Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/14/30. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The draft report began editorial review in April 2015 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Catherine Sackley is Deputy Chair of the Health Services and Delivery Research Researcher-led Board; Caroline Watkins is on the Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board; and Keith Wheatley is on the Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Sackley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Prevalence of stroke in the UK

The population of the UK and elsewhere is living longer. The average lifespan since 1960 in England and Wales has increased by 10 years for men and 8 years for women. 1 One in six members of the UK population were aged over 65 years at the time of the 2011 census,2 and the over-85-year-old age bracket is the fastest growing sector. 3 It is predicted that, by 2031, 22% of the population will be over 65 years old. 4 The incidence of stroke increases significantly with age. 5 According to British Heart Foundation statistics released in 2012, there are approximately 152,000 strokes in the UK5 and approximately 65,000 people experience their first transient ischaemic attack (TIA) each year. 6

Survival rates following stroke have improved significantly over the last 20 years because of medical advances in acute care and increased public awareness of stroke symptoms. However, owing to the decreasing levels of stroke mortality there is a significant rise in the number of people living with stroke-related disabilities.

In 2012, it was estimated that there are 1.2 million stroke survivors living in the UK. 5 Stroke represents the third most common cause of disability-adjusted life-years worldwide. 7–9 The disabilities experienced as a result of stroke are complex,10 potentially involving a multitude of physical and mental impairments, including difficulties as detailed in Box 1.

Arm and/or leg movement.

Balance.

Walking.

Swallowing.

Spasticity.

Cognition.

Depression.

Bowel control.

Performing personal activities of daily living (e.g. washing, bathing, dressing).

Pain.

Altered sensation.

Speaking.

Understanding the written or spoken word.

Urinary incontinence.

Vision.

Approximately 10% of patients are discharged from hospital directly to a long-term care facility,11,12 and 25% of stroke survivors require long-term institutional care as a result of the brain injury. 13 Clearly, clinically effective and cost-effective health technologies designed to ameliorate disability and improve quality of life for a growing population of older stroke survivors are needed.

Long-term care descriptors

In England, at the end of 2012 there were 4675 care homes with nursing facilities (218,387 beds) registered with the Care Quality Commission, and 12,917 residential care homes without nursing facilities (245,942 beds). 14 The distinction between homes that provide nursing care and those that offer only residential care is dependent on the skills of the care home staff, and not necessarily associated with the level of disability of the residents. Homes that provide nursing care employ qualified nurses, whereas homes that provide residential care are not required to employ qualified health professionals. It is estimated that between 20% and 45% of all people newly admitted to residential care settings in the UK have stroke-related disabilities. 11,15–17 The prevalence of stroke and dementia in the older population suggests a huge demand for long-term care facilities, and the provision of effective health-care technologies within those facilities, both now and in the future. 18

Health-care services within care home settings

Older people with complex health conditions are the main users of health and social care services. 19 From 1990 to 2010 in the UK there was a significant shift in long-term care for older adults away from geriatric hospitals, and more towards care homes. 20 Long-stay hospital wards benefit from established auditing systems which, prior to recent developments in social care provision, care homes did not. As a consequence, patients living in care homes have been described as ‘living on the margins of care’. 21 During this period there have been a number of initiatives, devised by government, in association with the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), that have introduced care standards to regulate, and improve, health care for the older population, and develop a more integrated service in care homes. 3,19,20,22–24

The National Service Framework for old age presented care standards with three themes: dignity in care; joined-up care; and healthy ageing – promoting exercise and activity, independence, well-being and choice. 19 The joined-up care theme outlined reforms to ensure a comprehensive health assessment is conducted prior to admission to a long-term residential facility, to establish individual health-care needs. 3 The National Service Framework listed standards for four main components central to the development of an integrated stroke service in older age: prevention, immediate care, early and continuing rehabilitation, and long-term support. 3,19

In addition to the National Service Framework, the RCP produced a series of guidelines to enhance the health of older adults in long-term care. 20 A component within these guidelines focused on ‘overcoming disability’ from a therapeutic perspective. 20 The guidelines highlighted the importance of the care home environment, and the use of aids, equipment and adaptations to address disability and improve function in long-term care facilities. The philosophy behind these guidelines was that small increases in functional capacity of older people are deemed to impact positively on quality of life and cost of care. 20 The section on ‘overcoming disability’ concentrates on providing access to resources to improve or maintain functioning in primary activities of daily living (ADL).

For the purposes of this trial, primary ADL are referred to as personal or self-care ADL. Personal ADL are defined as:

-

mobility

-

transfers (e.g. from bed to chair and back)

-

using the toilet

-

grooming

-

bathing

-

getting dressed

-

feeding.

These initiatives have instigated considerable progress in raising standards, increasing awareness of health-care issues in older age and lessening the long-standing stigma associated with this population. However, despite this progress, care services for older adults with high support needs, such as stroke survivors residing in care homes, are notoriously inconsistent, and most often dictated by financial constraints at a regional level. 25

More residents with a higher level of dependency and complex care needs are being admitted to care homes than ever before. 26 For residents with high levels of support needs, there is more of an emphasis on providing specialist care for a short period towards the end of life to ease suffering and promote dignity throughout. 16 It is critical to design health services with the needs, circumstances and preferences of the service users in mind. 19,27 Establishing an evidence base for clinically efficacious and cost-effective therapeutic health technologies, suitable for use by the NHS in care homes to promote dignity, joined-up care and increased independence is a research priority.

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy is the therapeutic intervention that promotes health by enhancing the individual’s skills, competence and satisfaction in daily occupations . . . to act on the environment and successfully adapt to its challenges.

Yerxa et al. 28 p. 6

Activity is essential to health and well-being. 29 In the re-drafted report published by the World Health Organization entitled International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF),30 the term ‘disability’ is described in reference to the interaction between an individual’s impairments, activity limitations, participation restrictions and their environment. This definition focuses on the individual’s capacity to engage in functional activity.

Occupational therapists aim to improve the quality of life of their patients by attempting to augment functional activity and increase their capacity to engage in personal ADL. 31 A philosophy of occupational therapy (OT) is that the intervention is most effective when it is integrated into the context of the individual. 31 OT typically applies a patient-centred goal-setting approach, so that the therapy package is individualised for each patient, and the goals of therapy are continually reviewed in relation to progress. 32 The treatment programme is planned around the patient’s goals. The patient is given as much autonomy as possible in maintaining or improving his or her own quality of life. Task-specific training, guidance and supervision is given to reinforce safe and effective practice of personal ADL. 33 Where necessary, training involves the use of adaptive equipment (e.g. adapted cutlery or walking aids) to facilitate an increase in capability, ameliorate activity limitations and provide therapeutic aid. Enabling modifications, tailored to individual needs, can be applied to the environment to promote safe and effective practice of ADL (e.g. the installation of bed levers, grab rails or a raised toilet seat). Particular attention is given to communication, to engender an informal atmosphere that will enable the exchange of ideas, and the offering of peer support. In summary:

Occupational therapy is a complex intervention. Practice includes skilled observation; the use of standardised and non-standardised assessments of the biological, psychiatric, social, and environmental determinants of health; clarification of the problem; formulation of individualised treatment goals; and the delivery of a set of individualised problem solving interventions. 34

Historically, OT services within the NHS have been situated in acute hospital services; however, nowadays therapists also operate as a part of local authority social care services throughout the UK. The ‘joined-up care’ initiative has helped instigate service reform to better suit the needs of users in the local community. 3,19 A review of the effectiveness of OT administered by local authority social services to older people at home has shown high satisfaction levels for the service. 34 It has also been suggested that the provision of adapted equipment to reduce dependency on additional services may be cost-effective. 35

Occupational therapy for stroke rehabilitation

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for stroke rehabilitation recommend that OT should be provided for people after stroke to help ameliorate difficulties with personal ADL. 36 The guidelines also stipulate that stroke survivors should be monitored regularly by occupational therapists with core competencies in this area. 36

Occupational therapy delivered to stroke survivors in their own homes has good evidence of benefit. 34,37 A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted by members of the research team to determine whether or not OT, focused on promoting increased activity and independence in performing personal ADL, improves recovery for stroke survivors. 34 Analysis of nine trials (1258 participants) found that OT increased personal ADL scores, measured using the Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living (BI). The standardised mean difference was 0.18 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.04 to 0.32; p = 0.01] in favour of OT, compared with receiving no intervention or usual care. This equates to a single-point difference (5%) on the BI (20-point scale). Furthermore, for every 100 people who received OT after a stroke, 11 (95% CI 7 to 30) would be spared a poor outcome, defined as death or deterioration in abilities to perform ADL [odds ratio (OR) 0.67, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.87; p = 0.003]. 34 The review concluded that targeted OT should be available to everyone who has had a stroke, to reduce disability and increase independence in performing personal ADL.

Although the systematic review concluded that OT is effective when administered in patients’ homes,34 the clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of OT administered to stroke survivors living in a care home setting was not known. Differentiating stroke survivors who live in their own homes from stroke survivors residing in care homes is important. Typically, stroke survivors living in care homes have increased physical and mental limitations as a result of their brain injury, and their functional capacity to perform personal ADL is often restricted. For instance, 78% of residents in a care home have cognitive impairment, 76% need some form of assistance with ambulation and 71% are incontinent. 17 Reduced functional capacity may limit stroke survivors’ ability to engage in, and respond to therapy. As a result, generalisation of results from community studies to care home settings should be treated with caution.

Occupational therapy for care home residents with stroke-related disabilities

In the Netherlands, 93% of care home residents regularly receive some form of OT;38 however, in the UK it is available to as few as 3–6% of residents. 39,40 An audit of over 1000 residents in England found that none had been assessed for OT. 41 The most recent stroke guidelines recommend reducing nationwide variability in rehabilitative care after stroke,42 including the care home setting. 43 Owing to the number of patients transferring directly from hospital to a care home environment following a stroke, as opposed to returning home,13,44 it is necessary for rehabilitation and social care services to achieve equivalent standards, especially for those patients with increased dependence.

Following admission to a care home, stroke survivors’ health state typically follows a downward trajectory. Observational data suggest that care home residents spend 97% of their daytime hours sitting inactive with eyes open or eyes closed. 45 Inactivity in older care home residents can pose further health risks, such as pressure ulcers, joint contractures, pain, incontinence and low mood. 46 The provision of OT as a means of augmenting levels of functional activity may reduce the likelihood of these further health conditions and reduce unnecessary dependence.

Current evidence evaluating the efficacy of OT across the whole care home population, not restricted to residents who have experienced a stroke, has shown conflicting results. 47,48–51 The evidence relating specifically to stroke survivors living in care homes is extremely limited. A systematic review considering the efficacy of providing OT to stroke survivors living in care homes was conducted by our research team. 52 Literature searches were performed within: MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, six trials registers and 10 additional bibliographic databases (all searches ended in September 2012). 52 The review process revealed only one relevant randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted to date; this was the OT intervention for residents with stroke living in UK Care Homes (OTCH) cluster randomised Phase II pilot trial discussed in full in Chapter 2. No firm conclusions of efficacy of OT provided to care home residents with stroke-related disabilities could be drawn from the systematic review. 52

Depression in stroke survivors residing in care homes

Symptoms of depression are common in older residents residing in care homes,53–57 and very common following stroke. 58 Experiences of depression following stroke may be directly attributable to the brain injury or an adverse psychological response to trauma. 58 Communication problems following stroke limit residents’ ability to express feelings of low mood and may be difficult to recognise by unqualified members of staff. 59 Presence of depression in care home residents is associated with poor outcomes and increased mortality. 57 Symptoms of depression include:

-

losing interest in everyday activities

-

finding it difficult to concentrate or make decisions

-

feeling worthless, guilty, helpless, hopeless or in despair

-

changes in appetite. 58

A previous study, assessing the feasibility of a trial evaluating the effectiveness of an OT programme at reducing levels of depression in a care home population, found no significant effects. 60 However, the trial was not powered to evaluate the efficacy of OT in alleviating in symptoms of depression. The OTCH trial sought to assess the influence of OT on levels of depression as a secondary outcome measure to the performance of personal ADL.

Assessing health-related quality of life in stroke survivors residing in care homes

A central philosophy underpinning OT is that the intervention involves engaging in activities that hold meaning for the individual. The personalised meaning behind the activities is thought to help promote increased quality of life for that individual. 31 Health-related quality of life (HRQoL), assessed according to a number of physical and emotional dimensions of interest,61 can be used to measure the perceived impact of a chronic disease. 62 The purpose of including a measure of HRQoL was to provide an additional multidimensional scale that considers both physical and emotional functioning to evaluate potential effects of the OT intervention not captured by the BI.

Training for care home staff

In the UK, the majority of care for older stroke survivors living in long-term care institutions is provided by the staff of those institutions. 63 During the OTCH Phase I stage, a number of care home staff in one area of the UK were interviewed. 41 From the staff responses, it was evident that none of the care homes was providing aids and appliances effective in reducing physical decline, that is there was a difference between policy and practice. It is therefore doubtful whether or not the RCP guidelines on ‘overcoming disability’ could be universally implementable across the UK. 20 The guidelines highlight the importance of the care home environment and the use of aids, equipment and adaptations to address disability and improve function in long-term care facilities. The results from the Phase I interviews were a strong indication that any development of health services in care homes needs to directly involve the staff who provide the majority of residents’ care.

A later report highlighted several aspects of staff involvement deemed fundamental in establishing a more positive culture in care homes. 64 It promoted the importance of staff training to move away from the prevalent model of task-based care system of doing things ‘for’ residents, and more towards a system with a shared commitment (‘doing with’) that includes emotional care. Consequently, the involvement of care home staff in the evaluation of OTCH was regarded as integral, in order to increase awareness of the broad spectrum of stroke-related disabilities and to provide continuity in care practices between staff and visiting therapists.

Aims and objectives of the Occupational Therapy intervention for residents with stroke living in UK Care Homes trial

Disabilities affecting ADL are commonplace for stroke survivors living in UK care homes, and yet access to rehabilitation services, particularly OT, is very restricted. The purpose of the study was to conduct a Phase III RCT to evaluate the effects of a targeted 3-month course of OT (with provision of adaptive equipment, minor environmental adaptations and staff education) for people with stroke sequelae living in care homes.

The primary outcome measure assessed was the capacity to perform personal ADL.

The secondary outcome measures assessed were mobility, depression and health-related quality of life.

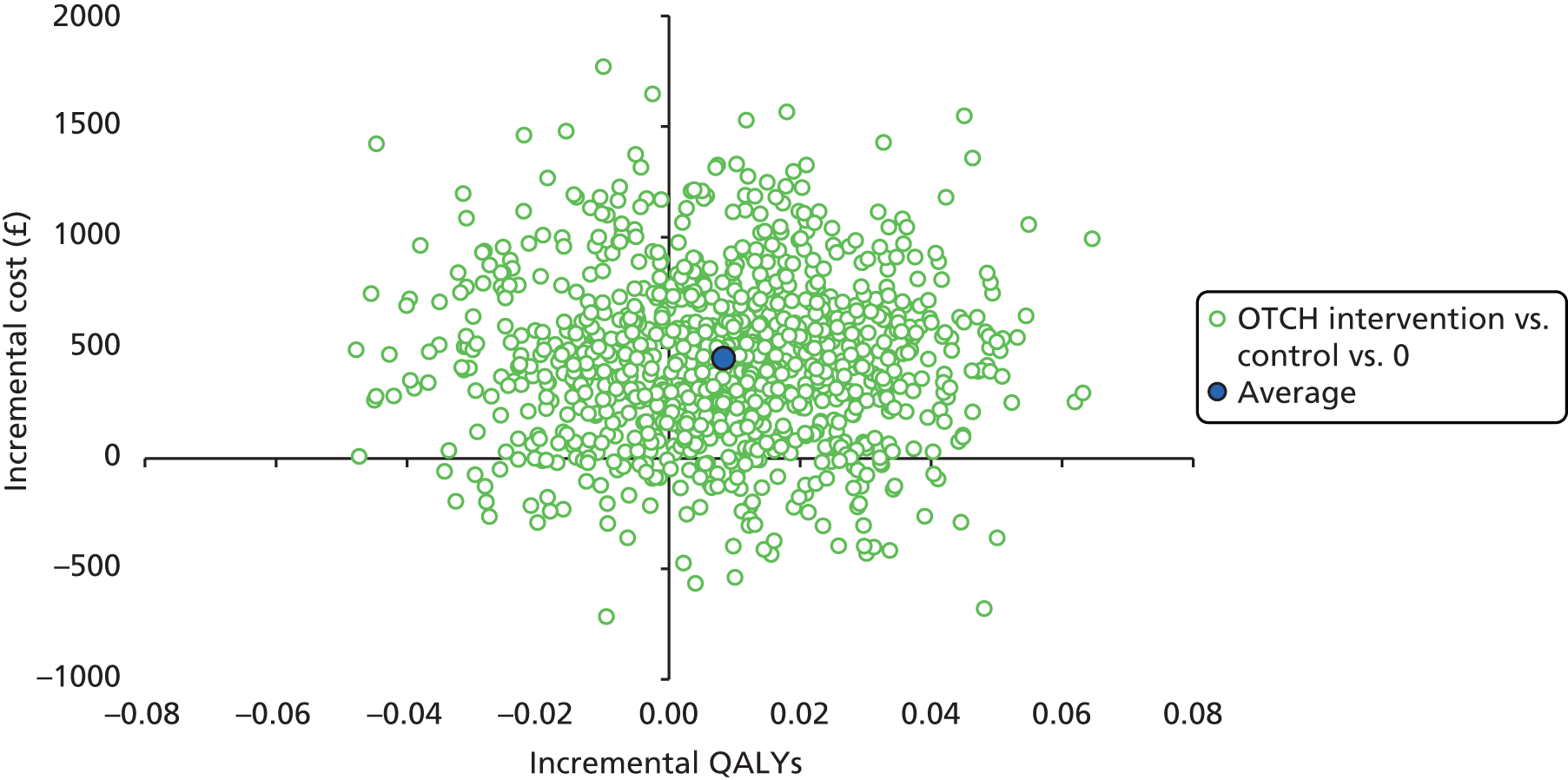

An economic evaluation of the intervention was conducted in parallel with the evaluation of clinical efficacy as part of the health technology assessment. Providing an OT service to stroke survivors resident in care homes was compared against usual care. The trial aimed to evaluate whether or not there is sufficient evidence to advocate the routine implementation of OT for all stroke survivors living in care homes.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The OTCH study was a Phase III, pragmatic, multisite, cluster RCT with economic evaluation, across several regions in England and Wales. The cluster design was justified because of the inclusion of an education component for care home staff and the potential need to apply minor modifications to the care home environment (e.g. install raised toilet seats). Furthermore, cluster randomisation at a care-home level reduced the potential for between-group data contamination during interaction between carers, therapists and residents. The flow diagram for this trial followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for cluster randomised trials. 65

Setting

Local care homes for older people in the UK were located in the following 12 trial administration centres (TACs):

-

University of Birmingham

-

Bangor University

-

University of Central Lancashire

-

University of Nottingham

-

Solent Healthcare Primary Care Trust (PCT)

-

Plymouth PCT

-

Wolverhampton PCT

-

Taunton PCT

-

Stoke-on-Trent PCT

-

Coventry & Warwickshire PCT

-

Bournemouth and Poole PCT

-

Dorset PCT.

Recruitment and consent

Care homes

Residential homes with and without nursing care with more than 10 beds, local to the 12 TACs, were identified from the Care Quality Commission website. Homes were identified randomly, to ensure a non-biased selection, using published care home lists. All funding models of care home were included (i.e. private, charitable, not for profit and local authority). Institutions for people with learning disabilities or drug addiction were excluded from the study. Homes were telephoned by a member of the research team and the trial was explained briefly. No homes were actively delivering OT as a component of standard care. A recruitment pack was mailed to interested homes. This included an invitation letter, a leaflet describing OT, study information sheets, designed in collaboration with service users, and a response form. Another telephone call was made to arrange a convenient time for the assessor to visit, and the homes were asked to consider which residents may be eligible. At the visit, the care home managers were given a full verbal explanation of the study and the opportunity to ask questions. If managers were interested in the study, they were asked to sign a written agreement for their home to participate. Following receipt of care home consent, residents were considered individually.

Residents

Care home managers assisted to identify potential participants. To be eligible for entry into the study potential participants were required to be resident in a care home and to have a history of stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) or TIA. The inclusion of residents with a history of TIA was warranted because of the growing evidence that TIA can cause long-term problems. 66,67 All efforts were made to include participants with communication and cognitive impairments to increase external validity of the trial as these symptoms are commonplace following stroke. Residents receiving end-of-life care were excluded. Care home members of staff searched residents’ files to determine a diagnosis of stroke or TIA. If required, the research team sought confirmation of this diagnosis with general practice records [see Appendix 1 for general practitioner (GP) correspondence details]. When a potential participant was identified as being eligible for the study they, and their family (when appropriate),68 were approached by the assessor or a senior member of the care home staff. Prospective participants (and their family) were given a full explanation of the study. This included a discussion of the treatment options in the trial and the method of treatment allocation. Potential participants (and family, if appropriate) were given an invitation pack consisting of an invitation letter, consent form and participant information sheet, designed in collaboration with service users (see Appendices 2–4 for participant information sheets and consent form). For eligible residents needing the assistance of a consultee (family member), a consultee package was mailed, which included a consultee invitation letter, consultee declaration form and consultee information sheet (see Appendices 5 and 6 for consultee information sheet and declaration form, respectively). Residents were given sufficient time to decide (at least 24 hours) whether or not they would like to join the study. A follow-up telephone call was made by the assessor to arrange a return visit to the care home.

Participants and consent

During a second visit to the care home the independent assessors obtained consent from all eligible residents who had indicated interest. If the resident was considered to be incapacitated, according to guidelines listed in the Mental Capacity Act 2005,68 a consultee was approached for consent. If the resident or consultee consented, the participant’s GP was informed in writing of their involvement in the trial. Following the consent procedure, baseline assessments were administered by the assessor. When all participating individuals in a home had completed baseline assessments, the care home was randomised. If a care home had at least one consenting resident, it was eligible for randomisation.

Randomisation, stratification and blinding

Care homes and participants were recruited and consented into the study before the randomisation process commenced to reduce bias. 69,70 Once the study co-ordinator received confirmation from assessors that all residents in a participating home had given their consent and completed a baseline assessment, the homes were grouped and randomised (1 : 1) to receive either the OT intervention or usual care (control). The allocation sequence was generated in software (nQuery Advisor version 7; Statistical Solutions, Saugus, MA, USA) by an independent statistician using blocked randomisation (block size 2) within strata [type of care home (with or without provision of nursing care)] and geographical location of the TAC at the Primary Care Clinical Research and Trials Unit, University of Birmingham, independent from the research team. Blocked randomisation was used to ensure groups were balanced with respect to the stratification variables. The details of the sequence were concealed from the research team, independent assessors and the study co-ordinator. Once the study co-ordinator received notification that all consenting participants in a care home had completed baseline measures and that the strata data had been logged, care homes were randomised. Care home allocation was revealed to the study co-ordinator, who then informed the care home manager and corresponding site therapist. If a care home had been allocated the OT intervention, the site occupational therapist then contacted the manager of the home to make arrangements for them to visit and commence the intervention. Treatment allocation was concealed from the independent assessors, but it was not possible to mask aspects of the intervention from staff or residents.

Procedure

The trial protocol is published elsewhere. 71

Control: usual care

Care homes in the control arm of the study continued to provide their usual care to residents. None of the participating homes provided OT as a component of routine care. After all the final outcome assessments had been conducted at 12 months, the care homes in the control arm were offered a 2-hour group training session for care home staff. The session was led by an occupational therapist and focused on promoting and supporting activity for care home residents after stroke. 72 It was based on the key principles of OT, such as the facilitation of independent daily living and promotion of activity among residents.

Occupational therapy intervention

We developed an OT intervention package for residents in a care home using evidence and expert occupational therapist consensus opinion, details of which are summarised below and presented in full in a previous publication. 73 The OT intervention was delivered by a qualified occupational therapist and/or an assistant, and it was targeted towards maintaining the stroke survivors’ capacity to engage in personal ADL, such as:

-

feeding

-

dressing

-

toileting

-

bathing

-

transferring

-

mobilising.

In order to promote external validity, the therapy a resident received was not dictated by the trial, but decided on by the therapy professional, in collaboration with the resident or consultee.

Patient-centred goal-setting

The OT intervention employed a patient-centred goal-setting approach to establish an individualised treatment plan for each participant. Goal-setting involves establishing mutually agreed targets between patient and therapist that will be aimed for over a specified duration of therapy. 42 In the initial assessment the therapist met with the participant (and/or carer/family member when appropriate) and recorded demographic details, current medication and discussed challenges experienced with daily activities (see Appendices 7–9). Together they agreed a treatment plan that was reviewed after each session. Two examples of the patient-centred goal-setting approach and treatment plan are presented in Table 1.

| Participant ID | Needs identified | Goals | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| *** | Maintenance of mobility | Check use of walking equipment | Checked ferrules |

| Improve body strength | Checked height of walking aid | ||

| Improve posture and balance | Encourage to mobilise | ||

| Exercises to improve strength and balance | |||

| Discussed armchair | |||

| Difficulties with transfers | Improve bed and toilet transfer technique | To try equipment to assist toilet transfers and bed transfers | |

| To try toilet seat equipment | |||

| Difficulties with personal care | To improve independence in personal care | To try use of perching stool | |

| *** | Difficulties with sit-to-stand transfers | Improve transfer technique | Assess dining room chair and armchair |

| Practice transfers | |||

| Slow, shuffling walking pattern | Improve walking pattern | Check shoes and walking stick | |

| Improve body strength and balance | Implement exercise regime | ||

| Reduce tightness of hamstrings | Advice on walking technique | ||

| Elevate feet on footstool to feel stretch on posterior thigh | |||

| Difficulties keeping food on plate during meal times | Facilitate feeding technique | Assess use of plate guard |

Intensity of occupational therapy (number of visits)

The frequency and duration of the OT was dependent on the resident’s and therapist’s agreed goals (within the framework of the home). In a study that piloted the intervention on a population of care home residents (not limited to stroke survivors), the number of face-to-face sessions ranged from 1 to 25 per resident over a 3-month period (median time 8.5 hours and mean time 4.7 hours), dependent on the individual needs of the resident. 73 The OT intervention included a continuous process of assessment, treatment and reassessment. 73 In line with current evidence on effective treatment, the intervention adopted a task-specific training approach. 33 Treatment logs were developed, and each occupational therapist was required to document the time spent and content of each individual therapy session. An example of the treatment log is given in Appendix 10.

Occupational therapy content

The content of therapy for the OTCH intervention was assigned to categories, and the time spent on each category was documented in the treatment log. Categories of therapy identified in the intervention design were listed as:73

-

assessment/reassessment and goal-setting – involving the assessment of a resident’s current levels of functional activity in personal ADL and mutually identifying functional goals of therapy

-

communication – including listening to residents’ concerns about personal ADL, providing information and guidance to residents, staff or relatives, initiating referrals to other agencies and ordering equipment

-

ADL training (cognitive and functional) – involving techniques to assist with feeding, bathing, using the toilet, getting dressed and grooming

-

transfers and mobility (cognitive and functional) – involving bed mobility, standing, walking and transfers to/from a chair

-

environment – involving environmental adaptations (e.g. adaptive equipment)

-

other – involving treating impairments directly, such as joint contracture.

Equipment provision

Adaptive equipment was provided as part of the study, which included personal items such as adapted cutlery and walking aids. If required, adaptations to the individual’s environment were made, such as provision of chair raisers, bed levers, raised toilet seats or grab rails. The occupational therapist demonstrated to the participant, and care staff, how to use adaptive equipment effectively, while adhering to safety regulations.

Examples of the type of such equipment are listed below:20

-

mobility: wheelchair, walking stick or walking frame

-

transfers: chairs/beds – correct height to suit different needs

-

toilet aids: includes raised seats and rails

-

bathing: grab rails, bath board, specialist baths and showers

-

getting dressed: dressing aids and clothing adaptations

-

washing: adapted taps

-

eating: adapted cutlery.

Involvement of care home staff

The implementation of the intervention required direct involvement of the care home staff to continue therapy practices, and use of adaptive equipment initiated during treatment visits. Therapists wrote in participants’ care plan after each visit. The care plans summarised the therapist’s assessment of the participant and provided recommendations for the staff to implement in order to maximise participants’ levels of functional activity. Examples of care plans left for care home staff are given in Table 2. The care home manager was continually updated on the progress of the intervention, and the research team adapted therapy visits around care home routines (e.g. meal times and leisure activities).

| Participant ID | Activity |

|---|---|

| *** | Mobility |

| Following walking practice over the last few weeks, and provision of a three-wheeled walker by the physiotherapist, Mr x is able to walk to the dining room from his bedroom, as his pain allows | |

| Recommendation: please continue to provide opportunities for Mr x to walk rather than use the wheelchair | |

| Transfers | |

| Mr x is able to manage all his transfers independently, as long as his pain is under control, including sitting up in bed and moving his legs round to the floor, standing from the bed (can be unsteady so supervision needed), standing from a chair, sitting on a chair and getting on and off the toilet | |

| Recommendation: please continue to offer verbal support rather than physical support as much as possible to facilitate Mr x’s transfers | |

| Personal care | |

| When provided with a bowl of soapy water and a flannel, Mr x is able to wash his upper body mainly independently, needing help with his back, bottom, legs and feet. He currently has help shaving, but may be able to manage this himself if provided with a shaving mirror | |

| Mr x is able to take off his nightwear independently with prompting. He is able to put on a vest and shirt by himself. He can manage some buttons himself, but needs some help with this. Mr x can dress in pants and trousers with minimal help to get these past his heels. He needs full assistance to put his socks and shoes on. Mr x is able to put his cardigan on with minimal help | |

| Recommendation: please continue to maximise Mr x’s participation in his personal care by providing verbal prompts and encouragement rather than physical help as much as possible | |

| *** | Eating/drinking |

| Mr x is able to eat and drink independently when positioned correctly in his bed, and with his table positioned to give him best access to his food. The Nursing sister and a member of care staff have been shown how best to position Mr x for eating/drinking | |

| Recommendation: please ensure Mr x is always positioned correctly and his food placed within reach to maximise his independence with eating and drinking | |

| Personal care | |

| Mr x is able to wash his face when provided with a cloth, prompting and encouragement | |

| Recommendation: please continue to enable Mr x to wash his face independently by providing a cloth, verbal prompts and encouragement rather than physical help as much as possible | |

| *** | Personal care |

| When provided with a bowl of soapy water and a cloth, Mrs x is able to wash her face and upper body mainly independently, needing help with her back, bottom, legs and feet | |

| Recommendation: please continue to maximise Mrs x’s participation in her personal care by providing verbal prompts and encouragement rather than physical help as much as possible | |

| Eating | |

| Mrs x has been provided with a ‘Knork’ fork to enable her to cut up food independently | |

| Recommendation: please ensure Mrs x has her adapted cutlery at meal times | |

| *** | Personal care |

| The occupational therapist assessment observed that Mrs x is able to participate in washing her face and top half, needing some help because of her right-side weakness. The occupational therapist supplied a suction cup denture brush to enable Mrs x to brush her dentures independently using one hand. Mrs x likes to have some buttons left undone on her cardigan, so she can spend time over the day doing them up herself | |

| Recommendation: please ensure Mrs x is always given time and opportunity to participate as much as possible in her personal care routine. A member of care staff at time of assessment gave excellent support, enabling Mrs x to do as much for herself as possible. Please ensure the denture brush is stuck to the wash basin so that Mrs x can access it easily to clean her dentures | |

| Seating/positioning | |

| Mrs x sits in a reclining chair. She is not currently adequately supported in a good seating position by this chair, which may be contributing to the high tone in her right leg, as she is having to try to hold herself up on her weak side. Mrs x does not want to try using pillows for support in her chair, but is willing to be assessed for more suitable seating | |

| Recommendation: Mrs x would benefit from assessment for specialist seating, to maximise her comfort and ability to function and minimise the risk of increased tone/contractures | |

| *** | Mobility |

| Mrs x has good movement in her legs, and is able to weight bear enough to use a standing hoist. She is keen to try walking again. As she has not walked for many months, however, this may or may not be possible | |

| Recommendation: Mrs x may benefit from a referral to community physiotherapists for a full assessment with a view to a period of rehabilitation | |

| Personal care | |

| When provided with a bowl of soapy water and a cloth, Mrs x is able to wash her face and upper body mainly independently, needing help with her back, bottom and legs and feet | |

| Recommendation: please continue to maximise Mrs x’s participation in her personal care by providing verbal prompts and encouragement rather than physical help as much as possible |

Training for care home staff

Providing regular staff development exercises in long-term care facilities is recommended within RCP guidelines. 20 A specific training workshop was provided to staff directly involved in the care of the residents receiving the OT intervention. 72 The workshop aimed to increase awareness of stroke, and the range of stroke-related disabilities residents may experience. Risks associated with inactivity were highlighted as well as describing the carer’s role in:

-

supporting mobility (e.g. safe and effective methods of transfer)

-

preventing accumulative problems from poor positioning (e.g. unsuitable armchairs)

-

facilitating resident participation in self-care activities. 72

The workshop promoted strategies for staff to improve residents’ capacity in performing personal ADL. A key message in the workshop was to encourage residents’ functional activity, and to create a suitable enabling environment to achieve maximum independence in performing personal ADL. It was expected that inviting care home staff to engage in further training would facilitate compliance and reduce loss to follow-up. A copy of the training workbook appears in Appendix 11. The training given to care home staff received UK Stroke Forum Education and Training endorsement. Training for staff allocated to the control arm was offered following completion of the 12-month follow-up assessments.

Quality assurance

Training of site assessors and occupational therapists

When a TAC initiated work on the trial, it received a trial set-up visit from a senior member of the research team and a trial occupational therapist. A full explanation of the study protocol was given to the trial assessors and occupational therapists. Details of the information passed on to the regional therapists during training are contained in Appendix 12. The assessors were provided with training on the trial paperwork and assessments. Completed examples of the paperwork were provided, including instructions on coding for missing data. The occupational therapists received training on completing the OT-specific paperwork, and the process of ordering specific therapy equipment.

Site monitoring and communication

Site recruitment rates were monitored, and the data uploaded onto the centralised trial database were reviewed when a home was ready for randomisation. If inadequate data had been entered, the TAC was contacted and asked to collect and enter the missing data. The process of randomisation was delayed if the site had missing data to upload.

Any amendments to the study protocol or processes were communicated directly to the sites after ethical approval was received. Acknowledgement was sought to clarify that research staff comprehended the amendments. Members of the research team were invited to attend study meetings, which were specific to their role in the study (e.g. assessors and occupational therapists). This provided an opportunity to discuss general challenges occurring in the study and clarify the trial protocol in relation to site-specific cases.

Compliance

Compliance was estimated by the number of intervention sessions recorded in the OT treatment logs (see Appendix 10), which also described the focus and content of each therapy session.

Outcome assessments

Assessment schedule

An overview of the assessment schedule is given in Table 3. A description of each of the assessment measures is listed in Appendix 13. Baseline assessments were conducted prior to randomisation to reduce possible recruitment bias. 69 The primary measurement end point was 3 months after randomisation. Additional assessments were conducted at 6 and 12 months after randomisation. Data were collected from participants where they were currently residing. If a participant moved to another home between assessments, then every attempt was made by the assessors to collect follow-up data from the participant. To maximise efficiency in data collection and reduce potential disruption to the care home’s daily routine, assessors visited a particular care home and tried to complete all follow-up assessments for participating residents in a single day. If a participant was unwell, in hospital or unavailable on the day of the assessment, the assessor returned to the care home within a 4-week window. Efforts were made for all participants to complete the primary outcome measure at each time point. However, if it was foreseen that participants would be unavailable, a proxy response was obtained from a member of the care home staff.

| Assessment | Time of administration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |

| Demographics | ✓ | |||

| Sheffield Screening Testa | ✓ | |||

| Mini-Mental State Examination | ✓ | |||

| BI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| RMI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Geriatric Depression Scale-15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EQ-5D-3L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Resource use log | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Adverse event log | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Demographic data and screening measures

An assessor collected demographic data directly from the participant or consultee, which included age, sex, ethnicity, comorbidities, history of falls and intake of current medication. A member of staff from the care home provided initial information about the participant’s stroke, such as the date, type and location of stroke. If this information was unavailable at the care home or additional clarification was required, the participant’s general practitioner was contacted to obtain the data. At baseline, the assessor administered the Sheffield screening test for acquired language disorders to assess receptive/expressive aphasia74 and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to assess cognitive function. 75 These assessments were not used to exclude individuals. The tests provided an indication of the participant’s capacity to understand instructions and directly engage in therapy. The screening tests also informed the research team if consultee assistance was required during recruitment.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the BI,76–78 which is regarded as the gold standard measure for assessing functional capacity in rehabilitation outcomes. 20,36,79 It is commonly used to assess stroke survivors. 80,81 The BI measures specific aspects of self-care targeted by the therapy, such as transfers (e.g. from bed to chair) and grooming, and how much help people need in completing personal ADL. 79 Furthermore, the BI was used in previous studies assessing the efficacy of OT, and the data from our study are suitable to be incorporated into meta-analyses. 34,48,49 For pragmatic reasons, we chose to use the shortened BI scale between 0 and 20. 77 A higher score signifies that a person has more independence in ADL. A 2-point change in score is widely accepted as having clinical meaning. 82 It equates to a change that is perceived by stroke survivors and clinicians as a step change in function. For example, a patient may change from being unable to dress and feed to being able to manage with some help or from being able to manage the toilet with some help to being able to manage alone.

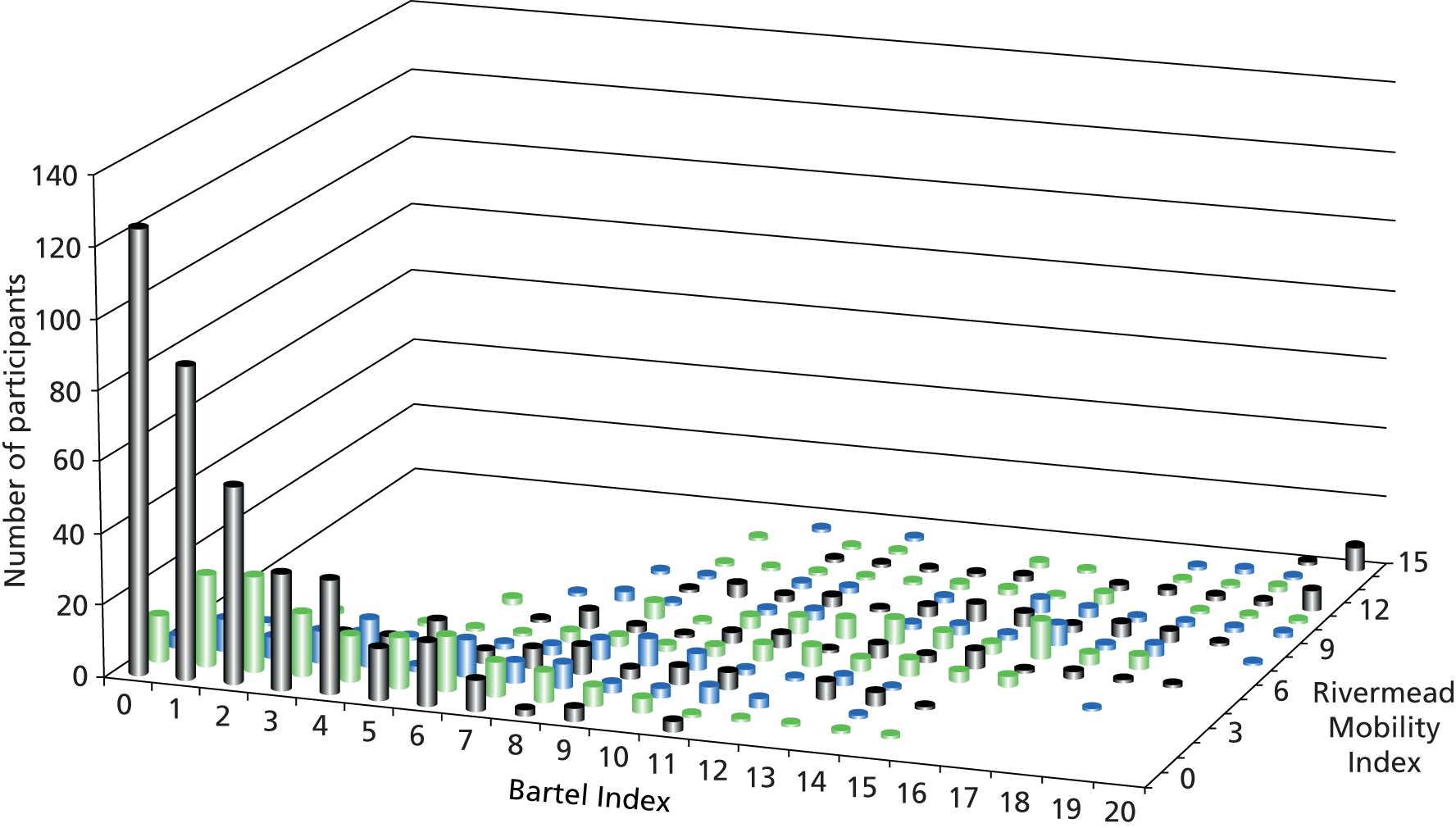

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures assessed mobility, mood and HRQoL. The HRQoL measure [European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, three levels (EQ-5D-3L)] is discussed in Chapter 4, Measuring outcomes. Mobility was assessed with the Rivermead Mobility Index (RMI),83 a 15-item measure of functional mobility. It is scored from 0 to 15 and a higher score denotes better mobility. It was deemed important to assess the RMI alongside the BI to increase responsiveness to change. 79 According to previous research that assessed the sensitivity of the RMI and BI in capturing change,79 both tests measure similar constructs but have the potential for floor and ceiling effects. The BI is geared more towards assessing global function, but the RMI relates specifically to mobility. The RMI is regarded as a more sensitive measure than the BI, but has the potential for floor effects (i.e. high percentage of scores at the low end of the scale). The BI, on the other hand, has the potential to give rise to ceiling effects (i.e. high percentage of scores at the top end of the scale). 79 Attempting to maximise responsiveness to change was a critical issue in the evaluation of the OTCH intervention because small increases in functional capacity of older people are deemed to impact positively on quality of life and cost of care. 20

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was administered to measure mood. 84 One point is assigned to each answer in accordance with the mark scheme. A higher score denotes more severe depression. The full 30-item version was initially administered with participants. 84 If residents were unable to self-complete or follow the interview process, the consultee version, which consisted of 15 items, was completed. 85 However, during the study it was decided to replace the full 30-item GDS with the shortened 15-item GDS,85 to reduce the burden on the residents and assessors. The protocol amendment occurred in 2010.

Adverse events

An adverse event was defined as an injury attributable to the intervention requiring a visit to a hospital or GP. A risk assessment found that there was a small increased risk of falling as a result of the OT intervention (e.g. because of an increase in use of ambulatory aids). This small increased risk was stated clearly in the participant information sheet. Every effort was made to minimise the risk of falls throughout the treatment of the participant and by training the care home members of staff (see Appendix 14 for the adverse event reporting form).

Sample size

A change of 2 points on the BI is widely accepted as being clinically meaningful. 82 In order to detect a difference of this magnitude between the treatment arms, a sample of 72 participants in each arm was required, based on an estimate of standard deviation (SD) of 3.7 points,47,48,49 90% power and 5% significance level. However, residents in this trial were cluster randomised by care home and, therefore, the sample size was inflated by a factor of 4.6, resulting in an increase to 330 residents per randomisation arm. This design factor was based on an estimate of intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.4 and an average of 10 residents per care home observed in previous research. 48,49 The ICC used in the sample size calculation was estimated from data related to several pilot studies from a single site with relatively small numbers of care homes. A larger estimate of ICC was used than the ICC observed during the OTCH pilot trial in the interest ensuring an adequately powered study. 48 Based on the attrition rate of 26% from the OTCH pilot study,48 it was estimated that 45 homes with 10 residents per home would be required in each arm of the study (900 residents in total) to detect a clinically meaningful difference using the BI. The sample size quoted in the original proposal was estimated at 840 residents from 84 care homes; however, this sample size was initially incorrectly inflated for expected attrition (26%). The correct figure should have been 900 residents from 90 homes. The revised estimate was identified at the start of the trial.

Occupational Therapy intervention for residents with stroke living in UK Care Homes pilot study

A pilot study of the OT intervention for residents in care homes with stroke-related disabilities was conducted in Oxfordshire, UK, and published prior to the trial. 48 The pilot study was undertaken to refine trial procedures and ensure the OT intervention was acceptable to residents and deliverable in the intended format. The design was a cluster RCT with the unit of randomisation trial at the care home level. Twelve homes (118 residents) were randomly allocated to either the OT intervention (six homes, 63 residents) or control (six homes, 55 residents). The control group received usual care. Usual care did not include OT. In the intervention group, a 3-month course of individualised one-to-one OT was provided to residents with stroke-related disabilities. The aim of the therapy was to maintain levels of functional activity in self-care tasks, adapt the physical environment (when necessary) and address specific impairments that limit performance in ADL or cause discomfort.

In addition, the OT intervention included training for care home staff directly involved in the care of the residents. Assessments were made at baseline and at 3-month (immediately following the intervention) and at 6-month follow-up. The measures used were the BI and RMI. The trial indicated a potential for the OT intervention to have detectable and lasting effects on morbidity. From baseline to the primary end point at 3 months the mean BI score increased by 0.6 points (SD 3.9 points) in the OT arm, but decreased by 0.9 points (SD 2.2 points) in the control arm. The mean difference between the groups was 1.5 points (95% CI –0.5 to 3.5 points, allowing for cluster design). The between-group difference in BI score was maintained at 6 months (difference of 1.9 points, 95% CI –0.7 to 4.4 points).

The analysis of the data suggested that OT may have a significant influence on maintaining functional independence in personal ADL for residents living with stroke-related disabilities within care homes. However, the analysis was exploratory because of its small sample size. The pilot study demonstrated feasibility of the research design. The method was practical and provided the relevant information to conduct a formal sample size calculation for a subsequent suitably powered definitive trial.

Data management

All pre- and post-randomisation data were initially captured by a blinded assessor on paper forms. The data were then entered manually onto the purposefully designed trial database system, which was located in the Primary Care Clinical Research and Trials Unit at the University of Birmingham. The data entry application server was accessible over the internet via secure remote access. All traffic through the data entry application to the database was automatically encrypted using 128-bit secure sockets layer. The database was only accessible from within the University of Birmingham’s information technology network. Only senior members of the research team had access to the database. The firewall for the database was configured to allow access from specific machines only. The data entry application and database used role-based security controls, which restricted access to parts of the data (i.e. uploading, editing and viewing). The data entry application forms were designed and set up by a data manager and computer programmers in collaboration with members of the research team.

Queries about data completeness were referred by the study statistician to the trial co-ordinator. Any missing data that needed to be clarified were obtained by telephone call with the participant or a care home member of staff. Completed questionnaires were entered onto the trial’s secure database by the assessor or a member of the research team. If changes were required on the paper questionnaires, they were formally documented and subsequently uploaded onto the database. The baseline and follow-up data were validated continuously throughout the trial for correctness and completeness. Furthermore, computerised validation checks were incorporated to minimise errors in the data sets (i.e. ranges, limitations and categorisation). Interim summary reports were generated for the Data Monitoring Committee.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted according to a pre-specified statistical analysis plan. 71

Recruitment

Recruitment rates and cluster size were analysed according to the stratification variables of type of care home (nursing or residential) and geographical location (TAC).

Analysis of baseline assessments

Baseline characteristics of participants were tabulated by treatment arm. Items included demographic details, including age, ethnicity and comorbidities. In addition, the screening measures assessing cognitive function and language impairment were summarised to gauge mean levels of stroke-affected disabilities between treatment arms.

Intention to treat

All analyses were performed using an intention-to-treat approach. All participants, including those who died, withdrew or were lost to follow-up, were analysed according to the intervention to which they were randomised, regardless of whether or not they complied with treatment. Participants who moved care homes during the course of the trial were analysed by the home to which they were originally randomised.

Statistical analysis was carried out using Proc Mixed and Proc Glimmix in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Multiple imputation was performed using the ICE command in Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Primary analysis

Outcome measures were compared at the level of the participant. The primary outcome was the BI score at the 3-month follow-up (immediately after the intervention). Linear mixed model analysis with identity link was used to compare the BI between the two arms. The analysis was adjusted for care home (as a random effect), baseline BI score and stratification factors [TAC (geographical location) and type of care home (nursing or residential)]. It was expected that there would be a significant number of deaths in this study during the follow-up phase; therefore, it was agreed, a priori, that participants who died before their follow-up date would be given a BI score of zero at all subsequent follow-ups. This approach was discussed at Trial Steering Committee (TSC) meetings and agreed by the independent Data Monitoring Committee. A Barthel score of zero represents complete dependency, which was thought to reflect the participant’s health state if they had been alive. This method of analysis has been used previously in a stroke population. 86 The influence this may have on the results was examined via a complete case analysis that did not impute BI scores for participants that died.

In addition, participants were categorised into three outcome groups based on an individual’s change in BI score at 3 months from baseline (below 0 or death, ‘poor’; 0 to 1, ‘moderate’; 2 and above, ‘good’) for a BI composite analysis. A non-linear mixed-effects model with cumulative logit link was used to compare this ordinal outcome between the groups. Adjustments were made for care home as a random effect, and TAC and type of care home as fixed effects.

Secondary analysis

Secondary outcomes: RMI (mobility), GDS (mood) and EQ-5D-3L (HRQoL) measures were compared at the participant level at the 3-month follow-up using mixed modelling with identity link. Adjustments were made by care home as a random effect and baseline score, with type of care home and TAC as fixed effects.

To examine whether or not there was an effect of the intervention on outcomes over the longer term, treatments were compared using a repeated measures mixed model across all 3-, 6- and 12-month time points.

For the continuous measures, adjusted mean differences between the treatment arms are reported with corresponding 95% CIs. Positive mean differences favour the intervention. Results for the categorical outcomes are presented as ORs with 95% CIs when an OR > 1 favours the intervention.

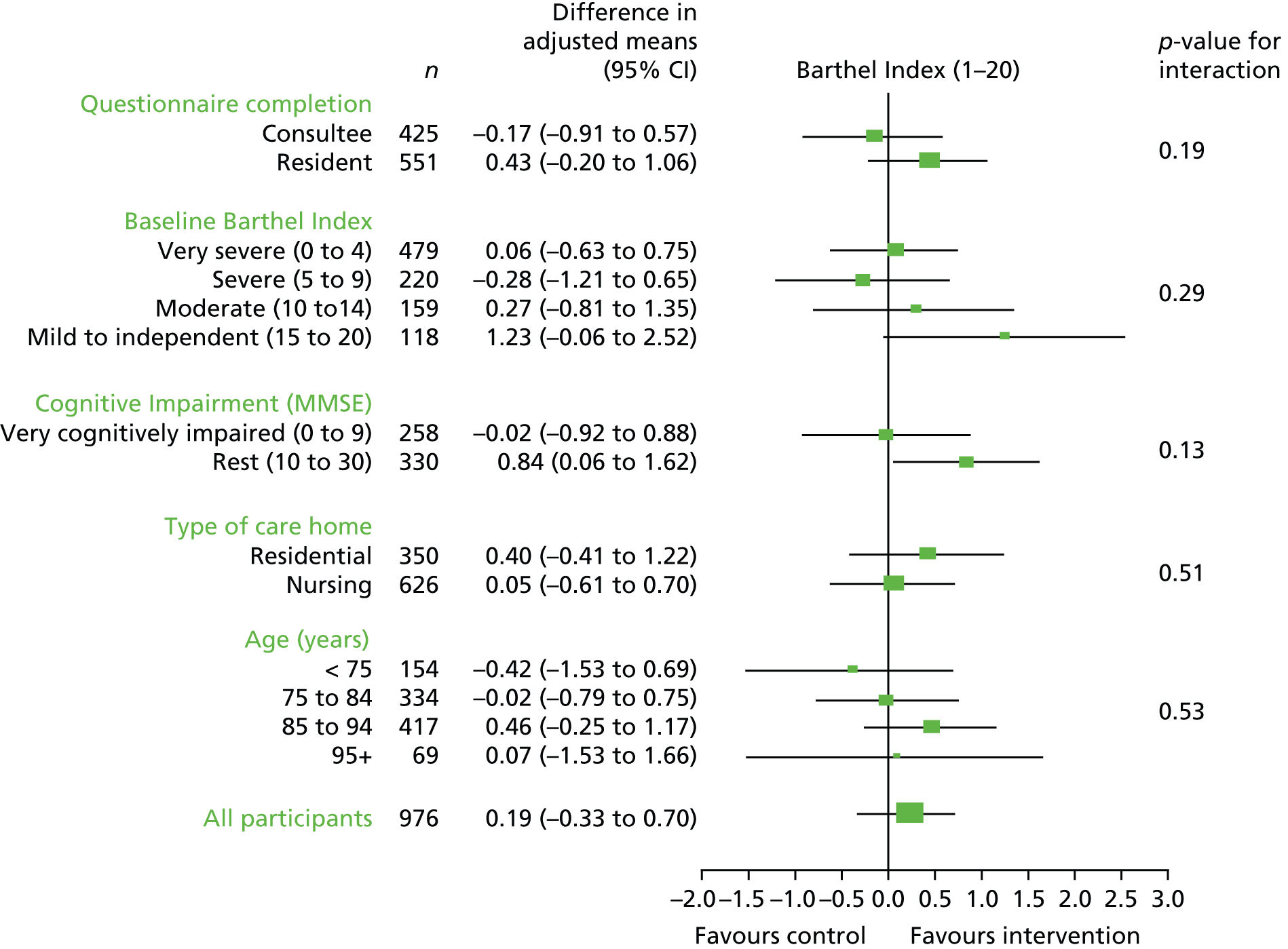

Subgroup analysis

Exploratory subgroup analyses were performed to further evaluate whether or not the effect of the OT intervention on BI differed by participants’ age, the type of care home in which participants’ resided, the severity rating of participants’ BI scores, the level of cognitive impairment (derived from the MMSE screening measure), and whether or not the measures were completed by the participant or a consultee. The subgroups were evaluated by the inclusion of covariate by treatment interactions in the mixed modelling.

Sensitivity analysis

Several sensitivity analyses were carried out to test the robustness of the conclusions.

-

Statistical methodology: to test the validity of the mixed modelling approach when many clusters had only one or two participants, the primary and secondary analyses were repeated excluding clusters with fewer than three participants.

-

Ceiling effects: to test the potential ceiling effect of the BI, participants with a baseline score of 18 or above were excluded from the primary analysis.

-

Missing Barthel data because of death: the primary analysis was repeated without imputing missing BI data following the death of a participant (complete case analysis).

-

Missing data: the effects of missing data were examined using various imputation methods including: best case (last observation carried forward); worst case (zero) and multiple imputation methods. Missing Barthel data following death were imputed with zeros for all imputation methods.

Intracluster correlation coefficient

The ICCs were calculated to quantify the effect of clustering, which arose from the care home effects in the primary outcome. The smaller the ICC, the less effect the clustering had on the precision of parameter estimates.

Falls

The proportion of falls in each treatment group during the first 3 months of the trial were compared using generalised mixed modelling with logit link. The number of falls in each treatment group that occurred in this period were compared using a negative binomial model. This method was chosen rather than a Poisson model because of the over dispersion of the falls data. Adjustments were made for care home, TAC and type of care home as previously described.

Ethical approval

Potential risks/benefits

The intervention itself was not experimental. OT is readily available for stroke survivors and their families in other settings. The intervention has been demonstrated by meta-analysis to be of benefit to stroke survivors and their families in these settings. 34,37 However, OT is not readily available in a care setting, and the efficacy and cost-effectiveness have not been assessed in long-term care. 40 Very few adverse events have been recorded through OT interventions. It is possible that walking aids can have a manufacturing fault, but this risk was carefully monitored and publicised. None of the aids or equipment used in this study was experimental. All equipment was in routine use throughout the NHS and social care services. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service, Coventry Research Ethics Committee (Reference 09/H1210/88) in October 2009.

Trial registration

This trial was registered as ISRCTN00757750 on 21 October 2009.

Governance

A TSC was established to monitor the governance of the study. The Trial Steering Group comprised the main research team, an independent chairperson, a geriatrician, an occupational therapist, a physiotherapist with expertise in rehabilitation research, a patient representative and a representative from the NIHR. A Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) was also established. This committee was independent of the trial and monitored accrued data at regular intervals to assess ethical, safety and data integrity aspects of the trial. The DMEC consisted of an independent geriatrician as chair, a statistician and an occupational therapist.

Amendments to the study protocol during the trial

The first substantial amendment was submitted on 15 March 2010 to approve changes to (1) the protocol to clarify the recruitment and randomisation process, the statistical analysis and the TACs and (2) the demographic front sheet, MMSE, OTCH resource usage form and the care home invitation letter. Furthermore, the substantial amendment included the addition of the OT treatment log, adverse events reporting form, OT leaflet and consultee Geriatric Depression Scale-15 items (GDS-15) to the study. The first substantial amendment was approved 23 March 2010.

A second substantial amendment was approved on 21 October 2010. This amendment included (1) a clarification of the consultee’s responsibilities and duties in the declaration process; (2) an update of the consent form and participant information sheet with grammatical changes for clarity; (3) a redesign of the resource usage questionnaire to capture the OT data after the 12-month follow-up assessment to ensure assessors remained blinded; (4) new paperwork including a GP letter notifying them that their patient was randomised to the control arm of the study; and (5) care home letters notifying them of the randomisation outcome.

On 17 August 2011, a third substantial amendment was approved and included (1) changes to the participant and consultee information sheets to provide more information regarding the security of the trial’s database; (2) a new covering letter and form to the participant’s GP to ask for confirmation of their patient’s diagnosis; and (3) shortening the GDS from the 30-item version to 15-item version to reduce the burden on participants and assessors, and to bring the questionnaire in line with the consultee GDS. A further minor amendment was submitted to revise the consent and declaration forms for version control, which was approved on 22 August 2011.

A final substantial amendment was approved on 26 July 2013 that confirmed the transfer in sponsorship of the OTCH trial from the University of Birmingham to the University of East Anglia.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was an integral part of the OTCH trial. Patients and carers were directly involved as research ‘partners’ and not just as ‘data providers’ (using the INVOLVE guidance; see www.invo.org.uk). A representative from the local stroke community was involved in the study design, listed as a co-applicant on the funding submission, recruited as a member of the TSC and is a co-author of this report. An additional stroke survivor was recruited onto the TSC which convened regularly throughout the course of the trial. Service users (and carers) were directly involved in developing the written material contained in the study protocol and participant information sheets. All support for patient and carer involvement was provided by the Stroke Research Network members. The Stroke Research Network team had expertise in training and supporting service users (and carers) for involvement in NHS, service evaluation and development. A wider patient/carer audience was consulted about the findings and recommendations drawn from the project. This occurred at meetings convened by West Midlands Stroke Research Network, The Stroke Association and Different Strokes.

Chapter 3 Results

The results are summarised, below, in Box 2.

Participating care homes were randomised equally to the two treatment arms (114 in each). The number of participants randomised to the intervention arm was larger than that randomised to the control arm, resulting in 568 residents randomised to the OT group and 474 to the control group. The two groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics. The majority of participants recruited were resident in nursing homes (64%). Over 70% of participants were rated as severe or very severe on the BI (primary measure) at baseline.

Primary outcomeAmong surviving participants, similar rates of completion of the BI were observed in each randomisation arm. Overall, 94% of survivors completed the primary outcome measure at 3 months, 94% at 6 months and 88% at 12 months. No significant differences were found in the primary outcome at 3 months. The 95% CI did not contain the clinically important difference of 2 units. The OR for the Barthel composite outcome, which took account of the change in Barthel score from baseline to 3 months, was 0.96. The OR CI at the 95% level crossed the null (0.70 to 1.33). No between-group differences were observed at later end points.

Sensitivity analysisExclusion of scores above 18 or clusters with fewer than three residents did not alter the results. Imputation of missing Barthel scores using three methods (best case, worst case and multiple imputation) did not change the conclusions. None of the exploratory subgroup analyses indicated a significant effect of treatment.

Secondary outcomesNo significant influences of the intervention were found on measures of mobility, depression or HRQoL at any of the follow-up time points.

Adverse eventsNo adverse events attributable to the intervention were reported.

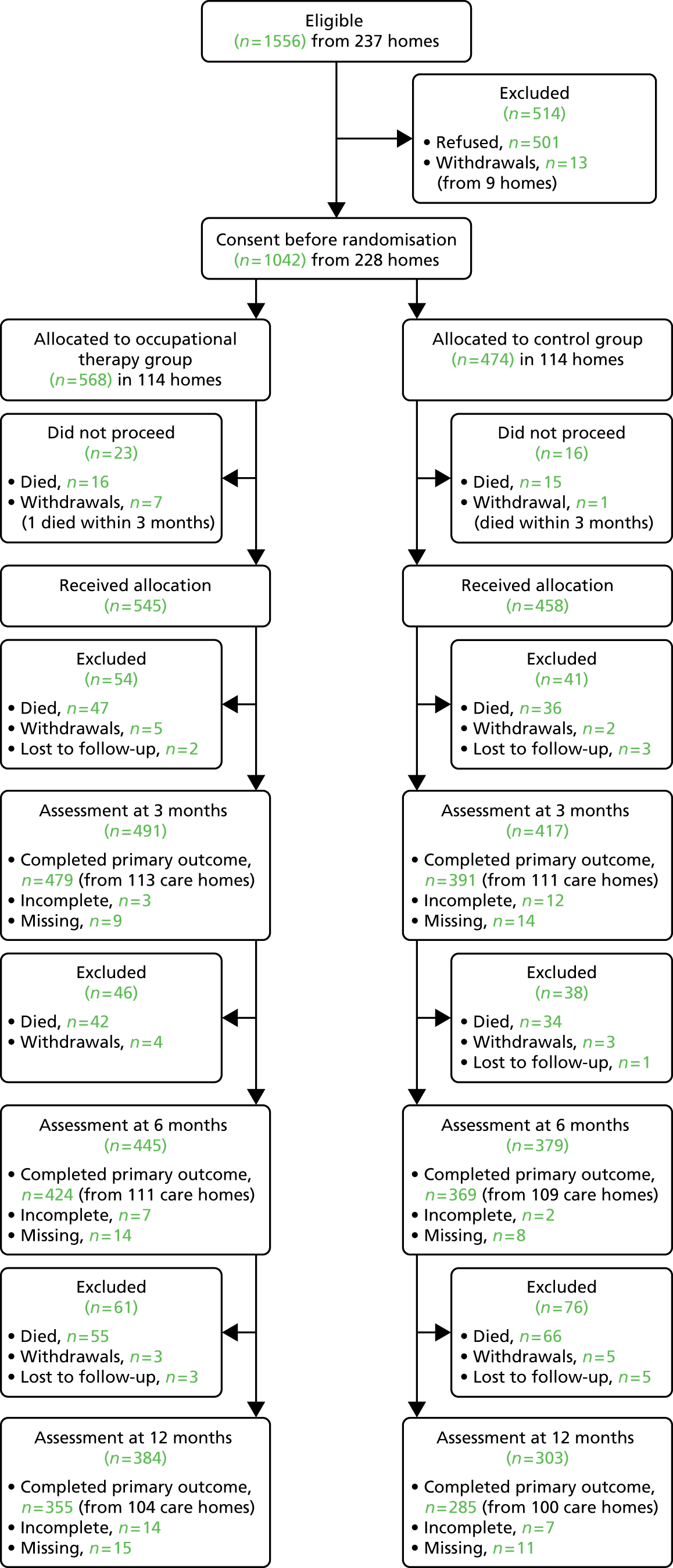

RetentionParticipant retention was good. Among the participants alive at 12 months, 355 out of 407 (87%) in the intervention arm had completed the BI and 285 out of 322 (89%) in the control arm had done so. Lost-to-follow-up data are presented in the CONSORT diagram (see Figure 1). A total of 313 (30%) participants died during the 12-month duration (161 from the intervention arm and 152 from the control arm).

FallsA significantly higher (adjusted) fall rate per resident was reported in the intervention arm (rate ratio 1.74, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.77; p = 0.02). The odds of residents experiencing a fall were not significant between groups at the 0.05 level (OR = 1.55, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.53; p = 0.07).

Sample sizeThe sample size calculation was based on an ICC of 0.4. The unadjusted ICC for the BI in this trial was 0.36 at baseline; however, for BI at 3 months, allowing for the effect of baseline BI score, treatment arm, location and type of care home, the ICC reduced to 0.09.

Randomisation

Participating care homes were randomised between 4 May 2010 and 28 February 2012. Participants were followed up at 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation.

Recruitment at a cluster level according to stratification factors: geographical location and type of care home

Twelve TACs across England and Wales were involved (with locations at the University of Birmingham, Coventry PCT, Dorset PCT, Wolverhampton PCT, University of Central Lancashire, University of Nottingham, Solent Healthcare PCT, Bournemouth and Poole PCT, Stoke-on-Trent PCT, Taunton PCT, Bangor University and Plymouth PCT).

The distribution of care homes according to the geographical location of the TACs is shown in Table 4. A total of 237 care homes gave consent. The average number of beds in consenting homes was 42 (SD 18.6 beds). Nine homes did not continue to the randomisation stage:

-

One TAC, involving four homes, withdrew prior to randomisation because of administrative problems. As a result, 11 TACs proceeded to the randomisation phase.

-

Four care homes with consent at a managerial level did not provide any consenting participants and were excluded.

-

One home was excluded after the two consenting residents were withdrawn by the care home manager, in order for the participants to receive end-of-life care.

| TAC | Total (%) | Intervention (%) | Control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bournemouth and Poole PCT | 12 (5) | 7 (6) | 5 (4) |

| University of Central Lancashire | 16 (7) | 8 (7) | 8 (7) |

| Coventry PCT | 14 (6) | 7 (6) | 7 (6) |

| University of Nottingham | 22 (10) | 10 (9) | 12 (11) |

| Plymouth PCT | 14 (6) | 8 (7) | 6 (5) |

| Solent Healthcare PCT | 26 (11) | 13 (11) | 13 (11) |

| Stoke-on-Trent PCT | 10 (4) | 4 (4) | 6 (5) |

| Taunton PCT | 8 (4) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) |

| Bangor University | 17 (7) | 8 (7) | 9 (8) |

| University of Birmingham | 73 (32) | 37 (32) | 36 (32) |

| Wolverhampton PCT | 16 (7) | 8 (7) | 8 (7) |

| Total | 228 | 114 | 114 |

A total of 228 care homes proceeded to the randomisation stage. Care homes were randomised 1 : 1 to receive the intervention or usual care (114 in each arm). The data for the type of care home are presented in Table 5. Of the care homes recruited, 121 (53%) provided nursing care. The distribution of residential and nursing homes was balanced between treatment arms. Retention of care home participation was good throughout the study. Data were collected from 204 homes (89% of homes randomised) at the 12-month end point (104 in the intervention group and 100 in the control group).

| Type of care home | Total (%) | Intervention (%) | Control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential | 107 (47) | 53 (46) | 54 (47) |

| Nursing | 121 (53) | 61 (54) | 60 (53) |

Participant recruitment within clusters: sample size

The flow of participants throughout the duration of the trial is depicted in the CONSORT diagram (Figure 1). Within the 237 consenting care homes there were 1556 out of 9840 (16%) eligible residents. The 16% figure represents the prevalence of stroke in the consenting care homes. Of those identified as eligible, 1055 out of 1556 (68%) were registered into the trial and 501 out of 1556 (32%) did not offer consent. A total of 13 participants (nine care homes) did not progress to the randomisation stage, two were withdrawn by the care home manger to receive end-of-life treatment and the remaining 11 participants were excluded because of the withdrawal of the regional TAC described above. Table 6 summarises participant and care home recruitment levels according to regional TACs.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

| TAC | Care home recruitment | Participant recruitment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consenting care homes | Beds in consenting homes | Randomised care homes | Eligible residents screened | Consenting residents | Randomised residents | |

| Bournemouth and Poole PCT | 12 | 434 | 12 | 55 | 48 | 48 |

| University of Central Lancashire | 16 | 954 | 16 | 142 | 86 | 86 |

| Coventry PCT | 14 | 537 | 14 | 107 | 56 | 56 |

| Dorset PCTa | 4 | 179 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0 |

| University of Nottingham | 22 | 897 | 22 | 175 | 126 | 126 |

| Plymouth PCT | 16 | 556 | 14 | 68 | 40 | 40 |

| Solent Healthcare PCT | 28 | 1006 | 26 | 180 | 110 | 108 |

| Stoke-on-Trent PCT | 10 | 400 | 10 | 76 | 48 | 48 |

| Taunton PCT | 8 | 392 | 8 | 71 | 45 | 45 |

| Bangor University | 17 | 604 | 17 | 119 | 104 | 104 |

| University of Birmingham | 74 | 3098 | 73 | 427 | 323 | 323 |

| Wolverhampton PCT | 16 | 783 | 16 | 125 | 58 | 58 |

| Total | 237 | 9840 | 228 | 1556 | 1055 | 1042 |

Participant recruitment exceeded the original target of 900. More care homes were recruited because the average cluster size was lower than predicted, but comparable between the two arms (intervention mean 5.0 participants, control mean 4.2 participants). The slight over-recruitment of 1042 participants was also because of staggered closure of sites that had already consented residents to the trial. Cluster size information is presented in Table 7. The number of care home residents with a history of stroke was lower than expected. A total of 1042 participants were randomised. More eligible residents resided in clusters randomised to the intervention arm (n = 568) than in clusters randomised to the control arm (n = 474), see Table 8. The disparity in participant numbers between the two treatment arms was a chance occurrence. Consent was obtained prior to randomisation. There were more eligible residents in care homes randomised to the intervention arm than in care homes randomised to the control arm. A larger percentage of participating care homes (53%) provided nursing care (see Table 5), and from these a larger percentage of participants (64%) were recruited (see Table 8).

| Cluster size (number of participants) | Frequency (%) | Randomisation arm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention, n (%)a | Control, n (%)a | ||

| 1 | 29 (13) | 11 (10) | 18 (16) |

| 2 | 38 (17) | 17 (15) | 21 (18) |

| 3 | 28 (12) | 13 (11) | 15 (13) |

| 4 | 43 (19) | 20 (18) | 23 (20) |

| 5 | 30 (13) | 18 (16) | 12 (11) |

| 6 | 15 (7) | 9 (8) | 6 (5) |

| 7 | 10 (4) | 5 (4) | 5 (4) |

| 8 | 11 (5) | 6 (5) | 5 (4) |

| 9 | 9 (4) | 8 (7) | 1 (1) |

| 10 | 4 (2) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| 11 | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) |

| 12 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| 13 | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 14 | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 15 | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 19 | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| 21 | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| 23 | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Total number of care homes | 228 | 114 | 114 |

| Median participants per home (interquartile range) | 4 (2–6) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (2–5) |

| Mean participants per home (SD) | 4.6 (3.3) | 5 (3.7) | 4.2 (3.0) |

| Type of care home | Randomisation arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 568), n (%) | Control (N = 474), n (%) | |

| Residential | 207 (36) | 166 (35) |

| Nursing | 361 (64) | 308 (65) |

Consent type

The majority of participants (61%) required the assistance of a consultee to offer consent on their behalf,68 indicating a lack of autonomy. The level of need for consultee assistance was similar across treatment arms (Table 9).

| Consenter | Intervention (N = 568), n (%) | Control (N = 474), n (%) | Total (N = 1042), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | 230 (40) | 174 (37) | 404 (39) |