Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/169/07. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The draft report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in July 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Resulting from this work, a manual has been written by Barry Wright and Chris Williams in conjunction with Carol Gray on the writing of Social Stories™ for children in mainstream schools in the UK.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Autism spectrum disorders and challenging behaviour

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are less able to learn social rules, conventions and behaviours by intuition compared with their typically developing peers. This may impact upon social interaction, social integration, learning and mental health and on occasions may lead to high levels of anxiety and or challenging behaviours. 1 Both parents and teachers report more behaviour problems in children with ASD than in typically developing children. 2 Many children with ASD therefore need additional support to understand and adopt social behaviours that are helpful to them. Social Stories™ (Carol Gray) are a non-intrusive, child-focused intervention designed to fill in the gaps of the child’s social understanding with the intention of helping them develop constructive behaviours and coping strategies.

Social Stories

Social Stories are short stories characterised by 10 predefined criteria developed by their original creator, Carol Gray. 3 These criteria both define and guide story development. They ensure that the story structure and content is descriptive, meaningful and safe for its audience. In particular, the content is tailored to the specific needs of each individual child, which can usually be incorporated into the story.

For the purposes of this study we are referring to Social Stories (using upper case letters) when these 10 criteria are adhered to (described more fully in the next section). A wider literature exists using stories in a range of ways to support children’s learning (e.g. generic stories about starting school or going to the dentist) but without adhering to these principles and we will refer to these as social stories (using lower case letters).

The ten criteria of Social Stories

Gray’s 10 criteria must be adhered to for a story to be considered a Social Story™. 3 The criteria give clear guidance on the elements that make a Social Story what it is and the process of researching, writing and formatting or illustrating one. They lead a Social Story to be developed and delivered in a certain way and consider the specific qualities of children with ASD. To give the later chapters the appropriate context, each of these criteria is described below using Gray’s original terminology as headings. 3

One goal

The first criterion emphasises the main purpose and overall tone of Social Stories. It states that the goal of a Social Story is to share accurate, socially meaningful information in a positive and reassuring way. Although they are often used in response to challenging behaviour, the focus of the content of the story would not be on that particular behaviour. The focus of the Story is usually provision of social information with the expectation that it will bring about changes in behaviour that benefit the child. Having one clear and shared goal enables those around the child to support them in a co-ordinated and supportive way.

Two-step discovery

This criterion emphasises the importance of gathering information before developing the story. This is an essential, non-negotiable part of developing a Social Story. It is the process by which the child and their needs are better understood. For example, ‘why is the child frustrated?’ or ‘what is it they do not understand?’. It is suggested that people who know the child best will be the best source of information for this stage. This criterion discourages ‘off the peg’ stories being used that are only partially suitable to the situation or the child.

Three parts and a title

The third criterion simply states that a Social Story is a story and needs a title describing the content, a beginning (introduction), a middle (body) and an end (conclusion). A good title should be clear to the child and easy to understand. It describes what the story is about.

Four-mat

The fourth criterion details four characteristics of the child which should be considered to ensure the story is appropriate for their cognitive ability. This criterion emphasises the importance of tailoring the Social Story to the child. The factors to be considered are their learning style, attention span, comprehension level and reading ability.

Five factors define voice and vocabulary

This criterion recognises the importance of the use of language and how the story is told. It details five separate rules when selecting the language used that are important in providing the story with the appropriate tone. The main emphasis is for the language to be positive and for the information presented to be accurate. The five rules are:

-

Write sentences in the first (I, we) and/or third person (she, it, they). Gray3 argues that ‘you’ statements are too directive and/or may be misunderstood by a child with ASD.

-

Use a positive and patient tone. The tone of the story needs to be positive, non-judgemental and non-authoritarian. An example of an unhelpful sentence in a Social Story would be: ‘I should not interrupt the head teacher when she is speaking in assembly’. An example of an alternative sentence to use would be ‘Children try to listen when the head teacher is talking to the group in assembly’. This constructive language is an important central feature of a Social Story.

-

Use information from the past in Social Stories. Past information can be useful in building self-esteem and remind people about previous positive events and outcomes.

-

Social Stories are literally accurate. Each word, phrase or sentence can be interpreted literally without changing the intended meaning. Children with ASD often have difficulty understanding complex, metaphorical phrases or words (e.g. ‘pull your socks up’) or phrases that might have multiple meanings (e.g. ‘take your seats’).

-

It is important to be accurate in meaning, especially when using verbs. For example, instead of ‘Jane will get the food from the supermarket’, a better sentence would be ‘Jane will buy the food from the supermarket’.

Six questions guide story development

The sixth criterion ensures that the appropriate content and information relevant to the situation is presented in the story. It encourages the writer to ask the six questions (who, what, where, when, why and how) about the situation that provides in-depth information about the child, and what needs to be explained in the Story to help the child. The questions are intended to explore the gaps in information for the child as the story is developed. For example, where and when does the issue occur? Who does it involve?

Seven types of sentences

The seventh criterion describes how the information included in a story should be presented by detailing seven types of sentence. Each sentence type has a different function in a story. The following are the common different types of sentences used.

-

Descriptive sentences: these are sentences that describe the situation factually and objectively. They may also describe the context and the information that we often assume everybody knows.

-

Perspective sentences: these sentences attempt to give the perspectives of different people. They can describe a person’s thoughts, feelings, beliefs, internal states and opinions. They can also describe a person’s sensations or physical health.

-

Coaching sentences (previously called directive sentences): this category of sentence accounts for three of Gray’s3 sentence types. These sentences gently guide or coach behaviour or suggest a more effective response. They often begin with ‘I will try to . . .’ or ‘I may choose to . . .’ or they list possible responses. There are three types of coaching sentences. Those which:

-

describe or suggest responses for the child (e.g. ‘I may choose to work on a table where there is no tinsel’ for a child who is so distressed by the presence of tinsel that they often tip the work tables over)

-

describe or suggest responses for the care-giver (e.g. ‘The teacher will try to set up some tables with tinsel and some tables without tinsel’).

-

are developed by the child themselves [e.g. ‘I may choose to . . .’ (the child chooses). . .]

-

-

Affirmative sentences: these are used to reinforce the meaning of other types of sentence. They may reinforce a point about safety or a positive statement. For example, ‘Children take turns going down the slide. This is very important.’ or ‘Sometimes I may lose the game. This is OK’.

-

Partial sentences: a partial sentence is one in which there are blanks that can be filled in by the child as they read.

A gr-eight formula

The eighth criterion defines the structure of the story by examining the balance of sentence types. It states that for something to be considered a Social Story, coaching sentences must amount to less than one-third of the total number of sentences in the story.

Nine makes it mine

This criterion emphasises the importance of using the child’s interests (e.g. trains or superheroes) in the story. A story should be written with knowledge of the child’s personal interests and preferences in an effort to make Stories more interesting and fun to read.

Ten guides to editing and implementation

The tenth criterion details the best practice for finalising and delivering the intervention. It emphasises the need to monitor and edit the story when necessary and the importance of having a quiet safe place to deliver it.

Evidence for the effectiveness of Social Stories

Social Stories can be effective in tackling challenging behaviour when they set out to explicitly teach social skills. 4 Until recently, research exploring efficacy and outcome has been confined to single-case studies. These case reports in children with ASD have suggested improvements in social interactions,5,6 choice making in an educational setting,6 voice volume in class7 and meal time skills. 8 Success has also been reported in addressing disruptive behaviours, including reducing tantrums9,10 and behaviours associated with frustration. 11 Non-comparative research has examined Social Story use in special education,12 mainstream education settings13 and within the home. 14

Two previous systematic reviews of Social Story effectiveness4,15 identified largely single-case designs and a paucity of good quality, comparative evidence on Social Stories. Both suggest further research, especially with the use of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate whether or not positive outcomes seen in case series can be replicated.

Although Social Stories have much potential to improve behaviour, the comparative evidence base is limited and attributed levels of effect are based mostly on single-case research. A well-designed RCT is required to address this important gap in our knowledge, and a feasibility RCT is required to plan the appropriate experimental design. Evidence suggests that Social Stories delivered in a general education setting produced significantly larger effect sizes on behaviour than those implemented at home or in self-contained settings, such as separate schools or self-contained classrooms. 4 Therefore, this study specifically focuses on the feasibility of assessing Social Stories delivered within a mainstream schooling system.

Overview

Social Stories for children with ASD represents a complex, individualised intervention. With this in mind the feasibility of conducting a full RCT must be examined. Our aim in this study was to develop a UK-accessible, manualised Social Stories training intervention for teachers of children with ASD in mainstream schools and to explore the effect of this on reducing challenging behaviour or other social difficulties. We conducted a feasibility study to inform the design of a full RCT, including a justification and description of appropriate costs, outcomes and parameters to include cost-effectiveness. The study was carried out in three phases, following the guidelines set out by the Medical Research Council in their framework for development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. 16

Theoretical phase

The initial pre-clinical phase was to conduct a systematic review of the current literature on social stories (including stories following Gray’s criteria). Chapter 2 details the findings of this systematic review. It included studies using social stories in all settings but paid particular attention to those used in mainstream schools. The review had two broad aims: firstly to provide a comprehensive description of how they have been used in education and clinical practice, and secondly to provide a quantitative estimate of the effectiveness of these interventions.

Phase 1

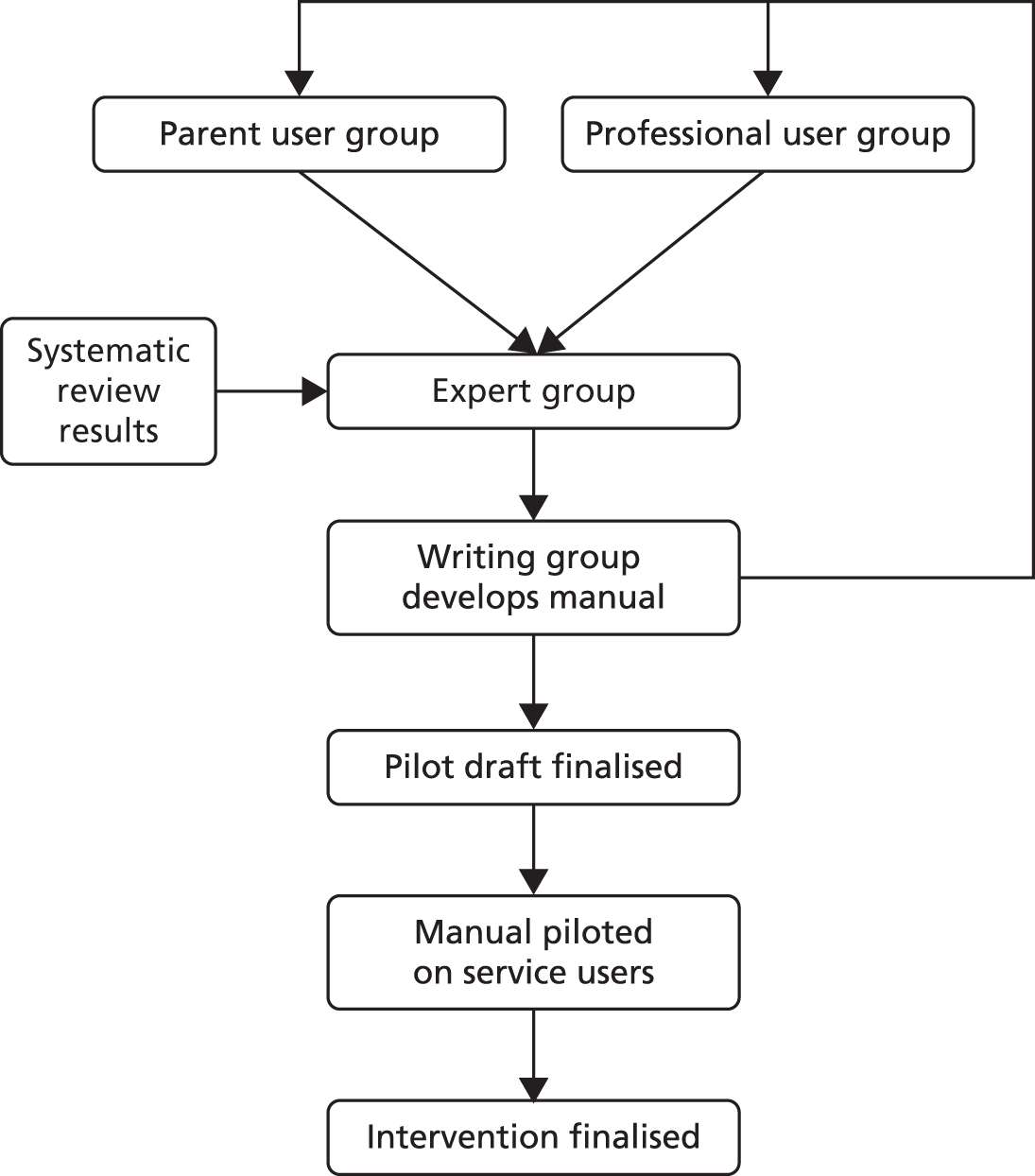

Chapters 3 to 6 detail phase 1 of the study. The aim of this phase was to develop a toolkit for writing Social Stories more accessible to a UK audience. It included a qualitative element to help develop the intervention and a small pilot study to refine it. This process was informed by patient and public involvement (PPI) on the study team who gave in depth advice for the qualitative interviews including assistance in the development of the topic guides and in supporting the research team in understanding the family perspective. Chapter 3 gives an overview of the development process as a whole. This process had strong PPI, including parent and teacher involvement and interviews with young people on the autism spectrum. Chapter 4 details the qualitative element in which interviews and focus groups were conducted with people with experience of using Social Stories. The aim of this process was to gather information relating to the optimum design and use of Social Stories, and to explore whether or not the intervention can feasibly be delivered in this particular context. Chapter 5 describes the progress at each stage of the developmental process for the intervention to be used in the feasibility study. Finally, Chapter 6 details the final stage of development of the intervention; a pilot study conducted with a small number of participants to examine the acceptability of the intervention before using it in the feasibility study.

Phase 2

Chapters 7 to 9 detail phase 2 of the study, the feasibility trial. Chapter 7 reports on the findings of the feasibility RCT and the considerations for conducting a full-scale trial. Chapter 8 details the health economic component of the study. Finally, Chapter 9 describes the findings of an additional qualitative component which consisted of interviews with the participating parents, teachers and children after they had completed their involvement with the feasibility trial. This additional component was suggested by our PPI representatives to give a richer quality of information to inform a fully powered trial.

Discussion

Chapter 10 attempts to bring together the conclusions from the previous chapters into a general discussion that critically evaluates the findings against the proposed objectives and makes recommendations for a future trial.

Objectives

-

To carry out a systematic review examining the use of social stories and other social stories for children with ASD, with particular reference to mainstream school-aged children and challenging behaviour.

-

To conduct a qualitative analysis of interviews and focus groups, to gather information relating to the optimum design and use of Social Stories in children with ASD in a mainstream school setting.

-

To form an expert writing panel and develop a manualised toolkit (including a training package) for writing and delivering Social Stories for use in mainstream schools.

-

To conduct a feasibility RCT comparing the developed manualised Social Stories training intervention with an attention control on challenging behaviour, demonstrating the feasibility of recruitment and delivery of the intervention and follow-up.

-

To establish the acceptability and utility of the developed manualised Social Stories intervention and trial to teachers, parents and children.

-

To identify parameters, outcomes and cost-effectiveness from the feasibility study in order to inform a future full-scale RCT.

Chapter 2 Theoretical phase: use of social stories in practice and evaluation of effectiveness – systematic review

Background

As discussed in Chapter 1, there have been a number of single-case studies on the use of social stories as an intervention for children diagnosed with ASD. It is currently unclear, however, how they have been used in education and clinical practice. There is also a lack of clarity about how closely the intervention used in the studies followed Gray’s criteria (if they could be considered Social Stories). Furthermore, although there are previous systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness of this intervention, there is no comprehensive review in this area. The current chapter seeks to close these evidence gaps.

Patient and public involvement representatives gave advice to systematic reviewers to help them to understand the issues facing children with ASD and on elements that were important to families. This informed the development of the review methodology and content. In particular the decision to carry out more in-depth assessments of the single-case designs was driven by PPI advice that rich information could be found in single-case reports.

While social stories are widely referred to in education and clinical practice their precise definition is malleable. On the other hand Social Stories (with capitals) have a clear definition and structure. 3 This phase aimed to obtain comprehensive information about the available research on how social stories (including those that follow the criteria and those that do not) are written and used, and how faithful this is to current theories on what makes them effective. The review had two broad objectives.

Objectives

-

To provide a comprehensive description of how social stories have been used in education and clinical practice as reported in the literature (overview of practice).

-

To provide a quantitative estimate of the clinical effectiveness of this intervention (overview of effectiveness).

Method

The protocol for the review is registered on the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42011001440).

Databases and additional resources

A wide range of databases and additional resources were searched to identify relevant information, including databases of peer-reviewed studies and sources of grey literature. The use of social stories spans the health and educational literature. Therefore, we sought to search databases that covered, health, mental health, education and social care. The full list of databases searched included:

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts

-

Australian Education Index

-

British Education Index

-

British Library integrated catalogue

-

British Nursing Index

-

Campbell Library

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

-

ClinicalTrials.gov

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

-

EMBASE

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database

-

Index to Theses

-

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

-

Library of Congress catalog

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database

-

OAIster

-

PsycINFO

-

Social Care Online

-

Science Citation Index

-

Social Science Citation Index

-

Social Policy & Practice

-

Social Services Abstracts

-

Zetoc.

The searches were not limited by date range, language or publication status. Each database was searched from inception to July 2011. Additional searches for dissertations/theses were undertaken using Google Scholar (advanced) (Mountain View, CA, Google).

The following organisation websites were also searched (accessed July 2011):

-

American Psychiatric Association (www.psych.org)

-

Asperger’s Syndrome (www.aspergerssyndrome.org)

-

Autism Education Trust (www.autismeducationtrust.org.uk)

-

Autism-Europe (www.autismeurope.org)

-

Autism Independent UK (www.autismuk.com)

-

Autism in Mind (www.autism-in-mind.co.uk)

-

Autism Research Centre (www.autismresearchcentre.com/arc/default.asp)

-

Autism Research Institute (www.autism.com)

-

Autism Society of America (www.autism-society.org)

-

Autistica (Autism Speaks) (www.autismspeaks.org.uk)

-

Mental Health Foundation (www.mentalhealth.org.uk)

-

MIND (www.mind.org.uk)

-

National Autistic Society (www.autism.org.uk)

-

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) (www.nccmh.org.uk)

-

National Institute of Mental Health (www.nimh.nih.gov)

-

Research Autism (www.researchautism.net/pages/welcome/home.ikml)

-

Royal College of Psychiatrists (www.rcpsych.ac.uk)

-

Scottish Society for Autism (www.autism-in-scotland.org.uk)

-

The Autism Acceptance Project (www.taaproject.com)

-

The Gray Center (www.thegraycenter.org)

-

UK Autism Foundation (www.ukautismfoundation.org).

We used a number of additional strategies to ensure the search was as comprehensive as possible. This included a hand search of reference lists of all studies included in the overview of practice stage and previously conducted systematic reviews in the area. It also included a reverse citation-search, conducted in ISI Web of Science Citation Databases and Google Scholar, for the same papers (i.e. those included in overview of practice and previous systematic reviews).

Search terms

The search terms were devised using a combination of subject indexing terms, such as medical subject headings in MEDLINE, and free text search terms in the title and abstract. The search terms covered two broad constructs, autism spectrum and social stories. They were developed through discussion between the research team and members of the PPI group, by scanning background literature and by browsing database thesauri. Full details of the specific search strategies for PsycINFO, MEDLINE and EMBASE are given in Appendix 1.

De-duplication

As a number of databases were searched, some degree of record duplication resulted. To manage this issue, the titles and abstracts of bibliographic records were downloaded and imported into EndNote version 7 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) bibliographic management software and duplicate records were removed.

Screening of citations

Two researchers independently examined the titles and abstracts of all identified citations using a pre-piloted, standardised screening form based on the population, intervention, comparator, outcome (PICO) criteria for the overview of practice and the evaluation of clinical effectiveness described below. Full papers were obtained for any citations that passed this first sift; these were again independently examined by two researchers using a pre-piloted, standardised forms. At both stages, any disagreements were resolved through consensus and referred to a third reviewer if necessary.

Inclusion–exclusion criteria

Detailed PICO criteria were developed to guide the screening of citations. PICO criteria for the participant and intervention criteria were the same for both the overview of practice and evaluation of clinical effectiveness reviews, but differed for the remaining criteria (comparator, outcome and study design). The PICO criteria are summarised below. Full criteria are given in Appendix 2.

Participants

Criteria for overview of practice and effectiveness

The sample must be aged between 4 and 15 years. The study must have included a participant or participants with a diagnosis on the autism spectrum [e.g. autism, atypical autism, pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), Asperger syndrome]. The diagnosis could be established by any method; a gold standard assessment such as the use of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule17 was not required.

Intervention

Criteria for overview of practice and effectiveness

Any intervention described as a social story was included, as was any study that used an intervention with similar characteristics to a social story. This did not include sensory stories. If the term social story was used it was not required that the term was trademarked.

Comparator

Overview of practice

For the overview of practice, any comparator, including no comparator, was included.

Overview of effectiveness

For between-groups designs (e.g. RCTs or non-RCTs), studies with any comparator were included (e.g. other active treatment including psychological or medication, placebo, attention control, treatment as usual, waiting list, etc.); however, a comparator had to be present. For single-case designs, any within-participant (e.g. alternative treatment or no treatment phase) or between-participant (e.g. small N design with counterbalancing across participants) comparator was included; a baseline phase of an AB design met the criterion for a within-participant comparator.

Outcome

Overview of practice

There were no specific outcome criteria for ‘overview of practice’.

Overview of effectiveness

Any study was included that used a standardised, numerical measure of behavioural outcomes or non-standardised, numerical measure of behaviour. For single-case designs, studies had to report repeated measurement of the target behaviour. Challenging behaviour was defined as any target behaviour that the author sought to reduce. To ensure the review was as comprehensive as possible, studies were not excluded if beneficial behaviours were measured.

Study design

Overview of practice

For ‘overview of practice’ any type of study design was included. This included RCTs, non-RCTs and quantitative single-case studies. It also included non-quantitative case studies, narrative descriptions of the use of an intervention and pre–post designs. Book reviews, guidance on using social stories for parents/carers, teachers or clinicians and actual social stories were excluded.

Overview of effectiveness

Single-case studies were defined as using repeated measurements of quantifiable (numerical) data on a single clinical case. 18 The approach may involve replicating the basic design over several people to form a single-case series. Examples of single-case designs include AB designs, reversal/withdrawal designs, changing criterion methods, multiple baseline, small N designs that use counterbalancing across participants and alternating treatment designs (ATDs). 18 Single-case studies that relied solely on pre- and post-treatment measurements were excluded. Narrative, non-quantitative case studies were also excluded. The decision to include a study was made on the actual design used not on the design the authors reported using. For example, if a design was described as a single-case study or single-case series but the design did not meet the definition given above, the study was excluded.

For between-groups designs, both RCTs and non-RCTs were included.

Data extraction

A coding manual was developed by the research team with guidance from Gray and PPI representatives to guide data extraction. This was piloted and refined before use. Two researchers independently extracted data. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and if necessary discussion with a third reviewer. Data on descriptive characteristics included setting and participants (e.g. setting in which the study was conducted, country, numbers of participants, age, gender, diagnosis or cognitive functioning), characteristics of the social story (e.g. number of stories per child, sentence length, delivery format, timing, who developed the story or who delivered the story) and details of the behavioural category targeted, including how it was measured and if it were challenging or beneficial. Additional information was extracted for particular study designs. For example, for the single-case studies, details were extracted about the design used (e.g. AB, reversal or alternating treatment) and for between-groups designs details of the comparator were coded. Data were also extracted on the extent to which the development and delivery of the social stories adhered to best practice guidance. To determine this, Gray’s3 10 criteria were used as a base, but the reviewers added five additional component parts, developed from criteria five and ten, for more detail. A description of these fifteen criteria and how they map onto Gray’s original ten is displayed in Table 1. The table also includes a final category, criteria statement, which indicates whether the study reported following Gray’s criteria. The researchers assigned to extract this data were experienced in writing Social Stories and their use.

| Concordance item | Description | Gray’s criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Positive goal | The story has a positive goal that is safe for the child | Criterion 1 |

| Information gathered | Information is gathered preceding story selection | Criterion 2 |

| Structured story | The story has a title, introduction, body and conclusion | Criterion 3 |

| Tailored for ability/attention | The story is tailored for ability and attention span | Criterion 4 |

| Tailored for interests | The story is tailored for interests | Criterion 9 |

| ‘Wh’ questions answered | The story answers ‘wh’ questions and clearly explains the situation to the child | Criterion 6 |

| Listed sentence types | The story uses the listed sentence types (e.g. coaching, descriptive, perspective). The story should not combine different sentence types within the same sentence | Criterion 7 |

| Balance of sentence types | The story follows the Social Story formula for the balance of sentence types: no more than one-third of the sentence types should be ‘coaching’ sentences | Criterion 8 |

| First/third person statements | The story contains only first and third person statements | Criterion 5 |

| Non-authoritarian | The story has a non-authoritarian tone | Criterion 5 |

| Avoids should/must | The story avoids the use of words such as should and must, etc. | Criterion 5 |

| Literally accurate | The story is accurate in a literal sense | Criterion 5 |

| Story edited | The story has been edited after the first draft | Criterion 10 |

| Appropriate setting | There is a plan for reading the story in a quiet, comfortable setting | Criterion 10 |

| Introduced appropriately | There is a plan for introducing the story in a positive manner | Criterion 10 |

| Criteria statement | The authors state that they followed the Social Story criteria in developing and delivering the story |

For the single-case designs, data on clinical effectiveness were extracted from graphs or comparably reported data of the target behaviour at different time points. For between-groups designs, information was extracted on the sample size of each group, post-treatment means and standard deviations (SDs).

Quality assessment

For single-case designs, the Single-Case Experimental Design (SCED) scale was used. 19 This is a quality assessment tool designed specifically for the evaluation of single-case studies. The SCED has 11 items, 10 of which evaluate key threats to the validity of single-case designs. An eleventh item, ‘specification of clinical history’, rates the extent to which the clinical history of the participant is described in sufficient detail to permit the assessment of whether or not the intervention may be relevant to other individuals. In the original recommendations for the SCED, items were scored a 1 if the validity criterion was met and a 0 if not met. We differentiated between a score of 0 if the criterion was clearly not met and ‘not reported’ if there was insufficient detail given to rate the criterion. This helped to distinguish between methodological limitations and reporting limitations. Table 2 provides a description of the items used in the SCED.

| SCED item | Description |

|---|---|

| Clinical history | The study provides critical information regarding demographic and other characteristics of the research participant that allows the reader to determine the applicability of the treatment to another individual |

| Target behaviours | The paper identifies a precise, repeatable and operationally defined target behaviour that can be used to measure treatment success |

| Design | The study design allows for the examination of cause and effect relationships to demonstrate treatment efficacy |

| Baseline | To establish that sufficient sampling of behaviour had occurred during the pre-treatment period to provide an adequate baseline measure |

| Sampling behaviour during treatment | To establish that sufficient sampling of behaviour during the treatment phase has occurred to differentiate a treatment response from fluctuations in behaviour that may have occurred at baseline |

| Raw data record | To provide an accurate representation of the variability of the target behaviour |

| Inter-rater reliability | To determine if the target behaviour measure is reliable and collected in a consistent manner |

| Independent assessment | To reduce assessment bias by employing a person who is otherwise uninvolved in the study, to provide an evaluation of the patients |

| Statistical analysis | To demonstrate the effectiveness of the treatment of interest by statistically comparing the results over the study phases |

| Replication | To demonstrate that the application and results of the therapy are not limited to a specific individual or situation (i.e. that the results are reproduced in other circumstances – replicated across subjects, therapists or settings) |

| Evidence for generalisation | To demonstrate the functional utility of the treatment in extending beyond the target behaviours or therapy environment into other areas of the individual’s life |

We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess the methodological quality and potential sources of bias for RCTs. 20 This measure contains a number of domains, such as random sequence generation, that relate to potential biases in a randomised trial. Each item was rated as high, low or unclear. Table 3 provides a description of the items used in this measure.

| Risk of bias item | Description |

|---|---|

| Selection bias: random sequence generation | Does the study describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether or not it should produce comparable groups? |

| Selection bias: allocation concealment | Does the study describe the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether or not intervention allocations could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment? |

| Performance bias: blinding of participants and personnel | Does the study describe all measures used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received? |

| Detection bias: blinding of outcome assessment | Does the study describe all measures used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received? |

| Attrition bias: incomplete outcome data | Does the study describe the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis? |

| Reporting bias: selective reporting | Does the study state how the possibility of selective outcome reporting was examined and what was found? |

| Other sources of bias | Are there other important concerns about bias not addressed in the other domains in the tool? |

For both the SCED19 and the Cochrane risk of bias tool,20 two researchers independently rated the quality of the studies. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and, when necessary, by referral to a third reviewer.

Data synthesis

There is as yet no agreement in the literature about how the effects from single-case designs should be quantified and collated. We therefore chose two estimates of effect rather than relying on a single one. The first, the percentage of non-overlapping data (PND),21 is the percentage of phase B (i.e. intervention phase) data that exceeds the highest point (or lowest depending on the direction of scoring) for the phase A data (i.e. baseline phase). There are potential problems with such an index of effectiveness; it relies, for example, on a single data point from the phase A, a data point that may in fact be a single, unrepresentative outlier of the index of behaviour during the baseline phase. It is, however, widely used and so was included as one estimate of effectiveness. Scruggs and colleagues21 recommend the following guidelines when interpreting PND values: a PND of ≥ 90% indicates that an intervention is highly effective, of ≥ 70 to < 90% indicates moderate effectiveness and of < 70% indicates questionable effectiveness or that the intervention is not effective. These guidelines were used here. The second estimate of effect was the percentage of data points exceeding the median (PEM). 22 The PEM involves calculating the median for the baseline phase and then identifying the proportion of data points in the intervention phase that exceed this value. Ma22 used the same guidelines to quantify improvement as used by Scruggs and colleagues21 and these were used to facilitate the interpretation of this calculation.

Results were grouped on the basis of four broad categories of target behaviours, three relating to the difficulties typically experienced by children diagnosed with ASD, corresponding to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria (social; communication; and restricted and repetitive behaviours/interests) and a fourth miscellaneous category. 23 With the exception of restricted behaviours, in which all of the identified studies in this category examined similar target behaviours, the categories were further divided into subcategories. For each subcategory, a single study may have included more than one participant, and in some cases a participant may have contributed data on more than one target behaviour within a subcategory. Data were summarised at the level of the target behaviour for each subcategory.

For the between-groups designs, the standardised mean difference (Hedges’ g) was calculated. Where insufficient data were reported to make this calculation, the results in the original paper are given. A number of the studies used a design in which the comparator group went on to receive treatment. In these designs, data were analysed up to the point at which the distinction between the treatment and comparator groups was maintained. There were an insufficient number of studies that were comparable in terms of the comparator and the target behaviour to conduct a meta-analysis.

Results

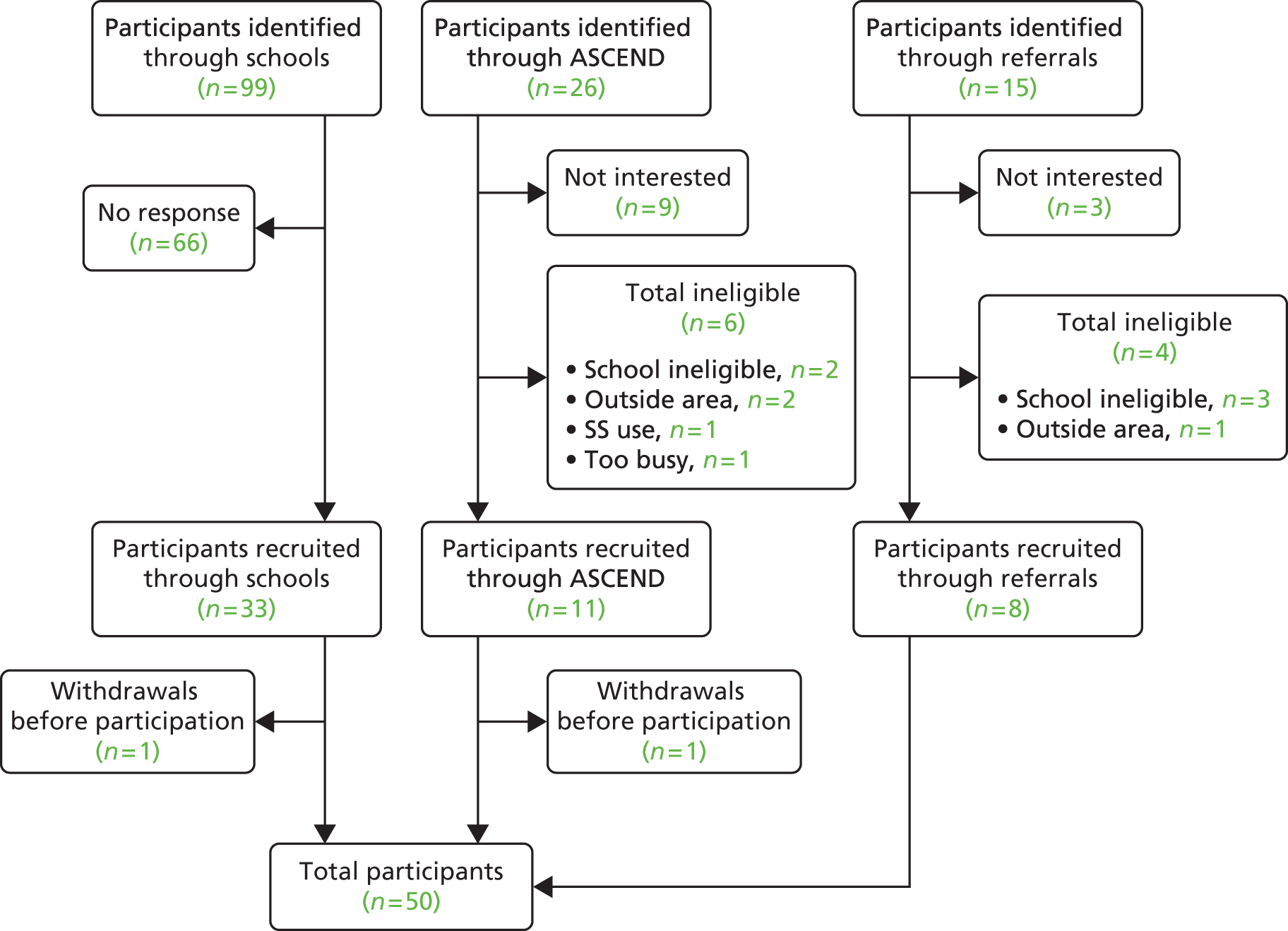

Figure 1 summarises the results of the search. The database searches identified 1072 records; an additional nine were identified through other sources. After the records were de-duplicated, this left 646 records for screening. In total, 135 met first-sift inclusion criteria, of which 99 met the final inclusion criteria for the overview of practice. Of this 99, 77 used single-case designs and seven used between-groups designs and so were included in the overview of clinical effectiveness. The reasons for exclusion for each of the 36 studies that passed the first sift, but were subsequently excluded are summarised in Appendix 3.

FIGURE 1.

Results of the literature search.

Overview of practice

Single-case studies

As we have described above, the first aim of the review was to provide an overview of how social stories have been used in clinical and educational practice. We did this first for the 77 single-case designs, then for the seven between-groups designs and finally for the 15 other designs. Table 4 provides a summary of this information for the single-case studies and, related to this aim, Table 5 provides a summary of the extent to which the use of the social stories adhered to the criteria set out by Gray. 3

| Study | Setting and participants | Social story intervention | Single-case design | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham (2004)27 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: two stories, 14 and 16 sentences; written story | Design: ACBD | Category: social ability, social communication, other |

| n = 4 | Timing: once a day, three times a week, over 17 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 7–14 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: four males | Delivered by: teachers (mixed) | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Adams (2004)11 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 24 sentences; NR | Design: reversal (ABAB) | Category: other |

| n = 1 | Timing: once a day, four times a week, over 12 weeks | Subcategory: emotional development | ||

| Age (years): 7 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: parents | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Agosta (2004)28 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: two stories, six sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABCA) | Category: social ability, other |

| n = 1 | Timing: at least three times a day, at least five times a week, over 28 days | Subcategory: social awareness, emotional development | ||

| Age (years): 6 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – unclear | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Antle (2007)76 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: one story, nine sentences; written story and photographs | Design: AB | Category: social ability, other |

| n = 1 | Timing: once a day, seven times a week, over 11 days | Subcategory: social awareness, life skills | ||

| Age (years): 5 | Developed by: research team and parents | Measure: frequency – unclear | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: parents | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Bailey (2008)56 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: one story; written story and illustrations | Design: ACABADAD | Category: social communication, other |

| n = 2 | Timing: over 36–38 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 10–15 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: two males | Delivered by: research team and target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Barry (2004)6 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: more than two stories; written story and photographs | Design: ABCD | Category: restricted behaviours |

| n = 2 | Timing: once a day, five times a week, over 14 days | Subcategory: restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour/interests | ||

| Age (years): 7–8 | Developed by: NR | Measure: other | ||

| Gender: one male, one female | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Beh-Pajooh (2011)57 | Setting: special education, Iran | Story characteristics: NR | Design: AB | Category: other, social ability |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, over 21 days | Subcategory: emotional development, social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 8–9 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Bell (2005)58 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 10 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: ABCD | Category: restricted behaviours, social ability |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, over 27 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 5–10 | Developed by: NR | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Bernad-Ripoll (2007)77 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: two stories; written story and photographs | Design: ABC | Category: other, social ability |

| n = 1 | Timing: over 10 days | Subcategory: emotional development, social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 9 | Developed by: NR | Measure: % of correct responses | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: high | ||||

| Bledsoe (2003)8 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, eight sentences; NR | Design: reversal (ABAB) | Category: other |

| n = 1 | Timing: at least once a day, at least five times a week, over 13 days | Subcategory: life skills | ||

| Age (years): 13 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Brownell (2002)29 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, seven sentences; written story and illustrations, musical format | Design: reversal (ABAC) | Category: social communication, social ability |

| n = 4 | Timing: once a day, over 20 days | Subcategory: unusual voice modulation, social interest | ||

| Age (years): 6–9 | Developed by: teacher (special education), research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: four males | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Chan (2005)78 | Setting: home, China | Story characteristics: one story; written story and illustrations, musical format | Design: reversal (ACAB) | Category: social ability, social communication, other |

| n = 4 | Timing: once per day, over 5 days for each format | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 4–12 | Developed by: research team | Measure: duration, frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: two males, two females | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Chan (2008)30 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: more than two stories; written story | Design: multiple baseline, reversal (ABA) | Category: social ability, social communication |

| n = 2 | Timing: 10–20 minutes, once a day, one to four times a week, over 5 weeks | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 5–6 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording, % of correct responses | ||

| Gender: two males | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Chan (2009)89 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story; written story and photographs, computer media, audio format | Design: AB | Category: other, social ability, restricted behaviours |

| n = 6 | Timing: once a day, over 34 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 7–9 | Developed by: teacher (special education) | Measure: % of intervals, frequency – event recording, % of correct responses | ||

| Gender: five males, one female | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: average | ||||

| Cihak (2012)31 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, seven sentences; DVD format | Design: ATD followed by BAB | Category: social ability |

| n = 4 | Timing: 30–35 seconds for 23 sessions | Subcategory: social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 11–14 | Developed by: teacher (special education and mainstream) and research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: four males | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: average | ||||

| Crozier (2005)32 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, eight sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABACA) | Category: social ability |

| n = 1 | Timing: once a day, five times a week, over 26 days | Subcategory: social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 8 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Crozier (2007)12 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 10 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABABA) | Category: restricted behaviours |

| n = 1 | Timing: 5 minutes, once a day, three times a week, over 17 days | Subcategory: restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour/interests | ||

| Age (years): 5 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: high | ||||

| Cullain (2000)90 | Setting: general education, home, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 5–17 sentences; written story | Design: AB | Category: all categories represented |

| n = 5 | Timing: twice a day, over 5 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 6 | Developed by: parents, teacher (special and mainstream education) and research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: four males, two females | Delivered by: teachers (both) and parents | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Daneshvar (2006)79 | Setting: community setting, USA | Story characteristics: two stories; four sentences; written story | Design: AB | Category: social communication |

| n = 4 | Timing: over 46–78 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 5–10 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of correct responses | ||

| Gender: two males, two females | Delivered by: NR | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Delano (2006)13 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story; written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABCDA) | Category: social ability |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day over 45 days | Subcategory: general communication skills | ||

| Age (years): 6 | Developed by: clinical workers/other professionals and research team | Measure: duration, frequency – interval recording | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Demiri (2004)33 | Setting: home, general education, USA | Story characteristics: NR, NR; written story | Design: AB | Category: all categories represented |

| n = 5 | Timing: once a day | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 5–7 | Developed by: research team, teacher (special education) and parents | Measure: % of correct responses | ||

| Gender: five males | Delivered by: parents and teacher (mainstream education) | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: average | ||||

| Dodd (2008)80 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: two stories, 15–17 sentences; written story and photographs | Design: multiple baseline (ABC) | Category: social ability |

| n = 2 | Timing: once a day, none to three times a week, over nine days | Subcategory: social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 9–12 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: two males | Delivered by: parents | |||

| Diagnosis: PDD-NOS | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: high | ||||

| Eckelberry (2007)34 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 15 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: AB | Category: social ability |

| n = 1 | Timing: at least once a day, at least five times a week, over 15 days | Subcategory: social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 6 | Developed by: research team and teacher (mainstream education) | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: NR | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Gilles (2008)81 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: one story; written story | Design: ABCD | Category: other |

| n = 9 | Timing: 8 weeks but only 8 days with social story | Subcategory: life skills | ||

| Age (years): 5–9 | Developed by: research team | Measure: other, sleep behaviours | ||

| Gender: seven males, two females | Delivered by: parents | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: mixed | ||||

| Graetz (2003)59 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, eight sentences; written story, illustrations and photographs | AB | Category: social ability, social communication, other |

| n = 5 | Timing: once a day, over 40 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 10–14 | Developed by: research team and teacher (special education) | Measure: % of correct responses, % of intervals | ||

| Gender: four males, one female | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Hagiwara (1999)60 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: more than two stories; computer media | Design: multiple baseline (AB) | Category: other |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, over 19 days | Subcategory: life skills, sustained attention | ||

| Age (years): 7–9 | Developed by: research team and teacher (mainstream education) | Measure: % of correct responses, duration | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Hanley (2008)35 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 21 sentence; written story | Design: reversal (ABA) | Category: social communication |

| n = 4 | Timing: < 15 minutes, four times per week, over 38 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 6–12 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency- event recording | ||

| Gender: three males, one female | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: group mix | ||||

| Hobbs (2003)24 | Setting: general education, UK | Story characteristics: one story, 13 sentences; written story and photographs | Design: AB | Category: social ability, restricted behaviours, other |

| n = 7 | Timing: once a day, over 10 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 6–10 | Developed by: teacher (special education) and research team | Measure: other | ||

| Gender: seven males | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Holmes (2007)36 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: more than two stories, 13 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABAB) | Category: social ability, social communication |

| n = 1 | Timing: three times a day, over 4 weeks | Subcategory: social awareness, general communication skills | ||

| Age (years): 11 | Developed by: research team and target student | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Hung (2011)37 | Setting: general education, Taiwan | Story characteristics: one story; written story | Design: reversal (ABAB) | Category: social ability |

| n = 1 | Timing: once a day, over 24 days | Subcategory: social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 6 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: teacher (mainstream education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Hutchins (2006)82 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 18 sentences; written story | Design: AB | Category: other |

| n = 2 | Timing: once a day, three times a week, over 6 weeks | Subcategory: emotional development | ||

| Age (years): 6–12 | Developed by: parents and research team | Measure: other | ||

| Gender: one male, one female | Delivered by: NR | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Ivey (2004)14 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: more than two stories; written story, illustrations and photographs | Design: reversal (ABAB) | Category: restricted behaviours |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, five times a week, over 12 weeks | Subcategory: restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour/interests | ||

| Age (years): 5–7 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: parents | |||

| Diagnosis: PDD-NOS | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: mixed | ||||

| Keyworth (2004)38 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, nine sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: ABCBCD | Category: social ability, social communication, restricted behaviours |

| n = 3 | Timing: 5 minutes, once a day, over 21 sessions | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 7–12 | Developed by: parents, teacher (mainstream education) and research team | Measure: % of correct responses | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: teacher (mainstream education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Kuoch (2000)39 | Setting: general education, Canada | Story characteristics: one story, 22 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABA) | Category: restricted behaviours, other |

| n = 2 | Timing: 3–4 minutes, over 44 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 5–6 | Developed by: parents, research team and teacher (mainstream education) | Measure: other | ||

| Gender: two males | Delivered by: teacher (mainstream education) | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Kuttler (1998)10 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: two stories, 5–7 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABAB) | Category: other |

| n = 1 | Timing: once a day, over 19 days | Subcategory: emotional development | ||

| Age (years): 12 | Developed by: parents, teacher (special education) and research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Lorimer (2002)9 | Setting: home, clinic/hospital, USA | Story characteristics: two stories, 9–11 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABAB) | Category: social communication, other |

| n = 1 | Timing: 5 minutes, at least once a day, over 14 days | Subcategory: turn-taking, emotional development | ||

| Age (years): 5 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: parents and clinician/other professional | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: high | ||||

| Mancil (2009)62 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, seven sentences; written story and photographs, computer media | Design: reversal (ACACBCBD) | Category: other |

| n = 3 | Timing: 5 minutes, once a day, five times a week, over 35 days | Subcategory: emotional development | ||

| Age (years): 6–8 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: two males, one female | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Mandasari (2011)61 | Setting: special education, Malaysia | Story characteristics: more than two stories; written story, computer media, illustrations and photographs | Design: ABC | Category: social communication |

| n = 3 | Timing: 10–15 minutes, two to three times a day, over 28 days | Subcategory: general communication skills | ||

| Age (years): 10–11 | Developed by: research team | Measure: other | ||

| Gender: three male | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Hsu (2009)40 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 11 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: ABCB | Category: other |

| n = 1 | Timing: 10 minutes, once a day, four times a week, for 14 sessions | Subcategory: sustained attention | ||

| Age (years): 7 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: teacher (mainstream education) | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Norris (1999)5 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: more than two stories; written story, illustrations and photographs | Design: AB | Category: social ability, social communication |

| n = 1 | Timing: 10 minutes, at least once a day, at least five times a week, over 18 days | Subcategory: social awareness, unusual voice modulation, social interest | ||

| Age (years): 8 | Developed by: research team and teacher (mainstream education) | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: female | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: average | ||||

| Okada (2008)63 | Setting: special education, Japan | Story characteristics: one story; written story, illustrations and photographs | Design: ABCD | Category: other |

| n = 2 | Timing: once a day | Subcategory: emotional development, life skills | ||

| Age (years): 12–13 | Developed by: teacher (special education) and research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: two males | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Okada (2010)64 | Setting: special education, Japan | Story characteristics: more than two stories, 10–13 sentences; written story, illustrations and photographs | Design: ABCDE | Category: other |

| n = 1 | Timing: once a day, five times a week, over 41 days | Subcategory: life skills | ||

| Age (years): 14 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: research team and target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Ozdemir (2008)41 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, computer media | Design: reversal (ABCDA) | Category: social ability |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, three times a week, over 45 days | Subcategory: social interest | ||

| Age (years): 6 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Ozdemir (2008)7 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, eight sentences, written story, illustrations and photographs | Design: reversal (ABCDA) | Category: social communication, other |

| n = 3 | Timing: at least once a day, at least five times a week, over 51 days | Subcategory: unusual voice modulation, life skills, emotional development | ||

| Age (years): 7–9 | Developed by: NR | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Pasiali (2004)83 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: one story, eight sentences, written, musical format | Design: reversal (ABAB) | Category: social ability, social communication, Restricted behaviours |

| n = 3 | Timing: 15 minutes, once a day, over 28 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 7–9 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: two males, one female | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Powell (2009)84 | Setting: home, USA | Story characteristics: two stories, 18 or 19 sentences, written | Design: multiple baseline (ABCD) | Category: social communication |

| n = 1 | Timing: NR | Subcategory: general communication skills | ||

| Age (years): 7 | Developed by: NR | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: female | Delivered by: family members | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Quilty (2007)42 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, written story and photographs | Design: ABC | Category: social ability |

| n = 3 | Timing: 27 days | Subcategory: social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 6–10 | Developed by: teacher (special education), research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: two males, one female | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Reichow (2009)43 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, written, illustrations and photographs | Design: reversal (ABABC) | Category: social communication |

| n = 1 | Timing: once a day, over 35 days | Subcategory: initiations and requests | ||

| Age (years): 11 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: average | ||||

| Reynhout (2007)65 | Setting: special education, Australia | Story characteristics: one story, written story and photographs | Design: ABC | Category: restricted behaviour |

| n = 1 | Timing: at least once a day, at least five times a week, over 70 days | Subcategory: restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour/interests | ||

| Age (years): 8 | Developed by: teacher (special education), research team and clinical workers/other professionals | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: teacher (special education) and research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Reynhout (2008)66 | Setting: special education, Australia | Story characteristics: one story, four sentences, written story and photographs | Design: ABCD | Category: other |

| n = 1 | Timing: at least once a day, at least four times a week, over 38 days | Subcategory: sustained attention | ||

| Age (years): 8 | Developed by: parent, teacher (special education) and research team | Measure: frequency – interval recording | ||

| Gender: female | Delivered by: teacher (special education), research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Sansosti (2006)44 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 12 sentences, written story and illustrations | Design: reversal (ABA) | Category: social ability, social communication |

| n = 3 | Timing: twice a day, 10 times a week, over 36 days | Subcategory: social awareness, general communication skills | ||

| Age (years): 9–11 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: parents | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: average | ||||

| Sansosti (2008)45 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, written story and illustrations, computer media | Design: ABCD | Category: social ability, social communication |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, five times a week, over 30 days | Subcategory: social interest, general communication skills | ||

| Age (years): 6–9 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: mixed | ||||

| Scapinello (2009)85 | Setting: home, Canada | Story characteristics: one story, nine sentences; written story, illustrations and photographs | Design: AB | Category: social ability, social communication, other |

| n = 8 | Timing: over 24 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 4–7 | Developed by: research team and parents | Measure: various | ||

| Gender: eight males | Delivered by: parents | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Scattone (2002)67 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 10 sentences; written story | Design: AB | Category: social ability, social communication, other |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, over 22 days | Subcategory: social awareness, unusual voice modulation, life skills | ||

| Age (years): 7–15 | Developed by: NR | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: teacher (mainstream education) and target student | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Scattone (2006)68 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 26 sentences, written | Design: AB | Category: social communication |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, over 33 days | Subcategory: general communication skills | ||

| Age (years): 8–13 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Scattone (2008)86 | Setting: Clinic/hospital, home, USA | Story characteristics: more than two stories, 10 or 11 sentences, written, DVD format | Design: multiple baseline (AB) | Category: social ability, social communication |

| n = 1 | Timing: at least once a week, at least seven times a week, over 22 days | Subcategory: social attention, initiation and requests | ||

| Age (years): 9 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: research team and parents | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: average | ||||

| Schneider (2010)46 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story; written story and illustrations | Design: AB | Category: social ability, restricted behaviours |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day, five times a week, over 71 days | Subcategory: social awareness, restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour/interests | ||

| Age (years): 5–10 | Developed by: clinical workers/other professionals and research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Scurlock (2008)47 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 21 sentences; written story | Design: AB | Category: other |

| n = 1 | Timing: 5 minutes, once a week, five times a week, over 2 weeks | Subcategory: emotional development | ||

| Age (years): 10 | Developed by: research team | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: target student | |||

| Diagnosis: Asperger | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: high | ||||

| Smith (2004)48 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: two stories, five sentences; written story | Design: reversal (ABA) | Category: social communication |

| n = 3 | Timing: 5 minutes, three times a week, over 23 days | Subcategory: initiations and requests | ||

| Age (years): 4 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: three males | Delivered by: NR | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Staley (2001)69 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: two stories, nine sentences; written story | Design: ABCDCD | Category: other |

| n = 1 | Timing: once a day, over 85 days | Subcategory: life skills | ||

| Age (years): 14 | Developed by: NR | Measure: other, frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: male | Delivered by: teacher (special education) and research team | |||

| Diagnosis: autism | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Styles (2009)25 | Setting: general education, UK | Story characteristics: one story, 11 sentences; written story | Design: ABC | Category: social ability |

| n = 6 | Timing: once a day, over 6 weeks | Subcategory: social awareness | ||

| Age (years): 7 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of intervals | ||

| Gender: five males, one female | Delivered by: teacher (mainstream education) | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Swaggart (1995)70 | Setting: special education, USA | Story characteristics: two stories; written story and photographs | Design: AB | Category: social communication, other |

| n = 3 | Timing: once a day | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 7–11 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of correct responses, frequency – event recording | ||

| Gender: two males, one female | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Swaine (2004)49 | Setting: general education, Canada | Story characteristics: two stories, 16–20 sentences; written story and illustrations | Design: ABCDEFDG | Category: social communication |

| n = 2 | Timing: twice a day, two times a week, over 4 weeks | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 11 | Developed by: research team | Measure: % of correct responses | ||

| Gender: two males | Delivered by: research team | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: low | ||||

| Tarnai (2009)87 | Setting: Social skills service, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 20 sentences; written story | Design: AB | Category: social ability, social communication, other |

| n = 6 | Timing: 2–3 minutes, twice a week, for eight sessions | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 9–13 | Developed by: research team and other agency staff | Measure: frequency – interval recording | ||

| Gender: five males, one female | Delivered by: other agency staff | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Tarnai (2011)88 | Setting: social skills service, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 32 sentences, written story and illustrations | Design: AB | Category: other |

| n = 6 | Timing: once a day, for four sessions | Subcategory: life skills | ||

| Age (years): 9–11 | Developed by: teachers (special and mainstream education), research team | Measure: % of correct responses | ||

| Gender: six males | Delivered by: other agency staff and target student | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD mixed | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Taylor (2009)50 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: one story, 13 sentences; written story | Design: AB | Category: social communication |

| n = 4 | Timing: once a day, over 10 days | Subcategory: turn-taking | ||

| Age (years): 6–8 | Developed by: teacher (special education) and research team | Measure: other | ||

| Gender: four males | Delivered by: teacher (special education) | |||

| Diagnosis: ASD | ||||

| Cognitive functioning: NR | ||||

| Thiemann (2001)51 | Setting: general education, USA | Story characteristics: more than two stories; written, illustrations and photographs | Design: multiple baseline (ABA) | Category: social communication |

| n = 4 | Timing: 10 minutes, once a day, seven times a week, over 30–38 days | Subcategory: various | ||

| Age (years): 6–12 | Developed by: NR | Measure: frequency – event recording | ||