Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/188/05. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Amanda Farrin is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Themed Call Panel. David Meads is a member of the Elective and Emergency Specialist Care National Institute for Health Research HTA panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Bennett et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Supporting self-management of analgesia and related treatments at the end of life

Summary of Health Technology Assessment brief

In October 2012, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) published a commissioning brief entitled ‘Self-management of pain relief, nausea and constipation for patients approaching the end of life’. Applicants were asked to address the research question of whether or not a patient support tool could improve the self-management of medication for pain, nausea and constipation in patients approaching the end of life. This call was based on the recognition that:

Enhanced patient-family health decision making can improve the overall quality of end of life care. As life-limiting illnesses progress, the number of disease related symptoms typically increases. Medication regimens can be complex and pain, nausea and constipation are among the common symptoms that often fluctuate and may be appropriate for self-management by patients and their family carers. Patient decision aids have been shown to be effective in facilitating informed decision making and it may be that a self-management aid could help patients and their families to manage their medication regimens to improve pain, nausea and constipation symptom control. A feasibility study is needed to develop a support aid and to assess its acceptability.

This report contains the research conducted in response to this brief (see Appendix 1 for full HTA brief).

Summary of current evidence and policy context

Approximately 160,000 people die from cancer each year in the UK, a number that is expected to rise to 193,000 by 2030. 1 Evidence suggests that 45–56% of patients with advanced cancer (72,000–89,600 each year in the UK), experience pain of moderate to severe intensity before they die. 2,3 Detailed information on pain in patients approaching the end of life with non-cancer diseases is less widely available.

Since 1986, the focus of pain treatment for patients approaching the end of life has been the use of strong opioids based on the World Health Organization’s ‘analgesic ladder’. 4 Initial studies suggested that this approach could control pain in around 73% of cancer patients. 5,6 Despite widespread availability of strong opioids in the UK, at least 32% of patients with cancer are undertreated for their pain. 3,7

Patients at the end of life report that their preferred place of care and death is home. 8 The National Survey of Bereaved People (VOICES) has evaluated the perceptions of the care given to recently deceased persons (not just those with cancer) since 2011. 9 In 2015, only 18% reported that pain was controlled ‘completely, all the time’ at home, compared with 38% in hospital and 63% in hospice. Not surprisingly, uncontrolled pain is the most frequent reason for community-based cancer patients to contact out-of-hours primary care services. 10

Although there is evidence that improved pain management for patients with advanced disease is associated with involvement of palliative care, the evidence base is not consistent in reflecting significant methodological heterogeneity. 11 Little is known about the service constituents that are responsible for improved pain management.

In 2008, the Department of Health published a strategy for end-of-life care as it recognised that many people did not have what could be described as a ‘good death’: being treated as an individual with dignity and respect, being without pain and other symptoms, being in familiar surroundings and being in the company of close family and/or friends. 12 A National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standard was subsequently issued in 2011 to define and support high-quality end-of-life care, specifically including pain management. 13

In 2016, the British Medical Association interviewed 269 members of the public and 237 doctors regarding the provision of end-of-life care by the NHS. 14 For both the public and doctors, pain was the most feared aspect of dying, echoing the findings of the national VOICES survey and underlining the importance of good pain control at the end of life.

A succession of key reports have emphasised the urgent need to improve end-of-life care services in the NHS because of unacceptable variation in access to and experience of care. 15 The Leadership Alliance for the Care of Dying People’s One Chance to Get it Right – Improving People’s Experience of Care in the Last Few Days and Hours of Life16 recognised that pain and symptom control should be among the five key priorities of care in the NHS. In 2015, NHS England led Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care: A National Framework for Local Action 2015–2020,17 which described access to care and maximising comfort as two of its six ambitions for improving services. The Parliamentary Health Committee on End of Life Care reported in 2015 that round-the-clock access to community nurses and specialist outreach palliative care for pain relief are some of the actions that could facilitate a shift in quality of care. 18

The Palliative and End of Life Care Priority Setting Partnership, led by the James Lind Alliance, undertook a survey of 700 patients and carers and a similar number of professionals involved in end-of-life care, regarding research priorities. 19 Of the 83 shortlisted areas, one-third of the top 10 research priorities related to symptom management, with pain specifically mentioned. In response to this, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) undertook a themed review of palliative care research that it funds, summarised in the NIHR report Better Endings. 20

Overall, NIHR research has identified persistent inequalities and variations in care, with poorly co-ordinated services and limited access to specialist palliative care. In addition, place of death may not be the most important aspect of care for many; managing pain and other symptoms and the quality of care are key for patients and their family, whatever the setting. These reports,12–15 all published in the last 2 years, serve to highlight that although good-quality end-of-life care can be defined, currently within the NHS patients experience poor pain control at home, the public remain understandably fearful of a painful death and there is unacceptable variation in access to good care in the NHS. Providing better support to enable patients to self-manage with more confidence is likely to be an important mechanism in improving outcomes for patients with pain from advanced disease. 21 Therefore, this research proposal was timely and important in supporting NHS priorities and informing ways to improve the experiences of dying patients and those that survive them.

Background rationale

One important influence on the quality of pain management for patients at home concerns the information and understanding that patients have regarding their pain and their analgesic medication. Misunderstandings by patients regarding opioids inhibit good pain control22 and we have found that this is particularly true for older patients. 23 Our own research has also shown that patients and their carers face daily dilemmas on the best way to balance pain relief with the adverse effects of analgesia and the consequent impact of both on daily activities. 24,25 Attitudes and knowledge of health-care professionals (HCPs) towards opioids is likely to influence the quality of information provided to patients26 and the increasing complexity of opioid choices in end-of-life care may further reduce the confidence of non-specialist practitioners. 27

However, addressing the concerns of patients leads to improvements in pain control,28 and this process relies on specific contexts that support behavioural change in patients, carers and professionals. 29–31 Although education and self-management support are largely seen as nursing tasks rather than medical tasks,30 our research suggests that pharmacists can make important contributions too. 32,33

Despite there being a good understanding of patient and carer concerns regarding opioid analgesia and related side effects, much less is known about the optimal means of addressing these concerns,34 which is why they have been highlighted by NICE guidance. 35 Simple information in the form of leaflets or video may help,36 but may be insufficient to make a tangible impact on patients’ perceptions of confidence to self-manage.

The research recommendation 4.1 from recent NICE guidance on the use of opioids in palliative care calls for clinically effective and cost-effective methods of addressing patient and carer concerns about strong opioids, including anticipating and managing adverse effects. 35,37 Moreover, the NICE guidance indicates that as well as constipation and nausea, drowsiness is one of the most common side effects of pain medication and one that bothers patients most. All three side effects need to be addressed for optimal pain management and we therefore extended the scope of the HTA brief to incorporate drowsiness in the intervention.

Feasibility study aims and objectives

We aimed to develop an intervention that enables patients approaching the end of life and their carers to more confidently manage medications for pain (specifically strong opioids), nausea, constipation and drowsiness at home. We designed this project with a patient-centred approach at the heart of our development plan, nested within a theoretically informed behaviour change framework. The expected benefits of the intervention for patients were improvements in symptom relief, feeling empowered with increased knowledge and skills to recognise worsening symptoms or adverse effects, being able to self-initiate therapeutic adjustments and knowing how and when to access help from the health-care system.

We defined our intervention as a set of materials and coaching procedures that deliver knowledge, facilitate the generation of specific action plans and enhance the user’s skills to monitor and reflect on their actions. We judged that our intervention would be optimally delivered by clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) who work within specialist palliative care teams. We thought that patients would be most likely to benefit from the intervention if they were adults (aged > 18 years), approaching the end of life, suffering from significant pain and being cared for in their own home, being treated with, or due to start treatment with, opioids for pain, and experiencing (or anticipating) adverse effects of these medications. We were particularly keen to embed the principles of experience-based co-design into the development, modelling and testing of our prototype intervention, and to evaluate this within a theoretical framework for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. 38,39

Our objectives were divided into three distinct phases, which is in line with the Medical Research Council framework on developing and evaluating complex interventions. 40 We also planned to use the explanatory models of normalisation process theory to evaluate factors that will support implementation. 41 This would offer a clear path for implementation into the wider NHS should the effectiveness of the intervention be established in a future definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Phase I: development objectives

-

Establish a patient and public involvement (PPI) panel.

-

Establish the content of a prototype intervention and a manualisation strategy that includes a protocol to standardise (1) the training of HCPs and (2) the delivery of the intervention by HCPs to patients and carers.

-

Understand self-management needs and capabilities of patients and carers related to strong opioid medication.

-

Define usual care.

Phase II: modelling objectives

-

Refine the prototype intervention and manualisation strategy.

Phase III: feasibility assessment objectives

-

Assess acceptability and up-take of the intervention in a mixed-methods observational study involving patients, informal carers and HCPs from four palliative care services.

-

Assess the feasibility of obtaining outcome data for a larger trial.

Patient and public involvement

We have had sustained PPI throughout all stages of the Self-Management of Analgesia and Related Treatments at the end of life (SMART) study. PPI has been an integral part of all our study processes from inception and development of the research ideas, development of the funding application, through to delivering the research project and interpreting the study findings. We have engaged with PPI in a number of ways. First, through a PPI coapplicant (JG), we benefited from expert PPI input to help prioritise the research question and ensure that the delivery of the intervention is undertaken in a way that is meaningful and relevant to patients approaching the end of life and their carers. Second, in the first phase of the project we established a dedicated PPI panel that informed and helped refine the content and delivery strategy of the SMART intervention as well as review patient study materials (i.e. information sheet, consent form, patient questionnaire). Last, we recruited an independent PPI representative to be part of the Steering Committee, which has oversight and responsibility for the project, and gave the study team insight and direction throughout the design, delivery and completion of the project.

Success criteria

Ultimately, we aimed to establish the acceptability and uptake of our prototype self-management support toolkit (SMST) and determine the feasibility of evaluating this intervention within a larger trial. In order to judge whether or not we had achieved our aims, we agreed our success criteria beforehand to be as follows.

Phase I

-

Establishment of a PPI panel and assessment of members’ support and training requirements.

-

Development of a usual-care protocol based on literature review and clinical practice observations.

-

Development of prototype intervention materials, manualisation strategy and usual care protocol.

Phase II

-

Establish members of focus groups.

-

Development of refined intervention materials and manualisation strategy.

Phase III

-

Sampling strategy: recruit three patients per month at each site within 4 months.

-

Feasibility of data collection: key clinical and health economic measures, and health-care resource measures, have sufficient complete data to estimate primary study end points.

-

Trial experience: patients and carers reporting acceptable and sustained use of intervention materials.

Chapter 2 Development of the SMART intervention

Phase I: overview of initial contextual work

This chapter describes the intervention development process. First, it summarises the literature scoped to inform the development of the intervention. Second, it recounts the exploratory activities undertaken with specialist palliative care health professionals, patients and carers, to derive a concept of self-management of analgesia (opioids) and related treatments (for nausea, constipation and drowsiness) at the end of life.

Through this development process it was possible to generate a preliminary model of self-management that was then tested further through interviews and focus groups with patients, carers and HCPs. This chapter will also describe how this model was then used to specify and inform the components, including content and form, of the SMART intervention. This process aligned with the theoretical modelling phase of the Medical Research Council framework for complex interventions. 42,43

Initially, contextual work was performed to frame self-management within the field of palliative pain management. Much is written about self-management, but the focus is predominantly on long-term condition management. 44 However, a survey of 90 cancer patients living at home receiving community-based palliative care identified three key factors associated with successful pain management. 45 The first factor is maintaining a sense of control over managing medicines by modifying the schedule of taking medicines around daily routines and planned activities. The second factor is negotiating a balance (trade-off) between symptom control and the impact of medicines’ side effects on cognitive and physical functioning. Furthermore, Hansen et al. 46 identified that 40% of end-of-life patients regularly do not use analgesia despite reporting moderate to severe pain and indicating an awareness that regular medication was the most effective self-management behaviour for controlling pain. These authors concluded that patients were making important trade-offs between pain relief and the side effects of medications and this helped maintain a sense of control. The third factor associated with successful pain management identified by Bennett et al. 45 is a broad base of support. Community palliative care nurses and community pharmacists were seen as key HCPs supplemented by support from a carer (family member or friend). The authors concluded that a community-based intervention that is flexible and responsive to patients’ needs, involving carers and community-based HCPs, is most likely to be successful.

Information provision has been identified as a fundamental component of interventions in advanced disease. 37,47 Tailored information provision equips patients and carers with the necessary skills and confidence to drive behaviour change. 39,48 However, on its own it is insufficient to drive significant improvements in patient-reported outcomes, such as pain and quality of life. Contextual factors associated with successful pain management are the development of a trusting relationship with health-care providers, having dedicated time to focus on medicines management and confidence in exerting self-control over a daily analgesic routine. 47,49 Identifying patient and carer needs was recognised by NICE as the basis for delivering tailored support in its guidance on improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer. 37 Therefore, in addition to information provision, regular assessment and review of patient needs is a key component in supporting self-management of pain medication in this context. 37,47

In order to understand the context more fully, six semistructured interviews were initially undertaken with patients and carers recruited from a palliative care outpatient service. Interviews focused on identifying the need to self-manage medicines at the end of life and exploring perceived barriers to and facilitators of managing medicines at home. This led to the delineation of five themes:

-

communication and understanding

-

addressing fears and concerns

-

information requirements

-

carer-specific needs

-

making trade-offs.

These themes were used to shape early thinking about the dimensions of the intervention, which were further refined in later phases, as described below.

Evidence synthesis

Scoping of the literature

Scoping of the literature was undertaken following the preliminary work described above. The objective of this exercise was to examine:

-

the content and form of previous interventions effective in improving pain management by patients (see Appendix 2)

-

key systematic reviews of what can be done to support self-management across a range of long-term conditions of relevance to this particular application at the end of life

-

key literature and reviews that identify factors that enable HCPs to support patient self-management

-

existing public guidance based on NICE clinical guideline 140 – Opioids in Palliative Care (Box 1)

-

description and potential components of self-management at the end of life (Box 2).

-

NICE (2012) information for managing pain with the strong opioids in people with advanced progressive disease – information for the public. 37

-

All Wales Medicines Strategy Group: Opioids in Palliative Care – Patient Information Manual. 50

Managing pain with strong opioids: some treatments may not be suitable depending on your circumstances, definition of palliative care and its purpose of alleviating pain and discomfort to improve quality of life.

Information about taking strong opioids: if you are offered strong opioids, HCPs should explain when and why strong opioids are used to treat pain; how effective they are likely to be at relieving your pain; about taking strong opioids for background pain and breakthrough pain, including how, when and how often to take them; how long pain relief should last, possible side effects and signs to watch out for that might mean there is too much of the medication in your system; and how to store strong opioids safely.

Discussing your concerns: if you are worried about addiction and side effects, your HCP should reassure you that addiction is very unlikely and that you will be monitored for side effects. Strong opioids can be offered at different stages and doing so does not necessarily mean that you are close to the end of your life.

Starting treatment with opioids: different forms, short acting vs. slow release, no standard dose.

If you have trouble swallowing: if pain is stable you should be offered a patch.

Reviewing pain control: need for regular reviews especially at the beginning.

Continuing treatment: sustained-release form.

Treating breakthrough pain: immediate-release form, advice from specialist if uncontrolled.

Managing side effectsConstipation: definition and statement that it affects nearly everyone who takes strong opioids. You should be offered laxatives and a description of how laxatives work; they can take time to work so take them as advised and your HCP may change the type of opioid if your constipation is severe.

Nausea: you may experience feeling sick when starting strong opioids or when the dose is increased, but this is likely to last only a short time. If it persists, you should be offered anti-sickness medication.

Drowsiness: you may experience mild drowsiness or problems with concentration when starting strong opioids or the dose is increased, but this is likely to last only a short time. Your HCP should warn you that having problems might affect your ability to carry out some tasks, such as driving. If you have severe or long-lasting problems and your pain is under control, your HCP may discuss the possibility of reducing the dose of opioid with you. If your pain is not controlled, then your HCP may consider changing the opioid and if the problems are not relieved by these changes then your HCP may seek specialist advice.

Questions to ask a HCP: tell me more about strong opioids for pain relief? Can you tell me about the side effects associated with taking strong opioids? Will I become addicted to strong opioids? How long will it take for this medication to work? What do I do if I am still in pain after taking strong opioids? What are my options for taking some other type of pain relief? Can you give me some written material about strong opioid treatment?

Sources of more information: CancerHelp UK, Macmillan Cancer Support, British Pain Society and NHS Choices.

The above authors provided a definition (via concept analysis) of self-management support within the context of palliative care:

. . . Assessing, planning, and implementing appropriate care to support the patient to be given the means to master or deal with their illness or its effects.

The authors proposed eight potential professional roles to support self-management. These roles were undefined but labelled as advocate, educator, facilitator, problem-solver, communicator, goal-setter, monitor and reporter.

References: Schumacher et al.52,53These authors demonstrated that, for oncology patients (and their carers) in the USA, the practical experiences of day-to-day management of pain medications could be both challenging and onerous. Navigating the systems with complex webs of people and rules was a lengthy and tedious challenge causing frustration, effort and added anxiety. These issues revolved around getting prescriptions, obtaining medicines, understanding, organising, storing, scheduling, remembering and taking.

UnderstandingOnce patients and carers obtained medicines they were immediately faced with understanding the medicines they had brought home. Lack of understanding led to uncontrolled pain. Many areas of confusion were evident; keeping the purpose and names of medications straight was one. Medication names were ‘not in English’ (i.e. plain English); many referred to medicines by appearance, and the use of abbreviations was seen as confusing, as were drugs with similar names. Lack of understanding about maximum daily dose limits was common (including not knowing that opioids do not have a dose ceiling). Understanding the meaning of dosing intervals was an issue for some (e.g. every 3 days). Utilising the wide variety of information sources was challenging and information printed on packs and inserts was too small for some to read.

OrganisingOrganising presented a host of issues because of the sheer number and various forms of medicines prescribed for regular use, p.r.n. (as required) or both. Participants used a wide range of highly individual strategies: elaborate daily rituals involving, for example, zip lock bags; differentiation of medicines by colour; lining up of medicine bottles with magnifying glass; taking out pills and putting them into a glass. Lack of organisational systems presented safety risks such as medicines sitting out in glasses:

Participants used their home environments for pain medication management in highly individualized ways. Countertops, drawers, tables, windowsills, cabinets, boxes, bags, dishes, alarm clocks, whiteboards, computers, and mobile devices were all used. Individuals and pets living in the home were taken into account. Visitors were a consideration, especially visiting grandchildren.

Schumacher et al. p. 78753

Storing

This refers to putting medicines safely away. Hiding medicines from patients was a strategy used when carers feared that the patient would get confused and take too much. Storing medication generally involved hiding them and locking them up.

SchedulingThis refers to working out the best time to take medicines in relation to daily lifestyles. Some used pain as a cue to take next regular dose earlier than scheduled, rather than take rescue medicines; this fitted with the mindset of taking medicines only when pain is present.

RememberingRemembering use of dosette boxes helped but this was not failsafe. All affected by fatigue, drowsiness and confusion.

TakingThis was straightforward for most, but some experienced challenges (e.g. erroneously cutting sustained-release pills).

Theoretical underpinning of the intervention

The literature-scoping work informed the selection of theory focused on self-efficacy and behaviour change to best suit the developing intervention. Self-efficacy is a key component of Bandura’s social cognitive theory. 54,55 The theory of social cognition states that knowledge acquisition can be directly related to observing others within the context of interactions and experiences. According to this theory, self-efficacy is the belief in an individual’s capabilities to organise and carry out courses of action to manage situations. Bandura states that behavioural techniques can be used to target the four sources of self-efficacy: mastery experience, role modelling, verbal persuasion and the regulation of physiological and affective states. Michie et al. 39 undertook a systematic search and consultation with behaviour change experts to identify frameworks of behaviour change interventions. These were then evaluated for comprehensiveness, coherence and a clear link to a model of behaviour. A new framework was subsequently developed to fully meet all these criteria: the behaviour change wheel. The wheel characterises behaviour change interventions around nine intervention functions aimed at addressing deficits in one or more of three essential conditions for behaviour change: Capability, Opportunity and Motivation (termed the COM-B system). The behaviour change wheel identifies three main target constructs (sources of behaviour), which are capability (physical and psychological), motivation (automatic and reflective) and opportunity (social and physical). Around these target constructs are nine intervention functions (education, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, training, enablement, modelling, environmental restructuring and restrictions), which represent ways to address deficits in one or more of the target conditions.

Key learning from studies conducted by the team

The intervention development was also informed by key learning from two studies undertaken by members of the research team. These were Cancer Carer Medicines Management (CCMM),56 funded by Dimbleby Marie Curie Cancer Care, and Improving the Management of Pain from Advanced Cancer in the Community (IMPACCT), a programme grant funded by the NIHR (RP-PG-0610-10114).

The SMART intervention drew on carer needs for medicines management at the end of life identified from the CCMM study (see Appendix 3), including needs for information about pain medicines and side effects, changing beliefs about opioids and providing skills and opportunities for self-evaluation. The results of the CCMM study also showed that a conversation-driven intervention, delivered by nurses in routine practice and supported with a toolkit of resources, was acceptable to carers and to nurses and was compatible with their existing practice. CCMM showed some evidence of benefit in influencing carers’ knowledge, beliefs and behaviours related to management of pain medicines. Principles of the CCMM conversational process (assessment, education and review), as well as elements of the toolkit (information leaflets, medication chart, pain diary and contact details for local and national services), informed the development of the SMART intervention.

Learning from the IMPACCT study was derived from a review of the optimal components of educational interventions for advanced cancer pain, which was carried out as part of the study (see Appendix 4). In this meta-review,57 the authors used Michie et al. ’s39 behaviour change wheel as theoretical underpinning. Mapping findings from six reviews and two papers led to identification of five out of the nine behaviour change wheel intervention functions. These were considered essential for successful interventions:

-

education, for example providing written information about pain management, including analgesic and non-pharmacological approaches

-

training, for example providing instruction, demonstration and coaching of new skills (techniques for managing daily drug regimes, relaxation techniques)

-

enablement and persuasion, for example overcoming cognitive and emotional barriers to pain management through addressing concerns about tolerance or addiction

-

environmental restructuring and resources, for example incorporating the delivery of education for self-management into the usual care provided by specific health professionals, such as specialist nurses, primary care practice nurses and community pharmacists

-

modelling, for example patients talking to other patients about their successful use of various pain management strategies.

Phase II: refining and detailing the intervention

This section describes the work undertaken to refine and detail the intervention. In particular it describes a series of interviews and focus groups conducted with patients, carers and HCPs. These data sources, together with work described in the previous section, were used to derive the content and form of the intervention for SMART.

Aim

The aim of this phase of the study was to refine and detail an intervention for self-management of analgesia (opioids) and related treatments (for nausea, constipation and drowsiness) at the end of life.

Objectives

The literature scoping informed the objectives and these were to:

-

explore views regarding the nature and components of supported self-management regarding analgesia and related treatments at the end of life, and test our preliminary model of self-management in this context

-

introduce participants to, and ask for their views on, aspects of self-management in this context – in particular our selected definition of supported self-management in palliative care (Johnston et al. 51) and practical difficulties regarding supply and medicines taking encountered by patients (Schumacher et al. 52,53) (see Table 2).

For HCPs, the objectives were to:

-

reveal the self-management promoting activities and behaviours already used by specialist palliative care HCPs and gain views on the professional supportive self-management roles proposed by Johnston et al. 51

-

rehearse previous examples of interventions to test possible delivery modes and how these could link to existing patterns of practice.

For patients and carers, the objectives were also to:

-

understand what supported self-management at the end of life was for them

-

explore patient and carer needs using the framework of Schumacher et al. ’s52,53 commonly encountered practical difficulties regarding supply and the taking of medicines

-

gain views regarding potential options for the content, form and delivery of the intervention.

Approach to data collection

Focus groups and interviews were held in two geographical regions: Hampshire and Yorkshire. They were conducted with patients, their carers and specialist palliative care health professionals (including service managers and commissioners).

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included if they:

-

were aged ≥ 25 years and considered to be in the last year of life

-

were experiencing pain

-

were being treated with, or starting, opioid analgesia

-

were experiencing, or anticipating, adverse effects of nausea, constipation and drowsiness

-

were living at home

-

were being cared for by specialist community-based palliative care services in Hampshire or Yorkshire

-

had capacity to consent.

Carers were included if:

-

they were the primary carer of a patient meeting the above inclusion criteria and

-

the patient gave consent to their involvement.

Health-care professionals were included if they were:

-

CNSs and doctors who were part of specialist palliative care teams or

-

service providers or managers of specialist palliative care services or

-

local commissioners of palliative care services.

Sampling strategy and recruitment

To access a range of individuals (HCPs, patients and carers), we aimed to recruit 35 participants via various strategies across four hospices and two acute NHS trusts. The sampling and recruitment strategy is detailed in Table 1.

| Hampshire | ||

|---|---|---|

| HCPsa | ||

| Acute trust 1 + hospice 1: eight hospital-based CNSs, six consultants and one specialist registrar were invited to participate. Of these, two hospital-based CNSs attended the focus group. 18 community palliative care CNSs were invited to participate, five attended the focus group that occurred at this hospice | Hospice 2: staff across the hospice were invited to attend. Three attendees participated in the focus group at this hospice and a further three travelled to attend the focus group at the other hospice | Acute trust 2: one lead nurse/commissioner was invited to take part in an interview and this took place |

| Patients and carersb | ||

| Acute trust: 17 patients were referred via a hospital-based palliative care team, all except four were approached by the researcher (seven did not meet the eligibility criteria). Two patients were recruited and interviewed | Hospice 1: 39 patients and carers attending day hospice sessions were informed about the study. Five patients and two carers (who met the eligibility criteria) approached the researcher after these sessions and four patients and two carers were recruited (n = 6) | Hospice 2: six patients were referred by day hospice staff as meeting the study’s eligibility criteria. All were spoken to by the researcher and five patients were recruited, with two carers (n = 7) |

| Yorkshire | ||

| Focus groupsc | ||

| HCPs: an entire community palliative care CNS team based at a hospice were invited to take part in a focus group and all attended on the day (n = 4). One palliative care consultant was invited to take part in an interview and this took place | Patients and carers: 10 eligible individuals were approached via a hospice outpatient clinic. Of the 10, four attended the focus group, four had agreed to participate but failed to attend, and two declined | |

Focus group and interview guides

Topic/interview guides (as well as supporting slide/card packs) were developed to meet the study objectives (see Appendices 5–8). A number of tools were used to manage the interview and focus group discussions:

-

a definition of supported self-management in the context of palliative care (Johnston et al. 51)

-

eight proposed professional roles to support self-management in the context of palliative care (Johnston et al. 48)

-

the practical difficulties around supply and medicine taking encountered by patients and carers in the work of Schumacher et al. 52,53

-

the content and form of previous interventions to improve pain management by patients. 58–61

The interviews and focus groups were conducted by the study’s researchers. The focus groups were conducted with a co-facilitator another researcher with expertise in the field, present to aid moderation.

Data analysis

The audio files from the interviews and focus groups were professionally transcribed. They were listened to by the researchers alongside the transcripts to check for complete accuracy. Both study researchers familiarised themselves with the data by reading and rereading the transcripts and identifying key issues, concepts and themes. Initial coding took the form of indexing on the transcripts, and each research fellow summarised the key themes from the data related to the sites in their regional area. The themes were discussed for comparative purposes. Natasha Campling then coded the entire data set for all issues, aspects and themes that were relevant to supported self-management in this field. Coding was performed in NVivo (version 11; QSR International, Warrington, UK) utilising framework analysis. 62

The development process

The process of intervention development is illustrated in Figure 1. The contextual work and literature scoping informed a preliminary model of supported SMART. This model, a definition of self-management,51 practical difficulties related to supply and medicine-taking52,53 and the content and form of previous interventions58–61 were used as tools within the focus groups and interviews to gain participants' views. The result was development of a concept of self-management, to inform the required components (including the content and form) of the intervention: a four-step educational approach and toolkit, plus a training package to enable nurses to deliver the intervention within a feasibility study.

FIGURE 1.

Intervention development process.

Findings from the intervention development interviews and focus groups

The sample

The sample was composed of 38 participants recruited via the two geographical regions of Hampshire and Yorkshire (Table 2). The demographics for the HCPs and patients and carers are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

| Patient and carer sample (n = 19) | HCP sample (n = 19) |

|---|---|

| Yorkshire | |

| 1 focus group, n = 4 patients | 1 focus group, n = 4 CNSs |

| 1 face-to-face interview, n = 1 consultant | |

| Hampshire | |

| 11 interviews, n = 11 patients, n = 4 carers | 2 focus groups: n = 10, 9 CNSs + 1 specialist registrar; n = 3, 2 inpatient unit nurses, 1 lecturer/practitioner |

| 1 telephone interview, n = 1 lead nurse/commissioner | |

| Overall total | |

| 38 participants | |

| Demographic characteristic | HCPs, n (N = 19) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 18 |

| Male | 1 |

| Professional background | |

| Nursing | 17 |

| Medicine | 2 |

| Main working environment | |

| Hospice inpatient | 4 |

| Hospice education | 1 |

| Community | 10 |

| Hospital | 2 |

| Community and day hospice | 1 |

| Hospital, hospice and community | 1 |

| Length of time in current post | |

| Years, mean (range) | 7 (0.5–24) |

| Length of time in palliative care specialism | |

| Years, mean (range) | 13 (1–27) |

| Demographic characteristic | Patients, n (N = 15) | Carers, n (N = 4) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 7 | 4 |

| Male | 8 | 0 |

| Age | ||

| Years, mean (range) | 66 (47–84) | 69 (52–80) |

| Cancer site | ||

| Bile duct | 1 | |

| Breast | 1 | |

| Colon | 1 | |

| Lung | 4 | |

| Lung (pleural mesothelioma) | 1 | |

| Oesophagus | 1 | |

| Pancreas | 1 | |

| Prostate | 3 | |

| Skin (melanoma) | 1 | |

| Uterus | 1 | |

| Educational level | ||

| Degree level or above | 4 | 2 |

| Below degree level | 6 | 2 |

| No qualifications | 5 | |

Concept of supported self-management in analgesia and related treatments at the end of life

The development process, informed by the varied sources of learning outlined in Evidence synthesis, enabled the generation of a preliminary model of supported self-management in analgesia and related treatments at the end of life. The model was tested, within this specific context, through the interviews and focus groups with patients, carers and HCPs. The model included the self-management definition, professional roles outlined by Johnston et al. 51 and the practical difficulties regarding medicines access, supply and taking outlined by Schumacher et al. 52,53

This process revealed new components of supported self-management within the end-of-life context. It displayed an ever-changing process enacted on a continuum of behaviours dependent on the responsibility taken by the patient, carer and specialist nurse. This was a complex web of behaviours, varying day by day, if not hour by hour, within this context. With continual disease progression, there were frequent changes in symptoms and side effects from both medication and palliative treatments, with behaviours profoundly affected. This context was complicated by the surrounding ‘swirl’ of what individuals and their families were already striving to deal with, the wider context of psychological distress and high levels of carer strain. Individuals in this context could be struggling to cope with a palliative care diagnosis and there was anxiety and clinical depression of both patients and/or carers. Consequently, the capabilities of the patient and carer fluctuated greatly, influencing supportive self-management roles and the required behaviours of the specialist nurse.

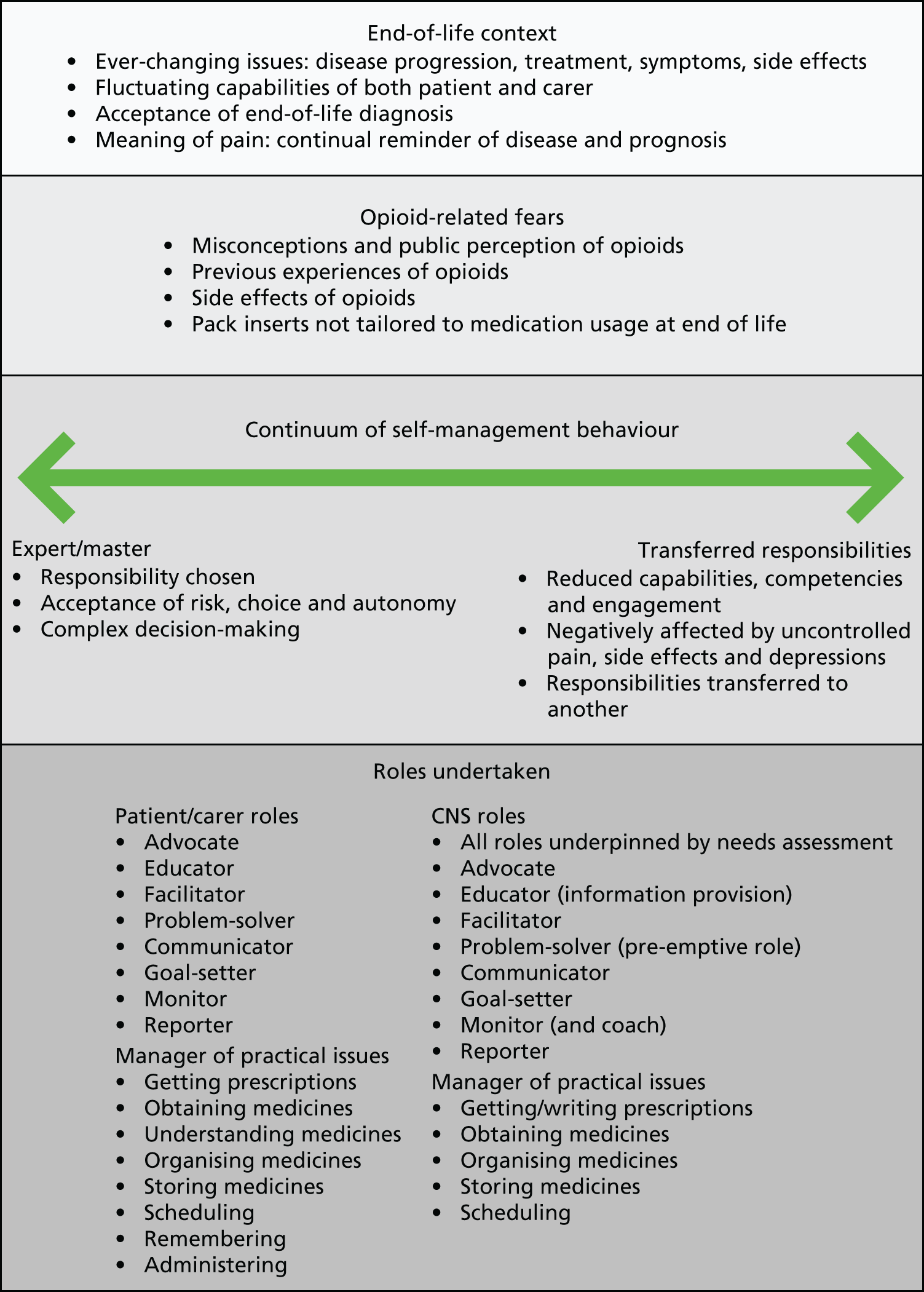

The concept is presented here as it is key to understanding the development and form of the intervention. The key components of the concept, the issues of responsibility and the supported self-management roles of the patient, carer and CNS are outlined. Figure 2 is a diagrammatic representation of the concept.

FIGURE 2.

A concept of supported SMART.

Patient roles

Some study patients participated in managing their medicines almost entirely themselves; however, this was the experience of a small minority. Those who had nurse specialist input and/or a carer who played a role in supporting self-management enacted their own roles differently as a result, leading ultimately to a change in their resulting behaviours. This was the experience of the majority of the patient sample. The roles undertaken by patient participants are mapped to the roles to support self-management proposed by Johnston et al. 51 in Table 5.

| Johnston et al.51 roles to support self-management | Intervention development interview and focus group participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Carers | CNSs | |

| Advocate | For themselves (e.g. requesting alternative opioids/forms if side effects are not acceptable) | Total advocacy role when needed | Right type and route of drug |

| Educator | Of carer if required, anticipation of future changes (i.e. planning for worsening condition) | Of patient and CNS when needed | Refining knowledge for individuals, providing instruction |

| Facilitator | Of relationships/access to medicines (e.g. GP, HCPs and carer, carer and community pharmacist) | Manager of the practical supply and medicine-taking issues when needed | Preparing for transitions, ‘home feels like you have not got someone to speak to just around the corner’ |

| Problem-solver | Access to medicines and navigating the supply system, side effects management and off-setting doses | Pre-emptive (e.g. regarding stock management or suggesting need for breakthrough analgesia) | Best drug and side effect profile for individual, sorting out when supplies get in a muddle, pre-emptive problem-solving (‘always have a plan B’) |

| Communicator | Of relevant information to all – family and HCPs | ‘Is it helping?’ Encouraging discussion with patient | Picking style of communication for individual, knowing the family and patient (mediator as well as communicator) |

| Goal-setter | Self-planning, planning with a GP or joint planning with CNS | Often in relation to getting out and about (e.g. getting out of the house for a coffee, going to a favourite place) | Proposing options and allowing the individual to decide what they would prefer and putting a plan together |

| Monitor | Writing down of breakthrough doses and noting effectiveness | Diary recording | How much information has been understood? Monitoring involvement of patient in decisions and reviewing effectiveness of medicines |

| Reporter | Of relevant symptom experiences and side effects | Evaluation of the effectiveness of the medications | To wider palliative care team and GPs |

The patients often played an advocacy role on their own behalf, for example requesting alternative analgesics/opioids where they found the side effects unacceptable and they were unable to manage them. They also educated their carer, if they had one, regarding their medicines so that if their condition changed or they had a bad day then they could rely on them to safely administer their medications. This often took the form of listing their medications, creating a simple timetable of what they took and when and keeping this in a location within their home that could be easily referred to. This aided their communicator role whereby they transferred relevant information regarding their medicines, their effectiveness and their experience of side effects to HCPs [particularly general practitioners (GPs) and CNSs]. Those patients who were under the care of a community palliative care CNS often set joint plans/goals with their CNS, whereas others not under the care of a CNS made their own plans and goals and/or negotiated these with their GP (e.g. coming off a neuropathic agent because of unacceptable side effects).

In addition, the patients facilitated relationships with their HCPs and carers so as to aid access to their medicines. Patients worked at relationships with those who were key to managing their medicines and supporting their self-management: CNSs and GPs, as well as community pharmacists. They often found that knowing their pharmacist aided the supply and stocking of their medicines, resulting in them obtaining their medicines quickly and without delays in the system. At times, pharmacists put in repeat prescription requests for patients because of these relationships, meaning that the patient then just had to arrange to collect the medications from the pharmacy or could use pharmacy delivery services, when available.

The role of facilitating/managing the practical issues related to supply and medicine-taking was frequently an onerous one for patients. They had to get prescriptions, obtain the medicines, understand them once they had been dispensed, organise the medicines at home to keep track of them, store them, schedule them around their routine, remember to take them and, finally, actually administer them.

The patients played a problem-solving role navigating the difficulties in the medicines supply system. They also problem-solved the side effects of their opioids, making decisions to appropriately balance the benefits of pain control with a manageable level of side effects. This was an individual balance (e.g. titrating laxatives on a daily basis to offset the common side effect of constipation). Others for whom nausea was an issue titrated antiemetics on a daily basis. The side effect of drowsiness led some to delay doses or take smaller doses to minimise this. Furthermore, at times a small minority of expert self-managers made complex decisions regarding the dose of opioid to take when it was prescribed within a range.

The patients monitored their symptoms, side effects and the effectiveness of their medicines, often keeping their own records of this, particularly in relation to the administration of ‘as required’ doses for breakthrough pain. This was facilitated by the input of community palliative care CNSs or GPs, who prompted patients to consider how much were taking, when they were taking it and how they found it (H2HCPfocusgroup). As a result, the patients were often in a position to accurately report their relevant symptom and side effect experiences, and changes, to their HCPs.

Carer roles

The supportive self-management roles of the carer fluctuated in relation to changes in the competencies and engagement of the individual patient. However, a few patients had always handed over responsibility for medicines management to their carer: ‘she just always did it . . . I tend to be . . . not worried enough about it you know. I basically need looking after that’s the truth of the matter’ (H1Pt004). The roles undertaken by carer participants are mapped to the roles to support self-management proposed by Johnston et al. 51 in Table 5.

Carers often took on an all-encompassing advocacy role for the patient, particularly when difficulties arose with challenging side effects or poorly controlled pain. Advocacy took the form of working or facilitating the supply system in relation to managing all the practical issues of getting prescriptions, obtaining the medicines, understanding the medicines, organising the medicines in the home environment to keep stock of them, storing them safely, scheduling them around the patient’s routine, remembering (i.e. reminding the individual to take the medicines) and actually administering the medicines if required.

Facilitating and advocating on behalf of the patient in relation to obtaining the medicines was complex, onerous and a hugely time-consuming process for many carers. One patient outlined his difficulties (lengthy delays) in obtaining his fentanyl patches through a non-palliative care specialist pharmacy. This left his wife needing to make in-person visits to speak to the pharmacist on his behalf, only for her to be equally frustrated and leave the pharmacy without the patches, in tears, because she could not answer the question ‘Who’s prescribed these?’:

I’m not sure if it’s the chemist . . . when I rang through and said ‘Here look, what about these patches?’ and the woman said ‘What are they?’ And then I said to her – and she said ‘Yes, well we have got them down on the list, but I don’t know where they are.’ So in actual fact, on like that again . . .

If you lived alone, somebody very elderly . . .

Yes, you need someone to work the system.

Yes! Yes!

As with the various roles of the patient and CNS, the carers’ roles were complexly interwoven. The facilitator role for carers, as in the following example, was one of monitoring pain and the effectiveness of medicines via a pain diary. In turn, this facilitated the administration of analgesia by the carer to the patient, creating the end result of confidence and control over the situation:

. . . I would take an example actually it was quite difficult, as a facilitator it’s not quite between health-care professionals and patient, it was actually between patient and carer. And it goes back to what we were saying earlier on about carers being reluctant to give it [morphine] or patients being reluctant to take it. And it’s where a diary was very useful ‘cos it actually empowered the carer to feel that she was doing something useful to help with her spouse’s pain but also that she felt more in control that she wasn’t giving it more often than she should do or she was writing that it had an effect or didn’t have an effect and where they were going with it. And she was far happier to give it if she was documenting things than just on his say so that ‘I’m in pain’, and he was saying that ‘I’m in pain and she won’t give it to me’ . . . She admitted she wasn’t giving it because she was frightened she was going to be giving too much and how would she know when to stop and the diary actually facilitated being able to give [it], it was confidence . . .

H1HCPfocusgroup

Carers often played a monitoring role highlighting and watching for condition, symptom and side effect changes. Indeed, their monitoring was often astute because of the acuity of observation by someone who knew the patient best. As a result, carers could play an educator role of both the patient and CNS, highlighting these changes as required. This linked closely with their communicator and reporting role, as carers often aided the monitoring of the effectiveness of medicines by asking the patient simple questions such as ‘Is it helping? Does that help?’:

. . . And every so often, I say to you don’t I? ‘How are you on the laxatives?’ And it seems ridiculous doesn’t it, because . . . that’s the best [thing] that’s happened, is you’ve managed to get it [opioids vs. constipation] at a level which is not a problem for you haven’t you . . . ?

Carer-H2Pt004

Consequently, the carers encouraged discussion with the patient and could report this information to HCPs, the CNS and GP as required.

The carers often took a lead in establishing small goals for the patient that they knew were of importance to the individual. With effective medicines and side effect management, goals frequently set were in relation to getting out of the house and continuing to visit favourite places for the individual.

The role of problem-solver was arguably the greatest of the roles played by the carer. In the words of one carer, ‘I try and stop problems happening’ (Carer-H2Pt004). As with the CNS problem-solving role, this was in the main pre-emptive carer role, resolving potential problems. This was particularly the case in terms of asking the individual about their pain, so as to be able to administer ‘as required’ analgesia. Carers also pre-emptively stock managed, requesting medicines before they ran out, and chased GP practices for prescriptions and pharmacies if medications had not been dispensed as requested (e.g. in a different form or were missing).

Clinical nurse specialist roles

In order to evaluate which roles were required, and at what point, the nurses assessed the competencies not only of the patient but also of the carer. The roles undertaken by the CNSs are mapped to the roles to support self-management proposed by Johnston et al. 51 in Table 5. It was recognised that nurses’ provision of supportive self-management roles would fluctuate in relation to patient and carer needs and that at times the roles would be challenging:

. . . I think all of these [roles] will probably peak in difficulty, at times depending on the situation. As a professional, there could be a nightmare sometimes, in a person’s home advocating for that patient, if . . . you have a family who have distinct feelings that are opposing the patient, that’s really . . . difficult. The monitoring, there will be times when that, even on the inpatient unit, that’s got to be a challenge at times, depending on the complexity of the patient, and the capacity of the staff, and staffing levels . . .

H2HCPfocusgroup

Within this challenging context, the nurses emphasised the importance of ensuring that the individual patient had the right drug via the right route. For them this was a clear role of advocacy:

I met a lady with head and neck cancer that was really compromising her mouth and she was just starting on opiates, thought patch that’s going to be the best way to go . . . Spoke to the GP who said fine, then they changed their minds and went back to the tablets because someone in the practice had gone on a palliative care course and was told that MST [Morphine Sulfate Tablets modified release] it’s cheap and cheerful start everyone on that. So then the relative rings up we’ve just gone to collect the patches and it’s tablets so I’m like ‘Oh god’ ring up again, ‘there is a reason why we said patches, I know they’re expensive but she can’t open her mouth’. So like ridiculous!

It’s about being that patient’s advocate isn’t it . . .

The supportive communicator role was vital to the nurses and they emphasised the complexity of communicating well to ‘the agenda of the patient’ using language that would be understood, while highlighting ‘what they need to know, because they might not be interested in all the things that you want to say’ (H2HCPfocusgroup):

. . . I think you have to really pick your style of communication with each individual, this is what X was saying about knowing your family, knowing your patient, ‘cos sometimes you are as much a mediator as communicator. We can sometimes have a relative that just simply doesn’t believe in morphine . . . they will withhold it from them . . . And then others where they will perhaps give a little too much, then you have to sort of be kind in how you say these things, because they want to make it better . . . Yes, so communication is quite hard; you have to get that right, don’t you . . . ?

H2HCPfocusgroup

All the supportive roles of the CNS interlinked and overlapped, particularly that of communicator and educator. This role of educator was viewed as one of providing ‘instruction and information regarding medicines’ (H2HCPfocusgroup). The ever-increasing role of the internet as a source of information for patients and their families was also recognised so that the supportive role of the nurses was often seen as one of helping to ‘refine’ this knowledge for individuals. The need to provide education for carers specifically was viewed as important, but it was argued that these supportive needs may not be met in practice:

. . . You get carers who the knowledge gap is so huge for them, they want to help they want to know what to do and we need to be filling that knowledge gap for them appropriately . . . I think for the carer what they want is the right information and we don’t currently meet that need I don’t think. We try . . .

H1HCPfocusgroup

In order to meet the informational needs of patients and their carers (within their educational role) the nurses recognised that a number of issues needed to be identified and then addressed. In summary, they were:

-

the starting point, working out how the individual best learns and then tailoring the information to this; verbal information reinforced by written information (+ technological alternatives if possible) at the right pace, via stepwise provision

-

identifying the types of pain and which medications are best suited to the types of pain for that individual

-

outlining each medicine, what it is, what it’s for and how to take it

-

explaining the requirement to adjust medications on an ongoing basis and establishing this as baseline understanding; highlighting that there are always alternatives if pain is uncontrolled or side effects are viewed as intolerable

-

informing on the side effects, the benefits versus the burdens and the likelihood of the individual experiencing them

-

outlining the need for laxatives and working out the balance between opioid dosage and laxatives required for the individual

-

discussing and revealing the individual’s fears, challenging and correcting opioid-related preconceptions

-

explaining the lack of dosing ceilings for opioids and being clear regarding the relative lack of required dosing intervals for ‘as required’ doses for breakthrough pain

-

highlighting the importance of monitoring the effectiveness of the medications (especially in relation to the pain experience); the need to record breakthrough doses so that regular opioid doses can be increased/altered if required

-

signposting the individual and carer to contacts for concerns/questions, outlining the most suitable contacts for specific situations that the individual may encounter.

Within their problem-solving role, the nurses sought to work out the best drugs and dosages with the most tolerable side effect profiles for the individual, recognising that this required fine tuning over time, often in conflict with the end-of-life context. The nurses also assisted the patients/carers with problem-solving in relation to the practical (supply and administration related) issues of getting prescriptions, obtaining the medicines, organising the medicines at home, storing the medicines safely and scheduling the medicines around their daily routines. For example:

. . . Getting prescriptions . . . we spend a lot of our time trying to sort that out, and you can understand how patients really struggle with [it]. I mean one chap . . . it has taken so many phone calls and so much of my time . . . a youngish intelligent chap and he has just really struggled with that. I think the other issue is sometimes they get 28 tablets and then you change them, then that knocks their whole sort of repeat prescription out of balance . . . When you’re wanting dosette boxes as well they’re really difficult, they’ve already started, then you’re adding something in and changing them, to add bits in, that’s really problematic . . .

H1HCPfocusgroup

This could be a time-consuming role for nurses as medication supplies got ‘out of sync’ for patients with any prescription alteration. For example, increases in dosage meant that supplies lasted for shorter periods and ran out in advance of supplies of other medications.

The problem-solving role was often implemented in a pre-emptive way. This was referred to as ‘mind-reading’ or being ‘a problem-solver in advance’, which necessitated always having ‘a plan B’ (such as knowing who to contact or consideration and education of the individual patient in relation to potential crisis episodes, e.g. chest inflections or bowel obstruction):

. . . You’re anticipating, you’re pre-empting what might happen to be able to talk it through with that patient and to that carer to be able to give them you know a toolkit of who to ring, when to ring and why they might ring. How to deal with the uncertainties of do I ring now, do I ring later, but the security of knowing that there is somebody to ring . . .

H1HCPfocusgroup

The professional participants stressed the imperativeness of this pre-emptive problem-solving role and the fact that it mirrored the wider requirements of end-of-life care in general:

. . . The notion of the discussion about symptom control and analgesia and medicine things, the pre-emptive nature of it links in with the much bigger picture, doesn’t it, I think of palliative and end of life care now. The fact that all of it is about pre-empting and pre-planning, advance care planning, you know the Gold Standard Framework; getting people on a register and pre-empting their kind of deterioration, all of those things. It mirrors in a more distilled way the bigger picture of things . . .

H2HCPfocusgroup

Indeed, part of the pre-emptive problem-solving role within the context of end of life was the requirement to prepare individuals and their carers for transition not only in terms of deterioration of condition, but also in terms of transition between care settings, frequently between inpatient units/hospices and home. This could also be seen as integral to the role of facilitator, whereby the nurses prepared the patients and their carers for these transitions by enabling them to use inpatient stays ‘like a pit-stop’ where they could initiate, develop or refine their information and knowledge of medication management. For example:

. . . So part of it before they go home is about talking through what our rationale has been for their medicines and what type of pain we’re looking at to take for certain things. What we’ll have on the discharge sheet that goes with them, there’s like a medication chart of what their drugs are and why they take them, when they take them but you can be a little bit more distinct can’t we on the type of pains so they’ve got some slight signpost, as to what to take, where when and how . . .

H1HCPfocusgroup

Another professional role was that of goal-setting. This was often about proposing different options to the patient in relation to their medicines management, allowing the individual to decide between the proposed courses of action and then putting a joint plan together based on the individual’s preferences. These plans were then relayed and discussed with the wider palliative care team and GPs as needed (to support medication changes) under the role of reporter. Furthermore, the CNS role of monitor intermeshed in practice with the role of goal-setter (involvement in decision-making and shared responsibility where possible). The nurses continually monitored ‘how much the patient has understood’:

. . . Whatever you do, if you are setting goals if you are solving a problem, or if you are educating, whatever you are doing you have to check that . . . the message has arrived . . .

H2HCPfocusgroup

. . . In terms of monitoring as well I think it’s about involving the patient in those decisions isn’t it so you know having given them some education actually when you’re reviewing things you know saying to them so are you happy then that we’re still on the same dose for now, you know they’ve got that involvement in that haven’t they, it’s like an agreed shared sort of responsibility . . .

H1HCPfocusgroup

The monitoring role was seen as an imperative professional responsibility, particularly when starting individuals on new medications. The nurses also emphasised the value of face-to-face monitoring in the context of end of life. In the words of one:

. . . You can see people’s responses, you can work with them at their timing to answer questions. I mean one gentleman I went into, I talked to him about his medication, and reading his bottles, and actually I discovered he couldn’t read. And it was something as basic as that, making sure that . . . I then put symbols on there that he felt represented like his water tablet, I put a droplet of water on a little label on his bottle. So I think it’s a blended approach really, you know, just to phone them up, say ‘How are you doing?’ and if you sense that this is not going . . . The things you are listening to aren’t representative of somebody managing, then you actually go back and reassess them face to face; there is nothing quite like eyeballing a patient . . . !

HCPW001

The continuum of self-management behaviours

The patient, carer and CNS roles outlined above were enacted on a far-reaching continuum. This continuum of behaviours ranged from, at one end, expertise and mastery, with the individual taking full responsibility for complex decision-making, accepting the associated risks, to, at the other end, transfer of responsibility to another (the carer and/or CNS) because of patients’ and carers’ reduced capabilities and engagement in self-management behaviours, sometimes negatively affected by uncontrolled pain, the side effects of opioids (particularly drowsiness), clinical depression and memory loss:

I’ve seen both sorts . . . Obviously this is reflecting a distinct change in the type of patient we are seeing as well. I would say the younger ones coming along are becoming masters; they are gaining information from the internet, using every resource they have; they are thinking outside of pure medication as being an option for their pain control, and yes, I have seen . . . I can think now in my mind’s eye of a ‘master’. But prior to when I began in Hospice care, everybody needed to be told, and there remains a little group of people, usually in the older age groups that still need that and actually feel quite burdened by being expected to choose, and make decisions.

Very much so. There is a shift in people’s tendency. Before it was ‘You decide, you are the expert’, now it is ‘Wait a moment, I am the expert of my body and my health, so I . . . give me the knowledge, give me the information so that I can make an informed decision’.

Is it something that you negotiate with patients, whether you expect them to self-manage and master all these things? Or is it something that is sort of tacitly understood?

. . . You can tell, straight away when you start talking to them about what they understand and what they want from us; that comes across very quickly, which group they are going to fall into . . .

All study participants highlighted the individual-level variation in the range of self-management behaviours enacted:

. . . You’ll get some who don’t want anything to do with their medicines and you sort it out and then people that want to know everything will want to do their own as much as they can . . .

H1HCPfocusgroup

Those patients who, when discussing the role they played in managing their medicines, reported feeling in control, often referred to how relatively ‘lucky’ they were in terms of being able to ‘think about it and work it out’. These individuals at one end of the continuum had accepted full responsibility for their role and were in their eyes ‘doing it all’ themselves, but with backup strategies in place and knowledge of whom to contact if anything changed.

The HCPs often spoke about those individuals at polar ends of the continuum but there was also wide variation in behaviours and choices made by those individuals who were not at either end of the continuum. Indeed, behaviours and choices were never static, but ever changing. In addition, there was wide variation within the group of individuals assessed by their HCPs as ‘self-managing’ of their analgesia and related treatments. For example, one professional discussed a patient who was managing his medications, but without the adjustments that she ideally would have recommended:

. . . A man that’s really angry and frustrated, he’s young but he was diagnosed late. He’s had lots of frustrations with chemo, and things like that. So he’s quite resistant to changes, and that’s fine, so we’ve just left him [medication wise] as he is; he’s not managed quite properly, not adequately in our eyes, but he is doing what he wants to do at the moment, so he’s doing it . . .

H4HCPfocusgroup

Where does the responsibility lie?

The competencies and engagement of the individual, and their acceptance of responsibility, affected their enactment of self-management behaviours and, thus, the roles required of the carer and CNS. The CNSs recognised the importance of assessing the individual’s ability to understand, their capabilities and their potential engagement (what the individual was currently doing and what they would like to do):

. . . Asking them to go to through their medicines, some people haven’t got a clue, and other people don’t even need to get the boxes or list out and they can tell you absolutely everything they’ve had, and they’ve got lists and the diary, and it all written down. And other people haven’t got a clue.

As well as trying to establish what level of understanding they’ve got, you are using that information about how much they have engaged with their medicines and things to try and determine the scope for them to self-manage . . .

For the nurses, it was about recognising that individuals make their own analgesia-related choices within their home environments and that their autonomy to do so should be respected:

. . . I always say that it’s their pain and it’s up to them how they choose to manage it we can give them the medications or the tools but you know ultimately if they’re happy to live with a certain level of pain, they don’t want to use their medications, that’s their choice we’re there just to give them and advise them how to use things but ultimately it’s up to them . . .

H1HCPfocusgroup

Indeed, some patients made deliberate decisions to withhold or reduce doses of opioids to offset the side effects that they were experiencing. These decisions were about balancing pain control against the things that they wished to achieve:

. . . So if I’ve got pain, sometimes I won’t have that [oxycodone immediate-release formulation; OxyNorm, NAPP Pharmaceuticals], and I choose not to, because I don’t want to get tired and sleepy as I want to drive, or I want to do something, so I’ll manage it in a different way, not necessarily by taking drugs . . .

H3Ptfocusgroup

The context of end of life

The overarching context of end of life had a profound influence on the supportive self-management behaviours of the patient, carer and CNS. Within this context, there were ever-changing issues related to continual disease progression and subsequent changes in symptoms and side effects from both medication and palliative treatments. As a result, the behaviours were ever changing.

This context was further complicated at the end of life by the surrounding swirl of what individuals and their families were already striving to deal with (the wider context), and of psychological distress and anxiety as well as high levels of carer strain. Thus, individuals in this context may be struggling to cope with a palliative care diagnosis and there may be anxiety and potential clinical depression of both patients and/or carers. As a result, the capabilities of both the patient and carer fluctuated greatly, influencing the supportive self-management roles and the required behaviours of the CNS in particular.

Opioid-related fears

The data demonstrated that patients’ and carers’ behaviours in relation to opioid management were strongly affected by misconceptions and common public perceptions of these medicines. It was commonplace for patients and their carers to hold fears or assumptions regarding opioids:

-

fear that the individual taking them will become addicted to these medicines, ‘you hear of so many people get[ting] addicted to certain things’ (H1Pt004)

-

assumption that there is a ceiling dose for opioids as with other medicines

-

fear of overdosing, even by taking just one extra dose

-

fear that these medicines are ‘killers’ because of press accounts of abuse of opioids (H2HCPfocusgroup)

-

assumption that the individual will develop a tolerance to the opioids and the pain will therefore not be controlled as a result

-

fear that death of the individual is imminent if they are started on opioids [i.e. ‘I’m dying’ (H1HCPfocusgroup)]

-

fear that if the individual takes these medicines now then there is ‘nothing later’ for them to take in the future ‘so I’ll avoid it if I can’ (H1HCPfocusgroup).

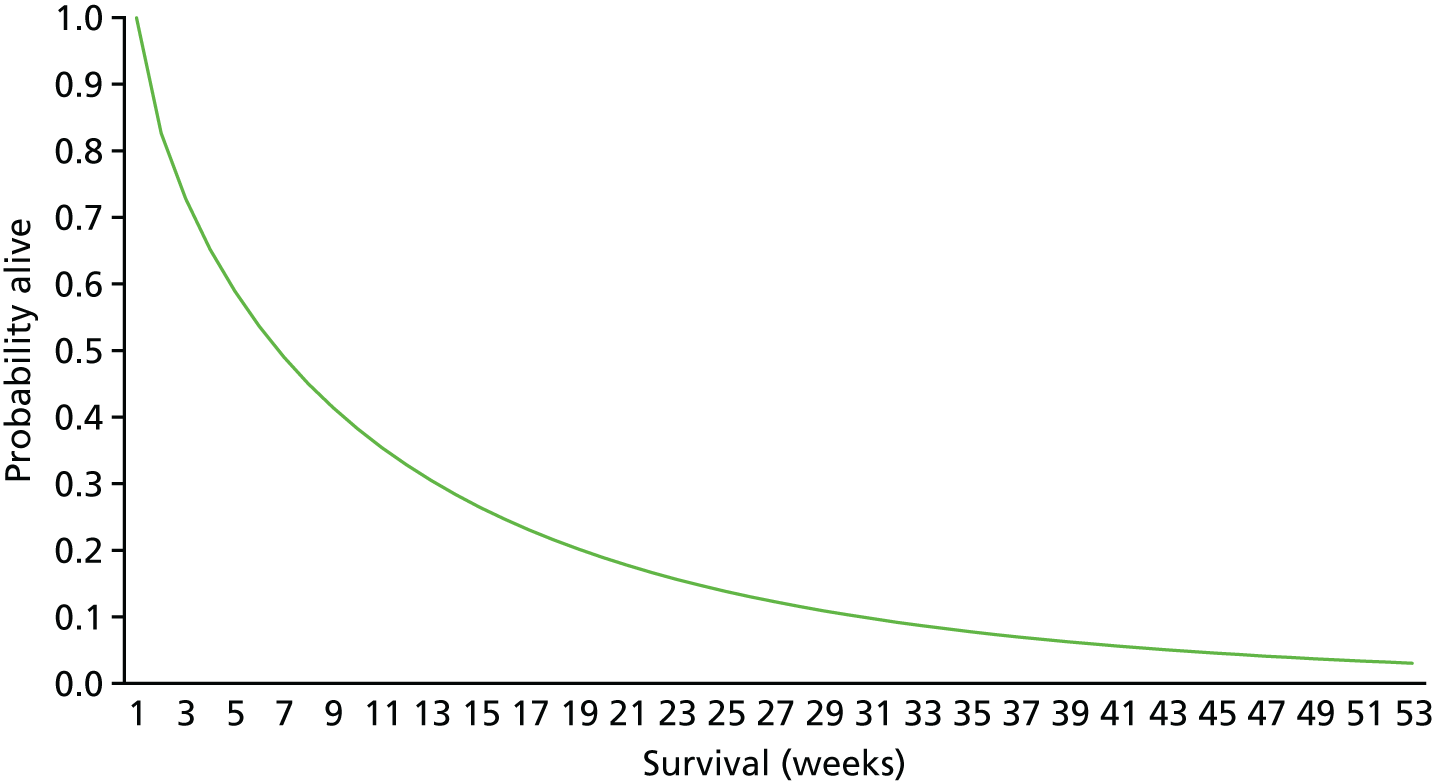

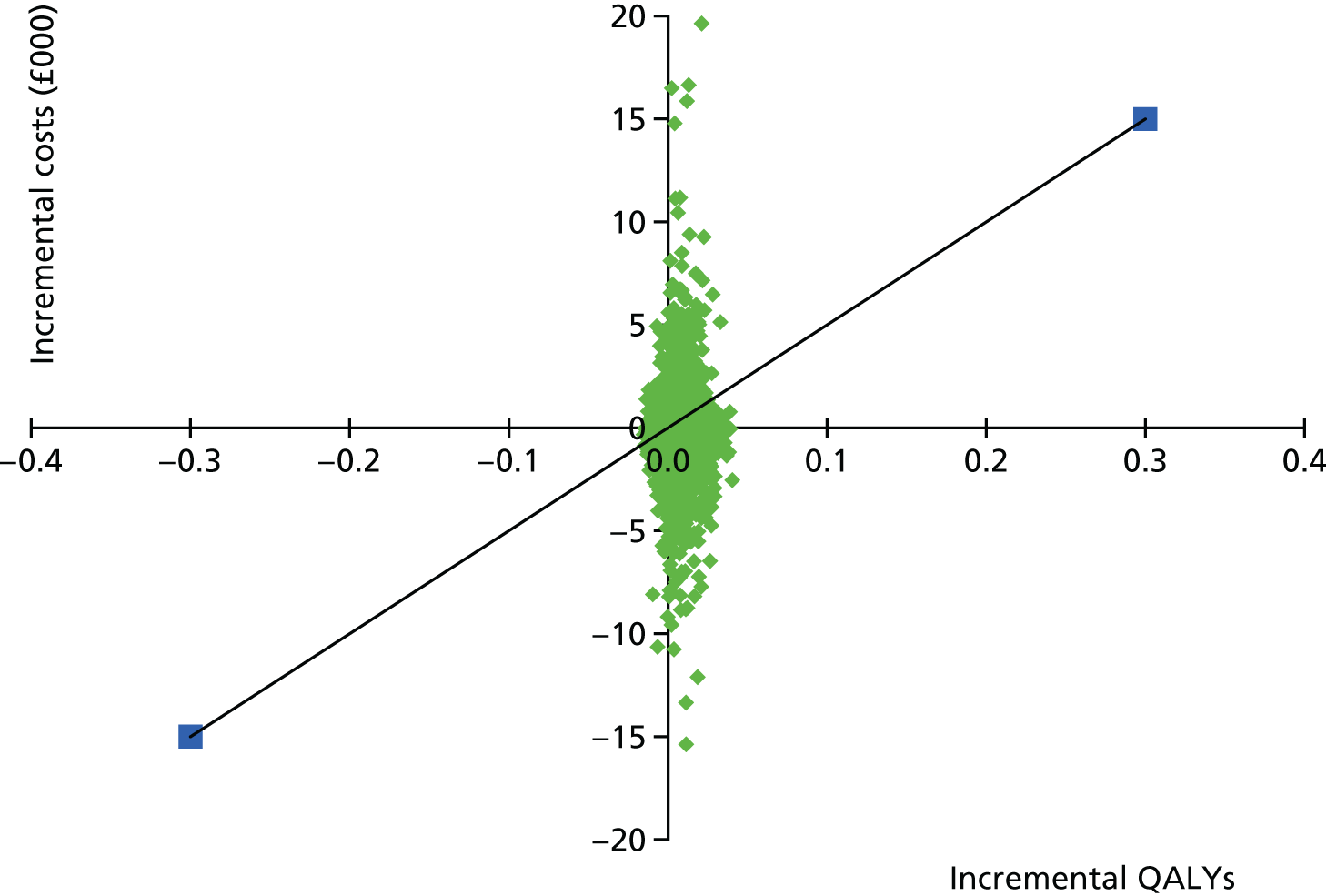

These fears and assumptions affected the self-management behaviours of patients. This was clearly articulated by one focus group participant who required a hospice admission as a result: