Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/70/04. The contractual start date was in May 2011. The draft report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elaine M McColl is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Journals Library Editorial Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Parry et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Falls and fear of falling

Falls are common, frequently devastating events in older people, with between 30% and 62% of older individuals falling per year. 1,2 Falls are responsible for considerable morbidity and mortality, with around 10% of falls resulting in fractures. 3 The economic costs of falls are considerable; as long ago as 2003, the cost of falls to the UK economy was estimated at £981M,4 with more recent data showing that 0.07–0.20 of the gross domestic product and 0.85–1.5% of total health-care expenditure in Western economies was accounted for by falls and their consequences. 5 Adverse consequences of falls are by no means limited to physical injury and escalating levels of dependence. Many older individuals, both fallers and non-fallers, suffer from a variety of adverse psychosocial difficulties related to falling,6–16 including fear, anxiety, loss of confidence and impaired self-efficacy (the self-perception of ability to perform within a particular domain of activities),10,13 resulting in activity avoidance, social isolation and increasing frailty. 6–16 The umbrella term for these problems is ‘fear of falling’, a common and disabling problem in older individuals, found in between 3% and 85% of community-dwelling elders who fall, and up to 50% of those who have never fallen. 8–10,16

Physical treatments for fear of falling

The optimal management strategy for fear of falling and its adverse physical and psychosocial consequences is poorly understood. Clinical and laboratory observations show that concerns about falling have a clear effect on gait patterns in older people. For example, experimental data in older people who are undergoing gait and balance studies on elevated walkways show disproportionately slow walking speeds and other dysfunctional gait adjustments17 alongside abnormalities in postural balance compared with younger subjects. 18 These experimental data and the observation of higher rates of falls and physical frailty in older individuals with fear of falling suggest that physical interventions may help to ameliorate fear of falling. Much of the research focusing on physical treatments includes home- and community-based exercise interventions, t’ai chi and multifactorial interventions aimed at reducing fall rates, with fear of falling reported as a secondary outcome in the majority of these studies. 8 A meta-analysis of nine studies examining t’ai chi in the management of fall prevention, fear of falling, and balance in older adults concluded that insufficient evidence existed to recommend such an intervention in this context. 19,20 A more recent randomised controlled study in 176 elders, randomised to one of three groups (intensive t’ai chi with cognitive–behavioural strategies, t’ai chi alone and a usual care control group) showed improvements in fear of falling as measured by the Falls Efficacy Scale13 (FES) in the cognitive strategies group compared with the other two groups. 21 So, although t’ai chi can help to prevent falls in older adults,22 its role specifically in the management of fear of falling is less clear.

A previous systematic review found 12 high-quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that included fear of falling among the outcomes that they assessed,8 but only one of these trials was primarily aimed at reducing fear of falling. 23 The interventions were conducted across a variety of settings – home-based exercise, community t’ai chi and home-based multifactorial interventions – and all improved fear of falling. 8 In a subsequent trial, a geriatric outpatient-based multifactorial intervention study found no such benefit. 24 More recently, a Cochrane review of exercise (three-dimensional exercise, such as t’ai chi and yoga, balance training or strength and resistance training) for reducing fear of falling in older people living in the community found that exercise ‘probably’ reduces fear of falling to a limited extent immediately after intervention, with inadequate evidence of an effect in the longer term. 25 The authors called for further evidence, with priority being given to the establishment of core outcomes, including fear of falling, in all trials of exercise intervention in community-dwelling elders. 25

Psychological treatments for fear of falling

Although such physical interventions may be of benefit in selected populations, the profile of the disorder and its psychosocial complications suggest that well-designed psychological interventions may help ameliorate the fear of falling more definitively. Several studies have examined an explicitly cognitive–behavioural therapeutic approach in fear of falling in community-dwelling elders, or used cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques as part of a wider multifactorial intervention strategy. CBT is an evidence-based form of therapeutic intervention, which seeks to alter difficult emotional and physical states by altering the behaviours and cognitions that maintain them. As used in the CBT interventions for fear of falling studies described below, fear of falling is usually conceptualised as an anxiety disorder maintained by negative reinforcement (avoidance behaviour) and fearful cognitions. Tennstedt et al. ’s26 Matter of Balance study assessed the ability of an eight-session, 4-week group cognitive–behavioural approach with exercise instruction to improve fear of falling and related activity restriction. A total of 434 community-dwelling elders aged ≥ 60 years were randomised to intervention and control groups, with significant differences seen in fear of falling as measured by the FES13 and activity during follow-up. The magnitude of improvement in FES scores attenuated over time, prompting the authors to suggest that a booster session should be used in future studies and in clinical practice. 26 Clemson et al. 27 similarly used what they described as a ‘small-group learning environment’ (although, in practice, some of the methods used included cognitive–behavioural techniques) of 12 individuals per group for 2 hours per session over 7 weeks to improve self-efficacy and reduce falls. 27 The intervention incorporated a variety of learning strategies to facilitate behaviour change, including education regarding exercises to reduce falls risks, medication and home environmental review, and medication management. 27 There was a 31% reduction in the number of falls [relative risk 0.69, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.50 to 0.96; p = 0.025] in the intervention group, although, interestingly, there was no corresponding change in FES scores. 27

More recently, Zijlstra et al. 28 conducted a RCT of a multicomponent cognitive–behavioural group intervention in older community-dwelling elders. Five hundred and forty participants were drawn from a random sample of 7431 individuals sent questionnaires who reported ‘at least some fear of falling’, although the method of assessment was not specified. Following randomisation, the intervention group underwent a structured 2-hour group CBT intervention (CBTi), based on the investigators’ previous work, once weekly for 8 weeks, with a booster session 6 months following the last session. A primary outcome was not specified and, although a power calculation was supplied based on a difference of 2.5 points, the authors fail to specify on which scale. The beginning of the trial predates widespread use of the FES–International version (FES-I)29 (advocated by the same group as the most appropriate measure for such studies),8 instead using a single-item question on fear of falling as well as an unspecified scale, probably the original FES from the description and reference supplied. 28 Other outcomes included perceived control over falling and daily activity as well as falls. There were no measures of physical function despite the prior evidence base suggesting improvement in fear of falling with the exercise-related interventions as described above. All outcomes showed significant differences between control and intervention groups at 2 and 8 months’ follow-up, with between-group differences persisting at 14 months in fear of falling and perceived control over falling, but not in the other outcome measures. There was a 30% attrition rate in the intervention group and 19.6% attrition rate in the control group. 28 The study intervention was carefully developed and grounded in cognitive–behavioural theory, but interpretation of findings is hampered considerably by the lack of clarity on sample size calculation and outcome measures, and the absence of generic quality-of-life measures and measures of physical functioning. The same research group later reported a before-and-after design study20 implementing a similar protocol into routine health care in 125 community-living older people, with significant improvements in concerns about falling.

The relative effectiveness of group-based psychological interventions thus remains uncertain. A theoretical re-examination of models of fear of falling and a recent cohort study of 500 older adults both suggest that the fear of falling population is a complex and heterogeneous one, in which psychosocial and physiological interventions also need to be individualised. 30,31 This suggests that individually based interventions may be more appropriate but, to date, trials have examined only group-level interventions.

What kind of intervention could be implemented in the UK NHS?

Fear of falling is a common, disabling and debilitating condition in older adults, but the current understanding of its management is limited. There is a small evidence base to support the use of some physical therapies to improve the syndrome, and promising early data from a few studies supporting the use of psychological therapies, in particular CBT. The cognitive–behavioural quintet32 of a situation or practical problem (falls, declining mobility, social isolation), altered thinking and emotion, altered physical symptoms with behavioural change, and activity reduction and avoidance is paradigmatic for fear of falling, and offers the hope of a viable therapeutic option. Previous studies are hampered by the factors already described, whereas the issue of the economic viability of such a treatment has yet to be explored. There is a need for many more trained cognitive–behavioural therapists than are currently available; the development of a cognitive therapeutic package for the management of fear of falling that can be delivered routinely by non-specialist staff such as health-care assistants (HCAs) is vital if this common and debilitating condition is to be tackled effectively. CBT can be delivered by suitably trained non-psychotherapist staff33,34 but, to our knowledge, this approach has not been attempted in a randomised controlled study in the context of fear of falling. In addition, only group interventions have been studied so far, with therapy delivered on a one-to-one basis yet to be tested in a fear of falling cognitive–behavioural intervention study despite suggestive evidence that this approach may prove more fruitful.

Any new treatment for potential implementation in the NHS needs to have clinical efficacy, but also needs to be able to be embedded into routine clinical practice. Understanding the dynamics of developing, delivering and trialling a novel cognitive–behavioural intervention by non-specialist staff as a process is useful because it will contribute to understanding the professional and organisational factors that promote or inhibit adherence to treatment protocols and intervention delivery, and how practical and methodological problems are defined, understood and resolved by the project team in the course of the study. The need for understanding the dynamics of complex interventions35 and undertaking process evaluation is now well understood. 36,37 Such work is important to underpin the transportability, workability and integration of interventions into routine clinical practice. In the case of this trial, our aim was to collect longitudinal ethnographic data that would help us to understand the social processes and relationships that lead the intervention and trial to take a particular shape and direction. In earlier studies of trials and other interventions, May and Finch38 developed a robust explanatory model of normalisation processes, which defines psychological and sociological mechanisms of behaviour and action that have been empirically demonstrated to be important in the implementation of complex interventions, and that have been revealed by evaluation in randomised controlled clinical trials. This approach is vital for the understanding and more widespread adoption of any cognitive–behavioural intervention in fear of falling.

Aims

Our aims were to develop a cognitive behaviour-based intervention to be delivered by HCAs on a one-to-one basis to community-dwelling older individuals attending falls services with an excessive or undue fear of falling and then to conduct a pragmatic, patient RCT of this intervention plus usual multidisciplinary care compared with usual multidisciplinary care alone, with integrated health-economic and process evaluations.

Chapter 2 Phase I: intervention development

This chapter reports the development of the CBTi for fear of falling, and the initial process evaluation work that was undertaken to inform the organisation and delivery of the CBTi in preparation for the RCT.

Developing the intervention

The aim of the development work was to develop a CBTi that could be delivered by HCAs (non-specialist, relatively low-paid staff) after training in basic CBT skills. The cognitive–behavioural model32 underpinning the intervention distinguishes between predisposing factors (what made a person vulnerable to a problem), precipitating factors (what triggered the current problem) and perpetuating factors (what is currently maintaining it). The model further distinguishes between physical, emotional, cognitive, behavioural and social factors in each domain. To develop the CBTi appropriately for the client group, assessment interviews with patients with fear of falling were undertaken. The intervention development process also included the preparation of supporting materials (‘manuals’).

Although existing literature on fear of falling indicated some of the likely intervention points, to further refine our intervention we chose to interview people who were affected by the problem. This work took the cognitive–behavioural assessment structure as its starting point, and followed on successful intervention development work that some of our team had previously undertaken in intervention development in other areas, such as medically unexplained symptoms. 34,39

Methods of intervention development

To develop the intervention, we conducted semistructured functional assessment interviews with 15 patients who had significant fear of falling. This number was determined by our previous research in developing psychosocial interventions. These interviews took the form of a standard cognitive–behavioural clinical assessment interview, used to elicit the predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors of participants’ problems, be they anxiety or depression (see Interview format). The model makes no assumptions about the content of any of its a priori domains; rather it assumes that there will be an interaction of physiological, cognitive, emotional, behavioural and social factors, which will be implicated, in some way, in the onset and maintenance of any given problem. It is the goal of the interview, then, to ascertain the unique interplay of factors maintaining the problem for each individual.

The patients were recruited from the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service. These patients were seen as part of normal clinical practice by the multidisciplinary team of physicians, HCA and senior physiotherapist, during which a FES-I29 (see Appendix 1) was administered as routine. The clinical team identified potentially eligible patients on the basis of their age and FES-I scores (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients

Consecutive patients aged ≥ 60 years of both sexes. Those with significant fear of falling, as defined by a FES-I score of > 23,40 were eligible for the study. Patients with cognitive impairment [Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of < 2441] were excluded from the study, as there is a paucity of data on the use of fear of falling measures in this patient group, and given the difficulties of conducting CBT interventions in those with significant cognitive impairment. Regionally, the population under study had a particularly low proportion of ethnic minorities. Therefore, given the level of communicative nuance needed for the development of a CBT intervention, we excluded those who did not speak English. To avoid participant burden, patients recruited to the CBTi development study were excluded from the Phase I process evaluation work (described later in this chapter) and vice versa.

Sample size

Fear of falling is one of a range of falls-related psychological concerns,42 with emotional and behavioural components including anxiety and activity avoidance, respectively. 43 In the CBTi development study we anticipated interviewing between 10 and 12 patients, although up to 30 were allowed for if data saturation was not reached with fewer numbers. Our rationale for this was that clinically significant anxiety (which fear of falling to be can be a manifestation of) tends to have a fairly narrow range of maintaining factors, which, most usually, are catastrophic beliefs and activity avoidance. The psychological construct of fear of falling as it appeared in the literature suggested that a similar range of maintaining factors was likely to be in operation in our patient group. We therefore expected that the number of patients needed to consistently identify such factors to be relatively small. In fact 15 patients were needed as the construct was more heterogeneous than we anticipated.

Identification, recruitment and consent of participants

The initial approach to patients for the CBTi development study was by a member of staff at the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service. The staff member provided a brief oral explanation of the research to those patients who met age, FES-I score and cognitive impairment eligibility criteria. Those expressing a preliminary interest were given a Patient Information Sheet (PIS) and an expression of interest (EoI) form (with stamped addressed return envelope addressed to the University) to take home and discuss with family and carers as they felt appropriate. There was no further direct study-related contact with the patients unless they returned the EoI form indicating their willingness to participate in the study. On receipt of an expression of interest form, a telephone call was made by the interviewer (VD) to discuss participation. Questions about the process were actively sought, and if patients required further time for reflection or discussion with family or carers this was encouraged. If patients consented, the interviewer (VD) contacted them by phone and arranged an appointment for the interview. Written consent was obtained prior to the commencement of the interview. These were conducted in the patient’s preferred location, at either at the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service or, in most cases (14/15 patients), at the patient’s home.

Interview format

The CBTi development interviews were undertaken by VD, a qualified cognitive–behavioural therapist and practitioner health psychologist. The main form of data collection was notes taken by the interviewer as the interview was being conducted, and notes and reflections made in collaboration with the interviewee. All sessions were also audio-recorded in case there should be any need to clarify points from the notes.

The format was a standard CBT assessment, as used by cognitive–behavioural therapists and clinical psychologists. It brings to light which factors are key in having caused the patient’s problem, and which factors are key in keeping the problem going. The structure is often referred to as the ‘three P’s’: what factors predisposed the patient to the problem (such as a history of anxiety); what factors precipitated the current problem (such as a fall or loss of physical capability) and what factors might be perpetuating the problem in terms of cognitions, behaviours, emotional, physical and social factors. Using this model as a template, we investigated the relevant factors in the cause and maintenance of the individuals’ fear of falling.

The interview began with a general open question about the main presenting problem, for example ‘tell me a bit about your concerns about balance and falls’. It then asked more detailed questions about how the problem was affected by different situations, times, people, places and events. Then more detail was sought on what could and could not be done as a result of the problem, and on what made the problem better or worse. Coping strategies and beliefs were then asked about, as well as any current treatments. Next the onset and development of the problem was explored, from what was happening in the interviewee’s life just before they started being concerned about falls, up to the present moment. More general questions were then posed about the interviewee’s current mood and mental state, and about the type of person they perceived themselves to be. This was followed by some questions about any past experiences of emotional or physical problems. Finally, a brief family and social history of family, spouse or partner, carers and social contacts was taken, as well as details of previous and current employment and relationship status as appropriate. The interview ended with the interviewer feeding back to the interviewee some of the information that might help make sense of their fear of falling problem, and with a general discussion of what the interviewee thought of as being the important factors in the cause and management of their problem.

Analysis

The cognitive–behavioural framework (of predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors) described above further distinguishes between physical, emotional, cognitive, behavioural and social factors in each domain. Finally, it looks for interactions between the perpetuating factors (such as how anxious thoughts may increase physiological arousal, and vice versa). As a first step of analysis, collected data were sorted into this framework, then their perpetuating factors were identified, and their possible interaction was discussed with participants to attempt an individualised formulation of their fear of falling. This analysis was discussed with them at the end of their interview, and their input was used to develop and refine it. As a last stage of analysis, the interviews were written up as case formulations for each interviewee in terms that attempted to model the onset and maintenance of their condition in terms of the cognitive–behavioural framework. Finally, comparisons were made between individual interviews and a tally of common factors and themes in different domains were made. Factors, and themes and patterns of interaction, were analysed to see if there were recurrent themes between interviewees with significant fear of falling.

Results: understanding fear of falling

The most striking initial finding was how heterogeneous fear of falling was, both in its development and in its maintaining factors. This is what necessitated running to 15 interviews. After this point it became clearer that there were three broad types of fear of falling into which the interviewed participants fell, namely primarily psychological factors, primarily physical factors and ‘the stoics’. To make this clear we will present the three categories with illustrative examples from participants.

Primarily psychological factors

About one-third of the interviewees conformed to the prevailing picture of fear of falling in the medical literature whereby fear, often but not always occasioned by a fall, is maintained by avoidance of activity, leading to loss of confidence, physical weakening and more fear of falling. However even in these cases, the picture was more complicated than this. Interviewee 1, who we will call Amelia, was the closest to the picture that we see in the literature. Her problem had begun 4 years prior to the interview when she had tripped and fallen on her face. Although nothing was broken, she vividly recalled the sense of being out of control and the ‘concrete coming up to meet my face’ (all quotes are directly from participants). Subsequent to this she had become very cautious about walking outside. She altered her walking in that it became much slower and she would almost continually look down. If possible she would ‘link up’, i.e. link arms, with a family member or a friend and increasingly took to either not going out on her own or sticking to areas that she knew well. To refer back to the CBT framework, these behaviours were reinforced and maintained by cognitions. She had come to perceive walking as dangerous, she had the image of the previous fall often in her mind when walking, and she was very aware of the fact that she could no longer ‘stride out’ as she used to (it was Amelia’s story that inspired the name of the intervention). These cognitions and behaviours in turn affected her mood. She was generally anxious when walking, and her mood was low (though she was not depressed) because her life contained much less enjoyment than previously. Her inability to ‘stride out’ and her lack of independence in turn generated a fair amount of frustration about her loss of ability. Physically, she reported being largely OK, but more tired than previously, and specifically mentioned that this type of walking (cautious and slow) was more tiring than how she used to walk, and also much less enjoyable.

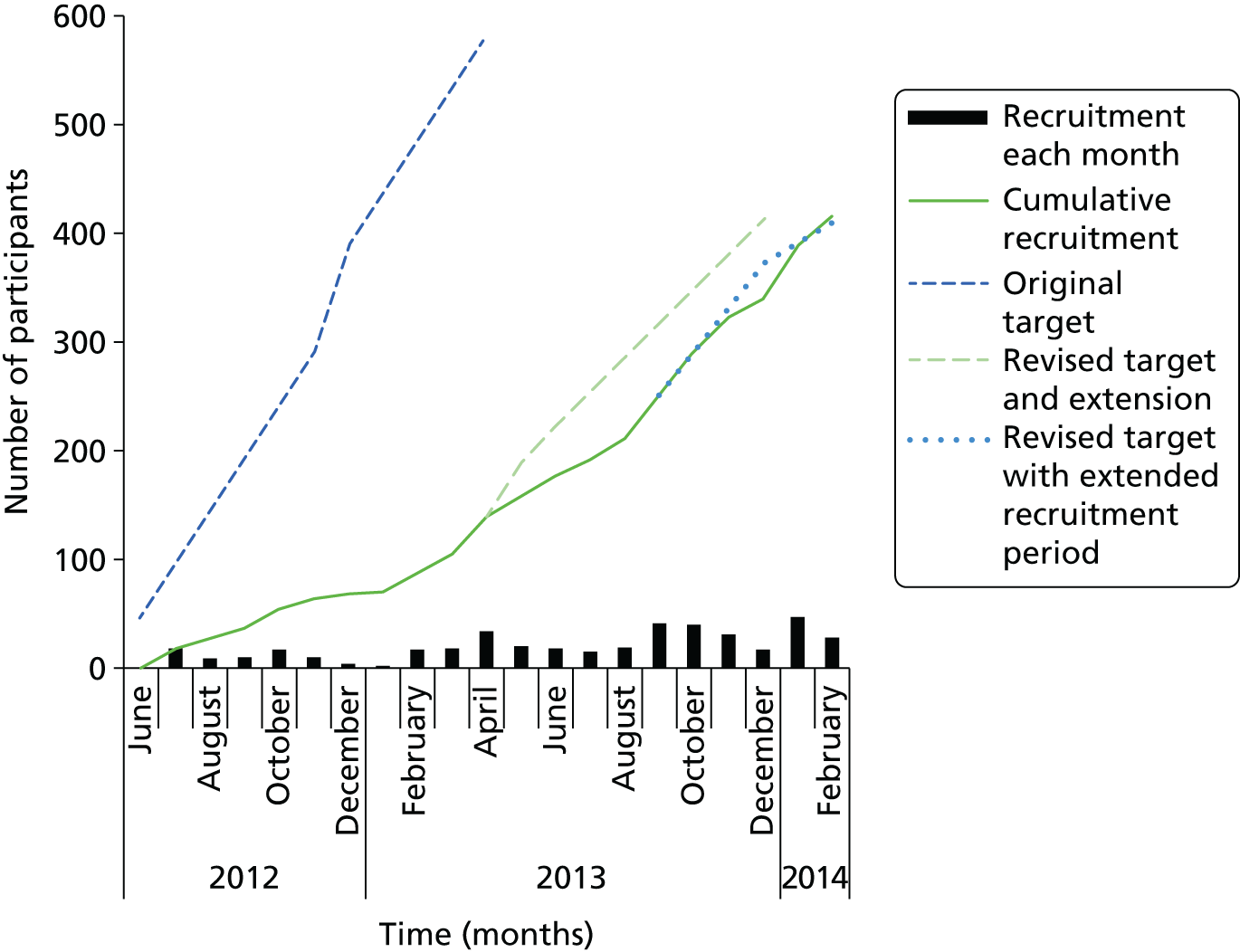

As such it was clear from this interview that in Amelia’s case, there was a traumatic precipitating event, although with no obvious predisposing factors. This was the case with most participants, where there was no past history of anxiety disorders. Furthermore, there was a clear interaction of physical, affective, cognitive and behavioural factors that were further reinforced by social isolation (she lived on her own). In CBT literature, the interaction of factors is often presented to the client in the form of a ‘hot cross bun’:44 Amelia’s hot cross bun is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Amelia’s hot cross bun.

Thus, it was clear that Amelia’s fear of falling was maintained by safety and avoidance behaviours, and by anxiogenic and catastrophic cognitions. As such, the obvious intervention would be to target these cognitions and behaviours with the appropriate evidence-based techniques.

However, she was one of the few participants who so neatly fitted this fear/avoidance model. Even when the factors maintaining the inactivity and avoidance were psychological, they were not always primarily to do with anxiety about falling. For instance, one participant was also largely physically capable, although he benefited from walking with a stick. However, he led a largely sedentary life because he was very self-conscious about being perceived as ‘old’. Although self-deprecatingly dismissing his own concerns as ‘vanity’, he nevertheless was clear that the main barrier to him going outside was that he felt very overlooked by his neighbours, and did not want to be seen as the old man with a stick. He was further restricted by social isolation and lack of companionship, and for him the main thing he thought would help would be someone to walk with. Another participant reported that since losing her best friend 2 years prior to the interview, she no longer saw the point in going out. The interview uncovered an interplay of ongoing grief and low mood, which were the main impediments to her engagement with the outside world.

Primarily physical factors

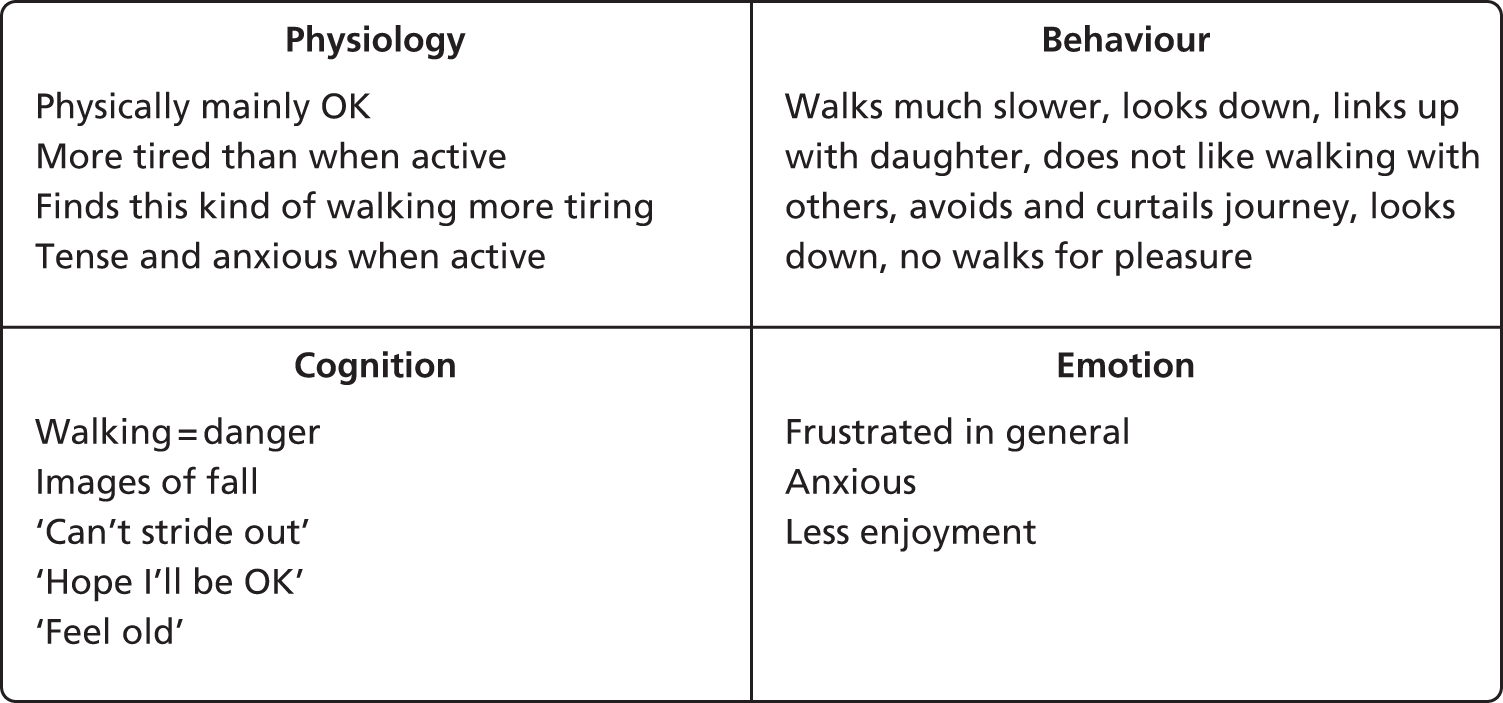

For another proportion of the interviewees, the primary impediments to walking were physical. For instance, one participant, whom we will call Fred, had multiple physical problems. He was overweight, had angina and breathlessness, a frozen right shoulder and a ‘shattered’ left shoulder (from a previous fall). As a result of pain and arthritis in his knees and ankles, he could walk only with sticks, and then with considerable pain. All of these physical ailments had left him severely limited in his physical capacity. He felt very vulnerable when out walking, as he was aware of being only one fall away from being bedbound or hospitalised. Although this latter anxiety was certainly a barrier to activity, he perceived his principal barriers to be his breathlessness, pain and fatigue. He also reported what emerged as a recurring fear among the cohort – that hospitalisation was a ‘one-way ticket to death’ – ‘once you go in you don’t get out’. Although he worked hard to maintain a social life, his activity was haunted by this fear of loss of independence and ultimate death. His ‘hot cross bun’ is presented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Fred’s hot cross bun.

About one-third of the cohort reported similar issues, with pain and fatigue, as a result of other physical problems, being the most commonly reported barriers to activity, rather than primarily fear.

‘The stoics’

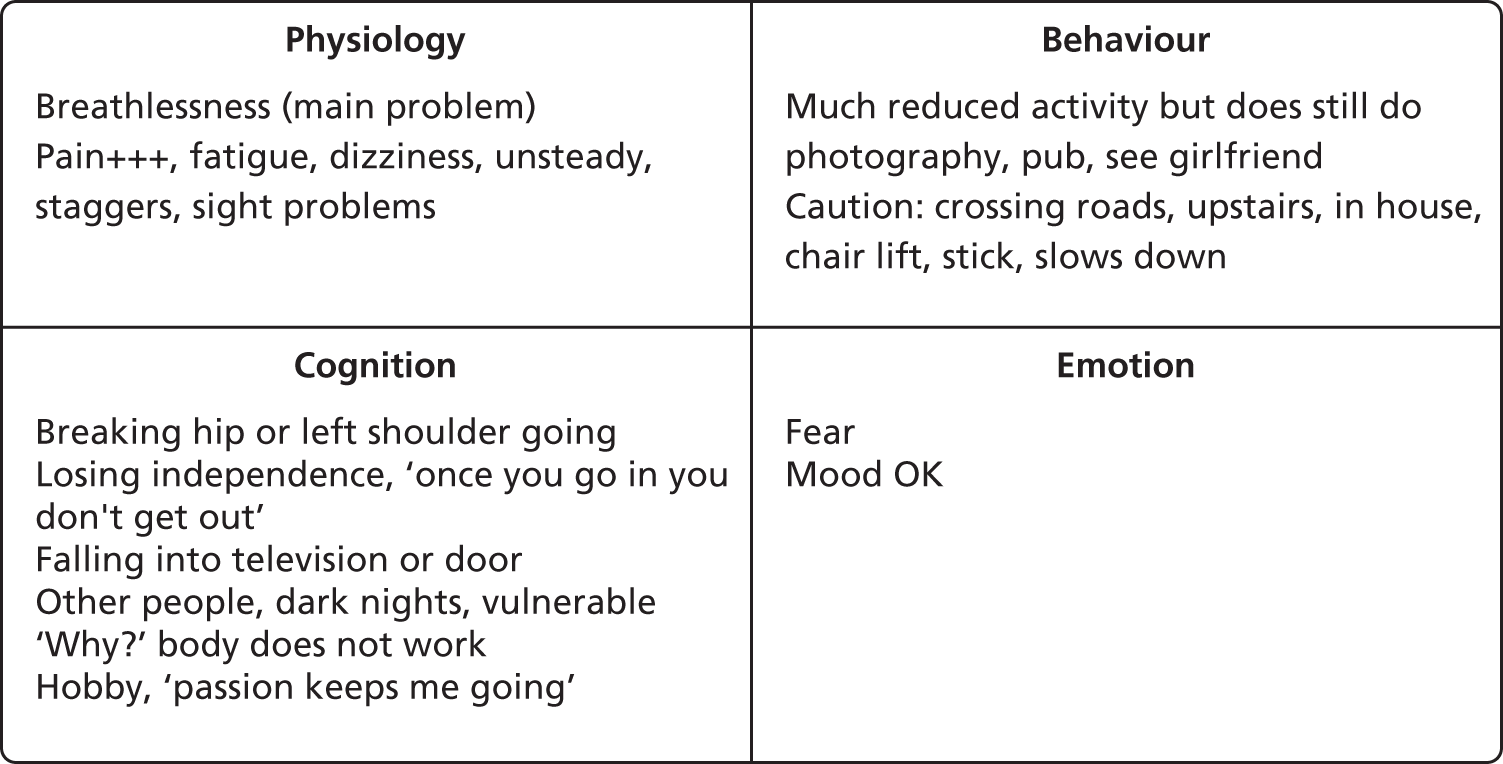

The third group were a surprising finding. These were participants who had considerable psychological and/or physical impediments to activity but who, nevertheless, continued to be active. We perceived an element of this in Fred above. Despite considerable physical problems and very real fears, he continued to pursue his hobby of photography, and he saw this as a ‘passion that keeps me going’. Another more marked example comes from a participant whom we will call Violet. She was the oldest, and perhaps the most physically frail of the people interviewed, and had a very unsteady gait. She also highlighted the heterogeneity of fear-of-falling precipitants. She had become aware of her unsteadiness only when her husband of 60 years had died, and she was no longer able to walk arm in arm with him. Now that he was gone she became aware that she would ‘suddenly list’ and ‘stagger unpredictably’. She had also seen her husband decline very rapidly after hospital admission and die there. Like Fred, she had the fear that admission to hospital was a ‘one-way ticket to loss of independence and ultimate death’. Despite both these physical and psychological ‘inducements’ to inactivity, Violet was the most active participant interviewed (Figure 3). Indeed she was difficult to pin down for interview as she was on (solo) holidays to Spain, Italy and the Netherlands during the study period.

FIGURE 3.

Violet’s hot cross bun.

Violet’s experience was not unique. Several other participants reported ‘keeping going’ despite obvious reasons to stop. This provided a new avenue of enquiry for these interviews: ‘What keeps you going?’. For each person it was different. For Violet it was the belief that ‘you are only here once’. She did not believe in God or an afterlife, and so was committed to get the most out of her life while she still could. Seeing her husband decline, although still a source of grief for her, was a further motivation to make the most of the time she had left. Another participant also struggled with both illness and anxiety, but kept going because she was committed to looking after her sisters, both of whom were housebound. She also had a dog to which she was committed to walking daily. In these cases it was clear that there was something that mattered more, a value that superseded the urge to avoid physical or psychological distress, and allowed the latter to be tolerated. We encouraged the interviewees to reflect on this, with the express purpose of helping us to help others with our intervention.

Shaping the intervention and training for the health-care assistants

One of the main conclusions that we drew from these interviews was that fear of falling was a heterogeneous condition and one for which a ‘one-size-fits-all’ intervention would not be appropriate. It also emerged that FES-I scores were, at best, a crude measure of the phenomenology of fear of falling uncovered in the interviews. The interviewer, the co-trainer and intervention supervisor (NSa, a clinical psychologist) and other members of the team (principally SWP and CB) discussed how we could turn these findings into (1) a replicable intervention and (2) a training programme for HCAs. The consensus was that, rather than focus exclusively on behaviour change techniques, we needed to equip the HCAs to arrive at the kind of individualised problem formulations that had emerged from the interviews. These formulations would form the basis of interventions by allowing the HCAs to assess the interplay of factors that were maintaining the fear of falling/activity avoidance in each individual. Only then would the deployment of behaviour change techniques be undertaken, in a tailored fashion. As to the latter, it was clear that there were some key intervention targets, which were fear and avoidance of activity; pain; fatigue; reduced activity; loss of confidence; catastrophic cognitions; grief; social isolation; and shame/self-image. Fear, pain and fatigue were the most commonly reported issues and so it became clear that the HCAs needed clear training for these, and some basic grounding in the evidence-based techniques for tackling the other recurrent issues.

From this discussion, we put together a ‘menu-based’ treatment protocol and designed the training accordingly. We also produced supporting training and client manuals (available on request from the corresponding author of this report, SWP). Treatment was menu based in the sense that once the assessment had been done, and the intervention targets agreed with clients, here would be a range of prescribed interventions to draw on for each of these targets, individualised to the specific client. We then put together the training programme. A detailed description of the intervention using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework45 is provided in Chapter 3 (see Table 6).

Duration of health-care assistant training

The training was delivered by VD and NSa over a period of 5 days in a classroom at the University of Northumbria.

Training content

The training gave an overview of CBT and then looked in more detail at the three P’s (predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating) model. Central to the HCAs’ training were the skills of engagement with the client, and assessment and formulation development. Standard CBT interventions for identified problems were described and practised: graded exposure for anxiety; activity monitoring, graded activity and behavioural activation for pain, fatigue and low mood; and sleep management for fatigue. For other recurrent issues HCAs were taught specific cognitive techniques, such as identifying thoughts; making explicit the links between thoughts, feelings and behaviour; thought diaries; thought challenging; and cost–benefit analysis for catastrophic and otherwise unhelpful cognitions. Furthermore, the HCAs were taught how to structure assessment and treatment sessions by working from formulation through to treatment plan in the first one to two sessions, then to specific treatment strategies in the middle three to four sessions, and then focusing on consolidation and discharge planning in the final sessions. An eight-session format was agreed as being most suitable in terms of intervention replicability, with the aim of weekly delivery.

The treatment plan was guided by end of treatment targets, which were worked out in collaboration with the clients, meaning that each client had specific and measurable goals that they were working towards throughout treatment. These individualised and personally meaningful goals aimed to capture that element of ‘valued activity’ that we found had kept the ‘stoic’ participants going, despite physical and/or psychological distress. The weekly implementation of treatment plans was carried out using specified interventions for specified targets in the form of client homework. Subsequent sessions were structured by homework reviews and problem-solving any additional barriers that had been identified before agreeing further target-setting for the next session. Finally, treatment review, skills embedding, and relapse prevention and preparation for discharge shaped the final sessions (Table 1).

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Assessment and formulation |

| 2 | Goals and target-setting |

| 3, 4, 6 | Continuation |

| 5 | Review |

| 7 | Relapse prevention |

| 8 | Final review |

| 6-month follow-up | Review and recap, goals, setbacks, outcomes |

Training delivery methods

A mixture of chalk and talk, observation, modelling and practice of the above techniques by the HCAs, as individuals and in pairs, formed the bulk of the training sessions. A strong emphasis was placed on ‘real play’, through which the HCAs were encouraged to use their own anxieties and experiences to work on in assessment, formulation and treatment. This was done with consent, and participants agreed that it helped to bring the techniques to life. Real fear of falling cases, derived from the interviews outlined above, suitably anonymised, were used to present the range of issues involved. The content of the training was summarised in both therapist and participant manuals (available from SWP) and the HCAs were encouraged to develop their own assessment and treatment props, which they did (see Appendix 2).

Post-training supervision

In the months following the above training the therapists engaged in both individual and group supervision. The former was of 1 hour every fortnight with NSa within which the focus was on skills development and consistency of intervention delivery. Individual client session audio tapes were shared and scrutinised with the supervisor. Discussion about internal and external challenges to the process of the study were also explored, as were individual issues that were pertinent. Group supervision was led by VD on a bimonthly basis, and focused on cases brought by the therapists for sharing and exploration of practice and interventions.

Acceptability and feasibility of the cognitive–behavioural therapy intervention

The previous section focused on the development of the CBTi and associated training materials; in this section we report the methods and results of Phase I of the process evaluation, which sought to understand the feasibility and acceptability of the CBTi from the perspectives of the different stakeholder groups involved (patients, clinicians and CBTi developers). (Phase II of the process evaluation is reported in Chapter 5, Process evaluation.)

Methods for process evaluation

Interviews with patients and carers

A sample of 14 patients (aged 60–85 years, nine female) and two family members (both female, age not specified) were interviewed. In contrast with the intervention development interviews, these explored patient and family members’ perceptions about the proposed CBTi, practical aspects of the CBTi (including how to describe the intervention, proposed delivery) and perceived relevance of the CBTi to their situation. Patients were recruited from the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service to reflect inclusion criteria for the RCT, using maximum variation sampling (for variety in age, gender and FES-I score). When appropriate, family members of these patients were invited to take part. Participants were interviewed in their own homes.

Interviews with professionals

The six professionals (three geriatricians, two physiotherapists and one HCA) who constituted the multidisciplinary team at the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service were interviewed. VD and NSa (hereafter psychologists) were also formally interviewed using a semistructured interview schedule (three interviews). These interviews explored perceptions of key factors that might impede or facilitate the proposed CBTi being effective and workable in practice.

Observation

Clinical sessions at the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service (n = 5) were observed to gain an understanding of the clinical context of the study. Professionals sought verbal consent from patients and any companions for the observation. No audio or audiovisual recordings were undertaken of these observations.

The regular meetings of the CBTi development team (VD and NSa) were audio recorded and observed by CB (n = 9 meetings). These data were supplemented with field notes that were taken of informal discussions (n = 8) with VD outside these meetings. Other related stakeholder engagement activities, including a briefing meeting for clinic staff, were also observed.

Data analysis

All qualitative data were analysed thematically using the constant-comparative technique. 46 This process allowed for the meaning of the data, and themes represented within them to emerge freely without the constraints that might be imposed on the data if coding to a prespecified coding frame. Themes were identified individually by CB and TF, who developed initial ideas and undertook coding independently, and then came together to discuss and compare ideas. We systematically worked through different data sources (professional interviews, patient interviews, intervention development meetings, interviews and informal discussions with the intervention development researchers, and field notes) identifying themes separately for each type of data prior to producing an overarching coding frame. The team members responsible for intervention development reviewed and commented on the coding frame thus providing some respondent validation. There were no formal opportunities for respondent validation by patients and carers; however, the identification of similar themes in the intervention development interviews conducted by VD, and those conducted as part of the process evaluation, provided some evidence of trustworthiness.

The process evaluation component of the study was designed not merely to evaluate the development of the CBTi, but also to collect data to inform and optimise the CBTi for delivery within the RCT. This was achieved through iterative data collection and feedback loops (that included formal and informal project-related meetings, and face-to-face and e-mail communications with the psychologists and the wider project team) to enable practical resolution of problems as they arose. The impacts of the process evaluation activities on the development and delivery of the CBTi are highlighted below.

Data reported here are attributed using the unique identifier allocated to the participant. Prefixes are as follows: ‘P’ denotes professionals; ‘C’ denotes patients interviewed for the process evaluation; ‘F’ denotes family members (caregivers); and ‘R’ denotes study team members.

Results: acceptability and feasibility

The first section of the results explores how the intervention developers adapted the proposed CBTi to fit with their emerging understandings of fear of falling and achieved an intervention which, from their perspectives, made sense. The second section highlights the concerns expressed by a range of stakeholders over the acceptability and feasibility of the proposed CBTi and RCT, in particular the ‘fit’ of trial structures and processes with older people; the staff who would be delivering the intervention; and the service in which patients were initially to be recruited. We examine the work undertaken by the research team to improve the coherence of the trial to stakeholders.

Based on their initial views that fear of falling could be conceptualised as anxiety based and avoidant, the psychologists had anticipated developing a simple, linear, manualised intervention centred on graded exposure. The initial clinical interviews conducted by VD (described in the initial section of this chapter) revealed that fear of falling was a complex and multidimensional phenomenon with diverse precipitating, perpetuating and predisposing factors. These observations created uncertainty about the feasibility of developing a CBTi that is suitable for all patients:

. . . it may be that there are certain groups within that, those complex dimensions that you’ve already described, that actually this may not be an appropriate intervention with all [. . .] groups [. . .]

R12, intervention development meeting, 22 November 2011

I’d be struggling to know what to do with them, to be honest. You can imagine a little change, but you’re up against the real, as it were.

R4, intervention development meeting, 22 November 2011

Broadening the focus of the CBTi to include work on pain, fatigue and other issues raised issues over the scope of the intervention and fit with the protocol:

So I think there’s a boundary issue about are we doing CBT for fear of falling.

The boundary issue is key.

Or are we doing CBT for fear of falling and actual (R4: and pain and . . .)

[. . .]

. . . in a sense you’ll be working with them with whatever they bring, I mean it might be that you know the pain is a major factor in them not going out or whatever so I think that’s a legitimate piece of work.

Intervention development meeting, 15 February 2012

The decision to focus on individualised formulations also created concerns over the potential mismatch between the complexity of the client group, the wide range of skills required to deliver the intervention (Box 1) and the allotted time frame:

Because you’ve identified very challenging, difficult clients [. . .] in terms of actual CBT, how do we get those relatively inexperienced therapists to actually be able to collect this information and actually then work – develop a relationship – and then work with these people over six sessions or however long it’s going to be. Because it’s such a small period of time.

R12, intervention development meeting, 22 November 2011

At the same time there was an emphasis on being realistic and focusing on the aim of the project:

We’re not training psychological therapists; we’re training some healthcare assistants to deliver a very, very short intervention. So we’ve got to be clear about what’s possible as well.

R12, intervention development meeting, 15 March 2012

Concerns were also raised about the potential generalisability of the intervention. There was an awareness that, in light of the careful selection, training and supervision of HCAs to meet the demands of this complex CBTi, the findings may not be replicable elsewhere:

All of which does raise some questions about generalisability, if we were recruiting the ones who are a bit savvy and we’re giving them a lot of training [. . .] that doesn’t necessarily translate into your ‘Joe Bloggs care assistant’ who is already working in a very busy . . . but we’ll see, I think we have to prove it’s doable first.

R4, intervention development meeting, 13 September 2011

-

Ability to develop a therapeutic relationship.

-

Formulation skills.

-

Managing uncertainty during the process of learning CBT skills.

-

Willingness to practise new skills under scrutiny.

-

Ability to contain potentially distressing emotions.

-

Knowing own limitations and ability to judge when referral to more experience professionals is required.

Achieving coherence in randomised controlled trial structures and processes

The process evaluation interviews that were conducted with patients and clinic staff indicated a number of other issues that needed to be addressed to maximise the feasibility and acceptability of the RCT in which the CBTi was to be evaluated. These issues were iteratively fed back by staff responsible for the process evaluation (CB and TF) to key members of the project team to allow the development and implementation of strategies to address them prior to the start of the RCT.

Perceived acceptability of cognitive–behavioural therapy intervention to older people

A key issue raised by all stakeholders was the extent to which CBT would be acceptable to older people, as illustrated by the following comments:

I imagine that some stoical North Easterners might think that it was wishy washy mumbo jumbo that wasn’t necessarily going to help, you know the idea of going and sort of seeing like, effectively having a sort of a counselling type sessions, some people might not take that seriously.

P2, interview, 6 December 2011

So I think although she would agree to any kind of help I think there’s a part of her that possibly feels she doesn’t need it, and I think it’s getting over that hurdle.

F2, interview, 9 March 2012

A key issue concerned the name of the CBTi. Patients and clinic staff indicated that the use of terms such as ‘psychological’ and ‘psychotherapy’ were potentially alienating to the intended client group:

what does psychotherapy treatment mean to you?

Sitting on a couch with a shrink!

And would you then sign up for that do you think?

I don’t know, I don’t know whether that would help me with the problems I’ve got.

C2, interview, 30 January 2012

All stakeholder groups participating in qualitative interviews were asked for advice and suggestions. It was seen as essential to ensure that the title was positive: avoid the word ‘falling’ (as well as any words beginning with ‘psych’) and to consider including terms such as ‘confidence’, to which people would be able to relate. In addition to being non-threatening, we wanted the name to convey a sense of the purpose and focus of the intervention so that it would not be mistaken for an exercise class. Following discussions, we agreed on STRIDE as the brief study title (Strategies for increasing independence, confidence and energy).

Although there were clear reservations about the concept and name of the CBTi, stakeholders were generally positive about the practical aspects of the CBTi, for example the number, frequency and duration of sessions, the timing of the follow-up session, and the intention to deliver the intervention at home. Patients emphasised the need for flexibility and for the sessions to fit around their other commitments. Several patients suggested group sessions, either instead of, or alongside, individual sessions, and although the likelihood of individual preferences was noted it was agreed that this could not be accommodated in the RCT.

Perceived value of cognitive–behavioural therapy intervention for fear of falling

Clinic staff expressed some reservations about the proposed CBTi for fear of falling, in particular the possibility that, for some patients, fear of falling may actually be protective with regard to falling:

I don’t know whether it’s protective or not which would be my other question, is it a good thing people have a fear of falling, if you take that fear of falling away are they going to fall because their sense of caution has gone?

P3, interview, 7 December 2011

Clinic staff also expressed reservations over patients’ willingness to engage with an intervention that focused primarily on fear of falling:

I’m not sure how receptive they will be to addressing fear of falling as a primary factor in the absence of anything else, any modifications to gait or aids or physical performance, so I don’t know how often it’s a stand-alone problem.

P3, interview, 7 December 2011

As the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service focused on identifying underlying medical causes for falls, it was not surprising that staff were uncertain about the value of psychological interventions such as CBT. In light of their key role in ‘selling’ the CBTi to eligible patients in Phase I of the study, we organised a briefing meeting for clinic staff in which the intervention developers fed back the results of the interviews, described the intervention and illustrated how it would be relevant to different types of clients. This enabled staff to recognise the similarities between the CBTi and their existing practice:

I mean I’ve used it a lot with working with older people and it’s not actually called CBT but it’s what you do with them from the point of view you’ve gradually got to build their confidence up through very simple increasing their activities and things and the way you talk to them and the way you encourage them and things like that as well, so yes I think it would be very, very helpful actually.

P5, briefing meeting for clinic staff, 17 February 2012

During this briefing meeting, we were able to provide reassurance about the venue of the treatment (usually in patients’ own homes) and also to address other concerns, for example mechanisms for informing patients’ general practitioners (GPs) about their participation.

Recruitment of patients to a randomised controlled trial

Observation of the clinical setting in which the RCT was to take place revealed that the service specialised in fast paced, routinised, structured assessments. Potential barriers to patient recruitment were time pressures and the lack of any routine discussion of fear of falling within the service. To facilitate recruitment in these difficult circumstances, we produced a user-friendly leaflet and a ‘script’ that staff could follow. This was designed to have minimal time implications and to allow staff to follow their existing approach to referring patients for strength and balance classes provided by a local voluntary organisation.

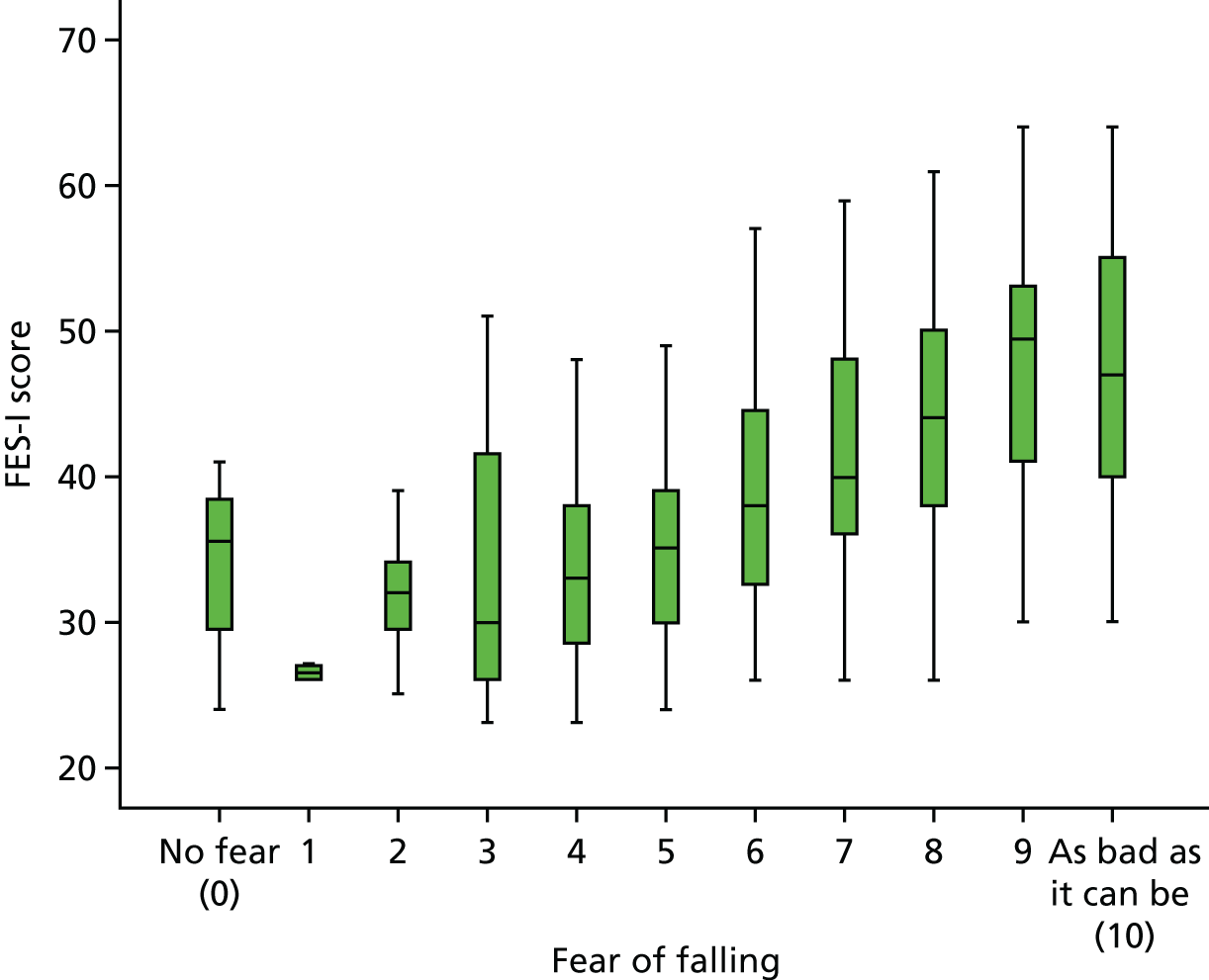

Relevance and acceptability of the primary outcome measure

A final issue that emerged from discussions with clinic staff related to the adequacy of the FES-I as a means of identifying potential participants and the primary outcome measure despite clear published evidence of its validity. 29 These concerns over the outcome measure undermined the perceived validity of the proposed RCT. A key concern was the perceived lack of correlation between apparent fear of falling and FES-I scores:

She’s an agoraphobic and was very, very frightened of falling [. . .] she won’t go to the hairdresser and that sort of thing, but because the FES was so low from that point of view then obviously she wouldn’t fit your criteria then would she?

P5, briefing meeting for clinic staff, 17 February 2012

Staff felt that responses on the FES-I often reflected functional limitations (e.g. arthritis or other pain) that affect mobility rather than fear of falling. Given the extent of clinic staff concerns over the use of the FES-I as the primary outcome measure, we added a visual analogue scale, on which patients could rate their fear of falling, to be included alongside other measures used in the RCT.

Chapter 3 Phase II: randomised controlled trial methods

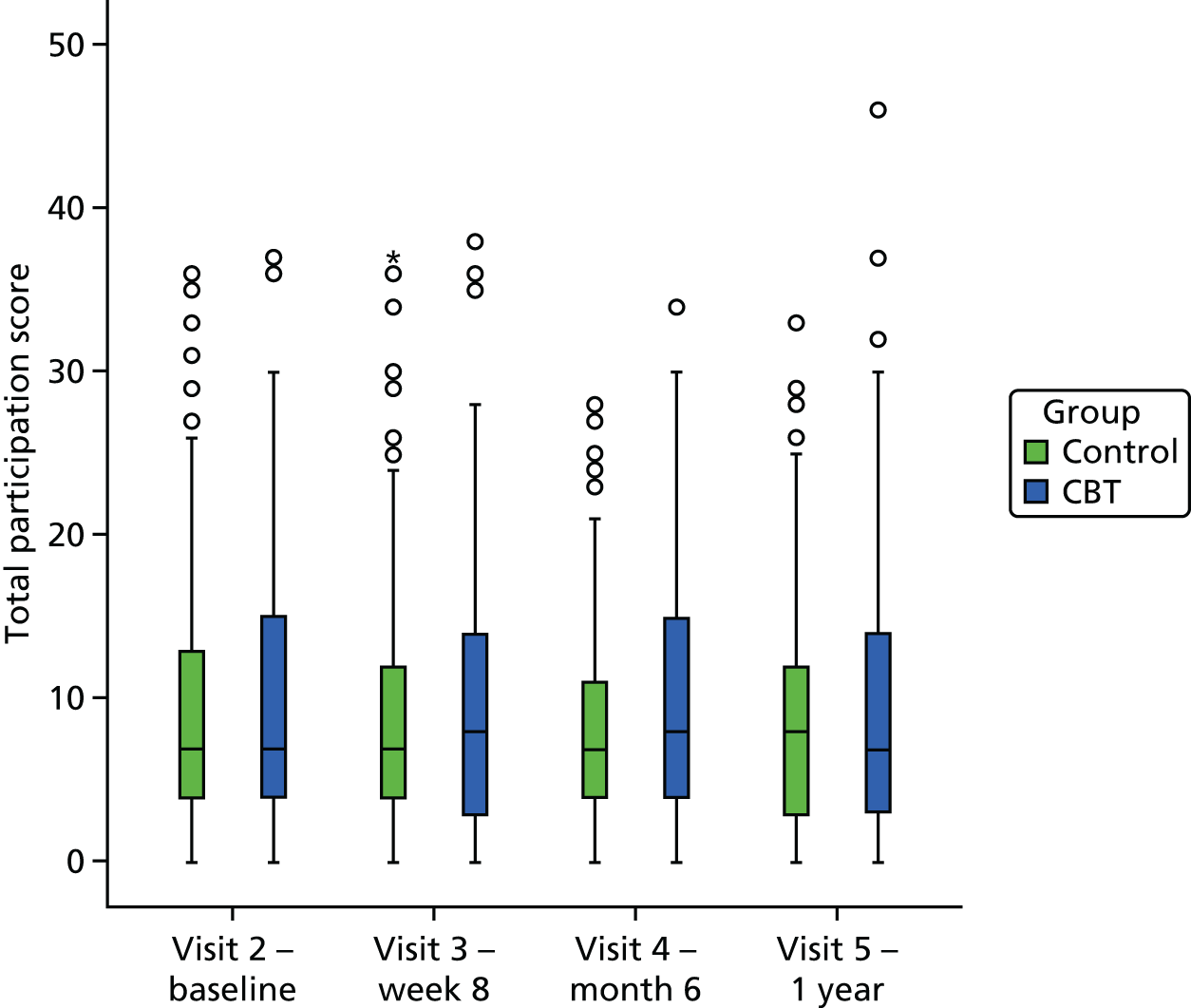

Objectives of the randomised controlled trial

Primary objective

To determine the effectiveness of a new cognitive–behavioural therapy-based intervention (CBTi) plus usual care compared with usual care alone (the control condition) in reducing fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults attending falls services.

Secondary objectives

To:

-

measure the impact of the intervention compared with the control on fall and injury rates in the trial participants, and its impact on functional abilities

-

measure the effectiveness of the intervention compared with control on anxiety and depression, quality of life, loneliness, social isolation and social participation

-

investigate the acceptability of the intervention for patients, family members and professionals

-

further investigate the professional and organisational factors that promote or inhibit the implementation and integration of the intervention

-

measure the costs and outcomes of the intervention in this setting.

Objectives (c) and (d) relate to the process evaluation, the methods and findings of which are described in Chapter 5; objective (e) relates to the health-economic evaluation, the methods and findings of which are described in Chapter 6.

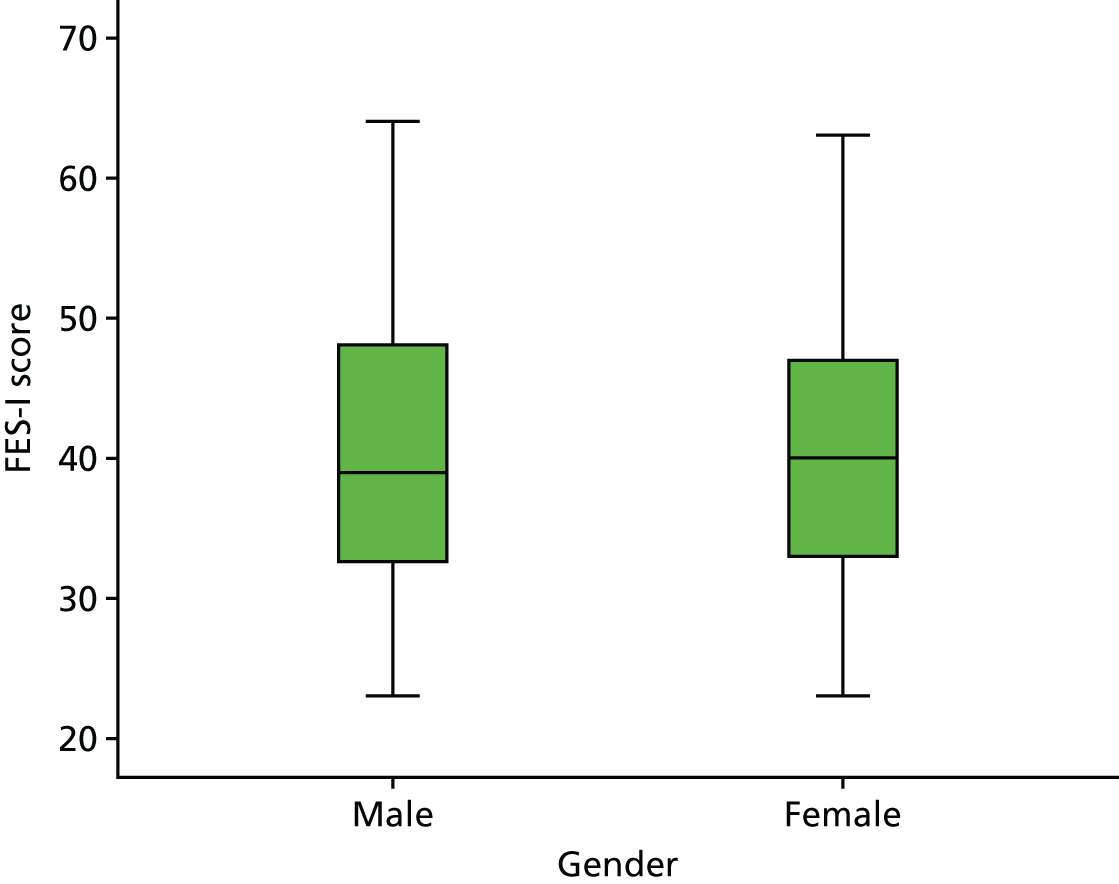

Summary/overview of trial design

Two-arm, parallel-group patient RCT of a novel CBTi plus usual multidisciplinary care compared with usual multidisciplinary care alone in older patients with significant fear of falling and who are attending multidisciplinary falls services. Patients were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio.

Trial registration and protocol availability

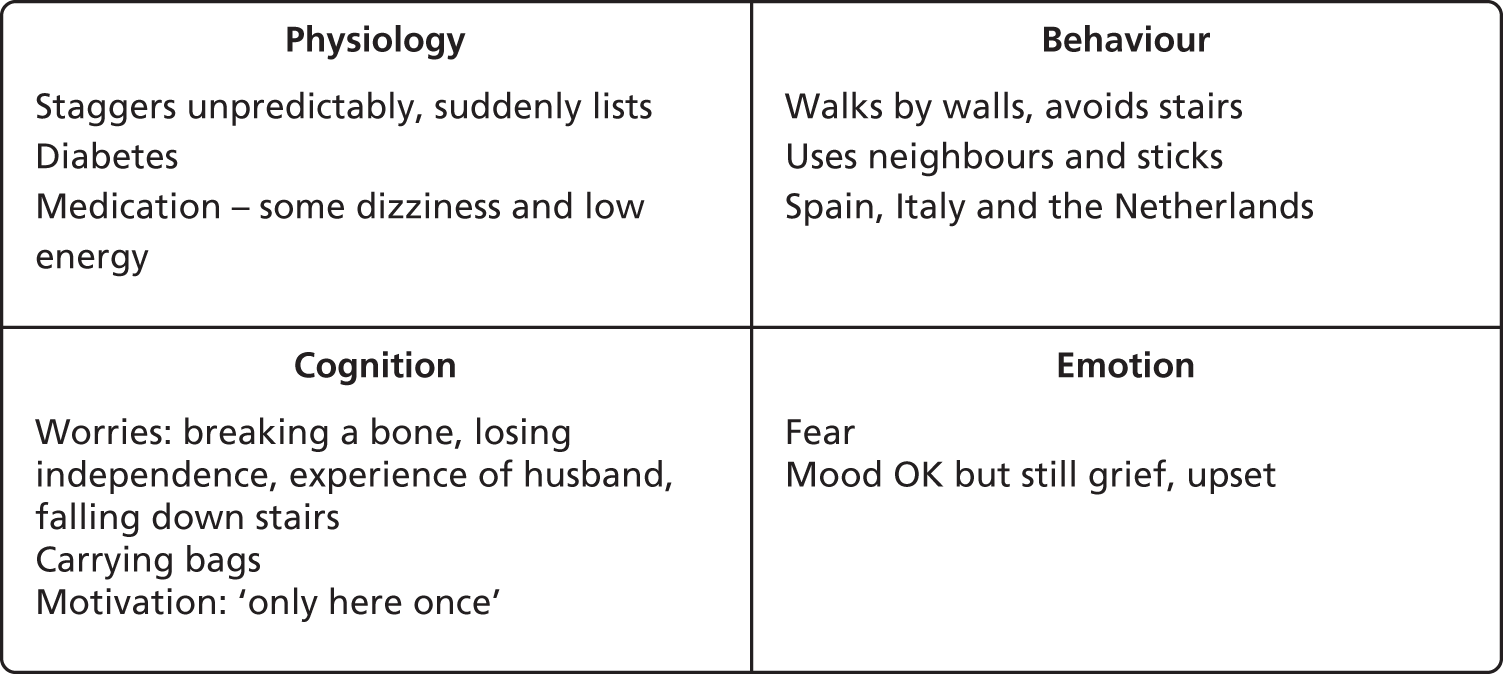

The trial was registered as ISRCTN78396615 on 17 May 2012. The latest version of the full protocol is available at www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hta/097004 and a published version is also available. 47 Table 2 summarises key changes to the original STRIDE trial protocol as approved by the research ethics committee (REC).

| Description | Version | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Update to recruitment procedures; administrative updates | 2.0 | 15 March 2012 |

| Update to prospective recruitment of participants to the RCT | 3.0 | 27 November 2012 |

| Revision of the sample size Update of the protocol to incorporate additional recruitment sites |

4.0 | 5 April 2013 |

| Staff member update Update of study duration Update of procedures for follow-up of non-returned self-completion questionnaires and completion of questionnaires via telephone |

5.0 | 6 March 2014 |

Ethics and governance

The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust was the sponsor for the trial. Favourable ethical opinion for Phase II (the RCT) was obtained on 16 February 2012 from the Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 REC (REC reference 12/NE/0006) and subsequent Research & Development and Caldicott approvals were granted by each participating site. Approval was sought and obtained for all substantive protocol amendments.

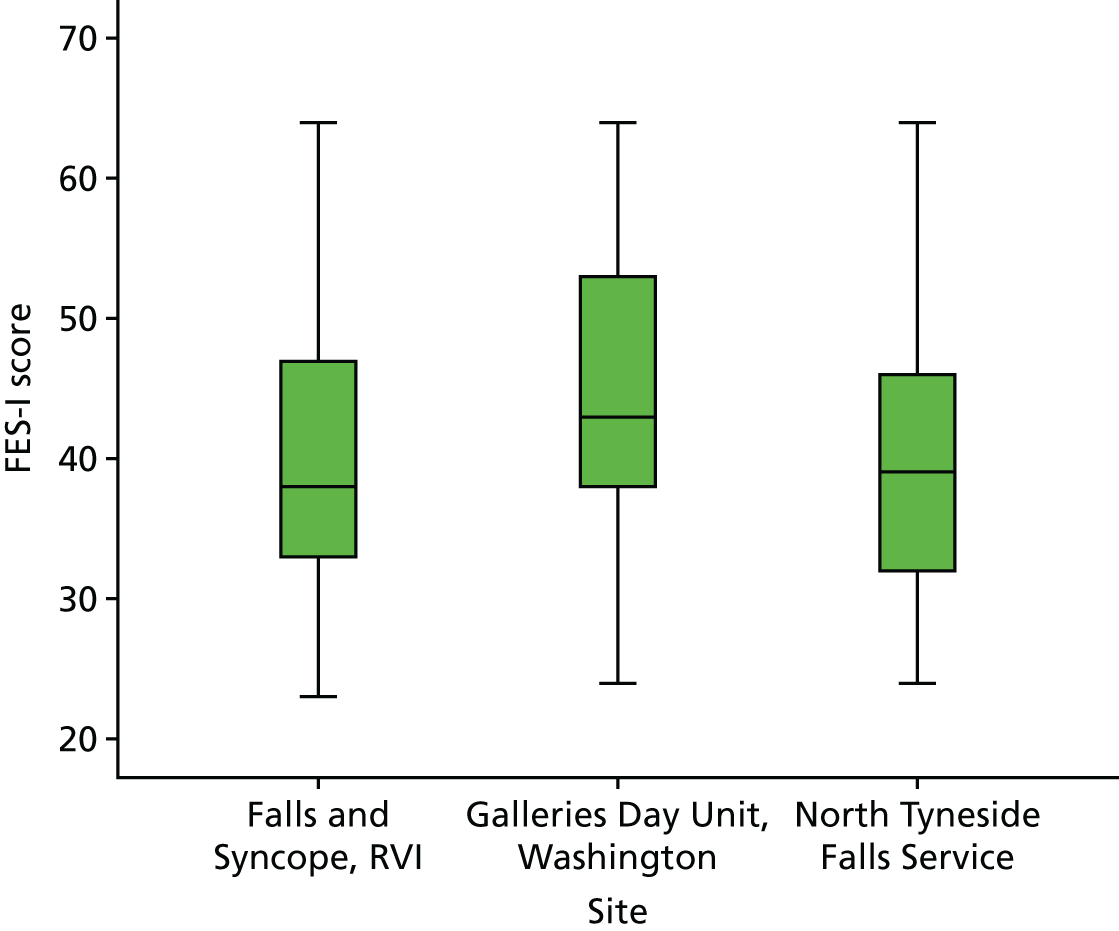

Trial setting

This trial was conducted in three community-based Falls Services in the North East of England: North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Galleries Day Unit, Washington, South Tyneside NHS Foundation Trust; and Falls and Syncope Service, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The trial was originally designed as a single-site study at North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service but, as a result of recruitment problems, the other sites were subsequently added (June 2013 for Galleries Day Unit; May 2013 for the Falls and Syncope Service).

The North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service was a community falls prevention service focusing on early identification of patients at risk of falls. The Galleries Day Unit was a nurse-led community falls service providing assessment and rehabilitation. The Falls and Syncope Service was a specialist centre serving both local and national communities. Key characteristics of each site are summarised in Table 3.

| Service specifications and characteristics | North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service | Galleries Day Unit | Falls and Syncope Service |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year established | 2009 | 2007 | 1991 |

| Aim | To investigate, diagnose and help manage syncope (blackouts/loss of consciousness) and falls | To provide assessment and rehabilitation to patients who are either known fallers or are at risk of falling | To investigate, diagnose and help manage syncope and falls |

| Staff | HCA; physiotherapist; consultant physician | HCA; physiotherapist; nurse | Nurse; physiotherapist; consultant physician |

| Age group, years | 60+ | 60+ | 16+ |

| Catchment area from which patients drawn | All GP practices within a geographically defined area | All GP practices within a geographically defined area | Primarily local (Newcastle, North Tyneside and Northumbria), but with regional and national referrals |

| Method of access of patients to service | Screening questionnaire administered by GP practice to patients aged 60+ years to identify patients at risk of falling, referrals from GPs | Health or social care professional (including the ambulance service) | Referrals from GPs, ambulance service, A&E department; tertiary referral centre |

| Patients’ living arrangements | Community dwelling | Any | Any |

| Premises | Shared rooms within a health centre | Dedicated rooms within a health centre | Dedicated clinic in a hospital |

| Availability | 2.5 days per week | 5 days per week | 5 days per week |

| Duration of initial appointment (minutes) | 90 | 120 | 90 |

| Typical number of visits | 1 | 8–12 for patients on rehabilitation programme | 3–4 |

| Documentation of care | Electronic care pathway only | Loose-leaf sheets | Care pathway booklet (with separate booklet for physiotherapist documentation) |

The routine (i.e. for patients outwith the STRIDE trial) patient assessment process is summarised in Table 4, using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on possible content of multifactorial falls assessment. 48 As can be seen there were marked variations between sites.

| Clinical assessments | North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service | Galleries Day Unit | Falls and Syncope Service |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of falls history | |||

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

| Assessment of gait, balance and mobility and muscle weakness | |||

|

PRN | Y | PRN |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | PRN (physio) |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | PRN (physio) |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

| Assessment of osteoporosis risk | FRAX | FRAX | FRAX |

| Assessment of perceived functional ability and fear relating to falling | |||

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

PRN | Y | PRN |

|

Y | Y | PRN (physio) |

|

Y | Y | PRN (physio) |

|

N | Y | N |

| Assessment of visual impairment | |||

|

Y | Y | Y |

| Assessment of cognitive impairment and neurological examination | |||

|

Y | PRN | PRN |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

PRN | PRN | PRN |

|

N | N | PRN |

| Assessment of urinary incontinence | PRN | Y | PRN |

| Assessment of home hazards | PRN | Y/PRN | PRN |

| Cardiovascular examination and medication review | |||

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

N | N | PRN |

|

N | N | PRN |

| Other | |||

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y |

|

PRN | PRN | PRN |

|

Y | N | N |

|

Via GP | PRN | PRN |

|

N | PRN | Y |

|

PRN | PRN | PRN |

A key characteristic of the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service was that all recording was carried out electronically during consultations; as each professional completed their assessment with an individual patient, the colour of the patient’s electronic record changed so that their colleagues could see that the assessment was completed and could access the notes. The consultant saw patients last, and, following detailed explanation of findings, printed out a summary of the assessment at the end of the consultation for patients to take home with them; a hard copy was also sent to the patient’s GP.

A key difference between the Falls and Syncope Service and the other two sites was that patients were not routinely assessed by the physiotherapist; this reflects the more varied patient group seen in the Falls and Syncope Service, a significant proportion of whom were younger patients who were referred for dizziness and blackouts rather than falls. The physiotherapist within this service therefore operated like an outpatient clinic, with patients being referred for assessment when required. Patients who were referred to the physiotherapist had an initial assessment of 60 minutes, with review appointments of 30 minutes. In contrast with the physiotherapy assessments in the other two sites, the dynamic gait index was performed, for which patients are asked to walk at different speeds, turn their head horizontally and vertically when walking, turn and stop, and to negotiate obstacles while walking. Other aspects of the physiotherapy assessment were similar to those observed in the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service and Galleries Day Unit. The Falls and Syncope Service also performed the Epley manoeuvre for patients with benign positional paroxysmal vertigo (BPPV), whereas patients attending the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service and Galleries Day Unit had to be referred to Ear, Nose and Throat services for this treatment.

The care pathways and interventions offered by the different sites post initial assessment also varied (Table 5). In the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service, following assessment, patients were referred:

-

back to their GP for medication or other review

-

to secondary care, day hospital, community physiotherapy and occupational therapy as appropriate

-

for bone densitometry at the local hospital, and/or

-

to targeted strength and balance training classes run in conjunction with the voluntary sector (Age UK) in North Tyneside.

Patients were also signposted patients to local exercise classes, such as t’ai chi run by Age UK. In the Galleries Day Unit, the main outcome of initial assessment was referral to the in-house rehabilitation programme, although other options were available including home exercises or in-house t’ai chi and referral to the lead consultant geriatrician and falls specialist at Sunderland Royal Hospital for ongoing investigation. Arrangements for follow-up and management, post initial assessment, were more fluid in the Falls and Syncope Service; this related to the range of investigations available within the service (e.g. carotid sinus massage, tilt table), as well as the options for physiotherapy intervention (within the service, community physiotherapy, day hospital, community strength and balance training via the Staying Steady project, etc.).

| Intervention | North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service | Galleries Day Unit | Falls and Syncope Service |

|---|---|---|---|

| Referral to community exercise | Strength and balance classes | Yes (Age UK classes or gym membership) | Staying Steady intervention |

| In-house physiotherapy | No | No | Yes (typically prescribed home exercises and reviewed four to five times) |

| In-house rehabilitation programme | No | Yes (typically 11–12 sessions) | No |

| In-house exercise/t’ai chi | No | Yes | No |

| Home exercises | Yes (sheets provided) | Yes (sheets provided and HCA could visit patients at home to provide 1 : 1 exercises where appropriate) | If referred to in-house or community physiotherapist, home exercises might be provided PRN (sheets provided) |

The in-house rehabilitation programme provided at the Galleries Day Unit comprised six stages, although most patients started at stage 4. Rehabilitation sessions typically lasted 15–20 minutes. The patients were reviewed by the physiotherapist typically before moving on to stage six when a decision was made whether or not to continue, repeat some of the earlier sessions or discharge the patient.

In the Falls and Syncope Service, patients requiring physiotherapy intervention were often given an individual exercise programme to follow at home and reviewed after about 6 weeks. Patients who were frailer and required more input tended to be referred to a day hospital where more support and dedicated transport were available. Many of the patients requiring intervention began with home exercises and were later referred to Staying Steady – evidence-based community exercise groups which ran over 36 weeks, alternating periods of exercise classes and home exercises. However, access to this intervention varied according to where patients lived and there were significant waiting lists in some areas of the city. In the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service, approximately 25% of patients were referred to strength and balance training classes run in conjunction with Age UK, with tailored exercise programmes for up to 10 individuals provided weekly for 10 weeks, following which participants were encouraged to attend follow-on exercise classes.

Study participants

Participants were community-dwelling older patients aged ≥ 60 years, of both sexes, attending one of the above falls services with excessive or undue fear of falling as assessed by the FES-I29 score of > 23. The cut-off score of > 23 was informed by a comprehensive longitudinal study of the clinical and psychometric properties of the FES-I in 500 community-dwelling elders, which suggested this threshold as indicating high levels of concern about falls. 40

As described below, patients provided written informed consent for participation in the study prior to any study-specific procedures.

Inclusion criteria

-

FES-I score of > 23.

-

Aged ≥ 60 years.

Exclusion criteria

-

Cognitive impairment [Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of < 24/30]. 41

-

Life expectancy < 1 year or unlikely for any other reason to be unable to complete 1-year follow-up

-

Requiring psychosocial interventions that are unrelated to fear of falling.

-

Current involvement in other investigational studies or trials, or involvement within 30 days prior to study entry.

-

Patients who had taken part in Phase I (i.e. qualitative work to develop the intervention) of the study. A small number of these patients acted as ‘pilot clients’ and received the intervention (as part of the training of the HCAs) but did not complete any of the outcome measures.

During the course of the study, it became apparent that some couples both fulfilled study eligibility criteria. To avoid contamination, it was decided that only one member of each household should be randomised. Therefore, if a spouse or partner of an otherwise eligible individual was already participating in the study, the second individual to be identified was excluded at the second stage of screening by research assistants (RAs) (see below).

Interventions

The control group received usual care for the falls services in which they were recruited, as described above. The intervention group received usual care as detailed above plus a CBTi. The rationale for this choice of intervention and the theoretical basis for it are described in greater detail in Chapter 2 (see Phase I: intervention development) and intervention materials (therapist and patient manuals) can be obtained from the corresponding author of this report (SWP). The CBTi was developed by our team in Phase I of this research; the development process is described in Chapter 2 (see Phase I: Intervention development). It was delivered face to face, on a one-to-one basis, by one of three trained HCAs, at participants’ homes, the North Tyneside Falls Prevention Service or community centres or facilities (e.g. Age UK offices in North Shields), Newcastle University or the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne (RVI), as per patient choice. HCAs were trained in basic CBT assessment, formulation and treatment skills by a qualified cognitive–behavioural therapist and practitioner health psychologist (VD) and a clinical psychologist (NSa) (hereafter ‘psychologists’). Assessment and formulation skills allowed them to identify, with the patient, the unique set of beliefs, behaviours, emotions and physical factors that were maintaining the fear of falling in that individual. Treatment sessions focused on targeting these beliefs and behaviours. CBTi sessions lasted approximately 45 minutes, with 15 minutes’ preparation time, and were based on an individualised formulation that identified and targeted the beliefs and behaviours maintaining fear of falling for that individual. The planned course of treatment was once per week for 8 weeks, with a single reinforcement session 6 months after the last CBTi session. The intervention is summarised using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework45 in Table 6.

| Item no. | Item | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brief name: Provide the name or a phrase that describes the intervention | STRIDE |

| 2 | Why: Describe any rationale, theory, or goal of the elements essential to the intervention | Based on the cognitive–behavioural model32 |

| 3 | What materials: Describe any physical or informational materials used in the intervention, including those provided to participants or used in intervention delivery or in training of intervention providers. Provide information on where the materials can be accessed (such as online appendix, URL) | Patient manual; therapist manual; training materials |

| 4 | Procedures: Describe each of the procedures, activities, and/or processes used in the intervention, including any enabling or support activities | Formulation, tailored intervention |

| 5 | Who provided: For each category of intervention provider (such as psychologist, nursing assistant), describe their expertise, background, and any specific training given | HCAs Five-day training programme. Two recent psychology graduates: one with experience as HCA managing patients with falls; one physiotherapist |

| 6 | How: Describe the modes of delivery (such as face to face or by some other mechanism, such as internet or telephone) of the intervention and whether or not it was provided individually or in a group | Individual face-to-face sessions |

| 7 | Where: Describe the type(s) of location(s) where the intervention occurred, including any necessary infrastructure or relevant features | Patients’ homes (or convenient clinic if preferred) |

| 8 | When and how much: Describe the number of times the intervention was delivered and over what period of time including the number of sessions, their schedule, and their duration, intensity or dose | Planned as eight sessions over a period of 8 weeks, with each session lasting about 1 hour; behavioural and cognitive homework (e.g. graded exposure to avoided situations, fearful thoughts recorded and challenged) to be completed between sessions. One review session scheduled at 6 months after completion of initial intervention |

| 9 | Tailoring: If the intervention was planned to be personalised, titrated or adapted, describe what, why, when, and how | Intervention to be determined by individual ‘hot cross bun’ formulations, as described in Chapter 2 (see Results: understanding fear of falling) |

| 10 | Changes: If the intervention was modified during the course of the study, describe the changes (what, why, when, and how) | No formal modifications were made although the intervention evolved during the study (see Box 2) |

| 11 | How well – planned: If intervention adherence or fidelity was assessed, describe how and by whom, and if any strategies were used to maintain or improve fidelity, describe them | Intervention delivery was monitored through individual and group supervision, which included listening to recordings of therapy sessions (see Table 37) |

| 12 | How well – actual: If intervention adherence or fidelity was assessed, describe the extent to which the intervention was delivered as planned | See Chapter 4 |

Other therapeutic interventions were permitted in both intervention and usual care arms of the study per routine clinical care. None was prohibited.

Outcomes

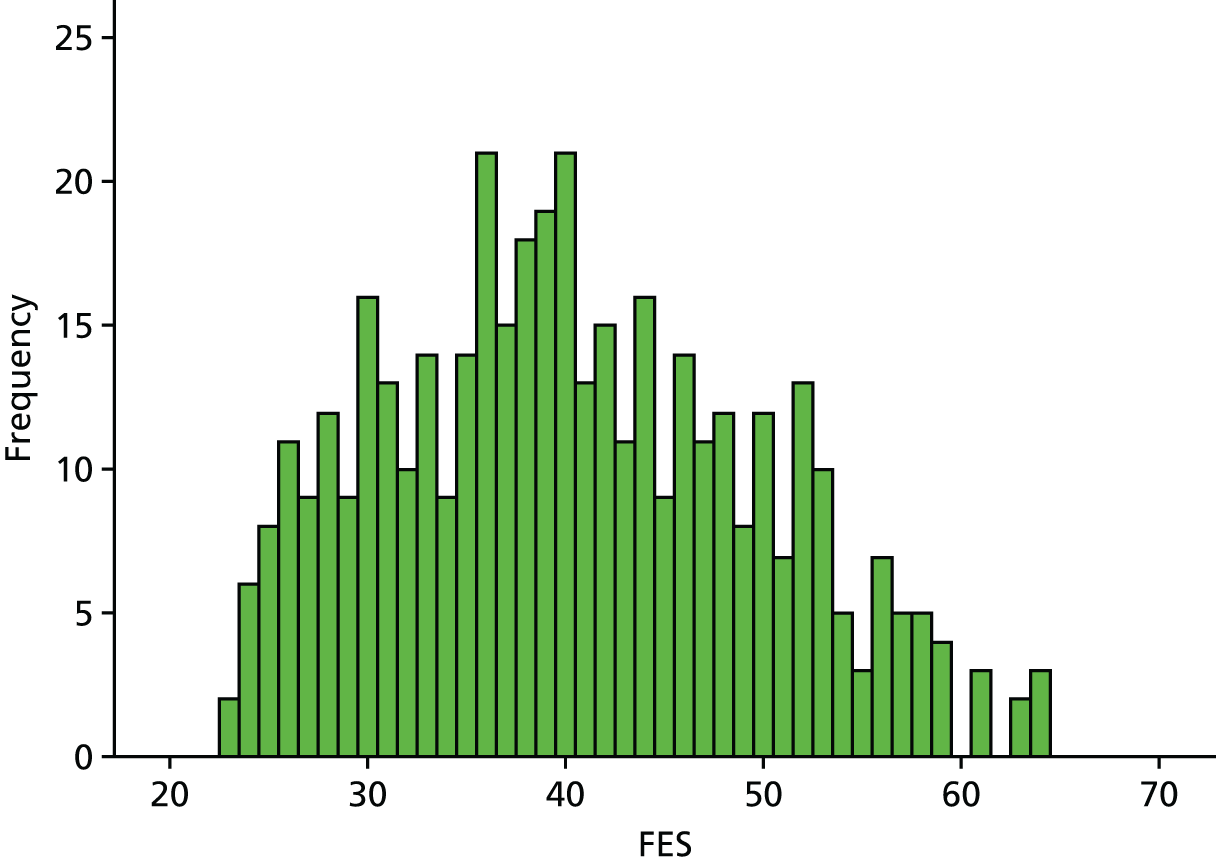

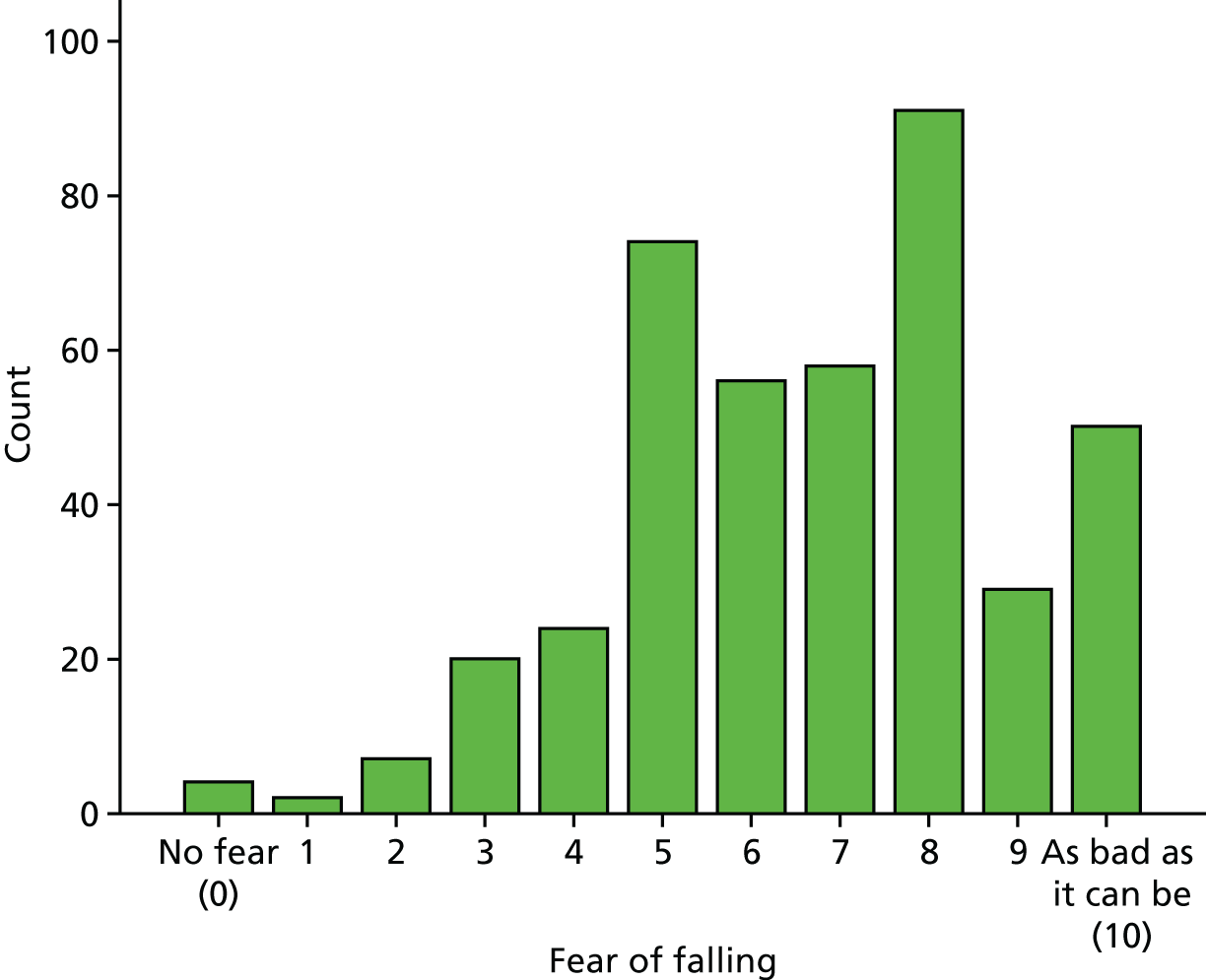

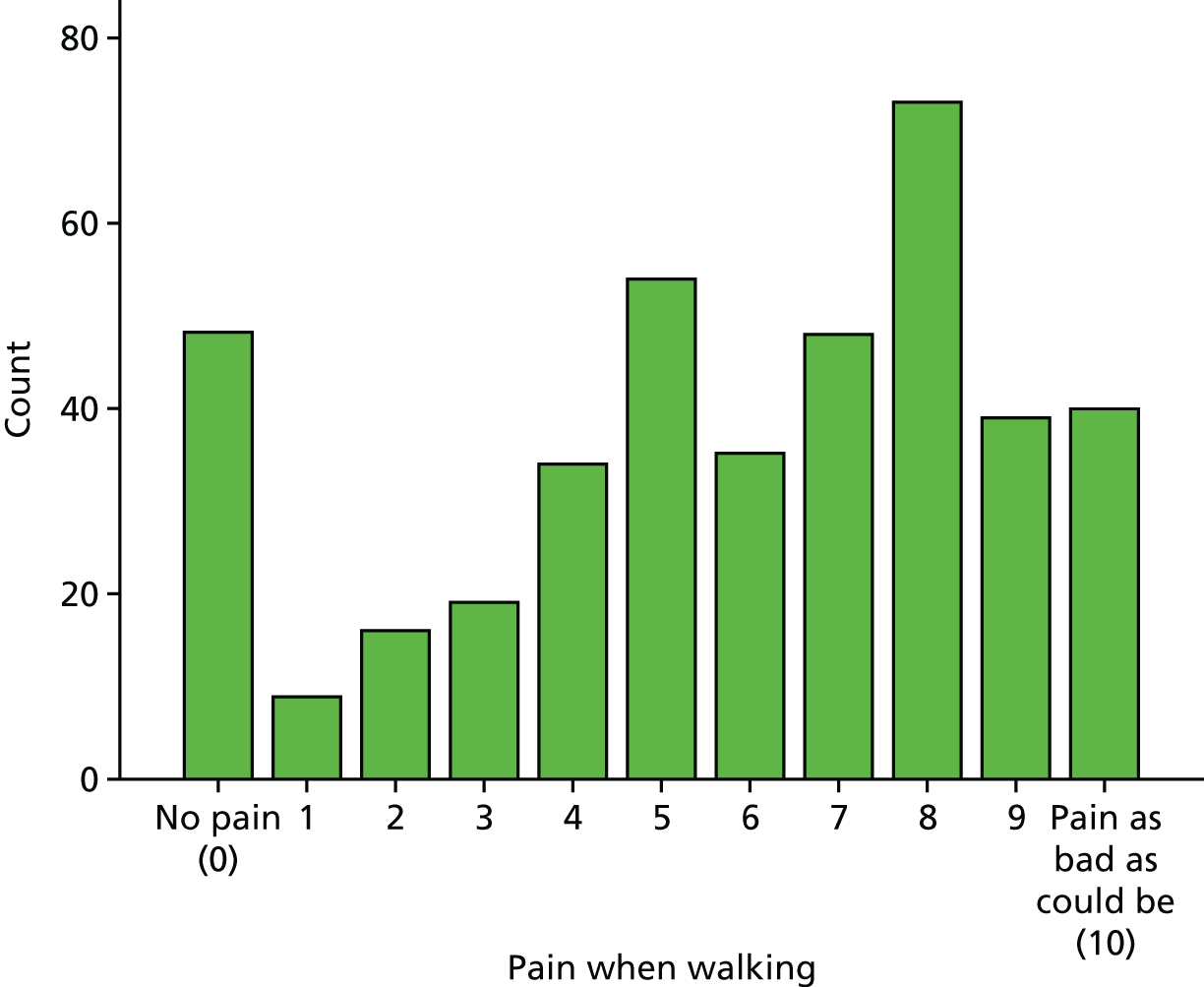

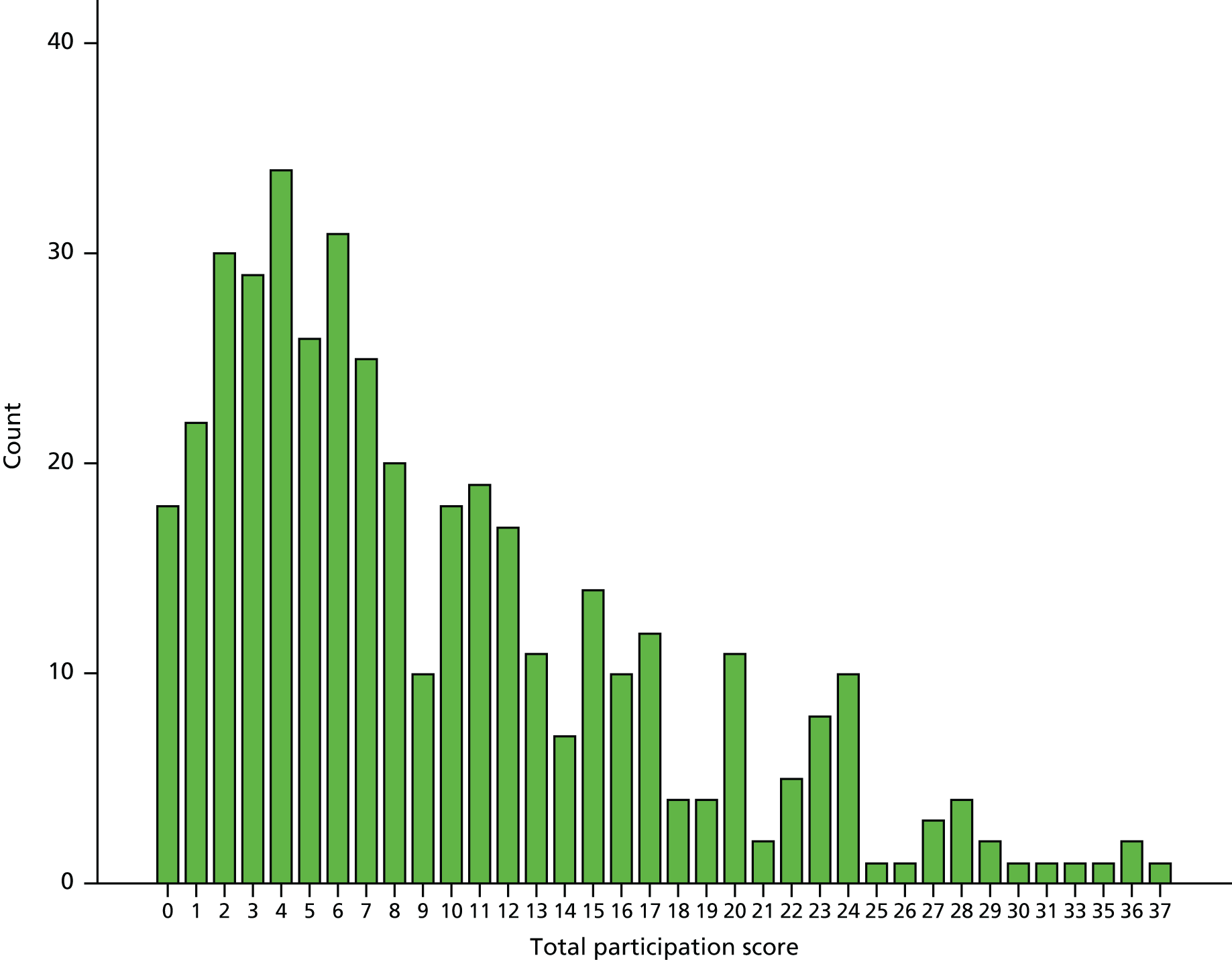

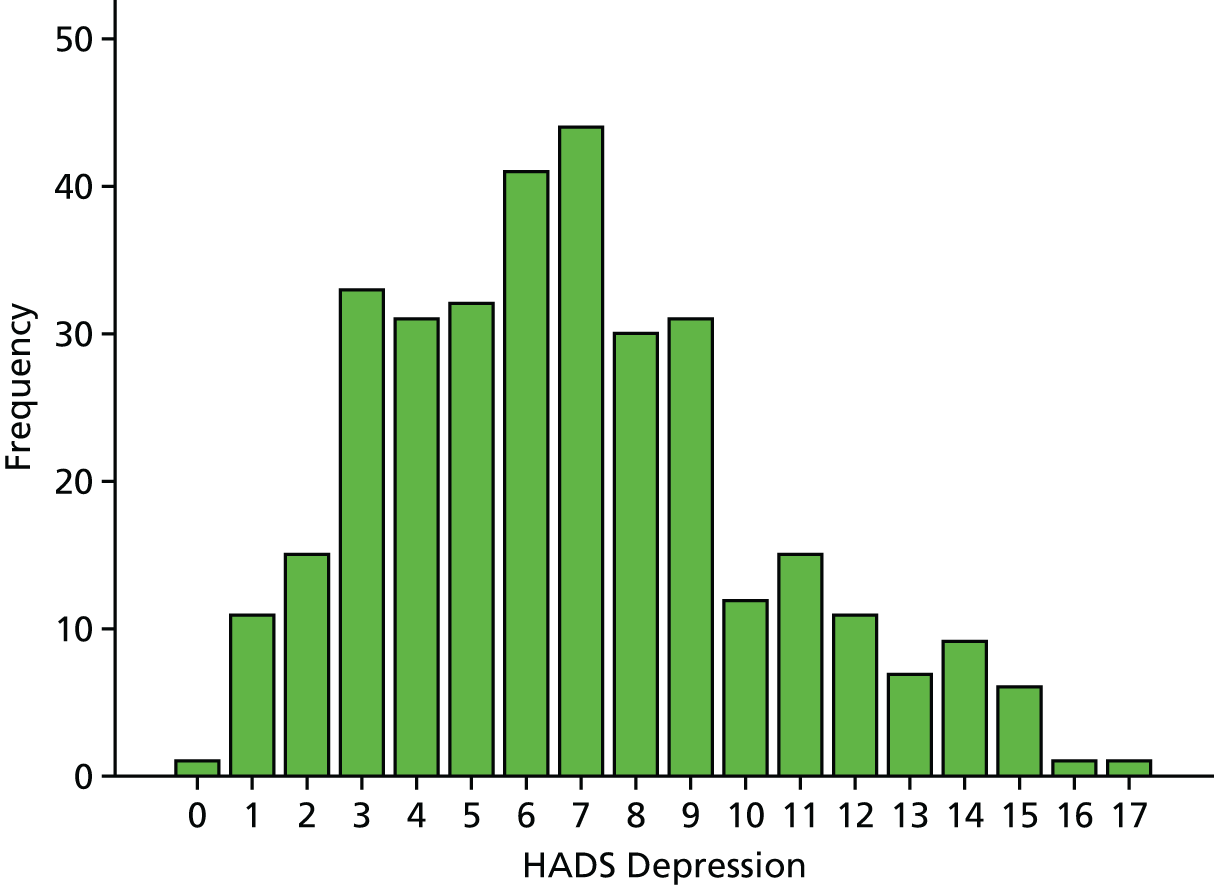

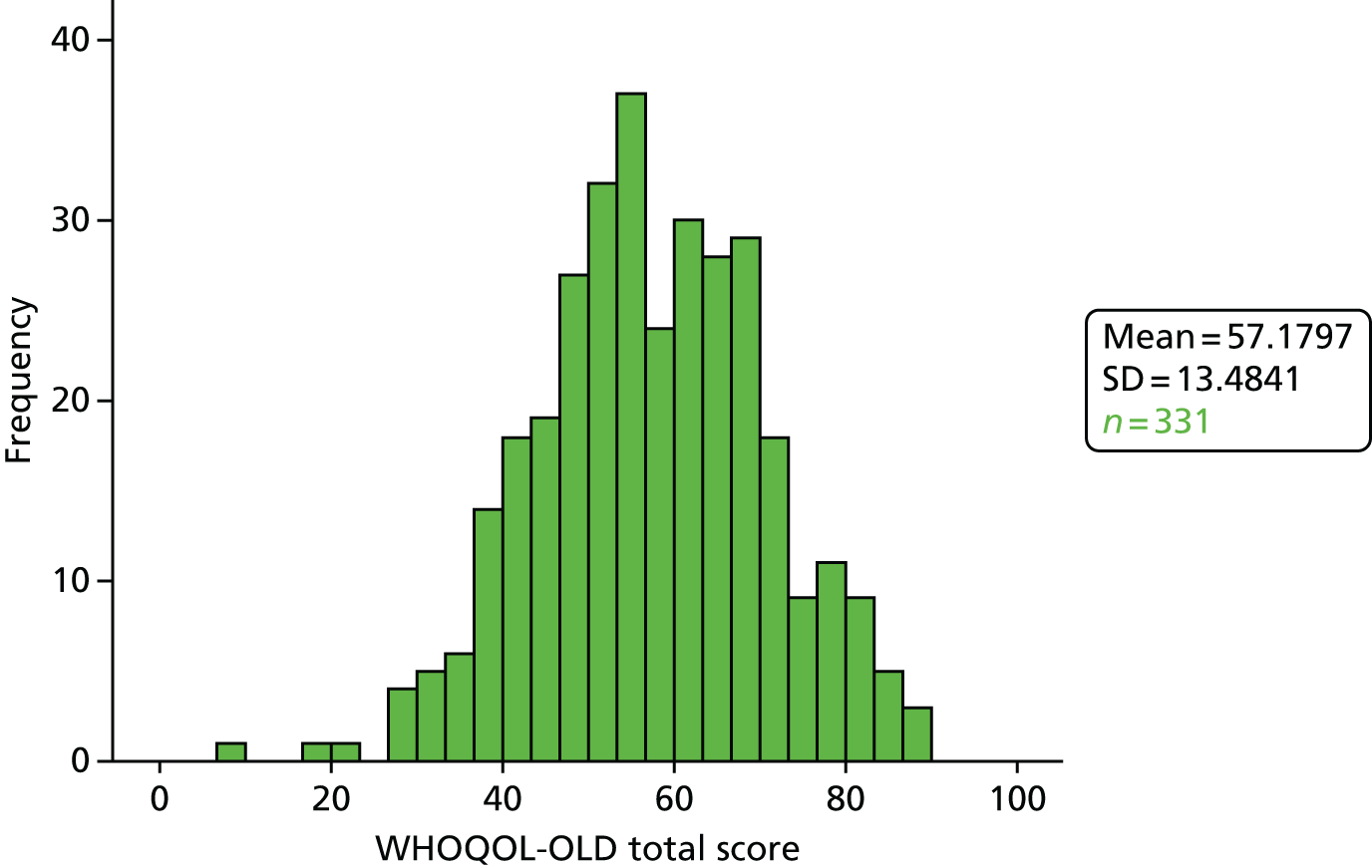

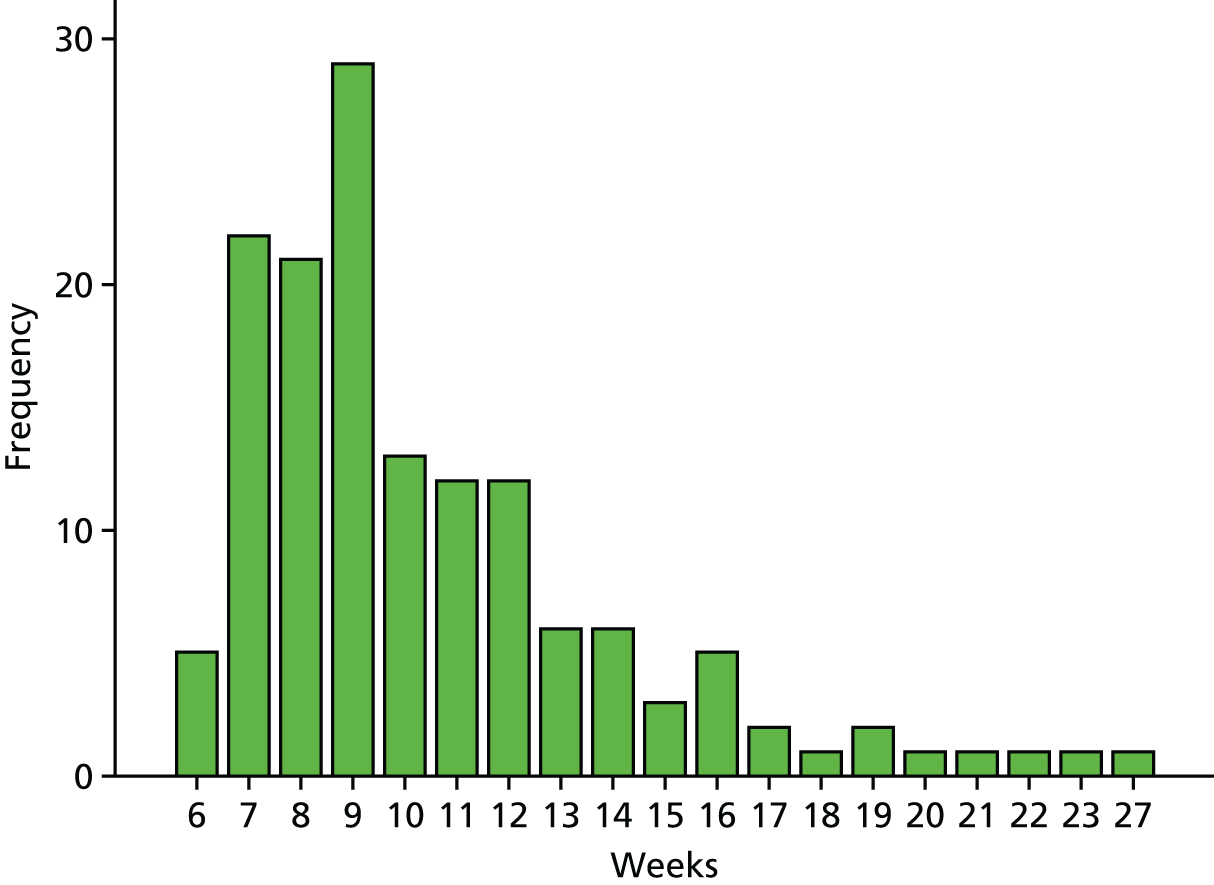

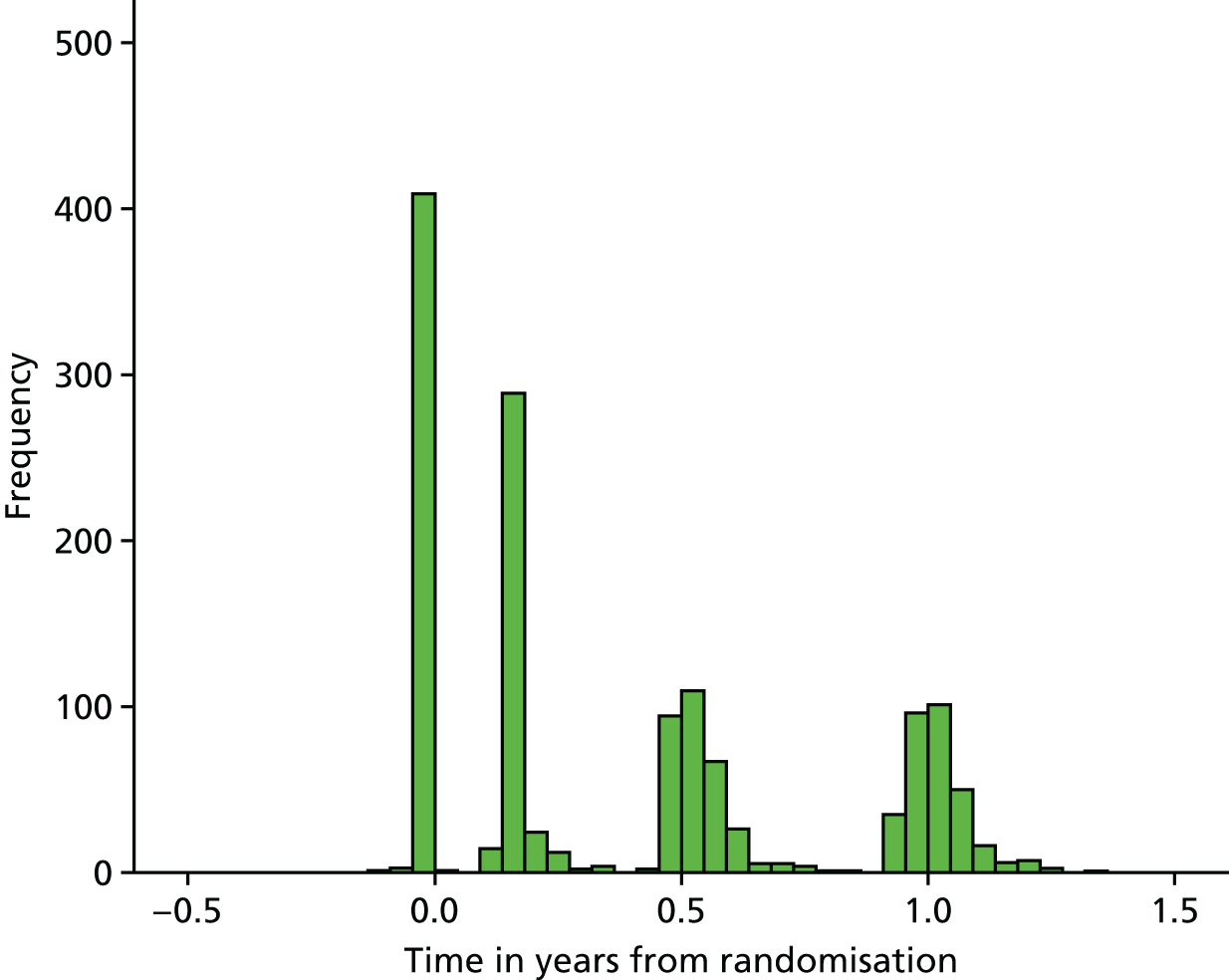

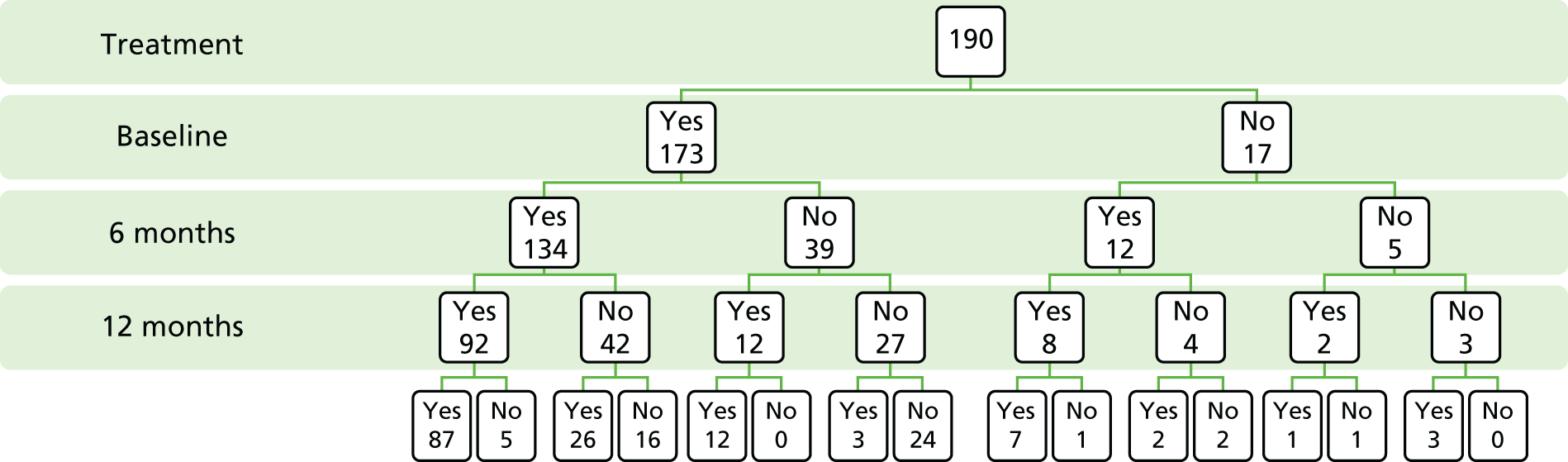

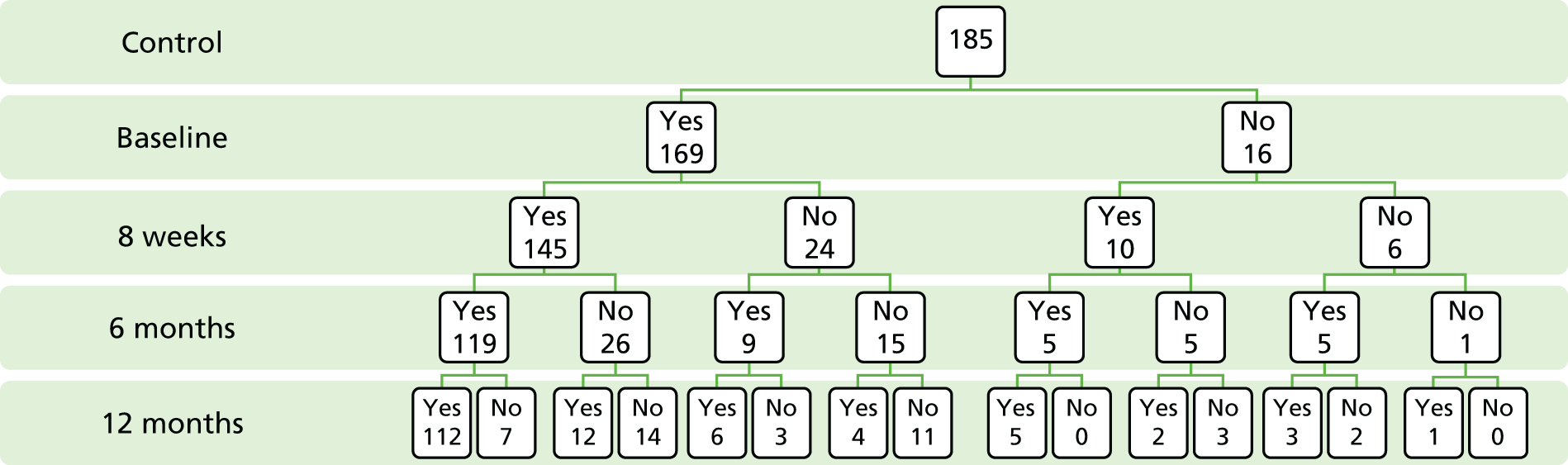

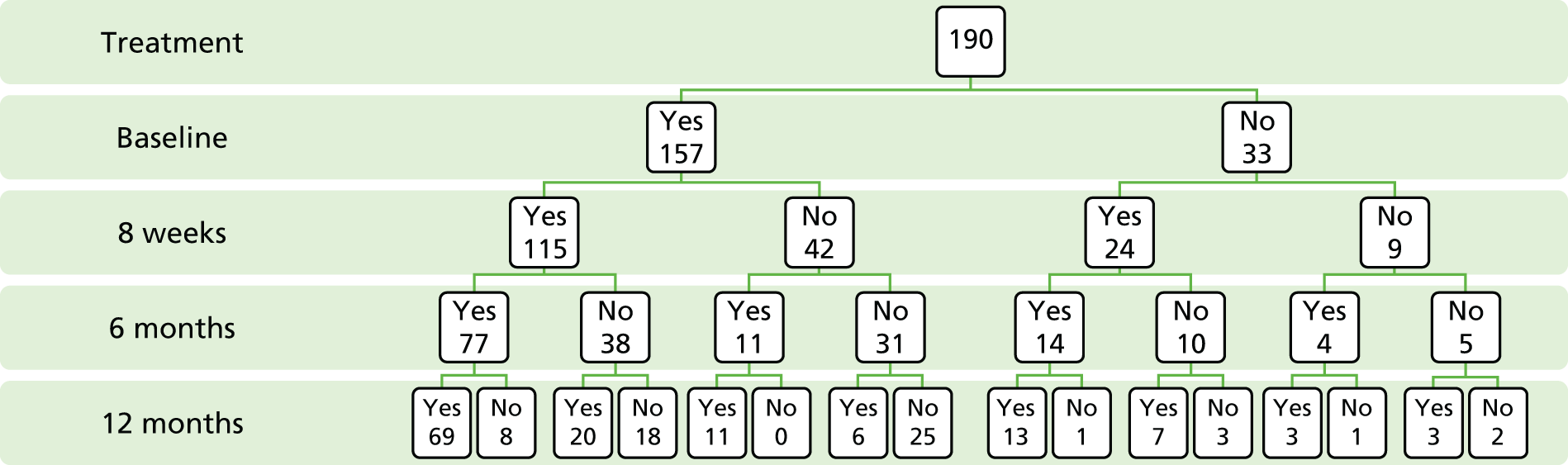

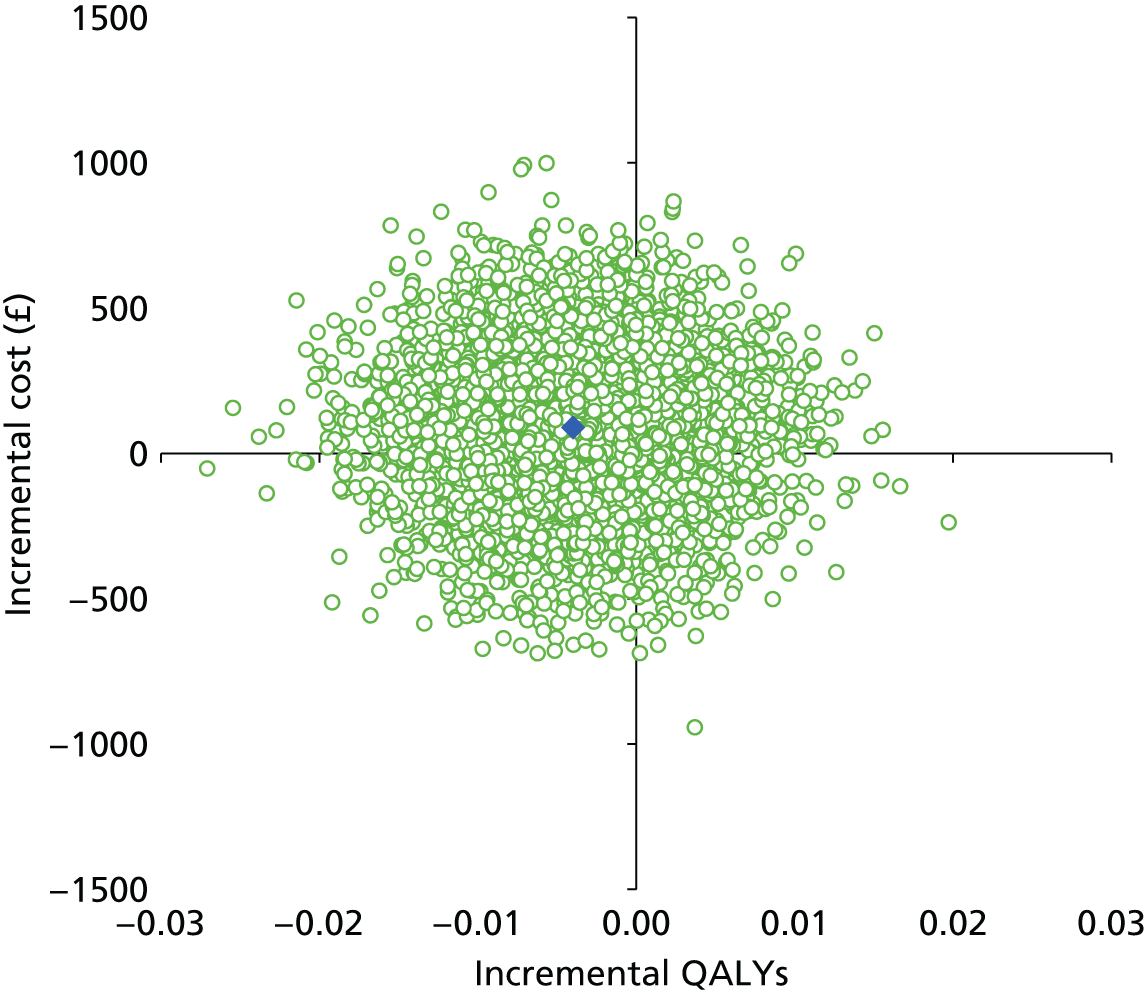

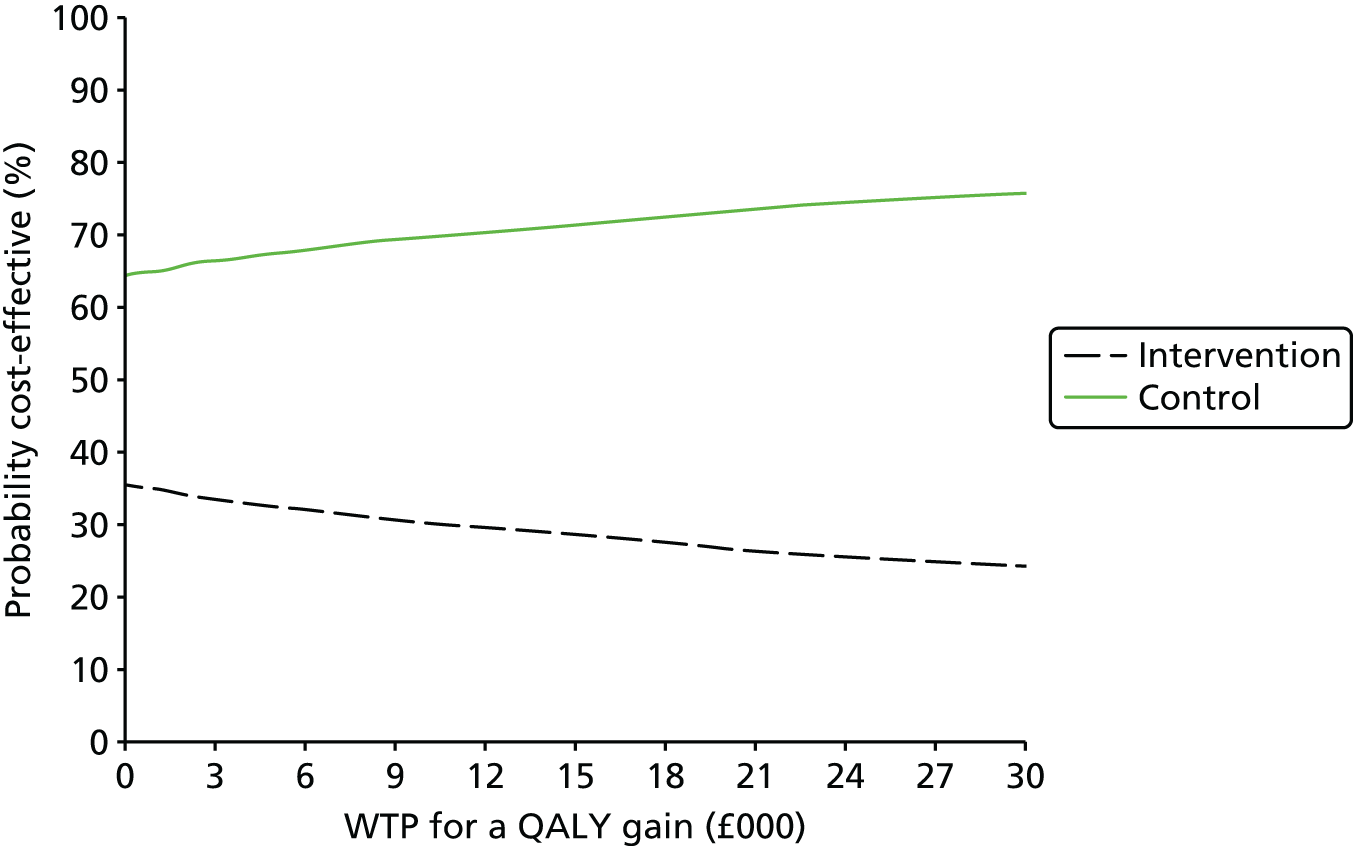

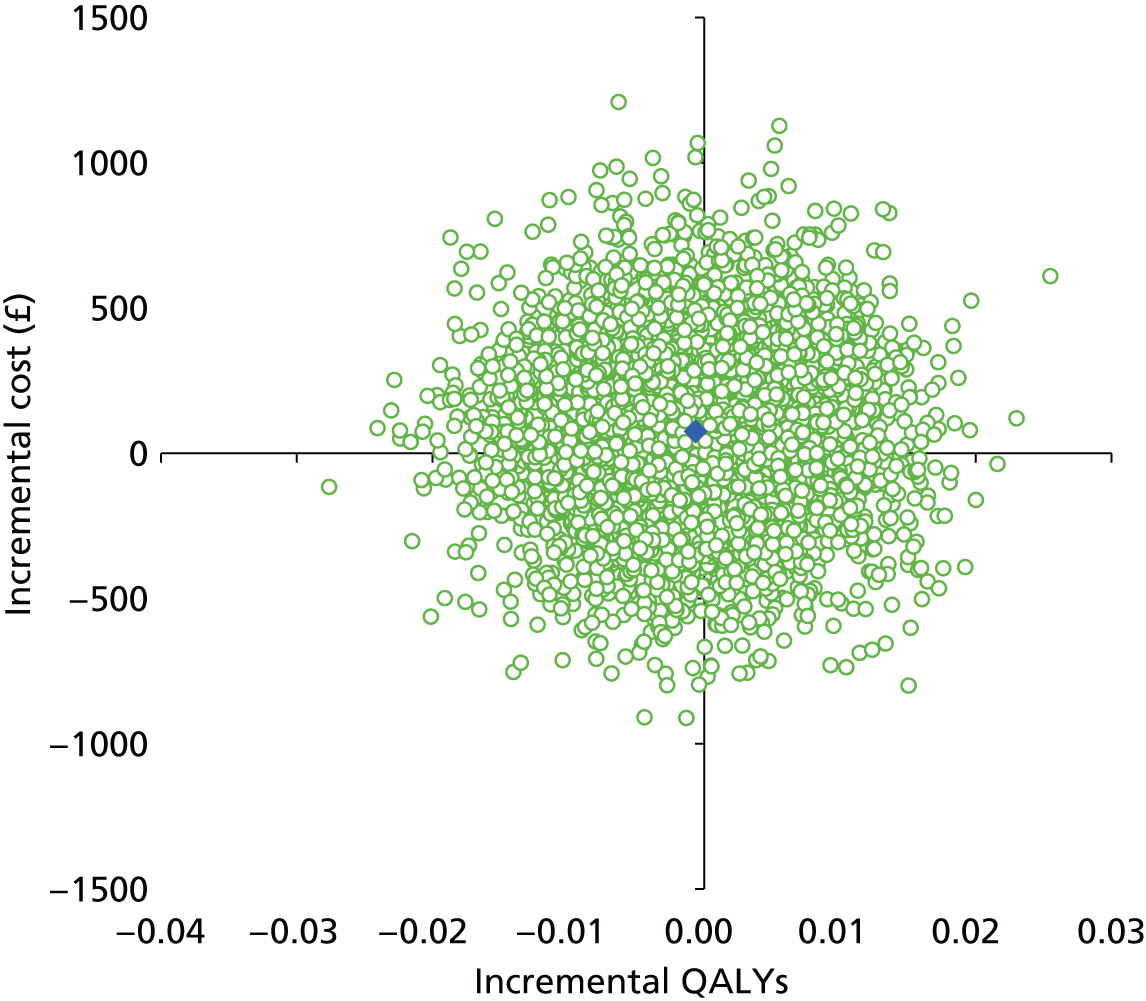

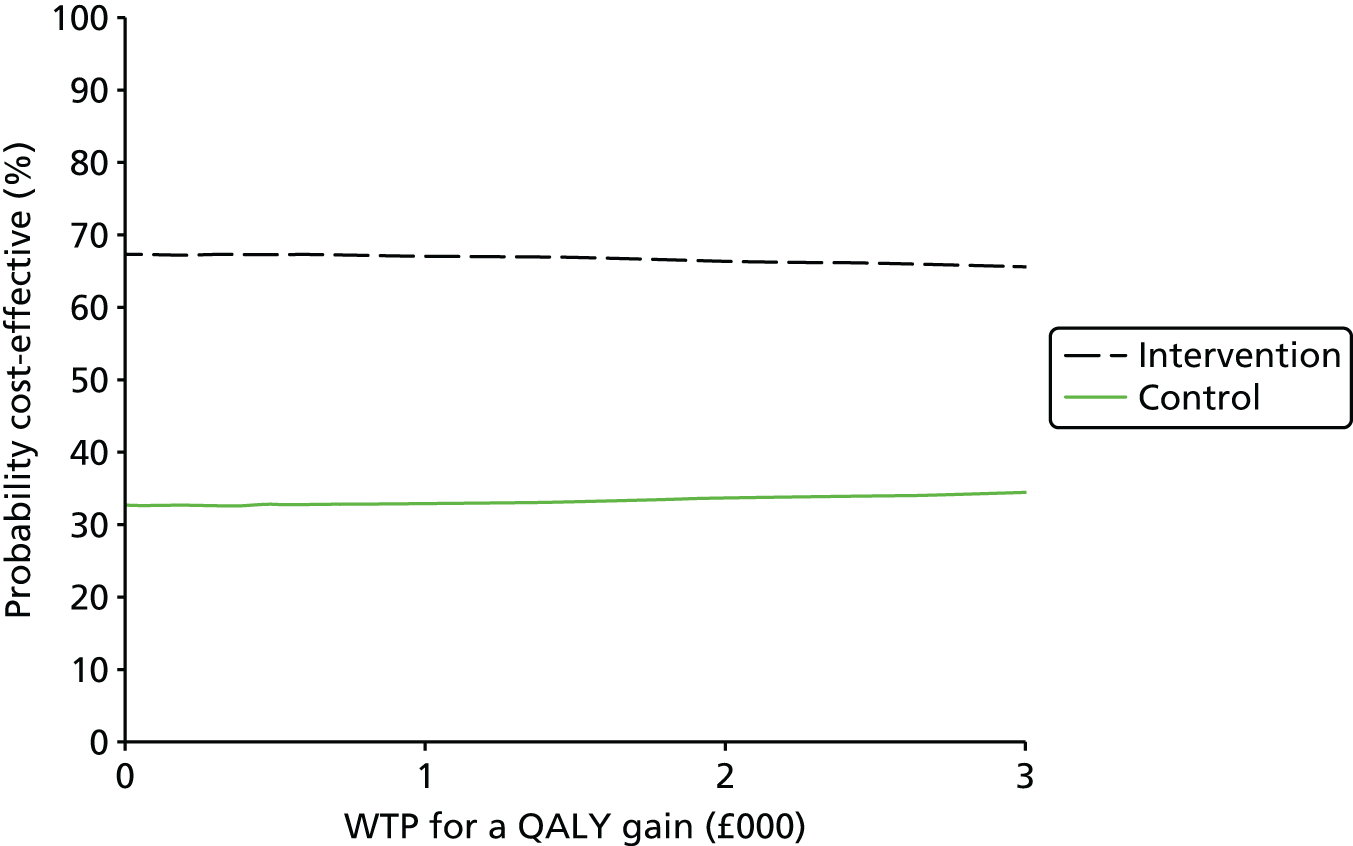

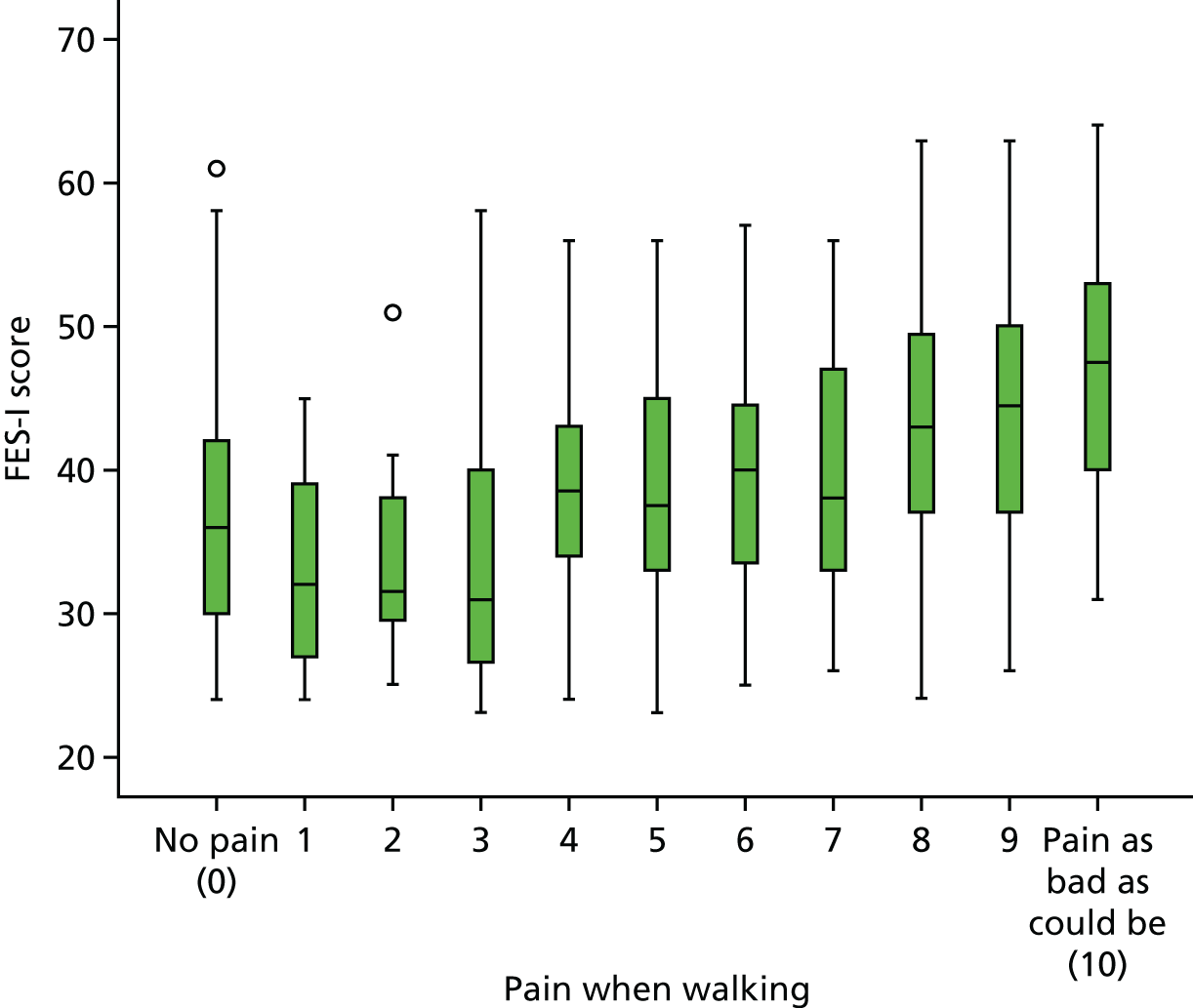

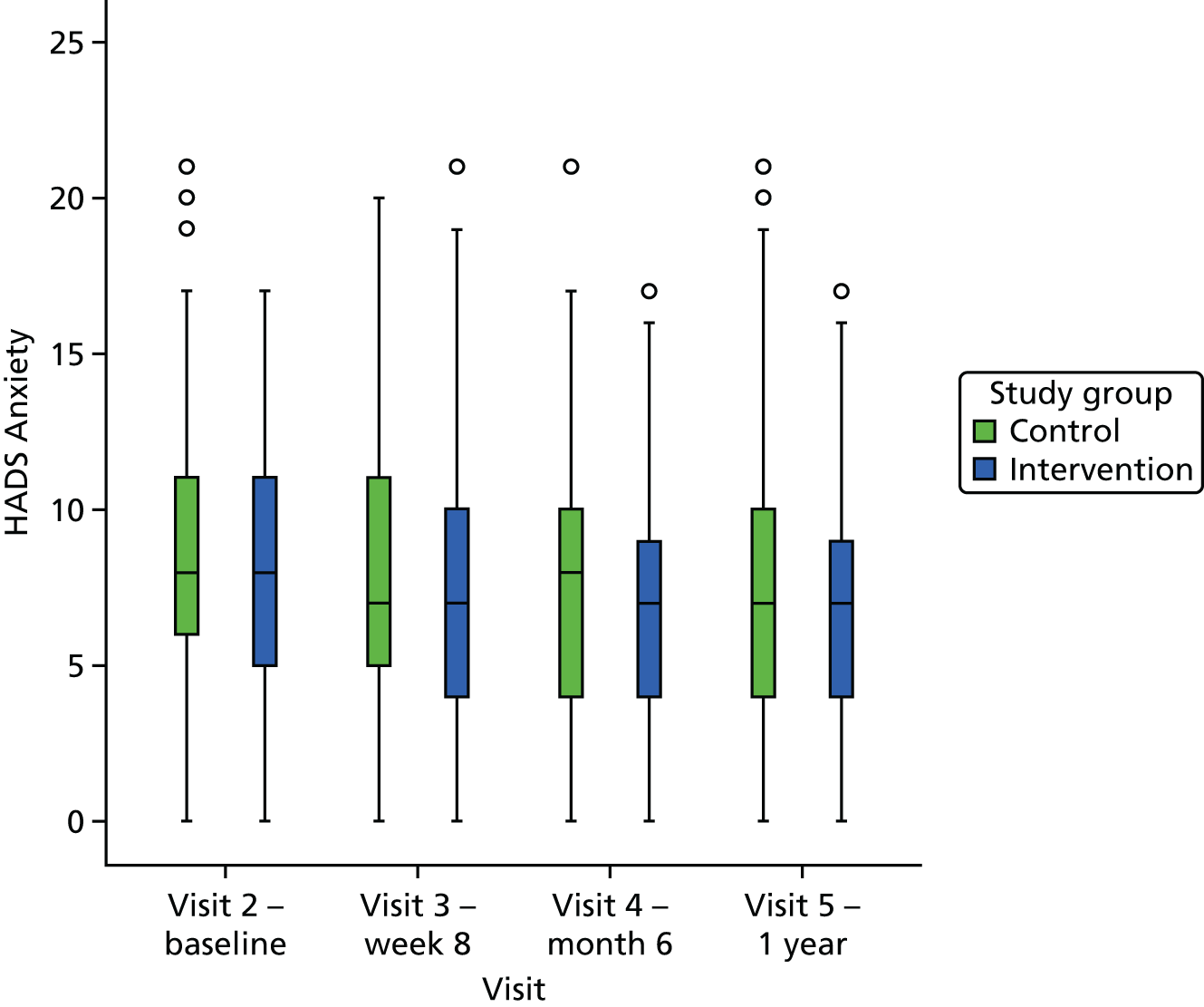

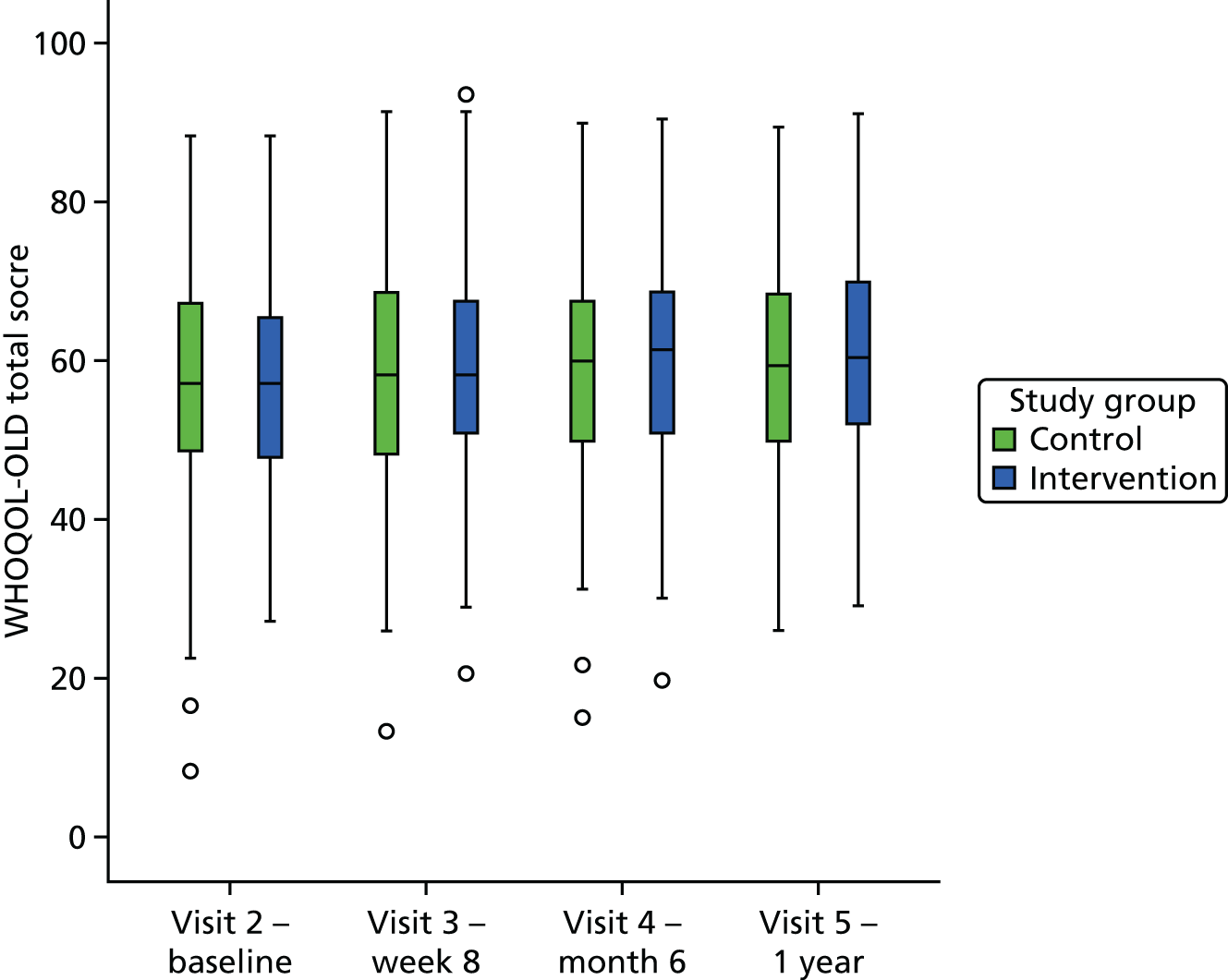

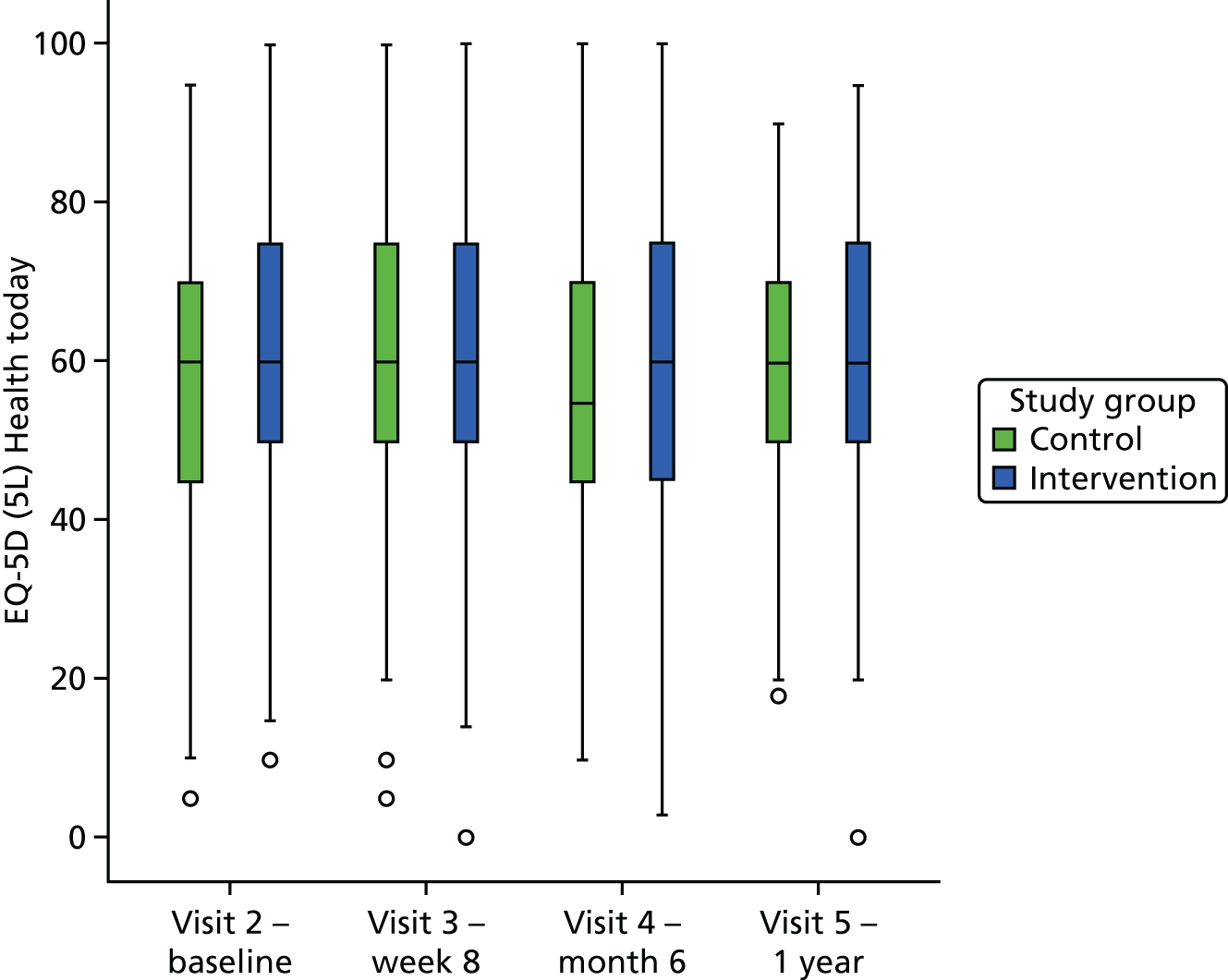

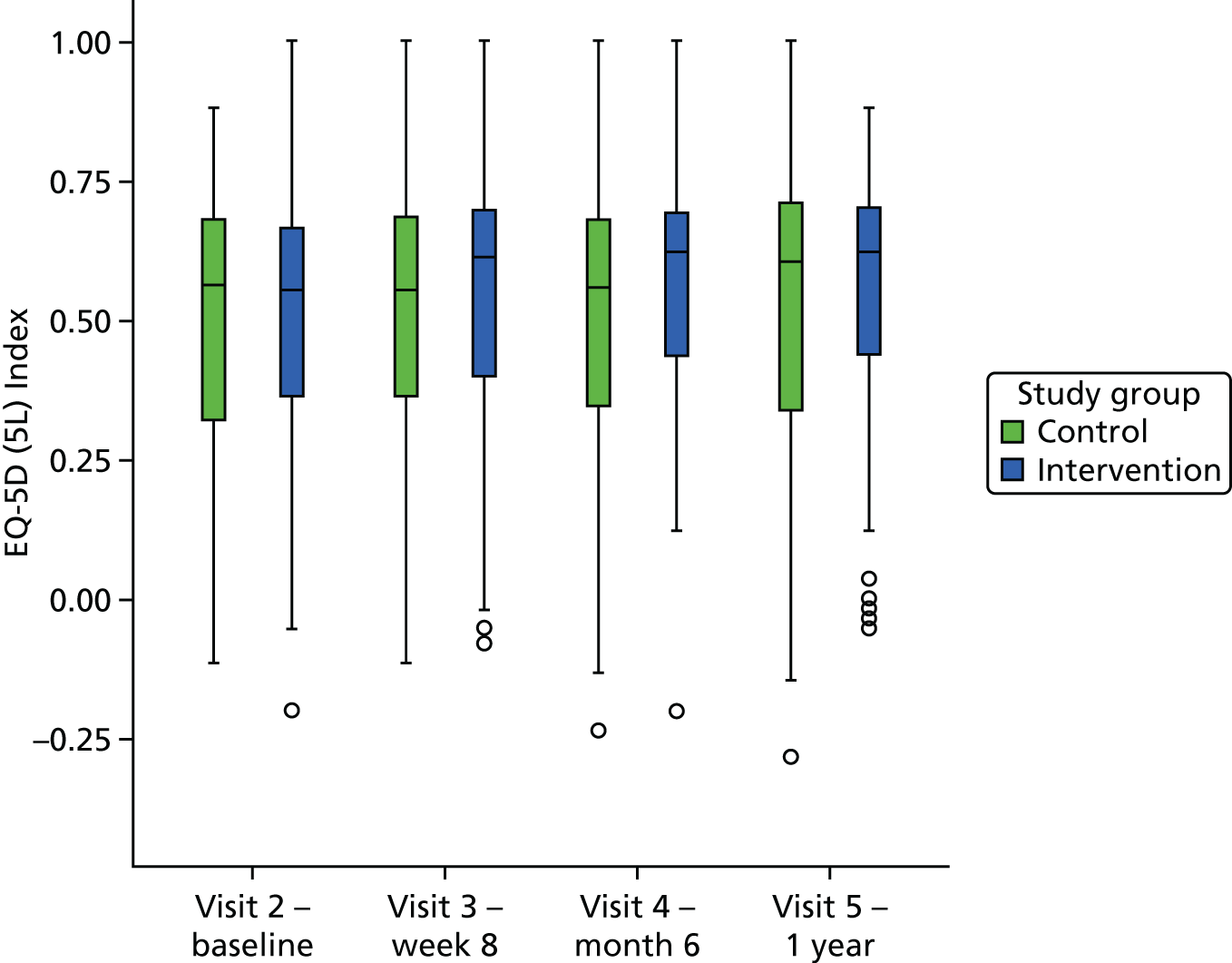

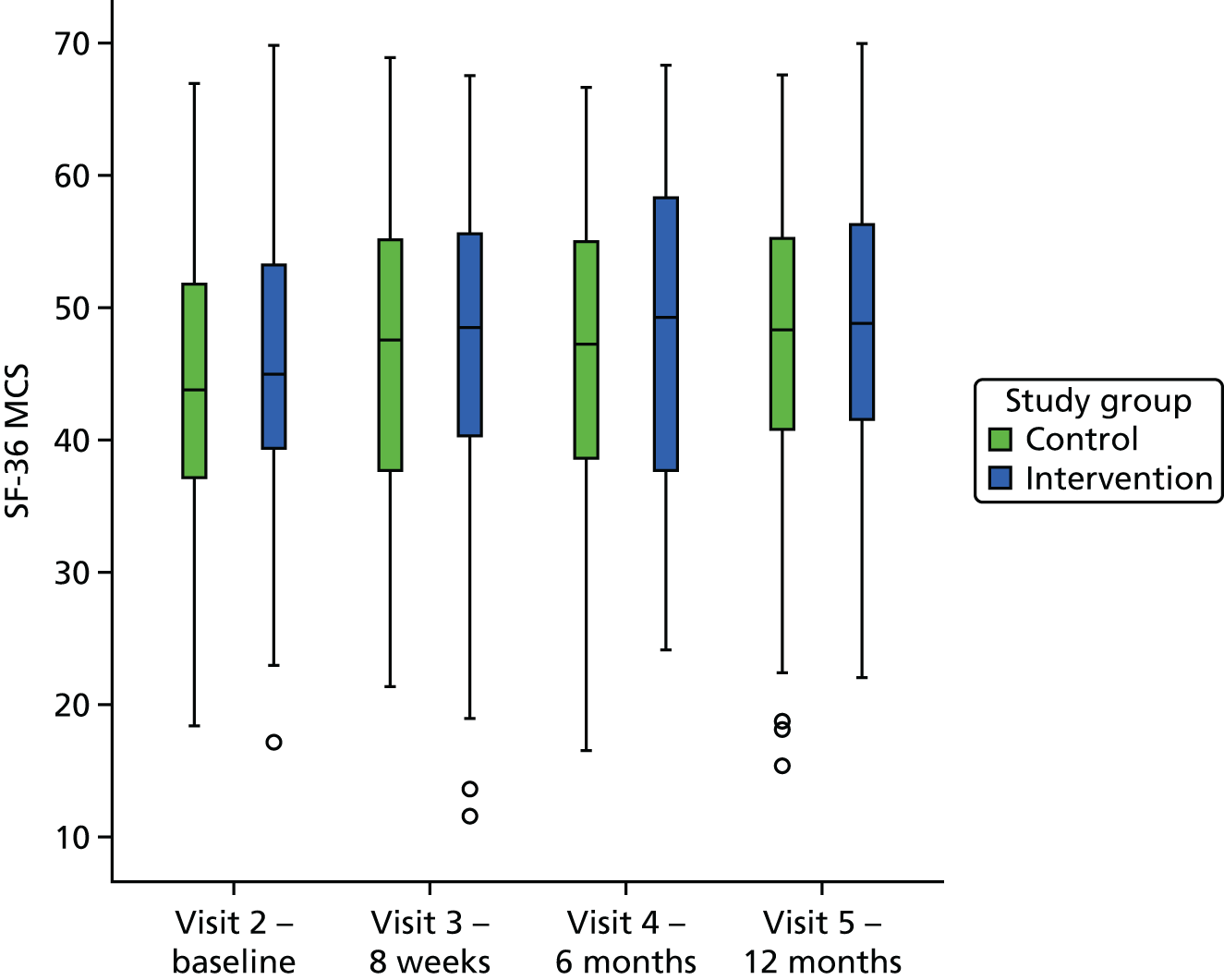

Primary outcome measure