Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/153/01. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The draft report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in April 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Matthew J Ridd is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) General Board. Nick A Francis was a member of the HTA Antimicrobial Resistance Themed Call Board during the study. Amanda Roberts is a member of the HTA General Board. As patient and public involvement co-applicant, Amanda Roberts also received an attendance allowance and travel expenses from the University of Southampton in order to attend meetings. Emma Thomas-Jones reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study. Hywel C Williams is Director of the NIHR HTA programme. Paul Little is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Santer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Eczema is very common, affecting > 20% of children at some point during their first 5 years of life. 1 Eczema has a significant impact on quality of life (QoL)2 and can cause distress to affected children and their families because of sleep disturbance, itching and scratching. 3 The term ‘atopic eczema’ (synonymous with ‘atopic dermatitis’) is widely used to denote a clinical phenotype, rather than those who are truly atopic as defined by the presence of immunoglobulin E-specific antibodies to common environmental allergens. In this study, we use the term ‘eczema’ throughout to refer to the ‘atopic eczema’ clinical phenotype, in accordance with the recommended nomenclature of the World Allergy Organization. 4,5

Skin complaints are the second most common reason for general practitioner (GP) consultations in children aged < 5 years. 6 Health and societal costs of eczema care are difficult to estimate as they vary widely by population under study, but eczema is thought to cause a similar economic burden to that for asthma. 7,8

Emollients for the treatment of childhood eczema

Guidelines suggest that emollients form the mainstay of treatment for eczema and should be used regularly by all patients alongside other treatments, such as topical corticosteroids (TCSs), when necessary to treat flare-ups. 9 Emollients are thought to act by providing a protective layer over the skin, decreasing moisture loss and occluding against irritants.

There are three methods of application of emollients: (1) leave-on (directly applied) emollients, where emollients are applied to the skin and left to soak in, (2) soap substitutes, where emollients are used instead of soap or other washing products, and (3) bath emollients (or bath additives), which are oil and/or emulsifiers designed to disperse in the bath. All three approaches are often used together (referred to as ‘complete emollient therapy’). 5,9 In this report, the term ‘bath additives’ rather than ‘bath emollients’ is used to emphasise the differences between the three methods of application (i.e. these three methods differ in their proposed actions and evidence relating to their effectiveness should also be considered separately).

Although there is widespread clinical consensus on the need for leave-on emollients and soap substitutes, there is less agreement regarding the additional benefits of emollient bath additives. 10–13

Bath additives for the treatment of childhood eczema

A previous systematic review has revealed no convincing evidence for the use of emollient bath additives in the treatment of eczema;10,11 available data consist of case series and very small trials. One study14 in which parents were asked to soak one of their child’s arms for 15 minutes a day for 2 weeks in a basin containing water with bath additive found that clinical assessment by blinded observer was worse for the arm that was soaked daily than for the unsoaked arm in eight of the nine children, suggesting the possibility that bath additives may be harmful. No trials of emollient bath additives have been published since 200715 and trial registries reveal no ongoing studies.

In addition to concerns about cost-effectiveness, potential harms from using bath additives include skin irritation and greasier bath surfaces, which can increase the risk of slips and accidents13 (listed in the Summary of Product Characteristics of leading brands). There is also a concern that people who use bath additives in place of leave-on emollients are receiving substandard emollient therapy. 12

The effectiveness of adding bleach bath additives has also not been demonstrated in a small randomised trial, although 5 out of 18 participants in the bleach bath group experienced mild burning/stinging or dry skin. 16 Two small randomised studies17,18 compared ‘bath emollient’ with ‘bath emollient plus antiseptic’ on a range of outcomes, but there were no significant differences between groups, including colony counts of Staphylococcus aureus. 19 For this reason, we chose to exclude bath additives that incorporate an antiseptic, because of the absence of benefit and the possible increased risk of skin irritation. 5,20

In 2007, the Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin noted that the NHS spends > £16M per year on bath additives (at an average cost of £6.29 per item), representing 38% of the total cost of treatments prescribed for preschool children with eczema and matching the proportion spent on emollients for application directly to the skin. 9

Despite the absence of evidence and the possibility of potential harms, bath additives are widely prescribed at a cost of > £23M per year to the NHS in England. 21 Currently, prescribing advice varies widely. An analysis of 216 formularies from Clinical Commissioning Groups in England and Local Health Boards in Wales22 showed that 68% recommended the use of bath additives, 15% allowed their use but did not encourage it, 13% did not mention bath additives and 5% did not recommend their use.

Pragmatic trial design

Pragmatic clinical trials aim to test the effectiveness of an intervention in a real-life setting in order to recruit a study population that is as similar as possible to the population on which the intervention is meant to be used. Whereas an explanatory clinical trial aims to answer the question ‘Can this intervention work under ideal conditions?’, a pragmatic approach seeks to answer the question ‘Does this intervention work under usual conditions?’. 23,24 Features of pragmatic trials include the use of clinically important outcomes and common participant-reported outcomes, long-term follow-up and encouragement of participants to adhere to the intervention only to the extent that would be anticipated in usual care.

Although relatively few pragmatic trials have been carried out in dermatology,25 we felt that a definitive pragmatic clinical trial, including outcomes of relevance to participants and including long-term follow-up, was the most appropriate design to address the question of the effectiveness of bath additives in addition to standard eczema care in everyday care. 5

Blinding

We chose an ‘open-label’ design as it would not be possible to create a convincing placebo for bath additives, which make the bath feel ‘greasy’, and many families of children with eczema will already have experience of using them. We wished to design a trial with a clinical outcome relevant to participants (as below). Ideally, we would also have included an objective assessment of eczema severity carried out by a blinded assessor. However, this would have increased burden for participants as additional face-to-face assessments would have been required, particularly as the relapsing and remitting nature of eczema means that follow-up assessment at a single time point is problematic. As our primary outcome was participant reported and, therefore, unblinded, incurring substantial additional costs for an objective secondary outcome did not seem warranted.

Participant-reported outcome measure

We wished to design a trial with a clinical outcome relevant to participants. In eczema, the appearance of the skin does not always closely reflect symptoms causing a major impact on the child and family, such as sleep disturbance and itch. 26 It was therefore particularly important to design a trial with a validated participant-reported primary outcome. 5

We chose the Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM)27,28 as our participant-reported primary outcome measure. POEM comprises seven questions about eczema symptoms over the previous week that are summed to give a score from 0 (no eczema) to 28 (worst possible eczema). POEM is a patient-reported outcome that can be used by proxy (carer report), demonstrates good validity, repeatability and responsiveness to change29 and is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)9 and the international Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative. 30,31

Capturing meaningful outcomes for people with eczema is complicated by the relapsing and remitting nature of the condition. Therefore, gathering information regularly over time is essential to understand disease burden32 and to assess the impact of interventions. We therefore chose to collect POEM scores on a weekly basis from participants, as has been used successfully in other eczema trials. 33 An article reporting on the acceptability and practicality of weekly POEM completion is in preparation. 34

Development of research priority

This trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme following a commissioned call advertised in February 2012. The research topic was suggested via the NIHR HTA website topic suggestion form and was approved in December 2011.

The James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) for Eczema published its top 10 priority topics in 2012. 35 Even though this call was not advertised directly as a result of the PSP, it does address some of the issues that patients, carers and clinicians highlighted, including priorities around bathing/washing and also around the best ways to use emollients.

Objectives

The objectives were to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of adding bath emollient to the standard management of eczema in children, which includes regular application of leave-on emollients with use of TCSs as required.

The trial was registered before commencing on 13 December 2013 and the protocol was published online in August 2015. 5

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

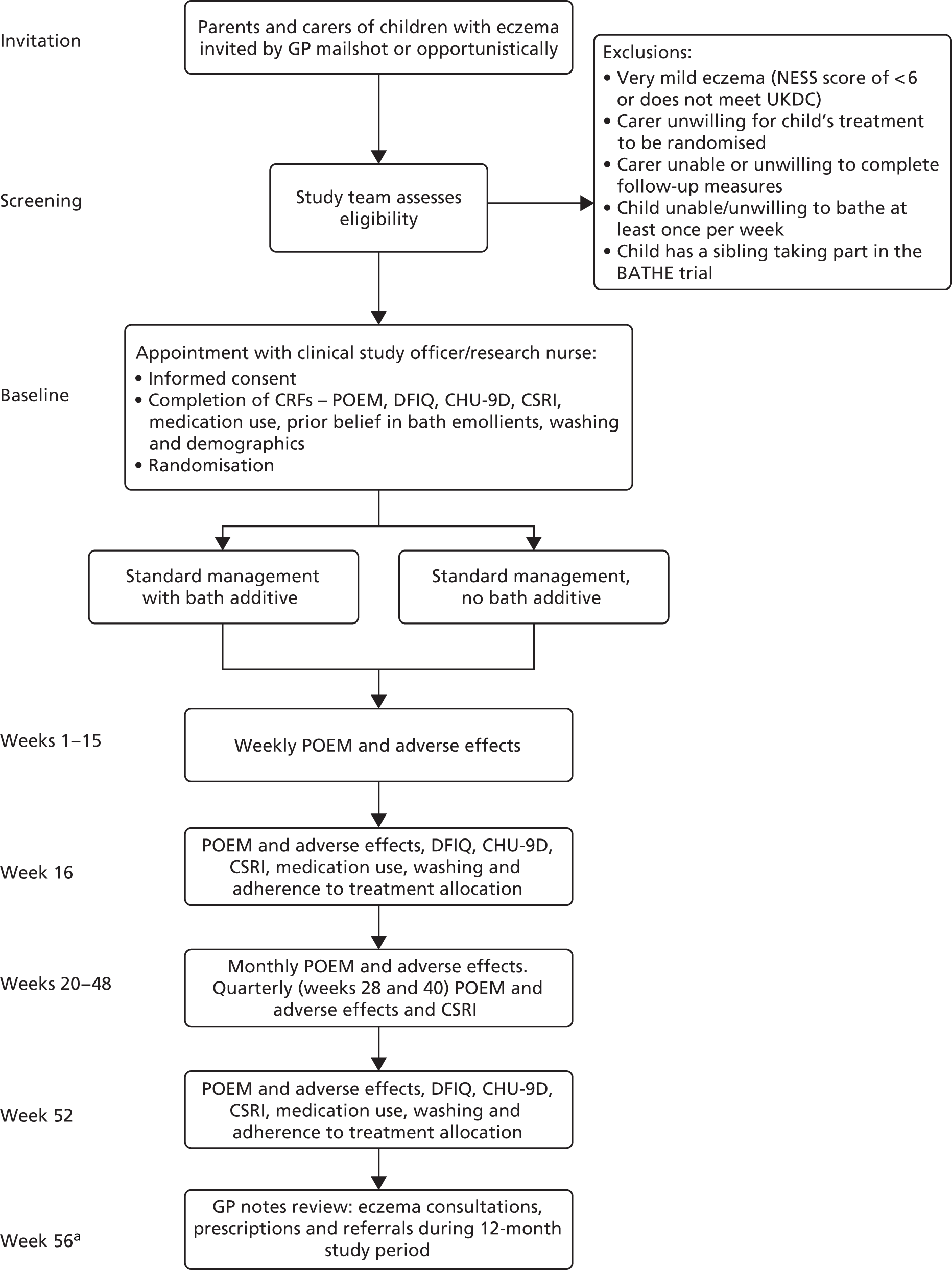

The Bath Additives for the Treatment of Eczema in cHildren (BATHE) trial was a pragmatic, randomised, open-label, multicentre, superiority trial with two parallel groups and a primary outcome of long-term control as measured by POEM weekly scores over 16 weeks. Children were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to either standard eczema care plus bath additives or standard eczema care only for 12 months (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow through study. a, At least 4 weeks allowed for clinical letters to be received at surgery and scanned into patient record. CHU-9D, Child Health Utility-9 Dimensions; CRF, case report form; CSRI, client service receipt inventory; DFIQ, Dermatitis Family Impact Questionnaire; NESS, Nottingham Eczema Severity Score; UKDC, UK Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis.

Changes to trial protocol

As recruitment was ahead of target, and following discussion with the Trial Steering Committee, in October 2015 the decision was taken to increase the target sample size from 423 to 491 participants, to allow an analysis by treatment adherence in addition to an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Assuming that 80% of participants were strictly adherent to their allocated treatment, recruitment of an additional 68 participants would be required to retain 90% power for a per-protocol analysis.

In addition, although not requiring an amendment to the trial protocol, concerns were raised that the participant information sheet was overly formal and text heavy and that this might be contributing to a lower than expected response rate. A colourful summary information leaflet was therefore designed, to be added to the patient invitation pack (see Appendix 1). The additional leaflet was included in mailshots from 12 June 2015 (63% of the invitations), but there is no evidence that its inclusion affected either the number of responses or the proportion of positive replies.

Participants

Participant identification

Participants were recruited exclusively through GP surgeries in Wales, the west of England and southern England. All recruiting sites were members of their local clinical research networks (CRNs) [NIHR CRN Wessex, NIHR CRN West of England and National Institute for Social Care and Health Research (NISCHR) in Wales] and were reimbursed for their time via the Service Support Costs scheme [Attributing the costs of health and social care Research and Development (AcoRD). URL: www.nihr.ac.uk/funding-and-support/study-support-service/early-contact-and-engagement/acord/ (accessed 10 September 2018)]. A total of 96 GP surgeries took part in the trial.

Postal invitation

Sites were provided with the instructions to conduct a search of their electronic records for potentially eligible children. The inclusion criteria were child aged between 12 months and 12 years, with a recorded diagnosis of eczema (Read Codes: eczema not otherwise specified, atopic eczema/dermatitis, infantile eczema) and who had obtained one or more prescriptions for drugs acting on the skin36 within the past 12 months. The lists that were produced were then screened for further exclusions by the children’s GPs (e.g. recent bereavement, child protection issues). When finalised, staff at the surgery merged the list of names and addresses with the trial invitation materials using a secure online mailing service. Trial staff were aware of how many invitation letters were being sent from each site, but did not have access to the details of the mailing list.

The trial invitation pack consisted of a covering letter printed on the surgery’s letterhead paper, an information sheet, a reply slip incorporating an eczema screening questionnaire (see Appendix 2) and a prepaid reply envelope. Children’s names were used within the text of the letter and invitation letters were addressed ‘to the parent/guardian’ of the child. Patient identification numbers were assigned to each invitee when the mail merge was performed and were printed on the reply slip to permit anonymous replies. The participant identification number format (six digits consisting of centre number, site number and patient number, in the format X-XX-XXX) also enabled trial staff to monitor response rates at the surgery level.

Opportunistic invitation

Sites were also provided with invitation packs to hand out opportunistically to parents/carers of children with eczema. Although it was hoped that all eligible children would have received an invitation through the post, packs were provided in anticipation of new eczema diagnoses and families newly registered with participating surgeries. The trial team was not generally notified when an invitation pack had been handed out by surgery staff, and the overall number of opportunistic recruitment packs distributed is not known; however, 35 (2.4%) of the responses received were returned from opportunistic invitations, of which 34 were from children who were willing to take part, 19 (54%) of whom went on to participate in the trial.

All documents in the mailing pack were supplied in both English and Welsh to patients of those surgeries where Welsh is spoken, except for the screening questionnaire. This questionnaire was supplied only in English as neither of the measures it incorporates [UK Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis (UKDC) and Nottingham Eczema Severity Score (NESS)] have been validated in the Welsh language. Materials that were included in the patient invitation pack can be found in Appendices 1–4.

Reponses

Parents/carers could respond to the invitation letter by either returning the reply slip in the prepaid envelope or by entering the same data into a secure online questionnaire hosted by the University of Southampton (URL: www.iSurvey.soton.ac.uk; accessed 3 August 2018).

Eligibility

Children were eligible to participate if:

-

they were aged between 12 months and 12 years

-

they fulfilled UKDC (see following paragraphs)

-

they scored mild to severe eczema severity over the past 12 months on the NESS (i.e. a score of > 5, excluding very mild eczema – see following paragraphs)

-

they bathed at least once a week

-

their parent/carer (or themselves) was willing for randomisation to either bath additive or no bath additive

-

they had no sibling(s) participating in the trial

-

they were not taking part in other clinical trials.

To avoid inviting ineligible children to baseline screening appointments, an initial assessment of eligibility was determined using a screening form, completed by the parent/carer, that combined the UKDC and the NESS, as below.

The UKDC are a refinement of the Hanifin and Rajka37 clinical criteria for diagnosing eczema and are the most extensively validated way of diagnosing eczema; they have been widely used in epidemiological and clinical studies. 38 The UKDC questionnaire consists of a single inclusion/exclusion question (‘in the last year, has your child had an itchy skin condition?’) followed by a further five questions about the clinical course of the disease. Atopic dermatitis, or eczema, is indicated by a score of three or more positive responses from these five questions.

For the purposes of the BATHE trial, the requirement for visible flexural dermatitis was approximated by assessing the NESS body diagram for marks indicating the presence of eczema in the wrist, ankle, elbow and facial areas (see Appendix 2). In addition, the question relating to child or family history of atopy, being age adapted and involving some explanation, was not included on the screening questionnaire form. This question was asked by telephone or e-mail only if an additional point was required to reach eligibility (i.e. the child scored ≥ 5 on the NESS and ≥ 2 on the UKDC).

The NESS assesses eczema severity over the previous 12 months and comprises three questions: duration of eczema symptoms over past 12 months, frequency of sleep disturbance and current extent of eczema as represented by parental marking of a diagram39 (see Appendix 2).

The NESS severity classifications are mild (score of 3–8), moderate (9–11) and severe (12–15). 39 However, the majority of children in primary care fall into the ‘mild’ category and a score of ≥ 9 would exclude 82% of children with eczema in primary care, whereas a cut-off point of ≥ 6 would exclude only 40% of children with ‘very mild’ eczema. Children with a score of ≤ 5 were excluded, as floor effects would make it unlikely that changes in eczema severity could be detected.

The screening forms were returned in a prepaid envelope to the trial centre in Southampton, where responses were entered into a secure database [Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)]. The database calculated eligibility for each child using an algorithm (see Appendix 5). To be eligible to take part in the BATHE trial, children were required to meet the UKDC and to score ≥ 5 on the NESS. Those who reached eligibility on the NESS but scored only 2 on the UKDC were contacted by the clinical studies officer/research nurse (CSO/RN) in order to ask the additional question about atopy.

When screening forms did not meet eligibility criteria, parents/carers were sent a letter of thanks and explanation, together with a booklet explaining the best way to wash children with eczema. Children’s details were not collected until the recruitment appointment and, therefore, children who were not recruited into the BATHE trial remained anonymous.

Recruitment

All contact with families regarding recruitment was conducted by a clinical studies officer or research nurse. In the Southampton and Bristol centres, the clinical studies officers were study-employed staff, whereas, in the Cardiff centre, recruitment was carried out by clinical studies officers or research nurses from the NISCHR, who may work across several research projects concurrently. The majority of trial staff were trained together at a whole-day workshop prior to the start of the recruitment period; however, the large number of staff in Wales meant that some new staff required handover training from trained research nurses.

Parents/carers of eligible children who expressed a willingness to take part in the trial were contacted by their local CSO/RN. After re-establishing eligibility, a recruitment appointment was made. The majority of appointments were held at the child’s GP surgery, with a small number held at the child’s home when this option was preferred by the family. The child did not need to attend the appointment, but whenever they were present efforts were made to include them in the discussion. Two summary child information leaflets were prepared to facilitate their understanding and assent forms were available for older children (see Appendices 6 and 7).

The mean number of days between completion of the screening form and the recruitment appointment was 24, and 370 (77%) participants were recruited within 30 days of the screening form completion date. When the time elapsed between completion of the screening form and the recruitment appointment was ≥ 30 days, the CSO/RN rechecked eligibility by asking parents/carers to confirm the time-sensitive questions from the NESS (questions five to seven of the screening form). Eligibility was recalculated by the CSO/RN and the data held in the trial management database were updated.

Baseline data were entered directly into the online software by the parent/carer wherever possible. This enabled the CSO/RN to familiarise the participants with logging in and using the software, but occasionally it added considerable time to the appointment. The recruitment process routinely took between 40 and 60 minutes and, therefore, parents/carers were reimbursed for their time and expenses with a £10 gift voucher.

Engagement

Following the baseline appointment, there were no other face-to-face meetings and so efforts were made to help participants to remain engaged with the trial throughout the full 12 months. A study logo of a rubber duck was adopted and used in many different ways: participating children (and their siblings) were invited to colour in and name a duck, which was then uploaded to a gallery on the study website. The logo was also used to identify small gifts, which were provided at the baseline appointment [a bath duck with study logo, Post-it® (3M, Bracknell, UK) notes and a novelty eraser] and birthday and Christmas cards and quarterly newsletters were sent about study progress. The newsletters were also uploaded to the study website, where participants were able to access key trial information and get in touch with the study team if required (URL: www.southampton.ac.uk/bathe; accessed 3 August 2018). No incentives were given to participants; however, a thank you card and a £10 voucher were sent to parents/carers shortly before each of the 16- and 52-week questionnaires were due in recognition of the time spent completing them, and all participants were eligible for inclusion in a prize draw for a tablet computer at the end of the study.

Interventions

Standard care with bath additive

In addition to the child’s usual skincare regimen, parents/carers were asked to use one of the three most commonly used bath additives [Balneum® (Almirall Ltd, Middlesex, UK), Aveeno® (Johnson & Johnson Ltd, Maidenhead, UK) or Oilatum® (Stiefel Skin Science Solutions, a GlaxoSmithKline company, Middlesex, UK)] at least once per week, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Having discussed any carer preferences, the CSO/RN asked staff at the surgery to set up a repeat prescription on the child’s medical record. In the event of an adverse reaction to the bath additive, parents/carers were free to change the prescription to another of the recommended products at any point during the trial. Bath additives other than the three recommended products are also available and parents/carers were free to choose any bath additive they wished, provided that it did not contain any additional active ingredients, such as antipruritic or antimicrobial agents. A full list of acceptable bath additives was provided to the surgery in the study site file and was available on the study website (see Appendix 8). Both groups also received further advice (as below).

Standard care without bath additive

Parents/carers were requested to avoid using any emollient product that had been designed to be poured into the bath for the 12 months of their participation. It was reiterated that it was not known whether or not bath additives provided any benefit to children with eczema and that we did not believe that their child would experience any worsening of their eczema as a result of participating in this trial. Parents/carers in the no bath additive group were advised that they should treat their child’s eczema exactly as they normally would, using leave-on emollients regularly and TCSs to treat flare-ups, and consulting health professionals as they normally would. As many participants had family members who also had eczema, and in accordance with the pragmatic nature of the trial, no specific instructions were given to parents/carers with regard to bath additives that might already be present in the home; instead, the main focus was on ensuring that parents/carers were in equipoise with and engaged with the aims of the research.

Advice given to both groups

We aimed for no difference in soap use between groups and both groups were therefore given the same advice about how to wash. Both groups were advised to use a leave-on emollient as a soap substitute. When parents/carers were keen to use existing wash products, they were advised that these could be used for direct application to skin but should not be added to the bath water, as this could potentially have the same effect as a bath additive. All participants were provided with a copy of the BATHE trial Study Washing Leaflet that was based on best practice guidelines developed by the Nottingham Support Group for Carers of Children with Eczema (see Appendix 9). 40

All parents/carers were reminded that they were free to use any other medications as they normally would and to visit their doctor or dermatologist as usual, if required. The standard operating procedure (SOP) that was used by recruiters during the baseline appointment is available in Appendix 10.

Data collection

Parents/carers were able to choose to complete the trial questionnaires either online or by post following discussion at the recruitment appointment, although online questionnaire completion was strongly encouraged. Online questionnaires became available on the seventh day following recruitment and every 7 days thereafter. Notifications were automatically sent by e-mail when the questionnaire went ‘live’ and reminders were sent after 48 hours if it had not been completed. Participants could also opt to receive the notifications and reminders by automated text. Both e-mails and text messages contained a hyperlink to the online questionnaire and participants were required to log in using their e-mail address and password in order to enter data. Of the 9784 times that parents/carers logged in to the website, 5963 logins (61%) were from mobile devices. A further 2909 logins (30%) were from computers or laptops, whereas 912 logins (9%) were from tablets. 34

The 16-week questionnaire, and subsequent monthly questionnaires, remained available to complete online for 28 days. However, in order to encourage timely completion of the primary and secondary outcomes, a reminder letter and paper copy of the 16- and 52-week questionnaires were posted out if the online questionnaire had not been completed within 7 days. A total of 80 reminders were posted at week 16 and 107 reminders were posted at week 52.

Weekly paper questionnaires were printed in booklets of four. The first booklet, covering weeks 1–4, was marked with the day of the week on which the questionnaires should be completed and then handed to the parent at recruitment. Subsequent questionnaires were posted to participants shortly before they were due, together with a prepaid envelope. The data from the paper questionnaires were entered into a secure database and were merged with the data collected online prior to analysis.

Data management

The online data collection software was built using LifeGuide software (University of Southampton, Southampton, UK) and validated by Southampton Clinical Trials Unit. The clinical data were separated from the personally identifiable information and both data sets were stored on secure servers.

In the trial office, data from paper screening forms and questionnaires were entered into a password-protected Microsoft Access database. The clinical data were again stored separately from personally identifiable information in two data sets on a secure server. Paper forms were separated from each other and stored in locked filing cabinets in the trial office.

The data sets were merged and stripped of any identifying data prior to analysis.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was eczema severity as measured by the POEM completed weekly for 16 weeks. The POEM is a patient-reported outcome that scores symptoms over the previous week. It consists of seven questions that can be completed by the child’s parent/carer and provides a severity score on a scale from 0 to 28. The published minimal clinically important difference of the POEM is 3.0. 41,42 The POEM was the only patient-reported outcome measure for eczema to demonstrate validity and repeatability in a systematic review by Schmitt et al. 29 and it was adopted as the preferred patient-reported outcome measure by the HOME initiative in 2015. 30,43 Our primary outcome measure is based on repeated measures of POEM data collected weekly over 16 weeks because these reflect the impact of this relapsing and remitting chronic condition better than comparing outcomes at a single follow-up point. Because of the burden of weekly data collection on participants, weekly data collection was limited to the first 16 weeks of the trial.

Secondary outcomes

-

The number of eczema exacerbations resulting in a primary health-care consultation over 1 year, assessed by a review of participants’ primary care records. An exacerbation for this trial is defined as a consultation where there is mention of eczema and a topical steroid or topical calcineurin inhibitor (TCI) has been prescribed. The notes review form was based on those used in other recent eczema trials and recorded the number of consultations, prescriptions and referrals over the 12 months’ trial participation (see Appendix 11). Notes reviews were carried out by members of the trial team at not less than 13 months after the recruitment date in order to allow time for clinic letters to be received and scanned into the patients’ notes.

-

Eczema severity over 1 year as measured by POEM every 4 weeks, from 16 weeks to 12 months.

-

Disease-specific QoL at baseline, 16 weeks and 1 year, measured by the Dermatitis Family Impact Questionnaire (DFIQ). 44 The DFIQ is an internationally recognised validated instrument that measures the impact of a child’s eczema on the family’s QoL. The questionnaire consists of 10 questions and the total score ranges from 0 (no impact on family life) to 30 (maximum impact on family life).

-

Generic QoL as measured by the Child Health Utility-9 Dimensions (CHU-9D) at baseline, 16 weeks and 1 year. CHU-9D45 is a paediatric QoL measure developed in children aged 7–11 years. It captures issues pertinent to childhood eczema, such as sleep disturbance and the child’s mood, and is therefore more suitable for measuring the QoL in families affected by eczema than the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). There are no suitable utility measures validated for very young children aged 1–4 years; however, personal communication (Dr Katherine Stevens, University of Sheffield, 2014) suggested guidance for using the CHU-9D in very young children. In addition, the CHU-9D performed well in children aged 1–4 years in the Supporting Parents and carers of Children with Eczema (SpaCE) trial and its use in younger age groups is currently being trialled elsewhere. 46,47

-

Type (strength) and quantity of topical steroid/calcineurin inhibitors prescribed during trial participation, measured by GP notes review.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated for repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) in weekly POEM scores over the 16-week observation period. Using weekly data from a similar population to that in the Softened Water Eczema (SWET) trial,48 we aimed to detect a mean difference of 2.0 [standard deviation (SD) 7.0] between the intervention and control groups. The published minimal clinically important difference for POEM is 3.0,41,42 but we wished to detect a difference of 2.0 because of the expectation of low baseline POEM scores in a population recruited entirely through primary care, and because we wished to be able to detect this small difference as the intervention is relatively inexpensive and even small effect sizes may be cost-effective. An alpha of 0.05 and a power of 90% with a correlation between repeated measures of 0.70 gives a sample size of 338 participants. Allowing for 20% loss to follow-up gave a total sample size of 423 participants.

We aimed to report a per-protocol analysis in addition to a primary ITT analysis, and early data suggested that approximately 80% of participants in both groups were strictly adherent to treatment allocation. We were concerned that if only 80% of participants were adherent to treatment allocation then we would have usable data for only 270 participants. To get back up to 90% power for this group, we submitted an ethics amendment requesting recruitment of an additional 68 participants, giving a revised target recruitment of 491 participants.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed using LifeGuide49 software hosted by the University of Southampton and validated by Southampton Clinical Trials Unit. At the time of trial setup, LifeGuide was unable to easily perform block randomisation and the additional programming time would have resulted in delays to the trial. Simple randomisation was therefore used, stratified by centre. Although this can result in imbalances, it was felt that with strata of > 100 participants each, the overall balance between groups would be preserved.

A backup randomisation system was established for occasions when internet access to LifeGuide was not available or when the parent had opted to complete the trial questionnaires on paper. A second set of random treatment allocations was programmed into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet by the trial statistician. The spreadsheet similarly allocated treatments on a 1 : 1 basis, stratified by recruiting centre, and the treatment allocation was not revealed until the participant had been recruited. A total of 30 randomisations were conducted using this offline method.

Allocation concealment mechanism

Both the online and the offline randomisation procedures were conducted immediately at the end of the recruitment appointment, following completion of the baseline questionnaire. It was therefore impossible for the treatment allocation to be known prior to study entry. Once randomisation was complete, however, the participant, CSO/RN and the participant’s clinical team were all aware of which group the child had been allocated to.

Implementation

Once recruitment and randomisation was complete, the lead GP at the site was notified of the child’s enrolment into the study and their allocated treatment group was noted on a form completed by the recruiting CSO/RN. The form requested that repeat prescriptions be set up for children allocated to the bath additive group and it also recorded the parent/carer’s preferred bath additive, if any. Practices were recommended to add a Read Code to the child’s electronic record to indicate that they were enrolled in a clinical trial and/or to add an electronic alert or other notification to remind clinicians of their treatment allocation. This, however, was not enforced and the focus remained on ensuring that parents/carers were fully engaged with the aims and requirements of the study.

Blinding

Given the nature of bath emollient, which adds a greasy film to water, it was impossible to manufacture a convincing placebo treatment or to blind the participants to their treatment allocation. Participants were therefore fully aware of the treatment regime they were being asked to adhere to and report on. In order to support families throughout their 12-month participation, the trial team were also not blinded to the treatment allocated.

The trial statisticians carrying out the analysis were blind to allocation group and the statistical analyses were independently verified.

Statistical methods

The primary analysis for the total POEM score was performed using a mixed multilevel mixed model (MMLM) framework with observations over time from weeks 1–16 (level 1) nested within participants (level 2) nested within centres (level 3). Unadjusted results are reported, as well as results adjusting for baseline POEM, recruitment region as covariates and any significant confounders. Confounders were defined as variables associated with both the exposure and the outcome that significantly contribute to the multivariable model (defined as a p-value of < 0.05 or by modifying the effect estimate by > 10%). The following variables were identified a priori as possible confounders: child age, child gender, carer age, carer gender, carer education, prior belief in bath emollients, type of emollient used, other medication used and other items used when washing (e.g. soap/shampoo/soap substitute).

The model used all of the observed data and made the assumption that missing POEM scores are missing at random. The model included a random effect for centre (random intercept) and patient (random intercept and slope on time) to allow for between-patient and between-centre differences at baseline and between-patient differences in the rate of change over time (if a treatment/time interaction was significant), and fixed effects for baseline covariates. An unstructured covariance matrix was used.

The assumptions of the normality of the residuals from the fixed part of the model and the normality of the random effects at the cluster level were checked.

For the analysis of secondary outcomes, repeated measures analysis in line with that used for the primary outcome was used for the monthly POEM up to 1 year. 5 For other secondary outcomes, linear regression was used for continuous outcomes if the assumptions were met; otherwise, non-parametric analyses were used. Logistic regression was used for dichotomous outcomes and a suitable count model, as determined by goodness of fit measures, was used for count data. All analyses controlled for stratification variables and potential confounders. Preplanned sensitivity analysis and exploratory subgroup analyses were carried out as set out in the statistical analysis plan.

To test the sensitivity of the results to missing data, a chained equations multiple imputation model was used to impute the missing values. This analysis used 100 imputations and included all the outcomes and covariates included in the adjusted analysis of the primary outcome.

For all models, participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised, regardless of their adherence to that allocation (ITT analysis). The only exception to this was the per-protocol analysis, for which participants were analysed on the basis of their reported use of bath additives. The reported use of bath additives was collected at 16 weeks and 52 weeks in both groups using the categorical response options ‘every time’, ‘more than half the time’, ‘less than half the time’ and ‘never’. This allows two possible definitions for adherence to the intervention.

Adherence definition one

Defined as the bath additive group using emollient bath additives ‘more than half the time’ or ‘every time’ and the no bath additive group using emollient bath additives ‘less than half the time’ or ‘never’.

Adherence definition two

These figures include only participants who reported using emollient bath additives ‘every time’ or ‘never’ (i.e. excluding participants who report using emollient both additives ‘more than half the time’ and ‘less than half the time’).

We report the effect sizes for the primary outcome based on both definitions of adherence. These can then be compared with the effect size in the ‘as randomised’ ITT population.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant recruitment

Invitation packs were sent to the parents/carers of 12,504 children and 1451 responses were received. A total of 1343 responses were returned by post; 832 respondents (62%) were willing to be contacted and 431 (32%) went on to participate in the trial. A total of 108 responses were received electronically; 88 respondents (81%) were willing to take part and 52 (48%) went on to be recruited. A total of 35 (2.4%) of the responses received were returned from opportunistic invitations; 34 respondents were willing to take part and 19 (54%) went on to participate in the trial.

A total of 237 parents/carers declined participation and returned a blank screening form. A further 104 answered ‘No’ to the first question of the UKDC (‘In the last year, has your child had an itchy skin condition?’) and did not fill in any other information about their child’s condition. A total of 188 parents/carers indicated that they were unwilling or unable to take part but did complete the screening questionnaire. Table 1 summarises the information received about these children’s eczema, in comparison with children who went on to take part.

| Respondent characteristic | Responder | |

|---|---|---|

| Declined participation (N = 185) | Recruited (N = 482) | |

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| ≤ 18 months | 9 (5) | 29 (6) |

| > 18 months but < 4 years | 59 (32) | 162 (34) |

| ≥ 4 years | 117 (63) | 291 (60) |

| Eligibility, n (%) | (N = 186) | (N = 482) |

| Eligible | 87 (47) | 482 (100) |

| Query eligible | 19 (10) | – |

| Not eligible | 80 (43) | – |

| Eczema severity (eligible responders), mean (SD) | (N = 87) | (N = 482) |

| NESS (0–15) | 9.14 (2.31) | 9.52 (2.33) |

| UKDC score (0–4) | 3.36 (0.48) | 3.25 (0.61) |

| Belief in bath additives (1–9)a | (N = 183) | (N = 475) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.6 (2.3) | 4.6 (2.0) |

| Do not know | 34 (18%) | 97 (20%) |

| Bath additive use in past month, n (%) | (N = 180) | (N = 481) |

| Never | 69 (38) | 126 (26) |

| Less than half the time | 36 (20) | 109 (23) |

| More than half the time | 23 (13) | 96 (20) |

| Every time | 52 (29) | 150 (31) |

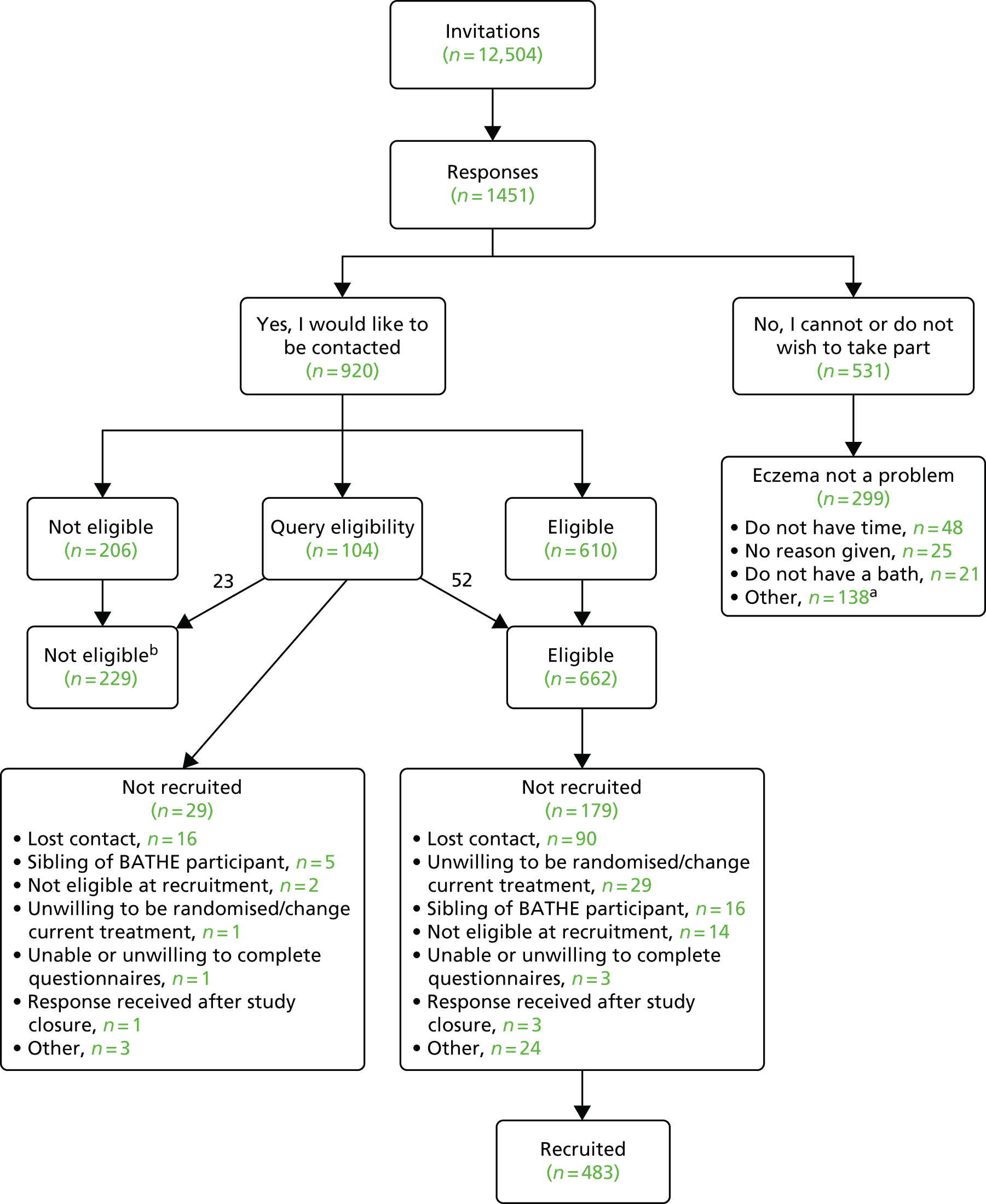

There were 920 replies expressing a willingness to be contacted and these replies also included a completed screening questionnaire. Of these, 229 did not meet the clinical criteria required to enter the trial. Overall, 662 children met the clinical eligibility criteria and were approached regarding participation, of whom 483 entered the trial and 179 were not recruited for the reasons shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows the flow of participants through the screening and recruitment process.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment flow chart. a, Unwilling to be randomised/change current treatment, n = 58; eczema no longer a problem, n = 31; child mostly showers, n = 16; child refused, n = 2; other/not specified reason, n = 29. b, Did not meet UKDC, n = 65; NESS score of < 6, n = 76; and did not meet either criterion, n = 88.

Figure 3 shows the number of participants who withdrew or who were lost to follow-up during the study period. Four participants formally withdrew during the 16-week primary outcome period, three from the Cardiff centre and one from the Bristol centre; all withdrawals were from the bath additive group. Permission was obtained from three parents to use the data already collected, and one requested that all data collected be removed. A total of 42 participants were lost to follow-up by the time of the 16-week primary outcome (22 in the bath additive group and 20 in the no bath additive group) and a further four 16-week questionnaires were not received from participants who remained enrolled.

FIGURE 3.

The BATHE participant flow chart. a, Reported eczema had not been a problem for some time, although screening form clearly indicated eligibility. b, One parent wished to bathe two children together but felt that bath additive was worsening the symptoms of the child not enrolled in the study; one was finding improvement with new creams and, despite reassurance, did not wish this to affect the study results; one child was withdrawn by their GP after experiencing a rash. CRF, case report form.

A total of 429 (89.6%) participants opted to complete their weekly questionnaire online. Of the remaining 51 participants, 27 (5.6%) requested the paper option at recruitment and 24 (5.0%) were switched from online to paper format after discussion with the study team. Reasons for this were primarily related to technical issues, as some parents/carers became discouraged after having problems logging in to the online database. Login problems were occasionally compounded by a failure to understand the automated nature of the system and the inability to complete POEMs retrospectively. This was particularly problematic for a small number of participants who experienced delays in obtaining their prescribed bath emollients and, therefore, did not ‘start’ participation in week 1. Although attempts were made to telephone all families during the first week, as a matter of courtesy and in order to address any problems, some parents could not be reached and it is not possible to determine how many participants were lost to follow-up because of technical or logistical problems.

The majority of trial participants needed no prompting to complete the trial and only 25% of the trial participants were contacted by telephone or e-mail during the 16-week primary outcome period because of failure to complete the questionnaires.

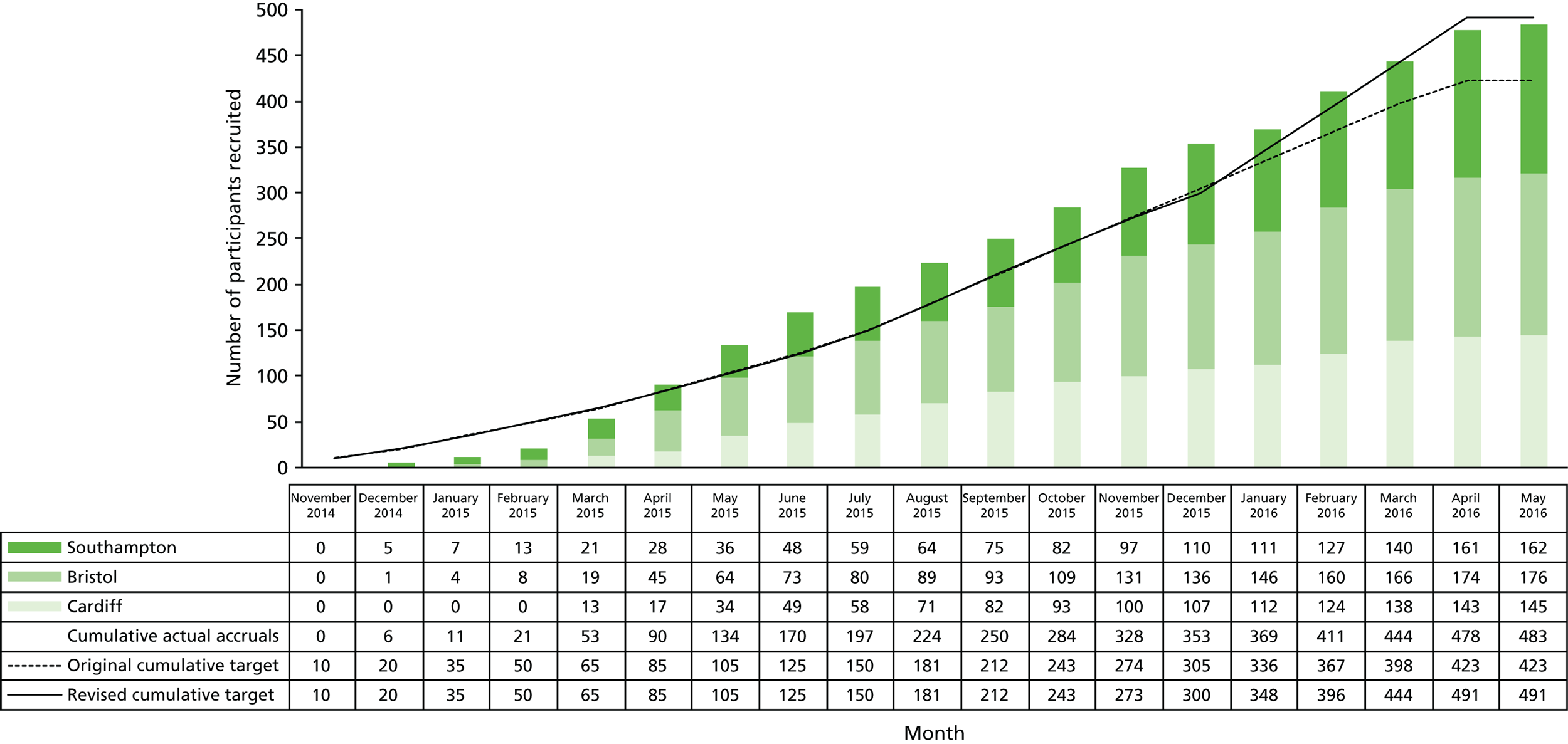

Recruitment dates

Recruitment took place from November 2014 to May 2016. The original target of 423 participants was reached in March 2016 and permission was obtained to continue recruiting participants up to an increased target of 491 participants as discussed in Chapter 2, Changes to trial protocol. Recruitment was stopped at the end of May 2016 as planned, with a total of 483 participants enrolled (Figure 4). The 52-week follow-up questionnaires and notes reviews of the last recruited participants were completed in June 2017.

FIGURE 4.

Recruitment by centre.

Baseline data

Table 2 shows that, although there were more participants allocated to the bath additive group than the no bath additive group (see Chapter 5, Discussion), the key characteristics were well balanced at baseline.

| Participant characteristics | Treatment group | Total (N = 482) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bath additive (N = 264) | No bath additive (N = 218) | ||

| Child age (years), mean (SD) | 5.4 (2.9) | 5.2 (2.9) | 5.3 (2.9) |

| Child gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 138 (52.3) | 100 (45.9) | 238 (49.4) |

| Female | 126 (47.7) | 118 (54.1) | 244 (50.6) |

| Carer age (years), mean (SD) | 36.5 (6.5) | 35.9 (6.7) | 36.2 (6.5) |

| Carer gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 11/258 (4.3) | 12/212 (5.7) | 23/470 (4.9) |

| Female | 247/258 (95.7) | 200/212 (94.3) | 447/470 (95.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 228/257 (86.0) | 176/215 (81.9) | 397/472 (84.1) |

| Black | 6/257 (1.9) | 9/215 (4.2) | 15/472 (3.2) |

| Asian | 15/257 (5.8) | 16/215 (7.4) | 31/472 (6.6) |

| Mixed race | 10/257 (3.9) | 9/215 (4.2) | 19/472 (4.0) |

| Chinese | 2/257 (0.8) | 3/215 (1.4) | 5/472 (1.1) |

| Other | 3/257 (1.2) | 2/215 (0.9) | 5/472 (1.1) |

| Highest qualification, n (%) | |||

| Not answered | 6/257 (2.3) | 3/213 (1.4) | 9/470 (1.9) |

| Degree or equivalent | 106/257 (41.3) | 90/213 (42.3) | 197/470 (41.7) |

| Diploma or equivalent | 56/257 (21.8) | 37/213 (17.4) | 95/470 (19.8) |

| A level | 25/257 (9.7) | 24/213 (11.3) | 49/470 (10.4) |

| GSCE/O level | 50/257 (19.5) | 38/213 (17.8) | 88/470 (18.7) |

| Other | 12/257 (4.7) | 16/213 (7.5) | 29/470 (6.0) |

| None | 2/257 (0.8) | 5/213 (2.4) | 7/470 (1.5) |

| Cost of living, n (%) | |||

| Not answered | 7/257 (2.7) | 3/213 (1.4) | 10/470 (2.1) |

| Finding it a strain | 11/257 (4.3) | 3/213 (1.4) | 14/470 (3.0) |

| Have to be careful | 105/257 (40.9) | 82/213 (38.5) | 187/470 (39.8) |

| Able to manage | 99/257 (38.5) | 90/213 (42.3) | 189/470 (40.2) |

| Quite comfortable | 35/257 (13.6) | 35/213 (16.4) | 70/470 (14.9) |

| Prior belief in bath additives (1–9)a | 5.1 (2.2) | 4.8 (2.3) | 5.0 (2.3) |

| POEM scores, mean (SD) | 9.5 (5.7) | 10.1 (5.8) | 9.8 (5.8) |

| Mild (0–7), n (%) | 114 (43.2) | 73 (33.5) | 187 (38.8) |

| Moderate (8–16), n (%) | 119 (45.1) | 114 (52.3) | 233 (48.3) |

| Severe (17–28), n (%) | 31 (11.7) | 31 (14.2) | 62 (12.9) |

| DFIQ score, median (IQR) | 2 (1–6) | 3 (1–7) | 3 (1–7) |

| NESS score, mean (SD) | 9.5 (2.3) | 9.5 (2.3) | 9.5 (2.3) |

| CHU-9D score (utility values), mean (SD) | 0.90 (0.1) | 0.90 (0.1) | 0.90 (0.1) |

Numbers analysed

The questionnaire response rate was high, with 76.7% of participants completing questionnaires for > 80% of the time points for the primary outcome (12 out of 16 weekly questionnaires to 16 weeks). There were no marked differences in completeness of the data by randomisation group (see Table 3 and Figure 5).

| Measure of completion | Treatment group | Total (N = 482) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bath additive (N = 264) | No bath additive (N = 218) | ||

| Number of weekly questionnaires completed during the 16-week primary outcome period, mean (SD) | 13.1 (4.5) | 12.7 (4.7) | 12.9 (4.6) |

| > 12 questionnaires completed, n (%) | 209 (79.1) | 161 (73.9) | 370 (76.7) |

| Weekly questionnaire return, n (%) | |||

| Week 1 | 224 (84.8) | 191 (87.6) | 415 (86.1) |

| Week 2 | 222 (84.1) | 183 (83.9) | 405 (84.0) |

| Week 3 | 223 (84.5) | 176 (80.7) | 399 (82.8) |

| Week 4 | 219 (83.0) | 182 (83.5) | 401 (83.2) |

| Week 5 | 216 (81.8) | 175 (80.3) | 391 (81.1) |

| Week 6 | 224 (84.8) | 175 (80.3) | 399 (82.8) |

| Week 7 | 209 (79.1) | 173 (79.4) | 382 (79.2) |

| Week 8 | 216 (81.8) | 172 (78.9) | 388 (80.5) |

| Week 9 | 221 (83.7) | 163 (74.8) | 384 (79.7) |

| Week 10 | 220 (83.3) | 168 (77.1) | 388 (80.5) |

| Week 11 | 203 (76.8) | 161 (73.9) | 364 (75.5) |

| Week 12 | 204 (77.2) | 165 (75.7) | 369 (76.6) |

| Week 13 | 203 (76.9) | 165 (75.7) | 368 (76.3) |

| Week 14 | 203 (76.9) | 167 (76.6) | 370 (76.8) |

| Week 15 | 207 (78.4) | 173 (79.4) | 380 (78.8) |

| Week 16 | 236 (89.4) | 194 (89.0) | 430 (89.2) |

| 52-week questionnaire return, n (%) | 209 (79.2) | 178 (81.6) | 387 (80.3) |

| Initial method of questionnaire completion, n (%) | |||

| Online | 235 (89.0) | 196 (89.9) | 431 (89.4) |

| By post | 15 (5.7) | 12 (5.5) | 27 (5.6) |

| Switched method of completion during study, n (%) | 14 (5.3) | 10 (4.6) | 24 (5.0) |

FIGURE 5.

Questionnaire completion during the 16-week primary outcome period.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

All 461 participants who had completed at least one POEM following baseline were included in this analysis. The results in Table 4 indicate no statistically significant difference in weekly POEM scores between the two groups over the 16-week period. Of the prespecified potential confounders (child age, child gender, ethnic group, carer age, carer gender, carer education, prior belief in bath emollients, type of emollient used, other medication used, other items used when washing, such as soap/shampoo/soap substitute), only ethnic group, steroid use and soap substitute use were statistically significant and, therefore, retained in the models. After controlling for baseline severity and these confounders, and allowing for the clustering of patients within centres and responses within patients over time, the POEM score in the no bath additive group was 0.41 points higher than in the bath additive group (95% CI –0.27 to 1.10). Unadjusted POEM scores showed < 1 point difference between groups. These differences are not considered to be clinically meaningful, given the published minimal clinically important difference for POEM of 3.0. 41,42

| Time period | Treatment group, mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bath additive | No bath additive | |

| Baseline | 9.5 (5.7) | 10.1 (5.8) |

| Week 1 | 8.3 (5.6) | 9.1 (5.9) |

| Week 2 | 7.8 (5.5) | 8.2 (5.9) |

| Week 3 | 7.4 (5.3) | 8.5 (5.9) |

| Week 4 | 7.6 (6.0) | 8.6 (6.1) |

| Week 5 | 7.6 (5.9) | 8.3 (6.0) |

| Week 6 | 7.8 (6.3) | 8.4 (5.7) |

| Week 7 | 7.5 (6.1) | 8.8 (6.1) |

| Week 8 | 7.3 (6.2) | 8.2 (5.8) |

| Week 9 | 7.2 (5.9) | 8.1 (5.8) |

| Week 10 | 7.3 (5.8) | 8.5 (5.8) |

| Week 11 | 7.6 (6.1) | 8.2 (6.0) |

| Week 12 | 7.7 (6.2) | 7.9 (5.9) |

| Week 13 | 7.1 (5.9) | 8.3 (6.2) |

| Week 14 | 7.2 (6.3) | 7.9 (6.3) |

| Week 15 | 7.0 (6.3) | 8.4 (6.5) |

| Week 16 | 7.1 (6.1) | 8.2 (6.3) |

There was no statistically significant interaction between treatment and time (interaction term 0.04, 95% CI –0.02 to 0.11; p = 0.204).

Patient Oriented Eczema Measure weekly for 16 weeks

There is some fluctuation in between-group differences in POEM score over the 16-week period, with some results statistically significant and others not. However, all the between-group differences are < 2 points, suggesting that even those that are statistically significant are not likely to be clinically meaningful as they are below the POEM minimal clinically important difference of 3.0 (Tables 4 and 5 and Figure 6). Moreover, it is likely that some significant results may be found because of multiple testing (type I error).

| POEM scores | Treatment group, mean (SD) | Univariate difference in mean POEM (95% CI) | Adjusted difference in mean POEMa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath additive | No bath additive | |||

| Primary outcome: 16-week repeated measures | – | – | – | – |

| Over the 16-week primary outcome period (repeated measures) | 7.5 (6.0) | 8.4 (6.0) | 0.90 (–0.03 to 1.83) | 0.41 (–0.27 to 1.10) |

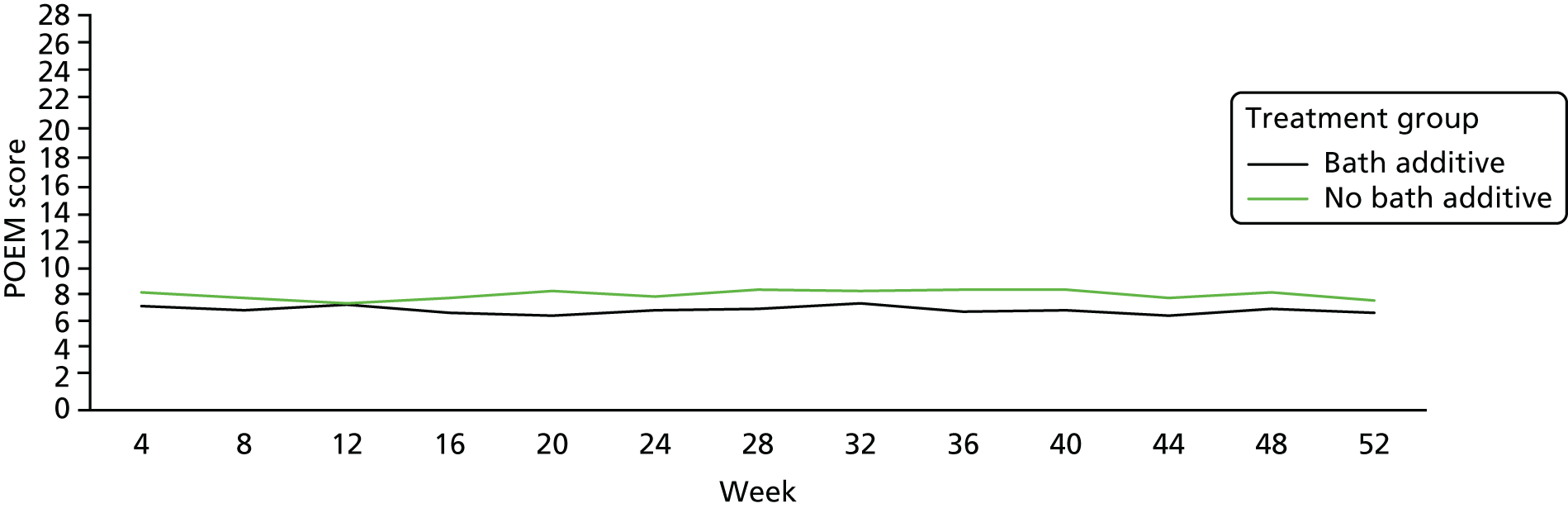

FIGURE 6.

Mean POEM scores over the 16-week primary outcome period, by group.

Imputed analysis

As a sensitivity analysis, primary outcome was examined using imputed values for all missing weekly data using an individual chained equations multiple imputation model. Table 6 shows that this produced an adjusted difference in mean POEM score between groups of 0.43 (95% CI –0.26 to 1.12). This is a very similar result to our primary analysis.

| Adherence to allocated treatment | Treatment group, mean (SD) | Univariate difference in mean POEM (95% CI) | Adjusted difference in mean POEMa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath additive | No bath additive | |||

| Primary outcome: 16 week repeated measures | – | – | – | – |

| Over the 16 week primary outcome period (repeated measures) | 7.4 (6.0) | 8.5 (6.0) | 0.96 (0.05 to 1.87) | 0.43 (–0.26 to 1.12) |

Adherence to allocated treatment (per-protocol analysis)

Parent/carer report of adherence to treatment allocation group at 16 weeks recorded 92.7% of participants in the bath additive group using bath additive ‘every time’ (73.8%) or ‘more than half the time’ (18.9%). Similarly, 92.1% of those in the no bath additive group said that they used bath additives either ‘never’ (87.4%) or ‘less than half the time’ (4.7%) (Table 7).

| Adherence to allocated treatment | Treatment group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bath additive (N = 233) | No bath additive (N = 191) | |

| Use of bath additives | ||

| Every time | 172 (73.8) | 14 (7.3) |

| More than half the time | 44 (18.9) | 1 (0.5) |

| Less than half the time | 15 (6.4) | 9 (4.7) |

| Never | 2 (0.9) | 167 (87.4) |

| Number of baths per week | (N = 221) | (N = 176) |

| 1–2 | 70 (31.7) | 54 (30.7) |

| 3–4 | 74 (33.5) | 56 (31.8) |

| 5–6 | 45 (20.4) | 39 (22.2) |

| ≥ 7, n (%) | 32 (14.5) | 27 (15.3) |

We considered two possible definitions of adherence and on neither basis was there a statistically significant difference between the groups (Table 8).

| Adherence to allocated treatment | Difference in mean POEM (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Adjusted | |

| 16-week repeated measures model | ||

| ‘More than half’ or ‘every time’ compared with ‘less than half the time’ or ‘never’ | 0.35 (–0.58 to 1.28) | 0.32 (–0.37 to 1.02) |

| ‘Every time’ compared with ‘never’ | 0.23 (–0.79 to 1.24) | 0.38 (–0.39 to 1.15) |

Participants were also asked about adherence at 52 weeks. Table 9 shows that adherence remained high.

| Exacerbations | Treatment group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bath additive (N = 203) | No bath additive (N = 176) | |

| Use of bath additives | ||

| Every time | 118 (58.1) | 9 (5.1) |

| More than half the time | 55 (27.1) | 4 (2.3) |

| Less than half the time | 20 (9.9) | 18 (10.2) |

| Never | 10 (4.9) | 145 (82.4) |

| Number of baths per week | ||

| 1–2 | 69 (36.5) | 57 (35.6) |

| 3–4 | 65 (34.4) | 50 (31.3) |

| 5–6 | 28 (14.8) | 29 (18.1) |

| ≥ 7 | 27 (14.3) | 24 (15.0) |

Secondary outcomes

Exacerbations

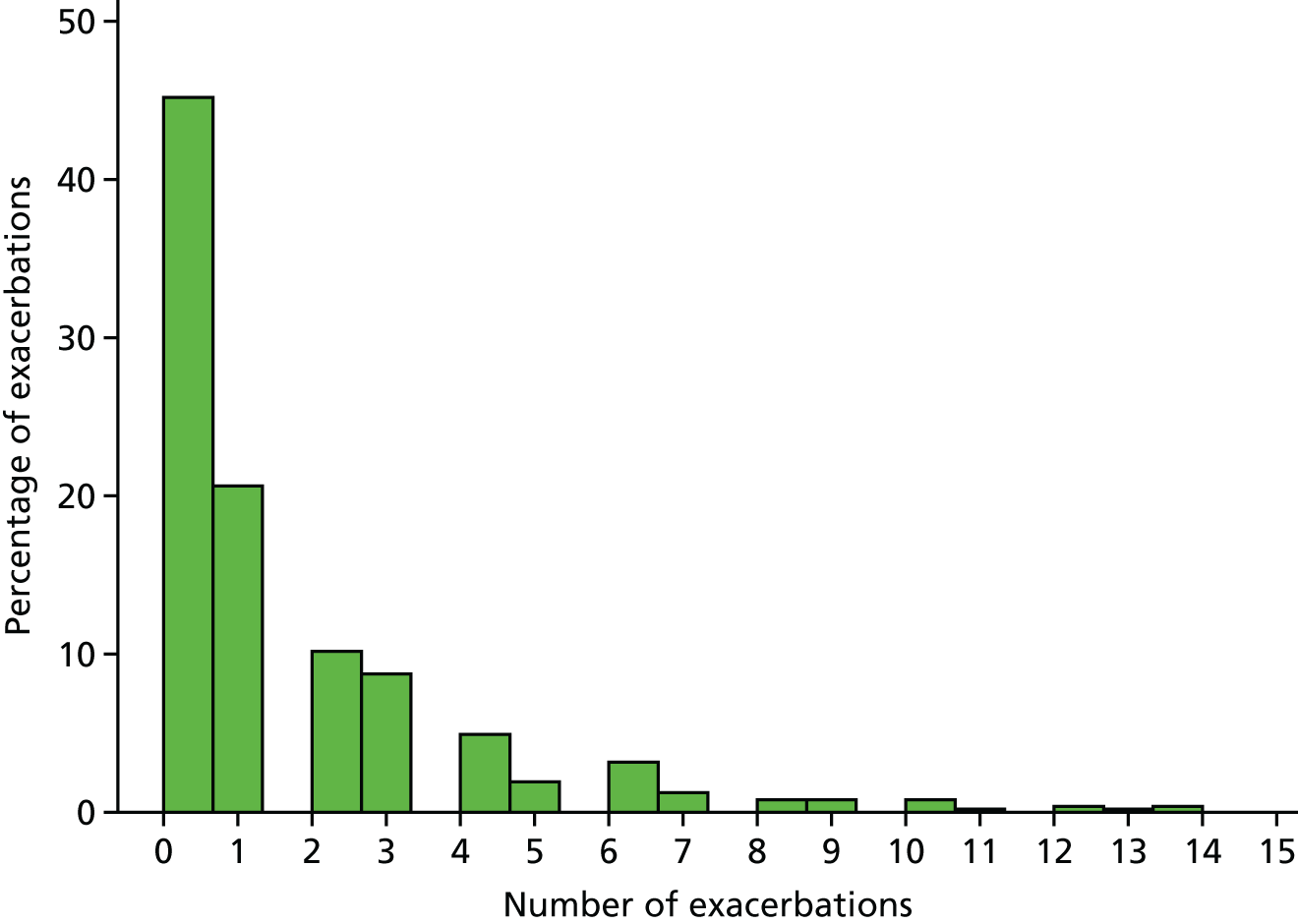

In total, we had exacerbations data for 470 (97.5%) children. Of these, 257 (54.7%) had at least one exacerbation as defined in the protocol (i.e. GP notes review recorded consultations in which there was mention of eczema and topical steroid or TCI was advised or prescribed).

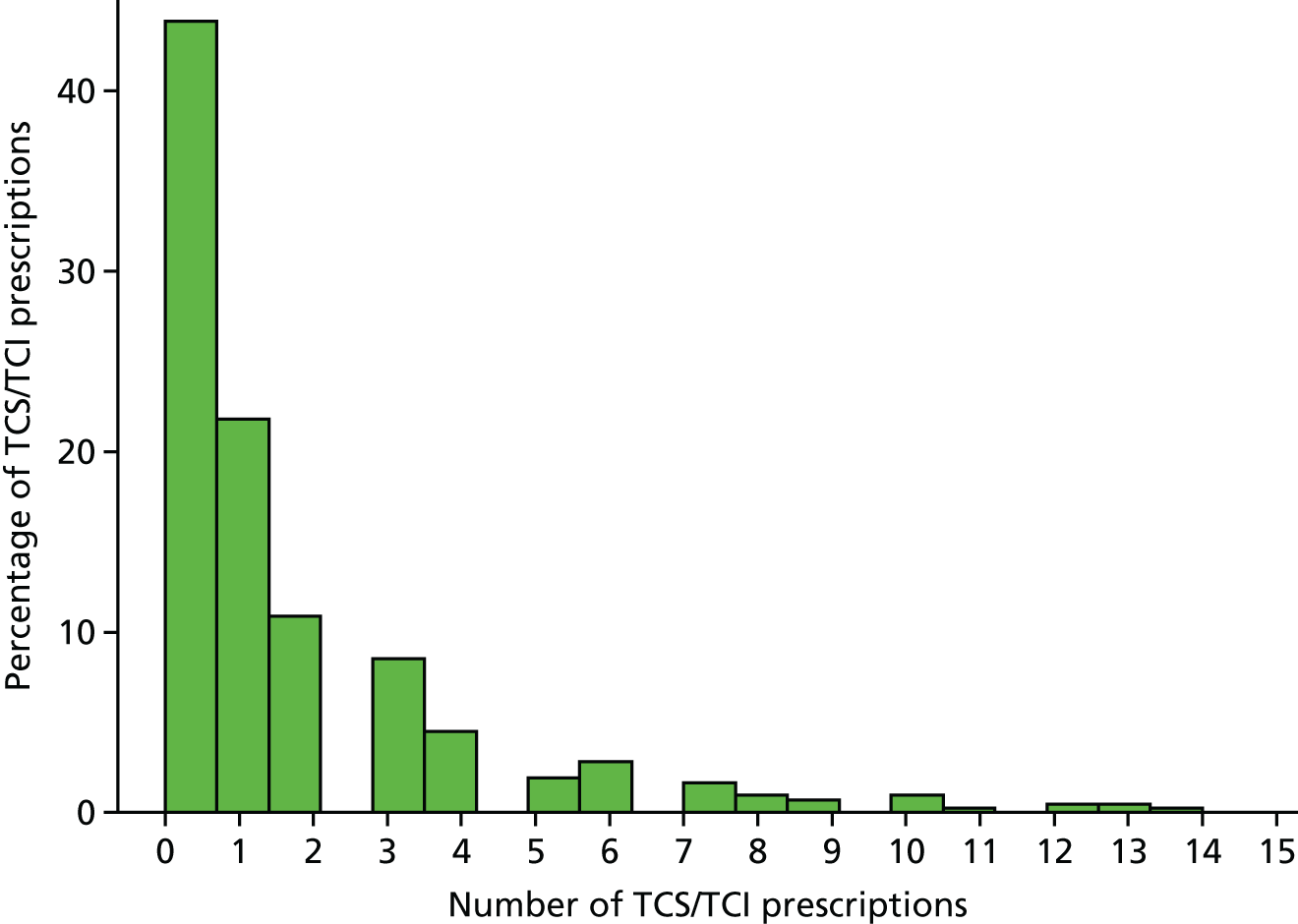

The distributions of the number of exacerbations is skewed and follows an approximately negative binomial distribution (Figure 7). As shown in Table 10, on average, the number of exacerbations was similar between groups. The unadjusted results indicated slightly more exacerbations in the no bath additive group, but in the adjusted model there was no significant difference in the number of exacerbations between groups.

FIGURE 7.

Distribution of exacerbations.

| Time point | Treatment group | RR exacerbations (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath additive | No bath additive | Univariate | Adjusted | |

| Median number of exacerbations (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 1.33 (1.02 to 1.75) | 1.24 (0.96 to 1.60) |

Eczema severity over 1 year (from baseline to 52 weeks): monthly Patient Orientated Eczema Measure scores

The difference between groups in monthly POEM scores from baseline to 52 weeks was explored and tended to be non-significant (Table 11 and Figure 8).

| POEM scores | Treatment group, mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bath additive | No bath additive | |

| Baseline | 9.5 (5.7) | 10.1 (5.8) |

| Week 4 | 7.6 (6.0) | 8.6 (6.1) |

| Week 8 | 7.3 (6.2) | 8.2 (5.8) |

| Week 12 | 7.7 (6.2) | 7.9 (5.9) |

| Week 16 | 7.1 (6.1) | 8.2 (6.3) |

| Week 20 | 6.9 (6.2) | 8.7 (6.5) |

| Week 24 | 7.3 (6.5) | 8.3 (6.7) |

| Week 28 | 7.4 (6.4) | 8.8 (6.5) |

| Week 32 | 7.8 (6.7) | 8.7 (7.0) |

| Week 36 | 7.2 (6.8) | 8.8 (6.8) |

| Week 40 | 7.3 (6.4) | 8.8 (6.7) |

| Week 44 | 6.9 (6.3) | 8.2 (6.4) |

| Week 48 | 7.4 (6.6) | 8.6 (6.9) |

| Week 52 | 7.1 (6.2) | 8.0 (6.4) |

FIGURE 8.

Patient Oriented Eczema Measure scores during the 52-week secondary outcome period, by group.

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups at 52 weeks, based on monthly POEM scores over the period, and the CIs were well below 2 points (Table 12).

| Time point | Treatment group, mean (SD) | Univariate difference in mean POEM (95% CI) | Adjusted difference in mean POEM (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath additive | No bath additive | |||

| Secondary outcome: monthly repeated measures | ||||

| Over the 52-week period (repeated measures) | 7.3 (6.3) | 8.4 (6.4) | 0.99 (0.03 to 1.96) | 0.75 (–0.05 to 1.55) |

Dermatitis Family Impact Questionnaire

The distribution of the DFIQ was very skewed, with almost two-thirds of participants (62.9%) scoring ≤ 4 out of 27 on the scale. Therefore, a non-parametric approach has been used. The quantile regression compares the median values rather than the means. There was no statistically significant difference in the DFIQ at either 16 or 52 weeks (Table 13).

| Prescriptions | Treatment group | Univariate difference in median DFIQ (95% CI) | Adjusted difference in median DFIQ (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath additive (n = 230) | No bath additive (n = 186) | |||

| Median DFIQ at baseline (IQR) | 2 (1–6) | 3 (1–7) | – | – |

| Median DFIQ at 16 weeks (IQR) | 2 (0–5) | 3 (1–7) | 1.00 (0.09 to 1.91) | 0.29 (–0.57 to 1.14) |

| Median DFIQ at 52 weeks (IQR) | 2 (0–5) | 2 (0–6) | 0.00 (–0.93 to 0.93) | –0.29 (–1.36 to 0.79) |

Health-related quality of life

See Chapter 4, Health economic evaluation, for a discussion of the CHU-9D.

Use of topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors

There were a total of 671 prescriptions for TCSs and 32 prescriptions for TCIs (Table 14). As shown in Figure 9, the distribution is skewed, with 44% children receiving no TCS or TCI prescription and 85% receiving fewer than five prescriptions over the 52-week study period.

| Number of prescriptions | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Bath additive (n = 258) | No bath additive (n = 164) | |

| Total number of TCS/TCI prescriptions | 325 | 346 |

| Median number of TCS/TCI prescriptions | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) |

FIGURE 9.

Prescriptions for TCSs and TCIs.

Subgroup analysis

All of these analyses are intended to be hypothesis generating rather than hypothesis testing as the trial was not powered to explore the effect in subgroups and there is a risk of type I error, in which a statistically significant result is found simply because the data have been tested multiple times rather than because a genuine difference exists between the groups. However, there seems to be weak evidence in favour of an interaction with age. We cannot exclude the possibility of a small effect of bath additives among children aged < 5 years, as the no bath additive group had a POEM score 1.3 points higher than the group with bath additives. The upper limit of the 95% CI was 2.3, still below the now widely accepted POEM minimal clinically important difference of 3 points but reaching what we said would be considered clinically meaningful in this trial (i.e. 2 points).

A significant interaction effect was also seen in the frequency of bathing as reported at 16 weeks. There was no statistically significant difference in those children who bathed 1–4 times per week; however, in those children who bathed ≥ 5 times per week, the POEM score was 2.3 points higher (95% CI 0.63 to 3.91) in the no bath additive group. The upper CI reached 3.9, suggesting that there may be a clinically meaningful benefit to bath additives in this group, but this is a small group, with only 77 in the bath additive group and 66 in the no bath additive group (Table 15).

| Primary outcome: 16-week repeated measures | N (%) | Treatment group, mean (SD) | Interaction term (95% CI) | Adjusted difference in mean POEMa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath additive | No bath additive | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| < 5 | 256 (53.1) | 6.99 (5.67) | 9.09 (6.01) | –1.43 (–2.02 to –0.15) | 1.29 (0.33 to 2.25) |

| ≥ 5 | 226 (46.9) | 7.97 (6.24) | 7.52 (5.92) | –0.29 (–1.21 to 0.63) | |

| Baseline severity | |||||

| Clear/mild (0–7) | 187 (38.8) | 4.78 (4.26) | 5.22 (4.58) | –0.05 (–1.14 to 1.05) | –0.07 (–1.08 to 0.95) |

| Moderate (8–16) | 233 (48.3) | 8.14 (5.54) | 9.18 (5.46) | 0.65 (–0.45 to 1.74) | |

| Severe/very severe | 62 (12.9) | 14.63 (6.16) | 13.03 (6.92) | –1.16 (–3.62 to 1.32) | |

| Use of leave-on emollient | |||||

| 0–4 days per week | 138 (28.6) | 7.64 (6.68) | 6.43 (5.42) | –0.02 (–2.05 to 2.01) | 0.26 (–1.34 to 1.86) |

| 5–7 days per week | 344 (71.4) | 8.61 (5.74) | 7.93 (6.14) | 0.69 (–0.39 to 1.76) | |

| TCS use | |||||

| Any | 241 (50.7) | 8.40 (6.19) | 9.35 (6.21) | 0.52 (–1.35 to 2.40) | 1.22 (–0.18 to 2.63) |

| None | 234 (49.3) | 6.63 (5.64) | 7.39 (5.66) | 0.58 (–0.64 to 1.81) | |

| Frequency of bathing at 16 weeks | |||||

| 1–4 times per week | 255 (64.1) | 7.93 (5.94) | 8.00 (5.82) | 2.14 (0.21 to 4.07) | –0.26 (–1.38 to 0.87) |

| ≥ 5 times per week | 143 (35.9) | 6.30 (5.70) | 8.75 (6.12) | 2.27 (0.63 to 3.91) | |

| Prior belief in bath additive | |||||

| 1–3 low belief | 106 (29.4) | 7.93 (6.10) | 9.27 (6.25) | 0.85 (–0.52 to 2.21) | 1.17 (–0.78 to 3.13) |

| 4–6 moderate belief | 158 (43.8) | 8.37 (6.06) | 8.68 (6.02) | –0.16 (–1.77 to 1.45) | |

| 7–9 high belief | 97 (26.9) | 5.70 (5.06) | 7.09 (6.05) | 1.80 (0.04 to 3.56) | |

| Use of soap substitute at 16 weeks | |||||

| Any | 89 (20.8) | 8.09 (6.10) | 9.31 (5.88) | 1.30 (–0.97 to 3.57) | 1.72 (–0.44 to 3.88) |

| None | 340 (79.3) | 7.17 (5.82) | 7.99 (5.87) | 0.36 (–0.63 to 1.35) | |

Adverse events

No serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported during the trial period; however, one SAE, which occurred in the bath additive group and was unrelated to the trial intervention, was detected during the notes review process.

Over the first 16 weeks, 34.5% in the bath additive group and 35.4% in the no bath additive group reported at least one adverse event on weekly questionnaires. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups [odds ratio (OR) 1.40, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.47] (Table 16).

| Adverse events | Treatment group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bath additive | No bath additive | |

| 16 weeks | ||

| Slips | 44 (17.5) | 52 (24.8) |

| Stinging | 4 (1.6) | 4 (1.9) |

| Redness | 35 (13.9) | 48 (23.0) |

| Refuses a bath | 21 (8.3) | 25 (12.0) |

| 52 weeks | ||

| Slips | 56 (22.2) | 63 (30.1) |

| Stinging | 7 (2.8) | 4 (1.9) |

| Redness | 44 (17.5) | 61 (29.2) |

| Refuses a bath | 30 (11.9) | 31 (14.8) |

Over the full 52-week study period, 40.2% of the bath additive group and 41.3% of the no bath additive group reported at least one AE on questionnaires. As at 52 weeks, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups (OR 1.36, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.33).

Chapter 4 Health economic evaluation

This chapter presents the economic analysis of the relative resource use, costs, clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness outcomes of emollient bath additives when used in addition to standard management versus standard management without bath additives for childhood eczema.

Introduction

Eczema is a skin condition that is very common in children. The economic implications of eczema in children are described in the introduction (see Chapter 1) of this report and are well documented in the literature. 33 Recommendations by the NICE guideline9 on childhood eczema suggest the use of a ‘complete emollient therapy’ that includes bath emollient (bath additives) in addition to emollient cream and soap substitutes. However, the guideline also highlights the uncertainty from limited evidence on the benefit of including bath additives in this combination of treatments. In addition to the clinical question that this uncertainty generates, there is also an economic question to be addressed. This is even more important in the current economic climate in which NHS resources are extremely limited. Given that some estimates have suggested that bath additives account for more than one-third of the total costs treating eczema in childhood,9,13 the relevance of the economic question becomes crucially important.

Economic evaluations alongside clinical trials (EEACT) provide timely information with high internal validity. 50 When conducting EEACT, the quality of the economic information derived depends on the features of the trial’s design. However, it is generally acknowledged that pragmatic effectiveness trials are the best vehicle for economic studies. 50 For the economic analysis, the pragmatic nature of the trial means that the external validity of the economic results is increased by avoiding protocol-driven biases, such as artificial resource use.

Economic evaluations alongside clinical trials involve the comparative analysis of alternative interventions in terms of their costs and benefits. 51,52 Methodological guidelines for EEACT differ in their recommendations for the most appropriate perspective that should be adopted. As a minimum, it is recommended that analysts adopt a health system perspective for analysis. For England and Wales, this is currently considered to include the NHS and personal social services. 53

The BATHE trial was a multicentre, pragmatic, non-blinded, randomised controlled trial with two parallel arms. The study population for the BATHE trial is described in Chapter 3, Results. Ideally, the economic evaluation would be factored into sample size calculations using standard methods, based on asymptotic normality, or by simulation. 54,55 However, it is common for the sample size of the trial to be based on the primary clinical outcome alone. As a consequence, sample size restrictions necessitate a focus on estimation rather than hypothesis testing for our economic evaluation. 56 The sample size in the BATHE trial was calculated for repeated measures ANOVA in weekly POEM scores over the 16-week observation period. In our protocol and the health economics analysis plan (HEAP) we stated our intention to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis using the primary outcome, POEM, a cost–utility analysis using utility values obtained from the paediatric CHU-9D and to also report cost per exacerbation avoided. However, the economic results in this study reveal that none of these outcomes showed a clinically important difference. Therefore, our approach was to proceed by reporting our findings and ultimately presenting our economic evaluation in the form of cost–consequences analysis,57 as per our HEAP. Following this, the economic evaluation was conducted from the NHS and Personal Social Services perspective; however, family-borne costs (FbCs), in the form of additional analyses, were also incorporated and the combined results are also reported in this chapter.

Methods

The range of cost and effectiveness outcomes used are described in this chapter. The economic evaluation used resource use, cost and effectiveness outcomes data collected for all of the participants enrolled in the BATHE trial as described in Chapter 3, Results. The time points of the evaluation were the 16- and 52-week follow-up periods used for the trial. The maximum 52-week follow-up period of the trial means that discounting of costs and outcomes was not relevant and was not conducted. The intervention was conducted in primary care settings; however, the setting for the economic evaluation covers both primary and secondary care resource use.

The analyses were carried out using the ITT approach, and individual patient data were estimated for each participant. All economic analyses were performed using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and Microsoft Excel.

Resource use and valuation, health-related quality of life and data collection tools

Resource use

The categories of resource use included in this study were determined by the perspective of the analysis (NHS). For each participant, health-care resource utilisation was measured using two data sources.

First, a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) questionnaire58 adapted for the BATHE trial was used to collect resources reported by parents/carers. The CSRIs were completed at baseline asking parents about resource use over the 3-month period prior to randomisation, at 16 weeks (the trial primary end point) and after that in 3-month intervals up to 52 weeks, as this is considered to be the most appropriate recall length for reporting. 59 The CSRI asked about resource use stemming from the child’s eczema and, in addition to providing information on primary and secondary care resource use, it also allowed reporting of resources associated with salient clinical events, such as days lost from school for children and from work for parents because of their child’s eczema as well as FbCs.

Second, GP electronic patient records were examined in order to record resource use on study case report forms called GP notes review (NR) throughout this report. The selection process for each resource variable was undertaken by assessors and the principal investigator (MS) identifying the ‘eczema-related’ items as opposed to ‘other’ resource use. The NR forms used in this study were designed to capture the frequency and intensity of care provided to each child, based on GP practice record and any complications experienced. The NR forms recorded GP and other primary care consultations, referrals to secondary care, as well as prescriptions and medications during the trial period for each participant.

We have used the triangulation of resource use data to validate our data by cross-verifying the same information. The data were used not in a complementary manner, integrating results, but for verification and better understanding of the data. Resource use, recorded using both approaches, is reported separately in the form of mean (SD) and 95% CIs, taking into account the skewness of the data.

Valuation

The valuation of resources used within the trial period involves quantifying each resource item used by multiplying it by the perspective unit cost of each item. The products estimated were summarised to calculate the individual cost for each participant. The principal costs are those associated with the use of bath additives and the primary and secondary health-care contacts and medications attributed to eczema. The comprehensive profile of resources captured for each participant was valued using national tariffs and expressed in Great British pounds, 2016 prices. The primary care resource use items were valued using the Personal Social Services Research Unit Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2016. 60 The resource use items from the secondary care data were mainly valued using the NHS Reference Costs for 2015 to 2016. 61 When necessary, the unit costs were adjusted for inflation using the hospital and community health services index. 61

Costs

Once resources were identified and valued, individual patient costs were estimated, mean estimates by group were calculated and differences in mean costs (ΔC) and mean effects (ΔE) between the groups were calculated. Arithmetic means were used to estimate differences between groups. Independent sample t-tests were used to test for differences in costs and effects observed between the groups; all statistical tests were two-tailed. However, cost data often do not conform to the assumptions for standard statistical tests for comparing differences in arithmetic means. They are usually right skewed and truncated at zero because of the small number of participants with high resource use and those participants who incur no costs. The assessment of uncertainty for each measure was estimated and reported in the form of SDs and CIs for point estimates using regression models. 50

There were five main cost categories created from the data collection tools: (1) primary care resource use, (2) secondary care, including hospital admissions and accident and emergency (A&E), (3) medications for eczema, (4) prescriptions for eczema and (5) FbCs. Days lost from school for children and days lost from work because of their child’s eczema for parents are also reported.

Effectiveness outcomes

Three alternative outcomes were identified as relevant and of interest to policy-makers, providers, funders of care and patients. These were:

Health-related quality of life