Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10147. The contractual start date was in August 2008. The final report began editorial review in March 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Adam Gordon declares receiving grants from the British Geriatrics Society during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Gladman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Life expectancy has risen in the developed world to the extent that most people expect not only to reach retirement age but also to live many more years in good health. But there is a downside. The very last few years of life, whether in the seventh or the tenth decade, are often spent in a vulnerable state with multiple, chronic, disabling physical and mental health conditions and age-related loss of function, as there has been little reduction in the number of years of life people can expect to live with disability. This vulnerable state, frailty, imparts an increased propensity to acute illness and consequent loss of function, which results in the medical crises that drive acute hospital admission. The numbers of frail older people admitted to hospital rises year on year, despite the development of increasingly sophisticated community health and social support services, and this rise in acute admissions causes problems with both the capacity of the system and the quality of care, safety and patient experience. This is one of the major challenges facing health and social care throughout the world, especially as demographic changes have reduced the number of people available to help and care for those who lose their independence. There is a significant cost associated with the final months of life, which appears to be independent of age. 1 This period is most predictable in people with cognitive impairment and associated progressive disability. 2

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

Mindful of these demographic realities, health services have been developed to take account of the problems faced by vulnerable older people. Instead of a health-care service designed to deal with single acute conditions by a single practitioner [such as the typical general practitioner (GP) or emergency department consultation], models of care described as comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) have been developed. These are characterised by an assessment of a range of health conditions, functions and activities and the physical and social environment, usually undertaken by a team of different health and social care professionals. Each case is carefully managed so that the team shares information and, using a care plan, provides a sufficient number of interventions to improve the patient’s overall outcome in an iterative manner over time (typically days, weeks or months). The value of such an approach, in principle, has long been firmly established; Stuck et al. ’s3 meta-analysis of 28 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving > 10,000 patients, published in 1993, was the first of many reviews that have demonstrated the benefits of CGA over routine care with respect to mortality, institutionalisation, readmission and mental well-being. The most up-to-date review, from Ellis et al. ,4 included 22 RCTs involving 10,315 participants in acute hospital settings and found similar findings, favouring acute units (wards) delivering CGA.

Although most UK hospitals provide geriatric medical wards that aim to deliver the benefits of CGA, it cannot be said that all vulnerable older people, whenever and wherever they face complex health problems, receive these benefits. This is partly because of the lack of models to deliver CGA in non-hospital settings and the relative lack of evidence of benefit of the few alternative models that do exist (e.g. liaison services5).

The Medical Crises in Older People research programme, funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) award, began when a small group of clinical academics in geriatric health care in Nottingham sat down and thought about the main research issues affecting their day-to-day practice and where CGA might be helpful. Three broad areas emerged: patients discharged from acute medical units (AMUs); patients with delirium and dementia in general hospitals; and health care for residents of care homes.

Frail older people discharged from acute medical units: the acute medical unit workstream

The first broad area was the care of vulnerable older people presenting to AMUs. The last few decades have witnessed a rising number of patients admitted as an emergency to hospitals and there has been a recognition that it is inefficient to admit them first and then identify their problems. Instead, acute medical assessment units have been developed through which all patients presenting as an emergency are assessed and triaged. Acute medical assessment units (also called medical admissions units) allow for immediate urgent care to be given, enable those who need admission to be correctly identified and allow those who could be managed in an ambulatory setting to be discharged. However, the number of vulnerable older people presenting in crisis to AMUs is rising and there is worrying evidence6 that those who are discharged are prone to re-present or go on to have poor outcomes. This appeared to be a setting where CGA was required but absent.

After the review of the literature, the research involved the undertaking of a cohort study of older people discharged from AMUs to identify and describe the older people coming through the units (Acute Medical Unit Outcome Study; AMOS). A key purpose of this was to test a screening tool (the Identification of Seniors at Risk or ISAR tool7) to enable a high-risk population to be identified, enabling the interventions to focus on this group and hopefully optimise cost-effectiveness. Older patients discharged from AMUs were followed up for 3 months and a range of adverse outcomes was recorded, including death, readmission and decline in physical or mental function and well-being. The health and social care costs incurred were recorded. The degree to which the ISAR tool could distinguish between those with good outcomes and those with poor outcomes and between low and high users of health and social care resources was calculated.

The next stage was the development of an intervention in which geriatricians assessed high-risk patients on the AMU and then case managed them in the community using a wide range of community services until the presenting medical crisis was resolved. The phrase ‘interface geriatrician’ was coined to refer to a geriatrician working in this way, partly in hospital and partly in the community. The justification for this development was on the basis that the absence of specific geriatric medical expertise in this setting was a missing link in the delivery of CGA for these patients. Developing the service required close links between the university research team and the health services to enable the necessary service investment to accompany the research.

The final stage was to evaluate the effect of this intervention in a RCT (Acute Medical Unit Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Intervention Study; AMIGOS), in which the clinical and economic effects of the interface geriatrician and usual care without interface geriatrician input were compared.

Frail older people with cognitive impairment in general hospitals: the medical and mental health unit workstream

The second broad area of concern was the care of confused older people in hospital with dementia, delirium or both. Psychiatrists have increasingly developed and marshalled the evidence that there is a high prevalence of mental health conditions complicating the care of older people admitted to general hospitals. 8 The care of such people is widely understood to be suboptimal and many of the accusations of poor-quality or undignified hospital care in the NHS relate to people with dementia. For some commentators it is taken for granted that hospitals are bad places for old and frail people and that the policy directive should be towards alternative forms of provision. However, hospital care is often inevitable and desirable; half of all people with hip fractures have dementia and these people need a prompt and skilled operation that cannot be carried out elsewhere. Our group was also worried that this prejudice against hospitals might become a self-fulfilling prophesy: the belief that hospitals are inevitably bad places for older people could be used as justification for not attempting to improve them, thus allowing them to become less suitable. The hospital care of older people with delirium and dementia appeared to be a context in which a particular variant of CGA was required.

An analogy was made between the care of confused older people in hospital at the start of the 21st century and that of patients with stroke some decades earlier. In the past, stroke patients were commonly found in hospital but received no specialist treatment and there was a presumption that little could be done to improve their outcomes. However, repaying investment in innovation and health services research, stroke units were developed during the second half of the 20th century and were proven to have powerful beneficial effects on the outcomes of people with stroke. This evidence has had a transformational effect on the care of people with stroke. We wondered if a specialist ward for confused older people, a medical and mental health unit (MMHU), could have a similar effect.

The first stage of this workstream required a cohort study to identify the numbers of people in hospital with cognitive impairment, their characteristics and their outcomes over the subsequent months. This would allow the needs of these patients to be known in sufficient detail to design an intervention to improve their experiences and outcomes.

The second stage was to develop a specialist MMHU, drawing on not only the cohort study but also on existing literature about practice in dementia care and on a linked observational research study undertaken by the study team about the care of older people with mental health problems in hospital (the Better Mental Health study9).

The third and final stage was to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this MMHU compared with standard hospital care in a RCT, given the acronym TEAM (Trial of an Elderly Acute care Medical and mental health unit). During the implementation of the workstream, on noting that the plans to evaluate the MMHU had omitted to compare the hospital experiences of patients, a further research grant to do this was sought (Research for Patient Benefit programme, reference number PB-PG-0110–21229 – ‘In a general hospital are older people with cognitive impairment managed better in a specialist unit?’); the results of this aspect of the research are reported as integral to the TEAM study.

Health care for residents of care homes: the care home workstream

The third area that our group identified was the health care of the residents of care homes. The 1980s and 1990s witnessed a huge expansion in the provision of care homes in the UK, from lower levels of provision than in other northern European countries. Around 3% of people aged > 65 years live in a care home in England and Wales: about 300,000 individuals in the UK. 10 By international standards UK care homes are small, with around 20 residents compared with ≥ 100 residents in institutions in countries such as the Netherlands and the USA. In the UK, the National Assistance Act 194811 enabled local authorities rather than the newly formed NHS to provide residential care, with the presumption that the health-care needs of residents would be met by the NHS, just as for people living in their own homes – the primary care system led by GPs contracted to the NHS. These factors meant that UK care homes did not have resident specialist medical staff, unlike those in the Netherlands and the USA. Residents of care homes are typical examples of vulnerable older people, whose ongoing care would be expected to be best if based on the principles of CGA. However, in the UK, primary health care provided by GPs and their teams has been characterised by Black and Bowman12 in an editorial in the BMJ as ‘haphazard’ and ‘idiosyncratic’, which, if correct, would make CGA difficult to deliver. We wanted to explore whether or not the benefits of CGA could be extended to this group.

The original notion of the grant holders was that CGA could be enabled if care home staff providing day-to-day care could use their routine observations to prompt timely health care. Thus, the original plan was to survey care home residents, implement an improved monitoring framework and then evaluate the framework. In fact, it became clear during the early stages of the programme that this original notion was flawed. The provision of health care in care homes appeared more complex than had been anticipated and the barriers to delivering CGA are similarly complex. It did not seem likely that improving the recognition of ill health among care staff alone would be sufficient to mount an effective CGA response. The workstream leads decided that it was necessary to take a step back, ask what was already known and define the problems more closely, rather than assuming that these were adequately specified and hence that proposed interventions could be justified.

The workstream was, therefore, modified to include a review of the literature evaluating interventions in care homes, a cohort study of care home residents and a study to illuminate the delivery of health care in care homes using a qualitative approach. It was therefore decided that the workstream should aim to understand the issues affecting the health care of residents of care homes and would prepare for further research to develop and evaluate rational service models. This was a significant modification to the original plan. On reflection, this was a great advantage of a research programme as opposed to a project: with most forms of project funding the team would not have had the flexibility to do this.

A literature review was required because the research team realised that there was a perception that there was no evidence base for health care in care homes but that this perception probably represented ignorance of the evidence base rather than absence of an evidence base. Without an explicit evidence base, it is difficult to engage policy-makers, commissioners or practitioners and hence compete for a fair position among other health priorities. The most powerful form of evidence base for the effectiveness of interventions is a systematic review of RCT evidence. This was, therefore, what was planned.

The rationale for the cohort study was similar to that used for the other two workstreams; to understand, and hence plan to meet, the health-care needs of residents of care homes, the residents’ problems needed to be described in clinical detail and the changes in their health and the resources that they already use needed to be quantified.

The case studies of existing innovations in the health care of care home residents and the interview study of health care in care homes both aimed to understand, describe and critically appraise the provision of health care in care homes. This knowledge, alongside the measured needs of the residents, seemed essential to the rational development and evaluation of interventions. For the care home workstream, unlike the other two workstreams, there was not a sufficient understanding of health and social care processes to propose feasible and potentially effective interventions. Therefore, the experimentation that health and social care practitioners were already making was explored.

Synthesis

The workstreams had many things in common: the participants in all workstreams were older people with varying degrees of frailty; the research approach intended to use a cohort study followed by development and evaluation of interventions; and all workstreams faced issues around recruitment in the presence of cognitive impairment and around health status measurement in frail older people. We decided to attempt to bring together findings from all three workstreams in a synthesis, with the particular objective of identifying factors that were likely to bring about health-care improvement.

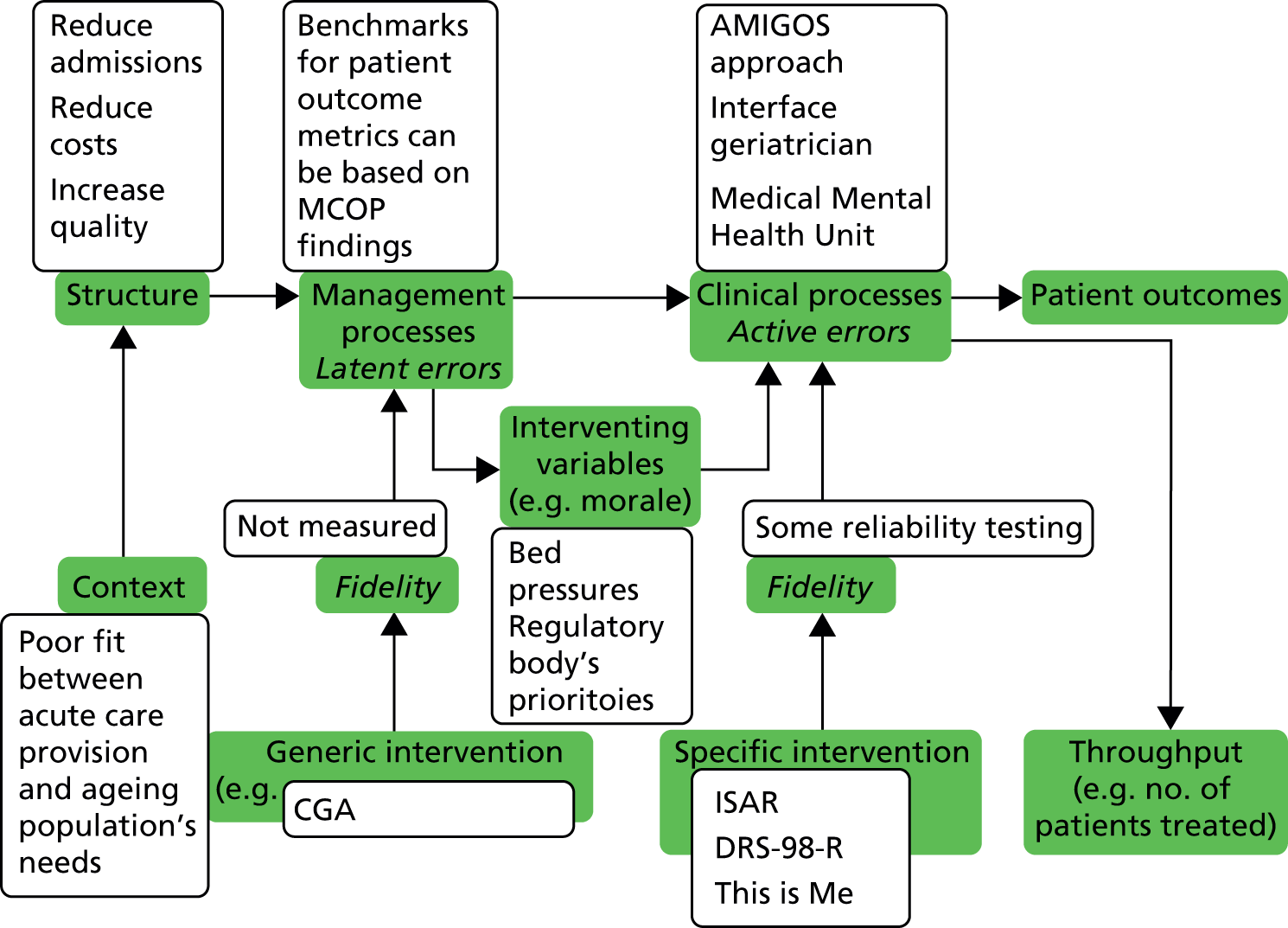

We chose to do this by describing the results of the research programme with reference to an established framework for understanding health care, adapted from Brown and Lilford,13 which applied the input–process–outcome chain (described first by Donabedian14) highlighting three essential measurement points:

-

‘proximal end points’ to describe content

-

‘at the level’ measures to assess fidelity and

-

‘distal end points’ to assess effect.

Structure of this report

The findings of the AMU, MMHU and care homes workstream studies are provided in Chapters 2–4 respectively. Because of the huge amount of work covered by this programme and to avoid duplicate publication, only summaries of the published research are provided. All publications arising from this programme are recorded on the Medical Crises in Older People Discussion Paper Series website [see www.nottingham.ac.uk/mcop/index.aspx (accessed 4 February 2015)]. The findings of the synthesis are reported in Chapter 5. In the final chapter we report briefly on general issues arising from the programme. There were considerable challenges to patient and public engagement in research involving people as vulnerable as those in this programme and over the course of the programme we learnt a lot. Similarly, the research was in many ways innovatory; after all, by studying frail older people we were focusing on those patients who are often excluded from research by virtue of their age or aspects that make them difficult to recruit, retain or measure in research studies. We present a subsection examining the impact of this work to date and discussing the optimisation of its future impact. The very final subsection draws all of the chapters and subsections together to highlight the most significant contributions that the Medical Crises in Older People programme has made to the care of frail older people and briefly outlines the most pressing research and development priorities that arise from this work.

Chapter 2 The acute medical unit workstream

Aim

The overall aim of the AMU workstream was to develop and evaluate services in which geriatricans provided specialist input to the care of frail older people presenting to an AMU but not requiring hospital admission.

Phases

In the first phase a preparatory literature review was carried out. This was followed by a descriptive phase using a cohort study (AMOS) to examine the value of a tool to risk stratify the population. The third phase was a developmental phase during which the services were developed, optimised and described. The fourth and final phase was a RCT to examine the benefits and costs of the novel service compared with those of usual practice (AMIGOS).

The interface between acute hospitals and community care for older people presenting to acute medical units: a mapping review

A preparatory stage before undertaking a systematic review is to undertake a mapping review. These are broad reviews of reviews and are helpful to establish whether or not previous systematic reviews have already been carried out, to appraise the likely extent of the literature and to help clarify the context of the systematic review. This mapping review, which has been published,15 was undertaken as a preliminary step to examine the evidence for interventions for older people at the interface between the community and acute hospital.

A wide range of searchable databases was examined for relevant systematic reviews (see Appendix 2 for the databases searched and the search strategy). Reviews were included if they addressed older people (aged 65+ years) being discharged rapidly (< 72 hours) from hospital and assessed health, function, institutionalisation or cost-related outcomes, including length of stay and readmissions.

In total, 300 individual reviews were identified, seven3,16–21 of which were relevant and of adequate quality [see Appendix 3 for the data extraction (results) table]. Three meta-analyses3,16,17 reported evidence in favour of CGA for frail older patients in acute hospital and, to a lesser extent, community settings. None of them directly assessed the interface for the group of patients discharged from AMUs. Two meta-analyses18,19 addressed alternative locations of care, including hospital-at-home schemes. Both found evidence in favour of CGA, although none was specific to the interface of interest. Two further reviews20,21 addressed the community–hospital interface, although not solely the group of patients attending AMUs. These reviews found evidence in favour of schemes working across the acute hospital–community care interface (e.g. in reducing falls, support for hospital at home and some evidence for community geriatrics). However, there was uncertainty about the role of services based in emergency care settings.

The mapping review showed that there was evidence to support the benefits of CGA in general, with strong evidence for inpatient CGA and weaker evidence for community-based CGA. No review specifically focused on patients discharged from AMUs or emergency departments, but sufficient material was identified to justify a systematic review of primary studies directly related to ‘interface geriatrics’.

A systematic review of comprehensive geriatric assessment to improve outcomes for frail older people being rapidly discharged from acute hospital

Given that the mapping review demonstrated that there was sufficient material to justify a systematic review of CGA for patients discharged rapidly from hospital, and no previous relevant review on the topic, we went on to perform a systematic review. This work has been published. 22

Standard bibliographic databases were searched for high-quality RCTs of CGA for patients discharged rapidly from hospital (see Appendix 4 for the databases searched and the search strategy). Of the 3399 full citations screened, five trials23–27 were of sufficient quality to be included [see Appendix 5 for the data extraction (results) table]. There was no clear evidence of benefit for CGA interventions in this population in terms of mortality [relative risk (RR) 0.92, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.55 to 1.52] or readmissions (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.08) or for subsequent institutionalisation, functional ability, quality of life or cognition.

This review justified the development and evaluation of our intervention.

Umbrella review of tools to assess the risk of poor outcome in older people attending acute medical units

A key step in the work of this workstream was to establish how frail or high-risk older people could be identified in emergency care settings such as AMUs. To do this an umbrella review of reviews was conducted to identify relevant systematic reviews of appropriate tools to assess the risk of functional decline in older people attending AMUs (see Appendix 6 for the databases searched and the search strategy). This work has been published. 28 Umbrella reviews are like mapping reviews in that they are reviews of reviews; however, they focus on a single question rather than also covering contextual issues.

Of the 323 citations identified in the search, four systematic reviews were included,29–32 reviewing nine different tools to assess adverse health outcomes [see Appendix 7 for the data extraction (results) table]. Three assessment tools were considered to be potentially suitable for use: the ISAR tool,7 the Hospital Admission Risk Profile33 and the Triage Risk Screening Tool,34 but only the ISAR tool had evidence to predict all aspects of adverse health outcomes, that is, death, institutionalisation, readmission, resource use and decline in physical or cognitive function.

From these reviews, the ISAR tool was found to be ‘fair’ in terms of sensitivity, specificity and area under a receiver operating characteristic curve. We concluded that the ISAR tool was the most appropriate screening tool to assess the risk of adverse health outcomes in older patients being discharged from an AMU and so it was chosen for the planned intervention and the AMIGOS trial. However, this tool needed to be validated in a UK population.

The Identification of Seniors at Risk score to predict clinical outcomes and health service costs in older people discharged from UK acute medical units: the Acute Medical Unit Outcome Study

Having identified the ISAR tool as the most promising risk assessment tool for our purpose, our next objective was to evaluate whether or not the ISAR tool predicted the clinical outcomes and health and social services costs of older people discharged from AMUs in the UK. This work has been published. 35

A cohort study was performed using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (area under the curve; AUC) to compare the baseline ISAR score with adverse clinical outcome at 90 days {where adverse outcome was any of death, institutionalisation, hospital readmission, increased dependency in activities of daily living [ADL] [decrease of ≥ 2 points on the Barthel ADL index36], reduced mental well-being [increase of ≥ 2 points on the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)37] or reduced quality of life [reduction in European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) score38]} and health and social services costs over 90 days estimated from routine electronic service records. The setting was two AMUs in the East Midlands, UK (Nottingham and Leicester). Appendix 8 shows the ISAR tool questions, Appendix 9 the baseline patient-identifiable data form, Appendix 10 the baseline patient interview form, Appendix 11 the baseline patient data collection form and Appendix 12 the follow-up patient data collection form.

In total, 667 patients aged ≥ 70 years who had been discharged from an AMU were included. Adverse outcome at 90 days was observed in 76% of participants. The ISAR tool was poor at predicting adverse outcomes (AUC 0.60, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.65) and fair at predicting health and social care costs (AUC 0.70, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.81).

We therefore confirmed that adverse outcomes were common in older people discharged from AMUs. The poor predictive ability of the ISAR tool in older people discharged from AMUs made it unsuitable as a sole tool for use in clinical decision-making, but it was sufficient to identify a higher-risk group suitable for a clinical trial.

The predictive properties of frailty-rating scales in the acute medical unit

Although we went on to use the ISAR tool to select our higher-risk group of patients, we wondered whether or not frailty-rating scales might have more predictive value. We had collected a large number of frailty-related variables as part of the AMOS study, reported in the previous section. We therefore compared the predictive properties of five frailty-rating scales using data collected for the AMOS study. This work has been published. 39

Participants were classified at baseline as frail or non-frail using the five different frailty-rating scales. 40–44 The ability of each scale to predict outcomes at 90 days (mortality, readmissions, institutionalisation, functional decline and a composite outcome comprising any of these) was assessed using the AUC.

In total, 667 participants were studied. According to all scales, frail participants were associated with a significant increased risk of mortality (RR range 1.6–3.1), readmission (RR range 1.1–1.6), functional decline (RR range 1.2–2.1) and the composite adverse outcome (RR range 1.2–1.6). However, the predictive properties of the frailty-rating scales were poor, at best, for all outcomes assessed (AUC ranging from 0.44 to 0.69).

We concluded that frailty-rating scales, like the ISAR tool, were of limited use in risk-stratifying older people being discharged from AMUs and offered no advantage over the ISAR tool in this setting.

Patient-based health and social care costs of older adults discharged from acute medical units

Introduction

The AMOS study also allowed us to produce patient-based UK NHS and social care costs for this group of older patients (aged 70+ years) who attended an AMU and were then discharged home. We estimated these costs partly to ensure that we had robust methods for our later RCT and partly because this group of patients has not previously been studied greatly yet we were aware of great interest elsewhere about the use of resources and hence service costs in this group of patients using emergency and non-elective care. This study has been published. 45

Methods

Data were collected retrospectively for 90 days from recruitment using Electronic Administration Record information extracted from various health-care services. Hospitalisation data were collected for 644 patients in Leicester and Nottingham (23/667 withdrew consent for their resource use data to be obtained). Hospital care data included inpatient stays, day cases and outpatient and critical care. Social care data were obtained for all participants. In a subset of 456 participants (in Nottingham), further approvals and access were gained to obtain data from general practices, ambulance services and intermediate and mental health care services. Resource use was combined with national unit costs46,47 to derive total patient costs. The costing perspective was NHS and local authority (social services) expenditure.

Results

Data were obtained from 48 out of 118 general practices (250/456 Nottingham participants) despite exhaustive attempts to acquire data from all practices. Thus, costs from all sectors were available for 250 participants. The mean (95% CI, median, range) total cost for this subgroup was £1926 (£1579 to £2383, £659, £0–23,612). Secondary care made up 76% of costs. Other costs were for primary care (10.9%), ambulance service use (0.7%), intermediate care (0.2%), mental health care (2.1%) and social care (10.0%). The 10% of the most costly participants accounted for 50% of the overall costs.

Discussion

Secondary care costs were the main cost driver in this patient group. Despite the expectation that this group would mainly incur ambulatory and community costs, many of these costs contributed little in this patient group. Consideration should be given to focusing primarily on secondary care costs in some research instances, such as when scoping work reveals that secondary care costs are likely to be dominant. Nevertheless, in view of the fact that we aimed to influence community care, we elected to use the same methods in our RCT and to ascertain ambulatory and community costs as well as hospital costs.

The role of the interface geriatrician across the acute medical unit–community interface

We proposed that the outcomes of frail older people discharged from AMUs might be improved by ‘interface geriatricians’, geriatricians working across the hospital–community interface. 48 In Nottingham and Leicester the community geriatricians (at the time, five in Nottingham and seven in Leicester) developed this style of working for the subsequent AMIGOS study. Community geriatricians went to the AMU to see higher-risk older patients (identified using the ISAR tool) who had been randomised to the intervention and who were to be imminently discharged. They assessed the patients and then arranged whatever further care they felt was necessary, with the expectation being that this would take place mainly in the community.

A team of interface geriatricians met regularly throughout the AMIGOS study to discuss cases as part of their clinical and professional development. The interface geriatrics style of working grew out of existing practice as the community geriatricians were already experienced in both hospital and community practice. The difference was the focus on this new group of patients who were at higher risk and who were being discharged from an AMU.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the interventions undertaken were typical of geriatric medical practice in any other setting. They comprised a comprehensive specialist geriatric medical assessment that included enquiry into mental health issues and cognition, geriatric syndromes and issues of polypharmacy, often employing the use of collateral history taking. A particular feature was that the initial assessment on the AMU was almost always followed by assessment at the patient’s home, which often revealed important diagnostic facts undetected on the AMU. These assessments led to a range of actions such as changes to medication and also communication of the geriatrician’s assessment findings to the patient and primary care staff. Although interface geriatricians often identified clear potential benefits arising from their actions, they were aware that in some cases they were unable to prevent poor outcomes, and for some patients they had little to offer.

This experience demonstrated that interface geriatrics was a feasible option and had the potential to benefit patients. However, warnings were sounded by the clinicians that the benefits of this approach might be limited, with concerns being that community services might not act on the advice given by the interface geriatricians, that the benefits might be diluted in the AMIGOS trial through the inclusion of some low-risk patients (because of the relatively poor discriminatory power of the ISAR tool) and that some of the marginal clinical benefits (such as satisfaction with having an adequate explanation of health conditions) might be difficult to detect using conventional outcome measures.

The Acute Medical Unit Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Intervention Study

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the addition of specialist geriatric medical input to frail older people attending an AMU and identified as being at high risk of readmission, functional decline or death. This study has been published. 49,50 Appendix 13 shows the patient screening data form, Appendix 14 the baseline patient-identifiable data form, Appendix 15 the patient baseline initial interview form, Appendix 16 the patient baseline initial data collection form, Appendix 17 the patient follow-up data collection form, Appendix 18 the carer baseline data collection form and Appendix 19 the carer follow-up data collection form.

Methods

A multicentre, individual-patient RCT comparing the intervention with usual care was undertaken. The intervention was interface geriatrics,48 as described in the previous section. Patients aged ≥ 70 years discharged from two UK AMUs (Nottingham and Leicester) and scoring ≥ 2 on the ISAR risk screening tool were recruited prior to discharge and randomised to receive the intervention or usual care. Carers of participants were also recruited. Follow-up was by postal questionnaire 90 days after randomisation. The primary outcome was the number of days spent at home (for those admitted from home) or the number of days spent in the same care home (if admitted from a care home). Secondary outcomes included mortality, institutionalisation, hospital resource use and scaled outcome measures (including quality of life, disability and mental well-being).

A postal questionnaire was sent at 90 days to carers or family members for whom there was baseline information. Baseline and follow-up carer measures were:

-

carer strain: Caregiver Strain Index51

-

carer-specific quality of life52

-

generic quality of life: EQ-5D. 38

In view of the small numbers, carer outcomes were not compared between groups.

A purposive sample of patient participants and carer participants was selected to have a semistructured qualitative interview at home 30 days after discharge. Analysis was performed in parallel with recruitment and interview and so the content of the interviews developed as data emerged. The emerging findings were not shared with the community geriatricians during the trial. Selection was determined by the researcher on the basis of emerging themes and recruitment continued until data saturation. The interviews covered the problems that led to admission, what participants perceived happened in hospital, what they wanted and expected, what helped and what did not help, discharge arrangements, resettlement at home, impact on everyday activities, transfer of care to community services and ongoing problems.

In the economic study, 417 participants (205 allocated to the intervention arm) were analysed at 90 days’ follow-up. Data were collected retrospectively for 180 days from recruitment using Electronic Administration Record information extracted from various health-care services, as for the AMOS trial, but in addition the cost of the interface geriatricians was also included. Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), based on EQ-5D valuations at baseline and follow-up, were obtained for 254 (60.9%) participants (127 per arm). Multiple imputation by chained equations was applied to deal with missing QALY values. Costs and QALYs were adjusted by baseline characteristics using regression methods. The difference in mean total costs and QALYs between arms and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were estimated, handling uncertainty by non-parametric bootstrapping.

Results

Of 1001 eligible patients, 433 were recruited: 217 in the control group and 216 in the intervention group. The two groups were well matched for baseline characteristics, and withdrawal rates were similar in both groups (5%).

In total, 201 (98%) received the intervention as intended with 133 (66%) having a response beyond the initial assessment; 122 of these were seen at home. The range of actions taken by the geriatricians was largely as intended and as might be delivered in routine practice, most commonly liaison with other practitioners, medication changes, giving health advice and referral for rehabilitation, further diagnostic tests and additional medical follow-up.

The mean number of days spent at home over 90 days’ follow-up was 80.2 in the control group and 79.7 in the intervention group (95% CI for the difference in means –4.6 days to 3.6 days; p = 0.31). There were no significant differences in any of the secondary outcomes.

In total, 65 carer participants (15%) were recruited from the 433 patient participants but only 46 (11%) were true carers (the others being informants). The 46 true carers gave a median of 2 hours per day physical care and 3 hours per day of supervision. Of these, 17 (37%) carers were spouses and 26 (57%) were children, with three (7%) ‘other’ carers. The mean age of the carers was 61.5 years and 31 (67%) were female, 22 (48%) were co-resident with the patient participant and 15 (33%) were in paid employment. At baseline, carer participants had high carer strain [median Caregiver Strain Index 7, interquartile range (IQR) 3–9] and poor carer quality of life (median carer-specific quality of life 8, IQR 5–9) and the median EQ-5D score was 0.81 (IQR 0.69–0.85). There was no significant change in these variables at follow-up.

In total, 18 older patients and six of their informal carers were interviewed. The thematic analysis revealed six themes, some with subthemes:

-

Staff recognition (subtheme: dispersal of blame). The majority of the patients wished to express the positive attributes of the staff on the AMU, saying that they felt well looked after on the ward. When problems were identified the patients were keen to point out that they did not blame the staff but rather apportioned blame on external factors.

-

Incomplete satisfaction (subthemes: perceived lack of treatment, constant disturbance, waiting, poor communication, discharge uncertainty, carer frustration). Although the patients wanted to portray a positive image of the staff on the AMU, all but two spoke about areas of dissatisfaction and these were clustered around the six subthemes.

-

Stoicism (subthemes: ageing assumptions, modest expectations, minimisation of needs, passive acceptance). There was an underlying attitude of stoicism. Patients did not have high expectations around improving the state of their health in light of the ageing process. Similarly, they were tolerant and understanding of any weaknesses experienced on the AMU. The patients had low expectations of hospital care, resulting in passive acceptance of any weaknesses experienced.

-

Eager to go home. Although the patients recognised that they needed hospital-based assessment, they did not want to remain on the AMU for any longer than was absolutely necessary.

-

Nebulous grasp of the geriatrician role. The patients spoke about the geriatricians possessing a pleasant bedside manner but the majority of patients were unsure what the geriatrician had done for them.

-

Outstanding needs (subthemes: unresolved health issues, unresolved daily living needs, impact on informal carer, value of independence). Patients had both outstanding health needs and daily living needs, which were not addressed as part of their stay on the AMU. These impacted on their informal carers. Despite the help received with daily living activities a lot of the patients voiced a desire to complete these activities themselves rather than have others complete them for them.

In the complete-case economic analysis involving the subgroup of 254 patients with EQ-5D valuations at baseline and follow-up completed, the differences in mean total costs and QALYs (intervention vs. control) were +£138.9 (95% CI –£1139.8 to £1434.5) and 0.004 (95% CI –0.012 to 0.020), respectively, resulting in an ICER of £38,583 per QALY, with a 47% probability of the ICER being < £30,000 per QALY. In the adjusted cost-effectiveness analysis, the differences were +£146.4 (95% CI –£60.6 to £340.7) and 0.002 (95% CI –0.006 to 0.011), respectively, resulting in an ICER of £73,200 per QALY, with a 36% probability of the ICER being < £30,000 per QALY).

In the full-sample economic analysis (imputation of missing QALY values), the mean cost of inpatient care was lower in the intervention arm (–£211.7, 95% CI –£1097.9 to £471.6) whereas all other care costs were higher (social care +£220.1, 95% CI –£299.5 to £691.5; day cases +£155.6, 95% CI £31.1 to £280.3; outpatient care +£46.3, 95% CI –£69.5 to £166.2). The intervention cost was +£115.6 per case (95% CI £106.0 to £125.8). In an adjusted cost-effectiveness analysis, the total cost for the intervention group was higher (+£213.4, 95% CI £94.8 to £331.2) with no QALY gain (–0.001, 95% CI –0.009 to 0.007) and so the intervention was dominated by standard care (3% probability of the ICER being < £30,000 per QALY).

Discussion

This specialist geriatric medical intervention applied to a high-risk population of older people attending and being discharged from AMUs had no impact on patient-level outcomes or subsequent use of secondary care or long-term care. It was not cost-effective.

The interview findings indicated some areas in which AMUs could improve patients’ experiences. They also demonstrated that most patients had background conditions and that the trip to the AMU contributed little to their management from their perspectives and was confined simply to the assessment of an acute medical condition (which for these patients was not sufficient to warrant admission to hospital from the AMU). They illustrate that the interface geriatricians seemed to have little impact on the main issues affecting the health and well-being of these patients, which were not the medical crises that had precipitated their presentation but the underlying health conditions in which these crises arose.

Together, the findings support the deduction from the AMIGOS findings that a more integrated follow-up response after an AMU attendance is warranted, involving chronic disease management if health outcomes are to be improved and preventing hospital admission if costs are to be minimised.

Chapter 3 The medical and mental health unit workstream

Aim

The overall aim of this workstream was to develop and evaluate a specialist unit for people with mental health problems in a general hospital.

Phases

The workstream had three phases. The first was a preparatory phase to describe and understand the nature of people with mental health problems in general hospitals and their carers. This involved a scoping review of mental health problems in older people in hospital and the Better Mental Health cohort study. The second phase was to develop a MMHU. The third phase examined the benefits and costs of the novel service compared with those of usual practice (the TEAM study).

A scoping review of mental health problems in older people in hospital

This review53 helped prepare the research team both for the linked Better Mental Health study and for the preparatory work for this workstream. The review found that mental health problems were common in patients in general hospitals and were associated with worse outcomes than for patients without them. The quality of care for such people, especially those with dementia, was felt to be poor.

The dominant theory on which dementia care was based was a psychosocial one, ‘person-centred care’, based on Tom Kitwood’s concepts of personhood and avoiding ‘malignant social psychology’. 54 This model has been refined to ‘relationship-centred care’, which focuses on relationships. In contrast to person-centred care, the most commonly used theories underpinning the training of general hospital nurses tended to be task focused.

The behaviour disturbances seen in people with dementia were likely to be sensitive to the social and physical environment, offering opportunities to improve care through environmental change. The literature was found to abound with possible interventions in terms of therapies or practices, many of which could be applied to hospitals in the UK, although there was very little written about the use of person-centred care approaches applied to general hospitals.

Dementia care in general hospitals has become an important topic for the NHS in the UK, as evidenced by the National Dementia Strategy published in 2009,55 a year after our programme began. The preferred service model to help meet the needs of patients with mental health problems in hospital was to use old-age liaison psychiatry services, although it was unclear what such services should comprise, there was no firm evidence of cost-effectiveness and it was not clear how they would facilitate person-centred care. 56

Tools such as Dementia Care Mapping,57,58 which examine how care is delivered and how to improve it, were noted. NHS quality improvement tools might also be employed to improve care and there were also other approaches to improve quality of care at the organisational level, although it was not clear whether or not they increased person-centred care. Possible mechanisms to affect change might be through commissioning, legal or regulatory means.

The Better Mental Health cohort study

The purposes of this study were to establish the number of older patients with mental health problems in general hospitals and to measure their health status and outcomes in order to design the RCT of the MMHU. This information could also be of use for the development of other services for this patient group. Papers have been published from this study. 59–62 Appendix 20 shows the screening form, Appendix 21 the patient baseline data form, Appendix 22 the carer baseline form, Appendix 23 the patient outcome form and Appendix 24 the carer outcome form.

Methods

Participants were from two sites at the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, an 1800-bed teaching hospital providing sole general medical and trauma services for a population of approximately 660,000 people. Individuals aged ≥ 70 years with an unplanned admission to 1 of 12 wards (two trauma orthopaedic wards, three acute geriatric medical wards and seven general medical wards) were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to be screened, being unconscious or too ill to be interviewed up to the fifth day of admission and an inability to speak English with no available interpreter. Consecutive admissions were identified from the hospital administration computer system and patients were approached between day 2 and day 5 of admission.

A two-stage assessment procedure was used. The first stage identified people unlikely to have a mental health problem. The second stage used more detailed assessments to characterise problems. The first-stage assessment used the Abbreviated Mental Test Score,63 the four-item Geriatric Depression Score,64 the two-item Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders anxiety screen,65 the four CAGE questions for alcohol misuse (Cut down, Anger, Guilt, Eye-opener)66 and a question asking ward staff if there was any other reason to believe that a mental health diagnosis might be present. Participants screening negative for cognitive impairment (Abbreviated Mental Test Score of > 7), depression (four-item Geriatric Depression Score of < 1) and alcohol abuse (CAGE score of < 2) and negative on the mental health diagnosis question, or who scored only on the anxiety questions, were excluded from further study. Patient–carer pairs were recruited from those screening positive for cognitive impairment if a carer could be identified and was willing to participate.

Participants were followed up 180 days after recruitment. Information was collected from the participants, family members and other informal or professional carers. Information on readmissions and total number of days spent in hospital was collected from hospital administration systems. Mortality, and dates and types of care home placements (residential or nursing, permanent or respite) were ascertained from the hospital administration systems, the patients’ GPs, the carer informants or care home. Surviving participants were interviewed at home with a carer or, if this was not possible, by telephone with an informant. Participants were tested for cognitive function and carers provided information on behavioural and psychological symptoms and ADL. Economic data were collected retrospectively for 180 days from recruitment using Electronic Administration Record information, as for the AMOS study (see Chapter 2).

Patient outcomes were survival to 180 days; days spent at home, defined as 180 minus the total number of days spent in hospital, in a care home or dead for patients living in the community at admission and as 180 minus the total number of days spent in hospital, in a new care home or dead for patients living in a care home at admission;67 change in ADL, defined as an increase or decrease of ≥ 2 points on the Barthel index36 at follow-up compared with admission and before the acute illness.

Carer participants were asked at baseline and at 6 months to complete a questionnaire, with help as required, giving demographic and care-giving details. It included the Caregiver Strain Index,51 with a score of ≥ 7 indicating high strain.

Electronic administrative records were sought for 6 months post admission from health services (general practices, hospitals, ambulance transport services, intermediate and mental health-care services) and social care services. Standardised costs were applied to all resource use types.

Of 1004 patients screened, 36% had no mental health problems or had anxiety alone. Of those screening positive, 250 took part in the full study. Adjusting for the two-stage sampling design, 50% of admitted patients aged > 70 years were cognitively impaired, 27% had delirium and 8–32% were depressed. In total, 6% had hallucinations, 8% delusions, 21% apathy and 9% agitation/aggression (of at least moderate severity). Of those with mental health problems, 47% were incontinent, 49% needed help with feeding and 44% needed major help to transfer.

Of the 250 patients recruited to the study, 180 were cognitively impaired and had carers willing to take part. After 6 months, 78 patients (31%) had died and 100 carers were followed up. Carers’ own health, in terms of mobility, usual activities and anxiety, was poor in one-third of cases. At the time of admission, high carer strain was common (42% had a Caregiver Strain Index ≥ 7), particularly among co-resident carers (55%). High levels of behavioural and psychological symptoms at baseline were associated with more carer strain and distress. At follow-up, carer strain and distress had reduced only slightly, with no difference in outcomes for carers of patients who moved from the community to a care home.

The median number of days spent at home for participants was 107.5 days (IQR 0–163 days); 38 (15%) spent > 170 days at home. The mortality at 180 days was 78 (31%), 104 (42%) were readmitted and 46/192 (46%) community-dwelling patients moved to a care home. In surviving participants, half improved in ADL ability at 180 days from admission, but only 24% recovered to their pre-acute illness baseline and 36% showed further decline in function during follow-up.

Health and social care costs were derived for the 247 participants for whom resource use data were available. Primary care data were available for 122 (49%) participants because of the reluctance of some general practices to allow access to data. In this subset with full data, the mean (95% CI, median, range) total cost of care was £9842 (£8573 to £11,256, £7717, £715–48,795). Secondary care contributed > 80% of the costs, with the remaining costs incurred in social care (10.7%), primary care (6.7%) and other sectors (2.1%).

In summary, the Better Mental Health cohort study showed that a large number of older people admitted to a general hospital had mental health problems, particularly cognitive impairment, that their outcomes were poor and that their use of health and social care resources was high.

The development of the medical and mental health unit

We describe elsewhere how the MMHU was developed. 68

The process was guided by discussions held with the acute hospital trust nursing, therapy and medical management; discussions held with the local mental health trust; negotiations with the trust research and development department and the two local commissioning primary care trusts about the funding of the unit (additional funding for staff of £280,000 per year for 3.5 years was granted); and advice from two existing units and from other experts. Other sources of relevant information included the emerging findings of the Better Mental Health cohort study; a book on dementia (and delirium) co-authored by Professor Harwood;69 and a multidisciplinary development group that met monthly, with representation of senior nursing, medical and general management, mental health NHS trust management, allied health professionals and ward staff.

Initially it had been anticipated that the MMHU would care for patients with any significant mental health problem. During the early pilot period it became clear that patients with depression alone did not benefit from being cared for on the MMHU and the criterion for entry was changed to cognitively impaired older people. Most of the patients cared for on the MMHU had dementia or delirium.

The MMHU formally commenced development work on 1 February 2009 and opened for business on 1 June 2009. The ward was formerly a 28-bed acute geriatric medical ward and staff were therefore familiar with the problems of those with combined medical and mental health needs, who made up about 75% of its previous case load.

Admission criteria were kept broad (‘confused and over 65’), allowing for easy case identification and transfer from the AMU and the exercise of discretion in particular cases. Exclusion criteria included those requiring detention under the Mental Health Act 2007;70 acute intoxication and the immediate management of patients with overdose; and an over-riding clinical need for alternative ward facilities.

The predominant philosophy was that of CGA. To enhance the care of those with delirium and dementia, additional aspects beyond the provision of a typical geriatric medical ward were developed. These were enhancing the staffing level and skill mix, introducing the person-centred care approach, a programme of organised activity, improving the environment to make it more suitable for confused patients and introducing a proactive and inclusive approach to family carers.

Comparison of a specialist medical and mental health unit with standard care for older people with cognitive impairment admitted to a general hospital: a randomised controlled trial

Papers from this study, the TEAM study, have been published previously. 71–74 Appendix 25 shows the patient baseline data form, Appendix 26 the carer baseline data form, Appendix 27 the patient outcome form, Appendix 28 the carer outcome form, Appendix 29 the medical data form and Appendix 30 the methods for the analysis of the staffing interview.

Methods

Patients were recruited who had been admitted for acute medical care to the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. Suitable patients were identified on the hospital AMU and were randomly allocated between the MMHU and standard care. Randomised patients were subsequently approached for recruitment to the study. This approach was necessary so that patients could be moved from the admission unit to the wards at any time of the day or day of the week at the pace required for the efficient operation of the hospital, yet allowing sufficient time for patients to be recruited ethically. Participants were aged > 65 years and had been identified by the admissions unit physicians as being ‘confused’. A family member or carer was recruited if available and willing to act as an informant.

Potentially suitable patients were entered into a computerised screening log and, if a bed was available on the MMHU, randomised 1 : 1 between the unit and standard care in a permuted block design, stratified for previous care home residence. Readmitted patients were assigned their original allocation. Regardless of allocation, patients had access to standard medical and mental health services, rehabilitation and intermediate and social care.

Standard care wards included five acute geriatric medical wards and six general (internal) medical wards. Practice on geriatric medical wards was based on CGA and staff had general experience in the management of delirium and dementia. Mental health support was provided, on request, from visiting psychiatrists, on a consultation basis. The 28-bed MMHU was an acute geriatric medical ward with five enhanced components, as described earlier.

The primary outcome was number of days spent at home (or in the same care home) in the 90 days following randomisation. In addition, a range of health status outcomes was measured: quality of life (DEMQoL,75 EQ-5D,76 London Handicap Scale77), behavioural and psychological symptoms [Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)78], dependency in personal ADL,36 cognitive impairment [Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)79], carer strain (Carergiver Strain Index51) and carer psychological well-being (GHQ-1237). Carer satisfaction was measured on 10 dimensions of care (overall, admission, car parking, feeding, medical management, being kept informed, dignity and respect, the needs of a confused patient, discharge arrangements, timing of discharge) using Likert scales (very/mostly satisfied, mostly/very unsatisfied; items taken from Counting the Cost80).

Structured non-participant observations of the experience of care on study wards were undertaken using Dementia Care Mapping. 81 Two trained researchers observed the care of 90 randomly subsampled participants. Observations were made every 5 minutes for 6 hours per patient. Clinical staff were not aware which patients were being observed. Quantified mood and engagement scores, activity, noise and staff interactions that significantly addressed or disregarded patients’ emotional and psychological needs (‘personal enhancers’ and ‘personal detractors’) were recorded, according to strict definitions. Inter-rater reliability was assessed throughout the study and was satisfactory (Cohen’s kappa between 0.50 and 0.85).

Outcome assessments were carried out by research staff who were not involved in recruitment or baseline data collection and who were blind to allocation. Carer satisfaction with hospital care was ascertained through a telephone call 1–3 weeks after discharge. Health outcomes were ascertained during interviews with patients and carers at home 90 days (±7 days) after randomisation. Routine health service records were examined for service use, mortality and readmissions.

In total, 40 family carers were purposively recruited from participants in the RCT, 20 from each setting, and took part in face-to-face semistructured interviews. An interview schedule was constructed to ensure that critical topics were covered, such as patient admission and settling in to the ward; carer relationship with staff; the ward environment; patients’ daily routines such as sleeping, meals, hygiene and activities; privacy and dignity; care and medical treatment; and discharge planning. Participants were encouraged to discuss both what they considered worked well and what they considered worked not so well on wards relating to quality of care. Interviews were conducted in the carers’ homes and consent was obtained to audio record interviews. Participants were reassured that privacy, confidentiality and identity would be protected. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and were coded for themes, which were compared and contrasted between settings to provide a detailed understanding of participants’ experiences and if and how the intervention added to carers’ perspectives of the quality of care.

A total of 22 ward staff from the MMHU were purposively recruited to take part in face-to-face semistructured interviews. The breakdown of the staff interviewed was as follows: two deputy ward managers, six general nurses, three mental health nurses, one student nurse, two occupational therapists, three health-care assistants, two activity co-ordinators, one junior doctor, one receptionist and one cleaner. The mean age of the sample was 37 (range 20–64) years and 15 (68%) were female. Length of experience in the profession ranged from 4 months to 29 years. Interviews lasted between 30 and 90 minutes. An interview schedule was constructed to ensure that the following topics were explored: education and training, job satisfaction, care of patients with dementia, team working, communication with carers and organisational barriers to change in practice and culture.

Twenty-six patients were approached and recruited from a sample of cognitively impaired patients aged > 65 years who had been recruited to the study. A trained dementia researcher assessed whether a traditional semistructured interview was appropriate or not by using MMSE scores combined with a general assessment of patients’ current cognitive function and conversation skills. All interviews were conducted on hospital wards and most were carried out at the bedside because of patients’ levels of illness and mobility or lack of an alternative location. Participants lacking capacity or appropriate communication skills were offered an interview using a Talking Mat. This is a low-tech, alternative and augmentative communication tool that uses images to explore specific topics and provides a visual scale that enables people to express their general feelings about individual options. This tool has been successfully used to assist communication for people with cerebral palsy,82 aphasia,83 learning disability84 and Huntington’s disease. 85 Research suggests that this communication tool can be used effectively with people at all stages of dementia. 86 However, using Talking Mats as a research tool in an acute hospital setting had not been done before. We explored its use as an adjunct to the TEAM interview work.

In the economic analysis, 599 (MMHU n = 309) participants were analysed at the 90-day follow-up, at which point 139 (MMHU n = 68) had died. Health (inpatient stays, day cases, outpatient care, critical care, ambulance service use, mental health trust and primary care) and social care resource use data were collected and combined with unit costs (from the NHS and personal social services perspective, cost year 2012/13) to estimate total costs. Primary care and inpatient resource use data were obtained for 468 out of 599 (78.1%) and 595 out of 599 (99.3%) patients respectively. For the remaining services, resource use data were complete. The per-patient additional cost of the MMHU was calculated as the excess health-care costs incurred at this ward over a period of 90 days (trial follow-up) compared with usual care in a general or geriatric ward, averaged across each patient allocated to the MMHU. QALYs, based on EQ-5D valuations at baseline and follow-up, were obtained for 272 out of 599 (45.4%) patients (MMHU n = 139), including 62 (MMHU n = 30) who had died by the follow-up [assumed baseline utility (EQ-5D valuation) until date of death]. In a complete-case cost-effectiveness analysis, including 209 out of 599 (34.9%) patients with complete QALY and cost data, the differences in mean total costs and QALYs between arms and the ICERs were estimated, handling uncertainty by non-parametric bootstrapping. Costs and QALYs were adjusted by baseline characteristics using regression methods. Additionally, a cost analysis was conducted for the complete-case resource use data set [complete inpatient and primary care data, 466 out of 599 (77.8%) patients].

Results

Between July 2010 and December 2011, 310 patients were recruited from the specialist unit and 290 from standard care. The recruitment rate was slightly higher on the specialist unit (71% vs. 66% of those randomised). Those not recruited were of similar age and sex and were from a similar area of residence (postcode), but care home residents assigned to the specialist unit were more likely to be recruited than those assigned to standard care (73% vs. 56%). In total, 462 participants lacked mental capacity, 227 (73%) assigned to the specialist unit and 235 (81%) assigned to standard care.

There was no statistically significant difference in the number of days spent at home between settings [median 51 days MMHU vs. 45 days standard care; 95% CI for difference –12 days to 24 days; p = 0.3). The median index hospital stay was 11 days in both settings and the mortality rates were 22% and 25% (95% CI for difference –9% to 4%), the readmission rates were 32% and 35% (95% CI for difference –10% to 5%) and the new care home admission rates were 20% and 28% (95% CI for difference –16% to 0%) for the MMHU and standard care respectively. Participants on the MMHU spent significantly more time with positive mood or engagement (79% vs. 68%, 95% CI for difference 2% to 20%; p = 0.03) and experienced more staff interactions that addressed their emotional and psychological needs (median four vs. one per observation; p < 0.001). More family carers in the MMHU group than in the standard care group were satisfied with care (overall 91% vs. 83%, 95% CI for difference 2% to 15%) and severe dissatisfaction was reduced in the MMHU group compared with the standard care group (5% vs. 10%, 95% CI for difference –10% to 0%; p = 0.004). There were no significant differences in any of the other outcomes.

In total, 20 carers each from the MMHU and standard care groups were interviewed. In the MMHU group this included two spouses, 13 daughters, two sons, one brother and two granddaughters and in the standard care group this included six spouses, six daughters, one granddaughter, five sons, one sister and one nephew. Seven of the patients from the MMHU were male and 13 were female, with a mean age of 87 (range 83–97) years, and 11 of the patients from standard care were male and nine were female, with a mean age of 85 (range 69–95) years. The main themes identified in exploring carer satisfaction related closely to met or unmet expectations and included activities and boredom, staff knowledge, dignity and personal care, the ward environment and communication between staff and carers. Neither setting was perceived as wholly good or wholly bad; however, greater satisfaction (and less dissatisfaction) with care was experienced by carers from the MMHU group. Carers were aware of improvements relating to activities, the ward environment and staff knowledge and awareness of the appropriate management of dementia and delirium. However, in some cases communication and engagement of family carers was still perceived as insufficient.

Health professionals suggested that working on the MMHU allowed them to provide better care than they had previously done to cognitively impaired patients. The six main improvements experienced by staff were across the following themes: confidence in competence; working with mental health professionals; increased knowledge of dementia; moving towards a person-centred acute model of care; improving coping strategies; and a positive change in attitudes towards patients with cognitive impairment. Staff commented positively about the skills mix of nursing care available to patients on the MMHU, specifically the introduction of three mental health nurses. Participants highlighted that this helped increase staff confidence and morale when staff were faced with unfamiliar or perceived challenging behaviour. Staff further commented that working on a specialised unit for patients with cognitive impairment had greatly increased their knowledge and awareness of dementia and delirium. Staff generally considered that they had a good understanding of the principles of person-centred care. A few nursing staff felt that the acute hospital setting was too task focused and an inappropriate place to deliver person-centred care. The specialist MMHU was considered a busy and sometimes challenging environment for the majority of staff interviewed. However, staff described a strong ward team spirit and supportive culture, which individuals highlighted helped improve stress-related coping strategies when dealing with unfamiliar situations. Participants acknowledged that their confidence in dealing with this patient group had increased. Staff expressed that this was closely related to the different types of training that they had received (educational and practical) for patients with cognitive impairment. Having a greater understanding of both dementia and person-centred care had helped staff display a more positive attitude towards this group of patients. Themes identified by participants with regard to improving patients’ and relatives’ experiences of care were staff–carer communication; staffing levels and resources; balancing an increased risk of falls against allowing patients to walk around freely; and organisational barriers to change in practice.

The use of Talking Mats increased the total number of patients able to be interviewed from eight to 15, but a substantial minority could not be meaningfully interviewed using either method:

-

eight out of 26 (31%) were interviewed conventionally (mean MMSE 19, range 14–24)

-

seven out of 26 (27%) were interviewed using Talking Mats (mean MMSE 9, range 1–18)

-

11 out of 26 (42%) were not interviewed conventionally or using Talking Mats (mean MMSE 12, range 0–24).

All of the eight patients interviewed using traditional semistructured methods were admitted to the MMHU. Five were female and three were male. Six had a prior diagnosis of dementia and all had cognitive impairment. Five themes emerged:

-

Feelings. Most of the participants reported positive emotions such as feeling content and enjoying the ward environment, but there were also less positive feelings such as boredom and isolation.

-

Memory and confusion. Of the eight patients interviewed, four appeared to be aware that they were, or had been, confused while in hospital.

-

Activity. Patients noted a lack of activity on the ward, with many references to them sitting by their bed. Only one patient reported that this was because of ill health. Although some patients felt frustrated by this, others did not seem to mind. Of the patients who talked about the activities room on the MMHU, two noted enjoying their time there and the organised activities conducted within. However, some patients spoke of not wanting to go to the activities room or take part in activities, preferring instead to remain inactive or wait for their family to come to see them instead.

-

Communication. This included lack of communication, communication regarding health and availability of staff to talk to.

-

Staff. Feelings towards staff were almost all positive. Care and kindness shown by staff was repeatedly mentioned. All of the patients reported being able to talk to staff when seeking assistance; however, all of the patients noted a lack of communication as well, with staff not communicating on issues such as health, discharge and patients’ likes and dislikes. Three patients talked to family members while they were in hospital, of whom two reported that their family member acted as a liaison between the patient and staff.

All Talking Mat interviews were conducted on the hospital wards (three on the MMHU and three on the standard care ward) and most took place at the bedside because of patients’ levels of illness, their mobility or the lack of an alternative location. Six of the seven participants who were interviewed using a Talking Mat had a previous diagnosis of dementia and most (n = 5) experienced delirium on admission. Functional abilities were poor and all participants had been acutely unwell, with comorbidities. The mean interview duration was 21 minutes (range 13–35 minutes). Five interviews were cut short because of increased confusion, cognitive decline or the effects of physical illness. Participants’ ability to express feelings about different aspects of the ward varied; with between four and 21 questions being answered. However, all participants were able to provide some information about their experiences. Participants on the MMHU placed 13 cards in the positive response (Thumbs Up) category whereas those receiving standard care placed 11 cards in the positive response category. In total, 22 cards were placed in the middle, neutral, section. Participants on the standard care ward placed more cards in the negative response (Thumbs Down) category (n = 10) than those on the MMHU (n = 5).

Five themes emerged from the data about the Talking Mat method of communication:

-

Communication. Participants understood how to use Talking Mats, which enabled them to express their feelings about aspects of care on the ward. The ability to carry out the interview varied between participants.

-

The person as an individual. Information from the Talking Mats coupled with dialogue expressed during the process provided information about individual differences and built a picture of who the participants were and their experiences of hospital care.

-

Cognitive impairment. Attention fluctuated during the interviews with all participants becoming distracted by something, for example the pictures on the Talking Mat or changing topics. ‘Confusion’ increased for most during the interview and was displayed in different ways, such as expressing delusions or becoming agitated.

-

Physical illness. Talking Mats served as a short-term, helpful distracter for those experiencing pain, although symptoms quickly returned and two interviews were terminated as a result.

-

Environment. Noise and lack of privacy was as much an issue as with standard interview techniques, but because of the frailty of the participants it was even harder to take them off the ward to be interviewed.

In the unadjusted complete-case cost-effectiveness analysis undertaken in the subgroup of 209 (MMHU n = 109) participants with complete QALY and resource use data, the mean total cost was non-significantly lower (–£584.8, 95% CI –£2375.9 to £1085.8) and the QALY gain was non-significantly higher (0.007, 95% CI –0.013 to 0.027) in the MMHU group than in the standard care group, giving a 60% probability of MMHU care being dominant and a 85% probability of the ICER being ≤ £30,000 per QALY. In an adjusted analysis, the mean total cost for the MMHU group was significantly lower than that for the standard care group (–£486.7, 95% CI –£854.6 to –£126.5) with no significant QALY gain (0.0003, 95% CI –0.0108 to 0.0117), giving a 53% probability of MMHU care being dominant and a 95% probability of the ICER being ≤ £30,000 per QALY.