Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/102/03. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The draft report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Allan House is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Efficient Study Design Board and of a Programme Grants for Applied Research subpanel. Amy Russell was an associate member of the Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board (Commissioned and Researcher-Led). Claire Hulme is a member of the HTA Commissioning Board. Amanda Farrin is a member of the HTA Themed Call panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by House et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Type 2 diabetes

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes, which varies markedly by ethnicity and social deprivation, has increased sharply in recent years, in line with increasing obesity in the general population. Current population prevalence from published figures is between 4% and 5%. 1

Diabetes in people with learning disabilities has been estimated to be more common than it is in the general population,2–5 with a cited prevalence of 9–11%. 6,7 People with learning disabilities also have higher rates of hospital admissions resulting from outpatient-treatable diabetes-related conditions. 8 There are a number of possible explanations for high rates of poorly controlled type 2 diabetes in adults with a learning disability: high prevalence of obesity9–11 and poor dietary habits, prescription medications that increase risk and poor self-management skills. 12 Overall, people with learning disabilities have poorer health outcomes and shorter life expectancy than the average population. 13,14

Learning disability

A learning or intellectual disability is defined as a significant impairment in a person’s intellectual functioning that has been present since childhood. It is less straightforward to define and identify than diabetes, especially at the milder end of the spectrum. It can be defined statistically based on test scores, which typically show a negatively skewed distribution, and in those terms it is often said that 2% of the general population will have some degree of learning disability. 15 However, the picture becomes more complex when an element of functional impairment in real-world activities is built into the definition. Part of the problem is that any functional deficit may not be entirely attributable to intellectual impairment but to (for example) emotional or social problems or missed schooling. Conversely, an adult with intellectual impairment may not come to the attention of statutory or non-statutory agencies if he or she is functioning independently or is well supported by family or some other informal carer. The functional approach to definition is now widespread and accounts for a shift in practice so that in routine discourse learning disability (referring to an intellectual impairment) and learning difficulty (referring to a functional state) are sometimes used interchangeably. An additional confusion is created by the alternative practice of using the term ‘learning difficulty’ to refer to specific educational deficits, such as dyslexia, that are not associated with a more global intellectual disability.

There is a move in academic writing towards the term ‘intellectual disability’ and much of the newer literature uses this term. However, the term learning disability is still used by the great majority of people with such impairments, by their families and other supporters and by third-sector organisations – it is easier to understand and to relate to personal experience. Another problem arises from use of the term learning disability to refer to specific deficits, such as dyslexia, even when it is not associated with more general intellectual impairment or functional deficit. This is not the way the term learning disability is used in this study. For the purposes of this monograph we use the term ‘learning disability’ to encompass all types of intellectual deficit that lead to problems with self-management, except when an alternative term is used in the naming of an agency, service provider or policy of relevance.

Case finding

Case finding for service planning and for research in diabetes is greatly facilitated in the UK by the fact that general practitioners (GPs) are required to maintain a register of all patients with diabetes and are remunerated through the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF)16 for undertaking various health assessments on an annual cycle.

General practices are also required to maintain a register of their patients with a learning disability and, as a result of increasing evidence of the health inequalities experienced by people with a learning disability, the Disability Rights Commission recommended the introduction of annual health checks17 for people on those registers. In 2009, a Direct Enhanced Service was introduced for adults (aged 18 years or over) with a learning disability and complex needs to be offered an annual health check via their general practice. 18 The Direct Enhanced Service encouraged the verification of general practice-based learning disability registers and local authority involvement in this process, as a means of facilitating the delivery of the health checks.

However, general practice learning disability registers are not uniformly completed throughout the UK. Most registers feature only those people in receipt of health or social services and, as a consequence, most people on the registers have a moderate, severe or profound learning disability. 19 A result is that learning disability registers typically include only 0.5% of the adult population, or about one in four of those with a learning disability. 20 This is an unfortunate state of affairs because it is apparent that adults with a learning disability have high rates of physical illness, and a recent report highlighted their poor levels of health care. 13,21 Take-up of the Direct Enhanced Service has also been variable even for those on the registers. For example in 2013/14, 42% of eligible adults with a learning disability received a health check in Leeds, 44% in Wakefield and 67% in Bradford. 22

Supported self-management

Supported self-help or self-management with health problems is now reasonably well established in that the principles are clear in terms of its core elements, although the intensity with which it is delivered, and its content, have varied considerably between studies. 23–25

In relation to intensity, the main variation is in amount of contact with the support/therapist, which ranges from regular face-to-face meetings to limited telephone contact. In supported self-management (SSM), the usual pattern is that a professional (or trained peer) acts as a ‘therapist’ to help and encourage the nominated patient in using the self-management materials.

With regard to content, all programmes contain an educational and an instructional component, the variation residing mainly in the degree of use of formal techniques for supporting change in behaviour and the degree to which they are theory based. Typical elements include:26

helping people to understand the short, medium and longer-term consequences of health-related behaviour

helping people to feel positive about the benefits of changing their behaviour

building the person’s confidence in their ability to make and sustain changes

recognising how social contexts and relationships may affect a person’s behaviour

helping plan changes in terms of easy steps over time

identifying and planning for situations that might undermine the changes people are trying to make (including planning explicit ‘if–then’ coping strategies to prevent relapse)

encouraging people to make a personal commitment to adopt health-enhancing behaviours by setting (and recording) achievable goals in particular contexts, over a specified time

helping people to use self-regulation techniques (such as self-monitoring, progress review, relapse management and goal revision) to encourage learning from experience

encouraging people to engage the support of others to help them to achieve their behaviour-change goals.

© NICE 2007. PH6 Behaviour Change: General Approaches. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph6. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of Rights NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication

The existing relevant self-management material in learning disability is largely educational and didactic with little or nothing that facilitates self-management, for example advice about self-monitoring. There is also little on the interaction between the person with diabetes and others supporting their care. Many adults with a learning disability do not live entirely independently even when they can be defined as living in the community, that is, not living in a hospital setting. Family members and other informal or formal carers often provide support in the form of help with shopping, cooking, monitoring and prompting about medication and so on. Arrangements here are diverse:27,28 some adults with a learning disability have never left the parental home, some live with a sibling or another relative, some live alone or in shared accommodation with non-resident support or peer support from those with whom they share, and some are married or cohabiting with somebody who may or may not have a learning disability. As many of the positive and negative influences on good diabetes management reside in the immediate social network,29–33 self-management needs to be negotiated not just with the person with diabetes but with their supporter, and flexibility will be needed in negotiating and implementing an intervention.

Research participation for people with a learning disability

The NHS Health Research Agency states that for consent to be considered both legal and ethical it must be given by someone who has been adequately informed; by a person with mental capacity; voluntarily and with no undue influence; and in circumstances in which there is a fair choice. 34 As people with a learning disability have, by definition, a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information,35 obtaining informed consent for participation in a feasibility trial provides an ethical challenge to researchers. In addition, many people with a learning disability have communication difficulties and may not always be able to express their understanding (or lack of it) to researchers.

In our study, consent to participation was necessary because the intervention was to change the process of self-management. To assist, advice is available in the form of guidance on implementing the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 36 The Department of Health provides guidance on assessing capacity and obtaining consent for both clinical care and research. 37 The UK Research Governance Framework38 requires that, when necessary, reasonable adjustments must be made to provide accessible research materials. For example, when a person has a learning disability, research information should use ‘easy-read’ or pictorial formats.

In relation to clinical trials, it seems that people with learning disabilities have problems in the same areas as do others:39 understanding randomisation, recognising that they may receive treatment as usual (TAU) and knowing that consent can be withdrawn. The approach to providing information about participation to be involved in a trial therefore needs to be flexible and participant centred, and go beyond standard information sheets – even ‘easy-read’ versions. It will involve finding a form of communication that matches the person’s needs and may well involve a supporter who is familiar with helping that person to make decisions. 40,41

In summary, there is evidence that adults with a learning disability have poor physical health, including high levels of obesity and associated type 2 diabetes. Usual first-line treatment in this situation would be SSM, but there are questions about the suitability of such an approach in the target population: about whether or not reasonable adjustments be made to the self-management intervention, whether or not the resulting intervention can be implemented effectively and, if so, whether or not it leads to useful change. In addition, there is a question about value for money, given the paucity of evidence for cost-effectiveness of behaviour change interventions generally and the likely additional complexity of delivering one in the current context. For these reasons, a pragmatic Phase III randomised controlled trial (RCT) of such an intervention seems appropriate, but there are feasibility questions to be addressed before a trial could be embarked on.

The present study was designed and commissioned to answer those feasibility questions. This report presents the study in the form of three main activities aimed at:

-

establishing the feasibility of identifying and characterising a sample from the target population

-

developing and field testing materials for use in a subsequent RCT

-

conducting a feasibility RCT.

Chapter 2 Methods for case finding and characterising the sample

The starting point in preparing for a RCT in this context has to be if it is possible to identify, consent and recruit a sample from the target population and, if it is, do the potential participants have health-care needs that are likely to be modifiable through SSM? It is not inconceivable, for example, that those who are most easily identified and are able to give consent are also those most able to manage42 their own care and to elicit support in doing so from others in their social network.

Aims and objectives

The aims, in line with the commissioning brief, were to:

-

develop and evaluate a case-finding method to identify participants who have a mild to moderate learning disability and type 2 diabetes who were not taking insulin and who might be suitable for SSM

-

develop procedures for determining, and recording, capacity and obtaining consent

-

recruit a sample meeting the inclusion criteria for the planned feasibility RCT, describe their personal and clinical characteristics and determine their willingness to be considered for participation in the RCT.

The proposed objectives were:

-

the establishment of a practical case-finding method to identify the eligible population without undue cost

-

a robust estimate of the number of people who met the eligibility criteria and the numbers who were willing to consider change in their diabetes management and to participate in the RCT

-

a characterisation of the study population in terms of health, diabetes control, resource use including medication costs, living circumstances and role of supporters in diabetes management.

Design

A cross-sectional observational study.

Setting

We chose three research sites in West Yorkshire, centred on the cities of Leeds, Bradford and Wakefield, to take part in the study. This maximised generalisability of the findings and provided a good test of feasibility of recruitment across a large population. The cities are in the lowest one-third in the UK in relation to deprivation. Bradford has an unusually large population of people of Pakistani heritage (approximately 25%), whereas Leeds and Wakefield are more typical of the UK, with about 15% of the population describing themselves as non-white British. Service configurations for diabetes varied across the three cities. In Leeds, most type 2 diabetes cases were managed exclusively in primary care, with referral to secondary care only for specific problems. There was a tiered system for diabetes care in Bradford, with almost half of general practices managing insulin transfer and several participating in collaborative care of complex cases. In Wakefield, primary care diabetes services were supported by local commissioning arrangements, in which specialist teams tailor their work to individual need. There was also a wide range of services for people with a learning disability in NHS community learning disability services, in social care and in third-sector organisations across these three cities.

Participants and eligibility criteria

People were eligible if they met the following criteria:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, controlled with diet alone or hypoglycaemic agents other than insulin

-

mild to moderate learning disability, identified by GP on clinical assessment and confirmed by researcher on the basis of functional history and performance at interview

-

living in the community (not in a hospital setting) and under the care of a general practice in the geographical area covered by the study or willing to agree to a data-sharing agreement.

People were excluded if they had insufficient mental capacity to consent to participate in the research; capacity was assessed at the first meeting with the researcher. The following exclusion criteria were applied after the initial visit and following information gained from the participant’s GP:

-

intellectual impairment acquired from disease or injury in adult life, defined as aged ≥ 16 years, such as that caused by adult-onset dementia or stroke

-

specific educational deficit, such as dyslexia, or autism without learning disability

-

type 1 diabetes, secondary diabetes (such as that caused by steroids, pancreatitis or endocrine disorders) and rare causes of monogenic diabetes (such as maturity-onset diabetes of the young)

-

referral into the study had been through the third sector or another non-medical professional, and eligibility could not be confirmed at interview or from a medical professional such as the GP.

Presence of a learning disability was initially decided by the referrers, who were provided with guidance on how to make the judgement. The person did not need to have a formal recorded diagnosis of a learning disability (as many individuals with intellectual impairment do not). Mild to moderate learning disability was defined by a researcher-led assessment of functional deficits (in daily activities, educational and social attainment and support needs, day-to-day cognitive functions of memory and knowledge) attributable to primary cognitive impairment or to secondary causes acquired in childhood. Mental capacity was assessed by the researcher, following guidelines from the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 36,43 We decided to include only those with mental capacity to consent themselves, excluding those without capacity even when a supporter might have consented, because we wanted to include only individuals who could participate themselves in self-management.

Ethics issues and approval

Ethics approval was granted for the study by the Yorkshire and Humber Research Ethics Committee (reference number 12/YH/0304).

Informed consent

In developing our informed consent procedures and materials we drew on the NHS Health Research Authority’s guidance on supporting informed participation in research, as well as the toolkit supporting informed consent with those lacking capacity [https://connect.le.ac.uk/alctoolkit (accessed 2 January 2018)], the Department of Health guidance on assessing capacity and obtaining consent both for clinical care and research37 and relevant literature. 44 We approached four other research teams identified from the National Institute for Health Research portfolio as working in the area of learning disability, and they kindly shared the materials developed for their own projects (see Acknowledgements). We also worked with our third-sector partners and learning disability specialists to develop appropriate materials.

All researchers were trained in assessing mental capacity by the learning disability consultant on the team (AS). In line with guidelines in the Mental Capacity Act 2005,36 the presumption was of capacity and a judgement of lack of capacity was made only after all practicable steps to help the participant make a decision had been taken by the researcher in collaboration with the person’s supporter. We were mindful that capacity is not fixed and context free, and so capacity was constantly reassessed during the information-giving and data-collection processes. Our aim was to develop a pragmatic approach to consent that balanced ‘self-determination, respect and safety’ with strategies to promote participation in the research. 44

Participants recruited into the study were provided with information about a system of research advocacy that we established with a third-sector organisation, People in Action [http://peopleinaction.org.uk (accessed 2 January 2018)]. They were provided with a confidential number that they or a supporter could call if they wanted to ask questions about the project, express concerns or withdraw if they did not feel they had the confidence to say so directly to a member of the research team.

We were aware that in some cases the supporter of a person with a learning disability may have a learning disability or other mental capacity issues themselves and so we did not make assumptions about their ability to support self-management. A supporter was defined as the main adult who was self-nominated by themselves, or nominated by the participant or by a professional who knows that person, as providing practical help and support in day-to-day living relevant to their diabetes management.

There was a further ethical challenge in considering how to explain the study to those people who had not previously been identified as having a learning disability. This was addressed by developing information materials in collaboration with third-sector organisations and their customers with a learning disability to ensure that the materials were fit for purpose and would be acceptable to our participants. We did not make reference to ‘learning disability’ or ‘learning difficulty’ anywhere in our participant or supporter materials. After suggesting a number of options to service users via People in Action, on its advice we used the abbreviation ‘OK-Diabetes’ to offer a simple memorable project name for participants, again with the aim in mind of not making reference to learning disability in our materials. In each interview, the interviewer discussed with the participant why they had been referred and that the study included people with learning disabilities. It was discussed whether or not a participant minded being in the study and if they felt they had a learning disability.

Safety

We developed a safeguarding policy for the project in consultation with the Safeguarding Adult Partnership Board in Leeds. This set out when researchers should break the confidentiality of the participant and who they should report concerns to depending on the level of perceived risk. The researcher’s obligation to report safeguarding concerns was discussed with the participant. Any non-urgent concerns that did not need an immediate response were reported back to the chief investigator and lead co-investigator for discussion and advice. We also developed a safety protocol for researcher lone working in which researchers were required to call a nominated member of the team prior to going into the interview, and once again straight afterwards.

Screening and case-finding methods

For the reasons described earlier (see Chapter 1, Case finding), we decided that case finding could not simply entail cross-checking people on the learning disability registers with QOF diabetes registers. We developed a multistrand approach to identification of potential participants involving collaboration with both NHS and non-NHS third-sector organisations.

Informing general practitioners and recruiting by direct referral

We wrote to all general practices at the three study sites using a covering letter from their Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) lead for either diabetes or learning disability. The covering letters were sent to practice managers and/or diabetes lead GPs, gave CCG endorsement to the study and urged practices to take part. Letters were followed up by telephone calls from a researcher. Practices were supplied with project information, examples of the easy-read information that would be sent to participants, a step-by-step guide to recruiting, a recruitment log to record methods of identification, a referral form with Freepost envelope for successful referrals and an easy-read template letter to send to participants who were unable to be reached by telephone. In our original proposal we intended to develop a checklist for health professionals to help them identify potential participants, particularly individuals who may have milder levels of intellectual disability and not be on the learning disability register. We developed a step-by-step recruitment guide for health-care providers (see Appendices 1 and 2), which, in addition to giving information on cross-checking learning disability registers with diabetes registers, informed practitioners how to run the Read Code search against electronic patient records. Our referral forms included a checklist based on one that was developed by the Royal College of Nursing to identify individuals with a learning disability. However, initial returns of the log, despite numerous missing data, suggested that practices were only running the computer-based searches or were finding them the most productive way of identifying people, suggesting that either this checklist was unhelpful or the majority of GPs were unwilling to try and identify a person as having a learning disability who was not already on the register. For this reason the study did not further develop the ‘simple checklist’ as expected, and instead it focused on register and Read Code searches, as these proved to be the most popular method of identification with clinicians.

Practices were offered the opportunity to meet the researcher to discuss the project, as many had concerns about referring a ‘vulnerable’ patient group. The researcher would attend the practice, explain the project and demonstrate the participant information materials to ensure that practice staff knew the study had taken communication issues into consideration. Over the course of the project, practices that did not respond were written to three times and received at least two follow-up telephone calls. Practices that took part in the study were paid service support costs by the Primary Care Research Network.

A researcher attended CCG meetings, giving talks on the project to practice managers and distributing project information. Time for Audit, Research, Governance, Education and Training (TARGET) training was also attended by a researcher who spoke with practice staff and distributed project information. ‘Research-ready’ practices (through what was then the Primary Care Research Network) were recruited through its regular research network meetings. The Commissioning Support Unit supported the project, circulating project information at its events, in newsletters and to its contacts. The researcher attended Continuing Professional Development training relevant to the project and presented to the clinicians there.

Case finding via searches of general practice databases

We developed Read Code searches to help general practices identify potential participants. Read Codes are clinical codes applied to patient records that can create searchable tags of information about a patient but are not limited to diagnosis codes. They can be about a patient’s identity (ethnicity for example), their social circumstances, living and care arrangements or about their symptoms. There are many Read Codes, and codes are not used routinely or consistently across practices. Some codes will automatically include a person on a list or register, such as the diabetes QOF register, or trigger a required response, for example depression symptom codes can trigger an automated reminder to screen for depression; however, not all codes are linked to registers or actions.

Different computer systems use different codes. Bradford and Wakefield use SystmOne (The Phoenix Partnership, TPP, Leeds, UK), whereas the CCGs in Leeds use a combination of SystmOne, EMIS Web (EMIS Health, Leeds, UK) and EMIS LV (EMIS Health, Leeds, UK). The research team met with system specialists and learning disability experts to design a search that could be run on any practice system to create a list of patients whose Read Codes indicated they might have a learning disability or had accessed learning disability services. It would then be up to a member of their direct care team to review these results. The search included diagnostic codes for learning disability and chromosomal or other physical abnormalities, service access codes (e.g. referred to community learning disability team) and functional ability codes (e.g. cannot read). Other codes were discussed but rejected for generating too many results, for example adding the code for ‘unable to perform personal care activity’ added over 16,000 people to the results for all of Bradford.

Two practices agreed to test the search and review the results. Both practices knew their patients with a learning disability very well. They agreed that the search had identified some of the patients known to the practice as having a learning disability but having no formal diagnosis. However, it was agreed there were too many false positives and several codes were removed that had not generated any new eligible patients. Once refined, the Read Code search of codes indicating potential learning disability was then linked to the records of patients who had type 2 diabetes but were not on insulin to further reduce the number of results and ensure eligibility. This search was linked to two other searches and uploaded to practice systems. Practices were able to search their:

-

learning disability register crossed with their QOF diabetes register (excluding type 1 diabetes and people on insulin)

-

whole list for patients with a Read Code that indicated learning disability and type 2 diabetes (excluding insulin)

-

whole list for patients with a Read Code that indicated learning disability.

A member of clinical staff was asked to review the results provided by searches 1 and 2 and recruit all potentially eligible patients. Search 3 was provided to allow practices to review their learning disability registers if they wanted to do so. Searches were embedded in the clinical systems of each practice so they could be directly accessed through their clinical reporting files. In consultation with GPs, it was agreed that if the patient lists generated by the Read code search were too long, clinical staff would not be expected to review them. In practice, the simplicity of this arrangement proved popular as it took only four ‘clicks’ to run all of our searches. Members of the research team gave support on the use of the searches if required.

Secondary care services

Project coapplicants (DN, RA and AS) were located in secondary care settings. They referred patients to the study and recruited colleagues to refer. One site assigned a clinical studies nurse for recruitment. We approached all secondary specialist learning disability services and diabetes services in the three cities directly by letter, indicating our inclusion and exclusion criteria. We asked them to review their case load for files flagged with a learning disability and to keep the study in mind as they saw new patients. A researcher attended the Comprehensive Local Research Networks Diabetes Research Network meetings and encouraged network members to refer to the study. A researcher visited all learning disability community teams and at these meetings a key person was identified who would be the liaison between the research team and the community teams. The learning disability leads for the hospitals were involved in the project recruitment as a key figure to support recruitment in secondary care. The research team also contacted retinal screening services and specialist dentistry services to identify potentially eligible patients.

Third-sector organisations

A significant amount of support for people with a learning disability is provided by non-statutory organisations, for example in relation to advocacy, housing and family issues, health, leisure and employment. In association with partner organisations, People in Action and Tenfold [www.tenfold.org.uk (accessed 2 January 2018)], we identified third-sector services that may be able to support the identification of potential participants in their client base. We worked closely with the learning disability partnership boards in each area to endorse our project to these services and local authority services. We recruited through a variety of services, including housing organisations, care/support organisations, Citizens Advice Bureaux, day centres, advocacy services, religious groups and community volunteering projects. A variety of recruitment methods was used including becoming familiar faces at learning disability events (e.g. in Learning Disability Week), day centres and learning disability organisation networks.

Recruitment procedure

The referrer obtained and documented consent from potential participants to be contacted by the research team. Participants were given a tear-off sheet from the back of the referral form to remind them that they had agreed to contact. A letter and patient information sheet were then sent to the potential participants by the team (and supporter if identified) giving easy-read information about the study (see Appendix 3). This was followed up by a telephone call giving the potential participant (and/or supporter) an opportunity to discuss the study further and obtain verbal consent for a face-to-face interview with the study researcher. Most face-to-face interviews were conducted in the home of the participant.

Following interview, after capacity, consent (see Appendix 4) and a provisional assessment of eligibility were established, participants were registered using a secure, automated 24-hour telephone registration service based at the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) at the University of Leeds. Following registration, researchers contacted the participant’s GP to inform them of registration (even if they were not the original referrers) and determine final eligibility via their medical notes.

Data collection

There were four main data collection points: (1) referral, (2) initial telephone contact with the referred participant or their supporter, (3) the face-to-face interview with the participant (and supporter if identified) and (4) the participant’s medical notes accessed by their GP. Table 1 summarises the data collected in this part of the study, and the source of the data. Most of the data used to characterise the consenting sample were collected during the face-to-face interview.

| Assessment (including who is involved) | Source of data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral | Telephone | Interview | Medical notes | |

| Screening | ||||

| Demographic data (including age, sex, ethnicity) | ✗ | |||

| Preferred method of contact | ✗ | |||

| Eligibility and consent | ||||

| Eligibility (assessed by referrer and study researcher and confirmed by clinician), including reason for exclusion | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Documented consent to contact | ✗ | |||

| Verbal consent to interview | ✗ | |||

| Mental capacity to consent | ✗ | |||

| Written consent, including access to GP notes | ✗ | |||

| Documented preference to further research contact | ✗ | |||

| Baseline data | ||||

| Presence and role of a supporter | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Demographic data (including first language, living arrangements, employment status, use of mobile phone and internet) | ✗ | |||

| Self-reported health assessment [including diet, physical activity, mood, smoking, alcohol consumption, comorbidities, self-care activities (e.g. foot check), general and dental health, engagement with health and dental services] | ✗ | |||

| Prescribed diabetes regime (medication) | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Current physical health state from QOF measures (BP, BMI, HbA1c level, QRISK®2 score) | ✗ | |||

| Service usage (visits to GP, practice nurse, diabetes clinics, home visits, ophthalmologist, podiatrist, dietitian, nephrologist, inpatient stays, attendance at A&E and ‘other’) | ✗ | |||

| Preferences for assistance with diabetes | ✗ | |||

Measures and research materials

All information and consent materials were provided in easy-read format (text supported by pictures) to both participants and supporters. The materials were developed in collaboration with our third-sector partners and produced by easy on the i, an information design service within the learning disability service of the Leeds York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust [www.easyonthei.nhs.uk (accessed 2 January 2018)]. This group includes people with a learning disability. The information resources and the interview schedule were reviewed by employees of CHANGE [www.changepeople.org (accessed 2 January 2018)] who had a learning disability and diabetes. CHANGE is a human rights organisation and service provider that runs an accessible information service.

Baseline researcher interview

The interview (see Appendix 5) used a standardised format to (1) check understanding of the study using an easy-read booklet; (2) assess mental capacity to be involved in the study; (3) obtain written (or verbal when necessary) consent; (4) obtain consent to review medical records for routine clinical measures; (5) establish diabetes management, including diet, physical activity, treatment, self-care awareness and engagement with health services; (6) record mood, feelings about diet, activity levels and having diabetes; (7) identify the role of supporters in the participant’s diabetes management; (8) elicit preferences for further assistance with diabetes management and consent to re-contact for further research; and (9) record a nominated supporter to be involved in further contacts, as applicable.

The interview guide was developed with, and reviewed by, staff from People in Action, a third-sector service provider for people with a learning disability. Measures that required long-term recall (defined as > 1 week) were found to be impractical. The full interview guide was piloted by two employees of CHANGE who had a learning disability and diabetes and was altered based on their feedback.

With one exception, we did not identify standardised existing research measures for mood, diet, attitudes to diabetes or knowledge about diabetes that were appropriate for people with a learning disability in this research setting. 45 Most of the standardised measures that we identified did not have sufficiently robust psychometric properties to overcome doubts about their utility. Even self-report questionnaires with 12–15 items were considered too taxing by our expert advisers and when they depended upon making ranking judgements, such as on a 4-point severity scale, they were beyond the intellectual ability of our participants. Instead, we used such standardised measures as the basis for deriving simple and important questions to ask in the interview. Respondent burden was also a major consideration in our choice of measures and influenced by the cognitive abilities of our sample. A standardised measure that might have been feasible but that takes substantial effort to complete could not be justified unless it met the core needs of the project. For example, although there are standardised depression measures used in learning disabled populations,46 a questionnaire such as the Glasgow Depression Scale,47 even if it could be completed, takes 10–15 minutes with a supporter and would produce a result only indirectly related to our core objectives.

However, because of their particular importance in this study, we did attempt to capture data on diet using the Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants (REAP) – Shortened Version. 45 Although this measure is not designed for people with a learning disability, we supplemented the questions with visual aids, for example, pictures of common foods and a retrospective food diary for the previous week to prompt recall.

The interview employed mainly closed questions (see Appendix 5). When possible, questions were phrased in an explorative conversational form to promote understanding. The interview process was supported by visual aids in the form of laminated picture cards that illustrated the topics the interview would cover and images related to questions about, for example, family, employment, diabetes care, diet, activity and mood.

Evaluating the research process

At the end of each interview the researcher asked the participant how they found the questions on a scale of easy to hard. They were also asked to assess the acceptability of the length of the interview. The interviews were conducted with all registered participants and transcribed.

After each interview, the researcher audio-recorded their own observations using a predefined topic guide. This covered reflections on the consent process and assessing mental capacity for involvement, how well participants understood or were able to respond to questions independently or with support, whether or not the study materials worked well and the researcher’s ability to complete the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), mood questions and health economics service use questions with the participant and observations about home life and relationship with supporter if present. Journals were initially transcribed to support discussions about eligibility associated with mental capacity; however, they were also used in the analysis phase to supplement the qualitative analysis.

Medical information

A medical information form sent to GPs after the baseline interview included questions to confirm eligibility, obtain recent diabetes-related test results [including glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level], comorbidities (as defined by presence on QOF registers), current diabetes medication and health service usage. The information relating to the last two items was collected on forms designed for the project as part of assessing the feasibility of an economic evaluation in a definitive RCT (see Chapter 3).

Outcomes

-

A robust estimate of eligibility, including the pattern and prevalence of uncertainty during eligibility assessments, as measured by: ‘not sure’ boxes ticked for eligibility criteria on the referrals booklet, and on the confirmation of eligibility at registration.

-

Evaluation of a simple case-finding method, according to:

-

the number and rates of referral, including duplicates, consent to research contact, researcher interview, capacity, registration and eligibility

-

methods of identification for the referred and eligible participants

-

contacts – (1) nature of initial contact, (2) number of contacts (by method), (3) who contacts were with, (4) reasons for terminating contact and (5) timelines, including duration of visits.

-

Communication problems for the referred and eligible participants.

-

Identification of a supporter.

-

Patient preferences for time and method of researchers contact.

-

-

Characteristics of the population, according to:

-

demographics – age, sex and ethnicity

-

patient-reported measures obtained through researcher interview including living arrangements, employment status, supporter details, diabetes medication, diabetes care, food, physical activity, general health, mood, feelings about current weight and having diabetes, satisfaction with diet and levels of exercise

-

use of health care and costs associated with health care

-

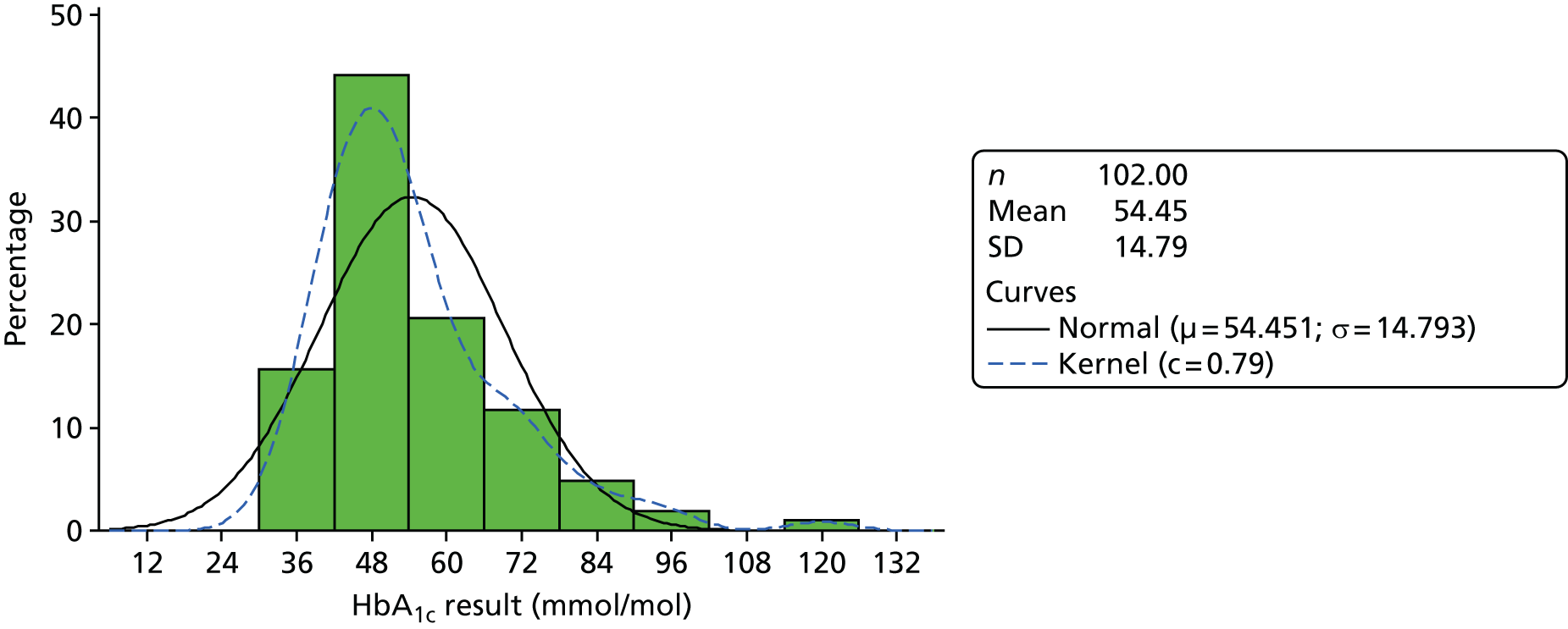

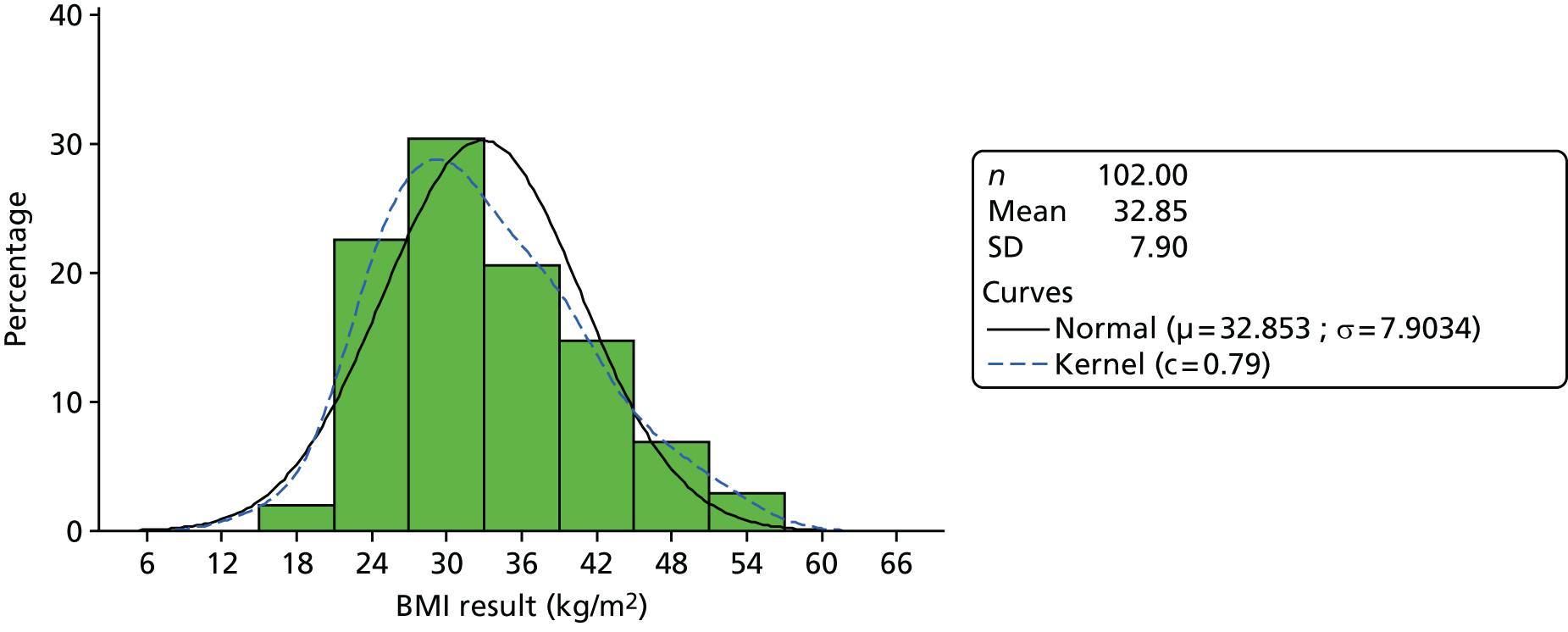

medical results, including candidate outcome measures [HbA1c level, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP)], other measures of diabetes control and cardiovascular health, presence on QOF registers and resource use including prescribed diabetes medication.

-

Statistical methods

Sample size

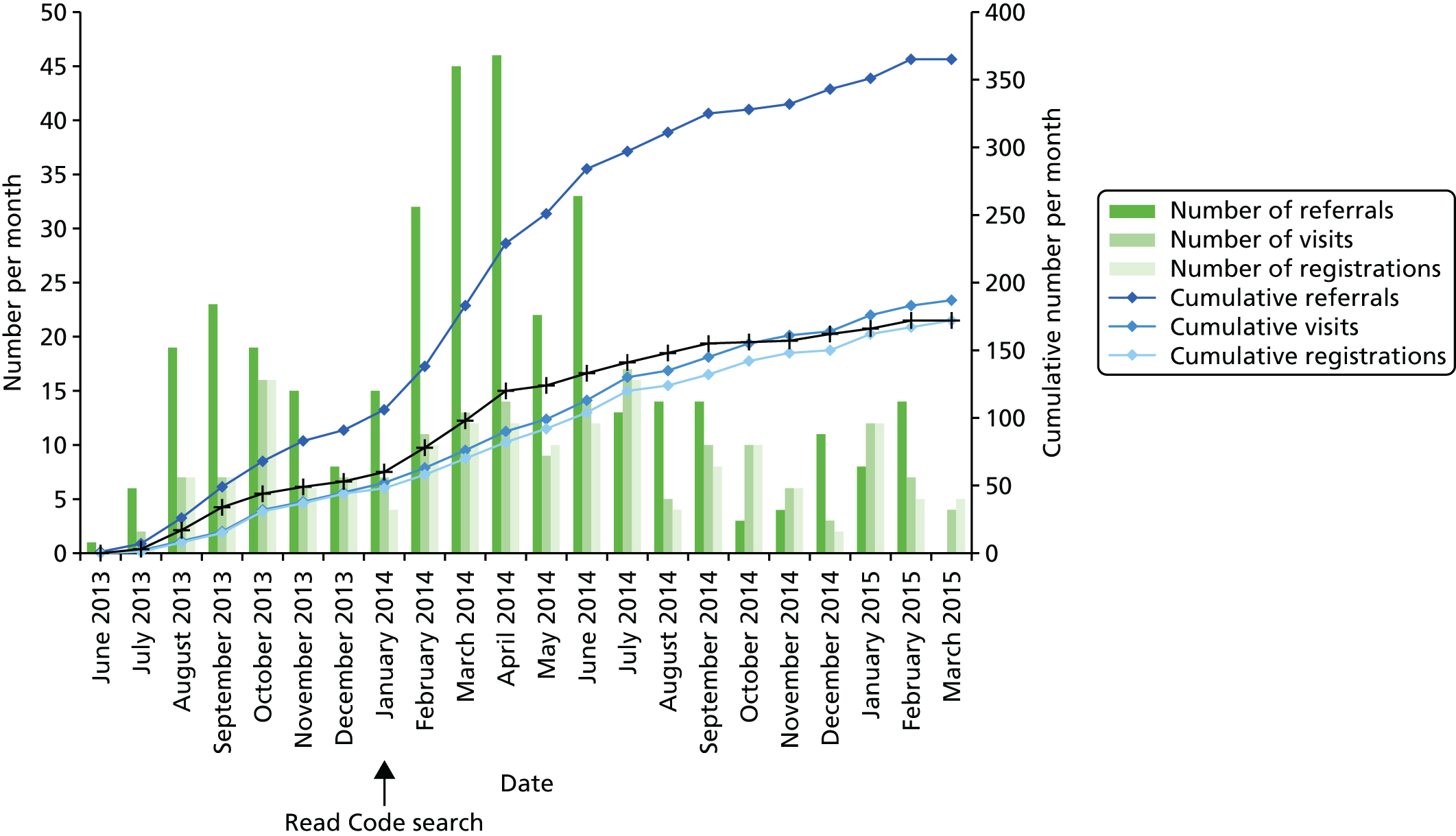

Across the three sites we expected an approximate total of ≈1400 people in the target population – assuming a 80% population of adults, 6% diabetes prevalence (in whom 20% use insulin) and 2% learning disability prevalence. We therefore aimed to achieve 50% GP involvement across Leeds, Bradford and Wakefield, equating to approximately 117 practices, and we assumed an eligibility rate of 50% to identify approximately 350 people meeting our eligibility criteria. A sample size of 350 people would allow a conservative estimation of the proportion eligible for the RCT of the target population to a reasonable degree of accuracy [to within 5.2% with a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI)]. It was this original target that is cited in our funding application and in the original study protocol.

Following a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme review of recruitment in June 2014, our original target of 350 was lowered to a minimum of 120 following acknowledgement of a lower than expected recruitment rate. The lower recruitment rate was a result of underestimating the use of insulin in type 2 diabetes, less than expected young-onset type 2 diabetes and a stronger than expected bias of learning disability registers to more severe cases. A higher than expected potential eligibility and acceptance rate for the feasibility RCT meant that we were confident with the new recruitment target. Case-finding recruitment was also extended in order to continue in parallel with RCT recruitment.

Patient populations

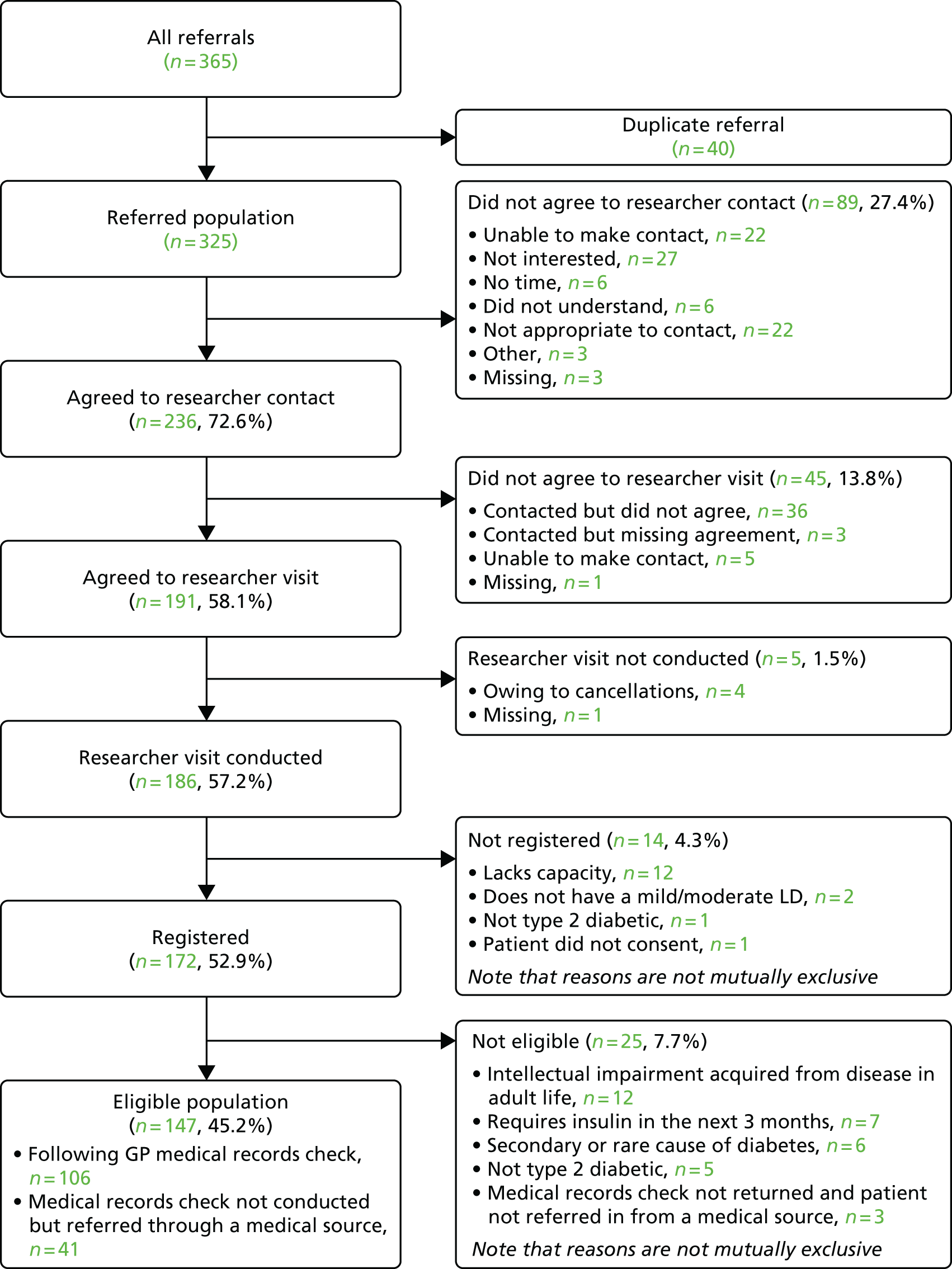

Referred population

The referred population consisted of all unique potential participants referred for entry into the case-finding part of the study, including those referred but not registered, and excludes duplicate referrals made for the same person through different sources. ‘All referrals’ refers to every separate referral from any source, including such duplicates.

Eligible population

Participants considered eligible at case finding were all those registered who met the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Participants found to be ineligible after registration (from GP medical notes review) or without documented evidence of informed consent were excluded from this population. When a completed medical review notes form was not received from a GP to confirm eligibility, participants were included if eligibility was confirmed by a researcher and if they were originally referred into the study via a medical professional.

Analysis methods

As this was a case-finding study for a feasibility study, outcomes were not subjected to formal statistical testing and so no hypotheses have been proposed.

For case-finding and eligibility outcomes, percentages were calculated using the total number of participants or forms expected in the relevant population as the denominator (including all participants with missing data for that variable), whereas for outcomes characterising the population, percentages were calculated using the total number of participants with available data as the denominator. Therefore, participants with missing data for each variable were excluded from the denominator and the number of participants excluded is presented alongside each summary. Analyses were carried out using statistical analysis software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

To provide a robust estimate of eligibility

Analysis presents the flow of participants through the study within a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) framework, including reasons for exclusion at each stage (referral, interview and consent to be approached for further research). A 95% CI for the proportion of eligible patients out of all referrals was calculated.

To evaluate a simple case-finding method to identify participants

Analysis generated descriptive statistics for patients agreeing to researcher contact, patients for whom a researcher visit was conducted, registered patients and the eligible population, when appropriate.

To characterise the population

Analysis generated descriptive statistics for participant demographics, participant-reported measures and measures of diabetes control including resource use for the eligible population, with the exception of demographics also summarised for the referred population. Measures of diabetes control were also presented categorically according to abnormal ranges on standard criteria. 48–51

Exploratory post hoc descriptive subgroup comparisons of diabetes control were made for BMI and HbA1c level by the patient’s response to a number of questions, including feelings around mood, diabetes, eating, weight and exercise, whether or not there was a supporter and whether or not they were taking medications.

Qualitative analysis

The analysis approach for the participant interviews and researcher journals is reported in Qualitative data analysis in the methods for the feasibility RCT, to avoid duplication.

Chapter 3 Development of resources for use in the feasibility randomised controlled trial

Alongside the case-finding study, we undertook work to develop and field-test materials related to the intervention and to its evaluation in the feasibility RCT.

Objectives

-

Identify existing information resources on diabetes self-management suitable for people in our target group to (1) act as TAU and (2) inform the intervention development.

-

Develop a standardised, but flexible, intervention supported by written materials to aid SSM of type 2 diabetes.

-

Field test the intervention, and assess it for acceptability and feasibility of delivery.

-

Develop a simple measure of adherence to the intervention.

-

Determine the most suitable measures for measuring costs (intervention costs and resource use) and the best approach to measuring quality of life in this population.

Developing intervention materials

Early in the study, we established a third-sector working group to collaborate on the development of the intervention materials. The Leeds & York Partnerships NHS Foundation Trust information design service, easy on the i, provided expertise in the development and evaluation of the materials. Our other third-sector partners, People in Action and Tenfold, and their customers with a learning disability, also provided input to the evaluation of the materials.

Development of the treatment as usual materials

Given the variability in care pathways across the three cities, we decided to ensure a basic level of diabetes care and knowledge in all participants. It was agreed this would be done by supplying a standard leaflet to all trial participants. The research team decided to review existing information resources to evaluate if any could be adopted as their standard leaflet.

Members of the third-sector working group, project team members and easy on the i reviewed 23 existing resources developed for use in the UK and aimed at people with a learning disability who have type 2 diabetes (see Appendix 6). We aimed to evaluate these resources in terms of their accessibility and the degree to which they covered the main elements of diabetes self-care, as identified in current guidelines:52

-

understanding what diabetes is

-

understanding the need for healthy diet and regular meal times

-

the importance of doing exercise

-

the importance of following treatment/medication regime

-

how to access services and important check-ups, such as retinal screening and foot care

-

what to do when not feeling well, for example in terms of following treatment

-

managing acute complications, that is, hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia.

Each resource was evaluated for comprehensive of coverage of these themes, the quality and appropriateness of images, clarity of text, ease of understanding (e.g. inclusion of medical terms) and relevance to our study population. No stand-alone resource met all these criteria to a high level. However, a leaflet developed over 10 years ago by Diabetes UK and a Leeds-based organisation, CHANGE, was identified as the best single resource in terms of the above criteria. This leaflet was no longer available in electronic format, was outdated in terms of its presentation (black and white line drawings) and some content no longer reflected current health advice guidelines. The team therefore approached Diabetes UK and CHANGE to collaborate on the design of a new resource.

CHANGE, working under the guidance of people with a learning disability, provided the graphic design expertise for the resource and reviews by people with a learning disability at each iteration. The new guide was informed by current best practice in developing accessible information provided by our expert advisers and from a review of the research and national guidelines in this area. Ramzi Ajjan, consultant endocrinologist with special interest in diabetes, reviewed the medical content. Christine Harris-Moores, specialist learning disability dietitian, reviewed the dietary advice. Diabetes UK ensured that the content met its current advice guidelines for type 2 diabetes.

Development of the supported self-management intervention

Supported self-management, which was specified in the commissioning brief as the intervention to be tested, is an existing approach to chronic disease management in which the underlying theory and the basic principles of implementation are already established. Development work in the current project did not, therefore, need to start from the early phases of intervention development as recommended by, for example, the UK’s Medical Research Council53 – elaborating theory and undertaking early-phase proof of concept and efficacy studies. Instead, we planned our development work in five phases:

-

Clarifying the principles of SSM – as summarised in review articles and didactic pieces, and as identifiable from the protocols and final reports of individual studies of self-management in diabetes.

-

Identifying the reported barriers to effective self-management of type 2 diabetes in adults with a learning disability – from published literature.

-

Reviewing existing materials that aim to support self-management of diabetes for people with a learning disability for examples of good practice – in consultation with service users.

-

Synthesising the outputs from the first three phases – to decide on those elements of SSM that are most relevant to the needs of our target population (will respond to likely barriers), and most likely to be acceptable and useful (match the identified good practices). This phase involved a series of problem-structuring and consensus meetings in the research team, checking interim outputs against guidelines on reasonable adjustments and by consultation with experts and service users.

-

Implementation and field testing of early versions – modifying the intervention materials in the light of feedback from research nurses.

At each stage there were regular consultation meetings involving members of the research team with people with a learning disability and their representatives in easy on the i, People in Action and Tenfold, as well as clinical experts in learning disability.

Phases I and II

We realised early in the project that there was no relevant RCT in the area of diabetes self-management in learning disability and, therefore, we did not undertake a formal systematic review of effectiveness studies. Instead, we aimed to use the published literature to identify (1) the principles of self-management that we would hope to embody in our own intervention and (2) those influences on self-management potential in our population that should inform the form or content of a SSM programme.

To help identify published information relevant to our intervention, an information scientist (JW) undertook initial searches in four main areas:

-

SSM in chronic disease

-

self-care in diabetes, including barriers to effective self-care

-

diabetes and a learning disability – a broad search to identify factors that might be specific to the target population

-

descriptions of specific interventions aimed at improving diabetes control in adults with a learning disability.

The search strategies are provided in Appendix 7.

We also reviewed two relevant National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,26,48 two Cochrane Reviews,54,55 a guideline on SSM published by Diabetes UK52 and outlines of national standards in diabetes management from the USA56 and the UK. 57

On the basis of these searches we identified and reviewed 707 titles and abstracts on the topics of self-management of chronic disease, including diabetes, and 350 titles and abstracts on the topic of diabetes in adults with a learning disability.

Titles and abstracts were reviewed by two of the applicants (AH and GL) and full versions of relevant papers were obtained. We categorised retrieved papers as follows:

-

individual self-management programmes or interventions (n = 22)66–87

-

research protocols describing individual self-management interventions (n = 8)88–95

-

observational studies reporting influences on self-management – barriers and enablers (n = 31). 29–33,96–122

Initially, we extracted data from the papers that described the form or content of self-management. We developed an initial framework derived from reviewing the two NICE guidelines,26,48 two Cochrane Reviews54,55 and the guideline on SSM published by Diabetes UK. 52 We then developed this framework by reference to six individual studies in the reports67,74,81,123–125 for which we found reasonably comprehensive descriptions of the intervention. The remaining studies were reviewed against this framework to identify any missing themes, using a modified approach based upon best-fit framework analysis. 126

Next, we reviewed papers describing barriers to effective self-management, influences on interventions or outcomes that were specific to adults with a learning disability. In a series of review meetings we organised the identified influences into a descriptive framework.

Finally, we combined the two frameworks in a narrative synthesis of these literatures to identify the general principles to be adhered to in implementing a pragmatic and sustainable programme of SSM, and the form and content of the specific intervention for this project.

Phase III

For existing self-care resources, a scoping exercise was conducted in which examples of good practice in interventions around health in people with a learning disability were sought from services in the UK. Sources included charities, for example Diabetes UK, local NHS trusts and patient groups, NHS Choices [www.nhs.uk/pages/home.aspx (accessed 2 January 2018)] and Easyhealth [www.easyhealth.org.uk (accessed 2 January 2018)]. The process here was different from that used to develop the TAU intervention described in Development of the treatment as usual materials. In that case we were seeking to identify the best-available resource to adopt in toto; in the present exercise we were seeking specific instances of desirable practice – individual images, approaches to explaining the principles of self-management, or user-friendly resources such as diary sheets.

We identified 18 examples of resources developed in the UK to support self-management of diabetes for people with a learning disability.

Resources were reviewed by a panel consisting of members of the research team and staff and service users from easy on the i. They were asked what they liked and disliked about each resource, and to note implications for the intervention in development. Results were recorded on a structured proforma.

Phase IV

Using the general approach of problem structuring and priority setting,127 preliminary versions of the SSM package – including not only format and content but also tailoring (for easy reading, visibility for those with poor acuity and so on) – were discussed initially in the research team. Finally, we considered guidance on reasonable adjustments to health care designed to ensure access for people with a disability, to check that we were meeting obligations in that respect.

When necessary, a further round of more focused (purposive) reviewing of literature was used to clarify which were the key principles for this population. We generated two lists (Box 1 and Table 2) that we used to help frame final decisions.

-

Food: buying, preparing, eating.

-

Weight control or weight loss.

-

Physical activity or exercise.

-

Looking after your body: foot care, dental care.

-

Healthy living: alcohol, smoking.

-

Taking tablets.

-

Visiting professionals: dental care, medical care, eye checks.

-

Maintaining emotional well-being.

-

Education: about diabetes and what it is, what self-management involves.

-

Problem-solving.

-

Goal-setting, planning.

-

Monitoring and feedback, for example blood glucose levels, weight, dietary intake, tablet take.

-

Skills development: foot care, self-monitoring of blood glucose, preparing food, use of IT.

-

Effective use of other people and resources, for example company when going swimming/walking.

-

Managing emotions and building confidence.

-

Written materials.

-

Charts: fridge door charts, plan your plate, diaries.

-

DVD.

-

Web-based programmes: static or interactive/moderated.

-

Telephone or short message service (SMS) contact: prompts or interactive.

-

IT: beeping fridges, watches, tablet boxes, smart phones, etc.

-

Groups, for example nurse-led, third-sector, exercise group, group education.

-

Professional contact: nurse, diabetes educator, GP.

-

Peer support: informal; trained peer support; family; couples work.

-

Literacy and other intellectual attainment.

-

Sensory impairments.

-

Language difficulties: non-English, comprehension or speech problems.

-

Autistic characteristics.

-

Self-nominated goals or problems.

-

Professionally identified priorities.

-

Living arrangements.

-

Supporter’s priorities.

| Example of | |

|---|---|

| Disability (barrier to good health care) | Adjustment (enabler of good health care) |

| Cognitive disabilities | |

| Memory problems | Prompts, support for appointments |

| Literacy or reading skills deficit | Accessible materials |

| Vision or hearing impairment | Visual aids |

| Speech problems | Time, trained staff |

| Understanding: health risks, necessary actions | Accessible information |

| Personal | |

| History of lack of dignity/respect in services | Staff training |

| Threat to safety including bullying | Safeguarding protocols |

| Lack of personal pleasure/relax and recreation activities | |

| Autonomy/choice | |

| Questionable mental capacity | Staff training in capacity assessment and inclusive practice |

| Practical (instrumental) barriers | |

| Transport | Funding, safe provision |

| Mobility | May need occupational/physiotherapy assessment |

| Finance | Personal budget |

| Treatment burden: timing, side effects | Support with adherence, modified regime |

| Social barriers | |

| Lack of social support/networks | Identify, train and support carers, advocacy, third sector |

| Mental health | |

| Autistic traits | Pacing of change |

| Challenging behaviour | Pacing of change, staff training |

| Low self-confidence | |

| Distress and mental disorder | |

| Other health needs | |

| Epilepsy | Safe environment |

| Physical symptoms or restrictions | |

| Difficulty negotiating health care | |

| Talking with professionals | Staff training and supervision |

| Communicating needs | Learning disability register, health action plan |

| Overcoming stigma | Advocacy |

Principles for priority setting were that:

-

the intervention should respond to known barriers to self-management reported by people with a (learning) disability, including practical problems such as transport, likely attrition from dropout when multiple attendances are expected and ability to accommodate the presence of a supporter

-

the format of the intervention should be likely to encourage self-maintained change beyond an early supported element; in our target population this particularly meant that the intervention should involve supporters who were involved with any aspect of lifestyle (shopping, food choice, physical activity, medication monitoring and so on) relevant to diabetes

-

the intervention should be designed to be readily integrated into usual health-care provision in the NHS to ensure sustainability.

Based on all the advice we received, we wanted to give particular salience to:

-

practical aspects of self-care, such as buying and preparing food, diet change to aim for weight loss and increasing physical activity

-

use of simple (accessible) written materials and charts

-

supportive contact both with a professional and with an informal supporter, if one could be identified

-

use of practical goal-setting, planning to meet goals and self-monitoring.

By contrast, we decided it would be less helpful to focus on:

-

a substantial component of healthy living interventions aimed at alcohol and smoking, because they were not major problems in our group

-

education beyond the basic information in the TAU booklet

-

information technology (IT)-based interventions, such as web, digital versatile disc (DVD), mobile phone, etc., as these were not readily accessible by our participants

-

group-based interventions, as attendance is typically poor and individualisation is harder.

Phase V

We decided that professional support would be provided by diabetes nurses with experience in primary care rather than learning disability nurses: very few of the target population would be in contact with (or taken on by) specialist learning disability services. In routine NHS practice, where 20–25% of patients would be using insulin, diabetes nurses would have more relevant experience; for our population (not all of whom would have been told they had, or would self-describe as having, a learning disability) the diabetes background would be more acceptable. We developed a training plan for the research nurses delivering the intervention covering the underlying principles of mental capacity and of self-management, the individualised elements specific to learning disability, trouble-shooting and dealing with problems (such as behavioural disturbance), and the details of the programme and the materials provided with it. Explicit links were made between the practicalities of the intervention and its rationale in self-management principles (Table 3).

| Principle | Relevant intervention materials (see Appendix 12) |

|---|---|

| Helping people to understand the short-, medium- and longer-term consequences of health-related behaviour | How to do it |

| Looking after my diabetes | |

| Helping people to feel positive about the benefits of changing their behaviour | I am going to . . . |

| Building the person’s confidence in their ability to make and sustain changes | I am going to . . . |

| Recognising how social contexts and relationships may affect a person’s behaviour | My life |

| Who, what, where? | |

| Supporter charts and card | |

| Helping plan changes in terms of easy steps over time | Weekly plan/change plan |

| Identifying and planning for situations that might undermine the changes people are trying to make (including planning explicit ‘if–then’ coping strategies to prevent relapse) | I am going to . . . |

| Encouraging people to make a personal commitment to adopt health-enhancing behaviours by setting (and recording) achievable goals in particular contexts, over a specified time | I am going to . . . |

| Helping people to use self-regulation techniques (such as self-monitoring, progress review, relapse management and goal revision) to encourage learning from experience | My rewards plan |

| Encouraging people to engage the support of others to help them to maintain their behaviour-change goals | Supporter pack and flash cards |

The training programme was delivered by two of the researchers (AH and GL) over three sessions of face-to-face contact with the nurses. An additional session on mental capacity assessment was delivered by Alison Stansfield to the nurses and all research interviewers.

Supervised use of the intervention with three initial cases in the RCT was also arranged. In each case the whole intervention was delivered over a maximum of four visits and the nurses met together with Allan House and Gary Latchford after each visit, to discuss any challenges with implementation. On the basis of this experience, early versions of the intervention were modified in format to make them easier for use by the nurses. In particular, the forms for keeping notes on each contact that were prepared for early versions were found to be overstructured by the nurses and intrusive for use in the field. Once they had familiarised themselves with the principles of self-management and the nature of each contact, the nurses preferred to make free-form notes during contact and then check afterwards that they had recorded all the necessary information and completed the essential standardised forms (case report forms) for the trial.

Both nurses and participants involved in the field-testing reported finding the materials easy to use and the nature of the intervention easy to understand.

The final intervention had four standardised components with associated materials. How they were delivered depended on participant and supporter characteristics and preferences.

-

Establishing the participant’s daily routines and lifestyle: this included current diet and activity routines, participation in daytime social activities or work, shopping and food preparation, current self-reported health and self-management. The main aim of this component was to identify the real social and personal influences in the life of the person with diabetes that would limit their ability to self-manage or that might be mobilised as a resource in supporting self-management.

-

Identifying all supporters and helpers and their roles: a key supporter and other helpers were identified when possible at case finding. Key supporters and other helpers were given written information about the project and if they agreed to support a goal set by the participant, then they were given a written reminder of their role. The main aim was to identify people who might be a useful resource in supporting self-management and to ensure that any changes were embedded in the social network for longer-term maintenance of change.

-

Setting realistic goals for change: the main aim was to avoid prescribing change in the way of good dietary practice or other lifestyle change instead but to support goals suggested by the person with diabetes that were specific, simple and achievable, given the person’s current routines and social support, and consonant with their willingness to make change. The main aim was to encourage engagement in a population usually thought of as having little agency and to introduce the idea of selectable elements in a repertoire of self-management options.

-

Monitoring progress against agreed upon goals: we devised a simple system that did not depend on high levels of functional literacy, using tear-off calendar sheets on which participants noted goal attainment in a yes/no format. The main aim was to encourage active participation in an activity that is a core feature of self-management.

We prepared materials to accompany these activities (see Appendices 8–12).

-

For the nurses: templates for a weekly timetable, a chart to record friends and family and other helpers, charts to be completed in collaboration with the person with diabetes – my life, my likes and do not likes, looking after my diabetes.

-

For the person with diabetes: an OK-Diabetes board to place in a prominent position at home with a visible record of goals including pictorial prompts, for example snack swaps, a written action plan in multiple formats and tear-off slips to record daily actions.

-

For supporters and helpers: an information sheet explaining the study and a card summarising what their role was in helping to support the person with diabetes in meeting their chosen goals.

The research nurse worked through the elements of SSM with the participant, explaining how to use materials and suggesting initial actions and activities. Further contact was negotiated with the person with diabetes. We expected that a total of three or four meetings of 30–60 minutes over 6–8 weeks would be provided, followed by telephone support and advice.

We took steps to ensure consistency in use of the SSM: (1) training and supervision sessions with research nurses, (2) annotation of the intervention materials by research nurses and (3) ensuring nurses had other experience and training in diabetes or learning disability care before the RCT.

Developing an adherence measure

We conducted a review of the literature to determine the methods of adherence measurement reported to date for similar interventions (self-care, self-management) in the same population (learning disability), to see if there were helpful techniques we could adopt.

Search strategy

We ran literature searches on the standard bibliographic databases in July 2013, and updated the searches in July 2015. Full search strategies for each database searched can be found in Appendix 7.

Papers were included if they:

-

described primary research studies

-

involved participants who were adults with a learning disability

-

described a standardised self-management or self-care intervention

-

described an intervention aimed at weight loss or improving self-management of diabetes.

We defined self-management as involving at least (1) some definition of actions relevant to improving the participants’ condition (overweight or diabetes), (2) setting and recording of specific goals or targets related to those actions and (3) monitoring of progress in achieving those goals. The person with a learning disability had to be an active agent in this process – albeit with the help of a supporter at times – so that they were not just a passive recipient of a programme designed and delivered by a third party.

Developing an organising framework

In a series of research team meetings we developed an initial framework for organising the data, based upon our reading of the wider adherence literature as well as the literature identified in the present search. We distinguished steps taken to:

-

ensure the intervention was delivered correctly in form, content and quality

-

measure for research that these approaches to ensuring quality of delivery were employed

-

measure actual provider adherence

-

measure participant adherence.

The first two steps fit with existing literature describing ‘fidelity’ – the degree to which provider delivery is in line with the intended form and content. The last two steps fit with the existing definition of ‘adherence’.

To ensure a measure of adherence was applied to all elements of the intervention and not just a selected few, our initial framework had four categories to describe an intervention:

-

The content of the intervention: topics or components covered, such as (for diabetes self-management) shopping for and preparing food, planning physical activity, taking tablets and avoiding unhealthy behaviours such as smoking or drinking too much alcohol.

-

The techniques employed in the intervention: how it is delivered, for example through education, training in goal-setting, use of self-monitoring and feedback techniques.

-

The platform or format by which it is delivered: for example, written materials, group sessions, self-completion charts, web-based resources or text messaging.

-

The degree of individualisation of the intervention: this could mean use of inclusion and exclusion criteria to define the sample from the target population to whom the intervention is delivered or modification of elements of the intervention to suit the needs of individuals within that sample, for example those with visual impairments.