Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/15/03. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The draft report began editorial review in September 2020 and was accepted for publication in February 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Robson et al. This work was produced by Robson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Robson et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP) affects up to 85% of women in the first half of pregnancy. 1 Symptoms usually start at 6–8 weeks’ gestation, peak by 9 weeks’ gestation and, for many women, subside by 20 weeks’ gestation. 2 Symptoms are often mild, but 30% of sufferers experience more severe symptoms that require medical intervention. 2 The most severe form, hyperemesis gravidarum (HG), affects around 1% of women and is characterised by intractable vomiting, dehydration, ketonuria and weight loss. 1,3 HG can result in prolonged hospitalisation, multiple treatments and, where interventions fail, termination of pregnancy (TOP). NVP is associated with emotional and psychological distress and has a profound impact on quality of life (QoL), affecting all aspects of a woman’s life. 4 Women often feel unsupported; suffer higher rates of depression, anxiety and stress;5 and feel dissatisfied with care. 6 Women with HG are also more likely to deliver preterm and to have infants small for their gestational age, although there is no association with congenital anomalies or perinatal death. 7

The aetiology remains unclear, and there is no cure for NVP: treatment focuses on relieving symptoms and preventing morbidity. Many women with mild symptoms are able to self-manage the condition using lifestyle modifications. Some also access other patient-initiated interventions (e.g. ginger and vitamins). Many women with moderate or severe disease require clinician-initiated interventions in the form of intravenous (i.v.) fluids and antiemetic drugs, primarily antihistamines (e.g. cyclizine), dopamine antagonists (e.g. metoclopramide) and 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (5-HT3) antagonists (e.g. ondansetron).

Rationale

Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy incur substantial costs to sufferers (through the purchase of therapies, extra living or child-care costs or lost earnings8) and to the NHS. NVP resulted in > 30,000 admissions to hospital in England in 2013–14, with one-third for HG with metabolic disturbance. 9 Based on data collected between 2013 and 2016, the annual cost of NVP to the UK NHS was estimated at nearly £26M; however, owing to perceived underestimation of costs, the authors suggested that the cost could be as high as £62M. 8 Antiemetics are the most commonly dispensed drugs in early pregnancy, with over 10% of pregnant women in the US Medicaid Program prescribed promethazine or metoclopramide. 10

The assessment of the severity of NVP often lacks consistency, and the management varies substantially. This, combined with inappropriate treatment for presenting symptom severity, can leave women feeling unsupported, dissatisfied with care and experiencing negative interpersonal interactions with health-care providers. 6,11 This, in part, may be because of a previous lack of evidence-based guidelines to inform effective treatments in clinical practice. To address this, in June 2016 the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) published guidelines on the management of NVP and HG. 12 Recommendations included the use of cyclizine, prochlorperazine, promethazine and chlorpromazine as first-line antiemetic therapies, and metoclopramide, domperidone and ondansetron as second-line antiemetic therapies.

In 2016, we reported a Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-funded evidence synthesis of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for NVP or HG. 13 Seventy-three studies were identified and the results were narratively synthesised because the planned meta-analysis was not possible owing to the heterogeneity in the assessment of symptom severity, interventions, methods and outcomes, as well as incomplete reporting. There was variation in both the quality of the studies and the quality of reporting. For almost half of all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) identified, there was insufficient detail provided to permit clear judgement of the risk of bias in a range of key areas. There was also insufficient evidence to form a judgement on cost-effectiveness. Two Cochrane reviews were reported around the same time: Matthews et al. 14 reviewed interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy (41 trials) and Boelig et al. 15 reviewed interventions for treating HG (25 trials). Both reviews also highlighted that the evidence surrounding the effectiveness of treatments was both sparse and of poor quality. All three reviews13–15 concluded that, although there was some evidence that some treatments were better than the dummy for mild symptoms, there was little evidence on the effectiveness of treatments in more severe NVP/HG. The reviews also suggested that, in addition to the use of objective symptom scoring systems, clearly defined outcomes were required so that future trials could be compared using meta-analyses. Furthermore, although the available evidence indicated that these treatments were likely to be safe, more research was needed to clarify this.

Many women with severe NVP/HG who fail to respond to first-line antiemetic therapy (e.g. histamine receptor or dopamine receptor antagonists) will require a hospital review and second-line antiemetic medication. The RCOG recommends a 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor antagonist (ondansetron) or a dopamine receptor antagonist (metoclopramide or domperidone) as second-line therapy. 12 Our review identified no trials involving domperidone and one trial showing comparable improvements in nausea and vomiting with metoclopramide and promethazine (a histamine receptor antagonist). 16 The evidence available for ondansetron was predominantly at high or unclear risk of bias. Two trials were identified comparing ondansetron with metoclopramide. 17,18 Kashifard et al. 17 compared ondansetron [4 mg per os (p.o.) three times per day] with metoclopramide (10 mg p.o. three times per day) in 83 women. Over the 14 days of the trial, the ondansetron group had lower vomiting scores than the metoclopramide group, but there was no difference in nausea scores. Abas et al. 18 compared ondansetron (4 mg intravenously three times per day) with metoclopramide (10 mg intravenously three times per day) in 160 women. Symptom improvement was seen in both groups, with no evidence of difference between groups at 8, 16 or 24 hours.

The primary research recommendation from our HTA evidence synthesis was the need for a RCT, with an economic evaluation, to determine which second-line hospital-prescribed therapy, in addition to i.v. rehydration, should be adopted as mainstream provision in the UK NHS. In response to this recommendation, the HTA programme sought to commission research to determine what was the most effective drug regimen for women with severe NVP requiring secondary care. Specifically, the brief called for a trial comparing both 5-HT receptor antagonists and dopamine receptor antagonists (interventions) with dummy 5-HT receptor antagonists and dopamine receptor antagonists (comparators) in a double-dummy, double-blind controlled factorial trial. The EMPOWER (EMesis in Pregnancy – Ondansetron With mEtoClopRamide) trial was undertaken to answer this research question.

Aims and objectives

Main trial aims

This trial aimed to determine which hospital-prescribed therapy [metoclopramide (metoclopramide hydrochloride, Actavis UK Ltd, Barnstable, UK; IV Ratiopharm GmbH, Ulm, Germany) and ondansetron (ondansetron hydrochloride dehydrate, Wockhardt UK Ltd, Wrexham, UK; IV Hameln Pharma plus GmbH, Hameln)], in addition to i.v. rehydration, should be adopted as the mainstream second-line treatment of severe NVP by the UK NHS when standard first-line treatment has failed. To achieve these aims, we set the following objectives.

Primary objectives

To determine whether or not, in addition to i.v. rehydration, ondansetron compared with no ondansetron and metoclopramide compared with no metoclopramide reduced the rate of treatment failure up to 10 days after initiation.

Secondary objectives

To determine whether or not, in addition to i.v. rehydration, ondansetron compared with no ondansetron and metoclopramide compared with no metoclopramide:

-

improved symptom severity at 2, 5 and 10 days after intervention initiation

-

improved quality of life at 10 days after intervention initiation

-

had an acceptable side effect and safety profile.

In addition, we also aimed to estimate the incremental cost per treatment failure avoided and the net monetary benefits from the perspective of the NHS and women.

Internal pilot and qualitative trial objectives

Owing to uncertainty around the willingness of pregnant women to be recruited into a complex drug trial, an internal pilot phase was incorporated alongside a qualitative substudy. The main objectives of the pilot phase were to assess the feasibility of recruitment and rates of retention in those randomised. The qualitative component aimed to improve our understanding of why women did or did not consent to participation in the trial.

Chapter 2 Methods

Setting and conduct

Trial design

This was a multicentre, double-dummy, randomised, double-blinded, dummy-controlled 2 × 2 factorial trial with an internal pilot phase. Women attending hospital with severe NVP who experienced little or no improvement while taking first-line anti-sickness medication were invited to participate. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 ratio to receive active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron; dummy metoclopramide and active ondansetron; active metoclopramide and active ondansetron; or dummy metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron. The trial aimed to compare whether or not, in addition to i.v. rehydration, ondansetron compared with no ondansetron and metoclopramide compared with no metoclopramide reduced the rate of treatment failure up to 10 days after initiation of treatment. The trial included an economic evaluation and a qualitative component.

Internal pilot

It was planned that there would be an internal pilot phase involving up to eight sites (subsequently extended to up to 15 sites) followed by a main phase with an additional seven to nine sites (22–24 sites in total).

To progress from the pilot trial to the main trial, 59 participants needed to be recruited within 6 months, with ≥ 40 participants retained to day 10.

Participants

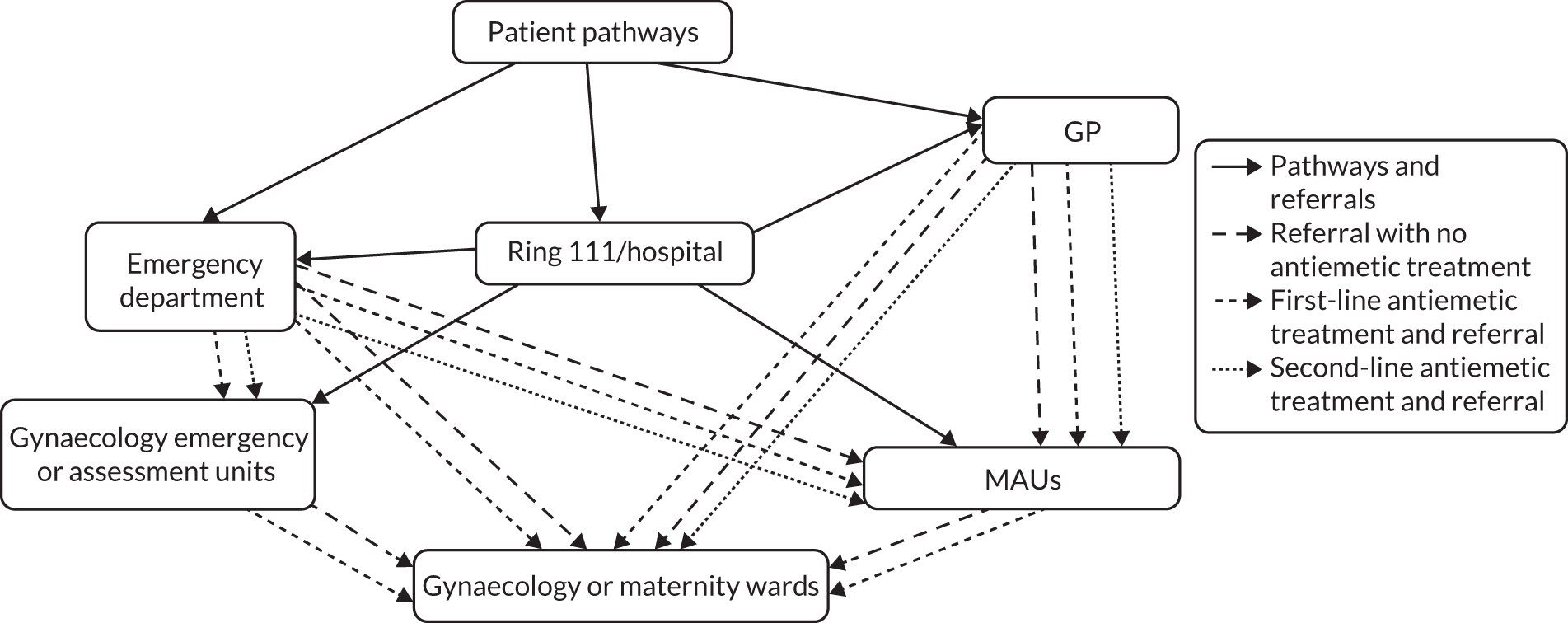

The trial recruited women aged ≥ 18 years who were < 17 weeks’ gestation and had attended a secondary care service suffering from severe NVP or HG, and who had received previous treatment with a first-line antiemetic therapy in the current pregnancy with little or no sustained benefit. Potential participants were first approached by the clinical staff on duty when they attended hospital for treatment. Participants presented at gynaecology/early pregnancy clinics, maternity assessment units (MAUs) or accident and emergency (A&E) departments. The trial was introduced to the participant and permission was sought for someone in the research team to approach them and provide more information about the trial. Patients who expressed an interest in taking part were provided with a copy of the participant information sheet (PIS). Those still interested after reading the information provided were then assessed for eligibility.

Screening

Screening logs were completed at recruiting sites to record reasons for patient ineligibility and for declining participation. In August 2018, the screening logs were extended to collect information on prior use of trial drugs in the current pregnancy. Confirmation of eligibility was performed by a General Medical Council (GMC)-registered medically qualified doctor who was trained in good clinical practice (GCP).

Eligibility

The eligibility criteria that were initially used during the trial are listed below.

Inclusion criteria

-

Pregnant women suffering from severe NVP.

-

Gestation of < 17 weeks.

-

Had previously taken first-line antiemetic treatment (cyclizine, chlorpromazine, promethazine or prochlorperazine, as recommended by RCOG12) as prescribed, over at least 24 hours with no sustained improvement in symptoms.

-

Age ≥ 18 years.

-

Able to give informed consent.

-

Able to read/understand written English.

Exclusion criteria

-

Allergy/hypersensitivity to any of the study drugs.

-

Prior treatment with trial drugs in this pregnancy.

-

Pre-existing diagnosis of a medical condition: type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease stages 3–5, Graves’ disease, significant cardiac disease (including long QT syndrome), phaeochromocytoma, epilepsy (or other seizure disorder) or severe liver disease (alanine transaminase or aspartate transaminase of > 2.5 times the upper limit of normal pregnancy).

-

Moderate renal impairment diagnosed during pregnancy (definition: serum creatinine level of > 100 µmol/l).

-

Severe diarrhoea [definition: > 10 loose, watery stools in 1 day (24 hours)].

-

Hypokalaemia (definition: serum potassium level < 3 mmol/l).

-

Pre-existing diagnosis of hypomagnesaemia.

-

Vomiting caused by another underlying condition/infection.

-

Concomitant use of apomorphine or serotonergic drugs [e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors and lithium].

-

Confirmed diagnosis of severe lactose intolerance (e.g. patients with rare hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, Lapp lactase deficiency or glucose–galactose malabsorption).

Early in the period of screening and recruitment, it became apparent that the exclusion criterion ‘Prior treatment with the trial drugs in this pregnancy’ was causing high rates of ineligibility across all sites. After review by all trial oversight bodies, the wording of this criterion was changed to:

-

received either i.v. ondansetron or metoclopramide

-

received either p.o. ondansetron or metoclopramide for > 72 hours (with or without i.v. rehydration).

The updated eligibility criteria were implemented at sites on 20 February 2019.

Women who presented with severe diarrhoea and met the inclusion criteria but were subsequently found to have a serum potassium level of > 3 mmol/l could still be offered participation in the EMPOWER trial.

Women who presented with severe NVP routinely had urea and electrolytes assessed clinically. In the absence of severe diarrhoea, women could still be approached, consented and given trial treatments before urea and electrolyte results were available; if the serum potassium level was subsequently found to be low (< 3 mmol/l), the hypokalaemia had to be corrected quickly with i.v. supplementation, but there was no need to withdraw them from the trial.

Consent

A copy of the PIS was provided to eligible women by the local site team. Patients were first provided with a short PIS to provide them with an overview of the trial. Those interested after reading the short PIS were provided with a copy of the full PIS. Potential participants were given a minimum of 1 hour to review the PIS. During this time, an i.v. cannula could be sited, blood could be taken for necessary clinical tests and i.v. fluids could be commenced. Consent was received by a GMC-registered medically qualified doctor trained in GCP. Women who agreed to participate were asked if they would also be willing to take part in an optional qualitative interview.

Women who declined to participate in the trial itself were still asked if they would like to be approached to participate in the qualitative interviews.

Once consent had been received, randomisation was undertaken.

Schedule of events

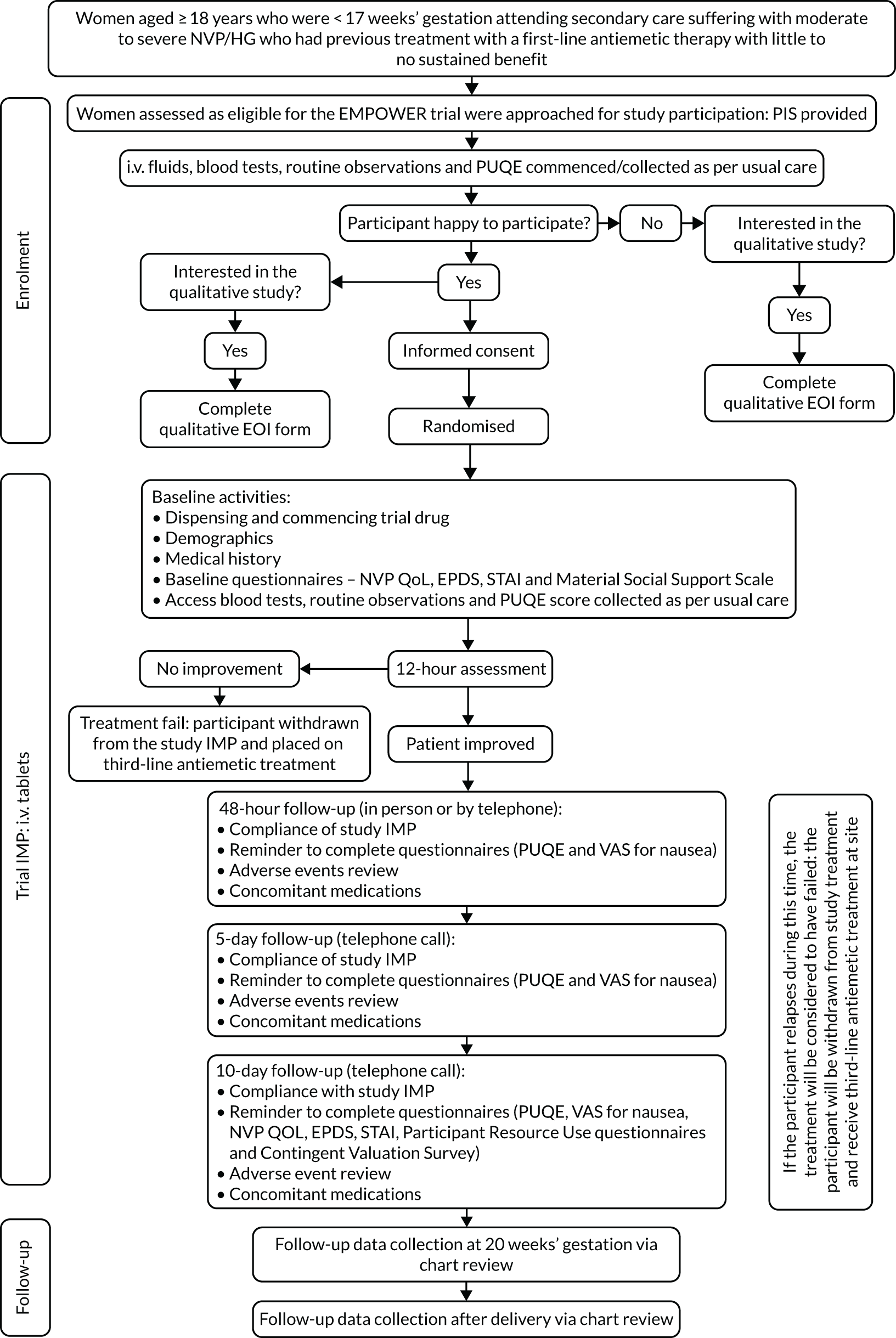

The schedule of events for the trial is shown in Table 1 and a participant’s journey through the trial is shown in Figure 1.

| Procedures | Visit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Baseline | Treatment phase | Follow-up at 20 weeks’ gestation | Follow-up after delivery | ||||

| 12-hour review | Time point 1: 48 hours | Time point 2: 5 days | Time point 3: 10 days | |||||

| Eligibility assessment | ✗ | |||||||

| Blood tests (of urea, electrolytes and full blood count) | ✗ | |||||||

| Observations (temperature, pulse, blood pressure, weight and urinalysis) | ✗ | |||||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | |||||||

| Randomisation | ✗ | |||||||

| Demographics | ✗ | |||||||

| Medical history | ✗ | |||||||

| Dispensing of trial drug | ✗ | |||||||

| Review participant for responsiveness to trial treatment | ✗ | |||||||

| PUQE | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| VAS for nausea | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| NVPQoL questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| EPDS | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Short STAI | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Maternal Social Support Scale | ✗ | |||||||

| Health-care utilisation questionnaire | ✗ | |||||||

| Willingness-to-pay questionnaire | ✗ | |||||||

| Adverse events assessment | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Assessment of IMP compliance | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Concomitant medications | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Pregnancy outcomes | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

FIGURE 1.

Trial flow chart. EOI, expression of interest; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; IMP, investigational medicinal product; PUQE, Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis; STAI, State–Trait Anxiety Inventory; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Once a participant was consented and randomised, the trial medication was dispensed by the research team and i.v. medication commenced as soon as possible. Baseline questionnaires were also completed by the participant.

While in hospital, participants were provided with a trial pack that included the questionnaires to be completed at 2, 5 and 10 days, a trial diary to record adverse events (AEs) and concomitant medications, and a trial identification (ID) card, including emergency contact details, for participants to carry with them while participating in the trial. All participants, unless they had been discharged from hospital, were reviewed at 12 hours to assess responsiveness to trial medication. If the participant had not responded to the trial medication within the first 12 hours of treatment, trial medication was stopped and the participant was placed on further treatment outside the trial.

Follow-up with the participants took place at 2 days post first dose of trial medication, at 5 days and at the final follow-up questionnaires at 10 days. These follow-ups were completed via telephone call by members of the research team. Participants were also followed up at 20 weeks’ gestation and post birth, but via medical chart review.

Participant expenses

No expenses were incurred by participants travelling for trial visits. Follow-up was completed via telephone or via review of the participant’s medical chart.

Details of the trial interventions

Participants were randomised to one of four groups. The groups that a participant could be allocated to are outlined below, along with the dose and route of administration:

-

metoclopramide [10 mg three times daily (i.v. and p.o.)] and dummy ondansetron (i.v. and p.o.)

-

ondansetron [4 mg three times daily (i.v. and p.o.)] and dummy metoclopramide (i.v. and p.o.)

-

metoclopramide [10 mg three times daily (i.v. and p.o.)] and ondansetron [4 mg three times daily (i.v. and p.o.)]

-

double dummy three times daily (i.v. and p.o.).

Delivery of the trial interventions

Participants initially received trial medication intravenously; trial medication could be administered intravenously for up to 4 days. Once the participant was able to tolerate fluids, they were converted to oral tablets. The oral medication was taken at the same frequency and dosage as the i.v. formulation. Both the i.v. and the p.o. medication were supplied in the same trial medication kit to prevent the necessity for a double prescription. The total duration of treatment for each participant was 10 days.

Treatment compliance

Participants took trial medication for a maximum of 10 days. Participants were contacted at 2, 5 and 10 days and compliance regarding taking oral medication was checked with participants at these time points.

Participants were asked to return all unused oral trial medication and all packaging (even if empty) to the trial team at each site. A stamped, addressed envelope was provided as part of the trial pack for participants to return medication after they had taken their final dose at day 10. Participants were reminded by the research team to post trial medication back to the site, but if they forgot there was the option to bring it with them to their next clinical appointment. The site team counted all returns (both tablet returns received from the participant and leftover ampoules returned to the pharmacy) and recorded these on the trial database.

Withdrawals

Participants had the right to withdraw from the trial at any time without having to give a reason; however, if provided, the reason for withdrawal was recorded. Participants remained in the trial unless they withdrew consent or the local principal investigator (PI) felt that it was no longer appropriate for the participant to continue. For participants who chose to withdraw, permission was sought to allow the research team to collect routinely collected data from their medical records. If the participant did not agree to this, only the data collected up to the point of withdrawal were retained. Participants who withdrew from the trial were not replaced.

Sites

The EMPOWER trial was conducted at 12 NHS sites in England. Site set-up commenced in October 2017.

Initially, seven sites were set up:

-

Newcastle upon Tyne NHS Foundation Trust

-

City Hospitals Sunderland Hospitals NHS Trust (now South Tyneside and Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust)

-

South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust

-

Guy’s and St Thomas’ Foundation Trust.

Five further sites were set up during the extended internal pilot:

-

Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust

-

University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust

-

St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust.

Outcome measurement

Primary outcome

The primary end point was the number of participants experiencing a treatment failure. Treatment failure was defined as the need for further treatment if a participant’s symptoms had worsened between 12 hours and 10 days post initiation of treatment. Where further treatment was required, a participant should have been placed on third-line antiemetic treatment (i.e. high-dose ondansetron or corticosteroids) unless the clinician considered further second-line treatment more appropriate.

Secondary outcomes

The following secondary patient-reported and clinical outcomes were collected:

-

Symptom severity, as measured by the Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE) score19–21 (see Appendix 1), collected at baseline and at 2, 5 and 10 days post initiation of treatment.

-

Severity of nausea, as measured by a visual analogue scale (VAS)17 for nausea, collected at 48 hours and at 5 and 10 days post initiation of treatment.

-

Quality of life, as measured by the health-related nausea and vomiting during pregnancy quality-of-life (NVPQoL)22 questionnaire (see Appendix 2), collected at baseline and 10 days post treatment commencing.

-

Depression, as measured by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)23 (see Appendix 3), collected at baseline and 10 days.

-

Anxiety, as measured by the six-item State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI),24 collected at baseline and 10 days [see https://oml.eular.org/sysModules/obxOml/docs/ID_150/State-Trait-Anxiety-Inventory.pdf (accessed September 2021); the six items used were items 1, 3, 6, 15, 16 and 17].

-

Social support, as measured by the Maternity Social Support Scale (MSSS)25 (see Appendix 4), collected at baseline.

-

Clinical indicators of antiemetic effectiveness:

-

the number of participants experiencing a treatment failure at 2 days

-

relapse rate at 5 and 10 days (defined as a PUQE score of ≤ 6 at 2 days followed by an increase to > 12 at 5 or 10 days)

-

remission rate at 10 days [defined as a PUQE score of ≤ 6 at 2 days with return to persistent symptoms (PUQE score of ≥ 7) at 10 days]

-

readmission rates (the number of participants readmitted with NVP within 10 days of recruitment and between 10 days of recruitment and 20 weeks of pregnancy)

-

total inpatient days related to NVP between recruitment and 20 weeks of pregnancy and between 20 weeks of pregnancy and delivery

-

additional antiemetic use.

-

-

Side effects and AEs – participants were asked about side effects/AEs that they experienced at 2, 5 and 10 days post treatment commencing. Severity was graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). 26

-

Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes – the numbers of women experiencing miscarriage, TOP and stillbirth were recorded. For each infant born, the mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery and birthweight were collected. Information on congenital anomalies detected prior to discharge was also collected. In the case of multiple births, this information was collected for each infant.

-

Key economic outcomes:

-

costs to the NHS and to participants (see Appendix 5)

-

willingness to pay (WTP) (see Appendix 6) for the benefits of antiemetic treatment

-

incremental cost per treatment failure avoided and net monetary benefits.

-

All data fields were locked on 5 December 2019, with the exception of fields relating to pregnancy outcome data, AEs/serious adverse events (SAEs), deviations/violations, investigational medicinal product (IMP) accountability and concomitant medication, which were locked on 9 April 2020.

Sample size calculation

As per the 2 × 2 factorial design, the intention was to have two main comparisons:

-

active metoclopramide (with either active or dummy ondansetron) and dummy metoclopramide (with either active or dummy ondansetron)

-

active ondansetron (with either active or dummy metoclopramide) and dummy ondansetron (with either active or dummy metoclopramide).

An antiemetic failure rate of 10% was assumed based on prior ondansetron studies (with rates of 13% at 48 hours27 and 7% at 5 days28) and our pilot RCT of midwife-led outpatient care,29 in which 10% of women had failure of a second-line antiemetic (primarily metoclopramide). With 266 participants in each comparison (i.e. 133 in each of four treatment combinations, 532 in total) and assuming no interaction between the two active treatments, it was estimated that we would have 90% power to detect an increase in failure rate from 10% in either antiemetic group to 20% in either dummy group (based on a two-sided test at the 5% level). This effect size was felt to be of clinical relevance to applicants and sufferers.

As the primary outcome was treatment failure between 12 hours and 10 days post treatment initiation, we anticipated obtaining outcome data from at least 90% of participants. Therefore, to account for a 10% dropout prior to assessment of the primary outcome, it was planned to recruit 600 patients (150 in each randomised group). Sample size calculations were performed using power twoprop in Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Randomisation

Randomisation was carried out centrally by the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) using a secure web-based system. Patients were randomised on a 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 basis using computer-generated random permuted blocks of size four and stratified by site to receive (1) metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron; (2) ondansetron and dummy metoclopramide; (3) metoclopramide and ondansetron; or (4) double dummy. Randomisation was performed by local research staff, who were delegated this task via the delegation log. The randomisation system generated a unique participant trial identifier and allocated a pack number to be dispensed to the participant. Pre-populated prescriptions were generated by the randomisation system.

Unblinding

The EMPOWER study was a double-blind trial. It was not planned that participants would be routinely unblinded once they had completed trial treatment.

However, participants could be unblinded in a valid medical emergency or for safety reasons where it was necessary for a treating clinician to know which treatment the participant had been receiving. Emergency unblinding could be carried out by the site PI (or another member of the team delegated this responsibility via the delegation log) by accessing the 24-hour randomisation system. A set of back-up sealed code-break envelopes were also held at sites in case of system failure or lack of availability of a delegated individual.

Following discussions with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), a decision was made to fully unblind all trial medications after the trial was stopped, allowing PIs to notify participants of the medication that they received during the trial.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis plan was drafted and finalised prior to data lock. Given that the trial closed to recruitment at the end of the pilot phase, only descriptive summaries of the data have been reported. No efficacy analyses have been undertaken owing to the small sample size. Had the internal pilot trial progressed to a full trial, the group comparisons would have been used as originally intended for this factorial trial. However, given that the pilot data are being reported, the focus of the results is on feasibility outcomes and, therefore, data have been summarised by randomised treatment group.

The progress of all participants through the trial is presented using a Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram, including the number of screened and eligible patients. Rates of eligibility and recruitment are summarised by site. Reasons for ineligibility or non-participation have been tabulated.

Baseline data are summarised descriptively. Numbers (with percentages) for categorical variables and medians (with ranges) for continuous variables were summarised by randomised treatment group and overall.

A summary of trial medication received is reported using numbers (with percentages) by randomised treatment group and overall. Reasons for premature treatment discontinuation are described.

Primary and secondary outcome measures were summarised descriptively by randomised treatment group and overall. Data are presented following the intention-to-treat principle, with participants retained in the groups to which they were randomised. The primary outcome measure of treatment failure between 12 hours and 10 days was tabulated. The rate of treatment failure [with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] was calculated out of those evaluable; participants choosing to withdraw from trial treatment before 12 hours and participants choosing to withdraw from the trial without allowing further use of routine data, between 12 hours and 10 days or without prior documented treatment failure were not considered evaluable. Readmissions for NVP, inpatient days related to NVP and additional antiemetic use were tabulated out of those evaluable. Relapse at day 5 or day 10 and remission at day 10, as defined by changes in the PUQE score, were tabulated out of those with completed PUQE questionnaires at day 2 and also at days 5 and 10. The completeness of participant-reported questionnaires was tabulated for each measure. Questionnaires were considered to be completed only if responses were available for all items. Questionnaire scores at each assessment point were summarised descriptively using numbers (with percentages) for categorical variables and medians (with ranges) for continuous variables. For each questionnaire, a score was calculated only if all items were completed. No imputation of missing data were used.

Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes were summarised descriptively, by randomised treatment group and overall, as numbers (with percentages) for categorical variables and medians (with ranges) for continuous variables. For multiple births, neonatal outcomes were summarised for each infant born.

Analyses were conducted in Stata® version 16.

Sources of bias

The primary outcome measure of treatment failure, defined as the need for further treatment because participants’ symptoms had worsened between 12 hours and 10 days, is likely to be partially subjective. This risk of ascertainment bias was reduced by the trial being double blinded, so neither the participant nor the clinical team were aware of the allocated treatment. Secondary outcome measures, including participant-reported questionnaires, were also completed or collected by participants, clinicians or research staff blinded to treatment allocation.

As far as possible, the reasons for eligible patients declining participation were recorded; however, patients were free to decline without giving a reason. It is possible that those who were too unwell to consider the trial information were more likely to decline than those with less severe symptoms; however, randomisation should have ensured that the treatment groups were balanced with respect to severity of NVP at baseline. The PIS illustrated the uncertainty and lack of high-quality evidence around the effectiveness of the trial drugs for women with NVP, and women had to be willing to be allocated to any treatment group, including double dummy.

Patients were not considered evaluable for the primary outcome measure if they withdrew from trial treatment prior to 12 hours or fully withdrew from the trial between 12 hours and 10 days without prior treatment failure. This could have introduced bias if participant withdrawal related to the effectiveness of trial treatment. Reasons for withdrawal were obtained where possible; however, participants were free to withdraw from the trial at any time without giving a reason.

Missing outcome data at follow-up, particularly for participant-reported outcome measures, could have introduced bias if data were not missing at random. Had the trial progressed to a main trial, patterns of missing data would have been explored and multiple imputation methods considered.

Health economic evaluation

The health economics analysis plan was finalised and approved before data lock. Given that the trial closed after the pilot phase, the proposed evaluation was no longer appropriate and the economic analysis was confined to two primary components:

-

Presentation of health service resource use data in the form of summary statistics.

-

Information on health-care resource use was collected via electronic case report forms (eCRFs) (for concomitant medication) and participant-completed health-care utilisation questionnaires (A&E attendance, receipt of primary care and other NHS/Personal Social Services care services), and was completed at 10 days post randomisation. Data on participant-related costs were also collected via the health-care utilisation questionnaire at the day 10 follow-up assessment. Participants were asked to provide information relating to the purchase of private health care or personal care. 30

An analysis of the completeness of the resource use data collected was conducted using descriptive statistics to calculate the number and percentage of participants, with data available for each resource item.

-

Presentation of WTP data in the form of summary statistics.

-

Participants were asked to directly express their WTP for a good service using a contingent valuation (CV) questionnaire. To ascertain their preferences, participants were presented with hypothetical scenarios and were asked how much they would be willing to pay to improve symptom severity for a 10-week period. The hypothetical scenarios were informed by input from women with experience of NVP, the literature and other experts. For a given level of income, a higher WTP value indicated that individuals derived greater benefit from a reduction in symptom severity.

Information gathered via the CV questionnaires is presented as mean [standard deviation (SD)] and median [interquartile range (IQR)] WTP amount to improve symptom severity over a 10-week period. The maximum and minimum WTP values for each of the four randomised treatment groups have also been reported.

All information was summarised by randomised treatment groups and overall. The analysis was conducted using Stata® version 15.

Qualitative evaluation

As part of the protocol for the EMPOWER clinical trial, an evaluation of women’s views of the acceptability of the trial design was carried out with the aim of improving our understanding of why women did, or did not, consent to randomisation and participation in the trial.

Recruitment to the qualitative study, as with the pilot trial, progressed slowly. The eligibility criteria were broadened in February 2019, as many women were found to be ineligible because of prior use of trial medication. As a result, the number of women available to approach for the qualitative study, particularly of decliners, was limited. In consultation with the TSC, it was therefore agreed to extend the qualitative component to include research staff to undertake a wider exploration of factors influencing trial recruitment.

Recruitment of study participants

Patient recruitment

Women who had been screened and were found to be eligible, and had accepted or declined to participate in the trial, were approached for recruitment to the qualitative substudy. Potential recruits were given a copy of the separate PIS and expression-of-interest (EOI) form. To be considerate to patients who were possibly still suffering from NVP, attempts by the qualitative researcher to contact and interview women were confined to the period between the 14th and the 28th day after the initial approach to participate in the EMPOWER trial. Brief 10- to 15-minute interviews were conducted with women who returned the form and were contactable (see Appendix 7). An option of an e-mail interview was also provided in case women were too ill to converse. Consent was obtained over the telephone, recorded and transcribed. A copy of their consent form, filled in by the researcher on their behalf, was sent to participants by e-mail or by post.

Research staff recruitment

Research staff contact details were accessed via NCTU. E-mails about the staff trial (with the PIS and consent form attached) were sent to staff who had screened or recruited women to the trial. Research midwives/nurses directly involved in trial recruitment, and site PIs who were interested in participating in the interviews, returned the consent form by e-mail or agreed to consent taken over the telephone. The large majority who were contacted were willing to participate and the telephone interviews lasted between 20 and 30 minutes (see Appendix 8).

Interview methods

To keep to the short period of time assigned for the patient interview, the topic guide was made up of a grid of questions and possible answers. This allowed the interviewer to quickly adapt the interview to the specific experiences of the woman being interviewed and allowed each participant’s priority topics to shape the conversation. The interview was semistructured, which allowed opportunities for women to expand on their answers wherever possible about positive and negative reasons for participating. The main questions in the grid were:

-

What did you think about when you were first asked to take part in the trial?

-

Why did you/did not you want to take part in the trial?

-

Did the way in which you were invited to take part affect your decision?

-

Was there anything about the trial itself that made you want/not want to take part?

Semistructured interviews were conducted with at least two research nurses/midwives and the PI from each trial site that had recruited at least one participant to the trial. Interviews covered the following topics: experiences of trial set-up and recruitment, difficulties and progress through the trial, and suggested improvements. They took place over the telephone at times convenient to the staff.

In the case of the research staff, a grounded theory approach with constant comparison during the data collection phase was adopted;31 although an interview topic guide was followed, this was adapted as findings from research staff interviews emerged and needed further exploration. A second topic guide was then designed based on these findings for the PIs because of their managerial responsibilities and oversight of the trial. The following were further topics that were explored in the course of the interviews with PIs:

-

proportion of women referred from A&E department

-

attempts to raise the profile of the trial with local general practitioners (GPs)

-

effect of the protocol amendment on recruitment

-

women with language difficulties

-

antidepressant use as a contraindication

-

involvement of research staff in the care of patients being recruited

-

awareness that trial drugs were being used in primary care.

An opportunity for triangulation with the patient data also arose as staff were able to describe particular cases of screening and recruitment that could be of interest to the trial. Recruitment to the patient group was more limited than originally anticipated. Nevertheless, data saturation was reached, that is the data obtained allowed us to reach the point at which no issues needed further confirmation or exploration, and no new themes emerged from either the patient or the trial staff data analysis.

Qualitative data management

Sound files of all interviews, Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) files of their transcriptions and Microsoft Word files of the four e-mails were stored on a password-secure server. The transcripts of patients and research staff were checked for accuracy, anonymised and entered into qualitative data management software NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for indexing and retrieval. Using the software, cases were created of the eight trial sites, with patient and clinician interviews grouped together for cross-checking. The presentation of results based on site characteristics was discounted because of the risk of participants being identifiable.

Qualitative data analysis

The data were analysed using a generative thematic approach,32 in which codes were developed inductively from the reading and re-reading of transcripts, to form an initial coding framework that was revised, expanded or collapsed as the analysis progressed. The analytical process followed the first four stages described by Braun and Clarke:33

-

familiarisation with the data – reading and re-reading of a sample of transcripts to identify and agree descriptive codes (ML and RG: one meeting on patient data and another on trial staff data)

-

coding the data – coding the data according to an initial coding frame and revising the coding frame as further interviews were analysed (ML)

-

searching for themes – analysis of the text coded in descriptive codes to determine at an interpretive level the themes that would best capture the findings from the data (ML)

-

reviewing the themes – data analysis team meeting to review possible themes with a clinician chief investigator (SCR) and medical sociologist co-investigator (RG).

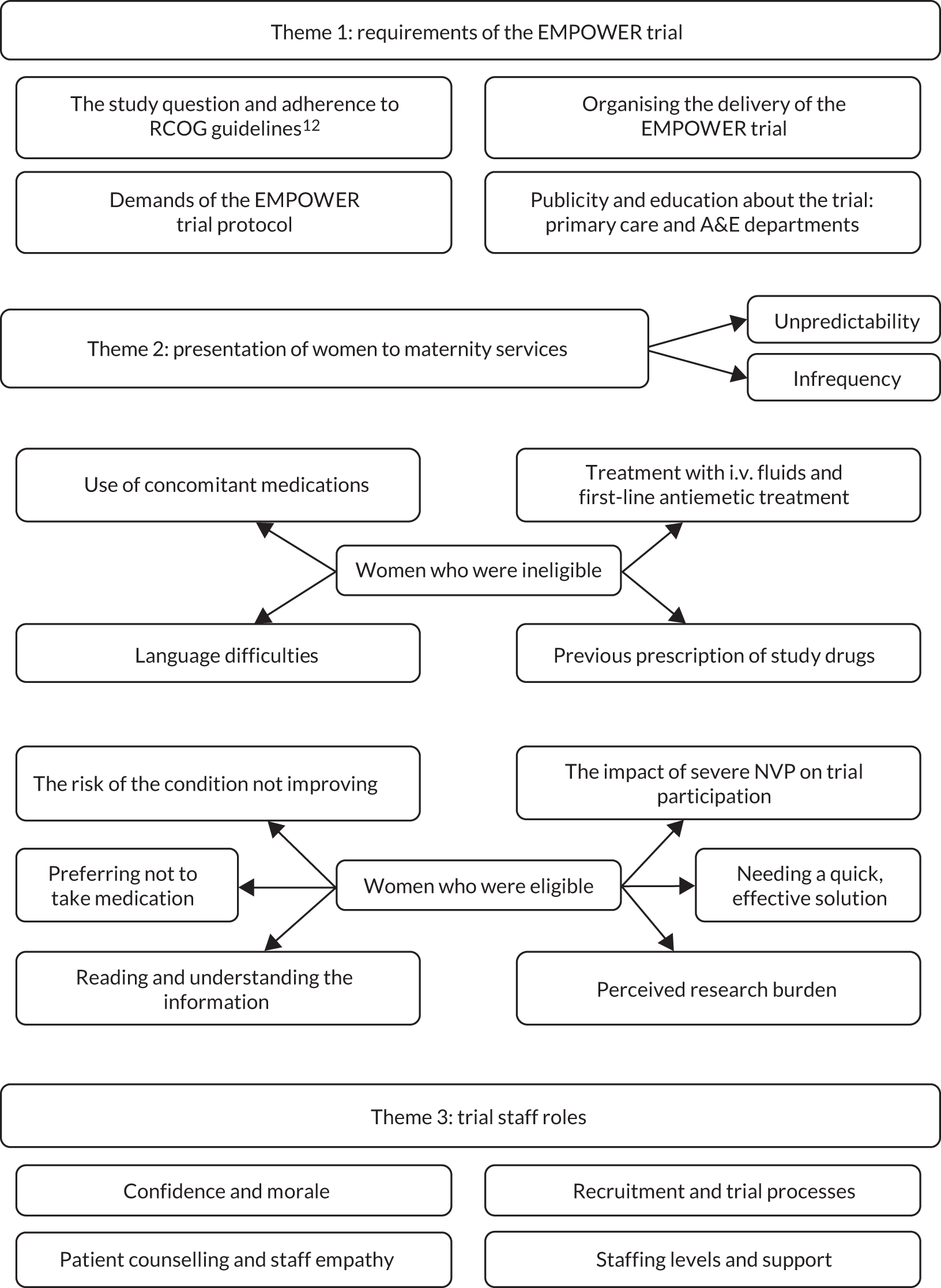

At a second data analysis team meeting, two broad themes were agreed for further analysis, that is the ‘hurdles’ to and ‘enablers’ of the trial process. Considering the complexity of the data with respect to the differences in the sample groups, it was decided that the best way to present the data was to chart the findings according to the framework approach. 34,35 The data were charted under the following groups:

-

patients who accepted participation

-

patients who declined participation

-

research midwives/nurses

-

PIs.

This enabled triangulation between the different types of experiential knowledge within the data sets overall.

In a third data analysis team meeting, the qualitative findings according to the two broad themes of ‘hurdles’ and ‘enablers’ were presented using illustrative quotations in a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). A decision was made to present the key themes in the data with selected quotations from the Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet in the text itself as in a standard qualitative report. This allowed a clearer link between the discussion of the themes and the available evidence from the qualitative data.

This descriptive analysis was complemented by a more interpretative strand of analysis in which the qualitative data were presented according to sociological, concept-led themes relating to ‘pathways’ and ‘boundaries’, and ‘ethics of care’. The data findings under themes that related to process evaluation, such as recruitment complexity and staff morale, were also presented because they had emerged from the coding of research staff interviews.

Definition of end of trial

The end of trial was defined as the date that the last infant born to an EMPOWER trial participant was discharged from hospital.

Trial management

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the trial. TMG meetings were well attended throughout and involved the chief investigator, statisticians, health economists, qualitative researchers, pharmacy representatives, sponsor representatives, trial management team members, patient contributors and local co-applicants. The TMG met regularly throughout the trial to ensure adherence to the trial protocol and monitor the conduct and progress of the trial.

Data management

The trial database was built by the trial data manager with input from the TMG using MACRO™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). The randomisation system and stock management were set up by the trial data manager using the NCTU randomisation system.

All visit data were entered into the MACRO™ database at each site by the local research team. Baseline questionnaire data were entered by local site staff. The 2-day, 5-day and 10-day questionnaires were returned to NCTU by participants and data entry was completed by the central trial team. The central team contacted participants by post after they had completed day 10 to remind them to return the questionnaires and unused IMP/packaging if they had not already done so. One further letter was sent approximately 2 weeks later if the questionnaires had still not been received by the central team.

Serious adverse event data were sent to the central trial team by secure e-mail and then entered centrally into the MACRO™ database.

Essential data will be retained for a period of at least 15 years following the close of the trial in line with sponsor policy and the latest directive on GCP (2005/28/EC). Data were handled, digitalised and stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 199836 and the Data Protection Act 2018. 37 In line with GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), the sponsor acted as the data controller and NCTU acted as the data processor for this trial.

It was planned to transfer outcome data at the end of the trial to the UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS) national database for participants who had consented to this. This was to be retained (under section 25138) for the purpose of surveillance. However, given the limited data available, a decision was made by the TMG, in consultation with UKTIS, not to transfer the data.

Data monitoring, quality control and assurance

Monitoring of trial conduct was completed using a mix of central review and on-site monitoring visits to ensure that the trial was conducted in accordance with the protocol and GCP.

Data were monitored centrally throughout the trial by the data manager and checked regularly for completeness, and any discrepancies were queried with sites using the built-in data clarification request function in MACRO™. Validations built into the database flagged potential errors with dates and out-of-range values. A full list of built-in validations was detailed in the data validation plan. Source data verification was conducted by the trial manager during the on-site monitoring visits, as set out in the monitoring plan.

A data quality report was produced and reviewed at TMG meetings. Data from MACRO™ were compared with data from the NCTU randomisation system to ensure consistency.

An independent Data Monitoring Committee (iDMC) was convened to monitor safety. The iDMC met at the start of the trial and three times throughout the trial.

A TSC was established to provide overall supervision of the trial. The TSC consisted of an independent chairperson, two further independent clinicians, an independent statistician, an independent health economist, two independent lay representatives, a patient contributor and the chief investigator. Other members of the TMG attended as required. The committee met five times throughout the trial.

Serious adverse event reporting

All AEs and adverse reactions (ARs) occurring from the start of administration of the IMP through to 24 hours post last IMP dose were recorded via the eCRF AE page and documented in the participant’s medical records.

Each participant was assessed at baseline and any conditions or symptoms that they were currently experiencing were recorded in the participant’s medical records and graded using the CTCAE.

During follow-up, participants were asked about any new or ongoing symptoms, and sites followed the below process:

-

For symptoms previously reported at baseline –

-

If the CTCAE grading remained the same or better, the symptom did not need to be recorded as an AE or AR. Symptoms were still documented in the patient’s medical records.

-

If the CTCAE grading was worse, this was recorded as an AE or AR in the eCRF AE page and documented in the patient’s medical records.

-

-

For new symptoms not recorded at baseline, these were recorded as an AE or AR and graded using CTCAE. These were recorded via the eCRF AE page and were documented in the patient’s medical records.

All AEs and ARs that met the definition of serious were regarded as a SAE or serious adverse reaction (SAR) and needed to be reported as part of the trial. SAEs and SARs were also collected from the start of administration of the IMP through to 24 hours post last IMP dose. Thereafter, any SAR that came to the attention of the site team had to be reported up until the point of trial closure. All deaths were to be reported as SAEs irrespective of the cause.

All potential reactions were assessed for expectedness using the reference safety information. The reference safety information was contained in section 4.8 of the Summary of Product Characteristics for each of the four medications used in this trial (metoclopramide tablets, i.v. metoclopramide, ondansetron tablets and i.v. ondansetron).

Amendments to the trial protocol

Following receipt of a favourable opinion of the trial protocol from the National Research Ethics System, substantial amendments were submitted and received Health Research Authority (HRA) approval and favourable Research Ethics Committee (REC) opinion [and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approval where applicable].

In summary, these were as follows:

-

Amendment 1 – protocol V2.1, 26 February 2018. This was updated on advice from the TSC regarding treatment options for those who fail on EMPOWER trial treatment: some clarifications regarding eligibility criteria were also provided.

-

Amendment 2 – protocol V3.0, 11 September 2018. This was updated to include staff participants in qualitative interviews.

-

Amendment 3 – protocol V4.0, 15 November 2018. The protocol was updated to reflect the extension of the pilot phase and to update the eligibility criteria to include women who had received suboptimal treatment with ondansetron or metoclopramide based on findings during the pilot phase.

-

Amendment 4 – protocol V5.0, 19 March 2019. This included an update to the exclusion criteria (amended in the last update to provide clarity following feedback from sites); provision of the option to collect PUQE, VAS and Health Utilisation Questionnaire data by telephone at day 10; and clarification that participants needed to have been off SSRIs for at least 2 weeks to meet this eligibility criterion.

Patient and public involvement

Both public co-applicants had suffered from severe NVP during pregnancy. Both contributed to the design of the trial; specifically, they prioritised the primary outcome and contributed to the selection of secondary outcomes, the duration of intervention use before assessment for treatment failure and the overall maximum duration of intervention use. During the trial, both public co-applicants continued to provide extensive input, including reviewing the design and content of the PIS, designing a one-page short-form schematic of the PIS, reviewing the design of the WTP questionnaire, helping with the design and content of the EMPOWER trial website, and providing support to the team regarding the eligibility challenges faced during the pilot. One co-applicant facilitated a wider review of opinions on various design elements via an online group of women with previous experience of HG. The two lay members of the TSC were also engaged throughout and attended TSC meetings and teleconferences, as well as numerous additional telephone calls and e-mails with the chief investigator and lead research midwife.

Ethics and governance

The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust was the sponsor for the trial (reference 08367). The trial received clinical trial authorisation from the MHRA on 22 November 2017 and favourable ethics opinion from the North East – Newcastle & North Tyneside 1 Research Ethics Committee (reference number 17/NE/0325) on 30 November 2017. HRA approval was also received on 30 November 2017. Subsequent research and development approvals were granted by each participating site. Required approvals were sought and obtained prior to implementation of all substantive protocol amendments.

Trial registration and protocol availability

The trial was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) registry as ISRCTN16924692 on 8 January 2018.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow

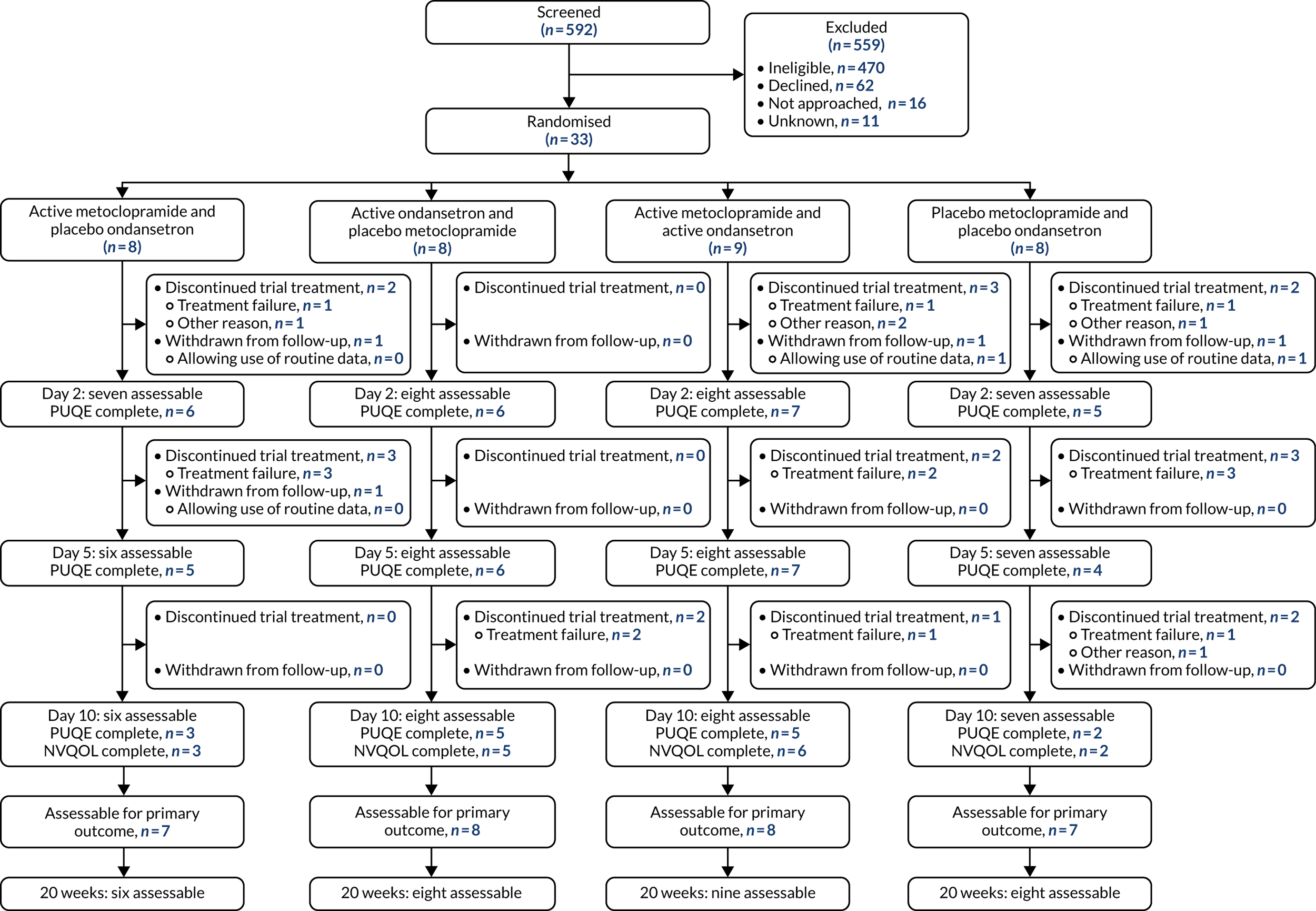

A CONSORT flow diagram of participant flow through the trial is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

Screening

Between 24 April 2018 and 12 August 2019, 592 patients were screened for eligibility. Table 2 summarises the number of patients screened by site. Overall, 122 (21%) patients were eligible. The proportion of eligible patients increased from 19% to 22% after the implementation of protocol version 4.0 to broaden the eligibility criteria around prior use of trial drugs.

| Site | Date recruitment opened | Overall, n (%) | Pre amendment (before 22 February 2019), n (%) | Post amendment (after 22 February 2019) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened | Eligible | Recruited | Screened | Eligible | Recruited | Screened | Eligible | Recruited | ||

| Newcastle | April 2018 | 93 | 26 (28) | 5 (19) | 60 | 15 (25) | 4 (27) | 33 | 11 (33) | 1 (9) |

| Sunderland | May 2018 | 43 | 16 (37) | 10 (63) | 32 | 9 (28) | 8 (89) | 11 | 7 (64) | 2 (29) |

| Leeds | May 2018 | 101 | 17 (17) | 5 (29) | 61 | 13 (21) | 5 (38) | 40 | 4 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Bradford | June 2018 | 88 | 9 (10) | 1 (11) | 59 | 6 (10) | 0 (0) | 29 | 3 (10) | 1 (33) |

| South Tees | June 2018 | 43 | 12 (28) | 6 (50) | 33 | 4 (12) | 1 (25) | 10 | 8 (80) | 5 (63) |

| Birmingham | July 2018 | 64 | 8 (13) | 2 (25) | 48 | 8 (17) | 2 (25) | 16 | 0 (0) | 0 (NA) |

| St Thomas’ | July 2018 | 81 | 26 (32) | 4 (15) | 20 | 6 (30) | 3 (50) | 61 | 20 (33) | 1 (5) |

| Nottingham | March 2019 | 34 | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | 34 | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Portsmouth | May 2019 | 25 | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | 25 | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| St George’s | May 2019 | 16 | 3 (19) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | 16 | 3 (19) | 0 (0) |

| Oldham | May 2019 | 3 | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 2 (67) | 0 (0) |

| Stoke | July 2019 | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (NA) | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (NA) |

| Total | 592 | 122 (21) | 33 (27) | 313 | 61 (19) | 23 (38) | 279 | 61 (22) | 10 (16) | |

Reasons for ineligibility are shown by site in Table 3. The main reason for ineligibility was prior treatment with trial medication(s) in the current pregnancy (n = 320; 68%).

| Site | Ineligible (N) | Reason, n (%)a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior treatment with trial drug(s) | Unable to read/understand written English | Aged < 18 years old | > 16+6 weeks’ gestation | Allergy/hyper-sensitivity to trial drug(s) | Pre-existing medical condition | Vomiting caused by another condition | Concomitant use of apomorphine or serotonergic drugs | Missing/unknown | ||

| Newcastle | 67 | 52 (78) | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 6 (9) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sunderland | 27 | 17 (63) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (11) | 3 (11) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Leeds | 84 | 37 (44) | 8 (10) | 1 (1) | 7 (8) | 1 (1) | 8 (10) | 1 (1) | 17 (20) | 4 (5) |

| Bradford | 79 | 62 (78) | 8 (10) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| South Tees | 31 | 27 (87) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Birmingham | 56 | 47 (84) | 6 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| St Thomas’ | 55 | 26 (47) | 5 (9) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21 (38) |

| Nottingham | 33 | 27 (82) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Portsmouth | 23 | 14 (61) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 4 (17) | 1 (4) |

| St George’s | 13 | 9 (69) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Oldham | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Stoke | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 470 | 320 (68) | 35 (7) | 6 (1) | 17 (4) | 3 (1) | 26 (6) | 13 (3) | 23 (5) | 27 (6) |

Further detail on prior use of ondansetron or metoclopramide is shown in Table 4. This information was collected only from 29 August 2018, once prior treatment with trial drugs was identified as a barrier to recruitment. Of those ineligible owing to prior exposure to trial drug(s), 83% had received ondansetron and 17% had received metoclopramide. Prior to protocol version 4.0, in which data on route of administration were available, 41 (37%) participants had received oral treatment only; however, only 10 participants were known to have received oral treatment for ≤ 3 days. Where the source of prescription was known, 57 (24%) participants had received treatment from their GP and the remaining 179 (76%) participants from secondary care. In those receiving treatment from secondary care, the main reason for non-recruitment was the lack of availability of research staff (58%), mostly owing to patients attending out of hours (82%).

| Overall (N = 262), n (%) | Pre-protocol amendment (before 22 February 2019) (N = 128), n (%) | Post-protocol amendment (after 22 February 2019) (N = 134), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug given | |||

| Ondansetron | 215 (83) | 107 (84) | 108 (82) |

| First line | 62 (36) | 18 (26) | 44 (43) |

| Second line | 108 (64) | 50 (74) | 58 (57) |

| Missing | 45 | 39 | 6 |

| Metoclopramide | 44 (17) | 20 (16) | 24 (18) |

| First line | 22 (58) | 8 (50) | 14 (64) |

| Second line | 16 (42) | 8 (50) | 8 (36) |

| Missing | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Not recorded | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Route of administration | |||

| Oral only | 82 (35) | 41 (37) | 41 (33) |

| Taken for ≤ 3 days | 12 (23) | 10 (48) | 2 (6) |

| Taken for > 3 days | 40 (77) | 11 (52) | 29 (94) |

| Missing duration | 30 | 20 | 10 |

| i.v. (± oral treatment) | 137 (59) | 55 (50) | 82 (67) |

| i.m. or PR | 14 (6) | 14 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 29 | 18 | 11 |

| Source of prescription | |||

| GP | 57 (24) | 28 (25) | 29 (24) |

| Secondary care | 179 (76) | 86 (75) | 93 (76) |

| A&E department | 39 (22) | 18 (22) | 21 (23) |

| Gynaecology/early pregnancy clinic | 61 (35) | 15 (18) | 46 (49) |

| Maternity | 75 (43) | 49 (60) | 26 (28) |

| Missing | 30 | 18 | 12 |

| Reason prescribed: if from secondary care | |||

| Woman’s request | 4 (3) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Doctor’s preference | 62 (40) | 27 (38) | 35 (40) |

| No research staff available | 93 (58) | 41 (58) | 52 (59) |

| Attended out of hours | 76 (82) | 33 (80) | 43 (83) |

| Other reason | 17 (18) | 8 (20) | 9 (17) |

| Missing | 20 | 15 | 5 |

Overall, 89 patients were eligible for the trial but were not recruited, with 62 (70%) of those declining participation. Reasons for eligible patients declining participation are shown in Table 5.

| Reason | Number of participants, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Reason that eligible participant was not recruited (N = 89) | |

| Declined | 62 (70) |

| Not approached | 16 (18) |

| Not recorded | 11 (12) |

| Reasons that participants declined (N = 62) | |

| Too unwell to consider information | 13 (21) |

| Worried care would be affected (e.g. chance of getting dummy)/does not want dummy | 14 (23) |

| Preference for specific treatment(s)/does not want (trial) drug(s) | 12 (19) |

| Too busy/other commitments/would find it difficult to participate | 7 (11) |

| Does not want to participate in research/sees no benefit in trial | 4 (6) |

| Worried subsequent care would be affected (e.g. would not know what drug received) | 1 (2) |

| No reason given | 7 (11) |

| Other reason | 4 (6) |

Recruitment

From the 122 eligible patients who were screened, 33 (27%) were randomised into the trial. As per the 2 × 2 factorial design, participants were randomised to receive active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron (n = 8); active ondansetron and dummy metoclopramide (n = 8); active metoclopramide and active ondansetron (n = 9); or dummy metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron (n = 8) (see Figure 2).

Despite the proportion of eligible patients increasing slightly following the implementation of protocol version 4.0, the proportion of eligible patients randomised into the trial declined from 38% to 16% (see Table 2). Of the 12 trial centres open to recruitment, seven enrolled at least one participant into the trial.

Internal pilot

It was initially planned that there would be an internal pilot phase involving up to eight sites followed by a main phase with an additional 14–16 sites (22–24 sites in total).

The progression criterion to the main trial was set at 59 participants to be recruited within 6 months, with ≥ 40 participants retained for data collection at day 10. The trial opened to recruitment on 24 April 2018 and by the end of October 2018 seven sites were open to recruitment, with only 17 participants recruited.

Screening data showed that a larger than anticipated proportion of women were ineligible owing to prior treatment with ondansetron or metoclopramide in the current pregnancy. Following advice from the TSC, trial co-applicants, TMG and the HTA programme, the eligibility criteria were broadened in February 2019 to allow patients who had previously received suboptimal treatment with ondansetron or metoclopramide (orally for < 72 hours) in their current pregnancy to be included. Women who had received either of the trial drugs intravenously or orally for > 72 hours (with or without i.v. rehydration) were still ineligible.

The pilot phase was extended to the end of August 2019. The revised stop–go criterion required 96 participants to be recruited by the end of August 2019. This was based on a recruitment rate of one participant per site per month, with an additional six sites open to recruitment by May 2019.

Progress was reviewed with the iDMC, TSC and HTA programme in July 2019. At this time, 32 participants had been recruited and five additional sites had been opened. The main reason for ineligibility continued to be prior treatment with trial drugs, despite the protocol amendment to broaden the eligibility criteria. It was therefore decided that the trial would close and not progress to a main trial. Following the closure of the trial to recruitment in August 2019, follow-up of participants continued until the final pregnancy outcome was reported in April 2020.

Figure 3 shows the cumulative accrual rates originally anticipated for the pilot phase, the revised target for the pilot phase and the actual recruitment.

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative recruitment by month.

Withdrawals and ineligible participants

No participants were found to be ineligible after randomisation.

Two participants withdrew from the trial without allowing any use of routine data; both were allocated to receive active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron. One participant withdrew on day 4 for personal reasons following treatment failure (this participant was evaluable for the primary outcome given that treatment failure was reported prior to withdrawal). The other participant wished to withdraw from the trial owing to perceived side effects of the medication on day 2. This participant was not evaluable for the primary outcome.

A further two participants withdrew from trial treatment and further follow-up assessments but allowed routine data to be collected (one metoclopramide and ondansetron, and one double dummy). Both of these participants withdrew prior to receiving 12 hours of trial drugs because they requested further medications or were not feeling better. Neither of these participants was evaluable for the primary outcome.

Numbers analysed

Thirty (91%) participants were evaluable for the primary outcome: seven (88%) active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron; eight (100%) active ondansetron and dummy metoclopramide; eight (89%) metoclopramide and ondansetron; and seven (88%) double dummy. For information on those who were not evaluable for the primary outcome, see Withdrawals and ineligible participants.

Thirty-one (94%) participants were evaluable for data collected on readmissions for NVP and further antiemetic treatments prescribed up to 20 weeks’ gestation: six (75%) active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron; eight (100%) active ondansetron and dummy metoclopramide; nine (100%) metoclopramide and ondansetron; and eight (100%) double dummy. Those who were not evaluable were those participants who withdrew from the trial without allowing any use of routine data. Between 20 weeks and delivery, 28 participants (85%) were evaluable, with three participants reporting a TOP prior to 20 weeks’ gestation.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PUQE, VAS for nausea, NVPQoL questionnaire, EPDS and six-item STAI) were expected from 29 (88%) participants at day 10, with four participants (two active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron; one metoclopramide and ondansetron; and one double dummy) withdrawing from follow-up assessments prior to this time point.

Baseline data

Demographic and clinical baseline characteristics are presented by randomised treatment group in Table 6. Further baseline demographics, including baseline values of participant-reported outcome measures, can be found in Appendix 9, Table 18; Appendix 10, Table 19; and Appendix 11, Table 20.

| Characteristic | Treatment group | Overall (N = 33) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron (N = 8) | Active ondansetron and dummy metoclopramide (N = 8) | Active metoclopramide and active ondansetron (N = 9) | Dummy metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron (N = 8) | ||

| Age (years), median (minimum, maximum) | 27 (18, 34) | 34 (21, 38) | 27 (21, 38) | 24 (18, 32) | 27 (18, 38) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White British, n (%) | 6 (75) | 6 (75) | 8 (89) | 6 (75) | 26 (79) |

| Other, n (%) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 1 (11) | 2 (25) | 7 (21) |

| Gestational age (weeks), median (minimum, maximum) | 76/7 (65/7, 133/7) | 86/7 (76/7, 162/7) | 76/7 (50/7, 125/7) | 94/7 (65/7, 155/7) | 85/7 (50/7, 162/7) |

| Multiple birth, n (%) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) |

| First-line medication received,a n (%) | |||||

| Cyclizine | 7 (88) | 7 (88) | 7 (78) | 5 (63) | 26 (79) |

| Promethazine | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 3 (33) | 1 (13) | 5 (15) |

| Prochlorperazine | 2 (25) | 3 (38) | 4 (44) | 4 (50) | 13 (39) |

| Gravida, n (%) | |||||

| 1 | 3 (38) | 1 (13) | 3 (33) | 5 (63) | 12 (36) |

| 2 | 1 (13) | 3 (38) | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 8 (24) |

| 3 | 2 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) |

| 4 | 2 (25) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) | 5 (15) |

| 5–8 | 0 (0) | 3 (38) | 1 (11) | 1 (13) | 5 (15) |

| Parity, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 4 (50) | 1 (13) | 4 (44) | 6 (75) | 15 (45) |

| 1 | 2 (25) | 4 (50) | 4 (44) | 1 (13) | 11 (33) |

| 2 | 2 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 3 (9) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 3 (38) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 4 (12) |

| Past pregnancies | 5 (63) | 7 (88) | 6 (67) | 3 (38) | 21 (64) |

| If yes, NVP in any past pregnancy | 3 (60) | 6 (86) | 6 (100) | 1 (33) | 16 (76) |

The median gestation at the time of trial entry was 85/7 weeks and ranged from 5 weeks to 162/7 weeks. Three (9%) women were expecting more than one baby. Overall, 12 (36%) women had not had a previous pregnancy. Of the 21 women who had had a prior pregnancy, 16 (76%) had experienced NVP in a previous pregnancy. All of the women had received at least one first-line antiemetic medication, with 26 (79%) receiving cyclizine, 13 (39%) receiving prochlorperazine and five (15%) receiving promethazine.

Treatment received

All of the participants received at least one dose of their allocated trial drugs. One participant (allocated to double dummy) received only oral trial drugs at her request. All of the other participants received the trial drugs intravenously initially. The number of i.v. doses received is summarised in Table 7. One participant (allocated to active ondansetron) received three i.v. doses; however, two were received on day 4 following a readmission to hospital (for reasons other than NVP) and being nil by mouth (incidental paronychia; see Safety).

| Treatment | Treatment group, n (%) | Overall (N = 33), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron (N = 8) | Active ondansetron and dummy metoclopramide (N = 8) | Active metoclopramide and active ondansetron (N = 9) | Dummy metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron (N = 8) | ||

| Number of i.v. doses | |||||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 1 (3) |

| 1 | 8 (100) | 7 (88) | 8 (89) | 5 (63) | 28 (85) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 2 (25) | 3 (9) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Converted to oral medication | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | 8 (89) | 7 (88) | 31 (94) |

| Completed 10-day treatment period | |||||

| Yes | 3 (38) | 6 (75) | 3 (33) | 1 (13) | 13 (39) |

| No: treatment failure | 4 (50) | 2 (25) | 4 (44) | 5 (63) | 15 (45) |

| Time until treatment failure (hours) | |||||

| ≤ 48 | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) | 3 (20) |

| 48.1–120 | 3 (75) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 3 (60) | 8 (53) |

| > 120 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) | 4 (27) |

| No: treatment discontinued for other reason | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 2 (25) | 5 (15) |

Thirteen (39%) participants completed the 10-day trial treatment period; however, one participant (who was allocated to receive active metoclopramide and active ondansetron) missed 16 doses of medication (equivalent to 5.3 days of treatment) because of side effects (drowsiness reported as an AE; see Safety). Fifteen (45%) participants discontinued treatment owing to treatment failure, as per the primary outcome. The remaining five (15%) participants chose to discontinue treatment prior to day 10. Two participants chose to discontinue treatment before 12 hours because they were not feeling better and requested further medications (one active metoclopramide and active ondansetron, and one double dummy); both received only one i.v. dose of the trial drugs and did not convert to oral medication. One participant (who was allocated to receive active metoclopramide alone) chose to discontinue treatment on day 2 owing to side effects (‘funny feeling in legs’, ‘increase in anxiety’ and ‘nightmares’ were reported as AEs). One participant (who was allocated to receive active metoclopramide and active ondansetron) chose to discontinue trial treatment on day 2 because she reported feeling better and decided to manage her symptoms without medication. Another participant (who was allocated to receive double dummy) chose to discontinue treatment on day 5 because she felt that the medication was not effective, but was feeling better so did not seek further review.

Primary outcome measure

Overall, 30 participants were evaluable for the primary outcome. Of those 30 participants, treatment failure between 12 hours and 10 days occurred in four (57%) participants allocated to active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron, two (25%) participants allocated to active ondansetron and dummy metoclopramide, four (50%) participants allocated to active metoclopramide and active ondansetron, and five (71%) participants allocated to double dummy (Table 8). Three participants (one active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron, one active metoclopramide and active ondansetron, and one double dummy) reported treatment failure within the first 48 hours. Further antiemetic treatments received are summarised in Table 8. One participant (who was allocated to receive active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron) did not have information available on further treatments received because she withdrew from the trial, including the use of any routine data, following treatment failure. Thirteen (93%) of those participants reporting a treatment failure received oral antiemetics, four (29%) received i.v. antiemetics and five (36%) received intramuscular antiemetics.

| Treatment group | Overall (N = 33) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron (N = 8) | Active ondansetron and dummy metoclopramide (N = 8) | Active metoclopramide and active ondansetron (N = 9) | Dummy metoclopramide and dummy ondansetron (N = 8) | ||

| Number evaluable, n (%) | 7 (88) | 8 (100) | 8 (89) | 7 (88) | 30 (91) |

| Treatment failure between 12 hours and 10 days, n (%); 95% CI | 4 (57); 18% to 90% | 2 (25); 3% to 65% | 4 (50); 16% to 84% | 5 (71); 29% to 96% | 15 (50); 31% to 69% |

| Treatment failure by 48 hours, n (%) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 1 (14) | 3 (10) |

| Further antiemetic treatment received, n (%) | |||||

| Ondansetron alone | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) | 3 (21) |

| Cyclizine alone | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 2 (14) |

| Metoclopramide alone | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (7) |

| Cyclizine and prochlorperazine | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) | 3 (21) |

| Prochlorperazine and ondansetron | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) | 3 (21) |

| Cyclizine and ondansetron | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| Metoclopramide and ondansetron | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Route(s) of further antiemetic treatment(s), n (%) | |||||

| Oral | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 3 (75) | 5 (100) | 13 (93) |

| i.v. | 1 (33) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 4 (29) |

| i.m. | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 3 (75) | 1 (20) | 5 (36) |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Secondary outcome measures

Clinical indicators of antiemetic effectiveness