Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/56/01. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The draft report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in February 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Willem Kuyken declares that he is a codirector of the Mindfulness Network Community Interest Company.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Kuyken et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Depression is a major public health problem that, like other chronic conditions, tends to run a relapsing and recurrent course,1 producing substantial decrements in health and well-being. 2 The World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that by 2020 depression will be the second leading cause of disability in the world. 3 The cost of mood disorders in the UK has been calculated at 7% of national income with a direct cost to health services of £3B. 4 More than 50% of patients experience at least two episodes of depression. 5 Moreover, without ongoing treatment, people suffering recurrent depression suffer relapse/recurrence at rates as high as 80%, even after successful acute treatment. 5,6 Thus, most of the prevalence, burden and cost of depression is a consequence of relapse/recurrence and the majority of the burden attributable to depression could be offset through interventions aimed at preventing depressive relapse/recurrence. 7

Current treatments for depression in primary care

Currently, the majority of depression is treated in primary care and treatment with maintenance antidepressant medication (m-ADM) is the mainstay approach to preventing relapse/recurrence. 8–11 To stay well the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that people with a history of recurrent depression continue m-ADM for at least 2 years. 8 However, many patients experience unpleasant side effects, rates of m-ADM adherence tend to be low and patients often express a preference for psychosocial interventions. 12–14 Service user organisations, such as Depression Alliance, therefore advocate greater availability of psychosocial therapies. Government advisors Layard and Clark4 recommend that there should be parity of esteem for mental and physical health. That is, today, evidence-based treatment should be as available for mental illness as for physical illness. They provide a compelling narrative that this would be a cost-effective approach to enhancing the mental health of the nation. In line with this, significant government initiatives, such as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, aim to offer accessible, acceptable and cost-effective psychosocial models of care and the last 10 years has seen significant progress in the accessibility of evidence-based mental health services in the UK. 4,15,16

Psychosocial approaches to prevent depressive relapse/recurrence

There is a strong evidence base for psychosocial treatments for recurrent depression, most notably cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy, and promising evidence for several other therapies. 8,17 Policy initiatives, user groups and professional consensus recommend as priorities for future research the development of psychosocial interventions to prevent depressive relapse/recurrence and the use of non-traditional delivery systems, such as group interventions, to maximise accessibility and cost-effectiveness. 18,19 Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is a psychosocial group-based relapse prevention programme. It was developed from translational research into mechanisms of depressive relapse/recurrence. 20 It is recommended by NICE as a psychological approach to relapse prevention for people who are currently well but who have experienced three or more previous episodes of depression. 8 There is much clinical enthusiasm for MBCT, as evidenced by the high rates of patient engagement, the development of MBCT therapist training programmes in the UK at the Universities of Bangor, Exeter and Oxford and more recently the development of an All Party Parliamentary Group on Mindfulness. 21 Implementation of MBCT throughout the NHS is patchy and variable but becoming more widespread. 22,23 In summary, MBCT shows the potential to contribute significantly to reducing the prevalence of depression in UK primary care settings.

Review of the evidence for mindfulness-based cognitive therapy up to the trial start date

Efficacy and effectiveness

The first two MBCT randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of patients with a history of recurrent depression, currently in remission and not receiving any active treatment, reported in 200024 and 2004. 25 Both found that MBCT plus usual care halved the rate of relapse/recurrence compared with usual care alone over 60 weeks of follow-up [hazard ratio (HR) 0.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.27 to 0.84;25 HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.6024]. In both trials patients were able to seek help as they normally would over the course of the study and rates of treatment update were comparable across both arms of the trial. However, to provide a robust test of the potential effectiveness of MBCT over usual care, both trials included only people not currently receiving antidepressant medication (ADM) at the time of study entry. Moreover, as a first test of MBCT, the comparison was usual care rather than another active treatment.

A systematic review published in 2007 that included these first two trials and two further replications in Europe showed a significant additive effect of MBCT over usual care for patients with recurrent depression, but only for patients who have experienced three or more previous episodes. 26 This is the same evidence that led to NICE’s guidance that MBCT be offered as a relapse prevention approach to patients with three or more episodes of depression.

Exploratory pilot trial

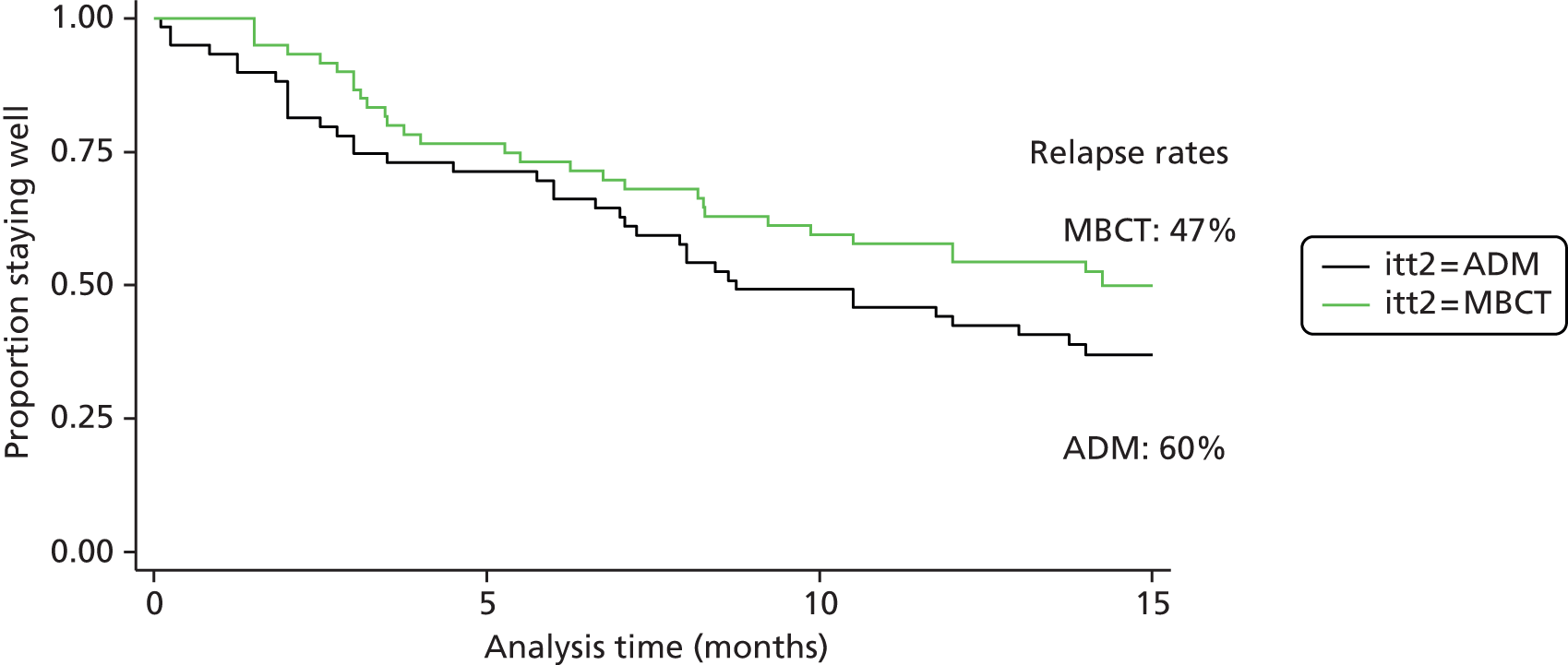

Through a Medical Research Council (MRC)-funded pilot trial27–29 we sought to address the gaps in the evidence base outlined in the previous section by comparing MBCT with the current mainstay approach to relapse prevention, m-ADM. In this pilot trial 123 patients who were currently taking m-ADM to manage recurrent depression were randomised to either continue m-ADM or take part in a MBCT course and then taper and discontinue their m-ADM. The findings suggested that MBCT may not only provide an alternative to m-ADM (relapse/recurrences at 15 months: MBCT 47%, m-ADM 60%), but also, in an adequately powered definitive trial, produce superior outcomes (Figure 1). 28 Finally, the study suggested that MBCT may also be superior to m-ADM in terms of improved quality of life, reduced residual depressive symptoms and reduced psychiatric comorbidity. The study’s stated aims and outcomes were:

-

Examine feasibility. The achievement of all study milestones within budget and on time demonstrated feasibility.

-

Establish recruitment methods. An acceptable and effective recruitment methodology was developed as evidenced by our over-recruitment by 54%.

-

Establish a training model for MBCT therapists. We developed a model of training with input from John Teasdale, one of the developers of MBCT.

-

Cost MBCT. The MBCT intervention was estimated to cost circa £200 per participant,28 which compares favourably with an estimated cost of £750 for individual CBT. 16

-

Elicit service user feedback. At the end of the pilot trial all participants were interviewed and asked about their experience of MBCT as a relapse prevention programme. 30 These studies informed the PREVENT study to maximise MBCT’s acceptability and application to supporting patients taper and discontinue their m-ADM.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve in the exploratory trial. Survival estimates by intention to treat.

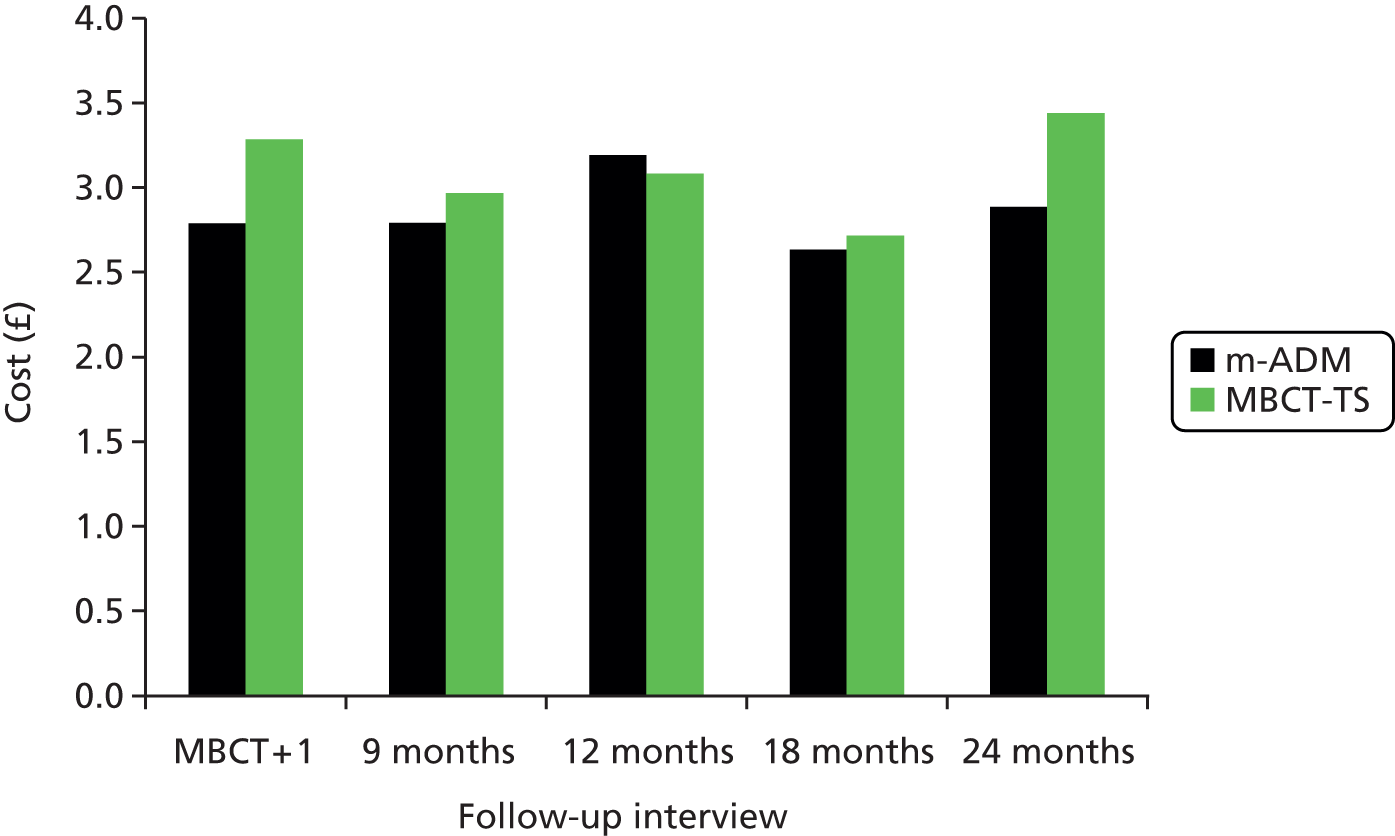

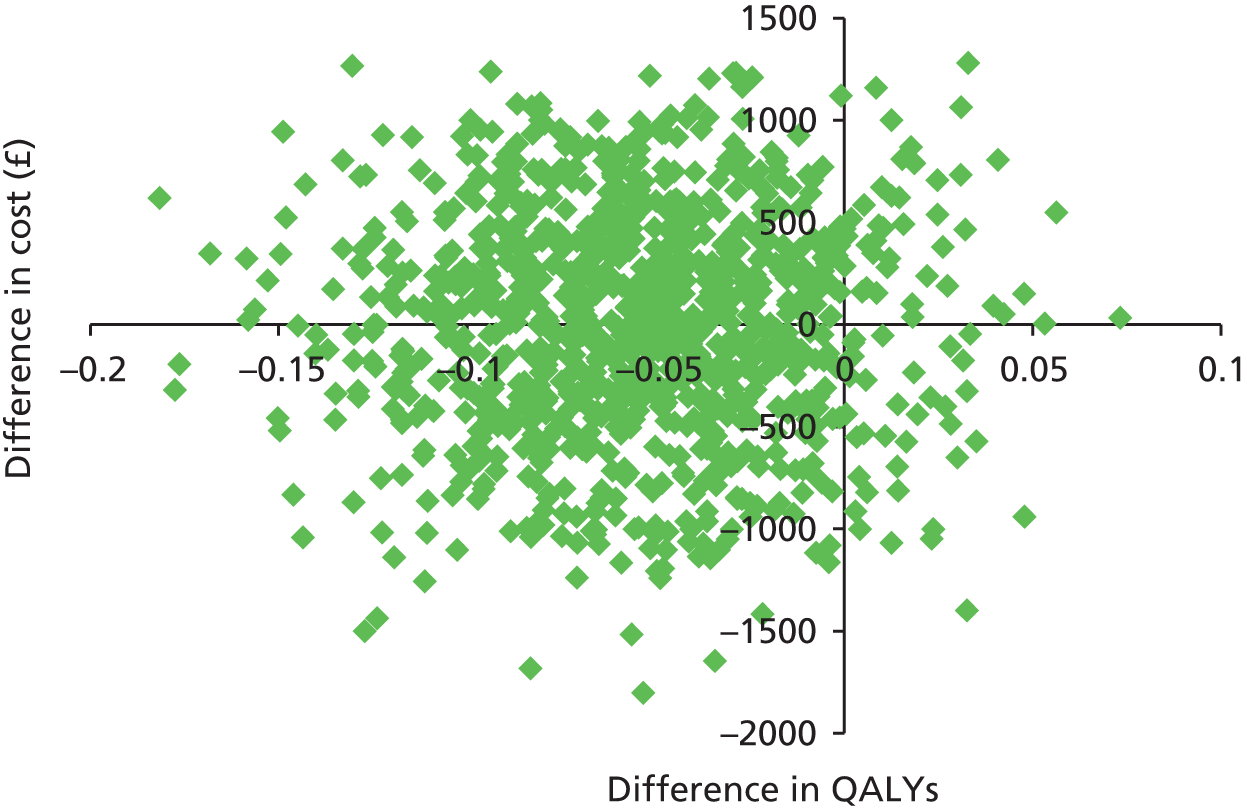

Costs and cost-effectiveness

To inform commissioning of care for people with recurrent depression we must establish MBCT’s cost-effectiveness over an adequate follow-up period. In our pilot trial28 we found that the per-person cost for the MBCT group was £274 more than that for the m-ADM group but this difference was not significant. Cost-effectiveness analyses suggested that the additional cost of MBCT may be justified in terms of improvement in the proportion of patients who undergo relapse/recurrence, but only if willingness to pay for such improvements is ≥ £600. In terms of depression-free days, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of MBCT is comparable with that in similar studies, with a ratio of £30 per depression-free day for total costs and £14 per depression-free day for health service costs. (Please note that these costs were reported in reference 28 in international dollars using a conversion rate of 0.6.) Recent ICERs for collaborative care programmes include £20 in terms of total outpatient costs31 and £12 in terms of total inpatient and outpatient costs. 32 Estimates of £8–14 have been reported for a depression relapse prevention programme. 33 Exploration of costs over time suggested that differences in cost converge and MBCT becomes cheaper than m-ADM over the final 3-month period of the study. If this trend were to continue, the relative cost-effectiveness of MBCT may increase over time. Future studies should consider longer follow-up periods to test this hypothesis.

Process studies to examine acceptability and mechanism of change

As with the cost-effectiveness of MBCT, the evidence for the mechanism of change in outcomes with MBCT therapy is limited. Coelho et al. 26 found no evidence of the ‘specific effectiveness of MBCT, despite this being the logical progression from the current research’ (p. 1004). In other words, no trials had shown whether MBCT works through its specific hypothesised mechanisms and/or through non-specific cognitive–behavioural, psychoeducation and group/therapist support components. They therefore recommended ‘the need for randomised controlled trials to compare MBCT with other non-pharmacological approaches’ (p. 1005) and the inclusion of tests of the specific and non-specific mechanisms of change.

Proposed mechanisms of action

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy’s theoretical premise is that depressive relapse/recurrence is associated with the reinstatement of negative modes of thinking and feeling that contribute to depressive relapse and recurrence. 34 This ‘reactivated’ network of negative thoughts and feelings can perpetuate into a depressive episode. Laboratory studies support this model by showing that recovered depressed patients revert to a depressive information processing style following a sad mood induction (for a review see Segal et al. 35). Following successful treatment for depression, those patients showing greater reactivation of dysfunctional thinking styles in response to a sad mood provocation are at the highest risk of relapse/recurrence over an 18-month period. 35 Moreover, patients who recovered with CBT showed significantly less cognitive reactivation than those who recovered with ADM. Attenuating the reactivation of dysfunctional thinking styles may therefore represent one mechanism by which CBT helps prevent depressive relapse/recurrence. Mindfulness skills are taught as a means to note distressing thoughts and feelings, hold such experiences in awareness and cultivate acceptance and self-compassion to break up associative networks and offset the risk of relapse/recurrence. 34 This dimension of mindfulness, which involves meeting distressing thoughts and feelings with kindness, empathy, equanimity and patience, is woven into mindfulness-based applications and is thought to be crucial to the change process. 36 Intentional attention is learned in the first three MBCT sessions using a range of core mindfulness practices (the body scan, mindful movement and mindfulness of the breath). As well as developing attention, these early sessions highlight habitual patterns of reactivity that arise during meditation (e.g. intrusive negative thoughts) and the associated aversion and judgements (e.g. ‘I am no good at this, I am just more aware of how badly I feel’). As the person learns mindfulness skills, he or she learns to give less authority to self-judgement and blame – the fuel for depressive thinking – and to respond to these states with compassion, in short to step out of habitual unhelpful patterns of thinking. 36 Elucidating these putative mechanisms of action of MBCT will improve theoretical understanding of how this relatively new treatment works and provide the opportunity to enhance efficacy through emphasis of these mechanisms.

Our previous mechanisms study, which was embedded in the pilot trial, demonstrated that, consistent with MBCT’s theoretical premise, increases in mindfulness and self-compassion across treatment mediated the effect of MBCT on depressive symptoms at 15 months’ follow-up. 37 Furthermore, MBCT changed the relationship between post-treatment cognitive reactivity and depressive outcome. In patients receiving m-ADM, greater reactivity predicted poorer outcome, replicating previous findings. 35 However, following MBCT there was no support for this toxic relationship between reactivity and outcome, with an indication that enhancement of self-compassion had nullified this relationship. These findings were consistent with an evidence synthesis arguing that MBCT works through a ‘retraining of awareness and non-reactivity, allowing the individual to more consciously choose those thoughts, emotions, and sensations, rather than habitually reacting to them’ (p. 569). 38 The results are also in line with data using a self-report measure of cognitive reactivity showing that MBCT attenuates reactivity and its impact on depression. 39 This is reflected in distinct neural responses to sad mood in people who had undergone MBCT, suggesting a neural basis for these findings. 40 The findings suggest that, whereas negative mood may reactivate dysfunctional thinking patterns in people who have participated in a MBCT class, it is their response to these dysfunctional thoughts that is altering their impact at follow-up.

Rationale for the research

In summary, the evidence for MBCT indicates that it is more effective than usual care in preventing depressive relapse/recurrence in people with a history of three or more episodes. Moreover, there is preliminary evidence from our pilot trial to indicate that it may be cost-effective and that it works through its hypothesised mechanism. An editorial published in 2012 in the British Medical Journal41 concluded that key remaining uncertainties include (1) whether or not MBCT provides an alternative for people wishing to discontinue m-ADM, (2) how acceptable MBCT is and (3) what mechanism MBCT works through.

Aims and objectives

The overarching policy aim and research question of the PREVENT trial was to establish whether MBCT with support to taper and/or discontinue antidepressant medication (MBCT-TS) is superior to and more cost-effective than an approach of m-ADM in a primary care setting for patients with a history of recurrent depression followed up over a 2-year period.

The specific objectives of the PREVENT trial were to compare MBCT-TS and m-ADM for patients with recurrent depression in terms of:

-

time to depressive relapse/recurrence over 2 years (primary outcome)

-

depression-free days, residual depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life at 1 month post treatment and 9, 12, 18 and 24 months post randomisation and psychiatric and medical comorbidity at 12 and 24 months post randomisation (secondary outcomes)

-

costs and cost-effectiveness as assessed by incremental cost per relapse/recurrence prevented and incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) at 1 month post treatment and 9, 12, 18 and 24 months post randomisation.

In addition, we asked whether or not an increase in mindfulness skills is the key mechanism of change of MBCT.

To address these policy and explanatory questions patients were recruited through primary care and treated in accessible primary care or community settings. This was a single-blind, parallel RCT examining MBCT-TS compared with m-ADM. The m-ADM was constant over the 2 years of the study and the psychosocial intervention was a front-loaded, 8-week relapse/recurrence prevention programme. Patients in the MBCT-TS arm received support to taper their ADM. The process studies employed mixed methods.

Chapter 2 Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with support to taper and/or discontinue antidepressant medication

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is an 8-week, group-based programme (12–15 participants per group) designed to teach skills that prevent the recurrence of depression. 20 It is derived from both mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), a programme with demonstrated efficacy in ameliorating distress in people suffering chronic disease,42 and CBT for acute depression,43 a programme with demonstrated efficacy in preventing depressive relapse/recurrence. 44 MBCT is based on theoretical and empirical work showing that depressive relapse/recurrence is associated with the reinstatement of automatic modes of thinking, feeling and behaving that are counterproductive in contributing to and maintaining depressive relapse and recurrence (e.g. self-critical thinking and behavioural avoidance). 45

Participants learn to recognise these ‘automatic pilot’ modes and respond to them in more functional ways by employing complementary cognitive–behavioural and mindfulness practices. This involves recognising early warning signs of depressive relapse/recurrence, being able to ‘turn towards’ them with kindly interest and decentring in ways that ‘nip them in the bud’. The cognitive–behavioural component involves responding to negative thinking and behavioural activation. In the latter stages of the course participants develop a ‘response/action plan’ that sets out strategies for responding when they become aware of early warning signs of relapse/recurrence. The mindfulness component involves extensive practice of mindfulness skills (e.g. meditation practices) designed to improve participants’ attentional control, ability to decentre from negative thinking and emotion regulation and increase self-compassion. There is a movement towards meeting difficulty with curiosity, a quality of allowing and self-compassion before deciding on skilful ways of responding. Participants are encouraged to bring these skills in to all aspects of their lives.

Adaptations made to the mindfulness-based cognitive therapy programme for the PREVENT trial

In the PREVENT trial delivery of MBCT followed the manual as described by Segal, Williams and Teasdale34 with a few adaptations based on (1) the need for therapists to support MBCT participants in tapering their ADM and (2) experience from the pilot trial. 28 Participants attended a one-to-one orientation session with the therapist followed by group sessions lasting 2.25 hours over 8 consecutive weeks. Session content included guided mindfulness practices (i.e. body scan, sitting meditation, movement); inquiry into participants’ experience of these practices; weekly review of home practice (i.e. 40 minutes of mindfulness practice per day with the guidance of a CD, bringing mindfulness into everyday life); and teaching of/dialogue around cognitive–behavioural skills. MBCT-TS patients also received an additional four group reunion sessions during the first year of follow-up to provide ongoing support and rehearse the key components of the interventions. The first of these booster sessions occurred within 3–5 weeks after the end of the 8-week MBCT-TS programme as this was the time when patients would be tapering their ADM and may be in most need of support. Such booster sessions significantly enhance relapse/recurrence prevention46 and were a match for general practitioner (GP) attention, which was part of ongoing clinical management in the m-ADM group. A list of the individual adaptations and when they were made is provided in Table 1.

| Rationale for adaptation | Adaptation | When it came into effect |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation for tapering of medication at session 6 by increasing understanding of relapse/recurrence and ways of taking action/responding at an earlier stage |

|

|

|

|

|

| Involving GPs in the participants’ response plan |

|

|

| Supporting participants around the early stages of tapering |

|

|

| Teaching about depression at an experiential level, allowing participants to track their process with awareness, to illustrate the potential for relapse/recurrence around a drop in mood and how mindfulness may offer the possibility of somewhere else to stand rather than being dragged down the spiral |

|

|

| Allowing more space for working with difficulty |

|

|

Chapter 3 Trial design and methods

Study design

The PREVENT trial was a two-arm, multicentre, single-blind superiority trial randomly allocating patients in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either MBCT-TS or m-ADM. The trial included a parallel economic evaluation to examine the cost-effectiveness of MBCT-TS compared with m-ADM and a mixed-methods process evaluation that used qualitative methods to assess the acceptability of MBCT-TS from the perspectives of patients and included a quantitative analysis of potential mediators.

Setting, participants and recruitment

We recruited participants from 95 general practices in urban and rural settings in four UK centres: Bristol, Exeter and East Devon, North and Mid Devon and South Devon. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient participation were refined through the pilot trial28 to maximise real-world applicability to the population of people in primary care with recurrent depression who are treated with ADM and who are interested in considering a psychological approach to relapse/recurrence prevention. They are also based on our experience of running a Devon NHS Primary Care Trust-commissioned depression service (see www.centres.ex.ac.uk/mood/).

Inclusion criteria

Participants were considered for inclusion if they:

-

had a diagnosis of recurrent major depressive disorder in full or partial remission according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)47

-

had had three or more previous major depressive episodes in which depression was the primary disorder and it was not secondary to substance abuse, bereavement or a general medical condition

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

were on a therapeutic dose of ADM in line with the British National Formulary (BNF)48 and NICE guidance8

-

were open either to continue taking antidepressants for 2 years or to take part in a MBCT class and consider stopping their ADM.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were considered unsuitable for inclusion if they:

-

were currently depressed, as assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)47

-

had a comorbid diagnosis of current substance abuse (patients with previous substance abuse were eligible for inclusion as long as they were in sustained full remission)

-

had organic brain damage

-

had current/past psychosis, including bipolar disorder

-

displayed persistent antisocial behaviour

-

engaged in persistent self-injury that required clinical management/therapy

-

were undergoing formal concurrent psychotherapy.

Recruitment procedure

The recruitment strategy for the PREVENT trial built on the protocol used in the pilot trial, which proved acceptable and effective. 29 This is summarised in the following pathway:

-

General practice searches identified patients who had been prescribed ADM at a therapeutic dose in the last 3 months.

-

GPs were then asked to screen this list to exclude any patients who they knew met the exclusion criteria.

-

Letters were sent to the remaining patients enclosing an information pamphlet and reply form.

-

Interested patients were telephoned to discuss the study and a short eligibility screening interview was conducted over the telephone. Information about the study and MBCT was available to help people to begin to make an informed decision about participation. This included the timings and locations of the MBCT groups. The vast majority of exclusions were identified at this stage.

-

Patients who met the telephone screening criteria were invited to attend a face-to-face baseline interview.

-

Consenting patients who met the PREVENT inclusion criteria joined the trial during the baseline assessment.

-

Within a month of the start of the next MBCT-TS group a current GRID-Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (GRID-HAMD)49 score was obtained for each participant so that randomisation could occur.

Although the majority of referrals were through GP surgeries, interested patients were also able to self-refer into the study. We employed a number of different strategies to advertise the trial including placing posters in carefully targeted sites, developing a website, regional media coverage and leaflet dropping in local chemists.

Patients were recruited in cohorts during recruitment ‘time slices’ that corresponded to the 6–8 weeks before the next MBCT-TS group was due to start. Baseline assessments were conducted as close as possible to the start of the MBCT-TS group as residual depressive symptoms are a powerful predictor of relapse/recurrence. 50 On average, each researcher recruited six patients per month (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Summary of the PREVENT recruitment process and follow-up assessments. BDI-ll, Beck Depression Inventory, second edition; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; MSCL, Medical Symptom Checklist; WHOQOL, WHO Quality of Life.

Randomisation and concealment

Patients were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to either MBCT-TS or m-ADM using computer-generated random permuted blocks and stratified by recruitment locality (four sites) and symptomatic status (asymptomatic: GRID-HAMD score < 8 vs. partially symptomatic: GRID-HAMD score ≥ 8). Stratification by locality enabled a proportionate workload for research staff and therapists. Residual depressive symptoms are a powerful predictor of relapse/recurrence. 50 Moreover, the pilot trial suggested the importance of this stratification variable in predicting outcome. 27 To ensure concealment randomisation was conducted using a password-protected trial website that was maintained by the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC)-accredited CTU. Participants were informed of the outcome of randomisation in a letter sent from the trial administrator. Research assessors were blind to treatment allocation; in cases in which blindness was broken participants were assigned to another research assessor. The fidelity of this masking was moderate, with assessors correctly guessing allocation for 56% of assessments. Given the nature of the interventions, patients and clinicians were aware of treatment allocation.

Patients were randomised in the month before the next MBCT-TS group began. If a participant’s baseline assessment occurred more than a month before the next MBCT-TS group began he or she received a brief ‘randomisation assessment’ before being randomised. During this assessment the patient was asked to give a verbal reaffirmation of his or her wish to take part in the trial and researchers ensured that the patient’s situation had not changed significantly and also obtained a current GRID-HAMD score.

Health technologies assessed

Maintenance antidepressants

The m-ADM relapse/recurrence prevention intervention consisted of maintenance of the ADM treatment that was an inclusion criterion for the trial. Participants were monitored and treated by their physician in a primary care setting. During the maintenance phase, physicians were asked to manage m-ADM in line with standard clinical practice and the BNF. Primary care physicians were asked to meet with patients regularly to review their medication. Changes in medication sometimes occurred during the maintenance treatment stage but physicians and participants were asked to ensure that the dose remained within therapeutic limits. The trial GPs (Dr Richard Byng and Dr David Kessler) and trial psychiatrist (Professor Glyn Lewis) provided materials for all participants and participating GPs on m-ADM and ongoing support as required.

We encouraged participants to adhere to medication for the full length of the trial by sending them letters signed by the chief investigator and their GP after each follow-up, reminding them that the trial was seeking to compare staying on antidepressants for 2 years with taking part in mindfulness classes and stopping ADM. If difficulties with continuation of medication were identified, the trial manager first contacted the participant to understand the difficulty and then whenever appropriate encouraged the participant together with his or her GP to consider maintaining m-ADM in line with standard clinical practice and the BNF. Patients in the m-ADM arm who did not maintain m-ADM in line with BNF and NICE guidelines still remained in the trial and follow-up data were collected as per those who did maintain m-ADM in line with guidelines.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with support to taper and/or discontinue antidepressant medication

A total of 21 MBCT-TS groups were delivered by four therapists in a variety of settings including university campuses, hospital sites and other community-based rooms. Two of the therapists ran seven groups, one ran five and one ran two groups. Two of the groups ran in the evening and the rest were held during the day from Monday to Friday. There were between 4 and 14 participants in each group with an average of 10 per group [standard deviation (SD) 2.6 per group]. The treatment programme involved eight 2.25-hour group sessions, normally over consecutive weeks, with up to four refresher sessions offered in the year following the end of the 8-week programme. In line with previous MBCT trials,24,28,51 an adequate dose of MBCT-TS was defined as participation in at least four of the eight MBCT-TS group sessions. If participants did not receive an adequate dose of MBCT-TS they were not asked to taper/discontinue their m-ADM; however, outcome data were still collected as per those who did receive an adequate dose.

The four MBCT therapists were all mental health professionals (two clinical psychologists and two occupational therapists). They had post-qualification experience ranging from 9 to 30 years, with an average of 19 years (SD 8.9 years). All had extensive training and experience in leading MBCT groups (minimum 4 years) and a long-standing ongoing personal mindfulness practice (minimum 7 years). An independent check on therapist competency was established before therapists progressed to running trial groups. An experienced MBCT therapist independent of the trial rated at least two videotapes of MBCT-TS therapy sessions and, using the Mindfulness-Based Interventions – Teacher Assessment Criteria (MBI-TAC),52 made an overall judgement about whether the therapists were competent. During the trial, all four therapists received supervision every 2 weeks for 3 hours; this was attended once per month by the chief investigator.

All trial groups were videotaped with a digital camera for therapist supervision and checks on therapist competence and adherence. Randomly selected samples of two sessions for each 8-week course (42 sessions in total) were assessed by a MBCT expert independent of the trial team. As for the initial competency checks the MBI-TAC was used and these checks indicated that the MBCT teaching was at and above required levels (Table 2). The mean total adherence score in the trial (23.6, SD 4.30) was at least comparable with those reported in the psychometric evaluation of this scale53 and indicate acceptable adherence to protocol. There were no significant differences between therapists’ total adherence scores as determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (F3,37 = 0.64; p = 0.59).

| MBI-TAC domains | Count (and percentage) for each rating across 42 tapes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incompetent | Beginner | Advanced beginner | Competent | Proficient | Advanced | |

| Coverage, pacing and organisation of the session curriculum | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 5 (11.9) | 14 (33.3) | 22 (52.4) |

| Relational skills | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 8 (19.0) | 10 (23.8) | 23 (54.8) |

| Embodimenta | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 8 (19.5) | 13 (31.7) | 19 (46.3) |

| Guiding mindfulness practices | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (7.1) | 1 (2.4) | 15 (35.7) | 23 (54.8) |

| Conveying course themes through interactive inquiry and didactic teaching | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.8) | 7 (16.7) | 15 (35.7) | 18 (42.9) |

| Facilitation of the group learning environment | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.8) | 12 (28.6) | 11 (26.2) | 17 (40.5) |

Participants in the MBCT-TS arm were encouraged to taper and discontinue their m-ADM and the study team provided guideline information to physicians and participants about typical tapering/discontinuation regimes and possible withdrawal effects; however, the actual timeline and regime used were determined by physicians and participants. The original MBCT manual34 was adapted to include more work on developing a relapse/recurrence signature and response plan that explicitly included participants considering reduction/discontinuation of m-ADM. Participants in the MBCT-TS arm who experienced a significant deterioration following tapering were encouraged to use the skills developed as part of the treatment. Letters signed by the chief investigator and trial GP were sent to each participant’s GP, copied to the participant, prompting the GP to have a discussion with the participant about a suitable tapering/discontinuation regime after 4–5 weeks of the MBCT-TS group. At the end of the MBCT-TS group another letter was sent reminding the GP to ensure that a tapering/discontinuation regime was in place. We also encouraged participants to taper/discontinue their medication by writing to them and their GP after each follow-up reminding them that the trial was seeking to compare staying on antidepressants with taking part in mindfulness classes and stopping ADM.

If at any time the study team became aware of difficulties with medication tapering/discontinuation, the trial manager first contacted the participant to understand the difficulty and then whenever appropriate encouraged the participant together with his or her GP to once more consider tapering/discontinuing m-ADM. Participants in the MBCT-TS arm who did not taper or discontinue their m-ADM still remained in the trial and follow-up data were collected as per those who did discontinue.

If participants experienced a relapse/recurrence during the course of the trial we encouraged them to discuss the most appropriate treatment with their GP and made no further requests that they consider tapering/discontinuing their medication. However, participants who had relapsed still remained in the trial and further secondary outcome data were collected on the same schedule as per participants who had not relapsed.

Data collection

Baseline assessments did not occur more than 3 months from the start of the next MBCT-TS group, with the start defined as the first orientation session. Following randomisation, participants were assessed at five time points: 1 month after the end of the 8-week MBCT-TS programme (or the equivalent time in the m-ADM arm), which varied between 12 and 24 weeks post randomisation, and 9, 12, 18 and 24 months post randomisation.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The occurrence of any depressive relapse/recurrence, and time from randomisation to relapse/recurrence, were assessed using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE),54 a form of the SCID47 designed for longitudinal studies of depression. A participant was judged to have had a relapse/recurrence if he or she was diagnosed as having a major depressive episode (a score of 5 for 2 consecutive weeks) at any time during the 24-month follow-up period. In conducting the SCID-LIFE interviews, researchers took care to establish the onset of the relapse/recurrence as closely as possible. If the day could not be established they tried to establish the closest week and take the mid-point of that week; if the week could not be established then the closest month or season was established and the mid-point taken.

An experienced clinical psychologist with formal training in the use of the SCID supervised the training of the research staff. To examine inter-rater reliability, we followed the method described in the first MBCT RCT,24 which had the added benefit of guaranteeing that all assessments were carried out blind to treatment condition. For every first actual, borderline or probable relapse/recurrence, a blinded and experienced rater second rated an audio recording of the SCID interview. In total, 198 recordings were second rated, with agreement being recorded on 89.9% of the recordings. The kappa coefficient for agreement between the study interviewer and the blinded rater was 0.62, suggesting good agreement. When there were disagreements between the first and second rater, consensus was reached through discussion. If a relapse/recurrence was considered marginal, a conservative position of no relapse was recorded. Once a judgement about relapse/recurrence was made, the onset of relapse/recurrence was dated from randomisation to the point at which criteria were met.

A subset of 112 SCID diagnoses were also second rated by an experienced rater who was independent of the trial and agreement was recorded on 95.5% of these diagnosis. The kappa coefficient for these ratings was 0.89, suggesting excellent agreement.

Secondary outcomes

Depression-free days were calculated using the SCID interview and residual depressive symptoms were assessed with the observer-rated interviewer-administered 17-item GRID-HAMD49 and a well-established self-report measure, the Beck Depression Inventory, second edition (BDI-II). 55 Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed with the full SCID,47 medical comorbidities were assessed at baseline, 12 and 24 months using the MSCL56 and health-related quality of life status was assessed using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)57,58 and the WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF). 59,60

Depression-free days

Depression-free days were calculated from the SCID by first establishing the duration in days of any episodes of depression throughout the follow-up period using the method described earlier. Care was taken to establish the last day of a relapse/recurrence or recurrence of clinically significant symptoms. As before, if the day could not be established then the mid-point of the shortest time period that could be established was used. Each new reported recurrence of depression required that there was a period of 2 months in which remission from the previous episode had been achieved. If there was no remission between two recorded episodes the second episode was regarded as a continuation of the first.

Residual depressive symptoms

The GRID-HAMD is a 17-item modified version of the popular depression rating scale developed by Hamilton in 1960. 61 This scale is an interviewer-administered measure of depressive symptoms with an emphasis on somatic symptoms. Scores range from 0 to 88, with higher scores representing higher levels of depression. The GRID-HAMD was designed to permit the rater to consider the dimensions of intensity and frequency independently for each relevant item in the scale. Symptom intensity is considered on the ‘vertical axis’ and symptom frequency on the ‘horizontal axis’. Symptom intensity, which includes degree of symptom magnitude as well as subjective distress and functional impairment, is rated as absent, mild, moderate, severe or very severe. Symptom frequency is rated as absent, occasional, much of the time or almost all of the time. The GRID-HAMD was administered at every assessment during the 24-month follow-up period.

The vast majority of depression trials fail to measure or report the reliability of their employed instruments, especially secondary outcome measures such as the GRID-HAMD. In the rare circumstances in which reliability is measured, it is carried out in an arbitrary and atheoretical manner. As such, and for the purposes of this trial, we compared the inter-rater reliability of the GRID-HAMD using a subsample of 20 assessments. This sample size was selected in accordance with the method of Walter et al. 62 for calculating the sample size for inter-rater reliability analyses. Walter et al. 62 estimated that a sample size of about 18–20 observations made between two raters is sufficient to obtain an expected intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.9, with a minimum acceptable ICC of 0.7. Further, there is evidence which suggests that the reliability of the GRID-HAMD ratings is dependent on the assessor’s experience. 63 Thus, 10 of the 20 observations were randomly selected from assessments completed by an experienced assessor and 10 were selected from assessments completed by a more novice assessor. All 20 assessments from both researchers were obtained from the 18-month follow-up period. The overall ICC for the 20 observations was 0.98, suggesting excellent agreement. The ICC for the 10 assessments completed by the experienced assessor was 0.99, while the ICC for the remaining 10 assessments completed by the novice assessor was 0.86, both suggesting excellent agreement.

The BDI-II55 is a 21-item self-report instrument developed to measure the severity of depression with an emphasis on affective and cognitive symptoms. Higher scores represent greater depression severity (range 0–63) and minimal (0–13), mild (14–19), moderate (20–28) and severe (29–63) symptom severity ranges have been specified. The BDI-II was administered at every assessment during the 24-month follow-up period.

Medical and psychiatric comorbidities

We used the MSCL and the SCID relevant modules at baseline and 12 and 24 months’ follow-up. The MSCL is a list of 115 common medical symptoms and respondents are asked to indicate those that they have experienced as bothersome in the past month. 56 The score is the total number of symptoms checked. Although the reliability and validity of the MSCL have not been evaluated, several studies of MBSR have shown significant reductions in the MSCL score associated with participation in the programme. 64–67

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life status was assessed using the EQ-5D-3L,57,58 a non-disease-specific measure for describing and valuing health-related quality of life. It has particular value as a measure because it is capable of generating a generic preference-based measure of outcome (the QALY) that allows for outcomes and cost-effectiveness to be compared across disease areas. 68,69 The measure includes a rating of own health in several domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) and a rating of own health by means of a ‘thermometer’ (score 0–100). It has been used extensively and thus has large comparative data sets and its psychometric properties are adequate. 57 The EQ-5D-3L was administered at every assessment during the 24-month follow-up period.

Quality of life was assessed using the WHOQOL-BREF,59,60 a generic 26-item measure covering the domains of physical health, psychological health, social relationships and environment. It differs from the EQ-5D-3L in providing a more subjective and holistic assessment of quality of life, rather than a self-report measure of health status. The WHOQOL-BREF is based on a longer version of the original instrument, the WHOQOL-100. 70,71 The WHOQOL-BREF was administered at every assessment during the 24-month follow-up period.

Adverse events

We followed the guidelines laid down by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for identifying, acting on and reporting adverse events, which were defined as any event that resulted in death, was life-threatening, required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity or consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect.

As soon as a researcher became aware of an adverse event they reported this to the trial manager, who then completed a serious adverse event form (see Appendix 1). Copies of these forms were sent to the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), the main NHS Research Ethics Committee and the trial sponsor. No adverse reactions were judged by these committees to be suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions or SUSARs.

Sample size

Different relapse prevention interventions with different populations produce different absolute rates of depressive relapse/recurrence. Therefore, we based our sample size on estimated HRs for MBCT-TS compared with m-ADM rather than estimated absolute relapse/recurrence rates. We canvassed service users and clinicians who concurred that a relative reduction in relapse/recurrence of 10% would be clinically important. We used the systematic review of MBCT compared with usual care for patients with recurrent depression that reported HRs of 0.28–0.47 for relapse/recurrence. 26 We applied several conservative assumptions (first row of Table 3). First, even though the pilot trial data suggest that the HR was improving in favour of MBCT as the length of follow-up increased,28 we assumed a HR of 0.63 at 15 months to power the trial at 24-months’ follow-up. Second, even though attrition from MBCT trials to date is consistently < 15%, we assumed an attrition rate of 20% over the 24 months of follow-up. Finally, in spite of evidence to the contrary, we assumed that there may be a small clustering effect (ICC = 0.01). The resultant sample size calculation assumptions and outputs are shown in Table 3, based on 90% power and significance set at 0.05. This led to a total sample size of 420 across the two groups.

| Study | Comparison | Mean HR | ICC | Design factor | Attrition rate | Sample size per groupa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative scenario | MBCT vs. m-ADM | 0.63 | 0.01 | 1.11 | 20% | 210 |

| Kuyken et al.28 | MBCT vs. m-ADM | 0.63 | –0.02 | 1.0 | 7%b | 160 |

| Ma and Teasdale25 | MBCT vs. usual care | 0.28 | –0.008 | 1.0 | 3%c | 14d |

| Teasdale et al.24 | MBCT vs. usual care | 0.47 | –0.04 | 1.0 | 5%c | 41d |

For the secondary outcomes, meta-analyses of generic mindfulness approaches suggest medium effect sizes in terms of changes in depressive symptoms72,73 and our pilot trial suggested medium effect sizes for the secondary outcomes of residual depressive symptoms, psychiatric comorbidity and quality of life. 28 The sample size estimate for our policy question enabled us to detect a medium between-groups effect size (standardised mean difference or Cohen’s d = 0.40) for the main secondary outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH-9) statistical guidelines for clinical trials74 and updated Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for trials. 75,76 All statistical analyses were undertaken in Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) following a predefined analysis plan agreed with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Baseline equivalence was assessed descriptively by comparing the summary baseline characteristics and outcome values in both groups (MBCT-TS and m-ADM). Although there was a difference in gender between groups (see Table 8), as we know of no strong evidence that gender moderates MBCT treatment outcomes28 it was decided not to include and adjust for this variable in statistical models.

The primary analysis model for all primary and secondary outcomes was conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, that is, between-group comparison based on the random allocation of patients and using complete data sets. All models adjusted for the stratification variables (centre and severity of depression). For the primary outcome the primary analysis included all patients and censored for missing data at 24 months’ follow-up. To examine the sensitivity of the results to missing data, secondary outcomes models were also run following multiple imputation (using the ‘ICE’ and ‘MIM’ Stata commands and 10 imputation cycles) and based on the assumption that data were missing at random.

The primary outcome (time to relapse/recurrence) was analysed using a Cox regression proportional hazards model including treatment condition (MBCT-TS/m-ADM). We assessed the proportionality of hazards over time by plotting −ln[−ln(survival)] against ln(analysis time) and tested this using Schoenfeld residuals. 23,24 We found no major violations of the proportional hazards assumption. Secondary outcomes were compared using hierarchical repeated measures regression models adjusting for outcome at baseline.

To explore potential treatment moderator effects, interaction terms were included in the Cox regression model for the primary outcome at 24 months for three predefined subgroups: the two stratification variables (centre and severity of depression) and participants in two groups characterised by how abusive their childhood had been. Participants with a more abusive childhood reported experiencing childhood physical or sexual abuse and/or scored above the median score for the Measure of Parenting Scale (MOPS)77 abuse subscale. Participants completed the MOPS at baseline as part of an embedded process–outcome study. 78 The abuse subscale asks participants to indicate how true they felt certain statements about their parents’ behaviour was, for example ‘parent was physically violent or abusive to me’, ‘parent made me feel unsafe’. Participants were categorised either in the lower abusive childhood group (i.e. scored below the median score for the MOPS abuse subscale and did not report childhood physical or sexual abuse) or in the higher abusive childhood group (i.e. scored above the median score for the MOPS abuse subscale or did report childhood physical or sexual abuse).

Given the variable levels of patient adherence to the stated treatment protocol in both the ADM-m and the MBCT-TC groups, we sought to undertake predefined secondary (per-protocol) analyses to examine the potential impact on the primary outcome at 24 months. We first described adherence in the PREVENT trial according to the principles set out by Dodd et al. 79 in their systematic review exploring adherence reporting in RCTs by reporting the rates of adherence in the format displayed in Box 1.

-

The number of participants who remained on a BNF therapeutically stable dose for the duration of the trial.

-

The number of participants who did not remain on a BNF therapeutically stable dose for the duration of the trial.

-

The number of participants who did not initiate MBCT-TS treatment.

-

The number of participants who initiated MBCT-TS treatment.

-

The mean, mode and SD of number of MBCT-TS sessions (0–8) and follow-up sessions attended (0–4).

-

The number of participants who completed MBCT-TS treatment.

-

The number of participants who made no reduction to their ADM dose.

-

The number of participants who reduced their ADM dose.

-

The number of participants who discontinued their ADM.

We then undertook two secondary analyses of the primary outcome comparing groups according to whether participants had (1) received an adequate dose of treatment and (2) adhered to treatment as invited. Definitions of these groups are displayed in Table 4.

| Group | Adequate dose of treatment | Adhering to treatment as invited |

|---|---|---|

| m-ADM | BNF therapeutic dose of ADM throughout follow-up period | BNF therapeutic dose of ADM throughout follow-up period |

| MBCT-TS | Attended four or more classes | Discontinued or reduced ADM and attended four or more classes |

Data management

Missingness within an outcome measure

Data entry and cleaning were overseen by the trial manager and research staff checked each outcome measure for missing data during every assessment and when possible collected missing items at this point. In cases in which ambiguous data were not clarified with the participant we operated a ‘score down policy’, meaning that if two items were checked the item with the lower rating was entered. When < 10% of the total or subtotal items for one outcome were missing, the mean as an integer of the missing items subscale was imputed in place of the missing value. If > 10% of the total was missing then the whole questionnaire was recorded as missing and, if > 10% of any one subtotal was missing, the whole of that subtotal was marked as missing.

Missing assessments

When substantive missing values arose, analyses was undertaken to assess their impact on the findings of the trial. Missing data were assumed to be ‘missing at random’,80 regression-based models were used to assess the relationship between covariates and outcome measure in completers and missing cases were substituted with a predicted outcome value. 81 A sensitivity analysis (with and without imputed data) was undertaken to assess the potential impact of imputation on the trial findings.

Ethical approval and research governance

Multicentre ethical approval for the study was given by the South West Research Ethics Committee (reference number 09/H0206/43) and local research governance approval was obtained for all sites (NHS Devon covering Exeter and Mid and North Devon – PCT0739; NHS Bristol, covering the Bristol site – 2010–004; NHS Plymouth and NHS Torbay, covering the South Devon site – PLY-TOR001). The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register with the reference number ISRCTN26666654. This trial was classed as a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP) as the MBCT-TS arm randomised patients to alter their standard ADM and as such approval to commence the trial was received from the MHRA (EudraCT number 2009–012428–10). A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is given in Table 5.

| Change to protocol | Date |

|---|---|

| Case note screening not undertaken by research staff and subsequent changes to the patient information sheet | December 2009 |

| Replacement of the follow-up measure SHAP with the DPES | December 2009 |

| Pilot of 3-month follow-up measures on formally depressed individuals who will not be taking part in the main trial | December 2009 |

| Ask pharmacists to insert a short flyer about the trial when dispensing ADM | December 2009 |

| Reimburse reasonable costs incurred when attending MBCT-TS groups for participants who would otherwise be unable to join the trial | July 2010 |

| Pilot qualitative feedback booklets with former NHS patients who have taken part in a previous MBCT group | July 2010 |

| Addition of the FFMQ, SCS, DPES, CERQ and DSC at the 24 months’ follow-up | April 2012 |

| Addition of two follow-ups at 36 and 48 months following an invitation from the National Institute for Health Research HTA programme to submit a bid; however, we were unsuccessful in obtaining the funding and therefore these additional follow-ups did not take place | April 2012 |

| Collaboration with the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) to give all participants an exit questionnaire at their final follow-up exploring the reasons why they chose to take part in the research | June 2012 |

| Change of principal investigator at the Bristol site because of a move to University College London (Dr David Kessler replaced Professor Glyn Lewis) | June 2012 |

| Permission to ask for consent to conduct further analysis on participants’ previously provided DNA sample | August 2013 |

The University of Exeter sponsored the trial, which was hosted in the Mood Disorders Centre [see www.centres.ex.ac.uk/mood/ (accessed 16 March 2015)], a clinical research setting specialising in translational research hosting current MRC-, Wellcome Trust-, National Institute of Mental Health- and National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-funded trials. The trial was overseen by the independent TSC (Chris Leach – Chairperson, Richard Moore and Glenys Parry) and the DMC (Paul Ewings – Chairperson, Andy Field and Joanne MacKenzie).

Informed consent

Our recruitment process gave patients several points at which they could learn about the project, either from reading the patient summary pamphlet and information sheet or through discussion with their GP, research staff or others. Consent was finally given through an interview with a researcher following an opportunity for questions. Research staff were trained and all interviews were recorded and supervised.

Participant welfare

Patients’ GPs approved their participation in the trial and were informed about the outcome of randomisation. The trial psychiatrist (Glyn Lewis) and GPs (Richard Byng and David Kessler) were on hand to offer participants’ GPs further information about the trial and to support GPs in their management of participants’ ADM. At the end of the MBCT-TS group, trial staff wrote to GPs to remind them that ADM tapering should normally have started and to ask them to be mindful of the possibility of relapse/recurrence. Over the follow-up period the MBCT-TS patients were invited to attend reunion sessions every 3 months and the therapists remained available by telephone throughout this period. If symptom exacerbation occurred without a full relapse/recurrence, initial management was encouraged to be within the appropriate treatment arm; however, if either patient preference and/or clinical judgement indicated other interventions, these were pursued.

Confidentiality

All of the information collected was kept strictly confidential and held in accordance with the principles of the Data Protection Act 1998. 82 Each participant was assigned a research number and all data were stored without subject identification. Data were held on a secure database on a password-protected computer at the University of Exeter. Access to data was and continues to be restricted to the research team. To enable follow-up contacts it was necessary to identify patients, but access to contact details (e.g. name and address) was restricted to the key members of the research team who arranged appointments. Any information about patients obtained (with their consent) from their medical records was recorded against their research number. Interviews audiotaped as part of the qualitative study (using a digital voice recorder) were transcribed verbatim and stored securely. Recordings of MBCT-TS sessions were stored securely (indexed by research number only) on a password-protected computer at the University of Exeter.

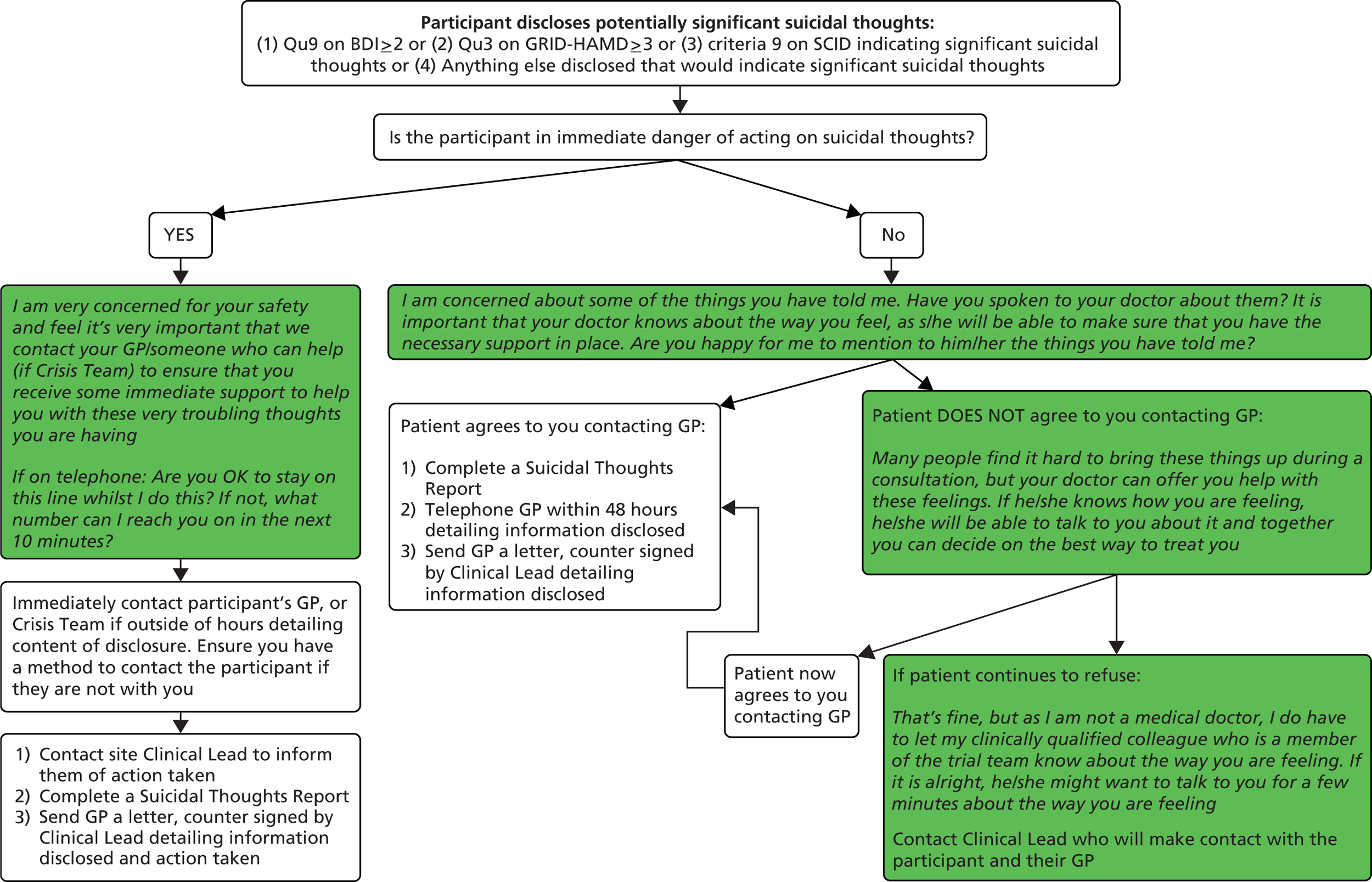

Disclosure of suicidal thoughts protocol

As the participants in this study have depression, it was appropriate to have a policy in place should any participant disclose suicidal thoughts to a research officer. Research officers assessed participants’ depression status at the study’s intake assessment and at each follow-up, which included questions about suicidal thoughts and plans. If a participant disclosed any suicidal thoughts the research officer followed the TSC-approved suicidal thoughts protocol and completed a suicidal thoughts report (see Appendix 1), which was countersigned by the site clinical lead. The information in this report was forwarded to the participant’s GP to better inform his or her clinical management. The patient information sheet informed the participant that if we were very concerned about his or her safety, or someone else’s safety, we would need to break confidentiality.

Unexpected serious adverse events

We followed the guidelines laid down by the MHRA for identifying, acting on and reporting adverse events [see www.mhra.gov.uk/Howweregulate/Medicines/Licensingofmedicines/Clinicaltrials/Safetyreporting-SUSARSandASRs/index.htm (accessed 16 March 2015)]. We adopted its definitions of adverse events and serious adverse reactions, reporting a total of 10 serious adverse events, none of which were classified as SUSARs by the TSC or the DMC.

Patient and public involvement

The PREVENT trial has benefited from the expertise of many people with lived experience of mental health difficulties including members of a locally organised voluntary group called the Lived Experience Group (LEG). The LEG has assisted the PREVENT trial at every stage of its development and the following sections detail a few examples of the ways in which the PREVENT trial has been shaped by patient and public involvement.

Protocol development

Patient and public involvement was sought in the development of the initial study protocol when developing the proposal and in the finalisation of the protocol prior to starting the trial through co-authorship (Rev. Paul Lanham).

Risk training

We sought the advice of the LEG both on the processes contained in the disclosure of suicidal thoughts protocol and in training and supporting our research team to activate this protocol. This training was particularly valuable as many of our team were anxious about discussing suicidal thoughts and did not feel confident in their ability to explore such thoughts with participants and GPs. The training gave researchers the chance to role-play these discussions, with advice and reassurance from the LEG.

Seeking consent

A member of the LEG provided specific training to our research staff to ensure that the consenting process was coherent and transparent.

Patient information

Given the variability of people’s experiences and the importance of the patient information sheet, we asked a number of different members of the LEG to review the early drafts and combined the suggestions into our final version.

Management and governance of the trial

Sitting on both our Trial Management Group and our TSC is the previous Chairperson of the Board of Trustees for the charity Depression Alliance, the Rev. Paul Lanham. Rev. Lanham has a lifetime history of living with mental health difficulties and his involvement has been key in helping to ensure that the trial is asking questions that are relevant and valid.

Qualitative interviews and feedback

A large component of our trial was asking the research participants about their experiences of the therapies offered (see Chapter 7). We did this predominantly by asking all participants to complete an eight-page feedback booklet and also by conducting in-depth interviews with a subset of participants. Both the feedback booklet and the interview questions were reviewed and then trialled by several members of the LEG, who suggested a number of fundamental changes. The benefit of these changes became apparent as we began the process of analysis and could see the richness of the data that were emerging.

Dissemination of results

It was very important to us that we disseminate the results of our trial to the participants who took part and that this was carried out in the most sensitive and accessible way possible. We organised three separate events across the recruitment sites to disseminate the results of our trial to participants and consulted with a PREVENT trial participant who had since joined the LEG about the format and content of these events. This participant co-organised and chaired the largest of the events.

Chapter 4 Trial results

Participant flow

During the 19 months of recruitment, between 23 March 2010 and 21 October 2011, we identified 28,597 patients from GP practice searches. GPs excluded 8989 patients as unsuitable and invitation letters were sent to the remaining 19,608 patients. Although we asked all GPs to provide reasons for excluding patients, in 56% of cases this information was missing. For the remaining exclusions the most common reasons given were dementia (2%), psychosis (2%) and substance abuse (1%). In total, 3060 patients responded positively to our invitation and a further 89 patients self-referred. Full telephone screens were completed for 2188 patients, which resulted in 498 patients attending for a baseline assessment, of whom 424 patients were randomised. The most common reasons why patients were not eligible for the PREVENT trial were that they had recently stopped taking ADMs or wanted to reduce them (30%), they had not had three previous episodes of depression (19%) or they were currently depressed (17%). The reasons given for not wishing to take part in the PREVENT trial are explored in Chapter 7. Primary outcome data were collected for 90.3% (383/424) of participants and the remaining participants’ data were censored at their last assessment. We retained 86.3% (366/424) of participants over the 24-month follow-up period, with 4.7% (20/424) lost to contact, 8.0% (34/424) withdrawing consent for further follow-up and 0.9% (4/424) dying during the trial; the pattern of missing data was similar across interventions. The flow of participants through the trial is depicted in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow chart illustrating the flow of participants into the PREVENT trial.

Missing data

The missing data rates for each time point are shown in Table 6.

| Outcome | Number of participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | MBCT+1 | 9 months | 12 months | 18 months | 24 months | |

| Primary outcome: days till relapse/recurrence, n (%) | ||||||

| Valid cases | – | 402 (95) | 398 (94) | 395 (93) | 387 (91) | 383 (90) |

| Censored prior to 24 months | – | 22 (5) | 26 (6) | 29 (7) | 37 (9) | 41 (10) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Depression-free days, n (%) | ||||||

| Valid cases | – | 402 (95) | 396 (93) | 392 (92) | 377 (89) | 366 (86) |

| Data missing | – | 22 (5) | 28 (7) | 32 (8) | 47 (11) | 58 (14) |

| Residual depressive symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| BDI-II | ||||||

| Valid cases | 416 (98) | 348 (82) | 293 (69) | 324 (76) | 291 (69) | 336 (79) |

| Individual missing items within valid cases | 16 (0.2) | 2 (0.03) | 3 (0.05) | 0 | 2 (0.03) | 0 |

| Participants who contributed no data | 8 (2) | 76 (18) | 131 (31) | 100 (24) | 133 (31) | 88 (21) |

| GRID-HAMD | ||||||

| Valid cases | 424 (100) | 369 (87) | 352 (83) | 365 (86) | 348 (82) | 366 (86) |

| Individual missing items within valid cases | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Participants who contributed no data | 0 | 55 (13) | 72 (17) | 59 (14) | 76 (18) | 58 (14) |

| Psychiatric comorbidity: SCID, n (%) | ||||||

| Valid cases | 424 (100) | – | – | 392 (92) | – | 366 (86) |

| Data missing | 0 | – | – | 32 (8) | – | 58 (14) |

| Medical comorbidity: MSCL, n (%) | ||||||

| Valid cases | 416 (98) | – | – | 323 (76) | – | 336 (79) |

| Individual missing items within valid cases | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | 7 (0.02) |

| Participants who contributed no data | 8 (2) | – | – | 101 (24) | – | 88 (21) |

| Quality of life: WHOQOL-BREF, n (%) | ||||||

| Valid cases | 414 (98) | 348 (82) | 292 (69) | 323 (76) | 290 (68) | 336 (79) |

| Individual missing items within valid cases | 36 (0.3) | 15 (0.2) | 8 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 3 (0.03) |

| Participants who contributed no data | 10 (2) | 76 (18) | 132 (31) | 101 (24) | 134 (32) | 88 (21) |

| EQ-5D-3L | ||||||

| Valid cases | 413 (97) | 347 (82) | 293 (69) | 324 (76) | 291 (69) | 336 (79) |

| Individual missing items within valid cases | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Participants who contributed no data | 11 (3) | 77 (18) | 131 (31) | 100 (24) | 133 (31) | 88 (21) |

Baseline characteristics

Of the 424 randomised participants, 212 were allocated to receive MBCT-TS and 212 were allocated to receive m-ADM. As indicated in Table 7, baseline characteristics were balanced between the two groups with the possible exception of gender. As we know of no strong evidence that gender moderates MBCT treatment outcomes28 we did not add gender to the primary analysis model. It is interesting to note that the psychiatric history of these participants differs in a number of ways from the history of those randomised in the pilot trial (Table 8),28 with PREVENT participants reporting lower BDI scores and fewer comorbidities and a smaller proportion previously attempting suicide. A much larger percentage of the PREVENT participants also previously accessed psychiatric treatment, which is likely to be the result of the recent significant progress made in improving the accessibility of evidence-based mental health services in the UK. 4,15,16

| Characteristic/variable | MBCT-TS (n = 212) | ADM (n = 212) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Female, n (%) | 151 (71) | 174 (82) |

| White, n (%) | 210 (99) | 210 (99) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 50 (12) | 49 (13) |

| Range | 22–78 | 20–79 |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Single | 42 (20) | 38 (18) |

| Married, cohabiting or civil partnership | 125 (59) | 140 (66) |

| Separated, divorced or widowed | 44 (21) | 33 (16) |

| Missing | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Level of education, n (%) | ||

| No educational qualifications | 10 (5) | 10 (5) |

| Some school qualifications | 36 (17) | 45 (21) |

| High school and/or vocational qualification | 84 (40) | 92 (43) |

| University degree/professional qualification | 77 (36) | 61(29) |

| Missing | 5 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Religion, n (%) | ||

| Christian | 133 (63) | 139 (66) |

| Other | 10 (5) | 4 (2) |

| None | 68 (32) | 68 (32) |

| Missing | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Salary (£ sterling) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 19,930 (13,387) | 18,024 (13,582) |

| Range | 1200–72,000 | 792–80,000 |

| Social class, n (%)a | ||

| Class 0 | 96 (45) | 76 (36) |

| Class 1 | 53 (25) | 52 (25) |

| Class 2 | 22 (10) | 38 (18) |

| Class 3 | 5 (2) | 6 (3) |

| Class 4 | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Class 5 | 35 (17) | 37 (17) |

| Not classified | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Stratification variables | ||

| Depressive symptomology at randomisation, n (%) | ||

| Asymptomatic | 163 (77) | 162 (76) |

| Symptomatic | 49 (23) | 50 (24) |

| Recruitment site, n (%) | ||

| Bristol | 33 (16) | 31 (15) |

| Exeter and East Devon | 72 (34) | 76 (36) |

| North and Mid Devon | 55 (26) | 54 (25) |

| South Devon | 52 (25) | 51 (24) |

| Psychiatric characteristics | ||

| Current depressive symptomology, mean (SD) | ||

| GRID-HAMD score | 4.8 (4.3) | 4.6 (4.3) |

| BDI-II score | 13.8 (10.2) | 14.5 (10.1) |

| Previous major depressive episodes, n (%) | ||

| Fewer than six episodes | 120 (57) | 106 (50) |

| Six or more episodes | 92 (43) | 106 (50) |

| Age (years) at first depression onset, mean (SD) | 24.4 (11.5) | 25.4 (13.3) |

| Time (months) since last depressive episode, mean (SD) | 21.2 (27.0) | 17.1 (23.0) |

| No. of comorbid DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric diagnoses, mean (SD) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.9) |

| Received outpatient psychiatric or psychological treatment, n (%) | 103 (49) | 108 (51) |

| Attempted suicide, n (%) | 48 (23) | 53 (25) |

| No. of previous suicide attempts, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.5) |

| Severity of reported childhood abuse, n (%) | ||

| High | 105 (50) | 111 (52) |

| Low | 105 (50) | 101 (48) |

| Missing | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Quality of life, mean (SD)b | ||

| How would you rate your quality of life? | 3.7 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.8) |

| How satisfied are you with your health? | 2.9 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.0) |

| Physical | 14.5 (6.5) | 14.4 (5.1) |

| Psychological | 12.6 (2.6) | 12.3 (2.6) |

| Social | 13.4 (3.4) | 13.1 (3.4) |

| Environment | 15.0 (2.4) | 15.1 (2.6) |

| Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-3L tariffs), mean (SD) | 0.760 (0.268) | 0.778 (0.211) |

| Characteristic/variable | MBCT (n = 61) | m-ADM (n = 62) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Female, n (%) | 47 (77) | 47 (76) |

| White, n (%)a | 60 (98) | 62 (100) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 48.95 (10.55) | 49.37 (11.84) |

| Range | 26–66 | 21–72 |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Single | 4 (7) | 9 (15) |

| Married or cohabiting | 42 (69) | 40 (65) |

| Separated, divorced or widowed | 15 (25) | 13 (21) |

| Level of education, n (%) | ||

| No educational qualifications | 9 (15) | 17 (27) |

| Some school qualifications | 16 (26) | 16 (26) |

| High school and/or vocational qualification | 24 (39) | 15 (24) |

| University degree/professional qualification | 12 (20) | 14 (23) |

| Religion, n (%) | ||

| None | 12 (20) | 16 (26) |

| Christian | 46 (75) | 45 (73) |

| Otherb | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Social class, n (%)c | ||

| Class 1 | 22 (36) | 23 (37) |

| Class 2 | 15 (25) | 12 (19) |

| Class 3 | 7 (11) | 7 (11) |

| Class 4 | 6 (10) | 2 (3) |

| Class 5 | 11 (18) | 17 (27) |

| Psychiatric characteristics | ||

| Depression, mean (SD) | ||

| HRSD score, mean (SD) | 5.62 (4.3) | 5.76 (4.69) |

| BDI-II score, mean (SD) | 18.51 (10.91) | 20.15 (12.86) |

| Depression diagnosis at intake, n (%) | ||

| In full remission | 42 (69) | 41 (66) |

| In partial remission | 19 (31) | 21 (34) |

| Previous episodes of depression | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.43 (3.04) | 6.35 (2.91) |

| Median | 6 | 6 |

| ≥ 10 episodes, n (%) | 23 (38) | 19 (31) |

| Number of comorbid DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric diagnoses, mean (SD) | 0.83 (0.96) | 1.04 (1.11) |

| Age (years) at first depression onset, mean (SD) | 26.34 (11.7) | 26.11 (12.65) |

| Time (months) since last depressive episode, mean (SD) | 24.20 (27.74) | 18.68 (23.89) |

| Severity of last depressive episode (no. of DSM-IV symptoms recorded), mean (SD) | 7.27 (1.3) | 7.04 (1.35) |

| Attempted suicide, n (%) | 20 (33) | 22 (35) |

| Number of previous attempts | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.69 (1.37) | 0.66 (1.05) |

| Range | 0–7 | 0–4 |

| Previous psychiatric treatment, mean (SD) | 17 (28) | 13 (21) |

| Quality of life, mean (SD)d | ||

| Physical | 22.64 (5.59) | 23.0 (5.18) |

| Psychological | 17.8 (3.82) | 18.03 (3.63) |

| Social | 9.52 (2.32) | 9.27 (2.65) |

Treatment adherence in each trial arm and the extent to which patients followed invitations to (dis)continue m-ADM are reported in Table 9; > 75% of patients adhered to treatment as intended. Details of the ADM that was taken are provided in Appendix 2.

| Treatment adherence | n (%) |

|---|---|

| m-ADM | |

| Remained on therapeutic dose | 162 (76) |

| Did not remain on therapeutic dose | 50 (24) |

| MBCT-TS | |

| Participants who did not initiate MBCT treatment | 6 (3) |

| Participants who initiated MBCT treatment | 206 (97) |

| Number of sessions attended | |

| Mean | 6 |

| Mode | 8 |

| SD | 2.4 |

| Completed four or more MBCT sessions | 176 (83) |

| ADM use among patients who attended four or more MBCT sessions | |

| No reduction in ADM dose | 23 (13) |

| Reduction in ADM dose | 29 (17) |

| Discontinued ADM | 124 (71) |

Primary outcome

Intention-to-treat analysis

We observed little or no clustering in primary or secondary outcomes by therapist. As model results accounting for clustering by therapist were identical to those obtained for the primary ITT analysis, outcome findings without consideration of therapist clustering are reported.

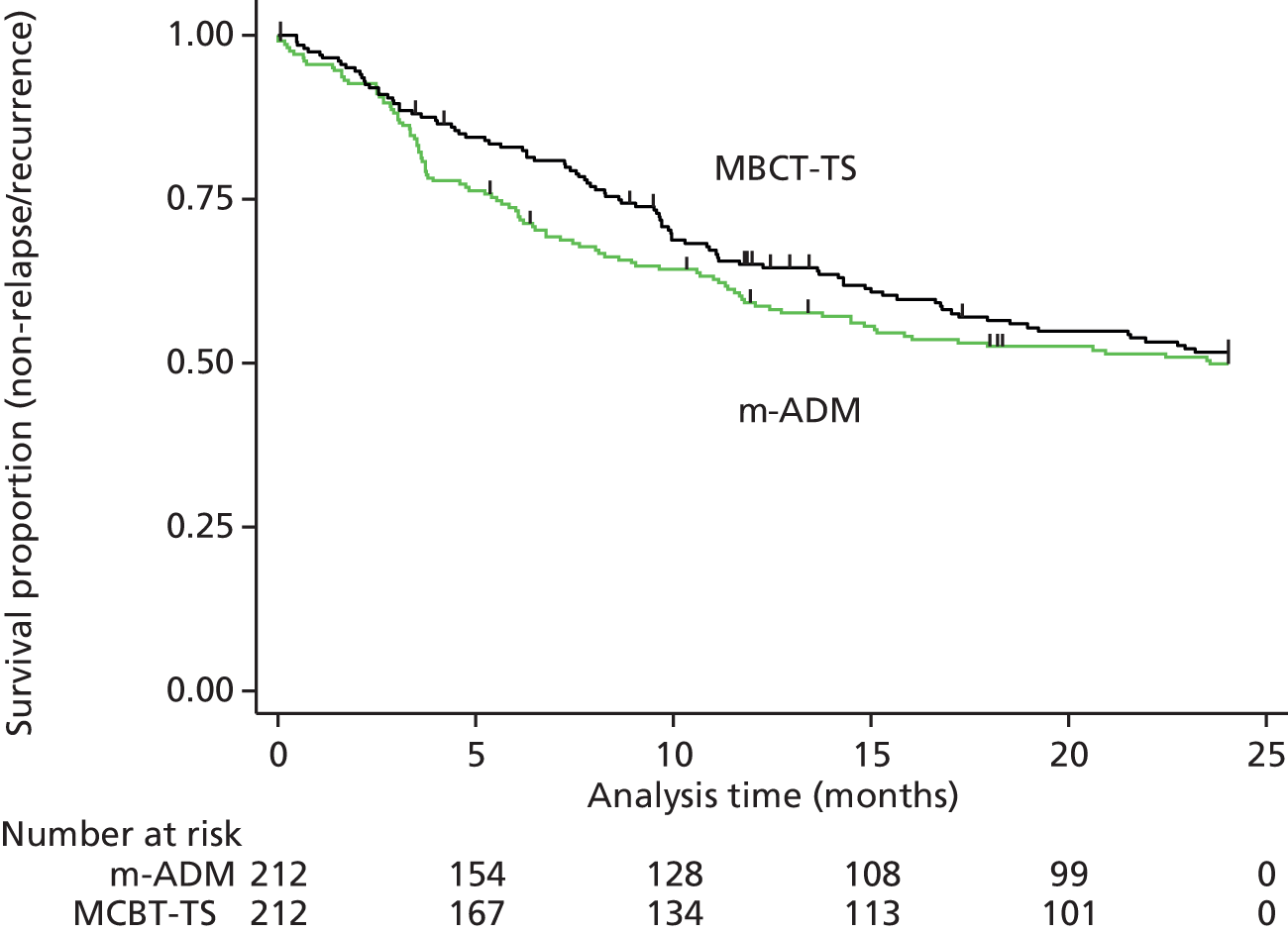

With respect to the primary outcome, the primary ITT analysis showed no evidence of a reduction in the hazard of relapse/recurrence with MBCT-TS compared with m-ADM (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.18; p = 0.43), with 44% (94/212) of the MBCT-TS patients relapsing compared with 47% (100/212) of the m-ADM patients (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Survival (non-relapse/recurrence) curves comparing relapse/recurrence of major depression for the MBCT-TS and m-ADM groups over the 24-month follow-up period for ITT participants.

Secondary analyses

Two secondary analyses of the primary outcome were undertaken to explore the impact of variations in intervention adherence in the MBCT-TS and m-ADM groups.

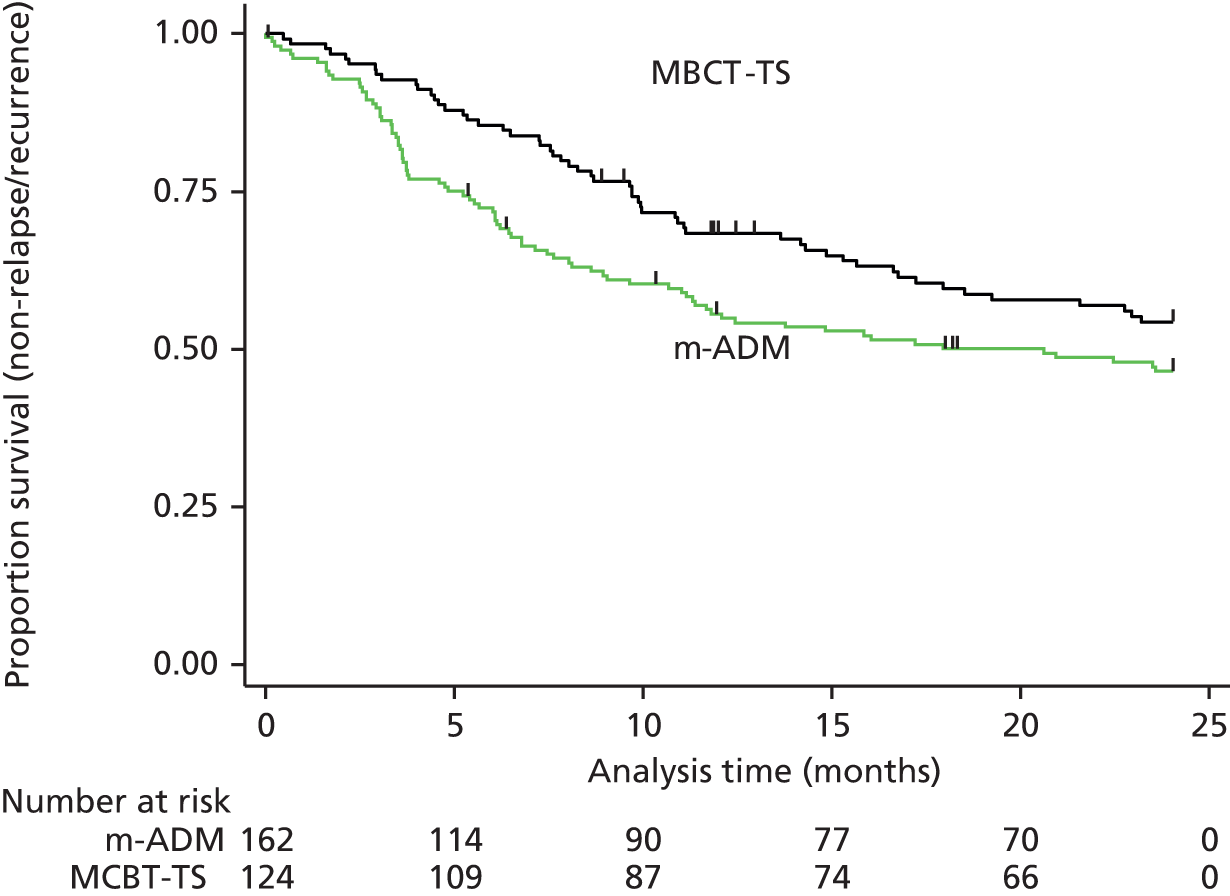

There was a non-significant reduction in the hazard of relapse/recurrence with MBCT-TS compared with m-ADM at 24 months in those participants who received an adequate dose of treatment (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.08; p = 0.14), with 46% (81/176) of the MBCT-TS patients relapsing compared with 49% (80/162) of the m-ADM patients (Figure 5). In this subgroup, the m-ADM group included more women and participants with a greater number of comorbidities than the MBCT-TS group (see Appendix 3).

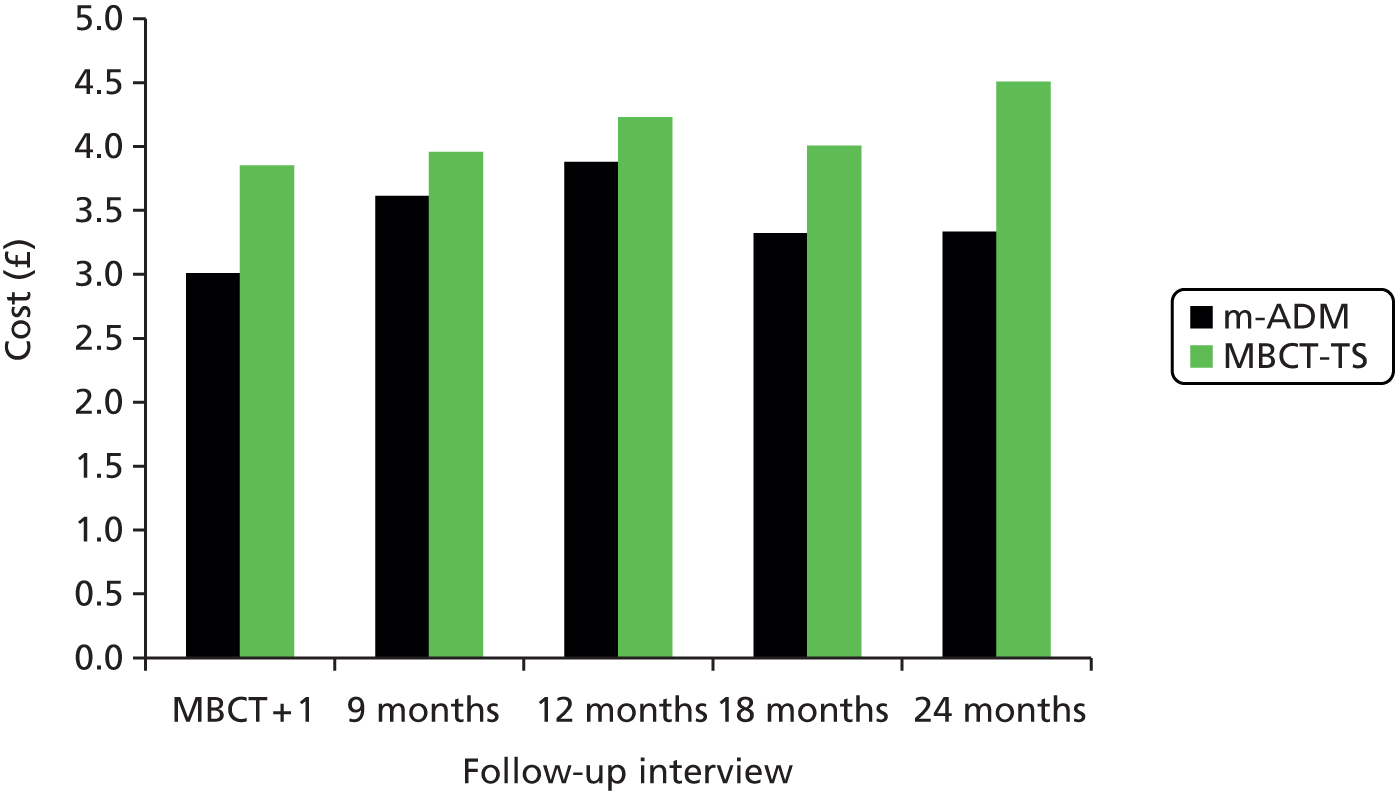

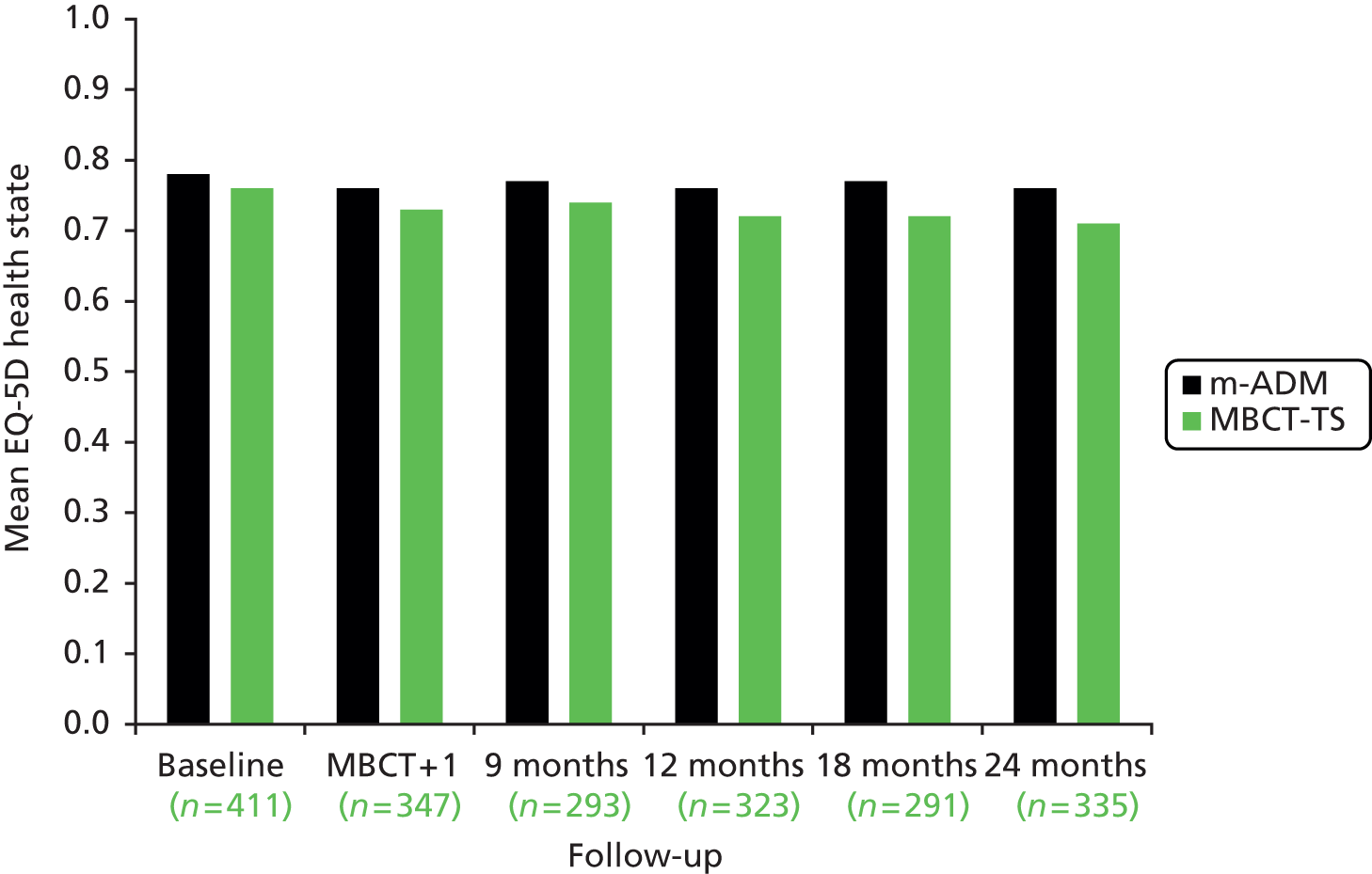

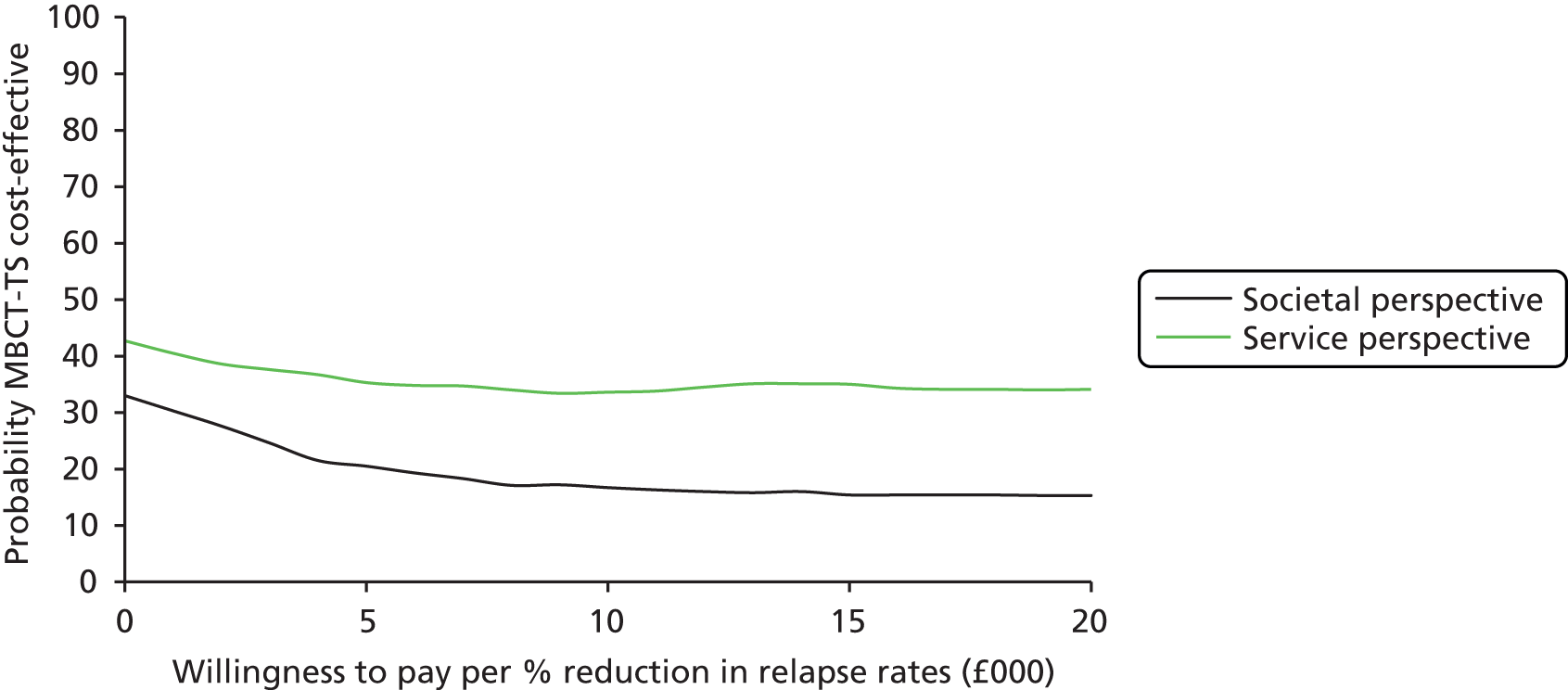

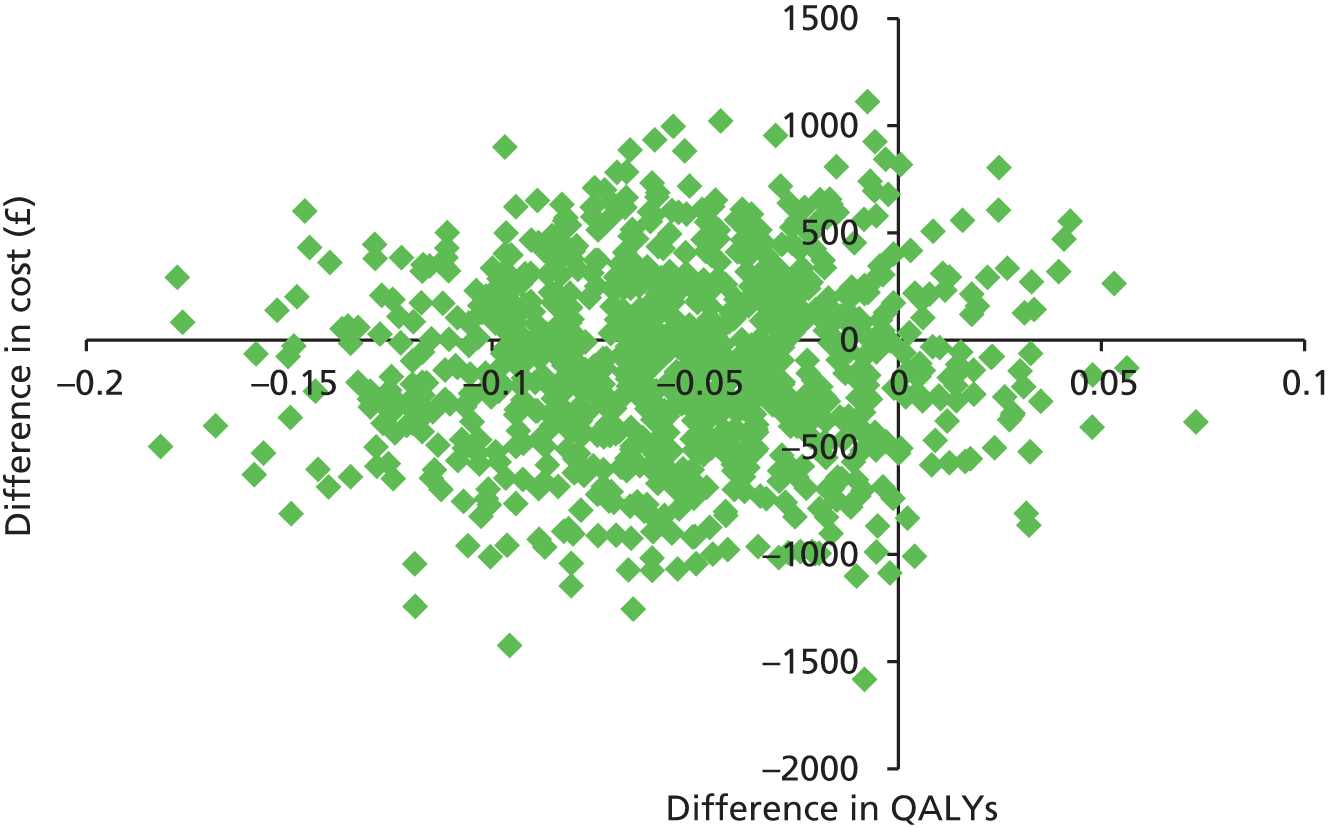

FIGURE 5.