Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/50/14. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The draft report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

All authors report grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the course of the study. David A Richards reports grants from the European Science Foundation. David A Richards and Rod S Taylor have received funding support from NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care. David A Richards reports NIHR Clinical Development and Senior Clinical Fellowship and Senior Investigator Panel memberships. Rod S Taylor reports membership of NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme themed call, NIHR HTA Efficient Study Designs Board and NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Boards. Simon Gilbody reports membership of the NIHR HTA Evidence Synthesis Board and NIHR HTA Efficient Study Designs Board. Willem Kuyken reports fees from Guilford Press for book royalties and Collaborative Case Conceptualisation.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Richards et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter uses material from Open Access articles previously published by the research team (see Rhodes et al. 1 and Richards et al. 2). © Rhodes et al. ;1 licensee BioMed Central Ltd. 2014 This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated and © The Author(s). 2 Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY license.

Scientific background and review of current literature

Clinical depression is one of the most common and debilitating of the psychiatric disorders. It accounts for the greatest burden of disease among all mental health problems, and is the second largest cause of global disability. 3 Lifetime prevalence has been estimated at 16.2% and rates of comorbidity and risk for suicide are high. 4–6 Depression is often recurrent, and without treatment many cases become chronic, lasting > 2 years in one-third of individuals. Over three-quarters of all people who recover from one episode will go on to have at least one more. 7 In the UK, depression and anxiety are estimated to cost the economy £17B in lost output and direct health-care costs annually, with a £9B impact on the Exchequer through benefit payments and lost tax receipts. 8 Globally, the economic impact of depression on aggregate economic output is predicted to be US$5.36 trillion between 2011 and 2030. 9

Reducing these substantial costs is a key objective for low-, medium- and high-income countries alike. Antidepressant medication (ADM) and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) are the two treatments with most evidence of effectiveness, both of which are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 10 Problems with ADM include side effects, poor patient adherence and relapse risk on ADM discontinuation. Service user organisations and policy think tanks advocate greater availability of psychological therapies, which many people prefer. 11 CBT, which is of similar efficacy to ADM,12 has several advantages: (1) it reflects the desire of many service users for non-pharmacological treatment; (2) it has no physical side effects; and (3) it modifies the illness trajectory in that benefits continue after the end of treatment, preventing recurrence. 13 However, CBT has several disadvantages: (1) its complexity makes it difficult to learn to implement in a competent fashion; (2) its efficacy is dependent on the skill of the individual practitioner; (3) patients are required to learn quite high-level skills; and (4) the high cost of training and employing sufficient therapists limits access to CBT.

As a consequence of the disadvantages above, many people do not receive adequate treatment, and, even when treatment is given, many respond only partially or not at all. 14 Despite the recent government initiative in England – ‘Improving Access to Psychological Therapies’ (IAPT; URL: www.iapt.nhs.uk/) – no more than 15% of people with depression will receive NHS-delivered CBT, and only 50% receiving CBT will recover. 15 It is therefore important to continue to test promising new treatments, especially if there are indications that such treatments reduce the risk of symptom return, are applicable to a wide range of depressed people including those with severe disease, are easy to implement in clinical practice and are therefore potentially more accessible,16 and are a cost-effective use of resources.

Globally, health services require effective, easily implemented and cost-effective psychological treatments for depression that can be delivered by less specialist health workers in order to close a treatment gap that can be as much as 80–90% in some low-income countries. 17 The English NHS, in order to meet public and professional expectations, requires a simple, equivalently effective, easily implemented psychological treatment for depression which can be delivered by less specialist (albeit appropriately competent) junior mental health workers (MHWs) to treat many more people with depression in a more cost-effective manner.

Rationale for the research

Behavioural activation (BA) is a psychological treatment based on behavioural theory that alleviates depression by focusing directly on changing behaviour. 18–20 This theory states that depression is maintained by avoidance of normal activities. As people withdraw and disrupt their basic routines, they become isolated from positive reinforcement opportunities in their environment. The combination of increased negative reinforcement with reduced positive reinforcement results in a cycle of depressed mood, decreased activity and avoidance which maintains depression. 19 BA systematically disrupts this cycle, initiating action in the presence of negative mood, when people’s natural tendency is to withdraw or avoid. 21,22 Although CBT incorporates some behavioural elements, these focus on increasing rewarding activity and initiating behavioural experiments to test specific beliefs. In contrast, BA targets avoidance from a contextual, functional approach not found in CBT (i.e. BA focuses on understanding the function of behaviour and replacing it accordingly). BA also explicitly prioritises the treatment of negatively reinforced avoidance and rumination. Furthermore, the BA rationale is easier to understand and operationalise for both patients and MHWs than CBT, which also focuses on increasing activity, but primarily on changing maladaptive beliefs. 23 Moreover, there is some evidence that CBT is less effective when delivered by less competent therapists. 12,24

In the UK, CBT is delivered by professionally qualified senior MHWs (mainly clinical psychology, nursing, occupational therapy, social work or counselling), who have obtained a further 1-year, full-time postgraduate qualification in CBT. Their training is long and expensive and their employment grade is costly compared with junior MHWs, who deliver much of the routine mental health care in the UK. The relative simplicity of BA treatment may make it easier and cheaper to train junior MHWs in its application than CBT, the argument of ‘parsimony’ first advanced by one of the early proponents of this approach, Neil Jacobson. 19 However, this is appropriate only if BA delivered in this way is as effective as, and more cost-effective than, CBT.

Limitations of previous trials

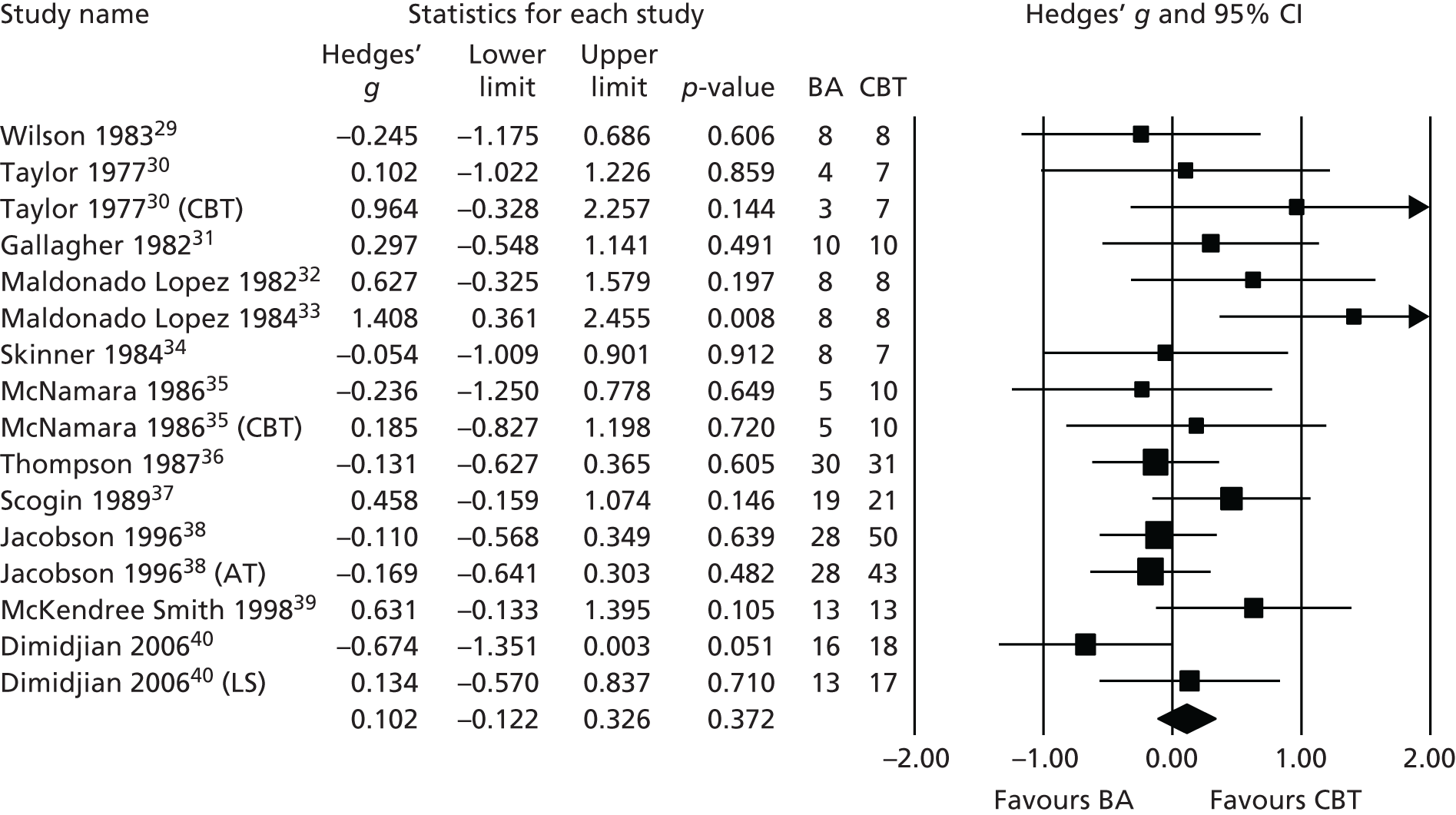

A number of systematic reviews have attempted to address the more general question of BA effectiveness compared with CBT. 10,25–28 All have commented on the relatively poor quality of component studies. We conducted a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of BA,25 and identified 12 studies with a total of 476 patients. At the primary end point we found no difference between the groups on depression symptom level [Hedges’ g = 0.102, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.122 to 0.326; I2 = 29%; p = 0.372] (Figure 1). At follow-up we found no difference between the groups on depression symptom level (Hedges’ g = 0.395, 95% CI −0.032 to 0.822; I2 = 61%; p = 0.070).

FIGURE 1.

Meta-analysis of pre-COBRA (Cost and Outcome of BehaviouRal Activation) trial BA vs. CBT primary outcome point, all included studies. AT, automatic thoughts; LS, low severity.

In a subsequent update of this review26 we found no additional trials comparing BA with CBT. Many of the trials included in our review were of limited methodological quality, all were underpowered for comparing treatments, and most did not utilise diagnostic interviews for trial inclusion. Treatments in many cases did not conform to modern clinical protocols for BA. Long-term outcomes were rarely reported, with average follow-up only to 4 months. These results have been replicated in two recent Cochrane reviews of behavioural therapies,27,28 which concluded that there was only low- to moderate-quality evidence that behavioural therapies and other psychological therapies were equally effective and called for ‘Studies recruiting larger samples with improved reporting of design and fidelity to treatment to improve the quality of the evidence’. 27

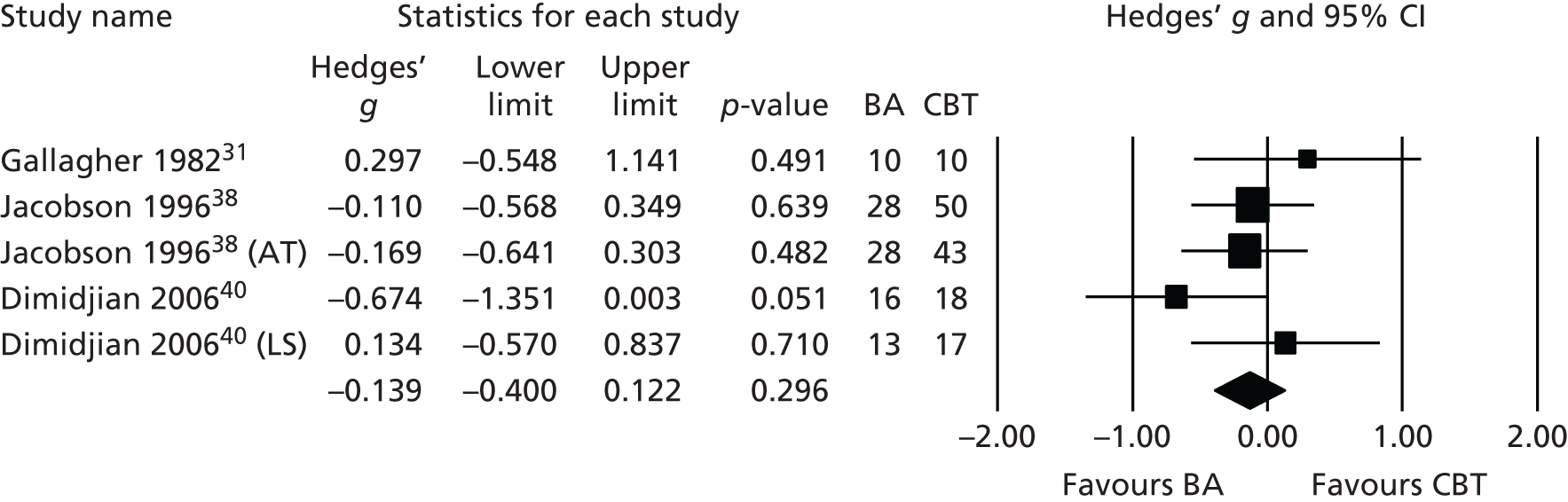

Most significantly, NICE10 reviewed the same evidence and regarded only a small subset of three trials31,38,40 as of sufficient quality to be able to contribute evidence of effect (Figure 2). In those studies no difference was found between BA and CBT at primary end point (Hedges’ g = 0.139, 95% CI –0.4.00 to 0.122; I2 = 1%; p = 0.296) or at follow-up (Hedges’ g = 0.135, 95% CI –0.456 to 0.186; I2 = 0%; p = 0.409).

FIGURE 2.

Meta-analysis of pre-COBRA (Cost and Outcome of BehaviouRal Activation) trial BA vs. CBT, subset of high-quality included studies in NICE review. AT, automatic thoughts; LS, low severity.

The conclusion of the NICE Guideline Development Group was that that the evidence base for BA was not ‘sufficiently robust’ for it to be recommended as an alternative to CBT. It was suggested that BA could be an option for clinicians, but the limited evidence base should be considered when making this treatment choice. 10 Consequently, NICE made a clear research recommendation ‘to establish whether behavioural activation is an effective alternative to CBT’ using a study which is ‘large enough to determine the presence or absence of clinically important effects using a non-inferiority design’ (p. 256). 10

Pilot work preceding this trial

In order to test uncertainties around our main objectives, we piloted BA in a Phase II RCT to examine whether or not MHWs without previous specialist training in psychological therapy can effectively treat depressed people using BA. 41 We compared BA against usual care. Relatively junior NHS MHWs (‘band 5’ – equivalent to a basic grade, qualified mental health nurse) with no previous formal training or experience in psychotherapy delivered BA. These workers received 5 days’ training in BA and, subsequently, 1 hour of clinical supervision, fortnightly, from a clinical nurse consultant or trained psychotherapist. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses indicated a difference in favour of BA of −15.79 points (n = 47, 95% CI −24.55 to −7.02 points) on depression (as measured via the Beck Depression Inventory-II), an effect size of −1.15 standard deviation (SD) units (95% CI −0.45 to −1.85 units). We also found a quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) difference in favour of BA of 0.20 points (95% CI 0.01 to 0.39 points; p = 0.042), incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £5756 per QALY and a 97% probability that BA is cost-effective at a threshold value of £20,000. 41

Conclusion

From our literature reviews and pilot work we concluded that BA was a potentially viable treatment for depression when delivered by junior MHWs, but that, as NICE had suggested, a non-inferiority trial of BA versus CBT was required to test whether or not BA was non-inferior to CBT and if BA could be a potentially cost-effective alternative to CBT for depression. We now report the results of this randomised trial to determine if BA is non-inferior to CBT in the treatment of patients with depression. This report is divided into chapters detailing the methods and results of our primary clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness questions followed by a chapter for our process evaluation. We conclude with a discussion chapter summarising our results and considering their implications for the treatment of depression in the UK and internationally.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter uses material from Open Access articles previously published by the research team (see Rhodes et al. 1 and Richards et al. 2). © Rhodes et al. ;1 licensee BioMed Central Ltd. 2014 This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated and © The Author(s). 2 Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY license.

Research objectives

-

To assess the clinical effectiveness of BA compared with CBT for depressed adults in terms of depression treatment response at 12 and 18 months.

-

To assess the cost-effectiveness of BA compared with CBT in terms of QALYs at 18 months.

In addition, we undertook a secondary process evaluation to investigate the moderating, mediating and procedural factors in BA and CBT that influence outcome, the methods for which are covered in Chapter 4.

Study design

We undertook a research assessor-blinded, multicentre, two-arm, non-inferiority, patient-level RCT for people with depression, to test the effectiveness of a psychological intervention for depression, BA, against the current gold standard, evidence-based treatment, CBT. We included clinical, economic and process evaluations. The rationale for a non-inferiority trial is that we needed to establish whether or not the clinical effectiveness of BA is not substantially inferior to CBT. Therefore, we powered our trial on the basis of clinical non-inferiority, and analysed our data accordingly. 42,43

Patient and public involvement

We involved patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives at all stages of the project. A PPI advisor (NR) was a full member of the Trial Management Group (TMG). He attended all meetings of the TMG and advised on patient-facing materials, including ethics materials and participant therapeutic manuals, and on the conduct of the trial including project management, questionnaire development, data collection and project dissemination. There was a PPI representative on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) from a depression consumer advocacy group who provided important checks and balances as part of the independent TSC oversight of the trial.

All sites had excellent local PPI mechanisms. We followed national good practice guidance for researchers on public involvement in research and the paying of PPI representatives actively involved in research. 44 We also worked with our PPI representatives to ensure that our dissemination strategies were inclusive and accessible to other people who use services. In addition, the trial was co-ordinated from the University of Exeter’s Medical School. The Medical School operates within a culture of PPI – guided by published theories of participation, empowerment and engagement – through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaborations in Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for the Peninsula Public Involvement Group.

Setting and participants

We recruited participants over a 20-month period from September 2012 to April 2014. Potential participants were identified by clinical studies officers (CSOs) or practice staff from the electronic case records of primary care and psychological therapy services in Devon, Durham and Leeds, indicating that the person had been identified as currently depressed at least once during the previous 2 months. Practices or services contacted patients to seek permission for researcher contact. The research team interviewed those who responded, provided detailed information on the study, took informed consent and assessed people for eligibility.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion

People aged ≥ 18 years with a major depressive disorder (MDD) as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) were eligible to take part in the study. 45 Researchers were trained to administer the SCID using established training and inter-rater reliability procedures in use at the University of Exeter for all of our trials.

Exclusion

People who were alcohol or drug dependent, acutely suicidal or cognitively impaired, had bipolar disorder, psychosis or psychotic symptoms, ascertained at baseline by research interviews, were excluded. We also excluded people currently undergoing psychological therapy.

Randomisation, concealment of allocation and blinding

Following interview, participants were allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio to either the BA or CBT arm stratified according to their symptom severity on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)46 (PHQ-9 of < 19 vs. ≥ 19 points), ADM use (currently using ADM or not) and recruitment site. The registered Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU) allocated participants remotely after the researchers had collected and entered baseline data into a computer database to ensure researcher blinding and allocation concealment. Investigators were not informed of participants’ allocations. The computer-based system allocated the first 20 participants to each arm on a truly random basis. For subsequent participants, allocation was minimised to maximise the likelihood of balance in stratification variables across the two study arms. Concealment was ensured by the use of a password-protected trial website and retaining a stochastic element to the minimisation algorithm. The computer-based allocation and website were set up and maintained by PenCTU, independent of the trial. The participant’s details were then sent to the relevant MHW to alert them to contact this person and begin treatment. The general practitioner (GP) was then informed of their patient’s involvement in the study.

In this type of trial, in which interventions are complex and clearly different from each other, it is not possible to blind participants or clinicians, so our procedures focused on helping to keep research workers blind to participant allocation and by protecting the study against assessment interpretation bias through the use of self-report measures. All research measures were applied to both groups, and researchers were instructed to maintain blindedness by reminding participants at follow-up of the need not to discuss their treatment with the researcher. We recorded instances where researchers were unblinded by patients disclosing their treatment during interviews.

Sample size calculation

We estimated the non-inferiority margin for the primary outcome (PHQ-9) using two potential approaches with reference to (1) the effect size of historical trials comparing BA versus control; and (2) the published minimum clinically important difference for the primary outcome (PHQ-9) of 2.59 to 5.00 points. 47 Based on our meta-analysis, BA was superior to control in depression score by a mean of 0.7 SD units (95% CI 0.39 to 1.00 SD units) or 3.8 PHQ-9 points (95% CI 2.1 to 5.4 PHQ-9 points) (assuming a SD of 5.4 from Lowe et al. ). 47 It has been proposed that non-inferiority margins be taken as ≈0.5 × mean control effect size (i.e. 0.5 × 3.8 = 1.90 points) or as the lower 95% limit of the control effect size (i.e. 2.1 points). 48,49 To ensure the adequacy of this trial to test non-inferiority between BA and CBT, we therefore examined a number of potential scenarios taking into account the potential uncertainty in the non-inferiority margin for the primary outcome.

We selected a conservative non-inferiority margin of 1.90 points and power of 90%. As a consequence, we needed to recruit a total of 440 participants to detect a between-group non-inferiority margin of 1.90 points in PHQ-9 at one-sided 2.5% alpha, allowing for 20% attrition caused by dropouts and protocol violators. Furthermore, although previous trials of CBT have shown little or no effects of clustering in outcome by therapists, even when delivering group CBT,50,51 if we were to assume a small therapist clustering effect (i.e. intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.01), this sample size would still have 80% power for a non-inferiority margin of 1.90 points on the PHQ-9 at one-sided 2.5% alpha, allowing for 20% attrition.

Our sample size was inflated by 20% for participant dropout to take account of participants who might exit the trial and refuse follow-up assessment, although our experience in running large primary care trials of depression treatment is that attrition rates would be less than this. Therefore, we planned to recruit 440 participants to the trial, 220 per arm. A summary of the sample size calculations is provided in Table 1.

| Approach | MCID (points) | Power (%) | Attrition rate (%) | Sample size per groupa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% BA control effect size | 1.90 | 90 | 20 | 220 |

| 50% BA control effect size | 1.90 | 80 | 20 | 160 |

| LCI BA control effect size | 2.10 | 90 | 20 | 180 |

| LCI BA control effect size | 2.10 | 80 | 20 | 135 |

| Lower MCID | 2.59 | 90 | 20 | 120 |

| Lower MCID | 2.59 | 80 | 20 | 90 |

Recruitment

Randomised controlled trials are vulnerable to selection bias and threats to external validity if there are systematic differences in behaviour between referring clinicians. We minimised this potential bias by recruiting participants through searching general practice records and referral logs from primary care to local depression and anxiety treatment services rather than by direct referral from GPs. We identified suitable participants by examining electronic case records for all patients in each general practice or treatment service. The search was conducted by practice staff or Clinical Research Network CSOs, identifying people with at least one identification code for depression recorded against their name in the last 2 months. In primary care practices we searched for the codes most widely used by GPs to classify participants as depressed. The list of potentially suitable participants was reviewed by GPs to identify any patients whom had known exclusion criteria. The remaining patients were written to, inviting them to take part in the study. For patients already referred to local psychological therapies services, we contacted those on the waiting list. Letters were sent with a short participant information sheet, stamped and addressed envelope and a ‘Permission for Researcher to Contact’ form to allow a researcher to contact them. If potential participants did not return the form, they were contacted by telephone by practice staff or practice-based Clinical Research Network CSOs to check that they had received the letter and asking them if they wished to participate in the Cost and Outcome of BehaviouRal Activation (COBRA) trial. Potential participants identified were interviewed by researchers on the telephone to confirm the presence of depressive symptoms and to explain the trial fully. If positive on the screen, potentially eligible participants were interviewed face to face by researchers to confirm eligibility, take consent, conduct a diagnostic interview and collect baseline measures. Eligible, fully informed and consenting participants were then entered into the study and randomised.

From our experience of previous trials, we calculated that 37% of potential participants interviewed at baseline would be likely to decline participation, would not meet our inclusion criteria or would meet one of the exclusion criteria. Therefore, we were required to interview 700 potential participants in order to induct our planned sample size of 440 eligible participants into the trial. Following random allocation of 440 participants, a maximum of 20% attrition would lead to our target sample size of 366 participants.

In order to identify 700 people for baseline interview, we planned to contact around 3400 potential participants through letter and/or telephone to inform them of the trial and offer them the chance to participate. In order to do so, we needed to identify 5300 potential participants from a sensitive coded search of practice case note records, as our existing data predicted that 1900 (approximately 36%) of these would be excluded by GPs against known trial exclusion criteria. Identifying 5300 potential participants was expected to generate at least 700 positive replies.

For an average-size practice of 7000 registered patients, we expected that searches would be likely to identify around 37 potentially eligible participants per search. Four searches per practice would, therefore, identify 148 potential participants per practice. Consequently, we planned to recruit at least 36 practices (12 per site) to identify sufficient potential participants to meet our target number of 5300.

Trial interventions

We developed our BA and CBT intervention protocols in line with (a) published treatment protocols,19,21,22,40,53,54 including that developed for BA and CBT in our trials;41,55 (b) advice from national and international collaborators (Martell, Dimidjian, Hollon); and (c) NICE recommendations10 for duration, and frequency, of BA and CBT. To recognise realities of real-world clinical presentations, our protocols included behavioural and cognitive strategies for managing comorbidity, particularly anxiety, where this is present in addition to depression. Therapists were able to provide participants with a maximum of 20 sessions over 16 weeks with the option of four additional booster sessions. 10

Behavioural activation

The overall goal of BA is to re-engage participants with stable and diverse sources of positive reinforcement from their environment and to develop depression management strategies for future use. MHWs delivering BA followed a written treatment manual. Sessions were face to face, of 1 hour duration, with the option of being conducted up to twice weekly over the first 2 months and weekly thereafter. The sessions consisted of a structured programme increasing contact with potentially antidepressant environmental reinforcers through scheduling and reducing the frequency of negatively reinforced avoidant behaviours. The central behavioural technique was a functional analysis of the participant’s problems, based on a shared formulation drawn from the behavioural model in the early stages of treatment, thereafter developed with the patient throughout their sessions. Specific BA techniques included the use of a functional analytical approach to develop a shared understanding with patients of behaviours that interfere with meaningful, goal-oriented behaviours and included self-monitoring, identifying ‘depressed behaviours’, developing alternative goal-orientated behaviours and scheduling. In addition, the role of avoidance and rumination was addressed through functional analysis and alternative response development incorporating recent trial evidence. 56

We selected MHWs from NHS Agenda for Change (AfC) band 5 staff, such as mental health nurses and psychological well-being practitioners (PWPs),52 who received 5 days’ training in BA. In line with the programme developed and tested in our Phase II trial,41 training focused on the rationale and skills required to deliver the BA protocol for depression and included sections on behavioural learning theory and its application to depression, developing individualised BA formulations and specific techniques used in sessions. Training was a mix of presentation and role-play with repeated practice and feedback. Workers were competency-assessed at the end of training using standardised marking criteria consistent with the BA protocol and further training was given if competency was not demonstrated in practical clinical exercises. BA workers received 1 hour of clinical supervision, fortnightly, from the three site leads or other members of the trial team who were clinically qualified in BA.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

The overall goal of CBT is to alter the symptomatic expression of depression and reduce risk for subsequent episodes by correcting the negative beliefs, maladaptive information processing and behavioural patterns presumed to underlie the depression. Therapists delivering CBT followed a written treatment manual. Sessions were face to face, of 1 hour duration, with the option of being conducted up to twice weekly over the first 2 months and weekly thereafter. The sessions consisted of a structured, collaborative programme. Treatment began with agreeing a problem list and goals for therapy, participants learning the CBT model, behavioural change techniques, and moved on to identifying and modifying negative automatic thoughts, maladaptive beliefs and, if indicated, underlying core beliefs. In later sessions, learning was translated to anticipating and practising the management of stressors that could provoke relapse in the future. Specific CBT techniques included scheduling activity and mastery behaviours, the use of thought records and modifying maladaptive beliefs and rumination content. The behavioural elements in CBT focused on increasing activity with practical behavioural experiments to test specific cognitive beliefs. CBT did not take the contextual, functional analytical approach of the BA trial arm.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy was delivered by NHS AfC band 7 senior MHWs with a specialist postgraduate diploma in ‘high-intensity’ CBT from an accredited university course. The CBT therapists also received a 5-day orientation training to the specific COBRA trial CBT protocol, including its adaptation for comorbidities, cognitive theory of depression, developing individualised cognitive formulations and specific techniques used in sessions. Therapists were competency-assessed at the end of training using standardised marking criteria consistent with the CBT protocol and further training was given if competency was not demonstrated. CBT therapists also received a subsequent 1 hour of clinical supervision, fortnightly, from established supervisors in the three sites with advice from other members of the trial team who were clinically qualified in CBT.

Outcomes

An overview of our data collection timings is presented in Table 2.

| Data | Source of data | Timing of data collection | Months after baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Gender, age, ethnic origin, education level, employment, marital status, number of children, presence or absence of ADM treatment, previous history and age at onset of depression, duration of any ADM treatment, and presence of any comorbid anxiety disorder | CRF | Baseline | |||||

| Primary outcome | PHQ-9 | CRF | Baseline | 6 | 12 | 18 | ||

| Secondary outcomes | DSM-IV depression status | CRF | Baseline | 6 | 12 | 18 | ||

| Number of depression-free days | CRF | 6 | 12 | 18 | ||||

| SF-36 | CRF | Baseline | 6 | 12 | 18 | |||

| Economic data | EQ-5D-3L | CRF | Baseline | 6 | 12 | 18 | ||

| AD-SUS | CRF | Baseline | 6 | 12 | 18 | |||

| Process evaluation data | Age at depression onset | CRF | Baseline | |||||

| Number of previous depression episodes | CRF | Baseline | ||||||

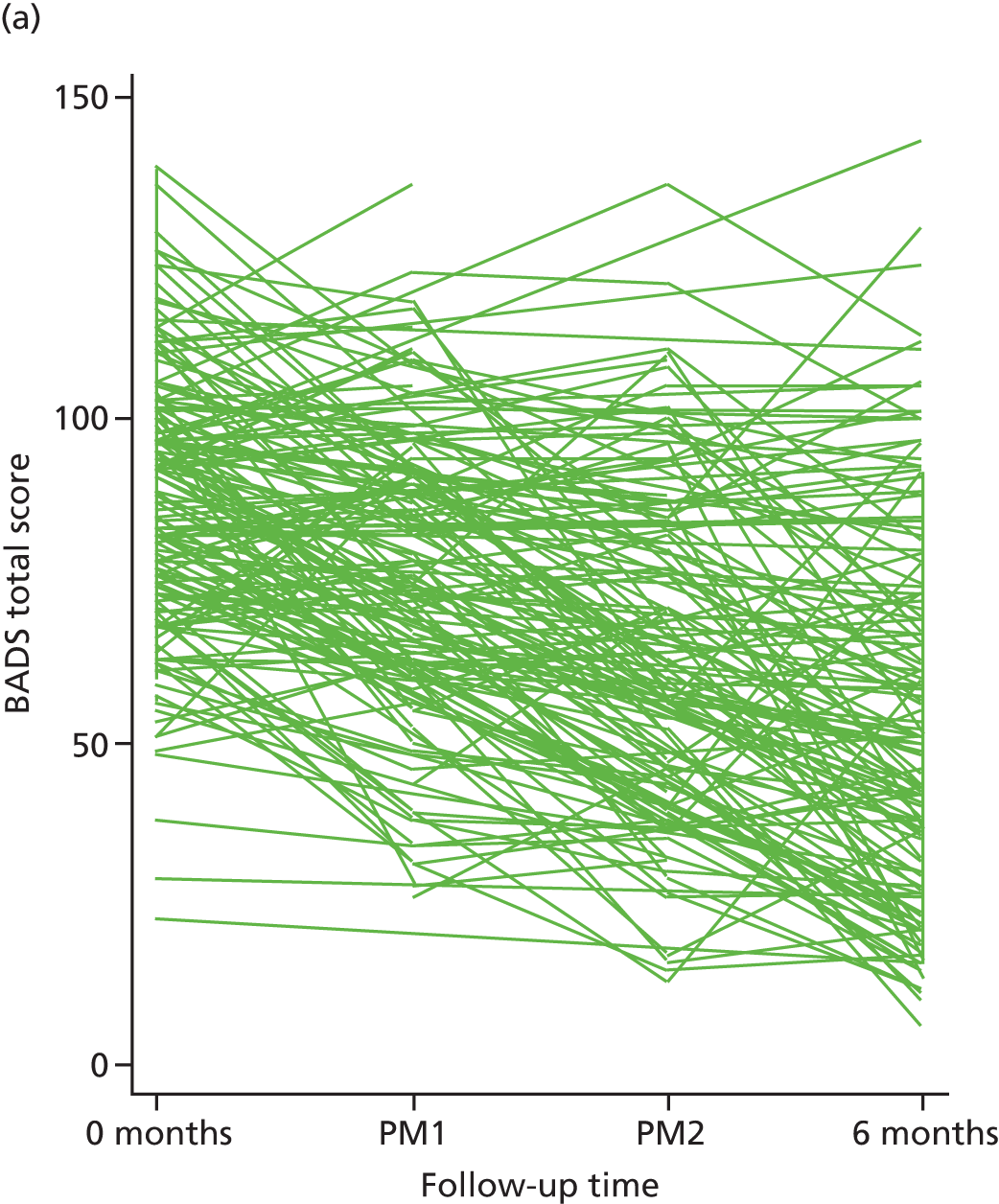

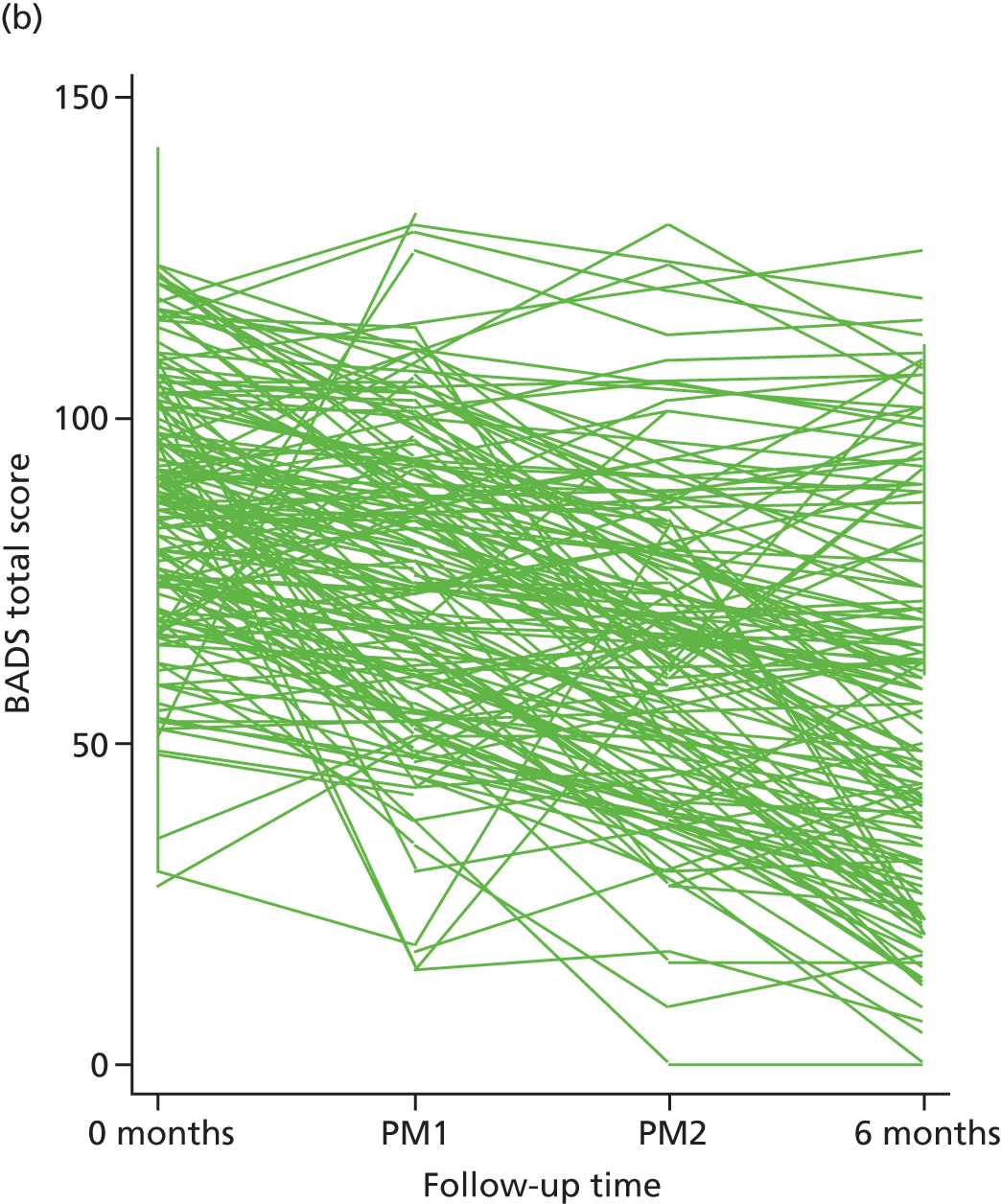

| BADS | CRF | Baseline | Therapy session 4 | Therapy session 7 | 6 | |||

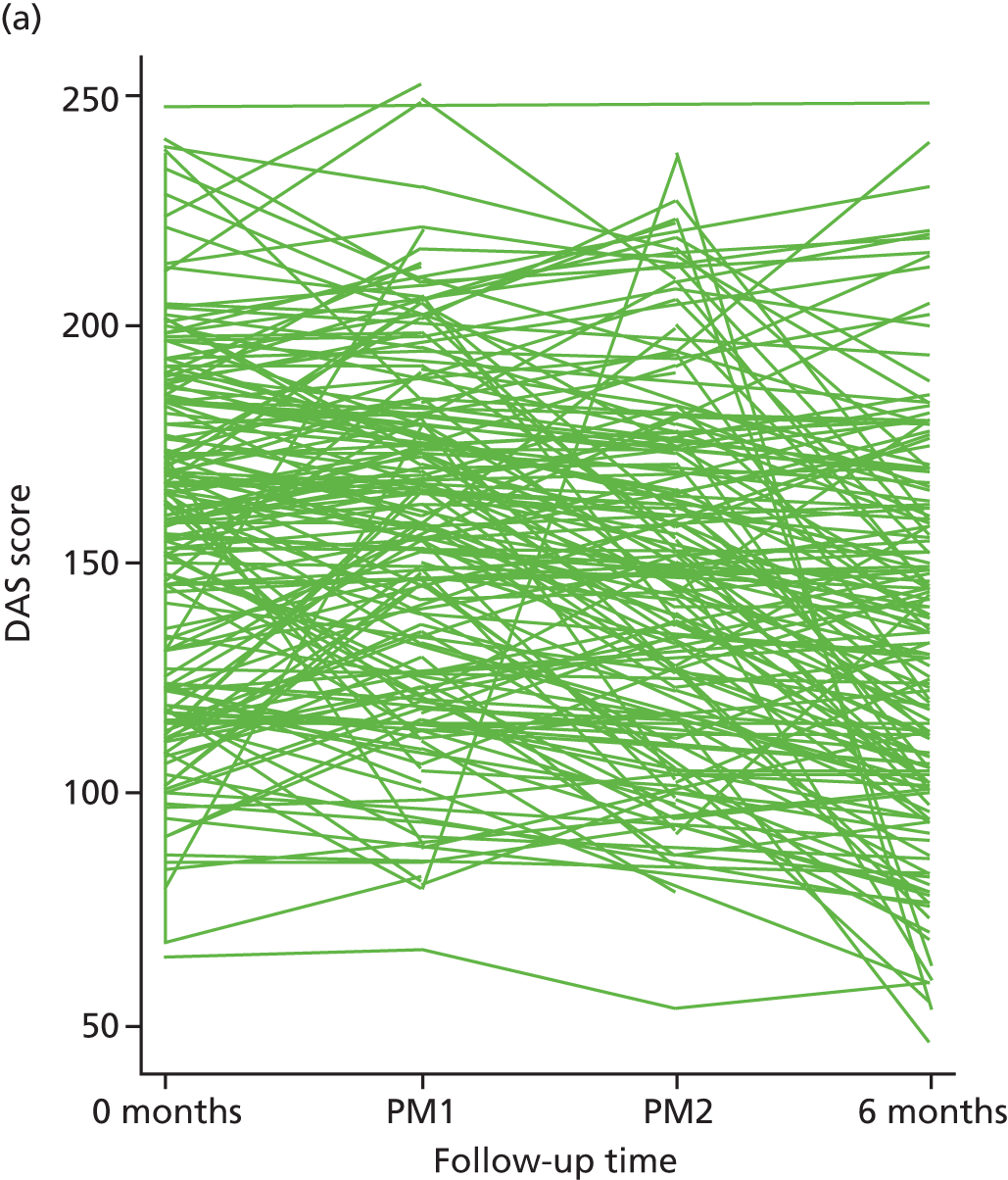

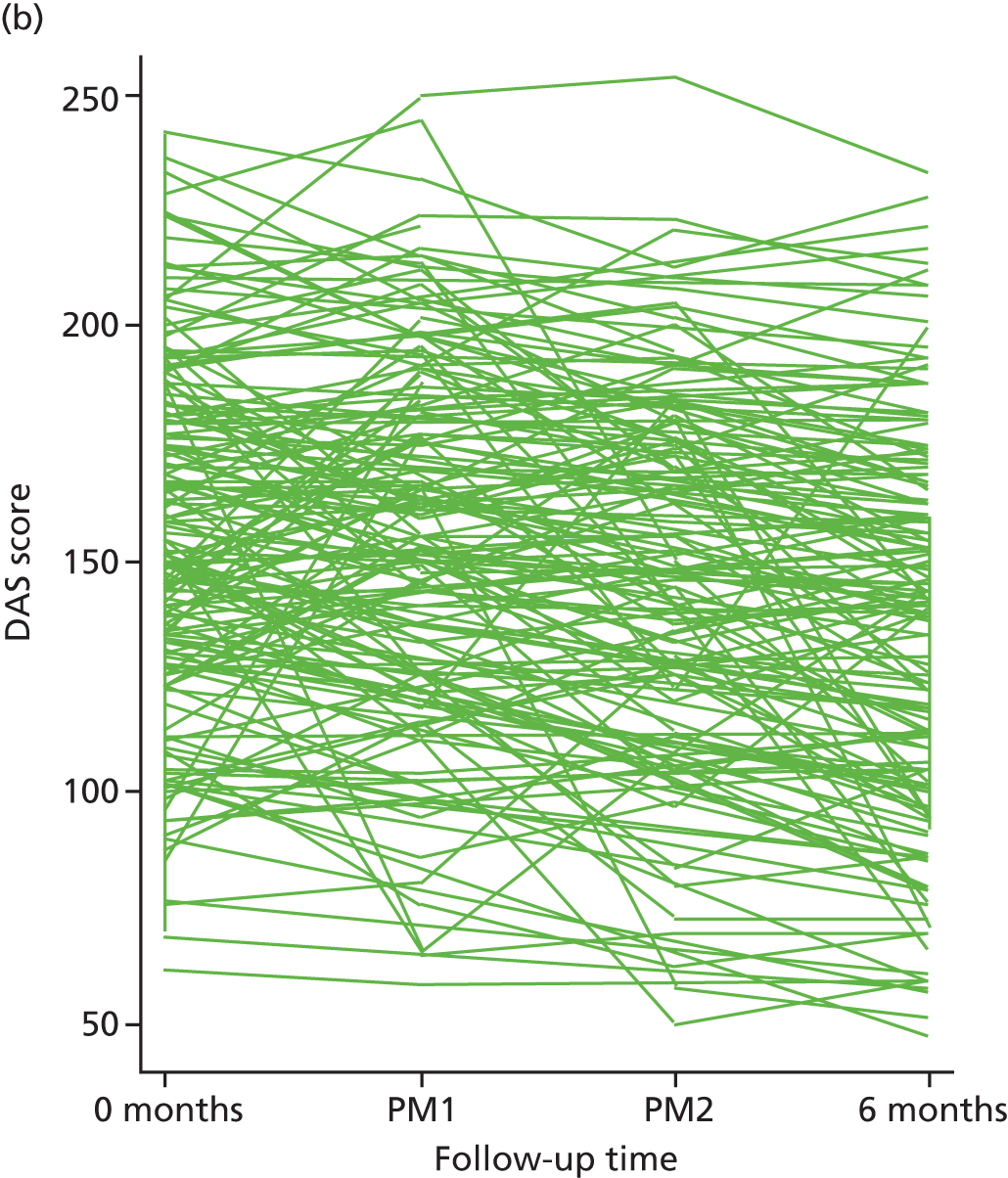

| DAS | CRF | Baseline | Therapy session 4 | Therapy session 7 | 6 | |||

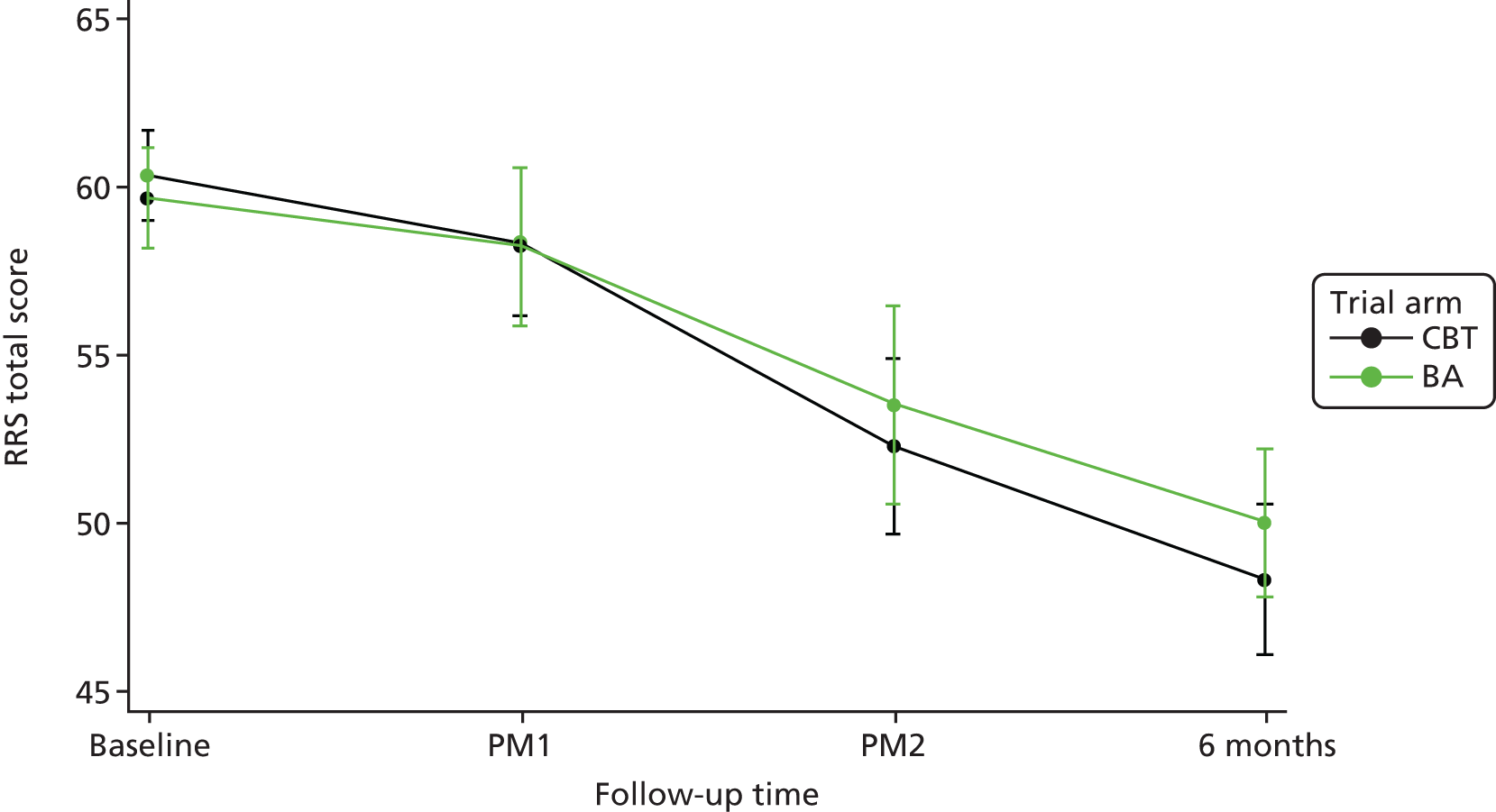

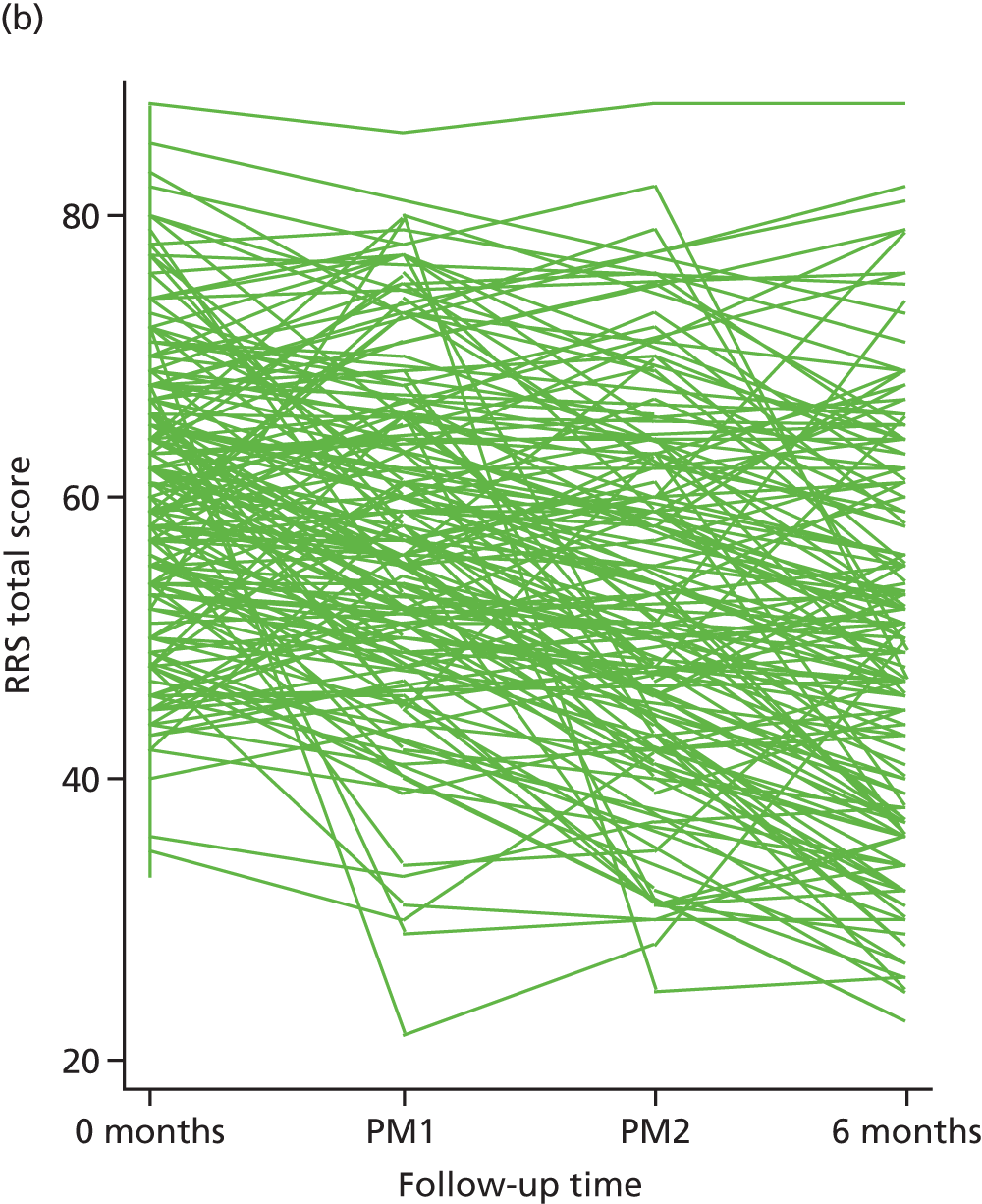

| RRS | CRF | Baseline | Therapy session 4 | Therapy session 7 | 6 | |||

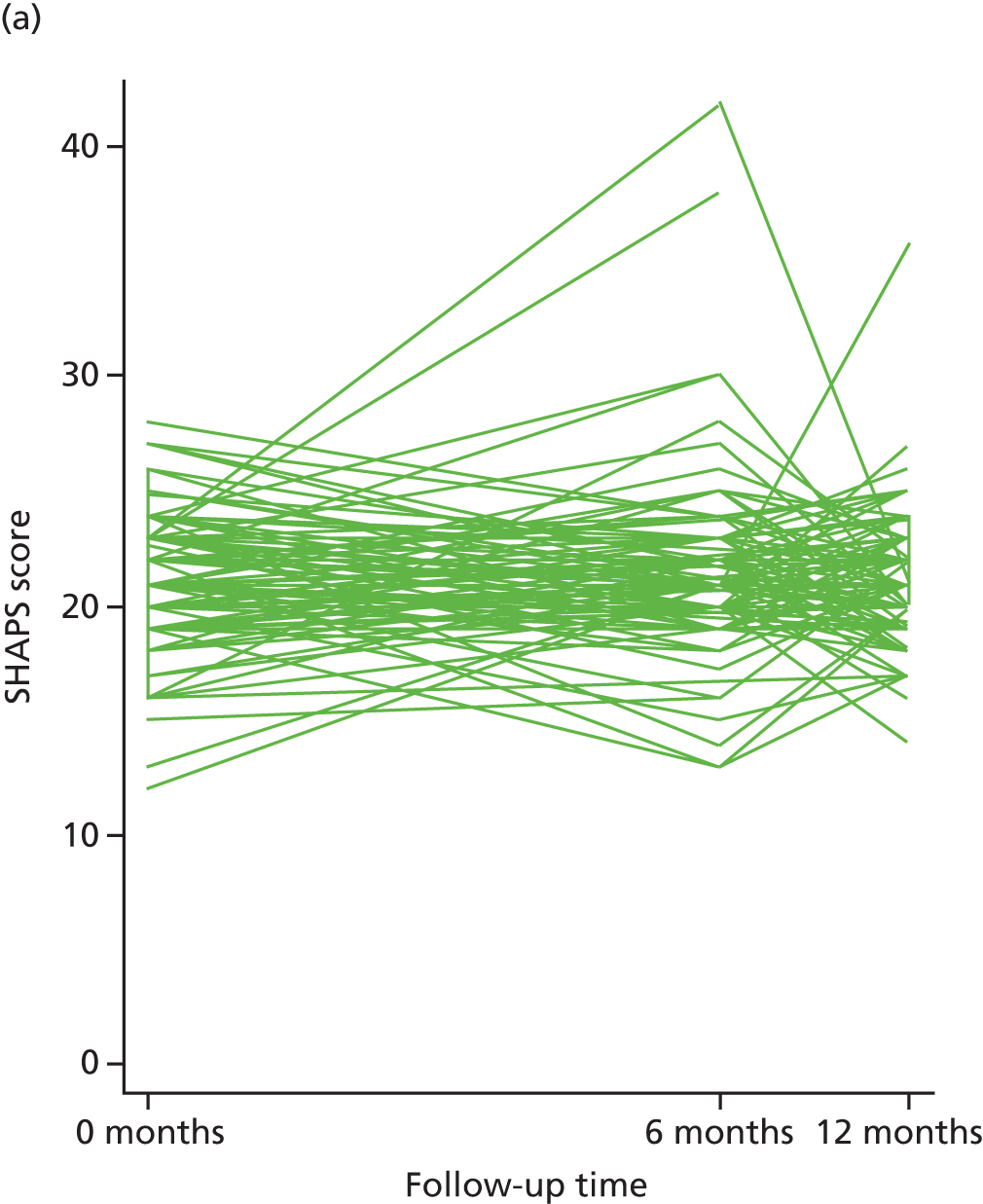

| SHAPS | CRF | Baseline | Therapy session 4 | 6 | 12 | 18 | ||

| Acceptability of BA and CBT | Qualitative interviews | Patients: on completion of therapy Clinicians: on completion of trial involvement |

||||||

| Treatment mechanisms and impact | Qualitative interviews | Patients: on completion of therapy Clinicians: on completion of trial involvement |

||||||

Baseline information

We collected demographic data at baseline through a purposely designed form. We recorded data on gender, age, ethnic origin, education level, employment, marital status, number of children, presence or absence of ADM treatment, previous history and age at onset of depression, duration of any ADM treatment and presence of any comorbid anxiety disorder.

Clinical data

We conducted follow-up assessments at 6, 12 and 18 months post-baseline assessment. Our primary outcome was self-reported depression severity and symptomatology, as measured by the PHQ-9,46 at 12 months. The PHQ-9 is a nine-item questionnaire that records the core symptoms of depression with established excellent specificity and sensitivity characteristics in a UK population. 57 Our secondary outcomes were DSM-IV MDD status and number of depression-free days between follow-ups, assessed by the SCID,45 anxiety assessed by the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire58 and health-related quality of life assessed by Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). 59 We also assessed the relative proportions of participants meeting criteria for ‘recovery’ (proportions of participants with PHQ-9 scores of ≤ 9 points) and ‘response’ (50% reduction in scores from baseline) on the PHQ-9. We also recorded the presence of DSM-IV anxiety disorders at baseline and follow-ups.

Economic data

We took the UK NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective consistent with the UK NICE reference case. 60 A broader societal perspective was explored in sensitivity analysis to capture the effects of productivity loss as a result of time off work due to illness, as depression is known to impact on an individual’s ability to work and can result in substantial losses in the workplace. 61 In addition, the use of complementary therapies was included in a further sensitivity analysis following advice from the clinical team that such therapies are commonly used by adults with depression. Narrower perspectives of intervention and mental health care were also examined in sensitivity analyses.

We collected participants’ use of BA and CBT from clinical records, with additional resource information (e.g. training, supervision and other non-face-to-face activities) collected from therapists and trainers. We measured all other health and social care services used, including medication prescription using the adult service use schedule (AD-SUS), designed on the basis of previous evidence of service use in depressed populations. 62 We measured productivity losses using the absenteeism and presenteeism questions of the World Health Organization’s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire. 63 The AD-SUS and the Health and Work Performance Questionnaire were completed by patients in interviews with a research assessor at baseline and at the 6-, 12- and 18-month follow-ups. At baseline, participants were asked to report service use over the previous 6 months. At all follow-up points, participants were asked to report service use since the last interview, to capture service use for the entire period from baseline to follow-up, even if participants had missed intermediate interviews.

We measured effectiveness for the economic evaluation in terms of QALYs calculated using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), a non-disease-specific measure for describing and valuing health-related quality of life, at baseline and at the 6-, 12- and 18-month follow-ups. 64 The EQ-5D-3L consists of five dimensions in the domains of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, each scored on three levels (no problems, some problems or extreme problems), and classifies individuals into one of 243 health states. Health states are converted into a single summary index utility score by applying weights to each level in each dimension derived from the valuation of EQ-5D-3L health states in adult general population samples. 65 QALYs were calculated as the area under the curve defined by the utility values at baseline and each follow-up. It was assumed that changes in the utility score over time followed a linear path. 66

Process data

In addition to information on age at depression onset and number of previous episodes collected using the SCID,45 we also collected data on changes in specific behaviour [as assessed via the Behavioural Activation for Depression Scale (BADS)],67 changes in beliefs [as assessed via the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS)],68 rumination [as assessed via the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS)],69 hedonic tone [as assessed via the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS)],70 acceptability of BA and CBT for participants and clinicians (assessed with qualitative methods), and per protocol (PP) treatment adherence (from therapist case records). We collected qualitative data via semistructured interviews to access participants’, BA MHWs’ and CBT therapists’ accounts of the mechanisms and impacts of treatment. Interviews focused on acceptability, views of the role of cognitive and behavioural change strategies and broader impacts of treatment in participants’ lives.

Intervention fidelity

We assessed the quality of, and adherence to, BA and CBT clinical protocols using audiotapes and written records of therapy sessions, which MHWs and therapists were instructed to take, with participant permission, for each clinical session. A random sample of tapes, stratified by therapist, therapy session and intervention, were sent to independent experts in both treatments for competency rating using the Cognitive Therapy Scale-Revised (CTS-R)71 (range 0–78, competency cut-off score = 36) for CBT and the Quality of Behavioural Activation Scale72 (range 0–84, competency cut-off score = 42) for BA. Independent rating of recorded therapy sessions was undertaken by the Oxford Cognitive Therapy Centre (Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust) and Dr Christopher Martell of the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, for CBT and BA, respectively.

Therapy ratings were used for several different purposes:

-

to assess each therapist’s competency, at the start of the trial, to deliver the interventions by rating the first two therapy sessions undertaken

-

to monitor whether or not levels of competence/adherence were maintained throughout the trial.

We asked all therapists in both treatment groups to record their in-session activity by completing specially designed therapy record sheets. These sheets included a list of therapeutic techniques specific to each type of therapy, with a tick box against each element. Therapists indicated which of the techniques they had used in each session.

Safety and adverse events

For adverse events (AEs), we recorded deaths from whatever cause, and all self-harm and suicide attempts. The independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) reviewed all AEs and made relevant trial conduct recommendations as a consequence.

Data analysis

We analysed and report primary and secondary outcomes in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for non-inferiority and equivalence trials. 43 All analyses were carried out using an a priori statistical analysis plan prepared in the first 6 months of the trial and agreed with the TMG, TSC and the DMC.

Equivalence of baseline characteristics and outcomes in the two groups were assessed descriptively. As differences between randomised groups at baseline could have occurred by chance, no formal significance testing was conducted. We also undertook a descriptive analysis of the baseline patient characteristics according to the recruitment method (recruitment from psychological therapies waiting list vs. GP case note review).

We undertook both ITT and PP analyses. PP analysis provides some protection for any theoretical increase in the risk of type I error (erroneously concluding non-inferiority). 73 The ITT population was defined as all randomised patients in the groups to which they were allocated with observed outcome data at follow-up. The PP population was predefined by the TMG as those patients who met the ITT definition and received eight or more treatment sessions for both groups. Although the CONSORT guidelines recommend a PP approach (i.e. analysis according to actual treatment received) as the conservative non-inferiority analysis option, given the potential biases of both PP and ITT analyses,43 we took the approach of the European Medicines Agency, that security of inference depends on both PP and ITT analyses demonstrating non-inferiority of the primary outcome. 74 We, therefore, checked for non-inferiority in both the PP and ITT populations. In order to check the security of inference of non-inferiority, sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome was undertaken for the ITT imputed population and PP analyses based on different definitions of adherence/protocol adherence.

The TMG predefined our PP population. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using different definitions of PP adherence. We included varying proportions of PP participants in these sensitivity analyses populations, depending on how much of each therapy they had received, ranging from 40% to 100% of planned therapy sessions. Our analysis plan specified that, if non-inferiority was consistently shown by these analyses, we would proceed to assess superiority of CBT compared with BA (i.e. the CI lower bound lies above 0). If we found that conclusions were inconsistent across analyses, we planned to revert back to primacy of the PP analysis to confirm or refute the non-inferiority hypothesis.

Our primary analysis compared observed primary and secondary outcomes between BA and CBT groups at 12 months after randomisation using linear regression models that adjusted for baseline outcome values and stratification/minimisation variables (symptom severity, site, ADM use). Although we initially planned to include therapist as a random-effects variable in our models, given the low levels of observed clustering we took a parsimonious approach and fitted our models without inclusion of therapist. We also checked that there was no difference in inference with and without the inclusion of a random-effects therapist term.

We estimated that the one-sided 97.5% CI for the between-group difference and non-inferiority of BA compared with CBT was accepted (in a 0.025 level test) if the lower bound of the 97.5% CI lay within the non-inferiority margin of –1.90 points in PHQ-9 score. We checked for non-equivalence of the primary outcome at all follow-up points using the same approach. We extended the primary analysis models to fit interaction terms to explore possible differences in treatment effect in baseline symptom severity and ADM usage.

We undertook secondary analyses to compare groups at follow-up across 6, 12 and 18 months using a mixed-effects, repeated measures regression approach. We also ran sensitivity analyses for both primary and secondary analyses to assess the likely impact of missing data using multiple imputation models. We also calculated the relative proportions of participants meeting criteria for ‘recovery’ (proportions of participants with PHQ-9 scores of ≤ 9 points) and ‘response’ (50% reduction in the PHQ-9 scores from baseline). Between-group differences are presented for continuous outcomes as CBT versus BA (i.e. CBT minus BA) and for binary outcomes as BA relative to CBT (i.e. BA divided by CBT).

No interim inferential analyses were undertaken. However, the DMC requested (October 2013) a check of the statistical power of the trial for the PP analyses. This calculation used the assumptions of our original power calculation and was based on the observed level of attrition of the primary outcome at 12 months and the proportion of patients who fulfilled the PP definition (eight or more treatment sessions; as of January 2014). All analyses were undertaken using Stata v.14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Economic analysis

Although studies designed to test equivalence of effects are considered to be a legitimate situation in which a cost minimisation analysis (where costs alone are compared given equal outcomes) may be appropriate,75 the same may not be true for non-inferiority designs. Even in situations where equivalence or non-inferiority are demonstrated, exploration of the joint distribution of costs and effects in a cost-effectiveness analysis is recommended to represent uncertainty75 and to help interpret the economic results. 76 For these reasons, we prespecified that we would undertake a cost-effectiveness analysis irrespective of whether or not non-inferiority in the primary clinical outcome was demonstrated. We assessed cost-effectiveness in terms of QALYs using the net benefit approach. 77 We explored Bosmans et al. ’s methods76 for economic evaluations alongside equivalence or non-inferiority trials, which requires specification of non-inferiority margins for both costs and effects. However, as our prespecified method of economic evaluation was cost–utility analysis, using QALYs, rather than cost-effectiveness analysis, using the PHQ-9, which was the measure on which the hypothesis of non-inferiority is based, no non-inferiority margin for economic effects was specified. In addition, there is a general lack of guidance on how to define an economically unimportant difference in costs with which to estimate an appropriate non-inferiority margin for costs.

We compared the costs and cost-effectiveness of BA and CBT at the final, 18-month, follow-up to capture the economic impact of events, such as relapse with unit costs from the 2013–14 financial year. 78,79 We discounted costs and QALYs in year 2 at 3.5%. 60 We used complete-case analysis, with missing data explored in a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE). Our primary analysis took the NHS/PSS perspective preferred by NICE. 80 The impact of productivity losses as a result of time off work, known to be a substantial cost in depression,81 were explored in sensitivity analysis. In addition, narrower cost perspectives were tested (e.g. an intervention perspective and a mental health-care perspective), to ensure that the NHS/PSS perspective had not captured irrelevant costs that may hide the true impact of BA and CBT on service use.

For each participant, a unit cost was applied to each item of service use reported to calculate the total cost for the duration of the trial. All unit costs are summarised in Table 3.

| Service | Unit | Cost (£) |

|---|---|---|

| BA | Per hour | 67.80 |

| CBT | Per hour | 86.20 |

| Medication | Per daily dose | Various |

| Inpatient | Per night | 527.17–602.52 |

| Outpatient | Per appointment | 49.00–411.00 |

| Accident and emergency | Per attendance | 108.96–266.85 |

| Ambulance | Per attendance | 231.00 |

| GP surgery | Per minute of patient contact | 2.90 |

| Practice nurse | Per minute of face-to-face contact | 0.73 |

| Case manager | Per home visit minute | 2.39 |

| Community occupational therapist | Per minute of face-to-face contact | 0.68 |

| Social worker | Per minute | 2.65 |

| Advice service | Per minute | 1.05 |

| Chiropractic/osteopathy | Per minute | 1.42 |

| Homeopathy | Per minute | 1.67 |

| Acupuncture | Per minute | 1.33 |

| Massage therapy | Per minute | 1.13 |

We estimated intervention costs using the bottom-up costing approach set out by the Personal Social Services Research Unit at the University of Kent. 82 We based BA MHW costs on NHS AfC salary band 5 (salary range: £21,909–28,462; US$31,662–41,130; €27,726–35,993) and NHS AfC band 7 (salary range: £31,383–41,373; US$45,350–59,786; €39,738–52,388) for CBT therapists, including employer’s National Insurance and pension contributions plus capital, administrative and managerial costs. 79 We calculated a cost per hour using standard working time assumptions,79 weighted to account for time spent on non-patient facing activities, which was estimated based on the results of a survey of trial therapists.

We costed hospital services using unit costs from the NHS Reference Costs 2013–14. 78 Unit costs for NHS primary care and social care services were taken from nationally applicable published sources. 79 Costs for complementary services were taken from the NHS Choices website. 83 The costs of medications were calculated based on averages listed in the British National Formulary84 for the generic drug and using daily dose information collected using the AD-SUS.

We valued productivity losses as a result of time off work due to illness using the human capital approach, which involves multiplying the individual’s salary by reported days off work due to illness. 85

We report differences in use of services between randomised groups descriptively as the mean by group and as a percentage of the group who had at least one contact. We tested for differences in mean costs per participant between groups using standard parametric t-tests, with the results confirmed using bias-corrected, non-parametric bootstrapping. 86 This is the recommended approach, despite the skewed nature of cost data, as it allows inferences to be made about the arithmetic mean. 87

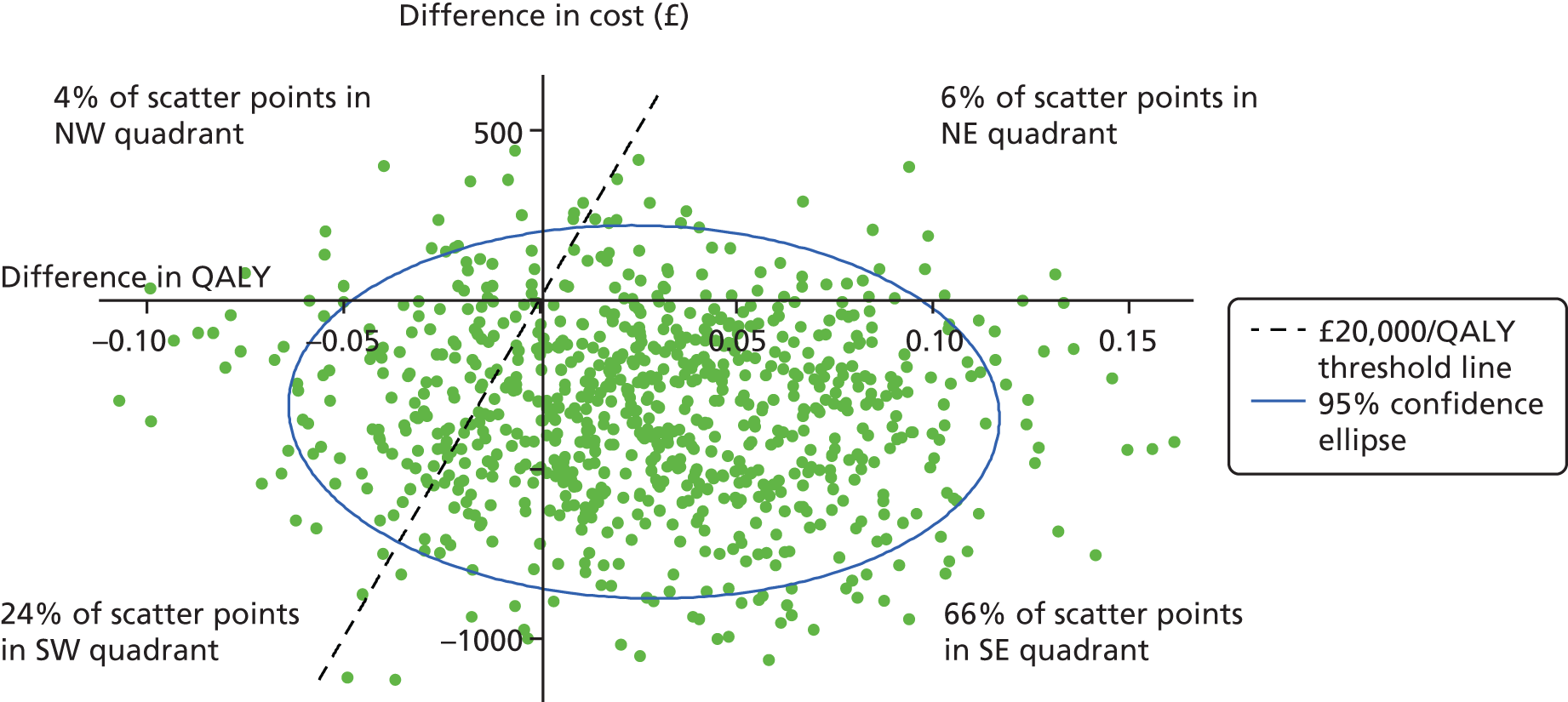

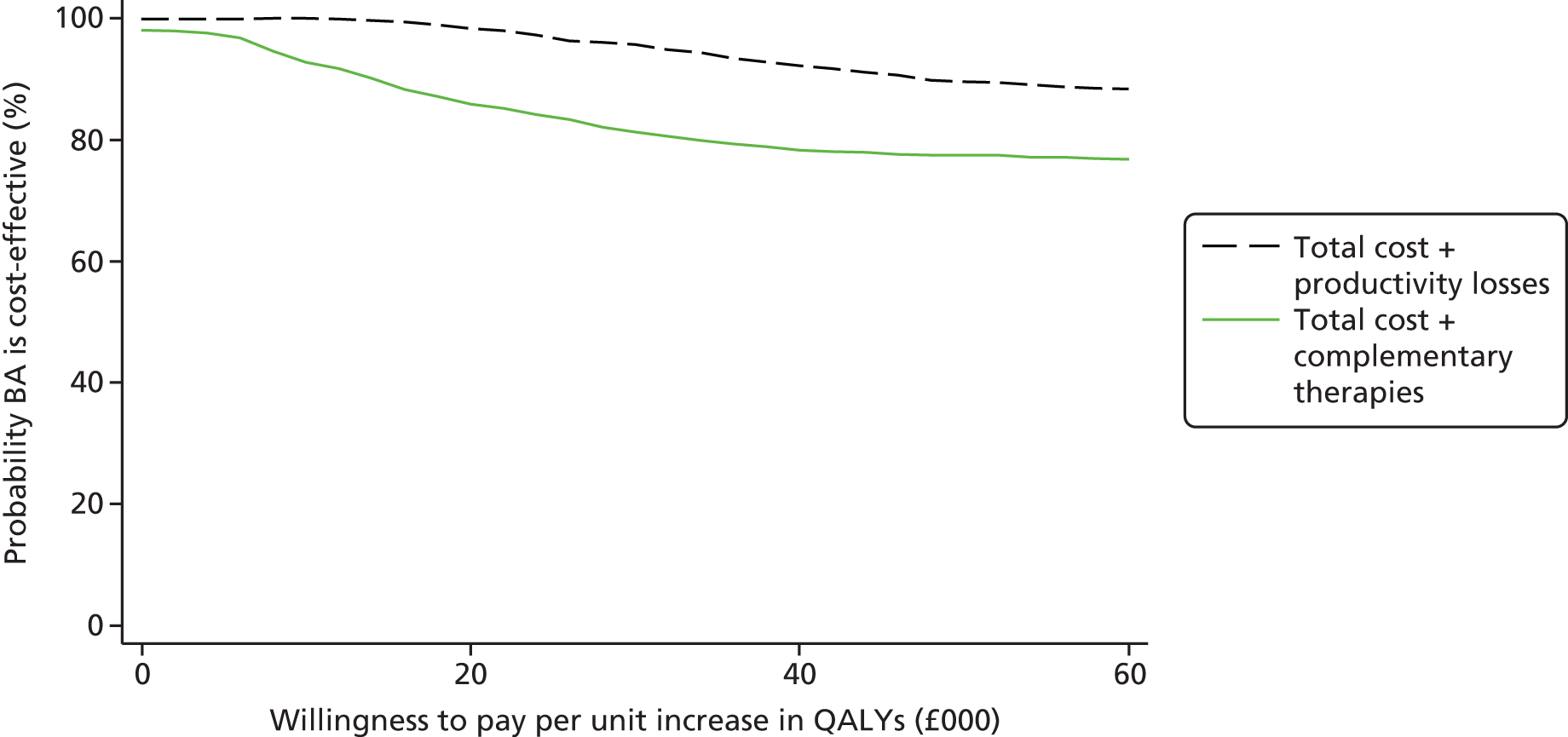

We explored cost-effectiveness using ICERs – the difference in mean cost divided by the difference in mean effect88 – and cost-effectiveness planes constructed to show the probability that BA is more or less effective and more or less costly than CBT. As ICERs are calculated from four sample means and are therefore subject to statistical uncertainty, the planes were generated using 1000 bootstrapped resamples from regression models of total cost and outcome by treatment group. These were then used to calculate the probability that each of the treatments is the optimal choice, for different values a decision-maker is willing to pay for a unit improvement in outcome (the ceiling ratio, λ). Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) are presented by plotting these probabilities for a range of possible values of λ to explore the uncertainty that exists around estimates of mean costs and effects, and to show the probability that BA is cost-effective compared with CBT. 89

All analyses were controlled for the following covariates: site, ADM use, symptom severity and baseline measurement of the variables of interest. Additionally, data have been truncated to exclude influential outliers (i.e. cases with total costs in the 99th percentile that make a significant difference to the results). 90 Between-group differences for costs are presented for continuous outcomes as BA versus CBT (i.e. BA minus CBT).

We carried out a number of independent sensitivity analyses to test assumptions made in the analysis:

-

the impact of including the use of complementary therapies

-

the impact of including productivity losses as a result of time off work as a result of illness

-

the impact of missing data, considered using MICE

-

the impact of taking an intervention perspective

-

the impact of taking a mental health-care perspective.

Process data analysis

A full description of the methods and analyses of our process data, including qualitative data, is presented in Chapter 4. Based on recent reviews,91 exploratory analyses examined baseline variables that might moderate outcome at multiple time points (6, 12 and 18 months) across the two treatments, including depression severity, age at depression onset, number of previous episodes, and baseline levels of cognitive and behavioural dysfunction, using the approach set out by Kraemer et al. 92 Although the power to detect moderate subgroup interactions was low, we were primarily interested in exploring the possibility of large interactions that could inform subsequent clinical decision-making regarding treatment allocation.

Mediational analyses investigated the hypothesised mechanisms of change (for BA, changes in specific behaviour such as reduced avoidance and rumination, learned capacity to apply behavioural principles to modify the environment; for CBT, changes in beliefs and underlying information processing style), pretreatment to mid-treatment, mid-treatment to post treatment across the trial arms using approaches to testing mediation that allow multiple mediators in one model. 92 The effects of the mediators on outcome at 12 and 18 months were modelled. This approach to examining mediation ensures that changes in putative mediators temporally precede changes in the primary outcome and allow baseline to post-treatment change in symptoms to be statistically controlled, necessary to rule out reverse causality. 93

Qualitative data analysis

Participant and therapist interviews were analysed using a framework approach94 combining deductive themes from the topic guides and inductive themes emerging from the data. Some interviews were coded independently to assess the reliability of coding and meetings were held to discuss and refine emerging themes. 95 Transcripts were examined thematically across the whole data set, as well as in the context of each interview, using constant comparison techniques. 96 Data were indexed and sorted using the identified themes and subthemes, and were summarised in framework matrices. 94 In keeping with the framework approach, we interrogated the data, searching for comparisons and contradictions and keeping interpretive notes. Alternative explanations or negative cases were identified, discussed and a consensus reached. 95

Ethics issues

We conducted the trial in such a way as to protect the human rights and dignity of the participants as reflected in the Helsinki Declaration. 97 Participants did not receive any financial inducement to participate. The study received National Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval from the South West REC in the UK (reference number 12/SW/0029). Local REC and NHS research and development approvals were also given for each recruitment site. To conform with data protection and freedom of information acts, all data have been stored securely and anonymised wherever possible. No published material will contain patient-identifiable information.

Obtaining informed consent from participants

We determined informed consent by a two-phase consent process. Participants received a study information sheet in the post and a form seeking their permission to be contacted by a member of the research team, not at this stage to give consent to trial participation. The information leaflets were produced using current guidelines for researchers on writing information sheets and consent forms98 and informed by our consumer/lived-experience user representatives. Participants who wished to partake in the trial returned their initial written consent to be contacted form to the site research team. Full informed written consent was obtained through an interview by a researcher where the information sheet was fully explained and where the opportunity to ask questions was given. The opportunity to withdraw from the trial was also fully explained. Researchers seeking consent were fully trained and supervised by the chief investigator and site leads. Communication and recording systems were set up to enable the trial team to monitor and act on participants’ wishes to withdraw from the trial.

Anticipated risks and benefits

All participants received usual GP care and, therefore, no treatment was withheld from participants in this trial. Both arms were active psychological treatments with previously demonstrated efficacy and no known iatrogenic effects. This trial may have in fact benefited individual participants, as CBT is not generally available for the majority of people with depression. By participating in this trial, participants also received an intensive level of monitoring such that any participants with worsening symptoms or who were at suicidal risk were identified and directed to appropriate care. We recorded all instances of AEs as detailed earlier.

Informing participants of anticipated risks and benefits

Participant information leaflets provided potential participants with information about the possible benefits and known risks of taking part in the trial. Participants were given the opportunity to discuss this issue with their GP or the trial manager prior to consenting. The trial manager would have informed the participant if new information came to light that may have affected the participant’s willingness to participate in the trial.

Management of suicide risk

Inherent in the nature of the population under scrutiny is the risk of suicide. We followed good clinical practice in monitoring for suicide risk during all research and clinical encounters with trial participants, developed for our previous trials. 55,99 Where any risk to participants attributable to expressed thoughts of suicide were encountered, we reported these directly to the GP (with the participant’s expressed permission), or if an acute risk was present we sought advice from the GP immediately and followed locally established suicide risk management plans. Systems were put into place to ensure that the chief investigator, trial manager and researchers were informed if there were any risks to the participants’ safety.

Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee

A TSC was set up and included an independent chairperson, an academic GP and at least two other independent members, along with the lead investigator and some other study collaborators. The TSC met at least once a year. The DMC was set up and was composed of an independent mental health professional, statistician and clinician. The role of the DMC was to review serious AEs thought to be treatment related and look at outcome data regularly during data collection.

Execution dates

The preparatory period started in March 2012. Recruitment ran from September 2012 to April 2014. Follow-up lasted 18 months after randomisation and was completed by October 2015. Data analysis and reporting were completed 12 months after this (September 2016). The entire study period lasted 54 months (March 2012 to September 2016).

Chapter 3 Results of clinical and economic analyses

This chapter uses material from an Open Access article previously published by the research team (see Richards et al. 2). © The Author(s). 2 Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY license.

Participant flow and retention

Between 26 September 2012 and 3 April 2014, we recruited 440 participants, randomly allocating 221 participants (50%) to the BA group and 219 participants (50%) to the CBT group. We recruited to time and target and the majority of participants were recruited from primary care (87%). Progress over the course of recruitment and achievement of the target is shown in Figure 3. Participant recruitment and retention is shown for both the ITT and PP analyses in the trial CONSORT diagram (Figure 4). There were no protocol deviations.

FIGURE 3.

Trial recruitment. Solid line shows target recruitment and dashed line shows cumulative actual recruitment.

FIGURE 4.

The trial CONSORT flow diagram. (a) 6-month follow-up, (b) 12-month follow-up and (c) 18-month follow-up.

Baseline characteristics of participants

Patient- and trial-level characteristics at baseline were well balanced between groups (Table 4). We also found no evidence of a difference in patient characteristics between recruitment methods (Table 5). The PHQ-9 primary outcome at baseline was negatively skewed, with a high proportion of participants scoring towards the upper end of the distribution (Figure 5), and scores were similar between groups [BA, 17.7 PHQ-9 points (SD 4.8 PHQ-9 points); CBT, 17.4 PHQ-9 points (SD 4.8 PHQ-9 points)] (Table 6).

| Characteristic | Trial arm | All (n = 440) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BA (n = 221) | CBT (n = 219) | ||

| Trial characteristic | |||

| Method of recruitment, n (%) | |||

| Case notes | 192 (87) | 190 (87) | 382 (87) |

| IAPT | 29 (13) | 29 (13) | 38 (13) |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) range | 43.9 (14.1) 18–82 | 43.0 (14.1) 19–84 | 43.5 (14.1) 18–84 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 79 (36) | 71(32) | 150 (34) |

| Female | 142 (64) | 148 (68) | 290 (66) |

| Number of episodes of depression including current | |||

| Mean (SD), n | 7.0 (15.0) 192 | 6.3 (13.8) 192 | 6.7 (14.4) 384 |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1–5) | 2.0 (1–4) | 3.0 (1–5) |

| First depression episode, age at onset (years), mean (SD) | 27.2 (15.0) | 26.3 (13.5) | 26.7 (14.2) |

| Duration of antidepressant treatment (weeks)a | |||

| Mean (SD), n | 106 (210), 157 | 81 (164), 168 | 93 (188), 325 |

| Median (IQR) | 21 (10–71) | 18 (7–51) | 19 (8–66) |

| At least one comorbid anxiety disorder, n (%) | 131 (59) | 141 (64) | 272 (62) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 68 (31) | 59 (27) | 127 (29) |

| Cohabiting (not married) | 29 (13) | 25 (11) | 54 (12) |

| Civil partnership | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Married | 84 (38) | 92 (42) | 176 (40) |

| Divorced/separated | 39 (18) | 42 (19) | 81 (18) |

| Number of children, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 74 (34) | 72 (33) | 146 (33) |

| 1 | 35 (16) | 31 (14) | 66 (15) |

| 2 | 67 (30) | 69 (32) | 136 (31) |

| 3 | 31 (14) | 27 (12) | 58 (13) |

| ≥ 4 | 14 (6) | 20 (9) | 34 (8) |

| Level of education, n (%) | |||

| No qualifications | 25 (11) | 30 (14) | 55 (13) |

| GCSEs/O-levels | 36 (16) | 43 (20) | 79 (18) |

| AS/A-levels | 28 (13) | 22 (10) | 50 (11) |

| NVQ or other vocational qualification | 54 (24) | 71 (32) | 125 (28) |

| Undergraduate degree | 44 (20) | 35 (16) | 79 (18) |

| Postgraduate degree | 28 (13) | 14 (6) | 42 (10) |

| Doctoral degree | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Professional degree (e.g. MD) | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White British | 204 (92) | 197 (90) | 401 (91) |

| Other | 17 (8) | 22 (10) | 39 (9) |

| Stratification/minimisation variables | |||

| PHQ-9 points category, n (%) | |||

| < 19 | 118 (54) | 118 (54) | 236 (54) |

| ≥ 19 | 103 (46) | 101 (46) | 204 (46) |

| Antidepressant use, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 172 (78) | 175 (79) | 345 (78) |

| No | 49 (22) | 46 (21) | 95 (22) |

| Site, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 74 (33) | 73 (33) | 147 (33) |

| 2 | 79 (36) | 78 (36) | 157 (36) |

| 3 | 68 (31) | 68 (31) | 136 (31) |

| Recruitment method | Recruitment method | All (n = 440) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care (n = 382) | IAPT (n = 58) | ||

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 43.6 (14.2) | 42.7 (13.4) | 43.5 (14.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 122 (32) | 28 (48) | 150 (34) |

| Female | 260 (68) | 30 (52) | 290 (66) |

| Number of episodes of depression including current | |||

| Mean (SD), n | 6.9 (15.3), 327 | 5.6 (7.2), 57 | 6.7 (14.4), 384 |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1–5) | 3.0 (2–5) | 3.0 (1–5) |

| Age at onset of first depression episode (years), mean (SD) | 27.0 (14.6) | 25.6 (13.2) | 26.7 (14.2) |

| Duration of antidepressant treatment (weeks)a | |||

| Mean (SD), n | 84 (165), 290 | 167 (313), 35 | 93 (188), 325 |

| Median (IQR) | 18 (8–64) | 23 (15–108) | 19 (8–66) |

| At least one comorbid anxiety disorder, n (%) | 246 (64) | 26 (45) | 272 (62) |

| Marital status, (%) | |||

| Single | 112 (29) | 15 (26) | 127 (29) |

| Cohabiting (not married) | 45 (12) | 9 (16) | 54 (12) |

| Civil partnership | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Married | 149 (39) | 27 (47) | 176 (40) |

| Divorced/separated | 74 (19) | 7 (12) | 81 (18) |

| Number of children, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 123 (32) | 23 (40) | 146 (33) |

| 1 | 58 (15) | 8 (14) | 66 (15) |

| 2 | 121 (32) | 15 (26) | 136 (31) |

| 3 | 49 (13) | 9 (16) | 58 (13) |

| ≥ 4 | 31 (8) | 3 (5) | 34 (8) |

| Level of education, n (%) | |||

| No qualifications | 50 (13) | 5 (9) | 55 (13) |

| GCSEs/O-levels | 71 (19) | 8 (14) | 79 (18) |

| AS/A-levels | 44 (12) | 6 (10) | 50 (11) |

| NVQ or other vocational qualification | 106 (28) | 19 (33) | 125 (28) |

| Undergraduate degree | 66 (17) | 13 (23) | 79 (18) |

| Postgraduate degree | 36 (9) | 6 (10) | 42 (10) |

| Doctoral degree | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Professional degree (e.g. MD) | 6 (2) | 1 (2) | 7 (2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White British | 353 (92) | 49 (84) | 402 (91) |

| Other | 29 (76) | 9 (2) | 38 (9) |

| Stratification or minimisation variables | |||

| PHQ-9 category, n (%) | |||

| < 19 points | 200 (52) | 36 (62) | 236 (54) |

| ≥ 19 points | 182 (48) | 22 (38) | 204 (46) |

| Antidepressant use, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 309 (81) | 36 (62) | 345 (78) |

| No | 73 (19) | 22 (38) | 95 (22) |

| Site, n (%) | |||

| Devon | 145 (38) | 2 (4) | 147 (33) |

| Durham | 157 (41) | 0 (0) | 157 (36) |

| Leeds | 80 (21) | 56 (97) | 136 (31) |

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of primary outcome (PHQ-9 score) at baseline.

| Outcome | Trial arm: n, mean (SD or %) | Between-group difference (CBT – BA) at 12-month follow-up: mean (95% CI), p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | BA | Observed data only | Observed and imputed data | |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| PHQ-9 | ||||

| Baseline | 219, 17.4 (4.8) | 221, 17.7 (4.8) | ||

| ITT 12-month follow-up | 189, 8.4 (7.5) | 175, 8.4 (7.0) | 0.1a (–1.3 to 1.5), 0.89 | 0.2a (–1.1 to 1.7), 0.80 |

| PP 12-month follow-up | 151, 7.9 (7.3) | 135, 7.8 (6.5) | 0.0a (–1.5 to 1.6), 0.99 | 0.0a (–1.6 to 1.6), 0.99 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| GAD-7 | ||||

| Baseline | 219, 12.6 (5.1) | 221, 12.7 (5.1) | ||

| ITT 12-month follow-up | 176, 6.3 (6.0) | 161, 6.4 (5.9) | –0.1a (–1.0 to 1.3), 0.82 | 0.0a (–1.3 to 1.4), 0.96 |

| PP 12-month follow-up | 146, 6.0 (5.8) | 129, 5.9 (5.5) | 0.01a (–1.3 to 1.2), 0.95 | –0.4a (–1.7 to 1.0), 0.60 |

| SCID number of depression-free days | ||||

| ITT 12-month follow-up | 160, 129 (58) | 150, 120 (56) | 9a (–3 to 23), 0.13 | 7a (–7 to 20), 0.27 |

| PP 12-month follow-up | 138, 132 (55) | 125, 119 (55) | 13a (0 to 26), 0.06 | 8a (–4 to 21), 0.21 |

| SF-36 v2 PCS | ||||

| Baseline | 65, 50.1 (13.1) | 69, 51.4 (11.9) | ||

| ITT 12-month follow-up | 168, 48.1 (12.2) | 150, 49.9 (11.6) | 1.6b (–1.0 to 4.2), 0.22 | –1.4b (–1.1 to 4.0), 0.27 |

| PP 12-month follow-up | 144, 48.0 (12.2) | 125, 49.9 (12.0) | 1.6b (–1.3 to 4.4), 0.28 | –1.3b (–1.5 to 4.1), 0.36 |

| SF-36 v2 MCS | ||||

| Baseline | 65, 23.2 (9.4) | 69, 22.5 (7.8) | ||

| ITT 12-month follow-up | 168, 41.7 (14.1) | 150, 41.6 (14.0) | 0.0b (–3.0 to 3.0), 0.99 | 0.0b (–2.8 to 2.9), 0.97 |

| PP 12-month follow-up | 144, 42.9 (13.6) | 125, 42.3 (13.3) | 0.5b (–3.7 to 2.7), 0.77 | 0.6b (–3.8 to 2.7), 0.73 |

| n/N (%) | n/N (%) | Odds ratio (BA/CBT) (95% CI), p-value | Odds ratio (BA/CBT) (95% CI), p-value | |

| SCID depression | ||||

| Baseline | 219/219 (100) | 221/221 (100) | ||

| ITT 12-month follow-up | 37/163 (23) | 31/154 (20) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6), 0.71 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6), 0.70 |

| PP 12-month follow-up | 30/141 (21) | 24/128 (19) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7), 0.80 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7), 0.75 |

| Recoveryc | ||||

| ITT 12-month follow-up | 124/189 (66) | 115/175 (66) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.5), 0.96 | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.9), 0.53 |

| PP 12-month follow-up | 104/151 (69) | 94/135 (70) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7), 0.96 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.0), 0.47 |

| Responsed | ||||

| ITT 12-month follow-up | 117/189 (62) | 107/175 (61) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1), 0.73 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4), 0.75 |

| PP 12-month follow-up | 100/151 (66) | 87/135 (64) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0), 0.64 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.4), 0.55 |

Delivery and receipt of the interventions

Ten MHWs provided BA [median 22 participants each (interquartile range 19–25 participants each)] and 12 therapists provided CBT [median 21 participants each (interquartile range 13–23 participants each)]. MHWs had a mean of 18 months’ mental health experience (SD 11 months’ mental health experience) and CBT therapists had a mean of 22 months’ experience (SD 24 months’ experience) post CBT qualification. We removed one CBT therapist from the trial in the early stages who did not meet acceptable competency.

Participants received a mean of 11.5 BA sessions (SD 7.8 sessions) or 12.5 CBT sessions (SD 7.8 sessions). Three hundred and five participants (69%) completed the PP number of at least eight sessions [BA 147 (67%) participants, mean 16.1 sessions (SD 5.3 sessions); CBT 158 (72%) participants, mean 16.4 sessions (SD 5.4 sessions)]. Participants completing fewer than eight sessions {135 participants (31%) [BA 74 participants (33%) and CBT 61 participants (28%)] completed a mean of 2.5 BA sessions (SD 1.9 sessions) or 2.6 CBT sessions (SD 2.1 sessions)}.

Primary outcome: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 at 12 months

We present primary and secondary outcomes at 12 months in Table 6. We found no evidence of inferiority of PHQ-9 score at 12 months in either the ITT [CBT 8.4 PHQ-9 points (SD 7.5 PHQ-9 points), BA 8.4 PHQ-9 points (SD 7.0 PHQ-9 points); mean difference 0.1 PHQ-9 points, 95% CI –1.3 to 1.5 PHQ-9 points; p = 0.89] or PP [CBT 7.9 PHQ-9 points (SD 7.3 PHQ-9 points), BA 7.8 PHQ-9 points (SD 6.5 PHQ-9 points); mean difference 0.0 PHQ-9 points, 95% CI –1.5 to 1.6 PHQ-9 points; p = 0.99] populations. The non-inferiority of BA to CBT was accepted for both the ITT and PP populations, as the lower bound of the 95% CI (one-sided 97.5% CI) of the between-group mean difference lies within the non-inferiority margin of –1.9 PHQ-9 points (Figure 6). We ruled out superiority of CBT to BA as the lower bound of the 95% CI includes zero for the ITT and PP populations. The inference of non-inferiority was robust to sensitivity analysis across different PP definitions (Table 7). Our predefined stratification variable subgroup analyses (Table 8) showed no ITT or PP between-group difference by depression severity, ADM or site.

FIGURE 6.

Mean difference and two-sided 95% CI for the primary outcome of PHQ-9 at 12 months and non-inferiority margin.

| PP definition | Time point, mean (SD), n | Between-group difference (CBT – BA):a mean (95% CI), p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12-month follow-up | ||||

| CBT | BA | CBT | BA | ||

| Standard PP definitionb | |||||

| ≥ 8 sessions attended | 17.4 (4.9), 158 | 17.6 (4.6), 147 | 7.9 (7.3), 151 | 7.8 (6.5), 135 | 0.0 (–1.5 to 1.6), 0.99 |

| Alternative PP definitionsb | |||||

| ≥ 0 sessions attended | 17.4 (4.8), 219 | 17.7 (4.8), 221 | 8.4 (7.5), 189 | 8.4 (7.0), 175 | 0.1 (–1.3 to 1.5), 0.89 |

| ≥ 4 sessions attended | 17.4 (5.0), 176 | 17.7 (4.6), 169 | 8.0 (7.4), 161 | 8.2 (6.8), 150 | 0.1 (–1.4 to 1.7), 0.86 |

| ≥ 12 sessions attended | 17.8 (4.8), 115 | 17.7 (4.8), 109 | 8.6 (7.1), 112 | 7.6 (6.2), 105 | –0.6 (–2.3 to 1.1), 0.52 |

| ≥ 16 sessions attended | 17.8 (4.8), 83 | 18.3 (4.7), 77 | 8.8 (7.0), 81 | 8.6 (6.1), 75 | 0.2 (–1.9 to 2.3), 0.86 |

| ≥ 20 sessions attended | 18.2 (4.7), 58 | 18.5 (4.6), 51 | 9.0 (6.7), 57 | 8.5 (6.1), 49 | –0.4 (–3.3 to 2.5), 0.78 |

| Stratification variable | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT | PP | |||

| Between-group difference (CBT – BA):a mean (95% CI) | Interaction coefficient (95% CI), p-value | Between-group difference (CBT – BA):a mean (95% CI) | Interaction coefficient (95% CI), p-value | |

| Depression severity | ||||

| PHQ-9 < 19 points | 0.4 (–1.3 to 2.0) | 1.1 (–1.8 to 3.9), 0.48 | 0.7 (–1.1 to 2.6) | 1.9 (–1.2 to 5.0), 0.23 |

| PHQ-9 ≥ 19 points | –0.6 (–3.5 to 1.8) | –0.9 (–3.5 to 1.7) | ||

| Receiving ADM | ||||

| Yes | 0.2 (–2.7 to 3.1) | 0.2 (–3.2 to 3.7), 0.90 | –0.4 (–3.5 to 2.7) | 0.6 (–4.3 to 3.2), 0.74 |

| No | –0.1 (–1.7 to 1.5) | 0.2 (–1.6 to 2.0) | ||

| Site | ||||

| Exeter | –1.2 (–3.6 to 1.1) | –2.1 (–5.5 to 1.4) | –1.2 (–3.9 to 1.5) | –1.7 (–5.5 to 2.1) |

| Durham | 1.0 (–1.6 to 3.6) | –0.9 (–4.5 to 2.6) | 0.6 (–2.2 to 3.4) | –1.3 (–5.3 to 2.6) |

| Leeds | –0.2 (–2.8 to 2.3) | 0.49b | 0.2 (–2.3 to 3.0) | 0.64b |

Response and recovery at 12 months

Between 61% and 70% of ITT and PP participants in both groups met criteria for recovery or response, with no difference in the proportions of patients in each group who recovered or responded (see Table 6).

Primary and secondary outcomes at all follow-up points

Tables 9 and 10 show the repeated measures comparison of primary and secondary outcomes across time points for both ITT and PP populations. For the primary outcome, there was no evidence of difference between the CBT and BA groups across observed or imputed outcomes over the period of the trial, as indicated by a non-significant time by treatment effect interaction. Although there was some weak evidence (p = 0.06) of a higher number of depression-free days at follow-up with BA than CBT in the ITT analyses, this difference was not apparent in the PP analysis (p = 0.11).

| Outcome | Time point | Between-group comparison, p-valuea,b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | ||

| Primary outcome | |||||

| PHQ-9, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | 17.4 (4.8), 219 | 9.7 (7.3), 195 | 8.4 (7.5), 189 | 8.5 (7.2), 189 | 0.95 |

| BA | 17.7 (4.8), 221 | 9.8 (6.9), 185 | 8.4 (7.0), 175 | 8.3 (7.1), 176 | |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| GAD-7, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | 12.6 (5.1), 219 | 7.5 (6.0), 186 | 6.3 (6.0), 176 | 7.0 (6.2), 167 | 0.32 |

| BA | 12.7 (5.1), 221 | 7.5 (5.8), 176 | 6.4 (5.9), 161 | 6.4 (5.9), 165 | |

| SCID number of depression-free days, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | – | 66 (41), 171 | 130 (58), 160 | 125 (60), 161 | 0.06 |

| BA | – | 70 (47), 164 | 120 (55), 150 | 129 (57), 153 | |

| SF-36 v2 PCS, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | 50.1 (13.1), 65 | 48.4 (11.7), 107 | 48.1 (12.2), 168 | 48.8 (12.5), 167 | 0.64 |

| BA | 51.4 (11.9), 69 | 49.4 (12.1), 111 | 49.9 (11.6), 150 | 49.6 (12.5), 160 | |

| SF-36 v2 MCS, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | 23.2 (9.4), 65 | 39.5 (12.4), 107 | 41.7 (14.1), 168 | 40.7 (14.4), 167 | 0.50 |

| BA | 22.5 (7.8), 69 | 37.5 (13.7), 111 | 41.6 (14.0), 150 | 42.3 (13.8), 160 | |

| Other outcomes | |||||

| Recovery,c n/N (%) | |||||

| CBT | 13/219, 6 | 111/195, 57 | 134/189, 66 | 127/180, 59 | 0.88 |

| BA | 208/221, 6 | 97/185, 52 | 115/175, 66 | 116/176, 66 | |

| Response,d n/N (%) | |||||

| CBT | – | 96/195, 49 | 117/189, 62 | 108/180, 60 | 0.94 |

| BA | – | 91/185, 49 | 107/175, 61 | 108/176, 61 | |

| Outcome | Time point | Between-group comparison, p-valuea,b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | ||

| Primary outcome | |||||

| PHQ-9, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | 17.3 (4.8), 158 | 9.1 (6.9), 152 | 7.9 (7.3), 152 | 8.0 (7.3), 147 | 0.51 |

| BA | 17.6 (4.6), 147 | 9.7 (6.7), 145 | 7.8 (6.5), 135 | 7.7 (6.7), 137 | |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| GAD-7, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | 12.6 (5.2), 158 | 6.9 (5.8), 149 | 6.0 (5.8), 146 | 6.5 (5.9), 141 | 0.45 |

| BA | 12.5 (5.0), 147 | 7.1 (5.6), 140 | 5.9 (5.4), 129 | 6.0 (5.7), 132 | |

| SCID number of depression-free days, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | – | 67 (40), 140 | 132 (55), 138 | 130 (59), 136 | 0.11 |

| BA | – | 68 (46), 137 | 119 (55), 125 | 130 (56), 123 | |

| SF-36 v2 PCS, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | 50.3 (12.4), 51 | 49.9 (10.9), 90 | 48.0 (12.2), 144 | 49.0 (12.6), 141 | 0.60 |

| BA | 50.4 (12.1), 46 | 49.9 (11.8), 87 | 49.9 (12.0), 125 | 49.6 (12.7), 130 | |

| SF-36 v2 MCS, mean (SD), n | |||||

| CBT | 23.4 (9.3), 51 | 40.2 (12.2), 90 | 42.9 (13.6), 144 | 41.6 (14.6), 141 | 0.58 |

| BA | 22.9 (7.8), 46 | 39.0 (13.3), 87 | 42.3 (13.3), 125 | 42.7 (13.8), 130 | |

| Other outcomes | |||||

| Recovery,c n/N (%) | |||||

| CBT | 9/158 (6) | 91/152 (60) | 104/151 (69) | 93/147 (63) | 0.77 |