Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/97/01. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in February 2015 and was accepted for publication in July 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Adams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This project involved three linked components:

-

A systematic review of existing research evidence on the effectiveness, acceptability, cost and efficiency of parental incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing the uptake of vaccinations in preschool children.

-

A qualitative study undertaken with a range of stakeholders (including parents, health and other relevant professionals, and policy-makers) exploring what is and is not acceptable about these schemes and what can be done to improve acceptability.

-

A discrete choice experiment (DCE) exploring the relative preferences of parents and carers of preschool children for approaches to delivering vaccination programmes, including parental incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes, and the predicted uptake rates of these.

These three pieces of work aimed to answer three overarching research questions, respectively. These questions were:

-

According to existing published and unpublished evidence, what is the effectiveness, acceptability and balance of costs and effects to society of using parental incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes to increase the uptake of vaccinations in preschool children in high-income countries?

-

According to key stakeholders in England (including parents, health and other relevant professionals, and policy-makers), what is and is not acceptable about parental incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing uptake of vaccinations in preschool children? Can anything be done to improve acceptability?

-

What are the relative preferences of English parents and carers of preschool children for a range of characteristics associated with schemes designed to encourage uptake of vaccinations, including parental incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes?

Chapter 2 provides a general introduction to preschool vaccinations and financial incentive interventions, both in general and as applied to preschool vaccinations. The three pieces of work mentioned above are then described in turn in Chapters 3–5. Chapter 6 provides an integrated discussion of findings and conclusions.

Project team and steering group

The work was guided by a project team, a wider steering committee and a lay Parent Advisory Group. Members of the project team, along with their roles, are listed in Chapter 9. In addition, the steering committee included Professor Shona Hilton (Glasgow University), Dr Monique Lhussier (Northumbria University) and Mr Rodolfo Hernandez (Aberdeen University). The steering committee and full project team formally met on three occasions, each time making a number of useful contributions to data interpretation and future directions for the work.

Parent Advisory Group (public involvement)

The Parent Advisory Group consisted of around eight members of an existing parent committee based at a Children’s Centre in North Tyneside. Participants were mothers and grandmothers of children using the centre. The Parent Advisory Group met on four occasions. The first meeting provided an opportunity for researchers and members of the group to get to know each other, and to introduce the project and reflect on findings of the systematic review. In the second meeting, preliminary attributes and levels for the DCE were discussed. The third meeting was used to discuss and ‘sense-check’ early results from the qualitative work. During the final meeting, the full findings from the project were considered and methods for dissemination discussed. The specific contributions made by the Parent Advisory Group are reported in Chapters 3–5.

Chapter 2 Background

Childhood vaccination programmes form a core component of public health strategies worldwide. Nationally and globally, childhood vaccinations have been highly effective in reducing the incidence of, and associated morbidity and mortality from, a range of infectious diseases. 1

Preschool vaccinations in England

The current schedule of recommended vaccinations offered by the NHS for low-risk, preschool children is shown in Table 1. The full schedule involves 14 injections (11 excluding the new influenza programme) plus two orally administered vaccines given at a minimum of eight visits between 2 and 60 months of age (five excluding the new influenza programme). Further vaccinations are recommended for ‘at-risk’ infants and for all children in school years. We refer to the full schedule described in Table 1 as ‘preschool vaccinations’ throughout.

| Vaccine | Recommended age | Coverage (all relevant doses) July–September 2014 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 12 months | At 24 months | At 60 months | ||

| DTaP, IPV and Hib, combined 5-in-1; primary course | 2, 3 and 4 months | 93.9 | 95.9 | 95.7 |

| PCV; primary course | 2 and 4 months | 93.5 | – | – |

| MenC; primary course | 3 months | N/A | 94.8 | – |

| Hib/MenC booster | 12–13 months | – | 92.2 | 92.6 |

| MMR; primary course | 12–13 and 40–60 months | – | 92.2 (one dose) | 94.5 (one dose); 88.5 (two doses) |

| PCV booster | 12–13 months | – | 92.3 | – |

| DTaP/IPV booster | 40–60 months | – | – | 88.6 |

| Rotavirusa | 2 and 3 months | 86–88 | – | – |

| Influenzaa | 2, 3 and 4 years | – | – | – |

Vaccination ‘coverage’ is defined as the percentage of those eligible for each primary course of vaccinations, or booster, who receive it. The World Health Organization (WHO) has set a goal of 90% coverage for all vaccinations, with 95% coverage for measles and diphtheria. 1,3 This high level of coverage is recommended both to protect as many vaccinated individuals as possible, and to achieve ‘herd immunity’, where the reservoir of people who can harbour infection is minimised to the extent that unvaccinated individuals are also effectively protected.

Table 1 shows coverage rates in England in 2014. Although coverage rates approach or exceed the WHO targets for most vaccinations, some show much lower rates, in particular both doses of measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) and the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTaP)/inactivated polio virus booster. Furthermore, coverage rates vary geographically with, for example, coverage of all three doses of the primary course of DTaP/inactivated polio virus/ Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) varying between 88.7% (Surrey and Sussex) and 97.1% (Cumbria, Northumberland, and Tyne and Wear). 4

Factors associated with uptake of preschool vaccinations

Systematic reviews have identified a range of factors associated with low uptake of preschool vaccinations. 5–8 These can be grouped into three categories: sociodemographic factors, attitudinal factors and health-care factors.

Sociodemographic factors associated with non-vaccination include being a child of a single, or younger, mother;7 being a younger child in a large family;5,7 and being a child of a family living in more deprived socioeconomic circumstances. 5,7 The association with lower socioeconomic position is not entirely consistent with some evidence that negative publicity around the MMR vaccine had a larger detrimental effect on coverage rates in children living in more affluent circumstances. 9 Looked-after children, those with physical and learning difficulties, those not registered with a general practitioner (GP), those from non-English speaking families, and asylum seekers have also been identified as being at greater risk of not being fully vaccinated. 10,11

Non- or suboptimal vaccination does not necessarily represent a simple omission. Overall, around 50% of UK parents and carers of children who have not received the full schedule of vaccinations have made a conscious decision not to vaccinate. 5 Evidence from systematic reviews suggests that attitudes related to low uptake of vaccinations map closely to the components of the Protection Motivation Theory model. 12 This suggests that behaviour change (e.g. taking a child for vaccination) in response to persuasive communications (e.g. a letter from a general practice surgery) is determined by both a threat appraisal (i.e. the perceived severity of the disease that could be prevented by vaccination and perceived vulnerability to that disease) and a coping appraisal (i.e. perceived efficacy of the vaccination and perceived self-efficacy, or self-confidence, of being able to take the child for the vaccination). 12 Parents who are less likely to have their children immunised are less likely to believe the diseases that vaccines protect against are serious5,6 and less likely to believe that their child is at risk of contracting them. 5,7 They are also less likely to believe that vaccines are effective5,6 and more likely to be concerned about potential side effects. 5–7

In terms of health-care factors, those who have experienced poor relationships with health-care professionals, forget appointments or are unaware of the vaccination schedule are also less likely to have their children vaccinated. 5,6 Parents who have not had their children immunised also tend to have less trust in health professionals. 5,6

It is important to note that these factors are not necessarily independent. For example, mothers living in more deprived circumstances are more likely to have larger families. 13 Furthermore, parents often hold mixed views about vaccination and do not always act in line with their attitudes and beliefs.

Current guidance on increasing vaccination coverage and decreasing differences in coverage

In 2009 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidance on reducing the differences in the uptake of vaccinations among children and young people. 11 This adds to the existing Department of Health strategy on reducing inequalities in uptake of vaccinations. 10 Both of these documents stress the importance of good information recording systems; appropriate training of all relevant health-care professionals; culturally specific parental information provided in a variety of formats; flexible access to vaccination services provided in a range of settings; and repeated, opportunistic checking of children’s vaccination status by a range of professionals. 10,11

The NICE guidance notes that there is little UK research on the effect of parental incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing vaccination uptake, but that evidence from other countries suggests that these may be effective. 11,14

Definition of parental incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing uptake of preschool vaccinations

Defining incentives in the context of preschool vaccinations is challenging. In general, behavioural incentives have been defined as motivating rewards which are provided contingent on behavioural performance. 15 However, this definition could be interpreted as including any reward (e.g. a sticker or praise) and not just those with real material value. Furthermore, this definition specifically excludes the converse of motivating rewards: penalties.

Briss et al. 16 identify incentives as interventions that increase demand for vaccinations. These are likely to include both rewards for immunising and penalties for not immunising.

Although rewards that do not have real material value may also increase demand for vaccinations, it is highly likely that in advanced societies, interventions offering rewards with real material value are conceptually different from those offering rewards with social, emotional or tokenistic value. As such, and following Briss et al. ,16 we restrict our definition of incentives to interventions that increase demand for vaccinations by offering contingent rewards with real material value (whether or not these are offered in the form of cash), but widen this to include interventions imposing contingent penalties with real material value (again, whether or not these are imposed in the form of cash).

One form of contingent non-cash penalty with real material value is withholding a universal service from those who do not engage in particular behaviours. If mandatory behaviours are those that are universally required by law, quasi-mandatory ones are those that are almost universally required by law. In the context of vaccinations, quasi-mandatory schemes are generally operationalised as programmes that make access to what would normally be considered a universally provided good or service contingent on either vaccination or a valid reason for non-vaccination, such as religious objections. The most common example is school enrolment programmes, where children must provide vaccination certificates (or evidence of exemption) in order to enrol in school. 17,18 Here, the universally provided service is education. The intervention is only quasi-mandatory as parents can, theoretically, choose not to send their children to a state-funded school. As such, quasi-mandatory interventions can be considered to be a particular type of incentive, that is contingent penalties that restrict access to ‘universal’ goods or services.

Thus, henceforth, we use the term ‘parental incentive scheme’ to describe both rewards and penalties with real material value that are contingent on having, or not having, a preschool child immunised.

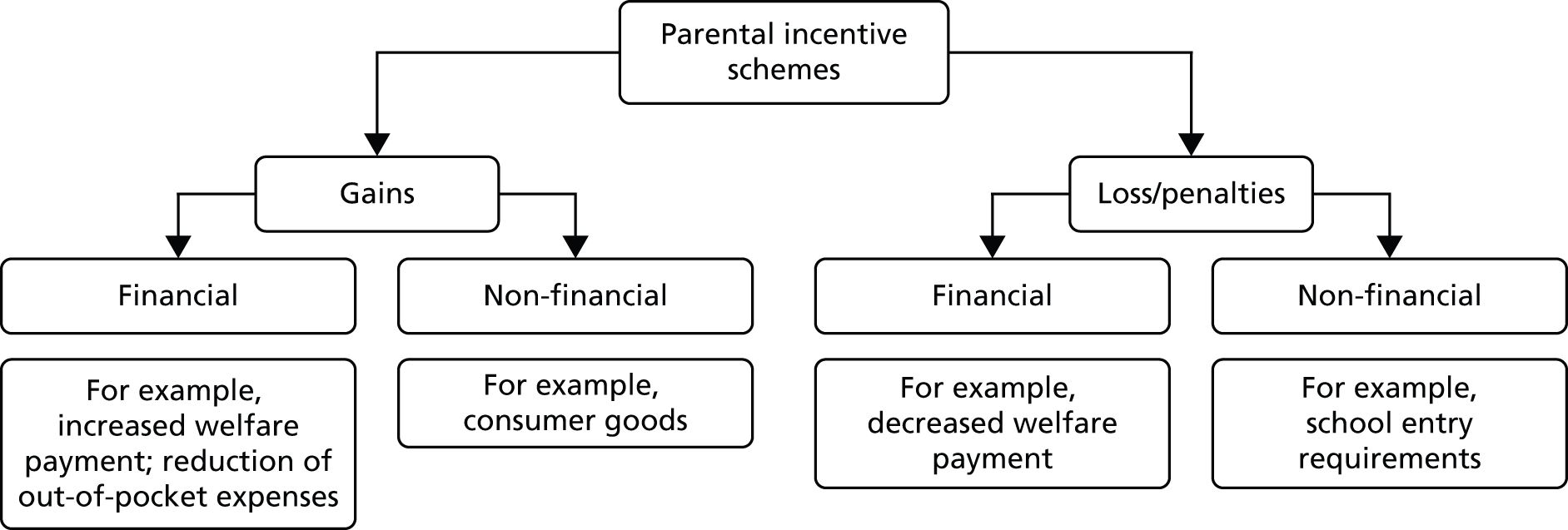

Parental incentive schemes can be further conceptualised using the framework in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework of parental incentive schemes for encouraging the uptake of preschool vaccinations.

Theory of health-promoting incentives and parental incentive schemes for preschool vaccinations

Parental incentive schemes are grounded in both psychological and economic theory.

Operant learning theory describes how behaviours can be modified by association of behaviour with rewarding and punishing stimuli. 19 A rewarding incentive that is provided contingent on performance of a behaviour, such as vaccination, would be expected to increase the behaviour by acting as a positive reinforcement. Similarly, a penalty that is associated with behavioural non-performance would also be expected to increase behaviour.

However, as has been previously described, incentive schemes may be more complex than ‘simply’ providing positive and negative behavioural reinforcers. 20 For example, in order for an incentive to be given (or imposed), there must be clear monitoring of behaviours to ensure that the conditions for receiving the incentive have been met. This monitoring could be self-monitoring, or it could be done by professionals – a process which would be expected to increase contact with professionals. Both self-monitoring and increased contact with professionals might be expected to have a positive impact on behaviour, independent of any effect of the incentive itself. 20,21

The economic concept of ‘time preference’ and the related psychological concept of ‘time perspective’ suggest that one important reason for not engaging in health-promoting behaviours is that the rewards and benefits of these behaviours are often delayed and uncertain, while the costs and harms are immediate and certain. 22 When this is coupled with the consistent human preference for immediate (vs. delayed) rewards and benefits, or cost and harm avoidance, the result is that many healthy behaviours are avoided. 23,24 For example, taking a young child to be immunised often involves a certain outcome of inflicting pain on the child today (i.e. a harm) for a gain in health, through disease avoidance (i.e. a benefit) that is uncertain and may be realised only after many years. Most parents, when temporally distant from both options, will value the long-term health benefit of avoiding life-threatening diseases in their children more than the pain avoided by not taking them for the vaccination. However, when faced with the immediate choice between inflicting pain and not, the immediate benefit, or harm avoided, is preferred and the vaccination is avoided. This suggests that one way of promoting healthier behaviours would be to change the temporal pattern of benefits and harms associated with them, for example by attaching an immediate reward, or incentive, to behavioural performance. 25,26

A number of theoretical concerns with the use of health-promoting incentives have also been raised. It has been suggested that providing extrinsic motivators, such as incentives, for behaviour change erodes internal motivation. The driver of behaviour becomes the incentive, rather than any personal desire to perform the behaviour or achieve the health outcome. 25,27 The expected effect of this is that any behaviour change achieved by introduction of an incentive would be unlikely to persist after the incentive is withdrawn. Incentives may also erode self-efficacy:28 an individual’s belief in their ability to perform a behaviour. This is a well-documented determinant of successful behaviour change. 29 It is possible that attaching an incentive to successful behaviour change substantially increases the costs of failure, making those who have failed on one occasion less likely to believe they can successfully achieve the change and so less likely to try again. Both of these issues may be less important for behaviours like vaccination that do not require sustained behaviour change.

Previous research on the effectiveness of health-promoting incentives

Despite this theoretical support for the use of incentive schemes, empirical evidence of their effectiveness is mixed.

Conditional cash transfer schemes that require performance of health-promoting behaviours are widespread in low- and middle-income countries. These schemes can supplement household income by up to 20%,30 are generally targeted at families with young children, and require behaviours such as regularly attending antenatal care, vaccination of children and regular school attendance. A recent Cochrane review reported that such conditional cash transfer schemes in low-income countries are generally successful in improving clinic attendance and the uptake of vaccinations. 31 This has prompted interest in health-promoting incentives in high-income countries. 32–34

One systematic review and meta-analysis described ‘overwhelming evidence of positive effect’ for financial incentives for abstinence among substance users,35 and this is supported by a further systematic review and meta-analysis. 36 However, both analyses highlight that the long-term effects of such incentives are not clear and that there is evidence of effects decreasing over time and after incentives are withdrawn – although it should be noted that this is the case with many public health and behaviour-change interventions. This conclusion is supported by a Cochrane review on the use of incentives to promote smoking cessation. 37 Similarly, two systematic reviews found short-term effects of financial incentives in promoting weight loss, but less evidence of long-term benefits. 38,39

The benefits of incentives are clearer when they are used to promote shorter-term, or one-off, behaviours such as attendance for screening, or supervised treatment. 28,40 A number of authors have concluded that, in high-income countries, incentives may be useful in promoting ‘simple’ one-off behaviours, but that their use in achieving more ‘complex’, long-term behaviour change may be minimal. 25,28,30,34

Attendance for preschool vaccinations is a series of discrete behaviours over a time-limited period. As such, it is the type of behaviour that would be expected to be responsive to incentives.

Previous research on the effectiveness of parental incentive schemes for preschool vaccinations

Previous research on the effectiveness of parental incentive schemes for increasing uptake of preschool vaccinations is considered according to the conceptual framework in Figure 1.

Financial and non-financial gains

In practice it can be difficult to separate financial and non-financial gains, as these have often been used in combination. For example, in 1998, Australia introduced legislation linking two welfare payments to preschool vaccinations. The Maternity Vaccination Allowance is a means-tested payment of AU$200 (£132; 75% of mothers are eligible) provided conditionally on children’s vaccinations being up to date by their second birthday. This is a direct financial gain. All families in Australia are also eligible for Child Care Benefit of AU$22–130 (£15–86) per week, which is given in part payment for child care costs dependent on children having up-to-date vaccinations. 41 As the benefit is child care costs, rather than straightforward cash-in-hand, this can be considered a non-financial gain. Within 2 years of the introduction of both payments, coverage among 2-year-olds in Australia increased from 80% to 94%. However, it is difficult to separate the differential effects of the two components of this programme.

In the USA, one study found that giving tickets for a lottery to win a US$50 (£32) grocery voucher in exchange for vaccination increased uptake in preschool children. Another study found that tickets for a lottery to win cash prizes of up to US$100 (£65) also had a small positive effect. 42 However, US$10 (£6) gift certificates for nappies and shoes given in exchange for attendance for vaccinations did not lead to statistically significant increases in coverage. 43

It would be expected that larger value and more certain rewards (e.g. cash) would be more effective than smaller and less certain ones (e.g. a lottery ticket). However, few, if any, studies in this area have justified the value, or type, of incentive offered or explored the relative effectiveness of different values, or types, of incentive. Similarly, it might be expected that financial incentives would be more effective in individuals living in more deprived circumstances. Again, few studies have explored the differential effect of incentives according to socioeconomic position.

Financial losses

Two studies have explored the use of welfare-linked financial penalties for failing to keep children’s vaccinations up to date. One study in Maryland, USA, imposed a US$25 (£16) monthly penalty on parents receiving welfare payments who did not vaccinate their children. 44 The intervention had no effect on coverage rates, but this may be because other benefits increased in response to the penalty, resulting in an average overall loss of only US$10 (£6) per month. In Georgia, USA, a similar intervention, where all benefits relating to the child in question were lost (value not stated), had a significant positive impact on coverage rates. 45 It is possible that these divergent findings are explained by differences in the actual value of the loss incurred in the different programmes. But, as above, the minimum level of effective loss has not been justified or explored by any authors.

Non-financial losses

The only non-financial loss incentives that have been studied in relation to preschool vaccinations are school enrolment requirements. In their systematic review of studies from industrialised countries, Briss et al. 16 concluded that ‘sufficient scientific evidence exists that vaccination requirements for child care, school and college attendance are effective in improving vaccination coverage and in reducing rates of disease’. This is supported from findings from an evidence analysis commissioned by NICE. 46 Both reviews included studies with a range of both vaccination and disease outcomes suggesting that the conclusion is not limited to any one type of vaccination. However, except for one study based in Canada, all of the studies were conducted in the USA, making them of limited relevance to a UK setting. There is also some evidence that such programmes can reduce inequalities in the uptake of vaccinations. 18

Previous research on acceptability of health-promoting incentives

The acceptability of health-care interventions has a number of dimensions and must be considered from the viewpoint of a number of stakeholder groups, particularly the target population, professionals involved in intervention delivery, and policy-makers responsible for intervention implementation. In order for any health-promoting intervention to be effective in practice, members of all stakeholder groups must be both willing and able to engage with it. 47

The best overall measure of acceptability of an intervention is probably take-up of that intervention (i.e. revealed acceptability). 48 However, this requires that interventions are already in place and is unable to distinguish between acceptability among different stakeholder groups. Thus, uptake might be low because the target population are unwilling to engage with an intervention, or because professionals are unwilling to deliver it. Overall uptake rates may also be confounded by factors that limit access to services and have little to do with acceptability. In a context where interventions have yet to be implemented, and in order to differentiate between acceptability among the different stakeholders, the views (i.e. stated acceptability) of relevant stakeholders must be captured. This can be done using in-depth qualitative methods or quantitative survey methods. Both are likely to yield important insights.

Health-promoting incentives have been described as ‘coercive’. 49 This is seen by some not only as ethically questionable but also, given that poorer individuals may be more receptive to financial incentives, as socially divisive. 50 There is also a potential and, in some cases, actual, risk of incentives designed to promote healthy behaviours perversely creating incentives to pursue less healthy behaviours. 25 For instance, the introduction of a cash transfer, conditional on attendance for antenatal care, in Honduras was associated with an increase in the birth rate. 30

In one study exploring stated acceptability of financial incentives versus hypothetical injections or tablets of equal effectiveness, incentives were rated as universally less acceptable and less fair by respondents in both the UK and the USA. 51 However, media coverage of health-promoting incentives in the UK is generally more positive, with only 13% of articles published in the popular and medical press on this topic during 2005–10 being entirely unfavourable. 52

Previous research on acceptability of parental incentive schemes for preschool vaccinations

Few studies have explored views around acceptability of parental incentive schemes for increasing uptake of preschool vaccinations. One study in the early 1990s (before the MMR controversy53 began) found that the majority of a small sample of UK primary school head teachers would be willing to ask about vaccination status at school enrolment and to recommend that children were fully immunised. 54 The issue of making enrolment contingent on full vaccination was not explored. A more recent study, conducted after the MMR controversy, found that parents and health visitors from the London area were not generally supportive of linking welfare payments to vaccination or restricting school entry to those who were fully immunised, as they felt that this undermined parental choice. 55

Conclusions and unanswered questions

There are empirical and theoretical reasons to believe that parental incentives may be effective as a method of increasing uptake of preschool vaccinations. Fewer studies have explored acceptability, and evidence on this is more mixed. Although a number of reviews have explored the use of parental incentives for increasing uptake of preschool vaccinations,16,40,46 no recent systematic review has explored the effectiveness, acceptability, and economic costs and consequences of such interventions in high-income countries. Furthermore, little attention has been paid to how both effectiveness and acceptability of parental incentives varies according to the characteristics of these schemes and their recipients – including incentive value (both absolute or relative to income), incentive type (e.g. cash or voucher, certain or uncertain reward), how such incentive schemes are organised and delivered (e.g. what other behavioural-change techniques are used alongside incentives) – or how acceptability and effectiveness interact. For example, it is possible both that more effective incentive schemes are more acceptable, and that the value of incentive required to make a scheme effective is considered unacceptably large and coercive.

This project comprised three distinct, but interlinked, stages: a systematic review of existing work exploring the effectiveness, acceptability and balance of economic costs and effects of parental incentive schemes for increasing uptake of vaccinations in preschool children; a qualitative study further exploring the stated acceptability of such schemes among a range of key stakeholders, including particular components that are and are not acceptable and what can be done to improve acceptability; and a DCE to establish the relative preferences for, and likely uptake of, a range of different vaccination strategies among parents and carers of preschool children. The results of the systematic review informed the qualitative study, and the results of both the systematic review and qualitative study informed the DCE.

Chapter 3 Systematic review

A systematic review of existing research evidence on the effectiveness, acceptability and economic costs and consequences of parental incentive and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing uptake of vaccinations in preschool children in high-income countries, compared with usual care or no intervention, was conducted.

Research questions

The systematic review aimed to answer the following research questions:

-

What is the existing evidence on parental incentive and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing uptake of vaccinations in preschool children in high-income countries, compared with usual care or no intervention, in terms of:

-

effectiveness

-

acceptability

-

economic costs and consequences?

-

This work has been described in a manuscript published in Pediatrics. 56 A condition of the licence for reproduction of substantial components of that article is that the full manuscript is reproduced, word for word, in full. This chapter is, therefore, reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, Vol. 134, Pages e1117–28, Copyright © 2014 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Introduction

Childhood vaccination programmes form a core component of public health strategies worldwide, and have been highly effective in reducing the incidence of, and morbidity and mortality from, a range of infectious diseases. 57

The WHO has a goal of 90% coverage for all vaccinations, with 95% coverage for measles and diphtheria. Coverage rates in the UK and USA approach or exceed the WHO targets for most preschool vaccinations. 58 However, coverage rates also vary substantially within countries with high overall coverage. For example, DTaP coverage at 19–35 months in the USA varies from 77% in Idaho to 91% in Connecticut. 59

Factors identified as contributing to variation in vaccination coverage fall into the categories of sociodemographic, attitudinal and health care. Parents living in less affluent circumstances, who lack trust in health-care professionals, have limited access to health care or believe that the disease protected against is not serious, are less likely to have vaccinated children. 5,6,8 Other factors related to uptake include concerns over pain, safety and side effects; access to transport and child care; and a lack of familiarity with vaccination schedules. 5,6

Financial incentives have been successfully used to promote uptake of vaccinations in developing countries,31,60 but are not always viewed as acceptable. Criticisms include that they are socially divisive and coercive. 49 However, recent work has found that financial incentives can be acceptable given that the problems addressed are perceived to be serious, other interventions ineffective, and the behaviours required particularly difficult to achieve. 51,52 Quasi-mandatory policies, such as requiring vaccinations for school enrolment (‘quasi’ because parents can exempt their child on e.g. philosophical or religious grounds), are widely implemented in some countries (e.g. the USA), and have the potential to have large impacts on families and communities, in terms of both vaccination rates achieved and education lost. They have also been reported to be effective in some cases. 61

However, to date, no existing systematic review has comprehensively explored the effectiveness of parental financial incentive and quasi-mandatory interventions in high-income countries. Similarly, there is a lack of existing review-level evidence on the cost-effectiveness and acceptability of these interventions.

One existing systematic review explored the effectiveness of financial incentives for the uptake of all healthy behaviours, including vaccinations, in low- and middle-income countries. 31 Given the substantially different resource and health-care settings in high- and middle- versus low-income countries, findings cannot be assumed to be generalisable. Two previous reviews on methods for increasing vaccination uptake have included sections on financial incentives, but neither focused on preschool children in particular. 16,62 There are many reasons why individuals may act differently for themselves than for their children, and findings on offering incentives to adults to vaccinate themselves are not necessarily generalisable to the context of offering incentives to parents to vaccinate their children. Furthermore, only one of these previous reviews was systematic and studies were included only up to 1997 – more than 15 years ago. 16

In order to fill this evidence gap, a systematic review of existing research evidence on the effectiveness, acceptability and economic costs and consequences of parental incentive and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing uptake of vaccinations in preschool children in high-income countries, compared with usual care or no intervention, was conducted.

Methods

The review was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) before searches commenced (registration number CRD42012003192). There were no substantive deviations from protocol. The review is presented in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidance. 63

Inclusion criteria

One systematic review was performed, which had three parallel components: effectiveness, acceptability and economic. Studies that met the criteria for either the effectiveness or the acceptability components were screened for inclusion in the economic component. Throughout, parental incentive and quasi-mandatory schemes were defined as ‘interventions that increase demand for vaccinations by offering contingent rewards or penalties with real material value; or that restrict access to universal goods or services’. The inclusion criteria for all three components are summarised in Table 2. No studies were excluded on the basis of language. Relevant articles were translated locally as required.

| Component | Effectiveness component | Acceptability component | Economic component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Parent of preschool children living in high-income countriesa | Member of any relevant stakeholder group living in high-income countriesa | Included in either of the other components |

| Intervention | Interventions that increase demand for vaccinations by offering contingent rewards or penalties with real material value; or quasi-mandatory schemes that restrict access to ‘universal’ goods or services | Interventions that increase demand for vaccinations by offering contingent rewards or penalties with real material value; or quasi-mandatory schemes that restrict access to ‘universal’ goods or services | Included in either of the other components |

| Comparator | Usual care or no intervention | Usual care or no intervention | Included in either of the other components |

| Outcome | Uptake of preschool vaccinations | Acceptability of the intervention | Economic costs and consequences of the intervention to parents or society |

| Study design | RCTs, cluster RCTs, controlled before-and-after studies, time series analysesb | Any study design | Included in either of the other components |

Information sources

The following databases were searched: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts, International Bibliography for the Social Sciences, PsycInfo, MEDLINE, Web of Science, EMBASE, Education Resources Information Center, Health Economic Evaluations Database and The Cochrane Library (see Appendix 1 for an example search strategy). The reference lists of studies meeting the inclusion criteria, and relevant reviews16,40,62 were searched for additional publications, and citation searches of studies meeting the inclusion criteria were run in the Science and Social Science Citation Indices. Grey literature was searched via e-mails sent to relevant online discussion groups and entry of the formal search strategy terms into GoogleTM (Mountain View, CA, USA; www.google.com). When both an internal report and a peer-reviewed paper on the same study were retrieved, peer-reviewed findings were favoured, but additional information from reports was used where relevant. Searches were carried out in February 2013, with no limits on earliest date of searches (i.e. database inception to February 2013).

Study selection

The initial screening of titles and abstracts was conducted by SW. Full texts were screened independently by two researchers (SW and JA) against the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Where publications lacked the details required for a decision, the authors were contacted for further details.

Data collection and data items

A data extraction form was developed to record data on nature and location of study participants, age and gender of children involved, time period, socioeconomic status of participants, type of intervention, study design, comparator, vaccination and results. Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (SW and JA), with consensus reached by discussion. To allow comparisons, values of financial incentive were converted to their equivalent commodity real-price value in US$ in 2012, the latest date for which data were available when searches were conducted. 66

Information on economic costs and consequences in all papers was assessed by a health economist (LT). This focused on whether or not studies reported the cost of delivering the incentive and the consequences of undertaking, or not undertaking, the desired activity. Methods for the review of the economic evidence followed those set out by the Cochrane and Campbell Collaborations. 67

Risk of bias

The quality and risk of bias of all studies meeting the inclusion criteria were independently assessed by two researchers (SW and JA). Quantitative studies were assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, which has acceptable test-retest and construct validity. 68 Qualitative studies were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist. 69 Methods derived from Campbell and Cochrane Economic Methods Group were used to assess the quality of studies in the economic component. 67 Quality ratings were used to inform the approach to synthesis.

Synthesis of results

A narrative synthesis was performed throughout. Within the narrative synthesis, interventions were described using an existing framework. 70 A meta-analysis was considered for all three components. In the effectiveness component, two studies could, theoretically, have been meaningfully combined in a meta-analysis. 44,45 However, one was at high risk of bias,44 leaving any sensitivity analysis with only one included study. Thus, meta-analysis was not considered appropriate for the effectiveness component.

Studies in the acceptability component were more heterogeneous in design, and meta-analysis was inappropriate. Following recommendations of the Cochrane and Campbell Collaborations, the economic data were not quantitatively synthesised; rather, a narrative synthesis was adopted.

Results

Four studies were identified that met the criteria for inclusion in the effectiveness component,42,44,45,71 six studies were identified for inclusion in the acceptability component72–77 and one study was identified for inclusion in the economic component (Figure 2). 76

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram showing the identification, inclusion and exclusion of studies.

Studies included in the effectiveness component consisted of one cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT),42 two non-clustered RCTs44,45 and one time series analysis. 71 Studies included in the acceptability component were primarily surveys,72,76 including one survey that made use of discrete choice modelling methods,75 with one qualitative study using semistructured interviews77 (Table 3).

| Study | Country | Population | n | Interventiona | Comparator | Outcome(s) | Study design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness component | ||||||||

| Yokley and Glenwick (1984)42 | USA | Preschoolers (aged < 5 years) registered at public health clinic not UTD with vaccinations Mean (SD) age of children = 37.3 (18.2) months; 50% male |

Intervention children, n = 183; control children, n = 191 | Parents sent tickets for cash lottery that could be entered when attended vaccination clinic, with prizes from US$55.20–221 | Usual care | n attending clinic for any reason n attending for vaccination n vaccinations given |

Cluster RCT clustered at family level with follow-up at 2 weeks, 2 months and 3 months | At each follow-up time point, the intervention was associated with significantly more attendance for any reason, attendance for vaccination and number of vaccinations |

| Minkowitz et al. (1999)44 | USA | Welfare claimants from Maryland Children aged 3–24 months; 51% male |

Intervention children, n = 911; control children, n = 864 | Loss of US$38.70 welfare benefits for failing to verify children’s vaccinations | Usual care | UTD for DTaP, polio and MMR | RCT with follow-up at 1 and 2 years | No difference in UTD rates for any vaccinations at 1- or 2-year follow-up |

| Kerpelman et al. (2000)45 | USA | Welfare claimants from Georgia Mean age of intervention children = 3.22 years; 50% male. Mean age of control children = 3.34 years; 48.5% male |

Intervention children, n = 1725; control children, n = 1076 | Loss of welfare benefit, with amount depending on family size and child’s age | Usual care | UTD for DTaP, MMR, polio, Hib and HBV UTD for full series at age 2 years |

RCT with follow-up at 1, 2, 3 and 4 years | At 1, 2, 3 and 4 years, intervention associated with greater uptake of all vaccinations. This difference was significant except for HBV at 1 year and Hib at 1 and 2 years At age 2 years, the intervention was associated with higher series completion |

| Abrevaya and Mulligan (2011)71 | USA | State- and individual-level data on parents from National Vaccination Surveys, 1996–2007 Children aged 19–35 months; 51% male |

324,553 children | Day-care or school entry restricted to those with varicella vaccination | Usual care | Varicella vaccination | Time series analysis from 1 year pre intervention to 7 years post intervention | At state level, mandate effective from introduction to 6 years post introduction, peaking at 2 years post introduction At individual level, mandate was effective from introduction to 5 years post introduction, peaking at 1 year post introduction |

| Acceptability components | ||||||||

| Schaefer Center (1997)76 | USA | Recipients and staff of incentive programme | 1331 | Penalty of loss of US$38.70 from welfare benefits for failing to verify children’s vaccinations | Usual care | Views on interventions | Survey | 73% of recipients thought that the penalty was fair 66.7% of recipients thought that the penalty would motivate parents 73.5% of staff thought that behaviour could be changed by penalties Majority of staff believed that both the threat and the imposition of penalty were effective |

| Freed et al. (1998)74 | USA | District and county health department directors | 75 | State laws allowing school or day-care entry to be restricted, criminal misdemeanour charges to be brought, or injunctions to be filed against parents for not keeping children’s vaccinations UTD | No comparator | Experience of, and views on, intervention | Survey | 100% were aware of their authority to enforce school and day-care restrictions; 83% were aware of criminal misdemeanour charges; 65% were aware that they could file injunctions 99% believed that non-vaccinated children should be restricted from school or day care 83% believed that misdemeanour charges should be brought 5% reported that misdemeanour charges had been brought; 24% had threatened to do so 83% believed injunctions should be filed; none had done so |

| Bond et al. (1999)73 | Australia | Parents of children regularly attending council-run day care in metropolitan area Children aged < 3 years (except 62 who were older); 50% male |

1722 families with 1779 eligible children | Additional welfare payments of AU$29.30–175 per week for child care; plus one off payment of AU$307 if UTD for all vaccinations | No comparator | Views on intervention | Survey | 30% believed that incentives should be given to parents for immunising their child, although ‘many’ believed that the child’s health and not monetary reasons should be the motivator ‘About 30%’ believed that the decision to immunise would not be affected by intervention |

| Bond et al. (2002)72 | Australia | Parents of children regularly attending council-run day care in metropolitan area Children aged < 3 years |

1706 families with 1793 eligible children | Additional welfare payments of AU$29.30–175 per week for child care; plus one off payment of AU$307 if UTD for all vaccinations | No comparator | Views on intervention | Survey | ‘About 30%’ believed that intervention had not influenced their decision to immunise 4% reported that they had kept their children’s vaccinations UTD because they relied on related payments |

| Hall et al. (2002)75 | Australia | Parents of children aged < 12 years 50% aged < 5 years |

50 | School entry restricted to those UTD for all vaccinations | Range of other interventions to promote vaccination | Stated preference for vaccination uptake | Survey; DCM | Most respondents preferred vaccination under most scenarios; 31% chose not to vaccinate in all scenarios. Requiring vaccination for school entry increased vaccination preference from 75% to 92% |

| Tarrant and Thomson (2008)77 | Hong Kong | Parents of children aged 6 months to 3 years receiving secondary health care | 15 | Day-care and school entry restricted to those UTD for all vaccinations | No comparator | Views on intervention | Semistructured person-centred interviews | Day-care and school entry restriction identified as contributing to high vaccination rates, within a system of other contributory factors |

Interventions in included studies comprised proof of vaccination for school or day-care entry,71,75,77 loss of welfare benefits44,45,72,73,76 or the imposition of criminal misdemeanour charges74 for non-vaccination, and entry into a cash lottery for attending for vaccination (Table 4). 42

| Study | Direction | Form | Magnitude (US$ 2012) | Certaintya | Target | Frequency | Immediacy | Schedule | Recipient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness component | |||||||||

| Yokley and Glenwick (1984)42 | Positive reward | Cash lottery | US$55.20–221 | Uncertain chance | Clinic attendance and vaccination uptake | Once | No more than 2 months | Fixed | Parent |

| Minkowitz et al. (1999)44 | Avoidance of penalty | Welfare benefits | US$38.70 | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Reassessed 6-monthly | Written warning prior to sanction | Fixed | Parent |

| Kerpelman et al. (2000)45 | Avoidance of penalty | Welfare benefits | Variable | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Reassessed 6-monthly | Oral or written warning prior to sanction | Fixed | Parent |

| Abrevaya and Mulligan (2011)71 | Avoidance of penalty | Day-care or school entry | Loss of education | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Unclear | Unclear | Fixed | Parent and child |

| Acceptability component | |||||||||

| Schaefer Center (1997)76 | Avoidance of penalty | Welfare benefits | US$38.70 | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Reassessed 6-monthly | Written warning prior to sanction | Fixed | Parent |

| Freed et al. (1998)74 | Avoidance of penalty | Day-care or school entry; criminal charges; parental injunctions | Loss of education, loss of parental freedom | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Unclear | Written warning prior to sanction | Fixed | Parent and child |

| Bond et al. (1999)73 | Avoidance of penalty | Welfare benefits | AU$29.30–175, plus one-off payment of AU$307 | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Weekly | Unclear | Fixed | Parent |

| Bond et al. (2002)72 | Avoidance of penalty | Welfare benefits | AU$29.30–175, plus one-off payment of AU$307 | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Weekly | Unclear | Fixed | Parent |

| Hall et al. (2002)75 | Avoidance of penalty | School entry | Loss of education | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Unclear | Unclear | Fixed | Parent and child |

| Tarrant and Thomson (2008)77 | Avoidance of penalty | Day-care or school entry | Loss of education | Certain | Vaccination uptake | Unclear | Unclear | Fixed | Parent and child |

Risk of bias within studies

Of the studies in the effectiveness component, three were at a low risk of bias,42,45,71 while the fourth was at a strong risk of bias. 44 All of the quantitative studies in the acceptability component were at a strong risk of bias, and, in particular, were weak on study design and on data collection methods (Table 5). The qualitative study in the acceptability component77 lacked details of recruitment and assignment of patients to intervention groups, justification of data collection methods, and adequate discussion of reflexivity and how data saturation and contradictory data were dealt with.

| Author | Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection | Withdrawals | Global rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness component | |||||||

| Yokley and Glenwick (1984)42 | |||||||

| Minkowitz et al. (1999)44 | N/A | ||||||

| Kerpelman et al. (2000)45 | |||||||

| Abrevaya and Mulligan (2011)71 | N/A | ||||||

| Acceptability component | |||||||

| Schaefer Center (1997)76 | |||||||

| Freed et al. (1998)74 | N/A | N/A | |||||

| Bond et al. (1999)73 | N/A | N/A | |||||

| Bond et al. (2002)72 | N/A | ||||||

| Hall et al. (2002)75 | N/A | N/A | |||||

Effectiveness component

All studies in the effectiveness component were set in the USA.

Individual- and state-level data from the US National Vaccination Survey were used to conduct an interrupted time series study of the effects of school and day-care entry mandates on uptake of varicella vaccination in preschool children. 71 Significant effects were seen in the year of mandate introduction at both individual and state level. At both state and individual level, mandates were associated with a 2.6%-point increase in vaccination uptake in the first year. The effects at the state level peaked 2 years after introduction and were extinguished by 6 years. At the individual level, the effects peaked at 2 years post mandate and were extinguished by 5 years.

A cluster RCT of children who were not up to date with DTaP, polio or MMR vaccinations compared a cash lottery ticket incentive (combined with a vaccination prompt) with a no-intervention control. 42 The cash lottery ticket incentive (US$55.20–221 in 2012 USD), and postal prompt advising that the lottery could be entered on attendance at the clinic, was associated with a significant 21% increase in numbers of vaccinations received, compared with control. The effect persisted to at least 3 months after the incentive expired, with a 31.6% increase in number of vaccinations received, compared with control.

In a RCT of families in receipt of welfare benefits, no effect was found from a penalty of US$38.70 (in 2012 USD) for failing to have a child vaccinated for DTaP, polio and MMR. 44 However, those who were penalised tended to have more children, qualifying them for extra welfare benefits, and this may have reduced the financial impact of the penalty. 44,76

A RCT found significant effects of cutting welfare benefits when children were not up to date for five preschool vaccinations. 45 Significantly more of the intervention (72.4%) than the control (60.6%) group achieved vaccination series completion. The authors note that parents rarely lost benefits and the threat, rather than the imposition, of the penalty appeared to be sufficiently incentivising.

Acceptability component

Of the six studies included in the acceptability component, three were conducted in Australia,72,73,75 two in the USA74,76 and one in Hong Kong. 77

Two studies were based on the Australian government’s incentive schemes introduced in 1998 linking child care subsidies to vaccination, collecting data before and after introduction of the scheme. 72,73 Prior to the introduction of the scheme, only 30% of respondents said that incentives should be given to parents for immunising their children, with many saying that health promotion rather than finance should be the motivation for vaccination, and that education could encourage this. 73 In the follow-up study, only 4% of parents reported child care benefits as motivating them to keep their children’s vaccinations up to date. 72

Hall et al. 75 used stated preference discrete choice modelling to predict the optimal characteristics of a preschool varicella vaccination programme. Survey data collected from parents indicated that requiring vaccination for school entry was associated with a greater preference for vaccination uptake.

Freed et al. 74 describe North Carolina’s statute requiring age-appropriate vaccination for school and day-care entry that allows criminal misdemeanour charges and injunctions to be brought against non-compliant parents. County health directors, whose decision it was to implement criminal statutes, were interviewed on their attitudes towards the statute. Most respondents (83%) believed that criminal charges should be brought, but only 5% were aware of this ever being done, and none had filed an injunction themselves. Most respondents (99%) agreed that children should be excluded from school or day care if they were not up to date with vaccinations. There was some belief that using a criminal law in this context was too expensive, excessively punitive and politically inadvisable, and that this explained the low enforcement rates. Some felt that clarification of the charges and process of parent warnings would help enforcement.

Only one qualitative study was included in the acceptability component. 77 Parents in Hong Kong, where vaccination uptake is high, were interviewed to identify factors which encourage this high uptake. Content analysis identified mandatory vaccination for child care and school entry as one important factor in a system of other vaccine-related services. Cultural and contextual factors found to be important included the relative importance of society versus individualism, trust of health professionals, and the high population density of Hong Kong increasing perceived susceptibility to infectious diseases.

In a survey of administrators and staff involved in delivery of a welfare benefit penalty for non-compliance with health behaviours, including vaccination of preschool children,76 70% agreed that behaviour could be changed by the intervention. Of these, 14% said that the penalties were very powerful and 28% said they were effective only when imposed, rather than just threatened. Recipients of the intervention reported that the penalty was fair (73%) and would motivate parents to meet health requirements (67%).

Economic component

Of the four studies included in the effectiveness component, none provided detailed information on the consequences of undertaking, or not undertaking, the desired activity. No study conducted a formal economic evaluation of the incentive scheme.

Only one of the studies included in the acceptability component included economic information on costs and consequences in the format of a cost–benefit framework. 76 As no evidence of effectiveness of the programme was found, the authors concluded that the costs of implementing the programme outweighed the benefits.

Discussion

Summary of findings

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to explore the effectiveness, acceptability and economic costs and consequences of parental incentive and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing uptake of preschool vaccinations in high-income countries. Few studies were found that met the inclusion criteria. There was substantial heterogeneity across studies in terms of both interventions and methods.

There was insufficient evidence to conclude whether or not parental financial incentives and quasi-mandatory interventions are effective for encouraging the uptake of preschool vaccinations. Interventions and evaluation were heterogeneous and results were inconsistent. One study at a low risk of bias did find short-term effects of quasi-mandatory interventions linking vaccinations to education, but the effects were extinguished by 6 years after introduction of mandates. Studies also found that these mandates were particularly acceptable, although the risk of bias in relevant studies was high and they were conducted in contexts where such interventions were the norm. There was insufficient evidence to draw generalised conclusions on the economic costs and consequences of these interventions.

Comparison of results to previous reviews

Previous reviews that have included work on these topics have had much wider scopes in terms of interventions, outcomes and populations considered. A systematic review commissioned by NICE explored the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of all types of interventions for increasing the uptake of preschool vaccinations. 62 Only two studies included in the current review44,45 overlapped with studies in the NICE review. Other studies identified in the NICE review as ‘incentives’ did not meet our definition, as they either involved changing the frequency of attendance for welfare benefits but not the level of benefit itself78–80 or did not involve incentives with real material value. 81 Similar to the current review, the NICE review concluded that incentives could be effective but that the strength and quality of the evidence varied and cost-effectiveness data were insufficient.

Briss et al. 16 reviewed a range of interventions to improve vaccination coverage across all ages using non-systematic methods. Similar to the current work, they concluded that there was some evidence to support the effectiveness of day-care and school entry mandates across all ages (not just preschool children), but insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of family incentives. Economic evidence was also limited.

Kane et al. 40 conducted a structured, but not systematic, review of the effectiveness of financial incentive interventions for uptake of a range of preventative health behaviours. She reported that these were most effective for short-term goals, such as vaccinations. However, this included vaccinations across all ages, not just in preschool children. It is possible that the effects of financial incentive interventions on uptake of vaccinations are different when considering incentives given directly to adults for receiving a vaccination themselves, compared with incentives given to parents for having their child vaccinated.

Strengths and limitations of included studies

Studies included in the effectiveness component tended to be at a low risk of bias, while those in the acceptability component were at a higher risk of bias. This reflects the cross-sectional survey designs in the acceptability component.

There was a lack of reported theory underpinning the design of interventions in included studies. Given the complexity of financial incentive interventions,70 more consideration of behaviour-change theory may help to guide the development of effective interventions.

There were a number of reports in included studies of threatened penalties not being imposed and belief that the threat of a penalty is sufficient for behaviour change. 76 This raises a number of important questions concerning intervention fidelity, and the effective component(s) or financial incentive interventions that should be explored further.

This is the first systematic review we are aware of that considered the acceptability of financial incentive and quasi-mandatory interventions. Only one of six included studies used qualitative methods. Further, in-depth, exploration of the acceptability of financial incentive, and quasi-mandatory, interventions to a range of stakeholders is required.

Those studies which found school entry mandates to be acceptable were conducted in settings in which these mandates were already common. The threat of withholding education from children may be less acceptable in other settings and this should be explored further. 55

Strengths and limitations of the review

Throughout, established criteria and protocols were used to inform methods and reporting. 63,65 This led to the exclusion of a number of studies that have been included in previous reviews. 16,40,62 In particular, we excluded uncontrolled before-and-after studies that are relatively straightforward to carry out using routine data. However, the lack of a control group makes it particularly difficult to infer causation from these studies.

A clear definition of parental incentive and quasi-mandatory interventions was also used,70 leading to the exclusion of interventions that have previously been considered incentives. In particular, we excluded studies related to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Programme for Women, Infants and Children in the USA,78–80 which offers low-income families vouchers that can be exchanged for nutritious food. Normally, enough vouchers for 3 months are provided per attendance at the programme. Under a vaccination initiative, families received only 1 month of vouchers at a time until their children’s vaccinations were up to date. As the absolute number of vouchers families were eligible to receive did not change, we did not consider this a financial incentive. Although it is always possible that studies that met the inclusion criteria were not found, this is unlikely given the exhaustive searching process used.

There was considerable heterogeneity across studies included in the effectiveness component in terms of intervention and methodology such that a meta-analysis was not considered appropriate. 44,45 This highlights the potential heterogeneity of financial incentive and quasi-mandatory interventions. 70 A more considered approach to intervention design may be required to begin to establish what configurations of financial incentive interventions are likely to be most effective in a range of different circumstances.

We attempted to describe the characteristics of interventions used in included studies. However, some details were missing and unobtainable from study authors. Such description of the complex components of incentives has been missing in previous research and this limits meaningful comparisons across studies. 70

Interpretation of findings and implications for policy, practice and research

Any interventions to increase the uptake of health-promotion behaviours need to be both effective and acceptable for widespread implementation. Consistent evidence that parental financial incentive and quasi-mandatory interventions are effective in encouraging uptake of preschool vaccinations was not found; the available evidence base was small, with substantial heterogeneity in both interventions and methods. Thus, it is not clear whether or not these interventions are effective and, if so, in what circumstances.

Despite this absence of evidence, quasi-mandatory schemes limiting school entry to those children who are up to date with required vaccinations are common in some countries, particularly the USA. Although such programmes may be effective, without robust evaluation it is difficult to conclude this, or justify any associated cost, or advocate for the expansion of such programmes to other vaccinations or countries.

Parental financial incentives and quasi-mandatory interventions for encouraging the uptake of preschool vaccinations are likely to be implemented on a large scale. This can make evaluation difficult. Creative evaluation strategies such as natural experiments and step-wedge designs may be most useful in these contexts. 82

Intervention development work, taking into account existing behaviour-change theory, may also be useful to develop more effective incentive interventions. This should involve further consideration of the effective component, or components, of financial incentive interventions. Strategies such as multiphase optimisation strategy may be particularly helpful in this context. 83

All of the studies included in the review were conducted in countries that tend to achieve overall high coverage of preschool vaccinations. Although pockets of poor coverage exist in these countries, population-wide interventions such as parental incentives and quasi-mandatory interventions may not be adequately targeted to those families that require the most assistance. Furthermore, these interventions may not adequately address the reasons for non-vaccination – including mistrust of health-care professionals, limited access to health care, chaotic lifestyles and low perceived susceptibility to and severity of vaccinated diseases. 5,6,8 Further consideration of reasons for non-vaccination should be taken into account when designing new interventions for promoting vaccination.

Overall, these interventions were not considered to be clearly unacceptable by any stakeholders. However, neither did parents report that financial incentives were particularly motivating in this context, and quasi-mandatory policies appeared to be considered more appropriate. However, only one study used an in-depth qualitative approach. 77 Furthermore, few studies appeared to make specific attempts to capture the views of parents with unvaccinated children. Further, in-depth, qualitative analysis is required to explore what aspects of these interventions are and are not acceptable, to whom, and why.

In addition, it is likely that acceptability is, at least partly, dependent on perceptions of effectiveness. This suggests that if high-quality evidence of effectiveness is generated, and then effectively communicated to the public, good levels of acceptability are likely to follow. Better understanding of how to effectively communicate research findings to the public would be valuable.

Although the acceptability of restricting day-care or school entry to vaccinated children appeared to be high, all studies reporting this were conducted in settings where these restrictions are already the norm. Only one study of the effectiveness of such quasi-mandatory policies was included in the effectiveness component, finding that these policies were effective for up to 5 years after introduction. 71 Such policies clearly have potential in countries where they do not currently exist. But effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability in new contexts need to be considered further across a range of stakeholders, using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Discrete choice experimental methods may be particularly useful.

Conclusions

This systematic review of the effectiveness, acceptability and economic costs and consequences of parental financial incentives and quasi-mandatory interventions to increase the uptake of preschool vaccinations identified a very limited evidence base in all areas. There is insufficient evidence to conclude whether or not these interventions are effective, although mandates limiting access to education to vaccinated children may be effective for up to 6 years post intervention. There was some evidence that quasi-mandatory interventions linking vaccinations to education were also the most acceptable interventions considered, although the risk of bias in these studies was high and this finding may be specific to contexts where such interventions are widespread. There was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions on the economic costs and consequences of these interventions.

Chapter 4 Qualitative study

A series of qualitative focus groups and individual interviews was conducted with a range of stakeholders (including parents, health and other relevant professionals, and policy-makers). This work drew on the systematic review by discussing with participants examples of parental incentives schemes identified in the review and focusing on issues of acceptability identified as understudied.

Research questions

The qualitative study aimed to answer the following questions:

-

What are stakeholders’ views, wants and needs concerning interventions to promote the uptake of preschool vaccination programmes?

-

Would parental incentive or quasi-mandatory schemes for encouraging uptake of preschool vaccinations be viewed as acceptable?

-

If not, why not?

-

If not, what, if anything, could be done to make such schemes more acceptable?

-

This study is presented in accordance with COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) guidance. 84

Methods

In this phase of the study we were keen to build on the results of the systematic review (much of which relied on non-UK studies) by exploring the acceptability of introducing financial incentives schemes or quasi-mandatory schemes for preschool vaccinations in a UK context. This part of the study used a qualitative approach to gather data about the views, wants and needs of parents as well as health and other professionals in relation to preschool vaccinations and their uptake; and the theoretical introduction of financial incentives or quasi-mandatory schemes to increase uptake of preschool vaccinations. A mixture of focus groups (parents) and semistructured individual interviews (health and other professionals) was undertaken to gather data for analysis.

We sought to answer two primary research questions, as described above. The research questions were both informed by extensive engagement with empirical literature and UK policy guidance.

Inclusion criteria

We attempted to capture the views of stakeholders, who we defined either as people who would be in receipt of such schemes (parents and carers of preschool children) or as those who would have a role either in creating such policies or commissioning and implementing the schemes (health and other professionals).

Parents and carers of preschool children

Parents and carers of preschool children would be the intended recipients of any parental incentives scheme. It is therefore crucial to capture their views in order to determine the acceptability of any proposed scheme. We were interested in hearing the views of both immunisers and partial or non-immunisers.

Health and other professionals

It is important to pay attention to the views of those professionals who could be involved in developing, commissioning and delivering preschool vaccinations and any change to the current system. These professionals include policy-makers, practice nurses, health visitors, GPs, community paediatricians and school teaching staff. Although, in England and Wales, preschool vaccinations are normally administered by practice nurses at a GP practice, other professionals have a role in the success (or otherwise) of the vaccination programme. Health visitors, GPs and community paediatricians have a key role in advising parents about the benefits of vaccinations and could have a role in administering any parental incentive scheme. Similarly, primary school staff may be required to administer any parental incentive scheme that is based around school enrolment. If any such scheme is not acceptable to those who deliver and administer it, it is unlikely that the scheme would be delivered to a high standard.

Sampling

Parents and carers of preschool children

No sociodemographic factors were found to be particularly associated with parental acceptability or effectiveness of parental incentive schemes in the systematic review. Accordingly, these were not specifically used to guide purposive sampling of parents and carers of preschool children. Instead, factors known to be associated with uptake of preschool vaccinations more generally5,7,10,11 were used to guide purposive sampling. A sampling frame was devised to capture the views of a demographic mix of parents and also, on the advice of the steering group, to include the views of parents both from a geographical subarea that had experienced a measles outbreak in 2012–13 and another which had not. We identified these areas in consultation with several members of the steering group and after perusal and discussion of the epidemiological data. We were interested to see whether or not greater familiarity with a recent disease outbreak would affect responses. We hoped to recruit both immunisers and partial or non-immunisers in these community samples. Parents were all resident in the north-east of England, with the no-measles-cases area being located in the northern end of the region and the measles outbreak area being located in the south of the region.

In each location, north and south, four focus groups were carried out in children’s centres, which served populations living in areas of relatively high deprivation, and one focus group was carried out in a baby and toddler group that drew a population of parents living in more affluent areas. Deprivation was assessed using the 2010 Indices of Multiple Deprivation85 quintile for the location of the group setting. Ten focus groups were carried out in total.

Owing to ethical constraints on the access to vaccination status data, it was not possible to obtain details of parents and carers who had refused vaccination or had only partially immunised their child. It was hoped that targeting recruitment in some of the most deprived and some of the most affluent areas would uncover some parents and carers who were partial or non-immunisers.

Health and other professionals

These participants were identified purposively, and through discussion with key stakeholders, because of their job role and current responsibility for developing, commissioning and delivering vaccination services. In the main, these were staff already employed in various levels of the health service, both strategic (n = 6) and operational (practice nurses, health visitors and GPs) (n = 13), but we also extended the sample to other professional groups (community paediatricians, school nurses and primary school head teachers) (n = 5) who might become involved if quasi-mandatory schemes were to be introduced.

Recruitment

Different recruitment strategies were used for each of the stakeholder groups.

Parents and carers of preschool children

Parents were recruited through children’s centres and baby and toddler groups in each of the two localities. Children’s centre area managers were sent an e-mail asking for permission to approach parents who used their centre’s facilities. A copy of the project information sheet was included in the initial contact. All area managers who were approached responded positively and a meeting was set up between the researcher (RM) and the area manager. Each children’s centre hosted regular meetings and groups for parents who were resident within their catchment area. Children’s centre staff handed out information sheets and posters about the research to parents. The staff then arranged a convenient time for the researcher to carry out a focus group with those parents who were interested in taking part. Participants were, essentially, a self-selecting sample.

Eight children’s centres recruited parents to focus groups, four in each locality (north and south of the region). Table 6 shows the demographic make-up of each of the groups.

| Focus group number(s) | Descriptor |

|---|---|

| 1 | South of region. Lower deprivation. Lower rates of childhood vaccination. High incidence of measles 2012–13 |

| 4, 5, 7, 8 | South of region. Higher deprivation. Lower rates of childhood vaccination. High incidence of measles 2012–13 |

| 10 | North of region. Lower deprivation. Higher rates of childhood vaccination. Low incidence of measles 2012–13 |

| 2, 3, 6, 9 | North of region. Higher deprivation. Higher rates of childhood vaccination. Low incidence of measles 2012–13 |