Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/150/04. The contractual start date was in November 2014. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stephen Morris is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Board and the Public Health Research Research Funding Board.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by St James-Roberts et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

There is evidence that around 20% of 1- to 4-month-old infants in Western countries cry for long periods without an apparent reason. 1–3 Much of this evidence comes from parents’ reports, but objective measurements have confirmed that most parents are accurate in judging that their baby cries substantially more than others of the same age. 4,5

Early studies of the cause of this crying assumed that it was attributable to gastrointestinal disturbance and pain, leading to the use of the word ‘colic’ (from the Greek word for the intestine) to describe it. 6,7 However, evidence has accumulated that most such infants are healthy and grow and develop normally,8,9 that many infants have a crying ‘peak’ at around 1 to 2 months of age3,10 and that this crying peak and the ‘unsoothable’ crying bouts that distress parents usually resolve spontaneously by 5 months of age. 11 Studies have concluded that only about 5% of infants cry a lot because of organic disturbances;2,12 in most cases, the crying is attributable to normal developmental processes. 13,14

Although most infants who cry a lot are well, the crying can distress some parents15,16 and disrupt their ability to provide care. This has encouraged a focus not only on the crying but on parents’ responses and subsequent outcomes. One reason for that focus is that parental worries and concerns, not infant behaviour, are responsible for health service contacts and costs. These costs are considerable. For instance, a 2001 estimate was that the time professionals spent advising parents about infant crying and unsettled behaviour in the first 3 months costs the NHS > £65M per year. 17 There is evidence, too, that the crying that parents judge to be excessive can trigger premature termination of breastfeeding,18 overfeeding,19 parental distress and depression,15,16 poor parent–child relationships20 and, in a small number of cases, infant abuse. 21 Although most infants who cry a lot in early infancy develop normally, parental vulnerabilities have been implicated when serious long-term disturbances are seen at school age. 22

The distinction underlying this recent research is between infant crying and its evaluation by, and impact on, parents. Crying has been described as a ‘biological siren’ that compels parents to respond to it. 23 As well as its loud and aversive sound, it is easy to understand why a feature particular to crying in the first 4 months – bouts that resist soothing techniques that are usually effective – triggers feelings of frustration in many parents. 24 However, its impact on parental emotions and actions depends partly on how parents cope with it, which depends on parental vulnerabilities, resources and circumstances. For instance, parental characteristics, such as depression, anxiety and high levels of arousal, have been found to influence how parents interpret and respond to infant crying. 25–28 Social isolation, although less studied, may also increase its impact. The implication for clinical practice is that assessments need to take account of parental vulnerabilities and supports, as well as infant crying. Equally, the findings imply that health services need to form a bridge between paediatric concern regarding infant crying and services for adult well-being and mental health. By bringing these two traditionally distinct scientific and professional areas together, interventions that support parenting have the potential to help parents, enhance parent–infant interactions and infant development and improve health services.

Against this background, it is striking that there are no evidence-based NHS practices for supporting parents in managing infant crying. Instead, parents turn to popular books, magazines or websites, which give conflicting advice,29 or take babies to clinicians or hospital accident and emergency (A&E) departments,12 adding to the burden and cost of infant crying to the NHS.

By developing evidence-based services that support parents, the Surviving Crying study, described in this report, was designed to take the first steps towards the provision of routine health-care services that improve the coping and well-being of parents whose babies excessively cry, their infants’ outcomes and how NHS money is spent.

To reduce terminological confusion, the phrase ‘excessive infant crying’ is used throughout this report to refer to a parent’s judgement that an infant is crying too much, often accompanied by a concern that the crying is a sign that something is wrong with the baby. The phrase ‘prolonged infant crying’ refers to a measure of crying duration.

Aims and objectives

This was a preliminary study to develop a novel intervention package of materials and services that support parents of excessively crying babies and to examine the feasibility of delivering and evaluating the package in the NHS. The aims included preparing for a possible future large-scale controlled trial and advising on the form it might take. The study comprised two stages:

-

the development of an intervention package

-

a feasibility study of package implementation in the NHS.

Stage 1 aims:

-

Update a 2011 systematic review2 in order to identify existing examples of support packages.

-

Allow parents to advise on the supports needed for parents whose babies are excessively crying. Parents were also asked to rate four example support packages identified by the literature review. Because the package needed to be accepted by parents in order to be effective, parents and NHS staff were closely involved in its development.

Stage 2 aims:

-

Assess parents’ and NHS health visitors’ (HVs’) or community public health nurses’ (SCPHNs’) willingness to enter and complete a study of the support package.

-

Measure parental use and parental and HV/SCPHN evaluation of the package components.

-

Identify measures for estimating package clinical effectiveness and cost.

-

Identify barriers to and facilitators of the research.

-

Assess the feasibility and design parameters for a future large-scale trial of the intervention package’s clinical effectiveness and cost, and establish whether or not parents would be willing to participate in such a trial.

Figure 1 is a flow chart showing the timetable for the study as a whole.

FIGURE 1.

The planned Surviving Crying study timetable. NIHR, National Institute for Health Research.

Ethics approval and governance

The study was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) database (registration number ISRCTN84975637). Ethics approval was granted by De Montfort University (DMU) (reference number 13450) and the National Research Ethics Service Committee East Midlands (Nottingham) (project ID 152836, National Research Ethics Service reference 14/EM/1202). Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust (LPT) provided local research and development approval (reference PAED0706). The study protocol can be accessed on the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library website (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/; accessed 6 December 2018). Approvals for a series of non-substantial and substantial amendments were obtained at various stages in order to conduct and progress the study, details of which are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1.

The study was regulated by a NIHR-appointed steering committee and co-ordinated by a management group, including the research team, senior LPT HVs, a paediatrician, a general practitioner (GP), a health economist, members of the Leicester Clinical Trials Unit and National Childbirth Trust (NCT), members of the charity Cry-Sis and parent representatives.

Patient and public involvement

The involvement of key stakeholders, particularly parents, was integral to the design and delivery of the feasibility study at all stages, and is described throughout the report. In summary, parents contributed in the following ways:

-

Twenty parents whose babies had cried excessively attended focus groups to describe their experience and provide information on what resources and support might have been beneficial. The support package was then developed to include these resources and information.

-

Most of these parents consented for aspects of their experience to be included in the website and information booklet developed as part of the intervention. These took the form of quotations from the focus groups and written or video accounts of their experiences and suggestions.

-

The focus group parents reviewed the draft intervention materials and made suggestions for improvements, which were included in the final version.

-

One of the focus group parents joined the Study Management Group and presented their experience as part of the Surviving Crying conference to disseminate the findings.

-

In stage 2 of the study, 52 parents provided feedback on the package components they had used, including what had been most valuable and suggestions for improvement.

An evaluation of the impact of patient and public involvement on the study is included in Chapter 14, Evaluation of patient and public involvement.

Structure of the report

Because the feasibility study was divided into two distinct stages, this report is arranged to reflect these stages and the elements of them. Thus, Chapters 2–6 provide an overview of the methods and results from stage 1 (the development of the intervention) and Chapters 7–13 describe the methods and results from stage 2 (the evaluation of the intervention). Chapter 14 then summarises the findings and identifies conclusions from the study, including making recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Stage 1: development of an intervention package – overview

Stage 1 had three key aims, which are described in detail in the following chapters:

-

Update a 2011 systematic review2 in order to identify existing examples of support packages (see Chapter 3).

-

To allow parents to advise on the supports needed for parents whose babies are excessively crying, parents of previously excessively crying babies were invited to focus groups to share their experiences and identify what resources or support would have helped them to cope. Parents also rated four example support packages identified by the literature review (see Chapters 4–5).

-

Develop a package of support materials to test in stage 2. Because the package needed to be accepted by parents in order to be effective, parents and NHS staff were closely involved in its development (see Chapter 6).

Chapter 3 Stage 1 literature review

Aims

As part of the process of developing the intervention for this study, a focused literature review was undertaken with three specific aims:

-

identify recent evidence of existing interventions to support parents of babies considered to be excessively crying

-

select a number of these interventions to show to parents attending focus groups in order to gain their feedback

-

search for evidence of interventions that were effective in supporting parents’ mental health, particularly in the postpartum period.

Method

Identification and selection of interventions to show to focus group parents

As set out in the study protocol, the review was based on an update of the 2011 systematic review by Douglas and Hill2 concerning the causes of excessive crying and interventions to manage term infants who cry excessively in the first few months of age. For the purposes of this review, ‘excessive crying’ was taken to mean any crying behaviour that was considered problematic by parents.

Full details of the inclusion criteria and search strategies are provided in Appendix 2. The materials identified through the initial search were reviewed against additional criteria to identify a selection of interventions that could be viewed and rated by focus group parents to inform the development of the intervention for this study. These criteria were:

-

intervention materials available in a published and exportable form

-

delivery costs that enabled the potential adoption of the intervention within the NHS

-

at least provisional evidence of clinical effectiveness

-

offering a variety of styles of presentation.

Contracts with the organisations involved in producing these interventions were arranged to allow the website and supplementary materials to be reviewed by the focus group participants.

Identifying evidence for interventions that support parents experiencing postpartum distress

As noted in Aims, the literature review also aimed to review recent evidence for interventions found to be effective in supporting parental coping and mental health, particularly during the postpartum period. This was based on the premise that, as noted in Chapter 1, Background, infant crying can be viewed as a stressor and its impact on parents is, therefore, partly attributable to how parents evaluate and cope with it and, consequently, to parents’ underlying vulnerabilities, circumstances and resources. The strategies described above were used to identify relevant research in this area.

Results

Appendix 2 provides full details of the literature review process and results. Once the initial screening process was completed, a total of 19 relevant articles remained, which referred to 11 different interventions (more than one article having been published in relation to some interventions). These interventions, details of which are provided in Report Supplementary Material 2, were reviewed against the additional criteria to consider their appropriateness within the context of this study. Three relevant packages were identified, together with one further intervention programme30 that met the inclusion criteria but was omitted by Douglas and Hill. 2 A programme that required a multiprofessional clinic31 was excluded because it was costly and difficult to export. Therefore, a total of four example packages that met the study inclusion criteria were identified:

-

Period of PURPLE Crying® (http://purplecrying.info/; accessed 6 December 2018)

-

What Were We Thinking! (www.whatwerewethinking.org.au; accessed 6 December 2018)

-

Coping with Crying (www.copingwithcrying.org.uk; accessed 6 December 2018)

-

Cry Baby (http://raisingchildren.net.au/newborns/behaviour/crying-colic/cry_baby_program; accessed 15 January 2019).

A brief description of each package is given in Table 1.

| Name | Origin | Format |

|---|---|---|

| Coping with Crying | UK | A film and website aimed at preventing parents from harming their babies because of crying. Includes videos of parents and experts discussing their experiences and advice, and one specifically highlighting the risks from shaken baby syndrome |

| Cry Baby | Australia | A web-based resource for parents with babies with crying or sleep problems. Presented in visual, written and audio format, with downloadable checklists and tips (shown in focus groups) |

| Period of PURPLE Crying | USA | A website with an accompanying DVD (not shown in focus groups) aimed at preventing parents from harming their babies because of crying. Includes comprehensive text on a range of relevant topics, plus short videos of experts and role-played scenarios |

| What Were We Thinking! | Australia | A website and workbook (sample pages shown in focus groups) as part of a course aimed at supporting new parents to cope with and negotiate their changed roles and responsibilities |

In relation to identifying evidence about support for parents experiencing postpartum distress, the review highlighted multiple randomised controlled trials (RCTs) indicating the effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) programmes in helping adults, including parents in the postpartum period, to cope with stressful conditions and moderate psychological distress. 32–35 As these findings were also supported by the recommendations of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),36,37 this was considered sufficient evidence to adopt this approach for the intervention developed for this study.

Chapter 4 Stage 1 focus group methodology

Introduction

This chapter and Chapter 5 report the second part of stage 1, in which a series of small focus group discussions were held with parents who had previously had a baby who had excessively cried when < 6 months of age. Using a mixed-methods approach, the aim was to gather qualitative and quantitative information about parents’ experiences, their preferred methods for accessing information and ratings of example package components. This chapter describes the recruitment to and delivery of the focus groups, and Chapter 5 reports the findings from them.

Method

Participants

A purposive sample of 20 parents participated in stage 1. The eligibility criteria for parents were:

-

living in the LPT area

-

previously had a healthy baby whose excessive crying in the first 6 months of age had caused concern for either parent

-

their baby was no longer excessively crying

-

English speaking or supported by an English speaker.

Parents whose baby was still crying or was judged to be ill at the time of crying by their HV/SCPHN or another qualified professional were excluded from participating. Parents who lived outside the LPT area were also excluded.

Participants were recruited to the study by two routes:

-

They were referred to the study team via their HV/SCPHN, having previously spoken with them about their baby’s crying.

-

They contacted the study team directly after seeing the call for eligible parents on the NCT website or on flyers distributed to local children’s centres in which HVs/SCPHNs were based. An example recruitment flyer can be accessed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/ (accessed 6 December 2018).

All parents received high-street shopping vouchers in acknowledgement of their participation; one was given at the end of the focus group session and another was given when they reviewed the developed package.

Table 2 shows the sociodemographic profile of participants, noting that complete information was not available for two parents. The two male parents attended with partners. Most parents were white British, had an undergraduate or postgraduate degree and were married or living with a partner at the time when their baby cried excessively.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex (N = 20) | |

| Female | 18 (90.0) |

| Male | 2 (10.0) |

| Age (years) (N = 19)a | |

| Mean (range) [SD] | 31.0 (19–42) [6.0] |

| Ethnicity (N = 19)a | |

| English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 14 (73.7) |

| Indian/Bangladeshi/Pakistani | 3 (15.8) |

| White/black Caribbean mixed | 1 (5.3) |

| Other (not specified) | 1 (5.3) |

| Highest education level (N = 19)a | |

| Postgraduate degree/qualification | 6 (31.6) |

| Undergraduate degree/qualification | 6 (31.6) |

| Higher post-A-level vocational qualification | 1 (5.3) |

| A level/NVQ level 3/BTEC diploma | 4 (21.0) |

| GCSE/O level/NVQ level 2/completed secondary school education | 2 (10.5) |

| Employment status when baby was crying (N = 19)a | |

| Maternity leave | 7 (36.8) |

| Employed part time | 5 (26.3) |

| Self-employed | 2 (10.5) |

| Unemployed and looking for work | 2 (10.5) |

| Not in paid employment | 3 (15.8) |

| Marital/living status (N = 18)a | |

| Married/cohabiting | 16 (88.8) |

| Living alone but supported by partner | 1 (5.5) |

| Single and living alone | 1 (5.5) |

Materials

A short participant demographic questionnaire was devised to obtain participant sociodemographic details prior to the focus groups. The questionnaire can be accessed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/ (accessed 6 December 2018). A brief semistructured topic guide was also developed (see Appendix 3), dividing the focus groups into two parts. Part 1 involved explaining the group aims and procedures, and introductions (participants could use pseudonyms if they wished to maintain anonymity). Participants were asked to describe their experience of having a baby who cried excessively: what was most challenging?; what helped?; what sorts of support would they have liked to have received at the time?; and their thoughts on what should be included as part of routine NHS care.

Part 2 involved parents completing rating scales to establish the best way of delivering a package of support (i.e. website, leaflet, direct and/or telephone contact with a professional) and which electronic devices they used to access information and support. Materials from the four example support packages identified by the literature review were evaluated by participants, using five 5-point rating scales, with an opportunity for participants to make written comments on features that they felt were important, they disliked or they felt could be improved. These questionnaires can be accessed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/ (accessed 6 December 2018). All four example packages included a website, together, in some cases, with supplementary materials. Sample materials from each package were shown to parents with a changed presentation order for each session to reduce order effects. Appendix 1 provides details of the materials shown and how these were sampled from the example packages.

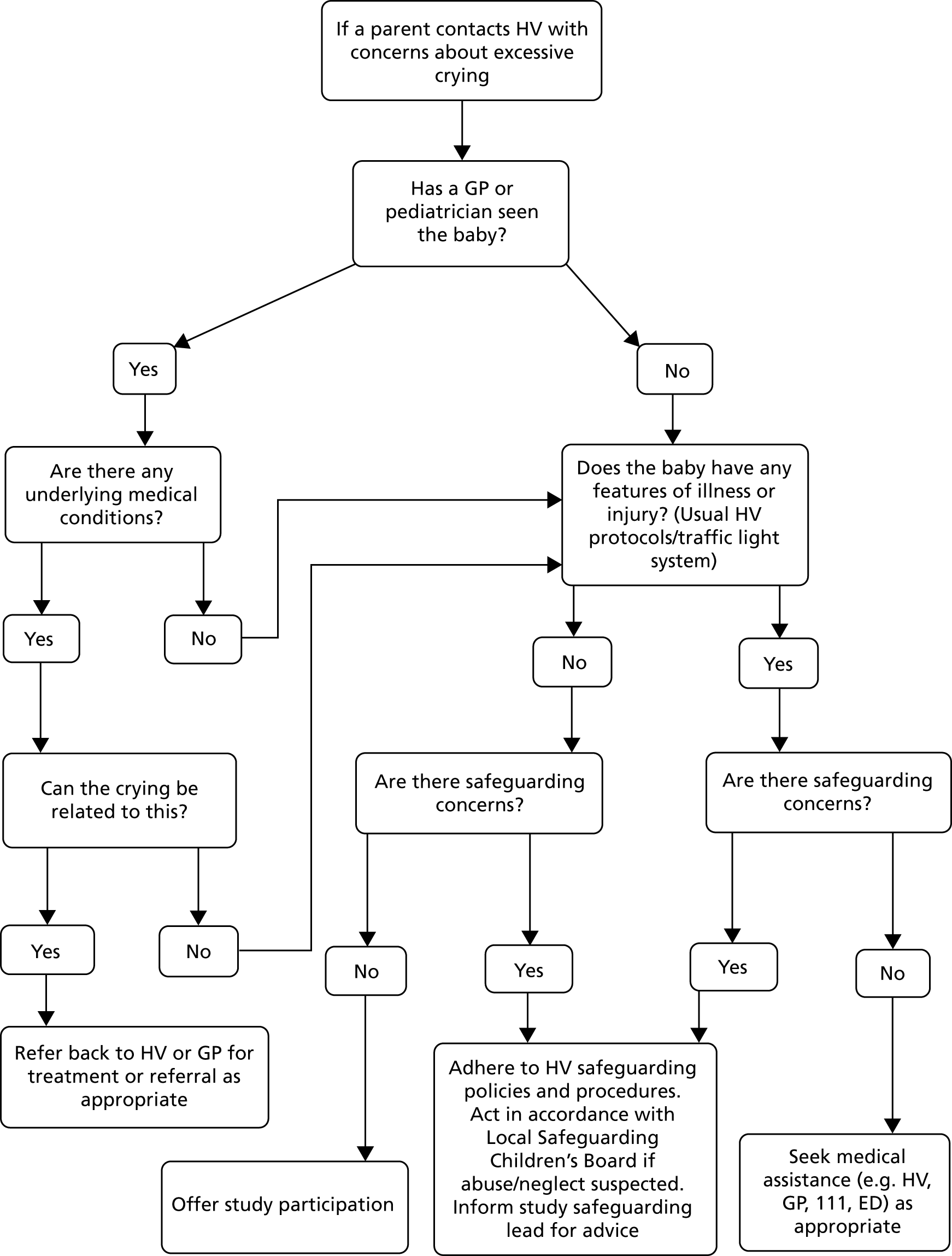

Safeguarding procedures

Together with LPT’s safeguarding officers, HVs/SCPHNs and the study paediatrician, the research team developed safeguarding protocols to ensure the safety of parents and babies involved in the study (see Appendix 4).

Procedure

Health visitor involvement

In the UK, HVs/SCPHNs provide universal primary care for parents with young babies and are the obvious choice for delivering the intended service within the NHS. With support from the LPT managers collaborating on the study, HVs/SCPHNs from five health-visiting teams within Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland attended briefing meetings about the study. A total of 55 HVs/SCPHNs gave written agreement to collaborate in stage 1 by referring eligible parents to the research team. All HVs/SCPHNs were given an information pack containing details about the study and how to approach and refer eligible parents.

All HV/SCPHN teams were revisited when the draft package was developed in order to obtain their overall views regarding its suitability.

Parent recruitment

The HVs/SCPHNs approached parents whom they knew to have previously had a healthy baby whose excessive crying in the first 6 months of life had caused concern for either parent. They provided brief details about the study in order to seek expressions of interest for researchers to contact them. To supplement HV/SCPHN contacts with parents, information about the study was also circulated via the NCT network, through researcher attendance at local parent and baby groups and through flyers that were distributed to local children’s centres, HV/SCPHN bases and local parenting/baby groups. An example recruitment flyer can be accessed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/ (accessed 6 December 2018).

On receipt of an expression of interest, the researchers contacted each parent by telephone to fully explain the study and assess eligibility. Eligible parents were sent a formal letter of invitation to participate from the principal investigator (PI) and an information sheet and consent form if their HV/SCPHN had not already provided them. Parents were invited to attend a pre-arranged focus group discussion, bringing their babies and/or older children with them if need be, and were invited to provide feedback on the draft.

Parent involvement

Participants were invited to attend pre-arranged focus groups over a 5-month period (April to August 2015), held at venues and locations convenient for parents. Seven arranged groups were cancelled or rearranged owing to a lack of parent availability. Focus groups continued when only one parent attended, provided the parent was happy for this to happen, and the structure and format remained the same. In effect, these sessions became interviews. Parental written consent was obtained prior to the focus group/interview sessions. In total, 10 focus groups/interview sessions were held.

Two researchers who were experienced in focus groups and interview methods facilitated each session and two others made observational notes or provided informal childcare. When only one parent attended, two researchers shared the duties. All sessions were audio-recorded for later verbatim transcription. Each session lasted approximately 2.5–3 hours. Parents were asked to revisit the example packages following the focus groups and were recontacted when possible by the researchers to establish if they had done so and whether or not this more extensive exposure had changed their initial opinions and ratings. At this point, parents were invited to further contribute to the development of the package by consenting to the inclusion of their stories and experiences in one of three ways:

-

permitting the use of anonymous direct quotations from the audio recording of the sessions

-

providing more detailed information about their experiences in a written format

-

appearing in video recordings talking about their experiences.

Analysis

Parent qualitative discussions

All sessions were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data analysis and its interpretation were informed by hermeneutic phenomenology38 and Ricoeur’s theory of interpretation. 39,40 Analysis was undertaken at three levels; an initial reading of transcripts with the identification of themes was progressed to an explanation and naive understanding of meaning facilitated by the clustering of related themes. This then progressed back and forth between explanation and understanding to assist deeper interpretation and understanding, reminiscent of Gadamer’s hermeneutic circle41 or hermeneutic arc. 40 Analysis was supported by the use of NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). All transcripts were read and reread several times and a line-by-line analysis of content was undertaken and grouped under themed headings that emerged from the data. To enhance credibility, these themed headings were shared and agreed with the researchers present at the focus groups. Initially, a large number of themes were identified; these were refined by grouping similar themes together under new overarching themes. This process was repeated until the following conceptual themes emerged: (1) disrupted experiences of parenthood, (2) feeling different and social isolation, (3) reluctance to seek support and (4) validation of experience and seeking help (see Appendix 5). Participant codes were assigned and potential identifiers removed in order to protect the anonymity and confidentiality of participants. One parent accompanied his partner and did not contribute to discussions, so only his partner’s data were included in the qualitative analysis.

Parent-completed questionnaires

Simple univariate descriptive analyses were conducted on data from the parent-completed questionnaires and a content-analysis approach was used to analyse the free-text comments. Some data were specific to the example package materials and these were summarised as a whole in order to maintain confidentiality of the providers of those packages.

Chapter 5 Focus group quantitative and qualitative results

Focus group quantitative data

Demographic data relating to focus group parents were presented in Table 2.

Baby characteristics

The 20 study participants had 19 excessively crying infants; one parent had experienced excessive crying with both her first and second child and two couples participated in the study (their baby’s data have been included only once). Table 3 presents the babies’ characteristics.

| Descriptive particulars | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Baby’s sex | |

| Male | 9 (47.4) |

| Female | 10 (52.6) |

| Baby’s birth order | |

| Firstborn | 10 (52.6) |

| Secondborn | 8 (42.1) |

| Thirdborn | 1 (5.3) |

| Baby’s feeding method when excessive crying started | |

| Breast milk only | 7 (36.8) |

| Breast plus formula milk | 6 (31.6) |

| Formula milk only | 6 (31.6) |

| Baby’s health in the period when he/she cried excessively | |

| Baby had a fever | 0 (0) |

| Baby seemed unwell | 2 (10.5) |

| Concerns about baby’s weight gain | 1 (5.3) |

| Baby had feeding problems | 11 (57.8) |

| Baby’s feeding checked by a health professional | 17 (89.5) |

| Baby’s weight checked by a health professional | 19 (100) |

| Baby’s age when the excessive crying started and stopped (weeks) | |

| Started, median (range) | 1 (0–9) |

| Stopped, median (range) | 19 (8.5–104) |

| Length of excessive crying, median (range) | 18 (4–100) |

Noticeably, only 10 of the babies were firstborn. Eight of the 18 families had other children who had not cried excessively. The babies were equally likely to be boys or girls, and they were almost equally divided between breastfeeding, formula feeding and mixed feeding when the crying started. None had a fever and only two seemed unwell. Although 11 of the babies (58%) were reported by their parents as having had problems with feeding, all the babies had been checked by clinicians for weight gain and 17 (89%) for feeding problems.

The median age at which parents reported that the babies started excessively crying was 1 week (range from birth to 9 weeks). However, there was a substantial variation in the age at which the crying stopped, ranging from 8.5 to 104 weeks (median 19 weeks). In line with this, the excessive crying duration ranged from 4 to 100 weeks (i.e. 1 month to just under 2 years), with a median length of crying of 18 weeks (i.e. 4 months).

Sources of information and support

Participants completed questionnaires about the sources of information that they used and would have found useful when their baby was excessively crying and which formats they felt were the best for presenting information about crying babies to parents (Table 4).

| Sources of information and support | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sources used by participants when their baby cried excessively (n = 20) | Used this source |

| Leaflets | 9 (45.0) |

| Magazines | 4 (20.0) |

| Books | 7 (35.0) |

| Websites | 16 (80.0) |

| Mobile phone apps | 5 (25.0) |

| Telephone conversations with HV/SCPHN, doctor or other health professional | 17 (85.0) |

| Visits to speak with HV/SCPHN, doctor or other health professionala | 10 (58.8) |

| Online discussion boards | 4 (20.0) |

| Other sources of information or support | 0 (0.0) |

| Sources participants would have found most helpful when their baby cried excessively (n = 18) | Would have liked this a lot |

| Extra visits from HVs/SCPHNs | 14 (77.7) |

| Extra telephone calls from HVs/SCPHNs | 11 (61.1) |

| Leaflets | 13 (72.2) |

| Websites | 18 (100.0) |

| Online activities to completeb | 4 (25.0) |

| Online discussion boardsa | 10 (58.8) |

| Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) | 11 (64.7) |

| Group to meet other parents | 18 (100.0) |

| Best format for presenting information to parents (n = 18) | Rated this as effective or highly effective |

| Leaflets from HV/SCPHN, doctor or hospitala | 13 (76.5) |

| Websites | 16 (88.9) |

| Mobile phone appsa | 14 (82.3) |

| Telephone conversation with HV/SCPHN, doctor or other health professionala | 13 (76.5) |

| Visit to speak with HV/SCPHN, doctor or other health professional | 16 (88.9) |

| Preferred device for accessing the internet (n = 18) | Preferred this device |

| Desktop computer, laptop or workbook | 3 (16.7) |

| Tablet computer | 8 (44.4) |

| Telephone | 14 (77.8) |

Noticeably, 10 parents (53%) had attended extra visits with a HV/SCPHN, doctor or other health professional about their baby’s crying and 14 (78%) reported that they would have found an extra visit with their HV/SCPHN helpful when their baby was excessively crying. Furthermore, 16 participants (89%) felt that a visit with a HV/SCPHN, GP or other health professional would be an effective format for presenting information about crying babies to parents, stating that this would give reassurance, advice and explanation for the infants’ crying.

Half of parents also had a telephone conversation about their baby’s crying with a HV/SCPHN, doctor or other health service professional. Eleven participants (61%) reported that they would have liked extra telephone calls from a HV/SCPHN when their baby was excessively crying and 13 (76%) reported that a telephone call with a HV/SCPHN, doctor or other health professional would be an effective way to present information to parents. The high usage of visits and telephone support from HVs/SCPHNs, doctors or other health professionals, particularly given that such a high proportion of parents rated them as effective, supports the qualitative finding that participants felt a need for more personal support rather than simply having more information available.

All parents stated that they would have found a group helpful when their baby was excessively crying, with 10 (59%) stating that online discussion boards and 11 (65%) stating that Facebook sessions would have been helpful sources of information; this emphasises the importance of contact with other parents.

Websites were used by 16 respondents (80%), although none reported using a crying-specific website. All 18 said that they would have found a website helpful and 16 (89%) said that websites were an effective format for presenting information. These parents felt that websites were effective sources of information owing to their accessibility in various situations and availability 24 hours a day.

Leaflets were identified by 13 parents (72%) as a resource they would have found helpful and as an effective format for presenting information, although only nine (45%) had used leaflets when their baby was excessively crying. Participants felt that leaflets made good reference material that could be perused in their own time; however, they expressed concern about the number of leaflets already given to new parents and felt that it would be easy to lose a leaflet or not have it available when needed.

Support sessions

All participants stated that they would have wanted support sessions with a professional if they had been offered to them at the time when their baby was excessively crying. Only one parent wanted one-to-one sessions only, with most parents (55%) wanting group sessions or a mix of both. Most parents would have preferred between four and five sessions, with a range from two to six sessions.

Parents’ feedback on four example packages

Parents completed rating scales on all four of the example packages, giving detailed, package-specific information on which aspects they did and did not like. All parents reported that it was important that materials such as those shown in the focus groups were included as part of routine NHS care.

In order to protect the identities of the packages used in the focus groups (and because the aim was to identify which features parents judged to be needed in future packages, rather than comparing existing packages), overall information is reported about the features of the packages that parents did and did not like, as summarised in Figure 2. This shows that parents positively rated all of the researcher-identified aspects of the packages, such as the practical suggestions for parents, the reliability of the information for parents, reassurance for parents and that the information was aimed at both parents and easy to access when needed.

FIGURE 2.

Aspects of the four sample packages that parents liked (n = 20). 1, Practical suggestions; 2, reassurance that I wasn’t doing anything wrong/it wasn’t my fault; 3, that I could trust what they said; 4, other parents’ experiences and ideas; 5, expert opinion and advice; 6, that the information is aimed at both parents; 7, videos; 8, workbooks; 9, interactive materials – responsive to your interests and concerns; 10, that the materials are easy to access when you need them.

Table 5 provides the reasons parents gave for their preference for certain materials. These largely echo the researcher-identified features of the packages and also reflect the wider discussion that took place in the focus groups. However, some of the participants’ comments went on to clarify what in particular they had liked, providing useful information for the development of the intervention package. For example, participants’ comments made it clear that they liked information that was ‘clearly explained’, ‘relevant’ and in ‘bite-size chunks’. The information and websites needed to be able to be ‘read and understood within a few minutes’, ‘clear’, ‘easy to navigate and find [the] information you are looking for’. Parents valued the reassurance, saying that the packages ‘seemed to “normalise” the crying more and helps you to feel better in yourself’. Participants were positive about other parents’ stories, with one explaining that it ‘gave a realistic situation which I could identify with’. Information aimed at the couple together was also valued; as one parent explained, ‘if your relationship is strengthened, workload shared and baby-related issues discussed and problem-solving done together then I think crying would be easier to deal with’.

| Website features | Number (%) of parents |

|---|---|

| Information: relevant, easily accessible and not too in depth | 11 (55.0) |

| Clear and easy format: clear, simple and easy-to-use format, able to find and understand information when needed | 10 (50.0) |

| Practical: practical tips, advice and suggestions of strategies for soothing the baby and coping tips for parents | 9 (45.0) |

| Gave reassurance: materials that took the crying seriously and acknowledged that sometimes babies do just cry | 7 (35.0) |

| Includes other parents’ experiences: other parents’ experiences, as they could identify with them (e.g. case studies) | 4 (20.0) |

| Dads and mums: information that was relevant to dads as well as mums | 3 (15.0) |

| Couples: parents liked the fact that the materials gave information for couples and ways for parents to support each other and work together | 2 (10.0) |

| Items specific to certain packages: specific items in the materials that parents liked included coping skills, videos, audio files and websites that were interactive | 8 (40.0) |

| Focused: specifically focused on uncontrollable, unsoothable crying | 1 (5.0) |

Twelve of the 20 parents were successfully recontacted after the focus groups. Eight had revisited one or more of the example websites. None of the parents wished to amend their responses given within the focus groups.

Focus group qualitative data

In the focus groups, participants reported what it was like to be the parent of an infant who cried excessively for no apparent reason. They described how they tried to make sense of what was happening, how they dealt with feelings of inadequacy, physical and mental exhaustion and concerns for their baby’s well-being. Data analysis identified four themes: (1) disrupted experience of parenthood, (2) feeling different and social isolation, (3) reluctance to seek support and (4) validation of experience and seeking help.

Disrupted experience of parenthood

Parent participants indicated that their expectations of parenthood were positive and that they had little prior awareness that some babies could cry excessively for prolonged periods:

I think the, the expectation that you have after you have been carrying your unborn child and then you have your baby and then this whole feeling of this is going to be wonderful, and you can’t wait to hold your baby and nurture and look after and everything else – and the screaming just doesn’t stop, it just seemed to go on in a bit of an endless cycle and you think to yourself ‘it’s going to stop, it will just be the first week’ and it, for me it didn’t, it didn’t for a long, long, time.

P1P19

Consequently, they were shocked by the experience of having an excessively crying baby and they gave accounts of the many strategies they adopted to comfort their babies. However, their inability to soothe the babies made parents feel that they were somehow responsible for the crying. This, subsequently, led to feelings of inadequacy, frustration and anxiety, which seriously eroded their confidence in their ability to parent these babies:

I would say it made you feel like you are no good at it, like you are helpless really, because you try everything . . . But when she carried on crying you try and feed them, you change them, there is nothing wrong with them you just feel like useless.

P1P7

The crying often resulted in parents feeling exhausted and sleep deprived. This tiredness reduced their ability to cope, and even daily tasks, such as eating and attending to basic personal needs, were compromised for some:

I wasn’t looking after myself, I wanted to but I just couldn’t because, everything was so consumed with the crying that I just didn’t, I just almost neglected myself.

P1P13

Many mothers perceived that their partners did not fully understand their experience of being at home all day with a baby who cried incessantly. They often felt that their experiences were invalidated and dismissed as an exaggeration, creating tension between couples:

I don’t think he really understood what it was like to be at home all day on your own with a crying baby. And whilst he never came home and said ‘well it’s a mess, where is my dinner?’ you still have to do those things. He’d come in and be, ‘oh I am so tired, I have been at work’, and expect to have a chill out and she would be there screaming the place down. I started to resent him . . . a complete breakdown in communication there.

P1P16

However, there were several examples of a positive shared parental approach:

He would do all the night feeds. I went to bed at 10 [p.m.] and then he would do the night feeds and then I would get up at 6 [a.m.]. With the crying to be fair he never lost his temper once, he didn’t shout. In the middle of the night he would wake up and say ‘oh give her to me’. And he slept downstairs for 3 months with her so that I got sleep.

P1P5

Feeling different and social isolation

Parents perceived that both they and their baby were somehow ‘different’ to families with ‘normal babies’:

The year I had my baby there were five of us that all went to school that all had our babies within a few months. All of their babies were happy, they never particularly cried. So we were very much the odd ones out.

P1P16

Negative comparisons between their situation and that of others increased their sense of isolation and loneliness. Parents recognised that meeting friends or attending groups could be beneficial, but physical exhaustion and the all-consuming nature of trying to soothe their babies made getting out of the house both physically and mentally challenging:

I went to them baby massage classes but I only went for one . . . because he was crying the whole time we were there. I couldn’t do a lot with him because I just thought it’s just gonna be embarrassing. Especially cos you’d have all the mums there and they’d be like ‘oh my baby is like so’, ‘he’s brilliant, sleeps 8 hours, happy to just sit there’, but that don’t make you feel better.

P1P17

Reluctance to seek support

These feelings, together with a wish not to impose on others, appeared to inform parents’ initial reluctance to seek professional support, even from partners or close family members in some cases:

It’s sort of like admitting defeat isn’t it . . . you feel like you have been defeated by this little child and it’s actually admitting that to your family. Even my other half I never told him how bad I actually felt.

P1P5

More worryingly still, reluctance to seek help appeared to be fuelled by fears of being judged by others, particularly health-care professionals, who some parents feared would take their baby away:

But you do think that don’t you? ‘Oh my god they [health-care professionals] are going to come round and take her off me.’

P1P1

A reluctance to seek support from others led parents to look for reasons for the excessive crying and self-help strategies from sources such as the internet. However, they reported difficulty with finding information specific to excessive infant crying and how to cope with it, and several questioned the quality of the advice on offer:

Yeah, [I used the internet] a lot, when I was trying to look on Google [Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA], some stuff came up but it wasn’t stuff that gave you proper advice or anything on what to do.

P1P10

Parents indicated that they found online parent forums valuable and were reassured to find that they were not the only parents dealing with an excessively crying baby:

[I was] looking for information. I was just looking for what other people had been through and what they’d said; the whole act of finding and reading what other parents have been through helped me – I felt like I wasn’t on my own.

P1P18

As well as providing reassurance, online forums also provided the opportunity to interact with other parents who were sharing the same experience and, as a consequence, participants felt less isolated.

Validation of experience and seeking help

Parents described trying to find a way of relieving their baby’s crying, often going through a mental checklist of things that may be causing the baby distress, such as their nappy, feeding, temperature, etc. When they had exhausted these options, they became concerned that their baby was unwell and sought advice and reassurance from health-care professionals. As no physical cause was found and the crying continued, many parents spoke of repeated appointments as they were convinced, despite reassurance, that there was something seriously wrong.

It [crying] went on and on for 2 weeks straight it was, he just cried so much. I remember going to the doctors and then the midwife was coming round and I asked, ‘what’s he crying for?’. And I just kept looking at him and thought ‘what’s wrong with him?’, ‘why is he crying?’.

P1P12

However, despite frequent contact with health professionals, some parents felt that their concerns were not taken seriously or that professionals thought that they were exaggerating. This increased their frustration at not being heard and added to their distress:

You are banging your head against a brick wall, you are knocking on everyone’s door and you are not getting anywhere. So not only did I feel undervalued from a mother’s point of view [and] feel that what I was doing was wrong, but as an individual, as an adult I felt like nobody was listening to me, nobody cared, nobody is taking me seriously, it was a nightmare.

P1P11

Other parents found health professionals to be sympathetic and helpful; however, they questioned their level of experience in relation to excessively crying babies and their knowledge and skills in the area:

I found that the health visitor was helpful, she was quite sympathetic. She didn’t have the answers that I felt that I needed, and she didn’t have probably the experience of babies that cry. But it just made it just nicer to talk to somebody who was sympathetic to talk to.

P1P8

Parents valued acknowledgement of their concerns. Moreover, when there was continuity of care, and they were able to build up a relationship with health-care professionals, parents felt more able to share their concerns:

My health visitor was really supportive; even now she’s really supportive. She was really nice, really good, even like now she is really good, and she always like rings me to see how I am. She has given me her number and said if you ever feel down, if you ever want to talk to anyone ring me and, I go to the groups and she is there sometimes and she has a chat and she is really helpful.

P1P9

The importance of continuity and the quality of the relationship with health professionals in supporting parents was evident:

It’s a lot of work, because we have had so many health visitors it’s like starting from scratch all over again. He has three already, he’s only 15 months old and not one of them knows him. So when they ring I just say ‘yes I am fine’. I just don’t bother now.

P1P5

Although parents used a variety of means to access information about crying babies, a home visit from a HV was particularly valued. Parents felt that these visits allowed HVs to see first-hand how the baby was crying, and in doing so supported validation of the parent experience:

I used to think she [HV] should come to my house and see what I am going through. She never came to my house, she’d ring me and she was just trying to tell me things to do over the phone.

P1P7

Implications of these findings

In the opinion of parents who have experienced an excessively crying baby, the supports available for parents in this position can be improved in several ways:

-

Parent education prenatally or in the first few postnatal weeks should include information about excessive infant crying, including signposting of parents towards resources and sources of help.

-

Training resources in how to support parents should be developed for health-care professionals involved with the care of parents before and after their baby’s birth.

-

Care models that provide continuity of care and allow parents to develop relationships that support disclosure of their concerns and anxieties should be promoted.

-

There is a need to promote awareness of excessive infant crying more widely to the general public using a number of media, including television, radio and articles in popular magazines.

Parents who have had an excessively crying baby have reported that it is a bewildering and anxiety-provoking experience that undermined their confidence in their skills and aptitude to be proficient parents and shattered their expectations of parenthood. Participants felt that they might have been able to cope better if they had more information prior to the birth of their baby or even in the early days of parenthood. Understanding the parent experience of excessive crying and the perceived stigma associated with this enables the identification of how to better support parents. For the parents of excessively crying infants, this would need to include enhancing the education and training of the health-care professionals who support them. It is important to bear in mind that few fathers and parents from ethnic minority groups were involved in this study, so the findings need to be generalised with care. Nevertheless, the findings highlight an unmet need in the NHS and identify the sorts of support services that parents would like to see developed.

Chapter 6 Stage 1 development of parental support materials

Note: please contact the corresponding author to request access to the practitioners’ manual.

Reflecting the literature review and focus group data, three package elements were developed: a Surviving Crying website, a printed version of the website materials and a programme of CBT-based support sessions delivered directly to parents by a qualified practitioner, together with a programme manual.

Website

Following an invitation to tender and a competitive selection process, a marketing and communications agency, Consider Creative (London, UK), was appointed to assist in developing the website and study materials. Its brief included:

-

developing the imagery, templates and required features of the website

-

testing the website to ensure compatibility with different devices and operating systems

-

setting up Google Analytics (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) to enable monitoring of usage of the website by different user groups – parents, HVs/SCPHNs and other visitors

-

hosting and maintaining the website

-

developing a set of template documents to enable production of the information booklet in the same style and appearance as the website.

Once the website structure had been designed and approved, the content was developed and uploaded by the study team, using an iterative process of drafting and revision.

As noted in Chapter 5, Focus group qualitative data, feedback from the focus groups had highlighted the importance for parents of knowing that their experience was not an isolated one and that other people had survived having a crying baby. As a result, in addition to providing expert information and advice, efforts were made to ensure that parents’ experiences were included throughout the website. As described in Chapter 4, Parent involvement, focus group parents were recontacted to obtain their consent for inclusion of their experiences within the website. All of those whom it was possible to contact (n = 16) gave consent for the inclusion of their quotations from the focus group transcripts, and 14 parents also consented to provide written or video accounts of their experiences, leading to the production of five written stories and three videos. Videos were filmed in parents’ homes and edited by DMU staff with expertise in this field. Names were changed throughout to protect anonymity. In addition, videos of three professionals providing information and guidance were produced.

To ensure ease of reading, information was presented using bullet points and subheadings, and all text was adjusted to a reading age of 9–12 years. Care was taken to ensure that all advice given on the website was evidence based, with the text checked by the study paediatrician for accuracy. Focus group parents were asked to comment on a draft version of the website and 16 of them provided feedback; HVs/SCPHNs and members of the Study Management Group also provided input, leading to some minor revisions. In consultation with DMU legal advisers, information regarding copyright, the use of cookies and terms of use, including a disclaimer, were drawn up and added to the website.

Once the content had been finalised, Consider Creative and the research team completed the testing of the website, including ensuring its suitability for a range of electronic devices (personal computers, tablet computers and mobile phones), and provided a mechanism to enable the study team to issue individual user names and passwords to parents and others accessing the website. They also created templates, based on the website imagery, to enable other elements of the package to be produced in a consistent style.

Figure 3 shows the home page of the resulting Surviving Crying website, as it appears on mobile phone, tablet computer, desktop computer and laptop computer screens.

FIGURE 3.

The Surviving Crying website home page displayed on a range of devices. Reproduced with permission from De Montfort University.

The home page of the website was deliberately kept simple and focused, with text stating that:

This website is for parents who are worried about their baby’s excessive crying. Here you’ll find:

Drawing on the expert knowledge of the PI, the findings from focus groups and the literature review, the website was designed with four main sections: ‘Expert Help and Advice’, ‘Your Stories’, ‘News and Research’ and ‘About Us’. In addition, prominently highlighted on each page was a link to a section entitled ‘Need Help Now’, which provided advice and information to parents who might be in crisis.

The website contained a mixture of content, including written information and advice, quotations and videos from parents and experts and downloadable checklists and tips. Relevant parent quotations and/or videos were selected to support each section topic. A more detailed description of the website layout and content is provided in Appendix 6. DMU holds the copyright for the website and log-in details are required to access it.

Information booklet

The finalised website text was used to form the content of the information booklet. Some adjustments were necessary to enable the material to be accessible in paper format, including the addition of an introduction and a contents page. All of the written content of the website was included in the booklet, but it was not possible to incorporate any of the content of the videos. The booklet was then produced in an A4 format, with spiral binding and plastic covers for ease of use. It was printed in colour using the templates created by Consider Creative to create a consistent image across the resources.

Support session resources and practitioners’ manual

Based on CBT studies identified through the literature review,36,37,42,43 and the longitudinal course of infant crying, a programme of practitioner CBT support was designed by the study team in collaboration with a CBT-qualified counselling psychologist with extensive experience in supporting adult mental health in the NHS. The resources underwent several iterative revisions, were piloted and then were reviewed by parent and HV/SCPHN members of the Study Management Group.

The programme was designed to include up to five sessions, each lasting 60–90 minutes, delivered to parents in person or by telephone within a 4- to 6-week period. The sessions were designed for delivery at home or at another location of the parents’ choosing. Depending on the availability of other parents, parents could choose whether to take part in one-to-one or small-group sessions. Three key topics were included in each practitioner-delivered session:

-

assessing infant crying and well-being, making arrangements to obtain any other information or support needed and providing parents with information and reassurance

-

monitoring the soothing and baby-care methods parents were using

-

supporting parents in developing coping strategies that helped them to manage their own emotions and actions and ensure their well-being.

Each support session was based on core CBT principles, which were introduced in session 1, entitled ‘Introduction to thoughts and emotions’. The materials for this session, plus an introduction to the sessions as a whole, were in the folder when it was given to parents. Materials for a range of other topics were also provided, to be delivered flexibly in response to parents’ needs over subsequent sessions. These were:

-

how to stay feeling good when you have a new baby

-

managing the stress of a baby who cries excessively

-

looking after yourself – getting support, asking for help and saying no

-

relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing

-

getting good-enough sleep.

Each session included home activities for parents to undertake between sessions and review at the next meeting.

The resources for the support sessions were provided in a plastic folder with clear pockets into which the information could be slotted over the course of the sessions. The materials used a template based on the website and booklet imagery and also included a large amount of full-colour graphics to illustrate the various topics.

In addition to the resources for parents, a practitioners’ manual was developed to enable the materials to be delivered by the CBT practitioner (please contact the corresponding author to request access to the practitioners’ manual). This manual provided an introduction to the study and an overview of the sessions, together with guidance on how to use the resources to facilitate the sessions, including a plan of activities and session notes. Record sheets for the practitioner to log their activities and the outcome of the individual sessions were also included.

Methods for evaluating the package materials

Measures of participation and cost, questionnaires assessing infant crying, feeding and health, parental well-being and crying knowledge, together with rating scales to evaluate each element of the support package, were developed. To avoid duplication, these methods will be described together with the evaluation findings in the following sections.

Chapter 7 Stage 2: feasibility study of package implementation in the NHS – overview

The aims of stage 2 were to:

-

assess parents’ and HVs’ (HVs/SCPHNs) willingness to enter and complete a study of the support package

-

measure parental use and parental and HV/SCPHN evaluation of the package components

-

identify measures for assessing package clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

-

identify barriers to and facilitators of the research

-

assess the feasibility and design parameters for a future large-scale trial of the intervention package’s clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and find out whether or not parents would be willing to participate in such a trial.

Reporting of stage 2 is divided into the following sections:

-

methods of recruitment and data collection (see Chapter 8)

-

baseline findings for parents and babies (see Chapter 9)

-

outcome measures and changes for parents and babies (see Chapter 10)

-

parental evaluation of the Surviving Crying materials (see Chapter 11)

-

the HV/SCPHN evaluation of the Surviving Crying materials (see Chapter 12).

Chapter 8 Stage 2 methods

Introduction

This section reports the methods used to recruit parents to the study, the process of data collection and the methods employed to analyse the quantitative and qualitative data. A series of structured questionnaires and rating scales, at baseline and outcome assessments, were used to show changes over time, to provide information about the uptake of each package component and to record parents’ and HVs’/SCPHNs’ evaluations of their suitability for use in the NHS. Data were also collected to indicate the extent to which a future large-scale trial would be worthwhile and to identify the intervention package components and methods for that trial.

Additional ethics approvals

Because stage 1 of the study developed a novel intervention package, ethics approval for its use and evaluation in stage 2 could not be applied for until the end of stage 1. Ethics approval was subsequently granted by DMU and the National Research Ethics Committee East Midlands (Nottingham). In addition, as in stage 1, a substantial amendment was obtained in order to widen recruitment using flyers.

Participants

From May to October 2016, participants were recruited to one of two groups:

-

The ‘referred crying group’ – parents who sought HV/SCPHN help because of their baby’s current excessive crying or parents who contacted the research team directly after seeing the call for eligible parents on the NCT website or from information distributed locally. Based on LPT birth numbers and an incidence of 20%, allowing for attrition, we expected to recruit one or two parents to this group each week, allowing the target of 30 parent cases to be recruited.

-

The ‘new birth visit group’ – HVs/SCPHNs invited parents to enter the study at the statutory primary home visit within 10–14 postnatal days. Ten parents per week were expected to give informed consent to be followed up to 8 weeks following birth, and screened for excessive infant crying by researchers, giving a total of 150 recruited parents, of whom 30 were expected to be parents of excessively crying infants.

The new birth visit group would provide figures for the incidence of excessive infant crying, allow us to ask these parents if they had any reservations about accessing NHS services for infant crying, might enable earlier detection and intervention and would indicate differences between the two recruitment groups. The two recruitment methods would indicate potential numbers and recruitment methods for a future RCT and allow adjustment of the recruitment strategy if the expected numbers were not forthcoming. The total of 60 cases was judged to be sufficient for the purposes of the feasibility study. Table 6 shows the expected recruitment figures and stage 2 timetable, including providing the support package and follow-up assessments.

| Week in year 2 | Group 1: referred crying group cases (n = 30) | Group 2: new birth visit group cases (n = 150) | Excessive crying cases selected from new birth visit group when infants are 5 weeks old (20% prevalence) (n = 30) | Parents offered package | Outcome measures 4 weeks later | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Group | ||||||

| 1 (n = 30) | 2 (n = 30) | 1 (n ≥ 30) | 2 (n = 30) | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | 2 | 10 | 2 | ||||

| 3 | 1 | 10 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | 2 | 10 | 2 | ||||

| 5 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| 6 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 7 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| 8 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 9 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 11 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 12 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 13 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 14 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 15 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 17 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 18 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 19 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 20 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 21 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 22 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| 23 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 24 | 2 | ||||||

| 25 | |||||||

| 26 | |||||||

| 27 | |||||||

| 28 | |||||||

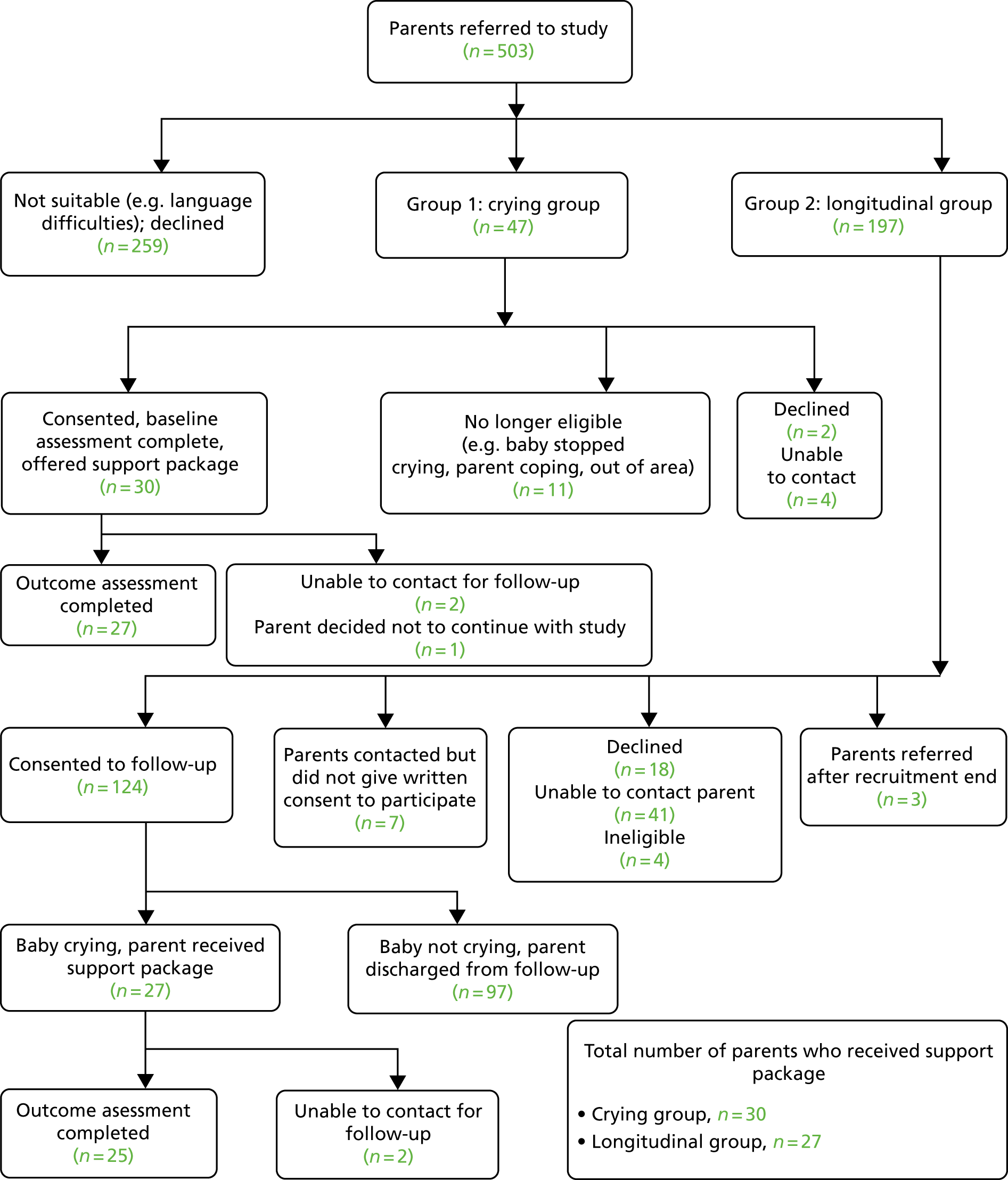

A total of 154 parents were recruited and consented to participate in stage 2, of whom 57 received the Surviving Crying support materials. To be eligible to participate, parents were required to have a healthy baby aged ≤ 6 months, be English speaking or supported by an English speaker and live within Leicester, Leicestershire or Rutland. Parents were eligible to receive the support materials if they had a baby who they judged to be excessively crying. Parents whose baby was older than 6 months, or was judged to be ill at the time of crying by their HV/SCPHN or another qualified professional, were excluded from participating. Parents who lived outside the LPT area were also excluded.

Thirty participants in group 1 received the support materials. In group 2, out of 124 parents who consented to take part in the study, 27 reported their baby to be excessively crying and subsequently received the support package (Table 7), with an incidence of 21.7%. Recruitment to this group proved more resource- and time-consuming than expected and it fell just short of the target of 30 cases.

| Participant consents | Group | All parents receiving support materials | All parents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred crying | New birth visit | |||||

| Excessively crying baby | No excessively crying baby | Total | ||||

| Number of parents consented | 30 | 27 | 97 | 124 | 57 | 154 |

Table 8 shows the sociodemographic profile of participants in both groups. There were no statistically significant differences between them.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Group | All parents with an excessively crying baby | All parents | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred crying | New birth visit | ||||

| Excessively crying baby | No excessively crying baby | ||||

| Parental sex, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 24 (80.0) | 27 (100.0) | 94 (96.9) | 51 (89.5) | 145 (94.1) |

| Male | 6 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.1) | 6 (10.5) | 9 (5.9) |

| Parental age (years) | |||||

| Mean age | 31.5 | 29.6 | 30.7 | 30.6 | 30.7 |

| SD (minimum–maximum) | 5.7 (20–43) | 4.7 (21–38) | 5.2 (16–42) | 5.3 (20–43) | 5.2 (16–43) |

| Parental ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White | 24 (80.0) | 23 (85.2) | 86 (88.7) | 47 (82.4) | 133 (86.4) |

| Mixed | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.7) | 3 (1.9) |

| Asian | 5 (16.7) | 2 (7.4) | 5 (5.1) | 7 (12.3) | 12 (7.8) |

| Black | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (3.1) | 1 (1.7) | 4 (2.6) |

| Other | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (1.3) |

| Highest education level, n (%) | |||||

| Postgraduate degree | 5 (16.7) | 6 (22.2) | 22 (22.7) | 11 (19.3) | 33 (21.4) |

| Undergraduate degree | 6 (20.0) | 7 (25.9) | 21 (21.6) | 13 (22.8) | 34 (22.0) |

| Higher post-A-level vocational qualification | 4 (13.3) | 3 (11.1) | 8 (8.2) | 7 (12.3) | 15 (9.7) |

| A level/NVQ level 3 | 8 (26.7) | 6 (22.2) | 19 (19.6) | 14 (24.6) | 33 (21.4) |

| GCSE/NVQ level 2 | 3 (10.0) | 2 (7.4) | 10 (10.3) | 5 (8.8) | 15 (9.7) |

| Secondary school education | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.9) |

| Primary school education | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (5.3) | 4 (2.6) |

| Other | 2 (6.7) | 2 (7.4) | 13 (13.4) | 4 (7.0) | 17 (11.0) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||||

| Full time | 6 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 6 (10.5) | 8 (5.2) |

| Part time | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) | 2 (1.3) |

| Maternity/paternity leave | 15 (50.0) | 18 (66.7) | 74 (76.3) | 33 (57.9) | 107 (69.5) |

| Self-employed | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | 3 (3.1) | 2 (3.5) | 5 (3.3) |

| Unemployed, looking for work | 2 (6.7) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (7.0) | 5 (3.3) |

| Not in paid employment | 4 (13.3) | 5 (18.5) | 14 (14.4) | 9 (15.8) | 23 (14.9) |

| Student | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.9) |

| Full-time carer | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Marital/living status, n (%) | |||||

| Married/cohabiting | 28 (93.3) | 22 (81.5) | 92 (94.8) | 50 (87.7) | 142 (92.2) |

| Living alone but supported by partner | 2 (6.7) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (7.0) | 5 (3.2) |

| Living with parents/friends | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) |

| Single parent living alone | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (2.1) | 3 (5.3) | 5 (3.3) |

Measures

Parent questionnaires

A short participant demographic questionnaire was developed and was completed with all participants at the time of obtaining consent. It can be accessed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/ (accessed 6 December 2018).

Participants with an excessively crying baby completed baseline questionnaires to rate their baby’s crying problem severity, feeding and health and well-being, using items from previous studies. 44 The questionnaires can be accessed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/ (accessed 6 December 2018). They also completed four validated rating scales to measure parental well-being: the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),45 the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS),46 the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) anxiety scale47 and the Maternal Confidence Questionnaire. 48,49

These measures were repeated at the outcome stage to indicate potential improvements and were supplemented with measures of length of breast-milk feeding and crying knowledge. Parents provided ratings of each package component (see Appendix 7) and their suitability for use in the NHS. They were also asked about their willingness to participate in a RCT to evaluate the package components.

Participant take-up of the study support package and the extent of use of each component was recorded. To permit future cost-effectiveness analyses, measures of costs of each component, together with crying-related NHS costs, were also developed; these are discussed in detail in Chapter 13.

Health visitor questionnaire

A HV/SCPHN questionnaire was developed in order to obtain feedback about their involvement in stage 2, their opinions as to how helpful the materials were for parents and the extent to which they were suitable for inclusion in the NHS and their views on the provision of training in supporting parents with excessively crying babies. This questionnaire can be accessed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/ (accessed 6 December 2018).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy practitioner questionnaire

A ‘session form’ to enable the CBT practitioners to record information about the CBT sessions was developed, detailing type, length and location of sessions, child attendance at the sessions and homework completion, and included free-text comments to capture information relating to the extent to which the sessions went as planned and the success of the sessions. This form can be accessed at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1215004/#/ (accessed 6 December 2018).

Procedure

Health visitor involvement

The HVs/SCPHNs from the health visiting teams involved in stage 1 attended briefing meetings about stage 2 of the study. Six further health visiting teams were approached to collaborate in the study after initial participant referrals to the study team were slower than anticipated. All HVs/SCPHNs were given an information pack containing details about stage 2 of the study and how to refer eligible parents.

A total of 124 HVs/SCPHNs from 12 HV/SCPHN teams within Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland gave written agreement to collaborate with the study team by identifying eligible parents.

Following the close of recruitment and follow-up of parents, HVs/SCPHNs were recontacted and asked to complete the HV/SCPHN questionnaire. Over a 3-week period, a total of 124 questionnaires were returned in one of the following ways:

-

hand-delivered to HVs/SCPHNs to complete and immediately return to the researcher

-

completed over the telephone with HVs/SCPHNs because of the pressures on their time

-

left at HV/SCPHN bases with a pre-paid envelope, for HVs/SCPHNs to complete and return in the post to the study team.

Of the 124 questionnaires delivered to HVs/SCPHNs, 96 (77%) were returned completed.

Parent recruitment and involvement

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram in Appendix 8 shows the flow of participants’ involvement throughout stage 2 of the study. A total of 503 parents were considered for the study, of which 259 (51.5%) declined to participate or were considered to be unsuitable or ineligible to participate by their HVs/SCPHNs. In total, 47 parents were referred to the referred crying group and 197 were referred to the new birth visit group.

The HVs/SCPHNs referred both groups of parents to the study team. As in stage 1, HVs/SCPHNs provided parents with brief written details about the study in order to seek parental expressions of interest to enable researchers to contact them. Information about the study was also circulated via the NCT network and flyers were distributed to local children’s centres, HV/SCPHN bases, GP surgeries and venues where parents of young children might attend (e.g. libraries). Parents were thus able to self-refer to the referred crying group.

On receipt of an expression of interest, the researchers contacted each parent by telephone to fully explain the study, assess eligibility and formally invite parents to participate. In instances when the study team were unable to contact the parent using the telephone number given, attempts were made to contact those parents by e-mail, if an e-mail address was available, and telephone conversations were then had with those parents. Appendix 8 shows the number of parents for both groups who were no longer eligible to participate at this point, declined to participate or could not be contacted.

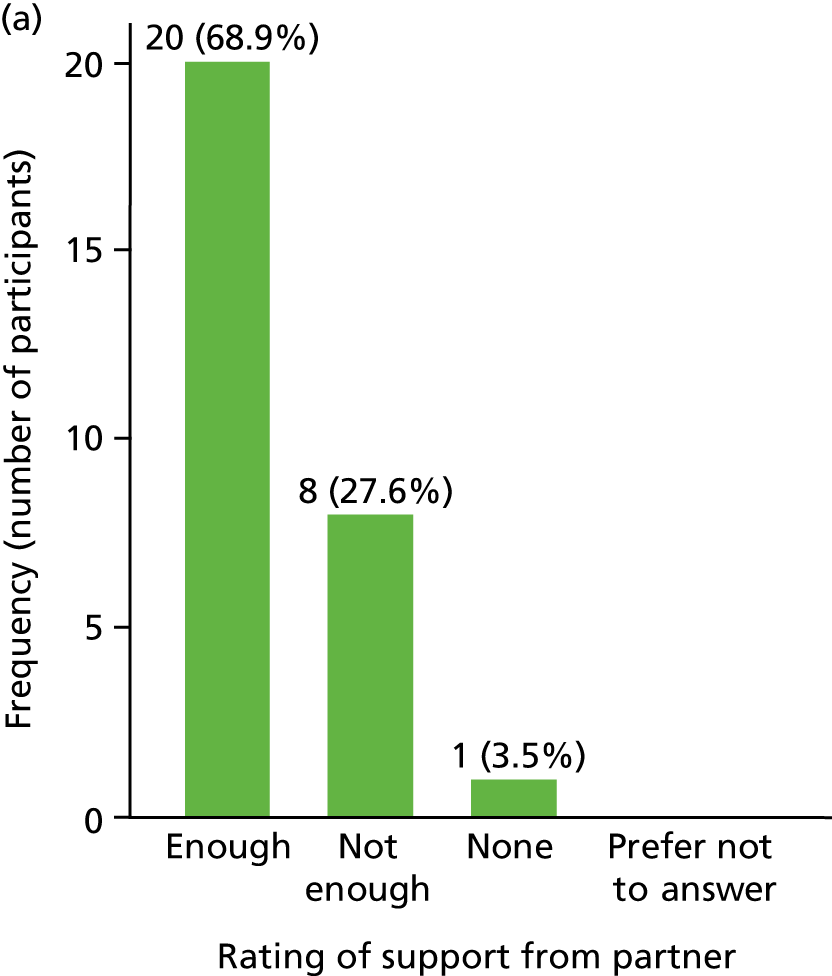

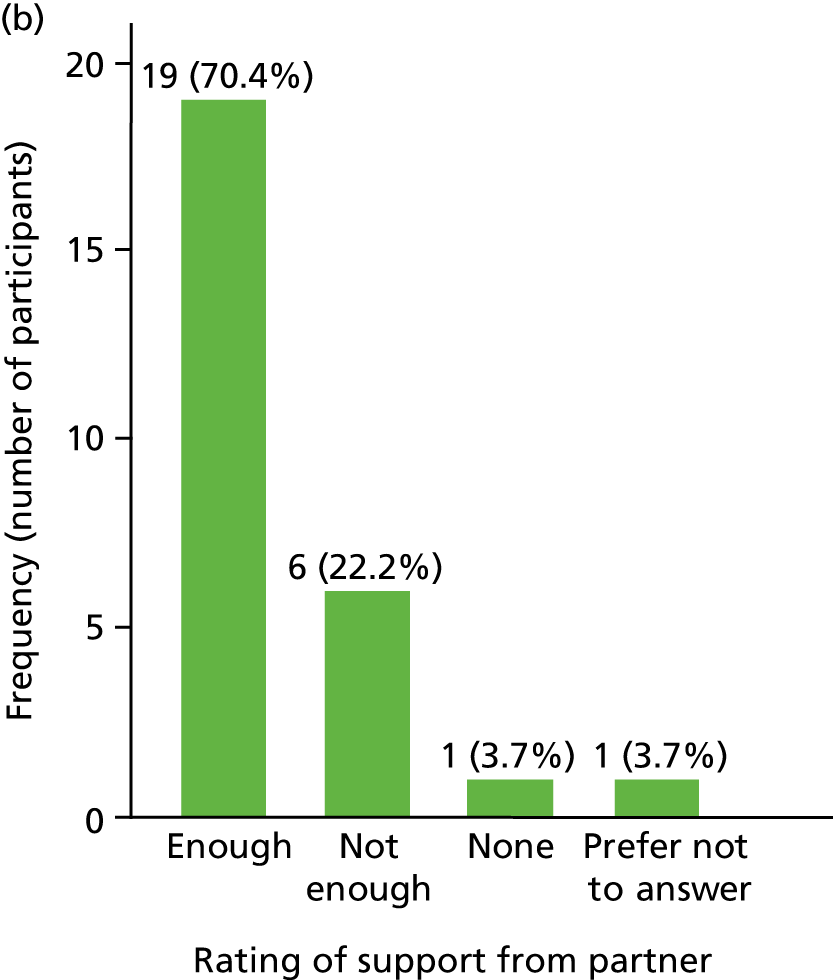

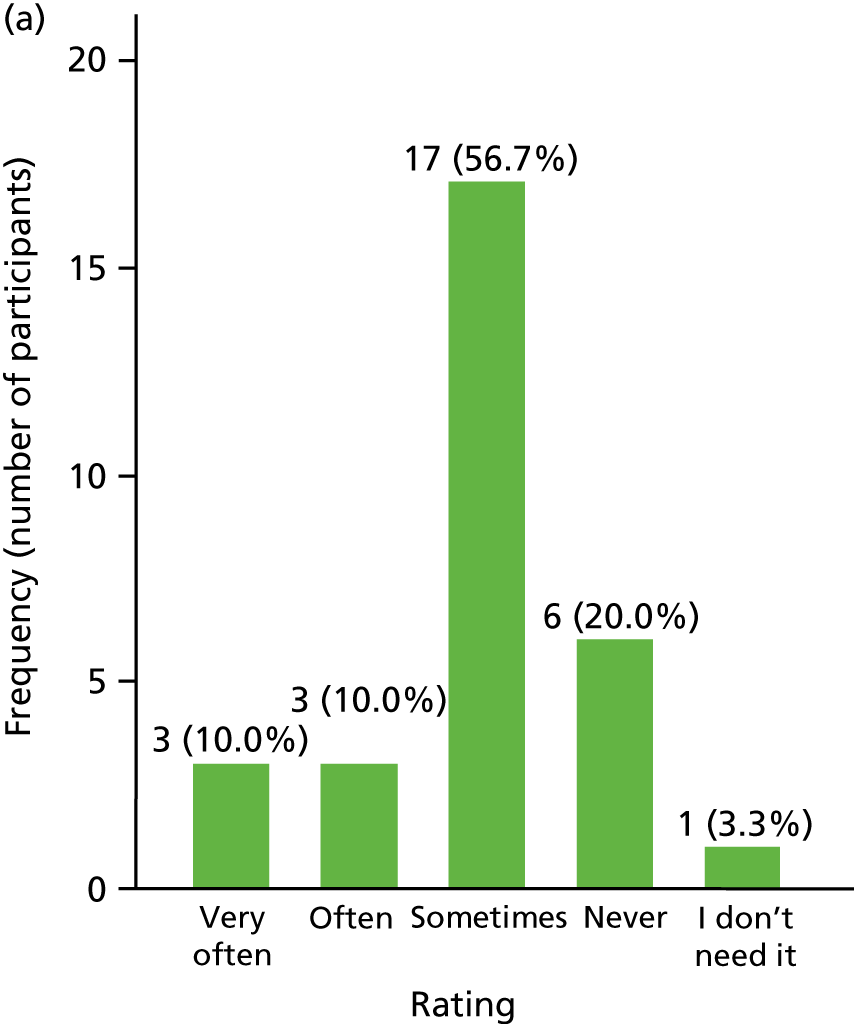

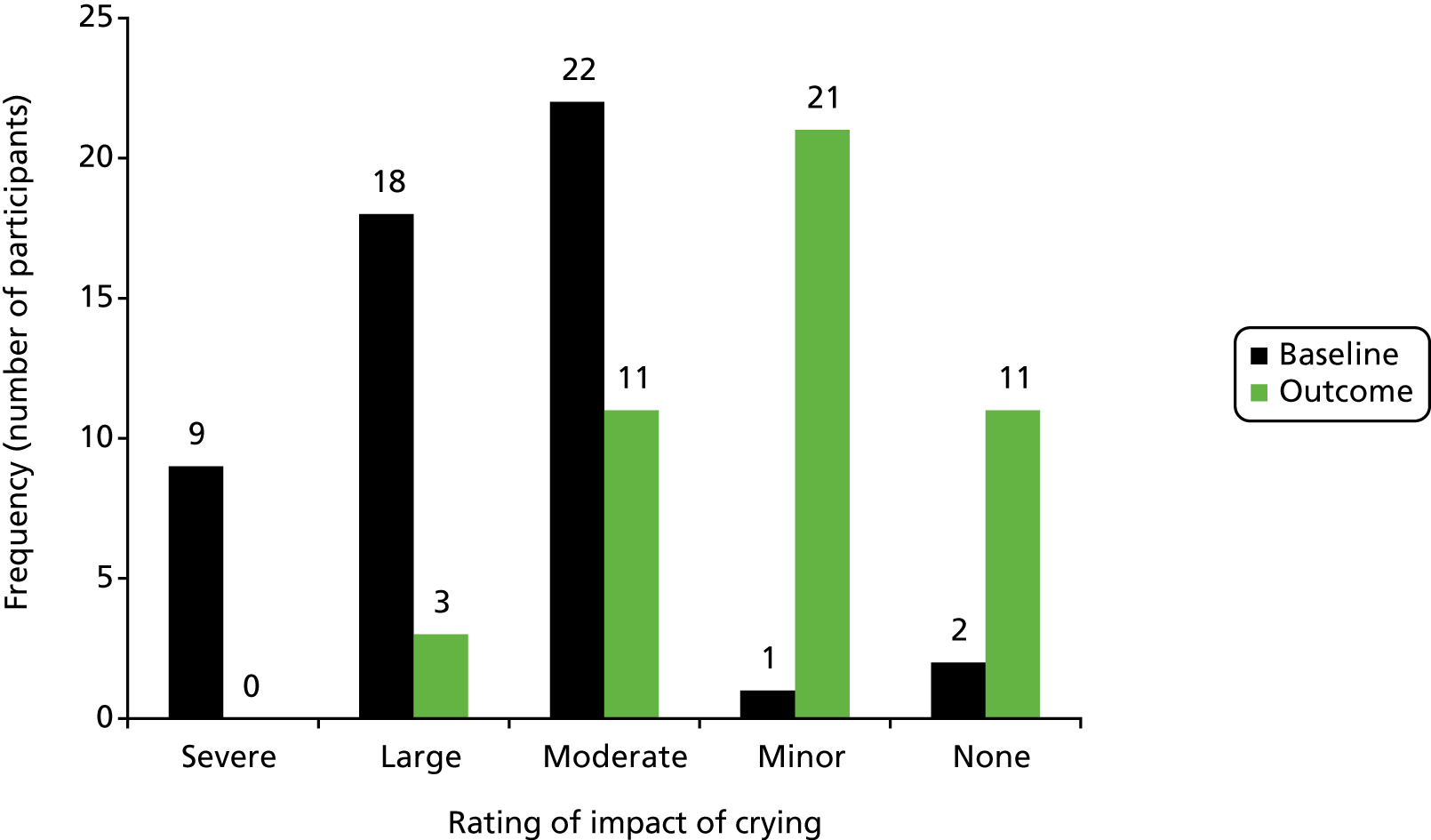

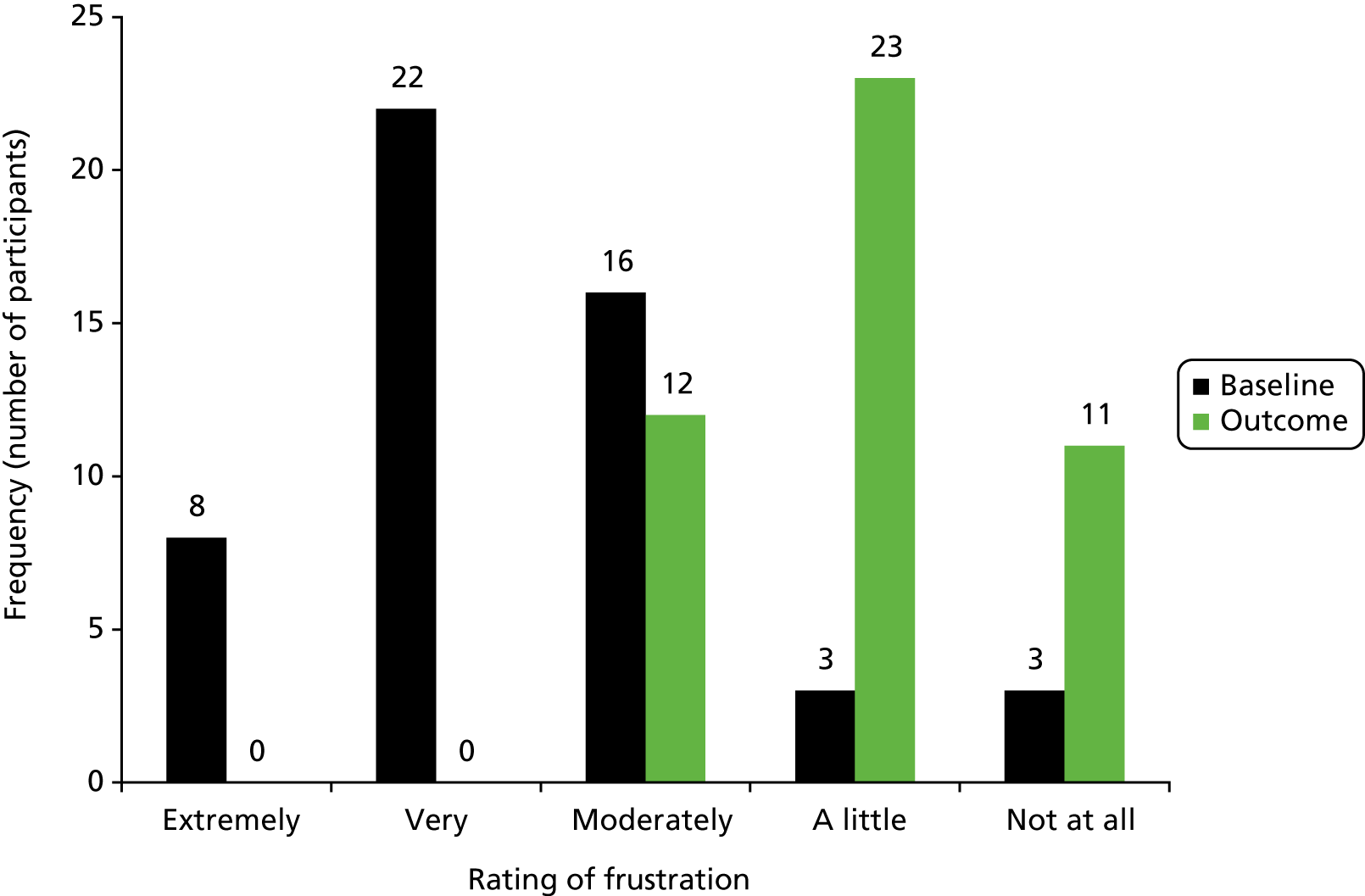

Group 1: referred crying group