Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/93/04. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in January 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Free et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Younger people bear the heaviest burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea, which can cause long-term adverse health effects including ectopic pregnancy and subfertility, especially in those with repeated infections. 1,2 Young people are most likely to report having at least two sexual partners in the last year with whom no condom was used. 1,3 The highest prevalence of STIs is in those from socioeconomically deprived areas and those with higher numbers of sexual partners. 1 Reinfection rates following treatment are high, with reinfection rates of 30% for chlamydia and 12% for gonorrhoea at 1 year. 4,5 Those with a STI are more likely to acquire human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), if exposed.

Safer sex behaviours such as condom use, notifying partner(s) about an existing STI and STI testing reduce the risk of STIs but young people can lack the knowledge, confidence and skills needed to adopt these behaviours. Existing interventions delivered face to face or in the media are limited in their appeal or effects or are too costly for widespread application. 6,7 Strategies to increase partner notification that can be delivered in primary care settings have been elusive. 8

Mobile phones provide a broad-reach delivery mechanism for effective, low-cost health behaviour support. 9–11 Support via text message is likely to be acceptable to young people and might increase safer sexual health behaviours. Mobile phones are able to provide confidential and non-judgemental support, which is essential for a sexual health intervention. 12 Interactive support can be delivered at any time and in any location, ensuring privacy, which is especially important for young people. Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) used in effective face-to-face interventions can be modified for delivery via text message. 13,14 The content can be personalised for different genders and ethnic groups.

The effects of safer sex support delivered by text message are not reliably known. We searched six databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health, Web of Science, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Library) from January 1990 to November 2014 to identify trials of mobile phone-based support to increase safer sex behaviours. We identified seven trials. 15–21 Interventions were limited; they included up to three BCTs and did not address partner notification. 22 None of the trials had a low risk of bias. Two trials reported statistically significant increases in testing for STIs. 17,18 Lim et al. 17 reported that mobile phone-based sexual health interventions can increase discussion of sexual health with a health-care professional threefold and lead to over a doubling of STI testing. Although some trial results look promising, the effects of text messaging on key safer sex behaviours, including telling your partner about your infection, correctly following treatment advice, obtaining STI testing for yourself and your partner(s) prior to unprotected sex and condom use, have not been reliably established.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme commissioned us to develop a mobile phone-based intervention to promote safer sex behaviour in young people in the UK aged 16–24 years and conduct a pilot randomised controlled trial of the intervention. The HTA programme commissioning brief was to:

-

develop the intervention

-

determine the acceptability of the package

-

determine the feasibility of a main trial

-

determine the parameters for a main trial.

In Chapter 2 we describe the development of the intervention based on evidence of factors influencing safer sex behaviours, theory, evidence-based BCTs, the content of existing effective face-to-face support, information technology (IT) expertise and user and provider views. Trials can fail to reliably establish the effects of interventions when they under-recruit or achieve low rates of follow-up. In the area of sexual health research low follow-up rates have been a particular issue. Therefore, in Chapter 3 we describe research conducted to develop our follow-up procedures based on evidence, testing prototype procedures and user views. In Chapter 4 we describe the pilot randomised controlled trial of the intervention. Outcomes for judging the success of the pilot trial were the recruitment rate and completeness of the postal chlamydia test follow-up. We also tested the intervention’s acceptability and appropriateness, evaluated all trial procedures and materials and obtained prevalence estimates for sexual risk behaviours and chlamydia reinfection rates to inform the sample size calculation for the main trial. In Chapter 5 we describe the qualitative interviews with participants conducted to explore their experiences and the acceptability of the intervention.

Chapter 2 Intervention development

In this chapter we describe the formative research that we conducted to develop a text message intervention informed by theory, evidence and expert and user views to increase safer sex behaviours. Participants were young people attending services who either were diagnosed with chlamydia or reported sex unprotected by a condom with more than one partner in the last year.

Objective

To develop an acceptable intervention designed to increase safer sex behaviours based on behavioural theory, evidence and expert and user views.

Methods

The theoretical basis of our intervention

The intervention was informed by the capability, opportunity and motivation model of behaviour (COM-B). 23 This is linked to a comprehensive model of behaviour change, the behaviour change wheel, which aims to capture the full range of intervention functions involved in behaviour change. 23 These include education, persuasion, environmental restructuring (encouraging people to change their environment to support the behaviour), training and enablement. Each intervention function can be implemented by a wide range of BCTs. 22

In the case of sexual behaviour, knowledge, beliefs, self-efficacy and skills as well as social and interpersonal influences have important effects on motivation, capability and opportunity. 24,25 Our intervention aimed to influence these factors to reduce sexual risk behaviour. It aimed to support participants in correctly following treatment instructions, by correctly taking their prescribed treatment, telling partner(s) about their infection and avoiding sex for a week after taking treatment. The intervention aimed to encourage participants to use condoms with new or casual partners and obtain testing for STIs for themselves and their sexual partner(s) prior to unprotected sex (see Figure 2 and Appendix 1).

Generating content

We identified factors influencing safer sex behaviours using evidence from systematic reviews of the literature. 24,26 We generated messages, selecting intervention functions23 and BCTs that might be employed to influence these factors.

We identified trials of interventions promoting safer sex behaviours that reported STI outcomes in a systematic review6 and obtained the protocols, the content of which was coded using Abraham and Michie’s14 and Michie et al. ’s27 2011 taxonomy of BCT. We computed the inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s kappa and percentage agreement) for the scoring of the presence/absence of BCTs. We described the BCTs identified in face-to-face interventions reporting statistically significant reductions in STI infection at follow-up. Messages were drafted to include all those BCTs that we had identified in effective face-to-face interventions and additional BCTs shown to be effective in changing other behaviours. We adapted them for delivery by text message where necessary.

To ensure that the intervention content was informed by technical experts and those experienced in working with young people on safer sex behavioural support, a sexual health counsellor (Melanie Otterwill) generated messages. Experts in sexual and reproductive health service delivery, research and public health (PB, KW, RF, JB, KD, CF) reviewed the messages and were asked to identify additional content that they considered should be included in the intervention.

Generating the automated information technology system for delivering the messages

An IT programmer developed an automated text messaging system to deliver the intervention, which had an automated link to the randomisation system and database.

Testing and refining the messages: obtaining user views in focus group discussions

We convened focus groups of people aged 16–24 years to seek their preferences regarding the intervention and modify the messages based on their views regarding their acceptability. We recruited participants attending community sexual and reproductive health services in an inner city in the south of England (south-east London), a city in the north of England (Greater Manchester) and a rural area (Cambridgeshire). Clinic staff invited participants to join the focus group discussions. A researcher provided verbal and written study information. Groups were single sex, including teenagers and those in their 20s. We obtained informed written consent from participants. We explored the participants’ preferences regarding the intervention and sought their comments on the preliminary messages, specifically with regard to their acceptability, and suggestions for improvement. A second facilitator made notes during the meeting regarding their views and suggestions for improving messages and, with participants’ agreement, recorded the meeting. Participants received £20 in thanks for their time. Data were stored confidentially and anonymised in publications or reports. According to the feedback received in the initial focus groups, we retained, discarded or modified messages and retested them in subsequent focus groups or by e-mail. We continued refining the messages and conducting focus groups until participants reported that the messages were acceptable, comprehensible and appropriate.

Testing and refining the messages based on feedback obtained in a survey

The messages modified by the focus group participants were then tested in a survey and adapted based on survey responses. We recruited young people from community sexual and reproductive health services located in south-east London and rural Cambridgeshire. The eligibility criteria for the survey were age 16–24 years, ownership of a personal mobile phone and either testing positive for chlamydia or reporting unsafe sex in the last year (more than one partner and at least one occasion of unprotected sex). The researcher working in the clinic provided written and verbal information and sought informed written consent. We offered participants a private room in which to complete the questionnaire.

We selected any messages for which the feedback had been ambiguous in the focus groups and a random selection of other messages for testing. The questionnaire asked participants to score each of the messages using a 3-point scale on how relevant they considered them to be (relevant, unsure or not relevant). They were asked to identify messages that were hard to understand or that they did not like and to provide suggestions as to how the messages could be improved. Participants received £5 for completing the questionnaire. We conducted a descriptive analysis reporting the scores for each message using Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). We removed or adapted messages that achieved low scores for perceived relevance.

Testing and refining the messages based on feedback regarding the intervention when delivered to participants’ mobile phones

The resultant messages were delivered to participants’ mobile phones and final adaptations were made based on their feedback about the intervention obtained in telephone interviews. Clinic staff identified potential men and women in their teens and early 20s who had been diagnosed with chlamydia. If they agreed to take part their details were passed to OM. OM recruited participants by phone and provided verbal and written information by e-mail to potential participants and asked them to text their consent. After obtaining informed consent, the text messages were sent to participants from our automated computer-based delivery system.

Seven days after enrolment, OM contacted the participants by phone and asked them for further feedback regarding the intervention. OM asked participants about the appropriateness of the timing, frequency and content of the messages and their experiences when trying to implement the advice in the messages. Based on their feedback we made further modifications to the intervention. We continued to recruit participants until no new data regarding how the intervention should be modified emerged from the interviews. Participants received £20 in thanks for their time.

Results

Content derived from evidence on barriers to safer sexual behaviours

In Table 1 we describe key evidence-based barriers to safer sexual behaviour and how our intervention addressed these and which BCTs and which functions from the COM-B behavioural theory we employed. The principles informing the content of the intervention based on evidence on factors associated with safer sex are also reported in Table 1.

| Target behaviour | Factors associated with or influencing sexual behaviour | Intervention functions | BCTs and other implications for the intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partner notification and correct treatment of a STI | Capability | ||

| Lack of knowledge regarding how to prevent infection/reinfection (partner notification) | Education | Provides information about the consequences of behaviour (partner notification and correct treatment) (5.1) | |

| Lack of knowledge regarding how to correctly treat a STI | Education | Provides instruction on how to treat STIs (4.1) | |

| Lack of skills in how to start a conversation and how to tell a partner | Education | Demonstrates how others told a partner about a STI (6.1) | |

| Opportunity | |||

| Social attitudes that STIs are associated with stigma impede partner notification | Creates an enabling environment for partner notification | Provides non-judgemental, non-stigmatising information (e.g. about how common STIs are and social support) (3.1) | |

| Models non-stigmatising ways of telling a partner about a STI (6.1) | |||

| Motivation | |||

| Lack of knowledge that you may not have symptoms of a STI and so you may not know that you are infected | Education | Provides information about the health consequences of partner notification (if you don’t tell them they may not be aware) (5.1) | |

| Sexual reputations are important and people act to protect them.24 As STIs are associated with stigma, telling a partner about a STI can have a negative impact on the reputation of both | Creates an enabling environment for partner notification | Reframes partner notification as responsible (rather than having a negative impact on identity) (13.2) | |

| Models telling a partner about a STI (6.1) (without this impacting on his or her reputation) | |||

| Condom use | Capability | ||

| Young people report problems using condoms (splitting, coming off) | Education | Provides examples of how others avoided common condom use problems (4.1) | |

| Provides a link to a web page that demonstrates how to use condoms correctly (6.1) | |||

| Young people report problems initiating condom use | Creates an enabling environment for condom use | Encourages problem solving (1.2) | |

| Encourages the creation of action plans (1.4) (BCT adapted so that examples of action plans are provided) | |||

| Young women can lack assertiveness and communication skills to negotiate condom use | Creates an enabling environment for condom use | Models how others negotiated condom use (6.1) | |

| Opportunity | |||

| Young people report not using condoms as they are not immediately available | Creates an enabling environment for condom use | Encourages young people to carry condoms (12.5) | |

| Motivation | |||

| Lack of knowledge about how you cannot tell if someone is infected; young people assess partners’ STI risk according to how well they know them or appearance | Education | Provides education about STIs and health consequences of UPI (5.1) | |

| Condom use is associated with a lack of trust in the relationship | Creates an enabling environment for condom use | Reframes condom use as demonstrating respect (13.2) | |

| Young people report negative attitudes towards condoms (reduced sensation, reduced pleasure, discomfort) | Creates an enabling environment for condom use | Emphases positive aspects of condom use and provides instruction about how to reduce the negative effects of condom use (4.1) | |

| Carrying condoms can affect a woman’s sexual reputation | Creates an enabling environment for condom use | Models women carrying condoms (6.1) | |

| STI testing | Capability | ||

| Lack of confidence in using services for testing | Creates an enabling environment for testing | Encourages testing and provides non-judgemental information about STIs | |

| Opportunity | |||

| STIs are associated with stigma and being ‘unclean’ | Creates an enabling environment for testing | Provides non-judgemental, non-stigmatising information about STIs | |

| Motivation | |||

| Lack of knowledge of how to prevent STIs by getting tested (lack of knowledge that STIs are common and that you may not know if you have one) | Education | Provides information about the health consequences of getting tested before UPI with a new partner (5.1) | |

| Evokes anticipated regret if not tested prior to UPI with a new partner (5.5) | |||

| Provides non-specific incentives (10.6) | |||

| Provides social rewards for testing (10.4) | |||

| Young people assess new partners’ STI risk according to how well they know them or appearance | Health consequences of getting tested before UPI with a new partner (5.1) | ||

Content derived from behaviour change techniques in effective face-to-face interventions promoting safer sexual behaviours

The BCTs identified in face-to-face interventions reporting statistically significant reductions in STI infection at follow-up are reported in Table 2. 27 The agreement in coding the BCTs in trials of all behaviour change interventions reporting STI outcomes was 100% except for goal-setting (kappa 0.74, agreement 90%), demonstrating condom communication (kappa 0.74, agreement 90%) and encouraging practice of condom communication (kappa 0.74, agreement 90%). In our intervention we included 21of the 25 BCTs found in effective face-to-face interventions when coded according to Abraham and Michie’s taxonomy of BCTs. 14

| Component | No. of effective face-to-face interventions with the component | Implication for intervention delivered by text message |

|---|---|---|

| You cannot assess risk according to how well you know someone socially or by their appearance | 3 | Included |

| Gender roles | 1 | Removed based on focus group feedback |

| Sexual pleasure | 1 | Removed based on focus group feedback |

| Relationships | 1 | Removed based on focus group feedback |

| Information on consequences of behaviour in general | 3 | Included |

| Information on personal risk | 4 | Included |

| Others’ approval | 2 | Included |

| Normative information about others’ behaviour | 2 | Included |

| Goal-setting – behaviour | 2 | We included action planning as this incorporates goal-setting |

| Goal-setting – outcome | 2 | We included action planning as this incorporates goal-setting |

| Action planning – barriers to reduce risk | 1 | Included but modified based on focus group feedback |

| Barrier identification/problem solving – strategies to reduce risk | 3 | Included |

| Set graded tasks | 0 | Not included |

| Prompt review of behavioural goals | 2 | Not included because of participant views that this was ‘too intrusive’ |

| Prompt review of outcome goals | 1 | Not included (as above) |

| Rewards contingent on progress towards goals | 1 | Automated interactive elements of intervention were not able to provide this |

| Rewards contingent on successful behaviour | 1 | Included in relation to getting tested |

| Shaping – providing rewards for an approximation to target behaviour | 0 | Not included |

| Prompt generalisation of a target behaviour | 1 | Not included |

| Prompt self-monitoring of behaviour | 0 | Not included |

| Prompt self-monitoring of behavioural outcome | 0 | Not included |

| Prompt focus on past success | 1 | Included |

| Provide feedback on performance | 1 | Included |

| Information on where and when to perform the behaviour | 2 | Included |

| Instruction on how to perform the behaviour | 3 | Included |

| Model/demonstrate condom use | 4 | Included via website link |

| Model/demonstrate communication | 4 | Included |

| Teach to use prompts/cues | 1 | Not included |

| Environmental restructuring | 0 | Included in relation to carrying condoms |

| Agree behavioural contract | 1 | Not included |

| Prompt practice – condom use | 3 | Included |

| Prompt practice – communication | 2 | Included |

| Use of follow-up prompts | 0 | Not included |

| Facilitate social comparison – intervention draws attention to others’ performance | 0 | Included |

| Plan social support/social change | 1 | Included |

| Prompt identification as role model/position advocate | 0 | Not specifically included but participants reported adopting this role (see Chapter 5) |

| Prompt anticipated regret | 0 | Included |

| Fear arousal | 1 | Not included – considered inappropriate by expert group |

| Prompt self-talk | 0 | Not included |

| Prompt use of imagery | 0 | Not included |

| Relapse prevention/coping planning | 2 | Included |

| Stress management | 0 | Not included |

| Emotional control training | 0 | Not included |

| Motivational interviewing | 0 | Not included |

| Time management | 0 | Not included |

| General communication skills training | 1 | Included |

Content derived from expertise

To ensure that the intervention content, tone and style were informed by technical experts and those experienced in communicating with young people regarding safer sexual behaviours, a sexual health counsellor (Melanie Otterwill) generated messages. Experts in sexual and reproductive health service delivery, research and public health (PB, KW, RF, JB, KD, CF) reviewed the messages and were asked to identify additional content that they considered should be included in the intervention.

Content derived from focus group discussions

We convened eight focus groups with 82 participants (nine of whom attended two focus groups). The focus groups included 32 men and 50 women and the median age of participants was 17 years. In total, 39 participants were from London, eight were from Manchester and 35 were from rural Cambridgeshire (Table 3).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 16–19 | 45 (55) |

| 20–24 | 15 (18) |

| No data | 22 (27) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 50 (61) |

| Male | 32 (39) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 30 (37) |

| Bisexual | 3 (4) |

| Gay/lesbian | 1 (1) |

| No data | 48 (59) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White British/white other | 45 (55) |

| Black/black British | 18 (22) |

| Asian British | 1 (1) |

| Mixed | 6 (7) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| No data | 11 (13) |

| Education/work | |

| School | 2 (2) |

| College/university | 37 (45) |

| Working | 6 (7) |

| Unemployed | 5 (6) |

| Long-term sick | 1 (1) |

| No data | 31 (38) |

Participants’ views regarding the messages informed the tone, style, language, punctuation, frequency and duration of the messages, the content of the messages and the way that BCTs were operationalised. Young people wanted messages in a non-judgemental, credible tone that they ‘could relate to’. The preferred style of messages was those containing practical information about what needs to be done, why and how, for example:

You can make sure you don’t get another infection by (1) getting the person you are having sex with treated, (2) using condoms every time you have sex, (3) you and your partner getting tested before sex without a condom and (4) having another test in 3 months.

They identified messages that were too negative, for example ‘I was shocked when I was told I had it’.

They also wanted to know how to carry out behaviours, for example starting a conversation about having a STI was seen as particularly challenging. Messages needed to avoid ‘patronising’ content or ‘telling people what to do’. They wanted exclamation marks to be avoided, as these were also experienced as patronising, for example ‘Having a test can feel like a big step. You did it!’

In terms of other aspects of language and punctuation, participants wanted messages to be easy to understand. They wanted slang terms to be avoided and some phrases or terms such as ‘your man’ were considered overfamiliar and to be ‘trying too hard’ to identify with youth culture, for example ‘Not sure how to convince your man to wear a condom? Text 3 for some tips’.

Focus group participants identified messages that did not meet these criteria and made suggestions about how they could be altered or improved. An acceptable frequency of messages was up to four a day, with message frequency reducing within the first 2 weeks.

When asked to give feedback regarding the messages, participants reported particularly liking short, positive and non-judgemental messages, for example:

If you make it a habit for you and your partner(s) to get tested before you have sex, you can avoid a lot of hassle and regret later.

They identified messages that were supportive and reassuring, for example:

You made the right decision to get a test. Getting treated quickly means you are less likely to have any problems.

They liked messages describing other people’s experiences of how they told a partner about an infection or how they dealt with other sexual health issues such as condom use problems:

Some people say they didn’t use a condom because their partner didn’t want to use one. If you’d like to hear how other people convinced their partner to use one text 3.

Here is an example of how others told their partner: ‘I said I don’t really want to tell you this but I have to – I found out I have chlamydia. It’s awkward to tell people but it’s not right not to, is it? They may not know. You can’t just let them walk round with an infection’.

‘I just couldn’t tell some partners so the clinic offered to do it for me. They gave me the option of keeping my name out of it’. Text 7 to hear more.

Although the intervention content that we developed based on the content of effective face-to face interventions was mostly appreciated, some content had to be adapted or removed, such as messages in which the content did not resonate with participants’ experience or messages that were ‘unrealistic’, for example:

One possible benefit of knowing that you’re safe is that you might enjoy sex more.

Participants reported that the text message designed to ‘review participants’ behavioural goals’ by asking if participants had told their partner about an infection was ‘too intrusive’. Some messages involving ‘action plans’ that encouraged participants to consider when, where and how they would carry out a behaviour were also considered ‘too intrusive’ and these were mainly reframed as suggestions regarding when, where and how a behaviour could be carried out, for example:

A lot of the time, sex isn’t planned. So it’s best to always have a condom on you. Find a time to put a few in your wallet. You could also keep a supply in places where you have sex (bedroom, partner’s house, car).

Men and women reported that messages covering gender roles, relationships and sexual pleasure were ‘too personal’ and ‘intrusive’ when delivered by text message and so this content was removed from the intervention.

Heterosexual men and women found messages about sexual pleasure without sexual intercourse ‘unrealistic’ and felt that this content reduced the credibility of the intervention, for example:

There are other ways of having safer sex without having intercourse. This might include kissing, fantasising, touching and mutual masturbation.

There were no clear differences in feedback on the content of the messages according to urban or rural residence. Men reported that they were able to negotiate condom use and so this content was included only for women.

Adapting the content based on a survey

In total, 100 participants were recruited and completed the questionnaire, of whom 74 were women and 26 were men (Table 4). The data set was 98% complete, with five instances of missing data.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 16–18 | 43 (43) |

| 19–24 | 57 (57) |

| No data | 0 (0) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 74 (74) |

| Male | 26 (26) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 92 (92) |

| Bisexual | 5 (5) |

| Gay/lesbian | 0 (0) |

| No data | 3 (3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White British/white other | 53 (53) |

| Black/black British | 31 (31) |

| Asian British | 1 (1) |

| Mixed | 14 (14) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| No data | 0 (0) |

| Education/work | |

| School | 6 (6) |

| College/university | 59 (59) |

| Working | 18 (18) |

| Training | 1 (1) |

| Unemployed | 13 (13) |

| No data | 3 (3) |

Of the 19 messages tested in women, there were three that < 40% of women scored as relevant and > 30% of women scored as not relevant (see Appendix 6, Table 12). One of these messages had received mixed feedback in the focus groups and was discarded from the message set. The other two messages were modified based on feedback obtained from the focus groups. For each of the remaining messages, the number of respondents reporting that the message was relevant ranged from 36 out of 74 (49%) to 66 out of 74 (89%), a median of 51 out of 74 respondents (69%).

Of the 17 messages tested in men, there were four messages that < 40% of men scored as relevant (see Appendix 6, Table 12). Two of these had received ambiguous feedback in the focus groups and were discarded. One received positive feedback in the focus group and was considered to be important and so was retained (‘You made the right decision to get a test. Getting treated quickly means you are less likely to have any problems. Text 2 to hear about how others felt when they found out that their test was positive’). One was modified based on further feedback obtained from participants: ‘You might be thinking about how they’ll react when you tell them. It might help by warming up the conversation and easing into it’ was changed to ‘You might be thinking about how they’ll react when you tell them. You could try practising what you’re going to say’. For each of the remaining messages, the number of respondents reporting that the message was relevant ranged from 12 out of 26 (46%) to 24 out of 26 (92%), a median of 18 out of 26 respondents (69%). No messages were considered ‘hard to understand’ or were ‘disliked’.

Testing and adapting the content based on telephone interviews with users after sending the text messaging intervention to users’ mobile phones

The eight participants who took part in the interview study, six women and two men, had a median age of 20 years (average 19 years). Six participants were from south-east London and two were from Cambridgeshire and participants were from a range of ethnic backgrounds (including white British, black British African, black British Afro-Caribbean and mixed ethnicity).

Participants were positive about the intervention content and delivery. In general, participants found the information in the messages useful and relevant to someone who has just received a positive chlamydia test result. They thought that the messages made them more aware of what chlamydia is and how to prevent it.

I think in general it was really good, like it was really helpful, it helps you know everything and gave you all the right information.

ID6

A few participants expressed a strong engagement with the messages, with one reporting that she discussed the information in the messages with friends and another saying that she kept the messages on her mobile phone because she valued the information in them and was planning to share them with her younger cousins:

I think I will keep it on my phone because I think it’s good information. I’ve got like younger cousins and stuff and now I have more information that I can tell them, I think I’m going to use it in that way.

ID5

It’s in my mind now.

ID2

You send me messages, I speak with friends or many people about chlamydia this week because it’s good information.

ID7

One participant commented that she was disappointed when it ended and that she goes through the messages in her room at night when she thinks a lot more:

I go back through my texts, say I was reading them . . . like when I’m in my room at night, I think a lot more, so when I go through my texts, they did kind of make me think a lot more.

ID3

A few comments were less complimentary. One found the message that ‘chlamydia is a common bacterial infection’ a bit ‘scary’ (ID1). An older participant (aged 23 years) said that he thought that some of the messages were a bit ‘silly’ (ID4). One participant indicated that some people might have trouble understanding the messages:

Well, some people are not going to understand because some people, like it’s difficult for them.

ID1

All but one participant reported that they told their partner about their infection. However, the participant who had not yet told her partner expressed an intention to tell him:

It might change his view on me, so it’s kind of scary, but I realise that I do need to do it. It would be better for me and him if I tell him.

ID3

One said that she would have told her partner anyway:

I was planning on telling him but I think it just gave me a push.

ID2

Two participants told their partner about their infection before they started to receive the messages. Four participants attributed telling their partner about their infection directly to the messages:

I forgot, innit, because I don’t want . . . like if I have sex with a girl that I don’t know, yeah, it’s just like maybe that just that one night, yeah, it’s over, I don’t want to know you again, like so . . . well, obviously I’ve got on my BlackBerry thing, so I pinged that, I was like ‘uh, you need to go check out yourself in the clinic, innit’. I didn’t tell her what I got.

Do you think if you didn’t get the text messages that you would have told her?

Well, I wouldn’t because the day I came here, you just gave me the pill then, I forgot about everything.

Another said that he ended up telling his partner about his infection because the texts were making him feel guilty for not doing so:

And how did you tell them?

I said um [laughs] I kind of ripped it off, you know like a plaster, like I just ripped it off, just ripped the plaster off. It just made me feel guilty, made me feel guilty for not telling so I had to tell someone.

One participant said that she did not know that chlamydia could be treated. She said that the clinic told her that it is treatable but she only realised that the infection was not too serious after receiving the messages:

I thought that Chlamydia was like, once you get it, you don’t get rid of it.

But, even though they told you that, what was the difference of receiving the text?

Because it was more than one person telling me, I felt, ‘OK, well, maybe it’s not that bad’ because I was a bit down and, yeah.

She said that she used a condom during the week after she was treated because the clinic had given her condoms and the messages reinforced the advice not to have unprotected sex during this time:

It was because of everything, really, like the texts and what the clinic told me. But, I guess, if the clinic didn’t give me condoms and you just texted me, then I probably wouldn’t have, but because they gave me condoms and they told me, and the text told me, it was like, it made things more serious and I realised like I don’t want to infect anybody I know.

ID3

Most thought that the tone of the messages was appropriate, although one participant thought that the messages sounded too automated and could have sounded more ‘humany’ (ID3).

Some participants gave feedback about the length of the messages and the timing and frequency of message delivery. Five recipients were happy with the frequency and one wanted more messages. Two recipients reported that there were too many messages, one of whom said that he was enjoying the messages at first but that it became too much after five or six messages and he wanted them to stop.

At what point did you want it to stop, like how far into it?

Like when obviously like five or six messages, I was like ‘oh, that’s too much now’ but it’s like the same thing, they’re saying the same thing but different words over and over again, so that’s kind of annoying.

Most thought that the length of the messages was about right:

I think they are not too long and they usually have the most important thing in the first sentence so they don’t try to say more, they just said what is important and I think that is great.

ID8

Most participants were unconcerned about keeping the messages confidential. Those who were concerned reported being confident about knowing how to protect their mobile phone and prevent others reading messages.

Participants reported that they especially liked the messages giving examples of how others had told their partner about having an infection. Based on this feedback we included the content about how others had told a partner about their infection in the core message set, rather than as part of the optional messages. An older male participant pointed out that the message ‘That’s great if you’ve told your partner . . .’ would make someone who has not told their partner feel bad. As a result we removed this message. No new issues were emerging in interviews and so no further participants were enrolled. We also ensured that information was included in the intervention that simply replying ‘stop’ to any messages would result in no further messages being sent.

Final intervention content

Intervention content for the pilot trial

The final message set was tailored according to sex and infection status at enrolment [no infection, chlamydia, gonorrhoea or non-specific urethritis (NSU)]. The message sets for those diagnosed with a STI were similar to each other except that the information provided was specific to the STI diagnosed. The number of messages targeting each behaviour and the number of messages employing specific intervention functions and BCTs are described (see Table 6).

For those diagnosed with a STI, messages over the first 3 days focused on engaging with the study, getting treatment, taking treatment and providing information about the infection. Over the next week messages targeted telling partner(s) about an infection. The messages provided non-judgemental, non-stigmatising information covering how common infections are; that an individual may not have symptoms and so may be unaware that they have a STI; that many people diagnosed with a STI have had only one sexual partner in the previous year; and that infections are easy to treat. Messages provided information about how to prevent infections. They provided suggestions about when, where and how to tell a partner about an infection and examples of how others told their partners, covering a range of different types of relationship (e.g. casual, long term). The messages then provided links to services that could inform partners and links to support for anyone concerned about violence in their relationship after telling a partner about an infection. Messages also aimed to provide social support, acknowledging people’s experiences.

For those diagnosed with an infection, after day 14 the messages targeted condom use and testing for STIs before having unprotected sex with a new partner. Participants who had not been diagnosed with an infection were sent the messages about safer sex behaviours (condom use and testing for STIs) starting on day 1. Over the following 30 days messages were sent providing information on how to prevent infections and how you cannot assess risk according to how well you know someone or by their appearance. Messages included instructions on how to use condoms, emphasised positive aspects of condom use and provided tips on preventing condom problems and examples of how others resolved condom use problems. Participants were prompted to think about risks that they had taken and what they could do differently in the future and also to consider how they had carried out safer sex behaviours in the past. Text messages included advice about getting tested before unprotected sex with a new partner. Participants were sent links to further web-based information about contraception, alcohol and sexual risk, how to use a condom and general communication about sex. Women were sent messages covering how other women had negotiated condom use. The messages were designed to provide social support for safer sex behaviours.

Control

The set of control messages consisted of 13 messages in total, which were spaced 30 days apart starting from the point of randomisation (see Table 6). The control messages contained no BCTs or information regarding sexual health. The messages were intended to help keep participants engaged in the study and to remind them of their participation, for example ‘Young people can experience health inequalities. Taking part in the texting study can help things to be equal. Thanks for taking part’. The messages expressed our appreciation of participants’ involvement in the study and suggested that participation in research can be personally beneficial: ‘Taking part in the texting study is a way to help you be actively involved in things that affect your life. Thank you for taking part’.

The information technology system delivering the messages

The IT system developed for message delivery was designed to be automated and to deliver different content according to allocation (intervention or control) and, for those receiving the intervention, according to participant characteristics (STI status and sex). Interactive messages could be sent in response to key words sent to the system from participants’ mobile phones requesting more content on specific topics. The system is held on a secure server with secure access. The system was fully tested with ‘dummy’ participants and the research team members’ mobile phones to check that the correct set of messages was delivered according to participant characteristics (STI status and sex) and the prescheduled time frame and to test that interactive content sent in response to key words was sent in accordance with the intervention protocol.

Discussion

Key findings

We have described the development of a theoretically informed intervention designed to address barriers to safer sex behaviours and increase safer sex behaviours in those aged 16–24 years diagnosed with a STI or reporting unprotected sex with more than one partner in the last year. We have described how the intervention content was derived from theory, evidence-based BCTs identified in effective face-to-face safer sex interventions, evidence regarding barriers to safer sex and expert and user views. Focus group discussions, a survey and telephone interviews with users informed and refined the intervention to ensure that it was acceptable to young people. In the survey participants reported that all of the messages were easy to understand and none was disliked.

Strengths and weakness of the intervention development work

Our work on intervention development has some weaknesses: although the intervention content associated with increased self-reported condom use is known,28 it remains unclear which BCTs are associated with increased effectiveness at reducing the incidence of STIs. We therefore included all of the BCTs in face-to-face interventions evaluated by randomised controlled trial and reporting reductions in the incidence of STIs at follow-up. To develop an intervention that was acceptable we excluded content that participants found to be unacceptable or irrelevant. Some evidence-based BCTs were modified based on feedback from young people and the effectiveness of the ‘acceptable’ but modified content is not yet known. Although the current intervention is tailored by infection status and sex, it is not tailored according to specific personal issues with regard to adopting safer sex behaviours. Thus, messages sent may not all be directly relevant to every participant. During the conduct of our work a new internationally agreed taxonomy of BCTs was published. 14,22 We included BCTs defined according to an older taxonomy in our intervention, but coded the final intervention using the new internationally agreed taxonomy. The intervention requires further adaptation to ensure that the content is appropriate for men who have sex with men and women who have sex with women.

Discussion in relation to existing research

In keeping with current guidance29 we used theory, evidence and testing to develop our complex intervention. The approach that we used to develop our behaviour change intervention based on theory, evidence regarding barriers to behaviours, evidence regarding the content of effective interventions and user views is not new. 30 There is no evidence that the content of interventions delivered by text message targeting safer sex has previously been based on a process designed to identify and then target documented barriers to safer sex behaviours. No previous intervention delivered by mobile phone informed by the COM-B comprehensive model of behaviour change has been reported. The recent development of validated taxonomies of BCTs allowed us to code the content of face-to-face interventions using a valid and reproducible methodology. There are no reports of previous interventions being developed based on empirical evidence regarding the content and BCTs employed in effective face-to-face interventions targeting safer sex behaviours. Our intervention includes content addressing attitudes, information and behavioural skills, which are found in the most effective interventions promoting condom use. 28 Our intervention includes a larger number of BCTs than previous interventions. No previous trials of interventions delivered by mobile phone have targeted the correct treatment of existing STIs, including providing support for telling partners about a STI. We ensured that the content of the text messages is consistent with the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV current safer sex advice,31 which recommends focusing on increasing motivation, skill acquisition (including communication skills) and provision of information about safer sexual practices.

Implications for the research project

The intervention was used in the pilot trial (see Chapter 4).

Chapter 3 Development of the trial materials and procedures

The importance of maximising follow-up responses

Any loss to follow-up (> 0%) in randomised controlled trials can represent an important threat to the validity of the trial results as participants lost are likely to be different from participants retained. The potential for bias is increased when the loss to follow-up is different in the intervention and control groups (differential loss to follow-up) because this further reduces the comparability of the results. 32 Although there are no universally agreed criteria with which to categorise the risk of such bias, some researchers have suggested that ≤ 5% loss to follow-up introduces minimal bias and ≥ 20% introduces significant bias. 33

Despite the importance of minimising loss to follow-up, many trials fall short of achieving their targets. A review of participant recruitment and retention in six high-quality journals found that 48% of trials reporting a sample size calculation did not meet their target at outcome assessment and analysis. 34 The authors suggest that their review may even overestimate the degree of retention because such journals are less likely to publish trials with poor retention.

Achieving high follow-up rates for collecting sensitive data such as sexual health data is particularly challenging. In sexual health research, response rates for self-reported data and STI testing kits have been relatively low in both RCTs and surveys. The National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal) study in the UK achieved a 57.7% response rate for face-to-face interviews and a 60% response rate for urine samples requested. 35 A UK cross-sectional population-based study reported an uptake of chlamydia postal screening of 31.5% in young people aged 16–24 years [the Chlamydia Screening Studies (ClaSS) project]. 36 A pilot trial of a sexual health website intervention for young people (Sexunzipped) achieved a 45% follow-up rate using chlamydia postal test kits and a 72% for self-reported data at 3 months. 37

A key criterion for progressing to a main trial in our HTA programme-commissioned research was demonstrating the feasibility of a main trial. We aimed to demonstrate in the pilot trial that a response rate of ≥ 80% at 12 months for chlamydia sample test kits was achievable. To achieve this we developed and tested all of our follow-up procedures prior to the pilot trial.

Objective

To develop follow-up procedures and materials to use in the trial to achieve > 80% follow-up.

Methods

Our approach for developing follow-up procedures consisted of three main steps.

Step 1: identifying evidence-based effective strategies to increase follow-up in trials

We searched for existing systematic reviews of trials of interventions designed to increase follow-up in research and contacted Public Health England’s Chlamydia Screening Programme team to identify any unpublished trials of interventions designed to increase response rates to postal STI test kits. We identified methods in systematic reviews for which there was there was good evidence (p ≤ 0.05) of success in increasing response to postal follow-up requests in trials. We developed prototype follow-up procedures incorporating the effective strategies identified (Table 5).

| Steps | Key findings | Implications for follow-up design |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify effective strategies to increase follow-up38–44 | Providing monetary incentives: OR 1.99 (95% CI 1.81 to 2.18);38 RR 1.18 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.28);39 RR 1.12 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.22) (£10 vs. £20);39 OR 2.02 (95% CI 1.79 to 2.27)44 | We included £5 cash with the initial postal request for the questionnaires and samples. We sent £20 cash to each participant on receipt of the sample |

| Sending post by recorded delivery: OR 2.04 (95% CI 1.60 to 2.61);38 RR 2.08 (95% CI 1.11 to 3.87);39 OR 2.21 (95% CI 1.51 to 3.25)44 | We did not send study materials by recorded delivery as this may have compromised confidentiality. However, we sent all materials using first class postage and included a first class stamp on the self-addressed return envelope | |

| Adding a ‘teaser’ comment on the envelope: OR 3.08 (95% CI 1.27 to 7.44)38 | We did not add a teaser comment on the envelope as this may have compromised confidentiality | |

| Pre-notifying participants to expect the questionnaire or postal test kit: OR 1.50 (95% CI 1.29 to 1.74);38 OR 1.54 (95% CI 1.24 to 1.92)44 | We notified participants before we sent the initial questionnaires and postal test kits | |

| Personalised letters: OR 1.16 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.28)44 | We addressed participants by their first name in letters, e-mails and text messages | |

| Coloured ink: OR 1.39 (95% CI 1.16 to 1.67)38,44 | Questionnaires were printed on white paper, had a light blue colour scheme and used black ink | |

| Following up with participants after the initial request: OR 1.44 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.65);38 RR 1.43 (95% CI 1.22 to 1.67);39 OR 3.71 (95% CI 2.30 to 5.97)41 | We contacted questionnaire non-responders and test kit non-responders | |

| Using a short questionnaire: OR 1.86 (95% CI 1.55 to 2.24);44 OR 1.73 (95% CI 1.47 to 2.03);38 OR 1.35 (95% CI 1.19 to 1.54)41 | We designed the questionnaire to be as short as possible by collecting only essential data | |

| Providing unconditional incentives: OR 1.61 (95% CI 1.27 to 2.04);38 OR 1.71 (95% CI 1.29 to 2.26)44 | We included £5 cash with the initial postal request for the questionnaires and samples | |

| Providing a second questionnaire and test kit: OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.13 to 2.00);38 OR 1.41 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.94)44 | We posted the questionnaire four times and sent the website questionnaire link twice. We sent the test kit four times and continued to send one each month to non-responders | |

| Mentioning an obligation to respond: OR 1.61 (95% CI 1.16 to 2.22)38 | We considered mentioning an obligation to respond in the letters but decided against it because our sexual health expert group thought that the target group may respond negatively | |

| Stamped return envelopes: OR 1.29 (95% CI 1.18 to 1.42);38 OR 1.26 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.41)44 | We sent self-addressed, stamped return envelopes for participants to return the questionnaire. Postal test kits included a prepaid box | |

| Assurance of confidentiality: OR 1.33 (95% CI 1.24 to 1.42)38 | We included the study identification number only on the questionnaire and included a statement about confidentiality on both the questionnaire and in the letter | |

| First class outward mailing: OR 1.12 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.23)44 | We sent all materials using first class postage | |

| Beginning questionnaires with general questions: OR 0.80 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.96)38 | We listed the key questions about treatment and sexual behaviour first | |

| Offering the opportunity to opt out: OR 0.76 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.89)38 | We did not include a statement about opting out in the letter | |

| Mentioning university sponsorship: OR 1.32 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.54);38 OR 1.31 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.54)44 | We included OM’s University of London address on all letters | |

| 2. Identify barriers to follow-up completion by testing the process | Test kits | |

| Some test kits do not fit through letter boxes | We selected a test kit that could fit through the smallest letter box | |

| The test kit included potentially distracting and non-essential components | We removed the following components from the test kit: the pen, condom, business promotional card, chlamydia information leaflet, urine sample tube (for women) and personal details form | |

| Most people could not open or broke the urine collection pouch that was included in the test kit | We removed the urine pouch and tested alternatives such as a urine collection cone and collecting urine directly in the sample tube | |

| The test kit included an instruction slip that was divided into two columns, one blue for the male urine sample and one pink for the female swab, and included non-essential graphics and information | We simplified and shortened the instruction slip. The revised slip was separated into two, one for the urine sample and one for the swab. The slips were plain white and included only the basic steps: three steps for the urine sample and four for the swab | |

| The test kit required the person to apply a laboratory tracking label | We applied the laboratory tracking label before we sent the test kits | |

| The test kit required the person to tick whether they were providing a urine or swab sample | We ticked a urine sample for men and a swab for women before we sent the test kits | |

| The pouch for urine collection included in the test kit was unnecessary | We did not include a pouch or any other container for urine collection | |

| Providing only a swab rather than a choice between a swab and a urine sample was acceptable for women | We included only a swab in the test kit for women | |

| Questionnaire and letters: | ||

| It is unappealing to list the less relevant questions first | We listed the key questions about treatment and sexual behaviour first | |

| A long questionnaire is unappealing | We included necessary questions only | |

| Including personal identifiable information on the postal questionnaire could cause confidentiality concerns | We included the study identification number only on the questionnaire and included a statement about confidentiality on both the questionnaire and in the letter | |

| Letters should include a statement about the importance of participating | We included a statement about how participants are helping to improve the health of young people | |

| The questionnaire should be short | We included necessary questions only | |

| 3. Consult with the target group | Young people wanted to be contacted before we sent the kits and questionnaire so that they knew to expect it | We contacted participants before we sent them any study materials |

| The envelopes should be identifiable to participants but not to anyone else | We sent all study materials in blue envelopes. We alerted participants to this when we contacted them before sending the materials | |

| Sending materials by recorded delivery could compromise confidentiality | We sent self-addressed, stamped return envelopes for participants to return the questionnaire | |

| Providing only a swab rather than a choice between a swab and a urine sample was acceptable for women | We included only a swab in the test kit for women | |

| The simplified and shortened instruction slip that we wrote was clear and acceptable | We included the simplified and shortened instruction slip rather than the pink and blue graphical instruction slip | |

Step 2: testing prototype follow-up procedures and materials

Sample postal testing kits routinely used in Cambridgeshire, Manchester and south-east London (our trial recruitment sites) and STI test kits used in NHS chlamydia postal testing services were obtained by OM. Successful receipt of the postal STI testing kit depended on the kit fitting through participants’ letterboxes. OM measured a range of London letterboxes on central London streets and measured the test kits to identify those that would fit through the smallest letterboxes measured. OM and CF attempted to complete all prototype follow-up procedures to identify barriers to follow-up completion and refine procedures to make follow-up as easy as possible.

Two researchers (OM and CF) attempted to follow the instructions for providing urine and swab samples that were included in postal STI testing kits that fit through the smallest letterboxes and completed the forms. Based on this experience, we generated ideas on how to make the follow-up processes easier. OM generated prototype test kits including combinations of the original materials and the newly generated materials (a choice of a vaginal swab or urine collection tube for women, a urine collection tube only for women and men and a swab only for women; a cone or pouch urine collection tube; a blue or brown envelope). OM provided volunteers from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s (LSHTM) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) with test kits and asked them to provide samples (which were disposed of) and feedback regarding their experience of completing the test. We consulted with experts in sexual health regarding the questionnaire design and follow-up procedures.

Step 3: consulting with users

See Chapter 2 for focus group methods.

We held one participant representative group to obtain the views of participants regarding the trial questionnaires and follow-up procedures and also asked participants for their views regarding trial follow-up procedures during focus group discussions convened to inform the development of the intervention. People aged 16–24 years who owned a mobile phone were eligible to take part. We asked for participants’ views on the pilot trial questionnaires, level of incentive offered and the acceptability of postal follow-up and materials (e.g. chlamydia test kit, envelopes).

Follow-up interviews

As part of the main trial we conducted interviews with participants seeking their views on the acceptability of the intervention. 45 We conducted follow-up interviews with these participants after sending the 3-month postal STI testing kits. The interviews followed a semistructured topic guide, which explored participants’ views on the trial materials and follow-up procedures.

Results

Effective strategies to increase postal follow-up

The follow-up strategies for which there is good evidence of increasing the odds of response according to systematic review and trial evidence38–44 are reported in Table 5. We employed all except four of the strategies. We did not send post by recorded delivery as users reported that recorded delivery would be unacceptable to them as they were concerned that it would draw parents’ attention to the package. 38,39,44 For the same reason we did not add a ‘teaser’ on the envelope (mentioning that there may be a benefit to opening). 38 We did not include a statement about an obligation to respond to the request because our sexual health expert group thought that our particular target group might respond negatively to this. 38

Testing the prototype follow-up procedures

The smallest London letterbox that OM measured was approximately 19 cm × 2.5 cm. The most appropriately sized postal testing kit that we found was provided by a laboratory diagnostic company and contained prepackaged components. The test kit included nine items: a urine sample tube and urine collection pouch (males and females), a vaginal swab tube (females only), a laboratory request form, a sample instruction leaflet, a chlamydia information leaflet, a business promotional card, a condom and a pen.

It was found by OM and CF that the components in the postal testing kit included many non-essential items. When CF opened the box all of the items fell out. Based on this experience we removed all but the essential content. CF broke the urine collection pouch when she attempted to open it and OM was unable to open it. Volunteer staff in the CTU (n = 12) were asked to provide a urine sample in the pouch. Only one person successfully used the pouch. The others broke it when they opened it, could not open it or did not know what it was for so did not use it. As an alternative four people were provided with a urine collection cone. No one reported difficulties in using the cone to collect urine or urinating directly into the urine sample bottle (men only).

The two sets of instructions were found to be overly complicated by OM and CF. The instructions for women could be confusing because they received a postal testing kit with both the swab and the urine tube but were required to provide only one sample. We provided the CTU volunteers with the original instructions or simplified instructions and found that they preferred the shorter instructions. Female CTU staff volunteers did not express a preference for providing a urine sample or a vaginal swab. CTU staff suggested that we include a statement in the postal letter to participants about the importance of their participation so that they would feel ‘proud’ about doing something good.

Experts in sexual health questionnaire design suggested that we list the key questions – those on treatment and sexual health behaviour – first.

User views

The focus group participant demographics are provided in Table 3. Participants wanted the questionnaires to be as short as possible. They had no objections to the prototype questionnaire design or content. They reported that the envelope used to send postal follow-up materials should be identifiable only to them. They suggested using a coloured envelope so that they would know what it was without others knowing. They reported that the short version of the sample STI test kit instructions was clear and acceptable. Participants asked to receive a text or phone call before we sent the questionnaire and STI test kit so that they would know to look out for them. They were concerned that sending follow-up materials by recorded delivery could call attention to the post and possibly compromise the confidentiality of their participation in the study. Some were concerned about parents asking questions about the content of a recorded delivery parcel. Women thought that it was acceptable to include a vaginal swab only in the kit rather than providing a choice between a swab or a urine sample, partly because it was what they were used to doing at the clinic.

Final follow-up procedures

The results of steps 1–3 informed the final follow-up procedures.

Materials

Questionnaires

Our follow-up questionnaire was two pages long. Research evidence38,40–42,44 and feedback from the target group suggested that the questionnaire should be as short as possible. We used a light blue colour scheme. 44 In accordance with guidance from our consultation with experts in sexual health questionnaire design and evidence from Edwards et al. 38 that the response rate is lowered when questionnaires begin with general questions, we ordered the key questions on treatment and sexual behaviour first. We did not include any participant-identifiable information on the questionnaire and included a statement about confidentiality. 38 We offered an online questionnaire as an alternative to postal completion. Participants had the opportunity to reply to key questions by text and e-mail.

Postal testing kit

We selected a postal testing kit that could fit through the smallest letterbox that we measured. Based on the findings of OM, CF and the volunteer testing of the kits, the kits contained only essential components (we removed the urine collection pouch, chlamydia information leaflet, business promotional card, condom and pen). We included only a swab for women and used the short, basic instruction slips. We used a pared-down laboratory slip that did not ask participants for personal details and included only the laboratory number and date that the sample was collected. We also filled out the laboratory form (ticked whether it was a urine or a swab sample) so that the participants would not be required to do it themselves. Participants had the option of providing their test sample at the clinic.

Letters

We kept the letters as short as possible. 38,40–42,44 The template was formal but the tone was casual, for example we addressed participants by their first name and used ‘Hi [name]’ instead of ‘Dear [name]’. 44 The letters included a statement saying that by completing the questionnaire and providing a sample participants were helping to improve the health of young people (a suggestion from our consultation with the CTU); a NHS/NIHR logo; and the trial co-ordinator’s University of London address. 38 All of the letters were from and hand signed by the trial co-ordinator.

Envelopes and postage

We sent all correspondence in blue envelopes, handwrote the addresses and used first class outward and incoming postage. 38,44 We did not send the post by recorded delivery or add a ‘teaser’ on the envelope (mentioning that there may be a benefit to opening) because of its potential to call attention to participants’ participation in the study, which could compromise confidentiality. 38

Mailings and incentives

We notified all participants by phone, e-mail or text before the initial mailing of both the questionnaire and the postal testing kit. 38,44 All initial mailings of the questionnaire and postal testing kit included a £5 unconditional cash incentive (subsequent mailings to non-responders did not). 38,40,43 Additionally, we sent £20 cash to all participants who returned the chlamydia test sample. 38,39,43,44 After the initial follow-up request, we contacted non-responders by phone, text message and e-mail, unless they opted out of further follow-up at any stage. 38,39,41,44

Month 1 questionnaire

The initial questionnaire posting included a £5 unconditional cash incentive. 38,40,43 We sent an e-mail message that included a link to the online questionnaire within a week of the initial questionnaire posting. 38,39,41,44 We posted the questionnaire again around 2–3 weeks later and sent a second e-mail within a week of this. 38,44 The third paper mailing included a statement in the letter saying that we would send £10 if we received the questionnaire within 2 weeks. 38,39,43,44 The fourth paper mailing included a statement in the letter that we would enter participants into a £50 prize draw if they returned the questionnaire within 2 weeks. 38,39,43,44 Finally, we e-mailed, texted and posted one or two key outcome questions to non-responders (according to their chlamydia status at enrolment). 38,39,41,44

Month 3 chlamydia test

The initial postal testing kit included a £5 unconditional cash incentive. 38,40,43 All letters mentioned that participants would receive £20 if they returned the sample. 38,39,43,44 We sent the testing kit to non-responders a further three times. 38,44 The fourth mailing included a statement in the letter saying that participants would be entered into a prize draw for £50 if we received the questionnaire within 2 weeks. 38,39,43,44 After each mailing we followed up with participants by telephone and e-mail. 38,39,41 We sent the testing kit to non-responders once a month. 38,44

Month 12 questionnaire and chlamydia test

We sent the initial 12-month questionnaire and testing kit together with £10 unconditional cash incentives. 38,40,43 All letters mentioned that participants would receive £20 if they returned the sample. 38,39,43,44 The initial letter included a statement saying that we would enter participants into a £50 prize draw if they returned both the questionnaire and the test. 38,39,43,44 We telephoned and sent an e-mail message that included a link to the online questionnaire around 3 weeks after the initial mailing. 38,39,41,44 We sent the questionnaire and testing kit to non-responders a further three times. 38,39,41,44 At each mailing we followed up with participants by phone and e-mail. 38,39,41 We sent the testing kit to non-responders once a month. 38,39,41 We e-mailed, texted and posted one or two key outcome questions to questionnaire non-responders (according to their chlamydia status at enrolment). 38,39,41,44

User views of the final follow-up procedures

We interviewed 17 of the original 20 main trial interview participants (we were unable to reach three) (R French, 2015, manuscript in review). None of the participants had any significant criticisms of the materials or the procedures and they found them acceptable. They thought that the pre-notification served as a reminder to look in the post. Similarly, participants mentioned that the blue envelopes helped them to recognise the study materials. One participant said that the letters were polite in that we were not telling participants that they had to send the questionnaires and samples back and another appreciated that the letters were short and to the point. Most participants thought that the instructions were clear and easy to follow and most did not have any problems with or criticisms of the postal testing kit. One participant said that initially he was not clear whether or not he should post the box on its own. Another participant said that it would have been easier if we had provided a pouch to collect the urine to pour it into the tube. One participant said that she initially had difficulty opening the swab but worked out how to do it. Another participant suggested that we include a condom in the kit.

Most participants said that they would have returned the questionnaire and chlamydia sample if they were not offered an incentive, with some indicating that the motivating factor was their health not the money. A few participants mentioned that the unconditional £5 motivated them to return the questionnaire and sample and another wanted to return them because we ‘treated’ him and said he would have procrastinated without it. Women preferred the swab sample collection method and none of the participants mentioned that they would rather have had a choice (swab or urine sample).

Discussion of the development of our follow-up procedures

Key findings

We have described the stepwise approach that we used to develop our follow-up procedures for this trial.

The approach involved using evidence-based methods to increase follow-up, testing prototype procedures and obtaining potential participant views on the procedures.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge this is the first description of a systematic approach to developing follow-up procedures. The approach has resulted in a follow-up package. In the single case study of our pilot trial it will not be possible to determine the effectiveness of the ‘follow-up package’ in isolation from other factors such as the management style and experience of the CTU and researchers conducting the pilot trial. It is not possible to determine which elements of the follow-up package are most important.

Discussion in relation to the existing literature

The approach mirrors methods used to develop behaviour change interventions, for example consulting with the user group, identifying barriers to performing behaviours and choosing techniques to enable the behaviours. 30,46 We used a similar approach to the approach used to develop follow-up procedures in the txt2stop pilot and main trial. The pilot trial achieved a 96% response rate for self-reported data collected by mobile phone or e-mail at 1 month and a 92% response rate at 6 months. 13 The main trial achieved a 95% (5524/5800) response rate for self-reported data collected by post, mobile phone or study website at 6 months and an 81% (542/666) response rate for postal salivary cotinine tests at 6 months. 10 An earlier trial achieved only a 74% response rate for self-reported data collected using voice and text messaging at 6 months and experienced differential follow-up between the intervention group and the control group (69% in the intervention group and 79% in the control group). 47

Implications for this research project

The follow-up procedures that we developed were used in the pilot trial (see Chapter 4).

Chapter 4 Pilot trial

Objectives

The pilot trial aimed to assess the feasibility of a main trial and to test all trial procedures.

The objectives were to:

-

recruit 200 participants within 3 months

-

successfully deliver ≥ 93% of messages from the aggregator to participants’ mobile phones (data provided by the aggregator)

-

complete follow-up of ≥ 80% for the proposed primary outcome for the main trial (the cumulative incidence of chlamydia).

Methods

Description of trial design

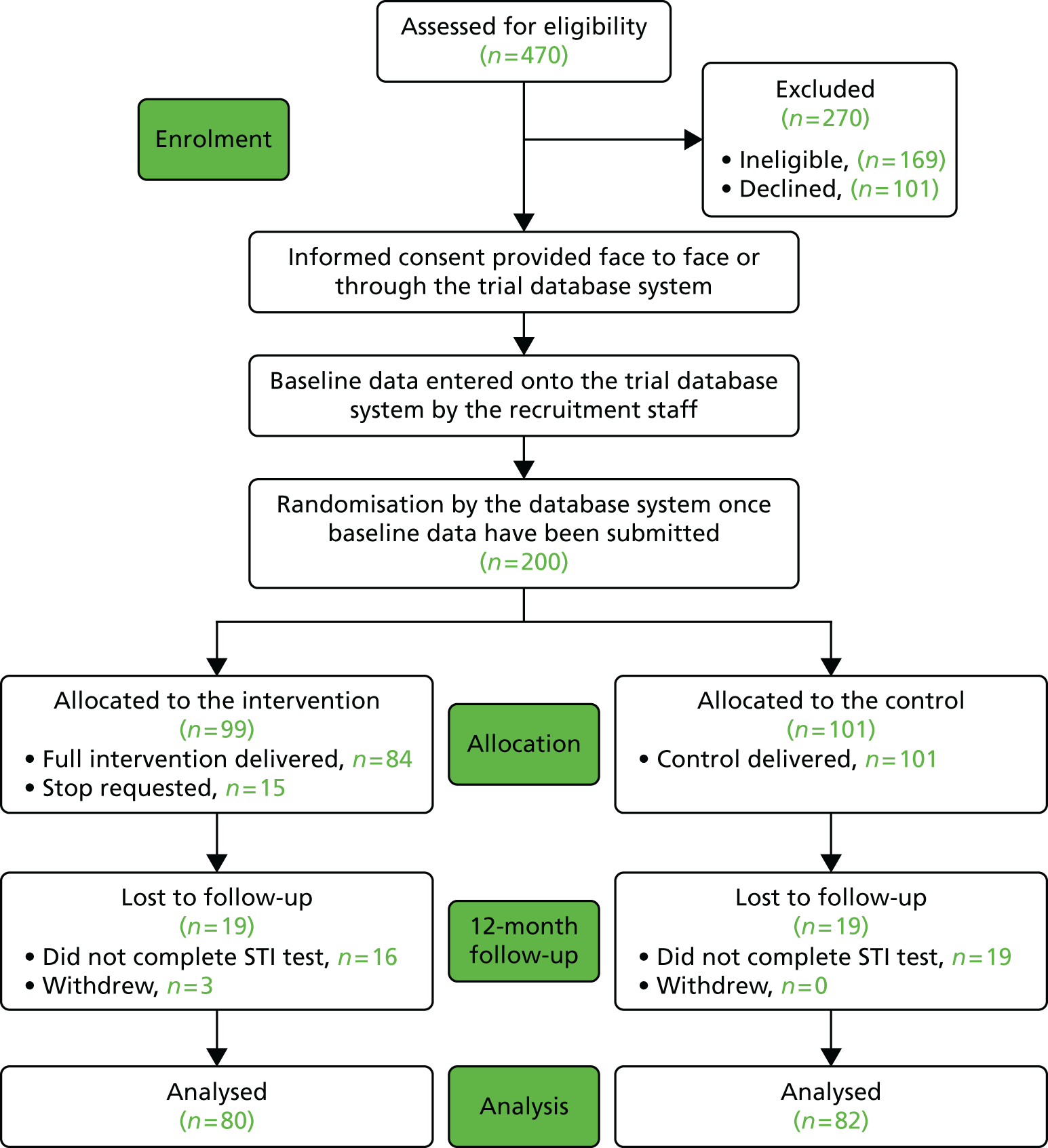

This was a pilot, parallel-arm randomised controlled trial with an allocation ratio of 1 : 1, conducted in multi-geographical areas of the UK.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

There were no changes to the methods after the trial commenced.

Participants

Eligibility criteria for participants

People aged 16–24 years with a positive chlamydia test result or who had had unsafe sex in the last year (defined as more than one partner and at least one occasion of sex without a condom) and who owned a mobile phone were eligible. People who satisfied these requirements were ineligible if they were non-English-language speakers or were unable to provide informed consent (e.g. people with severe learning difficulties).

Settings and locations where the data were collected

This trial identified potential participants through sexual health services in six geographical locations in the UK: London, Cambridgeshire (rural and urban), Manchester, East Anglia, Kent and Hull. Research staff recruited participants on site at the London and Manchester services. Staff at the Cambridgeshire, East Anglia, Kent and Hull services identified eligible potential participants and referred them to the trial centre (LSHTM) for recruitment.

Intervention

Intervention delivery and timing