Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/137/05. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Eleanor McGee was the manager of the First Steps children’s weight management programme (the programme on which this study is based). Peymane Adab is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research Funding Board. Jayne Parry undertakes committee work for the NIHR that attracts a small stipend, which is paid directly to the University of Birmingham where she is employed full-time.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Pallan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Epidemiology of childhood overweight and obesity

In England, 9% of 4- and 5-year-olds are classified as obese and a further 13% are classified as overweight. By age 10 and 11 years, the prevalence significantly increases, with 20% being obese and 14% being overweight. 1 Ethnic differences in childhood obesity prevalence exist, with the prevalence in 10- to 11-year-old South Asian children (those originating from the Indian subcontinent, including Pakistan and Bangladesh) at 25% compared with 18% in white children. 1 Specifically, Pakistani and Bangladeshi children have higher obesity levels than white British children; at ages 10 and 11 years, 28% and 33% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi boys were classified as obese in 2014/15 compared with 19% of white British boys, and 22% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi girls were classified as compared with 16% of white British girls. 2

Obesity is associated with a range of physical, psychological and social consequences in childhood,3 and up to 80% of obese children will remain obese in adulthood. 4 Obesity in adulthood is a risk factor for a variety of health consequences, including certain cancers, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus;5,6 thus, it is a major contributor to morbidity and premature mortality. The economic costs associated with overweight and obesity-related ill-health are considerable. Costs to the NHS in England were estimated to be £5.1B in 2006/7. 7 In addition, there are societal costs associated with a reduction in years of disability-free life, increased absences from work and early retirement, increased morbidity for those of working age and reductions in productivity. 8

South Asians are the largest minority ethnic population in the UK and are particularly susceptible to the health consequences of obesity. South Asians have higher levels of body fat and central obesity than white European populations9 and are more vulnerable to the cardiometabolic consequences of obesity than other ethnic groups in the UK. 10 Markers of increased cardiovascular risk are seen in South Asians, even in childhood. 11 Thus, South Asians represent an important target group for obesity intervention, particularly in childhood, given the disparity in obesity prevalence in children.

Effectiveness of current programmes addressing overweight and obesity in children

Evidence to date for effective childhood obesity behavioural treatment programmes is limited. In the Cochrane review conducted by Luttikhuis et al. 12 in 2009, a meta-analysis of a small subset of high-quality studies showed that behavioural intervention programmes have a small but clinically significant effect on weight status at 6 months post intervention [a reduction in body mass index (BMI) z-score of 0.06 and 0.14 compared with standard care in preadolescents and adolescents, respectively]. However, the review highlighted a range of methodological issues within the included studies, such as insufficient power, lack of allocation concealment, high attrition rates and lack of intention-to-treat analysis. Therefore, it was difficult to draw firm conclusions. Clinically meaningful effects on anthropometric measures have been reported in more recent randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of behavioural intervention programmes13–16 and in a comprehensive evidence review that informed the 2013 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s guidance on children’s weight management [public health guideline (PH) number 47],17 which included meta-analyses to estimate the pooled intervention effect of behavioural programmes targeting children and their parents or families. A 0.2 reduction in BMI z-score at the end of the intervention and a 0.1 reduction at the 6-month follow-up compared with standard care was estimated from 8 and 11 studies, respectively. 17 Evidence from studies suggests that even such small reductions in BMI z-score could lead to clinical improvements. 18 The absence of data on the cost-effectiveness of childhood obesity behavioural treatment interventions and the lack of data on longer-term outcomes have been highlighted. 12,19

Critical elements of effective programmes

Owing to limitations of the evidence, the most effective intervention components of behavioural child weight management programmes are, as yet, undetermined. In most studies to date, the measurement of processes and an assessment of the fidelity of programme delivery have not been undertaken or reported,12,20 which limits the interpretation of outcomes and assessment of which elements of the programme are likely to have had the most influence. However, the available evidence suggests that, in the preadolescent age group, interventions that address both diet and physical activity, include behavioural elements and involve parents are the most promising,12,20,21 although the specific nature of this parental engagement still needs to be determined. 21,22

Evidence of the clinical effectiveness of overweight and obesity management programmes in minority ethnic children

Evidence evaluating the clinical effectiveness of childhood obesity treatment programmes in minority ethnic populations is also limited and studies were undertaken mainly in the USA. 23–26 Existing studies have evaluated programmes with adaptations such as the delivery of materials in different languages, the tailoring of nutritional content and the ethnic matching of programme providers. Two RCTs that evaluated culturally adapted interventions, one targeting Chinese American children aged 8–10 years24 and the other targeting a mixed population of Hispanic, black and white children aged 8–16 years,25 have reported small to moderate reductions in BMI z-score in the intervention compared with the control groups (controls received no intervention and a low-intensity clinic-based intervention, respectively). Effects appeared to be sustained for at least 8 months. Another uncontrolled study in a Latino community in the USA reported positive effects on dietary and physical activity behaviours but no effect on BMI. 26 Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that interventions delivered in multiethnic populations may have a differential effect; a recent RCT of a multidisciplinary intervention targeting obese adolescents in the Netherlands reported a 0.35 reduction in BMI z-score over 18 months in participants of Western descent but no BMI z-score reduction in participants of other ethnicities. 27

In the UK, one small RCT (n = 72) has been undertaken to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of a family-based behavioural treatment programme targeting obese children in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse community of 8- to 12-year-old children (of whom 43% were non-white European). The programme, originally developed in the USA,28 was not culturally adapted and, although acceptable to the target population,29 it did not have a significant effect on weight. 30

Retention in children’s weight management programmes

Previous studies suggest that there is an association between better programme attendance and the weight loss achieved in children’s weight management programmes;14 however, retention of participants has been highlighted as a problem. Programme characteristics that are associated with greater dropout include having large group sizes and logistical barriers to attendance. 31,32 Lower retention in programmes has also been reported to be associated with socioeconomic disadvantage32 and ethnicity. 33,34

Development of culturally adapted children’s weight management programmes

To date, theoretical approaches to the cultural adaptation of child weight management programmes have been lacking,23 and little has been done in the way of evaluating the success of cultural adaptation of obesity treatment and health promotion programmes in general. In a comprehensive evidence synthesis review on the adaptation of health promotion programmes for minority ethnic groups, Liu et al. 35 stated the requirement for future trials to compare culturally adapted programmes with standard programmes.

Provision of childhood obesity treatment services in the UK

Although in the last 15 years there has been widespread provision of children’s weight management services across the UK,36 no programmes have been specifically designed to meet the needs of ethnically and culturally diverse communities, such as those living in many large cities in the UK. In Birmingham, the UK’s second largest city, 42% of the total population and 59% of the 0- to 15-year-old population are from minority ethnic communities. More than half of these residents are of South Asian ethnicity, although the great majority were born in the UK. 37

Since 2010, a child weight management programme, First Steps (a weekly programme delivered over a school half-term that targets parents), has been available in Birmingham. Participants are referred through health professionals, schools or the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) or are self-referred. Over one-third of the referrals received by the service have been for children and families from Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities, but an analysis of routine service data has highlighted differences in completion rates between different ethnic groups. Pakistani and Bangladeshi families are as likely to start attending the programme as other families but are less likely to complete the programme, which suggests that it is less well suited to families from these communities. Of those starting the First Steps programme, 40% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi families completed it compared with 65% of white British and African-Caribbean families.

Although there may be a number of reasons for this difference in completion, it may imply that aspects of the current programme are not culturally relevant to Pakistani and Bangladeshi families. The existing weight management programme in Birmingham has developed over time, based on research evidence and service provider experience, to try to make it more acceptable to the community that it serves. Prior to the introduction of First Steps in Birmingham, established and evidence-based child weight management programmes, such as Mind, Exercise, Nutrition . . . Do it! (MEND)13 and Watch It,38 had been commissioned. However, the intensity and duration of the courses resulted in very low uptake rates and high attrition, and service providers identified that there was a lack of flexibility to tailor the programmes to accommodate cultural and language requirements. The First Steps programme was designed to be more suited to the local population by placing a greater focus on parental engagement, increasing the visual programme content, including culturally appropriate foods in the programme materials and providing interpreters. Elements of the Watch It and MEND programmes that were observed to have worked in the local population were retained in First Steps (specific behaviour change strategies, and some nutrition content). Other elements that were incorporated were consistent with the evidence base. Routinely collected data at the first and last sessions of First Steps indicated that those who completed the programme achieved an average reduction in BMI z-score of 0.1 at programme end, which is comparable to effect sizes reported in clinical trials. 12 Given the evolution of the First Steps programme in the local ethnically diverse population, it provided a good foundation on which to develop a new programme that incorporated further cultural adaptations.

Rationale for the CHANGE study

The focus of the Child weigHt mANaGement for Ethnically diverse communities (CHANGE) study was to further develop and culturally adapt the current First Steps programme, using a theoretically informed approach, such that it better met the needs of the Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities within Birmingham. However, a programme delivered to families from only these communities would not address the needs of the wide range of cultural communities found in a city such as Birmingham. Communities across Birmingham provide an example of super-diversity, a term used to characterise the complexity of modern communities in Britain, in which there are dynamic relationships between multiple variables, including country of origin, ethnicity, language, religion, regional/local identities, migration history and experience, and immigration status. 39,40 This complexity creates a challenge to health-care providers to meet the health needs of all members of society. Thus, this study aimed to develop a programme that was culturally adapted to meet the needs of Pakistani and Bangladeshi families but that would also be flexible enough to accommodate the needs of all families and could be transferred to communities with a different cultural and ethnic composition. To ensure that the developed programme was suitable for all, we evaluated it in a feasibility study involving families from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Chapter 2 Study design

Aims and objectives

Study aims

The CHANGE study was designed in two phases. In the first phase, we aimed to adapt a weight management programme for children aged 4–11 years and their families, and to make it culturally relevant to Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities but also appropriate for families from all communities. In the second phase, we aimed to undertake a feasibility study of the culturally adapted intervention programme, using a cluster randomised design to compare the culturally adapted programme with the standard weight management programme.

Phase I objectives

-

To explore factors that promote or discourage engagement with, and completion of, existing childhood obesity treatment programmes among Pakistani and Bangladeshi families in the UK.

-

To use this information, together with existing research evidence and theoretical frameworks for cultural adaptation and complex intervention development, to design a theoretically informed childhood obesity treatment programme that is appropriate for all families but is culturally adapted to meet the particular needs of Pakistani and Bangladeshi families.

Phase II objectives

-

To assess the proportion of Pakistani and Bangladeshi families and the proportion of all families completing the adapted programme.

-

To assess the acceptability of the programme to Pakistani and Bangladeshi families and families from other ethnic groups.

-

To assess the feasibility of delivery of the adapted programme.

-

To assess the feasibility of participant recruitment, randomisation and follow-up.

-

To assess the feasibility of the collection of cost data from both a health and societal perspective to inform a future trial that evaluates intervention clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

-

To collect data on recruitment, attrition and other relevant measures to inform the parameters of any future trial.

Design and setting

Study design

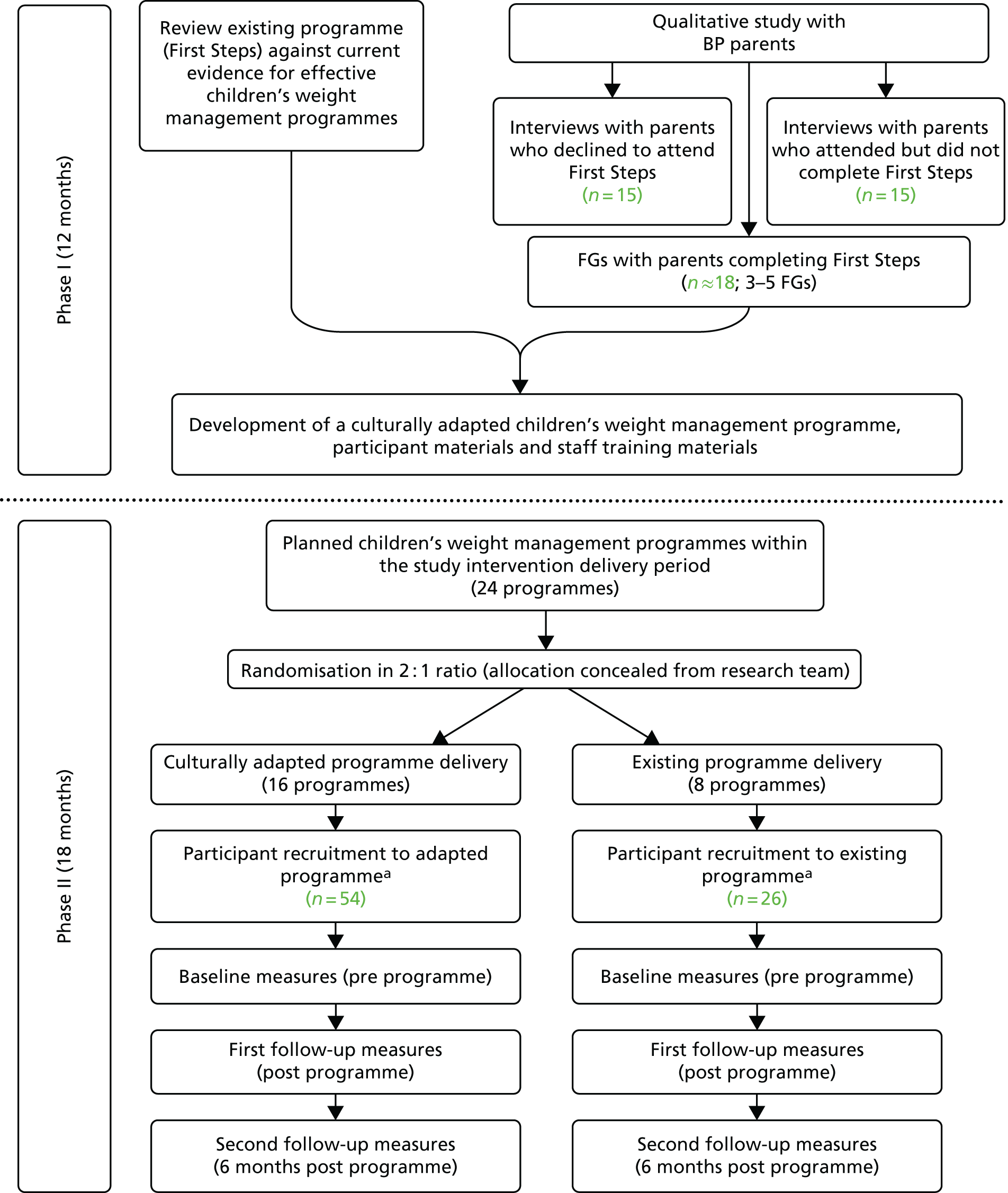

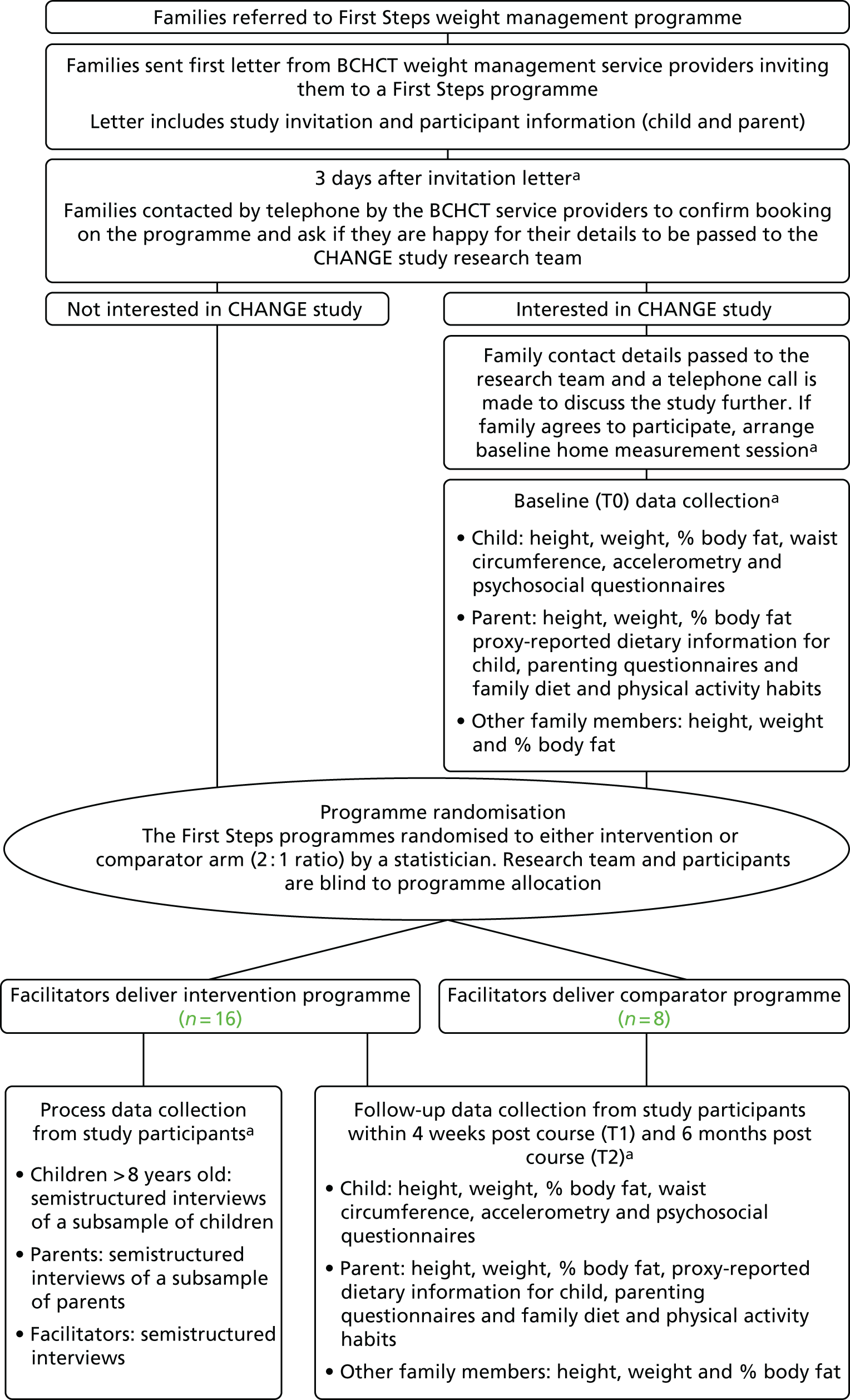

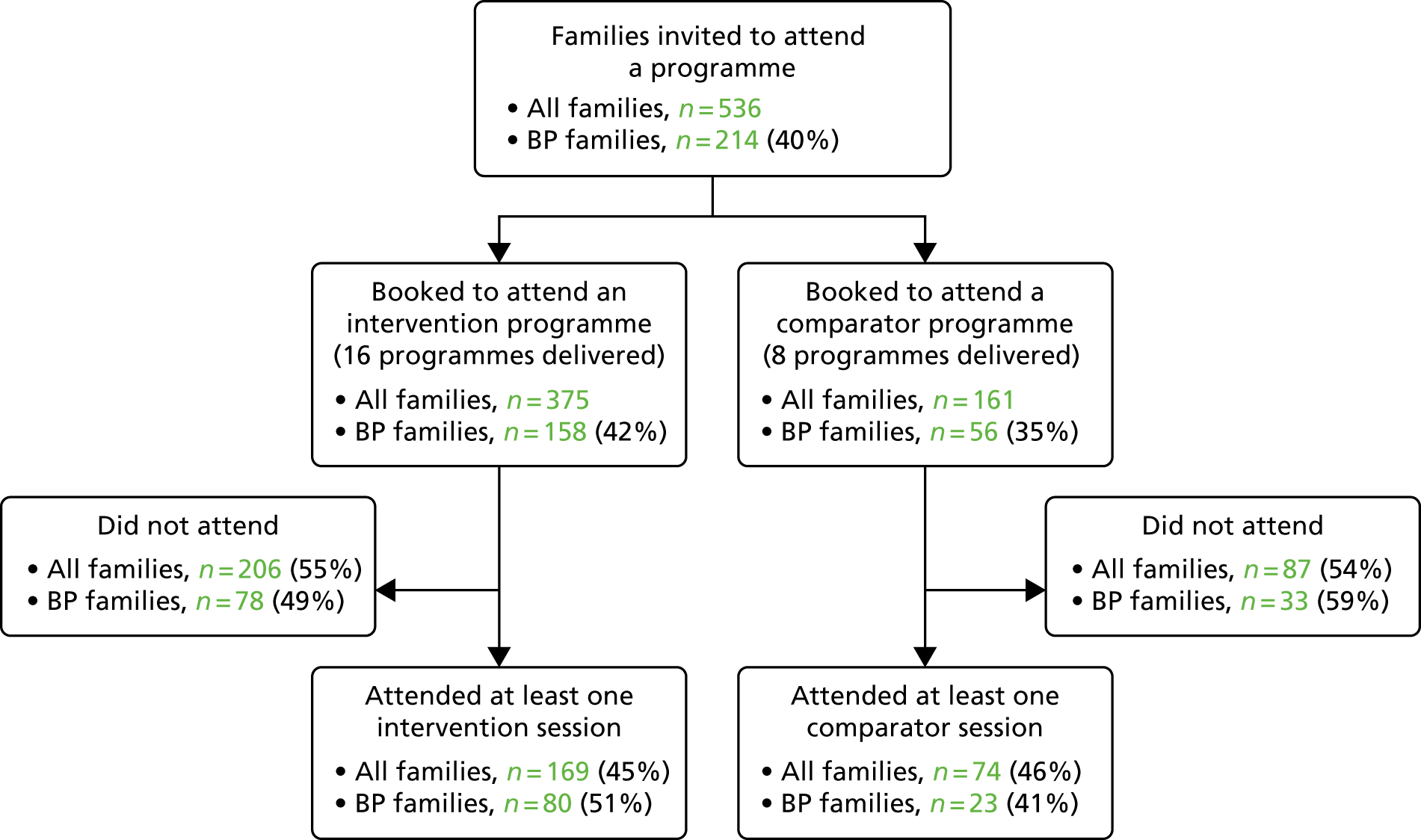

The first phase addressed the theoretical and modelling stages of the UK Medical Research Council’s framework for the development and evaluation of complex health interventions. 41,42 It involved adaptation of the current children’s weight management programme delivered in Birmingham, UK (First Steps). The adaptation process was informed by research evidence relating to the clinical effectiveness of childhood obesity treatment programmes and the experiences and view points of Pakistani and Bangladeshi families who had participated, or initially agreed but then declined to participate, in the current programme. The intervention adaptation process was guided by theoretical frameworks for complex intervention development and for adaptation of health promotion programmes for minority ethnic groups. 35,43 The second phase addressed the feasibility stage of the Medical Research Council’s complex health intervention framework. We conducted a two-arm cluster randomised feasibility study that compared the culturally adapted programme with the existing programme. Programmes were randomised to be delivered as either the adapted or the standard programme in a 2 : 1 ratio. This ratio was used to ensure that there were a sufficient number of families in the intervention arm to enable calculation of the primary outcome of the proportion of Pakistani and Bangladeshi families completing the adapted programme. Data were collected from participants at three time points: before programme attendance, after programme completion and 6 months after programme completion. The study design is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The CHANGE study flow chart: study design and participants. a, Participants are blind to the allocation of the programme that they are attending. BP, Bangladeshi or Pakistani; FG, focus group.

The study took place in Birmingham, which is the UK’s second largest city and has a population of nearly 1.1 million. Of this population, 16.5% are from Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities. Pakistani and Bangladeshi children constitute 26% of the Birmingham population that is aged 0–15 years. 37

At the time of the study, all families resident in Birmingham with a child aged 4–11 years who had a BMI over the 91st centile of the UK’s 1990 growth reference charts44 were eligible to attend the First Steps children’s weight management programme (the programme that was adapted in this study). First Steps was commissioned by Birmingham City Council and delivered by Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Trust (BCHCT). Children could be referred to the programme through several different routes: via health professionals, schools, the NCMP or self-referral. First Steps was a group-based programme delivered as weekly 1-hour sessions over 5–7 weeks in community venues. Session content included nutrition education, physical activity promotion and the promotion of positive lifestyle behaviour changes. The programme was aimed at parents/carers and children attended only the first and last sessions, at which their height and weight were measured. Participants for both phases of the study were identified through the existing children’s weight management services in Birmingham.

Public and patient involvement

A panel of parents of primary school-aged children from Bangladeshi and Pakistani communities was convened for the duration of the study. The Parent Advisory Panel was consulted at specific stages of the study to enable them to bring their values to the project and ensure that the development of the programme, outcome measures and research procedures were culturally appropriate. Input from the panel was sought for the planning of the qualitative studies in both phases I and II, the adapted intervention design, the planning of data collection procedures in the phase II feasibility study, the plans for disseminating the study findings and the preparation of the Plain English summary of the report. There was also a public member of the Study Steering Committee from the Pakistani community in Birmingham.

Study management

The study was overseen by an externally appointed, independent Study Steering Committee comprising three subject experts (two public health specialists with an interest in childhood obesity prevention and management and an expert on equality and diversity in relation to health and social care) and a public representative. A study management group, comprising the principal investigator, the study co-ordinator and two co-investigators, met regularly to guide the conduct of the study.

Ethics approval and study registration

Ethics approval was obtained in July 2014 from Edgbaston NHS Research Ethics Committee, West Midlands, UK (reference number 14/WM/1036). The study was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register as reference number ISRCTN81798055. The original study protocol was sent to and was approved by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme on 31 July 2014. A number of revisions and additions were made to the protocol during the course of the study and these are shown in Appendix 1. The final protocol was published as a journal article in 2016. 45

Chapter 3 Phase I: intervention design

Methods

Information from three main sources was used in the adaptation process: (1) data from a qualitative study conducted with Pakistani and Bangladeshi parents/carers of children with excess weight, who had previously had some contact with the First Steps programme; (2) local information from the First Steps programme that was being delivered at the time; and (3) existing children’s weight management literature.

The information collected was then used in the adaptation process that was guided by two theoretical frameworks. The behaviour change wheel (BCW)43,46 ensured that the pathways to change and how these were addressed in the adapted intervention were clearly articulated. The typology of cultural adaptation and health promotion programme theory proposed by Liu et al. 35 ensured that appropriate cultural adaptations across all aspects of the programme were considered for inclusion in the adapted intervention.

The methods for obtaining data to inform intervention adaptation and the process of adaptation itself are described in detail in the following sections.

Qualitative study with Pakistani and Bangladeshi parents

Community researchers

Researchers from Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities in Birmingham with qualitative research experience were recruited for this part of the study [community researchers: Aisha Ahmad (of Pakistani heritage), and Minara Bibi and Salma Khan (of Bangladeshi heritage)]. The community researchers received bespoke training to work alongside the study research team (Tania Griffin and Laura Griffith; both of white British heritage) to recruit participants and undertake interviews and focus groups (FGs). The community researchers were able to communicate in Urdu, Bengali, Mirpuri or Sylheti, when necessary, and to understand the cultural context of participating families.

Participants

The BCHCT identified all families that had been invited to take part in the First Steps programme from September 2013 to July 2014 (1 school year). The eligibility criteria for family participation in the First Steps programme were having a child aged 4–11 years with a BMI z-score on the 91st percentile or above and the ability of the child to attend and participate in a group setting. The families were categorised as (1) attended ≥ 60% of the First Steps programme (‘completers’); (2) started the First Steps programme but attended < 60% (‘non-completers’); or (3) did not attend the programme (‘non-attenders’). The BCHCT contacted families to explain the CHANGE study and confirm whether or not the family agreed for their details to be forwarded to the CHANGE study research team. Parents who did not speak English were contacted by the BCHCT in their preferred language. The university research team received contact details for families that had verbally agreed for their information to be passed on.

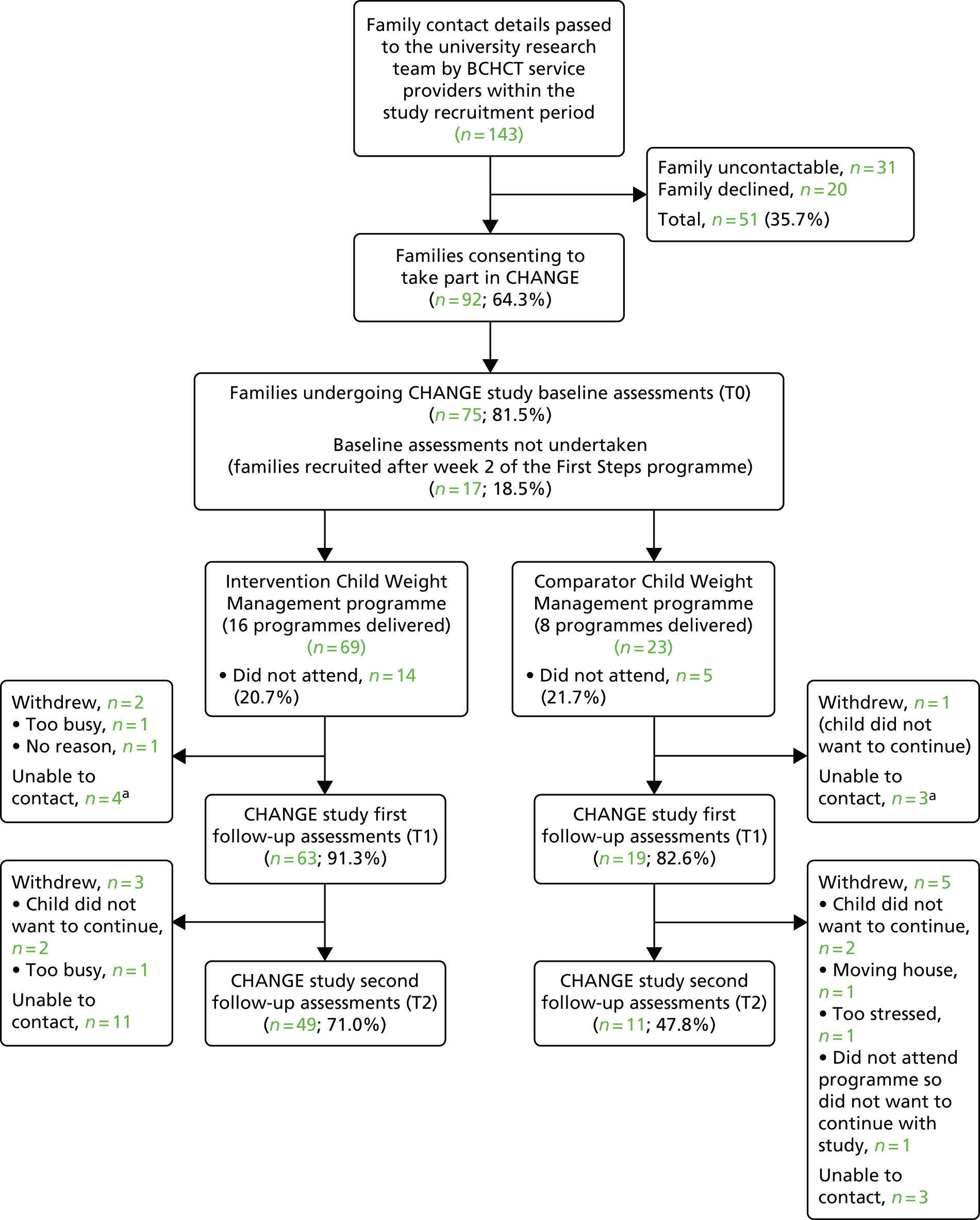

The research team sent a study invitation letter with a parent and child information sheet to all potential participants for whom they had contact details. These documents were reviewed by the Parent Advisory Panel (comprising Pakistani and Bangladeshi parents) to make sure that they conveyed information clearly and appropriately. To make provision for parents who did not speak English, a cover letter, translated into Urdu and Bengali, was included with the study information. This explained that they were being invited to take part in a research study relating to children’s weight management and that they would receive a telephone call in the next few days in which the study would be explained to them in detail in their preferred language. Within 7 days, potential participants were contacted by telephone and asked if they had any questions about the study and whether or not they would like to participate. If they were happy to participate, ‘non-completers’ and ‘non-attenders’ were asked if they would be willing to participate in a face-to-face interview or, if this was not possible, a telephone interview. ‘Completers’ were asked whether or not they would be willing to attend a FG in a community venue. FGs were the preferred method of data collection, as they explicitly use group interaction as a way of stimulating discussion. 47 However, to maximise participation, individual interviews were deemed to be more appropriate for participants in the first two groups, as they had not fully engaged with the First Steps programme and were, therefore, less likely to engage with FGs. We aimed to recruit 15 ‘non-completers’ and 15 ‘non-attenders’ to participate in interviews and to hold 3–5 FGs with ‘completers’. If a participant who had completed First Steps was unable to attend a FG but wanted to provide feedback, they were offered a one-to-one interview as an alternative. All participants received a £10 shopping voucher. The recruitment process is summarised in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The CHANGE study phase I participant recruitment.

Data collection

Interviews took place in the participants’ homes. FG locations were selected to be as convenient as possible, based on the postcodes of potential participants. Along with the information sheets, potential participants were also sent an invitation card detailing their closest FG, location date and time. Before the interview or FG commenced, participants were asked to give written informed consent and to complete a short questionnaire asking for demographic information about themselves and their family (see Appendix 2). Interviews and FGs were conducted by either a CHANGE study researcher or a community researcher with the relevant language skills. At the FGs, an observer was present in addition to the facilitator.

All researchers conducting interviews and FGs were trained in qualitative data collection and analysis and had attended CHANGE study-specific training and so were aware of the context of the study for follow-up questions. Semistructured interview and FG schedules were developed, which were informed by literature and input from the study Parent Advisory Panel. In addition to a general exploration of participants’ experiences of the First Steps programme, the specific research questions that were explored are shown in Box 1. The full interview and FG schedules can be found in Appendix 3.

-

What are the barriers to, and facilitators of, participating in and completing the programme?

-

Which aspects of the structure, content and delivery of the programme are perceived as problems?

-

Which aspects of the structure, content and delivery of the programme are valued?

-

What information, content or format would increase the appeal of the programme?

-

What might need to change about the current programme to ensure its cultural relevance?

Reproduced with permission from Pallan et al. 48 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Researchers recorded their observations and reflections after each interview or FG to provide context to local and cultural understandings and references and assist in interpretation at the data analysis stage.

Interviews and FGs recorded in English were transcribed verbatim and anonymised by an external transcription company (Clayton Research Support, Old Stratford, UK). Those conducted in a different language were translated and transcribed by the community researchers. A sample of translated transcripts was checked against the audio-recording by an independent researcher who understood the relevant language to check for accuracy. If a participant requested that an interview was not recorded, the researcher wrote notes summarising the interview content.

Data analysis

Data analysis was guided by thematic analysis approaches and used similar techniques to those developed by the Health Experiences Research Group at the University of Oxford. 49 Two researchers (Tania Griffin and Laura Griffith) reviewed the transcripts independently (approximately 50% each) and identified themes and codes to apply to the data. The researchers discussed their allocated codes, especially when differences occurred, and agreed on a final coding framework, which was then applied to all transcripts using NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Overarching themes from the data were then identified. Particular attention was given to the identification of whether or not there were differences between the three participant groups.

Review of children’s weight management literature

A comprehensive guideline on managing overweight and obesity in children was published in 2013 by NICE. 17 Two evidence reviews were undertaken to support the development of this guideline: one was a review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions to manage children’s weight50 and the other was a review of the barriers to, and facilitators of, implementing weight management programmes for children. 51 These reviews, together with more recent evidence on effective children’s obesity interventions, were referred to when planning the adapted intervention to ensure that it was coherent with the established evidence base on children’s weight management intervention. A systematic review of behaviour change techniques that are effective in influencing obesity-related behaviours in children was also identified52 and, again, it was ensured that the planning of the intervention was consistent with information from this evidence synthesis.

Information from the existing children’s weight management service

Direct observation of the current children’s weight management programme was undertaken to assess how the structure, content and delivery worked in practice. Observations were undertaken by a researcher (Tania Griffin), who made notes on the delivery of the programme by the facilitator, and the response and engagement of the participants who were present. In addition, the service managers were consulted so that a clear picture of the existing infrastructure and processes was gained, and current concerns with the programme were highlighted.

Process of intervention development

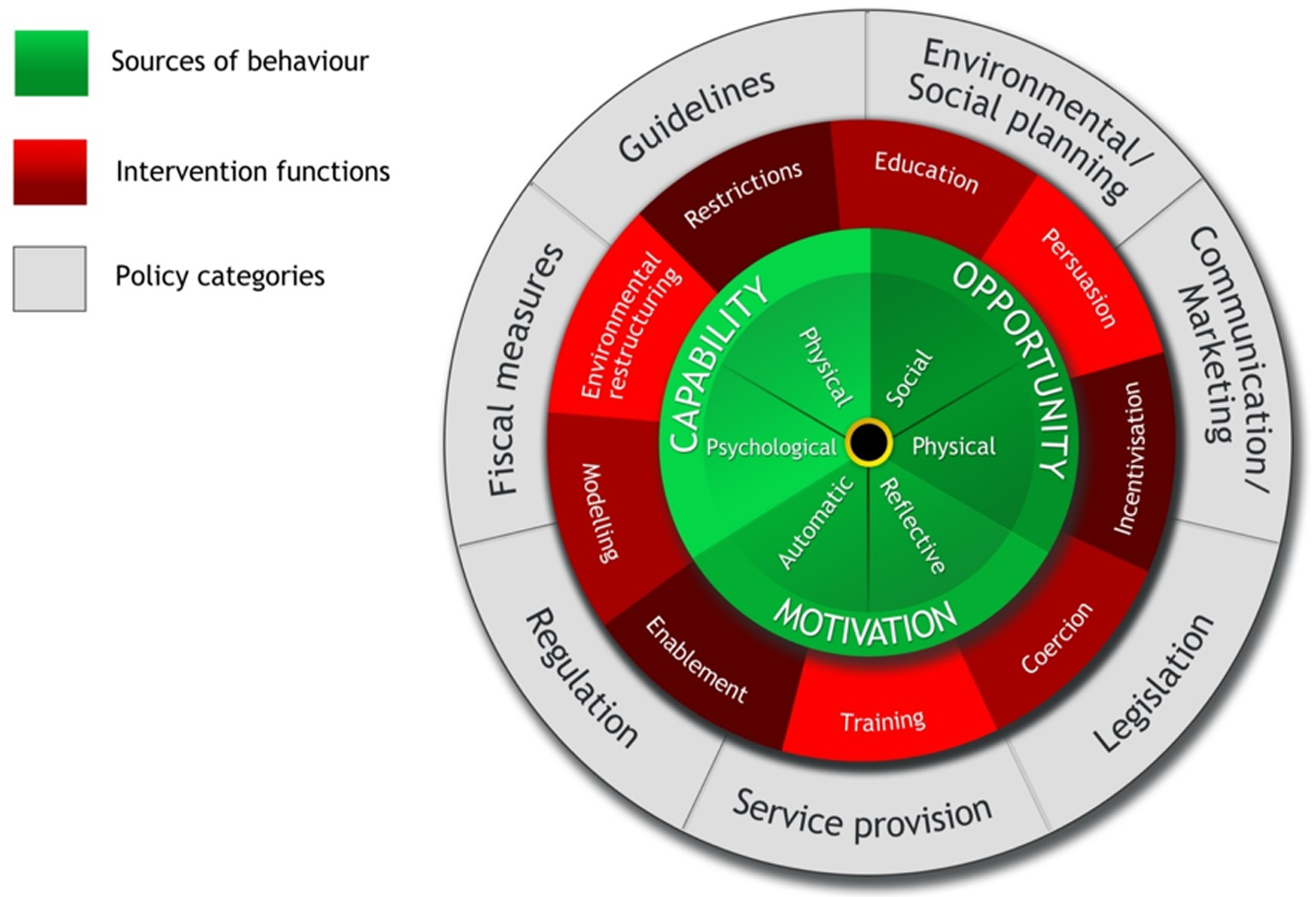

Application of the behaviour change wheel

The BCW framework,43,46 shown in Figure 3, was used to guide the adaptation process. This framework for intervention development has been developed from 19 behaviour change frameworks and incorporates a broad range of drivers of behaviour (e.g. individual perceptions and beliefs, unconscious biases and the social environment). The first step in the BCW is the identification of target behaviours requiring change. We identified that there are two different levels of family engagement with a children’s weight management programme; the first is continuing attendance at the programme sessions and the second is the change in health behaviours in response to the programme content. Therefore, three target behaviours requiring change were identified: (1) programme attendance, (2) dietary intake and (3) physical activity.

FIGURE 3.

The behaviour change wheel. Reproduced with permission from Michie et al. 46 Copyright © Susan Michie, Lou Atkins and Robert West 2014. All rights reserved.

The capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM-B) model at the centre of the BCW is a diagnostic tool to help understand the factors preventing improvement in the target behaviours. The three elements of this model are further broken down into physical capability (physical skill, strength and stamina), psychological capability (psychological skills to engage in the necessary mental processes), physical opportunity (opportunity provided by the environment, involving time, resources, locations, etc.), social opportunity (opportunity provided by interpersonal influences, social cues, cultural norms, etc.), reflective motivation (reflective processes, involving planning and evaluation) and automatic motivation (automatic processes involving emotional reactions, desires, impulses, inhibitions, etc.). We mapped the qualitative data from parents to the different elements of the COM-B model to gain a theoretical understanding of the factors preventing Pakistani and Bangladeshi families from adopting the desired behaviours. The BCW outlines nine different intervention functions (i.e. categories of mechanisms by which interventions may have their effects; see Figure 3). For each aspect of capability, opportunity and motivation, there are corresponding intervention functions that have been identified as being the most likely to achieve change. Once we had an understanding of which drivers of behaviour needed to change, we identified the corresponding intervention functions. This informed the detailed intervention planning.

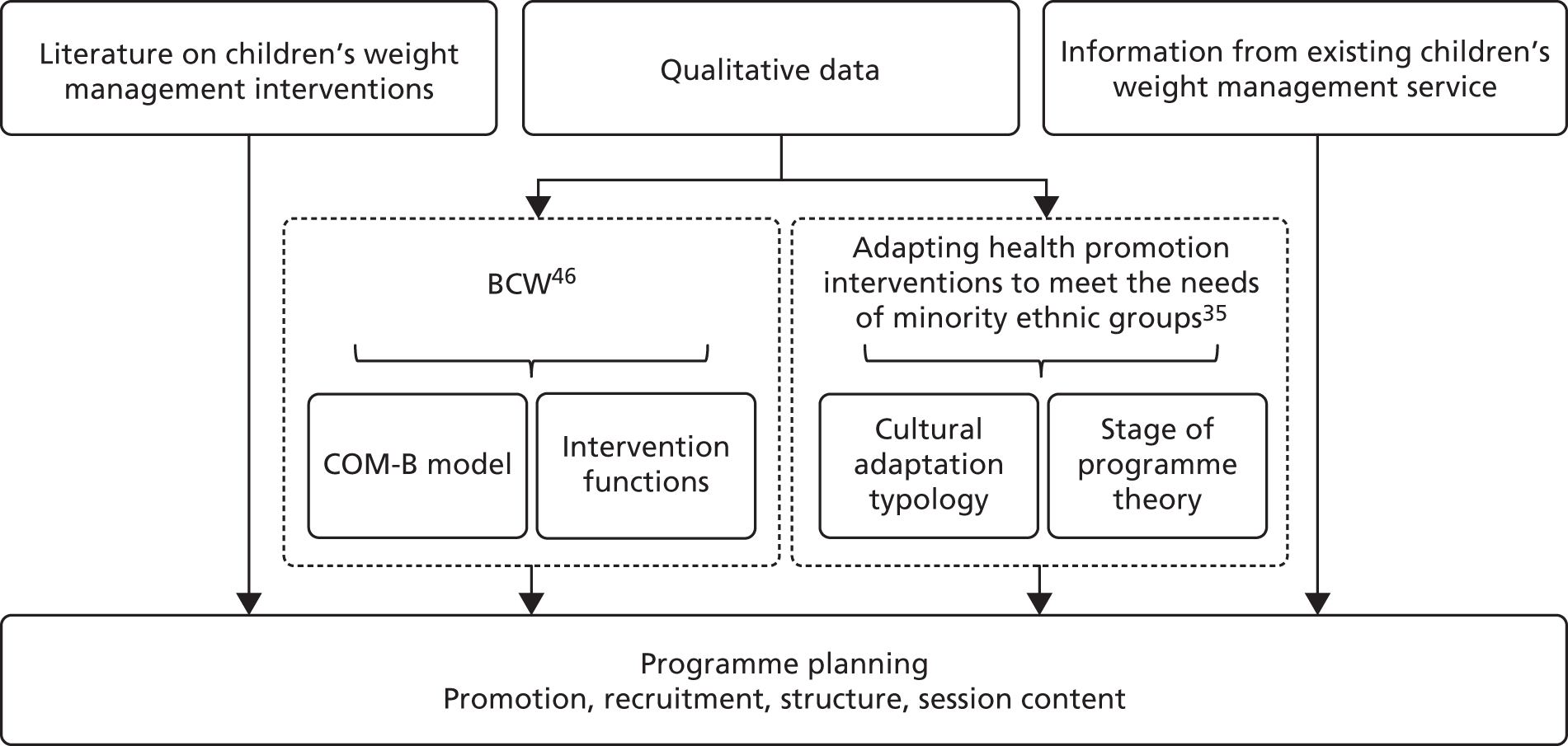

Cultural adaptation using the typology of cultural adaptation and health promotion programme theory

In parallel with the BCW, another theoretical adaptation process was employed specifically to address adaptation of the programme to make it more culturally acceptable to Pakistani and Bangladeshi families. In 2012, Liu et al. 35 published a comprehensive report that explored the adaptation of health promotion programmes targeting smoking, diet and physical activity for minority ethnic groups. As part of this report the authors undertook a systematic review of health promotion programmes adapted for minority ethnic groups, which included international research. From this work, they constructed a 46-item typology of cultural adaptation approaches. They also highlighted the importance of a systematic approach to cultural adaptation and recommended a generic theory of the health promotion programme cycle (Figure 4) to be used by those adapting programmes in conjunction with the typology of adaptation, thus ensuring that all aspects of the programme are considered during the adaptation process.

As part of our intervention programme adaptation process, we mapped relevant types of adaptation from Liu’s cultural adaptation typology to the themes identified from the qualitative data from Pakistani and Bangladeshi parents and determined which stages of the programme theory these adaptation types would need to be applied to. In this way, we identified how the standard programme needed to change to make it more culturally relevant to Pakistani and Bangladeshi families.

Detailed intervention planning

Identification of intervention functions to change target behaviours and cultural adaptation types at the relevant point in the programme cycle provided the foundations on which to plan the detailed structure, content and delivery of the adapted programme. Information gained from reviewing the children’s weight management literature, consultation with the local service providers and directly observing the local programme fed into the intervention adaptation process at this point. The detailed planning process was iterative, ensuring that all adaptations and additions to the programme were coherent with (1) the identified intervention functions and adaptation types, (2) the qualitative data, (3) local service information and (4) the existing evidence on children’s weight management.

During this process, we also gave consideration to designing the programme so that there was enough flexibility in delivery that it was appropriate for children of different ages and was coherent with current guidelines. During the adaptation process, there was continuing consultation with the children’s weight management service managers to ensure that the programme could be feasibly delivered. Figure 5 summarises the intervention adaptation process.

FIGURE 5.

The process of cultural adaptation of a child weight management programme. Reproduced with permission from Pallan et al. 48 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Results

Findings from the qualitative study with parents/carers

Participant characteristics

In total, 31 parents/carers participated in interviews and 12 participated in FGs. Of these, 36 were Pakistani and seven were Bangladeshi. This broadly reflects the proportion of families from these communities who are referred to the Birmingham children’s weight management service. The great majority of participants were female (37/43) and all participants were Muslim. We recruited 15 participants from each of the ‘non-completer’ and ‘non-attender’ groups; however, during the course of the interviews, it was identified that several participants who were initially identified as ‘non-completers’ were ‘non-attenders’. Therefore, nine participants were ‘non-completers’ and 21 were ‘non-attenders’. There were 13 participants in the ‘completer’ group. The average age of the participants’ children at the time of the study was 11 years and more participants had female children who had been referred to the service than male children. The majority of families had been referred to the service following identification that their child has excess weight through the NCMP. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| Participant characteristic | Participant type | All participants (N = 43) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completers (N = 13) | Non-completers (N = 9) | Non-attenders (N = 21) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 3 (23.1) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (14.0) |

| Female | 10 (76.9) | 7 (77.8) | 20 (95.2) | 37 (86.0) |

| Age of child (years),a median (IQR) | 11.0 (2.0) | 11.5 (3.0) | 11.0 (6.0) | 11.0 (3.0) |

| Sex of child referred to the programme (n)a | ||||

| Male | 7 | 5 | 8 | 20 |

| Female | 7 | 5 | 14 | 26 |

| Relationship to the child, n (%) | ||||

| Mother | 10 (76.9) | 7 (77.8) | 20 (95.2) | 37 (86.0) |

| Father | 3 (23.1) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (14.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Pakistani | 12 (92.3) | 8 (88.9) | 16 (76.2) | 36 (83.7) |

| Bangladeshi | 1 (7.7) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (23.8) | 7 (16.3) |

| Referral method, n (%b) | ||||

| Doctor | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (7.0) |

| School nurse | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (14.3) | 5 (11.6) |

| NCMP | 9 (69.2) | 4 (44.4) | 12 (57.1) | 25 (58.1) |

| Hospital/dietitian referral | 1 (7.7) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (9.3) |

| Leaflet/self-referral | 1 (7.7) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (14.3) | 6 (14.0) |

| Method of discussion, n (%) | ||||

| Interview | 1 (7.7) | 9 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 31 (72.1) |

| FG | 12 (92.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (27.9) |

Interviews and focus groups

Of the 31 interviews, 27 were face to face and four were conducted by telephone. The average length was 28 minutes, ranging from 15 to 47 minutes. The average interview length was slightly longer for ‘completers’ than for ‘non-completers’ (27 vs. 30 minutes). Three interviews were conducted in Bengali and six in Urdu. The remainder of the interviews were conducted in English.

There were seven FGs arranged; however, despite agreement from participants and attendance reminders being sent out the day before, no participants attended three of the FGs. Two of the FGs were conducted in English and each was attended by four participants; the remaining two FGs were each attended by two participants. The last two FGs were conducted in Urdu. The FG duration ranged from 35 to 50 minutes of discussion.

Qualitative data

The interviews and FGs were conducted so that they were free-flowing, to enable participants to raise any issues that were important to them. Several different themes emerged from the resulting data. The themes identified from the three participant groups were broadly coherent with each other; therefore, this section presents themes emerging from the data across all participants. Any differences that were found between ‘completers’, ‘non-completers’ and ‘non-attenders’ are reported within the themes. The participant’s identification number, sex, ethnicity and programme attendance status is shown after each quotation.

Logistical issues with programme attendance

Several practical issues were highlighted as barriers to families attending sessions. Almost all participants wanted the location to be closer to them. A location that was some distance away was a particular concern for parents who had to take other siblings to the programme or collect them from school:

Well, it shouldn’t be too far away, it’s better if it’s closer because sometimes the car isn’t available and then I could walk too.

Interviewee 154, female, Pakistani, non-attender (interview conducted in Urdu)

If it’s closer, then it’s better because it saves time; because sometimes we have to collect the children, and both mother and father needed to attend, so we both went.

FG3, participant 2, male, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

They did send out appointment but it was quite far in the distance; then I couldn’t actually travel ’cause I had the small children, as well.

Interviewee 114, female, Pakistani, non-attender

The reason why I couldn’t make it is because I’m not driving, so having to travel to the place and then coming back with another small child, at the time I think she was a baby, was really difficult for me . . . It was just that really, I really want to go as well.

Interviewee 144, female, Pakistani, non-attender

Many participants, regardless of whether or not they had attended, thought that their local school would be a convenient and familiar venue and would, therefore, encourage families to attend. However, this was not universal and some participants thought that a new environment might be more stimulating for children.

From FGs 1 and 2 came the following opinions:

I think if you go through the school it’s better. Everybody has to take their children to school. So if in the morning, when they’ve gone to school to drop their child off or in the afternoon, if the teachers come forward and talk to the parents then like ‘this is what’s happening and if you would like to attend’ maybe they would be, because everybody takes their kids to school and that would be a good way of catching them.

FG1, participant 3, female, Bangladeshi, completer

But the lady that said about the school that was really good like, that just clicked onto my brain and there should be more sessions in school I think and you will get more turn out like with the parents and stuff.

FG1, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer

I think it should be in different areas, because they get bored in their own schools, because the children develop their confidence going to a new setting, because they know why they’re attending, this is a better idea.

FG2, participant 4, female, Pakistani, completer

The timing of the programmes was often difficult, with participants commenting on other commitments that could prevent families from attending. Of note was the daily attendance at the mosque after school for some children from these communities, which would prevent them from attending sessions at this time. The suggestion of running programmes at the weekends was made by many participants. It was generally felt that this would be more convenient for families:

I think that it’s about timing because some people have young children and others are older so they need to pick them up from school, others are in college so they need to collect them, so I think it’s about timing.

FG3, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

. . . the timing and, you know, it’s not – and town is like, you know, busy and . . . so . . . especially after 4. It’s really hard. They have, like, their own activity. Mosque and everything. Tuition. This and that. So that’s why I couldn’t.

Interviewee 133, female, Pakistani, non-attender

Weekends, because after school they go to school and mosque, all Muslims, even Indian or Bengali or Pakistani, every Asian, children attend mosque after school.

Interviewee 139, female, Pakistani, non-attender

Well, you know this weekend, it would be better, the children would be home and you could take them instead of missing them and they’re taking time off from school.

FG1, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer

Several participants spoke about running the programme during school time and the need for children to take time away from school to attend. Generally, this was felt to be something that was important enough for a child to miss school for and that schools would allow it. However, in some cases it was a deterrent to attending, even though schools allow absence for health-care appointments:

I’m sure if it’s a school day, the school would give him an hour or so just to go into, it’s regarding health isn’t it, so I’m sure school would allow him to go for an hour or do the programme in the weekend like Saturday/Sunday.

Interviewee 129, male, Bangladeshi, non-completer

Yeah, I was just saying that, they need to go to every session, even though I know it’s school time.

FG1, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer

I was upset because I couldn’t go. I couldn’t have the time, I couldn’t take my – especially with schools now where they’re strict on the children, you know, attending school and not missing days. So it was hard for me.

Interviewee 104, female, Pakistani, non-attender

The requirement to attend to siblings was also raised. Some parents reported that having very young children in the family prevented them from attending; however, some participants in the completer group reported that younger siblings were present in the sessions and this did not cause any problems:

When I started receiving letters and phone calls from yourselves then I realised that there might be support. My daughter says to me that ‘mamma I want to go for exercise’ . . . I told her that I couldn’t go with her because I have other children. I have small children, my youngest is 2 years old.

Interviewee 109, female, Pakistani, non-attender (interview conducted in Urdu)

I didn’t have younger children but other families had young children with them. And they sat too, it wasn’t that the younger ones couldn’t sit and listen too.

FG2, participant 4, female, Pakistani, completer

Finally, parking near the venue was raised as an issue by some participants and, in some cases, was a deterrent to attending further sessions:

It’s not far but it’s like finding parking is the worst problem, that was the biggest problem for me not attending. The first day when we went, we were going round and round and then we managed to find a little space. The second time when I went I couldn’t find a space and I just said ‘oh enough’.

Interviewee 129, male, Bangladeshi, non-completer

Language barriers and programme attendance

Some parents who were unable to speak English reported difficulties in communication at the first contact, and for some this prevented them from attending:

Someone rang on my home phone speaking English and inviting me to attend the programme but I was asking her if I needed to take my daughter with me, because my English is not very good; but she could not understand what I was trying to ask her. I was asking if I needed to take my daughter with me. She couldn’t understand me so she said she will call me back but we never heard from her again.

Interviewee 150, female, Bangladeshi, non-attender (interview conducted in Bengali)

English-speaking participants also reported observing difficulties experienced by the non-English-speaking parents who attended the programme. However, some participants who completed the programme felt that non-English-speaking parents were able to understand the programme content, either because of the way the information was delivered or because they had brought a family member to interpret for them:

Yes, because I’ve seen some parents there that are, like, it was hard for them to understand and I was doing a lot of explaining to them as well.

Interviewee 123, female, Pakistani, non-completer

I don’t know English, they were English, but I understood everything because of the way they explained it, with gestures and all the information so that we could understand.

FG2, participant 2, male, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

So was there a translator there?

No. Because at first I didn’t really mention it because my daughter was with me and so I didn’t have any problems because my daughter would speak for me and she’d translate what I was saying back to them about what to do, etc.

FG3, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

In general, participants felt that the availability of interpreters (which were provided in the First Steps programme) would overcome the barriers to participation that were related to language:

If it’s local and an interpreter is available. We would like to attend because it will help our child. I know I can get advice and help on diet and exercise.

Interviewee 150, female, Bangladeshi, non-attender (interview conducted in Bengali)

My niece had taken her son to First Steps programme, but she herself didn’t understand English, right? . . . She told me what was there, but she felt left out, as a parent – saying that, you know, ‘If there’s enough information for me, because I can’t read,’ she said, ‘and I can’t understand, then it would have been easier if there was somebody to explain to me’.

Interviewee 113, female, Pakistani, non-attender

And language difficulties. Not for yourself but was there any ladies in the class that you think language was a barrier?

Well they brought someone along with them or they got the children to interpret for them.

Interviewee 1036, female, Pakistani, completer

Programme structure and delivery

The course duration of 5–7 weeks was generally thought to be appropriate by most families, although a few participants thought that more sessions would be helpful. The session duration of 1 hour was raised as an important consideration among some families, especially if they were required to travel some distance. It was felt that if they had made the effort to attend, the session duration should be longer:

It’s not reasonable for me going and going back and coming back, so that is an issue, as well. So if the hours were extended, like an hour and a half or 2 hours, that would be reasonable.

Interviewee 113, female, Pakistani, non-attender

I think 7 weeks is OK, to be honest, yeah. That’s not a problem. I think that’s just about right to be honest, yeah. Because if you make it too long, probably get a bit boring wouldn’t it.

Interviewee 143, female, Pakistani, non-attender

Aspects of the programme that deterred families from participation were the didactic nature of the programme sessions and the presence of too much paperwork. Participants disliked just sitting in sessions being given information and wanted a much more interactive format:

I thought it was going to be like kind of activities where they actually show you what kind of activities you can do with your children, what kind of sports and obviously get them interested in them [sic.] kind of activities. But obviously it was like just basically information just sit there and obviously giving us information about what kind of nutrition and diet and exercise and everything but I thought it was going to be more physical than obviously classroom based.

Interviewee 142, female, Pakistani, non-completer

I think there was a bit too much paperwork and what it is, she was giving out the information, yes she was trying her best, but I think the way she was delivering it everyone was like going half asleep . . . because some parents don’t take it in as that, and it’s like they need to get up and do.

Interviewee 107, female, Pakistani, non-completer

Those who attended or completed the programme valued messages being presented in a visual way, and participants’ experiences of interactive activities were viewed very positively:

The visual, it was the visual things really that she all brought the visual things and that really like makes it more better understanding then like you know.

FG1, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer

I was quite impressed with that because four spoons of sugar, I will just, in my head it’s four spoons of sugar, but when you actually see it in a packet it’s got four spoons in it, then you think my life it’s that much sugar, you know?

Interviewee 129, male, Bangladeshi, non-completer

[Participant talking about a related workshop that was not delivered as part of the main programme] It wasn’t really cooking it was just ready-made wraps, and you would just put salad in it, and we needed to cut it and put it in and whatever you need to put in there like butter they had brought along with them. So we cut it up, and the children cut it up and made them and then you have a look. In this way I think the children enjoy it too, so they understand that this is happening for them, so it sinks into their minds that if they do this then it will be of benefit to them.

FG3, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

The great majority of parents across all three participant groups felt that the programme would be more valuable if children attended all sessions:

It would have been a bit more ideal if the kids were more involved. That’s what I would – because then yes we need to have that understanding, but I believe the kids need to understand what they should have and the intake and how it’s with their body.

Interviewee 107, female, Pakistani, non-completer

I realised it was only first and last session that he has to attend, so I wasn’t really pleased with that, because I was thinking he needs to go there like to other sessions.

Interviewee 103, female, Pakistani, non-completer

They also felt that their children would take more notice if messages were given by an ‘outsider’ rather than their parents:

Because sometimes children don’t listen to their mum or dad but they listen to the teacher or outsider.

FG4, participant 1, male, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

. . . although my daughter does listen to me. I think getting the information first-hand would make a big difference. So it’s important for both mother and child to attend.

Interviewee 150, female, Bangladeshi, non-attender (interview conducted in Bengali)

There was also the view that the children need to understand why it was important to eat healthily or do physical activity, as this would be more likely to lead to a change in their behaviour. One participant felt that children in the group who lost weight would provide motivation for other children:

I think children should go [to] every session because then, you know, well how I look at [it] is if the children don’t go and then we’re telling [them] ‘oh you’ve got to do this, this’, they probably think we just sometimes, most kids, they will think oh just my parents being horrible to me, my parents, but when they go into classes and they see these other people they don’t know who are actually telling them, then they will listen more because they will think: hang on if I don’t know the chap there was telling me, so I think my dad is right, so yeah OK I’ll try that.

Interviewee 129, male, Bangladeshi, non-completer

If the children are involved then they will take notice of how hard they have worked, and if that child’s weight reduces then the other children are listening too so it will benefit them too.

FG2, participant 4, female, Pakistani, completer

They [children] need to go to every session, even I know it’s school time.

FG1, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer

So if like you know if like if these sessions are done but then it’s explained to the kids a little bit more about ‘this is what you need to do because it’s your life, you’re going to be affected in the future’ and stuff like that then it might help them.

FG1, participant 3, female, Bangladeshi, completer

Participants were generally positive about attending a group programme with other families and sharing experiences. Some really valued the sense of community that they gained from attending the group sessions:

I think this is a really good idea like when you go to a talk then you get to hear the views of others and that has an effect on you.

Interviewee 109, female, Pakistani, non-attender (interview conducted in Urdu)

There was [sic.] different community families, and friendly, Indian, Bengali, English, Sikh, and children mix up, and share their experiences.

FG2, participant 4, female, Pakistani, completer

Because it was the same lady [facilitator] for all five sections, and she nicely laughs and you know and mostly my son was happy you know and when different communities people sit and talk and like it was like a challenge between everyone and she used to push them to compete.

FG2, participant 4, female, Pakistani, completer

Programme content: weight status

The programme’s focus on weight loss was a barrier to some families’ participation. Some parents who never attended the programme did not identify their child as being overweight or that their weight was something that needed to be addressed but they were interested in helping their children to become more active:

I don’t see it as overweight, ’cause I know what they eat. I know they’re not eating the wrong food. Yes, they’re less active, but what do you do?

Interviewee 108, female, Pakistani, non-attender

My daughter, she’s not really overweight, it’s just that her weight has gone a bit over the mark.

Interviewee 104, female, Pakistani, non-attender

I mean, if you look at my son, he’s not overweight, I mean, he’s quite, for his age, he looks bigger than his age, I mean, he doesn’t look like really big or anything but he is quite heavy.

Interviewee 144, female, Pakistani, non-attender

Some parents who attended some or all of the programme reported that their children were sensitive about their weight and did not like being weighed. One parent who completed the programme reported that she did not have the support to attend from other family members:

I know it was weigh in and there was less time but with the kids I think if they approach them a bit differently because nowadays kids are very, very sensitive and every sort of thing just sticks in their head and I think, you know, ‘oh God, mum’ and then in school they’ll have that – because they had to come out of school and then it’s them like ‘oh, we’re going for the weigh in’ and she was embarrassed to even tell her brother and sisters what she was going for.

Interviewee 107, female, Pakistani, non-completer

My family members say that what’s the point of you going to the programme, and how it takes a lot of time and that there aren’t going to be any benefits. I said that they may not see the benefits but I do, because I can get my daughter’s weight down about 2/3 kg in 1 week if I focus on this information.

FG3, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

Programme content: nutrition

Participants, particularly non-attenders and non-completers, reported that they felt that the course offered no new insights for them. Several parents thought that their knowledge of what a healthy diet consisted of was good, and they already knew or had been previously told what their children should be eating. However, among the completers, some participants felt that their knowledge of the nutritional content of foods had significantly improved, and they particularly valued when they were also advised how to address nutritional content in their children’s diets:

I thought it would be just like talking through healthy and unhealthy but myself, I always look on the internet for healthy options, healthy meals and you know what’s good for me, what’s not good for me. So I’m constantly on the internet, right? So I thought I probably know it anyway.

Interviewee 104, female, Pakistani, non-attender

We went on the first session. The minute that plate came up and those sugary – you know, those little packets and everything, we thought, ‘Oh, we’ve been there, done that. Forget this.’

Interviewee 121, female, Pakistani, non-completer

What they were telling us on that first day, it’s like more or less we know it, you know, doctors and the nurses and surgery, they’re telling us what to do.

Interviewee 129, male, Bangladeshi, non-completer

But the way they explained everything it was very interesting. I didn’t know just a bottle of water with lemon juice had like so many rounds of sugar in there and all that stuff and like they said biscuits you think that’s the healthy option, actually it isn’t. You know like so it was quite an eye opener.

FG1, participant 3, female, Bangladeshi, completer

Because they brought a lot of material about foods with them, like sweet packets, crisps, sugar, etc., all these things were there and how much sugar was in them. How much salt is in things and how to swap these things and it will be effective. And I did this 100% and it took effect.

FG3, participant 1, female, completer (interview conducted in Urdu)

The relevance of the programme content to the food that families typically consumed was explored with the participants. Participants reported that they and their children ate both Western and South Asian food and that there needs to be a focus on both in the programme:

I think they should talk about both [South Asian and Western food]. We do eat Asian food a lot but my children like both so it would be beneficial to get advice on both.

Interviewee 150, female, Bangladeshi, non-attender (interview conducted in Bengali)

We do eat fish and we do eat baked beans and stuff, but we do eat our own food as well, so we need education on our own food.

Interviewee 113, female, Pakistani, non-attender

We eat a range of foods and my daughter likes eating food like this. They eat Pakistani food too but also English foods that are vegetarian.

Interviewee 109, female, Pakistani, non-attender (interview conducted in Urdu)

From FG1 the following was noted:

And what sort of foods would you like to learn about in cooking, westernised or traditional or a bit of both?

A bit of both, yeah.

A bit of – the children do have both.

FG1, participants 1 and 4, female, Pakistani, completer

They get to have, they get bored with this type of food all the time, they want to try something different. So that would be like a mixture really.

FG1, participant 4, female, Pakistani, completer

There was a concern among several participants that related to the consumption of ‘junk’ foods and takeaways:

She eats a lot of chocolates, sweets and crisps, she eats a lot of takeaways, like burgers, drinks a lot of fizzy drinks, she eats a lot of this stuff. Stuff like chapatti and curry, she eats less of.

Interviewee 154, female, Pakistani, non-attender (interview conducted in Urdu)

But, the temptation in this area is that we have cheap takeaways, and they are very tempting. You know, you think, ‘Why cook?’ And, you know, we’re tempted to, you know, just, ‘Oh, it’s an easier option. We’ll get chicken and chips. It’s only £1.50.’ So, you know, that’s why the weight is creeping up with children.

Interviewee 113, female, Pakistani, non-attender

Some participants commented that they would like to learn how to cook South Asian foods in a healthier way. However, one participant who had completed the programme commented that although she could change certain aspects of her child’s diet, she was not going to change the way she prepared traditional foods:

I want to know, if I’m making a chapatti, how many calories are in there? You know. If I’m making a curry – it’s really hard to – how many calories – you know, hand-size or, you know, it’s hard – in reality, it’s really, really hard. Maybe do a cooking session; say, ‘This is a portion.’ You know. ‘It’s right.’ Maybe do it that way . . . or even, like, give recipes on maybe even healthier Asian food, rather than – fair enough, do the English food, as well. OK, we have it once a week or whatever. And that’s ovenly – oven-made or it’s grilled. But help us with the type of food that we’re eating. Where are we going wrong?

Interviewee 108, female, Pakistani, non-attender

Yeah, because if I change using less oil, I can’t taste my curry without oil, since I was 3 and have grown up, I can’t change that but I can swap other things, fat milk with semi skimmed and white with wholemeal breads but I can’t change my curries.

FG2, participant 1, female, Pakistani

Some participants identified that shopping for healthy food was an issue, and that education about food labelling and purchasing healthy food options was required:

When you buy the shopping, more labelling, more information, because I understand what they say sometimes there’s energy and then the parents, some get confused because obviously and some English is not even there, so if they can like give a bit more which is more better and which is more healthy, like [drink brand], because I didn’t pick it up from there, [drink brand] does have a lot more sugar than we thought.

Interviewee 107, female, Pakistani, non-completer

Programme content: physical activity

Participants almost universally wanted some physical activity content in the programme. It was acknowledged that the facilitators spoke about physical activity but parents felt that the children should be doing physical activity in the programme sessions:

They should do more activities like, you know, physical activities to help them and not just concentrate on the food side.

Interviewee 123, female, Pakistani, non-completer

If they could like have a meeting for half an hour and then integrate like another half an hour to do the sports, I think that would be good as well.

FG1, participant 3, female, Bangladeshi, completer

I think that if you are doing this programme then you need to put some exercise sessions in it too, whatever is best for children . . . if you have the space then you should have exercise programmes in it too.

FG3, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

In response to the above: it’s exactly like what the sister [other participant] is saying. In terms of food, there’s calories and how much you should eat but besides this exercise is really important.

FG3, participant 2, male, Pakistani, completer (FG conducted in Urdu)

Several barriers to children undertaking physical activity were identified, including busy families lacking time, a lack of local opportunities and the perception of dangerous environments, particularly in terms of outdoor activities. Some participants suggested that practical advice about physical activity that children could do at home would be useful, which would overcome several of the identified barriers:

We rarely get to go to the park unless it’s a hot summer’s day. It’s just busy.

Interviewee 108, female, Pakistani, non-attender

There’s just nowhere for us to send them where they can get exercise. Whether they can play football or cricket or anything, they should do something. And I would enrol them there.

Interviewee 155, female, Pakistani, non-completer

I want to ride a bike . . . and my husband goes ‘can you see how dangerous it is, the cars out there’.

Interviewee 112, female, Pakistani, non-attender

And you can’t let them go to the parks alone. And it’s just round the corner but you just can’t . . . You just can’t let them out, ’cause a lot has been, you know, happening around here.

Interviewee 108, female, Pakistani, non-attender

And you can do something at home as well, children sitting down, it’s better to tell them to walk like 10 times on the stairs, up and down. That’s a good exercise for them.

FG2, participant 1, female, Pakistani, completer

Several participants also identified that they used cars when they felt that they should be walking with their children:

My sister gets into the car and drops them off to the secondary school, you see. But they need that exercise. They need to learn how to walk, as well. You know, the car is very convenient, but it’s really bad for the kids.

Interviewee 121, female, Pakistani, non-completer

Parents’ influence over their children

Among the parents who had completed part or all of the programme, a common theme was that even when they implemented changes in the home to try and encourage a more healthy diet, children would find ways of circumventing this. In some cases, parents also admitted to ‘treating’ their children to something unhealthy:

I’ve tried to cut down. You know they showed us a certain plate of vegetables, that’s how much and all that stuff and I’ve tried doing that, I’ve really tried getting into it but I find that he sneaks behind me, he goes in the kitchen and helps himself.

FG1, participant 3, female, Bangladeshi, completer

When he goes to my mum’s house, he helps himself a lot and then when we go to family, like, he doesn’t listen, he helps himself a lot.

Interviewee 103, female, Pakistani, non-completer

But the drink wise, he does drink sometimes fizzy drink and I’m not going to deny that I do bring sometimes, I feel bad, they like it, right, so just drink a bottle and give it to them, I say ‘look hide it’.

Interviewee 129, male, Bangladeshi, non-completer

Summary of the qualitative findings

A key set of barriers to attending a community weight management programme is logistical considerations. Families reported that they require a close, familiar location and a programme run at a convenient time. Language barriers to participation did exist for parents from Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities who do not speak English. A particular linguistic barrier comes at the recruitment stage, and so this part of a programme needs careful attention. Once participants attend the programme, language barriers do not present so much of a problem, particularly if interpreters are provided (as they are in the First Steps programme). The focus of the programme was on weight loss; therefore, parents who did not identify that their child had a weight problem did not engage as much or felt that there was nothing that they could do about it. However, the data suggest that these parents still recognised the value of healthy lifestyles and wished to encourage their children to adopt healthy behaviours.

There was strong support for a programme that involved children in all the sessions, as it was felt that they need to learn how to change their behaviour first hand, and would respond differently to messages given by someone other than their parents. It was also emphasised by many participants that physical activity should be included in the programme. The group environment and being able to share experiences and ideas with other families was generally valued highly by participants who had attended the programme, but there was a feeling among participants who had not attended much or all of the programme that they were not going to gain anything new from it, and that they already knew what was ‘good’ and ‘bad’ for their children. Although the First Steps programme includes South Asian foods, some parents felt that the nutritional content could be made more relevant to traditional South Asian diets, but many acknowledged the importance of also talking about Western foods, as typically their children’s diets consisted of a mixture of foods. Finally, there was a feeling that parents had difficulty ensuring that their children adhered to changes they made in the home, particularly regarding food, and, therefore, help with addressing this issue would be valued. Apart from language and dietary considerations, there were no other themes that related explicitly to Pakistani and Bangladeshi culture that emerged from the data. However, what emerged more prominently were the restrictions within which the families lived their lives (e.g. the competing demands of younger siblings, busy family lives and the perceived lack of safety in the local environments) and the impact of these on the families being able to undertake healthy behaviours.

Findings from a review of children’s weight management evidence

The NICE guideline on managing overweight in children and young people (PH47)17 presents a series of recommendations for the provision of children’s weight management services. These are listed in Box 2. Each recommendation was considered in the adapted intervention planning to ensure consistency with this evidence-based guideline (Table 2). The importance of parental involvement in interventions for childhood weight management was strongly emphasised in this guideline and other children’s weight management literature,17,53 as was the importance of combining both diet and physical activity elements into programmes rather than focusing on one element alone. 54,55 Therefore, these important aspects of the standard children’s weight management programme were retained in the adapted programme. In addition, behaviour change techniques, identified as being effective in a systematic review of behaviour change techniques in obesity interventions for children,52 were considered for inclusion in the adapted intervention design at the appropriate points. These behaviour change techniques included the provision of information on the consequences of behaviour to the individual, environmental restructuring, prompting practice, prompting the identification of role models or advocates, stress management/emotional control training and general communication skills training.

Lifestyle weight management programmes for overweight/obese children should:

-

be multicomponent and focus on diet, healthy eating habits, physical activity, reducing time spent sedentary and strategies for changing behaviour of the child and their family

-

include behaviour change techniques to increase confidence and motivation in ability to make changes

-

include parent skills training

-

provide a tailored plan to meet the needs of the child and family, taking into account factors such as child age, family social and economic circumstances, ethnicity and cultural background

-

incorporate learning of practical skills, such as reading nutrition labels

-

help identify and signpost families to opportunities to build physical activity into their daily lives

-

introduce simple physical activity opportunities within the programme

-

provide support materials and information that can be shared with other family members not in attendance

-

provide a form of ongoing support following the end of the course

-

be delivered in comfortable locations where the participants feel at ease

-

when possible provide continuity, in that the course facilitator should remain through the whole programme

-

be provided at flexible times to meet the needs of the community.

Reproduced from NICE. 17 © NICE 2013. Weight Management: Lifestyle Services for Overweight or Obese Children and Young People. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/PH47. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights.

| Factors to address identified from qualitative data | BCW | Cultural adaptation | NICE guidelines17 | Intervention adaptation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COM-B element | Intervention function | aTypology of adaptation35 | Programme theory stage | |||

| Behaviour target 1: improve session attendance and completion of the programme | ||||||

|

Convenient programme location Ease of travel and parking Convenient timing of programme |

Physical opportunity | Environmental restructuring |