Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/57/24. The contractual start date was in September 2012. The draft report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in December 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alan A Montgomery reports membership of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board. Catherine Sackley and Roshan das Nair report membership of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by das Nair et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from das Nair et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Background

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) are defined as an alteration in brain function, or other evidence of brain pathology, caused by an external force. 2 In 2013–14, the total number of people who were admitted for a TBI in the UK was 162,544 (254 per 100,000 population). 3 As well as TBIs sustained by civilians in daily life, TBIs among military personnel have also been a major contributor to mortality and morbidity. 4,5 The epidemiological variations seen in TBIs observed in the armed forces are the result of different approaches to screening, definitions of TBI and methods of reporting. 6

The costs of morbidity from TBIs are incurred by the health-care system and those outside it (in terms of loss of productivity as a result of short-term sick leave and early retirement), as well as through non-medical costs (e.g. transformation of the house or work environment). In addition, informal care by family or friends also adds to the costs of care for affected individuals. For TBI, the direct medical costs and indirect costs were estimated at US$60B in the USA in 2000. 7 The full costs of dealing with memory problems caused by TBI in the UK are not known. Care costs escalate when interventions are provided on an inpatient basis, but Salazar et al. 8 have demonstrated that the benefits of inpatient and home cognitive rehabilitation programmes for TBI, in terms of return to duty (for military personnel) or employment, were similar.

Impairment of memory is one of the most common cognitive deficits reported by people with TBIs, affecting 40–60% of patients. 9,10 These memory problems are not only persistent, but also debilitating and difficult to treat. 11 Memory deficits may also affect the extent to which patients engage with other interventions and rehabilitation. The safety of such patients can also be compromised, making them vulnerable citizens in the home (e.g. forgetting to turn the stove off), community (e.g. forgetting road rules) and work (e.g. forgetting important documents) settings. Memory problems consequently have a devastating effect on the psychological well-being of the individuals and others around them. 12

Cognitive rehabilitation is a structured set of therapeutic activities designed to retrain an individual’s cognitive functions. Memory rehabilitation is a domain-specific type of cognitive rehabilitation that focuses on improving memory and helping people deal with the consequences of memory problems. In the UK, memory rehabilitation is offered by some services as a means to help people cope with their cognitive problems.

Research evidence

Individual studies

Some randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation following brain injuries. These have mainly focused on attention, executive functions and visual neglect, but memory rehabilitation specifically has not been sufficiently researched. 13 Most evidence for memory rehabilitation comes from single case experimental design studies and controlled clinical trials, with the few RCTs and quasi-RCTs in this area offering some support for the effectiveness of intervention.

Wilson et al. 14 examined a paging system used as an external memory aid. This enabled participants to achieve more memory-related goals than when NeuroPage was not available. Doornhein and de Haan15 reported that patients who received a memory training programme performed significantly better than those in a pseudo-treatment control group on trained memory tasks, but no differences were observed in subjective ratings of everyday memory functions. Kaschel et al. 16 reported that imagery mnemonics significantly improved delayed recall of verbal material and reduced observer-rated reports of memory failures. However, systematic reviews of memory rehabilitation have not found evidence to support or refute the effectiveness of such programmes. 17,18 This lack of evidence is partly because of a lack of well-designed trials, which has led one of the largest meta-analyses to conclude that ‘the results for memory rehabilitation are mixed and weak’ (p. 33). 13 The authors of this review suggested that ‘researchers need to reduce reliance on single-subject and single group designs’ (p. 34) and recommended more RCT evidence, a view supported by others. 19 At a symposium on disorders of memory, Wilson20 called for ‘better evaluation of memory rehabilitation programmes’ (p. e4–5). This is a conclusion that more recent systematic reviews of memory rehabilitation following TBI,18 stroke21 and multiple sclerosis22 also reached. This conclusion has been attributed mainly to the dearth of high-quality RCTs, but may also reflect the lack of common outcomes measures that are responsive to the effects of memory rehabilitation.

In a small-scale RCT (n = 72) to evaluate a group memory rehabilitation programme,23 patients with memory problems were randomly allocated to one of three group treatment programmes: compensation strategy training, restitution or a self-help attention placebo control. Although the results showed no statistically significant differences in outcomes, they indicated that the interventions seemed worthy of further evaluation. This was supported by the qualitatively analysed participant feedback interviews,24 which suggested improvements in knowledge and skills with regard to memory aid use, among other improvements. This small trial provided feasibility and pilot data for the current trial.

Literature reviews

A narrative review25 found cognitive rehabilitation to be beneficial for treating cognitive deficits following brain damage. Cernich et al. 26 reviewed evidence for cognitive rehabilitation in TBI and recommended that, although RCTs had demonstrated the utility of specific rehabilitation approaches to attention retraining and retraining of executive functioning skills, further research was needed on rehabilitation techniques in other domains of cognition (such as memory). They also suggested that training in the use of supportive devices to improve an individual’s daily activities was central to their ability to function independently.

Systematic reviews, such as that by Cicerone et al.,27 published in 2000, concluded that there was strong evidence of the effectiveness of treatments for memory problems after a TBI. The updated review,25 published in 2005, continued to endorse this view. These reviews included both RCTs and single case studies. However, Rohling et al. ’s13 more stringent meta-analytic re-examination of both reviews by Cicerone et al. 25,27 included 115 studies of cognitive rehabilitation trials and found mixed, or at best, only weak, support for memory treatment. It is worth noting that, of all of the included studies (of TBI and stroke), only 30 (26.1%) were classified as being in ‘class I’ (i.e. well-designed, prospective RCTs) and only 14 specifically focused on memory. Also of note was that these studies were small, with an average of 16.9 and 18.5 participants in the treatment and control arms, respectively.

Bergquist et al. 28 found that people with TBI not only were willing to use the internet to receive cognitive rehabilitation, but also were satisfied with the treatment. Encouraged by results from imaging studies that have shown neuroplasticity, Spreij et al. 29 conducted a systematic review that offered novel insights into remediation-oriented approaches for the rehabilitation of memory deficits following acquired brain injuries (ABIs). They classified the 15 studies that they included in their review as falling within the rubric of (1) virtual reality (VR) training, (2) computer-based cognitive retraining (CBCR) and (3) non-invasive brain stimulation (NBS). They concluded that CBCR was the most promising of these interventions, with all seven of the CBCR studies they included showing positive effects. However, closer inspection of these studies (and the other VR and NBS studies) showed that they were not methodologically robust (some were not RCTs) and the outcomes included were mainly impairment-level measures. Furthermore, most of these studies included mixed diagnosis samples and, therefore, it was not possible to extract what the specific effects of these interventions would be on people with a TBI. More robust mixed-methods RCTs are therefore still required to evaluate the effectiveness of these newer forms of cognitive rehabilitation for people with TBIs.

Another review30 that focused specifically on computerised cognitive training (CCT) in ABI and on outcomes classified within the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)31 included 96 primary studies that evaluated CCT. The authors noted that only 15% of these studies represented ‘level 1′ evidence (i.e. good-quality RCTs). Interestingly, the authors also reported that, although the population with TBI was the most studied population, only two of the 31 TBI studies were considered to offer ‘level 1′ evidence. Overall, their findings suggest that CCT has limited positive impacts on outcomes that relate to activity or participation, although only 43% of the studies included an outcome measure that assessed activity or participation.

Clinical guidelines

There are recommendations for the provision of cognitive rehabilitation for people with ABIs. Older national and international guidelines for TBI rehabilitation, such as the Brain Injury Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine’s published practice guidelines for rehabilitation after TBI and stroke,32 the European Federation of Neurological Societies Task Force on Cognitive Rehabilitation’s guidelines for stroke and TBI33,34 and the national clinical guidelines for rehabilitation following ABIs from the Royal College of Physicians and the British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine,35 found limited high-quality evidence supporting some forms of cognitive rehabilitation, specifically, treatments for memory problems after TBI. This was mainly because of a lack of RCTs, with most evaluations being uncontrolled trials or single case experimental designs.

The national clinical guidelines for rehabilitation following ABIs from the Royal College of Physicians and the British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine35 recommend that patients with persistent cognitive deficits following ABI should be offered cognitive rehabilitation, which may include compensatory strategies, including the use of memory aids, to help manage memory problems in daily life and support independence. They further state that ‘trial-and-error’ learning should be avoided. Again, the level of recommendation is low because of the low quality of the evidence. Therefore, it is perhaps unsurprising that most previous recommendations have been qualified by the need for more research.

The national clinical guidelines for brain injury rehabilitation in adults from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)36 recommend training in the use of compensatory strategies for people with memory problems following TBI, focusing on improving the management of memory problems in daily life rather than underlying memory impairment. Recommendations differ depending on the severity of memory problems, with both internal and external strategies advised for those with mild to moderate impairment, whereas the focus for those with severe memory impairment should be on improving functional abilities through external aids.

However, this is a ‘grade D’ recommendation, based on level 3 (non-analytical studies) and level 4 (expert opinion) evidence and on extrapolating level 2 evidence (well-conducted case–control or cohort studies). This SIGN guideline forms the basis of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on head injury. 37

More recently, recommendations for the management of memory problems following TBI by an international team of researchers and clinicians38 concluded that there is ‘good evidence for the integration of internal and external compensatory memory strategies that are implemented using instructional procedures for rehabilitation for memory impairments’ but that the ‘evidence for the efficacy of restorative strategies currently remains weak’ (p. 369). However, this conclusion was arrived at on the basis of few RCTs, many of which had a small sample size and a large number of outcomes, did not report power analyses and did not consider the longer-term effects of the intervention.

On the basis of the foregoing discussion, and in response to a commissioned call by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme,39 we designed the ReMemBrIn trial to address the concerns raised by authors of individual studies, systematic reviews and clinical guidelines. The trial, funded by the HTA programme, was designed to assess the effectiveness of a group memory rehabilitation programme, on the basis of recent research suggestions from researchers and clinicians,19 our own pilot study23 and current clinical guidelines40,41 and clinical practice in the UK. Furthermore, in line with the Better Value in the NHS report,42 we designed this project to deliver value for money through innovative changes to current clinical practice leading to improved patient outcomes.

Rationale

Currently, patients with TBI experiencing memory problems do not routinely receive cognitive rehabilitation after the outpatient rehabilitation phase, even though their abilities and needs may change once they are discharged from clinical services. This is in part because of the current lack of evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of memory rehabilitation and because of resource limitations. This study sought to address these issues.

Research question

What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of memory rehabilitation for people with memory problems following TBI?

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective was to determine whether attending a group-based memory rehabilitation programme (the intervention) was associated with improved subjective reports of the management of memory problems in daily life, as measured using the Everyday Memory Questionnaire – patient version (EMQ-p),43 compared with a usual-care control.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were to assess:

-

whether the intervention was associated with improvements in participants’:

-

objectively assessed memory abilities

-

ability to achieve individually set goals

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

cognitive, emotional, and social well-being.

-

-

the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from das Nair et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Design

The ReMemBrIn study was a multicentre, two-arm, parallel-group randomised controlled superiority trial of a group-based memory rehabilitation programme, provided in addition to usual care, compared with usual care alone. Participants were randomised in clusters of between four and six. Clusters were allocated to memory rehabilitation or usual care in a ratio of 1 : 1.

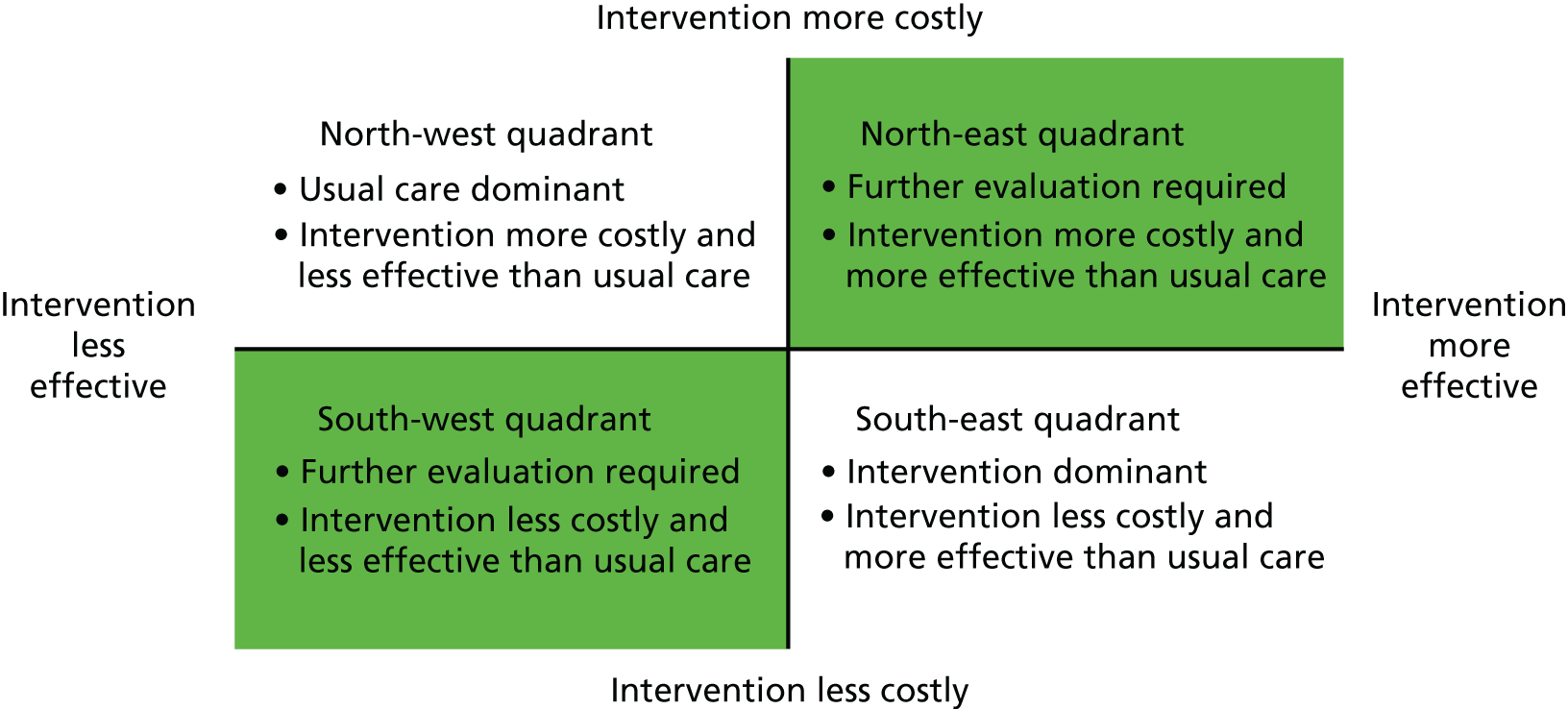

An economic analysis was conducted to determine the costs and cost-effectiveness of group memory rehabilitation compared with usual care (see Chapter 4). In addition, a nested qualitative substudy sought to explore participants’ experiences of the group memory rehabilitation and usual care (see Chapter 5).

Study setting and participants

Sites

The trial was conducted in nine sites in the UK (see Appendix 1). Each site was a NHS trust providing rehabilitation services for people with TBI.

We initially intended to recruit from four sites, but we activated new sites owing to old ones shutting down because of their participant pools being exhausted. The original four sites were opened to recruitment between February and April 2013. Because of staff turnover and staff recruitment difficulties, two of these sites were subsequently closed to recruitment and were replaced by two new sites that opened in March and November 2014, respectively. To address delays in recruitment, three additional sites were also opened between March and June 2015.

Identification of participants

Participants were identified through NHS services at the participating sites. This included searching hospital databases and departmental records for people with head injuries from rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery and clinical psychology and neuropsychology departments. In-clinic recruitment also took place from rehabilitation consultant-led clinics and outpatient TBI rehabilitation clinics. Participants were also identified from similar sources at other NHS trusts acting as participant identification centres (PICs). In addition, posters were displayed in clinic areas in the hospitals. Participants were also identified by self-referral as a result of publicity by local and national charities and patient groups (e.g. head injury charities) and advertising to the general public through the study website, on various support group websites and newsletters and through features on television and radio programmes. In order to include military personnel, participants were sought from a military rehabilitation centre and a NHS surgical centre treating personnel from the armed forces.

Clinical teams sent an invitation letter to individuals who were identified as potential participants. This letter included a participant information sheet, a consent form, a contact details slip and a prepaid reply envelope. If potential participants were interested in taking part, they were asked to complete the contact slip and return it in the envelope directly to the assistant psychologist (AP) at their nearest site.

Informed consent

Written consent was obtained by the AP and participants were given a copy of the consent form for their records. Participant information sheets and consent forms were based on those developed for the pilot study,23 and these had been checked for clarity and readability by a service user representative. Potential participants had the opportunity to read about the study and discuss it with other clinical staff members, family and friends and the research team before they decided whether or not to take part. They had a minimum of 24 hours to do this. Potential participants also had the opportunity to read the participant information sheet and consent forms with the AP at their first assessment.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible participants were those who:

-

Were admitted to hospital with a TBI sustained > 3 months prior to recruitment.

-

Had memory problems, defined as a score or ≥ 24 on the EMQ-p and/or a score below the 25th percentile on the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test – third edition (RBMT-3),44 as assessed at the initial screening assessment. A score of ≥ 24 on the EMQ-p is two standard deviations (SDs) below the mean for healthy participants (Professor Nadina B Lincoln, University of Nottingham, 2017, personal communication). The 25th percentile cut-off for the RBMT-3 indicates below average objectively assessed memory ability. 44

-

Were aged 18–69 years. The upper age limit was applied in order not to include those with age-related memory problems.

-

Were able to travel to one of the study sites and attend group sessions. Participants had to live within the geographical area covered by the sites and be able to travel to sites. We offered travel expenses to all participants who requested it. Participants also needed to be willing to receive treatment in a group if allocated to the intervention.

-

Gave informed consent.

Potential participants were excluded if they:

-

Were unable to engage in group treatment if allocated. This was assessed by the clinicians at the recruitment sites, with reasons for exclusion including severe aural sensory problems. Those who had behavioural problems that would interfere with group treatment were not considered.

-

Were participating in other psychological intervention studies, assessed by self-report.

-

Had impairment of language that would make them unable to take part in the rehabilitation group activities, defined as a score of < 17 on the Sheffield Screening Test for Acquired Language Disorders (SST)45 completed at the initial screening assessment. In accordance with the test manual, participants who scored < 17 on the SST were considered to have impairment of language that would limit their ability to complete the intervention.

Study procedures

We expected participants to be involved in the study for approximately 13 months from the initial screening assessment to the final follow-up visit 12 months from randomisation. The data collected at each time point are shown in Appendix 2 and are detailed below. Data were collected through a combination of self-report questionnaires completed by participants and their relatives/friends and face-to-face assessments with participants, completed by a research assistant (RA) during study visits. Visits took place at participants’ homes whenever possible. However, if there were concerns about the suitability of the home environment or if a participant preferred, assessments were conducted at NHS sites or community venues.

Initial screening visit

At the initial screening visit, the AP first explained the study and made clear that the initial assessments were required to check that the participant met the inclusion criteria, to obtain demographic and clinical data and to conduct baseline assessments for those who were eligible. The AP responded to queries and obtained informed consent prior to conducting the following initial assessments, questionnaire completion and demographic data collection:

-

EMQ-p:43 this is a subjective, patient-centred outcome measure with good ecological and face validity46,47 and has been previously used in cognitive rehabilitation studies. 23,48 The EMQ-p comprises 28 items asking about the frequency of memory failures in everyday life over the past month. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale (from ‘once or less in the last month/never’ to ‘once or more a day’). Total scores range from 0 to 112, with higher scores indicating more frequent memory problems.

-

RBMT-3:44 this is a standardised objective measure of memory, with adequate psychometric properties. This was chosen as an objective measure that closely reflected daily life memory ability. It has also been used as an outcome measure in other studies of memory rehabilitation. 16,23,49–52 A General Memory Index (GMI) score was derived to provide an assessment of overall memory abilities. GMI values range between 52 and 174 and are standardised on a representative sample from the UK44 to have a mean of 100 (SD 15). Lower scores indicate more significant memory impairment.

-

National Adult Reading Test (NART):53 the premorbid level of intellectual functioning, required to interpret RBMT-3 scores, was estimated using the NART.

-

SST:45 this was used to assess eligibility for the trial on the basis of language ability.

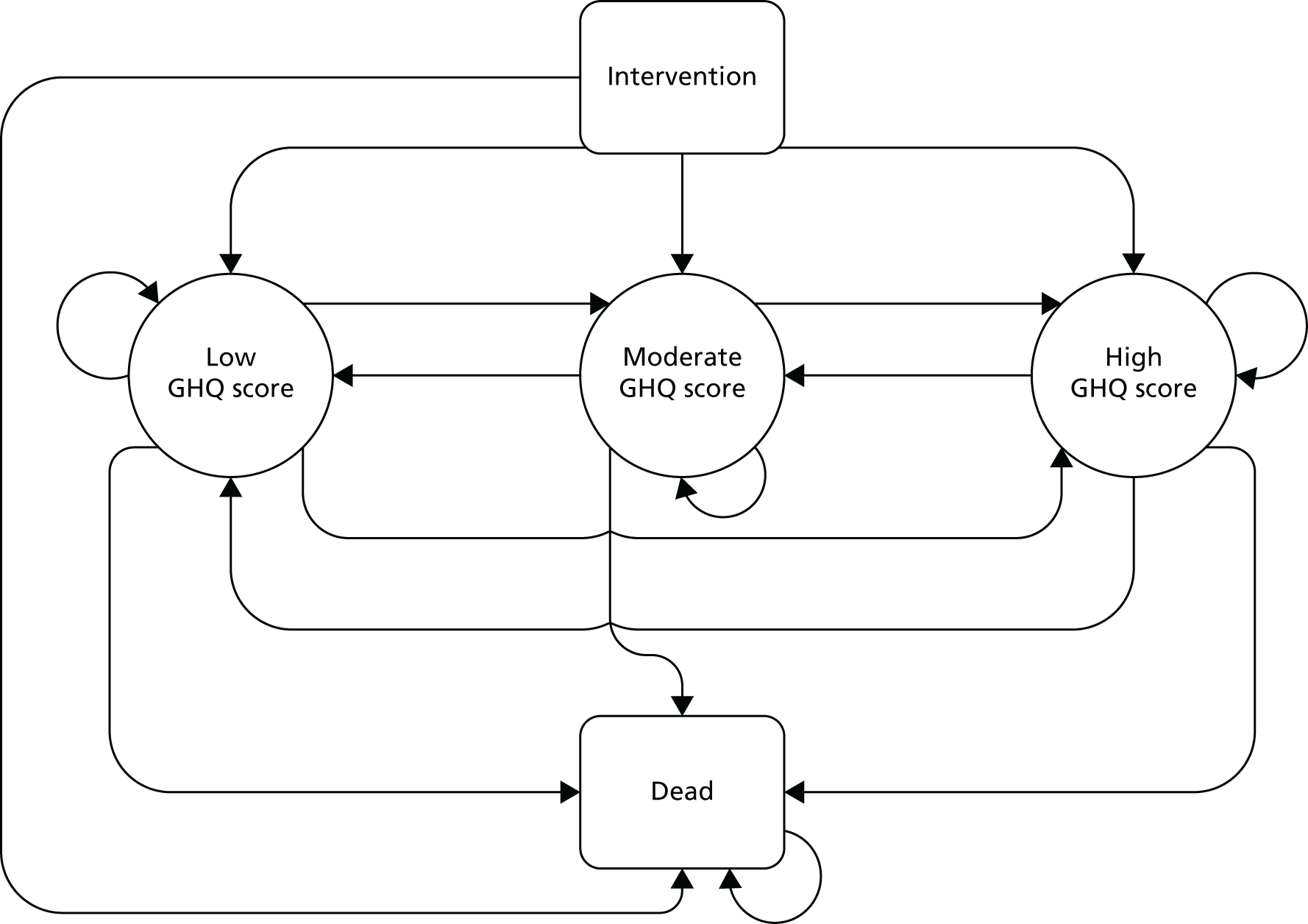

-

General Health Questionnaire 30-item version (GHQ-30):54 this is a 30-item questionnaire that was designed to detect psychological distress in the general population. It assesses participants’ mood over the past few weeks compared with their usual mood. The GHQ-30 was chosen as it is suitable for postal administration and is easy to complete. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (12-, 28- or 30-item versions) has also been shown to be responsive to the effects of psychological interventions in people with neurological conditions48,55–57 and has been used in previous TBI and rehabilitation studies. 23 Likert scoring was used for the GHQ-30 for the clinical outcome, with scores ranging from 0 to 90 and higher scores indicating more psychological distress. The alternative GHQ scoring methodology (0–0–1–1) was applied for the health economic evaluation.

In addition, we collected demographic information from participants at the screening assessment. This included gender, date of birth, ethnicity, date of TBI (self-reported by participants), duration of the initial hospital stay for the TBI, current employment status, living arrangements, military status and highest educational achievement.

The following clinical information on participants’ brain injury was collected from medical notes when these could be accessed at the recruiting site:

-

severity of injury assessed by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)58 score closest to admission and the worst total score

-

date of TBI (verified from medical notes)

-

type of brain injury (open or closed)

-

other neurological conditions.

Scores from the EMQ-p, RBMT-3 and SST completed at the initial screening visit were used to confirm eligibility for the trial. Patients who did not meet the eligibility criteria following the initial screening visit were notified by letter to thank them for their interest in the study and a brief report of their test results was provided if requested. Those who met the inclusion criteria were invited to continue in the trial, if they were happy to do so, and proceeded to the second assessment visit.

Participants continuing in the trial were asked to nominate a relative/friend who knew about their memory problems in daily life, although this was not a mandatory requirement of trial participation. A questionnaire booklet for the relative/friend was sent to eligible participants following the initial screening visit. Participants were asked to pass this on to their relative/friend and return completed questionnaires at the second assessment visit.

Second assessment visit

The following questionnaires were completed at the second visit, conducted 2 weeks (±1 week) after the initial screening visit:

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L):59 this is a validated, generalised health profile questionnaire used to assess HRQoL. EQ-5D-5L scores are used to derive utilities, which can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

-

Service use questionnaire (SUQ): we used a bespoke self-report SUQ to assess NHS health-care utilisation. The data collected included use of community-based services, such as contacts with general practitioners (GPs), practice nurses, other community-based professionals and community-based social care services and medication. Use of hospital services [including outpatient appointments, accident and emergency department attendance, day-care services and hospitalisation] was also captured. We asked participants to report services used for their memory problems and for other reasons separately. The period covered by the questionnaire was the previous 3 months. This was considered long enough for people to have received a range of services but not so long that they would have forgotten what they had received. The SUQ was adapted from a questionnaire used in previous studies. 60,61

In addition, the participants’ nominated relative/friend completed the following questionnaire prior to the visit, which was collected by the AP:

-

Everyday Memory Questionnaire – relative version (EMQ-r):43 this is a parallel version of the EMQ-p that offers an independent rating by a relative/friend of the memory problems that a person experiences. The EMQ-r was included to identify any effect of treatment on daily life problems as observed by another person, which might not have been detected by the participants themselves. EMQ-r scores range from 0 to 112, with higher scores indicating more frequent memory problems.

Participants were also asked to set the short- and long-term goals that they would like to achieve by the end of the study. With the assistance of the AP, each participant set between one and five personal short- and long-term goals. The AP also checked participants’ availability to attend for treatment in the event that they were assigned to the memory rehabilitation group, in order to form clusters of participants for randomisation.

Randomisation

Eligible patients were randomised following screening and baseline data collection.

Formation of clusters

Clusters of four to six participants were formed by the AP at each site prior to randomisation. This cluster size was selected as we considered this the optimal number of participants for the memory rehabilitation group sessions based on our previous experience of delivering the intervention. Furthermore, if the cluster sizes were larger participants may have needed to wait longer after the baseline assessments for a group to be formed. Clusters were based on participants’ availability to attend for treatment at the same time and same venue, should they be allocated to the memory rehabilitation arm. In the period while waiting for group allocation, the AP remained in regular contact with the participants to inform them when it was likely that there would be sufficient participants to form a group and to maintain their interest in the trial.

Participants who were awaiting randomisation at the time that their site closed to recruitment were sent a letter informing them that the AP had not been able to recruit enough people to create a group at a time and place that was convenient for them and that their participation in the trial was therefore at an end.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised in clusters of four to six to the memory rehabilitation arm or a usual-care control using a 1 : 1 ratio. The randomisation was based on a computer-generated pseudo-random code using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size, created by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) in accordance with its standard operating procedure (SOP) and held on a secure server. The randomisation was stratified by study site. Access to the sequence was limited to the NCTU information technology manager. The AP at the site accessed the allocation for each cluster by means of a remote, internet-based randomisation system developed and maintained by the NCTU. The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed from the study statistician until all participants were assigned and recruitment and data collection and all other study-related assessments were complete.

Intervention

Participants were randomised to group memory rehabilitation in addition to usual care or usual care alone.

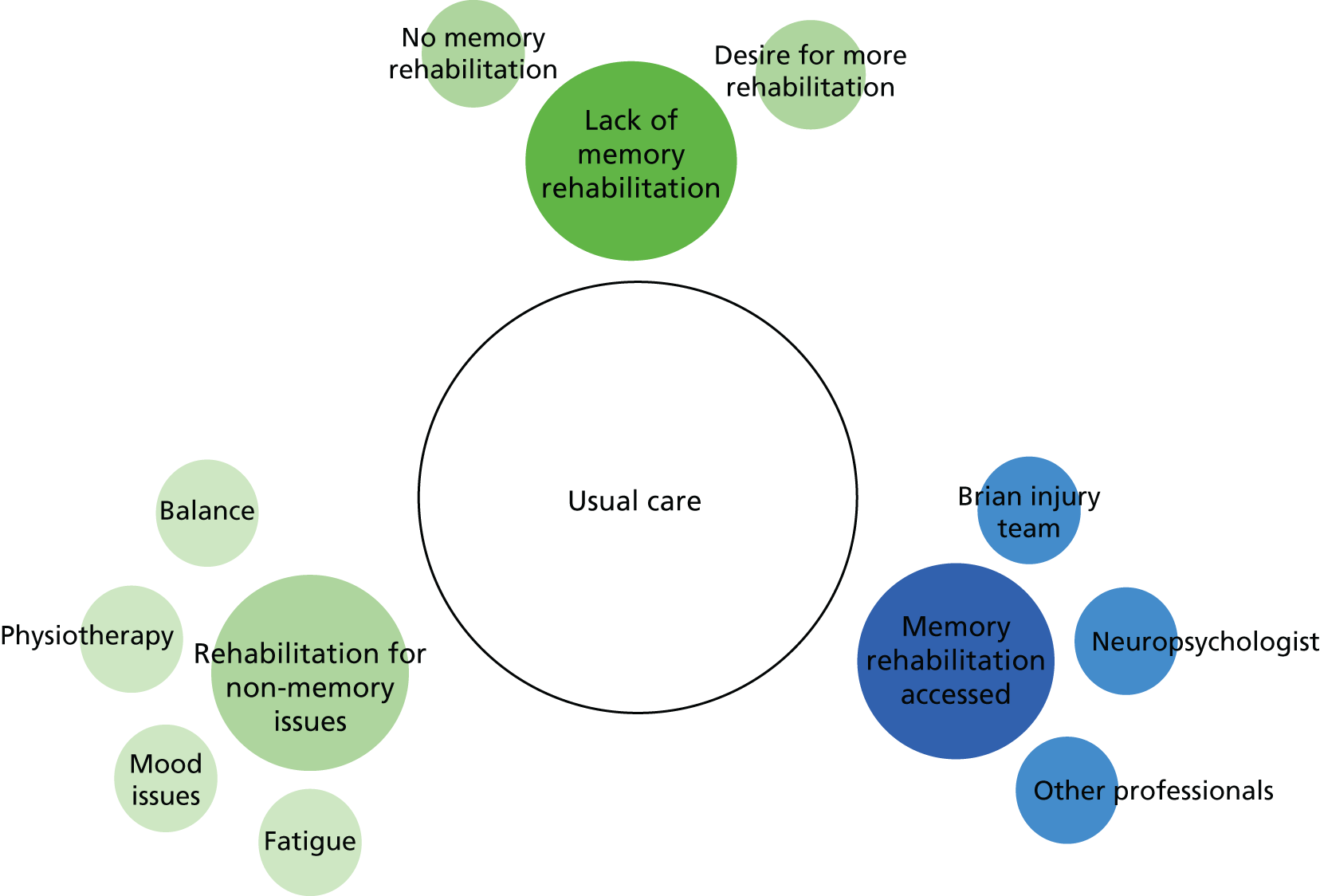

Usual care

All participants received their usual clinical care during the trial. Based on our knowledge of the recruiting sites, we expected that the majority of participants would no longer be receiving any formal rehabilitation but that they may be attending employment rehabilitation services or self-help groups or receiving support from specialist charities, such as Headway. Any additional interventions that people received were noted in the SUQ completed at the follow-up assessments.

Memory rehabilitation

The intervention was offered in groups of between four and six participants. Each group was led by an AP trained to deliver the intervention. Sessions were held at NHS sites or community venues. Participants were offered 10 group memory rehabilitation sessions, lasting approximately 1.5 hours each, which were planned to take place once a week for 10 weeks. However, sessions could be rearranged if necessary (e.g. because of staff or participant absence). The sessions followed a treatment manual. 18 The intervention included restitution strategies to retrain memory functions, including attention retraining (such as letter cancellation), and strategies to improve encoding and retrieval (such as deep-level processing). Compensation strategies were taught, including mnemonics (such as chunking, use of first letter cues, rhymes), use of external devices (such as diaries, mobile phones and calendars) and ways of coping with memory problems. The importance of ‘errorless learning’ (not making errors while learning new material and, therefore, preventing learning the errors)62 was also taught. The emphasis was on identifying the most appropriate strategies to help individuals overcome their memory problems and on providing participants with a range of memory techniques that they could adapt and use depending on their needs. This intervention provided an opportunity for revision of strategies taught during inpatient rehabilitation and discussion of their application in a community setting.

Treatment fidelity

The fidelity of the group rehabilitation programme was assured in a number of ways:

-

Manualised treatment. The group memory rehabilitation programme followed a manual (see Report Supplementary Material 1) that was developed and tested in the pilot study. A detailed description of the manual has been published. 18,23 The manual was accompanied by facilitator notes to guide delivery of the sessions (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

-

Training and supervision. Staff delivering the intervention (APs) were psychology graduates with clinical experience. A clinical psychologist provided study-specific training on conducting baseline assessments and the delivery of the intervention. In addition, monthly teleconferences between all APs, a clinical psychologist and NCTU staff provided an opportunity for peer group supervision. Furthermore, additional monthly one-to-one supervision with a clinical psychologist allowed for discussion of specific challenges relating to treatment or assessment. To ensure continuity and consistency, when staff changes occurred, old staff completed a ‘handover’ document for new staff, who were trained by the same trainers.

-

Fidelity assessment. Formal fidelity assessment of the group memory rehabilitation was undertaken through analysis of video recordings of treatment sessions. Intervention sessions were video recorded by APs facilitating the groups. APs were asked to video record all treatment groups, unless it was the first group run by the AP or participants had not given consent to be recorded. Practices for video recording drew on guidance on minimising the intrusiveness of the recording. 63,64

Sessions were selected for analysis in order to include sessions from the start, middle and end of the 10-week course and from each site. As far as possible, only recordings that covered a complete session were analysed. A coding schedule was developed based on the components of treatment described in the manual, listing possible activities for both the APs and participants (see Appendix 3).

A distinction was made between non-rehabilitation activities (e.g. social chat, information about sessions, preparing tasks or materials) and rehabilitation activities (e.g. discussing educational material, recap of previous session). An independent researcher coded the videos using a time sampling procedure. Observations were made on the minute, every minute, throughout the video recording. For each observation, the activities of the AP and participants were given the appropriate activity code. A sample of coding was checked by another observer and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Data from coding sheets were entered into the SPSS statistics programme for analysis (version 21; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Requirements for usual care were not specified and so no measures of fidelity were applied.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and the APs delivering the intervention to treatment allocation was not possible. RAs collecting outcome data at the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits were blind to treatment allocation. RAs were not involved in the delivery of the intervention. To prevent unblinding, at the start of each follow-up visit, the RAs reminded participants of the importance of the RAs remaining blind to treatment allocation and asked that participants did not discuss any aspects of their involvement in the study. At the beginning of each follow-up visit, the RAs recorded whether they had been unblinded prior to the visit and recorded their opinion of each participant’s treatment allocation using the following categories: definitely control, probably control, probably intervention or definitely intervention. At the end of each visit, the RAs recorded whether they had been unblinded during the visit and again recorded their opinion of each participant’s treatment allocation.

Follow-up

Outcomes were assessed at 6 and 12 months after randomisation to assess the immediate and longer-term effects of the intervention. The primary time point of interest was 6 months after randomisation. This time point was chosen to allow time to complete the 10 group sessions, while still allowing for one group session to be rescheduled if it had to be cancelled through illness or for other unforeseen circumstances. The 12-month assessment was carried out to determine whether or not any treatment gains had been maintained over time.

All reasonable attempts were made to contact any participant lost to follow-up during the course of the study in order to complete assessments. Participants were contacted by telephone in the first instance when follow-up visits were due. If telephone contact could not be made, a letter was sent to the participant’s last known address, so that the participant could contact the outcome assessor to arrange the appointment or provide updated contact details.

The following assessments were completed at the follow-up visits:

-

RBMT-3.

-

Assessment of individual goal attainment: each participant’s individual goals were evaluated in terms of the degree to which each goal had been met on a four-point Likert scale: ‘not met at all’, ‘met a little’, ‘mostly met’ and ‘fully met’. The participant and researcher discussed the extent to which goals were met and jointly determined the goal attainment. The average goal attainment score was used as the secondary outcome (with attainment coded as 0 for ‘not met at all’ and 3 for ‘fully met’). Goal attainment scaling (GAS) has been used in memory rehabilitation studies and has been recommended as an outcome measure of choice for cognitive rehabilitation. 65

In addition, a questionnaire pack was posted to participants before their 6- and 12-month appointments. Participants were asked to complete this questionnaire pack at home and return it by post to the trial co-ordinating centre in the prepaid envelope provided as soon as possible. If questionnaires had not been returned by the time of the follow-up visit they were collected by the RA at the follow-up visit.

The questionnaire pack included the following questionnaires for completion by participants:

-

EMQ-p.

-

GHQ-30.

-

EQ-5D-5L.

-

SUQ.

-

European Brain Injury Questionnaire – patient version (EBIQ-p):66,67 this contains 63 items that assess the subjective experience of cognitive, emotional and social difficulties experienced by people with brain injury; there are an additional three items that ask about the impact of the participant’s brain injury on their relative/friend. Each item is rated on a three-point Likert scale, ‘not at all’, ‘a little’ or ‘a lot’, depending on how much each has been experienced over the past month. The EBIQ-p is a clinically reliable measure that is used to determine the subjective well-being of people with brain injury and to assess change in subjective concerns over time. 67,68 It is used in rehabilitation centres as an outcome measure. 68 We used the modified subscales proposed by Bateman et al. 69 In this model, EBIQ-p scores range between 1 and 3 on each of seven subscales, with higher scores indicating greater difficulties. The seven subscales are:

-

somatic (seven items)

-

cognitive (12 items)

-

impulsivity (10 items)

-

depression (five items)

-

social interaction (five items)

-

fatigue (eight items)

-

communication (four items).

-

In addition, the following questionnaires, for completion by the participants’ nominated relative/friend, were included in the questionnaire pack sent to participants. Participants were asked to pass these on to their relative/friend for completion:

-

EMQ-r.

-

European Brain Injury Questionnaire – relative version (EBIQ-r). 67 This is a parallel version of the EBIQ-p, completed by the participant’s relative/friend to assess the cognitive, emotional and social difficulties experienced by people with brain injury.

Originally, all questionnaires were intended to be returned by post only; however, the procedure was changed after a HTA programme monitoring visit in December 2014 so that follow-up questionnaires were collected at the follow-up visit by the outcome assessor if these had not been posted back. This was in response to a poor return rate because of the previous reliance on postal returns.

The returned questionnaire packs were checked for completeness and participants were telephoned if items were missing or we needed clarification about their responses (e.g. unclear marking on questionnaires). Participants were also telephoned if their questionnaire packs were not received before the follow-up visit.

Qualitative feedback interviews

A sample of participants was invited to take part in qualitative feedback interviews, conducted within 2 months of the 6-month follow-up appointment. The interviews were intended to provide feedback on the participants’ experience of being involved in the trial, their experience of usual care and, for those in the intervention groups, their experience of receiving group memory rehabilitation. The qualitative analysis is described in detail in Chapter 5.

End of the study

Participants left the study when they had completed the 12-month follow-up. The end of the study was defined as the time of the last participant’s 12-month follow-up appointment, although questionnaires were accepted after completion of the final visit to allow for any delays in return.

Premature discontinuation from the intervention or withdrawal from follow-up was reported and reasons for withdrawal (if given) were documented. If a participant discontinued treatment but agreed to remain in the trial, outcome data collection continued in accordance with the protocol1 [the protocol is also available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/105724/#/ (accessed 1 August 2018)]. Participants were informed at the start of the study that data collected up to the point of withdrawal would be retained and used in the final analysis. We did not replace participants who withdrew.

Outcome measures

All measures were selected on the basis of their clinical utility, relevant psychometric properties and ease of use for participants. Furthermore, the measures reflect the three levels of the ICF31 domains – impairment, activity limitations and participation restrictions – thereby embracing the aims and spirit of cognitive rehabilitation. 70,71

Primary outcome

-

Frequency of memory failures in daily life assessed using the EMQ-p at 6 months’ follow-up.

Secondary outcomes

-

Objective measure of memory problems assessed by the RBMT-3.

-

Mood assessed with the GHQ-30.

-

Individual goal attainment.

-

Subjective experience of brain injury assessed with the EBIQ-p.

-

Subjective report of frequency of memory problems in daily life in the longer term assessed using the EMQ-p.

-

Subjective report of the importance of memory problems in daily life. To assess this, we added to the EMQ-p a measure of how important each item was. The rationale was that, even if some items were forgotten less frequently than others, these may be more significant if participants viewed these items as being more important than other items. The 28 EMQ-p items were therefore also rated for importance on a five-point Likert scale (from ‘not at all important’ to ‘very important’). Importance scores ranged from 0 to 112, with higher scores indicating more important memory problems.

Relative/friend-completed outcomes

-

Relative/friend report of the frequency of participants’ memory problems in daily life assessed using the EMQ-r.

-

Relative/friend report of the experience of brain injury assessed using the EBIQ-r.

Health economic outcomes

-

Quality of life assessed using the EQ-5D-5L.

-

Service use assessed using the bespoke SUQ.

Research governance

The study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations for clinicians involved in research on human subjects adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly (Helsinki, 1964)72 and later revisions, the NHS Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care (second edition)73 and the principles of the International Conference of Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. 74

Trial registration

The study was prospectively registered as ISRCTN65792154 on 17 October 2012.

Ethics

The National Research Ethics Service – East Midlands (Nottingham 1) gave ethics approval for the study for NHS participants (reference 12/EM/0324) and the Ministry of Defence Research Ethics Committee gave approval for recruiting military participants (reference 374/PPE/12).

Site initiation and training

Prior to the commencement of the study, members of the central research team (chief investigator and/or co-chief investigator and NCTU staff) met with study collaborators from each site to discuss implementation and training issues to ensure that all staff members were familiar with all aspects of the study. New staff were trained before starting work on the trial. A clinical psychologist and the NCTU staff provided study-specific training on the trial documentation and database.

Protocol deviations

A protocol deviation was defined as an unanticipated or unintentional divergence or departure from the expected conduct of the study inconsistent with the protocol, consent document or other study procedures. Protocol deviations were recorded on the electronic case report form by APs and RAs. Protocol violations were defined as deviations that affected eligibility or outcome measures, as assessed by the Trial Management Group (TMG).

Oversight

We convened a number of oversight groups to monitor study progress and conduct throughout the trial. The general roles and responsibilities of these groups were outlined in the protocol, with specific charters also developed for the independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC).

Trial Management Group

The TMG comprised the co-chief investigators and members of the NCTU responsible for the running of the trial, who met regularly throughout the trial. This group was responsible for the day-to-day running of the trial.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC was responsible for overseeing the conduct of the study. The TSC had an independent chairperson and five independent members. Independent members were rehabilitation professionals and patient/carer representatives who were not otherwise involved in the trial. Members of the study team, including the chief investigator, co-chief investigator, service user co-applicant and trial manager, were also part of the TSC. The TSC advised on recruitment strategies, monitored the progress of recruitment and checked adherence to the study protocol. Observers from the funder and the sponsor were invited to TSC meetings.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was an independent group, the members had no other involvement with the study. Members of this committee included two rehabilitation professionals and an experienced study statistician. The role of the DMC was to safeguard the interests of trial participants, with particular reference to the safety of the intervention, monitor the overall progress and conduct of the trial and assist and advise the investigators to protect the validity and credibility of the trial.

The TSC and the DMC met independently of each other, with the DMC providing reports to the TSC.

Safety monitoring

The risks of the study were assessed during protocol development. The assessment of memory may have made participants aware of memory problems that they did not know that they had. As a result, the main risk associated with this trial was considered to be distress caused by this realisation. However, such distress was considered unlikely and any distress caused was deemed likely to be mild. Overall, therefore, the risk of the trial was assessed as negligible. As a result, data on adverse events or serious adverse events were not collected in this study. The independent DMC instead was provided with a report detailing hospital and GP visits (either related to TBI or otherwise), recorded from participant-reported SUQs for all participants, and any deaths. This was agreed by the sponsor, the Research Ethics Committee, the DMC and the TSC.

‘Notable events’ occurring during both assessments and treatment were recorded throughout the trial. Notable events were those that were assessed by the APs or RAs as being out of the ordinary, such as problems arising during group sessions or issues that might pose a risk to participants or researchers. These were reviewed by the study team on an ongoing basis and were reported to the DMC/TSC during routine meetings.

Patient and public involvement

During protocol development, service user and carer representatives with experience of TBI and/or rehabilitation in NHS services advised on recruitment and dissemination options and contributed to the development of the intervention manual and the lay summary of the project. One service user representative had experience of NHS rehabilitation services following his head injury and participated in our pilot study, so was able to provided first-hand experience of the intervention. He told us what he and the peers in his group enjoyed and found useful and what they did not find useful. This information enabled us to make some changes to the manual and content of the intervention. We also recruited a carer representative who had caring responsibilities for a person with TBI. The service user co-applicant and a carer helped us advertise the study by being part of a video about our study and by taking part in a radio and television interview about brain injury and our study. The service user co-applicant was involved in project management decisions, project approval through the Integrated Research Application System and recruitment and consent (by contributing to the development of participant information sheets).

A service user and carer and representatives from relevant charities (e.g. Headway and Combat Stress) were members of the TSC and DMC. Their involvement in these committees enabled us to check with them when any amendments to the protocol were required.

We developed participant and public newsletters to keep participants and the public informed about the progress of our study. These were sent to participants, clinicians and local head injury charities so that they could be cascaded to interested members of the public. We sent the final plain English summary of our findings to our carer representative to assess its readability and we made changes where these were required. All service user involvement was resourced appropriately.

Payments to participants

Participants were not paid to take part in the trial but reasonable travel expenses for attendance at trial assessments and intervention sessions were reimbursed.

Statistical methods

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on the primary outcome measure (EMQ-p) at 6 months post randomisation. The main study aim was to detect a minimum clinically relevant difference in mean EMQ-p score of 12 points between the memory rehabilitation arm and the usual-care arm. In the absence of any agreed and published minimum clinical relevant differences on the EMQ-p, we deemed a 12-point difference on this measure to be a clinically significant change, based on our pilot data18 and clinical interviews. A common SD of 21.9 from the pilot study gave us an effect size of 0.55. For the sample size calculation, a two-sided type 1 error of 0.05 and power of 90% and a fixed-effects model at the level of the four original planned sites were used, with 10% of the total variation due to between-site variation. The participants were cluster randomised and a cluster size of six was used for the sample size calculation, with an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.1. Using the Optimal Design software (version 3.01; William T. Grant Foundation, New York, NY, USA) with these parameters, the calculation gave 10 clusters (five clusters for each allocation) per site (40 in total). Data from the pilot study, and taking account of the fact that the control arm received only usual care, suggested a possible dropout rate of 20%. Therefore, we needed 26 clusters for each allocation (52 in total), which amounted to 312 participants randomised in total.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses are detailed in the statistical analysis plan (SAP) [URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/105724/#/ (accessed 17 August 2018)], which was finalised prior to database lock and release of the treatment allocation codes for analysis. All analyses were carried out using Stata®/SE 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Preliminary analysis

We used descriptive statistics of demographic and clinical measures to examine balance between the two arms. The internal consistency of the EMQ-p, EMQ-r and GHQ-30 was also evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha.

Analysis populations

The main approach used in the analysis was to analyse participants as randomised regardless of the number of memory rehabilitation sessions attended [intention to treat (ITT)], for all primary and secondary outcomes.

Data used at each time point were as follows:

-

the outcomes at 6 months were questionnaires/visits completed within 9 months of randomisation (i.e. within 275 nights of randomisation)

-

the outcomes at 12 months were questionnaires/visits completed within 15 months of randomisation (i.e. within 456 nights of randomisation).

Outcomes completed outside these time periods were not used, other than in a sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome. The main analyses were based on participants with available data, with no imputation for participants with missing outcomes.

Descriptive analyses

We described the adherence to the intervention by tabulating the attendance at each session and summarising the number of sessions that each participant attended. The reasons for non-attendance at sessions were also described and summarised.

The numbers of participants returning the questionnaire booklet and completing the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits were summarised in the two arms along with the number of days between randomisation and completion. The pattern of missing outcome data was explored, overall and in the two arms, and baseline characteristics were compared between participants with and without primary outcome data.

Missing data in questionnaires

We imputed missing items in questionnaires using the mean of the completed items if < 10% of the items in the questionnaire were not completed. Scores were therefore calculable when ≥ 25 of the 28 items were completed on the EMQ-p and EMQ-r, ≥ 27 of the 30 items were completed on the GHQ-30, ≥ 11 of the 12 items were completed on the EBIQ-p and EBIQ-r cognitive subscale and ≥ 9 of the 10 items were completed on the EBIQ-p and EBIQ-r impulsivity subscale. Scores for all other EBIQ-p and EBIQ-r subscales were calculable only if all items in the subscale were completed. If > 10% of items were missed, outcomes were treated as missing.

If scores from the questionnaires remained missing at baseline after the process outlined above (or other baseline information was missing), in order to be able to include all participants in the regression analysis of the outcome score, we imputed these baseline data using the mean score at each site. These simple imputation methods are superior to more complicated imputation methods when baseline variables are included in an adjusted analysis to improve the precision of the treatment effect. 75 Note that this imputation was carried out only for the regression analyses and not for summarising the baseline scores.

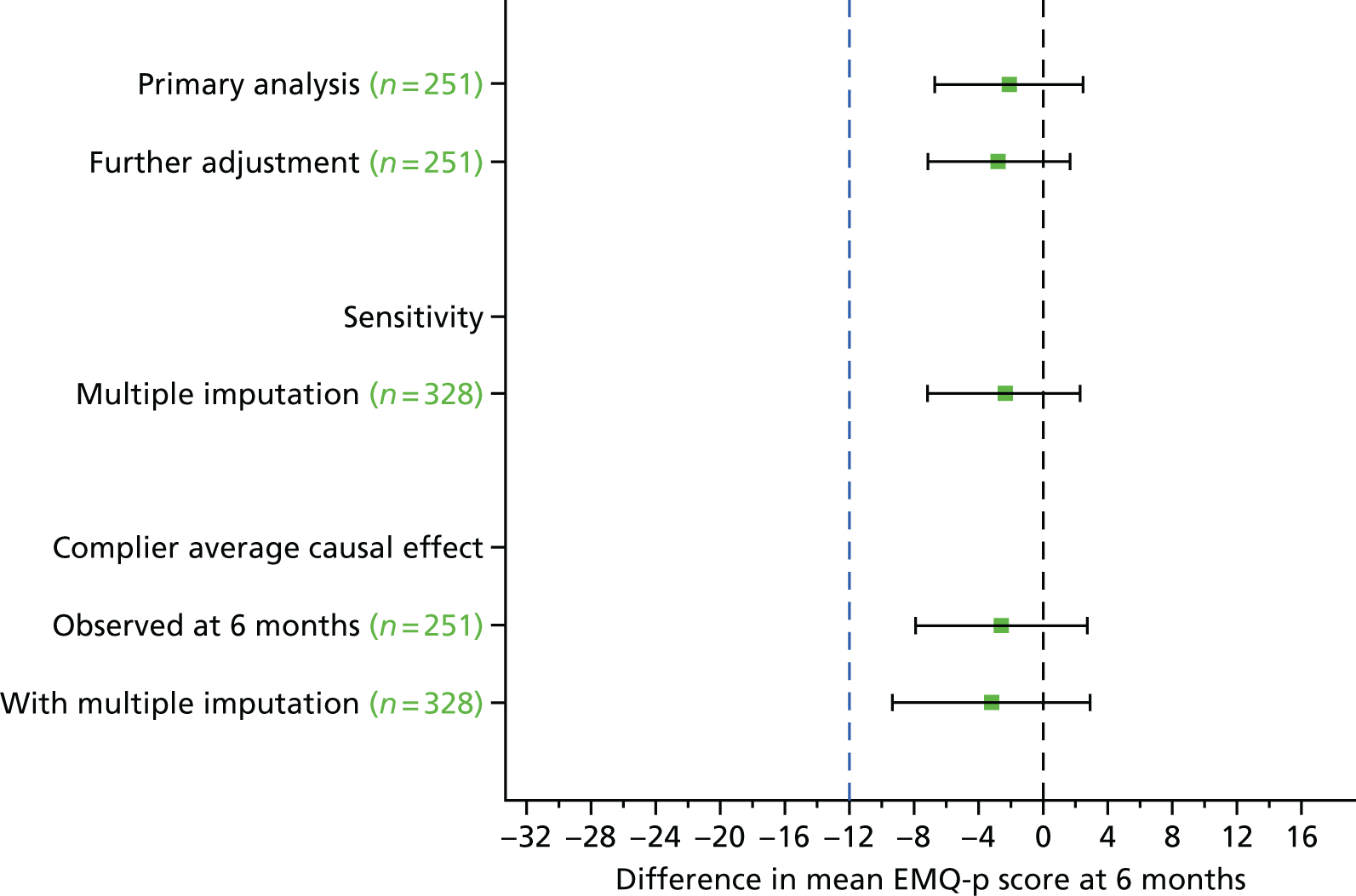

Primary outcome

For the primary analysis we estimated the difference in mean EMQ-p score between the two arms at the 6-month follow-up using a multilevel linear model, with baseline EMQ-p score and site as covariates. Although participants were randomly allocated in clusters, individuals in the usual-care arm had no contact with each other and outcomes in this arm were therefore assumed to be independent. However, participants in the intervention arm attended group memory rehabilitation sessions, which needed to be accounted for in the analysis. We therefore used a fully heteroscedastic model, as suggested by Roberts and Roberts,76 for the analysis of trials comparing group-based treatments with individual-based treatment as usual, when, as is the case here, there is adjustment for individual-level covariates. This model estimates group-level residual variance in the intervention arm and also permits individual-level residual variance to differ between the intervention arm and the control arm. 76,77 Assumptions made in the multilevel linear model were checked using diagnostic plots. The ICC in the intervention arm was estimated using the estimates of the group-level residual variance and individual residual variance in the intervention arm. 77

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome

We conducted the following sensitivity analyses:

-

Including all 6-month questionnaires. We repeated the analysis described above including participants whose 6-month questionnaires were returned after the 9-month post-randomisation window.

-

Additional adjustment for baseline variables with an observed imbalance. We included baseline variables with an observed imbalance (based on comparison of summary statistics only, not statistical testing) as additional covariates in the multilevel model for the 6-month EMQ-p score.

-

Multiple imputation of missing primary outcome data. We performed multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE) separately for each arm, under the assumption that missing data were missing at random. 78 Variables included in the imputation model were site, age and gender, baseline variables identified as predictive of dropout (by examination only), prognostic baseline variables (EMQ-p, RBMT-3 GMI and GHQ-30), RBMT-3 GMI at the 6- and 12-month visit and 12-month EMQ-p score. In addition, for the intervention arm, the number of intervention sessions attended was included. Forty data sets were imputed and the results of the analyses on the imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rules. 78

-

Estimation of the complier average causal effect. We used instrumental variable regression to estimate the effect of the intervention for participants who would comply with the allocated treatment whichever arm they were randomised to. 79,80 Participants in the intervention arm were classified as adherent if they attended at least four memory rehabilitation sessions. The instrumental variable regression model included baseline EMQ-p score and recruiting site and used a clustered sandwich estimator to estimate the variance to allow for correlation between randomisation clusters (vce cluster option in Stata). We estimated the complier average causal effect using both the observed data and the multiply imputed data.

We performed a prespecified exploratory subgroup analysis for the primary outcome according to memory impairment at baseline (using the RBMT-3 GMI score, an objective measure of memory) by including an interaction term in the model for the primary analysis. The RBMT-3 GMI score at baseline was categorised into three groups on the basis of classifications provided by the test publisher:81 significant memory impairment (scores of ≤ 69), borderline/moderate memory impairment (scores of 70–84) and average and above average range (scores of ≥ 85).

During the trial, a Rasch analysis of the EMQ-p was performed using an independent data set of patients with TBI (Rachel Johnson, Roshan das Nair and Nadina B Lincoln, University of Nottingham, 2017, personal communication). We performed an exploratory analysis using this Rasch conversion of the EMQ-p scores and compared scores between the two arms using the multilevel model described above.

After the planned analyses were conducted, at two meetings with collaborators and investigators, time since TBI was raised as a potentially important factor with regard to whether or not patients could benefit from the intervention. We therefore conducted a post hoc subgroup analysis of time since TBI, using the methods described above.

Secondary outcomes at 6 and 12 months

We analysed the secondary outcomes using the multilevel model described for the primary outcome. Estimates of the intervention effect are presented as difference in means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For the goal attainment outcome, the number of goals set was additionally included as a covariate. Estimates of the ICC in the memory rehabilitation arm for each outcome, calculated from the multilevel models, are provided in Appendix 4.

Of the seven subscales of the EBIQ-p (and EBIQ-r), the cognitive, depression, communication and difficulties in social interaction subscales were used in a formal comparison between arms, as the content of the group memory intervention was most likely to have an impact on these subscales. The other subscales (impulsivity, somatic and fatigue) were summarised using descriptive statistics only.

Sensitivity analyses for goal attainment secondary outcomes

Participants set at least one short- and one long-term goal but could set up to five. An interaction term between the number of goals set (one or more than one) and treatment arm was included in the model for the goal attainment score to explore whether there was evidence of any differential effect of the intervention according to the number of goals set at baseline. We hypothesised that it could be harder for participants who set more than one goal to meet all of their goals than for participants who set, and who therefore focused on, one individual goal.

Goals set at the start of the trial should have been SMART (specific, measurable, assignable, realistic and time-related) goals so that they could be assessed at the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits as being met or not being met. During the trial it became apparent that not all goals set by the APs at baseline were measurable. As a sensitivity analysis, each goal was classified as SMART or not by one of the trial APs and a sample was independently checked by the chief investigator. We then repeated the analysis for goal attainment including only SMART goals.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

Recruitment commenced in February 2013 and continued until December 2015 when the recruitment target was met (see Appendix 5). The original planned recruitment period was extended by 8 months because recruitment rates were lower than expected. This was in part because of staff turnover and delays in recruiting new staff, resulting in a number of sites being inactive during the recruitment period.

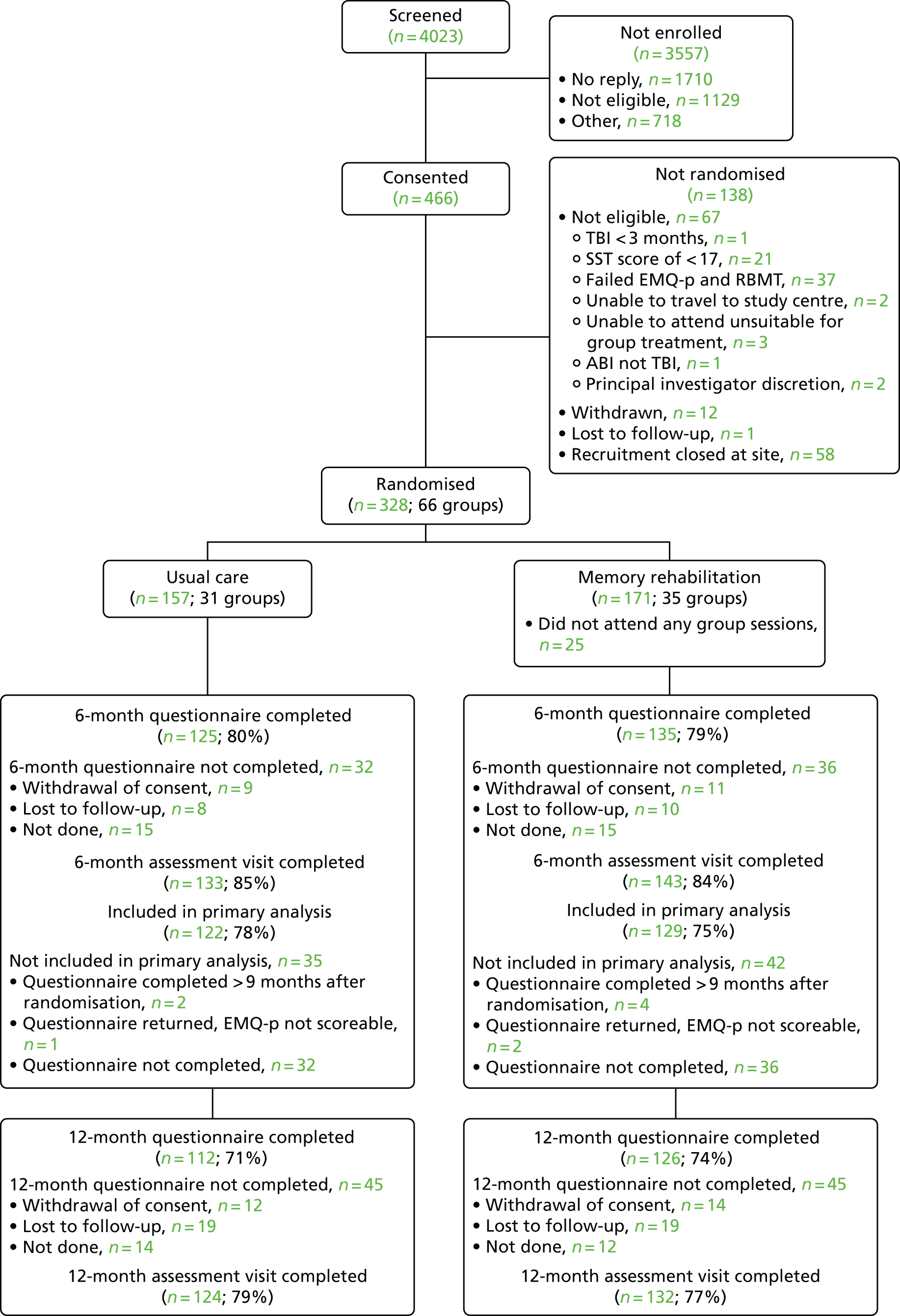

Between February 2013 and December 2015, we screened 4023 people and consented 466. Of the 3557 people screened but not consented, the main reason was not replying to the letter of invitation (n = 1710, 43%); 1129 (28%) people were not eligible for the trial and 718 (18%) were not enrolled for other reasons (Figure 1). Further details are provided in Appendix 6.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow chart. Reproduced from das Nair et al. 82 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Of the 466 people who gave consent, 328 (70%) were randomised. Non-randomisation after consent was the result of non-eligibility, recruitment being closed at the site (because of the site closing either during the trial or at the end of recruitment in December 2015) and participants withdrawing consent or no longer being contactable (see Figure 1).

Of the 328 participants randomised, 157 (48%) were randomised to usual care and 171 (52%) to memory rehabilitation in addition to usual care (see Figure 1). The mean size of the cluster randomised was five. The randomisation target of 312 was exceeded because of the requirement to randomise clusters of participants who could attend the intervention sessions at the same time, if allocated to the intervention, at the five sites remaining open at the end of recruitment.

Participants were randomised in clusters of four to six and the randomisation was stratified by site. The number of clusters randomised to each arm within each site was well balanced (see Appendix 7). More participants were randomised to the memory rehabilitation arm.

Participants waited a median of 18 days between the second assessment and randomisation (see Appendix 7). However, a small number of participants (n = 23) waited for ≥ 6 months to be randomised; this was because they had to wait both for other participants who could attend the intervention sessions at the same time and for the AP to be available within the site to deliver the intervention.

Baseline data

The mean age of participants was 45 years (SD 12 years), 239 (73%) were men and almost all (96%) were white (Table 1). We randomised 31 participants (9%) who were serving or who had served in the military, including participants from the Territorial Army and reservists (see Table 1). There was a wide variation in the time since the TBI at randomisation, from 3 months to almost 49 years. The median time since TBI was just over 4 years (see Table 1).

| Characteristic | Trial arm | Total (N = 328) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 157) | Memory rehabilitation (N = 171) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 45.1 (12.5) | 45.8 (11.5) | 45.4 (12) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 45 (36, 55) | 47 (38, 54) | 46 (36, 54) |

| Min., max. | 19, 69 | 20, 68 | 19, 69 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Men | 116 (74) | 123 (72) | 239 (73) |

| Women | 41 (26) | 48 (28) | 89 (27) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 147 (94) | 167 (98) | 314 (96) |

| Black | 6 (4) | 2 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Mixed race | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Residential status, n (%) | |||

| Lives alone | 44 (28) | 43 (25) | 87 (27) |

| Lives with others | 106 (68) | 120 (70) | 226 (69) |

| Living with informal carer | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Living with formal carer | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Living in care home | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | 10 (3) |

| Highest educational attainment, n (%) | |||

| Below GCSE | 26 (17) | 29 (17) | 55 (17) |

| GCSE | 54 (34) | 49 (29) | 103 (31) |

| A level | 42 (27) | 34 (20) | 76 (23) |

| Degree | 24 (15) | 41 (24) | 65 (20) |

| Higher degree | 10 (6) | 17 (10) | 27 (8) |

| Not known | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Employment status at screening (not mutually exclusive), n (%) | |||

| Not employed | 80 (51) | 85 (50) | 165 (50) |

| Employed full time | 25 (16) | 38 (22) | 63 (19) |

| In education full time | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Voluntary full time | 1 (1) | – | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Retired | 17 (11) | 15 (9) | 32 (10) |

| Employed part time | 25 (16) | 19 (11) | 44 (13) |

| Voluntary part time | 9 (6) | 17 (10) | 26 (8) |

| Current military service,a n (%) | |||

| Military | 4 (3) | 0 | 4 (1) |

| TA/reservist | 0 | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Non-military | 153 (97) | 169 (99) | 322 (98) |

| Previous military service, n (%) | |||

| Military | 14 (9) | 11 (6) | 25 (8) |

| TA/reservist | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Non-military | 141 (90) | 156 (91) | 297 (91) |

| TBI during service | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Time since TBI (months)b | |||

| Mean (SD) | 99 (114.8) | 102.6 (113.4) | 100.9 (113.9) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 46 (23, 116) | 58 (24, 148) | 52 (24, 129.5) |

| Min., max. | 4, 520 | 3, 587 | 3, 587 |

| Length of initial hospital stay for TBI (days)c | |||

| Mean (SD) | 81.8 (108.6) | 86.5 (143.5) | 84.2 (127.7) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 35 (7, 120) | 35.5 (10, 93.5) | 35 (9, 116) |

| Min., max.d | 0, 468 | 0, 999 | 0, 999 |

| n | 148 | 160 | 308 |

| Length of hospital stay unknown, n (%) | 9 (6) | 11 (6) | 20 (6) |

Characteristics assessed at baseline were well balanced, although a greater proportion of participants in the memory rehabilitation arm than in the usual-care arm had a degree or higher degree and the median time since TBI was slightly longer in the memory rehabilitation arm (approximately 4 years in the usual-care arm and approximately 5 years in the memory rehabilitation arm).

Data from the memory, mood and quality-of-life assessments completed prior to randomisation are shown in Table 2. Scores were well balanced between arms; however, when the RBMT-3 GMI was categorised into levels of memory impairment a smaller percentage of participants in the memory rehabilitation arm than in the usual-care arm were classified as having a significant impairment (39% in the usual-care arm vs. 29% in the memory rehabilitation arm; see Table 2).

| Assessment | Trial arm | Total (N = 328) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 157) | Memory rehabilitation (N = 171) | ||

| EMQ-p – frequency of problems | |||

| Mean (SD) | 50.1 (24.6) | 47.4 (21) | 48.7 (22.8) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 50 (33, 65.2) | 47.7 (30, 63) | 48 (32, 64) |

| Min., max. | 0, 105 | 5, 102 | 0, 105 |

| na | 156 | 171 | 327 |

| EMQ-p – importance of problems | |||

| Mean (SD) | 70.6 (22.4) | 65.7 (23.5) | 68 (23) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 72 (56, 87) | 69 (51, 83) | 70.5 (54, 84) |

| Min., max. | 2, 112 | 0, 112 | 0, 112 |

| n | 152 | 170 | 322 |

| RBMT-3 GMI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 76.3 (14.5) | 77.7 (13.6) | 77 (14) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 75 (65, 85) | 77 (67, 85) | 76 (66.5, 85) |

| Min., max. | 53, 114 | 53, 127 | 53, 127 |

| n | 157 | 171 | 328 |

| Level of memory impairment based on the RBMT-3, n (%) | |||

| Significant memory impairment (score of ≤ 69) | 61 (39) | 50 (29) | 111 (34) |

| Borderline/moderate memory impairment (score 70–84) | 54 (34) | 77 (45) | 131 (40) |

| Average or above average (score of ≥ 85) | 42 (27) | 44 (26) | 86 (26) |

| GHQ-30 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 35.3 (16.3) | 36.1 (15.4) | 35.8 (15.8) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 33 (21, 47) | 34 (25, 45) | 33 (24, 45.3) |

| Min., max. | 6, 90 | 6, 84 | 6, 90 |

| n | 154 | 170 | 324 |

| Estimated premorbid IQ from the NART | |||

| Mean (SD) | 106.5 (10) | 108.1 (10.2) | 107.4 (10.1) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 103 (99, 116) | 109.5 (100, 117) | 105 (100, 117) |

| Min., max. | 86, 126 | 87, 128 | 86, 128 |

| n | 155 | 170 | 325 |

| SST | |||

| Mean (SD) | 19.3 (0.9) | 19.4 (0.9) | 19.4 (0.9) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 20 (19, 20) | 20 (19, 20) | 20 (19, 20) |

| Min., max. | 17, 20 | 17, 20 | 17, 20 |

| n | 157 | 171 | 328 |

| EMQ-r – frequency of problems | |||

| Mean (SD) | 46.4 (24.4) | 42 (28.4) | 44.1 (26.6) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 46.7 (27, 65) | 35.3 (18.7, 64) | 38.5 (22, 64.5) |

| Min., max. | 0, 107 | 0, 108 | 0, 108 |

| n | 95 | 105 | 200 |

| EMQ-r – importance of problems | |||

| Mean (SD) | 71.5 (24.5) | 71.8 (21) | 71.7 (22.7) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 76 (64, 87) | 72 (60, 88) | 75 (60, 87) |

| Min., max. | 0, 112 | 4, 112 | 0, 112 |

| n | 90 | 101 | 191 |

The internal consistency of the EMQ-p and GHQ-30 at baseline using Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93 for the EMQ-p and 0.95 for the GHQ-30.

Relative/friend participation in the trial

In total, 210 relatives or friends of participants agreed to take part in the trial by returning a questionnaire at baseline or follow-up (64% in each arm). The scores from the EMQ-r were similar in the two arms at baseline (see Table 2). The internal consistency of the EMQ-r using Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96.

Group memory rehabilitation sessions

Attendance at group sessions

Participants attended a mean of 6.3 sessions (SD 3.5 sessions), with 131 (77%) participants attending four or more sessions (Table 3). There were several reasons that participants did not attend sessions; these are shown in Table 3.

| Summary | Memory rehabilitation (N = 171) |

|---|---|

| Number of sessions attended | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.3 (3.5) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 8 (4, 9) |

| Min., max. | 0, 10 |

| 0–2, n (%) | 36 (21) |

| 3–7, n (%) | 44 (26) |

| 8–10, n (%) | 91 (53) |

| At least four, n (%) | 131 (77) |

| Total number of sessions missed | 627 |

| Reason for missing sessions – number of sessions (number of participants)a | |

| Did not want to continue | 122 (16) |

| Withdrew from study | 52 (7) |

| Lost to follow-up (unable to contact) | 70 (7) |

| Forgot to attend | 11 (10) |

| Unwell | 83 (40) |

| Holiday | 59 (36) |

| Work/family commitments | 114 (34) |

| No reason given | 94 (23) |

| Otherb | 22 (16) |

Attendance at sessions decreased over time. Some groups were well attended throughout. In one group, the final four sessions were not attended by any participants (see Appendix 9).

In total, 17 APs delivered group sessions during the trial. The number of sessions that each AP ran ranged between 1 and 47, with a median of 20 (25th, 75th centile = 10, 28).

Analysis of treatment fidelity

The number of video recordings retrieved from each site are shown in Appendix 10 (see Table 35). No videos were retrieved from three sites. Sites 2 and 4 recruited only one intervention group each and, therefore, the sessions were not recorded as it was the first group conducted by the APs at those sites. At site 7, two intervention groups were recruited, one of which was the first for the AP; for the second group the recordings were not available for analysis. At two sites (sites 5 and 6) there were very few recordings retrieved as the APs did not understand that all sessions needed to be recorded. For 25 sessions the recording stopped partway through the session because of technical problems (e.g. the recorder battery being completely discharged). Overall, there were some recordings from six of the nine sites.

A selection of all recordings of complete sessions was analysed; seven recordings of complete sessions were not included because sufficient recordings from the site or the session had already been included in the analysis. In addition, as there were no complete recordings of session 1, two recordings that were almost complete were analysed for session 1. A summary of the video recordings analysed is provided in Appendix 10 (see Table 36). Between two and five recordings of each session were analysed. A total of 31 sessions were included in the fidelity analysis, approximately 9% of the 350 memory rehabilitation sessions delivered during the trial.

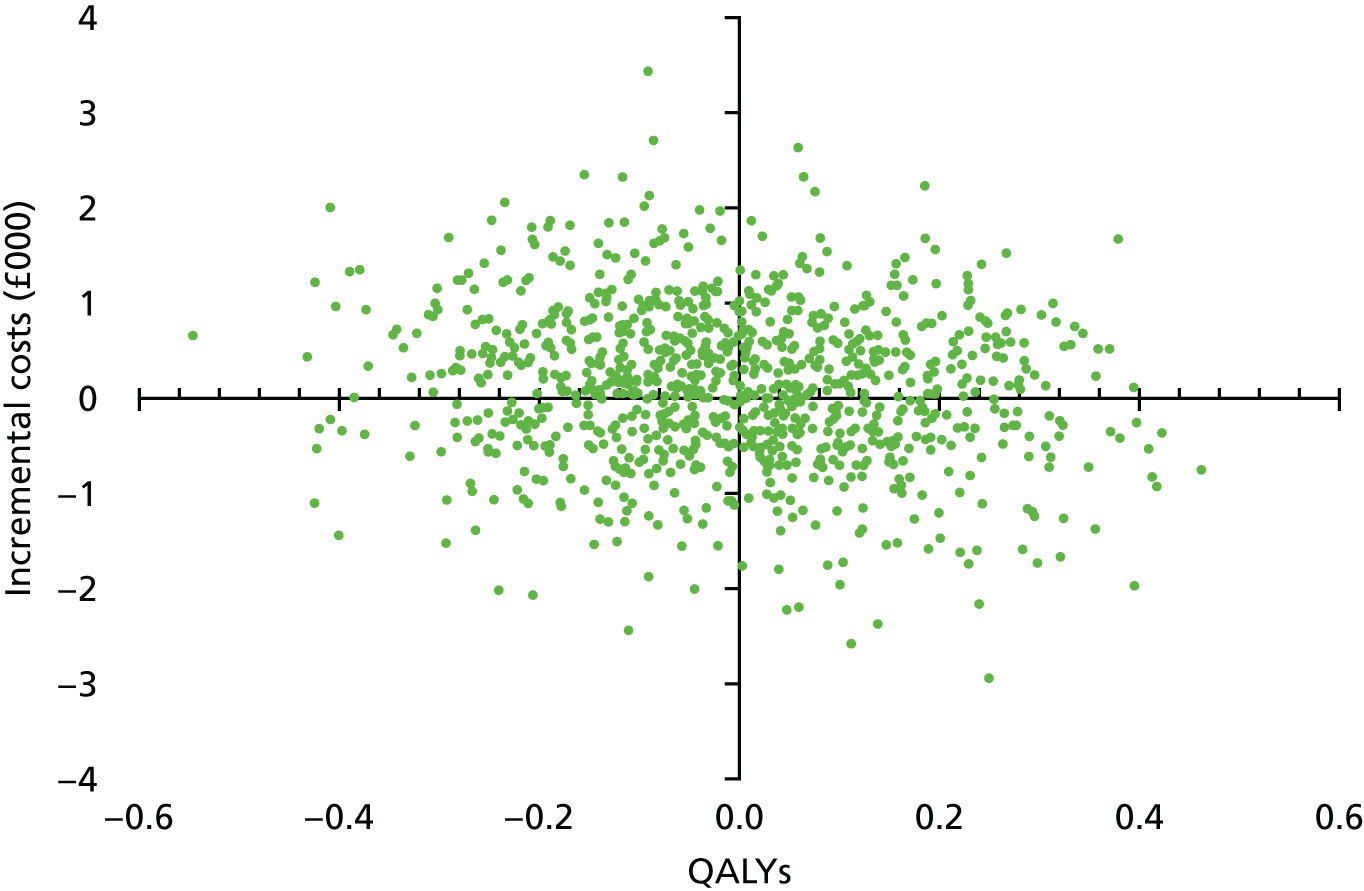

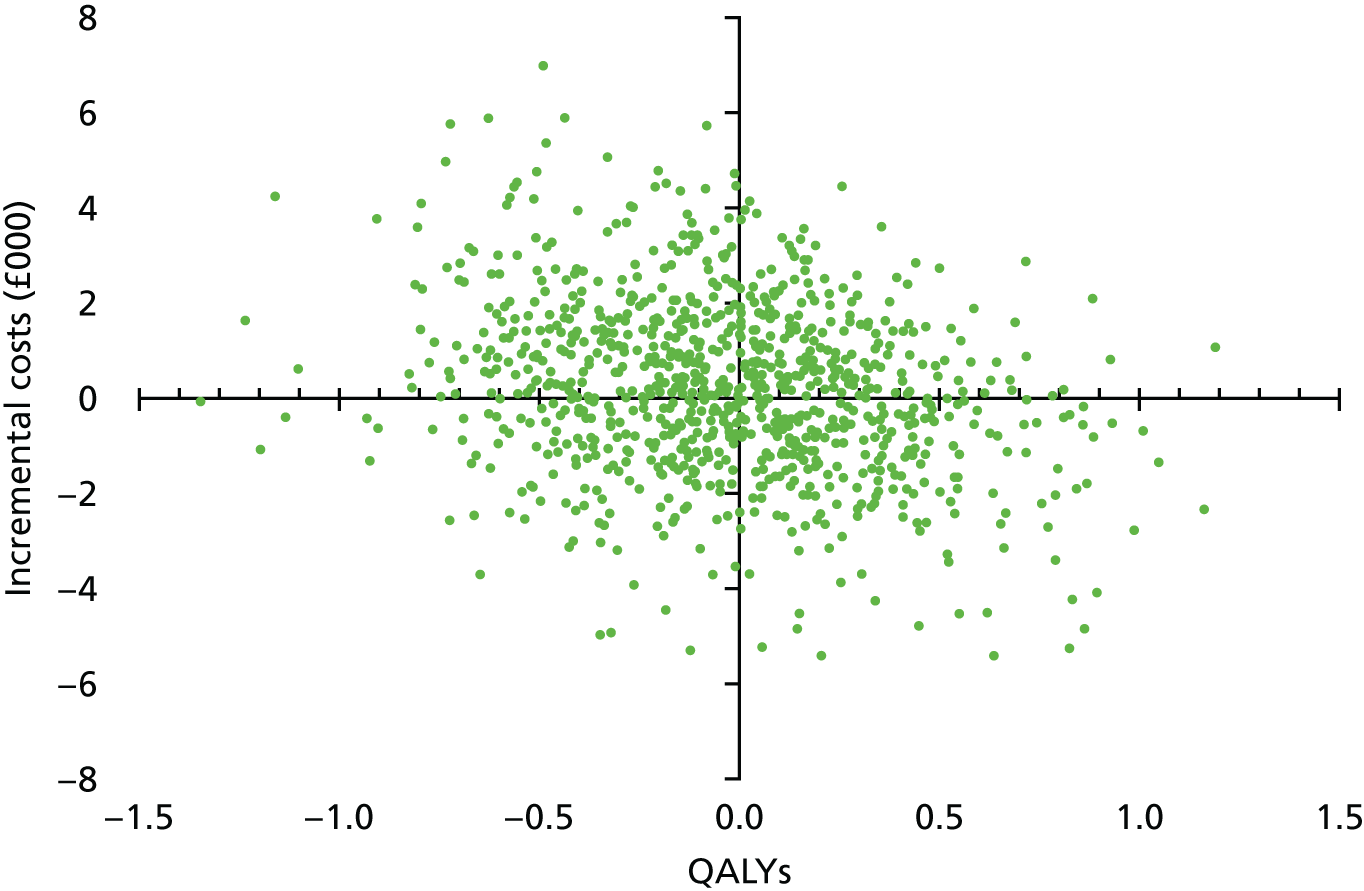

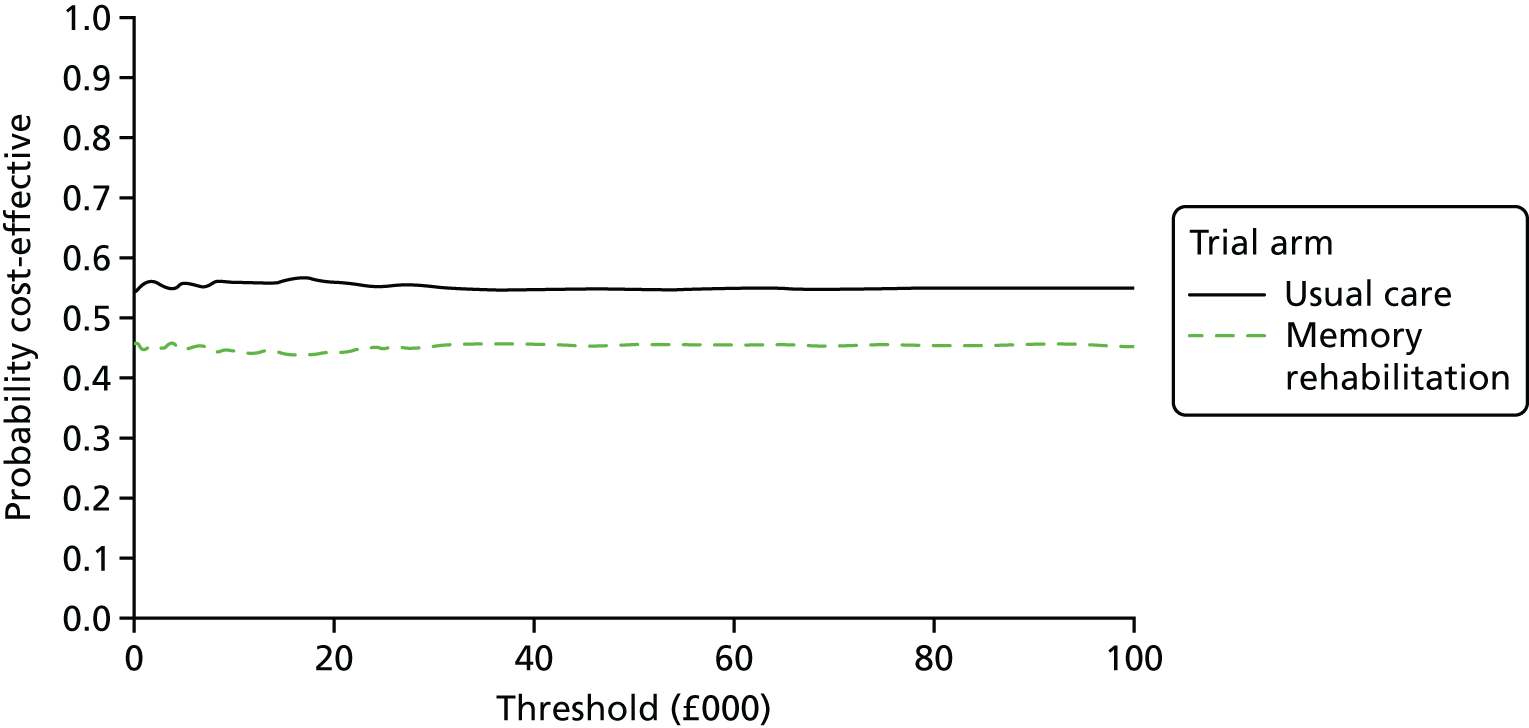

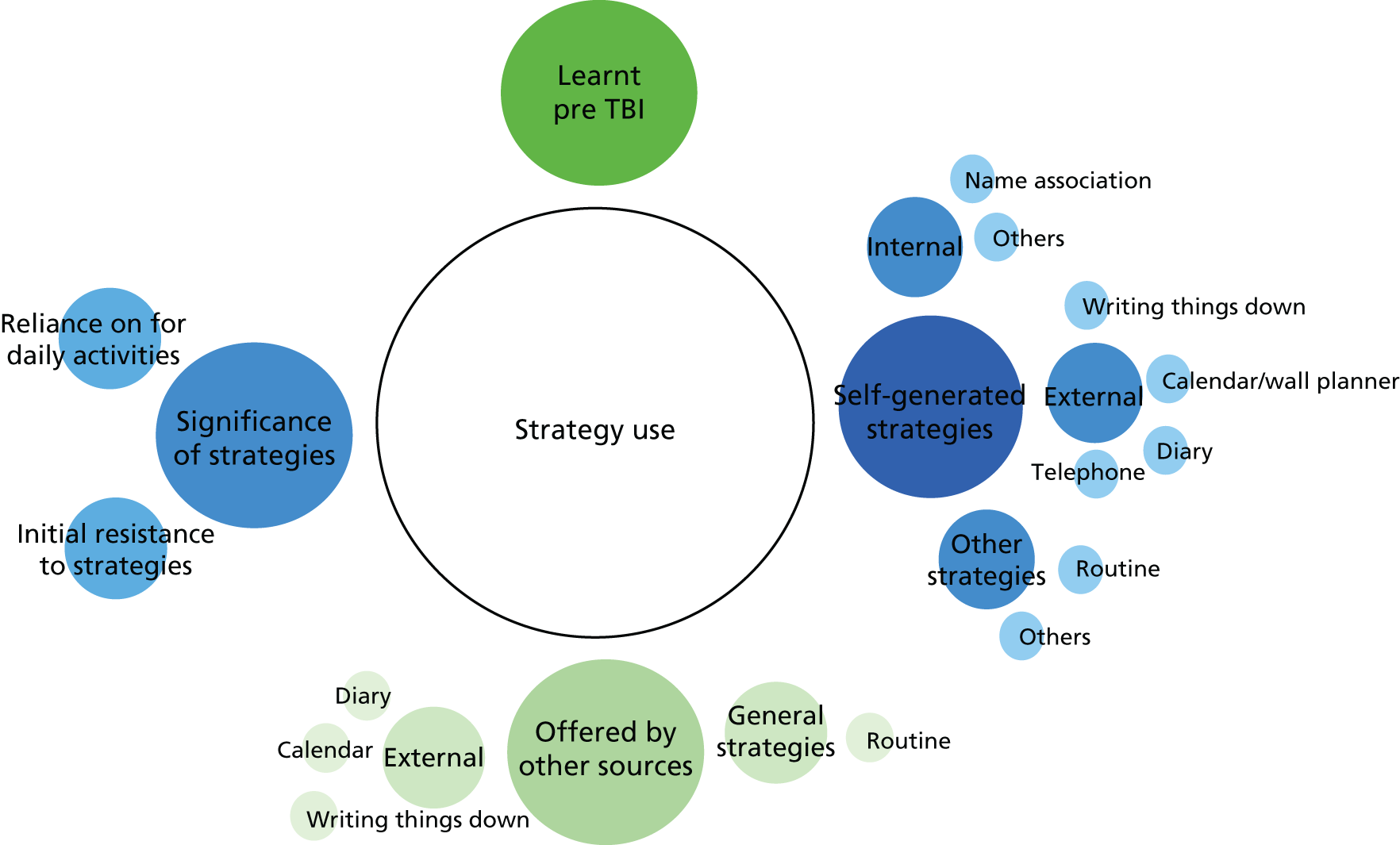

The frequency and percentage of each activity code were calculated for each session; these are provided in Table 4 for APs and Table 5 for participants.