Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/140/80. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The draft report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Mountain et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific and clinical background

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 82 million people will be living with dementia across the world by 2030, and that figure is estimated to rise to 152 million people by 2050. 1 It is, therefore, not surprising that dementia is a global and national priority. In 2015, the estimated worldwide cost of dementia was US$818B2 and it is predicted that by 2026 costs to the UK alone will be £24B. 3

Population prevalence increases with age, rising from 1 in 14 for people aged ≥ 65 years to 1 in 6 for people aged ≥ 80 years. 4 In the UK, dementia affects approximately 850,000 people, with 61% of those affected living in the community5,6 and half requiring some form of support. 7 The high prevalence of dementia and related costs has a significant impact on individuals living with the condition, their family carers, services and the economy.

Dementia is a significant cause of illness and disability in older adults. However, in the UK, overall funding for dementia still lags behind that for other common conditions of later life, such as cancer and stroke. 8 Globally, investment in dementia research (both cure and care) has been significantly less than what is indicated by the burden of the disease and the dependency it can create. Therefore, an urgent need for funding for dementia research worldwide has been highlighted. 9

In the last decade there has been a number of UK initiatives to begin to redress the previous neglect of dementia by policy-makers, services and society. In 2009, the UK Government announced the first National Dementia Strategy, which had a number of priorities, including increasing the rates of early diagnosis and improving support for people recently diagnosed with dementia. 10 As part of this strategy, the UK government mandated the establishment of memory services in each health locality. The aim of these services is to enable people experiencing symptoms of dementia to access expert diagnosis, help and, particularly, earlier diagnosis. 10,11 A national audit of memory services conducted in 2013 found a fourfold increase in numbers of dementia patients presenting to such services since 2010/11, with services seeing an average of 1206.2 patients annually compared with 317 in 2010/11. 12 It also highlighted that 49% of patients were in the early stages of the condition. 12 A subsequent audit in 2015 found that access to post-diagnostic services had increased since the previous audit. However, the assistance that people could expect to receive following diagnosis was patchy and inconsistent. 13

UK policy is now focused on the treatment and support required by people following diagnosis,14 with this being echoed by global recommendations. 1 Services are being strongly encouraged to provide post-diagnostic treatment and support to enable people to live well with the condition from diagnosis to end-of-life care. 15 Refreshed national guidance states that people with dementia should be offered a range of tailored activities to promote well-being, and that cognitive rehabilitation and occupational therapy should be considered to support functional abilities. 16 The World Health Organization’s Global Action Plan on Dementia1 confirms the importance of post-diagnostic interventions.

The value of psychosocial interventions for people recently diagnosed with dementia is, therefore, recognised and is also driven by the knowledge that a cure is unlikely in the near future. 17 Additionally, early diagnosis has led to the voice of people with dementia being more readily articulated in books and social media (e.g. Mitchell18), with individuals emphasising that they wish to be offered psychosocial treatment and support from the point of diagnosis. Psychosocial interventions can promote independence and self-efficacy, decrease reliance on carers for longer and can help people to continue to enjoy life. 19 However, this is a neglected area for research and for practice and, as a consequence, little investment (until recently) has been made into intervention development and testing.

Self-management is one example of a psychosocial intervention that might be provided post diagnosis to people with dementia. It is an established concept for those living with long-term conditions and is a cornerstone of health policy in the UK and internationally. 20 It involves people with long-term health conditions identifying strategies and knowledge (in partnership with professionals) that can enable them to take responsibility for their own health as far as they are able to. People with dementia were excluded from the 2005 UK Self-Management for Long-term Conditions policy. 21 In recent years, however, there has been a radical shift in thinking and work is now taking place to explore how people with dementia might be helped to manage their symptoms for as long as possible. There is a growing body of evidence to demonstrate how individuals with dementia can be supported to use self-management-based techniques (sometimes in combination with other interventions, such as cognitive rehabilitation and occupational therapy). 22–27 There is also increased interest in how people with dementia and other comorbid conditions might be enabled to self-manage their health. 28

A qualitative study that interviewed people with dementia who attended a self-management programme found that they considered the programme enjoyable and useful. 23 However, they felt that the programme could have been improved by having more emphasis on maintaining activities and relationships that improve positive well-being. 23 This work also found that people value support from others facing similar challenges. 23 The value of peer support is echoed in studies that have found that people with dementia and their carers benefit from peer support. 29,30

This research aimed to add to the body of evidence through research into the effectiveness of a mixed intervention for people in the early stages of dementia that draws on self-management, occupational therapy treatment techniques and peer support.

Study aims and objectives

The primary aim of the trial was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Journeying through Dementia (JtD) intervention for people in the early stages of dementia.

To meet this aim, the objectives were to:

-

conduct an internal pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the intervention to check the feasibility of rates of recruitment at scale

-

proceed to a full pragmatic RCT evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the JtD intervention

-

conduct fidelity checks regarding the delivery of the JtD intervention

-

undertake an embedded qualitative substudy to explore issues concerned with intervention delivery

-

identify how the intervention might be realistically delivered through services.

Intervention: rationale, methods and delivery

This summary of the intervention has been written in accordance with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDier) framework for reporting intervention development and testing. 31

Rationale, theory or goal of the elements essential to the intervention

Journeying through Dementia is a manualised psychosocial intervention for people with early-stage dementia. It was designed through consultation with people living with dementia and was intended to equip individuals with the necessary knowledge, skills and understanding to successfully self-manage their dementia symptoms and live well with dementia. 32 It was created in response to earlier diagnosis of dementia by memory services and the consequent requirement for post-diagnostic interventions. A key distinguishing feature of this intervention is that people with dementia do not necessarily need to involve a supporting carer to take part, thereby addressing the potential needs of the estimated one-third of people with this diagnosis who live alone in the community. 33

The intervention comprised the following two elements: (1) self-management and (2) occupational therapy principles.

Self-management in dementia

Dementia is a constant process of change and readjustment, with one core aspect being capacity to manage the symptoms of the condition. Self-management is one form of psychosocial intervention whereby those with a long-term condition are encouraged to manage their physical and mental health by identifying solutions that meet their own needs, usually in partnership with professionals. Self-management programmes are well established for people with long-term conditions, but their use with people with early-stage dementia is a relatively recent concept. 24

Occupational therapy principles

The JtD intervention is based on the occupational therapy programme Lifestyle Matters,34 which was inspired by an efficacious US intervention called Lifestyle Redesign. 35,36 In common with Lifestyle Redesign and Lifestyle Matters, the JtD intervention operationalises the understanding that individuals are occupational beings and that continued engagement in meaningful activity is key to well-being. 37

Underpinning theoretical framework

The JtD intervention is underpinned by social cognitive theory,38 thereby aiming to increase self-efficacy and effective problem-solving (using the knowledge and techniques described above), which in turns leads to positive emotions, ability to self-manage and life satisfaction.

The content of intervention and processes associated with being in a group target a number of key domains that have been shown to be associated with and/or predict quality of life in dementia. 39–42

-

Mood: the intervention leads to improvements in mood either directly through behavioural activation and learning new coping strategies or indirectly by improving sense of self-efficacy.

-

Relationships: the intervention helps the individual to build relationships and enhances their sense of being connected to others and the community.

-

Beliefs: the intervention helps to promote the understanding that life is meaningful despite dementia.

-

Functional skills: the intervention helps the individual retain skills in activities of daily living and cognitive functioning for as long as possible.

The intervention delivery was also informed by Mitchie et al. ’s43 theory of behaviour change, which emphasises the importance of capability, motivation and opportunity in driving change. Within the theoretical framework of the JtD intervention, behaviour change is associated with improved self-management and engagement in meaningful activity. Capability is addressed by imparting knowledge and training in emotional, cognitive and behavioural skills. Motivation is addressed by increasing knowledge and understanding, eliciting feelings about change and experiential learning to demonstrate positive feelings associated with behaviour change. Opportunity is addressed by making both physical and social environmental changes to enable participants to not only experience the behaviour change in situ (i.e. within the groups and one-to-one sessions), but also by incorporating change into their lives.

The Journeying through Dementia intervention

The manualised intervention contains the following menu of topics that map onto the elements described above. Included topics were identified through consultation with people with dementia prior to the study:32

Reproduced with permission from Craig44

The goals of the intervention are achieved in several ways. Participants may adapt the way an activity is performed, make adjustments to the wider environment or use compensatory techniques. The programme supports individuals to recognise, build on and use existing skills, and to develop new interests that might include drawing upon wider resources.

The intervention content and modes of delivery were tested in a feasibility study25 and found to be acceptable to both people with dementia and their supporters/carers. Reported benefits in people with dementia included increased confidence and self-efficacy, participation in activities and re-engagement in fun and friendships.

Procedures

Who provides: staff and training

To meet service capacity and resources, the intervention was designed for delivery by clinicians who are NHS Agenda for Change (AfC) band 4 or above. All facilitators received a 2-day training course prior to delivering the intervention.

It was intended that the intervention be delivered by a minimum of two trained facilitators at each site and that each trained facilitator would be expected to be involved with the JtD intervention for 1 day per week during the 12-week intervention delivery. This would include preparation of activities, delivery of the group sessions and one-to-one sessions, record keeping and supervision. It was also recommended that more than two facilitators should be trained and be available for intervention delivery at any one site to take account of staff absence.

Delivery methods

The following dimensions were woven into intervention operationalisation, both through the topics within the manualised intervention and the approaches encouraged by facilitators during training and subsequent supervision:

-

content that promotes individuals as occupational beings

-

the premise that continued engagement in meaningful activity is key to experiencing quality of life and well-being

-

menu-led content that allows participants and facilitators to select the topics of most relevance to them from a list of potential options, rather than being required to cover all aspects

-

an asset-based philosophy where group participants are a valued resource for each other and for the group

-

a focus on building self-efficacy within a supportive environment

-

maintaining the locus of control with the person with dementia

-

viewing participants holistically rather than solely focusing on their dementia

-

relationship centred

-

challenges to preconceptions regarding what people with dementia can achieve

-

enactment of activities in real-world settings.

Intervention delivery comprised a mix of facilitated group and individual sessions, with individual sessions feeding into group sessions and group sessions supporting individual sessions.

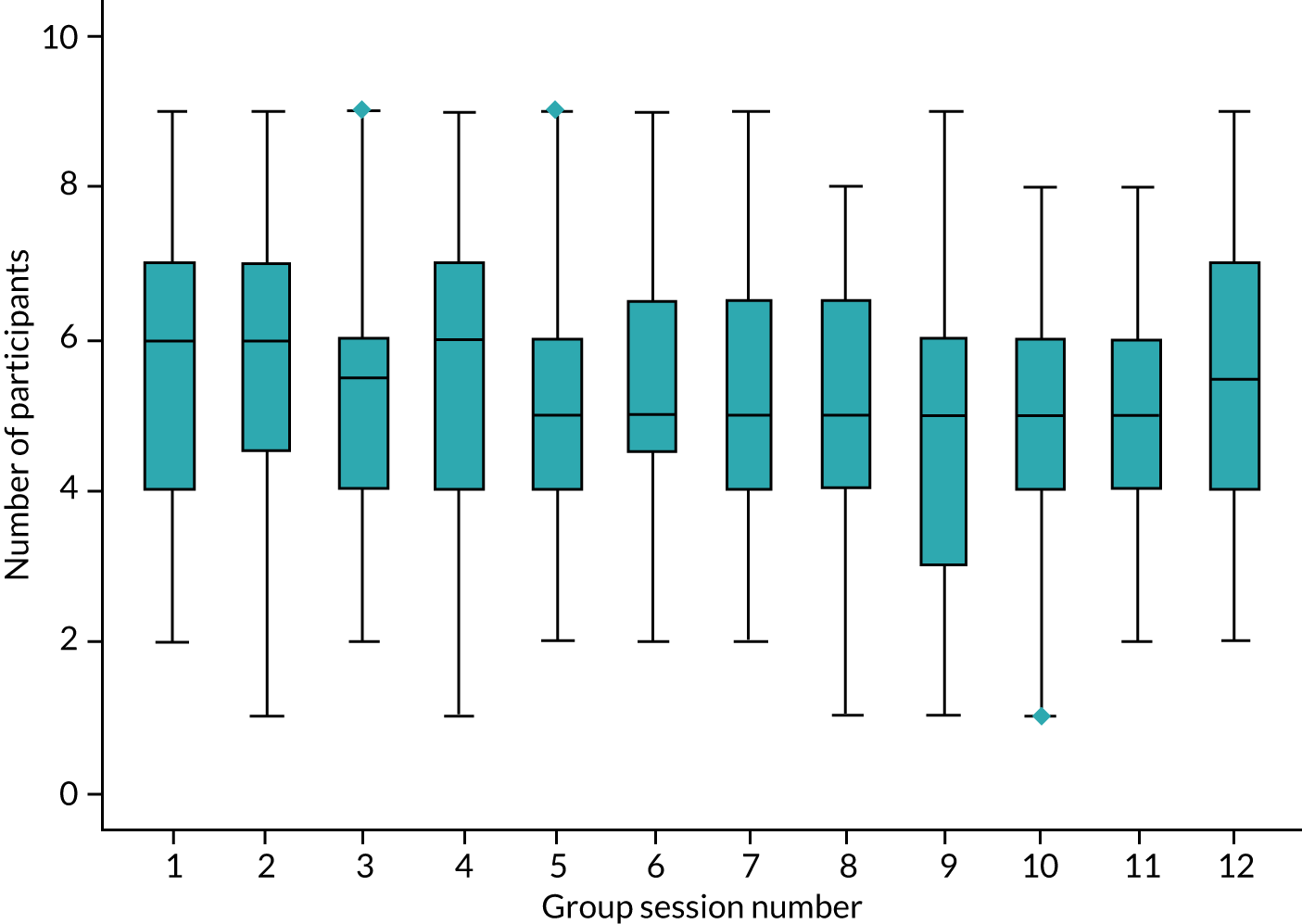

To meet intervention goals it was recommended that each intervention group involve a maximum of 12 people with early-stage dementia (to account for attrition) who would meet together on a weekly basis for 12 consecutive weeks. It was advised that all participants commence their involvement at week 1, as joining later in the 12-week programme would likely erode group cohesion. Each participant received four one-to-one sessions with one of the facilitators at intervals during the 12 weeks and, as far as possible, the same facilitator conducted all four one-to-one sessions with a participant.

Format of the sessions

Each group session involved the same familiar structure:

-

a welcome and sharing of aims

-

information giving to set the context

-

group discussion topics to build a shared understanding and draw on the strengths and skills of participants

-

a practical activity to provide an opportunity for active experimentation, particularly through out-of-venue activities

-

a summary of key messages and an opportunity to plan for the next session.

Each group was encouraged to select the content of their sessions from a range of topics. An essential component of each session was the enactment of activities in the community, which would involve support from each other and the facilitators.

The nature and content of the one-to-one sessions were guided by the participant’s expressed needs, interests and aspirations, and not those of others. The one-to-one sessions were not to be solely used as an aide memoire of the groups. The sessions involved some discussion and also enactment of activities in the home and/or community, depending on the participant’s goals. Examples of goals taken forward during the feasibility study25 included introducing a method to read recipes, maintaining a diary, attending a community group, engaging in physical activity and preparing resources to take to a forthcoming group session.

Participants were not required to nominate a supporting carer/supporter to take part, but if they did, supporter involvement was limited to certain sessions. This was to promote independence and self-efficacy in the person with dementia and to take account of the needs of participants without supporters/carers.

Location and necessary infrastructure

A local accessible venue was required for the 12 group sessions to assist people to maintain citizenship and community links, rather than promote a model of ill health. Facilitators were advised to identify such a location in advance of intervention delivery commencing and in sufficient time to inform participants of both the venue and the timing of group sessions. The venue was to be readily accessible by public transport, part of the local community, warm and inviting, have sufficient space for group activities and include a kitchen and good toilet facilities (e.g. a library, theatre, leisure centre or community hall).

When and how much

The 12-week intervention duration was based on clinical recommendations that advised that this is the maximum that is affordable for routine service delivery.

Supporter/carer involvement was invited at group sessions 1, 6 and 12 and in one-to-one sessions with the person with dementia, if this was requested by the individual participant.

Sessions: number of times delivered, duration and intensity/dose

Each group session lasted 2 hours and included breaks for refreshments and socialising.

Facilitators were asked to incorporate a minimum of three out-of-venue activities within the 12-week group intervention delivery to enable enactment of activities in real-life settings to take place.

The duration of the one-to-one sessions was not specified and facilitators were advised that they should take place at a venue agreed between the participant, facilitator and supporter/carer, if the person asked for supporter/carer involvement.

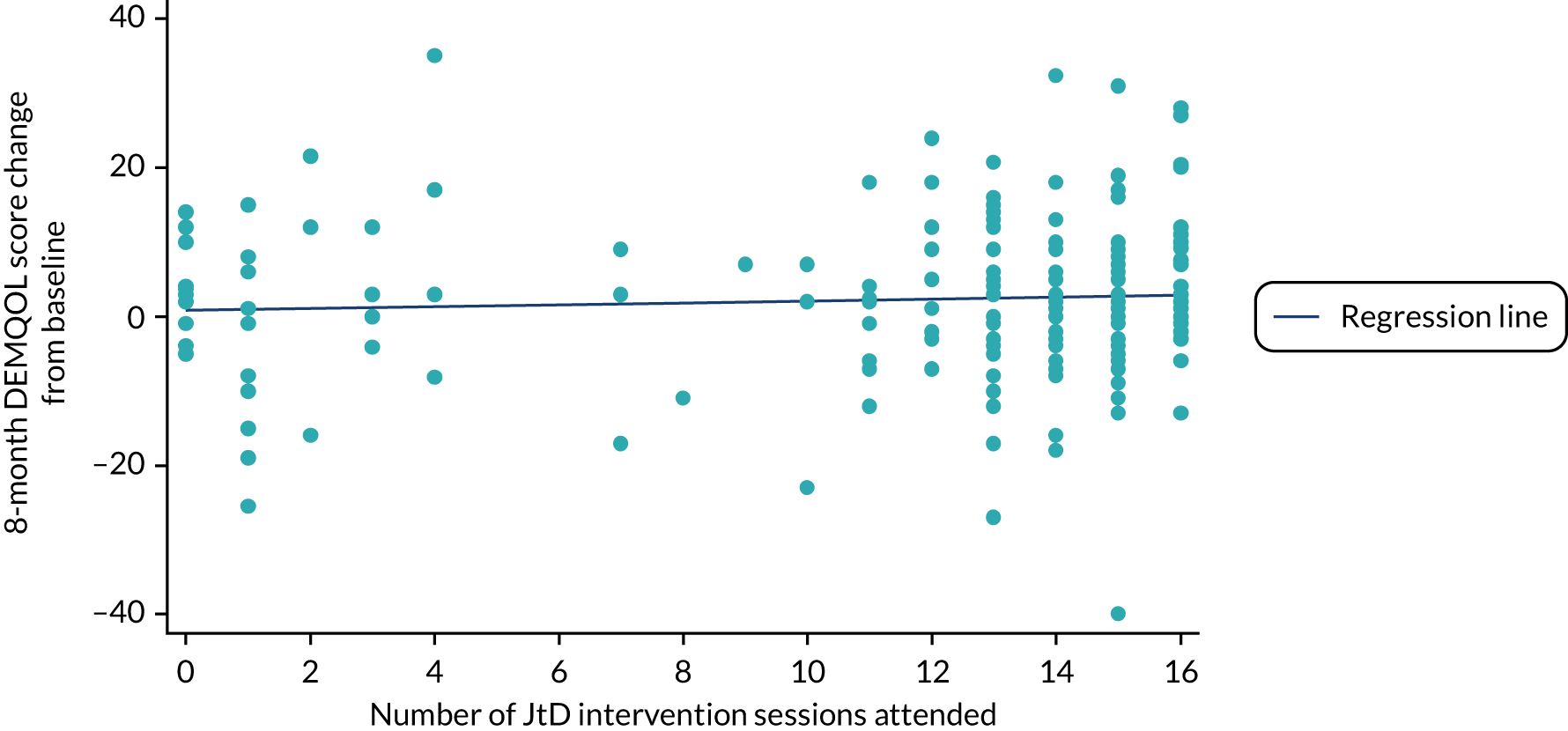

Prior to intervention delivery commencing for the trial, we determined that 10 sessions attended out of the potential 16 (irrespective of whether they were group sessions or one-to-one sessions) would constitute a therapeutic dose. This was a pragmatic decision taken by the study team, which took account of past experience of delivering similar interventions.

Intervention tailoring

Facilitators were encouraged to work with other topics that groups and individuals identified, as well as those in the intervention manual. However, they were asked to deliver the intervention as described in the manual and training.

Out-of-venue activities were tailored to the expressed needs of the group and the individuals within it, and they could be simple or more elaborate, depending on the group. For example, moving to a public cafe area within the same building so that participants support each other with the activities they find challenging. Within the group, the aims of individuals will differ. For one person it could be ordering a drink, for another it might be handling money and for a third it might be socialising in a public area. Another group could be enabled to practise their individual skills and nurture their interests in a more demanding out-of-venue activity.

The one-to-one sessions were in place to enable participants to work towards meeting individual goals, with or without a supporter/carer depending on wants, needs and circumstances. Goals could be very small and their achievement incorporated some degree of enactment. On occasion, one-to-one sessions were used to discuss issues of concern to individuals to help identify ways of managing the challenge (e.g. using public transport or continuing to drive). As with the group sessions, the overall aim was to enable participants to articulate how they wanted to use these sessions and be supported to identify and achieve realistic goals. Facilitators were advised that the first one-to-one session should be organised before commencement of the group so that they could introduce themselves to the participant and discuss the forthcoming 12 weeks, including how the participant would access the group venue (transport was not provided). We were also aware (from our previous Lifestyle Matters research45) that this initial face-to-face meeting was important for establishing one-to-one sessions in this form of mixed intervention.

Facilitator/supervisor training

People living with dementia played an integral role in the development of the training for the intervention, as well as in intervention development. Initial consultation led to insights that informed the training. This was then informed by consultation with the Scottish Dementia Working Group (a national campaigning group comprising people with dementia), which assisted with the design of the materials for the intervention and added to our understanding of what would make good facilitation.

Facilitator training was designed to mirror the modes of intervention delivery, in that it was group based (i.e. involving facilitators from more than one site at an independent venue), it sought to impart necessary didactic information to facilitators to achieve a shared understanding and it included experiential work, using exercises taken from the manualised intervention. For example, two trainers modelled group facilitation techniques and trainee facilitators were given the opportunity to rehearse and role play responses to potential scenarios that might arise in the groups they were to facilitate. Training took place as near as possible to commencement of intervention delivery.

Taught sessions within the training (didactic information) included the following:

-

the background, context and development of the JtD intervention

-

how the intervention was underpinned by evidence regarding needs for, benefits of and nature of post-diagnostic support for people affected by dementia

-

the underpinning philosophy and approach of the intervention

-

information on the models and modes of group work

-

information on the role of individual sessions

-

information on environment and resource management

-

information on methods of record-keeping and reflection through use of reflective diaries.

Discussion topics included the following:

-

prior experience, interest and motivations

-

understanding the experiences of people living with dementia (with responses to quotes by people with dementia and a film made by people living with dementia)

-

a walk through of the manual (identifying the components)

-

details on the preferred approaches to group facilitation

-

information on how the environment can support and inhibit interaction and self-efficacy

-

information on managing groups (including a discussion based around a series of personas).

Experiential sessions included the following:

-

what makes a good post-diagnostic support programme (using an interactive activity)

-

community resources (including a pictorial and mapping activity)

-

guidance on the planning, and facilitation of sessions (with trainees acting as group participants)

-

guidance on managing groups and delivering individual sessions (using role play)

-

information on methods of record-keeping and completion of other intervention-related documentation for the purposes of delivery and for research.

Facilitators were asked to document all group and individual sessions on a pro forma provided by the research team. They were asked to write records primarily for the benefit of participants and in accordance with Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) guidance for best practice in providing documentation for people with dementia. 46

Facilitators were asked to write session records as soon after the group as possible and post to all participants before the next session.

Facilitators were also asked to maintain registers of participant attendance and records of the supervision sessions they attended on other pro formas provided to them by the trial manager.

Facilitators were asked to post copies of all these records to the trial manager. These records were requested at the end of the 12 weeks for the first rounds of intervention delivery at all participating sites. For subsequent rounds, intervention delivery facilitators were asked to return records every 3 weeks. The reason for this change was to improve delivery of the intervention in accordance with the manualised intervention on an ongoing basis.

Facilitator supervision (for the purposes of this study)

Once intervention delivery commenced for the trial, facilitators all received weekly supervision from a suitably knowledgeable and experienced clinical professional (AfC band 7 and above) from their place of work, identified and nominated by the research site.

Ideally, people supervising would have themselves previously facilitated the intervention. For the purposes of this study, however, this was not possible, and so a ‘train the trainers’ model was adopted. This involved suitably experienced individuals being nominated as supervisors. Members of the trial team, who were experienced in delivering and supervising psychosocial interventions within trials, then delivered regular supervision to these supervisors.

The supervision protocol identified for the purposes of the study is outlined below (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for the full supervision protocol):

-

Suitably qualified professionals who agreed to supervise facilitators at site were invited to take part in the first day of the 2-day facilitator training, ideally with the facilitators they were to supervise, as well as with other supervisors and facilitators from different sites.

-

A second half-day session with other supervisors and the trial team member nominated to supervise them was then convened to discuss perceptions and any concerns regarding both intervention delivery and the associated research, as well as to go through practical details, including completion of necessary trial documentation for supervision (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for the supervisor booklet). This second session wase scheduled as close as possible to the initial training.

-

On commencement of intervention delivery, each facilitator then received weekly supervision in a format agreed between themselves and the person nominated at site to supervise them [e.g. face to face, Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), FaceTime (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) or telephone]. These supervisions included both individual and group supervisions.

-

Facilitators and those supervising them maintained records of the nature and duration of each supervision record, using the trial pro formas.

Modifications to facilitator identification and training, intervention delivery and supervision

Slower rates of recruitment at sites than those originally envisaged led to the need for a greater number of delivery sites (n = 13) and, hence, a greater number of facilitators and supervisors. Facilitator and supervisor attrition and absence also led to increased numbers being trained. Overall, we trained 69 facilitators (not all of whom delivered sessions) and 21 supervisors.

Identification of intervention facilitators

The intention was to recruit NHS band 4 staff with appropriate experience to deliver the intervention, but in practice a range of staff were recruited. Staff included experienced grade 8 occupational therapists and (in one instance) a grade 2 assistant (see Report Supplementary Material 3 for details of the numbers and pay grades of facilitators and supervisors).

Facilitator and supervisor training and supervision

The total number of 2-day facilitator training sessions delivered as originally intended was six. The number of facilitators trained as intended was 53 (of the overall 69 facilitators trained). The total number of supervisors’ training sessions delivered as intended was eight. The number of supervisors trained as intended was 17 (of the overall 21 supervisors trained).

Facilitator attrition occurred because of a significant number of assistant psychologists who fulfilled this role who then moved to different posts or higher training, and also because of staff sickness or pregnancy in other cases. In addition, new research sites had to be involved over time to meet the recruitment target. This led to supervisor and facilitator training being repeated and modified to meet the needs of those new to the study. Sixteen facilitators and four supervisors subsequently received a modified version of the training. The following modifications were delivered:

-

Site-based training to facilitators at four sites, rather than working with a group of other facilitators and supervisors at a central university venue.

-

Site-based training to supervisors at five sites, rather than working with a group of others at a university venue.

-

Shortened facilitator training from 2 days to 1.5 days, complemented by provision of online training presentations.

-

Shortened facilitator training from 2 days to 1 day, complemented by online presentations and resources in four instances.

-

In one case, for a relief facilitator who the site felt was unlikely to facilitate but wanted trained just in case, the full course was provided remotely via online presentations, accompanied by a telephone call.

-

Refresher training at local sites was delivered 10 times because of a protracted period between initial training and delivery.

Fidelity and consistency across selected facilitator training sessions were formally assessed (see Chapter 3, Fidelity study for more details).

Intervention delivery and attendance

The numbers of participants registered to receive the intervention for each round of delivery per site was < 12 participants for the majority of sites, with the range being between 4 and 12 participants (Table 1). Only two intervention groups achieved 12 participants. This led to 28 rounds of intervention delivery for the trial, whereas the original estimate was 20 groups (i.e. two rounds of intervention delivery at 10 sites). For further information about intervention delivery and attendance see Chapter 3, Journeying through Dementia intervention and Appendix 5, Tables 34 and 35.

| Site IDa | Intervention delivery round | Participants (n = 239b) |

|---|---|---|

| S01 | 1 | 7 |

| 2 | 8 | |

| 3 | 7 | |

| S02 | 1 | 7 |

| 2 | 7 | |

| 3 | 8 | |

| S04 | 1 | 9 |

| 2 | 6 | |

| S05: delivery site 1 | 1 | 12 |

| 2 | 7 | |

| S05: delivery site 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 2 | 7 | |

| S06 | 1 | 9 |

| 2 | 10 | |

| S07 | 1 | 12 |

| 2 | 11 | |

| S08 | 1 | 9 |

| 2 | 10 | |

| S09 | 1 | 8 |

| 2 | 9 | |

| S10 | 1 | 9 |

| 2 | 11 | |

| 3 | 11 | |

| S11 | 1 | 10 |

| S12 | 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 4 | |

| S13 | 1 | 6 |

| S15 | 1 | 11 |

Extent to which intervention was delivered as planned

As well as providing records for participants, the group and individual records maintained by facilitators were also used to enable ongoing review of intervention delivery.

The chief investigator and leads for supervision (KB/Jasper Palmier-Claus) aimed to review returned records in a timely manner and provide feedback to site supervisors on facilitator compliance with the intended intervention and identify where any adjustments were required. Feedback was provided by e-mail communication to all sites actively delivering the intervention at any time and was not site specific.

Issues identified through review of records maintained by facilitators included examples of good practice that matched the manualised intervention, needing improvement and examples of practice that was poor and also non-adherent to the intervention. Examples of good practice include:

-

records written in lay language and in the first person, focussing on key learning points for participants

-

records typewritten in sufficiently large font with text well spaced on the page

-

providing evidence covering all components of the intervention (including a discussion, goal-setting and activities)

-

documented adherence to out-of-venue activities

-

provision of additional, well-presented information (e.g. information on locations used for out-of-venue activities)

-

facilitators engaging in one-to-one activities chosen by participants

-

additional positive elements delivered above and beyond the manualised intervention (e.g. skill-sharing and having shared lunches among participants).

Examples of practice that needed improvement included:

-

poorly documented records or records that were too dense

-

no concrete examples documented within records

-

over-reliance on clinical terminology or professional language, including use of abbreviations

-

overly prescribed intervention content or not letting participants choose content and not responding to participant ideas for activities

-

different facilitators involved in one-to-one sessions with the same participant

-

facilitators focusing more on reviewing the groups in one-to-one sessions and encouraging group attendance rather than engaging in new purposeful activities

-

records recording referrals to health care

-

signposting only, rather than following up with activity

-

unrealistic goal-setting.

Examples of practice that was poor and also non-adherent to the intervention include:

-

use of NHS premises for the group

-

supervisors routinely adopting a facilitation role (our facilitator absence guidance stated that supervisors could occasionally, in unavoidable circumstances, step in as facilitators, but it was not appropriate for supervisors to take on the role of facilitator on a regular basis)

-

unclear which facilitators had been involved

-

group sessions conducted with only one facilitator

-

not conducting the three out-of-venue activities

-

supporters/carers attending out-of-venue activities and/or more than the three allocated supporter sessions (i.e. sessions 1, 6 and 12)

-

facilitators not undertaking one-to-one sessions

-

facilitators undertaking one-to-one sessions but not the group sessions

-

one-to-one sessions conducted with two facilitators rather than one

-

telephone-delivered one-to-one sessions

-

supervisors not providing opportunities for individual, as well as joint, supervision for facilitators

-

use of additional bespoke questionnaires to determine needs and assess risks.

Chapter 2 Methods

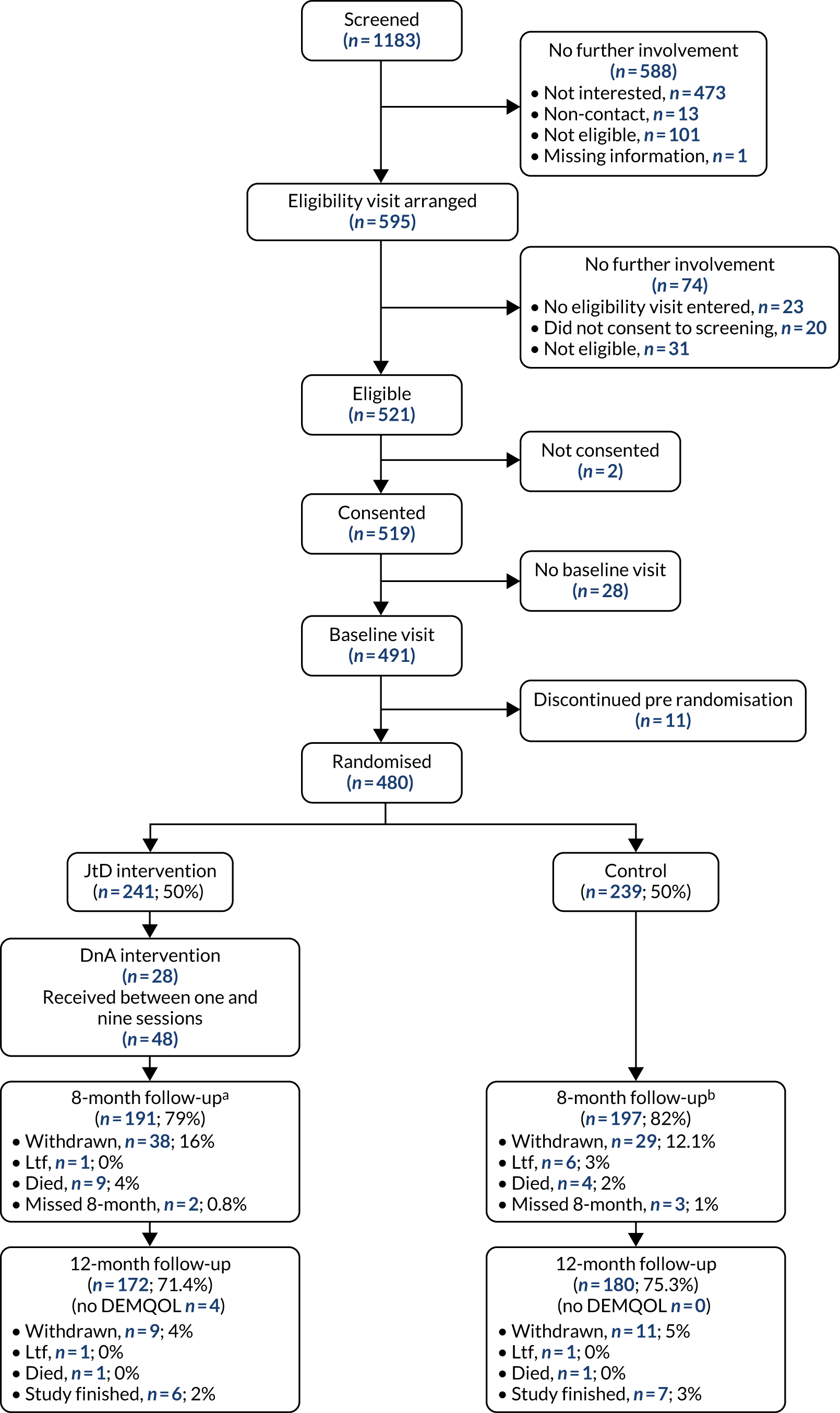

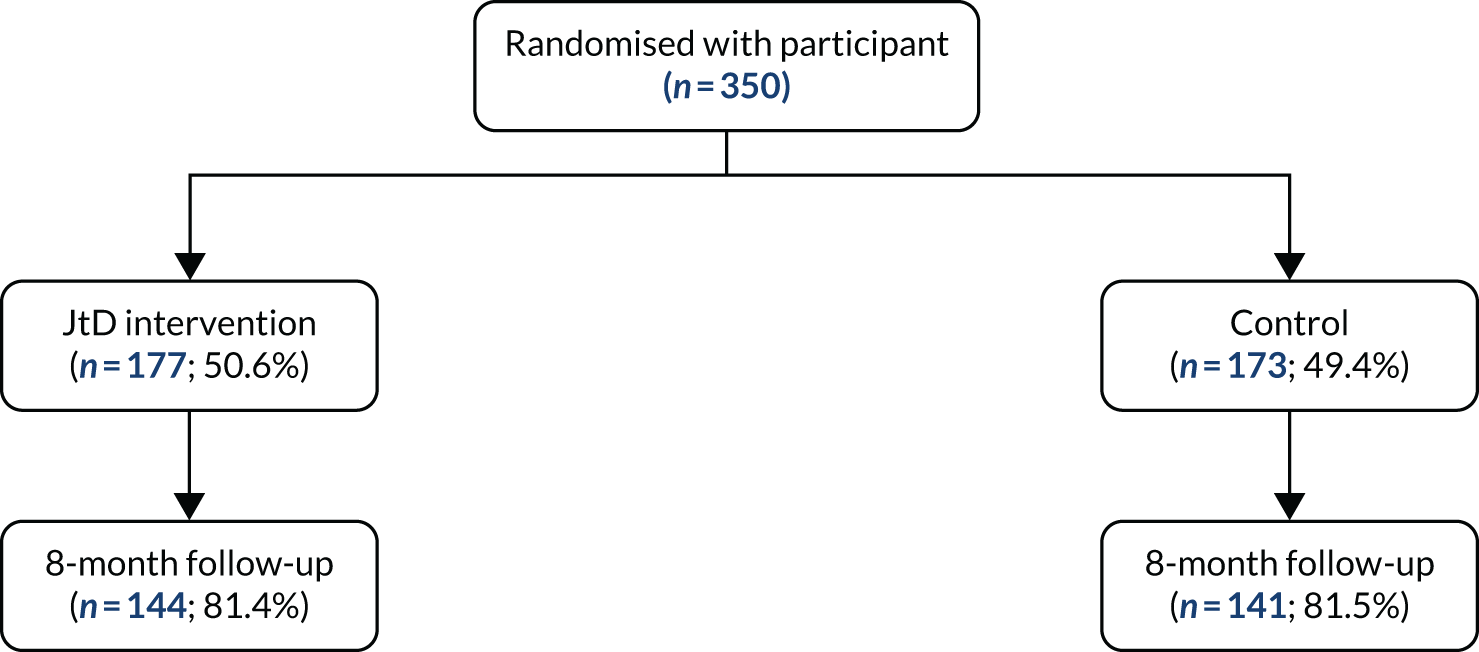

The study design was a pragmatic superiority two-arm parallel-group individually randomised controlled trial. It involved an intention-to-treat (ITT) comparison of the JtD intervention with usual care. 47 The full trial protocol is available via the funder website48 or as a publication. 47 The trial proceeded to a full trial after conducting an internal pilot RCT of the intervention to check the feasibility of rates of recruitment at scale. This chapter describes the detailed methods for the main trial and for two of the substudies: (1) an examination of intervention fidelity and (2) a qualitative study of experiences from those who took part. Methods relating to the health economic analysis and participant and public involvement (PPI) are described separately in Chapters 4 and 6, respectively.

Methods for the main trial

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

The most significant study changes after trial commencement are listed below. Study protocol amendments are listed in full in Appendix 2.

Recruitment period changes

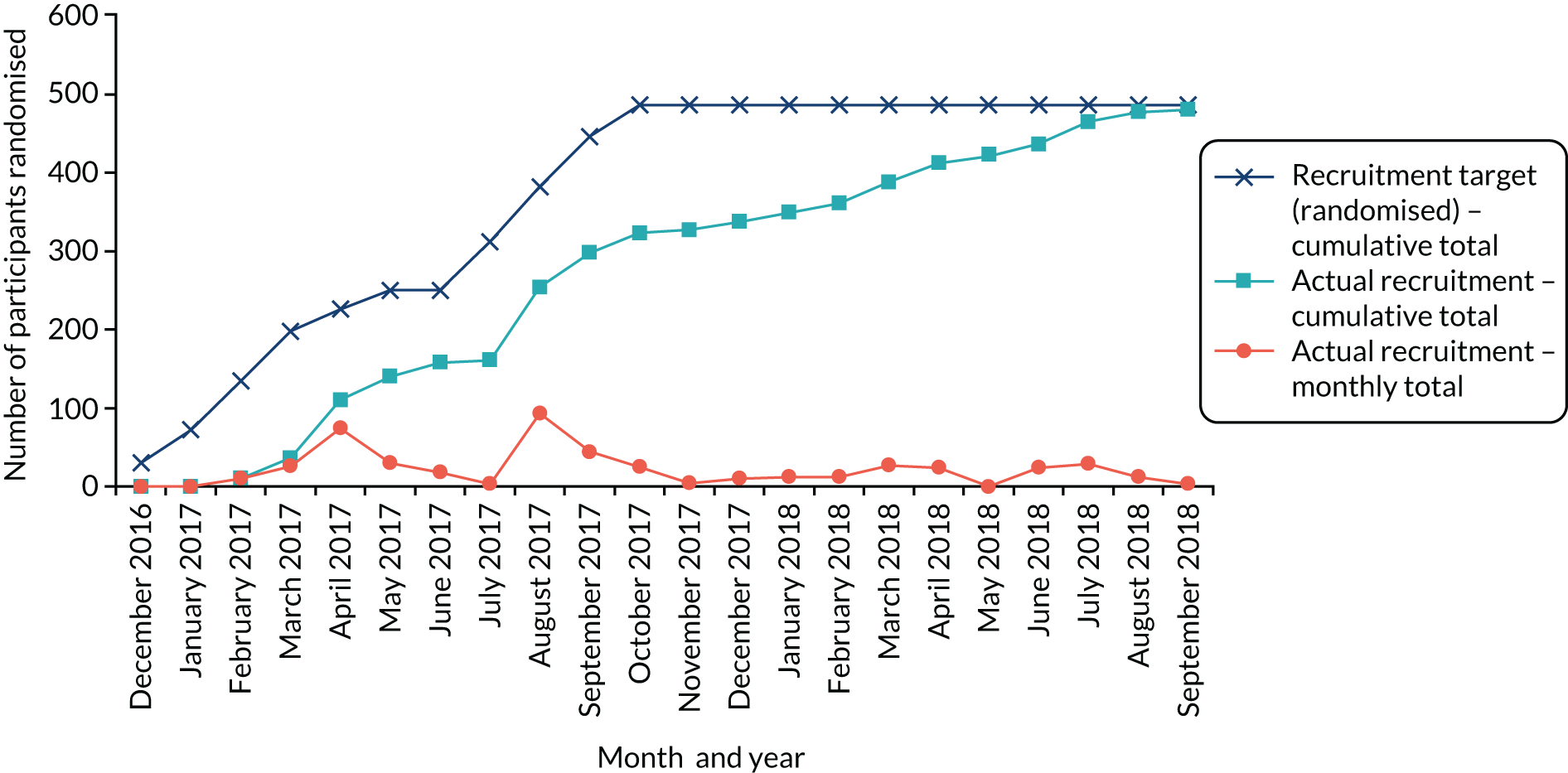

The original planned recruitment period was from October 2016 to end of September 2017 (12 months). However, because of issues with recruitment, the final recruitment period was November 2016 to August 2018 (22 months). The study was open to recruitment for 10 months more than originally planned. Recruitment was stopped in August 2018 to ensure that all 8-month follow-ups could be conducted within project timelines.

Number of recruiting sites changes

The project originally aimed to have 10 recruiting sites; however, because of issues with recruitment, 13 recruiting sites (across 14 NHS trusts) were involved. More NHS trusts than recruiting sites were involved because two neighbouring NHS trusts worked together to recruit participants and run the intervention.

Data analysis changes

In the event that there were > 10 couples living in the same household, where both individuals had a dementia diagnosis and both were enrolled in the study, the primary and secondary analyses were to be changed to take into account the hierarchical or clustered nature of the data. A multilevel mixed-effects model would be used [the random effects were the JtD intervention groups (top level) and couple/singles (lower level)]. Individual participants who were not part of a couple were to be treated as clusters of size 1. This analysis approach was not implemented in the study, as there were not > 10 couples living in the same household, where both individuals were diagnosed with dementia.

Changes to facilitator and supervisor training

Three changes to the plan for training of facilitators and supervisors were made. The first was that one of the initial training sessions (on 23 and 24 January 2017) had to be significantly modified during delivery because of the large numbers of attendees. Modifications included reducing time spent on a topic/activity or excluding it altogether (see Chapter 3, Training fidelity for further information on modifications). The second was that online resources were developed to assist with training part-way through the study. The third change was that many training sessions had to be delivered at the local sites, rather than centrally as planned (see Chapter 1, Facilitator/supervisor training for further information).

Follow-up window changes

In the final months of the trial a decision was made by the study team, with support from the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), to extend the time window in which the outcome data could be collected. The window already included the period 8 weeks after the 8 or 12 months post randomisation date. This was unchanged. The period in which data could be collected prior to the 8- and 12-month follow-ups was originally only 2 weeks. This was extended to 8 weeks. A gap of at least 52 days was preserved, when possible, between the 8- and 12-month follow-ups. This change allowed 12-month data to be collected from participants before the end of the trial where it may have otherwise been missed. The change meant that approximately 41 participants had their 12-month follow-up earlier than originally planned. Despite this change, 13 participants were still unable to receive their 12-month follow-up appointment.

Data collection procedure changes

To retain participants in the study and to be able to collect the maximum number of participant data, a decision was made that when it was the only feasible way (i.e. no physical visit was possible), outcome measures could be collected from participants over the telephone for the 8- and 12-month follow-ups. This included the primary outcome Dementia-Related Quality of Life (DEMQOL) measure, the reduced Health and Social Care Resource Use Questionnaire (HSCRU) and a telephone version of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). These measures were chosen as the most important to assess the effectiveness of the intervention, judged to not place a high burden on participants and were the most feasible to collect over the telephone. The telephone measures for participants were used only twice for the DEMQOL, once for the EQ-5D-5L (telephone version) and four times for the reduced HSCRU.

Further study document amendments

Amending the instrumental activities of daily living questionnaire (approved 24 January 2017)

An amended version of the published instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, which re-phrased some of the questions and gave an additional option for one of the activities covered in the questionnaire (travel) that the activity was not done at all. All participants used the updated version of the form during the baseline and 8-month assessments.

Amending the Sense of Competence Questionnaire (approved 13 March 2017)

This was a minor change to the Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SCQ), which we used at baseline and 8 months for the participating supporter (i.e. a supporter/carer who had signed up to be part of the trial). The study team decided to remove all headers/taglines at the top of the printed document that referred to demented persons. This was approved by the Health Research Authority as a minor amendment. This did not affect the questions.

Changes aimed at participant retention

In October 2018, after advice from the TSC and our PPI Advisory Group, the suite of documents used by the study to contact participants to arrange and confirm appointments was revised after a review of the live trial data indicated that withdrawal rates were high.

Participant and Public Involvement Advisory Group: supporting qualitative analysis

To assist with interpretation of the qualitative analysis, people with lived experience of dementia, from the University of Bradford Experts by Experience Group, were invited to take part in two successive workshops. Some of the individuals who took part were members of the Study Advisory Group and others were new to the study. Quotation/extracts from the interview data, which researchers identified as being representative of the categories identified during the analysis, were presented to group members for discussion. The workshop outcomes were used to refine and, when necessary, revisit the qualitative analysis. The study protocol was amended on 5 December 2018 to reflect the PPI role in this respect.

Changes to the fidelity substudy

The protocol was amended on 14 June 2017 to change methods from the use of filming to observation to assess facilitator adherence to the manualised intervention and participant receipt of the intervention. The decision was made to use observations as this method was more practical and would still achieve the aims of the fidelity substudy.

Changes to the qualitative substudy

Originally, qualitative interviews were planned with staff at the fidelity sites at the beginning and end of their delivery of the intervention to monitor their change in outlook based on their experience of delivering the intervention. However, as many of the facilitators to be interviewed had delivered the intervention in a previous wave within the study, there was deemed to be less value in conducting two interviews. The protocol was therefore amended on 28 November 2017, so that one interview was conducted with individuals to look more broadly at the facilitator experience of delivering the intervention.

The purposive sample for qualitative semistructured interviews with participants and participating supporters was changed to participants at sites who were part of the fidelity assessment. This change was to ensure meaningful triangulation of qualitative results with other fidelity assessments.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Participants in the trial were individuals with a formal diagnosis of dementia and their supporters where these consented to be involved. Supporters included family members, friends and neighbours named as supporters by the person with dementia. Where supporters were trial participants they were referred to as ‘participating’ supporters. Participants and participating supporters were selected based on the eligibility criteria outlined below.

People diagnosed with dementia

Inclusion criteria

-

People diagnosed with all forms of dementia.

-

A Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of ≥ 18 (taken < 2 months pre consent). MMSE is measured on a scale from 0 to 30 and higher scores indicate better cognitive function.

-

People with the ability to make informed decisions.

-

People living in the community or in sheltered accommodation, alone or with others.

-

People with the ability to converse and communicate in English.

-

People willing to engage in a 12-week group self-management intervention.

Exclusion criteria

-

People not diagnosed with a form of dementia.

-

People with a moderate or severe dementia with a MMSE score of < 18.

-

People assessed as lacking capacity.

-

People living in residential or nursing care.

-

People who are not able to converse or communicate in English.

-

People taking part in any other pharmacological or psychosocial intervention studies.

Participating supporters

Inclusion criteria

-

People aged ≥ 18 years.

-

People named by the person with dementia as their supporter.

-

People with the ability to converse and communicate in English.

-

People with the ability to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

People aged < 18 years.

-

The person with dementia for whom they provide support to is not participating in the trial.

-

People who are not able to converse or communicate in English.

-

People who are not able to give informed consent.

Participant identification and recruitment

Recruiting people living with dementia to clinical trials is known to be challenging and, therefore, a variety of participant identification methods were used to maximise recruitment. The recruitment strategies used varied between sites because of the different configurations of dementia care within NHS trusts (see Report Supplementary Material 4 for the overall participant identification and recruitment process within the JtD intervention).

Regardless of the method of identification, care was taken to cater to the needs of the individual, given the potential for cognitive and communication difficulties. Although there was a standardised identification and recruitment process, it was important that it allowed some degree of flexibility to cater to the specific needs potential participants may have had. Alongside the participant information sheet, a shorter information leaflet, which had been reviewed by the PPI Advisory Group, was used to provide a simplified overview of the trial. This was used before going into more detail with the full-length participant information sheet if the individual was still interested after receiving the initial information. In the first instance, any information about the trial was communicated to the person living with dementia; however, if the person with dementia requested, researchers could communicate with someone they identified as a participating supporter.

Anyone who expressed interest received a face-to-face visit from a researcher who had been offered training on the additional communication needs of people living with dementia.

Researchers were provided with suggestions for recruitment methods, but implementation of these methods was at the discretion of the researchers because of their knowledge of the individual NHS trust. Recruitment was continually kept under review and support was provided from the central team if required. The different methods used are described below.

Recruitment via secondary care services

Patients attending post-diagnostic appointments who were potentially eligible were informed about the JtD intervention by the health-care professionals or other relevant staff members while at the clinic. They were given brief written information about the trial and if they were interested verbal consent was taken to pass their contact details to a member of the research team who would then contact them and follow the recruitment procedure. On occasion, a member of the research team attended post-diagnostic clinics so that they were on hand to provide further information and answer questions. This was also helpful in reminding health-care professionals of the study and bringing it to patients’ attention.

Some NHS trusts screened patient lists for potentially eligible people and sent them an information pack containing a participant invitation letter and free-post response card. If the person with dementia was interested, they completed and returned the response card to the research team who then followed the recruitment process. As it is known that people with dementia may find it challenging to return the response card by post, if appropriate, those sent the initial recruitment pack would also be followed up with a telephone call by an NHS staff member.

Recruitment via primary care

Primary care general practitioners (GPs) were approached to recruit participants, namely by carrying out mail-outs to appropriate registered patients.

Recruitment through the Join Dementia Research database

The JtD trial was registered on the Join Dementia Research (JDR) database, which is a database hosted by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) to help people with dementia identify recruiting research studies that they may be interested in joining. The JDR database was used for recruitment to the JtD trial in two ways. First, those registered to the JDR database who were interested in the JtD trial were able to contact the research team directly. Second, the research team were able to search for potentially eligible people and contact them, provided permission was given to do so. Once the research team had details of the person with dementia, the JtD trial standard recruitment pathway was then followed.

Recruitment through service user groups

Service user groups, such as the Alzheimer’s Society support groups, were used to identify potentially eligible participants. Researchers visited such groups to explain the trial and anyone interested was given a response card to complete or return. Once researchers had details of the interested individuals, the recruitment process was followed.

Recruitment through general promotion

The JtD trial was promoted using posters and leaflets in general practices and community venues. Social media was also used to make people aware of the trial. For these general promotional methods, the researcher’s details were made available for those interested to contact them directly.

Baseline and follow-up visits

Visits types and timings

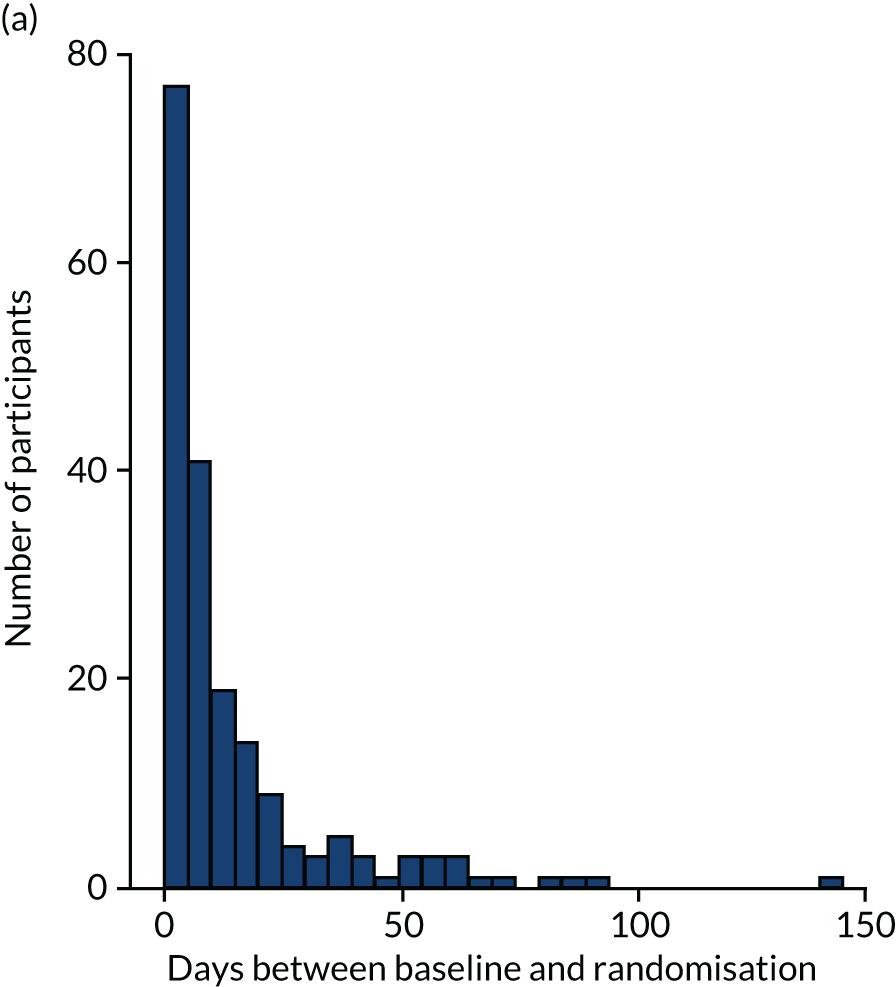

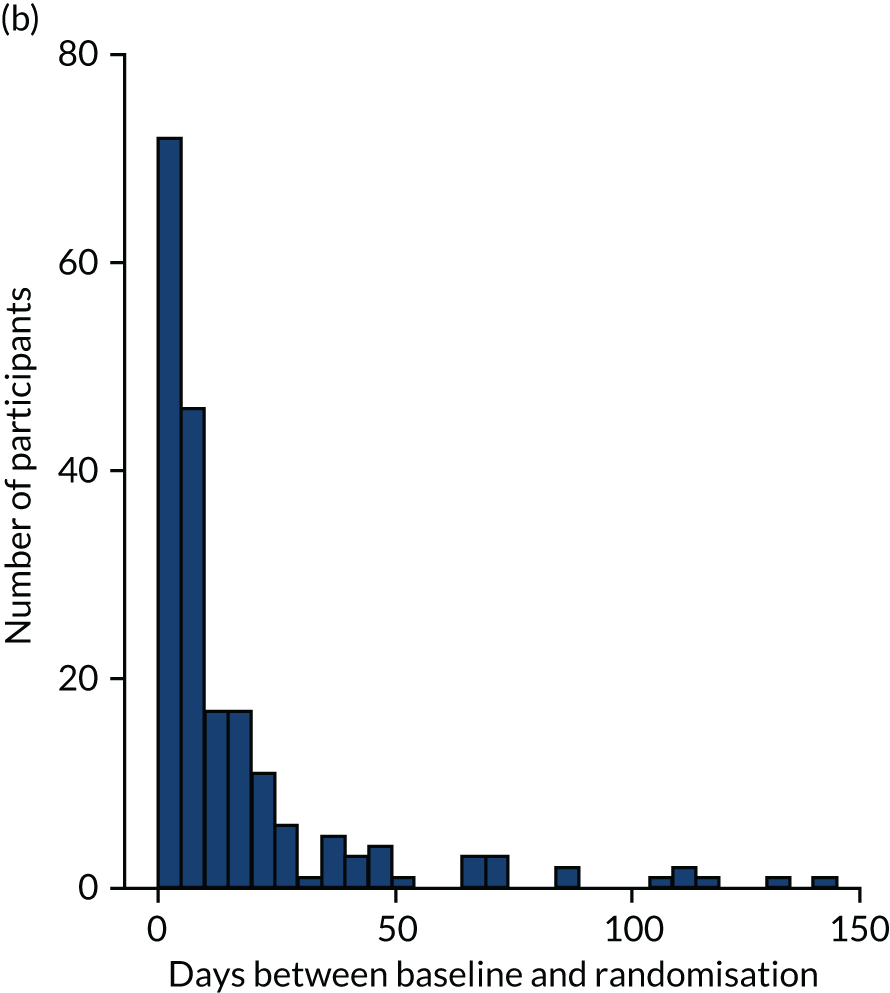

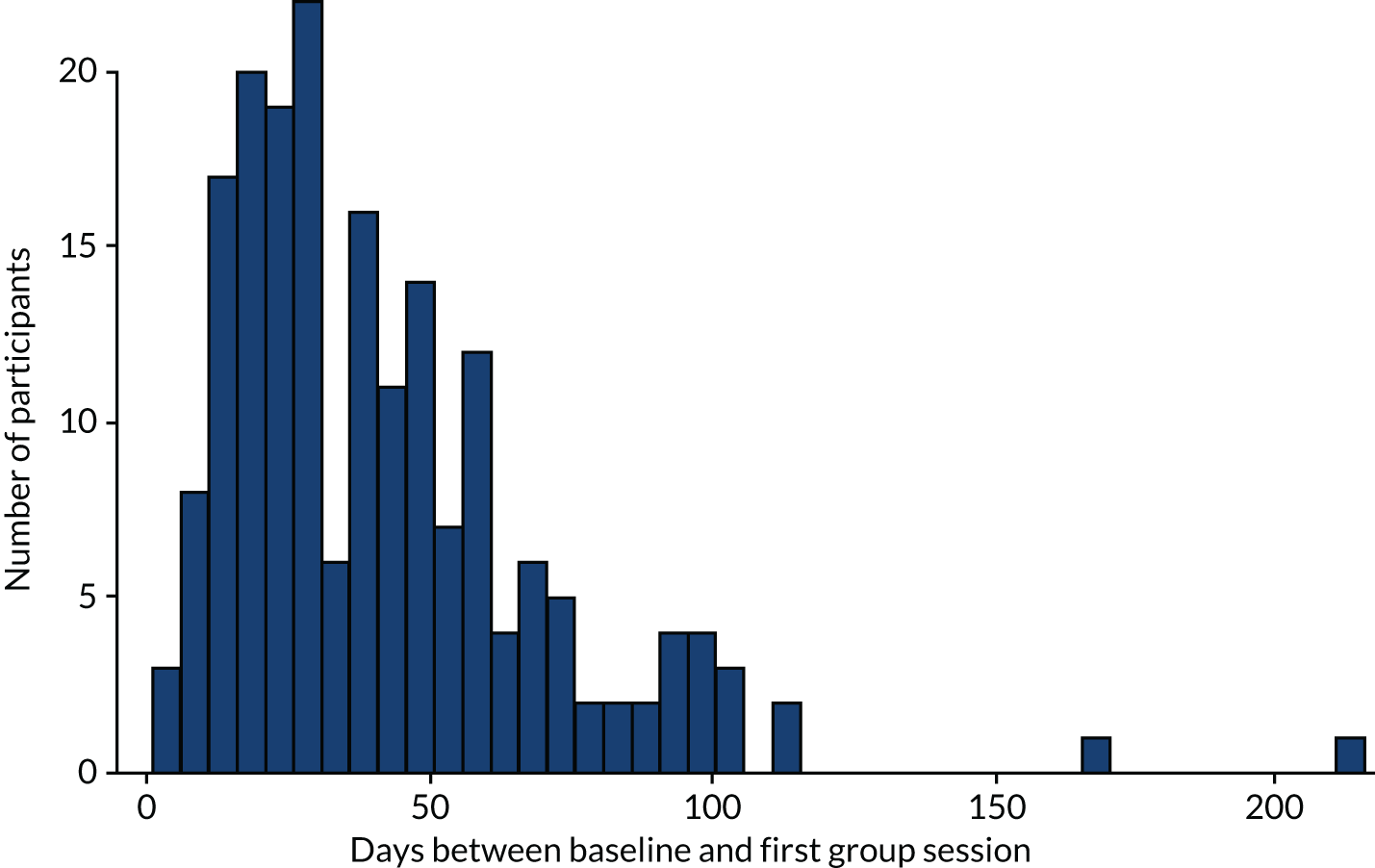

The aim was to conduct baseline visits for participants and participating supporters no more than 2 months before the intervention was due to start. Follow-up visits were conducted with participants and participating supporters at 8 months after the date of randomisation, and with only participants at 12 months after the date of randomisation. Follow-up visits were conducted in a period between 2 weeks prior to the target date and 8 weeks after. Later in the study, this period was extended to 8 weeks prior to the target date. However, in circumstances where visits within this period were not possible, attempts were made to collect outcome measures outside this period.

Staff conducting visits

Visits were conducted by one or two outcome assessors who were blinded to allocation for the 8- and 12-month follow-up visits. Staff followed lone working policies when conducting visits alone.

Planning visits

Baseline visits were arranged with participants and participating supporters at the time of consent being taken. The participant and participating supporter visits could be carried out at the same time or separately, depending on preferences. Additionally, when close to the intervention starting, consent and eligibility visits could be combined with baseline visits.

Four weeks prior to follow-up visits commencing, participants and participating supporters were contacted by post to let them know that a member of the study team would shortly be contacting them by telephone to arrange a visit. Outcome assessors would then telephone participants and participating supporters to request and arrange the visit. Written confirmation of the visit would be sent to the participants and, if participants wished, outcome assessors would make a brief telephone call shortly before the visit to confirm with the participant that it was still acceptable to go ahead. After introducing new retention procedures, researchers aimed to organise the 12-month visit time during the 8-month visit.

Consenting and assessing capacity

Written consent was obtained when participants joined the trial and confirmed verbally at subsequent visits. Capacity to consent was formally assessed when participants joined the trial and was assessed informally by researchers at each visit. At visits where the participant was felt not to have capacity to consent, attempts were made to support the person to demonstrate capacity, for instance by presenting information on the study in a different format or returning for a visit at a later date. When these attempts were unsuccessful during follow-up visits, the consultee process was enacted. The consultee process is described in Ethics arrangements and regulatory approvals.

Conducting visits

Visits were principally conducted in the participants’ homes or in other public locations, such as cafes, if the participant requested this. Measures were administered by the assessors using a verbal structured interview technique. Available responses were presented in an A4 format to aid participants, with large black print on a yellow background to assist those with visual impairments. The measures used are outlined in Outcomes.

In some circumstances, participants did not feel able to complete all the measures (e.g. because of fatigue). In these cases the researchers prioritised the DEMQOL, EQ-5D-5L and HSCRU (during follow-ups) as the key outcome measures. Additional visits could be made to complete measures when it was not possible to complete them in a single visit and participants were happy to be visited again.

Telephone measures

When it was not possible to arrange face-to-face follow-up visits with participating supporters, for example because of work commitments, data could be collected over the telephone. In specific circumstances a reduced set of measures (i.e. the DEMQOL, EQ-5D-5L and shortened HSCRU) could be collected by telephone from participants when it was not feasible to collect these data in any other way.

Outcomes

Outcome measure selection

The outcome measures selected were used to quantify the following key components of the intervention: mental well-being and mood, building relationships, a sense of connectedness, belief that life is meaningful despite a diagnosis of dementia, instrumental activities of daily living and strategies to maintain cognitive functioning. They also support analysis of the participating supporters’ perceptions of competence of caring for the person with dementia. Dementia-specific outcome measures were selected based on recommendations for research across Europe. 49 When there were no appropriate dementia-specific measures available, measures for the general population were used.

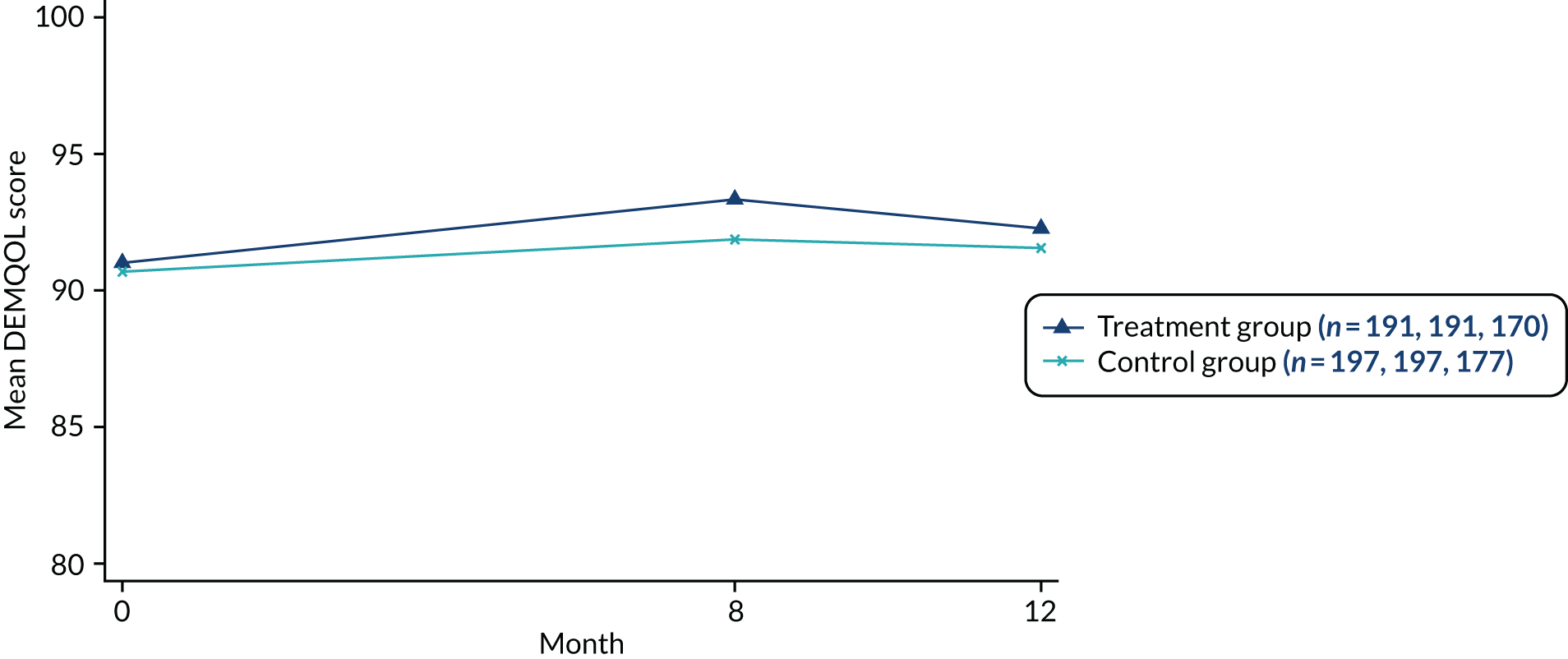

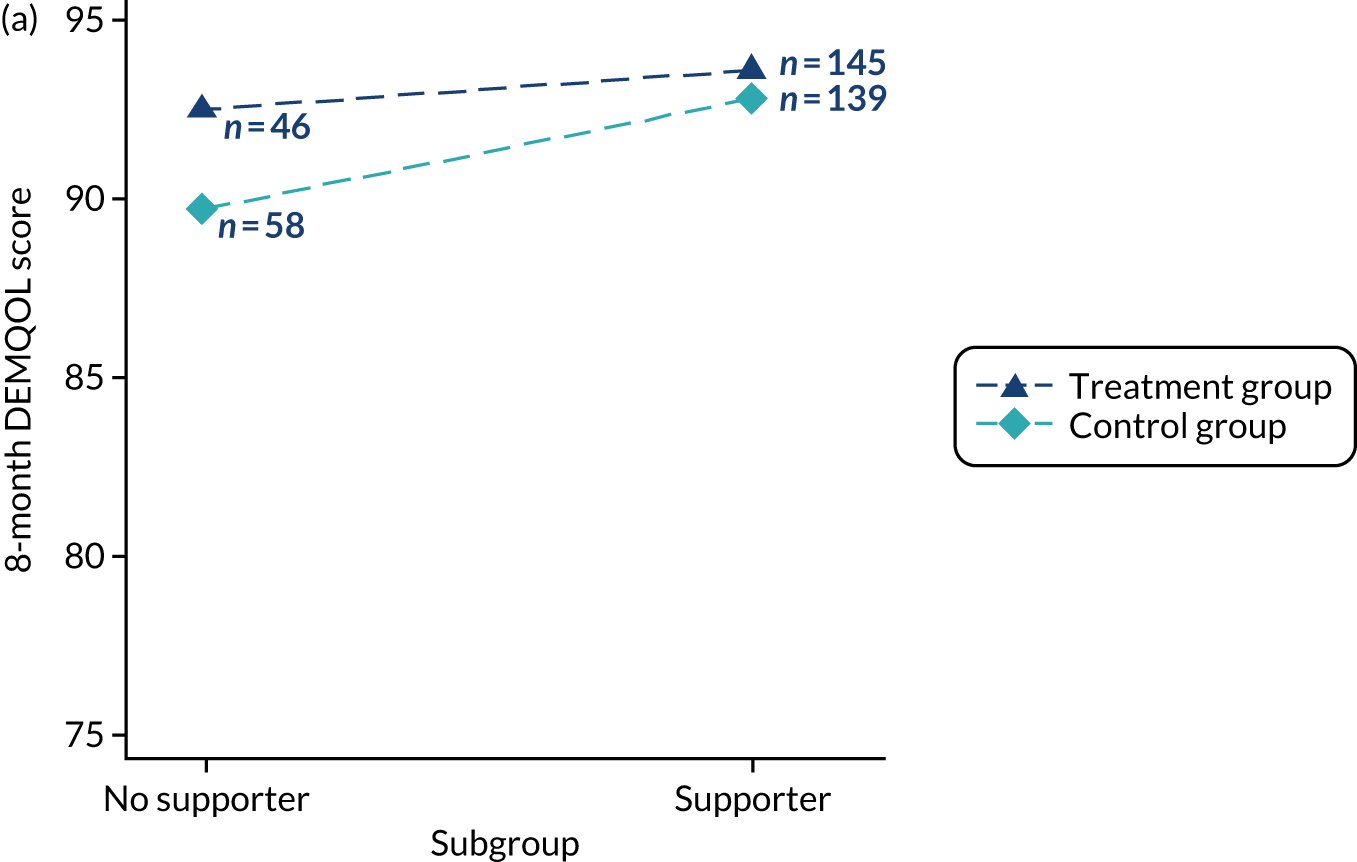

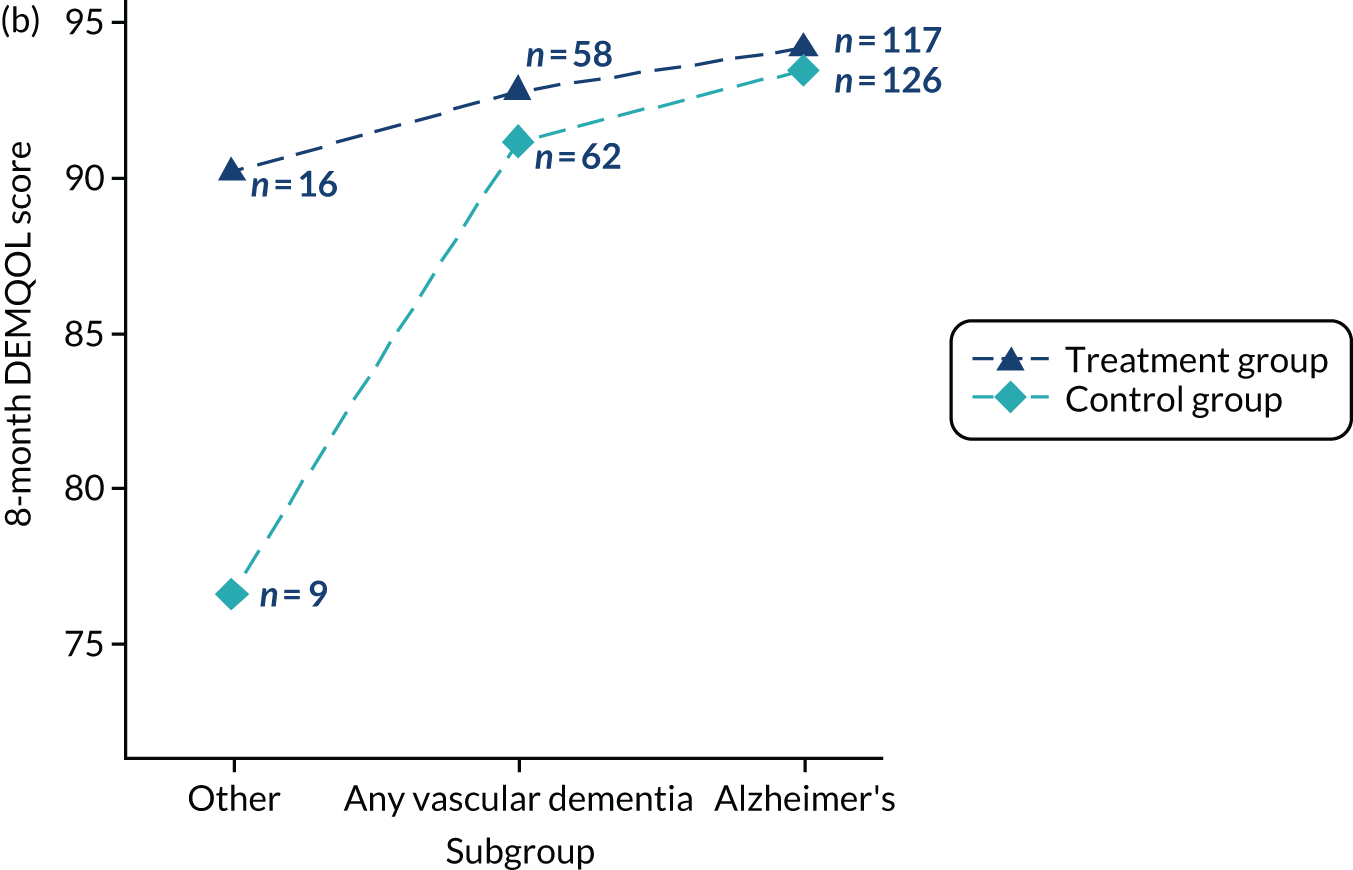

Primary outcome measure

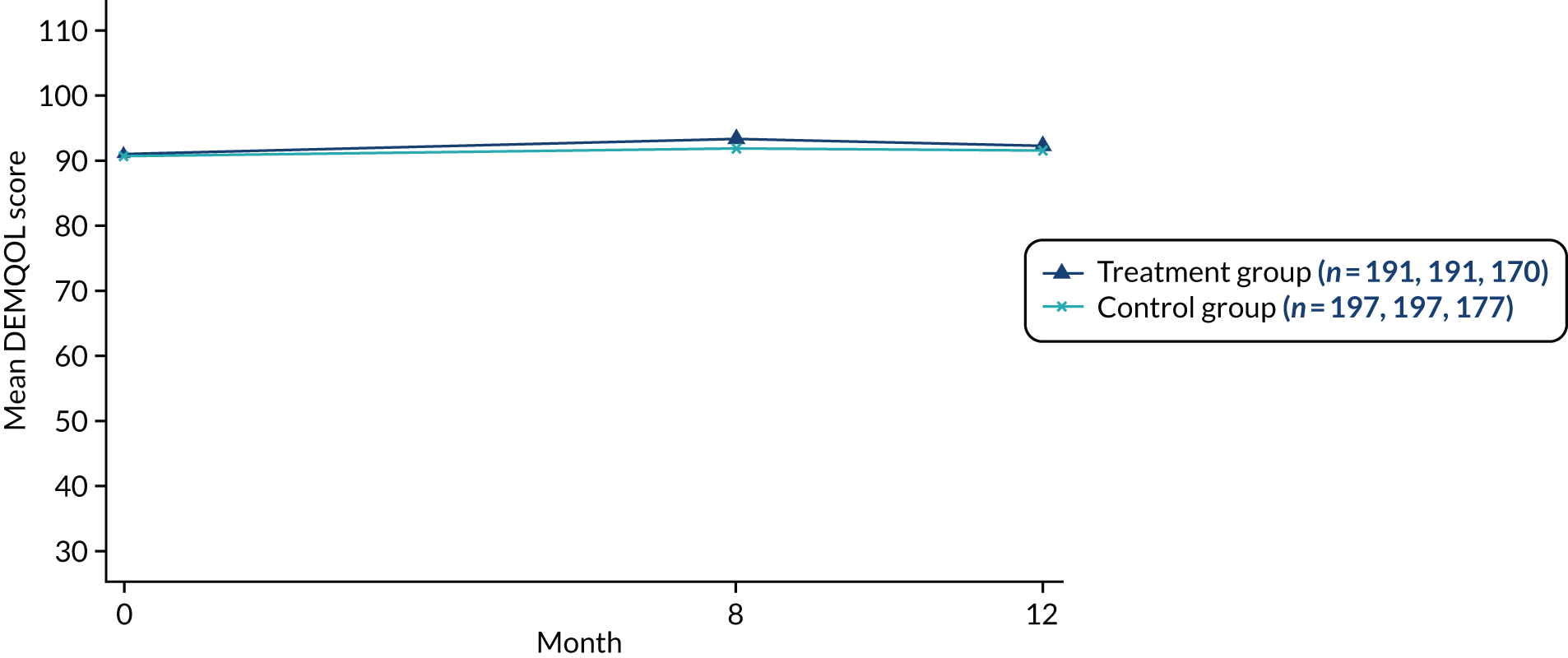

Health-related quality of life of the person with dementia at 8 months post randomisation, measured using the DEMQOL measure,50,51 was the primary outcome. The DEMQOL measure contains 28 items and covers 5 domains: (1) daily activities and looking after yourself, (2) health and well-being, (3) cognitive functioning, (4) social relationships and (5) self-concept. It is completed by the person with dementia, with a higher score indicating a better health-related quality of life. Health-related quality of life of the person with dementia at the 12-month follow-up interval, measured using the DEMQOL measure, was a secondary outcome measure. The DEMQOL is measured on a scale from 28 to 112 and higher scores represent higher health-related quality of life.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures for the trial are listed below.

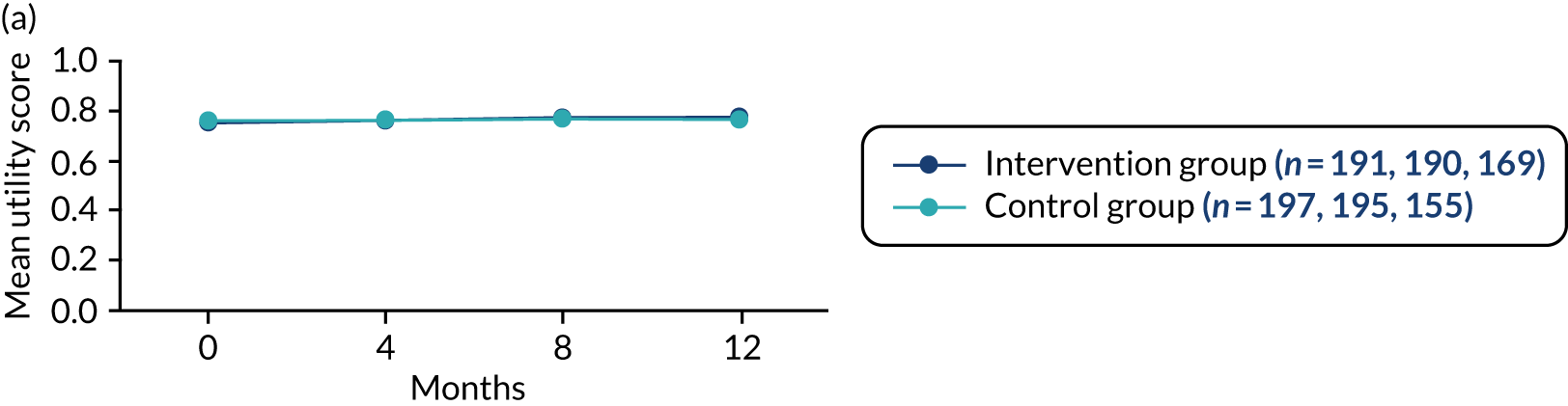

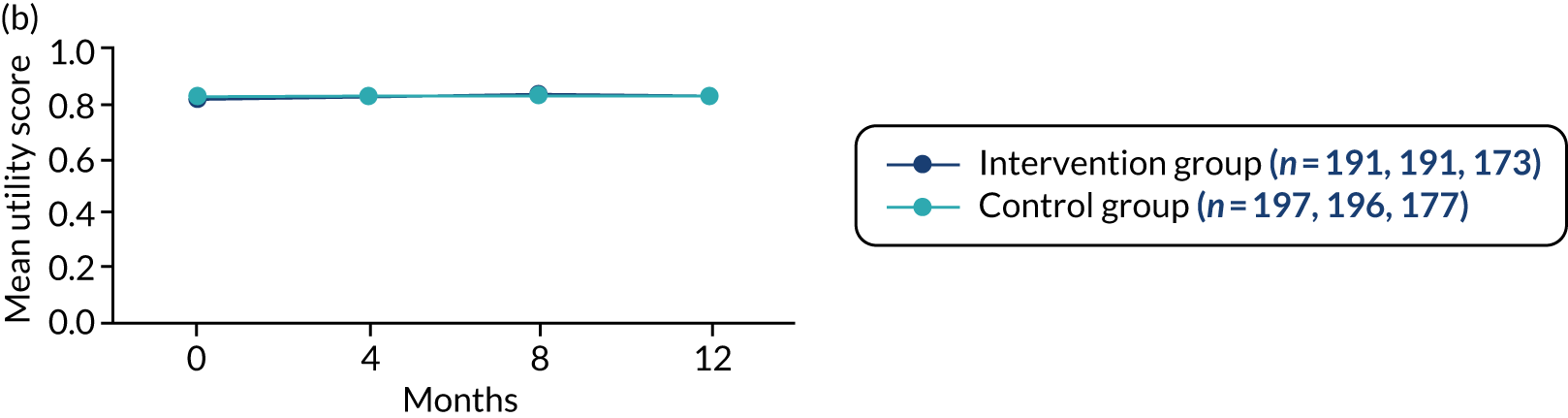

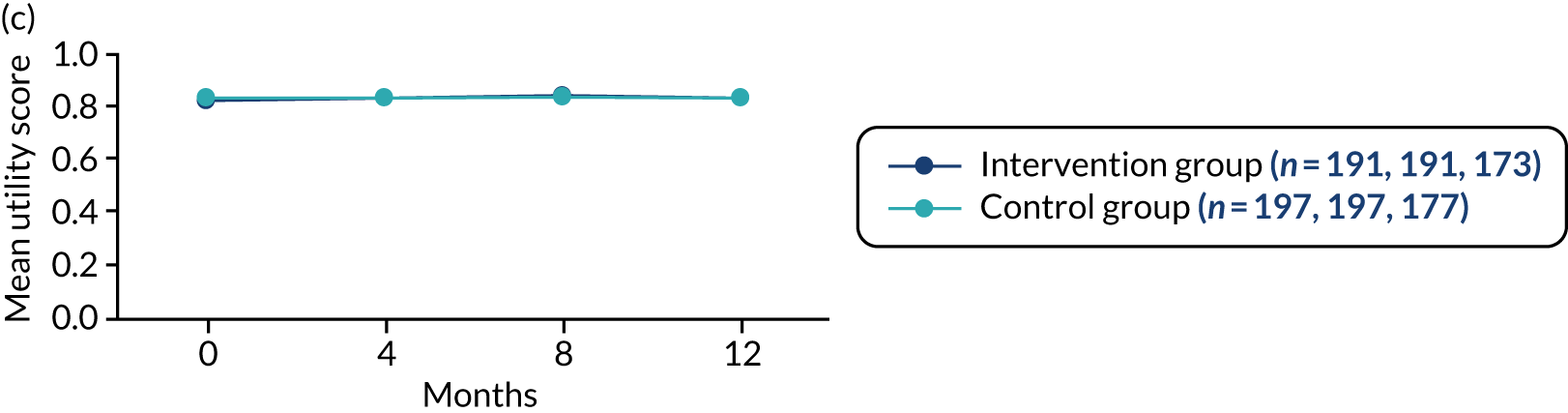

-

Generic health status was assessed for both the person with dementia and any participating supporters using the EQ-5D-5L. 52,53 The measure comprises an assessment of five dimensions of health: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain and discomfort and (5) anxiety and depression. A score closer to 1.00 represents full health. A visual analogue scale (VAS) also rates overall current health, with 0 representing the worst health imaginable and 100 representing the best health imaginable.

-

Depression, assessed for both the person with dementia and their participating supporter, was measured using Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9). 54,55 The PHQ-9 measures the severity of depressive symptoms based on the symptoms of major depressive disorder. A higher score represents more depressive symptoms.

-

Anxiety was assessed for both the person with dementia and their participating supporter using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). 56 The GAD-7 comprises seven items and assesses the severity of the symptoms of anxiety based on recognised symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder. A higher score indicates greater levels of anxiety.

-

The person with dementia’s perceived ability to feel self-efficient and manage day-to-day challenges was assessed using the 10-item General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE). 57 A higher score on the scale indicates greater self-efficacy.

-

The perception of a positive state of well-being of the person with dementia was measured using Diener’s Flourishing Scale (DFS). 58 This eight-item scale assesses key aspects of positive social and psychological functioning. A higher score corresponds to a more positive state of well-being.

-

The person with dementia’s perceived ability to self-manage was measured using the Self-Management Ability Scale (SMAS). 59 The SMAS is a 30-item scale for ageing individuals, measuring central cognitive and behavioural abilities that are presumed to contribute to successful self-management of ageing. Higher scores correspond to higher levels of ability to self-manage.

-

The functional ability of the person with dementia was measured using the IADL. 60 The IADL assesses functional ability in eight domains of complex activity by the selection of statements of capability. A higher score represents better functional ability and greater independence.

-

Health and social care resource use of the person with dementia was measured using a bespoke measure, the HSCRU. 61 The HSCRU records four key areas of resource use: (1) hospital episodes, (2) use of community health resources, (3) use of day services and (4) medication use. Hospital episode records details of attendance at accident and emergency departments, inpatient admissions, outpatient clinics and hospital transport use. Use of community health resources records the use of a wide range of health and social care provision, including frequency and location of use and who provides the service. Day service use includes name, location and provider of the service, and the frequency of use. Medication use information includes dosage, frequency and duration of use of memory enhancers, medication for mood, pain relief and hypnotics. The information gathered in the HSCRU supports the cost-effectiveness evaluation of the intervention.

-

Satisfaction of the supporter with their perceived competence in providing care to the person with dementia was measured by the SCQ. 62,63 The SCQ is a 27-item scale with three domains: (1) satisfaction with the care recipient, (2) satisfaction with one’s own performance and (3) consequences of involvement in care for the personal life of the caregiver. Higher scores indicate a better sense of competence. The SCQ has been shown to have good validity for supporters/carers of those with diagnosed dementia, but insufficient validity in a population of carers of persons with dementia in its early stages. 62,64 However, the SCQ was identified as an appropriate measure based on recommendations for dementia research across Europe, despite these concerns. 49

Scoring and interpretation of outcome measures

The DEMQOL score was calculated by summing the response to the first 28 items when at least half of the items were answered. Any missing items were imputed with the mean of the completed items. 65 The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were scored by summing the responses to items if no more than two items were missing. 66,67 The total SMAS score was calculated by summing responses across the six subdomains (each subdomain was classed as valid if no more than one item was missing and the total score was calculated if all subdomain scores were valid). The GSE was calculated by summing the response to items if at least seven items were complete. 68 The DFS, IADL, MMSE and SCQ were all calculated by summing the responses to the items on each scale, only if all items of the scale were completed. The EQ-5D-5L was scored using the mapping function developed by van Hout et al. 69 and no score was calculated if any item was missing. This was different from our intended scoring prespecified in the statistical analysis plan because of an updated positional statement by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published while the trial was ongoing. 70 For all outcome measures scored with missing items, the missing items were imputed with the mean of completed items for that scale.

Measures taken

The measures taken with both the participants and participating supporters at each of the visits are detailed in Tables 2 and 3.

| Measure | Baseline visit | 8-month follow-up visit | 12-month follow-up visit |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMQOL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| GAD-7 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| GSE | ✓ | ✓ | |

| DFS | ✓ | ✓ | |

| SMAS | ✓ | ✓ | |

| IADL | ✓ | ✓ | |

| HSCRU | ✓ | ✓ |

| Measure | Baseline visit | 8-month follow-up visit | 12-month follow-up visit |

|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| SCQ | ✓ | ✓ |

Sample size

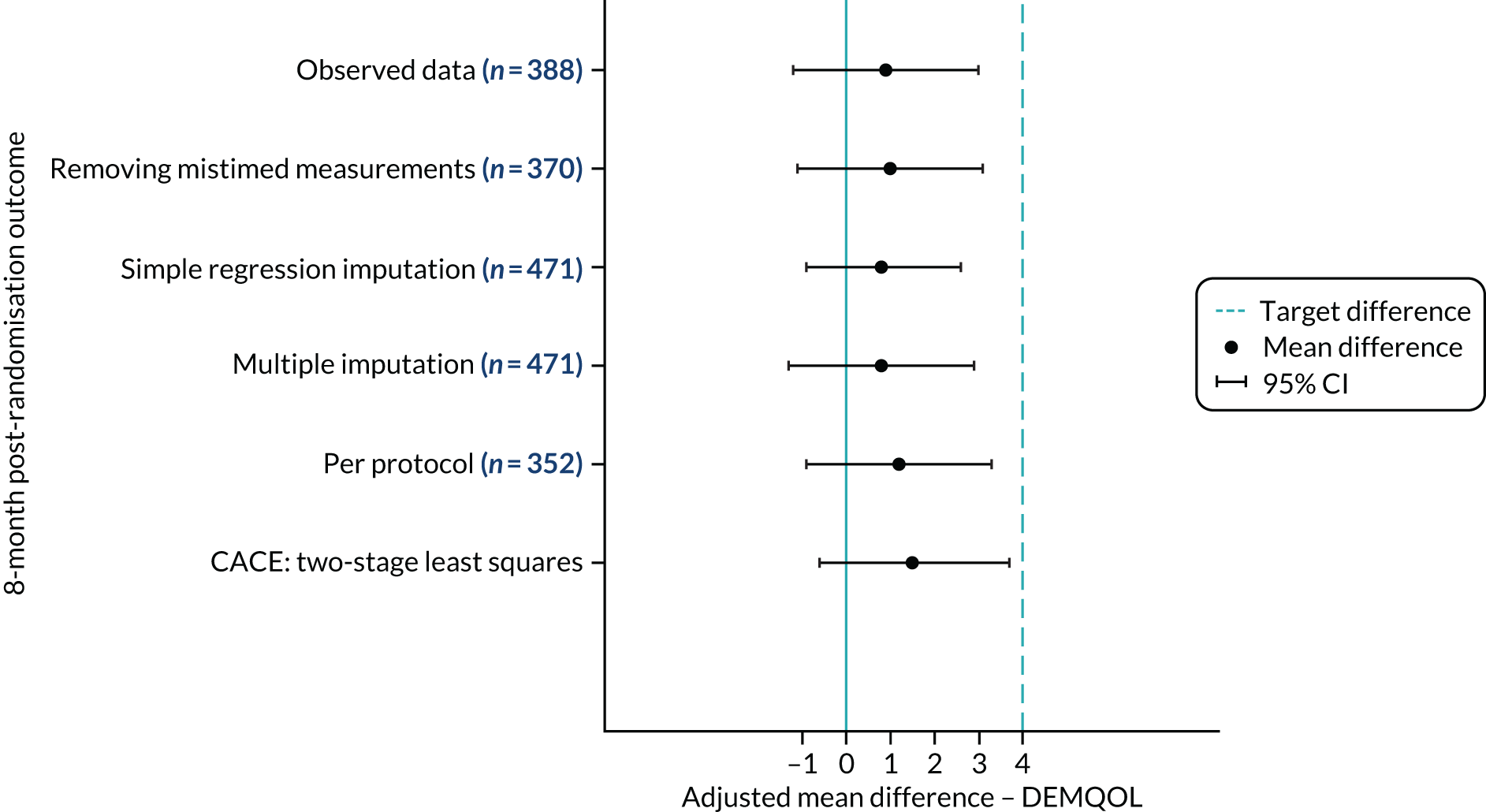

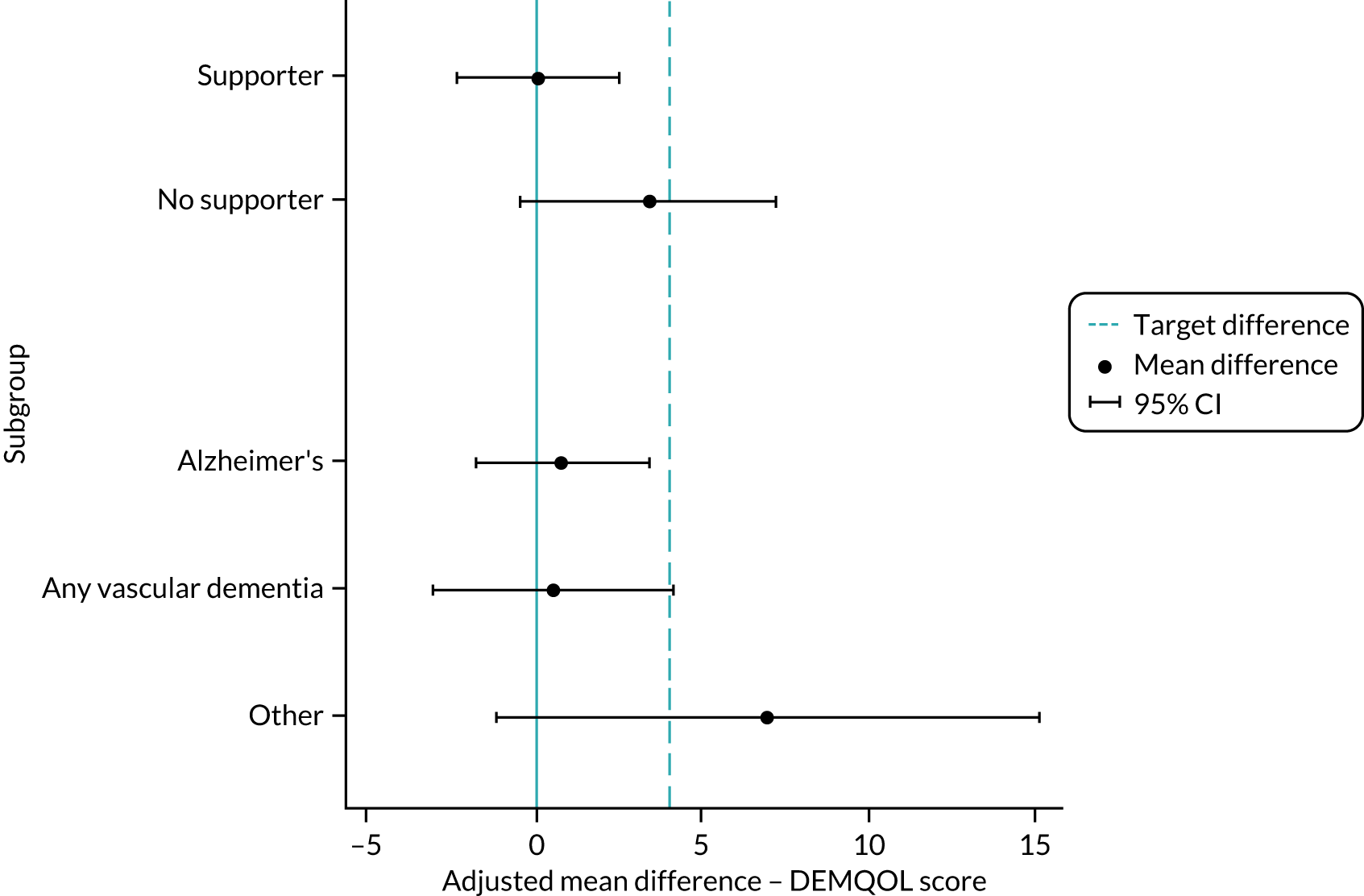

The sample size was calculated assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 11 points and that a difference of ≥ 4 points in mean DEMQOL score 8 months post randomisation was clinically and practically important. 51 The sample size was calculated to have 90% power for detecting this 4-point difference (or more) if it truly exists, which is equivalent to a standardised effect size of 0.36, as statistically significant at the 5% two-sided level. As the JtD intervention was a facilitator-led group intervention, the outcomes of the participants in the same group with the same facilitators may have been clustered. For an individual RCT without adjustment for clustering, the target sample size would be 160 participants per arm (i.e. 320 participants in total). Assuming an average cluster size of eight participants per facilitated group45 and an intracluster correlation of 0.03 this inflated the sample size, by a design effect of 1.21, to 194 participants per group (i.e. 388 participants in total) with valid primary outcome data. We assumed a 20% loss to follow-up and therefore the trial target sample size was to randomise to 243 participants in each arm (i.e. 486 participants in total).

There is no reported or established minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the DEMQOL measure. Data from the development and validation of the preference/utility-based DEMQOL-Utility (DEMQOL-U) score,51 which compared the performance of the DEMQOL (and DEMQOL-U) with other patient-reported outcome measures for people with dementia (e.g. the MMSE,71 the Bristol Activity of Daily Living Scale72 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory)73 with established MCIDs, reported changes on the DEMQOL of 5.4, 7.5 and 6.4 points, respectively, for patients who improved by more than the MCID on the anchor measure. This suggests that our proposed 4-point difference, although small, is likely to be of clinical and practical importance.

Internal pilot trial

The following stop/go criteria were reviewed after 8 months of active recruitment to an internal pilot trial:

-

recruitment of a minimum of 113 participants across the six pilot sites by the end of the fifth month of active recruitment (i.e. 75% of the 150 participant target)

-

recruitment of a minimum of 12 facilitators (i.e. two facilitators identified at each of the six pilot sites by the start of active recruitment to deliver the intervention)

-

no more than two of the six planned groups in the internal pilot with fewer than four participants registered for the group by the sixth month of active recruitment.

The TSC assessed whether or not they could recommend that the trial continue in the light of the feasibility results against the stop/go criteria. The results and recommendations were communicated to the funder [see Chapter 3, Internal pilot (stop/go assessment)].

Method used to generate and assign the random allocation

Randomisation was overseen by the Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU), using a computerised randomisation sequence generated before the start of recruitment. An unblinded member of the research team who did not conduct any outcome assessments entered the participants’ details into the remote web-based randomisation system. Participants were then randomly allocated to receive either the intervention or usual care. Owing to the group-based intervention, participants were randomised after the baseline outcome measures had been collected, which ideally occurred < 2 months before the intervention wave began at each site. In instances when a couple living in the same household both consented, they were randomised as a couple rather than individually. Participating supporters were allocated to the same group as the linked participant.

The participants and, if relevant, their participating supporters were informed of their allocation by letter. Participants allocated to the intervention were told that an intervention facilitator would contact them to discuss the next steps of the trial.

Following allocation of a participant to the intervention group, an unblinded member of the research team informed the appropriate intervention facilitators so that they could contact participants to arrange intervention delivery.

Type of randomisation and details of any restriction

Participants were randomised 1 : 1 to receive either the JtD intervention or usual care. The computer-generated randomisation was stratified by a stratification site and restricted by a fixed block of size 4. The stratification site was either the recruiting site or the group delivery site if the recruiting site was delivering more than one group simultaneously in different locations. The JtD intervention had 16 stratification sites across 13 recruiting sites. A fixed block size was used to ensure that the imbalance between treatment groups at each delivery site was controlled and minimal. Two intervention groups were planned at each site and a maximum number of 13 participants were allowed in each intervention group. The risk of predicting the allocation was deemed minimal, as it was performed by central unblinded members of the trial team and members of the trial team responsible for recruiting participants at site were blinded to treatment allocation.

Blinding and methods used to control bias

Blinding in the context of research studies refers to the concealment from individuals involved in a clinical trial of the allocation to an intervention or control group of participants in the trial. It is used to minimise or prevent differential treatment or outcome assessment of groups in the trial and reduce bias. 74 The trial was single blind as participants were aware of their allocation to either the JtD intervention group or the usual-care control group. Outcome assessments were completed by assessors who were blind to group allocation. The sections below on allocation concealment, blinding and other methods provide further information on the study’s approach to reducing bias.

Allocation concealment mechanism

Allocation concealment was maintained by using a centralised web-based randomisation service. A member of the trial team, unblinded to treatment allocation, informed participants of their allocation. Participants were not blinded to their allocation because of the nature of the intervention; however, they were advised that the outcome assessors were blinded to their allocation. If outcome assessors suspected that they had been unblinded, this was recorded in the case report form (CRF) and reported to the trial oversight committees.

Blinding

Outcome assessment

Most research sites nominated an unblinded researcher to facilitate communication with the central study team regarding the allocation of participants to the intervention. Baseline measures were completed prior to the randomisation of participants and so were completed by both blinded and unblinded researchers. Subsequent allocation to the intervention or control group was communicated to participants and group facilitators by an unblinded researcher, or by the central study team when there was no unblinded researcher at a site. Eight- and 12-month outcome measures were completed by blinded researchers. Facilitators of the intervention were not involved in outcome assessment.

When blinded research staff became unintentionally unblinded (e.g. a participant unintentionally disclosed their study arm during a visit) this was recorded on a paper unblinding form and then entered onto the research database by an unblinded researcher. The unblinding form recorded information from the assessors regarding whether they were sure or unsure that they had been unblinded, and to which arm of the trial they suspected the participant was allocated. Paper records of instances of unblinding were stored in a separate location to the CRFs to prevent blinded researchers viewing this information. To prevent unblinding, the study database was designed such that researchers were unable to view unblinding forms for sites at which they were blind.

During the trial, a system was implemented so that a person who was not conducting the outcome measures visit would make the telephone call to arrange the visit to lessen the chance of unblinding. A telephone script was used during the telephone call. The script asked the participant and supporter not to tell the outcome assessor what treatment they did or did not receive during the visit. The visit confirmation letter also reaffirmed the requisite not to disclose information about treatment to the outcome assessor. If unblinding occurred prior to assessment, for instance on the telephone while arranging an assessment visit, another blinded researcher would conduct the assessment. If unblinding occurred during an outcome visit, the visit continued; however, future assessments were conducted by a different blind assessor.

Data analysis

The trial statistician and the health economist were blinded during the intervention delivery and outcome assessment, but not blinded for the main analysis. The TSC was blinded throughout the study.

Methods used to control bias

The study used methods to protect against both facilitator bias and the risk of cross-contamination between the two study arms. Facilitator bias is when the same facilitators might also provide any interventions in the usual-care arm. Two approaches were used to address this. First, usual care (see Chapter 3, Usual care) is limited and most often restricted to NICE-recommended cognitive stimulation therapy (CST), which would not be readily influenced by training in delivery of the JtD intervention. CST follows a detailed and prescriptive session-by-session plan of group exercises and activities that are facilitator led and take place wholly within the delivery setting. In the JtD trial sites, other post-diagnostic services offered included Living Well with Dementia groups (three sites) and memory groups (two sites); however, these were not common. Living Well with Dementia groups vary in content, but may have contained some similar material to the JtD intervention. However, they do not include enactment of learnt skills in the community or the mix of individual and group sessions that the JtD intervention incorporates. Additionally, analysis indicates that at 8 months only one JtD trial participant was attending an NHS-run Living Well with Dementia group, indicating that these are rare (see Chapter 3, Usual care). Second, a proportion of the facilitators recruited were not those who would deliver usual care (e.g. approximately 25% of facilitators were trained research staff).

Cross-contamination could also occur between the two study arms, when, for example, participants in the intervention arm meet those in the control arm by attending memory clinics and discuss the intervention. As post-diagnostic services for people living with dementia are currently limited and often only involve CST, which is more likely to be offered later in the dementia trajectory, it is unlikely that participants met at these courses. Extended post-diagnostic follow-up is not common and so it is unlikely that participants from different arms of the study would meet up and discuss their involvement in the study during routine appointments.

Analysis populations

The ITT data set includes all participants who consented and were randomised according to randomised treatment assignments (ignoring any occurrences post randomisation, such as protocol or treatment non-compliance and withdrawals) and who had complete DEMQOL data at 8 months post randomisation. This excludes participants who withdrew before randomisation and includes participants found to be ineligible post randomisation. 75

The complier-average causal effect (CACE) data set is a subset of the ITT set. It included a subgroup of participants who were believed to comply with the JtD intervention (i.e. attending at least 10 of 16 sessions), excluded ineligible participants randomised in error and included participants who were randomised to usual care but received and complied with the JtD intervention.

The analysis population for participating supporters included participating supporters who met eligibility criteria, provided informed consent and provided follow-up data.

Statistical analysis

General considerations

All statistical analyses were performed in Stata® v15 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The usual-care arm was the reference group for all analyses. A comprehensive statistical analysis plan was developed while the statistician was blinded to treatment allocation. Data were reported and presented in accordance with the revised Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. 76 All statistical tests were two tailed at a 5% significance level and confidence intervals (CIs) were two sided, with 95% intervals. No adjustment was made for multiple testing.

Data completeness

A CONSORT flow diagram was used to display data completeness and participant throughput from first contact to final follow-up.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics, medical history and quality-of-life data for the participants were summarised and assessed for comparability between the intervention and control groups. No statistical significance testing was carried out to test imbalances between the treatment groups, but any noted differences were reported descriptively.

Primary effectiveness analysis

The mean DEMQOL total score at 8 months post randomisation was compared between participants in the JtD intervention group and participants in the usual-care group using a mixed-effects linear regression model adjusted for DEMQOL baseline total score and stratification site (fixed effect) and allowing for the clustering of the outcome by the JtD intervention groups (random effect). 77–79 A partially clustered mixed-effects linear regression model with homoscedastic errors was used to model clustering in the intervention arm. Degrees of freedom were computed using the Satterthwaite approximation. 80

Sensitivity analyses on primary outcome