Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number NIHR129388. The contractual start date was in March 2020. The draft report began editorial review in February 2022 and was accepted for publication in July 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Cooper et al. This work was produced by Cooper et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Cooper et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Tendinopathy

Definition

Tendinopathy is the term used to describe a spectrum of changes in damaged or diseased tendons that lead to pain and functional impairment. 1 It is primarily a degenerative condition related to overuse and is characterised by dysfunction and localised pain with loading that is variably associated with a range of altered tendon structural features. 1 Tendinopathy can affect any muscle-tendon unit in the body; however, it is most reported in the Achilles, patellar, lateral elbow, rotator cuff (RC) and hip tendons. 2

Epidemiology

Tendinopathy is prevalent in many sports and at all levels of participation but also affects non-athletic populations. Children, adolescents and adults of all ages can be affected by tendinopathies, many of which have a chronic or recurrent course,2 with adults aged 18–65 most affected. Lower-limb tendinopathy has a reported incidence of 10.52 per 1000 person-years, which is greater than the incidence of osteoarthritis (8.4 per 1000 person-years). 3–5 The prevalence of upper-limb tendinopathies has been estimated between 1.3% and 21%. 6,7 Prevalence of tendinopathy increases with age and women are more likely to be affected than men. Tendinopathy is therefore a common, painful and functionally limiting condition for which those affected by it seek support from healthcare professionals. It is therefore essential that healthcare professionals have the best available evidence on which to base their management of tendinopathy.

Aetiology

The aetiology of tendinopathy is multifactorial and complex, with the exact pathogenesis unclear. 1 However, excessive repetitive loading without adequate recovery is widely recognised as a contributing factor to its onset and progression. 8 These increases in load are thought to make tendons susceptible to pathological changes and degeneration, where tendon capacity is insufficient to cope with the mechanical demand. Other risk factors are associated with specific genetic factors, drug reactions, inflammatory conditions and a range of cardiometabolic co-morbidities. 1 Therefore, treatment options for tendinopathy typically focus on reducing pain and improving function by managing load demand and improving capacity through exercise. There is evidence that heavy, slow, progressive loading remodels tendon tissue over the medium term. 9 Changes to structural outcomes such as neovascularisation and tendon morphology (cross-sectional area of tendon) have been reported as a response to therapeutic exercise. 10 However, there is a mismatch between tendon structure and the degree of tendinopathic function and associated pain as improvements in observable structural change do not necessarily translate to clinical outcomes. Additional modalities are often deployed in an attempt to improve outcomes,11 which are partial at best, as reflected in the lack of studies demonstrating long-term effectiveness.

Exercise therapy

Exercise therapy is the mainstay of conservative management of tendinopathy, often used as a first- or second-line intervention, with only a small proportion of individuals seeking surgery to alleviate pain. Exercise therapy frequently includes resistance exercise, which can be classified by training variables such as contraction mode (isotonic-eccentric,12 isotonic-concentric,13 isometric,12) or load intensity scaled relative to a maximum (e.g. moderate load or heavy load), or by a combination of factors (e.g. time under tension14). However, other types of exercise, including flexibility, proprioception and balance, and whole-body vibration, with varying dosage and intensity, have also been reported. 8,15,16 In experimental studies, the success of exercise therapy is often measured against alternative exercise types, or splinting, bracing, electro-therapy modalities, manual therapies, injection therapies or, less commonly, a control situation (placebo, sham or wait-and-see).

Exercise therapy comprises the bulk of the tendinopathy management research to date, with much of that research focussed on eccentric resistance training,8 reported to be effective primarily in the management of Achilles and patellar tendinopathies. Several exercise therapy protocols have been investigated, including the Alfredson protocol, which comprises eccentric-only action,17 and more mixed or combined protocols18–20 that emphasise eccentric work but also involve concentric exercise with a focus on power and progression by speed and load to simulate the mechanism of injury, which often occurs at higher velocities. 19 However, at present no single protocol appears to have demonstrated superiority.

Other types of resistance training, including isotonic, combined and heavy slow resistance exercise,18,21 have also been recommended for management of some tendinopathies (e.g. patellar12). In addition to contraction mode and intensity, other factors including overall dosage (e.g. intensity, volume and frequency) and contextual factors such as supervision may also play a role in efficacy of exercise for tendinopathy and have also been studied. 22–24

Range of movement and flexibility exercises are often incorporated within strengthening regimes to facilitate improvements in the early phase of rehabilitation. 8 In the rehabilitation of shoulder-related tendinopathies, proprioceptive exercise including movement retraining and sensing of force and joint position have been used to retrain normal patterns of muscle recruitment, with supportive evidence provided in trials and systematic reviews. 25,26 Similarly, balance and core stabilisation exercises have been recommended for patients presenting with lumbo-pelvic instability associated with patellar and Achilles tendinopathies. 15

Depending on the complexity of the tendinopathy involved, exercise may be used in isolation or as part of a multi-component intervention, where it is often combined with modalities including the use of extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT),27 laser therapy28 or corticosteroid injections or following regenerative procedures such as prolotherapy, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or stem-cell injection therapies. 29 This approach reflects current expert opinion and evidence syntheses that recommend exercise-based physiotherapy as the first-line management for tendinopathy with the addition of other interventions in recalcitrant cases. 2,11

Education is typically deployed alongside exercise and other interventions but is variably reported and has not had extensive intervention development and testing. There are encouraging indications of efficacy,30 indicating the need to establish the link with treatment adherence and outcome, particularly as adherence is often considered the main challenge to effectiveness of exercise interventions. 31

Rationale for the evidence synthesis

This body of work aimed to examine the evidence base on exercise therapy for tendinopathies, specifically evaluating the effectiveness of exercise therapies to make recommendations for practice and future research. Tendinopathy intervention studies can be placed on a continuum, with progression from efficacy (performance under ideal and controlled circumstances) to effectiveness (performance under ‘real-world’ conditions), in keeping with intervention studies in any field. 32 Most of the tendinopathy intervention research appears to comprise efficacy, rather than true effectiveness studies such as large simple or pragmatic trials. 31,33 The focus appears to have been on comparisons between interventions and the moderating effects of dosage,22 and contextual factors such as supervised versus unsupervised exercise,34 with highly selected, homogeneous populations, trained providers and standardised interventions. 32 This has inevitably impacted on the body of work reported here and scope of the practice recommendations that are made. Whilst the first contingent synthesis employed ‘effectiveness review methodologies’, it was expected that the synthesis would investigate efficacy given the composition of the included research.

Previous systematic reviews on exercise for tendinopathy have typically focussed on individual tendinopathies35 and where meta-analyses were deemed appropriate, these have generally focussed on small numbers of homogeneous studies of specific intervention types, compared specific exercise modes (e.g. eccentric vs. concentric), or considered exercise as a single entity. This approach does not offer comparative efficacy of the wide range of exercise interventions, leading to a lack of established hierarchy of tendinopathy interventions. This project aimed to address that gap, that is, to explore which exercise therapies are most effective across all tendinopathies and, where possible, within relevant subgroups.

With increasing pressure and demands on healthcare services, the need for clear evidence-based practice guidance is increasingly important. To synthesise evidence in such a way that it is optimally relevant to real-world clinical practice, it is important to consider the factors that may moderate exercise therapy efficacy, for example the feasibility of delivering, and acceptability of undertaking, specific exercise interventions. This project therefore incorporated synthesis of evidence in these domains alongside synthesis of evidence of efficacy.

Due to the heterogeneity of tendinopathy sites, target populations and exercise protocols, and the focus on efficacy, feasibility and acceptability, a broad and comprehensive evidence synthesis was essential. This body of work therefore comprises two main phases. Firstly, a large scoping review was undertaken to map the tendinopathies and exercise interventions that have been studied, and the outcomes that have been reported. This informed the design of the second phase, in which several efficacy reviews were undertaken, alongside a mixed-method review on feasibility and acceptability of exercise for tendinopathy.

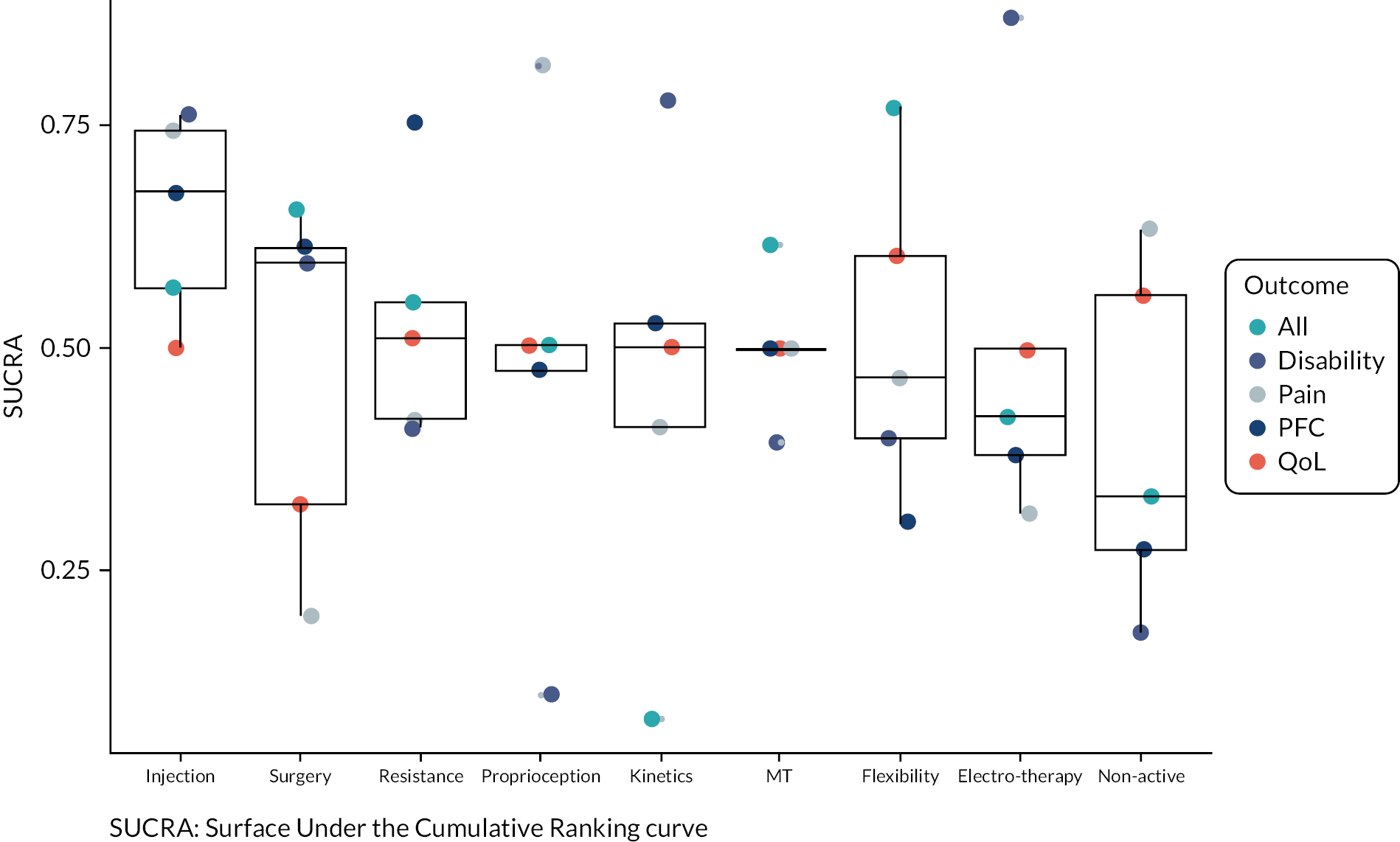

The novel approach for the efficacy reviews was to combine exercise-related research across all tendinopathies and to identify commonalities and heterogenic treatment effects, whilst also considering relevant variables and participant characteristics. We employed the use of a range of meta-analysis models including network meta-analyses (NMA) and meta-regressions where possible to best synthesise complex and heterogeneous data to compare the efficacy of different interventions across a range of tendinopathies and outcomes to better establish a treatment hierarchy. This extensive modelling approach was adopted to enhance existing knowledge regarding the most effective type of exercise therapy across multiple tendinopathy outcomes. This body of work is also novel in its simultaneous inclusion of evidence on efficacy, feasibility and acceptability of exercise therapy for tendinopathy. By conducting such a comprehensive evidence synthesis, it is possible to make some clear recommendations with direct implications for practice and service commissioners. Inevitably, findings from this synthesis have also identified gaps in the evidence base and recommendations are made that will guide future high-quality primary research and the prioritisation of research needs.

Structure of the report

The aim and specific review questions are outlined next (see Chapter 2), followed by the overall design for the body of work (see Chapter 3). The specific methods and findings of phase 1 (scoping review) are presented in Chapter 4. Thereafter, the specific methods and findings of phase 2 are presented in Chapter 5 (efficacy reviews) and Chapter 6 (mixed-method feasibility and acceptability review). Findings are discussed in each chapter, with a final synthesis and interpretation presented in Chapter 7 (discussion), along with recommendations for policy, practice, and research.

Chapter 2 Aim and objectives

The aim of this mixed-methods evidence synthesis was to examine the evidence base on exercise therapy for tendinopathies in order to make recommendations for clinical practice and future research. The specific review questions were as follows:

-

What exercise interventions have been reported in the literature and for which tendinopathies?

-

What outcomes have been reported in studies investigating exercise interventions for tendinopathies?

-

Which exercise interventions are most effective across all tendinopathies?

-

Does type/location of tendinopathy or other specific covariates affect which are the most effective exercise therapies?

-

How feasible and acceptable are exercise interventions for tendinopathies?

Review questions 1 and 2 were addressed by an initial scoping review. Thereafter, contingent systematic reviews were undertaken to address questions 3, 4 (effectiveness reviews) and 5 (mixed-method review).

Chapter 3 Overall design

Methodology

A mixed-method evidence synthesis was conducted in two phases in order to address the review questions (see Figure 1). This approach was informed by previous published work,36 which demonstrated its suitability for addressing clearly defined objectives and assimilating evidence according to relevance, rather than research design alone. This approach had also been employed by several of the review team members in a recent evidence synthesis workstream. 37

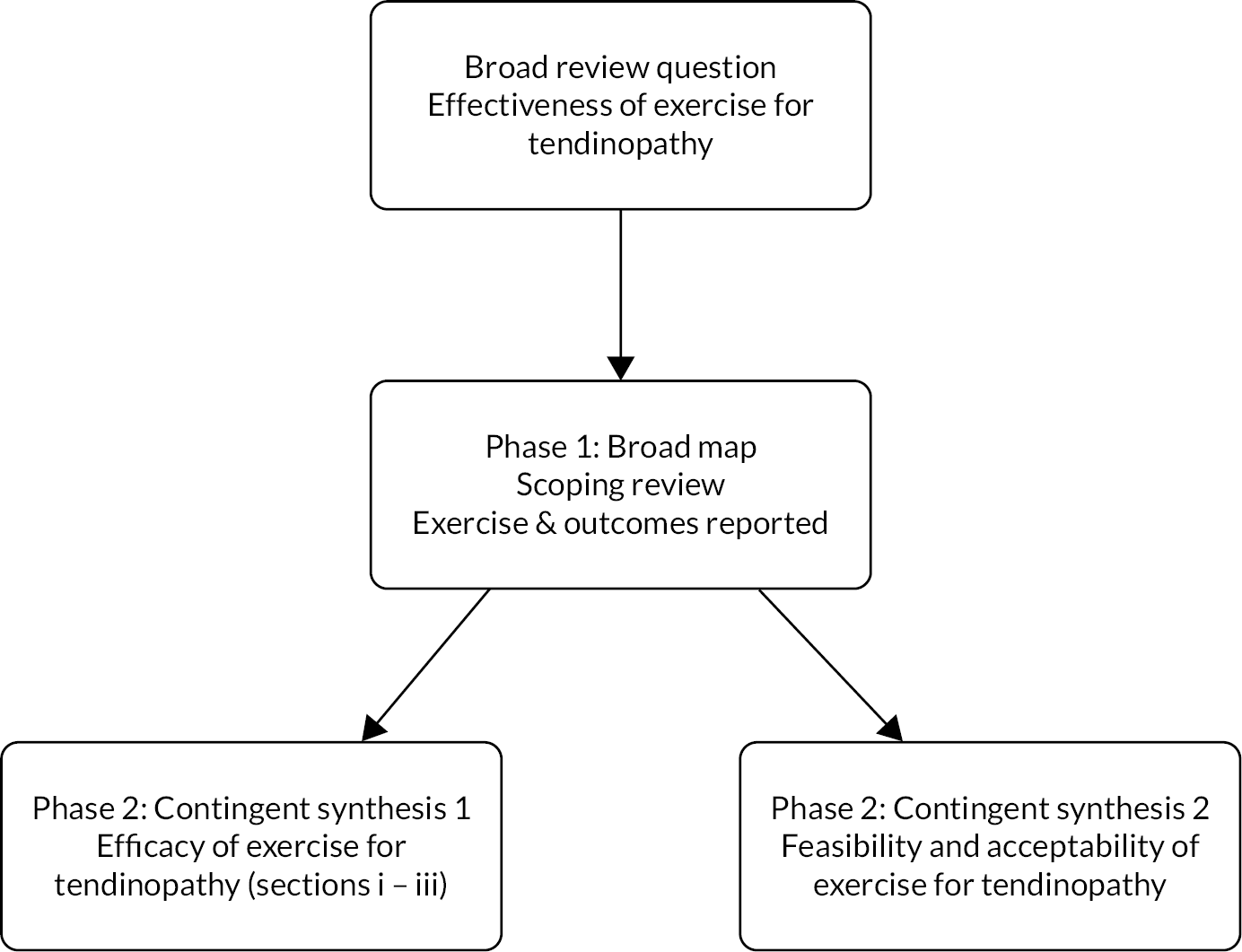

FIGURE 1.

Overall approach to the evidence synthesis, illustrating how the scoping review preceded the four contingent syntheses.

In phase 1 we conducted a comprehensive scoping review to map the tendinopathies, exercise interventions and outcomes reported in the exercise for tendinopathy literature. This enabled us to understand and describe the research field and informed the conduct of the contingent reviews by establishing the nature of the evidence, identifying domains that could be explored. Furthermore, it ensured we did not duplicate pre-existing high-quality syntheses. Few true effectiveness studies were identified, with most being conducted under controlled circumstances. Therefore, efficacy, rather than effectiveness, was explored in the contingent reviews. In phase 2 we conducted two workstreams: (i) efficacy of exercise for tendinopathy (consisting of three reviews) and (ii) feasibility and acceptability of exercise for tendinopathy (mixed-method review). Each review was informed by an a priori protocol and is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement38 and extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR). 39 Specific methods used in each review are reported in Chapters 4–6.

Population

The population for both phases of this evidence synthesis was people of any age or sex with a diagnosis of tendinopathy of any severity or duration and at any of the common anatomical locations. The terminology adopted for shoulder tendinopathy in the reviews was rotator cuff-related shoulder pain (RCRSP) as defined by Lewis (2016). 40 RCRSP describes the signs and symptoms of pain and impaired movement and function of the shoulder that may arise from one or more structures, and encompasses subacromial pain/impingement syndrome, RC tendinopathy and subacromial bursitis. 41 We have used the term RCRSP in this review in recognition of the difficulty in diagnosing the patho-anatomical cause of shoulder pain,40,41 and due to exercise therapy being the intervention of choice for its management. 42,43 We included studies where participants were described as having tendinopathy, subacromial impingement syndrome (as the terms have been used interchangeably in previous literature), or RCRSP. Therefore, participants with shoulder pain in our review may have tendinopathy with or without involvement of other structures. In keeping with previous research, we excluded large, full-thickness tears (for the shoulder and all other tendinopathies), and samples where tear size could not be determined. 44 We also excluded plantar heel pain as this is not considered to be a true tendinopathy and may respond differently to exercise compared to true tendinopathies. 45 We excluded hand and wrist tenosynovitis for the same reason.

The health technology

The health technology being evaluated was any type or format of exercise therapy for the treatment of any tendinopathy of any aetiology or duration. For the purpose of this review, exercise therapy was defined as any plan of physical activities designed to facilitate recovery or support longer-term self-management. Since physical activity is defined as ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure’,46 we included a broad range of exercise therapies, in isolation or combination. These included but were not limited to eccentric, concentric, heavy slow resistance, stretching, proprioceptive, cardiovascular and whole-body exercise. The exercise therapy could be used as a first- or second-line intervention for tendinopathy and could be delivered in isolation or with adjunct therapies including but not limited to manual therapies, ESWT, laser therapy, taping and splinting and various types of injection. The exercise therapy could be delivered in any setting including primary care, secondary care, community locations and in people’s own homes as a home exercise programme (HEP). A range of health or exercise professionals or support workers could be involved in delivering the exercise therapy, including but not limited to physiotherapists, medical doctors, strength and conditioning coaches and personal trainers. We included exercise therapy delivered in a supervised or unsupervised (self-management) manner in any setting, using any mode or delivery.

Stakeholder involvement

We involved stakeholders in two ways. Firstly, an individual with lived experience of exercise for tendinopathy who had previously contributed to developing the proposal was an active member of our project management group and study steering committee. She participated in meetings, reviewed public-facing materials and assisted us with interpreting findings from the lived experience viewpoint. An NHS specialist musculoskeletal physiotherapist with an interest in tendinopathy also contributed to the project management group. She contributed to meetings, reviewed output and assisted with interpreting findings from the practitioner’s viewpoint. We had anticipated recruiting more than one person with lived experience and one professional to be involved in the management of the review. However, recruitment coincided with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many professionals were advised to cease non-essential activities. This and the move to exclusively online communication were undoubtedly limiting factors. Nonetheless, the two stakeholders provided valuable input to the design and delivery of the review.

We held stakeholder workshops towards the end of phase 1 (scoping review), to inform the design of the contingent reviews. These were originally intended to be face-to-face events held in Aberdeen and London but were instead delivered online via Microsoft Teams due to COVID-19 restrictions on gatherings. People with lived experience of receiving exercise for tendinopathy (general population and performance athletes), strength and conditioning professionals and health professionals took part in two workshops, which provided valuable insight to assist interpretation of the scoping review findings and informed planning of the contingent syntheses. In addition to the workshops, largely due to the success of the online environment for widening participation, we also used an electronic survey as an additional means of involving additional stakeholders, particularly those based in different countries and time-zones for whom workshop participation would have been challenging. In this way we were able to approach internationally recognised authors in the field of tendinopathy and combine their views with those from the stakeholder workshops, providing a comprehensive interpretation of the findings. We also asked these internationally recognised authors to share the survey using their social media channels, thereby increasing its reach. Full details of the workshops and survey are provided in Chapter 4.

We are in the process of planning dissemination workshops for late 2022, which will be held via a combination of online and face-to-face delivery methods. We will invite participants from the workshops, and will recruit additional participants from NHS, private practice, performance sport, academia and the public to a series of workshops where we will present the findings of the contingent syntheses and seek participants’ views on implementation of the findings into practice and future research. This will ensure that we translate the findings of this evidence synthesis across the research-practice gap.

Stakeholder involvement in this review was therefore commensurate with recommendations specific to systematic reviews,47 with varying levels of involvement at various stages throughout the review. Table 1 maps user involvement in this review to the Authors and Consumers Together Impacting on Evidence (ACTIVE) framework48 and reporting of user involvement has been guided by the GRIPP2 checklist (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of patients and the Public 2). 49

| Framework constructs | Involvement in this evidence synthesis |

|---|---|

| Who was involved? |

|

| How were they recruited? | Advertised via

|

| Approach | Combined approach

|

| Methods | Direct and indirect methods used, dominated by direct

|

| Stage and level of involvement |

|

Chapter 4 Phase I: Exercise therapy for tendinopathy: a scoping review

Review 1 summary

This chapter reports on phase 1, which aimed to map the tendinopathy exercise interventions and outcomes reported in the literature via a Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scoping review. Eligibility criteria included Participants (any age or gender with any tendinopathy), Concept (supervised or unsupervised exercise of any type or format, delivered by any professional with any outcome evaluated) and Context (any setting in any highly developed country). A comprehensive search strategy identified 22,550 sources of evidence. Following screening, 555 studies were included representing 25,490 participants from 31 countries. A range of exercise interventions were reported including strengthening, flexibility, aerobic, proprioceptive and motor control exercises; we mapped intervention reporting to the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist. The main tendinopathies reported were RCRSP, Achilles, patellar and lateral elbow. A range of outcome measurement tools were reported; we mapped these to the International Scientific Tendinopathy Symposium Consensus (ICON) health-related domains for tendinopathy. The scoping review results, combined with the stakeholder workshops and survey that followed, directly informed the focus and methods of the Phase 2 contingent syntheses.

This chapter has informed the following manuscript:

Alexander, L.A., et al. Exercise therapy for tendinopathy: A scoping review mapping interventions and outcomes. SportRxiv preprint doi: https://osf.io/a8ewy/.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with JBI scoping review methodology50 and an a priori protocol was published in JBI Evidence Synthesis. 51 JBI scoping review methodology is the most up-to-date guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. It is based on the foundational framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley52 and further developed by Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien. 53 JBI methodology50 built upon the previous approaches and developed comprehensive guidance for reviewers who are planning and conducting a scoping review. This scoping review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR. 39

The aim of this scoping review was to comprehensively map the existing evidence on exercise for the management of tendinopathies, addressing the first and second review questions:

-

What exercise interventions have been reported in the literature and for which tendinopathies?

-

What outcomes have been reported in studies investigating exercise interventions for tendinopathies?

The results of this scoping review subsequently informed the contingent systematic reviews reported in Chapters 5 and 6.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were defined for this scoping review using the ‘PCC’ mnemonic relating to the Participants, Concept and Context, and informed by the definitions of participants and health technology provided in Chapter 3.

Participants

As described in Chapter 3, we included sources of evidence where participants were people of any age or gender with a diagnosis of tendinopathy of any severity or duration and at any anatomical location.

Concept

As described in Chapter 3, exercise interventions that could be categorised as one or more of strengthening, flexibility, aerobic, proprioception or motor control were included. They could be first- or second-line interventions and could be used in isolation or in combination with other interventions. Studies focussing on exercise following surgical repair were excluded as the review concerned non-surgical management of tendinopathy. Exercise interventions delivered by any health, exercise professional or support worker, either supervised or unsupervised, were included. Any outcomes used to evaluate exercise interventions for tendinopathy were included.

Context

Any setting including primary care, secondary care, community locations, clinics or people’s homes in any nation classified as having very high human development (defined as the top 62 ranked countries in the 2019 Human Development Index (HDI))54 at the time of conducting the review were included. The top 62 HDI countries were categorised as having ‘very high human development’ and included the UK, therefore findings from studies conducted in any of these 62 countries could be considered for generalising to the UK setting.

Search strategy

Following the JBI three-step search strategy, an initial search using exercise and tendinopathy terms was conducted in CINAHL and MEDLINE (step 1). Review of the titles, abstracts and index terms from the initial search results informed the development of a full search strategy that was constructed using a combination of subject headings and keywords which was then tailored to each database (step 2). The full search strategies for all databases and grey/unpublished literature were developed by the review team, which comprised experienced reviewers (n = 4), subject experts (n = 5) and a specialist information scientist. The search strategies were piloted and amended by the team before the final searches were conducted to ensure specificity and sensitivity. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, CINAHL, AMED, SPORTDiscus (all EBSCOhost), EMBase (Ovid), Cochrane library (Controlled trials, Systematic reviews), JBI Evidence Synthesis, PEDRo and Epistemonikos. Grey and unpublished literature was searched using trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN Registry, The Research Registry, EU-CTR [European Union Clinical Trials Registry], ANZCTR [Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry]), Open Grey, MedNar, The New York Academy Grey Literature Report, Ethos, CORE, and Google Scholar using modified search terms. All searches were conducted in April 2020 and the full search strategies are presented in Appendix 1.

Sources of evidence published in any language where a translation was accessible via Google Translate or the review team’s international networks were included. The seminal publication of Alfredson et al. ’s17 eccentric protocol for Achilles tendinopathy (AT) marked the start of a proliferation of high-quality research on the efficacy and explanatory mechanisms of well-described exercise interventions for tendinopathy. Therefore, databases were searched from 1 January 1998 onwards.

Step 3 usually involves hand-searching the reference lists of included studies. However, due to the comprehensive search strategy and volume of studies located and in consultation with our steering committee, it was decided not to conduct this step for the scoping review. Instead, we employed citation tracking using Scopus and hand-searching of reference lists of studies included in the scoping review as part of the efficacy review search strategy. The citation analysis enabled the review team to understand where articles were published (which journals and country), who was using the articles as well as identifying collaborative work between countries.

A range of study designs were included in this scoping review to ensure a comprehensive map was produced. The included study designs were experimental, quasi-experimental, observational, pilot, mixed-methods, qualitative and systematic review. The inclusion of systematic reviews enabled previous evidence syntheses to be mapped in order to avoid replication in the contingent reviews. Other designs including opinion, narrative or other non-systematic reviews, protocols and case studies were excluded.

Screening for inclusion

Following the search, all results were uploaded into ProQuest® RefWorks and duplicates were removed. Sources were then imported to Covidence (Melbourne, Australia) systematic review management software for two-level screening, following the identification and removal of remaining duplicates identified by Covidence. Firstly, titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers with conflicts identified by Covidence and resolved by a third reviewer. The full-text copies of all sources included following title and abstract screening were uploaded to Covidence. The full texts were then screened by two reviewers independently and all conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer. Training for all reviewers using the inclusion criteria was conducted in Covidence prior to the start of title and abstract screening. Ongoing communication occurred between reviewers throughout the screening stage via weekly team meetings and posts in Microsoft Teams. This enabled all queries around screening to be addressed in a timely manner. All sources excluded at full-text screening stage and the reasons for exclusion are available as supplementary material (Supplementary Material 1). Following full text screening, four tendinopathy experts external to the review team also reviewed the included study list for completeness.

Data extraction

A bespoke data-extraction tool (Supplementary Material 2) was developed for this review in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The tool was used to extract study demographic details as well as data related to the review questions.

The following demographic information was extracted from the included primary studies: author(s), year of publication, country, study title, aims/purpose, study design, participant details (age, gender, ethnicity, comorbidities and other characteristics), inclusion criteria, setting and tendinopathy diagnosis method. Extracted data relating to the review questions included: body area affected, tendinopathy type, the author’s focus on exercise, that is, primary (exercise as the novel intervention being studied), secondary (exercise as the control arm to another novel intervention) or neutral (exercise being compared with other intervention/s where neither is the novel intervention or main focus of study); exercise intervention details including reporting and monitoring; treatment adjuncts; primary and secondary outcomes including health domains and tools used to evaluate interventions, and key findings.

Data extraction from included systematic reviews was limited to demographic information including year of publication, author(s), country, aims/purpose, study type, number of included studies, inclusion criteria, settings, body area affected and tendinopathy type, as information on interventions and outcomes was extracted from the primary studies.

Piloting and iterative development of the data-extraction tool was conducted by the review team over ten rounds prior to commencing final extraction. Ten per cent of data extraction was replicated in an informal assessment of consistency that was identified as appropriate and reflected the extensive piloting and discussions among the review team. As per the screening process, data extraction was supported by the weekly team meetings and regular Microsoft Team chat. In accordance with scoping review methodology, critical appraisal was not conducted in this review. 50

Data synthesis

The extracted data were synthesised and integrated into a series of visual outputs to answer the review questions and present a comprehensive map of exercise interventions and outcomes; data are presented alongside an accompanying narrative in the Results section.

Extracted exercise intervention component data were mapped against the TIDieR checklist55 to identify if full and accurate reporting of interventions had occurred. The review team modified the TIDieR checklist for the purposes of this scoping review. The TIDieR template requires one to identify and note the location of each criterion in the study and supporting detail. The review team added to each criterion a grading of ‘Fully reported’ (if criterion was fully described), ‘Partially reported’ (if some components of the criterion were described but lacked detail) and ‘Not reported’ (if there was not enough detail to satisfy a partially reported definition). An additional criterion was then added by the team to reflect overall reproducibility of the intervention which reflected ‘Fully reproducible’ (all criteria fully reported to enable replication of the intervention), ‘Partially reproducible’ (if exercise components were described (what, when and how much) but other components were not reported (e.g. where, who)) and ‘Not reproducible’ if there was not enough detail to satisfy a partially reproducible definition. This allowed an evaluation of overall reproducibility of each intervention as a whole to facilitate reporting and clearer interpretation. For the ‘When and How much’ criterion, the intervention details were extracted on how often the intervention was delivered, over what time period, number of sessions in total, duration, intensity, dose and volume. For the ‘Tailoring’, ‘Modification’, and ‘How well’ criteria, details were extracted for each (including what, when, why and how the intervention was tailored or modified during the study, how adherence or fidelity was assessed, by whom, and strategies to improve and the actual adherence or fidelity reported).

The outcomes were recorded as domains informed by the ICON health-related domains. 56 For completeness, we adopted the 24 candidate domains identified at stage one of the ICON Delphi process to fully map all domains reported in the included sources, rather than the nine core domains finally recommended by Vicenzino et al. 56

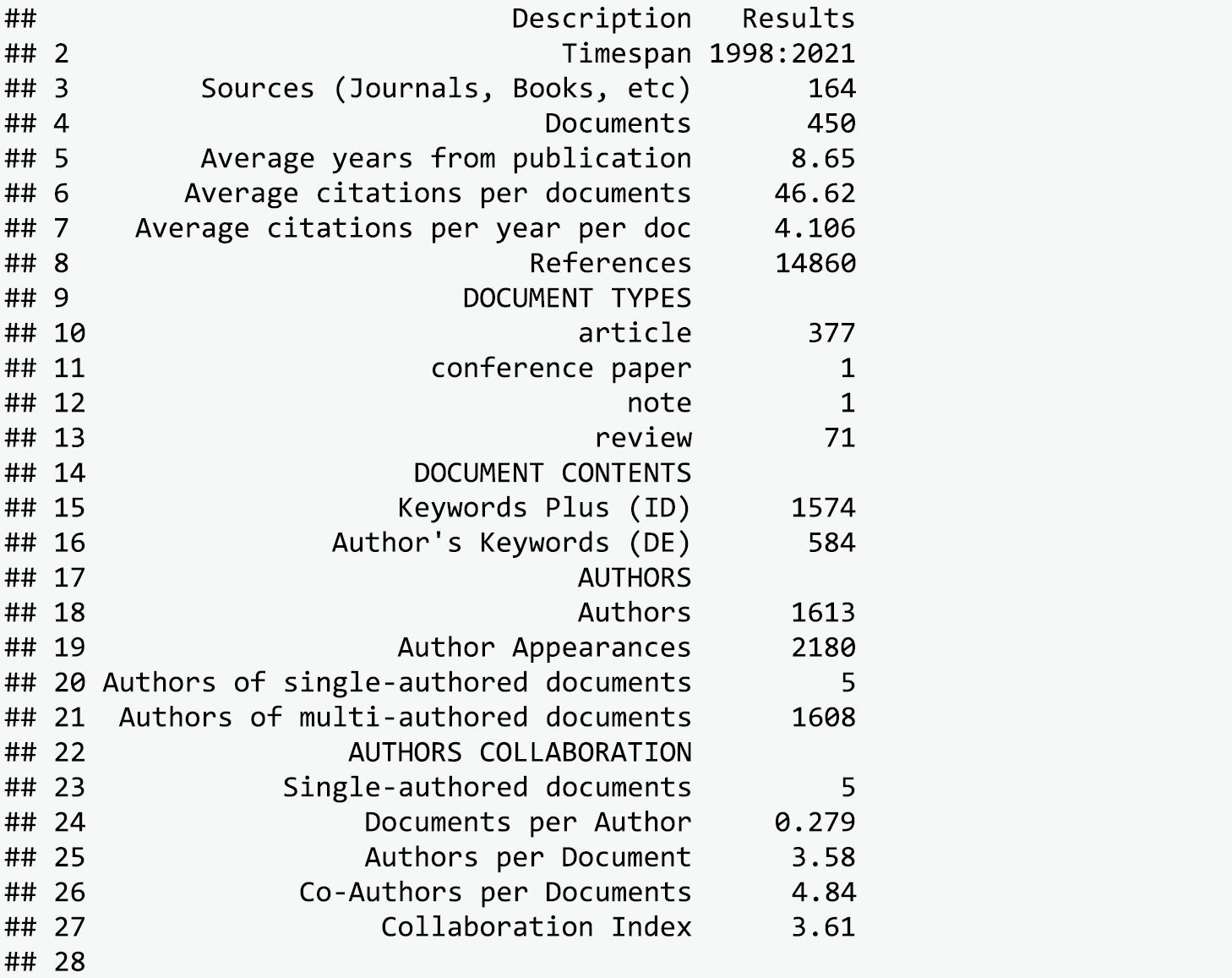

All data were imported from the MS Excel spreadsheet and analysed in the R programming environment (v.4.1.2; R Core Team 2021). 57 A citation analysis was also conducted using citation, bibliographical, author and keyword information obtained from Scopus and Bibliometrix. 58

Results

Description of included studies

The search identified 22,550 sources, of which 1994 were obtained in full text following deduplication and title and abstract screening. A further 1439 sources were excluded following full-text screening, leaving 548 studies from a total of 555 total sources, as seven studies were reported in more than one source. The main reasons for exclusion at full-text screening were wrong study design (n = 600, 42%), duplicate study (n = 351, 24%), wrong population (n = 150, 10%), wrong concept (n = 101, 7%) or not originating from a very highly developed country (n = 99, 7%) (see Supplementary Material 1). The study selection process is presented in Figure 2 and a table of included studies is presented in Table 33, Appendix 2.

FIGURE 2.

Study selection process – PRISMA flowchart.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

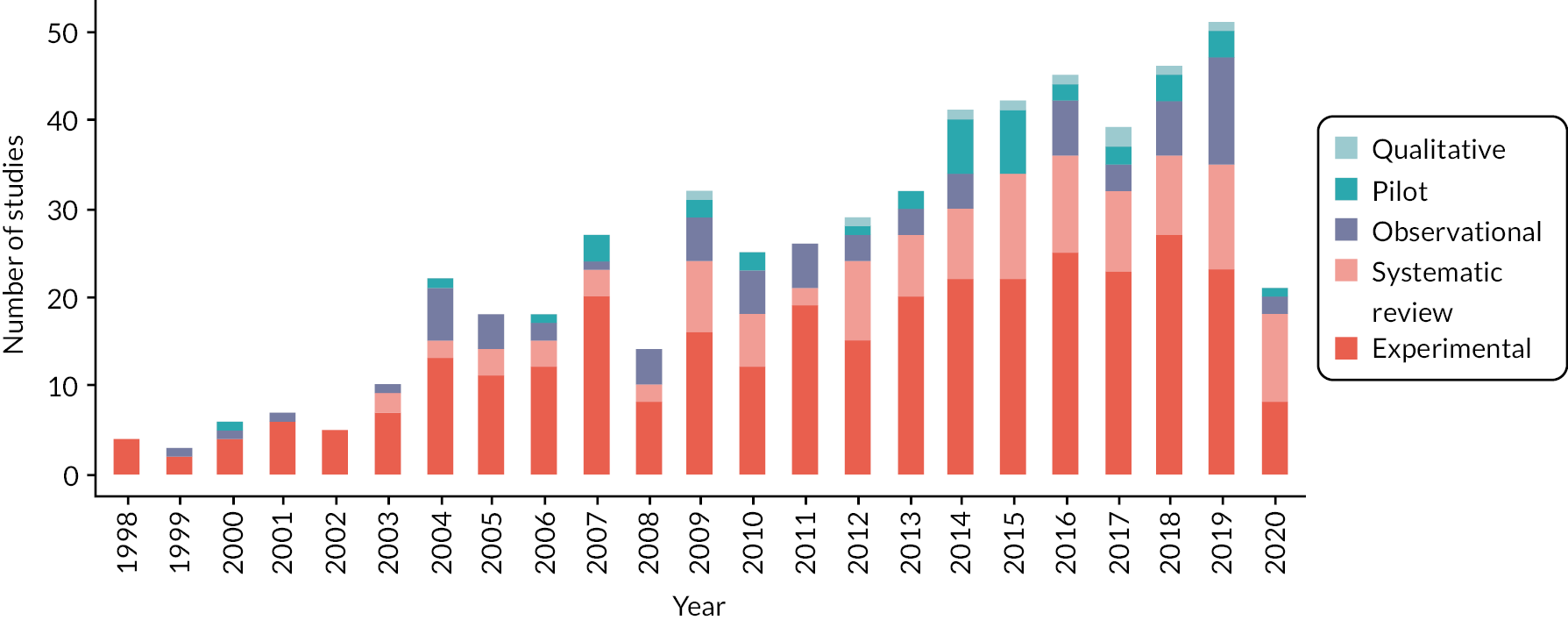

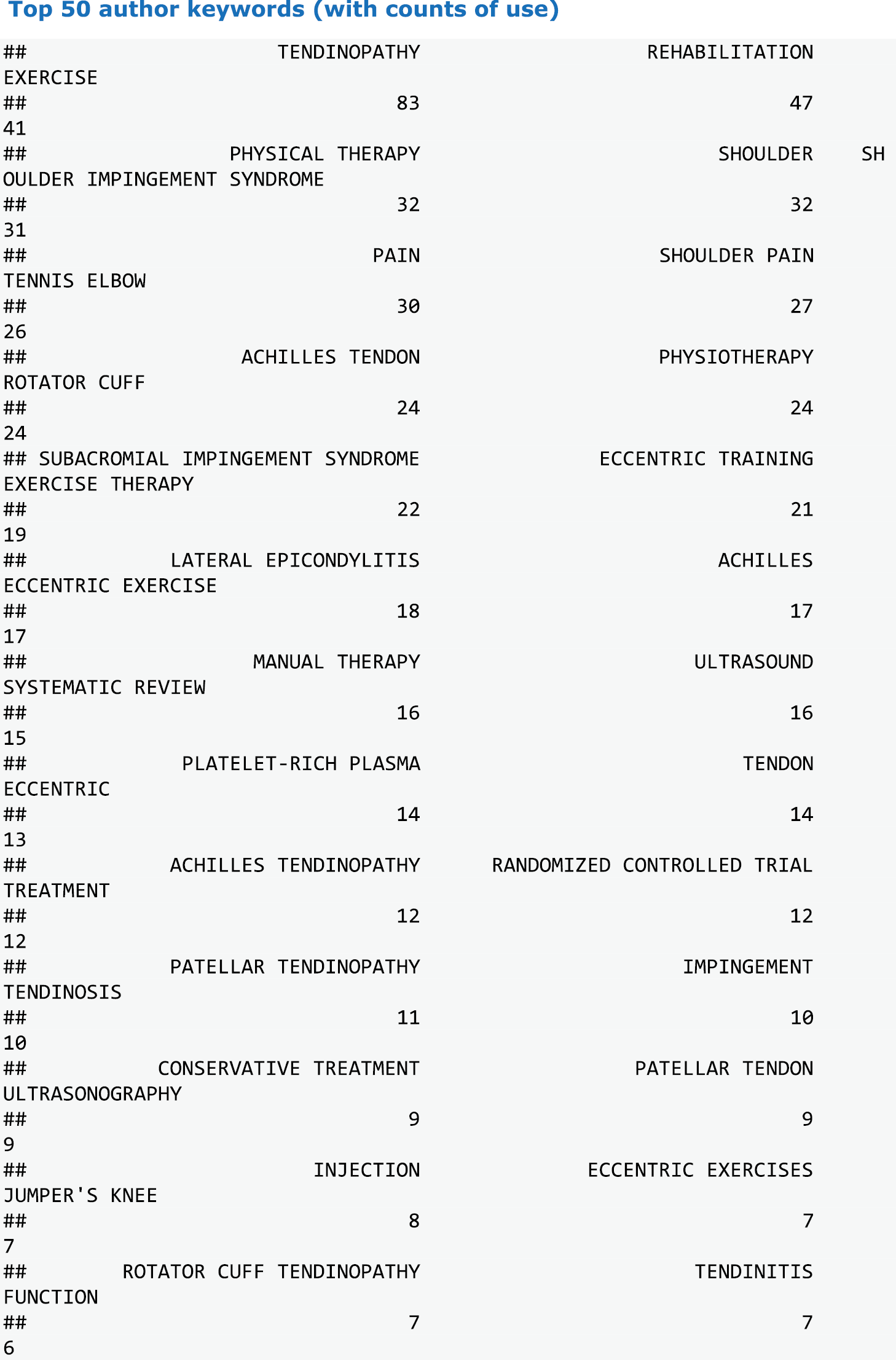

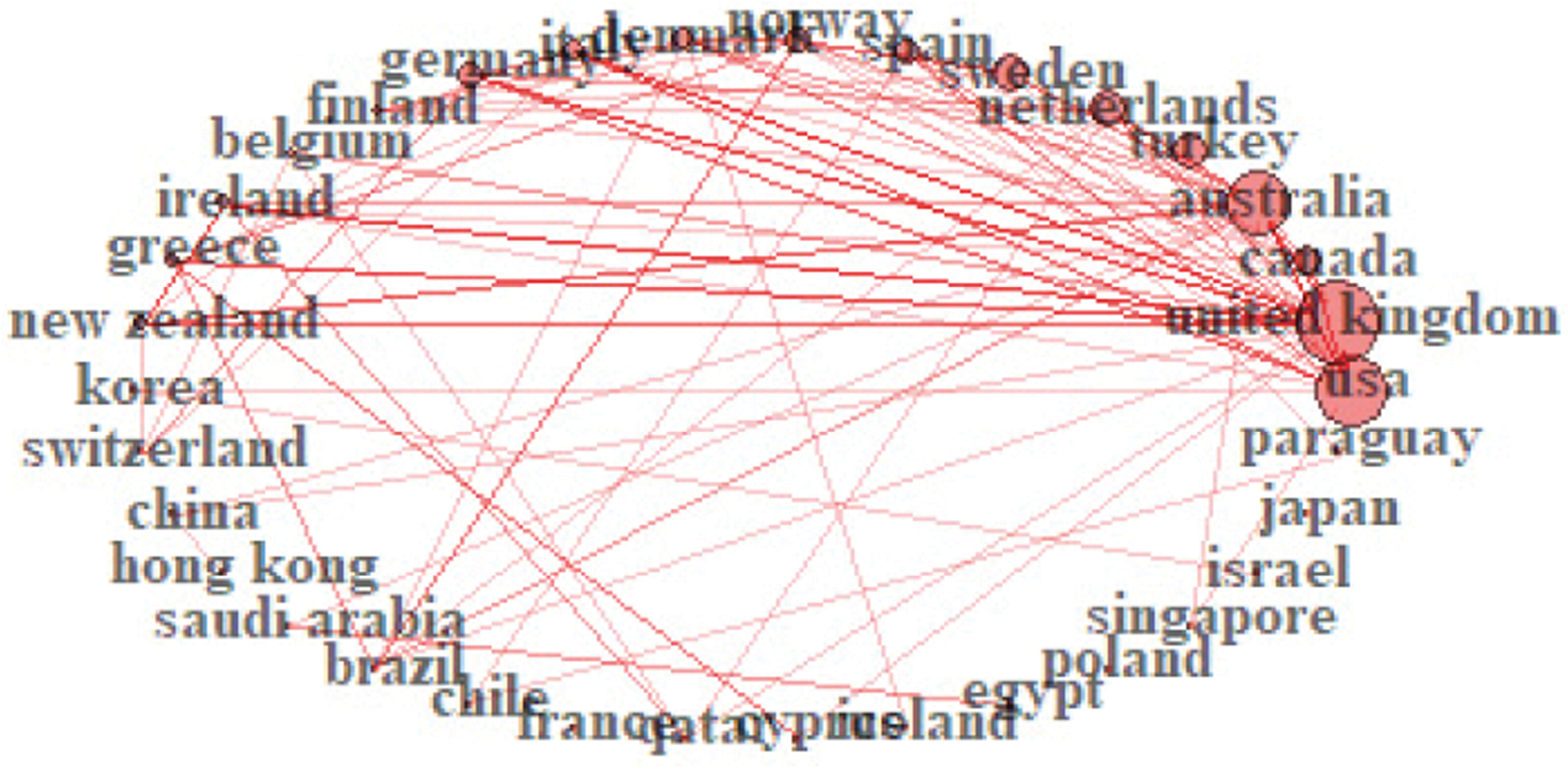

The 555 included sources comprised 119 (21%) systematic reviews and 436 (79%) primary studies. Sources were mostly published in English (n = 539; 97%), with 3% published in German (n = 6), Turkish (n = 5), Spanish (n = 3), Italian (n = 1) and Norwegian (n = 1). Automated translation was used for five sources, with the remainder being translated by colleagues of the review team. Assessment of the included studies’ publication dates identified a consistent increase in the volume of research from 1998, reaching a peak of 50 studies published in 2019 and an average of 37 studies published each year between 2010 and 2019 (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Number of included studies published over time and their study design.

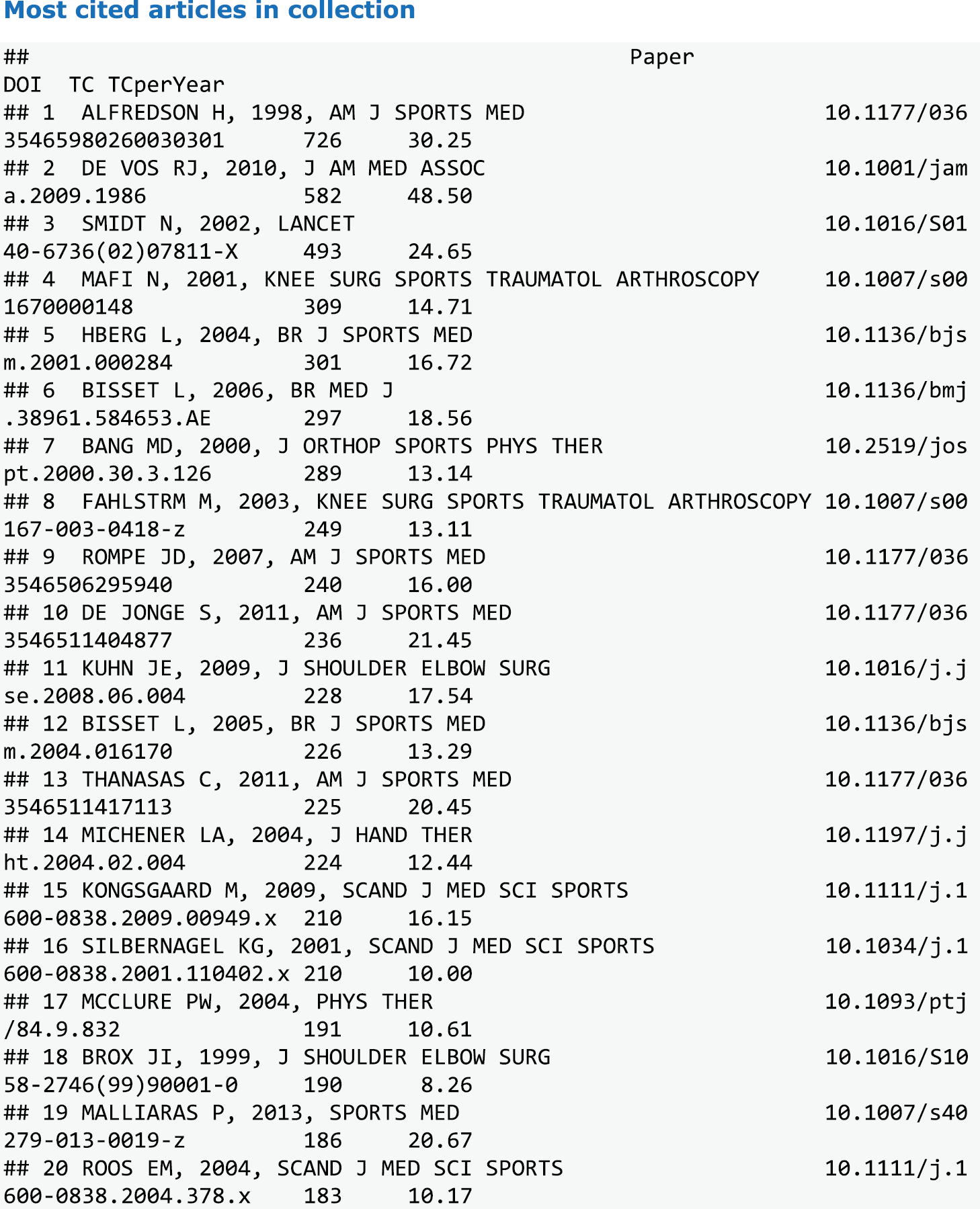

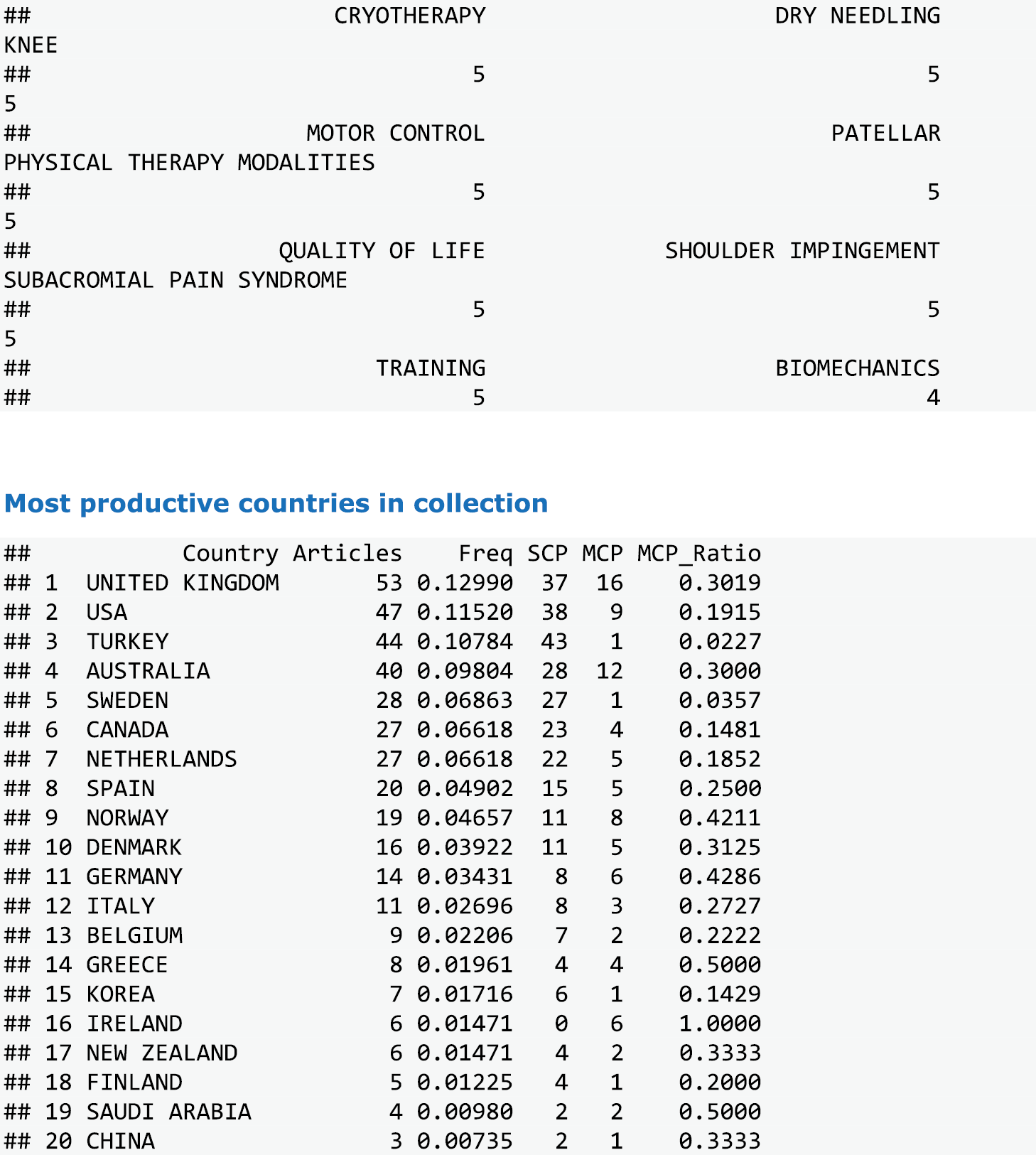

Citation analysis

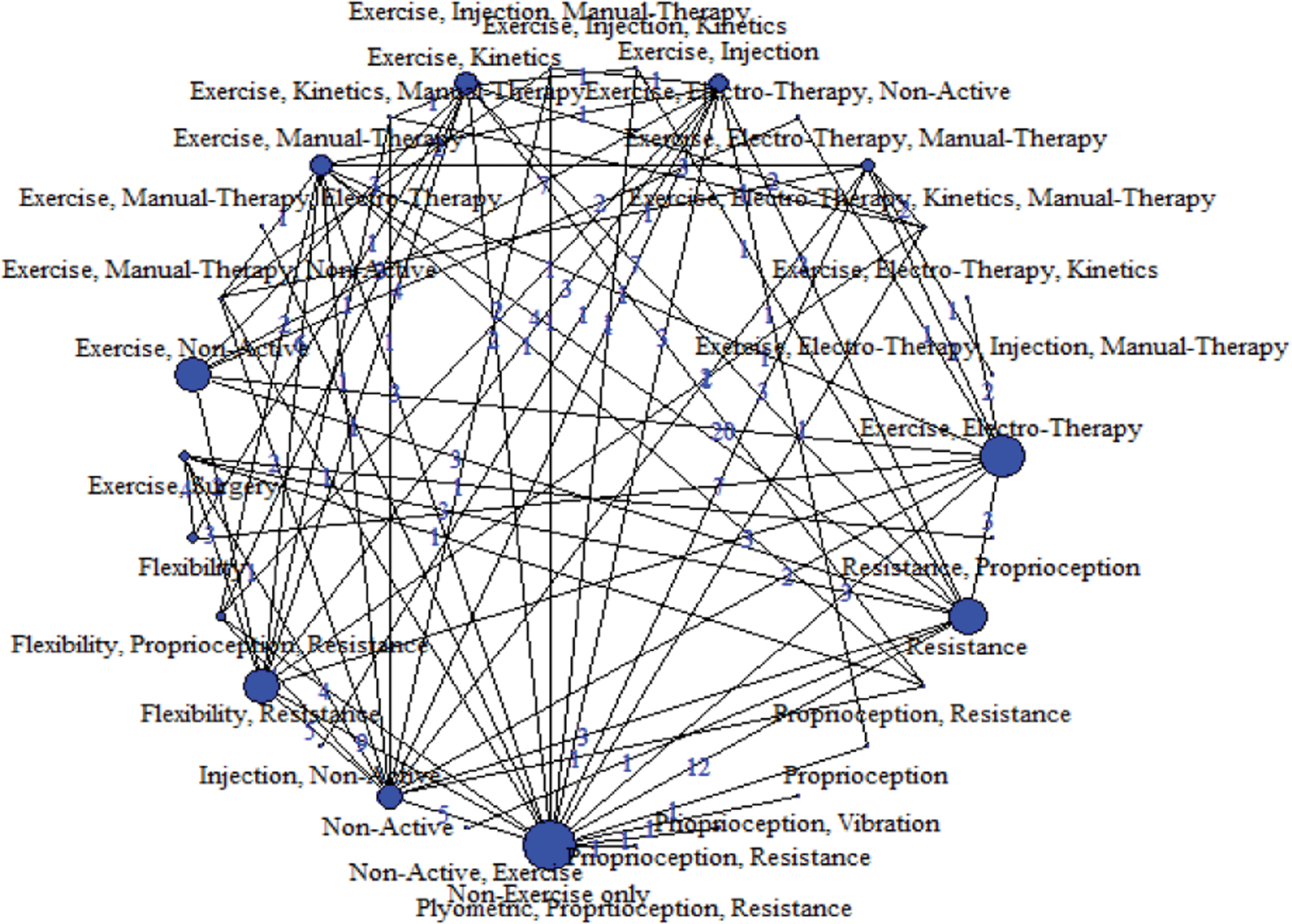

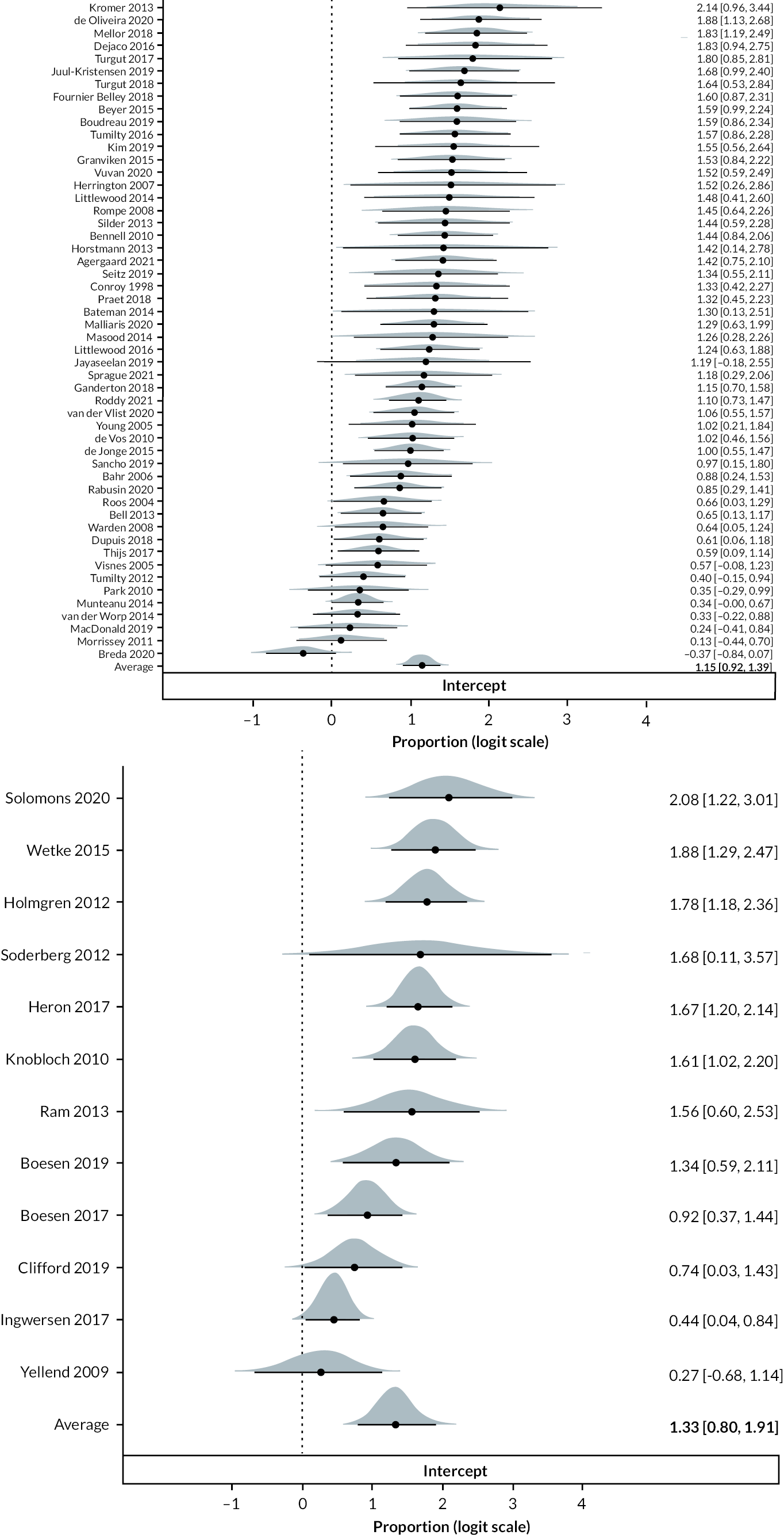

A citation analysis was conducted on the Scopus information obtained from 450 (81%) of the included sources, generating 14,860 references. The full citation analysis is available in Appendix 3. Of the 450 citations used to complete the analysis, they were published in: British Journal of Sports Medicine (n = 39, 9%), American Journal of Sports Medicine (n = 28, 6%), Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy (n = 15, 3%), Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine (n = 14, 3%) and Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology Arthroscopy (n = 14, 3%). Based on citations per year, the top-ranked studies included De Vos et al. (49 citations per year),59 Alfredson et al. (30 citations per year),17 De Jonge et al. (21 citations per year),60 Malliaras et al. (21 citations per year)61 and Thanasas et al. (20 citations per year). 62 Across the 14,860 references identified, they were obtained from the American Journal of Sports Medicine (n = 655, 4%), British Journal of Sports Medicine (n = 628, 4%), Journal of Orthopaedic Sports Physical Therapy (n = 304, 2%) and British Medical Journal (n = 262, 2%). A country collaboration network diagram of the included references is available in Appendix 3, Figure 23, and illustrates extensive collaborations across many countries particularly the UK, USA and Australia. Figure 24 (see Appendix 3) illustrates the rise in exercise for tendinopathy research from the early 1980s, reaching a peak in 2009.

Systematic reviews

There were 119 systematic reviews included in this scoping review. The reviews were classified by the review team as 72 (61%) systematic reviews without meta-analysis, 45 (37%) systematic reviews with meta-analysis and two (2%) umbrella/review of reviews. The number of studies included across the systematic reviews ranged from two to 84 with a median of 12 (IQR: 8–19). Four main tendinopathy types were the focus of the reviews, with 43 (36%) investigating RCRSP, 26 (22%) Achilles, 14 (12%) lateral elbow and 14 (12%) patellar tendinopathy. Five (4%) systematic reviews related to both Achilles and patellar tendinopathies, three (3%) focussed on gluteal or posterior tibial tendinopathies, two (2%) on hamstring or medial elbow tendinopathies and one (1%) on quadriceps. Most of the reviews were conducted by teams based in four countries: UK (n = 28; 23%), Australia (n = 17; 14%), USA (n = 14; 12%) and the Netherlands (n = 13, 11%). Exercise was the primary focus in 46 (38%) systematic reviews, a secondary focus (e.g. the control) in 49 (42%), and a neutral focus (i.e. equivalence between exercise and other interventions) in 24 (20%). Exercise was more commonly the primary focus of systematic reviews investigating lower-limb tendinopathy [Achilles (46%) and patellar (43%)), compared to upper-limb tendinopathy (RCRSP (34%) and lateral elbow (29%)].

The remainder of the results section and analysis relates only to the primary studies.

Primary studies

Study demographics

The predominant design for the 436 included primary studies was randomised controlled trial (RCT) (n = 236; 54%), followed by quasi-experimental (n = 81; 19%), observational (n = 75; 17%), pilot (n = 35; 8%) and qualitative (n = 9; 2%). The studies comprised information obtained from 25,490 participants (male = 10,463; female = 10,734), with study mean age ranging from 15 to 65 years. Most studies were conducted in a mixed setting (n = 116; 27%), with clinic (n = 91; 21%) and home settings (n = 61; 14%) also reported. A total of 31 countries were identified, with most studies conducted in four countries: Turkey (n = 60; 14%), USA (n = 48; 11%), UK (n = 43; 10%) and Australia (n = 32; 7%).

A range of additional participant characteristics were recorded across 362 studies (83%), with the most frequently reported characteristic being symptom duration (n = 253; 70%). Other less frequently reported characteristics included weight (n = 115; 32%), height (n = 113; 31%), affected side (including bilateral) (n = 105; 29%), body mass index (BMI) (n = 102; 28%), hand/limb dominance (n = 86; 24%), physical activity level (n = 82; 23%), employment status (n = 50; 14%), previous treatment (n = 34; 9%), number of physical activity sessions (hours of sport/week, mileage/week, or training/week) (n = 28; 7%), education level (n = 22; 6%), co-morbidities (n = 21; 6%), smoking status (n = 18; 5%), analgesic/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug NSAID use (n = 16; 4%), mechanism of injury/causation (n = 15; 4%), previous history/episodes (n = 14; 4%), sports participation interference (n = 13; 4%), location of symptoms (n = 13; 4%), manual occupation (n = 11; 3%) and ethnicity (n = 9; 2%). Of the nine studies reporting ethnicity, European/Caucasian participants were included in all, with African American (four studies), Hispanic/Latino (three studies), Asian (one study) and Māori (one study) also reported. Sixty studies (17%) did not report any additional characteristics for participants.

Which tendinopathies were reported?

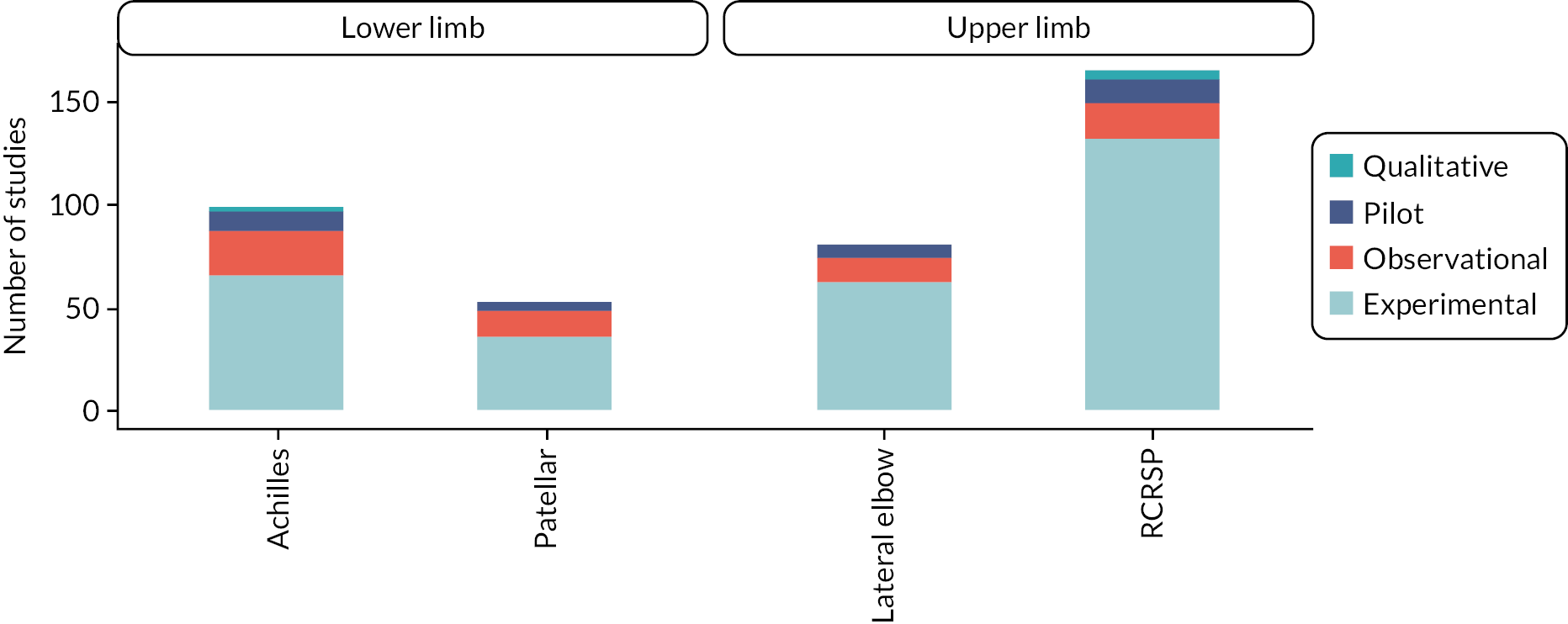

Four tendinopathy types accounted for over 90% of the results, with 167 (38%) studies focussing on RCRSP, 103 (23%) on Achilles, 82 (19%) on lateral elbow and 53 (12%) on patellar tendons. Less frequently investigated tendinopathies included gluteal, tibialis posterior and hamstring, which were the focus of 9 (2%), 7 (2%) and 3 (1%) studies, respectively. The breakdown of study design for the four most common tendinopathy types is illustrated in Figure 4. Experimental studies were the most commonly reported study design compared to the far smaller number of qualitative studies conducted across all the common tendinopathies.

FIGURE 4.

Primary study designs across main tendinopathy types.

Exercise interventions investigated

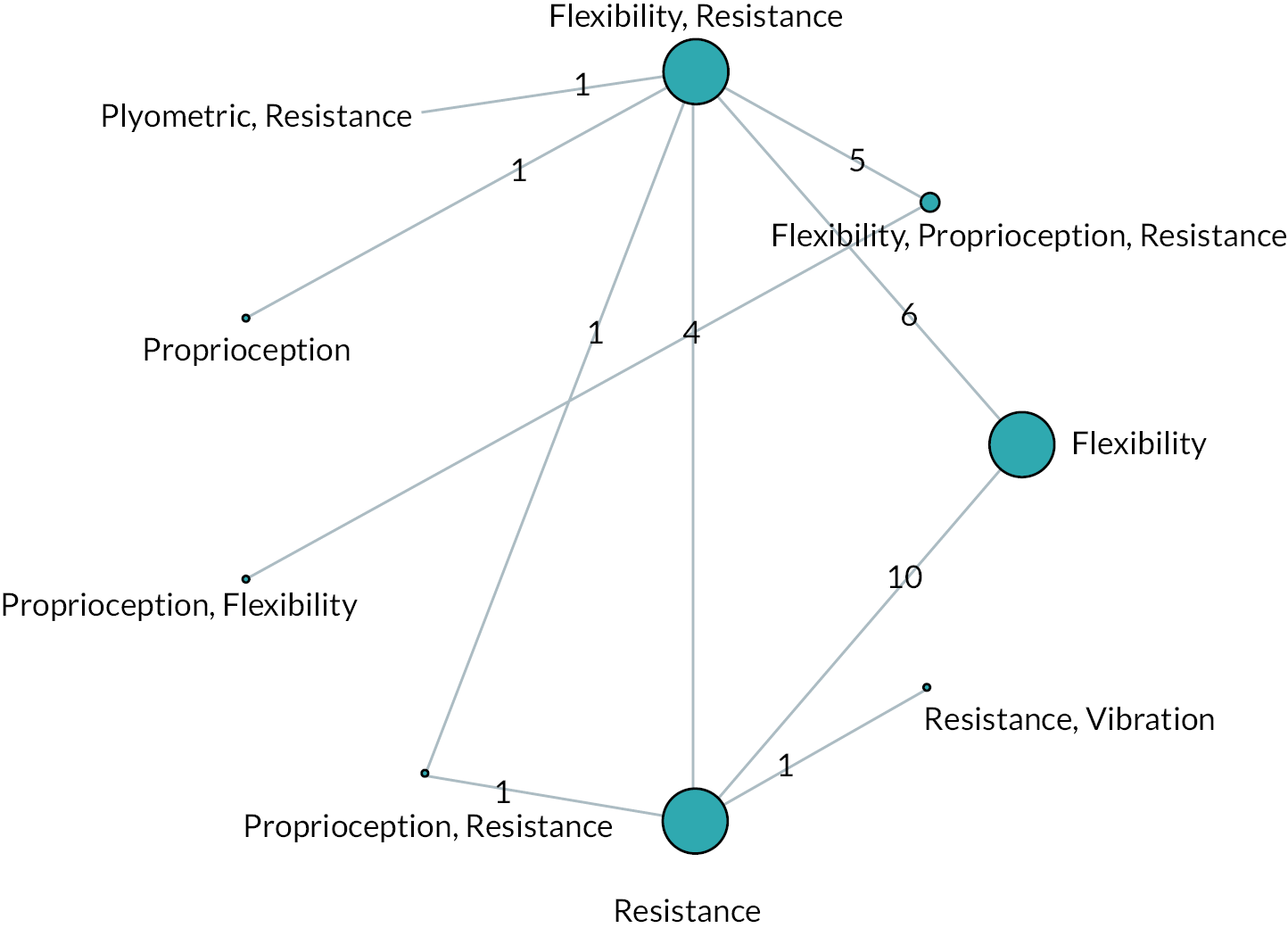

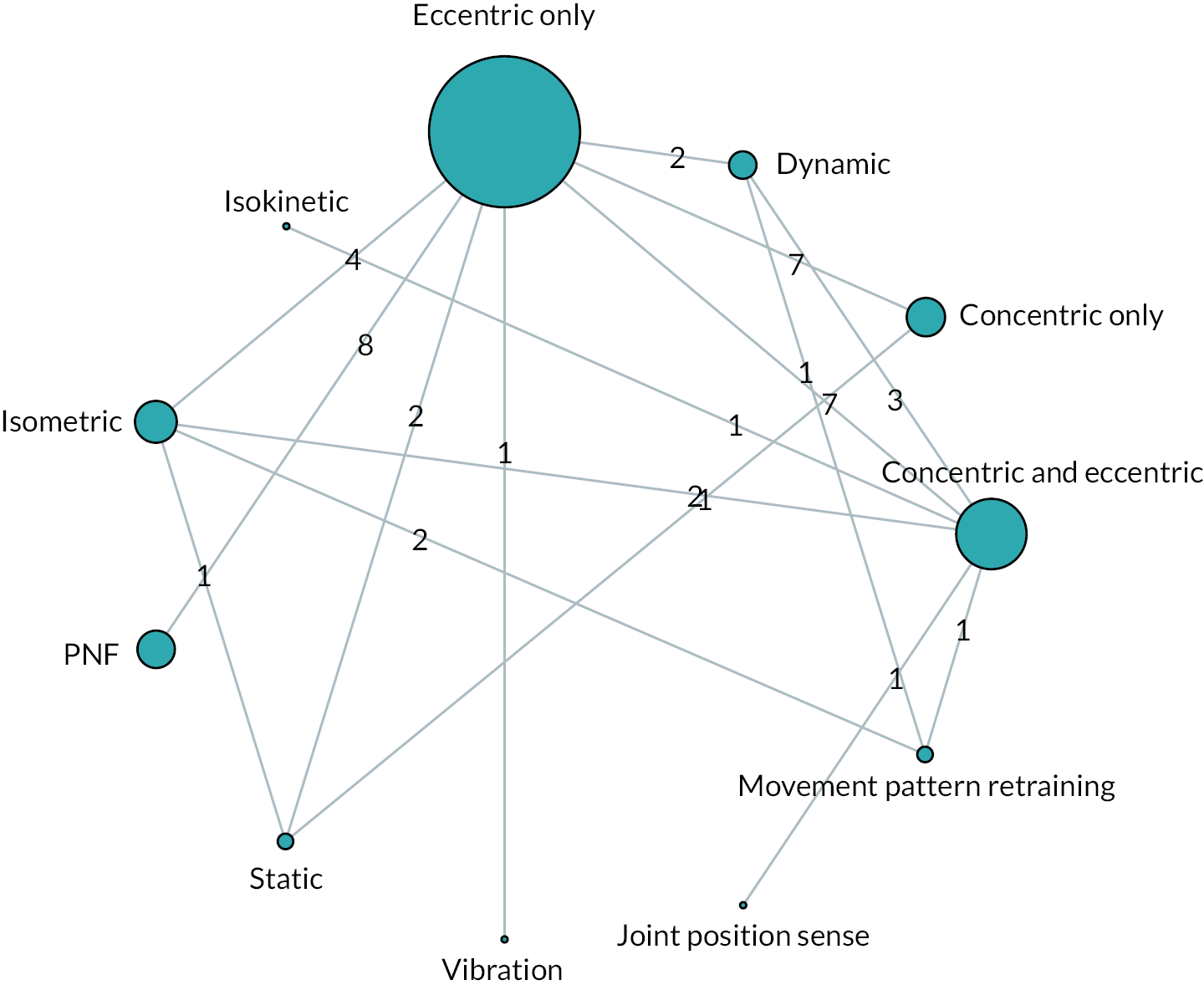

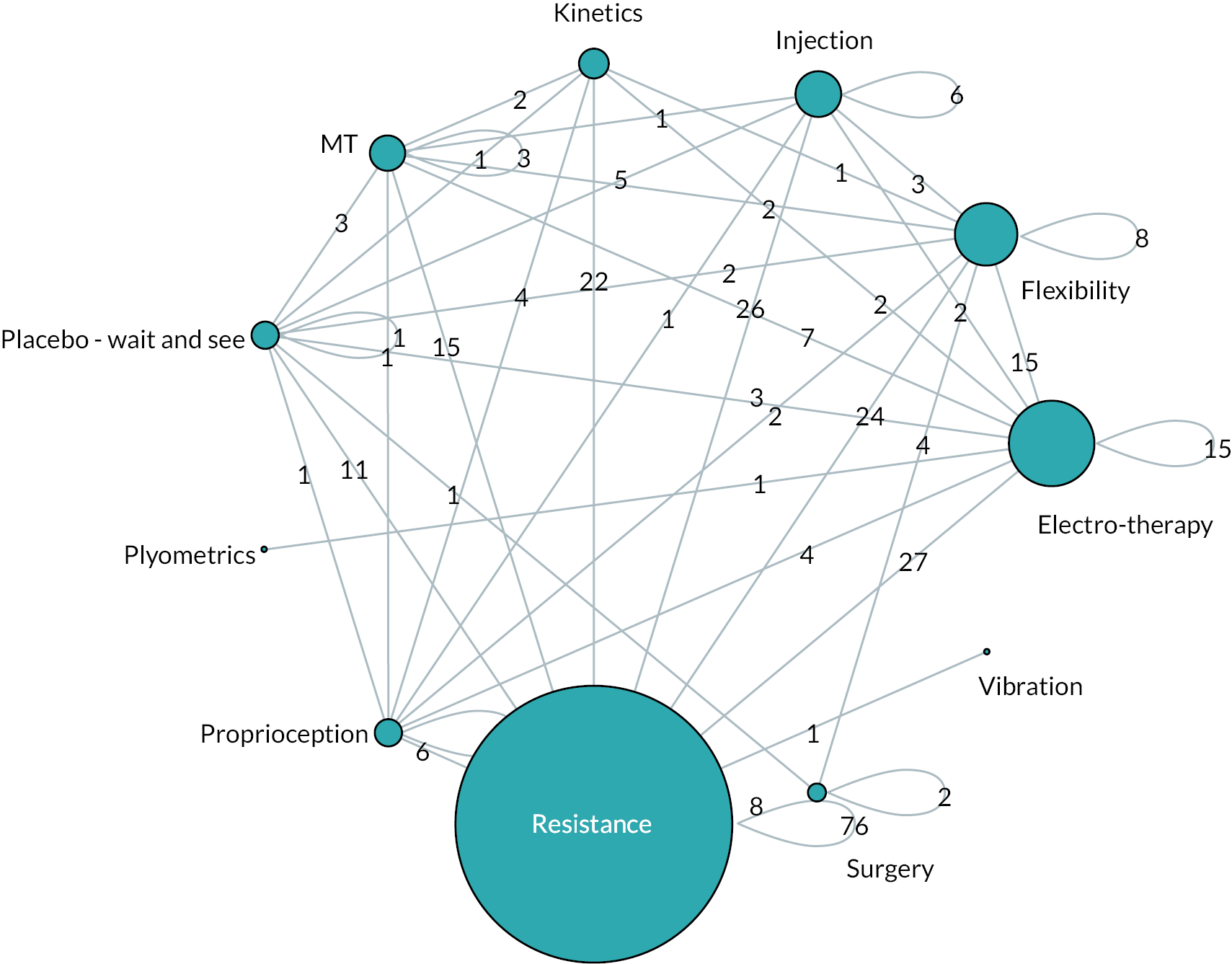

Exercise therapy interventions were reported as the primary focus of 161 (37%) studies, the secondary focus of 188 (43%) studies, and a neutral focus in 87 (20%) studies. The different exercise interventions were categorised as strengthening, flexibility (including dynamic range of motion (ROM) exercises), aerobic, proprioception or motor control and determined by the authors’ stated purpose. A mapping of the different exercise intervention components and subcomponents across different tendinopathy types is presented in Table 2.

| All (n = 436) |

RC (n = 165) |

Achilles (n = 99) |

Lateral elbow (n = 81) |

Patellar (n = 53) |

Other (n = 38) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strengthening | 367 (84%) | 128 (78%) | 92 (93%) | 62 (77%) | 53 (100%) | 32 (84%) |

| Eccentric | 205 (47%;56%) | 21 (13%;16%) | 88 (89%;96%) | 36 (44%;58%) | 45 (85%;85%) | 15 (39%;47%) |

| Concentric | 37 (8%) | 12 (7%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 9 (17%) | 7 (18%) |

| Eccentric + Concentric | 49 (11%;13%) | 32 (19%;25%) | 1 (1%;1%) | 6 (7%;10%) | 2 (4%;4%) | 8 (21%;25%) |

| Isometric | 68 (16%;19%) | 34 (21%;27%) | 5 (5%;5%) | 11 (14%;18%) | 10 (19%;19%) | 8 (21%;25%) |

| Progressive strength | 28 (6%;8%) | 19 (12%;15%) | 0 (0%;0%) | 5 (6%;8%) | 1 (2%;2%) | 3 (8%;9%) |

| Isotonic | 15 (3%;4%) | 11 (7%;9%) | 1 (1%;1%) | 2 (2%;3%) | 1 (2%;2%) | 0 (0%;0%) |

| Isokinetic | 17 (4%;5%) | 6 (4%;5%) | 1 (1%;1%) | 1 (1%;2%) | 3 (6%;6%) | 6 (16%;19%) |

| HSRT | 4 (1%;1%) | 0 (0%;0%) | 0 (0%;0%) | 1 (1%;2%) | 3 (6%;6%) | 0 (0%;0%) |

| Plyometric | 12 (3%3%) | 2 (1%;2%) | 4 (4%4%) | 3 (4%;5%) | 1 (2%;2%) | 2 (5%;6%) |

| Flexibility | 208 (48%) | 103 (62%) | 20 (20%) | 53 (65%) | 14 (26%) | 18 (47%) |

| Traditional stretching | 95 (22%;46%) | 42 (25%;41%) | 6 (6%;30%) | 30 (37%;57%) | 6 (11%;43%) | 11 (29%;61%) |

| Dynamic ROM | 72 (17%;35%) | 63 (38%;61%) | 0 (0%;0%) | 5 (6%;9%) | 1 (2%;7%) | 3 (8%;17%) |

| PNF | 14 (3%;7%) | 8 (5%;8%) | 0 (0%;0%) | 4 (5%;8%) | 0 (0%;0%) | 2 (5%;11%) |

| No detail | 75 (17%;36%) | 32 (19%;31%) | 12 (12%;60%) | 17 (21%;32%) | 7 (13%;50%) | 7 (18%;39%) |

| Proprioception | 21 (5%) | 10 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 5 (13%) |

| Motor control | 73 (17%) | 66 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (13%) |

| Aerobic | 24 (6%) | 4 (2%) | 6 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

The most common exercise type reported across all tendinopathies was strengthening (84%), followed by flexibility (48%). When investigated individually, there were some differences in exercise types between different tendinopathies. All patellar tendinopathy studies (100%) reported the use of strengthening exercise, compared to 77–93% of studies for other tendinopathies. There was also greater use of aerobic exercise (17%) reported in patellar tendinopathy studies compared to other tendinopathies (0–13%).

While eccentric was the most common strengthening exercise reported for Achilles (89%), patellar (85%) and lateral elbow tendinopathy (44%), RCRSP studies reported isometric (21%) followed by a combination of eccentric and concentric (19%) as the most common. For flexibility exercise, upper-limb tendinopathies reported this more often (RCRSP 62%; lateral elbow 65%) than lower-limb tendinopathies (patellar 25%; Achilles 20%).

Flexibility exercise was poorly described across all tendinopathies, with 17% of studies not providing sufficient detail to categorise the type of flexibility exercise included. Where flexibility was well described, dynamic ROM was the most common form of flexibility exercise used for RCRSP (38%), with static sustained stretching most common for all other tendinopathies (6–37%). Motor control exercise interventions were mainly reported for RCRSP.

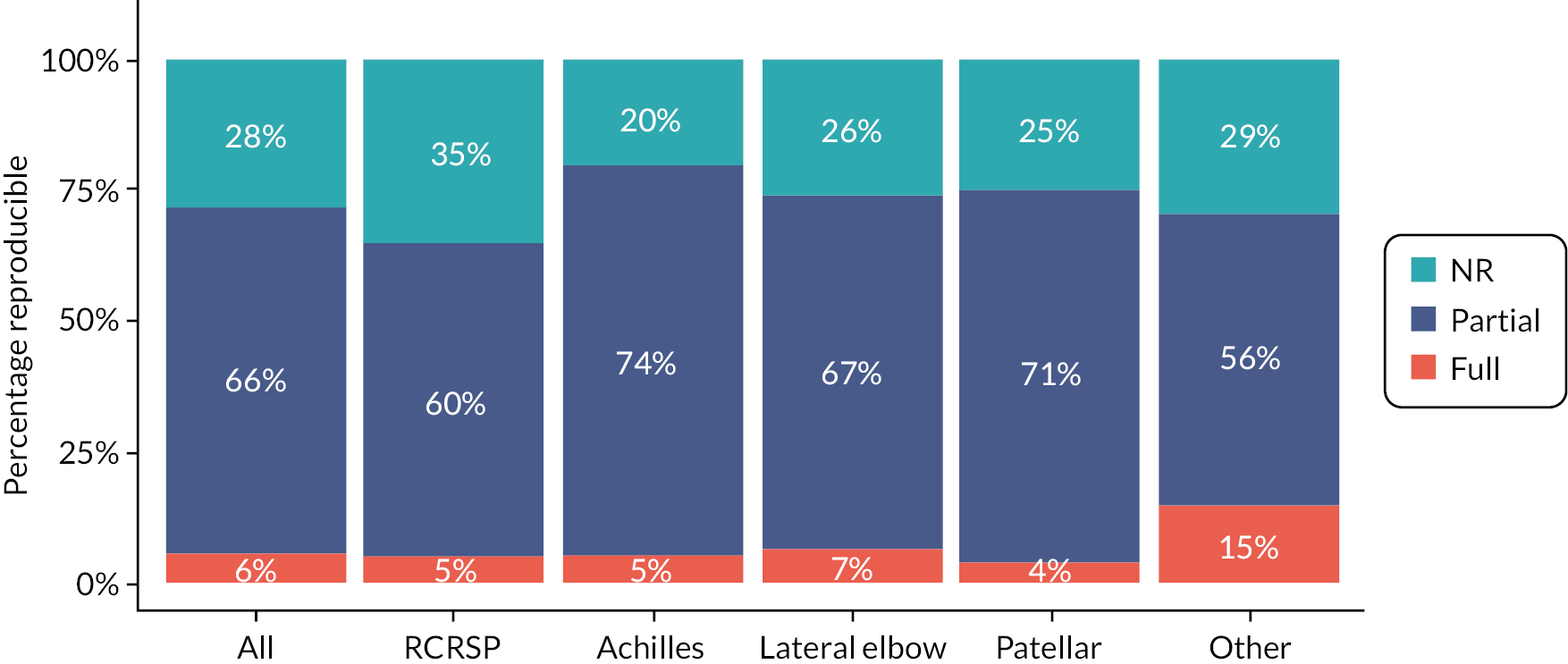

Exercise intervention reporting

All exercise interventions were mapped to the TIDieR checklist55 and are presented for all tendinopathies in Figure 5 and for the four main tendinopathies in Figure 6. The intervention setting was often not reported (51%) or only partially reported (19%). Additionally, over one-third of studies did not report the how (mode of delivery, 38%), who (intervention provider expertise, 37%), why (rationale, theory, or goal, 36%) or what (physical or informational materials used, 35%) components of interventions. Data from the TIDieR checklist were used by the review team to categorise study interventions as fully reproducible (all details reported to enable reproduction of the exercise), partially reproducible (some but not all details of exercise reported to enable partial reproduction of the exercise) or not reproducible (see Figures 5 and 6). Reproducibility was assessed across different tendinopathies, with most exercise interventions (56–74%) categorised as partially reproducible, and only a minority (4–15%) categorised as fully reproducible.

FIGURE 5.

Exercise therapy reporting across all tendinopathy types using the TIDieR checklist.

Who: intervention provider expertise; What(M): informational materials used; What(P): physical materials used; How: mode of delivery; Where: intervention setting; Why: rationale, theory or goal; NR: not reported; Partial: partially reported; Full: fully reported; Other: refers to all other tendinopathy types.

FIGURE 6.

Reproducibility of exercise therapies across tendinopathy types using the TIDieR checklist.

NR: not reported; Partial: partially reported; Full: fully reported; Other: refers to all other tendinopathy types.

Monitoring exercise adherence was planned by authors in 152 studies and the main method consisted of exercise diaries (71% of reported methods). Other methods included summary records from therapist (8%), self-report (7%), therapist individual session records (6%), follow-up phone calls to monitor attendance (4%), follow-up appointments to monitor adherence (3%) and adherence reported by family member (1%). Whilst exercise adherence was planned in 152 studies, adherence data were only reported in 89 (59%) of those studies, representing 20% of all primary studies in the review.

Reported adherence means ranged from 16% to 100% in individual studies and were 77% across all studies. Authors used varied grading of adherence from subjective terms such as ‘high’, ‘good’ and ‘adherent’ to aligning frequencies to rankings of poor to excellent (e.g. >75% ‘good’, 70% ‘good/excellent’, 25–75% ‘moderate to excellent’, 50% ‘good’, 27% ‘moderate to poor’). Studies also reported a reduction in adherence over time with 12-week adherence ranging from 27% to 94.2% and two-year adherence ranging from 41% to 87.4%.

Reporting of modifications (any modifications to the intervention during the study) and tailoring (planned personalisation, titration or adaptations) of exercise interventions were also recorded. Tailoring was reported in 247 (56%) studies and involved personalised progression of exercise interventions via increasing: sets, number of sessions per day, repetitions, resistance/load, speed, duration of muscle contraction, time spent on exercise, ROM, difficulty (up to 13–15 rating of perceived exertion), addition of new exercises, reducing base of support/stability, gradual increase in other physical and sporting activities, and progression from low to higher impact activities. Progressions were determined by the physiotherapist/exercise professional, improved quality of movement control, full range of movement, ratings of participant-perceived effort (e.g. less than 7, up to 11–14), fatigue, the absence of pain, pain rated as no more than 3–5/10 on a pain scale, or as ‘pain allowed’.

Tailoring also involved decrements in exercise via reduced loading and ROM due to participant-reported pain, typically including pain greater than 4–5/10 on a visual or verbal analogue scale or pain that did not rapidly subside (e.g. within 10–15 minutes post exercise). Modifications were reported in only 20 (5%) studies. Modifications included participants being withdrawn and referred for further investigation, follow-up appointments as required to facilitate self-management or for any difficulties, and alternative planes of motion or training technique modifications that were more comfortable for participants or due to additional musculoskeletal problems occurring during the study.

Exercise therapy adjuncts

Treatment adjuncts (non-exercise treatments in addition to the exercise component of interventions) were included in 140 studies (44%) and were not present in 109 (67 were not applicable due to study design). The main treatment adjuncts were injection, laser, ESWT, manual therapy (MT) and splinting/taping. Additionally, of the 316 experimental studies included, 49 (16%) included a specific non-exercise arm (whereby one or more of the groups were not prescribed any exercise as part of their intervention) whilst 184 did not include a non-exercise arm (83 were not applicable).

Health domains

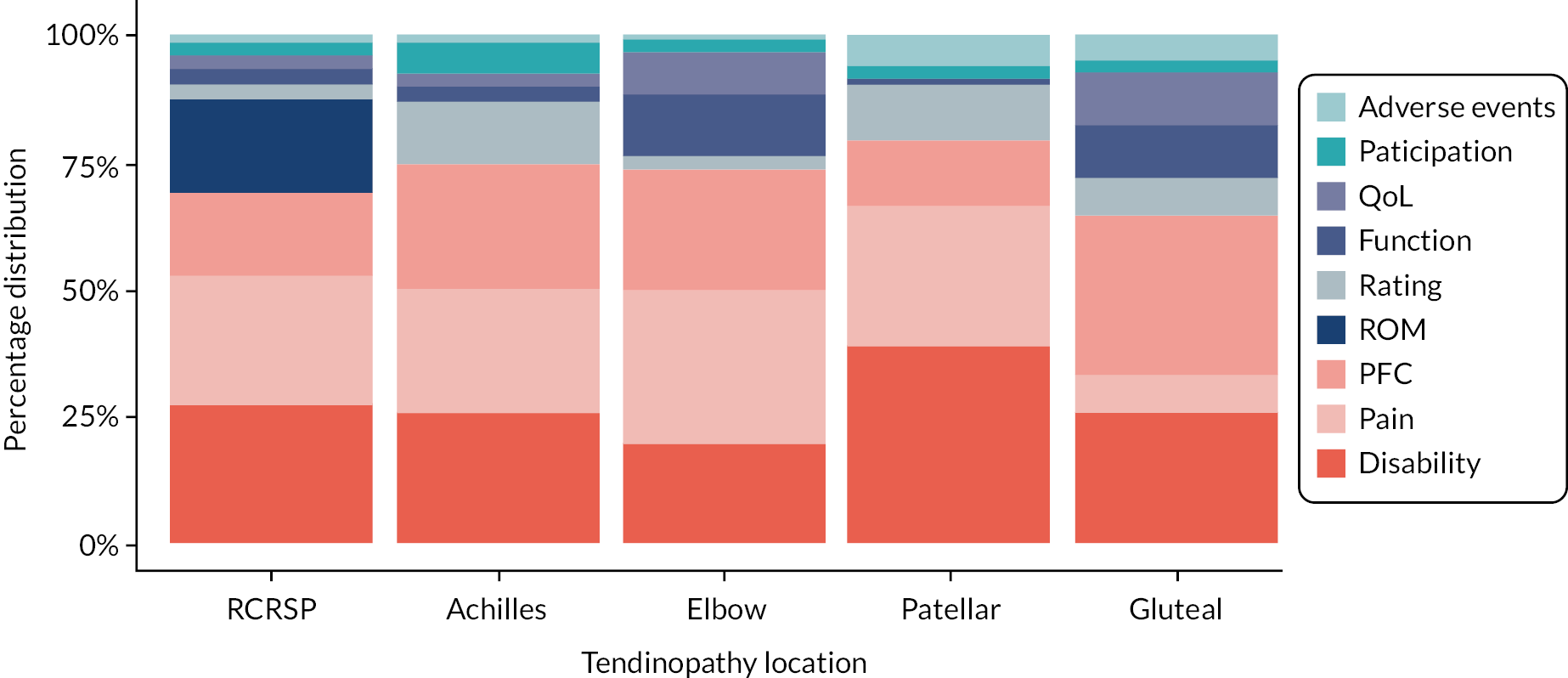

To answer the second review question on what outcomes have been reported, outcomes were broken down into health domains and the outcome measurement tools used for each domain. Primary and secondary health domains were extracted across all tendinopathy types and are presented in Table 3. Disability was the most common primary health domain (n = 282) for RCRSP (n = 123), Achilles (n = 67) and patellar (n = 40) tendinopathies (see Table 2). For lateral elbow, physical function capacity (PFC) was most common (n = 40). Secondary health domains also varied across tendinopathies, with Achilles and patellar both reporting participant rating of overall condition most frequently (n = 15 and n = 8 respectively), with disability the most common secondary domain for RCRSP (n = 27), and PFC (n = 14) for lateral elbow. Across tendinopathies, adverse effects or cost effectiveness were rarely the primary or secondary outcome.

| ICON domain Description (where required) |

Primary or secondary outcome | All (n = 436) |

RC (n = 165) |

Achilles (n = 99) |

Lateral elbow (n = 81) |

Patellar (n = 53) |

Other (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects/events Unintended treatment effect |

Primary | 11 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Secondary | 13 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | |

| Clinical examination findings e.g. clinical examination tests |

Primary | 19 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Secondary | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Disability Composite scores of patient-rated pain and disability due to pain, usually tendon-specific |

Primary | 282 | 123 | 67 | 35 | 40 | 17 |

| Secondary | 53 | 27 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 4 | |

| Drop out or discontinued treatment | Primary | 7 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Secondary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Economic impact costs | Primary | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Function Patient-rated – not referring to pain intensity |

Primary | 21 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| Secondary | 13 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Medication use | Primary | 9 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Secondary | 10 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| Other | Primary | 24 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| Secondary | 17 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Pain – clinician-applied stress/examination | Primary | 8 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary | 5 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| Pain on loading/activity Pain during tendon-specific provocation |

Primary | 108 | 42 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 6 |

| Secondary | 34 | 18 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 0 | |

| Pain over a specified time Pain intensity over e.g. 24 hours, 7 days |

Primary | 63 | 30 | 5 | 19 | 4 | 5 |

| Secondary | 38 | 21 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 1 | |

| Pain without further specification Pain without reference to specified time or activity |

Primary | 90 | 41 | 13 | 18 | 10 | 8 |

| Secondary | 16 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Palpation | Primary | 9 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Secondary | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Participant/patient rating overall condition Single numerical assessment |

Primary | 66 | 15 | 20 | 17 | 8 | 6 |

| Secondary | 46 | 13 | 15 | 6 | 8 | 4 | |

| Participation Patient rating e.g. level of/return to sport |

Primary | 25 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Secondary | 18 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | |

| Physical activity Self-report or wearables |

Primary | 6 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Secondary | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| PFC Physical tasks e.g. hops, squat tests |

Primary | 100 | 30 | 13 | 40 | 8 | 9 |

| Secondary | 44 | 18 | 7 | 14 | 4 | 1 | |

| Psychological factors e.g. self-efficacy, kinesiophobia |

Primary | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary | 9 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| QoL General well-being |

Primary | 17 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary | 26 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 | |

| ROM | Primary | 56 | 44 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Secondary | 18 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sensory modality specific pain e.g. quantitative sensory testing |

Primary | 11 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Secondary | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Structure (tendon tissue characteristics) e.g. imaging/biopsy |

Primary | 56 | 9 | 32 | 4 | 10 | 1 |

| Secondary | 18 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

Outcome measurement tools

An extensive range of primary and secondary outcome tools were reported across tendinopathies. A comprehensive map of the tools relative to health domains and tendinopathy types is provided here: Primary outcomes: http://www2.rgu.ac.uk/nhir/tendinopathy-primary-outcomes-interactive-table.html Secondary outcomes: http://www2.rgu.ac.uk/nhir/tendinopathy-secondary-outcomes-interactive-table.html. The most frequently reported tools included visual analogue scales (VAS) (RCRSP n = 73, lateral elbow n = 44, Achilles n = 29, patellar n = 22); Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment questionnaires (Achilles VISA-A n = 59, patellar VISA-P n = 39); Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) (RCRSP n = 45); dynamometer (lateral elbow n = 39, RCRSP n = 17); Goniometer (RCRSP n = 39); Constant Murley Score (CMS) (RCRSP n = 36); Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (DASH/Quick DASH) (RCRSP n = 35); ultrasonography (Achilles n = 20, patellar n = 11); patient-rated tennis elbow evaluation questionnaire (lateral elbow n = 17) and numerical pain rating scale (NPRS) (RCRSP n = 14).

The main secondary outcome tools were dynamometer (lateral elbow n = 15, RCRSP n = 13), VAS (RCRSP n = 15, Achilles n = 10, lateral elbow n = 8, patellar n = 8), NPRS (RCRSP n = 13, Achilles n = 5), ultrasonography (Achilles n = 11), goniometer (RCRSP n = 9), DASH (RCRSP n = 8), 36-item short-form survey (SF-36) (RCRSP n = 7), EQ-5D (gluteal n = 6), CMS (RCRSP n = 6), Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index (RCRSP n = 6) and algometer (lateral elbow n = 5).

Of the nine qualitative studies included, the majority were on RCRSP (five studies) followed by Achilles (n = 2), tibialis posterior (n = 1) and a mixed tendinopathy group (n = 1: Achilles/patellar/RCRSP). These studies represented 114 participants (people with tendinopathy and physiotherapists), of whom 59 were female and 36 male. The studies reported participants’ barriers and facilitators to exercise interventions, which included psychosocial impact, treatment burden, motivation, confidence, coping, pain, socialisation, and benefits of group exercise, recognising the challenges of exercise interventions and self-management. They also reported on a range of physiotherapist-related factors including views, clinical reasoning, perceived barriers and facilitators, and treatment awareness.

Discussion

This is the first scoping review to comprehensively map existing evidence on exercise therapy interventions and outcomes for the treatment of tendinopathies. A total of 555 sources were included, demonstrating the abundance of research, the need for it to have been mapped in this review, and also the need for a taxonomy of exercise interventions and reporting standards to allow comparisons of efficacy to be made. This review guided the subsequent contingent evidence syntheses reported in Chapters 5 and 6. It also identified research gaps which can inform future research and evidence syntheses. Finally, the review identified potential areas of improvement in clinical practice which will need to be explored further.

Although the number of RCTs in this field has increased recently, there were large numbers of quasi-experimental and observational studies identified by this review. The mapping of all these study designs directly informed the efficacy reviews reported in Chapter 5.

This review also identified a small number of qualitative studies which can contribute to understanding feasibility and acceptability of exercise for tendinopathy. These are reported, along with relevant quantitative designs exploring these phenomena, in the mixed-method review reported in Chapter 6. The small number of qualitative studies identified, compared with the volume of quantitative research, identifies a need for further primary research to fully understand patients’ and practitioners’ perceptions and experiences of exercise therapy interventions for tendinopathy in order to guide intervention development and assist with real-world implementation of findings from trials.

Exercise for tendinopathy

The findings that strengthening exercise was the most reported exercise type across all tendinopathies, particularly the lower limb, and that eccentric strengthening exercise was most common for three tendinopathies (Achilles, patellar, lateral elbow) are in keeping with previous evidence. 63 However, due to the variable levels of reporting, it would be difficult to determine whether many interventions described as strengthening would in fact achieve the required overload for strengthening to occur. This has implications for practice, and improved quality of reporting of exercise interventions in future studies is urgently required, along with better clarity about the definitions of terms such as ‘strength’ compared to ‘muscle activation’ or ‘endurance exercise’.

The findings related to RCRSP demonstrated the most clinical heterogeneity, with greater variation in strengthening exercise type, and exercise type per se, with flexibility, motor control and proprioceptive exercise reported in addition to strengthening. Dynamic ROM exercise for flexibility was more frequently reported than traditional active or passive stretching for RCRSP. This varied approach to the management of RCRSP suggests that there is, as yet, no consensus in the literature on how best to manage this complex tendinopathy. 64,65

Reporting of interventions was highly variable, with the TIDieR checklist classifying 15% or fewer included interventions as fully reproducible. This finding has implications for practice, as it would be challenging, if not impossible, for practitioners to adopt interventions demonstrated as efficacious in research studies, possibly resulting in suboptimal exercise prescription and patient outcomes. This identification of variable and typically inadequate reporting further supports the need for the development of minimum standards of reporting, using available guidelines such as TIDieR to assist the process. 66,67

Only 20% of included primary studies reported adherence, despite the planned intention to collect adherence measures in 35% of studies, which is similar to previous adherence reports three decades ago. 68 Adherence monitoring relied primarily on a range of participant self-report instruments with wide variation in scoring methods, and a lack of objective monitoring. These issues are further explored in Chapter 6 (mixed-method review of feasibility and acceptability).

Around half of the studies included personalised tailoring of exercise guided by pain, in keeping with the evidence that adherence to interventions that require exercising into or through pain (e.g. Alfredson protocol) will typically be lower. 69 The small body of included qualitative studies suggest that there may be several barriers to adherence (e.g. treatment burden, pain, psychosocial factors, motivation, confidence and coping). These are likewise further explored in Chapter 6.

Proposed initial reporting criteria for exercise interventions for the management of tendinopathy

Having mapped the exercise interventions on the management of tendinopathy, the review team produced initial criteria to inform the reporting of tendinopathy exercise interventions to ensure consistency and allow easier comparisons in the future. The proposed initial criteria (see Box 1) combined the results from the mapping of the type of exercise interventions during the scoping review and the recommendations in the TIDieR checklist. The initial reporting criteria identified in this scoping review require further funding and development with all relevant stakeholders to create a comprehensive taxonomy to guide exercise reporting in tendinopathy practice and research.

Including information on the place and method of delivery of exercise interventions is important to allow cost-effectiveness analyses. The increasing delivery of medical interventions remotely or in group settings presents opportunities for efficiencies, but currently there is lack of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of such approaches.

Information to be collected

-

Anatomical location of tendinopathy (e.g. RCRSP)

-

Exercise therapy class/treatment

-

Dominant therapy class (e.g. strength/resistance)

-

Exercise treatment (e.g. eccentric exercise)

-

-

Complete therapy class (e.g. strength/resistance + flexibility + proprioception)

-

Complete exercise treatment (e.g. eccentric exercise + static stretching + movement pattern retraining)

-

-

-

Exercise dose

-

Intensity (e.g. load (kg))

-

Volume (e.g. sets × repetitions)

-

Frequency (e.g. number of times per week)

-

Duration (length of time intervention delivered)

-

-

Non-exercise intervention class (e.g. electro-therapy)

-

Intervention (e.g. Shockwave) and delivery information

-

-

Intervention delivery

-

Intervention setting (e.g. primary/secondary care)

-

Delivered by whom (e.g. physiotherapist)

-

Delivered how (e.g. supervised one-to-one)

-

-

Exercise fidelity and adherence

-

Exercise fidelity and adherence measures used (e.g. proportion of exercise sessions completed)

-

Exercise attendance data (e.g. attendance [the number of sessions attended over the follow-up period])

-

Participant responsiveness (e.g. self-report of how far participants respond to, or are engaged by, an intervention)

-

-

Outcome domain – primary and secondary (e.g. disability)

-

Outcome measurement tools for primary and secondary domains (e.g. SPADI)

-

-

Demographic information

-

Patient characteristics (e.g. age, BMI, sex, ethnicity, activity levels, comorbidities, occupation)

-

Symptom duration

-

Reporting of participant characteristics

Reporting of participant demographics was also highly variable across studies, with very low reporting rates for some potentially important comorbidities and confounders such as age, gender, cardiovascular conditions, diabetes and non-Caucasian ethnicities. For example, low- to moderate-quality evidence has demonstrated a link between metabolic syndrome, obesity and RCRSP but this was not well reported in studies. 70 This has limited the ability to pool findings, evident in the small number of previous systematic reviews that have conducted meta-analyses. This limitation also influenced the meta-analyses that could be conducted in the efficacy reviews presented in Chapter 5. There is therefore an urgent need for full and transparent reporting of patient characteristics in tendinopathy research66,71,72 and to continue the development of the ICON standards for such reporting. 73 The wide age range reported across included studies and the lack of reporting of co-morbidities (particularly in older populations) lend support to demographic sub-grouping of participants to lessen the impact of confounders and to identify different responses to exercise across groups.

Outcomes

The finding that numerous primary (n = 335) and secondary (n = 194) outcomes were reported across a range of 22 health domains highlights the lack of consensus to date on outcome measurement for tendinopathy. The work of the ICON group led by Vicenzino et al. 56 demonstrates that there is a difference between outcomes reported in the evidence base and those currently recommended. For example, ROM was the second most commonly reported domain for RCRSP yet it is not considered a core domain by ICON. 56 Of the six core ICON domains agreed on by healthcare professionals and patients, only two (rating of condition and PFC) were reported as primary or secondary domains in this review. This may reflect the differences between researchers’ focus and what health professionals and patients feel are important in practice,56 also indicated by low reporting of quality-of-life outcomes. Adverse events and cost-effectiveness outcomes were also rarely reported.

Numerous outcome measurement tools were used across each health domain, highlighting the need for core outcome sets to be agreed for both research and practice. The ongoing international work on developing core outcome sets for Achilles, gluteal, lateral elbow and proximal hamstring tendinopathies74–77 and shoulder disorders78 will enhance standardisation of outcomes and enable future pooling of findings in systematic reviews. Outcomes reported for RCRSP in this review were not congruent with the core set endorsed by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials (OMERACT) network;78 only pain was common to both OMERACT and this review. The health domains and outcome measures identified in this scoping review informed the domains that could be included in the efficacy reviews (Chapter 5).

The finding that physical outcomes (e.g. pain, disability) were dominant, with infrequent reporting of psychosocial outcomes (e.g. psychological factors), conflicts with clinical tendinopathy management, where the long duration and impact on peoples’ lives mean that those more severely affected may experience more fear avoidance, kinesiophobia, anxiety and depression. 79,80 This finding further emphasises the need for qualitative research, and the use of more holistic, patient-centred outcomes in tendinopathy research. 81,82 This scoping review clearly demonstrates that research to date is skewed towards physical interventions and outcomes and has neglected the social and psychological aspects of presentation and management.

Limitations

There are some inevitable limitations to this scoping review. We were unable to locate 56 articles. The use of the HDI54 ensured that the international evidence gathered is compatible with the UK context; however, it is possible that some pertinent evidence may have been excluded as a result. Nonetheless, we are confident that including studies from countries ranked as having lower HDI would not significantly affect the results of this review, as a comprehensive search was conducted and translations were sourced for all included non-English-language studies. It should also be noted that this scoping review has comprehensively mapped what has been conducted in the field of research. Although practice is informed by the evidence base, there are well-documented evidence-practice gaps,83 and it is therefore not known to what extent the findings represent what is done in the practice setting.

Conclusions

This scoping review provides the first comprehensive map of exercise therapy interventions and outcomes for tendinopathy research. Several important recommendations for future research and its reporting have emerged from this review, and are itemised below. Practice recommendations are limited from scoping reviews, due to the lack of methodological quality assessment of included studies. The results from this scoping review directly informed the remainder of this body of work, reported in Chapters 5 and 6.

Recommendations for research

Research study types

-

There is a need for adequately powered and methodologically sound studies that can truly demonstrate the effectiveness of interventions.

-

To achieve (a) we recommend that intervention development studies are conducted prior to moving to adequately powered trials, including feasibility and acceptability studies. Qualitative studies (stand-alone or embedded within other designs) should explore participants’ perceptions and experiences of exercise for tendinopathy. There is an urgent need for cost-effectiveness analyses and for studies on the implementation of effective interventions in practice.

-

Future evidence synthesis should focus on conducting high-quality systematic reviews (such as quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method and cost-effectiveness) and combining high-quality reviews into umbrella reviews. For these to add meaningful findings, there is an urgent need for further high-quality primary studies that address the limitations identified in this review.

Research reporting

-

The description of exercise interventions for tendinopathy needs to follow minimum standards to ensure consistency and allow comparisons. For this purpose, the initial reporting criteria proposed by this review could be helpful but require further development and investment to create a comprehensive taxonomy and guidance.

-

Full reporting of participant characteristics including psychological factors, ethnicity, co-morbidities and activity level is required in future tendinopathy research.

-

Future research should consider sub-groups such as those based on gender age, sedentary/active/performance populations and ethnicity.

-

Future research should apply the ICON core health domains to ensure collection and reporting of all relevant biopsychosocial outcomes.

-

Future research should carefully consider adequate monitoring and reporting of adherence to exercise. This will require refinement of data-collection methods, and we recommend considering objective monitoring.

Patient and practitioner lived experience

-

There is a need for research on participants’ views and experiences of exercise interventions across tendinopathies and populations. There is also a need for research on practitioners’ views of management approaches for different tendinopathies, how to navigate the research-practice gap and address barriers to exercise intervention implementation.

Stakeholder engagement with scoping review findings

Two workshops were initially planned to be held in Aberdeen and London to discuss the results of the scoping review with people who had received exercise for tendinopathy, people who manage tendinopathy and academics/researchers with an interest in tendinopathy. The outcome from the workshops was intended to inform the conduct of the subsequent contingent reviews conducted in phase 2 of this body of work. The impact of COVID-19 led to the workshops occurring online via Microsoft Teams in September–October 2020. One workshop was held with people who had experience of receiving exercise as a treatment for tendinopathy and one with people involved in tendinopathy management and/or research.

Following initial introductions and an overview of the scoping review results, the workshops were designed to:

-

consult with stakeholders on what information they would like the project to provide, and

-

discuss what stakeholders thought the findings were saying, what was of interest to them, and discussing their thoughts on what the subsequent syntheses should focus on.

Participants were recruited via social media (including Twitter and Facebook accounts for the project and the project team members’ personal accounts, Council for Allied Health Professions Research Twitter, Robert Gordon University [RGU] School of Health Sciences Twitter and Facebook accounts), RGU volunteer patient group, NHS Grampian physiotherapy staff email, NHS Grampian Involve Facebook page, and snowball recruitment via word of mouth and through personal and professional contacts of the review team.

Nine people who deliver exercise therapy for tendinopathy or have an academic or research interest in the topic attended the first workshop. This represented four physiotherapists (from the NHS, sportscotland institute of sport and private practice), one podiatrist, two PhD students focussed on RCRSP and patellar tendinopathy, and two physical preparation coaches. There were five female and four male professionals. Four females with experience of exercise therapy for tendinopathy attended the second workshop. They had experience of RCRSP (n = 2) and recurrent patellar tendinopathy (n = 1), with one identifying as a high-performance athlete.

To augment the workshop findings, a short online survey (incorporating the same questions used in the workshops) was distributed via Jisc online surveys using the same recruitment methods as for the workshops, with emphasis on the review team’s professional networks. This enabled the views of non-UK-based clinicians and researchers to be considered, as they could provide feedback in an asynchronous manner. Twenty-six survey responses were obtained and the findings were combined with those from the workshops. We did not obtain demographic details of workshop or survey participants. They represented a convenience sample of people willing to engage with the review team and can therefore not be considered representative of the lay, clinical or scientific population. Nonetheless, their contribution was helpful in refining the direction of the project.

The outcome of the workshops and survey identified what was important to stakeholders and can be summarised as follows:

People with experience of exercise for tendinopathy

-

wanted to know what type of exercise they should do, at what dosage and how hard they should push themselves

-

said that key factors to consider in the exercise intervention include self-management, trust in the professional delivering the exercise, being motivated by the professional delivering the exercise, monitoring of exercise and individually tailored prescription of exercise

-