Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0108-10011. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The final report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in March 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Chris Salisbury is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Board and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) West. He also had an honorary consultant contract with NHS Direct, the NHS trust that hosted this research, in order for him to act as principal investigator. Glyn Lewis is a member of the NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Board and Jon Nicholl is a member of the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee. Catherine Pope is a member of the NIHR CLAHRC Wessex, which is a partnership between Wessex NHS organisations and partners and the University of Southampton and is part of the NIHR.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Salisbury et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Open access to software developed for this research programme

The software developed to support the Healthlines Service is freely available to developers who wish to use the content under a GNU General Public License version 3.

Please note that we are not able to provide any further support for this software nor answer technical queries about it. The software is made freely available ‘as is’, so that other organisations can make use of our work and develop it further for patient benefit.

The Healthlines software is available from the following open access repository: https://github.com/Healthlines/Healthlines-Applications (accessed 26 September 2016).

This repository includes all the code relating to the following areas:

-

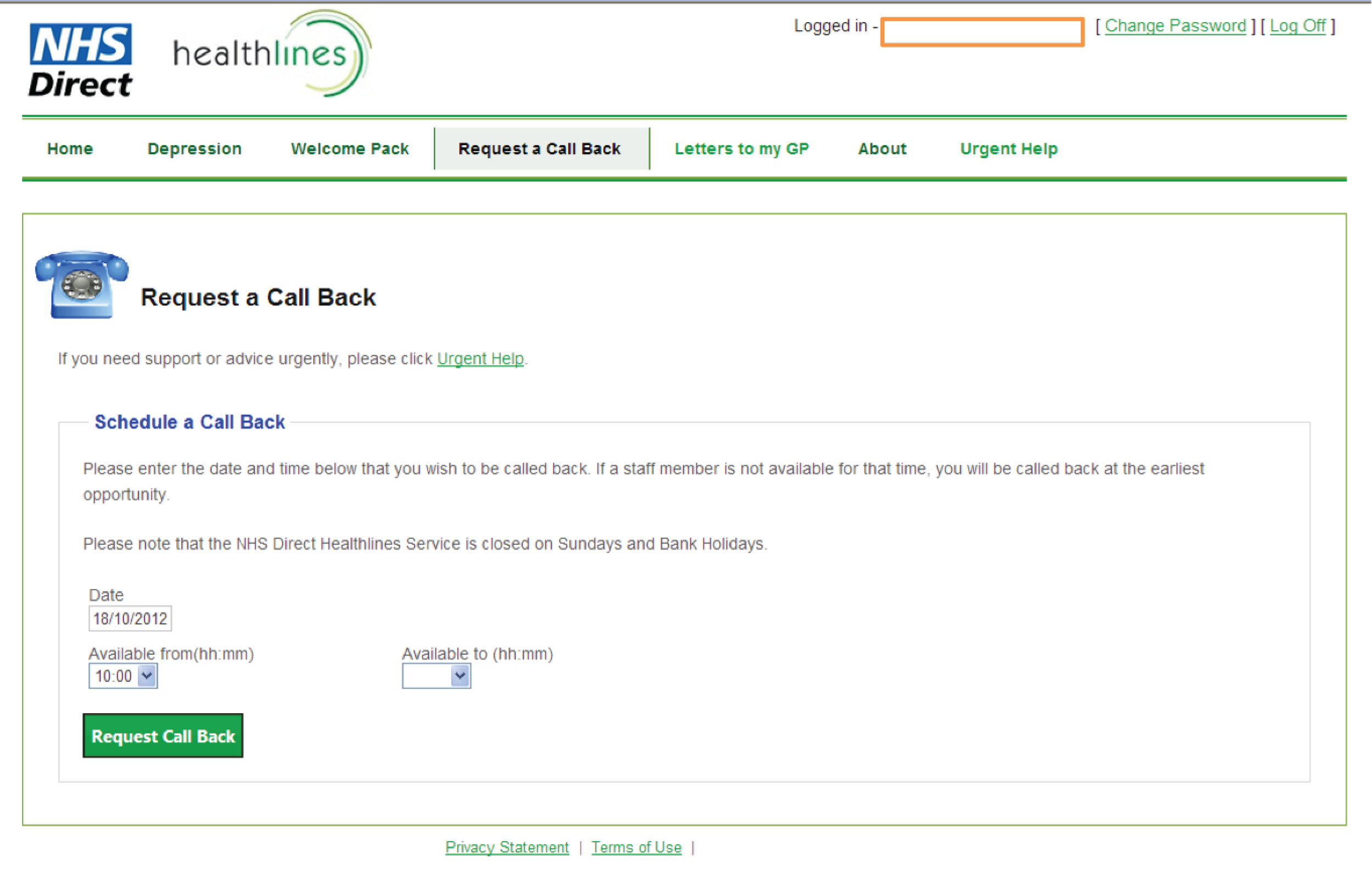

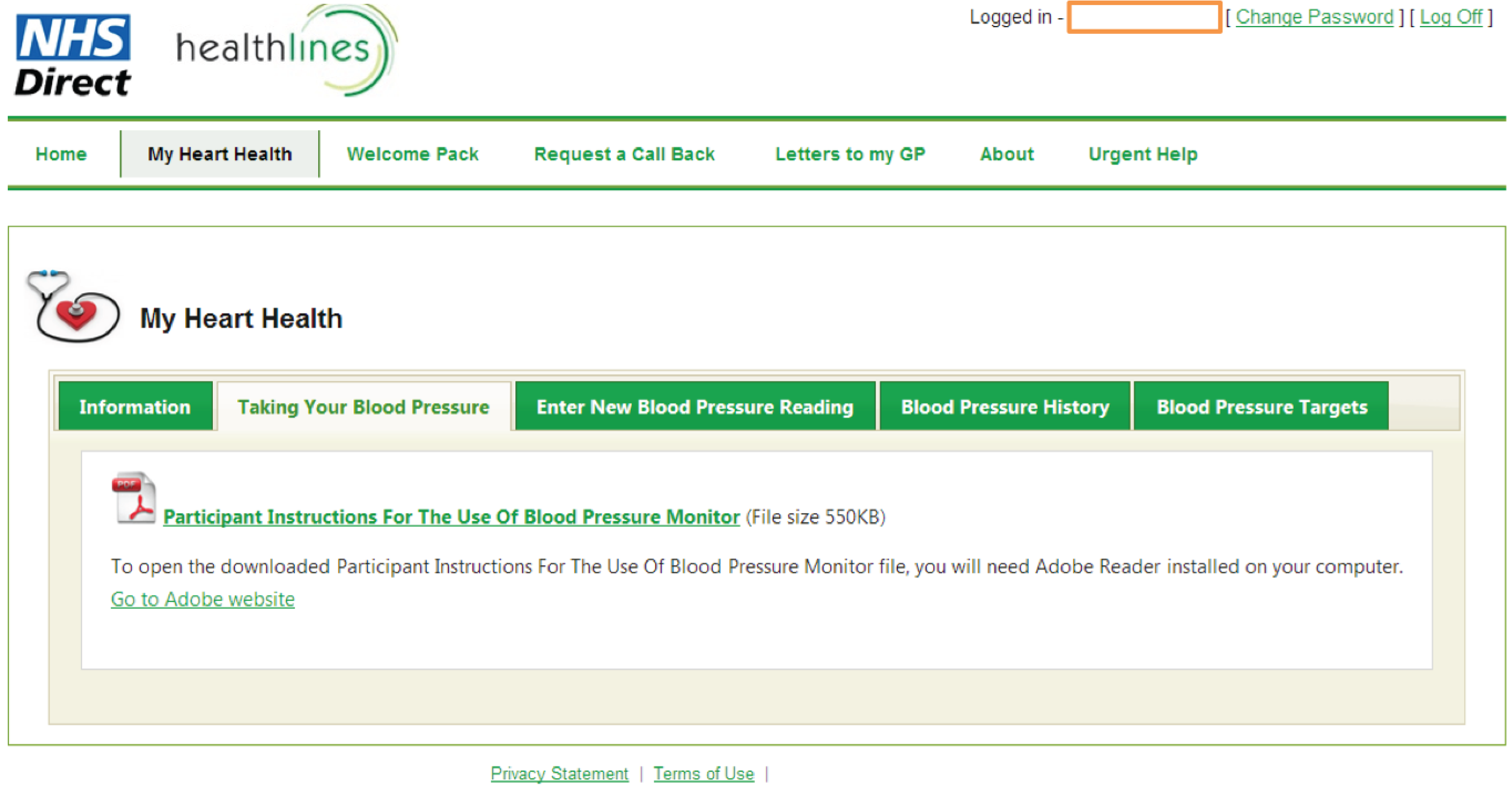

patient portal where patients can view previous interactions and add additional information

-

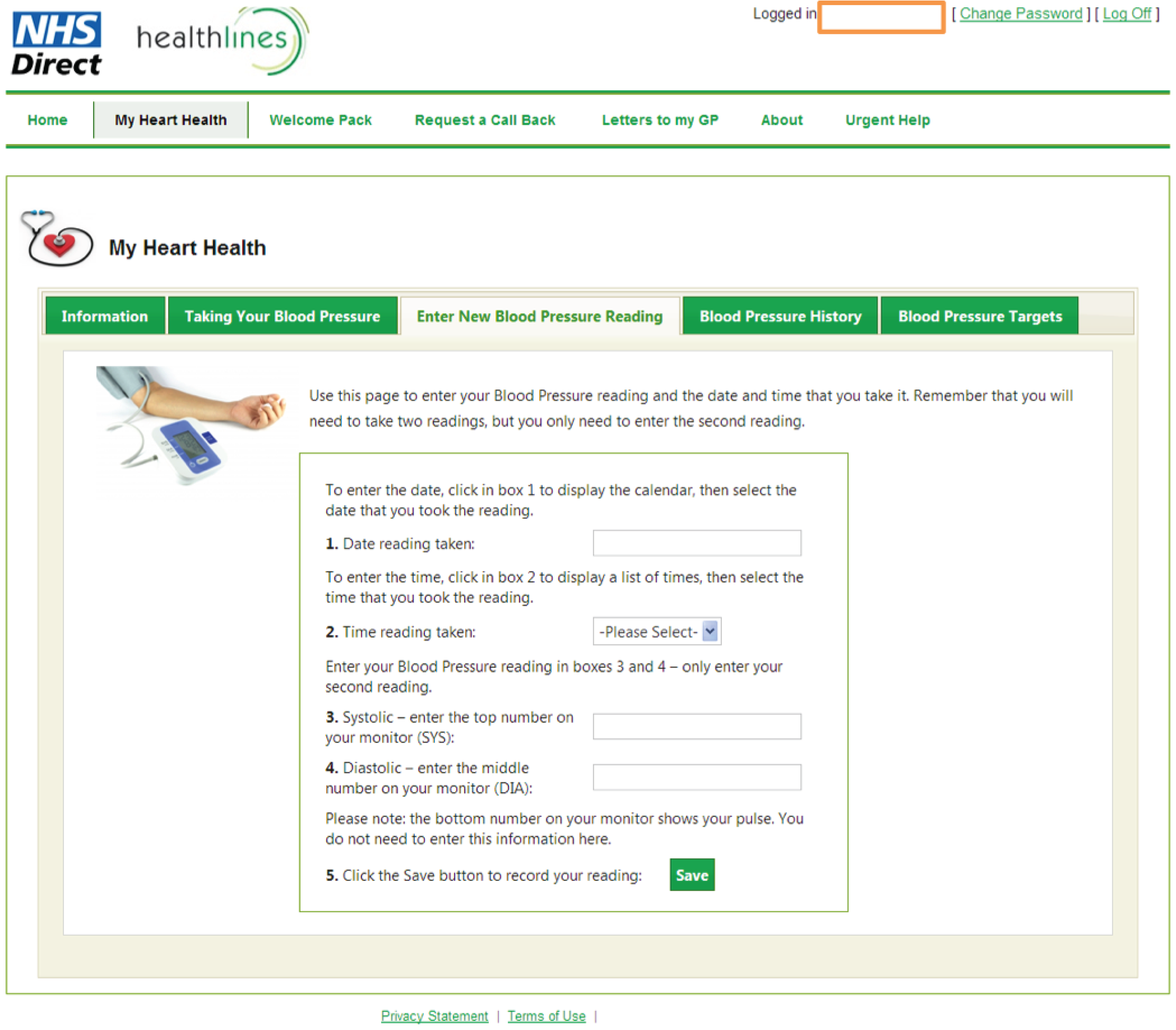

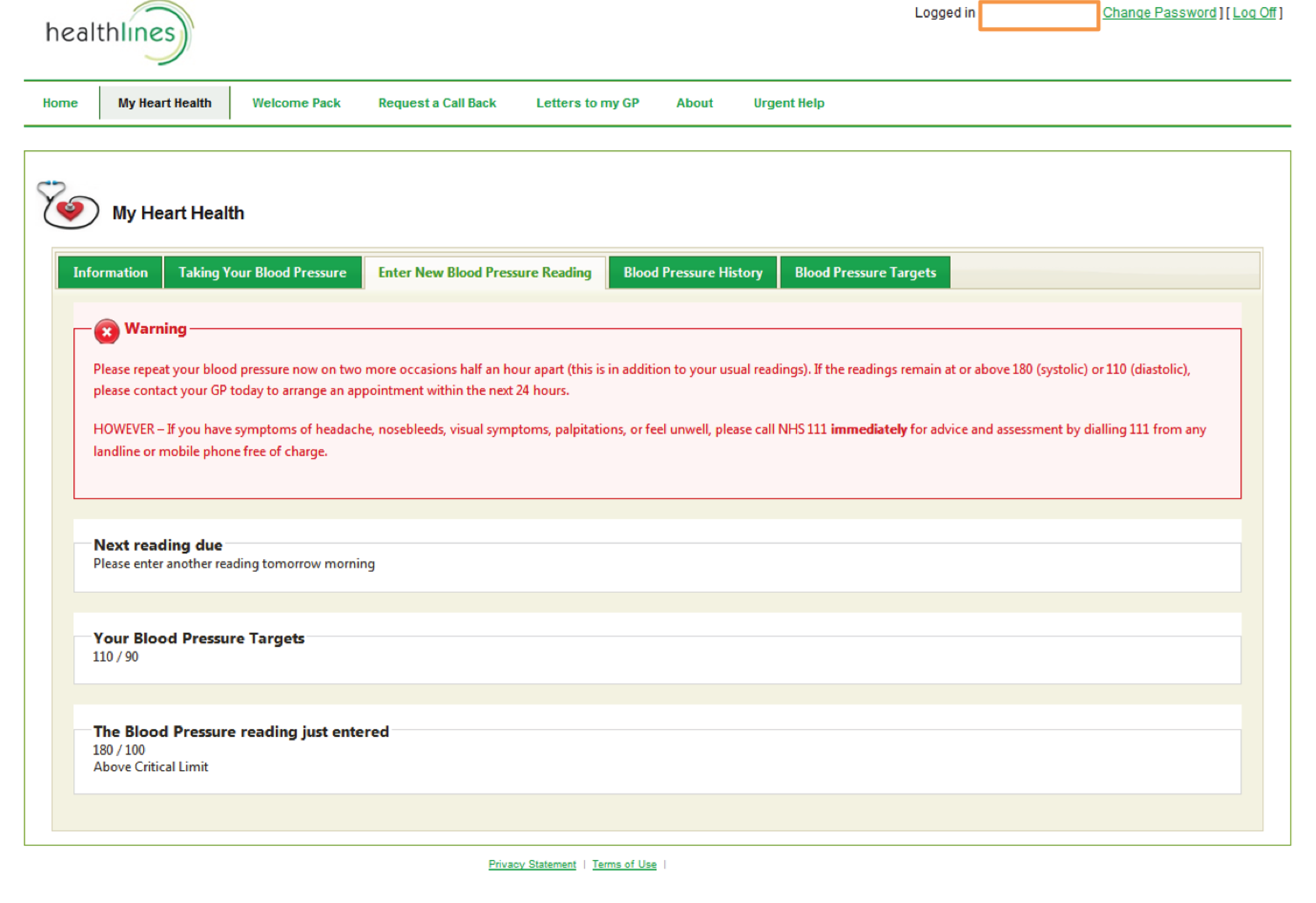

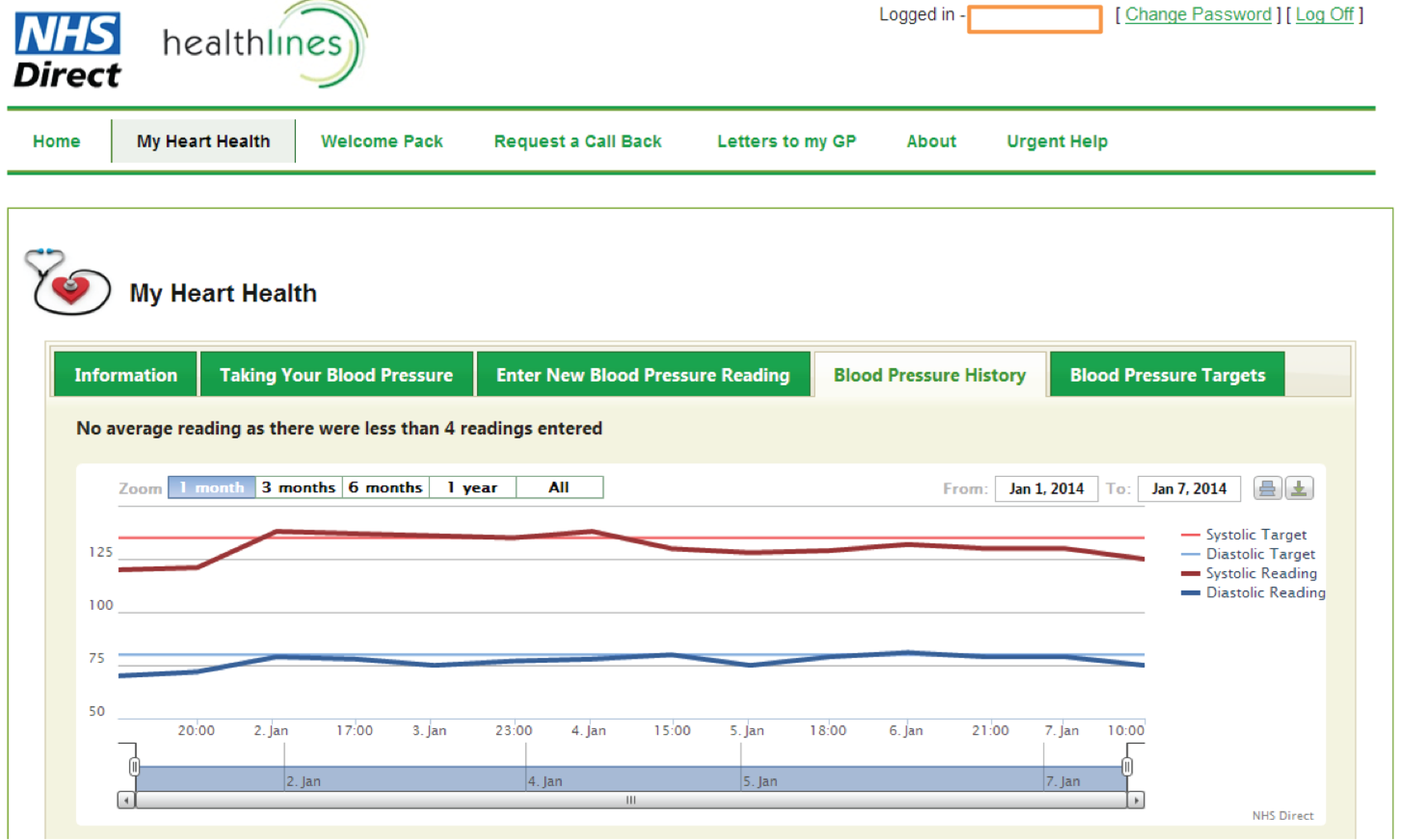

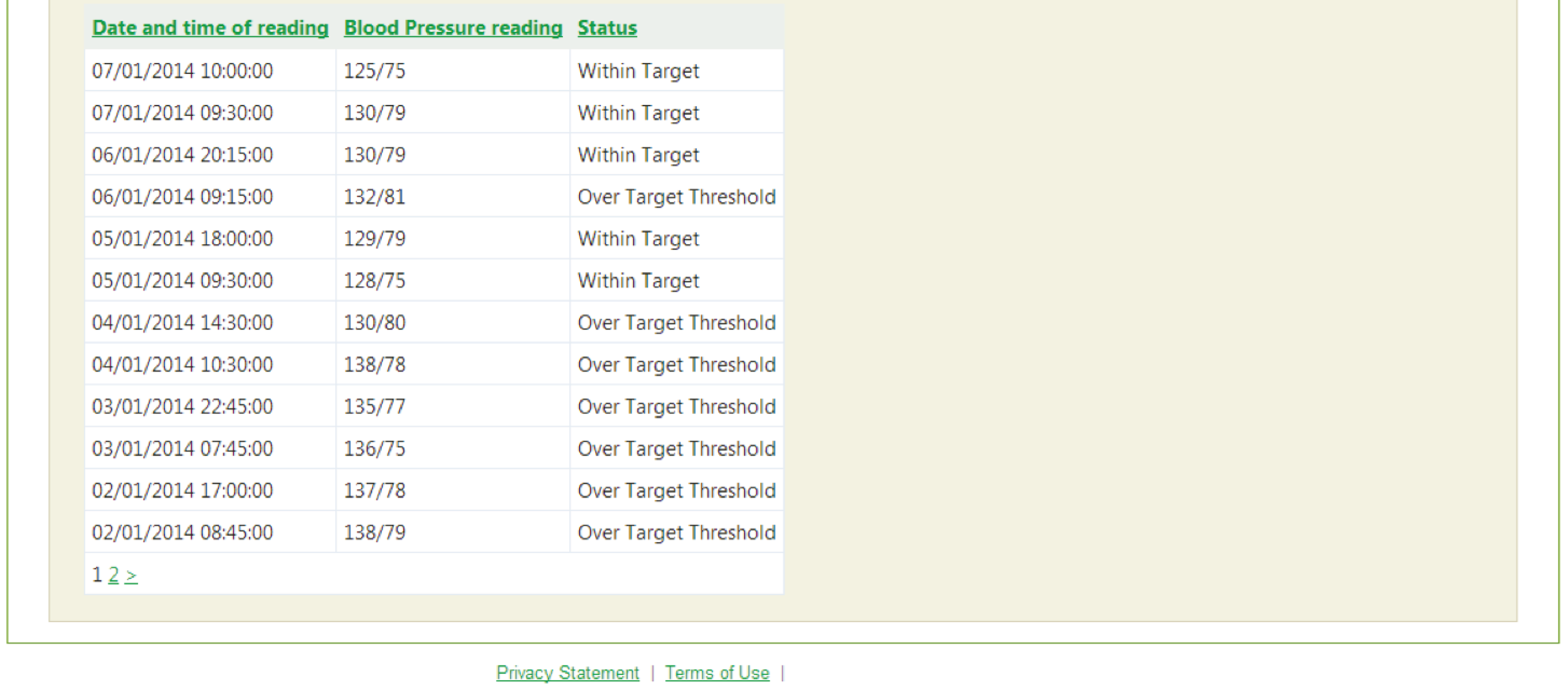

facility to support self-management of blood pressure, enabling patients to enter blood pressure readings and providing patients with graphical feedback about whether or not their blood pressure is within target limits

-

call handler management system (including call handling ‘scripts’ for each patient session, patient management)

-

administration tools (including importing patients, creating call handler scripts/flow)

-

general practitioner (GP) messaging solution (including ability to send details of patient interactions through to patients’ GPs by e-mail).

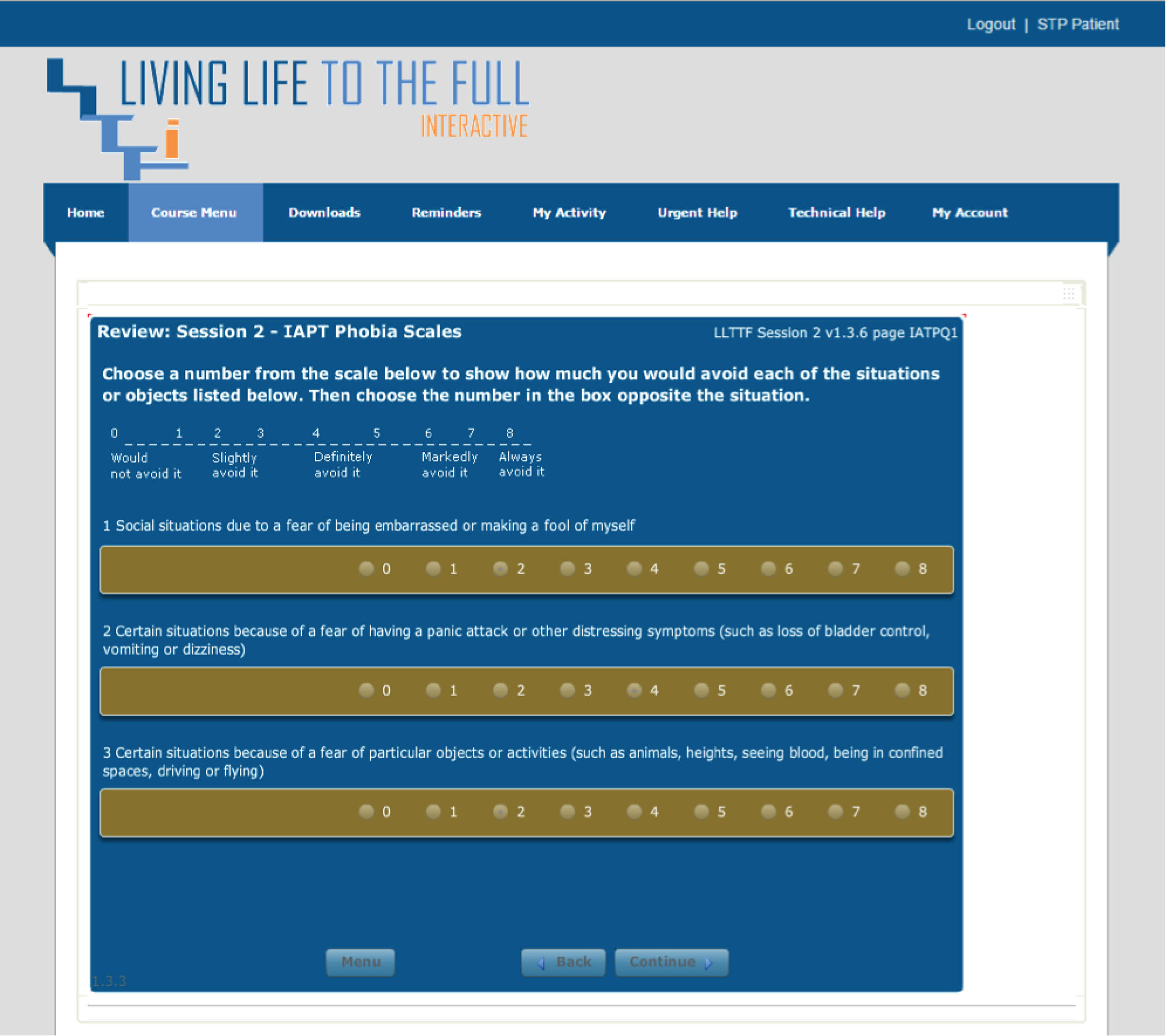

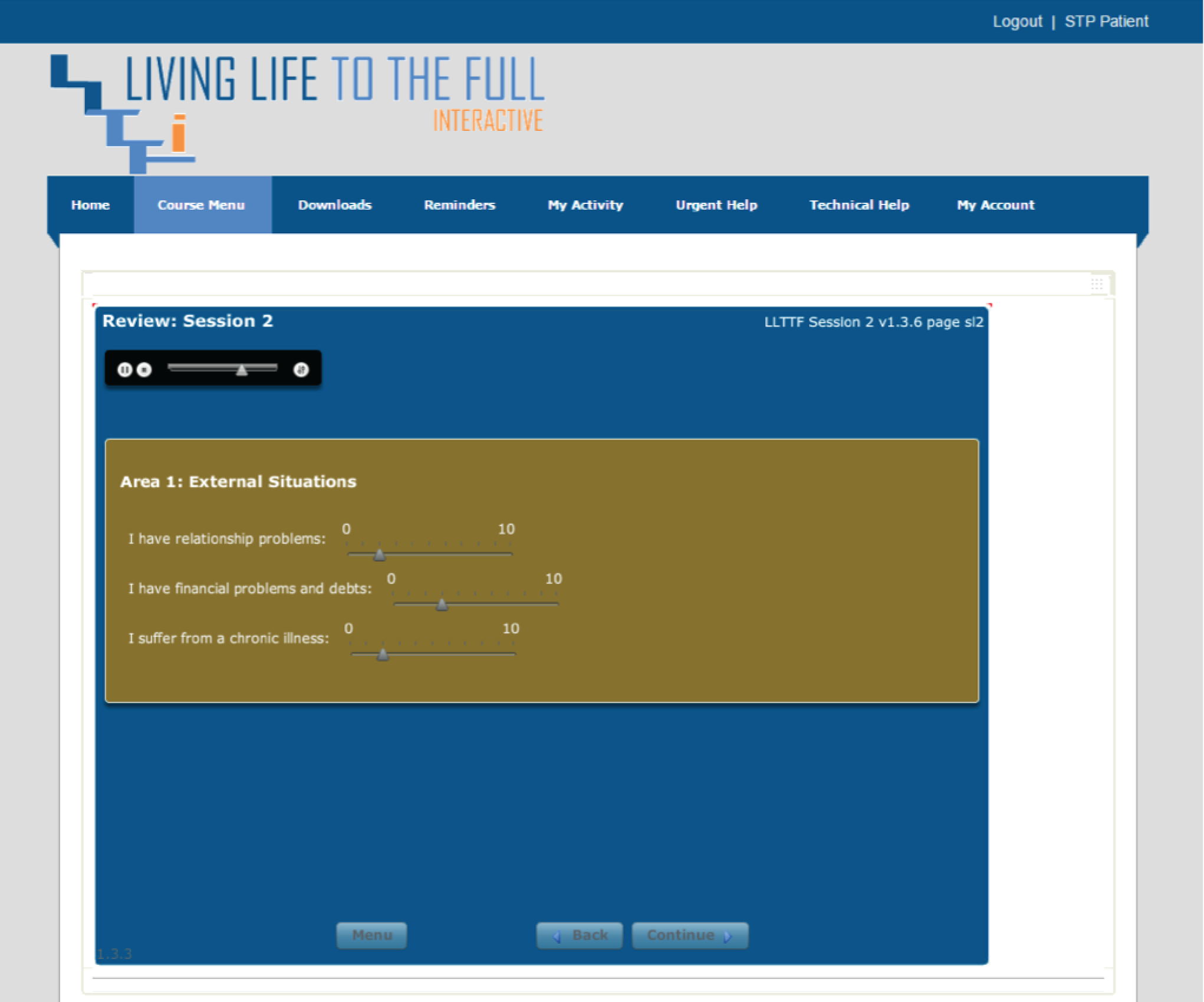

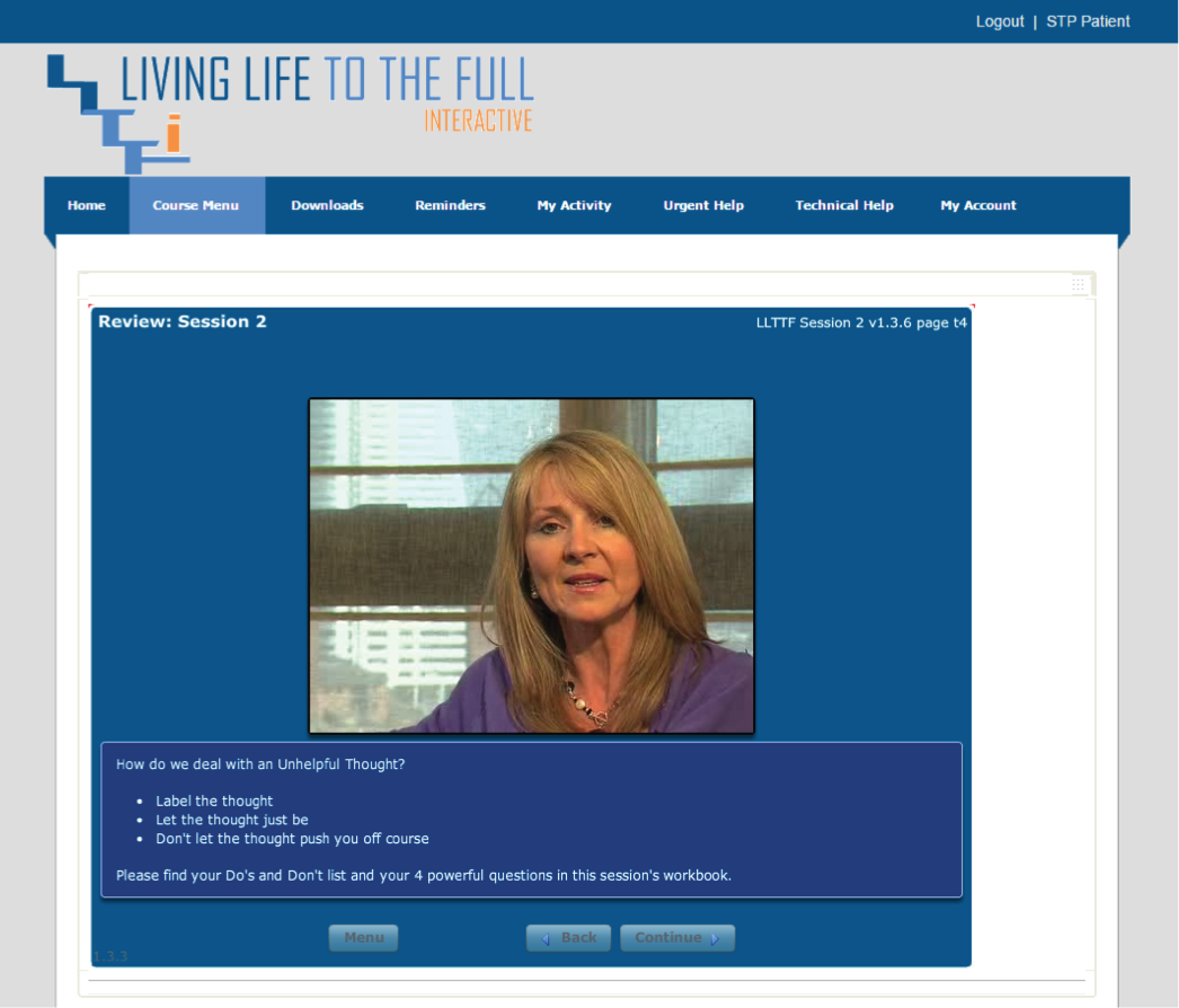

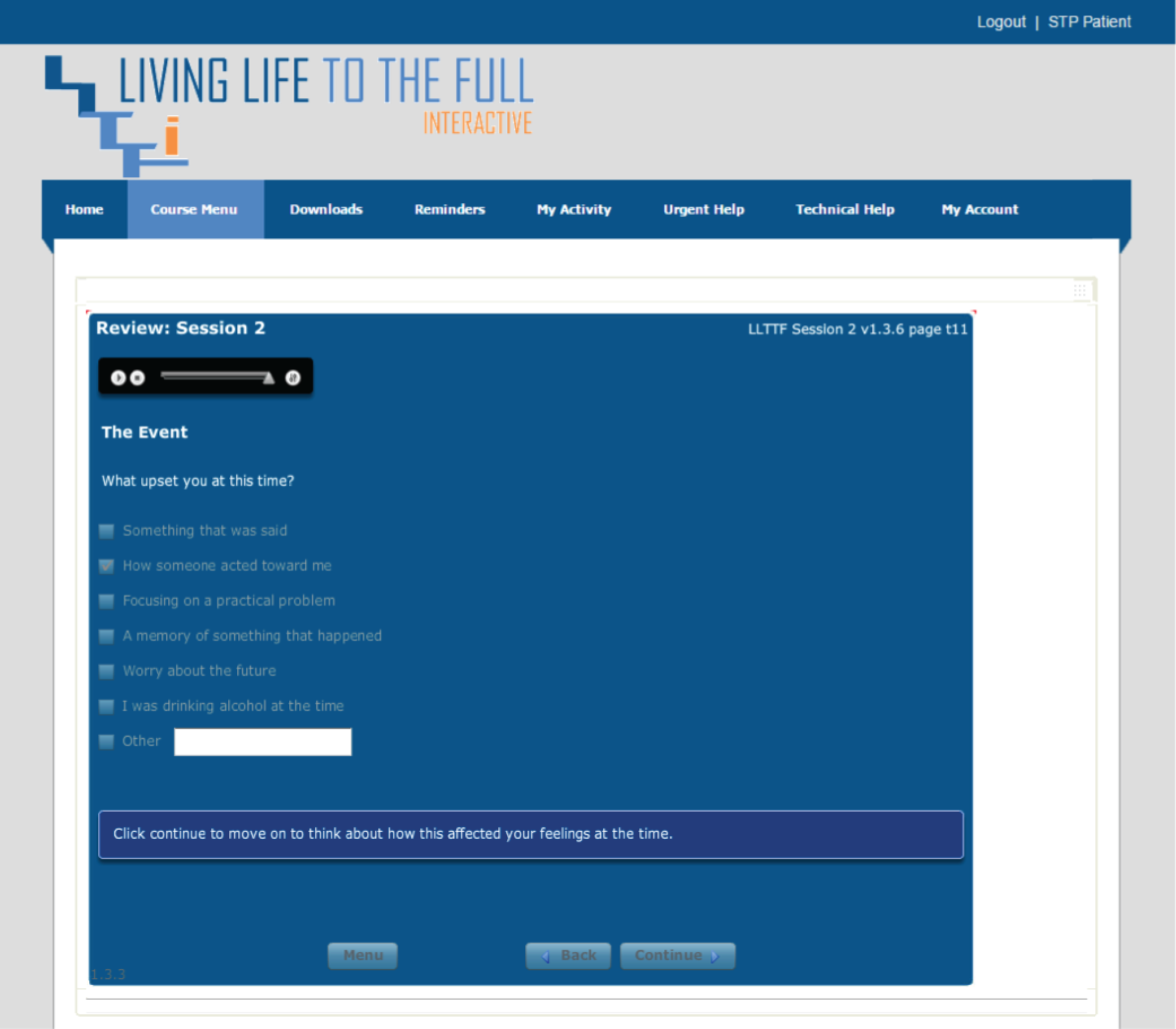

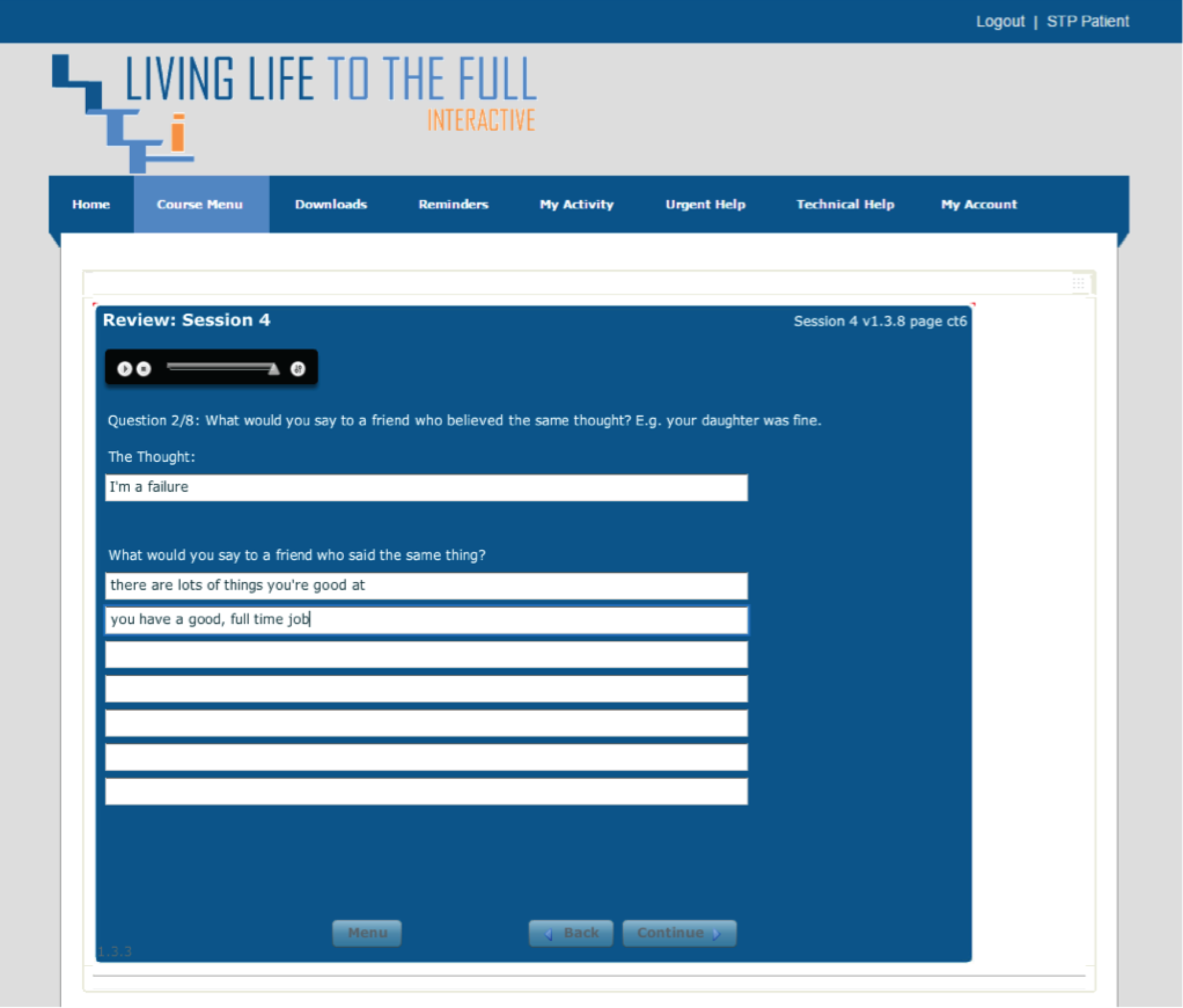

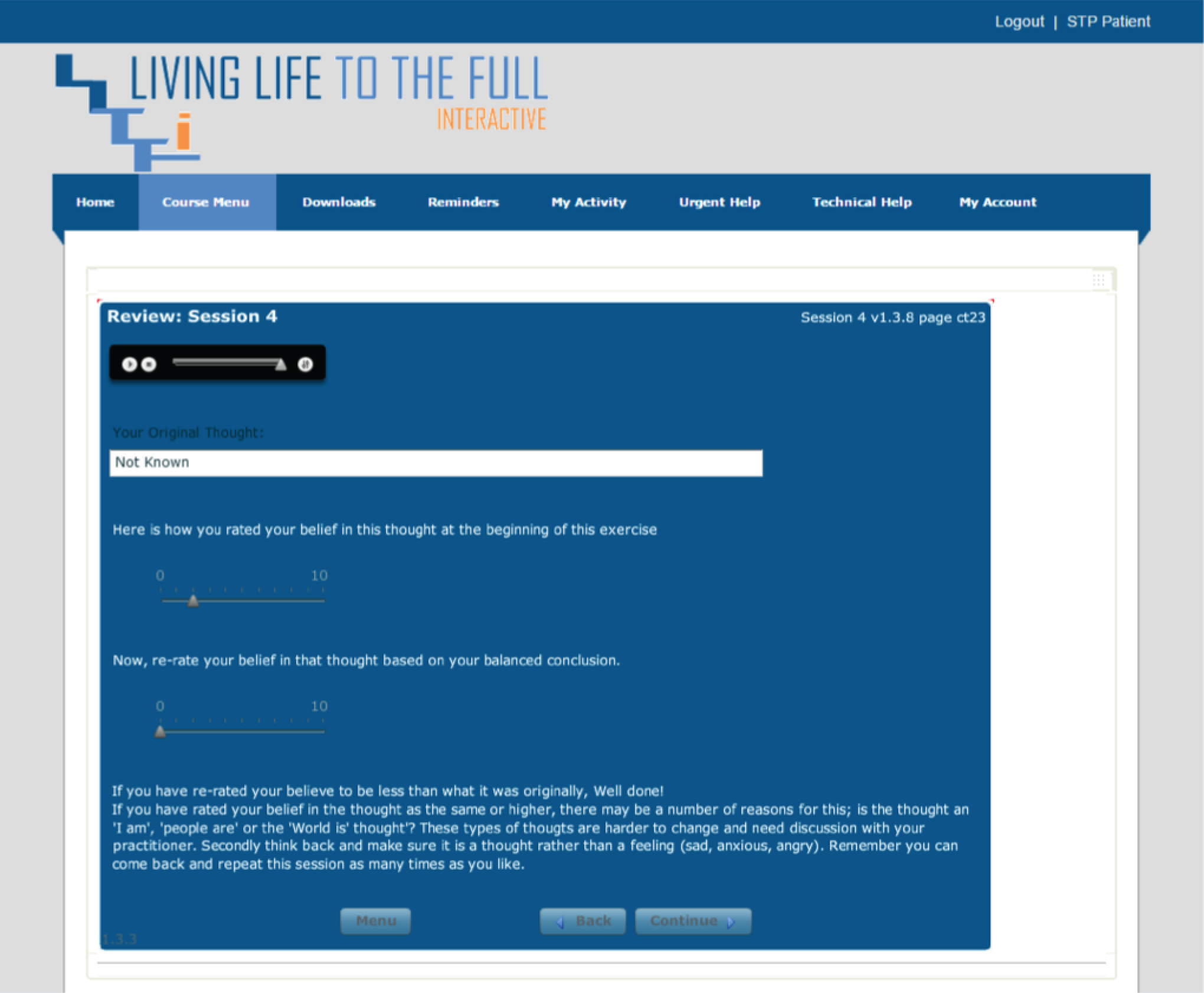

Content for the Healthlines depression intervention

Please note that the open access call handler protocols include ‘scripts’ that were designed to support the use of Living Life to the Full Interactive materials, which are licensed from Five Areas Limited. More information on the full range of Living Life to the Full Interactive materials can be obtained from www.fiveareas.com/ (accessed 26 September 2016).

Content for the Healthlines cardiovascular disease risk intervention

All code relating to call handling protocols for the cardiovascular disease risk intervention is not part of this repository as the intervention was largely based on material used under licence from Duke University (Durham, NC, USA). For further information about the content of the cardiovascular disease software, please contact Professor Hayden Bosworth at Duke University (hayden.bosworth@duke.edu).

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Background to the development of this research programme

NHS Direct was established in 1998 as a nurse-led telephone advice service for patients with health problems, as part of a commitment in the White Paper The New NHS: Modern, Dependable1 to ‘modernise’ the NHS and to make its services more accessible and convenient. As the government stated in the White Paper, the main aim of NHS Direct was ‘to provide people at home with easier and faster advice and information about health, illness and the NHS so that they are better able to care for themselves and their families’ (p. 8). 1

During the decade beginning 2000, NHS Direct expanded its offering of services considerably, beyond the original telephone advice line. The NHS Direct website was introduced at the end of 1999 and provided health information and advice, including ‘symptom checkers’ and signposting to other local NHS services based on users’ postcodes. Services available from the website expanded and the number of users grew such that the number of visits to the website rose from 1.5 million a year in 2000 to approximately 18 million in 2009. 2 In addition, NHS Direct introduced an interactive digital television channel providing similar advice as the website. NHS Direct also provided a number of services commissioned nationally or by other NHS trusts, including additional telephone advice services during periods of excessive demand, such as flu epidemics or health scares, a dental nurse assessment service, telephone-based pre- and postoperative assessments for patients having surgery, and local contracts to provide care for people with long-term conditions (LTCs), such as the Birmingham OwnHealth® scheme [see www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/3million-lives-birmingham-ownhealth-cs.pdf (accessed 7 September 2016)], based on allocating care managers to provide telephone support for patients with conditions such as diabetes or heart failure. In 2003, NHS Direct3 published a strategy document which stated (with justification) that the organisation was ‘the largest and most successful healthcare provider of its kind, anywhere in the world’ (p. 3).

As part of its strategic planning, during the latter part of the decade NHS Direct decided to enhance its commitment to research and development. It approached Professor Chris Salisbury to explore possibilities for research, particularly in relation to topics in which they could develop and test new services, which they could then offer to commissioners. Several possible areas for research were considered, but it became clear that a key opportunity lay in the potential of NHS Direct to provide support for patients with LTCs. A team of academics with interest and expertise in this topic area was therefore brought together and this research programme was developed in partnership between NHS Direct and the Universities of Bristol, Sheffield, Manchester and Southampton, with Professor Salisbury as Chief Investigator.

Background to the research topic

As the population ages, the priority for the NHS is increasingly to help people manage LTCs. These individuals consume a high proportion of health-care resources, yet there is considerable variation in management. 4 There is a need to redesign services both to cope with the increasing number of people needing health care and to improve the standard of care being offered. This ‘requires wholesale change in the way health and social care services deliver care and support’ (p. 41). 5 In 2004, the Department of Health6 first published a strategy for improving the care of LTCs based on promoting better health by supporting self-care, providing responsive high-quality services and providing case management for those with the greatest needs.

One approach to meeting the need to support improved health care for LTCs is to make greater use of technologies such as text messaging, telephone support, the internet and remote monitoring. These approaches can be described as telehealth, which can be defined as the use of electronic and telecommunication technologies to support health care at a distance from the patient.

There is strong international interest in the use of telehealth to help patients with LTCs. 7 At the time that this programme was commissioned, a number of systematic reviews had been conducted. 8–23 These concluded that telehealth interventions were promising, but that further research was needed in relation to:

-

mechanisms of action

-

effectiveness in a wider range of conditions

-

clinical outcomes

-

economic effects

-

relevance to the NHS.

Within the NHS, many organisations were developing telehealth interventions, but formal evaluation had been relatively limited.

Importance of the research and its relevance to the priorities and needs of the NHS

Over 15 million people in England have a LTC and treatment of LTCs accounts for 70% of total health-care expenditure. Improvements in LTC management could have major benefits in terms of patient health, quality of life and use of NHS resources. 5

In this programme we decided to test a new telehealth approach, delivered by NHS Direct, within two exemplar conditions. These were (1) patients with depression and (2) those at high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). We chose these examples for several reasons. They are very different types of conditions, one affecting mental health and one physical health. However, both conditions are very common and have a major impact on quality of life. They also account for a high proportion of health-care resources and there was good reason to suggest that the potential need for care is considerably greater than the capacity of the NHS to deliver care. Furthermore, in both cases there was some evidence of effective telehealth interventions, but this evidence was inconclusive. Further discussion of these points in relation to the exemplar conditions is provided in the following sections.

Studying two very different LTCs in parallel, and developing management programmes for them based on a common theory-driven approach, would enhance generalisability. The vision was that, if these telehealth programmes were both effective, this would provide a framework and a justification for the future development of further programmes for other LTCs.

Depression

Mental health problems are very common: 11% of adults aged 16–74 years in England and Wales suffer from depression or mixed anxiety/depression. 24 These disorders account for 25% of primary care consultations25 and the cost to society is approximately £25B. 26 There is increasing evidence that therapies of the type that could be delivered by NHS Direct, including computerised or telephone-based cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), are effective. 27

Developing the role of NHS Direct in the management of LTCs was also consistent with NHS policy to design services around patients’ needs, improve convenience of access to care, encourage active involvement in care and provide information to support self-care. 5,28 NHS policy at the time envisaged telehealth becoming a mainstream aspect of NHS care delivery28,29 and this enthusiasm for the potential of telehealth to manage patients with LTCs has continued since this programme was commissioned. 30 This interest in the potential of telehealth is perhaps not surprising given that over the last 20 years there has been an explosion in the use of technology, particularly call centres, the internet, mobile devices and ‘apps’, that has revolutionised almost all other transactions that used to be conducted through face-to-face consultations, including banking, shopping and customer support in various industries.

High cardiovascular disease risk

Cardiovascular disease [coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke] causes 36% of deaths in England and accounts for one-fifth of all hospital admissions. 31,32 In the past, hypertension, obesity and hyperlipidaemia were considered as separate LTCs, but there is increasing recognition that they should not be thought of as separate conditions but instead be considered in combination as factors that contribute to an individual’s overall CVD risk. Therefore, ‘raised CVD risk’ should be considered as a LTC, rather than treating hypertension, for example, as a LTC. To improve care for patients with a raised CVD risk it is important to manage all of their underlying risk factors through treatment of high blood pressure, weight loss, smoking cessation, cholesterol reduction and increased exercise. 31–33

One further factor in the decision to use raised CVD risk as an exemplar condition was the policy decision, announced in 2008, that the NHS was to begin a screening programme for CVD in those aged 40–74 years. This decision was based on predictions about the potential benefits of such as scheme, but the modelling used also suggested that screening was likely to identify a large number of people who would need to be offered intensive management of their CVD risk factors. 34 At the time that the Health Checks policy was announced, it was not clear how the NHS was going to provide the extra capacity to advise all of the extra people with raised risks who would be identified. Some new forms of help were, in time, introduced (e.g. health trainers), but it was apparent that the NHS needed to develop new approaches to meeting the extra needs identified through the Health Checks programme without overwhelming primary care services, which were already under pressure. Supporting people to use resources that were available online appeared to be a viable way to help meet this need and NHS Direct appeared to be ideally placed to both develop the online services and provide telephone support to signpost people to the most appropriate resources.

Need for research in this area

Lack of evidence about effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

At the time that this programme began, a number of systematic reviews of telehealth for a variety of LTCs had been carried out. 8–23 These showed that evidence of effectiveness was stronger for some conditions (e.g. heart failure) than for others (e.g. diabetes). There was good evidence that telehealth was feasible and could lead to improvements in specific health behaviours, but there was a lack of evidence about mechanisms of action, clinical outcomes, cost-effectiveness, patient satisfaction, impact on service utilisation and acceptability. 9,23

The need for theory

Much of the existing evidence about telehealth was inconsistent. This is unsurprising in view of the range of LTCs, interventions and health system contexts that had been considered. To address these inconsistencies, there was a need to develop a stronger theory about how and why certain types of intervention might be beneficial, then to develop interventions based on this theory and test them. In particular, evaluation was needed to provide robust evidence about clinical outcomes and economic impacts. Most previous research had focused on narrow intermediate outcomes and process measures rather than meaningful clinical outcomes.

The need to test wide-scale implementation alongside existing services

It was also important to learn how to implement telehealth interventions nationally and make them mainstream. Many telehealth studies have tested discrete ‘stand-alone’ technologies, such as a specific text messaging application or a specific website or home monitoring technology. These have been often tested in volunteer populations. However, evidence of efficacy in research populations does not provide evidence of effectiveness when the intervention is implemented on a wide scale in real-world application in the population who might benefit from it. Furthermore, telehealth interventions have often been developed without consideration of how they will integrate with other existing sources of health care.

This involves consideration not only of the technology but also of the organisational context. Most previous studies had been conducted in the USA, which has different problems of access to care, less well-developed primary care and different financial incentives. Research was needed on integration and mainstream implementation of telehealth in the NHS, particularly how a national telehealth provider such as NHS Direct could support local providers of primary care.

The promotion of telehealth-based long-term condition programmes by commercial providers

In the period around 2005, several commercial organisations were marketing telehealth programmes or telehealth applications to commissioners for the management of LTCs. This growth in telehealth has been encouraged by a succession of government policies. At the time that this research programme was being developed, NHS Direct was working with Birmingham East and North Primary Care Trust (PCT) and the pharmaceutical company Pfizer on the OwnHealth initiative to support patients with LTCs. This provided care for people with diabetes, heart failure or CHD. The intervention was based on a behavioural programme delivered by NHS Direct based on regular telephone support from nurses. Although evaluation was limited, patients enrolled in the project reported improvements in health behaviours and symptoms, improvements in some clinical outcomes, such as blood sugar control, and a reduction in primary and secondary care consultations. Patients had positive experiences of the service and found it accessible and easy to use. 35,36 This supports the feasibility of NHS Direct as a platform for delivering care for LTCs.

This programme grant was designed to build on these foundations to develop and test interventions to support patients with LTCs, including issues of implementation, so that (if successful) they could be rapidly rolled out nationally.

Target populations and generalisability

The introduction of NHS Direct reflected a policy drive to make the NHS more responsive to its users, for example by making it possible for people to seek advice at times and in ways that were convenient for them. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to NHS provision was no longer considered appropriate. Similar considerations also applied to telehealth programmes for LTCs to be developed by NHS Direct. We did not consider it likely that telehealth support for LTCs was necessarily going to be acceptable or appropriate for all or even most individuals with a LTC. However, it may be a good solution for some people, particularly those who may have difficulty accessing care through conventional means based on face-to-face consultations. This might particularly apply, for example, to those who are at work during the day or those who are housebound. The number of people with LTCs is so large that even if telehealth provided help for only a minority of these individuals it could still be a worthwhile option if it was more accessible, acceptable and cost-effective for this group of people.

This has implications for generalisability. In conventional research designs there are concerns if studies do not recruit a large proportion of the eligible population because findings from the study may not be applicable to the wider population. However, in this research programme we were interested in identifying which groups of the population were most interested in and might benefit from a telehealth programme delivered via NHS Direct. If an intervention was beneficial for these people it would not necessarily need to be relevant to other people who would prefer to receive help in more conventional ways.

Combining technologies for which there is already proof of concept

In each of our exemplar conditions there was existing evidence that specific telehealth interventions may be effective, but there was a need to test organisational interventions to deliver them on a wide scale. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) had highlighted the need for large-scale trials of LTC management programmes for depression. 27 This programme set out to draw on the evidence on the most promising ‘active ingredients’ of telehealth for LTCs to develop integrated, comprehensive and theory-driven programmes of care to be delivered by NHS Direct.

Within our exemplar conditions there was some evidence of effectiveness for interventions that could be offered by NHS Direct. For depression, it included provision of CBT by telephone or online,37–40 online self-help41,42 and bibliotherapy. 43,44 For CVD risk, this included blood pressure telemonitoring,19 web-based hypertension management45 and telephone-based interventions to promote medication adherence and/or risk reduction. 46–48

However, in real-life management of patients with LTCs, specific interventions are not offered to patients in isolation. Patients with depression may well be treated with antidepressants and receive psychological therapy at the same time. For patients with a raised CVD risk, clinicians need to seek to improve multiple risk factors, such as blood pressure, weight and smoking behaviour. Attention to these risk factors may involve the provision of advice, medication, encouragement and signposting to a range of resources.

In this research programme we were not seeking to develop new ‘cutting-edge’ technology for use in LTCs. Instead, we were seeking to use existing technologies for which there was already some ‘proof of concept’ evidence to suggest a likely benefit for patients with our exemplar LTCs and to test how to deliver these interventions on a large scale in a co-ordinated way through a platform such as NHS Direct.

The Whole System Demonstrator project

At the time that this research was developed we were aware of and needed to take account of several other relevant ongoing projects, in particular the Whole System Demonstrator (WSD) programme. The Department of Health White Paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: a New Direction for Community Services28 set out a vision for preventative care services and set up the WSD programme to establish evidence in a UK context by deploying telecare and telehealth services covering a resident population of over 1 million across three areas of the country. 49 This was therefore a very large demonstrator programme that explored integrated health and social care supported by new technologies, based on radical systems redesign. The WSD programme was subject to a comprehensive evaluation based on a multicentre cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) with accompanying economic evaluation. This was the largest robust evaluation of a telehealth programme ever attempted and it was important that our own research tested a different approach. The WSD programme focused on people with serious and life-threatening LTCs such as lung disease, heart failure and diabetes and, in particular, patients at high risk of hospital admission.

Focus on common long-term conditions and low-cost interventions

The rationale for the WSD programme is that some patients make very high use of expensive NHS resources and it may be possible using telehealth to support them in a more cost-effective way. However, the WSD approach was in itself also very resource intensive. Furthermore, those individuals with very high health-care needs, who are at the pinnacle of the ‘Kaiser pyramid’,50 represent only a very small proportion of patients with LTCs.

We therefore decided to think about telehealth in a different way and explored an approach to making self-management resources available via telehealth to large numbers of people with common LTCs. A core principle of epidemiology is that small shifts in the health of large numbers of people can have more impact on population health than large shifts in health in those with the greatest health problems. 51 The idea was that our intervention would be applicable to many people and so it was important to make use of inexpensive technologies that could potentially be widely available. Otherwise, the intervention would be unaffordable even if it was effective.

Furthermore, as we developed this research programme, our initial investigations suggested that most telehealth interventions being promoted were disproportionately expensive and were very unlikely to be cost-effective unless they had a big impact on hospital admission rates or led to big improvements in health. Previous research had not suggested that either was likely to be the case. 52–54 Because we were seeking to achieve small improvements in health in large numbers of people, it was important that the intervention could be delivered at minimum cost to maximise the likelihood that it would be both cost-effective and affordable at a population level.

The potential of NHS Direct

NHS Direct provided a unique opportunity to integrate a range of telehealth interventions for people with LTCs. It could reach people through several technological channels simultaneously, including an established network of telephone call centres, the NHS Direct website and a digital television service. No other service in the world offered this range of co-ordinated services or had the same potential to reach such a high proportion of the entire population.

NHS Direct had traditionally offered reactive services to people seeking health advice and information. But it also had the potential to provide proactive services, particularly for people who have difficulty accessing care through general practice, such as the housebound, commuters or those who do not speak English. For example, the nationally networked call centres of NHS Direct could, in theory, provide a nurse with expertise in diabetes who also spoke Hindi to patients anywhere in the country or could provide advice about smoking to patients at times convenient to them, such as in the evening.

NHS Direct was also a well-recognised and nationally recognised ‘brand’ and achieved high levels of satisfaction from its users. It had a national network of call centres, a cadre of well-trained staff with experience of providing health information and advice, well-established facilities for translation for people who could not speak English, availability of staff outside office hours and the ability to call on experienced nurses, pharmacists or information specialists who could research and provide specialised advice, for example about medication interactions. NHS Direct already had experience of testing case management-type approaches to the management of LTCs through the OwnHealth pilot projects. If it were possible to develop a cost-effective intervention for LTCs that could be delivered via NHS Direct in a research context, it would be possible to roll this out relatively quickly and easily to the entire population of England.

Postscript: closure of NHS Direct

This research programme ran from 2009 to 2015, with the trial of the intervention being conducted between 2013 and 2014.

NHS Direct was closed in March 2014 in favour of the less expensive ‘111’ telephone helpline and the NHS Choices website. The closure of NHS Direct had been announced in October 2013 but there had been widespread rumours of closure ever since the BBC leaked in August 2010 that the incoming coalition government planned to replace NHS Direct. 55

Although the potential of NHS Direct had provided the impetus for this research programme, the underlying research questions about the role of a comprehensive management programme for patients with LTCs based on telehealth remain entirely relevant. The closure of NHS Direct inevitably led to some difficulties in conducting the research programme and in particular meant some delays and pauses in the delivery of the intervention; however, we were able to complete the trial thanks to Solent NHS Trust community trust replacing NHS Direct as the host for the intervention and the research programme.

NHS Direct offered advantages because of its national reach and infrastructure. However, in practice, the NHS Direct intervention staff worked from one site (Nottingham) and the intervention that was developed through this programme could be delivered by other provider organisations and made available throughout the UK (as was demonstrated by our ability to successfully relocate the service to Solent NHS Trust). Therefore, we do not believe that the closure of NHS Direct has had an important impact on the relevance or findings of this research programme.

Aims and objectives

Aim

The aim of this programme of research was to develop, implement and evaluate new programmes of care delivered via NHS Direct for patients with LTCs and to provide evidence about the benefits and costs of these initiatives.

The intended benefits of these new forms of provision were to improve health outcomes for patients, facilitate self-management, improve the patient experience and improve the cost-effectiveness of care provision.

The programme focused on two exemplar conditions: depression and high CVD risk.

Objectives

-

To review evidence about telehealth interventions designed to improve health care for patients with LTCs in order to develop a theory about which types of interventions potentially delivered by NHS Direct are most likely to be effective.

-

Using qualitative methods, to critically examine how NHS Direct resources could best be incorporated into the LTC management of patients and integrated with current primary care professional practice.

-

To explore patient factors and access factors that are associated with unmet need and with willingness to use NHS Direct and specifically types of telehealth interventions that are most likely to be acceptable to different patient groups.

-

Based on the first three activities, to develop and optimise interventions offered by NHS Direct that are likely to be acceptable, effective and efficient.

-

To determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of LTC management provided by NHS Direct in the two exemplar conditions: depression and CVD risk.

Overview of the research plan

This programme consisted of five linked activities that address each of the objectives described in the previous section. Activities 1–3 were conducted in parallel and informed activities 4 and 5. Below is an overview of each of these activities:

-

Review and synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence about telehealth for patients with LTCs in order to develop a theory about which types of intervention potentially delivered by NHS Direct are most likely to be effective.

-

Qualitative research with patients and health professionals to examine how NHS Direct can best contribute to LTC management.

-

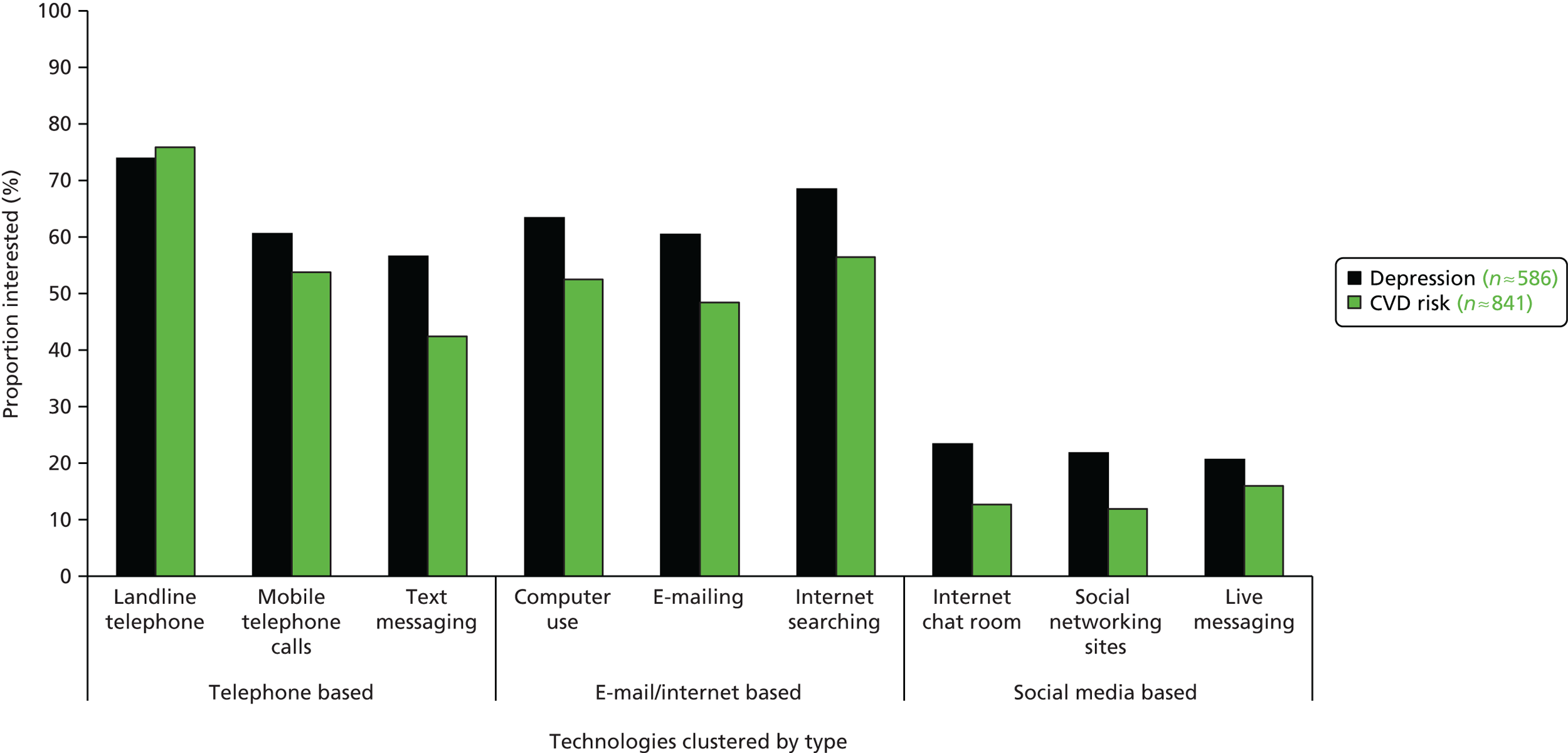

Survey of patients with two exemplar LTCs (depression, high CVD risk) to explore relationships between access to care, unmet need and willingness to use NHS Direct, to identify factors that are associated with interest in telehealth and the types of telehealth that are most likely to be acceptable to different patient groups.

-

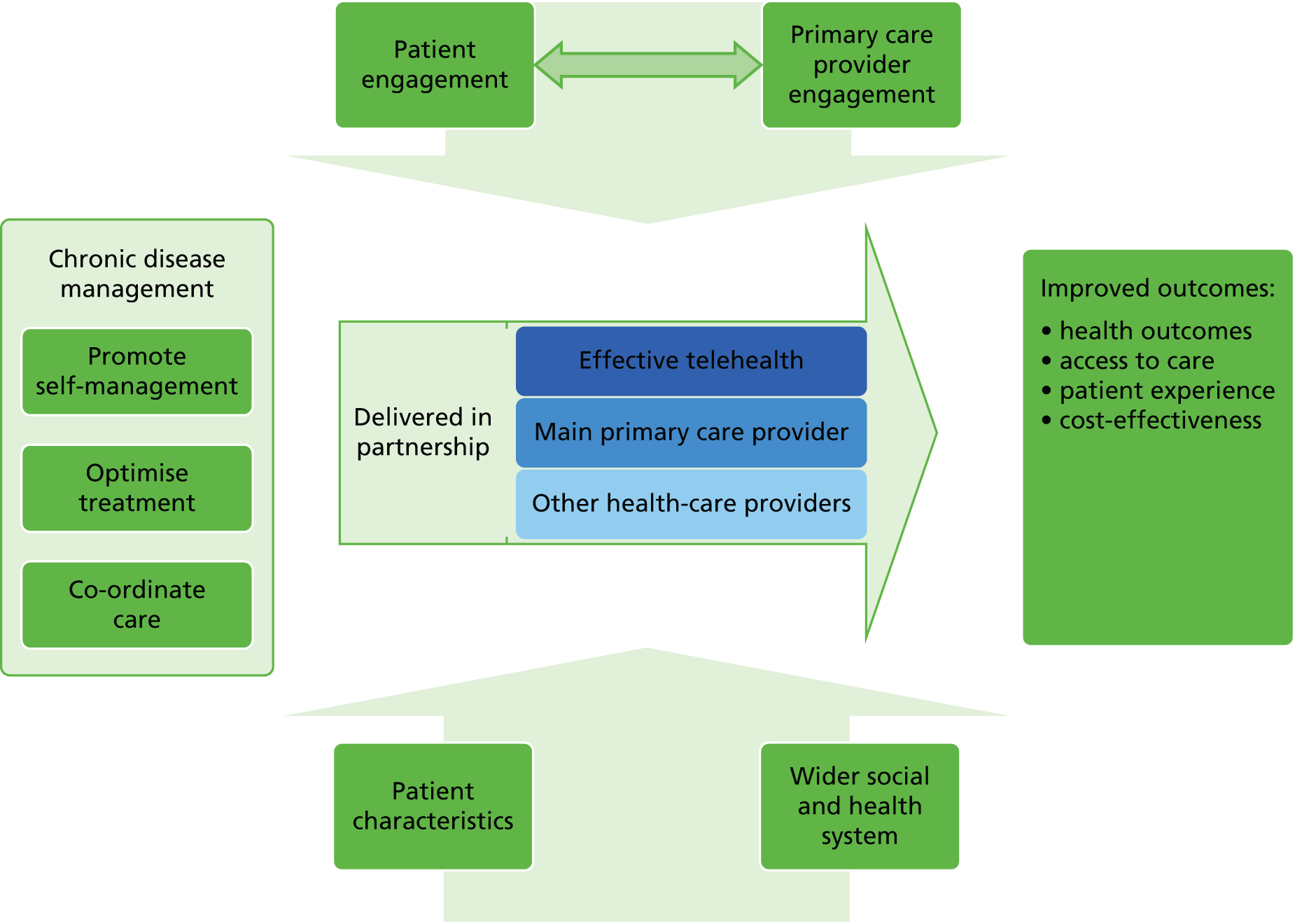

Development of a theoretical model that could be used for intervention design and implementation, as well as development of the interventions for our exemplar LTCs to be offered by NHS Direct that, based on activities 1–3, are likely to be acceptable, effective and efficient.

-

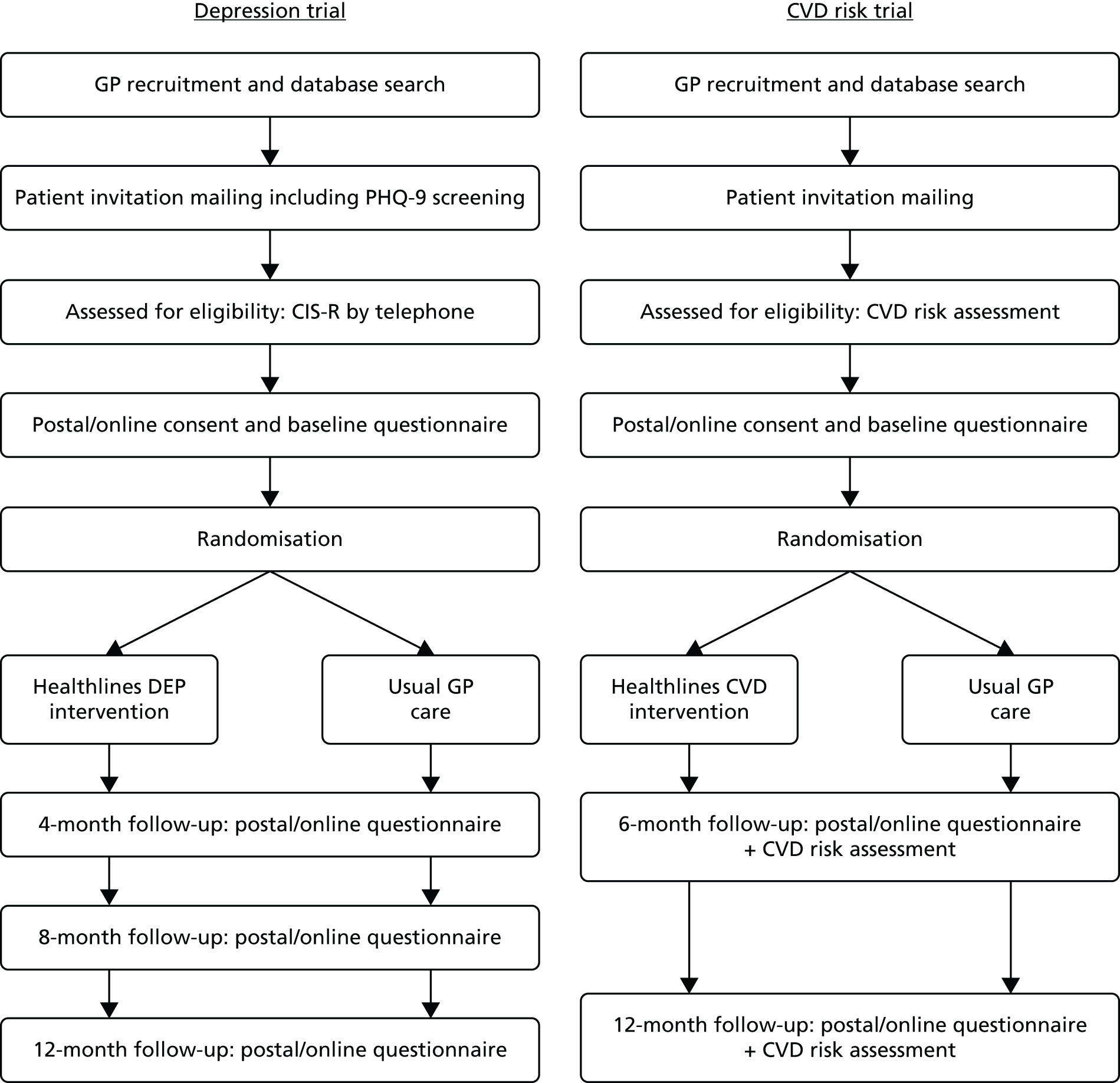

Randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of LTC management provided by NHS Direct in two exemplar conditions. We also used qualitative methods to study implementation and conducted an economic evaluation to assess cost-effectiveness and model future costs/benefits following national implementation.

The approach was based on Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on the evaluation of complex interventions and included defining and understanding the problem, paying attention to context, developing and optimising the intervention based on a theory about how the intervention is intended to achieve its aims and conducting a definitive evaluation. 56 To develop the intervention, we used an intervention mapping approach to integrate the various research components. Intervention mapping involves focusing specifically on the behaviour of users of NHS Direct. A key process in intervention mapping is to first identify the relevant psychological determinants of behaviour and then systematically map these onto evidence-based strategies and techniques for changing behaviour. We made use of recent approaches to intervention mapping and theoretical modelling of behavioural interventions. 57–59

Chapter 2 An evidence synthesis of telehealth interventions for long-term conditions

Abstract

Background: The objective of the evidence synthesis was to review and synthesise evidence about telehealth interventions to provide guidance on the types of effective interventions that could be delivered by the Healthlines study.

Methods: This was a mixed-methods evidence synthesis consisting of six sequential studies: (1) a meta-review of systematic reviews of home-based telehealth for LTCs published between 2005 and 2010; (2) a review of systematic reviews of telehealth for depression published between 2005 and 2010; (3) an evidence synthesis of qualitative research on telehealth published between 2000 and 2010; (4) a realist synthesis based on studies in 1–3; (5) horizon scanning to ensure the inclusion of up-to-date evidence; and (6) a systematic review of the effectiveness of telehealth interventions to reduce overall CVD risk and/or CVD risk factors.

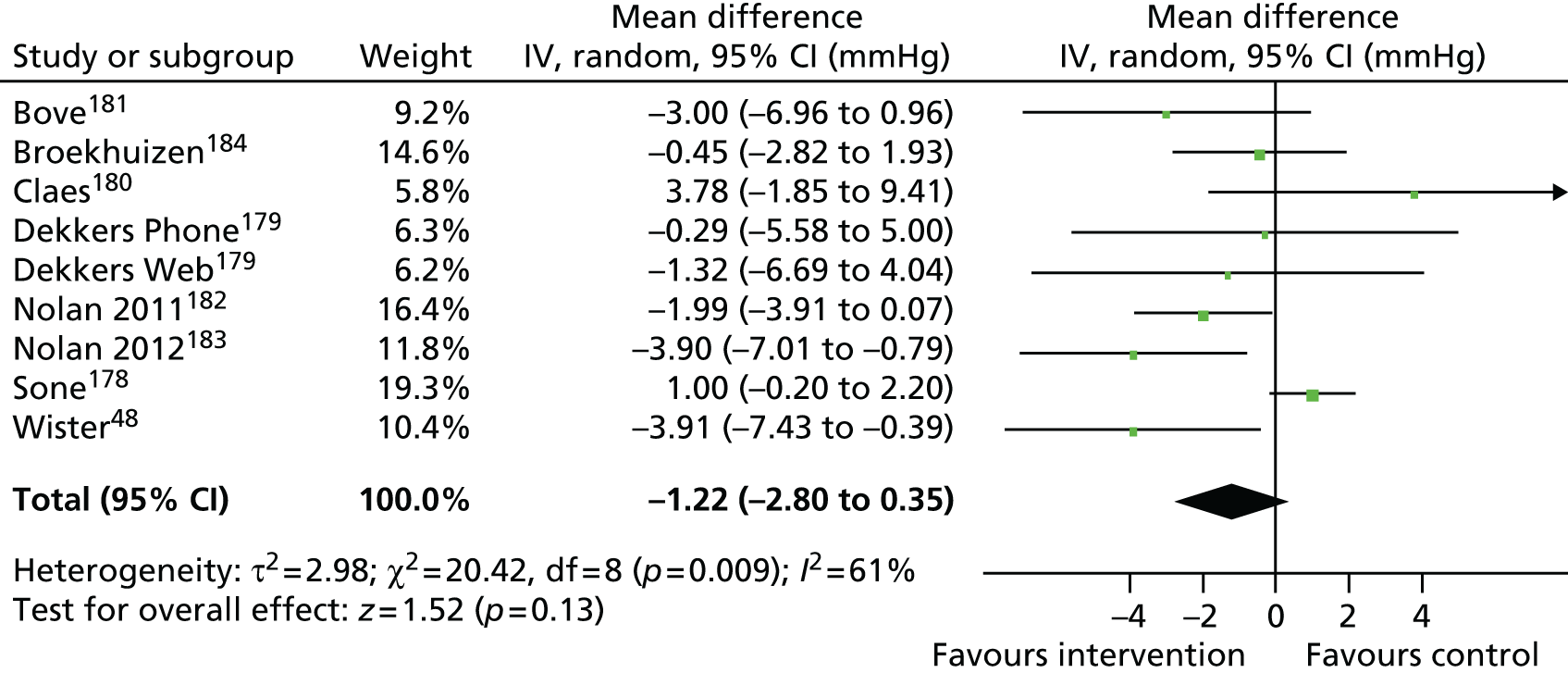

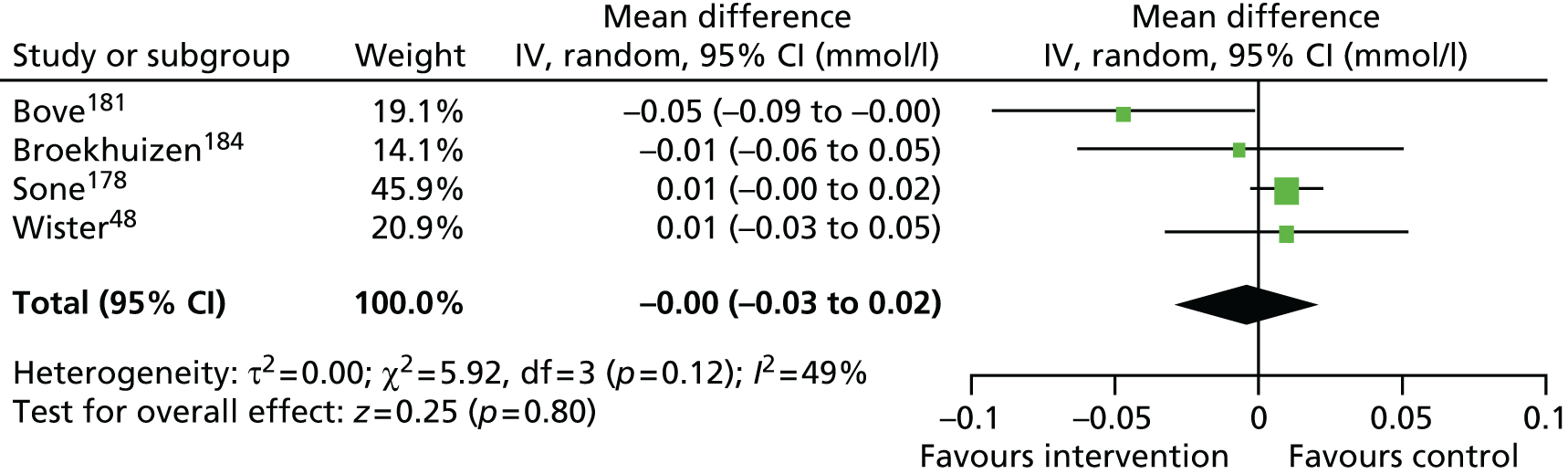

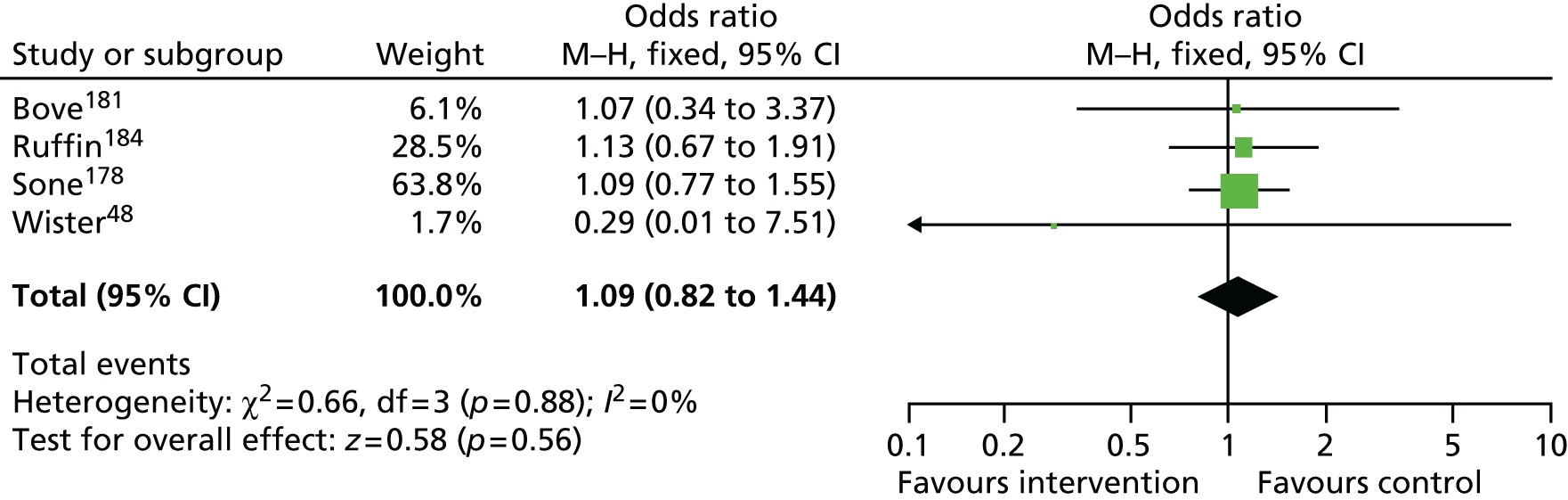

Findings: The evidence base addressing the effectiveness of home-based telehealth for LTCs and depression is large and generally positive. However, a number of systematic reviews recommend caution because of the poor quality of the studies (small sample sizes, weak study design and lack of adequate comparators). There is limited evidence on cost-effectiveness. Qualitative literature on patients’ views of telehealth are generally positive because of perceptions that it increases access to health care. Professionals are less accepting of telehealth than patients. Three mechanisms of action were identified in the realist synthesis: relationships between health professionals and patients; fit with patients’ needs and capabilities; and visibility through feedback. The systematic review found no evidence of an effect of telehealth on overall CVD risk, but weak evidence of a small reduction in systolic blood pressure and total cholesterol.

Conclusions: The evidence base shows that telehealth for LTCs is acceptable and can be effective. However, rigorous evaluation of telehealth interventions, including their cost-effectiveness, is needed.

Introduction

The objective of the evidence synthesis was to review and synthesise evidence about telehealth interventions to provide guidance on the types of effective interventions that could be delivered by NHS Direct. The aim was not to undertake a traditional systematic review with meta-analysis of the effect of different types of telehealth in different populations because a number of reviews had already been published. Rather, the aim was to undertake a mixed-methods review60 to offer an overview of the trial-based evidence and complement this with qualitative evidence to inform decisions about the Healthlines study intervention development.

Design

The mixed-methods evidence synthesis consisted of six complementary approaches undertaken in sequential order:

-

A meta-review of systematic reviews of home-based telehealth for LTCs published between 2005 and 2010, focusing on the breadth and quality of the evidence base, types of outcomes studied, acceptability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

-

A review of systematic reviews of telehealth for depression published between 2005 and 2010.

-

Evidence synthesis of qualitative research published between 2000 and 2010 to develop an understanding of patient and organisational perspectives of telehealth.

-

Realist synthesis based on studies in 1–3 to draw out underlying mechanisms that might enable telehealth interventions.

-

Horizon scanning to ensure the inclusion of up-to-date evidence emerging during the 15 months of this mixed-methods review.

-

Because of resource constraints, we were unable to conduct a review of the evidence base for the effectiveness of telehealth interventions to reduce overall CVD risk concurrent with reviews 1 and 2. However, in 2013, an opportunity arose to allow us to undertake a review of RCTs and systematic reviews in this area. This evidence synthesis was published61 and used for interpretation of the trials in the later part of the programme rather than for developing the intervention.

Meta-review of systematic reviews

Introduction

The evidence base for home-based telehealth for LTCs is large, with numerous systematic reviews of a variety of telehealth interventions. Before commencing our evidence synthesis, there were already numerous systematic reviews of a variety of telehealth interventions and three relevant meta-reviews published. Meta-reviews synthesise the evidence from systematic reviews. The first meta-review focused on internet interventions only (including virtual communities, internet-based educational and behavioural programmes and internet-based CBT) and showed improved outcomes, particularly for patients with depression. 62 The second was a wider review encompassing all types of real-time telehealth and conditions, which included, but was not specific to, LTCs or home-based telehealth. 23 This concluded that the quality of the evidence base was poor, but indicated benefits of telehealth for the management of chronic diseases. These benefits included improving health outcomes (and mortality in heart failure), but there was no benefit for resource utilisation or processes of care. The third meta-review focused on telemedicine and included e-health, information communication technologies, internet-based interventions and telehealth for both diagnosis and management of a wide range of conditions, concluding that 21 of 80 reviews identified telemedicine as effective and 18 reviews identified telemedicine as promising. 63 Although these reviews offered important conclusions regarding the effectiveness of telehealth, they did not focus exclusively on home telehealth or the management of LTCs. Therefore, there was a need for a further meta-review of home-based telehealth for managing LTCs to inform the Healthlines study intervention.

Methods

Definitions

A key problem with this evidence base is inconsistent terminology; multiple definitions exist and are used interchangeably even within the same countries. The definition of telehealth used here included three types of intervention: (1) telephone-based interventions, including telecoaching, telephone counselling and telephone follow-up; (2) telemonitoring of patient symptoms and vital signs in which monitoring occurs at home and electronic data are sent to another site; and (3) computerised, internet- and web-based treatments with or without practitioner support. We included active (in which the patient interacts with the intervention or manually enters data) and passive (in which monitors transmit data remotely without patients manually entering data) interventions; real-time (synchronous) and asynchronous (i.e. e-mail) interventions; those with and without health-care professional (HCP) input; and those offering social support and feedback as well as monitoring of symptoms and vital signs only.

Our definition of LTCs was guided by the NHS National Service Framework for LTCs64 and other health-care guidance. 28,65,66 The LTCs included in the meta-review are listed in Box 1.

-

Chronic illness or chronic disease.

-

Asthma.

-

CHD or heart failure or coronary heart failure.

-

CVD.

-

Stroke and TIA.

-

Hypertension.

-

Diabetes mellitus.

-

COPD.

-

Epilepsy.

-

Thyroid disease (hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism).

-

Cancer.

-

Dementia.

-

Depression (and anxiety).

-

Mental health including schizophrenia, psychosis, paranoia, obsessive–compulsive disorder, PTSD and agoraphobia.

-

Chronic kidney disease.

-

Atrial fibrillation.

-

Obesity.

-

Spinal cord injury.

-

Multiple sclerosis.

-

Motor neurone disease.

-

Parkinson’s disease.

-

Learning disabilities.

-

Arthritis.

-

Skin disease.

-

Hearing difficulty.

-

Headaches and migraine.

-

Visual problems.

-

Chronic liver disease.

-

Endocrine disorders (e.g. Addison’s disease, Cushing syndrome).

-

Bronchiectasis.

-

Cardiomyopathy.

-

Crohn’s disease/ulcerative colitis.

-

Glaucoma.

-

Haemophilia.

-

Hyperlipidaemia.

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus and other systemic autoimmune diseases.

-

Smoking (in relation to specific LTCs).

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE/Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), PsycINFO, Web of Science, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and The Cochrane Library from 2005 to March 2010 for systematic reviews of telehealth and LTCs. Our search terms included ‘meta-review or meta review’, ‘quantitative review or overview’, ‘systematic review or systematic overview’, ‘methodologic* review or methodologic* overview’, ‘review’ ‘quantitative synthes*’, ‘clinical trial’, ‘randomised or randomised controlled trial’ and ‘controlled trial’ and ‘telemedicine’, ‘telehealth or tele-health’, ‘telenursing’, ‘telemonitoring’, ‘Ehealth or e-health’, ‘telehomecare’, ‘telehealthcare’, ‘home healthcare’ and ‘assisted homecare’.

Inclusion criteria

We included published systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis) of telehealth for LTCs in English referring to home-based or mobile, synchronous (real-time) and asynchronous telehealth interventions. We focused on reviews of LTCs generally, not on reviews of specific LTCs, that is, we excluded reviews that focused exclusively on diabetes or depression, for example. We excluded reviews that focused exclusively on children, inpatient populations, service-to-service interventions, clinic-based interventions (i.e. not deliverable at home or on mobile technology, e.g. telecardiology) or smart home technology or that did not report outcomes. When reviews included some trials related to any of the above we included them, explicitly highlighting this and focusing on outcomes for patients relevant to our meta-review. We also excluded Cochrane reviews at protocol stage. Two reviewers independently reviewed abstracts to agree on papers for full-text retrieval. When there was doubt about a paper, the full-text paper was retrieved. Two independent reviewers reviewed full papers to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from systematic reviews using a standardised form. All data were extracted by a member of the review team (AR) and checked by a second team member (AOC or CP). When there were any discrepancies, reviewers discussed this as a team to agree a resolution.

Quality appraisal

We assessed the quality of each systematic review using the five core quality questions from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination for inclusion in DARE (see www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDweb/html/helpdoc.htm). 67 Two reviewers examined and agreed on the quality of the reviews according to these five core quality questions. A review was included if it met at least the first three mandatory criteria and four out of the five criteria.

Results

The evidence base

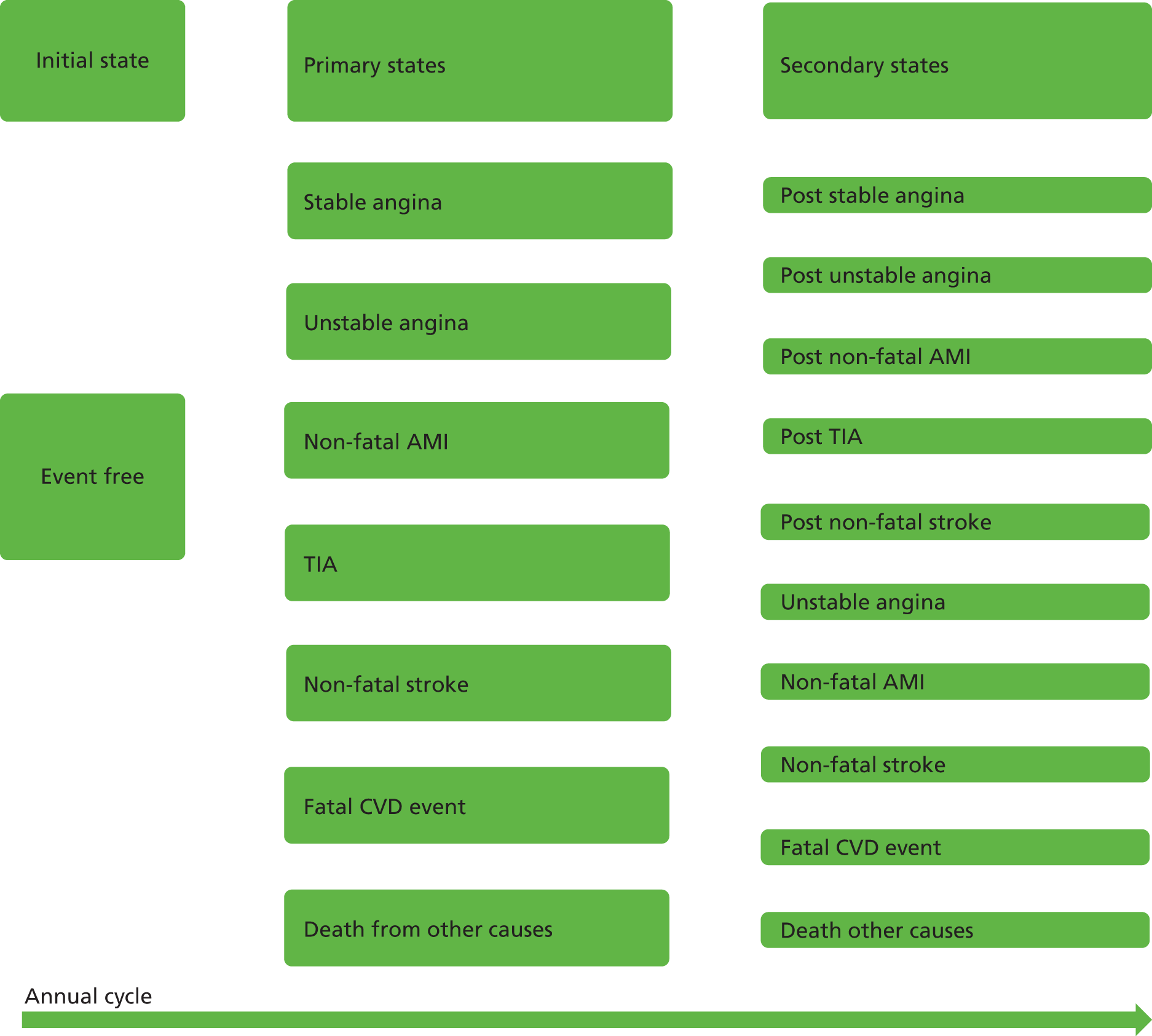

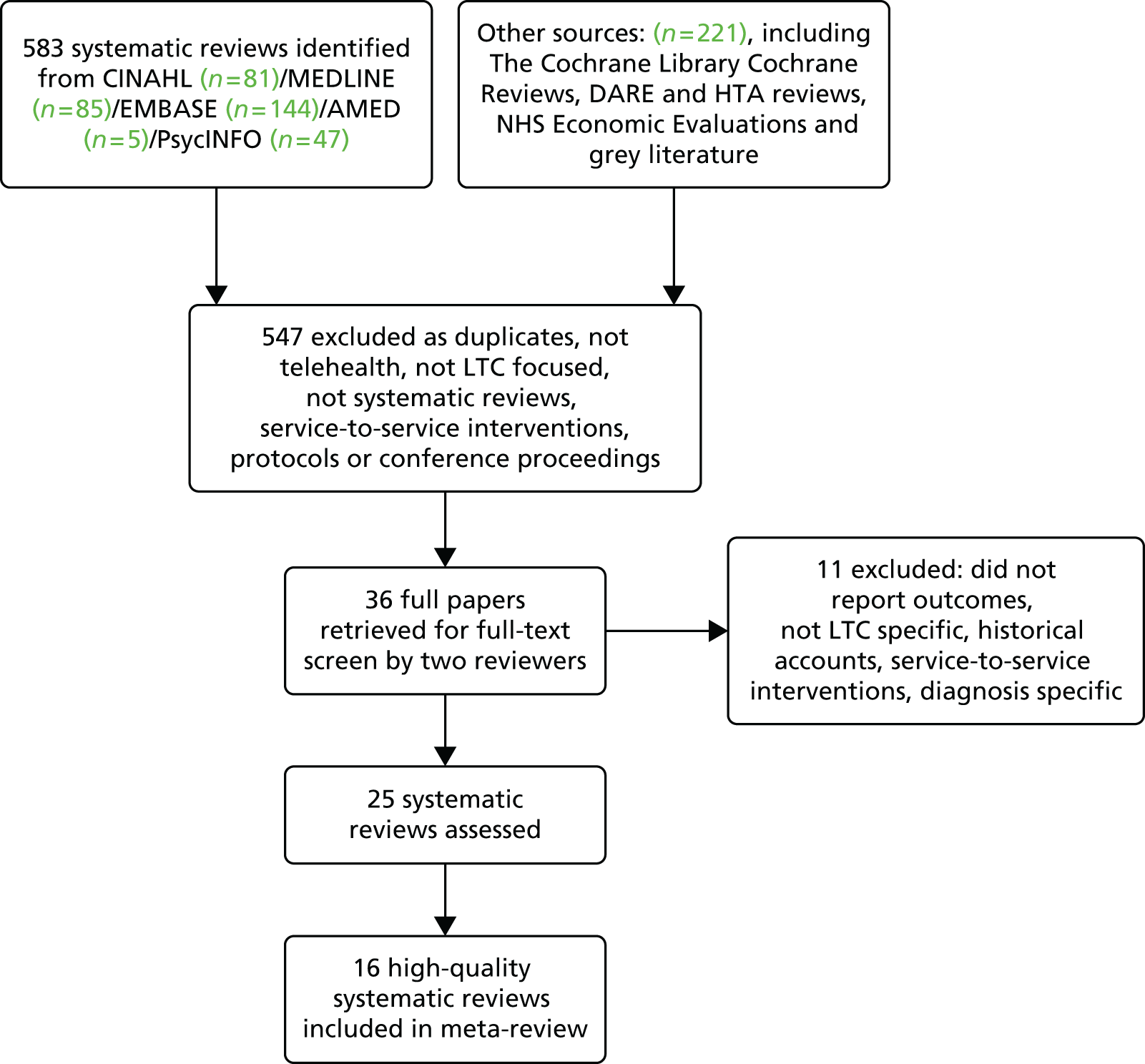

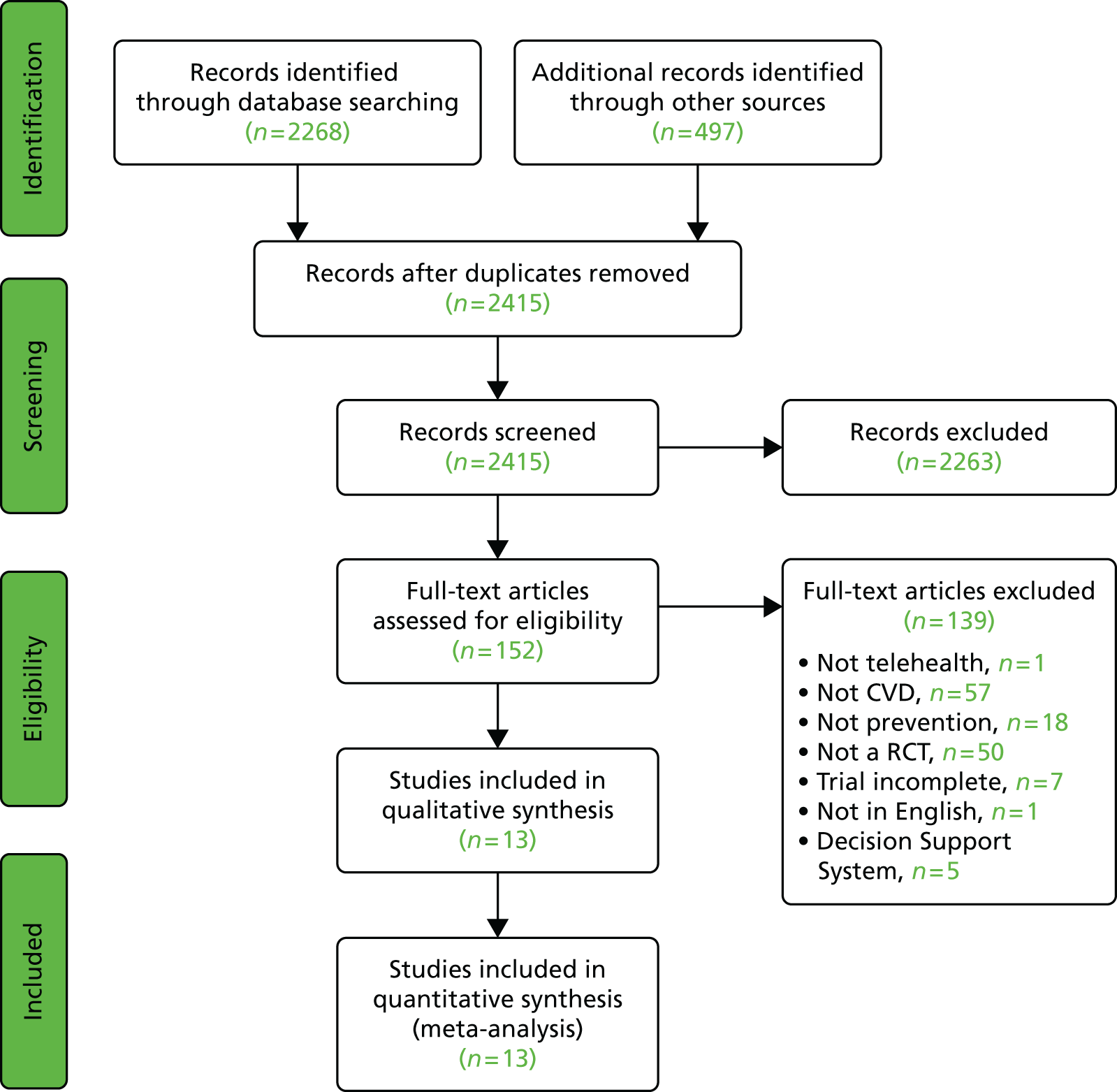

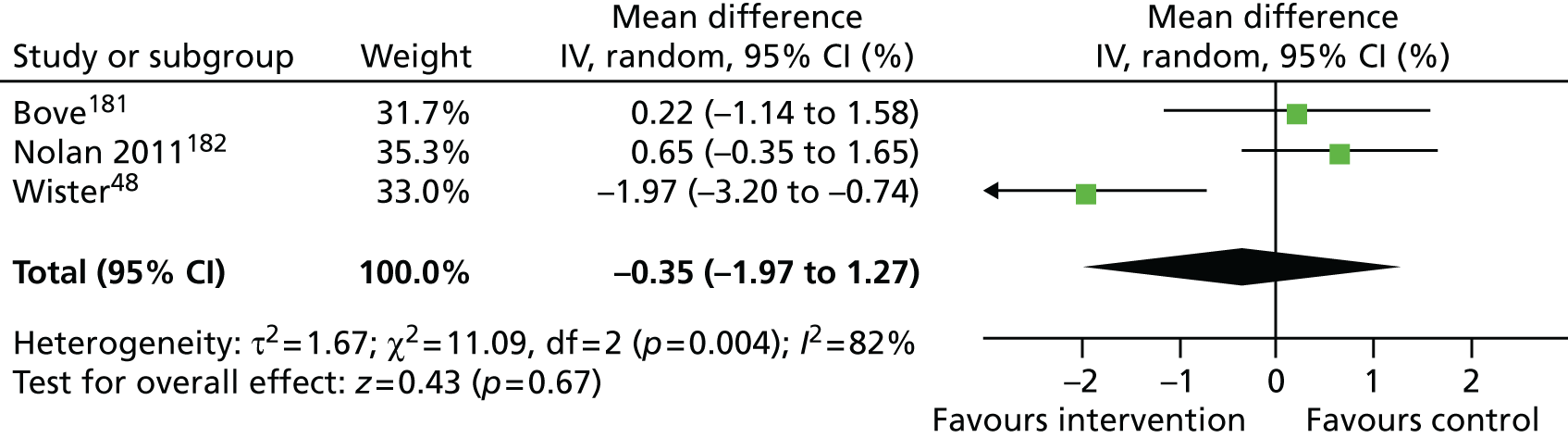

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram shows the stages that we went through to identify 36 reviews (Figure 1). Of these, 11 were excluded because they provided no outcomes, were not systematic or focused on acute care, a single condition or ‘smart home technology’. Twenty-one reviews satisfied the first three mandatory quality criteria and 16 of these met at least four criteria. Our meta-review includes these 16 high-quality systematic reviews,8,11,16,17,20,40,68–77 which cover 662 individual studies (Table 1). Six reviews included a meta-analysis. The reviews were undertaken by authors from Canada (n = 6), the USA (n = 5) and Europe (n = 5) and covered a range of telephone, mobile, internet-based and computer interventions. Details around data extraction are reported in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram for the meta-review of systematic reviews. CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; HTA, Health Technology Assessment.

| Review | Inclusion/exclusion criteria reported? | Search adequate? | Included studies synthesised? | Validity of studies assessed? | Sufficient details about studies presented? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barlow 200720 | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Botsis 200870 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bowles 200717 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Cole-Lewis 201071 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Cuijpers 200840 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Dellifraine 200816 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| García-Lizana 20078 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hersh 200672 | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Krishna 200973 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Murray 200511 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Oake 200968 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Paré 201069 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Polisena 200974 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Rains 200975 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Stinson 200976 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tran 200877 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Quality of the evidence base

We included only high-quality systematic reviews. Six of these 16 reviews urged caution regarding weak research designs of studies within them. 11,16,40,68,69,77

Effectiveness

Eleven of the 16 reviews concluded that telehealth was effective for some LTCs or improved some outcomes. 11,16,17,69–73,75–77 Meta-analyses tended to support telehealth, although effect sizes were often small or moderate. Reviews without meta-analyses produced more mixed conclusions, although none reported that telehealth was not effective at all.

Some specific conditions were highlighted by some systematic reviews. Positive effects of telehealth interventions were noted for diabetes in five out of 14 reviews17,70,72,73,77 and for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in four out of 12 reviews. 69,72,73,76 Three meta-analyses identified benefits for patients with heart failure or heart disease, including improved control of blood pressure in hypertension. 16,69,77 Two meta-analyses identified larger effect sizes for mental health than for other LTCs. 16,75

Specific outcomes

A range of positive outcomes, for example increased compliance or reduced burden of illness, was frequently reported. 16,17,69–71,73,77 Two reviews reported improved educational outcomes11,73 and seven reported significant positive behavioural change,11,17,20,68,71,73,75 particularly improved self-monitoring or management in patients with diabetes17 and better treatment adherence. 17,20,68 There were few firm conclusions about the impact of telehealth on quality of life, although one meta-analysis reported improvements associated with computer-mediated support groups. 75 The three reviews which suggested that telehealth improved social support11,73,75 were countered by three that reported inconsistent or insufficient evidence. 8,20,76

Resource utilisation

The evidence about the impact of telehealth on resource utilisation was mixed. Telehealth was shown to reduce admissions for heart failure, heart disease, diabetes and hypertension8,17,20,72 and reduce hospitalisations for elderly patients with LTCs. 70 However, other reviews showed limited impact on service utilisation11,76 and meta-analyses reported that the evidence for a positive impact of telehealth on resource utilisation was questionable. 11,68,77

Cost-effectiveness

Four reviews found some evidence for cost savings,20,70,74,77 but one was unable to determine cost-effectiveness. 11

Patient satisfaction

Three reviews commented on patient attitudes towards telehealth and indicated that patients find telehealth acceptable. 17,70,77

Types of technology

Telephone-based interventions worked well according to four out of the eight reviews that considered them alone or as part of more complex interventions. 8,20,70,77 The use of mobile phones and text messaging appeared to be effective,71,73 particularly for promoting behaviour change. Vital signs monitoring was reported as producing clinical benefits in approximately half of the trials in one review,20 but other reviews suggested that this might be limited to particular conditions, such as hypertension,69 diabetes,17,68,69,77 heart failure17,68 and respiratory conditions. 69 Vital signs monitoring was associated with increased mortality among COPD patients and appeared to offer no benefits for dementia,70 obesity or blood glucose control in diabetes. 72 Support for internet and computer technology was also mixed. Four out of the seven reviews addressing this showed some positive effects. 11,40,75,76 Text reminders appeared to work better than e-mail or internet reminders. 71 Videoconferencing was associated with improved outcomes across a range of LTCs in one review,16 but there was inconsistent evidence for its use in delivering support and education. 20

The role of health professionals

Few reviews compared different HCPs delivering the intervention or explored whether or not the presence of a professional was necessary. Professional care was not compared with lay or peer support. Telephone follow-up by nurses was shown to improve clinical outcomes and reduce service use. 20

Types of patients

Few reviews examined patient-specific characteristics. One review suggested that younger patients, male patients and possibly black ethnic groups benefited most from home telehealth,16 but another reported no differences in outcomes linked to age or sex. 71 Another identified that there was insufficient evidence with regard to disadvantaged groups benefiting, but some suggestion that computer interventions may benefit those living in rural communities. 11

Conclusions

The evidence base addressing the effectiveness of home-based telehealth for LTCs was extremely large and generally positive. However, a number of systematic reviews recommended caution when using this evidence base because of the poor quality of studies, citing small sample sizes, weak study design and lack of adequate comparators. There was also very limited evidence on cost-effectiveness. This was supported by a more recent evidence synthesis of the value of telemedicine in the management of five common LTCs: asthma, COPD, diabetes, heart failure and hypertension. 54 This concluded that most studies have reported positive effects but have measured outcomes in the short term only and that the evidence base is ‘on the whole weak and contradictory’ (p. 219). 54

The conclusion from this part of the evidence synthesis was that rigorous evaluation of telehealth interventions for LTCs, including their cost-effectiveness, is needed. The implications for the Healthlines study were that the evidence base was too diffuse to make a significant contribution to the development of the study intervention, although there was sufficient indication of positive effects from telehealth to make it worthwhile to develop a new intervention as proposed.

Review of depression

Introduction

After reading the meta-review, the Healthlines study team was interested in the evidence specific to telehealth interventions for the two exemplar LTCs in the study: depression and CVD risk factors. The review of CVD risk factors was not pursued at this stage because of resource constraints. Few trials or reviews had selected patients at risk of CVD and it was not feasible within the time available to conduct individual systematic reviews for the evidence in relation to each of the large number of factors that constitute raised CVD risk (hypertension, obesity, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, etc.). As we explain later (see Systematic review of telehealth interventions for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease), an opportunity did arise to carry out the CVD risk review at a later stage. However, we were able to review the evidence base for depression in the first phase of this programme, which is summarised here.

Methods

The focus of this review was on identifying systematic reviews of telehealth for depression and other mental health problems. We searched six databases for relevant systematic reviews that were published between January 2005 and March 2010. With regard to depression, we identified nine systematic reviews of telehealth and/or web-based interventions for depression,78–86 three of which provided a meta-analysis. 79,80,86 We also identified 11 reviews about a range of mental health problems or anxiety disorders15,40,87–95 and, of these, five provided a meta-analysis. 40,87–89,95 Most of these reviews included a small number of trials and small sample sizes, raising concerns about the quality of the evidence base.

Findings

When conducting this review we focused on five key questions that we sought to answer from the evidence base. We approached the evidence in this way because the main purpose of this work was to inform the development of the subsequent intervention to be tested later in the research programme. Each of the questions addressed by the review, as well as the available evidence derived from the depression review, is discussed in turn in the following sections.

Are mental health problems amenable to improved management using telehealth?

There was evidence of improved patient outcomes, including quality of life and medication adherence, for telehealth interventions for depression,78–80,85,94 anxiety-related disorders87,89 and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 88,95 Systematic reviews with meta-analyses for depression reported positive effects for telephone-based psychotherapy for depression,79 internet-based CBT80 and computerised psychological treatment. 86 Other reviews showed that telemedicine,78 internet-based interventions and support82 and computerised CBT81 improved symptoms. Positive effects were found in three of the four RCTs of computerised CBT for mild to moderate depression85 and improvements in mental health were linked to the MoodGYM and BluePages programmes in particular. 84 Three of the five systematic reviews with meta-analyses considering mental health problems or anxiety disorders reported moderate to large effects for mental health and/or anxiety. 87–89 For anxiety disorders, there were large effect sizes for computer-aided psychotherapy87 and remote communication technologies. 89 There were moderate effects overall for internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions for PTSD and panic disorder, but effects were small for depression and weight loss. 88

Which patient groups with mental health problems are most likely to use or benefit from telehealth?

Most RCTs of telehealth for mental health problems recruited adults, although some of the systematic reviews included trials involving youths, students or older school children. 78,84,86,88 There was some evidence that psychotherapeutic interventions delivered over the internet worked better for young adults (19–24 years) and adults (25–39 years) than for youths and older people. 88 Internet-based mental health programmes reduced anxiety in adults and students and performed similarly well in pilot studies with schoolchildren. 84 Patients with mild to moderate depression reported reduced symptoms after computerised CBT. 84,85,94 Telephone interventions for mental disorders were associated with significant symptom improvements for patients with mild depression. 15 One review reported that an internet-based programme (MoodGYM) may not be appropriate for people with low literacy levels. 84

Patients were generally satisfied with telehealth and internet or computerised treatments,83,91 especially computerised CBT, with some preference for therapist-led treatment. Therapists were generally less satisfied with telehealth than with usual care. 81

What kinds of technologies work best for mental health problems?

Telephone15,80,89,90 and internet79,82–84,86,88 interventions were associated with improvements in anxiety and produced large effect sizes with no difference in dropout rates compared with face-to-face care. 87 In contrast, computerised CBT with no or minimal therapist input was associated with high dropout rates. 81,85,87 Sub-analysis of technologies for computer-aided psychotherapies yielded non-significant differences between home computer and palmtop technologies. 87

How, where and by whom are telehealth interventions delivered?

In terms of how these interventions were delivered, internet-delivered interventions were largely found to be effective. 79,82–86,88,94 Telephone-administered psychotherapy interventions demonstrated significant benefits when delivered by mental health specialists. 80 There was some evidence that professional support for internet-based and computerised interventions resulted in larger effect sizes than unsupported interventions. 79,86

Individual therapy over the internet was more effective than group therapy, which suffered from greater attrition than individual therapy. 80 Interactive internet sites were significantly more effective than static (passive, information giving) sites in providing support for a range of mental health conditions, as were closed sites where participants were pre-screened. 88 Most systematic reviews reported on interventions in primary care settings. The duration of treatment was not related to symptoms or attrition rates80 and there was some evidence that effects could extend beyond the follow-up period. 78,87,88

What outcomes are associated with telehealth for mental health problems?

Most interventions were associated with moderate or large effects on depression and anxiety. 15,78–80,85–90,94 Other beneficial effects included the promotion of security and honesty and minimising potentially distracting behaviours91 and improved antidepressant medication adherence. 15 Most systematic reviews did not address cost-effectiveness, although there was some evidence of cost benefits of video conferencing in psychiatry91 and internet-based mental health programmes used by large numbers of patients. 84

Conclusions

The evidence base for telehealth for depression and other mental health problems was similar to the overall evidence base: although systematic reviews were available, these were based on a small number of trials with small sample sizes, creating an essentially weak evidence base. Nonetheless, the findings about effectiveness were generally positive. There was support for telephone-based and computerised- or internet-based interventions for depression. In fact, CBT interventions appeared to be very effective, with evidence that professional support could further improve the effectiveness of computerised CBT. There was little evidence of cost-effectiveness.

The implications of this part of the evidence synthesis for the Healthlines study were that further rigorous evaluation of interventions would be welcome, given the quality of the evidence base, but that there is support for a range of interventions, including computerised CBT. In addition, there was some indication that the provision of professional support for computerised interventions might be beneficial.

Synthesis of qualitative evidence

Introduction

In a third piece of work, we conducted a review of qualitative research into home-based telehealth for LTCs to develop an understanding of patient and organisational perspectives of telehealth.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched EMBASE, MEDLINE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PsycINFO for relevant articles between 2000 and 2010. In comparison to the other reviews described earlier, we included a longer time period here because we did not expect to find many papers. Our search terms included ‘meta-review or meta review’, ‘systematic review or systematic overview’, ‘qualitative exp’, ‘Review’, ‘meta-ethnograph*’, ‘meta-synthes*’, ‘observational method’, ‘focus group’, ‘narrative analysis’, ‘phenomenological research or phenomenology’ and ‘telemedicine’, ‘telehealth or tele-health’, ‘telenursing’, ‘telemonitoring’, ‘Internet’, ‘Ehealth or e-health’, ‘telehomecare’ and ‘telehealthcare’.

Inclusion criteria

We included any papers meeting our inclusion criteria for LTCs and telehealth as described earlier for the meta-review and also with a qualitative methodological focus, including qualitative interviews, focus groups and content analysis. We excluded opinion pieces, ‘data light’ studies, reports on service-to-service interventions, papers on generic internet use, papers looking exclusively at the content of an intervention and papers not meeting two of the 10 quality criteria (see Quality appraisal).

Data extraction

We identified 1876 references and retained 122 after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria to the abstracts. After removing duplicates, 69 papers were retained for full-text review. Two review team members then independently reviewed the 69 full-text papers in terms of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as assessed the quality of these papers, as described in the following section.

Quality appraisal

The quality of qualitative papers was assessed by two reviewers (AR, CP) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality criteria. 96 The 10 questions are shown in Box 2. We excluded papers that did not answer ‘yes’ to the first two CASP questions, which ask whether or not there were clearly stated research aims and whether or not appropriate qualitative methods were used. Very few studies satisfied all of the CASP quality criteria (see Appendix 2).

-

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

-

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

-

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

-

Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

-

Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

-

Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

-

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

-

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

-

Is there a clear statement of findings?

-

How valuable is the research?

The CASP quality criteria checklist was sourced from the Public Health Resource Unit, Institute of Health Science, Oxford. 96

Findings

The evidence base

Twenty-nine papers were included in the final review. 81,97–124 Details of the participants, methods and focus of these papers are provided in Appendix 3. There were two systematic reviews with qualitative and quantitative content81,97 and 27 primary studies of patient or stakeholder perspectives. Most papers originated in Europe (n = 18, including 11 in the UK), followed by the USA (n = 7), Canada (n = 3) and Australia (n = 1). The evidence base addressed a wide range of conditions, some of them relevant to the Healthlines study, particularly depression,98,99 hypertension100 and online counselling. 101

We identified three themes from these papers – perceived access, care and symptom management and technologies – and then focused on the question of which professionals or agencies should deliver services, as this was of particular interest to the Healthlines study in terms of designing the subsequent RCT. Evidence around each of these three themes is discussed in the following sections, followed by an examination of whether specific health professionals or agencies should deliver telehealth services.

Perceived access

Patients and professionals generally perceived that telehealth could lead to increased access and decreased emergency visits. 97,102–104 Rural patients with moderate depression perceived an improvement in access from using telehealth. 99 Patients reported advantages of online interventions for mental health and behavioural problems, including convenience, access and anonymity,98,99 but these were often balanced by concerns about lack of closeness and therapist trust, privacy and confidentiality fears and lack of visual cues. Patients shown a video of a Home Telecare Management System were positive, mentioning perceived benefits of less travel time and fewer medical visits, but there were some concerns about whether or not it could be used by some patients with disabilities. 105 Benefits of online support included the timing of sessions fitting into people’s routines. 98 Patients with severe symptoms from at least one LTC103 and patients with multiple chronic illnesses104 felt that they benefited from improved access. The perceived benefits of telehealth for older people included not having to travel99 and an ability of telehealth to reach an underserved elderly population. 106 Stakeholders believed that younger diabetic patients or those comfortable with technology would more likely benefit from virtual clinics. 107

It was suggested that adults with low literacy levels could benefit from e-health interventions, although concerns were also expressed around oversimplified interventions being perceived as too basic108 or that patients might be misunderstood and unable to express themselves adequately in relation to computerised CBT. 98 Online CBT was perceived as particularly beneficial for patients familiar with computers. 98 Conversely, patients with little or no information technology (IT) experience reported positively on technology for blood pressure control. 100 In a study of monitoring and messaging device alerts, clinicians reported that significant time, good knowledge and high engagement from patients was necessary, and patients with some health conditions (including tremors) could not use the technology. 109

Although there were benefits of telephone interventions overall, including mobile technology for asthma control and management,110 problems reaching transient populations with mental health problems were also cited. 111 However, internet programmes for people with chronic diseases reduced isolation and improved information sharing112 and patients with cancer involved in internet support groups appeared to benefit from empowerment and reduced isolation. 113

Care and symptom management

Professionals felt that telehealth aided diagnosis, could improve trust between patients and nurses and could lead to greater professional autonomy,103 but they were concerned about medico-legal implications. 104 Perceived benefits of a diabetes decision support system and telehealth included improved self-management, increased confidence and rapport with the diabetes team and increased patient openness. 106,114

A systematic review of internet-based CBT reported that there was an unintended consequence of an intervention in that it reinforced the health problem, rather than helped to address it. 97 Similarly concerning, a mobile technology for asthmatics was seen by professionals as engendering dependence on technology or the clinician. 110 Therapists, nurses and doctors were all less enthusiastic than patients about telehealth. 81,115

Improved self-management through monitoring in diabetes was noted,106,109,114,116 as was increased symptom awareness112,117 and better self-management for LTCs generally. 103 For example, middle-aged men with diabetes reported improved knowledge and management of symptoms linked to a diabetes decision support system, but the system was reported as not working for patients engaging in sport. 114 Reports also suggested that patients with poorly controlled diabetes benefited from frequent monitoring and medication adjustment109 and patients with good diabetic control benefited from telephone coaching,111 but a highly transient population had difficulties responding to telephone contact. 111 Patients of varied ethnic groups expressed improved peace of mind linked to home telecare. 105 Lastly, daily monitoring was perceived as promoting adherence. 118

Technologies

Some concerns were expressed about using technology, including technical difficulties and fear of technology. Although few technical problems related to online interventions were actually reported,98 there were some problems with imperfect technology. 106,109 For instance, nurses reported technology limitations of telehealth for COPD, including unpredictable equipment performance and poor picture quality, which impacted on the quality of care for these patients. 115 District nurses also experienced some technical problems with mobile technology (internet connections) for LTC care at home. 102

In terms of patient views, telehomecare technology for heart failure was perceived as positive, but spouses showed emotional responses when technology failed117 and the complexity of the technology was a concern for some heart failure patients. 118 The theme of ‘fear’ of technology, which was linked to older age, also emerged for some heart failure patients105 and training was advocated. Fears included computer anxiety and difficulties for older people in terms of understanding technology, expressed by participants in statements such as:

we have not grown up with computers . . . you only have to look at the level of resistance from older people using ATMs in the banks. A lot of old people when confronted with such a system, freeze up, as it is complicated for them . . . something they fear.

Rahimpour et al. (p. 492)105

However, patients with little or no IT experience reported positive attitudes towards technology for hypertension management. 100

Does it matter which professionals or agencies deliver telehealth services?

There was support in the literature for the view that health professional input was valued, particularly in the context of mental health problems. Psychologist delivery of internet CBT was viewed positively by patients98 and having a facilitator to improve the ‘personal’ experience was advocated. 99 Contact with a mental health clinician prior to telehealth was also seen as important. 99 Positive diabetes peer support was provided through virtual clinics116 and nurses were seen as good facilitators for providing online support by mothers of children with mental health problems. 119

Conclusions

Qualitative literature on patients’ views of telehealth suggests that it is generally accepted and appreciated because of perceptions that it increases access, particularly for remote and hard-to-reach patients or older patients, improves self-management if monitoring is involved and improves care or support, particularly in depression and mental health. However, the technology can be a barrier for some older patients, some patients with LTCs that involve physical disabilities and patients with low literacy levels. There were also some concerns about dependence on technology and health professional contact may be important for mental health interventions.

Professionals were less accepting of telehealth than patients, voicing concerns over loss of role, confidentiality, loss of face-to-face contact or the therapeutic relationship and loss of non-verbal communication. However, they also perceived some benefits of telehealth, such as increasing access and patient contact, improving communication and monitoring and facilitating self-management.

The implications for the Healthlines study were that there would be few problems with acceptability of interventions to patients with LTCs, there was potential to impact on self-management when monitoring was used, attention would need to be paid to directing computer-based interventions at people who were used to computers or technical support should be offered (particularly for older people) and health professional input might be of benefit for the intervention for depression.

Realist synthesis

Much of the text in this section is reproduced from Vassilev et al. 125 © Vassilev et al. ; licensee BioMed Central. 2015. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Introduction

This part of the evidence synthesis used a realist synthesis to focus on the mechanisms that might be at play within telehealth interventions.

Methods

We followed Pawson’s seven stages for a realist synthesis: identify the question and clarify the purpose of the review; theory elicitation; search the evidence; appraisal; extract the results; synthesise findings; and draw conclusions and make recommendations. 126 This was an iterative rather than a linear process and in our study we had searched for much of our evidence prior to theory elicitation.

Identify the research question

Our research question was, ‘How does telehealth improve the health of people with LTCs?’ We focused on identifying the mechanisms by which telehealth interventions appear to change health behaviours or outcomes.

Searching the evidence

We used the literature reviews described earlier (see Meta-review of systematic reviews, Review of depression and Synthesis of qualitative evidence). We reread these papers to inductively identify features that appeared to contribute to successful interventions. We discussed and refined these features within our team and then returned to the evidence base to seek out confirmatory and disconfirmatory evidence about potential mechanisms that underpin successful telehealth interventions. When relevant, we read the individual primary studies that were included in the systematic reviews to further explore the relevant issues. In addition, we ran MEDLINE searches to identify other key papers that had been published subsequent to our earlier literature searches.

Theory elicitation

We focused on three possible explanations or theories that suggested how telehealth works to change health outcomes. These emerged from our team thinking about issues that might be important to the success of these types of interventions in the context of the evidence we had read about and synthesised in the three earlier literature reviews (see Meta-review of systematic reviews, Review of depression and Synthesis of qualitative evidence). We identified these explanations or theories with the intention of returning to the literature to help us draw conclusions about their importance:

-

Relationships – relationships or connections between people (patients, peer groups and/or lay and professional carers) are a necessary component of telehealth interventions.

-

Fit – the extent to which a telehealth intervention can be integrated within everyday life and health-care routines determines the success of deployment/adoption.

-

Visibility – systems that increase the visibility of symptoms or health problems to self or others impact positively or negatively on the adoption of telehealth interventions depending on whether or not patients want anonymity.

Appraisal

We had undertaken quality appraisal of all papers in our earlier reviews.

Data extraction

We developed the evaluative framework using our initial ‘theories’ to compare and examine the findings within the high-quality literature identified in the three literature reviews (see Meta-review of systematic reviews, Review of depression and Synthesis of qualitative evidence).

Synthesis of findings

We compared findings from different studies, looking for examples that challenged, refined or supported the theories identified.

Findings

Relationships

We examined the literature to see whether or not, why and how relationships were important for the success of a telehealth intervention. In particular, we focused on the relationship contexts, specific aspects of relationships (e.g. continuity, communication, rapport), differences between peer-to-peer and patient–professional relationships and whether telehealth technology augmented or substituted for face-to-face/personal contact.

Evidence about professional input

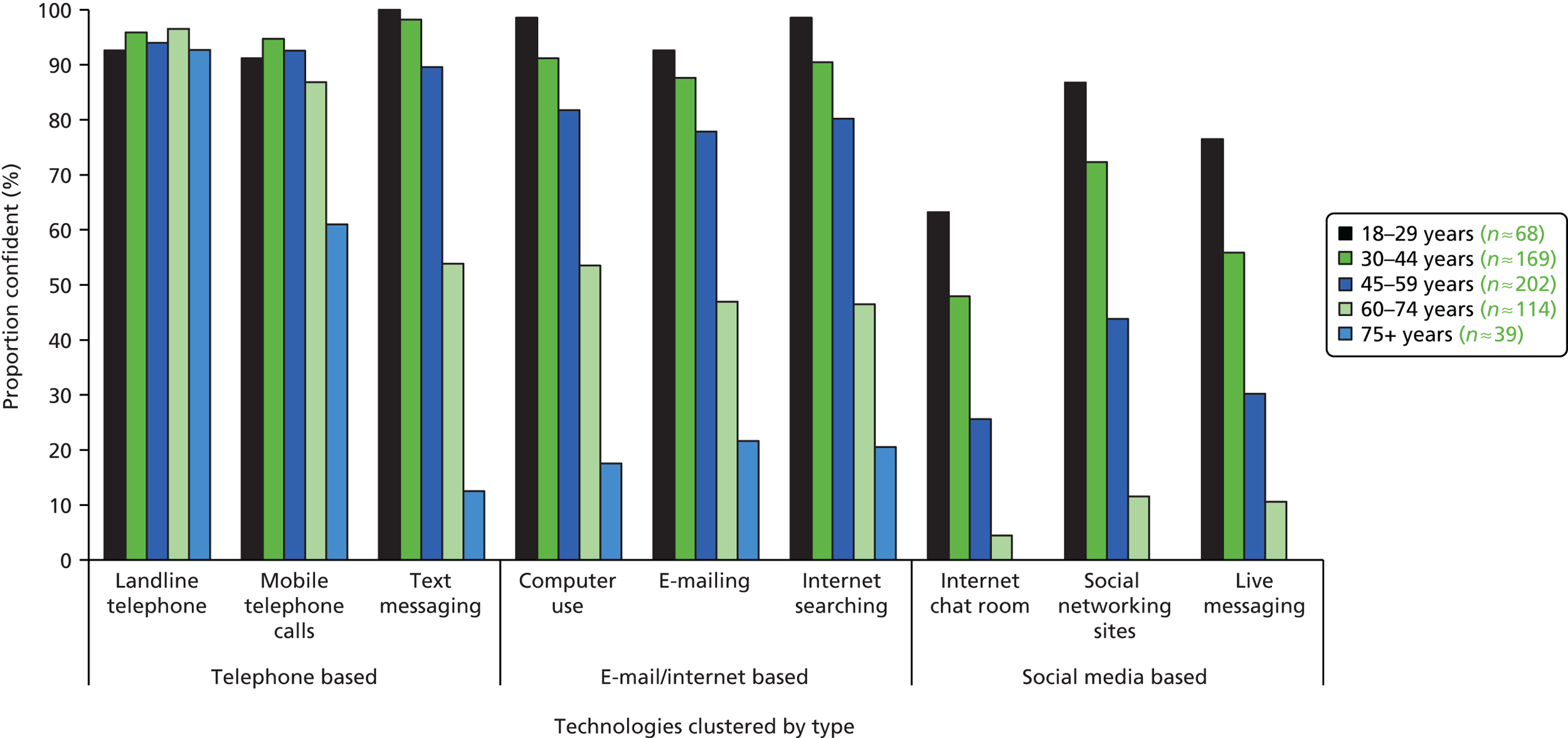

There was evidence to support the case that telehealth can work without professional input. For example, a RCT of an internet-based CBT programme, Beating the Blues, showed that computerised care outcomes were comparable to face-to-face care outcomes, nearly half of those completing the programme were reported to be clinically recovered and a computerised CBT programme for the management of mild to moderate depression was associated with clinically significant patient benefits. 127,128