Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/58/02. The contractual start date was in June 2010. The draft report began editorial review in December 2015 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Irwin Nazareth is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Funding Commissioning Panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Gilbert et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The problem

Smoking is the leading cause of ill health and mortality, and remains a major public health problem. Approximately 80,000 deaths in England in 2009 were caused by smoking1 and around 5% of all hospital admissions for those aged ≥ 35 years in 2011/12 were attributable to the habit. 2 Although the prevalence of smoking in the adult population in Great Britain has fallen by more than half since 1974, from 46% to 19% in 2013, the fall in prevalence has slowed and has changed little since 2007. 2 Furthermore, the gap in smoking prevalence between those in professional and managerial occupations and those in routine and manual workers shows no sign of diminishing; those living in the most deprived areas are more than twice as likely to smoke as those living in the least deprived areas. 3

A key objective of every UK government over the last two decades has been to reduce the prevalence of smoking,1,4 and various initiatives have been introduced aimed at reducing tobacco use. One of the key strategies to help current smokers quit was to implement government-funded specialist smoking cessation services in Health Action Zones in 1999, which were then rolled out throughout England in 2000. 5 These specialist services were established by Primary Care Trusts, operating predominantly in primary care settings, and offered intensive advice and support to smokers motivated to quit, in group or one-to-one sessions. Early evaluations suggested that the services were effective in their aim of supporting smokers to quit6,7 and were reaching smokers from more-deprived groups. 8 Since their introduction, the services, now known as the NHS Stop Smoking Services (SSSs), have continued to evolve. The most significant change took place during the course of this research in April 2013, when commissioning of local SSSs was transferred from the NHS to the local authority. The result of this was the tendering out of previously in-house services, leading to some SSSs being run by private and voluntary sector companies.

According to the latest figures available, 61% of smokers indicated more than ‘a little’ inclination to give up, and 26% of all smokers had made an attempt to quit in the previous year. 9 This figure has changed little over the years, but along with this evidence that the majority of smokers want to quit, there is a large literature suggesting that, despite this desire, programmes of support are consistently underused. The majority of smokers do not want to participate in formal cessation programmes but prefer to quit on their own. 10–13 More recent surveys and reviews have confirmed that this has changed little; although the trend for unassisted quit attempts may be decreasing, effective treatments remain widely underused and the majority of quit attempts are still unassisted. 14–16 The proportion of smokers in England using the SSSs is similarly low. Estimates in 2001–2 suggest that 2% of the adult smoking population in England set a quit date using SSSs. 8 In 2009, although 43% of smokers had sought some kind of advice or help to quit, the majority of these used self-help leaflets and books, and only 15% had asked a health professional for help. Just 8% were referred or self-referred to a stop smoking group. 9 West and Brown17 report that, of all quit attempts reported in 2011, 46.5% were unaided and only 4.1% reported using the SSS. Furthermore, figures from the Health and Social Care Information Centre show that since 2012 the number of smokers attending the SSS has a continuing downward trend. 18 Thus, these clinical interventions, provided free of charge by the NHS, reach relatively few self-selected smokers and only a small proportion of the total population of smokers in England.

Recruitment methods to cessation services generally employ a reactive approach, in which smokers are expected to seek out help and approach the service themselves. 11 General practitioners (GPs) and health professionals are encouraged to offer brief advice and to provide referral to services, but in 2008–9 only 55% of smokers reported being given advice, and only 8% were referred to the services. 9 Moreover, these smokers were generally expected to follow up their referral and contact the service themselves to make the appointment. There is a wide range of factors that will deter smokers from seeking help, these include a lack of time, lack of availability and accessibility of times and locations, perceived inappropriateness of the service, a perception that help is not necessary, a sense of a lack of empathy from health professionals and not wanting the social stigma associated with participation in formal programmes, as well as a lack of readiness to quit. 13,19,20

The problem to be addressed then is, given that the majority of smokers say they want to quit, how can more smokers be persuaded and motivated to take the plunge and seek, or accept, help to quit, which would lead to more successful quit attempts.

Rationale for intervention

Mass mailing and proactive strategy

Studies suggest that the direct marketing approach has potential as a population-based strategy for recruiting smokers into support services, and could provide treatment access to individuals who might not otherwise seek cessation care. Paul et al. 20 explored the acceptability of direct marketing and proactive contact offering cessation services to smokers. The authors reported that 92.8% of the sample found it acceptable for the health service to contact people to offer assistance and 55.7% said they were likely to take up the offer of individual counselling. This could be an overestimation of actual take-up of the service, but suggests that proactive contact is acceptable and that smokers are open to the idea of intensive counselling. The importance of proactively encouraging smokers to quit has also been demonstrated in studies exploring recruitment to telephone quit lines, lending support to the ‘cold call’ telephone approach. These studies suggested that demand and interest in using services or receiving information about quitting may be greater than is reflected in current usage rates, and that proactively offering services could result in an increase in uptake. 21–24 A recent systematic review of recruitment methods for smoking cessation programmes suggested that personal tailored messages and proactive and intensive recruitment strategies can enhance recruitment. 25 This review confirmed the conclusion reached by McDonald26 that interpersonal strategies have a positive effect on recruitment into smoking cessation programmes.

Lichtenstein and Hollis27 employed a more proactive recruitment method. They invited smokers attending a medical appointment to an immediate intervention where they were offered information about what attendance at the service would involve, and a strong referral message to the service. Attendance at the first session of the cessation programme increased to 11.3%, compared with 0.006% in a control group who received brief advice only. Fiore et al. 28 also showed that many primary care patients identified as smokers will accept treatment ‘if it is free, appropriately incorporated into the health-care delivery system to ensure convenience, and encouraged through proactive recruitment’.

In line with these findings, a major UK study used a proactive strategy to identify individual smokers and inform them about available cessation services. In a cluster randomised controlled trial, Murray et al. 29 identified all patients in general practices recorded as current smokers or with no status recorded. These patients were proactively informed by letter about the SSSs and given the option of being contacted by an advisor. Smokers in practices allocated to the intervention group indicating that they would like to speak to an advisor were contacted within 8 weeks by a researcher trained as an advisor and offered advice and an appointment. Smokers in control group practices received no further contact. Overall, the proportion of current smokers expressing interest was 13.8%, suggesting that more than the current 5% of the smoking population setting quit dates within the NHS were interested in receiving help. Furthermore, Murray et al. 29 reported a 7.7% absolute increase in smokers using the SSSs in the intervention group over the control group at the 6-month follow-up, and an increase of 1.8% in validated abstinence in those smokers requesting contact over the control group (4% vs. 2.2%).

This study by Murray et al. 29 was the first in the UK to assess a proactive method of recruitment to attract smokers into the SSSs. It demonstrated the potential to increase attendance, and also indicated that novel methods of marketing are needed in order to engage interested smokers to encourage use of the SSSs.

Individual computer-tailoring and risk information

One possible way of enhancing recruitment is to use individual characteristics to personalise and tailor communications. Computer-based systems can generate highly tailored materials, defined as ‘any combination of information or change strategies intended to reach one specific person and based on characteristics unique to that person’. 30 This technology offers a method for personalisation of communications to patients and can include an individualised risk communication element based on an individual’s own risk factors, more personally relevant to the consumer than information about population ‘average’ risks. 31

The use of fear in health promotion has been the subject of debate and is somewhat controversial, with claims that ‘shock tactics’ do not work, are too frightening, or can backfire and prove to be counterproductive by prompting a maladaptive behavioural response. There is also a general notion that healthy lifestyle campaigns and anti-smoking messages should be positive and reflect non-smoking role models rather than dealing with the ‘scary’ health consequences of smoking. 32 However, in a review of studies on fear appeals, Sutton33 concluded that increases in fear in communications are associated with increases in acceptance of the recommended action, in a linear relationship. Providing recipients with a reassuring message that adopting the recommended action would be effective, together with clear advice on how to go about it strengthens intentions to follow the advised course of action. 34

Fear messages about smoking can indeed push people to attempt to quit. The fear induced by such messages can be dealt with adaptively by a behavioural response that removes the reason to be fearful, such as quitting smoking, or maladaptively by, for example, denying the truth or personal relevance of the threat. 32 The likelihood of eliciting the desired response can be maximised by empowering the recipient and giving reassurance that it is possible, and also providing a ‘helping relationship’ that is needed to succeed. 35 This has been demonstrated to good effect in mass media campaigns, particularly that of the Australian national anti-smoking advertising campaign, which used graphic fear-based messages as a dominant part of the communication strategy, but tagged with the national quit helpline number and an additional advertisement encouraging calls to that number. 36 This strategy is also consistent with social cognitive models such as the health belief model, which posits that a greater perceived risk of a disease and perceived efficacy of the action in preventing it is associated with increased participation in a recommended behaviour. The health belief model also highlights the importance of providing a specific cue to action, which can act as a trigger and increase compliance with the recommended behaviour. 37,38

Additional justification for this approach lies in the evidence that smokers do not fully acknowledge their own personal vulnerability. Data show unequivocally that smokers acknowledge that their risks of health problems are higher than those of non-smokers. However, studies indicate that they substantially underestimate their own personal risk and tend to conclude that they are less likely to suffer health effects than other smokers. 39 A large literature demonstrates this ‘optimistic bias’ or ‘unrealistic optimism’. Weinstein et al. 40 provided further clear evidence that smokers engage in risk minimisation by convincing themselves that they are not as much at risk as other smokers. Moreover, smokers do not perceive the relationship between the amount smoked and their perceived risk. Thus, even if people are aware of the well-publicised risks, they resist the idea that the risks apply to them, and a key factor is getting participants to acknowledge that these risks are personally relevant.

Computer-tailoring can be used to customise an individual’s risk factors, enhancing perceived personal relevance and helping to overcome the tendency to deny that the information in the tailored messages applies to the recipient. These personal communications can both inform the smoker of their own personal risk, while at the same time promoting confidence and providing the helping relationship that is essential to encouraging acceptance of the advice and following the recommended course of action. These basic tenets were put together in the 3Ts (Tension, Trigger, Treatment) model proposed by West and Sohal. 41 They proposed that triggers can lead to sudden changes and that creating motivational tension can trigger action in smokers who are predisposed, or motivated, to change. The immediate availability of treatment can then prompt action.

Research has shown that individually tailored self-help materials have a small but useful effect over generic materials on smoking cessation. 42 The addition of personalised risk communication that is more personally relevant to the consumer has also been found to increase uptake of screening. 31 Computer technology can be used to produce a communication that combines the tenets of this model, and can also be combined with proactive recruitment methods with the potential to engage with and recruit a larger proportion of the smoking population in a relatively inexpensive way.

Opportunity to experience a support service without commitment

In addition to the factors noted as barriers to the use of support services, the literature also suggests that many smokers are unaware of, or have insufficient knowledge of or inadequate information about, the services available. 20,43 This lack of knowledge can also lead to the belief that ‘it wouldn’t help me anyway’. 20 The combination of ‘why quit’ messages, hard-hitting messages about the consequences of tobacco use and ‘how to quit’ messages, supportive and positive and emphasising quitting resources, was recommended in the Global Dialogue for Effective Stop Smoking Campaigns,44 an international review of the literature. This report also recommended that promotional efforts need to both build awareness that getting help will increase the chances of success and build awareness of and comfort with the quitting services.

Lichtenstein and Hollis27 demonstrated how a proactive and personal approach can be combined with an opportunity to gain more information about the service and what it involves at a no-commitment introductory session. Their intervention included an assessment, measurement of expired-air carbon monoxide (CO) level with an interpretation, video testimonials and the opportunity to ask questions, a voucher fee waiver and immediate scheduling of the smoker for the group. Thus, including a personal invitation with an appointment to a no-commitment introductory session offers the opportunity to gain an insight into what the service can offer, and also has the potential to increase service use.

This research study brings together evidence on proactive and direct mail recruitment, on personalised computer-tailoring and risk information, and on offering the opportunity to experience a support service without commitment, to evaluate a complex intervention comprising all of these elements, in encouraging and increasing attendance at the English SSSs.

The intervention is further enhanced by the addition of a repeated personal letter, with a further invitation sent 3 months after the original to all participants who fail to attend a taster session. This is consistent with recommendations made by Lichtenstein and Hollis27 who proposed that, with repeated advice over time, a greater proportion will be likely to respond.

Aims and objectives

Principal research question

We hypothesised that smokers, identified from general practice records, sent brief personal tailored letters based on characteristics available in their primary care medical records and on a short screening questionnaire, and invited to a ‘Come and Try it’ taster session designed to inform them about the SSSs, were more likely to attend the services than those who received a standard generic letter advertising the service.

Primary objective

The primary objective of the study was to assess the relative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a complex intervention, consisting of proactive recruitment by a brief personal letter tailored to individual characteristics available in medical records, and an invitation to a ‘Come and Try it’ taster session to provide information about the SSSs, over a standard generic letter advertising the service, on attendance at the SSSs of at least one session.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were to (1) assess the relative effectiveness of the intervention on biochemically validated 7-day point prevalent abstinence rates at the 6-month follow-up; (2) compare the cost-effectiveness of the intervention; (3) assess the relative effectiveness on additional periods of abstinence measured by self-report of not smoking for periods of 24 hours to 3 months at the 6-month follow-up; (4) assess the number of smokers attending the taster session and the number of smokers completing the 6-week NHS smoking cessation course; (5) assess the number of quit attempts made and any reduction in daily cigarette consumption; (6) explore the effectiveness of the intervention by socioeconomic status and social deprivation; (7) explore reasons for non-attendance and barriers to attendance at the SSS; and (8) determine predictors of attendance at the services and at the taster sessions (in the intervention group).

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design and setting

The Start2quit study was a pragmatic two-arm randomised controlled trial of a complex intervention, utilising general practices in England to recruit smokers into the trial.

Trial management and conduct

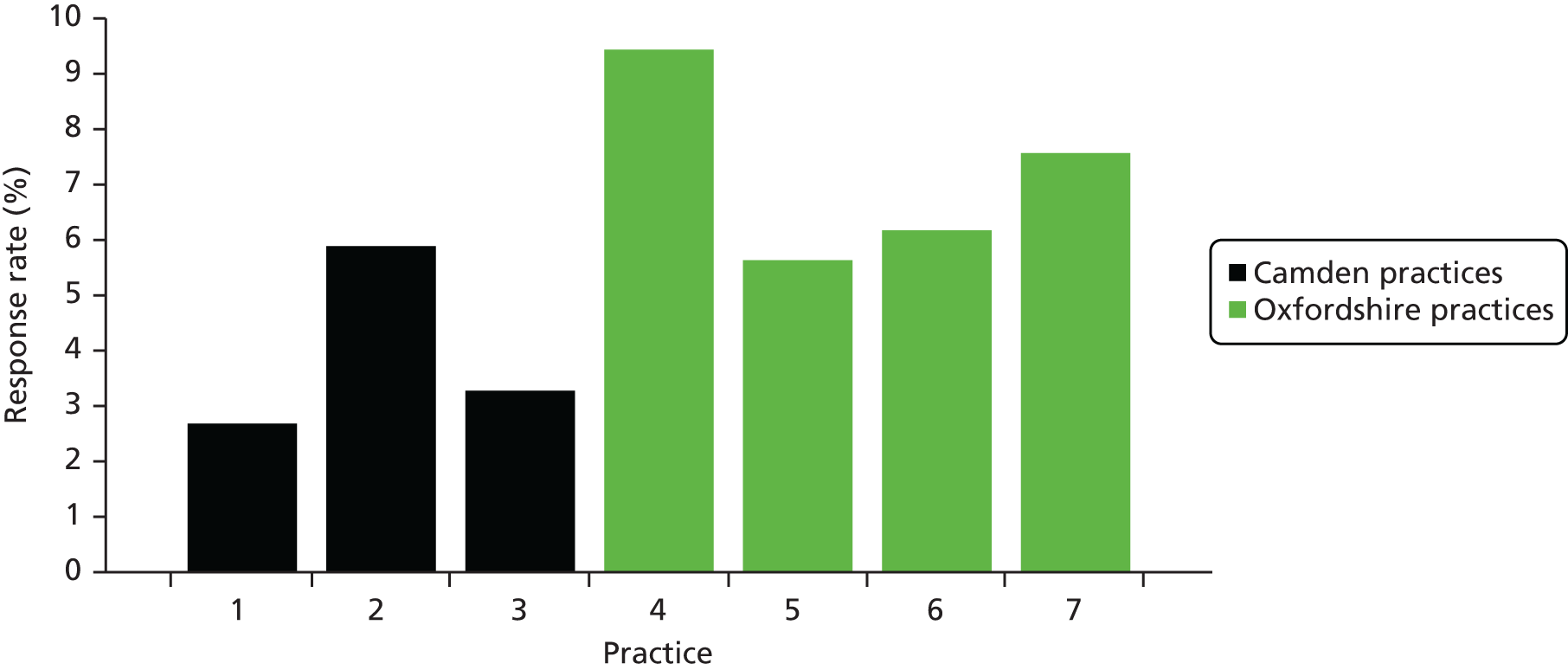

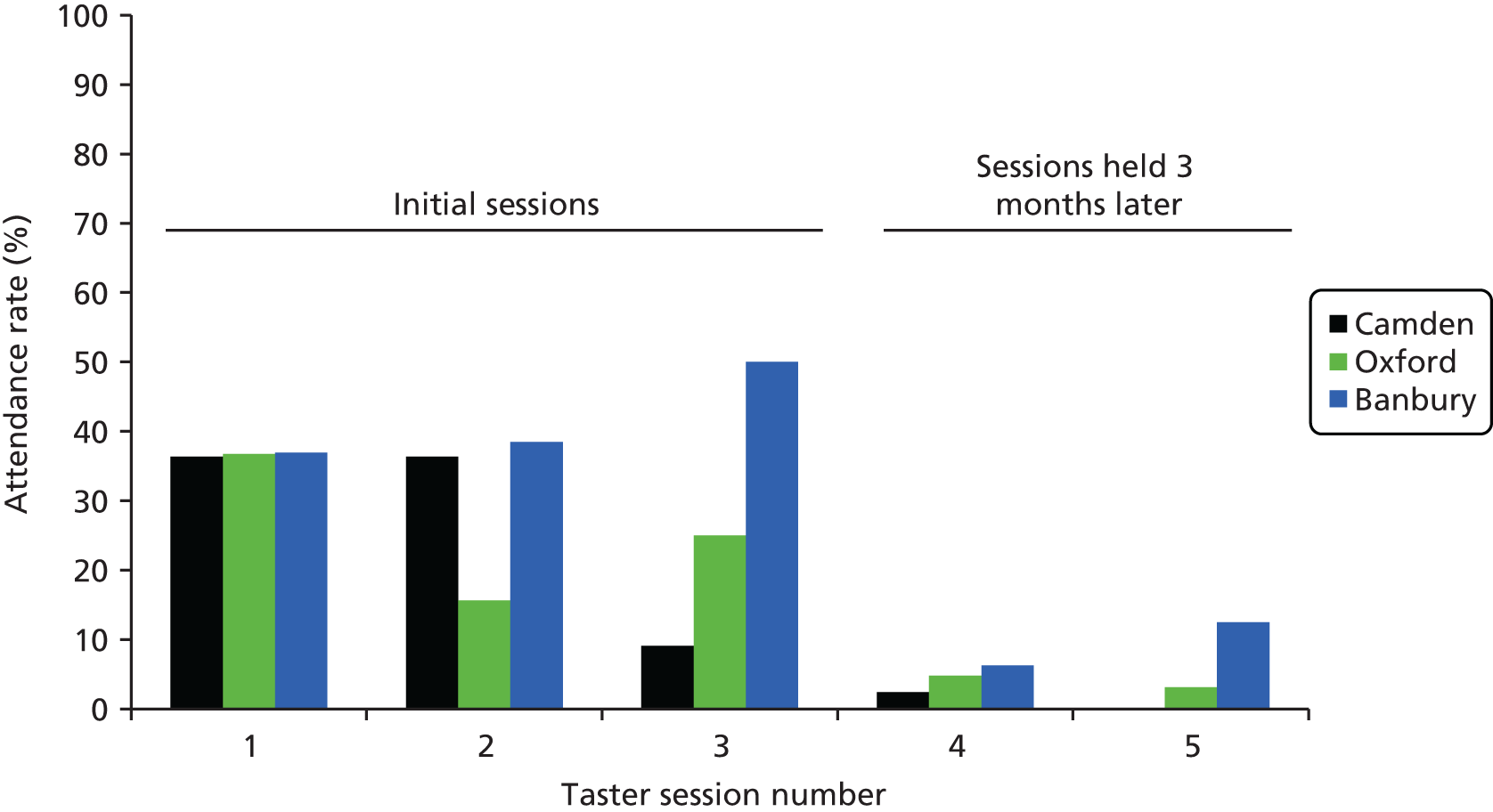

The trial was conducted in two stages. A pilot phase was conducted in seven practices covered by two SSSs between January and December 2011. The aims of the pilot phase were to assess the feasibility of the procedure, to ascertain recruitment rates and assess the uptake of the taster sessions, and to establish that the uptake of smoking cessation services in the intervention group was at least as good as that in the control group (i.e. the difference in proportions of intervention minus control was greater than zero).

The methodology of the pilot phase was essentially the same as the full trial, to enable combination of the data from both phases for analysis. However, lessons learnt on recruitment strategies from the pilot phase were applied to the main trial.

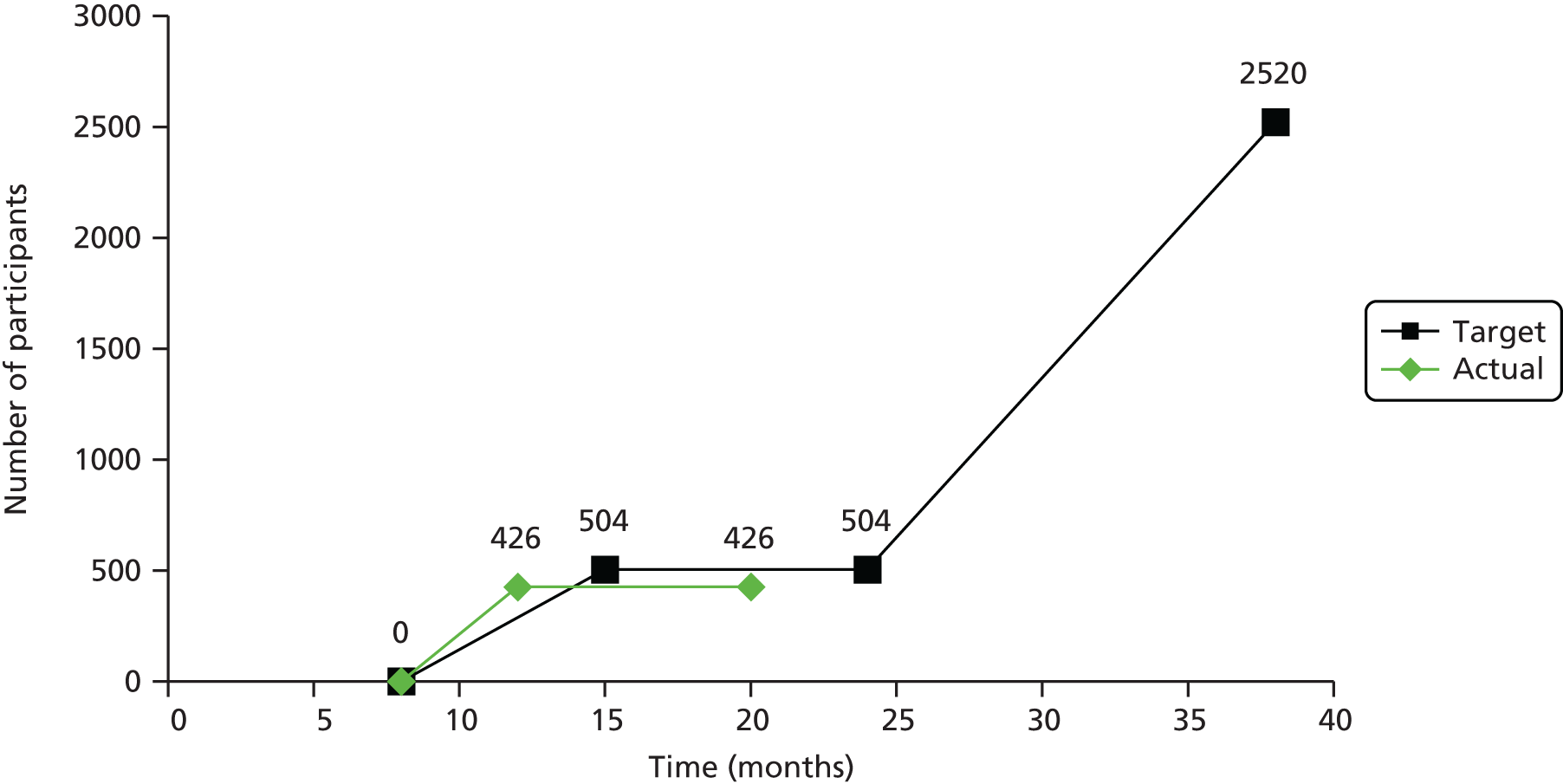

The trial was originally funded for 48 months. Additional funding, approved in July 2012 to carry out additional work, increased the size of the sample and extended the trial by 12 months.

Amendments to the final protocol including the trial extension are presented in Appendix 1. The report of the pilot phase submitted to the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme in January 2012 is in Appendix 2.

The study was approved by the London–Surrey Borders Research Ethics Committee and received approval from the local NHS trusts.

Participants

Target population

The target group was smokers motivated to quit who had not attended SSSs in the previous 12 months. We aimed to target smokers in areas of high deprivation and ethnic minorities, where smoking prevalence is high.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

All current smokers willing to participate and returning the signed consent form, aged ≥ 16 years, able to read English, motivated to quit and who had not attended SSSs in the previous 12 months were eligible for inclusion in the study. For the purposes of this research, motivation to quit was defined as answering ‘yes’ to either or both of the following questions:

-

Are you seriously thinking of quitting in the next 6 months?

-

Would you think of quitting if appropriate help was offered at a convenient time and place?

Exclusion criteria were minimal because the aim was to recruit all smokers into the services. However, smokers aged < 16 years were excluded because of the need for parental consent to participate for this age group, and any patients identified considered by the GP to be unsuitable for the project, for example the severely or terminally ill, were excluded.

Recruitment procedure

Stop Smoking Service and practice recruitment

We worked with the National Institute for Health Research Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) to identify SSSs willing to participate in the trial, and to then identify and recruit practices in the selected SSS areas. We aimed to select more practices in areas of high deprivation and of large ethnic communities to ensure full representation of smokers most in need of help, and to maximise the generalisability of the results. The SSSs and PCRNs assisted in identifying sufficient practices serving these populations.

The trial was originally planned to cover 10 different areas served by a SSS, and we initially recruited Camden (North London) and Oxfordshire SSSs and practices in those areas for the pilot phase of the trial. The extension of the trial and the increase in the size of the sample meant that the number of SSSs was increased to 18 in areas representative of the English SSS.

Participant recruitment

All smokers aged ≥ 16 years were identified from their medical records in participating practices. GPs screened the list to exclude anyone they deemed to be unsuitable for the research, for example severely or terminally ill, and the list was also screened to ensure that only one person from the same address was selected. All remaining persons on the list were sent a letter from their GP inviting them to participate in the trial, together with a participant information sheet describing the research, a consent form and a screening questionnaire. Participants were asked to consent to the use of information from their medical records and information given in the screening questionnaire to send them information about quitting, and for the researchers to access relevant data from their attendance at the SSSs. Data generated from the screening questionnaire were used both to assess the criteria for inclusion in the trial, to provide information for the computer-generated tailored intervention letter and to provide baseline characteristics. Participants returned these questionnaires to the practice using a Freepost envelope. Non-responders were sent a reminder and duplicate questionnaire after 3 weeks. All smokers returning the signed consent form and who were eligible to participate were randomised to the intervention or the control group. Patients had the opportunity to decline to participate but to return the questionnaire with basic information to update their smoking status in their GP practice records.

All recruitment materials can be found in Appendix 3. The baseline questionnaire is included in Appendix 4.

Interventions

Control group

Participants allocated to the control group were sent a standard generic letter from the GP practice advertising the local SSS and the therapies available, and asking the smoker to contact the service to make an appointment to see an advisor.

Intervention group

Participants allocated to the intervention group received the following:

-

a brief personalised and tailored letter sent from the GP that included information specific to the patient, using information obtained from the screening questionnaire and from their medical records

-

a personal invitation and appointment to attend a ‘Come and Try it’ taster session to find out more about the services, run by advisors from the local SSS

-

a repeated personal letter with a further invitation sent 3 months after the original to all participants who failed to attend a taster session following the first letter and invitation.

Each of these components is described in the following sections in detail.

Development of the tailored intervention letter

The overall objectives of the letter were to communicate personal risk level if the person continues to smoke, using individualised information on the risk of serious illness, and to encourage attendance at the SSS.

Letter content

The letter was tailored to the individual using characteristics from practice records (gender and age) and confirmed by the baseline screening questionnaire, information obtained from the screening questionnaire (number of cigarettes per day and previous quit attempts) and information from medical records about diagnosed conditions on the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) register. The final list of diseases consisted of all cancers (excluding lung because of its terminal nature); myocardial infarction; coronary heart disease and heart failure (combined because of terminology and the difficulty of telling someone they have a ‘weak heart’); lone atrial fibrillation; stroke and transient ischaemic attack; diabetes; epilepsy; hypertension; hypothyroidism; asthma; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); dementia (if the patient was able to consent); depression and severe mental illnesses (schizophrenia and bipolar disorders); and obesity. Possibilities around co-occurrence of diseases were considered and messages created for the following: COPD and heart failure; COPD and asthma; coronary heart disease and hypertension, stroke, dementia, severe mental illnesses, diabetes, obesity; and for multiple conditions. Because of additional risks associated with smoking for women who are pregnant or taking the contraceptive pill or hormone replacement therapy, personal risk information was also included for these smokers.

Personal risk information can be presented as an absolute or relative risk score, categorised, or as a list of the individual’s risk factors. As it was felt not appropriate to provide specific probability figures without the opportunity to discuss them with a health professional, risk was classified as high, very high or extremely high compared with non- or ex-smokers, as recommended by Edwards et al. 31

The offer of help was tailored to previous quit experience, and the letter was accompanied by a personal invitation to the taster session with details of time and place.

The content of the letter was developed in collaboration with GPs and primary care experts with knowledge of medical information available in records. Two service users also contributed.

Letter structure

The letter was headed ‘Personal Health Risk Report and Taster Session Invitation’. It consisted of four sections (Table 1). The amount of tailoring was maximised within the constraints of the short screening questionnaire and a brief letter, so that the final communication consisted of two pages. The section headings were coloured as a traffic light system, using red for the risks, orange to encourage the person to prepare to stop and green for the invitation to the taster session.

| Section | Objectives | Information included | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | To explain the purpose of letter, so that the individual will know that it is a personalised letter based on their assessment | ||

| 2. Personal risk in terms of dependence and general health | To tell the individual his or her dependence in the context of norms | Dependence | Questionnaire |

| To indicate a category of risk according to dependency in terms of the number of cigarettes smoked per day, the number of QOF-registered conditions and age | Age | Medical records | |

| Number of QOF diseases | |||

| 3. Disease-specific health risks and the benefits of quitting | To make the individual aware of the personal health consequences of continuing to smoke, and their own individual risk of serious illness in relation to dependence and own health status | Dependence | Questionnaire |

| To make the individual anxious because of perception of their own personal risk | Age | ||

| To change the individual’s balance of perceived ‘benefits’ against their understanding of the harm caused by smoking | Gender | Medical records | |

| QOF disease | |||

| 4. Invitation to taster session | To remind the individual that help and support is immediately available | Previous quit attempts | Questionnaire |

| To encourage them to seek out support and use the resources available |

The letter was generated by a computer program, signed by the GP and sent from the practice. The first letter was posted to the participant within 3 weeks of returning the completed questionnaire. A second identical letter and invitation was sent 3 months later to every participant who had not attended one of the earlier taster sessions.

Examples of the personal letter are included in Appendix 5.

Development of the taster session and training

The goal of the taster session was to offer information about the SSS, promote the service, address any concerns or queries smokers may have about the service provided and encourage sign-up to a course. It was not intended to replicate the first session of a course.

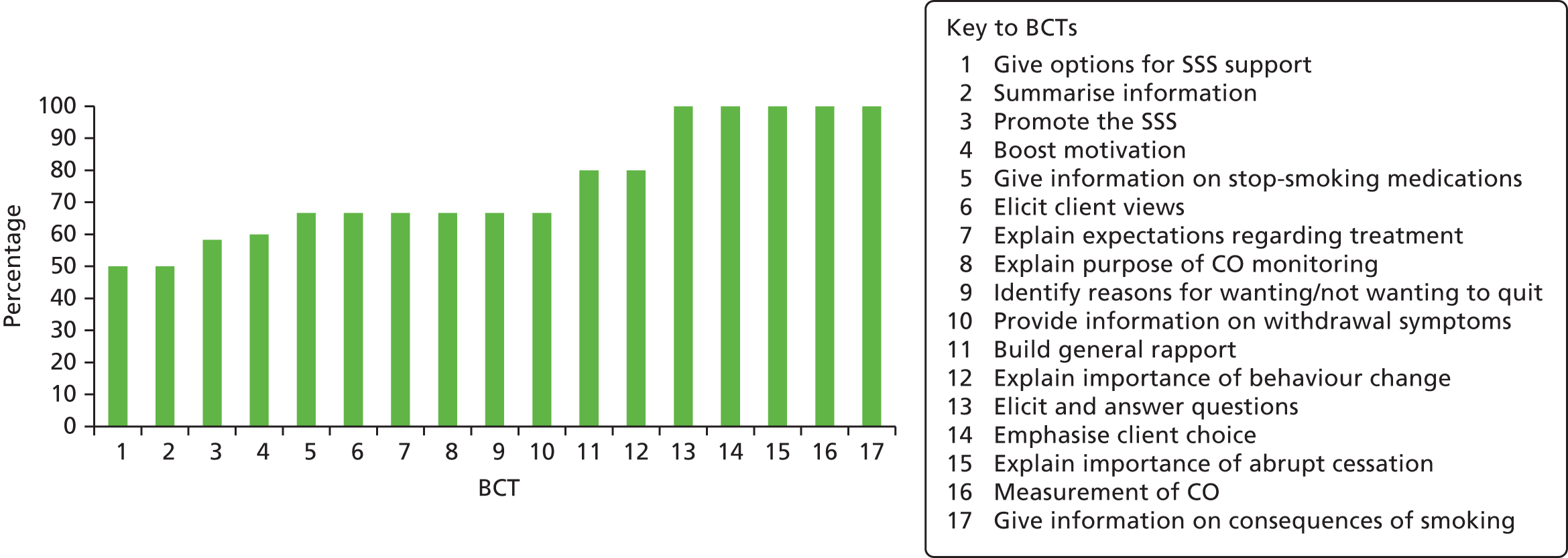

A draft of the content of the taster sessions was prepared by one of the co-investigators (SG), and was developed into a standard protocol in consultation with the research team. The final standardised protocol also included items from the NHS Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training’s Standard Treatment Programme46 to ensure conformity with national guidelines, and a detailed manual was produced. The standard protocol for the taster session included:

-

a motivational element, congratulating attendees on coming to the session

-

an introduction to the SSS, emphasising that it is a free service and based on well-researched evidence

-

emphasising the importance of stopping smoking and outlining the benefits of quitting, both health and financial/lifestyle

-

information about the services offered, outlining the structure the treatment programme in one-to-one or group sessions, the length of sessions and of the course

-

information about what to expect when they attend and the content of advice, for example emphasising that no-one will be forced to quit, but will be helped to explore the reasons for and against wanting to give up smoking, and helped to develop strategies to resist smoking after their quit date

-

interaction between attendees, discussing, among other things, reasons for stopping

-

discussion about withdrawal symptoms, with information about the available medications and range of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products available

-

the opportunity to have a measurement of CO level taken, with an interpretation

-

a 5-minute digital versatile disk showing group and one-to-one sessions in progress, and testimonials from previous successful attendees, produced by University College London (UCL) Media Services in collaboration with Camden SSS

-

the opportunity to ask questions about the service

-

details of how to contact the service and a clear and persuasive invitation to sign up for a group or individual session.

Between two and seven advisors in each SSS, already trained to give smoking cessation advice in group and one-to-one sessions, attended a 2-hour training session to enable them to facilitate the taster sessions according to the standardised protocol and manual. The training sessions took place within each SSS and were led by two members of the team (either HG or SG), and included an explanation and clarification of the study protocol and procedures, and specified the exact information to be delivered in the session. Only trained advisors led the taster sessions, and each session was run either by one advisor with additional administrative support provided by one other, or the presentation was divided between two advisors. They were encouraged to introduce themselves and describe their background and expertise to reassure attendees of their credibility and expertise.

It was intended that each SSS should run between 4 and 12 taster sessions, depending on the number of participants recruited and the area covered by the SSS, and that up to 50 participants were invited to each session, which lasted approximately 1 hour. Sessions were held in the early evening normally beginning between 18.00 and 19.00. On arrival attendees were asked to sign an attendance sheet provided by the research team. An evaluation form was developed for immediate assessment of attendees views of the session, the form included space to indicate interest in signing up to the SSS. Advisors encouraged attendees to complete these evaluation forms before leaving the session and, when possible, participants were given a date and time of a group or one-to-one session before they left. The taster session protocol in included in Appendix 6.

Fidelity

The training session included a basic introduction to the methodology of randomised controlled trials and of uniformity of an intervention. Thus, training emphasised the importance of standardising taster sessions, and of delivering all protocol-specified content, while allowing for differences in the organisation of the individual SSSs and also allowing for advisors to deliver the information naturally, as they would in their smoking cessation clinics. To assess fidelity to the protocol, the taster sessions were, with the consent of the attendees, audio-recorded. Advisors also completed a personal details form, gathering data on gender, age, highest educational qualification, type of smoking cessation training, time since smoking cessation training, number of patients seen in the previous 6 months and job title to account for differences in ‘therapist effects’.

Procedure and baseline data management

Procedure

Recruitment, collection of baseline data and delivery of the intervention took place over 4 years, between January 2011 to June 2011 for the pilot phase, and between January 2012 and December 2014 for the main trial. The procedure in each practice took 12 weeks to complete, during which time the research assistants visited the practice on four occasions, assisting practice staff with mailing invitation letters and questionnaires to patients, processing returned questionnaires, and generating tailored and generic intervention letters. A series of purpose-written computer programs written in Visual Basic for Applications (1997–2003, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) that read and write Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Microsoft Word® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) files facilitated these processes, and were installed on laptops for use in the practices.

The practice staff initially ran a search using the practice computer system to identify all patients recorded as smokers. The GPs then screened the list for exclusions. Research assistants visited the practice to first run the ‘Check for Duplicates’ computer program, which randomly selected one smoker from each address on the list, and then using the ‘Invite’ program-generated letters inviting smokers to participate, which were then mailed. Research assistants visited the practice a second time to process returns, using a third computer program ‘Risk’ which allocated identification numbers and randomised participants to the control or intervention group. This computer program also combined the data from the baseline questionnaire and medical records with the correct messages from a message library, written using Microsoft Word, to generate tailored letters and invitations to the taster session for those participants randomised to the intervention, and the generic letters for control participants. These were then mailed to the participants. The first taster session was held approximately 2 weeks after this mailing. Research assistants visited the practice on two further occasions to process responses from patients in the same manner as previously described. Further taster sessions were timed accordingly.

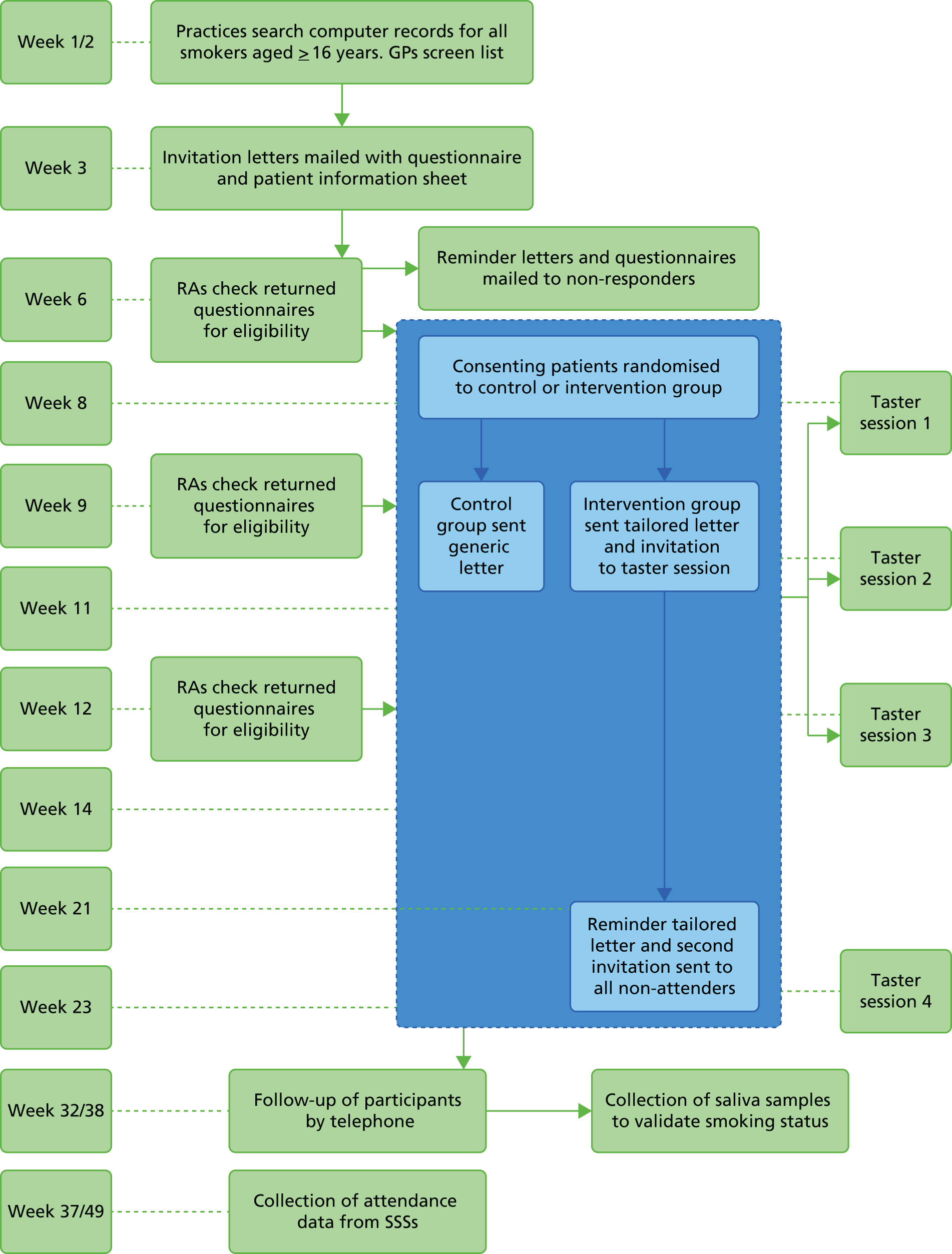

Three months later, all participants in the intervention group who had previously been invited to attend a taster session but had not attended were sent a second intervention letter (identical to the first) and a further invitation to a taster session (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study schedule showing the duration and timing of the procedure, intervention and follow-up. RA, research assisstant. Reproduced from Gilbert et al. 45 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY license.

Patients who returned the questionnaire with written consent but who were not eligible to take part in the study were sent a letter thanking them for responding and informing them that they did not fit the study criteria, and patients who returned questionnaires outside the time frame for processing were sent a similar letter informing them that the recruitment period had ended. Both of these letters were sent from the general practice and contained information about the local SSS, advising the smoker to contact the service for more information or to speak to an advisor.

Security and baseline data management

The patient-level data collected in this trial comprised information downloaded from practice records and information provided by participants on the consent form and baseline questionnaire. The information from the practice record was used to generate letters inviting patients to participate in the trial. It was also used, along with baseline questionnaire information, to generate the tailored and generic letters.

All data files and backup media remained in the practice until all eligible participants had been randomised and the tailored and generic letters generated. At this point data files were transferred to the study centre at UCL using proprietary encryption software (TrueCrypt, V61.1; TrueCrypt Foundation, Henderson, NV, USA).

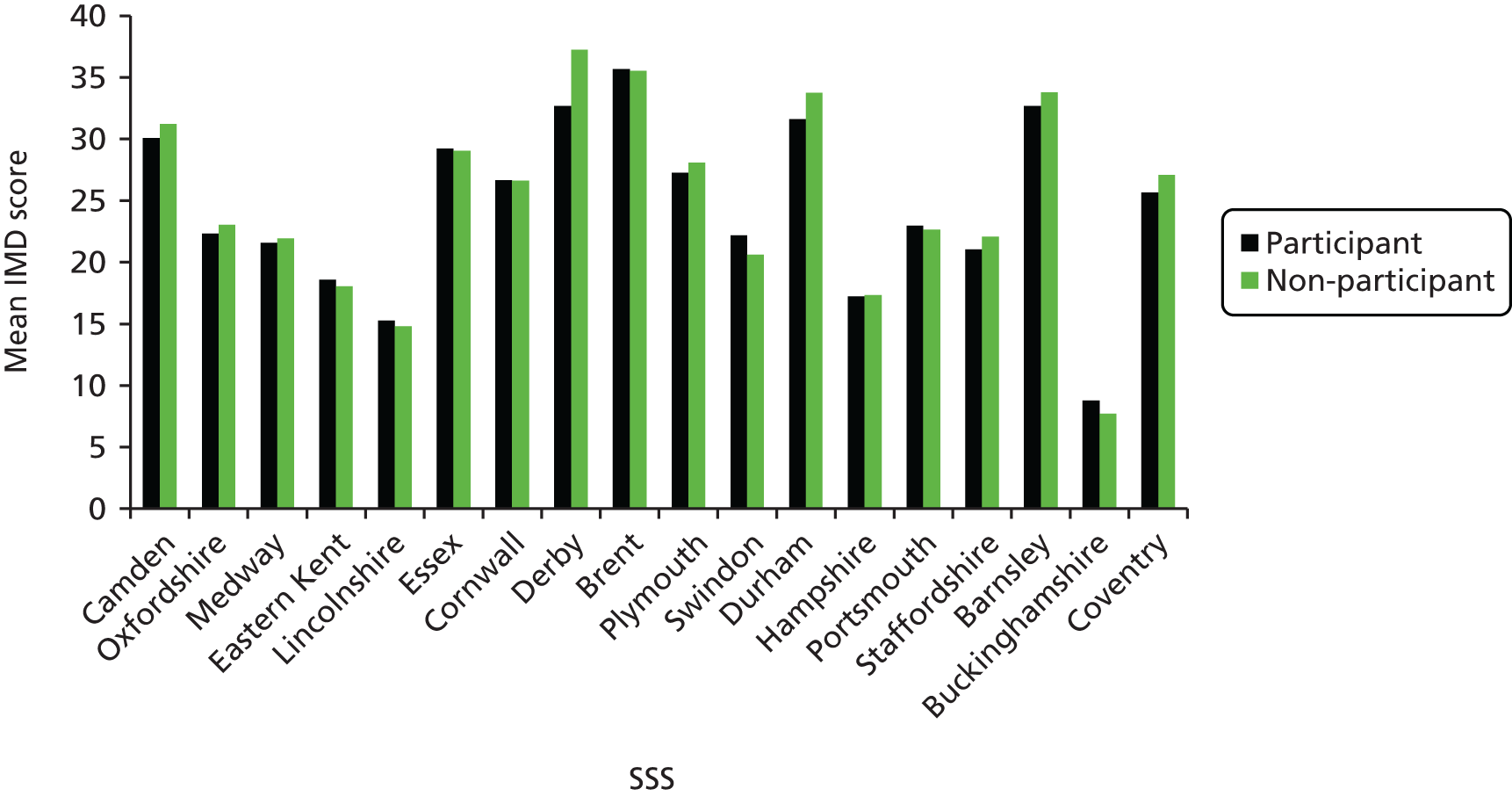

At the end of recruitment in each practice anonymised average data on patients who were invited to participate in the study but did not respond were collected to establish the external validity of our results. These anonymised data comprised gender, date of birth and postcode. Date of birth was converted to age at the time of the invitation and the postcode converted to an Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score via GeoConvert (2011, UK Data Service Census Support, University of Essex, University of Manchester). IMD is the government’s official measure of multiple deprivation at the small-area level, which provides a relative ranking of areas across England according to their level of deprivation. Names and all other identifying data were removed.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation, at the level of the study participant, was embedded into the computer program using permuted blocks. Participants were randomised in the ratio 3 : 2 (intervention to control) within the practice, stratified by gender and using a block size of five. For each practice, a computer program was run to create two randomisation tables, one for men and one for women. Each table consisted of 500 rows. In one column, there was a sequence of 2s and 1s in blocks of five (e.g. 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, where 1 and 2 were intervention and control, respectively). This sequence was created by listing all possible permutations of three 1s and two 2s (10 in all), then repeatedly selecting one permutation at random (with replacement) and adding each selection to the sequence. This procedure used the random number generating function rnd in Microsoft Visual Basic for Applications. For each table, the randomise statement was used to initialise the random number generator with a seed based on the system timer. Having created the tables for a given practice, another computer program was used to allocate participants from that practice to an intervention group by selecting the first unused code (1 or 2) from the table for men or the table for women, depending on the participant’s gender, and then marking that code as used. If the information about gender was missing for a participant, the randomisation table to be used was selected at random. Any imbalances were controlled for in the statistical analysis using covariates that were identified prior to examining the trial data. The use of a computer program that enforced randomisation after consent and baseline data entry ensured that concealment was preserved and differential entry prevented.

It was not possible to blind participants to the receipt of a personally tailored letter and invitation to a taster session. Although the personal letter was generated in the practice by a research assistant, the remainder of the research team in all cases were blind to the allocation of the participant, which was enforced by the data management. GPs and practice staff were not aware of their patients’ allocation. In follow-up interviews, the interviewer was blinded to the allocation of the respondent in order to avoid bias in outcome assessment. The interviewers could become unblinded during the course of the interview when participants were asked about the receipt of the letter and attendance at the taster session; however, the main outcome questions were asked at the start of the interview.

By randomising at the level of participant rather than by practice, there was a slight risk of contamination by communication between patients at the same practice allocated to different intervention groups. To reduce this risk we (1) ensured that only one person from the same household received a screening questionnaire; (2) monitored attendance at the taster sessions, to ensure that anyone attending who had not received an invitation was recorded and checked against participants in the control group; (3) kept a record of attendance at the taster sessions; and (4) measured the amount of contamination at follow-up by asking participants whether or not they had attended a taster session and, if not, whether or not they personally knew or had spoken to anyone else who had been invited to a taster session.

Follow-up data collection and evaluation procedure

At the end of the 6-month follow-up period in each SSS, valid data of attendance were collected from the SSSs using NHS monitoring data collected by smoking cessation advisors. A list of participants recruited from the particular SSS was sent to the local collaborator, who searched their user database for each participant named. For each participant whose name was present in the database, and had attended the service between the study entry date and the 6-month follow-up date, a case report form was completed. Data were collected on dates of attendance, agreed quit date, 4-week follow-up date, total number of sessions attended and treatment outcome. We also collected data on the type of advisor, the type and setting of support received, and pharmacological support used.

Research interviewers, independent from the service providers, conducted a computer-assisted telephone interview 6 months after the date of randomisation to assess self-reported SSS attendance, current smoking status, daily cigarette consumption, reasons for non-attendance and barriers to attendance in all participants.

Procedures were applied to maximise retention of participants at the 6-month follow-up. Interviewers made a maximum of 10 attempts to contact a participant by telephone. If, after 10 attempts, the interviewers had been unable to speak to a participant in person, they sent a text message prompting a response back to the mobile phone from which it was sent. The participant was sent the same message a second time if no response was received after 3 days, and, if no response was received after a further 3 days, the participant was sent a paper version of the follow-up questionnaire to complete and return by post. The paper questionnaire was also sent to participants unable to complete the telephone interview but willing to complete and return a postal questionnaire. A decision was taken late on in the trial to send a reminder for this postal questionnaire. If a participant did not fully complete or did not wish to complete the telephone interview, the interviewer attempted to ask the participant four basic questions most relevant to the primary and main secondary outcome.

Participants claiming 7-day abstinence at the 6-month follow-up were asked to provide a salivary cotinine sample to biochemically validate 7-day point prevalent smoking cessation. 47 Samples were obtained by post using a saliva sample kit. 48 Use of NRT at the time the sample was taken was assessed by questionnaire, as the cotinine content can be affected by continued use, and taken into account when the results of the analysis were received. To maximise return of samples, a £5 Marks and Spencer voucher was included with each kit, and a further £5 voucher was sent on return of the sample. Participants were contacted by a research interviewer to remind them to return their kit if saliva samples were not returned within 7 days, and after 10 unsuccessful attempts to contact the participant, they were sent a reminder text message. If the interviewer was successful in contacting the participant but their sample was still not returned after 7 days, the participant was sent the same reminder text message.

Figure 1 shows detail of the timing of assessments, intervention and follow-up.

Measures

Baseline measures

Inclusion criteria (age, intention and motivation to quit, and previous SSS attendance), demographics (gender, marital status, qualifications, employment and ethnicity), self-reported health, dependence on nicotine (number of cigarettes per day and time from waking to first cigarette), smoking history (age started and previous quit attempts), determination and confidence to quit were assessed in the baseline screening questionnaire.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The proportion of people entering the smoking cessation service (i.e. attending the first session of a 6-week course) over a period of 6 months from the receipt of the invitation letter, as measured by the NHS records of attendance at the SSSs.

Secondary outcomes

-

Seven-day point prevalent abstinence at the 6-month follow-up, validated by salivary cotinine for all participants reporting abstinence in both the intervention and control groups.

-

Additional periods of abstinence measured by self-report only: 24-hour and 7-day point prevalent, 1- and 3-month prolonged abstinence.

-

Three-month prolonged abstinence, measured by self-report and validated.

-

Self-reported changes in daily cigarette consumption, quit attempts, and changes in motivation and intention to quit in continuing smokers.

-

The number completing the 6-week NHS course.

Process measures

-

The number of smokers attending the taster session (intervention group only).

-

Self-reported attendance data.

-

Perception of the taster session.

-

Perception of the personal invitation letters.

-

Reasons for non-attendance at the taster session and barriers to attendance at the NHS services.

The number attending the taster sessions was taken from records, all other process measures were included in the follow-up interview 6 months after the date of randomisation. Perception of the taster session was also assessed by an evaluation form immediately after each session.

Reasons for non-attendance at the taster session and barriers to attendance at the NHS services were assessed using open questions. In addition, all participants who reported not attending the SSS were asked to complete the 40-item Treatment Barriers Questionnaire (TBQ), validated on a US population,49 to assess in more depth reasons and barriers to the use of the SSS.

Health economic measures

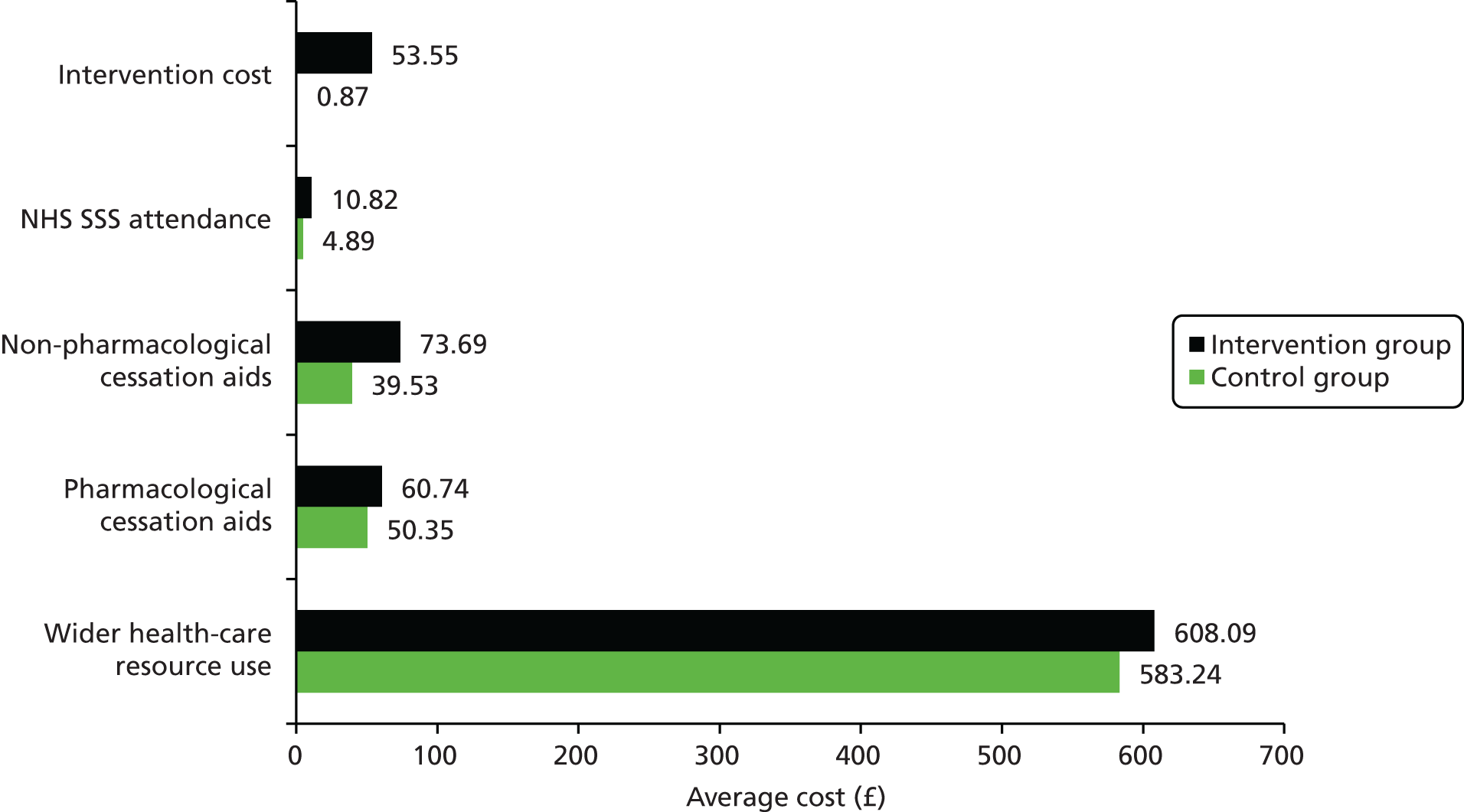

The economic component estimated the cost of providing the interventions, using primary cost data from a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective, as recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance. 50 We also measured patients’ use of health and social care services using a comprehensive service use questionnaires. Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were calculated from the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire using the area-under-the-curve method. 51 A cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) was undertaken to compare the tailored letter plus the taster session and the generic letter. In addition to the within-trial CEA, lifetime health-care cost savings and QALY gains associated with the two interventions were estimated based on a decision-analytic model. 52

Sample size and power calculations

Evidence from the study by Murray et al. 29 suggested that attendance at NHS services could be increased by 7.7% (from 8.9% to 16.6%) using a proactive intervention. To detect an effect of this size at 90% power and an alpha of 0.05 required a sample of 420 participants per group. However, in the absence of other similar trials, we conservatively assumed that the uptake of services in those who received the tailored letter and the taster session could be lower than that reported by Murray et al. 29 Therefore, we assumed an estimated increase of 4.6% [from 8.9% to 13.5%, odds ratio (OR) 1.65] requiring 1029 participants per group, 2058 in all, to detect this difference as statistically significant at the 5% level with 90% power.

We originally planned to recruit practices from 10 different SSSs. The taster sessions in each SSS were to be run by the same four advisors comprising 10 therapist clusters. Thus, before adjusting for clustering we would expect 103 patients per cluster. Although the intervention was manualised and structured training run to reduce the variability between the interventions delivered in each SSS, we decided to account for any persistent therapist effects that might apply to those randomised to receive a taster session. The literature reporting intracluster correlations is scarce; however, Adams et al. 53 found a single study54 of smoking cessation delivered in pharmacies, which reported an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.007: this shrank to 0 after adjustment. We therefore assumed an ICC of 0.005 for our study. Allowing for this ICC, coupled with a therapist cluster size of 103, required our existing sample size to be inflated by a factor of 1.51 only in the intervention group, where the effects would occur. Thus, 1554 would receive the tailored letter and taster session, with 2583 participants in total.

The study by Murray et al. 29 also found validated quit rates at 6 months of 4% in the intervention group, compared with 2.2% in the control group (a difference of 1.8%). With our planned sample size of 2583 participants, we had < 80% power to detect a difference of 1.8%. However, if the quit rate were to double from 2.2% to 4.4% (a difference of 2.2%), we still had 80% power to detect such a difference.

An extension to the trial was funded to permit evaluation with adequate power of the intervention effect on 7-day point prevalent abstinence at the 6-month follow-up. This required an 80% increase in the sample size to 1793 in the control group and 2707 in the intervention group (assuming the same therapist effect as the original protocol), giving a total of 4500. This would give 85.4% power to detect a difference of 1.8% at the 5% significance level, assuming quit rates of 4% compared with 2.2% in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The same sample size would have 95% power to detect the difference between quit rates of 4.4% and 2.2% (doubling of quit rate), respectively.

Practices generally identify 13–22% of their patients as smokers,55 depending on the characteristics of the patient population and the accuracy and completeness of the records. We initially estimated that six practices in each of 10 SSSs, with a list size of > 4000, would give approximately 240,000 patients and, assuming a conservative smoking prevalence of 15% in patients aged ≥ 16 years, 36,000 smokers. Based on previous studies,29,56 we estimated a response rate from two mailings of 7% from smokers motivated to quit, securing 2520 participants and meeting the requirements of the original sample size calculation. The extension to the trial required an additional 2000 participants and, based on recruitment figures at the time the extension was funded, we estimated that an additional eight SSSs (48 practices) would recruit 2060 participants, giving a total of 4580 and meeting the requirement of the new power calculation.

Interim analyses and stopping guidelines

The study was initiated with a pilot phase conducted in seven practices recruited from two SSSs. This was intended to be approximately 20% of the original total sample. The criteria for judging the success of the pilot phase and proceeding to full trial was based on:

-

achieving a 7% response rate (i.e. a mean of 42 participants per practice giving consent and agreeing to randomisation) in the first seven practices

-

a preliminary analysis that suggested that the uptake of smoking cessation services in the intervention group was greater than in the control group (i.e. the difference in proportions, intervention minus control, was greater than zero).

No other stopping rules were applied.

Statistical methods

All main analysis comparing groups for primary and secondary outcomes, and additional subgroup and adjusted analyses was conducted using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Baseline characteristics of participants were summarised in terms of the mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, maximum and number of observations and categorical data in terms of frequency counts and percentages. No formal statistical tests were performed.

Comparison of proportions was carried out for binary outcomes between the intervention and the control groups (entry to smoking cessation service, point prevalent and prolonged abstinence, number completing the 6-week SSS course). Univariable logistic regression analysis was carried out to take into account clustering at the SSS level, and multivariable logistic regression was also carried out to take into account any imbalance in important baseline characteristics known to predict smoking cessation outcomes, nominated prior to examination of the trial data, between the groups. Both unadjusted and adjusted estimates are reported. The unadjusted analysis is considered to be the primary analysis. The size of the difference between treatments is expressed as an OR including 95% confidence interval (CI) from logistic regression, with appropriate allowance for clustering.

The therapists were SSS based rather than practice based, and we initially intended that the therapist effect be accounted for by allowing greater variance between SSSs in the intervention group than in the control group, so that the difference in variance would represent the therapist effect. In fact, we discovered that the estimated variance for the primary outcome was slightly lower in the intervention group, rendering it impossible to fit a model including a special clustering effect for participants only assigned to the intervention. Hence, we allowed only for variance between SSSs, assuming it to be the same in the two groups, and thus fitted a random intercepts model.

Self-reported changes in daily cigarette consumption (the difference between cigarette consumption at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up) is a continuous variable and was compared with the two-sample t-test and with multiple linear regression to account for important baseline characteristics. ORs for the difference in means is quoted together with the 95% CI.

Furthermore, we estimated the ICC for our primary outcome and for the validated 7-day abstinent outcome. The ICC for a binary outcome can be estimated as:

The term σu2 can be interpreted as the component of outcome variance because of differences between SSSs, the denominator as the total variance and ρ as the proportion of the total outcome variance that is due to between-cluster variation. 57

Loss to follow-up after randomisation is reported. Analysis is based on intention to treat; that is, we assume that all randomised participants received the treatment that they were randomised to, and all those lost to follow-up are assumed to be still smoking.

Levels of significance

During the course of running the trial but prior to locking the database, based on further expert statistical advice, we devised an analysis plan for interpreting significance levels for analysis on multiple outcomes of interest. Hence, the interpretation of the results of the trial for the primary outcome, (1) engagement with SSS, and the main secondary outcome, (2) 7-day point prevalent abstinence, was governed by an alpha spending plan that preserved the study-wise alpha for (1) and (2). We hypothesised that these outcomes fall naturally into a hierarchy with (1) as a step prior to (2). We employed a hierarchical monitoring plan in which alpha was spent first on (1) and the remaining alpha was available for (2). The simple formula below describes alpha allocation in the hierarchy:

where subscript 2 = two sided; s = study-level critical alpha (0.05); e = engagement with SSS; and c = 7-day point prevalent abstinence. Thus, if the p-value for attendance at SSS was 0.02, there remains a p-value of 0.031 to spend on the second outcome of 7-day point prevalent abstinence and a p-value for that outcome of < 0.031 would be considered significant. If the p-value for the primary outcome (difference in smoking cessation service attendance) was > 0.05, then the overall study would be considered neutral and any finding on the second outcome considered exploratory with a nominal p-value.

Likewise, if there was a significant decrease in attendance within the intervention arm over the control arm, the second outcome would be considered exploratory with a nominal p-value.

Subgroup analyses

In order to assess whether or not the intervention was any more effective for any particular subgroup of smokers, we explored interactions between intervention and deprivation (defined in fifths), intervention and gender, and intervention and age (defined by categories 16–39 years, 40–64 years and ≥ 65 years), for the primary outcome (attendance) and 7-day point prevalent abstinence at the 6-month follow-up. We had planned at an early stage to analyse the interaction with deprivation,58 and with gender and age when drawing up our analysis plan,59 prior to the end of data collection.

Subsidiary analyses

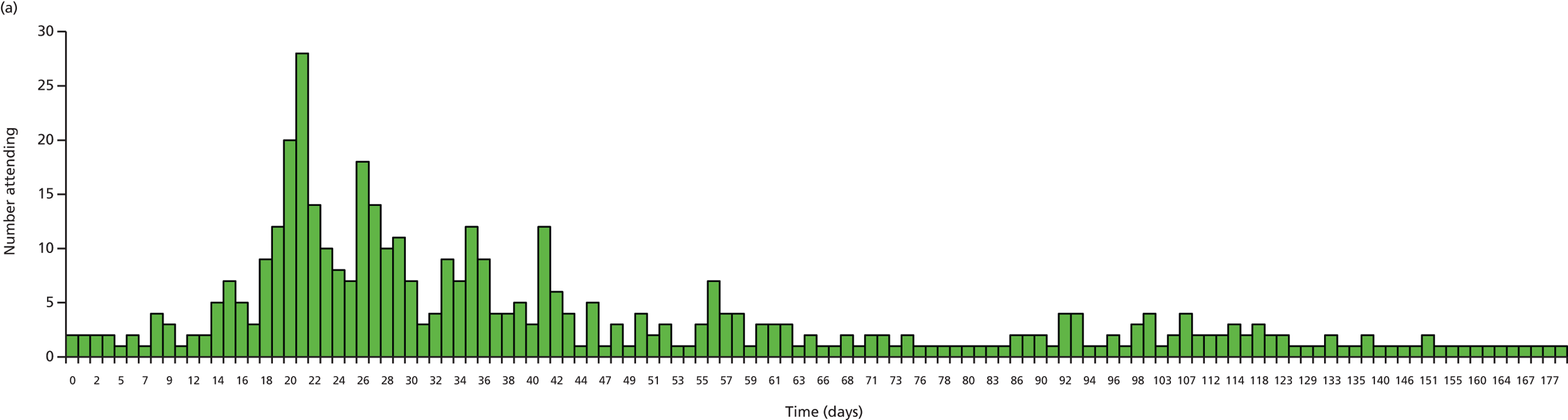

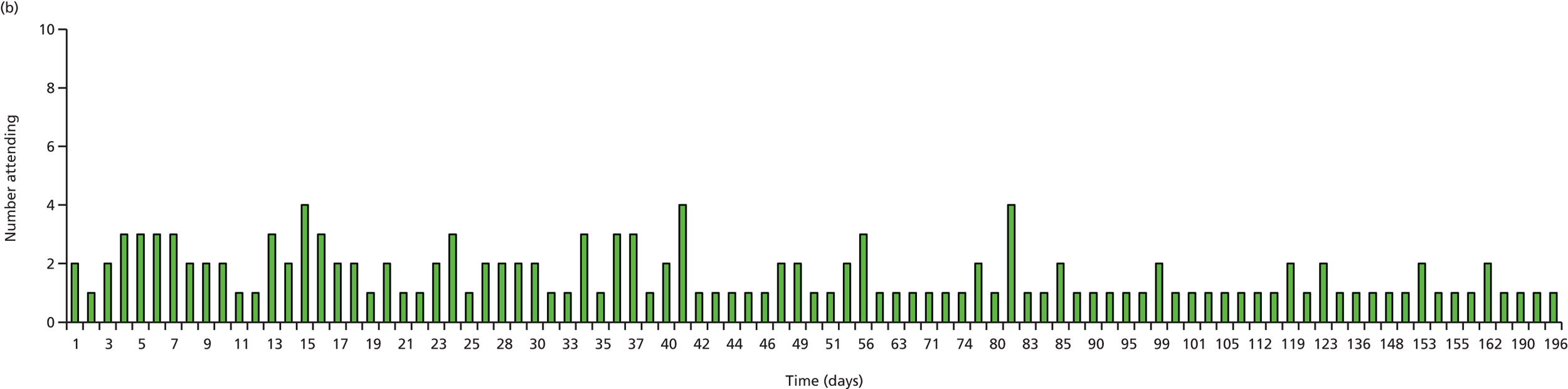

We also explored any delayed effect of sending repeat reminders to smokers on the uptake of service, and any differences in attendance due to seasonal variations.

Patient and public involvement

This trial was embedded in the NHS through the inclusion of a SSS manager as a coapplicant, who was involved in all stages of the research, from design and conduct to analysis. In addition, a past successful user of the Camden SSS was invited onto the Trial Management Group and has been involved in the study from the design stage onwards. The service user contributed to the design of both parts of the intervention and to the conduct of the trial and collection of data.

Another past user of the Camden SSS also contributed to the development of the intervention; thus, two service users were involved in the development of both parts of the intervention. They were consulted on the content of the brief personal letter at all stages of development, and were also consulted on the protocol for the taster sessions. Both service users also narrated their own experiences of quitting and these were used to create the video that formed a part of the taster session.

The Trial Management Group member was fully involved at all management meetings. Considerable effort was put into increasing response rate to the follow-up, and the service user was particularly helpful with suggestions of how to maximise this response, using her perception as a user to propose the use of text messaging and how the texts should be phrased. She also added greatly to the discussion of the results and of the practical implications of this method of recruitment to the SSSs.

Thus, the interests of all parties and the views of the public have been fully represented in the conduct of the study.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and participant flow

Practice recruitment

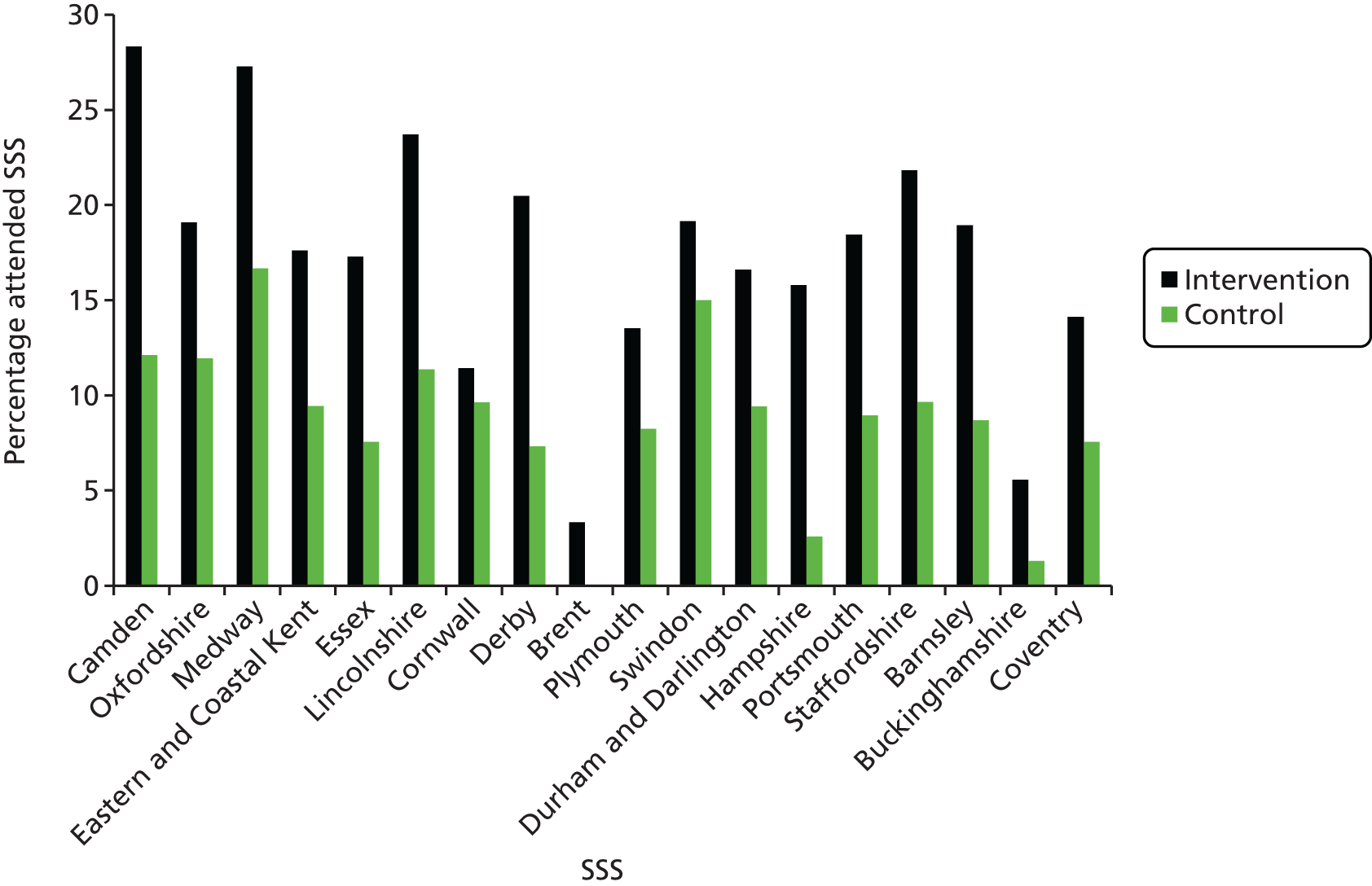

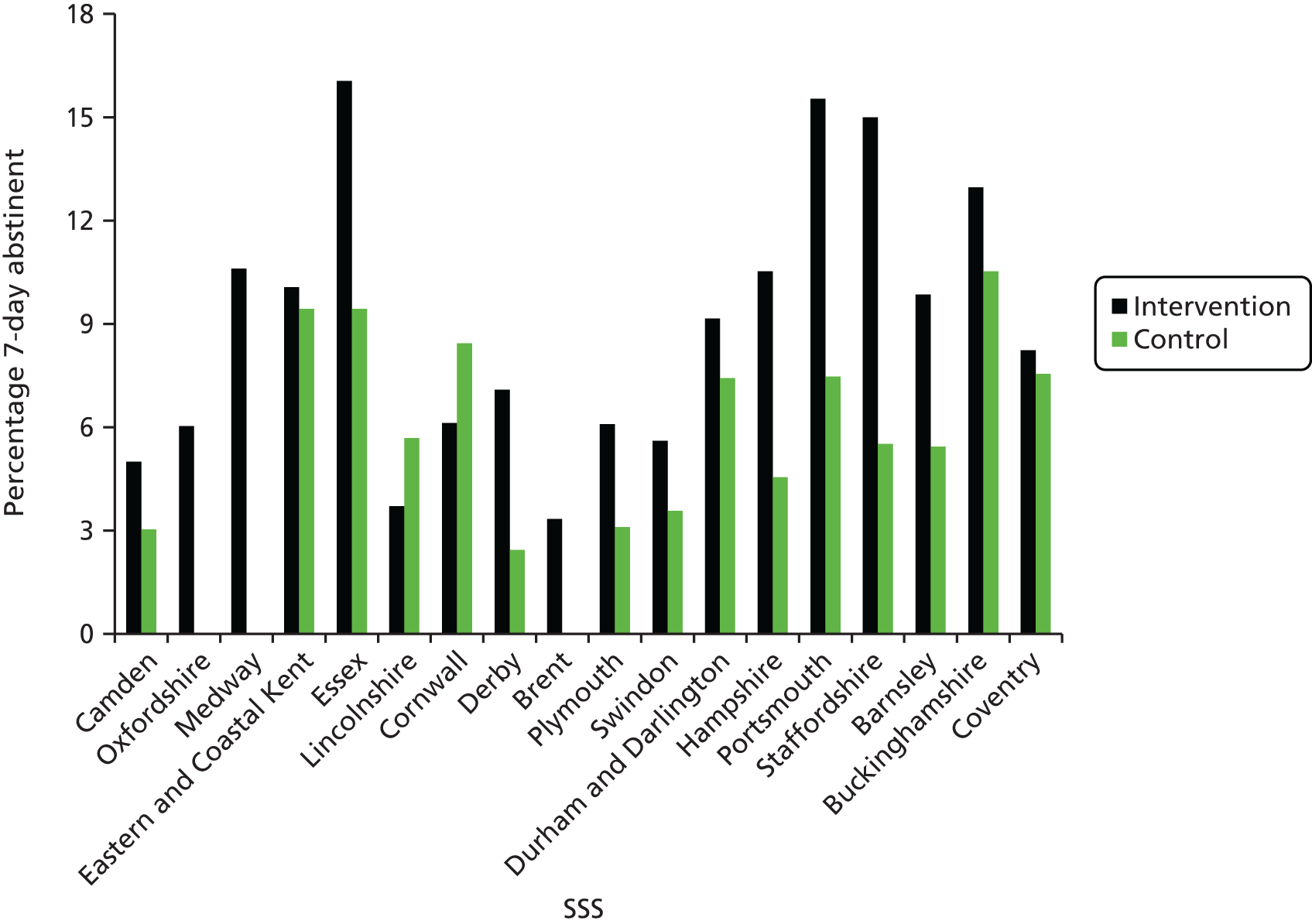

Eighteen SSSs spread across England, located in both high and low areas of deprivation and representing both large and small organisations, agreed to participate in the trial (Figure 2). Ninety-nine practices within the participating SSS areas, identified and approached by PCRNs, agreed to participate. The number of practices per SSS ranged from 3 to 10, and the practice list size ranged from 2205 to 26,000 (mean, 9723; median, 9725). Cumulative list sizes, shown in Table 2, ranged from 17,617 in Medway to 106,424 in Durham and Darlington. Current cigarette smokers aged 16–99 years were identified from computer records in participating practices (n = 141,488; 14.7% of the total list size). The proportion of smokers identified in each practice ranged between 4.8% and 39.7%, and within each SSS from 9.7% to 20.81%.

FIGURE 2.

Map showing level of socioeconomic deprivation in England and SSSs participating in Start2quit.

| ID | SSS | Number of practices | Cumulative list size | Mean % smokers | Mean % smokers range between practices | Mean practice IMD score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camden | 3 | 19,791 | 20.81 | 7.03–39.73 | 22.98 |

| 2 | Oxfordshire | 4 | 42,394 | 17.88 | 16.48–20.21 | 19.24 |

| 3 | Medway | 4 | 17,617 | 18.01 | 15.69–24.04 | 22.29 |

| 4 | Eastern and Coastal Kent | 4 | 43,814 | 14.43 | 13.31–15.23 | 16.14 |

| 5 | Lincolnshire | 6 | 47,000 | 12.40 | 6.83–21.91 | 12.30 |

| 6 | Essex | 3 | 46,916 | 12.11 | 6.65–19.65 | 24.27 |

| 7 | Cornwall | 7 | 65,528 | 17.42 | 13.27–22.20 | 29.06 |

| 8 | Derby | 4 | 47,307 | 14.47 | 8.17–18.62 | 49.67 |

| 9 | Brent | 4 | 21,905 | 11.74 | 8.38–14.78 | 41.86 |

| 10 | Plymouth | 6 | 55,344 | 19.11 | 10.79–24.72 | 32.41 |

| 11 | Swindon | 8 | 68,583 | 13.48 | 8.25–19.15 | 22.73 |

| 12 | Durham and Darlington | 10 | 106,424 | 16.11 | 7.27–25.11 | 28.63 |

| 13 | Hampshire | 9 | 99,829 | 11.15 | 5.98–16.53 | 20.68 |

| 14 | Portsmouth | 6 | 55,367 | 12.94 | 8.75–16.53 | 22.73 |

| 15 | Staffordshire | 7 | 65,239 | 19.29 | 16.27–23.87 | 21.74 |

| 16 | Barnsley | 4 | 46,488 | 19.96 | 15.22–30.54 | 29.75 |

| 17 | Buckinghamshire | 4 | 65,580 | 9.70 | 5.40–15.47 | 6.86 |

| 18 | Coventry | 6 | 47,422 | 13.34 | 4.79–19.80 | 24.98 |

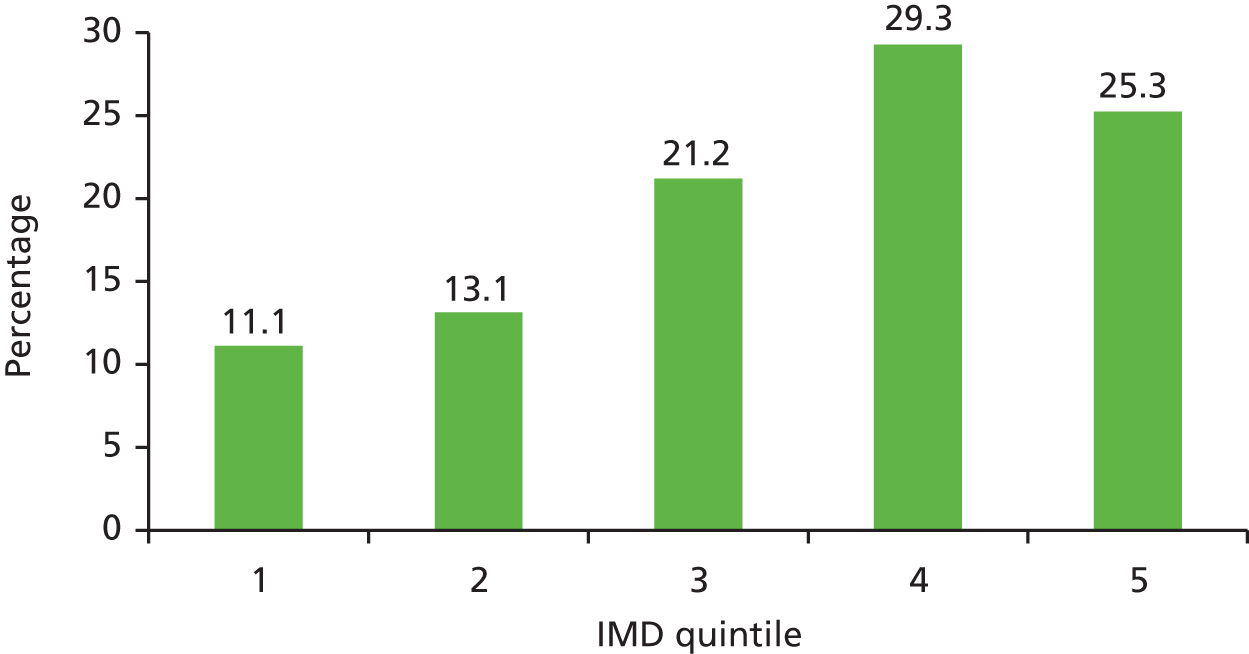

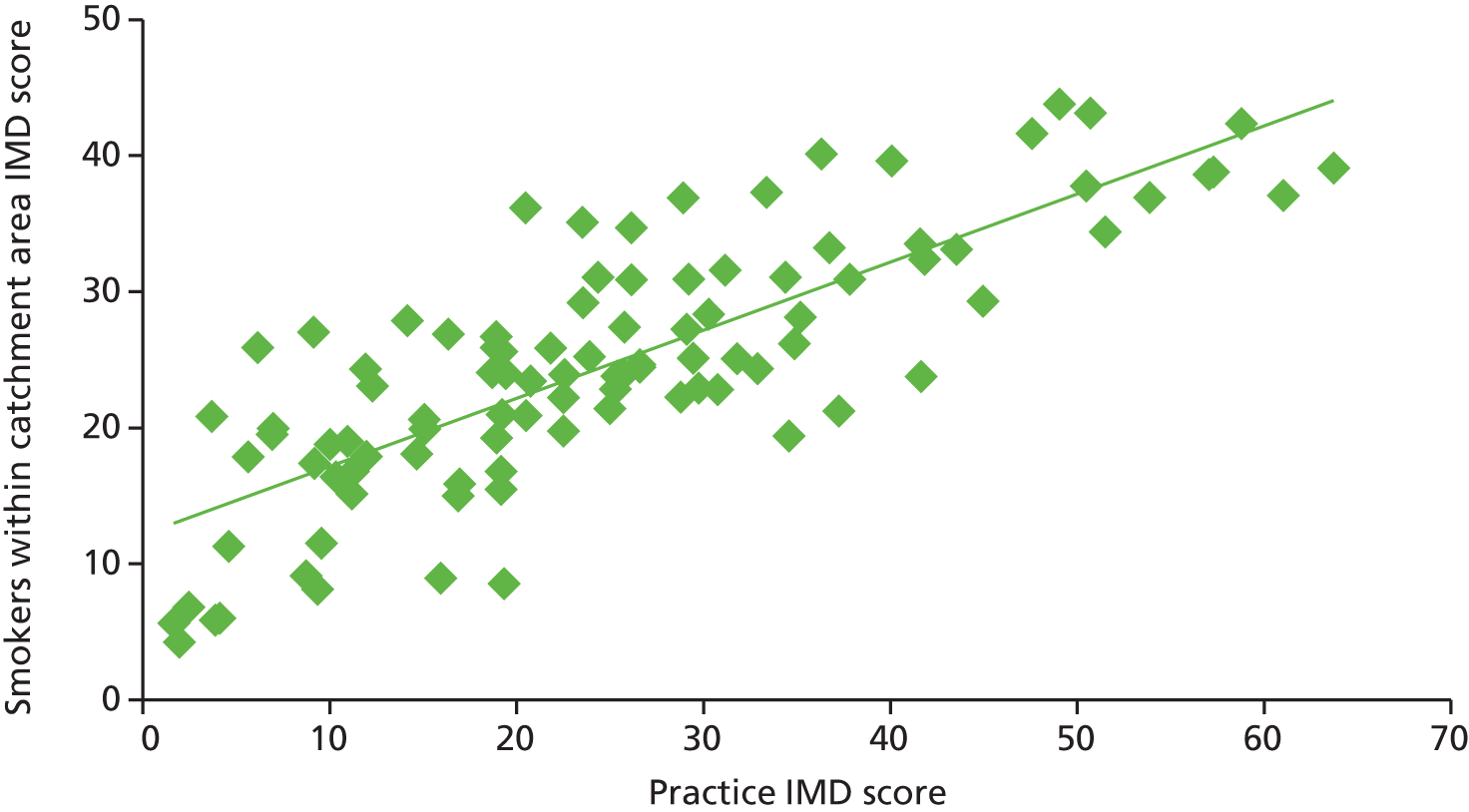

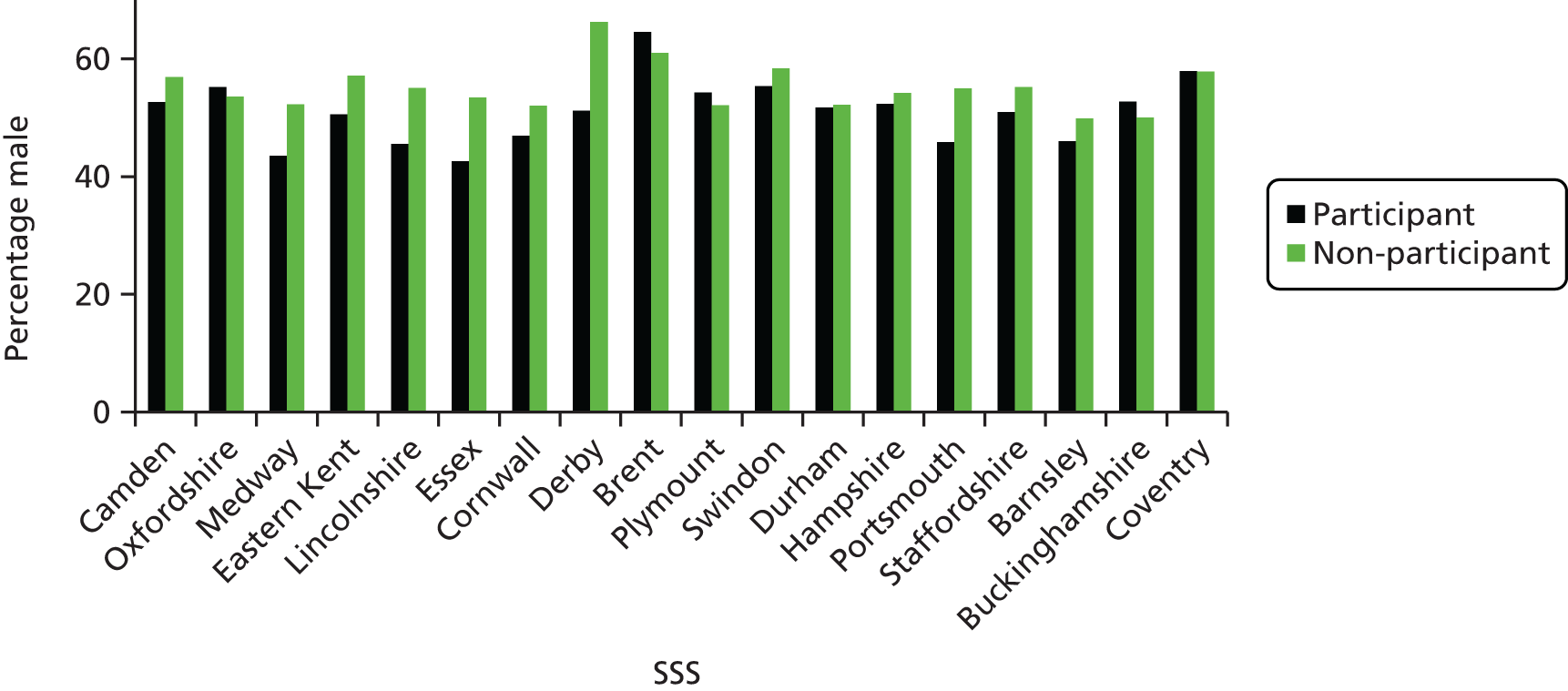

The study targeted higher-risk groups; therefore, practices in areas of high deprivation were preferentially selected as determined by the practice postcode converted to an IMD score (the government’s official measure of multiple deprivation at the small-area level). A majority (54.6%) of practices were located in areas of high deprivation (i.e. within the two highest quintiles of IMD scores, a score > 21.34) (Figure 3). This suggests that the catchment area for these practices were within areas of high deprivation or that a higher number of participants were living in highly deprived areas; however, the postcode of the practice does not always indicate the deprivation status of the catchment area. Nevertheless, a comparison of the mean IMD scores of all smokers identified for each practice with the IMD of the practice indicated a similar trend, and there was good correlation between smokers’ IMD scores and those of the practices (r = 0.80) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of practices (%) within each IMD quintile.

FIGURE 4.

The IMD scores of practices compared with the mean IMD scores of all smokers living in the practice catchment area.

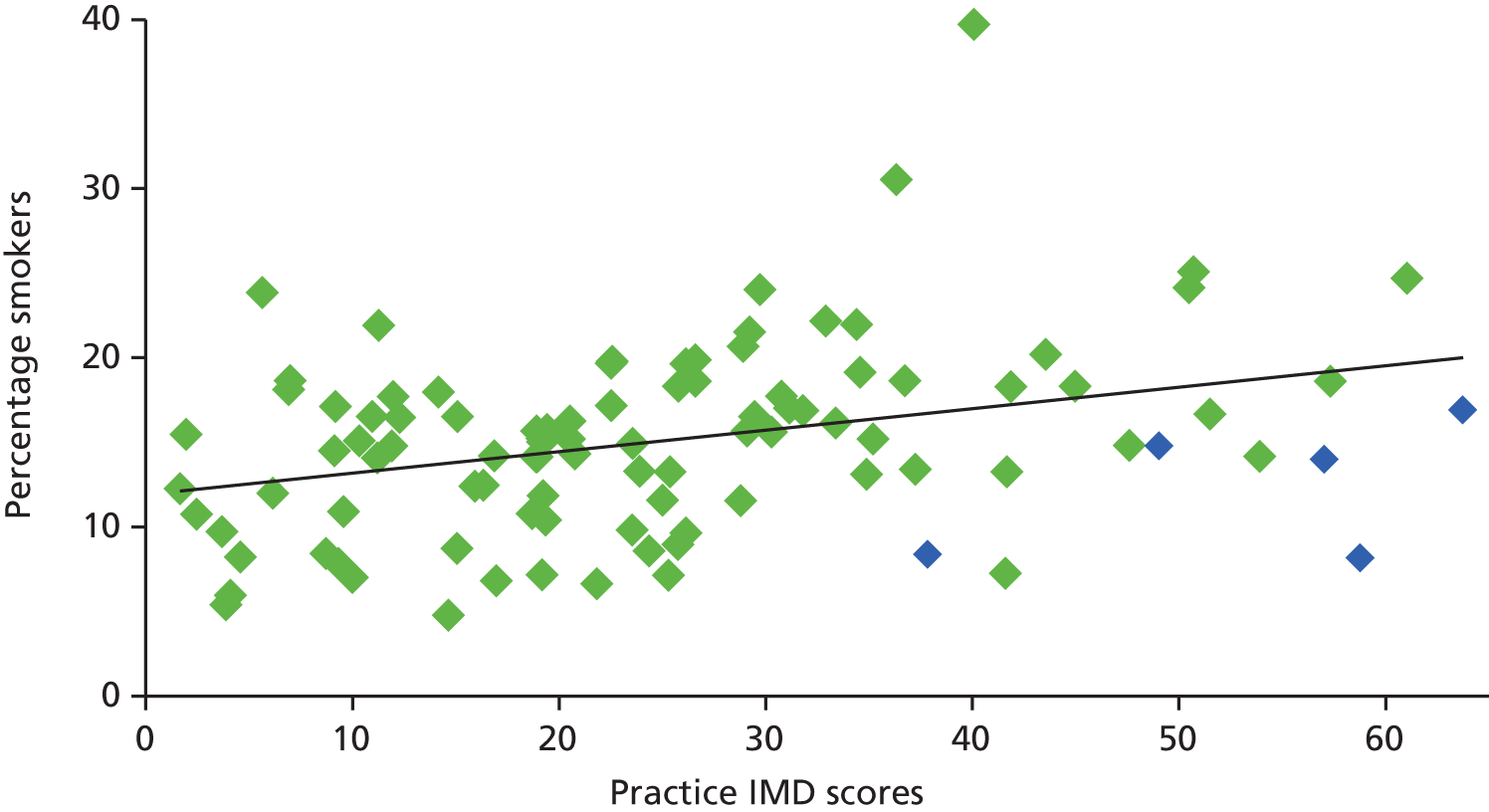

One would also expect to find a high proportion of smokers identified in areas of high deprivation, indicated by a high IMD score, and in many cases there appears to be a close match. However, in some areas the percentage was lower than would be expected, and this may be accounted for by a high ethnic population, in which smoking prevalence may be lower in women, for example in Derby and Brent (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

The IMD scores of practices and the proportion of smokers identified in the practice. Derby and Brent are highlighted in blue.

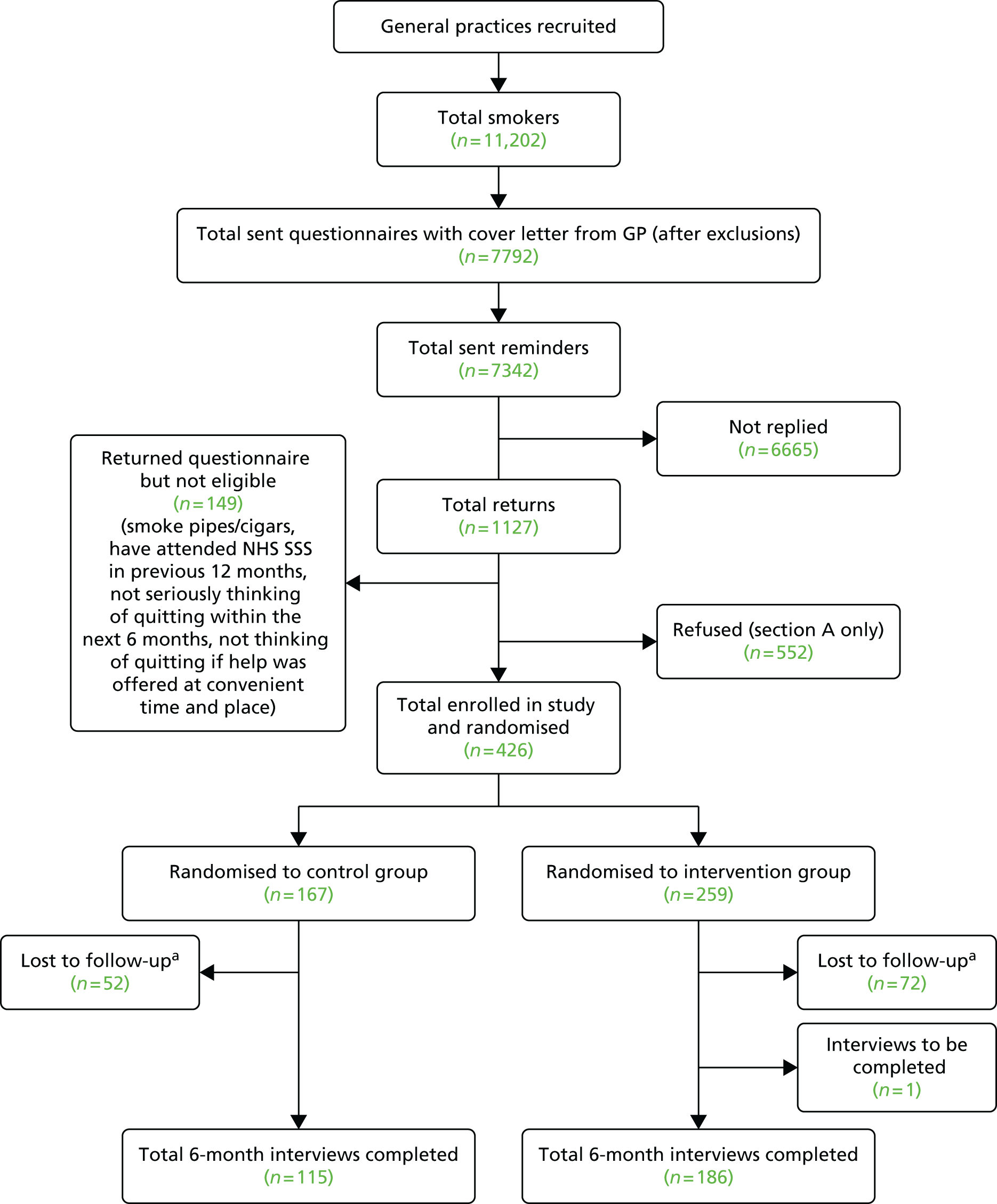

Participant recruitment

The recruitment of participants for the pilot phase of the trial was conducted between January and March 2011. Recruitment for the main phase began in January 2012 and was completed in October 2013.

General practitioners excluded 4186 patients considered to be unsuitable to take part in the study. Reasons for exclusion included patients unable to understand English sufficiently, serious pre-existing condition or terminal illness, and severe cognitive, mental or psychological impairment. However, most practices did not give the reasons for exclusion and we are unable to estimate numbers in each category. A further 25,086 patients were excluded because of duplicate addresses, ensuring that only one person from the same address was selected. All remaining persons on the list (n = 112,216) were invited to participate in the trial. Of these, 21,971 (19.6%) replied. However, 5333 replied to say they were non-smokers and 420 were returned to the practices unopened as a result of incorrect addresses or deceased. Records are not always accurate, and those returned from non-smokers are likely to represent only a portion of those recorded as smokers but are actually non-smokers. Thus, our best estimate of total potentially eligible is 106,463 (see Figure 6).

The total number of questionnaires returned from potentially eligible participants was 16,638 and, of these, 10,380 declined to take part in the study but returned the questionnaire with basic information only to update their smoking status in their practice records. A further 1874 were willing to take part in the study but did not fit the inclusion criteria, leaving 4384 participants enrolled in the trial, representing a response rate of 4.1%. Of these, 2636 were allocated to the intervention group and 1748 to the control group. One participant from the intervention group withdrew from the study before follow-up commenced and 4383 were analysed. See the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart (Figure 6) for details.

FIGURE 6.

The CONSORT diagram of recruitment and flow of participants through the trial. a, Percentage of total list size; b, total invitations sent minus non-smokers and wrong address/deceased; c, of total potentially eligible. Adapted from Gilbert et al. 45 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY license.

Follow-up

Follow-up data collection took place 6 months post randomisation and was conducted between August and November 2011 for the pilot phase and between August 2012 and July 2014 for the main study.

Complete validation data of attendance at the SSS were obtained for each participant from SSSs at the end of the quarter following the end of the 6-month follow-up period in each area. Additional data were obtained by telephone interview or postal questionnaire. In total, 2910 (66.4%) completed the full telephone interview, 302 (6.9%) completed a shorter paper version of the follow-up questionnaire returned by post and an additional 160 (3.7%) completed the four basic questions related to the primary outcome, giving a total response rate of 3372 (76.9%). There was no difference in follow-up response between the treatment groups: 76.7% and 77.3% in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The reasons for loss to follow-up were declined to complete the interview (n = 150), not able to be contacted (n = 857), and died within the 6-month follow-up period (n = 4) (see Figure 6). The timing of completing the follow-up ranged from 20 days prior to the due date (180 days after randomisation) to 194 days after the due date (mean, 27.53 days; median, 22 days). This was not statistically different between the intervention and the control groups.

There were large differences in recruitment between SSSs, ranging from 2.3% in Brent to 6.7% in Oxfordshire, and also in follow-up response. There were also large variations between practices within SSSs. We deliberately included some practices in areas with high ethnic minority populations, for example in Derby and Brent, but in these practices recruitment was especially low (Table 3).

| ID | SSS | Recruitment rate (%) | Recruitment rate range between practices (%) | 6-month follow-up response (%) | 6-month follow-up response range between practices (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camden | 3.2 | 2.7–5.8 | 65.6 | 61.0–78.6 |

| 2 | Oxfordshire | 6.7 | 5.5–9.2 | 72.1 | 69.7–74.1 |

| 3 | Medway | 5.1 | 1.8–5.9 | 72.2 | 68.2–80.0 |

| 4 | Eastern and Coastal Kent | 5.5 | 3.5–8.2 | 80.4 | 72.3–85.7 |

| 5 | Lincolnshire | 3.1 | 2.0–3.6 | 82.8 | 82.6–83.3 |

| 6 | Essex | 5.0 | 3.0–6.1 | 75.3 | 57.1–87.0 |

| 7 | Cornwall | 5.3 | 4.3–6.5 | 76.9 | 74.6–80.0 |

| 8 | Derby | 3.4 | 1.7–4.1 | 67.0 | 60.0–72.5 |

| 9 | Brent | 2.3 | 1.4–3.9 | 79.2 | 68.4–100 |

| 10 | Plymouth | 3.3 | 1.6–5.1 | 70.2 | 64.3–75.5 |

| 11 | Swindon | 4.7 | 3.8–6.1 | 74.9 | 68.3–79.3 |

| 12 | Durham and Darlington | 4.0 | 2.3–5.7 | 76.5 | 61.5–82.6 |

| 13 | Hampshire | 4.6 | 2.7–5.6 | 79.6 | 72.3–86.7 |

| 14 | Portsmouth | 3.0 | 1.3–5.1 | 82.9 | 74.3–96.8 |

| 15 | Staffordshire | 3.8 | 2.0–6.1 | 81.1 | 75.0–84.3 |

| 16 | Barnsley | 3.2 | 2.7–4.4 | 76.8 | 72.3–79.7 |

| 17 | Buckinghamshire | 4.5 | 3.7–5.4 | 85.3 | 82.0–93.3 |

| 18 | Coventry | 2.7 | 1.9–4.9 | 87.0 | 77.8–100 |

Biochemical validation of 7-day abstinence

Of the 630 participants who answered ‘not at all’ in response to the question ‘How often do you currently smoke cigarettes or rollups?’ at the follow-up, and who were asked to provide a salivary cotinine sample to validate abstinence, 595 (94.4%) agreed to send a saliva sample for analysis and 443 (70.3%) returned a sample; 399 (63.3%) samples were sent for analysis. Samples from 44 participants who reported that they had resumed smoking between follow-up and returning the sample were not analysed.

Of the samples analysed, 345 (54.8%) were validated (249 had a cotinine content of < 12 ng/ml, 36 were from participants using NRT and 60 from participants were using e-cigarettes). Of the 54 samples not validated, 30 had a cotinine content of > 12 ng/ml and were from participants not using NRT or e-cigarettes, five samples came from participants who had smoked in the previous 6 days and 19 samples were of insufficient volume to be analysed. There was no difference between the intervention and control groups.

Characteristics of participants

Baseline

Table 4 shows the demographic and smoking characteristics by intervention and control group.

| Characteristic | Group | Total (N = 4383) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 2635; 60.1%) | Control (N = 1748; 39.9%) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 1345 (51.0) | 886 (50.7) | 2231 (50.9) |

| Female | 1290 (49.0) | 862 (49.3) | 2152 (49.1) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 49.2 (14.3) | 49.5 (14.3) | 49.3 (14.3) |

| Range | 16–88 | 16–89 | 16–89 |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 664 (25.2) | 444 (25.4) | 1108 (25.3) |

| Living with a spouse | 1429 (54.2) | 961 (55.0) | 2390 (54.5) |

| Separated/divorced | 392 (14.9) | 252 (14.4) | 644 (14.7) |

| Widowed | 134 (5.1) | 83 (4.8) | 217 (5.0) |

| Missing | 16 (0.6) | 8 (0.5) | 24 (0.6) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Unemployed | 287 (10.9) | 190 (10.9) | 477 (10.9) |

| Paid employment | 1422 (53.9) | 903 (51.7) | 2325 (53.1) |

| Full-time student | 44 (1.7) | 32 (1.8) | 76 (1.7) |

| Home maker | 104 (4.0) | 89 (5.1) | 193 (4.4) |

| Retired | 495 (18.8) | 344 (19.7) | 839 (19.1) |

| Disabled/too ill to work | 254 (9.6) | 171 (9.8) | 425 (9.7) |

| Missing | 29 (1.1) | 19 (1.1) | 48 (1.1) |

| Highest qualification, n (%) | |||

| None | 672 (25.5) | 460 (26.3) | 1132 (25.8) |

| GCSE/CSE/O Level | 1042 (39.5) | 655 (37.5) | 1697 (38.7) |

| A Level | 306 (11.6) | 232 (13.3) | 538 (12.3) |

| Degree/equivalent | 454 (17.2) | 301 (17.2) | 755 (17.2) |

| Postgraduate | 82 (3.1) | 34 (2.0) | 116 (2.7) |

| Missing | 79 (3.0) | 66 (3.8) | 145 (3.3) |

| Ethnic background, n (%) | |||

| White | 2522 (95.7) | 1669 (95.5) | 4191 (95.6) |

| Black | 29 (1.1) | 22 (1.3) | 51 (1.2) |

| Asian | 36 (1.4) | 29 (1.7) | 65 (1.5) |

| Other | 27 (1.0) | 23 (1.3) | 50 (1.1) |

| Missing | 21 (0.8) | 5 (0.3) | 26 (0.6) |

| Deprivation (IMD score), n (%) | |||

| Quintile 1 | 334 (12.7) | 215 (12.3) | 549 (12.5) |

| Quintile 2 | 378 (14.4) | 244 (14.0) | 622 (14.2) |

| Quintile 3 | 574 (21.8) | 392 (22.4) | 966 (22.0) |

| Quintile 4 | 677 (25.7) | 453 (25.9) | 1130 (25.8) |

| Quintile 5 | 653 (24.8) | 436 (24.9) | 1089 (24.9) |

| Missing | 19 (0.7) | 8 (0.5) | 27 (0.6) |

| Live with smokers, n (%) | |||

| No | 1791 (68.0) | 1177 (67.3) | 2968 (67.7) |

| Yes | 835 (31.7) | 567 (32.4) | 1402 (32.0) |

| Missing | 9 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 13 (0.3) |

| Smoking characteristics | |||

| Daily smokers, n (%) | 2401 (91.1) | 1616 (92.5) | 4017 (91.6) |

| Non-daily smokers, n (%) | 214 (8.1) | 126 (7.2) | 340 (7.8) |

| Missing, n (%) | 20 (0.8) | 6 (0.3) | 26 (0.6) |

| Cigarettes per day | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.1 (8.6) | 16.8 (9.9) | 16.4 (9.2) |

| Range | 0.1–80 | 0.3–99 | 0.1–99 |

| Missing, n (%) | 10 (0.4) | 9 (0.5) | 19 (0.4) |

| Time from waking to first cigarette, n (%) | |||

| < 5 minutes | 568 (21.6) | 414 (23.7) | 982 (22.4) |

| 6–30 minutes | 1186 (45.0) | 802 (45.9) | 1988 (45.4) |

| 31–60 minutes | 436 (16.6) | 246 (14.1) | 682 (15.6) |

| 1–2 hours | 222 (8.4) | 152 (8.7) | 374 (8.5) |

| > 2 hours | 215 (8.2) | 132 (7.6) | 347 (7.9) |

| Missing | 8 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | 10 (0.2) |

| Nicotine dependence score (0–6)a | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.57 (1.49) | 2.67 (1.52) | 2.61 (1.51) |

| Low (score 0–2), n (%) | 1094 (41.5) | 669 (38.3) | 1763 (40.2) |

| Medium (score 3), n (%) | 850 (32.3) | 581 (33.2) | 1431 (32.7) |

| High (score 4–6), n (%) | 673 (25.5) | 487 (27.9) | 1160 (26.5) |

| Missing, n (%) | 18 (0.7) | 11 (0.6) | 29 (0.7) |

| Age started smoking (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.5 (4.5) | 16.5 (4.6) | 16.5 (4.5) |

| Range | 6–55 | 1–51 | 1–55 |

| Missing (%) | 12 | 7 | 19 |

| Intention and motivation to quit | |||

| When planning to quit, n (%) | |||

| In next 2 weeks | 481 (18.3) | 315 (18.0) | 796 (18.2) |

| Next 30 days | 606 (23.0) | 380 (21.7) | 986 (22.5) |

| Next 6 months | 1103 (41.9) | 759 (43.4) | 1862 (42.5) |

| Not in the next 6 months | 333 (12.6) | 218 (12.5) | 551 (12.6) |

| Missing | 112 (4.3) | 76. (4.4) | 188 (4.3) |

| Longest previous quit attempt, n (%) | |||

| < 24 hours | 243 (9.2) | 172 (9.8) | 415 (9.5) |

| 1–6 days | 474 (17.9) | 286 (16.4) | 760 (17.3) |

| 1–4 weeks | 436 (16.6) | 282 (16.2) | 718 (16.4) |

| > 1 month | 1454 (55.2) | 986 (56.4) | 2440 (55.7) |

| Missing | 28 (1.1) | 22 (1.3) | 50 (1.1) |

| Previously attended SSS, n (%) | |||

| No | 1763 (66.9) | 1135 (64.9) | 2898 (66.1) |

| Yes | 872 (33.1) | 613 (35.1) | 1485 (33.9) |

| ‘How much do you want to quit?’ (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely) | |||

| Mean score (SD) | 3.74 (0.91) | 3.79 (0.90) | 3.76 (0.91) |

| Not at all, n (%) | 14 (0.5) | 7 (0.4) | 21 (0.5) |

| A little, n (%) | 235 (8.9) | 152 (8.7) | 387 (8.8) |

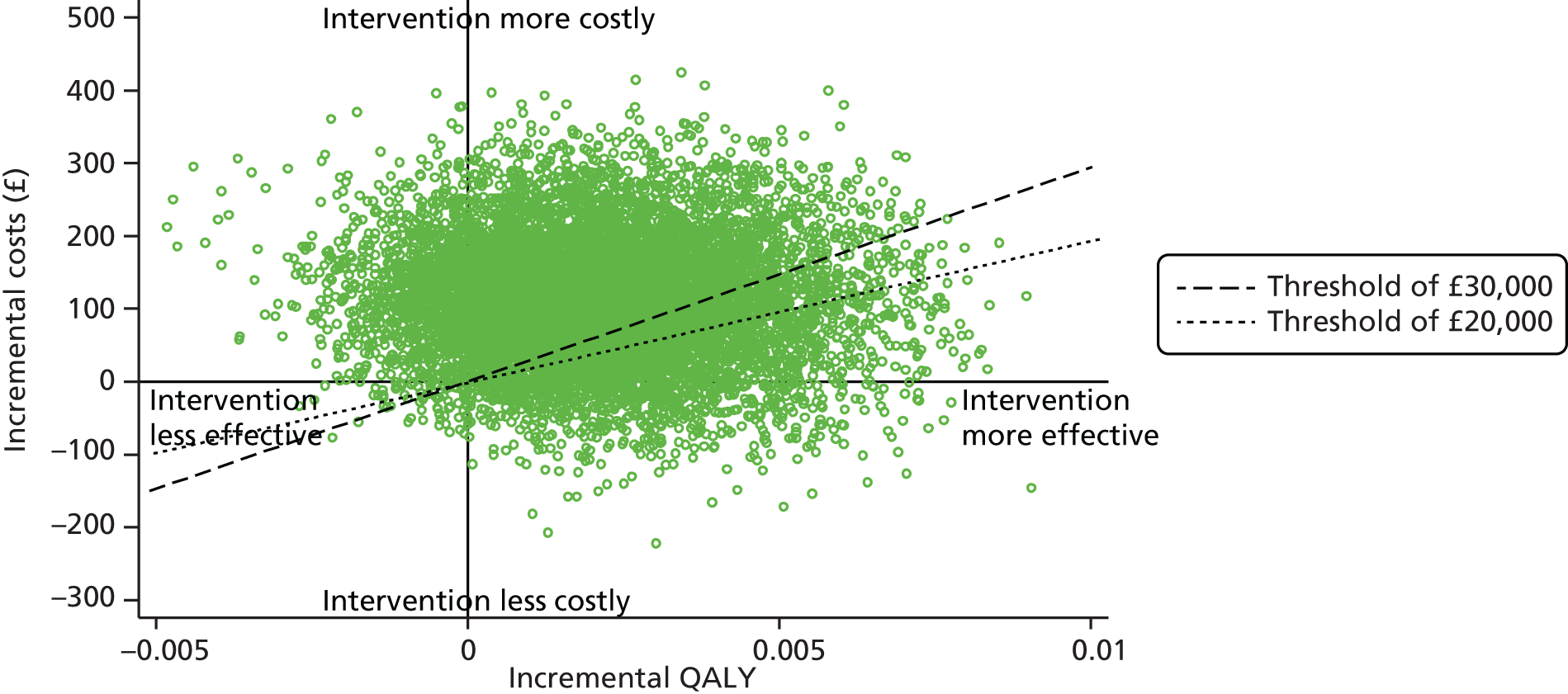

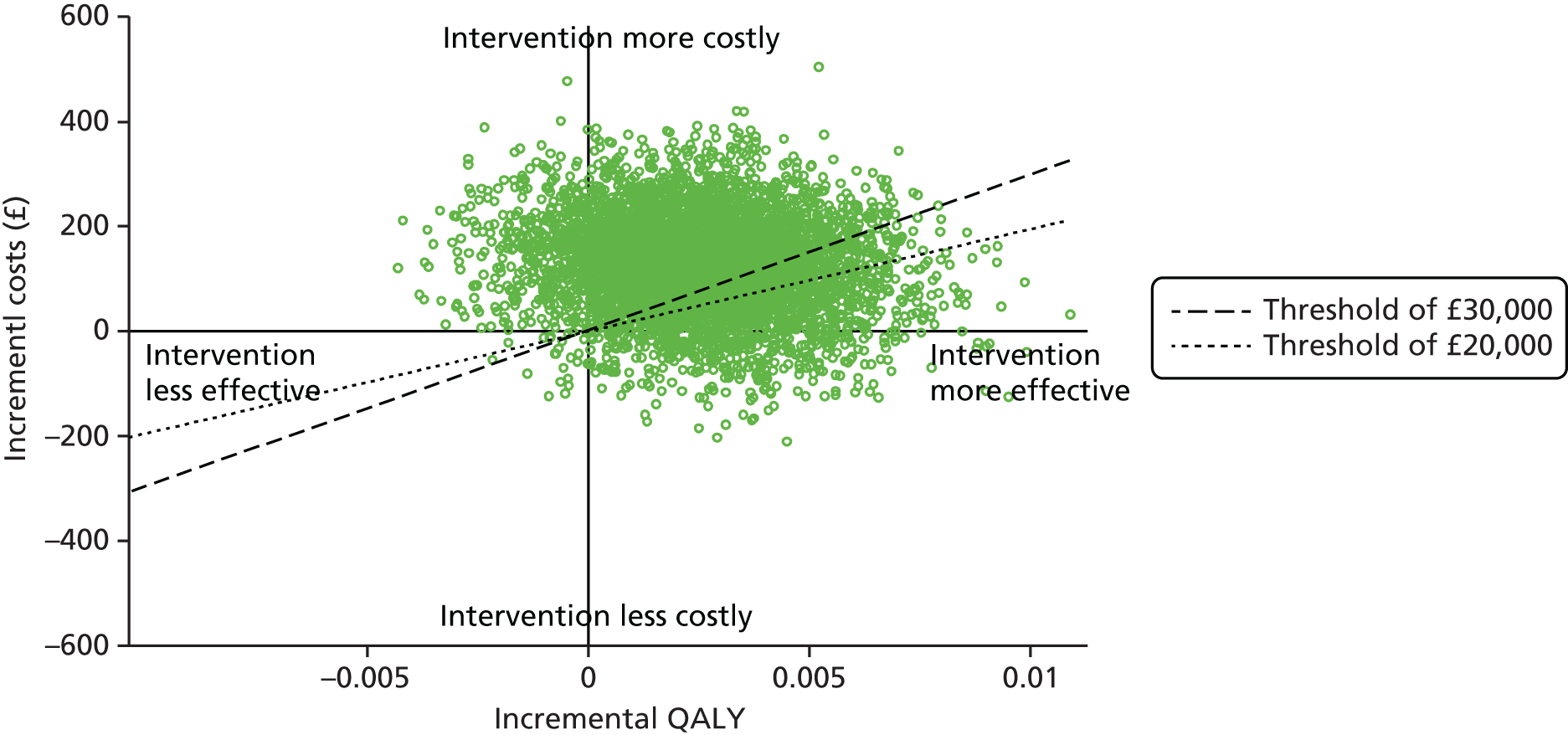

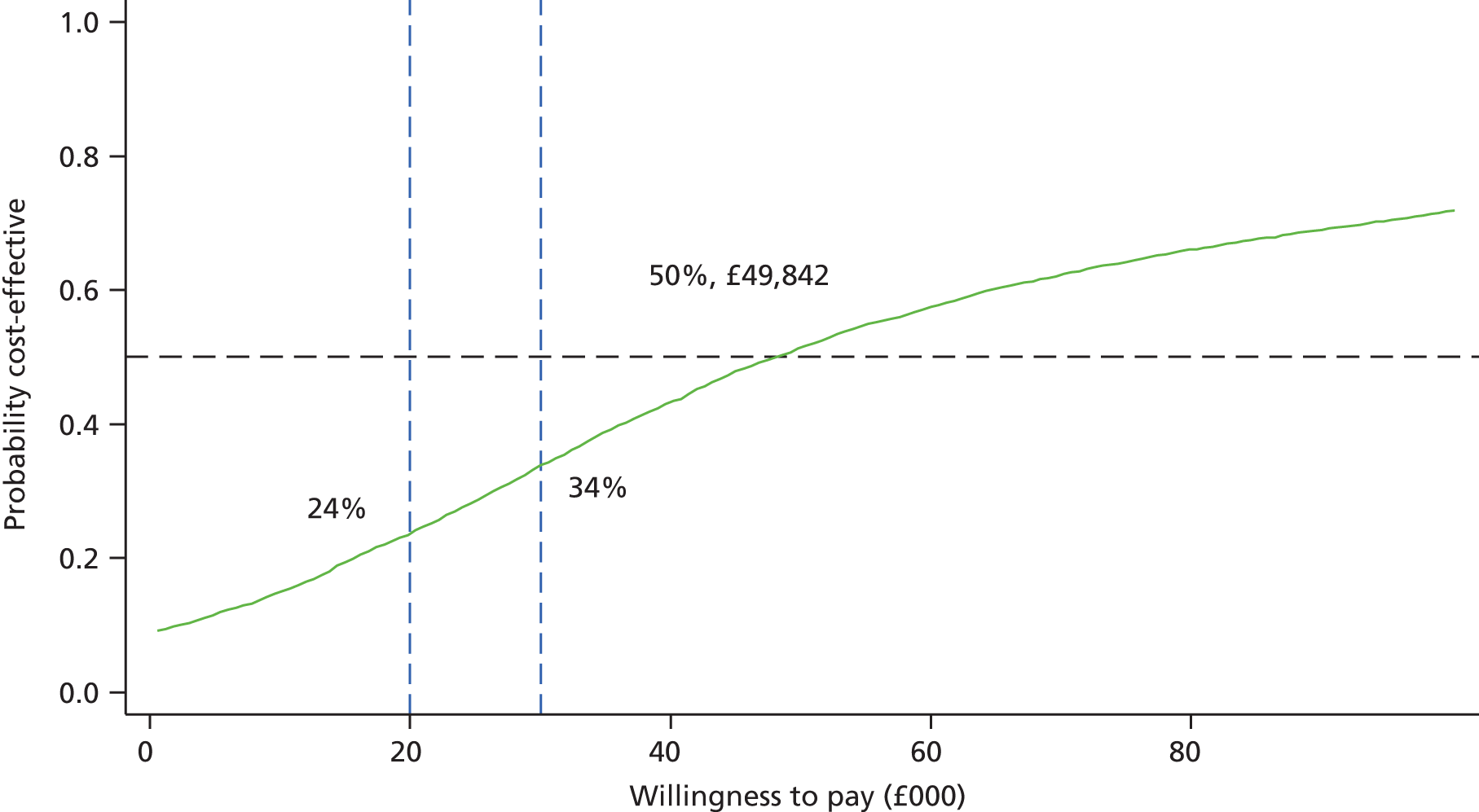

| Moderately, n (%) | 714 (27.1) | 429 (24.5) | 1143 (26.1) |