Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/98/05. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Emma Clark is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Elective and Emergency Specialist Care Panel. Dr Howard Thom has undertaken consulting work for Novartis Pharmaceuticals, ICON plc and Eli Lilly and Company. The work had no connection to joint hypermobility or Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. To our knowledge the organisations have no commercial interests in these areas.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Palmer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Joint hypermobility syndrome

Musculoskeletal problems represent some of the most common reasons for seeking primary health care. 1 Joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS) is a heritable connective tissue disorder, characterised by excessive joint range of motion and symptoms of pain, fatigue, proprioception difficulties, soft-tissue injury and joint instability. 2 Many experts now consider JHS to be indistinguishable from Ehlers–Danlos syndrome – hypermobility type (EDS-HT),3 although this report uses the term JHS. Asymptomatic generalised joint laxity (often described as being ‘double jointed’) is very common and generally asymptomatic, occurring in 10–20% of Western populations, with higher prevalence in Indian, Chinese, Middle Eastern and African populations. 4–6 However, symptomatic JHS is reported to be under-recognised, poorly understood and poorly managed in clinical practice. 7–9 Symptomatic joint hypermobility has been reported to affect approximately 5% of women and 0.6% of men. 10 It should be acknowledged, however, that there is currently a lack of good-quality epidemiological evidence for the true prevalence of JHS in the general population.

The revised (Brighton 1998) criteria (see Table 1) are now recommended for the diagnosis of JHS,11 although a range of other diagnostic criteria has been used historically. A key component of the Brighton criteria is the Beighton score, a 9-point score of joint mobility that has been in clinical use for many years. 5 One point is awarded for being able to place the hands flat on the floor while keeping the knees straight. One point is also awarded for each hypermobile peripheral joint as follows: 10° knee hyperextension; 10° elbow hyperextension; 90° extension of the fifth finger metacarpophalangeal joint; and opposition of the thumb to touch the forearm (points are awarded for the left and right limbs as appropriate). The Brighton criteria incorporate a number of other clinical features to confirm a diagnosis of JHS and exclude other differential diagnoses. Diagnosing JHS is often challenging, as symptoms may easily be attributed to other causes. Patients report a wide range of fluctuating symptoms in addition to pain, and it has been suggested that many patients presenting in primary care with everyday musculoskeletal conditions may have unrecognised JHS. 12 Indeed, the use of the Brighton criteria has revealed a very high prevalence of JHS in musculoskeletal clinics, with rates of 46% of women and 31% of men referred to one rheumatology service,13 30% of those referred to a musculoskeletal triage clinic in the UK14 and 55% of women referred to physiotherapy services in Oman. 15 However, the diagnosis of generalised joint laxity and JHS is contentious. Clinch et al. ,16 for example, suggested that a traditional cut-off value of 4/9 on the Beighton score was unlikely to be clinically meaningful, with 19.2% of 6022 14-year-old children meeting that criterion. A more stringent cut-off value of 6/9 reduced prevalence to 4.2% which seemed more discriminative. Remvig et al. 17 also found little agreement between clinicians on the criteria that should be used to diagnose JHS. Indeed, the median importance ratings were zero for Marfanoid habitus, skin signs, eye signs and varicose veins, hernias and rectal/uterine prolapse (minor criteria 5–8 in Table 1), suggesting that these are often not considered. This lack of consensus on diagnosis perhaps explains why JHS is often under-recognised in clinical practice. 7–9

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

When compared with healthy control subjects, JHS has been shown to have a significant impact on a wide range of outcomes, such as exercise endurance, gait, pain, proprioception, strength, function and quality of life in both children20–23 and adults. 24–27 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis has also confirmed the impact of JHS on a range of psychological variables such as fear, agoraphobia, anxiety, depression and panic disorders. 28

Physiotherapy, particularly exercise, is generally considered the mainstay of treatment,2,8,9,15,29–31 and professionals in a number of centres in the UK have developed a specialist interest in treating people with JHS. It should be recognised that ‘physiotherapy’ is not an intervention in itself but describes professional practice in which a range of interventions is often employed in complex treatment ‘packages’. 32 Exercise therapy seems to be ‘core’ to physiotherapy practice,32 but professional autonomy in the UK allows individual physiotherapists to assess, diagnose and treat using the best available evidence and their own professional judgement. Keer and Simmonds31 reported that pain relief and preventing the recurrence of joint pain are the main aims of treatment of JHS, with exercise key to achieving these aims. They reported research evidence supporting the importance of interventions targeting posture, proprioception, strength and motor control, in conjunction with education, physical activity and fitness. However, there is little empirical evidence supporting the efficacy of exercise or physiotherapy. Two recent systematic reviews included only a handful of eligible trials of physiotherapy and occupational therapy interventions for JHS, and found limited evidence for their clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. 33,34 Although there is some evidence that people with JHS who receive exercise interventions improve over time, there is little convincing evidence for the effectiveness of different forms of exercise or for exercise being more effective than a control condition. 33 The current lack of evidence on the most effective management options for JHS may contribute to anecdotally reported negative experiences of management. 7,35 Higher-quality multicentre trials are clearly required to investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy for JHS. The following section will consider the existing research evidence in more detail.

Evidence for the effectiveness of physiotherapy

Although physiotherapy is considered the mainstay of treatment for JHS, there is currently little evidence related to its effectiveness. The research evidence is at a very early stage of development, with a recent systematic literature review conducted by this research team33 identifying only three exercise studies in adults that met the inclusion criteria. 26,35,36 One further study was conducted in children. 37

Barton and Bird36 conducted a cohort study to investigate the effects of exercise in 25 hypermobile adults. They implemented a 6-week exercise intervention, which included warm-up exercises, specific joint exercises and proprioception exercises (the selection of exercises and number of repetitions were tailored to each individual). Patients were asked to perform the exercises three times per week. Outcome measures included a questionnaire developed for the project, the Beighton score and the range of movement of major joints. The results showed that the maximum distance walked and pain on movement improved significantly (both from the questionnaire). Range of motion in the knee joints also improved significantly, but there were no significant changes in any other outcome measure.

Ferrell et al. 35 also conducted a cohort study with 20 adults with joint hypermobility (18 completed the study and were analysed). Their intervention and outcome measures focused specifically on the knee joints, although they did also include the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) to assess general health perceptions. The exercise intervention included a range of closed kinetic chain exercises and a static hamstring strengthening exercise. Exercises were performed on 4 out of 7 days of the week for 8 weeks. A clear progression of the type of exercises and number of repetitions was described, although this did not seem to have been individualised. Also included as outcome measures were knee joint proprioception, balance, knee flexor and extensor muscle strength and knee joint pain. The results showed significant improvements over time in proprioception, balance, muscle strength, physical functioning and mental health.

Sahin et al. 26 conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in 40 adults diagnosed with JHS. It seems that 15 patients were randomly selected to receive proprioception exercises for 8 weeks and 25 received no exercise intervention, although there is some uncertainty about patient numbers. For example, in the text the control arm is said to have comprised 3 men and 17 women (n = 20 rather than 25) and one of the tables reported 15 participants in each of the exercise and control arms. Exercise was performed three times per week for 8 weeks, supervised by a doctor in a clinic. Unfortunately, the method of randomisation is not reported, nor are any details of assessor blinding provided. Proprioceptive acuity, pain and the occupational activity subscale of the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale – 2 (AIMS-2) questionnaire all significantly improved over time in the arm that received proprioception exercises. No other subscale of the AIMS-2 improved (physical status, emotional status, symptoms or social activity). No outcome changed over time in the control arm. Unfortunately, no direct statistical comparison of trial arm data after treatment was reported, so the significance of differences between arms cannot be determined.

The only other randomised trial of exercise in joint hypermobility included in the review by Palmer et al. 33 was conducted in children. 37 This study did not include a ‘no or minimal intervention’ arm but instead compared the effects of targeted (n = 30) with a more generalised exercise approach (n = 27). Treatment was received for half an hour per week for 6 weeks and exercises were progressed on an individual basis. Home exercises were also given, to be performed daily. Outcomes included pain (both child and parent reports), global evaluation of the impact of hypermobility (parent report), functional impairment (the child Health Assessment Questionnaire) and a 6-minute shuttle test. When both arms were combined, there were significant improvements in pain (both child and parent reported) and the child Health Assessment Questionnaire. Parental global assessment and the shuttle test did not improve significantly. There were no differences between arms, except for parental global assessment (in favour of the targeted intervention).

Subsequent to the census date used in the review by Palmer et al. ,33 a further randomised trial of exercise was conducted in children with knee pain and JHS. 38 It also compared two different types of exercise: one using exercise to neutral knee extension (n = 14) and one using exercise into the full hypermobile range (n = 12). Exercises were performed for 8 weeks. The primary outcome measure was knee pain, with secondary outcome measures of muscle strength, function and parent-reported quality of life. When the arms were combined, there was a significant improvement in knee pain, patient global impression of change, strength and parent-reported quality of life (in both physical and psychosocial health components). There was a difference between arms only in the parent-reported quality of life, in favour of the neutral exercise arm for physical health and in favour of the exercising into the hypermobile range for psychosocial health. No other differences were observed and there were no adverse events.

These studies seem to suggest that patients with JHS might improve over time with exercise, but it is important to note that only Sahin et al. 26 included an appropriate no-treatment control arm. The other papers were either uncontrolled cohort studies or comparative trials of different forms of exercise. Unfortunately, Sahin et al. 26 failed to report any direct head-to-head statistical analysis of between-arm differences and fundamental methodological details are unclear. Another systematic review of occupational therapy and physiotherapy interventions for JHS34 independently identified a high risk of bias in the study by Sahin et al. 26 and did not identify any additional RCTs of physiotherapy in this area. Also of note is that three of the five studies26,35,38 focused on the knee joint in what is a multiple-joint condition and all assessed a relatively brief intervention of ≤ 8 weeks. So, the true effectiveness of physiotherapy (including exercise) in JHS remains unknown. Observed improvements over time could be explained by the natural history of the condition, positive interactions with therapists or other unknown factors. Therefore, an appropriately controlled study is urgently required.

The commissioned research

The research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme called for proposals to answer the following question: does physiotherapy improve outcomes in adults with musculoskeletal pain associated with hypermobility syndrome? It specifically asked for assessment of a ‘whole-body’ physiotherapy intervention, with examples of proprioception, muscle strengthening, pain management strategies and hydrotherapy. The commissioning brief (HTA 10/98/05: whole-body physiotherapy package for hypermobility) requested a feasibility study in preparation for a possible RCT in outpatients or other specialist care settings. The comparator requested was no active physiotherapy, with clarification that advice on joint care could be given. Important outcomes of the feasibility study were specified as follows: the number of potential eligible patients with hypermobility syndrome; feasibility of recruitment; development and piloting of the intervention; and acceptability to patients in terms of quality of life. An estimate of the value of information (VOI) from a subsequent RCT was also specified. Outcomes requested for a later trial were function, musculoskeletal pain, quality of life, adverse events (e.g. dislocations and susceptibility to injury), range of movement, strength, proprioception and psychological well-being.

The study team carefully considered the commissioning brief when developing the research project, which is described in The research project.

The research project

The study team designed a study that aimed to develop and evaluate a complex physiotherapy intervention. The lack of research in this area meant that it was difficult to provide firm recommendations for what the physiotherapy intervention should look like. Therefore, preliminary work was planned to determine patient and health professional perspectives on physiotherapy, and to use this information to help design the intervention package. A number of broad guiding principles were agreed in advance. It was agreed that the intervention should include one-to-one patient–therapist interaction because of the complexity of individual patient needs. It was also agreed that the devised physiotherapy intervention should be easily implementable across the NHS, meaning that very specialist interventions or those requiring specialist facilities (such as hydrotherapy) would be excluded. The team was also mindful of trying to ensure that the frequency and duration of sessions and overall duration of treatment was broadly in line with usual care at the two NHS trusts taking part in the research (approximately six 30-minute sessions over 4 months). A subsequent UK-wide survey conducted by the research team has revealed that this pattern of care fits very well with what is delivered by physiotherapists nationally. 39 By agreeing such broad guiding principles, the research team wanted to ensure that the physiotherapy intervention package developed stood the best chance of being adopted in practice, should it ultimately prove to be beneficial.

As part of the commissioning process there was discussion with the funding committee about the identity of the comparator arm, with the study team initially preferring a delayed intervention arm. This preference was because of concerns about the ethics of delivering an advice-only control that was less than ‘usual care’ at the two centres involved, and the potential negative impact this would have on study recruitment. The funding committee asserted that a delayed intervention arm would cause problems for long-term follow-up in any future trial (as all patients would have received treatment) and that genuine equipoise was present because of the lack of robust evidence for the effects of physiotherapy. The study team therefore agreed to deliver an advice-only control intervention.

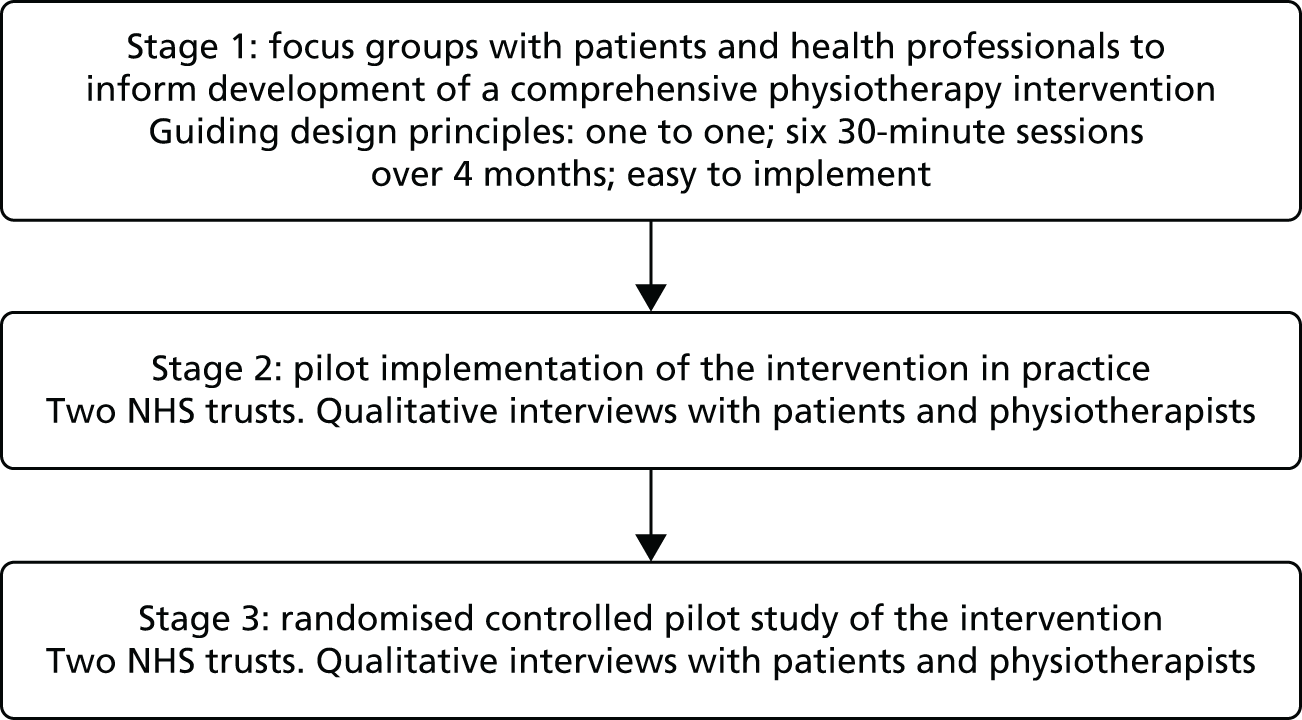

The commissioned study was, therefore, designed in three stages (Figure 1). Stage 1 aimed to understand the physiotherapy management of JHS, from patient and health professional perspectives. This information was used by a working group of researchers, health professionals and patient research partners to develop the physiotherapy intervention package. Stage 2 aimed to pilot the intervention in practice so that it could be adapted and refined as necessary before moving on to stage 3, which was a pilot RCT of the intervention, compared with an advice-only control arm. Full details of each stage of the research are contained in subsequent chapters.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the overall study design.

Chapter 2 Stage 1: Hypermobility – Perspectives On Physiotherapy study and development of a complex physiotherapy intervention

Aims

The aims of this first stage of the research included examining the views and experiences of individuals with JHS and health professionals of physiotherapy for the management of JHS (component 1). This was to inform the development of a comprehensive physiotherapy intervention for adults with JHS (component 2).

Component 1: focus groups with patients and health professionals to determine their perspectives on physiotherapy for joint hypermobility syndrome and the proposed trial

Introduction

In order to examine the views and experiences of physiotherapy for JHS, we conducted a series of focus groups with patients and health professionals. Qualitative methods were chosen as the most appropriate means of gathering data regarding beliefs, experiences and perceptions of physiotherapy interventions. 40,41 Qualitative methods are also valuable in the pretrial development phase both to help develop and refine the trial and to improve understanding of the experiences of patients receiving, and staff delivering, interventions. 42–44 Such use of qualitative methods in RCTs as part of preintervention development is well established. 45–48 Focus groups permit sharing and comparing of ideas among group members, which then facilitates the evaluation and interpretation of those ideas and the exploration of areas of consensus and disagreement. This component of the study was conducted under the name Hypermobility: Perspectives on Physiotherapy (HPoP). Findings from this component have previously been published as peer-reviewed journal articles. 49,50

Objectives

The specific objectives were as follows:

-

to investigate the lived experiences of individuals with JHS

-

to explore patients’ and health professionals’ views on current ‘usual care’ physiotherapy management of JHS

-

to examine what would be considered the optimal content and delivery of a physiotherapy intervention for adults with JHS

-

to investigate how to measure success of a physiotherapy intervention

-

to describe the attitudes and opinions of individuals with JHS and health professionals to facilitate the design of a pilot RCT of a physiotherapy intervention.

Methods

Seven focus groups were conducted with people with JHS and health professionals with a special interest in managing patients with JHS between January and February 2013 in four UK locations. Participants were recruited via mailed invitations to health professionals and patients from physiotherapy services at two NHS trusts, as well as to local members of the Hypermobility Syndromes Association (HMSA) and patients who had previously expressed an interest in assisting with research activity at two university locations.

Eligible patient participants were aged ≥ 18 years, had previously received a diagnosis of JHS, had attended physiotherapy within the preceding 12 months and were able to speak English. Individuals with other known musculoskeletal pathology causing pain, particularly osteoarthritis and inflammatory musculoskeletal disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, were excluded. Eligibility criteria for health professionals were that they should be post qualification and should have had some interest or involvement in treating people with JHS. The purposive sampling strategy aimed for diversity with regard to age, sex, socioeconomic situation and geographical location to capture maximum variation in views and experiences. Ethical approval was obtained from the North East NHS Research Ethics Committee (reference number 12/NE/0307) and all participants gave written consent. There was a substantial delay to securing appropriate NHS approvals for this stage of the research, which ultimately shortened the recruitment period available for the later pilot RCT (stage 3) by 4 months.

Separate focus groups were conducted with patients and health professionals. All focus groups were conducted in non-clinical settings. The focus groups were facilitated by two researchers (SP and JH). One researcher led the discussion using open-ended questioning techniques to elicit participants’ own experiences and views, and to ensure that all participants had an opportunity to take part. The other researcher summarised the discussion, audio-recorded the session and noted down who was speaking to aid transcription. Focus groups lasted between 71 and 100 minutes.

Topic guides were used to facilitate discussions and, in line with an inductive approach, were revised in light of emerging findings (see Appendices 1 and 2). Topic guides explored experiences of physiotherapy for JHS and views regarding physiotherapy treatment for JHS, including the optimal content and delivery of education, advice, exercises and support packages. In addition, focus groups explored attitudes to the proposed trial design and views on the most appropriate outcomes for the intervention.

In addition to the focus groups, patient participants were asked to complete a Physiotherapy Outpatient Satisfaction questionnaire51 to capture information about their last course of physiotherapy. Patients are asked to indicate their agreement to a total of 38 statements on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction. An average score out of 5 was produced for six subscales: expectations, therapist, communication, organisation, clinical outcome and satisfaction.

Analytic procedures

With written informed consent from participants, all focus groups were audio-recorded, fully transcribed and anonymised, checked for accuracy and then imported into the NVivo qualitative data analysis software (version 10, QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, VIC, Australia) to aid data analysis. Analysis began in parallel with data collection and was ongoing and iterative. Thematic analysis,52 using the constant comparison technique,53 was used to scrutinise the data to identify and analyse patterns across the data set. Transcripts were examined on a line-by-line basis, with codes being assigned to segments of the data and an initial coding frame developed. An inductive approach was used to identify participants’ perceptions of their experiences. To enhance analysis and enable team discussion and interpretation, team members (RT and JH) independently coded transcripts; any discrepancies were discussed to achieve a coding consensus and maximise rigour. Scrutiny of the data showed that data saturation had been reached at the end of analysis, such that no new themes were arising from the data. 54 All participants were assigned a letter as a pseudonym.

Findings

In total, four focus groups were conducted with 25 patients (three men and 22 women; aged 19–60 years) and three focus groups were conducted with 16 health professionals (three men and 13 women; 0–30 years post qualification; 14 physiotherapists and two podiatrists) (Table 2).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patients (N = 25) | |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–29 | 8 (32) |

| 30–39 | 7 (28) |

| 40–49 | 6 (24) |

| 50–59 | 2 (8) |

| > 60 | 3 (12) |

| Mean, (median) | 33 (36) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 22 (88) |

| Male | 3 (12) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 23 (92) |

| Other | 2 (8) (both self-reported as British white and Chinese) |

| Socioeconomic statusa | |

| 1 (affluent) | 8 (32) |

| 2 | 8 (32) |

| 3 | 4 (16) |

| 4 | 3 (12) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 1 (4) |

| Education | |

| Schooling to 16 years | 3 (12) |

| College diploma/equivalent | 6 (24) |

| University degree/equivalent | 10 (40) |

| Postgraduate degree | 6 (24) |

| Employment | |

| Employed full-time | 7 (28) |

| Employed part-time | 8 (32) |

| Student full-time | 4 (16) |

| No paid job | 5 (20) |

| Retired | 1 (4) |

| Health professionals (N = 16) | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 13 (81) |

| Male | 3 (19) |

| Role | |

| Physiotherapists | 14 (88) |

| Podiatrists | 2 (13) |

| Years since qualifying | |

| Newly qualified (< 1 year) | 1 (6) |

| 1–4 years | 1 (6) |

| 6–20 years | 7 (44) |

| > 20 years | 7 (44) |

Out of 25 patient participants, 24 completed the Physiotherapy Outpatient Satisfaction questionnaire. Table 3 presents the median scores for each of the subscales.

| Subscales | Median rating (IQR = Q3 – Q1) (maximum = 5) |

|---|---|

| Expectations | 2.80 (0.80) |

| Therapist | 4.17 (1.33) |

| Communication | 3.60 (2.00) |

| Organisation | 3.50 (0.88) |

| Clinical outcome | 2.33 (0.33) |

| Satisfaction | 3.00 (1.57) |

Table 3 suggests that, in general, satisfaction with physiotherapy was rather neutral (median rating 3.00/5), with median ratings of clinical outcome (2.33/5) and expectations (2.80/5) of treatment tending towards negative ratings. More positively rated were the therapist (median rating 4.17/5), communication (3.60/5) and organisation (3.50/5). So, the expectations of physiotherapy and the perceived outcome of treatment were rated as lowest of the six subscales.

Six themes, developed from the qualitative analysis, related to (1) the impact of JHS; (2) JHS as a difficult to diagnose, chronic condition; (3) physiotherapy to manage JHS; (4) optimising physiotherapy as an intervention for JHS; (5) measuring success, and managing expectations, of physiotherapy; and (6) patients’ and health professionals’ views on the proposed physiotherapy trial design.

Theme 1: the impact of joint hypermobility syndrome

Figure 2 illustrates the subthemes related to this main theme.

FIGURE 2.

Subthemes associated with theme 1: the impact of JHS.

All patients reported JHS symptoms including fatigue, pain, proprioception problems, recurring joint dislocation and ‘cycles’ of injury and recovery (Table 4), although there was wide agreement that the impact and consequences of these symptoms were different for each patient. The diverse nature of the symptoms was also noted by both patients and health professionals.

All of us are probably so different yet we’re categorised as the same.

Female patient A, 60 years old, focus group 2

It’s the heterogeneous group that makes it very interesting.

Female health professional D, 22 years post qualification, focus group 4

| Feature of JHS | Illustrative quotation |

|---|---|

| Pain | Most days I’m in some sort of pain, it’s always there, it never actually goesFemale patient A, 35 years old, focus group 5Every second, that’s the ankle, the knee, the back, the headFemale patient B, 32 years old, focus group 1 |

| Repeated cycles of injury, pacing or activity restriction and recovery | . . . it’s difficult to know how much to push yourself because then you are worried about injuring and then you’re setting yourself back, well it’s a vicious cycle reallyFemale patient B, 27 years old, focus group 5I find that I get to a level with exercise and then I’ll have a bad day or I’ll injure myself and so you kind of step back, you have to go backwards, and you never seem to go that far forwardFemale patient G, 42 years old, focus group 5 |

| Impact of JHS on activity | I will only go out if I know that we’re going somewhere where I can sit downFemale patient D, 32 years old, focus group 5I think it was one of the questions in there, it was about how much how much pain have you been in, well loads, has it stopped you doing anything, no, because we all sort of pushed through it and we still do it anywayFemale patient D, 21 years old, focus group 1 |

| Fatigue | You’re managing your pain and it’s a lot of pain, it’s a dull ache and it makes you sleepy and it makes you tired and you’re exhaustedFemale patient G, 30 years old, focus group 1 |

| Proprioception issues | It’s on your mind the whole time, because I’m constantly thinking about where my hands and feet areFemale patient G, 48 years old, focus group 2 |

Patients described difficulties in making the distinction between chronic and acute pain, and that it was challenging for them to understand how, or if, injuries had occurred:

Well, how do we know whether we’ve injured something, because we’ve got pain all the time?

Female patient C, 40 years old, focus group 1

However, patients also observed that their pain thresholds appeared to be unusually high and that their perception and interpretation of pain is somehow altered:

That would be the first problem, I can’t feel pain. I snapped some bones in my wrist, and up here somewhere, and it was ‘oh that’s not quite right’ and the doctor went ‘aren’t you screaming’, and I was like ‘why?’, and he said ‘that should really hurt’, oh OK, it’s a bit of a whinge, until he took me through into the hospital and he was going ‘painkillers’, no, don’t take them, doesn’t hurt that much, he did the operation and came through OK and they said ‘you can have the morphine if you want it’, and I didn’t bother, it didn’t hurt.

Male patient A, 50 years old, focus group 1

Repeated injuries were common and patients frequently talked about cycles of injury and recovery in which periods of injury required participants to pace and restrict activity. Consequently, some participants found living with JHS to be ‘very debilitating’, limiting the type of activities they could engage in and severely impacting on their engagement with the social world. Patients also described how prior experiences of repeated injuries led to heightened levels of anxiety and catastrophising about future injuries, or extrapolating their current or prior experiences to an imagined future (Table 5).

| Psychosocial impact | Illustrative quotation |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | I feel like I’m in a constant state of anxiety, waiting for the next injury and trying to pre-empt anything that’s going to cause itFemale patient G, 48 years old, focus group 2 |

| Catastrophising | I think also there’s an element of fear, I worry dreadfully and I’m frightened of what will come next [. . .] There’s all these ‘what ifs’ that boil up into this massive pile of anxiety inducing terror. What’s happened in reality is you’ve got a slightly aching wrist, but what’s actually happened is it’s gone from if that’s gone the next thing’s going to go, what if this and what if this, and what if I let everyone down and this sort of awful . . .Female patient E, 34 years old, focus group 2 |

| Fear of the future | Oh my god is this going to be like this for the next 60 years of my lifeFemale patient B, 27 years old, focus group 5I’m going to have it forever and it’s never going to get betterFemale patient E, 19 years old, focus group 6 |

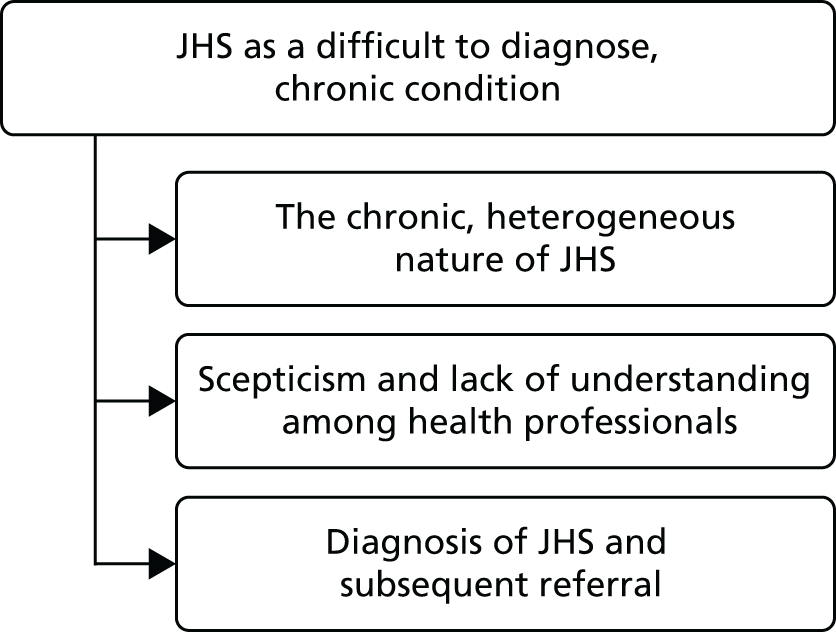

Theme 2: joint hypermobility syndrome as a difficult to diagnose, chronic condition

A number of subthemes were associated with this main theme (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Subthemes associated with theme 2: JHS as a difficult to diagnose, chronic condition.

The chronic, heterogeneous nature of joint hypermobility syndrome

Both patients and health professionals described the chronicity of JHS and its symptoms. Patients recognised that they were ‘going to have it forever’ (female patient E, 19 years old, focus group 6) and that ‘you won’t be fine, not completely’ (female patient C, 40 years old, focus group 1). Similarly, one health professional described having JHS as ‘almost like a recovering alcoholic, you are always a recovering hypermobility person’ (female health professional B, 28 years post qualification, focus group 4).

Scepticism and lack of understanding among health professionals

Both patients and health professionals felt that JHS is not a widely understood condition and sometimes not recognised as a syndrome among health professionals. Patients described a lack of understanding of JHS in health settings and reported feeling that sometimes their symptoms were not believed or understood by health professionals:

I think I was described as a biomechanical conundrum by one of the physiotherapists I saw . . . and this is what I found repeated over and over again, that hypermobility shouldn’t be causing pain, it’s just the way you are . . . you shouldn’t be in pain because you have mobility.

Female patient C, 53 years old, focus group 2

When I went back to physio[therapy] for strengthening exercises to help my joints after the hypermobility diagnosis, there was . . . I got that a little bit, ‘I’m not sure about this hypermobility . . .’.

Female patient B, 34 years old, focus group 2

I work in a rheumatology department who don’t recognise joint hypermobility as an entity and in fact, probably a lot of people tend to get diagnosed with things like fibromyalgia more than normal.

Female health professional E, 30 years post qualification, focus group 3

As joint laxity often causes no problems, and JHS symptoms vary, the unpredictable, diverse, evolving and fluctuating nature of their symptoms exacerbated others’ misunderstanding of the nature of JHS and patients’ reports of problematic symptoms to health professionals were often met with scepticism:

And if you’re inconsistent as well, they sort of go, she was alright with that last week, why is it this week she’s saying that, you know, that’s going to be difficult for her today.

Female patient C, 53 years old, focus group 2

Consequentially, health professionals perceived ‘a lot of mismanagement’ (female health professional E, > 20 years post qualification, focus group 4) of JHS by health professionals and that patients may be given erroneous information by some health professionals. One patient described a rheumatologist who had said ‘in his opinion, his professional opinion, that hypermobility doesn’t cause pain’ (female patient C, 53 years old, focus group 2). JHS-trained health professionals felt that they were required to ‘undo misconceptions, other health professionals’ understanding and what they have taught or implied to the patient about their condition. So for us we sort of have to unravel an onion so to speak, and it’s quite hard, yeah challenging I think’ (female health professional E, > 20 years post qualification, focus group 4).

Patients felt that JHS does not generally fit with health professionals’ models of acute injury and recovery, and that this may be a source of frustration for health professionals:

[Physiotherapists] get frustrated because their model of physiotherapy and what they’re taught and how joints move and how they get better, hypermobility is totally the opposite of what they’re expecting and they can’t understand that. I’ve had physio[therapist]s before say well stop the shoulder dislocating.

Female patient B, 32 years old, focus group 1

Diagnosis of joint hypermobility syndrome and subsequent referral

The heterogeneous nature of JHS symptoms, lack of recognition of the syndrome among health professionals and subjective diagnostic criteria were seen to contribute to often slow and convoluted diagnostic trajectories. Patients commonly remarked that ‘it takes so many years to get diagnosed’ (male patient E, 36 years old, focus group 5). Patients felt that education for health professionals was required, particularly, in order to facilitate timely diagnosis and referral:

I think it sounds like we’ve all been passed from pillar to post where people don’t recognise it or they just attribute the pain to something else, when a kind of snap diagnosis just comes out of the air and you know you progress from there, I don’t know, I mean there’s lots of things I still need to know about hypermobility but on the flip side I do think it’s the health professionals that need to know more.

Female patient G, 42 years old, focus group 5

Health professionals highlighted the difficulties in diagnosing JHS using the criteria available:

I think it’s the diagnostic criteria for hypermobility syndrome that’s actually part of the problem [. . .] So it’s almost going right back to the start, finding a slightly more sensitive diagnostic criteria that can help us to then manage it.

Female health professional F, 11 years post qualification, focus group 7

Both physiotherapists and patients recognised that, if JHS remained undiagnosed, chronic pain may develop that may be less likely to be responsive to physiotherapy. The biopsychosocial impact of living with untreated or inappropriately treated symptomatic hypermobility may lead to a more multidisciplinary approach being required:

And you see by the time – for me they come with quite a lot of psychological baggage, and you know, they are difficult patients. And then you’re trying to unravel what’s the primary and secondary issue here, is it that your mental health is actually what’s driving your hypermobility, or is it the fact you have such debilitating joints is making you mentally unwell. But by the time they get to us that’s so hard to deal with, [. . .] and they almost then, it’s a cry for help. So they’re desperate to get help so the psychological side comes out because the physical manifestation of what they’re suffering with is just so severe.

Female health professional E, > 20 years post qualification, focus group 4

Actually, there’s some that do quite well [with physiotherapy] as well in terms of . . . especially I think if you catch them early, really the key is, before they develop a lot of the chronic pain.

Male health professional B, 8 years post qualification, focus group 7

Patients also recognised that delays in diagnosis may result in the development of maladaptive responses to JHS, for example, compensatory postures, which are then difficult to rectify:

I was 15 when I was diagnosed and that was even too late really for me because the way I stand, the way I move, everything, my Pilates teacher – her grandson was 3 when he was diagnosed and he has Pilates, and physiotherapy now so he will get into habits of a life time.

Female patient G, 30 years old, focus group 1

For patients, receiving a diagnosis was considered to be essential in order to access appropriate treatment and patients felt that ‘the sooner you get the treatment the less likely it is that it is going to have such a great impact on your life’ (male patient E, 36 years old, focus group 5). However, physiotherapists felt that care pathways for JHS were not well defined and intimated that, as a result, patients may develop more complex problems or chronic pain issues:

I see the other end. I think we don’t have a structured pathway of care for hypermobiles, which is what I’m interested in developing, but we don’t have it. So there’s no rheumatologist in the trust that has a special interest in hypermobility, and my god I’ve tried to find one [. . .] So there isn’t a defined pathway of care for someone with generalised – with hypermobility syndrome, so . . .

Female health professional C, 25 years post qualification, focus group 4

So for me I feel that’s a key problem because I think we end up getting them too late, and if [name] had the support I feel to get these pathways better earlier.

Female health professional E, > 20 years post qualification, focus group 4

A diagnosis of JHS was considered to be necessary in order to access appropriate care pathways, for example, to be referred to secondary care for JHS rather than for a single-joint problem. Once patients had been diagnosed and referred to JHS-trained physiotherapists, many participants reported that their treatment was beneficial:

I found that once I was diagnosed with hypermobility the physio[therapy] I received [has] been really good.

Female patient G, 42 years old, focus group 5

I was originally seen by a physio[therapist] who hadn’t diagnosed with the hypermobility and then went back to a musculoskeletal specialist who then put me forward to specialist hypermobility physiotherapist and since then it’s been amazing; I feel like it’s been worthwhile and it felt like the right thing to do and I’ve been really enjoying it.

Female patient B, 27 years old, focus group 5

Theme 3: physiotherapy to manage joint hypermobility syndrome

Both patients and physiotherapists emphasised that physiotherapy would not be effective if individual joints were being treated in isolation and described difficulties in treating JHS within some NHS constraints, for example, where patients are generally referred for a single problematic joint:

Because of, I think, the way – at least in my experience – that the NHS seems to approach things, they have a sort of, ‘you’re here for one joint’ approach, which is quite difficult, because you go: ‘Well, I’m floopy all over’. And then you have to have the conversation about ‘Well, which is the most difficult?’ You’re like ‘Well, it’s kind of all related’, so if, like, if my knee is stronger and I’m doing less weird things with my knee, then my hip will feel better because – and I can say that, and to me it’s obvious, that if you fix – just because it’s your hip that hurts it doesn’t mean that it is actually the problem. It could well be that your knee is the issue, making you do weird things with your hip, but there’s this, ‘This is the joint, and we will deal with this joint,’ when that isn’t really . . .

Female patient C, 53 years old, focus group 2

Patients and health professionals reported that in the NHS, ‘usual care’ was normally up to six physiotherapy sessions to treat a specific joint. However, it was felt that this specific number of sessions was not necessarily appropriate for treating JHS.

They’ve got us as their clinical leads telling them to look at people globally, pick up this diagnosis, but then they’ve got their managers telling them you have to do six sessions [. . .] I should really be saying ‘I know you’ve got hypermobility, I know it’s all related, but actually I need six sessions with your back, I need six sessions with your shoulder and I need six sessions with your knee, and we need to negotiate that with your PCT [primary care trust] because otherwise [place name] is not going to get paid.

Female health professional E, 30 years post qualification, focus group 4

In all focus groups, the need for continuous, ongoing access to physiotherapy was highlighted, whether or not the patient was experiencing problematic symptoms. One patient felt:

The difficulty is, it’s a chronic condition and the only time you are actually able to access any care in the NHS is when you have an acute incident from it.

Female patient G, 48 years old, focus group 2

Health professionals, unless practicing privately, were equally frustrated by the lack of flexibility in the number of treatment sessions that could be offered:

And I think the limitations of, like, if you were receiving NHS treatment, then you’re only going to get so many sessions.

Female health professional D, newly qualified, focus group 3

In addition to the perceived limited number of sessions, physiotherapy may also be unsuitable and exacerbate symptoms if it ignores the complexity of JHS symptoms:

Then, as you say, being given some more exercises that weren’t helpful because they did seem to cause more pain which then sets you back even more and then you seem to get into the cycle of never sort of making any progress and then the treatment’s over because you only get a few sessions.

Female patient G, 48 years old, focus group 2

Theme 4: optimising physiotherapy as an intervention for joint hypermobility syndrome

Figure 4 illustrates the subthemes associated with this theme.

FIGURE 4.

Subthemes associated with theme 4: optimising physiotherapy as an intervention for JHS.

An ‘ideal’ physiotherapy service

All focus groups were able to provide descriptions of an ‘ideal’ physiotherapy intervention or suggested improvements which were based upon their own previous experiences of giving or receiving treatment. Health professionals’ and patients’ descriptions of ideal physiotherapy were notably similar (Table 6). Both felt that it was important to have continuity of therapist who was trained in JHS and who provided reassurance to the patient. Both patients and health professionals described the importance of flexible treatment, ensuring that the treatment is patient led, meeting and managing goals and expectations, taking a holistic, long-term approach and treating JHS rather than acute manifestations of the syndrome. The importance of ongoing, ‘maintenance’ physiotherapy for patients was also highlighted.

| Suggested improvements | Illustrative quotation from patient | Illustrative quotation from health professional |

|---|---|---|

| Therapist | ||

| Continuity of therapist to improve patient–therapist interaction/relationship | They get to know you as well, don’t they, and they know your lifestyle and they know what you do day in day out and therefore they can start to understand any trigger . . . they get to know you as a personFemale patient G, 30 years old, focus group 1 | For everybody, all patients, is continuity. But it’s especially difficult [for JHS patients] because they have so many different problemsMale health professional A, 6 years post qualification, focus group 3 |

| Therapist should be JHS expert | . . . the two physiotherapists I’ve had who’ve known about [erm] hypermobility have been a lot better than ones I’ve had in the past where they obviously haven’t had a clueFemale patient C, 60 years old, focus group 6 | . . . if they see somebody who hasn’t had an interest in that then they’re learning along with the patient at the same time. . . . So that’s quite difficult. It’s much better, isn’t it, to be seen by a specialist straight away who has got a broader knowledge base to be able to tap into their tools and skillsFemale health professional E, 30 years post qualification, focus group 3 |

| Therapists should provide reassurance and encouragement | quite often I’ll come out of the next physio[therapy] feeling much happier because they’ve reassured me that it’s not the end of the world and you know sometimes you have a bad week but it doesn’t mean that you won’t then have a good weekFemale patient F, 44 years old, focus group 1 | I think you’ve got to set achievable goals, then you’ve got to give a lot of reassurance and positive feedbackFemale health professional B, 28 years post qualification, focus group 4 |

| Physiotherapy | ||

| Flexibility in treatment, (e.g. number of sessions, content, specific techniques, mode of delivery, structure and focus) | . . . Or consider the person’s life style, . . . and that sort of flexibility, not just on what they’re asking the patient to do, even being flexible on the times of day or you know when these things can happen, you know make it interesting, you know we can’t all get in at 11 o’clock in the morning or 2 o’clock in the afternoon, we do need the half past 7’s the 8 o’clock in the morning, and the evening appointmentsFemale patient C, 40 years old, focus group 1 | Ideally, you’d want to have a service offer where they could tap into the service where they wanted to. If they suddenly got a flare up of something, say their hands started to give way or become more of a problem, then they could come back to youFemale health professional E, 30 years post qualification, focus group 3 |

| Patient-led treatment, while managing and understanding patient expectations | I think being patient led, . . . what it is that they want to achieve out of it and how the best way they can do that, and you know with a bit of guidance, like . . .Female patient B, 32 years old, focus group 1 | You try and tease out, you know, what are your expectations? No idea. So your hopes? No idea. I don’t know what I’m supposed to be doing . . . Forget that, what would you like to be doing? . . . Then you start to offer things and start to treat or start to address . . .Male health professional D, 5 years post qualification, focus group 7 |

| Meeting individual goals, to manage rather than cure | Or consider the person’s life style, you know consider what is going to be feasible, what they need to be able to get to in terms of achievement and you know and that sort of flexibility not just on what they’re asking the patient to do . . .Female patient C, 40 years old, focus group 1 | Because we’re very good at having goals, but you know, it’s making sure that the patients, they are the patients’ as wellFemale health professional G, 23 years post qualification, focus group 4 |

| Holistic, long-term approach | It’s not just your joints, it is all the other bits around it and that sort of slightly bigger picture, you’re probably going to be like this always, you need to think of different ways to manage different thingsFemale patient E, 34 years old, focus group 2 | . . . obviously if there’s a mechanical element to it we’d have to go into that, but as I say, the hypermobility is something that needs to be addressed more holisticallyFemale health professional E, 19 years post qualification, focus group 7 |

| Recognition of the need to treat multiple joints for JHS rather than individual problematic joints | I think they need to take notice that it is a full body condition rather than just individual, rather than just like one area, it is individual parts but they often concentrate on one area and then forget that the rest of the body hurts as well and that the pain can be interlinkedMale patient E, 36 years old, focus group 5 | If it was classified as a condition, [unclear 31:00] spondylitis or all those other rheumatological conditions which are, extend beyond one section, it’s treated differently isn’t it, so it’s got to do with its recognition presumably. It’s multi systemic, therefore you can treat multiple sites and therefore it may take longer in the endFemale health professional D, 22 years post qualification, focus group 4 |

| Focus on core strengthening and ‘correct’ movement | basically you’ve really got to give them a comprehensive set of useful exercises that will cover a whole range of joints, you know because most of our joints are affected, but particular core stabilityFemale patient E, 44 years old, focus group 1 | but really just concentrating on . . . on kind of core, and . . . good posture . . . concentrate on how they’re exercising, what they’re doing, technique rather than just exercising. Because a lot of them just . . . they find the most bizarre ways of doing things that I could never do in a million yearsMale health professional B, 8 years post qualification, focus group 7 |

| Maintenance physiotherapy for a chronic condition rather than acute problems arising from JHS | If it’s like say the diabetic clinic, where you get called every year to see them. . . . So could they not do a package where you actually went back every 6 months to see somebody regardless of how you were feelingFemale patient A, 60 years old, focus group 2 | So what we’ve tried to do is . . . a sort of self-referral back into the service, so they’re not having to go round the houses, and we pick them up quickly when they’re starting to get a flare up or a deteriorationFemale health professional E, > 20 years post qualification, focus group 4 |

Central role of education in managing joint hypermobility syndrome

Education for patients and health professionals and raising awareness of JHS within society as a whole was seen to be a key issue for participants in this study. Both patients and health professionals considered education to be a key underlying requirement to optimise the viability of physiotherapy for JHS. Because of the lack of understanding that patients perceived to be common among health professionals, patients felt that health professionals required more training in JHS. Some patients felt that they faced a situation in which they were providing education for the health professionals, and felt that this was not necessarily beneficial for them:

There’s lots of things I still need to know about hypermobility but on the flip side I do think it’s the health professionals that need to know more.

Female patient G, 42 years old, focus group 5

So there’s this odd situation where I’m explaining how it works to them and I think that it is not ideal and I think there does need to be better education for the physio[therapist]s because I think that is quite important that they tell you how and why things are happening to you, rather than vice versa because that’s unhelpful.

Female patient E, 21 years old, focus group 2

Health professionals also highlighted the need for education among health professionals and suggested a variety of educational sources, including websites, special interest and support groups and further professional training. One health professional highlighted the value of evidence-based guidelines:

Because if you get a patient in front of you, you need to be able to think, OK, what can I look at? What is the most effective? So guidelines that you were talking about, or maybe you can do, would be very helpful.

Female health professional E, 30 years post qualification, focus group 3

Health professionals felt that education was necessary for patients in order to facilitate a greater understanding of the condition:

I think a large part of it, as well, is to the education. To think that the patients don’t necessarily understand the condition. [. . .] Sometimes they don’t actually, nobody has never actually sat down and explained to them what that is and the implications. And what can actually be done to help them. So I think that’s a large part of it.

Female health professional D, newly qualified, focus group 3

Health professionals felt that education is necessary for patients develop realistic expectations of treatment and a better understanding of the rationale for particular treatment plans:

A lot of . . . I think what is . . . is education, ‘this is why I’m doing it’, and making sure they understand why I’m getting them to do these exercises . . . even if it doesn’t work and goes horrendously wrong, that’s fine, we can change that, but they’ve got to have an understanding of what we’re asking them to do and why we’re asking them to do it.

Male health professional B, 8 years post qualification, focus group 7

Patients similarly recognised that education helped them to fully engage with a prescribed treatment:

I think probably a third of my physio[therapy] session is me quizzing my physio[therapist] about what it is that’s hurting and why and what I can do about it and the way forwards, how I can perhaps do things slightly differently. So I think I get a huge amount of enlightenment from her . . . So I think education is really important and it needs to be part of what’s delivered to the hypermobile patient.

Female patient D, 54 years old, focus group 2

Theme 5: measuring success, and managing expectations, of physiotherapy

All participants recognised that the aim of physiotherapy was to manage, rather than cure, the symptoms of JHS, that ‘successful’ therapy did not mean the patient would be pain free; rather, the aim was for the patient to be able to manage their pain:

I think measuring success should be more about reaching a point of continuity where you know you might not be great all the time or you might not be really bad all the time but you’re manageable.

Female patient G, 30 years old, focus group 1

. . . you may not be expecting to get them pain free, but if they’re happy and if they’re managing the problem better, you know what to do to manage it, then you’re there.

Female health professional C, 19 years post qualification, focus group 3

Some health professionals raised concerns about patient expectation, that patients were expecting to gain more than the treatment could realistically offer. For example, one health professional felt that some patients often wanted, and expected, a ‘cure’:

I don’t want them to go away and think, well, she’s done nothing, when they expected me to fix it. So I have to say from the beginning, well, I can’t fix it, but this is what I can do. And to a point, that’s all you can do, isn’t it, really?

Female health professional E, 19 years post qualification, focus group 7

Some patients considered that physiotherapy would be successful if it resulted in some reduction in pain intensity, in some parts of their body. But contrary to some health professionals’ perceptions, patients did not appear to hold unrealistic expectations about the treatment that was being offered to them:

You can measure it [the success of physiotherapy] by parts of body I guess because I, although I don’t feel remotely better in many parts I still say that my last physiotherapy was a success because it significantly helped me with my shoulders so that I, I like suffer a lot less pain in that area of the body now, so I call it a success but when you get to my knees and ankles and neck and back it did do that much, the neck surgery was a success because that significantly reduced the neck pain although I still get probably more muscular now than any joints but that’s still again one part of it, so there’s lots of other areas that are still very bad, so erm I guess that in order to say that I’m better every bit would have to have improved significantly to say that they didn’t affect my day-to-day life, but to have individual parts improve is still a success.

Female patient F, 19 years old, focus group 5

Both patients and health professionals considered physiotherapy would be successful if it resulted in patients having a positive attitude, increased confidence and the ability to cope with daily activities relevant to the individual:

. . . whether that is feeling better equipped to handle your body going forwards, feeling like you’ve got the tools or feeling like you actually physically can do more, but I think it’s a little bit . . . it’s so subjective and almost impossible to measure. I think feeling better about your situation and your body, because I’m never going to feel brilliant. I think there are definitely ways you do feel better, whether that’s feeling better equipped or feeling you actually can now, I don’t know, walk 200 yards rather than one hundred without having to stop, or whatever, the feeling that you can or the feeling that you will be able to.

Female patient E, 34 years old, focus group 2

Because you may not be expecting to get them pain free, but if they’re happy and if they’re managing the problem better, you know what to do to manage it, then you’re there.

Female health professional C, 19 years post qualification, focus group 3

I feel more able to cope with my condition than I did before, and be able to measure that. Some kind of functional measure that might be patient specific – a functional scale.

Female health professional D, 22 years post qualification, focus group 4

Theme 6: patients’ and health professionals’ views on the proposed physiotherapy trial design

During the focus groups, patients and health professionals were presented with a proposed design of a physiotherapy intervention RCT (an assessment and advice session compared with an assessment and advice session plus six 30-minute physiotherapy sessions) as a means of creating debate to examine the range of opinions expressed on issues salient to the acceptability and feasibility of the proposed trial.

Views of proposed trial design

Trial inclusion/exclusion criteria and the implications of these were discussed by health professionals, in particular the potentially heterogeneous nature of the patient group which may include chronic pain comorbidities:

My thought is something that might skew the kind of outcome is if they were . . . if they’d come through a consultant pathway into this trial quite a lot of them are referred with dual diagnosis of hypermobility and fibromyalgia, and if they are referred with, you know . . . hypermobility may be the diagnosis, but if they’re referred for their fibromyalgia and they end up on a fibromyalgia coping skills programme they’ll get an awful lot of kind of input in that respect on how to manage a long-term condition, so it may not be that the input they’ve had for hypermobility is what’s been affected. So I don’t know how you would screen that, if you make that an exclusion criteria?

Female health professional A, 12 years post qualification, focus group 7

A minority of patients felt that the control arm, which consisted of a one-off advice session with a physiotherapist, would be acceptable to some patients because of the lack of current advice and information available:

I think it is a little bit of a case of . . . anything that makes you feel like you’re not on your own or anything that gives you any more information, or any more tips, or any ideas of things that might help. It’s that thing of feeling that you’ve got tools to help yourself, because you don’t want to be dependent on having to go and see a physio[therapist] every week or every month or however. I mean having someone who you can go back to check up on you and make sure everything is OK, that I think is ideal, but obviously difficult funding-wise in the NHS.

Female patient E, 34 years old, focus group 2

The majority of patient and health professionals, however, highlighted a number of concerns with the content of the control arm. Some health professionals felt that patients would require more than just advice:

I don’t think people generally like, what they would term, as being talked to. So if the advice was just talking, information giving but no hands-on or assessment of looking or something specific to their problem, I don’t think they would buy into that.

Female health professional B, 29 years post qualification, focus group 3

Some patients felt that they would not be willing to take part in the trial if they were randomised to the control arm because of the lack of ongoing physiotherapist support to ensure exercises are done correctly:

You then think ‘OK, I can do this’, and whatever you do, you could be doing it completely wrong which could be then be making you even worse, so then without, obviously you’ll then know that but you’ve just then wasted all that time just to know, OK, that was wrong. So I know with the physio[therapist]s that can happen as well but at least they got some sort of background to maybe steer you in the right place, so I think just straight out physio[therapy]’s going to be better.

Female patient D, 21 years old, focus group 1

I definitely would go no thanks I’m going to go down the physio[therapy] route because like you said you want constantly reassuring that you’re doing things the right way because someone would say that the diagrams with you know lean on the side, do this, do that, you could be doing it, but not doing it right, so you do need someone to say you’re doing it wrong and show you how to do it right, so I would definitely say no.

Female patient B, 27 years old, focus group 5

Patients felt that the control arm may not be viewed as equitable treatment in comparison with a physiotherapy intervention arm. Patients felt that those who were in enough pain to seek health care would require an active intervention to treat their symptoms and, therefore, may be reluctant to consent to the trial if the arms were not seen to be balanced:

I still think to leave everyone, if you told in that group ‘right half of you are going to go to physio[therapy] and half advice.’ I think wouldn’t you feel a little bit jipped, knowing ‘wait a minute how come I’m not going to get anything’?

Female patient A, 36 years old, focus group 5

If you’re in that much pain to actually go to the GP [general practitioner] to be referred. You need something . . .

Female patient B, 27 years old, focus group 5

Yeah, I think you definitely need something there that’s an alternative but obviously isn’t physio[therapy] but is something otherwise people are generally not going to be interested because they want to have something that they think might help them.

Female patient D, 32 years old, focus group 5

Patients and health professionals stated that if patients had specific problems that they felt needed treatment, they may be likely to withdraw from the trial if randomised to the control arm.

The only thing I would say is if I got . . . I would sign up, but if I got referred for the advice session and usual GP care I may well go back to my GP and ask for another referral. Because if you had a problem, you’d want some physio[therapy] . . . Depending on what level I was at when I . . . you know, if I felt I really needed it then obviously I’d be like, well, that’s a bit annoying.

Female patient A, 30 years old, focus group 6

See, because I think you might get people dropping out. Because if I had a problem and I was only being talked to and my problem wasn’t being identified and it was just general knowledge, I would soon seek somebody else, if I had the ability to do that.

Female health professional E, 30 years post qualification, focus group 3

Both patients and health professionals felt that the willingness of individuals to participate in the trial would be influenced by patients’ severity of symptoms and personal requirements and treatment expectations:

I think it depends on how bad you are and your symptoms are at the moment and myself is relatively manageable at the moment so I’d be willing to do that, I’d be happy to do that.

Female patient D, 32 years old, focus group 5

It depends on the individual to, wouldn’t it? If you’ve got somebody who’s got good feelings of self-ethnicity [sic] and internal locus for control, they might well go for it, because they think that’s fine, all I need is some good advice. For those who were thinking they might be getting treatment, they might well drop out if you were to allocate them.

Female health professional C, 19 years post qualification, focus group 3

Although more preferable to many patients than the control arm of the trial, some felt that the intervention arm of six physiotherapy sessions would not be enough to be beneficial:

I think you’ve also got to be realistic about what success you can get out of the group that had the physio[therapy] on just 6 half hour session because I don’t think in a 4-month period you will get much success I think you will be needing to look at it on a much longer term.

Female patient F, 44 years old, focus group 1

That is very quick, I mean even by the standards of what I’ve had into them, so . . . when I felt rushed with 10 sessions.

Female patient G, 30 years old, focus group 1

Suggested changes to trial design

Patients and health professionals offered a number of suggestions for augmenting the content of the control arm, including providing ongoing support through group meetings, gym membership and the provision of general, not targeted, exercises, so the two arms were perceived as more equitable:

So I think it has to, something else has to be, whether you do just get offered a holistic approach so they only, you meet with someone, the same number of sessions and talk about it or you just go to groups about it.

Female patient A, 36 years old, focus group 5

Can you give them six sessions of Pilates instead of the, with the advice leaflets and then they can come back to physio[therapy], you know does just going off and doing a Pilates class on your own help you manage it better than a physio[therapist].

Female patient B, 32 years old, focus group 1

What about one group has the specific one to one intervention and another group, basically, referred with exercise prescription to a gym? They’re still exercising, but it’s non-targeted, isn’t it?

Female health professional C, 19 years post qualification, focus group 3

I think if you gave an advice session plus like a free gym pass that you can use somewhere, I think that might be more of an incentive.

Female patient B, 32 years old, focus group 1

Both patients and health professionals suggested that having a delayed intervention for the control arm may be seen as more acceptable and could possibly encourage trial participation:

Maybe you could encourage more people, I think they’d be willing to do it anyway, ‘I’m not getting physio[therapy] right away although I was expecting to have some, at some point fairly soon’, you could try and get over the objections by saying that after this has completed then the people that were sent down the not doing anything route will just get referred onto physiotherapy anyway so they still get the physiotherapy they require.

Female patient D, 21 years old, focus group 1

Would they be able to receive, if you approve that having the six sessions [of physiotherapy] is beneficial, would they be then guaranteed to receive that at a later date?

Female health professional D, newly qualified, focus group 3

Conclusion

Both patients and health professionals described JHS as a painful, chronic condition with heterogeneous, fluctuating and evolving symptoms. Patients and health professionals reported a lack of recognition and understanding about JHS, and even some scepticism. Patients reported difficulties in being diagnosed and how they had encountered health professionals who they felt did not believe or understand their descriptions or their experiences of JHS. 49 The data indicate the importance of a timely diagnosis of JHS and referral for specialist care in order to facilitate effective treatment of JHS. Physiotherapy was viewed as beneficial if used to manage JHS holistically rather than to treat acute injuries in isolation. Patients valued physiotherapy when delivered by therapists who had an understanding of the chronic nature of JHS, as appropriate management could be delivered. The aim of physiotherapy should be considered to be long-term injury prevention and symptom amelioration. 50 Education for health professionals and patients, and raising awareness of the condition was seen as essential in order to optimise physiotherapy provision for JHS.

In relation to the proposed trial design, both patients and health professionals felt that the content of the control arm, consisting of a one-off advice session, may not be perceived as equitable to the physiotherapy intervention arm and concerns were raised that this may impact on trial recruitment and retention.

Strengths and limitations

The use of a qualitative methodology is a key strength in the current study, which is the first to our knowledge to undertake an in-depth investigation of the day-to-day experiences of managing JHS from both patients’ and health professionals’ perspectives. Employing focus group methodology allowed consensus to be gained regarding physiotherapy treatment, although it is recognised that using focus groups as a method of data collection did not permit as much in-depth exploration of some of the issues raised as other forms of data collection, for example, one-to-one interviews. The congruence between patients’ and health professionals’ descriptions and perceptions of JHS was notable.

Our participants were recruited from four different geographical locations in the UK and, therefore, had experiences of different health-care services. A diverse range of individuals in terms of demographics participated and analysis showed commonality in views and experiences. However, the research findings may be limited by the fact that our patient participants were already using the health system and the health professionals in these focus groups were experts in the field, providing specialist care for JHS.

The authors recognised that the participants cannot provide accounts of their experiences that are not influenced by the research act (the focus group) and that this represents a particular kind of social interaction, which plays a role in shaping the participants’ dialogue. The researchers were aware of this issue and it is hoped that any negative effects were ameliorated where possible, for example by the fact that multiple authors, from diverse methodological backgrounds, were involved in the data analysis.

Component 2: development of the physiotherapy intervention

Aim

Using the findings from component 1, the overall aim of this component of the study was to develop a comprehensive physiotherapy intervention package and associated training materials.

Methods

Development of the advice intervention

The research team were very conscious of some of the feedback from patients and health professionals as part of the HPoP study regarding the design of the control intervention. There was a concern that an advice-only intervention would have a negative impact on recruitment and retention. The initial preferred design of the study was to include a delayed intervention control arm. However, the HTA funding committee convincingly argued that this would cause problems for establishing the long-term effectiveness of the physiotherapy intervention in any future definitive RCT. In the absence of any convincing research evidence for the effectiveness of physiotherapy, the research team agreed that there was an argument for clinical equipoise between physiotherapy and an advice-only control. It was therefore agreed that all patients would receive a one-off advice session, supplemented by advice booklets from the HMSA56 and Arthritis Research UK. 57 It was also agreed that some specific key issues from the Arthritis Research UK booklet would be discussed in detail, but that all participants would also be given the opportunity to ask for specific advice related to their own circumstances. The research team agreed that the key topics for discussion from the Arthritis Research UK booklet57 should be as follows:

-

What is hypermobility? (p. 5).

-

How is hypermobility diagnosed? (p. 10).

-

Drugs (pp. 11–13) – although patients would also be advised to consult their GP if they wanted a review of their medication.

-

Self-help and daily living (p. 14).

This one-off advice session and the advice booklets would act as the control intervention for those patients randomised to the control arm of the trial in the later pilot RCT (stage 3) but would be piloted as part of stage 2.

Development of the physiotherapy intervention

A comprehensive whole-body physiotherapy intervention was developed using a working group of researchers, health professionals and patient research partners. The group included three physiotherapists, a consultant rheumatologist, a clinical psychologist and two patient research partners with JHS.

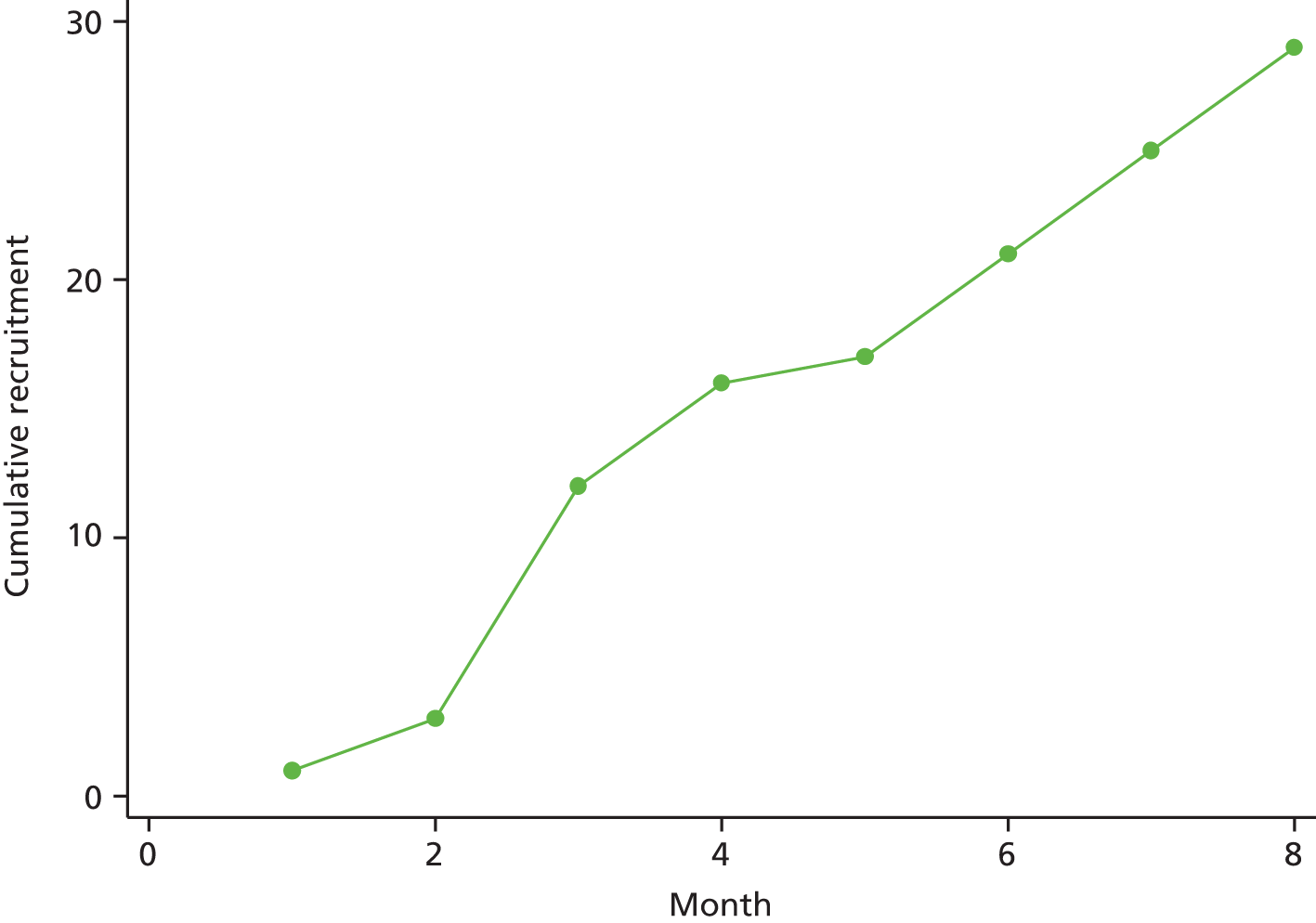

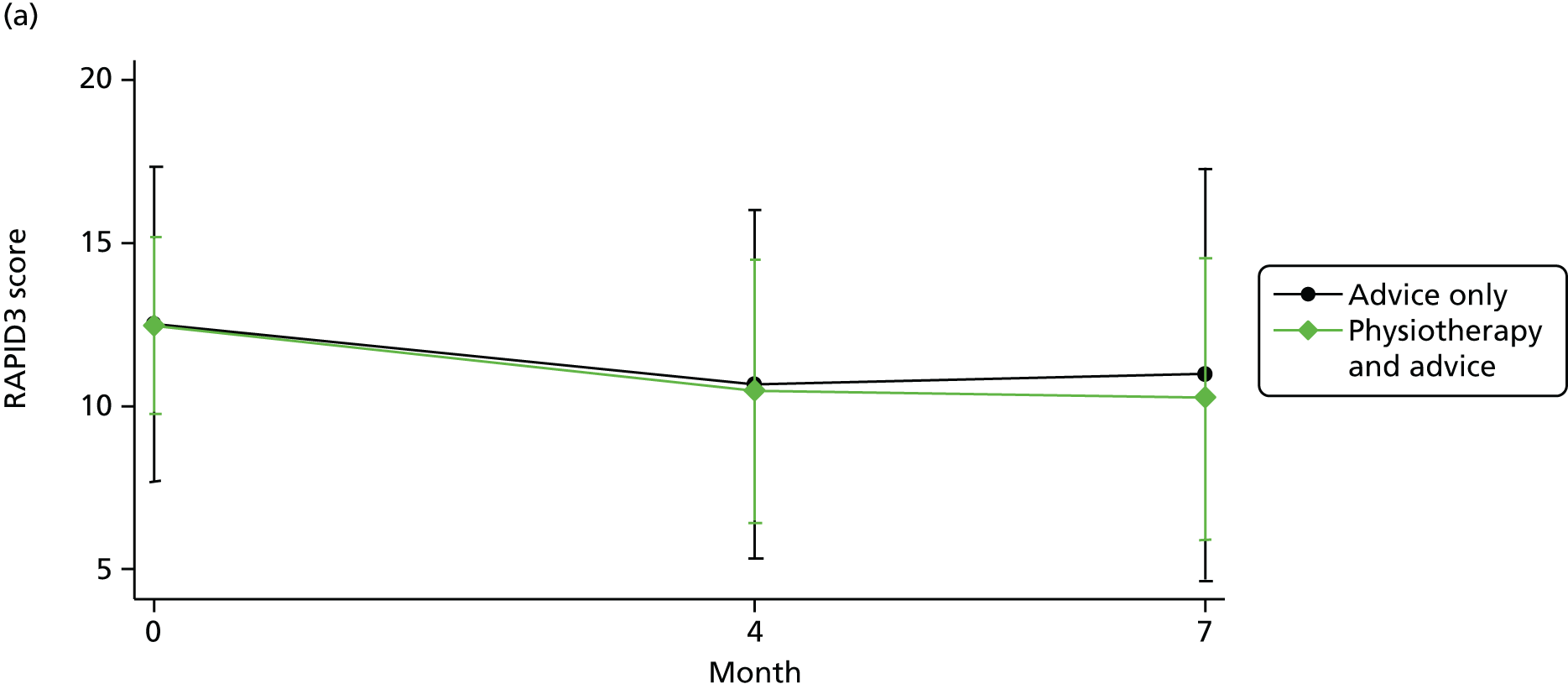

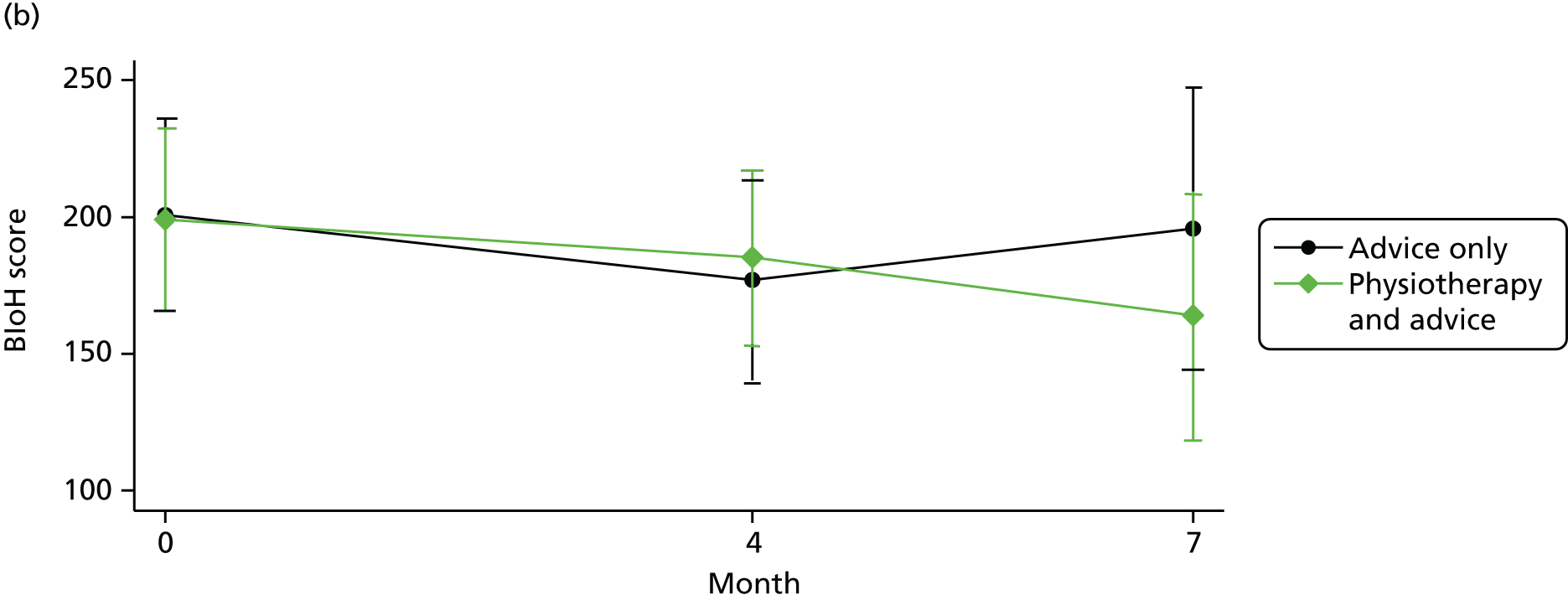

Discussion took place within the context of a number of guiding principles. These were related primarily to the resource context within which most physiotherapy services operate39 but also mirrored best practice as conducted at North Bristol NHS Trust. First, it was agreed that the intervention would be delivered on a one-to-one basis, as the needs of individual patients were considered to be so varied. Second, it was agreed that the intervention should be easy to implement in any outpatient department (and would therefore exclude complex or resource-intensive interventions such as hydrotherapy). Third, it was agreed that the intervention should include a maximum of six 30-minute treatment sessions over 4 months.