Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/111/01. The contractual start date was in May 2017. The draft report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in September 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Taylor et al. This work was produced by Taylor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Taylor et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Smoking is the main cause of premature death and preventable morbidity in high-income nations. 1 In England, the broader annual cost to society of smoking is about £11B, including £2.5B to the NHS in England. 2 The smoking prevalence rate among the UK population has reduced to 14.7%,3 but proportions vary widely by socioeconomic and mental health status, which contributes to growing health inequalities.

According to the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Public Health No. 10 guidelines for smoking cessation,4 smokers are recommended to focus on identifying a quit date and abrupt cessation, using pharmacological and motivational support as appropriate. For those not immediately intending to quit or not wanting to quit, the limited evidence suggests that smoking reduction may lead to a greater likelihood of quitting and subsequent successful abstinence. 5–8 A wide range of approaches to reduction, such as using pharmacological and behavioural support and self-initiated approaches, have been suggested. Motivational support appears to have the potential to reduce smoking, and the more that is provided, the greater the likelihood of successful quitting. 9

Smoking reduction studies fall into two types: (1) those involving smokers who want to quit but are willing to reduce first rather than quit abruptly (see Lindson et al. 6 for a review) and (2) those involving smokers who do not want to quit (immediately) but are interested in smoking reduction or harm reduction (see Lindson-Hawley et al. 7 for a review). None of the studies included in these reviews explicitly involved an intervention to promote physical activity (PA) as part of the behavioural support. Most of the ‘motivational-phase intervention’ studies included in the latter review, which involved the administration of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in one form or another, and, to a lesser extent, vaping or a pharmacological aid, provided imprecise evidence of effects on smoking cessation or reduction because of limitations in trial methods. Only two studies (deemed to be of low quality) investigated the effects of behavioural support or advice; these also provided imprecise evidence of effects on smoking cessation or reduction. 10,11 Since then, the findings have been published from two US trials involving smokers not motivated to quit. In one, with 560 participants, there was some evidence that three sessions of two different forms of behavioural support (delivered over 4 weeks), compared with usual care, increased quit attempts and 12-month non-carbon monoxide (CO)-verified abstinence. 12 There was some evidence that changes in targeted constructs mediated the intervention effects on specific outcomes. 13 In the other study, with 255 participants, there was some evidence that four sessions of health education [and, less strongly, motivational interviewing (MI)] support increased smoking abstinence at 6 months. 14 Neither of these studies involved the promotion of PA as a way to manage smoking behaviour.

Data from the English Smoking Toolkit Study (2011–14) suggest that 50% of smokers are interested in smoking reduction and approximately 30% of UK smokers reported using e-cigarettes to achieve this. 15 With concerns about the safety of e-cigarettes and the unwillingness of some smokers to use them, there is a need for other evidence-based approaches to self-regulate smoking. 16

Physical activity as an aid for smoking cessation and reduction

There is considerable interest among smokers in using PA to manage smoking acutely and chronically,17,18 with acute moderate-intensity exercise being as efficacious as vigorous exercise. 19–21 However, a systematic review revealed that only one of 24 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving smokers attempting to quit showed that an exercise programme can increase abstinence for at least 6 months, relative to a passive control condition. 22 However, most studies were of low quality and focused on efficacy, rather than being pragmatic and offering an acceptable and feasible intervention for smokers wanting to quit more generally.

The logic behind PA being helpful for managing smoking involves both implicit and explicit processes. 17 For example, a smoker could focus on being physically active with associated emotional benefits, which may reduce cognitive and emotional triggers for smoking implicitly. Explicitly, exercise can acutely manage cigarette cravings and withdrawal symptoms,19,20 and chronically manage weight gain following changes in smoking or nudge smokers towards a healthier identity. 23

Prospective population surveys and trials show that weight gain and fear of weight gain can create a reluctance to quit smoking and remain abstinent; this may be especially true among women and initially heavier smokers. 24–26 A meta-analysis study reported an average gain of 4.67 kg [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.96 to 5.38 kg] after 12 months of abstinence. 27 Among a range of options for preventing long-term weight gain after smoking cessation, PA appears to be one of the most promising,28 by increasing energy expenditure and metabolic rate, and also by self-regulation of energy intake, particularly emotional snacking. 29

The potential for the TARS intervention

In a unique randomised pilot trial, Exercise Assisted Reduction then Stop (EARS), there was encouraging support for the short-term effects of a behavioural intervention for increasing PA and smoking reduction on number of cigarettes smoked and abstinence. 23,30 Previous studies13,14,31 have reported that health education, motivational support targeting perceived confidence and self-regulation to manage smoking can facilitate long-term smoking abstinence, and a mix of these approaches was embedded in the pilot intervention. In the EARS pilot trial,23,30 intervention participants had an average of 4.2 sessions, by telephone or face to face, with a health trainer (HT), with a range of 0 to 8 sessions. Compared with the control group, intervention participants were significantly more likely to reduce smoking by at least 50% (39% vs. 20%), to attempt to quit (22% vs. 6%), and to have CO-verified abstinence at 4 weeks (and up to 8 weeks) after their quit day (14% vs. 4%) and at 16 weeks (10% vs. 4%). More participants in the intervention group reported using PA for controlling smoking: 55% versus 22%, and 37% versus 16%, at 8 and 16 weeks, respectively. 23 A health economic analysis estimated that the intervention cost was approximately £192 per participant and preliminary cost-effectiveness modelling indicated that the intervention is cost-effective. 23

Following the encouraging EARS pilot trial,23 the Trial of physical Activity-assisted Reduction of Smoking (TARS) sought to establish the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of behavioural support for increasing PA and reducing smoking on longer-term abstinence among smokers not immediately ready to quit.

Developing the TARS intervention

Following the work conducted in the EARS pilot trial, we refined the intervention to ensure that it addressed several issues raised in the process evaluation and that it was fully manualised for transparency and to be operational to guide HT training, supervision and intervention delivery across multiple sites. The intervention components and content and the delivery details have been described elsewhere. 32 Adaptations from the EARS pilot trial intervention included the following: (1) accommodating participants who were using or wanted to use vaping to manage smoking and align with guidance and practice in usual care; (2) improving the focus in the training and supervision of HTs on encouraging participants to manage social influence to increase PA and reduce smoking, which appeared to be the least evident HT competency;33 and (3) improving the focus in the training and supervision of HTs on promoting PA as well as smoking reduction (and quitting), which was also identified in an analysis of HT competencies. Additional patient and public involvement (PPI) work was conducted to assess smokers’ views of the intervention and opportunities for further refinement prior to finalising the intervention manual.

The intervention training manual was used to guide training and supervision of eight HTs across four sites. A group training session was held over 3 days for all HTs and their line managers at the University of Plymouth, the University of Oxford, the University of Nottingham and St George’s, University of London. The process evaluation involved a qualitative analysis of interviews with each HT after training to identify gaps in understanding of the intervention and scope for ongoing supervision. All HTs remained in post throughout the intervention delivery phase of the trial. Further interviews took place with all the HTs after they had had an opportunity to rehearse and deliver the early intervention sessions. Supervision sessions led by Tom P Thompson occurred less frequently as the HTs became more familiar with their role and operating procedures.

The trial was managed by the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU), but a secure parallel bespoke online programme was also developed to manage the flow of intervention participants and their engagement with the HTs. This allowed Tom P Thompson to manage the HT resource (i.e. assign intervention participants to particular HTs at each site, subject to availability) and also view a live record of the number of sessions with intervention participants and HT notes of sessions to facilitate remote supervision.

Aims and objectives

The overarching aim of the TARS was to establish if an individually tailored behavioural intervention for smokers wanting to reduce but not immediately quit provided an effective and cost-effective approach to supporting increases in PA, smoking reduction, number of quit attempts and subsequent prolonged smoking abstinence.

The specific aims of the trial were to establish if the intervention, compared with support as usual (SAU), would:

-

increase the proportion of participants achieving CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence at 9 months post baseline

-

increase the proportion of participants reporting a ≥ 50% reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked (between baseline and 3 months, and baseline and 9 months)

-

increase the proportion of participants achieving CO-verified 12-month floating prolonged abstinence at 15 months post baseline

-

increase self-reported PA at 3 and 9 months post baseline, and accelerometer-assessed PA at 3 months post baseline

-

improve body mass index (BMI), quality of life, sleep, cigarette cravings and other beliefs about smoking and PA at 3 and 9 months post baseline.

Further aims were as follows:

-

to estimate the intervention, health-care and social care costs, compared with SAU, at 9 months post baseline and determine the cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared with SAU (1) at 9 months and (2) over a longer-term/lifetime horizon

-

to conduct an embedded mixed-methods process evaluation to explore the mechanisms of action of the intervention and acceptability of trial processes.

Chapter 2 Methods

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from the study protocol, by Taylor et al. 32 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design

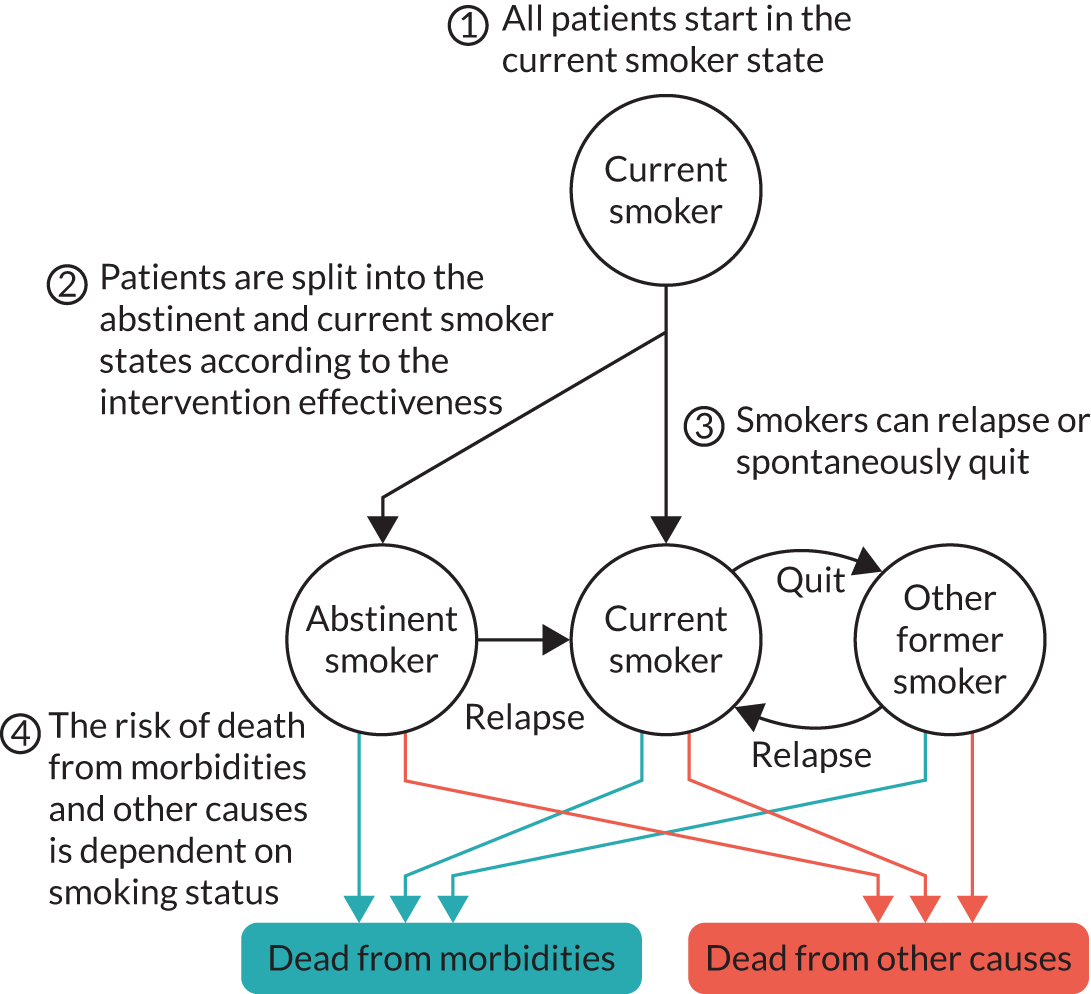

The TARS was a multicentred, pragmatic, two-group, parallel, randomised controlled superiority clinical trial. It compared the effects of (1) tailored support to reduce smoking and increase PA with (2) brief advice to reduce or quit smoking on CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence and other smoking and PA outcomes. The trial included a mixed-methods embedded process evaluation and economic analysis. The trial design is summarised in Figure 1, from Taylor et al. 32

FIGURE 1.

Participant pathway. Reproduced from Taylor et al. 32 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Recruitment to the trial took place over 16 months (January 2018 to May 2019). Follow-up measures were conducted at 3, 9 and 15 months post baseline. The 15-month assessment was conducted only with those participants who were CO-verified quitters at 9 months.

Ethics approval and research governance

The trial was approved by the South West – Central Bristol Research Ethics Committee (reference number 17/SW/0223) and the Health Research Authority. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number register (reference number ISRCTN47776579) prior to commencement.

Patient and public involvement

A group of current and former smokers was convened at an early stage to act as PPI representatives for the trial. The group reviewed the proposed methods, the intervention and any implications for this trial of the use of e-cigarettes and NRT. Views differed on the merits of e-cigarettes and NRT to reduce smoking, and how various forms of PA may help; this was explored further in the set-up phase of the trial. A PPI representative contributed to the trial via their membership of the TARS Project Management Group and Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Prior to and during intervention development and implementation, the trial team also engaged with key stakeholders involved in commissioning and delivering research-type community interventions outside stop smoking services, to assess where the proposed intervention would best fit and its perceived value.

Patient and public involvement representatives provided valuable input into the training of HTs across each site and built on substantial experience gained during the EARS pilot trial. Notably, HTs rehearsed with PPI smokers how best to approach some of the intervention components that had been less well delivered in the EARS pilot trial, such as self-regulation of PA alongside smoking, integrating the concepts of PA and smoking, and working on social influence on the two behaviours.

Participants and settings

Adult smokers wanting to reduce the amount they smoke, but with no immediate plans to quit smoking, were recruited from general practices, secondary care and community settings around four collaborating university sites in the UK: Nottingham, Oxford, Plymouth, and St George’s, University of London (South London).

Inclusion criteria

-

Adult smokers wanting to reduce but not quit smoking in the next month.

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Smoke ≥ 10 cigarettes per day for at least 1 year. This was irrespective of use of other nicotine-containing products, for example e-cigarettes and/or NRT products.

-

Able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

Unable to engage in at least 15 minutes of moderate-intensity PA (as judged by the potential participant).

-

Any illness or injury that might be exacerbated by exercise.

-

Unable to engage in the trial and/or the intervention because of a language barrier or for other reasons (e.g. if the person presents an unacceptable level of risk to the HT or research team members).

Participant identification and approach

The participant pathway is summarised in Figure 1.

A range of methods were employed to identify and approach potential participants, to ensure that the trial was as inclusive as possible:

-

An electronic record search using either EMIS Health (EMIS Health, Leeds, UK) or SystmOne (The Phoenix Partnership Ltd, Leeds, UK) at participating NHS general practices, and, in Plymouth, an electronic record search of stop smoking services records followed by an invitation sent by the general practice.

-

Opportunistically by NHS primary care practitioners, NHS secondary health-care practitioners, NHS Stop Smoking Services, community-based routes (including pharmacies, dental practices, local businesses, adverts in the local media and via social media). Potential participants were then invited to contact the local researcher for further details about the trial.

The strategy used to approach potential participants via general practices was informed by the findings of a study within a trial (SWAT) conducted in the early phase of recruitment to the TARS;34,35 see Report Supplementary Material 1 for details. In brief, the efficiency and value for money of three different invitation methods were compared. These methods were as follows: (1) a full postal information pack sent to potential participants via Docmail® (CFH Docmail Ltd, Radstock, UK) (the commercial communication service embedded in the general practice), (2) a single-page postal invitation via Docmail and (3) a text message sent from the general practice. Despite being the most expensive invitation method, the full postal information pack was the most efficient recruitment method; hence, this was predominantly used by general practices thereafter.

Non-responders to the invitation sent by the general practice were initially contacted by the local researcher, either by post (postcard or letter) or via e-mail, telephone call or text message, and (when possible) subsequently telephoned by a member of the general practice staff, so as not to disadvantage those with low literacy levels.

Screening and informed consent

On receipt of an expression of interest, received by post, e-mail, text message or telephone, the local researcher contacted the potential participant by telephone to discuss the trial and assess eligibility. At this point, the trial-specific participant information sheet was provided (by post or e-mail) to those who had not already received this (e.g. those self-referring via the community-based routes). Subsequently, the local researcher confirmed eligibility and sought informed consent from eligible and willing individuals, verbally (in person or by telephone), and a copy of the completed consent form was then posted to the participant and saved in the PenCTU’s participant records. All ineligible participants were advised to seek smoking reduction advice in line with local usual practice.

Intervention

The intervention was initially designed and evaluated for the EARS pilot trial. 23 There was acceptable training and delivery fidelity for the three HTs involved, and acceptable intervention engagement. There were some signals of effectiveness. The need to make some small adaptations was identified and incorporated into the HT manual,36 and into the training and supervision of eight HTs who delivered the intervention across four sites.

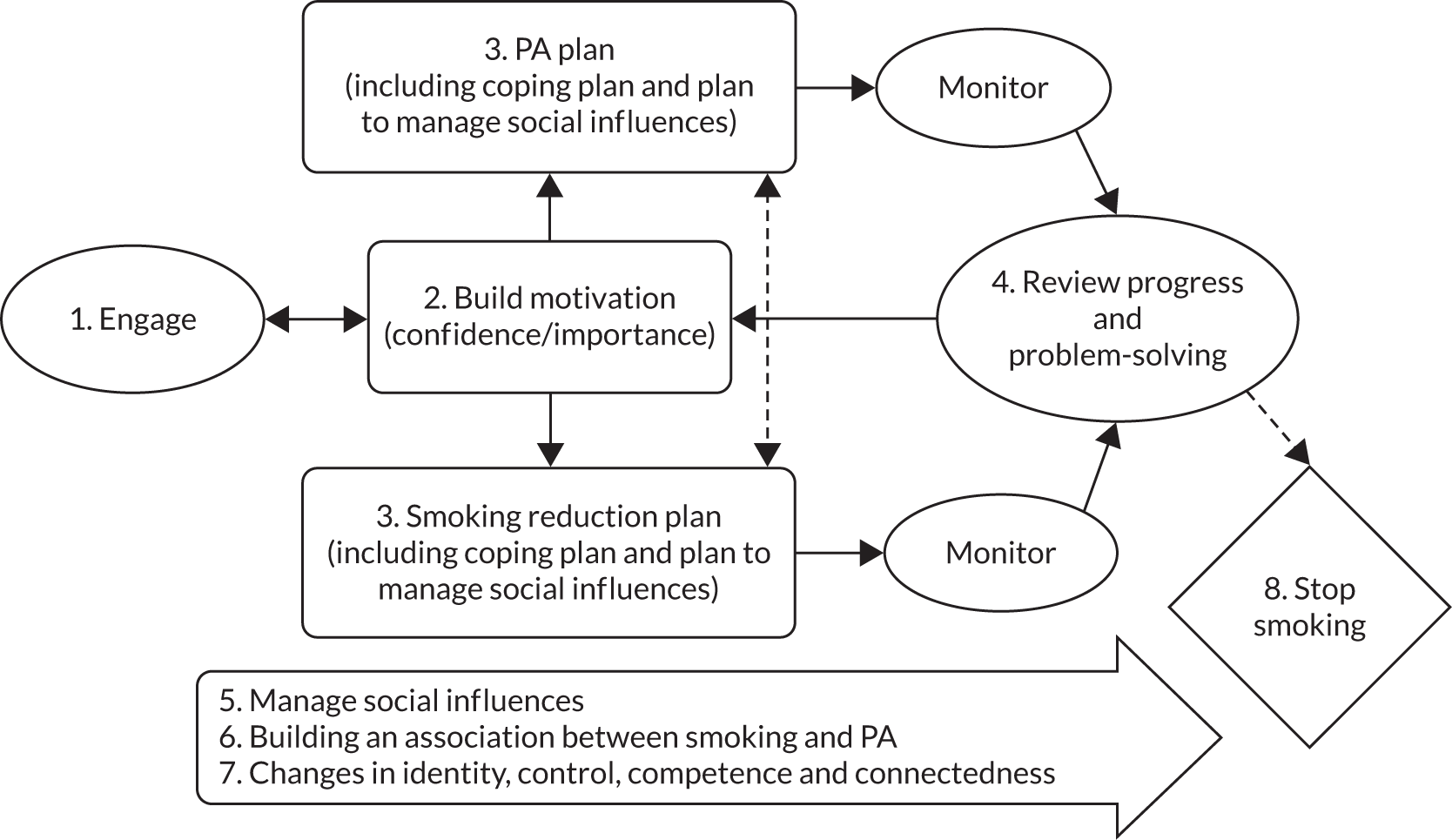

The intervention is described in detail elsewhere. 32 Briefly, participants in the intervention arm were offered individually tailored behavioural support from a HT in up to eight weekly sessions, the goal being to build a participant’s motivation and confidence to reduce smoking and increase PA, and possibly to make a quit attempt. An additional six weekly sessions were offered to those participants who wanted support after quitting smoking. The intervention was based on self-determination theory37 and the use of evidence-based health behaviour change techniques. Self-determination theory helps to link the basic human need to feel competent, autonomous and in control with motives that drive human behaviour. The TARS intervention aimed to enhance participants’ sense of competence, control and connectedness related to reducing smoking and increasing PA. The content had some overlap with interventions included in similar studies with a focus on smoking reduction for those smokers not wanting to immediately quit. 9–11,14 The components of the intervention are summarised in Appendix 1 and were used to assess delivery fidelity in the EARS pilot trial. 33

Support as usual

Following randomisation, all participants (intervention and SAU arms) received standardised written guidance on smoking reduction and cessation from the local researcher, with signposting to the support offered at local level (see Appendix 2). In the absence of formal programmes for use of e-cigarettes or licensed nicotine-containing products (LNCPs) to support reduction, for participants not wanting to immediately quit, participants in both arms purchased their own NRT or e-cigarette product.

Randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding

Following completion of baseline measures, participants were randomised by a member of the PenCTU by means of a web-based system created by the PenCTU in conjunction with a statistician independent of the trial team (ensuring allocation concealment from the research staff).

Participants were individually randomised to either the intervention or the control group (1 : 1 ratio) using random permuted blocks, with stratification by recruitment site and the two-item Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI). 38 For the purposes of stratification, HSI total scores were categorised as 0–4 (low) or 5 and 6 (high).

It was not possible to blind participants to their allocated group. Every effort was made to ensure that the local researchers conducting follow-up assessments remained blind to a participant’s allocation. Participant self-report questionnaire booklets and accelerometers were posted out from, and returned to, the PenCTU without knowledge of the trial arm allocation. However, it was possible that participants disclosed the nature of any support received to reduce smoking during contact with the researcher. In accordance with the statistical analysis plan (SAP), primary analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes was undertaken by the trial statisticians blinded to allocation group, after the 9-month follow-up. Analyses that necessitated unblinding (i.e. repeats of the primary analysis allowing for partial clustering, sensitivity analyses and analysis of 15-month data) were conducted unblinded.

Data collection and management

Data were collected and maintained at the PenCTU in accordance with the current legal and regulatory requirements [the Data Protection Act 1998,39 the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 201640 and later the Data Protection Act 201841].

Participant numbering

Following receipt of an expression of interest, each individual was allocated a unique number and was subsequently identified in all trial-related documentation by their identification number and initials only. A record of names, addresses, telephone numbers and e-mail addresses linked to participants’ identification numbers was stored securely on the trial database at the PenCTU for the purposes of the trial only.

Data processing

All data recorded in case report forms and questionnaire booklets were double-entered by PenCTU staff into a bespoke password-protected Microsoft SQL Server database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and encrypted using Secure Sockets Layer version 3 (QuoVadis Online Ltd, London, UK). Access to identifiable information was restricted and permission based.

A parallel, linked, secure, bespoke, online data system was used to manage intervention engagement post randomisation. This GDPR-compliant system captured all HT attempted and actual contact with intervention participants in real time to produce summary data and to aid supervision sessions and intervention management (e.g. for use should a HT be unavailable).

Raw data from the accelerometer were downloaded using the GENEActiv personal computer software (version 3.0_09.02.2015) (Activinsights Ltd, Kimbolton, UK) and analysed in R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using package GGIR version 1.2-8 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/GGIR/index.html). GGIR performs autocalibration with the reference of local gravity. 42,43 Raw acceleration data are used to compute Euclidean norm minus one [measured in milligravity units (mg)44]. Data were analysed from the first to the final midnight using 5-second epochs.

Non-wear was detected if the standard deviation (SD) of two axes was < 13 mg with a range of < 50 mg in windows of 60 minutes. Time spent in activity intensities was established using published thresholds. 45

Computed variables included average daily moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) accumulated in any 5-second epochs, and diurnal inactivity.

Data cleaning

Local researchers aided the completion of the baseline questionnaire over the telephone or face to face, but at follow-up the questionnaire was posted to participants. Possible confusion over the reporting of grams or ounces of loose tobacco led to some extreme and implausible values in self-reported smoking for some participants. Hence, loose tobacco amounts of ≥ 2 ounces were reassigned as grams (of relevance to 9 and 16 participants at 3 and 9 months, respectively). However, even after this change, at 3 and 9 months, 28 and 23 participants, respectively, smoked the equivalent of > 100 cigarettes, on average, per day over the preceding week. Therefore, data for the total number of daily cigarettes smoked (derived from self-reported number of cigarettes, cigars and amount of loose tobacco) were recalculated using a truncated upper limit of 100 cigarettes per day.

Some self-reported total weekly minutes of MVPA and sleep also included implausible values. In line with other surveys (e.g. International Physical Activity Questionnaire46), we opted to cap all values of MVPA to 1260 minutes per week (equivalent to 3 hours per day). At 3 months and 9 months, data from 43 and 38 participants, respectively, were truncated. Similarly, the sleep data were truncated to no more than a daily average of 12 hours in the previous week: at 3 months and 9 months, 7 and 6 responses, respectively, were truncated as a result. Values of sleep of < 3 hours were set as missing: at 3 months and 9 months, 16 and 19 responses, respectively, were classed as missing.

Baseline assessment

The baseline assessment booklet was administered to consented participants by the local researcher, over the telephone or in person, depending on local practice and a participant’s preference. Baseline measures are summarised in Table 1.

| Measure | Screening and baseline | Month | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 9 | 15a | ||

| Demographics (date of birth, gender, ethnic group, relationship status, partner’s smoking status, employment status, education completed) | ✗ | |||

| Self-reported measures | ||||

| Weight and height (to derive BMI) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| HSI38 | ✗ | |||

| Number of cigarettes (or equivalent) smoked in a typical day in the previous week | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Frequency of use of smoking management products (LNCPs or e-cigarettes) in a typical day in the previous week | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Quit attemptb (and date of quit attempt) | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Prolonged abstinence since quitting smoking (at least 6 months) | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| PA and sleep (7-day recall)47 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Health and social care utilisation (resource use questionnaire) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-5L48 and SF-12v249,50) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Serious adverse events | ✗ | ✗ | ||

Process measures:c

|

✗ | ✗ | ||

| Accelerometer-assessed minutes of MVPA (in a sample) | ✗ | |||

| CO-verified abstinence (for self-reported quit attempts at 3 and/or 9 months) or self-reported abstinence (at 15 monthsa) | ✗d | ✗e | ✗f | |

| Qualitative process evaluation in parallel (in a sample) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Follow-up assessments

Follow-up assessments, scheduled at 3, 9 and 15 months post baseline, are summarised in Table 1.

At 3 and 9 months, all participants were posted a self-report questionnaire booklet to complete and return to the PenCTU using prepaid, pre-addressed envelopes. See the questionnaire on the project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1511101/#/documentation). At 15 months, all participants with CO-verified abstinence at 9 months were posted a self-report questionnaire booklet to complete and return to the PenCTU. Participants received a £20 shopping voucher on receipt of a questionnaire booklet at the PenCTU. To increase response rates, motivational postcards (in sealed envelopes) were posted to participants before the questionnaires were sent out. Standard reminder letters were sent and telephone calls made to remind non-responders to return the questionnaire booklet. To maximise follow-up data on key outcomes, non-responders were then given the option to complete only the key questions about smoking behaviour and to submit these responses by e-mail, telephone or text, if preferred.

Participants who self-reported that they had quit smoking were invited to attend a face-to-face visit with the local researcher to verify abstinence. In making arrangements for the visit, the researcher checked whether or not a participant had restarted smoking in the interim; the visit went ahead only with participants who confirmed that they had not smoked a puff in the 7 days preceding the day of the visit. At the visit, abstinence was verified by expired CO, measured using a CareFusion MicroCO Meter (Williams Medical Supplies Ltd, Rhymney, UK). Expired CO of < 10 parts per million (p.p.m. ) indicated abstinence.

At 3 months, an objective measure of total weekly minutes of MVPA was collected in a sample of participants. Participants were asked to wear a waterproof GENEActiv accelerometer51 on the wrist of the non-dominant hand constantly for 1 week and then return the device to the PenCTU. The finite supply of accelerometers determined which participants were posted an accelerometer (i.e. if an accelerometer was available at the PenCTU to be posted, this was posted to the next participant due a 3-month questionnaire).

Contingency measure for biochemical verification during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020

In accordance with the UK government advice on reducing COVID-19 transmission, verification of self-reported abstinence by expired CO was discontinued from 20 March 2020, to avoid direct contact between participants and local researchers. As a contingency measure, biochemical verification of self-reported abstinence from smoking was achieved by a posted self-test saliva cotinine test, removing the requirement for participants to meet with a researcher face to face, as is the case with the expired CO assessment. This contingency measure applied to a minority of participants (see Chapter 3, Analyses of primary outcome).

The self-test saliva kit was supplied by ABS Laboratories (York, UK). A swab was provided for participants to place under the tongue. Once the swab had become soaked with saliva, the swab was placed into a tube provided, and then into a second (outer) tube ready for posting direct to ABS Laboratories for analysis using the prepaid, pre-addressed envelope provided. Cotinine concentration in the saliva sample was quantified using a validated in-house method (by ABS Laboratories) using protein precipitation with a deuterated cotinine internal standard and analysis by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. A saliva cotinine concentration of < 12 ng/ml indicated abstinence. 52

Process evaluation

A mixed-methods process evaluation focused on trial methods (in an internal pilot study), and if and how the intervention was working, using data from the trial database; audio-recordings of intervention sessions; and audio-recorded and transcribed interviews with participants, HTs, research assistants and general practitioners (GPs)/practice managers (PMs). The methods, procedures, data analysis and findings are reported in more detail in Chapter 4.

Measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence53 derived from CO-verified (following self-reported abstinence) point prevalence abstinence at both 3 and 9 months post baseline.

Secondary outcome measures

Only participants who were CO-verified abstinent at 9 months were followed up at 15 months.

Abstinence measures

-

Self-reported point prevalence abstinence at 3, 9 and 15 months post baseline.

-

Self-reported abstinence at 3 months was defined as follows: participant reported having made a quit attempt (going at least 24 hours without even a puff) since joining the trial and smoked not even a puff of a tobacco product (excluding LNCPs) since the reported quit date.

-

Self-reported abstinence at 9 months was defined as follows: participant reported either not having smoked a puff of a tobacco product (excluding LNCPs) since a quit attempt in the previous 6 months or having smoked fewer than five cigarettes since having made a quit attempt in the first 3 months and had a CO monitoring visit at 3 months.

-

Self-reported abstinence at 15 months was defined as follows: participant reported smoking fewer than five cigarettes since the 9-month CO assessment and not a puff of a tobacco product (excluding LNCPs) in the 7 days preceding the day of CO assessment.

-

-

CO-verified point prevalence abstinence at 3, 9 and 15 months was defined as self-reported abstinence and expired CO of < 10 p.p.m. Note that (1) at 3 and 9 months, only those reporting abstinence were contacted for expired CO assessment (to verify self-reported abstinence) and (2) at 15 months, only those who were CO-verified abstinent at 9 months and who self-reported abstinence at 15 months were contacted for an expired CO assessment (see Figure 1).

-

CO-verified floating prolonged abstinence over any 6-month period between either 3 and 9 months or 9 and 15 months post baseline.

-

CO-verified prolonged abstinence for at least 12 months, derived from CO-verified self-reported point prevalence abstinence at all three follow-up time points.

Non-abstinence smoking measures at 3, 9 and 15 months post baseline

-

Self-reported number of cigarettes smoked on a normal day in the previous week. The number of cigars and weight of loose tobacco were converted into an equivalent number of cigarettes (i.e. 0.45 g of tobacco was the equivalent of one cigarette). 23,54

-

Frequency of use of smoking management products (LNCPs or e-cigarettes) in a typical day in the previous week.

-

Reduction of number of cigarettes smoked (or equivalent) by at least 50% between (1) baseline and 3 months and (2) baseline and 9 months.

Self-reported physical activity at baseline and at 3 and 9 months using the 7-day Physical Activity Recall questionnaire47

-

Total MVPA over the previous 7 days.

-

Daily average time spent sleeping over the previous week.

Objectively assessed physical activity (by wrist-worn accelerometer) at 3 months (in a sample)

-

Average time spent in MVPA each day over 1 week.

Body mass index

-

Body mass index was derived from self-reported height and weight.

Health-related quality of life at baseline and at 3 and 9 months

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 48

-

Short Form questionnaire-12 items, version 2 (SF-12v2). 49,50

An economic evaluation was conducted alongside the trial to estimate (1) the intervention cost, (2) the trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis over 9 months and (3) a model-based long-term cost-effectiveness of the intervention over a lifetime horizon. The methods are described in more detail in Chapter 5.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on a two-sided Fisher’s exact test. For an increase of 6% in the CO-verified abstinence rate in the intervention group, compared with the SAU group, between 3 and 9 months post baseline [i.e. from 5% in the SAU group to 11% in the intervention group, corresponding to an odds ratio (OR) of 2.35 or a relative risk of 2.2; number needed to treat 17], 450 participants were required per group, and therefore 900 participants were required in total, to detect this difference at the 5% significance level with 90% power (Table 2). The abstinence rates used to calculate the sample size were conservative estimates, consistent with those from the preceding pilot trial23 and those reported from a systematic review of pharmacological interventions. 55,56

| Assumed relative risk | Percentage of participants achieving CO-verified prolonged abstinence | Power (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAU group | Intervention group | ||

| 2.20 | 5 | 11 | 90 |

| 2.43 | 3 | 7.3 | 80 |

| 2.70 | 3 | 8.1 | 90 |

| 2.20 | 4 | 8.8 | 81 |

| 2.40 | 4 | 9.6 | 90 |

| 2.04 | 5 | 10.2 | 81 |

| 1.92 | 6 | 11.5 | 80 |

| 2.08 | 6 | 12.5 | 90 |

| 1.76 | 8 | 14.1 | 80 |

| 1.89 | 8 | 15.1 | 90 |

| 1.66 | 10 | 16.6 | 80 |

| 1.77 | 10 | 17.7 | 90 |

As the primary analyses followed the Russell Standard on handling missing cessation outcome data due to loss to follow-up,57 with only participants who were unavoidably lost to follow-up not included (expected to be < 5% of recruited participants), the sample size was not inflated to allow for loss to follow-up.

Table 2 illustrates the range of likely effect sizes detectable, based on recruiting 450 smokers to each group, across plausible values for the control abstinence rate. Under these various scenarios, our sample size would allow us to detect a relative risk ranging, at best, from 1.66 to 2.70.

Statistical methods

The reporting and presentation of this trial is in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 58,59 The prespecified analyses were detailed in the SAP, approved by the chief investigator and independent statisticians on the TARS oversight committees; see the SAP on the project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1511101/#/documentation). The primary analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes were performed following the intention-to-treat principle. All analyses were undertaken using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), with statistical programming for the primary analyses independently double-coded in R and analyses cross-checked.

Adjustments

No adjustments for multiple analyses were made. Adjustments were made for the stratification variables, namely site as a fixed effect and HSI as a binary factor, as well as the corresponding baseline measure of the outcome being modelled, when appropriate, in fully adjusted models.

Interim analysis

No interim inferential analysis was planned, and none was conducted.

Inferential analyses

Primary analysis of the primary outcome

In line with the Russell Standard schedule,57 participants with missing responses were considered to still be smokers, with the exception of those unavoidably lost to follow-up (defined as participants who had died or moved to an untraceable address). The primary analysis used a multivariable logistic regression model to compare the CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence rate between 3 and 9 months between allocated groups, with adjustment for the stratification variables. Both adjusted and unadjusted ORs and corresponding 95% CIs are presented, along with the absolute between-group differences in floating prolonged abstinence rates, as recommended in the CONSORT guidelines for parallel-group randomised trials. 60 The interpretation of the primary effectiveness analysis was based on the adjusted OR from the logistic regression model. Intervention effectiveness is also presented as a relative risk, calculated from the estimated OR for the intervention and the baseline rate among the control group, along with the corresponding 95% CI.

Sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome

The following sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome were planned:

-

Participants with missing primary outcome data at 3 or 9 months, otherwise interpreted as still smoking, will be assumed to have quit for the months for which their responses are missing, and the primary analysis will be re-run on a new derivation of the primary outcome from the 3- and 9-month responses, assuming that missing denotes having quit. This may be considered a ‘best-case scenario’.

-

A complier-average causal effect analysis, if > 20% of participants allocated to the intervention group are categorised as not having completed at least two intervention sessions with a HT. Participants in the control group and non-compliers in the intervention group will be compared with compliers in the intervention group.

-

Additional analyses adjusting sequentially for potential confounding variables at baseline [Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), self-reported MVPA, use of LNCPs], in addition to the two stratification factors, if imbalance between allocated groups at baseline [> 10% for binary outcomes or > 0.5 SDs for numeric outcomes] is observed.

-

Additional analyses to explore any effect of changing the method of biochemical verification of abstinence from exhaled air testing to saliva testing.

Planned secondary analyses of the primary outcome

Although the trial was not powered to detect the influence of potential moderating variables on the primary outcome, secondary analyses were planned to explore whether or not the intervention effect was modified by any of the following baseline measures: (1) IMD, (2) the use of a smoking cessation medication or a vaping product, (3) self-reported MVPA level, (4) confidence to quit, (5) HSI and (6) recruiting site. The primary analysis multivariable logistic regression model was extended to include the interaction term of allocated group and each of the potential modifying variables. The statistical significance of intervention modification was determined by the p-value of the interaction term between the allocated group and each potential modifying variable and was set at the 1% level of significance.

An exploratory analysis of the HT effect was planned, using a multilevel, mixed-modelling approach, to allow for the partially nested data: participants allocated to the intervention group were partially clustered within the HT, in turn nested within sites.

To explore whether or not the primary outcome was influenced by the intervention dose actually received (i.e. number of HT sessions attended), the primary outcome was modelled on the number of HT sessions attended in the intervention group only, adjusting also for the stratification variables.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

The primary analyses of the secondary outcomes followed a similar approach to that for the primary outcome, using multivariable logistic or linear regression modelling as appropriate, with both adjusted and unadjusted results presented. Additional planned analyses included exploration of whether or not intervention effects were modified by any prespecified baseline characteristics, as outlined for the primary outcome, and exploration of the concordance between self-reported and objective measures of PA.

Adverse events

The recording and reporting of non-serious adverse events in this low-risk trial were not required. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were documented from the time of participant consent until a maximum of 8 weeks after the follow-up assessment at 9 months. Reportable SAEs were detected through self-reported hospital admissions or reported directly by local researchers or HTs. Participant-reported hospitalisations were reviewed by the chief investigator in the first instance, to assess the need for on-reporting, for example to avoid reporting hospitalisations for pre-elective procedures, and similar, as SAEs in this trial. SAEs were listed descriptively by group and included details of the event, and the likely relatedness to either treatment.

Model checking and validation

Checks were undertaken to assess the robustness of statistical models, including visual assessment of model residual normality and heteroscedasticity.

Changes to the project protocol

Omission of Short Form questionnaire-12 items, version 2, data at one site

Owing to an error in the production of the baseline questionnaire booklet, the response options for a number of the items in the SF-12v2 were incorrectly displayed in the booklet used by one of the four sites. Consequently, statistical analysis of SF-12v2 data could not be undertaken as intended and has therefore not been conducted.

Contingency measure for biochemical verification during the coronavirus pandemic

Because of COVID-19, the original method of verification of self-reported abstinence (expired CO) was replaced with a posted self-test for saliva cotinine level.

Participants who had been due to attend a face-to-face CO test for verification of self-reported abstinence from 20 March 2020 onwards were contacted by a researcher who explained the changes to the procedure and introduced the posted self-test for saliva cotinine as an alternative. Verbal consent to the alternative test was taken and documented prior to dispatch of the self-test kit to participants. Along with the kit, consented participants received a participant information sheet that described the new arrangements for verifying self-reported abstinence in this trial, and a step-by-step instruction sheet on how to use the kit. The number of participants for whom this was relevant is reported in Chapter 3.

Chapter 3 Quantitative trial results

Participant recruitment and flow through the trial

A total of 915 participants were recruited to the trial and randomised between January 2018 and May 2019 (16 months).

Figure 2 shows the CONSORT flow diagram for recruitment to the trial. Of the initial 1441 smokers expressing an interest in participating, 915 (63.5%) individuals were contactable and eligible, and eventually randomised. The main reasons for ineligibility were smoking < 10 cigarettes per day (n = 92, 6.4% of those showing an interest), being unable to engage in at least 15 minutes of moderate-intensity PA (n = 16, 1.1%) and wanting to quit immediately (n = 7, < 1%). We were unable to contact 385 (26.7%) smokers who showed an initial interest in the trial.

FIGURE 2.

The TARS CONSORT flow diagram. Follow-up at 15 months was contingent on CO-verified abstinence at 9 months. Reasons for ineligibility, losses to follow-up and not completing verification of self-reported abstinence are given in the following tables in Appendix 4. a, Table 30; b, Table 31; c, Table 32; d, Table 33; e, Table 34; f, Table 35; g, Table 36; h, Table 37; i, Table 38; j, Table 39. QB, questionnaire booklet.

Appendix 3 shows the number and percentage of participants who entered the trial via the different recruitment methods, by allocated group and overall. The findings from a SWAT to examine the effectiveness and associated costs of different approaches to primary care recruitment (i.e. full Docmail invitation, single letter via Docmail, and text message) have been reported elsewhere34,35 (see also Report Supplementary Material 1). The majority of participants (n = 659, 72.0%) were recruited via a general practice, via invitation letter (which may or may not have contained full details of the trial; some participants received full details and some received a brief version and an invitation to read more on the website or by contacting a researcher), text message or opportunistically.

Of the 915 randomised participants, 624 (68.2%) provided follow-up data at 3 months, and 583 (63.7%) provided follow-up data at 9 months (see Figure 2). There was little difference in the proportions followed up between allocated groups.

Baseline participant characteristics and allocated group comparability

Appendix 5 shows the success of the stratified randomisation algorithm in achieving balance between the allocated groups in terms of the stratification factors (HSI and recruiting site). Overall, the percentages of participants recruited in London, Plymouth, Oxford and Nottingham were 31.1%, 27.0%, 23.7% and 18.1%, respectively. Trial outcomes at baseline and follow-up are reported below.

Table 3 shows the baseline sample demographics and smoking indicators by allocated group and for the whole sample. There was good balance between allocated groups at baseline. The mean age of participants was 49.8 (SD 13.9) years, with a wide range (18–82 years). Overall, 55.4% of participants identified as female and 84.9% identified as being white. The majority of the participants (41.9%) were either married or had a partner. The proportion of participants with an advanced level of education (first or higher degree) was 28.6%, and 45.7% of participants were in paid employment. Just under one-third of participants (32.6%) reported having their first cigarette within 5 minutes of waking. The majority of the participants (59.3%) reported smoking 11–20 cigarettes per day at baseline, with a derived 18.5% having a high baseline HSI. The overall mean number of daily cigarettes (derived from self-reported bought cigarettes, loose tobacco and cigars) smoked at baseline was 18.0 (SD 13.4) (Table 4).

| Characteristic | SAU group (N = 458) | Intervention group (N = 457) | Both groups (N = 915) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 50.0 (13.6) [18.0, 82.0] | 49.5 (14.1) [18.0, 81.0] | 49.8 (13.9) [18.0, 82.0] |

| Female, n (%) | 263 (57.4) | 244 (53.4) | 507 (55.4) |

| IMD rank (derived from postcode), mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 14,467.6 (8655.3) [36.0, 32,745.0] | 14,393.1 (8823.2) [36.0, 32,844.0] | 14,430.4 (8734.8) [36.0, 32,844.0] |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 390 (85.2) | 387 (84.7) | 777 (84.9) |

| Black Caribbean | 19 (4.1) | 9 (2.0) | 28 (3.1) |

| Black African | 6 (1.3) | 9 (2.0) | 15 (1.6) |

| Black other | 11 (2.4) | 13 (2.8) | 24 (2.6) |

| Indian | 3 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) | 7 (0.8) |

| Pakistani | 2 (0.4) | 6 (1.3) | 8 (0.9) |

| Bangladeshi | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) |

| Other | 27 (5.9) | 26 (5.7) | 53 (5.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (< 0.1) | 1 (< 0.1) |

| Relationship status, n (%) | |||

| Single (never married or civil partnered) | 190 (41.5) | 200 (43.8) | 390 (42.6) |

| Married | 136 (29.7) | 119 (26.0) | 255 (27.9) |

| In a civil partnership | 5 (1.1) | 3 (0.7) | 8 (0.9) |

| Divorced or civil partnership dissolved | 57 (12.4) | 54 (11.8) | 111 (12.1) |

| Widowed or surviving civil partner | 9 (2.0) | 13 (2.8) | 22 (2.4) |

| Common-law partner (living together as if married) | 61 (13.3) | 67 (14.7) | 128 (14.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (< 0.1) | 1 (< 0.1) |

| Work situation, n (%) | |||

| Working full time in paid employment | 145 (31.7) | 155 (33.9) | 300 (32.8) |

| Working part time in paid employment | 67 (14.6) | 51 (11.2) | 118 (12.9) |

| Working as a volunteer | 15 (3.3) | 11 (2.4) | 26 (2.8) |

| In full-time education | 14 (3.1) | 21 (4.6) | 35 (3.8) |

| Looking after the home | 27 (5.9) | 18 (3.9) | 45 (4.9) |

| Retired | 76 (16.6) | 70 (15.3) | 146 (16.0) |

| Unemployed | 73 (15.9) | 83 (18.2) | 156 (17.0) |

| Other | 41 (9.0) | 48 (10.5) | 89 (9.7) |

| Education status,a n (%) | |||

| No qualifications | 95 (20.7) | 102 (22.3) | 197 (21.5) |

| GCSE | 259 (56.6) | 256 (56.0) | 515 (56.3) |

| A level | 125 (27.3) | 116 (25.4) | 241 (26.3) |

| First degree | 104 (22.7) | 83 (18.2) | 187 (20.4) |

| Higher degree | 38 (8.3) | 37 (8.1) | 75 (8.2) |

| Partner smokes, n (%) | |||

| No | 285 (62.2) | 264 (57.8) | 549 (60.0) |

| Yes | 132 (28.8) | 145 (31.7) | 277 (30.3) |

| N/A | 40 (8.7) | 46 (10.1) | 86 (9.4) |

| Missing | 1 (< 0.1) | 2 (< 0.1) | 3 (< 0.1) |

| Time after waking of smoking first cigarette (minutes), n (%) | |||

| > 60 | 45 (9.8) | 46 (10.1) | 91 (9.9) |

| 31–60 | 59 (12.9) | 55 (12.0) | 114 (12.5) |

| 6–30 | 205 (44.8) | 207 (45.3) | 412 (45.0) |

| ≤ 5 | 149 (32.5) | 149 (32.6) | 298 (32.6) |

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day, n (%) | |||

| ≤ 10 | 59 (12.9) | 61 (13.3) | 120 (13.1) |

| 11–20 | 272 (59.4) | 271 (59.3) | 543 (59.3) |

| 21–30 | 105 (22.9) | 84 (18.4) | 189 (20.7) |

| > 30 | 22 (4.8) | 41 (9.0) | 63 (6.9) |

| Descriptive data | Baseline | 3-month follow-up | 9-month follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAU | Intervention | SAU | Intervention | SAU | Intervention | |

| Total number of cigarettes smoked dailya | ||||||

| n | 454 | 452 | 283 | 275 | 240 | 244 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.4 (9.9) | 18.2 (13.2) | 26.8 (27.0) | 21.1 (23.6) | 24.2 (23.9) | 22.6 (25.8) |

| Median | 15.6 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 12.0 | 15.0 | 12.0 |

| Minimum, maximum | 2.2, 100.0 | 4.0, 100.0 | 1.0, 100.0 | 1.0, 100.0 | 1.0, 100.0 | 1.0, 100.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| n | 448 | 443 | 288 | 301 | 265 | 262 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.4 (5.8) | 26.4 (5.8) | 26.7 (6.1) | 26.1 (5.8) | 26.7 (5.9) | 26.4 (6.1) |

| Median | 25.4 | 25.3 | 25.9 | 25.1 | 25.9 | 25.0 |

| Minimum, maximum | 14.3, 49.8 | 15.2, 51.1 | 15.2, 50.5 | 14.1, 49.5 | 15.4, 50.5 | 14.4, 53.7 |

| Weight (kg) | ||||||

| n | 450 | 443 | 288 | 301 | 265 | 262 |

| Mean (SD) | 76.4 (19.2) | 76.7 (18.7) | 77.7 (19.5) | 76.3 (19.0) | 77.7 (19.4) | 76.9 (20.2) |

| Median | 73.0 | 75.0 | 75.2 | 73.0 | 75.0 | 75.7 |

| Minimum, maximum | 38.1, 175.0 | 39.4, 139.7 | 39.0, 160.0 | 39.0, 142.3 | 38.1, 160.0 | 40.0, 170.1 |

| Self-reported total weekly minutes of MVPAb | ||||||

| n | 458 | 457 | 300 | 308 | 269 | 273 |

| Mean (SD) | 462.4 (419.2) | 456.1 (434.0) | 319.1 (354.9) | 397.7 (389.9) | 330.7 (360.6) | 352.9 (375.5) |

| Median | 360.0 | 315.0 | 210.0 | 274.5 | 210.0 | 240.0 |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 1260.0 | 0.0, 1260.0 | 0.0, 1260.0 | 0.0, 1260.0 | 0.0, 1260.0 | 0.0, 1260.0 |

| Self-reported daily hours spent sleepingc | ||||||

| n | 454 | 452 | 278 | 287 | 247 | 260 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (1.5) | 6.9 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.7) | 7.1 (1.6) | 6.7 (1.6) | 7.0 (1.8) |

| Median | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Minimum, maximum | 3.0, 12.0 | 3.0, 12.0 | 3.0, 12.0 | 3.0, 12.0 | 3.0, 12.0 | 3.0, 12.0 |

| Accelerometer-measured average daily minutes of MVPAd | ||||||

| n | N/A | N/A | 51 | 54 | N/A | N/A |

| Mean (SD) | 77.1 (55.2) | 91.9 (55.2) | ||||

| Median | 74.3 | 86.6 | ||||

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 210.0 | 0.0, 264.9 | ||||

| Accelerometer-measured average daily minutes of MVPAe | ||||||

| n | N/A | N/A | 45 | 42 | N/A | N/A |

| Mean (SD) | 82.4 (53.6) | 95.2 (43.6) | ||||

| Median | 78.5 | 92.3 | ||||

| Minimum, maximum | 10.4, 210.0 | 20.2, 195.3 | ||||

Summary statistics for smoking outcomes, physical activity, sleep and weight/body mass index at baseline and at 3 and 9 months, by allocated group

Table 4 shows descriptive data by allocated group for self-reported smoking level, BMI, weight, and PA and sleep at baseline and at 3 and 9 months, together with accelerometer-recorded PA at 3 months. We do not report the number of cigarettes smoked at 15 months because there are too few participants for meaningful interpretation of these data.

The descriptive data for the total number of cigarettes smoked underwent data cleaning, described in Chapter 2. The summary statistics for the derived daily equivalent total number of cigarettes smoked, prior to truncation, are shown in Report Supplementary Material 2. At baseline, in both the cleaned/truncated and non-truncated data, there was good balance between allocated groups in the total number of cigarettes smoked daily, with a broad range. Among participants providing data at 3 and 9 months, the median number of total cigarettes smoked per day remained fairly stable for participants in the SAU group whereas, on average, intervention participants reduced their consumption compared with baseline. The summary statistics in Table 4 are produced from PA and sleep data that have also undergone data cleaning, described in Chapter 2. Descriptive data before cleaning/truncation for reported PA and sleep are reported in Report Supplementary Material 2.

The descriptive data captured from the separate self-reporting of cigarettes, cigars and loose tobacco consumed are shown in Appendix 6. The percentage of the overall sample who at baseline reported smoking even a puff of bought cigarettes, loose tobacco or cigars was 54.2%, 49.7% and 1.0%, respectively (with some participants smoking more than one tobacco product). Appendix 7 shows the descriptive data when participants with missing data were removed from the calculation of the summary statistics: the percentage of the overall sample who at baseline reported smoking even a puff of bought cigarettes, loose tobacco or cigars was then 64.5%, 62.0% and 1.5%, respectively. The number and percentage of participants who reported using any LNCP at each time point, by allocated group, are also shown in Appendix 7. Additional information about the reported weekly and daily use of LNCPs is shown in Report Supplementary Material 3. At baseline, overall, only 14.0% of participants used any LNCP, increasing to 40.8% and 39.0% overall at 3 months and 9 months, respectively, among participants who were followed up (see Appendix 7) (or 26.0% and 22.8% if we assume that those who were missing at follow-up were not using LNCPs).

Table 5 shows the self-reported, CO-verified point prevalence and 6-month floating prolonged abstinence outcomes across time points by allocated group. At 3 months, 5.5% of participants in the intervention group self-reported being abstinent, compared with 2.8% in SAU group, which dropped to 3.7% and 1.7%, respectively, based on CO-verified abstinence. At 9 months, 8.3% self-reported being abstinent in the intervention group, compared with 7.9% in SAU group, which dropped to 5.5% and 4.6%, respectively, based on CO-verified abstinence. Descriptive data for CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence (between different time points) are also shown in Table 5. The number and percentage of participants who reported a quit attempt of at least 24 hours, by allocated group, are shown in Appendix 8. At 3 months, 19.2% of responding participants in the intervention group reported a quit attempt, compared with 13.5% in the SAU group. At 9 months, 27.6% of participants in the intervention group who responded reported one or more quit attempts in the previous 6 months, compared with 25.3% in the SAU group.

| Abstinence outcomes | Follow-up, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 9 months | 15 monthsa | ||||

| SAU | Intervention | SAU | Intervention | SAU | Intervention | |

| Self-reported point prevalence abstinence | ||||||

| Yes | 13 (2.8) | 25 (5.5) | 36 (7.9) | 38 (8.3) | 14 (3.1) | 16 (3.5) |

| No | 443 (96.7) | 431 (94.3) | 415 (90.6) | 412 (90.2) | 437 (95.4) | 434 (95.0) |

| Irretrievably lost to follow-upb | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) |

| CO-verified point prevalence abstinence | ||||||

| Yes | 8 (1.7) | 17 (3.7) | 21 (4.6) | 25 (5.5) | 7 (1.5) | 11 (2.4) |

| No | 448 (97.8) | 439 (96.1) | 430 (93.9) | 425 (93.0) | 444 (96.9) | 439 (96.1) |

| Irretrievably lost to follow-upb | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) |

| CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence between 3 and 9 months | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (0.9) | 9 (2.0) | ||||

| No | 447 (97.6) | 441 (96.5) | ||||

| Irretrievably lost to follow-upb | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) | ||||

| CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence between 3 and 9 months or 9 and 15 monthsa | ||||||

| Yes | 10 (2.2) | 14 (3.1) | ||||

| No | 441 (96.3) | 436 (95.4) | ||||

| Irretrievably lost to follow-upb | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) | ||||

| CO-verified 12-month floating prolonged abstinence between 3 and 15 monthsa | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.3) | ||||

| No | 450 (98.3) | 444 (97.2) | ||||

| Irretrievably lost to follow-upb | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.5) | ||||

Descriptive summary of serious adverse events, by allocated group

Seven SAEs were reported (seven participants). Summaries are shown in Appendix 9. No SAEs were linked to the intervention or trial methods. Self-reported hospitalisations for three participants could not be followed up, as we were unable to make contact with the participants concerned and their GP did not respond to our enquiries.

Data collected at 15 months

Descriptive data collected for the self-reported number of cigarettes smoked per day and LNCP use at 15 months are not reported in any of the tables or appendices because of the small numbers of participants who provided these data at this time point, given that only those who were CO-verified abstinent at 9 months were contacted for follow-up at 15 months. As Table 5 shows, a higher proportion of intervention participants than SAU participants had CO-verified point prevalence abstinence at 15 months (2.4% vs. 1.5%) and CO-verified floating prolonged abstinence rates, when prolonged abstinence rates including 15-month data were considered.

Analyses of primary outcome

Under the Russell Standard criteria,61 assuming all non-responding participants were still smoking except those irretrievably lost to follow-up (shown in Table 5), the allocated groups contributing to the primary analysis differed in size by only one participant (Table 6). As Table 6 shows, 2.0% (n = 9) of intervention participants had CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence between 3 and 9 months, compared with 0.9% (n = 4) of SAU participants. From the prespecified primary analysis, the adjusted OR is 2.30 (95% CI 0.70 to 7.56). In other words, the odds of achieving the primary outcome in the intervention group were, on average, more than double the odds in the SAU group. However, the difference was not statistically significant. Table 6 also presents the adjusted absolute difference and relative risk. The unadjusted analyses gave very similar results to the adjusted analyses, across the different methods of estimating the effect of the intervention (see Table 6).

| Analysis | Number of participants in analysis | Outcomes per group, n (%) | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysisa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAU | Intervention | SAU | Intervention | ORb (95% CI); p-value | Absolute between-group differences in riskc (95% CI); p-value | Relative riskd (95% CI); p-value | ORb (95% CI); p-value | Absolute between-group differences in riskc (95% CI); p-value | Relative riskd (95% CI); p-value | |

| Primary analysis | 451 | 450 | 4 (0.9) | 9 (2.0) | 2.28 (0.70 to 7.46); 0.173 | 0.01 (–0.00 to 0.03); 0.161 | 2.25 (0.70 to 7.27); 0.173 | 2.30 (0.70 to 7.56); 0.169 | 0.01 (–0.00 to 0.03); 0.157 | 2.27 (0.71 to 7.29); 0.169 |

| Best-case scenario sensitivity analysis | 451 | 450 | 124 (27.5) | 109 (24.2) | 0.84 (0.63 to 1.14); 0.262 | –0.03 (–0.09 to 0.02); 0.262 | 0.88 (0.71 to 1.10); 0.263 | 0.84 (0.62 to 1.14); 0.260 | –0.03 (–0.09 to 0.02); 0.259 | 0.88 (0.71 to 1.10); 0.261 |

Applying the prespecified best-case scenario to the primary outcome, the direction of effect switched to favouring the SAU group, with 27.5% of participants (n = 124) categorised as being CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstainers in the SAU group, compared with 24.2% (n = 109) in the intervention group, with an adjusted OR of 0.84 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.14). This was reflected in all estimates of the intervention effect, both adjusted and unadjusted, and none of these results was statistically significant.

Owing to the sparse primary outcome data, the planned complier-average causal effect analysis, to estimate the intervention effect among participants attending at least two HT sessions, was not performed. Instead, descriptive statistics of the primary outcome by the prespecified categories of engagement are presented in Appendix 10. All nine participants in the intervention group who achieved the primary outcome attended at least two HT sessions.

The SAP prespecified a sensitivity analysis including additional adjustment for selected baseline characteristics if any were imbalanced between allocated groups. As there was no evidence of imbalance, this sensitivity analysis was not required.

The SAP also detailed planned sensitivity analyses to explore the impact of the required changes in verifying self-reported abstinence as a result of COVID-19; however, again because of the sparse primary outcome data, only descriptive statistics are reported. At the 9-month follow-up, 46 CO tests and two saliva tests were carried out among participants who had self-reported being abstinent from smoking. There were 24 out of 25 (96.0%) subsequent CO-verified abstinences in the intervention group and 20 out of 21 (95.2%) in the SAU group. Both saliva cotinine tests (one in each allocated group) verified the self-reported abstinence at 9 months. At the 15-month follow-up, 12 CO tests and nine saliva cotinine tests were carried out in participants who self-reported being abstinent from smoking. All 12 CO tests confirmed self-reported abstinences (eight in the intervention group, four in the SAU group). Of the nine saliva cotinine tests, three out of five (60.0%) confirmed the self-reported abstinences in the intervention group and three out of four (75.0%) confirmed the self-reported abstinences in the SAU group.

Secondary analyses of the primary outcome

The planned formal interaction analyses of the primary outcome with respect to prespecified potential moderating variables were not undertaken as there were too few instances of CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence between 3 and 9 months. However, the distributions of the 13 participants who were CO-verified abstinent across the prespecified moderating variables are shown in Appendices 11 and 12. The sparseness of the primary outcome data also meant that there was inadequate information to support the planned mixed-effects modelling with partial clustering by HT and the exploration of whether or not the number of HT sessions attended was associated with the primary outcome in the intervention group.

Primary analyses of the secondary outcomes

We described how self-reported smoking data were cleaned/truncated in Chapter 2; descriptive data are presented for cleaned/truncated data in this chapter and for non-truncated data in Appendices 13, 14 and 17, and Report Supplementary Material 2. Sensitivity analyses revealed no effects on the analyses as a result of these data-cleaning procedures.

Table 7 shows the estimated intervention effects on the 3-, 9- and 15-month point prevalence and 6-month floating prolonged abstinence smoking outcomes. Only self-reported point prevalence abstinence at 3 months was (marginally) statistically significant, in favour of the intervention group (5.5% vs. 2.9% for the intervention and SAU groups, respectively). The adjusted OR was 1.99 (95% CI 1.00 to 3.94). This effect was weaker and marginal, again in favour of the intervention group, for CO-verified point prevalence abstinence at 3 months (adjusted OR 2.19, 95% CI 0.93 to 5.14). There was no evidence of an intervention effect on point prevalence abstinence (from self-reported or CO-verified measures) at 9 or 15 months. When expressed as a risk difference, the estimated intervention effect on CO-verified 12-month floating prolonged abstinence between 3 and 15 months was marginal (adjusted analysis: risk difference 0.02, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.04), whereas, despite a point estimate adjusted OR of 6.33, the OR was not statistically significant (95% CI 0.76 to 53.10).

| Outcome | Number of participants in analysis | Outcomes per group, n (%) | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysisa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAU group | Intervention group | SAU group | Intervention group | ORb (95% CI); p-value | Absolute between-group differences in riskc (95% CI); p-value | Relative riskd (95% CI); p-value | ORc (95% CI); p-value | Absolute between-group differences in riskc (95% CI); p-value | Relative riskd (95% CI); p-value | |

| CO-verified abstinence at 3 months | 456 | 456 | 8 (1.8) | 17 (3.7) | 2.17 (0.93 to 5.08); 0.074 | 0.02 (–0.00 to 0.04); 0.067 | 2.12 (0.93 to 4.87); 0.075 | 2.19 (0.93 to 5.14); 0.071 | 0.02 (–0.00 to 0.04); 0.064 | 2.14 (0.93 to 4.90); 0.072 |

| CO-verified abstinence at 9 months | 451 | 450 | 21 (4.7) | 25 (5.6) | 1.20 (0.66 to 2.18); 0.540 | 0.01 (–0.02 to 0.04); 0.540 | 1.19 (0.68 to 2.10); 0.540 | 1.21 (0.66 to 2.19); 0.539 | 0.01 (–0.02 to 0.04); 0.539 | 1.19 (0.68 to 2.10); 0.539 |

| CO-verified abstinence at 15 months | 451 | 450 | 7 (1.6) | 11 (2.4) | 1.59 (0.61 to 4.14); 0.343 | 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.03); 0.338 | 1.57 (0.62 to 4.03); 0.343 | 1.61 (0.62 to 4.21); 0.332 | 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.03); 0.328 | 1.59 (0.62 to 4.04); 0.332 |

| Self-reported abstinence at 3 months | 456 | 456 | 13 (2.9) | 25 (5.5) | 1.98 (1.00 to 3.91); 0.051 | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.05); 0.046 | 1.92 (1.00 to 3.71); 0.051 | 1.99 (1.00 to 3.94); 0.049 | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.05); 0.045 | 1.93 (1.00 to 3.72); 0.050 |

| Self-reported abstinence at 9 months | 451 | 450 | 36 (8.0) | 38 (8.4) | 1.06 (0.66 to 1.71); 0.801 | 0.00 (–0.03 to 0.04); 0.801 | 1.06 (0.68 to 1.64); 0.801 | 1.07 (0.66 to 1.72); 0.794 | 0.00 (–0.03 to 0.04); 0.794 | 1.06 (0.69 to 1.64); 0.794 |

| Self-reported abstinence at 15 months | 451 | 450 | 14 (3.1) | 16 (3.6) | 1.15 (0.55 to 2.39); 0.706 | 0.00 (–0.02 to 0.03); 0.706 | 1.15 (0.57 to 2.32); 0.706 | 1.15 (0.56 to 2.40); 0.700 | 0.00 (–0.02 to 0.03); 0.700 | 1.15 (0.57 to 2.32); 0.700 |

| CO-verified 6-month floating prolonged abstinence between 3 and 9 months or 9 and 15 monthse | 451 | 450 | 10 (2.2) | 14 (3.1) | 1.42 (0.62 to 3.22); 0.407 | 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.03); 0.405 | 1.40 (0.63 to 3.13); 0.407 | 1.43 (0.62 to 3.26); 0.398 | 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.03); 0.396 | 1.41 (0.64 to 3.13); 0.399 |

| CO-verified 9-month floating prolonged abstinence between 3 and 15 monthse | 451 | 450 | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.3) | 6.08 (0.73 to 50.72); 0.095 | 0.01 (–0.00 to 0.02); 0.057 | 6.01 (0.73 to 49.75); 0.096 | 6.33 (0.76 to 53.10); 0.089 | 0.02 (–0.00 to 0.04); 0.053 | 6.17 (0.75 to 50.84); 0.091 |

Additional information on the estimated intervention effects on the proportion of participants self-reporting at least one quit attempt of at least 24 hours’ duration, reported at 3 and 9 months, is provided in Report Supplementary Material 4.

Table 8 shows that there was a statistically significant intervention effect in terms of the proportion of participants reducing their smoking level by at least 50%, relative to baseline, at both 3 months (18.9% in the intervention group vs. 10.5% in the SAU group, adjusted OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.35 to 2.90) and 9 months (14.4% in the intervention group vs. 10.0% in the SAU group, adjusted OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.29).

| Outcome | Number of participants | Outcomes per group, n (%) | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysisa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAU group | Intervention group | SAU group | Intervention group | ORb (95% CI); p-value | Absolute between-group differences in riskc (95% CI); p-value | Relative riskd (95% CI); p-value | ORb (95% CI); p-value | Absolute between-group differences in riskc (95% CI); p-value | Relative riskd (95% CI); p-value | |

| Reduced smoking by ≥ 50% between baseline and 3 months | 456 | 456 | 48 (10.5) | 86 (18.9) | 1.98 (1.35 to 2.89); < 0.001 | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.13); < 0.001 | 1.79 (1.29 to 2.49); < 0.001 | 1.98 (1.35 to 2.90); < 0.001 | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.13); < 0.001 | 1.79 (1.29 to 2.49); < 0.001 |

| Reduced smoking by ≥ 50% between baseline and 9 months | 451 | 450 | 45 (10.0) | 65 (14.4) | 1.52 (1.02 to 2.28); 0.042 | 0.05 (0.00 to 0.09); 0.040 | 1.45 (1.01 to 2.07); 0.042 | 1.52 (1.01 to 2.29); 0.043 | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.09); 0.042 | 1.44 (1.01 to 2.05); 0.044 |

Table 9 shows that there was a statistically significant intervention effect on the total number of cigarettes smoked per day at 3 months (derived from self-reported cigarettes, cigars and loose tobacco smoked), with the intervention group reporting smoking, on average, almost six fewer cigarettes per day than the SAU group, relative to baseline (adjusted mean difference –5.62, 95% CI –9.80 to –1.44). There was no evidence of a difference at 9 months. These conclusions were consistent when the analyses were re-run on the pre-truncated data (see Appendix 13).

| Cigarettes smoked | SAU group | Intervention group | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysisa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Mean differenceb (95% CI) | p-value | SAU group (n) | Intervention group (n) | Mean differenceb (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Number of cigarettes smoked daily from cigarettes, cigars and loose tobacco at 3 months | 283 (61.8) | 26.8 (27.0) | 275 (60.2) | 21.1 (23.6) | –5.69 (–9.92 to –1.46) | 0.008 | 280 | 274 | –5.62 (–9.80 to –1.44) | 0.009 |

| Number of cigarettes smoked daily from cigarettes, cigars and loose tobacco at 9 months | 240 (52.4) | 24.2 (23.9) | 244 (53.4) | 22.6 (25.8) | –1.55 (–6.00 to 2.90) | 0.494 | 237 | 243 | –0.95 (–5.37 to 3.46) | 0.671 |

Table 10 shows that there was a significant intervention effect on self-reported weekly MVPA at 3 months, but not at 9 months. At 3 months, the intervention group reported doing an average of 82 minutes more MVPA per week (95% CI 29 to 134 minutes) than the SAU group, having adjusted for baseline MVPA and stratification factors, based on the analysis of the truncated data. These conclusions were consistent when the analyses were re-run on the pre-truncated data (see Appendix 14). There was no evidence of a significant between-group difference in accelerometer-recorded MVPA among the subsample of those wearing an accelerometer at 3 months (regardless of whether or not this analysis was adjusted for baseline self-reported MVPA). The correlation between self-reported and accelerometer-measured MVPA (with at least 1 day of 10 hours of wear-time) at 3 months among the subcohort receiving the accelerometer devices was 0.204 (95% CI –0.002 to 0.409). This was too low, according to the prespecified cut-off point (of > 0.3) stipulated in the SAP, to justify further analysis comparing agreement between the two measures of MVPA at 3 months.

| MVPA | SAU group | Intervention group | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysisa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Mean differenceb (95% CI) | p-value | SAU group (n) | Intervention group (n) | Mean differenceb (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Self-reported total weekly minutes of MVPA at 3 months | 300 (65.5) | 319.1 (354.9) | 308 (67.4) | 397.7 (389.9) | 78.60 (19.17 to 138.03) | 0.010 | 300 | 308 | 81.61 (28.75 to 134.47) | 0.003 |

| Self-reported total weekly minutes of MVPA at 9 months | 269 (58.7) | 330.7 (360.6) | 273 (59.7) | 352.9 (375.5) | 22.16 (–39.97 to 84.29) | 0.484 | 269 | 273 | 23.70 (–33.07 to 80.47) | 0.413 |

| Average daily minutes of accelerometer-measured MVPA at 3 monthsc | 51 (11.1) | 77.1 (55.2) | 54 (11.8) | 91.9 (55.2) | 14.80 (–6.58 to 36.18) | 0.173 | 51 | 54 | 14.24 (–7.88 to 36.37) | 0.204 |

| Average daily minutes of accelerometer-measured MVPA at 3 monthsd | 45 (9.8) | 82.4 (53.6) | 42 (9.2) | 95.2 (43.6) | 12.80 (–8.11 to 33.71) | 0.227 | 45 | 42 | 13.88 (–7.74 to 35.50) | 0.205 |

As the results in Appendices 15–17 show, there was no evidence of a statistically significant intervention effect on any of the remaining secondary outcomes (LNCP use, BMI or sleep) at 3 or 9 months.

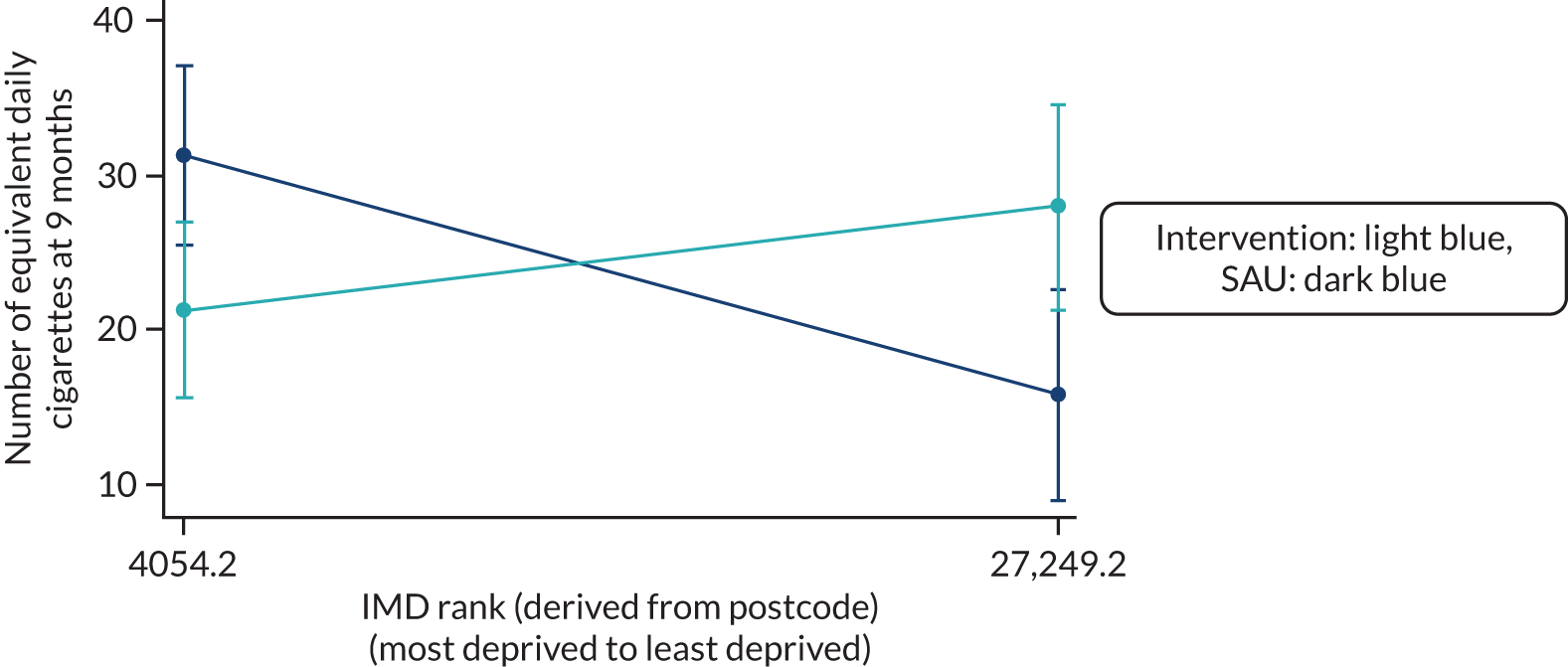

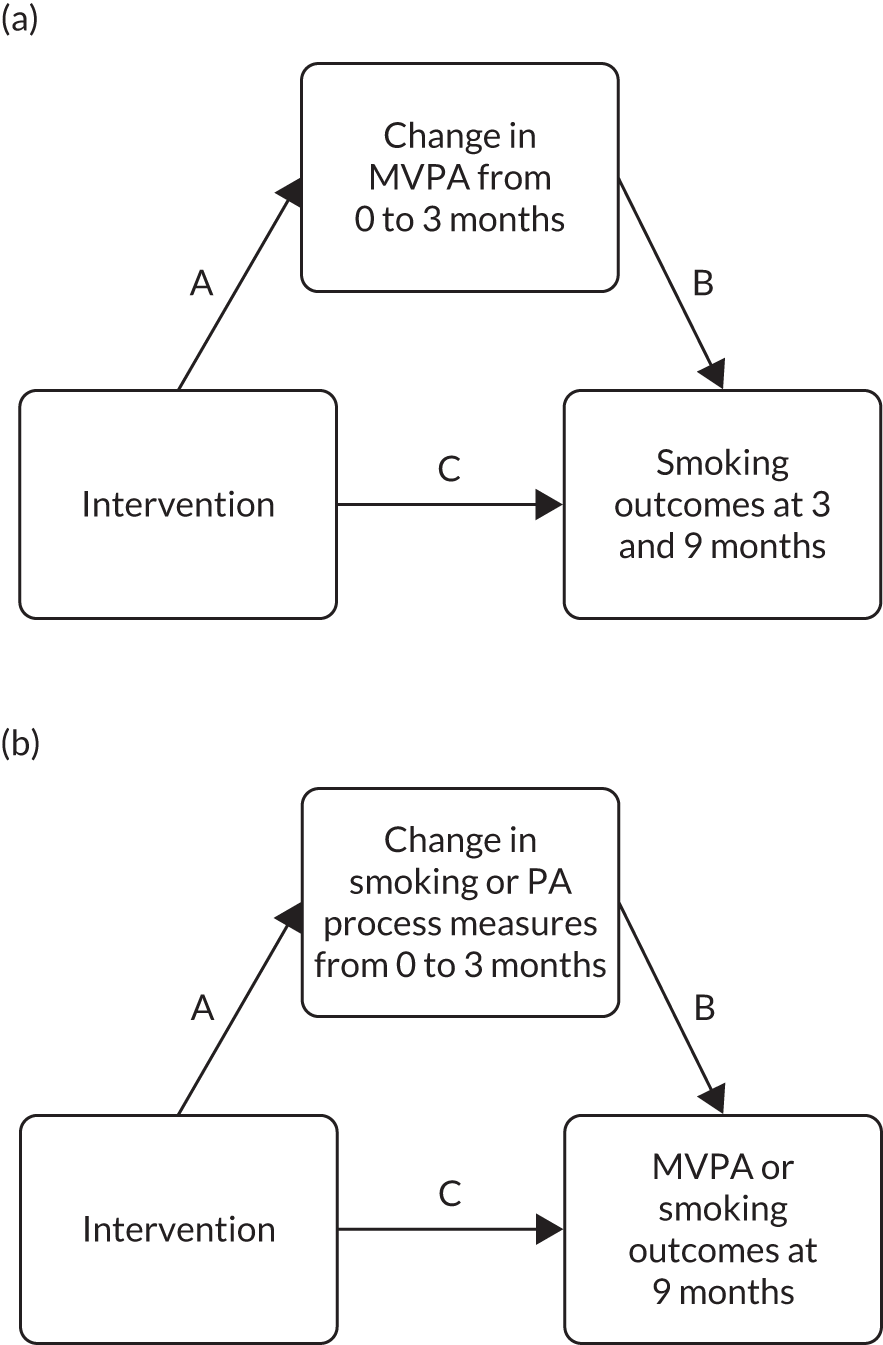

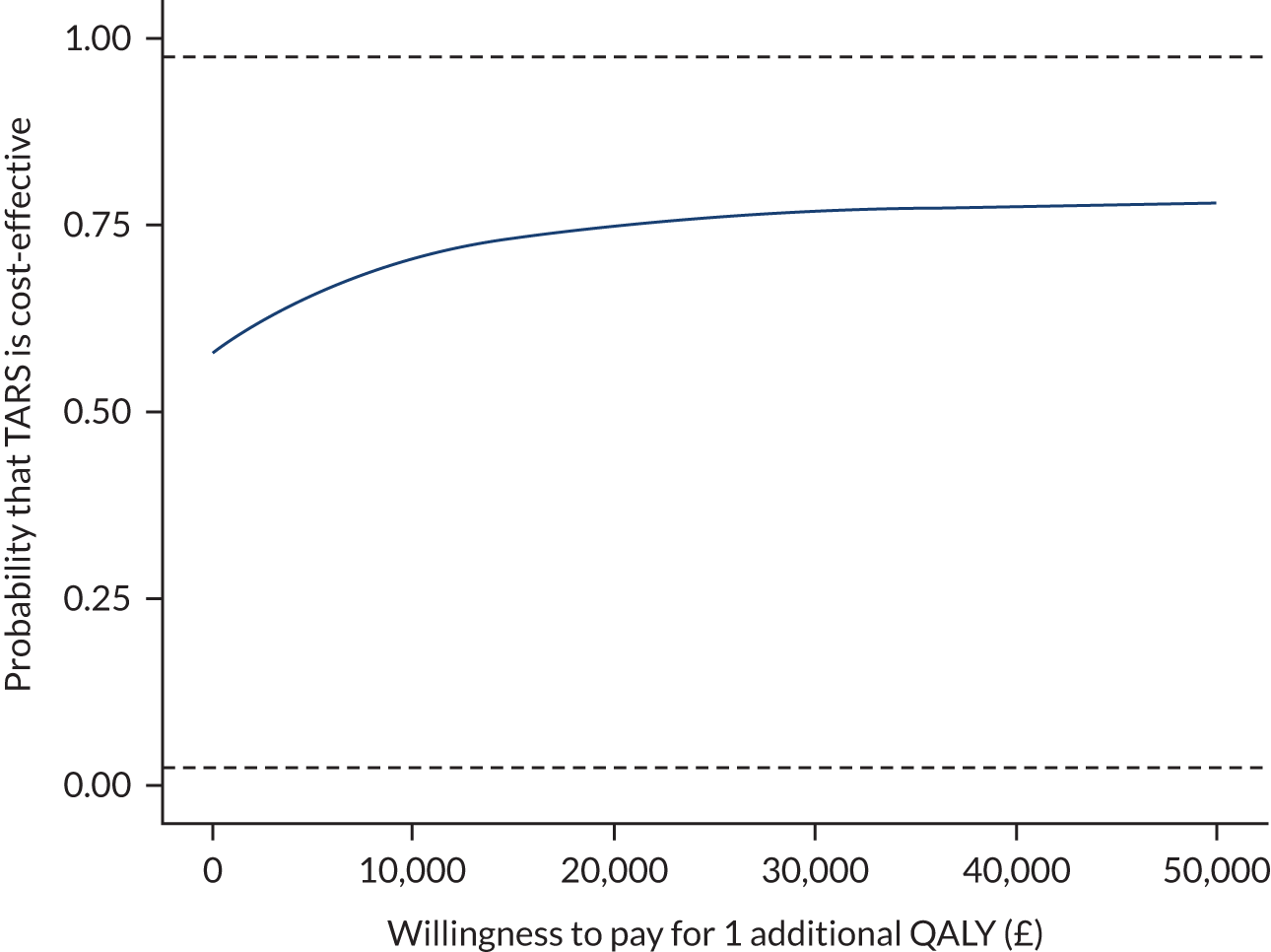

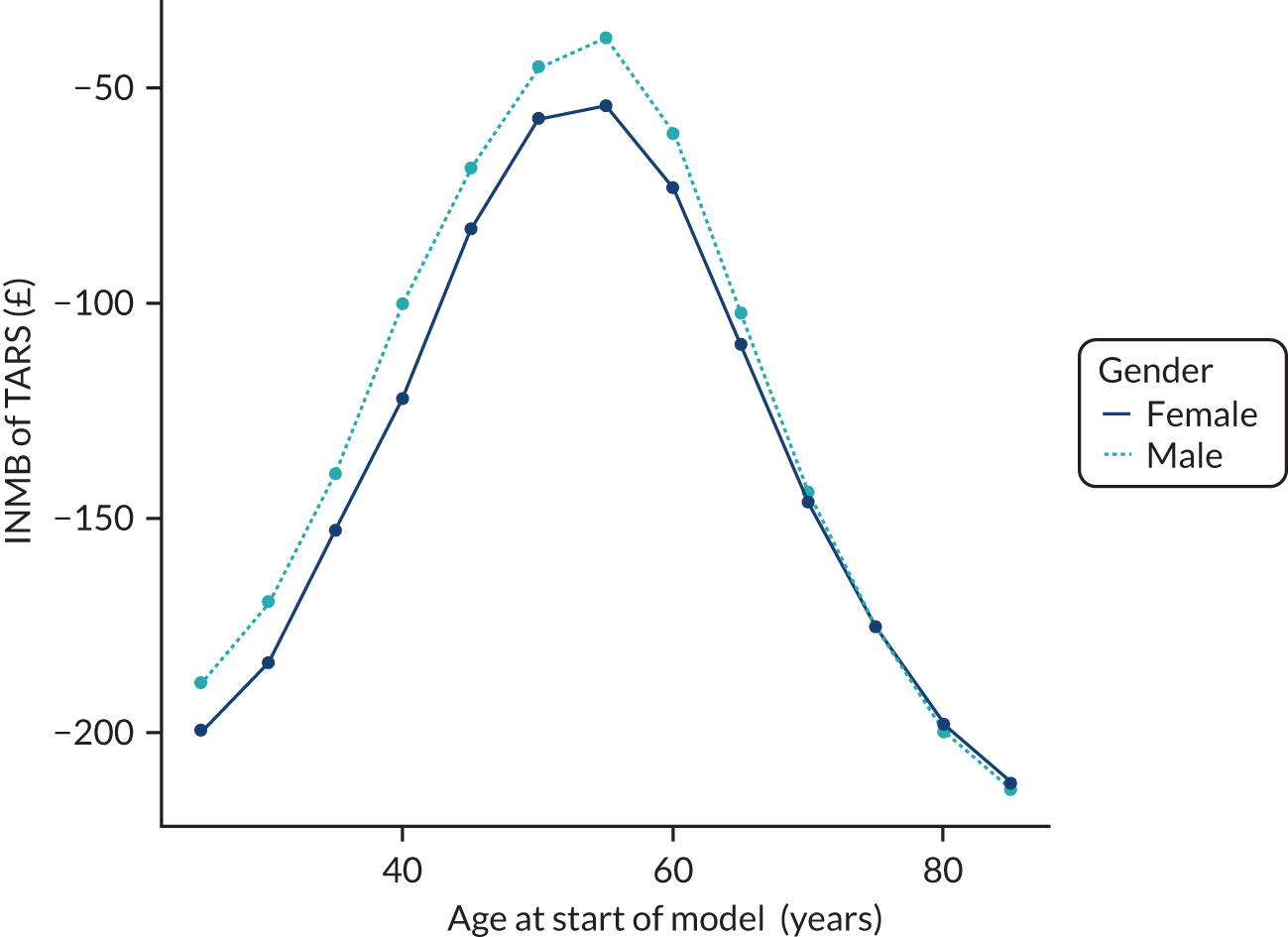

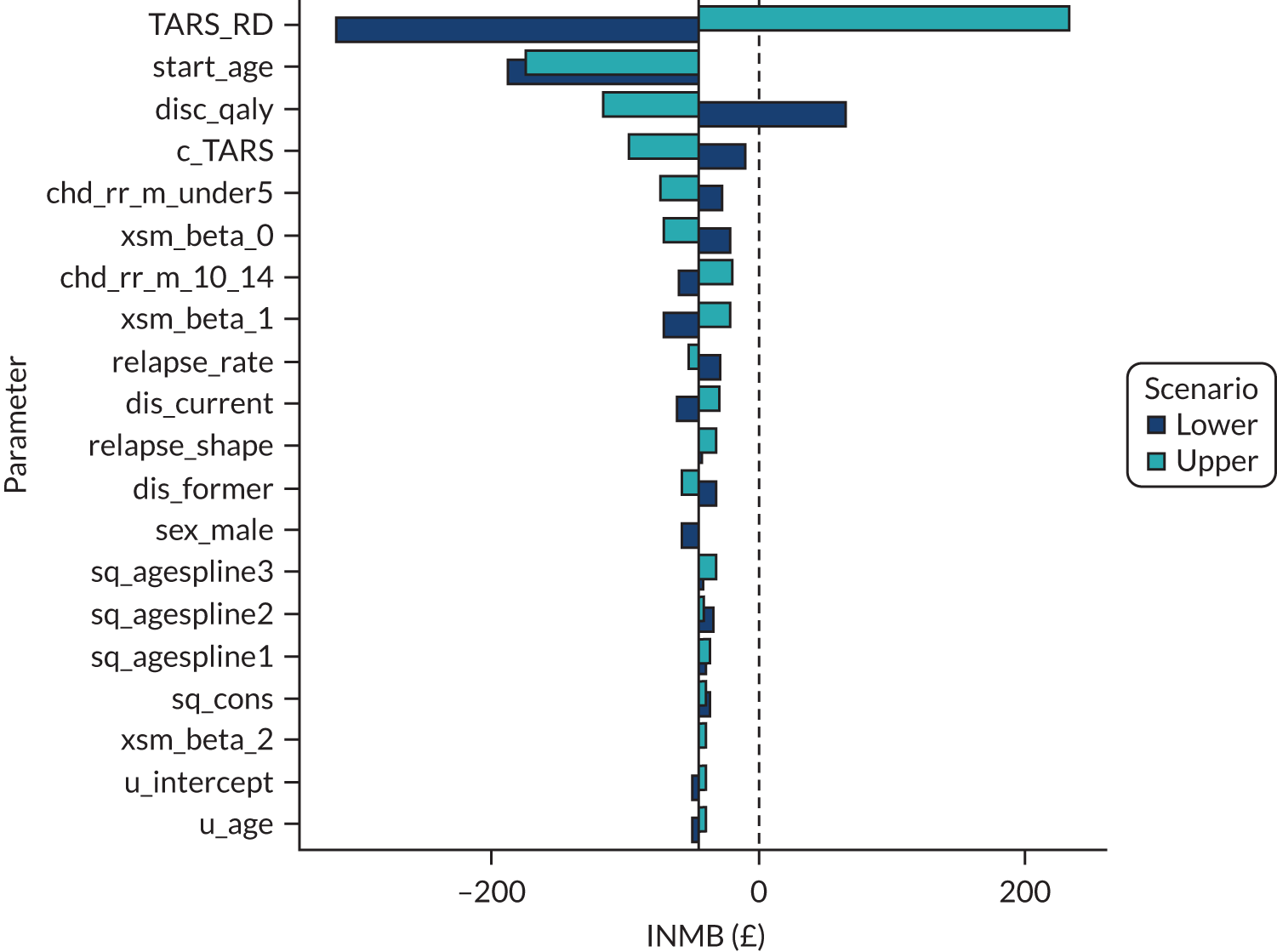

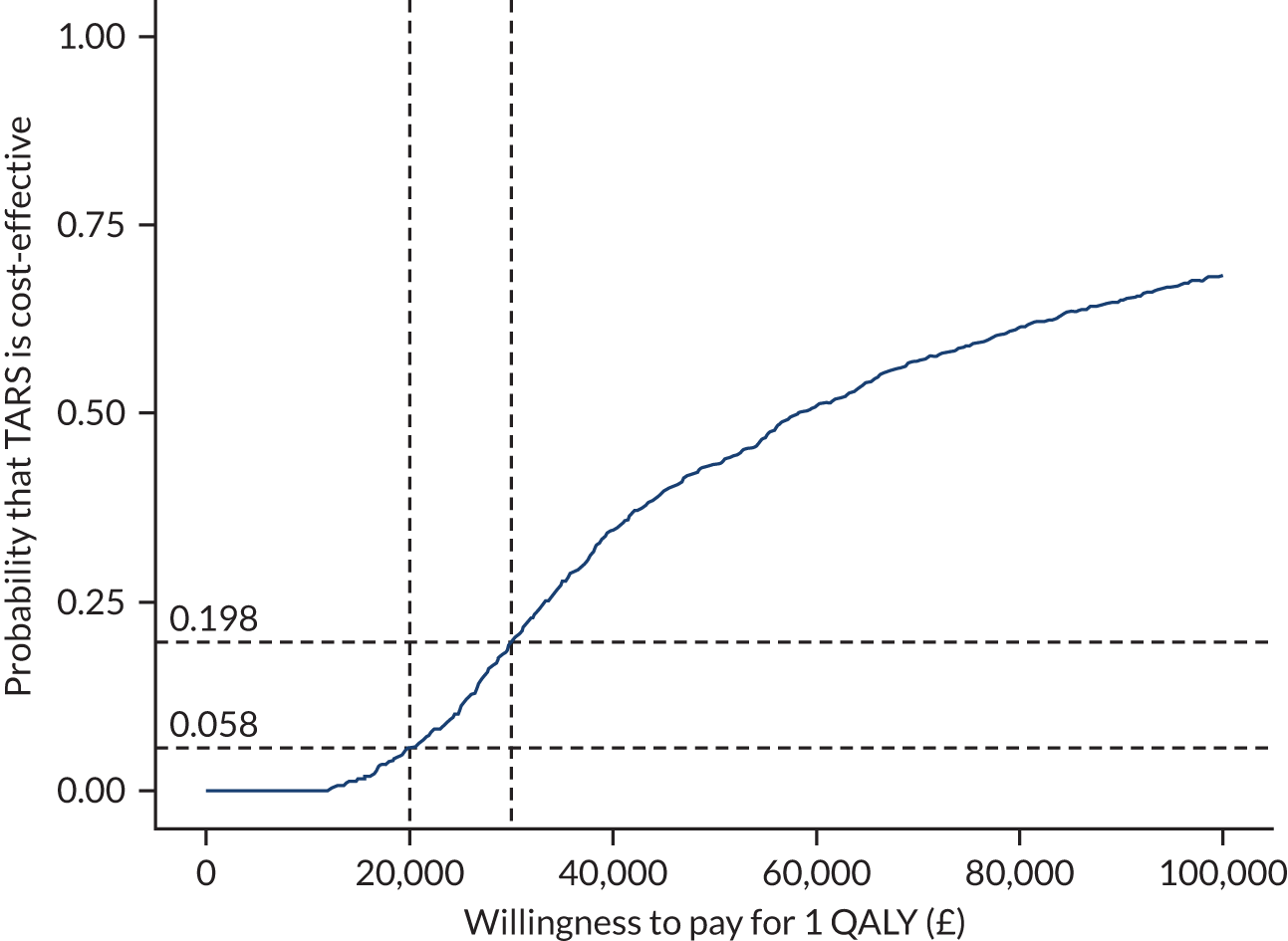

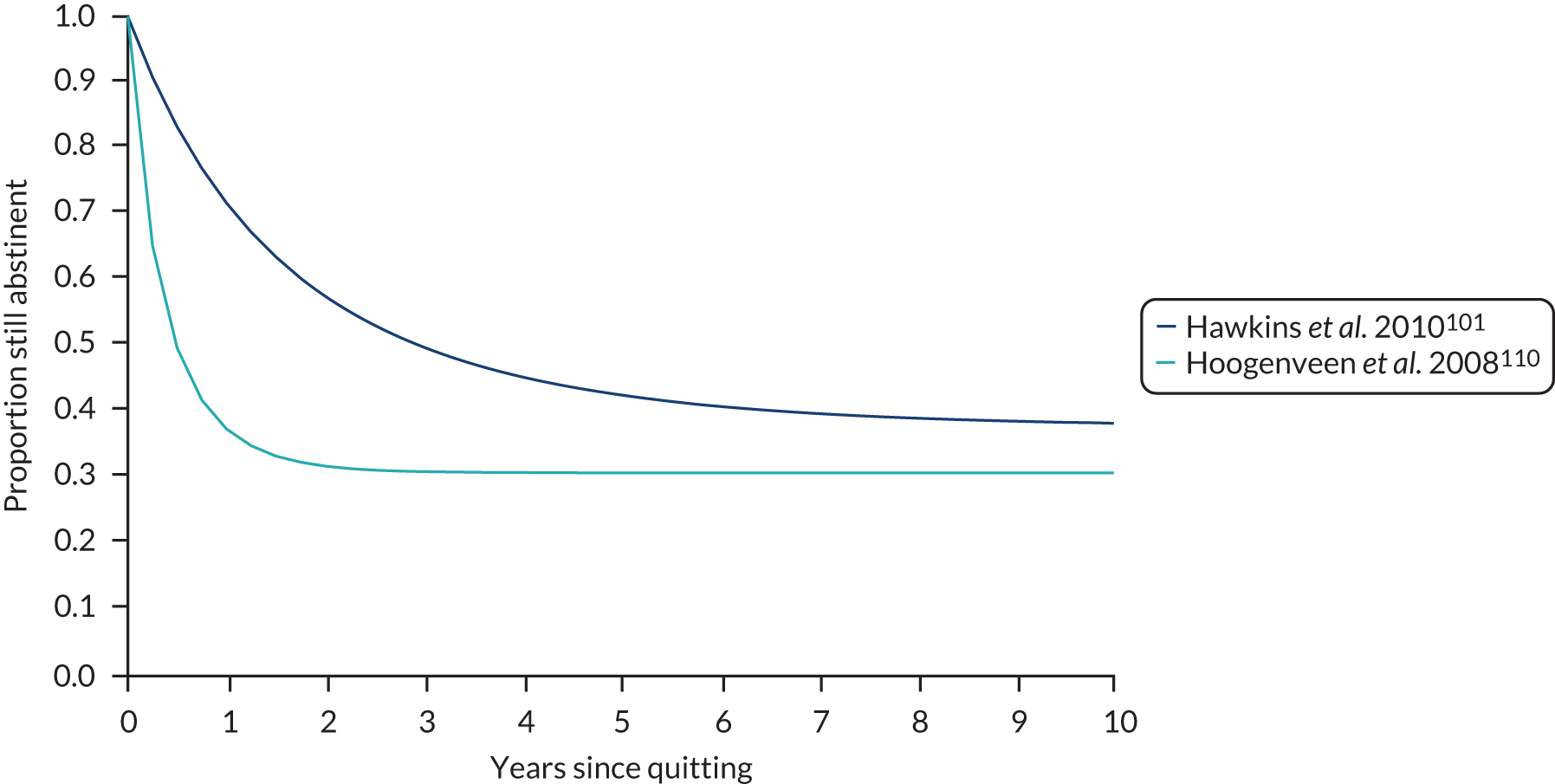

Secondary analyses (potential modifiers) of secondary outcomes