Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1005. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in February 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Iliffe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 EVIDEM-ED: a cluster-randomised controlled trial to improve early diagnosis and clinical management of dementia in primary care

Abstract

Aim To test a customised educational intervention developed for general practice, promoting both earlier diagnosis of dementia and concordance with management guidelines.

Design/method The intervention, based on practice-based workshops, was tested in an unblinded cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) with a pre- and post-intervention design, with two arms: usual care compared with the educational intervention. Twenty-three general practices participated and the records of 1072 patients with dementia were audited. Our primary outcome was an increase in the proportion of patients with dementia who received at least two documented dementia-specific management reviews per year. Secondary outcomes were practitioner concordance with management guidelines in a subset of 167 patients with dementia; satisfaction and met need among 84 carers; and attitudes, knowledge and confidence with dementia diagnosis and management in general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses.

Findings The estimated odds ratio (OR) of having two or more reviews in the intervention group compared with the usual care group was 0.83 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 to 1.33; p = 0.44]. Case detection rates were unaffected by the intervention. The estimated incidence rate ratio (IRR) for the intervention group compared with the usual care group from multilevel Poisson regression modelling was 1.03 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.86, p = 0.93). Carers’ recall of advice given suggested that a large minority had not received the information recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) dementia guidelines. Carers of patients taking cholinesterase inhibitors reported more advice on some aspects of care.

Discussion An educational intervention customised to the needs of each practice did not appear to alter the documentation of clinical management of patients with dementia, nor did it increase case identification.

Background: why this study was necessary

Demography and impact

There is increasing interest in earlier diagnosis, because of:

-

the ageing of the population and the rising prevalence of dementia

-

the costs of care for people with dementia, and

-

the perceived benefits for the person with dementia (PWD) and their carers of early intervention, with concerns about delays in diagnosis, especially in primary care.

Dementia is one of the main causes of disability in later life; in terms of the Global Burden of Disease, it contributes 11.2% of all years lived with disability, higher than stroke (9.5%), musculoskeletal disorders (8.9%), heart disease (5%) and cancer (2.4%). 1 The total costs of caring for people with dementia in the UK have been estimated at between £17B and £18B per year2 – more than heart disease (£4B), stroke (£3B) and cancer (£2B).

Delayed recognition

Dementia syndromes are underdiagnosed and undertreated in primary care in all countries3,4 with an estimated 50% of primary care patients of more than 65 years not diagnosed by their primary care physicians. 5,6 The complex reasons for this include patient, family, practitioner and service causes, and are discussed in detail elsewhere. 7

The evidence suggests that there are tangible benefits to earlier recognition of dementia. Early disclosure of the diagnosis seems to be what people with dementia want to have8 and younger professionals want to give. 9 The benefits of making a diagnosis include ending uncertainty about the cause of symptoms and behaviour change, with greater understanding of problems; giving access to appropriate support; promoting positive coping strategies; and facilitating the planning and fulfilment of short-term goals. 10,11 There is also the potential for using cholinesterase inhibitor medication to modify symptoms and delay the need to seek care home moves among people with dementia.

Enhancing skills in primary care

The insidious nature of dementia means that it is most likely to present as a problem within primary care, but there are obstacles to earlier recognition in this setting. Therefore, considerable efforts have been made to provide educational programmes to enhance the diagnostic skills of primary care practitioners. Because of the apparent time constraints in primary care consultations, much research focus has been on the development of brief screening tests for assessing cognitive function. However, despite the availability of user-friendly cognitive function tests, there has been little evidence of improvement in primary care recognition of, and response to, dementia syndromes over the decade since the introduction of cholinesterase inhibitors. The UK evidence is particularly compelling on this point, especially from early educational interventions,12 and recent analyses by members of the EVIDEM (Evidence-based Interventions in Dementia) programme of incidence and prevalence in a large GP data set. 13

We find persuasive the argument that the problem of underdiagnosis is probably due to the interaction of case complexity, pressure on time and the negative effects of reimbursement systems that do not reward time commitment and systematic follow-up. 14,15 However, in our view there is also considerable evidence that the main problem is not that primary care practitioners simply lack diagnostic skills, but that they lack the resources and management skills in both clinical management and in prioritisation of the needs of their patients with dementia. We have presented the evidence for this elsewhere. 16

The response of primary care to the needs of people with dementia may be due, in large part, to the limited availability of support services but this does not mean that an educational intervention is unlikely to have an effect. Improved confidence in clinical knowledge and skills is still needed to allow practitioners to improve their performance with this patient group. It does mean that the effects of an educational intervention would probably be weak, unless other obstacles to earlier diagnosis and better management of dementia were reduced. Education alone does not usually change practice.

Fortuitously, three changes in UK NHS funding, in the law and in NHS priorities, created an environment conducive to changes in practice and thereby opening an opportunity to test an educational intervention in optimal circumstances. In 2006, the introduction of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), led to financial incentives for primary care to establish a dementia register and carry out annual reviews of patients. This was followed by the implementation of the Mental Capacity Act (MCA, 2005)17 in 2007, which clarified the law on the assessment of capacity to make decisions. The third was the launch of the National Dementia Strategy (NDS) in 2009,18 which prioritised improvements in the care of people with dementia, along the entire disease trajectory, and introduced new resources (such as ‘dementia advisors’ in some areas). GPs came under increasing pressure from primary care trusts (PCTs) to make diagnoses earlier, and to limit the prescription of antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). They also began to experience rising demand for advice about memory loss symptoms, and to more frequently encounter situations in which they had to make difficult decisions about the best interests of people with dementia.

The timing for an educational intervention around dementia diagnosis and management in primary care could hardly have been better. Practitioners were under pressure to improve the quality of the care they gave, and were reimbursed for doing so, but knew that they lacked knowledge and skills and so were motivated to learn. 19

Components of the trial

The EVIDEM-ED trial began with literature reviews that scoped the area, followed by co-design of an educational intervention. This was field tested for feasibility and acceptability before being tested in a definitive cluster randomised trial.

Literature reviews

In order to inform the planned trial of an educational intervention designed to change clinical practice, we carried out two literature reviews. The first was a rapid appraisal of the published, English language literature on barriers to earlier diagnosis of dementia. The second was a review of interventions in primary care designed to alter clinical practice with patients with dementia.

Review 1: Investigating Barriers to Good Practice

A full account of this review appears elsewhere. 20

Method

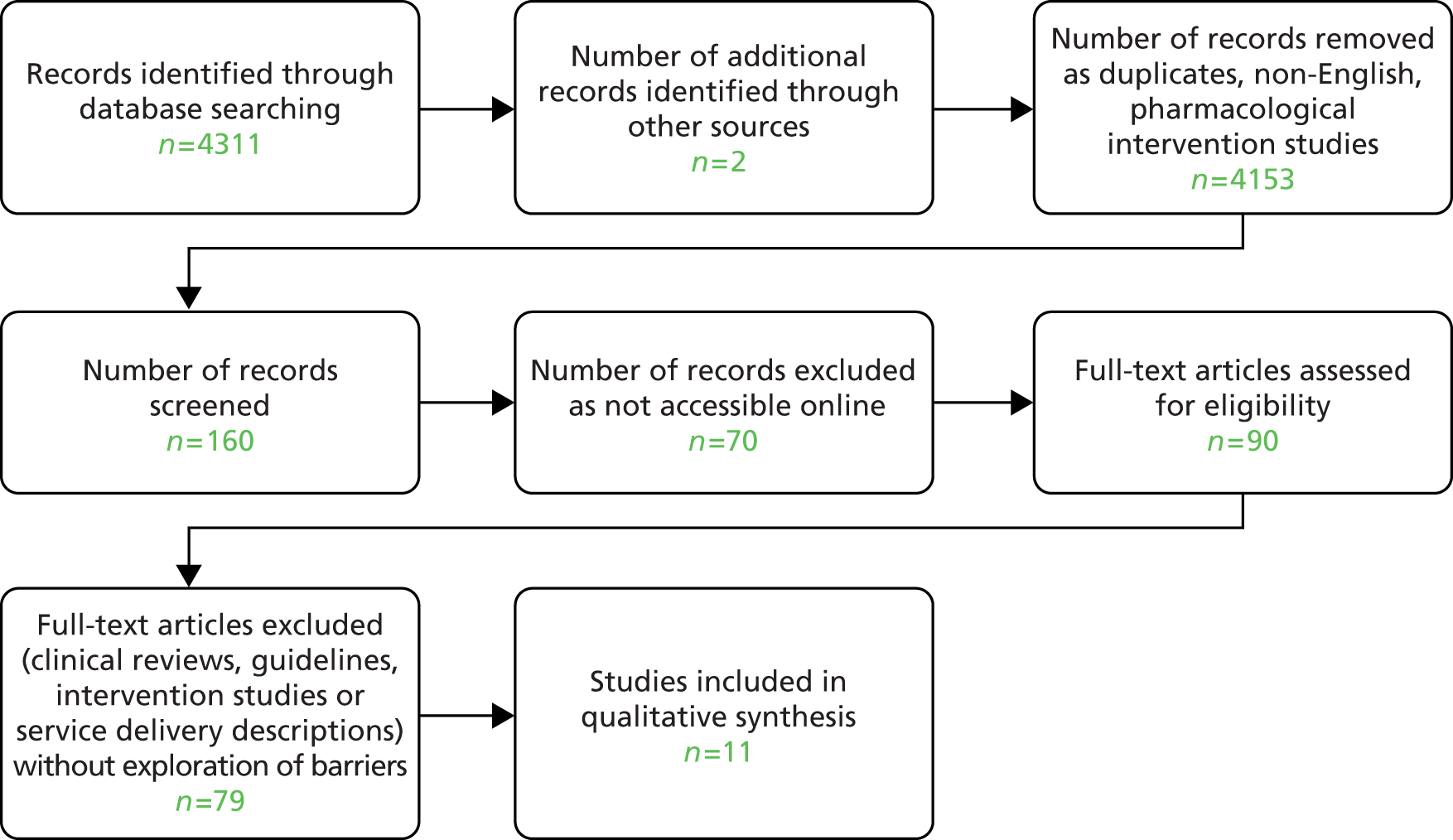

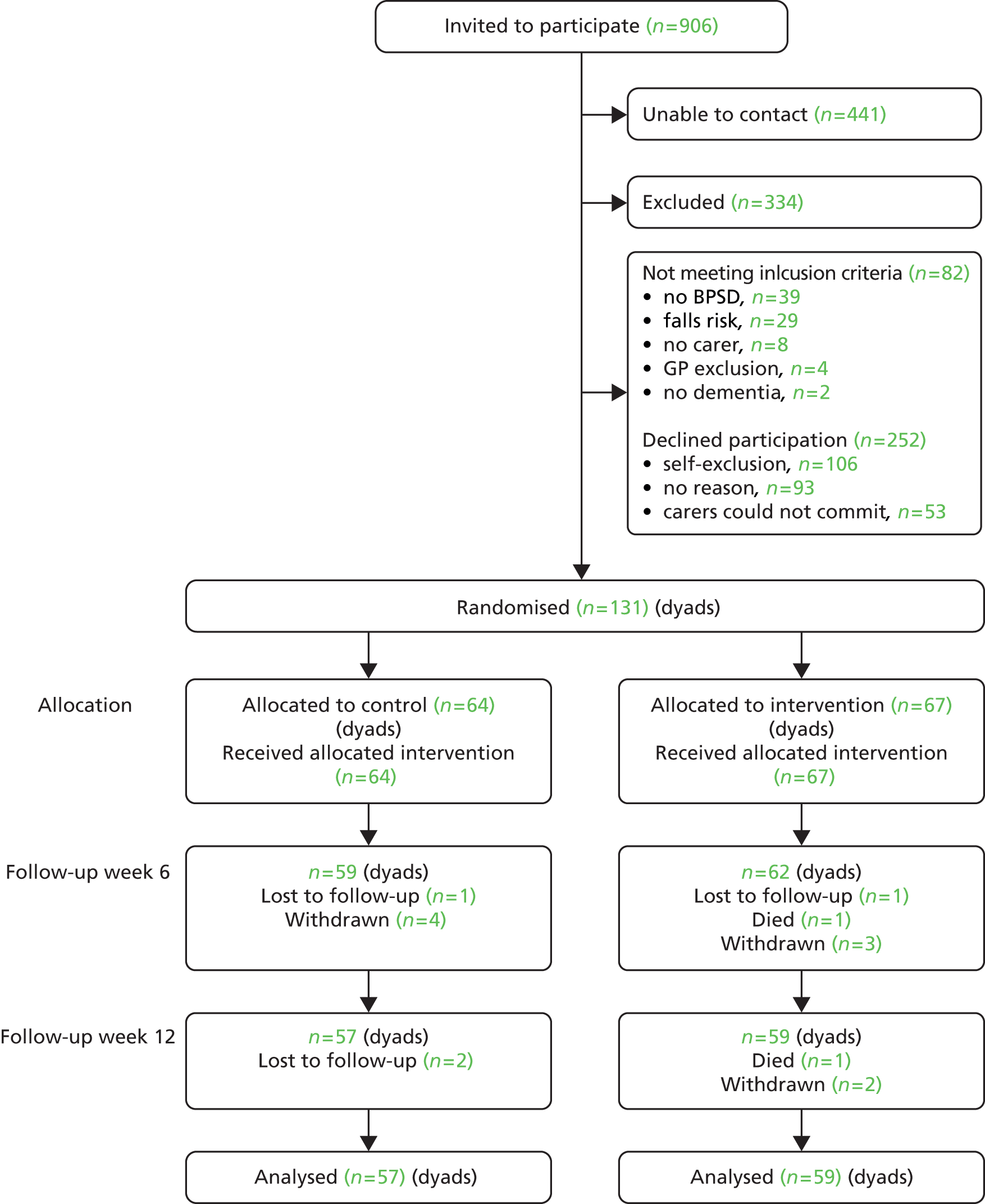

Publications in English, up to August 2009, relating to barriers to the recognition of dementia were identified by a broad search strategy, using electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO. Exclusion criteria included non-English language, studies about pharmacological interventions or screening instruments, and settings without primary care. Figure 1 shows the selection process for papers.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for EVIDEM-ED: Review 1, Investigating Barriers to Good Practice.

Results

Eleven empirical studies21–31 were found (see Appendix 1). The main themes from the qualitative studies were lack of support, time constraints, financial constraints, stigma, diagnostic uncertainty and disclosing the diagnosis. Quantitative studies yielded diverse results about knowledge, service support, time constraints and confidence. The factors identified in qualitative and quantitative studies were grouped into three categories: patient factors, GP factors and system characteristics. These are discussed in detail in the published review. 20

Conclusion

Much still needs to be done in service development and provision, GP training and education, and the eradication of stigma attached to dementia to improve the early detection and management of dementia. Implementation of dementia strategies should include attention to all three barriers, and further research should focus on their interaction.

Review 2: Changing Service Provision and Clinical Practice

We conducted a second review of potential solutions to the problem of underperformance in primary care. This second review aimed to identify and appraise empirical studies of interventions designed to improve the performance of primary care practitioners. A full account appears elsewhere. 32

Methods

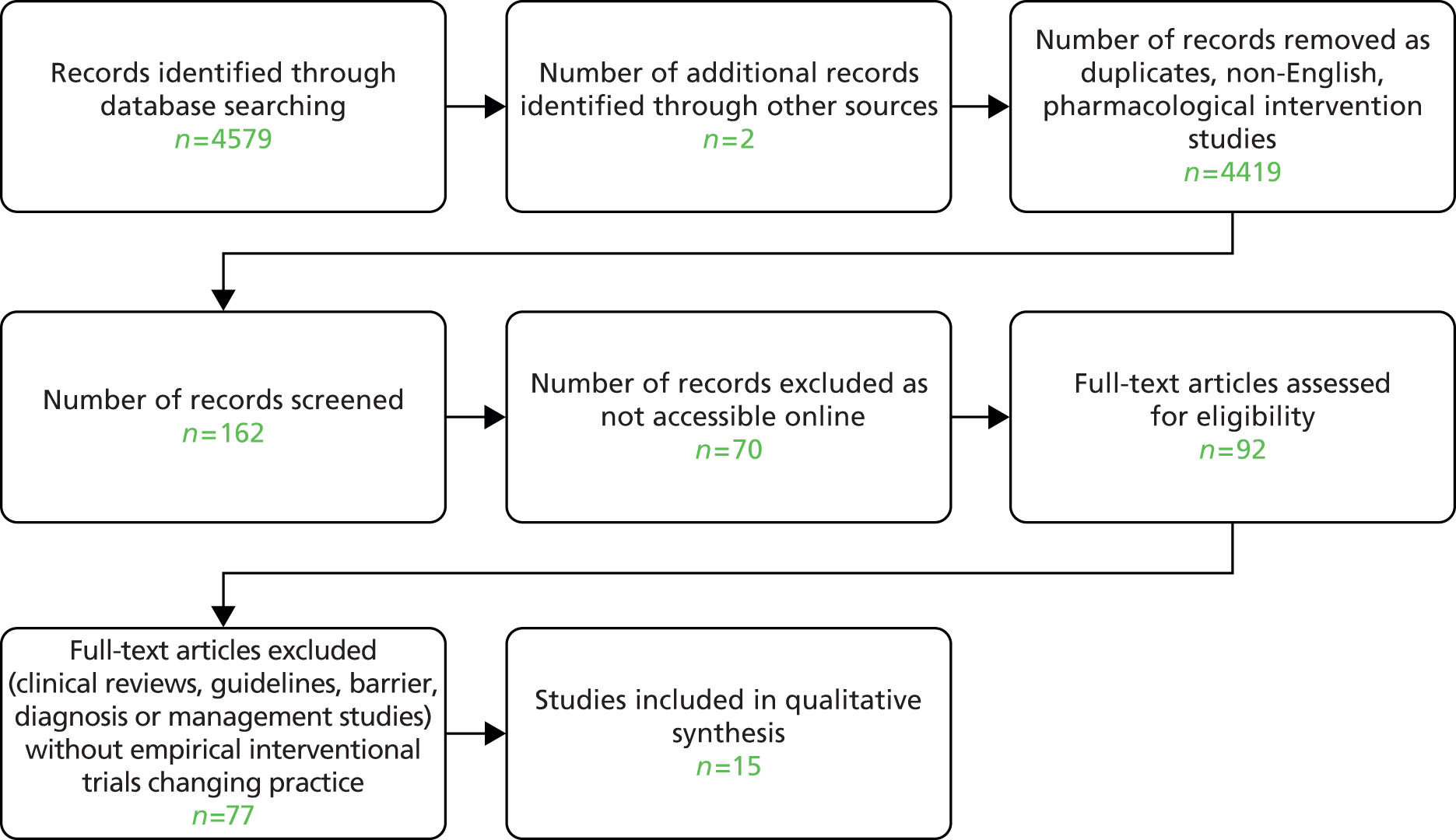

A rapid appraisal approach was adopted to inform the implementation of the NDS in England,18 introduced in 2009. To avoid delays in the analysis and completion of the review, papers that were not easily accessible were not included. Publications about the detection and management of dementia in the community were searched for using MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO, without restricting the date or language of publication. Searches were carried out up to February 2010. A broad search strategy was adopted and search terms are listed in Box 1. This was executed as a two-step process with educat* added as the second step, after all of the other search terms. Bibliographies of articles discovered were also examined for additional relevant literature.

Dementia OR Cognitiv* Impair* OR Alzheimer’s Disease

AND

Primary Care OR General Practi* OR Family Pract*

AND

Diagnos* OR Manag*

AND

Educat*

This search resulted in a total of 4579 articles. To prevent narrowing of the search scope and therefore potentially reducing the search sensitivity, the terms were not refined, but instead each title was reviewed with its abstract if available to ascertain its relevance. A number of exclusion criteria were then applied. All studies of pharmacological interventions were excluded, as were studies of the performance of cognitive function tests. Publications were excluded if they reported on the diagnosis or treatment of dementia in anywhere but a primary care setting (for example, the benefits of respite in long-term care facilities); if they related to a population outside the scope of this review (for example, interventions for caregiver health); or if they were clinical discussions about dementia diagnoses or care. Letters were also excluded, as were publications in languages other than English. Two other relevant articles were found, one directly from bibliographic searching, and a second was sourced following a recommendation from an expert in the field. Figure 2 shows the search process, presented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 33

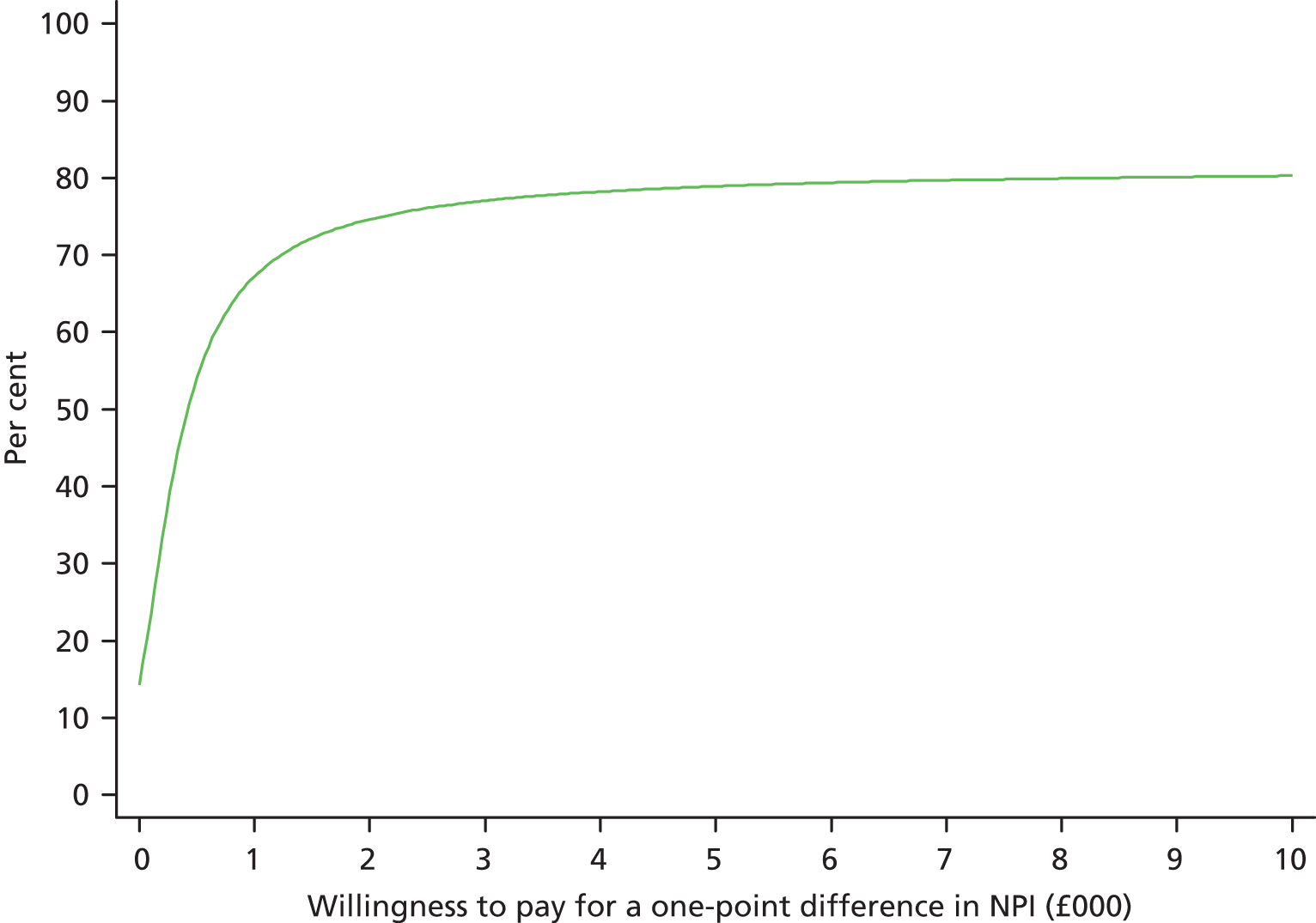

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart for EVIDEM-ED: Review 2, Changing Service Provision and General Practice.

After applying these criteria, 162 articles remained, but 70 of these were not readily obtainable and these were also excluded for pragmatic reasons; 77 of the remaining 92 papers were excluded after analysis because they were clinical reviews, guidelines, studies of barriers or studies without interventions that were designed to change practice. References in the 92 papers were reviewed to identify other intervention studies.

Data were extracted from each study report to allow comparison of interventions and to assess the quality of study designs. The characteristics chosen for comparison (including location and type of study, size, recruitment process, methodology, outcome measures, results and conclusions) and a detailed description of each intervention can be found in the published review. 32 Randomised trials were assessed for quality using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale. 34 The PEDro scale was chosen because its assessment of blinding is very relevant to empirical studies in dementia. In quality-rating scales that consider double-blinding as the central methodological issue, studies would lose points for failing to be blinded. The PEDro rating scale divides blinding into participants, therapists and assessors, recognising that although not all of the components of trials can be blinded, it is preferable that some groups are blinded rather than none at all. 35

Results

Fifteen studies were identified of which one used qualitative methods only and three were unpublished. Of the 11 studies29–31 included in the review, 10 were RCTs (see Appendix 1). Six21–24,27,30 reported educational interventions and five25,26,28,29,31 trialled service redesigns, either by changing the service pathway or by introducing case management. Educationally, only facilitated sessions and decision-support software improved GPs’ diagnosis of dementia, as did trials of service pathway modification. Some of the case management trials showed improved stakeholder satisfaction, decreased symptoms, and care that was more concordant with clinical guidelines.

Conclusion

The quality of the studies varied considerably. Education interventions are effective when learners are able to set their own educational agenda. Although modifying the service pathway and using case management can assist in several aspects of dementia care, these would require the provision of extra resources, and their value is yet to be tested in different health systems.

Aims and objectives of the EVIDEM-ED study

Using the insights from the two reviews, we designed an educational intervention for general practice, combining timely diagnosis and psychosocial support around the period of diagnosis in concordance with management guidelines. 36

The objectives of the EVIDEM-ED project were to:

-

develop an educational intervention suitable for the workplace use that has the potential to change management practice in dementia care among GPs and practice nurses

-

include shared care guidelines for medication use by patients with dementia, as part of management in general practice

-

develop and test electronic resources that promote the above objectives.

Developing the educational intervention

The theoretical basis of the intervention is described in full elsewhere. 16 In summary, the educational intervention was constructed using the following principles:

-

Diagnosis in primary care depends upon pattern recognition and the use of ‘illness scripts’ (more or less complex representations of diseases) in non-linear pathways to find the most probable explanations for presenting symptoms.

-

The first stage of diagnosing is not testing, but starting to suspect the possibility that a dementia syndrome may be emerging (the trigger phase). The doctor needs an index of suspicion to construct a diagnosis, which is often ‘triggered’ by a symptom within the patient’s story.

-

A specific problem with dementia is that all involved – patients, families and GPs – are reluctant to diagnose dementia, a serious and largely unmodifiable disease, which carries a huge burden of stigma.

-

The diagnostic task is complex, therefore, because the accumulating cognitive impairments are occurring within complex personalities, themselves embedded in social relationships.

-

Any educational intervention needs to be flexible enough to correct context-specific deficits. In other words, there is no ‘cook book’ or ‘one size fits all’ grand intervention that will alter clinical behaviour in primary care.

A workplace approach

In primary care settings, the most effective educational methods hinge on adult learning approaches – problem-solving, small group work, solution focus, ‘academic detailing’ (on site rather than off site) – that permit flexibility in learning and allow adaptation of guidelines to local circumstances.

A co-design approach to the production of an Educational Needs Assessment (ENA) tool was adopted in order to gain the insights and experiences of a range of practitioners. 37 This involved an expert group of designers and an expert panel of ‘critical friends’ working in an iterative technology development process38 to develop a prototype ENA tool for dementia diagnosis and management. The prototype was refined and subsequently ‘field tested’ with volunteer practices. A full description of this process can be found elsewhere. 39

The expert group

The multidisciplinary expert group was made up of three GPs, an old age psychiatrist, a carer and a psychologist, and was attended by three members of the research team. Members of the expert group were chosen on the basis of their expertise or experience in dementia care, or in professional education, or both. The aim of the expert group was to decide which skills and attributes were essential for a primary care team to possess in order to deliver effective care for patients with dementia.

The expert group was given three objectives: to (1) design a care pathway that would assist practitioners in earlier diagnosis and enhance subsequent clinical management (the care pathway); (2) identify the attributes a practice would need to implement the care pathway (the task matrix); and (3) use the task matrix to derive a set of questions that would identify the practice’s learning needs (the ENA).

The expert group was also asked to frame its work in terms of adult learning approaches, in other words, that learning would be problem-solving, case based and usable by practitioners at different points on the spectrum from novice to expert. 40,41

A modified nominal group technique was used with the expert group to develop the prototype ENA tool. Nominal groups are potentially powerful learning and development tools. 42 They have a particularly useful role in analysing health-care problems43 and can help bridge the gap between researchers and practitioners. 44

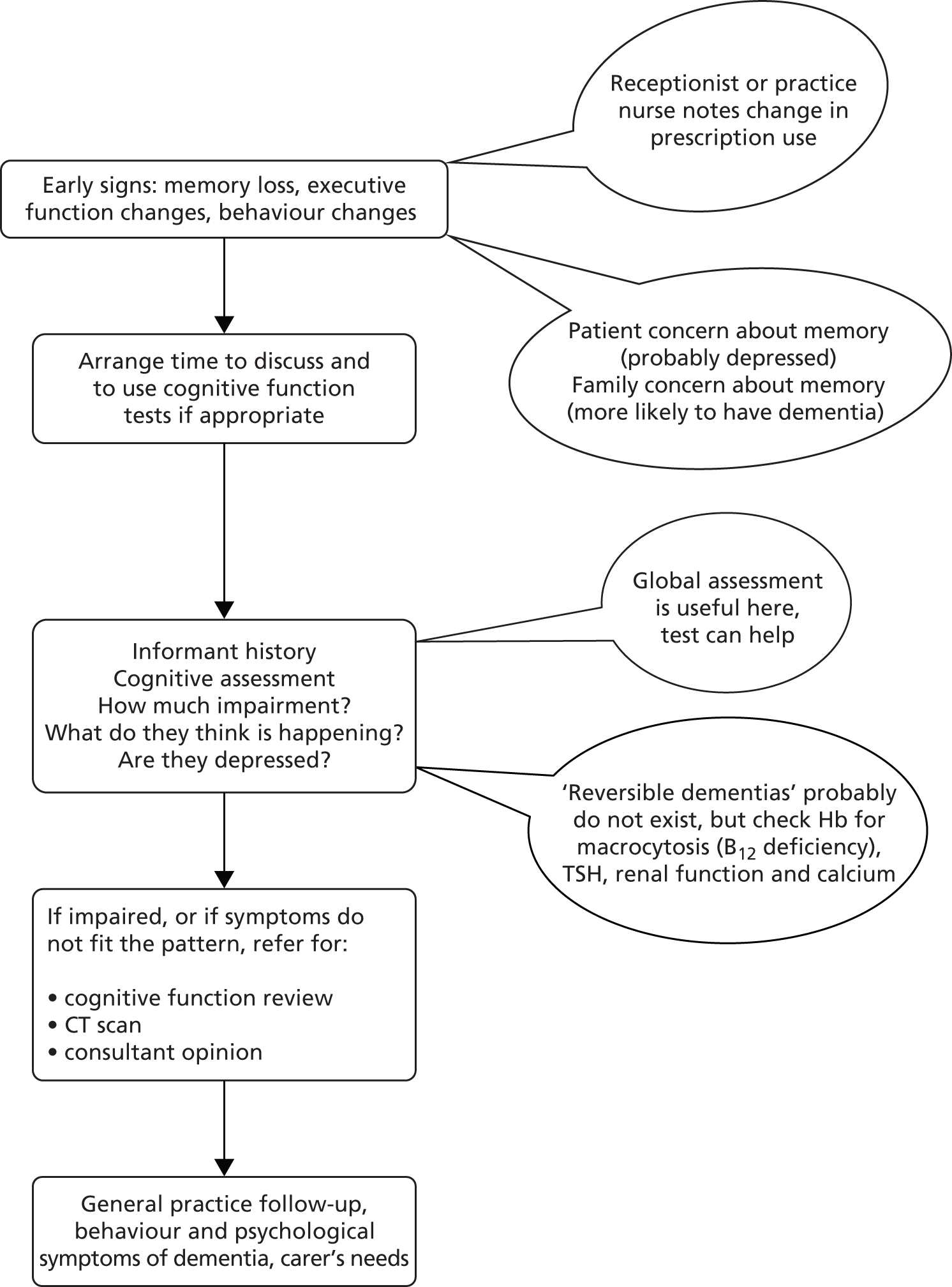

The expert group met initially to decide what the elements of a training programme designed to change practice in dementia should be. This meant identifying what tasks were needed to be performed in order to identify patients with dementia, and to care for them appropriately in the primary care setting. The expert group designed a flow chart and identified elements of the diagnostic process outlining the pathway that a clinician might follow once they suspect that a patient has dementia (see Appendix 3, Figure 29). In addition, the elements of a training programme for primary care teams were identified (see Appendix 4). From this, the expert group developed questions that would identify the practice’s strengths and weaknesses in the care of people with dementia.

This cyclical process of adapting and refining ideas took place over one calendar year, and necessitated four meetings of the expert group. The prototype ENA was sent to the expert panel after the fourth meeting of the expert group.

The expert panel

The expert panel comprised a group of external, independent people who had registered their interest in the EVIDEM project by subscribing to a mailing list on the website. The expert panel had 13 members (one of whom dropped out in the course of the development process), with a mix of carers, patients, and professionals, including two GPs, a social worker, a practice nurse and an Admiral Nurse (a community nurse specialising in support of people with dementia and carers). Seven panel members were carers of people with dementia.

Expert panel members were blinded to each other as well as to the expert group members. They received and sent comments on all the documents by e-mail or post. The purpose of the panel was to review the proposals made by the expert group to ensure that no themes were omitted and to decide how comprehensive, valid and feasible the ENA was as a tool. They were also charged with assessing if the development of the prototype concurred with known factors favouring the adoption of an innovation, using literature that had been circulated to them in advance. When this had been completed the expert panel returned their comments and suggestions to the expert group for review.

Field-testing the Educational Needs Assessment tool

After incorporation of the feedback from the expert panel, a prototype version of the needs assessment tool suitable for field testing was prepared. This is shown in Table 1.

| Question | What the answers tell us | What we do |

|---|---|---|

| 1. How would you rate your current care for people with dementia and their carers (using a simple scale of good enough/satisfactory/needs substantial improvement)? | Answers will indicate whether focused educational input is needed or broader input (this is a very subjective assessment – the practice may be better or worse than it thinks) | Gives the research team some sense of scale of need and time commitment, and may permit preliminary selection of learning materials and resources |

| 2. What grounds or criteria is your rating based on? | Identifies more clearly the areas of strength and weakness, from practice perspective. e.g. Is the major problem with diagnosis, or disclosure of the diagnosis, or judging impairment, or knowing what the appropriate responses and resources are? | Sense of priorities for learning will begin to emerge here |

| 3. Does the number of people in your practice diagnosed with dementia correlate with the local prevalence figures? | Reflects (1) local demography and (2) under-recognition | GPs tend to overestimate prevalence and likely future workload, so some reframing possible (we need epidemiological data) |

| 4. How do you arrive at your decision for diagnosis of dementia? | Tells us about the diagnostic procedure followed in the practice. It will also inform us on who makes the diagnosis | Helps identify roles within the practice team. Skill mix and experiences within the group can then be shared between colleagues with the opportunity for peer-to-peer learning |

| 5. How many older people with suspected dementia did you refer last year? | Reveals the practice culture (transfer of responsibility to specialist services vs. GP care) | We will know if we need to increase their capacity to provide GP care or simply reinforce existing good practice |

| 6. After diagnosis, what follow-up do you provide to people with dementia and their carers? | Opens up discussion about (1) systematisation of care within the practice and (2) resources available to the practice | (1) Case management methods (2) Local (and national) directory of resources |

| 7. Are you using a shared care protocol for cholinesterase inhibitors? If ‘yes’ then (1) who was involved in producing the protocol, and (2) who is involved in its implementation (e.g. hospital consultants, community psychiatric nurses, Care of Older People team)? | Awareness of protocol (if it exists), and its appropriateness for general practice | Rehearse use of (GP developed) shared care protocol |

| 8. How effective do you think cholinesterase inhibitors are and how effective have you found them in your practice? | Awareness of realistic likely impact of cholinesterase inhibitors | Discussion of trial data on cholinergic drug effects |

| 9. What non-pharmacological alternatives do you have available to help your patients (and their carers)? | Will indicate extent of networking with local services and identify practice resources usable by people with dementia | Provision of information about cognitive reframing, other psychosocial support methods |

| 10. Based on your experience, what do you think are the important quality markers in caring for people with dementia? (What would you want for yourself?) | Elicits both clinical and personal experience; may provide very useful case vignettes | Fit the practice’s conception of quality markers to the NICE/SCIE guideline indicators36 |

| 11. Is there anything that you would like improve? If yes, what is it and why would you like it to change? | Prioritisation of learning needs | Highly focused educational input |

This ENA template was then field tested in volunteer general practices. The practices were based in north west and north east London, and were recruited directly by the EVIDEM programme as part of a RCT of an educational intervention. Practices were informed about the process and asked to choose either field-test status or RCT participation. The first five respondents wanting to join the field test were enrolled.

To carry out an ENA, two members of the research team held a group meeting at each practice. A team member experienced in group-based learning in general practice (the expert tutor), facilitated discussion of the needs assessment tool. The other acted as a participant observer, ensuring that all questions were asked and clarifying points where necessary, as well as taking notes about the assessment process. The practices were asked to invite whichever members of staff they thought should participate, including attached staff from community services. The times of meetings were left to the practice to choose. The research project paid for lunch when lunchtime meetings were preferred.

An educational prescription was agreed at the end of each needs assessment process, and up to three follow-up visits were arranged to work through the themes identified for the educational prescription. The educational prescriptions were used to collect and collate learning materials for each practice, and the subsequent workshops were also used to revisit and revise the questions in the ENA. The research team assembled material in written and electronic form for each of the items on the educational prescription workshops led by the expert tutor who had facilitated the ENA process, again with a participant observer from the research team.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the practices in the field test, the participation of different disciplines, the number of workshops held with each practice, and the themes identified in their ‘educational prescription’.

| Practice | List size | Non-clinical staff present? | Community staff present? | Diagnostic methods | Shared care protocol | BPSD management | Carers needs and quality markers | MCA 200517 and legal issues | Complex case discussion | Improved service awareness and collaboration | Care planning | No. of workshops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Inner city, GP led | 6300 | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | 3 |

| 2. Outer city, GP led | 9100 | – | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | 2 |

| 3. Outer city, nurse led | 6000 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | 3 |

| 4. Outer city, GP-led training practice | 5200 | – | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | 2 |

| 5. Inner city, GP led | 10,500 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | 3 |

As a result of the field testing, the variety of learning materials used was broadened to include more reference material for use during sessions. The timing planned for topics was also amended and the expert tutors became more knowledgeable and aware of areas of need that were consistent across individuals and groups. The practices involved in the field test made it clear that they did not want decision-support software embedded in their electronic medical record systems but instead preferred simple, easily accessible guidance in an electronic format that functioned as ‘look-up’ documents.

The educational prescriptions developed through the ENA appeared acceptable and useful in volunteer practices. The time commitment (no more than 4 hours, spread out at the practice’s discretion) appeared manageable. The pilot group of practices prioritised diagnosis, assessment of carers’ needs, quality markers for dementia care in general practice, and the implications of the MCA 200517 for clinical practice. The content of the ENA seemed to be comprehensive, in that no new topics were identified by practices in the field trial. On the basis of this pilot, the ENA tool was used in the full trial.

Developing a learner’s manual

The themes identified by practitioners in the field test were researched by EVIDEM staff and a learner’s manual was constructed (available via www.EVIDEM.org.uk). This manual was designed in a modular form with Microsoft Word version 97–2004 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) documents that could be accessed during consultations if necessary. The content of the learner’s manual was developed using the expertise of all members of the EVIDEM team. The manual contains modules on the following:

-

dementia diagnosis and cognitive assessment tools

-

differential diagnosis of dementia by illness and types

-

disclosure of dementia diagnosis and cultural diversity

-

use of cholinesterase inhibitors, NICE/Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) guidelines and shared care of medication

-

management of BPSD and Department of Health (DH) guidelines for using antipsychotic drugs

-

non-pharmacological interventions for dementia

-

medication review and dementia

-

needs of people with dementia and primary care

-

case studies for management of people with dementia

-

carer needs and support in general practice

-

end-of-life care

-

holistic care in dementia – personhood approach

-

MCA, advance directives and Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA)

-

Independent Mental Capacity Advocates (IMCAs) and Court of Protection

-

financial and legal guidance: where to go for help

-

dementia and driving.

Implementing the EVIDEM-ED trial

Trial design

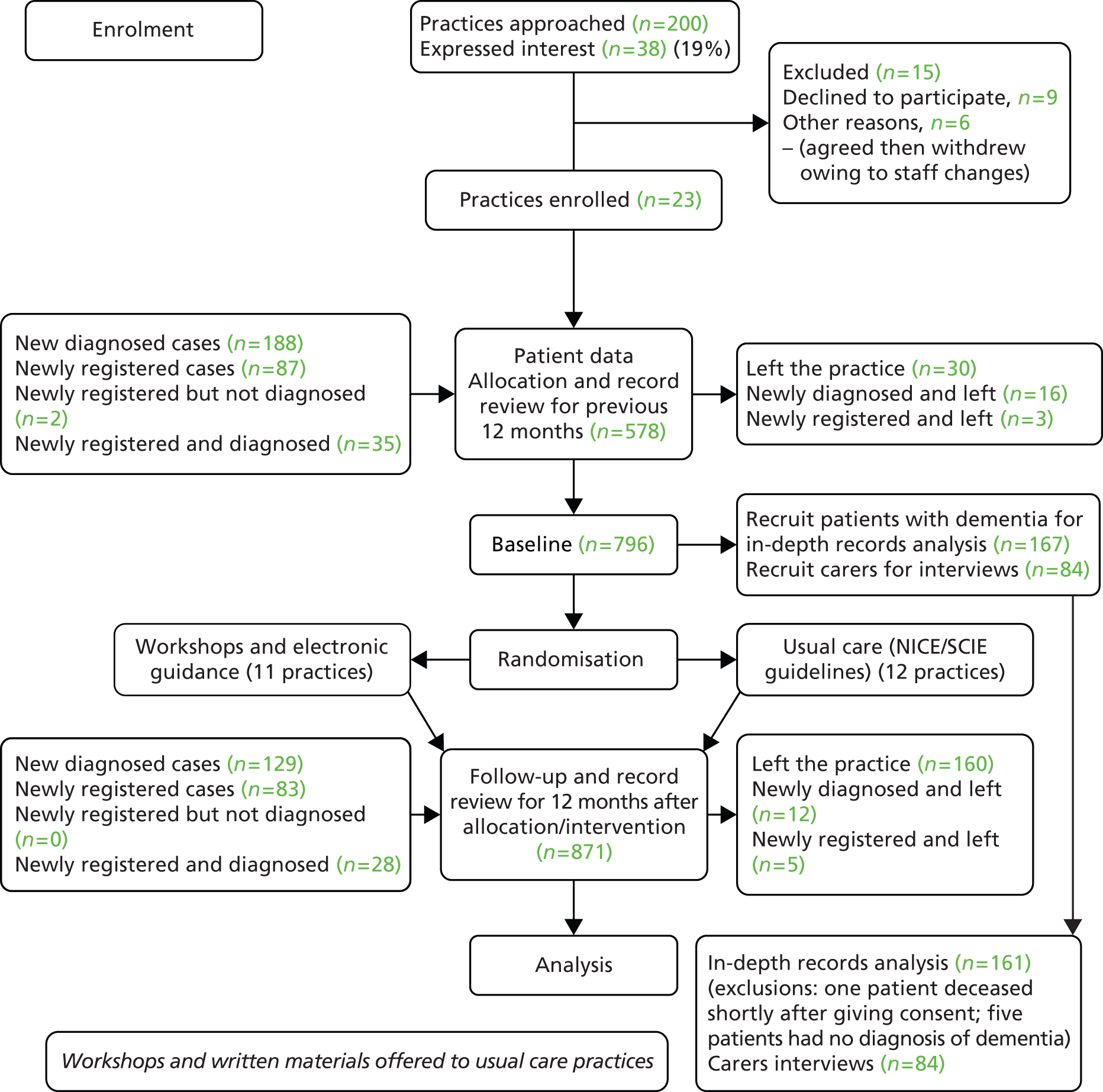

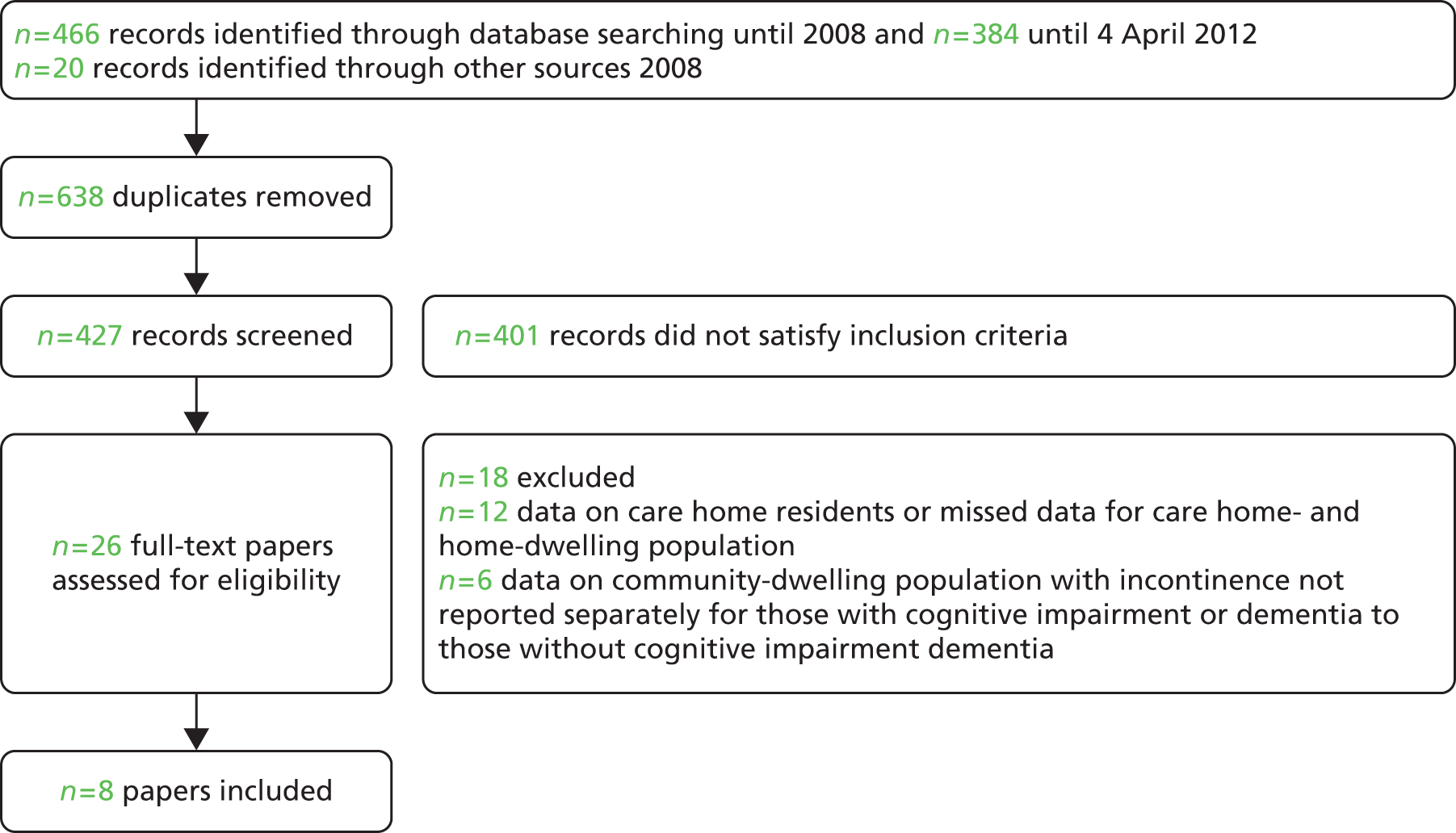

The effectiveness of an educational intervention combining practice-based workshops and computer-based support was tested in a pragmatic, unblinded, cluster RCT, with a pre and post design, and with two arms: usual care compared with educational intervention [see CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram in Figure 3]. The researchers were aware of group allocation but carers and people with dementia were not informed. A full description of the trial design – including management structure, participant involvement and patient and public involvement (PPI) – is available in the published protocol. 45

FIGURE 3.

EVIDEM-ED: CONSORT flow diagram.

Standard significance tests assume that random sampling has taken place, and that the behaviour or knowledge of any one individual is not affected by others in the sample. However, this study, like many in the health service field, is based on clusters of individuals who may influence each other – in this case colleagues in a practice who share information or similar views, or patients who receive similar treatment. 46 This ‘clustering effect’ can mean that false conclusions are drawn about relationships in the data. This effect was controlled for by using cluster membership (i.e. respondents in each practice).

Study setting

The study took place within primary care practices in the geographical area covered by the North Thames (NT) Dementias and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Network (DeNDRoN) – Metropolitan North London, Essex, Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire. Approval for the trial was received from Southampton & South West Hampshire Research Ethics Committee (REC) (A): reference 09/H0502/77.

The educational intervention

The educational intervention consisted of practice-based workshops with a tailored curriculum designed by a multidisciplinary expert group and supplemented by electronic resources. The educational interventions reflected different approaches to adult learning, namely workshops directly relevant to clinical practice, allowing learning to occur through peer reflection about real cases, and electronic resource materials suitable for ‘real-time’ use in consultations.

Recruitment

Primary care practices

Interested general practices in the North Thames DeNDRoN were identified in collaboration with the local Primary Care Research Networks (PCRNs): the Primary Care Research Network-Greater London (PCRN-GL) and the Primary Care Research Network-East of England (PCRN-EoE). Practices were contacted by the trial research team, by letter and awareness raising through general practice educational meetings, and regular newsletters.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for practices in this study were (1) routine data collection from clinical encounters on electronic medical records and (2) team commitment to participate in educational workshops held in the practice. (All staff working in the practice were eligible to participate in the study.)

Exclusion criteria

Practices that did not routinely capture clinical data in electronic records were excluded.

Patients with dementia and their carers

An in-depth study of medical care for patients with dementia was carried out in a subset of the practice populations. Patients identified by the practice were invited by their usual GP to permit analysis of their medical records, and their carers (where known) were invited to participate in face-to-face interviews, with telephone follow-up 12 months later.

Inclusion criteria

Being on the QOF register with a Read Code for dementia of any type documented in their medical records, with no lower age limit.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were (1) participants who were unable to speak English, for whom there was no available interpreter; (2) either the patient or carer was involved in concurrent research; (3) the key clinical professional working with the patient felt that an approach to the person with dementia or their carer would be inappropriate or may increase distress; and (4) any other important reason that the lead clinical professional might have about why the person with dementia or their carer should not be contacted.

Every effort was made to include those who met the inclusion criteria and who might adequately understand verbal explanations or written information given in English.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcome, measured in the audit sample

We derived our primary outcome measure and the effect size from discussions with practitioners in the feasibility phase of the trial. The consensus was that the clinical tasks involved in providing good-quality care required at least two encounters per year, and that the educational intervention would promote this effectively in the majority of those in the intervention arm. Our hypothesis was, therefore, that the proportion of patients receiving two dementia-specific management reviews per year would increase between the intervention and control groups of patients by 50%, that is, 20% (usual care) compared with 70% (intervention), after the introduction of the educational intervention. Data relating to dementia-specific patient reviews and consultations relevant to dementia management were extracted from the practice records, first by electronic searches and then by hand-searching by research clinicians. Read-Coded dementia reviews were counted for each patient with dementia in the 12 months prior to intervention/randomisation and the 12 months following intervention/randomisation. Using the same time periods, all face-to-face consultations in which any aspect of dementia was documented as Read Code or free text were counted as ‘opportunistic reviews’, regardless of the problem triggering the consultation.

Sample size

Based on the study having 90% power to detect as significant, using a 5% two-tailed significance level, a 50% difference in the proportion of individuals with two or more dementia-related GP visits (usual care 20% vs. intervention 70%), the required sample size, based on individual randomisation, would be 23 per group – a total of 46 individuals. However, owing to the use of cluster randomisation, the total required sample size needed to be inflated in order to take account of this clustering. The number of patients recruited per practice was also inflated in order to maintain the sample sizes in the presence of attrition. 47,48 With 20 practices (10 per arm), the power to detect the differences postulated would be maintained if the intraclass correlation coefficient were of the order ≤ 0.37. Thus the effective sample size with 10 patients per cluster and 20 practices needed to be 200. If the expected attrition rate as 1/3 (33.3%) then 15 patients would need to be recruited per practice in order to maintain the sample size of 10 per practice.

Secondary outcomes, measured in the subset of patients with dementia who permitted review of their medical records

Concordance with guidelines

Documented concordance with the best practice recommendations from the intervention were assessed by the researchers examining the medical records of the subset of patients who had agreed to participate in the in-depth study. A medical records data extraction pro forma based on the intervention and best practice guidelines was developed (see Appendix 7).

Medical records at each practice were reviewed and analysed by independent clinical researchers, and diagnostic and management actions were coded using the pro forma, noting whether or not the action was taken in primary care.

Concordance with guidelines for diagnosis was operationalised by first identifying the index consultation. This was taken as the first consultation, communication or other entry in the patient record which indicated that dementia was being considered as a possible diagnosis – that is, by the use of the Read Code and/or the recording of symptoms of dementia. Examples of symptoms included were short-term memory loss, confusion, wandering, personality change and depression. The content of all consultations in the 6 months prior to the index consultation were reviewed. A count of specific actions recorded as part of the index consultation and/or in the period leading to formal diagnosis was then made. The actions were informed by the NICE/SCIE dementia guidelines36 and agreed by the Project Management Group (see Appendix 2) as reflecting the working definition of good practice in the diagnosis of dementia. They were as follows:

Diagnosis in primary care

-

Request for blood tests.

-

Cognitive testing completed.

-

Informant history taken.

-

Referral to consultant, nursing or secondary care.

-

Depression and/or psychosis considered.

-

Carer concerns recorded.

-

Behavioural and psychological symptoms related to dementia recorded (apart from depression, elsewhere classified).

Information was given by the practice to either the carer or patient or both, on:

-

signs and symptoms

-

course and prognosis

-

treatments

-

local care and support services

-

support groups

-

sources of financial and legal advice and advocacy

-

medicolegal issues

-

local information sources, including libraries and voluntary organisations.

The following actions were coded at time of index or up to formal diagnosis:

-

anti-dementia medication prescribed

-

medication review undertaken

-

computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan requested.

Management in primary care

-

Had antipsychotic medication been prescribed?

-

Evidence of:

-

consent and capacity; evidence that the provisions of the MCA 2005 have been followed and evidence of recall, reasoning, decision-making, and, if relevant, agreement from next of kin, carers or other consultees?

-

care plan

-

BPSD addressed and managed

-

advance statements

-

living will (advance decision to refuse treatment)

-

LPA

-

preferred priorities

-

direct payments/personal budgets, functional abilities, activities of daily living (ADL) or the use of global assessments

-

discussion about carers’ needs.

-

Information was given by the practice to either the carer or patient or both, on:

-

local care and support services

-

sources of financial and legal advice and advocacy

-

medicolegal issues.

No attempt was made to measure the number of times a particular action – for example, record of contact with carers – was recorded, but only whether or not such contact was recorded in the pre-intervention and/or post-intervention periods by a member of the practice.

Measurement of unmet needs in patients and carers

Unmet needs were captured using a structured interview schedule with carers, developed by the research team in a previous trial. 21

Consent

People with dementia were identified by practice managers and their lead clinician checked whether or not they fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Before seeking consent from patients to participate in the study, practitioners were asked for their opinion about the capacity of the person with dementia to give informed consent to taking part in the study, using the MCA 200517 as the framework for their judgement.

For patients judged as having decision-making capacity, the following information was posted to the person with dementia: (1) a covering letter explaining the involvement of the practice and signed by the lead clinician; (2) a participant information sheet; and (3) a response letter and prepaid envelope to be returned to the research team. A researcher arranged to see those patients with dementia and their carers who expressed an interest in participating in the study. This encounter took place at the preference of the carer, at the patient’s home, in the GP practice or at the research team’s offices at the Royal Free Hospital. Its purpose was to seek consent from the carer and consent/assent from the person with dementia, where possible, for their participation in the study and for allowing access to patient records.

For those judged by the lead clinician to lack capacity to give informed consent, a consultee (as defined in the MCA 200517) was identified and consulted about possible involvement of the person with dementia in the trial. The relevant clinician wrote to the consultee, providing full information about the trial.

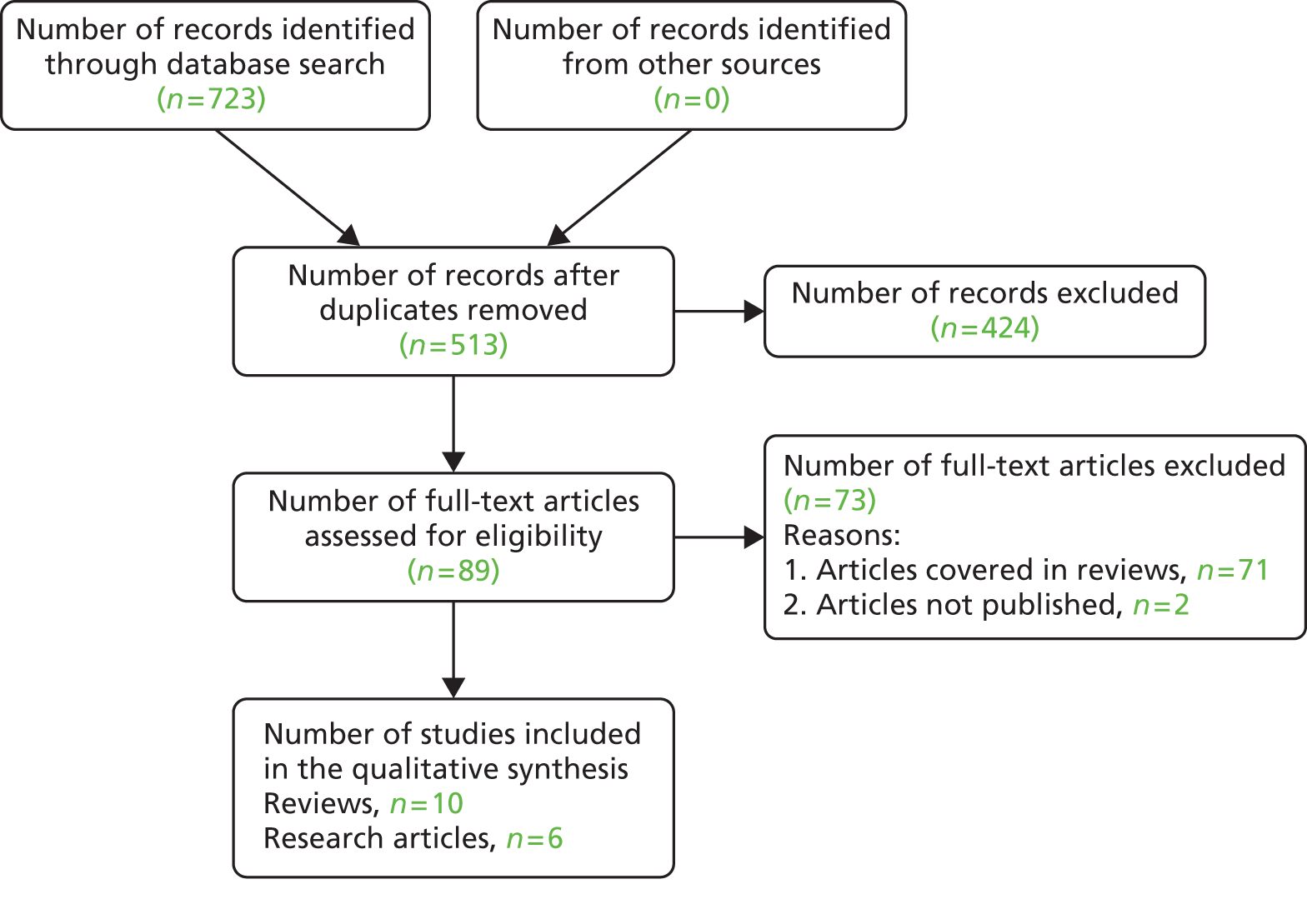

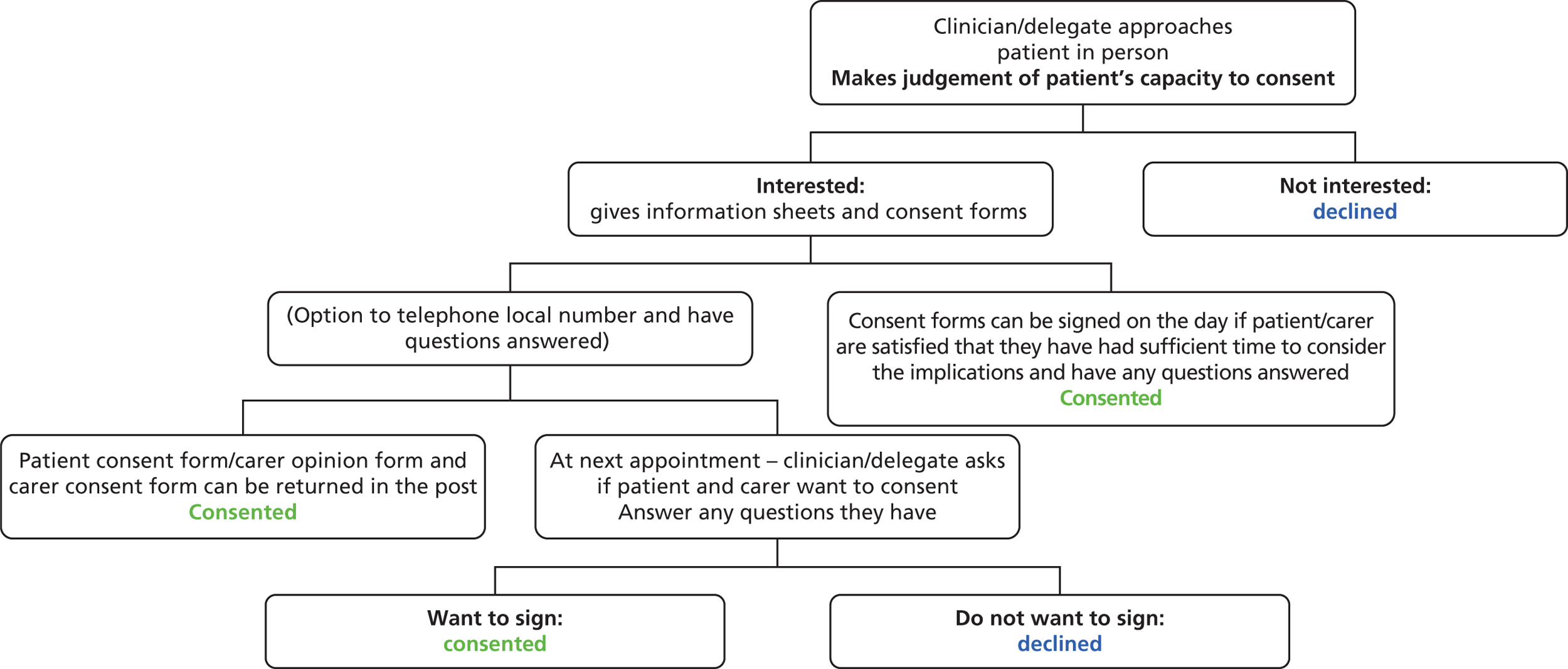

Figure 4 shows the process of identifying participants and how they were approached, recruited and consented/consulted about EVIDEM-ED.

FIGURE 4.

Flow chart of how participants were identified, approached, recruited and consented/consulted about EVIDEM-ED (2009–10).

Randomisation and masking

Participating practices were randomised to intervention or usual care arms by an independent researcher using a computer randomisation programme. 49 Independent clinicians undertaking record reviews could have deduced the allocation of the practices and could have become unblinded.

The process for obtaining participant informed consent was in accordance with the REC guidance, the MCA 200517 and good clinical practice (GCP).

With the informed consent of the person with dementia or following discussion with their consultee, members of the research team examined medical records in the GP surgery, using the pro forma to guide data extraction. No personalised information was recorded or retained by the researcher, and each case was allocated a unique study number for the purposes of recording data. All other information was stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act (1998). 50

Statistical analyses

Primary outcome: number of reviews

Multilevel logistic regression modelling was used to compare the proportion of patients who had two or more reviews during the 12 months post intervention/randomisation (post period) between the usual care and intervention arms. Two-level random-effects models were fitted in order to take account of the cluster randomisation. The models adjusted for the proportion of patients within each practice with two or more reviews during the 12 months pre intervention/randomisation (pre period). Separate analyses of the dementia related reviews, opportunistic reviews and the total reviews were undertaken.

As sensitivity analyses, the above were repeated only for those patients with information available for the full 12-month pre and post periods.

Diagnoses

Multilevel Poisson regression modelling was used to compare the diagnoses rates, in those aged ≥ 65 years, between the intervention and usual care arms in the post period. The number of newly diagnosed patients was used as the outcome with the practice list size of those aged ≥ 65 years used as the exposure. Two-level random-effects models were fitted in order to take account of the cluster randomisation. The number of diagnoses during the pre period was adjusted for in the model.

Multilevel logistic regression modelling was undertaken to compare concordance with management guidelines in the post period between the intervention and usual care arms using two-level random-effects models. Models were adjusted for the concordance levels in the pre period.

Findings

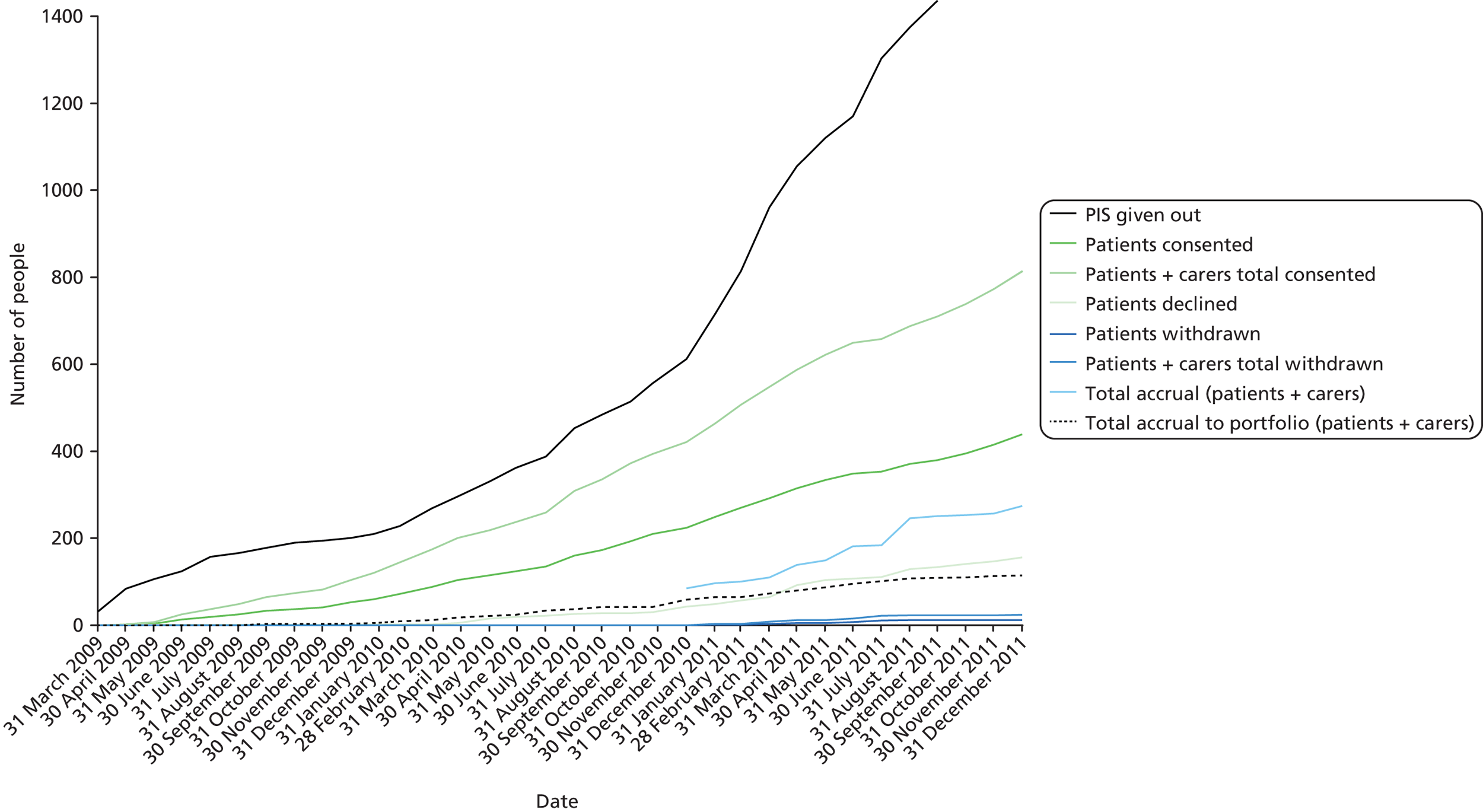

Of 200 practices we approached, 23 agreed to participate and provided the required level of access and data. The practices came from 12 different primary care organisations in urban, semirural and rural areas. Practice enrolment was from 2008 to 2010. Practices received a mean of three workshops, including the needs assessment workshop at the beginning of the trial (range 2–4). These were staggered across the practices and took place from 2009 to 2011.

Practice information

Eleven practices were randomised to the intervention arm and 12 to the usual care arm. The number of patients with dementia per practice ranged from 5 to 123 in the intervention arm and from 6 to 108 in the usual care arm. The characteristics of the practices by arm of study are shown in Table 3. There was a slightly higher mean list size, a slightly higher mean deprivation score, and a slightly higher mean number of GPs in the intervention practices.

| Variable | Summary measure | Usual care practices (n = 12) | Intervention practices (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of GPs | Mean (SD) | 4.6 (2.7) | 5.1 (2.1) |

| Median | 5.5 | 5 | |

| Min. | 1 | 2 | |

| Max. | 9 | 9 | |

| List size | Mean (SD) | 7892 (4684) | 8382 (4711) |

| Median | 9239 | 6849 | |

| Min. | 1133 | 2682 | |

| Max. | 14,358 | 19,323 | |

| Deprivation scorea | Mean (SD) | 19.9 (10.0) | 20.4 (7.6) |

| Median | 17.5 | 22.0 | |

| Min. | 7 | 8 | |

| Max. | 40 | 29 | |

| Care homes | No. of practices with patients residing in care homes | 9 | 9 |

| Min. per practice | 0 | 0 | |

| Max. per practice | 6 | 15 | |

| Total no. homes per group | 17 | 30 |

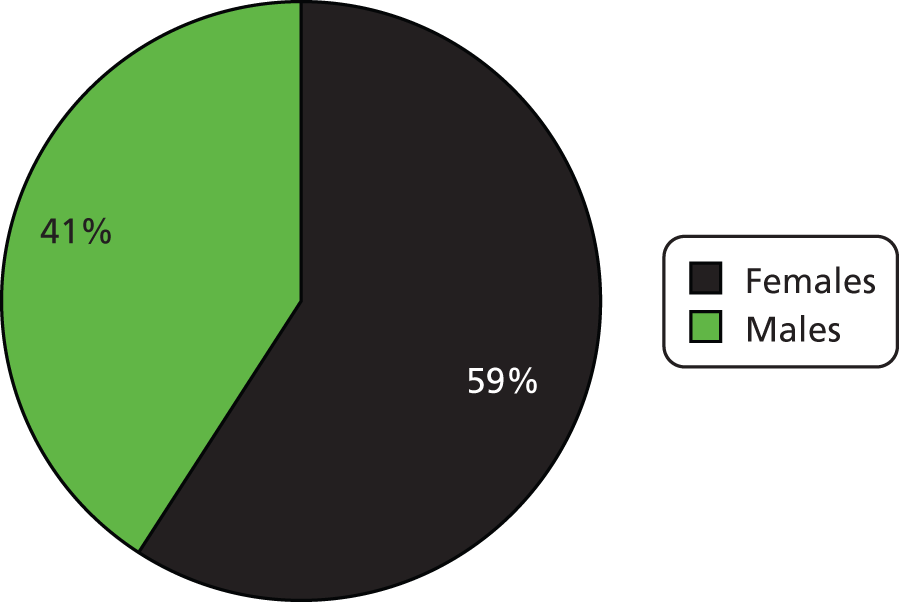

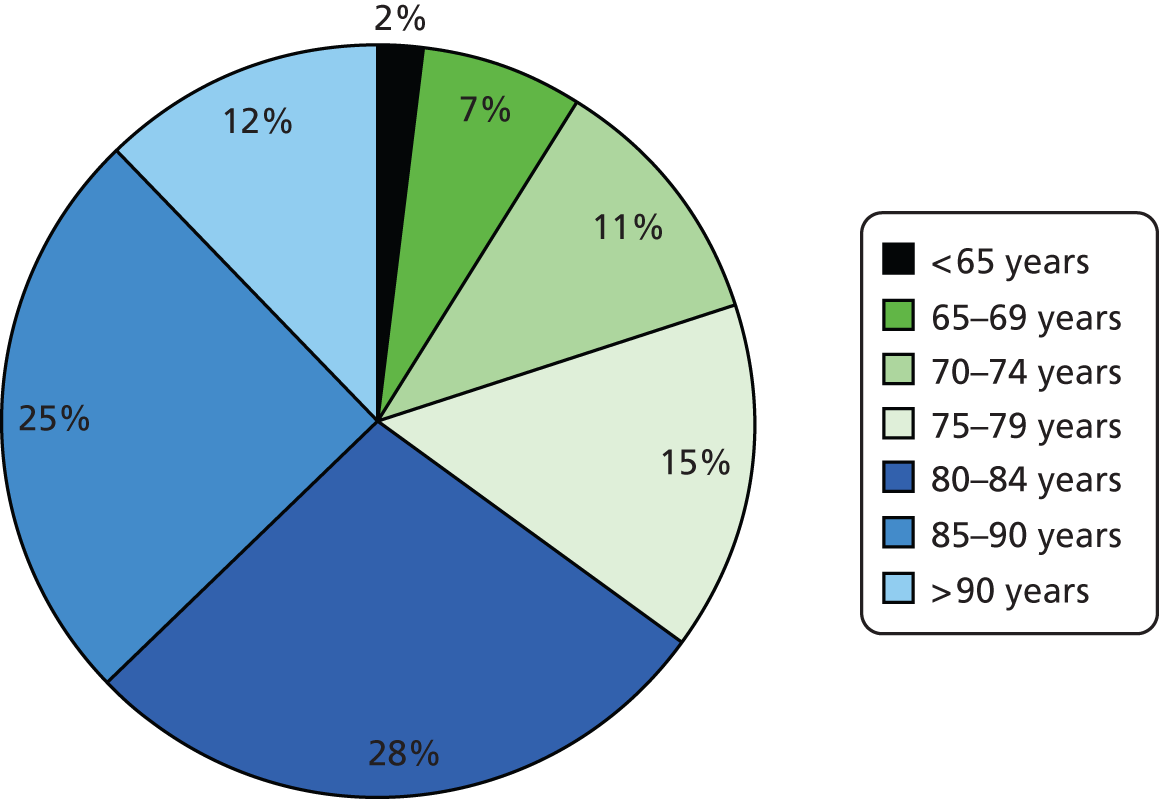

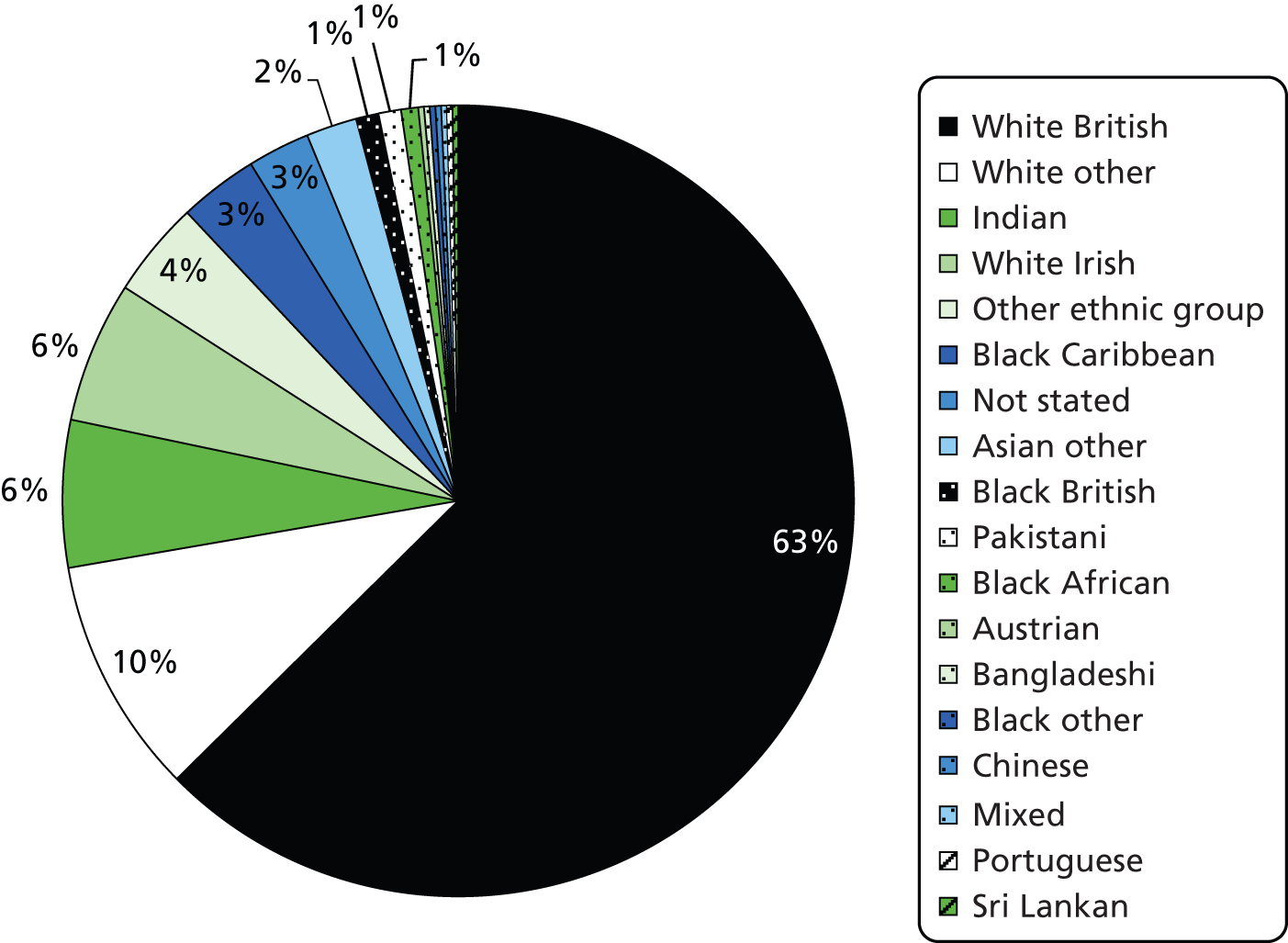

Patient information

A total of 1072 (intervention 512, usual care 560) patients had information available in their medical records at audit showing the number of reviews (dementia/opportunistic/total) in the 12 months (or a proportion of) before intervention or randomisation and/or the 12 months (or a proportion of) after. Of those, 61% (n = 313) were female in the intervention group and 70% (n = 382) were female in the usual care group. The mean age for those people with dementia in the intervention group was 83 standard deviation (SD) 8.7; minimum (min.) 33; maximum (max.) 104 years and 83 (SD 8.8; min. 55; max. 109) years for those in the usual care group.

Dementia management reviews

The mean total number of dementia management reviews (planned and opportunistic) for people with dementia in the intervention group in the period before randomisation was 0.89 (SD 0.92; min. 0; median 1; max. 4). For the period after randomisation it was 0.89 (SD 1.09; min. 0; median 1; max. 8).

For those people with dementia in the usual care group prior to the intervention, the mean total number of dementia management reviews (planned and opportunistic) was 1.66 (SD 1.87; min. 0; median 1; max. 12). For the period after intervention it was 1.56 (SD 1.79; min. 0; median 1; max. 11). This difference at baseline appears to have been due to one practice in the usual care group having medical responsibility for several care homes.

Primary outcomes

The numbers of each type of review for each patient in the pre and post periods were dichotomised for the primary analyses. These were classified according to whether the individual had < 2 or ≥ 2 dementia management reviews. A summary can be seen in Table 4.

| Variable | Usual care practice patients (%) | Intervention practice patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Dementia (pre) | 15.1 | 4.9 |

| Dementia (post) | 9.6 | 6.1 |

| Opportunistic (pre) | 21.3 | 6.6 |

| Opportunistic (post) | 21.4 | 8.3 |

| Total (pre) | 39.0 | 18.2 |

| Total (post) | 35.9 | 19.8 |

Estimated ORs (odds of having two or more reviews in the intervention group vs. the usual care group), along with the p-values and 95% CIs for those with a full and partial data period are presented in Table 5.

| Reviews (≥ 2 vs. < 2) | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| For all cases including proportion of data collection period pre and/or post | |||

| Dementia | 0.94 | 0.33 to 2.62 | 0.899 |

| Opportunistic | 0.96 | 0.53 to 1.74 | 0.890 |

| Total | 1.05 | 0.72 to 1.53 | 0.811 |

| For full pre and post data period | |||

| Dementia | 0.83 | 0.32 to 2.10 | 0.688 |

| Opportunistic | 0.62 | 0.25 to 1.56 | 0.310 |

| Total | 0.83 | 0.52 to 1.33 | 0.444 |

There were no significant differences in recording of dementia management reviews for patients diagnosed by the current practice between the usual care and intervention arms.

Case detection

In order to get a realistic estimate of case identification that was comparable with studies published elsewhere we analysed rates of diagnoses by age group.

Pre period: in the pre-intervention/randomisation 12-month period, there were 239 newly diagnosed cases of dementia. Eleven of these (4.6%) were in people aged < 65 years. Of the 228 newly diagnosed cases in those aged ≥ 65 years, 99 were in the usual care practices and 129 in the intervention practices.

Post period: in the post-intervention/randomisation 12-month period there was a total of 169 newly diagnosed cases of dementia. Six of these (3.7%) were in people aged < 65 years. Of the 163 newly diagnosed cases in those aged ≥ 65 years, 78 were in the usual care practices and 85 in the intervention practices.

The primary analysis considered diagnosis rates in those registered with the practice list and this was used as the denominator for the calculation of rates. For the usual care practices combined the total patient population was 15,699 compared with 11,541 for the intervention practices.

Table 6 shows the case detection rates in the pre-intervention/randomisation and the post-intervention/randomisation periods. These are displayed separately for the intervention practices (combined) and the usual care practices (combined). The rates by practice were also calculated and the min. and max. rates, across the practices, are also displayed in Table 6.

| Rates | Usual care practices (%) | Intervention practices (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre period | Combined | 0.63 | 1.12 |

| Min. | 0.00 | 0.17 | |

| Max. | 4.40 | 3.45 | |

| Post period | Combined | 0.50 | 0.74 |

| Min. | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Max. | 4.10 | 1.06 | |

Case detection rates were unaffected by the intervention. The estimated IRR for the intervention compared with the usual care group from the multilevel Poisson regression modelling was 1.03; the p-value was 0.927 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.86).

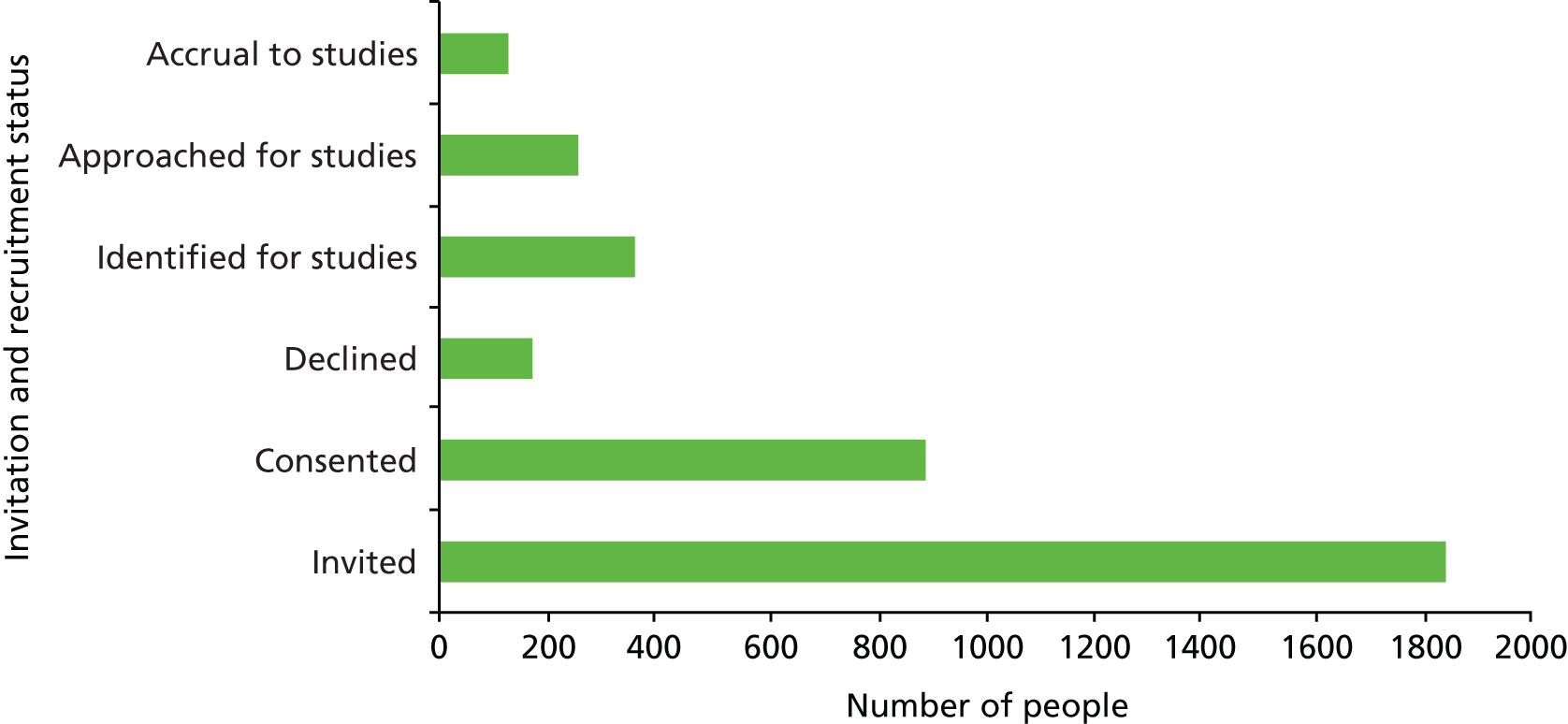

Secondary outcome analysis

An in-depth study of the medical records of 167 people with dementia was carried out to capture the detail of clinical management before and after diagnosis. Nineteen of the 23 practices in the trial invited patients with dementia and/or their carers to permit analysis of medical records; four practices were unable to send invitations at baseline, for organisational reasons. The total number of people invited was 763, of whom 190 expressed an interest (25%) and, after further discussion with researchers, 167 (22%) allowed review of medical records. The medical records of some of the 167 participants were incomplete because they had joined their practice after the index consultation, or after diagnosis, and the previous records had not reached their new practice. One hundred and sixty-one had documentary evidence of a formal diagnosis, and 136 had documentary evidence of the index consultation and a formal diagnosis. Figure 5 shows the characteristics of the secondary outcome sample.

FIGURE 5.

EVIDEM-ED: patient medical record data characteristics.

Symptoms were recorded at index consultation for 101 patients, and, of those, 39% had one or two symptoms, 45% had three or four symptoms, and 17% had five or more symptoms recorded.

Comorbidity and repeat medication use

Forty-two members of the subset (25.3%) had 0–3 comorbidities recorded, 64 (38.6%) had 4–6 comorbidities and 60 (36.1%) had 7 or more comorbidities. Data on comorbidities were missing for one member of the subset. Six members of the subset (3.6%) had no repeat medications documented in the medical record, 59 (35.5%) had 1–5 medications, 82 (49.4%) had 6–10 medications and 19 (11.4%) had more than 10 medications. Data on repeat prescription of medication were missing for one member of the subset.

Table 7 shows the characteristics of dementia type by randomisation group.

| Characteristics | Randomisation group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Intervention | ||||

| Age, years | Mean | 82 | 81 | ||

| SD | 8 | 8 | |||

| Min. | 57 | 60 | |||

| Max. | 102 | 97 | |||

| n | 97 | 64 | |||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 29 | 29.9 | 29 | 45.3 |

| Female | 68 | 70.1 | 35 | 54.7 | |

| Total | 97 | 100.0 | 64 | 100.0 | |

| Location | Community | 55 | 59.8 | 40 | 62.5 |

| Care home | 37 | 40.2 | 24 | 37.5 | |

| Total | 92 | 100.0 | 64 | 100.0 | |

| Diagnosis | Senile dementia/dementia | 28 | 28.9 | 12 | 18.8 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 41 | 42.3 | 21 | 32.8 | |

| Vascular dementia | 13 | 13.4 | 17 | 26.6 | |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4.7 | |

| Mixed dementia | 8 | 8.2 | 4 | 6.3 | |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 3 | 3.1 | 3 | 4.7 | |

| Other | 4 | 4.1 | 4 | 6.3 | |

| Total | 97 | 100.0 | 64 | 100.0 | |

Concordance with diagnostic and management guidelines

Table 8 shows the concordance of medical records with guidelines about the diagnostic process in the 136 people with dementia for whom we had an index consultation and a formal diagnosis. Table 9 shows the concordance of medical records with guidelines about management after diagnosis in the same number of cases.

| Diagnostic actions within primary care concordant with guidelines (N = 136) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Request for blood tests documented (full or partial screen according to NICE guidelines) | 76 (56) |

| Results of cognitive testing | 53 (39) |

| Informant history documented | 78 (57) |

| Referral to specialists at index consultation | 87 (64) |

| Depression or psychosis considered | 52 (38) |

| Carer concerns recorded | 74 (54) |

| BPSD considered, apart from depression | 42 (31) |

| Documentation of information given to carer or patient or both on: | |

| Signs and symptoms | 5 (4) |

| Course and prognosis | 0 (0) |

| Treatment option | 18 (13) |

| Care and support available | 20 (15) |

| Support groups available | 7 (5) |

| Financial, legal and advocacy advice | 11 (8) |

| Medicolegal matters | 12 (9) |

| Local services (e.g. libraries, voluntary organisations) | 4 (3) |

| Management actions (taken after formal diagnosis) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Anti-dementia drugs prescribed | 71 (52) |

| Medication review | 56 (41) |

| Referred for CT/MRI scan | 7 (5) |

| Prescribed antipsychotic drugs | 26 (19) |

| Consent and capacity; evidence that the provisions of the MCA have been followed and evidence of recall, reasoning, decision-making and, if relevant: | 33 (24) |

| Agreement from next of kin? | 15 (11) |

| Care plan made | 70 (52) |

| BPSD addressed and managed | 101 (74) |

| Discussion of advance statements recorded | 4 (3) |

| Discussion of living will (advance decision to refuse treatment) recorded | 1 (1) |

| Discussion of LPA recorded | 12 (9) |

| Preferred priorities for care (e.g. DNAR order) | 12 (9) |

| Discussion of direct payments/personal budgets recorded | 4 (3) |

| Functional abilities, ADL or global assessments documented | 74 (54) |

| Discussion about carers needs | 45 (33) |

| Evidence that information was given by the practice to either the carer or patient or both, on: | |

| Local care and support services | 5 (4) |

| Sources of financial and legal advice and advocacy | 6 (4) |

| Medicolegal issues | 16 (12) |

| Local information sources, including libraries and voluntary organisations | 3 (2) |

Two-thirds of patients were referred for specialist assessment at the index consultation. When referral to a specialist was documented at the index consultation, 58 (69%) were made to old age psychiatrists, 14 (17%) to memory clinics, four to neurologists (5%) and five (6%) to geriatricians. NICE guidelines for diagnostic work-up were adhered to in the majority of patients, with documentation of the blood screen, informant history and carer concerns, but not for cognitive function testing. Among those with cognitive test results documented, 30 (58%) were for the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE),52 two (4%) were for the Six Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6CIT) and 19 (37%) were for the Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS).

A locum reading the medical records of patients in the subset for the time period between index consultation and formal diagnosis would only occasionally learn what information had been given about signs and symptoms of dementia, the disease course and prognosis, the resources available locally that could provide support, and the relevant medicolegal concerns.

The number receiving cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine (Ebixa®, Lundbeck) (n = 71) was similar to the number with a formal diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or mixed dementia (n = 74). Among those receiving anti-dementia medication, 56 (82%) received donepezil (Aricept®, Eisai & Pfizer), 7 (10%) received galantamine (Reminyl®, Janssen), 2 (3%) received rivastigmine (Excelon®, Novartis) and one received memantine. These medications were offered but declined by two patients.

One in five were prescribed antipsychotic medication, of which the most commonly used was quetiapine (Seroquel®, AstraZeneca) (n = 13, 52%), followed by amisulperide (patent expired 2008, multiple manufacturers/trade names) (n = 4, 16%), haloperidol (Haldol®, Johnson & Johnson) (n = 2, 8%) and risperidone (Risperdol®, Johnson & Johnson) (n = 2, 8%); six individuals received aripipprazole (Aripiprex®, Otsuka and Bristol-Myers Squibb) or olanzapine (Zyprexa®, Eli Lilly and Company).

One in four records showed that mental capacity had been assessed. The majority of records showed evidence of care planning, assessment of, and response to, BPSD and functional assessment.

A locum encountering these patients and reading their medical records would not know whether they had considered or made any decisions about advanced statements, ‘living wills’, Power of Attorney (POA), preferred priorities of care, use of direct payments or personal budgets, sources of support and medicolegal concerns, such as driving.

Concordance with diagnostic guidelines at baseline differed between those patients from practices subsequently allocated to intervention or usual care groups, as shown in Table 10.

| Diagnostic action | Randomisation group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Intervention | |||||

| n | % | Total | n | % | Total | |

| Dementia blood screen | 47 | 81.0 | 58 | 29 | 69.0 | 42 |

| Cognitive function test | 34 | 58.6 | 58 | 17 | 39.5 | 43 |

| Informant history considered | 45 | 78.9 | 57 | 32 | 71.1 | 45 |

| Referral made | 50 | 87.7 | 57 | 37 | 84.1 | 44 |

| Depression/psychosis considered | 30 | 52.6 | 57 | 22 | 51.2 | 43 |

| Carer concerns | 47 | 81.0 | 58 | 26 | 60.5 | 43 |

| BPSD recorded | 27 | 47.4 | 57 | 15 | 34.9 | 43 |

| Signs and symptoms | 1 | 2.1 | 48 | 4 | 8.9 | 45 |

| Course and prognosis | 0 | 0.0 | 47 | 0 | 0.0 | 45 |

| Treatment | 13 | 27.7 | 47 | 5 | 11.1 | 45 |

| Care and support | 11 | 22.4 | 49 | 9 | 20.0 | 45 |

| Support groups | 3 | 6.1 | 49 | 4 | 9.1 | 44 |

| Financial, legal and advocacy | 7 | 13.7 | 51 | 4 | 8.9 | 45 |

| Medicolegal matters | 4 | 8.0 | 50 | 8 | 17.8 | 45 |

| Local services | 2 | 4.0 | 50 | 2 | 4.4 | 45 |

| Anti-dementia drugs prescribed | 40 | 66.7 | 60 | 31 | 58.5 | 53 |

| Medication review | 34 | 65.4 | 52 | 22 | 51.2 | 43 |

Concordance with management guidelines at baseline differed between those patients from practices subsequently allocated to intervention or usual care groups, as shown in Table 11. Concordance with management guidelines at follow-up is shown in Table 12.

| Management action | Randomisation group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Intervention | |||||

| n | % | Total | n | % | Total | |

| Prescribed antipsychotic drugs | 18 | 25.4 | 71 | 8 | 12.9 | 62 |

| Valid patient consent | 20 | 28.2 | 71 | 12 | 20.3 | 59 |

| Recall and reasoning | 8 | 11.6 | 69 | 6 | 10.2 | 59 |

| Care plan | 40 | 59.7 | 67 | 30 | 50.0 | 60 |

| BPSD mentioned/managed | 58 | 81.7 | 71 | 43 | 71.7 | 60 |

| Advanced statements | 2 | 2.9 | 70 | 2 | 3.3 | 60 |

| Living will | 1 | 1.4 | 69 | 0 | 0.0 | 60 |

| LPA | 10 | 14.5 | 69 | 2 | 3.3 | 60 |

| Preferred place of care | 11 | 15.7 | 70 | 1 | 1.7 | 60 |

| Direct payments | 3 | 4.3 | 70 | 1 | 1.7 | 60 |

| Functional abilities/ADL | 52 | 74.3 | 70 | 22 | 36.7 | 60 |

| Carer’s needs | 23 | 37.7 | 61 | 22 | 37.9 | 58 |

| Care and support services | 22 | 34.9 | 63 | 12 | 20.0 | 60 |

| Support groups | 0 | 0.0 | 64 | 5 | 8.3 | 60 |

| Financial and legal advocacy | 4 | 6.2 | 65 | 2 | 3.3 | 60 |

| Medicolegal issues | 10 | 15.4 | 65 | 6 | 10.0 | 60 |

| Local services | 3 | 4.8 | 63 | 0 | 0.0 | 60 |

| Management action | Randomisation group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Intervention | |||||

| n | % | Total | n | % | Total | |

| Prescribed antipsychotic drugs | 22 | 22.7 | 97 | 7 | 11.3 | 62 |

| Valid patient consent | 25 | 26.3 | 95 | 5 | 8.1 | 62 |

| Recall and reasoning | 18 | 20.0 | 90 | 3 | 4.8 | 62 |

| Care plan | 52 | 54.2 | 96 | 27 | 43.5 | 62 |

| BPSD mentioned/managed | 59 | 61.5 | 96 | 45 | 73.8 | 61 |

| Advanced statements | 5 | 5.2 | 96 | 3 | 4.8 | 62 |

| Living will | 2 | 2.1 | 95 | 2 | 3.2 | 62 |

| LPA | 8 | 8.3 | 96 | 4 | 6.6 | 61 |

| Preferred place of care | 13 | 13.5 | 96 | 5 | 8.1 | 62 |

| Direct payments | 3 | 3.2 | 94 | 2 | 4.0 | 50 |

| Functional abilities/ADL | 63 | 65.6 | 96 | 30 | 48.4 | 62 |

| Carer’s needs | 25 | 27.5 | 91 | 18 | 30.5 | 59 |

| Care and support services | 15 | 16.9 | 89 | 7 | 11.7 | 60 |

| Support groups | 0 | 0.0 | 93 | 2 | 3.3 | 60 |

| Financial and legal advocacy | 2 | 2.1 | 95 | 1 | 1.7 | 60 |

| Medicolegal issues | 11 | 11.5 | 96 | 4 | 6.7 | 60 |

| Local services | 0 | 0.0 | 93 | 0 | 0.0 | 48 |

Table 13 shows ORs (with 95% CIs, p-values and numbers included in each model) from models which take into account the practice clustering and are adjusted for baseline levels of concordance. ORs represent the odds of concordance for the intervention compared with usual care practices. There are only two statistically significant differences, both favouring the usual care group. Participants from practices in the intervention group were less likely to have details of valid patient consent, and of care plans, documented in their medical records.

| Management action | OR (95% CI); p-value (n) |

|---|---|

| Prescribed antipsychotic drugs | 0.75 (0.20 to 2.76); 0.664 (131) |

| Valid patient consent | 0.18 (0.03 to 0.94); 0.042 (127) |

| Recall and reasoning | 0.08 (0.01 to 1.24); 0.071 (121) |

| Care plan | 0.44 (0.20 to 0.98); 0.045 (125) |

| BPSD mentioned/managed | 1.65 (0.59 to 4.59); 0.339 (128) |

| Advanced statements | 0.49 (0.07 to 3.35); 0.470 (128) |

| Living will (advance decision to refuse treatment) | 0.58 (0.05 to 6.55); 0.659 (127) |

| LPA | 0.52 (0.13 to 2.14); 0.363 (126) |

| Preferred place of care | 1.17 (0.04 to 35.94); 0.926 (128) |

| Direct payments/personal budgets | 1.39 (0.18 to 10.77); 0.756 (116) |

| Functional abilities/ADL | 0.65 (0.24 to 1.79); 0.407 (128) |

| Carer’s needs | 1.10 (0.11 to 11.04); 0.938 (116) |

| Care and support services | 0.74 (0.20 to 2.72); 0.646 (118) |

| Support groups | 8857496 (0 to ∞); 0.995 (121) |

| Financial and legal advocacy | 2310740 (0 to ∞); 0.995 (123) |

| Medicolegal issues | 0.51 (0.15 to 1.81); 0.300 (123) |

| Local services | Unable to estimate as a result of all values being zero |

Professionals’ knowledge and skills analysis

Practitioners’ knowledge about dementia

Knowledge about dementia was measured by a self-completed 14-item multiple-choice quiz, for questions which were drawn from two US instruments: the University of Alabama at Birmingham Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Test53 and the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Test. 54 The questions reflected the content of the educational intervention, and covered current and future prevalence, risk factors, diagnosis (including differential diagnosis), medication and management (see Appendix 5). Where necessary, wording was adapted to reflect development in knowledge about dementia or cultural differences. A scoring system of ‘correct’ = + 1, ‘do not know’ = 0, ‘wrong’ = –1 was adopted to maximise variance and to allow investigation of the mix of the three types of answer. These scores were transformed to give a theoretical range of –100 to 10055 (see Appendix 5). The scores of GPs on knowledge skills and attitudes were compared with those obtained using the same instrument in the previous trial of educational interventions, in 2001–2.

Professional knowledge, skills and attitudes at baseline: general practitioners

Ninety-two GPs completed questionnaires at baseline, with very few missing data except for age. There were no statistically significant differences in knowledge, skills and attitudes between GPs in the two arms of the trial. Forty-six (50%) were women, and their age range was 26–65 years, mean = 37 years, median = 41 years.

Sixty-six (72%) were principals, 12 were salaried (13%), six were registrars (6.5%) and four were locums or categorised themselves as ‘other’ (8.5%). Sixty-one (66%) had worked in old age psychiatry, elderly medicine or general psychiatry.

Eleven (12%) had discussed the implications of the NDS18 in the practice, 16 (17%) had discussed the NDS in a professional development setting and seven (7.5%) had discussed it with specialist colleagues. Fifteen (7.5%) had been offered training in dementia diagnosis and/or management by local specialist services. Twenty-five (27%) had discussed the implications of the MCA 200517 with their practice, 31 (34%) had discussed it in a professional development setting, and 15 (16%) had discussed it with a specialist colleague.

Confidence in reaching a diagnosis was similar to the earlier findings, but respondents were significantly more confident about advising on management of BPSD in 2009–10 than in 2001–2, as shown by Table 14.

| Confidence in: | 2001–2 | 2009–10 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaching a diagnosis | 81 (64%) | 63 (68.5%) | n.s. |

| Advising on BPSD management | 40 (32%) | 41 (45%) | 0.03 |

At both time periods, about one in five GPs disagreed with the statement that much can be done to improve the quality of life of people with dementia or their carers. A similar proportion disagreed that families would rather be told the diagnosis as soon as possible (Table 15).

| Attitude | Agreementb | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2 | 2009–10 | ||

| Much can be done to improve the quality of life of carers of people with dementia | 105/124 (84%) | 74/92 (81%) | n.s. |

| Families would rather be told about their relative’s dementia as soon as possible | 99/120 (83%) | 76/92 (83%) | n.s. |

| Much can be done to improve the quality of life of people with dementia | 98/124 (77%) | 77/91 (84%) | n.s. |

| Providing diagnosis is usually more helpful than harmful | 79/122 (65%) | 66/92 (72%) | n.s. |

| Managing dementia is more often frustrating than rewarding | 46/124 (38%) | 31/92 (34%) | n.s. |

| Dementia is best diagnosed by specialist services | 41/125 (33%) | 41/91 (44%) | 0.03 |

| Patients with dementia can be a drain on resources with little positive outcome | 17/118 (14%) | 11/92 (12%) | n.s. |

| It is better to talk to the patient in euphemistic terms | 11/117 (9%) | 15/92 (16%) | n.s. |

| There is little point in referring families to services as they do not want to use them | 4/121 (3%) | 4/92 (4%) | n.s. |

| The primary care team has a very limited role to play in the care of people with dementia | 6/125 (5%) | 9/92 (10%) | n.s. |

Respondents were significantly more likely to agree that dementia is best diagnosed by specialist services in 2009–10 than in 2001–2, although at both time periods only a minority agreed with this proposition.

The 2009–10 respondents were significantly less familiar with management of dementia-related symptoms, availability of services or how to access them, than respondents in 2001–2 (Table 16).

| Perceived barrier | 2001–2 | 2009–10 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too busy/not enough time during surgery visits | 98/118 (83%) | 69/92 (75%) | n.s. |

| Lack of social service support available to practice | 69/118 (58%) | 54/92 (59%) | n.s. |

| Lack of funding within the practice | 54/118 (46%) | 35/92 (38%) | n.s. |

| Lack of team staff in the practice | 60/118 (50%) | 40/91 (44%) | n.s. |

| Unfamiliar with advances in the management of dementia related symptoms | 53/119 (45%) | 61/92 (66%) | < 0.001 |

| Unfamiliar with available services to help keep patients at home | 49/119 (41%) | 57/92 (62%) | < 0.01 |

| Unsure how to refer patients to available services to help keep them at home | 29/119 (24%) | 33/92 (36%) | 0.04 |

Differences between the two time points in perceived difficulties in diagnosis and management of patients with dementia are shown in Table 17. Not all questions were the same at the two time points.

| Perceived difficulty | Mean score | |

|---|---|---|

| 2001–2 (scale 1–7) | 2009–10 (scale 1–6) | |

| Responding to co-existing behaviour problems | 4.6 | 3.7 |

| Discussing the probable diagnosis: | 4.5 | 3.6 |

| With the co-ordinating support services for carers and people with dementia | 4.3 | – |

| With the co-ordinating support services for people with dementia | – | 3.8 |

| With the co-ordinating support services for carers | – | 3.8 |

| Responding to the family’s concerns: | 3.9 | – |

| Getting information about support services for carers and people with dementia | 3.8 | – |

| Getting information about support services for people with dementia | – | 4.1 |

| Getting information about support services for carers | – | 4.2 |

| Responding to co-existing psychiatric problems | 3.8 | 3.9 |

| Discussing the probable diagnosis with the family | 3.5 | 3.3 |

| Reaching a probable diagnosis yourself | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Getting information about anti-dementia medication | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| Getting specialist assessment services advice by telephone | 2.8 | 3.5 |

A consistent one in five respondents in 2009–10 cannot answer the questions, suggesting that they are not engaged with patients with dementia (Table 18).

| Resource | Available and satisfactory | Available but not satisfactory | Needed, but not available | Not needed | Cannot say | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2, n = 126 | 2009–10, n = 92 | 2001–2 | 2009–10 | 2001–2 | 2009–10 | 2001–2 | 2009–10 | 2001–2 | 2009–10 | |

| Information about what old age psychiatry services offer | 67 (59%) | 33 (36%) | 34 (30%) | 31 (34%) | 10 (9%) | 15 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (11%) | 13 (14%) |

| Protocol for assessment and investigation of a patient with possible dementia | 27 (32%) | 28 (30%) | 10 (12%) | 24 (26%) | 43 (51%) | 22 (24%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 43 (34%) | 17 (18.5%) |

| Brief screening instrument for early identification | 46 (48%) | 37 (40%) | 12 (13%) | 19 (21%) | 31 (33%) | 15 (16%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 32 (25%) | 19 (21%) |

| Nurse with mental health training working in association with the practice | 37 (34%) | 2 (2%) | 8 (7%) | 4 (4%) | 54 (50%) | 64 (70%) | 7 (7%) | 4 (4%) | 19 (15%) | 18 (20%) |

| Shared care protocol for cholinesterase inhibitors | – | 10 (11%) | – | 13 (14%) | – | 37 (40%) | – | 7 (8%) | – | 25 (27%) |

| Information about benefits (attendance allowance, council tax, etc.) | 48 (46%) | 13 (14%) | 26 (25%) | 17 (18.5%) | 25 (24%) | 37 (40%) | 3 (3%) | 6 (6.5%) | 23 (18%) | 18 (20%) |

Nearly four in five GPs responding in 2009–10 thought that dementia prevalence would double by 2021, and 41% estimated the average caseload as ≥ 21. The overestimation on both questions is consistent with findings from 2001–2 (Table 19).

| Question | Correct n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2, N = 126 | 2009–10, N = 92 | ||

1. A GP with a list of 1500–2000 people can expect to have the following number of people with dementia on their list:

|

48 (38) | 32 (35) | n.s. |

2. By 2021, the prevalence of dementia in the general population in the UK is expected to:

|

14 (11) | 16 (17) | n.s. |

3. One of the risk factors for the development of Alzheimer’s disease is:

|

71 (58) | 55 (60) | n.s. |

4. All of the following are potentially treatable aetiologies of dementia except:

|

107 (86) | 71 (77) | n.s. |

5. A patient suspected of having dementia should be evaluated as soon as possible as:

|

108 (86) | 73 (79) | n.s. |

6. Which of the following procedures is required to definitely confirm that symptoms are due to dementia?

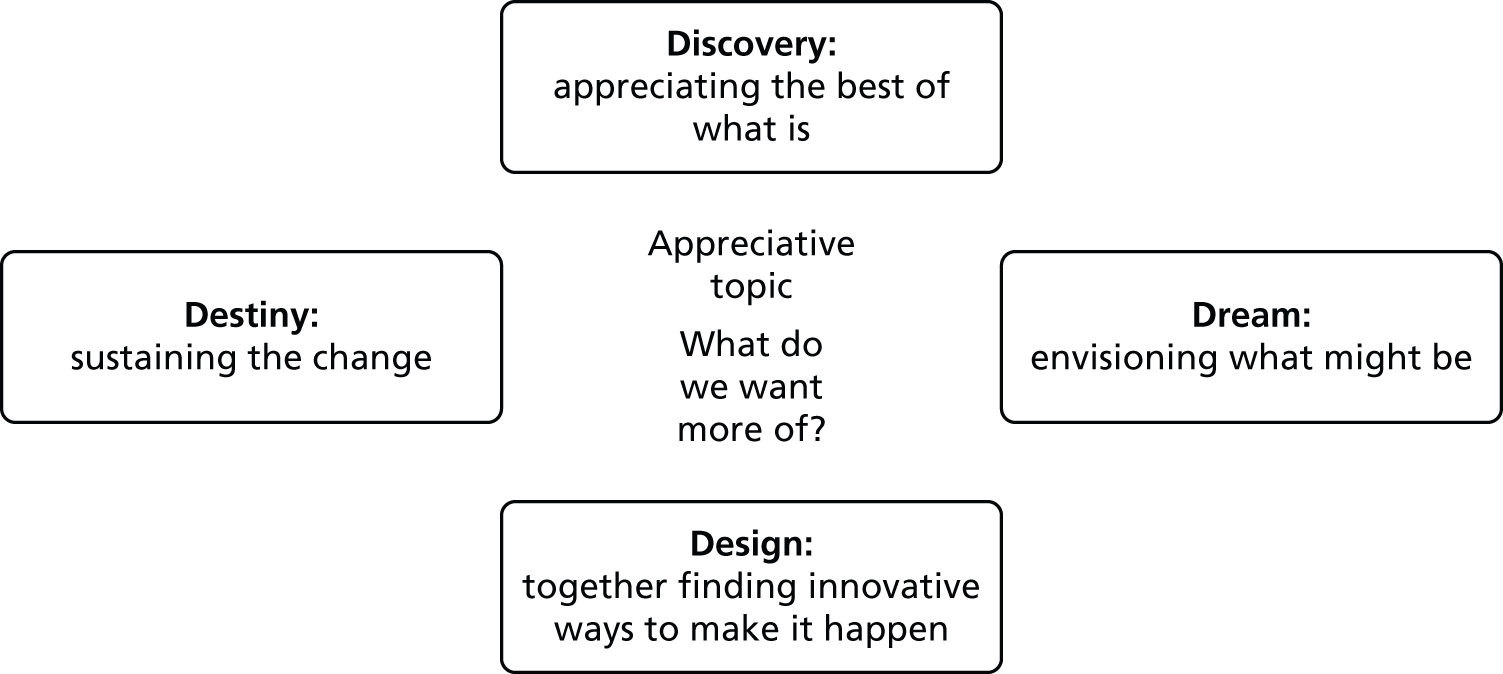

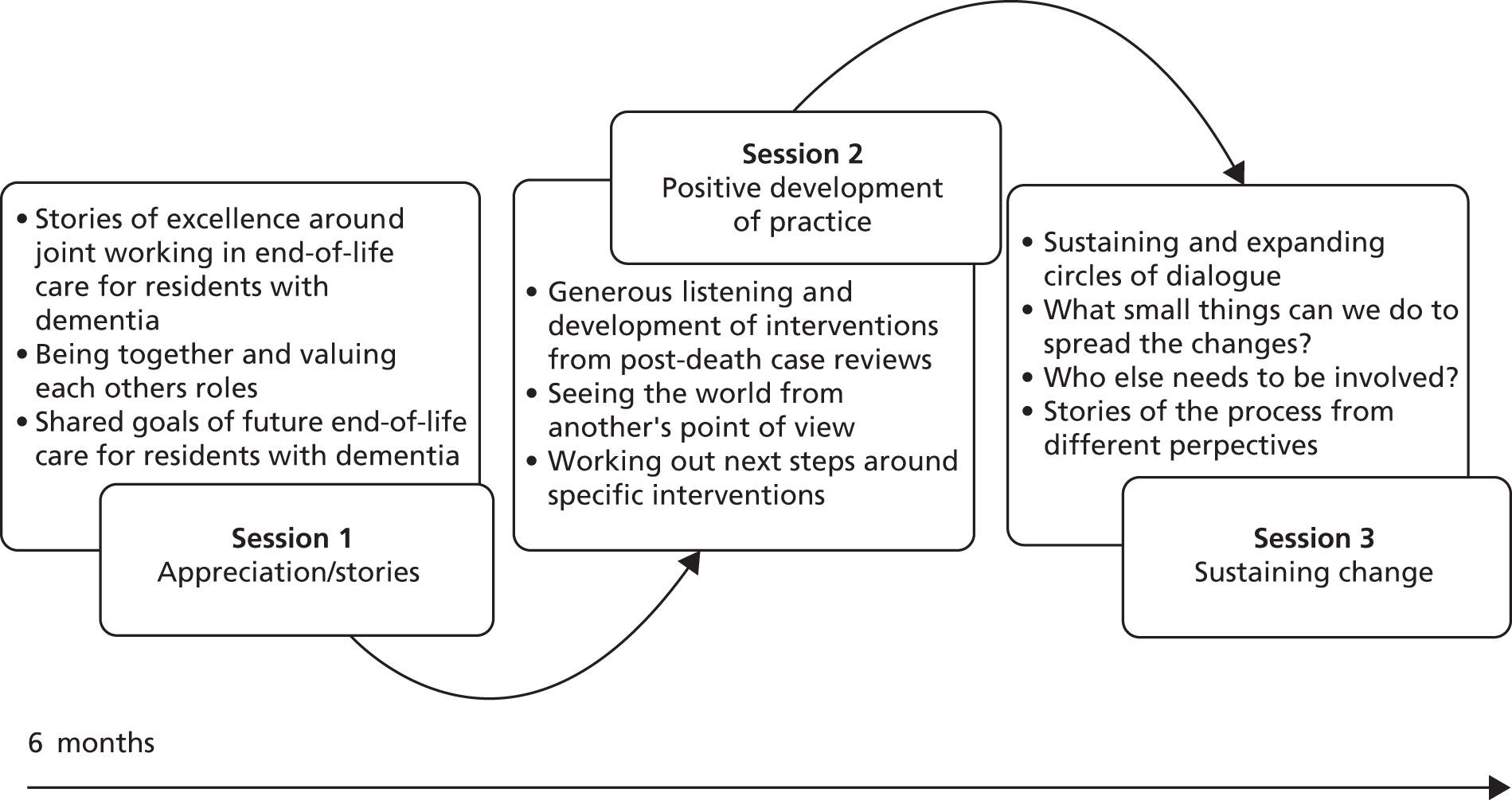

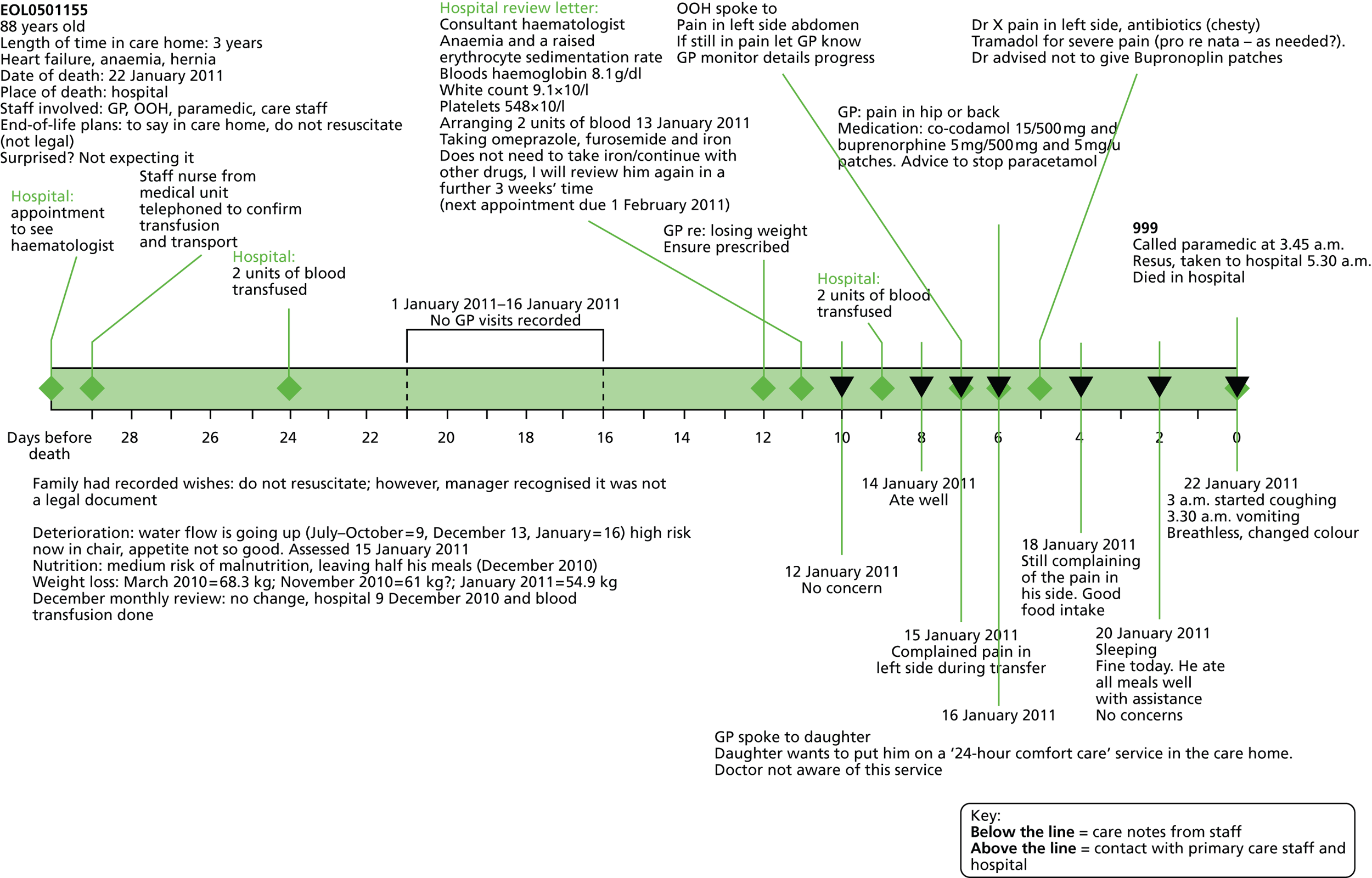

|