Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/80/04. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The draft report began editorial review in April 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sarah E Lamb was on the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Additional Capacity Funding Board, HTA End of Life Care and Add-on Studies Board, HTA Prioritisation Group Board and the HTA Trauma Board.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Lamb et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Definition and prevalence of dementia

Dementia is a syndrome characterised by acquired, progressive deterioration in memory, general cognitive function, self-care and personality. Probable dementia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)1 criteria is defined by:

-

memory impairment with cognitive disturbance in at least one of the following domains – aphasia (language impairment), apraxia (motor impairment), agnosia (impairment of object recognition) or executive functioning (planning, sequencing, abstracting)

-

functional decline – increasing impairment in functional ability (social, occupational, personal/self-care) related to cognitive deficits.

Dementia affects older people to a much greater extent than younger people. As a rule of thumb, the prevalence of dementia in developed countries doubles in successive 5-year age groups within the age range of 65–99 years, from under 1% for people aged 65–69 years, to about 35% in people aged 95–99 years. 2 Prevalence is similar in men and women. 2 About 60% of cases of dementia in developed countries are caused by Alzheimer’s disease, and about 20% by vascular dementia,3 while mixed Alzheimer’s/vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies are the other common causes.

Recent reports have suggested that the prevalence of dementia is reducing across Western Europe4 and in the USA. 5 The hypothesised reasons for this reduction are an increase in educational achievements in successive birth cohorts and other medical, social and behavioural factors that are still under investigation. However, current prevalence figures indicate that in the UK > 800,000 people have dementia, with an annual cost to the economy of £23B. 6 Although more recent estimates of dementia prevalence have revised this figure down to 670,000 people,7 this is still a very substantial number of people.

Reducing the burden of dementia is a priority for the UK government. In February 2015, the Prime Minister reiterated the 2012 dementia statement and set a challenge for the UK to become the best country in the world for dementia care and research. 8

Evidence for the effect of exercise on cognition

There is currently no cure for dementia, only interventions to reduce risk and alleviate symptoms. The protective effects of moderate levels of physical activity on the progression of subjective memory impairment and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia have been observed consistently in several large-scale epidemiological studies. 9–11 Studies of Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic mice and dogs suggest several potential mechanisms by which exercise may prevent the progression of dementia. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is stimulated by exercise in mice with Alzheimer’s disease, leading to increased concentrations in many areas of the brain including the hippocampus, which is thought to have a key role in mediating some of the effects of dementia. 12 Other effects of exercise observed in murine dementia models include improved synaptic function,13 attenuated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production,14 delayed loss of myelinated fibres in the brain15 and a reduction of damaging beta amyloid oligomers. 16 Epidemiological studies of the human brain have shown positive associations between physical activity and the volume of the hippocampus and other areas of the central nervous system sensitive to pathological change in dementia,17 all of which are targets that are considered important for treatment. 18

These studies provide evidential support for the theoretical model of increasing physical activity and exercise in people with dementia with the aim of alleviating cognitive symptoms. At the time of finalising the protocol, the then most recent Cochrane review of exercise programmes for people with dementia (final search date October 2013)19 included 17 studies, nine of which assessed the effect of exercise on cognition. No clear conclusions could be drawn regarding the effect of exercise on cognition in people with dementia because of unexplained heterogeneity in the data, and the review was unable to make recommendations as to the type and dose of exercise (i.e. intensity, frequency and duration).

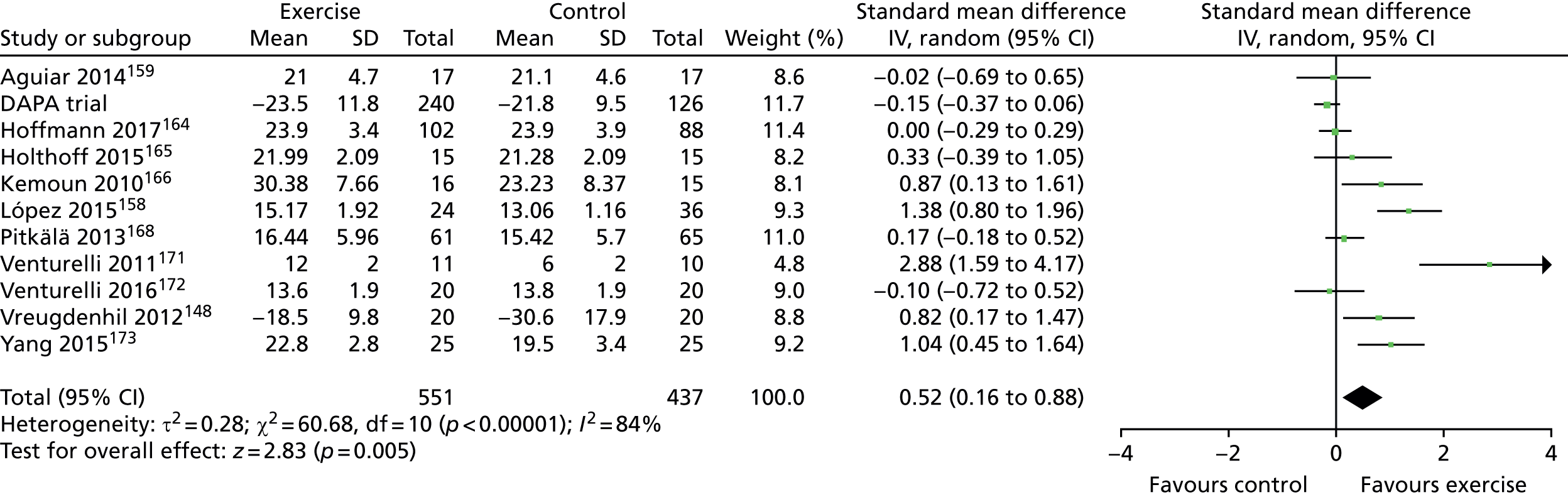

The Cochrane review19 ended its searches in October 2013 and we ran an update to this review with searches ending in September 2016. We identified an additional 14 studies investigating dementia and MCI patients (reported in Chapter 6) and two other systematic reviews20,21 of patient trials have been reported during the trial. One of these systematic reviews concluded that exercise was an effective intervention20 and the other that it was not. 21

Current management of dementia in the UK

The treatments for dementia recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)22 are cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine), but only for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, not for vascular dementia. Memantine is supported by NICE for limited use in moderate to severe dementia or in patients who are unable to tolerate cholinesterase inhibitors. 22 Many people with mild to moderate dementia (MMD) and their families require additional services, mainly to mitigate functional loss, such as carer training, home carers, day care, respite admissions, sitting services and carer support services.

Potential role of exercise in the management of dementia

Physical exercise is a candidate non-pharmacological treatment for dementia and there is a considerable amount of literature given to expanding underlying mechanistic hypotheses and rationale.

Although much of the current evidence informing the choice of type of exercise to improve cognition is derived from animal studies, and studies of healthy humans or people with MCI, it is a widely held belief that exercise has the potential to be an important intervention in the management of people with dementia. In addition to any possible effects on cognition, exercise should improve physical fitness and functioning, and the selection of the right type of exercise stimulus could reduce fall risk, improve mobility and reduce cardiovascular risk factors, just as in people who are not cognitively impaired. The main challenge is to design a programme that people with dementia can engage with, and adhere to in the longer term, which is of sufficient intensity and frequency to achieve the desired effect.

To date there are no recommendations as to which behaviour change techniques (BCTs) are the most effective for people with dementia. There are, however, recommendations regarding generic BCTs to increase physical activity adherence in adults23 and for older people without dementia. 24,25 The key active components include self-regulatory BCTs (e.g. goal-setting, self-monitoring), feedback and reviewing of previously set goals.

The Dementia and Physical Activity trial

The aim was to establish whether or not exercise is effective in slowing or improving cognitive decline in community-dwelling adults with MMD.

Research objectives

To undertake a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT) to estimate the effects of an exercise or physical activity intervention that is feasible for delivery within the current constraints of NHS delivery.

Our objectives were to:

-

refine an existing intervention for delivery to community-dwelling populations of people with dementia, including a systematic review to inform intervention development

-

pilot critical procedures in the intervention and trial

-

complete a definitive, individually RCT to estimate the effectiveness of exercise in addition to usual care on cognitive impairment (primary outcome), function and quality of life in people with mild or moderate dementia, and on carer burden in carers

-

complete a parallel cost study and conduct an economic analysis from a health-care and societal perspective

-

investigate intervention effects in predefined subgroups of gender and dementia severity

-

undertake a qualitative study into the experiences of participants and carers taking part in the intervention.

Overview of report

The report is structured in seven chapters. We present the methods, results and a brief discussion of each of the main components of the study within each chapter. The results of the systematic review, which we have undertaken as a continual process throughout the trial, are presented in Chapter 6. We finish with an overarching discussion and conclusion.

Chapter 2 Intervention development and description

Parts of this report are based on Brown et al. ,26 in which the intervention description has been published. © 2015 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Introduction

The development of the intervention followed a pathway and method we established in earlier National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-funded studies27–30 and in accordance with the Medical Research Council recommendations for the development of complex interventions. 31 Exercise interventions in older people are underpinned by a well-established physiological and clinical evidence base and guidelines; however, these do not necessarily include people with cognitive impairment. 32 We examined existing relevant reviews and undertook a systematic review specifically to identify RCTs that examined the effect of exercise upon cognitive function in people with MCI or dementia, as summarised in Chapter 6. In addition, we considered the observational and animal study evidence base specific to exercise and cognitive impairment. Finally, patient, carer and clinician expertise was used to draw the intervention package together into a programme. The refinement, acceptability and feasibility of trial procedures and the exercise intervention were tested in pre pilot and pilot studies between June 2011 and July 2012.

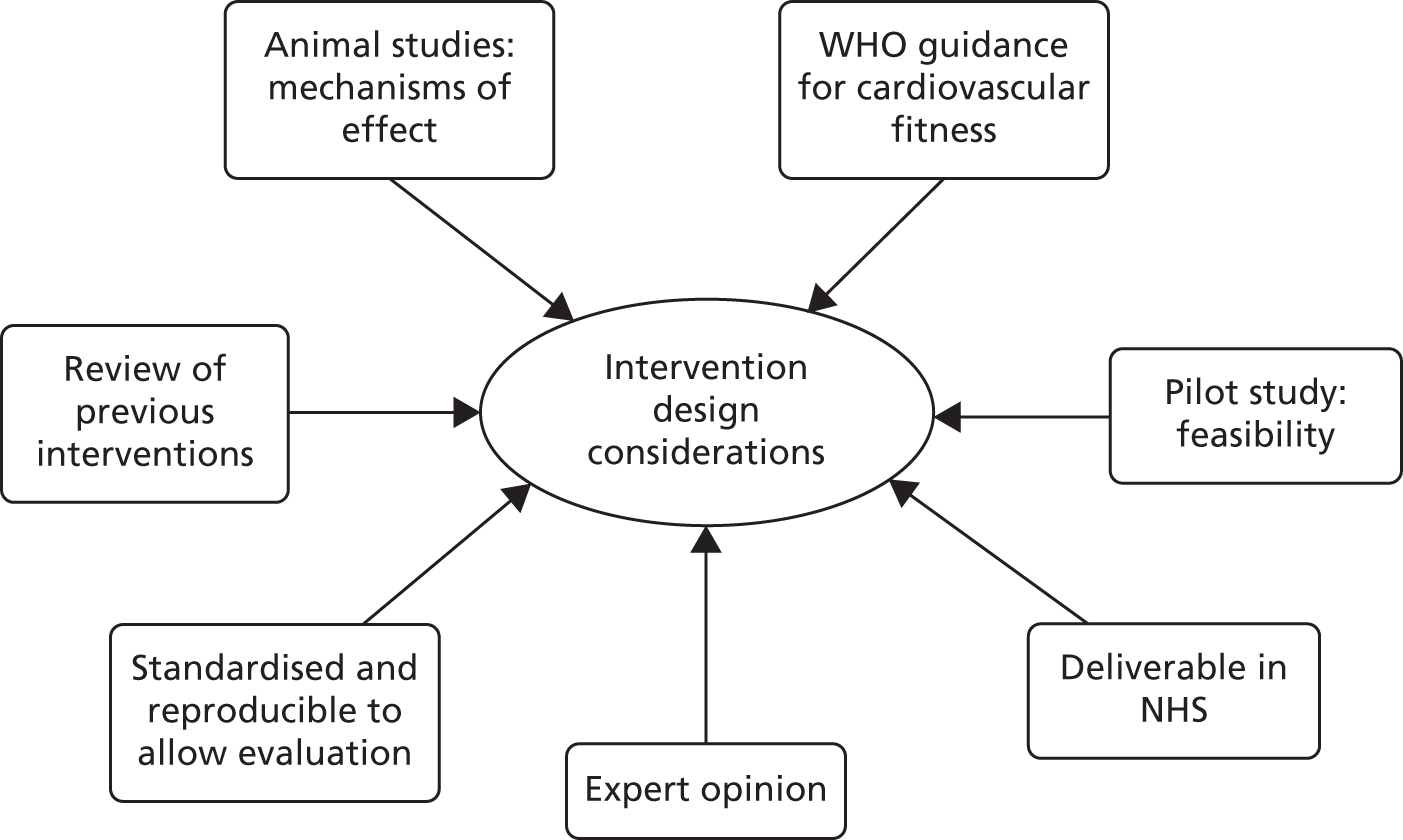

Figure 1 demonstrates the various information sources and considerations that were combined to formulate the final Dementia and Physical Activity (DAPA) intervention.

FIGURE 1.

Intervention design considerations. WHO, World Health Organization. © 2015 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Rationale and development of the intervention

Evidence review

We defined exercise as ‘a subcategory of leisure time physical activity in which planned, structured and repetitive bodily movements are performed to improve or maintain one or more components of physical fitness’. 33 Physical activity was taken to mean any activity (including exercise itself) that could mimic the physiological effects of exercise, for example gardening or housework. From our systematic review of trials and review of systematic reviews, we developed an evidence-based rationale for the intervention content.

The most recent Cochrane review of exercise programmes for people with dementia19 included 17 studies, nine of which assessed the effect of exercise on cognition. No clear conclusions could be drawn regarding the effect of exercise on cognition in people with dementia because of unexplained heterogeneity in the data. The review was unable to make recommendations as to the type and dose of exercise (i.e. intensity, frequency and duration).

Exercise type

To inform our decision around the types of exercise to deliver, we examined existing exercise models and evidence for mechanisms of action. There is evidence that aerobic exercise increases vascularisation of the brain and triggers the release of neurotrophic substances, which support cognitive functions. 34 Studies in healthy older adults report that increased aerobic fitness is associated with better preservation of grey matter volume and larger hippocampus volume. The hippocampus contributes to spatial memory and consolidation of short-term memory. 35 In dementia patients, the hippocampus is atrophied. Similarly, resistance training alters levels of circulating substances (insulin-like growth factor 1, homocysteine)36 in a manner that may positively affect cognitive function. Supporting evidence is summarised in Table 1. Hence, it was decided to include both aerobic and resistance training elements in the exercise programme.

| Evidence | References | Implications | Element of the DAPA intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic exercise leads to increased brain vascularisation in animal model | Lista and Sorrentino34 | Increased oxygenation to the brain enhances cognitive performance | Inclusion of aerobic exercise |

| Aerobic exercise leads to release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in animal model | Lista and Sorrentino34 | Formation of new neurones and new synapses in the brain | Inclusion of aerobic exercise |

| Amount of cardiovascular exercise required for general health and fitness | Garber et al.32 | The American College of Sports Medicine recommends 150 minutes per week at moderate intensity for adults | Dosage of aerobic activity |

| Resistance training at 50% 1RM leads to decreased homocysteine levels | Vincent et al.37 | High levels of homocysteine linked to increased risk of cognitive impairment | Inclusion of resistance exercise |

| Resistance training leads to increased levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 | Suetta et al.36 | Low levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 linked to reduced cognitive performance | Inclusion of resistance exercise |

| Feasibility of people with dementia using exercise bicycles | Yu and Swartwood38 | Exercise bicycles can be used by people with dementia | Use of exercise bicycles for aerobic exercise |

| Prevalence of dyspraxia in people with dementia | Zoltan39 | Dyspraxia is not uncommon in people with dementia | Use of simple, functional movements, such as sit-to-stand |

| Behavioural interventions, for example goal-setting, feedback on physical activity | Conn et al.40 | These strategies increase physical activity in healthy adults | Use of behavioural interventions |

| Peer support in maintaining physical activity | Cress et al.41 | Peer support is associated with exercise adherence in older adults | Use of group exercise, involvement of carers |

| Social component of physical activity | NICE42 | The social component of activity is important to older adults, so group exercise is recommended | Use of group exercise |

| Written goal-setting and planning, recording physical exercise | Cress et al.41 | Written contracts assist exercise adherence in older adults | Use of written goals and exercise plans, use of exercise calendar |

| Use of exercise logs | NICE42 | Written exercise logs recommended for older people | Use of exercise calendar |

| Performance feedback | Cress et al.41 | Provision of accurate feedback and positive reinforcement assists exercise adherence in older adults | Use of 6MWT review, verbal feedback during classes |

| Feasibility of the DAPA intervention | DAPA pilot | Intervention practicable in this population | Entire intervention |

Dose of exercise

There is a robust evidence base around the quantity of exercise needed to elicit health benefits in healthy older people, but these are not specific to cognitive outcomes. 32 Our systematic review (see Chapter 6) found that protocols for exercise interventions ranged from 60 to 210 minutes of exercise per week, with an average of 122 minutes per week. Although there is no direct evidence to inform dosing for improvement in cognitive performance, there is a link between cardiovascular status and dementia. We used the guidance, produced by the World Health Organization (WHO), for the quantity and quality of exercise required for cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal good health for adults and older adults. 43 This WHO guidance recommends at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity cardiorespiratory exercise. The same guidance recommends resistance exercises for the major muscle groups two or three times a week for musculoskeletal good health. Hence, we selected the target intensity as, at least, moderate to moderate to hard level for both exercise forms for an overall total of 150 minutes per week.

To gauge an individual’s fitness and exertion levels (mild, moderate, hard) we used the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). This assessment is relatively simple to implement, and an adapted version has been shown to be reliable in people with Alzheimer’s disease. 44 It requires less time to complete than the Incremental Shuttle Walk Test45 and, unlike the cycle ergometry test,46 requires no special equipment. We selected the Borg Scale of Perceived Exertion, adapted for use by people with dementia,47 as the primary method of assessing exercise intensity during sessions, coupled with soft indicators such as sweating, skin colour and breathing rate. Although heart rate could have been, and was occasionally planned to be, used as an indicator, these measures are complicated in situations in which, as we expected, there was a higher prevalence of beta-blockers and drugs/devices/conditions influencing heart rate.

We selected cycling as the core aerobic exercise38 because the cycling action is a simple, intuitive one and the risk of falls is minimised.

For resistance exercise, the gold standard method for identifying an initial resistance load is the one-repetition maximum using an isokinetic dynamometer. 48 However, exposing untrained individuals to resistance that is higher than 80% of the one-repetition maximum increases the likelihood of an adverse event (AE) and is not recommended for older people. 49 Given the probable frailty of the participants, we selected a validated method to prescribe the resistance by estimating the maximum number of lifts that could be made with good form for a given weight. 49 As dyspraxia is common among people with dementia,39 the exercises chosen were simple, functional movements aimed at enhancing participation and were selected to engage the major muscle groups, in accordance with the guidance from the WHO. 32

Duration of exercise intervention

Determination of the total duration of an intervention was challenging. Our systematic review (see Chapter 6) identified intervention duration ranges from 1.5 to 12 months, with an average duration of 5 months. Our funders requested that the duration of the intervention was 4 months in order to maximise the chance of it being found to be cost-effective, which is documented in Appendix 1.

To maximise the chance of the intervention being cost-effective, we used group supervision (with each participant working to their individual prescription) for 4 months, and included BCTs plus suggestions for continued activities to encourage continued physical activity.

Exercise intervention adherence

Behavioural modification is an important component of the intervention, to make adherence to the exercise intervention more likely. Simply providing information about the health benefits of exercise is not effective in increasing older adults’ participation in exercise. 41 The BCT taxonomy of Michie et al. 50 provides standardised definitions of 93 techniques used in behaviour change interventions and promotes clarity in the reporting of intervention content. During our intervention development there was no specific guidance for which BCTs to use for people with dementia. We adapted guidance for healthy older people32 and the NHS guidance for behaviour change,51 and examined BCT evidence for healthy older adults. A review identified self-efficacy as the most consistent predictor of initiation and maintenance of physical activity in adults aged > 50 years. 52 The BCTs of ‘goal-setting’ and ‘activity contracts’ are associated with increased physical activity levels and improved self-efficacy in adults. 53 The NHS guidance for behaviour change details how to implement these BCTs into an intervention. Group exercise, compared with individual home-based exercise, has been shown to improve exercise adherence in older people. 54 Substantial parts of the DAPA behavioural intervention depended on telephone contact, and there is precedence for this. A study of older women undertaking a 26-week group-based exercise programme found that those who were given a telephone-assisted coping plan, via a single telephone call, had better adherence to the programme than those who were given only written advice. 55 Staff encouraged a fun atmosphere in the classes, as enjoyment has been shown to improve exercise adherence in adults attending exercise groups. 56 Encouragement from spouses and carers has been recognised to strengthen self-efficacy and improve adherence. 57 Carers were welcome to come along to the sessions. They had no formal role during the class and did not participate as either coaches or individuals during the session. A break-out area was organised where carers could chat among themselves. When they wished to be, carers were involved in identifying activities that the participants were likely to find enjoyable and in encouraging compliance with home exercise.

Expert opinion

A key part of the intervention development process was the advice received from clinicians and other experts, including patient groups. The intervention development team gained opinions from specialist physiotherapy teams and visited exercise or physical activity group programmes that were being run for the target population. The team members also talked to people with MMD and their carers via local Alzheimer’s Society activities, as well as within the pre-pilot and pilot studies.

Guidelines

The intervention design was supported by information from a number of guidelines, principally the American College of Sports Medicine’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription,32 NICE’s dementia guidelines58 and the WHO’s Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. 43

The pilot studies

We ran two pilot studies. The first tested the feasibility of using the OPERA trial intervention59 (a randomised trial of an exercise intervention for older people in residential and nursing accommodation based on a music approach) in the DAPA trial target population. It was found that even the highest level of the OPERA exercise activities were not able to create an adequate exercise challenge, as the DAPA trial population were younger and fitter than the OPERA population. As a result, the intervention development team created an innovative and specially targeted exercise programme.

The acceptability and feasibility of the new intervention (including the behaviour change support strategies) was then tested in a second pilot study (n = 6 people with dementia).

Informal feedback interviews were conducted with the participants, carers and physiotherapists involved. No qualitative analysis was conducted on these data, but the data were used in real time to inform intervention development. Participants found the DAPA intervention to be acceptable, feasible and enjoyable. The exercise activities were able to create an adequate exercise challenge for the DAPA trial target group (using heart rate monitoring). This pilot study also highlighted that some participants needed more assistance and supervision than others and that the involvement of carers facilitated attendance and adherence in terms of timings, transport and emotional support, and so this also was accounted for in the programme design. Participants identified concerns that they held before starting the groups, which were used to inform our recruitment strategy information documents. Outcome measures and some aspects of the recruitment processes were also tested during the pilot phases.

The Dementia and Physical Activity intervention

A summary of the final DAPA intervention is provided in Figure 2. The exercise intervention was divided into two parts: a supervised part lasting 4 months and a supported, unsupervised component lasting an additional 8 months. The supervised part comprised a pre-exercise assessment, twice-weekly exercise sessions of approximately 1 hour’s duration (including 50 minutes of exercise at the target intensity) for 4 months with a target of at least 50 minutes of unsupervised activity at moderate intensity, to achieve a total of 150 minutes per week. The exercises sessions were a combined aerobic and resistance training schedule at moderate to hard intensity, with supervision in groups of up to eight participants.

FIGURE 2.

The DAPA intervention. © 2015 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Individual pre-exercise assessment

The pre-exercise assessment assessed the participant’s general health, current fitness and activity levels. The participant and/or carer was asked about cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, musculoskeletal and psychiatric conditions, as well as diabetes mellitus and recent acute illnesses (for details please see Appendix 2). Current and previous physical activity levels, along with any physical, perceptual or sensory limitations, for example limited range of shoulder movement, were noted and considered in the individual tailoring of exercises. Carers were encouraged to attend when possible to provide additional information to the therapist, for example on medications, comorbidities and exercise preferences.

The main element of the pre-exercise assessment was to set the initial intensity of exercise for the sessions. A 6MWT was completed using two marker cones set up 15 m apart, and the participant was instructed to walk between and around the cones for 6 minutes, with standardised directions and phrases of encouragement. 44 The distance walked in 6 minutes was noted. The participant also wore a heart rate monitor, and the resting and average heart rates were recorded. This allowed calculation of the initial target aerobic intensity according to Luxton. 60 For resistance exercises, the maximum weight that could be lifted in good form over 20 repetitions was estimated.

Exercise sessions

Exercise sessions required a venue with sufficient accessible space and numbers of fixed cycles, weighted jackets and dumb-bells. The sessions required a physiotherapist and an exercise assistant, unless the number of participants were substantially fewer than the target of eight. The exercise assistant was usually an exercise instructor or had worked in health care, for example as a physiotherapy assistant.

Warm-up

A simple warm-up comprising movements of the neck, shoulders, trunk, hips and knees, together with marching on the spot was performed, lasting about 5 minutes.

Aerobic

The target intensity for aerobic training was 25 minutes in each session, with at least 15 minutes at moderate to hard intensity. Intensity was individually tailored to each participant’s baseline fitness, recognising that a low load may be a moderate challenge to some but a low challenge to others. The period of cycling was built over the sessions. For all sessions, the first 5 minutes of the aerobic exercise was spent cycling at low intensity. At the outset of the programme all participants were started at low intensity. The aerobic challenge was progressed by increasing the total duration spent cycling, up to 25 minutes, as well as the duration spent exercising at moderate and hard intensity over the ensuing sessions.

Resistance

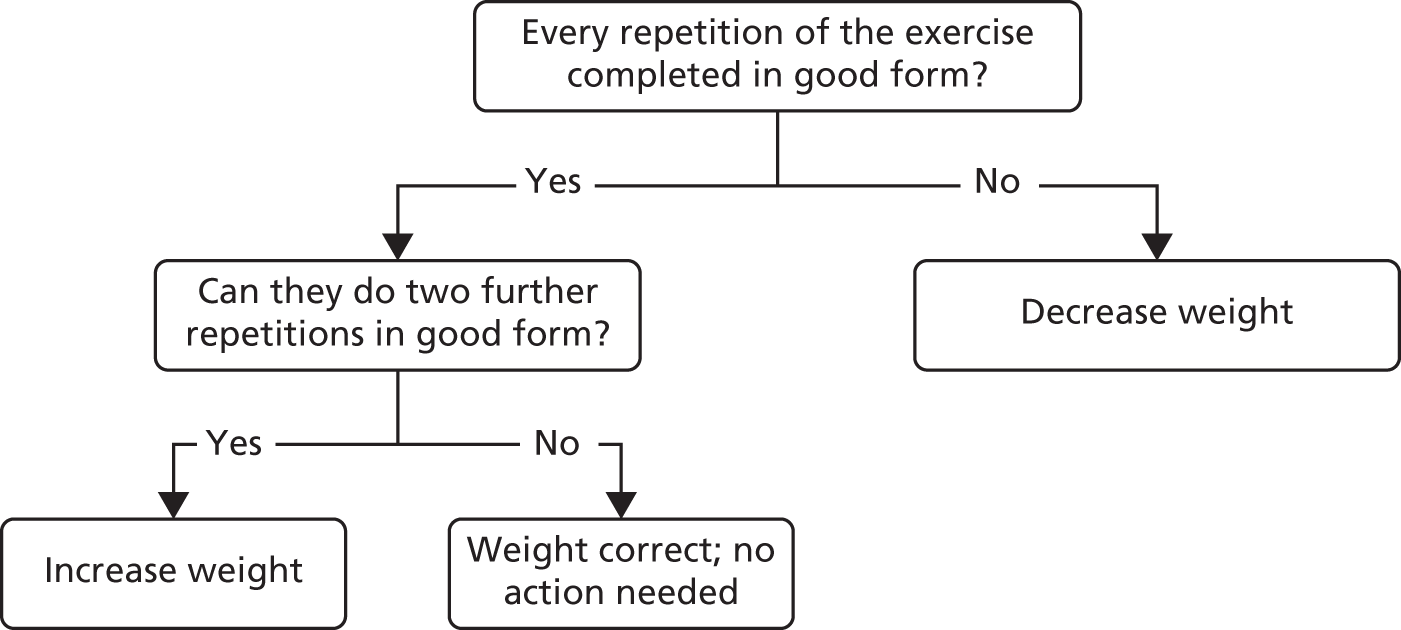

Progression was individually tailored using recognised methods. 61 The resistance exercises always included sit-to-stand, using weighted belts and jackets, and biceps curls, using dumb-bells as resistance, and were set according to principles shown in Figure 3. Suppliers are detailed in Appendix 3.

FIGURE 3.

Calibrating load for resistance exercises. © 2015 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Role of exercise assistant and physiotherapist

The physiotherapists were responsible for the examination and assessment of the participants, setting the prescription and reviewing and progressing the exercise prescription. The physiotherapists supervised the exercise assistants during the sessions. The role of the exercise assistants was to assist in welcoming carers and participants to the class, to monitor and encourage people during the class and to provide assistance when required. The physiotherapists undertook the telephone follow-up calls.

Good form = correct postural alignment maintained, contraction is controlled, full range of movement is used, normal breathing is maintained.

Ratamess et al. 61

The initial resistance load was determined on the basis that the lift should be at least moderately hard and on clinical observations, with the ability to lift 20 repetitions in ‘good’ form being the principal guide. Table 2 gives typical ranges of initial resistance for the sit-to-stand exercise. The weight lifted was increased, with participants performing 15 repetitions 3 weeks into classes and 10 repetitions at a higher weight again at 7 weeks. The weight was subsequently increased if the participant could perform two additional repetitions with good form, or decreased if the participant could not perform the required number of repetitions. A further 1–3 exercises (depending on time available) were selected from shoulder forward raise, shoulder lateral raise and shoulder press, again using dumb-bells as resistance. The resistance training element of the exercise class lasted approximately 25 minutes. The participants were congratulated and presented with a certificate at their last exercise class, to reinforce continuation with unsupervised exercise.

| Sit-to-stand form category | Gender, starting resistance (kg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| Excellent: no use of hands, compensations or momentum, good control throughout the movement | 8–12 | 6–8 |

| Fair: use of hands, compensations or momentum but able to perform movement without these when prompted, with reasonable control throughout the movement | 4–7 | 3–5 |

| Poor: use of hands, compensations or momentum in order to perform movement, poor control observed | 0–3 | 0–2 |

Unsupervised activity

During the supervised part of the intervention, the participant was encouraged to undertake an additional 50 minutes of activity per week at a moderate intensity at home. The physiotherapist helped the participant to find an enjoyable or, at least, an acceptable activity, to maximise the likelihood of adherence, and to signpost the participant to local exercise facilities or groups. After the 4 months of exercise classes, all of the 150 minutes of activity per week at moderate intensity was carried out unsupervised.

Behaviour change techniques

Goal-setting

During the supervised exercise intervention, a system of goal-setting was used that focused on the goals and activities that were important to the participants. The first goal-setting took place between weeks 3 and 5 of the supervised exercise sessions and focused on an action plan with specific physical activities, which were to be undertaken at agreed locations and times. The second goal-setting took place between weeks 13 and 16 and focused on a plan for the transition from the supervised to the unsupervised exercise period. This focused on how, and where, to perform the unsupervised exercise and included an exercise opportunities booklet detailing local facilities and opportunities.

Review behavioural goals (objective and subjective)

Between weeks 17 and 22, the 6MWT was used to review participants’ progress and to act as a prompt to revise goals and identify barriers or facilitators. An exercise calendar was given to participants and carers to encourage self-monitoring of behaviour, as a visual prompt to remind the participant to undertake physical activity and to assist the physiotherapist to monitor unsupervised exercise. The face-to-face meeting with the participant and (if possible) carer was to review the targets from the second target-setting discussion and amend them if necessary, together with praise and problem-solving assistance.

Behavioural contract

The action plan (goal-setting) was signed by the participant and physiotherapist to reinforce the commitment to carry it out.

Identification of barriers or facilitators and solutions

Telephone contact was made with participants who did not attend exercise sessions to identify and problem-solve any barriers to class attendance and encourage the habit of regular attendance. During the unsupervised part of the intervention, three telephone calls and one face-to-face meeting took place. The telephone calls were made approximately 2–3 weeks, 14–16 weeks and 22–23 weeks after the supervised exercise sessions had finished, and were intended to provide praise and encouragement and assist in solving any difficulties encountered in exercising independently.

Dementia-specific considerations

People with dementia commonly have difficulties with communication,62 as well as poor memory. Using aids to memory and communication (e.g. name badges for staff, participants and carers), observation of facial expression and body language, and the use of alternative wording to aid understanding were included as part of the conduct of the exercise classes. Background noise and distractions were minimised by having a separate room (not a public gym) for the sessions. Demonstration and instruction on how to perform the exercises were provided by the physiotherapist or exercise assistant. For participants with dyspraxia, copying a movement (mirroring) was sometimes easier than following verbal instructions, and hands-on guidance was appropriate for some individuals. 63 In some cases, a modified (but safe) version of the movement was allowed, if the participant was unable to perform the movement correctly.

Quality control assessments

The intervention sites were visited by trial research physiotherapists (Nicola Atherton, Deborah Brown, Katie Spanjers, Lousia Stonehewer and Janet Lowe) to conduct quality control (QC) assessments. The first QC assessment at each site was conducted during the first few weeks of delivering the interventions. The aim of these visits was to ensure that the intervention was being delivered in a standardised manner and that the physiotherapist and exercise assistant could demonstrate competency in all aspects of the intervention. The QC assessor also provided, as needed, clinical supervision and support to the intervention staff. Items assessed included:

-

correct adherence to the exercise procedures focusing on ensuring effective delivery of an adequate exercise dose

-

correct completion of all paperwork, especially the structured treatment forms that record the exercise intensity and duration (enabling accurate calculation of the exercise dose delivered)

-

evidence of the use of a person-centred care approach with appropriate support given to participants

-

communication between the staff regarding participants’ progress and needs

-

completion and return of AE documentation (when required).

This visit also allowed the provision of support and advice to staff to enhance their clinical competencies and assist with the smooth running of the exercise group.

A second QC visit was made after some of the formal behavioural support activities (such as goal-setting) had commenced. When possible, these activities were observed; when this was not possible, assessment was made through inspection of the documentation and a discussion with the physiotherapist who carried out the activity, with corrective guidance being given as needed. The QC assessor also assessed the continued correct adherence to the exercise procedures, with an emphasis on the use of progressions and provision of adequate exercise challenges, and the correct completion of clinical records. The QC forms are available in Appendix 4. At the end of each of these visits, feedback was provided to the staff delivering the intervention and further visits arranged if problems were found in the QC assessment or if the staff needed further support. A QC form was completed and signed by both the assessor and the physiotherapist (provided that the latter agreed with its findings).

Results of the quality control visits

There were 26 physiotherapists and 17 exercise assistants delivering the DAPA intervention across the DAPA trial sites. Of the physiotherapists, in the first QC assessment, 23 were rated as ‘satisfactory’, two were rated as ‘minor concerns’ and one had missing forms. Those who were rated as ‘minor concerns’ were followed up within 2 weeks of the initial assessment and both then reached a ‘satisfactory’ rating. Of the exercise assistants, 13 achieved a rating of ‘satisfactory’, three were rated as ‘minor concerns’ and one had missing forms. In the follow-up assessment, all three exercise assistants who had been rated as ‘minor concerns’, then reached the ‘satisfactory’ rating.

In the second QC assessment, all physiotherapists were rated as ‘satisfactory’, apart from three who had a missing assessment, and all exercise assistants were rated as ‘satisfactory’, apart from one who was rated as ‘minor concerns’ and one who had missing forms (unable to complete the QC visit). The exercise assistant who was rated as ‘minor concerns’ was rated as the same at their follow-up assessment.

The third and fourth QC assessments were performed only on physiotherapists, as they carried the predominant load and responsibility for the intervention. At the third QC assessment, all physiotherapists were rated as ‘satisfactory’ and one had missing forms.

At the fourth QC assessment, 10 physiotherapists were rated as ‘minor concerns’. In the follow-up assessment, it was not possible to reassess 4 out of these 10 physiotherapists and the remaining therapists were reclassified as a rating of ‘satisfactory.’

In all cases where forms were missing, the QC visit could not be completed within the scheduled time period, before the next QC visit was due.

Manuals are available at www.octru.ox.ac.uk/trials/trials-completed/dapa (accessed 17 April 2018).

Patient and public involvement

The study benefited from broad-ranging patient and public involvement. At the outset of the study people who had experience of caring with people with dementia were identified and asked to join the Trial Steering Committee and were independent voting members of the committee. We made broad informal consultation with carers and people with dementia as we undertook the pilot work for the study both for the design of the intervention and for research design. We engaged in public meetings on dementia and research to gain input into the study. At the end of the study, we presented the results to members of the public, including an invitation for all participants to attend the meeting along with their carers. We had good attendance and feedback about the study, which we were able to incorporate into our final report.

Chapter 3 Randomised controlled trial: methods, results and brief discussion

The protocol for the RCT was published in Atherton et al. 64

Aim

The primary aim was to estimate the effect of the exercise intervention on cognitive and functional decline in community-dwelling adults with MMD.

Randomised controlled trial design

The design was a multicentred, randomised parallel-group trial comparing a 4-month, supervised, moderate- to hard-intensity exercise training regime with follow-on behavioural support for long-term physical activity change with usual care.

Methods

Participant recruitment and setting

We recruited adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of any type of dementia and their carers (when available). The dementia needed to be mild to moderate at the time of recruitment. Participants were recruited from 15 regions in the UK.

Approach and initial information

Participants were recruited from four sources:

-

NHS secondary care memory clinics and services: authorised NHS staff identified potential participants using electronic or case record searches to screen for eligibility. The lists were reviewed by a clinician involved in the clinical care of the participant and checked for patients who should be excluded. Potential participants and their carers were approached by their clinician or authorised NHS staff member either face to face at a clinic or by letter.

-

General practice registers of people with dementia: general practices searched their registers of patients to identify people with a diagnostic code for dementia. In most practices, this was done by a search of databases using Read Codes or Quality Outcomes Framework codes. General practitioners approved the final list of names and sent invitation letters to potential participants.

-

Research network participant-interested databases [e.g. the Dementia and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Network (DeNDRoN); Join Dementia Research]: the UK Department of Health and Social Care has funded a number of networks and projects to enable people with dementia to register their interest in participating in research and to enable a rapid and simple approach. Participants were identified by a nursing or clinical staff of DeNDRoN from these databases. Participants deemed as meeting the inclusion criteria were contacted by DeNDRoN staff by telephone to explain the study and, if potentially eligible, sent an invitation letter.

-

Other dementia resources (e.g. Alzheimer’s cafes): we approached community-based dementia resources directly to determine if they were willing to approach potential participants. When service providers agreed and approached potential participants, a researcher from the team then visited the centres and provided further explanation about the study to potential participants and their carers. When participants or carers were interested, the researcher assessed their potential eligibility and contacted their health-care provider to confirm eligibility.

All procedures were consistent with relevant legislation to ensure data confidentiality. All invitations were accompanied by written information about what was involved in the study, supplemented by a verbal explanation when the opportunity arose. In all instances, the participants indicated their potential willingness to participate by sending a reply slip to either the local co-ordinating centres or the research office at the University of Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (WCTU) (depending on the local set-up). Once a participant confirmed their willingness to participate, they were contacted by a member of the recruitment team (a registered nurse or allied health professional with appropriate research training) to further assess eligibility and explain the trial. In all instances, participants received the written and verbal information and were given a minimum of 48 hours to decide whether or not they wished to join the trial. Potential participants were visited in their own homes to record consent in writing and to confirm eligibility [Standardised Mini Mental State Examination (sMMSE) score and functional abilities]. A baseline assessment was carried out and the participant was registered and randomised.

Eligibility criteria

Participants were required to:

-

have probable dementia according to the DSM-IV criteria1

-

have probable MMD (a score of > 10 on the sMMSE)65

-

be able to participate in a structured exercise programme determined by:

-

being able to sit in a chair and walk 10 feet without human assistance

-

having no unstable medical conditions, for example unstable angina, or acute or terminal illness

-

-

live in the community, alone or with a friend, relative or carer, or in sheltered accommodation.

Consent

People with MMD may lack the necessary mental capacity to provide fully informed consent. All potential participants were assessed for their capacity to consent by the registered research nurses or physiotherapists conducting the baseline visit. All nurses and physiotherapists were trained specifically in assessing and taking consent in trials recruiting people with dementia using the principles of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 66 Training was provided by the NIHR Clinical Research Network or DeNDRoN and/or the lead research physiotherapist responsible for recruitment. When potential participants were assessed as having capacity, informed consent was obtained from the individual. If potential participants were assessed as lacking capacity, agreement to participate was still sought from these individuals. In this situation, additional advice would be sought from the primary carer or personal consultee on whether or not the person who lacked capacity should take part in the project and what their past and present wishes and feelings would have been about taking part. If participants were unable to give informed consent, and for whom no personal consultee was available, a nominated consultee (e.g. health-care professional) who was well-placed and prepared to act on behalf of the potential participant was sought. When a potential participant lacked capacity to provide informed consent, and a nominated consultee could not be found, that person was not recruited. Agreement for continued participation was checked at each follow-up visit. Consent was sought from carers, for the data on carers, after consent for participation had been secured from the person with dementia.

Risks and benefits

All participants had access to usual care, and thus no treatment was withheld from trial participants. There is some limited evidence of a very small increased risk of injury as a result of becoming more physically active. In our physical activity programme, however, health-care professionals tailored progressive exercises to individual need/ability and delivered the programme to small groups of participants in a supervised and safe context.

Intervention

The usual-care arm

All participants had, or were receiving, usual care consistent with the recommendation of NICE’s clinical guidance,67 comprising diagnosis, information provision and limited social support. We recognised that the usual-care interventions vary across the country and, hence, we stratified the randomisation by region to ensure these effects were randomly distributed. There was no limit on co-interventions during the trial; medications and other treatments could be initiated, continued or discontinued at the discretion of the clinical team responsible for the care of the participants. We collected data on treatments provided to both arms of the trial at baseline and during the follow-up period, and described these in the study reports. Exercise is not currently part of recommended usual care for people with dementia, but each study participant (in both the control and intervention groups) was given one of two information sheets produced by the Department of Health and Social Care, appropriate to their age group. The information sheets recommend physical activity levels for adults (aged 19–64 years)68 and older adults (aged ≥ 65 years). 69

The Dementia and Physical Activity (intervention) arm

The intervention arm is fully described in Chapter 2.

Assessment data

Baseline data on the participants (persons with dementia)

Potential participants were visited at home by a registered research nurse or physiotherapist. Informed consent was obtained (see Consent), then eligibility was checked, including carrying out the sMMSE. Once the participant was confirmed as being eligible, descriptive data were collected, including age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, educational attainment and employment status.

The next stage was to collect the data for the primary and secondary outcomes, as given in Table 3. The type of dementia (vascular, Alzheimer’s or mixed) was ascertained after the baseline visit by reference to the participant’s medical notes.

| Domain | Measure | Description | Completed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | |||

| Cognition | ADAS-Cog70 | Takes 30–40 minutes to complete. Includes 11 tasks targeting three domains (memory, language and praxis). Scores range from 0 to 70 points, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive impairment. A 4-point difference is considered clinically important79 | Participant |

| Secondary | |||

| Function | BADLS71 | Takes 15 minutes to complete. Includes 20 daily activities. Scores range from 0 to 60 points, with higher scores indicating greater impairment | Carer (rating participant) |

| HRQoL | EQ-5D-3L72 | Takes a few minutes to complete. Includes health state classification system with five dimensions and a VAS thermometer. Scores on the classification system range from 0 to 25, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Scores on the VAS range from 0 to 100, with 100 equating to the best health state. These two scores can be combined into an index value 0.0–1.0, the higher value indicates better quality of life |

Participant (rating self) Carer (rating self) Carer (rating participant)a |

| Dementia quality of life |

QoL-AD73 QoL-AD proxy |

Takes 10–15 minutes to complete. Includes 13 items. Scores range from 13 to 52 points, with higher scores indicating less impairment |

Participant (rating self) Carer (rating participant)a |

| Behavioural symptoms | NPI74 | Takes 10 minutes to complete. Includes 12 behavioural domains. Scores range from 0 to 144 points, with higher scores indicating greater impairment | Carer (rating participant) |

| Carer burden | ZBI75 | Takes 5 minutes to complete. Includes 22 items regarding direct stress to carers. Scores range from 0 to 88 points, with higher scores indicating greater stress | Carer (rating self) |

| Health- and social-care usage to inform the health economics analysis | CSRI76 | Administered by trained assessor. Takes 20 minutes to complete. Includes 29 items covering five domains regarding information about use of health- and social-care services, other economic impacts (such as time off work because of illness) and sociodemographic information. Used to inform health economic study | Carer with participant (rating participant) |

The primary outcome was the global cognition score of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog). 70 The funder’s brief was clear that the primary purpose of the trial and of the exercise programme should be to determine whether or not exercise can modify cognitive functioning. Cognitive deficits are central to dementia and widely understood as the most important treatment target. 77 The ADAS-Cog was collected directly from the participant, takes about 30–40 minutes to administer and has established sensitivity to change. It is widely considered the gold standard primary outcome in treatment trials for dementia, with relatively well-established treatment effect sizes. 78 We also collected the maze and number of cancellation optional items of the ADAS-Cog as additional items to be reported separately.

Initially, the primary outcome measure was to be the sMMSE, which, although widely used in clinical evaluation, is a very global, relatively insensitive measure of cognitive function. The ADAS-Cog is acknowledged to be more sensitive in detecting cognitive change in individuals with MMD than a variety of other measures, including the sMMSE. 79 The use of a valid but more sensitive primary outcome measure (the ADAS-Cog) made it possible to reduce the sample size of the study.

Secondary outcomes were chosen to reflect the broad impact of dementia on function, behaviour and quality of life. When possible, we chose instruments that were dementia specific, well validated and not excessively burdensome. Secondary outcomes are also detailed in Table 3. In all instances we used the published guidance about who the primary respondent for the questionnaire should be. We used the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS). 71 This carer-rated instrument of participant ability is dementia specific, sensitive to change and widely used in clinical trials. We also collected data using the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) scale. 73 This is a 13-item dementia-specific scale that can be completed by a carer or participant; both were collected for the DAPA trial but the participant response was considered the primary data source. We also collected the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L),72 a 5-dimension generic (i.e. not dementia-specific) measure of health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The EQ-5D-3L was reported by both the participant and carer, with the participant being the primary data source, and it allows a calculation of health utilities for application in economic evaluations.

We used the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI),74 which includes important predictors of carer breakdown such as depression and agitation. We collected cost data using the Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI). 76 This detailed questionnaire is designed to be used with a carer and covers all social, health care, medication use and out-of-pocket expenses. Initially, mood was to be a secondary outcome, as measured by the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. 80 This was removed prior to the collection of any data as mood is covered by the NPI and it would have added unnecessarily to participant burden during data collection.

Carer

We recorded carer age, gender, ethnicity, details about the relationship they had with the person with dementia and how much care they provided. Carers were asked to complete the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI)75 and the EQ-5D-3L72 to assess their own HRQoL. These outcomes are all among those recommended by a consensus recommendation of outcome scales for non-drug interventional studies in dementia. 81

Outcome assessment training and quality control

All staff involved in recruitment and baseline assessments received a 1-day face-to-face training session, supplemented by a detailed operational recruitment manual. The ADAS-Cog is a measure that needs initial training, shadowing and practise over time to become proficient. Recruitment staff had differing experience in using this measure; therefore, training was adapted to accommodate this. Those who had a working knowledge of the measure attended a data collection training day that included rating a video, discussion around individual items and performing an ADAS-Cog simulation with a trainer to assess practical competency. Based on competency, it was decided whether or not the rater required further shadowing and training. Inexperienced raters had an initial introduction to the measure, shadowed experienced raters and practised until they were ready to undertake the training day. Raters were also required to pass a competency test. This day included training for the sMMSE screening tool and other outcome measures.

The QC included the observation of at least one baseline home visit per researcher to ensure recruitment and data collection processes were followed correctly. All questionnaire data were sent to the WCTU, where it was checked on receipt for discrepancies and errors. Feedback was provided to the research nurses and therapists by e-mail to improve standards. Further QC visits were used to check source data collection and completion of paperwork as necessary.

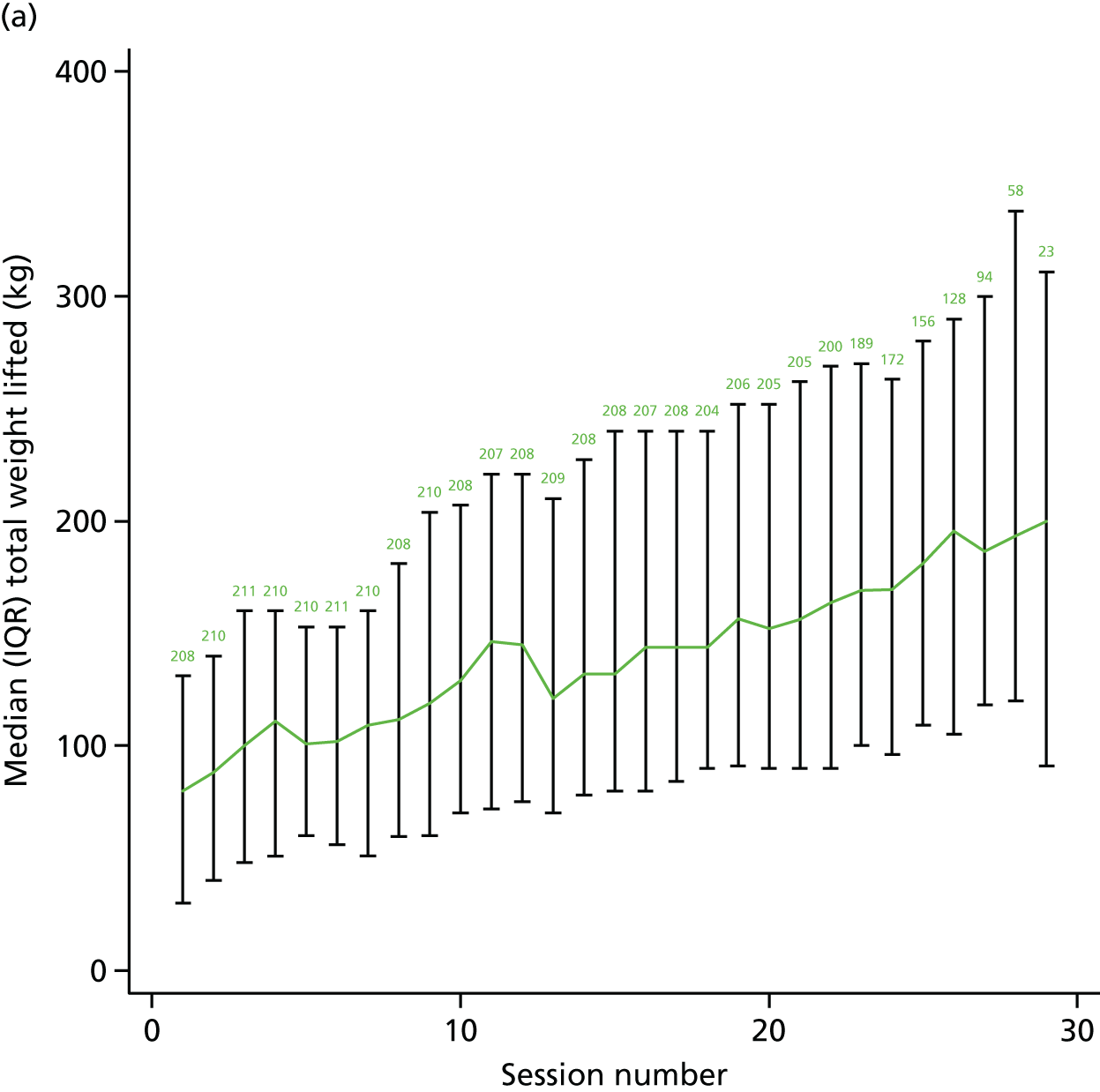

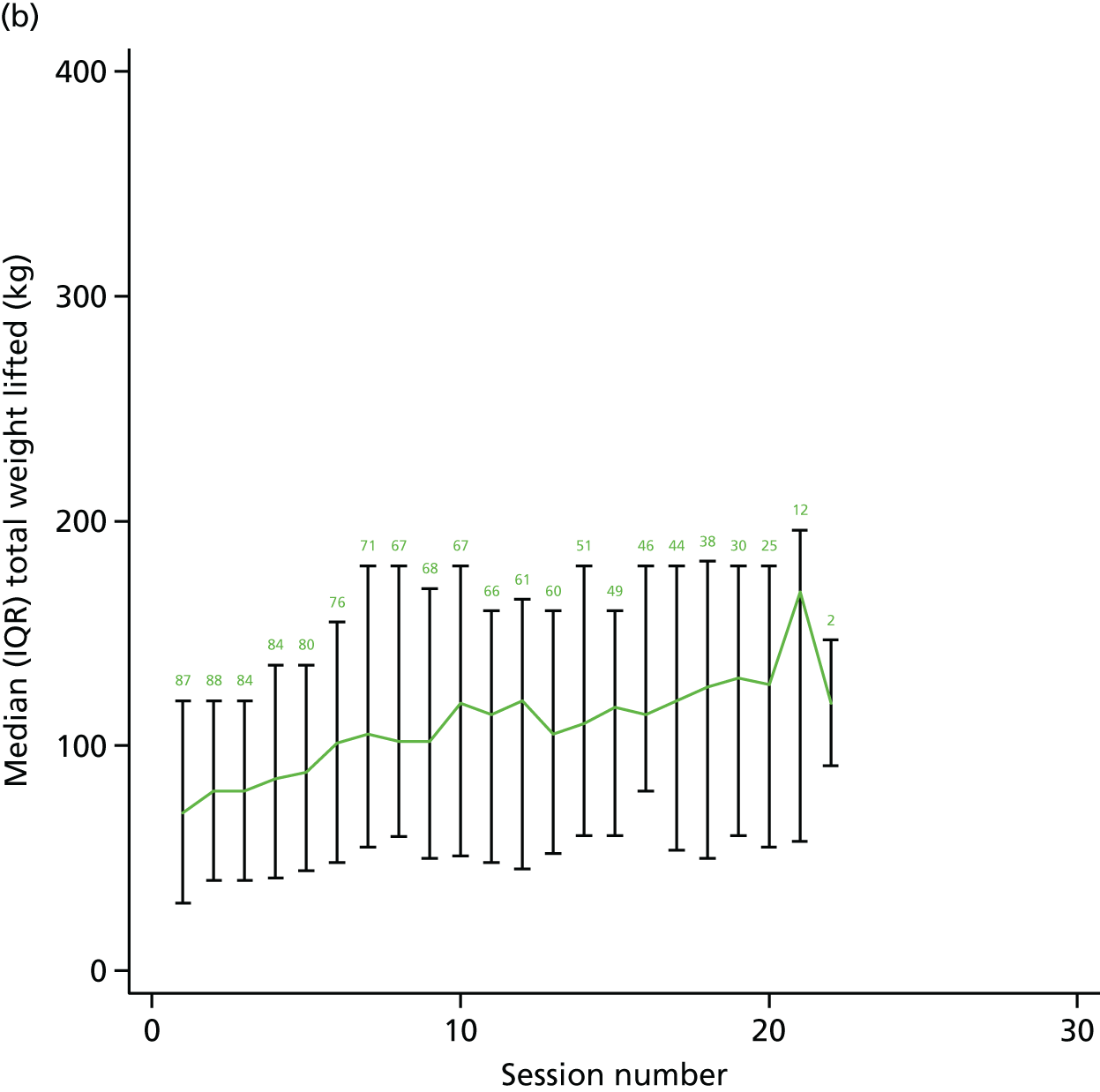

Process evaluation

A range of process evaluation measures was undertaken. Some were trial process evaluation markers, including time from randomisation to first assessment and first group attendance. In addition, we collected detailed information about baseline prescription of exercise, assessment variables including comorbidity and baseline 6MWT, session attendance and the dose of exercise delivered in each session. Dose was collected on the amount of weight lifted and total number of repetitions in each session. For the cycling activity, we recorded the amount of time at low-intensity and moderate- to high-intensity exercise. We reassessed 6MWT distance at 6 weeks after the beginning of the group intervention. Data were summarised for each participant for each session and we report the weight lifted during a session as the product of the number of repetitions and the amount of weight lifted for each exercise divided by the number of participants who attended that session number.

Follow-up

Follow-up data collection was also conducted face to face and, in most instances, we were able to maintain continuity in the personnel who collected the data across all time points. These interviews were also carried out in the participants’ homes. Data for the primary and secondary outcomes were collected in the same way as at baseline, together with some additional data. The carer was asked ‘How much benefit have you gained from being in the DAPA trial?’ and ‘How much has the dementia of the person you care for changed in the past 6 months?’. The CSRI was usually completed by the carer for the participant at these time points, but a person with no carer could give as much information as they were able.

Randomisation and masking

The unit of randomisation was the individual patient. Randomisation was stratified by region and dementia severity (sMMSE score of ≥ 20 for mild and < 20 for moderate). Participants were randomised to:

-

usual care

-

usual care plus exercise programme (intervention).

Randomisation was 2 : 1 in favour of the intervention group, to allow exercise groups to be assembled in a shorter period of time and minimise participant withdrawal between randomisation and the exercise classes commencing.

The random allocation sequence was generated by an independent statistician, using a computerised random number generator, and implemented by a central telephone registration and randomisation service at the WCTU.

Research clinicians registered participants after obtaining consent, confirming eligibility and undertaking the baseline assessment. Once registered, the allocation was generated and, after the researcher had left the participant’s home, the WCTU trial team informed the participant of their allocation and made arrangements for treatment referral. Neither the intervention providers nor participants could be masked to treatment allocation. If a research clinician became unmasked, then follow-up assessments were conducted by different research workers, and all study personnel who were involved with data entry, follow-up assessments, and management were masked until the final analysis was complete.

Post-randomisation withdrawals

Participants were able to withdraw from the trial intervention and/or the trial at any time without prejudice. Participants who withdrew from the intervention were followed up, whenever possible, and data were collected as per the protocol until the end of the trial, unless they specifically withdrew from follow-up.

Participants who became unable to participate in the exercise intervention were withdrawn from the intervention by the physiotherapist but followed up at 6 and 12 months, unless they indicated that they did not wish this. Carers were able to withdraw from the trial without this affecting the inclusion of the participant with dementia.

Documentation was completed on withdrawal to confirm the date and reason for withdrawal (if available).

Data management

All data were managed within the framework of the Data Protection Act 199882 and the standard operating procedures of WCTU. Data were entered onto a bespoke application and stored on a secure WCTU server with daily, weekly and monthly back-ups. All case report forms and accompanying papers (excluding consent forms) were stored in a lockable cabinet at WCTU in individual, numbered participant files. The files were kept in numerical order and had restricted access. Consent forms were stored separately in a different cabinet to the case report forms, as they contained identifiable information. Intervention forms were anonymised and stored in a lockable cabinet. All data were checked for completeness and validity prior to data entry. Researchers were requested to check data for completeness prior to returning the case report forms to the trial team at WCTU. A further check was made by an appropriate member of the trial team and queries were clarified by the completing researcher prior to data entry. Data were not checked and entered by the same trial personnel.

A detailed data management plan was written that provided full details of the management of the data, including formalising the tracking and collection of data from centres and participants, and guidance on telephone contact with participants and carers.

Data analyses

Sample size

A sample size of 360 participants would provide 80% power to detect a minimum clinical between-group difference of 2.45 points [baseline standard deviation (SD) of 7.8 points based on 66 participants] on the ADAS-Cog at 12 months with a 5% level of significance and 2 : 1 randomisation in favour of the intervention. This equated to a standardised effect size of 0.31. An overall difference of 2–2.5 change points on the ADAS-Cog is considered to be a worthwhile target. 83 To account for therapist effects, we inflated the sample size using a design effect of 1.04 (intracluster correlation = 0.01) assuming that there are five participants per group (recognising that it may not be possible to achieve and retain eight recruits to each group), which gave a sample size of 375. The sample size was further inflated to account for 20% loss to follow-up, of which 10% was estimated would be attributable to death. Thus, a final minimum sample size of 468 participants was required, with 312 participants to be randomly allocated to the intervention arm and 156 participants to the control arm.

Note that the sample size initially calculated was 728 participants based on the sMMSE score as the primary outcome. The use of ADAS-Cog score rather than sMMSE score as the primary outcome allowed the sample size to be reduced to 468. This change in sample size occurred before we started the trial and was approved as a formal protocol amendment.

Primary analyses

Data were summarised and reported in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for RCTs,84 and we used intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses as the primary analysis.

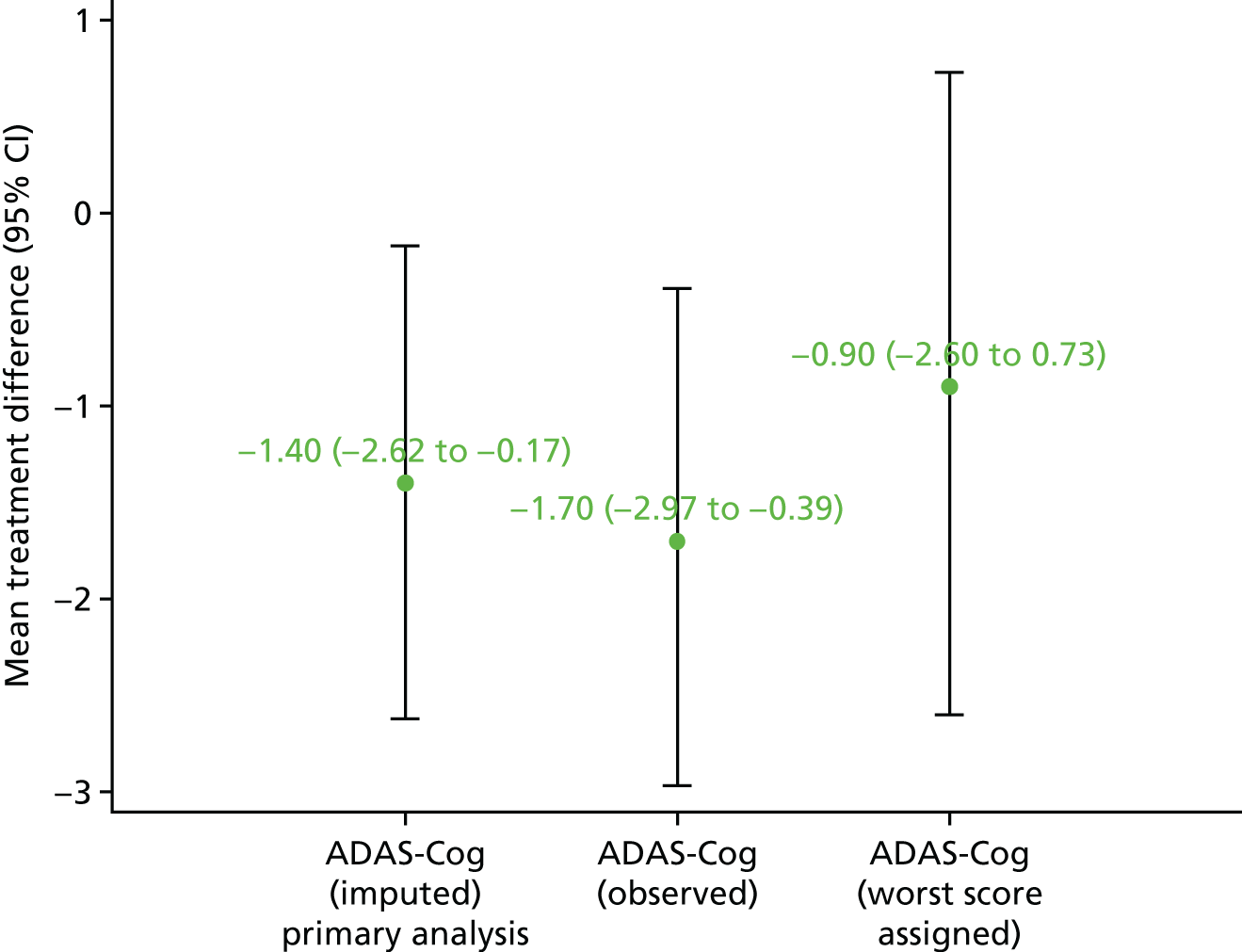

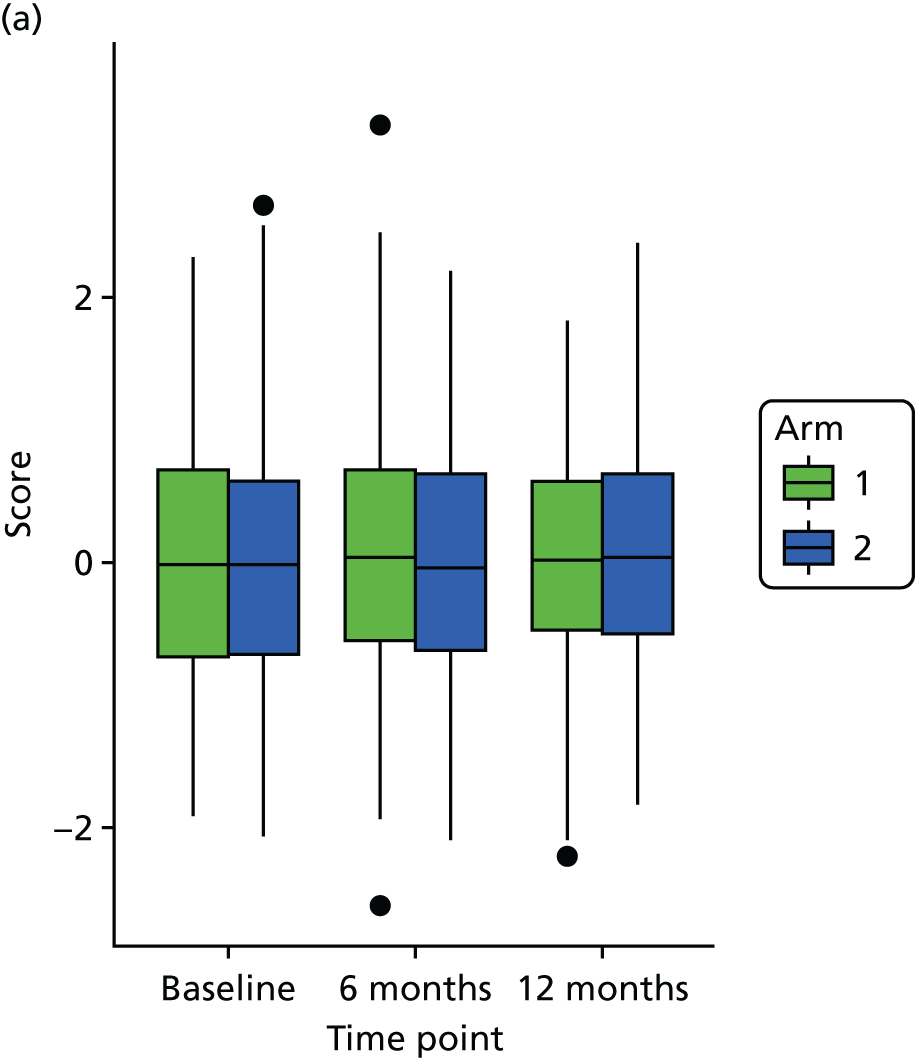

For the primary analyses, multilevel models were used with a random effect for region to estimate the treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The clustering effects of therapist and group were assessed by measuring the intracluster correlation. Therapist and/or group effects were not included in the multilevel model if the clustering effects were found to be negligible. The models were adjusted for important covariates (age, gender, region, sMMSE score and baseline ADAS-Cog score). Owing to the nature of the population, certain items on the ADAS-Cog were missing and, hence, the missingness was classed as being not random. Thus, for the primary analyses, participants with missing ADAS-Cog outcome at each time point in the observed data had their item-level responses reviewed on an individual basis. If any items were missing as a result of the participant being either cognitively unable, too distressed or refusing to answer, then we estimated the treatment effects using multiple imputation (MI) methods. This approach was taken as we are aware that the missing item-level responses for the ADAS-Cog are non-ignorable. Therefore, doing a complete-case analysis (as done so in the first sensitivity analysis) could give highly biased results. However, baseline variables, such as baseline ADAS-Cog score and sMMSE score, are quite likely to be good predictors of missing items. We therefore applied MI methods, which is considered a plausible approach to address non-ignorable missing data, to impute missing item-level data, enabling us to compute and analyse the ADAS-Cog scores. 85

Sensitivity analyses

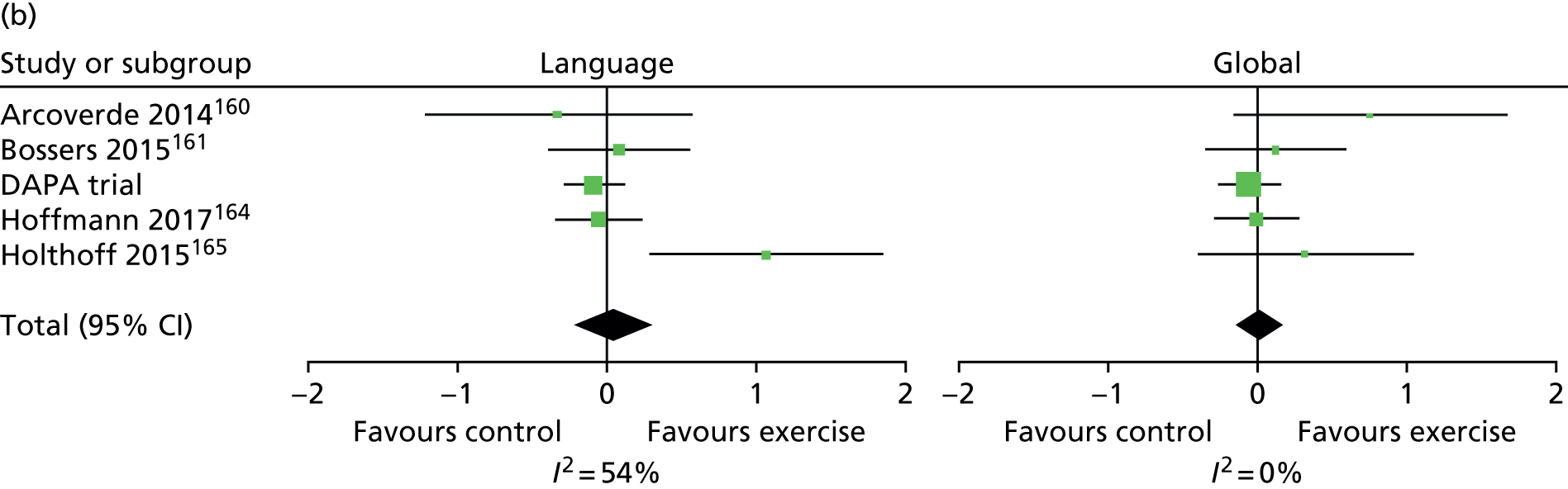

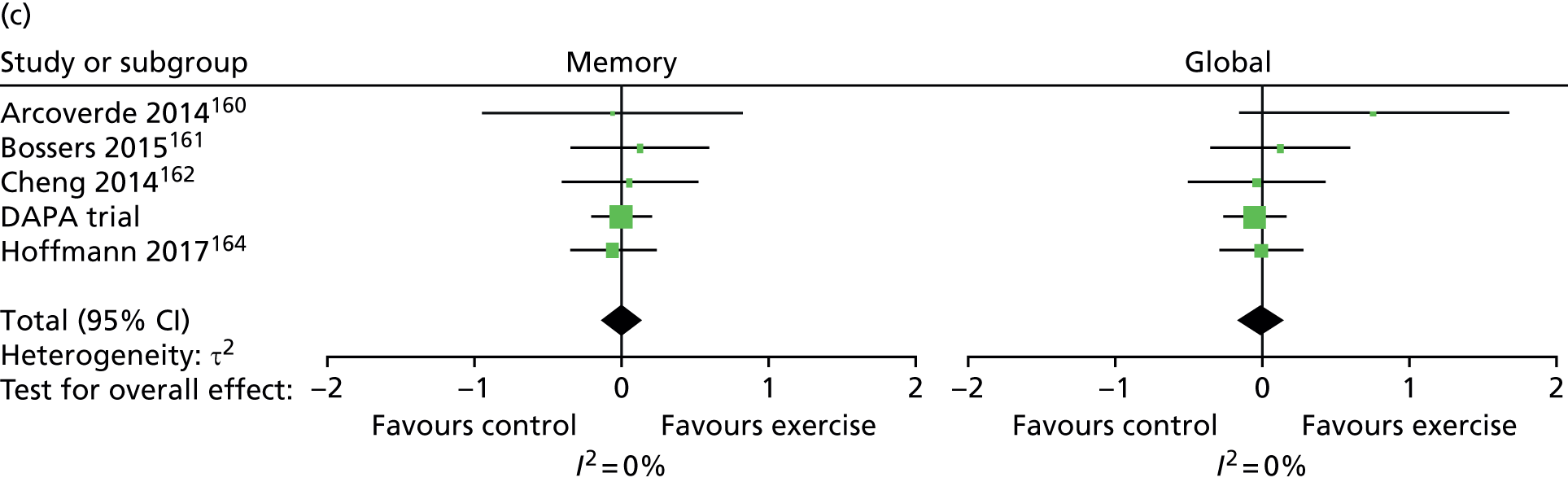

In addition to the primary analysis, three sensitivity analysis data sets were used to carry out sensitivity analyses. For the first sensitivity analysis, the treatment effect was estimated using the observed data with missing values present in the ADAS-Cog. This sensitivity analysis data set consisted of participants who provided complete primary outcome data. For the second sensitivity analysis, participants with missing ADAS-Cog outcome in the observed data had the worst score assigned at the item level, provided the item was missing as a result of the participant being either cognitively unable, too distressed or refusing to answer. For the third sensitivity analysis, an item response theory (IRT) approach was used. Between the estimation of the sample size and the finalisation of the statistical analysis plan, the literature had moved to suggest that the ADAS-Cog does not measure a single patient trait (cognitive impairment) but rather it measures cognitive impairment in multiple cognitive domains. 86 Therefore, IRT was used to assess treatment effects in each of the cognitive domains, namely language, memory and praxis86 (see Appendix 5).

Secondary analyses

For secondary analyses, we estimated treatment effects over the 12-month time period using longitudinal models adjusting for the same variables used in the primary analysis.

Subgroup analyses

Prespecified subgroup analyses looking at severity of cognitive impairment (sMMSE score of ≥ 20 for mild and < 20 for moderate), type of dementia (Alzheimer’s vs. other), physical performance (no problems walking vs. some problems/confined to bed, taken from the EQ-5D-3L) and gender (female vs. male) were conducted using formal tests of interaction. 87

Complier-average causal effect analysis

We measured compliance with the intervention by the number of sessions attended. This information was collected by the therapist providing the treatment. Complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis was used to assess the effect of compliance with the intervention on the primary outcome. 88

Data set access

The final data set was accessible to all study members after data lock. The chief investigator assumed overall responsibility for the data report and had full access to the trial data set. There were no contractual agreements that limited access for investigators.

Serious adverse event and adverse event reporting

An AE was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant that did not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment. These were most likely to be identified by the physiotherapist during the exercise sessions, from information at the sign-in, or after completion of the exercise sessions during support telephone calls or the face-to-face meeting.

As each participant had a pre-exercise assessment done, this provided information on comorbidities. The trial population included many participants aged > 70 years old and, therefore, they had many of the common chronic diseases of older age, for example osteoarthritis. It was expected that participants would experience some uncomfortable effects of participation in the intervention, for example muscle or joint soreness in response to exercise. Provided that these followed an expected pattern (e.g. as for delayed-onset muscle soreness), needed simple modifications to the exercise activity (e.g. changes to the bicycle seat height) or were non-serious exacerbations of existing medical conditions, they were not considered as AEs.

A serious adverse event (SAE) was an AE that fulfilled one or more of the following criteria:

-

resulted in death

-

was immediately life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

required medical intervention to prevent one of the above.

The SAEs to be reported were defined as those that occurred within 2 hours of completing the exercise sessions or follow-on physical activities. SAEs were reported to the Trial Co-ordinating Centre within 24 hours of the physiotherapist becoming aware of them. The Trial Co-ordinating Centre was responsible for reporting AEs to the sponsor and ethics committee within required timelines.

The relationship of SAEs to trial treatment was assessed by the chief investigator and this was recorded on each SAE form. All SAEs were recorded in the trial database, when appropriate, reported to and reviewed by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) throughout the trial, and were followed up to resolution.

Monitoring and approval

Trial Steering Committee

A Trial Steering Committee was responsible for monitoring and supervising the progress of the trial towards its interim and overall milestones.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The DMEC was independent of the trial and monitored the ethical, safety and data integrity aspects of the trial.

Formal approvals

The original ethics approval for this project was granted on 19 January 2012. A substantial amendment for the pre-pilot study was granted on 31 May 2012. Another amendment regarding randomisation was granted on 17 July 2012. The third amendment for a change to the primary outcome measure to ADAS-Cog was also granted on 17 July 2012. Amendments 4–6 were changes to the intervention materials based on the results of the pre-pilot study, and these were granted on 17 January 2013. Amendment 7, regarding sample size, was granted on 7 July 2014; and the final amendment, to add more elements to the qualitative study into the project, was granted on 19 January 2015.

Results

Participant flow

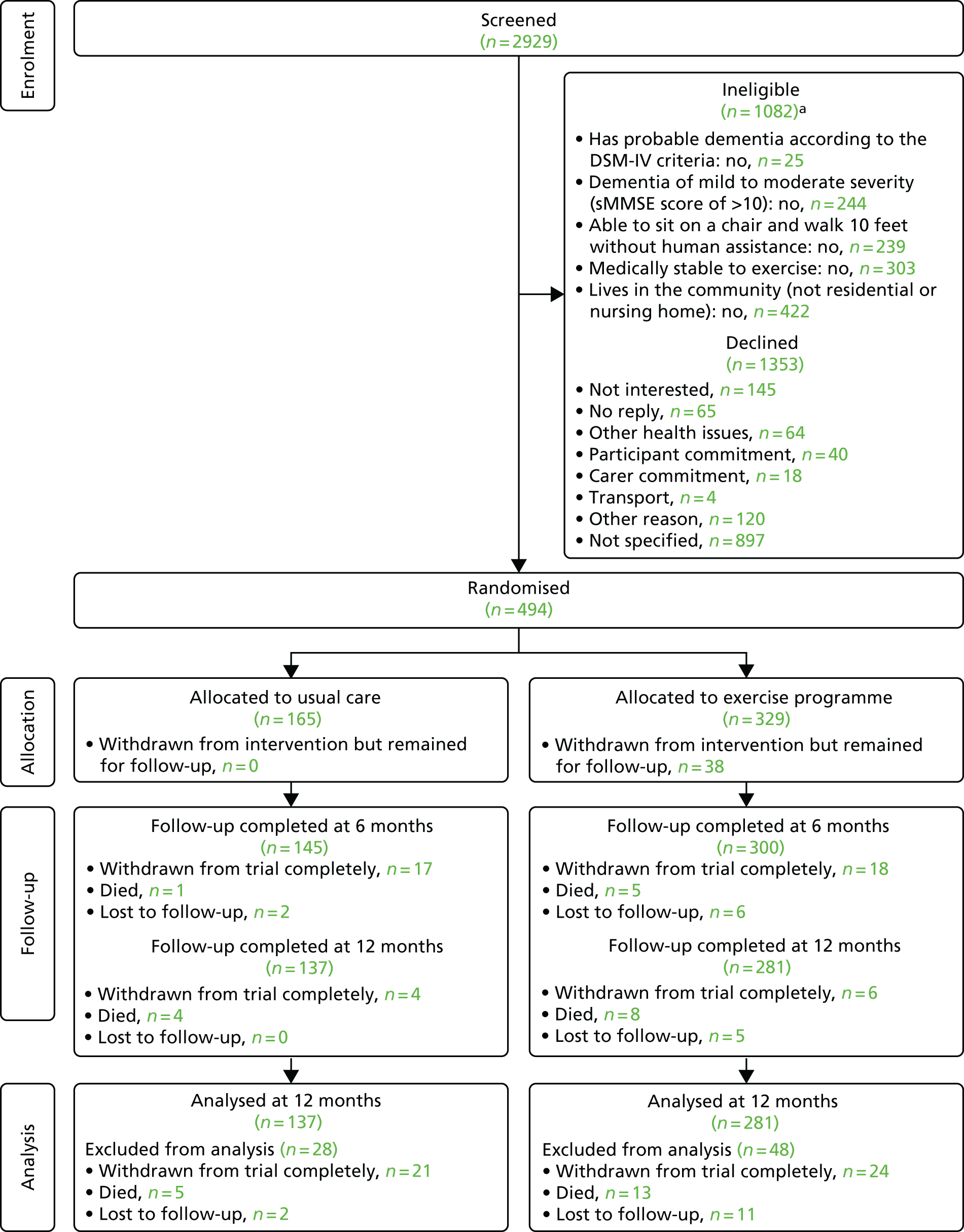

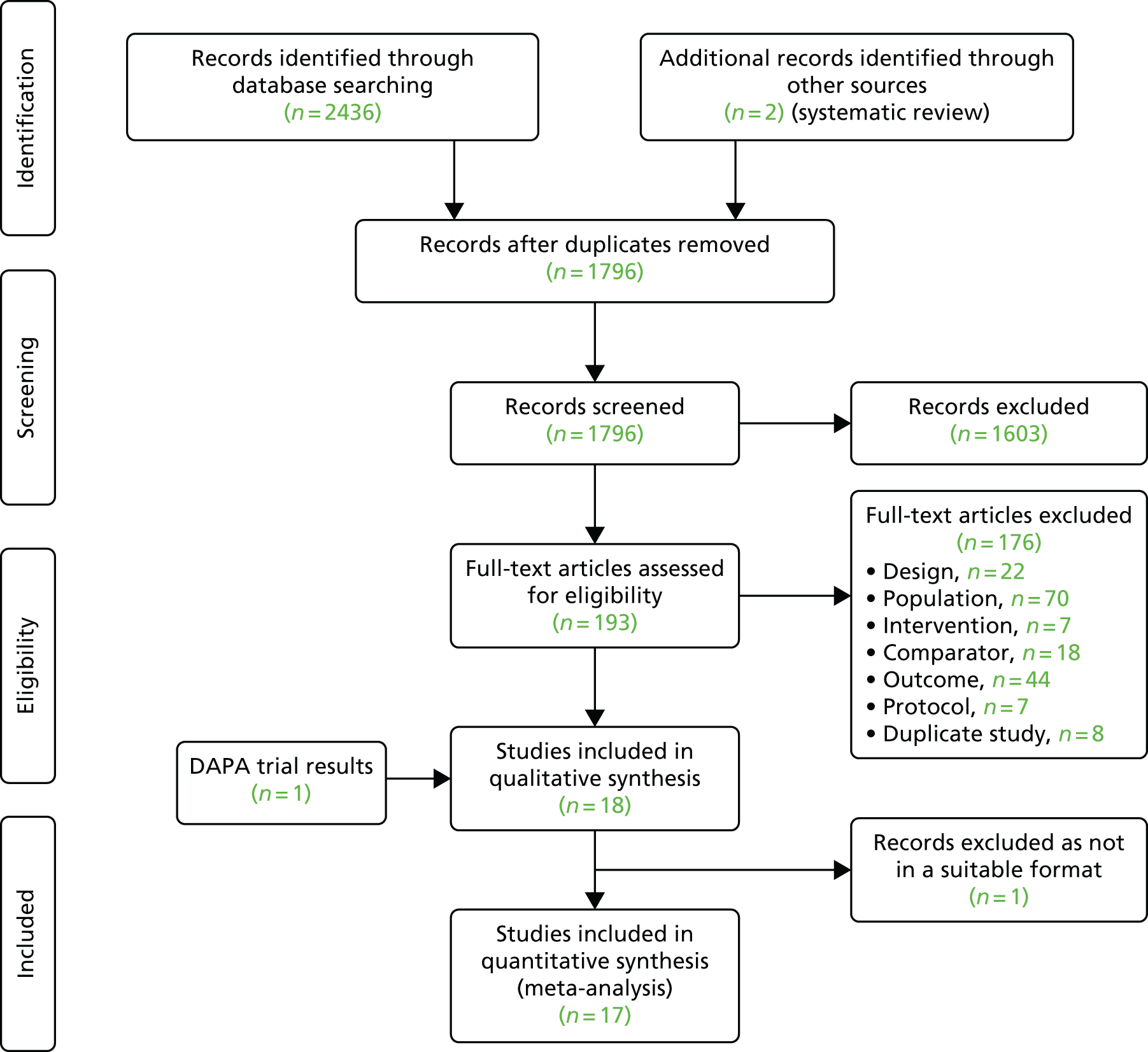

The CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 4) describes the overall flow of participants through the study and Table 53, Appendix 6, describes the flow summarised by each region.

FIGURE 4.

The CONSORT flow diagram for the DAPA trial. a, Participants have more than one reason for ineligibility.

Recruitment

Screening

Recruitment occurred between 1 February 2013 and 24 June 2015 across 15 different regions. A total of 2929 potential participants were identified through the screening process, of whom 1082 were ineligible. The remaining 63% (1847/2929) of people were approached to participate in the trial through various organisations within each region (see Appendix 6, Table 54) using different approach methods (Table 4). Around 41% (750/1847) of these people were sourced through secondary care organisations and the main approach method was by letter (50%) and telephone (25%). Of the 1847 people approached, 73.3% (1353/1847) declined and 25.4% (461/1847) were eligible but were unwilling or unable to participate.

| Approach method | Region (n) | Total (n) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berkshire | Black Country | Coventry | Devon and Exeter | Gloucestershire & Herefordshire | Greater Manchester West | Leicester | North East London | Northampton | Nuneaton | Oxford | Rugby | Solent | South Warwickshire | Worcester | ||

| Alzheimer’s Cafe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Clinic | 0 | 67 | 34 | 0 | 1 | 18 | 69 | 19 | 0 | 14 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 1 | 30 | 277 |

| Letter | 2 | 92 | 187 | 13 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 131 | 80 | 74 | 0 | 107 | 216 | 918 |

| Telephone | 37 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 16 | 22 | 215 | 0 | 165 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 467 |

| Other | 6 | 12 | 30 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 122 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 58 |

| Total | 45 | 171 | 252 | 24 | 22 | 36 | 101 | 41 | 217 | 146 | 279 | 99 | 19 | 148 | 247 | 1847 |

Recruitment

Of the 2929 participants screened, 17% (494/2929) of the participants were deemed eligible and consented to trial participation (Table 5). The majority of participants were able to provide informed consent (376/484, 76.1%), some required a personal consultee (117/494, 23.7%), and one required a nominated consultee (1/494, 0.2%). The personal consultee was the carer in most situations.

| Method of consent | Treatment, n (%) | Total (N = 494), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 165) | Exercise programme (N = 329) | ||

| Participant | 126 (76.4) | 250 (76.0) | 376 (76.1) |

| Personal consultee | 38 (23.0) | 79 (24.0) | 117 (23.7) |

| Nominated consultee | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Although the original target sample size was set as 468 participants, by the time this target was reached a further 26 participants had been recruited and randomised because of the nature of recruiting participants to fill exercise groups. The final recruitment total was, therefore, 494 participants. There were no participants randomised in error. The proportion of participants in each arm across all regions is listed in Table 6 and across the randomisation strata is given in Table 55, Appendix 6.

| Region | Treatment, n (%) | Total (N = 494), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 165) | Exercise programme (N = 329) | ||

| Berkshire | 13 (31.7) | 28 (68.3) | 41 (8.3) |

| Black Country | 15 (33.3) | 30 (66.7) | 45 (9.1) |

| Coventry | 18 (33.3) | 36 (66.7) | 54 (10.9) |

| Devon and Exeter | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | 10 (2.0) |

| Gloucestershire & Herefordshire | 6 (33.3) | 12 (66.7) | 18 (3.6) |

| Greater Manchester West | 6 (33.3) | 12 (66.7) | 18 (3.6) |

| Leicester | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | 17 (3.5) |

| North East London | 6 (33.3) | 12 (66.7) | 18 (3.6) |

| Northampton | 21 (33.9) | 41 (66.1) | 62 (12.6) |

| Nuneaton | 8 (34.8) | 15 (65.2) | 23 (4.7) |

| Oxford | 25 (33.3) | 50 (66.7) | 75 (15.2) |

| Rugby | 8 (33.3) | 16 (66.7) | 24 (4.9) |

| Solent | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | 10 (2.0) |

| South Warwickshire | 12 (33.3) | 24 (66.7) | 36 (7.3) |

| Worcester | 14 (32.6) | 29 (67.4) | 43 (8.7) |

Participant baseline data

Participant baseline characteristics

The dementia diagnosis of participants at the baseline assessment has been summarised in Table 7, with the most common diagnoses being dementia in Alzheimer’s disease with late onset at 35.6% (176/494), atypical or mixed type at 20.9% (103/494) and unspecified at 15.4% (76/494). The baseline demographic characteristics and outcome measures of the randomised participants are summarised by treatment group in Table 8. Overall, the demographic characteristics were well matched across treatment groups, with the majority of participants being white males with an average age of 77.4 years (SD 7.9 years), who were married and living with their wife/husband/partner.

| Dementia diagnosis | Treatment, n (%) | Total (N = 494), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 165) | Exercise programme (N = 329) | ||

| Dementia in Alzheimer’s disease | |||

| With early onset | 9 (5.5) | 25 (7.6) | 34 (6.9) |

| With late onset | 56 (33.9) | 120 (36.5) | 176 (35.6) |

| Atypical or mixed type | 33 (20.0) | 70 (21.3) | 103 (20.9) |

| Unspecified | 29 (17.6) | 47 (14.3) | 76 (15.4) |

| Multi-infarct dementia | 3 (1.8) | 7 (2.1) | 10 (2.0) |

| Mixed cortical and subcortical vascular dementia | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (0.4) |

| Vascular dementia, unspecified | 17 (10.3) | 27 (8.2) | 44 (8.9) |

| Dementia in | |||

| Pick’s disease | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (0.8) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 5 (3.0) | 13 (3.9) | 18 (3.6) |

| Other specified diseases classified elsewhere | 2 (1.2) | 3 (0.9) | 5 (1.0) |

| Unspecified dementia | 8 (4.9) | 14 (4.3) | 22 (4.5) |

| Characteristic | Randomised sample | Sample providing primary outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 165) | Exercise programme (N = 329) | Usual care (N = 137) | Exercise programme (N = 278) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 78.4 (7.6) | 76.9 (7.9) | 78.1 (7.7) | 76.9 (7.7) |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 106 (64.2) | 195 (59.3) | 86 (62.8) | 166 (59.7) |

| Living arrangements, n (%) | ||||

| Live alone | 35 (21.2) | 62 (18.8) | 29 (21.2) | 46 (16.5) |

| Live with relatives | 5 (3.0) | 18 (5.5) | 4 (2.9) | 15 (5.4) |

| Live with wife/husband/partner | 125 (75.8) | 248 (75.4) | 104 (75.9) | 216 (77.7) |

| Living with friends | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 157 (95.2) | 321 (97.6) | 130 (94.9) | 274 (98.6) |

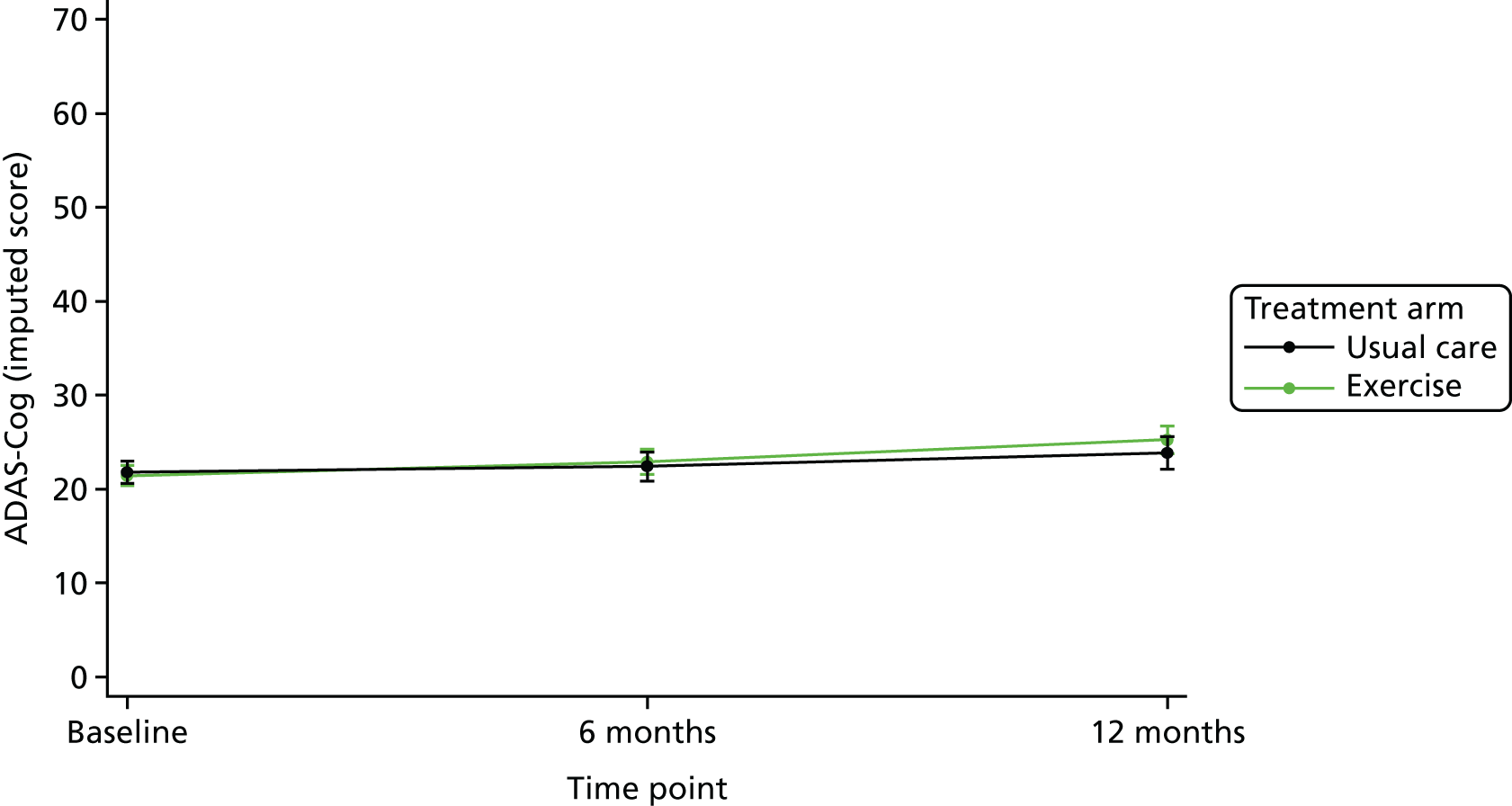

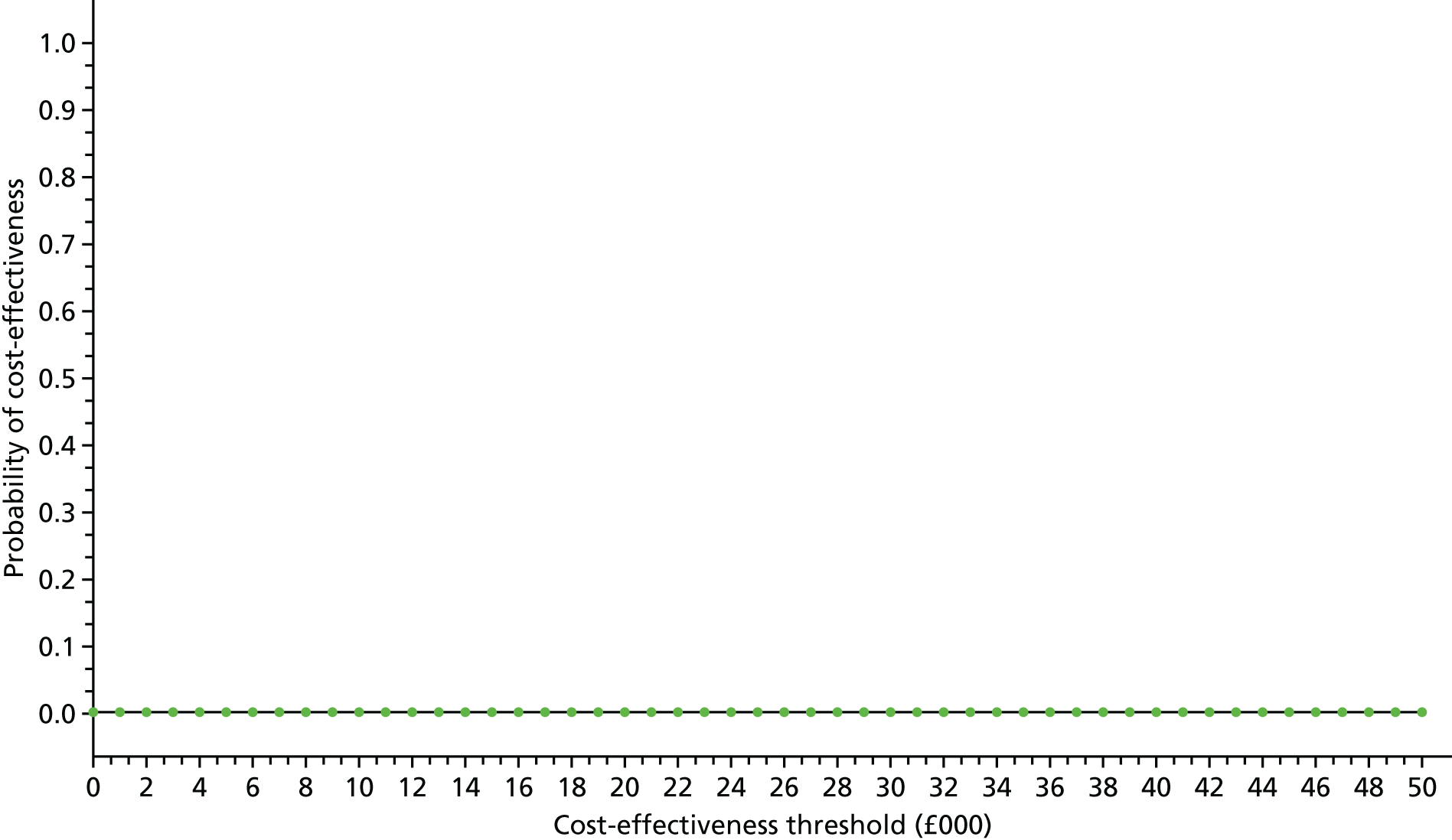

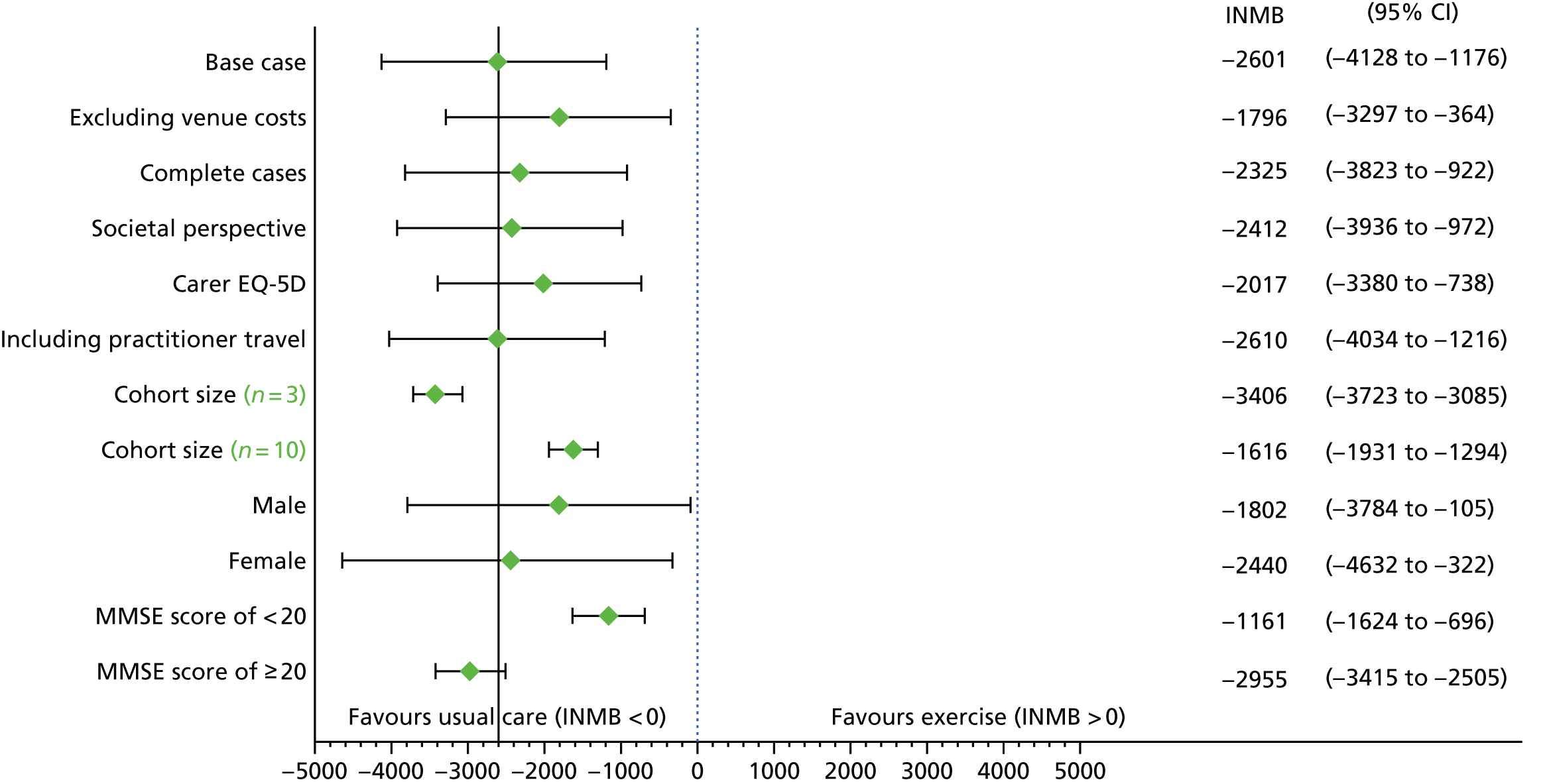

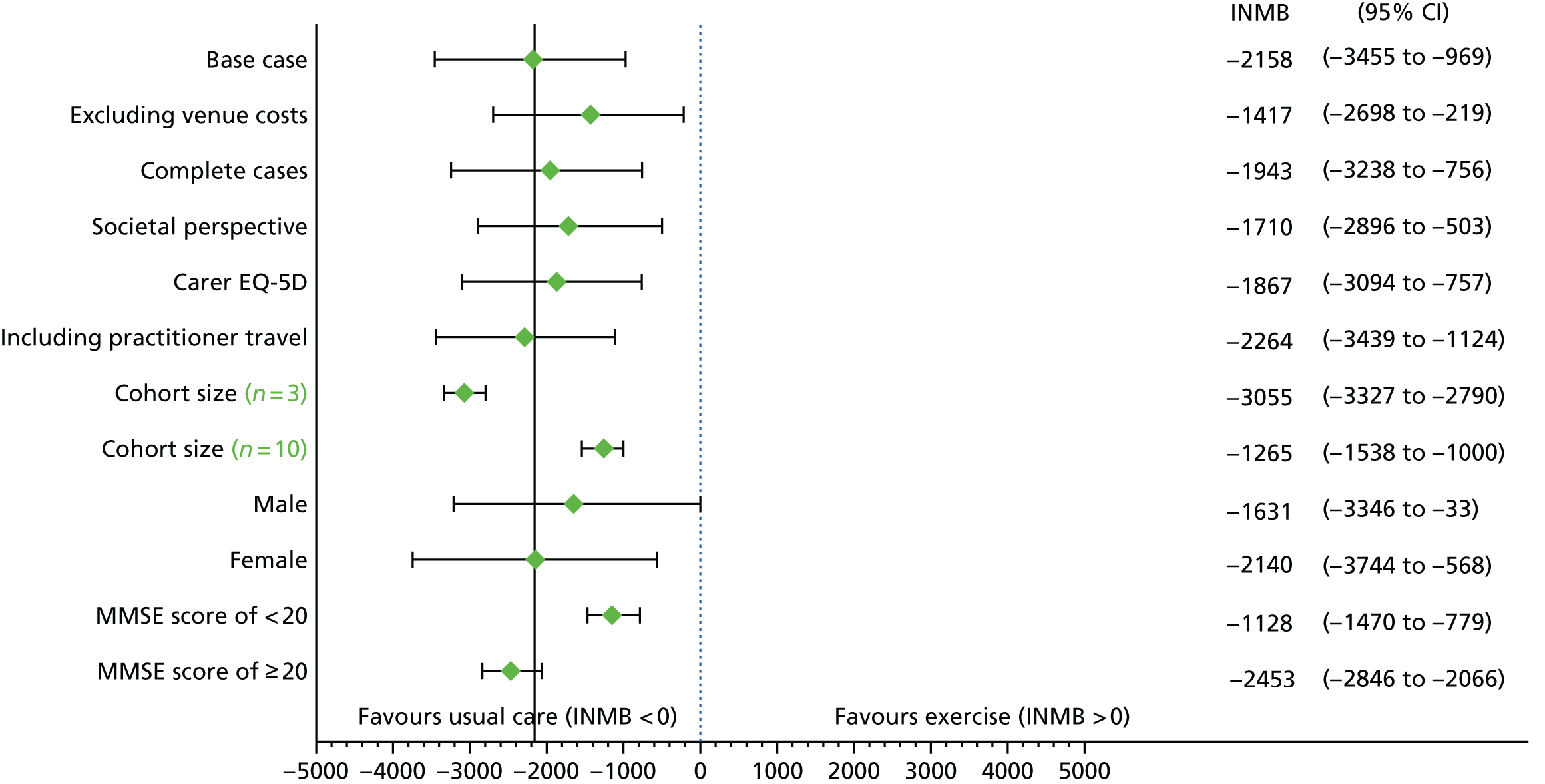

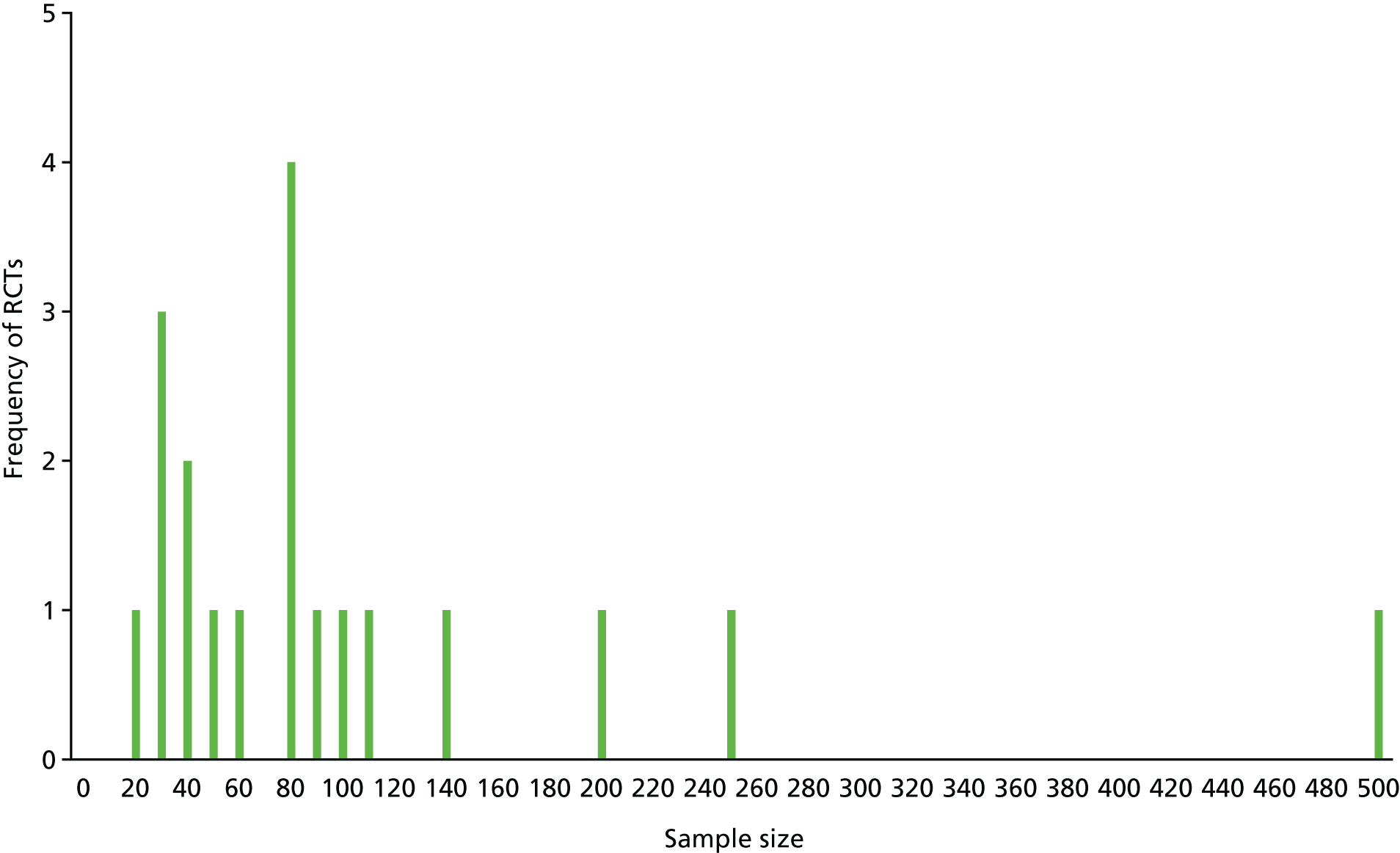

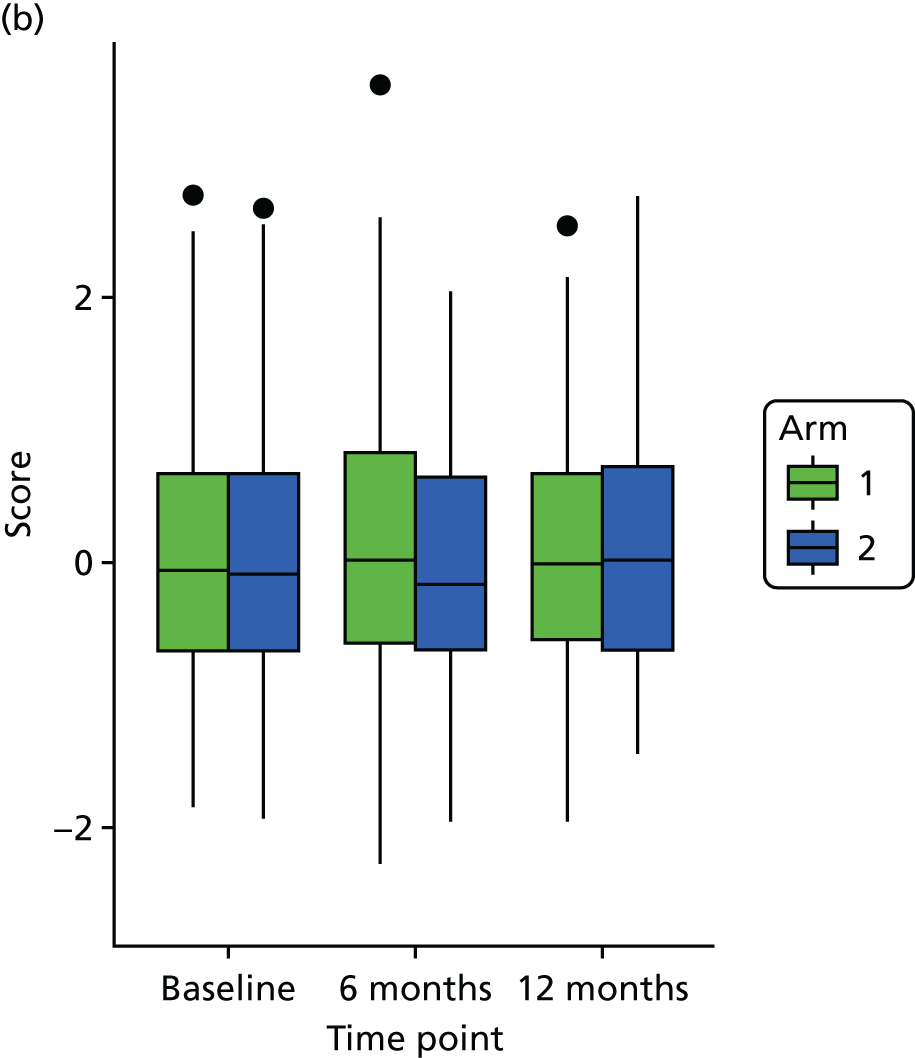

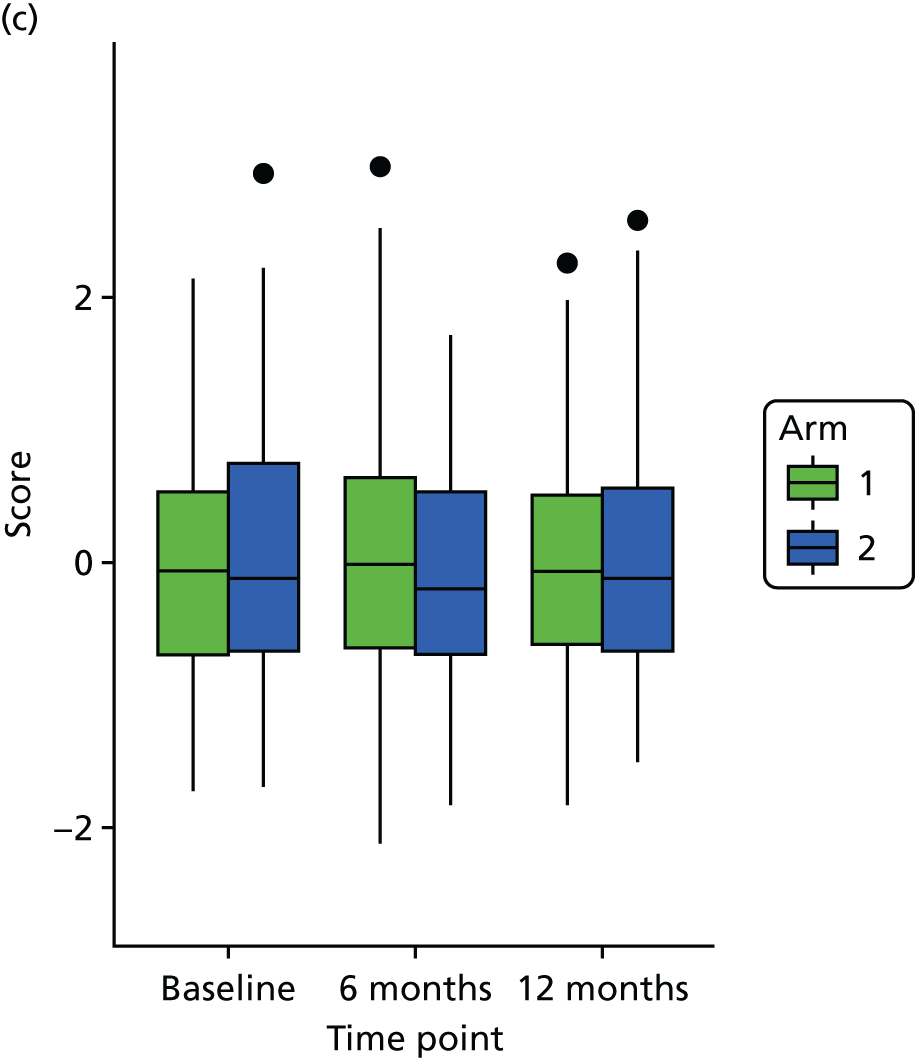

| Other | 8 (4.8) | 8 (2.4) | 7 (5.1) | 4 (1.4) |