Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/104/40. The contractual start date was in September 2012. The draft report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in December 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Gus Gazzard, David Garway-Heath, Rachael Hunter, Gareth Ambler, Catey Bunce, Richard Wormald, Keith Barton, Gary Rubin and Marta Buszewicz have received a grant from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) for the submitted work. Gus Gazzard reports grants from Lumenis (Borehamwood, UK) during the conduct of the study; grants from Ellex Medical Lasers (Adelaide, SA, Australia), Ivantis, Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA) and Thea Pharmaceuticals (Keele, UK) outside the submitted work; and personal fees from Allergan (Dublin, Ireland), Alcon (Fort Worth, TX, USA), Glaukos Corporation (San Clemente, CA, USA), Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Osaka, Japan) and Thea Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. David Garway-Heath reports personal fees from Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Durham, NC, USA), Alcon, Allergan, Bausch + Lomb (Rochester, NY, USA), Quark Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Ness Ziona, Israel), Quethera Limited and Roche (Basel, Switzerland); grants from the Alcon Research Institute; and grants and personal fees from Pfizer (New York, NY, USA) and Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, outside the submitted work. In addition, David Garway-Heath was a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials Board from 2014 to 2017. Keith Barton received a grant from NIHR for the Treatment of Advanced Glaucoma Study during the conduct of the study. In addition, Keith Barton reports grants from Johnson & Johnson Vision (Santa Ana, CA, USA), New World Medical (Rancho Cucamonga, CA, USA), Alcon, Merck & Co. (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Allergan and Refocus Group (Dallas, TX, USA); that he has had other financial relationships with Alcon, Merck & Co., Allergan, Refocus, AqueSys Inc. (Taipei, Taiwan), Ivantis, Carl Zeiss Meditec AG (Jena, Germany), Kowa Europe GmbH (Düsseldorf, Germany), Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Transcend Medical (Scottsboro, AL, USA), Glaukos (San Clemente, CA, USA), Amakem NV (Diepenbeek, Belgium), Thea Pharmaceuticals, Alimera Sciences (Alpharette, GA, USA), Pfizer, Advanced Ophthalmic Implants Pte Ltd (Singapore), Vision Futures (UK) Ltd (London, UK), London Claremont Clinic Ltd (London, UK) and Vision Medical Events Ltd (London, UK), outside the submitted work; and that he has a patent with Ophthalmic Implants (PTE) Ltd. Stephen Morris was a member of NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Research Funding Board (2014–19), the NIHR HSDR Commissioned Board (2014–16), the NIHR HSDR Evidence Synthesis Sub Board (2016), the NIHR HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board (2007–10), the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board (2009–13), the NIHR Public Health Research Funding Board (2011–17) and the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research expert subpanel (2017–present). Marta Buszewicz was a member of the HTA Mental Health Panel from January to May 2018. In September 2018 this panel was amalgamated into the HTA Prioritisation Committee C (mental health, women and children’s health), of which Marta Buszewicz was also a member. Marta Buszewicz has also been a member of the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit, London, funding panel since May 2017.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Gazzard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension

Primary open-angle glaucoma (OAG) is a common, irreversible optic neuropathy affecting the vision of predominantly older adults. It is strongly associated with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), but may also occur with IOP in the normal range. Glaucoma results in progressive visual field (VF) loss and is a leading cause of blindness worldwide. In the UK, glaucoma affects over half a million individuals, with over one-quarter of a million aged > 65 years. 1 It is a leading cause of visual morbidity, accounting for 12% of blind registrations. 2 Glaucoma is a significant cause of falls, road traffic accidents3 and loss of independence in the elderly (even in the case of mild asymptomatic disease),3,4 and can significantly reduce the quality of life (QoL) of these patients. 5–8

Ocular hypertension (OHT) is a state of raised IOP without optic nerve damage, which can progress to OAG in some patients. 9,10 Those with a higher IOP, lower central corneal thickness (CCT) and a family history of OAG are more at risk of developing glaucoma. 11 IOP is the only modifiable risk factor for the development of OAG, the reduction of which is proven to slow down the progression of OAG or the conversion of OHT to OAG. 10,12–14 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that patients with OHT at high risk of developing OAG should be offered treatment. 15

Current first-line treatment options

Medical therapy (eyedrops) is widely used and is currently the most commonly used first-line treatment for mild to moderate disease,16 leading to approximately 1.2 million prescriptions per month in the UK. 17 Medical treatment is usually lifelong; patients may need to instil multiple eyedrops, which can become expensive, while also experiencing side effects that limit the acceptability of the treatment and impair their QoL. 18–21

Although the effectiveness of IOP-lowering eyedrops is irrefutable, they come with a number of aesthetic, sight- and potentially life-threatening side effects: pain on instillation, conjunctival hyperaemia, elongation and darkening of eyelashes, iris colour changes, periocular skin pigmentation, allergic reactions, accelerated cataract formation, cystoid macular oedema, anterior uveitis and reactivation of herpes simplex keratitis,19,20 in addition to serious respiratory (e.g. airway obstruction) and cardiovascular side effects in some, falls and increased mortality. 22,23 These adverse effects influence the acceptability of eyedrops to patients, as well as patients’ concordance with medical treatment plans and their QoL. Indeed, reported non-compliance rates for medical treatment range from 24% to 80%, depending on definition. 24–26 Approximately 22% of initial treatment regimens need adjustment27 and up to 50% of patients discontinue their medication within 6 months of the initial consultation. 24 Although patients with diagnosed glaucoma are more likely than those with suspected glaucoma to adhere to therapy,24 side effects are likely to have a direct adverse effect on patients diagnosed with OHT, in whom proper IOP control can reduce the incidence of OAG. 28 Medical management of OAG and OHT requires regular monitoring and modification of therapy by ophthalmologists, as well as multiple hospital visits for patients. 29

Long-term use of topical IOP-lowering medication induces significant subclinical conjunctival inflammation and conjunctival fibroblast activation by medications or preservatives,30–32 and has been shown to have a negative impact on the success rates of subsequent surgical intervention33 (long-term eyedrop use is a known powerful risk factor for later surgical failure). 31,34

Laser trabeculoplasty (an alternative treatment method) has been inconsistently performed in the UK; NICE has identified a lack of evidence governing its use. 17 The procedure involves a single, painless outpatient application of laser to the trabecular meshwork using a contact lens. It is easy to deliver by clinicians competent in gonioscopy and has a wide safety margin. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) uses bursts of nanosecond pulses with a larger spot (400 microns) and lowers IOP by increasing the aqueous humour outflow through the trabecular meshwork by causing increased macrophage activity and trabecular tissue remodelling. 35,36

The IOP-lowering effect of SLT is comparable with that of prostaglandin analogues,37,38 the current first-line medical treatment recommended by NICE. SLT can delay and, in some cases, prevent the need for eyedrops. 38 The effects are not permanent; however, SLT does not prejudice the effectiveness of later medical or surgical treatments. Because minimal trabecular meshwork damage is caused, SLT has also been shown to have good efficacy on repeat treatment. 39–41

The use of SLT for lowering IOP has been inconsistent and has in the past often been reserved as a last resort before surgery, possibly because of concerns arising from older forms of laser trabeculoplasty. Use of SLT as a first-line treatment has the potential to offer patients an eyedrop-free window of several years, remove the concerns about concordance with medication and reduce both hospital visits and side effects compared with medical therapy.

Glaucoma filtration surgery is usually reserved for those who continue to lose vision despite other treatments. It has a significant failure rate and may cause permanent ocular discomfort and, rarely, chronic pain. 42,43 A study comparing medical management (eyedrops) with surgery (trabeculectomy) as a first-line treatment for advanced OAG is currently under way. 44

Economic burden of treatment to the NHS

The treatment of OAG and OHT can incur significant costs to both the patient and the NHS. Direct treatment costs in the UK were estimated at an equivalent of US$1337 per patient per year in 1999;45 up to 61% of these costs were for IOP-lowering medication. 46 In 2012, > 8 million glaucoma treatment-related items were dispensed in the community alone, costing > £105M, with increases in the number of items dispensed and their cost reported annually. 47 Both direct costs and indirect costs are higher for more severe disease,48 suggesting that effective IOP control early in the course of the disease is likely to reduce later costs, as well as improve vision-dependent health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Extensive economic modelling of SLT has taken place in various health-care systems worldwide. In the USA, the 5-year cumulative costs per patient were lower for SLT than for eyedrops and surgery, whereas an Australian study found that every AU$1 spent on laser treatment resulted in a saving of AU$2.50 compared with initial medical therapy, with projections of increasing cost savings over time. 49,50 The time threshold at which bilateral SLT would become less costly than bilateral use of topical medication has also been modelled. 51 It was found that SLT became less costly than most brand-name medications within 1 year and less costly than generic latanoprost and generic timolol eyedrops after 13 and 40 months, respectively. This is supported by a projected 6-year cost comparison of primary SLT with primary medical therapy in OAG treatment in a Canadian health-care model;46 if primary SLT had to be repeated between 2 and 3 years, use of primary SLT over mono-, bi-, and tri-drug therapy produced a 6-year cumulative cost saving of CA$580.52, CA$2042.54 and CA$3366.65 per patient, respectively. Similar findings have also been published for the management of both mild and moderate glaucoma. 52

Although the limited existing data are very difficult to apply to the UK population, the above data would suggest annual savings to the NHS of £2.4M in direct treatment costs for new OAG patients alone from a Laser-1st (initial SLT followed by routine medical treatment) paradigm. This rises to £16.8M per year if a conservative 20% of new OHT/OAG referrals require treatment. Australian data give far higher predictions: were SLT to be extended to previously diagnosed patients, as is common practice in the USA, cost savings would be up to 20 times higher. Indirect cost savings (e.g. reduced visual loss) are, of course, greater still.

Use of selective laser trabeculoplasty as a first-line treatment for open-angle glaucoma/ocular hypertension

Initial treatment with SLT potentially offers an ‘eyedrop-free window’ of several years, removes concerns about concordance and possibly reduces the need for multiple eyedrops, even years later. Even when insufficient as a sole therapy, SLT may reduce the intensity of subsequent medical treatment and possibly the need for later surgery. A single outpatient treatment is likely to be more acceptable to patients than daily self-administration of eyedrops, securing 100% concordance from those attending for treatment and resulting in fewer hospital visits and fewer side effects than eyedrop therapy alone.

Although SLT is an existing technology, proven to lower IOP, neither HRQoL nor cost-effectiveness has been compared with outcomes in patients who received eyedrops as a first-line treatment. A Laser-1st pathway allows an eyedrop-free period and, possibly, lower intensity of treatment. This is likely to be associated with greater HRQoL, improved patient acceptability and better treatment compliance, with fewer patient visits resulting from treatment changes and fewer adverse events (AEs), at a much lower cost than treatment with eyedrops. 46,50,53

Uptake of SLT by surgeons in the UK has so far been limited because of past experiences with older laser technology. SLT is delivered in an outpatient setting using topical anaesthesia and is quick and pain free. It is simple and safe to deliver and has a wide safety margin and good repeatability. Widespread uptake of SLT has the potential to substantially improve HRQoL for many patients and produce substantial cost savings to the NHS (lower medication costs, reduced side effects, fewer hospital visits, lower surgery rates and indirect savings from care costs for fewer visually impaired patients).

Rationale for research

Research recommendations by NICE17 and a Cochrane systematic review54 have identified the need for robust randomised controlled trials investigating the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of SLT as a first-line treatment for OAG and OHT.

Aims and objectives

Hypothesis

Our hypothesis is that, in patients with newly diagnosed OHT or OAG, primary treatment with SLT (Laser-1st) leads to a better HRQoL than primary treatment with IOP-lowering eyedrops (Medicine-1st), and that this is associated with reduced costs, better clinical outcomes and an improved tolerability of treatment.

Primary objective

To determine if, in a pragmatic study that mirrors the realities of clinical decision-making, a Laser-1st pathway delivers a better HRQoL at 3 years than a Medicine-1st (routine medical treatment only) pathway, in the management of patients with OAG and OHT.

Secondary objectives

To determine whether or not a Laser-1st treatment pathway:

-

costs less than the conventional treatment pathway of Medicine-1st

-

achieves the desired level of IOP with less intensive treatment over the course of the study

-

leads to equivalent levels of visual function after 3 years

-

is better tolerated by patients.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) trial was designed to evaluate the difference in HRQoL, cost and clinical efficacy between two first-line treatment arms for OAG and OHT. The LiGHT trial is a multicentre, randomised clinical trial, unmasked to treatment allocation, with two treatment arms: initial SLT followed by routine medical treatment (Laser-1st) and routine medical treatment only (Medicine-1st). 55,56

Eligible patients were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either SLT (Laser-1st) or medical therapy (Medicine-1st) as the first-line treatment for OAG or OHT. All measurements influencing treatment escalation decisions [VF, Heidelberg retinal tomography (HRT) and IOP] were made by masked observers. Patients were monitored for 3 years and monitoring intervals were guided by a defined protocol to avoid bias in clinical decision-making. A clinical decision algorithm, attempting to capture the complexities of clinical practice, defined triggers for escalation. This was a pragmatic trial aiming to mirror the ‘real-world’ patient experience of treatment as closely as possible and seeking to capture the full effects of laser treatment.

Ethics approval and research governance

The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was granted by the City Road and Hampstead Research and Ethics Committee (former Moorfields and Whittington Research Ethics Committee then East London and The City Research Ethics Committee 1, reference 12/LO/0940) on 20 June 2012. The LiGHT trial is registered as ISRCTN32038223 [the full protocol can be accessed at URL: www.moorfields.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/LiGHT%20Trial%20Protocol%203.0%20-%2020-5-2015_3.pdf (accessed 3 May 2019)].

Patient population

The LiGHT trial aimed to recruit patients with newly diagnosed OAG or OHT in one or both eyes from six collaborating specialist glaucoma clinics at large ophthalmic centres in the UK (see Appendix 1).

Inclusion criteria

Parts of this text have been reproduced from Gazzard et al. 58 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Patients were required to have newly diagnosed OAG or OHT in one or both eyes, which needed treatment. Definitions of OAG and OHT, as well as criteria for initiating treatment, are shown in Appendix 2. The following criteria were also specified:56

-

A decision to treat had been made by a glaucoma specialist consultant ophthalmologist.

-

Patients were aged > 18 years and were able to provide informed consent.

-

Patients were able to complete QoL, disease-specific symptom and cost questionnaires in English (physical help with completion and assistance with reading was permitted, as long as an interpreter was not required).

-

It was possible to perform a VF test in the study eye(s) with < 15% false positives.

Exclusion criteria

Parts of this text have been reproduced from Gazzard et al. 58 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Patients were not considered for the study if there was:56

-

advanced glaucoma in the potentially eligible eye as determined by Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial (EMGT I)59 criteria (77 VF loss mean deviation (MD) worse than –12 dB in the better eye or –15 dB in the worse eye)

-

secondary glaucoma (e.g. pigment dispersion syndrome, rubeosis, trauma, etc.) or any angle closure

-

any contraindication to SLT (e.g. unable to sit at the laser-mounted slit-lamp, past history of or active uveitis, neovascular glaucoma, inadequate visualisation of trabecular meshwork)

-

an inability to use topical medical therapy because of, for example, physical infirmity and a lack of carers able to administer daily eyedrops

-

a previous treatment for OAG or OHT

-

congenital or early childhood glaucoma

-

a visually significant cataract in symptomatic patients who want to undergo cataract surgery

-

any current, active treatment for another ophthalmic condition in the hospital eye service (this applied to both eyes, even if one was not in the trial, as the fellow eye might affect the patient’s visit frequency)

-

any history of retinal ischaemia, macular oedema or diabetic retinopathy

-

age-related macular degeneration with neovascularisation in either eye or geographic atrophy

-

visual acuity (VA) worse than 6/36 in a study eye; non-progressive VA loss better than 6/36 owing to any comorbidity was permitted provided that it did not affect the response to treatment or later surgical choices and that it was not under active follow-up (e.g. an old, isolated retinal scar no longer under review or amblyopia)

-

any previous intraocular surgery, except uncomplicated phacoemulsification, at least 1 year before recruitment (this applied to both eyes, even if one was not in the trial, as it could affect the required treatment intensity and visit frequency for any glaucoma in the fellow eye)

-

pregnancy at the time of recruitment or intention to become pregnant within the duration of the trial

-

medical unsuitability for completion of the trial (e.g. suffering from a terminal illness or too unwell to be able to attend hospital clinic visits)

-

recent involvement in another interventional research study (within 3 months) of any topic.

Recruitment

Internal pilot study

We conducted a 9-month internal pilot at Moorfields Eye Hospital (MEH) (the central trial site and largest recruiting site). This ensured that recruitment rates were adequate and that all procedures were in place, before roll-out to other sites. Data collected included number of eligible patients approached, proportion entering the trial and recruitment rates.

Recruitment strategy and identification of participants

Patients attending the hospital eye service for the first treatment of OAG/OHT were assessed for eligibility before treatment and, if eligible, were informed of the study by the local trial co-ordinator (along with written information). To maximise potential coverage of all eligible patients, a trial staff member was available daily to attend clinics and counsel potential subjects. Local trial staff screened all new referrals (by referral letter or electronic patient record) and identified those possibly eligible, with reminders for the clinic staff. Regular education of clinical staff and clinic-wide information posters for staff and patients raised awareness of the study and reminded clinicians of the opportunity for recruitment. 56

Recruitment process and informed consent

Eligible patients were approached and introduced to the aims, methods, anticipated benefits and potential hazards of the study, and were eventually invited to participate by a member of the LiGHT team. Introducing the patients to the study and inviting them to participate was done either by face-to-face discussions with the trial team members or by the use of audiovisual material (video); the video conveyed the same information as the face-to-face discussions with the trial team members, but was delivered by the chief investigator (video content/script is shown in Appendix 3). The use of the video in the recruitment process maximised the time efficiency of the recruiters, as often more than one patient had to be approached simultaneously.

After the invitation to participate, ample time was given to the patients to consider participation. Written informed consent was obtained on a separate day, usually the day of the baseline assessment (see Baseline assessment), by either the good clinical practice (GCP)-trained local trial ophthalmologist or the local trial optometrist who had been delegated this duty by the chief investigator/principal investigator (PI) on the delegation log. Consent was obtained with the support of extensive clearly written information (in English) that had been reviewed and approved by our patient-led lay advisory group (LAG). Patients who had difficulty in giving informed consent did not form part of this study. A copy of the signed informed consent was given to the participant and the original signed form was retained at the study site.

If new safety information resulted in significant changes in the risk/benefit assessment, the consent form was reviewed and updated if necessary. All patients, including those already being treated, were given any new information, a copy of the revised form and reconsented to continue in the study.

Baseline assessment

At the baseline assessment, and after informed consent was provided, participants underwent VA testing, slit-lamp examination, automated VF testing [Humphrey Field Analyser Mark II (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) and the Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm standard 24-2 programme], HRT optic disc imaging, IOP measurement, gonioscopy, CCT measurement and assessment of the optic discs, maculae and fundi. The patients also completed the following baseline questionnaires: EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),60 Glaucoma Utility Index (GUI),61 Glaucoma Symptom Scale (GSS),62 Glaucoma Quality of Life-15 (GQL-15; a visual function, rather than quality-of-life measure)8 and a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) questionnaire. 63

Randomisation and masking

Following the completion of all baseline assessments, eligible patients were randomised to one of two treatment groups: SLT (Laser-1st) or topical medical therapy (Medicine-1st). Randomisation was undertaken online on the same day by the clinical staff who obtained informed consent, using a web-based randomisation service (Sealed Envelope, London, UK) and achieving full allocation concealment. Stratified randomisation with random block sizes was used to randomise in a 1 : 1 ratio at the level of the patient, with the stratification factors of diagnosis (OHT/OAG) and treatment centre. Following randomisation, the details of the treatment and specific arrangements and instructions were communicated to the patients by a member of the trial team. Owing to the pragmatic design of this trial, the patients and clinicians were unmasked to the treatment arm; however, all clinical measurements (IOP, VF, HRT) were carried out by masked observers and treatment decisions were masked by the use of a computerised evidence-based decision support algorithm. 56

Treatment arm allocation

Laser-1st pathway

Selective laser trabeculoplasty was delivered to 360° of the trabecular meshwork with one 360° retreatment used as the first escalation of treatment, if required. To ensure quality control of SLT delivery and to minimise variation between surgeons, standardisation was achieved by a stringent protocol defining laser settings and technique, including the range of acceptable powers (see Appendix 4). All treating clinicians were given training before recruitment and had at least one laser treatment directly observed by the chief investigator. After two SLT treatments, if further treatment escalation was required, the Laser-1st pathway patients embarked on medical treatment and followed the Medicine-1st algorithms. Significant complications of laser treatment, if they occurred (e.g. corneal oedema, intraocular haemorrhage, severe uveitis, IOP spike > 15 mmHg, peripheral anterior synechiae), meant that a second treatment with SLT was contraindicated. Other new medical conditions (such as a new history of uveitis or rubeosis) also precluded repeat SLT. 56

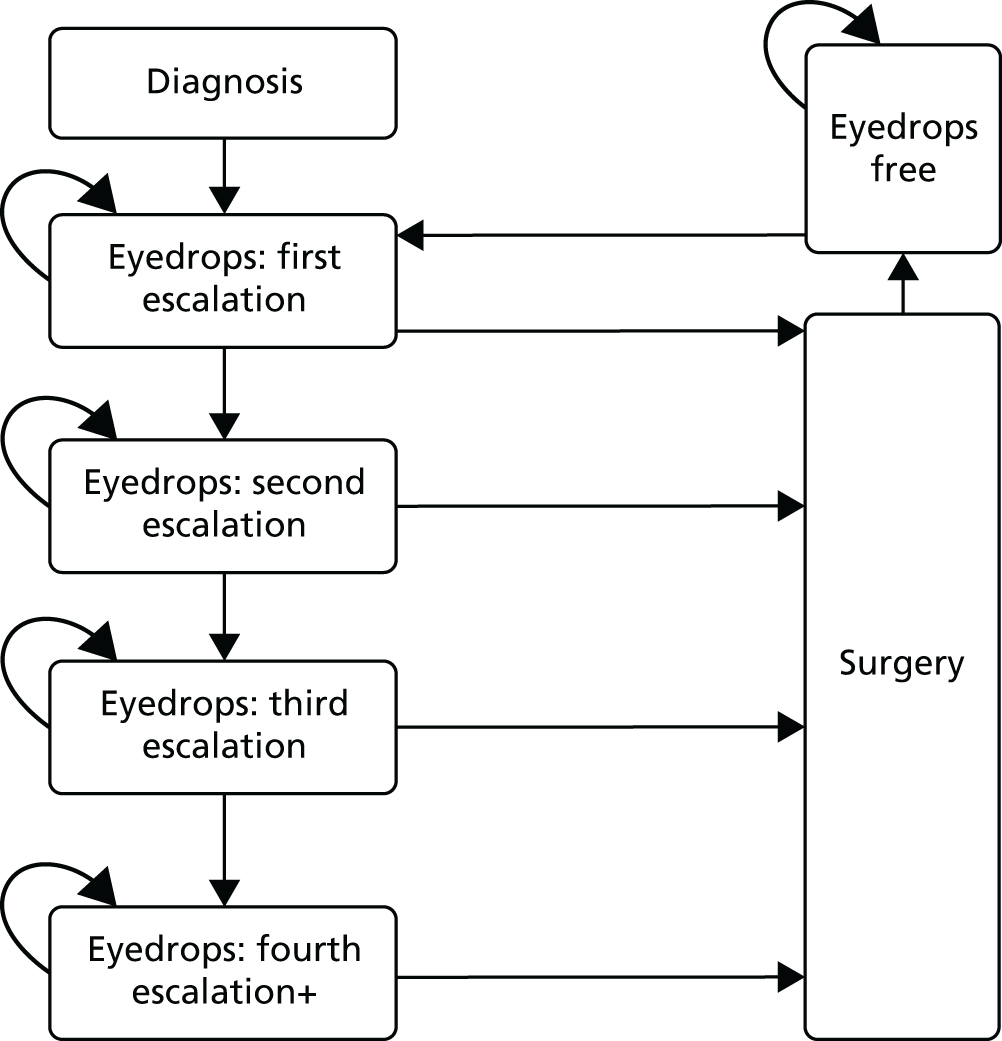

Medicine-1st pathway

Medical treatment of glaucoma involves several distinct steps that require standardisation: choice of drugs, number of agents permitted and rules for switching between or adding drugs. International best practice guidelines advocate changing medication if the target is not reached, with the addition or switching of medication (based on the magnitude of initial response). 64–66 Surgery was offered once maximum treatment intensity was reached; this varied between patients, but required definition to minimise inter-surgeon variation (see Maximum medical treatment).

Choice of agent

No mainstream medications were prohibited, but medication classes for first-, second- or third-line treatment were defined as per NICE1 and European Glaucoma Society guidance:67

-

first line: prostaglandin analogue

-

second line: beta-blocker (once in the morning or in a prostaglandin analogue combination)

-

third or fourth line: topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor or alpha-adrenoceptor agonist.

Systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors were permitted only as a temporising measure while awaiting surgery and did not influence treatment escalation. Cholinergic agonists were not accepted as topical medications for OAG.

Treatment changes

Treatment was escalated under the following circumstances:

-

Strong evidence of progression (see Defining progression) irrespective of IOP.

-

IOP above the target IOP (see Adding/switching medication) by > 4 mmHg68 at a single visit (irrespective of evidence for progression).

-

IOP above target by < 4 mmHg plus less strong evidence for progression (see Defining progression). If the IOP was above target by less than the threshold with no evidence for progression, then the target IOP was re-evaluated.

Adding/switching medication

The incremental escalation of the treatment protocol defined stepwise increases in treatment. Patients’ medications were switched if the pre- and post-treatment IOP difference was no greater than the measurement error. If there was a greater reduction but the eye was still not at target, then the next medication was added. The progression of glaucomatous optic neuropathy (GON) when at target IOP, also triggered a stepwise increase in treatment and a lowering of the target. 56

Maximum medical treatment

Maximum medical treatment (MMT) is the most intensive combination of eyedrops a given individual can reasonably, reliably and safely use. The MMT varies between patients depending on their comorbidities, side effects and patient-specific concordance factors. Although there is variation in the attitudes of surgeons to polypharmacy, it is widely accepted that additional medications result in a lower percentage reduction in IOP. Evidence shows there are profound reductions in compliance with complex dosage schedules. NICE guidance15 recommends offering surgery after only two drugs have failed to control IOP. In the LiGHT trial, treatment with multiple different medications was limited and MMT was defined in terms of the maximum number of drugs (three) and dosages per day (five drops). The MMT was often less owing to drug intolerance, contraindications and patient factors. 56

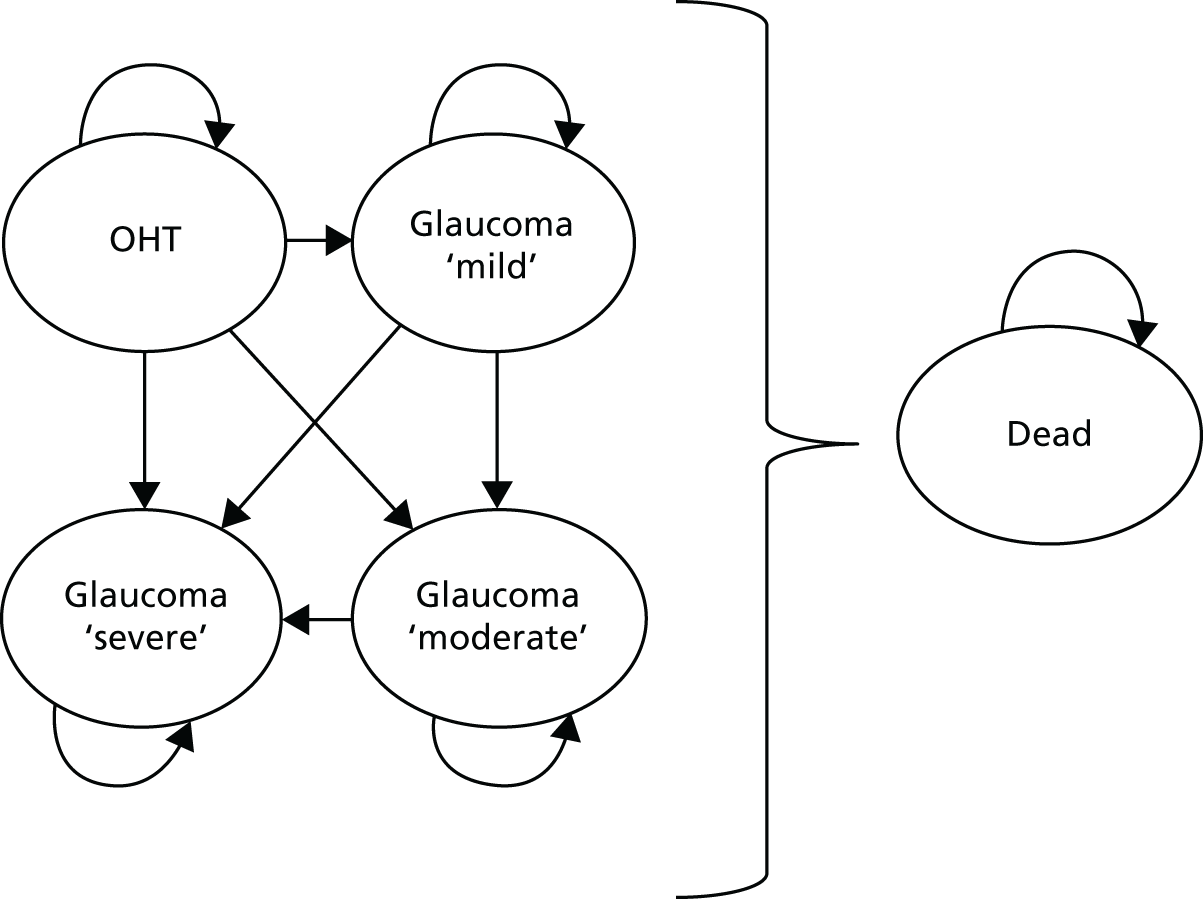

Disease stratification and initiation of treatment

The NICE-recommended thresholds were used for defining disease (OAG or OHT) for entry into the study, as well as in initiating treatment (see Appendix 2). 15 The patients’ clinical evaluation and test outcomes were then entered into the clinical decision algorithm and a disease category and stage were determined. The algorithm used severity criteria from the Canadian target IOP workshop,69 with central-field loss severity criteria defined according to Mills et al. 70 (Table 1). Severity stratification determined the follow-up frequency.

| Severity | Definition for treatment target IOP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optic nerve | VF MD | Central (10°) scotoma on VF | |||

| OHT | Healthy | Any | No GON-related VF loss | ||

| Mild OAG | GON | + | > –6 dB | + | None |

| Moderate OAG | GON | + | < –6 dB and > –12 dB | or | At least one central 5º point < 15 dB but none < 0 dB and only one hemifield with a central point < 15 dB |

| Severe OAG | GON | + | < –12 dB | or | Any central 5º point with sensitivity < 0 dB. Both hemifields contain point(s) < 15 dB within 5º of fixation |

Computerised decision algorithm

The follow-up and treatment escalation protocols were enabled by custom-written clinical decision support software (DSS), which permitted real-time decision-making based on the analysis of multiple clinical measures, including HRT optic disc analysis, VF assessment and IOP measurements. Predefined objective indicators of either disc or field deterioration [change in mean neuroretinal rim area, as determined by HRT, or VF glaucoma progression analysis (GPA)], or IOP above target all triggered earlier follow-up and/or increased treatment intensity.

Setting individual target intraocular pressure

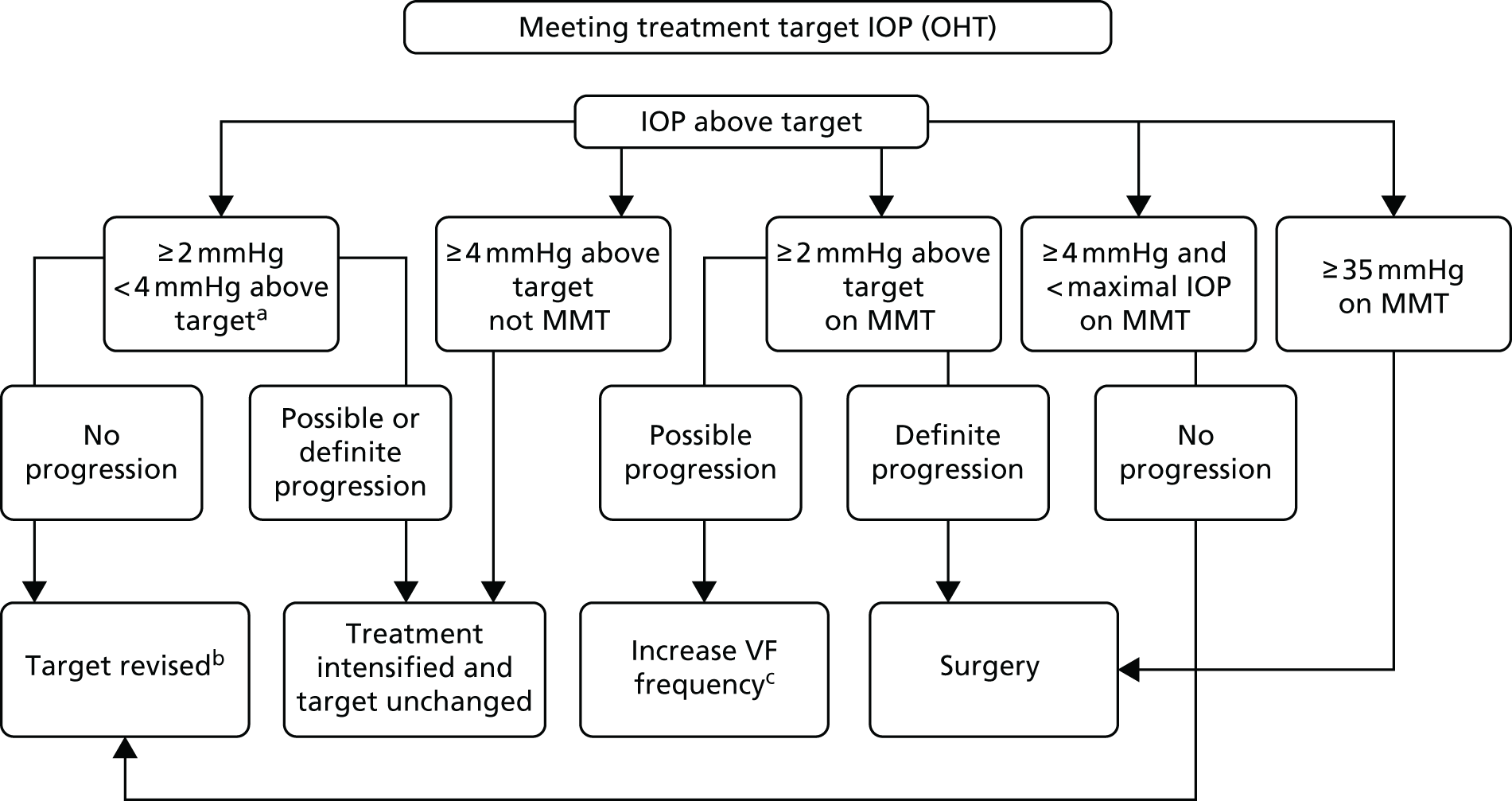

Once the decision to treat was made, a treatment target IOP (target) was set. The target was eye specific and was objectively defined and adjusted by the computerised decision algorithm to avoid bias from unmasked treating clinicians. The lowest permitted target was 8 mmHg for OAG and 18 mmHg for OHT. Although CCT has an effect on IOP measurement and risk of progression, the true magnitude of this interaction is unknown because of complex non-linear interactions between CCT, ‘true’ IOP and corneal material properties; CCT was therefore not used in the algorithm for setting a target IOP. 56 Myopia and family history were also not included in this algorithm, as data on the effect size of these risk factors on progression rates are weak. 71 The target IOP was either an absolute reduction to below a specified level or a percentage reduction from baseline, whichever was lower. The process of setting the IOP target is illustrated in Figure 1. Greater reductions were required for greater disease severity as defined by Canadian glaucoma study criteria. 73

FIGURE 1.

Process for target IOP setting. a, Disease stratification according to Mills et al. 70 POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma. Adapted by permission from BMJ Publishing Group Limited. The Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) trial. A multicentre randomised controlled trial: baseline patient characteristics, Konstantakopoulou E, Gazzard G, Vickerstaff V, Jiang Y, Nathwani N, Hunter R, Ambler G, Bunce C, volume 102, pp. 599–603, 2018. 72

Failure to meet target intraocular pressure and target intraocular pressure re-evaluation

Parts of this text have been reproduced from Gazzard et al. 58 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Diurnal fluctuation and measurement error both lead to variation in measured IOP. Kotecha et al. 68 have shown that inter-visit variation may nonetheless be as much as ± 4 mmHg. 68 To prevent an inappropriate escalation to a more intensive treatment, it is therefore important to repeat measurements that deviate only slightly from target. Criteria for failure to meet, and to reassess, target IOP follow those of the Canadian glaucoma study,74 taking into account that inter-visit variation in IOP measurement may be as much as ± 4 mmHg:

-

If IOP in an eye was ≥ 2 mmHg but < 4 mmHg above target on two consecutive visits and showed possible or definite progression, then the treatment was intensified and the target remained unchanged.

-

If IOP in an eye was ≥ 2 mmHg and < 4 mmHg above target on two consecutive visits and showed no progression (with a minimum of three post-baseline follow-up VF tests required to confirm progression, as per EMGT I),59 then the target was adjusted upwards. In this case the target IOP was revised to the mean of the previous three visits, during which progression did not occur. If VF testing had been carried out at fewer than three follow-up visits, additional visits were required to confirm stability before the target was relaxed.

-

If IOP in an eye was ≥ 4 mmHg from target at any visit, then the eye was considered to have failed to reach target and treatment intensity was increased to the next level (unless already at the maximum), irrespective of any progression, unless the clinician identified poor concordance with treatment. In such cases the target remained unchanged. In the presence of poor concordance and in the absence of progression, additional measures to improve concordance before escalation of treatment were permitted, as in usual clinical practice.

-

If the IOP of an eye on MMT was ≥ 2 mmHg from target and showed definite progression, then glaucoma drainage surgery was offered to the patient.

-

If the IOP of an eye on MMT was ≥ 2 mmHg from target and showed possible progression, then the follow-up frequency was increased until progression was either confirmed or ruled out.

-

If the IOP of an eye on MMT was ≥ 2 mmHg from target but below maximum IOP (maximum IOP is that above which surgery may be offered even without progression: OHT, 35 mmHg; mild glaucoma, 24 mmHg; moderate and severe glaucoma, 21 mmHg), and showed no progression (with at least three follow-up VFs), then the target was adjusted (revised to the mean of the previous three visits) with an increase in follow-up frequency. If VF testing had been carried out at fewer than three follow-up visits, additional visits were required to confirm stability.

-

A patient with an eye with IOP above the maximum IOP may have been offered surgery without progression at the discretion of the treating surgeon.

-

If there was progression and the IOP was at target, then the target IOP was reduced by 20% (according to the Canadian glaucoma study protocol),74 with a lower limit of 8 mmHg, and treatment intensified accordingly.

Failure to meet target can be a result of poor concordance as well as a lack of drug efficacy. As is normal practice, compliance was discussed and patients were counselled at each visit, using validated ‘ask–tell–ask’ techniques. 75–77 Patients were given standard written information from the International Glaucoma Association, face-to-face instruction in eyedrop administration and the offer of further nurse-led support.

Where poor concordance was thought to be the contributing factor, education with written information and repeated face-to-face instruction in eyedrop administration was given. If the decision was made to educate rather than escalate a patient who was not at target, then the reason for an algorithm over-ride was recorded (non-concordance) and the patient recalled after 8 weeks for a repeat IOP check visit. 56

Treatment escalation

To minimise bias for escalating treatment, standardised criteria for any additional intervention were used, in accordance a protocol following international guidelines by the European Glaucoma Society,64 American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern65 and the South East Asia Glaucoma Interest Group. 66 Treatment is escalated under the following circumstances:56

-

Strong evidence of progression irrespective of IOP (see Defining progression).

-

IOP above target by > 4 mmHg at a single visit (irrespective of evidence of progression).

-

IOP above target by < 4 mmHg and less strong evidence of progression (see Defining progression). If the IOP is above target by < 4 mmHg with no evidence of progression, then the treatment target IOP is re-evaluated (see Failure to meet target intraocular pressure and target intraocular pressure re-evaluation).

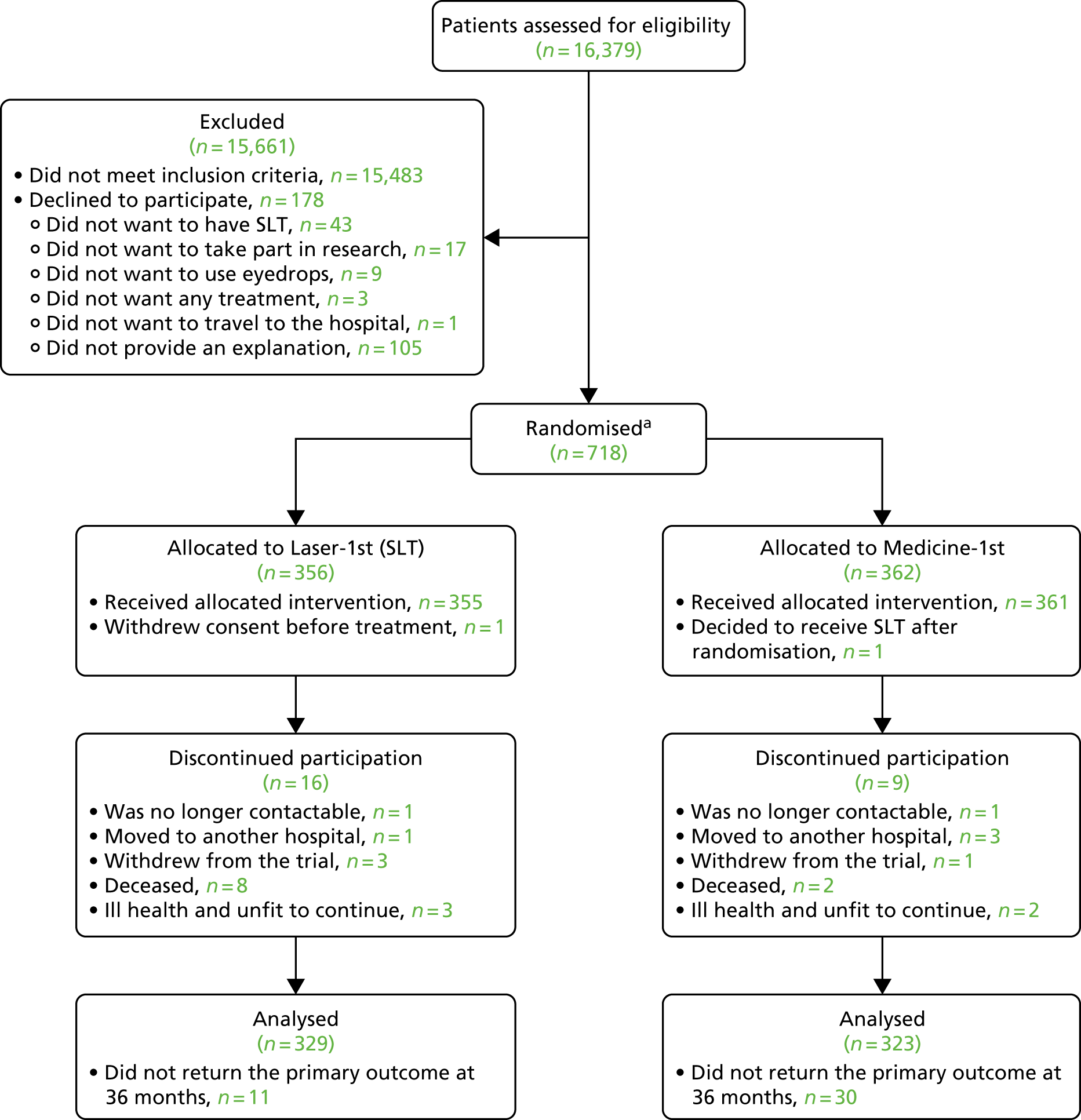

The process for escalating treatment is shown in Figures 2 and 3.

FIGURE 2.

Process for escalating treatment in OHT. a, On two consecutive visits; b, as per protocol; and c, until progression confirmed/refuted. VF progression required three follow-up VF assessments. Maximal IOP, IOP above which surgery was offered even without progression or 35 mmHg for OHT. Adapted by permission from BMJ Publishing Group Limited. The Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) trial. A multicentre randomised controlled trial: baseline patient characteristics, Konstantakopoulou E, Gazzard G, Vickerstaff V, Jiang Y, Nathwani N, Hunter R, Ambler G, Bunce C, volume 102, pp. 599–603, 2018. 72

FIGURE 3.

Process for escalating treatment in OAG. a, On two consecutive visits; b, as per protocol; and c, until progression confirmed/refuted. VF progression required three follow-up VF assessments. Maximal IOP, IOP above which surgery was offered even without progression or 35 mmHg for OHT. Adapted by permission from BMJ Publishing Group Limited. The Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) trial. A multicentre randomised controlled trial: baseline patient characteristics, Konstantakopoulou E, Gazzard G, Vickerstaff V, Jiang Y, Nathwani N, Hunter R, Ambler G, Bunce C, volume 102, pp. 599–603, 2018. 72

More stringent criteria than those used for laser or medical treatment were applied before being referred for surgery. This reflected the greater risk to a patient’s vision from surgical complications. Strong evidence of progression and/or failure to meet target was usually required in all but the most severe disease. However, extreme elevations of IOP could be an indication for surgery without progression, with lower thresholds in more damaged eyes. Any patient in whom IOP was at or above the maximum was reviewed (in person or remotely) by the PI, who decided whether or not surgery was indicated. In accordance with the principle of patient-centred care, the decision to operate was always a collaboration between clinician and patient. When an IOP-lowering surgical intervention was indicated, cataract surgery was permitted (in the presence of cataract, i.e. not clear lens extraction) when this was the consultant’s usual practice.

Defining progression

Visual field progression

Worsening of VF loss was defined as ‘likely’ or ‘possible’ in the absence of any identifiable retinal or neurological cause. The ‘minimum data set’ to determine VF progression was two reliable baseline VF measurements followed by three follow-up VF tests. ‘Likely VF progression’ was defined as ≥ 3 points on the Humphrey Visual Field (HVF) GPA software (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) at p < 0.05 for change on three consecutive occasions. ‘Possible VF progression’ was ≥ 3 points on Humphrey Visual Field GPA software at p < 0.05 for change on two consecutive occasions. VF series were independently assessed for progression using the automated algorithm software at each visit. Any treatment escalation triggered by worsening VF loss had to be agreed by a senior clinician after excluding retinal or neurological causes. 56

Optic disc progression

Chauhan et al. 78 showed that sequential HRT three-disc assessment performed as well as, or better than, ‘experts’ judging monoscopic photos. Simultaneous stereoscopic disc photography has been considered a gold standard, but it is rarely available. Worsening of disc damage was defined as a rate of neuroretinal rim loss exceeding 1% of baseline rim area per year on a minimum of five repeat HRT images. This slope value was selected as approximately double that of age-related rim area loss and gave a similar specificity to VF trend analyses. 79

Open-angle glaucoma progression

Progression of glaucoma is defined as:

-

Strong evidence: GPA ‘likely progression’ and/or HRT rim area > 1% per year (p < 0.001).

-

Less strong evidence: GPA ‘possible progression’ and/or HRT rim area > 1% per year (p < 0.01).

Algorithm over-ride

In the following cases the algorithm was over-ridden by the treating consultant if:

-

Poor concordance was thought to be the contributing factor to failure to meet IOP target and was followed by patient education and a recall 8 weeks after for an IOP check.

-

It was felt that it was in the patient’s best interest to over-ride the algorithm’s decision to either revise the target IOP (upwards or downwards) or to escalate treatment.

The reason for the over-ride was recorded.

Follow-up procedure

Follow-up intervals were set at entry to the study, based on disease severity and lifetime risk of loss of vision, according to NICE guidance,15 and subsequently adjusted on the basis of IOP control, disease progression or adverse reactions. Disease stability, along with all available data, was taken into consideration, but testing for progression did not independently determine follow-up intervals. The routine schedule of appointments for patients who remained at or below the target IOP, without progression or treatment change, and who had no adverse reactions requiring earlier assessment, is shown in Table 2. Additional VF tests were permissible at any visit if clinically necessary to confirm possible progression. Variation in follow-up intervals was permitted to accommodate the clinician’s judgement and/or patient choice. 56

| Disease severity category | First visit | Routine follow-up intervals in months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second visita | Third visit | Fourth visit | Fifth visit | Sixth visit | Seventh visit | Eighth visit | ||

| OHT | Randomisation and treatment | 2 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Mild OAG | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 12 | |

| Moderate OAG | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| Severe OAG | 1–2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

Participants in the Laser-1st arm were reviewed 2 and 8 weeks after SLT application. After the 8-week review in the Laser-1st group and for all treatment changes in the Medicine-1st arm, patients were reviewed at 2 months, following which their treatment was changed (with consequent early assessment of response to second treatment) or they entered a disease severity-tailored routine follow-up schedule. Follow-up of patients with severe OAG was at the discretion of the consultant ophthalmologist. If an eye showed ‘possible progression’, then the follow-up frequency was increased to every 3–4 months until progression was confirmed or ruled out with additional VF testing or HRT. No further tests were conducted at additional visits for IOP check alone. All contacts with medical professionals and optometrists were captured for cost data. Information on contact with health-care providers was collected via the CSRI, a validated method of collecting health-care cost data. 63

Follow-up intervals were planned within the ranges specified by NICE guidance15 and were independently determined on the basis of IOP control or adverse reactions, to minimise bias. The main driver for follow-up frequency was treatment in pursuit of control. Disease stability was considered using all available data, but testing for progression did not independently determine follow-up. Patients who required medication changes or additional laser treatment and patients who suffered AEs or showed progression of glaucoma were seen sooner and reverted to schedule when stable. The worse or more unstable of each patient’s two eyes determined the follow-up interval, whereas treatment was individualised to the needs of each eye.

Follow-up clinical assessments

The schedule of assessments (all assessments were part of routine care) is shown in Table 3. After the full baseline assessment, all patients underwent VF testing and HRT to assess progression at each follow-up visit. The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L) and other HRQoL questionnaires were assessed at baseline and 6-monthly thereafter, with additional questionnaires as outlined in Questionnaires.

| Investigation | Time of follow-upa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | First checka | Third visit (6 months) | First year | 18 months | Second year | Patient specificb | Third year | |

| Clinical examination (including disc and IOP) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dilated fundus examination | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gonioscopy | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| VF test | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Optic nerve imaging (HRT) | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| EQ-5D-5L | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| GUI | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| GSS | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| CSRIc | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

Questionnaires

The content of the questionnaires was determined by the use of a number of validated, widely accepted existing questionnaires as follows:

-

EQ-5D-5L

-

GUI

-

GSS

-

GQL-15.

Additionally, a modified CSRI was used and two questions regarding concordance. The content of the questionnaires used can be found as supplementary material [see URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/0910440/#/documentation (accessed 23 April 2019)]; a sample of each questionnaire completed is presented in Appendix 5. The patient and public involvement group reviewed the final questionnaire for layout and clarity to ensure ease of completion.

Questionnaire delivery and follow-up

The baseline questionnaires were self-completed by participants in a private room, at the time of enrolment, after informed consent had been given but before randomisation. Participants were required to have sufficient English knowledge that translation was not required [practical assistance with the layout (e.g. some questionnaires were printed double-sided, some questions had conditional formatting depending on the patients’ response) and completion of the form were permitted].

Subsequent questionnaires were sent out by post for self-completion at 6-monthly intervals; up to two written reminders followed by one telephone follow-up were implemented in the case of non-response. In the event of a telephone follow-up, if the patient was willing, only the primary outcome measure was collected. Aiming to incentivise LiGHT participants to return the vital final questionnaire, a high street voucher worth £5.00 was sent by post along with the final set of questionnaires to each participant. The central site at MEH managed all questionnaires across all collaborating sites.

Follow-up has been extended beyond the primary study to look additionally at HRQoL outcomes at 6 years; questionnaires are will be posted to participants every 6 months for the duration of the extended period.

Adverse events and serious adverse events

An AE was defined as an unfavourable medical occurrence in a patient that was not necessarily caused by the treatment. GCP guidelines67 were used to determine if AEs should be classified serious [serious adverse events (SAEs)]. AEs and SAEs were reported in accordance with standard operating procedures (SOPs) and GCP guidelines, to achieve standardisation across sites and between treatment arms, with an annual safety report to the Research and Ethics Committee.

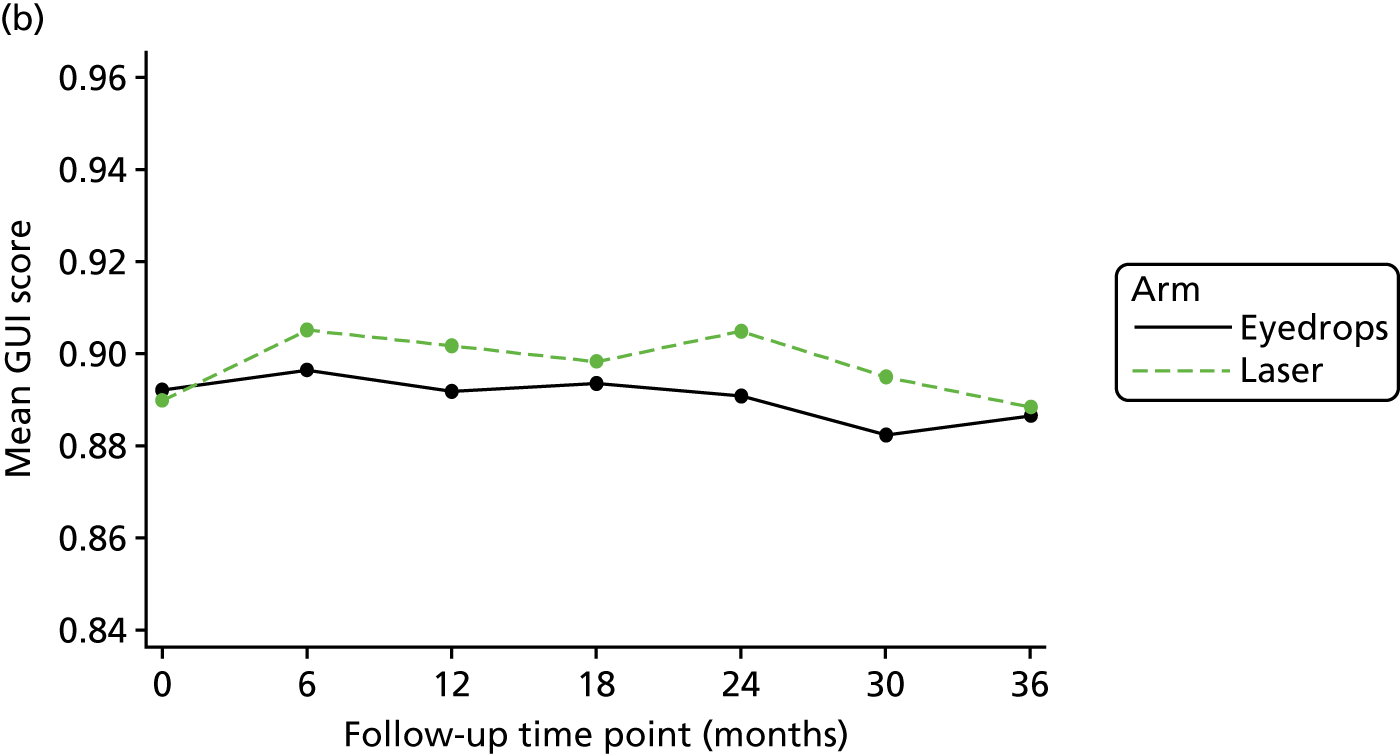

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was HRQoL in patients with OAG or OHT treated with SLT first, compared with HRQoL in patients treated with topical medication first, measured using EQ-5D-5L utility scores at 3 years.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcomes were as follows:56

-

Treatment pathway health-care resource use, cost and cost-effectiveness. Health-care resource use was ascertained from the record of treatment episodes and additional health-care contacts using a modified CSRI. 63 The cost components included the cost of SLT, number of visits, number and type of medications and glaucoma surgeries, and clinical tests.

-

Glaucoma-specific treatment-related QoL was measured using the GUI, from which quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) can also be derived.

-

Patient-reported disease and treatment-related symptoms using the GSS.

-

Patient-reported visual function using the GQL-15.

-

Objective measurements of pathway effectiveness for IOP-lowering and visual function preservation (e.g. treatment intensity and time taken to achieve target IOP, the number of target IOP revisions, proportion of patients achieving target after each year of treatment, number of patients with confirmed disease deterioration and rates of ocular surgery).

-

Objective safety measures for each pathway.

-

Concordance assessed by two questions shown to predict the probability of non-concordance. 80

Reproduced with permission from The Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) trial. A multicentre randomised controlled trial: baseline patient characteristics, Konstantakopoulou E, Gazzard G, Vickerstaff V, Jiang Y, Nathwani N, Hunter R, Ambler G, Bunce C, volume 102, pp. 599–603, 2018 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. 72

Data collection and management

To standardise data collection and management, researchers were trained to follow specific SOPs for each stage of data handling. Identical electronic and hard-copy case report forms (CRFs) were designed according to a standard CRF template. A web-based database for the Priment Clinical Trials Unit, managed by the company ‘SealedEnvelope’, was used for database entry with direct data entry at the time of patient visit. This included extensive internal consistency and range checking, with a hard-copy backup CRF in case of information technology (IT) failure. Records were identifiable only by unique, confidential trial identification number with no patient-identifiable information included. All data were contemporaneously entered directly into the web-based database CRF.

Data from patient completed questionnaires received by post were scanned on receipt for e-copy back-up and entered onto the database within 1 week of receipt by the trial data management officer. Questionnaire data were from validated, standardised tools (EQ-5D-5L, GUI, GQL-15, GSS and CSRI) (see Table 3). The central site at MEH managed the inputting of data from all questionnaires across all collaborating sites.

Statistical analysis plan

The statistical analysis plan has been published previously. 81 All patients were analysed in the treatment arm to which they were randomised. All analyses were performed in Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Sample size

The sample size for the study was 718 participants. This number of participants was required to detect a difference of 0.05 in EQ-5D-5L between the two arms at 36 months using a two-sample t-test at the 5% significance level, with 90% power, assuming a common standard deviation (SD) of 0.1982 and a 15% loss to follow-up. 81

Baseline

The baseline characteristics of each arm were summarised as means and SDs for continuous, symmetric variables, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous, skewed variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. These summaries were based only on observed data. No significance testing was performed.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was HRQoL measured using the EQ-5D-5L at 36 months. The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire was analysed using a linear regression model, with an adjustment for the randomisation factors (severity and centre), baseline IOP, the baseline value of EQ-5D-5L and whether one or two eyes were affected at baseline.

For the primary outcome, the unit of analysis was the patient. If both of a patient’s eyes were included in the study, we used the worse eye at baseline for severity and baseline IOP covariates. The worse eye was defined using the MD at baseline, with the worse eye having the most negative MD.

The primary analysis used outcome data measured at 36 months. If these were missing, we imputed these missing data using the outcome measured at 30 months.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were analysed using regression methods appropriate for the type of outcome. These models were also adjusted using the covariates mentioned above. The results from all secondary analyses are presented as estimates with confidence intervals (CIs).

Exploratory analyses

We used mixed-effect models, using all patient outcome data over the 36 months, to investigate how the primary and secondary outcomes changed over time. Such models allow the analysis of repeated outcome measurements data (recorded every 6 months), as well as taking into account the correlation between measurements from the same patient. Standard regression models assume independence between observations, which typically means that separate models are required for each time point. The mixed-effect models allowed modelling all time points (baseline and 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months) in a single model, by explicitly modelling both the within- and the between-patient variability. 83

By using interaction terms between randomisation arm and time, we investigated differences between the groups over time.

We also used a similar mixed-effect model using all patient data over the 36 months, to evaluate the treatment effects at 36 months by using the exact times that the questionnaires were completed. Finally, using all the patient data over the 36 months, we used a mixed-effects model to explore the average treatment effect over the 36 months.

Analysis of missing data

Potential bias as a result of missing data was investigated by descriptively comparing the baseline characteristics of the trial participants with complete follow-up measurements with those who had incomplete follow-up or no outcome data.

Analysis of homogeneity

To explore the homogeneity (or otherwise) of the intervention effect on the primary outcome, we examined the treatment effect across the following: age (as a continuous measure); severity of glaucoma (using the two groups OHT/OAG used during randomisation process); baseline IOP (as a continuous measure); and sex. The results from these analyses should be treated as exploratory and hypothesis generating, as the trial was not powered for these analyses.

Sensitivity analyses

First, we ran sensitivity analyses that adjusted for variables associated with missingness. We performed logistic regression analyses (with missing ‘yes’ or ‘no’ as the outcome), to identify predictors of missing data. When predictors associated with both missing data and outcomes were found, we refitted the primary analysis model, adjusting for these predictors of missingness.

Second, to take into account any missing data, we used a multiple imputation approach. The imputation model included the outcome of interest, sociodemographic variables and any other variables potentially related to missingness and HRQoL. The imputations were performed separately by treatment arm.

Economic evaluation

The aim of the economic evaluation was to calculate the mean incremental cost per QALY of Laser-1st compared with Medicine-1st. Health and social care costs and QALYs were calculated for the within-trial period (36 months). The outputs were:

-

mean total patient-level QALYs by trial arm

-

mean cost per patient of laser treatment in the Laser-1st arm

-

mean cost per patient of eyedrop treatment for glaucoma by trial arm

-

mean cost per patient of surgery by trial arm

-

mean total health-care cost per patient over 3 years by trial arm

-

mean increment cost per QALY of Laser-1st compared with Medicine-1st and 95% CIs

-

cost-effectiveness planes

-

cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

Quality-adjusted life-years

Mean patient-level QALYs by trial arm were calculated as the area under the curve using patient-level responses to EQ-5D-5L at each follow-up time point84 and the formula by Devlin et al. 85 Patients who died were imputed as zero from the date of death until the end of the trial. We assumed a straight line from the last follow-up time point until death. As the EQ-5D-5L is the primary outcome for the trial, mean patient responses at each follow-up time point are reported as part of the repeated-measures analysis. The mean incremental difference in QALYs was calculated using ordinary least squares regression and included covariates for randomisation arm, baseline EQ-5D-5L values, randomisation factors (severity and centre), baseline IOP and number of eyes affected at baseline.

Quality-adjusted life-years were discounted from 12 months to 3 years at an annual rate of 3.5%. 86 Ninety-five per cent CIs were calculated using bootstrapping, bias corrected and 5000 replications, given that we assume that the data are not normally distributed. Although there was a high rate of return for the EQ-5D-5L at 36 months (91%), data were missing for each time point, which meant that only 73% of patients had complete data across all time points for calculation of QALYs. Multiple imputation using chained equations was used to impute the data for 35 data sets, including age, highest education attainment, employment and diabetic status, included as variables identified as being predictive of missingness.

Cost of selective laser trabeculoplasty

The cost of SLT was calculated using bottom-up microcosting based on data collected from sites. Sites reported the cost of the machine maintenance costs, how sessions were run (dedicated sessions for SLT or as part of a routine session), the grade and number of staff for each session and the number of patients treated per session and per year. Staff wages and overheads were taken from the Personal Social Services Resource Unit (PSSRU). 87 The cost per patient of using the machine was based on an annuitised formula,88 accounting for the number of patients seen in a ‘typical’ site per year and assuming a laser lifetime of 10 years. The number of SLTs per patient was reported.

Cost of drops for open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension

We report the mean cost of eyedrops by trial arm over 3 years. Information on eyedrops prescription, including drug name, dose, number of eyes, number of drops per eye and frequency, was collected as part of trial monitoring processes. Each prescription was costed using the British National Formulary (2018) to calculate the cost per bottle. 89 This was divided by the number of drops per bottle to calculate the cost per day. To calculate the number of days per medication, it was assumed that patients would take the medication from the day of prescription until the next medication change. The mean total cost per patient was then the cost per day of the prescribed eyedrops multiplied by the number of days the medication was prescribed for.

Total ophthalmology-related costs

In addition to eyedrops and laser, information was collected from the patient files on ocular surgery and planned and unplanned specialist ophthalmologist visits. These included a 2-week IOP check as part of the trial process; however, this check would not occur if the service was rolled out and hence this IOP check was removed from the primary analysis. Descriptive statistics for ophthalmology resource use are reported in Chapter 3, Ocular-related costs. Ocular surgery and ophthalmologist outpatient appointments were costed using the NHS Reference Costs 2016–17. 90 We report the mean cost per patient at 3 years for each type of ophthalmology cost, as well as total costs discounted at an annual rate of 3.5%86 by trial arm. Ninety-five per cent bias-corrected CIs were calculated using bootstrapping and 5000 replications. Given that data were taken from patient files, it was not possible to identify missing data (it was assumed that if patients did not have an appointment or surgery reported, this was because none occurred). As a result, the intention to treat (ITT) was based on all the patients, assuming that the appointment data collected are correct.

Other health-care costs

Health-care resource use, including optician contacts, community health-care contacts and acute health-care contacts, was collected from a modified version of the CSRI91 at baseline and at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months, asking about eye-related and non-eye-related resource use in the past 6 months. Information on inpatient stays and day cases was checked against SAE data. SAEs not reported in the CSRI were included in the total inpatient cost. Resource use was costed using unit costs from PSSRU87 except for optometrist visits,92 heart bypass surgery90 and cancer deaths (Table 4). 93 Mean costs by trial arm at each time point were by ocular- and non-ocular-related costs over 3 years.

| Resource use | Unit cost (£) (per contact) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Trabeculectomy | 1436 | NHS Reference Costs 2016–17 90 |

| Ophthalmology appointments | 91 | NHS Reference Costs 2016–17 90 |

| Optometrist visit | 52 | Violato et al.92 |

| Planned inpatient stay | 3903 | Curtis87 |

| Unplanned inpatient stay: short durationa | 628 | Curtis87 |

| Unplanned inpatient stay: long durationb | 2953 | Curtis87 |

| A&E attendance: admitted | 221 | NHS Reference Costs 2016–17 90 |

| A&E attendance: not admitted | 128 | NHS Reference Costs 2016–17 90 |

| Outpatient attendance | 137 | Curtis87 |

| GP contact: in practice | 31 | Curtis87 |

| GP contact: telephone | 24 | Curtis87 |

| GP contact: at home | 80 | Curtis87 |

| GP practice nurse | 36 | Curtis87 |

| Social care | 59 | Curtis87 |

| Home care | 26 | Curtis87 |

| Other community contacts | 57 | NHS Reference Costs 2016–17 90 |

| Cancer death | 6129 | Georghiou and Bardsley93 |

Total health and social care costs

The cost components included in the analysis were the cost of SLT, OAG medication and other health-care costs. We report the mean cost per patient in addition to an adjusted cost, adjusting for baseline service use using regression analysis. Mean costs were based on a complete-case analysis, with only optician and CSRI resource use excluding inpatient stays missing (an analysis imputing for missing CSRI data using chained equations has been included). The mean incremental difference in costs is calculated using ordinary least squares regression and includes covariates for randomisation arm, baseline EQ-5D-5L values, randomisation factors (severity and centre), baseline IOP and number of eyes affected at baseline. We used bias-corrected bootstrapping to calculate 95% CIs, given that we assumed that the data are not normally distributed. All costs are reported in 2016/17 Great British pounds.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

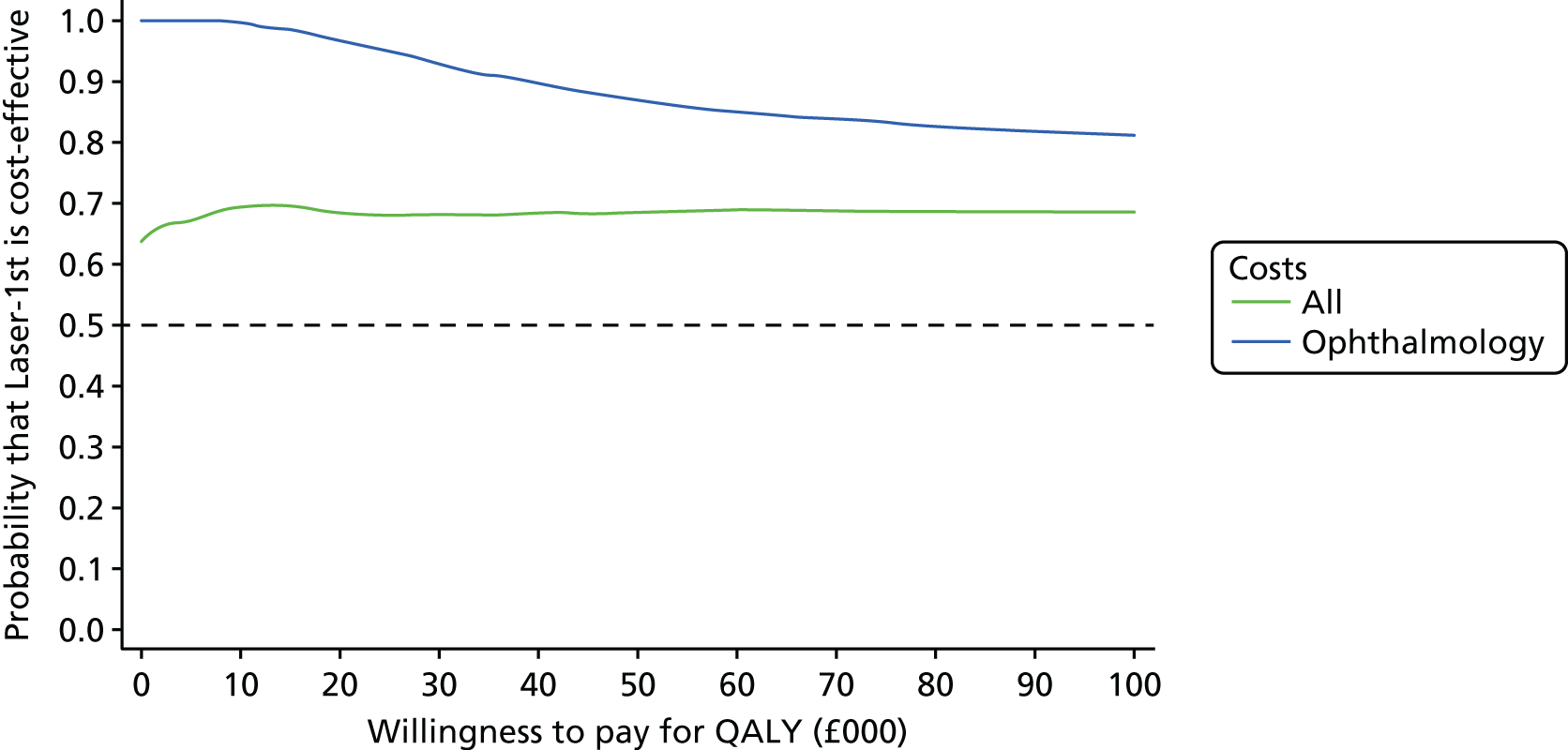

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was defined as the mean incremental cost of Laser-1st compared with Medicine-1st and divided by the mean incremental QALYs of laser treatment compared with eyedrops. The mean incremental differences were adjusted for baseline values, randomisation factors (severity and centre), baseline IOP and number of eyes affected at baseline. To account for the correlation between costs and QALYs, seemingly unrelated regression was used to calculate the numerator and denominator of the ICER. ICERs are reported for total costs, as defined in Total health and social care costs, and ophthalmology only costs, as defined in Total ophthalmology-related costs. Costs and QALYs from 12 months until 36 months are discounted at an annual rate of 3.5%. 86 The final results for total costs and QALYs are based on data imputed using chained equations for QALYs and CSRI, and using the missing at random methodology described in Leurent et al. 57 for calculating CEACs using bootstrapping and multiple imputation for 200 draws of each of the 35 imputed data sets for 7000 replications in total.

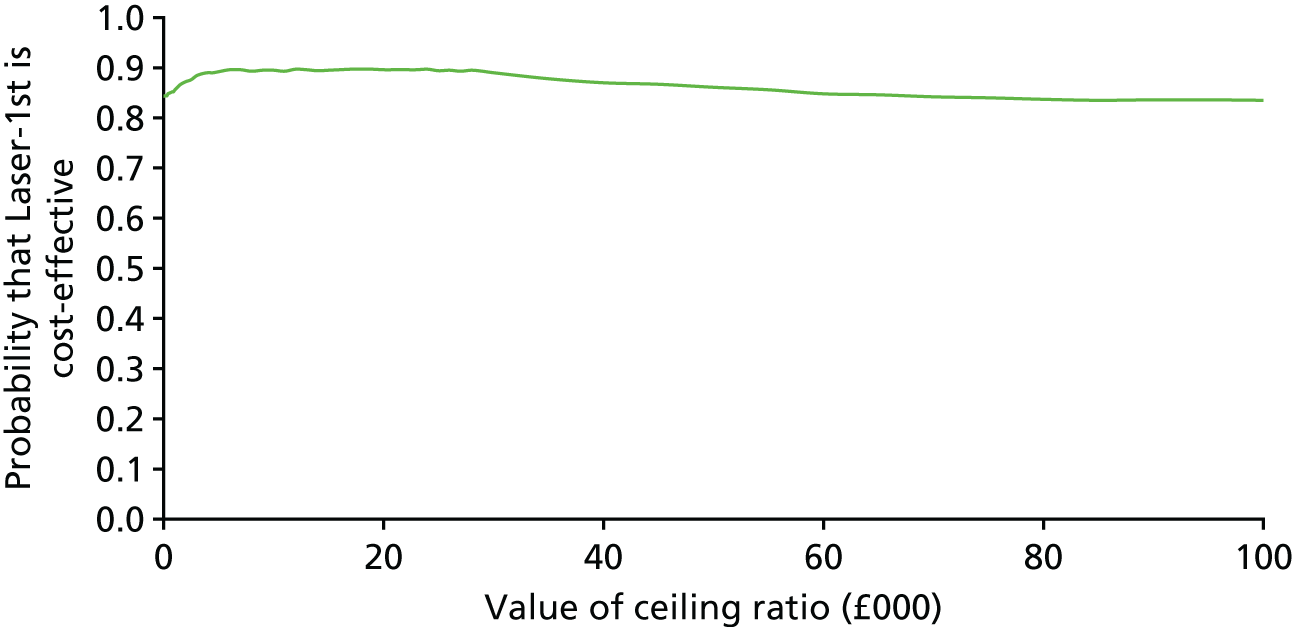

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve

A CEAC is reported using the bootstrap imputed data (200 draws of each of the 35 imputed data sets for 7000 replications in total), for a range of values of willingness to pay for a QALY. We report the probability that Laser-1st is cost-effective compared with Medicine-1st at a willingness to pay for a QALY of £20,000 and £30,000 for (1) total costs and (2) ophthalmology only costs.

Secondary analyses

The following secondary analyses were conducted:

-

For the primary analysis SLT was costed using microcosting. Some assumptions of the microcosting, for example the number of patients per site per year, or how sessions are run, may have an impact on the total cost. As a result, we planned to examine the impact of modifying the assumptions on the total cost of SLT per patient and hence the ICER. The cost of SLT as estimated from NHS reference costs90 was used in the analysis.

-

In the primary analysis we removed the cost of the 2-week IOP check, given that this was unlikely to occur in practice. One could hypothesise that patients obtained some minor benefit from this check and hence its costs could be included in the analysis. A secondary analysis including the 2-week IOP check has been included.

-

QALYs were calculated using utility scores generated from the GUI61 and the same methodology for calculating QALYs as above. The results were combined with the costs, as above, to report the mean incremental cost per QALY of Laser-1st compared with Medicine-1st, using the GUI.

Patient and public involvement: lay advisory group

Glaucoma patients and relatives from the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Consumer Panel formed our independent LAG. Consultation on trial design, choice of outcome measures, recruitment and treatment acceptability took place by e-mail and through online discussions via the Facebook social networking site (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; Group: ‘Public Eye – LiGHT Trial Discussion Forum’). All of the suggestions made have been incorporated (e.g. requests to monitor all symptoms in detail, a safety concern about ‘rapid loss of pressure control’ after SLT and more explanation of the relationship between eyedrops and surgical failure). An ‘expert patient’ with treated glaucoma reviewed and commented on the study protocol as a service user member for the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and another service user representative from the International Glaucoma Association was invited to join. The LAG contributed to the development of tailored information leaflets and consent forms with further consultation with service user groups and via the Friends of Moorfields charity. A survey of 100 new patients attending MEH to assess the acceptability of an invitation to participate in such a trial, before the commencement of the trial, had a 70% positive response.

Patients diagnosed and treated for glaucoma also provided input to a questionnaire sent in 2015 (see Appendix 6), allowing us to design an extension for the main LiGHT trial; the questionnaire looked into the views of these treated patients on current treatment options and their willingness to switch from eyedrops to laser.

As required by the NHS, in line with INVOLVE national guidelines and in accordance with UK Clinical Research Collaboration policy, the results are being communicated to patients, for example via NHS Choices and patient advocate groups (e.g. International Glaucoma Association), and the findings have been published in open access media. 58

Study oversight and management

Study co-ordination in London

The Trial Management Team was composed of the chief investigator, central trial manager (CTM), central trial optometrist (CTO), central research optometrist (CRO), lead trial statistician and trial statistician, members of the University College London Priment Clinical Trials Unit, trial data officers, co-applicants and trial optometrists. The team met monthly on average to ensure the smooth running of the trial and troubleshooting. The duties of the CTM were to support the organisation of the study [investigator meetings, TSC and Data Management Committee (DMC) meetings, training, etc.] and have a study management role, including monitoring data collection according to established milestones, maintaining trial records, co-ordinating data management between local sites and the central clinical trial unit, facilitating user involvement in the project through LAG meetings and working alongside the CTO and facilitating the recruitment and follow-up of study participants.

Local organisation in centres

The chief investigator (consultant ophthalmologist) was the local PI at the central site (MEH), who co-ordinated the local ethics approval and sat on the TSC. The local study co-ordinator administrated the follow-up and recall of patients, liaising with the Trial Management Team. The local trial clinicians were an ophthalmologist, a fellow or an optometrist who were responsible for the recruitment, treatment and follow-up of trial participants. They had regular conference calls with the Trial Management Team for the duration of the study. The local trial clinicians were directly accountable to the local PIs. There were regular conference calls to all local clinicians and PIs to troubleshoot local issues. The chief investigator closely supervised the CTM, CTO and CRO with regular meetings.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC was composed, in accordance with GCP, of an ophthalmologist as the independent TSC chairperson, a chief investigator, an independent clinician with relevant expertise, a sponsor representative, a Central and East London Comprehensive Local Research Network representative, an independent health economist, an independent statistician and two patient representatives. The trial manager, chief investigator, lead trial statistician and trial statistician were invited to report as required. The TSC met at least 6-monthly and minutes were taken.

Data and safety monitoring

Data and safety monitoring by the University College London Priment Clinical Trials Unit involved regular reports from the CTM, including recruitment and drop-out rates, adherence to SOPs, number failing to meet target or progressing, and AEs. The chief investigator maintained day-to-day responsibility for the trial with the CTM to ensure that the trial was conducted, recorded and reported in accordance with the protocol, GCP94 guidelines and SOPs.

The DMC was composed of the following individuals in accordance with GCP guidelines: (1) a DMC chairperson, (2) an independent trial statistician and (3) two additional glaucoma or ophthalmic trials specialists. The DMC met annually (or more often if appropriate), timed to report to the TSC. During recruitment, interim reports were supplied to the DMC, together with any analyses it requested.

The above committees followed SOPs set by MEH and the University College London Priment Clinical Trials Unit, and complied with guidelines issued by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health and Technology Assessment panel for clinical trials.

Data monitoring

We completed double data entry for the EQ-5D-5L for all completed questionnaires for all time points. The second data entry was completed by a different individual to the person doing the first entry. The first data entry was then matched with the second data entry and any discrepancies were checked and resolved by referring back to the hard-copy questionnaire.

The trial research team performed checks on 100% of the clinical baseline and eligibility data. Monitoring activity across sites was carried out at scheduled intervals and was adapted to the demonstration of errors by the collaborating sites (see Appendix 7). Protocol deviations and violations were recorded throughout the study and appropriate action was taken to prevent similar events from taking place in the future.

Protocol amendments

A series of minor amendments have taken place after the commencement of the trial and were submitted to the funder, as well as gaining ethics approval. Below is a list of the major protocol amendments:

-

addition of audio-visual material to assist with recruitment of patients

-

collection of blood, tears and saliva samples

-

addition of the ocular response analyser (Reichert Ophthalmic Instruments, Inc., Buffalo, NY, USA) to the assessments

-

extension of the trial to 6 years

-

ocular surface disease questionnaire (extension only).

Chapter 3 Results

The main results of the study have been published in Gazzard et al. 58 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Recruitment

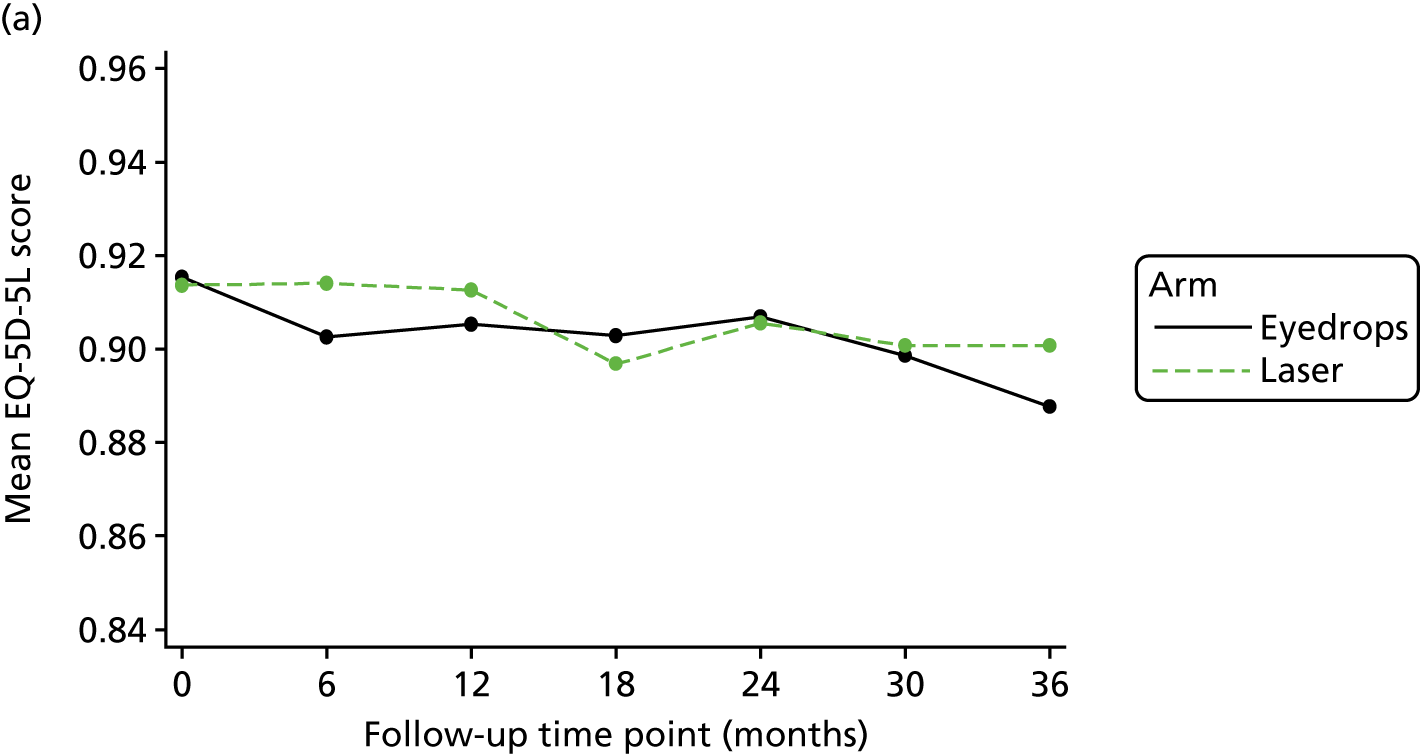

A total of 16,379 patients were assessed for eligibility; 15,483 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the 896 patients who were eligible across the six participating NHS centres, a total of 718 (1235 eyes) were recruited for the study (80.1% participation rate). A recruitment chart for the total recruitment period can be found in Appendix 8. A total of 178 eligible patients declined to participate. Of the patients who declined to participate, 43 did not want to have SLT, 17 did not want to take part in research, nine did not want to use eyedrops, three did not want to receive any treatment, one did not want to travel to the hospital and 105 did not provide an explanation.

Participant flow

A total of 718 patients (1235 eyes) were randomised: 356 patients (613 eyes) were allocated to SLT (Laser-1st pathway) and 362 patients (622 eyes) to medical treatment (Medicine-1st pathway) (Figure 4). Two patients were randomised twice owing to failure, as a result of which the initial randomisation was not visible. Subsequently, a second randomisation was carried out; one of these patients had initially been randomised to medication (non-visible randomisation), but was subsequently randomised to, and received, SLT. The second patient was initially randomised to SLT (non-visible randomisation), but was later randomised to, and received, medication. Four patients who did not meet the eligibility criteria were randomised in error and were subsequently removed from the study (see Appendix 9).

FIGURE 4.

The LiGHT trial Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. a, Two patients were randomised twice owing to IT failure, as a result of which the initial randomisation was not visible, and subsequently a second randomisation was carried out. Reproduced from Gazzard et al. 58 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

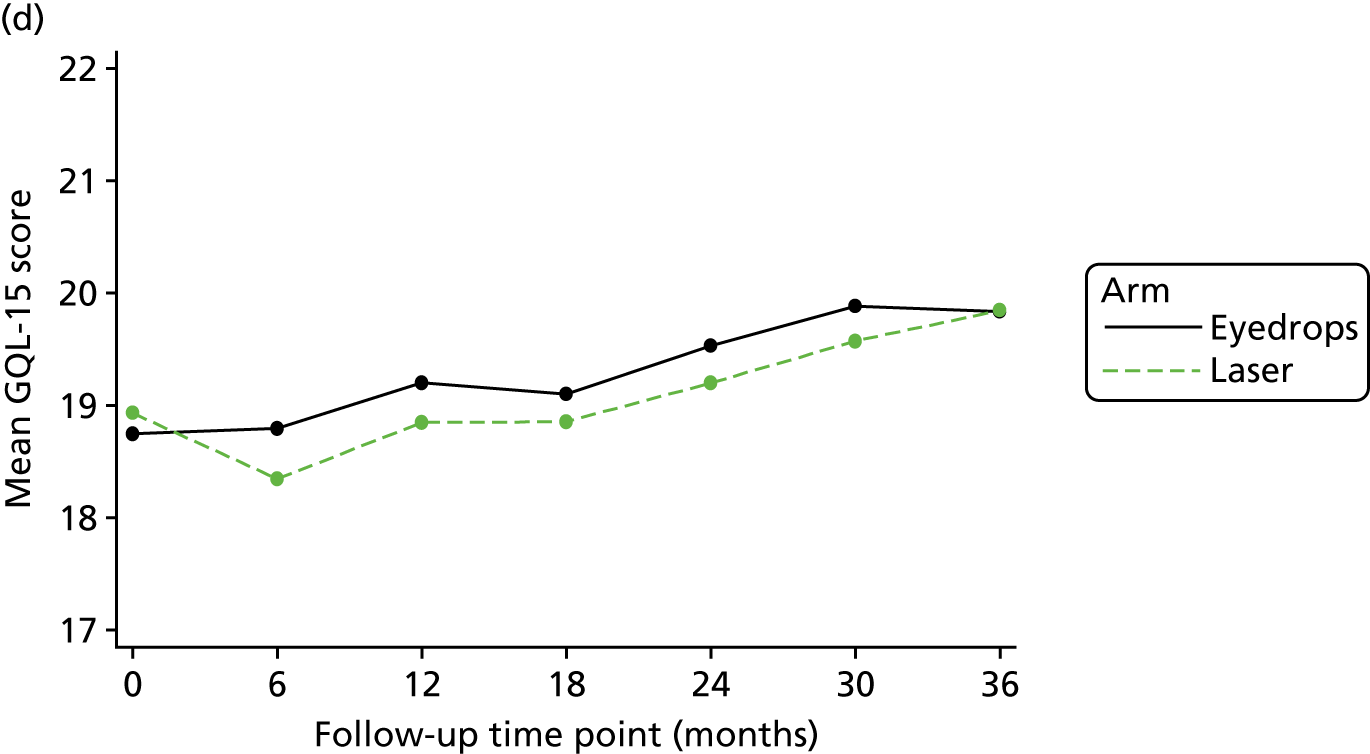

Participant baseline characteristics