Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0108-10020. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The final report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Peter McCulloch is a member of the Health Technology Assessment panel on Interventional Procedures, and codirector of the Patient Safety Academy, sponsored by Health Education Thames Valley and the Oxford Academic Health Sciences Network.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by McCulloch et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Recognition and quantification of patient harm: history

Health-care workers, since time immemorial, have had to recognise that their efforts are ultimately doomed to failure. The mortality rate among human beings is 100% and, although much can be done to extend life and relieve suffering, deterioration in function and death are, in the final analysis, unavoidable. Hippocrates taught that the most important function of a physician was not diagnosis or treatment but prognosis: allowing the patient to know whether they could expect to survive or whether they should make plans for their own death. Early medical and surgical treatments were of limited efficacy, and this was well recognised for millennia, leading human cultures for most of recorded history to put more faith in the power of religion or magic than in the powers of those who used chemical (herbal medicine) or physical (surgical) methods. In this context, the attitude of patients generally gave physicians a paradoxically privileged position in regard to the results of their efforts. As the expectation of cure was generally low, any success was likely to receive praise and reward, whereas most failures were attributed to the inevitable course of nature, fate or the will of divinities. This did not relieve physicians from all risk of blame by any means: the risk of deliberate or accidental poisoning by physicians is recognised in some stories and histories from ancient times, and the Code of Hammurabi from around 1780 bc recommends penal amputation of the hand for unsuccessful surgeons, an early example of ‘shame and blame’ audit cycle completion which must surely have led to some problems in workforce planning for the Babylonian health system. In the main, however, the recognised low probability of success meant that the reliability of most medical treatments was not seriously scrutinised for centuries, as it was considered impossible to distinguish failure through imperfect or incorrect treatment from failure because of the natural course of disease and injury and the divinely ordained nature of the world. This is reflected in the very similar attitudes taken to disease, death and the efforts of physicians and healers in writings from diverse cultures from China to ancient Rome to the early Muslim empire. 1,2 The gradual development of science in Europe after the Reformation led, over the course of four centuries, to the beginnings of a different culture in which the effects of treatments could be explained according to theories which corresponded with verifiable facts, and the understanding of human physiology and pathology increased dramatically. The effects of treatments began to be more predictable and, in the case of surgery after the discovery of antisepsis and anaesthesia, much improved. As this change came about, it began to be more obvious that some clinicians had better results than others and the idea of medicine as a profession became prominent, with the medical degree marking out, from less trustworthy competitors, those whose skill and judgement could be trusted because of their recognised training and adherence to a common set of guiding principles. The improvement in efficacy brought about by more scientific treatment therefore had the effect of putting more pressure on the physician to behave according a set of accepted norms decided by his (and at this stage it was always his) peers, but there was still a wide margin of leeway for variation in outcomes.

In the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth, the ever-increasing industrialisation of the process of medical treatment in hospitals, together with continuing advances in the effectiveness of medicine and surgery, led to wider understanding among the profession, and eventually among the public, of the wide variation in success rates that existed between centres for the treatment of the same condition. As treatments became more invasive, potentially toxic and complex, evidence of deaths and harm due to treatment began to emerge, but, more importantly, public attitudes to these occurrences changed. Having become accustomed to the expectation that medical treatment could achieve something in the majority of cases, patients began to question whether or not all adverse effects of treatment were inevitable. Professional concerns of this kind were raised in the nineteenth century by Semmelweiss and in the early twentieth century by Codman,3 but the savage treatment of both of these pioneers reflects the complete rejection of critical self-examination which characterised the medical profession throughout much of its existence. Modern medicine was hailed in the second half of the twentieth century (with much justification) as one of the great achievements of the scientific revolution. Its failings and costs were generally regarded within the profession as both acceptable and unavoidable but critical voices now challenged this perception, beginning with luminaries such as Ivan Illich4 and Archie Cochrane. 5 The inexorable rise of lawsuits against doctors in the USA was a stimulus to the first systematic research on patient harm caused by treatment, and this showed from studies of case records that treatment caused specific identifiable harm in about 3.5% of patients. 6 The US Institute of Medicine produced a landmark report6 in 1999, which extrapolated from such figures to calculate that treatment was killing 44,000–98,000 Americans every year and called for urgent reform. 7 Since then a number of studies in a range of countries and health systems have attempted to quantify the problem. A reliable, objective and verifiable standard definition of treatment-related harm has not yet emerged, so that rates of harm in different studies cannot be directly compared. Most studies have been conducted in hospitals and reported rates of harm are considerably higher than the initial US studies, running between 8% and 14%. 7,8 It has therefore been established that treatment-related harm and avoidable failure of effective treatment delivery are major causes of cost, morbidity and mortality in modern health care.

Analysis of causes: human factors

Beginning shortly after the first attempts to accurately describe the size and severity of the problem of patient harm, a literature has developed around analysis of the causes. This has been informed from its inception by earlier work done in other fields in which complex human work systems are at risk of catastrophic accidents. The seminal work on industrial accidents by James Reason9 formed the intellectual foundations for most theories of health-care safety. Reason emphasised the multifactorial nature of accidents and the complexity of their causes preventing prediction. He provided taxonomy for the types of errors humans make in work situations and developed the famous ‘Swiss cheese’ model to illustrate how barriers to harm need to be multiple and well maintained to reduce risk. Studies from the aviation industry were also very influential. The success of US aircraft carrier deck teams in performing difficult and dangerous tasks under extreme pressure was studied for clues as to how to develop ‘high-reliability organisations’. 10 The use of mnemonics, prompts and checklists, as well as other formal methods of structuring communication among aircrew was studied, inspiring the well-known World Health Organization (WHO)’s surgical safety checklist11 among other ideas for improvement. The work of Helmreich12 on aircrew communication and relationships and their association with the risk of accidents was another pillar of the emerging theory of patient safety. His work showed the importance of clear communication in sharing mental models and ensuring high levels of situational awareness. His work on ‘power distance’ and the authority gradient in cockpits, and the adverse effect this has on the communication necessary for safe operation, was something that rang a chord with investigators studying the equally hierarchical world of medicine. The training courses adopted by airlines in response to Helmreich’s findings, generally known as crew resource management (CRM), were extensively adopted and tested in health-care settings, on the assumption that the underlying causes of error and harm were analogous. Another school of thought emphasised the role of inappropriate or poorly defined systems of work in ‘setting up’ clinical staff to fail9,13 and, therefore, advocated systems analysis and improvement using industrial techniques such as the Toyota production system.

Analytical studies of samples of errors and accidents leading to patient harm provided support for both schools of thought. Observational studies of operating theatre teams provided abundant evidence of communication and teamwork problems, many of which did seem very similar to those observed in aviation. 12,14–16 Analyses of very serious incidents, such as those resulting in the inadvertent administration of intrathecal vincristine to cancer patients, showed how systems of work led ineluctably to a situation in which there was a high risk of a fatal error. 14 The literature from both schools was, however, agreed on the need to de-emphasise the responsibility of the individual health-care professional. Rene Amalberti,15 one of the most creative thinkers on patient safety, described medical professionalism as one of the biggest barriers to safe health care. This apparent paradox is explained by the adverse results of the focus on the individual, which the medical model of professionalism promotes so strongly. The professional ethos of medicine sets an unattainable standard of perfection, wherein the good clinician never forgets, never omits, never errs in judgement, is never too tired or emotionally upset to function and constantly updates their knowledge so that their expertise is always adequate to deal with the problems they face. When harm has occurred and an individual clinician has fallen below this standard in any way, the typical response is to attribute the harm entirely to the breach of professional standards. This results in high levels of guilt among individuals, but also encourages hypocrisy, dissimulation and attempts to shift responsibility onto others rather than objective analysis of what happened. These attempts are far from irrational because this approach to professional behaviour has led to a culture of blame in which it is generally accepted that all errors must be someone’s responsibility, and that there is a moral necessity to punish that person for their lapse so that professional standards will be protected. Psychological and ergonomic studies have of course demonstrated beyond doubt the error-prone nature of even the most attentive and dedicated human professional and, therefore, punishment for error is unlikely to decrease the chance of its repetition, while the fear of it distorts communication and co-operation between workers anxious to avoid the possibility of blame. In actual practice, the use of the professional ‘blame culture’ is strictly related to hierarchy, so that the same error by an eminent and respected senior clinician and a new recruit from another institution are dealt with completely differently. The possibility of future error is not, however, decreased in either case.

Focus on surgery: specific problems

The operating theatre has attracted more attention than any other part of health care when it comes to analysing hazards and proposing solutions. It is difficult to quantify the amount of patient harm that can be attributed to errors in theatre, but it has been suggested that it is the highest-risk environment for hospital patients. These data reinforce the common-sense argument that the site where clinicians deliberately invade the body, risking damage to vital structures and the introduction of infection, is bound to be one in which serious inadvertent harm may occur. There is a significant literature around the observation of teamwork and communication in the operating theatre and its relationship with patient outcome. The negative effects of hierarchy and inter-professional ‘tribal’ barriers on communication and co-operation have been described and discussed, and evidence has been produced for a relationship between technical error rates and the quality of team interactions. Several groups have developed systems for evaluation of the quality of non-technical skills and teamwork behaviours in operating theatre personnel, as either individuals or teams. Some of these have been integrated into training systems designed to improve team outcomes by enhancing team interactions.

However, some surgeons argue that the operating theatre may in fact be safer than other parts of the surgical patient pathway, as the operation is generally performed by senior team members with a high degree of skill, assisted by a group of appropriately skilled colleagues, whereas post-operative care can sometimes be organised so that very junior staff members are faced with crisis situations outside normal hours, which they are not equipped to deal with. This view has been lent some support by recent work on ‘failure to rescue’. Several studies have highlighted a recurring theme in reports of death and serious harm after surgery, which is the frequency with which deterioration is recognised but left untreated for long periods of time. A number of classic behaviour patterns appear to be responsible for this, including diffusion of responsibility and reluctance to send bad news up the chain of command in hierarchical organisations. Recent work has shown that high-volume units with excellent outcomes do not have substantially lower rates of serious complications than lower-performing lower-volume units, but they deal with these situations more effectively and, therefore, more frequently avoid death or other serious sequels. There are no reliable data on whether preoperative or intraoperative factors are more influential in generating adverse outcomes and, given the intimate inter-relationship between the two, attempts to assign relative risk to either are probably futile. Both the study of error and process breakdown and the efforts to minimise it necessarily require quite different approaches in the two environments. Operations require strongly co-ordinated efforts over a limited period of time from a disparate multidisciplinary team (MDT) using highly specialised and sophisticated equipment. Postoperative care takes place continuously over a much longer period and involves a larger group of staff working in shifts, making transfer of information a key element in achieving success. The bulk of the routine work falls on nursing staff and junior doctors and, therefore, the willingness and ability of these staff groups to access advice and support from more senior medical staff or specialists outside the immediate team is another critical determinant of performance.

Attempts to correct problems

Serious efforts to identify the underlying causes of accidents and errors leading to patient harm in medicine lagged several decades behind similar efforts in some other areas of work. This delay can perhaps be attributed in varying degrees to the effects of the strong ‘person-based’ professional ethos in medicine which inhibited thinking about wider systems issues as causes of ineffectiveness, and partly to the fact that individual incidents in medicine normally affect a single patient. They are therefore less likely to create widespread concern, media attention and threats to the survival of corporate entities than, for example, the large-scale disasters represented by aeroplane crashes or industrial accidents in the power-generation industry. Whatever the reasons, the fact that medicine came to this field of work relatively late meant that there was already an established body of theory and practice available, some of which has been described earlier (see Chapter 1, Analysis of causes: human factors). Medicine undoubtedly benefited from the availability of a paradigm within which ideas about causes, effects and solutions for medical error could be developed, but the transmigration of ideas and principles from very different fields of work into the medical arena also carries serious risks of inappropriate extrapolation. What holds true in civil aviation, military operations or nuclear power generation may not be equally true in the very different context of medical care. Expert practitioners from other fields of work have repeatedly emphasised how disconcerting they found the hospital environment when asked to give help or advice within it. The features that characterise hospital medicine, as against practice in other fields in which safety work is more advanced, are the complexity of the process of patient care and the distributed nature of responsibility for action. The professional model in health care was developed from a simpler one in which treatment was directed by professional doctors with a high degree of specialist knowledge or training, either at university or within a guild or craft society. They were assisted by (almost invariably female) carers whose focus was on patient comfort and psychological well-being but who were charged with implementing the instructions of doctors for the performance of the key curative treatments. The separation of these roles has survived vast changes in the nature and capacity of treatments, the industrialisation of hospital medicine and ever-increasing specialisation but a host of other specialists have been superimposed on the basic model: physiotherapists, dietitians, pain specialists, pharmacists, infection specialists, wound care specialists and many others. As the process of care has become more complex and expensive, the role of professional business managers has become ever more prominent, leading to their eventual emergence as the leaders of the hospital organisation, responsible for employing and directing the doctors as well as all the other specialties. However, the persistence of professional roles and attitudes means that managers do not have the direct line management authority common in other industries over the activities of specialists within their area of responsibility. In order to achieve change in the work of their department, managers commonly need to negotiate with a hierarchy of doctors and nurses who have responsibility for policy within their specialty cadre for the same part of the hospital’s work. The creation of true MDTs under unitary control is therefore impossible and progress can only be made by consensus. At a lower level, the traditional model of doctor responsibility for the care of the individual patient has been diffused by modern multidisciplinary care to the extent that it is often unclear who has the authority to make decisions about, for example, whether or not a patient should receive a particular antibiotic or nutritional supplementation technique. Change over time has also affected relationships between doctors caring for the same patient. A traditional model attributed responsibility for patient care to a single consultant, assisted by one or two junior doctors who followed his or her instructions. As the technological and pharmacological possibilities for more and more intensive care increased during the twentieth century, this model became unworkable, since the number and timing of the decisions required expanded to exhaust even the most dedicated professionals. Specialisation and shift work made the jobs of hospital doctors physically possible once again, but the cultural transformation required to fully implement a shift and specialty-based system have not occurred. Doctors continue to be reluctant to hand over responsibility for patients they regard as ‘theirs’ and, conversely, do not always assume total responsibility for patients they accept as part of their case load if they regard them as ‘belonging’ to another specialist. This is a particular problem in surgery, as the fact of having operated on a patient creates an obligation in the mind of the specialist (and his or her colleague) to continue to take ultimate responsibility for the patient’s care until the underlying problem can be regarded as resolved. In this complex environment, it is not surprising that models, tools and procedures devised to prevent error and enhance safety in very different, and usually simpler workplaces may not always be effective.

Models of harm in health care and their implications: critique

Although Reason’s initial description of the multiple imperfect barriers to harm in complex systems, the so-called ‘Swiss cheese’ model,9 was a major conceptual breakthrough, it did not attempt to detail or classify either the potential sources of harm or the barriers which may prevent it. Given the complexity of the modern health-care environment, models which provided a structure for thinking about the opposing forces involved in increasing or protecting against risk to the patient were very necessary, and several attempts have been made to build these. Charles Vincent13 was among the earliest authors to attempt a comprehensive description of the hospital environment from the point of view of patient safety risk and possible sources of harm. The final iteration of this framework is commonly known as the ‘London Protocol’. 13 The protocol has been recommended by some authorities for use in ‘root cause analysis’ investigations of safety incidents in health care, but its greatest value is perhaps to ensure that the influences on harm and error which are more distant from any specific clinical episode are not forgotten in an overall assessment. Although it certainly achieves this, the difficulty in either defining or quantifying influences such as ‘management culture’ can be problematic. When it is unclear if an influence is important or not, and it can be neither defined nor measured, there is a strong tendency to ignore it and focus on easier parts of the problem. This is particularly likely if, as is usually the case, there is potential risk to any investigator in incorporating within their search the activities of individuals with power and influence in the organisation. For many clinical incidents the more proximate influences are indeed the ones which most urgently need fixing, but defining these very often leads remorselessly to questions about the governance structure that allowed these errors to occur.

Another popular framework for discussing risk and error in health care is the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model of Pascal Carayon et al. 17 The five dimensions of SEIPS are tools/technology, person, tasks, organisation and environment. This format does seem able to encompass most or all of the common influences on risk. However, the categories of the five-dimension classification are not mutually exclusive: it is relatively common for a problem to be classifiable in more than one category and the dimension categories are not of a comparable nature. It would be helpful for those considering potential risks or analysing real incidents to be able to use a simple system that categorised sources of risk more conclusively, using a system which made it easy to decide how any particular factor should be described. We therefore developed the three-dimensional (3D) model specifically for the analysis of risk at the microsystem level, which is between health-care worker and patient. 18 This simplified model essentially ignores the higher organisational influences and concentrates instead on factors that can be easily identified by visiting the workplace. The model postulates that all influences at this level can be described in terms of systems of work, workplace team culture and the technology used to complete the work. These three dimensions interact in unpredictable and bidirectional ways, potentially modifying the effects of external interventions directed at just one of the dimensions. By analogy with thermodynamics, we would predict that an imbalance represented by an increase or decrease in risk in one of the dimensions will tend to be countered by any interactions with another dimension that allow diffusion or diminution of that risk. So, for example, if teams receive better training in teamwork to improve their culture, but are forced to continue using an inefficient and risky work system, much of the benefit will ‘bleed away’ via this interaction between culture and system. The model is illustrated in Figure 1. Initial validation work on this model showed that it seemed informative in analysis and explanation of typical safety incidents in operating theatres. We therefore adopted it as a basis for thinking about safety problems in surgery at the microsystem level. This led us to develop a hypothesis that formed the basis for the work described in this report.

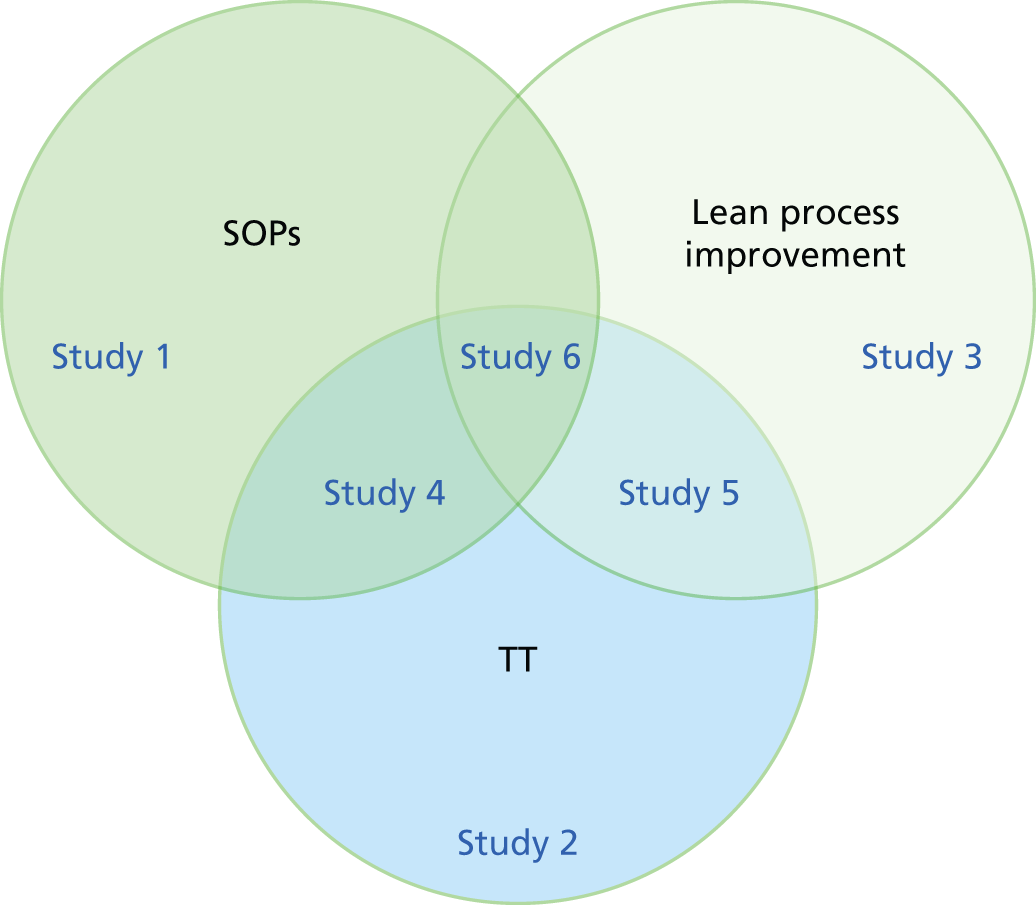

FIGURE 1.

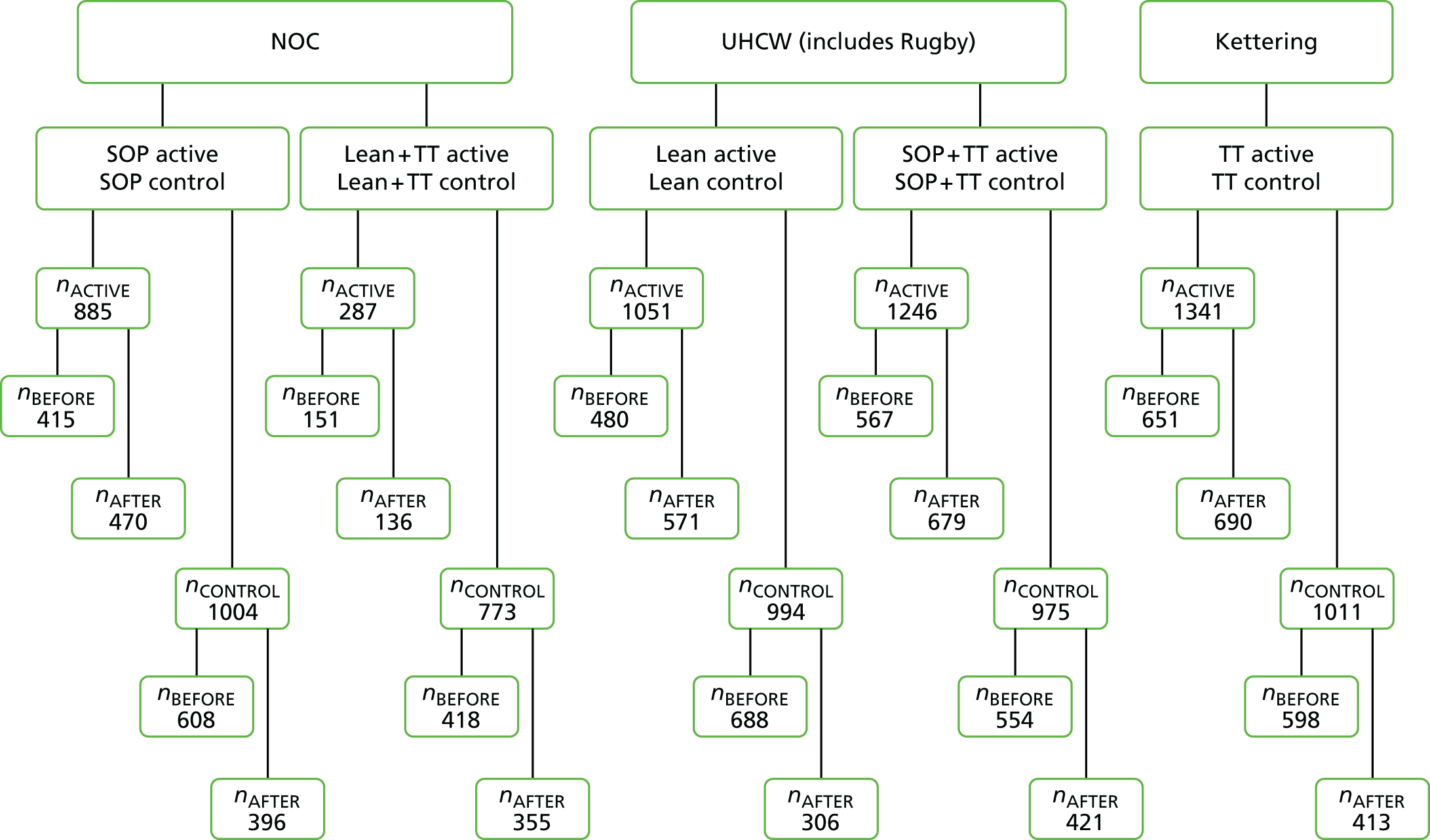

Schematic of studies. SOP, standard operating procedure; TT, teamwork training.

Chapter 2 Study design

Study design background

Having created the 3D model for safety in surgery,18 we spent some time thinking about whether or not it was literally true in all circumstances. We imagined three dimensions that were completely mutually exclusive, so that every influence on the risk of harm to patients could be described as an example of culture, system or technology, or a defined mixture of two or more of these. We soon realised that many influences were in fact mixtures, which made it all the more interesting to consider whether or not they could be modified by an intervention that affected one part of the mixture. We imagined the risk of patient harm as similar to a gas, which had a certain pressure in each of the globes we drew to represent a dimension. The higher the pressure, the more likely would be patient harm. The interactions between the dimensions, we had said, could be of any type. They might allow two-way flow of risk, or only one way or they might only affect the speed or direction of other interactions, for example, making the flow of risk intermittent instead of continuous or forcing an interaction that normally allowed flow for a limited time only to remain open all the time. What would be the real-life equivalents of these theoretical constructs? An example of an interaction between system and culture might be the reaction of staff to a new handover system. Owing to poor culture, the staff decide to corrupt the system so that it no longer fulfils its purpose but is easier for them. The high-risk concentration in the culture dimension has now passed into the system dimension via the interaction around the handover system, which increases the overall risk. We realised that this was a key point. If risk is merely exchanged between dimensions during interactions, overall risk remains constant. This is not a good description of reality. In order to model reality, therefore, the interactions between the dimensions have to be capable of creating or destroying more risk. This modification of the model allows us to make predictions about the effects of modifying two or more of the dimensions in the model system. Each interaction point between dimensions can now allow net risk to flow into or out of a dimension, but it could also create or destroy overall risk. If we attempt to lower the total risk in the system by concentrating only on the culture, for example, the interactions between culture and the other two dimensions may affect our likelihood of success. If the net effect of all the interactions is to allow net flow of risk into the culture domain, or to create more total risk, our efforts are likely to be frustrated. It is likely that this is in fact the case in any real-life system in which we are trying to reduce risk, as if the net effect of interactions were already in the direction of reducing risk, the need for our activity would not have arisen. If we now consider an intervention that reduces overall risk in two or more dimensions, the potential for synergy becomes obvious. Not only is the overall risk being reduced over a larger percentage of the overall organisation but the malign interactions between the dimensions are being dismantled from two directions, destroying the possibility of a homoeostatic correction of the risk pressure in either of the dimensions affected via interaction with the other.

It is possible that culture-focused interventions are generally more or less effective than systems-focused interventions, but it is also possible that there are important elements of context which would make it very difficult to extrapolate from a comparison of the two in any particular setting. We felt that collecting data about the effectiveness of different interventions in settings that were as similar as possible might help us draw some tentative conclusions about this, but that a systematic literature review would probably be a more appropriate way of trying to reach a general conclusion. We therefore rejected the idea of focusing on whether systems or culture interventions were better as our primary research question.

Our hypotheses therefore are that interventions addressing two or more dimensions of the three dimensions of patient risk are more likely to be successful than those which address only one. Our analysis of the current literature shows that most interventions have focused heavily on one dimension. Training sessions held with staff at which they consider their relationships with other staff, for example, are clearly about culture, although a small-system aspect may creep in via, for example, discussion of formal systems and routines for communications such as situation, background, assessment, recommendation. Methods for improving the reliability of systems by data-driven analysis and measurement, on the other hand, have little direct impact on culture but address systems problems. Integrated approaches may have greater potential than either type of intervention alone. This was the underlying rationale for our programme. For purely practical reasons we decided to focus on system and culture and not to work on technology. An overhaul of technology in one small area of a hospital is not a practical proposition for organisational reasons, and the decisions needed to bring about a radical reform of a hospital’s use of technology would require very large resources and a long period of time to implement. On the other hand, we could conduct small-scale studies of culture and system interventions without major disruption to overall hospital function or budgets. This omission leaves the theoretical construct partly tested at best and further studies to evaluate the impact of technology rationalisation with or without attention to the other dimensions in the future would be highly desirable. We decided to focus our efforts on the two dimensions over which we felt that we could exert some control within a study setting with present resources. We were influenced in doing so by our recognition that the current literature on safety interventions has also focused largely on these two dimensions, but surprisingly has largely neglected the potential for interaction between approaches dealing with them.

The primary focus of the study is patient safety and quality of outcome in surgery. The main questions relate to the effectiveness of methods to improve safety and quality. The selected primary outcome measures are discussed in Chapter 3. The three intervention approaches tested were culture enhancement [teamwork training (TT)] and two contrasting approaches to systems improvement [lean systems and a systems approach based on development of standard operating procedures (SOPs) through application of ergonomic methods].

Study design and rationale

We reviewed the literature looking particularly at the detail of interventions used to reduce risk of harm to patients or to increase the reliability with which surgical processes were carried out. We identified TT methods based on CRM as a common type of intervention that seemed to be focused largely on improving workplace culture. We identified a range of methods for improving workplace systems and considered the possibility that they might interact differently with a culture change intervention. We therefore chose two different systems’ improvement approaches to study because they were clearly quite distinct in several important respects.

We were acutely aware of the practical constraints on research interventions to improve safety identified in previous research: intervention studies need to be carried out at a certain scale in a real-life environment. Working with an individual clinician, for example, would not be appropriate. The smallest unit feasible without moving to an artificial controlled environment such as a simulator is the ‘microsystem’ of a single ward or operating theatre. With a realistic set of resources, we had a choice of conducting a small number of studies at a scale larger than this, or a larger number at this scale. It seemed clear that testing our hypothesis would require several parallel studies examining different possibilities, so we opted for a number of small studies rather than one or two larger ones.

This approach also allowed us to compare the effects of different interventions indirectly, using a comprehensive pooled analysis of all of the results in five identical studies. The interventions used in these studies were TT alone, SOPs alone, lean alone, TT and SOPs and TT and lean.

Another important consideration was the need for controlled studies. From previous work we were aware that the live hospital environment is a highly unstable one in which influences over which the experimenter has no control arise regularly and which can grossly distort outcomes of interest. Recent publication of two large-scale studies had shown the importance of controlling for such influences even in large-scale experiments. 19,20 In both studies the control group revealed the existence of a secular trend to improved outcomes, which would have been wrongly attributed to the intervention if the studies had not been controlled. We therefore considered that a control group was essential for each study. The complications involved in setting up studies with two interventions and a control group are significant in any clinical study, but in studies for which the interventions being compared are training programmes, which require long-term staff co-operation and which need to be set up so as to avoid contamination of control groups, they become daunting. We therefore took a different approach. Rather than attempt to compare interventions directly we decided to carry out a series of controlled studies of single interventions and of the combinations of each systems intervention integrated with the culture intervention. The controlled studies permit analysis of the difference in change after the intervention between the active study group, which received it, and the control group, which did not.

We therefore concluded we could assess the interactions with six individually controlled studies, illustrated in Figure 1.

We also expected that we would find out which aspects of each of the quality improvement (QI) approaches were useful and that we would learn a good deal about what was effective during the process of conducting our five studies; therefore, we were interested in creating a final intervention study in which we integrated TT with aspects of both lean and the SOP approach. We chose to extend the range of the clinical context for this final study to encompass not only the operating theatre but also the entire patient journey from admission to discharge. This was the sixth and final intervention project in the programme. The aim was to pilot test an integrated intervention strategy based on the learning from the previous five studies, with a view to conducting future controlled studies at a larger scale.

We recognised the need to develop both a pre-planned statistical approach to analysis of these studies and a health economic analysis of the costs and effects of the interventions. It was clear that there would be a considerable amount of practical learning on an experiential basis during the study, particularly on what proved successful and what did not, and about the challenges and barriers to delivery. We therefore ensured that we had a qualitative study plan which would allow us to analyse the underlying causes of success and failure, barriers and delays, and to point to potential ways of avoiding these problems in future interventions. We also recognised the importance of knowledge translation: being able to explain and disseminate the essential learning from the studies in an effective way that would result in adoption of the valuable parts of our work by others, with actual benefit for NHS patients.

Study logistics

The research team aimed to study 100+ operations in each individual study, maintaining a 1 : 1 active-to-control ratio when possible. This would result in 25 active and 25 control pre-intervention operations, and 25 active and 25 control post-intervention operations. The control cases used were to be parallel teams, when available, and were not subjected to any intervention.

The interventional studies all follow a controlled interrupted time series design, incorporating a 3-month pre-intervention phase, an intervention phase (usually also 3 months) and a post-intervention phase (at least 3 months) (Table 1).

| Intervention | Phase | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre intervention (3 months) | Interventional (3 months) | Post intervention (≥ 3 months) | |

| Active | 25 cases | 25 cases | |

| Control | 25 cases | 25 cases | |

Process data collection was to be completed through observation of the 25 cases within each section. Clinical outcome data were to be collected from the patients undergoing treatment, with the surgical teams involved in the study arm within the 3-month phases. For example, during the 3-month pre-intervention phase, all patients of surgeons participating in the intervention would have their clinical outcome data collected (identified only by time frame and operating surgeon).

The duration of the studies ranged from 6 months to 20 months. Approximately 600 staff subjects were observed over five sites in three NHS trusts.

Study settings

To examine the hypothesis that combined interventions functioned better than single-dimension interventions, we needed to conduct studies of both types of interventions while keeping the factors that might introduce bias and error to a minimum. We therefore decided to identify a hospital environment that was as standardised as possible. This meant finding a surgical specialty that carried out the same types of operation in more or less the same way at high volume in many different hospitals. We rejected studying minor procedures such as endoscopy, as both the level of complexity and the degree of risk in such procedures are much lower than those in the environment in which we were actually interested, which is the surgical operating theatre. Emergency general surgery, on the other hand, carries a high risk of harm to the patient and the variability of the procedures performed is potentially large. These factors meant that identifying and studying a stable team in a stable situation was unlikely.

We therefore chose to target a small selection of elective procedures from elective adult orthopaedic surgery, which in the UK is very much focused on a small repertoire of operations performed at high volume: hip and knee replacement, arthroscopic surgery and cruciate ligament repairs. In the latter stages of the study, it became necessary to either expand beyond elective orthopaedic operations or extend beyond the original hospital trusts involved. We chose to extend the operation types, as the negotiations associated with changing trusts were logistically challenging. The additional types of surgery included were elective plastic reconstructive surgery, orthopaedic trauma surgery and vascular surgery.

These operations comprise, at least in adult practice, a small repertoire of relatively complex procedures that are repeated at high volume in many centres across the UK. This allows for a choice in setting of study (from university teaching hospital to district general hospital; Table 2). The large number of these procedures (mainly hip and knee replacements) also makes them highly relevant to NHS priorities and any improvement in outcomes would be of major importance to the NHS. We sought the opportunity of studying our methods in three quite distinct contexts and, therefore, approached three trusts that carry out this kind of work within travelling distance of our Oxford base. The Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre in Oxford is a free-standing specialist hospital that focuses on elective orthopaedics and plastics. The University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust is a large university hospital with a high orthopaedic workload. Part of this is dealt with at the main site, a very large operating theatre suite with more than 30 theatres. The remainder of surgeries are performed at Hospital of St Cross (Rugby), several miles from the main site; this is a small elective unit specialising in high-volume surgical procedures. Kettering General Hospital is a small semirural district hospital that has developed a busy general orthopaedic unit but has very little academic or training input from outside.

| Hospital Trust | Hospital site | Description | Surgical specialties partaking in study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust | Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre | Specialist centre | Orthopaedics and plastic |

| John Radcliffe Hospital | University teaching hospital | Neurosurgery and vascular | |

| University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust | University Hospital Coventry | University teaching hospital | Elective and trauma orthopaedics |

| Hospital of St Cross (Rugby) | District general hospital | Elective orthopaedics | |

| Kettering General Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | Kettering General Hospital | District general hospital | Elective orthopaedics and vascular |

For the final study, utilising the learning from the suite of five intervention studies, we chose to work with the neurosurgery department at the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. By this time we felt that further interventional work with the orthopaedic surgeons in the trusts we had worked with was impractical, as the staff were thoroughly familiar with the team, and most had been exposed to one or another study in the past. Neurosurgery represented a relatively high-risk discrete specialty, with a unique patient pathway that we could study from beginning to end.

Initial liaison and manner of working with trusts

We discussed the programme with senior management at all three trusts at an early stage. A senior clinician or manager acted as liaison on each site. With their help we identified the consultants and associated theatre teams and who would be best suited to involvement in the study, and arranged to hold information and engagement meetings with the surgical teams from the surgeries involved. For logistic reasons some of these meetings involved only the surgical consultants and others only theatre staff, but all groups were engaged and had the programme explained and discussed with them. We appointed four research fellows of whom two worked largely in Oxford and the other two were managed from Warwick and worked largely there and at Kettering. Dr Catchpole and, latterly, Dr Morgan were responsible for ensuring day-to-day communication and co-ordination with the clinical staff and management at the hospitals involved, together with the programme manager.

Study team and expertise

The initial team of investigators was assembled with the needs of the studies we had planned very much in mind. The co-investigators each brought with them expertise that contributed an important element to the team.

Mr Peter McCulloch (PM; Principal Investigator) set up the Quality Safety Reliability and Teamwork Unit in Oxford in 2005 specifically to conduct scientific studies of interventions to improve surgical practice and patient safety. His expertise in study design and methodology together with his experience as a consultant surgeon helped him to design studies appropriately.

Dr Ken Catchpole (KC) brought experience and knowledge in the application of ergonomics [human factors (HFs)] to health care, and to surgery in particular. Dr Catchpole joined the team after a successful 3-year collaboration with the paediatric cardiac surgery team at Great Ormond Street Hospital, during which he devised a number of methods for analysing their work in theatre and demonstrated important principles, such as a demonstrable link between accumulation of small errors and the likelihood of a major error, and between the non-technical and technical performance of a theatre team.

Dr Steve New (Lecturer in Operations Management at the Saïd Business School) is an expert on process improvement methods, particularly lean methodology, and has considerable experience of real-life improvement projects using these methods.

Professor Doug Altman (Head of the Centre for Statistics in Medicine at Oxford) provided advice on the development of the statistical plan and model.

Dr Gary Collins (Senior Statistician at the Centre for Statistics in Medicine) was in operational charge of the analysis plan and delivery of the statistical analyses.

Professor Alastair Gray (Professor of Health Economics at Oxford) devised a plan for collecting both costs and outcomes to allow the analysis of the cost-effectiveness of the interventions we instituted. This work was then implemented and subsequently led during the evolution of the study by Dr Oliver Rivero-Arias.

Professor Crispin Jenkinson was brought into the programme to assist with the study of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), on which he is a recognised expert, as part of the overall health economic analysis.

Professors Renee Lyons and Alison Kitson contributed to the development of a knowledge translation plan for qualitative analysis, explanation and dissemination of learning from the programme.

Professor Damian Griffin (Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Warwick University) acted as liaison and project manager for the practical studies conducted at that site, and supervised the work of the research staff involved.

Dr Tony Berendt, Dr Karen Barker and Ms Elaine Strachan-Hall acted as liaison and facilitators for the study at the Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre site.

Dr Dravid acted as liaison and facilitator for the study at the Kettering General Hospital site.

Professor Graham Martin (GM) was bought into the team towards the end of the project to assist with revision of the plans for qualitative analysis. His expertise in working with Professor Mary Dixon-Woods on analysis of health-care improvement interventions proved invaluable in ensuring delivery of this important part of the programme.

Dr Lauren Morgan (LM) joined the team in 2011 as a replacement for Dr Catchpole when the latter accepted a post in California, USA. As well as HFs expertise, she brought to the team organisational and negotiating skills that proved highly valuable in implementing the study programme.

The investigators who carried out the bulk of the data collection and intervention delivery were Dr Lauren Morgan (above), Dr Mohammed Hadi (MH) and Dr Eleanor Robertson, Ms Sharon Pickering (SP) and, latterly, Ms Lorna Flynn (LF), Ms Laura Bleakley (LB) and Ms Julia Matthews (JM).

Final programme

The final programme of studies contained a number of modifications of the original plan, some for logistic reasons and others because discussions between the members of the research team led to an evolution in ideas on how best to answer the main questions we set out to address. Our final hypotheses were:

Primary hypotheses

Single interventions

Teamwork training: CRM-based training given to a theatre team improves teamwork performance and process error rates.

Standard operating procedures: SOPs developed and applied by a theatre team improve teamwork performance and process error rates.

Lean process improvement: lean process improvement developed and applied by a theatre team improves teamwork performance and process errors rates.

Integrated interventions

Teamwork training and SOPs: TT and SOPs together result in greater improvements to teamwork performance and process error rates than either intervention alone.

Teamwork training and lean process improvement: TT and lean process improvement together result in greater improvements to teamwork performance and process error rates than either intervention alone.

Secondary hypotheses

The measures being collected include a set of clinical outcomes or surrogates (e.g. length of hospital stay, returns to theatre, 30-day mortality), a set of observational process measures (e.g. operative durations, WHO checklist completion) and a set of PROMs [e.g. European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)]. With each of the primary hypotheses, there are three associated sets of secondary hypotheses:

Clinical outcomes

Intervention (lean, TT or SOPs, or a combination of these) results in improvements in clinical outcomes compared with current practice or a single intervention for pairs.

Observational outcomes

Intervention (lean, TT or SOPs, or a combination of two of these) results in improved theatre process efficiency compared with current practice or a single intervention for pairs.

Patient-reported outcome measures

Intervention (lean, TT or SOPs, or a combination of two of these) results in more improved patient-reported outcomes than current practice or a single intervention for pairs.

Safer delivery of surgical services workstreams

Our initial proposal to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) called for four workstreams: (1) a preparatory stream involving literature review, development of statistical, knowledge translation, health economic models and project planning; (2) a stream focused on the development of more advanced and appropriate measurement techniques for team performance; (3) a stream focused on the experimental implementation and evaluation of improved intervention methods; and (4) an analytical stream comprising statistical, health economic and knowledge translation analyses and dissemination of learning. The detailed planning of the third workstream became the strongest focus of the programme, as detailed and explained above (see Chapter 2, Study design and rationale). The second workstream was modified partly in response to the needs of the third and partly for practical reasons.

A number of pilot attempts, led by Dr Catchpole, to develop a simplified universal measure for team non-technical skills which could be used in any part of the health-care systems, ended in failure and re-evaluation of our goals. We concluded that this part of the task we had set ourselves was infeasible and focused instead on improving our existing Oxford Non-Technical Skills (NOTECHS) scale for theatre team non-technical skills. At the same time it became evident that we needed to revise our methodology for evaluating the technical performance of theatre teams. An important part of workstream 2 therefore became the development of validated measures for evaluating technical performance (the glitch count) and for measuring compliance with the mandatory procedures of the WHO’s surgical checklist. Our final study design strengthened considerably the potential for interpretation of our five parallel studies. Our final qualitative assessment programme was, we feel, also an improvement on the initial plan, allowing the incorporation of learning from an extremely successful specialist team with expertise in this area. Our health economic analysis, on the other hand, was significantly affected by the problems which arose over administration of PROMs and extraction of clinical details from individual patient records. Data protection regulations proved more challenging than we had appreciated and it proved impossible to collect all the data we wanted. One final difference between the proposal and the plan as delivered was the element of delay that developed during the study. This was partly because of the difficulties of negotiating training time for clinical staff with hospital management, which proved much more challenging than we had expected, and partly because of protracted initial negotiations over the contract, which resulted in an unrealistic start date for the programme. This means that we are unable, at this stage, to provide a complete picture of the final intervention on neurosurgery, as some studies are still in the process of analysis. Despite these changes, the final body of work is substantial, coherent and successful in integrating mixed methods in the analysis of the key question underlying the programme: how can we most effectively combine methods to improve safety and quality in surgery? The results carry important messages which should influence thinking on the design of such interventions in the future.

Chapter 3 Methods

Parts of the text in this chapter have been reproduced from Robertson et al. 21 © 2014 Robertson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited; and from Morgan et al. 22 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/. Furthermore, text has also been reproduced with permision from Pickering SP, Robertson ER, Griffin D, Hadi M, Morgan LJ, Catchpole KC, et al. Compliance and use of the World Health Organization checklist in UK operating theatres. British Journal of Surgery, © 2013 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd;23 and Flynn L, McCulloch P, Morgan L, Robertson E, New S, Stedman F, et al. The Safer Delivery of Surgical Services Programme (S3): explaining its differential effectiveness and exploring implications for improving quality in complex systems. Annals of Surgery vol. 264, iss. 6, pp. 997–1003. 24

Observational methods

Methodological approach

The observational methods are used to collect real-time prospective data in the clinical setting. The benefits of this approach, along with the requirements to achieve robustness, are described in detail by Carthey,25 who includes the requirement for training of, and demonstration of reliability between, observers. Structured observation is chosen over unstructured ethnographical approaches because of the requirement to demonstrate reliability and the requirement to translate observational data into quantitative data to facilitate the comparison required for the evaluation.

Observer background and training

The clinical observers were either surgical trainees (ER and MH) or operating department practitioners (JM) with greater than 1 year of theatre experience. The HFs specialists had at least an undergraduate qualification in HFs (LM, SP and LB). The clinical observers gained experience of HFs principles from in-house lectures and literature reviews and the HFs observers gained experience of the theatre environment from theatre observational practice and mentoring by clinical observers. All observers trained in the use of the observational methods over a 2-month period with self-study and group practice sessions using video-recordings of operating teams in simulated settings.

The clinical observers developed a process map of the main operation types to be observed, which took the form of a descriptive list of the operative process, including relevant procedures and steps. These process maps formed the basis for the training and subsequent structured observation.

Non-technical skills

Non-technical skills assessment tools adapted from aviation have been used in the operating theatre to understand the influence of behaviour on outcome. A number of methods have been developed for assessing teamwork skills in operating theatres, based on direct observation or video analysis. 26–28 The development of the first NOTECHS assessment method was conducted via a European collaboration,29 which has since been followed by further developments. The Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery,30 Oxford NOTECHS scale,26 Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills31 and Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC)32 provide whole-team assessments; Anaesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills,33 Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons34 and Scrub Practitioners’ List of Intraoperative Non-Technical Skills35 focus on subteam performance.

As the complexity of surgical teamworking becomes clearer, so the demands for more sophisticated methods of measurement have followed. The validity and reliability of the Oxford NOTECHS system was demonstrated in live theatre environments,26 but a number of imperfections were noted in discussion and through experience. The system tended to group results close to the median and, therefore, had a suboptimal capacity to discriminate between teams whose performance was not extreme. We therefore sought to develop a modified version of the non-technical skills assessment method, which we termed Oxford NOTECHS II, and which is of greater utility than the original.

Development of Oxford Non-Technical Skills II scale

The Oxford NOTECHS II scale is built on extensive work in developing, evaluating and validating the original Oxford NOTECHS. 26 The final version was developed through group discussion between members of the research team. The four original Oxford NOTECHS domains of leadership and management, teamwork and co-operation, problem-solving and decision-making and situation awareness remain unchanged. The behavioural markers for each of the Oxford NOTECHS II parameters are largely unchanged from before (Table 3). There is no alteration to the consideration of the theatre team as three subteams: surgical (operating and assisting surgeons); anaesthetic (anaesthetists and anaesthetic nurses/practitioners) and nursing (scrub and non-anaesthetic circulating nurses and practitioners).

| Leadership and management | |

|---|---|

| Leadership | Involves/reflects on suggestions/visible/accessible/inspires/motivates/coaches |

| Maintenance of standards | Subscribes to standards/monitors compliance to standards/intervenes if deviation/deviates with team approval/demonstrates desire to achieve high standards |

| Planning and preparation | Team participation in planning/plan is shared/understanding confirmed/projects/changes in consultation |

| Workload management | Distributes tasks/monitors/reviews/tasks are prioritised/allots adequate time/responds to stress |

| Authority and assertiveness | Advocates position/values team input/takes control/persistent/appropriate assertiveness |

| Teamwork and co-operation | |

| Team building/maintaining | Relaxed/supportive/open/inclusive/polite/friendly/use of humour/does not compete |

| Support of others | Helps others/offers assistance/gives feedback |

| Understanding team needs | Listens to others/recognises ability of team/condition of others considered/gives personal feedback |

| Conflict-solving | Keeps calm in conflicts/suggests conflict solutions/concentrates on what is right |

| Situation awareness | |

| Notice | Considers all team elements/asks for or shares information/aware of available of resources/encourages vigilance/checks and reports changes in team/requests reports/updates |

| Understand | Knows capabilities/cross checks above/shares mental models/speaks up when unsure/updates other team members/discusses team constraints |

| Think ahead | Identifies future problems/discusses contingencies/anticipates requirements |

Oxford NOTECHS II differs from the original Oxford NOTECHS scale in that it uses an 8-point rather than a 4-point scale for dimensions, and it assigns all teams a baseline score of 6, a behavioural marker of ‘consistently maintaining an effective level of patient safety and teamwork’ (Table 4), with subsequent observations of behavioural markers potentially resulting in deviation upwards or downwards. 26

| Behaviour | Frequency | Oxford NOTECHS II scale score |

|---|---|---|

| Compromises patient safety and effective teamwork | Consistently | 1 |

| Inconsistently | 2 | |

| Could directly compromise patient safety and effective teamwork | Consistently | 3 |

| Inconsistently | 4 | |

| Maintains an effective level of patient safety and teamwork | Inconsistently | 5 |

| Consistently | 6 | |

| Enhances patient safety and effective teamwork | Inconsistently | 7 |

| Consistently | 8 |

Validation

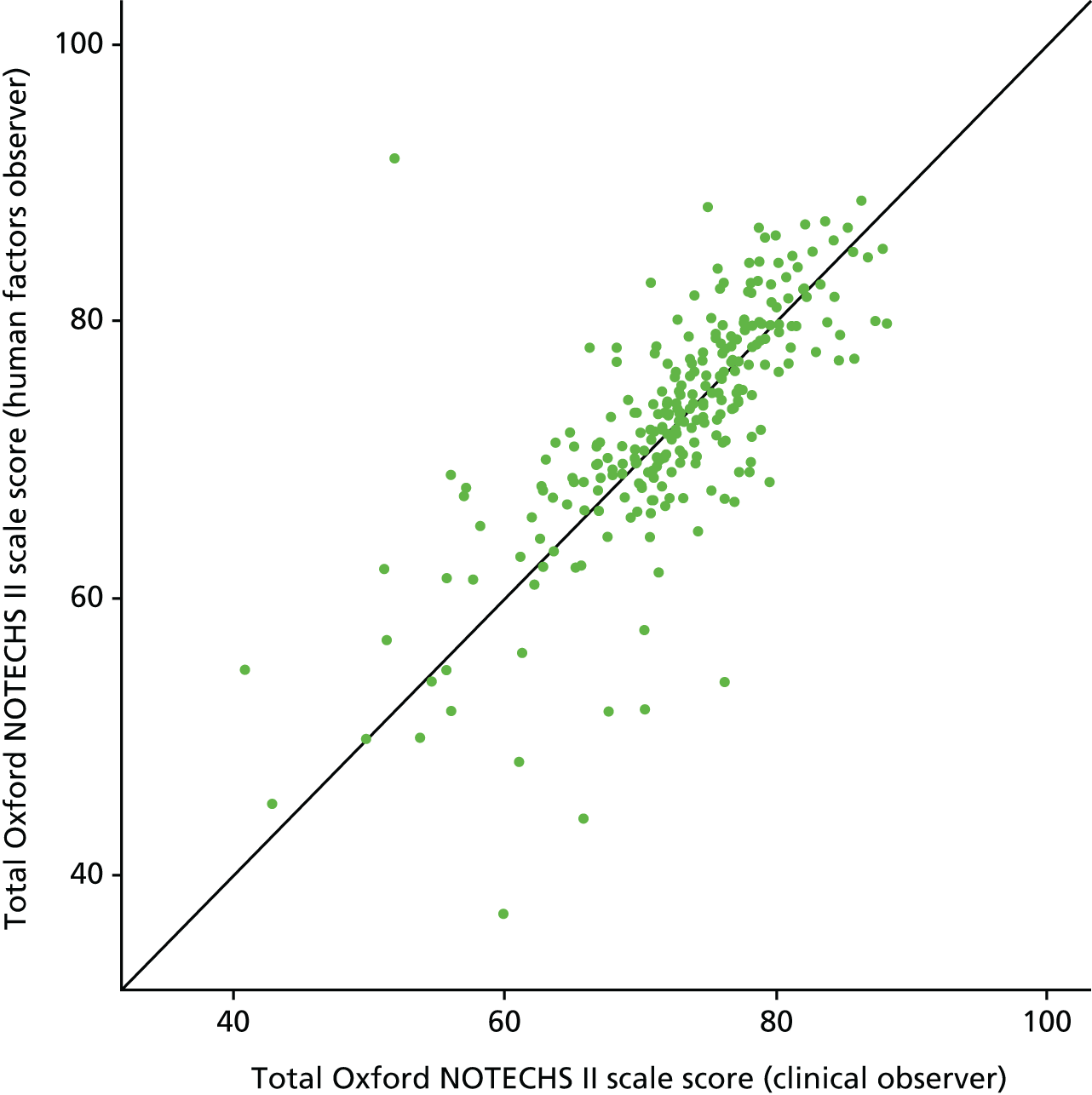

An initial live test of inter-rater reliability in 20 elective orthopaedic operations across multiple sites showed good inter-rater agreement. Subsequent analysis on the whole data set confirmed the maintenance of good inter-rater agreement for total Oxford NOTECHS II scale score between the HF and clinical observers (Figure 2 and Table 5).

FIGURE 2.

Oxford NOTECHS II scale score: HF observer and clinical observer.

| Domain | Team (% agreement, intraclass correlation coefficient) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Nursing | Anaesthetic | |

| Leadership and management | 59, 0.881 | 59, 0.777 | 64, 0.739 |

| Teamwork and co-operation | 55, 0.757 | 45, 0.343 | 64, 0.676 |

| Problem-solving and decision-making | 55, 0.725 | 63, 0.397 | 78, 0.385 |

| Situational awareness | 53, 0.770 | 48, 0.683 | 56, 0.675 |

The Oxford NOTECHS II scale scores correlated with the quality of completion of the WHO’s surgical safety checklist. We found a weak correlation between NOTECHS II scale score and glitch rate.

Method for Oxford Non-Technical Skills II scale

The three theatre subteams are each scored on four parameters (leadership and management, teamwork and co-operation, problem-solving and decision-making, and situation awareness) resulting in a total of 12 scores. The final scores were calculated at the end of the operation (during suturing/applying dressings) and entered into procedure-specific data collection books in an independent manner. 36 Once the operation was complete, each observer’s scores were individually entered on a secure database.

The record sheet for scoring the Oxford NOTECHS II scale is shown in Table 6.

| Domain | Behaviours | Surgeon team | Anaesthetic team | Nursing team | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership and management | Leadership | ||||||

| Maintenance of standards | |||||||

| Planning and preparation | |||||||

| Workload management | |||||||

| Authority and assertiveness | |||||||

| Teamwork and co-operation | Team building/maintaining | ||||||

| Support of others | |||||||

| Understanding team needs | |||||||

| Conflict-solving | |||||||

| Problem-solving and decision-making | Definition and diagnosis | ||||||

| Option generation | |||||||

| Risk assessment | |||||||

| Outcome review | |||||||

| Situation awareness | Notice | ||||||

| Understand | |||||||

| Think ahead | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Consistent | Inconsistent | Consistent | Inconsistent | Inconsistent | Consistent | Inconsistent | Consistent |

| Behaviour compromises patient safety and effective teamwork | Behaviour in other conditions could directly compromise patient safety and effective teamwork | Behaviour maintains an effective level of patient safety and teamwork | Behaviour enhances patient safety and teamwork, a model for all other teams | ||||

The total NOTECHS II scale score for each operation was used for the evaluation of the operating team’s non-technical skills performance.

Glitch count

Events within the theatre process have been given several descriptive terms in the literature, including ‘minor problems’, ‘operating problems’37 and ‘surgical flow disruptions’. 38 In each case, categories to aid description were provided including (but not exclusively) technical and environmental factors, technology and instruments, issues relating to training and procedures, teamwork and patient factors. The theoretical basis for deriving the proposed set of categories was to extend the theories proposed by Reason9 and Helmreich,12 in acknowledging the variety of system-sourced factors that can contribute to the visible imperfections in system performance. The categories are broadly based on the SEIPS model. 17

Description of the glitch count method

Glitches are defined as ‘deviations from the recognised process with the potential to reduce quality or speed, including interruptions, omissions and changes, whether or not these actually affected the outcome of the procedure’. 8 To capture these, direct observations are made of entire operations from the time the patient entered the operating theatre to the time they left, by pairs of observers comprising one clinical and one HFs researcher. The glitches were collected independently by each observer, individually noting the time and detail of the glitch within data collection booklets. This results in a set of glitches captured by each observer. These are de-duplicated and summed to provide a total glitch count for an operation. We recorded the detail of the glitch (e.g. ‘diathermy not plugged in when surgeon tried to use it’) along with the associated time point. All glitches were categorised post hoc (Table 7) and entered into a secure database. The observers spent a period of 1 month in training and orientation to the data collection methods before any real-time data were collected. Whole operating lists were observed whenever practical. If a patient left theatre mid-operation (e.g. to go to radiology), the observations were paused until the patient returned to theatre.

| Glitch category | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Absence | Absence of theatre staff member, when required | Circulating nurse not available to get equipment |

| Communication | Difficulties in communication among team members | Repeat requests; incorrect terminology; misinterpretations |

| Distractions | Anything causing distraction from the task | Telephone calls/bleeps; loud music requiring to be turned down |

| Environment | Aspects of the working environment causing difficulty | Low lighting during operation causing difficulties |

| Equipment design | Issues arising from equipment design, which would not otherwise be corrected with training or maintenance | Compatibility problems with different implant systems; equipment blockage |

| Maintenance | Faulty or poorly maintained equipment | Battery depleted during use; blunt equipment |

| Health and safety | Any observed physical risk to personnel | Mask violations; food/drink in theatre |

| Planning and preparation | Instances that may otherwise have been avoided with appropriate prior planning and preparation | Insufficient equipment resources; staffing levels; training |

| Patient related | Issues relating to the physiological status of the patient | Difficulty in extracting previous implants |

| Process deviation | Incomplete or re-ordered completion of standard tasks | Unnecessary equipment opened |

| Slips | Psychomotor errors | Dropped instruments |

| Training | Repetition or delay of operative steps as a result of training | Consultant corrects assistants operating technique |

| Workspace | Equipment or theatre layout issues | De-sterilising of equipment/scrubbed staff on environment |

Development of the glitch count

A sample set of 94 glitches were collected during the initial training phase, grouped into common themes, and then assigned titles and definitions (Table 8). The reliability of the categorisation process was assessed using Cohen’s kappa. Agreement was good between the four observers [κ = 0.70, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66 to 0.75]. Two observers (one clinical, one HFs) were present at each operation. In contrast with previous methodologies,37 no immediate evaluation of the glitch significance was made, as the impact of a particular glitch on process or outcome is context dependent. Prior to the final analysis, all four observers reviewed the glitch data jointly. Glitches noted by both observers were categorised by consensus when there was a difference and an overall glitch score was assigned comprising the sum of all unique glitches seen (i.e. those unique to observer A plus those unique to observer B plus those in common). Some glitches were deleted (if the team considered this event was not a glitch), split (if the contextual data contained more than one glitch occurrence) or recategorised during this consensus process.

| Glitch category | Observer, n (% of category) | Total observed, n (% of total) | Difference, % (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFs and clinical | HFs | Clinical | ||||

| Absence | 123 (42.1) | 202 (69.2) | 213 (72.9) | 292 (5.1) | 3.8 (–3.9 to 11.5) | 0.362 |

| Communication | 128 (38.3) | 218 (65.3) | 244 (73.1) | 334 (5.8) | 7.8 (0.5 to 15.1) | 0.036 |

| Distractions | 585 (43.6) | 887 (66.1) | 1039 (77.4) | 1342 (23.4) | 11.3 (7.9 to 14.8) | < 0.001 |

| Environment | 5 (33.3) | 8 (53.3) | 12 (80.0) | 15 (0.3) | 26.7 (–12.4 to 65.7) | 0.245 |

| Equipment design | 224 (37.6) | 379 (63.7) | 440 (73.9) | 595 (10.4) | 10.3 (4.9 to 15.7) | < 0.001 |

| Equipment maintenance | 146 (52.5) | 206 (74.1) | 218 (78.4) | 278 (4.8) | 4.3 (–3.1 to 11.7) | 0.273 |

| Health and safety | 171 (40.4) | 243 (57.4) | 350 (82.7) | 423 (7.4) | 25.3 (19.1 to 31.5) | < 0.001 |

| Patient related | 36 (30.0) | 49 (40.8) | 107 (89.2) | 120 (2.1) | 48.3 (37.1 to 59.6) | < 0.001 |

| Planning and preparation | 304 (38.5) | 495 (62.7) | 596 (75.5) | 789 (13.7) | 12.8 (8.2 to 17.4) | < 0.001 |

| Process deviation | 227 (37.0) | 375 (61.1) | 465 (75.7) | 614 (10.7) | 14.7 (9.4 to 20.09) | < 0.001 |

| Slips | 256 (50.4) | 386 (76.0) | 377 (74.2) | 508 (8.8) | –1.8 (–7.3 to 3.7) | 0.562 |

| Training | 36 (23.4) | 70 (45.5) | 120 (77.9) | 154 (2.7) | 32.5 (21.6 to 43.4) | < 0.001 |

| Workspace | 67 (24.1) | 165 (59.4) | 180 (64.7) | 278 (4.8) | 5.4 (–3.0 to 13.8) | 0.221 |

| Overall | 2308 (40.2) | 3683 (64.1) | 4361 (75.9) | 5742 | 11.8 (10.1 to 13.5) | < 0.001 |

Reliability and validity of the glitch count

A total of 429 operations were observed between November 2010 and July 2012 and 5742 glitches were observed. The total number of glitches observed in a single operation ranged from 0 to 83 (mean 14 glitches).

We investigated possible differences in the profile of glitches that each observer collected in theatre (see Table 7). Of the 5742 glitches, 64% were observed by the HF observers and 76% were observed by the clinical observers (p ≤ 0.001). The clinical observers consistently noted more glitches per operation than the HFs observers, but the difference varied markedly between glitch categories. Clinical observers noted a much larger proportion of environmental, training, health and safety, and patient-related glitches, while there was minimal difference between the observers for absence, slips and equipment maintenance.

Agreement between observers was assessed using Fleiss’s kappa for multiple observers (a chance-corrected proportional agreement). A value of zero indicates no agreement better than chance and a value of one indicates perfect agreement. Values can be interpreted39 as < 0.20, poor; 0.21–0.40, fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, good; and 0.81–1.00, very good. The agreement between the four observers is shown in Table 9.

| Summary | Cases agreed |

|---|---|

| Agreement between the four observers | |

| Agreement between all four observers, n (%) | 28 (56) |

| Agreement between three or more observers, n (%) | 42 (84) |

| Kappa (95% CI) | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.75) |

The World Health Organization’s checklist evaluation method

The WHO launched the Safe Surgery Saves Lives campaign40 in January 2007 to improve consistency in surgical care and adherence to safety practices. In June 2008, the WHO’s surgical safety checklist11 was designed to help operating room staff improve teamwork and ensure the consistent use of safety processes. The WHO’s checklist has become one of the most significant and widely used innovations in surgical safety of the last 20 years. 41–44

Large benefits have been reported following implementation of the checklist, including reductions in adverse events41 and cost savings. 43 Based on these reports, the WHO’s surgical safety checklist has been regarded as highly successful. Claims have been made for its capacity to induce indirect changes, such as improved situational awareness, in line with the evidence that structured briefings and checklists improve factors such as team communication and information sharing. 39

The WHO’s surgical safety checklist has since been taken up by national health-care governance organisations in the USA and the UK to ensure target compliance. In the NHS, hospitals are required to audit and report their adherence rates to meet set targets, and compliance is encouraged by a financial incentive. However, clinical audit studies of the WHO’s surgical safety checklist compliance have questioned the quality of compliance with the time-out (T/O) and sign-out (S/O) sections of the checklist. 44

Audits of the WHO’s surgical safety checklist compliance to fulfil regulatory requirements intend to record whether or not all sections of the checklist are performed. However, these audits commonly record only the fact that an attempt was made, and not whether or not the attempt was adequate to fulfil its intended purposes. Reports of problems with implementation and application45 of the WHO’s surgical safety checklist in the operating room have suggested that achieving compliance to a level in which benefit can reasonably be expected is more complex than expected. 46

Development of the World Health Organization’s checklist evaluation

A sample of the WHO’s form for each site is provided within the data collection booklet to assist the observers in noting whether or not the WHO’s form is completed or which parts are consistently missed.

The categories for scoring the WHO’s checklist completion are taken from Lingard et al. 39

The time (hour:minute) of commencing the WHO checks and the duration of checks (minute:second) are collected along with free-text contextual data regarding the content.

Description of the World Health Organization’s checklist evaluation method

Observers recorded whether or not a T/O or S/O was attempted and, if it was, the attempted process was critiqued on three quality parameters: whether or not all information was communicated, whether or not all the team was present, and whether or not active participation was noted. These parameters each received a yes or no result individually. ‘All team present’ required all the team taking part in the operation at its commencement to be present; ‘all information communicated’ required all points on the checklist to be verbally addressed; and ‘active participation’ required whole-team interaction and engagement with checklist completion. Observers recorded these parameters independently for the T/O and S/O, including the onset time and the duration of the process. Who led the T/O and S/O was also recorded, being defined as the team member who read out loud the checklist questions to the rest of the team. Following the conclusion of each operation, observers compared findings and resolved any disagreement by discussion.

The observation of the WHO T/O and S/O was performed within the context of a wider study of work, the Safer Delivery of Surgical Services (S3), which aims to quantify the effect of QI interventions on theatre processes and safety. The observation of the WHO T/O and S/O was selected as an outcome measure for the S3 programme. Within this paper we are presenting all pre-intervention assessment data.

Sign-in data were not available as they are completed in the anaesthetic room. Each of the points below is considered with a binary yes or no answer (Table 10).

| Status | Yes/no |

|---|---|

| Content (relevant information communicated?) | |

| Occasion (patient awake?) | |

| Audience (all team present?) | |