Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/42/02. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The draft report began editorial review in March 2022 and was accepted for publication in August 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Mackenzie et al. This work was produced by Mackenzie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Mackenzie et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced, with permission, from Logue et al. [Logue J, Stewart S, Munro J, Bruce J, Grieve E, Lean M, et al. SurgiCal Obesity Treatment Study (SCOTS): protocol for a national prospective cohort study of patients undergoing bariatric surgery in Scotland. BMJ Open 2015; doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008106], Grieve et al. (Grieve E, Mackenzie RM, Munro J, O’Donnell J, Stewart S, Ali A, et al. Variations in bariatric surgical care pathways: a national costing study on the variability of services and impact on costs. BMC Obes 2018; doi.org/10.1186/s40608-018-0223-3) and Mackenzie et al. [Mackenzie RM, Greenlaw N, Ali A, Bruce D, Bruce J, Grieve E, et al. SCOTS investigators. SurgiCal Obesity Treatment Study (SCOTS): a prospective, observational cohort study on health and socioeconomic burden in treatment-seeking individuals with severe obesity in Scotland, UK. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e046441; doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2020-046441].

Obesity

Body mass index (BMI) is an indicator of body fat calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by their height in metres squared. Obesity is defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and severe obesity as BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2. 1

Obesity and, in particular, severe obesity are associated with a variety of negative health outcomes, including increased risk of most major chronic diseases and premature death. 2 Obesity-related comorbidities are defined as conditions either directly caused by obesity or known to have their presence or severity affected by obesity. Consequently, it is anticipated that these comorbid conditions will improve or enter remission in the presence of effective and sustained weight loss. 3 A non-exhaustive list of known obesity-related comorbidities includes:

-

premature mortality

-

cardiovascular conditions

-

hypertension

-

atherosclerosis

-

myocardial infarction (MI)

-

stroke

-

congestive heart failure

-

cardiac arrhythmias

-

-

metabolic conditions

-

type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

-

prediabetes

-

dyslipidaemia

-

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

-

-

pulmonary conditions

-

obstructive sleep apnoea

-

asthma

-

-

musculoskeletal conditions

-

degenerative arthritis

-

immobility

-

pain

-

-

reproductive conditions

-

polycystic ovary syndrome

-

infertility

-

sexual dysfunction

-

-

genito urinary conditions

-

impaired renal function

-

kidney stones (nephrolithiasis)

-

stress urinary incontinence

-

-

central nervous system conditions

-

impaired cognition

-

headache

-

idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumour cerebri)

-

-

psychosocial conditions

-

impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

depression

-

anxiety

-

other psychopathy

-

-

cancers.

People with severe obesity are at increased risk of several of these comorbidities, including T2DM, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and depression. This can lead to the development of multiple morbidities, often at a young age, which, in turn, causes reduced HRQoL, increased healthcare costs and heightened risk of mortality. 4

In recent years, severe obesity has emerged as a major public health concern, with rates increasing rapidly in a number of countries across the world, including the United States of America (USA) where the prevalence of BMI > 40 kg/m2 among adults rose by 96% between 2000 and 2018, and around 9.2% of the adult population is now considered to have severe obesity. 5 Similarly, levels of severe obesity have risen in the United Kingdom (UK), with 3.3% of all adults in England6 and 3% of all adults in Scotland now estimated to have a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2. 7

Obesity treatment

As the prevalence of severe obesity rises, effective treatment is a priority. Treatments for severe obesity may be surgical or non-surgical. Bariatric surgery is the collective term for a number of surgical interventions with the primary purpose of achieving large-scale weight loss. Non-surgical treatment usually involves a multicomponent approach comprising behavioural therapy, dietary change and increased physical activity, and can also involve pharmacotherapy. 8,9

Bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery procedures can be restrictive, malabsorptive or a combination of the two and include Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB). 3

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

RYGB is a restrictive-malabsorptive surgical procedure which involves transecting the stomach to create a small gastric pouch and connecting it to the small intestine. Ingested nutrients are thereby diverted from the body of the stomach, duodenum and proximal jejunum. 3,10 Consequently, less food is required for satiety and fewer calories are absorbed from food consumed.

Sleeve gastrectomy

In the restrictive SG procedure, a large portion of the stomach is removed, creating a tubular stomach based on the lesser curvature of the stomach. 3 As a result, patients are unable to consume as much food as they were prior to surgery and satiety is achieved sooner.

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding

LAGB is a minimally invasive restrictive bariatric procedure which involves using laparoscopic surgery to place an adjustable band around the top portion of the stomach. This creates a small pouch which results in less food intake and increased food transit time. The band is connected to a small device placed under the skin which allows post-surgical band tightening. 11,12

Endocrine changes associated with bariatric surgery

Many of the beneficial metabolic effects of bariatric surgery have been attributed to altered peptide hormone profiles, particularly gastrointestinal (GI) and pancreatic peptide hormones. These alterations include increases in peptides that increase satiety, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), gastric inhibitory polypeptide, pancreatic peptide YY3-36, oxyntomodulin and gastrin. 3,13,14 Bariatric surgery is also known to cause an increase in peptides which reduce levels of the appetite-stimulating hormone, ghrelin. 3,13,14

Bariatric surgery and weight loss

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 published datasets of long-term (≥10 years) outcomes shows that all current bariatric surgical procedures are associated with substantial and enduring weight loss. 15 Eighteen reports of gastric bypass showed a weighted mean excess weight loss (EWL) of 56.7%, while 17 reports of LAGB showed 45.9% EWL and two reports of SG showed 58.3% EWL. 15 As such, there is high-quality evidence that bariatric surgery achieves sustained weight loss.

Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery

A 2014 Cochrane systematic review of 22 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for bariatric surgery found it to be more clinically and economically effective for the treatment of severe obesity than non-surgical measures after 2 years. 8 This finding was supported by data from trials with longer term follow-up, and cohort and modelling studies. 15,16 Indeed, in their 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 datasets reporting long-term (≥10 years) outcomes following bariatric surgery, O’Brien and colleagues reported that surgical procedures resulted in a weight loss effect three to four times greater than that of non-surgical therapy. 15 Similarly, Borisenko et al. found bariatric surgery to be cost-effective at 10 years post surgery16 and results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study demonstrate cost-effectiveness of surgical procedures over 15 years, particularly in those with diabetes. 17

Clinical effectiveness and outcomes of bariatric surgery

Mortality

With regard to clinical outcomes following bariatric surgery, mortality rate has been one of the most extensively investigated to date. Observational studies have reported that patients undergoing bariatric surgery have a subsequent longer life expectancy than patients receiving non-surgical treatment for obesity; several large-scale cohort studies published in the last decade18–28 have reported a significant reduction in relative risk of long-term all-cause mortality for patients following bariatric surgery as compared to non-surgical controls. A recent meta-analysis29 of these studies (n = 269,818 bariatric surgery patients and 1,270,086 controls) revealed that bariatric surgery is associated with a 62% reduction of all-cause mortality for the whole operated population as compared to controls (pooled odds ratio = 0.62, p < 0.001).

Complications and hospitalisations

Complications following bariatric surgery have been poorly reported in the literature. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2017 assessed early (<30 days post surgery) major complications associated with bariatric surgery: anastomotic leak, MI and pulmonary embolism. 30 The review included 71 studies and 107,874 patients undergoing RYGB, LAGB or SG in the USA and reported that rates of the three major complications after either one of the procedures ranged from 0% to 1.6%. Mortality following these complications ranged from 0% to 0.6%. 30

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Over the last 10 years, bariatric surgery has been shown to be an effective treatment for T2DM in patients with obesity. 9,15,31,32 A number of RCTs and cohort studies have demonstrated that surgery is associated with a greater improvement in hyperglycaemia as compared to alternative treatment and that this effect is sustained for at least 5 years postoperatively. 33–36 Improvement in hyperglycaemia is associated with a reduction in mortality37,38 and diabetes-related complications,39,40 including retinopathy, nephropathy and CVD. Improvement and remission of T2DM post bariatric surgery has been shown to be mediated by both weight-loss-dependent and weight-loss-independent mechanisms. 41,42

Cardiovascular disease

Bariatric surgery is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular mortality. 24,26,28,29 Two recent retrospective studies of patients with diabetes undergoing SG and RYGB report bariatric surgery is associated with significantly lower incidence of major cardiovascular events after 8 years. 43 Recently, Doumouras and colleagues44 demonstrated, in a population-based matched cohort study of 2638 patients with severe obesity and CVD, that bariatric surgery is associated with a significantly lower incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality, coronary events and heart-failure hospitalisations. While these results are yet to be confirmed in a large RCT, they suggest that bariatric surgery may be an effective intervention for patients with severe obesity and ischaemic heart disease or heart failure.

Health-related quality of life

It is currently well established that post-surgical HRQoL is improved on comparison with preop HRQoL for up to 10 years. 45–48 When patients who decide to proceed to surgery are compared to those who opt for non-surgical treatment only, baseline HRQoL is often far lower in those who select surgery, showing at least a perception of reduced HRQoL in these individuals. 49 A 2020 study by Poelemeijer et al. found that severe post-surgical complications and failure to achieve desired weight loss had a negative effect on postoperative (postop) HRQoL outcomes at 12 months. 48 There is a need for further research to examine correlations between HRQoL, weight loss, complications and clinical outcomes.

Anxiety and depression

The literature suggests that bariatric surgery is associated with long-term reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms. In a systematic review of 14 prospective studies, 13 studies (93%) reported statistical and clinically significant reductions in the severity of patient-reported depressive symptoms up to 3 years after bariatric surgery. Similarly, there were reductions in overall anxiety symptom severity at ≥2 years post-surgical follow-up. 50

Cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery

Obesity has an enormous economic impact; the total cost to the UK National Health Service (NHS) is estimated to be £6.1 billion per year. 51 Estimates of costs to the NHS include direct costs, indirect costs and the cost of treating obesity-related complications. More broadly, obesity has a serious impact on economic development; the overall cost of obesity to the UK economy is estimated at £27 billion. With increasing levels of obesity and severe obesity, these costs are set to rise, with the UK-wide NHS costs attributable to overweight and obesity projected to reach £9.7 billion per year by 2050 and the wider cost to UK society estimated to reach £49.9 billion. 52

Provision of bariatric surgery represents a relatively high upfront cost but surgical intervention is demonstrated to be cost-effective for adults with severe obesity when compared to non-surgical treatments. Cost savings arise from health benefits of a reduction in onset of incident diabetes, remission of existing diabetes and lower mortality. 4 Indeed, economic analysis for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) confirmed that the financial outlay for bariatric surgery is justified for the NHS. 53 In patients with diabetes, it was found that the cost of surgery would be negated within 3 years due to the reduction in prescriptions required. 54

A systematic review of the economic evidence suggests that RYGB surgery, compared with standard care for obesity, is associated with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) of between US$5400 (approximately £3172) and US$25,000 (approximately £20,779), with a cost per life-year gained of US$8171 (approximately £5000). 55 BMI change results from randomised trials of RYGB identified in the review were considered within a health economic simulation model using contemporary UK health data and appropriate modelled costs for NHS bariatric surgery follow-up, including complications. RYGB had an ICER of £10,126 compared to no intervention. These cost savings largely accrue from reduced resource use (including fewer outpatient clinic visits, hospitalisations, length of stay in hospital and medications) postoperatively. 56,57 These reductions in health service utilisation can partially be explained by patients undergoing definitive treatment for comorbid problems, such as total knee replacement or urology surgery, previously denied because of their obesity. The major reduction in utilisation, however, reflects improvement in medical conditions such as hypertension or diabetes, a direct result of weight loss. 56,58–60 Surgery also has indirect cost benefits; for example, state disability allowances are reduced if improved activity levels allow patients to return to paid employment. 61

Furthermore, bariatric surgery is comparably cost-effective to other public health interventions in the UK, including smoking cessation and the use of statins for primary prevention of CVD. 62 The 2022/23 NHS England Tariff Process for bariatric surgery was £8972 for RYGB, £5859 for SG and £2494 for LAGB.

UK bariatric surgery guidelines

UK NICE guidelines63 currently indicate that bariatric surgery is a treatment option for those with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, or between 35 kg/m2 and 40 kg/m2 in the presence of other significant diseases (T2DM or hypertension, for example), which could be improved if they lost weight. People with a BMI of 30–34.9 kg/m2 with onset of T2DM within 10 years and people of Asian ethnicity with onset of T2DM at a lower BMI are also considered for assessment, as are any adults with a BMI > 50 kg/m2. In all cases, non-surgical weight management must have been attempted but not resulted in clinically beneficial weight loss before bariatric surgery is indicated. 53,63

In Scotland, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidance64 is followed. These guidelines are broadly similar to those of NICE, stipulating that bariatric surgery should be considered for those with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 and one or more severe comorbidities which are expected to improve significantly with weight reduction, such as mobility problems, arthritis and T2DM. As per NICE guidelines, there is a requirement for evidence of completion of a multicomponent, structured weight-management programme that has not resulted in significant and sustained improvement in comorbidities. 64

Bariatric surgery rates

Despite evidence that bariatric surgery is a more clinically and economically effective intervention for the treatment of obesity than non-surgical options, for the UK NHS, like many other health systems, the volume of bariatric surgery procedures commissioned is very low. In fact, despite obesity prevalence being among the highest in the European Union, the UK performs only nine bariatric surgery procedures per 100,000 people,4,65 while Sweden, a country with a similar health service but lower obesity prevalence, performs 70–80 procedures per 100,000 people. 66 In North America, the rate of surgery is around 40–50 per 100,000 people, with the majority of these operations performed in the USA. 65 Moreover, despite escalating levels of severe obesity in the UK, numbers of NHS bariatric procedures are falling, with a reduction of 31% between 2011/2012 and 2014/2015. 4,6 Rates of surgery have also been observed to vary between countries in the UK; no NHS bariatric surgery is performed in Northern Ireland, while few NHS weight-loss operations take place in Wales and Scotland as compared to England. 4

It has been suggested that one reason for low bariatric surgery rates in the UK is that rather than general practitioners (GPs) referring directly to surgical services, patients must follow a complex pre-surgical tiered pathway and barriers are often encountered (see Table 1). 4 Other barriers include the perception among patients and clinicians that bariatric surgery is high risk, and the fact that commissioners restrict funding for bariatric operations, despite evidence of cost-effectiveness. 4 The latter may be due to the initial high cost of bariatric surgery, with savings recouped in subsequent years.

| Tier | Intervention | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Societal interventions to enhance weight loss (e.g. food tax, encouraging walking) |

|

| 2 | Primary care provision of advice or referral to community groups for lifestyle interventions (e.g. behavioural weight-management programmes) | |

| 3 | Secondary care-based medical management (e.g. dietary advice, medication) |

|

| 4 | Multidisciplinary team selection for bariatric surgery with follow-up for 2 years |

|

The low prioritisation of bariatric surgery within the UK and the strict criteria for access to surgery, including complex pre-surgical pathways and pre-surgical weight-loss requirements,67 results in low numbers of individuals with severe obesity actually receiving surgery. Those receiving surgery generally do so after many years of alternative conservative interventions, at a point when their mean BMI is extremely high, at around 45 kg/m2, and they are at a median age of 47 years. 68 To date, it is unclear how this delay in treatment impacts on health, physical functioning and HRQoL.

UK bariatric surgery care pathways

Pre- and postop care is a major component of the total cost of bariatric surgery. 67 However, anecdotal evidence suggests that bariatric surgery care pathways vary considerably, including clinical psychology provision. International bariatric guidance, while based on best practice, does not specify the optimal model of care69,70 and there is little evidence of whether intensive pre- and postop care improves outcomes and is cost-effective compared to less intensive care. Further investigation is therefore required as to the extent the intensity of pre- and postop bariatric surgical care is a factor affecting patient outcomes after surgery.

Surgical Obesity Treatment Study (SCOTS)

Background

In 2010, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme issued an open call for research proposals for a long-term longitudinal cohort study of patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the UK, stating that, ‘Obesity is a growing problem in the UK, with a growing number of people among the morbidly obese. Concomitantly, there is an increase in requests for bariatric surgery but insufficient evidence of long-term effectiveness and safety of these procedures. There are existing registries of bariatric surgery, but these suffer from problems of collected data, completeness of follow-up, or data availability for secondary analysis. There is a need for a long-term study of bariatric surgery, so that the outcomes and complications of different procedures, their impact on QoL and nutritional status, and the effect on comorbidities can be monitored in both the short and the long term’. Following this call, the Surgical Obesity Treatment Study (SCOTS) was commissioned to address some of the uncertainties around the clinical effectiveness of bariatric surgery in the longer term.

The original SCOTS study design included a 10-year follow-up period. However, due to unforeseen recruitment issues, the result of reductions in both NHS and private surgical numbers in Scotland, both the study design and statistical plans were revised by the funder in 2016 (Report Supplementary Material 2). The study follow-up period was reduced from 10 years to 3 years. Objectives were revised to reflect research published between 2010 (the time of writing of the original SCOTS research proposal) and 2016 when the protocol was revised.

Study aims and objectives

The aim of SCOTS prospective observational cohort study was to investigate the short- and medium-term outcomes and complications following bariatric surgery in Scotland.

The specific objectives were to establish in a cohort of patients with obesity undergoing bariatric surgery:

-

the physical and mental health, and social burden of severe obesity;

-

incidence of acute and chronic postop complications (acute complications, defined as up to 3 months post surgery, include surgical site infection, chronic complications include revisional surgery, plastic surgery and chronic pain, for different bariatric surgical procedures);

-

the effect of surgical experience and the pre- and postop care pathway on complication rates and weight loss, for different bariatric surgical procedures;

-

the effect of the pre-surgical pathway and criteria on bariatric surgery patient selection

-

change in HRQoL, anxiety and depression over time pre- and postoperatively for a mean of 3 years from date of bariatric surgery;

-

the weight status pre- and postoperatively for 3 years after bariatric surgery;

-

the glycaemic control, lipids, blood pressure, medication prescription and rate of diabetes complications (microalbuminuria and renal disease, and retinopathy) in those who have pre-existing diabetes or develop diabetes during 3 years follow-up since bariatric surgery;

-

changes in socioeconomic factors (employment, benefit receipt, sick leave and healthcare use) for 3 years since bariatric surgery.

For the second objective outlined above, the specific definitions of acute and chronic postop pain have been disregarded due to the data collection at this time point being removed from the protocol in 2016. Complications were subsequently based on health record data and therefore have different definitions.

The effect of surgical experience on complication rates and weight loss, as per the third objective, was not examined as the information collected was not deemed appropriate for this objective. UK bariatric surgeons also perform laparoscopic upper GI surgery, which adds to their overall technical skills and experience. This more general experience was not collected.

With regard to the fourth objective, the effect of eligibility criteria on bariatric surgery patient selection was not examined as these criteria were standardised across Scotland in 2014.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Logue et al. 71 and Mackenzie et al. 72

Patient involvement

Patients identified via bariatric surgery peer support groups in Scotland were involved in the design and conduct of this research. During the protocol development stage, patients provided input with regard to data collection and defining research questions. Two focus groups were held with patients to discuss methods of recruitment; they contributed to recruitment procedures and development of materials. Patients were included in a promotional recruitment video, with consent. A patient member was included on the independent study steering committee and patients were invited to a meeting to discuss plans for dissemination of study results.

Study design

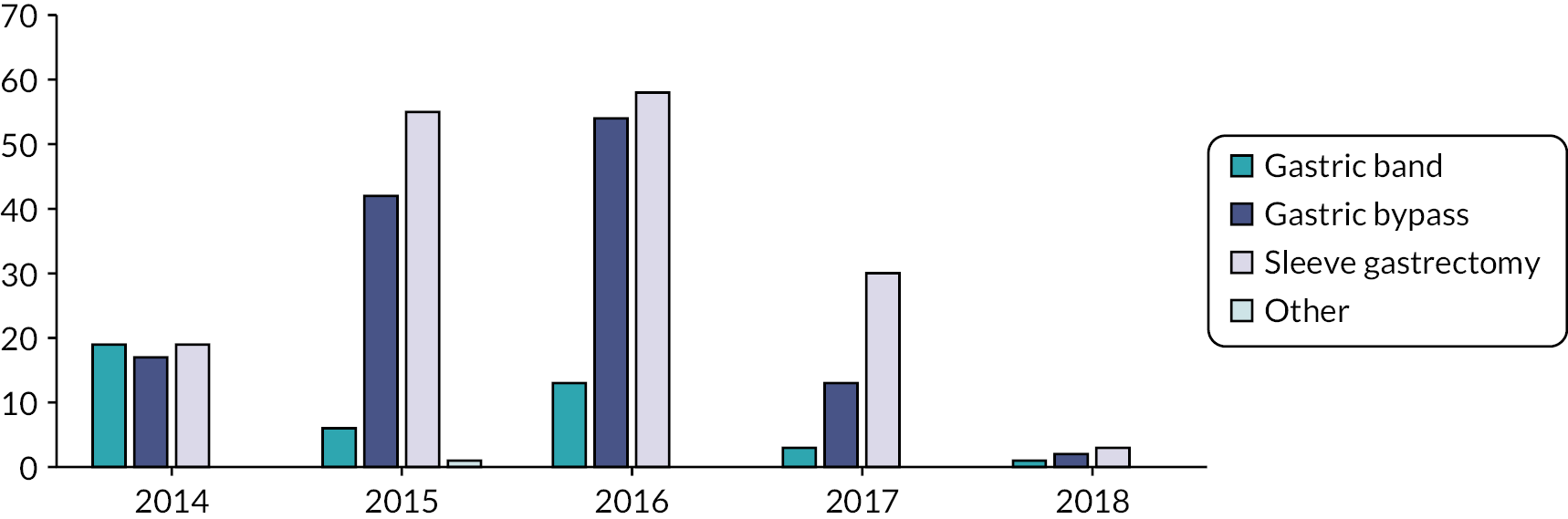

SCOTS was a national, prospective, observational cohort study of adults aged over 16 years eligible for primary bariatric surgery in Scotland. Participants were recruited from 3 December 2013 to 28 February 2017. A mean of 3 years postop follow-up continued until October 2020. A detailed protocol for the SCOTS study was published71 but was amended in 2016 with follow-up reduced from 10 to 3 years.

Study setting

The study was conducted in 10 NHS-funded and 4 private hospitals in Scotland. Centres were eligible to participate if they performed bariatric surgery. Bariatric procedures included gastric banding, gastric bypass and SG. All patients’ healthcare interactions in Scotland are recorded by use of a single patient identification number. Information technology systems are common across all 14 health board areas, and a single government-funded department (Information Services Division) collates information for research purposes. This has allowed these systems to be utilised for post-surgical patient follow-up in SCOTS.

Study participants

Adult patients (aged 16 years and over) scheduled to undergo a primary bariatric procedure at any hospital in Scotland were eligible for invitation to the study.

Inclusion criteria

For inclusion in SCOTS, patients had to:

-

be aged 16 years or over and undergoing their first bariatric surgery in NHS hospitals or private practice in Scotland

-

have capacity to consent

-

be residents of Scotland

-

be able to provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from SCOTS if they:

-

had previous weight-loss surgery or at the time of potential recruitment were undergoing a repeat procedure.

Patients with limited English language were eligible for participation in the data linkage aspect of the study only.

Participant screening

Eligibility checks were undertaken by clinical bariatric surgery teams or research nurses while patients attended preop bariatric assessment clinics. Patients were approached at least 4 weeks prior to surgery. Patients were consented in clinic or referred to the SCOTS research team, who provided further study information and then obtained fully informed consent. Patient information sheets were provided at least 24 hours before patients consented to the study. In the case of those patients who were to be recruited by the research team, a patient information sheet was provided when permission was sought to hand over contact details to the research team. An independent contact was provided on the patient information leaflet so that patients could discuss participation in research studies with someone independent of the study team, should they wish to do so.

Patients consented for clinical data linkage (part one), postal, electronic and/or telephone follow-up (part two) and whether they were interested in future research. Those requiring a translator were consented for clinical data linkage only.

Withdrawal of subjects

Participants could withdraw from the study at any point for any reason. Level of withdrawal was recorded. Data were retained unless complete withdrawal was requested.

Study procedures / data collection

Part one: health record linkage

The study collected data by record linkage to participants’ clinical outcomes. Information on participants’ operations was recorded by the clinical team. Participants were then followed using their medical records until 1 October 2020. This part of the study observed patients’ care, not altering their planned care in any way. No additional tests or treatments were given to patients who consented to be part of the study. If patients did not consent to participate in this part of the study, they were not asked to participate in part two or part three. Health record systems sources for all data and outcomes are summarised in Table 2.

| Planned analysis | Outcomes/data being presented | Potential predictors being considered/data being described |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | Baseline data being described for the total SCOTS population and by age group, BMI group and separately by SIMD quintile | Summaries for the total SCOTS population and various subpopulations of baseline characteristics, including: |

| One-year surgical complications | These will include:

|

Predictors of non-progression to surgery using baseline data, including:

Predictors of surgical complications using baseline or other follow-up data, including: |

| Three-year outcomes | These will include: | Predictors of 3-year outcomes (all-cause mortality, readmissions, change in weight) using baseline or other follow-up data, including: |

|

Additional predictors for the 3-year diabetes outcomes and complications, to those noted above, for the population with diabetes:

Additional predictors to those noted above for the 3-year outcomes, for the QoL outcomes:

|

Part two: outcome data collection

Recruited participants completed questionnaires preoperatively and 3 years postoperatively. All participants were asked if they would be willing to be contacted about other research in the future.

Outcome measures

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) questionnaires collected health-related information, including weight, medical history, smoking status, alcohol use, GI symptoms, urological health, depression, anxiety, HRQoL and obesity-specific QoL (O-QoL), life optimism, physical activity, health-care utilisation, employment and social security.

Questionnaires/instruments utilised for PROMs:

-

Comorbidity was assessed by self-report using a questionnaire designed specifically for this study (Report Supplementary Material 3).

-

GI reflux symptoms were evaluated using a questionnaire developed for the REFLUX trial. 73

-

Urological health was assessed using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS),74 where a score ≥ 8 indicates moderate to severe symptoms, and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF), wherein a score ≥ 6 indicates moderate incontinence. 75

-

Female reproductive health data were obtained using a modified version of the questionnaire developed for the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery study. 76

-

Information on male erectile dysfunction was obtained using a modified version of the questionnaire developed for the Massachusetts Male Ageing Study. 77

-

Anxiety and depression were assessed using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7)78 and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)79 instruments, respectively. A PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 is indicative of moderate to severe depression, while a GAD-7 score ≥ 6 is reflective of moderate to severe anxiety. 78,79

-

Smoking status was ascertained using a questionnaire specifically developed for this study (Report Supplementary Material 3).

-

Alcohol use was determined using a modified version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). 80

-

HRQoL was assessed using the Rand 12-item Short Form Survey (SF-12)81 and Euro QoL 5-level EQ-5D version (EQ-5D-5L)82,83 instruments.

-

O-QoL was assessed using the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite) questionnaire. 84 Standardised scoring was used when interpreting IWQOL-Lite questionnaires. 85

-

Life optimism was determined using a modified version of the Life Orientation Test (LOT), wherein a score range of 0–13 reflects low optimism (high pessimism). 86

-

Data on physical activity were obtained using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) – Short Form. 87

-

Information on participants’ employment, social security status and healthcare utilisation was obtained using questionnaires specifically developed for this study (Report Supplementary Material 3).

-

Questions relating skin excess following bariatric surgery were specifically developed for this study (Report Supplementary Material 3).

-

Information on postop plastic surgery was obtained using questions adapted from Ertelt et al. 88

Each participant’s quintile of the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD), an area-based measure of socioeconomic status,89 was derived from their postcode. Combining a number of indicators of socioeconomic status across seven domains, the SIMD provides a relative measure of deprivation which can be used to compare data zones by ranking them from most to least deprived. The seven domains include income, employment, health, education, skills and training, housing, geographic access and crime. 89

Clinical data

Height and weight at the start of the weight-management programme were reported by clinical staff at the time of recruitment, allowing BMI to be calculated. Date of surgery, operation type, weight at operation and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade were reported by the clinical teams. Weight at routine clinical follow-up visits and any revisional bariatric surgery procedures were also recorded.

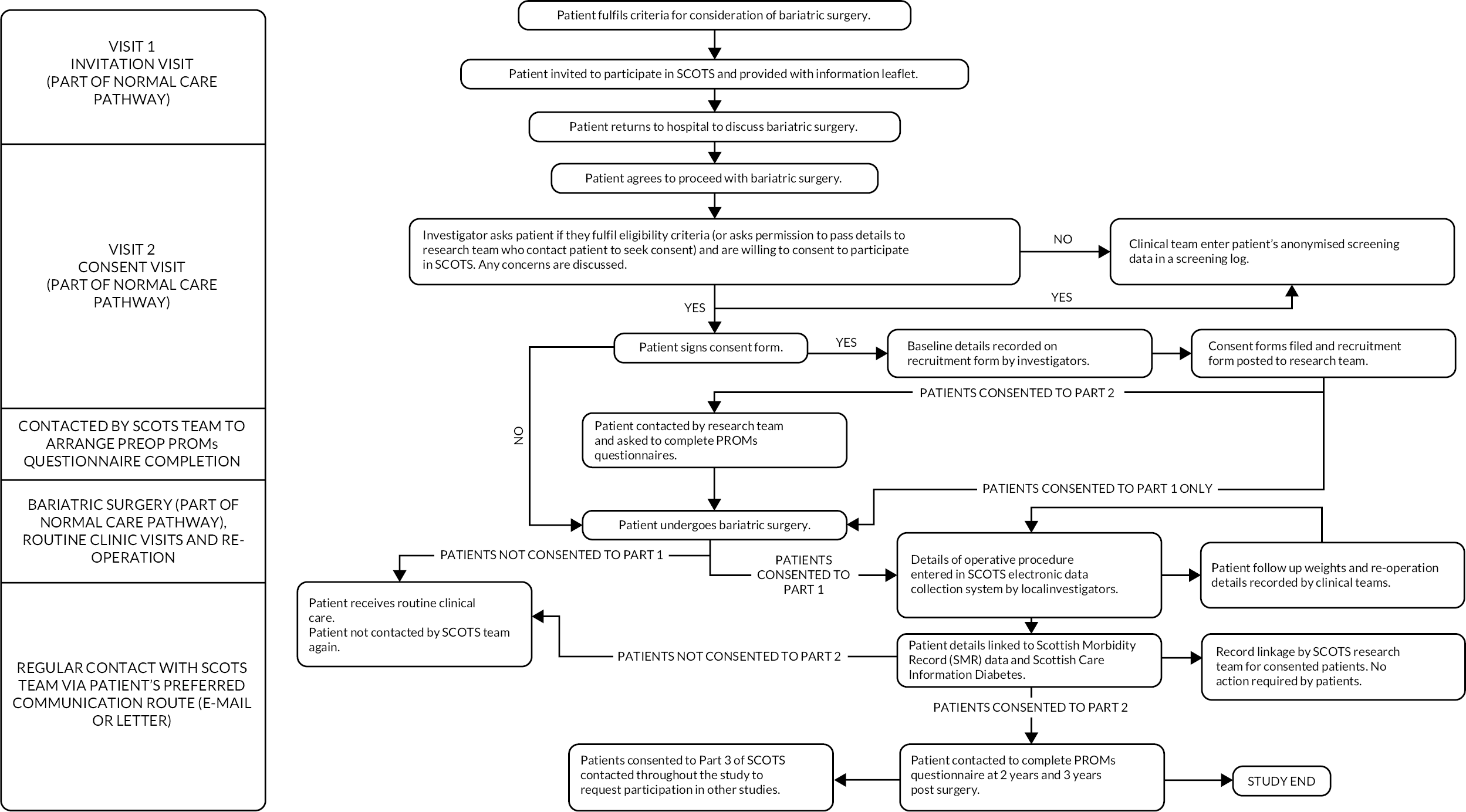

Outcomes and data sources are summarised in Table 2. Figure 1 summarises the patient journey through the study.

FIGURE 1.

SCOTS flow chart summarising patient journey through the study.

Procedures for data collection

Patient-reported outcome measures

Completion of questionnaires could be either by post or electronically via a secure link sent by e-mail. Two reminders were sent by the participant’s chosen method and a third reminder, if required, was sent by post to all participants. No further strategy was used after three reminders.

Where patients did not complete PROMs and there was no reliable clinical weight record, they were contacted after 3 years from their date of bariatric surgery requesting completion of a weight questionnaire (simply asking their current weight). The patients were offered an incentive (£30 high-street voucher) for completing both the year-2 and year-3 questionnaires. For those no longer in clinical follow-up / not completing PROMs, an incentive (£10 high-street voucher) for completing the year-3 weight questionnaire was offered.

Clinical data

A bespoke electronic data-collection system / web-based portal was developed for SCOTS. This was secure, password-protected and used to collect clinical data from participating sites. It also allowed patients to complete questionnaires online. Information from written questionnaires was entered into the database manually by the research team, as required.

Following their operation, patients had their weight-loss surgery details entered into the SCOTS electronic data collection system / web-based portal. The clinical teams then used the electronic data-collection system to include follow-up weights, gastric-band adjustments and reoperations (including reasons for reoperations).

A detailed breakdown of patient contact within the study is described in Table 3.

| Patient contact | Time | Routine care | SCOTS | Part 1 | Part 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 year to 6 weeks before surgery | Agree bariatric surgery | Patient given/sent invitation-to-participate letter and patient information sheet (and asked if they are willing to be contacted by SCOTS research team for further information and informed consent if no local recruitment). | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 year to 6 weeks before surgery | Patient pre-surgical clinic visit | Patient asked if they are willing to consent to participate in SCOTS. If so, patient signs consent forms. Clinical team and patient complete contact details and baseline height and weight. | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | At least 4 weeks before surgery | Patient contacted by SCOTS team to complete preop questionnaire. | 1 | 1 | |

| 4 | Date of surgery | Patient has bariatric surgery | Clinical team enters details of bariatric surgery on SCOTS electronic data-collection system. | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | Patient admitted to hospital | If patient hospital admission is possibly related to bariatric surgery, identified by record linkage to SMR01. | 1 | 1 | |

| 6 | At routine follow-up visits | Patient attends routine clinical visits | Clinical teams enter weight and reoperation details. | 1 | |

| 7 | 2 years post surgery | Patient has routine annual diabetes care (if has diabetes) | Patient completes 2-year post-surgical questionnaire. Blood results available via SCI Diabetes. |

1 | |

| 8 | 3 years post surgery | Patient has routine annual diabetes care (if has diabetes) | Patient completes 3-year post-surgical questionnaire. Blood results available via SCI Diabetes. |

1 | |

| 9 | 3 years onward | Patient continues to have routine diabetes and post-bariatric surgery care | Patient contacted to thank them for completing PROMs. Record linkage continues. Patient informed about future SCOTS publications. | 1 | |

| Total | 5 | 9 |

Bariatric surgery care pathway site survey

Bariatric surgery care pathway update questionnaire

To establish preop assessment and postop care pathways used in bariatric surgery sites in Scotland, a questionnaire was distributed to each health centre (Report Supplementary Material 4). This covered pathways for referral, eligibility criteria, the different components of service delivery, the professionals involved and frequency and length of sessions and consultations. The questionnaire was distributed by e-mail and responses collected over a 2-year period which served as a consistency check for within-centre reporting over multiple years. Follow-up discussions by phone and e-mail were undertaken with centres where clarifications were required, on staffing grade for example. A limitation was that practice was not observed at any site to cross validate with the self-reported information.

Costing

Costs were based on publicly available information for staff time. Unit costs were taken from the Personal Social Services Research Unit 201590 and the Information and Statistics Division Scotland tariffs 2015. 91 Cost was calculated per person participating in the bariatric surgery care pathway by multiplying the salary costs of staff, according to grade or band, by the average number of annual sessions provided by that staff member and accounting for the length of session. Multidisciplinary team (MDT) costs were calculated from the number, type and grade of different specialists involved according to their time spent on delivering these sessions. All group sessions were cost per person by taking the average number of patients expected to participate. The assumption was made that costs such as those of equipment and instruments were constant, and the variability in costs was therefore in the staffing, which was more likely to affect patient outcomes.

Costings analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to present average cost per patient along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), as well as the range of costs. Data were costed in Excel and statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 12. A base case cost was calculated as the most likely average cost per person; a maximum cost was calculated based on optional or additional patient-dependent consultations. We assume zero optional or additional sessions in the base case and at least two for the maximum-cost scenario analysis. Where length of sessions or consultations was not provided, 30 minutes was assumed based on other responses received.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed as available, without any imputation for missing data. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3). Continuous data are reported as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and lower (Q1) and upper (Q3) quartiles depending on data distribution, and counts and percentages are reported for categorical data. Comparisons between groups were made by Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorial variables. Paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used for change outcomes for continuous variables, McNemar test for dichotomous categorical variables and Bowker test for agreement for grouped categorical outcomes.

Binary logistic regression models were used for non-progression to surgery, admission to intensive-therapy unit (ITU) / high-dependency unit (HDU), readmission, <10% weight loss, reduction in diabetes medication, ‘need for specialist aids’ and ‘equipment in the home to assist with daily living’ outcomes. Length-of-stay outcomes were modelled with negative binomial regressions. Linear regression models were used for change in weight, change in HbA1c and change in QoL outcomes.

Regression model effect estimates, incidence rate ratios (IRRs) or odds ratios (ORs), and corresponding 95% CIs and associated p-values, are provided. The value of p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

A complete case analysis was performed with numbers of participants with available data listed. All results using health record data were subject to Public Health Scotland’s disclosure control protocol and outcomes affecting fewer than five participants cannot be reported (shown as xxx in tables).

Populations and outcome definitions

Five populations are considered within this report:

-

All operated – all operated patients of those consenting to part 1 of SCOTS. Patients in this population will have an operation type of gastric band, gastric bypass, SG or other.

-

Non-progression to surgery – patients who did not have an operation and had a completed non-progression to surgery form completed.

-

All operated and consented to PROMs – all operated patients as defined above who also consented to PROMs and had at least some data entered prior to their operation.

-

All operated and year 3 PROMs – all operated and consented to PROMs patients as defined above and have at least some 3-year data reported.

-

All operated and diabetes – all operated patients as defined above and who have at least one record in Scottish Care Information – Diabetes (SCI Diabetes) (i.e. regardless of patient-reported T2DM status in preoperative PROMs).

SMR01 and death record linkage outcomes

The matched initial bariatric operation was identified as the record in Scottish Morbidity Record 01 (SMR01), where the date of admission corresponding to a date of operation matches (on month and year) with the date of initial bariatric operation as entered into the electronic case-report form (eCRF). In instances where there may be more than one unique SMR01 admission with the same month and year as the initial bariatric operation as detailed in the eCRF, the Chief Investigator reviewed each SMR01 admission to note which ones were the initial bariatric operation. Note, for private patients the record corresponding to the initial bariatric operation may not have been provided. Admission to ITU/HDU during initial operation was identified from the SMR01 records where the initial bariatric operation occurred and has a ‘significant facility’ code for either ‘HDU’ or ‘Intensive Care Unit’.

Readmission was defined as any new stay admission record in SMR01 occurring after the initial bariatric operation where the admission was recorded as either urgent or emergency. If no matched bariatric operation occurred in the SMR01 data (i.e. for private patients), then the initial operation date as defined in the eCRF was used. Readmissions were considered within the same or subsequent calendar month, within the same or subsequent 11 calendar months or within the same or subsequent 35 calendar months. Different readmission codes (endocrine, circulatory, surgical) were defined using observed International Classification of Disease-10 codes (Report Supplementary Material 5).

Reoperations both within the period of ITU/HDU admission and up to 3 years post surgery were identified by OPCS Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 4 (OPCS-4) codes within SMR01. The following OPCS-4 codes were considered ‘bariatric surgery gastrointestinal complications or revisions’: G305 (maintenance of gastric band); G332 (revision of anastomosis); G387 (removal of gastric band); G436 (endoscopy and injection of lesion); G451 (upper GI endoscopy + biopsy); G459 (upper GI endoscopy); T309 (unspecified opening of abdomen); T315 (drainage of ant wall – laparoscopic); T413 (division of adhesions); T423 (closure of connection of stomach to jejunum).

Mortality was defined by any record within the deaths record. Exact date of death was provided, so mortality within 30 days of operation or within a year of operation was obtained using the exact date of initial bariatric operation as entered into the eCRF.

Diabetes record linkage outcomes

For all outcomes arising from the SCI Diabetes data, the preoperation value is the result available closest to the date of operation, including values entered on the date of operation or up to 18 months previously. The 3-year value is the value closest to the date of operation as entered in the eCRF + 3 years, and only includes values entered within the window of 27–45 months post operation. When more than one value is available, with one value occurring prior to the expected 3-year date and the other value occurring after the 3-year date, the value occurring prior to the expected 3-year date was used. Outlying values deemed implausible were removed, including HbA1c <12 mmol/mol and >348 mmol/mol and systolic blood pressure values of 0 mmHg and >1400 mmHg. Microalbuminuria was defined as an albumin : creatinine ratio ≥2.5 mg/mmol for men and ≥3.5 mg/mmol for women.

For retinopathy outcomes, data from the National Retinal Screening Programme were used, specifically focusing on the retinopathy and maculopathy data for the left and right eyes. Participants are categorised into two mutually exclusive groups at each time point (preoperation and 3 years post operation): no disease (bilateral R0 M0) or observable or referable disease in any eye. For the change in retinopathy status between preoperation and 3 years post operation, patients with retinopathy data at both time points are categorised into the four following mutually exclusive groups: no disease at both preoperation and 3 years post operation; no disease at preoperation but observable or referable disease at 3 years post operation; some disease at preoperation but no disease at 3 years post operation; observable or referable disease at both preoperation and 3 years post operation.

Prescribing Information System data were used to identify whether each participant with diabetes was prescribed any of the following specific categories of medications (British National Formulary paragraph drug code) at each time point (preoperation and 3 years post operation): insulin (6.1.1.1, 6.1.1.2); sulfonylureas (6.1.2.1); biguanides (6.1.2.2); glitazones (subset of 6.1.2.3); sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 Inhibitors (subset of 6.1.2.3); GLP-1 agonists (subset of 6.1.2.3); dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (subset of 6.1.2.3); meglitinides (subset of 6.1.2.3); acarbose (subset of 6.1.2.3). Combination drugs and newer agents (6.1.2.3) were reviewed by the chief investigator and assigned to each individual category for the component medications. For the count of medications, the number of unique medication categories for each participant within the time point of interest was obtained.

Clinician- and participant- recorded outcomes

Weight was recorded at multiple time points by both the participant (self-reported if they consented to PROMs) and the clinician. Clinician-reported weight was used preferentially at each time point with participant-reported weight used when no clinician weight was available. For the purposes of obtaining a 12-month post-operation clinician-reported weight, a window of 9–18 months following the date of operation was used and the weight occurring closest to the 12 months following operation was used for analysis. Similarly, for the 36-month weight, a window of 33–42 months after the date of operation was used. For weight on date of operation, if no weight at operation was recorded, weight at the start of the weight-management programme was used instead. BMI was calculated for each source [weight (kg)/ height (m)67] and using the height reported upon recruitment into the study.

Sample size

At the time of study development, 230 operations were funded in NHS Scotland each year (of which approximately 60 were bypass). Bariatric surgeons performed an additional 270 private procedures per year and they were willing to commit to entering data (approximately 80 bypass). Therefore, 500 procedures per year were expected to be entered into the database with a belief that as numbers of people with severe obesity (BMI > 40) are rising rapidly, this number will increase despite financial constraints.

From previous studies,92,93 we expected a 10-year mortality of around 5% (100 deaths). This sample size would allow the mortality rate to be estimated with 95% CI to within ± 1% (i.e. for a 5% 10-year death rate, the 95% CI will be between 4% and 6%). We planned to compare this mortality rate with an age-sex-matched healthy population from the Registrar General of Scotland’s life tables (assumed known with no sampling error). One hundred deaths were sufficient to allow us to build a predictive model for death post surgery (conventionally one requires around 10 events per prognostic covariate considered). An initial sample size of 2000 was proposed as it would easily provide adequate power for the original outcomes under investigation.

However, there were a number of unforeseen recruitment issues that have impacted on the numbers stated above and in 2016 the sample size was revisited. In order to explore whether the sample at that time was likely to show meaningful results, the available statistical power for detecting 3-year difference in HbA1c and QoL (physical and mental components) was calculated using the numbers of participants available as of 29 July 2016. The majority of data to inform sample size were taken from papers where bariatric procedure was LAGB as this is recognised as the least effective of the bariatric procedures so will give a conservative estimate of measure of effect. This shows that there is >99% power to show differences in these outcomes at 3 years with the current sample size.

In order to explore the likely event rate for cardiovascular events and deaths, we performed health record linkage for currently recruited participants, linking with inpatient care and death records. Follow-up is from the date of surgery, so for those patients who went on to have surgery details entered (n = 180), there are 272 separate admissions. Of those 272, there were 72 ‘emergency’ admissions, and 4 of these, in three patients, are ‘circulatory disease’ using the main condition only. The codes included for these hospital admissions are:

-

angina pectoris (x1)

-

acute MI (x1)

-

pulmonary embolism without mention of acute cor pulmonale (x1)

-

orthostatic hypotension (x1).

Using date of operation as the starting point, we have a total (crude) follow-up time of 203.52 years (the mean is 1.13 years and the median is 1.04 years). As the number of cardiovascular events is so low, it is impossible to extrapolate this to a future event rate at this time. It should be noted that the participants have been cleared as healthy for elective surgery, meaning that it is unlikely that there would be many cardiovascular events in early follow-up.

Following discussions with the NIHR, it was agreed that recruitment will stop at approximately 400 patients and these numbers will be sufficient to answer the majority of objectives initially set.

Ethics, regulatory and reporting requirements

The study was performed according to the Research Governance Framework for Health and Community Care (second edition, 2006)94 and was registered prospectively at the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) registry: ISRCTN47072588. A favourable ethical opinion for the study was obtained from the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee 4 on 7 February 2013 (13/WS/0005).

Permission for linkage and access to data from participants’ electronic health records was granted by the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel for Health and Social Care on 11 October 2019.

Chapter 3 Variations in bariatric surgical care pathways: the variability of services and impact on costs

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced, with permission, from Grieve et al. 67

Introduction

With bariatric surgery care pathways known to vary considerably, the first step in obtaining better evidence of what works is to establish what is currently delivered. To this end, a survey of NHS-funded SCOTS study sites was undertaken in order to describe current services, to estimate their costs and explore differences in financial impact. This was necessary to facilitate further investigation as to what extent the intensity of preop and postop bariatric surgical care is a factor which may affect patient outcomes after surgery.

Results

A comparison of Scotland’s tier-four pathways by bariatric site

All 10 NHS-funded SCOTS study sites provided information on their bariatric surgery services. The questionnaires were completed, generally by the bariatric dietician or nurse, and returned by e-mail or hard copy to the investigator. Most patients were referred via GPs, diabetes clinics or consultants. Age range of patients was 18–60 years. Each site’s bariatric surgery preop and postop care pathways and eligibility criteria regarding glycaemic control and target weight loss pre-surgery were compared (see Table 4). It was assumed that BMI and comorbidity eligibility criteria would comply with NICE guidance. Note that one site (site 10) specified sleep apnoea treatment; this was not costed in calculations as a cost of surgery as it is considered a cost related to an obesity comorbidity, which would have been treated regardless of the bariatric surgery.

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | Site 6 | Site 7 | Site 8 | Site 9 | Site 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-surgery targets – weight loss, glycaemic control (targets not specified by NICE) Most sites stated other factors such as attendance rates at clinics and lifestyle changes |

5% weight loss HbA1c < 64 mmol/mol |

5–10% weight loss HbA1c – control but no target Smoking cessation Remittance binge eating |

10% weight loss HbA1c < 69 mmol/mol |

5% weight loss in tier 3, further 5% weight loss tier 4 HbA1c – control but no target |

Weight loss > 5 kg in 6 months | 5–10% weight loss. If < 50 BMI, must reach target HbA1c < 64 mmol/mol |

Weight loss > 5 kg HbA1c < 75 mmol/mol |

Weight loss ≥ 5 kg | Weight loss > 5% HbA1c < 75 mmol/mol |

10% weight loss HbA1c < 75 mmol/mol Smoking cessation Sleep apnoea – 3-month treatment |

| Preop assessment a : | ||||||||||

| Assessment of any psychological or clinical factors that may affect adherence to postop care requirements (such as changes to diet) | MDT including clinical psychologist | Dietician, clinical psychologist | Dietician only | Dietician, clinical psychologist | Dietician, clinical psychologist | MDT including clinical psychologist | MDT including clinical psychologist | MDT includes diabetologist | MDT including clinical psychologist | MDT including clinical psychologist |

| Psychological support | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | If required | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Session format (group or 1:1) | Group | 1:1 | Either | Both | 1:1 | Both | Both | 1:1 | Both | Both |

| Postop assessment: | ||||||||||

| Regular postop assessment, including specialist dietetic and surgical follow-up | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Psychological support | As required | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | As required | Yes | Yes | No | As required | Not stated |

| Session format (group or 1:1) | 1:1 | 1:1 | 1:1 | Both | 1:1 | 1:1 | Both | 1:1 | 1:1 | 1:1 |

Classification of Scotland’s tier-four pathway costs

Results of a sensitivity analysis (SA) show nearly a five fold difference in costs per patient for preop services (range £226–£1071) and more than a three fold difference for postop services (range £259–£896, see Table 5). The provision of services was variable regarding the format of delivery of sessions (group as one-to-one sessions), and frequency and length of access to psychology and dietetics before and after surgery. Access to psychological support was variable both preoperatively and postoperatively, with sessions lasting from 30 minutes to 2 hours, if this was actually provided. Similarly, for dieticians, some sites offered a one-off appointment pre-surgery, while others provided a regular group service over a number of weeks. Postop follow-up was more consistent, with regular reviews by dieticians, though this was far from standardised across sites. The full cost breakdown is provided in Report Supplementary Material 6.

| Site | Preop (base case) | Preop (SA) | Postop (base case) | Postop (SA) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | £681 | £1071 | £458 | £526 | High |

| 2 | £212 | £423 | £259 | £259 | Low |

| 3 | £185 | £231 | £452 | £458 | Medium |

| 4 | £340 | £359 | £225 | £261 | Low |

| 5 | £138 | £226 | £414 | £483 | Medium |

| 6 | £408 | £798 | £209 | £356 | Medium |

| 7 | £498 | £544 | £339 | £339 | Medium |

| 8 | £472 | £472 | £339 | £339 | Medium |

| 9 | £425 | £539 | £248 | £896 | High |

| 10 | £478 | £478 | £398 | £398 | Medium |

| Tier 4 summary costs | Mean | SE | 95% CI | Min/Max | |

| Preop (base case) | £384 | £53 | £264, £503 | £138, £681 | |

| Preop (SA) | £514 | £81 | £331, £697 | £226, £1071 | |

| Postop (base case) | £334 | £30 | £266, £402 | £209, £458 | |

| Postop (SA) | £432 | £59 | £299, £564 | £259, £896 |

Discussion

Bariatric surgery care pathways are widely regarded as varying considerably and international bariatric guidance is not specific with regard to the optimal model of care. 70 The results described in this chapter illustrate the large nationwide variability in preop and postop care, a likely consequence of widespread uncertainty regarding best practice and a lack of more detailed guidance with respect to service delivery. There is little evidence as to whether intensive preop and postop care improves outcomes and is cost-effective compared to less intensive care. This is likely to be more complicated than one standard pathway for all, with patient preferences also paramount in terms of type of provision (one-to-one or group sessions, for example). Furthermore, pre-surgery targets vary widely95 but are often low-cost group interventions and funded from a separate budget to surgery. Maximum cost is around £100–£200 per patient. However, these targets do add to the complexity of the pathway for the patients and variation in time and access to surgery, and therefore the usefulness of these targets is currently a subject of debate. 96–99

Impacts resulting from the benefits of dietician and psychological support prior to bariatric surgery have been published. Livhits et al. 100 undertook a systematic review which found that preop weight loss appears to be associated with greater weight loss postoperatively. In a more recent review, Gerber et al. 101 found the same beneficial effects from preop weight loss. On the other hand, it has been shown that psychological support before and after bariatric surgery had no impact on weight loss. 102 This study recommends further research to evaluate the longer-term implications for both weight loss and psychological support, and thereby the most effective timing for delivery of these interventions. As to why some sites offer more comprehensive services than others, decisions on staff resourcing are possibly being made on the basis of cost and availability of specialists, as there is currently no evidence as to whether these different models of care pathways improve outcomes. Indeed, this study illustrates how variable these costs are, even across health centres within the same country context, and this difference alone is worth highlighting. Therefore, it is important to evidence outcomes of these services.

Furthermore, there is a concern that bariatric surgery cost-effectiveness models may either omit pre-surgery and post-surgery care costs as part of their economic analyses or treat patients and the delivery of these services homogeneously by applying average costs. In a systematic review of a critical appraisal of economic evaluations of bariatric surgery,103 the considerable heterogeneity of what costs are included in economic studies and the frequent omission of different types of healthcare resource use were highlighted. Despite the identification of preoperative and postoperative costs, there was no detail reported on care pathways explicitly as an important cost component of an economic evaluation of bariatric surgery. A recent study by Gulliford et al. ,104 estimating the costs of bariatric surgery drawn from UK NHS tariffs, included preoperative weight management as part of the cost of the surgical procedure but only referred to the cost of medical weight-management services. There was no reference to bariatric surgery care pathway costs being included. 104 In the same model, a flat rate of £875 was also included for postoperative reviews. Procedure costs are not captured here and are assumed to be relatively standardised given the clear guidance on surgical procedures and, in Scotland, there is national procurement so device costs would also be standard across all sites. In their systematic review, Picot et al. 105 found the costs of bariatric surgery generally to be presented as standard unit costs with aggregate costs differing dependent on what is included in the total costs of surgery rather than any differences due to site variation. One study106 did find variation by gender but offered no explanation as to why.

The aim of this research was to understand whether differences in these care pathways are predictors of health outcomes, and thus influence cost-effectiveness from the benefit side. This study underlines the need to better understand the cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery care pathways, and whether the varying level of intensity of services offered is an important factor in influencing outcomes. The SCOTS study provides the follow-up data required to assess whether this classification of preop and postop care pathways is a predictor of health outcomes. Classification of the intensity of preop and postop bariatric surgical care can now be considered for investigation as a factor which may affect patient outcomes after surgery. If further findings do demonstrate that more intensive (and expensive) services lead to better outcomes, it is not envisaged that this will change bariatric surgery from being cost-effective at the usual willingness-to-pay thresholds for reimbursement on the NHS given the modelled ICER of £10,126 per quality-adjusted life year. 55 However, budgetary impact is an important consideration and it is acknowledged that these costs do matter for payers, hospital resource use and more local-level decision-making. Should these pathways be found to be predictors of better health outcomes, the case for investment in these care pathways would be self-evident.

Conclusions

This study, focusing on preop costs and the first 12 months following surgery in which the majority of costs will occur, has illustrated the large nationwide variability in preop and postop care pathways across Scotland, and the subsequent financial impact on the provision of bariatric surgery services. This is a likely consequence of widespread uncertainty regarding best practice and a lack of more detailed guidance regarding service delivery. Health economic analyses do not always capture these costs103 or apply a flat rate. 104 There is a lack of evidence base and a clear requirement for the evaluation of bariatric surgical services to identify the care pathways preceding and following surgery which lead to the largest improvements in health outcomes and remain cost-effective to the health provider.

Chapter 4 Health and socioeconomic burden in treatment-seeking individuals with severe obesity: profile of the SCOTS national cohort

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Mackenzie et al. 72

Introduction

There is a lack of evidence to inform the delivery and follow-up of bariatric surgery for people with severe obesity. SCOTS is the first national epidemiological study established to investigate long-term outcomes following bariatric surgery. In addition, SCOTS collected clinical and patient-reported health outcomes from treatment-seeking individuals from across Scotland with severe obesity before they underwent bariatric surgery. This chapter describes the health-related characteristics of the recruited SCOTS cohort and examines relationships between age, preop BMI and other health-related factors.

Results

Recruitment

Participants were recruited over an approximate 3-year period from December 2013 to February 2017 with follow-up continuing until October 2020.

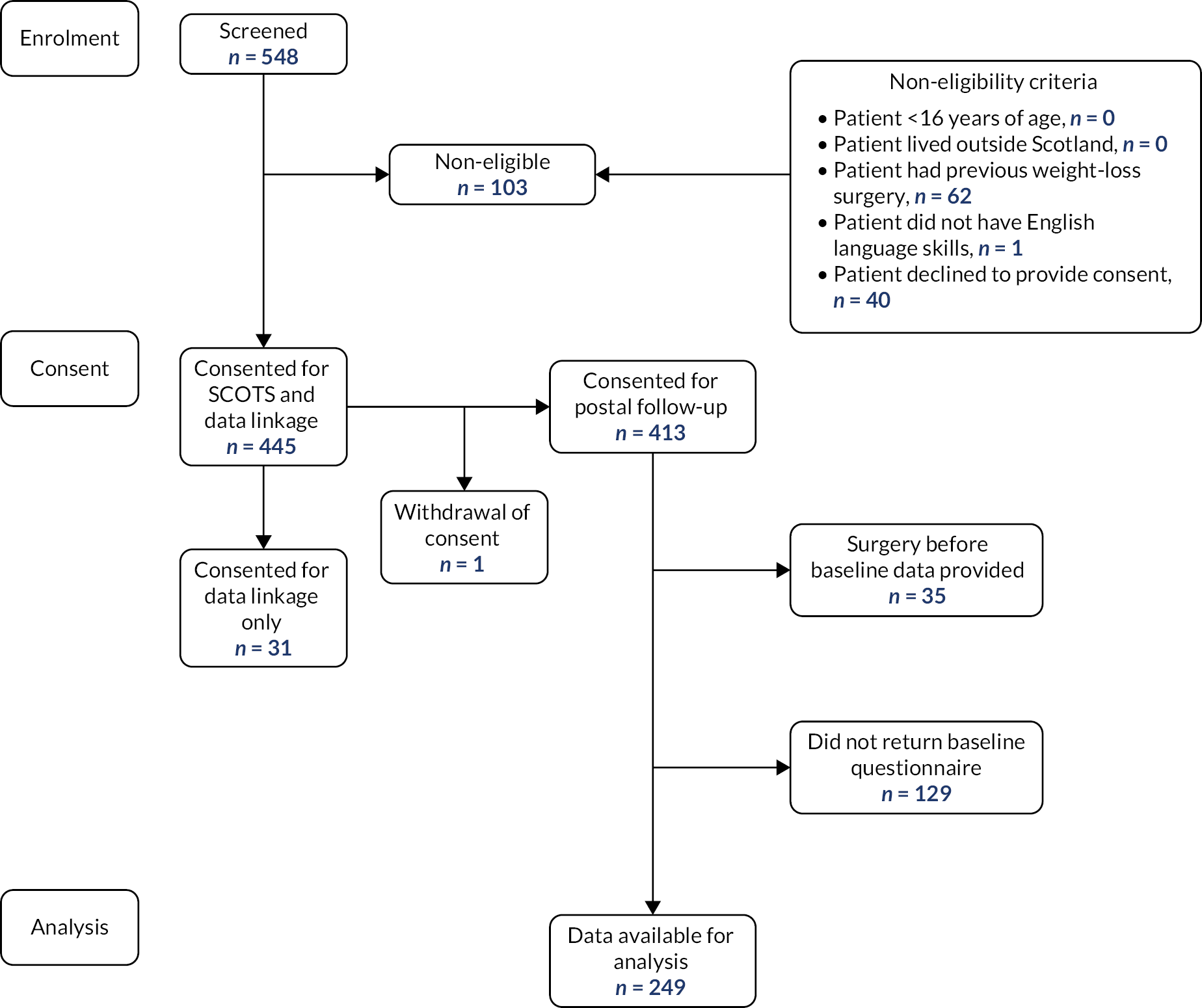

Over the recruitment period, a total of 548 patients were approached and screened for eligibility to participate. Of these, 103/548 (19%) were excluded or declined to participate (see Figure 2). We recruited 445/548 (81%) participants but one participant withdrew consent, leaving a recruited sample of 444 (81%). Of the recruited sample, 413/444 (93%) consented to data linkage and questionnaire follow-up, while 31/444 (7%) consented to data linkage only. Of these 413 participants, a total of 164/413 (40%) were not included in the subsequent analysis: 129 did not return a baseline questionnaire and 35 had bariatric surgery before their baseline PROMs questionnaires were completed. Of the 129 who did not return baseline questionnaires, 84/129 (65%) progressed to surgery, 43/129 (33%) did not progress to surgery and the status of 2/129 (2%) was unknown. Completed preop baseline PROMs data for 249/413 participants (60% of those consented) were available for analysis (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Screening, consent and follow-up.

Characteristics of recruited and analysed sample

Demographic data are summarised in Table 6. Participant characteristics were similar between the total recruited sample (n = 444) and the analysed subset (n = 249) with completed PROMs before bariatric surgery (see Table 6). Mean age was 46 years (±9.1 years), with a higher proportion of women than men (71% vs. 29%). Half of recruited participants were aged 35 to 49 years, with one-third being over 50 years. The median BMI was 47 kg/m2 (Q1 43; Q3 54), with more than 21% having a BMI of ≥55 kg/m2. Over half of the participants (55%) lived in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation (SIMD quintiles 1 and 2). There were no statistically significant differences between the analysed subset (n = 249) and the non-analysed subset (n = 195).

| Recruited sample N = 444 |

Analysed samplea N = 249 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, N (%) | Male | 123 (27.7) | 72 (28.9) |

| Female | 321 (72.3) | 177 (71.1) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 46.2 (9.1) | 45.9 (9.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Age group, N (%) | <35 years | 61 (13.7) | 36 (14.5) |

| 35–44 years | 116 (26.1) | 63 (25.3) | |

| 45–49 years | 109 (24.5) | 63 (25.3) | |

| 50–54 years | 79 (17.8) | 43 (17.3) | |

| 55+ years | 79 (17.8) | 44 (17.7) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Median (Q1; Q3) | 47.2 (42.7; 53.6) | 47.6 (42.8; 53.8) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | |

| BMI group, N (%) | BMI < 40 | 52 (11.7) | 24 (9.6) |

| BMI 40–44 | 115 (26.0) | 64 (25.7) | |

| BMI 45–49 | 116 (26.2) | 64 (25.7) | |

| BMI 50–54 | 71 (16.0) | 44 (17.7) | |

| BMI 55+ | 89 (20.1) | 53 (21.3) | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | |

| SIMD quintile, N (%) | Quintile 1 (most deprived) | 135 (30.5) | 70 (28.3) |

| Quintile 2 | 108 (24.4) | 65 (26.3) | |

| Quintile 3 | 84 (19.0) | 51 (20.6) | |

| Quintile 4 | 68 (15.4) | 34 (13.8) | |

| Quintile 5 (least deprived) | 47 (10.6) | 27 (10.9) | |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | |

| Marital status, N (%) | Married/civil partnership/co-habiting | Not collected | 155 (63) |

| Single/separated/divorced/ widowed | 91 (37) | ||

| Missing | 3 | ||

| Ethnic group, N (%) | White | Not collected | 243 (97.6) |

| Mixed | 4 (1.6) | ||

| Asian/Asian Scottish/Asian British | 1 (0.4) | ||

| African Caribbean/black | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Missing | 0 | ||

| Education, N (%) | School only | Not collected | 58 (23.5) |

| Formal qualifications through training at work | 54 (21.9) | ||

| Qualification (other than a degree from college or university) | 64 (25.9) | ||

| Degree from college or university | 71 (28.7) | ||

| Missing | 2 | ||

| Current employment status, N (%) | Working full time | Not collected | 124 (50.0) |

| Working part time | 24 (9.7) | ||

| Unable to work because of illness or disability | 64 (25.8) | ||

| Student/unemployed and seeking employment/ unemployed and not seeking employment/ carer/other | 36 (14.5) | ||

| Missing | 1 |

Comorbidities

For the analysed sample (n = 249), self-reported medical comorbidities and physical, mental and functional measures are presented in Table 7. Over 40% reported having at least one of hypertension, T2DM, back problems, anxiety/depression and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Over 60% of the sample reported more than three comorbidities. Over 40% of male participants reported erectile dysfunction, while one-third of males described urinary incontinence. Half of female participants reported urinary incontinence. Mean depression scores reflected mild depression, although 44% of participants had scores indicating moderate to severe depression. Anxiety scores for all participants were indicative of mild anxiety (median 5.0), with half of participants having scores indicative of moderate to severe anxiety. The mean life optimism score for participants was reflective of low optimism (high pessimism). Very few participants smoked (5%) and, on average, alcohol consumption was moderate.

| N = 249 N (%) |

Missing N (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity, self-report | Deep vein thrombosis | 8 (3.2) | 0 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 4 (1.6) | 0 | |

| Hypertension | 107 (43.0) | 0 | |

| T2DM | 124 (49.8) | 0 | |

| Angina/heart attack | 17 (6.8) | 0 | |

| Heart failure | 2 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Stroke/mini stroke | 6 (2.4) | 0 | |

| Arthritis | 73 (29.3) | 0 | |

| Back problems | 115 (46.2) | 0 | |

| Chronic bronchitis | 4 (1.6) | 0 | |

| Eczema/psoriasis | 33 (13.3) | 0 | |

| Asthma | 70 (28.1) | 0 | |

| Thyroid problems | 32 (12.9) | 0 | |

| Migraine | 49 (19.7) | 0 | |

| Anxiety/depression | 114 (45.8) | 0 | |

| Kidney disease | 7 (2.8) | 0 | |

| Liver disease | 2 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Cancer | 4 (1.6) | 0 | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 44 (17.7) | 0 | |

| Sleep apnoea | 66 (26.5) | 0 | |

| CVD | 20 (8.0) | 0 | |

| N (%) self-reported comorbidities | None | 9 (3.6) | 0 |

| 1–2 | 80 (32.1) | 0 | |

| ≥3 | 160 (64.3) | 0 | |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux | Yes | 97 (40.4) | 9 (3.6) |

| Female reproductive health, N = 75a | Mean (SD) age years, last natural menstrual period | 39.4 (10.9) | 4 (5.3) |

| Female reproductive health, N = 177 | Polycystic ovarian syndrome, N (%) | 28 (16.8) | 10 (5.6) |

| Male reproductive health, N = 72 | Impotence, N (%) | 28 (41.2) | 4 (5.6) |

| IPSS score ≥ 8, N (%) | 34 (47.9) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Incontinence | Median (Q1; Q3) ICIQ-UI SF score | 4 (0.0; 10.0) | 10 (4.0) |

| ICIQ-UI SF score ≥ 6 | 105 (43.9) | 10 (4.0) | |

| Incontinence, females, N = 177 | ICIQ-UI SF score ≥ 6, N (%) | 83 (49.4) | 9 (5.1) |

| Incontinence, males, N = 72 | ICIQ-UI SF score ≥ 6, N (%) | 22 (31.0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Depression | Mean (SD) PHQ-9 score | 9.6 (6.3) | 5 (2.0) |

| N (%) PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 | 107 (43.9) | 5 (2.0) | |

| Anxiety | Median (Q1; Q3) GAD-7 | 5 (2.0; 9.0) | 6 (2.4) |

| N (%) GAD-7 score ≥ 6 | 114 (46.9) | 6 (2.4) | |

| Smoking status | Current | 13 (5.4) | 9 (3.6) |

| Former | 105 (43.8) | ||

| Never | 122 (50.8) | ||

| Alcohol use | Median (Q1; Q3) AUDIT | 3 (1.0; 6.0) | 20 (8.0) |

| Quality of life | |||

| SF-12 | Mean (SD) PCS | 37 (11.4) | 13 (5.2) |

| Mean (SD) MCS | 45.5 (10.3) | 13 (5.2) | |

| EQ-5D-5L | Median (Q1; Q3) | 0.6 (0.3; 0.8) | 12 (4.8) |

| Mean (SD) VAS | 55.3 (22.1) | 12 (4.8) | |

| IWQOL-Lite (Standardised Scoring) | Mean (SD) Physical Function | 56.9 (25.4) | 6 (2.4) |

| Mean (SD) Self Esteem | 70.7 (27.1) | 7 (2.8) | |

| Mean (SD) Sexual Life | 57.1 (31.7) | 18 (7.2) | |

| Mean (SD) Public Distress | 58.1 (27.2) | 6 (2.4) | |

| Mean (SD) Work | 43.6 (29.2) | 13 (5.2) | |

| Mean (SD) Total score | 58.5 (21.7) | 7 (2.8) | |

| Life optimism | Mean (SD) LOT score | 13 (4.9) | 14 (5.6) |

| Physical activity | ≥1 walking, moderate or vigorous activity in last 7 days | 201 (83.4) | 8 (3.2) |

| Median (Q1; Q3) IPAQ score (MET minutes/week) | 720 (40.0; 1800.0) | 6 (3.0) | |

| Healthcare utilisations | Using any aids or specialist equipment | 67 (28.9) | 17 (6.8) |

| Median (Q1; Q3) GP visits in last 3 months | 2 (1.0; 3.0) | 79 (31.7) | |

| Median (Q1; Q3) visits to other health/social care providers in last 3 months | 3 (1.0; 5.0) | 73 (29.3) | |

| Social security | Unable to work due to illness or disability | 64 (25.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Receiving DLA (caring) | 44 (18.6) | 13 (5.2) | |

| Receiving DLA (mobility) | 47 (19.9) | 13 (5.2) | |

Health and obesity-related quality of life

Mean SF-12 Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores were low: PCS 37.0 (11.4), MCS 45.5 (10.3). The median EQ-5D-5L score of sample participants was 0.6 (Q1 0.3; Q3 0.8), while the mean EQ-5D-5L visual analogue scale (VAS) was 55.3 (±22.1). Participants had a mean IWQOL-Lite Physical Function score of 56.9 (±25.4) and a mean total score of 58.5 (±21.7, see Table 7), where an increase in IWQOL-Lite score indicates a worsening in QoL.

Physical activity

Over 80% of SCOTS participants reported undertaking at least 10 minutes of either walking, moderate or vigorous activity in the last 7 days and the median IPAQ score for the sample was 720.0 MET minutes/week. Almost one-third (29%) of participants reported using aids or specialist equipment to assist with their daily activities in the home (see Table 7).

Comorbidity by BMI and age