Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0608-10050. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The final report began editorial review in December 2015 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Martin Roland and John Campbell have acted as advisors to Ipsos MORI, the Department of Health and, subsequently, NHS England on the development of the English GP Patient Survey. Jenni Burt has acted as an advisor to Ipsos MORI and NHS England on the GP Patient Survey. Pete Bower has received funding from the National Institute for Health Research in addition to the programme grant.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Burt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction to the IMPROVE (improving patient experience in primary care) programme

Context

Improving the health status of individuals and populations is a central ambition of health-care systems in high-income countries, and the US Institute of Medicine has suggested that high-quality health-care delivery should be safe, effective, patient-centred, timely, efficient and equitable. 1 Berwick et al. 2 have noted the importance of patient experience of care as one of the suggested ‘triple aims’ of an advanced health-care system. A recent US report highlighted the important contribution that listening to, and acting on, patient feedback can potentially make to health-care improvement efforts. 3

New developments within the English NHS highlight the embedding of public performance assessment within the regulation of the health-care system, including NHS England’s consultation on the production of general practitioner (GP) league tables4 and the Care Quality Commission’s (CQC) parallel development of a rating system for primary care. 5 A transparent health-care system is regarded by policy-makers as essential to enable patients to make informed choices about the care that they receive6 and patient feedback on health-care services is now commonly gathered in the USA, Canada, Europe, Australia and China.

Efforts to improve quality of care in the NHS over the last 15 years have focused on providing prompt access to care (e.g. the time taken to see a GP or hospital waiting times) and on providing evidence-based clinical care [e.g. through the development of National Service Frameworks and the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)7]. A direct link between patient feedback and quality improvement efforts was previously operationalised by including results arising from patient surveys as a component of the QOF. 7 This performance management system provides financial incentives for GPs within the NHS to achieve agreed quality indicators covering areas including chronic disease management, practice organisation and additional services offered. With the introduction of the QOF it was possible, for the first time, to rank all practices according to their patient feedback and the results of surveys, aggregated at practice level, formed the basis of a pay-for-performance scheme between 2009 and 2011, when the UK government withdrew the pay-for-performance arrangements for patient experience.

Some of these policies have been highly effective. For example, associated with a wide range of quality improvement initiatives over a decade, there have been greater improvements in the UK for the clinical care of conditions such as heart disease and diabetes than in any other major developed country. 8 Although relatively neglected in the early years of the millennium, patient experience of health care is now a high policy priority, and in 2008 the Next Stage Review suggested that:

. . . quality of care includes quality of caring. This means how personal care is – the compassion, dignity and respect with which patients are treated. It can only be improved by analysing and understanding patient’s satisfaction with their own experiences.

Department of Health, p. 47, emphasis in original. 9 © Crown copyright 2008, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0

The review9 noted, however, that ‘[up until 2008] progress has been patchy, particularly on patient experience’ (p. 48) and announced the development of quality accounts for all NHS organisations in which ‘healthcare providers will be required to publish data . . . looking at safety, patient experience, and outcome’ (p. 51) (© Crown copyright 2008, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0).

Since 2008, therefore, there has been a major policy initiative to improve patient experience in the NHS. Most recently, the focus on patient experience has been enshrined in the NHS Outcomes Framework, which, in Domain 4, focuses on ensuring that ‘patients have a positive experience of care’10 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). In primary care, these policy initiatives and statements have been implemented primarily through the development and conduct of the GP Patient Survey,11 first sent to 5.6 million patients in January 2009. The large sample size was intended to provide sufficient responses to characterise patient experience of primary care in all 8300 general practices in England. Detailed responses for individual practices were published on the NHS Choices website12 and made available online and included information on access to GP services and interpersonal aspects of care, out-of-hours care and care planning. The questionnaire specifically included validated questions about interpersonal aspects of care based on questionnaires that the authors of the present report previously designed and on which we have previously reported. 13 This large-scale survey is, of course, an expensive undertaking and its utility and impact need to be commensurable with this investment.

In seeking to achieve improvement in the quality of NHS services, gathering data is important both to inform the process of service development and innovation and to assess the impact of such changes in practice. It has been suggested that data to support such improvement initiatives need to be of sufficient quality to assess whether or not an innovation can be made to work, rather than being the more rigorous level of research data needed to assess whether or not an innovation works. 14

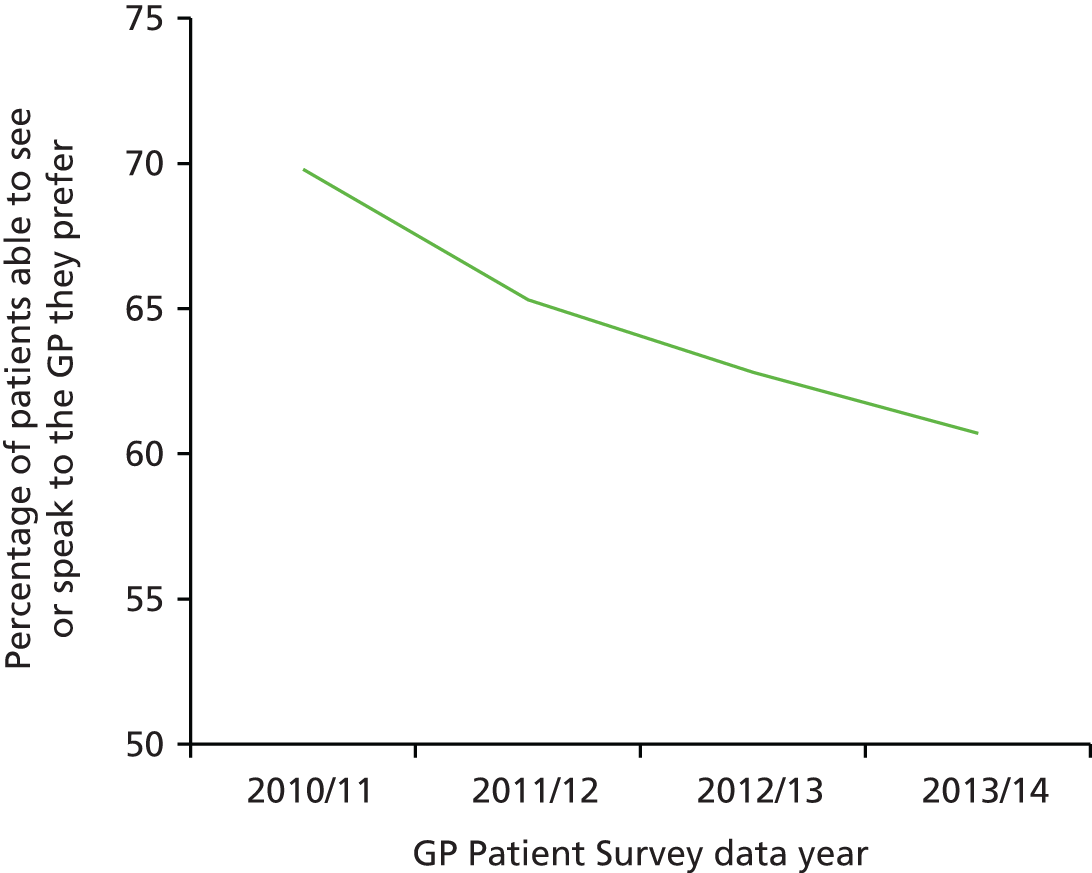

Communication in the consultation has always been an important part of primary care and is closely linked to continuity of care. At the outset of this research, there had been many anecdotal accounts that GPs were more focused on meeting clinical targets identified on their computer screens than on the needs of the patient sitting in front of them. It seemed therefore an appropriate time to balance the focus on improving clinical care with a renewed focus on interpersonal care and communication in the consultation. The ability of patients to choose their own doctor is also important. Our research prior to commencing this programme showed that continuity of care had deteriorated since the introduction of the new GP contract in 200415 and previous research had also highlighted that patients were less likely to report overall positive experiences if they were not able to choose a doctor whom they know. 16,17

Experience and satisfaction

Previous research has identified considerable confusion and overlap relating to the concepts of patient experience and satisfaction. The two concepts are closely linked, although at a simple level reports of experience relate to recounting or commenting on what actually happened during the course of a clinical encounter whereas reports of satisfaction focus on the patient’s or carer’s subjective evaluation of the encounter (i.e. asking for ‘ratings’ of care rather than simple ‘reports’ of care). Individual items in a survey may thus examine patients’ reports of their experience of care, whereas other items may explore patients’ evaluation of that care, with the linkage between report and evaluation/rating item pairs offering potential for the development of cut points in scales of performance. 18 In practice, however, the terms are often used interchangeably and survey items designed as report items often have an evaluative component; for example, the question ‘Were you involved as much as you wanted to be in decisions about your care and treatment?’ from the NHS Inpatient Survey19 contains elements of both. Within the GP Patient Survey,11 the instrument behind much of this programme of work, items often relate to ratings of care. For example, the communication questions ask patients to consider ‘how good’ the doctor was at providing various elements during a consultation, including giving enough time, involving in decisions about care and treating with care and concern.

Patient satisfaction may be seen as a multidimensional construct, focusing on the subjective experiences of patients, and related to their expectations of care and the perceived technical quality of the care provided. 20 Russell21 has recently summarised some of the problems associated with surveys of patient satisfaction with care, including problems with the validity and reliability of satisfaction survey instruments, the lack of a universal definition of the term ‘satisfaction’, the disinclination for patients to be critical of care received because of not wanting to jeopardise their treatment, satisfaction being determined by factors other than the actual health care received and the frequently non-specific nature of the findings arising from such surveys. In contrast, reports and surveys of patient experience may offer the potential to discriminate more effectively between practices than do reports of patient satisfaction,22 thus potentially offering greater external accountability of health-care providers, enhanced patient choice and the ability to improve the quality of care and measure the performance of the health-care system as a whole. 23

Patient experience matters

Patient experience is an important end point for NHS care in its own right. Patients consistently report that personal care is central to effective care and, in that context, the development and refinement of GPs’ interpersonal skills is a key priority. 23,24 It is noteworthy that many complaints regarding care centre not on technical and ‘clinical’ aspects of care, but on issues relating to interpersonal aspects of care and communication. 25,26 Good communication with patients is not just an end in its own right; it brings three important additional benefits.

First, our research27 has confirmed earlier work which showed that patients balance a range of beliefs and concerns when making decisions about taking medicines. Adherence is related both to the quality and duration of the consultation and to the doctor’s ability to elicit and respect the patient’s concerns. 28–30 Better communication may lead to improved patient outcomes31 through, for example, improved blood pressure control in hypertensive patients. 32

Second, there is a close relationship between poor communication and serious medical error. 33 This is partly because not listening to the patient’s perspective may lead doctors to miss important clinical information and partly because patients react more negatively when things go wrong if communication has been poor during the clinical episode in question. A significant proportion of cases referred to medical defence societies have at their heart poor communication in the consultation34 and improving communication with patients and engaging them more closely in their care is seen as key to improving patient safety. 35,36

Third, the increasing emphasis in the NHS on self-care and prevention demands good information and shared decision-making in the consultation. Our research shows that GPs and practice nurses are currently poorly prepared for roles in which they encourage patients to take greater responsibility for their own care37 or their lifestyle choices.

Although intuitively of importance, enhanced patient experience of care also matters on account of an important range of other associations reported in the research literature, including improved safety-related outcomes,38 improved self-reported health and well-being,39 enhanced recovery,31 increased uptake of preventative health interventions40,41 and reduced utilisation of health-care services including hospitalisation and emergency department visits. 42

Capturing patient experience of care

Although several approaches have been adopted to obtain information on patient experience of care – for example through the use of focus groups, patient participation groups, in-depth patient interviews, feedback booths placed in health-care settings and direct observation of patient experience43 and the use of compliment and complaint cards to capture qualitative feedback – the only practical approach to capturing large-scale feedback with the intent of providing actionable information remains the use of surveys of patients. In primary care in England, this culture of feedback has been embedded into routine practice in several ways. Central among these is the use of structured patient feedback obtained through surveys of patients’ experience of care, at both national and practice levels. 44

Qualitative approaches may be judged to offer greater depth of feedback than quantitative approaches,45 but such approaches are intensive in respect of data collection, although Locock et al. 46 have drawn on secondary analysis of a large national qualitative data archive to inform service improvements.

Newer forms of capturing feedback, such as the use of tablets and kiosks to capture real-time feedback (RTF), is an area of great current interest, but, as yet, these newer forms lack a strong evidence base from primary care. During the course of this research a report from a preliminary observational study47 suggested that RTF offers potential in primary care settings and similar findings48 have emerged from reports provided by patients with cancer attending oncology outpatient departments. Although there may be potential for the widespread use of real-time data capture of patient experience in primary care, the acceptability and feasibility of the approach in routine primary care is not known and nor is the nature of the feedback provided. Such an investigation needs detailed feasibility and pilot work using an experimental design of RTF of patient experience of primary care.

Large-scale surveys of NHS patients and staff have been in use since the mid-1990s, building on the experience of smaller-scale surveys conducted at local level or on the experience of surveys conducted for research purposes. Large-scale surveys of patient experiences of primary care were first introduced in 199849 with the express purpose of addressing issues relating to the quality of care and reducing inequalities in care by taking account of patients’ views in informing local service developments. Surveys of patients have been used extensively since the introduction of the UK QOF in 2004, when two questionnaires [General Practice Assessment Questionnaire (GPAQ)13 and CFEP50] were ‘approved’ for use by the NHS and adopted as the basis of linking the pay of GPs to their participation in the patient survey programme. 51

Such surveys may be administered in a variety of ways. In health-care contexts, paper-based surveys are most commonly used, although digital e-platforms are now commonly and widely used as a means of capturing information, most frequently using online processes. Computer-administered personal interviews52 and computer-administered telephone interviews may also be used, most commonly in research settings.

The NHS has established a major programme of surveys53 developed for a wide range of settings. Several of these surveys focus on patient experience of care, emulating the suite of Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys introduced in the USA in 1995. 54

The content of primary care surveys of patient experience

Historically, the content of UK primary care surveys has evolved from the 1998 survey,55 which covered a wide range of issues including primary care access and waiting times, GP–patient communication, patients’ views of GPs and practice nurses in terms of knowledge, courtesy and other personal aspects of care and the quality and range of services provided such as out-of-hours care and hospital referrals. The GP Patient Survey in 2008 developed and presented an expanded suite of items from the surveys of 2006 and 2007, which were focused almost exclusively on the accessibility of GP services; the 2008 survey focused on domains of care identified as being of importance to patients56,57 including the accessibility of care, technical care, interpersonal care, patient centredness, continuity, outcomes and hotel aspects of care. More recently, the English NHS has outlined eight domains believed to be of critical importance in respect of patient experience. Overlapping with earlier thinking, these include respect for patient-centred values, information, communication and education, emotional support, physical comfort, continuity and access to care,58 all being reflected, at least to some extent, in the ongoing GP Patient Survey programme. 11

Most recently, the Friends and Family Test has been introduced widely across the NHS, acting as a single-question proxy for patient experience based on the willingness of respondents to recommend their health-care provider to close acquaintances. The widespread use of the test has been accompanied by specific guidance on its implementation in practice59,60 and research reports have recently started to emerge following the use of the test in hospital settings, in which concerns have been raised about the reliability of the test. 61,62 The test was rolled out to general practice settings in December 2014.

Out-of-hours services

Beyond the domains mentioned in the previous section, additional areas of enquiry incorporated in the 2008 version of the GP Patient Survey included out-of-hours care and care planning. Variation in patients’ experiences of out-of-hours care has been identified as an area of concern since 2000, with numerous influential reports considering the structures suitable for delivering out-of-hours care, as well as highlighting the variable experience of patients across the UK in respect of service delivery. In 2000, Dr David Carson reported on the structural aspects of out-of-hours care pertaining at the time and recommended an expanded role for NHS Direct as a facilitator of access to these GP-led services, proposing that patients should use a single telephone access point to enter the system. 63 Much less emphasis was placed on patients’ experience of out-of-hours care, although recommendations were made regarding the need to monitor patients’ experience of the developing service. The transfer of responsibility for out-of-hours care from GPs to primary care trusts (PCTs) was foreshadowed in a report by the House of Commons Health Committee,64 which once again focused on structural and organisational issues relating to care provision. It was not until 2006,65 following the publication of national quality requirements in respect of out-of-hours care in October 2004,66 that patient experience of such services began to attract serious attention, with a recognition that, by 2006, although patient experience of out-of-hours services was generally ‘good’, one in five patients was dissatisfied with the service at that time. In addition, 40% of respondents in an independent survey of out-of-hours service users reported that the overall quality of the service was less than ‘good’. 65 The incorporation of six items in the 2008 GP Patient Survey with the intent of capturing information on aspects of out-of-hours GP services thus represented an extension of earlier versions of the questionnaire, recognising the growing importance of patient experience of care, and offered the potential to examine the experience of patients from various subgroups of the population and the potential to compare out-of-hours service providers in respect of their patients’ experience of care.

Measuring patient experience of care

The potential utility of questionnaires capturing patient feedback is, like other questionnaire-based feedback, dependent on the psychometric performance of the questionnaire in practice. Issues centring on the validity of the resulting data – whether or not the questionnaire items are measuring what is intended to be measured rather than some extraneous domain – underpin the reliability of inferences and conclusions that might be drawn following data collection. Validity and reliability themselves each consist of several elements and demonstrating validity of an assessment is generally regarded as having priority over demonstrating reliability.

Our previous research identified concerns expressed by doctors regarding the use of patient survey data for the purposes of providing individual feedback regarding a doctor’s performance. 67 Some of those concerns focused on the reliability and validity of the resulting data and on the conclusions being drawn regarding a doctor’s professional practice.

The validity of items within a questionnaire may be assessed in a number of ways, for example in exploring the pattern of item response using quantitative approaches such as factor analysis to investigate the latent variables identifiable within the theoretically related item responses. Qualitative approaches may also be used in the questionnaire design phase; for example, cognitive interviews were undertaken with patients from a range of sociodemographic backgrounds in the early stages of developing the GP Patient Survey. 68 Such interviews are designed to assess the interpretability and accessibility of the putative questionnaire items. Qualitative studies using cognitive interviewing or similar approaches may, however, be undertaken following respondents’ completion of questionnaires, seeking to explore the basis on which respondents are providing their evaluation. Such studies are unusual, but they potentially offer great value in exploring respondents’ insights and whether or not items presented are interpreted as originally intended.

Patients’ varying experiences of care

Our earlier research, and the research of others, has previously identified substantial variation between practices in patients’ reports of their experience of, and satisfaction with, care received and recent studies have also identified a range of patient experience being reported among doctors providing care in similar clinical specialties and settings. 69–73 This acted as the basis for the inclusion of patient feedback as an element required by UK regulatory authorities for the routine appraisal and revalidation of doctors. Despite these observations, few studies have examined the relationship between feedback on patient experience aggregated at practice level and the performance of individual doctors within practices, with one observational study74 identifying a substantial range of performance among doctors from a sample of eight Scottish general practices; the authors noted a number of possible contributing factors that might have accounted for differences observed at doctor level, including the experience of the doctors themselves, as well as the doctors’ mental health and professional disillusionment.

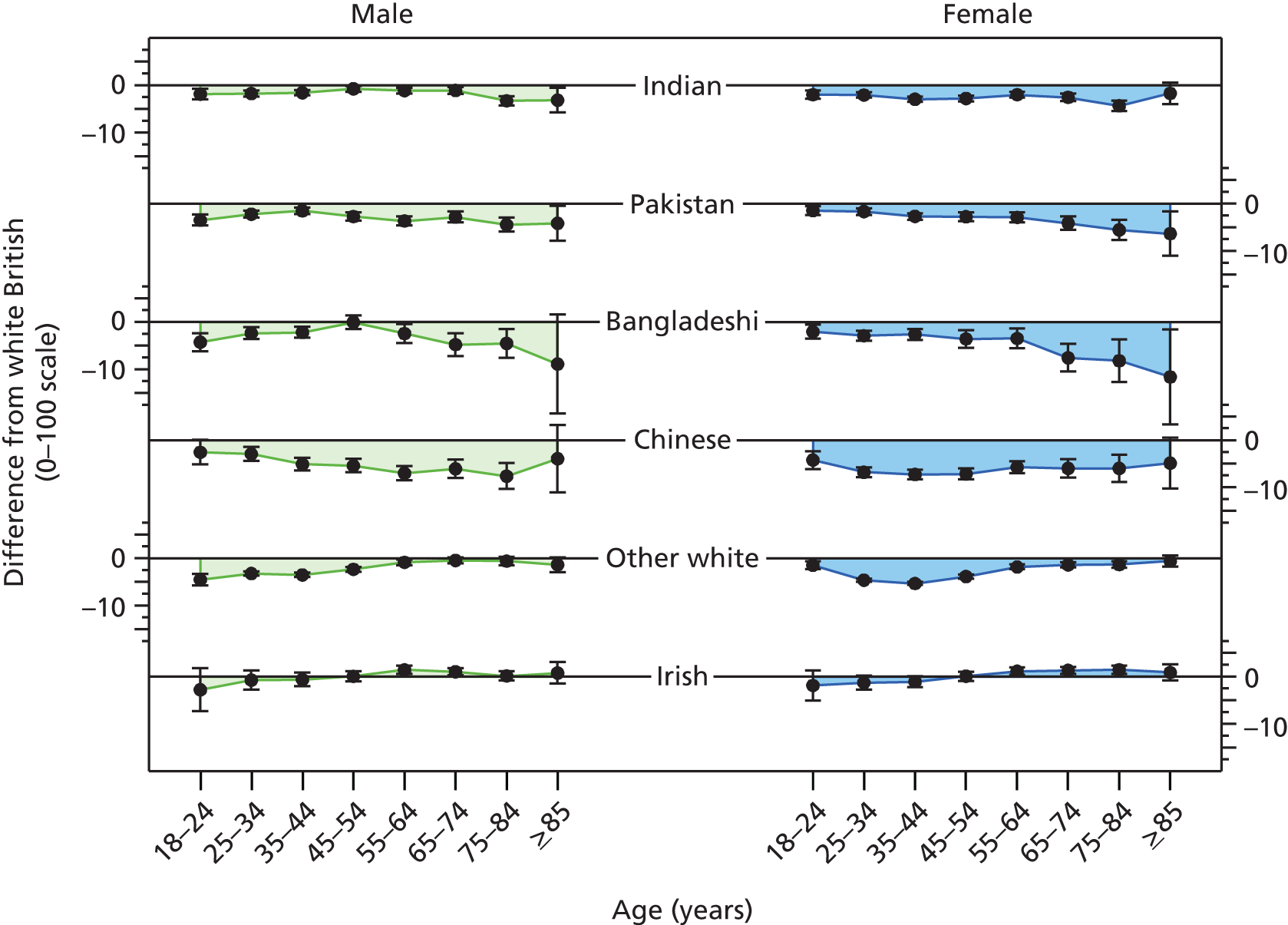

Systematic differences in patients’ reports of their experience of care have also been reported to be related to the characteristics of patients themselves. Older patients, patients from white ethnic backgrounds, the better educated, the less deprived and those reporting a better health status have generally reported more favourable experiences of care than younger patients, those from minority ethnic groups, the less well educated and more deprived and those with a poorer health status. Similar differences have been reported across many health-care systems and have given rise to calls to take account of the characteristics of participating patients when considering the results of patient feedback on care. To date, however, such calls have generally not been heeded in practice, as the relative contribution of practice, doctor and patient to overall variation in feedback remains to be defined. Uncertainty regarding the need for, and effect of, such ‘case-mix adjustment’ remains a concern for doctors in their consideration of patient feedback.

Specifically in respect of variation in experience among patients from different ethnic backgrounds, previous analyses have identified variations in patient experience in relation to ethnic group, age and gender and have found an interaction between ethnicity and age for cancer referrals. 75,76 However, no studies to date have yet investigated such an interaction in respect of patients’ experience of communicating with their GP, for example investigating differences between older and younger patients, by gender and among patients representing a range of minority ethnic groups.

In addition, although communication between doctors and patients is a core component of patient experience,77 and minority ethnic groups have reported lower patient experience scores for communication than the majority population,75,78,79 such differences are not consistent for all minority ethnic groups. Previous analysis of patient experience data conducted by the authors highlighted that South Asian patients reported particularly negative experiences, including for waiting times for GP appointments, time spent waiting in surgeries for consultations to start and continuity of care. 75 However, such analyses have not been repeated using GP Patient Survey data.

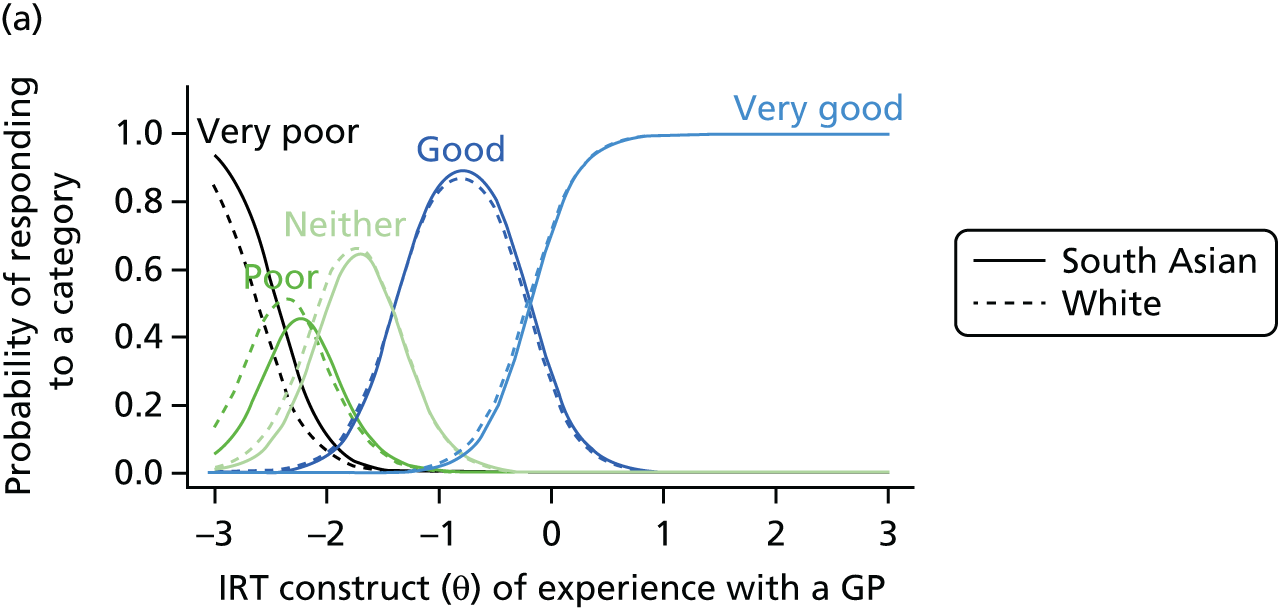

A number of potential explanations have been suggested for the lower ratings provided by South Asian and other minority ethnic groups in respect of their experience of care. Broadly, these relate to whether South Asian patients (1) receive lower-quality care or (2) receive the same care but rate this more negatively. 75 For example, differences in the use of questionnaire response scales might lead to South Asian groups being less likely to endorse the most positive options when asked to evaluate a doctor’s communication skills. 80 Alternatively, there could be systematic variations in evaluations of consultations because South Asian respondents vary in their expectations of, or preferences for, care. However, recent evidence from the USA points to lower quality of care as the main driver of variations. 81 Gaining understanding of why minority ethnic groups give relatively poor evaluations of their care is key to forming an effective response, as determining appropriate action is difficult until it is ascertained whether differences in evaluations relate to true differences in care or to variations in expectations, scale use and preferences. Exploring these observed differences between patients from various ethnic backgrounds is challenging using only observational, real-world data. More robust approaches are required, drawing on experimental designs in which some key elements of the consultation–interaction can be accounted for in the analysis, for example through the use of standardised consultations and video vignettes. 81,82

Using patient survey data to improve care

Although there is a belief, articulated in the Darzi Review,9 that patient surveys can be used to improve care, a systematic review from 200883 suggested that there is considerable uncertainty about how and whether or not this can actually be achieved. Several causal pathways for achieving improvements in provider performance through the release of publicly reported performance data have been proposed. 84–86 Some invoke market-like selection, claiming that patients will modify their choice of provider using publicly available data, such as that provided by patient experience websites. 84,87–89 Evidence to support this pathway is, however, weak. 85 A more likely mechanism driving performance improvement in response to the publication of performance data is health professionals’ concern for reputation, in which peer comparison motivates individuals and organisations to improve their care. 85,86

Furthermore, at the outset of this research, PCTs were poorly prepared to support and work with general practices to improve patient experience. In addition, the Darzi review9 had noted that progress in improving patient experience in the NHS had been slow, and our research had identified that some aspects of care, especially out-of-hours care90,91 and continuity of care,15 may actually have worsened in recent years. In addition, as observed earlier, it had been noted that patients from minority ethnic communities consistently reported lower evaluations of the quality of primary care. 75 Although these problems had been clearly identified in published research, the research had provided less clarity about the meaning and interpretation of these findings and the best way to intervene to improve patient experience.

Irrespective of its potential to stimulate change, the publication of performance data is central to the openness and transparency that are seen as essential for a safe, equitable, patient-centred health-care system. 92 Thus, regardless of any effect on quality improvement, such initiatives are likely to be here to stay. 85 In refining the information made public, it is important that performance data are accurate and relevant to all potential users. The US-based Robert Wood Johnson Foundation93 has noted that, whilst there is a patient preference for information to be provided at the level of individual clinicians (and not at practice level), such information is only rarely available. Currently, there is some move towards publication of performance data from an organisational level to that of individual doctors. In the UK, for example, patients referred to the cardiology service at the University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust may go online to view both mortality and patient experience data for each cardiologist or cardiac surgeon. 94 However, within English primary care, the practice-level aggregation of data from the GP Patient Survey used to derive practice performance indicators potentially masks variation in performance among individual GPs, thereby inappropriately advantaging or disadvantaging particular doctors. Current indicators may consequently fail to provide users, providers or commissioners with an accurate assessment of performance within a practice.

Although intuitively simple, patient satisfaction is a complex concept95 and patient questionnaire scores must be interpreted carefully. For example, practices need to understand if low ratings for communication reflect particular consultation behaviours or whether they are in fact the result of broader issues such as practice culture or the structure and availability of consultations and appointments.

Once the causes of low ratings have been better understood, interventions to improve care can then be designed. However, the current literature on the effects of feedback of patient assessments is insufficient in scope, quality and consistency to design effective interventions. 83 There are many reasons why simple feedback on patients’ experience of care is likely to have limited effects. Our research is designed to address these gaps in knowledge, enable managers, patients and professionals to have confidence in the meaning of patient assessments and provide effective interventions to improve care when problems are identified.

Summary

In summary, therefore, capturing patients’ experience of primary care is a current ambition of major importance in UK government health policy. Patient surveys, incorporating opportunities for people to comment on various aspects of their care, are a convenient means of capturing relevant information at scale. It is not clear, however, how health-care staff operating in practices respond to the resulting information. Previous experience suggests that staff may rationalise scores on the basis of concerns regarding the scientific properties of the survey, or uncertainty regarding the implications arising from providing care in their particular circumstances, for example taking account of the sociodemographic mix of respondents. On a similar vein, it remains unclear the extent to which overall practice performance, based on aggregated patient feedback, might relate to the performance of individual doctors within the practice. It is also unclear whether or not patients provide reliable evaluations of care – and the extent to which such evaluations might vary according to the sociodemographic characteristics of respondents. New modes of capturing patients’ experiences of their care have become available in recent years, but to date it is not clear whether or not novel, technology-based approaches can be successfully implemented in routine primary care settings, nor the extent to which any resulting data might reflect the results of the wider population.

In recent years, care provided by out-of-hours GP services has been a particular area of interest for the NHS and has been the subject of national audit and standard setting. However, it is not clear whether or not patients’ reports of their experience of out-of-hours care are valid and reliable. Neither is it clear the extent to which factors relating to the structure and organisation of such care might be associated with systematic differences in patients’ reports of their care. Furthermore, as for in-hours care, it is not clear how staff providing out-of-hours care might respond to patient feedback and how service managers might utilise such information in the planning and design of services aimed at being responsive to the needs of NHS patients.

Aims of the programme

This programme had seven aims:

-

to understand how general practices respond to low patient survey scores, testing a range of approaches that could be used to improve patients’ experience of care

-

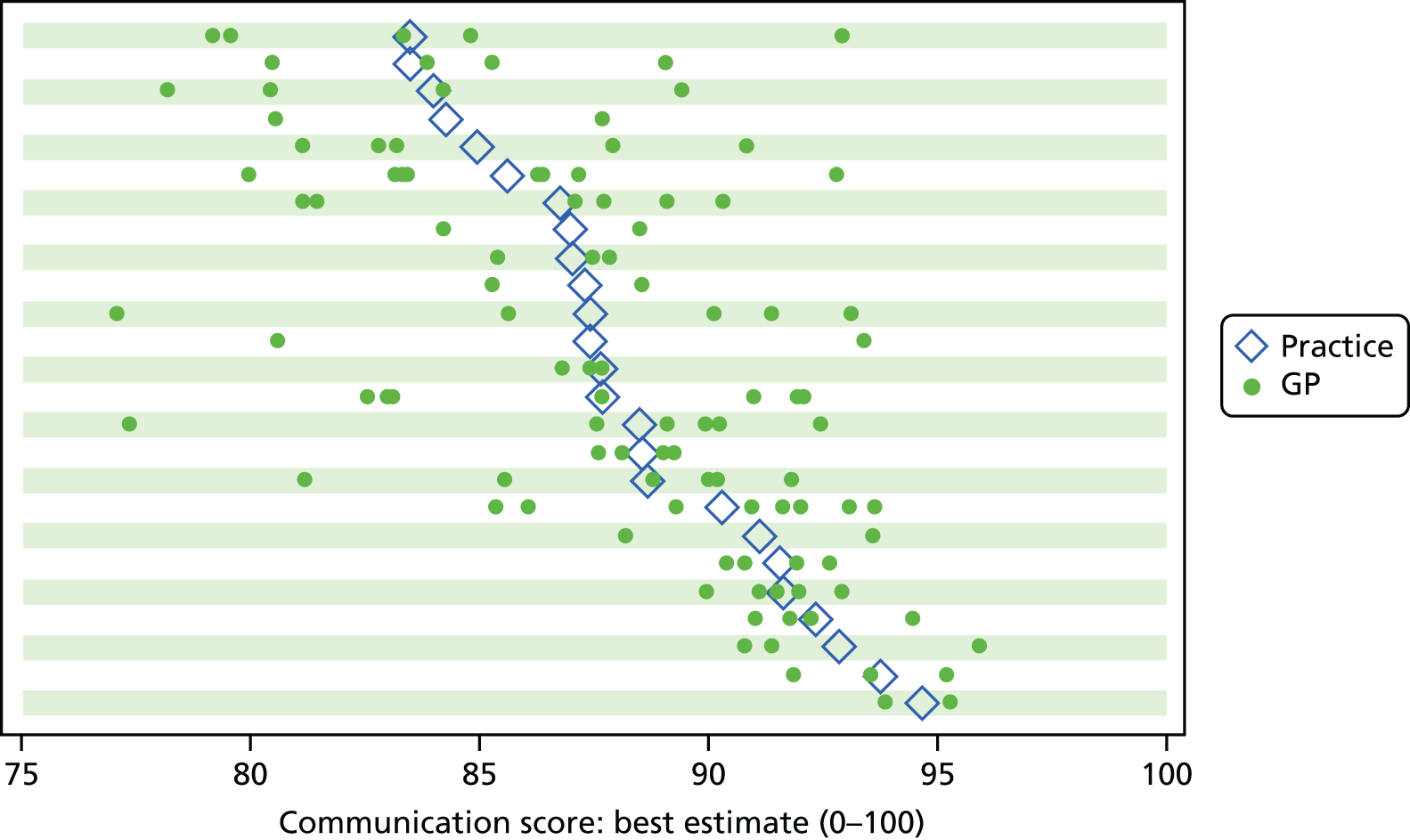

to estimate the extent to which aggregation of scores to practice level in the national study masks differences between individual doctors

-

to investigate how patients’ ratings on questions in the GP Patient Survey relate to actual behaviour by GPs in consultations

-

to understand better patients’ responses to questions on communication and seeing a doctor of their choice

-

to understand the reasons why minority ethnic groups, especially South Asian respondents, give lower scores on patient surveys than the white British population

-

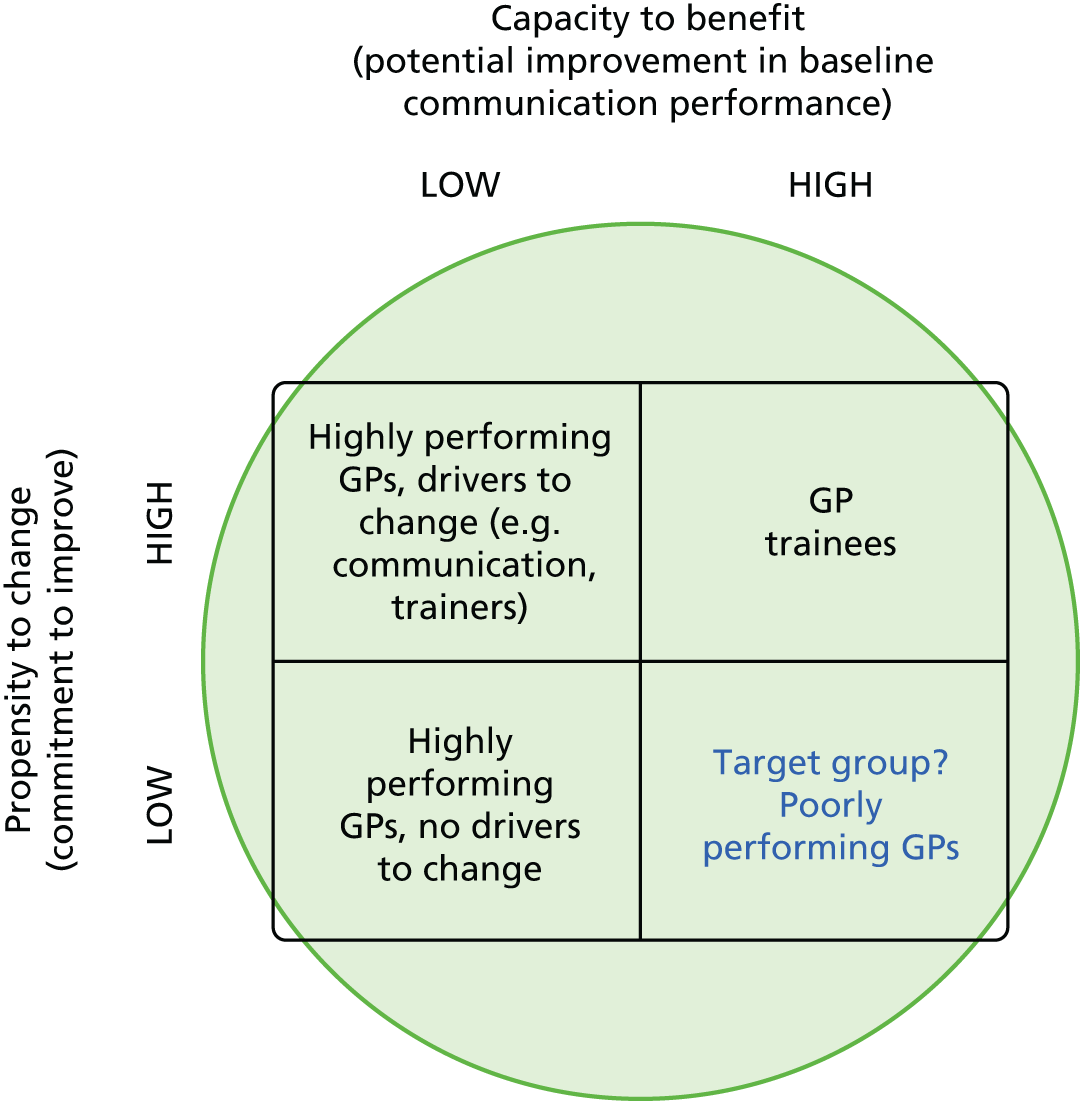

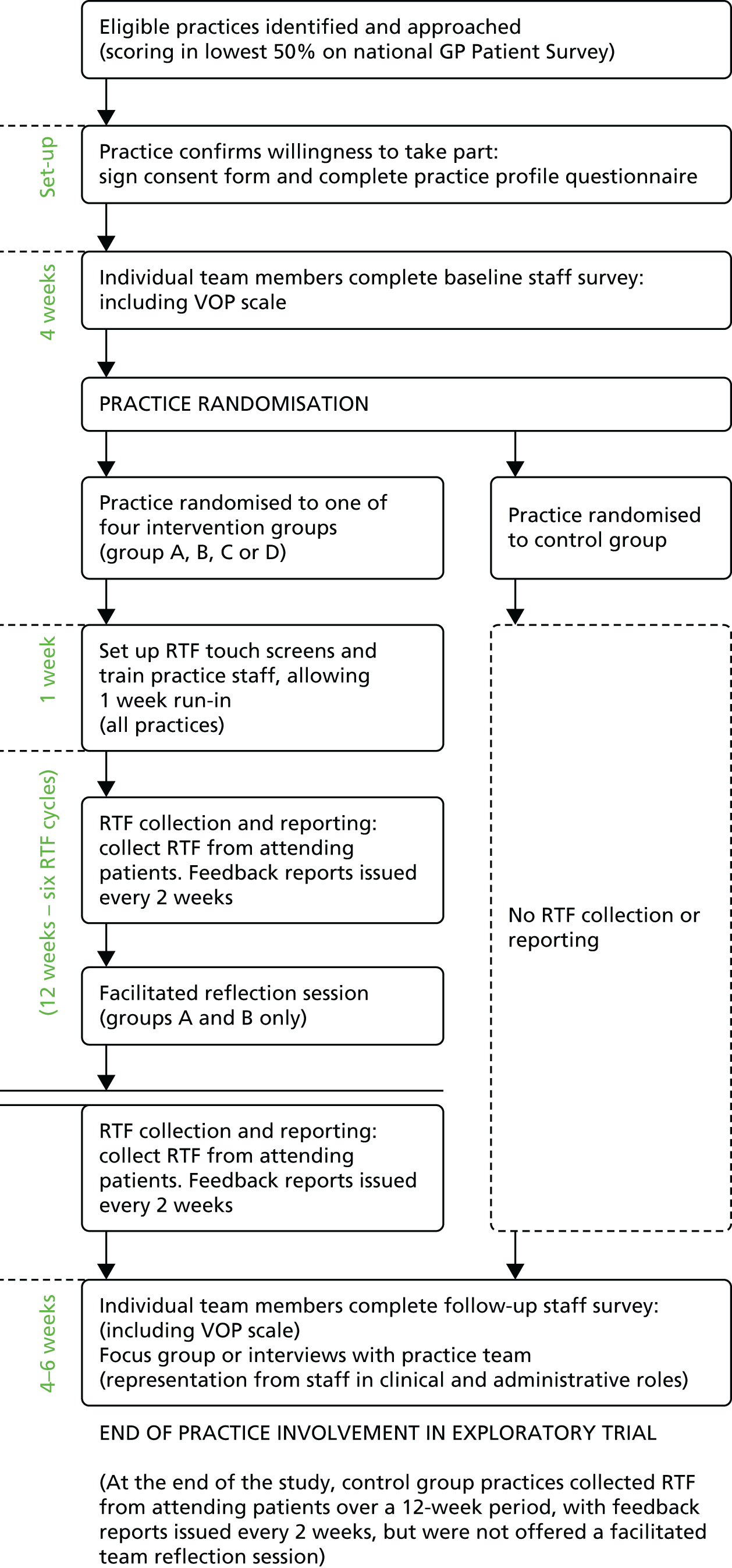

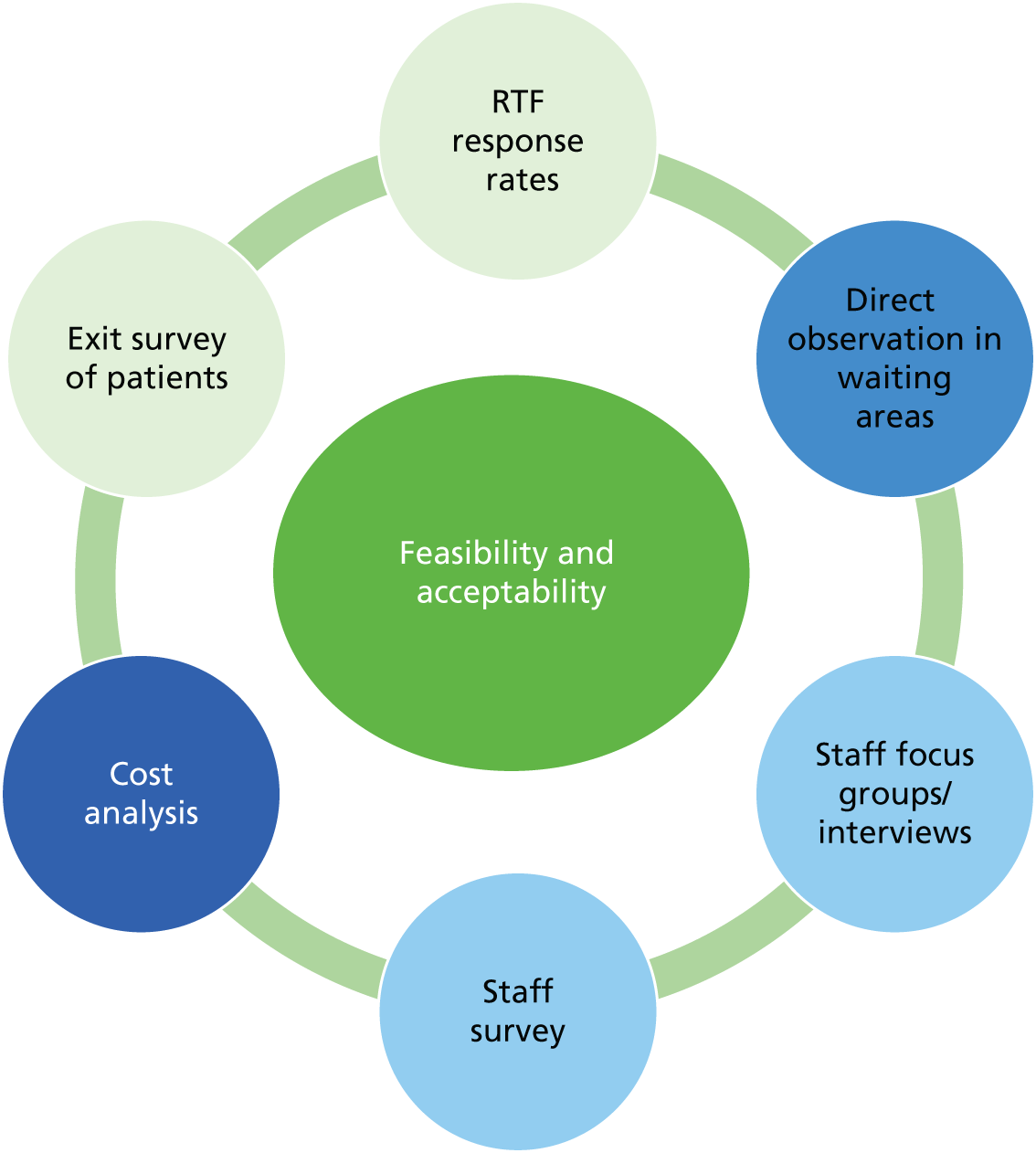

to carry out an exploratory randomised controlled trial (RCT) of an intervention to improve patient experience, using tools developed in earlier parts of the programme

-

to investigate how the results of the GP Patient Survey can be used to improve patients’ experience of out-of-hours care.

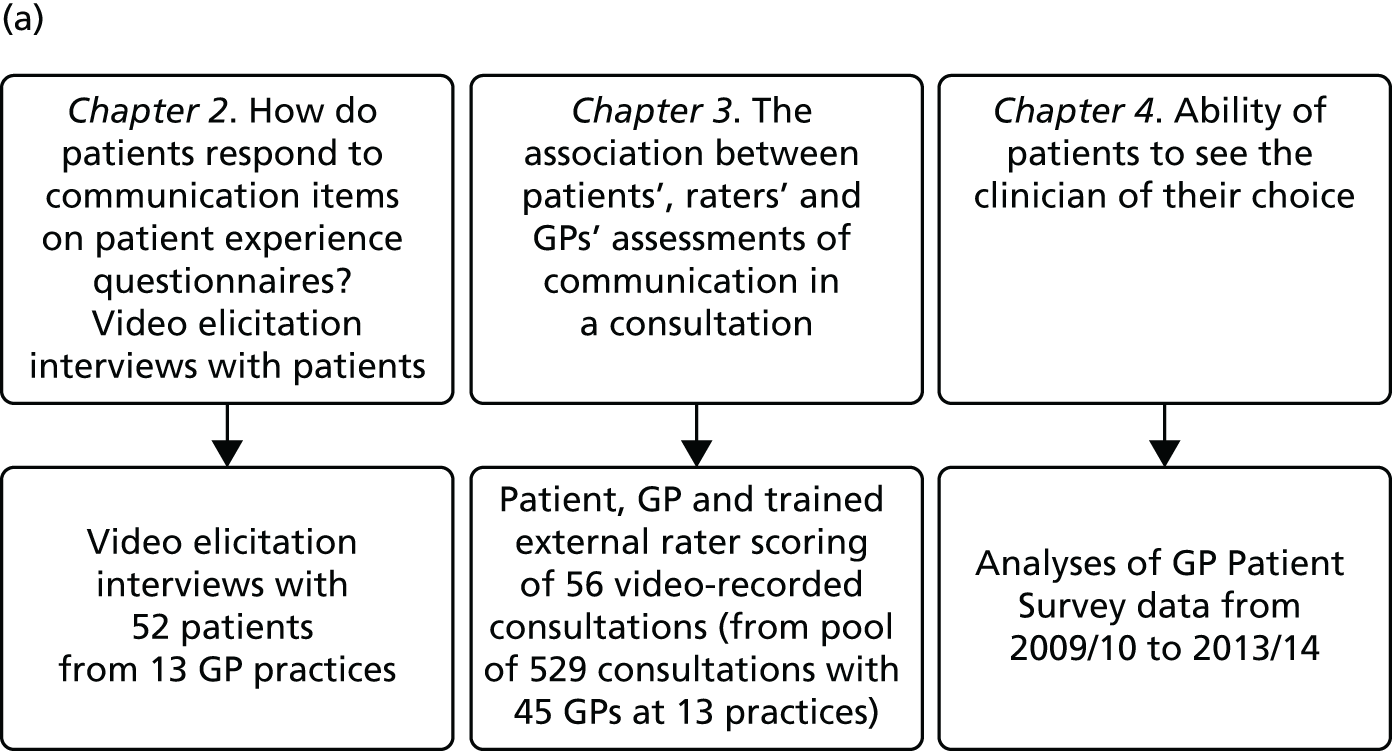

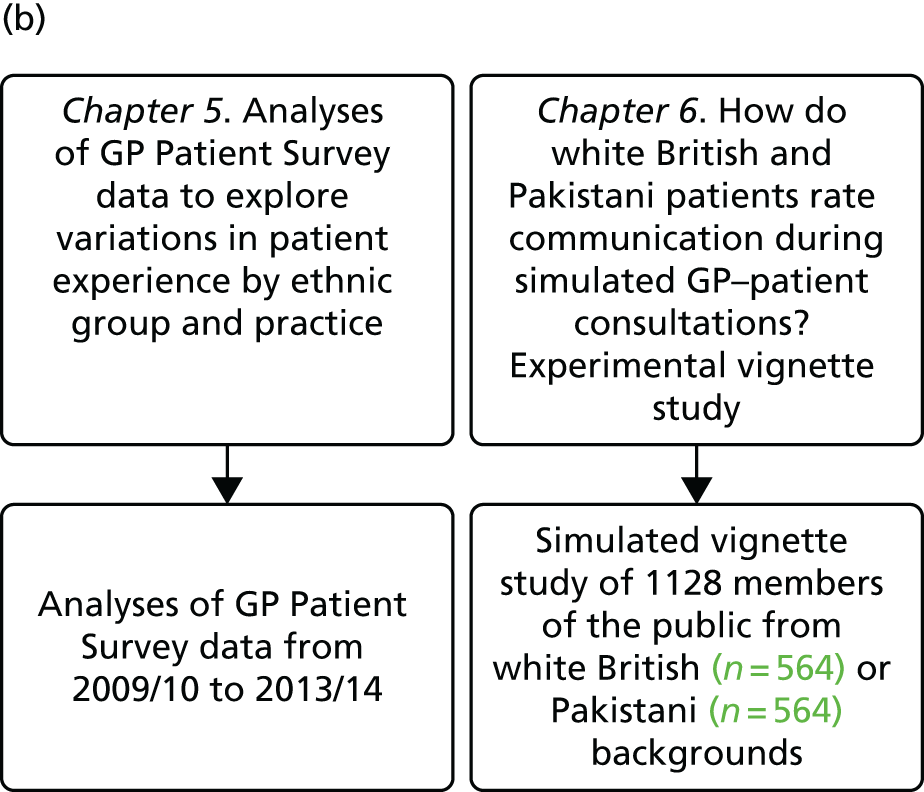

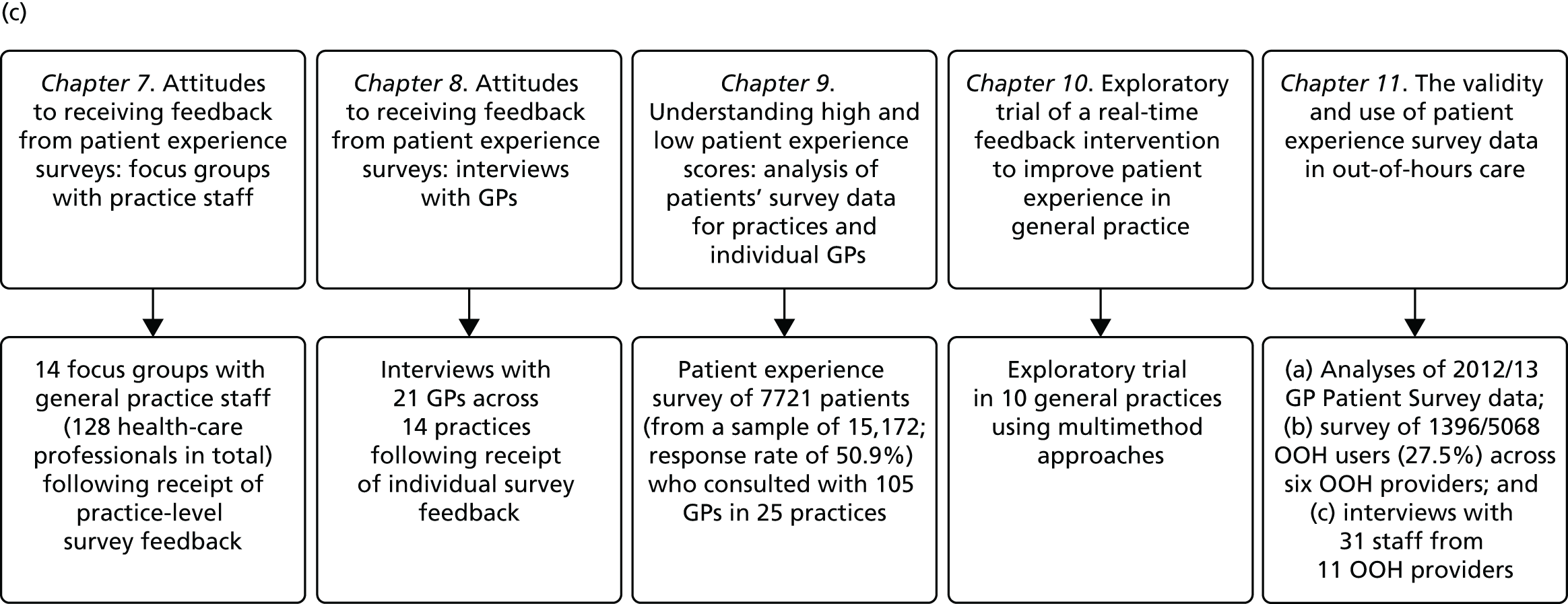

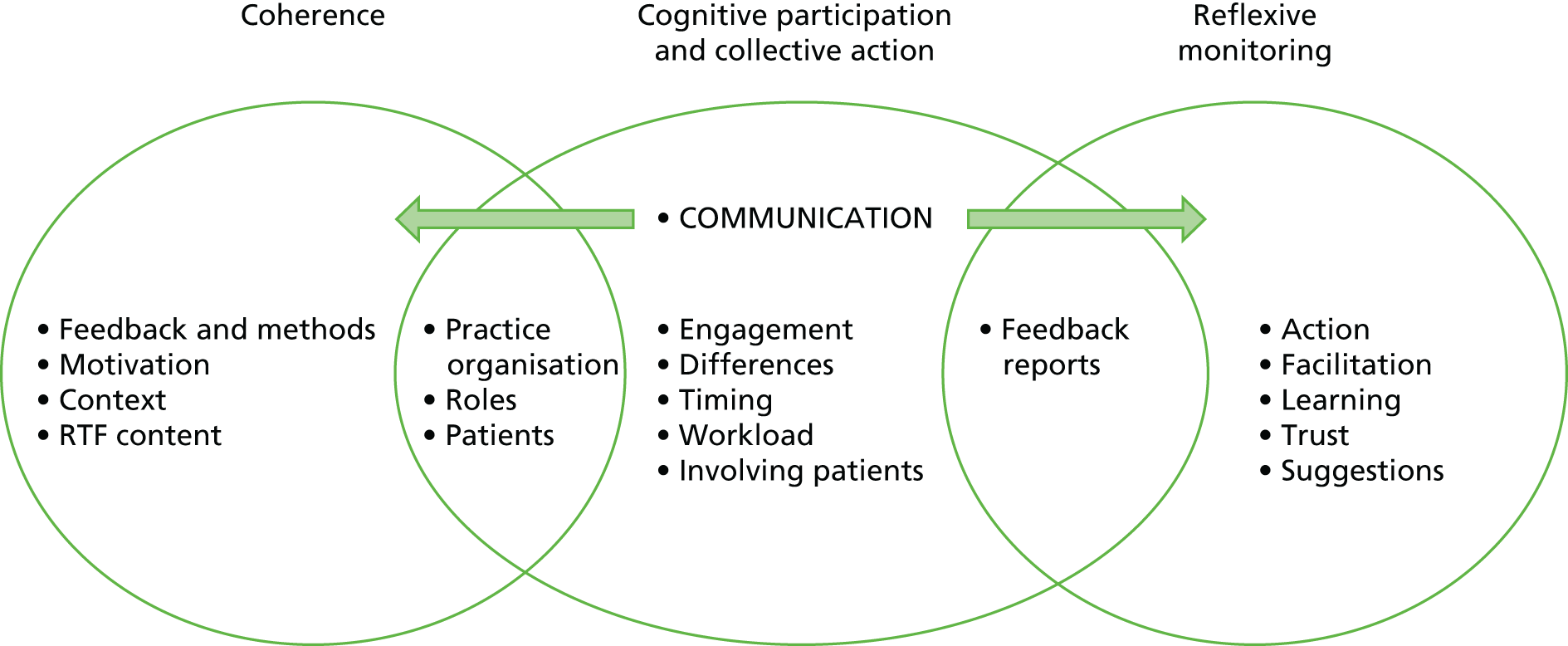

In presenting our work, we report our research and findings under three major themes: (1) understanding patient experience data, (2) understanding patient experience in minority ethnic groups and (3) using data on patient experience for quality improvement. These are outlined in brief in the following sections. The relationships between individual studies and the three themes are shown in Figure 1, which also outlines methods and participants.

FIGURE 1.

The IMPROVE (improving patient experience in primary care) programme themes and studies contained within workstreams: (a) understanding patient experience data; (b) understanding patient experience in minority ethnic groups; and (c) using data on patient experience for quality improvement. OOH, out of hours.

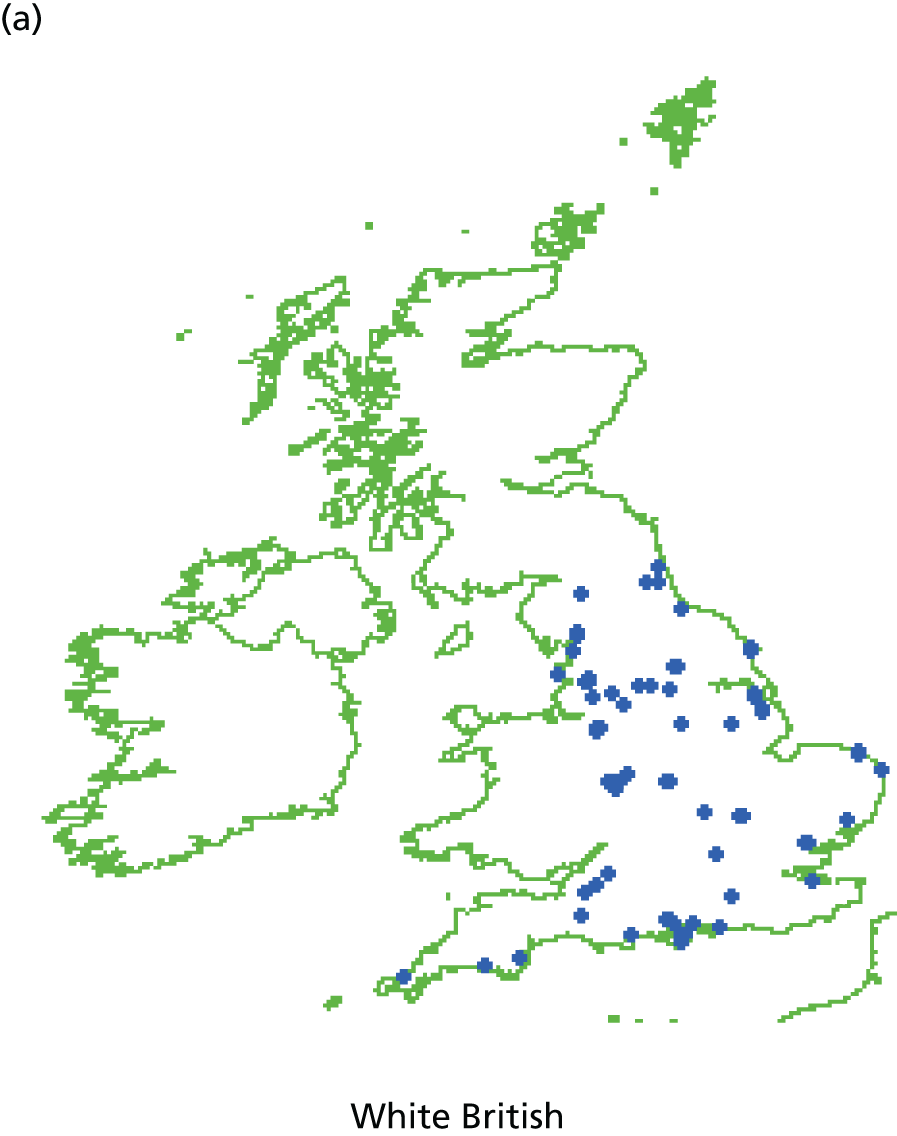

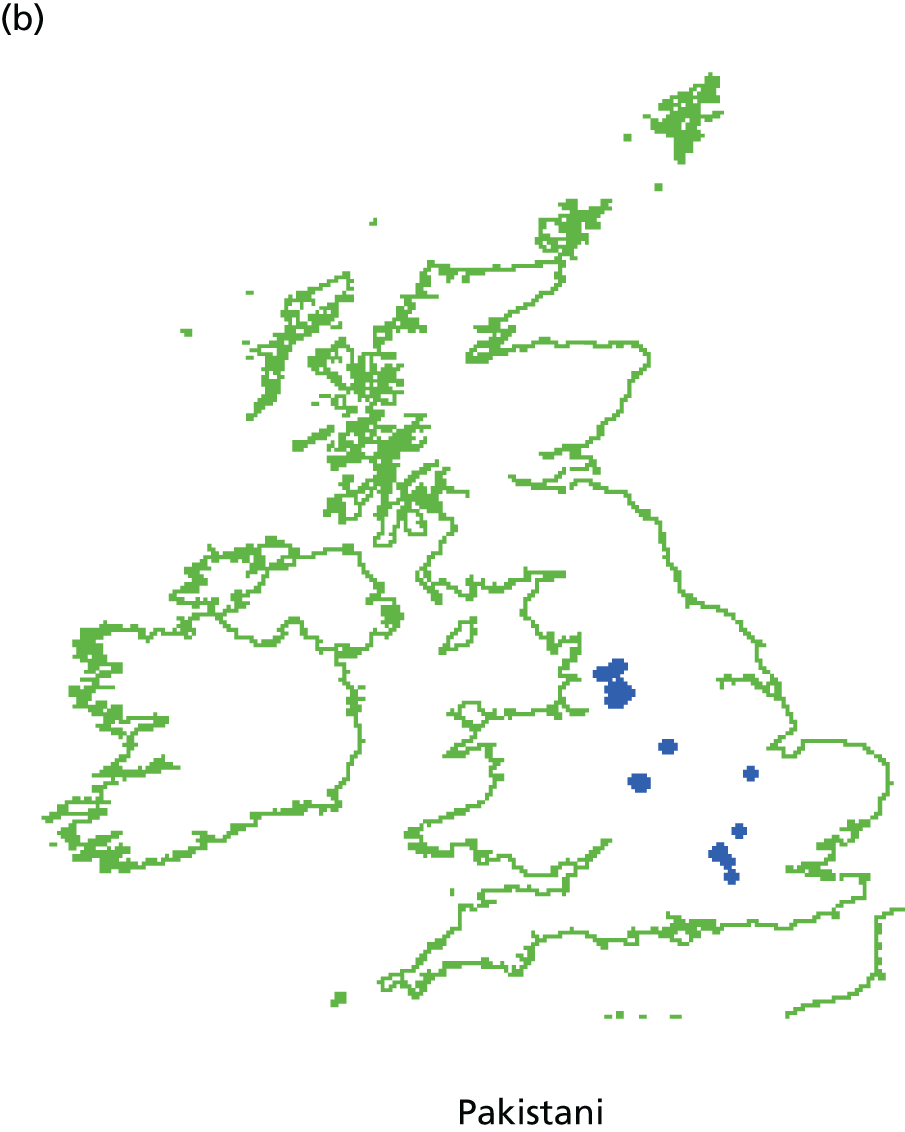

During the course of the programme we conducted empirical studies across a number of general practices and out-of-hours providers. General practices were initially recruited to take part in a suite of studies (presented in Chapters 7–9) in which we conducted a patient experience survey at the level of individual GPs, gave feedback from this survey to both the practice and the individual doctors (see Chapter 9) and, for some practices, conducted focus groups with practice staff and interviews with GPs. Sampling was initially designed around the survey study: practices were sampled on the basis of location (two study areas, the South West and North London/East of England, covering both urban and rural settings), performance on the GP Patient Survey, practice size and area-level deprivation. Once the survey was completed, a number of practices were purposively sampled to take part in focus groups with staff (see Chapter 7) and interviews with GPs (see Chapter 8) and additional filming of consultations (see Chapter 3). Out-of-hours providers were recruited from across England. We worked with up to 11 providers in varying workstreams (see Chapter 11). We additionally completed multiple analyses of GP Patient Survey data11 (see Chapters 4, 5 and 11) and, for an experimental vignette study, collected data from members of the general public (see Chapter 6).

1. Understanding patient experience data

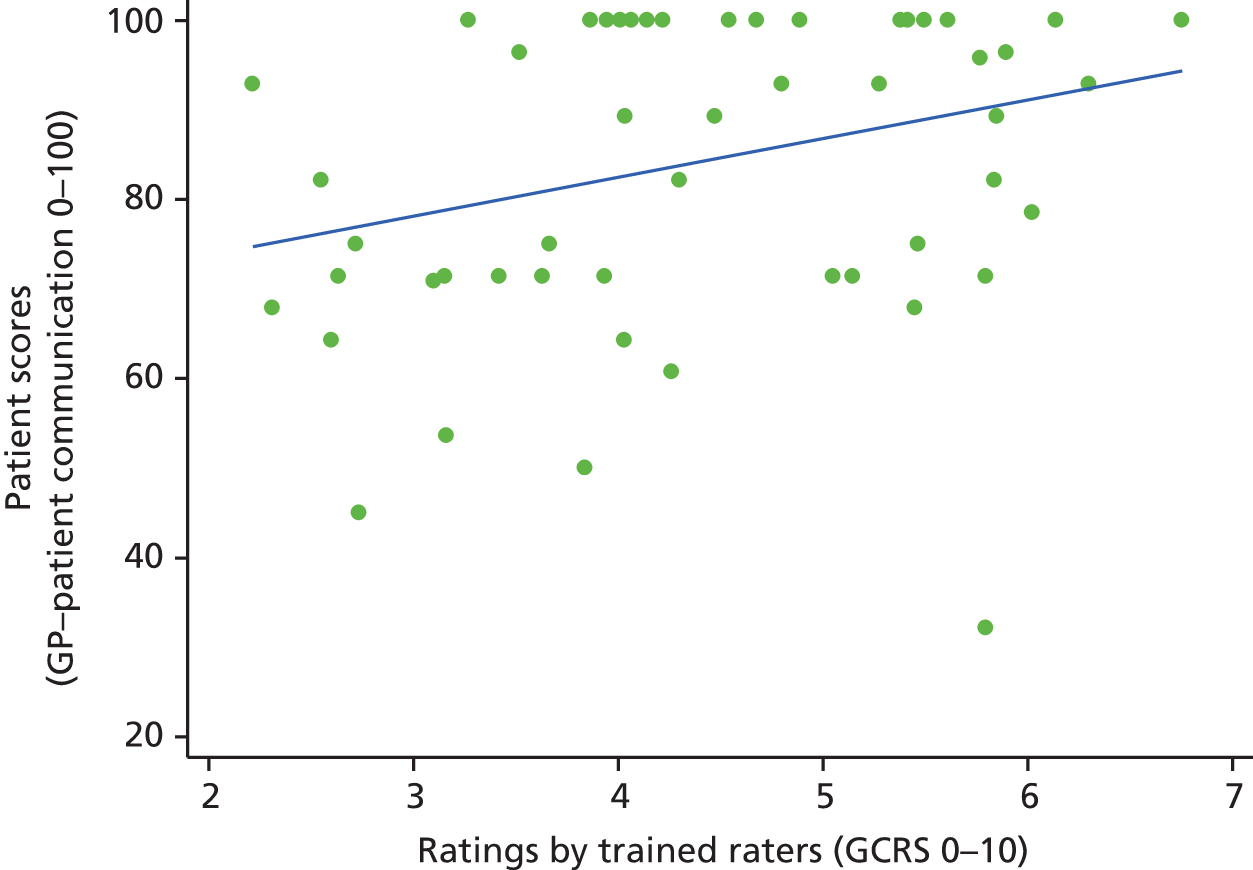

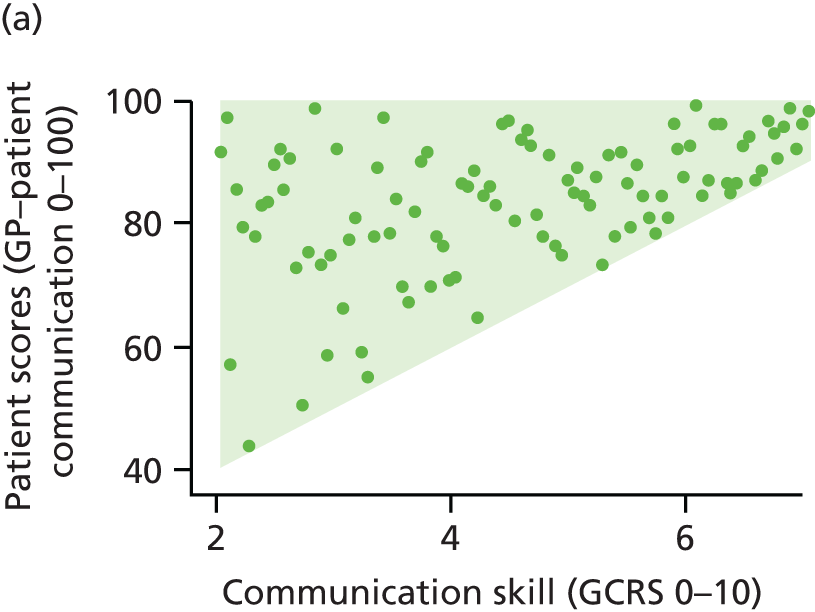

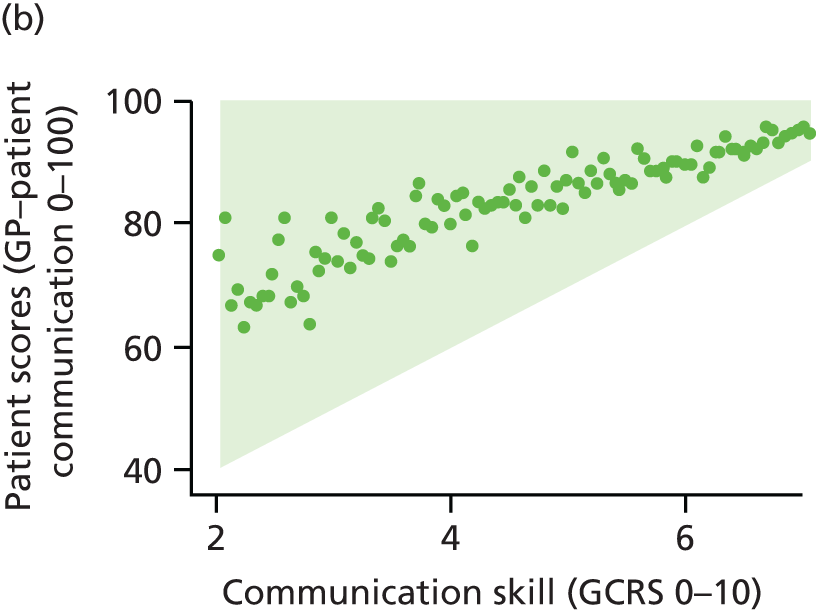

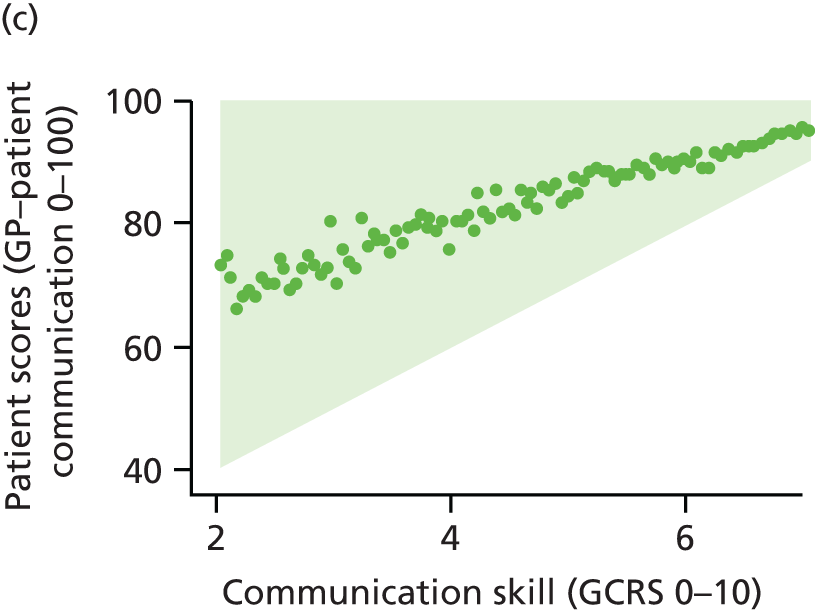

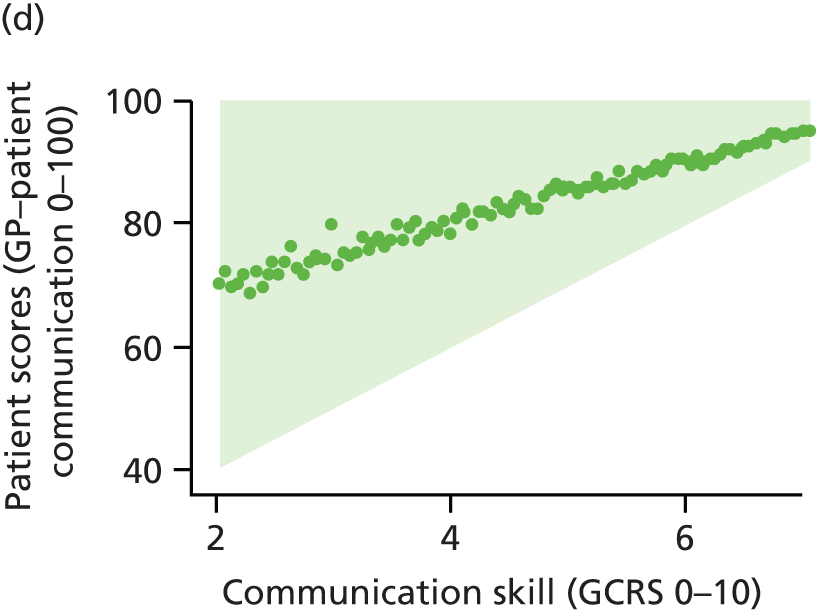

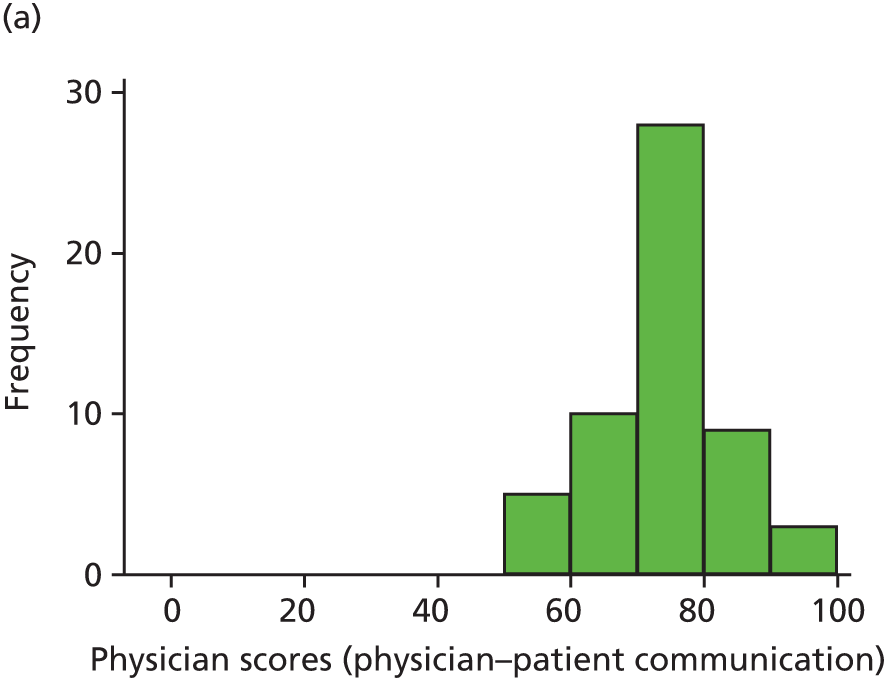

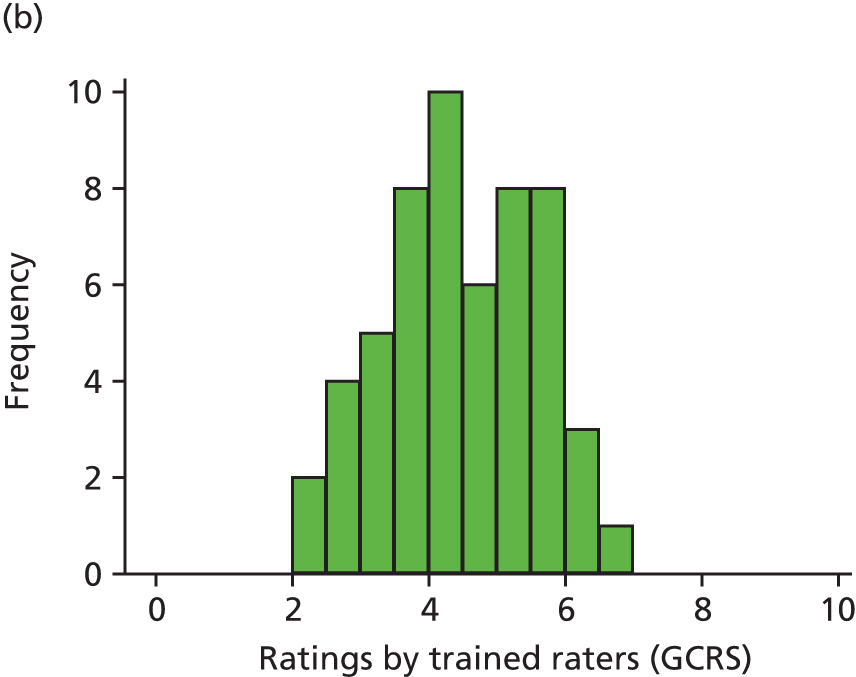

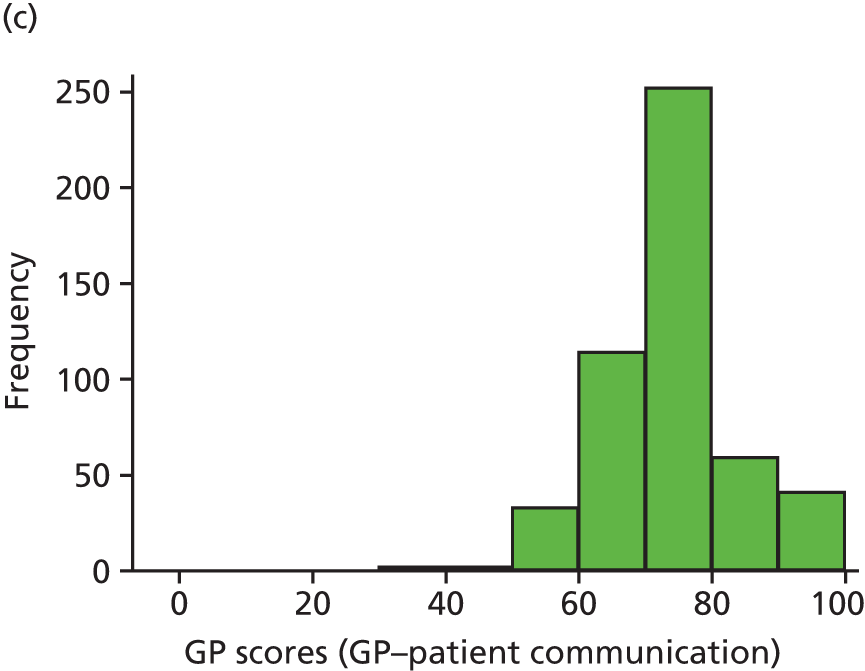

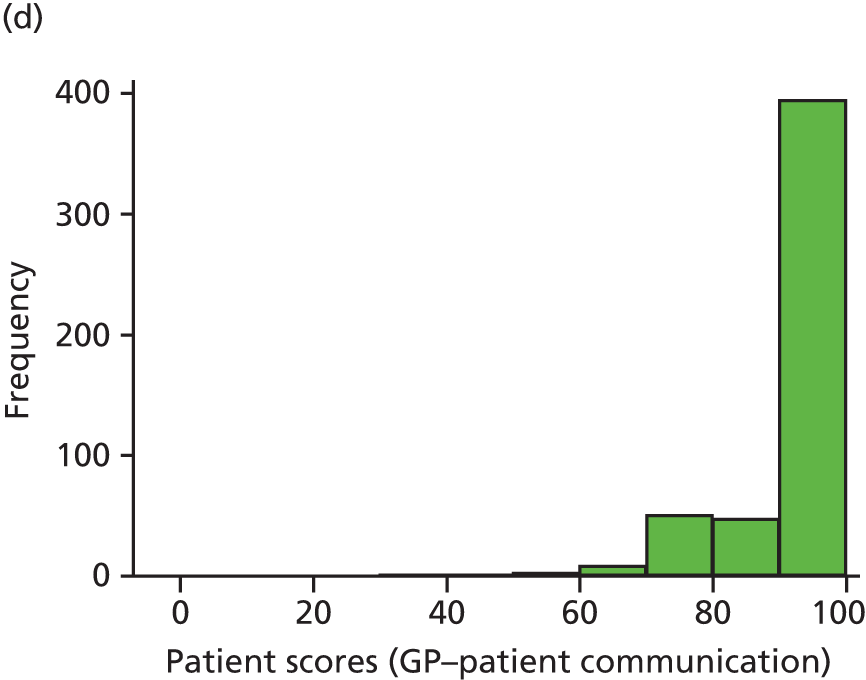

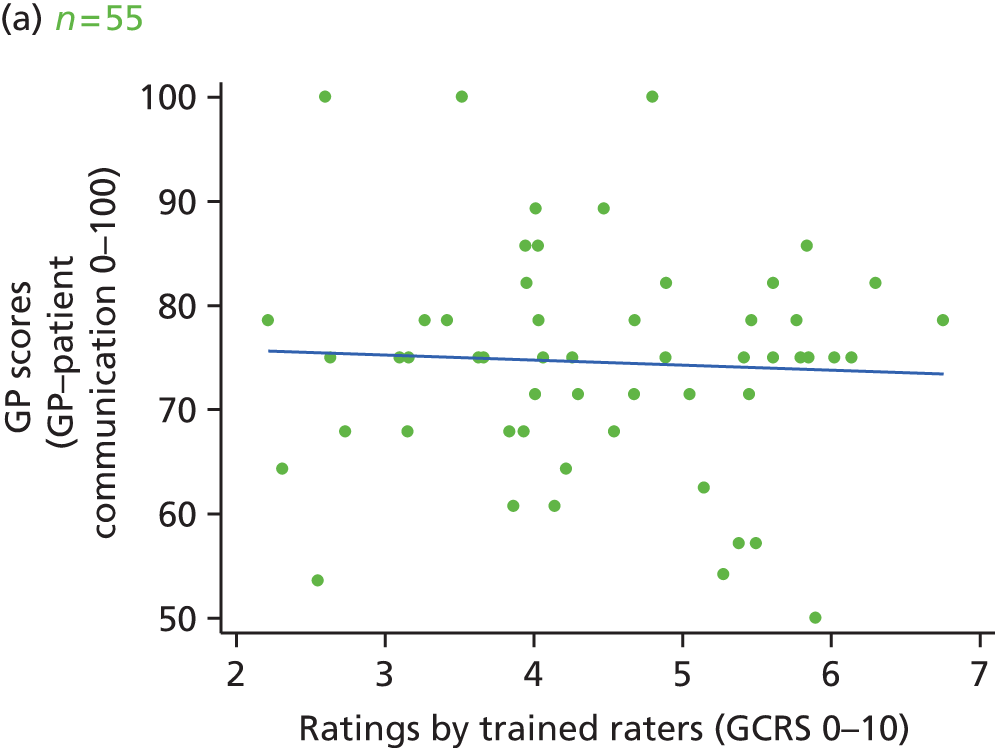

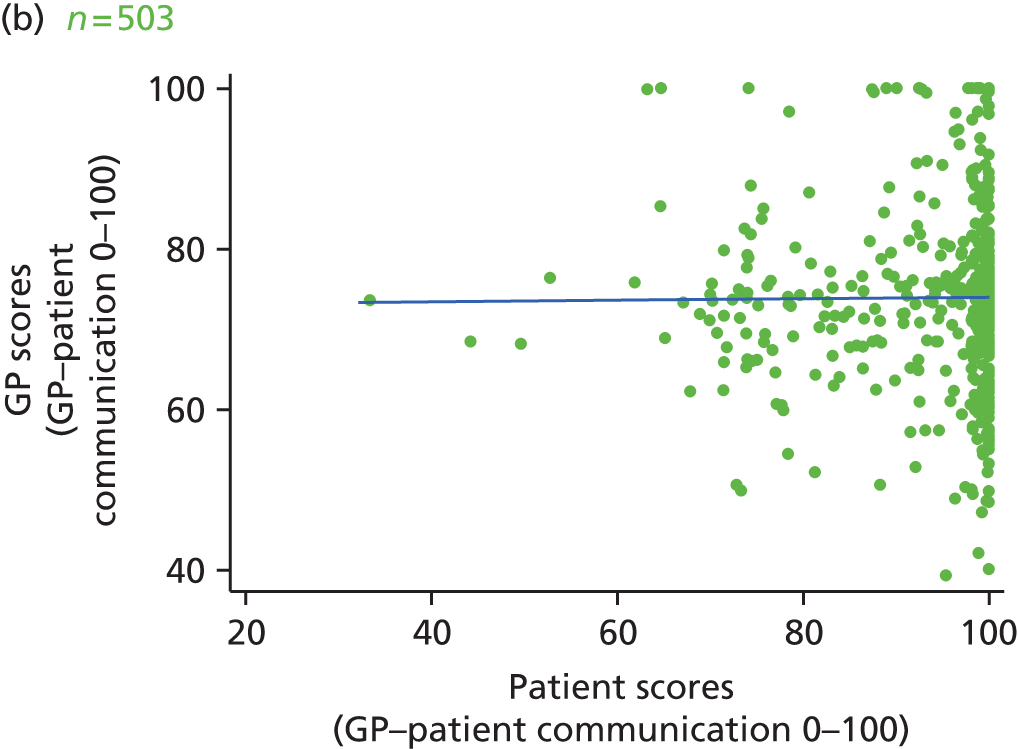

In this theme we explored the meaning of data gathered through patient experience surveys by video recording (with consent) a large number of GP–patient consultations. Patients and GPs completed a questionnaire evaluating the quality of communication during the consultation and trained external raters (all GPs) also scored a small number of filmed consultations for quality. We additionally interviewed a sample of patients who consented to have their consultations filmed, reviewing their recorded consultation with them while talking through the options that they chose on the questionnaire about their experiences. This theme relates to aims 3 and 4. In addition, we conducted analyses of GP Patient Survey data to explore variations in patient experience in patients whose contact was with a nurse rather than a GP. This was additional to the original aims of the programme.

2. Understanding patient experience in minority ethnic groups

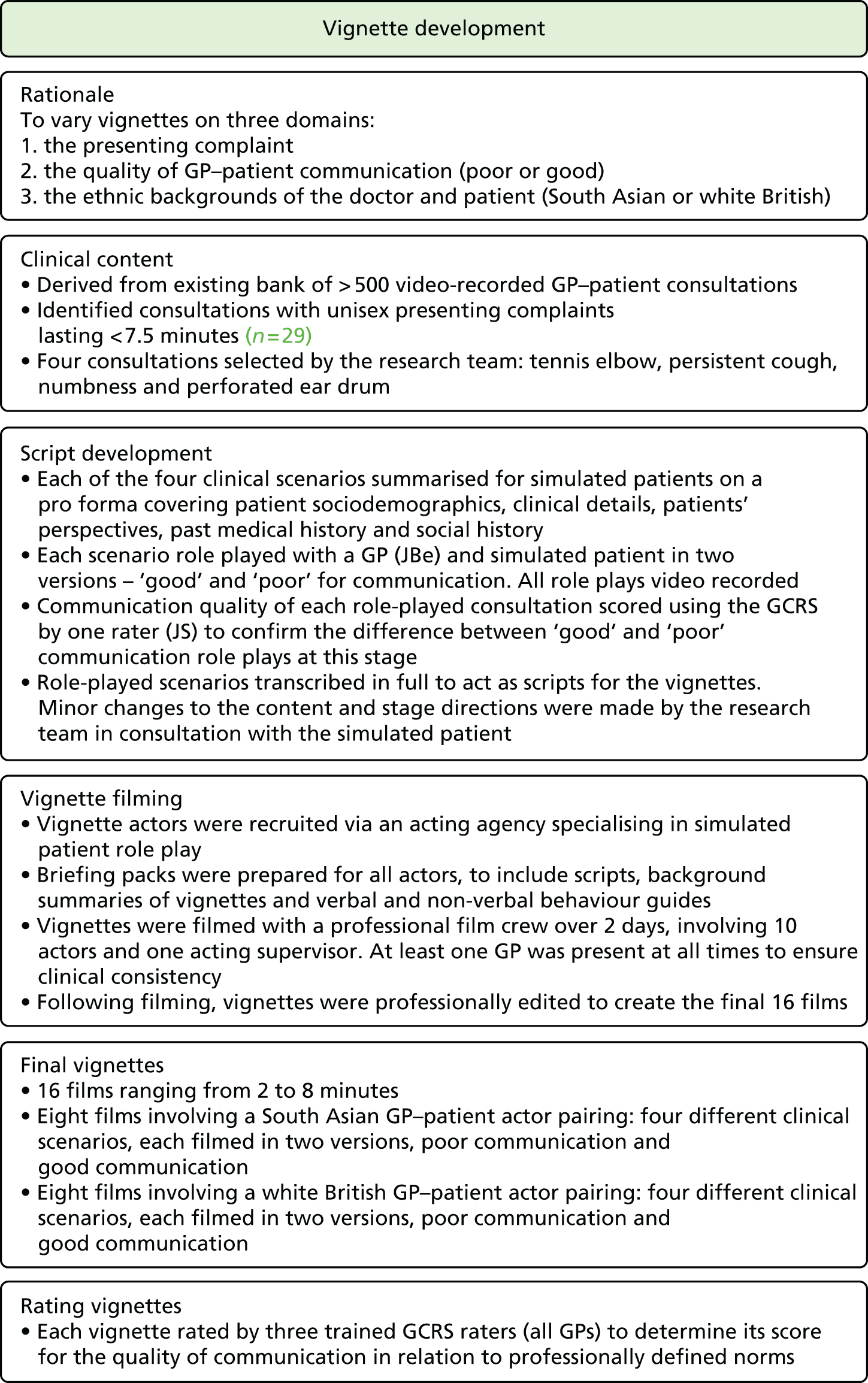

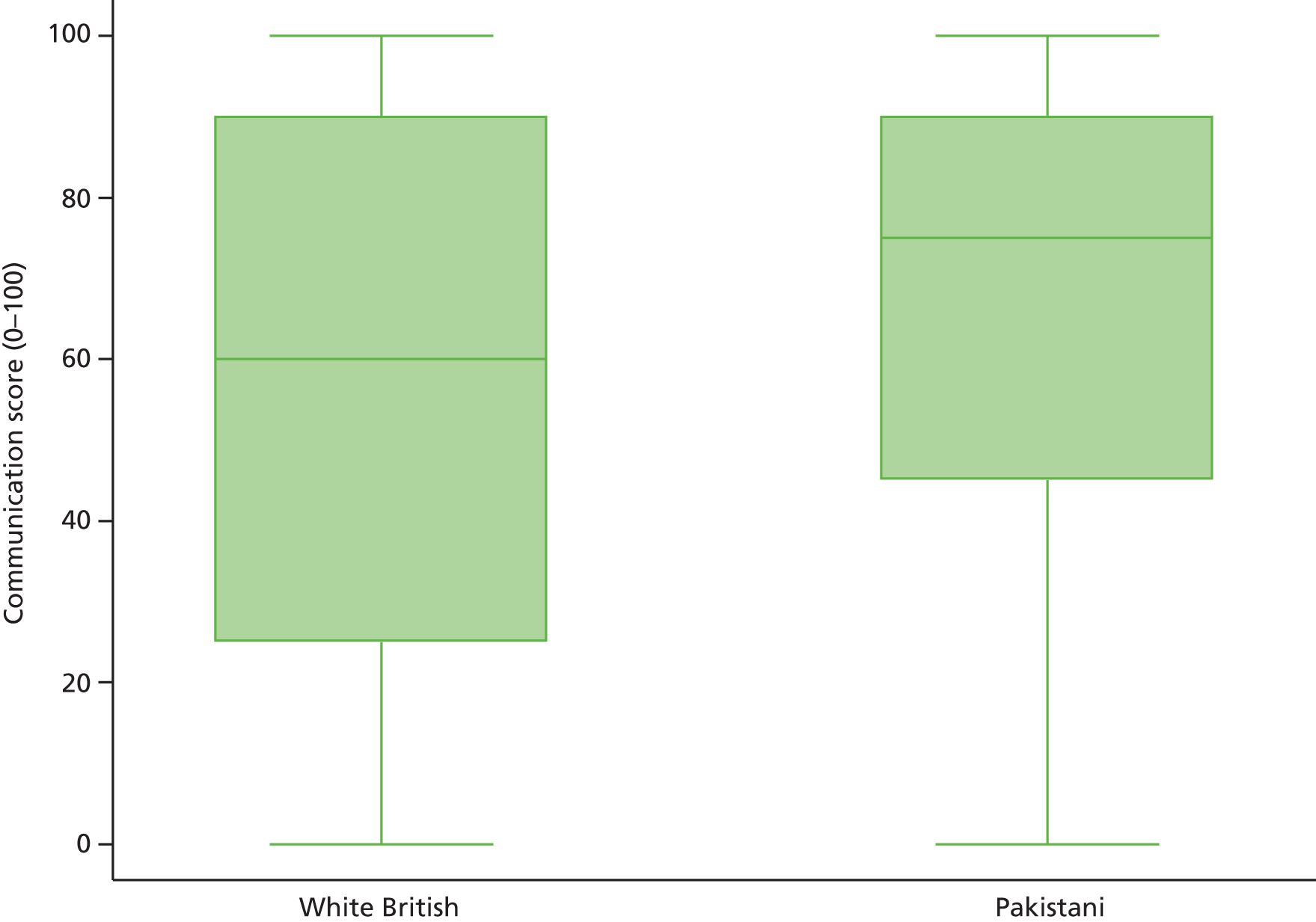

Here, we conducted a number of studies to explore why South Asian groups often have lower patient experience scores than white British patients in national surveys and provide more robust evidence of the drivers of this variation. These included a series of analyses of GP Patient Survey data and an experimental vignette study in which we showed simulated GP–patient consultations to white British and Pakistani respondents. This theme relates to aim 5.

3. Using data on patient experience for quality improvement

In trying to understand how patient experience data are currently used, and how they could be used, we carried out a wide range of studies. We completed a large-scale survey of patients at 25 general practices and carried out focus groups with practice staff and interviews with GPs. We conducted similar research in out-of-hours services. Finally, we looked at a different way of collecting patient experience data, using RTF kiosks in general practices. This theme relates to aims 1, 2, 6 and 7.

Patient and public involvement

Our programme of work was supported by two study advisory groups: one was based in Cambridge and provided support across all streams of work except for the out-of-hours research and the other was based in Exeter and was convened specifically to provide input to the out-of-hours workstreams. In this section we briefly outline the formation and working of these groups over the course of the programme.

Formation and composition of the main study advisory group

In the original application for the IMPROVE (improving patient experience in primary care) programme we set out our plans to establish an advisory group composed of 50% lay members and 50% professional members, to provide continuing advice and input throughout the course of the programme. We envisaged that this group would provide advice on the design of all strands of the work, assist with the production of study materials and work with us on the interpretation of data. At the start of the study we therefore set out to invite a mix of lay people registered with a general practice, GPs and practice managers to join the group.

We worked with the patient and public involvement (PPI) co-ordinator of the West Anglia Comprehensive Local Research Network to identify potential lay members with an interest in patient experience and primary care research. Potential patient representatives were provided with guidance outlining what was involved in advisory group membership and were informed that any costs incurred in preparing for or attending advisory group meetings would be reimbursed. Four lay members were recruited through this route. Additionally, we recruited one local GP to the advisory group from a practice with a large minority ethnic patient list. Despite a number of attempts to recruit an additional GP and two practice managers to the group, to ensure that we had input from all key stakeholders in the research, we were unable to do so. In spite of offering reimbursement to practices (e.g. we paid for a locum to enable our one GP member to attend advisory group meetings), GPs and practice managers were reluctant to commit to provide input into a research study over a number of years. We therefore proceeded with input from one GP only.

As a large focus of our work was on patient experience in minority ethnic communities, and particularly South Asian communities, we had additionally planned at the start of the study to recruit two additional lay members from a minority ethnic background to join the advisory group and provide specific advice on the development of our work in this area. In the event, this proved very difficult to achieve and we were unable to locate suitable representatives willing to sit on a formal group. We therefore considered alternative approaches to ensuring that we had input from these communities as we developed our study ideas and materials. As a result, we recruited a part-time researcher, Hena Wali Haque, and a senior advisor, Professor Cathy Lloyd, with specific expertise in and knowledge of research with minority ethnic groups. Hena liaised early on in our work with community groups representing Pakistani and Bengali communities and provided input on study materials and design. Although we would have preferred to have had such representation directly on our study steering group, through this route we were able to benefit from guidance on the most appropriate and effective approach to our research in this area.

We drew on guidance from INVOLVE to develop policies and documentation relating to the involvement of our advisory group members. 96 These included details of payment for particular activities, reimbursement, confidentiality, and data security. Group members completed a checklist to indicate what they were willing to assist with during the course of their involvement (e.g. reviewing different types of documents or attending meetings).

Formation and composition of the out-of-hours study advisory group

A stakeholder advisory group was convened specifically to provide guidance throughout the out-of-hours research. This consisted of three members from out-of-hours service providers, two academics with a particular expertise in this area and one lay representative. We had originally aimed to recruit two out-of-hours service users through local service providers, with assistance and guidance from local PPI groups; however, despite significant efforts, it proved difficult to recruit service users with relevant, lived experience. Our experiences were echoed by out-of-hours service providers, who noted that the relatively infrequent contacts that people made with out-of-hours services may in part drive the difficulties in recruiting service users to sit on advisory groups such as ours.

Activities of the main study advisory group

We set out to convene a face-to-face meeting of the main programme advisory group once a year throughout the course of the research. All meetings took place in Cambridge, with the first meeting taking place in October 2011 and the fifth and final meeting taking place in March 2015. At these meetings, group members reviewed and suggested changes to the study design, reviewed progress, discussed challenges and reflected on findings and interpretation. Particularly crucial input came, for example, in designing our approach to the recruitment of patients to our workstream involving the video recording of GP–patient consultations and in reflecting on the findings of our video elicitation interviews with patients. To keep group members up to date with progress and the research team, we sent out study newsletters on a roughly quarterly basis, with 13 being sent over the course of the programme.

Informal contact with group members by e-mail and letter continued throughout the rest of the year outside of the more structured meetings. One advisory group member, for example, was instrumental in organising a pilot focus group to reflect on study questionnaires. Additionally, all study materials aimed at patients or GPs (information sheets, consent forms and questionnaires) were reviewed and commented on by advisory group members and members were sent a summary of all findings and our conclusions to reflect on.

Activities of the out-of-hours study advisory group

Our out-of-hours advisory group, based in Exeter, had a more specific remit in guiding our research in this area. The group met initially to review study methods and procedures in light of the findings of the preliminary piloting and testing of methods (see Chapter 11, Workstream 2) and to comment on topic guides supporting interviewing in workstream 3. However, because of the logistical challenges of organising face-to-face meetings around staff availability, after an initial face-to-face meeting we communicated with the advisory group by e-mail and telephone.

Section A Understanding patient experience data

Chapter 2 How do patients respond to communication items on patient experience questionnaires? Video elicitation interviews with patients

Abstract

Background

Patient feedback instruments used in national survey programmes are robustly tested and evaluated, yet there remains a paucity of evidence on the drivers of a patient’s choice of response option. The objective of this study was to understand how patients’ responses to a questionnaire relate to their actual experience of a consultation with a GP, focusing on both implicit and explicit processes that respondents use to answer survey items.

Methods

We video recorded GP–patient consultations at 13 practices. Immediately following the consultation, patients were asked to complete a questionnaire about the GPs’ communication skills. We purposively approached a sample of these patients to take part in a video elicitation interview (n = 52), in which they were shown the video of their consultation and asked to reflect on their completion of the questionnaire.

Results

Although participants were able to raise concerns about doctors’ behaviours during the interview, they were reluctant to do so in their questionnaire responses. We identified three important drivers of this mismatch: (1) the patients’ relationship with the GP, (2) the patients’ expectations of the consultation and (3) perceived power asymmetries between patients and doctors.

Conclusions

Patients were inhibited in providing feedback to GPs through the use of questionnaires, with patients struggling to transform their experiences into a representative quantitative evaluation of GP performance. Our results suggest that patient surveys, as currently used, may be limited tools for enabling patients to feed back their views about consultations.

Introduction and rationale for the study

The overall purpose of patient surveys in primary care, such as the national GP Patient Survey,11 is to improve patient experience by feeding back patients’ evaluations to GPs and to the public. This process makes an important assumption, which is that the behaviours that doctors need to change are accurately assessed by responses given in patient experience questionnaires. For questionnaire items that relate to doctor–patient communication, the evidence that the items reflect doctors’ behaviour rests on their face validity and the cognitive testing that has already been carried out. Face validity is often taken as sufficient. However, further understanding of questionnaire completion is needed before helpful advice can be given to GPs. For example, if more is understood about the nature of poor consultations identified by patients, better support and advice can be provided to GPs to improve the quality of their consultations.

Previous studies have examined the process of patient questionnaire completion in specialist clinics. 97,98 These highlighted that patients may struggle to accurately represent their experiences of a consultation on standard survey instruments. Further, concerns have been raised about the perceived requirement for patients to assess health care from a ‘consumerist’ perspective. 99,100

To date, little is known about the ways in which questionnaire responses relate to patient experience within primary care and, specifically, patients’ perceptions of communication during GP consultations. The aim of this study was to understand, through the use of video elicitation interviews, how patients’ responses to a questionnaire relate to their experience of a consultation with a GP.

Changes to study methods from the original protocol

The aim of this workstream, as stated in the original protocol, was to understand better patients’ responses to questions on communication and seeing a doctor of their choice (aim 4).

In our application we set out plans to address this by conducting interviews with 40 patients, with 20 from a white British background and 20 from an Asian background. Interviews with minority ethnic participants were designed to contribute to our understanding of variations in patients’ experience of care in these groups, complementing our analyses of GP Patient Survey data and our experimental vignette study (see Chapters 5 and 6, respectively). We envisaged all interviews drawing on psychological approaches to cognitive interviewing, focusing on (1) comprehension of the question, (2) recall and assessment, (3) decision processes and (4) response processes.

We have expanded on our original design in several important ways. First, following our application, literature on the use of video elicitation interviews to stimulate recall and reflection on a medical encounter was published and to us appeared to be of direct utility for the aims of this study. 101 Video elicitation approaches, outlined in the methods section, use a series of detailed and specific prompts to enable participants to ‘relive, recall and reflect’ on their recent medical consultation. 101 We therefore adopted this approach in preference to that of cognitive interviewing.

Second, following discussions with practices, we were concerned that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to recruiting patients to the study from both white British and South Asian backgrounds was unlikely to be sufficiently sensitive and robust. We therefore made the decision to conduct the South Asian interviews as a stand-alone study, recruiting three additional practices with a particularly large proportion of South Asian patients on their lists and using dedicated researchers fluent in South Asian languages, together with appropriate study materials. This resulted in 23 interviews specifically with patients from a Pakistani background, conducted in the language of their choice. Our analyses of these interviews identified broadly similar concerns between our South Asian sample and the sample in the main study and we report these briefly in this chapter.

Finally, we expanded our original sample size of 20 interviews with white British patients to > 50, from a variety of backgrounds (but all were fluent in English). Video elicitation interviews are challenging to conduct well and we felt that it was important to enable the research team to build up sufficient confidence and expertise to generate rich data, as well as to reach a more diverse patient population. This chapter focuses in the main on interviews with the English-speaking population (n = 52).

Methods

This strand of work was conducted alongside the quantitative study outlined in Chapter 3. The recruitment of practices, GPs and patients was, thus, the same for both. The work outlined in this chapter focuses on subsequent interviews with patients who gave consent for their consultation to be video recorded. The IMPROVE study advisory group made important contributions to study design, particularly our approach to recruiting patients and the use of both a ‘brief’ and a ‘full’ study information sheet, and reflected on our analysis and findings.

Recruitment of general practices

The study was conducted in general practices in two broad geographical areas (Devon, Cornwall, Bristol and Somerset and Cambridgeshire, Bedford, Luton and North London). Practices were eligible if they (1) had more than one GP working a minimum of four sessions a week in direct clinical contact with patients and (2) had low scores on GP–patient communication items used in the national GP Patient Survey [defined as practices below the lower quartile for mean communication score in the 2009/10 survey, adjusted for patient case mix (age, gender, ethnicity, self-rated health and deprivation)102]. Low-scoring practices were chosen to maximise the chance of consultations within the practice being given low patient ratings for communication (nationally, 94% of patients score all questions addressing doctor communication during consultations as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ in the GP Patient Survey). Some, but not all, of these practices had previously participated in our individual GP-level patient experience survey (see Chapter 9 for details).

Recruitment of patients and recording of consultations

Video recording of GP–patient consultations took place for one or two GPs at a time within each participating practice. A member of the research team approached adult patients on their arrival in the practice to introduce the study. The patients were given a summary of the study as part of a brief information sheet, as well as a detailed full information sheet and a consent form. A member of the research team discussed these documents with each patient and sought consent to video record their consultation. Video cameras, set up in participating GPs’ consulting rooms, were controlled by the GP; physical examinations took place behind a screen and were thus not captured on camera. Data collection ceased when we reached our required number of video-recorded consultations that patients judged to be less than good for communication, as required for the quantitative analysis described in Chapter 3. All videos were stored on an encrypted secure server accessible only to members of the core research team. The recordings were made available to GPs for the purposes of continuing professional development. Immediately after the consultation, the patients were asked to complete a short questionnaire. This contained items relating to GP communication that were adapted from the GP Patient Survey (Table 1), alongside participant information including age, ethnicity and health status.

| Thinking about the consultation that took place today, how good was the doctor at each of the following? Please put a ✗ in one box for each row | Very good | Good | Neither good nor poor | Poor | Very poor | Doesn’t applya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giving you enough time | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Asking about your symptoms | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Listening to you | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Explaining tests and treatments | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Involving you in decisions about your care | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Treating you with care and concern | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Taking your problems seriously | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Video elicitation interviews and analysis

The patient questionnaire contained a tick-box question asking patients if they were willing to participate in a face-to-face interview about their experience of the consultation. We subsequently contacted (by telephone or e-mail) those patients who expressed an interest in taking part. We aimed to interview at least one patient per participating GP. When more than one patient expressed an interest, we used a maximum variation sampling approach to reflect a mix of patient characteristics and questionnaire responses. Prior to the commencement of the study, we were particularly interested in interviewing patients who had given at least one response of ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ in relation to a doctor’s communication skills.

We conducted video elicitation interviews with all participants (n = 52). In these interviews, participants were shown a recording of their consultation with the GP and asked specific questions relating to the consultation and their questionnaire responses (Box 1). The video elicitation technique is an established interview method that allows in-depth probing of experience during the interview by enabling participants to ‘relive, recall and reflect’ on their recent consultation. 101

Data generation focused particularly on participants’ recall of and reflection on the consultation and how this was expressed in their choice of responses on the questionnaire immediately post consultation. In each interview, the video of the consultation was used to encourage more accurate recall of specific events during the interaction. Our approach did not aim to establish the facts of what occurred, but rather explored the meaning to patients of actions that were performed in the consultation. The interview guide used was semistructured; however, we maintained a tight focus on specific moments and events captured in the recording.

Participants were asked some brief introductory questions about whether or not they had previously consulted with this doctor and whether the problem that they were consulting about was new or ongoing. Participants were then shown their consultation on the researcher’s laptop. They were encouraged to reflect as they watched the recording. Participants were also given their questionnaire responses and invited to talk through them. The recorded consultation was used as a prompt, enabling further in-depth discussion of their experiences in the consultation and their responses to the survey questions. Participants were also asked to identify behaviours in the consultation that they considered as contributing to their question responses and which could be changed to improve consulting performance.

The interviewers watched each consultation usually on at least two occasions before the interview and identified particular points at which they wanted to stop the recording or when they wanted to use prompts specific to the consultation content or to the respondent’s answers on the questionnaire. During the interview, the video recording of the consultation was shown to the participant, usually on two occasions. The participant was encouraged to stop the recording at any point to discuss a particular element of the consultation with the interviewer. The interviewer also stopped the recording as appropriate in response to a request from the participant, or to something said by the participant, or to her own prepared notes.

The analysis followed the principles outlined by Lofland et al. 103 These form a series of reflexive steps through which data are generated, coded and recoded, making particular use of memos to aid analytical thinking. Data analysis took place in two stages. The first stage occurred during data collection. A coding frame was devised from the topic guide, previous literature and early interviews. Each interviewer (JN, NL and AD) coded her own interviews in NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). A number of analysis meetings were convened in which the interviewers and other members of the project team (JB, NE and JBe) discussed the data and themes. To ensure familiarisation with all of the data, the lead author (JN) listened to all interviews and read all of the transcripts. The coding frame was refined in response to discussions and as analysis progressed.

Ethics considerations

Approval for the study was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee East of England – Hertfordshire on 11 October 2011 (reference number 11/EE/0353).

Results

Participant recruitment

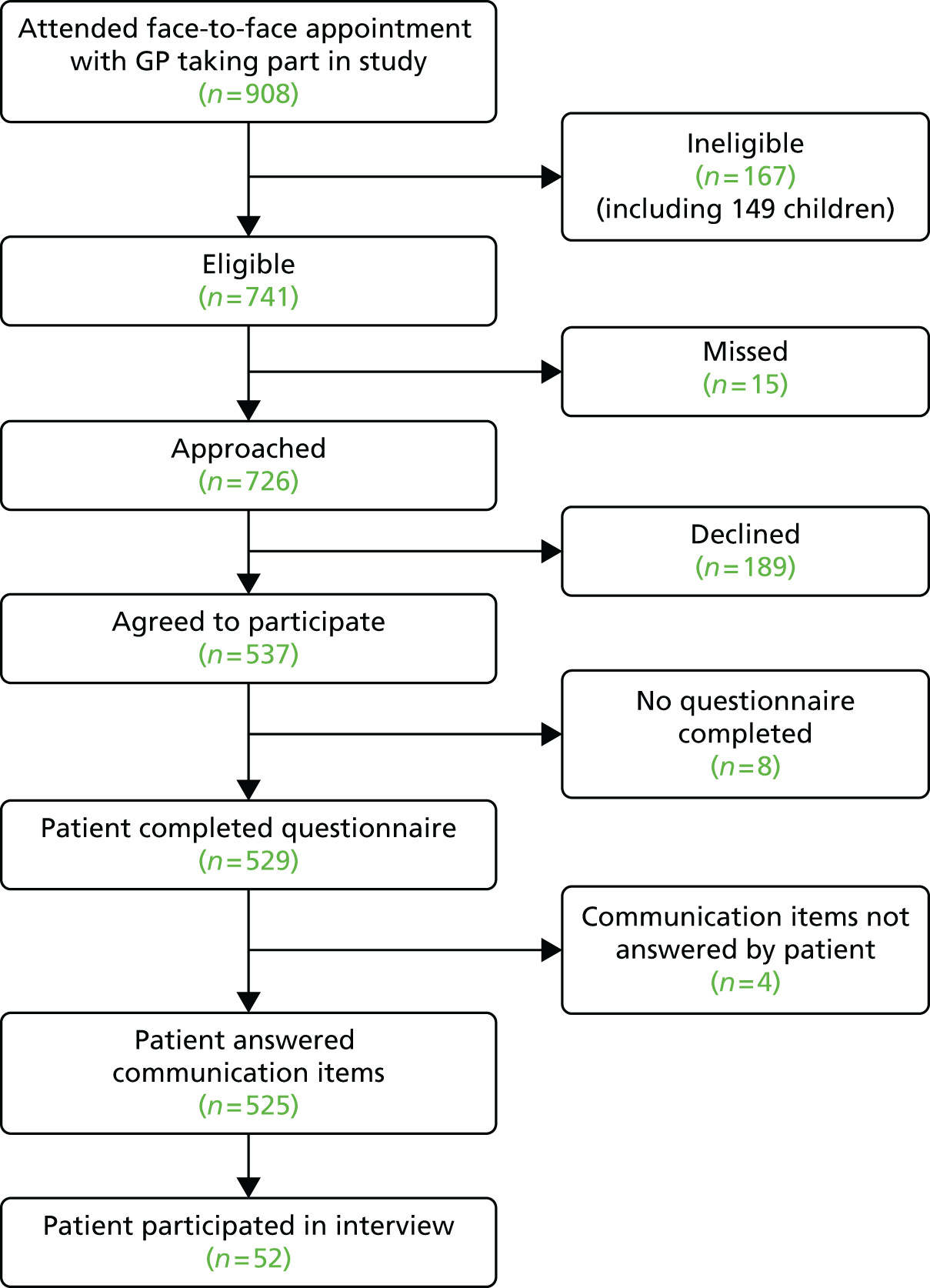

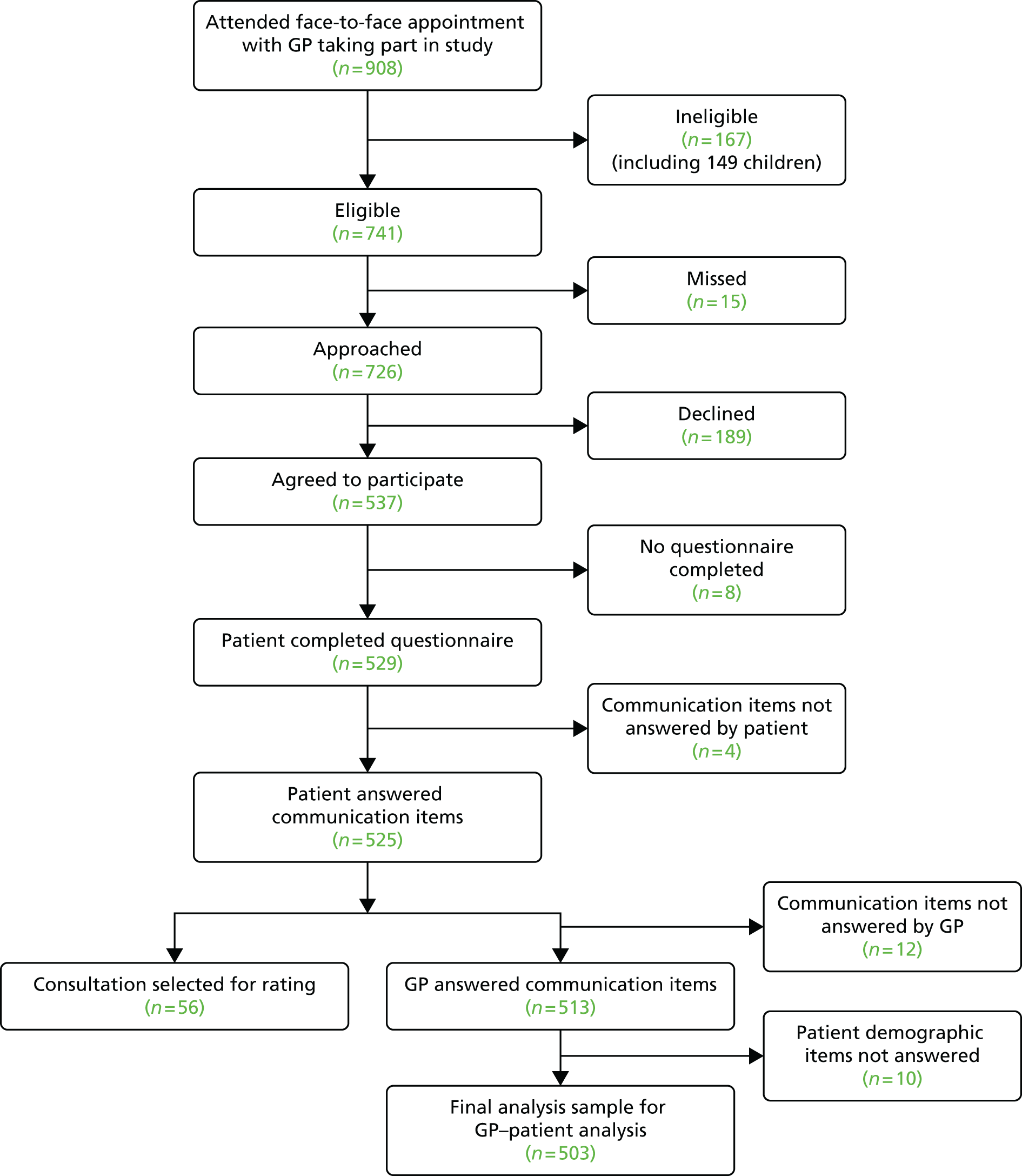

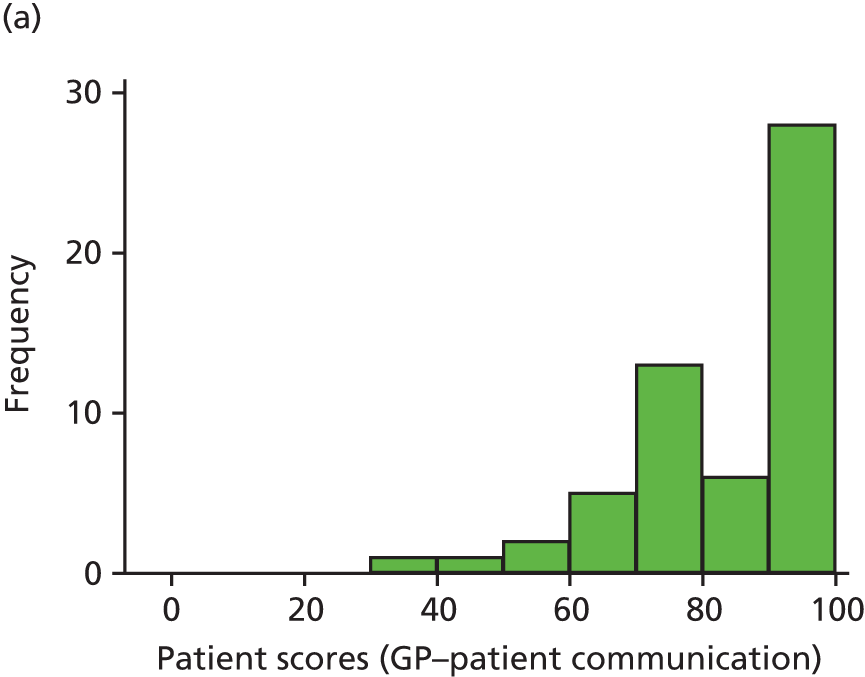

Consultations were videoed with 45 participating GPs from 13 general practices. During the period of data collection, a total of 908 patients had face-to-face consultations with participating doctors. Of these, 167 (18.4%) were ineligible (mostly children) and 529 completed a questionnaire (71.4% response rate) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Flow of patients through the video elicitation interview recruitment process.

Video elicitation interviews

A sample of patients whose consultation was video recorded participated in a video-elicitation interview. In total, interviews were conducted with 52 patients (35 women and 17 men) who had consulted with 34 different doctors across 12 GP surgeries in rural, urban and inner-city areas in the South West and East of England.

The interviews took place between August 2012 and July 2014, and were conducted in a location chosen by the participant within a maximum of 4 weeks of the recorded consultation (Table 2). Researchers preferred that interviews were not conducted at the GP surgery in case it inhibited patients in their narrative. However, a few participants specifically requested that their interviews be held at the GP surgery.

| Location | Number of interviews |

|---|---|

| Participant’s home | 44 |

| GP surgery | 6 |

| Other location (chosen by participant) | 2 |

All of the interviews were conducted in English and lasted between 26 and 97 minutes (average 58 minutes). The participants were aged between 19 and 96 years, with 22 (42%) aged > 64 years and 30 (58%) aged between 19 and 64 years. The participants consulted for a range of conditions, some chronic and some minor. The names used in the following sections are not respondents’ real names.

Questionnaire completion

In interviews participants were well disposed towards the process of questionnaire completion and generally keen to contribute their views. Most participants described completing the questionnaire with relative ease and as a simple task. Despite this willingness to contribute, there was little variety in questionnaire responses: the majority of participants reported care to be ‘good’ or ‘very good’ across all seven communication items on the questionnaire. Indeed, no respondents in our interview sample chose to score ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’, despite our original aspiration to focus in particular on patients who expressed dissatisfaction with their care. Twelve respondents did, however, use the ‘neither good nor poor’ option in at least one domain, although five of these also scored ‘very good’ on at least one other domain. As a result, in our small sample we had a lower proportion of scores in which every domain of GP communication was judged to be ‘good’ or ‘very good’ than in the national GP Patient Survey sample (77% in our sample vs. 94% nationally). Thus, despite the lack of ‘poor’ responses, we were able to explore patients’ responses in those who had expressed more dissatisfaction than average.

Disconnect between the ‘tick and the talk’

Although scores on the questionnaire were largely positive, some narratives in the interviews were more critical of aspects of GP communication. We outline three types of narrative relating to the relationship between questionnaire responses and further reflection on the consultation experience expressed during the interview.

Rewatching the consultation endorsed positive questionnaire scores

For some participants, their reflection on the consultation during the video-elicitation interview led to a repeated endorsement of the questionnaire responses they had given, and thus their narrative account was consistent with their previous evaluation of care. In all cases these responses were positive. Participants had been pleased with the quality of the consultation at the time of completion of the questionnaire. On rewatching the consultation this view was endorsed and in some cases further strengthened. Some respondents pointed to elements in the videoed consultation that had impressed them:

. . . his [GP’s] movements, his mannerisms . . . I’m asking the question, he didn’t exactly ignore me, he says no, that’s for gout. He actually explained it . . . And he’s still doing some work . . . So he’s not stopped and put all his attention on me, because if you stop doing that you probably forget what you’re doing here, so he’s done both. He’s answered my question and he’s also continued working, and that’s a good thing for me.

Colin (53151034)

High quantitative scores were followed by some criticism in interviews

Some participants scored the consultation highly on the questionnaire, yet the subsequent interview was peppered with tones of criticism about aspects of the consultation.

Criticism in the interview was often subtle, with participants often seemingly unaware of the discrepancy between their narrative and their questionnaire responses. Although they spoke of their consultation in a tone that was not particularly positive, participants remained loyal to the positive scoring they had applied on the questionnaire immediately following the consultation:

I gave it ‘good’ because . . . well she was listening to me, but I guess most of the time she was the one talking rather than listened to what I was saying . . . Not in a negative way, like completely, but I feel she didn’t really give me proper time to properly explain myself a little more . . . giving me a little bit more time, to explain my symptoms.

Steven (60121017)

Participant reappraises the consultation during the interview

A small group of participants who had scored their GP highly on the questionnaire underwent a process of reappraisal of the consultation during the video-elicitation interview. They voiced criticism of the doctor’s behaviour and proceeded to review their original score. Through the process of rewatching, participants spontaneously identified more negative aspects of the consultation that they had not been aware of previously:

I suppose you’re proving to me that I marked that wrong [taps questionnaire] [laugh] . . . Yeah, but he [GP] did, he did, he was concentrating on my leg and not worrying about the fact that the tablets were upsetting me.

Mm. And how did you feel?

Well, I felt the same thing. He, sort of, ignored the fact that he’d got all these side effects and all that.

Emma had scored elements of her consultation as ‘very good’ on the questionnaire:

. . . now I’m thinking, well no, he didn’t really sort of ask about symptoms or think, y’know, so perhaps not so good. Listening – yeah he listened but didn’t pick up on things, like you say, like the cough, he didn’t sort of pick up on erm, little things.

Emma (27131004)

On occasion there was a dramatic shift in point of view when the consultation was reshown. During the rewatching of the interview, Martha began to critique more aspects of the consultation, such as the doctor’s lack of explanations and unexpected examination:

I remember him just like, because he, because it’s quite rushed . . . you, er, can’t, you don’t, I don’t know, you’re just, it’s just like, er, er, and then, fine, I don’t know, I suppose I remember thinking why is he taking my temperature, and then just seeing how it must be OK, erm, I, I definitely remember him when he was just doing that with my, feeling my neck [slight pause] wondering what he was doing. [laughs] I just remember thinking, this is a bit weird, like why is this connected to my ear.

Martha (62111010)

In a number of the interviews, therefore, there was a mismatch between the subsequent account and previous responses to questions. At times participants were happy to critique an experience during the interview, sometimes at great length, yet they had been reluctant to do so on the questionnaire. Participants were able to explain in great detail elements of the consultation that they experienced to be negative, yet when asked to complete the questionnaire on that basis they still scored the doctor as ‘good’. The use of the video-elicitation method identified the possibility that other factors fed into the choice of response options on the questionnaire, aside from the doctor’s behaviour in the consultation.

There was, therefore, on a number of occasions, a disconnect between the ‘tick’ and the ‘talk’: differences between the narrative given in the interview and the responses recorded previously in the questionnaires. Although participants were able to raise concerns about doctors’ behaviours during the interview, at times they appeared reluctant to do so in their questionnaire responses.

Factors that influence patients’ reluctance to criticise on the questionnaire

This reluctance to record negative responses on the questionnaire leads to the question of why patients were reluctant to do so, given the negative views often apparent in their narratives. We therefore sought to further understand this phenomenon. We identified three key factors that appeared to influence patients’ reluctance to criticise doctors’ communication skills within the questionnaire:

-

the patients’ relationship with their GP

-

the patients’ expectations of the consultation

-

perceived power asymmetries between patients and doctors.

The following sections will examine each of these explanations in turn.

The patients’ relationship with their general practitioner

Participants often spoke about the significance of the GP or the surgery in their lives. This affiliation was sometimes with the practice, even if the doctors had changed over the years. Some elderly patients interviewed had been with their surgery most of their lives and a number of participants expressed loyalty to a practice even if they did not often visit. Gratitude towards the wider health service and NHS provision was also commonly expressed.

In commenting on relationships with individual GPs, care given previously to participants or to their family and friends was often praised:

. . . but I mean I’ve known him for – I mean he actually phoned when my mum died, you know. So that was nice of him, you know.

Janice (67131043)

Some participants spoke particularly of their relationship with the doctor. In some cases this was the notion of ‘getting on with’ the doctor and liking him or her as a person. For some there were specific interests that were shared, such as an interest in sport or knowledge of the GP’s family:

Oh yes, yes [laughter] they go to my church as well you see, so in that sense the relationship I had with Fiona and Paul is very much the old-fashioned family doctor, where you know them.

Alan (19144016)

Some participants used the term ‘friend’ to describe their relationship with their GP, often going on to explain that the relationship was different from a friendship:

And as I said, y’know, he isn’t a friend but you feel as if you are seeing a friend.

Bob (25111005)

I can see now the relationship. I have to be careful, you know, when I said to somebody one day well, you and I have a very good relationship, and I thought oh no, that’s not the right word.

Janet (53181024)

This was the case for participants who had not previously seen the doctor they consulted with, as well as for those who had a long relationship with their doctor. However, some found it difficult to create a relationship with the GP, which could lead to challenges in building a rapport.

Most respondents articulated that they were responding to the questionnaire based on the recorded consultation at hand. However, in explaining their scores, participants would often reflect on previous consultations with the GP. Consequently, it appeared challenging for them, when evaluating communication skills, to differentiate between this particular consultation and their wider relationship with the GP. This loyalty to and closeness with the GP at times inhibited patients from giving negative survey responses.

The patients’ expectations of the consultation

A variety of patient expectations influenced the scoring process. First, we identified expectations that related to the communication skills of the GP, based either on previous experience of consulting with that same GP or on experiences of consultations with other GPs. Expectations were important, and participants used this relational knowledge of other GPs to compare care received in the consultation with experience of previous consultations as they reflected during the interview. Some participants compared the care they had received with high-quality care they had received from other doctors. More commonly, however, participants compared a GP’s behaviour with poorer care that they had received. In particular, patients appeared to benchmark GPs’ skills based on their experiences with other GPs:

And he’s [GP], he’s not as clipped as Dr Williams, but he can be sometimes a bit clipped in the way he speaks to you.

Dave (67131012)

Narratives covered both positive and negative expectations of care from a particular GP, so, for example, if the participant had high expectations and these were not met, he or she was disappointed. Conversely, if a participant had poor expectations of a GP but the consultation was better than he or she had expected, he or she might score the GP more positively, even if overall the experience of the consultation was poor.

Second, expectations relating to the outcome of consultations were often referred to in justifying questionnaire scores. Participants tended to rate consultations more positively on the questionnaire if the outcome was what they desired, for example if they wanted a particular type of medication, a referral or reassurance about their medical problem:

I worry that, like, yeah, that he’s just going to be really dismissive. So the fact that he gave me medicine meant that it was higher than I expect . . . like it was better than I expected it to be, em, but perhaps by the more standards it wasn’t amazing.

Martha (62111010)

Perceived power asymmetries between patients and doctors

Descriptions of power asymmetries were prevalent in many of the accounts. Participants were often reluctant to criticise their GP, fearing repercussions for him or her. One respondent, who shared a story of poor experience as a patient in her general practice, had scored the GP as ‘neither good nor poor’ on some elements. When asked why she had not used the ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ options on the questionnaire, she replied:

. . . you don’t want to get anybody into trouble, you know, but you do wish they did behave a little better, you know, treated you a little better, you know, in their response to you.

Esther (53131010)

At times participants expressed an associated dependency on the GP, with a corresponding view that they could not be critical for fear of compromising the relationship.

Participants often spoke of the trust they placed in the doctor. For some, the doctor had a status that they were in awe of. Although Amanda felt that this relationship had changed over time, the doctor was still revered:

And I think the gap is not as wide as it used to be between doctors and patients is it? I mean when I was a young girl the doctor was even more of a god, whereas now it’s less, it’s definitely getting lesser, yeah definitely.

And in terms of the GPs at the surgery, I know you mentioned about GPs being on a pedestal, how do you feel the GPs are there?

Oh I think they all are, yeah definitely yeah. But years ago perhaps it was a six-foot pedestal whereas now it’s probably a couple of foot [laughs].

In some ways participants had an inability to critique the doctor, or at least had a reluctance to do so. For example, some participants seemed to feel that they lacked the authority to judge the doctor’s communication skills.

Allowances were often made by participants for elements of the GP’s behaviour that they did not like, such as the GP looking at the screen a lot during the consultation:

She [GP] was reading so and I mean there’s an awful lot on there [laugh] there’s loads on that screen, bless her, so she’s probably thinking oh my God, how many [laugh] but no I don’t take a lot of notice to be honest.

Sue (24155004)

Respondents often commented on how busy the doctor was that day or how much he or she had to do. On a number of occasions participants were dismissive of other patients and the unreasonable requests they made of GPs.

During interviews, participants could be critical of their own behaviour, taking responsibility for their own poor communication during the consultation:

What makes you say that you weren’t a very good patient?

Because I was spending too much time . . . I wasn’t giving out information as clearly as I should do, and, you know, I had gone in with an agenda.