Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0707-10189. The contractual start date was in January 2009. The final report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in August 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Martin R Underwood is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Journals Library Editorial Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Taylor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background to the study

Chronic conditions, especially musculoskeletal conditions, impose an increasing burden on society and the NHS. 1 Despite increased understanding of the factors contributing to the development of chronic pain, the population burden of chronic pain is rising, with more cases now than 40 years ago. 2

A key component of the UK Department of Health’s response to the perceived growing burden of chronic disease3 was to promote self-management4 and the most tangible aspect of this was the introduction and promotion of its flagship, lay-led (i.e. peer-led), self-management training course, the Expert Patients Programme. 5 This decision was made based on a belief and some limited evidence, mainly from the USA, that such self-management programmes for long-term conditions improve health status, slow disease progression and reduce health-care use. 6 The Expert Patients Programme was rolled out and implemented within the NHS from 2005 onwards. 3 By 2007 the Department of Health had invested £18M in the programme. 7 In 2008 the then prime minister, Gordon Brown, announced further expansion of the programme. 8

The Expert Patients Programme is a complex intervention. It is an anglicised version of the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program developed in the 1980s. 9 It is based on Bandura’s social cognitive theory of behaviour,10 which suggests that positive behaviour changes are more likely to occur if a person is confident of making the change and expects a good outcome. The Expert Patients Programme consists of a structured, 6-week course (2.5 hours per week) covering education, coping strategies such as relaxation, visualisation, positive thinking, action planning and goal-setting. It includes strategies to deal with anger, fear and frustration, and aims to promote better communication with health-care professionals (HCPs) and physical activity. The courses are led by trained and accredited laypeople who themselves have a chronic condition. The objectives of self-management programmes are to encourage participants to take responsibility for their own health, increase their knowledge about their health condition, identify positive or dysfunctional coping strategies, teach more effective management strategies, create networks for support and reduce isolation. 11 The UK Department of Health’s aims were to increase quality of life, reduce the demand for consultations and drugs and avoid unnecessary investigatory tests, thus generating longer-term cost savings and increasing patient satisfaction. 5 Despite a reduced emphasis on the Expert Patients Programme in recent years, the concept of supporting better self-management among people with chronic conditions remains central to the UK Department of Health agenda. 12

The optimal way to support people with chronic musculoskeletal pain to manage their condition is unclear. Systematic reviews report, at best, only modest benefits for lay-led self-management programmes compared with usual care for long-term musculoskeletal conditions such as low back pain and osteoarthritis (OA). 13,14 For OA self-management there is moderate-quality evidence (11 studies including 1706 participants) that indicates small benefits up to 21 months in terms of self-management skills, pain, OA symptoms and function, although the magnitudes of the effect sizes are of doubtful clinical importance. 13 The authors of this review found no improvement in positive and active engagement in life or quality of life. Similar findings were reported from lay-led self-management courses for low back pain. 14 Despite these modest effects there is still considerable popular support for these types of programmes. Some authorities argue that a small average benefit for many patients may still be worthwhile compared with a larger benefit for smaller numbers of patients with less common disorders. 15 Nevertheless, the Expert Patients Programme and other programmes of this nature need further research and validation. Squire and Hill16 have argued that a clear policy based on good research and evidence is required to guide clinicians, service delivery organisations and researchers in the content and delivery of self-management programmes for chronic pain patients.

A note on terminology

Although it is obvious that only the affected individual can ‘self-manage’ his or her condition, courses to promote better self-management are commonly referred to as ‘self-management courses’, whereas a more accurate term might be ‘self-management support courses’. For brevity we have used the term ‘self-management course’ throughout this report but it should be understood that by this we really mean ‘self-management support course’.

Chronic musculoskeletal pain

The focus of this research programme is on chronic, non-malignant musculoskeletal pain. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines chronic pain as that which has persisted beyond normal tissue healing time, usually interpreted as 3 months. 17 Estimates of the prevalence of chronic pain vary, but one estimate is that 7.8 million people in the UK suffer moderate to severe pain that has lasted for > 6 months. 2

Musculoskeletal health care is costly. In 2011 in the UK, NHS trusts (secondary care services) spent around 10% of their patient care expenditure on musculoskeletal disorders (around £5.16B), and in 2009/10 there were around 21 million primary care consultations for musculoskeletal conditions in the UK. 6,18 Musculoskeletal pain is more commonly reported by women and those from socially or financially disadvantaged groups. 19 Chronic pain can cause considerable disruption to people’s lives. Around one-quarter of those who have chronic pain report severe disruption (> 2 weeks in the last 3 months) to their usual activities and chronic pain was associated with poorer mental health and well-being and lower levels of happiness and higher levels of anxiety and depression.

Psychology and chronic pain

The presence of chronic pain is strongly associated with adverse psychological factors. 20 European guidelines on the management and prevention of low back pain21 include psychological criteria to identify those at risk of poor outcomes, known as ‘psychosocial yellow flags’. These were developed to determine whether or not patients required more detailed assessment and to identify those for whom physical intervention could be less appropriate because of the dominance of psychological problems that would affect a successful outcome of the treatment. Psychological factors that consistently predict poor outcome include:

-

beliefs that back pain is harmful and potentially disabling

-

fear-avoidant behaviour and reduced activity levels

-

low mood and reduced social interaction

-

expectation that passive rather than active participation in treatment will help.

These factors can be identified during a consultation or with screening questionnaires. 22,23

Treatment approaches for people living with chronic low back pain that address some of the psychological issues include cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and reactivation and reassurance strategies. 24 These encourage new behaviours and activity to overcome and change the psychological constructs limiting recovery and activity. Self-management courses incorporate some of the same strategies but more work is needed to maximise and quantify the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these programmes. Redirecting resources to develop appropriate psychological interventions, with potentially more sustained benefits and fewer side effects than drug treatment, may have long-term clinical and economic advantages.

The biomedical model as opposed to the biopsychosocial model might be of limited benefit, especially for patients with high levels of health anxiety. 25 Linton et al. 24 suggest that a key component in establishing reassurance in patients is empathy and emotional support from the clinician. Emotional support outweighs the need for information and explanations in patients with unexplained pain. 26 A systematic review, however, found that cognitive reassurance was more effective in sustaining long-term improvements in patient outcomes than affective reassurance. 27 Cognitive reassurance includes objective information giving with clear explanations, whereas affective reassurance includes concepts such as empathy and warmth. The components of an effective self-management intervention should be designed in the knowledge that individual factors will determine different responses by patients to different components. Conceptually, the identification of groups of people for whom the same components will prove effective must be considered before implementing interventions. Indeed, the failure to adapt specific components that target the needs of different subgroups may explain the negative findings in some recent trials of behavioural interventions. 28

Self-management and evidence

We use the following broad definition of self-management throughout:

Self-management education programmes are distinct from simple patient education or skills training, in that they are designed to allow people with chronic conditions to take an active part in the management of their own conditions.

Foster et al. 14

The UK national evaluation of the original Expert Patients Programme for the self-management of chronic conditions reported a statistically significant increase in patients’ self-efficacy (which can be interpreted as self-confidence in relation to a specific context) and self-reported energy levels but no reduction in health-care utilisation. 15 Others found that the beneficial effects of lay-led self-management programmes for chronic conditions were modest in the short term and demonstrated a paucity of evidence on long-term benefit. 14 Two subsequent systematic reviews13,29 have reported improvements in patients’ confidence to manage their symptoms and small effects on pain and disability; both studies concluded that the benefits were too small to have any meaningful effect. Possible explanations for these findings included:

-

Suboptimal content of interventions.

-

Suboptimal delivery of interventions.

-

Programmes are effective only for some patients.

-

Measuring outcomes that may not be relevant to the intervention – the majority of studies measured change in pain symptoms, which are unlikely to change in chronic conditions. Self-management interventions may have a greater effect on confidence, positive outlook and coping methods than pain.

-

Poor targeting of the interventions (i.e. to those least likely to benefit).

-

Supporting self-management is an inherently ineffective approach.

Measuring outcomes

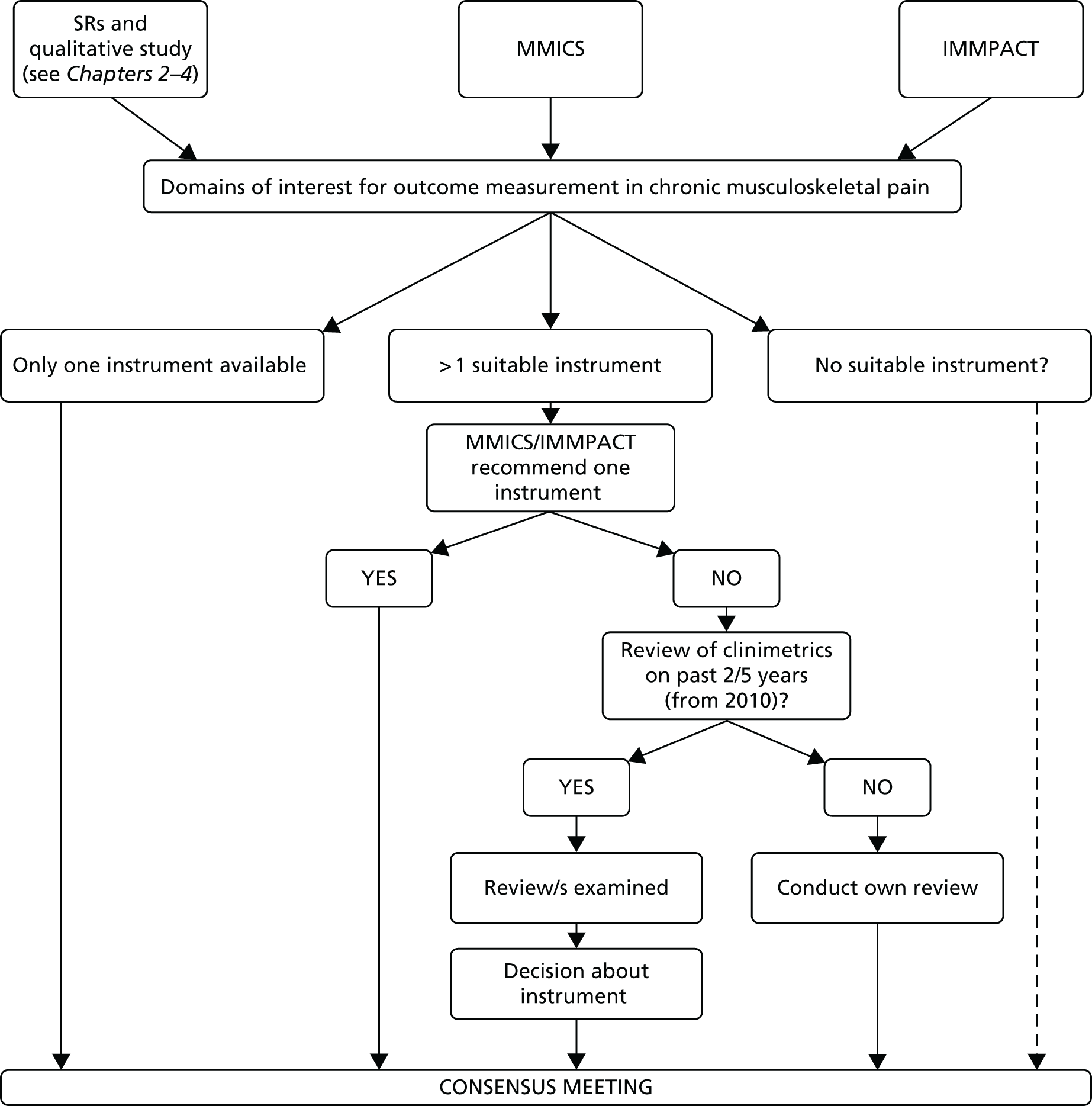

The fourth point above illustrates one of the key methodological challenges in measuring outcomes in populations experiencing persistent symptoms resulting from long-term conditions: selecting suitable outcomes. Typically, these will depend on the aim of the study. Measuring patient-centred outcomes, that is, those that are meaningful, relevant and important to patients, has already been recognised in both the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT)30 and Multinational Musculoskeletal Inception Cohort Study (MMICS)31 recommendations. IMMPACT and MMICS were international consensus studies that recommended a list of outcome measures for research in chronic pain and back pain populations, respectively. Both made recommendations with regard to measures for pain, psychological states, patient satisfaction, disability, global health/well-being, health-care use, symptoms and adverse events, physical functioning, work-related outcomes, tests and examinations, financial issues, lifestyle, weight and social/demographic factors.

Predictors, moderators and mediators

In many areas of health-related research, attention has started to focus on better matching of subgroups of patients to interventions. This aims to improve the effectiveness of treatment by targeting those most likely to benefit and avoiding offering treatment to groups for whom treatment is neither acceptable nor beneficial.

For example, in research in the musculoskeletal pain and mental health population, identification of subgroups is considered a priority. 22 The terminology around subgroup effects can be confusing. We have adopted the distinctions between predictors, moderators and mediators to describe how participant factors affect outcomes in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) suggested by Kraemer et al.:32

-

Predictors are baseline variables that affect outcome (significant main effect only) but do not interact with treatment. Such factors significantly predict outcome equally for target interventions and control conditions.

-

Moderators are baseline variables (such as patient baseline characteristics) that interact with treatment to change outcome for each subgroup. These specify for whom and under what conditions treatment works.

-

Mediators are variables measured during treatment (factors that change during the intervention) that impact on outcome, with or without interaction with treatment, for example mood might be a mediator for a different outcome such as employment status. Mediators help inform the process and potential mechanisms (including causal mechanisms) through which treatment might work and therefore can be used to improve subsequent interventions through strengthening the components that best influence the identified mediators.

There is evidence from prospective cohort studies reporting predictors of outcomes for people with chronic musculoskeletal pain, but far less from RCTs reporting moderators and mediators. 20,33–35 Most of what is published, at least for low back pain, is of poor quality. 36 RCTs are the best study design to explore moderators and mediators but those that include planned subgroup analysis require very large samples. 37,38 Such subgroup analyses must also be based on good theoretical reasoning and previous evidence to support the hypothesis that the correct subgroups have been identified a priori. 39 In practice, these analyses are usually undertaken as secondary analyses and, consequently, are statistically underpowered, leading to a lack of robust data for mediators and moderators in self-management interventions.

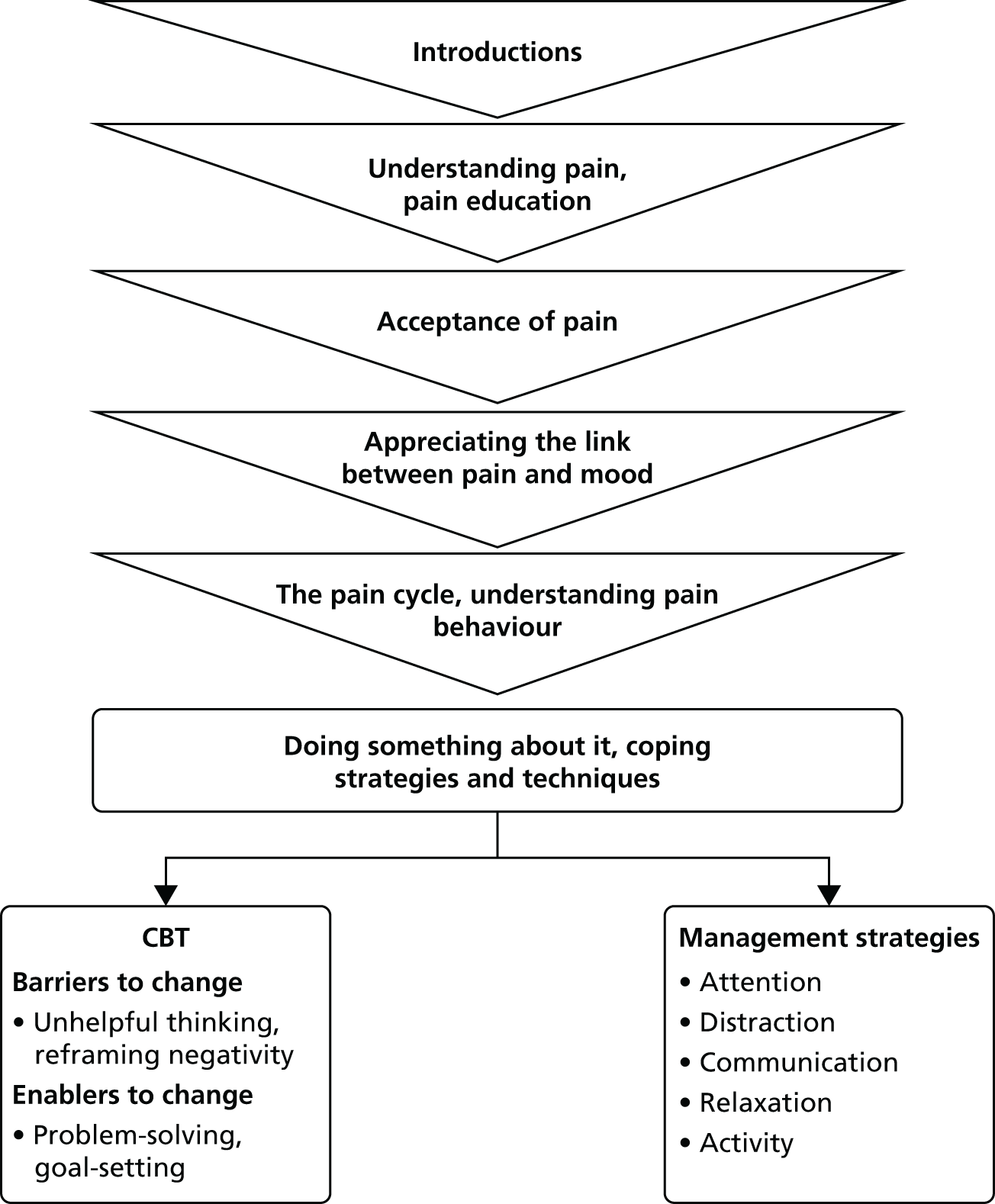

Components of courses

Self-management involves undertaking tasks that enable a person to live with their chronic condition(s). Component tasks may include addressing the medical, social or role and emotional management of their condition(s). 40 This suggests that interventions aimed at improving self-management may require several different components. There are several meta-analyses of different treatments for those with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Psychological approaches (such as CBT),41–43 exercise and activity21 are beneficial, whereas patient education on its own has little or no effect. 44,45 The evidence for mind–body therapies (such as relaxation) is equivocal. 46–48 Self-management education courses or programmes for chronic musculoskeletal pain combine some or all of these approaches, but the evidence to date suggests that the overall effects of such courses are modest. 13,14

As the content and characteristics of interventions promoting self-management for chronic pain vary considerably, there is a need to determine which components and course characteristics of these complex interventions are most likely to be beneficial to participants. To date, there have been few attempts to dissect the functional details of multicomponent, self-management programmes for chronic pain.

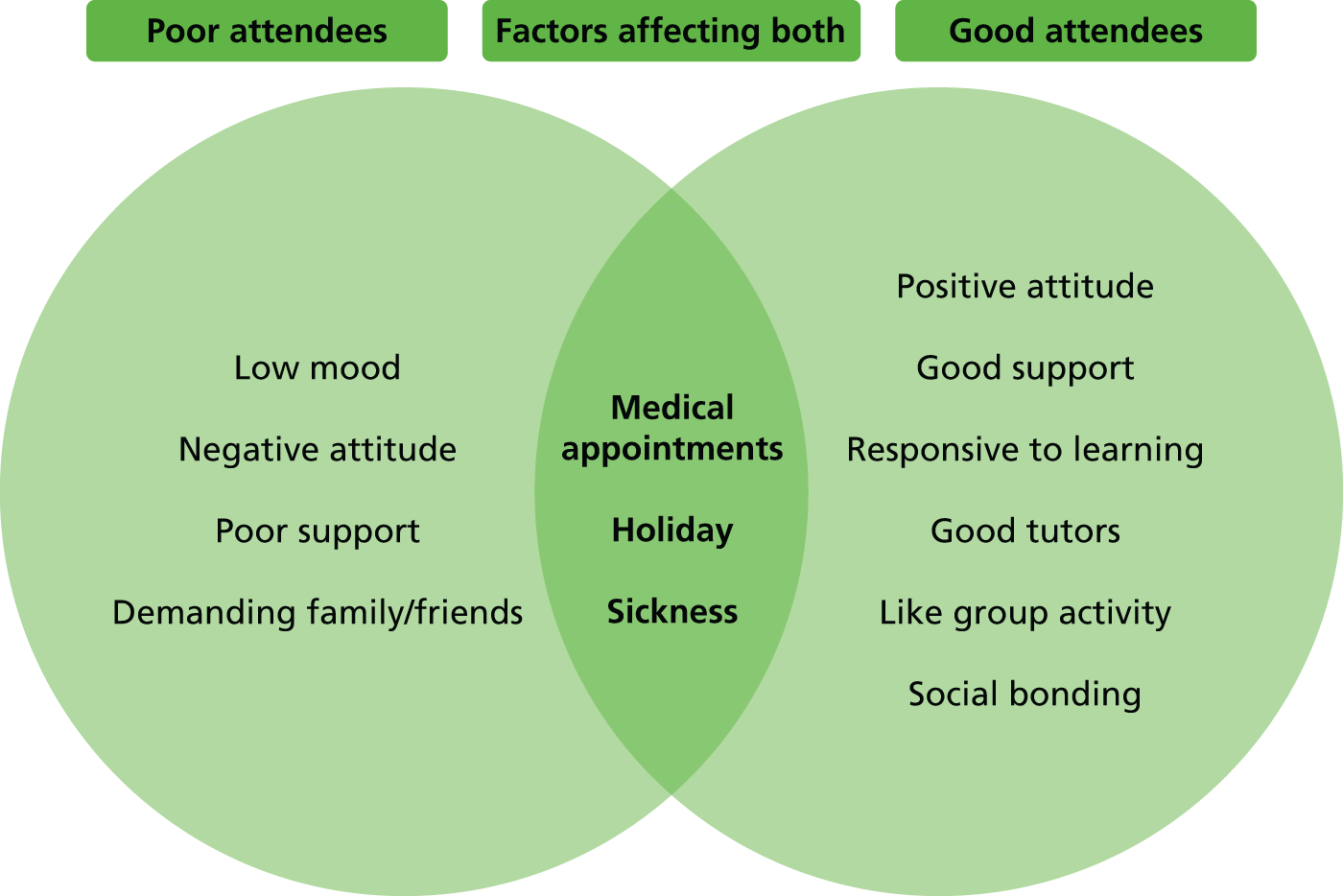

Adherence and dose

Attendance rates are a barrier to the effectiveness of self-management programmes. A national evaluation of the Expert Patients Programme evaluated courses at different case study sites, with participation rates at each site (participants attending at least four out of six sessions) ranging from 62% to 88%. 49 The number of sessions attended at group self-management courses may impact on outcomes, with many factors influencing continued attendance or if participants attend at all. Participants’ physical and mental health, their confidence within a group environment and their expectations about the learning experience may affect whether or not they attend the first session. Expectations can be influenced to some extent by the recruitment process in terms of information giving beforehand, and appropriate screening may identify any serious physical or mental impediments to attendance. However, after attending the first session, other factors come into play. On an individual level, relevance of content and perceived difficulty of the material are important, as well as whether or not the participant’s own diagnosis and disease experience chimes with those of the rest of the group. One qualitative study sampling ‘completers’ of group CBT or group education for chronic pain found that motivation to attend was influenced by group cohesion and the actions of the facilitators for one group. 50 Facilitator competency during the delivery of courses is something that can be influenced by adequate training and preparation.

Reach and uptake

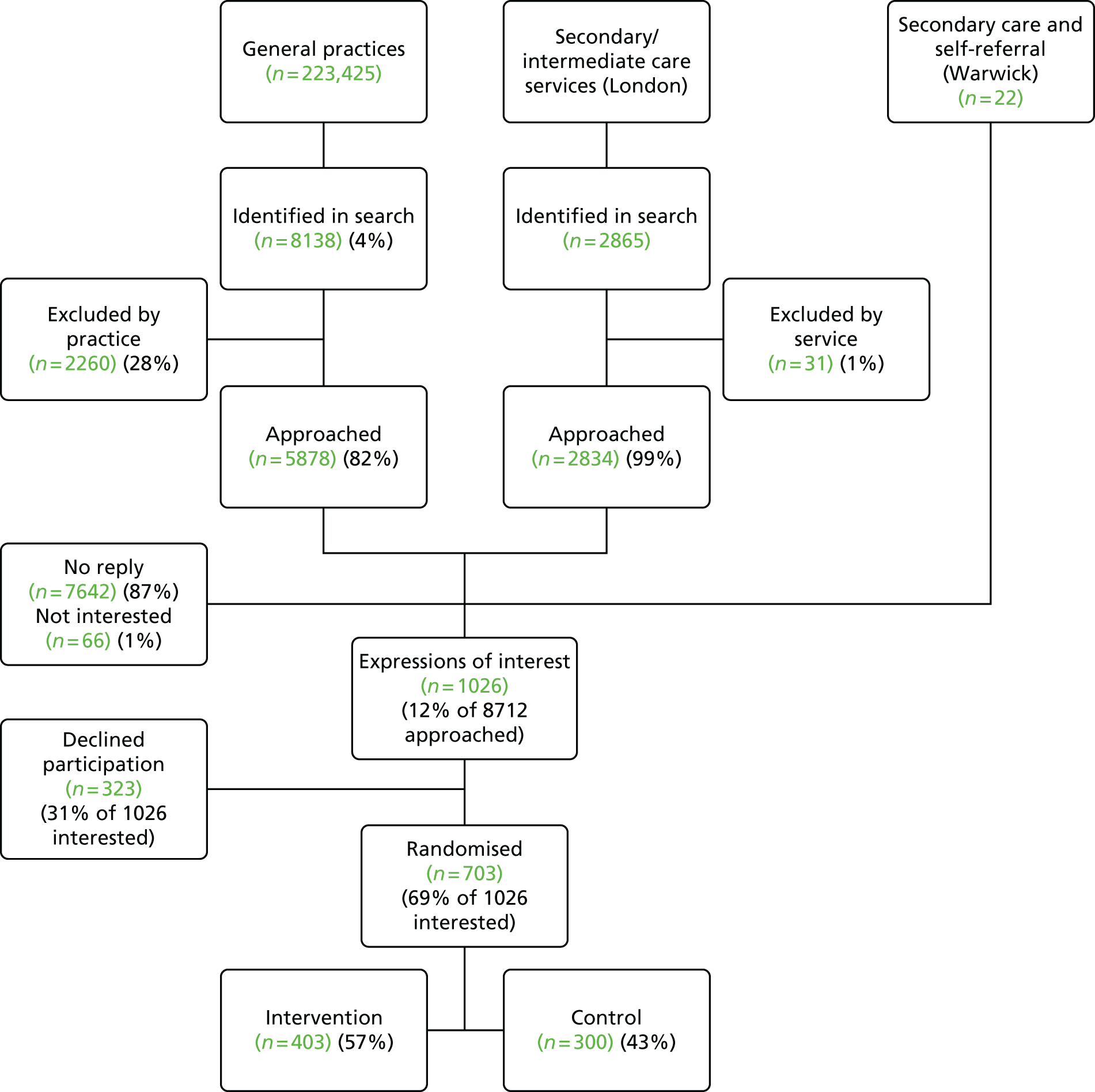

Identifying potential study participants with chronic pain from general practice is challenging. There are no universally acknowledged Read codes to identify chronic musculoskeletal pain and each general practice may have a different coding practice. Some UK-based studies have tackled this problem by sending out a blanket screening questionnaire to all registered patients over a certain age, excluding any major physical or psychiatric comorbidity. 51,52 Eligibility was then assessed from the screening questionnaires returned and suitable participants formally invited into the study. Enrolment rates for eligible patients were high at 53%51 and 50%,52 respectively, but the numbers of screening questionnaires sent out in the initial blanket mail-out were 12,44851 and 45,994,52 respectively. Another approach is to directly query the general practice patient record systems looking for indicator Read codes, prescriptions for analgesics and frequency of consultations and to send out invitations to potentially eligible patients, excluding any major physical or psychiatric comorbidity53–56 Once a potential participant has expressed an interest in the study, actual conversion to enrolment into the study can be influenced by a number of factors, for example some potential participants may not enrol because they think that the control arm is not a credible option or some may not be able to attend courses on weekdays because of other commitments such as work or child care.

Summary of evidence gaps: the need for research in this area

Treatment for chronic musculoskeletal conditions such as low back pain has done little to reduce their prevalence and health impact over the last two decades. 57,58 Chronic pain frequently coexists with other pain syndromes59 and traditional treatment approaches focus on conditions separately, which is unlikely to have a substantial impact on the population, or individual, burden of chronic pain. 59 There has been a shift towards a more biopsychosocial approach. 60 Two increasingly used psychosocial interventions are cognitive–behavioural approaches and self-management support programmes. Both approaches are rapidly expanding. However, the evidence has not been sufficient to justify such widespread and rapid introduction.

Some investigators have used RCTs to evaluate the effectiveness of self-management programmes but few have explored the effectiveness of different components of these programmes or courses. RCTs have found that self-management interventions may change attitudes but produce only modest improvements in clinical outcome. Overall, these data do not indicate whether specific aspects of the courses are effective or ineffective; it may be, for example, that social networking or the approach of the tutors is the most important factor.

We proposed to explore the components or elements of chronic pain self-management programmes that may be more effective than others and determine the most appropriate outcomes to measure. Without this work there are the twin hazards of continuing to spend NHS resources on ineffective interventions or failing to invest adequately in delivering an effective and cheap intervention. Even quite modest overall effects may be worth identifying because of the enormous personal, social and economic costs of chronic painful disorders.

Aims and objectives

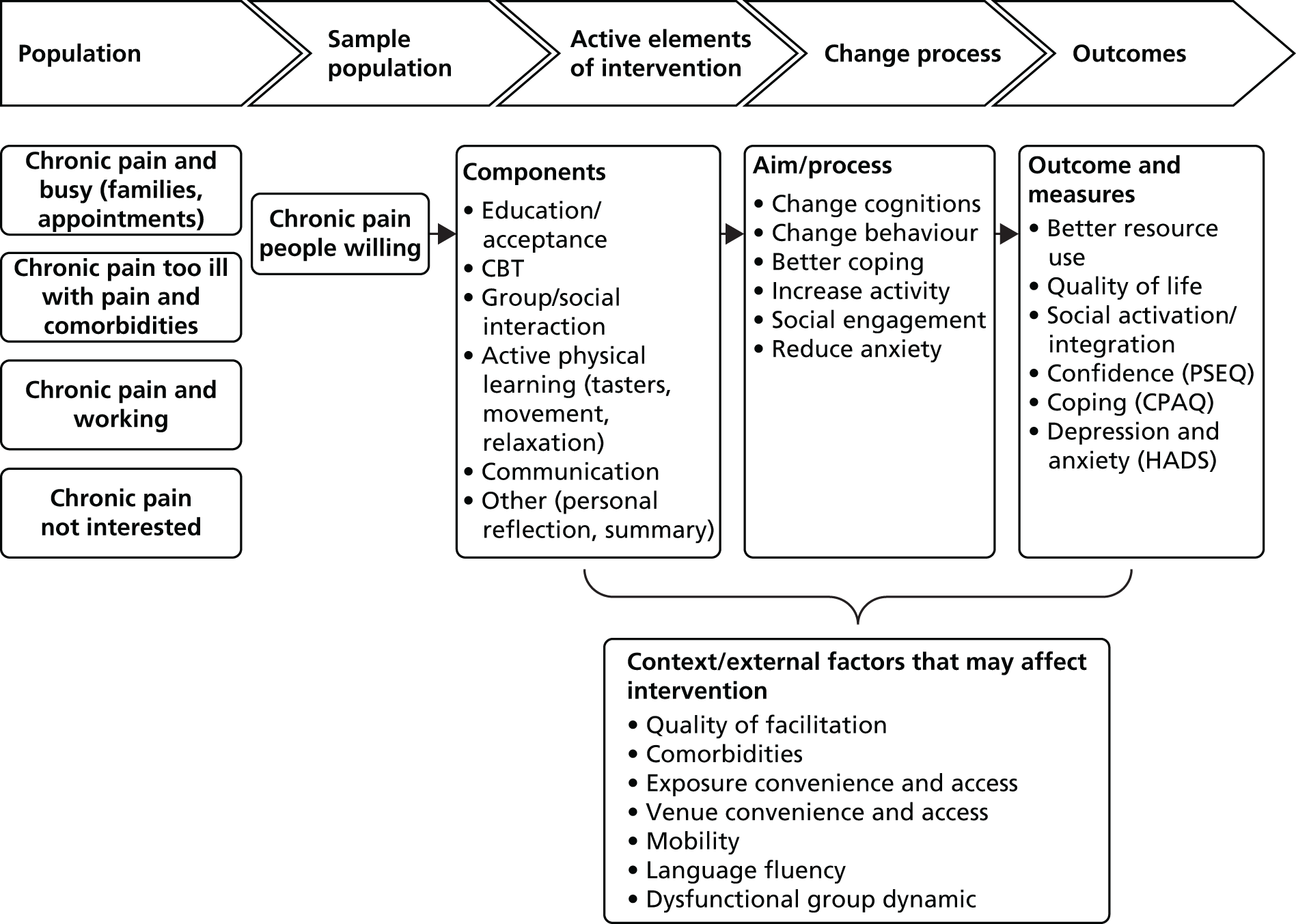

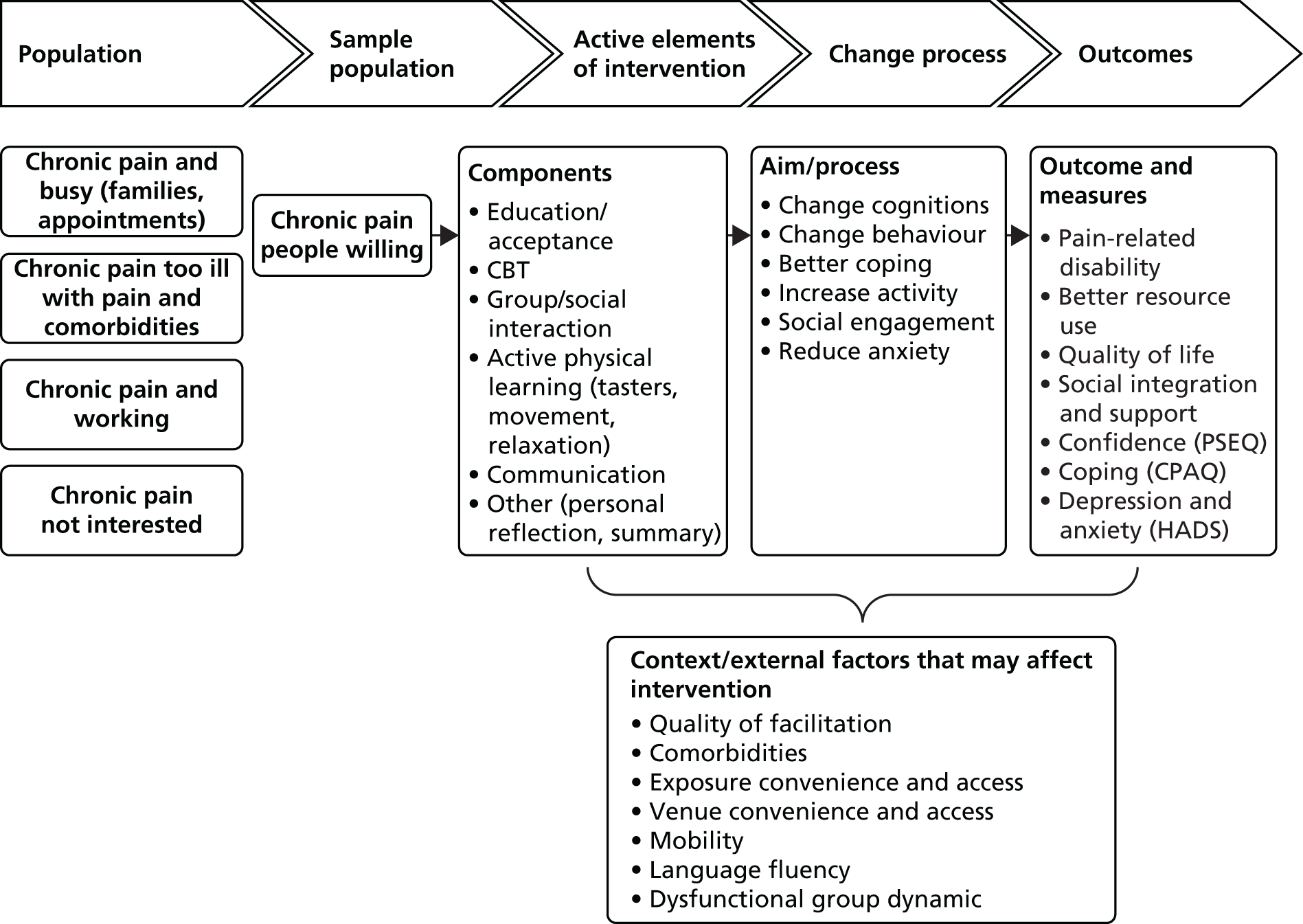

The overall aim of this programme of research was to develop and test a self-management intervention for people living with chronic musculoskeletal pain.

The objectives were to develop a new self-management approach and provide evidence for, or against, its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. We proposed developing an intervention to promote individual independence, improve quality of life and reduce the level of need for health-care resources, thus lessening a proportion of the economic, personal and social burden of chronic pain conditions.

To achieve this we first needed to identify what was already known about good-quality self-management programmes for chronic pain by examining the existing scientific literature and evidence in a systematic manner. We also wanted to consult experts and patients to identify and explore best practice, theoretical underpinnings for self-management and ways to measure patient outcomes. Once this preliminary work was completed we devised and evaluated our new programme/intervention in a feasibility study to ensure that we had the best possible intervention and systems for measuring the effect of the intervention on patients.

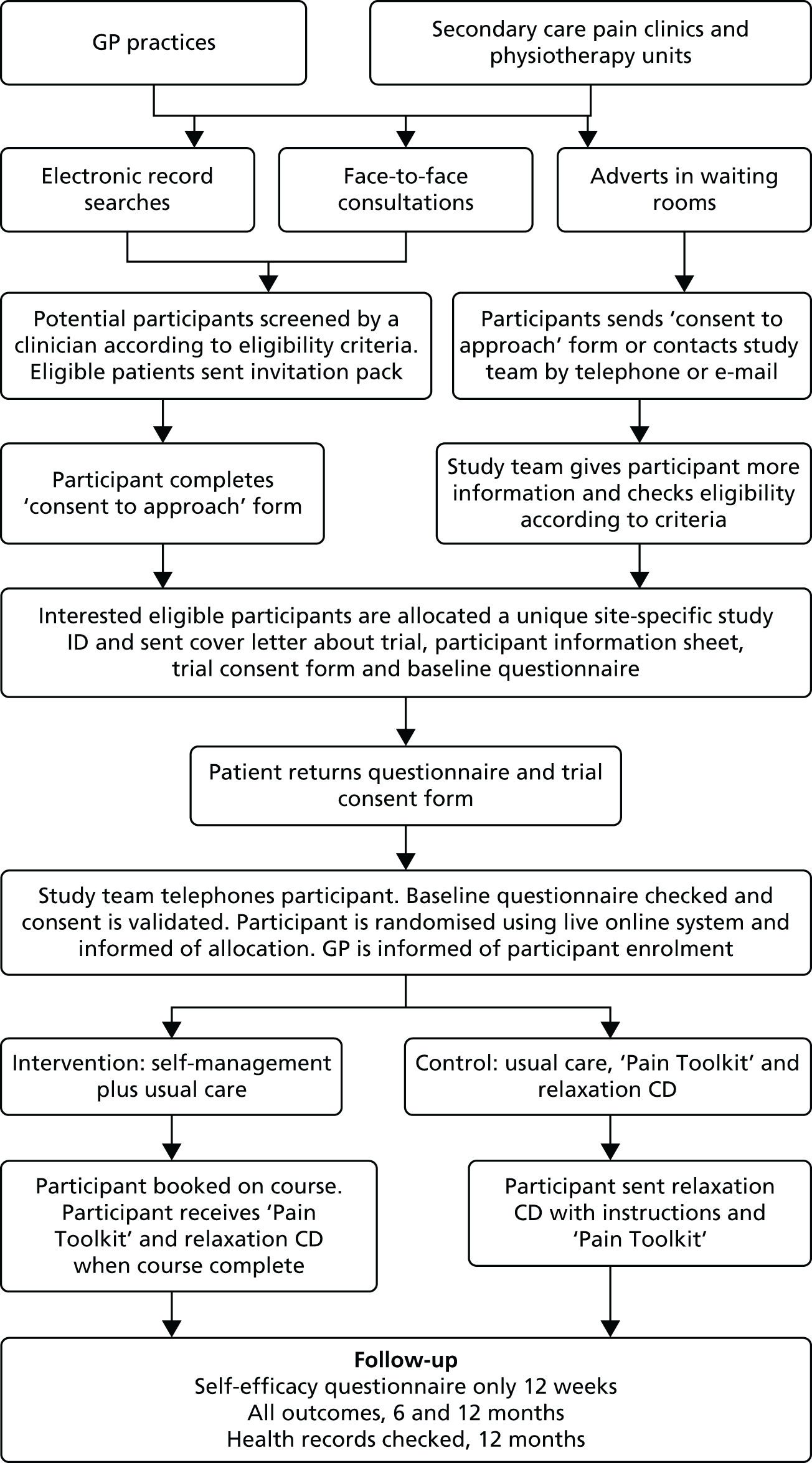

Finally, we tested the new intervention in a pragmatic RCT. We collected information on both the clinical effectiveness and the cost-effectiveness of our intervention. The findings provide the information needed to decide whether or not the NHS should invest in such services in the future.

Overview of the study and the report

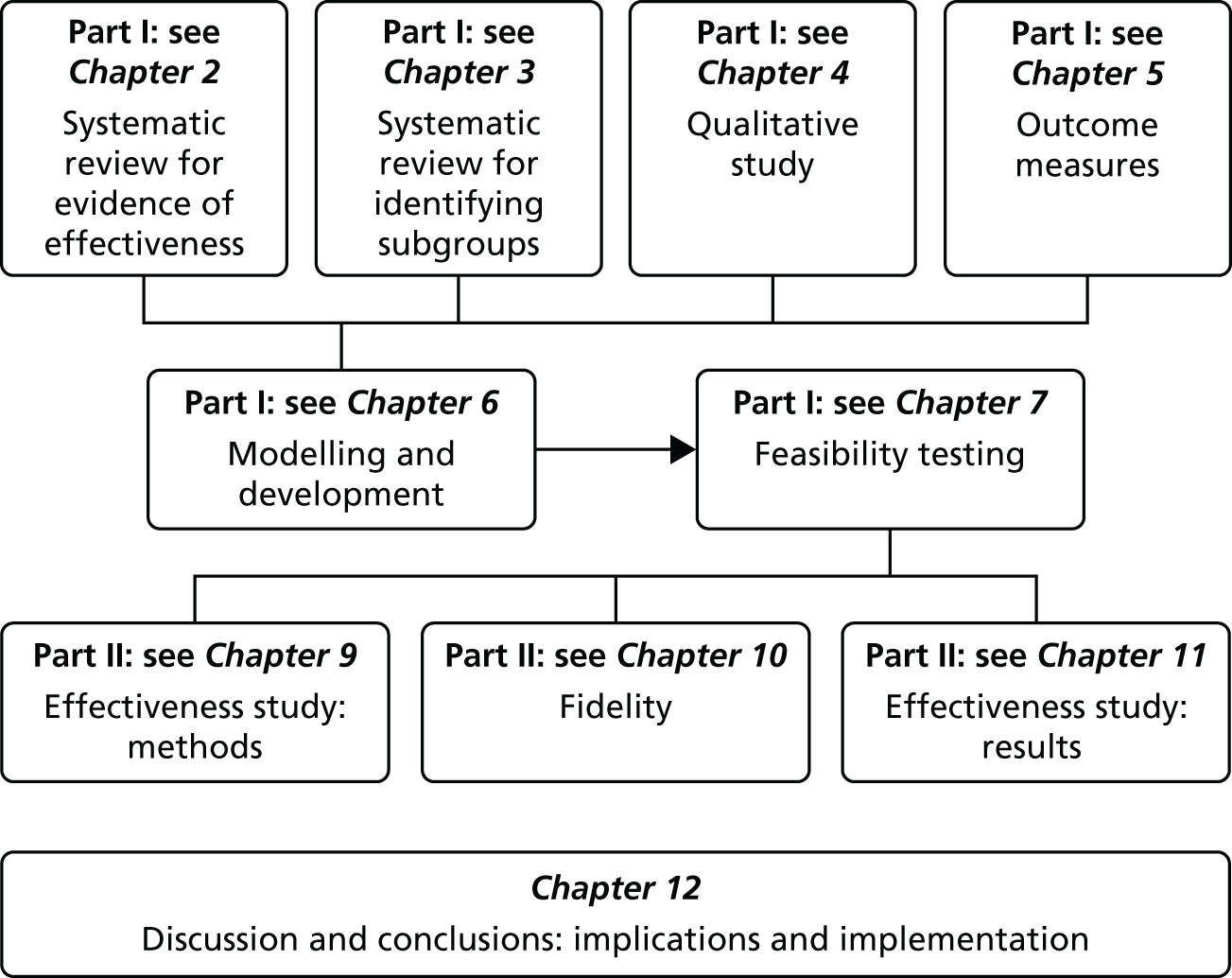

There are two parts to this report: the development of the intervention and testing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the intervention. Figure 1 illustrates the overall design of the study.

FIGURE 1.

The structure of the study and report.

Part I: development, design and feasibility testing of the intervention

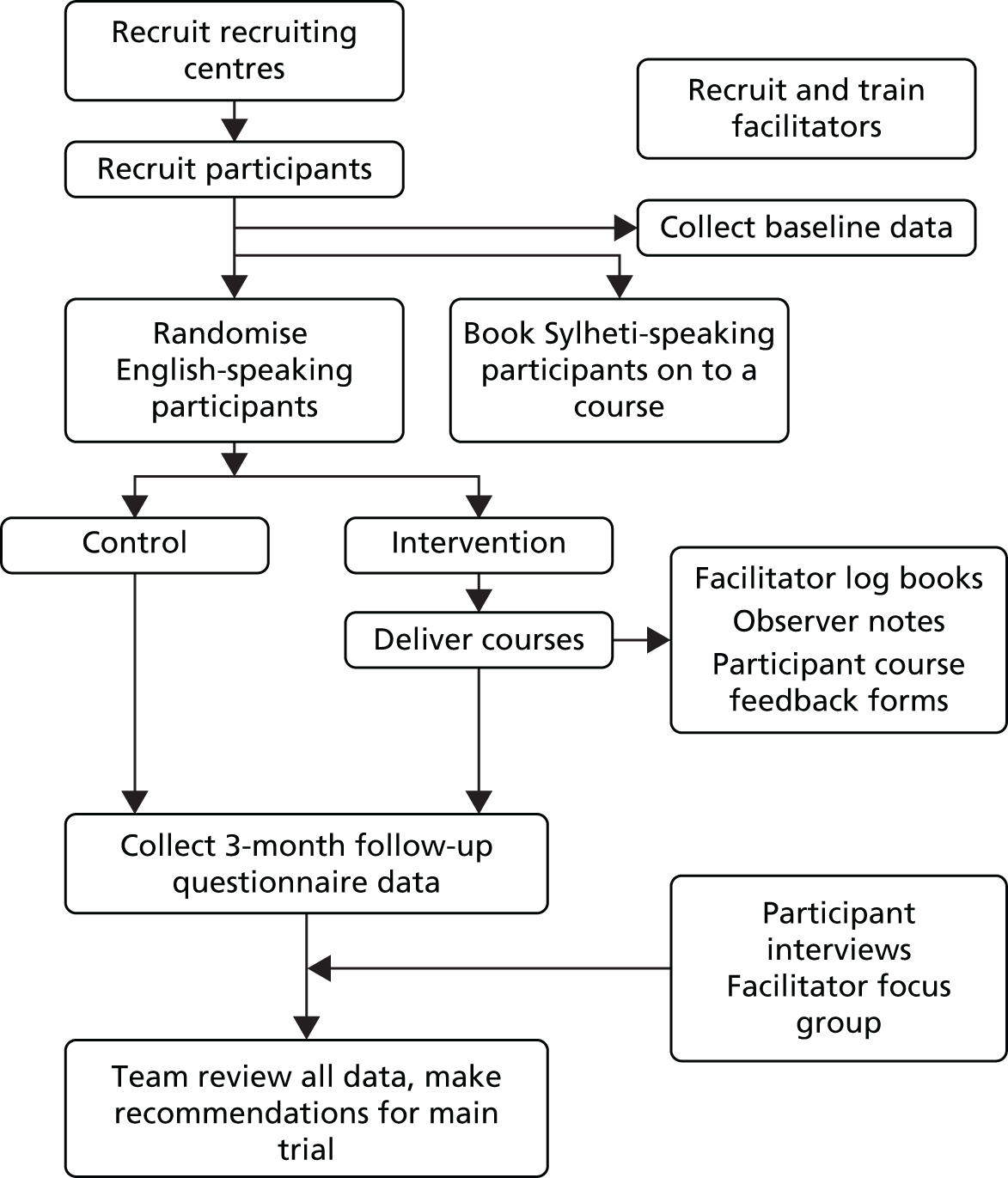

The development phase consisted of two systematic reviews, a qualitative study, modelling, the design of the intervention and a feasibility study. Chapter 8 summarises the findings from part I and is not shown as part of the study design illustrated in Figure 1.

Part II: clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the intervention

The testing phase consisted of a RCT and a cost-effectiveness analysis and study of the fidelity of the delivery of the intervention in the RCT.

At the end of part II we bring together the findings and discuss these in relation to current thinking in the field of chronic pain and self-management.

Patient and public involvement

We included patients and the public in phases 1 and 2 of the research. In phase 1 we recruited four people (one male and three females) with a chronic condition to a patient advisory group. These people gave advice and made comments on all of our patient-related documentation, resulting in substantial improvements to the documentation. In addition, they played a role in the outcomes study (see Chapter 5) by reviewing outcome measurement tools and commenting on their acceptability, brevity, comprehension and ease of completion (in retrospect we feel that we could have included more patient advisors in this phase of the study). People with experience of chronic pain were heavily involved in the development and refinement of the intervention, particularly in terms of their collaboration during the feasibility study when we collected data from all participants and from the lay facilitators on their experiences of every session (using a questionnaire) and at focus groups and interviews following the completion of the courses. The free and frank discussions at the focus groups enabled us to refine the intervention and the training to deliver the intervention. We also consulted extensively with the Bangladeshi community through interviews during the feasibility study of the intervention delivered in Sylheti. Two professional bilingual Bangladeshi advocates also provided extensive advice on patient-related material, running the courses in Sylheti and outcome measures in the Sylheti-speaking community.

In phase 2 we included two patient representatives with a chronic condition on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), one female and one male. Both were experienced representatives who had previously sat on National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) research priorities panels. These people gave valuable advice to the TSC and the excellent recruitment rates and low attrition seen in the study are, in part, a reflection of their contribution.

In addition, Social Action for Health [see www.safh.org.uk (accessed 11 April 2016)] was a coapplicant in the study. Social Action for Health is a community interest company providing socially orientated services to the local community. Members of Social Action for Health were part of the trial study team and represented the patient perspective for decisions made throughout the progress of the study.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, patients were integral to the design and delivery of the intervention as we recruited patients with experience of chronic pain to deliver our intervention for the feasibility study and the main trial.

Chapter 2 Systematic review: evidence for the effectiveness of components and characteristics of pain and self-management programmes

Abstract

Introduction: Evidence for self-management courses and course components that are beneficial for participants has not been established.

Aims: To systematically re-examine the overall effectiveness and determine the most successful course content and optimal delivery methods of self-management courses.

Methods: We searched 10 relevant electronic databases for RCTs and systematic reviews. RCTs were categorised according to the presence of psychological, mind–body therapy, physical, lifestyle and educational components; group or individual delivery; tutor; setting; and duration of the interventions studied. Outcomes analysed were pain intensity, global health, quality of life, physical function, self-efficacy, depression, anxiety and social function in the short term (< 4 months), medium term (4–8 months) and long term (> 8 months). Data were extracted comparing self-management with usual care or a waiting list control. Data were combined as a standardised mean difference (SMD) meta-analysis (random effects) with subgrouping. When statistical pooling was not possible we carried out a narrative synthesis.

Results: Forty-six RCTs published from 1994 to 2009 were included in the original meta-analyses and a further 18 RCTs were included in updated analyses to 2013. Heterogeneity between studies was generally high. Overall, the number of components or duration of the interventions did not influence effectiveness, but courses with a psychological component, courses delivered in groups and courses delivered by a HCP appeared to work well, showing significant effect sizes on several outcomes during post-course follow-up (short, medium and long term). Data were sparse on subgroup comparisons and on the detail of the components of individual interventions.

Conclusions: Our analysis provided useful information to inform the design of our intervention.

Introduction

The evidence for the effectiveness of self-management support courses61 (commonly known as ‘self-management courses’ and sometimes referred to as ‘pain management programmes’) for chronic musculoskeletal pain is limited. There is even less information on the effectiveness of specific components or on the content of courses and the way that they are delivered.

Aim

The aim of this review was to identify the types of courses (content and characteristics) that are most likely to be effective in helping those with chronic pain.

We sought to identify the evidence on:

-

the overall effectiveness of self-management courses

-

the key components and characteristics of potentially effective self-management programmes (including self-management education strategies) for people with chronic musculoskeletal pain.

We did this by comparing research on delivery characteristics (including setting) and components of self-management programmes for chronic musculoskeletal disorders that appear to have been successful or unsuccessful.

Method

We conducted a systematic review of RCTs examining the effectiveness of different types of self-management interventions (with and without individual components).

In addition, we systematically searched for systematic reviews to see if any other researchers had performed this type of work and used citation tracking from relevant reviews to supplement our searches.

We completed the initial systematic review of articles published between January 1994 and April 2009 to inform the design of the intervention study. At the end of the study we updated the review for selected outcomes [those measured in the COPERS (Coping with persistent Pain, Effectiveness Research into Self-management) study] to September 2013 to allow us to put our final results into context (see Chapter 12). The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the reviews are shown in Table 1.

| Definitions | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Type of study |

|

|

| Types of participants |

|

|

| Types of self-management interventions |

|

|

Outcome measures

The outcomes that we were interested in were extracted and grouped into the following categories:

-

global health measures

-

pain intensity

-

physical/functional capability

-

quality of life

-

self-efficacy

-

anxiety

-

depression

-

social role/function

-

Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)62 general mental health (excluded in update review)

-

number of visits to HCPs (excluded in update review)

-

fatigue (excluded in update review).

The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the final value and/or change scores for each group at each follow-up interval were extracted.

Search method

Electronic literature searches

The initial searches were conducted between January 1994 and April 2009 as self-management courses and the understanding of chronic pain have advanced considerably during this period. The following electronic databases were searched to identify all relevant studies: MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) using the Health Information Resources [see www.library.nhs.uk (accessed 11 April 2016)], Web of Science Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and The Cochrane Library [Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials].

Other sources

We also checked the citation lists of relevant systematic reviews and guidelines identified in our electronic database searches for any additional relevant studies.

Study selection

Two reviewers conducted the searches and independently screened all titles and abstracts for potentially eligible studies. Full texts of all potentially relevant articles were obtained. Inter-rater reliability for screening titles and abstracts was checked on a sample of the studies (approximately 10%). The full texts of all retrieved articles were scrutinised by both reviewers to determine whether or not to proceed to full data extraction. Disputed articles went to a third reviewer for arbitration.

Assessment of study bias

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality according to the following criteria modelled on The Cochrane Collaboration methods. 39 We asked:

-

Did the study have an adequate randomisation sequence?

-

Was allocation concealment carried out?

-

Was there a description (i.e. numbers provided) of withdrawals and dropouts?

-

Was outcome assessment blinded?

-

Was there an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis?

Each question was rated as yes/no or unclear (see Table 3).

Data extraction

The two reviewers working independently each extracted data about country of origin, number randomised to each arm, who delivered the course (HCP or lay tutor or a combination), whether the course was delivered to groups or individuals or was self-delivered, setting [community, medical, occupational, remote (telephone/internet) or mixed], total number of sessions and contact hours, course duration, course components (see Table 2), description of control group and the description and results of any moderator analyses. Data were extracted, when possible, at four time points: baseline, short-term follow-up (< 4 months), medium-term follow-up (4–8 months), long-term follow-up (> 8 months) or a mixture of follow-up points.

Description of self-management components

To handle the vast number of data arising from the studies, we categorised self-management interventions into psychological, mind–body therapy, physical, lifestyle or medical education components, as described in Table 2. Each study was coded so that the intervention arm was described using two or more components from the list. We accept that these categorisations represent our interpretation of the published reports of studies and that some components may well have overlapped between our broad categories.

| Psychological | Mind–body therapies | Physical | Lifestyle management | Medical management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Final study selection

Following data extraction, the RCTs were further selected to include only comparisons of the self-management intervention(s) with waiting list controls or usual care.

Meta-analysis methods

The meta-analyses were carried out using Review Manager v5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Calculations were based on final values as these were the most commonly reported data. Change score data were also collected when possible. When studies reported p-values for change from baseline for each group, this enabled a SD for the change score to be calculated. 39 Change scores were analysed in the same way as the final value data for the outcomes when there were sufficient data and compared with the final value results for the same outcomes as a sensitivity analysis. We used a random-effects model because of the heterogeneity in study populations and interventions.

When there was more than one measurement tool for an outcome we combined data across studies using a SMD meta-analytical approach (see section 9.2.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions39), where

For those instruments for which an increase in score indicates improvement we reversed the sign on the mean score to enable us to combine these as a pooled SMD with measures from instruments for which a decrease in score is beneficial.

The resulting SMDs were interpreted using Cohen’s d63,64 (where d is derived from the difference between two independent means divided by the within-population SD as above). The effect sizes were conventionally defined as follows: ‘minor’ < 0.2, ‘small’ ≥ 0.2, ‘moderate’ ≥ 0.5 and ‘large’ ≥ 0.8.

Meta-analysis comparisons

We tested:

-

Overall effectiveness. Total effect size or SMD for self-management interventions with regard to our prespecified outcome categories compared with the control.

-

The effect of course delivery mode. We grouped the studies at each follow-up interval into different course delivery modes [group, individual, mixed (group and individual) or remote (internet, mail, telephone)] and compared the pooled SMDs for each subgroup.

-

The effect of course leader. We grouped the studies and outcomes at each follow-up interval into those that were delivered by a HCP, those that were delivered by a lay tutor and those using a mix of delivery methods and compared the pooled SMDs for each subgroup.

-

The effect of course setting. We grouped the studies at each follow-up interval into those delivered in the community, those delivered in a medical setting (primary care or hospital) and those delivered in an occupational setting and compared the pooled SMDs for each subgroup.

-

The effect of course duration. We grouped the studies at each follow-up interval into those with courses of ≤ 8 weeks and those with courses of > 8 weeks and compared the pooled SMDs for each subgroup.

-

The effect of contributing self-management components. We tested whether or not the presence of a particular self-management component improved the effectiveness of the interventions. We compared the pooled SMDs of studies with psychological, mind–body therapy, physical, lifestyle and medical education components with the pooled SMDs of studies without these components.

-

The effect of number of components. We tested whether or not the number of components (two, three, four or five) influenced the effect size, comparing the pooled SMDs at short-, medium- and long-term follow-up intervals.

We produced forest plots of final value data for each comparison showing the pooled SMD for each subgroup.

Assessment of publication bias

Funnel plots were generated using Review Manager v5 for the outcomes with the most studies. The funnel plots were visually examined for symmetry about the y-axis and resemblance to an inverted funnel to denote absence of bias.

We present data from the original review meta-analysis and the updated review data.

Results

The results of the review of the effectiveness of self-management interventions are shown first followed by the effectiveness review of self-management courses with and without the different components and characteristics.

Literature search

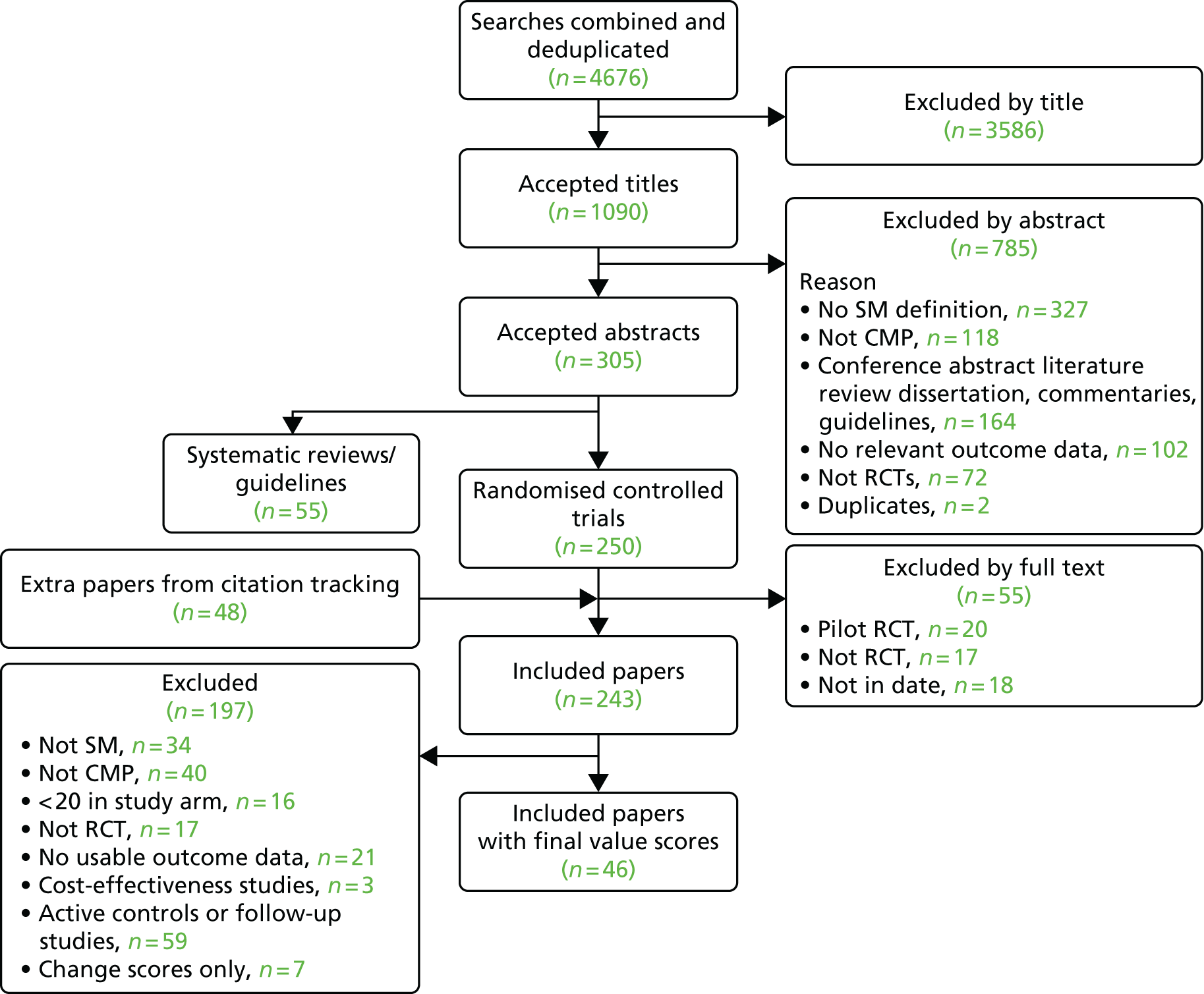

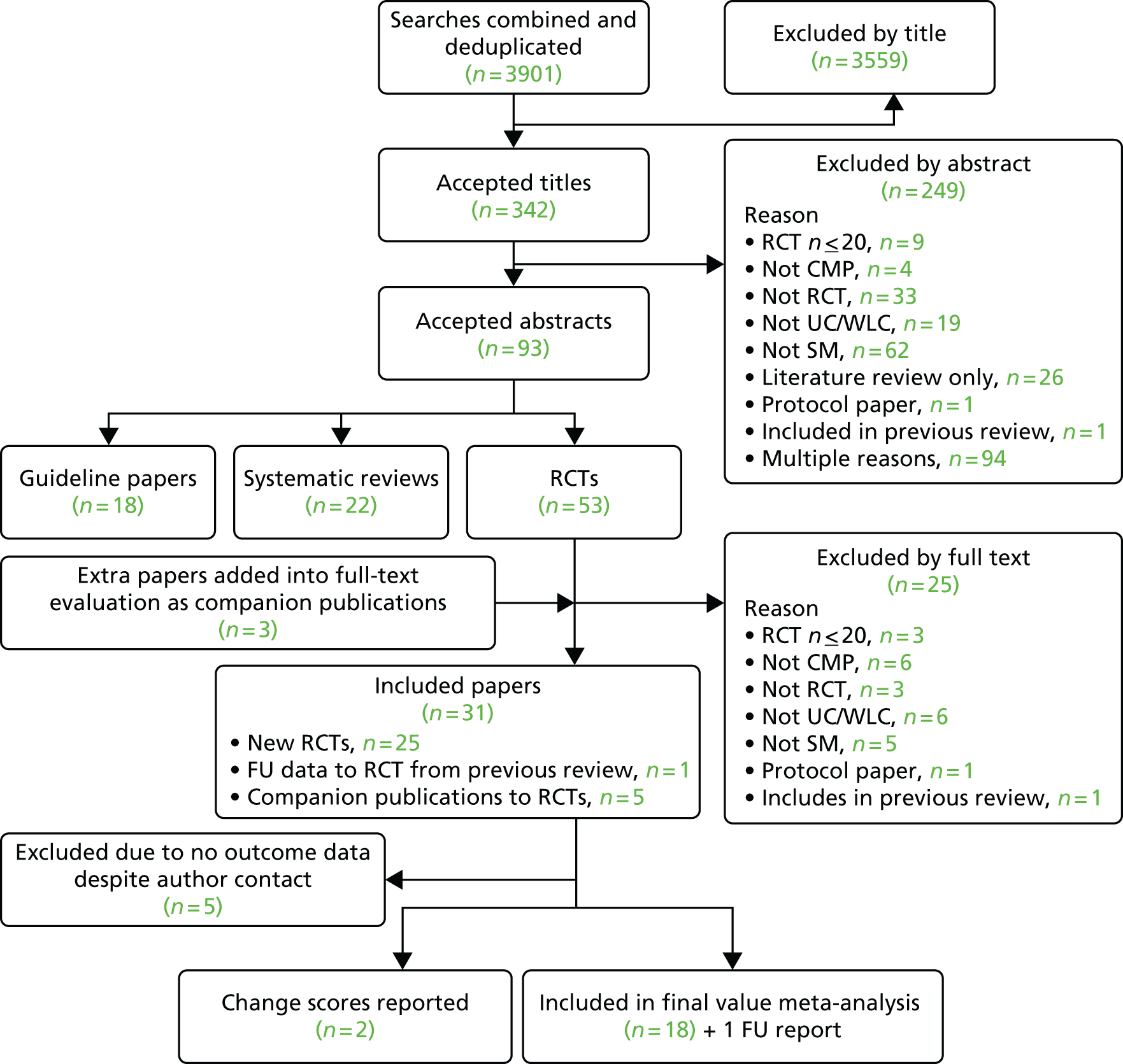

The initial search produced 4676 results and of these we included 46 RCTs. When we updated the search to September 2013 we included a further 18 trials in the meta-analyses for the overall effectiveness of self-management interventions.

Figure 2 shows the flow chart for the initial search and Figure 3 shows the flow chart for the updated search.

FIGURE 2.

Searches for the systematic review 1994–2009. CMP, chronic musculoskeletal pain; SM, self-management.

FIGURE 3.

Systematic review update June 2009–September 2013. CMP, chronic musculoskeletal pain; FU, follow-up; SM, self-management; UC, usual care; WLC, waiting list control.

Effectiveness analyses

For our original meta-analyses we included 46 RCTs54,65–111 with final-value data comparing self-management programmes with usual care or waiting list controls (n = 8539) (Table 3). Thirteen RCTs were conducted in the USA,72,74,77,83,85,86,91–93,95,104,106,108 seven in the Netherlands,69,81,94,96,98,102,110 five in the UK,54,67,70,88,97,103 five in Canada,68,76,80,87,107 three each in Sweden,82,89,99 Norway75,78,79,84 and China,100,105,111 two in Germany71,73 and one each in Turkey,65 Iran,66 Switzerland,90 Spain101 and Brazil. 109 Of these studies, 13 (28%) were on OA (hip or knee),74,81,88,91,92,94–97,101,104,105,111 12 (26%) were on low back pain,54,66,71,73,77–79,83,89,93,102,109,110 nine (20%) were on mixed pain,68,70,75,76,80,84,99,100,106 five (11%) were on fibromyalgia,69,82,85,87,90 three (7%) were on mixed arthritis (OA and rheumatoid arthritis)72,107,108 and one (2%) each was on temporomandibular joint disorder,86 osteoporosis,65 upper limb pain98 and knee pain. 67,103 The mean age of participants for the 44 studies reporting age was 55 years (range 38–82 years). In the 41 studies reporting gender breakdown, 72% were female participants, with two studies having exclusively female patients. Thirty-six studies were health care professionally led, six were mixed health care and lay led and four were lay led. Twenty-seven studies were conducted in a medical setting, sixteen in the community and three in occupational settings. Twenty-seven were delivered in groups, five were delivered remotely via the internet and five were delivered individually; nine used mixed group and individual delivery.

| Study | Country | Population | n | Self-management component details | Control arm | Course characteristics | Follow-up | Quality assessmenta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | Leader | Setting | Duration | QA1 | QA2 | QA3 | QA4 | QA5 | |||||||

| Corey 199668 | Canada | Mixed pain | 200 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 4 weeks | L | U | U | Y | Y | N |

| Vlaeyen 199669 | The Netherlands | Fibromyalgia | 131 | P + MBT + PA + LS | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | S | U | U | Y | U | N |

| MBT + PA + LS | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | S | U | U | Y | U | N | ||||

| Williams 199670 | UK | Mixed pain | 78 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 8 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | Y | N |

| Basler 199771 | Germany | Low back pain | 94 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 12 weeks | M | U | U | Y | U | N |

| Fries 199772 | USA | OA + RA | 809 | MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Remote | HCP | Community | 52 weeks | M, L | Y | U | N | U | Y |

| Keller 199773 | Germany | Low back pain | 65 | P + MBT + PA + ED | WLC | Group + individual | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | S | U | U | Y | U | N |

| Mazzuca 199774 | USA | OA | 211 | P + PA + LS + ED | UC | Individual | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | M, L | U | Y | Y | U | N |

| Haldorsen 199875 | Norway | Mixed pain | 469 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group + individual | HCP | Medical | 4 weeks | L | U | Y | Y | Y | N |

| LeFort 199876 | Canada | Mixed pain | 110 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Group | HCP | Community | 6 weeks | S | U | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Von Korff 199877 | USA | Low back pain | 255 | P + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | Lay | Medical | 4 weeks | S, M, L | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Glomsrod 2001,78 Lonn 199979 | Norway | Low back pain | 81 | PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 13 weeks | L | Y | U | Y | U | Y |

| Currie 200080 | Canada | Mixed pain | 60 | P + MBT + LS | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 7 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | U | Y |

| Hopman-Rock 200081 | The Netherlands | OA | 120 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | S, M | U | U | Y | Y | N |

| Mannerkorpi 200082 | Sweden | Fibromyalgia | 69 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Community | 24 weeks | M | U | U | Y | Y | N |

| Moore 200083 | USA | Low back pain | 266 | P + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group + individual | HCP | Medical | 3 weeks | S, M, L | U | U | Y | U | Y |

| Haugli 200184 | Norway | Mixed pain | 174 | P + MBT + PA + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Occupational | 45 weeks | S, L | U | U | Y | Y | N |

| Oliver 200185 | USA | Fibromyalgia | 400 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP + lay | Community | 52 weeks | L | U | U | Y | U | N |

| Dworkin 200286 | USA | TMD | 124 | P + MBT + LS + ED | UC | Individual | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | S, M, L | U | U | Y | U | Y |

| King 200287 | Canada | Fibromyalgia | 124 | P + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Group | HCP | Community | 12 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| P + LS + ED | WLC | Group | HCP | Community | 12 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | ||||

| Quilty 200388 | UK | OA | 87 | PA + LS | UC | Individual | HCP | Community | 10 weeks | M, L | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Buhrman 200489 | Sweden | Low back pain | 56 | P + MBT + PA + LS | WLC | Remote | HCP | Community | 8 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | U | N |

| Cedraschi 200490 | Switzerland | Fibromyalgia | 164 | P + MBT + PA + LS | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | M | Y | Y | Y | U | N |

| Hughes 200491 | USA | OA | 150 | P + PA | UC | Group | HCP + lay | Community | 8 weeks | S, M, L | Y | U | Y | U | N |

| Mazzuca 200492 | USA | OA | 186 | PA + LS + ED | WLC | Individual | HCP | Medical | 4 weeks | S, M, L | U | U | Y | U | N |

| Haas 200593 | USA | Low back pain | 109 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Group | Lay | Community | 6 weeks | M | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Heuts 200594 | The Netherlands | OA | 273 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | S, L | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Pariser 200595 | USA | OA | 92 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Remote | HCP | Community | 6 weeks | S | U | U | N | U | N |

| Tak 200596 | The Netherlands | OA | 109 | PA + LS | UC | Group + individual | HCP | Medical | 8 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Victor 200597 | UK | OA | 193 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Group + individual | HCP | Medical | 4 weeks | S, L | U | U | Y | Y | N |

| Bernaards 200698 | The Netherlands | Upper limb pain | 314 | P + PA + LS | UC | Group | HCP | Occupational | 24 weeks | M, L | Y | N | U | Y | N |

| Brattberg 200699 | Sweden | Mixed pain | 60 | P + LS | WLC | Remote | HCP + lay | Community | 20 weeks | S, L | U | U | Y | U | N |

| Li 2006100 | China | Mixed pain | 64 | P + LS + ED | WLC | Group + individual | HCP | Occupational | 3 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | U | Y |

| Núñez 2006101 | Spain | OA | 100 | P + PA + LS | UC | Group + individual | HCP | Medical | 12 weeks | L | Y | U | Y | U | N |

| Smeets 2006102 | The Netherlands | Low back pain | 111 | P + PA | WLC | Group + individual | HCP | Medical | 10 weeks | S | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Alp 200765 | Turkey | Osteoporosis | 50 | P + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP + lay | Medical | 5 weeks | S, M | Y | U | U | Y | N |

| Hurley 2007,67 Hurley 2012103 | UK | Knee pain | 418 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group + individual | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | M | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Johnson 200754 | UK | Low back pain | 234 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Community | 6 weeks | S, L | Y | U | Y | N | Y |

| Martire 2007104 | USA | OA | 143 | P + PA + ED | UC | Group | Lay | Community | 6 weeks | S, M | U | U | Y | U | Y |

| Tavafian 200766 | Iran | Low back pain | 102 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 4 days | S | U | N | Y | U | Y |

| Yip 2007105 | China | OA | 182 | PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP + lay | Medical | 6 weeks | S, M | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Ersek 2008106 | USA | Mixed pain | 256 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Community | 7 weeks | S, M, L | Y | U | Y | U | N |

| Laforest 2008107 | Canada | OA + RA | 113 | P + MBT + LS + ED | WLC | Individual | HCP | Community | 6 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | Y | N |

| Lorig 2008108 | USA | OA + RA | 866 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Remote | Lay | Community | 6 weeks | M, L | U | U | Y | U | Y |

| Ribeiro 2008109 | Brazil | Low back pain | 60 | PA + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 5 weeks | S, M | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| van der Hulst 2008110 | The Netherlands | Low back pain | 163 | P + PA | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 7 weeks | S, M | Y | U | Y | U | Y |

| Yip 2008111 | China | OA | 95 | PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP + lay | Medical | 6 weeks | S, M, L | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Studies included in the update | |||||||||||||||

| Crotty 2009112 | Australia | OA hip or knee | 152 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group + individual | HCP + lay | Medical | 6 weeks | M | Y | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Jenkinson 200951 | UK | Knee pain | 389 | PA + LS | UC | Individual | HCP | Community | 104 weeks | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kroenke 2009113 | USA | Mixed pain | 250 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Individual | HCP | Community | 52 weeks | M, L | Y | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Chiauzzi 2010114 | USA | Low back pain | 209 | P + PA + LS + ED | UC | Remote | Self | Community | 4 weeks | S, M | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Glombiewski 2010115 | Germany | Low back pain | 128 | P + MBT + LS | WLC | Individual | HCP | Medical | 32 weeks | M | Y | U | U | U | Y |

| Hamnes 2012116 | Norway | Fibromyalgia | 150 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 1 week | S | Y | Y | U | U | U |

| Hansson 2010117 | Sweden | OA hip/knee/hand | 114 | PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 5 weeks | M | Y | U | Y | Y | U |

| Hsu 2010118 | USA | Fibromyalgia | 45 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 3 weeks | S, M | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Lamb 201053 | UK | Low back pain | 701 | P + MBT + PA + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Mixed | 6 weeks | S, M, L | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Williams 2010119 | USA | Fibromyalgia | 118 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Remote | Self | Community | 24 weeks | M | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Luciano 2011120 | Spain | Fibromyalgia | 216 | P + MBT + PA + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 9 weeks | S | Y | U | U | Y | Y |

| Morone 2011121 | Italy | Low back pain | 73 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 4 weeks | S, M | U | U | Y | Y | N |

| Brosseau 2012122 | Canada | OA knee | 222 | P + PA | UC | Group | HCP | Community | 52 weeks | L | Y | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Carpenter 2012123 | USA | Low back pain | 141 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Remote | Self | Community | 3 weeks | S | Y | U | U | Y | U |

| Coleman 2012124 | Australia | OA knee | 146 | P + MBT + PA + LS + ED | WLC | Group | HCP | Community | 6 weeks | S, M | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kao 2012125 | Taiwan | OA knee | 259 | P + PA + LS + ED | UC | Group | HCP | Medical | 4 weeks | S | Y | U | Y | U | N |

| Martin 2012126 | Spain | Fibromyalgia | 180 | P + MBT + PA + ED | WLC | Group | HCP | Medical | 6 weeks | M | Y | U | U | U | N |

| McBeth 201252 | UK | Mixed pain | 442 | P + PA + LS | UC | Remote | HCP | Community | 24 weeks | M, L | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| P + LS | UC | Remote | HCP | Community | 24 weeks | M, L | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||

For the update review we included an additional 19 sets of data; one trial67 was included in the original meta-analyses but published longer-term follow-up data after our 2009 cut-off103 and we included this study in the update analyses. Of the 18 new studies, five were from the USA,113,114,118,119,123 three from the UK,51–53 two each from Australia112,124 and Spain120,126 and one each from Italy,121 Germany,115 Sweden,117 Norway,116 Taiwan125 and Canada122 (n = 3745). Five focused on low back pain,53,114,115,121,123 five on OA,112,117,122,124,125 five on fibromyalgia,116,118–120,126 two on mixed pain52,113 and one on knee pain only. 51 Fourteen were health care professionally led,51–53,113,115–118,120–122,124–126 one was mixed health care and lay led112 and three were self-led. 114,119,123 Nine were conducted in a medical setting,112,115–118,120,121,125,126 eight in the community51,52,113,114,119,122–124 and one in a mixed setting. 53 Ten were delivered in groups,53,116–118,120–122,124–126 four were delivered remotely via the internet52,114,119,123 and three were delivered individually;51,113,115 one used a mixed method of delivery. 112 The mean age of participants for 17 of the 18 studies reporting age was 54 years (range when specified 25–84 years) and 2509 (67%) of the 3745 participants were female (see Table 3).

Quality assessment

Around half of the original 46 studies (54%) reported an adequate randomisation sequence, and in the remainder of the studies this was unclear. Allocation concealment was present in nine studies (20%), absent in two (4%) and unclear in 35 (78%). Masked outcome assessment was reported in 19 studies (41%), with the remainder unclear. Nearly all studies (91%) reported reasons for dropping out of the study and, in the 44 studies reporting this, the mean attrition rate across all study arms was 18% (range 6–47%). One study reported a 100% completion rate and 11 studies had an attrition rate of > 20%. Only 22 studies (48%) reported that they had analysed their data on an ITT basis, using last observation carried forward or imputation methods to fill in missing data (see Table 3). Quality assessment in the updated articles showed that 17 out of 18 studies reported adequate randomisation procedures, 9 out of 18 used concealed allocation, 10 out of 18 reported withdrawals, in 14 out of 18 researchers were masked to outcomes and in 15 out of 18 ITT analyses were conducted (see Table 3).

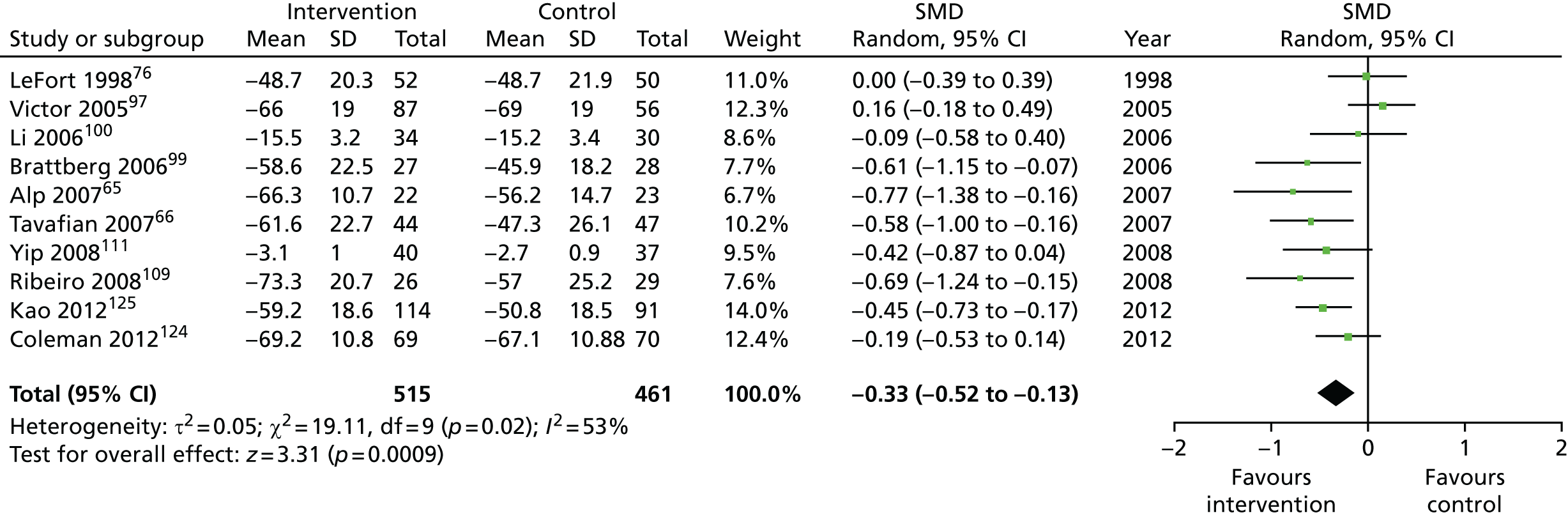

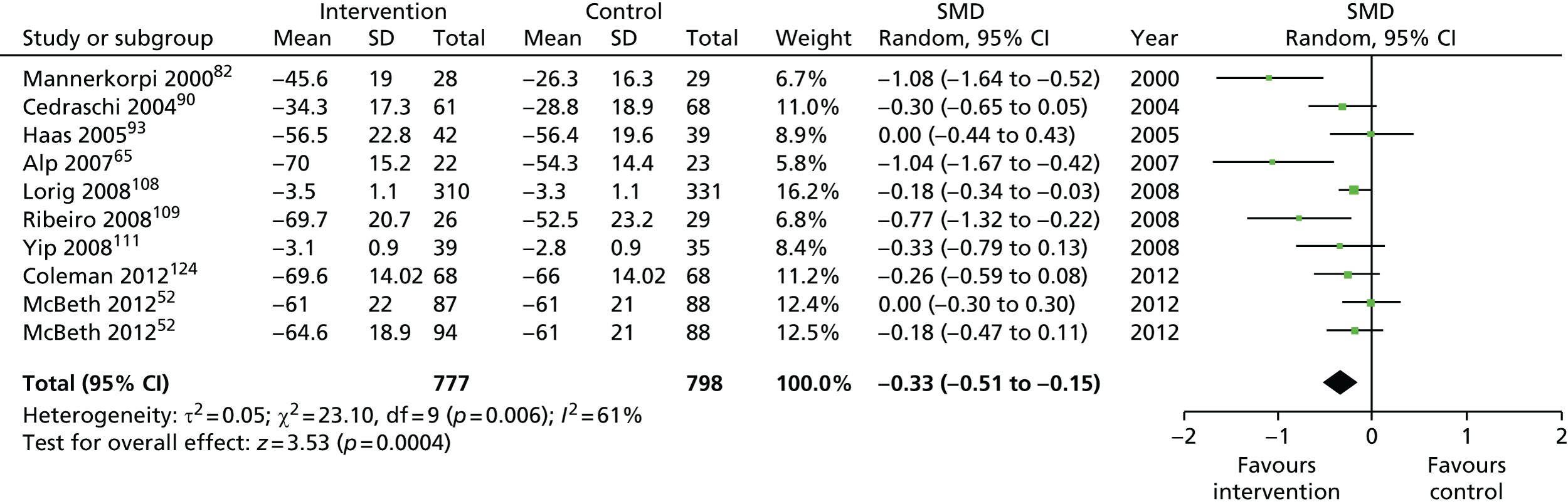

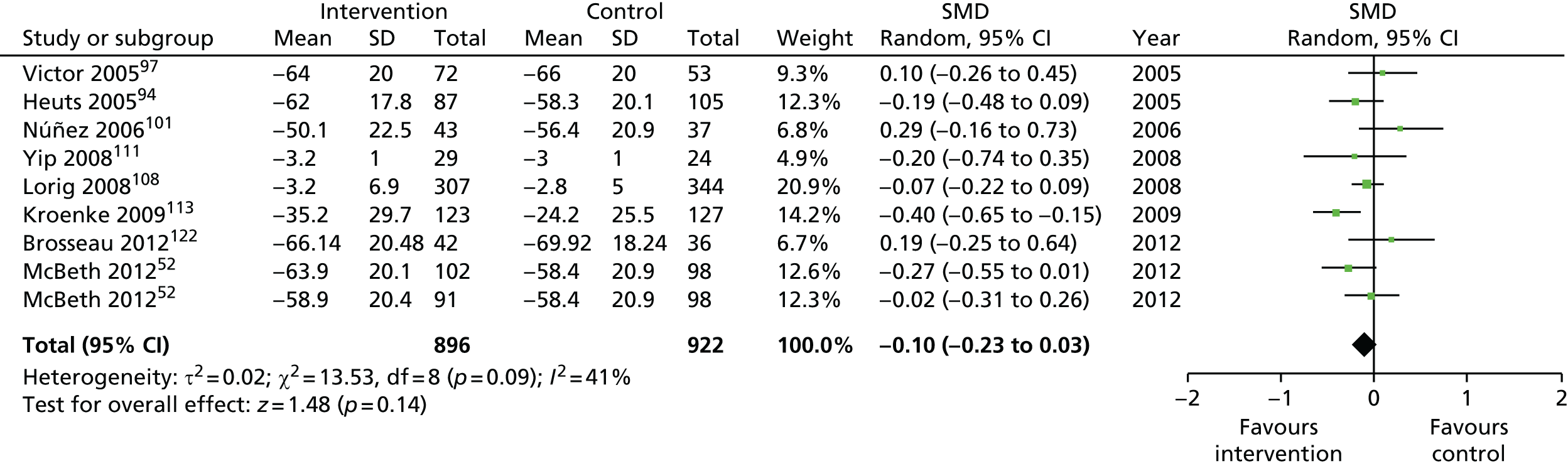

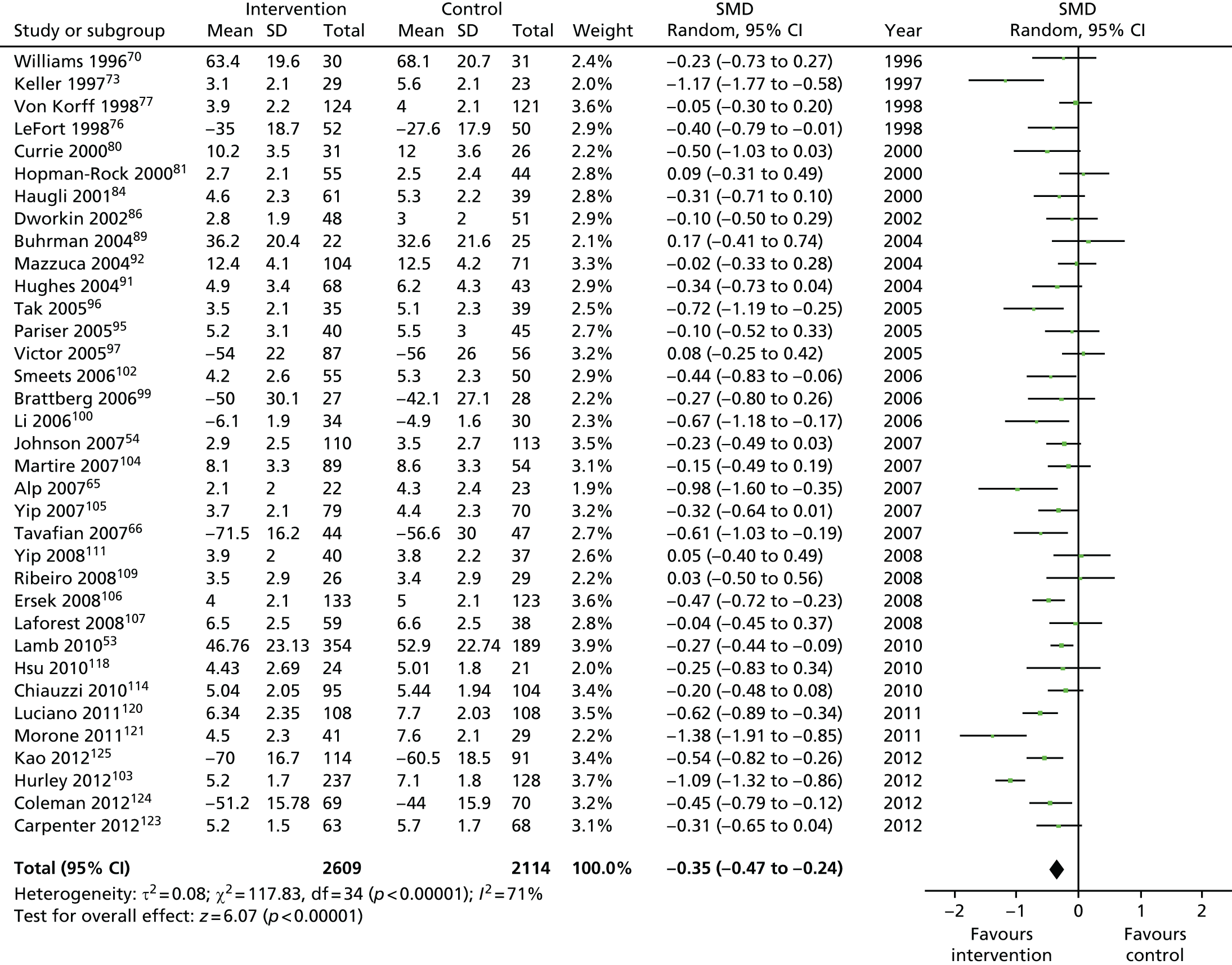

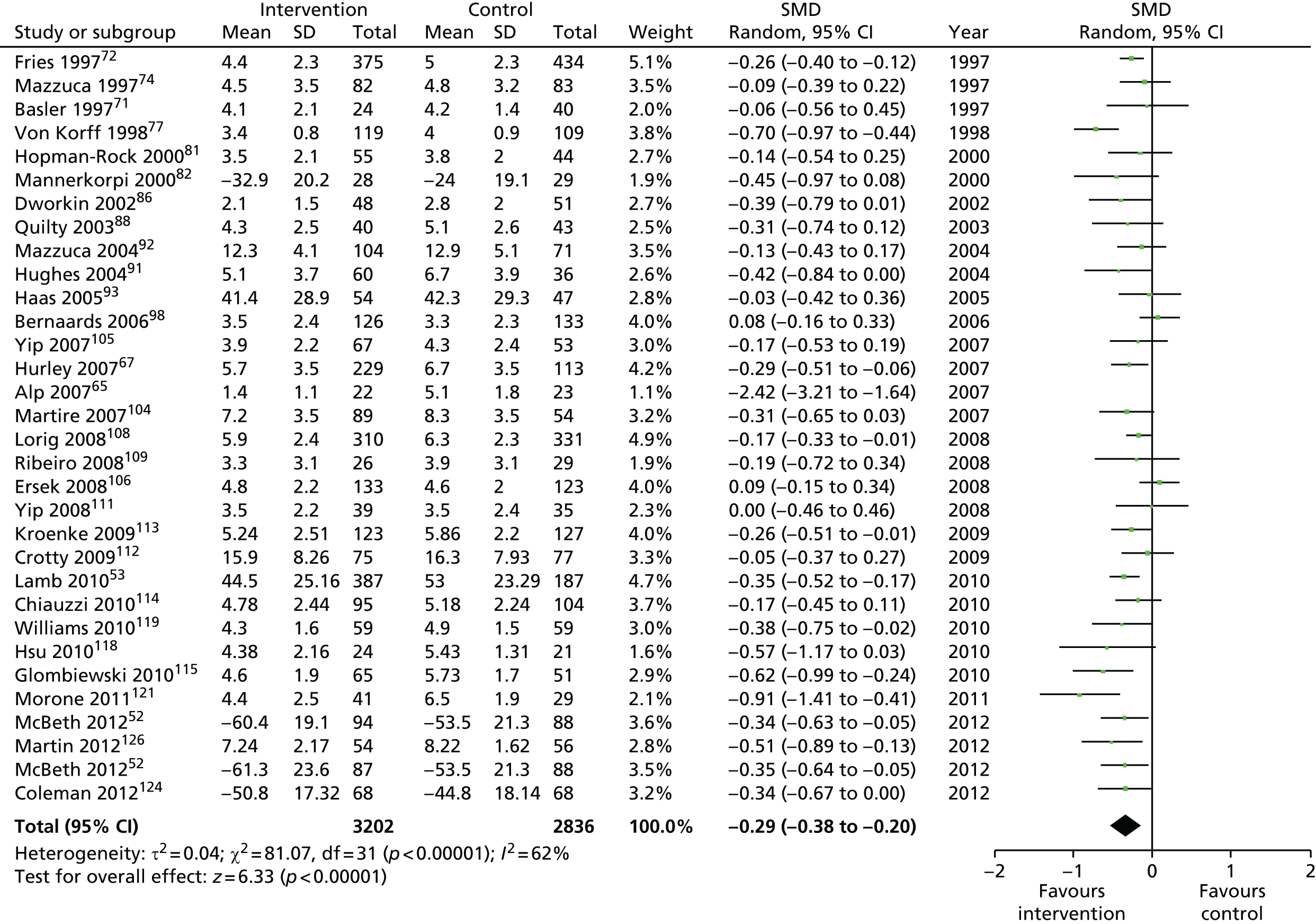

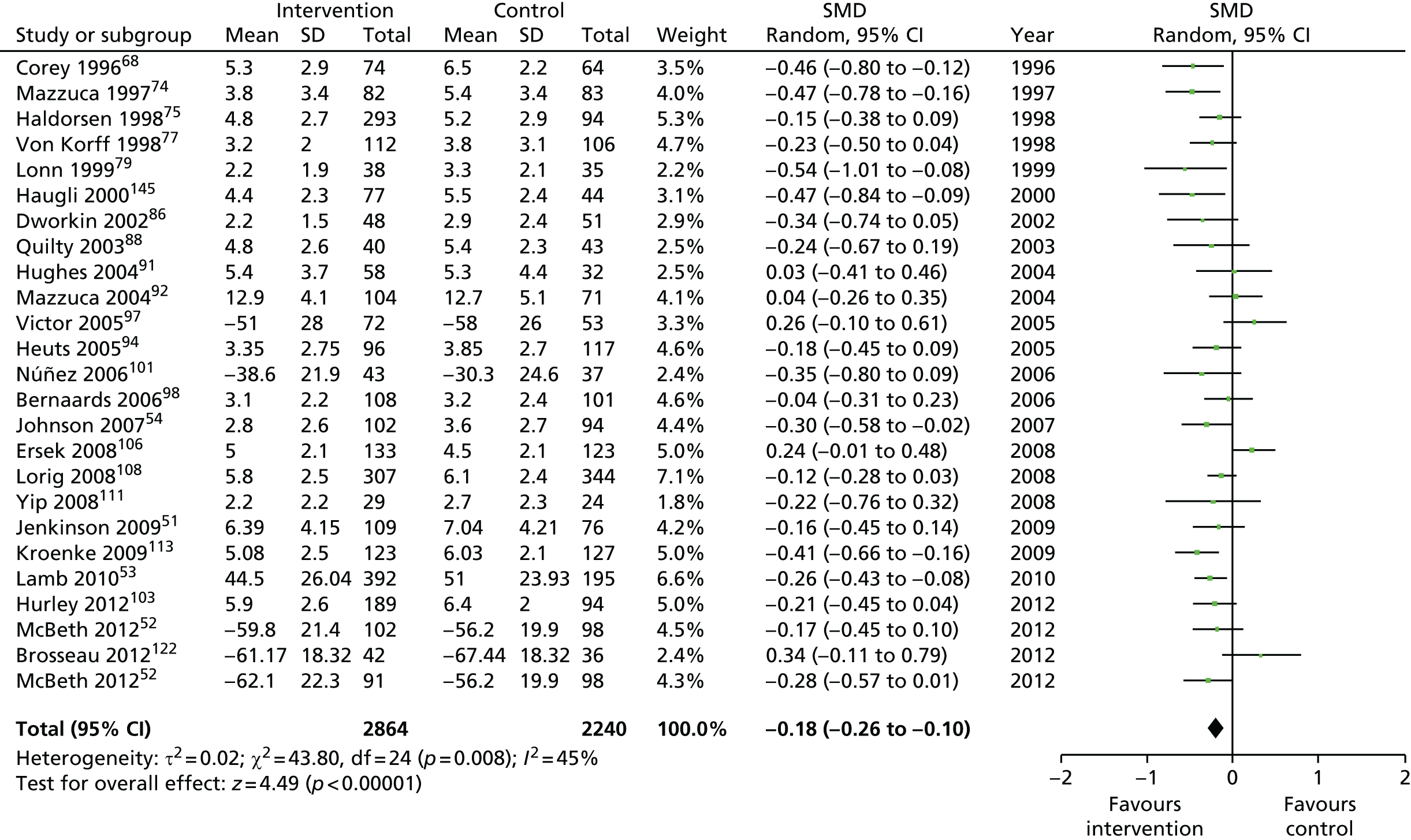

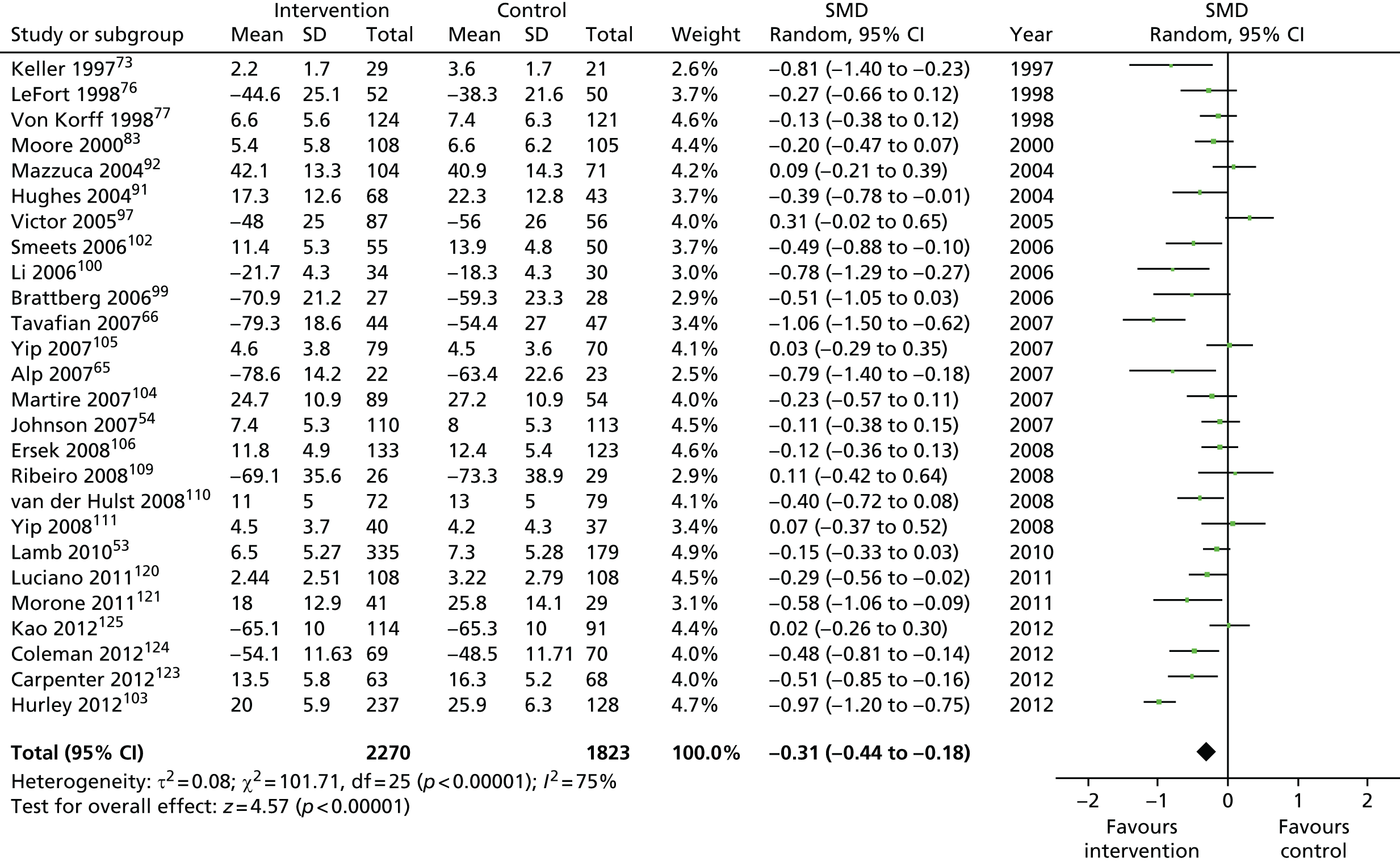

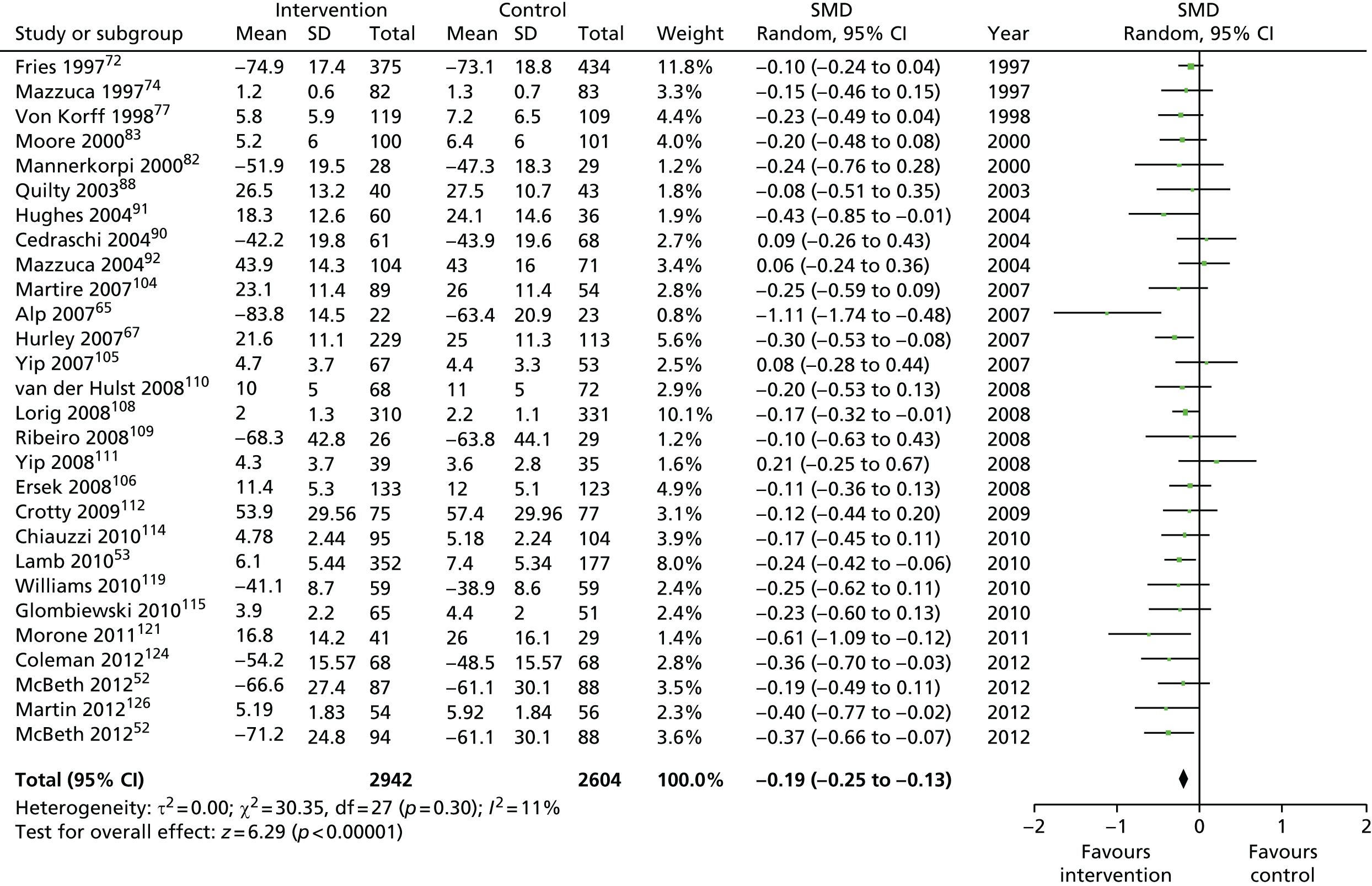

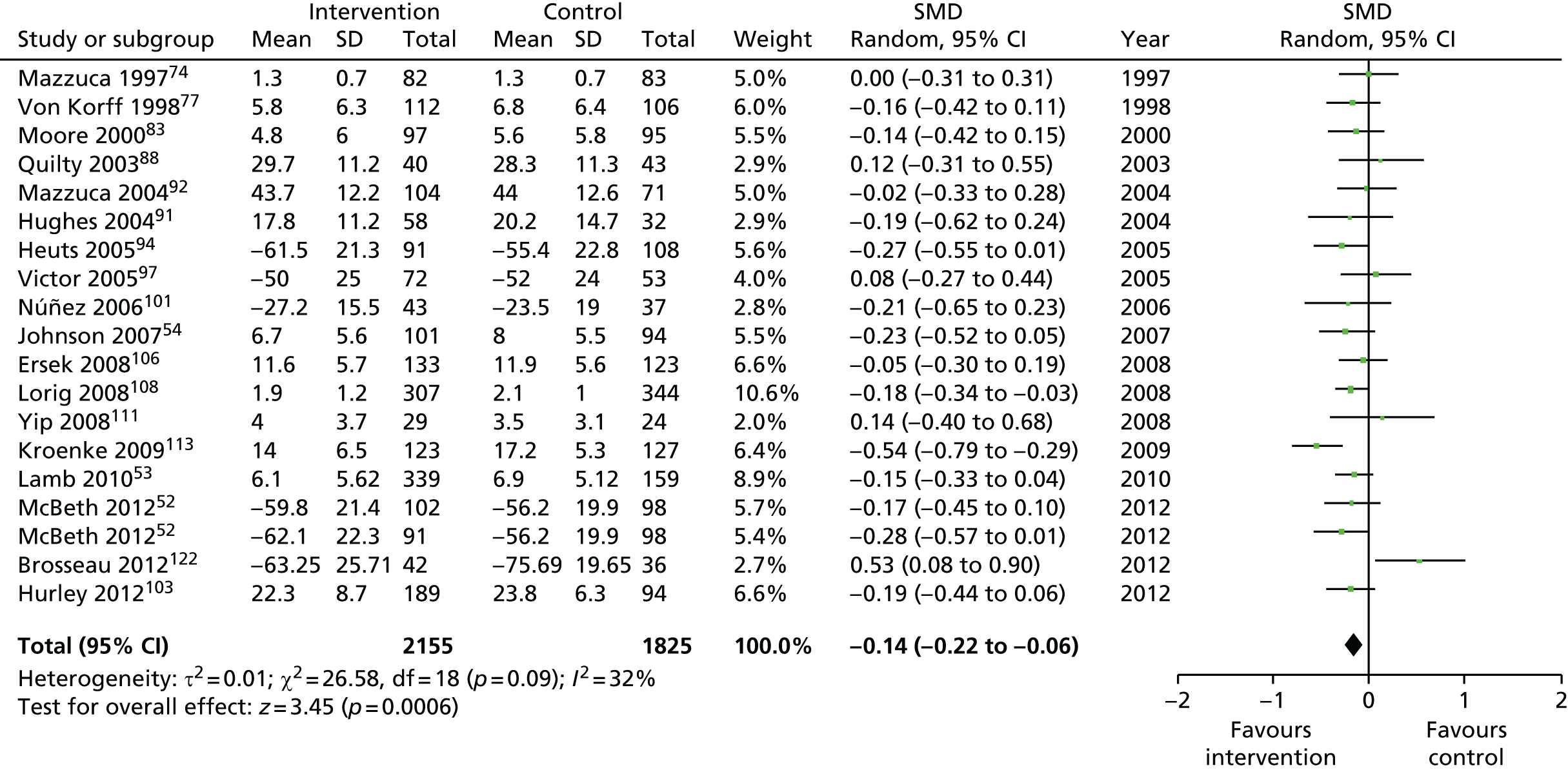

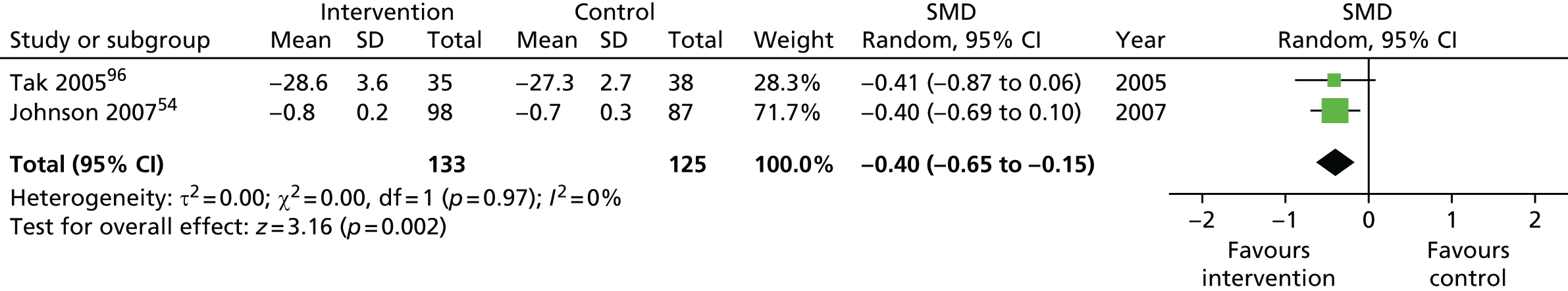

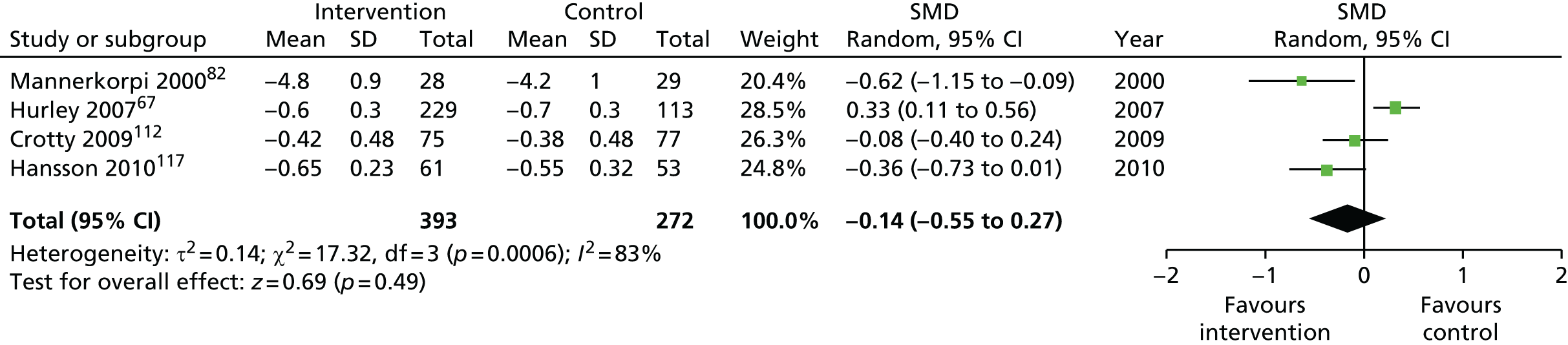

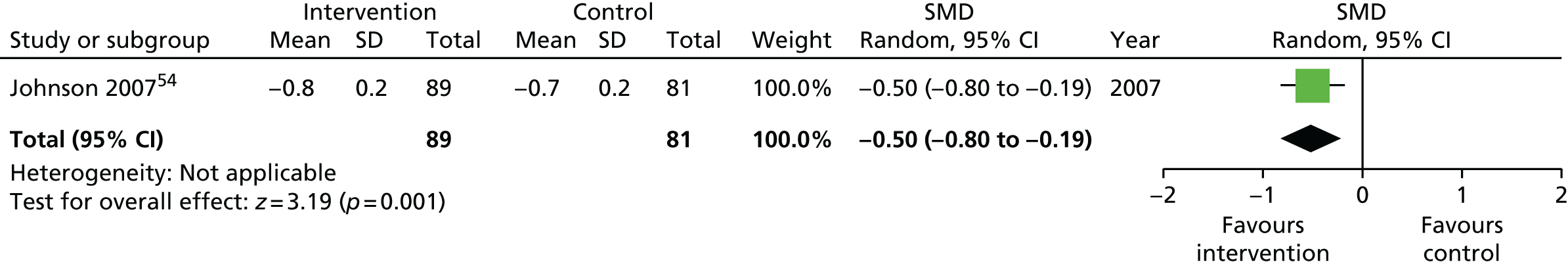

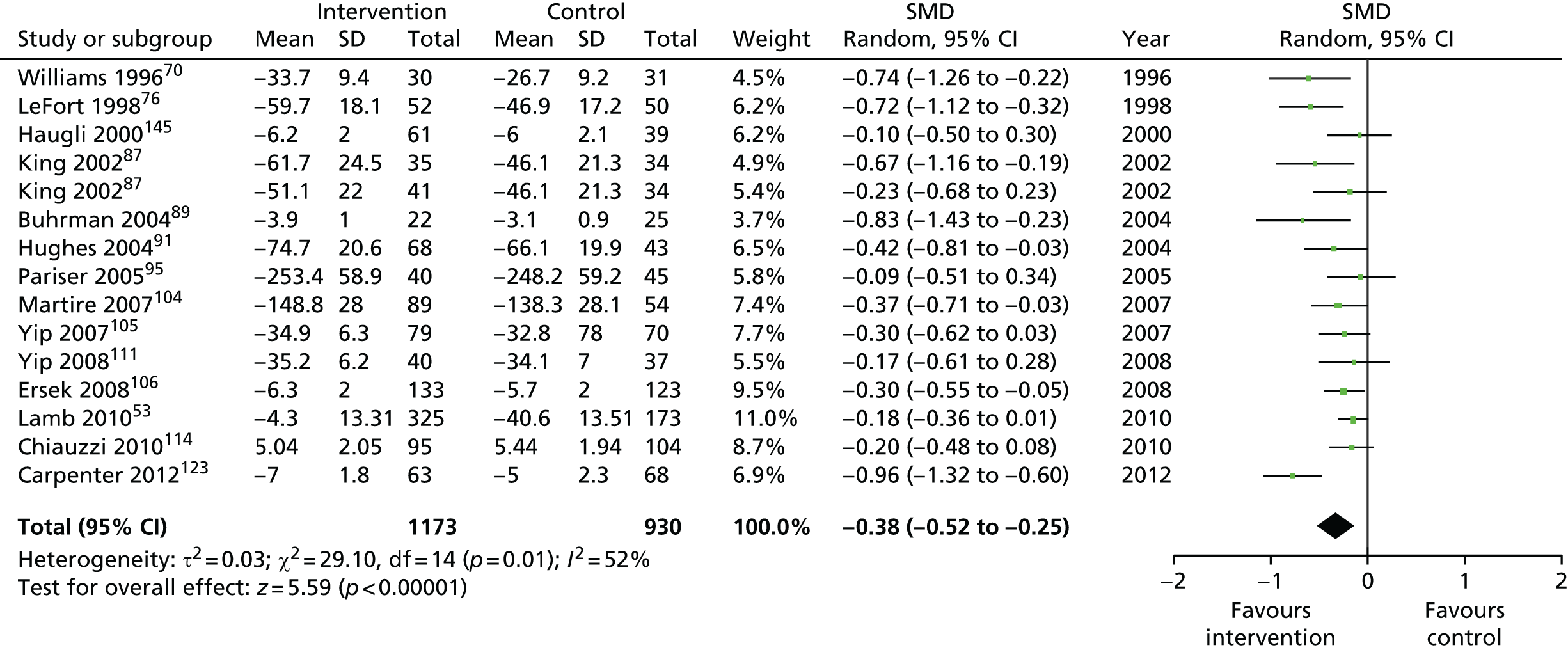

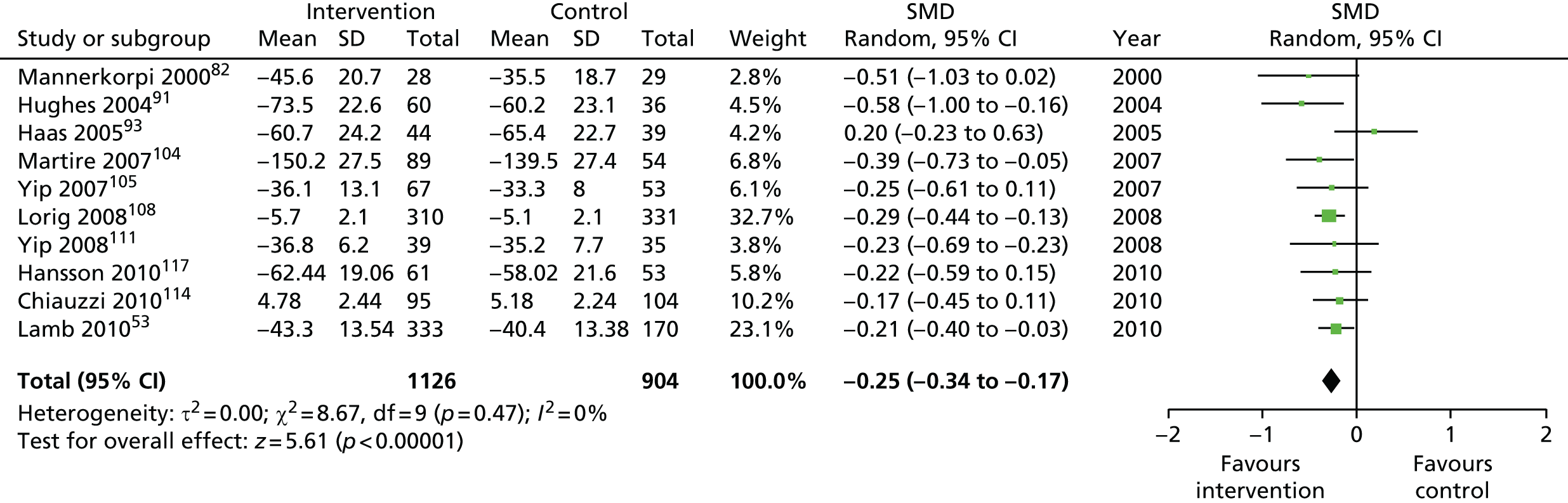

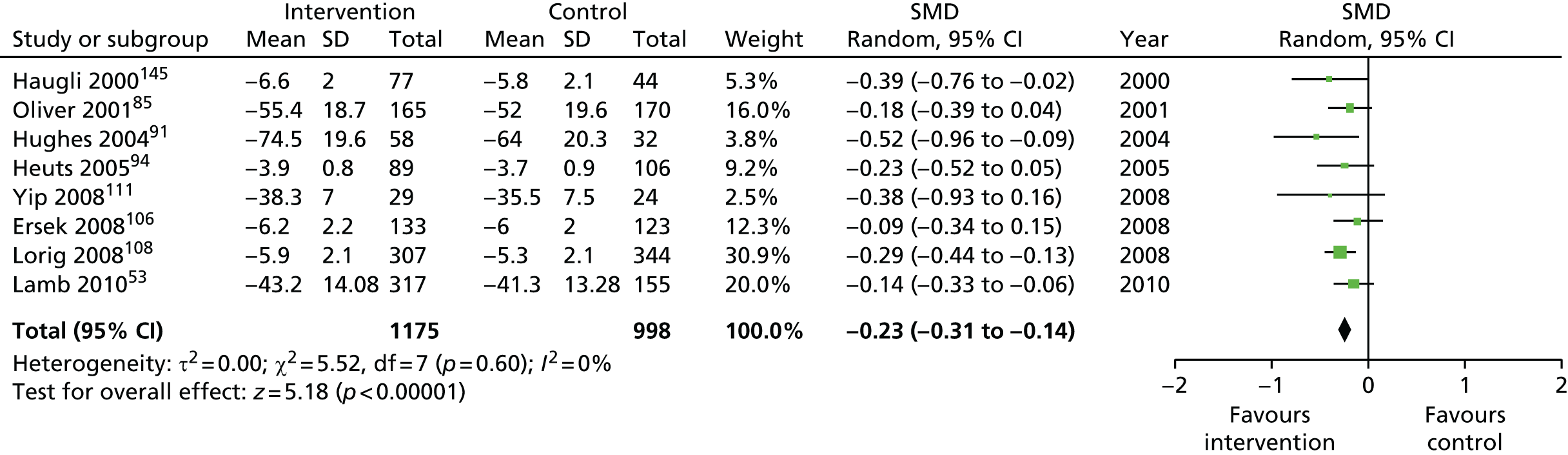

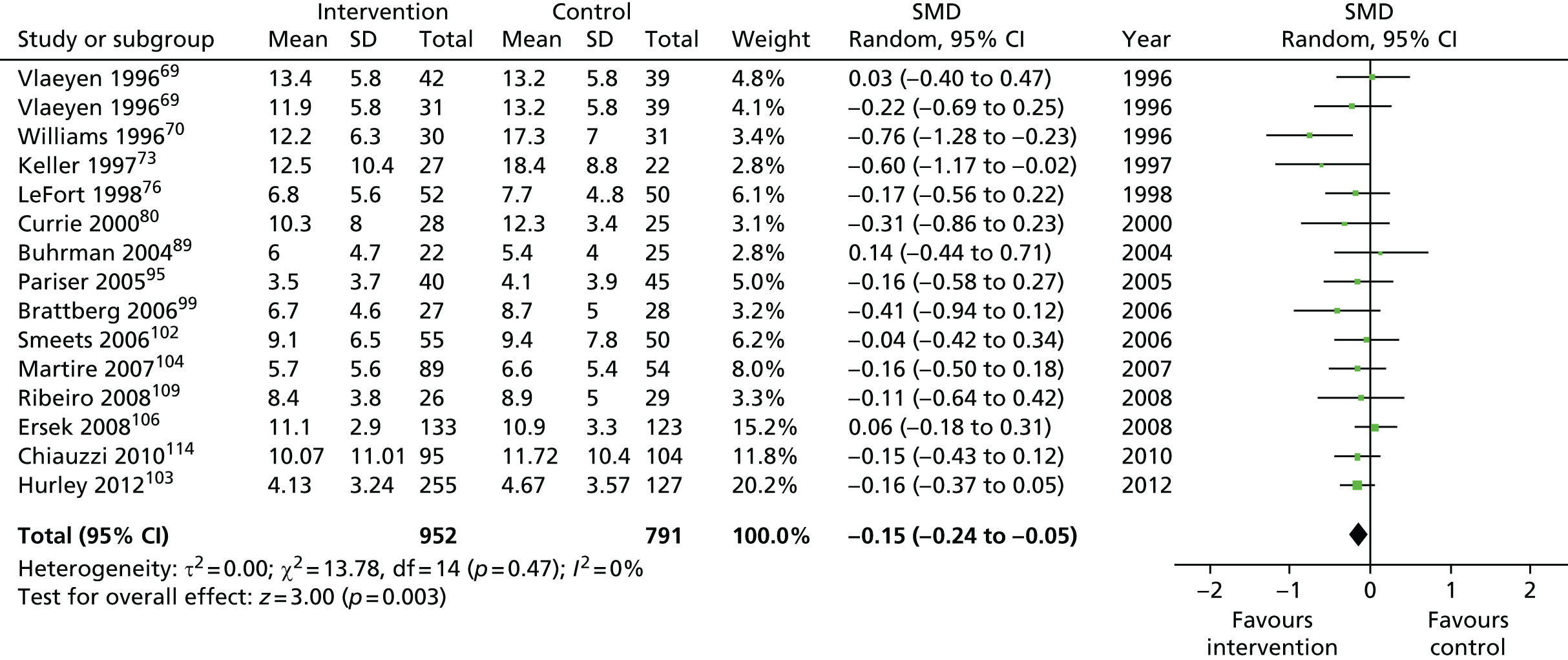

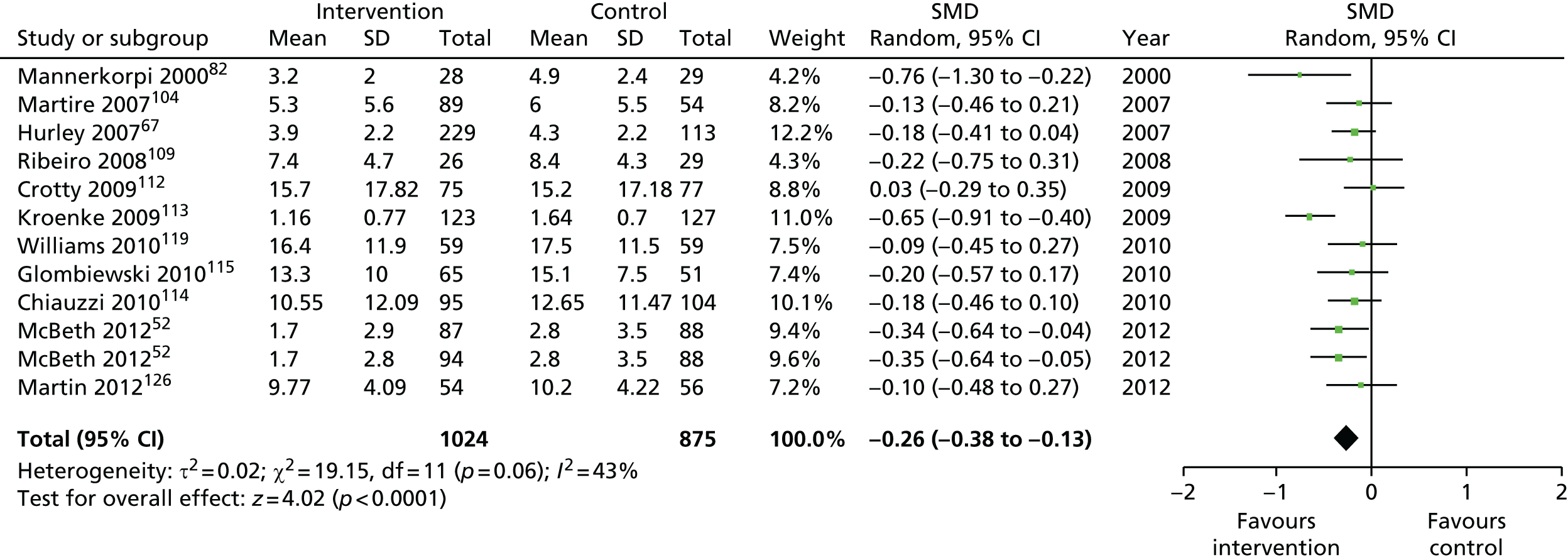

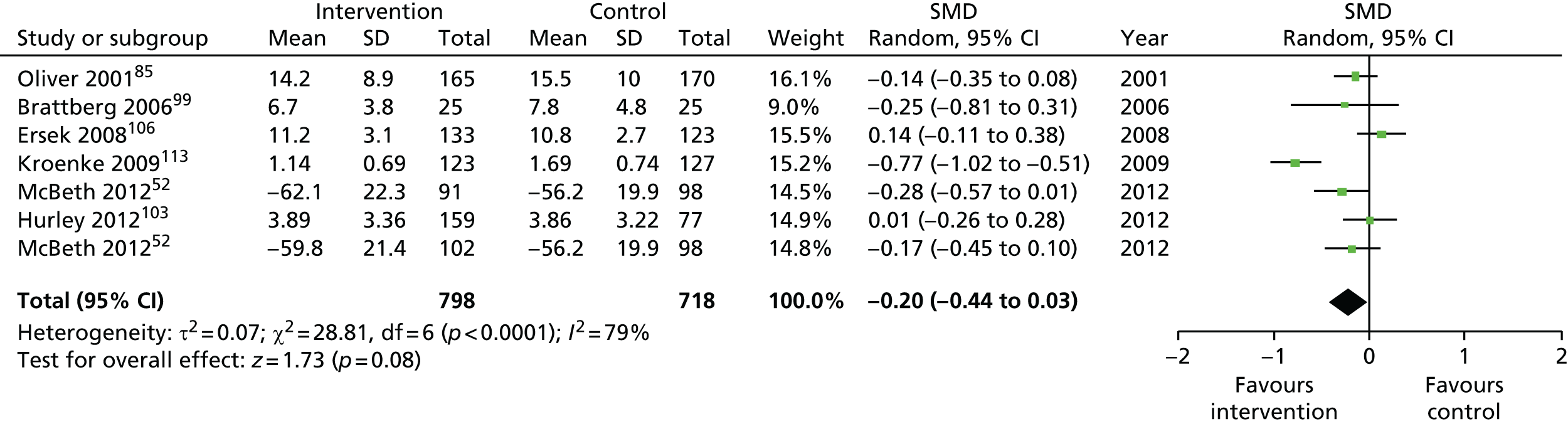

Overall effectiveness of self-management programmes

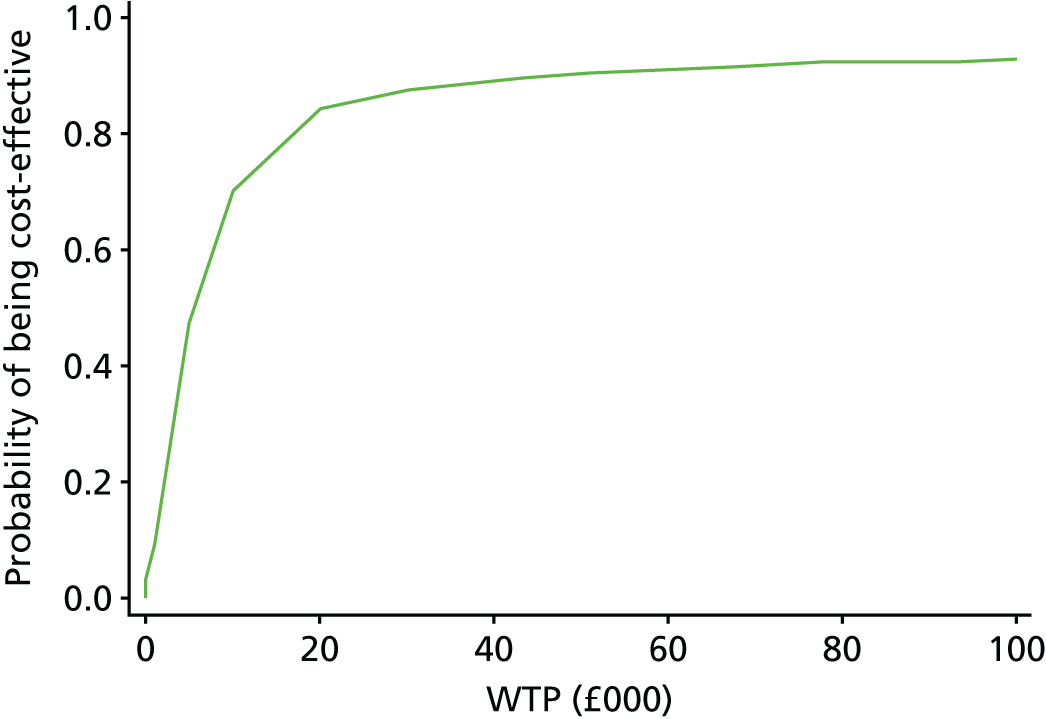

We used the data from the original review (up to 2009) to inform our intervention design (Table 4). The final column of this table includes the updated meta-analyses. The addition of studies from the updated search made little difference to these findings with the exception that there are more studies reporting depression and those reporting medium- and longer-term results show small effects on most outcomes. The differences in results between 2009 and 2013 showed changes in effect sizes for anxiety (small significant medium effect size in the long term) and social function (in the medium term) (see Appendix 1 for forest plots). In summary, these data suggest that the interventions studied have small beneficial effects on global health, pain intensity, physical function, quality of life, anxiety and social function in the short term and sometimes the medium term but that these effects are much reduced in studies reporting longer-term follow-up (beyond 8 months). For quality of life and anxiety, the effects in studies reporting longer-term follow-up remain small rather than ‘minor’, but closer examination reveals that in each case there was only one small study supplying longer-term follow-up data, raising the possibility of publication bias. For depression the beneficial effects are ‘minor’ in the short term but small in the medium term; however, there are far fewer studies reporting medium-term (or long-term) effects. Unlike the other outcomes, there appears to be a small beneficial effect on self-efficacy in studies reporting short-, medium- and long-term follow-up.

| Outcome | Follow-up (months) | January 1994–April 2009 | January 1994–September 2013 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants (number of studies) | Effect size (95% CI) | Number of participants (number of studies) | Effect size (95% CI) | ||

| Global health | |||||

| Short term | < 4 | 632 (8) | –0.34 (–0.59 to –0.08) | 976 (10) | –0.33 (–0.52 to –0.13) |

| Medium term | 4–8 | 1082 (7) | –0.46 (–0.73 to –0.19) | 1575 (10)a | –0.33 (–0.51 to –0.15) |

| Long term | > 8 | 1101 (5) | –0.05 (–0.18 to 0.08) | 1818 (9)a | –0.10 (–0.23 to 0.03) |

| Pain intensity | |||||

| Short term | < 4 | 2810 (26) | –0.27 (–0.37 to –0.16) | 4723 (35) | –0.35 (–0.47 to –0.24) |

| Medium term | 4–8 | 3911 (20) | –0.25 (–0.38 to –0.12) | 6038 (32)a | –0.29 (–0.38 to –0.20) |

| Long term | > 8 | 3332 (18) | –0.18 (–0.28 to –0.07) | 5104 (25)a | –0.18 (–0.26 to –0.10) |

| Physical function | |||||

| Short term | < 4 | 2453 (19) | –0.26 (–0.40 to –0.12) | 4093 (26) | –0.31 (–0.44 to –0.18) |

| Medium term | 4–8 | 3759 (18) | –0.15 (–0.23 to –0.07) | 5546 (28)a | –0.19 (–0.25 to –0.13) |

| Long term | > 8 | 2482 (13) | –0.12 (–0.20 to –0.04) | 3980 (19)a | –0.14 (–0.22 to –0.06) |

| Quality of life | |||||

| Short term | < 4 | 258 (2) | –0.40 (–0.65 to –0.15) | 258 (2) | –0.40 (–0.65 to –0.15) |

| Medium term | 4–8 | 399 (2) | –0.11 (–1.05 to 0.82) | 665 (4) | –0.14 (–0.55 to 0.27) |

| Long term | > 8 | 170 (1) | –0.50 (–0.80 to –0.19) | 170 (1) | –0.50 (–0.80 to –0.19) |

| Self-efficacy | |||||

| Short term | < 4 | 1275 (12)a | –0.37 (–0.50 to –0.24) | 1173 (15)a | –0.38 (–0.52 to –0.25) |

| Medium term | 4–8 | 1214 (7) | –0.29 (–0.44 to –0.14) | 2030 (10) | –0.25 (–0.34 to –0.17) |

| Long term | > 8 | 1701 (7) | –0.25 (–0.35 to –0.15) | 2173 (8) | –0.23 (–0.31 to –0.14) |

| Depression | |||||

| Short term | < 4 | 1162 (13)a | –0.15 (–0.28 to –0.03) | 1743 (15)a | –0.15 (–0.24 to –0.05) |

| Medium term | 4–8 | 597 (4) | –0.25 (–0.47 to –0.03) | 1899 (12)a | –0.26 (–0.38 to –0.13) |

| Long term | > 8 | 641 (3) | –0.04 (–0.26 to 0.18) | 1516 (7)a | –0.20 (–0.44 to 0.03) |

| Anxiety | |||||

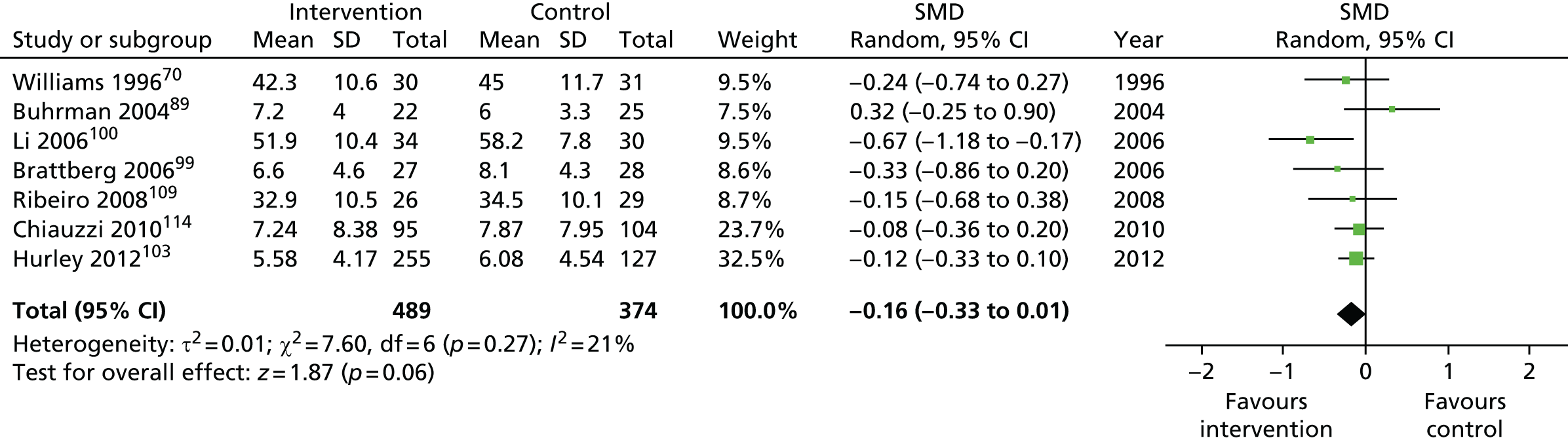

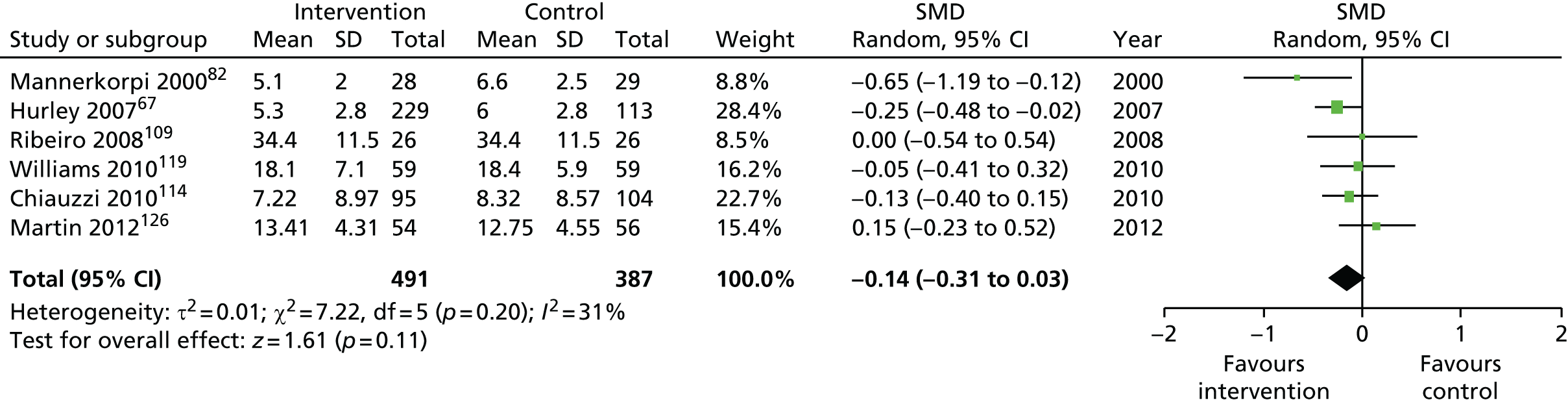

| Short term | < 4 | 282 (5) | –0.23 (–0.54 to 0.08) | 863 (7) | –0.16 (–0.33 to 0.01) |

| Medium term | 4–8 | 451 (3) | –0.28 (–0.56 to 0.00) | 878 (6) | –0.14 (–0.31 to 0.03) |

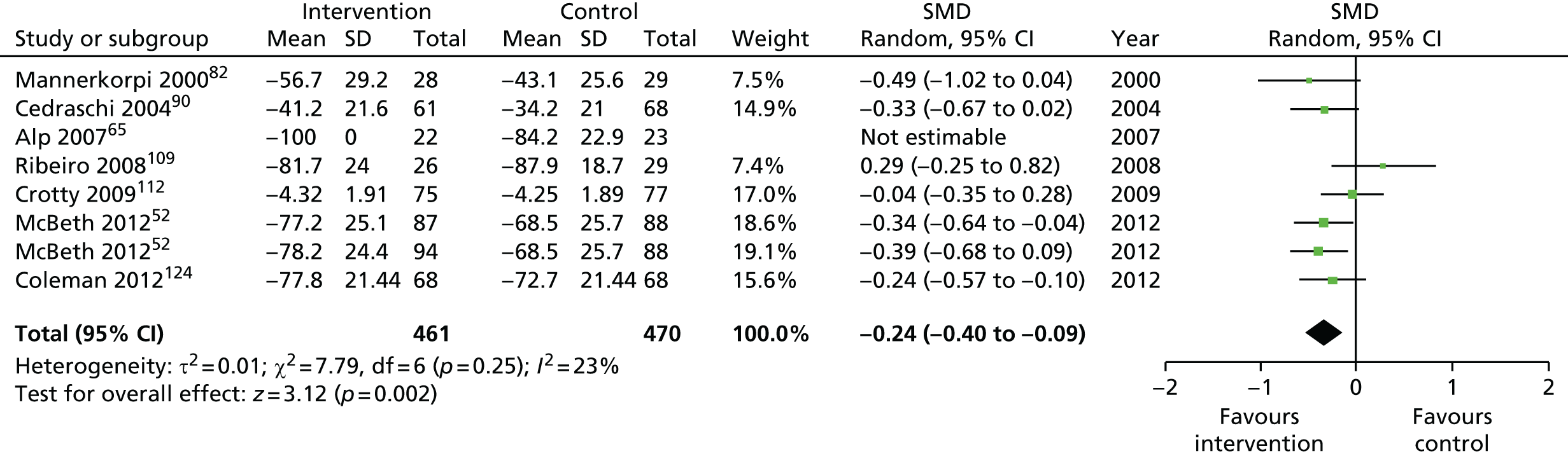

| Long term | > 8 | 50 (1) | –0.28 (–0.84 to 0.27) | 553 (3) | –0.41 (–0.58 to –0.24) |

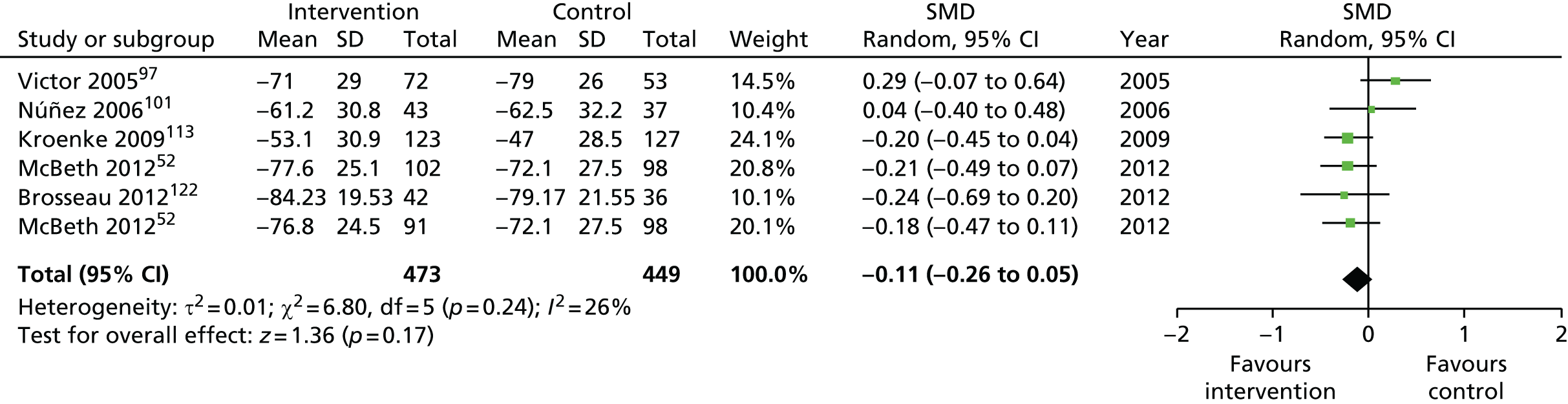

| Social function | |||||

| Short term | < 4 | 555 (7) | –0.31 (–0.57 to –0.04) | 899 (9) | –0.33 (–0.53 to –0.12) |

| Medium term | 4–8 | 286 (4) | –0.19 (–0.61 to 0.22) | 931 (8)a | –0.24 (–0.40 to –0.09) |

| Long term | > 8 | 205 (2) | 0.19 (–0.09 to 0.47) | 922 (6)a | –0.11 (–0.26 to 0.05) |

Effectiveness of the different characteristics of self-management programmes

The data for these analyses come from the studies identified in the original search (1994–2009).

For ease of reading we present the statistically significant SMD effect sizes [with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] only for data favouring self-management over waiting list control or usual care for each outcome subgroup comparison except for fatigue, SF-36 general mental health and visits to HCPs. Tables showing all of the results are available from the corresponding author.

In Tables 5–7 we present small (≥ 0.2), moderate (≥ 0.5) and large (≥ 0.8) effect sizes for different outcomes at different follow-up intervals. Results that favoured the control arm, favoured neither subgroup, were non-estimable or resulted in minor effect sizes are presented in the accompanying text for each outcome.

| Outcome | Course delivery mode (95% CI) | Course leader (95% CI) | Course setting (95% CI) | Course duration (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Individual | Mixed | Remote | HCP led | Lay led | Mixed | Medical | Community | Occupational | ≤ 8 weeks | > 8 weeks | |

| Global health | 0.45 (0.17 to 0.73) | 0.61a (0.07 to 1.15) | 0.56 (0.26 to 0.86) | 0.42 (0.05 to 0.80) | 0.30 (0.03 to 0.58) | 0.61a (0.07 to 1.15) | ||||||

| Pain intensity | 0.24 (0.12 to 0.35) | 0.59 (0.03 to 1.15) | 0.27 (0.14 to 0.39) | 0.28 (0.11 to 0.45) | 0.46 (0.11 to 0.81) | 0.24 (0.12 to 0.36) | 0.22 (0.03 to 0.42) | |||||

| Physical function | 0.25 (0.09 to 0.40) | 0.28 (0.10 to 0.47) | 0.24 (0.03 to 0.45) | 0.21 (0.07 to 0.34) | 0.78a (0.27 to 1.29) | 0.26 (0.10 to 0.41) | ||||||

| Quality of life | 0.40a (0.10 to 0.69) | 0.40 (0.15 to 0.65) | 0.40a (0.10 to 0.69) | 0.40 (0.15 to 0.65) | ||||||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.37 (0.25 to 0.50) | 0.38 (0.23 to 0.52) | 0.37a (0.03 to 0.71) | 0.37 (0.07 to 0.66) | 0.41 (0.26 to 0.57) | 0.39 (0.25 to 0.54) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 0.67a (0.17 to 1.18) | 0.67a (0.17 to 1.18) | ||||||||||

| Depression | 0.25 (0.04 to 0.46) | |||||||||||

| SF-36 social function | 0.38 (0.09 to 0.68) | 0.51 (0.11 to 0.91) | 0.54a (0.04 to 1.04) | |||||||||

| Outcome | Course delivery mode (95% CI) | Course leader (95% CI) | Course setting (95% CI) | Course duration (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Individual | Mixed | Remote | HCP led | Lay led | Mixed | Medical | Community | Occupational | ≤ 8 weeks | > 8 weeks | |

| Global health | 0.54 (0.21 to 0.88) | 0.67 (0.20 to 1.15) | 0.54 (0.22 to 0.87) | 0.36 (0.12 to 0.6) | 1.08a (0.52 to 1.64) | |||||||

| Pain intensity | 0.25 (0.02 to 0.47) | 0.20 (0.02 to 0.37) | 0.29a (0.06 to 0.51) | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.32) | 0.24 (0.01 to 0.47) | 0.25 (0.08 to 0.42) | ||||||

| Physical function | 0.26 (0.09 to 0.44) | |||||||||||

| Quality of life | 0.62a (0.09 to 1.15) | 0.62a (0.09 to 1.15) | 0.62a (0.09 to 1.15) | |||||||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.29 (0.08 to 0.50) | 0.29a (0.13 to 0.44) | 0.37 (0.16 to 0.59) | 0.30 (0.09 to 0.52) | 0.27 (0.11 to 0.43) | |||||||

| Anxiety | 0.25a (0.02 to 0.48) | 0.65a (0.12 to 1.19) | 0.65a (0.12 to 1.19) | |||||||||

| Depression | 0.76a (0.22 to 1.30) | |||||||||||

| SF-36 social function | ||||||||||||

| Outcome | Course delivery mode (95% CI) | Course leader (95% CI) | Course setting (95% CI) | Course duration (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Individual | Mixed | Remote | HCP led | Lay led | Mixed | Medical | Community | Occupational | ≤ 8 weeks | > 8 weeks | |

| Global health | ||||||||||||

| Pain intensity | 0.20 (0.04 to 0.36) | 0.26 (0.15 to 0.36) | 0.23 (0.03 to 0.42) | |||||||||

| Physical function | ||||||||||||

| Quality of life | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | ||||||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.23 (0.10 to 0.35) | 0.29a (0.13 to 0.44) | 0.25 (0.10 to 0.40) | 0.29a (0.13 to 0.44) | 0.26 (0.01 to 0.52) | 0.23 (0.11 to 0.36) | 0.39a (0.02 to 0.76) | 0.26 (0.14 to 0.37) | 0.23 (0.04 to 0.42) | |||

| Anxiety | ||||||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| SF-36 social function | ||||||||||||

Effect sizes for course delivery mode (see Tables 5–7)

Of the 46 studies, 27 (59%) involved group interventions, five (11%) remote interventions and five (11%) individually delivered interventions; the remaining nine (20%) used a mixture of both group delivery and individual delivery (see Table 3). We assessed the four types of delivery methods against eight outcomes over three time periods, giving a potential of 96 subgroup effect sizes. Twenty-three small to large beneficial effects favouring self-management were found. Only one effect size comparison favoured the control (mixed led, medium term, quality of life: –0.33, 95% CI –0.11 to –0.56). Forty of the subgroup effect sizes showed no difference between self-management interventions and the waiting list control/usual care, seven showed minor (< 0.2) benefits favouring self-management and 48 were non-estimable because of a lack of data. Courses delivered to groups appeared to have the most statistically significant beneficial effects compared with control groups in the short, medium and long term. Data on outcomes for courses delivered to individuals were very sparse. Mixed and remotely delivered interventions may be beneficial but not as much as courses delivered to groups.

Effect sizes for type of course leader (see Tables 5–7)

The majority of courses [36/46 (78%)] were delivered by HCPs, with six courses (13%) delivered by a combination of HCPs and laypeople and four courses (9%) delivered by laypeople only (see Table 3). Effect sizes were calculated for these three different types of leader combinations. A total of 90 comparisons were made. Small to large beneficial effects sizes were shown favouring self-management in 12 instances and minor benefits (< 0.2) were shown in nine. Thirty-nine subgroup comparisons showed no significant benefit in either study arm and 28 comparisons were non-estimable because of a lack of data. No comparisons favoured the control arm.

Health-care professional-led self-management courses showed beneficial effects in the short, medium and long term over a range of outcomes. Lay-led courses had a small, statistically significant beneficial effect on self-efficacy only. Mixed HCP- and lay-delivered courses showed moderate to large benefits for SF-36 social function scores and global health status, but data for several comparisons were sparse with some effect sizes obtained from only one study.

Effect sizes for course setting (see Tables 5–7)

Twenty-seven (59%) studies were conducted in medical settings, 16 (35%) in community settings and three (7%) in occupational settings. A total of 90 comparisons were made. Small to large beneficial effects favouring self-management were shown for 22 subgroup analyses, with one comparison favouring the control (medical setting, medium term, quality of life: –0.33, 95% CI –0.11 to –0.56). In 31 comparisons there was no difference between the study arms, five comparisons showed minor benefits (< 0.2) for self-management and 28 comparisons were non-estimable because of a lack of data.

Pain intensity was significantly improved at all three follow-up time points in the studies conducted in medical settings but not in the studies in community settings.

Self-efficacy showed small to moderate statistically significant improvements favouring self-management in medical and community settings at most time intervals. Data for self-efficacy for self-management courses in an occupational setting were sparse. Physical function appeared to show statistically significant effect sizes favouring self-management in medical, community and occupational settings in the short term. Overall, medical and community settings had better outcomes than occupational or remote settings but there were too few studies in occupational settings to draw firm conclusions.

Effect sizes for course duration (see Tables 5–7)

Two course duration periods were assessed: ≤ 8 weeks and > 8 weeks. A total of 60 comparisons were made. Around one-third of the comparisons (18/48) showed small to large beneficial effects favouring self-management. However, one comparison favoured the control (< 8 weeks, medium term, quality of life: –0.33, 95% CI –0.11 to –0.56). All other subgroup analyses showed no benefit for either arm or minor benefits for self-management (25/48), or were non-estimable because of a lack of data (5/48).

Small to moderate statistically significant beneficial effect sizes were shown for a mix of outcomes for both short and longer durations of self-management courses at all time intervals. Statistically significant effect sizes did not appear to be enhanced by increased duration of courses.

Effectiveness of the different components of self-management programmes

In Tables 8–13 we present small (≥ 0.2), moderate (≥ 0.5) and large (≥ 0.8) effect sizes for different outcomes at different follow-up intervals. Results that favoured the control arm, favoured neither subgroup, were non-estimable or resulted in minor effect sizes are presented in the accompanying text.

| Outcome | Psychological (95% CI) | Lifestyle (95% CI) | Medical education (95% CI) | Physical activity (95% CI) | Mind–body therapies (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | |

| Global health | 0.53 (0.18 to 0.88) | 0.29 (0.02 to 0.56) | 0.69a (0.15 to 1.24) | 0.30 (0.03 to 0.58) | 0.61a (0.07 to 1.15) | 0.34 (0.02 to 0.66) | 0.48 (0.24 to 0.72) | |||

| Pain intensity | 0.28 (0.16 to 0.41) | 0.20 (0.09 to 0.32) | 0.36 (0.10 to 0.62) | 0.21 (0.09 to 0.33) | 0.38 (0.17 to 0.59) | 0.23 (0.11 to 0.35) | 0.28 (0.04 to 0.51) | 0.21 (0.06 to 0.36) | 0.28 (0.12 to 0.44) | |

| Physical function | 0.34 (0.18 to 0.50) | 0.22 (0.04 to 0.39) | 0.36 (0.17 to 0.55) | 0.24 (0.10 to 0.38) | 0.22 (0.08 to 0.36) | 0.65 (0.28 to 1.02) | 0.24 (0.10 to 0.38) | |||

| Quality of life | 0.40a (0.10 to 0.69) | 0.40 (0.15 to 0.65) | 0.40a (0.10 to 0.69) | 0.40 (0.15 to 0.65) | 0.40a (0.10 to 0.69) | |||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.41 (0.25 to 0.56) | 0.41 (0.24 to 0.57) | 0.31 (0.09 to 0.52) | 0.35 (0.21 to 0.48) | 0.56 (0.18 to 0.94) | 0.39 (0.25 to 0.52) | 0.42 (0.17 to 0.67) | 0.35 (0.19 to 0.51) | ||

| Anxiety | 0.36 (0.04 to 0.67) | 0.51 (0.14 to 0.88) | 0.39 (0.09 to 0.70) | |||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||

| SF-36 social function | 0.35 (0.05 to 0.65) | 0.35 (0.05 to 0.65) | 0.48 (0.11 to 0.84) | 0.39 (0.12 to 0.66) | ||||||

| Outcome | Psychological (95% CI) | Lifestyle (95% CI) | Medical education (95% CI) | Physical activity (95% CI) | Mind–body therapies (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | |

| Global health | 0.45 (0.10 to 0.79) | 0.52 (0.10 to 0.95) | 0.42 (0.13 to 0.70) | 0.77a (0.22 to 1.32) | 0.51 (0.17 to 0.85) | 0.46 (0.19 to 0.73) | 0.33 (0.01 to 0.65) | 0.67 (0.26 to 1.09) | ||

| Pain intensity | 0.29 (0.11 to 0.48) | 0.22 (0.11 to 0.33) | 0.22 (0.09 to 0.35) | 0.22 (0.09 to 0.35) | 0.20 (0.08 to 0.33) | 0.30 (0.05 to 0.55) | ||||

| Physical function | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.30) | 0.25 (0.06 to 0.44) | ||||||||

| Quality of life | ||||||||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.30 (0.09 to 0.52) | 0.23 (0.06 to 0.40) | 0.46 (0.20 to 0.73) | 0.26 (0.12 to 0.40) | 0.58a (0.16 to 1.00) | 0.29 (0.14 to 0.44) | 0.36 (0.17 to 0.55) | |||

| Anxiety | 0.38 (0.01 to 0.74) | 0.31 (0.11 to 0.50) | 0.38 (0.01 to 0.74) | |||||||

| Depression | 0.25 (0.03 to 0.47) | 0.25 (0.03 to 0.47) | ||||||||

| SF-36 social function | 0.38 (0.09 to 0.67) | 0.38 (0.09 to 0.67) | 0.38 (0.09 to 0.67) | |||||||

| Outcome | Psychological (95% CI) | Lifestyle (95% CI) | Medical education (95% CI) | Physical activity (95% CI) | Mind–body therapies (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | |

| Global health | ||||||||||

| Pain intensity | 0.20 (0.07 to 0.34) | |||||||||

| Physical function | ||||||||||

| Quality of life | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | 0.50a (0.19 to 0.80) | |||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.25 (0.15 to 0.34) | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.33) | 0.45 (0.16 to 0.73) | 0.24 (0.14 to 0.33) | 0.52a (0.09 to 0.96) | 0.25 (0.15 to 0.35) | 0.23 (0.13 to 0.33) | 0.47 (0.13 to 0.81) | ||

| Anxiety | ||||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||

| SF-36 social function | ||||||||||

| Outcome | Two components (95% CI) | Three components (95% CI) | Four components (95% CI) | Five components (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health | 0.65 (0.27 to 1.04) | 0.77a (0.16 to 1.38) | ||

| Pain intensity | 0.37 (0.15 to 0.59) | 0.23 (0.03 to 0.42) | ||

| Physical function | 0.37 (0.19 to 0.55) | 0.37 (0.07 to 0.67) | ||

| Quality of life | 0.40a (0.10 to 0.69) | |||

| Self-efficacy | 0.42a (0.03 to 0.81) | 0.28 (0.10 to 0.47) | 0.50 (0.04 to 0.96) | 0.43 (0.15 to 0.72) |

| Anxiety | 0.67a (0.17 to 1.18) | |||

| Depression | ||||

| SF-36 social function | 0.54a (0.04 to 1.04) | 0.63a (0.03 to 1.23) |

| Outcome | Two components (95% CI) | Three components (95% CI) | Four components (95% CI) | Five components (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health | 0.77a (0.22 to 1.32) | |||

| Pain intensity | 0.32 (0.06 to 0.59) | 0.63 (0.11 to 1.16) | ||

| Physical function | 0.21 (0.01 to 0.42) | |||

| Quality of life | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.58a (0.16 to 1.00) | 0.30 (0.08 to 0.52) | ||

| Anxiety | 0.38 (0.01 to 0.74) | |||

| Depression | ||||

| SF-36 social function |

| Outcome | Two components (95% CI) | Three components (95% CI) | Four components (95% CI) | Five components (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health | ||||

| Pain intensity | 0.36 (0.20 to 0.52) | |||

| Physical function | ||||

| Quality of life | 0.5a (0.19 to 0.80) | |||

| Self efficacy | 0.52a (0.09 to 0.96) | 0.39a (0.02 to 0.76) | 0.22 (0.11 to 0.32) | |

| Anxiety | ||||

| Depression | ||||

| SF-36 social function |

Effectiveness of self-management courses that include a psychological component (see Tables 8–10)

Only eight (17%) of the interventions in the included studies did not have a psychological component. A total of 48 comparisons were made, 21 of which showed no differences or minor effect sizes of < 0.2 between self-management and control. Eleven of the comparisons were non-estimable because of a lack of data. For interventions that included a psychological component we found small statistically significant effect sizes favouring self-management for pain intensity, physical/functional capability, SF-36 social function and self-efficacy for both short- and medium-term follow-up and there was evidence of benefit in the long term for self-efficacy but not for the other outcomes. There was no evidence that depression improved significantly for interventions with a psychological component although at medium-term follow-up anxiety was improved compared with the control groups. There was little evidence to support self-management interventions without a psychological component but most comparisons, except for pain, physical/functional capability and self-efficacy, had only one study or none at all examining this subgroup.

Effectiveness of self-management courses that include a lifestyle component (see Tables 8–10)

We included a variety of elements for the lifestyle component such as sleep management, relationship advice, diet advice, ergonomic guidance for return to work and stress management. Seven (15%) of the included studies involved an intervention that did not include a lifestyle component. A total of 48 comparisons were made, 17 of which showed no differences or minor effect sizes of < 0.2 between self-management and control. Ten of the comparisons were not estimable because of a lack of data. Overall, there was no discernible difference in the effect on self-efficacy, physical/functional capability, depression or global health status between interventions with and those without a lifestyle component.

Effectiveness of self-management courses that include a medical education component (see Tables 8–10)

Thirty-five (76%) of the interventions included a medical education component. A total of 48 comparisons were made, 21 of which showed no differences or minor effect sizes of < 0.2 between self-management and control. Ten of the comparisons were not estimable because of a lack of data. There was some evidence in favour of a medical education component with regard to anxiety in the short term and pain intensity and depression in the medium to long term. Significant moderate benefits in terms of self-efficacy were noted compared with control groups in interventions without an educational component in the short term and in medium- and long-term single studies. Data for many comparisons were very sparse.

Effectiveness of self-management courses that include a physical activity component (see Tables 8–10)

A total of 48 comparisons were made, 18 of which showed no differences or minor effect sizes of < 0.2 between self-management and control. Twenty of the comparisons were not estimable because of a lack of data. Only six (13%) of the included studies involved an intervention that did not include a physical activity component. Interventions that included a physical activity component showed some small statistically significant effect sizes favouring self-management for the following outcomes: pain intensity (medium term), self-efficacy (short term), SF-36 general mental health (short term) and global health status (short term).

Most comparisons were limited by having only one study or no studies without a physical activity component.

Effectiveness of self-management courses that include a mind–body therapy component (see Tables 8–10)

Twenty-six (57%) of the included studies involved a mind–body therapy component. A total of 48 comparisons were made, 23 of which showed no differences or minor effect sizes of < 0.2 between self-management and control. Six of the comparisons were not estimable because of a lack of data. We found no discernible patterns with regard to the effect of including mind–body therapy in self-management interventions. In the short term, interventions that did not include mind–body therapy showed small significant benefits over a wide range of outcomes compared with control groups. In the medium term the picture was mixed, with small benefits over control groups seen for different outcomes both for interventions with a mind–body therapy component and those without. Depression consistently failed to improve with self-management, irrespective of whether or not the course included mind–body therapy.

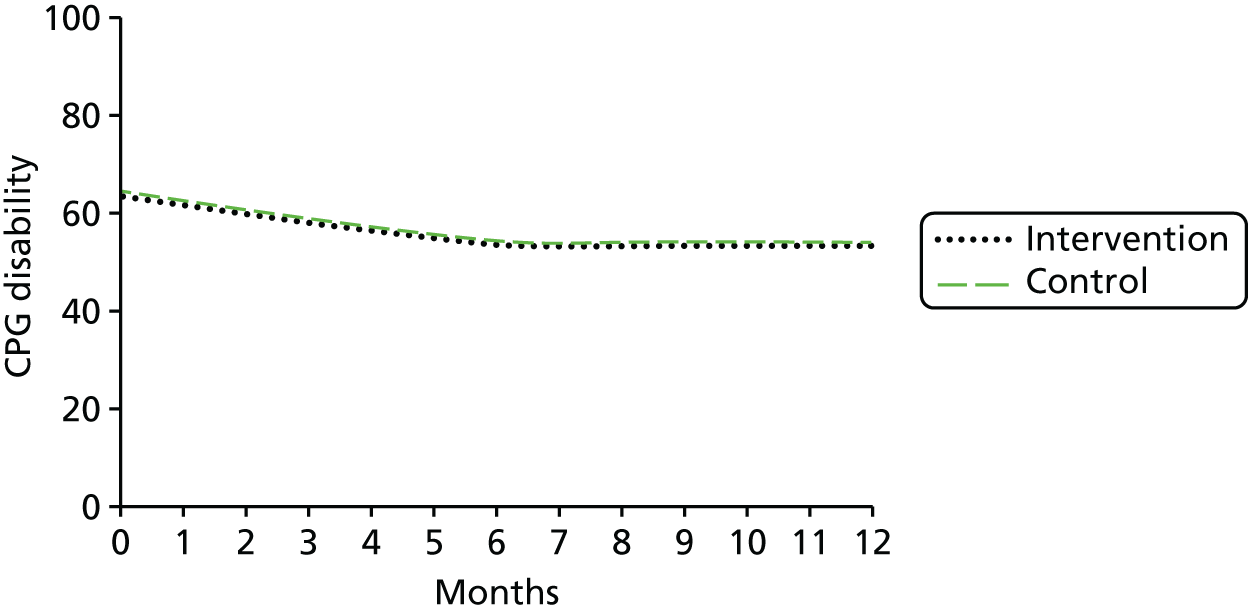

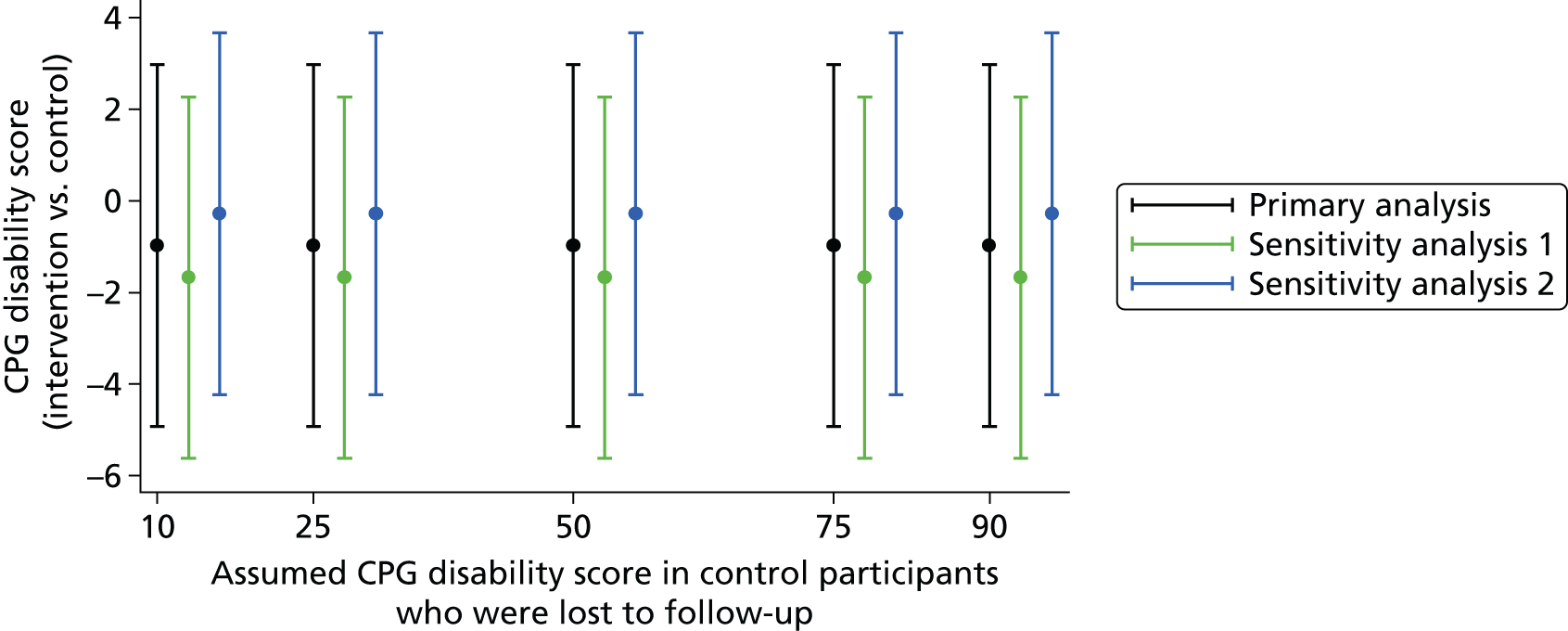

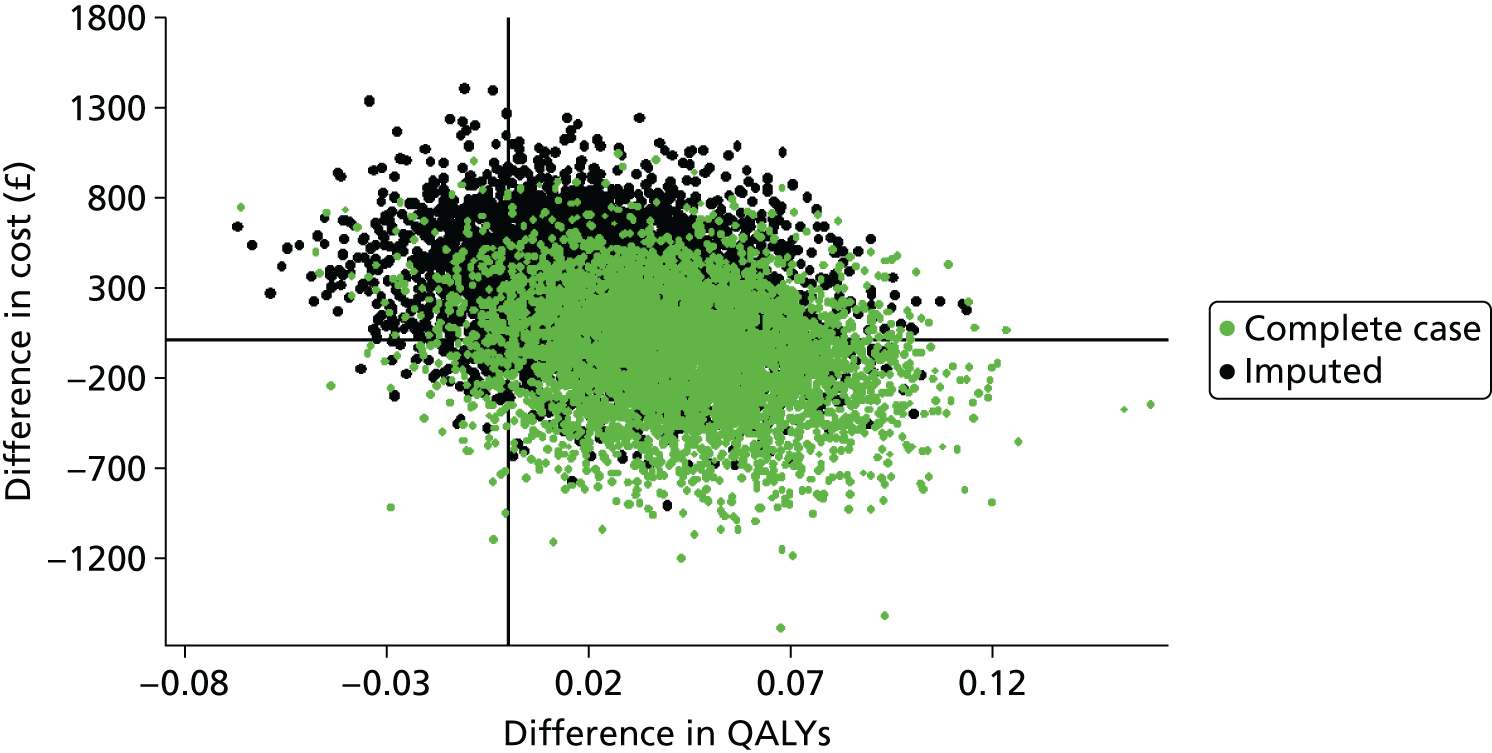

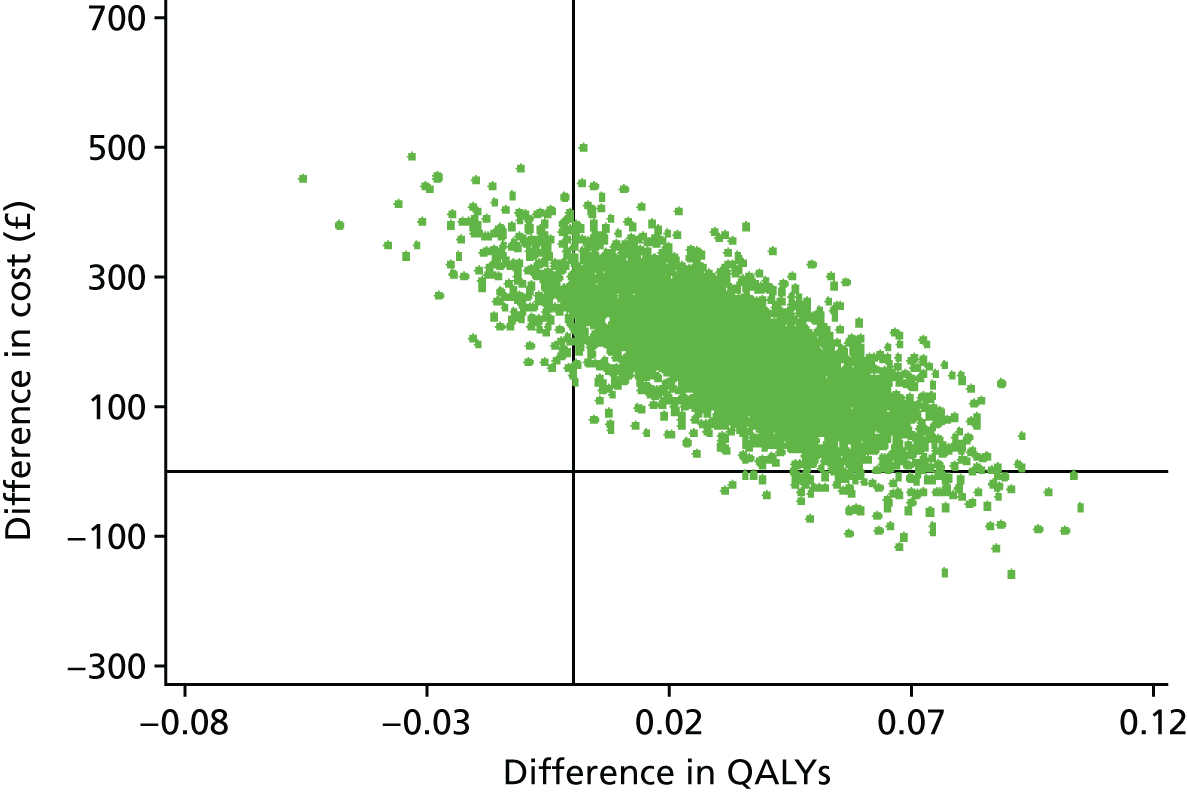

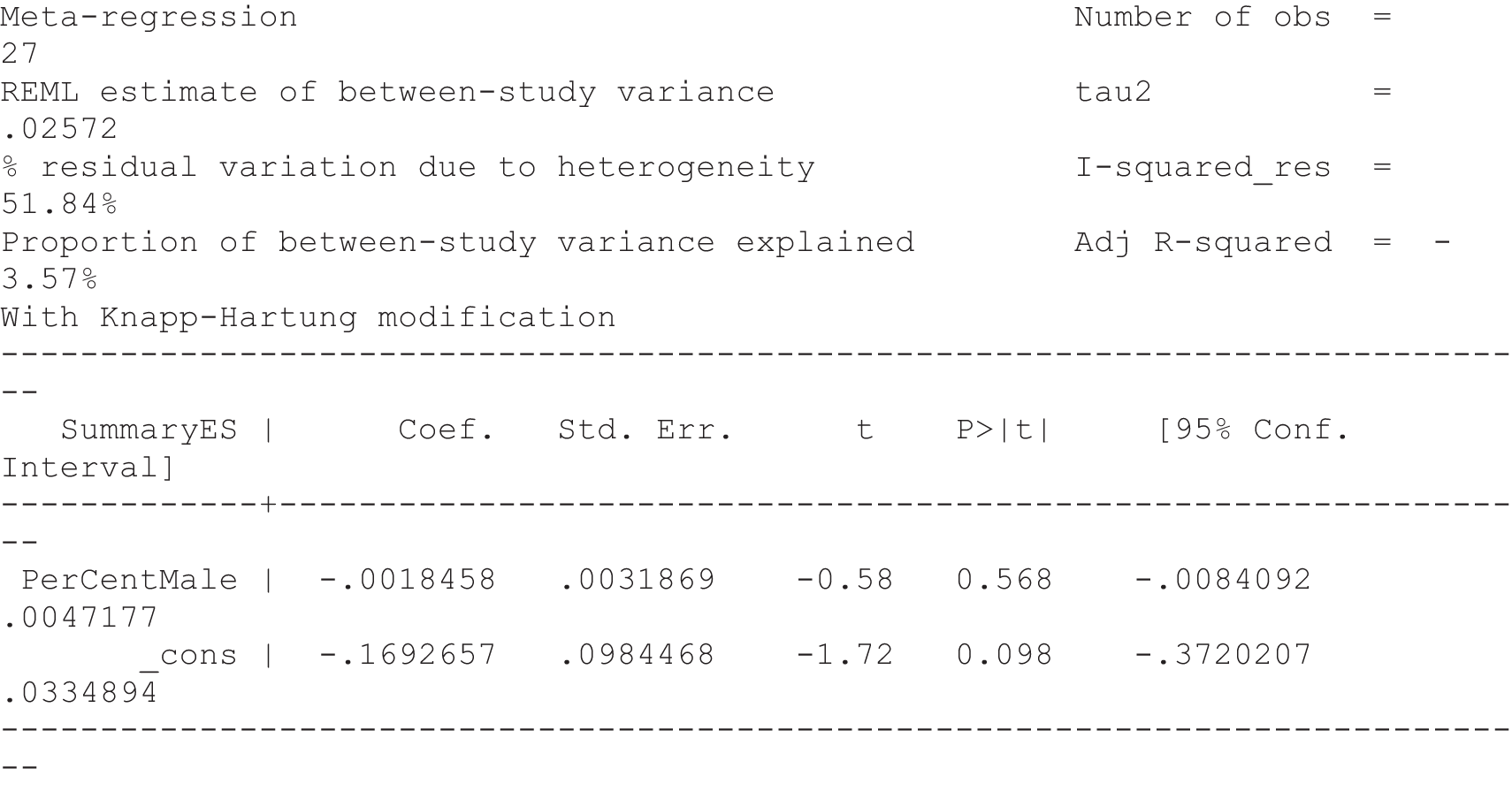

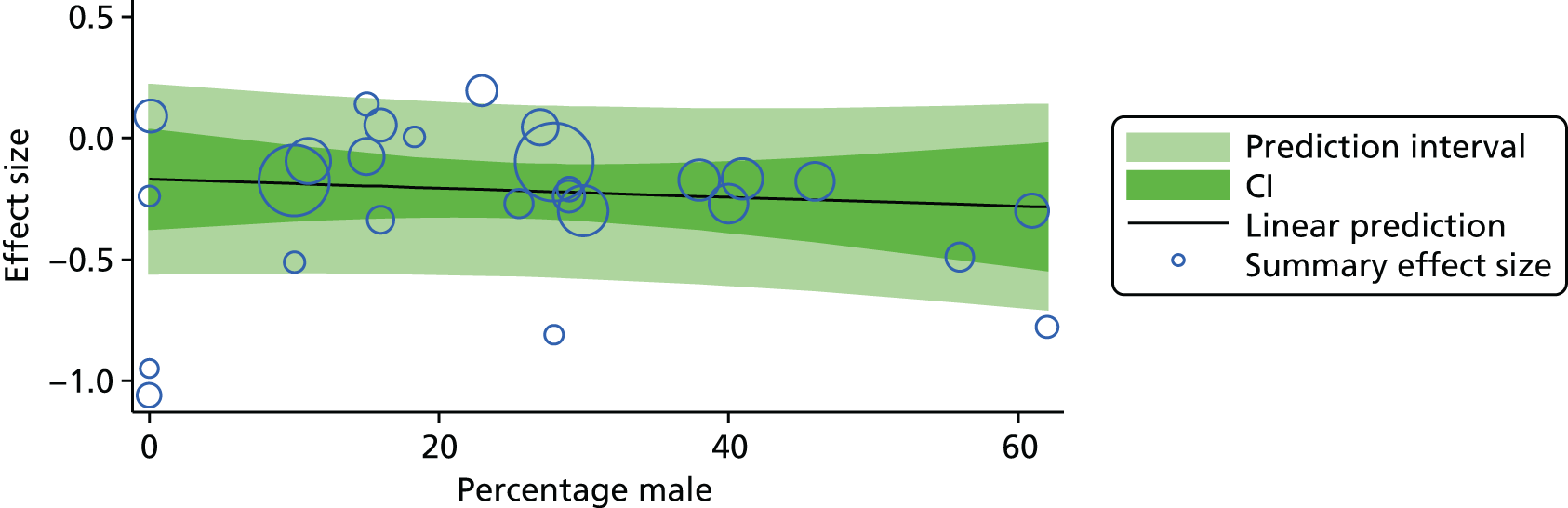

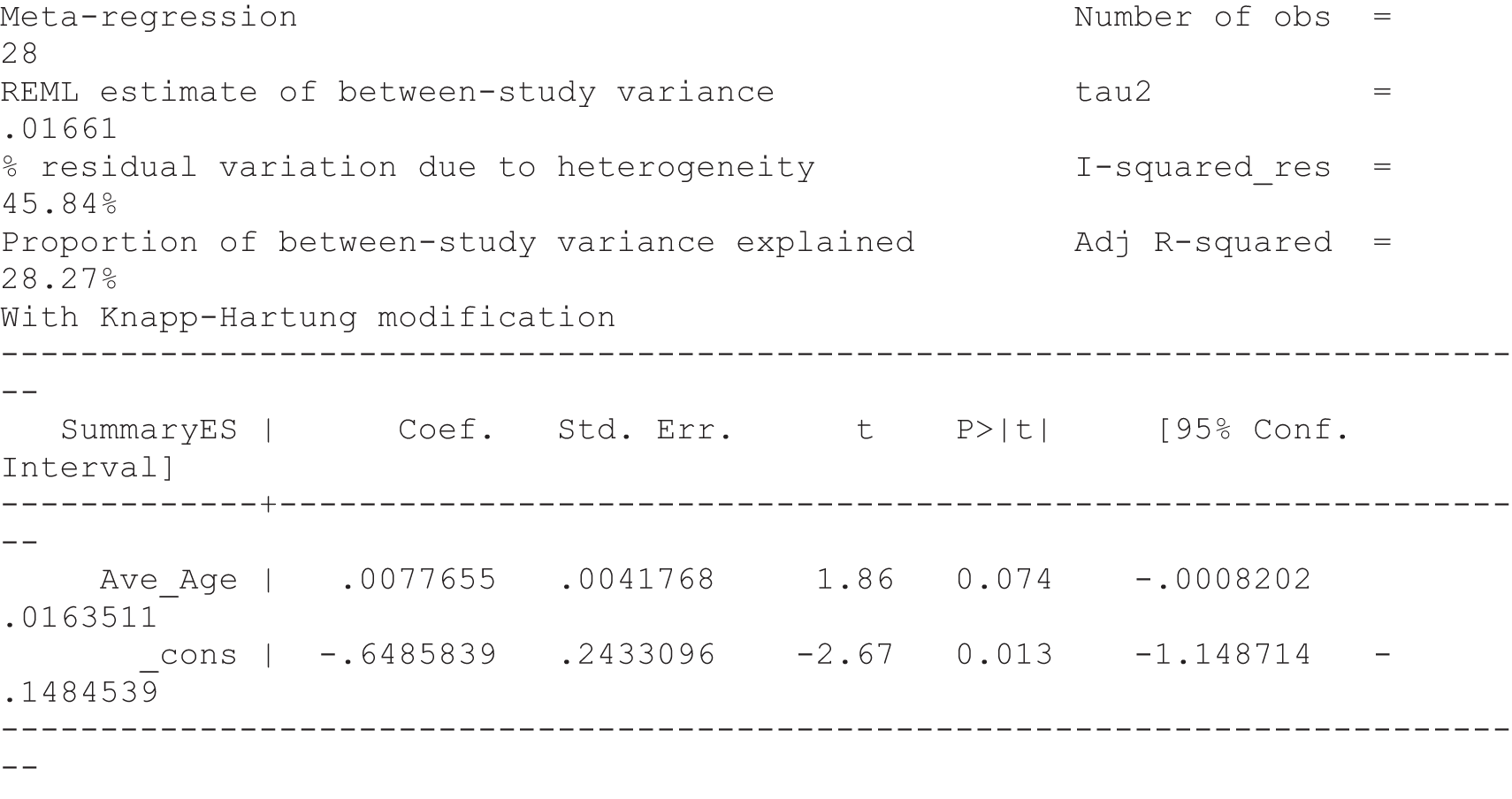

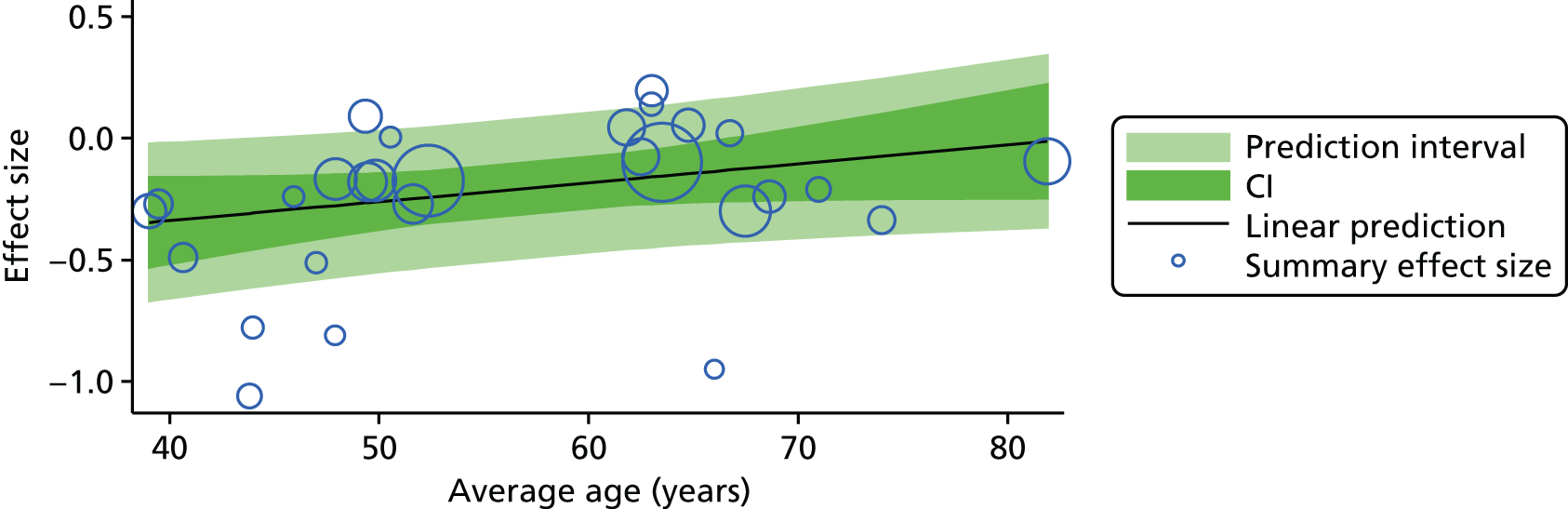

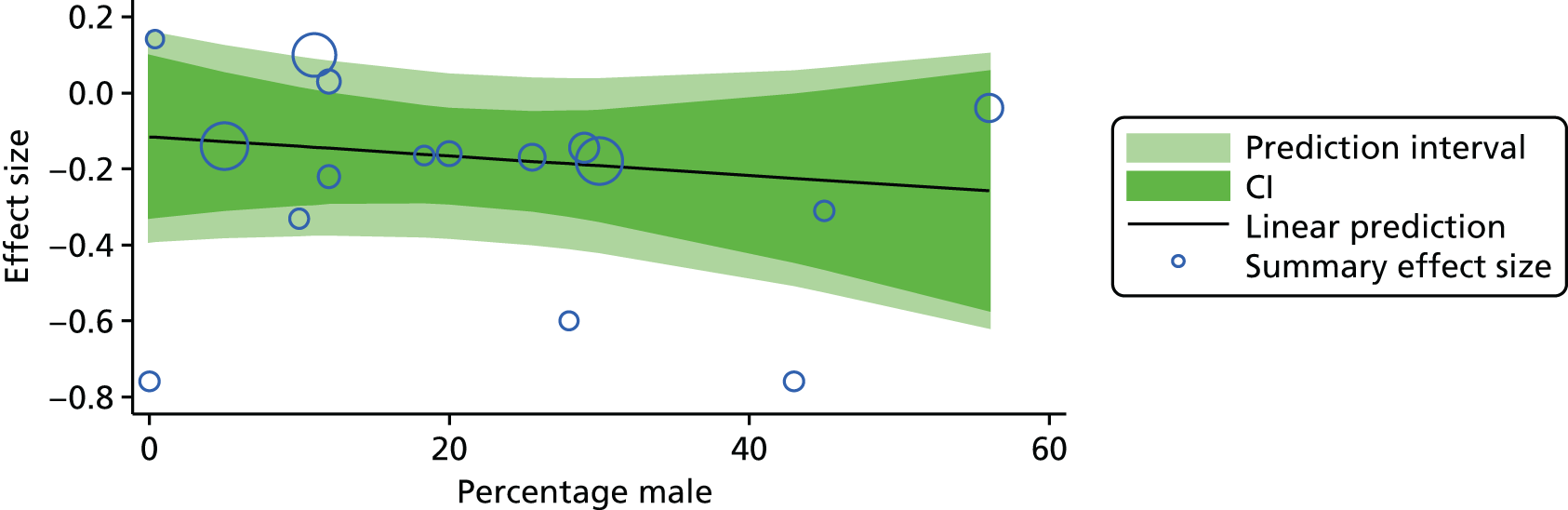

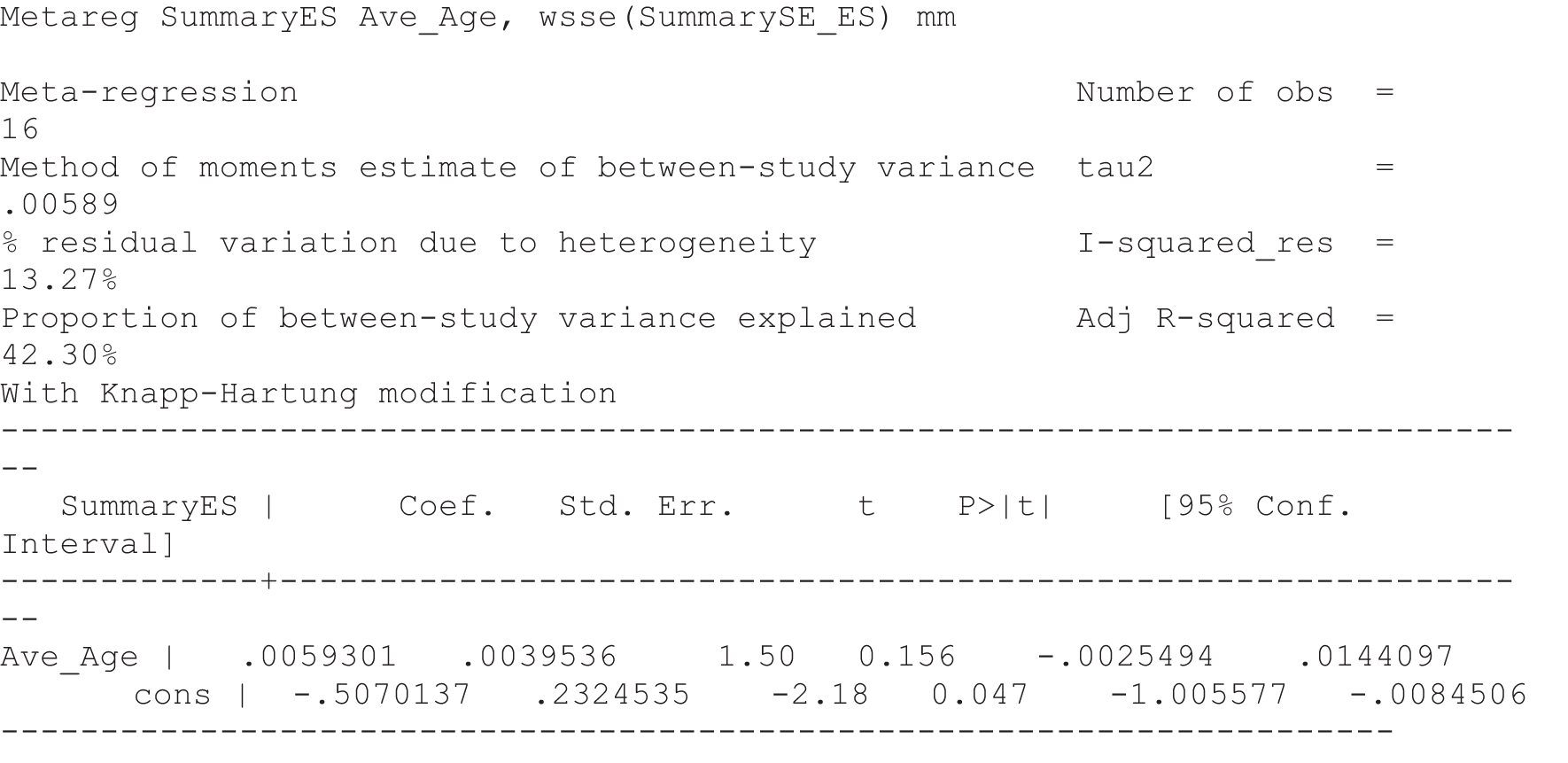

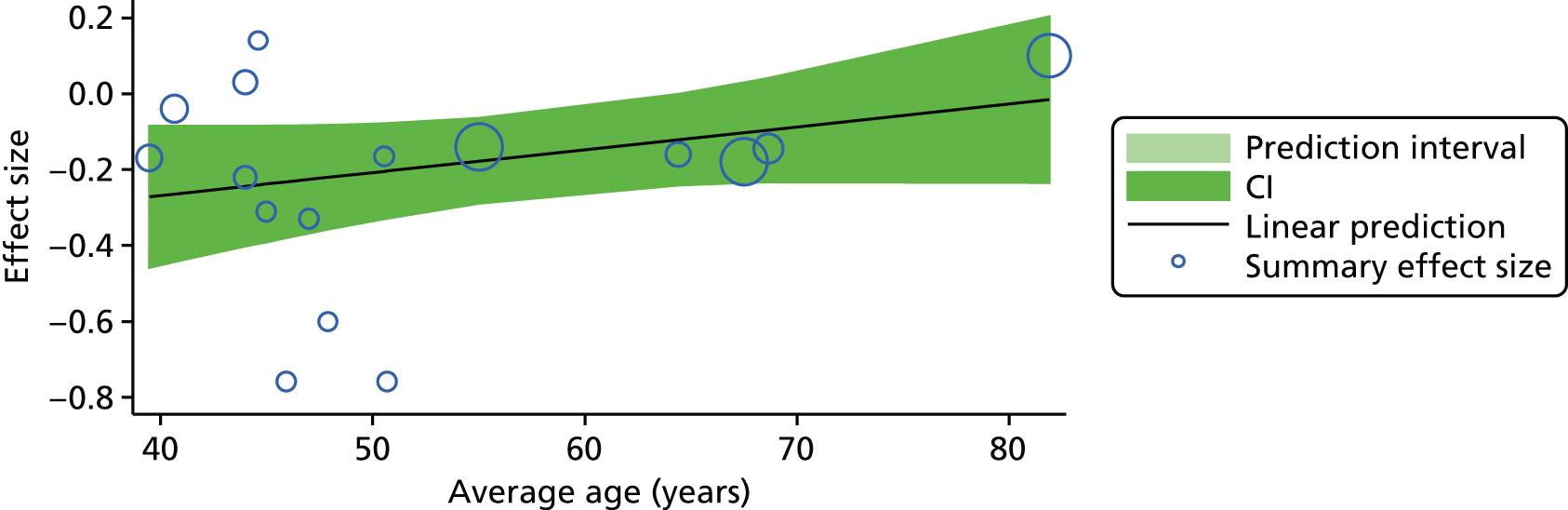

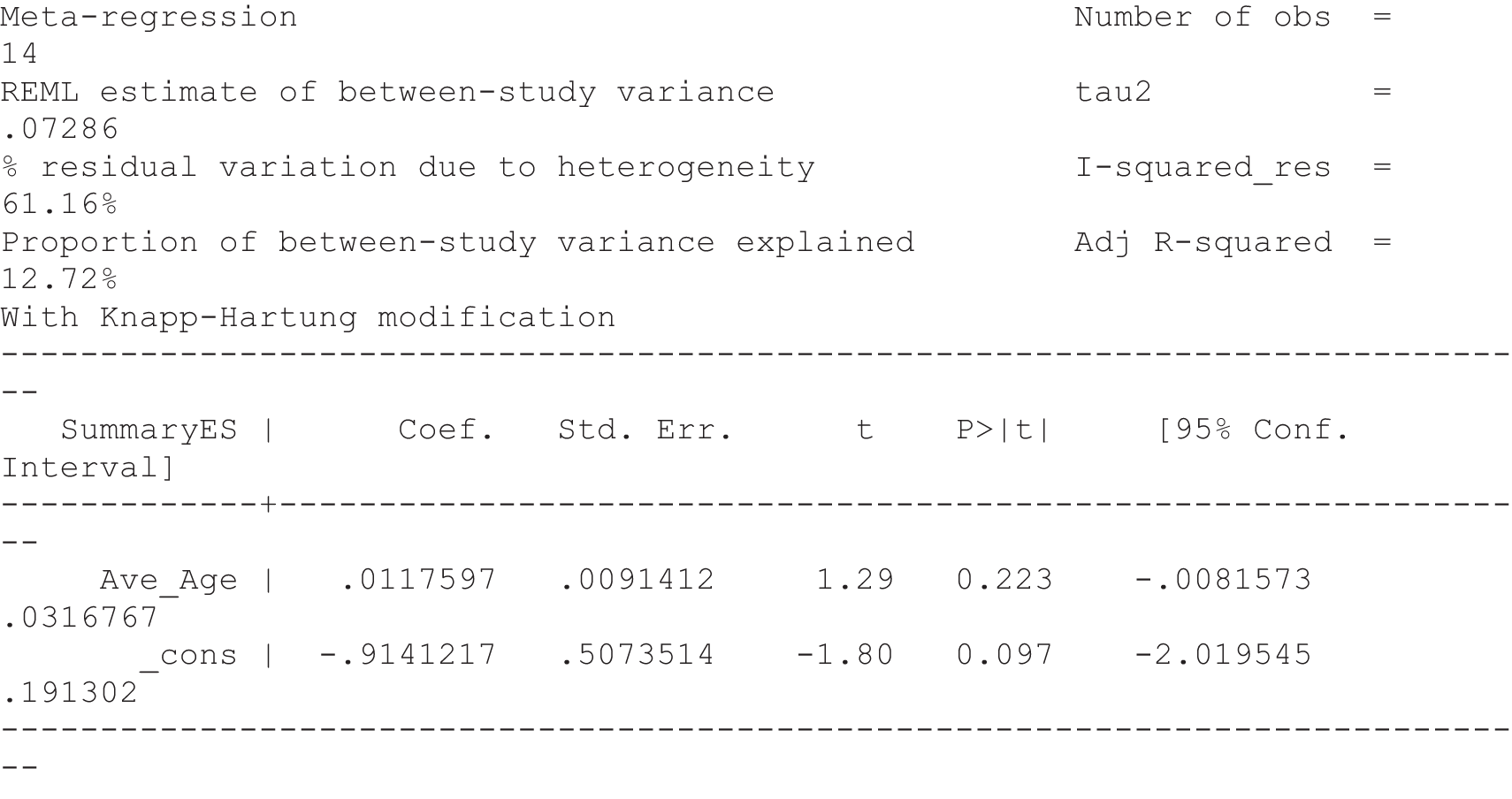

Effect of the number of components included in self-management courses (see Tables 11–13)