Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 14/192/109. The contractual start date was in May 2016. The draft manuscript began editorial review in September 2022 and was accepted for publication in September 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Crawley et al. This work was produced by Crawley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Crawley et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis in children

Paediatric myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is common in the UK, with an estimated prevalence of 0.5%. 1 Before and during this study, ME/CFS was defined as generalised fatigue, causing disruption of daily life, persisting after routine tests and investigations have failed to identify an obvious underlying cause. 2,3 This definition changed in 2021, and a diagnosis of ME/CFS now requires the following additional symptoms: post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep or sleep disturbance and cognitive difficulties. 4 Adolescents with ME/CFS are disabled,5,6 and use significant healthcare resources over a considerable period prior to accessing ME/CFS treatment. 7 Only 8% of adolescents appear to recover within 6 months with usual care,8 and this is consistent with adult data. 9 Usual care includes no treatment, treatment delivered by general practitioners (GPs) or by therapists that are not specialised in ME/CFS. Parents often stop or reduce time at work in order to care for their affected children. 10

At the time that Fatigue In Teenagers on the interNET in the National Health Service (FITNET-NHS) was conducted, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommended a minimum 3-month duration of fatigue before making a diagnosis in adolescents. 3 NICE recommended that adolescents with ME/CFS were offered either cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), which focuses on cognitive behavioural strategies to identify, challenge and change cognitive processes and resume activities); graded exercise therapy (GET), which stabilises physical activity levels, before gradually increasing at a manageable rate; or Activity Management, a goal-oriented and person-centred approach tailored to the needs of the person, which establishes a baseline for all activity, mainly cognitive, such as school and homework, in adolescents, which is then increased. 3,11 There is good evidence that CBT and GET are moderately effective in adults with ME/CFS. Four systematic reviews have shown that CBT and GET are moderately effective in improving function and reducing fatigue. 12–15 In particular, Pacing, graded Activity and Cognitive behavioural therapy, a randomised Evaluation trial (PACE) showed that both CBT and GET were more effective than specialist medical care or specialist medical care plus adaptive pacing therapy (a form of Activity Management that does not routinely increase activity but uses the envelope theory (patients work within their envelope of energy). 16

There is less evidence for the treatment of paediatric ME/CFS. However, when adolescents are offered treatment, the outcomes appear to be better than those seen in adult trials. We have conducted two systematic reviews8,17 to investigate treatment outcomes for paediatric ME/CFS, as well as a systematic review investigating recovery in paediatric ME/CFS using observational and trial data. 18 These supplement two previous systematic reviews on interventions in paediatric ME/CFS. 12,19 All five reviews identified good evidence from four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (including the Dutch FITNET) that CBT is effective for paediatric ME/CFS. 8,20–22 Only the FITNET trial investigated internet-delivered CBT, and none of the published paediatric trials reported on cost-effectiveness. A search of trial registries located no other relevant trials prior to starting FITNET-NHS.

The FITNET trial, which was conducted in adolescents with ME/CFS in the Netherlands,8 showed that internet-based CBT was effective compared to usual care at 6 months. Usual care in the FITNET trial was not quantified, but participants probably had access to individual or group-based rehabilitation programmes, CBT face-to-face, or graded exercise treatment; these interventions being provided by therapists who were often not specialists in ME/CFS. Compared with usual care, adolescents in the FITNET group were more likely to attend school full-time [75% vs. 16%, relative risk 4.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.7 to 8.9; p < 0.0001], less likely to have severe fatigue (85% vs. 27%, relative risk 3.2, 95% CI 2.1 to 4.9; p < 0.0001), and more likely to have normal physical functioning (78% vs. 20%, relative risk 3.8, 95% CI 2.3 to 6.3; p < 0.0001) at 6 months. Adolescents in the FITNET group were also more likely to have recovered at 6 months (defined as no longer severely fatigued or physically impaired, attending school, and perceiving themselves as completely/nearly completely recovered) (63% vs. 8%, relative risk 8.0, 95% CI 3.4 to 19.0; p < 0.0001). Improvement was maintained at 12 months. The FITNET-NHS intervention has been developed based on the Dutch FITNET8 and tailored to deliver specialist CBT treatment for adolescents with ME/CFS over the internet in the UK, and its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness will be assessed in this study.

Since we started FITNET-NHS, a large observational implementation study of FITNET in the Netherlands was conducted. 23 In this study, the 244 participants were allowed to be seen face-to-face (unlike in FITNET-NHS) and 41% were seen face-to-face at least once. Participants had improved fatigue, physical function and school attendance after treatment, and deterioration in fatigue and physical function was low (1.2% and 4.1%, respectively). A cost-effectiveness study was not conducted.

ME/CFS and comorbid depression and/or anxiety

Comorbid anxiety and depression affect more than 30% of adolescents with ME/CFS. 24–26 Most, but not all,27 studies in adults suggest that CBT for the treatment of ME/CFS is less effective in patients with comorbid depression16,28 compared to those without depression. The only study investigating predictors of outcome in adults treated with internet-delivered CBT for the treatment of ME/CFS is less effective in those with than without comorbid depression. 29 However, CBT appears to be a more effective treatment than GET for adults with ME/CFS and depression. 15,16 The paediatric trials conducted to date have either excluded adolescents with elevated comorbid depression and/or anxiety symptoms20 or not been powered to investigate treatment efficacy in this group. 8,21,22 As a substantial proportion of adolescents diagnosed with ME/CFS have comorbid depression and/or anxiety, FITNET-NHS was designed to treat those with comorbid depression and/or anxiety as well as ME/CFS and to examine if the effects of FITNET-NHS differ in this subgroup of adolescents as a secondary outcome. Negative thinking patterns contribute to the development and maintenance of depression and had not been investigated in paediatric ME/CFS prior to commencement of the FITNET-NHS trial. We embedded a substudy to investigate whether adolescents with ME/CFS and comorbid depression differed from those who are not depressed on cognitive errors and cognitive and behavioural responses to symptoms of ME/CFS. 30

National Health Service policy and practice

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance in 2007 stated that adolescents with ME/CFS should be offered referral to a specialist service immediately if they are severely affected, within 3 months if they are moderately affected and within 6 months if they are mildly affected. 3 Current NICE guidance recommends that children and young people should have access to a ME/CFS specialist team ‘who they can contact with any concerns about the child’ (recommendation 1.10.4). 4 However, only around 10% of UK adolescents have access to a local NHS ME/CFS specialist service, and most adolescents cannot access the treatment they require because they live too far away from a specialist service. For those that do access a service, few are assessed within NICE-recommended time scales. 7 In some cases, GPs and paediatricians (or equivalent specialist doctors) advise on sleep, symptom control and Activity Management, but the specialist CBT for ME/CFS, for which there is an evidence base, is not available other than through specialist services.

Internet-delivered CBT is not only important for children who are unable to access specialist services, but has been vital during the COVID-19 pandemic. It has the potential to be adapted to other long-term conditions; however, few studies have investigated the acceptability, efficacy and cost-effectiveness. 31–33 Further understanding of internet-delivered CBT, particularly around how it is received by adolescents, will inform future treatment studies.

Justification of research

There is good evidence that CBT is effective in the treatment of paediatric ME/CFS. 20–22 However, most adolescents in the UK are unable to access specialist CBT for ME/CFS delivered face-to-face. Therefore, delivery of specialist CBT using the internet is an attractive option. In this study, we set out to demonstrate whether implementation of FITNET-NHS in the UK is feasible and acceptable during the internal pilot study, and whether it is effective and cost-effective during the full trial. We chose Activity Management, delivered via videoconference, as the comparator intervention because it was the only NICE (2007)-recommended3 approach offered by some paediatricians (or equivalent specialist doctors) outside specialist services. Although standard care and Activity Management were usually delivered face-to-face, videoconferencing was becoming more routine before FITNET-NHS started and became routine during the pandemic. For this trial, every aspect was delivered remotely. The study set out to find out if FITNET-NHS is effective and cost-effective because if so, its provision by the NHS has the potential to deliver substantial health gains for the large number of adolescents with ME/CFS but unable to access treatment because there is no local specialist service.

Objectives for the full trial

The overall aim of this study was to investigate whether CBT specifically designed for ME/CFS and delivered over the internet (FITNET-NHS) is effective and cost-effective compared to remotely delivered Activity Management for adolescents with ME/CFS who do not have access to a local specialist ME/CFS service.

Primary objective

Specifically, the primary objective of the full trial was to estimate the effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared to Activity Management in the NHS for paediatric ME/CFS.

Secondary objectives

-

Estimate the effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared to Activity Management for those with mild/moderate comorbid mood disorders (anxiety/depression).

-

Estimate the cost-effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared to Activity Management.

-

Estimate the cost-effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared to Activity Management for those with mild/moderate comorbid mood disorders (anxiety/depression).

The objectives for the pilot study are described in Chapter 3.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a RCT comparing FITNET-NHS with Activity Management when remotely delivered in the NHS for adolescents with ME/CFS. Participants were allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio, minimised by age and gender, between the two interventions. The first 12 months of the trial formed an internal pilot study (with continuation of the trial based on achieving defined stop/go criteria) including integrated qualitative methods to optimise recruitment and retention.

The study methods were prespecified in a published protocol. 34 A key change to the trial was published in a protocol update paper. 35 Protocol changes are presented in detail in Chapter 4.

Participants

Patients aged 11–17 years, with ME/CFS, who did not have a local specialist ME/CFS service were recruited at the specialist paediatric ME/CFS service, Bath Royal United Hospital.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged 11–17 years.

-

ME/CFS diagnosis (defined using NICE guidance,3 see Table 1).

-

No local specialist ME/CFS service.

| NICE 2007 guidance | NICE 2021 guidance | CDC criteria | IOM criteria | CC criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of fatigue | 3 months (paediatric) | 4 weeks (paediatric) | 6 months | 6 months | 6 months |

| Symptoms | 1 or more of:

|

All of:

|

4 or more of:

|

3 or more of:

|

4 or more of:

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|||||

| Exclusionary diagnoses | Conditions that explain the fatigue | Conditions that explain the fatigue | Any active medical condition that may explain the presence of chronic fatigue. Any past or current diagnosis of: |

If patients do not have these symptoms at least half of the time with moderate, substantial or severe intensity | Active disease processes that explain most of the major symptoms of fatigue, sleep disturbance, pain, cognitive dysfunction. |

|

It is essential to exclude certain diseases: Addison’s disease, Cushing syndrome, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, iron deficiency, other treatable forms of anaemia, iron overload syndrome, diabetes mellitus, cancer | ||||

|

It is essential to exclude treatable sleep disorders such as upper airway resistance syndrome and obstructive or central sleep apnoea; rheumatological disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, polymyositis and polymyalgia rheumatica; immune disorders such as AIDS; neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis, parkinsonism, myasthenia gravis and B12 deficiency; infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, chronic hepatitis, Lyme disease, etc.; primary psychiatric disorders, substance abuse | ||||

| Alcohol or other substance abuse within 2 years. Severe obesity (BMI > 45) |

Exclusion criteria

-

Not disabled by fatigue.

-

Fatigue was due to another cause.

-

Patients or parents unable to complete video calls or FITNET-NHS modules, for example, being unable to read FITNET-NHS material, having significant development problems, limited internet access, or being unwilling/unable to set up personal e-mail address/video call account.

-

Patients reporting pregnancy at assessment.

Setting

Patients (aged 11–17 years) were assessed by their GP, referred for local paediatric assessment and had blood tests (see Table 2) to exclude other causes of fatigue, in accordance with NICE guidance. 3 Where there was no local specialist paediatric ME/CFS service (about 90% of the UK), GPs and paediatricians (or equivalent specialist doctors) were able to refer those with ME/CFS to the Bath Specialist Paediatric ME/CFS Service.

| Full blood count | Screening blood tests for gluten sensitivity |

|---|---|

| Creatinine, urea and electrolytes | Serum calcium |

| Thyroid function | Creatine kinase |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate/plasma viscosity | Ferritin levels |

| C-reactive protein | Liver function tests |

| Random blood glucose | Vitamin D (if housebound) |

Patients were referred using normal clinical referral pathways from GPs across the UK to the Bath Royal United Hospital (via NHS e-referral service).

Between September 2018 and March 2020, GP surgeries in some areas of the UK were also offered the option of being set up as patient identification centre (PIC) sites (see Protocol Changes for more details). The PIC site work involved: (1) a database search to identify potentially eligible patients; (2) GP approval of a list of patients for mailing out an invitation letter; (3) letter mailout (directly to the patient if aged 16–17 years or to the parent/carer if aged 11–15 years) to invite families to consider the trial and ask them to make a GP appointment for a clinical referral to the Bath Royal United Hospital if they were interested.

At regular intervals, the trial was publicised to UK GPs via e-mails distributed by local National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Networks (CRNs), including regular bulletins and magazines released to GPs and other health professionals, supplying e-mailed referral flyers to disseminate to clinical staff (example flyer in Report Supplementary Material 1), and (from April 2018) a brief video for clinicians (a summary of a video is given in Report Supplementary Material 4), and (from November 2018) patient posters/flyers for display in GP surgeries (an example poster for patients is given in Report Supplementary Material 1).

The clinical team at the Bath Specialist ME/CFS Service reviewed referrals and performed initial screening to identify patients aged 11–17 years who were thought to have ME/CFS and no local specialist service. Referrals were accepted by the service if the patient had been assessed by a paediatrician (or equivalent specialist doctor) and had the NICE 2007 guidance screening blood tests (Table 2). 3

Recruitment

Potentially eligible patients were contacted via telephone by the clinical team to discuss ME/CFS treatment from Bath Services and the possibility of taking part in this research. Patients interested in the FITNET-NHS study were sent study information via e-mail to include: (1) a participant information leaflet (see Report Supplementary Material 5), (2) a link to the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) questionnaire36 to complete (with an additional question for them consenting to the data being used for research purposes if they later decide to consent to the study), (3) a link to an online ‘consent to contact’ form (for electronic signing). Online forms were stored on a secure electronic system used for data capture called research electronic data capture37 (REDCap: www.project-redcap.org/).

The specialist nurse offered a final eligibility assessment via telephone/video call with both the referred patient and their parent/carer (hereafter ‘parent’) to confirm the patient’s ME/CFS diagnosis. This was completed using questions routinely used by the Bath Specialist ME/CFS Service on length of illness and other symptoms. These include four questions on fatigue: (1) debilitating persistent or relapsing fatigue for at least 3 months, but not life-long; (2) not the result of ongoing exertion and not substantially alleviated by rest; (3) post-exertional malaise; and (4) severe enough to cause substantial reduction in previous levels of occupational, educational, social or personal activities, one on length of illness and twelve on symptoms. Patients who answered ‘yes’ to these four questions and therefore had 3 months of disabling fatigue plus one further symptom were assessed as having ME/CFS. 3 The specialist nurse also identified patients who fulfilled the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) diagnostic criteria at the eligibility assessment as this enables a comparison of our results with those of other trials.

During the eligibility assessment the specialist nurse ensured that patients did not have depression or anxiety sufficiently severe to cause their fatigue by reviewing RCADS responses. 38,39 The RCADS has 47 items with subscales that assess obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety, panic, generalised anxiety, separation anxiety and depression with age- and sex-adjusted thresholds for each subscale. 40 Patients who scored above the threshold were considered to have a comorbid mental health problem. Those scoring above the borderline threshold answered further screening questions to determine whether they were at risk of harm and/or whether their mental health problem was sufficiently severe to explain the fatigue. This included questions about whether they wanted their low mood or anxiety or their fatigue treated first as well as questions about hopelessness, their sleep pattern, eating and whether they were experiencing anhedonia. Those who were considered as primarily having a mood problem or other cause for their fatigue (rather than ME/CFS) were told about the provisional diagnoses, offered referral to the appropriate provider and were not eligible for this trial. The referring clinician was informed about alternative diagnoses and signposted to relevant services.

If the patient was eligible and they and their parent were willing, the recruiting team at Bath Specialist ME/CFS Service arranged a telephone/video call recruitment consultation. The research team explained the trial design and interventions; ensured the patient and parent had had an opportunity to read the age-appropriate patient information leaflet (PIL) and answered any questions about the research project. Recruitment discussions were audio-recorded with families’ consent.

If patients were willing to take part in the FITNET-NHS trial, the research nurse requested consent/assent from both the patient and parent during the recruitment consultation using an online consent form (signed electronically) on the secure electronic system, REDCap. Patients aged 11–15 years completed an assent form, while patients aged 16–17 years and parents completed a consent form. Patients deciding not to take part in the FITNET-NHS trial were still offered treatment from the service. This could be remote or face-to-face depending on clinical need and geographical location/transport.

Randomisation

The research team performed randomisation while the participant was on the telephone/video call. An automated web randomisation service operated by the Bristol Trials Centre was used. The web randomisation service automatically allocated participants in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either FITNET-NHS or Activity Management. Allocation used minimisation to facilitate balance by age (11–14 or 15–17 years) and gender assigned at birth (male or female) and retained a random component to prevent accurate prediction of allocation (i.e. allocation concealment was preserved).

Recruited patients (hereafter ‘participants’) and their parents were informed of their allocated intervention at the end of the recruitment consultation. GPs were informed (via letter) about the intervention to which their patient had been allocated.

Blinding

Because of the nature of the interventions, it was not practical to blind either the participant, family or the clinical service to treatment allocation. The investigators who wrote the statistical analysis plan and analysed the clinical and economic outcomes were blinded to treatment allocation (this did not include the trial statistician who presented unblinded data to the confidential Data Safety and Monitoring Committee).

Interventions

In this section we use the TIDieR subheadings to describe the two study interventions. 41

Fatigue In Teenagers on the interNET in the National Health Service

Rationale

FITNET-NHS is a web-based modular ME/CFS-specific CBT programme designed to be used by adolescents and their parents. It is a UK version of the Dutch FITNET platform (which was shown to be highly effective8 or paediatric ME/CFS in the Netherlands. FITNET-NHS has been translated into English and adapted to be a fully remote service for use within the NHS. As a web-based intervention, it can be provided for adolescents who do not have a local service.

Theory

Content for participants was designed to encourage active collaboration and self-discovery. Participants were encouraged to monitor their activity, establish a manageable baseline and build on this gradually. Content for parents is designed to encourage parents to explore and address their beliefs and behaviours towards their child with ME/CFS focussing on their role as carers, and complement the patient sessions.

Materials

The programme has psycho-educational and CBT sections for patients and a parallel programme for their parents. There are 19 chapters in total for patients and parents to work through in their own time (see Appendix 1 for chapter titles). The initial psycho-educational chapters are available (on logging into the web-based platform) to all patients and parents immediately after receiving log-in codes. Chapters 1, 2 and 3 introduce CBT and explain the role of therapists and parents, present ME/CFS as a multifactorial model with predisposing, precipitating and maintaining factors and discuss the role of the family. Chapter 4 focuses on treatment goals, including the goal of full-time education. Chapters 5–19 focus on cognitive and behavioural strategies, starting with addressing sleep patterns, with exercises designed to notice and change behaviour patterns and on identifying unhelpful thinking processes and changing these to more helpful ones, with a focus on goal attainment. These chapters are unlocked by the therapist based on individual patient’s needs, goals and formulation.

There are diaries included within the web-based platform which are visible to the therapist so that patients can record their sleep, activity levels, and helpful thoughts, and then discuss these with their therapist (Report Supplementary Material 6 presents a selection of screenshots from the FITNET-NHS platform).

Procedures

FITNET-NHS treatment is delivered using asynchronous individualised e-consultations (comprising written messages sent separately to the patient and their parent) delivered within the web-based platform itself. Each patient and their parent are set up on the platform by the therapist. The patient and parent then each set up an independent password-protected account. The therapist works with patients and parents separately and responding together is discouraged. Parents can read the content of the patient chapters but cannot see their child’s answers to the questions. Therapists can view patients’ question responses and diaries and they use e-consultations to help the patient through the programme. Therapists request that their patient responds via message within the platform before a specific date at which the therapist delivers their next detailed and tailored message.

Therapist messages would include comments on the information the participant provided in their diaries, completed chapters, and e-messages on the platform. Therapists would highlight achievements (such as the participant reaching a set goal/task during the week), would notice patterns (such as an increase in activity, or an improvement in sleep onset time) and would prompt further reflection or thought for them (such as asking further questions about anything the patient had mentioned). Therapist messages would also seek to answer any questions the participant may have raised, or address any difficulties with tasks that the patient may have mentioned. The same processes occurred between participants’ parents, and therapists.

When treatment was complete, participants could opt for further treatment in the clinical service (after a medical review), or organise further treatment locally.

Delivered by

FITNET-NHS was delivered by clinical psychologists or CBT therapists. At the start of the study, therapists received four days of intensive training held over 2 months. The training sessions were video-recorded, and training materials (PowerPoint presentation, and supplementary written material) were developed for new members of staff. The therapists received at least monthly supervision by the Dutch FITNET team, including reviews of e-consultations sent to ensure intervention fidelity until 2010. Supervision was then provided within the UK team without oversight from the Dutch FITNET team. Therapists who joined after the trial started received similar intensive training using the training material and supervision from experienced members of the UK team who had attended the initial training.

When and how much?

Contacts were initially weekly and tended to be spaced out towards the later stages of therapy, but frequency varied according to need. FITNET-NHS Treatment was designed to last approximately 6 months, though this was expected to be variable between participants.

Tailoring

Chapters 5–19 are unlocked (i.e. made visible and accessible) to patients (with the corresponding section unlocked for the parent) based on clinical presentation, needs and clinical formulation. For example, Chapter 16: Plan for work would only be opened for somebody who wanted to work. Therefore, each patient is likely to have a different combination of chapters at different points and not all will complete every chapter. The language used in the e-consultations is also tailored to the participants and to the questions/responses raised in the e-consultations.

Modifications were made during the study. Please see Chapter 4.

Fidelity was assessed in FITNET-NHS supervisions (see above).

Activity Management via videocall

Rationale

Activity Management is a behavioural treatment offered throughout the UK in paediatric services. Patients and their families often call this Pacing. It was recommended by NICE in 2007 and in 2021. 3,4

Materials

Participants received information on ME/CFS, Activity Management, sleep and symptom management. Participants could use an online app (ActiveMe) to record activity.

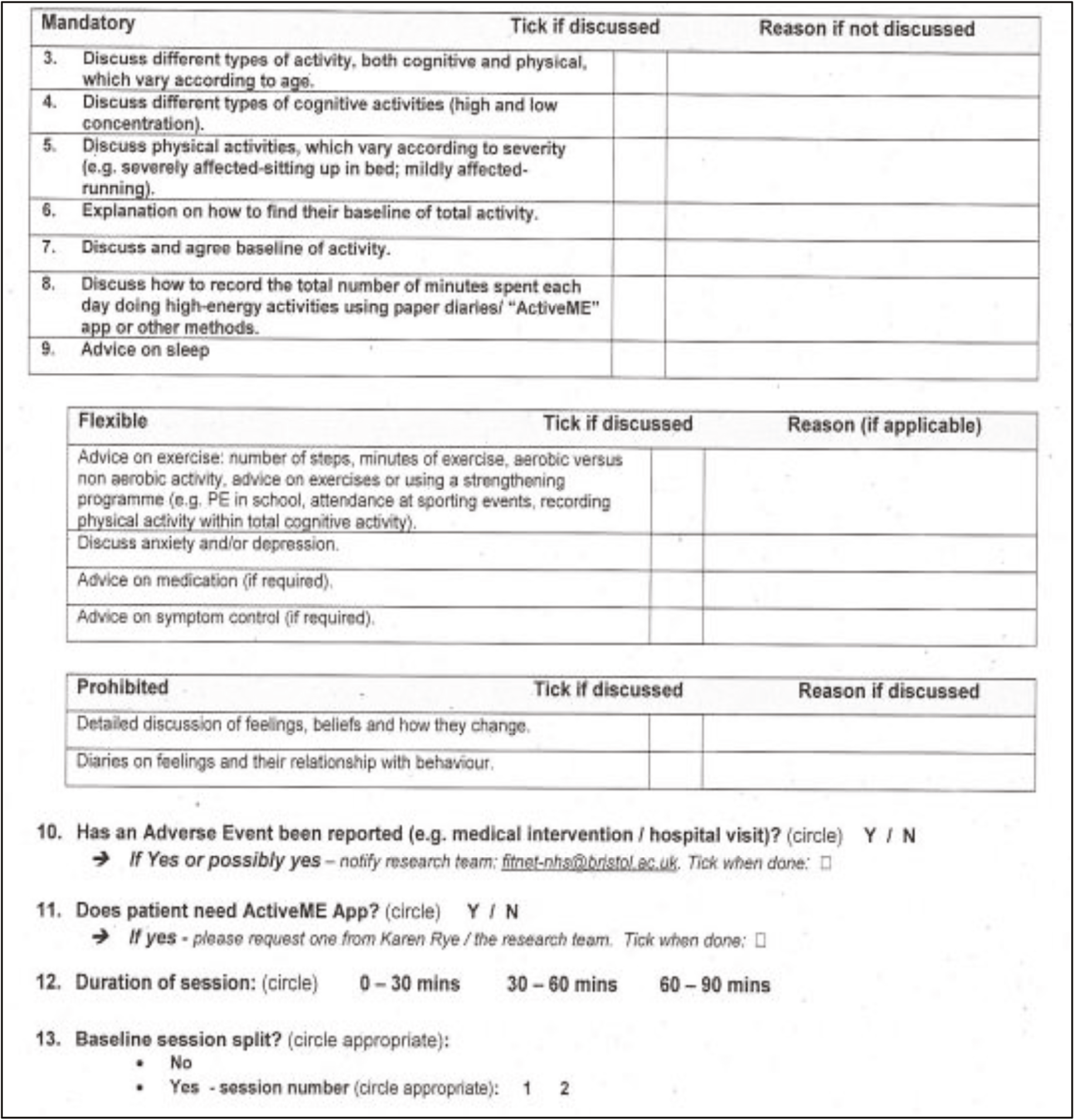

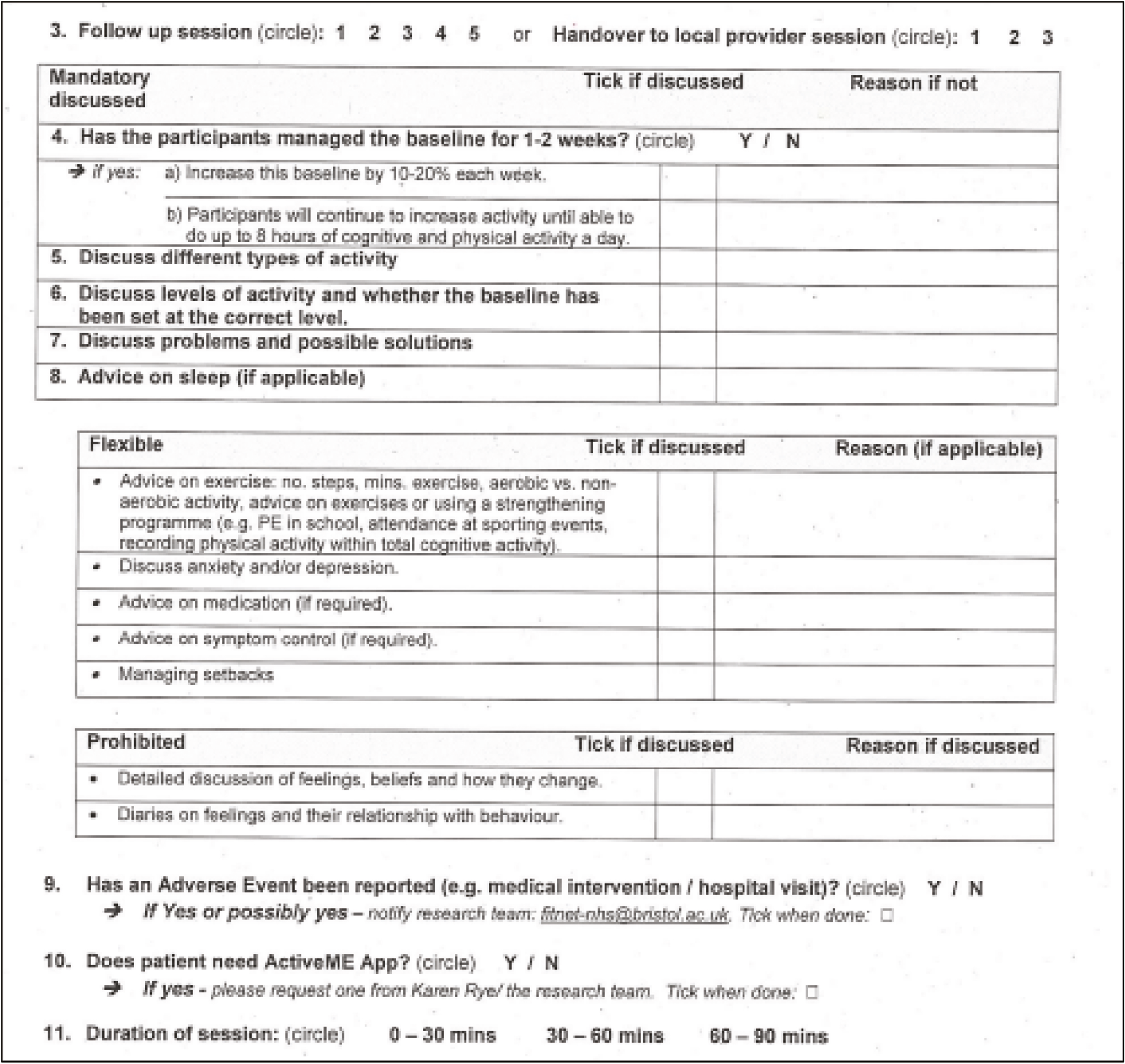

Procedures

Activity Management was delivered via videocall (using Skype). During the initial appointment, the clinician carried out a detailed assessment of physical and cognitive activity with the participant. Clinicians discussed the different types of physical activity and the different types of cognitive activity (high-concentration and low-concentration), which varied according to age. High-concentration cognitive activities include time at school or doing schoolwork, reading, some craft/hobbies, socialising and screen time (phone, TV, computer, other devices). The participant and therapist agreed a ‘baseline’, which is the average level of activity. For severely affected adolescents, this might include sitting up in bed; for those with mild ME/CFS, this might include walking fast. The baseline could either be estimated in collaboration with the specialist therapist or calculated after a period of recording activity. Using a baseline for activity, usually means limiting activity on good days. Once the baseline was agreed with participants, they were asked to record the total number of minutes spent each day doing high-concentration cognitive activities using paper diaries or the iPhone/iPad app ‘ActiveME’. Participants were asked to scan and e-mail or post the paper diaries or e-mail outputs from ‘ActiveME’ to the therapists. Recording activity was used to help participants understand whether they are doing the same each day or varying their activity and whether the baseline has been set at the correct level. Participants were then encouraged to increase their activity gradually. When participants managed the baseline for 1–2 weeks, they were encouraged to increase this gradually (by no more than 10–20%) each week in a flexible and individualised way. During the follow-up video calls, the clinician reviewed physical and cognitive activity and sleep and helped participants problem-solve. Participants were encouraged to increase activity until they were able to do up to 8 hours of cognitive and physical activity a day.

Following the course of video calls, the participant’s clinician handed over to the participant’s nominated local therapist or doctor to deliver care (offering phone call hand-over as well as treatment summary letter).

Delivered by a ME/CFS clinician (usually a physiotherapist/occupational therapist) at the Bath Specialist ME/CFS Service.

When and how much

The initial assessment took up to 90 minutes, and an option was added to enable this to be split into two sessions if needed (due to the energy level of the participant). The first follow-up video call was arranged 2–6 weeks after assessment depending on participant and their parent preference. Further follow-up video calls were organised with gaps of 2–6 weeks between them. Follow-up calls were designed to take approximately 60 minutes each time. The total time in treatment varied depending on the number of sessions and the gap between sessions but was designed to last about 6 months.

Tailoring

Clinicians could individualise sessions but were prohibited from exploring participant cognitions and emotions in detail. Sessions were guided using a checklist (see Appendix 1 for details) with flexible elements that could be used. The speed and timing of activity increase (or decrease), as well as the time between sessions were individualised with participants.

Modifications

Please see Chapter 4 for details on the modifications. The most important modification was increasing the number of Activity Management sessions from 3 to 6 in November 2017 in response to feedback from families and clinicians.

Fidelity was assessed using the intervention checklists of mandatory, flexible and prohibited elements (see Appendix 1 for details).

Outcomes

The primary outcome for the full trial was disability measured using the 36-item Short Form Health Survey Physical Function subscale (SF-36-PFS)42 reported 6 months after randomisation. This subscale has 10 items and scoring ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better physical function.

The secondary outcomes are listed below and were measured at baseline (shortly after randomisation, and before treatment began) and at 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation unless otherwise specified:

-

SF-36-PFS42 measures at 3 and 12 months after randomisation (the 6-month measure formed the primary outcome)

-

fatigue [Chalder fatigue scale43 and checklist individual strength (CIS) fatigue severity subscale]44

-

school attendance (self-report days per week attendance at school and/or receiving home tuition)

-

mood (RCADS)36

-

pain visual analogue scale (VAS)45

-

Clinical Global Impression Scale46

-

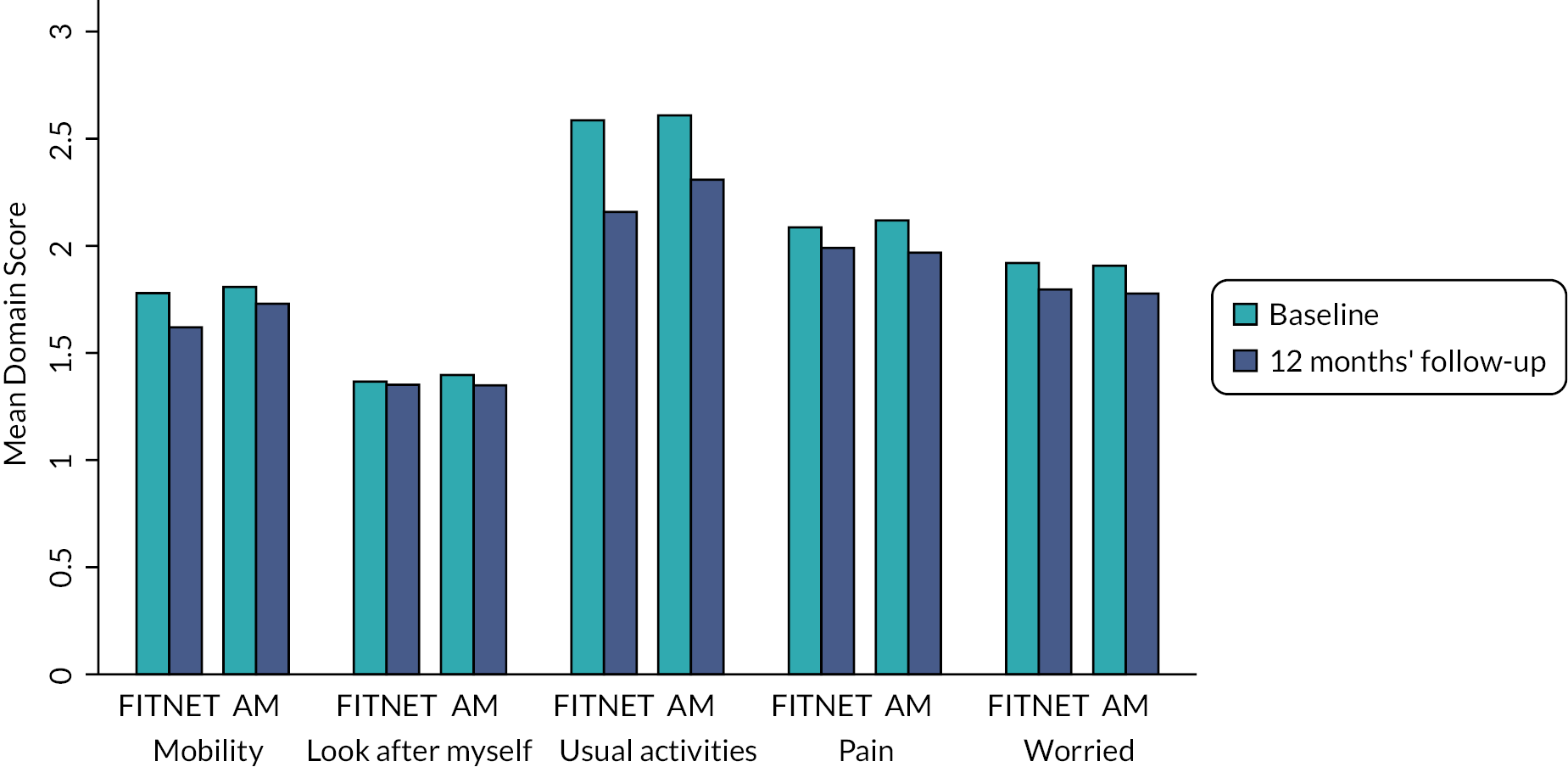

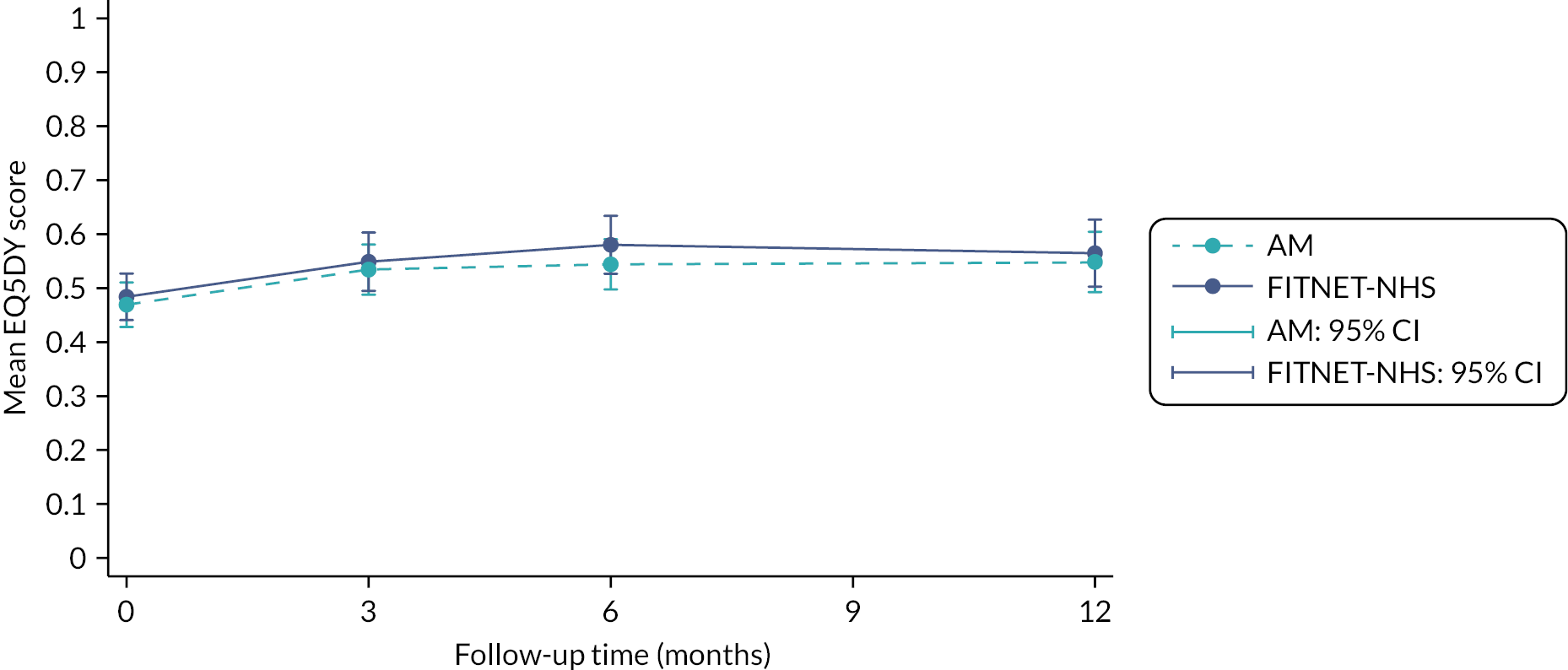

quality of life [(EuroQol-5 Dimensions Youth (EQ-5D-Y)]47

-

Parent-completed child’s healthcare use and parent’s out-of-pocket resource use questionnaire (RUQ)

-

parent-completed work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire general health (WPAI:GH)48 (parent-related productivity and activity).

These measures were chosen as being important and relevant domains49 used in UK services, child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and/or tested in previous trials. 8,50,51

The following measures were also collected from participants at the eligibility assessment: age, sex, postcode (for data on deprivation – indices of multiple deprivation), ethnicity, symptoms (both CDC and NICE criteria to enable comparison of results with those of other studies using CDC criteria), months of illness, and diagnoses of comorbid illnesses.

At baseline, the first 205 participants completed the following additional questionnaires (not repeated at follow-up):

-

cognitive behavioural responses to symptoms questionnaire (CBRSQ)28,29

-

children’s negative cognitive error questionnaire – revised (CNCEQ-R). 31

These additional questionnaires were included to explore differences in negative thinking between those participants with ME/CFS and comorbid mood disorders and those without. The CBRSQ has previously been used with adults with ME/CFS in the PACE trial,52 and with adolescents. 53 The results from these questionnaires will be reported elsewhere. Table 3 shows the full schedule of data collection at baseline and at follow-up.

| Data item | Baseline | Follow-up (months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral letter | Eligibility assessment | Following recruitment | 3 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Assessment data | Age and postcode | X | |||||

| Sex and ethnicity | X | ||||||

| Symptoms list (CDC and NICE criteria) | X | ||||||

| Months of illness | X | ||||||

| Comorbid conditions | X | ||||||

| Questionnaires (child) | SF-36-PFS | X | X | X | X | ||

| Chalder fatigue and CIS fatigue | X | X | X | X | |||

| School attendance | X | X | X | X | |||

| RCADS | X | X | X | X | |||

| Pain VAS | X | X | X | X | |||

| Clinical Global Impressions Scale | X | X | |||||

| EQ-5D-Y | X | X | X | X | |||

| CNCEQ-R | X | ||||||

| CBRSQ | X | ||||||

| Questionnaires (parent/carer) | Healthcare resource use | X | X | X | |||

| WPAI:GH | X | X | X | X | |||

Clinicians rated each participant’s treatment adherence on discharge from trial treatment, rating these on a 3-point scale: (1) non-starter (never began treatment/not contactable after enrolment); (2) started then stopped (made a start but then discontinued treatment/became uncontactable); (3) 80% + completion (majority of clinically relevant modules/sessions required had been attended/completed).

Data collection methods

All baseline and follow-up questionnaire data were collected on REDCap, a secure system used by many institutions for large multicentre studies. Participants were sent a web link to access their REDCap forms asking these to be filled in (Report Supplementary Material 2 gives examples of how the participant and parent questions appeared). Completed forms that had been submitted could not be re-accessed by participants, and forms that had been partially completed and exited could be re-accessed by the participant for completion only via entering a code unique to that specific survey, generated by REDCap, to ensure data security. An automated reminder e-mail was sent to participants who had not filled in their baseline questionnaire 7 days after it was first sent, with a further automated reminder e-mail after 14 days if it was still incomplete. Newly recruited participants were also contacted by phone, text and/or letter to try to gain the baseline data prior to commencing treatment if the baseline remained incomplete.

At the follow-up time points, an e-mail was sent to participants automatically with a link to complete questionnaires online. If these were not completed, automated reminders were sent at 2 weeks and then again at 4 weeks after the questionnaire was due. If questionnaires were not completed, we tried to contact participants by telephone or text. An e-mail with a link to a reduced set of questionnaires (SF-36-PFS, Chalder fatigue, school attendance, EQ-5D-Y and Clinical Global Impression Scale only) was also sent 6 weeks after the questionnaire was due for participants who had not completed their questionnaires, with the aim of capturing a minimal data set. If participants were contacted by phone and did not want to complete the minimum data set, we asked if they would be willing to complete the primary outcome only.

Harms/adverse events assessment

The FITNET-NHS trial investigated whether adolescents randomised to one treatment group were at higher risk of having a serious deterioration in health compared to the other treatment group. We defined a serious deterioration in health as either: (1) clinician-reported serious deterioration in health (reported during FITNET-NHS or Activity Management session) reported as an adverse event; (2) a decrease of ≥ 20 in SF-36-PFS between baseline and 3, 6 or 12 months or scores of ‘much’ or ‘very much’ worse on the Clinical Global Impression Scale; or (3) withdrawal from treatment because of feeling worse. Safety outcomes were reported to the Data Safety Monitoring Committee.

An adverse event is any untoward medical occurrence in a patient which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment. Data on adverse events were collected for each participant from the point at which they consented to take part in the study until the end of the follow-up period (12 months). On being alerted about an adverse event from a member of the clinical team, the research team provided the person reporting the event with a link to an online adverse event questionnaire (within REDCap) to record these details in accordance with Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and University of Bristol guidelines on reporting.

ME/CFS is by its nature a fluctuating illness. The description of activity and function in ME/CFS is one of boom–bust, which usually occurs over several days and sometimes weeks. ‘Payback’ or ‘crashes’ or ‘flares’ are to be expected in young people whether or not they are undergoing treatment. Payback, crashes or flares can mean that an adolescent who was previously mobile becomes bed-bound or is unable to go to school. Episodes can last days or occasionally weeks. Treatment is designed to reduce these over time but the risk of flares without treatment, during or post treatment is not known. Between 30% and 40% of adolescents were expected to experience significant comorbid anxiety and depression. In most cases, this is because of the prolonged disabling nature of ME/CFS. This means that it is not unexpected for adolescents with ME/CFS to be referred to CAMHS for treatment. It was expected that some adolescents would be started on medical treatment, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Data on medication for mood were collected via parent questionnaires and review of medical records of the participant. Other medication expected to be used by this patient group is melatonin (to improve sleep) and amitriptyline (to improve chronic pain and sleep).

All adverse events were recorded on an electronic case record form (stored on REDCap), including an assessment of whether it was expected or not expected and if it was (or possibly was) related to trial treatment. All adverse events were reported and reviewed by the Data Safety and Monitoring Committee during the study.

Any adverse event was to be defined as serious if: it resulted in death, was life-threatening, required unplanned inpatient hospitalisation (overnight) or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity or resulted in congenital anomaly or birth defect. Any adverse event meeting any one of these criteria was reported by the clinical team/participant or parent to the research team, recorded in detail on an online case record form (via REDCap) and reported to the Sponsor and Principal Investigator by the research team within 24 hours of being notified, in accordance with the Sponsor’s protocol.

For all serious adverse events, the subject was actively followed up, and the investigator (or delegated person) provided follow-up details every 5 working days and submitted a Serious Adverse Event Follow-up report to the sponsor and the Principal Investigator until the serious adverse event had resolved or a decision for no further follow-up had been taken.

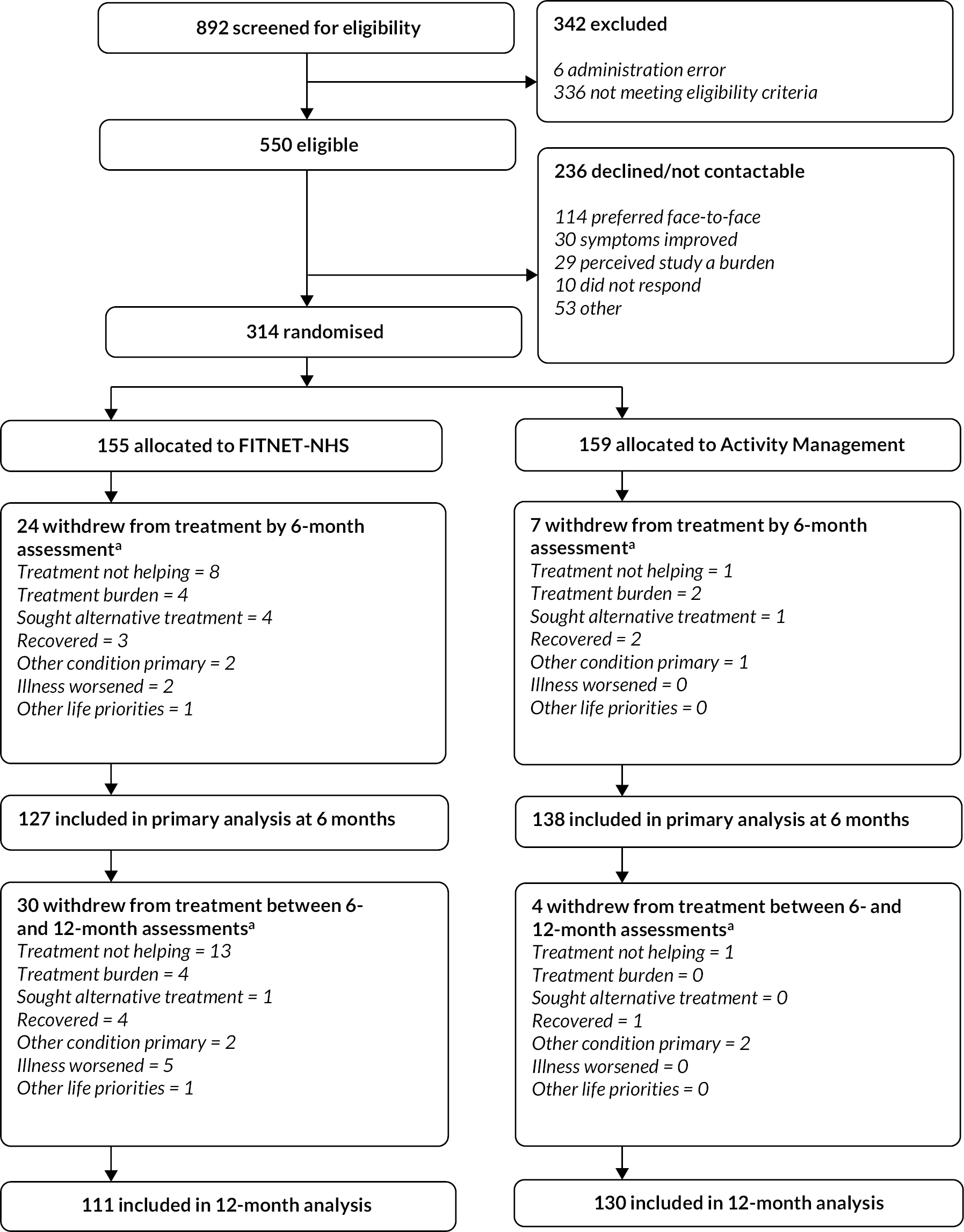

Sample size

We planned to randomise 314 participants, assuming 15% attrition (withdrawal or non-provision of primary outcome data); see Chapter 4, Sample size for the original sample size calculation. Therefore, we expected data to be available for 266 participants for the primary analysis. This sample size gives 90% power at 5% significance to detect a 10-point [approximately 0.4 standard deviation (SD)] difference for the SF-36-PFS for our primary outcome. This is the minimally clinically important difference (MCID) defined previously in paediatric ME/CFS using triangulation of three methods: the anchor method, the distribution method and qualitative methods. 54

Statistical methods

Full details of the statistical methods have been presented in the FITNET-NHS statistical analysis plan, written without access to the accumulating outcome data, and made publicly available on 6 October 2021. 55 All analyses were conducted using Stata version® 17.0 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA, 2021).

For the primary outcome, the null hypothesis tested was that the population mean SF-36-PFS score at 6 months’ follow-up was equal between groups allocated to FITNET-NHS or to Activity Management. We used an intention-to-treat analysis, comparing study participants who completed the required measures, in the treatment groups to which they were allocated (the full analysis population). We used multivariable linear regression adjusting for baseline values of the outcome, baseline age and gender. The treatment effect was estimated as an adjusted difference between sample means.

The outcome variable (yi) was patient response at 6 months post randomisation. Treatment covariates were: treatment allocation (x1i = 1: FITNET-NHS; x1i = 0: Activity Management), baseline SF-36-PFS (x2i), age at recruitment (x3i as a continuous measure), and gender (x4i = 1: male; x4i = 0: female). Finally, a dummy variable distinguishing those participants without a baseline assessment of outcome (x5i = 1: no baseline assessment; x5i = 0: baseline assessment available) was used. 56 A normal distribution was assumed for the residual errors: ei ~ N(0,σe). The coefficient for the treatment allocation covariate (β1) is the intention-to-treat estimate of treatment effectiveness, comparing FITNET-NHS to Activity Management. In statistical notation:

The residuals from the model were checked for a normal distribution, and as having a similar SD in the two treatment groups.

The statistical analysis plan pre-specified the following sensitivity analyses to aid interpretation of the results. We did not need to adjust our primary analysis model for prognostic variables (baseline variables) for which there was a baseline imbalance between treatment arms of more than half a SD between means (or more than 0.1 between proportions). We also adjusted for any variation across participants in the time between randomisation and the 6-month outcome assessment.

Because of changes in the first lockdown during the COVID pandemic (for example, school, social activities), we prospectively decided to repeat the analysis with the addition of a binary covariate distinguishing participants recruited before and after 1 September 2019 as this defines those with a 6-month primary outcome before or after the start of the first lockdown. Furthermore, during the pandemic, we noticed an increase in time between randomisation and treatment. We therefore repeated the analysis using 12-month assessment (rather than 6-month assessment) for those who did not start treatment until after the 3-month assessment.

We estimated the effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared with Activity Management for the SF-36-PFS primary outcome in participants completing one or more modules/sessions of their allocated intervention. This is a change from the corresponding sensitivity analysis described in the published protocol paper,35 which can more easily be applied in an equivalent manner to participants irrespective of their allocation.

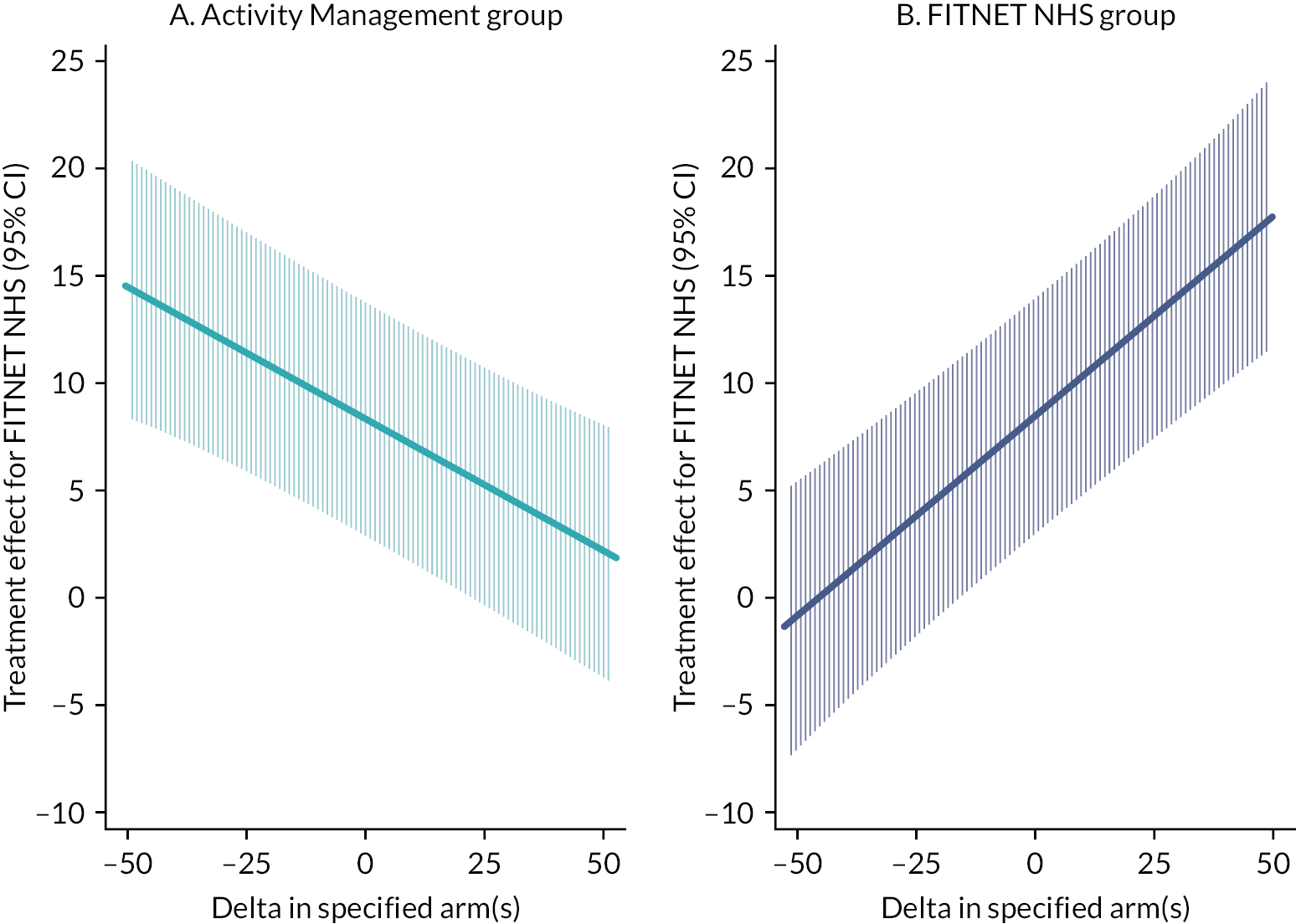

We explored the robustness of the findings from the analysis of the primary outcome to assumptions about the missing outcome data using a pattern mixture model approach. 57 This was used to indicate how different the missing and observed measurements would need to be on average, for the observed treatment comparison to be considered an artefact of the missing data.

The primary analysis was adapted to each of the other questionnaire measures at 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments in turn (with the twelve-month assessment of SF-36-PFS included as a secondary outcome). The corresponding baseline measure of the questionnaire being analysed was included. The primary analysis was adapted to the Clinical Global Impression Scale, with an ordered logistic regression model being employed. The seven response categories were kept separate when included in this model. There was no baseline assessment of this measure.

In a single pre-specified subgroup analysis, we estimated the effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared with Activity Management on the primary outcome in participant subgroups defined by the presence or absence of baseline anxiety or depression, defined by using the age- and gender-specific clinical thresholds for each subscale on the RCADS. Evidence that the intervention effect differs between subgroups was examined by adding interaction terms to the multivariable linear regression model for the SF-36-PFS primary outcome only.

Measures of harm and adverse events were tabulated, along with a count of the number of participants who met one or more of the above measures.

Economic evaluation methods

The primary objective of the economic evaluation was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared to Activity Management delivered by videocall to treat children aged 11–17 years with CFS/ME, from the perspective of the NHS in the UK over a 12-month follow-up period.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

estimate the cost-effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared to Activity Management for subgroups with and without mild/moderate comorbid anxiety/depression

-

estimate the cost-effectiveness of FITNET-NHS compared to Activity Management from a wider perspective (including the participant and family costs, and impacts on participant education).

A health economics analysis plan (HEAP), which followed intention-to-treat principles, was pre-specified by the study team. 55 The trial was conducted in the UK, where the health system is predominantly publicly funded, provided by the NHS, and care for UK residents is free at the point of access. The primary analysis was conducted from the NHS perspective, which involved assessing the impact on secondary, primary and community care. A within-trial cost–utility analysis (CUA) was conducted for the primary analysis. This involved comparing mean incremental differences in costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) over the first 12 months from randomisation.

Measurement of resources

Resource use identified as relevant from an NHS perspective included: (1) training for FITNET NHS; (2) delivery of FITNET and Activity Management; (3) primary and community care visits; (4) prescribed medications; and (5) secondary care. Relevant resource use from a wider perspective, in addition, included: (1) participant and family out-of-pocket costs for private tuition, average travel cost incurred per return journey for a secondary, primary or community care visit, over-the-counter medication costs; (2) loss in productivity and time in education; (3) school counsellor costs; and (4) any other patient and family costs incurred due to the child’s CFS/ME.

Study records captured training costs for FITNET-NHS. Electronic health records were used to capture treatment delivery costs as well as secondary care use. All other costs were captured via a RUQ, which parents completed on behalf of their child. The RUQ had been piloted prior to the trial. It captured data on: primary and community care, medication use, participant and family expenses and productivity loss, and education impacts. The RUQ was completed online at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Table 4 summarises the key resources measured.

| Resource category | Unit cost (£) | Source of unit cost |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention training | ||

| Non-NHS staff time and travel to deliver training | Variesa | Study records |

| NHS staff time to deliver training | Variesa | Study records |

| NHS staff time to receive training | Variesa | Study records |

| Car mileage | 0.45 | HM Revenue and Customs, 202064 |

| Treatment delivery costs | ||

| Initial consultation (90 minutes) | Varies | Curtis and Burns, 202058 |

| Follow-up consultation (60 minutes) | Varies | Curtis and Burns, 202058 |

| Additional consultation (30 minutes) | Varies | Curtis and Burns, 202058 |

| Primary and community care | ||

| GP contact | 34b,c,d | Curtis and Burns, 202058 |

| GP Home visit | 104b,c,e | Curtis and Burns, 201361 |

| Nurse contact | 10.85c | Curtis and Burns, 202058 |

| NHS 111 call | 12.26 | Pope et al., 201762 |

| Walk-in centre | 39.76f | National Cost Collection, 202059 |

| Child and adolescent mental health contact | 97g | Curtis and Burns, 202058 |

| Other contact | 51.45c,h | Curtis and Burns, 202058 |

| Medications | Varies | Prescription Cost Analysis, 202063 |

| Secondary care | ||

| Outpatient visits | 234.15i | National Cost Collection, 202059 |

| Accident and Emergency visits | Variesj | National Cost Collection, 202059 |

| Inpatient admissions | Variesk | National Cost Collection, 202059 |

Data on staff training for FITNET-NHS between 2016 and 2020 were logged by a senior clinician at Bath Specialist CFS/ME service. Records included dates when the training took place and the number of clinicians and trainers who attended the training. A clinician involved in the delivery of the training estimated the duration for a typical training session.

Patient-level data on the delivery of FITNET-NHS and Activity Management were accessed via Bath Royal United Hospitals NHS Trust’s electronic patient record system (known as Millennium). These data included the number and type of appointments provided (e.g. staff type and whether it was an initial or follow-up appointment). A clinician involved in the delivery of the CFS/ME service at Bath Royal United Hospital estimated the typical consultation duration for each appointment type (e.g. initial, follow-up and additional e-consultations or videocalls). Two further clinicians from the service verified these estimates. It was estimated that the first appointment for both FITNET-NHS and Activity Management took 90 minutes and follow-up consultations took 60 minutes. In addition, for the FITNET-NHS group, if a patient required substantially more support on a particular week, then an additional 30-minute time slot was logged in the Millennium system.

Patient-level records on admitted care, outpatient visits, emergency department attendances and specialist secondary mental health care at NHS hospitals in England were requested from NHS Digital. Specifically, hospital episode statistics (HES) collates hospital care paid for by the NHS and provided by any acute NHS or independent hospitals in England. Due to delays in receiving data from NHS Digital, we were not able to include secondary mental health care costs in this report. In addition, NHS Digital were only able to provide the emergency care data set (ECDS) from April 2018. As the ECDS only became the official data source for Emergency Care in England from April 2020, our measure of patient Emergency Care visits may be incomplete between April 2018 and March 2020.

Data linkage was carried out by NHS Digital. The FITNET-NHS research team provided NHS Digital with patient identifiers (NHS number and date of birth) and a pseudonymised participant ID number. Data were only requested for the 306 (97.45%) participants who provided consent for their medical records to be linked. NHS Digital were able to link 296 (94.27%) participants. NHS Digital removed the patient identifiers and returned the pseudonymised linked data to the FITNET-NHS research team. The Millennium data set was used as the primary source for outpatient visits taking place at the CFS/ME service at Bath Royal United Hospital. Therefore, in order to avoid duplicates, outpatient visits that took place at Bath Royal United Hospital were dropped from the HES data set before analysis.

Please refer to Appendix 2 for an overview and timeline of the data access request service (DARS) application process. In summary, we began the application process on 14 March 2019 and eventually received most of the data requested in February 2022.

It was intended that routine data from GP electronic patient record system providers would be used as the main data source for primary and community care. The system providers were unable to provide access to pseudonymised data and so the RUQ was used as the sole source for primary and community care resource use. The RUQ was completed by parents on behalf of their child, and included: (1) all types of GP surgery and telephone consultations with the GP and Practice Nurse/Nurse Practitioner; (2) all types of GP home visits; and (3) all types of other primary and community-based contacts (e.g. walk-in centre visits, telephone calls to 111). Medications include any prescribed medications as well as a list of specific medications (e.g. Amitriptyline, Melatonin, Paracetamol, Ibuprofen, Codeine) commonly used for ME/CFS symptoms.

The RUQ asked parents to provide data on the costs they had incurred as a result of their child’s CFS/ME. Parents were asked to report on out-of-pocket costs they incurred for the following: (1) return journey to primary or community care centre, or hospital (for public transport, this included the cost of a return fare for the child and parent; for private vehicle, this included the cost of parking and fuel costs); (2) any over-the-counter medications purchased for their child; (3) any other out-of-pocket expenses the parent or the immediate family have incurred due to child’s illness; and (4) hours absent from work and regular activities due to child’s health problems. Parents were also asked to report any impact on their productivity in the past seven days using an adapted six-item WPAI:GH V2.0. 48 The WPAI:GH V2.0 questionnaire was adapted so that parents were asked about how their child’s health impacted on their productivity. More specifically, they were asked to report on: how many hours of work they missed; how much their productivity was affected on a scale of 0–10; and how much their usual activities were affected. Lastly, parents were asked to report whether children had received support from a school counsellor.

Children were asked whether they were currently receiving home tuition, and if so, they were asked to specify how many hours of home tuition they had received in the previous week. Children were also asked to report on the proportion of the week they typically attended school in the previous school term.

Valuation of resources

Resources were valued using 2019/20 prices. Where a unit cost was not available for 2019/20, it was inflated using the NHS cost inflation index (NHSCII). 58 Hospital-based healthcare staff delivering FITNET-NHS and Activity Management, as well as care provided by primary and community-based healthcare staff was valued using the 2020 Unit Costs published by the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU). 58 Secondary care resource use, excluding the FITNET-NHS and Activity Management interventions, was costed using the 2020 NHS reference costs from the National Cost Collection. 59 When a unit cost was unavailable for a specific inpatient or emergency care visit, simple mean imputation was used. This involved us using the mean costs of the children in our study who had an inpatient or emergency care visit. Prescribed medications were assigned a unit cost based on the prescription cost analysis (PCA) for 2020. 59 Actual costs reported by the parents were used for out-of-pocket costs. Productivity costs were derived from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings using median pay per hour. 60 Table 458,59,61–64 and Table 558 summarise the resources collected and their valuation from the NHS and wider perspective, respectively.

| Resource category | Unit cost (£) | Source of unit cost |

|---|---|---|

| School counsellor | 97a | Curtis and Burns, 202058 |

| Out-of-pocket costs | Varies | Cost reported by participants |

| Productivity: absenteeism | 15.14 | ONS AHSE, 2020b,c |

| Productivity: presenteeism | 15.14 | ONS AHSE, 2020b,d |

| Tuition costs | 28 | Varies, 2021e |

Measurement and valuation of outcomes

The EQ-5D-Y was collected at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months, using a participant self-completed questionnaire completed online. At the time of study design, it was anticipated that an EQ-5D-Y UK child scoring algorithm (value set) would be available by the time of analysis. However, a value set for the EQ-5D-Y is not yet available for the UK and it is not recommended to use the UK adult EQ-5D-3L value set as a proxy for children. 65 Instead, a proxy EQ-5D-Y value set derived for the German population was used to calculate utility scores for each participant. 66

Economic analysis

The analysis took an intention-to-treat approach, whereby all participants who did not withdraw their consent to have their data used in the study were analysed according to group they were randomised to. As costs and outcomes were not assessed beyond 12 months, discounting was not required.

Mean and SD resource use and number of respondents were estimated and presented by group for each resource use category (e.g. outpatient visits, medication use, etc.). Utility scores derived from the EQ-5D-Y were used to calculate the QALYs for each patient using an area-under-the-curve approach. 67 Seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) was used to estimate mean costs and QALYs and 95% CIs in each group and the incremental difference in costs and QALYs between the groups. SUR accounted for the correlation between costs and effects. 19 In addition, costs and QALYs were estimated with baseline age and gender as covariates; baseline EQ-5D-Y score was also a covariate in the QALY regression.

In order to reduce possible bias due to missing data, our primary analysis used multiple imputation by chained equation (MICE) using predictive mean matching. We assumed data were missing at random (MAR).

All cost and outcome variables were included in the imputation model as well as the covariates baseline age and gender. The imputation model was stratified by treatment allocation group and a random seed was set to provide reproducible imputations. We created 50 imputed data sets. Rubin’s rule was used to pool and analyse multi-imputed data sets. Total utility scores, primary care costs and medication costs were imputed for each data collection timepoint (baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months) due to questionnaire data not being returned. In addition, secondary care costs were imputed for a minority of participants (n = 19) due to data linkage not being possible. Imputed utility scores at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months were used to calculate mean QALYs and the mean incremental difference in QALYs per group. Similarly, imputed costs at 3, 6 and 12 months for the various cost categories were summed up to calculate total mean costs, and the mean incremental difference in costs per group.

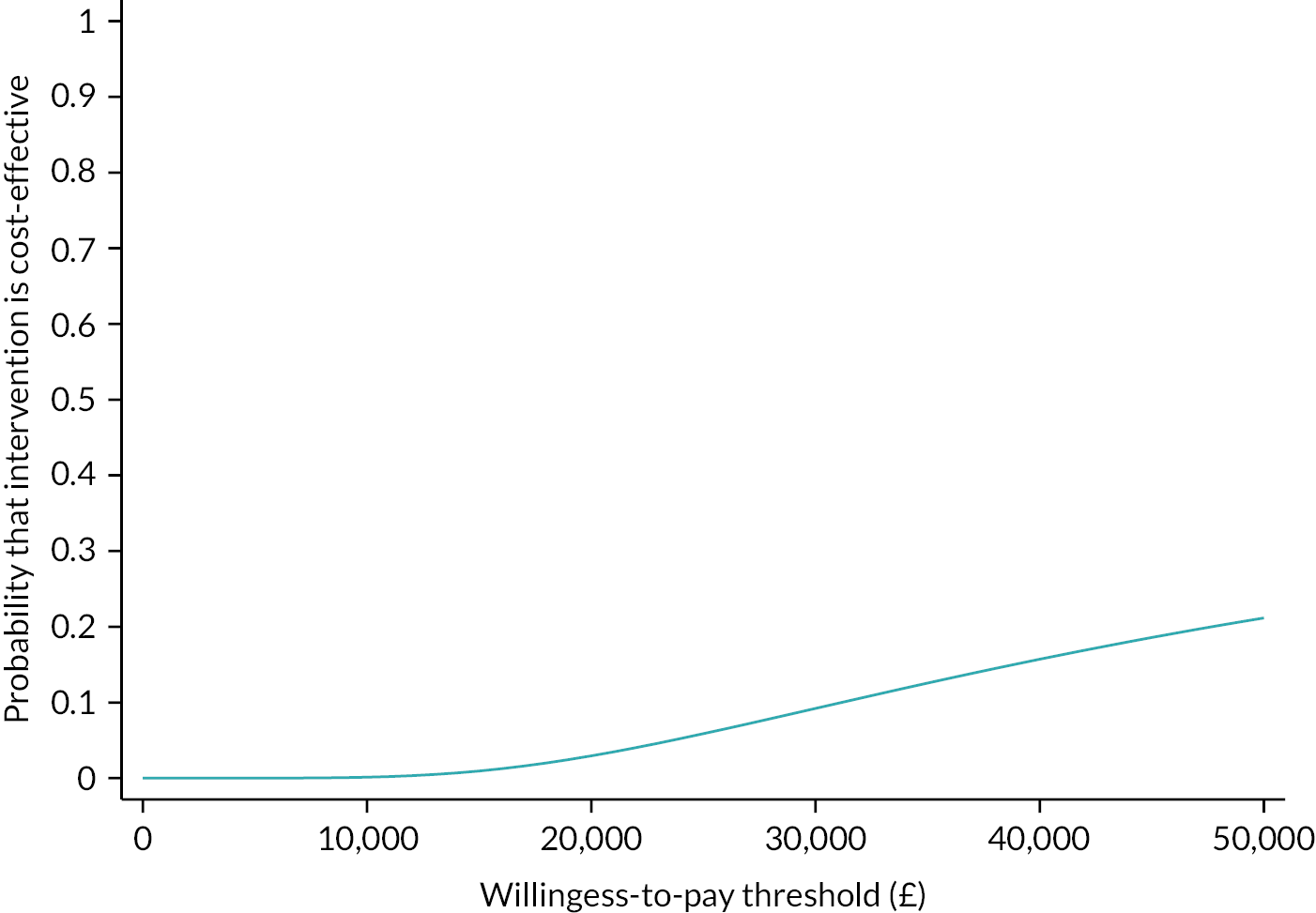

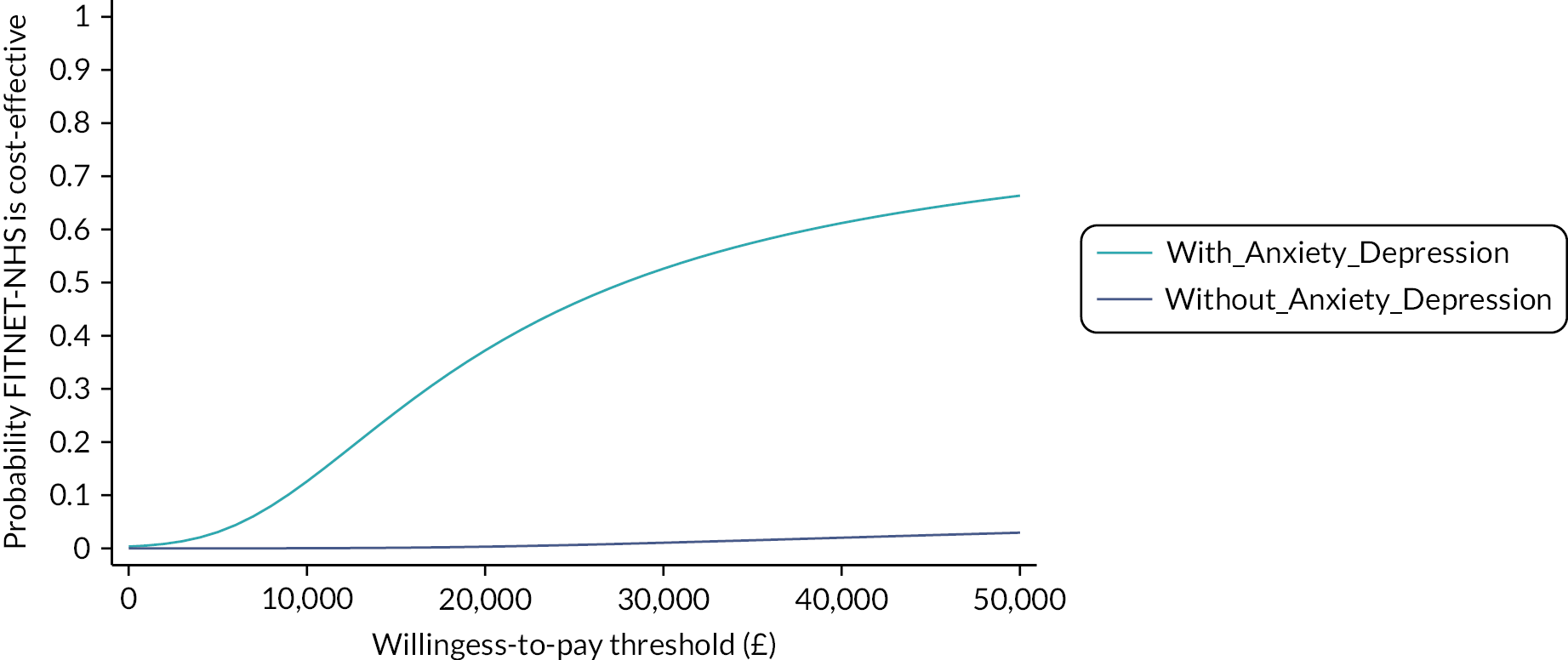

The primary analysis combined cost and QALY data to calculate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio and an incremental net monetary benefit (iNMB) statistic. 68 INMB was used to estimate cost-effectiveness at the UK NICE-recommended cost-effectiveness thresholds of £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY. We used a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 per QALY in the primary analysis. Uncertainties in the point estimates of iNMB were quantified using 95% CIs estimated from the regression. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) was used to illustrate the probability of FITNET-NHS being cost-effective compared to Activity Management across a range of willingness-to-pay thresholds.

In line with the clinical effectiveness analysis, a subgroup analysis was performed to explore the interaction between comorbid anxiety/depression disorder and the cost-effectiveness of FITNET-NHS. Comorbid anxiety/depression at baseline was included as an interaction term with treatment allocation to assess any modification of cost-effectiveness in these subgroups.

Uncertainty in the primary analysis was explored through sensitivity analyses. Firstly, we conducted sensitivity analyses that were pre-specified in the HEAP:

-

Handling missing data: a complete-case analysis was performed, where only participants who had complete cost and QALY data were included in the analysis. This analysis assumed data were missing completely at random (MCAR).

-

Intervention costing: the primary analysis was repeated using the 2019/20 tariff paid by the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) (instead of the reference cost used in the primary analysis) for FITNET-NHS and Activity Management consultations.

Further, post hoc sensitivity analyses were performed to explore the impact of alternative methodological choices:

-

We repeated the analysis including participants with ME/CFS as redefined in the NICE (2021) criteria.

-

Handling missing data: data may be missing due to unobserved factors that may be correlated with both treatment and outcome. We therefore conducted a sensitivity analysis assuming health-related quality-of-life data were missing not at random (MNAR). Following Laurent et al. (2018),69 we fitted pattern mixture models using multiple imputation. Specifically, in each treatment group we assumed missing health-related quality-of-life values were 0%, 5% or 10% lower than participants with similar characteristics who do not have missing values. We allowed the missing values to differ by group. We expected any between group difference to be small, and so we assumed the between group difference would not be greater than 5%. This results in six MNAR scenarios.

-

Excluding training costs: training all staff on how to deliver FITNET-NHS was a one-off cost. If FITNET-NHS were to be implemented widely across the NHS, it is likely that training in delivery would become a routine element of clinical training in ME/CFS care.

-

Intervention costing: the FITNET-NHS intervention was primarily delivered by Band 7 clinicians. It is possible that other clinicians could be trained to deliver FITNET-NHS. We conducted an analysis to explore how total intervention delivery costs would change if FITNET-NHS was delivered by Band 6 clinicians.

-

Valuation set: the impact of using an alternative value set was explored given there is no UK-value set. The proxy EQ-5D-Y value set derived for the Spanish population was applied. 70

General practitioner data extraction

We initially intended to visit GP surgeries and extract data on the number of GP visits, referrals and tests. 34 However, conversations with EMIS (Egton Medical Information System) Health suggested that we could obtain all of these data reliably through them. EMIS Health provides electronic patient record systems and software for the majority of general practices for FITNET-NHS participants. Key primary care resource use categories extracted for the health economic analysis included: consultations, medications and tests.

Negotiations with EMIS Health started in the summer of 2019 and continued until the Spring of 2022. Data extraction was planned in February 2020 but on 14 April 2022, EMIS informed us that data extraction was not going to be possible before this report was written. Working with EMIS was therefore abandoned. For a full description of the process and difficulties experienced, please see Appendix 2.

Qualitative methods

Qualitative methods inspired by those used in the QuinteT Recruitment Intervention to optimise RCT recruitment71 were integrated into the pilot and main phase of the trial to explore trial conduct and acceptability of the recruitment process and interventions through analysis of recruitment to trial consultations and in-depth interviews with recruiters, trial therapists and participants (adolescents and their parents). Findings were fed back to the Trial Management Group (TMG) with suggestions to change aspects of the design, conduct, and organisation of the trial to optimise recruitment particularly during the pilot phase and beyond as appropriate.

Families interested in taking part in the trial were contacted by a research nurse by telephone to briefly introduce the trial. They were e-mailed the PILs and later followed up with a second in-depth call (telephone/videocall options offered) to conduct a full eligibility assessment, discuss the trial in further depth and answer questions. We aimed to audio-record (with consent) all the second in-depth recruitment consultations in the pilot phase, and continue to record as needed in the main trial, to identify any areas for improving informed consent processes to optimise recruitment. 71,72 A member of the research team (RP) analysed the majority (69/89) of recordings in the pilot phase of the trial (November 2016 to October 2017). This was followed by smaller samples at 3 further time points in the main trial: (1) to ensure adherence to training (February 2018); (2) when a new recruiter joined the trial (May 2019); and (3) when recruitment slowed (October–December 2019). Information provision by the recruiters, recruitment techniques, patient intervention preferences, and trial participation decisions in particular were scrutinised in the recordings. Findings were presented to the TMG and actions were taken to address identified recruitment problems such as training recruiters.

Trial staff (recruiters and therapists) for both treatment arms were interviewed during the pilot and early phase of the main trial to ascertain their views on: recruiting into the trial (eligibility criteria, decisions, recruitment pathway), provision of trial information, treatment preferences, the feasibility of delivering the intervention to adolescents, treatment effectiveness and potential changes needed to trial processes and interventions. We had a limited pool of therapists delivering the intervention and aimed to interview them all. Trial staff were interviewed in person and participants were interviewed via videoconference (Skype) or telephone.

We undertook one off in-depth interviews with participants and their parents to understand their experiences and views of trial processes, provision and acceptability of patient information, reasons for accepting or declining participation, treatment preferences and acceptability of both the content and delivery of treatments. The majority of families were interviewed in the pilot and early phase of the main trial. A few families that withdrew were interviewed later in the trial. Participants were purposively selected for maximum variation (intervention, age and gender). 73 Families were given a choice of being interviewed over videocall (Skype) or telephone, together or alone.

Interviews followed a checklist of topics to ensure that key areas described above were explored but was sufficiently flexible to allow new issues of importance to participants to emerge (Report Supplementary Material 3 gives examples of the interview topics). Both the recruitment consultations and interviews were audio-recorded with consent using encryption software, transcribed verbatim and anonymised.

Transcriptions were prepared by a professional service (Bristol Transcription and Translation Services Limited, Bristol, UK). The data were imported into NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to provide a visible audit trail of the data analysis. A reflective journal was kept in NVivo to note down any emerging findings and initial observations of differences between subgroups. These were then explored moving through the whole data set, searching within and between participant groups, and revised based on supportive or disconfirming evidence in the data, facilitating a robust analysis. We ensured quotes were selected and presented to ensure they represented a range of participants.

A proportion of transcripts were double-coded: 10% of recruitment consultations, 100% therapist interviews, 32% of participant interviews, and compared in order to improve the trustworthiness of the analysis. 74 Any discrepancies were identified and discussed with reference to the raw data. Qualitative findings of issues arising and potential solutions were discussed and agreed with the TMG to improve aspects of the conduct of the trial, provision of patient information and training of recruiters.

Qualitative data analysis

Qualitative data analysis was an ongoing and iterative process commencing soon after data collection to inform further data collection. 75 Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim in full or part, checked for accuracy and imported into NVivo to aid data organisation and analysis.

Only relevant sections of recruitment consultations were transcribed verbatim: where the recruiter described the trial, treatments, randomisation and explored patient preferences. Later in the trial, calls were listened to, to identify examples of good practice, areas for improvement and any new findings. Only quotes to illustrate findings for training were transcribed verbatim. Participant interviews were transcribed in entirety.

The data were systematically assigned codes and analysed thematically using techniques of constant comparison. 76 The data were examined for patterns and themes incorporating a mixture of deductive and inductive coding, to enable development of both anticipated (e.g. themes around equipoise) and emergent themes (specific to the FITNET-NHS trial) as interviews progressed. Transcripts were read line-by-line for content and meaning, and a provisional coding framework developed, with new codes added and existing codes merged or split. Through this process, broader categories and higher-level recurring themes were developed.

What and how trial information was conveyed by recruiters was a particular focus of the analysis such as: equipoise, language use (e.g. avoiding terms such as ‘standard vs. experimental treatment’), use of open questions, explaining randomisation, checking patient understanding and exploring patient preferences. Participant responses and any misconceptions about the trial and treatments as well as patient preferences were explored. Examples of difficult communication (e.g. participant confusion) were studied in detail to identify patterns relating to the success or failure of conveying trial information. The findings were used to help improve informed consent and trial recruitment.

Anticipated areas for exploration based on the topic guide formed the initial coding framework and included: reasons for participating in the trial, acceptability of patient information and the recruitment process, acceptability of treatment and perceived treatment effectiveness. Inductive coding was subsequently undertaken to construct subthemes and expand the coding framework, identifying themes around benefits and disadvantages of online treatment, facilitators and barriers to treatment, suggested practical changes to the trial and treatments. The data were compared between subgroups (age, gender, treatment arms) to explore any differences. Interviews with participants continued until data saturation was reached, where new interviews produced little or no change in themes in the data. 77

Trial governance

The trial was supported throughout by The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Safety and Monitoring Committee and the TMG. Appendix 3 provides details of these committees.

Further award information is available from the National Institute for Health and Care Research Journals Library website including all versions of the study protocol:

www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/14192109#/

The trial was registered in the ISRCTN registry (number: 18020851) and the International Registered Report Identifier (IRRID): RR2-10.1186/s13063-018-2500-3.

Chapter 3 Results – internal pilot

Internal pilot results

Full details of the within-pilot phase results are presented in our publication78 (see Publications). A brief summary of the main within-pilot results is presented below.

The outcome for the pilot phase was the viability to continue to full trial, based on stop/go criteria agreed with the TSC prior to commencing recruitment. The criteria for not proceeding to full trial were:

-

if the recruitment rate was substantially below target (less than an average of 15 adolescents per month) during the last 6 months of the internal pilot study (allowing for seasonal variation) AND if the qualitative data collected suggest that these rates could not be improved by changing recruitment methods, OR

-

the qualitative data suggest the interventions are not acceptable to adolescents and/or their parents.

A total of 89 out of 150 (59% of potentially eligible referrals) young people and their parents were recruited, with 75 out of 89 (84%) providing 6-month outcome data.

Qualitative interviews found that overall, recruitment, consent and randomisation processes were acceptable to participants and their parents. Some issues with recruitment were identified and addressed. Remote treatment was acceptable; however, participants and clinicians described both advantages and disadvantages of remote methods with some families preferring to travel for face-to-face treatment. No serious adverse events were reported.

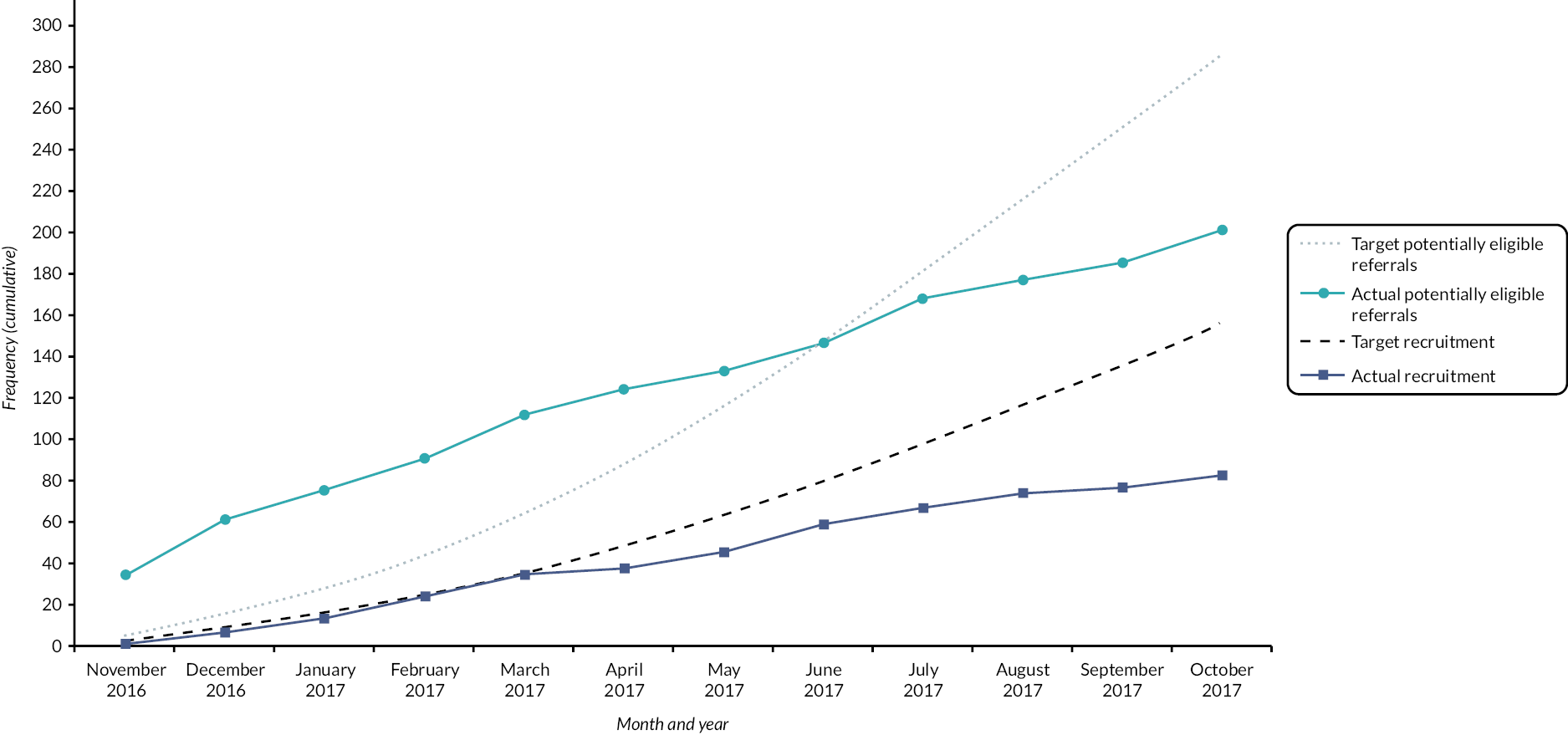

While the recruitment rates in the within-pilot phase were lower than initial projections (see Appendix 4, Figure 7 for pilot phase recruitment graph), consultation with the TSC, Data Safety and Monitoring Committee, TMG, the funder and the Sponsor confirmed that the stop criteria had not been met and the study should proceed to full trial. The TSC made the following specific recommendation on 26 October 2017: