Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/78/02. The contractual start date was in June 2015. The draft report began editorial review in January 2019 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Louise Robinson reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Professor award and a NIHR Senior Investigator award outside the submitted work. Lynn Rochester reports grants from the Medical Research Council, the European Union, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Wellcome Trust (London, UK), Parkinson’s UK (London, UK), NIHR [Programme Development Grant, Physical Activity Interventions to Improve Outcomes for people with Rare Neurological Conditions (PARC), co-applicant (2018–20); and Health Technology Assessment, PDSAFE: a randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of PDSAFE to prevent falls among people with Parkinson’s disease, co-applicant (2013–17)] and the Stroke Association (London, UK) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Allan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and context

Recent estimates suggest that there are 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK, of whom 70% live in the community. 1 People with dementia (PWD) living in their own homes experience almost 10 times more incident falls than other older people and their falls are more likely to result in injury. 2 When injuries are sustained, PWD are less likely than cognitively intact older people to recover well. 3

Evidence shows that falls are a common reason for hospital admission in PWD4 and that most admissions for PWD with an injury are due to a fall. 5 Despite this, current UK guidelines for treatment of older people following a fall do not specifically address the needs of PWD;6 the new dementia guidelines7 recommend that falls services address the specific needs of PWD, but provide few details on how this can be achieved. The World Health Organization8 report on falls prevention in older people refers to cognitive impairment only as a risk factor for falls. There is little evidence regarding the care pathways currently experienced by PWD presenting with a fall-related injury.

For older people without dementia, there is good evidence that a multifactorial intervention by a specialist falls service will prevent further falls. 9–12 Such interventions are usually tailored to the individual and are directed at known risk factors for falls. However, their effectiveness for PWD is unclear. 13 It is possible that the lack of demonstrated efficacy is because risk factors for falls may differ in PWD or be more frequent or specific to dementia, for example wandering,14 behavioural disturbance,15 Parkinsonism,16,17 severity of cognitive impairment,16 functional impairment18 and use of neuroleptic drugs. 19,20 Nevertheless, and despite the lack of evidence, PWD are often referred directly to the local falls service. Such services are not usually tailored to meet the needs of PWD. It is possible that the referral may achieve other benefits for the PWD, such as medication review, treatment of other comorbidities or provision of aids to support activities of daily living (ADL), but it is not known if a falls service is the best setting for addressing these goals. Indeed, it is not known what goals are of most importance to PWD who fall.

In designing any kind of intervention to address the problem of fall-related injuries in PWD, it is vital that the intervention addresses outcomes of importance to PWD themselves, their informal carers (i.e. unpaid family members of friends who support the PWD, hereafter referred to as carers) and their care professionals. We accessed the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) database21 and found no consensus regarding suitable outcomes for fall-related injury, although there were two publications regarding interventions of relevance in this situation: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE) consensus on a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials22 (domains include falls, injuries, psychological consequences of falling, health-related quality of life and physical activity) and the European Consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care23 (domains include patient mood, quality of life, ADL, behaviour, carer mood and carer burden).

There is a range of ways in which improved management of fall-related injuries might reduce adverse sequelae for PWD and their carers. First, any fall in older people, whether injurious or not, is known to frequently result in fear of falling and psychological morbidity, which may lead the person to restrict their mobility, resulting in deconditioning and a cycle of further loss of mobility and frailty. 24 A successful intervention may reduce psychological morbidity and improve well-being. 25 Second, if physical recovery from the injury itself is poor, further restriction of mobility may happen and independence in ADL may decline. These restrictions may result in reduced social participation, increased burden for informal carers and increased need for formal care. Such problems lead to reduced well-being and quality of life for PWD, and substantial costs to both health and social care systems. A successful intervention may support the maintenance of physical ability and independence or reduce the degree of physical decline and loss of independence. We are not aware of any clinical trials that have specifically tried to address the management of all fall-related injuries in PWD.

Therefore, although PWD who sustain fall-related injuries currently receive a range of health interventions, a single model of care for this specific situation has not previously been described to our knowledge. Given all of the aspects of care relevant to the situation as described previously, it is apparent that a new model of care would take the form of a complex intervention. Given the frequency of falls in PWD, it is clear that this is an important area for research, although the potential demand for such an intervention is not known. There is also no current consensus on the best outcomes with which to measure the impact of such an intervention or its cost-effectiveness. This report describes the process of developing and testing the feasibility of a new intervention to help this patient group.

Research objectives

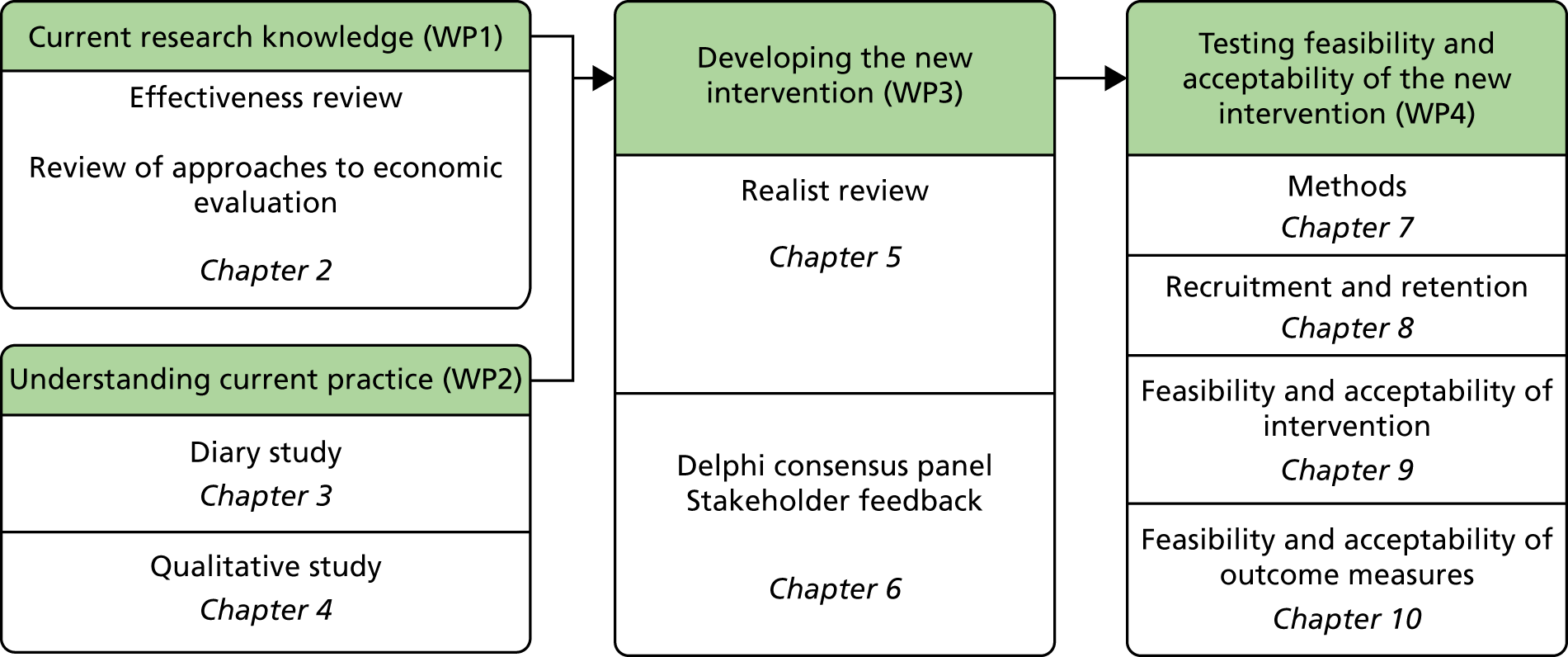

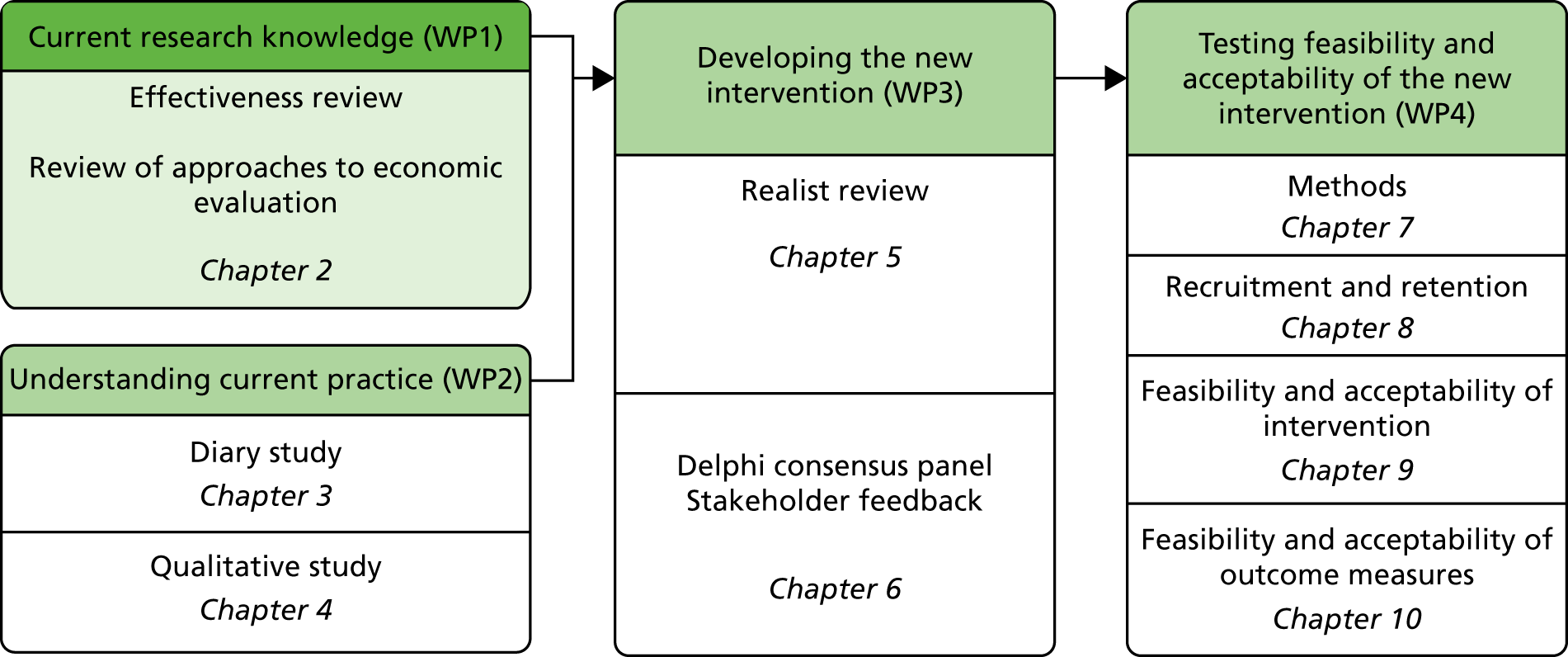

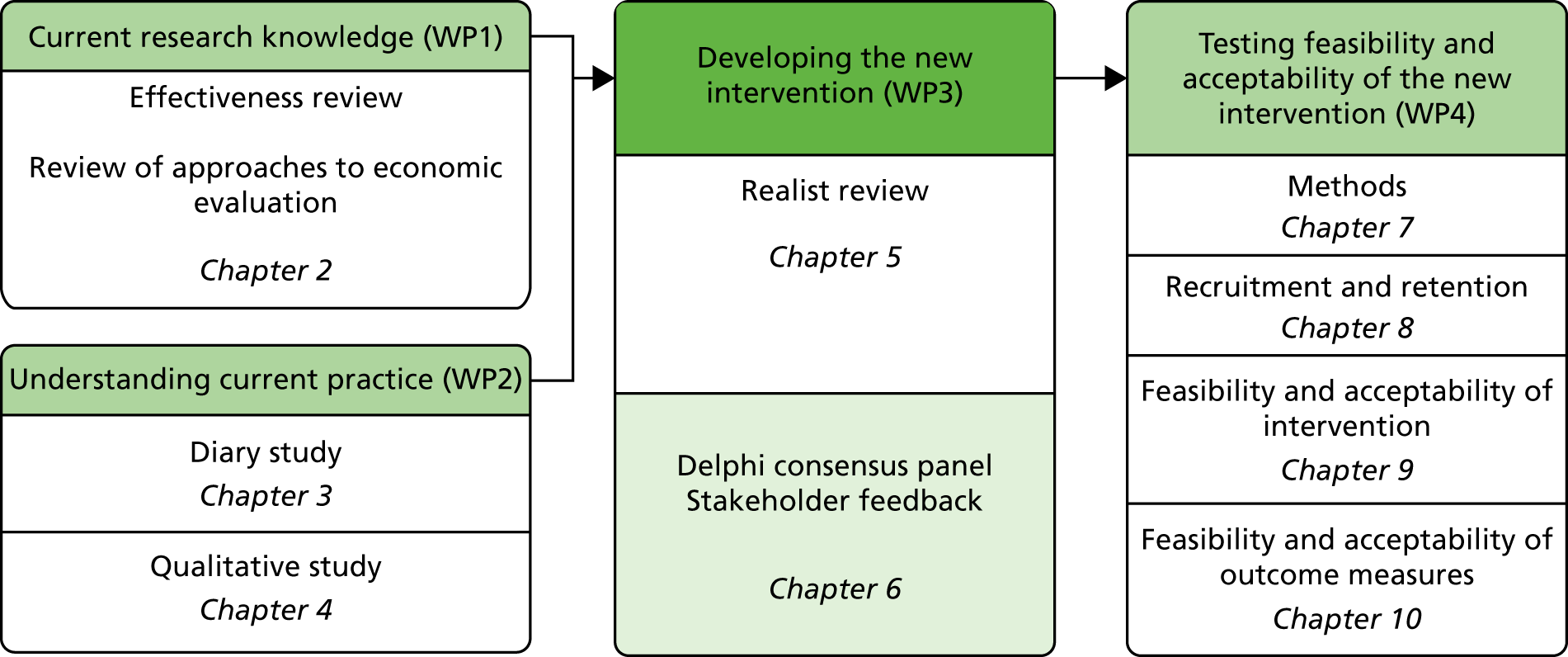

The overall aim of this study was to assess, through a series of work packages (WPs), whether or not it is possible to design a complex intervention to improve the outcome of fall-related injuries in PWD living in their own homes (Figure 1). During the course of the study, the objective was broadened to include people with a fall necessitating health-care attention and not just those with injurious falls.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of study and report structure.

Primary objectives

Work package 1: current research knowledge

-

To conduct a systematic literature review to synthesise the current evidence regarding the management of fall-related injuries in PWD.

-

To investigate what evidence is currently available regarding the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving the outcome of fall-related injuries in dementia.

Work package 2: understanding current practice

-

To quantify PWD presenting to health services with a fall-related injury in three UK sites.

-

To understand current care pathways (‘usual care’) experienced and the services used by a subgroup of PWD who completed a falls diary for 12 weeks following a fall.

-

To identify care needs and ideas for intervention, and prioritise the outcomes that are important to participants and their carers.

Work package 3: developing the new intervention

-

To develop an intervention to improve outcomes for PWD following a fall, drawing on the findings of WP1 and WP2.

-

To describe the outcome measures to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

-

To validate the proposed intervention through qualitative work with stakeholders, including some participants from WP2.

Work package 4: testing the feasibility and acceptability of the new intervention

-

To conduct a non-randomised feasibility study to deliver the new intervention to 10 PWD in each of the three sites.

Secondary objectives

-

To use the data collected in WP1 and WP2 to develop data-collection tools for use in the evaluation of a new intervention.

-

To assess the factors influencing the acceptability and implementation of the intervention and to determine whether or not to progress to a full-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Chapter 2 Reviews of effectiveness and approaches to economic evaluation

Parts of this chapter are adapted from Robalino et al. 26 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

There is no consensus on how best to manage PWD who have had a fall. As part of this study, two reviews were conducted. The first focused on the effectiveness of different interventions targeted at PWD who have experienced a fall. The aim of this review was to help inform the development of the intervention to be piloted in WP4 (see Chapter 7). In addition to assessing the intervention’s effectiveness and safety, it was important to evaluate whether or not it would represent value for money. The second review, therefore, synthesised existing evidence on economic evaluations of falls prevention interventions in PWD. It was not stipulated in the economic review that the population had to have previously experienced a fall as the methods for evaluating a falls prevention intervention would be the same among those with and without a previous fall. The aim of this review was to identify the most appropriate methods and outcomes for an economic evaluation of the intervention to be developed for PWD following a fall.

Effectiveness review

The aim of this systematic review was to synthesise all existing research evidence evaluating the effectiveness of interventions intended to improve the physical and psychological well-being of PWD who had experienced a fall. The full review has been published separately. 26

Methods

The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO (reference CRD42016029565). 27 The review was informed by Cochrane methods28 and described in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. 29

Selection of eligible studies

Eligible studies were randomised or quasi-experimental trials that recruited PWD living in the community who had experienced an injurious or non-injurious fall and received any type of intervention aiming to improve the fall outcomes of PWD. Comparator groups in the trials had to be receiving usual care. Eligible primary outcomes were measures of performance-oriented assessment of mobility (e.g. the Tinetti score30) and measures of performance in ADL (e.g. Barthel Index31). Secondary outcomes of interest were length of hospital stay, place of discharge post intervention, recurrent fall or injury and readmission to hospital.

We excluded trials that (1) recruited only cognitively intact patients or a mix of patients where results for PWD were not reported separately, (2) recruited exclusively from care homes or (3) were not published in the English language.

An experienced information specialist searched eight bibliographic databases and two trials registries for reports of eligible studies from database inception to November 2015 and updated the MEDLINE search in January 2018. The search contained the following facets: [dementia] AND [falls or fall-related injuries] AND [interventions or RCT filter where available]. For each facet, thesaurus headings and keyword synonyms were combined in accordance with good practice in systematic review literature searching, and translated as appropriate between databases. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were searched for further eligible studies, and all results were collated in an EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) library. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts in EndNote, and then they screened the full texts of the resulting potentially eligible studies. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and reference to a third reviewer. One reviewer extracted data to a bespoke data extraction form in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and a second reviewer checked it. Data extracted included details of the study population [e.g. Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score32], setting (e.g. ward), the intervention (e.g. care team and services used), the comparator and outcomes (e.g. mobility and length of hospital stay) measured at baseline and follow-up. We e-mailed authors to request data missing from eligible studies.

Critical appraisal and synthesis

Two reviewers independently used the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool33 to critically appraise each included study outcome, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion and referral to a third reviewer. The Cochrane tool facilitates a judgement of low, unclear or high risk of each of selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting bias.

We planned to carry out a meta-analysis, but few of the included studies measured the same outcome, and, even when they did, different outcome measures were used, thereby precluding a valid statistical analysis. Consequently, we carried out a narrative synthesis, broadly categorising studies by intervention and presenting detailed results by outcome.

Results

Selection of eligible studies

The initial search returned 1071 studies after deduplication (Figure 2). Of these, 991 were excluded by screening titles and abstracts, and the full texts of 80 were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 69 were excluded because they were not RCTs or quasi-experimental studies, they did not include PWD or the PWD did not reside in the community. A total of 11 studies remained for narrative synthesis, but four had missing data that could not be obtained. Seven studies were included in the narrative synthesis.

FIGURE 2.

Effectiveness review PRISMA flow diagram of study inclusion and exclusion. Adapted from Robalino et al. 26 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

Characteristics of included studies

Six RCTs and one quasi-experimental study were included in this review. 34–40 In the quasi-experimental study, patients were recruited in two phases. In the first phase, all consecutive patients from two sites were recruited to the control group; in the second phase, all were recruited to the intervention group. The trials recruited mostly patients with hip fractures in hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) in high-income countries. All studies included both cognitively intact patients and patients diagnosed with dementia, except one that recruited patients with at least mild dementia (MMSE score of < 24 points). 34

Five studies evaluated multidisciplinary in-hospital post-surgical geriatric assessment, which varied in terms of the type of ward (e.g. geriatric vs. orthopaedic), mix of multidisciplinary staff and components of the intervention. 35,37,40 All studies in this group included a core team of a geriatrician, nurse, occupational therapist (OT) and physiotherapist, plus other staff, such as social workers or dietitians, as required. The interventions included different combinations of components, for example early-discharge planning, post-discharge home visits and weekly team meetings.

One study evaluated multifactorial assessment and intervention in patients presenting at an ED post fall, utilised a multidisciplinary team (MDT) similar to that used in the in-hospital geriatric assessment and followed up with risk assessments in patients’ homes. 34 Patients were then offered a variety of interventions based on the risk assessments; these interventions included home-based exercise, home hazard modification, medication review and optical correction by an optician.

The final study provided an annual dose of intravenous zoledronic acid to participants in an attempt to reduce recurrent falls and further fractures by improving bone health. 36

Critical appraisal of studies

The included studies were mostly at low risk of selection bias, and many were at high risk of performance and detection biases due to difficulties in blinding participants and/or personnel to interventions and outcomes (a common scenario with complex interventions). The risk of bias for attrition and reporting was less well reported.

Outcomes

Three RCTs34,37,38 and one quasi-experimental study40 reported different measures of mobility following the intervention, of which three studies reported limited improvement or retention of mobility in the intervention group compared with the control group. Those studies utilising multidisciplinary in-hospital postsurgical geriatric assessment reported short-term improvements in gait, but long-term improvements were either not reported or proved statistically insignificant. 37,38,40 The studies used different mobility scales that exhibited relatively little overlap in the components measured.

Three studies reported recurrent falls post intervention,34,36,37 of which one37 reported a reduction in inpatient falls in the treatment group (4%) compared with the control group (31%) (p = 0.006), although there was no difference in the rate of new fractures. A second study34 reported no difference in the number of patients with falls, the median number of falls or the median number of weeks before the second fall. The final study36 found no difference in falls for PWD, but reported a reduction in recurrent fractures at 6 months in the cognitively impaired patients.

Three studies reported on post-intervention ADL,37–39 utilising four tools that had limited overlap, with only two common items (feeding and transferring). The results were not consistent between studies.

Three studies measured length of hospital stay using multidisciplinary in-hospital post-surgical geriatric assessment, but with varying components. 35,38,39 Two studies35,39 showed a decreased length of stay for those with mild or moderate (but not severe) dementia, and the other study38 reported a significantly higher median length of stay in the intervention group.

All of the studies utilising multidisciplinary in-hospital post-surgical geriatric assessment and intervention reported on the place of discharge. 35,37–40 Three reported that PWD were more likely to return to independent living following the intervention,35,39,40 and the other two described no difference between the intervention and control groups. 37,38

Two studies reported no evidence of impact on readmission rates to hospital. 34,38

Discussion

The effectiveness of interventions to improve outcomes for PWD who fall was highly heterogeneous in terms of all interventions compared, the outcomes considered and the patient populations considered. Three of these studies used multidisciplinary in-hospital post-surgical geriatric assessment, which showed improvements in some outcomes within their treatment groups, regardless of mental status. 41–43 Overall, the risk of bias in the studies was mixed and their results conflicted even when similar interventions were utilised.

Four eligible studies provided no useable data for this review;41–44 we contacted the authors to clarify reported results or request subgroup data where they were reported to be available, but received no response.

The term ‘Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment’ (CGA) was not used consistently with respect to the staff delivering the intervention, frequency of MDT meetings, discharge planning, post-discharge in-home follow-up, falls assessment and prevention, or medication management. Current evidence suggests that CGA is likely to benefit older people hospitalised with acute conditions owing to these services generally providing a multidimensional, multidisciplinary approach that includes the identification of medical, social and functional needs, as well as the development of an integrated and co-ordinated care plan to address those needs. 45,46 The question of whether or not there is a need for adaptation of CGA for PWD has not been addressed.

Generally, the earlier a patient is mobilised, the better the outcome with regard to reduced length of stay and discharge to independent living. Patients with mild and moderate dementia showed better outcomes than those with more severe dementia.

Strengths and limitations

This review used robust methods including prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria, a comprehensive search and duplicate screening, data extraction and critical appraisal procedures. However, we were unable to include all of the relevant studies in the synthesis; despite efforts to contact authors of four studies, we were unable to obtain their data grouped according to dementia status.

The searches were carried out to inform the panel meeting in WP3 and updated in January 2018 for publication of the effectiveness review. As they have not been updated again for this report, the findings should be interpreted as informing only that WP and not for current clinical decision-making.

Conclusions

We found gaps in the evidence base. Most of the study populations presented with hip fracture in hospital so interventions may not be applicable to soft tissue injuries or other types of fracture, and these studies provided no guidance about managing fall-related injuries in primary care. Most of the studies were not aimed at PWD, and subgroup analysis was used to report the effects of interventions targeted at the general older population on PWD.

Review of approaches to economic evaluation

The aim of this review was to understand the current cost-effectiveness evidence base in the area to inform the design of a potential future economic evaluation of the DIFRID (Developing an Intervention for Fall related Injuries in Dementia) intervention should it proceed to a definitive trial. The review identified economic evaluations of fall prevention interventions in PWD to make recommendations about:

-

how best to capture the resources used to provide the intervention and any changes in subsequent use of services

-

appropriate outcomes that would (1) capture the benefits of the intervention, (2) be appropriate for use with PWD and (3) provide information for an economic evaluation relevant to policy-makers.

Drawing on the findings of the review, we developed and piloted data collection tools to collect information on health-care resource use in WP2 (see Chapter 3) and WP4 (see Chapter 10).

Methods

Searches were formed of two facets and were based on an amended version of the NHS Economic Evaluation Database search filter where necessary. 47 The facets were (1) dementia and (2) falls or fall-related injuries. Only studies including full economic evaluations were eligible (i.e. studies that compared two or more interventions in terms of both their costs and their outcomes). 48 The search was extended to incorporate patients with cognitive impairment as many approaches might be equally applicable to this patient group.

Electronic database searches were conducted in August 2016. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE and NHS Economic Evaluation Database. An example of the search strategy used in MEDLINE is provided in Appendix 1. Citations of potentially relevant studies were also checked for additional eligible studies, as were citations in any previously conducted literature reviews relevant to the topic that were identified. Protocols of ongoing studies were also included if they provided information on the planned economic evaluation.

Selection of eligible studies

The following inclusion criteria were applied:

-

reported in the English language

-

reports of full economic evaluations – cost–benefit, cost–utility, cost-minimisation and cost-effectiveness analysis

-

patients had any diagnosis of cognitive impairment

-

the intervention was falls prevention

-

the comparator was usual care or no intervention

-

the economic outcomes were costs, falls, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) (e.g. incremental cost per QALY gained or incremental cost per fall prevented).

We adopted the same exclusion criteria as were used in the effectiveness review with the exception that care home studies were included. An additional criterion for the cost-effectiveness review was that studies were excluded if they did not incorporate falls into the economic evaluation.

Critical appraisal and synthesis

Titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the search were assessed by two reviewers using EndNote. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were then obtained. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and a third reviewer when needed. Data were extracted by one reviewer using a prespecified data extraction form. Data collected included details of the study population (e.g. PWD), the intervention (e.g. rehabilitation classes), the comparator and outcomes (costs and falls or QALYs). The range of interventions, populations and outcomes reported in the included studies was described. The quality of included studies was assessed against a commonly used checklist for reporting economic analyses. 49

Similarly to the effectiveness review, risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. 33

Results

Selection of eligible studies

The initial search returned 1252 reports. Eleven papers were excluded after deduplication and 124 were excluded as they were not in English. A further report was identified from an ineligible report that was a literature review concerning fall interventions. 50 Overall, six reports were deemed potentially relevant and the full papers were obtained.

Four reports were excluded after the full texts were reviewed. One paper was a critical review of another paper that was selected for full review. 51 One paper estimated the cost-effectiveness of falls prevention of a range of interventions using the results of a systematic review to populate a Markov model. 50 The population included in that review were people aged ≥ 65 years, but their exclusion criteria included ‘special populations (e.g. stroke or osteoporosis)’; therefore, we cannot assume that people with cognitive impairment were included in the model. 50 Two of the excluded papers, one protocol and one economic evaluation based on a RCT, evaluated exercise-based interventions in PWD in nursing homes [the LEDEN (Effects of a long-term exercise programme on functional ability in people with dementia living in nursing homes) study52] and patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [FINALEX (FINnish ALzheimer disease EXercise trial)53]. The aims of these studies were to improve functional ability (LEDEN) and to improve physical functioning and mobility (FINALEX). Overall, although both studies collected falls as a secondary outcome, it was not the primary objective of their intervention and neither incorporated number of falls as an outcome measure in their economic evaluations. The LEDEN study protocol outlined the outcome measures for the economic evaluation as costs and changes in functional ability measured using the Alzheimer Disease Cooperative Study ADL-severe. 54 FINALEX estimated the ICER as the cost per dyad (patient with AD and their carer who was a spouse they resided with). 53

Included studies

Two papers met the inclusion criteria, both of which were protocols. 55,56 The i-FOCIS RCT aims to examine whether or not an individually tailored, cognitive impairment-specific approach to the delivery of an exercise and home-hazard-reduction programme can reduce the rate of falls in community-dwelling cognitively impaired older people. 56 The Encouraging Best Practice in Residential Aged Care (EBPRAC) programme aims to improve evidence-based clinical care for residents in aged-care homes and to enable nationally consistent application of this care. 55 Both proposed studies will be undertaken in Australia.

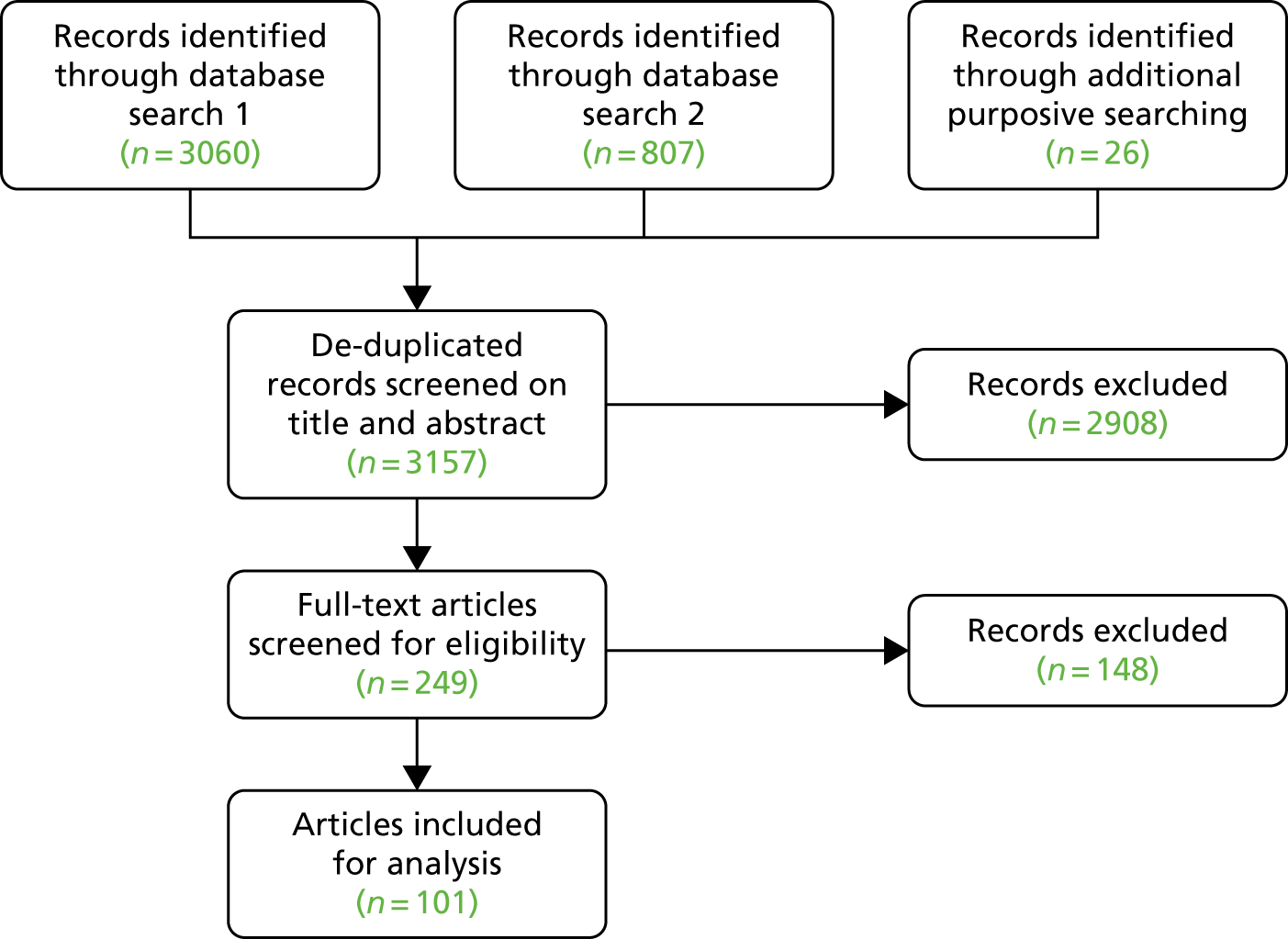

A PRISMA breakdown of study inclusion and exclusion is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Economic evaluation review PRISMA flow diagram of study inclusion and exclusion. CI, cognitive impairment.

Participant and study characteristics

The studies have different target populations. One study targets people aged ≥ 65 years living in the community with cognitive impairment (n = 360)56 and the other targets residents of residential aged-care facilities, including PWD (nine residential aged-care facilities, 670 patients and 650 staff will be invited to participate). 55

Perspective of the studies

The protocols55,56 suggest that the economic evaluations will be conducted from the perspective of (1) the health and community service provider (i-FOCIS) and (2) the societal and residential aged-care facility (EBPRAC).

Resource use data (costs)

The i-FOCIS RCT will capture information on the consumable, reusable and capital resources required to deliver the interventions as part of the trial. Data on health-care resources, including medications, will be captured via self-reported monthly calendars for 12 months. Costs will be collected from routine sources and out-of-pocket expenses for the patients and their carers will be estimated from a previous published study. 57

The EBPRAC programme will determine the resources needed to deliver the intervention by monitoring the resource use during the project implementation for 12 months. These resources will be costed using market values where possible. Fall-related health-care resource use will be collected from two participating sites. There is no information provided on where these costs will be collected from.

Outcome measures

The rate of falls will be the primary outcome for both of these studies, and both economic evaluations will incorporate this into their analysis. The primary economic outcomes are the cost per fall prevented (i-FOCIS56) and the cost per fall (EBPRAC55). The i-FOCIS RCT incorporated additional outcome measures in the economic evaluation: falls requiring medical attention, ED presentation avoided, hospital admission avoided and QALYs estimated using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L).

Economic evaluation

The i-FOCIS RCT will analyse its data as a within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis. Appropriate sensitivity analyses, including deterministic and stochastic analyses, will be used to address any uncertainty in costs, effects and cost-effectiveness. The probability of the intervention being considered cost-effective at current willingness-to-pay thresholds will be presented as cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

The EBPRAC programme will determine whether or not there is a reduction in the cost per fall associated with the intervention by analysing the cost per fall pre and post intervention implementation. Cost per fall will be estimated by modelling the costs collected from two participating sites. Sensitivity analyses will be carried out to address any uncertainty surrounding costs and effects.

Duration of the studies and data-collection time points

The i-FOCIS RCT has a 12-month follow-up, with clinical and quality-of-life outcomes collected at baseline, 6 months and 12 months. The number of falls and health-care resource use are collected using monthly diaries. The EBPRAC programme will be a 2-year study; it also includes a review of the literature, hence it is unclear when the intervention will be implemented. However, although the study team will review falls data every 6 months, it is unclear when other outcome measures will be collected. An economic model will be used to estimate costs and effects 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years post intervention implementation.

Quality of the studies

As the papers suitable for inclusion were protocols, there is insufficient detail on the methodology of the economic evaluations for us to evaluate the quality of the proposed analyses using standard criteria. 49 The i-FOCIS RCT is not accounting for any longer-term costs and benefits that may be accrued after the intervention is implemented. If the intervention is effective, this could create potential bias if the follow-up is not sufficiently long for benefits and possible cost savings in subsequent care to offset the cost of the intervention. The i-FOCIS RCT is not considering the potential impact of the intervention on carers, despite their involvement in the home exercise programme by supervising practice sessions and assisting in delivering the sessions at home.

The duration of the EBPRAC programme is unclear, but if costs and outcomes are going to be estimated beyond a 1-year time frame in an economic model then discounting needs to be considered. There was no detail provided on the type of economic evaluation model being undertaken. Therefore, it is unclear if the approach provided will be sufficient to capture costs and benefits in the longer term.

Discussion

Both cost-effectiveness and cost–utility analyses are currently being incorporated into studies evaluating a falls-prevention intervention in people with cognitive impairment. It is likely that the DIFRID intervention, described in Chapter 6, will involve a number of health-care resources and a MDT given the complexity of the health problem. It is recommended that each individual resource needed to deliver the intervention should be identified and costed using routine sources where available. Costs estimated from routine sources are arguably less reliable than those estimate from time-based materials costing; however, they can be a good representation of the estimated cost associated with these resources. Arguably, for a study seeking to inform NHS and social care decision-makers, the perspective of the economic evaluation should be that of the health-care provider (the NHS) and Personal Social Services. The inclusion of direct and indirect costs to the person with dementia and the carer is important to understand the impact of care on these people as this informs judgements about efficiency and fairness (i.e. equity). Such costs for a UK context are best considered as part of a sensitivity analysis.

For the cost-effectiveness analysis, the effectiveness outcome would be reported as a physical unit: the number of falls. 55,56 The inclusion of this outcome measure would enable comparison of the DIFRID intervention with other interventions aimed at reducing the number of falls in PWD. In WP2 (see Chapter 3), the number of falls was self-reported by participants and captured in a falls diary. Although using self-reported data may not be the most reliable source of data collection, it is also being used in the i-FOCIS RCT56 and has been successfully used in other studies. 58

For the cost–utility analysis, the preferred generic utility-based measure of health-related quality of life is the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). 59 As a generic measure, the EQ-5D facilitates the comparison of interventions across conditions and is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for use in technology appraisals in England. 60 This questionnaire has five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The original version of the EQ-5D, now called the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), has three levels (no problems, some problems and extreme problems) for each question. The tool has been revised and has been expanded to five levels (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems) for each question (EQ-5D-5L). 61 The EQ-5D-5L is recommended as part of this economic evaluation as it is arguably more sensitive than the three-level version62 and it is also being used in the i-FOCIS study. 56 Furthermore, the methodological work on improving the tool and providing scoring systems is now concentrated on the EQ-5D-5L. A proxy version of the EQ-5D-5L should also be completed by carers as previous studies have found that PWD are unlikely to report ‘extreme problems’. 63,64 The proxy version, on average, estimates lower quality-of-life values than the self-completed version and is more likely to be sensitive to changes in quality of life. 63–65 The inclusion of both the self-completed version and the proxy version of the EQ-5D means that any uncertainty in the overall cost-effectiveness depending on who completed the EQ-5D can be explored. 64

For the economic evaluation, costs and outcomes should be discounted at recommended rates60 if the follow-up period of the study is beyond a 1-year time horizon. Consideration also has to be given to any uncertainty that arises as part of trial-based economic evaluations. Deterministic sensitivity analysis can be used to address any uncertainty surrounding assumptions made during the analysis. A stochastic sensitivity analysis, using, for example, the bootstrapping technique,66 would be appropriate to explore the impact of the statistical imprecision surrounding estimates of costs, effects and cost-effectiveness. Uncertainty surrounding the cost-effectiveness ratio should be presented on the cost-effectiveness plane67 and as CEACs.

Strengths and limitations

There are a number of limitations of this review. First, although the comprehensive search generated over 1200 hits, only six full-text papers were deemed eligible for further review after the screening process and only two protocol papers were eligible. This indicates that few fall prevention interventions in PWD have included economic evaluations. Second, not including falls recovery in the search terms means that we may have missed some potentially eligible studies that focused on recovery and rehabilitation post fall. Third, the strict inclusion criteria of falls prevention interventions meant that two potentially relevant studies were excluded51,52 and additional sources evaluating interventions for PWD more generally were not identified. The rationale for focusing the review on economic evaluations of falls prevention interventions was to ensure that any recommendations made for a future definitive study are comparable with existing literature in this area. Finally, the risk of bias was not determined for the two eligible studies. This is a potential limitation of our results but in the context of this review it was not a major concern as the focus was to identify the most appropriate economic evaluation methodology.

The searches were carried out to inform the panel meeting in WP3. As they have not been updated for this report, the findings should be interpreted as informing only that WP and not for current clinical decision making.

Conclusions

The inclusion of economic evaluations to determine the efficiency of alternative courses of action is recommended to inform policy-makers in the UK. 60 To conduct an economic evaluation, considerations need to be made to both the costs and the outcomes of these courses of action. Given the low level of evidence from existing studies, future economic evaluations should (1) identify and cost all of the resources required to deliver the intervention and any subsequent health and social care resource use, (2) measure outcomes using both number of falls and QALYs (using the EQ-5D-5L) and (3) undertake sensitivity analyses to address any uncertainty in the analysis.

Chapter 3 Incidence of fall-related injuries and the diary study

Introduction

The reviews reported in Chapter 2 indicate a lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of fall interventions for PWD and limited attention to the economic evaluation of such interventions. PWD who sustain fall-related injuries may currently receive a range of health interventions, but the current models of care for this specific situation have not previously been described and the potential demand for such an intervention is not known. In order to develop a new complex intervention for this situation, we wished to describe current usual care and assess the demand for a future intervention to ascertain the feasibility of recruitment in WP4. We planned to do this by measuring the incidence of fall-related injuries presenting via three settings: the ED, paramedic attendances and primary care consultations.

In a subgroup of people presenting with fall-related injuries, we piloted a data collection tool in the form of a diary to collect data about falls, help at home and usual care. Information on usual care was obtained by analysing the health-care services used by diary participants after a fall-related injury. We planned that this diary would also be used to refine the design of a data collection tool used in WP4 to meet the requirement to identify subsequent health and social care resource use and capture data on the number of falls (see Chapter 2).

In order to obtain further information about experiences of usual care, some participants in the diary study also took part in a qualitative interview (described in Chapter 4). This chapter describes the incidence of fall-related injuries and the findings of the diary study.

Aim

The aim of the diary study was to determine the feasibility of recruiting PWD through different settings and to pilot the data collection tool prior to the feasibility study in WP4.

Methods

Setting

The study was carried out in three sites (Newcastle upon Tyne, North Tees and Norwich), reflecting a range of NHS practice to allow for generalisability. These sites covered both urban areas and rural areas, included a NHS trust with a long history of innovation in falls services and had dementia diagnosis rates both above and below the national average.

Three potential clinical settings were identified where we anticipated PWD with a fall-related injury would present:

-

Primary care – patients with a known diagnosis of dementia presenting with a fall-related injury to any primary care professional at participating practices in the NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) involved in the study (Newcastle Gateshead CCG, Hartlepool and Stockton CCG and Norwich CCG).

-

The community – paramedics attending calls to a person with possible dementia presenting with a fall-related injury. This applied to calls within the postcodes served by the CCGs mentioned above.

-

Secondary care – patients with possible dementia, resident within the postcodes served by participating CCGs, presenting to the EDs of participating sites.

The study took place in all three settings at each research site.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were required to:

-

Have a known diagnosis of dementia, made prior to entry into the study, by a specialist in dementia care (geriatrician, neurologist or old-age psychiatrist). The potential participant’s general practitioner (GP) was asked to confirm that the potential participant was on the practice’s Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) register of PWD, or the GP confirmed that the person’s records contained confirmed Read codes that would result in the QOF register being updated to include this person. Appropriate Read codes (and their equivalent International Classification of Diseases codes) for including a person on the QOF register are given in Appendix 2.

-

Have sustained at least one fall-related injury within the 48 hours prior to their identification as a potential study participant. The fall causing this injury was known as the index fall. A fall was defined as an event whereby a person comes to lie on the ground or another lower level with or without loss of consciousness. 68 Injuries were defined using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition, Clinical Modification, diagnosis codes: ‘Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes S00-T88’. 69 A fall-related injury was defined as an injury that came about as a direct consequence of the index fall.

-

Be dwelling in the community at the time of the index fall.

-

Have a carer to assist with completion of the diaries (for those in the diary study).

Exclusion criteria

Participants found to be dwelling in residential or nursing care accommodation or to have been a hospital inpatient at the time of the index fall were excluded.

In addition, potential participants were excluded from the diary study if:

-

A diagnosis of dementia could not be confirmed by consultation with the GP or via the secondary care notes within 2 weeks of their being identified as a potential participant.

-

The participant or carer refused to provide consent.

Recruitment

In primary care, patients on the dementia QOF register had a flag applied to their records. If a primary care consultation with these patients took place, the professional was alerted to determine whether or not the consultation was due to a fall-related injury and, if it was, the consultation was added to the screening log. Consent was to be sought from the patient and/or their carer for the research team to contact them with further information about the diary study.

In the community, paramedics attending a person with a fall routinely refer the person to the local integrated falls services via a logistics desk. Basic information about comorbidities is sought by the person receiving the referral at the time of the referral. During the period of recruitment, the teams were asked to include a question about whether or not it was possible that the person may have dementia. This information could be obtained by a direct history of known dementia or confusion from the person or their carer, or, if not available, if the person appeared to be confused in the opinion of the paramedic. All persons with possible dementia who had sustained an injury were added to the screening log. The paramedic was to seek verbal consent for the research team to contact the person with further information about the diary study.

In secondary care, ED staff were asked to consider whether or not patients presenting with fall-related injuries had possible or known dementia and record this in their notes. ED staff were also asked to seek verbal consent from these patients at the time of the consultation for the research team to contact them with further information about the diary study. All cases of fall-related injuries presenting to the ED were screened by a clinical trials assistant (CTA) for evidence of a dementia diagnosis, possible dementia or other evidence of confusion, and all such cases were added to the screening log.

The CTA at each site monitored the screening logs 5 days per week for potential participants. They made a record of any duplicates presenting to the ED via the paramedics and recorded on both logs. The presence or absence of dementia was determined for all cases on the screening log.

For the diary study, CTAs contacted those who had given consent to be contacted by the research team. A participant information sheet (PIS) was sent by post as soon as practicable after the potential participant was detected. The potential participant was contacted by telephone once they received the PIS to answer any questions and determine whether or not they were interested in taking part. However, owing to small numbers of potential participants in the ED being asked for consent to release their details to the research team, this process was changed during the course of the study in accordance with an amendment submitted to Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 Research Ethics Committee. This allowed the CTA to send potential participants a PIS after they had left the department if the clinician had been unable to gain verbal consent for contact by the research team during the ED consultation (usually because of time constraints).

In the absence of published data on usual care provided to PWD following an injurious fall, we used the diary study to capture information on existing care pathways. We anticipated that up to an average of 20 patients per site would need to join the diary study in order identify the full range of usual care pathways provided (1–2 participants per week at each site). Once data saturation was reached, we aimed to continue to record incidence, but participants would not be asked to join the diary study.

Consent

Consent was not obtained for the diagnosis of dementia to be checked before adding the participant to the screening log. Approval was given by the Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group (reference 16/CAG/0057) for the researcher to obtain the name, age, sex, injury code and NHS number from the ED or paramedic service and use this information to contact the relevant GP to find out if the person was on their dementia QOF register. If the participant did not become a member of the diary study, patient-identifiable information was discarded.

Participants in the diary study were required to give informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. 70 Owing to the nature of dementia, some participants lacked the capacity to give full informed consent. In these cases, the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act (2005) applied. 71 Participants were asked to give consent appropriate to their level of understanding, ranging from written informed consent to account being taken of verbal and non-verbal communication in determining willingness to participate. In those individuals found to be without capacity to give full informed consent, the CTA identified a personal or nominated consultee and sought their advice regarding participation. Any patient appearing distressed by participation or withdrawing consent was excluded from the study without prejudice to clinical care. A favourable opinion was given by the North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/NE/0011).

Baseline assessments

Baseline data were recorded for participants consenting to the diary study. Data included medical history, medication history, dementia subtype and further details of the type and code of injury, location and circumstances of the fall, early treatment, any referral made by the attending professional and involvement of a carer. Cognition was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). 72

Diary study

The diaries were completed by the PWD, who were assisted by their carer as needed. Each diary collected information over a 4-week period. Participants were asked to complete three diaries in total. The objectives of the diary were to determine the feasibility of collecting information on number of falls (the predicted primary outcome for a future definitive study) and to identify potential patient pathways following a fall. It was agreed to pilot a Health Utilisation Questionnaire (HUQ) within the diary; this collected information to support a health economic analysis from the perspective of the health-care provider and Personal Social Services in a definitive trial. The format of this diary was similar to that of the data-collection tool used in the i-FOCIS trial. 56

For WP2, the diary and the HUQ were combined as one data-collection tool. The HUQ collected information on help at home (from carers or professionals), primary and secondary health-care resource use, social care and out-of-pocket expenses. The recall of the HUQ questions varied from daily to every 4 weeks. The rationale for daily recall for home help was to understand the daily burden on carers and determine whether or not the introduction of the intervention would affect their daily activities. Weekly recall was used to collect information on the most-common health-care resources likely to be used following a fall. Finally, 4-week recall was used for social care and participant expenses to minimise the burden on participants. The diary, including the HUQ, used in WP2 is provided in Appendix 3.

The HUQ was detailed as its purpose was to understand and record the type of health and social care used by PWD and the frequency of any reported use. The diary was piloted and amended prior to WP2 using feedback from patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives from VOICE (www.voice-global.org), a local involvement group. The main changes to the diary before it was administered in WP2 were extending the health-care treatment options provided in particular physiotherapy appointments. The overall aim of the diary study from an economics perspective was to inform the data collection tool to be piloted in WP4.

Analysis

Participant characteristics were analysed using descriptive statistics. Monthly presentation rates of potentially eligible participants were calculated for each setting per dementia case recorded on the QOF registers, giving an estimate of the potential future demand for an effective complex intervention in the NHS. The proportion of potentially eligible participants consenting to initial contact and then to full participation in the diary study was calculated, giving an indication of likely recruitment rates to WP4 and any future clinical trial.

Results

Incidence of fall-related injuries

Data were collected from the ED and paramedic attendances in all three sites. Primary care data were collected from eight general practices in Newcastle and 15 general practices in Norwich. Practices in North Tees declined to take part in the study owing to the burden of extracting the data required.

The total number of people presenting with fall-related injuries recorded across all sites and settings was 257 (Newcastle, 65; North Tees, 40; Norwich, 152), which gives a presentation rate of 42 cases per month. The majority of cases presented in the ED (n = 211), followed by primary care (n = 40), with very few presenting via paramedic attendances alone (n = 6). Table 1 gives the number of falls in each setting in the three sites. In the ED, the monthly presentation rate per dementia case recorded on the CCG QOF registers was 0.0029 (0.0027 cases per month per dementia case in Newcastle, 0.0024 in North Tees and 0.0033 in Norwich). In primary care, the monthly presentation rate per dementia case recorded on the practice QOF registers was 0.0035 (0.0058 cases per month per dementia case in Newcastle and 0.0028 in Norwich).

| Setting | Site, n (%) | Total (all three sites), n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newcastle | North Tees | Norwich | ||

| Primary care attendance | 14 (21.5) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (17.1) | 40 (15.6) |

| Paramedic attendance | 4 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) | 6 (2.33) |

| ED attendance | 47 (72.3) | 40 (100.0) | 124 (81.6) | 211 (82.1) |

| Total | 65 (25.3) | 40 (15.6) | 152 (59.1) | 257 (100.0) |

The mean age of the fallers was 85 years [standard deviation (SD) 6.1 years]. Fallers were older in Norwich than in Newcastle [Newcastle, mean 84 years (SD 6.61 years); North Tees, mean 84 years (SD 6.04 years); Norwich, mean 86 years (SD 5.80 years); mean difference –2.07 years; p = 0.022]. Two-thirds of fallers were female (Newcastle, 65%; North Tees, 80%; Norwich, 66%), which did not differ significantly between sites (p = 0.192). Table 2 gives the dementia subtype diagnoses of the fallers. The most common dementia subtype was AD (58%), followed by vascular dementia (VAD) (26%). It took a mean of 10 days from the date of the fall to confirm whether or not patients were on the dementia QOF register, but this was established within 1 week in 81% of cases. Table 3 summarises the types of injuries with which fallers presented. The most common type was soft tissue injury (44%), followed by head, neck and facial injury (37%). Nearly 11% of fallers presented with a fracture.

| Dementia subtype | n (%) |

|---|---|

| AD | 148 (57.6) |

| Vascular dementia | 66 (25.7) |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | 4 (1.5) |

| Parkinson’s disease dementia | 1 (0.4) |

| Frontotemporal dementia | 1 (0.4) |

| Unspecified dementia | 37 (14.4) |

| Total | 257 (100.0) |

| Injury type | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Soft tissue injury (head, neck and facial injury) | 94 (36.6) |

| Other soft tissue injury | 113 (44.0) |

| Hip fracture | 12 (4.7) |

| Other fracture | 15 (5.8) |

| Amputation injury | 1 (0.4) |

| Unspecified injury | 17 (6.6) |

| Multiple unspecified injuries | 5 (1.9) |

| Total | 257 (100.0) |

Diary study

Recruitment

Thirteen participants were recruited to the diary study: 12 were recruited via the ED and one was recruited via a paramedic. The mean age of the participants was 87 years, and seven participants (54%) were female. Seven participants had AD and six had VAD. The mean MoCA score was 13.6 points, indicating moderate cognitive impairment. One participant withdrew before completing any diaries but initial baseline data were retained.

Early treatment of the participants

One participant already had a falls unit referral in progress and one further participant was offered a falls unit referral but declined. One participant was already receiving physiotherapy, three participants were offered a new physiotherapy referral and one was referred to a rehabilitation unit. One participant was referred to their GP. No referrals were made for the remaining five participants.

Data completeness

The return rate for the first diary was 75% (n = 9), but this reduced to 50% (n = 6) for diaries 2 and 3. One participant went into a care home during the study and completed diary 1. One participant died during the study but had completed diaries 1 and 2 and partially completed diary 3. Carers were contacted to return the remaining outstanding diaries but, despite several telephone reminders, they were never returned.

Number of falls

A total of 11 falls were reported by four participants during the diary study. Two participants reported having one fall each, one participant reported having four falls and one participant reported having five falls. In the falls diaries returned, few data were missing.

Health-care utilisation questionnaire

The level of missing data within the HUQ section of the diaries was relatively low, suggesting that those participants who completed the diary had few problems with completing these questions. The individual response rate to the weekly HUQ questions is provided in Appendix 4. The lowest response rate to an individual question, based on those who responded to the diary, was 50%. However, it should be noted that in later diaries it appeared that some participants only completed the HUQ questions that were relevant to them, suggesting that the frequency of the questions became burdensome. This is supported by the following extract from the qualitative data:

We’re not going to do the diary. There’s no point. There’s no point doing the diary [. . .] What could we say? It’s hard work, every day, writing.

Carer 9b (joint interview with carers 9a and 9b)

Data on nine participants who completed at least one diary were summarised to inform any modifications to the HUQ for WP4. Although these data are not necessarily reflective of all PWD who have had a fall, they give us an indication of the types of resources used by PWD and the frequency of their use. On average, little use of health care was reported during the 12-week study period. The maximum reported health care was for diary 1 in week 2, when six participants reported using at least one health-care service.

Appendix 4 summarises the total resource use per participant in the diary study. On average, participants reported using at least one health-care service for 3 weeks of their 12-week follow-up period. Arguably, the median results presented are more representative of the actual health-care resource use as one participant reported high health-care resource use: 28 day-case visits and 30 nights in hospital over the 12 weeks. Although high, this volume of care is not unusual in clinical trials, in which a small number of participants tend to have very high use of services.

Participant out-of-pocket expenditure

Paid health and social care

At the end of each diary, there was a section on out-of-pocket expenditure, which recorded whether or not participants had paid for any health or social care and, if so, what they had paid for and how much they paid. Over the 12 weeks, three participants reported paying for care; however, only two participants provided information on the cost. One participant reported paying for care in all three diaries and paid a total of £664 for home care and day centre care. The other participant reported paying £35 for a visit to a chiropractor. The participant who did not provide information on how much they paid stated they had paid for spectacles.

Paid other help

Over the 12-week diary period, five participants reported paying for additional help, most commonly a cleaner (four participants). Appendix 5 summarises the type and cost of paid help. The average total cost paid by these five participants over the 12 weeks was £98.

Carer’s Allowance

Two participants reported receiving a Carer’s Allowance: one carer received £90 per week and the other received £50 per week.

Help at home

As part of WP2, it was decided to collect daily information on help at home to gauge the level of assistance reported by PWD. The inclusion of the ‘help at home’ section was to identify what activities carers usually participated in.

The open-text boxes allowed participants to provide detailed information on the help they received. This ranged from help with medications to 24-hour care. The majority of care reported related to daily activities such as making dinner and going to the shops. Assistance could benefit the person with dementia and/or the carer:

Carer for meds [medications] and breakfast. Pick up and drop off for church. Carer for meds and tea.

Data from diary (DS11)

Paramedic came looked him over took him to North Tees Hospital. My three daughters and two granddaughters called after it just happened, made me a cup of tea, went to hospital with me. Then brought me home. Six hours they stayed with us.

Data from diary (DS05)

Opportunity costs for carers

The most frequent activity that carers would be undertaking if they were not assisting the person with dementia was housework (71%), followed by leisure time (57%). Fewer than 30% of carers missed paid work to assist the person with dementia.

Discussion

The incidence of fall-related injuries was much lower than expected. In our previous study, the total incidence of falls in people with mild to moderate dementia was 9118 per 1000 person-years. 2 A secondary analysis of the data in our previous study showed that there were 0.044 injuries per person per month among PWD with AD or VAD. Our findings that only 0.0029 cases per person per month presented to the ED and 0.0035 cases per person per month presented to primary care suggest that fewer than 15% of injuries sustained by PWD are brought to the attention of health-care practitioners. This assumes that our procedures for identifying both fall-related injuries and that a person with a fall-related injury had dementia were robust. In primary care, we are confident that the diagnosis of dementia was robust because the GPs had direct access to QOF registers. In the ED, where carers gave a history of dementia, this is likely to have been accurate. However, a carer may have been absent or the carer may not have been aware of the diagnosis. In the case of diagnosis by paramedics, the very small number of cases suggest that systems for picking up dementia were not robust. This has implications for WP4 and any future trial of an intervention to improve outcomes for PWD with fall-related injuries. If dementia is not identified at the time of presentation, it would be difficult to ensure that a referral to an appropriate intervention is made.

The limited number of diary data collected indicated that most PWD received very little health-care input following the index fall. Although 8 out of the 13 participants were offered an initial referral to a falls unit, physiotherapy or a rehabilitation unit, the diaries of the 12 participants who completed them show very little use of these services over the course of the subsequent 12 weeks. This suggests that people may have received an initial assessment but were deemed not appropriate for further input or were still waiting for the referral to be followed up. Further evidence of this was found in our qualitative study, which is discussed in Chapter 4.

Strengths and limitations

For the diary study, we did not reach our target of 60 participants. We believe that the requirement for health professionals to seek permission from potential participants to share their contact details with the research team contributed to poor recruitment owing to time constraints, particularly in the ED. Although we submitted an amendment to modify recruitment procedures (see Recruitment), approval was not received in time to make a material difference. The modified approach was implemented in most sites in WP4.

With regard to data completion, 75% of participants completed the first diary and 50% completed diaries 2 and 3. Where diaries were returned, the daily recording of falls was successful, and this is supported by the use of a diary in other studies with PWD. 58 The relatively poor completion rates for the HUQ, compared with completion rates for a falls diary alone in previous studies, suggest that the additional questions may have been off-putting or too time consuming for participants. The low rates of reported health-care and social care use suggest that the HUQ could be simplified for the feasibility study (see Chapter 7). A limitation of the HUQ was that a number of unrelated expenses (e.g. spectacles) were reported. Furthermore, some regular expenses were only reported once (e.g. for a cleaner); participants may have thought that it was unnecessary to include these in all diaries.

Conclusions

The incidence and diary studies suggested that recruitment rates to a future trial may be lower than anticipated. However, PWD were found to be receiving very few services, suggesting that there is scope for a new intervention to improve outcomes.

Chapter 4 Current pathways and opportunities for intervention

Parts of this chapter are adapted from Bamford et al. 73 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. Parts of this chapter are adapted from Wheatley et al. 74 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

The effectiveness review provided limited guidance on the core components of an intervention to improve outcomes for PWD with fall-related injuries and highlighted uncertainty over the most appropriate outcome measures. Although the diary study provided some insight into current service use in the 12-week period following an injurious fall, low recruitment rates meant that we were unlikely to have captured the diversity of care pathways. Qualitative work was conducted with a range of stakeholders to provide additional data.

Aim

The qualitative component of WP2 aimed to develop a better understanding of current pathways and identify opportunities for intervention. Objectives were to:

-

explore the range of services currently available to PWD following an injurious fall

-

identify the needs of PWD and carers following an injurious fall and ascertain the extent to which these were currently met

-

explore ideas for service development or intervention with a range of stakeholders

-

identify outcomes of importance to PWD and their families.

We included health and social care professionals, PWD who had experienced a fall and their carers. We also aimed to identify the care needs of, and outcomes of importance to, PWD and their families.

Methods

Sampling

Participants were drawn from the three sites described in Chapter 3. Professionals were initially identified through interviews with the principal investigator of each site. We then used snowball sampling75 to identify relevant health and social care services in each area. Recruitment continued until data saturation was reached.

Professionals taking part in interviews and focus groups were asked whether or not they and their colleagues would be willing for us to observe routine practice. We selected a diverse range of services across the three sites for observation. All patients due to be seen on the agreed date(s) for observation were eligible to take part.

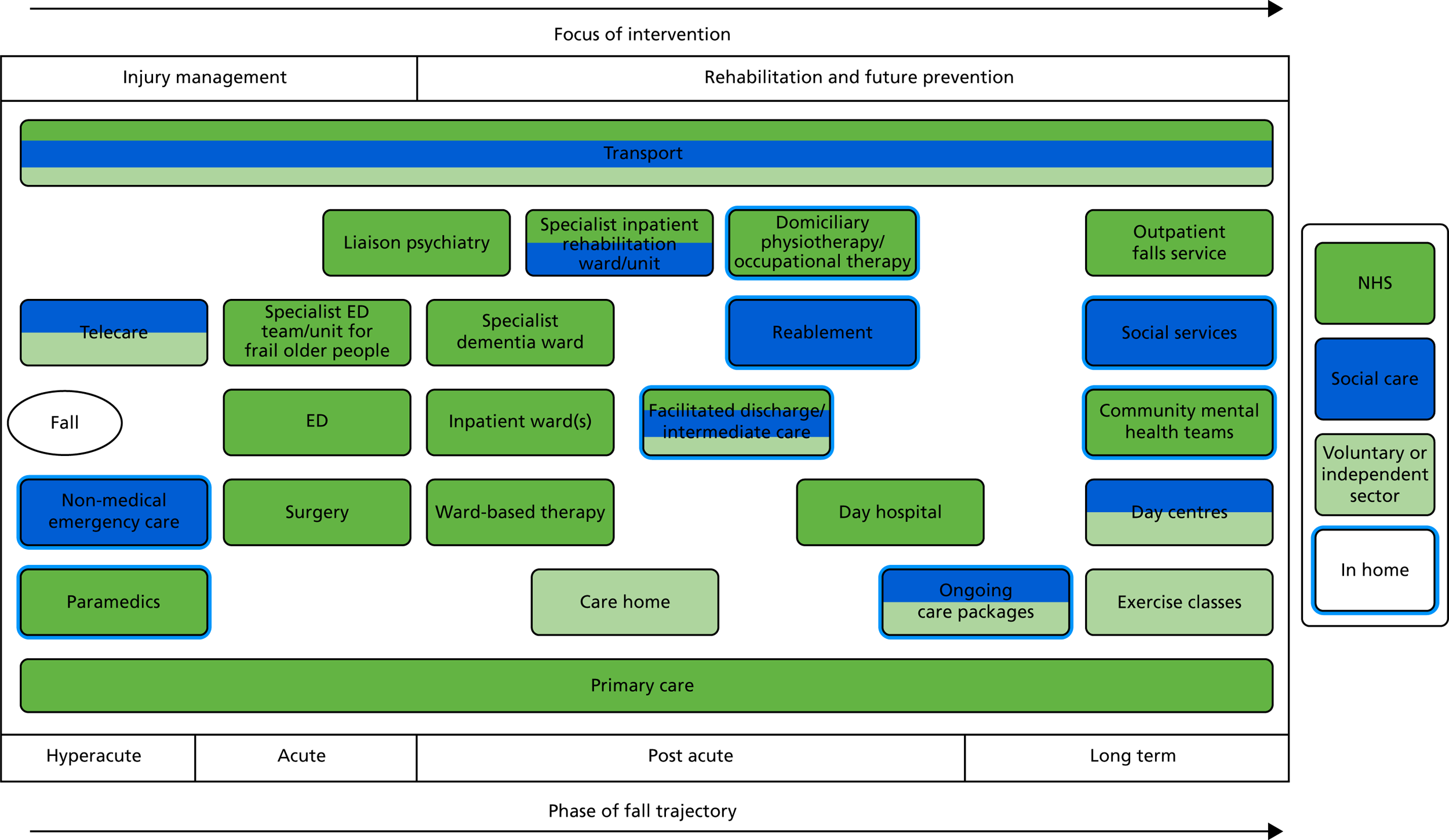

Patients and carers were recruited for interviews through either observation or the diary study (see Chapter 3). The process of sampling and recruitment is summarised in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of sampling and recruitment processes. Reproduced with permission from Bamford et al. 73 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

Recruitment and consent

Professionals who were invited to all parts of the study were provided with a PIS. Prior to data collection, professionals gave either verbal consent (telephone interviews) or written consent (face-to-face interviews, focus groups, observation).

The PWD and carers seen by participating services on dates selected for observation were provided with a brief information sheet by staff (in advance of home visits or on arrival at clinics). Verbal consent was sought for observation. Prior to observation of group interventions (e.g. exercise classes), we obtained verbal consent from all participants.

Some PWD and carers who were observed were invited to take part in an interview. In selecting potential interviewees, the researcher aimed to sample people with a range of injuries, presenting to different services and who lived in the community. Only PWD thought to have capacity to consent to an interview were invited. In addition, participants in the diary study (see Chapter 3) were asked if they were willing for their details to be passed to the qualitative team as part of the initial consent process. We also recruited a small number of participants without cognitive impairment from exercise groups. Regardless of how potential interviewees were identified, a PIS was provided to those who expressed an interest. Formal written consent was sought prior to the interview.

Data collection and analysis

Interviews and focus groups

Topic guides were used to structure interviews and focus groups (see Appendix 6). Those for professionals explored service organisation, the perceived success of current interventions, the views and use of outcome measures, experience of working with PWD, challenges specific to falls in PWD and ideas for intervention. Most interviews with professionals were carried out by telephone. We supplemented professional interviews with five local focus groups held in participants’ places of work.

Interviews with PWD and carers explored their falls history, experience of services, desired outcomes and ideas for intervention. Interviews with exercise group participants without cognitive impairment focused on their views and experiences of the inclusion of PWD in such groups. Interviews with all patients and carers were conducted face to face, in their homes or in another venue of their choice. Participating dyads were interviewed either individually or jointly according to their preference.

Observation

During observation, we considered the interactions, content and if and how interventions were tailored to individuals. Detailed ethnographic field notes were recorded during and after each period of observation,76 which usually lasted for a single shift or clinic session. In field notes, patients were identified only by age and sex; the only information recorded on companions was their relationship to the patient.

Data management and analysis

Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded. Professional interviews and focus groups were initially summarised onto a structured pro forma. Data-rich audio recordings were transcribed in full. All interviews with patients and carers were transcribed for analysis. Transcripts were checked and anonymised, with participants allocated a unique identifier, prior to analysis.

We adopted a separate thematic approach to each data set (interviews and focus groups with professionals, interviews with patients and carers, observation) to avoid assuming that themes from one data set were necessarily relevant to another. We then mapped areas of consistency and discrepancy across data sets to create a new integrated coding frame. This was then applied to each data set using NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Research governance approvals

Newcastle University provided an ethics review for the initial interviews and focus groups with professionals, and any necessary permissions were obtained from research and development departments of participating trusts. Approval for observation and interviews with patients and carers was given by Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 Research Ethics Committee (reference 15/NE/0397), Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/NE/0011) and the Health Research Authority. Additional approvals were received from participating trusts and social services departments as required. For non-statutory agencies, approval was sought from senior managers.

Results

Qualitative findings relating to care pathways for PWD following a fall and the need for staff training have been published73,74 and are summarised below. Quotations are accompanied by a participant identifier, with role and service type given for professionals.

Participants

In total, 53 professionals were interviewed across the three sites and an additional 28 took part in five focus groups. Interviews lasted between 20 and 60 minutes and focus groups lasted between 40 and 65 minutes. Participants included consultants, GPs, nurses, OTs, physiotherapists, paramedics, service managers, support workers and clinical commissioners.

Initial observations focused on services that we anticipated would be difficult to capture through the diary study (Table 4). Although we intended to recruit additional PWD and carers for observation through the diary study, this proved impractical as a result of low recruitment rates and limited use of community services by diary participants (see Chapter 3). In total, 20 professionals were observed delivering care to 85 patients.

| Service type | NHS | Social care | Third sector |

|---|---|---|---|

| First response services | Paramedics |

|

|

| Hospital services |

|

Facilitated discharge team | |

| Other residential services | Specialist rehabilitation unit | Specialist rehabilitation unit | |

| Domiciliary services |

|

Telecare | |

| Community services (including primary care) | Exercise classes |

We approached 17 PWD and 19 carers for interview (21 were identified through observation, 15 were identified through the diary study), of whom four PWD and nine carers consented to and completed interviews. We additionally included four cognitively intact older people from exercise classes.