendance at health care within 28 days (infants) | 127 (46.4%) (n = 274) | 128 (48.9%) (n = 262) | 256 (47.6%) (n = 536) | – | 0.90 (0.64 to 1.27) | 0.56 |

| Reattendance at health care within 6 months (episodes) | 802 (n = 295) | 774 (n = 293) | 1576 (n = 588) | – | – | – |

| Reattendance at health care within 6 months (infants) | 214 (84.6%) (n = 253) | 209 (80.1%) (n = 261) | 423 (82.3%) (n = 514) | – | 1.37 (0.87 to 2.16) | 0.18 |

| Antibiotics after discharge | 24 (7.8%) (n = 305) | 10 (3.3%) (n = 304) | 34 (5.5%) (n = 609) | – | – | – |

| SpO2 measured at 28 days (season 1 only) | 99 (IQR 97–100) (n = 94) | 99 (IQR 97–100) (n = 101) | 99 (IQR 97–100) (n = 195) | 0.111 (–0.350 to 0.572) | – | 0.64 |

An earlier discharge from hospital and attendance at primary care in an earlier part of disease recovery might be associated with a higher level of antibiotic prescribing after discharge in the modified care group. Infants in the modified care group received fewer courses of antibiotics in the 28 days after discharge than the standard care group (see Table 11; a 58% relative reduction).

Hospital treatments

The hospital treatments received by both treatment groups are shown in Table 12. Use of intravenous fluids, antibiotics and bronchodilator (salbutamol) was similar in both groups.

| Parameter | Standard, n (%) | Modified, n (%) | All, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Need for supplemental oxygen | 223 (73.1) | 169 (55.6) | 392 (64.4) |

| Use of nasogastric tube feeding | 141 (46.2) | 125 (41.3) | 266 (43.8) |

| Use of intravenous fluids | 29 (9.5) | 28 (9.2) | 57 (9.4) |

| Use of antibiotics | 44 (14.4) | 39 (12.8) | 83 (13.6) |

| Use of salbutamol | 25 (8.2) | 21 (6.9) | 46 (7.6) |

Supplemental oxygen was provided to 73.1% of infants in the standard care group and 55.6% of those in the modified care group. It was understood that there could be a difference between the groups, as oxygen saturation measured in the ED may decline following admission to hospital (in association with disease progression and continuous monitoring). The difference (17.5%) should approximate to those infants in the modified care group in whom oxygen saturation fell below 94% but remained above 90%, so the monitor would display at ≥ 94% and they would not have been commenced on supplemental oxygen. In other words, approximately one in six infants admitted to hospital who would receive oxygen at a target oxygen saturation of 94% would not do so at a target oxygen saturation of 90%.

The proportion of infants receiving nasogastric tube feeding was lower in the modified care group (41.3%) than in the standard care group (46.2%).

Anxiety scores

We wished to understand whether or not earlier discharge from hospital at an earlier stage of disease recovery might be associated with greater anxiety for parents looking after their child at home.

Parents’ levels of anxiety were similar at the time of their child’s admission to hospital, but the intervention did not result in parents experiencing greater levels of anxiety and there were no significant differences in anxiety scores at 7, 14 and 28 days or at 6 months (Table 13).

| Parameter | Standard care, median (IQR) | Modified care, median (IQR) | All, median (IQR) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety score at admission | 7 (4–10) | 7 (4–11) | 7 (4–11) | – | – |

| Anxiety score at 7 days | 4 (2–8) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–7) | –0.18 (–0.75 to 0.39) | 0.53 |

| Anxiety score at 14 days | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 0.00 (–0.57 to 0.56) | 0.99 |

| Anxiety score at 28 days | 3 (1–7) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–6) | –0.27 (–0.88 to 0.34) | 0.39 |

| Anxiety score at 6 months | 4 (1–7) | 3 (1–6) | 4 (1–7) | –0.16 (–0.82 to 0.49) | 0.62 |

Family life

Discharging a child from hospital earlier in the course of their illness could have an impact on family life, with lead carers having to give up time to care for the child, secondary carers taking additional time off work and children returning later to paid and unpaid child care than they otherwise would have done (Table 14). Lead carers were generally mothers (94.4% overall), and mothers of infants in the modified care group lost fewer hours to usual activities, with 23% fewer hours lost at 7 days, 28% at 14 days, 25% at 28 days and 21% at 6 months. In contrast, levels of activity lost by secondary carers (typically fathers) were similar regardless of intervention group, and most of this time was lost in the first 7 days. Relatively few children had childcare placements and the time to return to child care was similar between groups.

| Parameter | Standard | Modified | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead carer (= mother), n (%) | 288 (95.4) | 283 (93.4) | 571 (94.4) |

| Lead carer work status (= employed), n (%) | 43 (14.2) | 39 (12.9) | 82 (13.5) |

| Lead carer hours missed, 0–7 days, median (IQR) | 58.3 (25.1–96.5) | 44.8 (24.6–72.0) | 49.3 (24.8–85.5) |

| Lead carer hours missed, 0–14 days, median (IQR) | 62.3 (25.7–97.3) | 45.0 (25.3–72.7) | 50.9 (25.6–85.5) |

| Lead carer hours missed, 0–28 days, median (IQR) | 63.4 (27.5–101.2) | 47.3 (25.7–76.4) | 53.4 (26.3–89.3) |

| Lead carer hours missed, 0–6 months, median (IQR) | 67.6 (28.1–114.8) | 53.2 (30.4–86.2) | 59.0 (29.0–97.8) |

| Secondary carer work status (= employed), n (%) | 233 (83.3) | 251 (89.6) | 484 (86.5) |

| Secondary carer hours missed, 0–7 days, median (IQR) | 15.0 (8.0–24.0) | 16.0 (8.0–27.0) | 15.0 (8.0–24.0) |

| Secondary carer hours missed 0–14 days, median (IQR) | 15.0 (8.0–27.5) | 16.0 (8.3–30.5) | 16.0 (8.0–30.0) |

| Secondary carer hours missed 0–28 days, median (IQR) | 16.0 (8.0–33.8) | 17.3 (8.5–34.0) | 16.5 (8.0–34.0) |

| Secondary carer hours missed 0–6 months, median (IQR) | 22.0 (10.0–43.0) | 18.0 (9.0–36.0) | 20.0 (9.5–40.0) |

| Child well enough to return to child care by 7 days, n (%) | 24 (48.0) | 18 (52.9) | 42 (50.0) |

| Child well enough to return to child care by 14 days, n (%) | 28 (54.9) | 22 (62.9) | 50 (58.1) |

Prespecified subgroup analyses of secondary outcomes