Notes

Article history

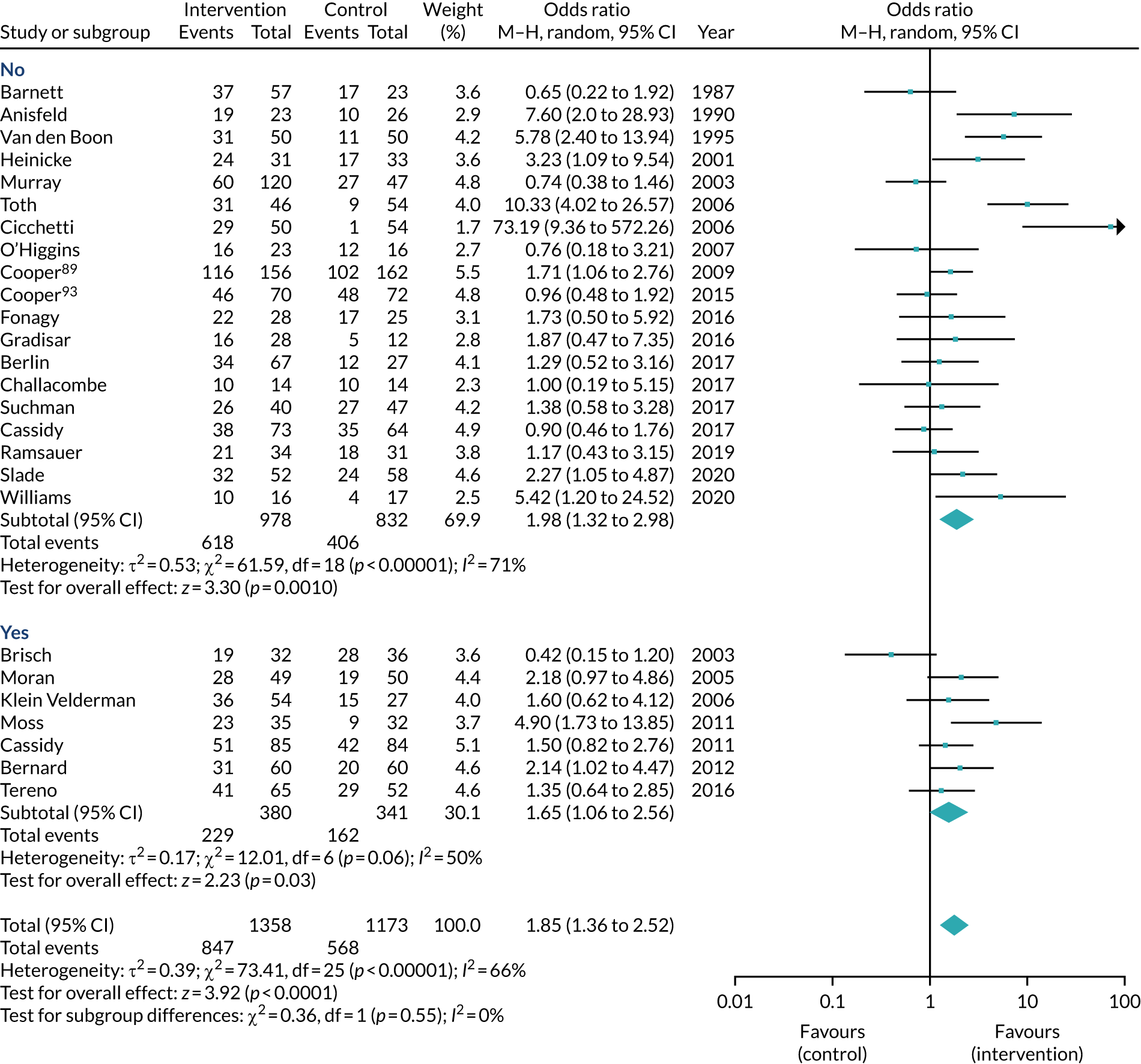

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number NIHR127810. The contractual start date was in July 2019. The draft report began editorial review in May 2021 and was accepted for publication in September 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Wright et al. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Wright et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Attachment

Attachment theory, originally developed by John Bowlby, focuses on understanding the functional significance of the distress that infants experience when alarmed, frightened or very uncomfortable and how they deal with that distress. Attachment, then, refers to the proximity-seeking of an attachment figure by the infant when they are alarmed or frightened, with the anticipation that they will receive a caregiving response. Bowlby conceptualises it as the ‘lasting psychological connectedness between human beings’. 1 An attachment figure tends to be the primary caregiver of an infant, someone the infant can seek out when they are distressed.

Bowlby’s attachment took an explicitly evolutionary perspective when seeking to understand these phenomena; Bowlby suggested that infants are born with an innate instinct to form attachments with their caregiver. 2 The proximity that infants seek is thought of as a mechanism that increases fitness and improves the chances of survival; they produce behaviours to gain attentive responses and protection from their caregiver, particularly pertinent at times of threat.

Two concepts are particularly central to attachment theory: a secure attachment develops as the product of interactions between infant and caregiver. These interactions are the result of care-seeking and caregiving behaviours. It is thought that caregiving behaviours also serve a biological function, that of protecting the attached individual from psychological and physical harm. 3 Care-seeking (i.e. attachment) behaviours are apparent in the first few months of an infant’s life and become most clearly apparent at around 7–9 months of age. Prior to this, attachment behaviours initially encourage proximity in general, but in the second half of the first year these behaviours become directed towards individual attachment figures,4 and it is at this point that selective attachments can be unambiguously identified.

A second key concept is that the quality of a child’s attachment underpins, in part, their later development. An infant’s instinct to seek a recognised caregiver for safety and security is vital in promoting healthy social and emotional development. 1 Although attachment acts as a predictor of later individual differences in socioemotional development, and is thought of as a cause of these differences, there is no evidence to suggest that attachment relationships cannot be altered. 2 For example, an insecure attachment relationship at 12 months can later change to a secure one, and this is likely to be associated with better outcomes subsequently.

Attachment patterns

The quality of an infant–caregiver attachment relationship is assessed by observing their attachment behaviours, and these can be categorised as attachment patterns. 5 To assess attachment patterns, the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP), proposed by Mary Ainsworth, was developed, which initially identified three attachment patterns present in infants. 6 These patterns represent the ways in which infants behave when they are anxious and search for protection, which are believed to be innate but are shaped partly by the infant’s history of interactions with the caregiver, and particularly by how the caregiver has responded to the infant’s bids for comfort and contact. ‘Secure attachment (B)’ refers to infants who actively seek proximity to their caregiver, and although they may be distressed during separation they seek contact actively when the caregiver returns, and, once settled, they are happy to return to exploring on their own. 7 This attachment pattern is likely the result of sensitive and consistent caregiver responses. By contrast, ‘insecure avoidant (A)’ infants may cry little during separation and do not seek proximity on reunion. This is thought to be a consequence of previous emotional unavailability at the moment when the child has signalled emotional need. Last, an infant with an ‘insecure resistant (C)’ pattern constantly seeks reassurance and tends to cry and resist comfort, this pattern occurring largely as a result of unpredictable caregiving behaviour. 7 The term ‘disorganised attachment pattern’ was introduced by Main and Solomon8 to describe infants who do not fall into one of the A, B and C categories. Instead, these infants show distorted, conflicted and contradictory behaviours in the strange situation. 9 This attachment pattern and, to a lesser extent, ‘insecure’ attachment patterns have been associated with psychopathology later in life10 and act as significant predictors of mental ill-health. 11

In normative populations across different countries, the majority of children have a secure attachment pattern. 12 The distribution of insecure patterns in normative samples varies with culture.

‘Severe attachment problems’ can be defined as disorganised attachment patterns or attachment disorders. 13 In recent policy guidance, disorganised attachment and attachment disorders [e.g. reactive attachment disorder (RAD)] have been referred to as ‘severe attachment problems’ to indicate their clinical significance and differentiate them from more normative patterns of avoidance and resistance. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,14 attachment disorders include RAD, or a disinhibited attachment disorder, which is now termed ‘disinhibited social engagement disorder’ (DSM-5). 15 Children with RAD often do not seek proximity when they feel distressed and do not acknowledge comforting caregiving behaviours, often behaving in a withdrawn manner. 14 These children also show a lack of positive interaction with and emotions towards others. The diagnosis of RAD requires evidence of experiences of severe neglect or multiple different caregivers, with the behaviours being present before the age of 5 years. 14 Disinhibited attachment disorder in DSM-IV has been replaced by ‘disinhibited social engagement disorder’ in DSM-5. 15 The main characteristics of this disorder are active approaches towards and overfamiliar interaction with unfamiliar adults, with reduced or absent reticence; diminished or absent checking back with an adult caregiver after venturing away, even in unfamiliar settings; and willingness to go off with an unfamiliar adult with minimal or no hesitation. This is thought to be based on the lack of development of stranger awareness due to early extreme neglect or care by multiple different caregivers, similar to RAD.

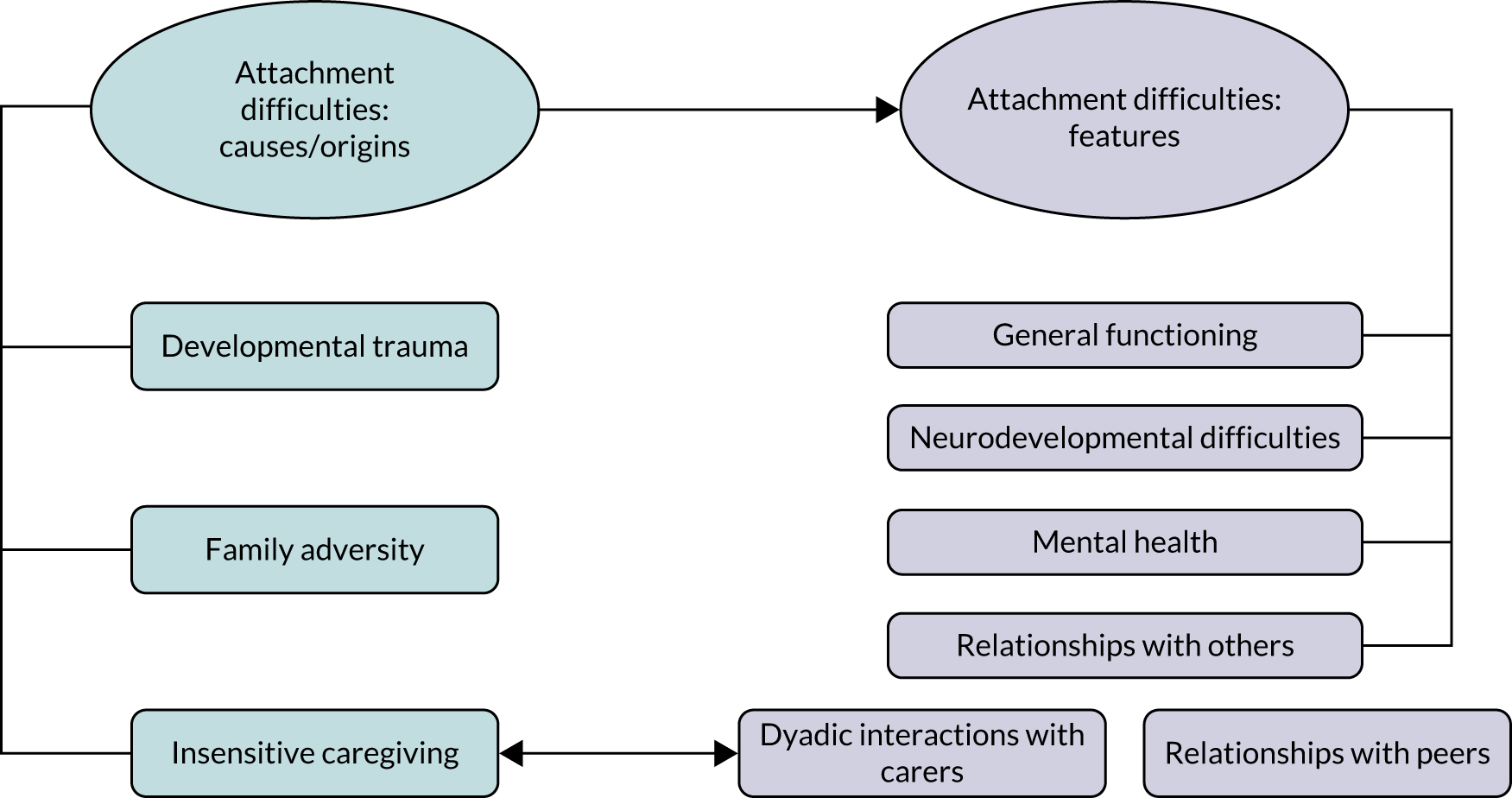

Attachment and maladaptation

Research has found a significant association between early attachment classification and children’s developmental outcomes. 16 For instance, a longitudinal study from infancy to childhood found that a higher rate of antisocial behaviour in preschool was seen in children with an insecure attachment pattern than in those with a secure attachment pattern. 17 Insecure/disorganised attachment patterns are associated with more common major mental health disorders such as depression and personality disorders. 10,18,19 Early studies provided evidence that insecure attachment, specifically insecure avoidant attachment, is a predictor of later antisocial behaviour and anxiety disorders. 20

Meta-analyses have revealed significant and robust but modest associations between avoidant attachment and lower social competence, higher levels of internalising problems and higher levels of externalising problems; and between resistant attachment and lower social competence. 16 Fearon et al. 21 have shown a significant association between insecure and disorganised attachment patterns in infancy and later externalising behaviour problems. Disorganised attachment has associations with specific maladaptive behaviours later in life. Some infants with disorganised attachment develop controlling behaviour, either punitive or caregiving, towards their parents in middle childhood. 11,22 Disorganised attachment is specifically linked to internalising and externalising behaviour problems in early school years and at 6 years old. 23,24 Similarly, a large-scale longitudinal Minnesota study25 found that disorganisation was linked to internalising behaviour problems in middle childhood and psychopathology at 17 years of age.

Secure attachment is accompanied by more positive outcomes across the lifespan, including better peer relationships, more independence and fewer behaviour problems. 16,21,26–28

Influences on attachment patterns

The quality of care during the first years of life and the continuity of this care are predictors of adaptation through childhood and adolescence. 29

A vital factor found to affect attachment is whether or not the caregiver provides consistent and attuned interactions when the infant requires them. Inconsistent responses can affect the quality of attachment relationships. Maternal sensitivity as a response to infant cues has been found to be a predictor of a secure attachment classification globally. 30,31 Parenting practices such as maternal responsiveness and sensitivity are associated with reduced severe attachment difficulties. 32,33

The opportunity for secure attachment is reduced in a number of populations, especially those who have been maltreated and/or are living in alternative care. Those living in alternative care such as foster care or institutions differ in terms of attachment pattern from those living with non-maltreating biological or adoptive families. 34

Assessing attachment

Strange Situation Procedure

Attachment patterns can be assessed through observational procedures such as the SSP. 6 The SSP was the first assessment of attachment patterns, developed by Ainsworth and Wittig. 6 The procedure involves a direct observation of the interaction between an infant, their caregiver and a stranger. In an eight-episode sequence, the infant interacts with the caregiver while an experimenter is in the room; the infant and caregiver are left alone; a stranger then walks in; the caregiver leaves the infant alone with the stranger; the caregiver returns to the room and the stranger leaves; the caregiver exits and leaves the infant on their own; the stranger returns; and finally the stranger leaves and the caregiver enters. During the sequence, the interactions between the infant and the caregiver are observed partly in terms of how the infant responds to separation from the caregiver, but mainly when reunited with the caregiver. The interaction between the infant and stranger is not measured; the stranger is there purely to act as a stressor. Ainsworth and Wittig described three attachment patterns resulting from these observations: secure attachment, insecure resistant attachment and insecure avoidant attachment. A fourth pattern, as described previously, is ‘disorganised attachment’,9 which appears to be a predictor of psychopathology. 13,25

The validity of the SSP has been found to be similar among western cultures; however, there are potentially cross-cultural differences in less westernised populations. 12

Attachment Q-Sort

The Attachment Q-Sort (AQS) is also used to assess attachment security. The AQS was developed to better define secure base behaviour in a non-stressful environment at home. This assessment can also be used with preschool children. 35 There are two AQS assessments: observer and self-reported. A meta-analytic study36 has established that the observer AQS shows convergent validity with the SSP and predictive validity with measurements of maternal sensitivity.

Other assessments

Interviews such as the Child Attachment Interview have been used to capture a child’s account of their relationship with their parents; this is an adaptation of the Adult Attachment Interview for use with children aged 7–11 years. 37 The Disturbances of Attachment Interview is administered to caregivers and is used to assess attachment disorders in children. 38

Other questionnaires are also used in attachment research. 13 For example, the Randolph Attachment Questionnaire (RADQ)39 assesses the presence of symptoms related to attachment disorders,40 although it includes several questions that are not directly related to the construct of attachment and so lacks specificity. 41

As mentioned previously, the most consistent predictor of attachment is caregiver sensitivity. 42 A large number of instruments are designed to assess sensitivity. The original sensitivity assessment was developed by Mary Ainsworth. 5 Since then, numerous similar instruments have been developed and validated. For example, the Infant Care Index has a similar format to other observational methods, whereby a play interaction between infant and caregiver is coded and caregiver sensitivity is one construct that is measured. 43 This is not, however, designed to assess attachment. Similarly, the Emotional Availability Scale is used to code caregiver sensitivity during infant–caregiver interaction. 44

Current treatment approaches

Interventions largely focused on improving caregiver sensitivity have been developed to reduce disorganised attachment and promote secure attachment. 45 Research has shown that attachment-focused interventions are effective. 13,46–48 Interventions focusing on parental sensitivity are found to be effective in reducing disorganised and insecure attachment, more so than broader interventions. 49 The NICE guidelines on attachment, published in 2015, recommend video feedback as an intervention. This involves video-recording the parent–child interaction, with feedback about the interaction and then further guidance on improving caregiver sensitivity, for example Video Feedback to improve Positive Parenting (VIPP) or Video Interaction Guidance (VIG). 14 It is important to thoroughly examine the evidence behind recommended interventions to inform practice.

Study summary

The present study comprises both a national survey and two comprehensive systematic reviews. First, a survey was utilised to map the UK services currently delivering attachment interventions to families and then a scoping of the literature was conducted to identify common and effective interventions for attachment problems in infants and young children, which was followed by two systematic reviews. The study encompasses three stages. The first involved preparatory work to establish a stakeholder group and Expert Reference Group (ERG) to advise us throughout the study. This group included patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives, those working directly with families with lived experience, researchers, academics, teachers, clinicians and charities and third-sector organisations. Second, a large-scale national survey was distributed to establish the attachment treatments used currently in UK services. In stage 3, a systematic review on interventions for children with or at risk of attachment problems was conducted and evidence for the commonly used interventions was sought.

Study rationale

It is essential that UK services employ the most effective interventions to improve child–caregiver attachment. There is a need for clarification about which manualised interventions are currently used to improve attachment in infancy and to explore the evidence base for their effectiveness. This is a complex area to review, because there are significant problems with the usage of attachment terms and concepts in routine practice, and diverse interventions are used for a wide range of children with the stated aim of promoting security of attachment. We also note that there is poor availability of evidence-based interventions in UK health and social care, which suggests both the need to identify and disseminate evidence-based approaches and the need to evaluate interventions that have a strong foundation in current services but for which good evidence is lacking.

The lack of evidence supporting interventions for attachment is a significant problem because resources in child mental health services are already limited. 50 Without thorough research, we do not know whether existing interventions are clinically effective, safe or used in appropriate population groups, and they may not be cost-effective if they are time-consuming and/or ineffective. This could cause a potential waste in resources or, even worse, harm to the well-being of children and their families. Therefore, it is important that interventions showing a good research evidence base are utilised to provide the most effective services. There are also challenges in the appropriate assessment of attachment for supporting referrals and for routine outcome monitoring, with few evidence-based, reliable and valid tools that clinicians can use. This research also investigates which assessment tools clinicians/practitioners working with children with attachment difficulties use to assess attachment security and attachment disorders.

Study aims and objectives

This research aims to:

-

conduct a large-scale survey of the structured interventions that are routinely used across UK services to improve child attachment to their caregiver

-

carry out a systematic review to carefully assess the research that supports these manualised interventions and other parenting interventions for children with (or at risk of) severe attachment problems aged 0–13 years

-

develop recommendations for carrying out future clinical trial research on the effectiveness of those commonly used interventions that have not been properly tested in the past.

Chapter 2 Methods

Survey

Overview

We undertook an online survey to identify the interventions that services currently deliver to support children with or at risk of disorganised attachment patterns or attachment disorders in the UK (aim 1). This survey focused on relevant UK services [including local authorities (LAs), child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), voluntary agencies, education services, fostering and adoption agencies and health visiting services] and collected details about the interventions used for these attachment problems. The results from the survey informed the systematic review. This allowed the research team to robustly evaluate the existing evidence behind routinely used attachment interventions.

Ethics considerations

The survey was conducted in accordance with the University College London Code of Conduct for Research and was approved by the University College London Research Ethics Committee prior to data collection (project ID 16687/001; approval granted 18 November 2019). Only the research team could access the data, which were held on a secure server. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents. The information necessary to make informed consent was included in an information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 1), which details the survey aims and the content and length of the survey, and gives data protection and storage information. Respondents were able to begin the survey only once they had read the information sheet. Respondents had to indicate their consent online to be able to complete the survey. Those respondents who had not indicated that they had read the information sheet and/or given their consent skipped to the end of the survey and provided no data for the survey results. All data were provided anonymously, and all respondents were given careful instructions not to reveal any personally identifying information concerning themselves or their client(s). All free-text responses were checked by the research team to ensure that no individuals had been inadvertently identified in participant responses.

Questionnaire development

Methods for designing survey

The survey was designed in consultation with the ERG and subject to modification after an initial pilot study. The questionnaire is in Report Supplementary Material 2, and it has the following section headings:

-

section 1 – consent

-

section 2 – about your work

-

where you work (nature of service setting)

-

your work supporting attachment (summary of children seen, referrers)

-

section 3 – therapeutic practice to support secure attachments (use of cross-package therapeutic techniques for promoting attachment)

-

section 4 – specific attachment intervention packages.

Development of general survey structure

A checklist was created to capture information about commonly used attachment interventions and techniques. When planning this work, we were aware of two significant problems that may affect the interpretation of the survey results. The first is that clinicians vary in their understanding of what an attachment problem is and what (if any) reliable tool they use for assessment; some therapists may also use eclectic practice rather than manualised interventions, combining treatment elements from several different approaches. A simple list of interventions on its own might therefore miss important elements of practice. Following the work of Chorpita et al. ,51 the research team drew on a taxonomy of common treatment elements of attachment interventions, cross-referenced against intervention manuals. We used this knowledge of treatment elements identified within those therapies to help design the survey to capture routine practice on the ground beyond, or in addition to that captured by, named intervention programmes. We also provided respondents with an opportunity to describe, in their own words, what the term attachment meant in terms of their practice.

Generation of intervention list

The survey listed a set of attachment-focused interventions identified by the ERG, by representatives from the research team’s network of partner organisations working in the attachment domain and from previous systematic reviews of attachment-focused interventions. Interventions had to be used for work directly with children and/or work with parents and caregivers. The research team took advice from the ERG, tapping into extensive links and networks with families, voluntary agencies, clinicians, services and experts, and scoping of published research, to identify interventions used to address attachment problems with families. Advice was sought from those who attended the first ERG meeting to inform the survey design. The survey itself also included open-text fields for services to specify any interventions they were using that were not already listed.

Detailed information about interventions and techniques

For each intervention that the respondent endorsed having used in the previous year to address attachment-related difficulties, the survey requested information concerning the number of children, approximately, to whom they had provided the intervention, what training they received, whether supervision was provided to deliver the intervention, any changes to the approach and how the outcome of the work was assessed. We were guided by the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist. 52 This included information regarding:

-

the typical number of sessions

-

core practice procedures and materials

-

mode of delivery (individual child face to face, individual parent face to face, working jointly with parent and child, parent or child groups, telephone contact with parent).

The common elements that were used to identify attachment-focused techniques (beyond any named interventions) were modelling sensitivity; supporting parent–child interaction; exploring mental representations of attachment; education and guidance; and ‘other’. Sixteen individual practice elements were identified within these five themes. For example, ‘in vivo feedback of attachment interactions’, ‘video-feedback of positive interactions’ and ‘tools to stimulate reflection on own parenting history’ were subsumed under the parent–child interaction theme. Each of these elements was accompanied by a textual description of what the intervention element consists of, and respondents were asked to endorse whether or not this element formed part of their practice with children who have attachment difficulties. For example, the element referred to as ‘raising attachment awareness’ was accompanied by the following text from the review manual:

The therapist provides suggestions/recommendations/guidance to the parent on attachment-related constructs. Attachment-related constructs would include matters relating to the parent’s sensitivity and responsiveness to the child’s cues and needs. This includes joint observation of the child/infant during intervention sessions, and raising the parent’s awareness of the importance of attachment, and healthy parent-child relationships.

Inclusion criteria

The study was designed to capture a broad range of practice and, therefore, the sole inclusion criterion for the survey was that UK-based practitioners had to work therapeutically with children (aged 0–13 years) with or at risk of attachment difficulties and/or their caregivers. The age range for children was selected as 0–13 years as this study was a follow-up to previous work that involved children in this range. 13 The age range was relatively wide to capture all children and child groups of interest in clinical practice. The survey asked respondents to base their responses on therapeutic work they had carried out in the last 12 months. There was no minimum number of children with whom practitioners were required to have worked across this timescale. In addition, respondents had to do only some proportion of their therapeutic work with children who have attachment difficulties. The survey focused only on face-to-face working and excluded online provision as a result of discussion with the ERG.

Ethics-informed questionnaire development

Ethics approval was obtained prior to commencement of the research. As per this approval, the information collected was kept in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018,53 GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and University College London standard operating procedures. 54 Information was stored and archived by University College London. Survey responses were anonymous. We requested in the information sheet that respondents did not supply any personal information or information that could identify another person. In addition to this, the research team reviewed the data in open-text fields to ensure that no personal information had been supplied inadvertently. The survey asked respondents to select the type of organisation and service they worked in, as well as their role, using predefined dropdown lists. Respondents could also specify and write this information in open-text fields if the appropriate response had not been included in the predefined lists. The survey asked respondents for their service location in order to geographically map service provision. Respondents could include the name of the service(s) they worked in, but this was not mandatory.

Respondent pathway

The survey was built online using the secure data platform REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, version 8.5.27). 55 The questions were ordered to follow two pathways: one for respondents who worked in only one service and one for respondents who worked in multiple services (a respondent could describe up to two services they worked in). The survey was distributed over six screen pages. Respondents had to answer the majority of questions, in turn, in order to progress, although some questions did not require an answer and respondents were given the option to write ‘not applicable’. Respondents were able to review and change their answers using ‘previous’ and ‘next’ buttons, and monitor their progress through the questionnaire with a ‘page 1 of 6’ page indicator display.

Pilot

A small-scale pilot was conducted with the project team members, colleagues and practitioners to assess the survey’s usability and technical functionality, and minor changes to the survey format and wording were implemented as a result.

Survey distribution

Generation of list of services/providers to be surveyed

The draft survey was reviewed by the ERG before it was deployed in the pilot study and the final large-scale mail-out. In addition, after a consultation with the ERG, a comprehensive contact list of services and providers to be surveyed was generated based on previous work that mapped intervention delivery in services and organisations across the UK.

Modes of distribution

After refinements, the survey was delivered online using REDCap, with optional paper fill-in and face-to-face meetings if requested by respondents. The survey was distributed as an open survey link via e-mail invitation that included information about the study and promotional materials such as flyers in addition to information regarding social media. Flyers were also distributed at conferences and events.

Survey procedure

Participation was voluntary and no incentives were offered or passwords required to complete the survey. The first distribution e-mail and post on social media were conducted in January 2020; reminder e-mails and social media posts were sent after distribution and the survey was closed in June 2020. The research team judged that the 625 responses received by the end of June 2020 provided sufficient data to meet the aim of this phase of work.

Types of providers and services covered

The survey covered a substantial range of providers supporting children with attachment difficulties in the UK. Furthermore, the data collected from the survey were supplemented by service-level responses from managers in both services and Clinical Commissioning Groups. We wanted to reach all types of services that work with children aged 0–13 years with or at risk of attachment problems and/or their caregivers. Attachment interventions occur in a range of organisations, and so the following were contacted: NHS, LA, voluntary sector (including organisations specialising in relevant areas such as attachment and perinatal mental health working with children, parents, mothers, and families), education (including schools and virtual schools), private provider organisation, individual private practice and social enterprise. In addition to this, we contacted a large array of service types in these organisations, including general practitioner/primary care, CAMHS, child health disability service, looked-after children’s service, adoption/fostering service, parent advice/information service, child safeguarding team/service, perinatal mental health service, health visiting service, midwifery service, specialist education (e.g. teacher of the deaf, specialist preschool/nursery service), counselling service, and parent–child support service/family centre/children’s centre. Numerous roles were covered, including clinical psychologist, counselling psychologist, educational psychologist, psychiatrist, nurse, health visitor, social worker, family therapist, psychotherapist and other therapist (e.g. art, drama, play, music). Respondents also had the opportunity, using open-text boxes, to specify any other relevant organisation, service type and role in relation to the service they worked in.

Survey dissemination

The survey was circulated to relevant practitioners including a large Learning Network at the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families (AFNCCF) linking professionals and stakeholders (including families) with an interest in child mental health. The AFNCCF is also home to the Children and Young People Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (CYP IAPT) collaborative of collaboratives, consisting of all CYP IAPT CAMHS. CAMHS services were also contacted via the Anna Freud Centre’s Youth Well-being Directory. We also contacted a range of other networks identified through our Expert Reference Group, including the DDP Network, Attachment Parenting UK, iHV and The Fostering Network. In addition to this, we worked closely with Parent-Infant Partnership UK, which has recently undertaken its own mapping exercises in relation to partially overlapping parent–infant services for children, which was used to supplement our initial longlist.

All NHS UK trusts and social care/LAs were mapped, identifying senior managers in services and contacts including NHS England and its Clinical Commissioning Groups in England, Health Boards in Scotland and Wales, and the Health and Social Care Board in Northern Ireland. We worked directly with service leads, who distributed the e-mail invitation to all practitioners working with children aged 0–13 years. In addition to this, directories such as the National Directory of NHS Research Offices and the Contact, Help, Advice and Information Network (CHAIN), an online network for people working in health and social care, were used to supplement our list. Furthermore, we contacted the heads of communication teams in NHS trusts to ask them to disseminate the survey to key departments and workers and include the survey e-mail invitation in internal communications such as newsletters and intranets. The e-mail invitation was also distributed through professional organisations to their members via mailing lists and newsletters such as relevant professional bodies/groups, including (but not exclusive to) the British Psychological Society, Royal College of Psychiatrists, the Royal College of Nursing, the British Association of Social Workers, the Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice, the Association of Child Psychotherapists, the British Association of Art Therapists, the British Association of Play Therapists, the Association of Directors of Children’s Services Ltd, the Consortium of Voluntary Adoption Agencies and the Consortium of Adoption Support Agencies. This was especially important for reaching private providers.

Social media coverage

To ensure widespread coverage, social media platforms were used to reach potential respondents who would be missed by these sampling methods (e.g. if the services were relatively new or less well known or networked private providers). We used feeds via Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA, www.twitter.com), Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA, www.facebook.com) and Instagram (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA, www.instagram.com) to raise awareness of the project, explain the research methods being used and promote practitioners’ involvement in the survey. Social media was also used to raise awareness that the survey was live. This was followed up with reminders and messages about the value and importance of receiving responses from as many different practitioners as possible. The project-specific account was set up as Attachment Matters Study @Attachment2020 across Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Tweets and posts were sent to followers to encourage their involvement in the study and provided information about the different elements of the project as these progressed. Social media accounts ‘followed’ relevant individuals and charitable and professional organisations to raise visibility and encourage reciprocal links and followers. Details of the social media accounts was sent to relevant networks, organisations and charities as well as being featured on flyers for the project for general awareness-raising. Shortly after the closure of the survey, the Twitter account had gained 771 followers, the Facebook account 222 followers and the Instagram account 162 followers. After the initial wave of survey promotion, the social media posts focused on the next steps after the closure of the survey. The social media accounts remained live after the survey ended as they formed part of the dissemination strategy for the final results. In addition to this, the survey was publicised on a large number of relevant organisation websites/blogs/newsletters, Facebook groups, and Twitter and Instagram accounts, for example newsletters, websites and social media platforms for AIMH, Home-Start UK, Family Action, and PANDAS Foundation.

Data collection and modes of analysis

Analysis of results overall

Quantitative data from the online survey were analysed using Microsoft Excel, the primary purpose of which was to produce descriptive statistics relating to the background information of respondents and interventions offered. Qualitative data from the survey’s free-text sections were subject to thematic analyses. Free-text comments were placed under the headings of the original questions. These were then grouped into clusters of thematically related topics and distinct topic clusters for further analysis. A narrative summary was drafted related to each cluster of topics. In this way, the themes presented in Chapters 3 and 4 were defined and the findings were drafted. Once the results had been analysed, a report was created detailing the UK services providing interventions; where these services were located, both geographically and organisationally; and the number of children practitioners had worked with over the last year.

The thematic analysis process involved six phases: familiarisation with the data, coding, generation of the initial themes, a review of themes, defining and naming themes and drafting the findings. There was movement back and forth between the phases. These phases facilitated the rigorous process of data interrogation and arrangement.

Familiarisation with the data

The research team underwent the process of familiarisation to obtain a thorough overview of all of the qualitative data collected before the analysis of individual items, which involved reading through the text and taking initial notes.

Coding

The free-text survey responses were placed under the headings of the original questions. The data were coded to identify key sections in the text to describe the content. Once all text had been coded, the research team collated all of the data into groups identified by code, allowing a condensed overview of the main points and common meanings that recurred throughout. The data were grouped into clusters of thematically related topics and distinct topic clusters for further analysis. A narrative summary was drafted of each cluster of topics.

Generating initial themes

The research team then reviewed the codes that had been created, identifying patterns among them, and initiated the generation of themes.

Reviewing themes

Once the themes had been generated, the research team compared the original data set against the themes to ensure that these were accurate representations of the data.

Defining and naming themes

Once the final list of themes had been created, the research team named and defined each, developing a detailed analysis and determining the narrative for each. This involved formulating exactly what was meant by each theme to enable a good understanding of the data, with clear and comprehensible names for each.

Drafting the findings

The findings were drafted and presented with data extracts and the analysis was contextualised in relation to existing literature.

Generating routinely used interventions

We quantitatively reported the frequency of different intervention types, and estimates of the numbers of children receiving these different types of therapy, across geographical areas to identify routinely used interventions for improving attachment in infants and young children. This information was presented to the ERG. We identified the 10 most commonly used interventions (based on the number of respondents who reported using each intervention) and these were included in the systematic review search strategy.

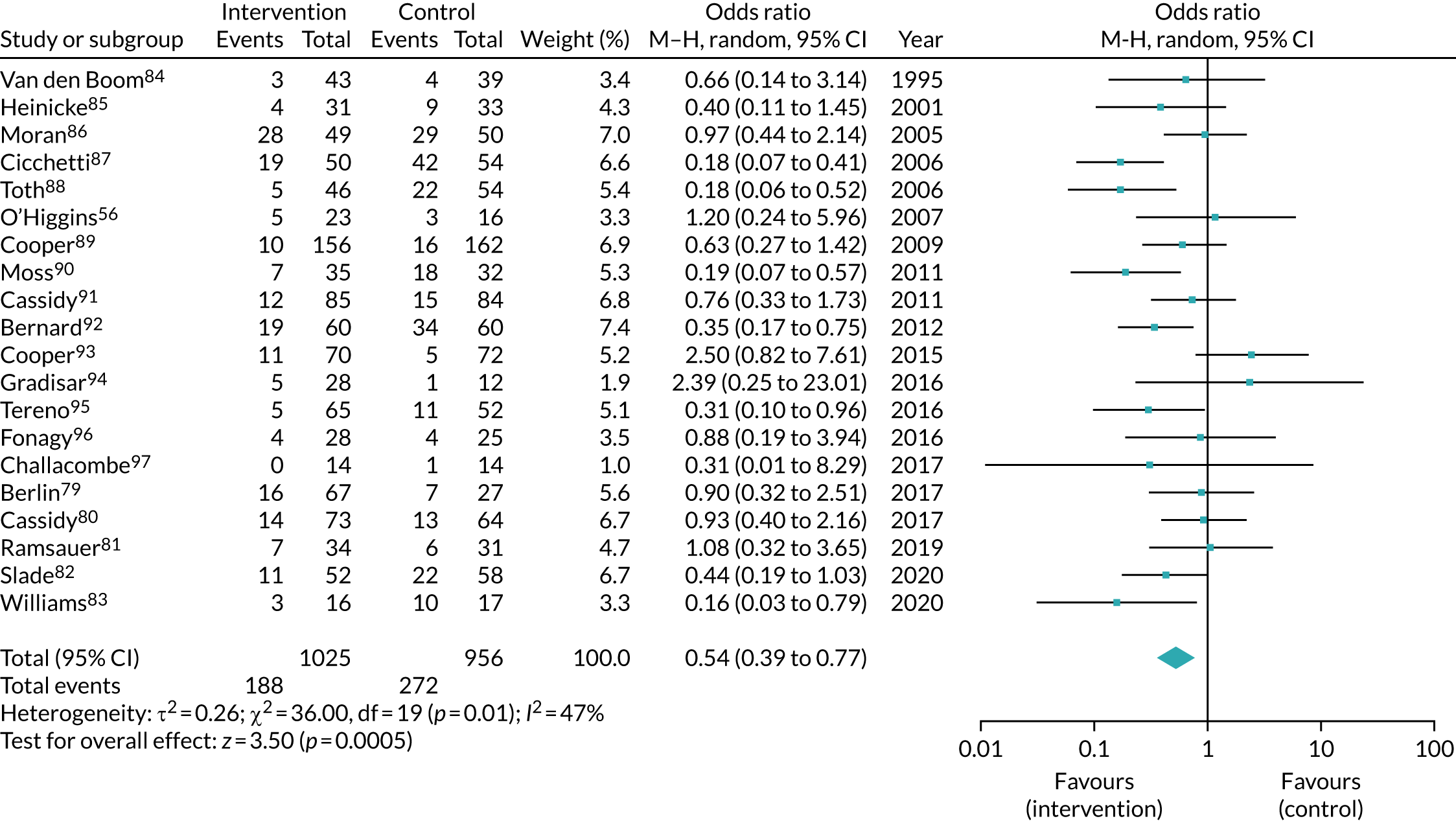

Systematic review (reviews 1 and 2)

The systematic review phase was split into two separate reviews to allow us to capture both the existing randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence for all attachment parenting interventions (review 1) and the best available research evidence to support each of the most commonly used interventions in current practice, as identified by the survey (review 2).

Review 1 is an update of a previous systematic review conducted by the team in the same field. This systematic review was originally conducted as part of a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) project to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of parenting interventions for children with or at risk of an attachment disorder or disorganised attachment patterns. 13 Part of this review was previously updated and published in 2017 as a systematic review47 of the effectiveness of parenting interventions aiming to reduce disorganised attachment in children at risk of attachment problems. The research team used the same searches and processes to update this review to include all RCT evidence for parenting interventions that aim to either reduce disorganised attachment or promote secure attachment in children at risk of an attachment disorder or disorganised attachment patterns. The results of this review (review 1) were then combined with those results from 2015 and the 2017 updates to provide a comprehensive overview of published RCT literature in this field. Where possible, this also included meta-analyses.

Review 2 is focused on the available evidence for the named interventions identified in the survey as the ‘most commonly used’ (based on the frequency with which respondents reported using the intervention). Chapter 3 contains further information on how the most commonly used interventions were identified from the survey results. We included all available study designs, including, but not limited to, RCTs, non-randomised comparisons, pre and post studies and case series. To maximise the breadth and informativeness of the second review, we also included studies that assessed parental sensitivity and not only those studies assessing child attachment.

Both reviews were registered on PROSPERO (CRD42019137362) at study set-up, and this record was updated in June 2020 to reflect the finalisation of the PICOS criteria and search strategy after the survey results became available and after discussion with the ERG. Both reviews followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist to ensure that they adhered to the PRISMA guidelines.

Search strategy (reviews 1 and 2)

The search strategy was drafted by the research team with the ERG. For review 1, we used the same search strategy as for the previous reviews (2015, 2017), and this strategy was modified for review 2. 13,47 It was finalised with an information specialist, who ran the searches in June 2020. Databases searched for both review 1 and review 2 were ASSIA, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CDSR, Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index Social Science & Humanities, EMBASE, ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Science Citation Index, Social Care Online, Social Policy & Practice, Social Science Citation Index and Social Services Abstracts. The two independent reviewers also conducted thorough reference checking and grey literature searching. The search strategy is in Appendix 4.

For review 1, we searched for records published after 2016, to line up with the previous update (2017). 47 For review 2, there was no limit on publication date. Both published and unpublished records were included for both reviews.

PICOS criteria

Review 1

The final PICOS for review 1 were as follows.

Population

Parents/caregivers of young children 0–13 years who had a disorganised classification of attachment or were identified as at high risk of developing severe attachment problems (attachment disorders or disorganised attachment patterns).

Intervention

Any parenting intervention that aimed to reduce disorganised attachment, improve secure attachment or treat attachment disorders was included. This included any interventions targeted at developmental trauma that sought to improve attachment. It included interventions involving the parent with or without the child, with parent or caregiver, in groups or one to one, with or without video feedback, and interventions involving a range of strategies or models, such as behavioural advice, provision of information, environmental change advice, activities, or support for the development of parental sensitivity. Interventions were included that were aimed at parents or caregivers, including foster carers. Interventions involving only teachers or teaching assistants (without parents or caregivers) were excluded.

Comparator

Comparators included no intervention, an alternative intervention, an attention control, and treatment or care as usual.

Outcome

The outcome was change in attachment (e.g. increase in secure attachment, decrease in disorganised attachment, or post-intervention comparisons between groups), measured using a validated attachment instrument that enables the classification of child attachment style.

Study design

Studies that did not use a true RCT design were excluded. Both published and unpublished papers from 2016 until present were included, as were foreign-language papers. We matched the PICOS criteria to those of the previous review to enable the results to be combined.

Review 2

The final PICOS for review 2 were as follows.

Population

Parents/caregivers of young children or children themselves aged 0–13 years who had disorganised classification of attachment or were identified as high risk of developing attachment problems (attachment disorders or disorganised attachment patterns).

Intervention

Interventions identified in the national survey as being most commonly used in the UK (based on frequency of respondents reporting using the intervention), aimed at reducing disorganised attachment, improving secure attachment, treating attachment disorders or improving parental sensitivity were included. This included interventions involving the parent with or without the child, the child with or without the parent and with either parent/caregiver.

Comparator

Where the study is a RCT we included any comparator (including control conditions or other active comparators). We included other designs and applied the same comparator criteria for any study using a comparison group (e.g. non-randomised controlled designs). Other empirical designs such as pre–post designs were included in the absence of a comparator.

Outcome

Change in attachment (increase in secure attachment or decrease in disorganised attachment), measured using a validated attachment instrument (either measuring attachment classification or a continuous attachment measure) or a change in parental sensitivity measured using a validated tool. This latter was chosen as a proxy indicator for attachment because of research showing strong associations between child attachment and parental sensitivity. 42

Study design

Studies including the 10 specific identified interventions were carefully scrutinised for available research evidence, including cohort studies, observational studies, case–control and case series evidence. Both published and unpublished papers were included, with no restrictions on years since publication, and foreign-language papers were included.

Review strategy: review 1

Screening

Sifting was conducted by two independent reviewers, both of whom screened all papers at all sift stages. Agreement was consistently above a baseline of a pre-agreed 80%. Where there was a disagreement, the paper was pulled through to full-paper screening and discussed together with input from an independent reviewer. Authors were contacted to clarify details and provide raw results where necessary. Translation services and library services were accessed as needed.

Record title and abstracts were screened in an initial phase against the PICOS criteria. If they met the inclusion criteria at this stage, the full paper was screened against the PICOS criteria. All records in the full-paper sift were reference checked, and books, systematic reviews and meta-analyses were checked for any additional relevant papers. Records that met the criteria at this stage were data extracted by the same two reviewers working independently. We ensured to follow the same process as for the previous review and update.

One paper discovered that met the inclusion criteria was dated pre 2016. 56 Although the study had been conducted pre 2016, it was made available only post 2016 and therefore had not been identified in the searches for the previous reviews. As the paper met the inclusion criteria, it was subsequently included.

Data extraction

Child attachment classifications were extracted as the primary outcome and information was collected on the demographics of the sample and the characteristics of the interventions. The data extraction was structured using the framework of intervention descriptions provided by the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 52 Many interventions are poorly described in publications, limiting their replicability. The checklist covers the rationale for or theoretical basis of the intervention, materials and procedures, who delivered its main components, where it was delivered and the frequency and duration of delivery. The data extracted were the same as in the previous reviews and update to allow data to be combined in the meta-analysis, and to allow for the same exploratory analyses to be conducted. The data extraction tables are in Appendix 2. These show the headings used to extract detailed information about the intervention and study design based on the TIDieR checklist, including participants, sample risk, intervention focus, intervention duration, intensity, delivery, control group, measure of attachment and attachment outcomes.

The data resulting from the extraction were split into outcome data for increasing secure attachment and outcome data for reducing disorganised attachment. All papers provided data for both of these, except for one. The authors of one paper that provided data on secure attachment did not respond to multiple requests within the required time frame to provide results for disorganised attachment and so the paper was included in the secure analyses only. 57

One paper met the inclusion criteria but did not provide enough information to allow data extraction for the meta-analyses. 58 The authors reported a change in attachment but did not provide the raw numbers of children in either group, and so the paper could not be included in the meta-analysis. The paper was excluded because the authors did not respond to multiple requests for these additional data within an appropriate timeframe.

Risk-of-bias assessment

A risk-of-bias assessment was conducted of all included papers by two independent reviewers using the Revised Risk of Bias Tool for Randomised Trials (ROB-2). 59

Meta-analyses methods

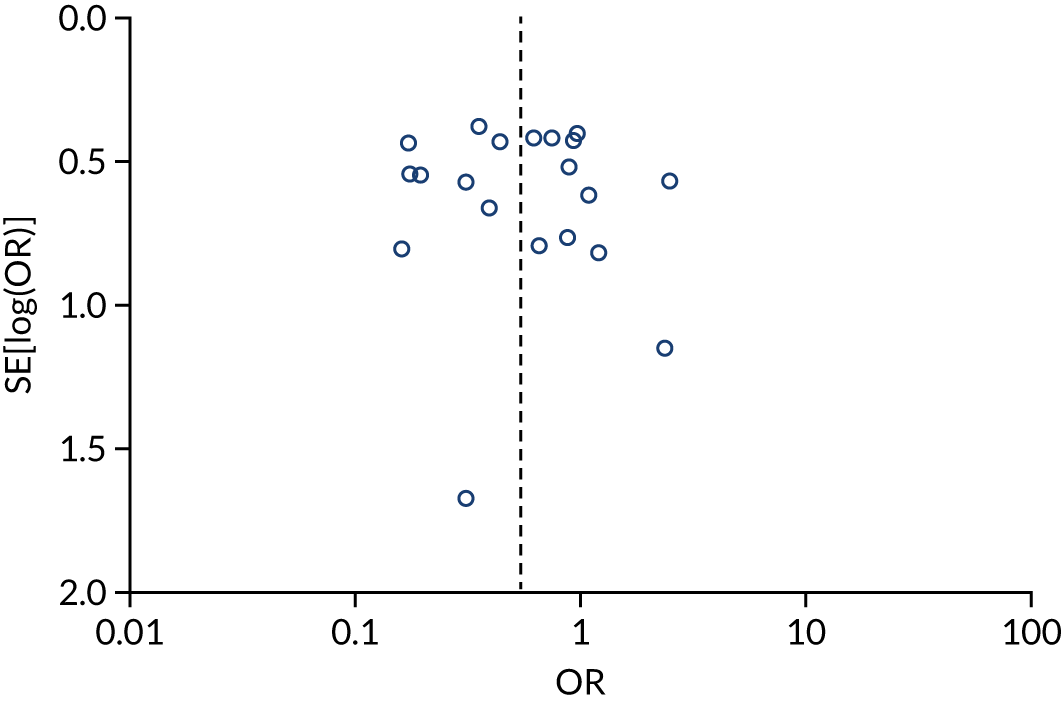

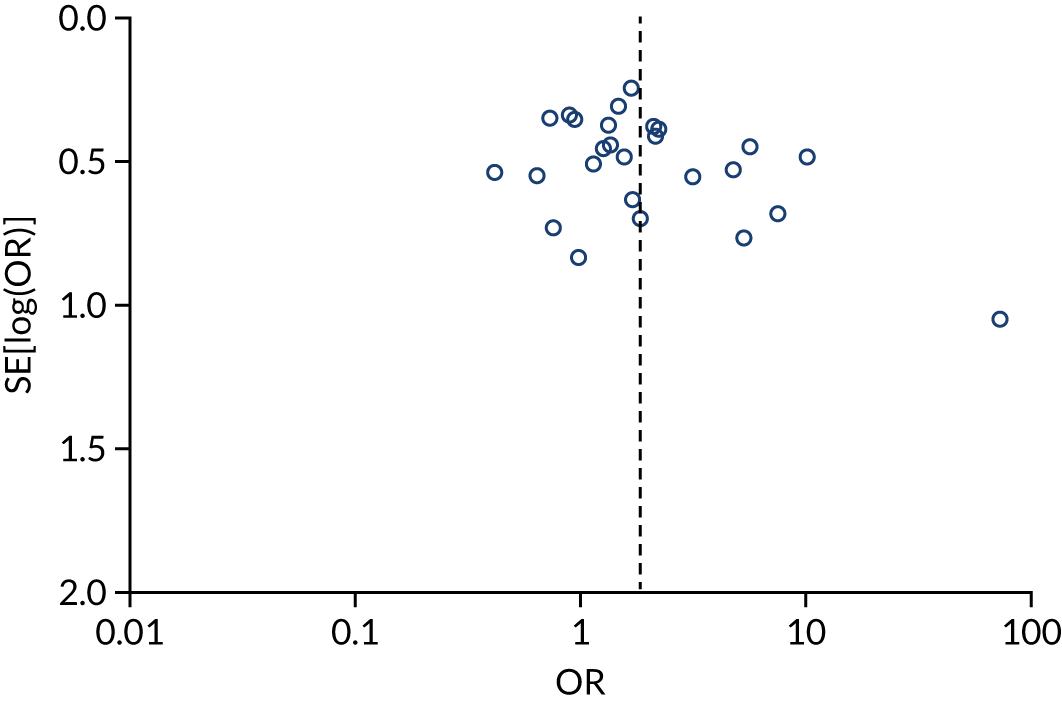

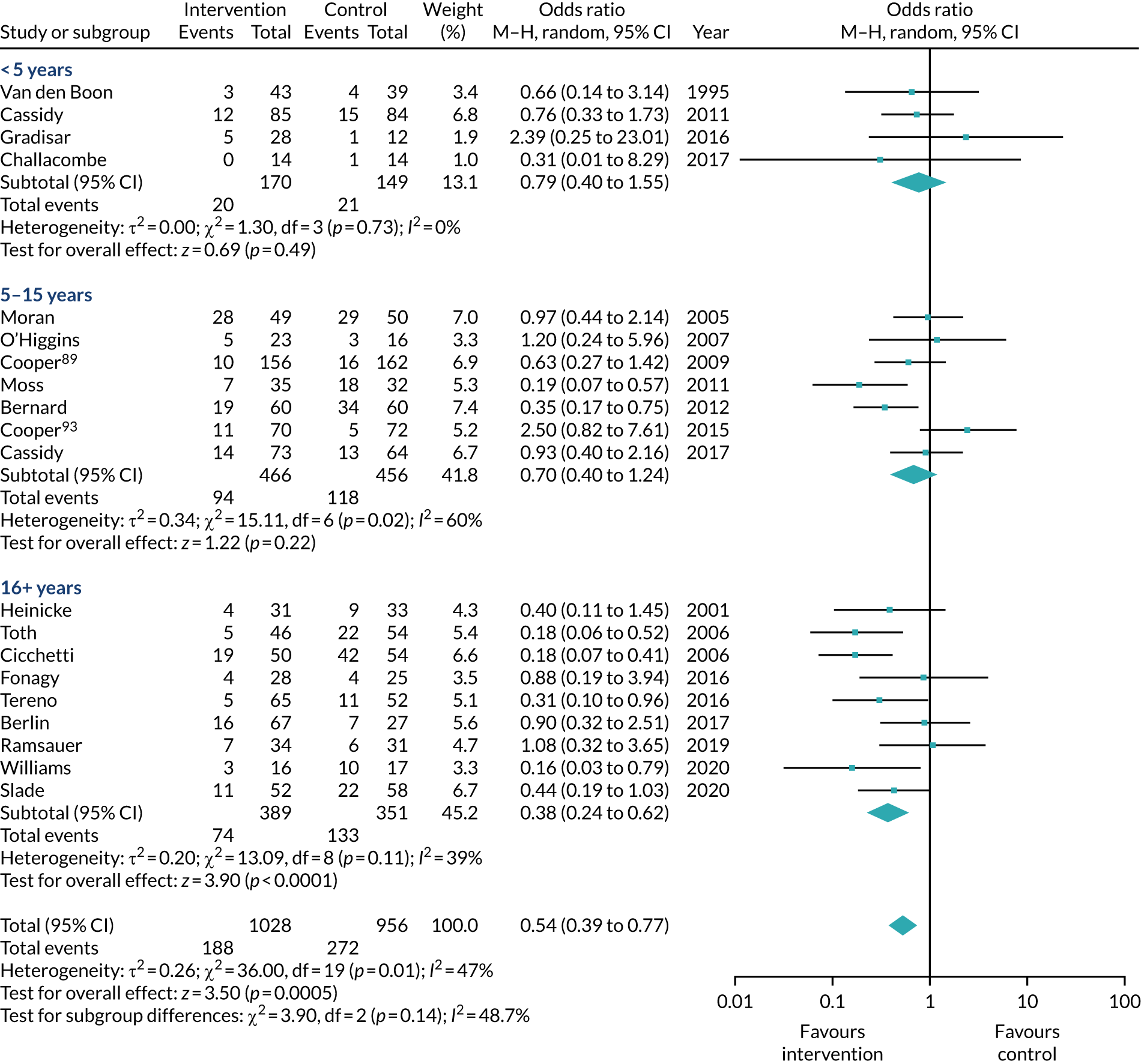

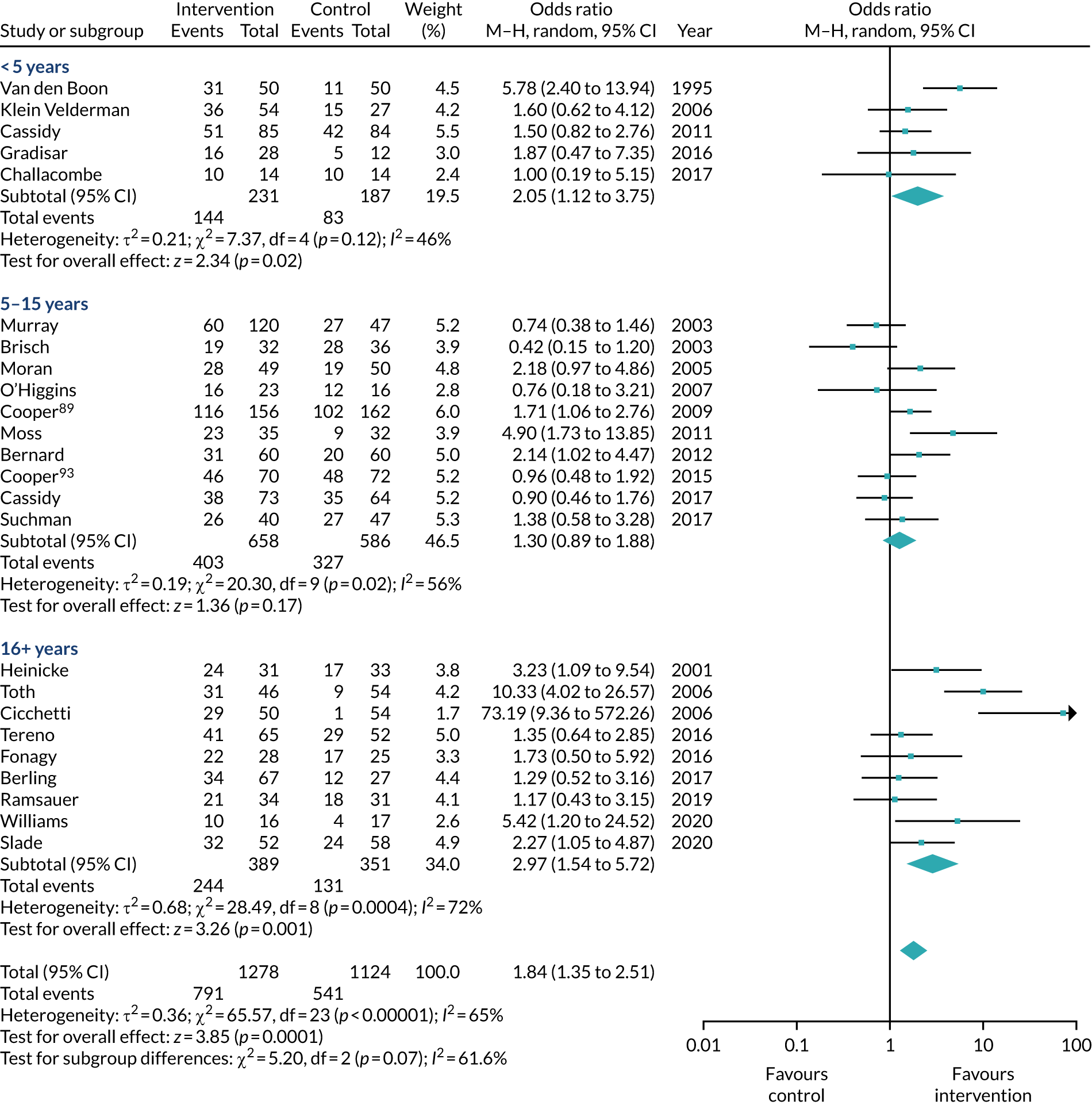

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q through the chi-squared test and was quantified using the I2-test. If there was statistical heterogeneity, a fixed-effects model was not appropriate and a random-effects model was used. Publication bias was assessed by examining the asymmetry of the funnel plot and the Harbord regression-based test was used. 60 Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3. The results were considered statistically significant when the two-sided p-value was < 0.05. Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated61 to make comparisons with previous meta-analyses on attachment interventions.

The included studies were stratified into groups based on their characteristics, and subgroup analyses were undertaken on the number of sessions, use of video feedback, age of child and whether or not a male caregiver was included.

Review strategy: review 2

Screening

Sifting was conducted by two independent reviewers, both of whom screened all papers at all sifts. Agreement was consistently above a pre-agreed baseline of 80%. When there was a disagreement, a paper was pulled through to full-paper screening and discussed, with input from an independent reviewer if necessary. Authors were contacted to clarify details and provide raw results where necessary. Translation services were used if needed and we used library access services for those records we were unable to access directly.

The titles and abstracts of records were screened in an initial phase against the PICOS criteria. If they met the criteria, the full paper was screened against the PICOS criteria. We conducted significant reference and grey literature checking. All records in the full-paper sift were reference checked, and books, attachment systematic reviews and meta-analyses were checked for any additional relevant papers. Records that met the criteria at this stage were data extracted by the same two reviewers each working independently.

Data extraction

Child attachment and/or parental sensitivity outcomes were extracted as the primary outcome and information was collected on the demographics of the sample and the characteristics of the interventions. This was structured using the framework of intervention descriptions provided by the TIDieR checklist and based on characteristics used in previous reviews. 52 Research has shown strong associations between child attachment and parental sensitivity,42 and parental sensitivity is also recommended as an attachment outcome in NICE guidelines. 14 The data extraction table for review 2 is in Appendix 2 (see Table 23). This shows the headings used to extract detailed information about the intervention and study design based on the TIDieR checklist, including participants, sample risk, name of manualised intervention focus, study design, control group, measure of attachment, attachment outcomes, measure of parental sensitivity and parental sensitivity outcomes.

Chapter 3 Survey results

Introduction

The current survey was intended to inform the design of a systematic review of interventions for severe attachment problems by identifying which interventions are routinely used in practice in the UK.

In this chapter we first summarise the completion rate of the survey from different parts of the UK and organisational characteristics relating to the services that responded to the survey. Following this, the findings from the quantitative components of the survey are explored and the most commonly reported interventions are described.

Completion rate

The survey was circulated to 1279 respondents. The actual number of individuals or organisations in receipt of survey invitations is likely to be greater than this number as survey participation was also encouraged through social media, flyers and conferences. A total of 2656 practitioners initially agreed to participate in the survey, that is, they clicked into the survey questionnaire via the link in the e-mail invitation or on social media and consented to taking part in the survey (however, note that an unknown proportion of these may have realised they did not meet the inclusion criteria or may have logged into the survey site more than once). A total of 625 respondents completed the survey. The overall completion rate in terms of the number of respondents who finished the survey (n = 625)/the number of respondents who agreed to participate in the survey (n = 2656) was 23.5% (although the denominator here is likely to have been inflated by individuals returning to the survey site more than once prior to completion, or by those who looked at the survey and then decided they did not meet the survey criteria). The completion rate in terms of the number of respondents who completed the survey (n = 625)/the number who began the survey (by completing the first question) (n = 965) was 64.8%. The 625 respondents completed the survey with respect to 734 different services.

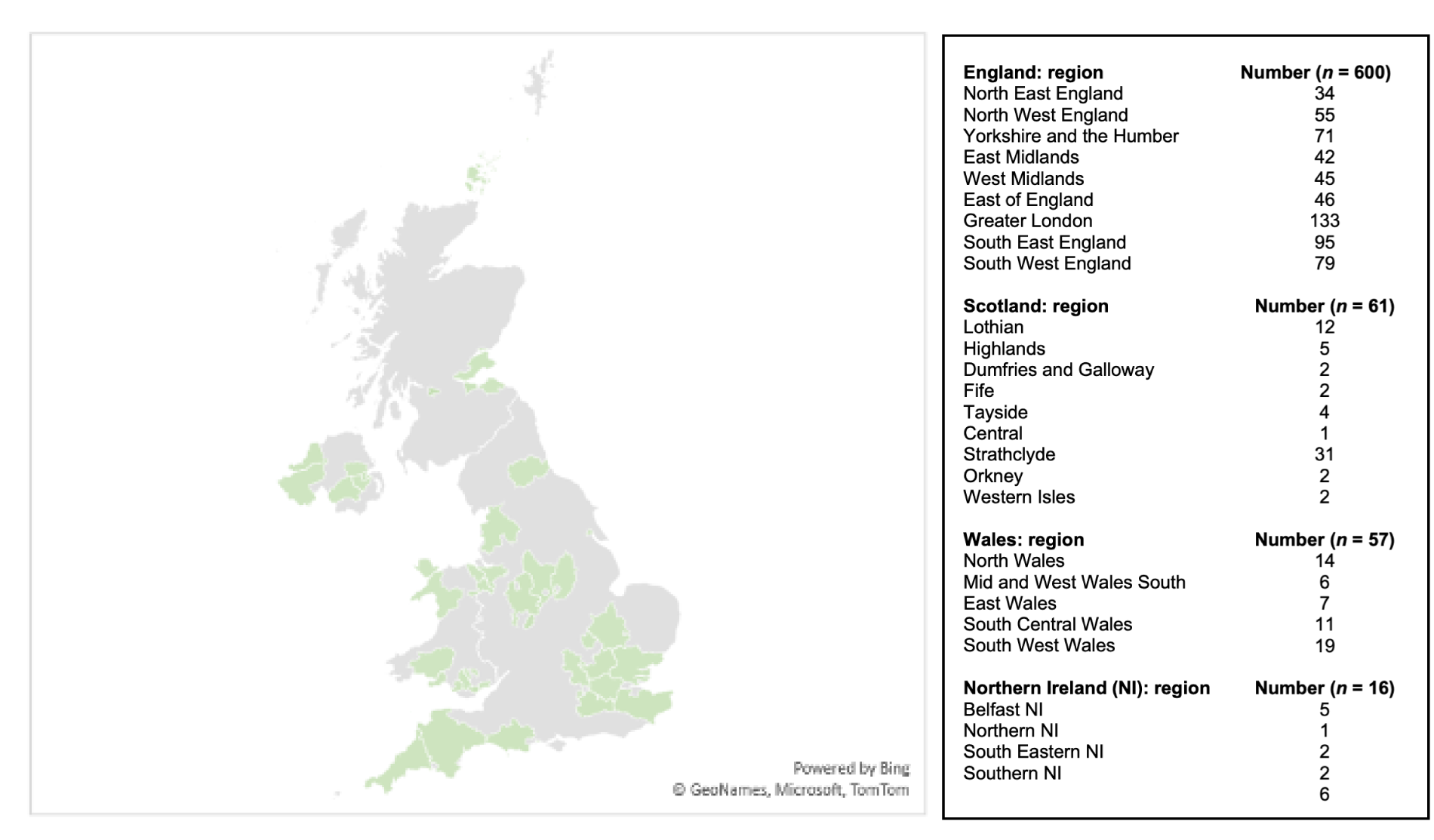

Scope of the survey

Descriptive statistics regarding the pattern of responses to this survey are presented by service as well as by practitioner. Respondents were asked where the service they worked in was located in terms of region and town. Responses were received from all four UK nations (Figure 1). The majority of services were in England (n = 600), with a significant number based in southern England (n = 353) and northern England (n = 160) and a small proportion located in central England (n = 87). A smaller proportion of services were based in Scotland (n = 60), Wales (n = 58) and Northern Ireland (n = 16).

FIGURE 1.

Map showing the geographical distribution of survey responses across the UK. Microsoft product screenshot reprinted with permission from Microsoft Corporation.

Organisational characteristics

Respondents were asked about the type of organisation in which they worked. The most common services were in the NHS (41.6%, n = 305); 17.8% of respondents were from LAs (n = 131), 10.9% (n = 80) were from the voluntary sector, 8.3% (n = 61) were from a private provider organisation, 7.6% (n = 56) were from individual private practice, 6.8% (n = 50) were from an educational organisation and 1.8% (n = 13) were from a social enterprise (Table 1).

| Organisation type | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| NHS | 305 (41.6) |

| LA | 131 (17.8) |

| Voluntary sector | 80 (10.9) |

| Educational | 50 (6.8) |

| Private provider | 61 (8.3) |

| Individual private practice | 56 (7.6) |

| Social enterprise | 13 (1.8) |

| Other | 38 (5.2) |

Thirty-eight (5.2%) organisations were identified as an ‘other’ type; this included a university department (n = 1); an adoption/regional adoption agency (n = 4); another type of voluntary sector (including a children’s charity and a mental health charity) (n = 14); commercial manufacturing (n = 1); a community interest company (n = 1); counselling (n = 1); Department of Justice (n = 1); a grant-aided special school (n = 1); a parent (n = 1); self-employed (n = 2); an independent organisation (n = 1); NHS and LA collaboration (n = 4); mental health (n = 1); multiagency − NHS, LA, voluntary (n = 2); NSPCC (n = 2); and training − play therapy (n = 1).

Respondents were asked about the type of service(s) they worked in within their organisation. The most common was CAMHS (23.7%, n = 174). Similar proportions of service types were from looked-after children’s services (8.4%, n = 62), adoption/fostering services (8.7%, n = 64), counselling services (7.6%, n = 56), parent–child support service/family centre/children’s centres (7.5%, n = 55), health visiting services (6.0%, n = 44), perinatal mental health services (5.4%, n = 40) and specialist education (e.g. teacher of the deaf, specialist preschool/nursery service) (4.4%, n = 32). A smaller proportion were from child safeguarding team/services (2.5%, n = 18) and general practitioner/primary care (1.0%, n = 7). In addition, the same proportion in terms of service type (0.7%, n = 5) were from child health disability services, parent advice/information services and midwifery services (Table 2).

| Service type | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| General practitioner/primary care | 7 (1.0) |

| CAMHS | 174 (23.7) |

| Child health disability | 5 (0.7) |

| Looked-after children’s | 62 (8.4) |

| Adoption/fostering | 64 (8.7) |

| Parent advice/information | 5 (0.7) |

| Child safeguarding team/service | 18 (2.5) |

| Perinatal mental health | 40 (5.4) |

| Health visiting | 44 (6.0) |

| Midwifery | 5 (0.7) |

| Specialist education (e.g. teacher of the deaf, specialist preschool/nursery service) | 32 (4.4) |

| Counselling service | 56 (7.6) |

| Parent–child support service/family centre/children’s centre | 55 (7.5) |

| Other (please specify) | 167 (22.8) |

A total of 22.8% (n = 167) services were reported as an ‘other’ type. These services were organised into the following groups; children’s care service (1.9%, n = 14), combined/collaboration service (i.e. various combinations of the following: looked-after children, adoption, fostering, CAMHS, education, LA and CAMHS provider collaborative) (1.0%, n = 7), education service (2.3%, n = 17), other family/parental service (2.9%, n = 21), general health service (0.7%, n = 5), mental health service (1.5%, n = 11), other therapy/psychological treatment service (10.5%, n = 77) and training service (1.1%, n = 8).

Roles and occupations of respondents

Respondents were asked about their role in the service. A sizeable proportion of respondents were clinical psychologists (n = 123, 16.8%). A considerable proportion were social workers (n = 58, 7.9%), psychotherapists (n = 57, 7.8%), health visitors (n = 41, 5.6%) and nurses (n = 34, 4.6%). A smaller proportion comprised 21 family therapists (2.9%), 19 educational psychologists (2.6%), 17 psychiatrists (2.3%) and 10 counselling psychologists (1.4%) (Table 3).

| Role | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Clinical psychologist | 123 (16.8) |

| Counselling psychologist | 10 (1.4) |

| Educational psychologist | 19 (2.6) |

| Psychiatrist | 17 (2.3) |

| Nurse | 34 (4.6) |

| Health visitor | 41 (5.6) |

| Social worker | 58 (7.9) |

| Family therapist | 21 (2.9) |

| Psychotherapist | 57 (7.8) |

| Other therapist (e.g. art, drama, play, music) | 122 (16.6) |

| Other (please specify) | 232 (31.6) |

A total of 31.3% (n = 230) of roles were identified as ‘other’. These were characterised into groups: other psychologist (n = 18, 2.5%), other psychotherapist (n = 14, 1.9%), other education practitioner (n = 33, 4.5%), other nurse (n = 14, 1.9%), other social worker (n = 7, 1.0%), other therapeutic clinician (n = 15, 2.0%), other family/parental related role (n = 26, 3.5%), other child-related role (n = 9, 0.8%), advisory role (n = 5, 0.7%), other allied health professionals (n = 12, 1.6%: speech and language therapist, n = 5, 0.7%; and occupational therapist, n = 7, 1.0%), senior management role (n = 39, 5.3%), other mental health specific role (n = 8, 1.1%), midwife (n = 5, 0.7%), foster carer/parent (n = 9, 1.2%), well-being/support worker (n = 11, 1.5%), medical doctor (n = 5, 0.7%) and trainer (n = 3, 0.4%).

Age of children practitioners work with

Respondents were asked the age range of the children with whom they worked. There was no predominant age range: practitioners worked with children from 0–3 years (56.0%, n = 350), 4–6 years (65.3%, n = 408), 7–9 years (68.0%, n = 425), 10–11 years (65.9%, n = 412) and 12–13 years (58.4%, n = 365) (Table 4).

| Age range (years) | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| 0–3 | 350 (56.0) |

| 4–6 | 408 (65.3) |

| 7–9 | 425 (68.0) |

| 10–11 | 412 (65.9) |

| 12–13 | 365 (58.4) |

Tools and measures for assessing attachment difficulties

Respondents were asked to use an open-text field to list any measures or tools used to assess attachment difficulties or the parent–child relationship; 581 (93.0%) respondents completed this field. Of those 581, 37 commented ‘N/A/none’. Table 5 shows a selection of the types of measures and tools reported (only those reported at least three times are presented).

| Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Parent Attachment AAI (n = 20) Attachment Style Interview (n = 4) Dynamic-Maturational Model (n = 4) Mental health Edinburgh Postnatal Scale (n = 9) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (n = 4) General Anxiety Disorder (n = 7) Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (n = 8) Clinical Interview (n = 14) Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (n = 5) |

Child Emotional/behavioural ASQ (n = 21) SDQ (n = 77) Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function (n = 6) Boxall Profile (n = 14) Child Behaviour Checklist (n = 4) Mental health/well-being Adverse Childhood Experiences (n = 7) Trauma Symptom checklist (n = 11) Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (n = 3) Assessment Checklist (n = 38 – 14 Assessment Checklist for Children (ACC), 10 Assessment Checklist for Adolescents (ACA), 2 Assessment Checklist for Children plus (ACC+), 1 The Assessment Checklist (Tarren Sweeney), 11 Brief Assessment Checklist (3 BAC, 4 Brief Assessment Checklist for Children BAC-C and 4 Brief Assessment Checklist for Adolescents BAC-A)). Levels of Adaptive Functioning (n = 4) Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (n = 19; 17 children and 2 parent version) Children’s Global Assessment Scale (n = 4) |

Relationship Parent report PSI (n = 24) Brief Parental Efficacy Scales (n = 3) Tool to Measure Parenting Self-Efficacy (n = 6) Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (n = 9) MORS (n = 35) Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (n = 7) Observation Keys to Interactive Parenting Scale (n = 6) COS (n = 3) Theraplay (n = 23) MIM (n = 50) WWW (n = 3) Care Index (n = 16) SSP (n = 8) Parent–Infant Interaction Observation Scale (n = 11) Newborn Behavioural Observations (n = 11) |

Other Goal-setting (n = 13) BERRI (n = 3) CORC (n = 3) Sensory Attachment Intervention (n = 3) Social Responsiveness Scale (n = 4) Child Attachment and Play Assessment (n = 7) Coventry Grid (n = 21) DDP (n = 11) Family Relations Test (n = 10) Dyadic assessment of naturalistic caregiver–child experiences Dance (n = 7) VIG (n = 20) Meaning of Child Interview (n = 4) Solihull (n = 8) Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy (n = 3) SCORE Index of Family Functioning and Change SCORE-15 score 15 (n = 10) Kim Golding (n = 16) – 6 Carers Questionnaire, 1 Attachment Observation Schedule and Being a Parent Questionnaire, 7 Thinking about your child, 1 Attachment profiles (Kim Golding/Louise Bomber books) Story Stem (n = 28) Thrive (n = 6) Observation (general) (n = 153) |

The most commonly used measure was the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (n = 77) (Table 6). A large proportion of respondents also mentioned the Marschak Interaction Method (MIM) (n = 50). Many respondents noted using the Mothers’ Object Relations Scales (MORS) (n = 35). In addition, respondents reported using variations of the Assessment Checklist (n = 38). Frequently reported measures also included the Parenting Stress Index (n = 24), Story Stem (n = 28), Adult Attachment Interview (n = 20), Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) (n = 21) and Coventry Grid (n = 21). Many respondents also noted using general observation to measure attachment (n = 153).

| Intervention | Respondents, n (%) | Services, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Other | 368 (58.9) | 436 (59.4) |

| Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy | 150 (24.0) | 173 (23.6) |

| Individual Child Psychotherapy | 147 (23.5) | 168 (22.9) |

| Theraplay | 137 (21.9) | 151 (20.6) |

| VIG | 96 (15.4) | 108 (14.7) |

| Child–Parent Psychotherapy | 75 (12.0) | 86 (11.7) |

| Parent–Infant Psychotherapy | 74 (11.8) | 89 (12.1) |

| Circle of Security | 64 (10.2) | 72 (9.8) |

| Watch, Wait and Wonder | 50 (8.0) | 58 (7.9) |

| Video Feedback to Promote Positive Parenting | 26 (4.2) | 28 (3.8) |

| Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up | 10 (1.6) | 11 (1.5) |

Generally speaking, two measures are considered the ‘gold standard’ for assessing attachment in infants and toddlers: the SSP and the AQS. It is interesting that no respondents reported using the AQS and a very small number (n = 8) of respondents reported using the SSP, each of whom worked in only one service, meaning that eight services used the SSP. Of these eight respondents, three stated that they did not explicitly carry out the SSP: one noted that they used informal observation that mirrored the SSP, one said that they used the Crowell Procedure and then incorporated elements of the SSP, and one reported that they used the psychoanalytically based State of Mind Assessment of the child, including some aspects of the SSP.

Findings: routinely used interventions

Based on initial discussion with the ERG, and previous reviews of the attachment interventions literature, the survey included several named attachment interventions that respondents could report having used. These were Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC), Individual Child Psychotherapy (ICP), Parent–Infant Psychotherapy (PIP), Child–Parent Psychotherapy (CPP), Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy (DDP), Circle of Security (COS), Video Feedback to Promote Positive Parenting (VIPP), VIG, Theraplay and Watch, Wait and Wonder (WWW). We included manualised parenting interventions only, with the exception of ICP; the ERG strongly advised including ICP as it is very commonly used in this context.

Respondents were also asked to list any other attachment interventions that they used when working with children and/or caregivers. Respondents could list up to three other interventions (see Appendix 1, Table 21, for the list of other interventions). The most common response was ‘other’ (n = 368, 58.9%), indicating that respondents used interventions not in our initial list. This set of ‘other’ interventions included a wide range of interventions, and no individual interventions were reported more frequently than any of those in the named set presented in Table 6. Therefore, we refer to this set of 10 named interventions as ‘routinely used interventions’ for attachment as identified by this survey.

Out of the list of named interventions prespecified by the ERG, a substantial number of respondents (24.0%, n = 150) reported using DDP, 23.5% (n = 147) reported using ICP, and 21.9% (n = 137) reported using Theraplay. In addition to this, a similar proportion reported using VIG (15.4%, n = 96), CPP (12.0%, n = 75), PIP (11.8%, n = 74), COS (10.2%, n = 64) and WWW (8.0%, n = 50). A smaller proportion of the sample reported using VIPP (4.2%, n = 26) and ABC (1.6%, n = 10).

Outcome measures

For each reported intervention, respondents were asked how they assessed the outcome of work with a particular child or caregiver; the responses were given in an open-text box. Table 7 shows the outcome measures that respondents reported using to assess work for each of the routinely used interventions with a particular child or caregiver. Responses were varied, with respondents noting multiple outcome measures; these were subsequently categorised by the research team. Assessments often included a variety of self-report measures (e.g. SDQ, MIM, ASQ). Below, we summarise the assessments used for each of the most commonly reported interventions.

| Informal clinical feedback | Observation | Assessments | Goal-setting | Reviews | Report writing | Other | None | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Individual Child Psychotherapy | 48 | 14 | 95 | 16 | 34 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| PIP | 20 | 11 | 47 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| CPP | 20 | 11 | 41 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| DDP | 46 | 13 | 75 | 13 | 32 | 5 | 11 | 22 |

| COS | 15 | 6 | 30 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 13 |

| VIPP | 3 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 11 |

| VIG | 26 | 14 | 55 | 14 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 8 |

| Theraplay | 45 | 25 | 65 | 14 | 15 | 6 | 13 | 26 |

| WWW | 20 | 10 | 24 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

A large proportion (n = 95, 64.6%) of respondents who work with ICP reported using some form of assessment to assess the outcome with a particular child or caregiver. A similar proportion stated that they used informal clinical feedback (n = 48, 32.7%) and reviews (n = 34, 23.1%). A smaller proportion of respondents used observation (n = 14, 9.5%), goal-setting (n = 16, 10.9%) and report writing (n = 9, 6.1%), and a similar number of respondents (n = 10, 6.8%) noted that they use no outcome measures or chose ‘other’, which included internal work targets (n = 1, 0.7%), multidisciplinary team meetings (n = 1, 0.7%), improvement in target child behaviour, carer attunement and the parent–infant relationship (n = 5, 3.4%), expressing feelings verbally to therapist (n = 1, 0.7%), and through CAMHS (n = 1, 0.7%).

As for PIP, a substantial proportion of respondents stated that they used assessments (n = 47, 63.5%), whereas a smaller number used feedback (n = 20, 27%), reviews (n = 6, 8.1%), report writing (n = 3, 4.1%) and no outcome measures (n = 7, 9.5%). The same number of respondents (n = 11, 14.9%) stated that they used observation and goal-setting. Two respondents chose ‘other’, namely improvement in parent–infant relationship and lessening of symptoms in child (n = 1, 1.4%) and multiagency care plans usually related to placement stability (n = 1, 1.4%).

In relation to CPP, respondents frequently noted assessments (n = 41, 54.7%). A similar proportion was noted for feedback (n = 20, 27%), observation (n = 11, 14.7%) and reviews (n = 13,17.3%). Five respondents stated that they used goal-setting and report writing, and a small number worked with no outcome measures. Seven chose ‘other’, namely informal increased reflective capacity of the caregivers and attunement in the relationship and positive change in child’s presentation (n = 3, 2.3%), multidisciplinary team meetings (n = 1, 1.3%), ongoing process of supervision, case supervision and individual reflective practice (n = 1, 1.3%), monitoring interaction and responsiveness against pre-agreed outcomes (n = 1, 1.3%) and using CPP forms (n = 1, 1.3%).

As for DDP, a large proportion of respondents used assessment (n = 75, 50%), with a significant proportion also using clinical feedback and reviews (n = 46, 30.7%). Eleven chose ‘other’, namely clinical judgement (n = 1, 0.7); any success achieved (n = 1, 0.7); ability to show positive distance travelled (n = 1, 0.7); positive outcome for the family, which they felt really improved their communication with one another (n = 1, 0.7); parent reflective capacity and parents felt a sense of relationship (n = 1, 0.7); case supervision with clinical psychologist, reflection – improvement in carer child relationships and behaviour or actions on referral forms (n = 1, 0.7%); increased attunement with the child and understanding and use of the attitude and approaches of PACE (playfulness, acceptance, curiosity and empathy) to connect with and other commentary about the child’s inner emotional world (n = 1, 0.7%); positive outcome (n = 1, 0.7%); child feels listened to and validated, improvement in emotional regulation and caregiver relationship (n = 1, 0.7%); placement stability, discharge (n = 1, 0.7%); and improvement in parent–child relationship as reported by dyad (n = 1, 0.7%).

Most of the respondents who used COS used assessments (n = 30, 46.9%). Five chose ‘other’, namely progress of family (n = 1, 1.6%), engagement with school and educational outcomes (n = 1, 1.6%), psychoeducation for caregivers (n = 1, 1.6%), mother’s understanding of the concept of COS and examples of her supporting exploration (n = 1, 1.6%), and ongoing process of supervision, case supervision and individual reflective practice (n = 1, 1.6%). VIPP respondents were found to mostly use assessments (n = 7, 26.9%). Two chose ‘other’: changes in carer management, feelings and the relationship, child more regulated/feeling more contained and held and behaviours reflecting this (n = 1, 3.8%); and generally the intervention being well received by parents (n = 1, 3.8%).

In addition to this, respondents who worked with VIG report using assessments (n = 55, 57.3%). Eight chose ‘other’: improvements, trust and attachments growing (n = 1, 1.04%); changes in carer management, feelings and the relationship, child more regulated/feeling more contained and held and behaviours reflecting this (n = 1, 1.04%); outcomes negotiated with the caregiver and indicators of change from third parties such as school; also in some cases if the child is taken into care or not (n = 1, 1.04%); ongoing process of supervision, case supervision and individual reflective practice (n = 1, 1.04%); positive outcome (n = 1, 1.04%); in the community every 2 or 3 weeks (n = 1, 1.04%); VIG outcome measures (n = 1, 1.04%); and supportive family (n = 1, 1.04%).

A substantial number of respondents who used Theraplay used assessments (n = 65, 47.4%), with a significant proportion of these being clinical feedback (n = 45, 32.9%) and observation (n = 25, 18.3%). Thirteen chose ‘other’, namely child’s behaviour (n = 1, 0.7%); quality of interactions between the child, peers and adults in school (n = 1, 0.7%); improvement in attachment to main caregiver, their confidence in working with their child and way the relationship develops in terms of increased responsiveness and enjoyment of the child (n = 1, 0.7); improvement in child’s behaviour and relationship between caregiver and child (n = 1, 0.7%); game with a child and therapist or with a caregiver with the child, where communication would be the focus of the game and co-operation is needed to achieve the end goal, assessing the ability of the child to remain focused and listen and promoting caregivers’ ability to lead the game and remain in control (n = 1, 0.7%); clinical supervision, reflection, case management, improvement in behaviours and child carer interactions (n = 1, 0.7%); placement stability (n = 1, 0.7%); facilitating play sessions with parent to child and, over time, seeing if there is a difference (n = 1, 0.7%); no assessment diagnostically, therapeutic alliance built on holding space and time and trust, which allows child to work through and express emotionally in a safe and boundaried play space (n = 1, 0.7%); reflective practice and supervision (n = 1, 0.7%); quality of interaction between the caregiver and the child (n = 1, 0.7%); and use alongside other modalities (n = 1, 0.7%).