Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/53/25 and 11/136/108. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The draft report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jamie Inshaw, Anna Turkova, Nigel Klein, Sarah Bernays, Julia Kenny, Eleni Nastouli, Karen Scott, Lynda Harper, Sara Paparini, Rahela Choudhury, Tim Rhodes, Abdel Babiker and Diana Gibb report grants from the PENTA Foundation during the conduct of the study. Jamie Inshaw, Anna Turkova, Nigel Klein, Julia Kenny, Eleni Nastouli, Karen Scott, Lynda Harper, Rahela Choudhury, Abdel Babiker and Diana Gibb report grants from the European Commission (FP7) during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Butler et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically improved the prognosis for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected children. It has reduced early morbidity and increased survival, with > 80% of children expected to reach adulthood. 1 HIV infection has been transformed from a devastating, rapidly progressive lethal condition into a chronic disease. Now the challenges for the treatment of HIV-infected children are to (1) maximise the benefit of ART, which prevents illness and encourages growth and development, (2) minimise long-term drug toxicity, (3) minimise the development of drug resistance so that children continue to have therapy options as they move through adolescence and into adulthood, and (4) improve quality of life as much as possible for young people on ART.

Following recent results from a randomised controlled trial, in 2008 paediatric ART guidelines advocated starting ART in infancy (< 12 months of age) in all those diagnosed, because of a high risk of disease progression. 2 Subsequent guidelines from the World Health Organization (particularly for African countries) recommended starting ART in all children aged < 2 years (20103) and then in all children aged < 5 years (20134), mainly for programmatic reasons. Even if ART is not started early, vertically infected children face many more years of ART than adults, often given throughout childhood. Therefore, there is a growing population of older children and young people who have already been on ART for many years and are continuing to face the challenge of taking daily medication. 5

A major challenge for young people with HIV infection, as for any chronic illness, is maintaining long-term adherence to treatment regimens. 6–8 The importance of adherence to the long-term success of ART in maintaining virological suppression and preventing the emergence of resistance has been established. 9–16 However, experience with HIV-infected young people suggests that, with current treatment strategies, adherence rates fall far below the 90–95% adherence associated with long-term success. 17–19 Furthermore some studies have demonstrated a decline in adolescent adherence over time associated with duration on therapy. 19 Impediments to adherence for young people have been broadly categorised into two main groups: problems with medication, such as taste and palatability issues, and adherence difficulties related to social situations. 20 Although there have been considerable attempts to improve drug formulations, thus partly addressing the first impediment, the social dimensions are more complex; interference with daily life recurs as a common theme in assessments of poor adherence in young people.

New treatment strategies that promote adherence, minimise the development of resistance and reduce long-term drug exposure while improving quality of life are required for young people ‘burning out’ on daily ART regimens. Approaches to achieve this include (1) simplification of therapy (i.e. minimising the number of pills or swapping from twice-daily to once-daily dosing), (2) treatment interruptions [e.g. based on levels of CD4 as in the Paediatric European Network for Treatment of AIDS (PENTA) 11 trial;21 not currently advocated] and (3) very short treatment interruptions (particularly at inconvenient times for taking medication such as weekends) with the aim of maintaining viral suppression (one such possible strategy is to give therapy during the week but allow a break at the weekend).

Intermittent therapy

CD4-guided treatment interruptions

The large Phase III Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) trial evaluating a CD4-guided strategy in adults of stopping ART when the CD4 count was > 350 cells/mm3 and restarting ART when the CD4 count fell to < 250 cells/mm3 was stopped early because of evidence of increased disease progression and cardiovascular events, albeit at low rates, in the interruption arm. 22 Treatment interruption when viral load (VL) rebound occurs is now not recommended in adults.

The PENTA 11 Phase II trial [a randomised trial that compared CD4-guided planned treatment interruptions with continuous therapy (CT) in children aged 2–15 years] reported no significant increase in clinical progression in children undergoing planned treatment interruptions. 21 Further data on CD4 recovery and VL suppression following reintroduction of continuous ART in all children in this trial are awaited and interruptions using this strategy cannot be currently recommended. However, the initial findings of PENTA 11 provided reassurance for two other paediatric trials to investigate the impact of treatment interruptions {one evaluating interruptions following early limited ART in infants23 and the other evaluating CD4-guided interruptions in 600 older children [the BANA II trial; see www.bipai.org/Botswana/clinical-research.aspx (accessed 6 April 2016)]}.

Fixed-length treatment interruptions

In adults, trials of a fixed-length ART schedule of 1 week on and 1 week off therapy, based on the theory of autoimmunisation,24 showed high virological failure rates in patients following the 1 week on and 1 week off strategy compared with those on continuous or CD4-guided ART. 25,26

Very short treatment interruptions

An alternative approach is to use very short interruptions (short-cycle therapy; SCT) such that viral rebound should not occur, thus minimising the emergence of resistance as well as not compromising antiviral efficacy. This concept is based on the notion that > 95% adherence may not be necessary for virological suppression with all antiretroviral (ARV) regimens and that each ARV combination may have a unique adherence–resistance relationship. 9 Mathematical models of adherence and the emergence of resistance support this and the notion that otherwise strongly adherent patients might miss an acceptable number of doses of selected ARVs before resistance emerges. 27

Short-cycle therapy in adults and adolescents

Two Phase II trials of SCT in adults reported before the start of the BREATHER trial. First, a small single-arm pilot study of 5 days on, 2 days off ART in adults in the USA showed that long-term suppression of VL could be achieved. 28 Two of nine patients on protease inhibitor (PI)-based highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) had confirmed virological rebound by 48 weeks compared with one of 10 patients on nevirapine (NVP)-containing HAART and none of eight patients receiving efavirenz (EFV)-based regimens. As a result of this pilot, the randomised FOTO (Five On Two Off) trial in 60 adults with a VL of < 50 copies/ml on tenofovir (TDF)/emtricitabine (FTC)/EFV was conducted comparing daily ART with a strategy of 5 days on, 2 days off treatment. The 24-week results showed that all 25 patients in the FOTO arm and 24 of 28 patients (86%) in the daily arm who reached week 24 had a VL of < 50 copies/ml at this time point. 29 Reasons for not reaching 24 weeks were psychological (n = 2), because of the time burden (FOTO arm) (n = 3), pregnancy (n = 1) and loss to follow-up (daily ART arm) (n = 1); of note, all had a VL of < 50 copies/ml at discontinuation. There were six blips (VL 50–500 copies/ml) in the FOTO arm and nine in the daily ART arm to week 24; there were no instances of virological failure (confirmed VL > 400 copies/ml).

Second, in a trial in Uganda,30,31 146 adults who had a suppressed VL of < 50 copies/ml on a three-drug ART regimen were randomised to receive a week on, week off ART regimen (n = 32; this arm of the study was discontinued early), a 5 days on, 2 days off schedule (SCT) (n = 57) or CT (n = 57). The majority of subjects (94%) received an EFV-based regimen. The trial showed that SCT was not inferior to continuous HAART; there were 11 cases of failure in the CT group (including one death) and six in the SCT group (failure defined as VL > 1000 copies/ml, a decrease in CD4 count from randomisation of > 30% or a CD4 count of < 100 cells/mm3 on two consecutive occasions through the 72 weeks of follow-up; or VL > 400 copies/ml or development of an opportunistic infection at 72 weeks). Levels of resistance were no different between the SCT group and the CT group. For patients on HAART containing stavudine, there was a significant decrease in the incidence of lactic acidosis in the SCT arm compared with the CT arm.

The US-based Adolescent Trials Network conducted the only study of SCT in adolescents prior to the BREATHER trial, which had a non-randomised single-arm design to assess VL suppression (< 400 copies/ml, confirmed) on SCT (4 days on HAART, 3 days off) over 48 weeks. 32 Thirty-two participants aged 12–24 years and on a stable PI-based HAART regimen for at least 12 months were enrolled. Twelve of the 32 (38%) participants had confirmed virological rebound by 48 weeks, seven out of 15 (47%) of those infected before 9 years of age and five out of 17 (29%) of those infected after 9 years of age (p = 0.5). However, 75% of children had been exposed to five or more drugs in the past, with a previous history of virological failure. Overall, adherence was good (88% of participants showed > 90% adherence), with no difference between those with and those without VL rebound (p = 0.6).

Antiretroviral agents, viral load rebound and resistance

The plasma half-life of ARV agents in an ART regimen [or intracellular half-life of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTIs)] and their genetic barrier to resistance are important factors that may influence VL rebound and the development of resistance during a strategy of stopping therapy for 2 days every week.

An ART regimen containing three drugs, with relatively similar long half-lives and maintained therapeutic concentrations of > 2 days when treatment is stopped, would be an ideal regimen to avoid risk of VL rebound during the interruption and minimise the development of resistance. The regimen with the most favourable pharmacokinetic profile is TDF/FTC/EFV (median intracellular half-life of 150 hours, median intracellular half-life of 39 hours and plasma half-life of between 36 and 100 hours, respectively). 33 Coformulation of TDF/FTC/EFV34 in a single pill makes this a very attractive combination for older adolescents and young adults. However, in the Ugandan trial,31 EFV was given with either stavudine/lamivudine (3TC) or zidovudine (ZDV)/3TC without evidence of inferior virological performance, even though stavudine, 3TC and ZDV have shorter half-lives than TDF and FTC. PI drugs [e.g. lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra®; AbbVie Inc.), the most commonly used PI in children and adolescents] have substantially shorter half-lives and therefore if a regimen containing two NRTIs (with longer half-lives) and a PI (with a shorter half-life) is stopped, ‘functional dual NRTI therapy’ may result, with a risk of VL rebound and the development of resistance.

Data on viral dynamics in the first few days following treatment cessation are scarce. Jacobsen et al. ,24 in a four-arm study of planned treatment interruption ± HIV immunisation, reported viral rebound to > 50 copies/ml following treatment interruption at a median [interquartile range (IQR)] of 15 (8–31) days for those with a prior planned treatment interruption and 21 (13–30) days for those without a prior planned treatment interruption. Harrigan et al. ,35 while assuming a constant rate of viral increase that starts as soon as the patient stops therapy, suggest that many patients stopping therapy (previously suppressed) will have an increase in plasma viral HIV ribonucleic acid (RNA) of about 0.2 log/day and will reach detectable levels (> 50 copies/ml) only within 1–2 weeks of stopping therapy.

A substudy of PENTA 11 evaluated the pharmacokinetics, VL rebound and resistance profiles in 35 children stopping non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based ART. 36 In total, 21 children followed a staggered stop strategy whereby the NNRTI (NVP or EFV) was stopped at randomisation and the remaining two NRTI drugs were stopped 7–14 days later, and 14 children followed a replacement strategy whereby the NNRTI was replaced with a PI and all drugs were stopped 7–14 days later. Results of HIV VL testing in eight children following the staggered stop strategy and seven children following the replacement strategy showed that the majority of children still had undetectable HIV RNA 5–8 days after stopping all drugs (minimum 12 days after stopping the NNRTI). No NNRTI resistance mutations were detected in any of the children in the substudy.

Rationale and objectives

Adherence issues tend to worsen for older children and adolescents after they start taking charge of their own medication (after HIV diagnosis is disclosed); self-consciousness and not wanting to be different from peers predominate. There is the additional burden of secrecy around HIV infection and ART,15 and social and family pressures prevent young people from sharing information of their diagnosis or treatment with friends. 37 The result is often worsening adherence with frequently missed doses, particularly at weekends, which are typically times of socialising. Factors contributing to this include alcohol ingestion19 as well as the absence of school and overnight stays with friends at weekends. Therefore, a regimen in which ARVs need be taken only as part of the daily routine during weekdays could be attractive for older children (> 8 years) as well as teenagers and young people (16–24 years) who continue to be followed at paediatric or affiliated adolescent units.

Data from adult studies evaluating the strategy of 5 days on, 2 days off were promising, with low rates of virological rebound seen. However, no randomised trial had been undertaken in older children and adolescents, a population with potentially more to gain in terms of quality of life, long-term adherence to medication and the potential for better treatment options in adulthood. The effect on overall adherence of allowing 2 days off treatment per week was unknown and it was therefore important to first evaluate the strategy in young people who have a history of good adherence, the argument being that offering this strategy could prevent ad hoc missed doses occurring. In view of the relatively shorter half-life of PIs and because both adult trials referred to above were undertaken with EFV-based regimens, enrolment was limited to children who are on, or who are willing to switch to, a regimen containing EFV.

The BREATHER trial aimed to assess whether or not young people with chronic HIV infection undergoing SCT of 5 days on and 2 days off following complete virological response to first-line ART for at least 12 months maintained the same level of VL suppression as those on CT. Importantly, because of insufficient data on short-term VL rebound after stopping ART in this population, the trial incorporated an initial pilot phase to assess the safety of the SCT strategy.

Risks and benefits

The potential risks of the SCT strategy were as follows:

-

The main risk was that the SCT strategy would prove ineffective at maintaining VL suppression, either because VL could not be maintained below detection levels during 2 days off ART or because of non-adherence to the strategy by extending the time off treatment. However, if a raised VL was confirmed on repeat testing (carried out within 1 week) then the participant was placed back on CT.

-

An additional risk was that young people who had been fully adherent to ART before enrolment in the study might extend the permitted very short interruptions and that overall adherence would decline. Of note, there was equipoise about whether adherence would be better or worse in the SCT arm than in the CT arm as young people in the continuous arm may also not take their treatment regularly. All young people were given a diary to record when they had taken ART and were asked to comment about difficulties in remembering to take medication. Rebounding VL comes with the risk of development of resistance (particularly to EFV and 3TC, which have low genetic barriers to resistance), which in turn may limit future therapeutic options. Resistance testing was performed on all young people who lost virological suppression in either arm at the point of loss of suppression (≥ 50 copies/ml), as well as on any subsequent samples with a HIV-1 RNA level of ≥ 1000 copies/ml.

The potential benefits of the SCT strategy were:

-

improvement in quality of life from having weekends free from taking medication

-

improved long-term adherence during the week

-

decreased long-term toxicity of ARV drugs (particularly relevant for some NRTI drugs, e.g. ZDV and TDF)

-

decreased cost, which is important to any health-care service and in particular for many parts of the world where HIV prevalence is highest.

Young people and carers were fully informed of the possible benefits and known risks by means of a patient information sheet as appropriate and this was reinforced by discussions with the study research teams at the individual sites prior to enrolment.

Pilot study

Because of insufficient data on short-term VL rebound after stopping ART in this population, the trial incorporated an initial pilot phase in selected centres. The aim of the pilot phase was to ensure that the SCT strategy did not result in a high proportion of young people with an increased VL (≥ 50 copies/ml) of ART in the first few weeks.

Those enrolled in the pilot and randomised to SCT were permitted to take only Saturday and Sunday off treatment. They received VL testing on Monday, prior to resumption of ART. Recruitment to the main trial commenced only when all pilot participants had completed 3 weeks on the study and the results were reviewed by the Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) to ensure that there were no safety concerns. Preset criteria for stopping included a HIV-1 RNA level of ≥ 50 copies/ml (validated by a HIV-1 RNA level of ≥ 50 copies/ml on the same sample) at weeks 1, 2 or 3 following weekend interruption and before restarting ART in more than five participants as this would have given evidence that VL suppression rates on a SCT strategy in general were < 90% [10/15 suppressed = 66%, 95% exact confidence interval (CI) 38% to 88%]. Data from the pilot phase were reviewed by the IDMC who identified no safety concerns and recommended that recruitment continue.

Substudies

Plasma and cells were stored for both arms throughout the trial for the virology, inflammatory biomarkers and immunology substudies. The rationale behind the biomarker substudy was to determine whether or not any markers of inflammatory response were increased among children in the SCT arm compared with the CT arm, even if VL suppression was no different. This has been observed in adult trials such as the SMART trial in which interruptions resulted in an increase in VL. 22

There was also a qualitative substudy that aimed to (1) evaluate the acceptability of SCT and of the trial from the perspectives of young people participating; (2) explore whether or not they perceived that SCT facilitated improved adherence; (3) document how young people experience life with ART; and (4) understand how their experiences in adolescence affect their capacity and willingness to adhere to taking their treatment. As well as producing knowledge to better support optimum adherence among adolescents, the study also aimed to (5) compare the HIV treatment and trial experiences of young people in the UK, Ireland, Uganda and the USA.

Chapter 2 Methods

This open, randomised, parallel-group Phase II/III trial was performed in 24 centres worldwide (see Acknowledgements for the different sites). This was a strategy trial.

Trial entry criteria

The trial enrolled HIV-1-infected young people aged 8–24 years inclusive who had been on a stable first-line ART treatment containing at least two NRTIs/NNRTIs and EFV for at least 12 months and who were willing to continue the regimen throughout the study period. Previous dual therapy and/or substitution of NRTIs was allowed providing any changes were not the result of disease progression or immunological or virological failure (with virological failure defined as two successive HIV-1 RNA results of > 1000 copies/ml) subsequent to virological control having been achieved on ART. They must have had viral suppression (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/ml) for at least the previous 12 months (at least the last three measurements, including screening). Young people who had experienced a single VL of > 50 copies/ml but < 1000 copies/ml (preceded and followed by a VL of < 50 copies/ml) in the last 12 months could be enrolled. They must have had a CD4 cell count of ≥ 350 × 106/l at the screening visit.

Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or risk of pregnancy in females of childbearing potential, acute illness, receiving concomitant therapy for an acute illness or a creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation of grade 3 or above at screening. Participants could not be on a regimen including NVP or a boosted PI (young people could be switched to an EFV-based regimen) or have had previous ART monotherapy (except for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission).

The age group of 8–24 years was chosen as young people between these ages are likely to undertake independent weekend activities and thus SCT could improve their quality of life by giving them more control over when they take their HIV medication, helping them to maintain their privacy regarding HIV infection and treatment taking while socialising at weekends.

Randomisation and treatment strategies

Participants were randomly assigned 1 : 1 to maintain CT or switch to SCT. Randomisation was performed centrally by the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit (MRC CTU) at University College London (UCL) according to a computer-generated randomisation list, using random permuted blocks stratified by age at randomisation (8–12, 13–17 and 18–24 years) and by African compared with non-African country.

The trial sites enrolled patients and assigned participants to interventions by either accessing the trial randomisation server directly or contacting the relevant trial unit who performed the randomisation on their behalf.

Young people randomised to SCT followed a cycle of 5 days on ART (Monday–Friday or Sunday–Thursday) and 2 days off (Saturday and Sunday or Friday and Saturday). Participants randomised to the SCT arm were able to choose which 2 days off ART they preferred and whichever days were chosen were continued throughout the entire time on SCT within the study. Young people randomised to CT continued their current ART regimen and stopped or switched drugs in their ART regimen only for virological, immunological or clinical failure according to local practice. However, if simplification of the ART regimen or substitution of one drug (not EFV) was deemed necessary for clinical reasons, this was allowed after discussion with the appropriate trials unit.

Clinical examinations

A clinical examination was performed at screening, randomisation and certain follow-up protocol visits. At each visit the following data were recorded: body weight and height and all adverse events (AEs) since the last protocol visit, including in particular haematological abnormalities, pancreatitis, diarrhoea, clinical lipodystrophy, acute illnesses and change in HIV disease stage since the last protocol visit.

A physician assessment of lipodystrophy and Tanner stage was performed at week 0 and repeated every 24 weeks until the end of the study. A pregnancy test was performed for all females of childbearing potential at screening (weeks –4 to –2) and repeated every 24 weeks until the end of the trial and at other time points if required.

Ethnic-origin data were collected because it is known that ethnicity is a factor in the concentration levels of EFV.

Laboratory tests for efficacy and safety monitoring

-

Haematology: haemoglobin, mean corpuscular red blood cell volume (MCV), platelets, white cell count, neutrophil and lymphocyte counts.

-

Biochemistry: creatinine, albumin, total bilirubin, ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, calcium, phosphate.

-

Lipids/glucose: triglycerides, cholesterol [total, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein, very-low-density lipoprotein], glucose (participants should have been fasting overnight at randomisation, weeks 24 and 48 and then every 48 weeks during the main trial).

-

Lymphocyte subsets: CD3 (absolute and percentage), CD3 + CD4 (absolute and percentage*), CD3 + CD8 (absolute and percentage*), total lymphocyte count (if measured by immunology laboratory) (*CD45RO/RA if measured).

-

Virology: HIV-1 RNA (VL) using an ultrasensitive assay and resistance testing [locally or on stored samples (when VL was detectable)].

Screening visit

At the screening visit a trial number was assigned and used on all paperwork and labels. A clinical assessment was completed and the participant and/or carer completed an adherence questionnaire according to the young person’s age and knowledge of HIV diagnosis.

Blood was taken for haematological and biochemical investigations, for measurement of T-cell subsets (including RO/RA phenotype when available), for measurement of HIV-1 RNA VL (it was requested to use the same assay at least throughout the pilot phase and ideally throughout the whole trial, although the assays used varied across centres according to clinical practice and management) and for plasma and cell storage (at clinical centres where this was possible).

Randomisation visit

Randomisation (week 0) took place no more than 4 weeks after the screening visit and ideally as soon as possible after eligibility had been confirmed. The eligibility criteria and consent were reconfirmed verbally and noted on the randomisation form. Once a patient was randomised, a clinical assessment was completed, which included measurements of height and weight, presence of AEs, change in HIV disease stage and ethnic origin. The following investigations were performed: haematology, biochemistry, glucose and lipid profiles (fasting) and T-cell subsets (plus RO/RA phenotype if available). Blood was taken for plasma storage (plus cell storage if the participant attended a clinical centre where this procedure was possible or where a courier could be arranged). A quality-of-life questionnaire [Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; see www.pedsql.org/ (accessed 6 April 2016)] was completed for all participants (and carers) and an acceptability questionnaire was completed for those young people randomised to SCT (and carers). Participants were given a diary to record when they took their ART, which included a reminder to restart therapy after the 2 days off ART in the SCT arm.

Follow-up

Young people were followed until the last randomised participant had completed 48 weeks of follow-up. All young people were seen for clinic visits at weeks –4 to –2 (screening), 0 (randomisation), 4, 12, 24, 36 and 48.

Sample size

This trial planned to enrol a minimum of 160 young people, at least 80 per arm.

Assuming that 90% of young people in the CT arm and in the SCT arm maintained a HIV-1 RNA level of < 50 copies/ml to week 48, 155 young people would have provided at least 80% power to exclude a difference of 12% between the two arms (i.e. to exclude suppression rates of < 78% in the SCT arm) (one-sided alpha = 0.05). 38 A minimum of 160 young people (80 per arm) had to be enrolled to allow for loss to follow-up (in previous PENTA trials loss to follow-up has been < 3%).

The power calculations were based on the assumption that 90% of patients in the CT arm would remain virally suppressed to week 48. Any decrease in this percentage was likely to underpower the study and would lead to an equivocal result, as could other changes to the assumptions.

A sample size of 220 participants would have increased the power of the study by at least 10% for varying levels of suppression. At its meeting in December 2012, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) recommended that the study should remain open to randomisation until the end of the defined recruitment period, even if the total number of participants enrolled exceeded 160, as this would enhance the power of the study; this was communicated to and agreed by the IDMC. The specified sample size was increased in protocol version 1.7 (dated 24 April 2013) from a recruitment target of 160 to a target of at least 160 but not exceeding 220 participants (see Appendix 1).

The trial was not formally powered to detect differences between CT and SCT, but to exclude substantial virological disadvantages [i.e. HIV-1 RNA suppression rates (< 50 copies/ml) of < 78%] in the SCT arm by following a 5 days on, 2 day off strategy, that is, a non-inferiority trial.

A non-inferiority margin of 12% was chosen to represent a clinically acceptable difference in the rate of virological suppression (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/ml) between the two arms and to allow the trial to be adequately powered and feasible to conduct based on estimates of available young people followed in PENTA centres.

Pilot study

The first participants randomised in the study (n = 15 in the SCT arm and n = 17 in the CT arm) were included in the pilot phase and had weekly HIV-1 RNA measurements during the first 3 weeks of the study. Those randomised to the SCT arm and included in the pilot phase stopped taking their ART on Saturdays and Sundays, that is, they followed a cycle of 5 days on ART (Monday–Friday) and 2 days off ART (Saturday–Sunday) during the pilot phase. Recruitment to the CT arm ran concurrently.

Young people in the pilot phase had four additional phlebotomy visits (HIV-1 RNA and blood store only) at weeks 1, 2, 3 and 8. For young people in the SCT arm the blood draws were on the Monday after the first, second and third weekends off ART and before ART recommenced; for young people in the CT arm these blood draws were at any time during the first, second and third weeks.

The IDMC met at the end of the pilot phase to review the interim data (see Appendix 2 for dates of all IDMC meetings).

Management of young people and viral load tests

-

Pilot phase. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for HIV-1 RNA can occasionally yield spurious results suggestive of low-level viraemia. During the pilot phase only, any HIV-1 RNA measurement detected of ≥ 50 copies/ml at weeks 1, 2 or 3 was repeated on the same sample to ensure that the result was valid and reproducible.

-

SCT arm. Participants with a HIV-1 RNA measurement of ≥ 50 copies/ml had a confirmatory VL measurement taken on a separate sample within 1 week. No further interruptions to ART were undertaken until the repeat test result was obtained. Participants with a confirmed viral rebound of ≥ 50 copies/ml recommenced CT and should not have undergone further interruptions to their therapy. Participants with an isolated HIV-1 RNA measurement of ≥ 50 copies/ml and a subsequent measurement of < 50 copies/ml could remain on SCT. There could be a maximum of three such occurrences during the lifetime of the study. After the third increase, CT was resumed with no further interruptions.

-

CT arm. Participants with a HIV-1 RNA measurement of ≥ 50 copies/ml had a confirmatory VL measurement taken on a separate sample within 1 week. Participants with a confirmed VL of ≥ 50 copies/ml received standard clinical care.

Study duration

Young people were followed until the last randomised participant had completed 48 weeks of follow-up, at which point the main trial was considered complete. Participants who were followed after week 48 were seen every 12 weeks until the main trial was complete. Participants randomised to the SCT arm continued to follow the SCT strategy until the main trial was complete unless the clinician or the family had concerns, which the clinician discussed with the appropriate trials unit.

Following the recommendations of the TSC (December 2013) and the subsequent protocol amendment (version 1.9) and participant consent, ongoing long-term follow-up of the trial for a further 2 years commenced in July 2014 (see Appendix 1). Stable and virologically suppressed young people who were randomised to SCT can opt to continue SCT during the long-term follow-up if they have 12- to 16-week VL monitoring and if agreed by the clinician and family. Management of HIV-1 RNA VL will continue as during the main study period.

Data collection and handling

Sites in the UK and Ireland were managed by the MRC CTU, subsequently the MRC CTU at UCL. Sites in the USA, Germany, Uganda, Thailand (HIV Netherlands Australia Thailand Research Collaboration) and the Ukraine were managed by the MRC CTU at UCL in collaboration with national co-ordinators. Sites in Spain, Belgium, Denmark and Argentina are managed by the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM SC10-US19) in collaboration with national co-ordinators. Program for HIV Prevention and Treatment (PHPT) sites in Thailand were managed directly by the PHPT.

Data were recorded on case report forms (CRFs); the completed CRFs were sent to the appropriate trials unit for data entry and a copy kept at the local clinical centre. Data from the CRFs were entered onto databases held at the co-ordinating trials units and exported into Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis. After completion, adherence and acceptability questionnaires were sent to the appropriate trials unit for data entry.

Data received at each of the trials units were checked for missing or unusual values (range checks) and for consistency within participants over time. If any such problems were identified, a missing data report of the problematic data was sent to the local site by password-protected e-mail for checking and confirmation or correction, as appropriate; any data that were changed were crossed through with a single line and initialled. The amended data were returned to the appropriate trials unit and filed in the notes at the site. The trials units sent reminders to sites under their management for any overdue and missing data.

Interim analysis

The trial was reviewed by the PENTA IDMC. No member of the PENTA Steering Committee or the BREATHER TSC or any clinician (investigator) responsible for the clinical care of trial participants could be a member of the IDMC. The IDMC reviewed all aspects of the trial, including the number of participants recruited.

The IDMC met four times in strict confidence over the course of the trial: 28 October 2011, 5 September 2012, 31 July 2013 and 7 February 2014, with the last meeting being about VL monitoring only. The IDMC was to inform the chairperson of the TSC if, in its view, the results provided either:

-

unequivocal evidence* that was likely to convince a broad range of HIV clinicians, including the study investigators, that one of the two treatment strategies (CT or SCT) was performing poorly for all participants or for a particular category of participants and there was a reasonable expectation that this new evidence would materially influence patient management or

-

good evidence* that CT was superior to SCT in terms of the primary outcome and the non-inferiority of SCT was extremely unlikely to be demonstrated with continued enrolment and/or follow-up.

*The criteria for the strength of evidence could not be defined precisely and were left to the judgement of the IDMC. However, as an example, if in an interim analysis the 99% CI for the hazard ratio for the primary outcome excluded 1, this may be considered as providing good evidence of a difference in risk between the two groups. If the 99.9% CI also excluded 1, this may be regarded as providing unequivocal evidence of a difference between the two groups.

Clinical site monitoring

Trial-related monitoring at trial sites was carried out according to the trial protocol. Trial sites had to agree to provide access to source data/documents. Consent from parents/carers/young people, as appropriate, for direct access to data was also obtained.

In addition to a site initiation (either through a visit or in a teleconference), all clinical centres were monitored at least once during the trial and the following data were validated from source documents:

-

eligibility and signed consent

-

clinical disease progression to new Centers for Disease Control (CDC) C event or death

-

HIV-1 RNA VLs ≥ 50 copies/ml (primary end point only)

-

a random sample of CD4 measurements

-

a random sample of laboratory results

-

a random sample of original records of ARV prescriptions (with batch numbers)

-

a random sample of clinical data

-

all original records of ARV prescriptions (with batch numbers) for all young people participating in the qualitative substudy.

Patient and public involvement

Polly Clayden, a patient advocate, has been an independent member of the PENTA Steering Committee for many years and was closely involved in the discussions about the protocol during its development. She works at i-Base, a treatment activist group, which is developing a young person Community Advisory Committee with the UK Children’s HIV Association (CHIVA). Members of the study team, particularly in the UK and Ireland, are closely involved with CHIVA, which promotes issues relevant to children infected or affected by HIV, including the needs of adolescents and good practice in transitional care. Collaborator Magda Conway is an independent consultant with extensive experience of working directly with young people with HIV. She has been awarded a grant by the Elton John AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) Foundation to strengthen networks of young people living with HIV in the UK and facilitated a group discussion with MRC CTU staff and a CHIVA youth group prior to the finalisation of the study protocol. CHIVA was closely involved in developing a communication and dissemination strategy for the main trial results and created a one-page results information leaflet (see Appendix 3) that was sent out to sites to give to their patients.

Protocol changes

See Appendix 1.

Main study statistical methods

Primary end point

The primary analysis was performed on the intention-to-treat population. We used Kaplan–Meier techniques to estimate the proportion of young people failing in each arm by the 48-week assessment, adjusting for stratification factors: age range (8–12, 13–17 and 18–24 years) and recruitment from an African site. Using these proportions, we were able to estimate the difference in the proportion failing between arms and obtain a 90% CI around the difference, using bootstrap standard errors. This CI was used as an indicator of whether or not the results were consistent with the non-inferiority of SCT compared with CT. The non-inferiority margin was prespecified at 12% so that, if the upper bound of the 90% CI of the difference between arms (SCT – CT) was < 0.12, non-inferiority would be demonstrated.

The primary analysis was repeated but without adjusting for stratification factors. Additionally, an analysis was performed investigating the crude proportion of young people who experienced virological failure up to the end of the 48-week assessment.

Secondary end points

All analyses performed on the primary end point were repeated but instead considering the end point as a confirmed VL of ≥ 400 copies/ml.

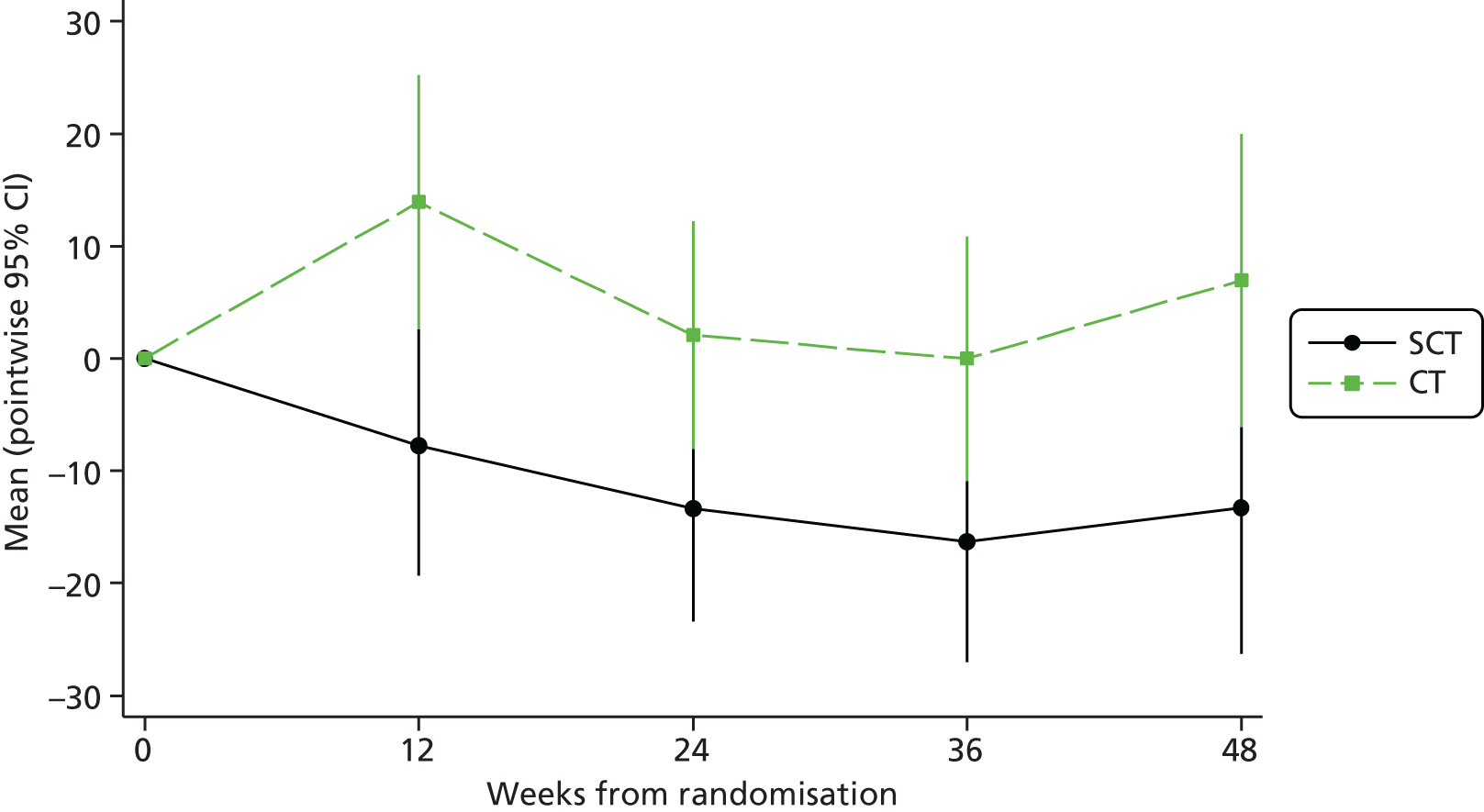

Immunology, biochemistry and lipids were evaluated at each follow-up visit up to 48 weeks after randomisation by fitting normal regression models, adjusting for randomised arm and baseline value.

Changes in ART from SCT to CT at any point during the first 48 weeks of the trial for those randomised to SCT were summarised by reason for changing strategy. Changes in ART regimen were summarised by arm.

Major HIV-1 resistance mutations39 at the point of VL failure or any time after VL failure were summarised for any VL failures in the first 48 weeks, overall and by drug class. CDC stage B and C events, as well as any deaths, were summarised by arm.

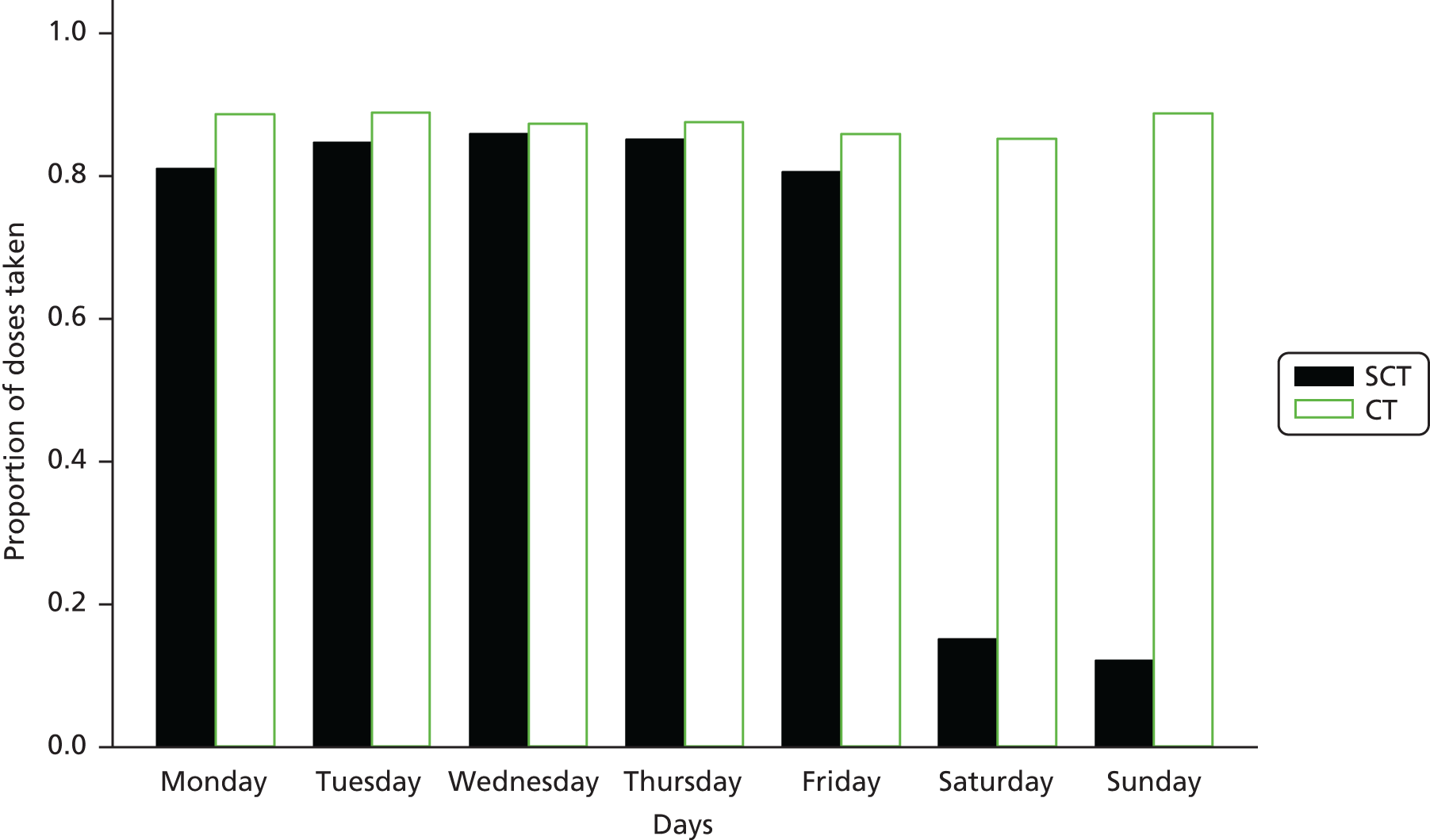

Measuring adherence was an important aspect of the analysis as we were attempting to see whether or not randomised strategies were being adhered to. We measured adherence to the protocol in two ways: first, through adherence questionnaires and, second, through a MEMSCap™ Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMSCap Inc., Durham, NC, USA) substudy on a subset of 61 patients.

Acceptability questionnaires were summarised at baseline and week 48, and the comparison between what young people found difficult before the study and what they found difficult during the study was examined using McNemar’s test.

Safety

Grade 3 and 4 clinical and laboratory AEs were summarised by arm. The difference in rate of grade 3 and 4 AEs between arms per 100 person-years was calculated using Poisson regression (with a random effect for person) and the number of young people with any grade 3 or 4 AE was compared between arms using a Fisher’s exact test. The same analyses were performed for ART-related AEs, treatment-modifying AEs and serious adverse event (SAEs).

Inflammatory biomarkers substudy

Rationale behind methods and markers selected

The blood volume that can be collected in children is limited, which was a major influence on the techniques selected for use in this study. In view of the global recruitment of the PENTA 16 trial, the assay selection was also influenced by its robustness to freezing at –80 °C for variable periods of time.

A panel of 19 biomarkers has been studied in several trials by the immunology laboratory at the UCL Institute of Child Health. Together they cover markers of inflammation (interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, C-reactive protein, tumour necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 10, interleukin 6, interleukin 8), cardiovascular injury (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, angiopoietin-1 and -2, E-selectin, P-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 3, thrombomodulin, serum amyloid A, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule, vascular endothelial growth factor) and disordered thrombogenesis [d-dimer, tissue factor (TF)].

Methods

Blood was collected in ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) and spun within 4 hours of collection at 1500 g (≥ 2500 rpm) for 15 minutes to separate cells from plasma. The supernatant was removed and placed in aliquots with a minimum of 500 µl of plasma in each cryovial. Samples were frozen at –70 °C immediately. Repeat freeze–thaw cycles were avoided.

All samples were transported to the Institute of Child Health during September 2014 and the assays were run in batches between October and December 2014. All standards were run in duplicate. Initial work within the laboratory showed that the coefficient of variance between duplicate samples was ≤ 10%. Given the small volumes of blood available and the cost of the plates, 95% of samples were run singularly, with 5% duplicated to ensure consistent intra- and inter-assay precision. The lower limit of detection, determined by the mean plus 2 standard deviations of the output signal of 10 blank samples, was calculated for each biomarker.

Meso Scale Discovery technique

A total of 17 biomarkers were analysed using Meso Scale Discovery® (MSD) assays (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). MSD assays use an electrochemiluminescence detection method similar to a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique. High-binding carbon electrodes in the base of microplates have a 10 times greater binding capacity than polystyrene. Electrochemiluminescent (SULFO-TAG) labels are conjugated to detection antibodies. Within the analyser, electricity applied to the plate electrodes causes light emission by the SULFO-TAG labels. Light intensity is then measured to quantify analytes in the sample. Multiple excitation cycles of each label amplify the signal to enhance light levels and improve sensitivity allowing ultrasensitive assays to be run [see www.mesoscale.com/technical_resources/our_technology/ecl/ (accessed 18 February 2015)].

Five MSD plates were used. Table 1 lists the plates with the biomarkers on each plate. Assays were conducted according to standard manufacturer’s protocols. Samples were read using the QuickPlex SQ analyser (MSD).

| Method | Plate | Biomarker | Units | Lower level of detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSD | Vascular injury-1 | TM | ng/ml | 0.064 |

| ICAM-3 | ng/ml | 0.064 | ||

| E-selectin | ng/ml | 0.064 | ||

| P-selectin | ng/ml | 0.064 | ||

| Vascular injury-2 | SAA | pg/ml | 10.9 | |

| CRP | pg/ml | 1.33 | ||

| VCAM-1 | pg/ml | 6.0 | ||

| ICAM-1 | pg/ml | 1.03 | ||

| Custom cytokine | IL-6 | pg/ml | 0.192 | |

| IL-8 | pg/ml | 0.132 | ||

| IL-10 | pg/ml | 0.0806 | ||

| MCP-1 | pg/ml | 0.116 | ||

| TNF-α | pg/ml | 0.0798 | ||

| VEGF | pg/ml | 0.229 | ||

| IL-1RA | IL-1RA | pg/ml | 2.44 | |

| Angiopoeitin-1 and -2 | Angiopoietin-1 | pg/ml | 24.4 | |

| Angiopoietin-2 | pg/ml | 2.44 | ||

| ELISA | TF | TF | pg/ml | 0.69 |

| D-dimer | D-dimer | ng/ml | 0 |

Tissue factor

Tissue factor levels were measured using a commercial quantitative sandwich ELISA kit (Quantikine® ELISA Human Coagulation Factor III/Tissue Factor R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). A total of 100 µl of assay diluent was added to 96-well microplates precoated with a monoclonal antibody against human TF. Subject plasma was diluted twofold in Calibrator diluent RD5-20 (R&D Systems). The 100-µl standards and then 100-µl diluted subject plasma were added and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature on a horizontal orbital microplate shaker set at 600 rpm. The plate was manually washed four times using wash buffer and excess fluid was removed by tapping the plate on a paper towel before 200 µl of TF enzyme-linked polyclonal antibody conjugate was added. After a further 2 hours’ incubation the wash cycle was repeated and 200 µl of substrate solution [stabilised hydrogen peroxide/chromogen (tetramethylbenzidine)] was added. The plate was then protected from light during a final 30-minute incubation, after which 50 µl of stop solution was added, and optical density was measured within 30 minutes using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific Multiskan® EX) set to 450 nm. A four-parameter logistic curve fit was calculated using Ascent software 2.6 (Thermo Labsystems Oy, Basingstoke, UK) and the concentration read from the standard curve and multiplied by the dilution factor of two.

D-dimer

The commercial TECHNOZYM® D-dimer ELISA assay (Technoclone, Vienna, Austria) was chosen following a comparison of two ELISA methods with two automated methods used in the NHS coagulation laboratory at Great Ormond Street Hospital. This provided consistent results and required smaller volumes of blood than the automated methods.

Undiluted samples were used after pilot runs showed that most patients had levels of D-dimer below the limit of detection when a twofold dilution was used. A total of 100 µl of calibrator and sample were added to wells precoated with anti-D-dimer monoclonal antibody and were then incubated at 37 °C for 60 minutes. Following manual plate washing three times using wash buffer (pH 7.3), 100 µl of conjugate (monoclonal Anti D-dimer-POX) working solution was added before a further 60-minute incubation at 37 °C. Following a second plate wash, 100 µl of substrate solution (chromogen tetramethylbenzidine) was added. After a 10-minute incubation at room temperature, 100 µl of stop solution (sulphuric acid) was added and the plate read immediately using a microplate reader (Multiskan EX) set to 450 nm. A linear regression curve fit was calculated using Ascent software 2.6 and the concentration read from the standard curve.

Statistical methods

Two linear regression models were fitted for each biomarker, at 48 and 96 weeks, adjusting for baseline biomarker value and randomised arm. However, because of the non-normal distribution of each biomarker, the natural logarithm was used to fit the models.

Immunology substudy

Rationale for an immunology substudy

A study comparing CD4-guided planned treatment interruptions of ART with CT in HIV-1-infected children was performed between 2004 and 2006. 40 The key immunological findings were that (1) there was a rapid fall in CD4 cells that occurred early following treatment interruption; (2) there was a rapid increase in CD8 cells peaking at 8 weeks after the planned treatment interruption; and (3) there were changes in naive and memory cell subsets within both the CD4 and the CD8 cell populations. 41 This study informed our focus on these cell populations to determine whether or not treatment interruption in the BREATHER trial would have an impact on immune dynamics.

Methods

The CD4 and CD8 lymphocyte subsets were quantified locally on fresh samples collected. In some centres, CD45RA and CD45RO subpopulations of CD4 and CD8 cells were also evaluated on fresh samples. In centres able to separate and store cells, additional whole blood was collected in EDTA and peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated by density gradient centrifugation, divided into aliquots and frozen. A range of established markers was used to quantify naive and memory cells. These varied between laboratories but always included antibodies to detect CD45RA and CD45RO; in some laboratories, CD27 and CD31 were also included.

Statistical methods

Linear models of the CD45RA/CD45RO ratio, adjusting for baseline CD45RA/CD45RO ratio and randomised arm, were fitted at 48 weeks. Similar models were fitted for CD45RA%/CD45RO%, CD8RA/CD8RO and CD8RA%/CD8RO%. Because of non-normal distributions of these ratios, the natural logarithm of each ratio was used to fit the models.

Virology substudy

Statistical methods

We compared the proportion of individuals at week 48 with a VL of ≥ 20 copies/ml with the proportion with a VL of ≥ 50 copies/ml from the main trial analysis. Additionally, we investigated the difference between arms in the proportion of young people with a VL of ≥ 20 copies/ml at week 48 and tested the difference using a Fisher’s exact test.

We examined how many individuals who failed during the first 48 weeks of the main trial had a screening (or baseline if no screening sample available) VL of ≥ 20 copies/ml.

Finally, we compared the proportion of young people in each arm who had a VL of < 20 copies/ml at screening (or baseline if no screening sample available) and a VL of ≥ 20 copies/ml at week 48 using a Fisher’s exact test.

Laboratory methods

Ultrasensitive quantitative HIV-1 ribonucleic acid assay

The quantitative HIV-1 RNA assay used the Qiagen QIASymphony® SP (Manchester, UK) automated nucleic acid extraction procedure for extraction of HIV-1 RNA from 1 ml of plasma sample. An ABI Prism 7500 (Foster City, CA, USA) real-time PCR instrument with Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) reagents was used for amplification and detection of HIV-1 RNA. The quantification is based on an in-house standard curve calibrated against the World Health Organization hepatitis C virus international standard in IU/ml. The assay uses brome mosaic virus RNA as an internal control, which is introduced at the extraction stage. The multiplex real-time RT-PCR detects both HIV and brome mosaic virus with differently labelled TaqMan® probes.

Quantitative total HIV-1 deoxyribonucleic acid assay

The quantitative HIV-1 deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) assay used the Qiagen DNA mini blood kit for extraction of DNA. An ABI Prism 7500 real-time PCR instrument with Invitrogen RT-PCR reagents was used for amplification and detection of HIV-1 DNA. The quantification is based on a standard curve using 8E5 cells and carrier RNA (Qiagen lot:139285838). Absolute maximum amount of input DNA in a PCR is 600 ng per reaction. The lower limit of dilution is 10 HIV copies/million cells (patients on HAART and undetectable HIV RNA in plasma usually have a total HIV DNA level of around 100 HIV copies/ml). The assay uses pyruvate dehydrogenase DNA as an internal control. The multiplex real-time RT-PCR detects both HIV and pyruvate dehydrogenase with differently labelled TaqMan probes. Results are reported as copies of HIV per million cells.

Qualitative substudy

Sample

All young people recruited into the BREATHER trial in the UK, Ireland, Uganda and the USA aged 10–24 years were eligible to participate in the qualitative substudy, subject to the appropriate consents and self-awareness of HIV infection (for at least 6 months). Although the trial included children from the age of 8 years, the qualitative study involved trial participants who were aged ≥ 10 years only and aware of their HIV status. Although we appreciate that age can be an inadequate proxy for HIV awareness, this decision was guided by ethical concerns about the extent to which children under the age of 10 years could have achieved the considerable understanding about HIV infection necessary for the in-depth discussions in the qualitative interviews.

In our design we had envisaged that we would adopt a purposive sampling strategy giving primary emphasis to ‘responsibility for medication’ (sole, shared, carer), with secondary dimensions including age (spread as per trial), gender, ethnicity, membership of HIV youth support groups, current domestic situation (living with parent(s), extended kin) and school attendance. However, given the lower than expected levels of recruitment into the trial in the UK and Ireland, we involved anybody who was eligible and willing to participate. In the US site, given the nature and timing of the fieldwork we adopted the same strategy, which meant that we involved all participants who had thus far been recruited into the trial. In Uganda, excluding those who were in the pilot, we initially adopted a similar recruitment strategy as in the other sites and then purposively selected the last 10 in our sample to ensure that we were reflecting a broad range of sample characteristics. The qualitative sample in each site reflects the diversity of the trial population.

Overall, 102 interviews were conducted with 43 young people (Table 2). In total, 26 young people were recruited in Uganda from one clinic (Joint Clinical Research Centre, Kampala), seven were recruited in the UK from three clinics (NHS hospitals in London, Nottingham and Dublin) and 10 were recruited in the USA from one clinic (St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN).

| Country | Total (n) | Male (n) | Female (n) | On SCT (n) | On CT (n) | Switched or left trial (n) | Age (years), mean | Age (years), range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uganda | 26 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 10 | 2 (to CT) | 18 | 11–22 |

| UK (and Ireland) | 7 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | – | 15 | 12–17 |

| USA | 10 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 (from trial) | 21 | 18–22 |

| Total | 43 | 26 | 17 | 22 | 18 | 3 | 17 | 11–22 |

Recruitment response and retention through the repeated phases of the qualitative study was high (around 40%). We had very high rates of participation in the Uganda (26 out of a possible 66 trial participants) and US sites (10/14). Recruitment was most challenging in the UK and Ireland (7/23). Overall, we included 40% of the trial participants who were aged ≥ 10 years. However, the actual proportion of eligible participants recruited is likely to have been higher than this, given that this figure does not account for the participants who would not have been eligible despite being within the age range because of a lack of awareness of their HIV status.

The majority of refusals occurred in the UK sites, with the reasons for refusal varying. Very few participants had taken part in qualitative research before and some of the young people were unwilling to talk to the researchers and were uncomfortable with the idea of the qualitative interviews. Others instead mentioned not wanting to take on any additional clinic attendance and time commitments. This may reflect the amount of overall research being conducted with the relatively small UK cohort, but could also be indicative of the desire that young people have to minimise the time spent in the clinic and focus on other aspects of their lives aside from HIV.

Types of data collected

-

One-to-one interviews with young people living with HIV. In Uganda, participants were interviewed three times over the course of the study (in the early stages of the trial; towards the end of the trial; and during the follow-up period) to explore their experience of adherence and the process of the trial. In the UK and US sites, only the first two interviews were conducted. Interviews lasted approximately 1–2 hours and were audio-recorded, subject to consent. Baseline interviews captured life with HIV on HIV treatment as described by young people and included, but did not focus specifically on, young people’s perceptions of the trial or of SCT. The second interview reconstructed the life and treatment trajectory of participants since the start of the trial, focusing on adherence during this specific time period as well as reflections on intervention and trial acceptability. The third interview in Uganda was conducted as participants moved into the follow-up stage of the study. In these interviews we explored any changes in their treatment experience and their attitudes towards continuing in the intervention or control arm. The third interviews are being conducted in the UK only at trial end to explore participants’ reactions to the outcome of the trial. Reactions to the trial results will be explored informally in Uganda through meeting observations and discussions. It is worth noting that the focus of the third interview has changed from the preliminary study design in response to the changes made in the trial. The third interview was initially planned to explore how participants would adapt had they been required at the end of the trial to switch back from the SCT arm to CT. However, this has not occurred and participants have been retained in the same arm through the follow-up phase. The focus of the qualitative enquiry has shifted to reflect these changes and instead will consider how participants respond to continuing in the same arm and their attitudes towards SCT once the main trial findings have been disseminated.

-

Audio diaries of young people living with HIV. We piloted the use of audio diaries in the UK and Uganda sites. This is an innovative method that we have used before and we consider such diaries to be a valuable method in capturing personal reflections. 42 We wanted to explore whether or not this method would enable participants to generate data at the time and space of their choosing and if this would provide particular insights into the immediacy and variability of treatment and adherence experiences. We therefore offered this method to assess its feasibility and value for research with young people. All participants were offered the chance to keep an audio diary in the Uganda and UK sites. Ethical approval was not given for the audio diaries to be used in the US site. In Uganda, 12 participants agreed to contribute a personal audio diary and in the UK three participants took up the opportunity. We found that there were significant challenges to using audio diaries with this age group in these sites for such a sensitive topic. Despite participants’ initial enthusiasm to use the diaries we found that their lack of privacy within their own home, exacerbated for many (especially those in Uganda) by a lack of physical space, meant that it was difficult for them to first record their diaries with ease and second be confident of securely storing them before returning them to the research team. These conditions undermined the value of the method, as the premise that participants may be able to speak more freely about immediate events with greater convenience could not be realised. Those who did record something mainly recorded public interactions or songs, which were not related to our topic of enquiry. We may conclude from this pilot that use of audio diaries is unlikely to be a feasible method given the restraints of a lack of privacy.

Ongoing research: planned data collection

-

Phase 3 interviews with young people in the trial in the UK post publication of trial findings. In the UK we are conducting a third and final interview which explores attitudes towards SCT in light of the trial findings. Our research focus has been adjusted to reflect the trial plans. It remains rare for participants to be asked about their response to trial findings and we anticipate that this may provide a valuable model for informing the design of any further development of this intervention and future roll-out.

-

Interviews with carers of young people in the trial (Uganda). In Uganda, all participants have been asked to consent to their carers being contacted to take part in an interview. Using thematic sampling criteria, informed by our initial analysis, we are inviting 15 carers to participate in an interview to explore their response to the trial findings. The interview also explores their decision-making process in consenting for their child to participate in the trial, their reflections on how their expectations aligned with their experience of the trial and their perceptions of the barriers to and facilitators of adolescents’ adherence, including the impact of the trial.

-

Focus groups with young people living with HIV not involved in the trial. In Uganda data are being collected in focus groups with up to 25 HIV-positive young people aged 10–24 years who participated in the trial. This is subject to the appropriate consents and self-awareness of HIV infection (for at least 6 months). These focus groups explore young people’s understandings of the results of the trial, their experience in the trial and its influence as their adherence patterns, through peer discussion. We endeavour to ensure that these groups reflect the diversity of the trial population. Data transcription and, where appropriate, translation from these additional sets of data collection are ongoing. Data analysis is being carried out iteratively to inform subsequent data collection and refine questions.

Consent procedures and ethics

Consent was sought from all trial participants aged 10–24 years who had been aware of their status for at least 6 months. Participants were approached in different ways depending on the local procedures of each of the research sites. In the UK, research nurses contacted and consented participants, although the researcher had a number of conversations over the telephone with participants to answer their questions and discuss the topic before they decided whether or not to take part. In the USA, trial staff carried out both the contacting and the consent procedures. In Uganda, the researcher met the carers in the clinic and explained the qualitative study to them and then asked for their consent for the children to participate. This was followed by an ‘assent’ procedure with the children themselves. In all sites, final arrangements for the interviews were organised with the researcher.

In line with Good Clinical Practice principles [see www.ich.org/products/guidelines/efficacy/efficacy-single/article/good-clinical-practice.html (accessed 6 April 2016)], informed consent was treated as a process. This involved reminding participants at each stage of the study what the qualitative study was about, answering any related questions that they may have had, providing information as appropriate and reiterating that participants could withdraw at any time during the process of data collection. We did not need to break confidentiality on any safeguarding issues, although we had plans in place should this have been necessary.

The data that were collected were transcribed verbatim and, when appropriate, were translated into English by the research assistant. Personal identifying details were removed. We have been given an exemption from the mandatory request by the Economic and Social Research Council to archive the Ugandan data given the sensitivity and contextually dense nature of the data collected.

Modes of analysis/interpretation

The study adopted a grounded analytic approach to thematic analysis, using systematic case comparison and negative case analysis throughout. 43 We orientated analyses by themes emerging within/across individual accounts, exploring the acceptability of the trial; the potential value of SCT; and barriers to adherence as it converges with changing priorities during adolescence, as well as to the advancement of social science research and theory on HIV treatment adherence.

All interviews and audio diaries were transcribed verbatim by the data assistants. As discussed above, the limitations in the audio diary data meant that these data have not been integrated into our analysis. In line with our iterative analysis approach, we analysed data as we collected it to inform the direction of subsequent interviews, further coding and case selection. In addition to giving attention to ‘negative cases’ through case comparisons in our analysis, we sought respondent validation on emerging conclusions and maximised internal reliability and reflection through comparing coding between multiple researchers. Coding was undertaken in two linked phases. Our first-level coding drew on a combination of a priori themes reflected in the study topic guide and inductive or in vivo codes. 44 Our second-level coding sought to break down first-level coded data into smaller units, which also involved moving from codes that operate at the level of participant description and meaning to concept-driven categories. This process is similar to moving from ‘open’ to ‘axial’ to ‘selective’ coding in grounded theory. 43 We have maintained an audit trail of the analytical process, including analytical memos and how case comparisons and attention to emerging negative cases have informed ongoing analyses. We have conducted analysis by site and across the study to identify if gender, age and country are significant in how we can disaggregate our findings.

Chapter 3 Results from the main trial

Baseline characteristics

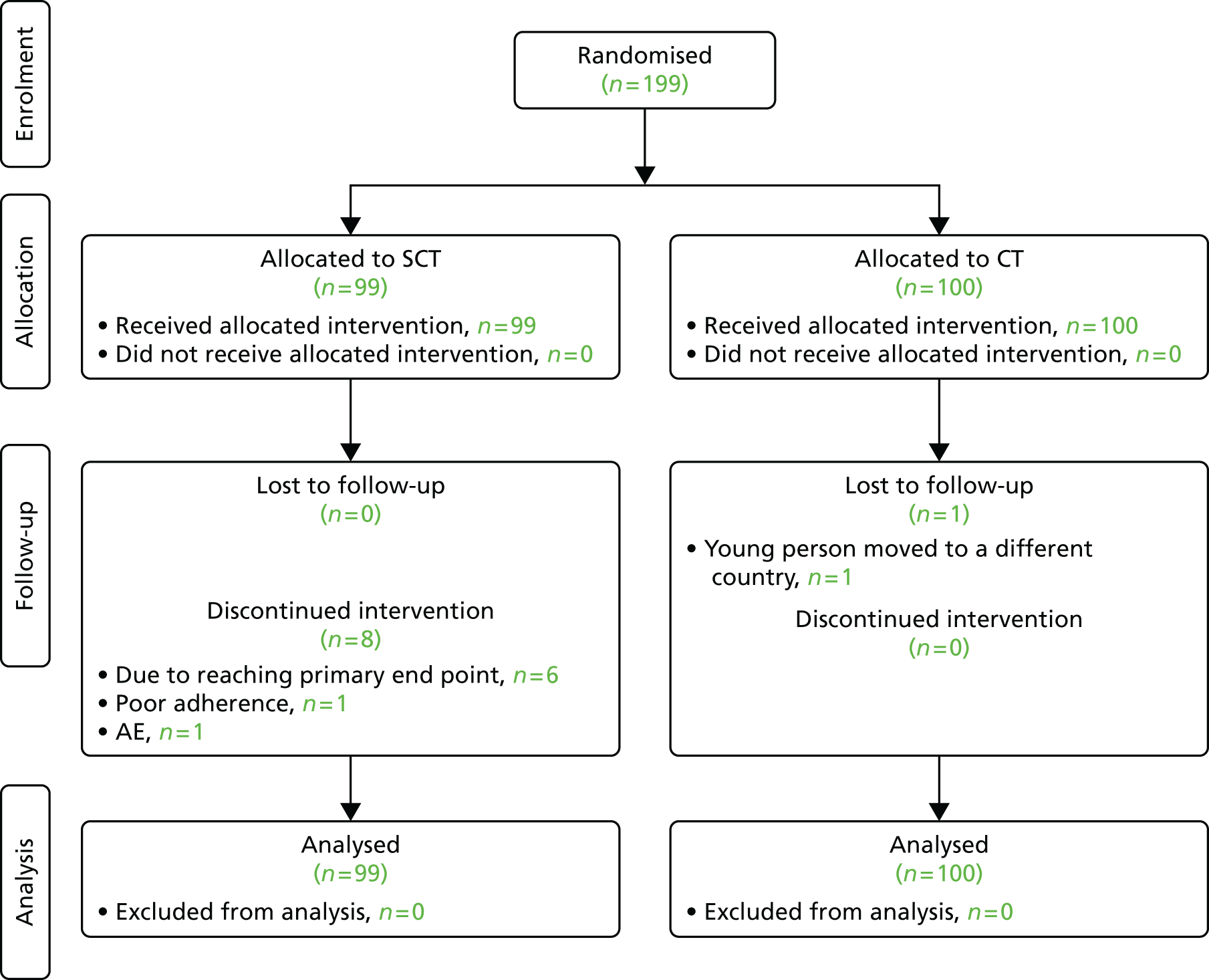

In total, 199 young people were randomised from 11 countries between 1 April 2011 and 28 June 2013 (Table 3). A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram for the trial can be found in Figure 1.

| Country (number of sites) | Dates of first and last randomisation | Number randomised | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCT | CT | Total | |||

| Argentina (2) | 13 December 2012 | 28 May 2013 | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Belgium (1) | 29 April 2013 | 6 May 2013 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Denmark (1) | 25 September 2012 | 4 December 2012 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Germany (1) | 26 June 2013 | 26 June 2013 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Ireland (1) | 11 April 2012 | 9 October 2012 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Spain (5) | 5 September 2011 | 4 July 2012 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| Thailand (3) | 5 July 2011 | 27 June 2013 | 15 | 21 | 36 |

| Uganda (1) | 23 May 2011 | 28 June 2013 | 35 | 35 | 70 |

| UK (7) | 1 April 2011 | 10 June 2013 | 14 | 12 | 26 |

| Ukraine (1) | 21 March 2013 | 17 June 2013 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| USA (1) | 22 August 2012 | 24 April 2013 | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Total (24) | 1 April 2011 | 28 June 2013 | 99 | 100 | 199 |

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

Baseline demographic data were well matched between arms, with 105 (53%) male participants, a median (IQR) age of 14.1 (11.9–17.6) years and a median (IQR) weight of 45.2 (33.8–56.0) kg. In total, 35% of all young people randomised were recruited from an African site; 180 (90%) young people were vertically infected; and 41 (21%) were white, 112 (56%) were black and 37 (19%) were Asian (Table 4).

| Characteristic | SCT | CT | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young people randomised, n | 99 | 100 | 199 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 57 (58) | 48 (48) | 105 (53) |

| Female | 42 (42) | 52 (52) | 94 (47) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.5 (3.9) | 14.7 (3.9) | 14.6 (3.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 13.7 (11.7–17.7) | 14.4 (12.0–17.5) | 14.1 (11.9–17.6) |

| Range | 8.0–24.2 | 8.3–24.0 | 8.0–24.2 |

| Age range, n (%) | |||

| ≥ 8 to < 13 years | 38 (38) | 39 (39) | 77 (39) |

| ≥ 13 to < 18 years | 39 (39) | 41 (41) | 80 (40) |

| ≥ 18 to < 24 years | 22 (22) | 20 (20) | 42 (21) |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 46.9 (18.2) | 45.6 (14.8) | 46.2 (16.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 45.5 (33.1–56.2) | 45.1 (33.9–55.7) | 45.2 (33.8–56.0) |

| Range | 18.0–114.3 | 20.0–90.1 | 18.0–114.3 |

| Route of infection, n (%) | |||

| Vertical | 90 (91) | 90 (90) | 180 (90) |

| Sexual contact | 7 (7) | 7 (7) | 14 (7) |

| Blood product | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | |||

| White | 24 (24) | 17 (17) | 41 (21) |

| Black: African or other | 58 (59) | 54 (54) | 112 (56) |

| Mixed black/white | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 4 (2) |

| Asian | 15 (15) | 22 (22) | 37 (19) |

| Other | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 5 (3) |

| Recruited from African site, n (%) | 35 (35) | 35 (35) | 70 (35) |

There was a minor imbalance at baseline in CDC events, with 13% of young people in the SCT arm having had a CDC stage C event compared with 21% in the CT arm. The median (IQR) CD4% at randomisation was 34.0% (29.5–38.5%) and the median (IQR) absolute CD4 count was 735.0 cells/mm3 (575.5–967.5 cells/mm3) (Table 5).

| Characteristic | SCT | CT | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young people randomised, n | 99 | 100 | 199 |

| CDC stage, n (%) | |||

| N | 16 (16) | 10 (10) | 26 (13) |

| A | 25 (25) | 25 (25) | 50 (25) |

| B | 45 (45) | 43 (43) | 88 (44) |

| C | 13 (13) | 21 (21) | 34 (17) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| CD4% | |||

| Mean (SD) | 34.7 (6.8) | 34.1 (6.4) | 34.4 (6.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 34.5 (29.3–39.0) | 34.0 (29.5–38.1) | 34.0 (29.5–38.5) |

| CD4%, n (%) | |||

| < 30% | 26 (26) | 27 (27) | 53 (27) |

| ≥ 30% to < 40% | 52 (53) | 55 (55) | 107 (54) |

| ≥ 40% | 21 (21) | 18 (18) | 39 (20) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CD4 (cells/mm) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 787.3 (297.6) | 798.7 (308.3) | 793.0 (302.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 722.5 (581.0–965.0) | 747.3 (575.3–972.8) | 735.0 (575.5–967.5) |

| CD4 (cells/mm), n (%) | |||

| ≥ 350 to < 1000 | 79 (80) | 79 (79) | 158 (79) |

| ≥ 1000 to < 1500 | 17 (17) | 17 (17) | 34 (17) |

| ≥ 1500 | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Twenty-nine (14.6%) young people had had previous exposure to PIs at randomisation, but none had switched from PIs because of virological failure, and at trial entry all young people were on regimens containing NRTIs and EFV only.

In baseline acceptability questionnaires completed by young people randomised to SCT, 70 out of 80 (87.5%) young people who answered the questionnaires said that they thought that taking weekends off treatment would make things either much easier or a little easier compared with taking ART continuously.

Follow-up

At the end of the trial, the median (IQR) follow-up time was 85.7 (62.0–118.3) weeks. Two young people, both from the CT arm, were lost to follow-up by the end of the trial, one because of leaving the country after the week 24 visit and the other because of transferring to an adult clinic and withdrawing consent after the week 48 visit. Attendance to clinic visits was good, with > 90% of young people still in follow-up attending each visit (Table 6).

| Follow-up | SCT | CT | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants randomised, n | 99 | 100 | 199 |

| Seen at the following weeks, n (%) [%]a | |||

| 1 | 15 (100)b [100]b | 17 (100)b [100]b | 32 (100)b [100]b |

| 2 | 15 (100)b [100]b | 17 (100)b [100]b | 32 (100)b [100]b |

| 3 | 15 (100)b [100]b | 17 (100)b [100]b | 32 (100)b [100]b |

| 4 | 98 (99) [99] | 98 (98) [98] | 196 (98) [98] |

| 8 | 15 (100)b [100]b | 15 (88)b [88]b | 30 (94)b [94]b |

| 12 | 98 (99) [99] | 99 (99) [99] | 197 (99) [99] |

| 24 | 99 (100) [100] | 100 (100) [100] | 199 (100) [100] |

| 36 | 98 (99) [99] | 97 (97) [98] | 195 (98) [98] |

| 48 | 95 (96) [96] | 94 (94) [96] | 189 (95) [96] |

| 60 | 93 (94) [97] | 89 (89) [98] | 182 (91) [97] |

| 72 | 68 (69) [96] | 70 (70) [99] | 138 (69) [97] |

| 84 | 66 (67) [100] | 56 (56) [97] | 122 (61) [98] |

| 96 | 43 (43) [91] | 44 (44) [96] | 87 (44) [94] |

| 108 | 39 (39) [100] | 38 (38) [97] | 77 (39) [99] |

| 120 | 26 (26) [96] | 26 (26) [100] | 52 (26) [98] |

| 132 | 12 (12) [86] | 17 (17) [106] | 29 (15) [97] |

| 144 | 13 (13) [100] | 13 (13) [93] | 26 (13) [96] |

| 156 | 8 (8) [100] | 7 (7) [100] | 15 (8) [100] |

| 168 | 1 (1) [100] | 0 (0) [0] | 1 (1) [100] |

| Weeks from randomisation to last visit | |||

| Median (IQR) | 86.3 (62.4–118.9) | 84.9 (60.9–117.1) | 85.7 (62.0–118.3) |

| Range | 49.0–169.0 | 25.0–158.0 | 25.0–169.0 |

| Mean | 94.8 | 92.5 | 93.7 |

| Lost to follow-up, n (%) | 1 (1)c | 2c (2) | 3c (2) |

Primary end point

Thirteen young people reached the primary end point by the end of the 48-week assessment, six from the SCT arm and seven from the CT arm. In the primary analysis, the estimated probability (90% CI) of reaching the primary end point was 6.1% (2.1% to 10.2%) for individuals in the SCT arm and 7.3% (2.9% to 11.7%) for those in the CT arm. The estimated difference between arms (SCT – CT) was 1.2% in favour of SCT (90% CI –7.3% to 4.9%) and so the upper bound of the 90% CI was less than the non-inferiority margin of 12% (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to first detected HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/ml (confirmed) up to the week 48 assessment.

| Week 48 assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm | Number of events | Person-years at risk | Estimated probability of failinga | 90% CI |

| SCT | 6 | 99.53 | 0.061 | 0.021 to 0.102 |

| CT | 7 | 98.75 | 0.073 | 0.029 to 0.117 |

| Difference (SCT – CT) | –0.012 | –0.073 to 0.049 | ||

Therefore, at the end of the 48-week assessment, the results are consistent with the non-inferiority of SCT compared with CT.

When not adjusting for stratification factors, the estimated probability (90% CI) of reaching the primary end point was 6.1% (3.2% to 11.7%) in the SCT arm and 7.3% (4.0% to 13.1%) in the CT arm. The estimated difference between arms (SCT – CT) was 1.1% in favour of SCT (90% CI –6.8% to 4.6%) and so the upper bound of the CI was less than the non-inferiority margin of 12% (Figure 3). Therefore, non-inferiority was demonstrated in this analysis as well as in the primary analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier graph of time to first detected HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/ml (confirmed) up to the 48-week assessment.

| Week 48 assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm | Number of events | Person-years at risk | Estimated probability of failing | 90% CI |

| SCT | 6 | 99.53 | 0.061 | 0.032 to 0.117 |

| CT | 7 | 98.75 | 0.073 | 0.040 to 0.131 |

| Difference (SCT – CT) | –0.011 | –0.068 to 0.046 | ||

| p-valuea = 0.754 | ||||

The crude proportion (90% CI) of young people experiencing virological failure was 0.061 (0.027 to 0.116) in the SCT arm and 0.070 (0.033 to 0.127) in the CT arm. Therefore, the estimated difference in crude proportion (90% CI) between arms (SCT – CT) was –0.009 (–0.067 to 0.048) (Table 7).

| Treatment arm | Number of events | Estimated proportion | 90% CI | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCT | 6 | 0.061 | 0.027 to 0.116 | |

| CT | 7 | 0.070 | 0.033 to 0.127 | |

| Difference (SCT – CT) | –0.009 | –0.067 to 0.048 | 1.000 | |

Secondary end points

Virology

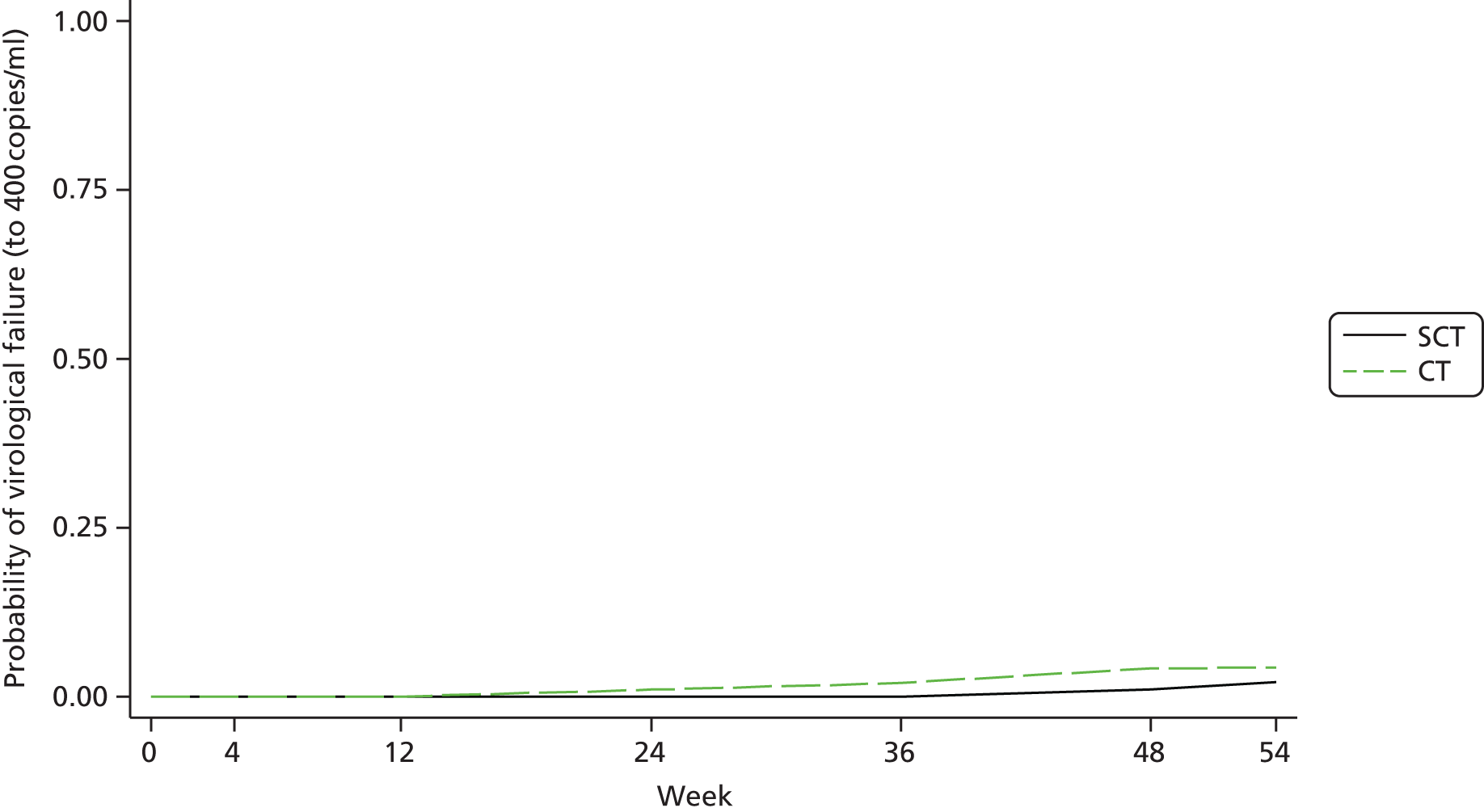

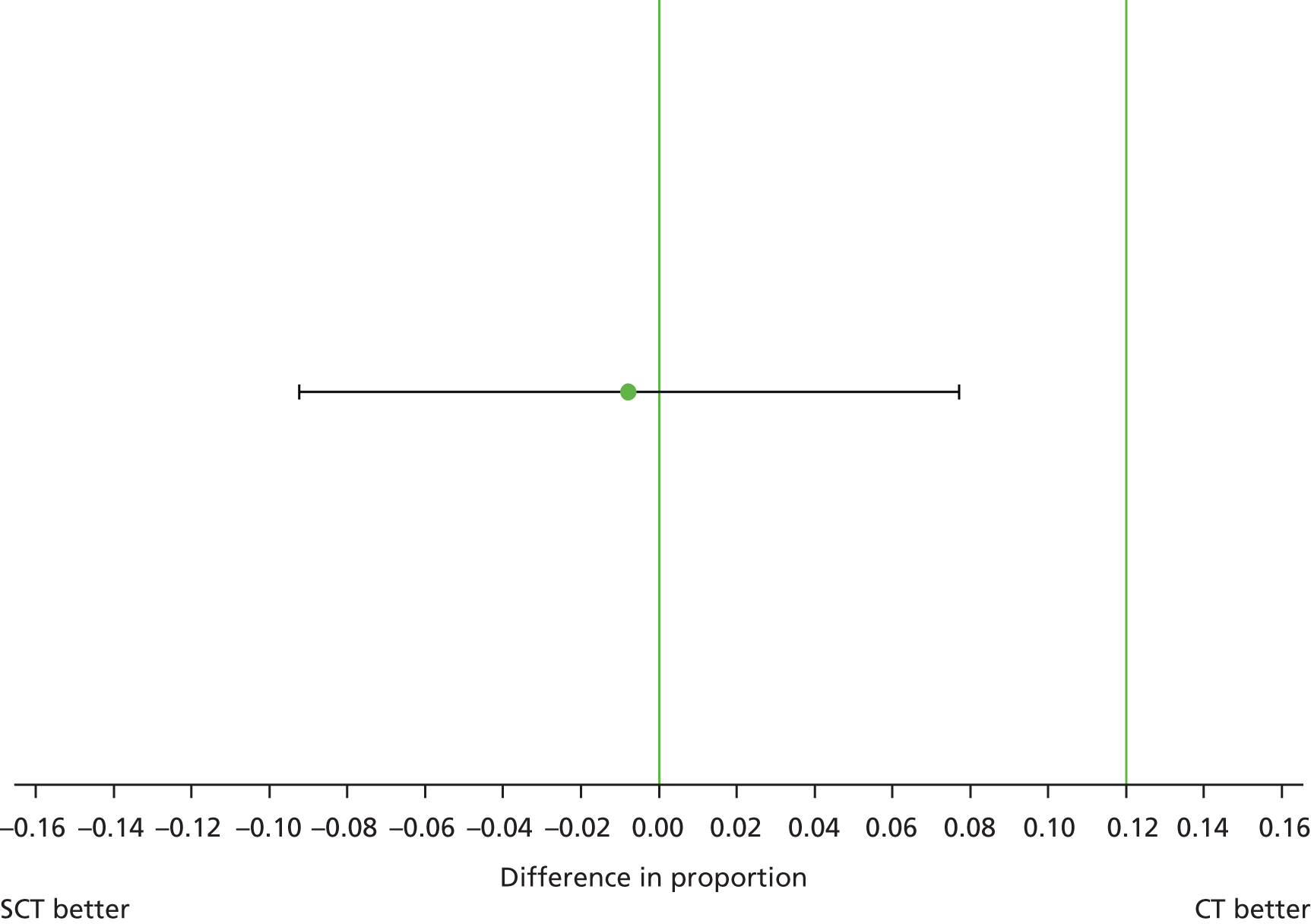

The primary analysis was repeated but with the end point as a confirmed HIV-1 RNA VL of ≥ 400 copies/ml. The estimated difference between arms (SCT – CT) in the proportion of virological failure was 2.1% in favour of SCT (90% CI –6.2% to 1.9%), which is consistent with the non-inferiority of SCT compared with CT (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.