Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/34/01. The contractual start date was in May 2012. The draft report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Robert C Stein reports grants from the NIHR-UCLH Biomedical Research Centre during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Celgene Ltd and grants from Amgen Ltd outside the submitted work. Christopher Poole reports personal fees from Genomic Health outside the submitted work. Andreas Makris reports personal fees from Genomic Health during the conduct of the study. John MS Bartlett reports the following, all outside the submitted work: personal fees and other (support in kind) from BioNTech AG; personal fees from GE Healthcare; other (support in kind) from NanoString Technologies Inc.; other (support in kind) from Genoptix Medical Laboratory; grants from the NIHR HTA programme; grants from Cancer Research UK; grants from Celgene Ltd; grants from Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) High Impact Clinical Trials (HICT) Programme; grants from The Breast Cancer Research Foundation; grants from Medical Research Council; grants from Pfizer (UK); grants from Breakthrough Breast Cancer; grants from European Union; grants from The Breast Cancer Institute (UK); grants from European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; grants from Roche Pharmaceuticals Limited; personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo Pharma Development; and personal fees from Rexahn Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Stein et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The current treatment of breast cancer

Breast cancer is a major public health problem. It is the most commonly occurring cancer in the UK, with an annual incidence of 50,000, and it is the second most frequent cause of cancer death in women, with about 12,000 deaths in 2011. 1 Of the women who develop breast cancer, 80% are over 50 years old at diagnosis and most deaths occur in this age group.

The treatment of primary breast cancer, which is undertaken with curative intent, includes local (surgery and radiotherapy) and systemic [chemotherapy, anti-oestrogen and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-targeted drugs] therapies. The goal of adjuvant systemic treatment is to eliminate occult microscopic metastatic disease and thus prevent incurable distant relapse. Decisions on adjuvant therapy are informed by an individual patient’s risk of developing future overt metastatic disease. This risk is a function of both tumour stage (size and number of involved axillary lymph nodes) and tumour biology. Relevant biological features include tumour grade, oestrogen receptor (ER) status and HER2 status. ER and HER2 status also predict sensitivity to anti-oestrogen drugs and anti-HER2-targeted therapy, respectively. Distant relapse, which affects a minority of patients, typically occurs after an interval of several years; later relapse is a feature of both ER-positive and lower-grade tumours. 2

Anti-oestrogen therapy with tamoxifen, and more recently aromatase inhibitors (AIs), is considered to be the mainstay of systemic adjuvant therapy for post-menopausal women with ER-positive disease, the most common presentation of breast cancer. AIs have been shown to be superior to tamoxifen in a number of large randomised clinical trials,3 and current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends that these drugs should be offered to the majority of post-menopausal patients. 4

During the 2000s, there was a large expansion in the use of adjuvant chemotherapy, especially for post-menopausal women. Decisions on chemotherapy are based on perceived risk. In the UK, as in many other countries, it has become standard to offer chemotherapy with anthracyclines and/or taxanes to all women under 70–75 years of age with axillary node involvement. For those without nodal involvement, who are at inherently lower risk, chemotherapy is usually reserved for those with ER-negative and/or HER2-positive tumours or with high-grade tumours.

Although undoubtedly highly effective for some women, chemotherapy may be extremely unpleasant, with common side effects such as hair loss, fatigue, nausea, painful mouth ulcers, weight gain, muscle pain, diarrhoea or constipation, and loss of sensation in hands and feet. Rates of admission to hospital with serious complications have mostly been reported to be in the range 20% to 25%5–7 and there is a small risk of early death from treatment, reported to be in the range 0.2% to 0.3% in recent studies. 8,9 Patients are frequently unable to work both during treatment and for some time thereafter,10 which has considerable cost to society. Many are left with anxiety, fatigue and depression, which may severely affect their quality of life for months or even years afterwards. 11,12 There is also a small long-term risk of treatment-induced leukaemia and cardiomyopathy13 (although there is considerable uncertainty about the incidence of chemotherapy-induced cardiovascular complications). 8,14 It does not seem beyond the bounds of possibility that the overall mortality from early and late complications of chemotherapy lies in the range 1% to 2%.

Chemotherapy itself is expensive. The cost of delivering a course of fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide and docetaxel (FEC-T) or of fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (FEC) alone, which are the two most commonly used adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in the NHS, is estimated at £4600 and £3800, respectively15 (updated to 2014 prices). This includes drug costs, outpatient visits and hospital admissions for the management of complications. Approximately 18,500 patients with breast cancer (41% of diagnoses) received chemotherapy in the UK in 2006. 16 As a result, adjuvant chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer imposes a financial burden of approximately £80M per year on the NHS.

Prognostic and predictive nomograms such as ‘Adjuvant! Online’ (Adjuvant! Inc., San Antonio, TX, USA; www.adjuvantonline.com)17 and PREDICT (www.predict.nhs.uk)18 have been increasingly used since the mid-2000s. These are derived largely from clinical trial-acquired follow-up data to inform decisions about the use of systemic adjuvant therapy. However, such tools provide information only on what will happen to groups of patients on average and are not reliable at predicting outcomes for individuals. Thus, within a population of women with ER-positive tumours, who may, as a group, benefit from a statistically significant and clinically meaningful reduction in the risk of relapse consequent to the addition of chemotherapy to adjuvant endocrine therapy, there will be individuals who gain nothing as well as those who gain everything.

The advent of new technologies that offer improved means to characterise the biology of individual tumours heralds an era of more personalised medicine with respect to their potential to inform rational treatment decisions on a patient-by-patient basis. The Optimal Personalised Treatment of early breast cancer usIng Multiparameter Analysis (OPTIMA) trial is designed as a prospective test of the success of these technologies in identifying that sizeable subgroup of women with breast cancer (among those who might be expected to be routinely offered adjuvant chemotherapy based on conventional criteria) whose tumours are intrinsically insensitive to chemotherapy. For these women, the benefit of receiving such treatment would not outweigh the harm from treatment, as they would experience only toxicity and delay in starting more effective adjuvant endocrine therapy and radiotherapy.

Redefining breast cancer

The traditional classification of breast cancer is based on morphology, most notably tumour grade, which when combined with stage (tumour size and extent of nodal spread) provides valuable prognostic information, as exemplified by the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI). 19 In recent years, multiple additional prognostic markers have been defined through studies of tumour protein and gene expression.

The best established of these are receptors for steroid hormones, specifically ER and progesterone receptor (PgR), and HER2 gene amplification. Positive ER expression confers a good prognosis and also predicts sensitivity to anti-oestrogen drugs. HER2 gene amplification with associated HER2 receptor overexpression is an adverse prognostic feature but predicts sensitivity to HER2-targeted drugs such as trastuzumab (Herceptin®, Roche). The value of Ki-67, a marker of proliferation which is not routinely measured, is more controversial20 and is subject to difficulties in assay standardisation. 21–24

Since 2000, with the emergence of gene expression profiling (GEP) using microarray technology, a new molecular classification of breast cancer has been developed. 25–27 This classification divides breast cancers into four main ‘intrinsic subtypes’: luminal A, luminal B, HER2 enriched and basal-like. These subtypes differ markedly in their clinical behaviour and response to therapy, as shown in the summary table (Table 1). This goes some way to explaining the highly heterogeneous clinical behaviour of the disease. Among the intrinsic subtypes, luminal A has a significantly better prognosis than the other subtypes. 28,29 Luminal A breast cancer is broadly recognised as having a low proliferation rate (typically grade 1 or 2), being strongly positive for steroid hormone receptor expression and expressing HER2 at normal levels, although some 25% of such cancers have a different molecular subtype. 30 Molecularly classified luminal A breast cancer makes up 50–55% of all breast cancers diagnosed in the developed world. 30

| Characteristics | Intrinsic subtypes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal A | Luminal B | HER2 enriched | Basal-like | |

| Prognosis | Good | Moderate | Poor | Poor |

| Proliferation | Low | Moderate | High | High |

| Chemosensitivity | Low/nil | Moderate | High | High |

| ER | Strong | Variable | Nil | Nil |

| HER2 amplification | Uncommon | In subset | Usual | Nil |

The original research into intrinsic subtypes required complex microarray analysis of frozen tissue samples to analyse the simultaneous expression of thousands of genes within each breast cancer, with associated bioinformatics challenges. This GEP technology is widely regarded as too complex and variable to bring into the clinical setting. Recently, progress has been made in mapping the original microarray-based system onto immunohistochemical markers that can be used in routine pathology laboratories,2,31 although correlation with molecular subtyping is imperfect. 28 Several molecular assays which assign subtypes by measuring expression of a subset of the genes identified as significant in the original GEP studies are now marketed but are not in widespread clinical use. The four intrinsic subtypes do not provide a full description of breast cancer, and recent work suggests that there may be as many as 1032 but, until a more robust molecular classification is developed, the intrinsic classification provides an extremely useful framework for thinking about breast cancer.

Differential sensitivity of breast cancer subtypes to chemotherapy

The strongest evidence for the effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy comes from the meta-analyses of over 101,000 patients in 123 chemotherapy trials conducted around the world, known as the Oxford Overview. 9 For a post-menopausal woman with steroid hormone-sensitive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen, the Oxford Overview suggests that 10-year breast cancer mortality is reduced from about 32% to about 21% by anthracycline–taxane chemotherapy. Although this is clearly worthwhile, nine patients need to be treated for one life to be saved.

Most published adjuvant chemotherapy trials have made the assumption that chemotherapy benefits are similar for breast cancer, irrespective of tumour characteristics. Up to the mid-2000s, the majority have not restricted patient entry by tumour grade or receptor status. The underlying assumption in these trials that the proportional benefits of chemotherapy apply uniformly to all cancers irrespective of histological characteristics of the tumour is supported by the Oxford Overview analysis, although limited histological information is available from those older studies that included a no chemotherapy comparison. 9 The development of the intrinsic classification requires re-evaluation of all of the available evidence on adjuvant chemotherapy treatment. Now that different subtypes of breast cancer that behave in different ways are recognised, it is necessary to investigate the appropriate use of chemotherapy within the new classification.

It can be argued that the effectiveness of chemotherapy for luminal A breast cancer is low in comparison with the other subtypes, irrespective of tumour stage. 33 Retrospective ad-hoc subgroup analysis of a number of large trials of taxane versus non-taxane chemotherapy regimens have mostly suggested that there is no significant benefit for the newer and more toxic regimens for women with ER-positive HER2-negative cancers (e.g. see Hayes et al. 34), most of which would be luminal A tumours although not all such analyses confirm this, most notably the Oxford Overview. 9 Similar analyses of comparisons of anthracycline chemotherapy with older cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil (CMF) regimens suggest that the anthracycline benefit is limited to patients whose tumours expressed high-risk markers. 35 A recent analysis36 of two pivotal trials37,38 of CMF chemotherapy with or without endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone in women node-negative cancers failed to demonstrate a clear chemotherapy benefit in those women whose tumours were demonstrated to be ER-positive using modern assays, in contrast to other subgroups. Furthermore, those trials of chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy that included endocrine therapy predated AI therapy, which is a more effective treatment than tamoxifen.

A second line of evidence that chemotherapy sensitivity is influenced by tumour biology comes from studies of presurgical (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy. Analysis of the outcome of treatment according to intrinsic subtype of individual tumours is particularly striking, with a ‘pathological’ complete response rate of 6% in luminal tumours compared with 45% in basal type. 39 A separate study showed that the chances of achieving a pathological complete response for patients with luminal B tumours was 2.4-fold greater than for patients with luminal A tumours. 28 Similar findings have been reported in the Investigation of Series Studies to Predict Your Therapeutic Response With Imagine and Molecular Analysis (I-SPY) 1 trial,40 which systematically evaluated chemotherapy response in relation to a number of biomarker profiles.

The third and particularly relevant line of evidence comes from the retrospective analysis of historical trials comparing chemotherapy plus tamoxifen with tamoxifen alone in ER-positive breast cancer according to the results of the Oncotype DX® (Genomic Health Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA) test performed on archival tumour tissue. The evidence that assays such as Oncotype DX are able to predict chemotherapy response is discussed below.

Multiparameter assays in breast cancer

The development of the intrinsic classification has transformed our understanding of breast cancer and is changing clinical management to a more individualised approach. In parallel, it is driving intensive research efforts to develop simpler molecular tools that classify breast cancers and, more importantly, quantitate the risk of relapse for individual patients following particular treatment. These new tests typically involve the simultaneous measurement of expression of a number of genes either at the protein or messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) level. Most of the better-validated assays are commercialised and are either available or in the process of being marketed for clinical use. Although the early multiparameter assays that relied on mRNA measurement required fresh tissue, all the commercialised assays now work on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. One of the main drivers for the development of multiparameter assays is the clinical uncertainty surrounding the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy for women with ER-positive HER2-negative breast cancer, so the majority of assays have focused on this group of patients. Most assays have been developed and validated in (largely) node-negative populations whose prognosis is not complicated by the effect of lymph node involvement.

The output of the available assays takes the form of either a simple numerical score that can be used against a calibration chart to estimate recurrence risk [e.g. Oncotype DX41 and Breast Cancer IndexSM (BCI) (bioTheranostics, San Diego, CA, USA)]42,43 and/or assignment to either a predefined risk category or subtype. The most common measure of relapse is the risk of developing metastatic disease by 10 years from diagnosis. Most commercially developed assays are strongly influenced by steroid hormone sensitivity, HER2 status and proliferation. A number of assays have been evaluated only in ER-positive populations.

All of the available assays have been retrospectively tested on archival material, mostly from historical trials; to date, no prospective evaluation of any multiparameter assay has been published. Although it has been argued that retrospective analysis of tumour samples can provide satisfactory validation when used with appropriate precautions,44 a recent consensus panel has argued strongly for prospective validation studies. 45 Four systematic reviews46–49 have examined the data supporting the validation of multiparameter assays, particularly Oncotype DX and MammaPrint® (Agendia, Irvine, CA, USA) in detail. Table 2 lists most of the multiparameter assays that have been described for ER-positive HER2-negative breast cancer. Several of these are described in detail below (see Individual multiparameter assays).

| Assay (vendor) | Details of multiparametric assay | Output | Availability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perou et al.25 and Sorlie et al.26,27 (non-proprietary) | The original description of the intrinsic classification using 495 genes (the most highly cited papers in breast cancer) | Subtype | – | Perou et al., 200025 Sorlie et al., 200326 Sorlie et al., 200127 |

| Oncotype DX (Genomic Health Inc.) | A 21-gene qRT-PCR expression assay (using 16 cancer-related and five normalisation genes) | Risk score | Central laboratory (USA) | Paik et al., 200441 |

| MammaPrint + BluePrint (Agendia, Irvine, CA, USA) | A 70 + 80 gene microarray-based expression signature | Risk category and subtype | Central laboratory (the Netherlands) | Glas et al., 200650 Mook et al., 201051 |

| Rotterdam signature (non-proprietary) | A 76-gene microarray-based expression signature | Risk score | Not in clinical use | Foekens et al., 200652 |

| Mammostrat (Clarient/GE Healthcare, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA) | A five-gene immunohistochemical assay | Risk score | Central laboratory (USA) | Ring et al., 200653 |

| Prosigna (PAM50) (NanoString Technologies Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) | A 50-gene expression assay using the NanoString system | Subtype and risk score (± clinical data) | Regional laboratories | Geiss et al., 200854 Dowsett et al., 201355 |

| BCI (bioTheranostics, San Diego, CA, USA) | A seven-gene qRT-PCR expression assay | Risk score | Central laboratory (USA) | Ma et al., 200842 |

| IHC4 (AQUA and non-proprietary) | Quantitative immunohistochemical assay for ER, PgR, HER2, Ki67 | Risk score (± clinical data) | Academic | Cuzick et al., 201156 |

| MapQuant (Genomic Grade Index, Bordet Institute, Brussels, Belgium) | A 97-gene microarray-based expression assay | Risk category | Not currently available | Sotiriou et al., 200657 |

| EndoPredict (Sividon, Sividon Diagnostics, Cologne, Germany) | A seven-gene qRT-PCR expression assay | Risk score (± clinical data) | Regional laboratories | Filipits et al., 201158 |

| NPI+ | A 10-gene immunohistochemical assay | Subtype and risk category (± clinical data) | In development | Rakha et al., 201459 |

| MammaTyper (BioNTech Diagnostics GmbH, Mainz, Germany) | A five-gene qRT-PCR assay | Subtype | In development | Aigner et al., 201260 |

Individual multiparameter assays

Oncotype DX

This is a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based expression assay testing expression of 21 genes, 16 of which are cancer related and five are for normalisation. The assay is used in FFPE specimens. The initial study41 described the derivation of the 21-gene signature assay from expression array analysis of tamoxifen-treated cancers and its translation and validation into a multiplex PCR diagnostic assay. The test output is the continuously variable numerical ‘recurrence score’ (RS), which has a monotonic relation to the risk of distant recurrence at 10 years following tamoxifen treatment of ER-positive node-negative breast cancer. Individual patient risk can be estimated from the calibration provided with the results. Additionally, the patients are divided into three risk categories (low, intermediate and high), where intermediate is defined (from the initial validation study) as a 10–20% risk of developing distant metastases over 10 years. Genomic Health performs this test centrally in a single US laboratory; the UK list price for the assay is £2580.

Multiple additional studies,61–65 comprising the retrospective analysis of patients’ outcomes in Phase 3 trials within ER-positive breast cancer, have confirmed the value of Oncotype DX as a predictor of residual risk following endocrine therapy and have extended the original observations to patients with positive lymph nodes, and also to patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. 66 Oncotype DX has been demonstrated to reclassify risk defined by Adjuvant! Online,17 which is a risk predictor that uses conventional histopathology information. 64,67 Oncotype DX has also been shown to predict chemotherapy sensitivity in the neoadjuvant setting. 68,69

Analysis of individual patient Oncotype DX RSs has been performed retrospectively on a subset of patients included in two historical clinical trials of chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy. The analyses of the B-20 trial of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP B-20) trial in women without axillary nodal involvement61 and in the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) trial 8814 (SWOG88-14) trial in women with node-positive disease62 have shown that there is no chemotherapy benefit for women with an RS in the low- or intermediate- risk groups. The analysis of the SWOG88-14 trial is particularly important as it shows that even in heavily (≥ 4) node-positive patients who have a poor prognosis by virtue of stage, there is no benefit to the addition of chemotherapy to adjuvant endocrine therapy, compared with endocrine therapy alone, if the RS is low. These data are widely interpreted to suggest that Oncotype DX is able to predict whether or not tumours are likely to be sensitive to chemotherapy. Incorporating clinical data (tumour stage, grade and age) for patients with node-negative disease into the test improves its performance as a prognostic test but crucially does not improve its ability to predict chemotherapy sensitivity. 64,70

A number of studies (e.g. Ademuyiwa et al. 71 and Albanell et al. 72), including two conducted within the UK,73,74 have shown that the use of Oncotype DX leads to changes in chemotherapy decisions in about one-third of patients, although these studies involve small sample sizes and often have poorly described protocols.

Limitations of Oncotype DX highlighted by the systematic reviews46–49 include the fact that there are relatively few data about the performance of the test in node-positive patients and that the data supporting the ability of the test to predict chemotherapy benefit are not robust. 49 Additionally, Oncotype DX, unlike some other tests, is only able to predict recurrence risk over the first 5 years after diagnosis. 75 No prospective studies reporting the impact of Oncotype DX on long-term outcomes, such as overall survival have been identified. In addition, the test has not been prospectively trialled against any alternatives. There is no evidence that the Oncotype DX assay is any more informative than other gene expression assays. 76

In 2007, an American Society of Clinical Oncology expert panel reviewed the evidence and recommended the use of Oncotype DX in routine care. 77 The test has proved to be popular with patients and clinicians, and is undoubtedly the global market leader in the field. Genomic Health reported that as of 31 December 2014, more than 500,000 tests have been preformed, the majority for invasive breast cancer, generating a total revenue of US$1.4B for the company over a 7-year period. 78

MammaPrint

The MammaPrint assay is based on 70 genes, identified by GEP, that were shown to predict outcome in a mixed population of young breast cancer patients with node-negative disease, none of whom was treated with adjuvant tamoxifen. 79 Following an initial validation study performed in a similar population,80 the test was commercialised. Initially it was performed using array technology on fresh-frozen tissue,50 but since 2012 it has been available for FFPE tissue samples. 81 Currently the test is marketed by Agendia as part of the SYMPHONY profile and is performed in central laboratories located in the Netherlands and in the USA; the current list price of SYMPHONY is €2675. The output from MammaPrint is essentially a simple binary division into low risk and high risk. The BluePrint® (Agendia, Irvine, CA, USA) assay provides subtyping information (luminal type, basal type and HER2 type); combining the MammaPrint and BluePrint results for patients with ER-positive tumours allows tumours to be divided into luminal A and luminal B subtypes.

Following the initial validation study,80 MammaPrint has been reported to provide valid prognostic information in a number of additional studies, and evidence has shown that it is able to reclassify risk against existing prognostic variables. 51,82–85 Several studies40,86,87 have shown that MammaPrint is able to predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, including differentiating between high- and low-risk ER-positive disease. A study of patients pooled from several data sets has provided evidence that MammaPrint is able to predict chemotherapy benefit in patients with ER-positive disease and up to three involved lymph nodes. 88 There is evidence that MammaPrint results influence chemotherapy decisions made by European oncologists (predominantly Dutch) in clinical practice89,90 without any apparent increase in recurrence after 5 years. 91

Overall, the evidence supporting MammaPrint is broad-based and convincing but, in comparison with studies validating the use of Oncotype DX, it is less comprehensive, with individual studies tending to have a lower quality. This is also the conclusion of the four systematic reviews of the field. 46–49 The limitations of the evidence in support of Oncotype DX also apply to MammaPrint. Although one study92 has purported to show that MammaPrint is able to predict outcome beyond 5 years, it clearly does not predict late relapse.

MammaPrint is widely used in clinical practice in parts of Europe but has never achieved the global penetration of Oncotype DX. Its use in the UK is very limited, probably because the requirement for fresh tissue up to 2012 was widely considered to be an obstacle by clinicians and, as such, it was ‘second to market’.

IHC4

There is long-standing evidence that the conventional immunohistochemistry markers, ER, PgR, HER2 and Ki67 (a marker for cell proliferation),33,93 are able to identify patients at increased residual risk following endocrine therapy. The IHC4 test relies on quantitative immunohistochemistry for these four markers. The component scores have been integrated into a viable predictor of residual risk in post-menopausal women with ER-positive disease. The assay was developed using outcome data and stored tumour blocks from women who participated in the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial. 56 IHC4, using conventional manual colorimetric immunohistochemistry, has been developed in an entirely academic setting and, as there are no proprietary data, there is limited incentive for its commercial development. Genoptix, a US-based company, promotes the test using proprietary automated quantitative immunofluorescence (AQUA®). 94 The output from IHC4 is a numerical score, with a division into three risk groups using the same definitions as Oncotype DX.

The original IHC4 validation study was performed on a large patient cohort (n = 1125), and the report included a second validation performed on an independent patient cohort. 56 A completely independent study has been performed on around 4500 patients recruited from the Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multinational (TEAM) study, using both conventional immunohistochemistry and quantitative immunofluorescence. 95 Both methods of detection provided significant prediction of residual risk following endocrine therapy with reasonable correlation, although the performance of quantitative immunofluorescence was superior on the basis of the c-index. One study96 has demonstrated that IHC4 is able to reclassify risk defined by Adjuvant! Online or the NPI. In addition to these studies, a detailed comparison has been performed between IHC4 and Oncotype DX in the transitional cohort of the ATAC trial (transATAC). 56 Correlation between the two was modest, but the two assays provide a similar amount of prognostic information. As both tests are strongly influenced by measures of proliferation, steroid hormone receptor signalling and HER2 status, and were developed with similar patient cohorts, this is unsurprising.

The validation of IHC4 as a predictor of residual recurrence risk involves far more patients than validation studies performed for any other multiparameter assay. Additionally, the similarity between IHC4 and Oncotype DX implies that, by extension, the ability of Oncotype DX to predict chemotherapy sensitivity is like to apply to ICH4. The low estimated cost of £150 for performing IHC4 using conventional immunohistochemistry49 and its portability are potential strong advantages for IHC4 over other multiparameter assays. However, its portability is also its principal weakness, as the reproducibility of manual quantitative immunohistochemistry, particularly for Ki67, is limited. 21–24 It remains to be demonstrated whether or not quantitative immunofluorescence established in local laboratories is more reproducible.

Prosigna® (PAM50)

PAM5028 is a quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR expression assay developed in an academic setting using 50 genes selected from the original set identified by Perou et al. in their pioneering microarray studies of intrinsic subtype. 25–27 The assay provides subtyping information and additionally a numerical risk of recurrence (ROR) score; there are several variants of the ROR score incorporating varying amounts of clinical and conventional histological information.

The ProsignaTM test, which measures the expression of the PAM50 gene set using the NanoString platform,54 has been developed by NanoString Technologies (Seattle, WA, USA). 97 The assay can be performed in suitable local laboratories using hardware and reagents provided by the company. The analytical validity of the assay has been demonstrated in a distributed environment98 and the company was granted the necessary US Food and Drug Administration approval in September 2013 for its marketing as a prognostic assay in post-menopausal patients. Prosigna was independently trained and validated but Prosigna and PAM50 subtype predictions and ROR scores are highly concordant.

PAM50, and by inference Prosigna, can be used in all subtypes of breast cancer, but detailed validation studies have been performed on patients with ER-positive disease. 28,55,75,99–101 PAM50 has been validated as a predictor of residual risk in two studies28,99 and has been shown to reclassify risk defined by Adjuvant! Online using conventional pathology. Similarly, Prosigna has been demonstrated to predict residual risk and to reclassify risk in the large transATAC cohort and in approximately 1500 mostly node-negative patients treated with endocrine therapy alone from the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG-8) study of endocrine therapy in post-menopausal women. 55,100 Prosigna, in contrast to Oncotype DX and IHC4, is able to predict late (beyond 5 years) recurrence in these two patient cohorts (transATAC and ABCSG-8). 75,101

Response rates to neoadjuvant chemotherapy have been shown to vary between both PAM50-28,40 and Prosigna102-defined intrinsic subtypes. Response rates have been reported to be lower for luminal A than for luminal B tumours and both luminal subtypes are less chemotherapy sensitive than non-luminal subtypes. Additionally, Prosigna ROR scores have been shown to be predictive of chemotherapy response. 102 Three studies have explored the ability of PAM50 to predict outcome in trials comparing two chemotherapy regimens, two of which were conducted in early breast cancer103,104 and one in advanced disease. 105 None of the three studies selected patients by receptor expression, so the numbers of patients with luminal disease analysed was comparatively small. None of the studies showed an overall statistically significant benefit for patients with luminal B versus luminal A disease. One of the adjuvant studies compared an anthracycline containing regimen with CMF with an overall positive result. 103 The second adjuvant study, which was also positive, showed that patients with luminal A breast cancers appeared to benefit from paclitaxel treatment, unlike those with higher-risk subtypes,104 which is a counterintuitive finding. In the study conducted in advanced disease,105 which showed no overall benefit for the addition of gemcitabine to docetaxel, there appeared to be a significant benefit for patients with luminal B versus luminal A disease, which was lost in multivariate analysis.

Mammostrat®

Derived following expression array analysis identifying markers of residual risk in early breast cancer, the Mammostrat® assay (Clarient/GE Healthcare, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA) relies on immunohistochemical analysis of five markers (p53, NDRG1, SLC7A5, CEACAM5 and HTF9C). The test classifies patients into three risk groups. First described in 2006,53 this assay was validated across multiple retrospective institutional and clinical trial cohorts, including the NSABP B-14 and NSABP B-20 trials, and the TEAM trial. 53,106,107 One health economic analysis suggests that the test is cost-effective in US health care. 108

Mammostrat was developed by Clarient and, following US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2007, the assay was commercialised in the USA as a marker of residual risk in early breast cancer. GE Healthcare acquired Clarient in 2010. Clarient/GE Healthcare discontinued development of the test in 2014. Although still commercially available in the USA, its future is uncertain.

MammaTyper®

This is a four-gene quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR expression assay being developed commercially by BioNTech Diagnostics GmbH. The assay measures ER, PgR, HER2 and Ki67 mRNA. 60 These data are combined to allocate tumours to an intrinsic subtype rather than provide a risk score as IHC4. The definition of intrinsic subtype is based on an immunohistochemical definition, which does not map accurately onto PAM50/Prosigna defined subtypes. 99 Formal clinical validation studies of the assay are currently being conducted.

Comparative performance of multiparameter assays

Very limited information on direct comparisons between multiparameter assays is available. Comparisons have been performed between Oncotype DX, IHC4, Prosigna and BCI results from approximately 1000 post-menopausal patients treated with endocrine therapy from the transATAC cohort. 43,55,56,75 These have focused on high-level statistical analysis of the prognostic value of different tests within this population. Information on the proportion of patients testing ‘positive’ (i.e. high risk) for individual tests is more opaque and, in particular, data on results at the individual patient level are lacking. Nonetheless these comparisons have been of substantial value in allowing comparisons between tests, albeit limited to comparing their overall prognostic impact. Taken collectively, the results of these pivotal studies support the conclusion that all four assays provide similar prognostic information at the population level. They also provide evidence that Prosigna and BCI provide statistically more prognostic information than Oncotype DX and IHC4, and in contrast to Oncotype DX and IHC4, they provide information about the risk of late (beyond 5 years) relapse. No conventional parameters of performance (e.g. area under the receiver operator curve) have been presented at any time for any of the currently available assays, which makes it difficult to evaluate their performance in this regard. However, the statistical improvements in performance for Prosigna and BCI are modest, but important, leaving space for further improvement.

An alternative approach is to use published assay algorithms, or to ‘reverse engineer’ assays, and to apply these to gene expression data sets, with associated outcome data as an ‘in silico’ experiment. 109,110 Such comparisons have, like the direct comparisons, shown that the results of the various multiparameter assays are moderately correlated with respect to the prognostic information provided. The major limitations of this methodology are, first, that different array platforms lack probes that match to prognostic signatures, such that ‘missing genes’ may compromise analysis, and, second, that the algorithms used by the assays are calibrated according to the method used to measure gene expression and may not translate well into semiquantitative analysis of microarray data sets used for this analyses. Signatures compared, in a similar manner using arrays and reverse engineering, in the I-SPY 1 trial include MammaPrint and PAM50. 40 There was again a modest correlation between assay performance, and most provide predictive information about response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and outcome. Once again, the analysis of I-SPY 1 provided no information on the comparative performance of assays at patient level.

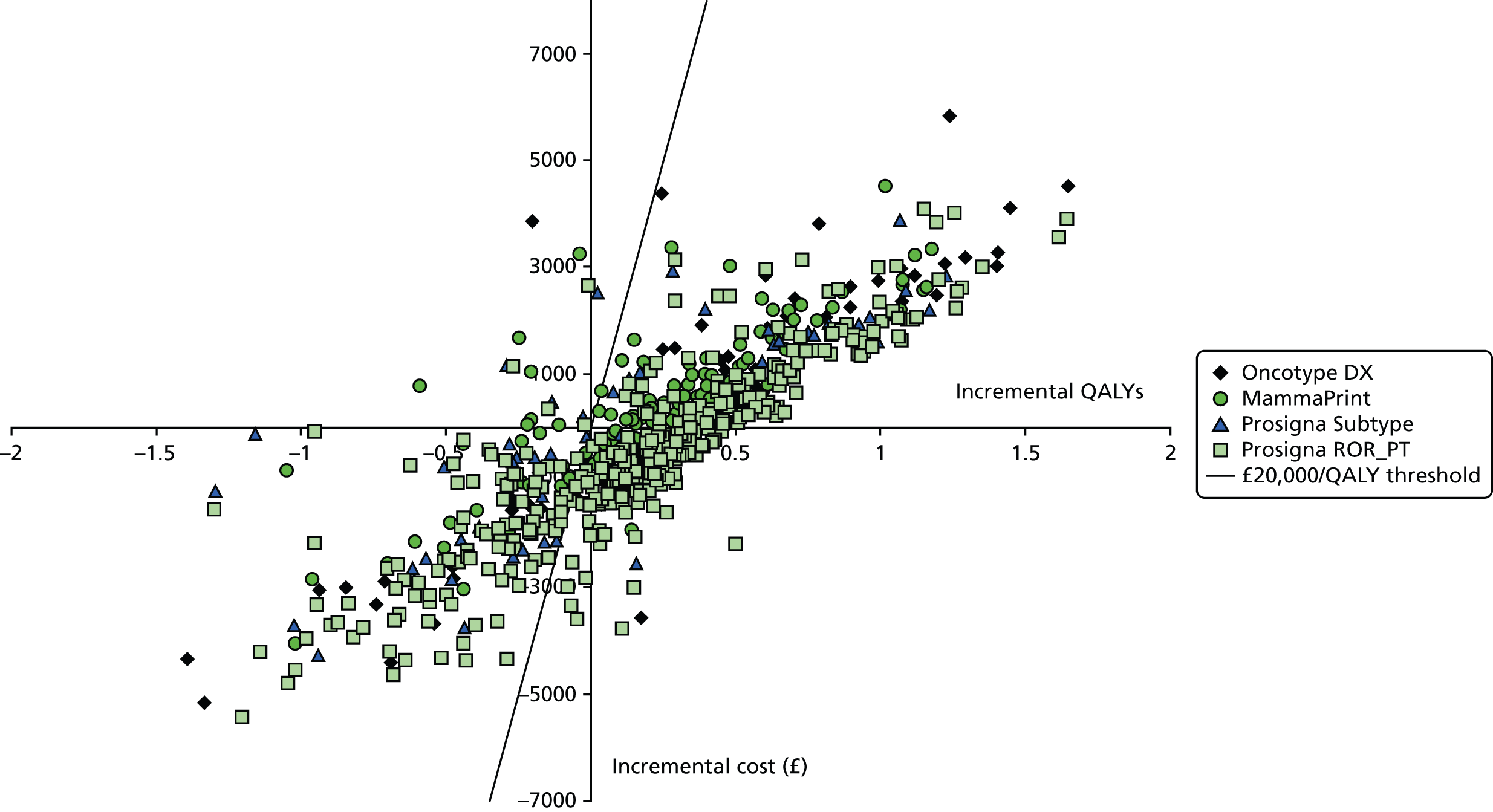

Cost-effectiveness analyses of multiparameter testing

We performed a systematic review of literature on the cost-effectiveness of multiparameter testing; the methods are described in Appendix 1. Six studies assessed the impact of Oncotype DX (one in each of Canada,111 the USA,112 the UK,74 Germany,113 Australia114 and Japan115), and one assessed the impact of MammaPrint in the Netherlands. 116 No head-to-head comparisons of the alternative genomic tests have been conducted. Four studies74,112,113 either were funded by the test manufacturer or were carried out by researchers who worked for the manufacturer. 114 All studies compared the given genomic test with current conventional management, which consisted of current national guidelines and tools based on patient clinicopathological data (such as Adjuvant! Online,17 PREDICT18 and the NPI19).

The majority of studies considered mixed populations, including patients with both lymph node-negative and lymph node-positive disease. 74,113,115,116 Two studies112,113 assessed populations that included only patients with lymph node-positive disease, both of which evaluated Oncotype DX. Four studies reported specific details of patients’ level of lymph node involvement;112,113,115,116 most restricted their populations to patients with low levels (1–3) of lymph node involvement, with only one study111 including patients with higher (1–9) lymph node involvement.

The single MammaPrint study estimated that the test would lead to a 0.21 decrease in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) together with a US$2882 fall in costs, from a Netherlands societal perspective. 116

Of the six studies assessing Oncotype DX,74,111,115 two estimated that the test would dominate standard care strategies, with Oncotype DX found to produce a gain in QALYs and a reduction in costs. 112,113 Both of these studies were funded by the manufacturer. Vanderlaan et al. 112 found that, from a health-care payer perspective and using a lifetime horizon, Oncotype DX was estimated to produce a gain of 0.17 QALYS per patient and reduce costs by US$384 (based on 2009 costs). Eiermann et al. 113 found that, from a German health-care payer perspective and over 30 years, Oncotype DX was estimated to produce a gain of 0.06 QALYS and reduce costs by €561 per patient.

The remaining four studies74,111,114,115 found Oncotype DX to be more costly and more effective than standard care. The highest incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) value was estimated in the only study that included patients with high levels of lymph node involvement (1–9 positive nodes). Lamond et al. 111 found that, from a Canadian third-party payer perspective and over a lifetime horizon, Oncotype DX was estimated to produce a 0.06 QALY gain at an incremental cost of CA$14,844 (based on 2011 costs) [95% confidence interval (CI) CA$3616 to CA$25,646] per QALY. They found that there was almost a 100% probability of Oncotype DX-guided treatment being cost-effective, but that the results for the lymph node-positive group were more sensitive to one-way sensitivity analyses than the results in a lymph node-negative population. For the remaining three studies (which assessed mixed lymph node populations), the ICER results were £6232/QALY,74 JP¥568,533/QALY (equivalent to US$5685)115 and AUD$9986/QALY. 116

In addition to these studies, two studies15,49 have considered the likely cost-effectiveness of multiparameter assays for use in the NHS. Hall et al.,15 who performed a cost–utility analysis of Oncotype DX in a node-positive population by modelling outcome data from the SWOG88-14 Oncotype DX study62 to the NHS, concluded that Oncotype DX is unlikely to be cost-effective for this population. Ward et al. ,49 who undertook the external evidence review for the NICE DG10 guidance117 in a node-negative population, concluded that Oncotype DX could be cost-effective if offered to a higher-risk subset of such patients. They considered that MammaPrint and IHC4 may also be cost-effective, but the evidence was not sufficiently robust to draw a firm conclusion, while limited evidence suggested that Mammostrat is unlikely to be cost-effective.

The literature review also identified two budget impact analyses,118,119 both of which were funded by or affiliated with the manufacturer of the test. Ragaz et al. 118 assessed the impact of Oncotype DX on US and Canadian health-care costs in both lymph node-positive and lymph node-negative patients, and estimated that Oncotype DX could save US$330.8M in the USA and US$46.2M in Canada. Zarca et al. 119 assessed the impact of MammaPrint on health-care costs in France on node-positive (1–3) breast cancer patients, and estimated that MammaPrint could save €9043 per 100 patients per year compared with current practice.

Availability of multiparameter testing in the UK

Four multiparameter assays have been evaluated by NICE (Oncotype DX, MammaPrint, IHC4 and Mammostrat) for potential use in the NHS. The resulting guidance117 was published in September 2013. The guidance states that Oncotype DX ‘is recommended as an option for guiding adjuvant chemotherapy decisions for people with ER-positive, lymph node-negative and HER2-negative early breast cancer’. The recommendation was limited to patients at ‘intermediate risk’, defined as a NPI score of > 3.4, and relies on a discounted price for Oncotype DX. The guidance and resulting funding decisions apply only to England. The three other technologies evaluated were recommended for use only in research at this time. Five additional technologies, including PAM50, BCI and NPI+, were removed from the scope in November 2011, almost 2 years before the final guidance was published, on the grounds that at that time there was insufficient evidence to justify their inclusion in the economic analysis performed by the external assessment group. 120 The appraisal was also limited to patients with node-negative disease, as the evidence for the use of the tests was considered less robust in the node-positive population. The NICE committee recommendation for the use of Oncotype DX was made on the basis that the test provides superior prognostic information to conventional clinicopathological risk assessment. The committee, however, did not consider the evidence that Oncotype DX is able to predict the benefit of chemotherapy above and beyond providing prognostic information to be robust and recommended further research into this question for all four technologies.

The OPTIMA study

There are a number of important unanswered questions for clinicians and patients on the practical use of multiparameter assays in making decisions about chemotherapy. These include whether or not tests might be useful for patients with axillary node involvement, how best to use the tests, what threshold to use where this is not clearly defined and which of the available tests provides the most reliable results. Three ongoing international randomised controlled trials (RCTs) will generate prospective evidence for the validity of test-directed treatment assignment. 121–123

-

Trial Assigning IndividuaLized Options for Treatment (Rx) (TAILORx). 121 This US-based intergroup trial randomised patients to chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy, or endocrine therapy alone based on an Oncotype DX test result. Eligible patients have ER-positive breast cancer without nodal involvement. All patients undergo Oncotype DX, and those with a RS in the range 11–25 are eligible for randomisation. Recruitment was suspended in October 2010, when 10,000 (out of a target of 11,000) patients had been enrolled. The primary analysis is expected in 2017. The majority of patients randomised in TAILORx would not currently be offered chemotherapy in the UK.

-

Microarray In Node-negative and 1- to 3-positive lymph node Disease may Avoid ChemoTherapy – European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 1004 (MINDACT – EORTC 1004). 122 This pan-European trial is comparing adjuvant chemotherapy treatment decisions based on genetic profiling using the MammaPrint test run on fresh tissue, with decisions based on clinical parameters. Eligible patients can have up to three involved axillary lymph nodes. The MINDACT study has met its recruitment target of 6000 patients; the primary analysis is planned to take place in 2016.

-

Rx for Positive Node, Endocrine Responsive Breast Cancer (RxPONDER). 123 This is a US-based intergroup study that opened to recruitment in 2011. Eligible patients will have ER-positive, HER2-negative tumours with one to three involved axillary lymph nodes. All patients will undergo Oncotype DX testing prior to trial entry. Patients with a RS of ≤ 25 are eligible to be randomised between chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone. The trial aims to test over 10,000 patients and to randomise 4500. The primary analysis is currently intended to take place in 2022.

The lack of comparative data with other multiparameter tests means that it is possible that other existing tests may allow more reliable identification of chemotherapy-sensitive disease than Oncotype DX or MammaPrint. Although NICE has recommended that Oncotype DX may be used to guide adjuvant chemotherapy decisions, it may not be the most cost-effective platform for making test-directed chemotherapy decisions in the NHS.

The OPTIMA trial seeks to advance the development of personalised treatment in breast cancer by establishing an appropriate and effective method of multiparameter analysis, to identify which women with ER-positive HER2-negative, lymph node-positive primary breast cancer are likely to benefit from chemotherapy, and which are not. It is axiomatic to the study that the benefit of chemotherapy is not evenly distributed among breast cancer subpopulations, contrary to the assumption made by NICE in DG10,117 and that the multiparameter assays are able to predict chemotherapy sensitivity. The potential ability of multiparameter assays to predict chemotherapy sensitivity was recommended as a topic for future research in the DG10 guidance. The study population is similar to that included in the NICE appraisal in respect of ER and HER2 status, but at higher risk, so would ordinarily be offered chemotherapy by virtue of either axillary lymph node involvement or because other adverse clinicopathological features; the majority of such patients would not be eligible for NHS-funded Oncotype DX testing. The OPTIMA study is an adaptive trial that allows more than one technology to be evaluated. It is planned to run in two phases with an initial feasibility study, now completed, to compare the performance of technologies in order to establish which of these will be included in the main trial, and to evaluate the acceptability of the approach to patients and its cost-effectiveness. The main study will use an end point of non-inferiority after 5 years because events often occur late in breast cancer and no intermediate end point that allows early prediction of recurrence has yet been identified.

OPTIMA prelim (the feasibility phase of OPTIMA) was funded by the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in 2012 (reference 10/34/01) and completed the primary phase recruitment on 3 June 2014. The main objectives of OPTIMA prelim were to demonstrate that recruitment to a large-scale randomised trial of test-directed chemotherapy is feasible in the UK and to select a multiparameter assay to use as the primary treatment discriminator in the main OPTIMA study. This report describes the methodology used in OPTIMA prelim and the results of the study.

Chapter 2 Methods: recruitment and study conduct

Trial design

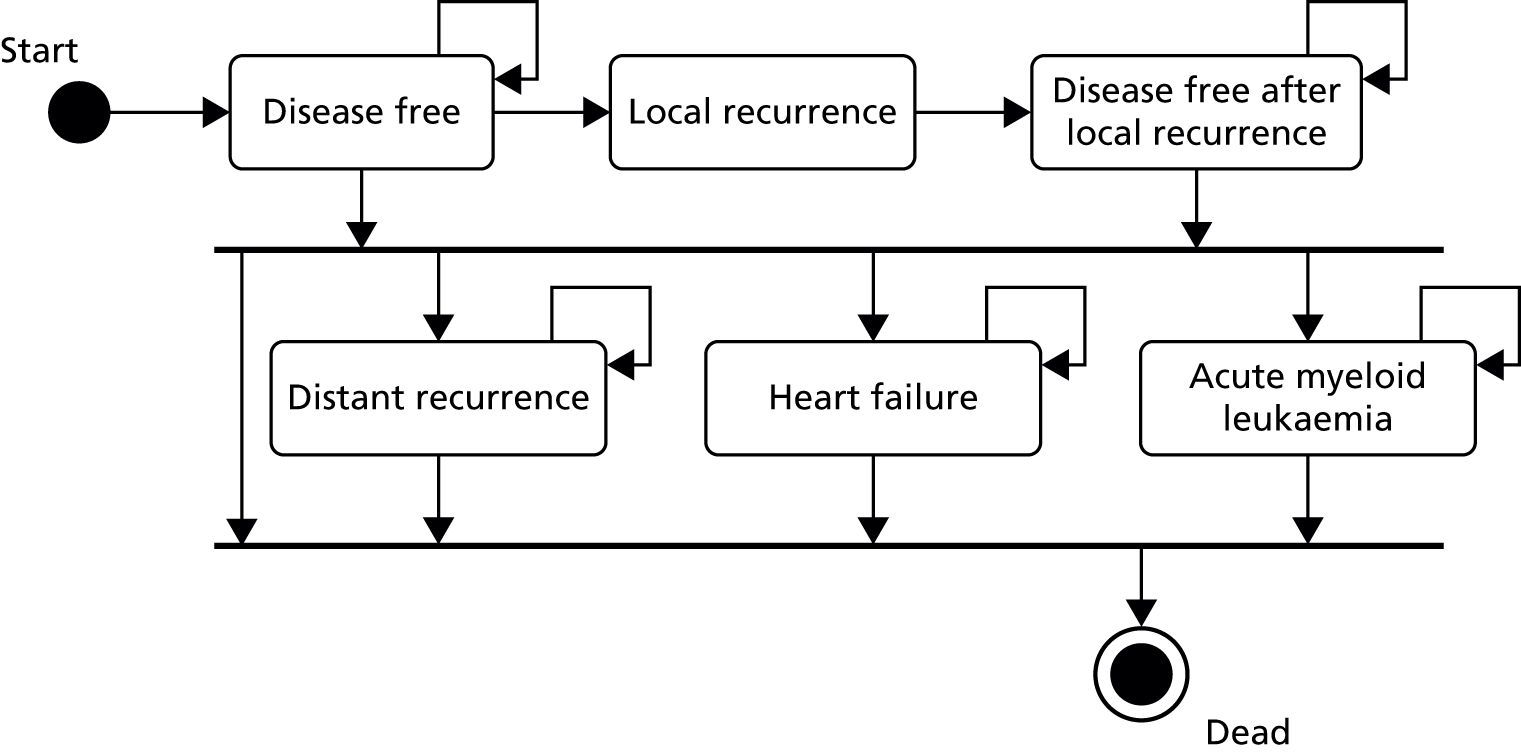

The OPTIMA trial is a multicentre, partially blind randomised clinical trial with a non-inferiority end point and an adaptive design. The preliminary or feasibility phase of the study, which has the same structure as the main trial, is referred to as OPTIMA prelim (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The OPTIMA prelim trial schema. FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridisation; non-amp, non-amplified; pT, pathological tumour size. Note that pN refers to the pathologically determined nodal status; pN1 represents 1–3 positive nodes; pN2 represents 4–9 positive lymph nodes.

OPTIMA prelim aimed to establish whether or not a large trial of multiparameter test-based treatment allocation (‘test-directed’ treatment) is acceptable to patients and clinicians, with 300 patients randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio. A 200-patient extension phase was built into the design of OPTIMA prelim to allow a smooth roll through to the main trial. A second key aim of the study was to compare the performance of alternate multiparameter tests to allow the selection of multiparameter tests to be evaluated in the main trial.

OPTIMA trial compares the standard treatment of chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy with multiparameter test-directed treatment allocation to either chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone. The randomisation of patients allocated to chemotherapy is concealed from treating centres. In the main trial, it is expected that approximately 1860 patients will be randomised to each arm in a two- or three-arm design (with either one or two test arms). Patients will be followed up for 10 years.

The OPTIMA trial is adaptive with respect to the technology used to make a chemotherapy treatment assignment. The technology used in the OPTIMA prelim was Oncotype DX, which was chosen as the best-validated test when the trial was designed. A RS cut-off point of > 25 versus ≤ 25 was selected as the threshold for allocation of patients to chemotherapy or to no chemotherapy. To avoid any potential confusion in the use of nomenclature, the two groups defined by this cut-off point are referred to either by RS value or as RS low or high score. The value of 25 was chosen (1) as it is the mid-point of the predefined intermediate-risk range (RS of 18–31), (2) because from the retrospective analyses of the NSABP B-20 and SWOG88-14 studies,61,62 this is roughly the level at which there appears to be a clinically meaningful benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy, and (3) because it is the upper limit at which randomisation is permitted in the ongoing TAILORx and RxPONDER trials. 123,124

Trial objectives

The OPTIMA prelim objectives were:

-

to evaluate the performance and health economics of alternative multiparameter tests to determine which will be evaluated in the main trial

-

to establish the acceptability to patients and clinicians of randomisation to test-directed treatment assignment

-

to establish efficient and timely sample collection and analysis, which is essential to the delivery of multiparameter test-driven treatment.

The OPTIMA main trial objectives are:

-

to evaluate whether or not test-directed chemotherapy treatment and endocrine therapy is non-inferior to chemotherapy followed by endocrine treatment for all patients in terms of invasive disease-free survival (IDFS).

-

to establish the cost-effectiveness of a test-guided treatment strategy compared with standard practice.

OPTIMA prelim success criteria

The prespecified criteria used to determine the success of OPTIMA prelim were recruitment of 300 patients no more than 2 years from the first centre opening to recruitment, and, for the final 150 patients:

-

patient acceptance rate should be at least 40%

-

recruitment should take no longer than 6 months

-

chemotherapy should start within 6 weeks of signing the OPTIMA prelim consent form for no less than 85% of chemotherapy-assigned patients.

Outcome measures

OPTIMA prelim

Patient acceptability

-

Time between consent and starting chemotherapy.

-

Recruitment time.

-

Agreement between tests.

The OPTIMA main trial

Primary outcomes

-

IDFS.

-

Costs and QALY.

Secondary outcomes

-

Quality of life as measured by the European Quality of Life 5-Dimesions (EQ-5D)125 and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) questionnaire for patients with breast cancer. 126,127

-

Distant disease-free survival.

-

Comparative performance of multiparameter assays (if more than one adopted).

-

Patient compliance to long-term endocrine therapy.

-

Overall survival.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Female, aged ≥ 40 years.

-

Excised invasive breast cancer with local treatment either completed or planned according to trial guidelines.

-

ER-positive [Allred score of ≥ 3 or histoscore (H-score) of ≥ 10 or as otherwise established by the reporting pathologist] as determined by the referring centre and centrally confirmed.

-

HER2-negative (i.e. immunohistochemistry score of 0–1+) or fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) or other in situ hybridisation non-amplified, as determined by the referring centre and centrally confirmed.

-

Axillary lymph node status: (1) 1–9 involved (macrometastases, i.e. > 2 mm OR micrometastases, i.e. > 0.2–2 mm) OR (2) node negative AND tumour size ≥ 30 mm. Nodes containing isolated tumour cell clusters only, that is ≤ 0.2 mm in diameter, were considered to be uninvolved.

-

Considered appropriate for adjuvant chemotherapy by treating physician.

-

Patient assessed as fit to receive chemotherapy and other trial-specified treatments with no concomitant medical, psychiatric or social problems that might interfere with informed consent, treatment compliance or follow-up.

-

Bilateral and multiple ipsilateral cancers were permitted provided at least one tumour fulfils the entry criteria and none meet any of the exclusion criteria. Patients with bilateral tumours where both tumours fulfil all eligibility criteria including size and nodal status were excluded. Note that for separate synchronous primary cancers, whether ipsilateral or bilateral, it was anticipated that laboratories would, as per standard good practice, assess ER and HER2 on the different lesions. Centres were requested to send a block for each separately reported tumour for central eligibility testing provided sufficient material was available. If there were multiple invasive foci deemed to derive from one main cancer (satellite foci), which had the same histological features including, for example tumour type and grade, it was not required that every focus has its receptor status reassessed.

-

Written informed consent for the study.

Exclusion criteria

-

Ten or more involved axillary nodes or involved internal mammary nodes.

-

ER negative OR HER2 positive/amplified tumour on central eligibility testing.

-

Metastatic disease. Note that formal staging according to local protocol was recommended for patients where there was a clinical suspicion of metastatic disease or for stage III disease (tumour > 50 mm with any nodal involvement OR any tumour size with four or more involved nodes).

-

Previous diagnosis of malignancy unless:

-

managed by surgical treatment only and disease free for 10 years

-

previous basal cell carcinoma of skin, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated with surgery only.

-

-

The use of oestrogen replacement therapy (HRT) at the time of surgery. Patients who were taking HRT at the time of diagnosis were eligible provided the HRT was stopped before surgery.

-

Presurgical chemotherapy, endocrine therapy or radiotherapy for breast cancer. Treatment with endocrine agents known to be active in breast cancer including ovarian suppression was permitted provided this was completed > 1 year prior to study entry.

-

Commencement of adjuvant treatment prior to trial entry. Short-term endocrine therapy initiated because of, for instance, prolonged recovery from surgery was permitted but had to be discontinued at trial entry.

-

Trial entry more than 8 weeks after completion of breast cancer surgery.

-

Planned further surgery for breast cancer, including axillary surgery, to take place after randomisation, except either re-excision or completion mastectomy for close or positive/involved margins, which could be undertaken following completion of chemotherapy.

-

Patients with more than two involved axillary nodes (as defined in the inclusion criteria) identified by sentinel node biopsy or by axillary sampling where further axillary surgery was not planned.

Study conduct

Ethical and regulatory approval

The South East Coast–Surrey Research Ethics Committee approved the trial on 22 June 2012. Local research and development department approval was obtained at each participating NHS trust prior to patients being enrolled into the trial. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles and guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice, UK legislation, Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) standard operating procedures and the Research Ethics Committee approved protocol. The trial is registered as Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN42400492.

Management of the trial

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) provided overall supervision of the trial, with an independent chairperson and majority of independent members. The Trial Management Group (TMG) comprised a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, statisticians, a translational scientist and a patient advocate, all with considerable expertise in all aspects of trial design, running, quality assurance and analysis. The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee carried out the independent monitoring of the trial. Details of the membership of the TSC, TMG and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee can be found in the Acknowledgements (see Acknowledgements and Contributors).

Trial centres

A total of 35 hospitals from 31 NHS trusts and health boards in England, Scotland and Wales participated in OPTIMA prelim. As the demonstration of recruitment feasibility was a major end point for OPTIMA prelim, it was important to ensure that trial centres were broadly representative of the UK. Rather than issue a general invitation to participate in the study, individual centres were approached in five main geographical clusters: Scotland, the West Midlands, East Anglia, North London and South West/South Wales. Both district general hospitals and cancer centres were included. A list of all participating centres can be found in the Acknowledgements (see Acknowledgements and Contributors). Prior to activating a centre to recruitment, a trial initiation meeting was held, in person or via teleconference, to provide study-specific training to all staff members working on the trial. Continued support was offered to existing and new staff at participating centres to ensure that they remained fully aware of trial procedures and requirements.

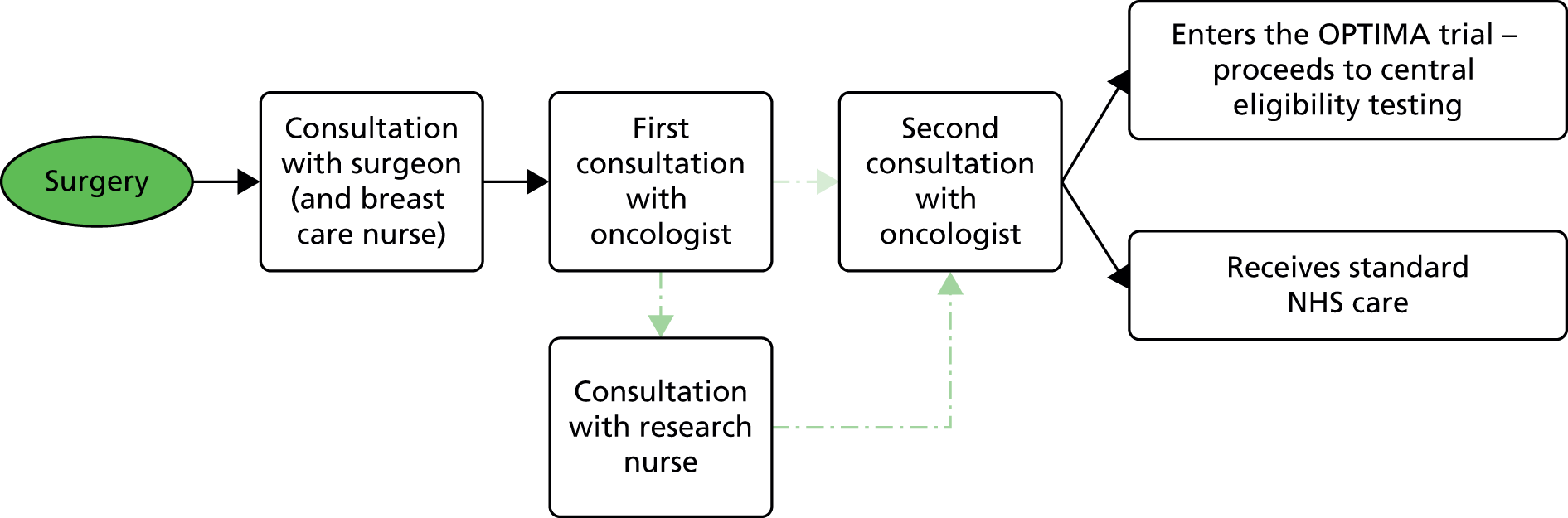

Patient information and informed consent

Patients who were potentially eligible for participation in the study according to the criteria (see Eligibility criteria) were identified at the multidisciplinary breast cancer meetings held at each of the centres. Patients were invited to participate in the OPTIMA prelim study during the initial consultation with their oncologist, where treatment options were discussed. Here the local principal investigator or their designee discussed the trial with the patient and provided the patient with a copy of the patient information sheet (PIS) (see Appendix 2). In many cases a research professional would be present in this consultation and/or meet with the patient afterwards to continue discussing the trial. Patients were given sufficient time to consider participation in the trial and subsequently the opportunity to ask any further questions and to be satisfied with the responses. Patients who were willing to participate were asked to provide written informed consent (see Appendix 2 for a copy of the consent form). Consent for the study included consent for use of the participant’s tissue samples, removed at the time of surgery, as part of the OPTIMA prelim. Participants were also asked to donate the remainder of their samples for future unspecified research projects; however, this was optional.

Randomisation procedure

Trial entry was defined as the time consent was given, which started the randomisation procedure. Once written informed consent had been given and chemotherapy selected from the regimens permitted in the protocol (Table 3), the researcher registered the patient with the CTU. During registration, eligibility was confirmed according to the results of local pathology testing and the patient was allocated a unique participant registration number.

| Regimen | Drugs | Dose | Cycle schedule |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEC75–80 | Fluorouracil | 500–600 mg/m2 | i.v. q. 3 weeks × 6 cycles |

| Epirubicin | 75–80 mg/m2 | ||

| Cyclophosphamide | 500– 600 mg/m2 | ||

| FEC90–100 | Fluorouracil | 500 mg/m2 | i.v. q. 3 weeks × 6 cycles |

| Epirubicin | 90–100 mg/m2 | ||

| Cyclophosphamide | 500 mg/m2 | ||

| FEC-Pw | FEC100 (as above) | i.v. q. 3 weeks × 3–4 cycles | |

| Followed by paclitaxel | 80–90 mg/m2 | i.v. q. 1 week × 9–12 cycles | |

| TC | Docetaxel | 75 mg/m2 | i.v. q. 3 weeks × 4–6 cycles |

| Cyclophosphamide | 600 mg/m2 | ||

| FEC-T | FEC100 (as above) | i.v. q. 3 weeks × 3 cycles | |

| Followed by docetaxel | 100 mg/m2 | i.v. q. 3 weeks × 3 cycles | |

| E-CMF | Epirubicin | 100 mg/m2 | i.v. q. 3 weeks × 4 cycles |

| Followed by cyclophosphamide | 600 mg/m2 OR 100 mg/m2 p.o. daily × 14 days | i.v. D1, 8 q. 4 weeks × 4 cycles | |

| Methotrexate | 40 mg/m2 | ||

| Fluorouracil | 600 mg/m2 | ||

Once the participant was registered, the centre sent relevant tumour block(s) from the surgical resection to the central laboratory for confirmatory testing of ER and HER2 status as soon as possible.

In order to avoid unnecessary delays in the randomisation procedure, on receipt of the tumour block, the central laboratory prepared samples for Genomic Health in parallel with undertaking eligibility testing. The central laboratory informed the CTU of the patient’s ER and HER2 status, and those eligible were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to standard treatment (control arm) or to test-directed treatment. Randomisation was performed centrally by a computer using a minimisation algorithm stratified to ensure balance across trial arms by chemotherapy regimen: anthracycline–non-taxane [FEC75–80, FEC90–100, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil (E-CMF)] vs. taxane–non-anthracycline [docetaxel and cyclophosphamide (TC)] vs. combined anthracycline and taxane [FEC-T, fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel (FEC-Pw)], number of involved nodes (none vs. positive sentinel node biopsy without axillary surgery vs. 1–3 vs. 4–9 nodes), menopausal status (pre-/perimenopausal vs. post-menopausal). Oncotype DX testing proceeded immediately for all participants [tumour blocks from participants randomised to the control arm underwent Oncotype DX testing as part of the pathology study (see Chapter 3, Pathology research in the preliminary studies)]. Genomic Health reported the test result to the CTU, which subsequently informed the research centre, by fax and e-mail, whether or not the participant was to receive chemotherapy according to randomisation and RS for those randomised to test-directed treatment. It was anticipated that the randomisation procedure, from date of consent/registration to treatment assignment, would take between 3 and 4 weeks.

Blinding

OPTIMA prelim was a partially blinded trial. For participants who were allocated to receive endocrine therapy alone, it was not possible to blind either the participant or the clinicians at the centre. However, for participants allocated to receive chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy, the participant and the centres were blind to the participant’s randomisation. In order to maintain blinding, for participants randomised to the standard arm, the CTU delayed informing the treating centre of the treatment allocation by a time period equivalent to that taken to perform the Oncotype DX test for those randomised to test-directed treatment. In practice this was on receipt of the Oncotype Dx test result as this was performed for all participants in OPTIMA prelim irrespective of randomisation. To assess the success of the OPTIMA prelim and perform a comparison of multiparameter tests, the randomised treatment allocation remained blinded to the analyst, as it was not needed in the analysis of the OPTIMA prelim.

Trial treatment

With the exception of mandating whether or not a participant received chemotherapy, treatment pathways for patients joining the OPTIMA prelim study were designed to be as similar as possible to those for equivalent patients who were either ineligible or chose not to join the study. The process of consent and subsequent Oncotype DX testing was expected to delay the start of systemic treatment (with either chemotherapy or endocrine therapy) by about 3 weeks compared with non-trial-treated patients. This delay is not expected to be clinically deleterious. 128 Although the protocol contained recommendations for the management of all aspects of patient treatment based on national/international guidelines (where available) and consensus views on best practice, the expectation was that participating centres already follow these and, therefore, that treatment would follow the local implementation of best practice and national guidelines.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy was chosen at the time of registration from the list of protocol-permitted regimens (see Table 3). The regimens included in the list were selected from those with good evidence for efficacy and which are widely used in the NHS.

Endocrine therapy

The OPTIMA prelim protocol specified that endocrine therapy should be started no later than 2 weeks after treatment allocation in participants assigned to receive no chemotherapy and 4 weeks after the final dose of chemotherapy for all other participants. Concomitant endocrine therapy and chemotherapy was not permitted in the OPTIMA prelim. It was also not permitted for endocrine therapy to be delayed until after radiotherapy. Permitted endocrine therapy for participants in the trial was:

-

post-menopausal at trial entry: AI (anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane permitted)

-

premenopausal at trial entry: tamoxifen for 5 years and ovarian suppression with either

-

a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for a minimum of 3 years or

-

bilateral surgical oophorectomy (radiation menopause was not permitted).

-

Within the OPTIMA prelim study ovarian suppression was recommended for all premenopausal women (1) to ensure that the patients within both arms received equally balanced endocrine treatment and (2) to eliminate the risk of confounding from different rates of chemotherapy induced menopause between the arms.

Surgery

All participants received appropriate surgery, performed according to local guidelines. Primary surgery consisted of a wide local excision or mastectomy. If breast conservation surgery was undertaken, then the acceptable circumferential and deep/superficial margin widths were determined by local protocol. If required, re-excision for clear margins was permitted to take place before or after chemotherapy.

All participants underwent preoperative axillary staging with an ultrasound scan and needle biopsy or fine-needle aspiration of any suspicious or indeterminate nodes. Participants with preoperative pathologically proven axillary lymph node involvement underwent axillary clearance. Participants with involved axillary lymph nodes identified at sentinel node biopsy (including macrometastases, micrometastases, and isolated tumour cell clusters) received further management according to local protocol. Centres could choose to avoid axillary clearance following a positive sentinel node biopsy for participants who had undergone breast-conserving surgery and who fulfilled the following criteria:

-

no palpable nodes

-

no more than two involved nodes

-

clinical tumour size T1–T2 (≤ 5 cm).

All planned axillary surgery was completed prior to randomisation to allow for stratification by the extent of axillary involvement.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy was given in accordance with local guidelines. The protocol stated the following recommended best clinical care as a reference for centres.

-

Breast radiotherapy was required for all patients who had undergone breast-conserving surgery. Whole breast, including the primary tumour bed, was the target volume. Centres could give a tumour bed boost in conjunction with whole-breast radiotherapy as per local guidelines. Partial breast radiotherapy was permitted, but only for patients who had a negative sentinel node biopsy or a full axillary clearance.

-

Participants who had undergone a mastectomy were required to receive chest wall radiotherapy if they had four or more positive axillary nodes or T3 tumours with any node positivity. Chest wall radiotherapy was recommended for tumours with a positive deep margin. Centres could also consider chest wall radiotherapy for patients with 1–3 positive axillary nodes or high-risk node-negative disease. The chest wall was the target volume.

-

Treatment of the supraclavicular fossa was required when four or more axillary lymph nodes were involved and could be given according to local guidelines for patients with 1–3 involved axillary nodes. Axillary radiotherapy, in addition to breast radiotherapy, was permitted using a four-field technique, when patients with up to two involved sentinel nodes did not undergo clearance. The axilla was not otherwise routinely irradiated. Internal mammary nodes were not routinely irradiated.

Recommended schedules after breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy were:

-

40 Gy in 15 fractions, five fractions per week

-

50 Gy in 25 fractions, five fractions per week

-

45 Gy in 20 fractions, five fractions per week.

Dose fractionation for tumour bed boost and regional lymph nodes was given according to local protocol.

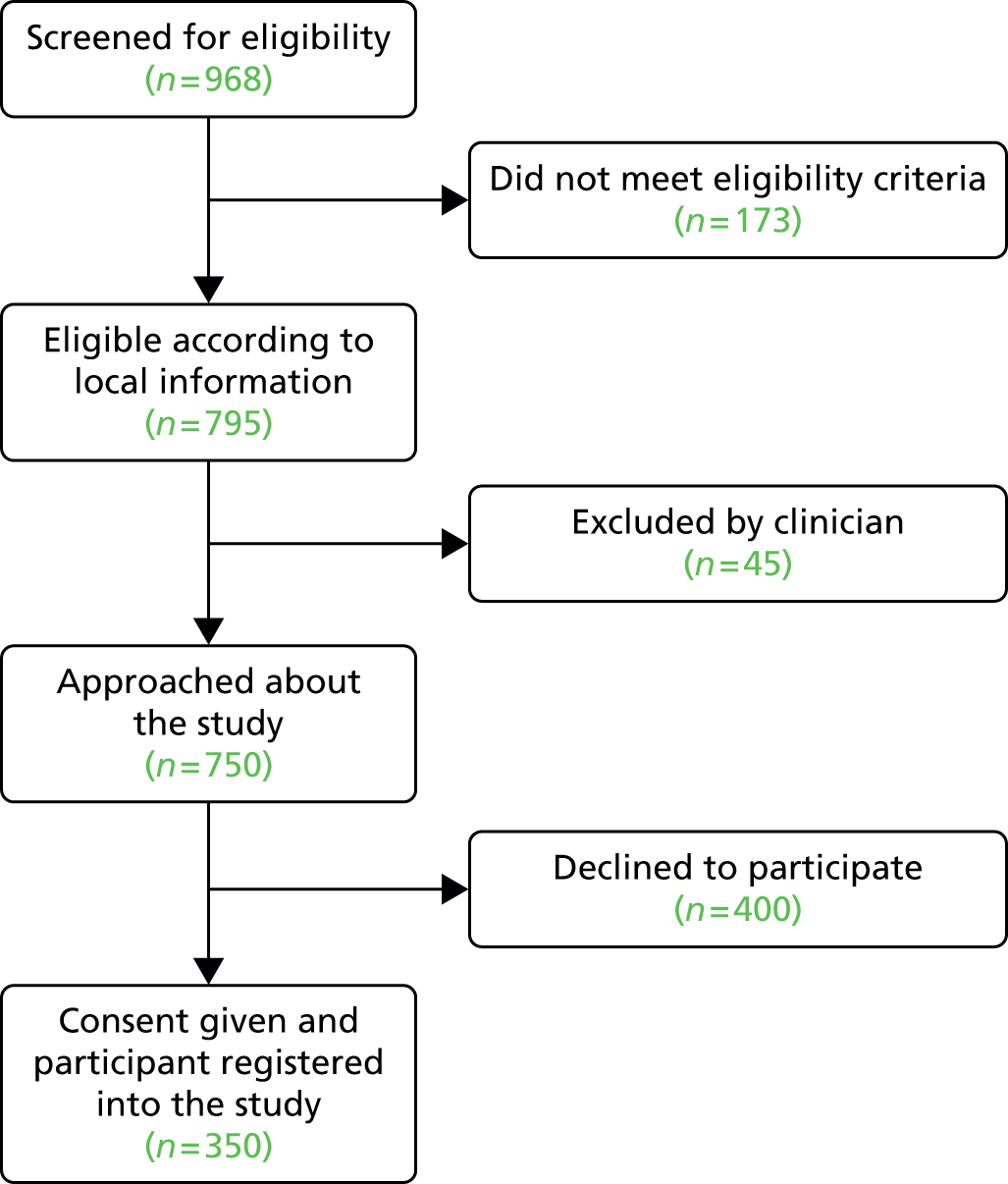

Screening information

In order to assess patient acceptability, each participating centre maintained a screening log to document all patients considered for the trial but subsequently excluded. Where possible, the reason for non-entry to the trial was documented. Screening logs were requested by the CTU on a monthly basis. No patient-identifiable data were recorded on the screening log.

Data collection

Clinical and resource use data generated by all centres were collected on study case report forms (CRFs), which were monitored and entered into the trial database by the CTU. The participant’s details were entered onto the local centre’s patient identification log; at no time was this log forwarded to the CTU. To preserve participants’ anonymity, only their allocated trial number and initials were used on the CRFs and any correspondence. With participants’ permission, their name, date of birth, address and NHS/Community Health Index number were also provided to the CTU on the registration CRF to allow flagging with the Office for National Statistics. Participants’ confidentiality was respected at all times.

Case report form completion guidelines were provided to all centres to aid consistency of completion. Data management and monitoring were conducted in accordance with the CTU standard operating procedures, which are designed to ensure that trial data are as complete and accurate as possible, and comply with the Data Protection Act 1998. 129 Data management practice included verification, database validation and formal data checking following data entry. All missing and ambiguous data were pursued until resolved or confirmed as unavailable. Monthly reminders were sent to participating centres in order to flag any forthcoming or outstanding clinical visits or questionnaires.

Quality of life and health resource use assessment

The patient questionnaire was designed to assess quality of life and health resource use. The baseline questionnaire was provided by the centre and completed by participants after they had given written informed consent but before randomisation. Further questionnaires were administered at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months from date of consent. These further questionnaires were either given to participants at a clinic appointment or sent by post. The OPTIMA prelim study used two instruments to gather information on quality of life as the basis for evaluating both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness: EQ-5D124 and the FACT questionnaire comprising FACT – General126 and FACT – Breast cancer. 127

Follow-up

Participants are followed up annually for 10 years from trial entry. Annual follow-up appointments could be conducted in the clinic or via telephone for participants who had been discharged from clinical review. The method of follow-up is recorded on the CRF.

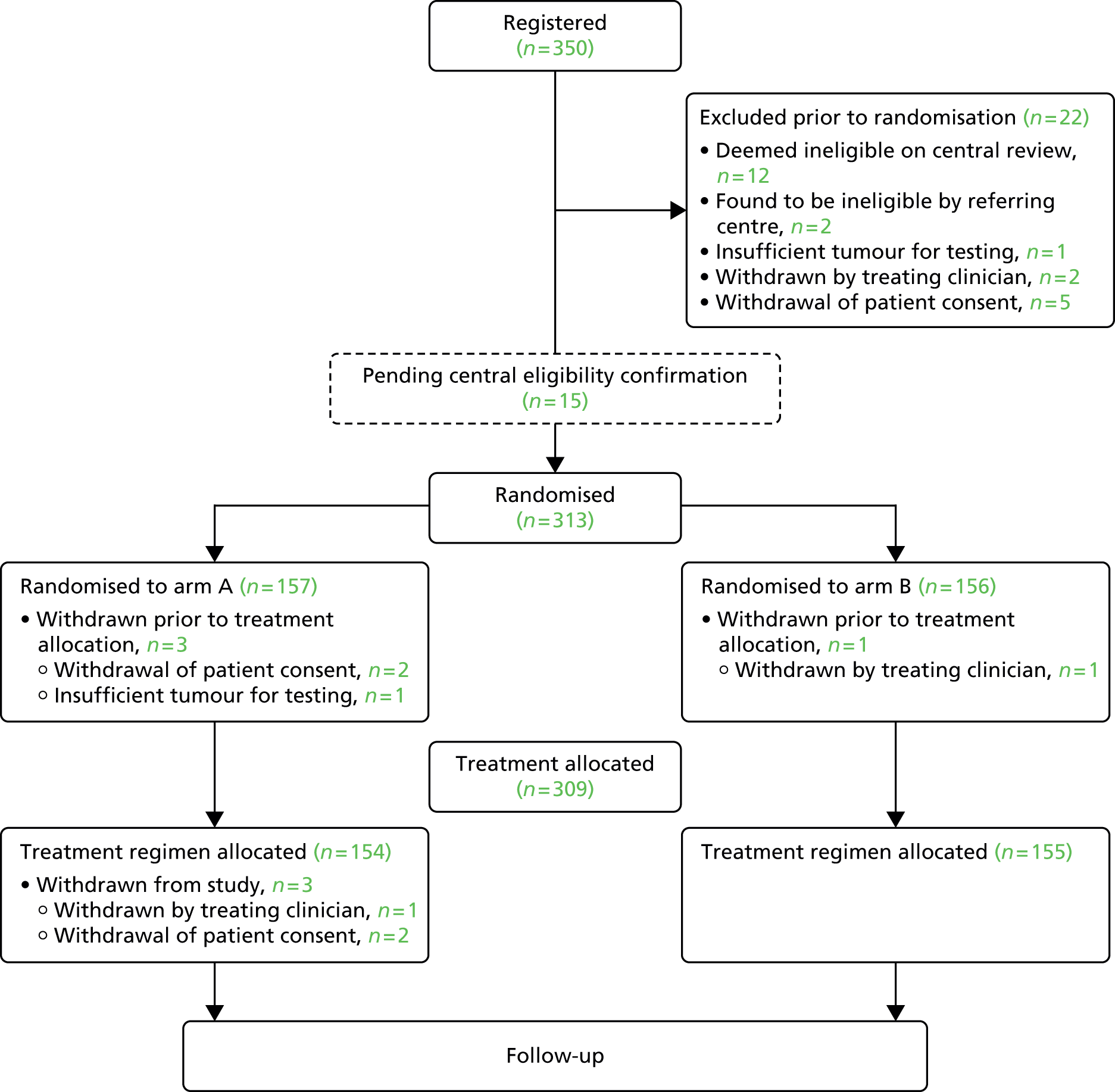

Withdrawals

Participants had the right to withdraw from the trial at any time and for any reason. Those participants who were deemed ineligible by central review were not randomised and did not count towards the sample size. Participants who were registered but not randomised were not classified as withdrawals. Owing to the cost, the multiparameter assay was cancelled for those who withdrew consent post randomisation but prior to treatment allocation. For the purposes of the preliminary study, randomised participants who had not yet been allocated treatment and for whom an Oncotype DX result was not obtainable were not followed up. Participants who declined to comply with their trial-allocated treatment remained on-study and are followed up in accordance with the protocol.

Analysis of the OPTIMA prelim success criteria

The acceptability of the trial was assessed as the proportion of eligible patients consenting to participate in the OPTIMA prelim. The characteristics of the patients for whom the trial and the concept of test-driven therapy were acceptable were provided. The time from signing the OPTIMA prelim consent form to starting chemotherapy was calculated and the proportion of chemotherapy-assigned patients starting treatment within 6 weeks was determined. Compliance with the test-directed treatment decision was assessed through the proportion of patients choosing not to follow the result of the randomisation.

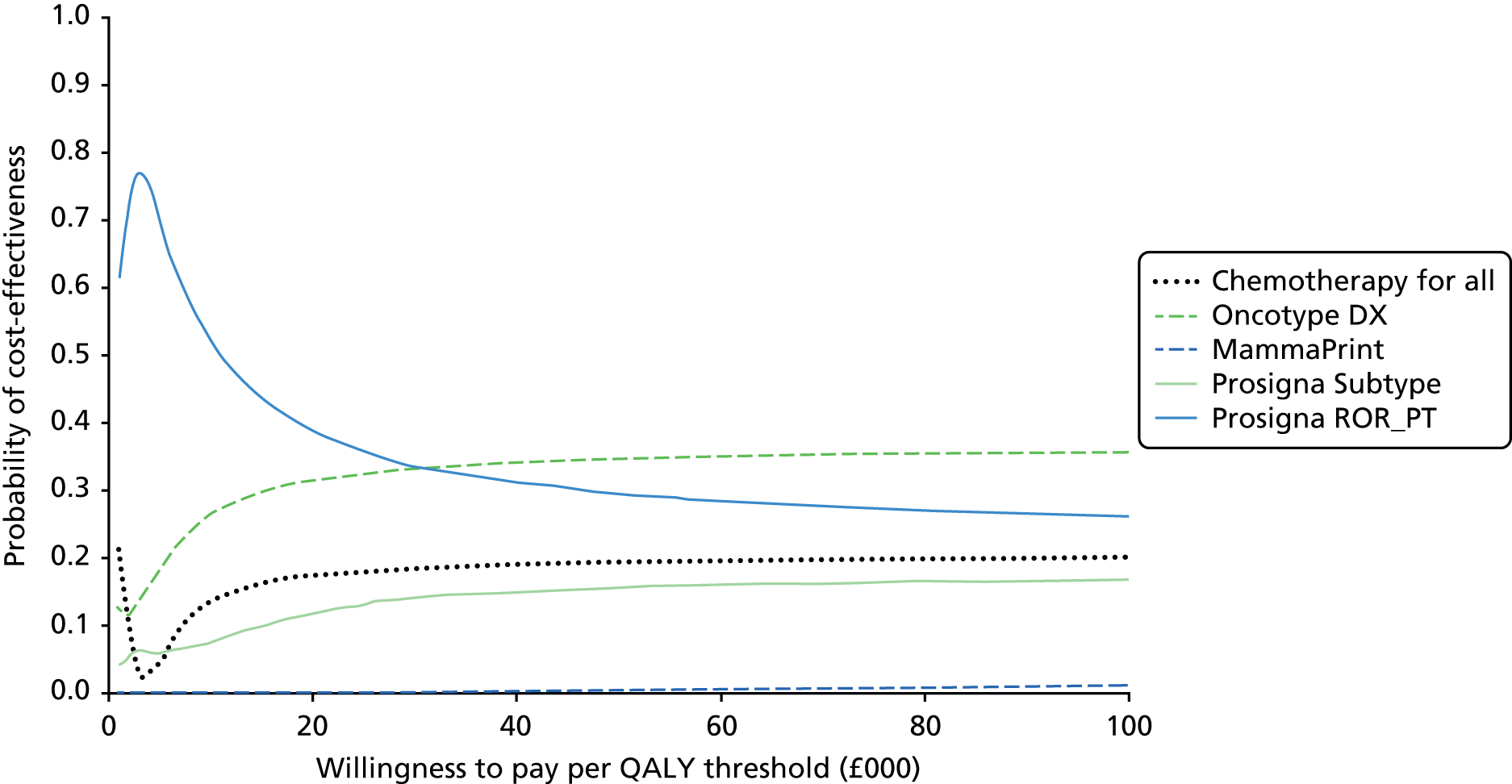

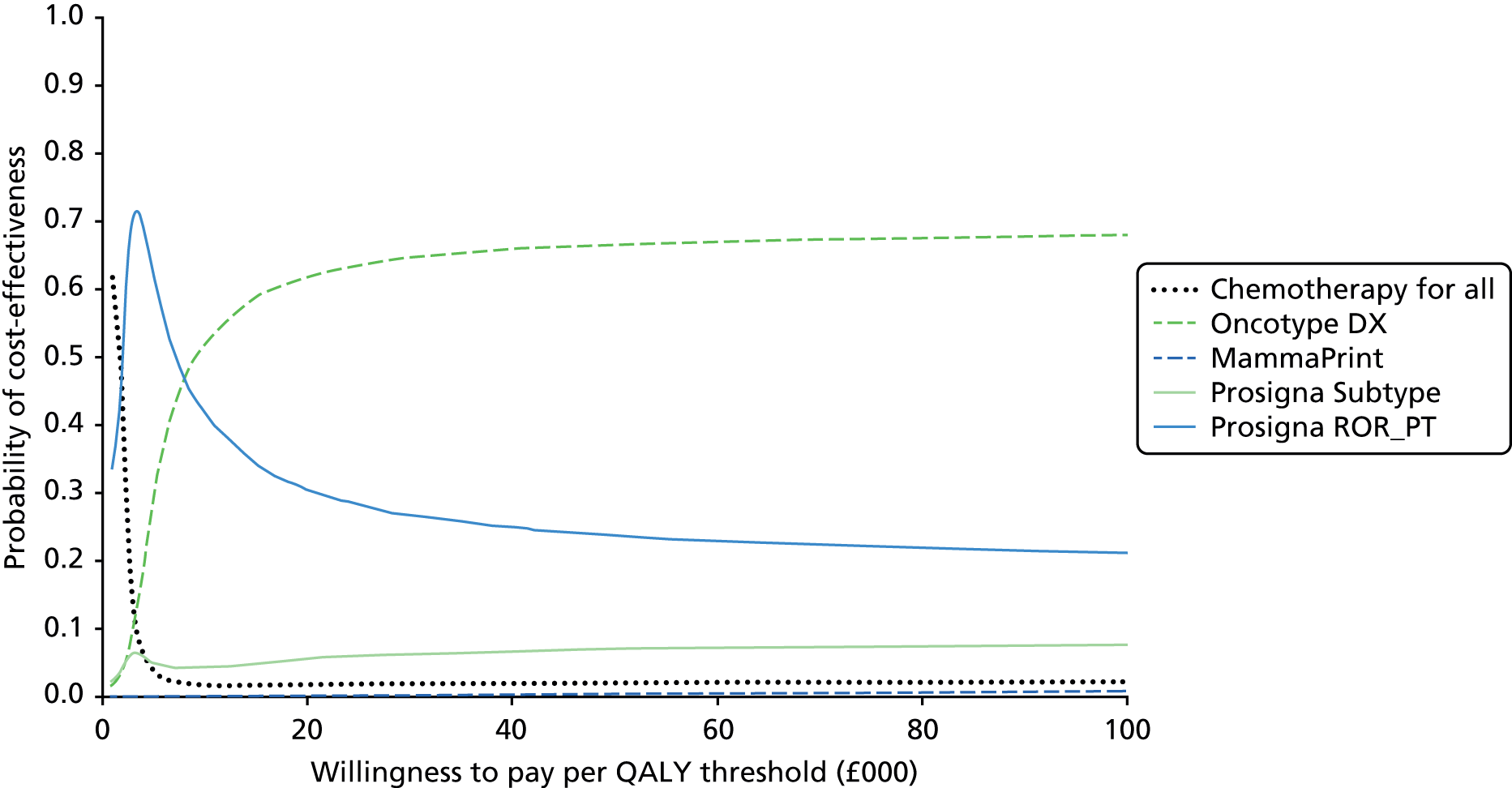

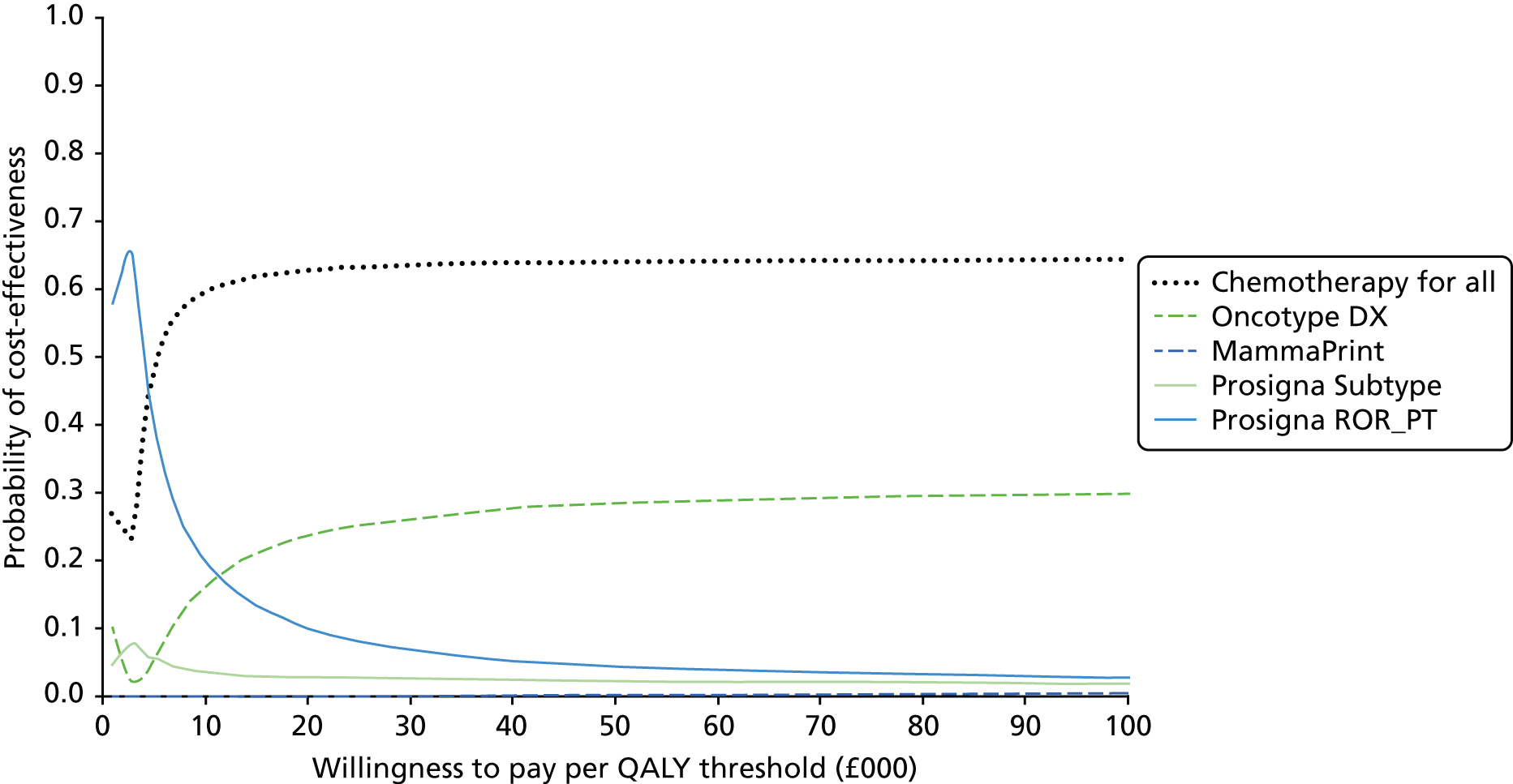

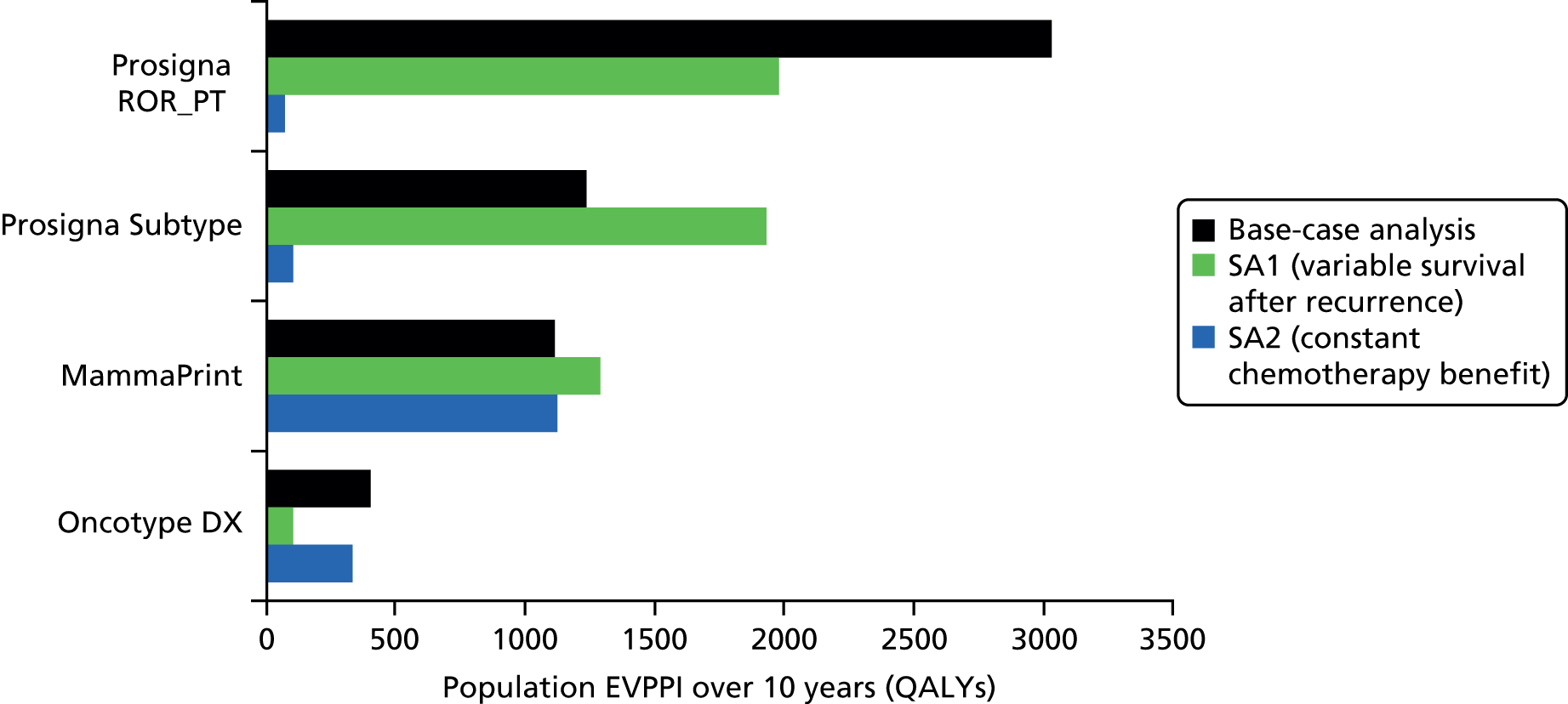

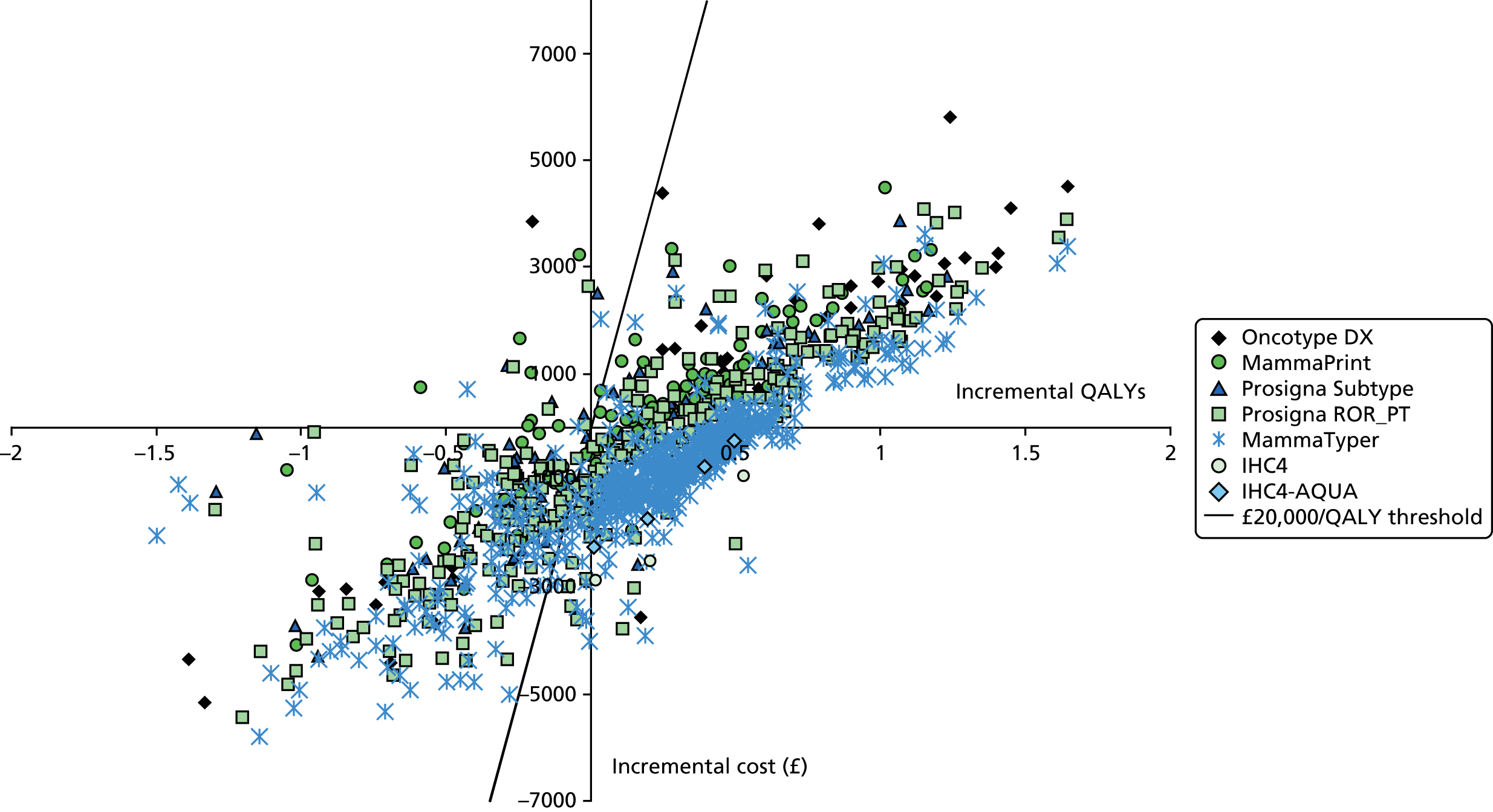

Decision to continue to the main trial