Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/116/68. The contractual start date was in May 2011. The draft report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stefan Priebe is a member of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Mental, Psychological & Occupational Health Panel. Til Wykes and Ulrich Reininghaus report grants from King’s College London. Sandra Eldridge is a member of the HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board and reports grants from Queen Mary University of London. Frank Röhricht has a copyright pending on the body psychotherapy schizophrenia manual (Röhricht F. Body-oriented Psychotherapy in Mental Illness: A Manual for Research and Practice. Goettingen: Hogrefe; 2000).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Priebe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Schizophrenia and negative symptoms

Schizophrenia is a severely disabling mental health disorder that affects approximately 0.7% of the population. 1 The main symptoms are commonly characterised into ‘positive’ symptoms, which include hallucinations, disordered thinking and delusions, and ‘negative’ symptoms, which refer to deficits in emotional experience and expression. Specific symptoms relating to emotional expression include blunted affect and alogia (impoverished speech), whereas deficits in emotional experience can include asociality, anhedonia (inability to anticipate or experience pleasure) and amotivation. 2

Negative symptoms have been found to be highly detrimental to social outcomes, quality of life and functioning,3,4 and so are important targets for treatment. However, despite developments in both antipsychotic medication and psychological treatments, the effectiveness of most treatments on negative symptoms has been found to be limited. 5 This being the case, the negative symptoms are currently recognised as an unmet therapeutic need in a large proportion of cases. 5

Schizophrenia and arts therapies

‘Arts therapies’ is an umbrella term for a range of different therapies, which include music therapy, art therapy, body psychotherapy (BPT), dance movement psychotherapy and drama therapy. Common to all of them is that they have a central non-verbal component, with the focus on utilising creative activities to achieve psychological change. In a review on treatment strategies in schizophrenia by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), arts therapies were found to be the only type of treatment to demonstrate clear, consistent improvement in negative symptoms;6,7 however, the sample size for the meta-analysis was small (six trials, n = 382), leading to the suggestion that the evidence base should be increased with more large-scale trials of arts therapies. Furthermore, none of the studies compared the intervention with an active control, so it remains unclear whether it is the specific effects of the psychotherapeutic component of arts therapies or the non-specific effects of regular group activity that are driving the changes. Finally, no studies evaluating evidence on the cost-effectiveness of such interventions were identified. Consequently, the research recommendations suggested that further trials should be conducted to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of arts therapies for patients with schizophrenia, that such trials should be sufficiently powered and that they should use an active control.

Since the recommendations were published, a full-scale, multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the effectiveness of art therapy has been completed [Multicenter evaluation of Art Therapy in Schizophrenia: Systematic Evaluation (MATISSE)]. 8 In this study, no significant improvements in either negative symptoms or any of the secondary outcomes were found in the art therapy group, relative to either the active control group or standard care. The MATISSE trial8 was designed as a pragmatic trial with the aim of testing the impact of group art therapy delivered in current clinical practice, meaning that one specific model of therapy was not evaluated. Consequently, the type of treatment provided was not consistently applied, which has been criticised by some art therapists, who have suggested that what was evaluated is not what is routinely delivered in the UK. 9,10 In response to this critique, the MATISSE study team have since published a more comprehensive description of the therapy delivered,11 which contends that such a method of implementation is consistent with the principles of pragmatic trials. Regardless, new trials of arts therapies that implement a standardised therapy, recognised as appropriate for the patient group beforehand, would be a significant advance in the evidence base.

Following the MATISSE trial,8 a second important issue is that it is not currently clear whether any lack of effectiveness in the treatment of negative symptoms is specific to the art therapy that was delivered in this context or endemic to all ‘arts therapies’ as a whole. In recognition of this, the MATISSE8 trial research recommendations suggest that ‘Data from exploratory trials of other creative therapies, including music therapy and body movement therapy, have shown promising results and randomised trials examining the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of offering these interventions to people with schizophrenia should be conducted’ (p. xii). 8 Therefore, research on other arts therapies modalities might help to assess whether the lack of efficacy of art therapy on negative symptoms is particular to this type of psychotherapy or is indicative of arts therapies as a whole.

Body psychotherapy and schizophrenia

Of the six studies included in the NICE review,6 three studies12–14 evaluated the effectiveness of music therapy, two studies15,16 evaluated the effectiveness of art therapy and one study17 evaluated the effectiveness of body-orientated psychotherapy. The BPT trial was an exploratory RCT, which tested a manualised form of the intervention in outpatients with persistent negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Compared with a control group receiving supportive counselling, patients in the experimental group showed a significant improvement in negative symptoms. The effect size was large, and maintained at 4 months’ follow-up. The major limitations of the study were that it was a small exploratory trial, based at one site and with only one body psychotherapist, and that the control condition was supportive counselling, which turned out to be unattractive to patients. In addition, the non-specific effects of physical activity could not be controlled for and the study was insufficient in size to evaluate cost-effectiveness. Following these findings, an open uncontrolled trial of manualised BPT18 was conducted by the same authors, but different therapists, which yielded similar results; however, no other rigorous trials on BPT or a similar method have been identified in a recent Cochrane review update. 19

Regarding earlier trials on BPT and schizophrenia, which are not included in the NICE review, the earliest trial was published in 196520 and found significant improvements of affective contact and general functioning. Since then, further investigations of body-orientated psychotherapy have suggested some improvements in a range of outcomes, including some indicators of negative symptoms. 21–23 However, all of these studies, which were exclusively conducted before 1980, have serious methodological shortcomings, such as small sample sizes, vaguely defined outcome criteria, no systematic assessment of psychopathology, no recording of medication, no intention-to-treat analysis and a poorly defined description of the intervention under investigation. Overall, there is current and historic evidence to suggest that BPT might be effective in the treatment of schizophrenia; however, further evidence from rigorous, full-scale trials is required.

Theoretical basis for body psychotherapy as a treatment for schizophrenia

Body-orientated psychotherapies have a long tradition in psychiatry and have existed in many different forms, which can lead the field to appear somewhat heterogeneous. In a review of the field,24 Röhricht identified the three main historical roots of BPT as neo-Reichian psychotherapies, concentrative movement therapy and dance movement psychotherapies, but suggested that, in practice, a substantial degree of overlap exists between the different schools of thought. In the review it was proposed that the immediacy of bodily experience may be an important tool in reality testing and developing a sense of inter-relational embodiment, and so therefore may offer unique benefits in working with those with psychosis.

Three different models of mechanism have been proposed in support of the hypothesis that BPT may be an effective treatment for schizophrenia and negative symptoms. Regarding the first,25 one of the core features of negative symptoms relates specifically to diminished emotional expression. Consequently, patients can often experience significant barriers when engaging in conventional psychotherapies in which verbalising emotions and cognitions may be a core component of the treatment. BPT offers an alternative, non-verbal model of facilitating emotional interactions, which some patients might find preferable or more accessible.

The second model of mechanism relates to the link between movement and emotion. Patients with schizophrenia often experience significant deficits in emotional experience, and can display a range of motor abnormalities. 25,26 Central to BPT is the link between movement and emotional experience, encouraging the patient to focus on the immediacy of experiences, which may result in, or from, movement. In doing so, this further opens greater opportunities for reality testing, and can reinforce the idea that the body can be a source of creativity and pleasure. This may be significant when working with patients who report significant deficits in anticipating pleasure. 27 This emotional learning can be further enhanced by the group experience, when patients can observe and imitate expressive movements in other patients.

The third model of mechanism is related to how BPT can potentially enhance body and self-experience. Patients with schizophrenia can frequently have misperceptions regarding their body, and altered body experience in the form of disturbed body perception and body image. 28,29 As such, a therapeutic method that places particular emphasis on the patients’ perceptions and experiences of their body, and its movements may be an effective way of addressing these symptoms.

Features of the body psychotherapy treatment

Presuming that the therapy is effective, there are a number of potential advantages, inherent in BPT, which may make it an attractive option to health providers. First, as a group-based method, BPT is relatively inexpensive. In addition, it can be administered by existing clinicians, employed by the UK NHS, after minimal additional training, and the groups can be held in standard therapy spaces. Second, BPT can be flexibly combined with other treatment methods, including all pharmacological interventions. Third, given that the focus of treatment is non-verbal in nature, centring instead on body movement and creativity, the treatment may be more accessible to patients who present with negative symptoms, such as alogia. Lastly, because BPT is so distinct from conventional treatment methods, it may appeal to patients who struggle to engage in other forms of treatment. The latter point is underlined by findings of a qualitative evaluation of the exploratory trial,18 in which patients fed back positively about both its focus and methods.

Effects of physical activity in schizophrenia

As previously highlighted, one of the limitations in the earlier exploratory trial17 was that the control condition was group-supportive counselling, which meant that the non-specific effects of physical activity could not be controlled for. In a recent Cochrane review,30 there is some evidence to suggest that exercise may be at least partially effective in the treatment of negative symptoms, whereas others31 have examined possible neurological effects of increased physical activity in schizophrenia. This being the case, at present it is not clear whether or not the psychotherapeutic content of the sessions provide any additional benefit over and above what may be achieved from regular activity.

In order to examine the specific effects of this particular treatment, BPT was compared with a structured physically active control group, namely a beginner’s Pilates class. Pilates was chosen as the active control condition as it can be delivered in a structured format by a trained instructor, does not foster group interaction and does not include elements that are broadly equivalent to mindfulness like other low-intensity activities, such as yoga or t’ai chi. By comparing BPT with an active control, this investigation will allow for the evaluation of the specific effects of the therapy. In the event that no significant difference between the treatment conditions is found, disentangling whether they are both equally effective, as opposed to neither being effective, may be impossible to achieve in the absence of a treatment-as-usual arm. However, in a small trial32 examining the effectiveness of yoga therapy, in comparison with an active control condition, a significant improvement in negative symptoms was found, which suggests the approach adopted in this trial is a feasible one.

Aims and objectives

Following the recommendations of NICE,6 we conducted a multisite, RCT to compare the effectiveness of BPT with a physically active control condition, namely Pilates. In controlling for the effects of therapist attention and regular structured physical activity, the specific components of the treatment under investigation were the focus on body experience at a cognitive and emotional level, the facilitation of emotional group interactions, and the link between movement and emotion. The Pilates group controlled for the effect of therapist attention and structured physical activity as alternative explanations of the effect discovered in the exploratory trial.

The aims of this trial were to:

-

test the effectiveness of a manualised group BPT intervention in reducing negative symptoms of schizophrenia compared with an active control

-

test the effectiveness of a manualised group BPT intervention in general psychopathology, quality of life, daily activities, objective social situation and treatment satisfaction in patients experiencing negative symptoms of schizophrenia compared with an active control

-

test whether or not any effects on primary and secondary outcomes are maintained at 6 months’ follow-up

-

assess the cost impact, cost-effectiveness and cost–utility of BPT.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The study is an assessor-blinded, parallel-arm RCT. A detailed study design description is available in the published protocol. 13 Prior to recruitment, the study was registered through the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) system (ISRCTN84216587).

Amendments to the protocol

Through the implementation of the project, five amendments were made, all approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) and the study sponsors prior to implementation. The changes included are listed below.

Amendment 1

On the advice of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) an additional inclusion criterion was added, specifying that the type of antipsychotic medication prescribed to participants should not change for at least 6 weeks prior to baseline assessment, although a change in dosage is acceptable. In addition, the Calgary Depression Scale33 was added to the case report file (CRF) battery, again on the suggestion of the TSC. During the set-up phase, the complexities of arranging the logistics for each session were becoming increasingly apparent, so the protocol was changed to include a volunteer cofacilitator to aid both the therapists and instructors for each group. Last, a minor amendment was made to the consent form, including the additional clause ‘I agree that if I withdraw, or am withdrawn from the study for any reason, then the researcher can continue to use the information I have already given them’ at the request of one of the NHS research sites.

Amendment 2

The Social Network Scale (SNS)34 was added to the CRF in an attempt to record an objective measure of the social network of participants.

Amendment 3

The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS)35 and the Scale to Assess Negative Symptoms (SANS)36 Anhedonia subscale item were replaced by the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS)37 in the CRF battery, a new instrument that follows a much closer conception of what we currently understand negative symptoms to be. 2

Amendment 4

The filming of the groups was extended to also include the physical activities arm of the study and the CAINS interviews37 to enable inter-rater reliability assessments. A minor revision of the participant information sheet and consent form was conducted in order to reflect these changes.

Amendment 5

During data collection, it was becoming apparent that a number of participants struggled to remember historical information regarding the number and type of hospitalisations in addition to their medication details. To rectify this issue, a final amendment to the protocol was made in order to allow research assistants to check medical records to accurately source this data. A minor amendment to the consent form was made, adding a clause through which participants could either consent or refuse permission to access medical records. For participants who had already consented to take part in the trial prior to this amendment being approved, an addendum to the original form was attached and additional consent was sought in their next assessment.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged between 18 and 65 years.

-

Diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10).

-

Symptoms of schizophrenia present for at least 6 months.

-

Scores of ≥ 18 on the negative symptoms subscale of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). 38

-

No change in the type of antipsychotic medication prescribed within the previous 6 weeks (although the dosage may change).

-

A willingness to participate in a BPT or Pilates group.

-

An ability to give written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

A severe physical disability or condition that prevents patients from participating in light activity.

-

An insufficient command of English in relation to the nature of the group intervention and assessment interviews.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome criterion used to test for the effectiveness of BPT was the change in negative symptoms measured by the PANSS,38 completed at the end-of-treatment stage. The PANSS is a 30-item semistructured interview that is designed to provide an overall measure of the symptoms of schizophrenia. In the original format, 16 of the items relate to general psychopathology, seven items relate to positive symptoms of schizophrenia (such as hallucinations and delusions) and seven items relate to negative symptoms. Each item is rated on a scale of 1–7, covering both the severity and frequency of the symptoms assessed, resulting in a range of 7–49 for positive and negative symptoms and 16–112 for general symptoms. The subscales of the PANSS have been found to have good internal consistency,39 good inter-rater reliability and concurrent validity,40 and the scale is recognised to be one of the established symptom scales in schizophrenia research. 41

As a exploratory outcome, the alternative Marder factor solution of the PANSS was also adopted, given concerns that the original format includes some items that have more recently been found to relate to cognitive, rather than negative, symptoms. 42,43 In this alternative configuration, the ‘abstract thinking’ and ‘stereotypical thinking’ items are dropped, and replaced with the ‘active social withdrawal’ and ‘motor retardation’ items. In addition to the Marder-configured subscale, the standard positive and general PANSS subscale scores were also used as secondary outcomes to measure other aspects of psychopathology.

Other secondary outcomes include the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA),44 which measures aspects of both subjective and objective aspects of quality of life; the participants’ current objective social situation measured on the SIX;45 extrapyramidal symptoms measured on the Simpson–Angus Scale (SAS);46 depression measured on the Calgary Depression Scale;33 an alternative measure of negative symptoms that evaluates expressive and experiential deficits, CAINS;37 four items taken from the Time Use Survey (TUS) to get a measure of the types of activities in which participants take part; an adaptation of the Social Network Scale (SNS)34 to measure the frequency of their social contacts over the past week; and, finally, participant satisfaction with the group into which they are randomised using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ). 47 In addition, the EQ-5D-5L (European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, five-level version)48 and the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) were completed in order to allow for an analysis of cost-effectiveness, cost–utility and cost impact of the intervention. 49 All of the scales were completed at all three assessment stages (baseline, end of treatment and 6 months post treatment) other than the CSQ, which was completed only at the end-of-treatment stage. For all scales, interviewees were asked to report their symptoms and experiences over the previous week, apart from the TUS, which collects information over the previous month; the CSQ, which aimed to assess the satisfaction of the groups over the whole 10 weeks; and the visual analogue scale of the ED-5Q-5L, which asks participants how they would rate the quality of their health on the day on the interview. At the baseline assessment, the CSRI was used to assess the previous 3 months of service use, whereas at the end-of-treatment and 6-month follow-up stages only the previous month was assessed. All outcome measures were scored as part of a structured interview with the researcher.

The MANSA44 is a 16-item questionnaire that is designed to measure quality of life. The scale consists of 16 items: 12 covering subjective quality of life and four covering objective indicators. The 12 subjective items are measured on a 1- to 7-point Likert scale, covering satisfaction with employment, finances, recreational activities, friendships, safety, housing, health, sex life, family and overall life satisfaction. The four objective items are ‘yes or no’ questions and cover whether or not the participant has been a victim of a crime, has been accused of crime, has anyone he/she considers to be a close friend or has seen a friend in the past 7 days. The summary score from the MANSA is calculated by taking a mean of the 12 subjective items, with a high score indicating a greater satisfaction with quality of life.

The SIX45 is an instrument designed to measure the individual’s objective social situation. The scale consists of four questions: employment (whether or not he/she is employed, unemployed or taking part in voluntary, protected work); housing (whether or not he/she has independent accommodation, sheltered/supported housing or is homeless); the participant’s living situation (lives alone or with partner/family); and friendship (has he/she met a friend in the past week). The responses of each item are added together, resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 6, with a high score indicating a more positive social situation.

The CAINS37 is a recently devised assessment of negative symptoms, comprising 13 items, each rated on a scale of 0–4. The first nine items relate to experiential/pleasure deficits, whereas the last four items relate to expressive deficits of the disorder. For each subscale a mean score of the responses is calculated, resulting in a range of 0–4 for both experiential and expressive deficits. In both cases a higher score represents more severe psychopathology.

The Calgary Depression Scale33 is an assessment tool that is designed to measure depressive symptoms and is specifically adapted for schizophrenic populations. In order to appropriately differentiate from negative symptoms, which also include anhedonia and amotivation, the scale primarily focuses on the interviewee’s low mood, hopelessness, feelings of guilt and perception of self. The scale comprises nine items, rating from 0 (absent) to 3 (severe), giving a total range of 0–27, with a higher score representing a more severe psychopathology.

The size of the participants’ social network was measured using a simplified version of the SNS, which was first used in an observational study by Dunn et al. 34 looking at the social life of long-stay patients. In this study,34 the focus was on establishing the size of the social network in which participants typically operated during their day-to-day lives. Participants were required to list all of the people to whom they had spoken in the past week, identify their relationship to that individual and then report on how many days in the past week they had spoken to them. Unlike in the original form of the schedule, participants were not asked to report any additional details regarding the quality of their relationship with individuals.

The SAS46 is a scale designed to measure movement disorder symptoms that are related to extrapyramidal side effects (EPSs). The scale includes 10 different items, rated from 0 to 4, with a higher score denoting a greater severity of EPS. To rate each item, the assessors were required to observe different aspects of the interviewee’s movement or physical appearance, such as his/her gait, severity of any tremor, and whether or not he/she produces excess saliva, and, by conducting simple physical examinations, including checking wrist, elbow and shoulder rigidity. Given that a significant proportion of assessments were conducted in the participant’s home, and by non-medically trained researchers, two items that required medical apparatus, such as a medical table (head dropping and leg pendulousness), in addition to the glabellar tap, were not conducted. Therefore, the adapted summary score produced for the purposes of this study ranged from 0 to 32.

A measure of the number of activities in which participants took part was captured by the TUS. The aim of the questionnaire was to provide a brief summary of the range of activities undertaken by the interviewee over the previous week. The scale included four items: asking the participant whether or not they had (1) eaten out at a café, restaurant, pub or wine bar; (2) been shopping for non-household/essential items; (3) been to any type of place of entertainment, such as a club, bingo hall, cinema, museum or casino, etc.; or (4) been on any outdoor trips, such as going to the park, beach or any other place of natural beauty. Participants reported how many times they had been to each place in the past month, and for the length of time for each time they went there. The items themselves were taken, and adapted, from an interview schedule drafted by the Office for National Statistics to measure time use. 50

The CSQ47 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire that assesses how satisfied the interviewee is with the intervention they received. Each item is rated from 1 to 4, with a larger score representing a greater satisfaction with the treatment.

The ED-5Q-5L48 is a scale that is designed to evaluate self-reported health-related quality of life, and was used as the main outcome measure in the economic analysis. The scale consists of five items, which, together, produce a summary score and a separate visual analogue scale. The item section of the questionnaire asks the interviewee whether or not he/she experiences impairments in health (related to mobility, self-care, conducting activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). These are rated as ‘1’ (no problems), ‘2’ (slight), ‘3’ (moderate problems), ‘4’ (severe problems) or ‘5’ (unable/extreme), and this gives rise to 3125 distinct health states (from 11111 to 55555). These were weighted by standardised value sets based on UK tariffs51 to estimate utility, which are anchored by ‘1’ (full health) and ‘0’ (death). The weights attached to each health state are then combined using area-under-the-curve methods to derive the total quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) that are accrued over the follow-up period.

The visual analogue section of the EQ-5D-5L ranges from 0 to 100, and asks the interviewee to place a cross on a continuous line, which would represent how they would rate their health today, with ‘0’ being ‘the worst health you can imagine’, and ‘100’ being ‘the best health you can imagine’.

The version of the CSRI49 used in this study aimed to assess the cost of services received and comprised four discrete sections. The first related to whether or not the participant had been in contact with any community health service providers and, if so, how many times and, on average, how long for. The second part aimed to measure whether or not the participant had been in receipt of any specialised services, related to physical or mental health, and the setting in which they were seen (i.e. inpatient stay, outpatient hospital appointment or community services). The third section related to the type and amount of mental health medication that he/she was prescribed. The fourth section measured the amount of sick days the participant may have had, presuming that he/she was in employment. In any retrospective assessment there is a trade-off between recall accuracy and obtaining a representative measure of service use. Although one option would have been to assess service use over the whole intervening periods between assessments, this was not conducted, as there were concerns that this would result in a loss of accuracy of the data. Given that many of the participants would have had their condition for a prolonged period of time, it was assumed that service use would be relatively stable. Consequently, only the previous month was assessed at both the end-of-treatment and 6-month follow-up stages. For the purposes of this investigation, informal care was not assessed, given concerns that there would be no way to obtain robust measures in this context.

Service use measured with the CSRI was combined with relevant unit costs52,53 to derive total costs. These costs include salary components, capital and administrative overheads and training, and are reported in terms of face-to-face contact time with participants. The costs of the interventions were calculated using a bottom-up microcosting approach, based on the time spent by professionals providing the intervention (instructors), training (consultant psychiatrist) and supervision (therapist supervisor). The costs were divided by the typical number of people attending a group (eight). The cost of one BPT or Pilates session was £9, whereas training and supervision for the BPT instructors were estimated at £44.14 per participant receiving the intervention.

In the original protocol, an assessment of non-verbal communication and gestural behaviours, using the NEUROGES-ELAN system, was proposed. 54 The NEUROGES-ELAN system is a coding and annotation tool that is designed to analyse gestural behaviour. However, because of the difficulties in implementation, gestural and non-verbal communicative behaviours were instead captured on an observational basis using the CAINS expressive subscale. 37

Blinding and randomisation

Randomisation was conducted by the Pragmatic Clinical Trials Unit (PCTU) based at Queen Mary University of London [Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) Reg: 32], independent of the research team using a computer-generated sequence. Participants were randomly allocated with equal probability to the intervention or control group, stratified by region, in batches using randomly permuted blocks of four and six, beginning each batch at the start of a new block to preserve balance. The Chief Investigator, all assessors and the trial statistician were blinded to the treatment allocation until all end-of-treatment data were collected and the statistical analysis plan was signed off. In order to prevent bias, eligibility and baseline assessments took place prior to randomisation. Prior to each meeting with the research assistant, participants were reminded not to disclose any details of the intervention in which they took part. In the event of unmasking, this was recorded, specifying whether or not this occurred before or after the primary outcome measure (the PANSS assessment) was completed.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from NHS mental health community services in five different Trusts: Mersey Care NHS Trust, Greater Manchester West Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, North East London NHS Foundation Trust, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and East London NHS Foundation Trust. The study was presented to clinical mental health teams, assertive outreach teams, recovery and rehabilitation teams, early intervention services and clinicians who run the outpatient clinics in the area, in order to provide information regarding the nature of the study. These clinicians were then asked to identify all patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who had not recently changed their antipsychotic medication and were presenting with negative symptoms, and to ask these patients for their consent to be approached by a researcher. The clinicians who approached these potential participants were typically psychiatrists, community psychiatric nurses or social workers, depending on the clinical setting from which the participant was recruited. On the patient’s agreement, the researcher would then contact him/her to arrange a meeting, during which he/she would be given an information sheet and an explanation of the trial. Assessments were completed either in the patient’s home, local community treatment sites or on university premises. After the patient had provided informed consent, a full PANSS assessment was then conducted to establish whether or not he/she had a rating of at least 18 on the negative symptoms subscale, as per the inclusion criterion, before being formally recruited onto the trial. When participants gave their consent, eligibility relating to diagnosis and medication history was confirmed, based on their medical records. Once approximately 16 participants at the study site were recruited, researchers then recontacted patients in order to arrange a second meeting, during which the full baseline assessment was conducted, including a second PANSS assessment. All assessments occurred within 1 month of the arranged group start date. The duration of the assessments ranged from approximately 30 to 120 minutes, and the assessments were conducted either in the patient’s home, local community mental health services or university premises.

After completion of the baseline assessments, the assigned trial ID numbers would be passed to a statistician at the PCTU for randomisation. Once randomised, the relevant names, contact details and any necessary risk information was then passed on to the Pilates instructor or BPT (depending on their allocation) via the trial manager, who was the only research team member who was unblinded to treatment allocations. The trial manager was not in direct contact with any participants, and was not involved in any of the assessments that were completed. The cofacilitators then contacted the patients to assist in the logistics of attending the groups, arranging taxi support if required. All of the groups took place in local community hospitals, civic buildings, community arts spaces and disability support centres. The design, implementation and the nature of the settings in which the groups took place remained largely consistent throughout the duration of the study.

On completion of the BPT and Pilates groups, the researchers contacted the patients again in order to complete an end of treatment assessment, which was required to be completed within 1 month of the groups finishing. The end of treatment assessment involved all of the structured interviews and questionnaires included in the baseline assessment CRF, in addition to the CSQ which was used to measure the participants’ satisfaction with treatment. Six months after completion of the intervention, the final follow-up assessment was conducted, which, again, included all of the same interviews and questionnaires from the baseline assessment. Participants were paid £25 expenses for each assessment interview that they attended.

Treatment and control conditions

Both BPT as the treatment condition and Pilates as the active control were delivered in 20 sessions of 90 minutes each, over a 10-week period, with two sessions each week, held on non-consecutive days. Twenty sessions was deemed appropriate, given that this is the length that is specified in the manual, and this has been found to be sufficient in two trials17,55 evaluating BPT as a treatment for severe mental illness, and, in a review on music therapy, 16 sessions were sufficient to result in medium effect-sized improvements in negative symptoms. 56 Dependent on the randomisation, between 7 and 10 participants were assigned to each BPT group or Pilates class, respectively. To limit the impact of any one body – psychotherapist or Pilates instructor – on outcomes, each one was permitted to run a maximum of only two groups.

Treatment condition

The treatment under investigation was BPT, as outlined in an updated version of the manual used in the 2006 exploratory trial. 17,57 The main goals of BPT as a treatment for negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenia are to reconstruct a coherent ego structure through grounding and bodily awareness; strengthen self-referential processes as a prerequisite for safe social interaction and reality testing; widen and deepen the range of emotional responses to environmental stimuli; improve boundary demarcation, enabling differentiation between self and other; and help patients to explore a range of expressive and communicative behaviours, with the aim of reducing emotional withdrawal and improving prosocial capabilities.

Each of the 20 sessions comprised five discrete sections. The first part was the opening circle, which aimed establish the group as a therapeutic space, facilitate basic communication between participants, and draw participants’ focus towards the body. Typical activities included breathing exercises, structured communication activities and self-massage. The second section was the warm-up, which aimed to promote self-awareness, emotional stimulation and reality-testing. In this section the focus is on physical movements, exploring the personal kinesphere, general space and physical sensations. The third section included structured tasks, aimed to address specific body image disturbances, such as boundary loss and desomatisation. Techniques adopted included mirroring tasks, body sculpturing using ropes or art materials and group tasks used to explore distinction between self and other. The fourth section centred on creativity, including activities that support participants to use their bodies and movement as a source of expression and pleasure. Tasks in this section included dancing, creating music or collage, or other elements of play using various objects. In the final section, the closing circle, the time is used to disengage from the therapy, and reflect on any events, thoughts or feelings that may have been brought up by the session.

Each BPT group was facilitated by an Association of Dance Movement Psychotherapy (ADMP)-accredited therapist, who had attended an additional two-day training course in delivering the intervention in its manualised form. In each group the therapist was supported by a volunteer as cofacilitator. Each therapist and cofacilitator received a minimum of three supervision sessions by a senior dance movement psychotherapist over each group, either in person or via video link. In two cases, a fourth supervision session was held in order to address specific issues that arose as the groups were ongoing. At the end of every session, therapists completed a BPT session guide sheet (see Appendix 1) to assist in reviewing the session and planning for the next. The principal aim of this exercise was to further encourage adherence to the manual.

Adherence to the manual was assessed using a specifically developed adherence scale (see Appendix 2) that was administered by body psychotherapists who were trained in assessing the sessions. A total of four sessions, spanning one from each quartile, was selected from each group in order to ensure the continuity of adherence over the whole 20-session treatment. Given that the first and final sessions adopted a slightly different structure to the norm (the first session focused primarily on introducing the method to participants, whereas the final session focused on planning for afterwards), they were omitted from the adherence rating. In order to allow for the aspects of the intervention that relate specifically to group process to be rated, only groups with a minimum of three participants in attendance were considered for adherence rating. The scale assesses whether 10 core components of BPT have been implemented, with a score of 0, 1 or 2 (no, limited, definite implementation) for each component. The total score ranges therefore from 0 to 20.

Control condition

In order to mirror the structure of the BPT condition as closely as possible, the Pilates group was also a 90-minute, 20-session, twice-a-week intervention, which was held on non-consecutive days. The Pilates group was described to patients as a fitness and physical health intervention, with the intention to limit the risk of different acceptance rates of the two interventions once patients are informed about their allocation. All of the classes were held in the same venues as the BPT groups.

Each class was facilitated by a Register of Exercise Professionals (REPS) level 3-qualified Pilates instructor and assisted by a cofacilitator. Prior to the classes starting, a brief training session was arranged between the instructor and an experienced clinician. During this meeting the instructors were provided with an outline of the study, an explanation of what schizophrenia and negative symptoms are, what to typically expect in the groups, and what to do if any untoward events or potential risk issues emerged. On any occasions on which it was felt that the Pilates instructor may benefit from additional support, an additional supervision session with an experienced clinician was arranged outside of the classes.

Prior to the groups starting, a brief Pilates guide was developed by the research team in collaboration with instructors who were involved in the trial (see Appendix 3), using the Pilates Union Matwork Manual as a guide. 58 The intervention guide provided a brief summary of how to run the groups and a loosely structured exercise plan, allowing for considerable flexibility to accommodate differing fitness levels between participants. The use of props (other than mats and head blocks), music and additional activities designed to encourage group interactions was not permitted. Instructors were advised to pay attention to patients and respond to them without addressing or verbalising emotions and without promoting group interactions, if possible.

Sample size calculation

A 20% reduction in the PANSS score has been used as an indicator of clinically significant improvement in the past,59 which, if applied specifically to the negative symptoms subscale, would equate to a difference of between 3 and 4 points, given the eligibility criteria. To detect a difference of 3 points with a standard deviation (SD) of 5, with 90% power for 5% significance, 58 patients were required in each arm. To allow for clustering by group, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for treatment group of 0.1, and seven patients per group with analysable data at the end of treatment, gives an inflation factor of 1.6, meaning that 93 participants in each arm were required. At 6 months we predicted a loss to follow-up of 31%, so recruiting 256 participants would leave 88 per arm at 6 months, and 91% power to detect a difference of 3 points at this time point. One hundred and twenty-eight patients per arm, i.e. 16 groups of approximately eight patients in each arm, would give 94% power for the end-of-treatment analysis, assuming that 87.5% of patients have analysable data.

Analysis plan

Prior to conducting the analysis, an analysis plan was drafted by the trial statistician. The primary analysis was of available cases of the PANSS negative subscale at the end of treatment, following intention-to-treat principles. We used a mixed-effects model fitted by restricted maximum likelihood with fixed effects for the treatment group, baseline PANSS negative scores (because it was expected to be highly correlated with the outcome at end of treatment, so increasing the precision of the estimated treatment effect) and centre (because it was used to stratify the randomisation), and random effects for therapy groups to allow for clustering by group. Secondary outcomes were analysed using the same approach. To evaluate the impact of missing data in a sensitivity analysis, multiple imputation of the data set was performed and the analysis was replicated. The data were exported from Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and missing data were multiply imputed in REALCOM-IMPUTE software60 to give 10 completed data sets, using a multilevel model with therapy groups included as a random effect. These were imported back into Stata, analysed and the results pooled using Rubin’s rules. Depending on whether or not the outcomes were continuous, count or ordinal in nature, Stata’s xtmixed or xtmepoisson commands were used. In all of the analysis, completed statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

In order to assess the impact of BPT in those who complied with treatment, a simple complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis was completed on all scales, which report a continuous outcome score (the PANSS, CAINS, SAS, Calgary Depression Scale, MANSA and SIX). In contrast with the rest of the analysis, a multilevel model was not adopted. Compliance was originally defined as attending at least 10 sessions; however, this was reduced to five sessions prior to the analysis plan being signed off following a recent study55 evaluating the effectiveness of BPT for chronic depression, which found a significant effect of treatment at this threshold.

In the final part of the analysis, preplanned subgroup analyses were conducted on the PANSS negative subscale, the CAINS expressive and experiential subscales and the Calgary Depression Scale by fitting an interaction term between the moderator of interest and the treatment group. The differences in treatment response were explored between those with higher negative symptoms at baseline and a longer duration of illness. High symptoms were defined as a score of > 23 on the PANSS negative subscale, whereas a low score was ≤ 23. In an examination of the possible effect of duration of illness, two different cut-offs were used. In the first analysis, participants with a duration of illness of > 5 years and ≤ 5 years were compared, and, in the second analysis, those with a duration of illness of > 15 years and ≤ 15 years were compared. All analysis was completed using Stata.

Economic analysis plan

A health and social care perspective was adopted in the analyses, in line with NICE recommendations. Costs were compared for the groups using a bootstrap regression model to account for non-normality in the distribution of cost data. Missing costs and QALY data were imputed using a regression-based method to estimate missing values based on other variables in the data set. The economic analysis was completed by a health economist who was independent to the trial statistician.

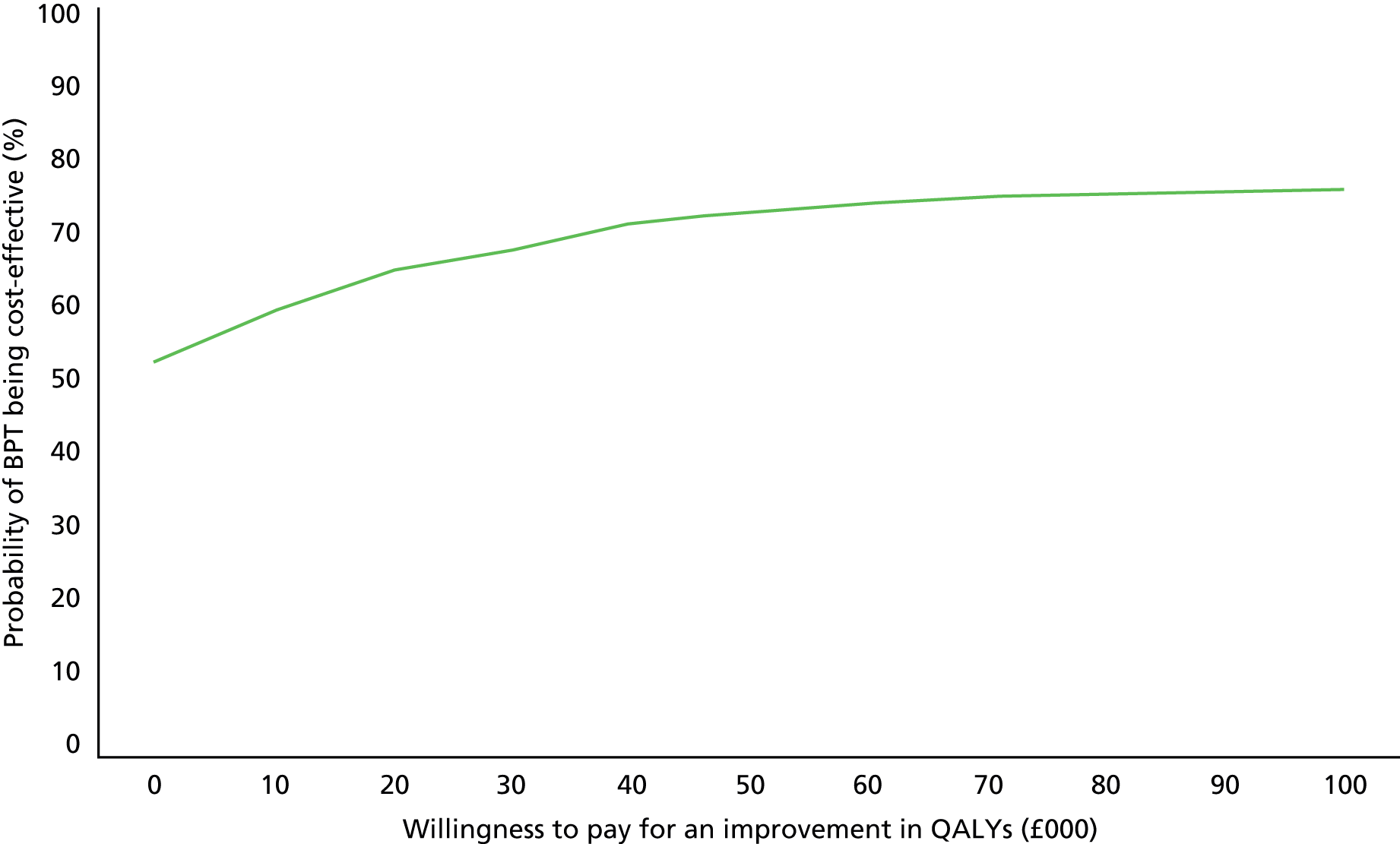

Cost-effectiveness was assessed by estimating an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) to show the extra cost incurred by BPT to generate one extra QALY. This is defined as the cost difference divided by the outcome difference, after adjusting for costs and outcomes measured at baseline. This is most meaningful in the event of BPT being more (less) expensive and more (less) effective than Pilates; otherwise, one of the alternatives is dominant (less expensive and better). However, there will inevitably be uncertainty around the cost and outcome differences. To deal with uncertainty around the ICER, a cost-effectiveness plane (CEP) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were created. For the CEP, 1000 bootstrapped estimates of cost and outcome differences were produced, adjusted for baseline and plotted these against each other. This then showed the probability that BPT had (1) higher costs and better outcomes; (2) higher costs and worse outcomes; (3) lower costs and worse outcomes; or (4) lower costs and better outcomes than Pilates. The CEAC was produced using the net benefit approach, for which the QALY difference is multiplied by the societal value (threshold) placed on a QALY and the incremental service cost is subtracted. A positive incremental net benefit means that BPT is more cost-effective and the proportion of positive values for each societal QALY value gives the probability that BPT is cost-effective at that threshold.

In this study, the cost-effectiveness of receiving BPT rather than Pilates was examined. Both BPT and Pilates are delivered by a therapist/instructor and in groups, so we estimated costs for both interventions. However, in routine practice, BPT is likely to be considered as an additional service, rather than as an alternative to other active therapies such as Pilates. Consequently, in a sensitivity analysis, the impact of removing the Pilates group costs from the total costs in the control arm was explored.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from by the Camden and Islington National REC (REC reference 10/H0722/44) on 13 July 2010. The trial was overseen by an independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), which reported to a TSC that was established prior to the trial start date. The TSC consisted of researchers with experience of trial design and implementation in psychosis, a statistician and a service user who had previously undergone a treatment of BPT.

During the study, all of the data were stored in line with the Data Protection Act and all video-recorded data were encrypted and password protected on hard disk drives, which were locked in file cabinets. On completion of the project, all of the data have been archived for a period of 25 years. In both study arms, participants received input in addition to their treatment, and their standard care was not compromised at any time. All patients were initially approached by a clinician who asked for their consent before they were contacted by a researcher. Once contacted, all potential participants were fully informed about the study and asked for written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement came principally in the form of trial oversight. The TSC included a service user who had previously attended a BPT group similar in nature to the therapy evaluated in the current investigation. This service user provided input on which outcomes would be important to evaluate, and reviewed the appropriateness of the measures used to evaluate these outcomes. In addition, they provided input on the settings in which both of the assessments and groups should take place, emphasising the importance of consistency throughout.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant recruitment and retention

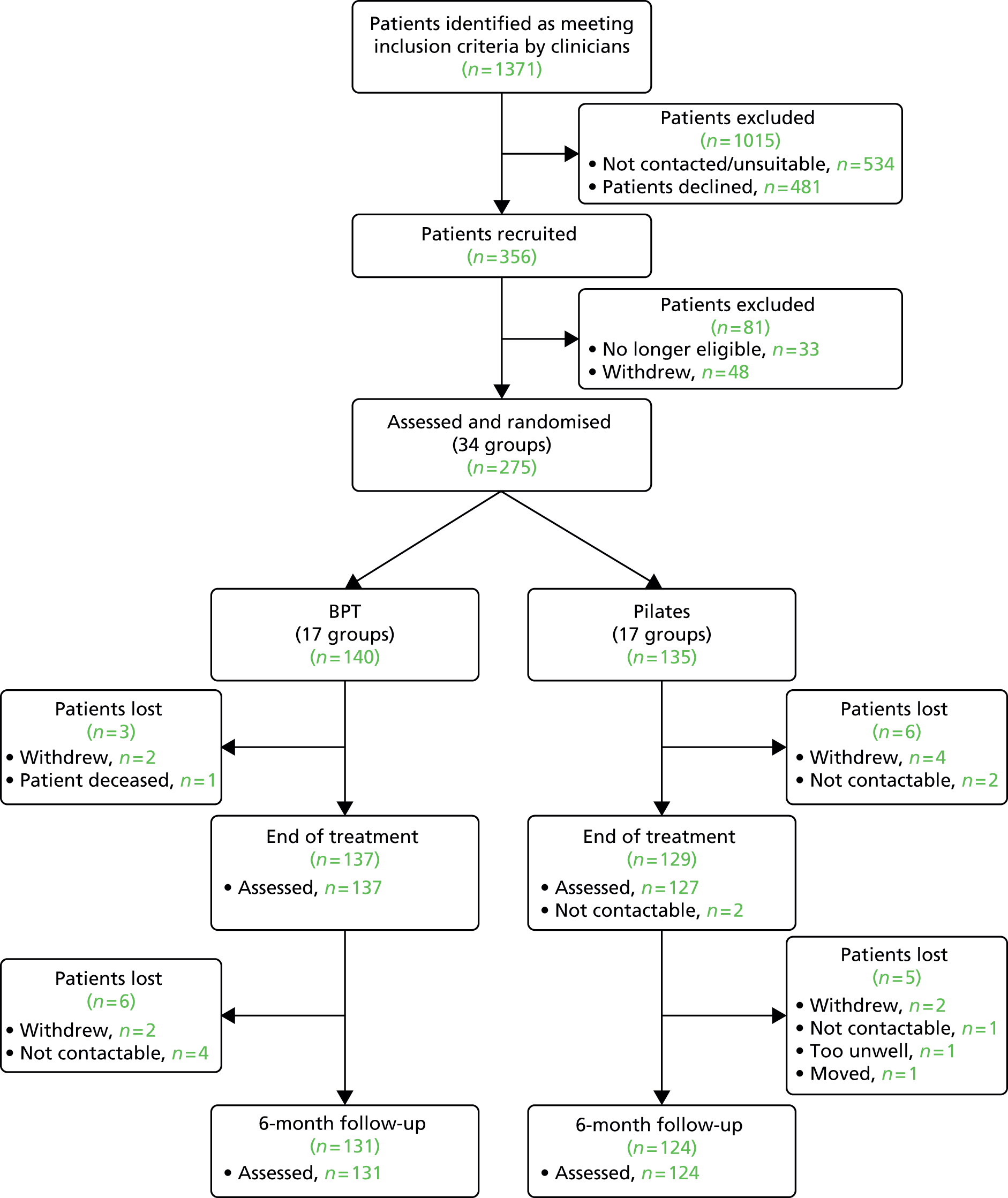

The participant study dropout at each stage of the project is presented in the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram (Figure 1). Recruitment took place from December 2011 until June 2013. In the study it was necessary to screen a far higher number of potential participants than anticipated in order to recruit the required number. In total, 1371 individuals were identified as potentially eligible, but, in the end, only 356 were recruited, of which 275 were randomised. This was due to a number of factors. First, a relatively large number of screened patients were found to be ineligible, either because of the potential participant subsequently being found to have a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder or the severity of negative symptoms being below the eligibility threshold. Second, given the group design of the study once all of the therapy/control places were provisionally filled, no more participants were approached unless a participant subsequently dropped out. Consequently, a number of participants were initially screened as potentially eligible, but were not approached owing to the lack of available spaces on the trial in their area. A relatively large number of potential participants declined to take part; however, given the nature of the groups, the typical symptom presentation of the patients who would be eligible, and the requirement to attend a group twice a week at specified times, this figure would not be considered excessive.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Following randomisation, the study attrition rate was lower than anticipated. Of the 275 randomised, 266 (96.7%) were assessed at end of treatment and 255 (92.7%) went on to complete the 6-month follow-up. In both cases this was significantly higher than the retention figures that were proposed in the protocol and used for the sample size calculation. One participant died after completion of the groups as a result of an illness that was not related to the intervention, and did not complete either the end-of-treatment or 6-month follow-up assessment. The data of this participant were omitted, leaving a final total of 274 participants who were potentially included in the analysis, presuming data availability.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Study participants were, on average, 42.2 years old (SD = 10.7 years) and predominantly male (74%), unemployed (96%) and living alone (57%). The baseline outcome scores for the whole sample are presented in Table 2. The participants presented with moderate levels of negative symptoms (PANSS negative subscale score = 23.2, SD = 4.3), mild positive symptoms (PANSS positive subscale score = 14.1, SD = 4.9) and low to moderate symptoms of depression (Calgary Depression Scale score = 4.7, SD = 4.4). The level of inter-rater reliability for the PANSS was high (PANSS total ICC = 0.85). Assessor blinding was maintained prior to the primary outcome assessment in over 249 out of 264 of cases (94.3%).

| Variable | BPT (N = 140) | Pilates (N = 135) | Total (N = 275) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centre, n (%) | |||

| East Londona | 41 (29) | 40 (29) | 81 (29) |

| North East Londona | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | 16 (6) |

| South London | 36 (26) | 32 (24) | 68 (2) |

| Manchester | 23 (16) | 23 (17) | 46 (17) |

| Liverpool | 32 (23) | 32 (24) | 64 (23) |

| Age (years) mean (SD) | 41.1 (10.1) | 43.3 (11.1) | 42.2 (10.7) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 103 (74) | 100 (74) | 203 (74) |

| Female | 37 (26) | 35 (26) | 72 (26) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 71 (52) | 67 (53) | 138 (52) |

| Black | 39 (29) | 38 (30) | 77 (29) |

| Asian | 13 (9) | 16 (13) | 29 (11) |

| Other | 14 (10) | 6 (5) | 20 (8) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Unemployed | 131 (94) | 132 (98) | 263 (96) |

| Other | 8 (6) | 3 (2) | 11 (4) |

| Living situation, n (%) | |||

| Alone | 83 (60) | 73 (54) | 156 (57) |

| With others | 56 (40) | 62 (46) | 118 (43) |

| Number of children, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Duration of illness (years), median (IQR) | 11 (7–18) | 10 (7–19) | 11 (7–18) |

| Number of hospitalisations, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5.5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (1–5) |

| Medication: defined daily dose,b mean (SD) | 1.48 (1.11) | 1.71 (1.28) | 1.59 (1.20) |

| Outcome | BPT group (N = 140) | Pilates (N = 135) | Total (N = 275) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean | SD | n (%) | Mean | SD | n (%) | Mean | SD | |

| PANSS | |||||||||

| Negative | 140 (100) | 23.3 | 4.3 | 135 (100) | 23.1 | 4.4 | 275 (100) | 23.2 | 4.3 |

| Positive | 138 (99) | 14 | 5.1 | 135 (100) | 14.1 | 4.7 | 273 (99) | 14.1 | 4.9 |

| General | 137 (98) | 32.9 | 8.3 | 133 (99) | 32.5 | 8.1 | 270 (98) | 32.7 | 8.2 |

| Total | 135 (96) | 70.1 | 13.6 | 133 (99) | 69.5 | 13.3 | 268 (97) | 69.8 | 13.4 |

| PANSS Marder negative | 140 (100) | 20.7 | 5.7 | 135 (100) | 20.3 | 5.1 | 275 (100) | 20.5 | 5.4 |

| CAINS | |||||||||

| Experience | 136 (97) | 22.1 | 5.6 | 134 (99) | 21.5 | 5.5 | 270 (98) | 21.8 | 5.6 |

| Expression | 140 (100) | 8 | 3.5 | 133 (99) | 7.5 | 3.9 | 273 (99) | 7.8 | 3.7 |

| Calgary Depression Scale | 140 (100) | 4.8 | 4.2 | 134 (99) | 4.6 | 4.6 | 274 (99) | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| MANSA | 126 (90) | 53.4 | 11.6 | 126 (93) | 52.7 | 10.9 | 252 (92) | 53 | 11.2 |

| SAS | 128 (94) | 1.7 | 2.1 | 126 (93) | 2.3 | 2.7 | 254 (92) | 2 | 2.5 |

| SIX | 140 (100) | 2.4 | 1.1 | 135 (100) | 2.3 | 1.1 | 275 (100) | 2.4 | 1.1 |

| n (%) | Median | IQR | n (%) | Median | IQR | n (%) | Median | IQR | |

| SNS | |||||||||

| Friends seen | 133 (95) | 1 | 0.0–2.0 | 129 (96) | 1 | 0.0–2.0 | 262 (95) | 1 | 0.0–2.0 |

| Family seen | 133 (95) | 2 | 1.0–3.0 | 129 (96) | 2 | 1.0–4.0 | 262 (95) | 2 | 1.0–3.0 |

| Others seen | 133 (95) | 0 | 0.0–1.0 | 129 (96) | 0 | 0.0–1.0 | 262 (95) | 0 | 0.0–1.0 |

| Total seen | 133 (95) | 4 | 2.0–5.0 | 129 (96) | 4 | 2.0–5.0 | 262 (95) | 3 | 2.0–5.0 |

| TUS | |||||||||

| Number of activities | 139 (99) | 3 | 1.0–6.0 | 135 (100) | 3 | 1.0–6.0 | 274 (99) | 3 | 1.0–6.0 |

| Time spent (hours) | 139 (99) | 1.5 | 0.0–3.5 | 135 (100) | 1.8 | 0.3–4.0 | 274 (99) | 1.6 | 0.2–3.8 |

Uptake of interventions

The number of BPT and Pilates sessions attended are presented in Table 3. In the BPT arm, 106 participants (75.7%) attended at least 5 of the 20 sessions, thus fulfilling the minimum attendance threshold required to be defined as a treatment complier in the CACE analysis. It was estimated that approximately 25% of participants were provided with taxis to support attendance.

| Number of sessions attended | BPT group (N = 140) | Pilates group (N = 135) | Total (N = 275) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0, n (%) | 11 (8) | 18 (13) | 29 (11) |

| 1–5, n (%) | 30 (21) | 40 (30) | 70 (25) |

| 6–14, n (%) | 45 (32) | 42 (31) | 87 (32) |

| 15–20, n (%) | 54 (39) | 35 (26) | 89 (32) |

| Median number attended (IQR) | 11 (5–17) | 8 (1–15) | 9 (2–17) |

Therapist adherence to manual

Of the 17 different BPT groups, 16 were assessed for adherence to the manual using the BPT Adherence Scale (see Appendix 2). One group was not assessed because of the lack of video data available for the sessions. In total, 64 sessions (18.8% of all sessions conducted) were assessed. Overall, the therapist adherence to the manual was relatively high, with a mean score of 17.6 out of the maximum of 20 (SD = 0.21). In all of the groups there was evidence that the body psychotherapists were able to follow the structure of the sessions as laid out in the manual, and establish a safe and cohesive therapeutic environment. Areas that were less consistently implemented related to how the exercises completed related specifically to negative symptoms, and the introduction of coping strategies that were designed to deal with negative symptoms specifically.

Primary outcome

The main outcomes of the trial are shown in Table 4. There was a small reduction in mean PANSS negative symptoms between baseline and end of treatment in both the BPT and Pilates groups (within-group mean reduction in the BPT group = 1.5, SD = 3.5; Pilates group = 1.5, SD = 3.8). After controlling for baseline scores, study centre and therapy group, no significant difference between the treatment and control condition was detected [adjusted difference in means = 0.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) –1.11 to 1.17; p = 0.959, model-based ICC = 0.099].

| Outcomea | BPT group | Pilates group | Adjusted difference in means/IRR at end of treatment (95% CI)b,c | Adjusted difference in means/IRR at 6 months (95% CI)b,c | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of treatment | 6 months | Baseline | End of treatment | 6 months | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| PANSS | ||||||||||||||

| Negative (n = 254) | 23.3 | 4.3 | 21.8 | 5.4 | 21.7 | 5.7 | 23.1 | 4.4 | 21.5 | 4.7 | 21.7 | 5.1 | 0.03 (–1.11 to 1.17), ICC 0.099 | –0.18 (–1.68 to 1.31), ICC 0.137 |

| Positive (n = 253) | 14 | 5.1 | 13.1 | 4.7 | 13.4 | 4.7 | 14.1 | 4.7 | 13.3 | 4.2 | 13.6 | 4.9 | 0.06 (–0.71 to 0.84), ICC < 0.001 | –0.12 (–1.03 to 0.79), ICC < 0.001 |

| General (n = 249) | 32.9 | 8.3 | 30.2 | 8 | 30.1 | 8.1 | 32.5 | 8.1 | 29.9 | 7.3 | 30.4 | 7.5 | 0.32 (–1.31 to 1.94), ICC 0.096 | –0.70 (–3.07 to 1.67), ICC 0.205 |

| Marder negative (n = 253) | 22.2 | 4.7 | 20.7 | 5.7 | 20.2 | 5.7 | 21.9 | 5 | 20.3 | 5.1 | 20.1 | 5.6 | 0.23 (–0.86 to 1.32), ICC 0.678 | 0.04 (–1.38 to 1.45), ICC 0.075 |

| CAINS | ||||||||||||||

| Experience (n = 246) | 22.1 | 5.6 | 20.5 | 5.8 | 20.8 | 6.7 | 21.5 | 5.5 | 19.8 | 5.8 | 20.6 | 6.2 | 0.05 (–1.13 to 1.22), ICC 0.037 | –0.04 (–1.48 to 1.40), ICC 0.041 |

| Expression (n = 253) | 8 | 3.5 | 7.3 | 3.7 | 7.1 | 4 | 7.5 | 3.9 | 7.5 | 4.1 | 7.1 | 4.3 | –0.62 (–1.23 to 0.00), ICC 0.022d | –0.27 (–1.05 to 0.50), ICC 0.023 |

| Calgary (n = 253) | 4.8 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.2 | –0.01 (–0.72 to 0.71), ICC < 0.001 | –0.20 (–1.18 to 0.79), ICC 0.086 |

| MANSA (n = 254) | 4.4 | 0.9 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 4.6 | 1 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 4.6 | 0.9 | 4.5 | 0.9 | –0.11 (–0.27 to 0.58), ICC < 0.001 | 0.10 (–0.12 to 0.32), ICC 0.050 |

| SNSe (n = 232) | ||||||||||||||

| Relatives seen | 2 | 1.0–3.0 | 3 | 1.0–4.0 | 2 | 1.0–4.0 | 2 | 1.0–4.0 | 2 | 1.0–4.0 | 2 | 1.0–4.0 | 1.13 (0.89 to 1.32) | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.15) |

| Friends seen | 1 | 0.0–2.0 | 1 | 0.0–2.0 | 0.5 | 0.0–2.0 | 1 | 0.0–2.0 | 1 | 0.0–2.0 | 1 | 0.0–2.0 | 0.94 (0.80 to 1.42) | 0.91 (0.63 to 1.30) |

| Total number seen | 3 | 2.0–5.0 | 4 | 3.0–6.0 | 4 | 2.0–6.0 | 4 | 2.0–5.0 | 4 | 3.0–6.0 | 4 | 2.0–6.0 | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.14) | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.12) |

| TUSe (n = 254) | ||||||||||||||

| Number of activities | 3 | 1.0–6.0 | 3 | 1.0–7.0 | 3 | 1.0–7.0 | 3 | 1.0–6.0 | 2 | 1.0–7.0 | 2 | 1.0–7.0 | 1.03 (0.89 to 1.42) | 1.04 (0.81 to 1.33) |

| Time spent (hours) | 1.5 | 0.0–3.5 | 1.5 | 0.3–4.0 | 1.5 | 0.0–3.0 | 1.8 | 0.3–4.0 | 2 | 0.3–4.5 | 1.5 | 0.2–3.8 | 1.03 (0.80 to 1.32) | 0.96 (0.73 to 1.25) |

| SAS (n = 229) | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 2.4 | –0.65 (–1.13 to –0.16), ICC < 0.001d | –0.50 (–0.94 to –0.07), ICC 0.007d |

| SIX (n = 254) | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1.2 | –0.02 (–0.17 to 0.20), ICC < 0.001 | –0.10 (–0.27 to 0.08), ICC < 0.001 |

| CSQ (n = 237) | – | – | 25.3 | 4.6 | – | – | – | – | 25.9 | 4 | – | – | –0.68 (–1.80 to 0.44) | – |

Secondary outcomes

Significant reductions in mean SAS (–0.65, 95% CI –1.13 to –0.16; p = 0.009, ICC < 0.001) and mean CAINS expression subscale (–0.62, 95% CI –1.23 to 0.00; p = 0.049, ICC = 0.022) were detected in the BPT group compared with the Pilates group at the end of treatment. No other significant differences were found in the secondary outcomes at this stage. In both groups, participants reported a high level of satisfaction with the treatment they received (BPT CSQ = 25.3, SD = 4.6; Pilates CSQ = 25.9, SD = 4.0).

At the 6-month follow-up, no significant difference in means in the PANSS negative symptoms subscale score was detected between the BPT and Pilates study arms (–0.18, 95% CI –1.68 to 1.32; p = 0.812, ICC = 0.137). There was a significant difference in mean SAS scores at 6-month follow-up (–0.50, 95% CI –0.97 to –0.07; p = 0.028, ICC ≤ 0.001). No other significant differences were detected on any other outcome at follow-up.

Ancillary analyses

Analysis following imputation

Multiple imputation of the data set was performed and the analysis was replicated in order to evaluate the impact of missing data. During the study there was minimal participant dropout and, when the assessment was conducted, the full assessment was completed in almost all of the cases. Consequently, only minimal differences between the analysis of the imputed and non-imputed data sets were noted. The findings are reported in Table 5.

| Outcome (n = 274) | Adjusted difference in means/IRR at end of treatment (95% CI)a | Adjusted difference in means/IRR at 6 months (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| PANSSa | ||

| Negative | 0.09 (–1.08 to 1.25), ICC 0.102 | –0.09 (–1.58 to 1.39), ICC 0.135 |

| Positive | 0.07 (–0.70 to 0.84), ICC < 0.001 | –0.19 (1.14 to 0.76), ICC < 0.001 |

| General | 0.26 (–1.38 to 1.89), ICC 0.087 | –0.58 (–2.93 to 1.76), ICC 0.202 |

| Marder negative | 0.18 (–0.93 to 1.28), ICC 0.752 | 0.09 (–1.37 to 1.55), ICC 0.083 |

| CAINS | ||

| Experience | –0.3 (–1.34 to 1.28), ICC 0.069 | –0.10 (–1.58 to 1.38), ICC 0.056 |

| Expression | –0.60 (–1.22 to 0.02), ICC 0.026 | –0.30 (–1.06 to 0.50), ICC 0.031 |

| Calgary Depression Scale | 0.00 (–0.74 to 0.75), ICC > 0.001 | –0.17 (–1.17 to 0.84), ICC 0.087 |

| MANSA | –0.17 (–0.37 to 0.02), ICC 0.033 | 0.07 (–0.20 to 0.34), ICC 0.074 |

| SNS (IRR)b | ||

| Relatives seen | 0.96 (0.81 to 1.14) | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.27) |

| Friends seen | 0.89 (0.62 to 1.27) | 0.84 (0.60 to 1.18) |

| Total no. seen | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.14) | 1.00 (0.83 to 1.20) |

| TUS (IRR)b | ||

| Number of activities | 1.11 (0.85 to 1.44) | 1.05 (0.78 to 1.42) |

| Time spent (hours) | 1.00 (0.74 to 1.36) | 0.98 (0.72 to 1.34) |

| SAS | –0.62 (–1.15 to –0.09) to ICC < 0.001c | –0.58 (–1.07 to –O.09), ICC < 0.001c |

| SIX | –0.03 (–0.17 to 0.12) to ICC < 0.001 | –0.09 (–0.27 to 0.09), ICC 0.002 |

In the PANSS negative subscale, no significant difference was detected between the experimental and control condition either at the end of treatment (adjusted difference in means = 0.09, 95% CI –1.08 to 1.26; p = 0.885, ICC = 0.102) or the 6-month follow-up stage (adjusted difference in means = –0.09, 95% CI –1.58 to 1.39; p = 0.902, ICC = 0.135). In the secondary outcomes at end of treatment, extrapyramidal symptoms were found to be significantly lower in the BPT arm (adjusted difference in means –0.62, 95% CI –1.15 to –0.09; p = 0.021, ICC < 0.001). In contrast with the available case analysis, the difference in the CAINS experience was not significant at the 5% level, despite only a minimal change in the estimate (–0.60, 95% CI –1.22 to 0.02; p = 0.056, ICC = 0.026). At the 6-month follow-up, no significant differences were detected between BPT and Pilates, other than in extrapyramidal symptoms (–0.58, 95% CI –1.07 to –0.09; p = 0.021, ICC = 0.001).

Complier-average causal effect analysis

To estimate the causal effect of treatment accounting for departures from the randomised intervention, a CACE analysis was conducted, using a minimum attendance of 5 and 10 BPT sessions to define those who complied with treatment. The minimum attendance of five sessions was prespecified and the minimum of 10 sessions was exploratory in nature. The results are presented in Table 6, including both the estimates for both 5 and 10 sessions as an indicator of compliance. In the primary outcome at end of treatment, no significant adjusted difference in mean PANSS scores between BPT and Pilates was detected (–0.13, 95% CI –1.41 to 1.64). In the secondary outcomes, only a significant difference in means in the SAS was detected (–0.82, 95% CI –1.51 to –0.12).

| Outcome | ITT: coefficient (95% CI) | CACE: coefficient (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum 5 sessions | Minimum 10 sessions | ||

| PANSS | |||

| Negative | 0.09 (–1.08 to 1.25) | 0.11 (–1.41 to 1.64) | 0.15 (–1.89 to 2.19) |

| Positive | 0.07 (–0.70 to 0.84) | 0.09 (–0.93 to 1.11) | 0.12 (–1.23 to 1.48) |

| General | 0.26 (–1.38 to 1.89) | 0.34 (–1.81 to 2.49) | 0.45 (–2.41 to 3.31) |

| Marder negative | 0.18 (–0.93 to 1.28) | 0.23 (–1.22 to 1.69) | 0.31 (–1.62 to 2.25) |

| CAINS | |||

| Experience | –0.03 (–1.34 to 1.28) | –0.04 (–1.76 to 1.68) | –0.06 (–2.35 to 2.24) |

| Expression | –0.60 (–1.22 to 0.02) | –0.79 (–1.60 to 0.02) | –1.05 (–2.15 to 0.03) |

| Calgary Depression Scale | 0.00 (–0.74 to 0.75) | 0.00 (–0.97 to 0.98) | 0.01 (–1.30 to 1.31) |

| CSQ | –0.83 (–2.05 to 0.40) | –1.09 (–2.70 to 0.53) | –1.45 (–3.60 to 0.70) |

| SAS | –0.62 (–1.15 to –0.09)a | –0.82 (–1.51 to –0.12)a | –1.09 (–2.02 to –0.16)a |

| SIX | –0.03 (–0.17 to 0.12) | –0.03 (–0.23 to 0.16) | –0.04 (–0.31 to 0.22) |

| MANSA | –0.17 (–0.37 to 0.02) | –0.23 (–0.49 to 0.03) | –0.30 (–0.65 to 0.04) |

Subgroup analysis

Preplanned subgroup analyses were conducted in order to assess whether or not there was any difference in response between participants with high and low symptoms, and between those with a long or short duration of illness. The outcomes assessed included the PANSS negative subscale, the CAINS subscales, and the Calgary Depression Scale. The composition of the subgroups for each instrument evaluated is reported in Table 7, and the results of the subgroup analyses are presented in Tables 8–10. No significant differences in response were detected in the primary outcome between patients with higher negative symptoms at baseline (adjusted difference in means = 1.19, 95% CI –0.56 to 2.94; p for interaction = 0.184) or a longer duration of illness, both when split at 5 years of illness duration (adjusted difference in means = –1.57, 95% CI –4.09 to 0.96; p = 0.224) and 15 years of illness duration (adjusted difference in means = –1.28, 95% CI –3.39 to 0.83; p = 0.234). With regards to the CAINS subscales and Calgary Depression Scale, again no significant differences in response between the subgroups were detected.

| Outcome | Subgroup category | N | BPT, n (%) | Pilates, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS negative subscale | PANSS negative < 23 | 129 | 63 (46.3) | 66 (52.0) |

| PANSS negative ≥ 23 | 134 | 73 (53.7) | 61 (48.0) | |

| Illness ≤ 5 years | 37 | 18 (15.8) | 19 (18.1) | |

| Illness > 5 years | 186 | 96 (84.2) | 86 (81.9) | |

| Illness ≤ 15 years | 155 | 79 (69.3) | 76 (72.4) | |

| Illness > 15 years | 64 | 35 (30.7) | 29 (27.6) | |

| CAINS experience subscale | PANSS negative < 23 | 129 | 63 (46.3) | 66 (52.0) |

| PANSS negative ≥ 23 | 134 | 73 (53.7) | 61 (48.0) | |

| Illness ≤ 5 years | 37 | 18 (15.8) | 19 (18.1) | |

| Illness > 5 years | 186 | 96 (84.2) | 86 (81.9) | |

| Illness ≤ 15 years | 155 | 79 (69.3) | 76 (72.4) | |

| Illness > 15 years | 64 | 35 (30.7) | 29 (27.6) | |

| CAINS expressive subscale | PANSS negative < 23 | 128 | 64 (48.1) | 64 (51.2) |

| PANSS negative ≥ 23 | 130 | 69 (51.9) | 61 (48.8) | |

| Illness ≤ 5 years | 36 | 18 (16.2) | 18 (17.5) | |

| Illness > 5 years | 178 | 93 (83.8) | 85 (82.5) | |

| Illness ≤ 15 years | 151 | 77 (69.4) | 74 (71.8) | |

| Illness > 15 years | 63 | 34 (30.6) | 29 (28.2) | |

| Calgary Depression Scale | PANSS negative < 23 | 129 | 63 (47.4) | 66 (52.4) |

| PANSS negative ≥ 23 | 130 | 70 (52.6) | 60 (47.6) | |

| Illness ≤ 5 years | 36 | 18 (16.2) | 18 (17.3) | |

| Illness > 5 years | 179 | 93 (83.8) | 86 (82.7) | |

| Illness ≤ 15 years | 151 | 76 (68.5) | 75 (72.1) | |

| Illness > 15 years | 64 | 35 (31.5) | 29 (27.9) |

| Outcome | Adjusted difference in means | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS negative subscale (n = 263) | |||

| Treatment | –0.57 | –2.00 to 0.87 | 0.437 |

| Illness severity | –0.56 | –2.23 to 1.11 | 0.510 |

| Treatment × illness severity | 1.19 | –0.56 to 2.94 | 0.184 |

| CAINS experiential subscale (n = 263) | |||

| Treatment | 0.05 | –1.54 to 1.63 | 0.955 |

| Illness severity | 0.42 | –1.13 to 1.97 | 0.592 |

| Treatment × illness severity | –0.01 | –2.16 to 2.15 | 0.997 |

| CAINS expressive subscale (n = 258) | |||

| Treatment | –0.16 | –1.01 to 0.69 | 0.710 |

| Illness severity | 1.16 | 0.25 to 2.08 | 0.013 |

| Treatment × illness severity | –0.89 | –2.03 to 0.26 | 0.130 |

| Calgary Depression Scale (n = 259) | |||

| Treatment | –0.59 | –1.60 to 0.43 | 0.256 |

| Illness severity | –0.81 | –1.84 to 0.22 | 0.123 |

| Treatment × illness severity | 1.19 | –0.25 to 2.62 | 0.105 |

| Outcome | Adjusted difference in means | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS negative subscale (n = 219) | |||

| Treatment | 1.47 | –2.00 to 0.87 | 0.437 |

| Illness duration | 0.79 | –1.01 to 2.59 | 0.388 |

| Treatment × illness duration | –1.57 | –4.09 to 0.96 | 0.224 |

| CAINS experiential subscale (n = 219) | |||

| Treatment | 1.01 | –1.78 to 3.80 | 0.479 |

| Illness duration | 1.84 | –0.29 to 3.97 | 0.090 |

| Treatment × illness duration | –0.68 | –3.73 to 2.38 | 0.663 |

| CAINS expressive subscale (n = 214) | |||

| Treatment | 0.70 | –0.82 to 2.22 | 0.367 |

| Illness duration | 1.57 | 0.40 to 2.76 | 0.009 |

| Treatment × illness duration | –1.60 | –3.23 to 0.04 | 0.055 |

| Calgary Depression Scale (n = 215) | |||

| Treatment | –0.78 | –2.66 to 1.10 | 0.413 |

| Illness duration | –0.08 | –1.55 to 1.40 | 0.921 |

| Treatment × illness duration | 0.68 | –1.38 to 2.74 | 0.517 |

| Outcome | Adjusted difference in means | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS negative subscale (n = 219) | |||

| Treatment | 0.56 | –0.87 to 1.20 | 0.441 |

| Illness duration | –0.24 | –1.81 to 1.34 | 0.770 |

| Treatment × illness duration | –1.28 | –3.39 to 0.83 | 0.234 |

| CAINS experiential subscale (n = 219) | |||

| Treatment | 0.18 | –1.20 to 1.66 | 0.795 |

| Illness duration | 0.09 | –1.78 to 1.96 | 0.923 |

| Treatment × illness duration | 0.92 | –1.63 to 3.47 | 0.479 |

| CAINS expressive subscale (n = 214) | |||

| Treatment | –1.61 | –1.01 to 0.67 | 0.710 |

| Illness duration | 0.01 | –1.00 to 1.02 | 0.983 |

| Treatment × illness duration | 0.03 | –1.34 to 1.40 | 0.969 |

| Calgary Depression Scale (n = 215) | |||

| Treatment | –0.33 | –1.26 to 0.61 | 0.495 |

| Illness duration | 0.13 | –1.13 to 1.39 | 0.841 |

| Treatment × illness duration | 0.32 | –1.39 to 2.04 | 0.711 |

Adverse events

No serious adverse events occurred during the groups. During the follow-up phase, one participant died, but this was unrelated to the trial or the intervention they received. Throughout the implementation of the project there was no evidence of exacerbation of psychotic symptoms as a consequence of taking part in the BPT or Pilates groups.

Economic analysis

Service use

The proportion of those who used different health services, and the mean number of contacts that these participants made are presented in Table 11. At baseline, service use was broadly similar. Slightly more participants in the Pilates group accessed their general practitioner (GP) services (70% in comparison with 61%) and, in those who did report making contact, a slightly higher number of appointments were made in the Pilates group (mean = 2.1, SD = 1.5, in comparison with mean = 1.8, SD = 1.1). A higher proportion of participants in the Pilates group reported regular contact with a social worker (39% in comparison with 24%) and general psychiatric outpatient contacts (51% in comparison with 43%), whereas in the BPT group it was more common for participants to be in contact with a community psychiatric nurse (30% in comparison with 20%). In the 3 months prior to the baseline assessment, only two patients, both in the BPT group, reported a psychiatric inpatient admission. Almost all patients (97% of those in the Pilates group and 99% in the BPT group) reported being on at least one mental health medication. Most were prescribed antipsychotic medication, such as olanzapine (Zyprexa; Eli Lilly and Company), clozapine (Clozaril, Novartis), flupentixol (Depixol, Lundbeck Ltd) or risperdal (Risperdal, Janssen Pharmaceutica) and antidepressant drugs, such as fluoxetine (Prozac, Eli Lilly and Company), citalopram (Cipramil, Lundbeck), mirtazapine (Remeron, Merck and Company) or sertraline (Zoloft, Pfizer).