Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/20/03. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The draft report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in August 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rona Campbell receives personal fees from the Wellcome Trust for work as a member of an Expert Review Group. She is also Director of DECIPHer Impact Limited, a not-for-profit company that is wholly owned by the University of Bristol and Cardiff University.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Mezey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter situates the necessity for developing effective interventions to reduce rates of teenage pregnancy in the context of recent shifts in policy discourses, outlines the rationale for mounting a peer mentoring intervention specifically to reduce rates of teenage pregnancy in looked-after children (LAC) and discusses research on peer mentoring, all of which have led to the aims and objectives of our study. The structure of the report is also outlined.

Teenage pregnancy in the UK

Teenage pregnancy rates in England (under 18 years and under 16 years) are compiled by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), combining information from birth registration and abortion notifications. Data for 2008 showed that there were 38,750 conceptions in the under-18 age group, a rate of 40.5 per 1000 girls aged 15–17 years. This is a fall of 13.3% in the under 18s and a fall of 11.7% in the under 16s since the start of the teenage pregnancy strategy in 1998. 1 The under-18 conception rate for 2011 was the lowest since 1969 at 30.9 per 1000 women aged 15–17 years. 2 However, rates of teenage pregnancy in the UK remain among the highest in Europe. 3 Data on births per 1000 population among women aged 15–19 years in countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 19984 and from the United Nations Population Division5 in 1994 illustrate that rates of teenage pregnancy in the UK are more than three times higher than in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Italy and France. Teenage parenthood may be negotiated positively by some young people6,7 and early motherhood can be perceived as a means of rectifying early negative life experiences. 8 However, it is also associated with a wide range of adverse socioeconomic and health outcomes for them and their children. 9–16

Teenage pregnancy has been recognised as an important cause, and consequence, of social exclusion. 17 Women who give birth as teenagers are more likely to be living in poverty than women who delay becoming mothers. 9,11,15 Furthermore, the children of teenage parents are more likely to become teenage parents themselves, suggesting a continuing intergenerational impact. 12

The association between socioeconomic deprivation and teenage pregnancy is widely evidenced in the UK. 16,18–20 In response to the report that identified teenage pregnancy as both a cause and a consequence of social exclusion,17 the UK Government set up the Teenage Pregnancy Unit (TPU) in 1999. The unit embarked on a strategy aimed at halving the rate of conception in under 18s over the following 10 years. Risk factors for teenage pregnancy include educational disadvantage and low expectations for employment; a lack of accurate information about contraception and sexually transmitted infections (STIs); and sexualised images in the media combined with a lack of openness about sex. 17 Using multiple regression data from all local authorities in England, Bradshaw and colleagues21 found that deprivation explained about three-quarters of area variation in teenage conceptions and abortions. A systematic review of 10 controlled trials and five qualitative studies evaluating early childhood interventions or youth development programmes found that the main associations with early pregnancy were dislike of school, poor material circumstances and an unhappy childhood and low expectations for the future. 22

Teenage pregnancy and looked-after children

The term ‘looked-after children’ is used in England to refer to children who are in the care of the state. Children and young people can be subject to a care order (Section 31 of the Children Act 198923) but the term ‘looked-after children’ is also used to describe children and young people who are looked after on a voluntary basis at the request of, or by agreement with, their parents (Section 20 of the Children Act 198923). Children may also be removed from their parents and placed in care on a non-voluntary basis, for example under an assessment or an emergency protection order. The majority of LAC (75%) in England are placed with foster carers. 24

There is a strong link between teenage pregnancy and age of first intercourse. The third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NatSAL) found that the median age of first sexual intercourse among young people (both males and females) aged 16–24 years in the UK is 16 years; however, 31% of young people report having had sex before the age of 16 years. 25 LAC generally become sexually active earlier than other groups of young people26 and between 20% and 50% of those aged 16–19 years with a background of care become parents compared with a rate of around 5% in the general population. 27–30 One recent study found that one-quarter of young women leaving care were pregnant or were young parents within a year of leaving care31 and, once pregnant, young women who have been in care are more likely to continue a pregnancy to term. 32

Looked-after children are more likely to have experienced several of the risk factors for social exclusion than children living at home. 27,33–39 They typically report disrupted and unstable family backgrounds and experience frequent placement moves, which threaten and undermine their emotional and physical security and which are associated with unplanned pregnancies and early motherhood. 16,40–44 LAC are at greater risk of disengaging from education, truancy and school exclusion than non-LAC,45 which are risk factors for and may be exacerbated by teenage parenthood. 46–48 Educational outcomes for LAC remain poor compared with those for other children. In 2012, only 15% of LAC achieved grades A* to C GCSEs (General Certificate of Secondary Education) in English and mathematics at Key Stage 4, compared with 58% of young people who were not looked after. 49

Disengagement and low educational attainment are risk factors for becoming NEET (not in education, employment or training) and LAC are around twice as likely to be identified as NEET at the age of 19 years as a non-looked-after group. 24 They also have higher rates of learning difficulties,39 which may impair their ability to understand and negotiate safe and stable sexual relationships and their knowledge and decision-making around contraceptive use and fertility.

Looked-after children are also much less likely to receive meaningful sex and relationships education (SRE) from their parents or carers than children living with their family of origin. 50 Following the establishment of the TPU, SRE was introduced in schools to help improve knowledge and awareness and to address the problem of teenage pregnancy. 51,52 However, high rates of truancy and school exclusion51,52 and frequent placement moves mean that LAC are more likely to miss out on curriculum-based SRE, as well as health interventions and other school-based interventions to reduce teenage pregnancy, than non-LAC. 36,37,53 Based on an investigation of the effect of the 1972 education reform, known as the Raising of School Leaving Age, a recent research study predicts that teenage fertility rates will fall in response to legislative changes from summer 2013 that will require 16- and 17-year-olds to participate in education or training. 54

Looked-after children are around three times more likely to run away or go missing than non-LAC. 55,56 This in turn puts them at risk of being physically or sexually abused or exploited. 57–60 Perhaps not surprisingly, therefore, a disproportionate number of sex workers are, or were previously, LAC. 61–64 In 2011, the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre gathered data on 2083 victims of sexual exploitation and found that 311 (34.7%) of 896 children whose living situation was known were looked after at the time of the exploitation. 28

Childhood abuse and neglect increase the risk of a young person becoming a teenage parent65–67 and can also give rise to long-term mental health problems. 68 Various studies have reported significantly higher rates of mental health problems among LAC than among other disadvantaged young people who lived in private households. 69,70 A national survey of the health of LAC by the ONS found that 45% had at least one type of mental disorder and two-thirds had at least one physical health complaint. 70 The same research found that, compared with children in private households, LAC were around three times more likely to drink regularly, four times more likely to smoke and four times more likely to be taking drugs. 70

The policy perspective

Teenage pregnancy

In the UK, policy discourses around the prevention of teenage pregnancy have changed in recent years. The Teenage Pregnancy Strategy71 resulted in various positive outcomes, such as an increased number of school- and college-based contraception and sexual health (CaSH) services and support for teenage parents through, for example, Care to Learn, which helps towards childcare costs for young people aged < 20 years who wish to study, and the Family Nurse Partnerships, which aim to improve pregnancy outcomes for first-time mothers. In some areas where there was effective implementation of the strategy the rate of under-18 conceptions fell by up to 45% from the 1998 baseline1 (under-18 conceptions in England as a whole fell by 13% from the 1998 baseline to 2008). Immediate challenges to maintaining the achievements of the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy were identified as public spending cuts, a lack of young person-friendly CaSH services and variation in provision and quality as well as unequal provision of SRE. 1

Since the change of government in 2010, the aim of reducing teenage pregnancy has come to be positioned within the remit of improving health inequalities. In 2012, the TPU was disbanded and responsibility for improving the quality of SRE in schools and colleges and integrating it within personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE) was taken over by the Department for Education. Subsequent initiatives included increasing the availability of young person-friendly CaSH services and targeted SRE advice for groups of young people at risk of teenage pregnancy. From April 2013, local authority (LA) health and well-being boards have had a statutory duty to improve the health and well-being of the local population and reduce health inequalities, through joint strategic needs assessments, as well as to support young people to prevent unhealthy lifestyle choices, which include risky sexual behaviour. 72 Reducing the rates of teenage pregnancy and STIs now forms a key part of the work of local areas to tackle child poverty and address health inequalities. 72 This reflects research evidence that illustrates the impact of socioeconomic disadvantage on rates of teenage pregnancy.

Looked-after children

In March 2012 there were just over 67,000 children and young people in England and Wales under the care of local authorities, designated as ‘looked after’. This is an increase of 13% compared with 31 March 2008. 24 The increase in care applications in recent years can, in part, be attributed to a number of high-profile cases involving the deaths of young children, which it was judged could have been prevented if they had been removed from their homes at an earlier stage. 73,74 In 2012 the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass), which safeguards the welfare of children involved in family court proceedings, received a record amount of care applications and they are expected to rise further as a result of changes to the benefits system. 75 Recent amendments to the Children and Families Bill76 have increased the age at which children in England can remain with their foster parents, from 18 years to 21 years, which it is hoped will encourage LAC to remain in education for longer.

Child protection policy in the UK is based on the Children Acts 198923 and 200477 and in the past decade a raft of major initiatives has been introduced to promote the rights and health and welfare of children and young people. In the wake of the enquiry into the death of Victoria Climbie in 2000, the government published the Keeping Children Safe report,73 the Every Child Matters programme78 and the Children Act 2004. 77 The 2010 Working Together to Safeguard Children guidance79 outlines statutory and non-statutory guidance on how organisations and individuals should ensure that services are ‘joined up’ and the National Healthy Care Standard [see www.ncb.org.uk/media/173813/healthy_care_standard_entitlements_and_outcomes.pdf (accessed 21 July 2015)] is intended to help LAC and young people achieve the five outcomes described in Every Child Matters. 78 In recent years, the Care Matters White Paper80 and the Children and Young Persons Act 200881 created independent reviewing officers to oversee the process of placement moves of young people in care and brought in higher education bursaries and other changes designed to encourage them to remain in education for longer.

Statutory and other guidance on promoting the health and well-being of LAC82,83 were brought in to improve collaborative working between local authorities, primary care trusts (PCTs) and strategic health authorities (SHAs) and to collect, monitor and share information more effectively. Following successful piloting of virtual school heads to promote the educational achievement of LAC,84 and in response to the latest statistics on educational GCSE outcomes for LAC,49 the government intends to enshrine in law a virtual head teacher for LAC in every council. 85 However, there is still a lack of consistent support and advocacy for LAC and care leavers. Various barriers to participation for LAC have been documented, including a lack of an advocate to take proactive action on their behalf, lack of meaningful and sensitive involvement in their education plans, lack of an effective voice at reviews and lack of confidentiality. 86–89

Rationale for developing a peer mentoring intervention to reduce pregnancy in looked-after children

Positive youth development and peer support

Although the TPU considered that the decline in the under-18 conception rate in some LA areas had occurred as a result of targeted work with LAC and care leavers,90 there has been no independent evaluation of the effectiveness of the various measures put in place to address this issue and none using an experimental design.

Positive youth development (PYD) programmes, focusing on the development of strong bonds with appropriate adults and maintaining regular involvement in positive activities, appear to be more successful at preventing young people from engaging in risky behaviours than programmes that focus on the ‘problem’ that has to be solved. 91 A systematic review including a statistical meta-analysis of controlled trials of early childhood interventions and youth development programmes showed that the teenage pregnancy rate was 39% lower amongst individuals receiving an intervention than amongst those receiving standard practice or no intervention [relative risk 0.61; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.48 to 0.77]. 22 The interventions aimed to promote engagement with school and counter the effects of early adverse experiences through learning support, guidance and social support and to raise aspirations through career development and work experience.

One systematic review of PYD programmes in the USA, using experimental or quasi-experimental evaluation design,92 found 15 programmes that had led to an improvement in at least one sexual and reproductive health outcome for young people. However, a non-randomised UK study to evaluate the effectiveness of development programmes for young people at reducing teenage pregnancy, substance use and other outcomes93 found no evidence of effectiveness and some suggestion of an adverse effect. Methodological limitations of this study may have affected outcomes and it was recommended that any further implementation of PYD programmes in the UK should be randomised trials.

A number of studies have focused on peer support, which includes mentoring, befriending, counselling and other types of support provided by someone who has knowledge, or experience, relevant to their mentee. 94–97 The Randomised Intervention trial of PuPil-Led sex Education in schools (RIPPLE) project, which employed peer educators to provide sex education within schools, appeared to be effective in reducing self-reported pregnancies by the age of 18 years. 95 An informal, peer-led approach to adolescent smoking prevention has also been shown to be effective. 96 However, the only comprehensive systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-led health promotion interventions for young people, half of which were concerned with sexual health, concluded that, although a peer-led approach was promising, there were too few studies to be able to identify what constituted an effective model. 97

Mentoring and peer mentoring

‘Mentoring’ is a somewhat ambiguous concept that has been used as a broad term to describe a variety of interventions and practices. 98,99 A common thread linking all mentoring schemes is the development of a trusting relationship between an older, more experienced person and a younger, less experienced person over an extended period of time, with the aim of providing social support. 98 The UK-based Mentoring and Befriending Foundation (MBF) advises that mentoring usually involves some form of goal-oriented work in addition to building a relationship, which is the cornerstone of befriending. 98 Mentoring can take place in a formal or an ‘artificial’ context, in which the mentor is acting in a voluntary or paid capacity, involving an external organisation, or it can be naturally occurring, usually involving a non-familial adult who is already present in the young person’s life. 99,100

There has been an increase in ‘peer mentoring’ programmes in recent years101 and particularly in schools. 102 However, the definition of ‘peer mentoring’ varies widely across programmes. Over one-third of schools in England operate some form of peer mentoring/peer support scheme to reduce bullying and promote self-confidence and self-esteem, some of which have been effective. 102 The MBF review102 of peer mentoring programmes in schools demonstrated the interchangeable use of the terms ‘peer education’, ‘peer support’, ‘peer befriending’, ‘peer buddying’ and others. Most programmes characterise the ‘peer’ element in relation to mentors being slightly older than, or having had similar life experiences to, the young people who they are supporting. In relation to LAC, the Scottish Government’s report Peer Mentoring Opportunities for Looked After Children and Care Leavers103 identified the most important criterion for being a peer as having a shared experience of being in care.

Impacts of peer mentoring schemes have been variable. In 2006, the MBF conducted a national pilot of formalised peer mentoring schemes in 180 secondary schools in England. Self-report and qualitative data demonstrated some benefits; however, there was no clear impact on pupils’ behaviour, school attendance or educational attainment. 104 A study of year 10 students supporting year 7 pupils with the transition from primary to secondary school found that, following the mentoring, year 7 pupils reported increased self-esteem and confidence and less anxiety. 105

A US meta-analysis of 55 evaluations of mentoring programmes found small benefits in general from mentoring but greater benefits for disadvantaged youth. 106 Very few controlled evaluations of mentoring have been carried out in the UK. However, an evaluation of the Mentoring Plus programme found that mentoring had positive impacts on training, education and work engagement in disaffected young people. 107,108 There were no clear impacts on offending, which was a general aim of the programme rather than a goal set as part of the programme.

Peer mentoring and policy

The concept of peer mentoring for LAC is consistent with the coalition government’s key factors for success, particularly ‘aspirational personal and social development programmes, targeted SRE and sexual health advice for at risk groups of young people’ (p. 49) and the requirement on local areas to address child poverty and health inequalities. 73 There is little evidence for the effectiveness of using peer mentors, as opposed to adult mentors, for LAC and care leavers; however, non-peer mentoring for care leavers has been shown to increase confidence, self-esteem and aspirations. 109 One large-scale study, supported by the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF), evaluated one-to-one mentoring relationships to increase educational engagement and performance for 449 LAC aged 10–15 years. 110 The programmes were managed mainly by voluntary organisations and the majority of mentors were adults, although some providers included peer mentors. The evaluation found marked improvements in school work, attendance and participation in hobbies and social activities, as well as in young people’s feelings about themselves, the future and relationships with others. Providers that were located within a LA were found to be the most successful at delivery.

Mounting an intervention

Given the available evidence, we believe that a system of peer mentoring and support, involving a young person whose experience of life post care has been positive, may be a promising approach to intervention with this group. Factors influencing decisions around pregnancy in LAC include low self-esteem, loneliness, mistrust of others, lack of assertiveness and lack of perceived choices or options in life. 44,111 The concept of resilience, associated with building self-esteem and self-efficacy, is increasingly seen as offering a framework for intervention with disadvantaged and vulnerable young people and has been shown to be protective in the context of care and teenage pregnancy. Resilience can be enhanced by the presence of positive role models and at least one secure attachment relationship. 112–114 Having access to a trusted confidant who provides care, respect and guidance, through and beyond the period of care, may go some way towards creating emotional security and improving self-esteem and confidence, as well as providing an opportunity to deliver important messages and information around relationships, sexuality and pregnancy. This approach has the potential to assist young people to develop new identities and make choices regarding their education and personal development, increase their self-confidence and self-esteem115–117 and provide real opportunities for alternative life choices. 48,118

Social support interventions119 involving trained volunteers have been shown to be effective in other areas of health care,120,121 with adolescents122 and in foster care. 123 There is some evidence that mentoring can help to increase the confidence, self-esteem and aspirations of young people in care109 and may also have a positive impact on training, education and work engagement. 107 Relatively less is known about the impact of peer mentoring as opposed to adult mentoring.

Potential pitfalls

We were aware of the potential challenges involved in accessing and engaging LAC,124 of finding positive role models125,126 and of sustaining such an intervention. We nevertheless considered that a peer mentoring approach would benefit from research, geared towards intervention refinement and experimental evaluation. In particular, we hoped to be able to explore the acceptability and feasibility of such an intervention; the need for and nature of rewards for the mentor; the training and support needs of the mentors; the means by which sustainability can be ensured; and the management of the post-intervention transition in a way that supports both mentor and mentee. From the available evidence we were convinced that not only was this a promising avenue to pursue given the aims of the project, but also the systematic and rigorous exploration of peer mentoring in this context would be generalisable and of benefit to a broader field.

Study aim and objectives

This study aimed to develop a peer mentoring intervention to reduce teenage pregnancy in LAC and to undertake an exploratory randomised controlled trial (RCT) to assess the feasibility of evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention in a definitive trial.

The objectives were to:

-

develop a complex intervention to reduce teenage pregnancy in girls and young women who are ‘looked after’

-

conduct an exploratory RCT of the intervention in three LAs in England, pilot recruitment, randomisation and consent procedures, examine recruitment and retention rates and the feasibility of collecting reliable and valid data on the primary and secondary outcome measures and estimate what might be feasible effect sizes and intervention costs for a future full-scale RCT

-

embed a process evaluation within the exploratory trial to assess the acceptability of the intervention and the trial procedures to LAC and those working as mentors and to document what constitutes usual care in this context for those LAC randomised to the control arm.

Chapter 2 Study methods

This chapter describes the study research design and methods used. The research aims and objectives are as set out in the previous chapter.

Research design

This was an intervention development and pilot study of peer mentoring for children and young people who have been in care, followed by an exploratory RCT, based on Phase I and Phase II of the MRC’s original framework for evaluating complex interventions. 127 We also looked at feasibility criteria and acceptability of the intervention to establish whether progression criteria for a Phase III trial could be met. The components of the peer mentoring intervention were based on existing evidence about mentoring interventions and discussions with key stakeholders; it was aimed to pilot this (Phase I) in one LA with six mentor–mentee dyads (actual n = 4). Phase II consisted of an exploratory RCT of the intervention in three LA areas. The target was to recruit 48 LAC mentees (young women aged 14–18 years) and 24 care leaver mentors (young women aged 19–25 years). The LAC mentees were individually randomised with half receiving the peer mentor intervention and half receiving ‘usual support’ (see Usual support condition). However, only 26 LAC were recruited and available for randomisation (see Chapter 5 for the reasons for this).

Selection of local authorities

Local authorities were selected on the basis of advice from the Advisory Group, in particular the TPU and the Who Cares? Trust. The team sought the involvement of two London-based and one non-London-based LA. The three LAs were selected because of their size and numbers of LAC in the areas that they covered and their perceived ability to support a research programme in this area. We looked for LAs with a previous track record, either in terms of peer mentoring or in terms of their interest in, and willingness and ability to engage in, the research.

An initial meeting was set up with the Director of Children’s Services (DCS) and key senior staff members in the three LAs for the Principal Investigator and team to present the project and provide an opportunity to ask any questions, to advise on any practical difficulties and to suggest changes. Following the first meeting, all three LAs agreed to participate. Further meetings were then held with the senior social workers from the LAs who had been identified as being able to take on the role of project co-ordinators (PCs). Following these meetings, the team, with the assistance of the LA staff, drew up an operational policy for the project, setting out in detail the roles and responsibilities of the LAs and specifically the PCs. The LAs received no reimbursement for participation in the project.

To preserve the anonymity of participants, the two London LAs are referred to as LA1 and LA2 and the non-London-based LA is referred to as LA3 in this report. The Phase I pilot was undertaken only in LA1. The exploratory trial mentoring was to be conducted in all three LAs. However, the non-London-based LA withdrew from the project before commencement of the exploratory trial and a replacement non-London-based LA (LA3) was then identified. However, LA3 experienced problems with recruiting and retaining mentors, which meant that no mentoring relationships could be established and LA3 had to withdraw from the project. This left only the two London LAs in the exploratory trial. Further details of the problems encountered and the reasons for mentor dropout are described and discussed later in this report (see Chapters 5 and 8).

Ethical approval and research governance

Ethical approval to conduct this research was granted in December 2010 by the Research and Ethics Committee based at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (reference number 5866) (see Appendix 1). Local approval was obtained from the three LAs to ensure that the trial met their standards for research governance. Permission to conduct national surveys of social work staff was obtained from the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (see Appendix 2). The trial was registered with the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration [BRTC; see www.bristol.ac.uk/cobm/research/brtc.html (accessed 20 April 2015)], a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC)-registered clinical trials unit. The BRTC provided a randomisation service for the exploratory trial and a trial database.

Developing the peer mentoring intervention (Phase I)

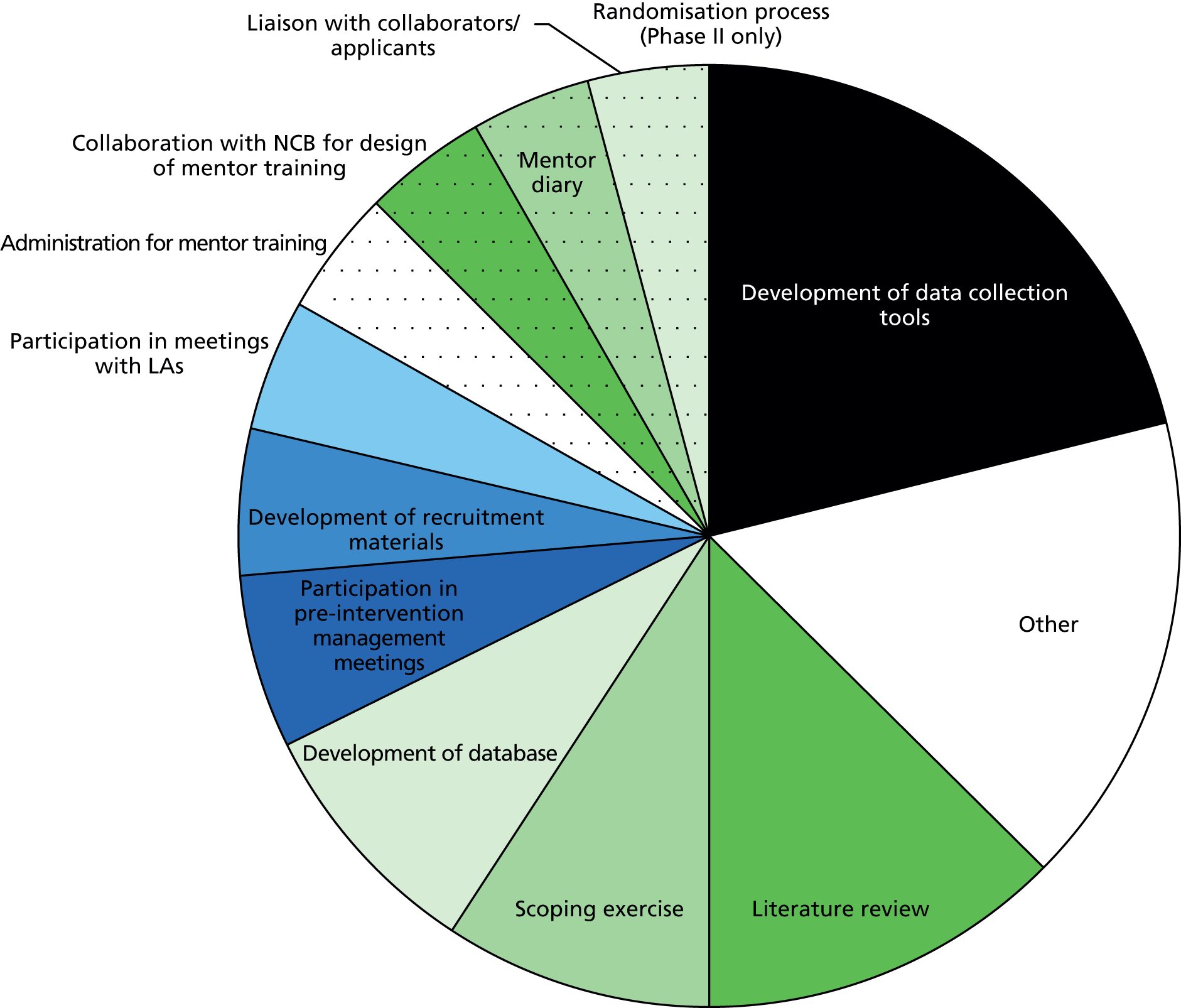

Existing evidence (see Chapter 1) suggested that peer mentoring would be an appropriate approach to reducing teenage pregnancy. However, a scoping exercise and targeted review of the literature was undertaken as part of Phase I to assist with the process of defining the intervention components, logic model and delivery plan.

Scoping exercise

Information was sought regarding local or national voluntary or statutory sector projects as well as published or unpublished reports, papers and web links relating to the following three types of intervention:

-

peer mentoring interventions for LAC

-

peer mentoring interventions to reduce teenage pregnancy

-

other interventions to reduce teenage pregnancy in LAC.

Directors of Children’s Services for England and Wales and virtual head teachers, teenage pregnancy co-ordinators, children’s and young people’s charities, mentoring organisations and members of the study Advisory Group were contacted (n = 457) between April and May 2012 to see if they were able to provide relevant information. Reminder e-mails were sent throughout the 2-month period. Initial responses were followed up by telephone or e-mail to explore professionals’ views on the components of existing interventions. Particular attention was paid to questions around the selection, training and support of mentors, the specification of the mentoring relationship (e.g. amount and types of contact and duration of relationships), exit strategies and views on contextual factors affecting the effectiveness of these interventions.

Targeted literature review

A targeted literature review was conducted at the same time as the scoping exercise. The following databases were searched between March and April 2011 for published and unpublished literature on peer mentoring for LAC with the aim of reducing teenage pregnancy: PsycINFO, Social Sciences Citation Index, MEDLINE, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (SIGLE) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Studies pre-1992 were excluded. An initial search of these databases revealed only limited available literature and so the search strategy was broadened to include studies that used more traditional (i.e. adult to youth) mentoring methods. The literature review encompassed the following types of mentoring:

-

mentoring and peer mentoring for young people

-

mentoring and peer mentoring for LAC

-

mentoring and peer mentoring to increase positive sexual behaviours and/or reduce teenage pregnancy

-

mentoring and peer mentoring for pregnant and parenting adolescents.

For a detailed description of the search strategy used in the review, see Appendix 3.

A further database search was conducted in December 2012 to incorporate more recent literature into the review.

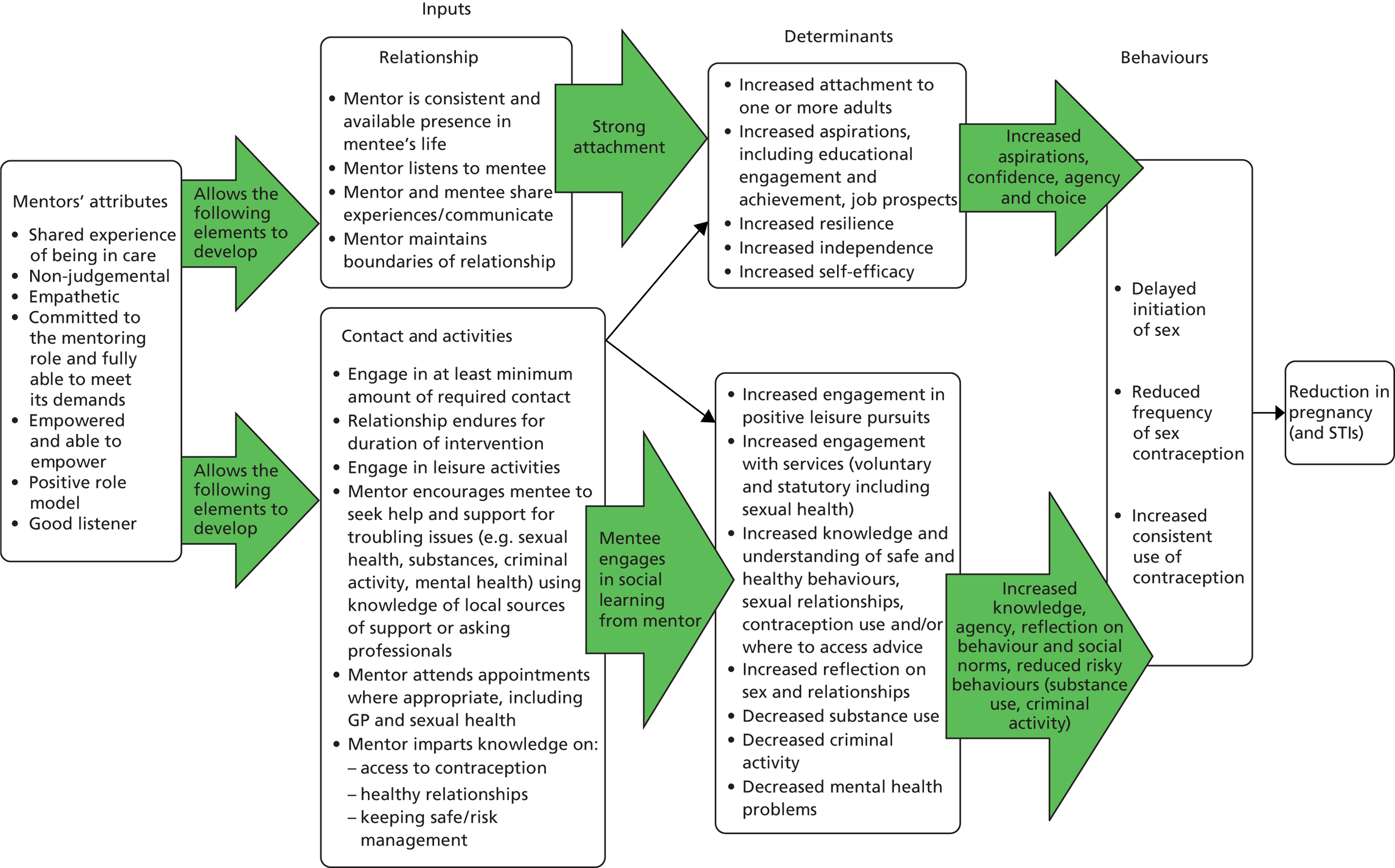

Intervention logic model

The behaviour–determinants–intervention (BDI) logic model63 is a standardised approach to theorising and informing the development of social interventions for community health problems, including sexual health and teenage pregnancy. Drawing on the literature review and scoping exercise, a BDI logic model was designed to describe and explain the intended causal mechanism of the intervention. The BDI logic model is presented in Chapter 3 of this report.

Piloting the peer mentoring intervention

A 3-month pilot of the methods for recruiting participants and the delivery of the intervention was undertaken in LA1. The recruitment target was six mentors and six mentees. The findings were used to refine the mentor training programme and other intervention components and to test the research methods and instruments to be used in the exploratory trial.

Methods used included observation of the training programme, a focus group with mentors on the last day of training and individual semistructured interviews with participants at the end of the 3-month period. Semistructured interviews were also held at the end of the 12-month intervention to explore the mentoring relationships and any impacts on mentors and mentees. These interviews were not included in the original protocol but were added because of the lower than planned level of recruitment in the exploratory trial.

Exploratory randomised controlled trial (Phase II)

A RCT was undertaken in LA1, LA2 and LA3 with 26 young women aged 14–18 years, randomised to receive the peer mentor intervention or the usual support provided to LAC. Randomisation was stratified by LA. Participants, both mentors and mentees, were interviewed 1 year post randomisation, at which time the mentoring had concluded. For details on the recruitment process see Chapter 5.

Components of the peer mentoring intervention

Mentor training and support

A 3.5-day training programme was designed by the research team in collaboration with the National Children’s Bureau (NCB) and Straight Talking, a teenage pregnancy organisation (see Chapter 6 for details). All potential mentors were offered the training, after which they were asked whether they were still willing to act as mentors and were consented. Only those who completed the training programme were permitted to work as peer mentors. We anticipated that pilot training would be delivered to 8–10 young people from LA1 and that the exploratory trial training would be delivered to 10–12 young people from each of LA1, LA2 and LA3. Training was delivered locally, in each of the LAs, to make attendance easier for participants, generally at a location arranged through the LA. Participants were paid £30 in shopping vouchers for attendance at training. The pilot training took place between 31 August 2011 and 5 September 2011. Exploratory trial training ran from 13 to 16 February 2012 in LA3, from 22 to 25 February 2012 in LA2 and from 20 to 23 March 2012 in LA1.

A booster training day, delivered by the NCB and Straight Talking, was held approximately 4 months into the intervention. This focused on discussing issues that had arisen for mentors within the mentoring relationship and problem solving.

Mentors were provided with ongoing support from the PC in each LA for the duration of the intervention, through monthly support groups and ad hoc troubleshooting and the provision of advice in-between these meetings on an individual basis. The PC role was refined during the pilot stage and is described later in this report (see Chapter 3).

Mentor role

It was agreed at the outset that each mentor should be required to take on only one mentee at a time, for a period of up to 1 year. Contact between the mentor and the mentee was by a variety of means (face-to-face meetings, e-mail, telephone conversations and texts). Mentors were provided with a mobile phone to facilitate communication with their mentee. Mentors received a monthly stipend in recognition of their work and contribution to the study, as well as money for activities with their mentees (described later in this chapter). They were also offered the opportunity to gain an accreditation for their peer mentoring through the Award Scheme Development and Accreditation Network (ASDAN). Mentors signed a mentoring ‘contract’ that outlined the responsibilities expected of them in terms of maintaining contact with their mentee, attending support group meetings and using the money and mobile phone appropriately. The mentor role was refined during the pilot phase and then further refined before commencement of the exploratory trial (see Chapter 3).

Study participants (Phases I and II)

Inclusion criteria

Participants aged 14–18 years

Young women were considered eligible to participate if they met the following criteria:

-

they were aged between 14 and 18 years

-

they were currently under the care of the LA in children’s homes or with foster carers or were care leavers. 128

An age of 14 years was specified as the lower limit because of the evidence suggesting that LAC are at risk of early sexual initiation. 28 This age was also chosen because ethical guidelines require additional consent to be sought when obtaining information on sexual behaviour below the age of 14 years. 129

The inclusion criteria did not specify whether the young women were sexually active or had previously been pregnant. However, these data were collected at baseline and follow-up.

Mentors

Young women were considered eligible to participate as mentors if they met the following criteria:

-

they were aged between 19 and 25 years

-

they had experienced the care system

-

they were deemed safe to work with children and vulnerable young people by having a satisfactory Criminal Records Bureau check [now referred to as the Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS)].

The scoping and peer mentoring literature review (see Chapter 3) identified the qualities and characteristics desired of peer mentors in previous work. These findings were relayed to PCs to assist them in the selection of suitable peer mentors.

Exclusion criteria

Young women (both mentors and mentees) were originally to be excluded if they were pregnant at the time they were approached to give consent, but they were not necessarily excluded if they already had a child (see Chapter 5 for details on exceptions to these criteria because of recruitment difficulties).

Recruitment

Pilot study recruitment was scheduled over a 2-month period between July and August 2011. Recruitment for Phase II was scheduled over a 3-month period between December 2011 and February 2012, although in practice we were unable to keep to these recruitment windows (see Chapter 5).

Recruitment leaflets and posters were designed by the research team in collaboration with a service user representative to ensure that they were appropriate. The leaflets summarised information about the study, explained confidentiality and anonymity procedures and included researcher contact details. To make the study accessible to young people and other stakeholders and for easy referral it was named ‘the Carmen study’ (derived from the words ‘care’ and ‘mentoring’). These materials were given to PCs to distribute to professionals and young people within their LA (see Appendix 4 for the written information included in the recruitment leaflets).

When a potential mentee indicated that they might be interested in participating, the researcher made an introductory telephone call and arranged to meet. The initial meeting with one or both of the researchers (DM and FC) was held on LA premises or at the participant’s home address if the participant preferred. At the meeting the researchers checked that the participant understood the nature of their involvement, details about the mentoring programme and the randomised nature of the trial (Phase II only). If the potential mentee was happy to enter the trial the researcher completed the consent procedures and baseline interview. Participants were given a £15 shopping voucher for completing this.

When a potential mentor indicated a willingness to participate, the researcher made an introductory telephone call and checked that potential mentor could attend the training. The potential mentor was then sent a letter with details of the training times and venue. If they were still interested in participating after completing the training course, a meeting was arranged with the researchers to complete the consent procedures and baseline interview. These meetings were held in the same locations as meetings with potential mentees. Participants were given a £10 shopping voucher for completing this.

Informed consent and safeguarding

Verbal and written consent was obtained from participants before completing the baseline interview (see Appendix 5 for consent forms). Baseline interviews were completed before randomisation. Young people aged < 16 years were invited to have their social worker or other LA individual present when obtaining consent. If they preferred to attend alone, the researchers spoke to their social worker to confirm their capacity to consent. Young people aged between 16 and 18 years could also elect to have a third person present if they wished. Fraser guidelines,129 which set out criteria for determining if a child is mature enough to make decisions around contraception and sexual matters, were followed. Participants were advised to direct initial queries about the research to the researchers and any other queries or concerns to the PC. A copy of the mentee consent form was sent to the mentee’s social worker, together with details of the PC.

We developed protocols for dealing with a disclosure of significant risk or ongoing harm involving a mentor or menteed young person. Before giving consent, all participants were informed of the limits of confidentiality in research interviews and that their social worker or another member of their care network would be informed if any such disclosures were made. Mentors were also advised to inform the PC if their mentee made any disclosures to them.

Randomisation

Mentees participating in the exploratory trial were individually randomised. Randomisation was stratified by LA using blocking and was undertaken using the BRTC automated randomisation service. After obtaining consent from the mentee, the researcher contacted the randomisation service to obtain the allocation. This information was then communicated to the mentee, their social worker and the PC.

Mentees were randomised to either the intervention arm of the trial or the usual support arm. Those in the intervention arm received a peer mentor in addition to their usual services.

Usual support condition

Those in the usual support arm received the services already available to them because of their status as a looked-after young person. These services aim to promote their educational achievement, physical health and social and emotional well-being. 83

Sample size

The sample size in the exploratory trial was not intended to have sufficient power to detect a significant difference in the primary outcome measure. However, the target sample size, 48, was sufficient to test whether the trial methods were robust and to provide sufficient data to check the reliability of the psychometric measures being used as secondary outcome measures.

Measures

Baseline measures

The following data were collected from LAC aged 14–18 years (see Appendix 6 for the baseline questionnaire):

-

sociodemographic data (age, ethnicity, etc.)

-

care history (current and previous)

-

forensic history and alcohol and drug use

-

educational attainment and achievement – attainment, school attendance, history of exclusions, truancy and suspensions, future educational/vocational intentions

-

sexual activity, contraception use, condom use to prevent STIs, history of pregnancy and STIs (some questions were adapted from the second NatSAL, a large UK study of sexual behaviour130)

-

physical and psychological health (see Explanatory variables for list of standardised measures used)

-

interpersonal and social functioning including number of confidants/close friends and engagement in leisure/sporting activities.

Additional information (including care history, sexual health and contact with other agencies) was collected from mentees’ social workers using a questionnaire (see Appendix 7). Consent for obtaining this information was obtained from mentees.

Outcome measures for mentees

Follow-up data collection took place when the peer mentoring intervention ended; this was scheduled at 12 months after the baseline interview. Follow-up interviews with Phase II mentors and mentees took place in June and July 2013. Participants were given a £20 shopping voucher for this.

Primary outcome measure

As the key purpose of the intervention is to reduce the rate of pregnancy, the ideal would be to have pregnancy as the primary outcome for this exploratory trial and in any subsequent definitive trial. However, this makes sense only if there is a reasonable chance of detecting a meaningful reduction in the rate of pregnancy between the intervention group and the control group in a Phase III trial. It is difficult to estimate accurately what the rate of pregnancy is for LAC and teenagers. Some studies have suggested that the rate may be as high as 40%. 131 However, data collected on live births to LAC in combination with routine data on teenage conceptions and abortions for the population as a whole in England suggest that the rate may be 10%. 72 If we assume that it would not be feasible to mount a Phase III trial with > 1000 LAC randomised to the intervention and control groups, Table 1 suggests that, if the pregnancy rate in LAC is between 20% and 40% and an effect size of 10% is deemed reasonable, using pregnancy as the primary outcome measure in a definitive trial would be possible. However, as the lower part of the table indicates, if the pregnancy rate for LAC is nearer to 10% then the intervention would have to have the effect of halving the pregnancy rate in the intervention group to have a reasonable chance of detecting this change.

| Pregnancy rate (%) | n required per arma | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | |

| 40 | 35 | 1511 |

| 40 | 30 | 376 |

| 35 | 30 | 1417 |

| 35 | 25 | 349 |

| 20 | 15 | 945 |

| 20 | 10 | 219 |

| 10 | 8 | 3313 |

| 10 | 7 | 1422 |

| 10 | 6 | 771 |

| 10 | 5 | 474 |

| 10 | 4 | 316 |

Although data on live births to LAC are routinely recorded, routine data on abortions for women aged < 18 years do not distinguish between those who are looked after and those not in care. Thus, it is not possible to calculate a pregnancy rate for this group. Our estimate of a pregnancy rate of 10% rests on an assumption that the ratio of live births to termination of pregnancy in LAC is the same as that for all teenagers, even though there is some suggestion that this may not be the case. 28 An important function of this exploratory trial was to (1) conduct further analyses of routine data on births to LAC and conception and abortion rates in teenage women, to produce more robust estimates of the pregnancy rate in the subgroup of LAC that our intervention is designed for; (2) explore the feasibility of collecting pregnancy data from the young people themselves; and (3) consider in detail what other surrogate measure for pregnancy could be used as a primary outcome measure in a Phase III trial should it become clear that using pregnancy as the primary outcome is not feasible. Current candidate surrogate measures collected included age of first sexual intercourse, use of contraception compared with incidents of unprotected sex in the previous 3-month period and number/nature of sexual relationships and STIs. Of these, our primary surrogate markers were age of first sexual intercourse and use of contraception compared with incidents of unprotected sex in the previous 3-month period. We examined whether all of the effects of our intervention were mediated through and reflected in the surrogate measures as well as in the primary clinical outcome.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome data for mentees were collected using a questionnaire, measuring change to those feelings, thoughts and behaviours collected at baseline.

Explanatory variables

Data were collected on variables that may help to explain the mechanisms by which the intervention achieved its effect. These were informed by the development of the BDI model (see Chapter 3 for more details). The following psychological measures were self-completed by mentees at baseline and follow-up:

-

Self-Esteem Scale132 – 10-item self-report measure of global self-esteem. Answers are given on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’, with a higher score indicating greater self-esteem. This measure has demonstrated reliability and validity with young people.

-

General Health Questionnaire133 – 12-item scale to detect symptoms of anxiety or depression. A score of ≥ 4 defines common mental disorder with a maximum score of 12 indicating a high likelihood of psychiatric illness.

-

General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHQ)134 – 8-item scale, with each item identifying intentions to seek help from different sources. Good reliability and validity with young people.

-

Locus of control135 – This 29-item scale was shortened to a 10-item scale to ensure that it was appropriate for the young people participating. It measures generalised expectancies for internal compared with external control of reinforcement (internal locus of control characterises those seeing their own actions determining life events; external locus of control characterises those seeing events in life as generally outside their control). Scores range from 0 to 13, with a low score indicating internal control and a high score indicating external control.

-

Attachment style136 – Self-report questionnaire classifying four attachment styles: secure, fearful, dismissive and preoccupied. Good reliability and validity, including for use with adolescents.

Outcome measures for mentors

Mentors completed a baseline questionnaire prior to the commencement of the intervention (see Appendix 8). The questionnaire recorded:

-

sociodemographic data (age, ethnicity, etc.)

-

care history

-

education and employment status

-

physical health, alcohol use and pregnancy history

-

interpersonal and social functioning including number of confidants/close friends and engagement in leisure/sporting activities.

Mentors also completed three psychological measures – the Self-Esteem Scale, the GHQ and the locus of control – pre intervention and following completion of the intervention to assess change.

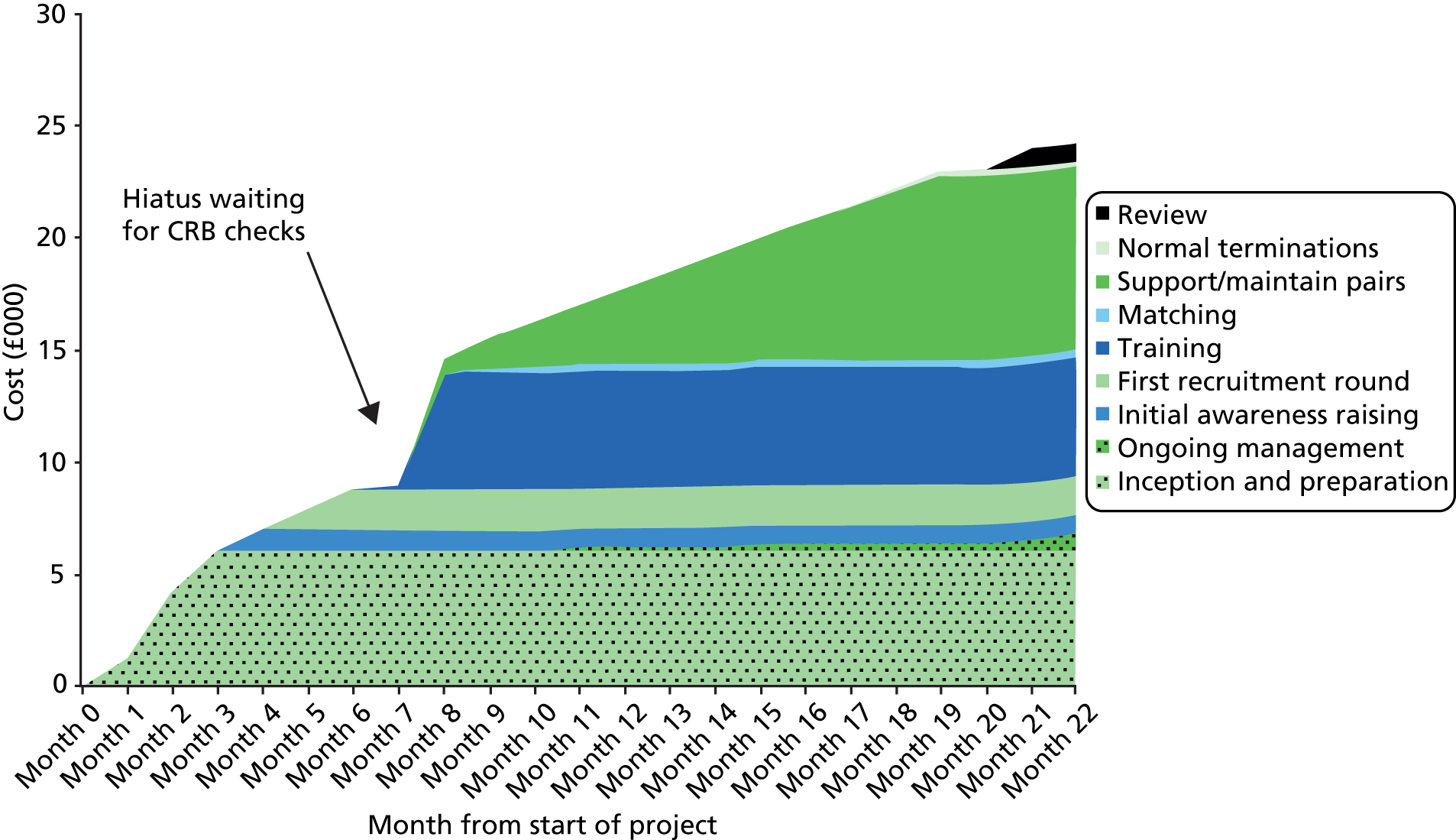

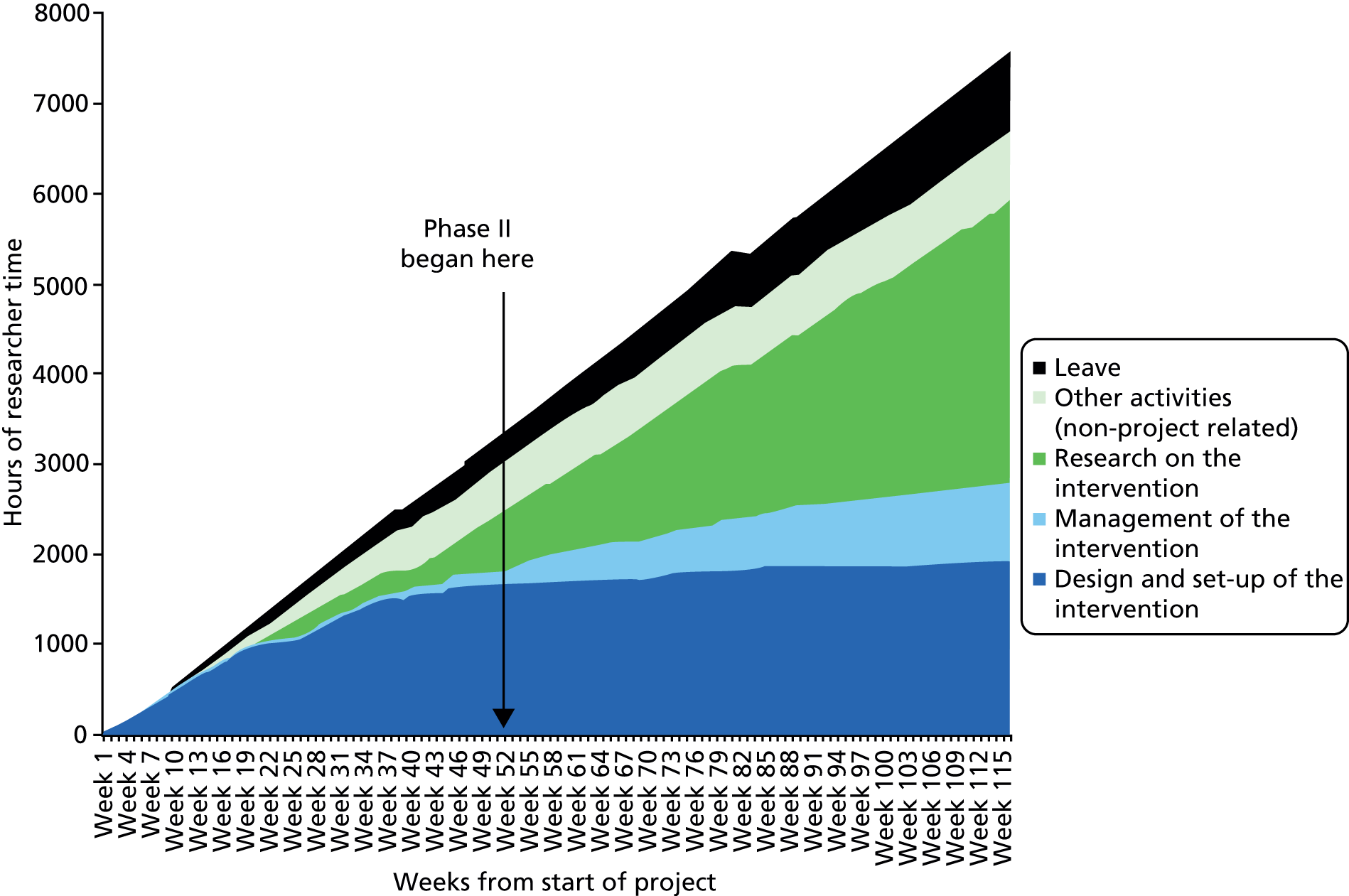

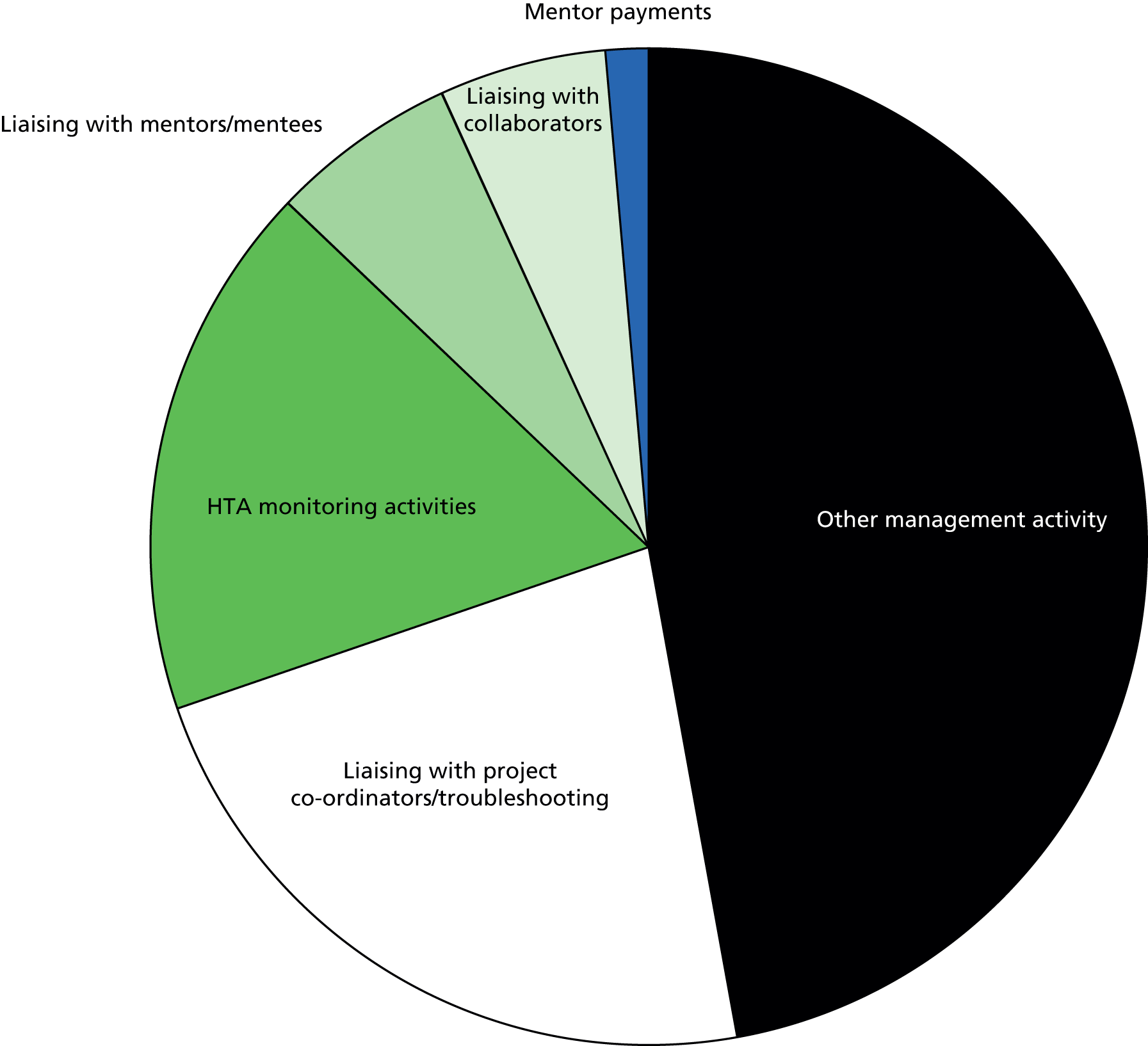

Economic evaluation

The first intention of the economic evaluation was to determine the costs of the intervention and develop a model of the running costs suitable for estimating the costs of a larger trial. Timesheets were provided for PCs to record the time that they spent delivering the scheme. They were also asked to record details of expenses associated with these activities. In the event, these methods were used infrequently by the co-ordinators and the project costs had to be estimated from the small number of data that they did return, qualitative remarks made during interviews and the time that the researchers had to commit to supporting the co-ordinator role. Mentors were also asked to record the time spent on activities with their mentee and retain records of all expenses incurred whilst undertaking the role.

The second intention was to develop a conceptual model to detail the connection between the value added by the intervention and the probabilities of various medium- to long-term outcomes for the young women and any children they may have, aimed at supporting the design of future interventions.

Process evaluation

A process evaluation was undertaken to examine implementation and receipt of the intervention and to assess feasibility and fidelity, accessibility, acceptability and contextual factors affecting implementation. The process evaluation was also used to gain insights into the mechanism of action of the intervention.

The process evaluation was informed by data from semistructured interviews with mentors, mentees and PCs and mentor diary data, focus groups, survey data and interviews with other professionals.

Follow-up semistructured interviews

At the end of the Phase II mentoring intervention (June 2013), follow-up semistructured interviews were conducted with mentors, mentees and PCs (see Appendix 9 for qualitative interview schedules). We originally intended to qualitatively interview a sample of mentors and mentees; however, low recruitment numbers resulted in us attempting to interview all participants at follow-up. The interviews explored their experiences of the mentoring relationship in terms of its acceptability, appropriateness and impact, their views of whether mentoring is effective, their views of how it effects change and their suggestions for how mentoring could be enhanced. With regard to the research, views were examined on the consent and randomisation procedures. Interviews were also sought with mentors or mentees who left the programme early, to understand their reasons for exiting the study. Interviews were conducted by the researchers (DM and FC) on LA premises or at participants’ home address, depending on their preference.

Assessing the feasibility of a Phase III trial

To assess the feasibility of delivering the peer mentoring intervention in a Phase III trial, the following domains were explored:

-

availability of eligible participants for a Phase III trial

-

feasibility of recruiting mentors and mentees

-

acceptability of the consent and randomisation procedures

-

participant retention

-

evidence of harm to participants

-

characteristics and appropriateness of proposed outcome measures

-

costs for a full trial

-

ability to manualise the intervention.

Training evaluation

The training sessions were observed to assess whether the specific components were being delivered and the appropriateness of the approaches used and the level of the mentors’ engagement with the training material presented/discussed. A semistructured checklist was used to guide the researchers’ observations and the observations were recoded qualitatively. Participants completed a questionnaire at the beginning of training and at the end of each day and participated in a focus group on the last day (see Appendix 10 for schedules), giving feedback to the researchers on the training provided. Further feedback regarding training delivery and the training process was provided by the trainers to the researchers.

Mentor diaries

Mentors were asked to keep a structured diary logging the frequency, nature and content of their communication with mentees, as well as their reflections about their mentoring experiences (see Appendix 11 for schedule). A mobile phone-based application known as Magpi [see www.magpi.com (accessed 21 April 2015)] was downloaded onto the mobile phones and used to capture the information. Mentors were also given an option of completing the diary online. Diary entries were sent electronically to the researchers and were held on a secure, confidential server. The researchers provided guidance on completing the diary at the mentor training. Mentors were asked to complete the diary after each contact with their mentee, as well as weekly, even if no contact had taken place that week.

During the Phase II exploratory trial, researchers collected information from mentors and mentees over the telephone, taking the form of a ‘snapshot’ diary at three time points – 3, 6 and 9 months into the intervention – asking about contact in the previous week (see Appendix 12 for schedules). The diaries were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Amendments introduced to the study

A number of additional elements (not originally included in the study protocol) were introduced to the study in May 2012. This was in response to recruitment difficulties that had resulted in target participant numbers not being met (see Chapter 5) to enable us to further explore the barriers to recruitment and assess the feasibility and acceptability of undertaking a Phase III definitive trial. These additional elements are described in Table 2.

| Title | Original protocol | Change made | Reason for change | Month in projecta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criterion for ages of mentors | 18–25 years | 19–25 years | When possible, minimum 5-year age gap between mentees (age 14–18 years) and mentors | 1 |

| LAs | LA1, LA2, Southend | LA1, LA2, LA3 | Having initially indicated a willingness to participate, Southend LA subsequently decided not to take part in the research study | 1 |

| Inclusion criterion for number of mentee placements | Three or more placements | One or more placements | Low recruitment numbers within the first few weeks resulted in the inclusion criterion being widened | 2 |

| Payments for participant interviews | £10 for individual interviews and £20 for focus groups | Payments made in shopping vouchers – £15 for mentee baseline interviews, £15 for mentor baseline interviews, £20 for follow-up interviews | Feedback from social workers that payments should be made in vouchers rather than in cash | 4 |

| PC role | One PC per LA | Two PCs per LA | LAs felt that the PC role required too much time commitment for one person | 5 |

| Mentor training | 3-day course | 3.5-day course | The design of the intervention necessitated a longer training period for mentors than had originally been anticipated | 5 |

| Social worker questionnaire | Not included in the original protocol | Mentees’ social workers were sent questionnaires at baseline and follow-up | To compare self-report information with case records; to identify whether there had been any variation in contact with agencies at the 1-year follow-up | 5 |

| Mentor payments | £40 per month in recognition of their contribution to the study | Payments in recognition of role made in Love2Shop vouchers | Feedback from social workers that payments should be made in vouchers rather than cash | 12 |

| Additional £40 per month for activities with mentees | Activity payment costs for London boroughs increased to £60 per month | Feedback from pilot mentors/mentees that activity payments were insufficient | ||

| Mentor diary | Magpi technology used to collect data | Diary completed using Magpi or online | Feedback from pilot mentors/mentees that they would like to complete the diary online | 12 |

| Semistructured interviews with LA staff | Not included in the original protocol | 13 interviews with PCs, senior managers and social workers | To understand individual experiences of participant identification and referral to the study and also barriers to recruitment | 15 |

| Focus groups for refining the intervention | Four focus groups before the start of the pilot study | Focus groups conducted during Phase II – five focus groups with LA staff and two with LAC | To assess feasibility and explore views on the peer mentoring intervention | 15 |

| Surveys of LA staff and young people | Not included in the original protocol | National survey of LAC and care leavers; national survey of DCSs/social workers; local survey of social workers from LA1, LA2 and LA3 | To assess feasibility and explore views on the peer mentoring intervention | 15 |

| Interview with university student | Not included in the original protocol | Interview with a university student from St George’s, University of London | To assess feasibility and explore views on the peer mentoring intervention | 24 |

Semistructured interviews with professionals

In June and July 2012, 13 semistructured interviews were conducted with PCs, senior managers (referred to as SM in quotations) and social workers (referred to as SW in quotations) from LA1, LA2 and LA3 (see Appendix 13 for schedules). We interviewed all PCs and senior managers involved in the study and a sample of social workers, who were chosen because of their involvement in recruitment. A senior manager was defined as a person who had management responsibility within the field of LAC/care leavers and who did not have a caseload. The purpose of these interviews was to understand individual experiences of participant identification and referral to the study and also barriers to recruitment. Interviews were conducted either in person on LA premises (in a private office) or on the telephone and lasted from 30 minutes to 1 hour. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Surveys of local authority professionals and female looked-after children and care leavers

The following surveys were conducted (see Appendix 14 for schedules):

-

A survey of social work staff in the three LAs (whose caseload included LAC or care leavers) explored their involvement with the study and barriers to recruitment. Senior managers were asked to distribute the survey, which was open from 11 January to 21 March 2013. In total, 22 responses were received (three from LA1, five from LA2, 14 from LA3).

-

A national survey of two groups of young women from the UK (LAC aged 14–18 years and care leavers aged 19–25 years) was open from 3 September to 14 December 2012. The purpose of the survey was to examine views on recruitment, randomisation and the peer mentoring intervention as well as young people’s experiences of other mentoring schemes. The survey was advertised through the Who Cares? magazine, produced by a national charity for LAC. Other organisations were contacted by e-mail and on Facebook and Twitter, including children’s charities, youth services and Children in Care Councils (CiCCs). Flyers were distributed during National Care Leavers’ Week in October 2012. In total, 27 responses were received to the 14–18 years survey [mean age 16.78 years, standard deviation (SD) 1.15 years]; 15 respondents lived in southern England, five lived in London, four lived in the Midlands and three lived in Northern England. For the 19–25 years survey, 37 responses were received (mean age 21.58 years, SD 2.13 years); 11 respondents lived in southern/eastern England, 10 lived in London, eight lived in the Midlands, five lived in northern England and two lived in Scotland (one response was missing).

-

Two surveys were e-mailed to DCSs in 152 LAs in England and Wales. One survey was completed by DCSs and/or senior managers within children’s services. This survey assessed the availability of eligible participants within their LA, their views on peer mentoring and randomisation and their interest in participating in a larger trial. The second survey was completed by social workers whose caseload included LAC aged 14–18 years or care leavers aged 19–25 years. This survey assessed respondents’ views on the peer mentoring intervention and randomisation. The surveys were open from 11 January until 21 March 2013. In total, 85 responses were received to the DCS survey (25 from LAs in London, 24 from LAs in northern England, 20 from LAs in southern/eastern England and 16 from LAs in the Midlands). For the social worker survey, 118 responses were received (47 from LAs in northern England, 29 from LAs in the Midlands, 29 from LAs in southern/eastern England and 13 from LAs in London).

The surveys were constructed using LimeSurvey [see www.limesurvey.com (accessed 21 April 2015)], a survey software tool, and were completed online. Recruitment was facilitated by the circulation of the survey URL. There was an opportunity to enter a prize draw in the surveys of young people and social workers, with one respondent in each survey winning a shopping voucher (£30 for young people and £50 for social workers).

Focus groups with female looked-after children and care leavers and local authority professionals

Focus groups with LAC/care leavers and professionals working with LAC were held to explore their views on the peer mentoring intervention (see Appendix 15 for focus group schedules). Two focus groups were held in an additional LA (referred to as LA4) with (1) two LAC aged 14–18 years and (2) five female care leavers aged 19–25 years. This LA was chosen because of its expression of interest when contacted during the scoping exercise. Recruitment flyers were provided to a LA4 Children’s Rights, Participation and Engagement Manager in May 2012, who distributed them to eligible young women. The groups were held at a local youth centre in July 2012. Participants were given a £20 shopping voucher for their participation.

In May 2012, managers were asked to distribute preliminary written information to their staff and to nominate individuals to participate in focus groups about the project. Following this, two additional groups were held in each of LA1 and LA2 consisting of (1) social workers working with LAC and care leavers and (2) health and education staff. One focus group was held with social workers in LA3. The groups were held on LA premises or in local education centres between August and November 2012. The number of participants in each group ranged from three to six. The length of the focus groups ranged from 1 hour to 90 minutes.

All focus group discussions were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Interview with university students

Following advice from the Trial Steering Committee that university students may be a fruitful avenue of recruitment in a future trial, because of their perceived status as aspirational role models for young people in care, we attempted to arrange a focus group with university students who had experience of the care system. The aim was to explore their interest in acting as peer mentors and the potential barriers that they may encounter. For ease of recruitment, students were selected from St George’s, University of London (SGUL) and Kingston University. Recruitment was conducted through the SGUL Student Centre, who contacted all eligible female students aged 19–30 years who had experience of the care system (the upper age limit was extended because of feedback from social work professionals that mentors could be older than 25 years). The head of the Student Centre reported that there were approximately 10 eligible participants. Two students expressed an interest in participating but only one of them subsequently presented for interview, in July 2013 (see Appendix 16). The participant was given a £20 shopping voucher for her participation. The interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis

For the purpose of this report we adopted a pragmatic thematic approach to the analysis of qualitative data, seeking to provide a largely descriptive account137 of the peer mentoring process that would complement the analysis of quantitative data and enable further refinement of the intervention and research procedures. Although we borrowed analytical techniques of coding and comparing data from grounded theory,138 we used these tools to organise our data, rather than seeking to build theory about the processes underpinning the peer mentoring relationship (this approach will inform additional, in-depth qualitative outputs from the study).

Transcripts from the process evaluation interviews were read a number of times by researchers (DM and FC) to familiarise themselves with the data. Participant and LA area attributes were assigned to each transcript to allow analytical themes to be explored in relation to the experiences of different groups and to compare processes across areas.

An initial ‘open coding’ was undertaken of a selection of transcripts from different participant types and LAs. Coding involved assigning labels to data (passages of text) – where possible retaining language used in the transcripts – that indicated the relevance of that data to the research questions being addressed. In this study, the coding process was guided by the team’s key questions about the processes of mentoring and relationship building and the progress of the relationships between dyads, what made a relationship work and what did not. Questions asked of the data included how the mentor and mentee experienced the relationship; the expectations of mentors and mentees about the workings/dynamic of the relationship; what mentors and mentees thought was a safe and appropriate relationship; and the impact of this supportive relationship on their relationships.

Following open coding, researchers adopted an iterative process139 whereby they looked for patterns, similarities and differences, as well as silences, in the coded data. This process was used to coalesce codes into categories or themes that constructed our descriptive account of the mentoring process. The iteration was a reflexive process and was key to sparking insight and developing meaning. The researchers visited and revisited the data and connected them with emerging insights, progressively refining the themes. The themes emerging from the data were driven by the inquiries above but also by the researchers’ interpretations of what the data were telling them based on their experiences of having undertaken the interviews and of the fieldwork environment. The researchers undertaking the coding (DM and FC) presented the emerging analysis to members of the research team through regular meetings and to members of the Advisory Group on two occasions to validate themes from the wider team perspective.

Through the iterative process we developed an analytical framework – a comprehensive set of themes – that was applied to all semistructured interview and focus group data. Themes that made up the framework were created as ‘nodes’ in the NVivo qualitative analysis software package (version 10; QSR International, Warrington, UK) and all transcripts were coded to those nodes, that is, sections of text were assigned, using the software, to the themes to which they were relevant.

The resulting coded NVivo database was used to facilitate the management of the large qualitative data set. In undertaking the process evaluation ‘query’ functions within NVivo were used to collate data relating to particular themes that described the mentoring process and to enable comparisons between data from different types of participant (see Chapter 8).

As well as the process evaluation, qualitative data also explored the structure and components of the intervention (examined through follow-up interviews and mentors’ diaries). NVivo software was used to collate qualitative data from all sources to support and make comparisons with the quantitative data collected through baseline and follow-up interviews and survey data, that is, data sources were triangulated139 (see Chapter 7).

Quantitative data analysis

Because of the small sample size in this study no hypothesis testing has been conducted comparing the outcomes of the intervention and usual support groups. Baseline data have been presented for all participants (by randomised allocation) using descriptive statistics (see Chapter 5), frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, means, SDs and minimum and maximum values for continuous normally distributed variables and medians with minimum and maximum values for discrete count variables. The pilot study sample has been added to the Phase II sample for reporting of quantitative data in Chapters 5 and 7. For the follow-up data (see Chapter 7) descriptive statistics are again used to report the primary and secondary outcomes by randomised allocation. Individual data are presented for the pregnancy and sexual behaviour outcomes given their importance and paucity. Frequencies and percentages are reported for categorical variables and medians and minimum and maximum values for all quantitative variables (given the smaller sample size at follow-up). For the three psychological measures (GHQ, Self-Esteem Scale and locus of control) mean changes from baseline to follow-up with 95% CIs are presented. All analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Chapter 3 Phase I: development and piloting of the intervention

To inform the components of our intervention, a scoping exercise and literature review of peer mentoring interventions was conducted during the development phase. The first section of this chapter contains the results of the scoping exercise and literature review, including evidence on what constitutes ‘best practice’ in mentoring and peer mentoring and the way that the effectiveness of an intervention can be increased when particular features are adopted. The review was used to inform the design of the mentoring intervention, which is outlined later in the chapter.

Scoping review findings

The scoping review identified small-scale projects in Great Britain that were in the development stage or established. Information about peer mentoring for LAC and interventions to reduce teenage pregnancy was sought, with a specific focus on LAC. Fifty-two responses were received from 457 professionals contacted during the scoping exercise. The breakdown of responses by professional organisation is presented in Table 3. Many programme providers could not be contacted because of high staff turnover within organisations and, in some cases, the lack of response was due to a lack of relevant interventions. However, in some regions, professionals were more responsive and contacts in their area snowballed. From the responses, 19 relevant peer mentoring interventions were identified (Table 4).

| Organisation | Number of professionals contacted | Number of professionals who responded |

|---|---|---|

| Advisory Group | 12 | 6 |

| Children’s charities | 13 | 6 |

| Sexual health/teenage pregnancy organisations and teenage pregnancy co-ordinators | 45 | 11 |

| Mentoring organisations | 2 | 0 |

| LAC organisations | 32 | 11 |

| DCSs | 152 | 14 |

| Virtual head teachers | 201 | 4 |

| Total | 457 | 52 |

| Intervention type | Number of interventions identified | Regions |

|---|---|---|

| Peer mentoring for LAC, aiming to improve outcomes generally (six involve mentors with experience of the care system) | 7 | London (four boroughs), Cornwall, Central Bedfordshire, Wakefield |

| Peer mentoring for LAC to improve educational outcomes (four involve university students acting as mentors) | 5 | London (six boroughs), Bradford, Leeds, Lincolnshire, Walsall |

| Peer mentoring for LAC who were pregnant (mentors had experience of the care system and being a parent) | 1 | North Lincolnshire |

| Peer mentoring for teenage parents (not specifically LAC) | 4 | Hull, Leeds, Leicester, North Lanarkshire |

| Online peer mentoring for young people about sex, relationships and pregnancy | 1 | Nationwide |

| Peer mentoring course to train LAC to be school mentors | 1 | Wakefield |

The scoping review did not identify any interventions designed to reduce teenage pregnancy in LAC or other young people. Most interventions were focused on promoting positive outcomes for LAC, including raising educational outcomes and supporting them through their transition from care to independence (13 out of 19 interventions). Some of the interventions used mentors with experience of the care system but these were focused on goal-setting and promotion of independent living skills. Peer mentoring interventions with LAC aimed at improving educational attainment often employed university student mentors, who were not specifically required to have experience of care.

Initiatives to prevent teenage pregnancy