Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 04/33/01. The contractual start date was in September 2006. The draft report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Wendy Atkin receives funds from Cancer Research UK (Population Research Committee – Programme Award C8171/A16894). Jonathan Myles also receives funds from Cancer Research UK and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA). Jonathan Myles was part funded by the following NIHR HTA awards: 11/136/120 and 09/22/192. Andrew Veitch has received expenses-only sponsorship from Boston Scientific and Norgine to attend Digestive Diseases Week 2015, Washington, DC, USA, and Digestive Diseases Federation 2015, London, UK.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Atkin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The call for proposal

This project was undertaken in response to a call for proposals by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme in anticipation of an unsustainable increase in requirements for surveillance colonoscopy with the impending introduction of the national Bowel Cancer Screening Programme (BCSP) in 2006. There was real concern that an increase in adenoma detection from the BCSP would diagnose many people as intermediate risk (IR), with a consequent impact on endoscopy resources. Therefore, a call was issued to determine the optimum frequency of colonoscopic follow-up in patients who were identified with intermediate-grade adenomas.

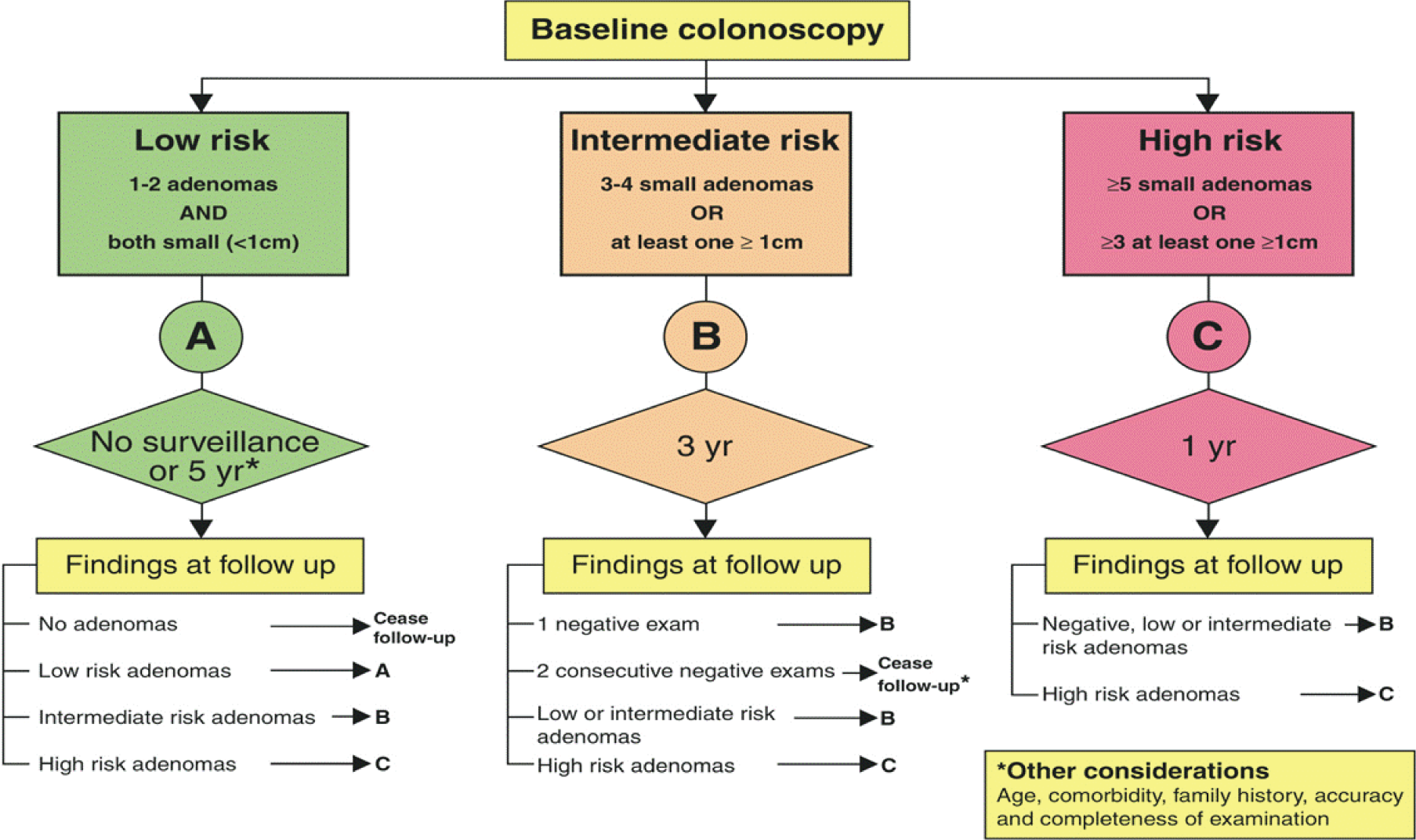

The current UK surveillance guideline was developed in 2002 and defines three risk groups (low, intermediate and high risk) with different surveillance recommendations. 1 From existing evidence it was suggested that, for the low-risk group, colonoscopy surveillance might not be necessary, whereas for the high-risk group surveillance was definitely indicated with an additional clearing examination 12 months after initial diagnosis (but this group constitutes only around 10% of people with adenomas2). The IR group, representing around 40% of patients with adenomas, was recommended to have a 3-yearly surveillance colonoscopy. However, this recommendation was based on limited evidence to indicate the optimum surveillance interval and the need for repeated surveillance. 1

Available evidence suggested that it might be safe to stop surveillance in the IR group after one or two negative examinations, depending on the age of the patient and the quality of the examination. Importantly, it was also proposed that patients with intermediate adenomas (IAs) may vary in their risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC) and that there might be subgroups with different surveillance requirements. 3 The need to determine the optimum frequency of colonoscopic follow-up in IR patients was identified as a priority by the Department of Health (DH).

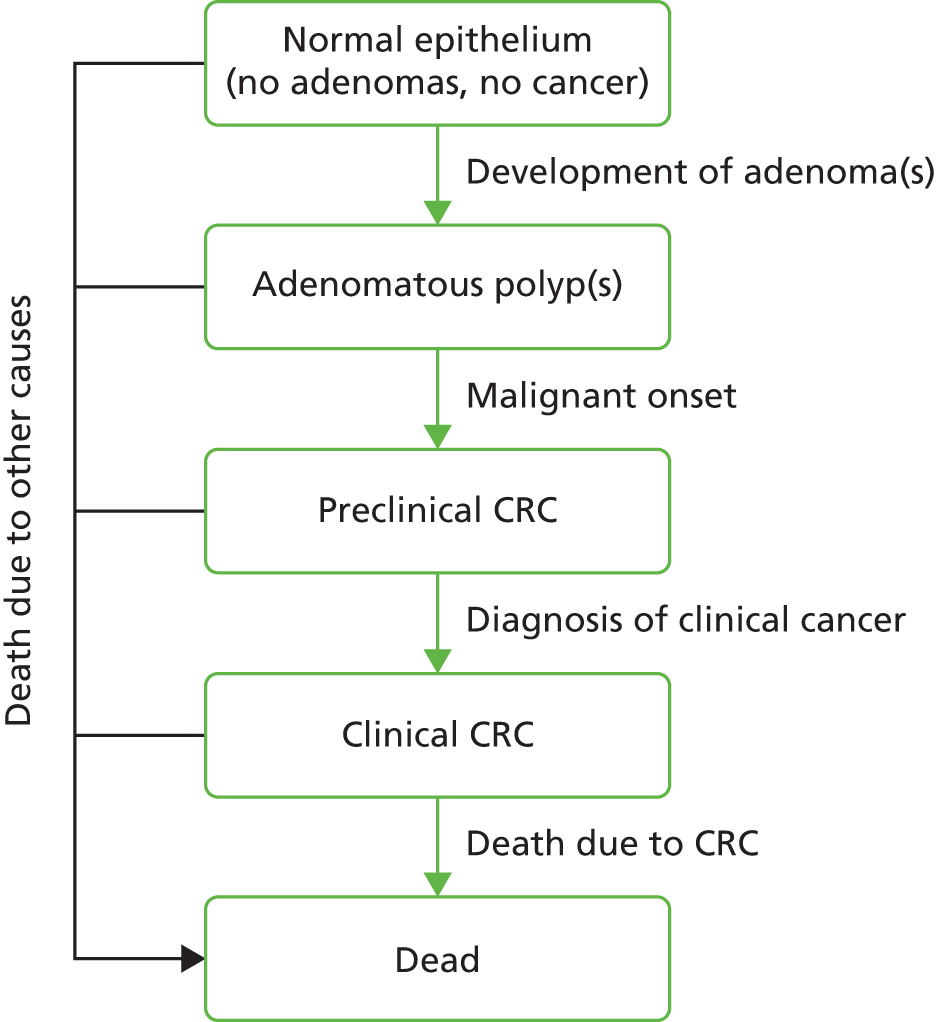

Rationale

Colonoscopy is the most widely used procedure for investigating colonic symptoms, and for surveillance of people at increased risk of CRC because of a personal or family history of CRC or adenomas. It is widely accepted that most CRCs develop from adenomatous polyps,4–7 and that the detection and removal (polypectomy) of these precursors through screening or surveillance reduces the risk of CRC. 8–13 Adenomas are very common and tend to recur. As such, the future risk of CRC after polypectomy is thought to depend on findings during baseline colonoscopy, particularly the number, size and histological grade of removed adenomas,3,14,15 as well as the completeness of examination and clearance of prevalent adenomas. This evidence was used to stratify patients into risk groups, each with different colonoscopic surveillance recommendations. 1,16–18

Since Atkin et al. 3 first suggested a variability in risk of CRC after adenoma removal in 1992, many countries have developed adenoma surveillance guidelines, most of which are based on either the UK or US guidelines. The indication for surveillance depends primarily on the presumed risk of recurrence of advanced adenomas (AAs),15,19–23 and development of CRC, and also by age, comorbidity and patient compliance. The current UK surveillance guideline was first commissioned and developed by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) in 2002 and has since been adopted by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the European Union (EU) (Figure 1). 24 Both UK and US guidelines identify three risk groups, but the definitions and surveillance recommendations differ slightly. 1,2 Both guidelines identify a low-risk group, for which no surveillance or 5-yearly surveillance is recommended; an intermediate-(UK)/higher-risk (US) group, for which 3-yearly surveillance is recommended; and a high-risk group, for which additional colonoscopy is recommended. In the UK, the guideline specifies a single clearing colonoscopy at 12 months before continuing on 3-yearly surveillance. 1,2,16,17,25

FIGURE 1.

UK adenoma surveillance guidelines 2002. Reproduced from Surveillance guidelines after removal of colorectal adenomatous polyps. Atkin WS, Saunders BP, Gut, vol. 51, pp. V6–9, 2002,1 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

The fact that guidelines vary – particularly in defining the IR group and their surveillance recommendation18,26 – is indicative of the uncertainty about the optimum adenoma surveillance regime. After adenoma removal, some patients have a risk of CRC similar to, or lower than, that of the general population,3,27,28 implying that not all patients are at sufficient risk to warrant surveillance. 3,14,27–31 The IR 3-yearly surveillance regime is based on results of the National Polyp Study,20 which compared two follow-up colonoscopies with one follow-up colonoscopy within 3 years and found no difference in the detection of adenomas with advanced pathology. Two other studies32,33 also found the incidence of adenomas with advanced pathology to be similar regardless of interval length. However, another trial found a non-significantly higher risk of CRC in patients who were examined at 4 years than in those examined at 2 years. 29,34

As colonoscopy is both costly and invasive, surveillance should be undertaken only in those who are at increased risk and at the minimum frequency required to provide adequate protection against the development of cancer. 25 There is evidence of both over- and underutilisation of colonoscopy, and a potential for more efficient allocation of endoscopy resources. 35 The IR group comprises nearly 20% of those subjects participating in the BCSP who undergo colonoscopy for a positive test,36 and nearly half of adenoma patients,2 yet no study has yet systematically examined whether or not there is heterogeneity in risk among patients who are currently offered 3-yearly surveillance. We sought to address the unanswered questions surrounding the current IR group surveillance strategy, that is:

-

What is the effect of interval length on detection rates of AA and CRC at follow-up examinations in IR patients?

-

Are there subgroups of IR patients who do not require surveillance, or who require only one follow-up? Similarly, are there are subgroups that might benefit from shorter or longer surveillance intervals?

-

Does the risk of AA or CRC at first and second follow-ups vary by patient, procedural and polyp characteristics, and surveillance interval length?

-

Can we define factors that affect the risk of CRC after baseline in IR patients, for example number of surveillance visits, patient/procedural/polyp characteristics?

Background to the design

As a randomised controlled trial (RCT) or prospective observational study would take many years to complete, the use of pre-existing hospital patient data in a retrospective cohort study was the recommended design. It was thought that this method would be quicker, cheaper and more convenient. In addition, the use of such hospital patient data ensured that there would be sufficient variation in adenoma surveillance intervals to enable comparison between them. This may not have been possible with data collected prospectively because of the widespread adoption of UK surveillance guidelines. Furthermore, longer patient follow-up times could also be obtained in this retrospective study design.

We also requested access to data from researchers of a number of screening studies on findings at surveillance colonoscopy. Eight screening data sets were identified; however, only three provided adequate data for our analyses (see Chapter 4, Screening data set, Background).

At the time there was no systematic call or recall of patients in adenoma surveillance, so the principal investigator (PI) also wrote to the manufacturers of the patient management systems that were used to manage patient data in hospitals in the UK NHS. The manufacturers were able to identify hospitals that had used their software for a sufficiently long period of time. These hospitals were contacted and were provided with a questionnaire to complete in order to determine their suitability for the study.

Aim and objectives

The overall aim was to examine the optimum frequency of surveillance in patients who were found to have IR adenomas and assess the risks and benefits with respect to prevention of cancer/AA; anxiety, morbidity and mortality; costs and cost-effectiveness; and implications for the NHS.

The primary objective was to assess whether or not there was substantial heterogeneity in the detection of AA or CRC according to baseline characteristics and interval to first follow-up colonoscopy. The study planned to determine if there was a subgroup of IR patients who do not require surveillance and whether or not the size of this group is clinically significant. Finally, the study examined whether subgroups could be identified for which the currently recommended 3-year interval is too long, or for which the interval can be safely extended, or if there is a group that requires a second examination but no further follow-up.

An economic analysis aimed to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of alternative adenoma follow-up strategies, including a policy of no follow-up for individuals who have intermediate-grade adenomas. It also planned to estimate the impact of alternative adenoma follow-up strategies on colonoscopy services, and the total cost impact of alternative adenoma follow-up strategies in England and Wales.

A psychological impact analysis aimed to examine the anxiety-inducing effects of colonoscopic surveillance or being informed that colonoscopy surveillance is required.

Study design and setting

This was a retrospective cohort study using data from two sources. A cohort of patients attending UK NHS hospitals for diagnostic or surveillance endoscopy formed the largest data set – termed the ‘hospital data set’. Three smaller data sets were obtained from a research or screening setting, and involved average-risk individuals undergoing screening: one from a UK screening trial, a second from a UK pilot screening programme and a third from a US health surveillance programme – termed the ‘screening data sets’. The core results were derived from the hospital data set, as there were difficulties in obtaining additional screening data sets, and limited data completeness in the screening data sets that we were able to obtain. A health-economics evaluation and psychological study were also conducted.

Structure of this report

The findings of the hospital and screening data sets are reported and discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, respectively. The methods, which were largely the same for the two data sets, are described in Chapter 2, with any additional methods unique to the screening data set described in Chapter 4. The health-economic evaluation is reported in Chapter 5 and the psychological study is reported in Chapter 6. Finally, Chapter 7 presents a synthesis of results from the preceding chapters, as well as strengths/limitations and future work.

Chapter 2 Methods

Hospital selection

The hospital data set comprised routine gastrointestinal endoscopy and pathology data for patients having diagnostic and surveillance procedures. Participating hospitals were required to have recorded endoscopy and pathology data electronically for at least 6 years prior to the study start in 2006. After contacting endoscopy and pathology database manufacturers, 28 NHS hospitals were identified as meeting these criteria, and their participation in the study was requested. A number of hospitals were excluded because of difficulties with data extraction and data quality issues (see Data collection from hospitals, below). In total, 18 hospitals were included in the study. Two of these merged into the Imperial College Healthcare Trust (Charing Cross and Hammersmith hospitals) and thus there were 17 hospital sites included; these are listed in Table 1.

| Trust | Hospital | Study name | Study code | Collection dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brighton & Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust | Royal Sussex County Hospital | Brighton | BRI | May 2001 to April 2008 |

| North Cumbria Acute Hospitals Trust | Cumberland Infirmary | Cumberland | CI | August 1998 to September 2009 |

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | Charing Cross Hospital/Hammersmith Hospital | Charing Cross/Hammersmith | CX/HH | October 1997 to November 2007 |

| Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Trust | Glasgow Royal Infirmary | Glasgow | GRI | May 1996 to August 2009 |

| University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust | Leicester General Hospital | Leicester | LGH | April 1998 to March 2008 |

| Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals Trust | Royal Liverpool University Hospital | Liverpool | RLUH | January 2000 to October 2009 |

| Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust | New Cross Hospital | New Cross | NC | January 1993 to November 2007 |

| University Hospital of North Tees Trust | University Hospital of North Tees | North Tees | NT | June 1986 to December 2006 |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital NHS Trust | Queen Elizabeth Hospital | Queen Elizabeth | QEW | March 1999 to May 2006 |

| Queen Mary’s Sidcup NHS Trust | Queen Mary’s Hospital | Queen Mary’s | QMH | October 1998 to July 2009 |

| Shrewsbury and Telford Hospitals NHS Trust | Royal Shrewsbury Hospital | Shrewsbury | SH | January 2002 to September 2009 |

| St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust | St George’s Hospital | St George’s | SGH | February 1992 to July 2009 |

| London North West Healthcare NHS Trust | St Mark’s Hospital | St Mark’s | SMH | January 1985 to July 2007 |

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | St Mary’s Hospital | St Mary’s | ICMS | December 1984 to July 2010 |

| Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Trust | Royal Surrey County Hospital | Surrey | SCH | September 1997 to May 2010 |

| South Devon Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | Torbay District General Hospital | Torbay | TDG | November 2000 to August 2007 |

| Yeovil District Hospital Foundation Trust | Yeovil District Hospital | Yeovil | YDH | February 1997 to May 2008 |

Patient eligibility

Inclusion criteria

Patients with IR adenoma(s) and a baseline colonoscopy were eligible for inclusion in the study. Following the UK guideline, IR patients were defined as those with three or four small adenomas (of < 10 mm) or one or two adenomas, at least one of which was large (≥ 10 mm).

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded for having certain conditions if the condition increased their risk of CRC or could have led to an abnormal pattern of surveillance. Some diagnoses resulted in exclusion regardless of when they occurred, for example hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), a genetic condition that confers an increased risk of cancer throughout an individual’s lifetime. Other conditions resulted in exclusion only if they were diagnosed at, or prior to, baseline, or, in other cases, patients were censored after diagnosis of a particular condition rather than excluded altogether.

Patients were excluded if they had any of the following diagnoses at, or prior to, baseline:

-

CRC or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

-

resection/anastomosis

-

volvulus.

Patients were excluded if they had the any of the following diagnoses at any time:

-

family history of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

-

HNPCC

-

Cowden syndrome

-

juvenile or hamartomatous polyps.

Patients with polyposis could be excluded depending on polyposis type and time of diagnosis. Details of time-dependent exclusions for polyposis and colitis can be found later in the report (see Appendix 5).

Patients were also excluded if they had no baseline colonoscopy, or had one or more procedures without a date, or had more than 40 endoscopic procedures recorded.

Research governance

Data were collected from hospitals in England and Scotland. The following research governance approvals were obtained to permit data collection and follow-up via external agencies:

-

Approval was granted from the Royal Free Research Ethics Committee (REC) for the study throughout the UK (REC reference 06/Q0501/45). The REC agreed that all sites should be exempt from site-specific assessment. Further approval was granted for substantial amendments to allow changes to database hosting arrangements and logistical arrangements for data collection and follow-up.

-

Approval to access patient identifiable information without consent in England was granted from the Patient Information Advisory Group (PIAG) [later the National Information Governance Board (NIGB) and currently the Ethics and Confidentiality Committee at the Health Research Authority] in accordance with Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 200137 (re-enacted by Section 251 of the NHS Act 200638). Further approval was granted for substantial amendments to allow data to be extracted and anonymised, and to link identifiable information obtained from multiple sources including hospital endoscopy and pathology databases, the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database, and databases held by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), National Health Service Information Centre (NHSIC) [subsequently the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC)] and National Health Service Cancer Registries (NHSCR) [reference PIAG 1–05(e)/2006]. This was necessary because of the retrospective nature of the study and the large number of patients involved. Support was favourable based on the study’s System Level Security Policy and compliance with Imperial College’s policy on data handling and storage, and a recommendation from the Caldicott Guardian for the North West London Hospitals NHS Trust, who approved the arrangements to ensure patient confidentiality and anonymity. In Scotland, similar approvals were obtained in 2013 from the Community Health Index Advisory Group. Permission was granted to use the Community Health Index (CHI) to enable the Information Services Division to clean the patient information within the study data set, and to match identifiable information to data from the cancer and death registries.

-

Research approval for the study was obtained from all relevant NHS care organisations for the study sites, which were provided with the ethical approval documentation and the study protocol. As none of the members of the study team had a contractual relationship with the NHS, honorary contracts/letters of access were applied for and obtained for staff who were required to carry out work at the various study sites, in agreement with the Research Governance Framework.

-

Where necessary, applications were made to the custodians of external data sets to enable specific researchers to access information controlled by external sources and to allow the study data set to be linked to external data sets. In England, researcher status was approved and obtained from the ONS and NHSIC for individual researchers, and applications to use individual records for medical research were made to the NHSIC and the UK Association of Cancer Registries (UKACR). In Scotland, the Privacy Advisory Committee (PAC) granted approval for patient record linkage with NHS National Services Scotland (NSS) using CHI numbers, so that patients in Glasgow could be followed up to obtain details of cancers and deaths (reference PAC Application 66/11).

To ensure that patient confidentiality was maintained throughout the study, no patient-identifiable information – except date of birth – was stored on the study database. All patient identifiers were left at the individual study sites in secure locations, and all information kept at the trial office was in a pseudo-anonymised format. In addition, access to the Oracle database was controlled by username and password security, as well as a firewall that restricted access to the database server to a limited number of IP addresses. The majority of computers in the trial office were given access to the database, whereas specific access to the data via the Oracle Application Express (APEX) version 3.2.1.00.10 (Oracle Corporation, Redwood City, CA, USA) coding application was controlled via APEX’s built-in user management facility.

Data collection from hospitals

The data were extracted from hospital endoscopy and pathology databases by the study programmer. A minority of databases had an interface that permitted bulk extraction of the data according to specific criteria and in these cases data were extracted with assistance from hospital staff who were familiar with the systems. However, for most endoscopy and pathology databases, the application interface was not designed for bulk data extraction, so data extraction and processing was complex, with a number of problems encountered, for example:

-

When the maintenance and support of the endoscopy and pathology databases had been outsourced to the database manufacturers, often only they could help with extracting the data or by writing software enabling the study programmer to do so.

-

Specialist support was required when data were held on legacy systems.

-

Information technology (IT) staff at the hospitals sometimes had to restore archived data temporarily so that they could be extracted.

-

Most hospitals had replaced databases over the years, and therefore some data overlapped or were duplicated (e.g. the same patient had records on more than one system).

-

Sometimes several hospital visits were necessary to extract data from multiple databases, at the convenience of the local IT experts.

-

The data outputs from these databases were in a combination of structured and unstructured formats. Structured data could be easily cleaned and converted into a standardised format for uploading. Unstructured data (usually large text fields) needed bespoke programs written to extract, clean and convert the data into a suitable format.

Owing to various technical difficulties with data extraction, inability to access databases, partial availability of electronic data, unreliable Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) coding and logistical difficulties due to local staff availability, nine hospitals were excluded from the study (Table 2). From the 17 hospitals that were included in the study, data were extracted from 27 endoscopy and 29 pathology systems. (A summary of data collection at each hospital can be seen in Appendix 1.)

| Hospital | Reason for exclusion | Summary | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blackpool Victoria | Software/data collection issue | Incompatibility of old vs. new software systems for importing endoscopy data Difficulties in bulk data transfer from pathology reports |

Following the creation of extraction programs and test runs, the statistics program was unable to extract all of the necessary endoscopy data. The main endoscopy reports could not be extracted from the older EndoScribe data imported into the newer ADAM system The pathology system did not allow the uploading of pathology reports in bulk |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary | Software/data collection issue | Old software systems used to record data Difficulties in bulk data transfer |

Pre-2005 SNOMED coding for pathology data was unreliable The Co-Path system proved to be problematic and complex to extract multiple records – it would have taken too long and would have slowed down the system for the hospital |

| City Hospital, Birmingham | Difficulties in obtaining R&D approval | Delays and limited resources | The study encountered long delays in R&D approval, owing to staff shortages in the R&D department and time-consuming internal procedures |

| George Eliot, Nuneaton | Software/data collection issue | Old software systems used to record data Difficulties in bulk data transfer |

The same difficulties with the Co-Path system as encountered with Bradford Royal Infirmary |

| King George, Ilford | Data collection issue | Impractical to extract the data Difficulties in bulk data transfer |

The majority of older pathology data were initially inaccessible because of software licensing issues. When access was achieved, the reports could be accessed only one at a time, making it impractical to extract the data |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital | Technical issues Missing data |

Raw endoscopy and pathology data were extracted between November 2009 and August 2010 from the Micromed, EndoScribe and Scribe databases and the pathology database over several visits to the hospital, and partly cleaned and anonymised. However, on subsequent visits to complete the task the data had been misplaced Re-extraction would have been costly and time-consuming |

|

| Pinderfields, Yorkshire | Software/data collection issue | Incomplete data | The data provided by a new HICSS system (Ascribe Ltd, now EMIS Group plc, Leeds, UK) were lacking any endoscopy procedures other than colonoscopy (e.g. sigmoidoscopy and rigid sigmoidoscopy) |

| Queen Alexandra, Portsmouth | Missing data | Missing pathology data 2006–8 | |

| University Hospitals of North Staffordshire NHS Trust | Software/data collection issue | Difficulties in bulk data transfer | Not possible to do a bulk data extraction at this hospital |

Data extraction

Endoscopy data

Endoscopy databases were searched first in order to identify patients undergoing colonic examinations, as the pathology databases contained a wide range of extracolonic samples. Before removal from the hospital, the extracted data were split into patient identifiers and endoscopic data. Patient identifiers included surname and forename(s), hospital number(s), NHS number, gender, postcode and date of birth. Endoscopic data included date of procedure, type of procedure, indications, endoscopist name, endoscopist comments, polyp information (such as size, shape, location, information on any biopsies taken), segment reached, quality of bowel preparation, complications encountered, diagnosis and any other information. The list of patient identifiers was cleaned to remove errors, inconsistencies and duplicates, and a unique study number was assigned to every patient. Study numbers were made up of a three-letter code, representing the hospital, followed by a six-digit number.

Pathology data

Pathology databases were searched for reports on colorectal lesions. The preferred search method used in most hospitals was SNOMED (College of American Pathologists), which defined the site and type of colonic lesions present. When this was not possible, Systematized Nomenclature of Pathology (SNOP) (College of American Pathologists) codes (four-digit versions of SNOMED codes), keywords or SNOMED International 3.0 codes (College of American Pathologists) were used (see Appendix 1 for details of the methods used to collect pathology data at each centre). Initial validation checks were performed to ensure that the pathology extract included the date of report, unique report number, type of procedure where specimens were taken, number of specimens and histological details.

Linking endoscopy and pathology data

Patients identified from endoscopy records were matched to their pathology records using a combination of hospital number, name and date of birth. Patient study numbers were then assigned to the matched pathology records. Manual inspection of the data and preliminary analyses were performed at the hospital to check that a sufficient number of pathology records were linked to a patient and that they occurred on, or near, the date of an endoscopy. When there was cause for concern (e.g. very few endoscopies linked to pathology reports; or endoscopies at which a biopsy was taken did not have an associated pathology report; or a large number of pathology reports could not be linked to an endoscopy, suggesting that the endoscopy extract did not retrieve all records), further investigations were undertaken and the data were re-extracted from the endoscopy and pathology systems where necessary.

Pseudo-anonymising data

In order to maintain patient confidentiality in accordance with the EU Directive on Good Clinical Practice (Directive 2005/28/EC), the Data Protection Act 199839 and the NHS Caldicott Principles, all patient identifiers except date of birth were removed from the pathology and endoscopy data, and the anonymised data were encrypted before being removed from the hospital.

A ‘patient-linking-file’ in Microsoft’s .xls or .xlsx format (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), storing each patient’s identifiable information and study number was created, encrypted, and left at each hospital site. The raw endoscopy and pathology data and patient-linking-file were copied on to CDs and stored in secure locations at the hospital under supervision of the local PI.

Development of the master database

A master database was created to store the data in a standardised, structured format. To facilitate the statistical analysis, the data had to be classified into quantitative and qualitative variables, ensuring that data from different hospitals were classified in the same way, as there was wide variation in the raw data (e.g. field names were different; some data were coded or semi-coded, whereas other data were in free-text fields; and data types varied). The PI, study researchers, statistician and study programmer defined the data requirements for the study and designed the structure of the master database (see Appendix 2). The master database was designed to store the following:

-

the original source data (to safeguard against data loss during coding)

-

fields to store structured data that had been automatically extracted, cleaned and standardised using bespoke programs

-

fields to store the structured data which were manually coded.

Reference data (sometimes referred to as look-up tables) were used to categorise and define permissible values for data fields on the database. This method restricted the values to be recorded in a data field, thereby preventing coding errors and also ensuring uniformity of data from different hospitals.

It was necessary to transform the variety of data received from different hospitals into a standardised data set. As the volume of records was very large, it was necessary to code and categorise the data as much as possible using automatic coding without compromising the integrity of the data. Programs were developed to transform, clean and automatically code the data where possible. This involved several steps:

-

identifying the fields containing information required for the study, taking into account varying field names, data types and value representations

-

extracting information from free-text fields using programming techniques such as ‘regular expressions’ and ‘fuzzy matching’, and translating them into the codes used on the master database

-

translating values in the raw data into the codes used on the master database if the information was already in a coded structured format

-

identifying and consolidating overlapping data, and removing any redundancies (e.g. the same endoscopy or pathology reports extracted from two different systems)

-

identifying errors in the data and validating and correcting them (e.g. misspellings, different date formats, accounting for false-positive matches)

-

transforming polyp data to fit the structure of the polyp table in the master database. Some raw data sets had structured data on polyps (i.e. each polyp was represented as a separate table record); for other data sets, the study programmer had to separate the data into individual records.

After data transformation and cleaning, the raw data and structured data were uploaded to the master database, ensuring that the data were linked correctly across tables. Exclusions of ineligible patients were made automatically where possible, using programming techniques such as ‘regular expressions’ and ‘fuzzy matching’ to identify relevant keywords or phrases in the reports. Approximately 17% of patients were excluded using automatic exclusions.

Manual data coding

The records of the remaining 83% patients who had not been auto-excluded were manually interpreted and coded; this also involved checking the automatic coding on these records.

A web-based coding application with a graphical user interface was developed using APEX, allowing the study researchers to read, interpret and code the information in the database efficiently. This was called the Endoscopy and Pathology Reports Application (EPRA). The development of the EPRA evolved over time as new data items were encountered at different hospitals, and as processes for coding and analysing the data were developed. A change log of new features was maintained on the study database and updated when a new version of the EPRA was released. (Details and screenshots of the EPRA are provided in Appendix 3.)

Documents detailing standard operating procedures (SOPs) were produced to ensure standardised coding methods between study researchers. SOPs covered all basic coding methods, rules for coding individual fields within the database, and more complex processes used for tasks such as polyp numbering (see below). All SOPs can be found in Appendix 4.

A specific study researcher was allocated a patient’s complete set of records to ensure that the study researcher had access to all available information. The study researchers were responsible for:

-

checking and correcting data that had been automatically coded

-

checking that endoscopy and pathology records were properly linked

-

coding the raw endoscopy and pathology data into structured data

-

creating individual polyp records from the data provided in endoscopy reports. In some cases, the study researchers found that polyps were described as groups rather than as individual polyps. This is discussed further below

-

raising queries on records that could not be fully coded due to incomplete or insufficient information

-

creating a blank ‘pathology-based procedure report’ in cases for which the pathology record had no linked procedure report. Clinical information available in the pathology report was used to deduce details about the procedure from which the histological sample was obtained.

Coding accuracy and data interpretation were monitored to maintain consistency, using the following methods:

-

Study researchers systematically reviewed a blinded random sample of records that had been coded by other study researchers.

-

Regular meetings and continuous discussion/feedback were used to ensure uniformity of coding.

Records that had not been coded because of incomplete or insufficient information were reviewed by the study researchers, and further data were obtained from hospitals, where possible, in order to complete the coding.

Polyp numbering

A polyp found at one endoscopy examination that was not removed or only partially removed could be seen again at a later examination. To ensure that there was no double-counting of polyps, each polyp was assigned a unique polyp number that could be used to link sightings of the same polyp at different examinations. This process was called ‘polyp numbering’.

In approximately 17,000 patients, polyps were found on at least two occasions and were reviewed for manual polyp numbering. All sightings of an individual polyp were assigned the same unique polyp number. Each polyp was also assigned a match probability (to the nearest 10%), to indicate the degree of certainty that two polyps were the same lesion. The polyp that appeared to have the greatest number of matches with a high degree of certainty was chosen as a reference polyp, and all possible matches were considered in relation to this polyp. Polyp numbering guidelines were used to match polyps accurately and methodically, using all of the available information from the endoscopy and pathology reports. Particular attention was given to the following factors, listed in order of importance. Sightings at different examinations were considered more likely to be the same polyp if:

-

they occurred in the same segment of the colon, or in adjacent segments

-

there was an indication that the polyp at the earlier examination was not removed or was only partially removed

-

the quality of bowel preparation at the first examination was poor, making it less likely that a lesion would be removed

-

the lesions had similar grades of dysplasia

-

the lesions were the same histological type

-

the lesions had similar degrees of villousness.

Quality checks were carried out by the study researchers, who manually reviewed and checked a random sample of records for which polyps had been numbered by other study researchers.

Polyps matched with an arbitrary probability of ≥ 70%, using the above criteria, were considered the same lesion. More details on polyp numbering can be found in Appendix 6.

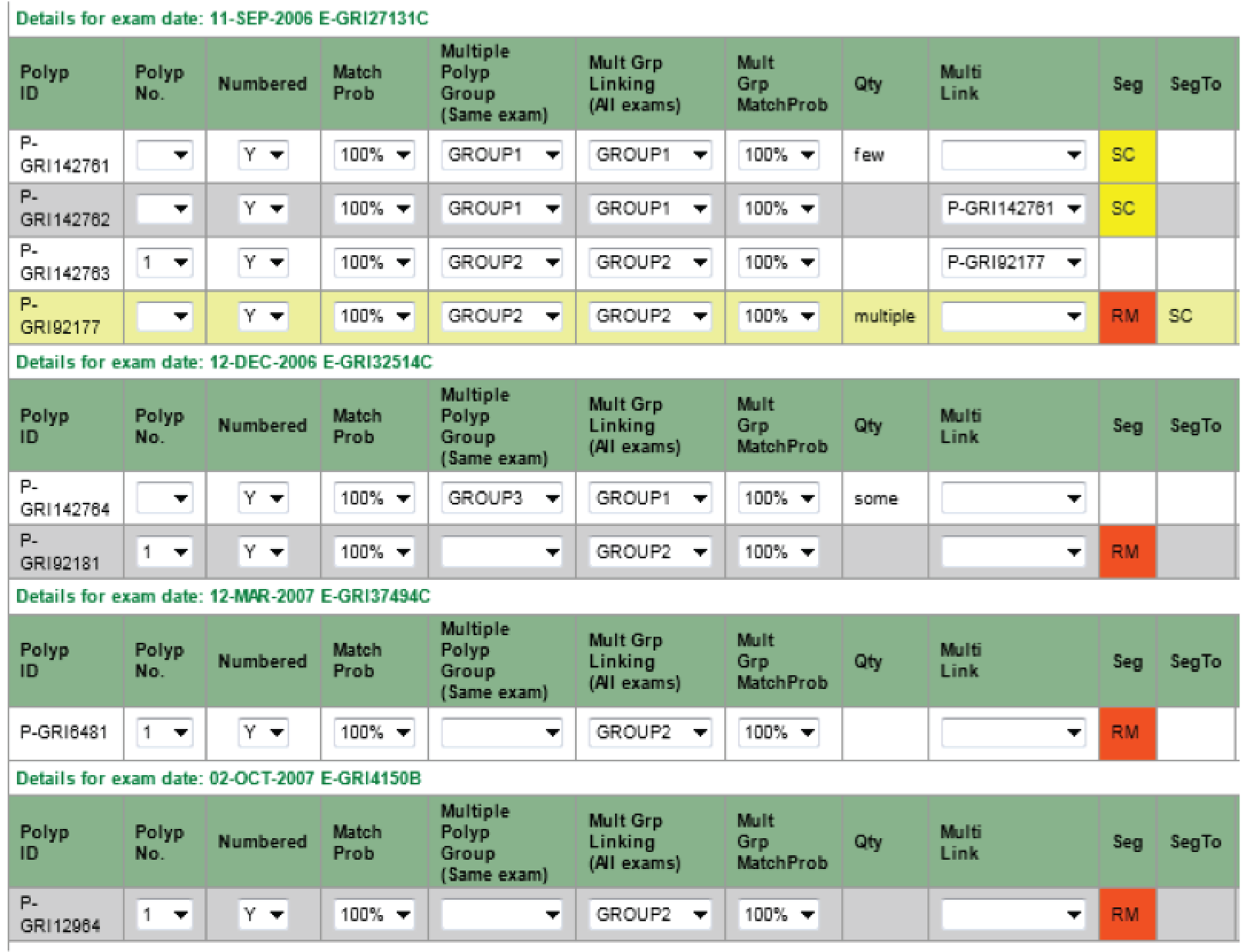

Polyp groups

Sometimes endoscopy reports described groups of polyps using terms such as ‘several’, ‘many’ and ‘multiple’, rather than individual polyps. During manual coding, specific fields were used to record this information. Each group of polyps was recorded as a single record and populated with information such as site, shape and histology, where this was common to all polyps within the group. Descriptions of the size and number of polyps in the group (e.g. ‘tiny’, ‘multiple’) were recorded. Where information was given for an individual polyp within the group, a polyp record was created and linked to the group record. The whole group (and the individual polyps linked to it) was allocated a unique group number.

Patients with multiple polyps could have groups of polyps seen at more than one examination, and a group of polyps seen at a later examination could include some or all of the polyps seen at a previous examination. In order to link groups of polyps seen at more than one examination, a separate group linking number was assigned to each group of polyps. This task was completed after all polyp groups had been recorded for a patient. Groups of polyps seen at more than one examination were matched and a probability was assigned, indicating the study researcher’s certainty that groups of polyps seen at separate examinations were of the same group.

The records for groups of polyps were then expanded into individual polyp records so that they could be analysed. An estimate of the number of polyps in each group was deduced from a value coded for the approximate number where available; otherwise the average of the minimum and maximum number of polyps recorded by the endoscopist was used. Alternatively, a numeric value was estimated for each vague number description (e.g. ‘some’, ‘several’, ‘few’), taking the average value for all groups in which both the specific descriptor and a numeric value was reported; these values used to define the number of polyps in the such groups are shown in Table 3.

| Description | Estimated no. of polyps |

|---|---|

| A few | 3 |

| Some | 3 |

| A number of | 3 |

| Several | 3 |

| Many | 5 |

| Multiple | 5 |

Additional information on the number of individual polyps seen at previous or subsequent examinations which were considered to be part of the same group was used to refine the estimate of the number of polyps in that group (see Appendix 6).

Once a final estimate had been derived for the total number of polyps in each group at each examination, a program was written to create individual polyp records. Where a polyp record was created based on the presence of a polyp at a previous or subsequent examination, the program assigned the same polyp number to the new polyp record, to show they were the same lesion.

Creating summary values for polyp characteristics

Most polyps were seen and removed at a single examination, and information about a polyp’s features was available from a single endoscopy and pathology report. Alternatively, a polyp might be seen at more than one examination with descriptive information contained in numerous endoscopy and pathology reports. In both of these scenarios, a single polyp characteristic might be coded for in multiple data fields. It was therefore necessary to create summary values for each lesion, taking into account information provided in reports on polyp characteristics at individual examinations and across examinations. However, the following issues had to be resolved first.

Missing polyp information

When information on a polyp characteristic was missing from the endoscopy report, it was sometimes possible to obtain supplementary information from the pathology report, or from other examinations at which the same polyp was detected.

Inconsistent polyp information

Polyp information reported in an endoscopy and pathology report for a specific examination could be inconsistent. Similarly, information reported across multiple sightings of a single polyp could be inconsistent. Sometimes it was clear from available information that an inconsistency was due to a coding or transcriptional error in one or more hospital reports. Rules were identified to determine which data items were likely to be errors; these records were manually reviewed and errors corrected where possible. Inconsistencies that could not be explained by error were resolved using hierarchies of rules (see Appendices 7 and 8).

Vague polyp information

Wherever possible, information on polyp characteristics was recorded on the database exactly as reported in endoscopy or pathology reports, and usually precise values were provided. However, in rare cases the observations recorded in the endoscopy report about size and location could be vague; for example size could be merely described as tiny or < 10 mm, and location could be described using a range of values; this was particularly problematic when there were multiple lesions seen at an examination. These vague descriptions of size, and ranges of values for size and location, were recorded in specific fields on the database. Rules were defined to derive a summary value for size and location of each individual polyp at an examination by combining all the available information. These rules are described in greater detail in this section and in Appendices 7 and 8.

Summary values were determined for polyp size, histological features, location and shape, and were derived separately for each visit. Summary values for polyp characteristics were derived using hierarchies of rules. In general, three stages were involved:

-

data cleaning to identify, review and resolve any errors in the polyp data

-

assessment of polyp characteristics at a single examination

-

assessment of polyp characteristics across examinations within a visit, if a polyp had multiple sightings.

Size

Polyp size information was recorded in several fields on the database, as shown in Table 4.

| Size field | Variable namea | Description | Derived valuesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endoscopy size | ENDO_SIZE | Field used to record the exact size of a polyp (in millimetres), when described precisely in the endoscopy report | Derived endoscopy sizeENDO_SIZE, ENDO_SIZE_MIN and ENDO_SIZE_MAX were combined using a hierarchy of rules to give a single derived endoscopy size for each sighting of a polyp |

| Minimum endoscopy size | ENDO_SIZE_MIN | Field used to record the minimum size of a polyp when a size range was described in the endoscopy report (e.g. 8–10 mm) | |

| Maximum endoscopy size | ENDO_SIZE_MAX | Field used to record the maximum size of a polyp when a size range was described in the endoscopy report | |

| Endoscopy size descriptor | ENDO_SIZE_OTHER | Field used to record the size of a polyp when it was described in vague terms in the endoscopy report (e.g. tiny, > 10 mm, < 5 mm, etc.) | Derived endoscopy size descriptorA numeric value was derived from a description (see Table 5) |

| Pathology size | PATH_SIZE | Field used to record the exact size of a polyp or biopsy specimen as described by the pathologist in the pathology report | Derived pathology sizeThe precise size given in most pathology reports is used |

Exact sizes (endoscopy or pathology size) were available for 65% of polyps (of all types, including adenomas) but 8% of polyps had a numeric size with a minor discrepancy, or a size range (minimum and maximum endoscopy size); both of these issues were resolved to give an accurate size. In only 6% of polyps was the size estimated based on a qualitative size description (endoscopy size descriptor). This does not account for other sightings of the same polyp, so the proportion without a precise, numerical size is likely to have been even smaller than this. These proportions relate to all patients for whom we had data, rather than just IR patients, as adenoma risk groups could not be discerned until summary values for size had been defined.

The ‘endoscopy size descriptor field’ was used in cases for which a ‘vague’, qualitative or approximate size description was given in the endoscopy report. A numerical value was derived for each size description by analysing reports in which both qualitative size descriptions and a precise numerical size were given. The median and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for each numeric size field and cross-tabulated against associated categories of the endoscopy size descriptor field, as shown in Table 5.

| Endoscopy size descriptor category | Endoscopy size (mm) | Derived value size | Rationale for derived value size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | n | |||

| Tiny | 3 (2–3) | 660 | 3 mm | Used the median |

| Small | 3 (3–5) | 1574 | 5 mm | Used the larger value of 5 mm to draw a distinction between ‘Small’ and ‘Tiny’ |

| < 5 mm | 3 (2–3) | 35 | 3 mm | Used the median |

| 5–9 mm | n/a | 0 | 7 mm | No examples so took the halfway point |

| < 10 | 8 (8–8) | 3 | 8 mm | Used the median of available examples |

| ≥ 10 mm | 15 (13–15) | 79 | 15 mm | Used the median |

| Large | 20 (12–30) | 2701 | 20 | Used the median |

The endoscopy size and minimum and maximum endoscopy sizes were combined using a hierarchy of rules to give a derived endoscopy size for each sighting of a polyp (see Appendices 7 and 8 for details). The numerical values assigned to the endoscopy size descriptor field were used as the derived endoscopy size descriptor. Most pathology reports provided a precise size, which was coded for each individual polyp biopsied or resected at an examination – this was taken as the derived pathology size. Derived endoscopy and pathology sizes were automatically assigned when possible. Study researchers manually reviewed polyps for which derived endoscopy and pathology sizes could not be assigned automatically.

Finally, the three derived polyp sizes – derived endoscopy size, derived endoscopy size descriptor and derived pathology size – were compared across examinations within a visit, and the largest of each derived size was identified. The largest derived sizes were compared and the largest of these was used as the summary polyp size. The only time the largest size was not used was if it was the derived endoscopy size descriptor, and the derived endoscopy and derived pathology size was also available, which were considered more accurate. Full details of these methods are provided in Appendices 7 and 8.

Histopathology

In all patients for whom data were collected, including low-, intermediate- and high-risk patients, histological data were available for 66% of polyps (all types of polyps, including adenomas). In some cases (34%), data on histological features of a polyp were missing because no biopsies were taken, a pathology report could not be identified at the hospital, or the polyp in question was not retrieved at endoscopy or not mentioned in the pathology report. This value does not account for other sightings of polyps – they may have been removed at another examination – and we would expect some of these polyps to have been insignificant and therefore not excised. Rules were applied to the data to resolve such issues and derive polyp histology, where possible. First, if a polyp had any degree of villousness or dysplasia coded then the polyp was assumed to be an adenoma. If the polyp was ≥ 10 mm in size and no histology was recorded at any sighting of the polyp, the histology was set to ‘specimen not seen’ or ‘not able to diagnose’. If the polyp without histology was ≥ 10 mm in size and the patient had at least one adenoma recorded then the polyp was then assumed to be an adenoma.

A polyp seen at more than one examination may not have been diagnosed as an adenoma until a later sighting. As baseline started from first sighting of an adenoma, it was necessary to apply adenomatous histology back to earlier sightings, provided that the sighting without histology occurred no more than 3 years prior to the adenoma diagnosis. Adenomatous histology was applied to earlier sightings of a polyp only if the histology for the earlier sighting was unknown or recorded as hyperplastic, granulation tissue, previous polypectomy site, normal mucosa, not possible to diagnose, or specimen not seen; this ensured that histology of greater severity than an adenoma was not overwritten.

A single polyp seen at more than one examination could have different histological features recorded at each sighting. To resolve these inconsistencies, histological types encountered in the study were split into two groups: group 1 consisted of the outcomes of interest (CRCs and adenomas), along with all histological types that could potentially occur in such lesions over time (Table 6); group 2 consisted of all other histological types (data not presented). Group 1 histological types were listed from most to least severe within the following groups – CRC, possible CRC, benign lesion, no polyp features/not possible to diagnose – as shown in Table 6. When there was no clear-cut order in terms of malignant potential, histological types were arbitrarily ordered by the specificity of the description. Initially, polyps with histology from groups 1 and 2 recorded at different sightings were reviewed to check whether or not there was a reporting or coding error. Then, for remaining polyps with histology from both groups, group 1 histology took precedence for the purpose of this study, except when the group 1 histology was uncertain or unimportant (e.g. ‘normal mucosa’, ‘granulation tissue’, ‘previous polypectomy site’, ‘not possible to diagnose’ or ‘specimen not seen’), in which case the group 2 histology took precedence.

| Category | POLYP_TYPE |

|---|---|

| CRC | Cancer with remnant of sessile serrated lesion |

| Cancer with remnant of mixed/serrated adenoma | |

| Cancer with remnant of mixed adenoma | |

| Cancer with remnant of serrated adenoma | |

| Cancer with remnant of adenoma | |

| Cancer | |

| Possible CRC | Cancer or adenoma with HGD? (cancer in dispute) |

| Cancer with unknown primary | |

| Possible cancer (suspicious features but may be non-adenomatous) | |

| Benign lesion | Sessile serrated lesion |

| Mixed polyp (adenomatous and metaplastic features) | |

| Serrated adenoma | |

| Adenoma/assumed adenoma | |

| Unicryptal adenoma | |

| Metaplastic/hyperplastic polyp | |

| No polyp features/not possible to diagnose | Previous polypectomy site |

| Granulation tissue | |

| Normal mucosa | |

| Not possible to diagnose | |

| Specimen not seen |

The histology of adenomas was further defined using their greatest degree of villousness and worst dysplasia recorded within a visit.

Polyp location

The following rules were used to define a value for polyp location across all visits:

-

Where the segment was recorded at a surgical procedure, this took precedence over any segment recorded at other types of procedure.

-

If there was no surgical procedure, the most frequently described segment was taken.

-

If no segment was mentioned more frequently than another, the most distal segment was taken.

-

In cases where a segment range was given, the following rules were applied:

-

If only one range was described, the most proximal and distal segments were recorded on the database as the true range (proximal defined as descending colon to terminal ileum; distal defined as anus to sigmoid colon).

-

If several site ranges were described, the smallest segment range was used as the true range, provided that the difference in the position of the most proximal and distal segments in the range was ≤ 2. Table 7 was used to allocate a position to each segment in order to calculate this difference. If the segment range differed by more than two, the records were manually reviewed to reach a decision.

-

| Position | Segment |

|---|---|

| 1 | Ileum |

| 2 | Caecum |

| 3 | Ascending colon |

| 4 | Hepatic flexure |

| 5 | Transverse colon |

| 6 | Splenic flexure |

| 7 | Descending colon |

| 8 | Sigmoid colon |

| 9 | Rectosigmoid |

| 10 | Rectum |

| 11 | Anus |

Polyp shape

It was unclear if the most appropriate method for assigning the true shape of a polyp would be to use an order of precedence, as with other polyp characteristics, or if the first description might be the most accurate, as the shape of a polyp may have been altered once it was biopsied/resected. Shape values included flat, sessile, pedunculated or subpedunculated. It was decided that the first recorded shape of a lesion would be used.

Procedure information

Procedure date and order

In most cases, the procedure date was simply the date of the endoscopy. However, if the endoscopy report was not available, the pathology report was used to derive the examination date. Up to three dates might be specified on the pathology report. The examination date was derived using the following order of precedence:

-

date that the biopsy specimen was taken

-

date that the biopsy specimen was received at the laboratory

-

date of the pathologist’s report.

In the rare cases when it was not possible to derive a procedure date, the patient was excluded from the study. Where procedures occurred on the same day, the reasons were specified and the examinations were numbered to assign an order, otherwise it was specified why it was not possible to do so.

Procedure type

The master database contained two types of procedural report: endoscopy reports extracted directly from endoscopy databases and pathology-based procedure reports generated using clinical and procedural information from the pathology report. The latter were created by study researchers in cases when no endoscopy report was available.

In cases where the procedure type was not reported or not specified (e.g. ‘endoscopy’), procedure type was derived by applying a hierarchy of rules based on available information. For example, when a procedure type was unknown, yet there was evidence that the transverse colon or beyond was reached, the procedure type was probably a colonoscopy. When information such as bowel preparation and depth of insertion was given, the procedure was probably a colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS). Likewise, if a lesion with a size of ≥ 10 mm was removed, or multiple adenomas were removed, the procedure was also probably a colonoscopy or FS. Full details of rules for deriving procedure type are given in Appendix 7.

For some patients, it remained uncertain whether or not they had a baseline colonoscopy even after procedure type was derived (i.e. derived procedure type was ‘colonoscopy or FS’ at baseline). As patients had to have a baseline colonoscopy for inclusion in the study (a baseline colonoscopy was necessary to accurately stratify patients into risk groups), procedures that were derived as ‘colonoscopy or FS’ were reclassified as colonoscopies, based on adenoma risk group and type/timing of follow-up examinations. For example, patients with a derived procedure type of ‘colonoscopy or FS’ at baseline who were classified as IR or high risk (see Defining adenoma surveillance risk groups, below) were assumed to have had a colonoscopy at some point during baseline, and so the derived procedure was relabelled as such (see Appendix 7). Unlike baseline examinations, no derived procedure types were relabelled at follow-up examinations. Instead, for each follow-up visit, the most complete whole-colon examination available was defined using a hierarchy from ‘complete colonoscopy’ to ‘unknown procedure type’.

For patients without a baseline colonoscopy who had a colonoscopy at follow-up visit 1 (FUV1), the baseline visit was shifted so that FUV1 became the baseline visit and the original baseline visit became a ‘prior’ visit. To ensure that risk was not underestimated as a result of shifting baseline in this way, any adenomas found at prior examinations (original baseline) were used to determine risk as well as those found during the baseline visit.

Colonoscopy quality

Where there were several colonoscopies within a visit, the most complete examination and the best bowel preparation achieved at any colonoscopy was taken as the highest quality examination achieved at that visit. The quality and completeness of a colonoscopy was assessed, based on the segment of the colon reached, the most proximal polyp site, the quality of bowel cleansing prior to the examination and whether or not the examination was marked as incomplete.

The quality of the colonoscopy was important for defining visits (see Defining baseline and surveillance visits, below) as well as being a potential risk factor in the final data analysis.

Defining baseline and surveillance visits

For the purposes of this study, a ‘visit’ (baseline or follow-up) was defined as one or more examinations, performed in close succession, with the aim of completing a full examination of the colon and removing all detected lesions. This is based on the assumption that a single endoscopy is not always sufficient to visualise the entire colon (e.g. owing to poor bowel preparation) or to remove large, numerous or residual lesions.

Lesions found during the baseline visit were used to classify baseline risk of CRC and to stratify patients into adenoma surveillance risk groups (see Defining adenoma surveillance risk groups, below). In addition, certain diagnoses during baseline rendered the patient ineligible for the study, including CRC (see Patient eligibility, above). Follow-up visits were then defined around the baseline visit, with the length of time between visits being used to determine surveillance intervals.

Baseline visit

The baseline visit included the examination with the first adenoma sighting and any completion examinations that occurred within the subsequent 11 months. For high-risk adenomas, surveillance examinations are scheduled 1 year after the initial examination, in accordance with UK surveillance guidelines, so 11 months was chosen as the most appropriate time frame to capture any completion examinations into the baseline visit, without including high-risk follow-up examinations. After including all examinations within 11 months, a small proportion of patients had additional procedures that occurred shortly after the ‘latest’ baseline examination and thus needed to be included into the baseline visit. Baseline was therefore extended a second time, to include any examinations within 6 months of the latest baseline examination. Finally, in a handful of special scenarios, a third repeated extension was performed to capture examinations within 6 or 9 months of the latest baseline examination (6 months if the latest baseline examination was a colonoscopy and 9 months if it was a sigmoidoscopy). These rare cases included scenarios for which:

-

the latest baseline examination was incomplete

-

quality of bowel preparation at the latest baseline examination was poor

-

a large polyp (≥ 15 mm) was seen at the latest baseline examination

-

the same polyp was seen at the latest baseline examination and the next examination, which occurred within 6/9 months

-

the latest baseline examination was followed directly by a surgical examination.

After the extension of baseline, the length of baseline was assessed; only 2% of patients with IR adenomas had a baseline that exceeded 11 months in length.

Surveillance visits

A surveillance or follow-up visit was defined using similar rules for baseline. A follow-up visit comprised the first examination after baseline (or after a follow-up visit) and any further examinations within the subsequent 11 months. As with the baseline visit, the final examination in a follow-up visit was identified, and the follow-up visit was extended as necessary, using the same criteria as for the extension of baseline. This procedure was repeated until all examinations had been grouped into a follow-up visit. Visits following a diagnosis of CRC, volvulus or resection/anastomosis were censored, as patient follow-up would be affected by such diagnoses.

Surveillance interval

Surveillance intervals were timed from the last most complete examination of one visit to the first examination of the next visit, as defined in the NHS BCSP. 40

Defining adenoma surveillance risk groups

Once the baseline visit and true polyp values were defined, patients could then be stratified into adenoma surveillance risk groups. The risk groups were defined using the criteria for stratification of patients as low risk, intermediate risk or high risk, as described in the current UK Guideline (adopted by NICE). These definitions were applied based on all adenomas found within the baseline visit, and are given below. In addition, patients who could not be classified into a specific adenoma risk group were grouped into broader categories.

-

Low risk One or two small (< 10 mm) adenomas [no large (≥ 10 mm) adenomas or adenomas of unspecified size].

-

Intermediate risk Three or four small adenomas (no large adenomas or adenomas of unspecified size) or one or two adenomas, of which at least one is large.

-

High risk Five or more adenomas (any or unknown size) or three or more adenomas, of which at least one is large.

-

Low/intermediate risk One adenoma of unknown size or two adenomas, of which none is large but one or more has an unknown size.

-

Intermediate/high risk Three or four adenomas, of which none is large but one or more has an unknown size.

Patient follow-up

We matched our study patient data with records from external repositories of national patient data: HSCIC, NHSCR Scotland and NSS in order to achieve the following:

-

List clean patient records obtained from hospitals To correct patient information that had been entered incorrectly into hospital databases.

-

Identify duplicate records across hospitals Patients who had procedures at more than one hospital, and would have been allocated a different study number for each hospital where their data were collected.

-

Identify duplicate records in the same hospital Some patients were seen at the same hospital but, as a result of variations in patient identifiers, they had not been identified as the same patient.

-

Obtain cancers and deaths data Necessary to determine the incidence of CRC and the mortality status of patients in the cohort. The HSCIC provided the cancers and mortality data for patients residing in England or patients who resided in Scotland and had moved to England; the NHSCR provided the cancers and mortality data on patients who resided in England but had now moved to Scotland (the NHSCR and HSCIC work in partnership); and the NSS provided us cancers and mortality data on patients who resided in Scotland.

List cleaning

The patient-linking-file that was left at each hospital by the study programmer inevitably contained some patient identifiers that had been entered incorrectly into the hospital databases. It was therefore necessary to use the HSCIC/NHSCR’s list cleaning and tracing service and NSS’s linking service to validate and link the patient records to their database.

When the data sets were sent to HSCIC/NHSCR, no match was found for 5% of the patients. This revealed a limitation of having missing information, in that there was a higher chance of the supplied information matching more than one patient on the HSCIC database, resulting in rejection of a match. The study programmer worked closely with HSCIC to create bespoke matching algorithms that accounted for minor differences in dates of birth, names and NHS numbers in order to get the correct match, and, in some cases, additional data were collected from hospital to resolve the differences. Ultimately, matches were found for 99.65% of all 253,798 patients by the HSCIC/NHSCR and NSS.

Duplicate patient records

The national data repositories provided a list of duplicate patients found across the cohort (including patients from England/Wales and Scotland). When all of the duplicates had been identified, each set of duplicate records on our master database were merged into one record and an audit log was kept to show which records had been merged.

Cancer matching

Cancer and mortality (deaths) data for patients in our cohort were obtained from national patient data repositories (HSCIC, NHSCR Scotland and NSS). These data had to be added to the master database, taking into account the patient and cancer data already present, to ensure that there was no duplicated or missing data. This process was termed ‘cancer matching’.

To identify duplicate records of cancers, a program was written to identify CRCs in the national repositories’ data set and link them with the procedures and individual polyp records (including cancers) on the master database. Data quality checks were carried out, and samples of records that had been linked automatically were manually reviewed.

Cancers were linked to individual polyp records based on a hierarchy involving the cancer diagnosis date from the external source, the date the polyp or cancer was identified in the hospital data, the location of lesions, the polyp number, the time between the date of cancer diagnosis, and the date of the procedure during which the lesion was identified. For cancers reported in hospital pathology reports but not in national repositories, the hospital data were accepted as conclusive evidence of cancer, except when the histology was recorded by the study researcher as ‘cancer in dispute’ or ‘cancer query’.

The histology for cancers recorded on the study database as ‘in situ’ cancers and ‘cancers in dispute’ was compared with data from the national registries and automatically reclassified if necessary, using a hierarchy of rules. For example, polyps mapped to an in situ cancer from external sources were reclassified as ‘assume adenoma’ with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) if they were not already coded as such. Similarly, polyps in the database not mapped to a cancer from external sources, but with a histology recorded as ‘cancer in dispute’, were reclassified as ‘assume adenoma’ with HGD. A full list of the rules is given in Appendix 7 (see rule 13).

Values for the cancer diagnosis date, and site of the cancer, were assigned by comparing the data recorded on the study database with data from the national registries and applying a hierarchy of rules to arrive at the true value. For example, if the external cancer date preceded the mapped endoscopy date then the external date was used. Likewise for site, if no site was given in the mapped endoscopy data (or the site was non-specific), the site used in the external cancer data was used. A full list of the rules is given in Appendix 7 (see rule 11).

Variables

Outcomes

The primary outcome measures were adenoma, AA and CRC detected at the first and second follow-up visits, and CRC incidence after baseline, and after first follow-up. Previously seen lesions were excluded from some analyses, as they were thought to be a proxy measure for patients undergoing polypectomy site surveillance, and confounded the analysis. Outcomes that had not been seen at a previous visit were termed ‘new’ outcomes (see Chapter 3, New and previously seen lesions at first follow-up).

Advanced adenoma was defined as an adenoma of ≥ 10 mm, or with villous or tubulovillous histology, or HGD. CRCs were ascertained using pathological data recorded on the study database and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) codes in data from national repositories. To determine which cancers from the national repositories were outcomes of interest, they were grouped according to site and morphology (details are given in Appendix 7, rules 11 and 13). Only cancers from national repositories that fell into the site groups ‘malignant lesions of the colon/rectum’ and certain ‘in situ neoplasm – colon’ were selected for the study. Specifically, outcomes included adenocarcinomas of the colorectum and carcinomas with unspecified morphology located between the rectum and caecum that were assumed to be adenocarcinomas. Cancers with unspecified morphology located at sites related to the anus were likely to be squamous cell carcinomas and were therefore not classed as outcomes unless they were linked to a rectal lesion, in which case they were assumed to be adenocarcinomas. CRCs reported as a cause of death in national repositories were classed as outcomes if the patient did not have cancer recorded in the cancer registry or hospital data.

Colorectal cancer sites were defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) ICD versions ICD-8, ICD-9 and ICD-10, and included site codes C18–C20 (www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/). Morphology of colorectal neoplasia was coded with the Manual of Tumor Nomenclature and Coding codes,41 the WHO International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) ICD-O-1 codes42 and ICD-O-2 codes. 43

Exposures

The main exposures of interest were the length of the surveillance interval between baseline and first follow-up, and between the first and second follow-ups. The surveillance interval was defined as the period of time from the last most complete colonic examination at one visit to the first examination of the next visit (as in the NHS BCSP). 40 In order to define interval, a patient’s examinations were split into baseline and follow-up visits (see Defining baseline and surveillance visits, above). Interval length was then calculated and converted into a categorical variable with seven groups: > 18 months, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 years (all ± 6 months) and ≥ 6.5 years. Patients with the shortest interval were used as a reference group to compare with those who were exposed to a longer interval.

The other exposure of interest was the effect of adenoma surveillance on risk of CRC after baseline. Patients who attended at least one follow-up visit at which cancer was not diagnosed were considered to be exposed to surveillance.

Risk factors and potential confounders

Patient, procedural and polyp characteristics at baseline and follow-up were assessed as a priori risk factors and confounders; these included age and gender, examination quality (based on completeness of examination, quality of bowel preparation and difficulties encountered), calendar year of examination and hospital attended, and the number, size, location and histology of polyps and adenomas, villousness and dysplasia. All potential risk factors and confounders examined are listed and defined in Table 8.

| Factor | Definition |

|---|---|

| Number of adenomas | Total number of adenomas seen during a visit |

| Size of adenoma | Size of the largest adenoma seen during visit |

| Villousness of adenoma | Worst degree of villousness of an adenoma seen during visit |

| Dysplasia of adenoma | Worst degree of dysplasia of an adenoma seen during visit |

| Distal or proximal adenomas | Detection of distal or proximal adenoma(s) at a visit. Proximal defined as descending colon to terminal ileum; distal defined as anus to sigmoid colon |

| Distal or proximal polyps | Detection of distal or proximal polyp(s) of any type, including adenomas, at a visit. Proximal defined as descending colon to terminal ileum; distal defined as anus to sigmoid colon |

| Age, years | Age of patient at time of visit |

| Gender | Gender of patient |

| Length of visit | Total length of a visit (in days, months or years) |

| Number of examinations | Total number of examinations that make up a visit |

| Most complete examination | Most complete procedure during visit (at baseline this was based on colonoscopy). Completeness was determined from segment reached by scope or location of polyp(s). A complete colonoscopy was one during which the scope reached, or polyps were found in, the caecum or beyond. If no colonoscopy was performed during the visit then the next most complete procedure type was used |

| Best bowel preparation at colonoscopy | Best bowel preparation at a colonoscopy during a visit. If there was no colonoscopy then this was classified as ‘no known colonoscopy’ |

| Difficult examination | Composite variable of examination quality. Ascertained from endoscopy report information. Coded ‘yes’ if there was poor bowel preparation, the maximum segment was not reached (i.e. caecum for colonoscopy, sigmoid colon for sigmoidoscopy) and another indicator of poor examination quality was provided, such as patient discomfort, looping, technical difficulty, equipment failure, etc. |

| Number of sightings of a unique adenoma | The greatest number of times an adenoma was seen during a visit |

| Number of hyperplastic polyps | Total number of hyperplastic polyps in a visit |

| Number of large hyperplastic polyps | Total number of large (≥ 10 mm) hyperplastic polyps in a visit |

| Number of polyps with unknown histology | Total number of polyps for which there is no histology available |

| Calendar year | Year during which the visit took place |

| Hospital | Hospital at which the visit took place |

| Family history of cancer/CRC reported | Patient has a family history of cancer or CRC indicated at an examination during or prior to a visit |

Grouping of variables

All of the aforementioned risk factors were considered separately for the baseline visit and FUV1. In some instances it was necessary to add an additional level to a variable; for example, at FUV1 some patients did not have any adenomas or a colonoscopy, whereas at baseline every individual had an adenoma and a colonoscopy. The quantitative variables interval length and calendar year were grouped into categorical variables for some analyses and used in their continuous form in other circumstances. The remaining quantitative variables (visit length, age, adenoma size, number of examinations, number of sightings of a unique adenoma and numbers of specific polyp types) were grouped into categorical variables. Standard categorisations were created for all categorical variables and these were used in the presentation of univariable results. When appropriate, the process of selecting risk factors for inclusion in multivariable models involved the investigation of the categorisation of some variables, and the final categorisation was selected by evaluating the difference in effect between levels of the variable. When data were missing for a particular variable, an ‘unknown’ category was created in order to avoid losing patients from the models, particularly those models adjusting for several confounders. Models were tested with, and without including, the ‘unknown’ category to assess the difference it made.

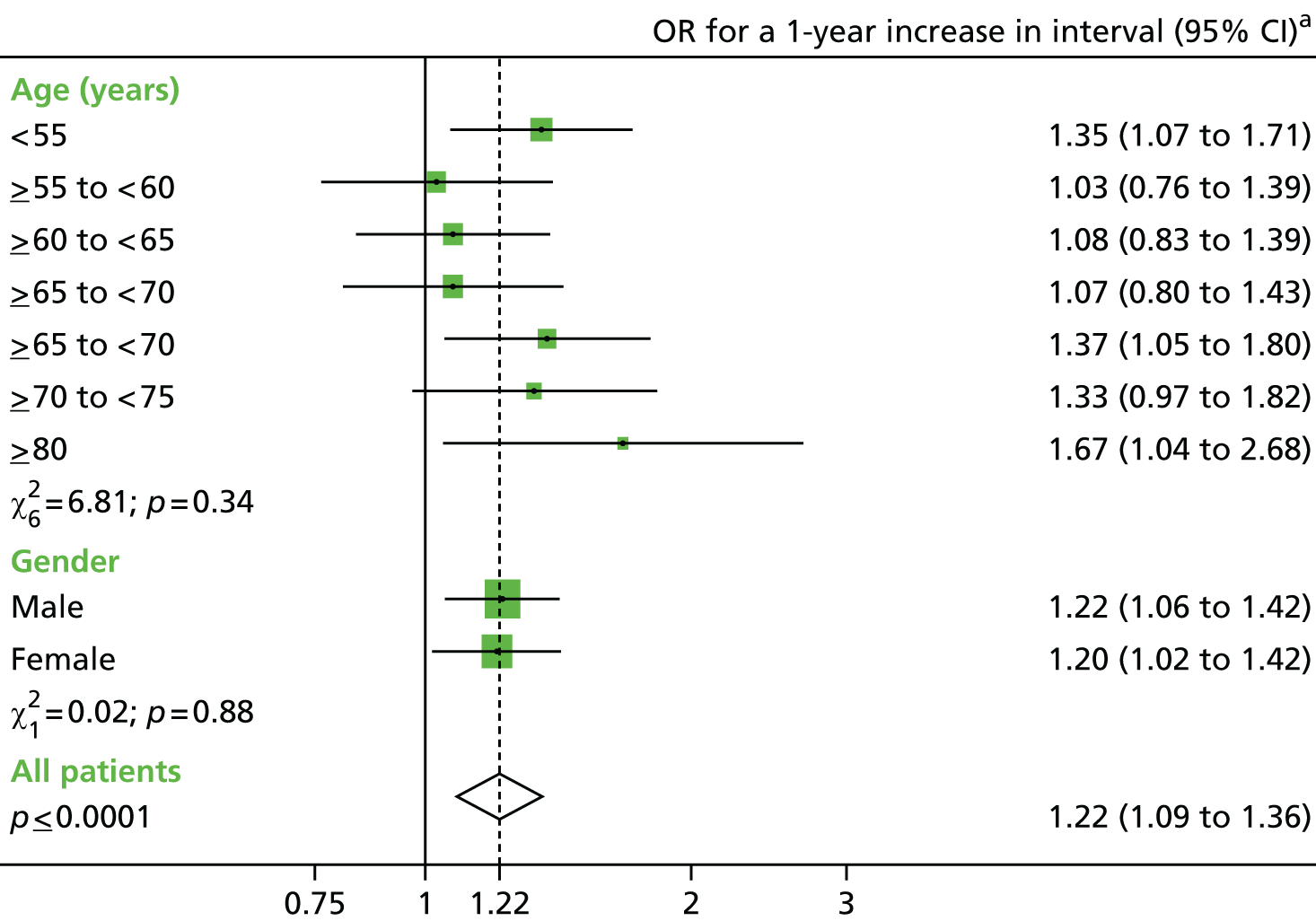

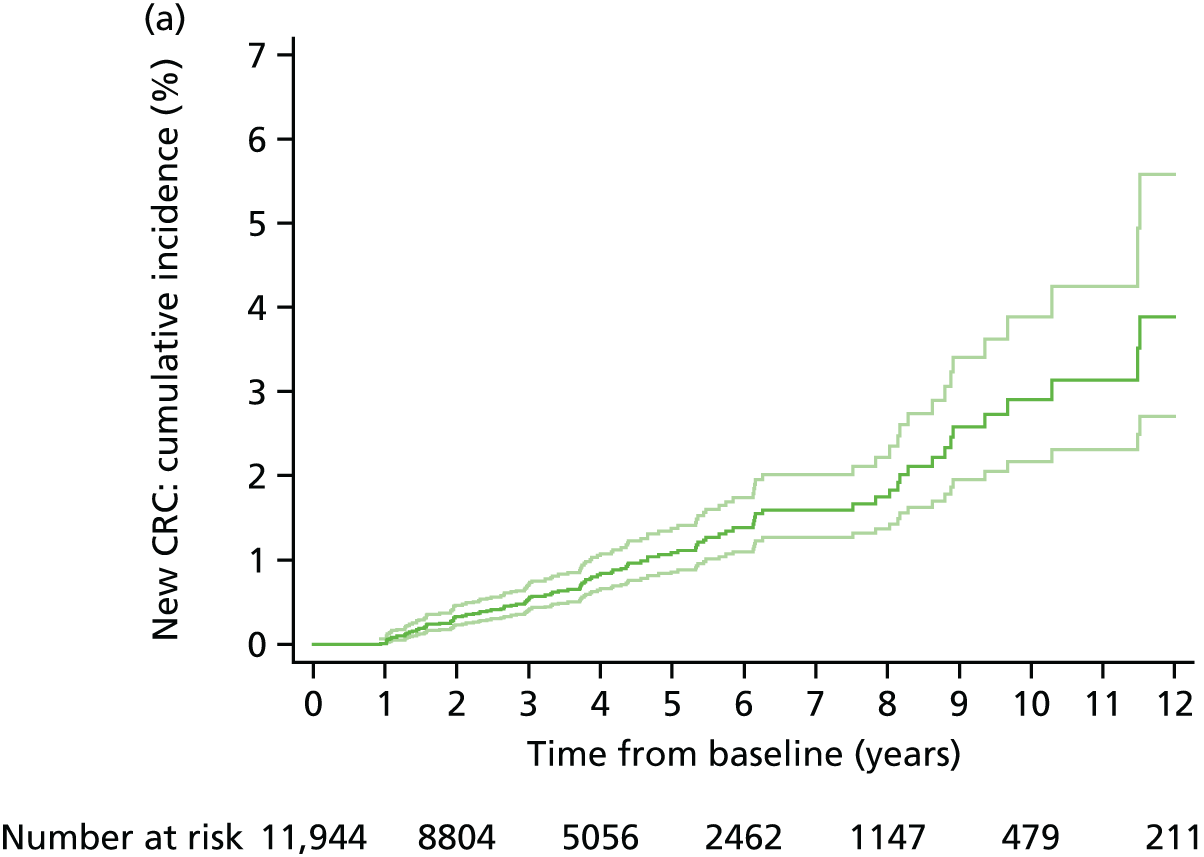

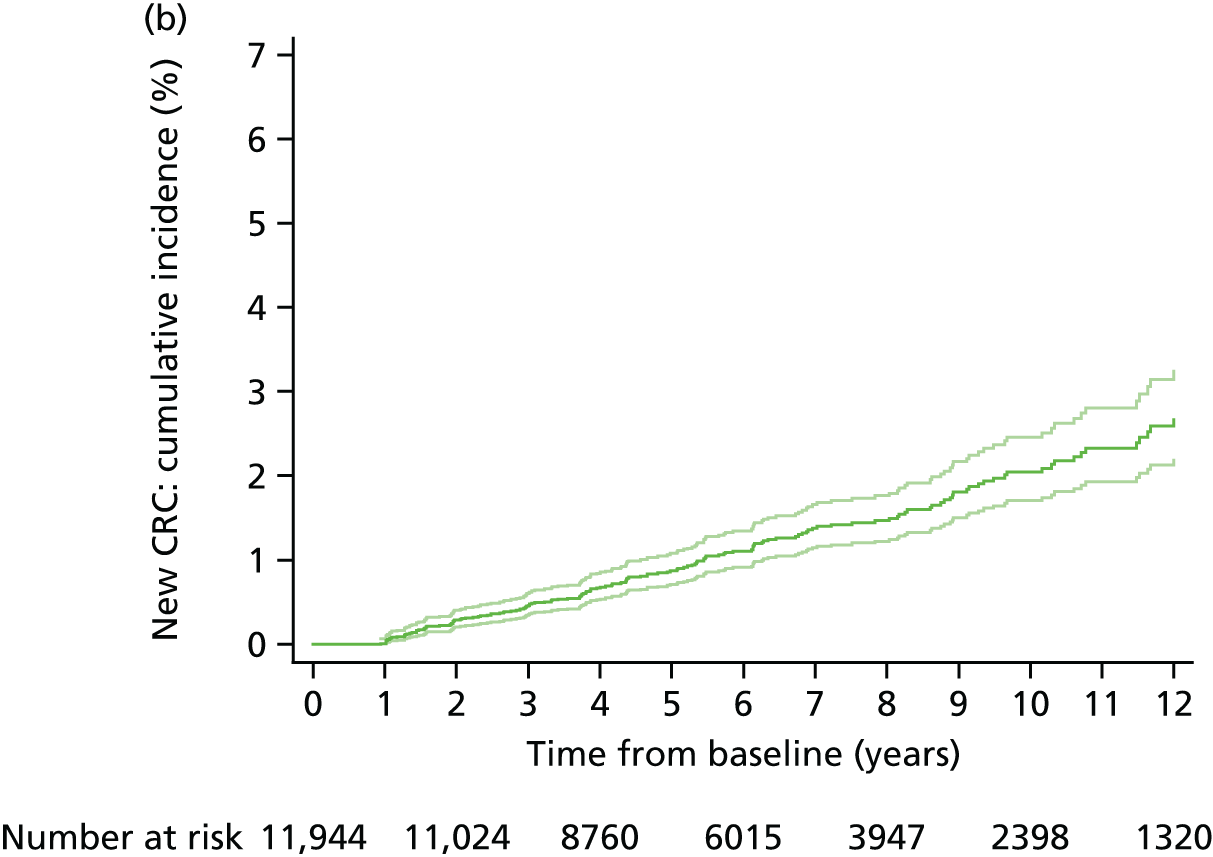

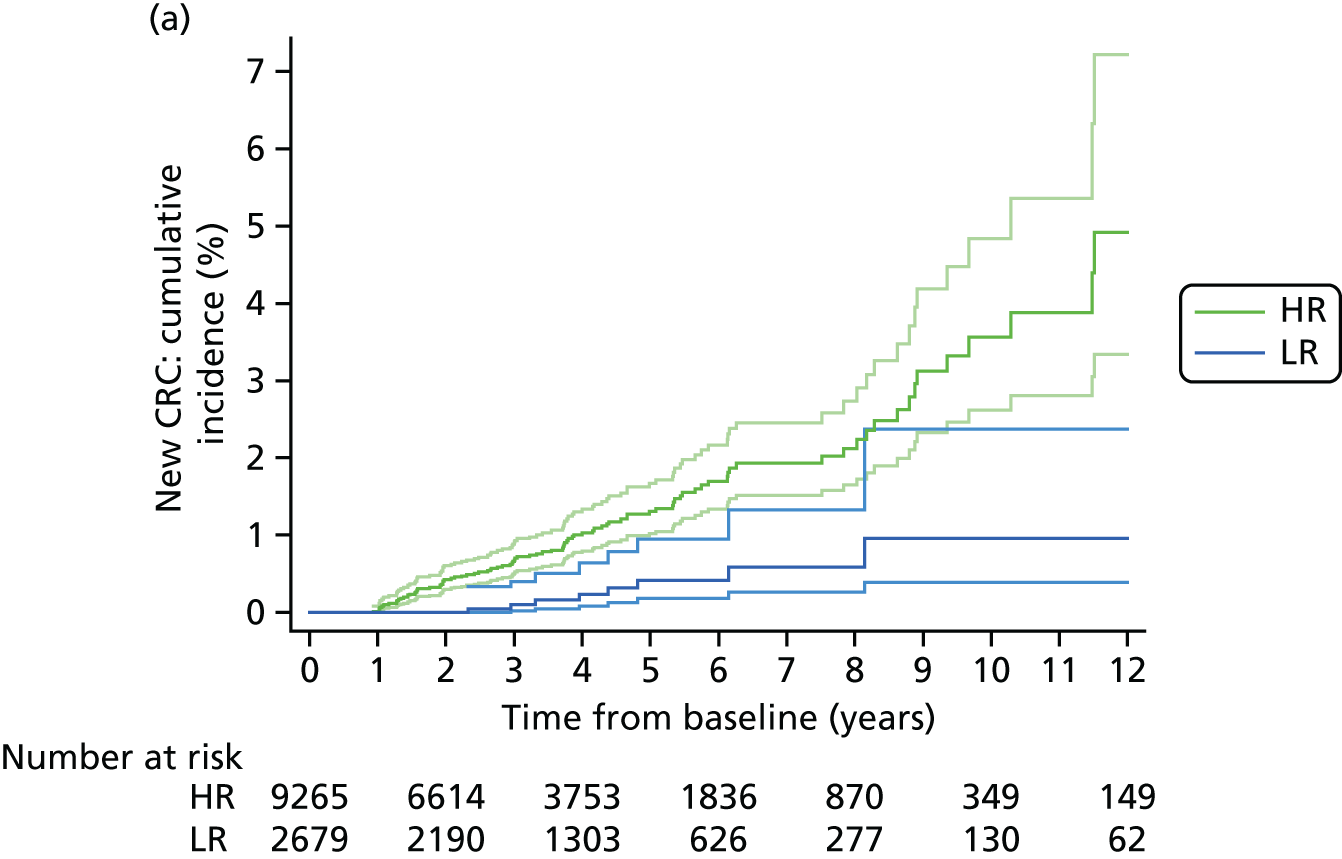

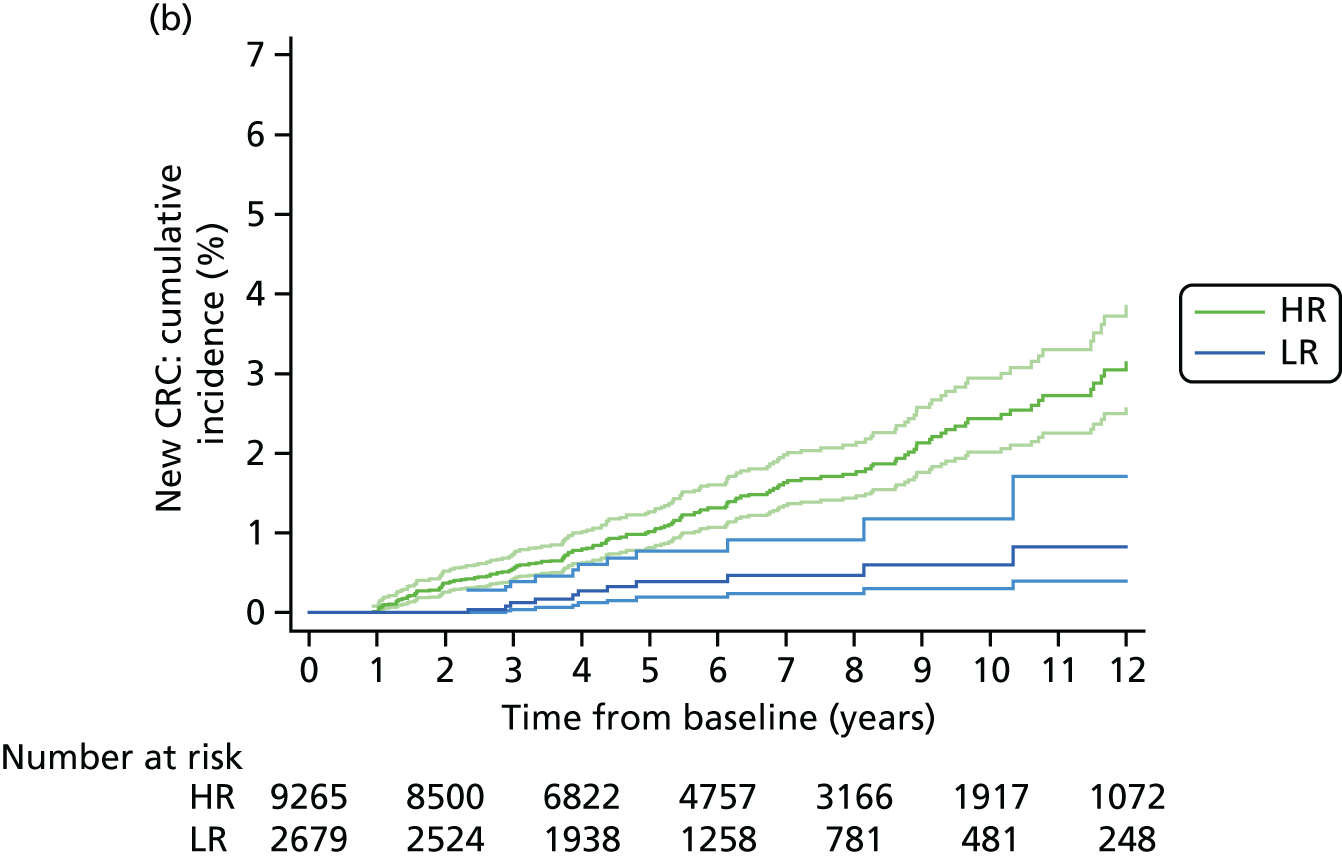

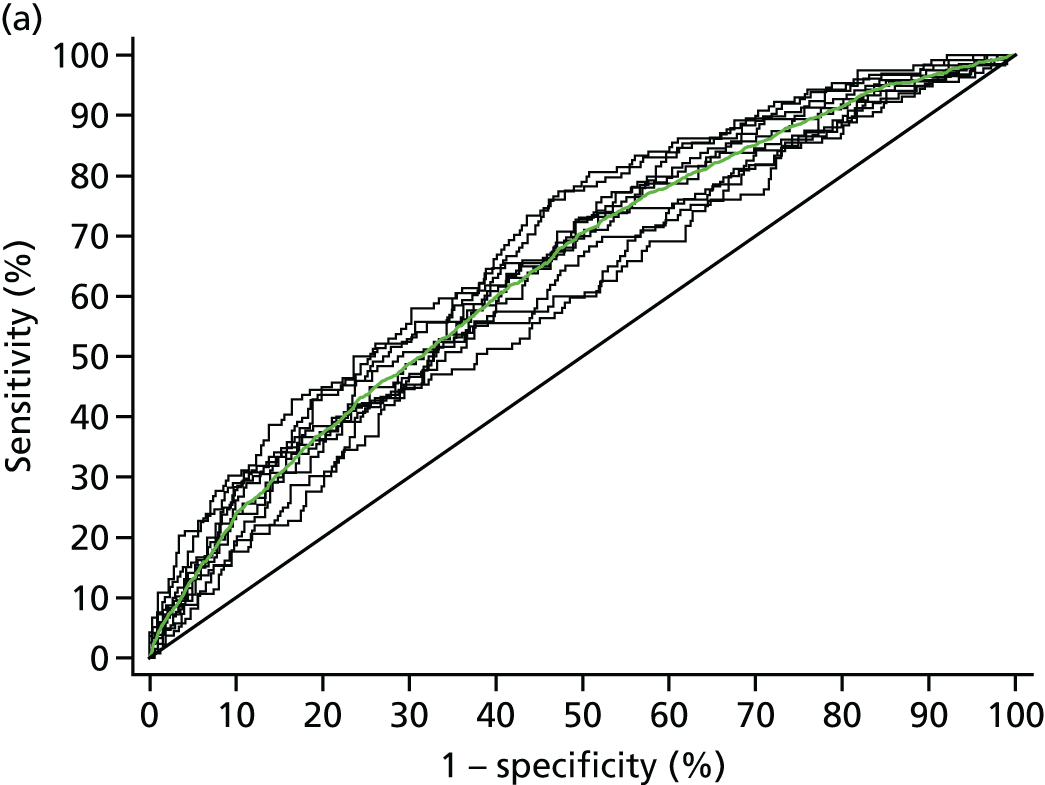

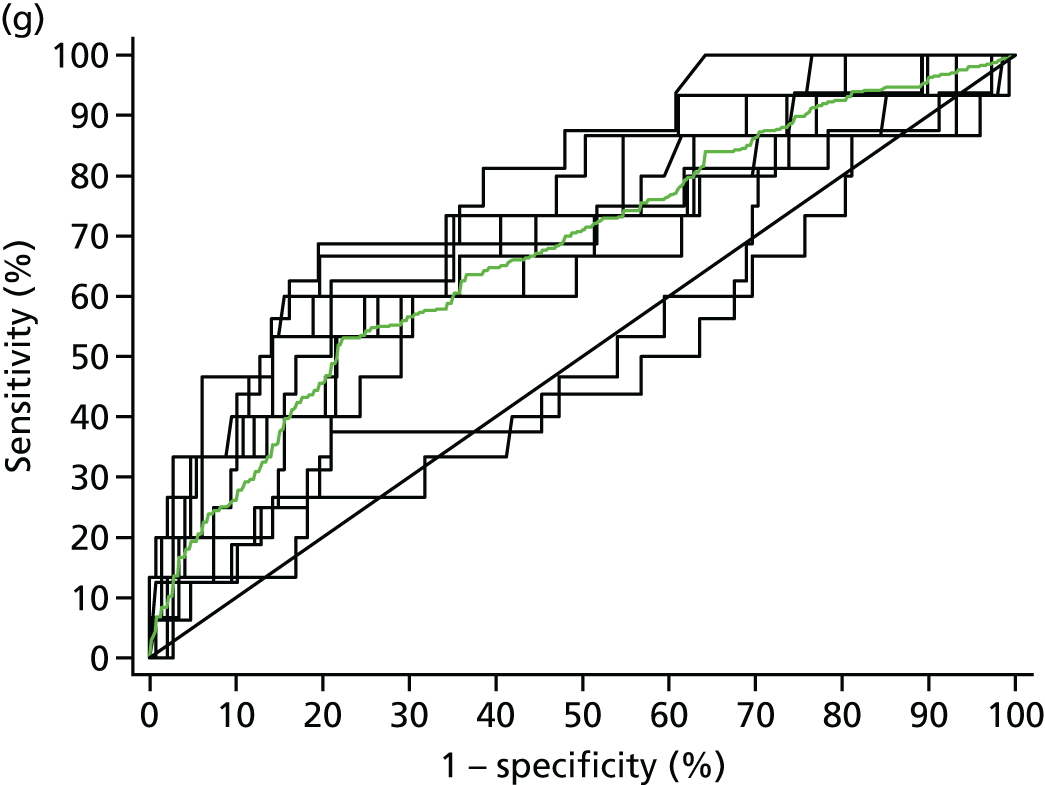

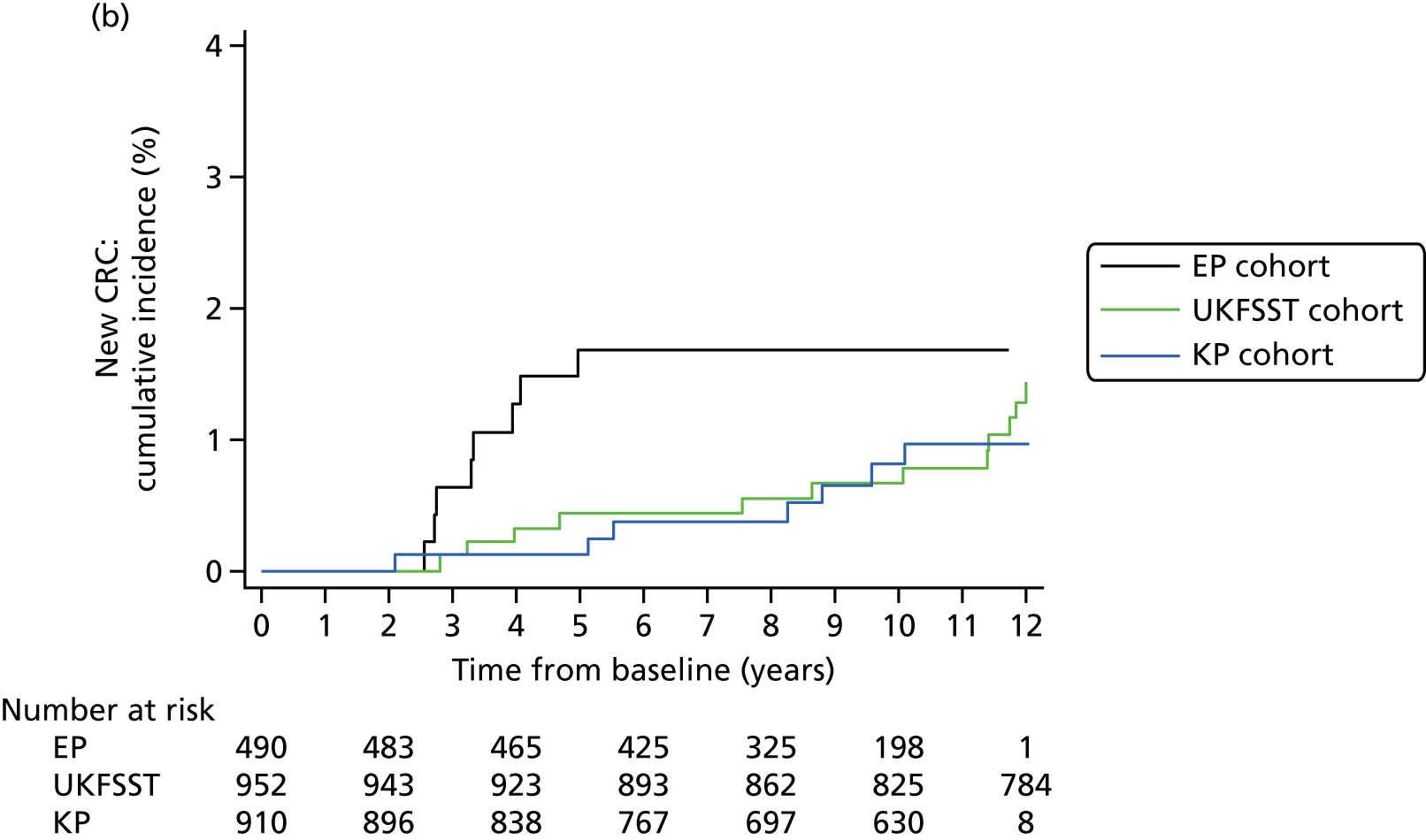

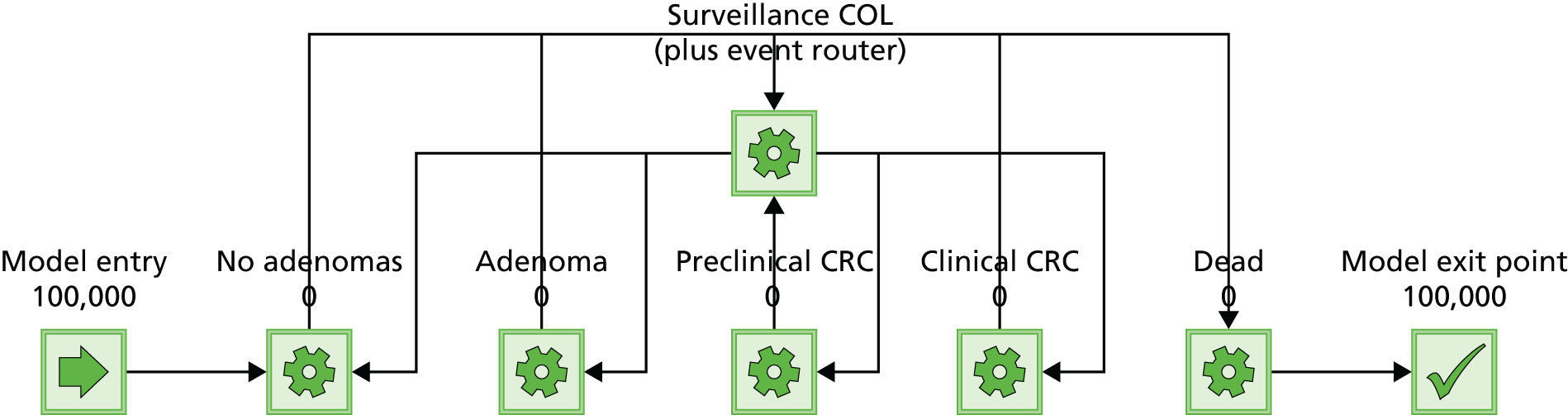

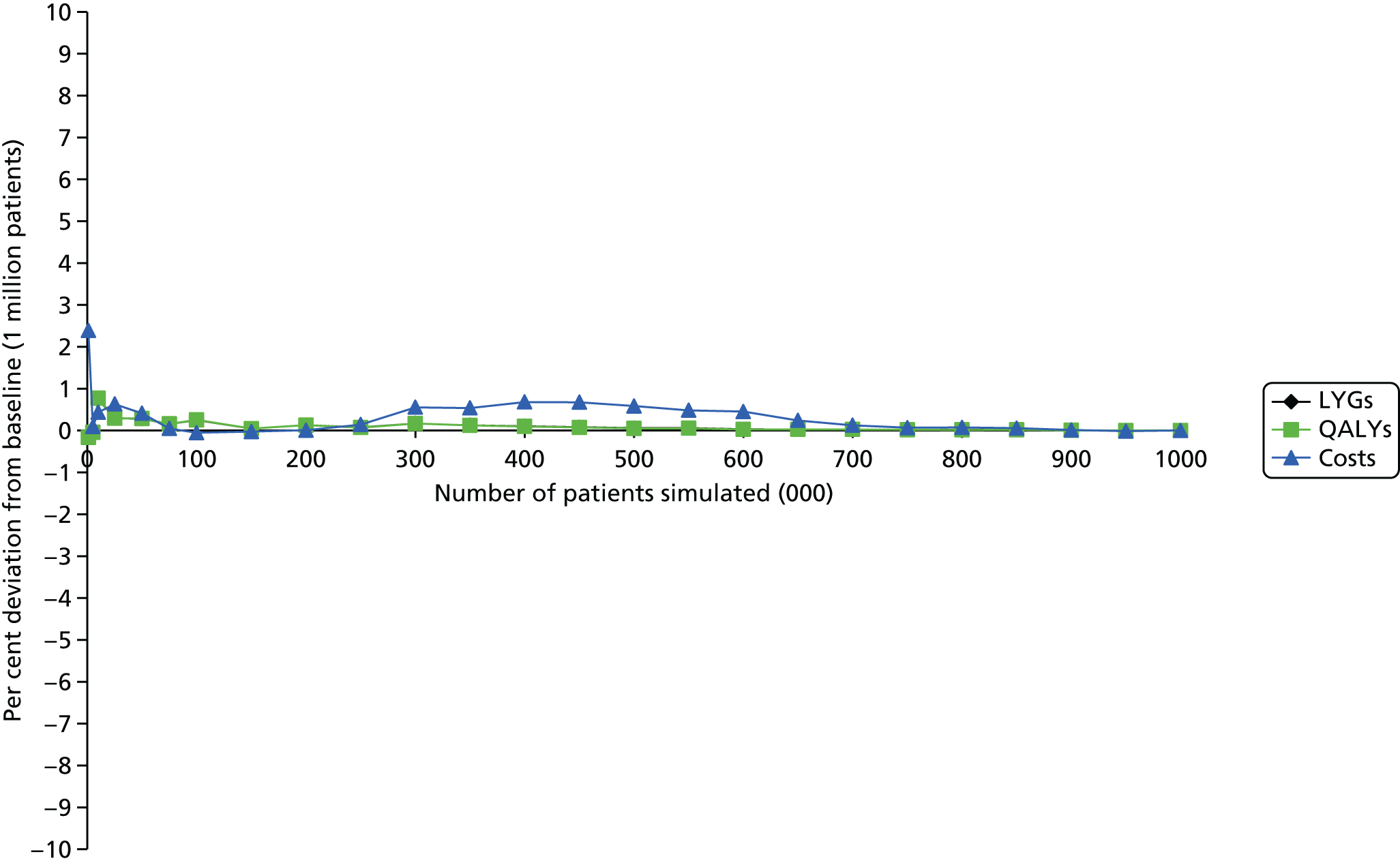

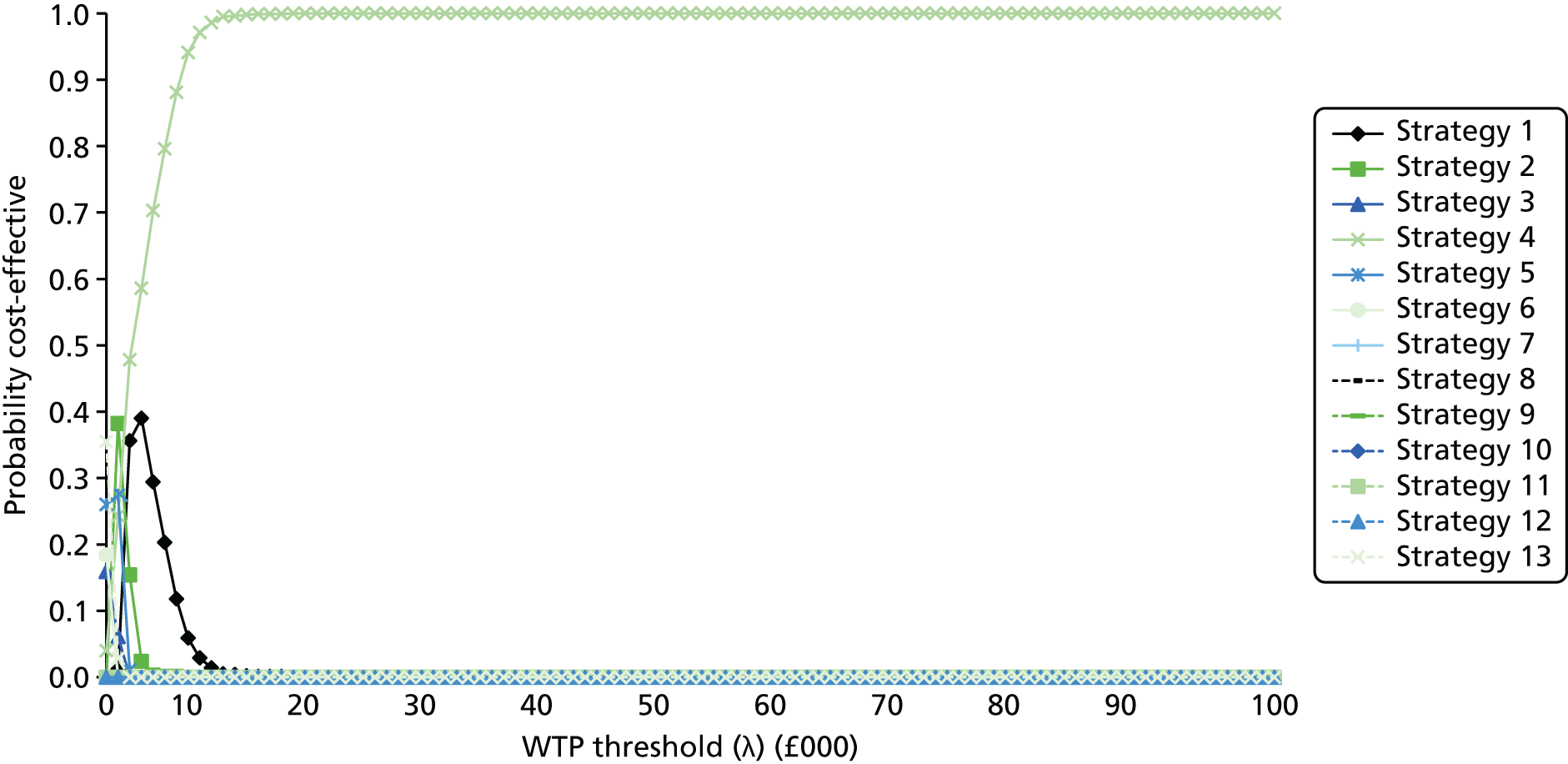

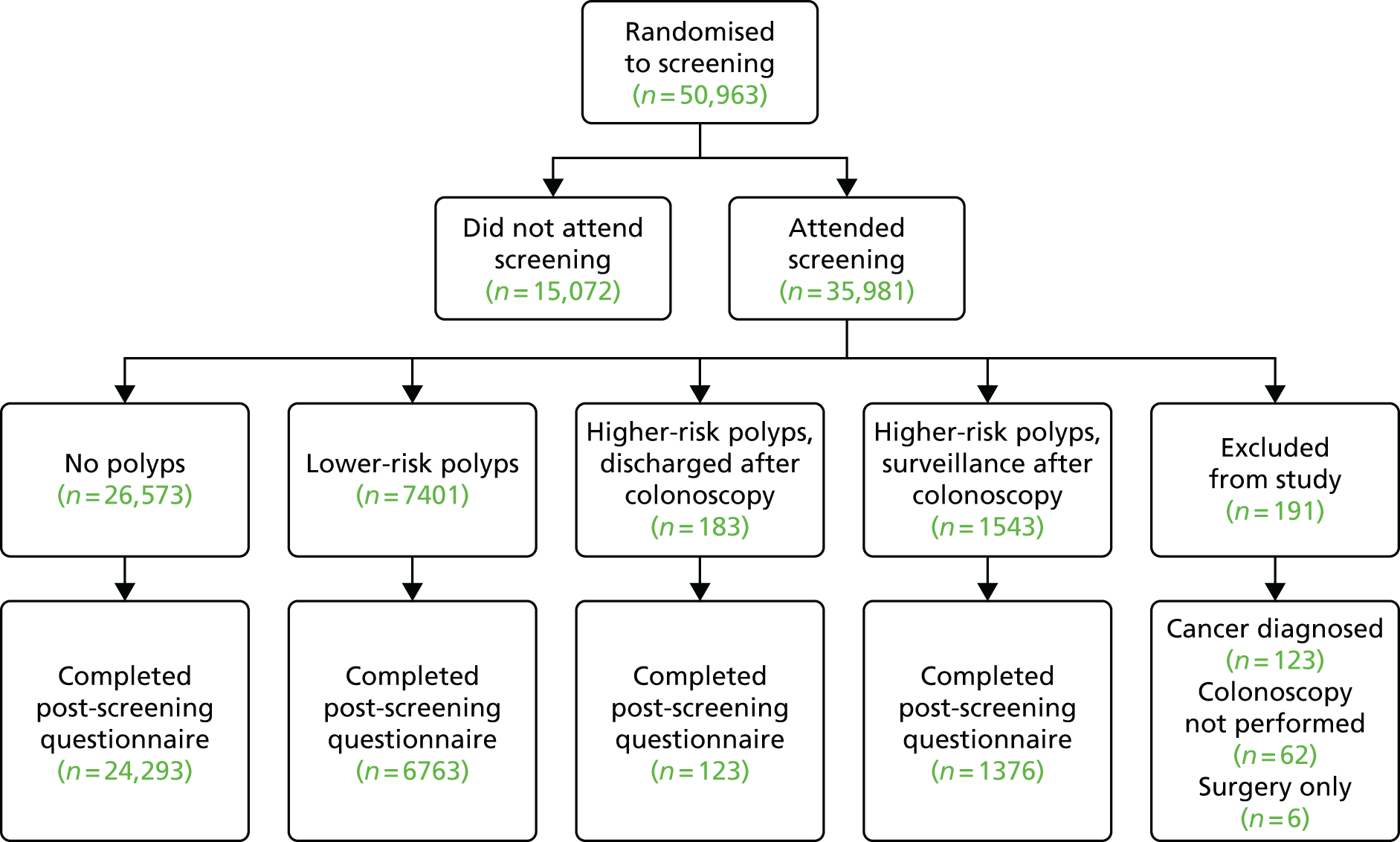

Study size