Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/35/61. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in November 2016 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Luyt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Haemorrhage into the ventricles of the brain is one of the most serious complications of preterm birth, despite improvements in the survival of preterm infants. Large intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) carries a high risk of neurological disability and, by causing a progressive obliterative arachnoiditis at the basal cisterns and the outlet foramina of the fourth ventricle, disturbs the flow and absorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). 1 This leads to post-haemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD).

Severe IVH with PHVD is a neurological complication seen in preterm infants, with significant neurodisability in survivors. Infants most at risk (those born at < 32 weeks of gestation and with a birthweight of < 1500 g) have high rates of grade 3 or 4 IVH (around 6%), estimating approximately 800–900 new cases of grade 3 and 4 IVH annually in the UK. 2 Preterm birth rates are rising3 and survival rates of extremely preterm infants continue to improve;4 therefore, it can be projected that the number of infants affected by PHVD will increase in the future.

In the US National Institute of Child Health and Development Neonatal Network, one-third of infants with birthweights of < 1000 g develop IVH, and, of those, about 10% require implantation of a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt for PHVD. 5 In a European study,6 29% of all preterm infants with severe IVH required implantation of a VP shunt.

Of children with PHVD, 40% will develop cerebral palsy (CP) and approximately 25% will have multiple disabilities. The National Institute of Child Health and Development study,5 the largest of its kind, studied > 1000 preterm infants at 18–22 months corrected age with severe grade IVH (grade 3 and 4), of whom almost 25% had PHVD (defined as requirement for a VP shunt). They demonstrated significant risk of cognitive impairment with PHVD with a median Mental Development Index (MDI) score 20 points lower in children with PHVD than in those with severe grade IVH without PHVD. The median MDI in children with grade 3 IVH and PHVD was 61 points, and in those with grade 4 IVH and PHVD it was 50 points. Overall, 68% of children with severe grade IVH and PHVD had moderate cognitive impairment [MDI below two standard deviations (SDs)] and 41% had severe cognitive impairment (MDI below three SDs). Furthermore, 70% of children with PHVD had CP and 30% had visual impairment. The presence of a haemorrhagic parenchymal infarction, in addition to PHVD, increased the risk of CP to between 80% and 90%. 5 A logistic regression analysis7 of factors affecting school performance at 14 years of age in a cohort of 278 preterm infants showed that peri- or intra-ventricular haemorrhage was the primary risk factor for special education. Intraventricular blood and ventricular expansion have adverse effects on the immature periventricular white matter by a variety of mechanisms including physical distortion, raised intracranial pressure,8 free radical generation facilitated by free iron9 and inflammation. 10

The prevalence of visual defects is higher among prematurely born children than children born at term11 and, in particular, the spectrum of vision problems known collectively as ‘cerebral visual impairment’ (CVI) is a recognised complication of preterm brain injury, particularly if involving the periventricular white matter. 12 Visual functions correlate with neurodevelopmental outcome and brain volume in preterm infants. 13 Severe CVI is the leading cause for children being registered as blind in the UK14 and the developed world and may additionally be associated with ocular, optic nerve or refractive problems that cause further impairment. Less severe CVI can damage visual skills and have an important effect on school performance and tasks of everyday life. 15 Clinical assessment of CVI is difficult before the age of 5 years; however, a recent study16 found evidence of CVI in 89% of children with known central nervous system damage.

Every preterm infant with severe CP or severe cognitive or visual impairment will require lifelong parental and social care. The cost to society resulting from the complications of prematurity is significant. Based on 2003 US figures,17 the estimated lifetime costs per infant with CP, severe cognitive impairment or blindness is £614,000, £675,000 and £400,000, respectively. Data from the UK EPICure study18 indicate that, by 11 years of age, the annual health and social service costs of children with serious neurodevelopmental disability are almost double those of children without disability (£1225 vs. £695, respectively). This adds a significant additional economic burden on the NHS and social care. This estimate excludes the substantial economic burden on parents/carers, special educational services and other public funds. A recent confidential inquiry into premature death in adults with learning disabilities in England highlighted the complex lifelong health and social care needs of individuals with learning disabilities. On average, each person with learning difficulties had five additional medical conditions and received seven prescription medications; 64% of individuals lived in residential care homes, the majority with 24-hour paid-nursing care. 19

Reducing the rate of VP shunt insertion has been an important long-term objective in the management of IVH and PHVD. The large amount of blood and protein in the CSF combined with the small size and instability of the patient makes early VP shunt surgery impossible. Shunt implantation at the generally accepted weight threshold of 2 kg, usually around term age, is still associated with a higher infection and malfunction rate. 20,21 Unfortunately, several interventions have failed to reduce the need for shunt insertion, and no intervention has reduced neurodisability rates as a result of PHVD. Repeated lumbar punctures (LPs) are often ineffective at allowing removal of enough CSF. Direct ventricular puncture through the anterior fontanelle leads to needle track damage through the brain parenchyma. Repeated LPs or ventricular taps do not reduce the risk that a shunt will eventually be required; they have no effect on neuromotor impairment and are associated with a significant risk of ventriculitis (at 7% in the Ventriculomegaly Trial22–24).

In an effort to control PHVD by reducing CSF production, the International PHVD Drug Trial Group25 investigated the effects of acetazolamide and frusemide in a randomised trial in 1998. Not only did these drugs not lead to an improvement in neuromotor development or CSF diversion requirements, but the data monitoring committee stopped the trial because of worse outcome in the treated group.

In practice, once two LPs or one ventricular tap have been necessary to control the ventricular dilatation, insertion of a ventricular reservoir is preferred. A reservoir provides an easy and safe route for repeated aspiration of ventricular CSF, with low infection rates. 6,26 Insertion requires an anaesthetic in a neurosurgical theatre and can be safely performed in babies weighing < 800 g. This is a temporary measure and allows repeated drainage of CSF until the need for permanent CSF diversion can be established through VP shunt insertion. The most commonly encountered risks after reservoir insertion are infection and malfunction. 6,26

The timing of insertion of a ventricular reservoir remains controversial. In a retrospective study,27 early insertion, before crossing the 97th + 4 mm ventricular index line, was associated with lower rates of VP shunt insertion. The Early vs Late Ventricular Intervention Study (ELVIS; ISRCTN43171322)28 randomised between the two treatment thresholds, with death or shunt dependence and disability at 2 years being the main treatment outcomes. The trial has ended but results are as yet not published. Endoscopic lavage is a new neurosurgical intervention used for PHVD in which the ventricles are washed out under direct vision using a small endoscope. A small feasibility study29 using historical controls seemed promising in terms of safety and reducing the need for VP shunt insertion. Long-term outcomes are not known and the research group concluded that this intervention needs to be tested objectively in a randomised controlled trial (RCT).

In summary, no medical or surgical intervention for PHVD has objectively demonstrated either a reduction in the need for a permanent VP shunt or a reduction in death or neurodisability. Current practice in the UK consists of repeated LPs followed by insertion of a ventricular reservoir to enable regular tapping to reduce pressure. The complications are a combined infection and device failure rate exceeding 10%, as highlighted above.

Drainage, irrigation and fibrinolytic therapy (DRIFT)30–32 is a surgical approach that was developed because of the unsatisfactory results of other treatments. The objectives are to reduce pressure and distortion early and to remove proinflammatory cytokines and free iron from within the ventricles. The procedure involves insertion of right frontal and left occipital ventricular catheters under anaesthesia. Tissue plasminogen activator (TPA), a fibrinolytic, is injected intraventricularly at a dose that is insufficient to produce a systemic effect and this is left for approximately 8 hours. Under continuous intracranial pressure monitoring, the ventricles are irrigated by artificial CSF through the frontal catheter. The occipital ventricular catheter is simultaneously connected to a sterile closed ventricular drainage system and the height of the drainage reservoir adjusted to increase or decrease drainage to maintain an intracranial pressure below 7 mmHg and a net loss of 60–100 ml of CSF per day. The drainage fluid initially looks like cola but gradually clears, at which point irrigation is stopped and the catheters removed. This commonly takes 72 hours but can take up to 7 days.

After initial feasibility testing showed that DRIFT was technically possible and promising,30 the DRIFT randomised trial started recruiting in 2003. Babies were elegible for the study if they were born preterm, they had had IVH and their cerebral ventricles had expanded over predetermined limits. With parental consent, 77 babies were randomised in Bristol, Katowice (Poland), Glasgow or Bergen (Norway) to either DRIFT or standard therapy, which consisted of non-surgical conventional management (LPs to control excessive expansion and pressure symptoms). If repeated LPs were needed, a ventricular reservoir was surgically inserted to facilitate tapping CSF.

There were no differences in the short-term outcomes: need for VP shunt or death at 6 months. 33 At 2 years post term, severe disability or death was significantly reduced in the DRIFT group. 32 There was an important decrease in severe cognitive disability (Bayley MDI three SDs below the mean) from 59% to 31% [adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.17, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.05 to 0.57] and the difference in median MDI was > 18 points. Sensorimotor disability remained substantial in both treatment groups at 2 years: overall, 48% were unable to walk, 20% were unable to communicate and 9% had no useful vision. Severe sensorimotor disability was less common in the DRIFT group but without reaching statistical significance.

Although short-term neurodevelopmental measures are essential in the initial management of perinatal interventions, longer-term measures provide far greater validity in assessing long-term functioning (and the medical, societal and financial implications of these). Therefore, the main objective of the follow-up study of the DRIFT trial was to assess if the cognitive advantage seen at 2 years with DRIFT continued through to school age. Secondary objectives were to assess the long-term visual and motor function, emotional and behavioural difficulties, brain structure and quality of life (QoL) as well as the cost-effectiveness of DRIFT.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial design

The DRIFT study was originally conducted in 2003–6 as a multicentre RCT that recruited premature infants with PHVD. Infants were randomised to receive standard treatment or surgical DRIFT. Now, 10 years on, the children have been followed up to investigate the difference in cognitive ability at school age between the two groups.

The school-age follow-up of the DRIFT trial was designed in partnership with the children and parents who attended a small feasibility study in Bristol. Families gave their input into the methods for initial contact, parent and participant literature, feedback on the study assessments and the timing of the assessments so as to not distract from school attendance. These families gave valuable advice on how to make the assessment day engaging for the children. Mr Steven Walker-Cox and his son, who have lived experience of prematurity and DRIFT, helped to write the letter of invitation, study materials and information leaflets and consent/assent forms for parents and children. They also contributed to the research ethics application.

Research ethics approval (14/SW/1078) was granted by the National Research Ethics Service Committee South West-Central Bristol prior to commencing the school-age follow-up. The University of Bristol acted as sponsor.

Participants

Children previously enrolled in, and randomised to, the DRIFT trial between 2003 and 2006 were from Bristol, Katowice, Glasgow or Bergen.

Children were eligible for the DRIFT trial if they matched all of the following criteria:

-

IVH documented on ultrasonography.

-

Age of no more than 28 days.

-

Progressive dilatation of both lateral ventricles with each side:

-

ventricular width 4 mm over the 97th centile (a)

OR

-

anterior horn diagonal width 4 mm (1 mm over 97th centile) (b)

-

thalamo-occipital distance 26 mm (1 mm over 97th centile) (c)

-

third ventricle width 3 mm (1 mm over 97th centile) (d)

OR

-

measurements above (a) or (b–d) on one side combined with obvious midline shift indicating a pressure effect.

-

Exclusion criteria were:

-

prothrombin time of > 20 seconds

OR

-

accelerated partial thromboplastin time of > 50 seconds or a platelets count of < 50,000/µl.

Interventions

DRIFT was developed as a surgical approach for reducing iron and proinflammatory cytokines from CSF and reducing pressure and distortion early. The procedure involves insertion of right frontal and left occipital ventricular catheters under anaesthesia. TPA, a fibrinolytic, is injected intraventricularly at a dose that is insufficient to produce a systemic effect and this is left for approximately 8 hours. Under continuous intracranial pressure monitoring, the ventricles are irrigated by artificial CSF through the frontal catheter. The occipital ventricular catheter is simultaneously connected to a sterile closed ventricular drainage system and the height of the drainage reservoir adjusted to increase or decrease drainage to maintain an intracranial pressure below 7 mmHg and a net loss of 60–100 ml of CSF per day. The drainage fluid initially looks like cola but gradually clears, at which point irrigation is stopped and the catheters removed. This commonly takes 72 hours but can take up to 7 days.

Standard treatment consisted of up to two LPs to drain CSF followed by insertion of a ventricular reservoir with regular tapping of CSF to reduce ventricular distension to within the specified dimensions.

Primary outcome

Cognitive disability at school age

Cognitive assessments were undertaken by child psychologists. The British Ability Scales version three (BAS III)34 (see Appendices 1 and 2) was used for children with a developmental age of ≥ 3 years. For children who did not meet this threshold, the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID III)35 (see Appendix 3) was administered. The final scores were in the format of a cognitive developmental quotient (0 to 100+). The primary analysis was based on the cognitive scores of surviving children, although a sensitivity analysis that included children who died (as a result of their disability) was also carried out, in which the cognitive development quotient for these children could reasonably be assumed to be zero.

Secondary outcomes

Cerebral visual function

For the main visual outcomes, we used parent-reported data as they were available for the majority and could be compared with the 2-year outcomes. Parents were asked whether their child had vision that was of ‘No concerns’, ‘Normal with Correction’ or ‘Useful but not fully correctable’ or was ‘Blind or perceives light only’. A binary outcome was created that split these into a good visual outcome (no concerns/normal with correction) or a poor visual outcome (useful but not fully correctable/blind or perceives light only). A 23-question assessment of CVI was also carried out by the vision specialists36 (see Appendix 4). A mean score was created from all available questions and analysed between the groups. In the case of those who attended assessments in Bristol, vision specialists directly assessed a range of visual functions including visual acuity, visual field, eye movements and vision processing skills.

Sensorimotor disability

Assessments of motor function and disability were made by a paediatric physiotherapist. Children were assessed using the Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2 (Movement ABC)37 (see Appendix 5). As well as this assessment, the number and severity of CP were also compared between the two groups.

Emotional/behavioural function

Parents were asked to fill out the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)38 (see Appendix 6), which assesses how their child behaves in various circumstances; their final score classifies them as having ‘normal behaviour’ or ‘abnormal behaviour’.

Methods

Sample size

In total, 77 children (54 from Bristol and 20 from Poland, two in Glasgow and one in Bergen) were randomised to the DRIFT trial during 2003–6, of whom, 69 survived until the age of 2 years. Based on a similar effect size documented with severe cognitive disability at age 2 years, a two-group continuity-corrected chi-squared test with a 5% two-sided significance level would have 80% power to detect the difference in severe cognitive disability between a control group proportion of 59% and OR of 0.17 (i.e. an intervention proportion of 19.7%) when the sample size in each group is 28. With 60 infants (30 in each group), we would have 97% power (with an alpha of 5%) to detect a mean cognitive difference of one SD (commonly 15 points) between the DRIFT and control groups.

It was anticipated that 45 UK children would be assessed in Bristol and 15 Polish children in Katowice, assuming a 90% follow-up rate. Those from Bergen and Glasgow would be sought if numbers were proving difficult to obtain.

Randomisation

A computer-generated randomisation scheme was used to assign infants to treatment groups in a 1 : 1 ratio. 31 Given that the trial was taking place in four different centres, the randomisation process was stratified by centre in blocks of eight, 10 or 12. Each infant was allocated to treatment using sequentially numbered, doubled-up envelopes that each contained either a ‘DRIFT’ or ‘standard treatment’ card.

Envelope preparation and random number allocation were carried out using StatsDirect software (StatsDirect, Altrincham, UK) by a research assistant not involved in enrolment or treatment. Patients were enrolled by one of the neonatologist investigators, all of whom, at that stage, were blind to treatment allocation. When the informed consent process was completed and signed, the next trial envelope was opened and treatment allocation confirmed.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention delivery, once the envelope had been opened, it was not possible to blind practices/parents to their allocation to either DRIFT or standard treatment. At 10 years, all investigators (child psychologists, visual specialists, etc.) were blinded to treatment allocation and grade of IVH as these were not apparent. All analysts (statisticians/health economists) were blinded to treatment allocation as far as possible. Given that the results were published at 2 years in favour of the DRIFT arm, it could be argued that the statisticians could have easily assumed which group was which. However, they continued the analysis with groups A and B, and only the senior statistician was shown the allocation in order for a draft abstract to be written (February 2016). As soon as the deaths were analysed in April 2016, the statistician felt that she could no longer be classed as ‘blinded’.

Statistical methods

The main statistical analyses were prespecified using a statistical analysis plan (SAP) and the health economics using a health economics analysis plan. The final version of the SAP was accepted and agreed on 6 April 2016. Although a short interim analysis was completed in February 2016 on children assessed up to that point, no major changes were made to the SAP after this time. Given the large differences seen between the two groups at 2 years, it was difficult for the statistician to remain blinded. Final data analysis started on 6 April 2016 and finished in October 2016. Stata® 14.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all statistical and health economic analyses in this trial. Binary outcomes were presented as n (%) while continuous outcomes were presented as mean (SD)/median [interquartile range (IQR)], as appropriate. For secondary and subgroup analyses, emphasis was placed more on descriptive statistics than on p-values. An informal Bonferroni technique was applied when interpreting p-values; alpha divided by four secondary and seven subgroup analyses: 0.05 ÷ 11= 0.0045. The p-values for exploratory outcomes were interpreted with extreme caution.

Primary analysis

Cognitive assessments were undertaken by child psychologists. The BAS III (see Appendices 1 and 2) was used for children with a developmental age of ≥ 3 years. For children who did not meet this threshold, the BSID III (see Appendix 3) was administered. The final scores were in the format of a cognitive developmental quotient; therefore, a continuous variable. The primary analysis was conducted using the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle using linear regression. The DRIFT team had determined, a priori, the variables that they believed might confound the final result. Compatible with the previous investigation at 2 years, adjustments were made for grade of IVH, birthweight and gender.

Null hypothesis: the average score for cognitive disability is the same for both groups.

Alternative hypothesis: the average score for cognitive disability is different between the groups.

As stated in the protocol, we were also interested in the proportion of children alive and without severe cognitive disability (BAS III score of < 3 SDs for age) at 10 years compared with those with severe disability or who had died owing to disability. To avoid splitting the 5% alpha between two primary outcomes, it was added as a sensitivity analysis.

The primary hypothesis was that neurosurgical DRIFT would reduce severe cognitive impairement in children assessed at school age. This was measured using cognitive ability tests. At 10 years children were assessed using the BSID III (for those anticipated to be performing at below the 3 years level), BAS III early years (for those anticipated to be performing between the 3 years and 7 years levels) or BAS III school age scoring system (for the remainder).

A quotient score was generated in the following way:

-

Cognitive and language developmental age-equivalent (DAE) scores yielded from the BSID III were collected and averaged to produce an overall DAE.

-

DAE scores from the BAS III early years assessment were averaged across the core scales (verbal comprehension, picture similarities, naming vocabulary, pattern construction, matrices and copying) to produce an overall DAE. DAE scores of ‘less than 3′ were given an age of 2 years and 11 months.

-

DAE scores from the BAS III school age assessment were averaged across the core scales (recognition of designs, word definitions, pattern construction, matrices, verbal similarities and quantitative reasoning) to produce an overall DAE. DAE scores of ‘less than 5′ were given an age of 4 years and 11 months.

-

All DAE scores were then divided by the child’s actual age and then multiplied by 100 to achieve the child’s ‘Cognitive Quotient Score’.

Secondary analysis

Visual assessment

Visual assessments consisted of parent-reported outcomes and assessments carried out by vision specialists. The main visual outcome was parent reported, as used at 2 years. For the main visual outcomes, parents were asked whether their child had vision that was of ‘No concerns’, ‘Normal with correction’ or ‘Useful but not fully correctable’ or was ‘Blind or perceives light only’. A binary outcome was created that split these into a good visual outcome (no concerns/normal with correction) or a poor visual outcome (useful but not fully correctable/blind or perceives light only). Differences in the proportions of visually impaired children between the groups were assessed using logistic regression.

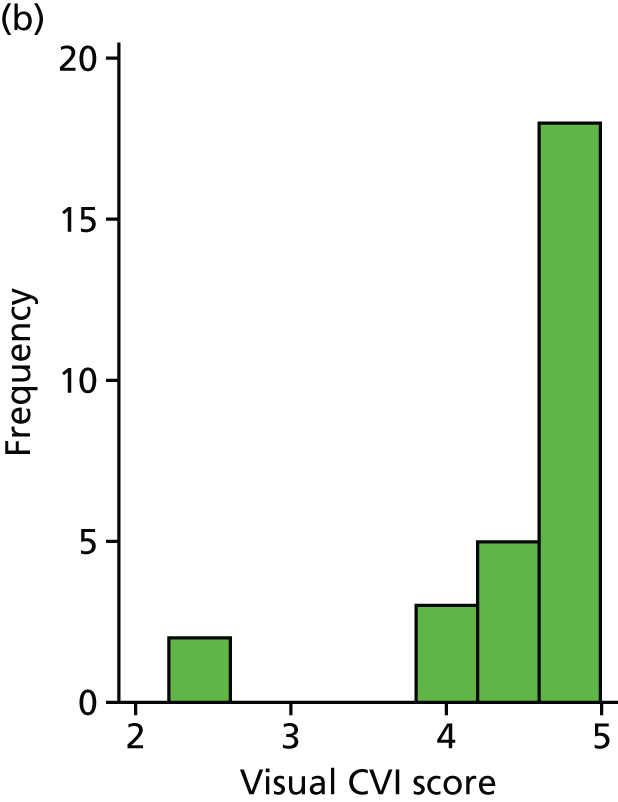

A 23-question assessment of CVI was also administered by the vision specialists. 36 An average score was derived from the answers to all available questions and analysed between the groups. This was based on applicability of the questions as in some cases (such as blindness) the questions were not appropriate. After analysis of the data, it was decided that the child who was blind should not have been given this visual assessment and, therefore, was removed from the analysis. Originally, we had prespecified that we would use a linear regression model to compare CVI scores. However, on inspection of the data, it became clear that the data were negatively skewed (with 22% of children scoring the maximum score of 5; see Results). Therefore, both a comparison of means and a non-parametric test were carried out to assess if interpretation was similar.

Motor function and disability

Assessments of motor function and disability were made by a paediatric physiotherapist. Children were assessed using the Movement ABC37 (see Appendix 5). Scores were then classified according to test recommendations as mild (green), moderate (amber) or severe (red). These was analysed using ordinal logistic regression. Children who could not complete the task owing to CP were automatically placed in the severe category (as prespecified in the analysis plan).

Cerebral palsy

The number of diagnosed cases of CP was also compared between the two groups using logistic regression. At 10 years, children were either diagnosed with CP or not diagnosed with CP. Severity of CP was classified using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS):39

-

Level 1 – children walk at home, school, outdoors and in the community and can climb stairs without the use of a railing.

-

Level 2 – children walk in most settings and climb stairs holding onto a railing.

-

Level 3 – children walk using a hand-held mobility device in most outdoor settings.

-

Level 4 – children use methods of mobility that require physical assistance or powered mobility in most settings.

-

Level 5 – children are transported in a manual wheelchair in all settings.

Children without CP or with CP level 1 or 2 were classified as ambulant.

Emotional/behavioural function

Parents were asked to fill out the SDQ38 (see Appendix 6), which assesses how children behave in various circumstances, with the final score being used to classify a child’s behaviour as ‘normal or ‘abnormal. Differences in the overall score between the two groups were assessed using linear regression. Differences between subscores were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U-test.

Sensitivity analysis

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to test robustness of the results from the statistical analyses and, in some cases, increase understanding of the relationship between the dependent and independent variables. All were performed in the same way as the primary analysis. All sensitivity analyses were prespecified before final analysis began. At 2 years, a binary outcome was used; therefore, the team decided to duplicate this at 10 years (removing the sensorimotor element). Accounting for deaths in a trial that focuses on neurodevelopmental outcomes is a hotly debated topic. 40 The team felt that various methods should be included as sensitivity analyses to ensure that results were consistent. Death was included in four different ways. Initially, only the three deaths post 2-year follow-up were included and given a score of 0. The team felt confident that this was appropriate given that these deaths could directly be linked to the child’s disability. These three deaths were also included in a binary outcome that combined them with those who had severe disability and an ordinal outcome of five categories where death was considered the worst outcome. Last, all deaths were included in the binary outcome (including the eight deaths before 2 years). Although this outcome reflects that used at 2 years it includes deaths which were unrelated to cognitive ability. Cause of death before 2 years was difficult to determine and many were linked to neonatal complications.

Sensitivity analyses included:

-

cognitive ability quotient (using BSID III/BAS III age-equivalent scores), including deaths as 0

-

proportion alive and without severe cognitive disability at 10 years versus severely disabled/died owing to disability

-

grading of disability (mild/moderate/severe/dead) as an ordinal outcome

-

imputation of missing data at 10 years (details below)

-

cognitive ability quotient for the Bristol cohort only.

Similarly to Biering et al. ,41 we chose to carry out five different imputation models, summarised in Table 1, that made different assumptions about the data, particularly death.

| Assumption | Deaths | Lost to follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre 2 years of age | Post 2 years of age | ||

| 1 | ✗ | CQ = missing, NI | CQ = missing, NI |

| 2 | ✗ | CQ = missing, death = 1 | CQ = missing, death = 0 |

| 3 | ✗ | CQ = 0, NI | CQ = missing, NI |

| 4 | ✗ | CQ = 0, death = 1 | CQ = missing, death = 0 |

| 5 | ✗ | ✗ | CQ = missing, NI |

Initially, baseline variables were assessed to determine if they were predictive of missingness in the primary outcome using logistic regression. We then established, using linear regression, if they were appropriate predictors of the primary model. Any baseline variables associated with the primary outcome of interest or its missingness were added to the imputation model to inform the imputation process.

Using Stata 14’s ‘mi impute chained’ function, we created 40 imputations and used predictive mean matching, as regression produced inappropriate imputations. A random seed of 65,898 was chosen for all models. All children lost to follow-up were assumed to be alive, as imputing a death indicator variable proved impossible.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroups were used to test whether or not the effects of the DRIFT intervention were more pronounced in certain subgroups of children. Although underpowered, tests of interaction between the dichotomised variables and treatment therapy were carried out to test whether or not treatment effect differed between subgroups. These interaction terms were added to the primary analysis model. All subgroup analyses were prespecified in the analysis plan apart from maternal education.

Subgroup analyses included:

-

gestation (≥ 28 weeks vs. < 28 weeks)

-

grade of IVH (grade 3 vs. 4)

-

age of randomisation (day 1–20 vs. ≥ 21 days)

-

unilateral versus bilateral dilatation on ultrasonography at randomisation

-

gender

-

pre- and post-enhanced vigilance in 2006

-

maternal education (post hoc).

Exploratory analyses

Although added before final analysis in April 2016, these were not prespecified in the trial protocol; therefore, they are only exploratory analyses and should be interpreted with this in mind.

-

Educational outcomes:

-

mainstream schooling versus special school

-

special educational needs (SEN) support, yes/no

-

Key Stage 1 (KS1) scores

-

Key Stage 2 (KS2) scores

-

neurosurgical interventions after the neonatal period.

-

-

Proportion with reservoirs.

-

Shunt, yes/no (as assessed at 6 months).

-

Death, yes/no (as assessed at 6 months and 2 years).

Neuroimaging

At 10 years, children assessed in Bristol who consented, and had no contraindications, to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were eligible for structural brain MRI.

Structural MRI scans were acquired on a 3 tesla Siemens Skyra scanner (Erlangen, Germany) with the use of a 32-channel radiofrequency head coil using 3D full volume T1-weighted inversion recovery gradient echo. Magnetisation-Prepared Rapid Gradient-Echo sequence (MP-RAGE) was also acquired in the sagittal plane, comprising 192 slices; repetition time: 1900 ms; time of echo: 2.2 ms; 0.9 mm isotropic voxel; matrix: 128 × 128. T2 Turbo Spin Echo Axial plane time to acquisition: 2:53; voxel size: 0.4 × 0.4 × 3.0 mm; 40 slices.

Participants were scanned after parental consent, participant assent and a safety check. They were excluded if contraindications to MRI were identified or if travel to Bristol was not possible.

Scans were assessed blinded to treatment allocation in one sitting by a team of three neonatal specialists with neuroimaging interests (ASC, AW, KL) and two neurosurgeons (IP, KA). Each scan was classified by consensus as follows:

-

residual catheter tracts visible (frontal or occipital)

-

parenchymal lesions

-

ventricular reservoir in situ

-

VP shunt in situ

-

evidence of possible active hydrocephalus (dilated ventricles)

-

residual clinical condition requiring neurosurgical referral.

Chapter 3 Trial results

Participant flow

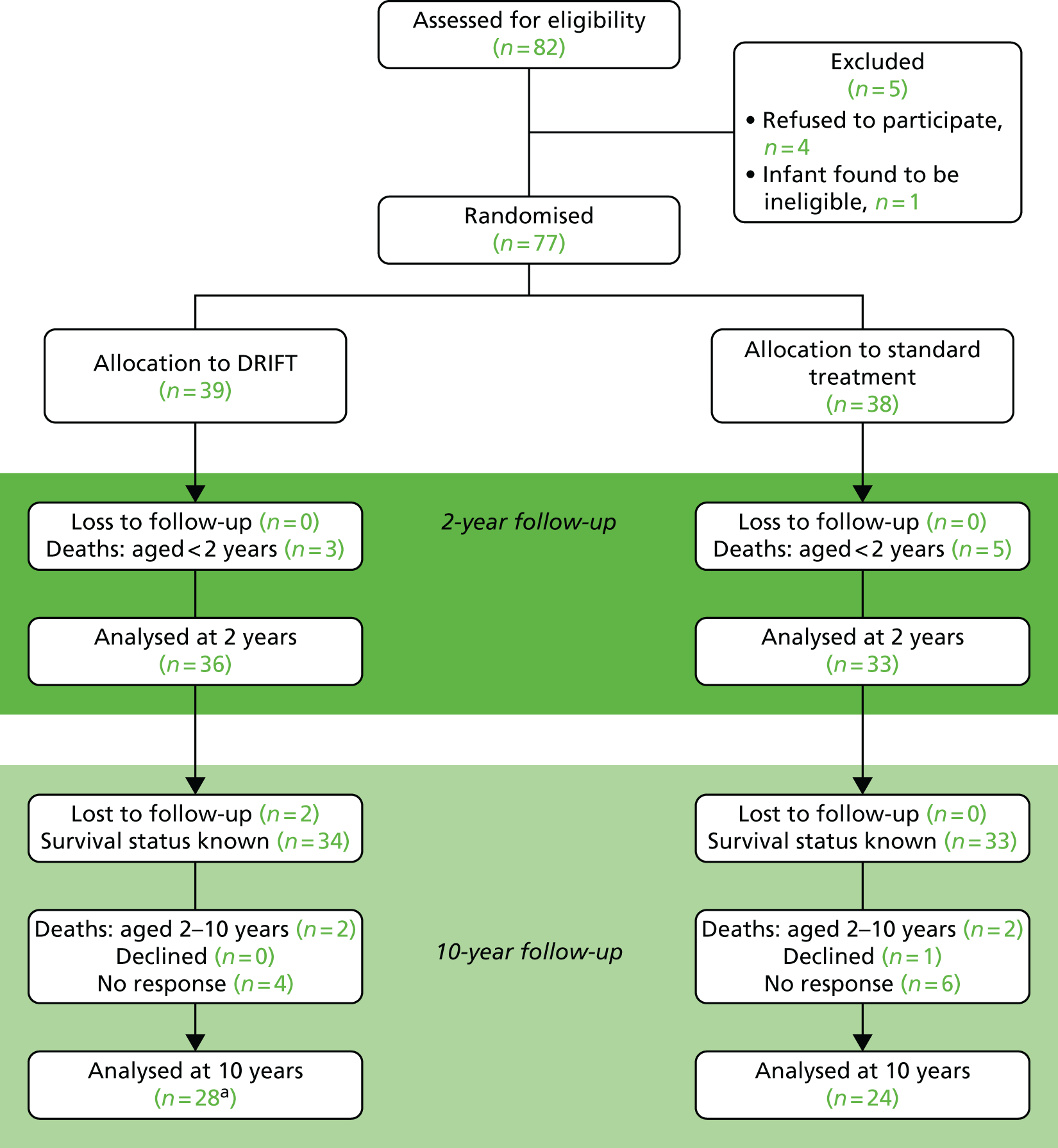

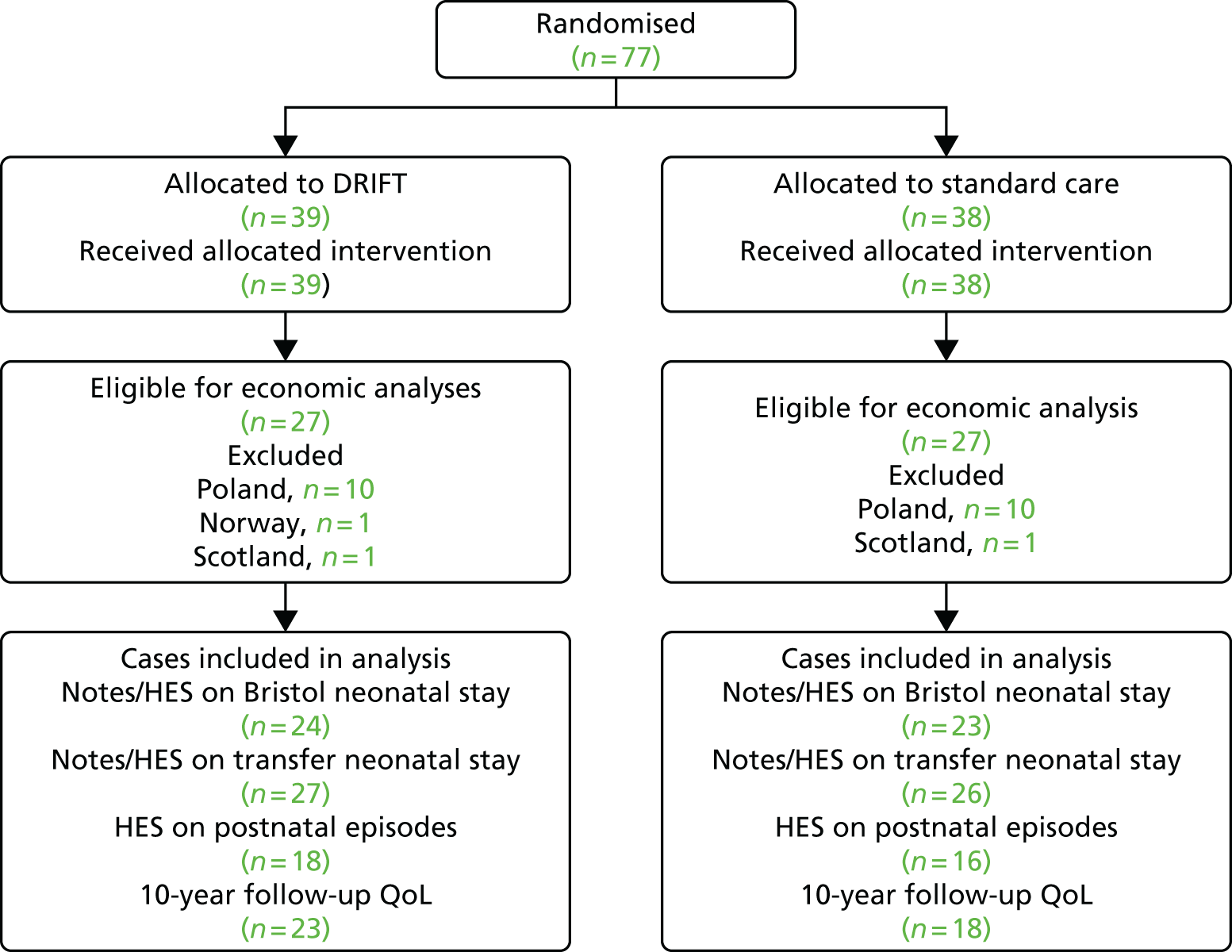

Figure 1 shows the layout of the trial and the different levels of drop-out and analysis. At 2 years’ follow-up there had been eight deaths but no loss to follow-up. At 10 years’ follow-up, four more deaths had occurred as well as two children who could not be traced, one who declined to participate in the follow-up and 10 non-responders.

FIGURE 1.

DRIFT CONSORT diagram. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials. a, One child did not complete a cognitive text and, therefore, could not be included in the primary analysis.

Recruitment

Originally, when the trial began, 77 babies were recruited to either receive DRIFT or standard treatment (n = 39 and n = 38, respectively). During this period, the trial was temporarily stopped by the Data Monitoring Committee, which was concerned by the rate of secondary haemorrhages; however, the trial was allowed to continue with increased vigilance. After a further 6 months, an a priori interim analysis was performed and the trial was closed owing to the low chance of seeing a significant result in the primary outcome – reduction in shunt surgery/death. 31 These children were then followed up and underwent numerous tests at approximately age 2 years. 32 Overall conclusions were that the 6-month time point was too soon after randomisation to be able to evaluate the intervention, while the 2-year follow-up showed promising results in favour of the DRIFT intervention. At 2 years’ follow-up there had been three deaths in the intervention arm and five in the standard treatment arm. The intervention appeared to reduce severe cognitive/sensorimotor ability or death (adjusted OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.82). At this time point, all of the parents consented to take part, giving a sample size of 77 (including the eight deaths).

Approximately 8 years later (between September 2015 and April 2016), the parents were then contacted and asked to take part in the 10-year follow-up study. Unfortunately, trial investigators were unable to find a contact address or telephone number for two patients (in the DRIFT arm). This left 67 patients whose survival status was known. Of these, two patients in the DRIFT arm and two patients in the standard treatment arm died, one patient declined to participate (in the standard treatment arm) and 10 gave no response, leaving 52 available for assessment (see Figure 1). The death certificates confirmed that two deaths were due to the patient’s disability; in the other two cases, death certificates (one per arm) were not available, so the cause of death was assumed to be disability based on these participants’ low scores at 2-year follow-up.

For the primary outcome, we obtained a cognitive score for 51 children: 27 in the DRIFT arm and 24 in the control arm. The distribution of patients across centre and gender can be seen in Figure 2. In the sensitivity analysis (substituting scores of 0 for those who died post 2 years), we had 29 and 26 for DRIFT and standard treatment, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Assessment of children at 10 years, by centre.

Baseline data

There were 77 patients who were randomised to the DRIFT trial; baseline comparisons are shown in Table 2. The team prespecified in the analysis plan that any baseline characteristics that differed by > 10%/0.5 SDs would be adjusted for in a sensitivity analysis. Only gender showed an imbalance of this magnitude at baseline; therefore, this sensitivity analysis was removed (given that this was already a prespecified covariate). Birthweight showed moderate imbalance, approximately 0.36 SDs.

| Characteristic | DRIFT | Standard treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) or n (%) | N | Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Total number of participants | 39 | 38 | ||

| Centre | ||||

| Bristol, UK | 39 | 27 (69) | 38 | 27 (71) |

| Katowice, Poland | 10 (26) | 10 (26) | ||

| Glasgow, UK | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | ||

| Bergen, Norway | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sociodemographics at birth | ||||

| Age at randomisation (days) | 39 | 19.18 (4.73) | 38 | 18.47 (4.95) |

| Gender: malea | 39 | 29 (74) | 38 | 24 (63) |

| Median IMD 2015b (IQR) | 22 | 23.50 (29.00) | 23 | 20.00 (24.00) |

| Clinical characteristics at birth | ||||

| Birthweight (g) | 39 | 1104.08 (346.23) | 38 | 1251.21 (468.34) |

| Gestation (weeks) | 39 | 27.69 (2.64) | 38 | 28.21 (2.89) |

| Grade of IVH: 4 | 39 | 20 (51) | 38 | 19 (50) |

| Maternal age at birth (years) | 17 | 28.24 (6.70) | 19 | 27.47 (6.06) |

Among the 52 children available for follow-up assessments at 10 years, there were imbalances in gender and birthweight (Table 3). There were 22 males in the DRIFT arm (79%), whereas the standard treatment arm had a lower proportion of males (63%). Birthweight was much higher in the standard treatment arm (mean 1322 g) than in the DRIFT arm (1102 g). After including the three deaths (used in the sensitivity analysis of the primary analysis), this reduced the imbalance in gender to 9% and all other balances/imbalances remained.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | |||

| N | Mean (SD) or n (%) | N | Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Total number of participants | 28 | 24 | ||

| Centre | ||||

| Bristol, UK | 28 | 23 (82) | 24 | 19 (79) |

| Katowice, Poland | 3 (11) | 4 (17) | ||

| Glasgow, UK | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | ||

| Bergen, Norway | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sociodemographics at birth | ||||

| Age at randomisation (days) | 28 | 18.68 (5.00) | 24 | 19.17 (4.53) |

| Gender: malea | 28 | 22 (79) | 24 | 15 (63) |

| Median IMD 2015b (IQR) | 18 | 23.50 (30.00) | 18 | 25.50 (14.00) |

| Clinical characteristics at birth | ||||

| Birthweight (g)a | 28 | 1101.89 (335.54) | 24 | 1322.46 (534.68) |

| Gestation (weeks) | 28 | 27.64 (2.56) | 24 | 28.50 (3.05) |

| Grade of IVH: 4 | 28 | 14 (50) | 24 | 11 (46) |

| Maternal age at birth (years) | 14 | 28.50 (6.99) | 12 | 28.17 (6.32) |

Among those assessed at 10 years, secondary haemorrhages were experienced by 29% of the DRIFT arm compared with 13% of the standard treatment arm. On average, at 10 years, mothers in the DRIFT arm had a higher education level than those in the standard treatment arm (Table 4). Unfortunately, this was not recorded at baseline, so we cannot be sure where this sits within the causal pathway (i.e. whether this is a confounding factor or determined as a result of the intervention).

| Characteristic | Trial arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | |||

| N | Mean (SD) or n (%) | N | Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Measures at 2 years | ||||

| Experienced second IVHa | 28 | 8 (29) | 24 | 3 (13) |

| Shunt | 28 | 11 (39) | 24 | 8 (33) |

| Reservoira | 28 | 13 (46) | 24 | 19 (79) |

| Infection | 28 | 0 (0) | 24 | 1 (4) |

| Measures at 10 years | ||||

| Age at 10-year assessment (years) | 28 | 10.56 (1.07) | 24 | 10.76 (1.06) |

| Weight (kg) | 28 | 35.41 (10.05) | 23 | 34.73 (10.51) |

| Height (cm) | 28 | 139.09 (12.22) | 23 | 142.26 (11.34) |

| Head circumference (cm) | 28 | 52.88 (2.53) | 23 | 52.00 (3.43) |

| MRI performed at 10 years | 28 | 15 (54) | 24 | 12 (50) |

| Median IMD at 10 yearsb (IQR) | 18 | 23.50 (30.00) | 16 | 25.50 (24.00) |

| Maternal educationa | ||||

| Left school at age 16 years | 28 | 10 (36) | 23 | 11 (48) |

| Further education | 6 (21) | 5 (22) | ||

| University degree | 12 (43) | 7 (30) | ||

In order to determine whether or not those lost to follow-up/died differed from those used in the final analysis, baseline characteristics were compared (Table 5). Comparing baseline characteristics between those in our sample with those who have died and those who have either declined or have been lost to follow-up shows us the representativeness of our sample.

| Characteristic | Sample at 10 years | Deaths | Uncontactable/declined | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N a | Mean (SD) or n (%) | N a | Mean (SD) or n (%) | N a | Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Total number of participants | 52 | 12 | 13 | |||

| Centrea,b | ||||||

| Bristol, UK | 52 | 42 (81) | 12 | 6 (50) | 13 | 6 (46) |

| Katowice, Poland | 7 (13) | 6 (40) | 7 (54) | |||

| Glasgow, UK | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Bergen, Norway | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Sociodemographics at birth | ||||||

| Age at randomisation (days) | 52 | 18.90 (4.75) | 12 | 18.25 (5.75) | 13 | 19.08 (4.57) |

| Gender: male | 52 | 37 (71) | 12 | 8 (67) | 13 | 8 (62) |

| Median IMD 2015a,c (IQR) | 36 | 25.00 (25.50) | 5 | 9.00 (9.00) | 4 | 21.5 (15.5) |

| Clinical characteristics at birth | ||||||

| Birthweight (g)a | 52 | 1203.69 (448.17) | 12 | 961.92 (151.53) | 13 | 1266.92 (397.32) |

| Gestation (weeks)a | 52 | 28.04 (2.80) | 12 | 26.67 (2.35) | 13 | 28.77 (2.71) |

| Experienced second IVH | 52 | 11 (21) | 12 | 2 (17) | 13 | 3 (23) |

| Shuntb | 52 | 19 (37) | 12 | 5 (42) | 13 | 7 (54) |

| Reservoirb | 52 | 32 (62) | 12 | 8 (67) | 13 | 6 (46) |

| Infection | 52 | 1 (2) | 12 | 0 (0) | 13 | 0 (0) |

| Grade of IVH: 4a | 52 | 25 (48) | 12 | 8 (67) | 13 | 6 (46) |

Overall, a greater proportion of infants from Poland were lost to follow-up than in the other centres, largely because we are unable to trace patient records in Poland. This is because in Poland, in contrast to the UK, there is no system of single personal numbers that allows patients to be traced. Overall, of those who were lost to follow-up, 57% required a shunt while only 37% of those in our sample had a shunt. There were fewer reservoirs among those lost to follow-up than our sample. Those who did not survive were characteristically more vulnerable and, on average, had lower birthweights and shorter gestation periods and were more likely to have a grade 4 IVH. However, surprisingly, the deprivation index was lower for those who died, suggesting that they were less deprived than those who survived. Given the small sample sizes for IMD, this is most likely a chance finding (p = 0.048).

Numbers analysed

Contamination was not a problem in this trial as the intervention was given shortly after birth and could not be requested by the control arm. When DRIFT was followed by persistent enlargement of ventricles and excessive head growth (2 mm/day), management continued with LPs and ventricular reservoir. 31

Among the original recruits (77 babies), there were three deaths in the DRIFT arm and five in the standard treatment arm by 2 years. We are unable to determine the survival status of two children at 10 years. Deaths and losses to follow-up were all relatively balanced between the group (chi-squared test: p ≥ 0.261) (Table 6); therefore, the further analysis of infants lost to follow-up was not performed. The two children for whom we could not establish survival status were explored in a sensitivity analysis by including them in a best- and a worst-case scenario.

| Losses | Trial arm, n/N (%) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | ||

| Loss to follow-up | |||

| Deaths at 2 years of age | 3/39 (8) | 5/38 (13) | 0.432 |

| Complete loss to follow-upb | 2/36 (6) | 0/33 (0) | – |

| Of those with known survival status | |||

| Deaths (post 2 years of age) as a result of disability | 2/34 (6) | 2/33 (6) | 0.975 |

| Deaths (post 2 years of age) not as a result of disability | 0/34 (0) | 0/33 (0) | – |

| Declined participation | 1/34 (3) | 1/33 (3) | 0.982 |

| Non-responders | 3/34 (9) | 6/33 (18) | 0.261 |

| Attended 10-year follow-up | 28/34 (82) | 24/33 (73) | 0.345 |

The numbers analysed for each outcome were also relatively balanced between the groups, especially for the cognitive outcomes (chi-squared test, where the lowest p-value seen was 0.197) (Table 7).

| Assessment | Trial arm, n (%) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | ||

| Completion | |||

| BAS III school age score | 21 (78) | 13 (54) | |

| Full completion | 21 (100) | 12 (92) | 0.197 |

| Items missing (score created) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | |

| BAS III early year scores | 4 (15) | 5 (21) | |

| Full completion | 3 (75) | 5 (100) | 0.236 |

| Items missing (score created) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | |

| BSID III scores | 2 (7) | 6 (25) | |

| Full completion | 2 (100) | 3 (50) | 0.206 |

| Items missing | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | |

| Visual assessment (parent) | 27 (96) | 24 (100) | 0.350 |

| Visual assessment (CVI) | 28 (100) | 21 (88) | 0.054 |

| Full completion | 22 (79) | 14 (67) | 0.350 |

| Items missing (score created) | 6 (21) | 7 (33) | |

| Movement ABC | 17 (61) | 13 (54) | 0.634 |

| CP status | 28 (100) | 24 (100) | – |

| SDQ | 28 (100) | 22 (92) | 0.119 |

| Full completion | 26 (93) | 22 (100) | 0.201 |

| Items missing (score created) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | |

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

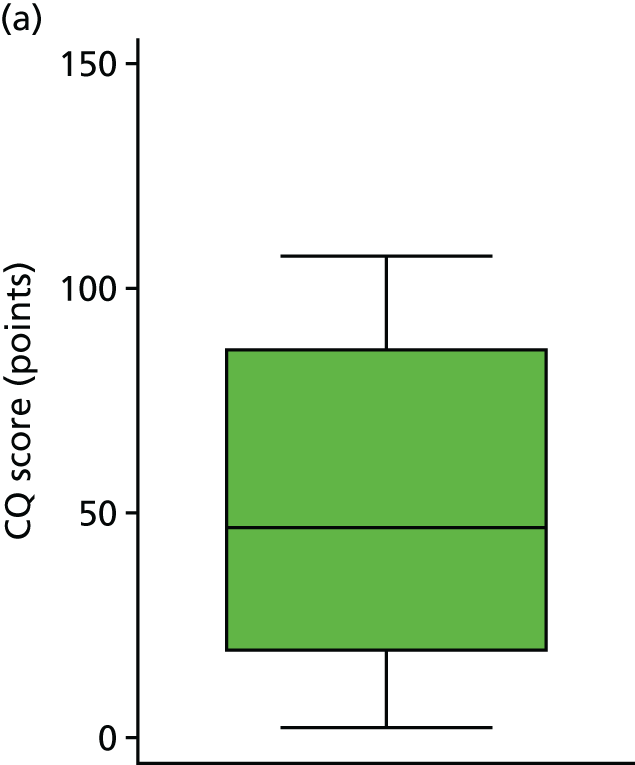

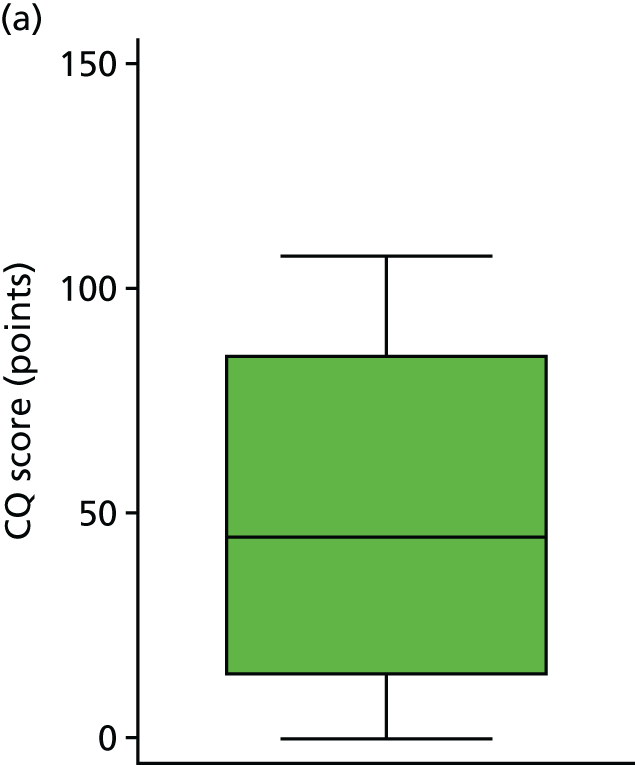

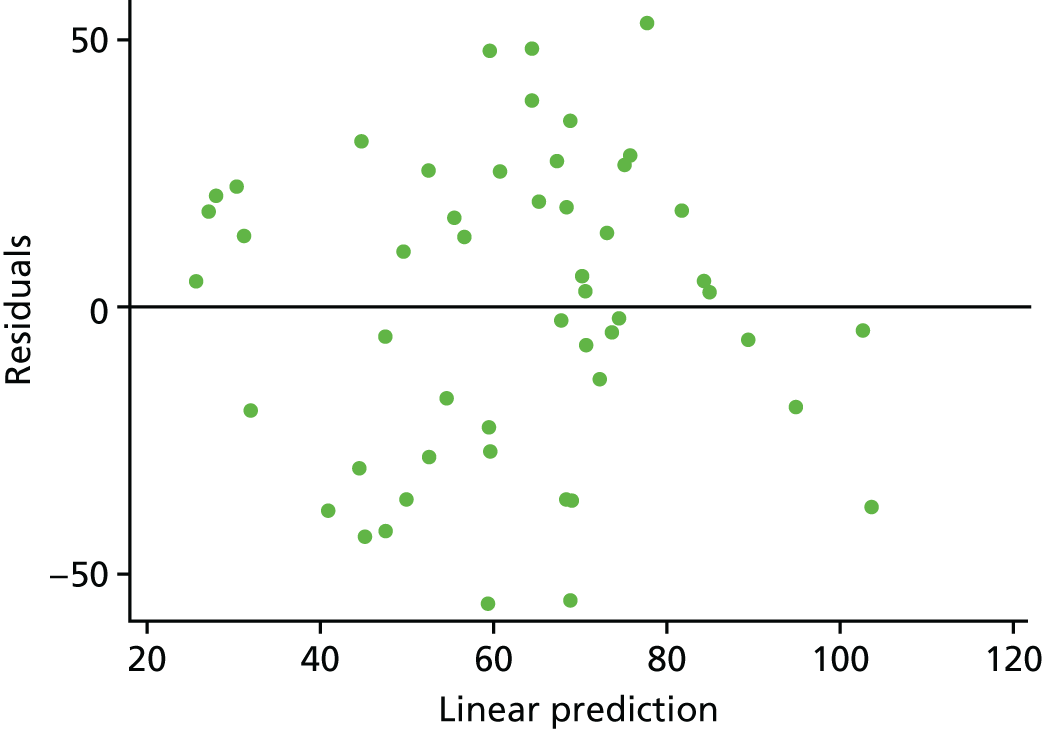

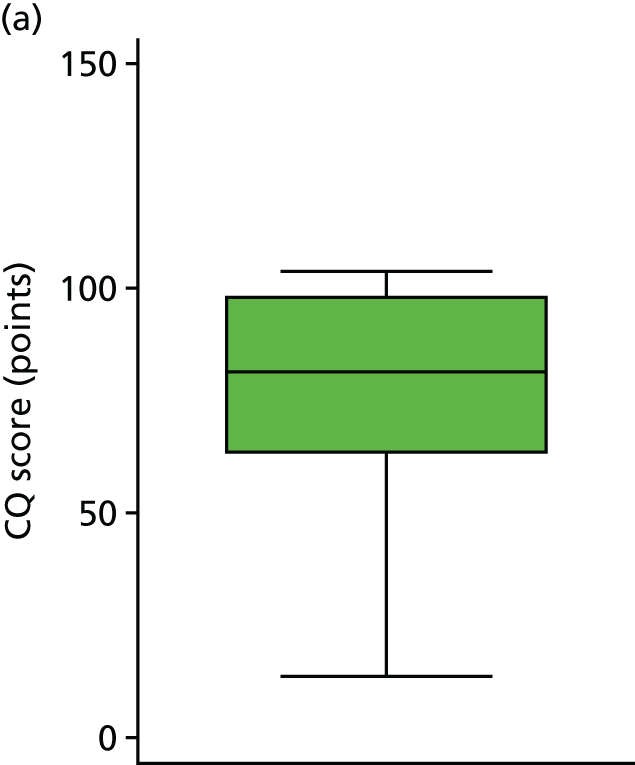

The primary hypothesis was that DRIFT would reduce severe cognitive disability in children assessed at school age. The histogram in Figure 3 shows the distribution of cognitive quotient (CQ) scores (range 2.07–130.60 points). The graph shows a relatively normal distribution, albeit slightly bimodal. The box plot in Figure 4 shows the distribution of CQ scores for each group, by trial arm. The results show that those in the DRIFT arm had a median CQ score of 72.3 points, whereas those in the standard treatment arm had a median CQ score of 46.7 points. The maximum CQ score was 130.6 points (achieved in the DRIFT arm), which means that one child had a cognitive ability age 30% higher than his actual age. The highest score achieved in the standard treatment arm was 107.2 points. There were two quotients of < 30 points in the DRIFT arm, compared with seven in the standard treatment arm.

FIGURE 3.

Histogram of CQ scores, excluding deaths.

FIGURE 4.

Cognitive quotient scores, by trial arm. (a) Standard treatment; and (b) DRIFT.

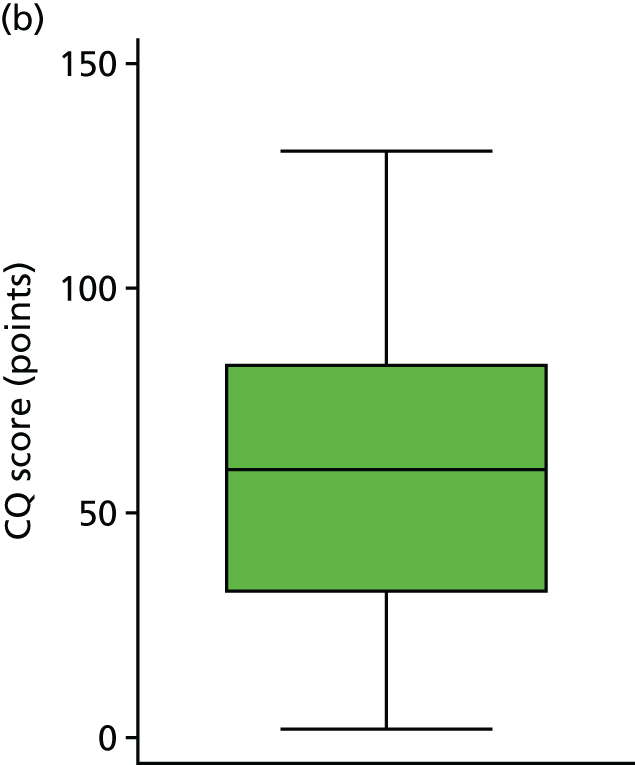

The histogram in Figure 5 shows the distribution of CQ scores (giving those who died a score of 0 points) (range 0.00–130.60 points). The graph shows a relatively normal distribution, slightly skewed by the scores of 0 points. The box plot in Figure 6 shows the scores by trial arm (giving those who died a score of 0 points). The results show that those in the DRIFT arm had a median CQ score of 72.0 points whereas those in the standard treatment arm had a median CQ score of 44.6 points.

FIGURE 5.

Sensitivity analysis: histogram of CQ scores, including deaths as a score of 0 points.

FIGURE 6.

Sensitivity analysis: CQ scores, by trial arm. (a) Standard treatment; and (b) DRIFT.

Table 8 shows the results for the primary analysis, both including and excluding deaths. Given the larger than expected attrition/death rate, precision was lower than hoped and was exacerbated further by large SDs for the cognitive ability quotient. Despite this, results are in parallel with those at 2 years, with crude estimates giving very weak evidence that the DRIFT intervention increases cognitive ability at 10 years (p = 0.096). After adjusting for gender, birthweight and grade of IVH, this evidence was strengthened and indicated that children who were in the DRIFT arm of the trial had, on average, a CQ score of 23.47 points higher than those who received standard treatment (p = 0.009). This translates into a developmental cognitive advantage of 2.5 years.

| Outcome | Trial arm, mean (SD) | Difference in meansa (95% CI) | p-valuea | Adjusted difference in meansb (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | |||||

| CQ score (points) | 69.33 (30.06) | 53.68 (35.70) | 15.65 (–2.86 to 34.16) | 0.096 | 23.47 (6.23 to 40.71) | 0.009 |

| CQ score (points)c | 64.55 (34.04) | 49.55 (37.22) | 15.00 (–4.28 to 34.27) | 0.125 | 22.33 (4.77 to 39.89) | 0.014 |

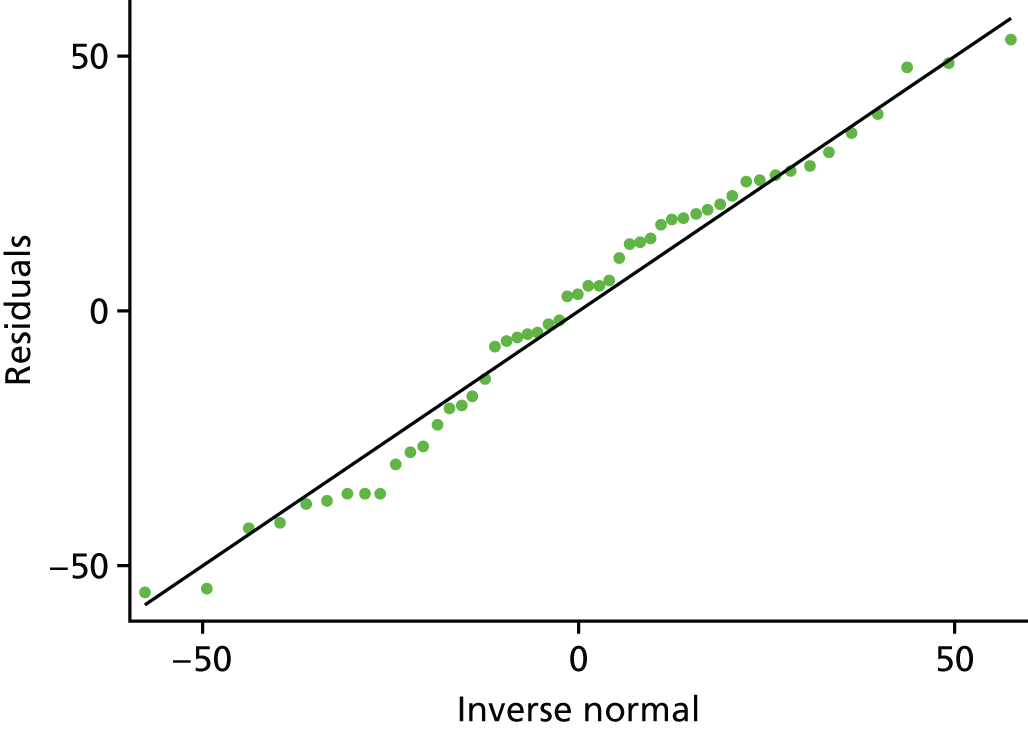

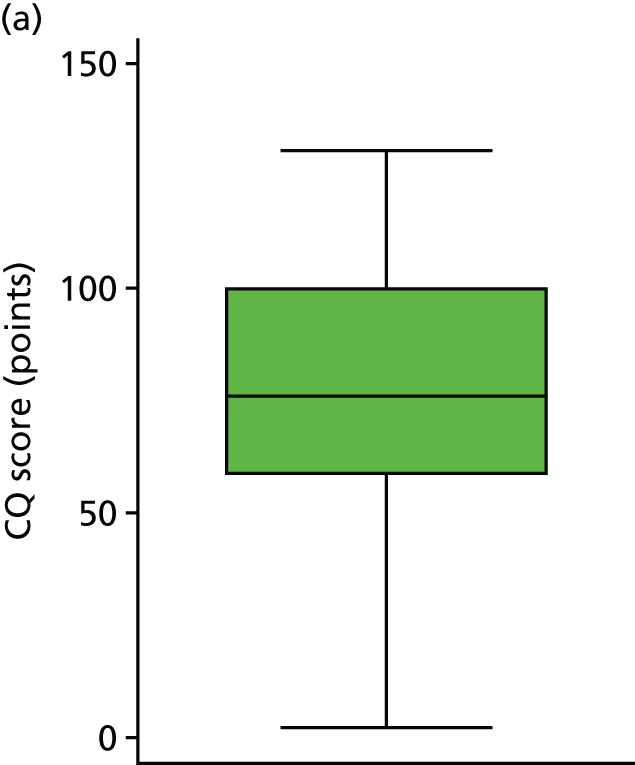

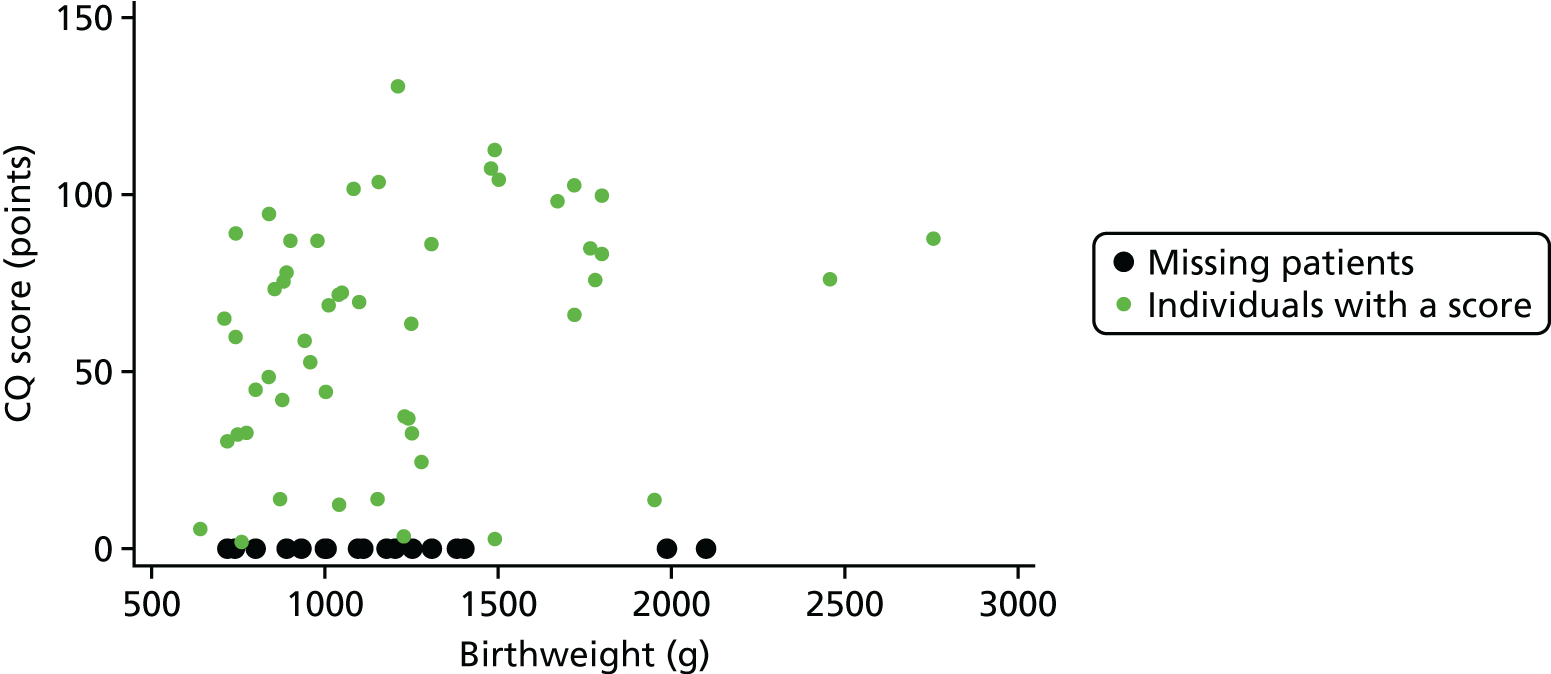

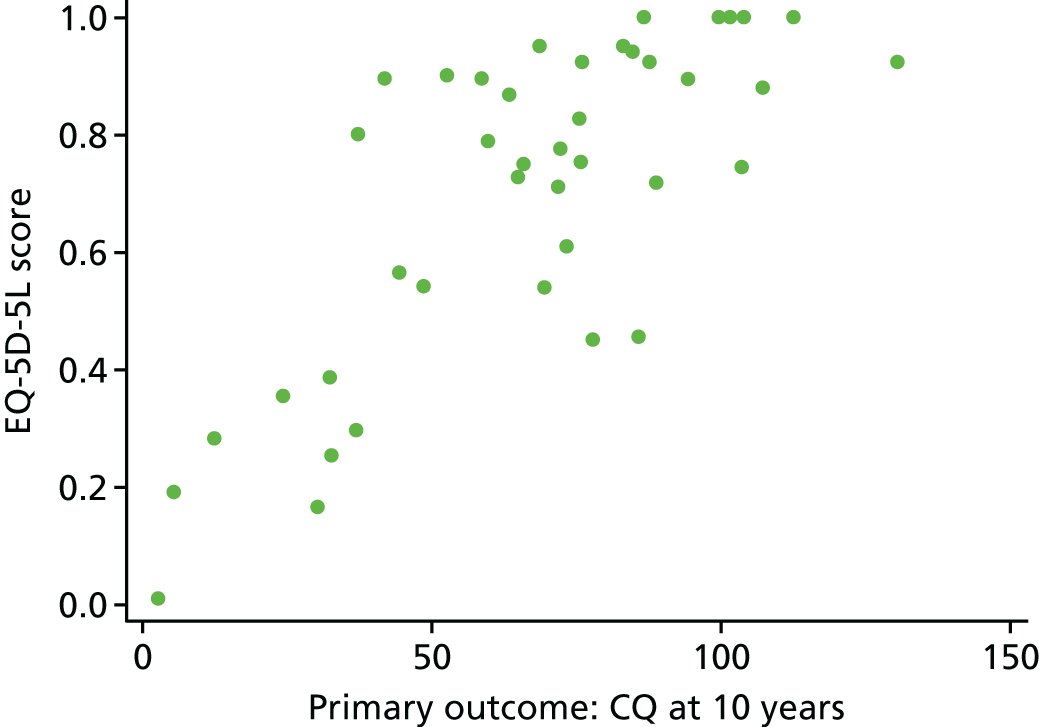

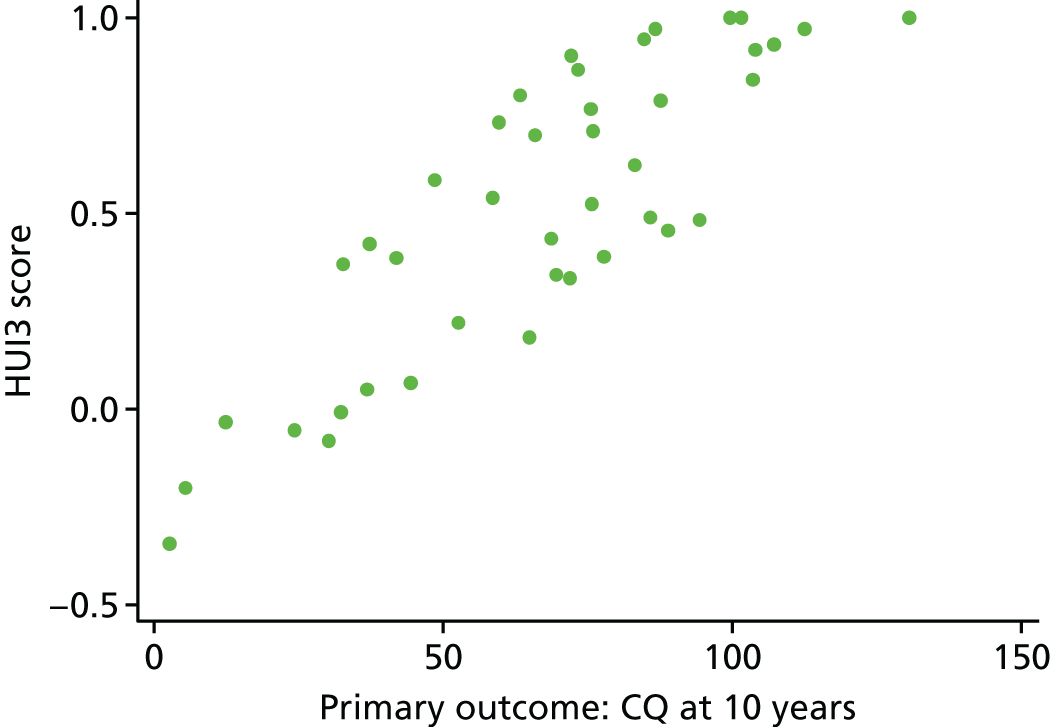

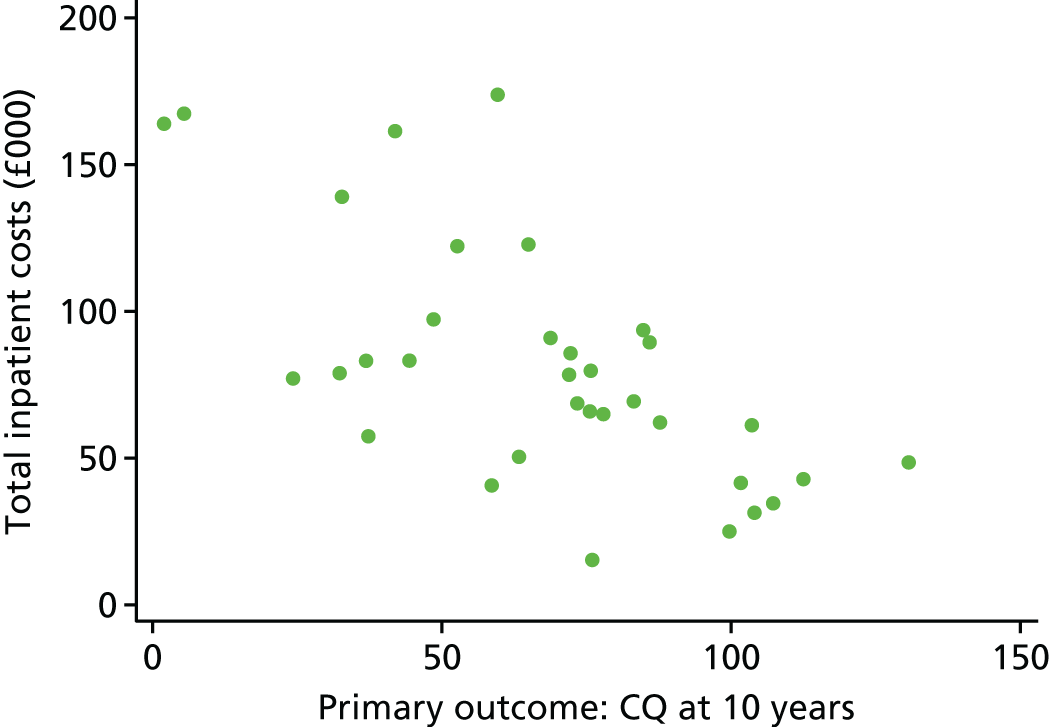

Given the look of the histogram (see Figure 3), we felt that it was important to explore the regression assumptions to ensure that we had used the right model for our data. Looking at the mean and median of our overall data, it was clear that they were similar: median 68.71 (IQR 54.28), mean 61.96 (SD 33.44). The skewness and kurtosis were –0.21 and 2.08, respectively; therefore, we were satisfied that the distribution was fairly symmetrical but slightly platykurtic (flat). The relationship between CQ score and birthweight was fairly linear (linear regression p-value = 0.015; Figure 7). After running the adjusted model, the residuals are approximately normally distributed (Figures 8 and 9). There is also no evidence to suggest that there is an increasing variance over the values of the linear predictor (Figure 10). Therefore, the team felt confident that a linear regression model was appropriate.

FIGURE 7.

Regression diagnostic: relationship between CQ score and birthweight.

FIGURE 8.

Regression diagnostic: plotted histogram of residuals from the primary regression model.

FIGURE 9.

Regression diagnostics: residuals vs. normal distribution, estimated from the primary analysis model.

FIGURE 10.

Regression diagnostics: residuals vs. predicted values, estimated from the primary analysis model.

Assessing prespecified covariants

Covariates were prespecified in the SAP and included birthweight, IVH grade and gender. These were the same covariates used in the 2-year follow-up study in which these variables had previously been shown to be imbalanced at 6-month follow-up. Table 9 shows how each of the covariates were individually related to the cognitive ability quotient. The results show that, for each additional gram of birthweight, CQ score at 10 years increased by 0.02 points (or 20 points per 1 kg). Those with grade 3 IVH had CQ scores that were, on average, 24.37 points higher than those with grade 4 IVH. Girls had CQ scores that were, on average, 13.96 points higher than those of boys. Figures 11 and 12 illustrate the spread of CQ scores across gender and IVH grade.

| Covariate | Difference in mean cognitive abilitya (95% CI) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive ability at 10 years | ||

| Birthweight | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | 0.035 |

| IVHb | –24.37 (–42.09 to –6.66) | 0.008 |

| Genderc | –13.96 (–34.88 to 6.96) | 0.186 |

FIGURE 11.

Relationship between cognitive outcome and gender. (a) Female; and (b) male.

FIGURE 12.

Relationship between cognitive outcome and grade of IVH. (a) Grade 3 IVH; and (b) grade 4 IVH.

Figure 13 shows the relationship between cognitive outcome and birthweight (g). Although the fitted line appears to be curved, the outlying values of birthweight may be suggesting more curvature than there actually is. A simple likelihood ratio test comparing the model with and without a quadratic term gives a p-value of 0.346, suggesting that the null hypothesis of a linear relationship is not rejected.

FIGURE 13.

Relationship between CQ score and birthweight with a linear and quadratic fit line.

It is also important to establish which of these three covariates are strengthening the relationship between arm and CQ score. Table 10 shows the regression coefficients after adjustment for each covariate on its own.

| CQ adjusted for | Difference in meansa (95% CI) | p-valuea | Difference in meansb (95% CI) | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birthweight | 21.79 (3.90 to 39.67) | 0.018 | 21.90 (3.68 to 40.12) | 0.019 |

| IVH grade | 16.22 (–1.06 to 33.50) | 0.065 | 16.56 (–1.29 to 34.41) | 0.068 |

| Gender | 19.16 (0.63 to 37.70) | 0.043 | 16.04 (–3.39 to 35.57) | 0.104 |

All three covariates strengthen the relationship between cognitive score and trial arm. Birthweight has proved to be the strongest adjustment, offering a strong difference between the groups with and without deaths included as zero. Gender and IVH grade both strengthen the difference between the groups, but to a smaller degree than birthweight.

Although gender shows a very weak relationship with cognitive ability at 10 years, and only a small adjustment when added as a covariate, it was imbalanced between the arms using the 10%/0.5 SDs rule. IVH and birthweight are both predictors of cognitive score, so adjustment is appropriate. Overall, these three covariates are appropriate for this analysis when taking into account both their relationship with the outcome and distribution across arms.

Secondary outcomes

Visual

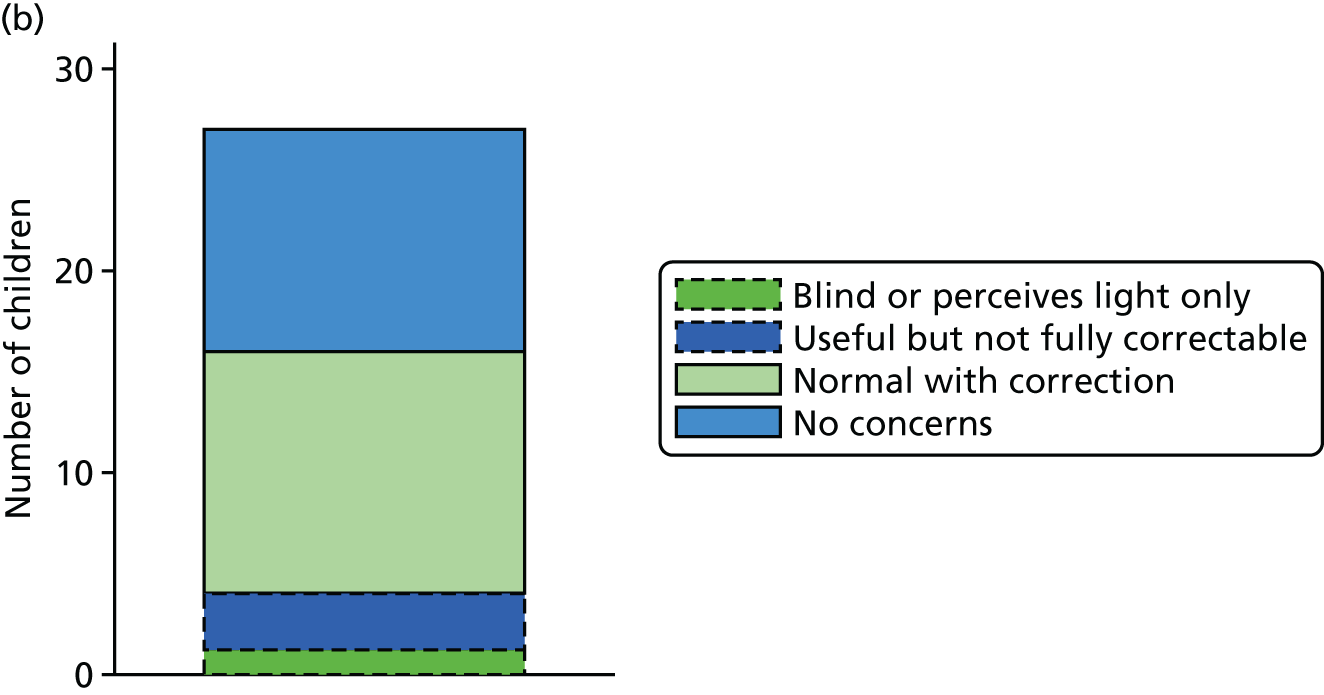

Figure 14 shows the four categories of sight by arm. The two lightest shades (solid outer line) make up a positive visual outcome and the two darkest shades (dashed outer line) make up a negative visual outcome. There appears to be a larger proportion of ‘good’ visual outcomes in the DRIFT arm than in the standard treatment arm. A logistic regression model below shows this difference in greater detail.

FIGURE 14.

Visual outcome, by trial arm. (a) Standard treatment; and (b) DRIFT.

As well as this binary outcome, a 23-question visual assessment task (see Appendix 4) was also filled out by vision specialists, who asked the parents various questions relating to CVI. Each question was scored 0–5, with higher scores indicating better cerebral vision.

Table 11 shows the results from the visual questions. For the binary visual outcome, this was answered for 27 and 24 children in the DRIFT arm and standard treatment arm, respectively. Overall, the results show that those in the DRIFT arm were almost four times more likely to have a ‘good’ visual outcome than those in the standard treatment arm (adjusted OR 3.73); however, the p-value provides only very weak evidence to support this (p-value of 0.136). We realised after analysing the result that one child had been given the CVI questionnaire even though he was blind. As a sensitivity analysis, we re-ran the analysis removing this child as their result was considered inappropriate. The result remained unchanged. The mean score for CVI is very slightly lower in the DRIFT arm; however, this result is consistent with chance (p-value of 0.502). The Mann–Whitney U-test (a suitable non-parametric comparator to the regression model) gave a very similar result, with even weaker evidence of a difference (p-value of 0.618). The team felt that it was safe to conclude that there is little evidence that the intervention had an effect on parent-reported CVI. Figures 15 and 16 show the distribution of CVI scores including and excluding the blind child, respectively.

| Outcome | Trial arm, n (%)/mean (SD) | Differencea (95% CI) | p-valuea | Adjusted differenceb (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | |||||

| Visual function (parent reported) | ||||||

| Good vision | 23 (85%) | 17 (71%) | 2.37 (0.60 to 9.40)c | 0.221c | 3.73 (0.66 to 21.14)c | 0.136c |

| CVI mean score | 4.50 (0.70) | 4.65 (0.38) | –0.15 (–0.49 to 0.19)d | 0.379d | –0.12 (–0.47 to 0.24)d | 0.502d |

| CVI median score | 4.76 (0.67) | 4.78 (0.48) | 0.618e | |||

| CVI mean scoref | 4.59 (0.55) | 4.65 (0.38) | –0.07 (–0.35 to 0.22)d | 0.640d | –0.04 (–0.33 to 0.26)d | 0.793d |

FIGURE 15.

Histogram of visual results, by trial arm. (a) Standard treatment; and (b) DRIFT.

FIGURE 16.

Histogram of visual results after removal of blind child, by trial arm. (a) Standard treatment; and (b) DRIFT.

Sensorimotor

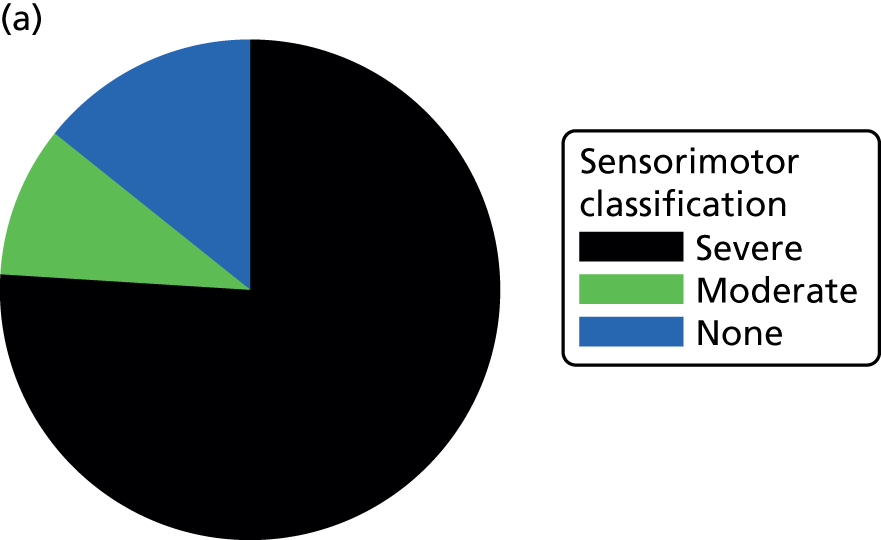

It was prespecified that any child for whom the Movement ABC classification score was missing and who was diagnosed with CP would automatically be placed in the severe category. The results of which are presented in Figure 17.

FIGURE 17.

Sensorimotor ABC classification, by trial arm. (a) Standard treatment; and (b) DRIFT.

Overall, the percentage of children with ‘severe’ sensorimotor scores was higher in the DRIFT group: 83% vs. 74% (see Table 11). On closer inspection, it became clear that, although many more children were slipping into this category, within this category, scores were higher in the DRIFT group [DRIFT, mean 38.69 (SD 11.76); standard treatment, mean 29.69 (SD 11.21) for the ‘severe’ category]. Figure 18 shows the distribution of the sensorimotor scores, by group.

FIGURE 18.

Sensorimotor score, by trial arm. (a) Standard treatment; and (b) DRIFT.

Closer inspection of the results showed that the assumption that children diagnosed with CP would score < 55 was appropriate as the average sensorimotor score among children in this category who completed the test was 28.92 (maximum 45.00) and the average sensorimotor score among children without a CP diagnosis was 59.74 (maximum 88.00). Nevertheless, we conducted the same test, using only those who had carried out the test, and achieved a score to see whether or not the assumption made an impact on our findings. Reassuringly, this gave a very similar result.

It was also thought (post hoc) that a dichotomised outcome would also allow us to feel confident with the conclusions drawn; therefore, this was carried out in the same way as the original (prespecified analysis) but dichotomising on a score of < 55 or ≥ 55 (severe vs. moderate/mild disability). All of these analyses are presented in Table 12.

| Outcome | N (D : S) | DRIFT, n (%)/mean (SD) | Standard treatment, n (%)/mean (SD) | Differencea (95% CI) | p-valuea | Adjusted differenceb (95% CI) | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor disabilityc,d | |||||||

| None/green (3) | 2 (7%) | 3 (14%) | |||||

| Moderate/amber (2) | 27 : 21 | 2 (7%) | 2 (10%) | 0.55 (0.13 to 2.34)e | 0.416e | 3.66 (0.33 to 40.34)e | 0.290e |

| Severe/red (1) | 23 (85%) | 16 (76%) | |||||

| Sensorimotor disabilityc,f | |||||||

| None/green (3) | 2 (12%) | 3 (23%) | |||||

| Moderate/amber (2) | 17 : 13 | 2 (12%) | 2 (15%) | 0.48 (0.10 to 2.29)e | 0.359e | 2.45 (0.23 to 26.66)e | 0.461e |

| Severe/red (1) | 13 (76%) | 8 (62%) | |||||

| Sensorimotor disabilityc,g | |||||||

| Severe/red vs. rest | 27 : 21 | 23 (85%) | 16 (76%) | 1.80 (0.42 to 7.75)h | 0.432 | 0.19 (0.012 to 3.29)h | 0.257 |

| Continuous scorei | 17 : 13 | 45.94 (17.40) | 46.96 (24.87) | –1.02 (–16.82 to 14.78)j | 0.896 | 11.29 (–1.87 to 24.46)j | 0.089 |

Reassuringly, all of the models gave a similar result, with the conclusion that, although small positive effects were seen in the DRIFT arm, after adjustment, these results were consistent with chance. Adjustment did appear to change the conclusion from negative to positive for the DRIFT intervention. Looking at each of the covariates individually, as with the primary outcome, birthweight caused the largest shift in treatment effect. When using the continuous measure, we did achieve weak evidence to suggest that those in the DRIFT intervention had better sensorimotor scores than the standard treatment arm; however, this was not prespecified as an outcome and has a very low sample size. Therefore, there were no strong differences seen between the arms when looking at motor ability.

The number of children diagnosed with CP was also prespecified as a secondary outcome. Children in the DRIFT arm were 1.1 times more likely than those in the standard treatment arm to have CP (Table 13). After adjustment for gender, birthweight and grade of IVH, this changed to a 63% lower odds of CP in the DRIFT group; we know this is largely because those in the DRIFT group had less favourable baseline characteristics. Looking at each of the covariates individually, as with the primary outcome, birthweight caused the largest shift in treatment effect. Although the DRIFT arm included a higher percentage of children with CP than the standard treatment arm (61% vs. 58%, respectively), it appeared that children in the DRIFT arm were less likely to have CP categorised as severe. After adjustment, those in the DRIFT arm were 80% more likely to be ambulant than those in the standard treatment arm. However, given the large CI and p-value, there was not strong enough evidence to support this and it could have simply happened by chance. As with the Movement ABC scoring, the results provided no substantial evidence to suggest a difference between the groups.

| Outcome | DRIFT, n (%) | Standard treatment, n (%) | Differencea (95% CI) | p-valuea | Differenceb (95% CI) | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | ||||||

| Without CP | 11 (39) | 10 (42) | ||||

| With CP | 17 (61) | 14 (58) | 1.10 (0.36 to 3.35) | 0.862 | 0.37 (0.07 to 2.00) | 0.249 |

| CP level | ||||||

| 1 | 7 (41) | 5 (36) | ||||

| 2 | 4 (24) | 3 (21) | ||||

| 3 | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | ||||

| 4 | 0 (0) | 2 (14) | ||||

| 5 | 4 (24) | 4 (29) | ||||

| Ambulatory status | ||||||

| Ambulant (level 1–2)c | 11 (65) | 8 (57) | 1.38 (0.32 to 5.88) | 0.667 | 1.32 (0.24 to 7.25) | 0.751 |

| Non-ambulant (level 3–5)c | 6 (35) | 6 (43) | ||||

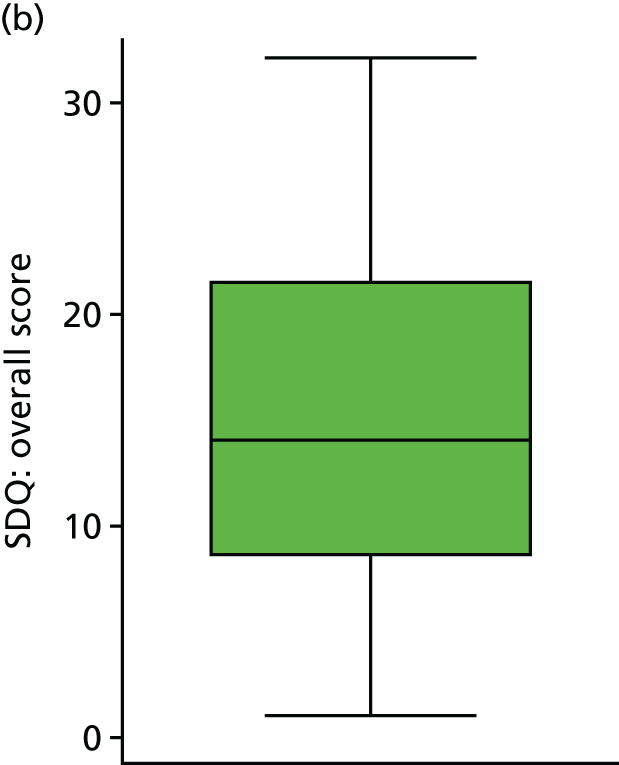

Emotional/behavioural difficulties

To assess emotional and behavioural difficulties, parents were asked to fill in the SDQ (see Appendix 6). The results are shown in Table 14. The subscales were almost all skewed to the left, indicating more ‘normal’ behaviour; therefore, subscales were assessed using the Mann–Whitney non-parametric U-test. However, the total score did approximately follow a normal distribution and, therefore, was assessed using linear regression (as prespecified in the analysis plan).

| Outcome | N (D : S) | DRIFT, mean (SD)a | Standard treatment, mean (SD)a | Difference (95% CI)b | p-valueb | Difference (95% CI)c | p-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional/behavioural difficulties (as predefined means) | |||||||

| Emotional symptomsd | 28 : 22 | 3.32 (2.88) | 2.59 (2.11) | 0.502 | |||

| Conduct problemse | 28 : 22 | 2.68 (1.93) | 1.55 (1.44) | 0.033 | |||

| Hyperactivity/inattentionf | 28 : 22 | 5.54 (3.18) | 6.14 (2.85) | 0.555 | |||

| Peer relationshipsg | 28 : 22 | 3.36 (2.63) | 3.09 (2.29) | 0.760 | |||

| Pro-social behaviourh | 28 : 22 | 7.11 (2.63) | 6.95 (2.28) | 0.567 | |||

| Impact scorei | 28 : 22 | 2.46 (2.53) | 2.23 (2.94) | 0.530 | |||

| SDQ total scorej | 28 : 22 | 14.89 (8.48) | 13.36 (6.59) | 1.53 (–2.89 to 5.94) | 0.490 | 2.01 (–2.78 to 6.81) | 0.401 |

Higher values of the SDQ total score indicate more ‘abnormal’ behaviour and there was no difference between the two groups (adjusted mean difference 2.01, 95% CI –2.78 to 6.81; p = 0.401). Although the ‘Conduct Problems’ subscale showed more favourable results in the standard treatment arm (p = 0.033), this is, given the large number of tests carried out here for a single secondary outcome, most likely a ‘chance finding’. Figure 19 shows how the total score varied between groups.

FIGURE 19.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire score, by trial arm. (a) Standard treatment; and (b) DRIFT.

Magnetic resonance imaging findings

There were no major differences relating to residual neurosurgical conditions needing referral; results are presented by arm in Table 15.

| Scan findings | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| DRIFT (N = 16) | Standard treatment (N = 12) | |

| Residual catheter tract | 3 (19) | 4 (33) |

| Parenchymal lesion | 7 (44) | 5 (42) |

| Reservoir | 9 (56) | 9 (75) |

| VP shunt | 7 (44) | 4 (33) |

| Possible active hydrocephalus | 2 (13) | 1 (8) |

| Residual condition | 2 (13) | 2 (17) |

Residual catheter tracks were more often seen in the standard treatment group and in association with ventricular reservoirs.

Sensitivity analyses

Various different techniques were used to address the primary analysis; these are of an exploratory nature. Reassuringly, all of the analyses gave compatible results (presented in Table 16). As well as adjustments to the way the outcome was measured, we also looked into adjustments for factors that may influence overall effect. First, we adjusted for centre (post hoc) and established that this made no difference to the conclusion. Compared with the original crude model, adjusting for centre weakened the average difference from 15.65 to 14.55 CQ points. The proportion of Polish children was higher in the standard treatment arm than in the DRIFT arm and, consequently, the proportion of children from Bristol was higher in the DRIFT arm. On average, CQ scores were higher in Bristol children than in Polish children (mean difference 14.40, 95% CI 14.08 to 42.88), which may explain the weakened effect after adjustment for centre. The binary outcome gave very similar results to the continuous CQ outcome. Both the unadjusted and adjusted models provided strong evidence to suggest that DRIFT had a positive impact on children’s cognitive outcomes at 10 years. Using the figure estimated, we calculated a number needed to treat (NNT) of three using the following calculation: 1/(14/26 – 8/29). Including all deaths (pre and post 2 years of age) as a negative outcome gave the same result. The ordinal outcome, unsurprisingly, offered a similar result to our primary analyses. In total, 50% of children in the standard treatment arm had severe cognitive disability (> 3 SDs below the population mean), compared with 21% of children in the DRIFT arm. Those in the DRIFT arm were at 3.63 times more likely to be in a higher category (better outcome) than those in the standard treatment arm, after adjustment for covariates. This method allowed us to differentiate between deaths and grades of disability by increasing the number of categories.

| Sensitivity analysis | N (D : S) | Trial arm, n (%)/mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI)a | p-valuea | Adjusted difference (95% CI)b | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | ||||||

| Original primary analysis | |||||||

| CQ | 27 : 24 | 69.33 (30.06) | 53.68 (35.70) | 15.65 (–2.86 to 34.16)d | 0.096 | 23.47 (6.23 to 40.71)d | 0.009 |

| CQc | 29 : 26 | 64.55 (34.04) | 49.55 (37.22) | 15.00 (–4.28 to 34.27)d | 0.125 | 22.33 (4.77 to 39.89)d | 0.014 |

| Continuous measure of cognitive ability | |||||||

| CQ (Bristol cohort only) | 23 : 19 | 71.76 (27.42) | 57.83 (34.78) | 13.93 (–5.46 to 33.33)d | 0.154 | 24.88 (6.82 to 42.94)d | 0.008 |

| CQ (Bristol cohort only)c | 24 : 20 | 68.77 (30.56) | 54.94 (36.24) | 13.84 (–6.48 to 34.15)d | 0.177 | 23.27 (4.65 to 41.88)d | 0.016 |

| Binary measuree | |||||||

| Alive and without severe cognitive disability (post 2 years) | 29 : 26 | 21 (72%) | 11 (42%) | 3.58 (1.16 to 11.04)f | 0.026 | 9.96 (2.12 to 46.67)f | 0.004 |

| Alive and without severe cognitive disability (including all 12 deaths) | 32 : 31 | 21 (66%) | 11 (35%) | 3.47 (1.23 to 9.78)f | 0.019 | 7.69 (1.96 to 30.11)f | 0.003 |

| Cognitive disability category | |||||||

| 1. Dead | 29 : 26 | 2 (7%) | 2 (8%) | ||||

| 2. Severe | 6 (21%) | 13 (50%) | |||||

| 3. Moderate | 7 (24%) | 2 (8%) | 2.04 (0.77 to 5.42)g | 0.151 | 3.63 (1.21 to 10.90)g | 0.022 | |

| 4. Mild | 8 (28%) | 4 (15%) | |||||

| 5. No cognitive disability | 6 (21%) | 5 (19%) | |||||

| Additional adjustments for the original primary analysis (CQ score) | |||||||

| Adjusted for centre | 27 : 24 | 69.33 (30.06) | 53.68 (35.70) | 13.76 (–4.45 to 31.92)d | 0.135 | 22.00 (5.69 to 38.30)d,h | 0.009 |

| Adjusted for centre (Bristol vs. others) | 27 : 24 | 69.33 (30.06) | 53.68 (35.70) | 14.55 (–3.78 to 32.87)d | 0.117 | 23.19 (6.35 to 40.04)d,h | 0.008 |

| Adjusted for maternal educationi | 27 : 23 | 69.33 (30.06) | 55.90 (34.77) | 11.50 (–6.86 to 29.87)d | 0.214 | 20.08 (2.96 to 37.21)d,h | 0.023 |

| Adjusted for baseline imbalancej | 27 : 24 | 69.33 (30.06) | 53.68 (35.70) | 24.58 (6.69 to 42.46)d | 0.008 | ||

Adjustment for maternal education was a decision made after data analysis had begun. Unfortunately, maternal age and education were not collected at baseline; however, maternal education (left school at 16 years of age, further education or university degree) was measured at 10 years. The team felt that, although imprecise, this was an adequate estimate of maternal education at baseline. The mean CQ score for infants born to ‘university degree’ mothers was 75.49 points, for infants born to ‘further education’ mothers was 50.84 points and for infants bon to mothers who ‘left school at 16’ was 57.84 points (p = 0.094). The proportion of mothers with a university degree was higher in the DRIFT arm than in the control arm (43% vs. 30%). Therefore, adjustment resulted in a weakened effect estimate. However, it should be pointed out that adjustment for birthweight, IVH, gender and maternal education still produced compatible results to the primary analysis (p = 0.023).

An adjustment for imbalances at baseline was prespecified in the analysis plan and defined as any difference of ≥ 10%/0.5 SDs between the groups. Referring back to Table 2, the variables classed as imbalanced were gender and birthweight. Adjustment for only these two factors resulted in strong evidence that the DRIFT intervention improves cognitive outcome at 10 years.

Best- and worst-case scenarios

Unfortunately, two patients could not be followed up at 10 years and their survival status was, therefore, unknown. Given the number of deaths post 2 years of age, it is unlikely that these patients would have died; however, it is important to understand the significance of these patients by calculating the extremes. Therefore, for a best-case scenario, the two children in the DRIFT arm were presumed to be alive and well (with the median score of their group), and vice versa for the worst-case scenario; the two children in the DRIFT arm were presumed, dead (with a score of 0). Results from these analyses are presented in Table 17. These assumptions are very extreme and the results, as expected, show that the best-case scenario strengthens the unadjusted treatment effect, whereas the worst-case scenario weakens it to produce a treatment difference consistent with chance (but still in favour of DRIFT).

| Sensitivity analysis | N (D : S) | Trial arm, mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI)a | p-valuea | Adjusted difference (95% CI)b | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | ||||||

| Different scenarios for the two patients with unknown survival status | |||||||

| Best-case scenarioc | 31 : 26 | 65.04 (32.94) | 49.55 (37.22) | 15.49 (–3.13 to 34.12) | 0.101 | 20.67 (3.68 to 37.65) | 0.018 |

| Worst-case scenariod | 31 : 26 | 60.38 (36.62) | 49.55 (37.22) | 10.83 (–8.83 to 30.50) | 0.274 | 15.28 (–3.72 to 34.29) | 0.113 |

Multiple imputation

In order to carry out a multiple imputation model, we must first assess whether or not the data are missing at random (MAR). In Figures 20 and 21, the red markers highlight the gestations/birthweights when the CQ score is missing. When checking cognitive scores across gestation and birthweight levels, it appears that missing data are evenly spread across these variables. At first glance, the MAR assumption appears to be valid across these two variables.

FIGURE 20.

Testing the MAR assumption: gestation.

FIGURE 21.

Testing the MAR assumption: birthweight.

Logistic regression was used to test which baseline characteristics and follow-up data points were predictive of missing CQ at 10 years. There were several variables that were predictive of missing CQ [centre, receiving a shunt at 2 years, mental development quotient (DQ) at 2 years and disability level at 2 years]. There were also several variables that were useful predictors of CQ [trial arm, age at entry (days), birthweight, gestation, IVH grade, the following measures at 2 years: mental DQ, motor DQ, gait, sitting, hand, speech, vision, disability, and the following measures at 10 years: vision, seizures, shunts, cerebral palsy, sensorimotor, hyperactivity, peer relationships and prosocial].

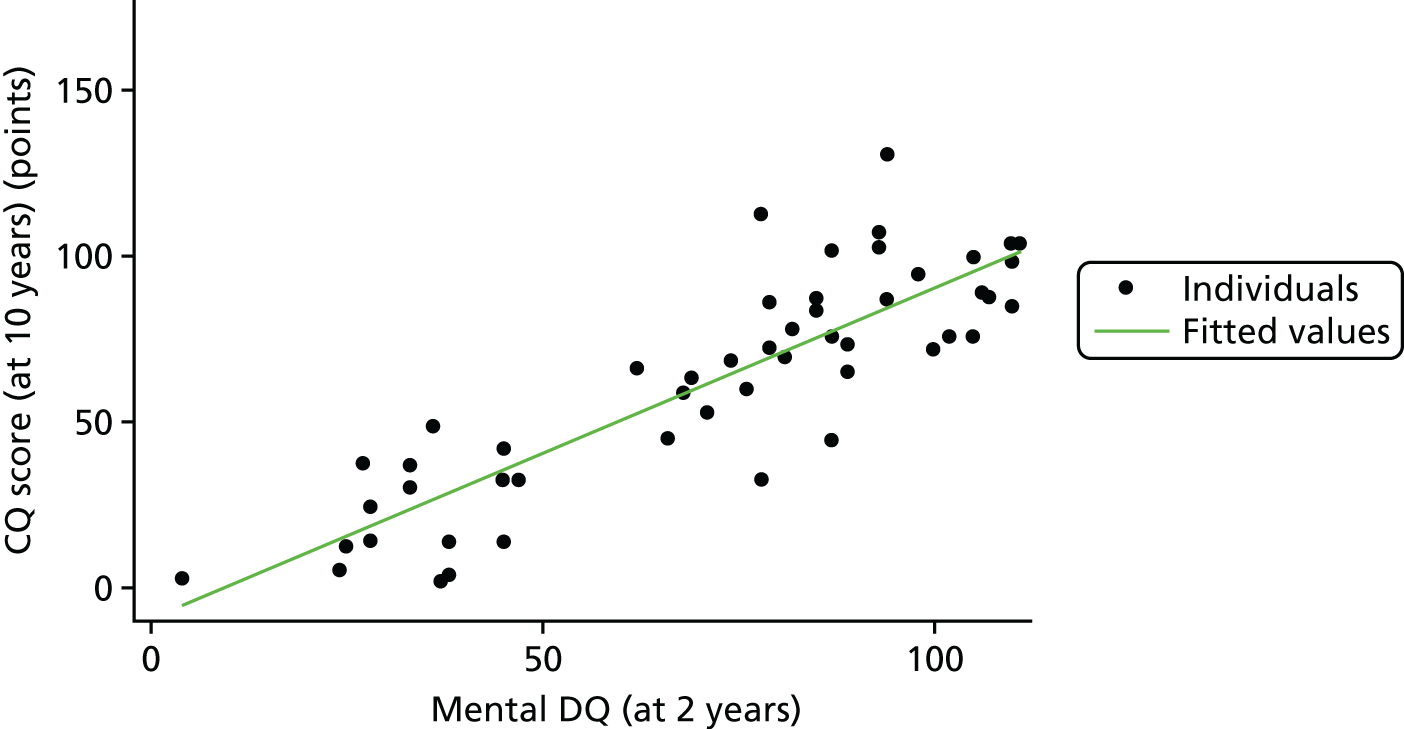

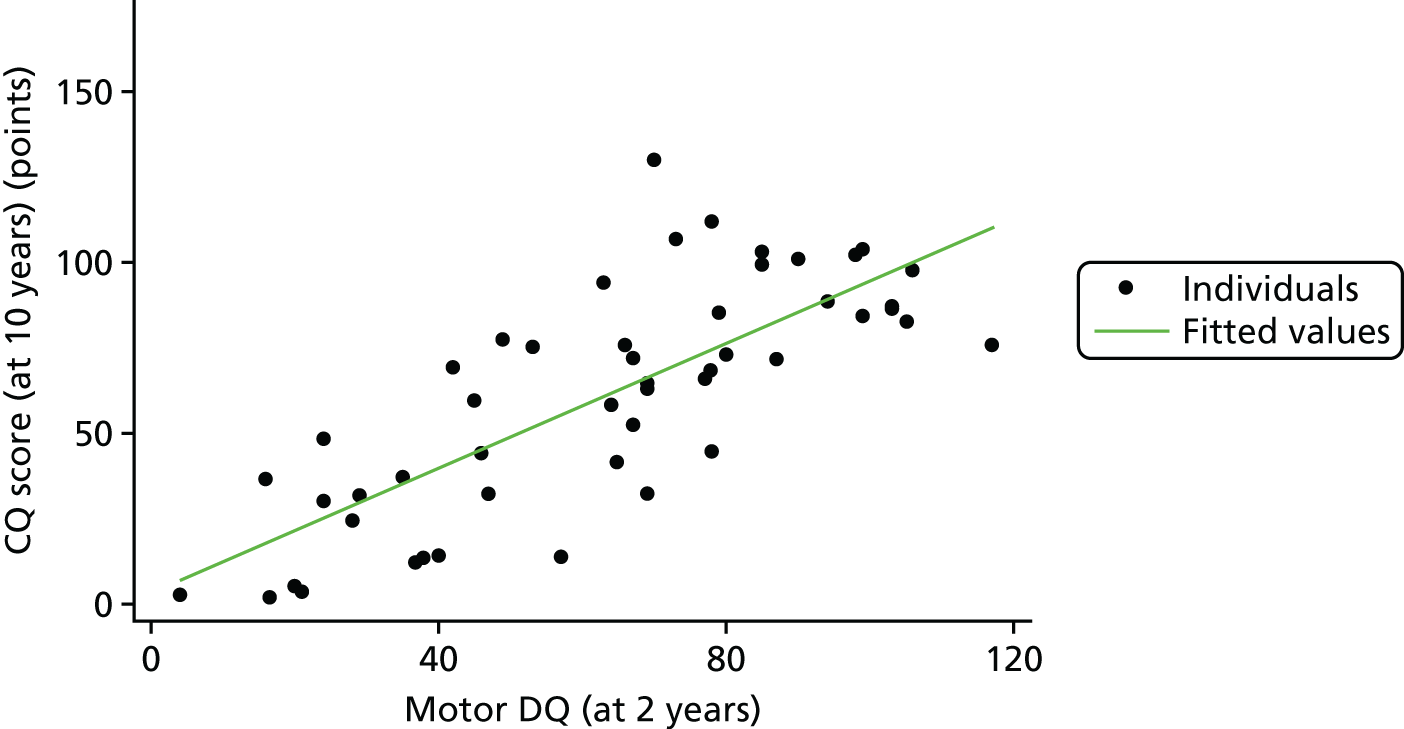

To examine the relationship between mental and motor DQs at 2 years and CQ at 10 years, we created a scatterplot. The scatterplots in Figures 22 and 23 show how well a straight line fits each of these relationships.

FIGURE 22.

Relationship between 2-year and 10-year scores: mental DQ.

FIGURE 23.

Relationship between 2-year and 10-year scores: motor DQ.

Assumptions for each multiple imputation model are described in Table 1. Each assumption has its own strengths and weaknesses, each treating death due to disability in a different way. The results are presented in Table 18.

| Sensitivity analysis | N (D : S) | Trial arm, mean (SE) | Difference (95% CI)a | p-valuea | Adjusted difference (95% CI)b | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIFT | Standard treatment | ||||||

| Imputation of cognitive DQ | |||||||

| Assumption 1 | 36 : 33 | 65.24 (5.63) | 50.81 (6.23) | 14.43 (–2.10 to 30.96) | 0.086 | 21.17 (5.66 to 36.68) | 0.008 |

| Assumption 2 | 36 : 33 | 65.42 (5.45) | 50.87 (6.31) | 14.54 (–1.98 to 31.07) | 0.083 | 21.42 (6.21 to 36.64) | 0.007 |

| Assumption 3 | 36 : 33 | 62.95 (5.80) | 49.41 (6.44) | 13.55 (–3.84 to 30.93) | 0.124 | 20.53 (4.49 to 36.56) | 0.013 |

| Assumption 4 | 36 : 33 | 62.80 (5.91) | 49.58 (6.47) | 13.22 (–4.49 to 30.93) | 0.140 | 20.08 (3.79 to 36.38) | 0.017 |

| Assumption 5 | 34 : 31 | 66.85 (5.42) | 53.70 (6.43) | 13.14 (–3.67 to 29.96) | 0.123 | 20.47 (4.62 to 36.31) | 0.012 |

To ignore death completely would result in a stronger result (p = 0.005 vs. p = 0.009). To impute for those deaths would offer a slightly stronger result (p ≤ 0.008 vs. p = 0.009), whereas to give them a hypothesised value of zero slightly weakens the result (p ≥ 0.015 vs. p = 0.009). However, in the five models developed here, the results remain compatible with the main analysis and with each other.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were almost all selected a priori and explored using formal tests of interaction; maternal education was the only post hoc subgroup analysis. Given the small sample size in this study, these analyses were heavily underpowered, resulting in the risk of false-negative results. With this in mind, focus was concentrated more on the estimates and CIs than on the p-values. Subgroup analyses results are presented in Table 19.

| Subgroup | N (D : S) | Subgroup specific, mean (SD) | Interactiona (95% CI) | p-valuea | Interactionb (95% CI) | p-valueb | |