Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1209-10057. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in January 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mike Gillett has undertaken consultancy work for NHS England and Public Health England (PHE), for the National Diabetes Prevention Programme. Thomas Yates has been a member of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidance on preventing type 2 diabetes. Sabyasachi Bhaumik has been a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research (researcher-led) panel for the last 3 years and before that he was a member of the Community and Psychological Therapies panel of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) for 3 years. He is the chairperson of the Diaspora Committee of the Royal College of Psychiatrists and was the chairperson of the Faculty of Psychiatry of Learning Disability for 4 years. He is also a co-editor of the only prescribing guidelines in intellectual disability nationally, and the third edition of this book, The Frith Prescribing Guidelines for People with Intellectual Disability, was published in 2015 by Wiley. Chloe Thomas has undertaken consultancy work for NHS England and PHE, for the National Diabetes Prevention Programme. Susannah Sadler has undertaken consultancy work for NHS England and PHE, for the National Diabetes Prevention Programme. Sally-Ann Cooper has received grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study, and grants from NIHR and from the Scottish Government outside the submitted work. Melanie Davies is a member of NICE public health guidance on preventing type 2 diabetes and an advisor to the UK Department of Health for the NHS Health Check Programme. She has acted as a consultant, an advisory board member and a speaker for Novo Nordisk, Sanofi Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca and Janssen Pharmaceutica, and as a speaker for Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp. She has received grants in support of investigator and investigator-initiated trials from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi Aventis and Eli Lilly and Company. She received grants and support from NIHR during the conduct of this study. Kamlesh Khunti (chairperson) is a member of the NICE public health guidance on preventing type 2 diabetes and an advisor to the UK Department of Health for the NHS Health Check Programme. He has acted as a consultant, served on advisory boards and been a speaker for Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck Sharp & Dohme. He has received grants in support of investigator and investigator-initiated trials from Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck Sharp & Dohme. He also received grants and support from NIHR during the conduct of this study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Dunkley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Easy-read summary

The images and symbols used in the easy-read summary are reproduced with permission from the following organisations.

Change Picture Bank. © CHANGE www.changepeople.org

Somerset Total Communication. © STC 2016. All rights reserved. These symbols may not be reproduced as a whole by any means.

Somerset Total Communication (STC), c/o Resources for Learning, Parkway, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 4RL. Telephone: 01278 444949. E-mail: stc@somerset.gov.uk. www.somersettotalcommunication.org.uk; www.SupportServicesforEducation.co.uk.

People First.

Widget. Widgit Symbols © Widgit Software 2002–2017. www.widgit.com

Chapter 1 Introduction

Rationale

The focus of this research programme was to estimate the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and impaired glucose regulation (IGR) among people with intellectual disability (ID) and to develop and test a lifestyle education programme for the prevention of T2DM that would be suitable for use in this population.

This research programme was developed to address gaps in the evidence base with regard to determining the prevalence of T2DM and IGR in adults with ID, and the lack of suitable prevention programmes that are specially tailored for people with ID. Since this research began, priorities set out in the 2015–16 UK NHS England Business Plan1 have highlighted the need to improve services for people with ID and to establish a national ID mortality review, with both diabetes and obesity identified as health priorities. 2 An additional health priority that was identified for all patients is the prevention of obesity and T2DM via a national ‘evidence-based lifestyle management programme’ to support people to make healthy lifestyle changes. 1

The current evidence base for screening and successfully managing those at risk of diabetes – through diet, exercise and behaviour therapy – relates to the general population. It is not currently known whether or not screening for T2DM and IGR or prevention strategies through lifestyle education can be successful in people with ID.

Aims and objectives

The aims of the programme were to:

-

establish a programme of research that significantly enhances the knowledge and understanding of IGR and T2DM in people with ID

-

test strategies for the early identification of IGR and T2DM in people with ID

-

develop a lifestyle education programme and educator training protocol to promote behaviour change in a population with ID and IGR [or high risk of T2DM/cardiovascular disease (CVD) based on elevated body mass index (BMI) score].

Overview of the programme of research

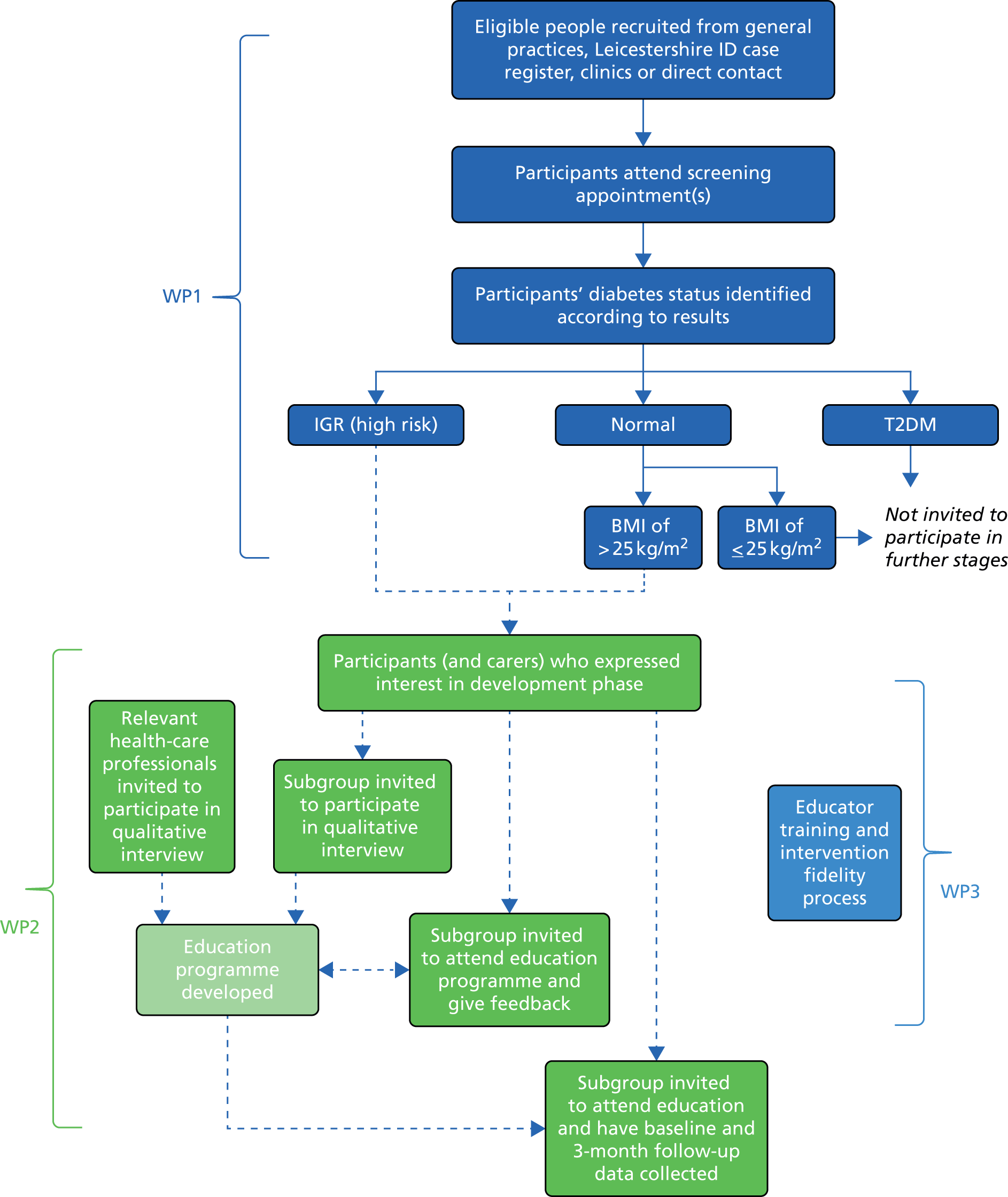

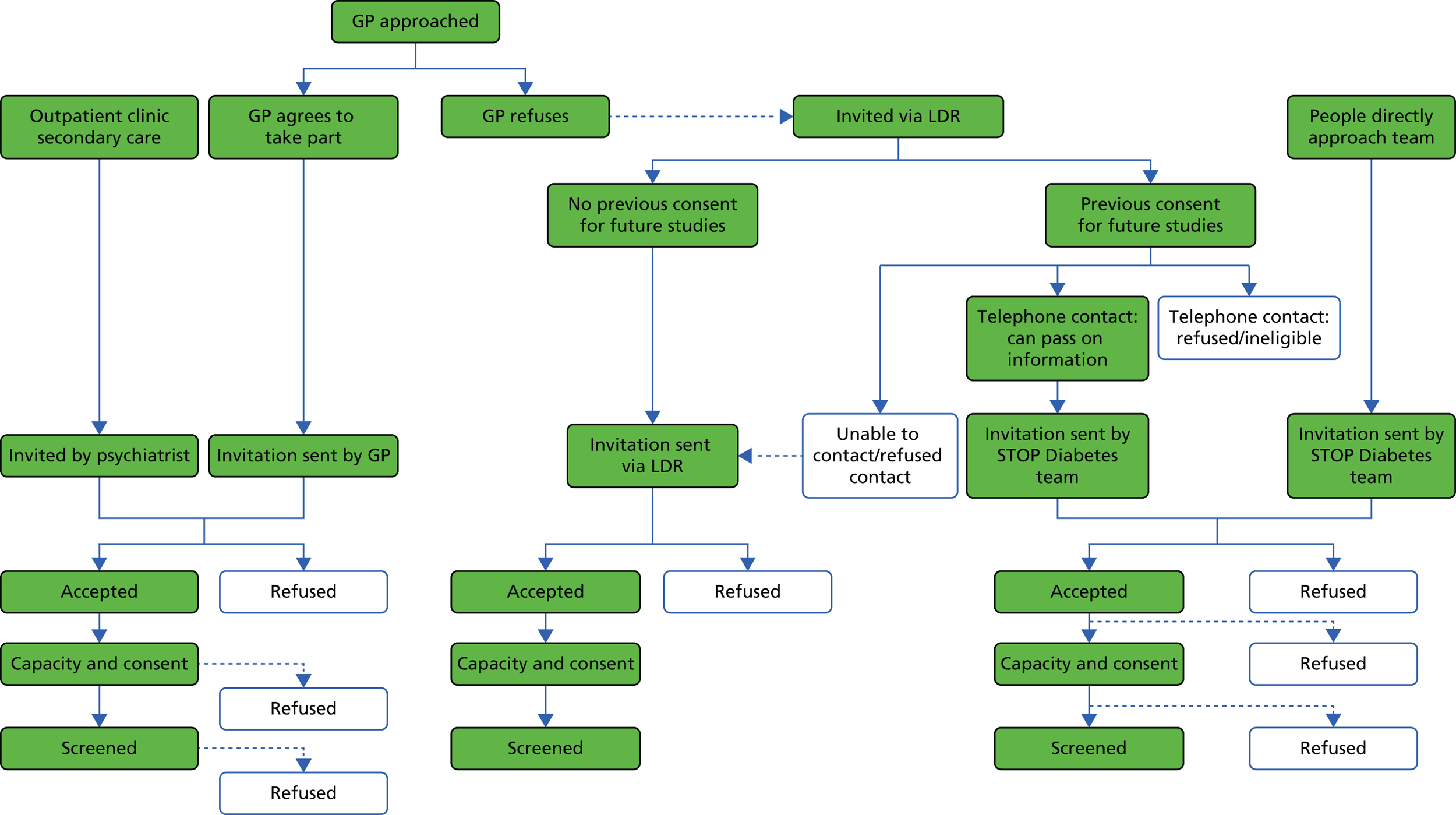

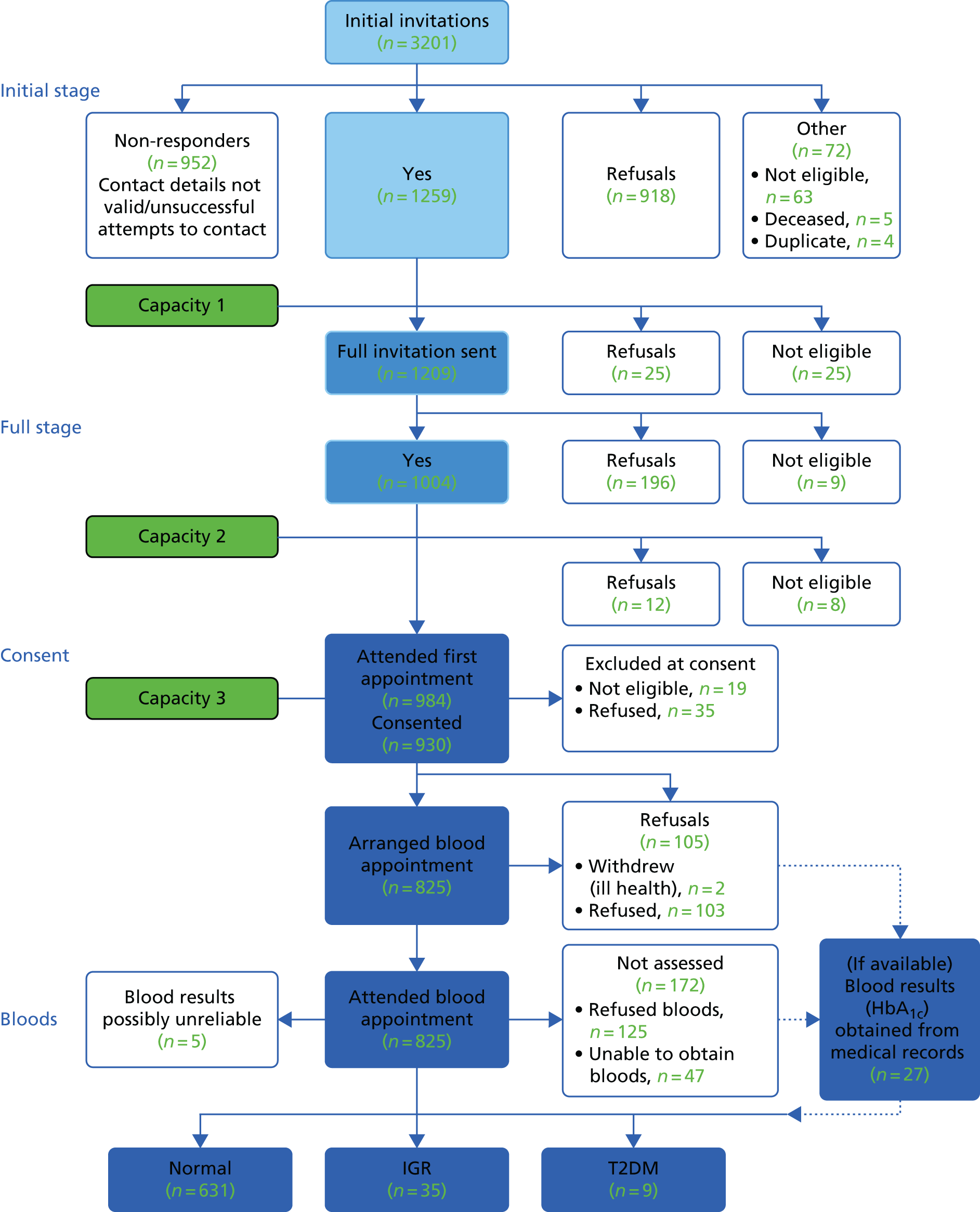

To achieve these aims, three distinct work packages (WPs) were developed (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Programme of work.

Work package 1

The aims of WP1 were to:

-

develop and assess the feasibility of a diabetes screening programme in a community setting for adults with ID (see Chapters 5 and 6)

-

determine the prevalence and demographic risk factors for T2DM and IGR in people with mild to profound ID (see Chapters 5 and 6)

-

validate the Leicester Self-Assessment diabetes risk score in people with ID (see Chapters 5 and 6)

-

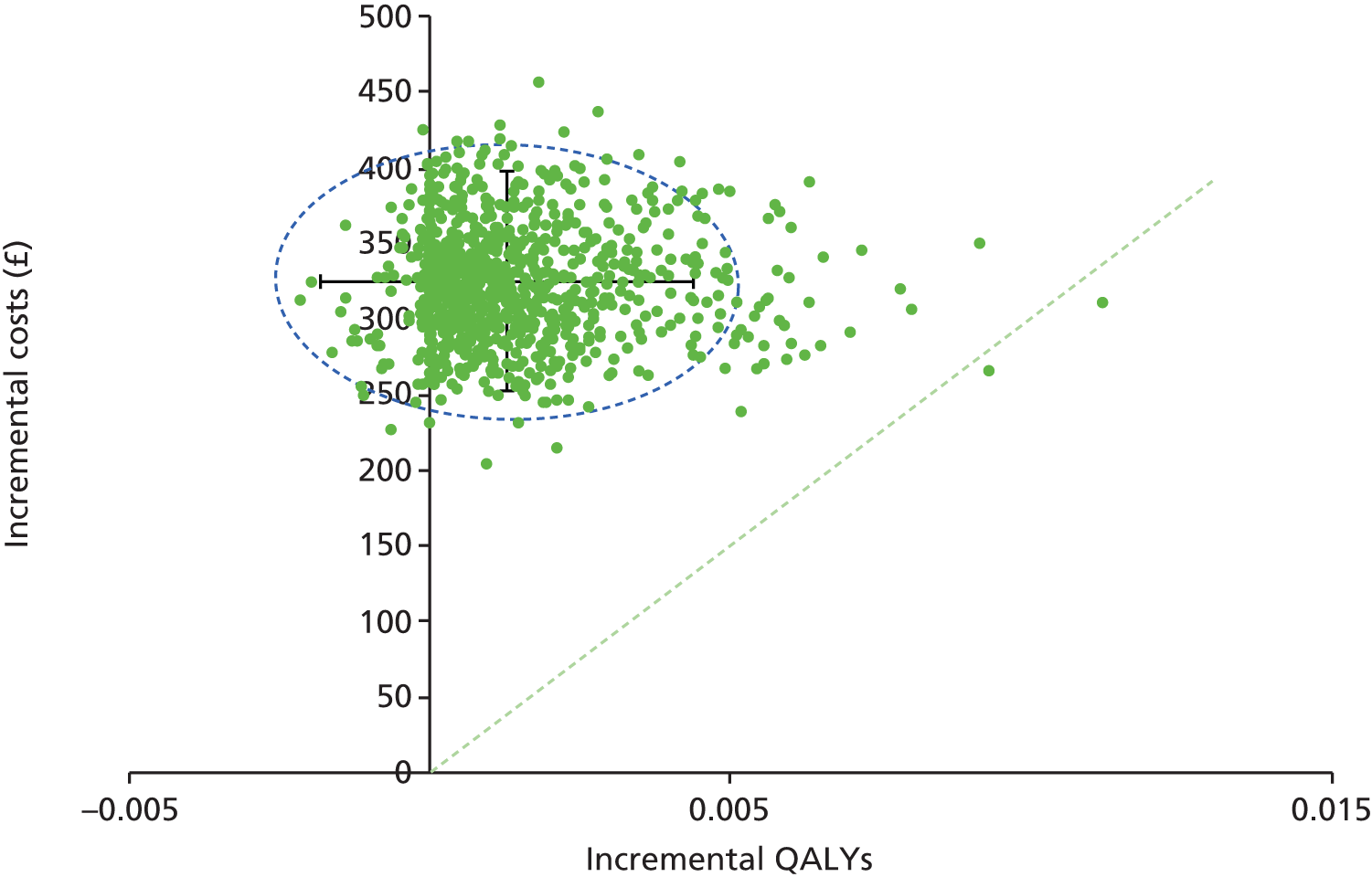

determine the cost-effectiveness of lifestyle intervention (see Work package 2), compared with current care (see Chapter 12)

-

establish data linkage to Hospital Episode Statistics and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) (see Chapters 5 and 6).

Work package 2

The aims of WP2 were to:

-

develop a lifestyle education programme for people with ID and IGR (or high risk of T2DM/CVD based on elevated BMI) (see Chapters 8 and 9)

-

assess the feasibility of collecting outcome measures before and 3 months after attendance at lifestyle education (see Chapter 10).

Work package 3

The aim of WP3 was to:

-

develop a quality assurance (‘intervention fidelity’) process for the assessment of educators who are delivering the education (see Chapter 11).

Scope of the report

The remainder of this chapter provides a brief overview of the ethics and governance arrangements, and provides the detailed background for this research programme.

Subsequent chapters contain individual summaries, but, briefly, comprise:

-

a systematic review of the prevalence/incidence of T2DM in people with ID (see Chapter 2)

-

a systematic review of multicomponent behaviour change interventions in people with ID (see Chapter 3)

-

details of the involvement of people with ID throughout the programme of research (see Chapter 4)

-

methods for the screening programme (see Chapter 5)

-

results from the screening programme (see Chapter 6)

-

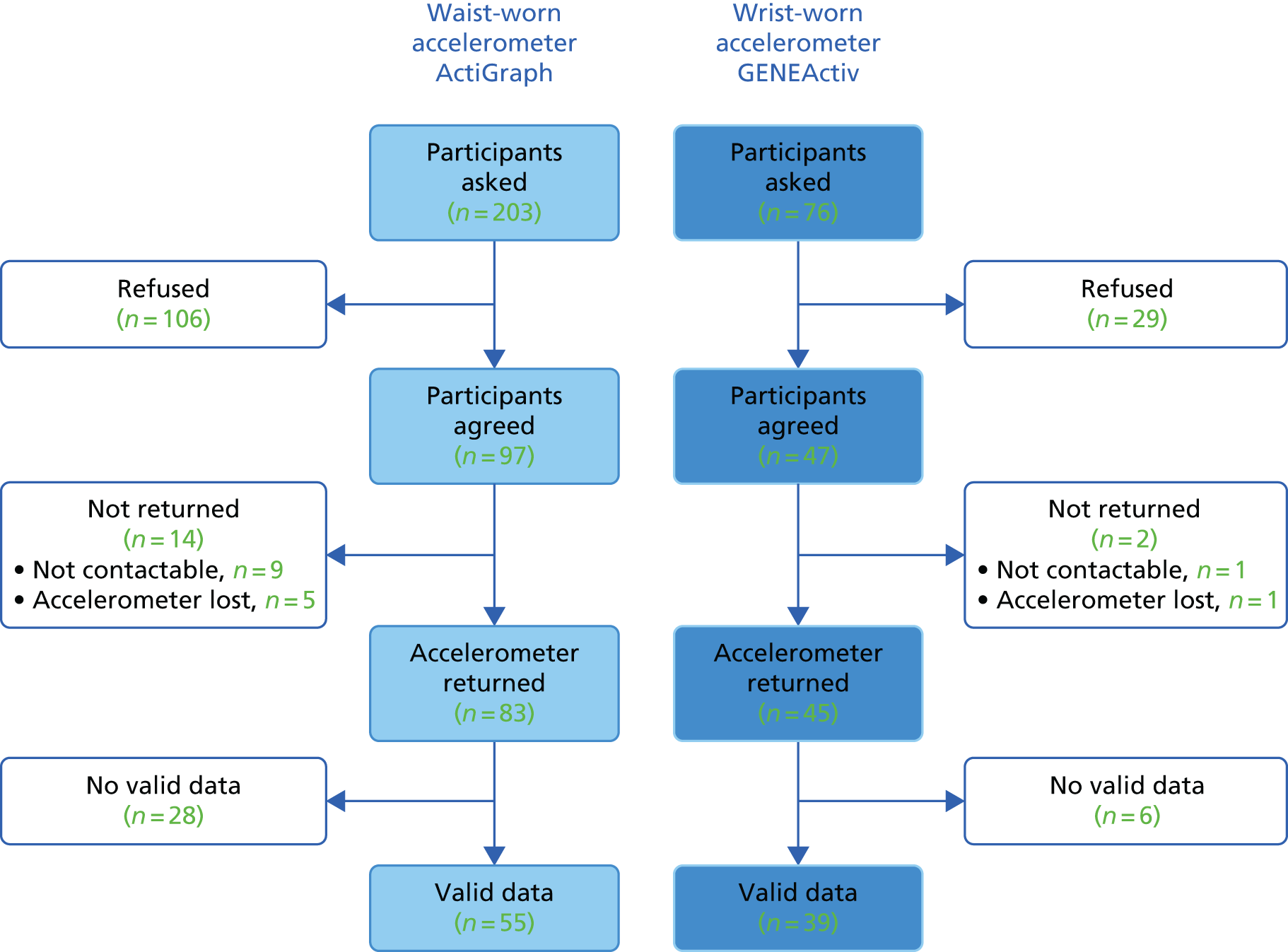

methods and results from a physical activity substudy (see Chapter 7)

-

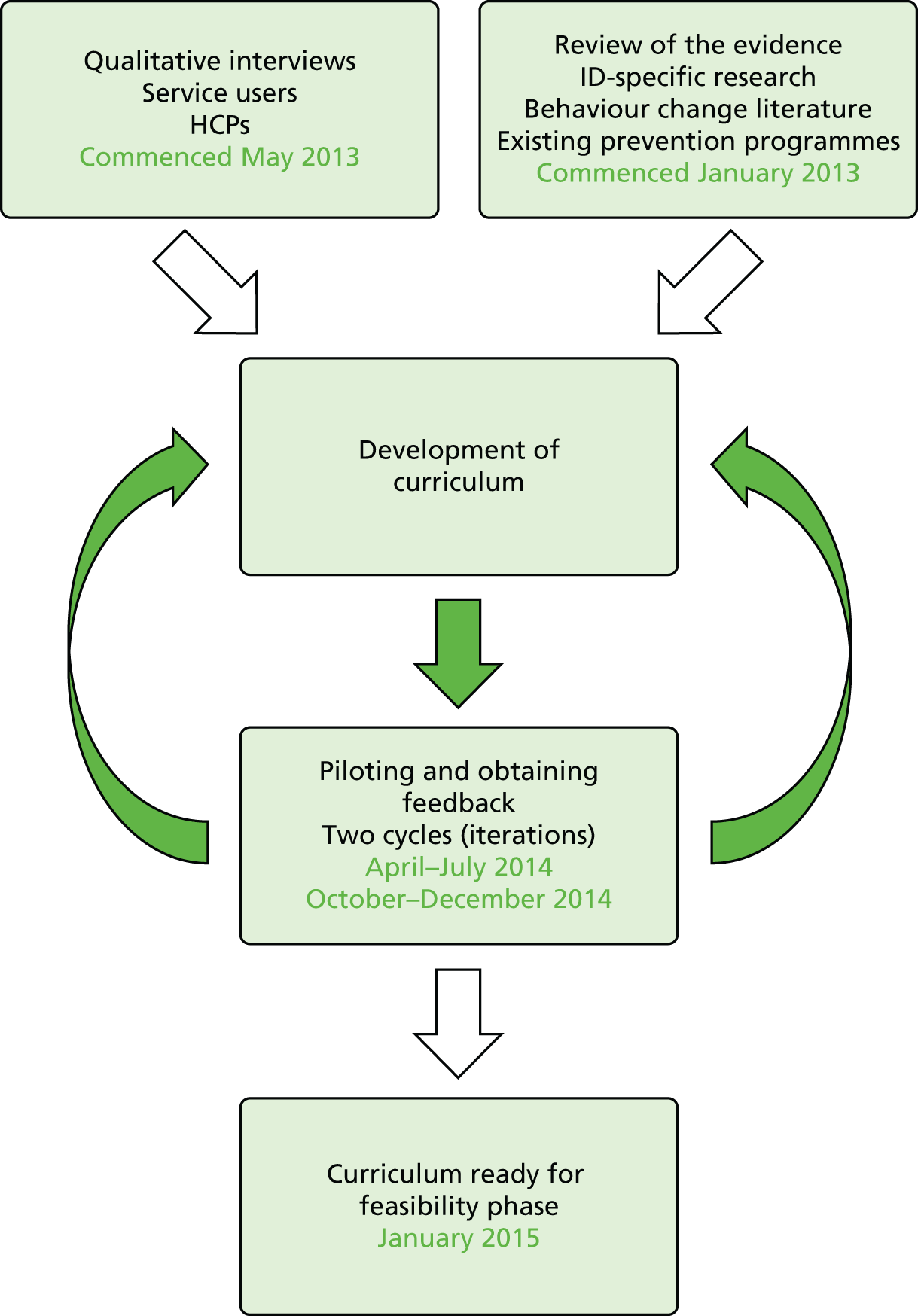

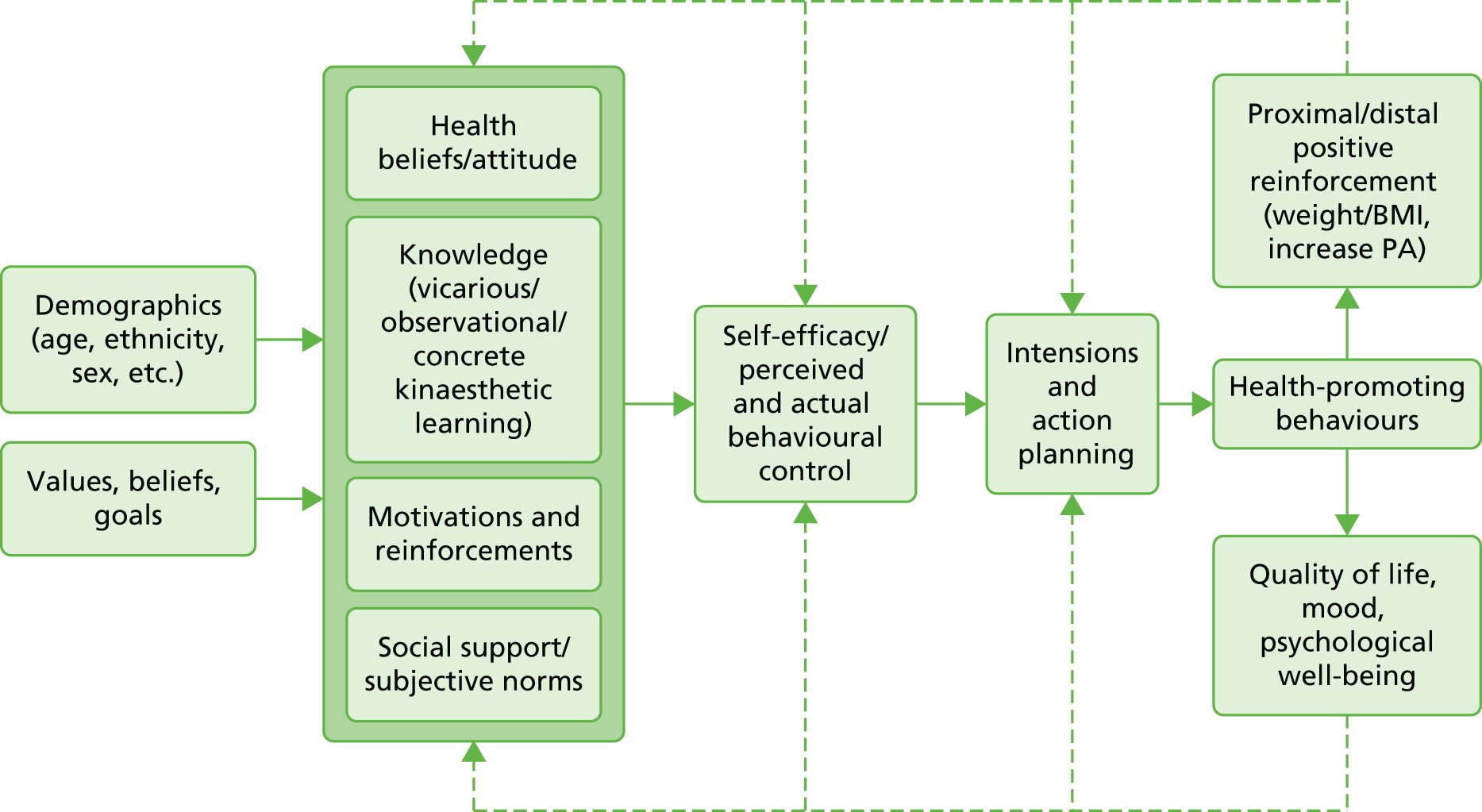

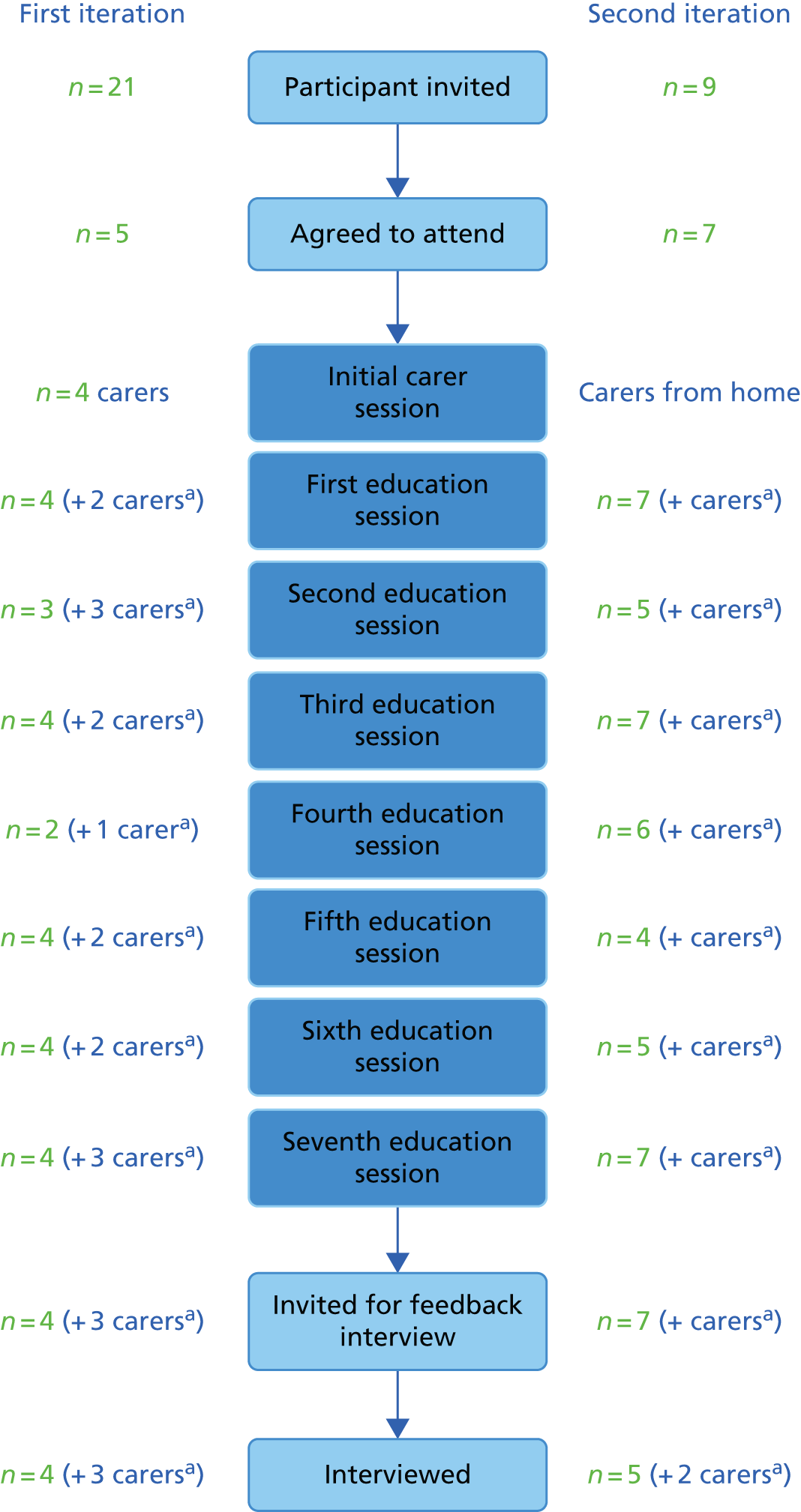

details of the development of the lifestyle education programme (see Chapters 8 and 9)

-

methods and findings from a feasibility phase collecting pre- and post-intervention outcome measures (see Chapter 10)

-

details of the development of the intervention fidelity process (see Chapter 11)

-

methods and results for the economic analysis undertaken (see Chapter 12)

-

discussion of findings and conclusions (see Chapter 13).

Ethics and governance

Approvals

The University of Leicester acted as sponsor for the programme of research. NHS research ethics approval was obtained from the East of England – Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/EE/0340). Research and development approval was obtained for the research sites from Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust (LPT); Leicester City Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), East Leicestershire & Rutland CCG and West Leicestershire CCG; and the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust.

Adherence to mental capacity legislation

Obtaining consent was the largest ethics consideration for this programme. Strict standard operating procedures needed to be established to ensure that valid consent was obtained in accordance with English capacity legislation,3 while taking into account the heterogeneity in capacity of individuals. More details on the assessment of capacity and taking consent are contained in the methodology section for the screening programme (see Chapter 4). This included providing people with all of the information that was relevant to making the decision on whether or not to participate in the research, and communicating this information in a way that was appropriate to them (such as using simple language and visual aids).

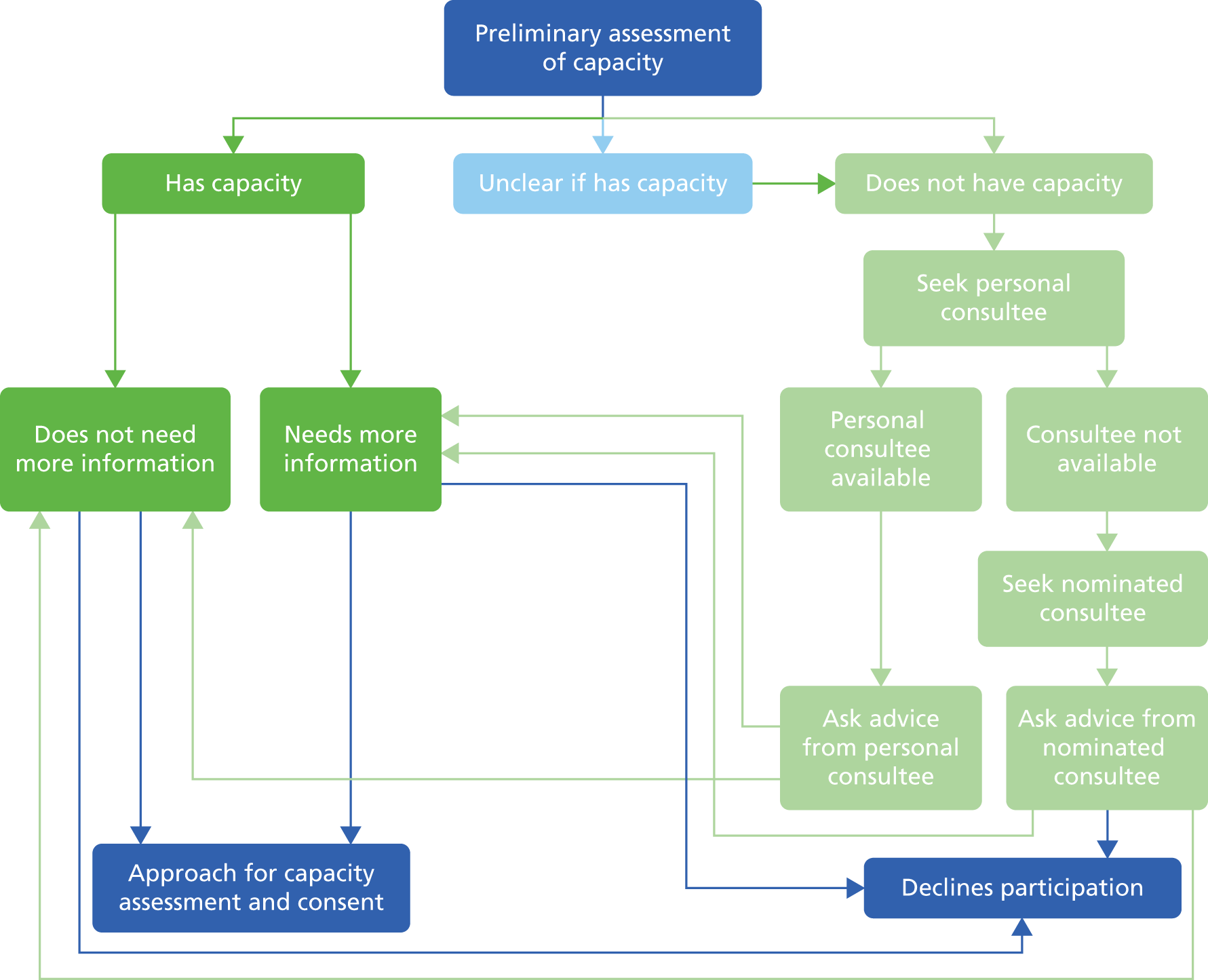

The process for those who lacked capacity involved talking to a ‘consultee’, whose role was to consider the study from the participant’s perspective (see Appendix 1, Figure 26). Regardless of whether or not the person with ID had the capacity to decide on participation, the research was discussed with the individual to help him or her to understand the project as far as he or she had the capacity to do so, and to ascertain any opinion that he or she had on participation. For example, if a person without decision-making capacity appeared even slightly anxious or reluctant to take part, then this was respected, and he or she was not recruited to the study.

Programme steering group

Strategic oversight and direction of the research programme was provided by the programme steering group (Figure 2), which comprised the chief investigator (KK), the lead researcher/project manager (AD) and co-applicants listed in the application, with ad hoc attendance from service users. The meetings were held four times per year and were independently chaired by Dr Colin Greaves, University of Exeter (see Figure 2). The meetings involved discussion of contractual issues, staffing, protocol and ethical amendments, public involvement (a rolling agenda item), recruitment progress, economic analysis, education development, anticipated timelines and progress against project aims.

FIGURE 2.

Governance structure of the STOP Diabetes programme. NETSCC, NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre.

Operational groups

The research team (researchers, ID research nurses and research administrator) met frequently throughout the programme to plan the individual components of the programme and to discuss progress. The details of these meetings were fed back to the steering group.

The education development team [a multidisciplinary team of health-care professionals (HCPs) and researchers with expertise in the field of both ID and developing diabetes and CVD prevention programmes] met regularly to oversee and facilitate the development of the lifestyle education programme (WP3). Progress and key decisions were fed back at steering group meetings.

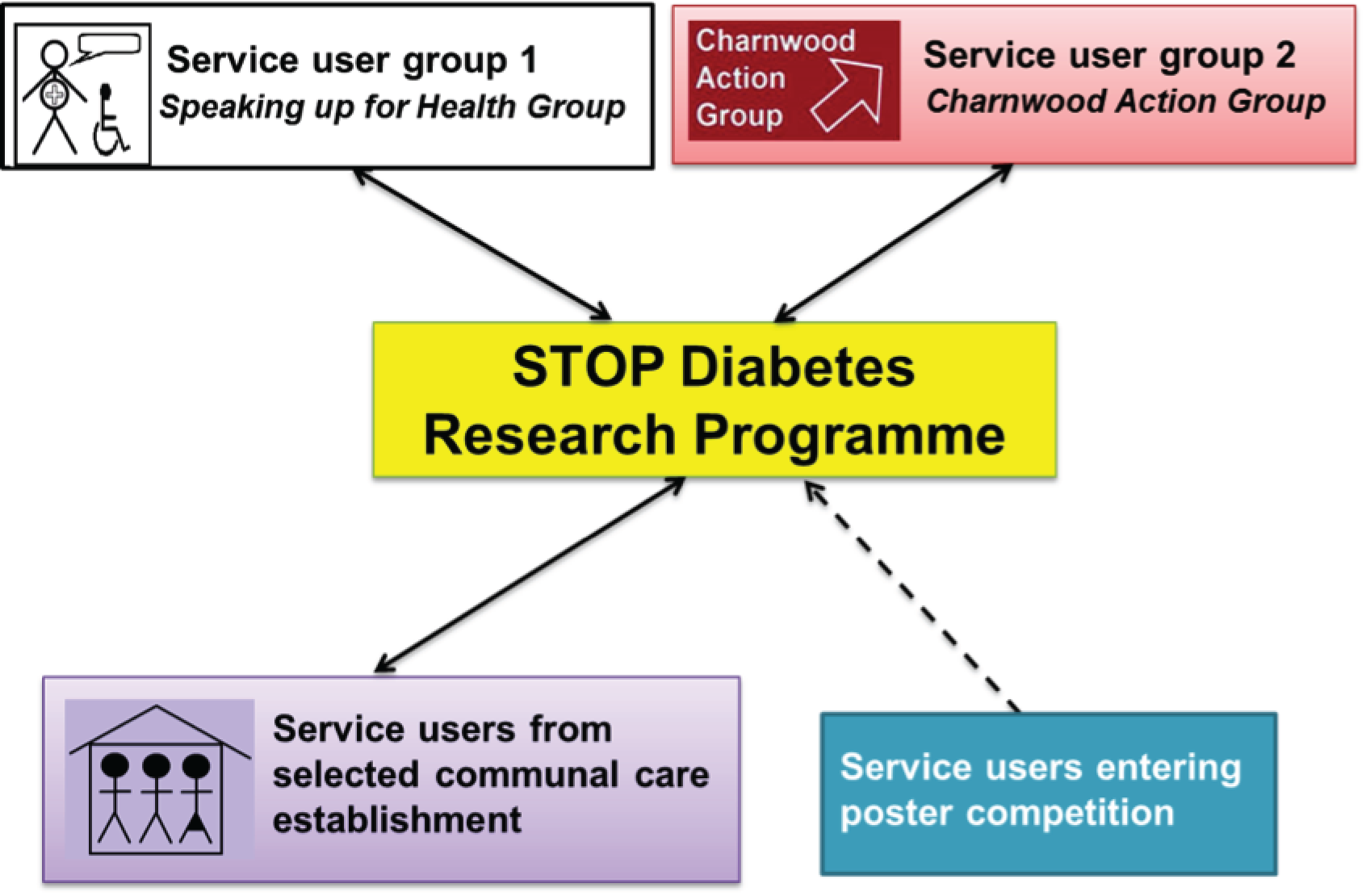

Service user groups

A number of service users were involved in the research programme, but two service user self-advocacy groups were particularly influential. The groups met regularly, facilitated by an experienced supporter, and their comments were fed back to the steering group. More information about these and other service users’ involvement is detailed in Chapter 4.

Data protection

A six-digit study code was used to identify all of the study participants. This code was used for all hard and electronic copies of data that were collected for this programme (including questionnaires, anthropometric data and blood samples), which were retained in a secure setting.

The Leicester Clinical Trials Unit (UK Clinical Research Collaboration registration number 43) was responsible for the development of a secure database for the data that were collected as part of this research programme.

Background

Definition of intellectual disability and case identification

Intellectual disability, also known as learning disability, is a lifelong condition with onset before adulthood, characterised by a reduced ability to understand new or complex information and learn new skills, and a reduced ability to cope independently. 4 Severity levels for ID are typically categorised by broad intelligence quotient (IQ), alongside the required deficits in independent living skills, into mild (IQ 50–69), moderate (IQ 35–49), severe (IQ 20–34) and profound (IQ < 20) ID. 5 Acknowledging the wide variation that exists between individuals with ID, typical abilities suggested for each category are outlined in Table 1 [based on World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)]. 5 More recently in the UK, the Learning Disabilities Public Health Observatory has offered a ‘working definition’, which includes brief practical guidance to improve the recognition of ID and to assist agencies in targeting services. 6

| Severity of ID | Suggested abilities and skills | IQ level |

|---|---|---|

| Mild |

|

|

| Moderate |

|

|

| Severe |

|

|

| Profound |

|

The aetiology of ID can be broadly divided into problems that occur in the antenatal, perinatal or postnatal periods, or as a result of multiple factors. Common causes of ID include genetic and chromosomal disorders – both non-inherited (e.g. Down syndrome)7 and inherited (e.g. fragile X syndrome) – and non-genetic factors, such as infection and environmental factors. However, in the majority of cases no specific cause is found. 8

A recent meta-analysis of population-based studies suggests that, overall, around 1% of people worldwide have ID, with wide variation dependent on age group and the income of the country (lower, middle and higher); for adults, the proportion is around 0.5%. 9 The evidence from existing ID registers and general practice lists in England suggests that the prevalence of ID is approximately 3–5 per 1000 individuals. 10,11 However, it is thought that the true prevalence could be as high as 2% of the adult population, as people with mild ID are generally under-represented. 11

For the current research programme, cases were identified via (1) records held on adults with ID in general practices and (2) a register of adults attending ID services owned by the local mental health trust (LPT), the Leicestershire Learning Disability Register (LLDR; see below).

General practices in the UK are now incentivised to maintain a register of people with ID. 12,13 Locally, for practices within Leicester City, East Leicestershire and Rutland, and West Leicestershire CCGs, the total number of adults (aged ≥ 18 years) on general practice registers with an identified ID is estimated to be around 4300 (based on figures provided by LPT).

The LLDR comprises adults with ID (aged ≥ 19 years) who live in the unitary authorities of Leicester city, Leicestershire and Rutland. 14 The register was established in 1987 to help facilitate the provision and monitoring of services, and to enable the collection of public health data. It is currently a joint venture between LPT and Leicester City CCG. Enrolment is via a large network of service providers, including specialist ID services, social services and primary care. Currently, there are ≈3900 people with mild to profound ID on the register. However, as the learning disability register is based on service use, some adults, particularly those with mild ID who have little or no support from services, may not currently be identified. This potentially accounts for some of the differences between the number of people identified on this register and the number on local general practice registers.

Type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose regulation

Type 2 diabetes is a serious chronic disease, characterised by prolonged hyperglycaemia. 15 Its symptoms can reduce quality of life and lead to serious health complications, including blindness, renal failure and amputation; 50% of new cases have demonstrable atherosclerosis at diagnosis. 15–17 The prevalence of diabetes in England is estimated to be 6.2%,18 rising to 8.0% [95% confidence interval (CI) 5.7% to 11.7%] when undiagnosed cases are included. 19 T2DM accounts for around 85–90% of diabetes cases; it creates a huge economic burden on NHS resources, at a cost of £8.8B annually (≈10% of total NHS expenditure). 20

Impaired glucose regulation is a condition in which blood glucose concentrations are elevated above the normal range but do not satisfy the criteria for T2DM. 21,22 Approximately 12% of the UK adult population have IGR, of which an estimated 5–12% go on to develop T2DM each year. Observational studies show a consistent and continuous association between glycaemia and CVD risk, whereby people with IGR have a significantly elevated risk of CVD. 23–25 Given the economic burden associated with this condition and its related comorbidities, this group represents an important target for preventative strategies. 26 Other commonly used terms to describe IGR include pre-diabetes, non-diabetic hyperglycaemia and high risk of diabetes; throughout the report, this high-risk group will be referred to as having IGR.

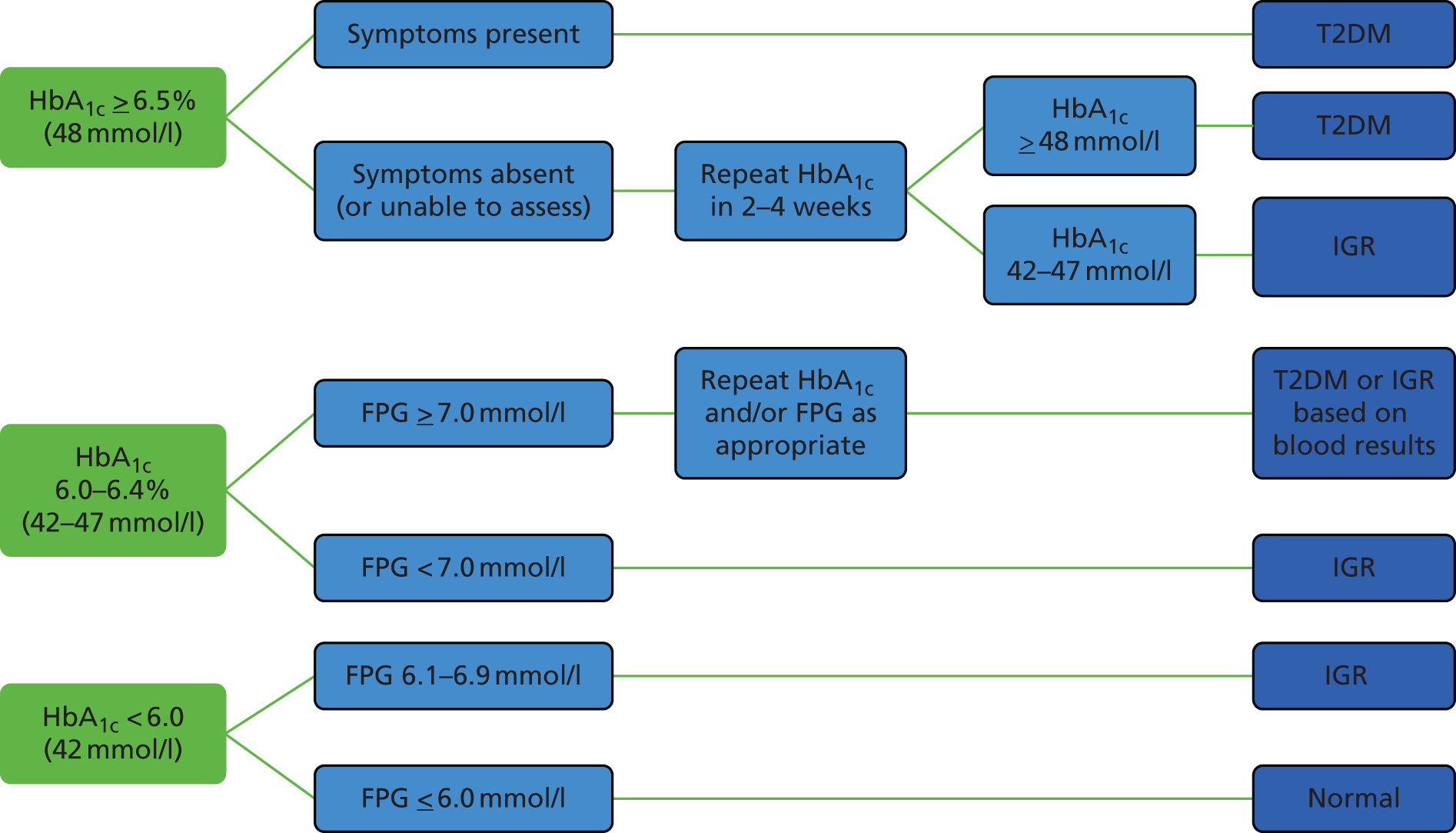

Previously in clinical practice, T2DM and IGR were identified using the ‘gold standard’ oral glucose tolerance test. 22 However, since the publication of updated WHO guidance in 2011 and subsequent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance in 2012, there has been a shift away from the use of the oral glucose tolerance test to the glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test. 27,28 The potential benefits of the HbA1c test include it being a non-fasting blood test, less inter-test variability and its ability to provide an indication of longer-term hyperglycaemia (over 6–8 weeks). 29 A HbA1c level of ≥ 48 mmol/l (6.5%) is suggestive of T2DM, whereas a level of 42–47 mmol/l (6.0–6.4%) is suggestive of IGR or a high risk of diabetes. 27 Further details on the methods used to identify T2DM and IGR for this programme of research are provided in Chapter 5 (see Outcomes) and Figure 15.

Risk factors for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in people with intellectual disabilities

In the general population, increasing levels of obesity and sedentary lifestyles have been associated with a rise in non-communicable diseases, including T2DM and CVD. 30–33

Chronic conditions are becoming increasingly important for people with ID as their life expectancy increases. 34 There are a number of risk factors for T2DM that are known to be highly prevalent in people with ID, suggesting that T2DM and CVD may be more prevalent in this group. These risk factors include:

-

increased antipsychotic drug use for the management of challenging behaviour40,41 and psychosis,42 which are associated with weight gain, hyperglycaemia and worsening of other metabolic CVD risk factors43–45

-

genetic conditions associated with obesity (e.g. Prader–Willi syndrome). 46

Physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour are both common among people with ID, with only a minority (18–33%) achieving the recommended 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily,47,48 and < 15% of people with ID complete the recommended 10,000 steps per day. 49 Furthermore, < 10% of adults with ID who live in supported accommodation have an intake of fruit and vegetables that is sufficient for a balanced diet. 50 The evidence suggests that paid carers know little about public health recommendations on dietary intake. 50

However, little is known about T2DM, CVD and associated risk factors in the population with ID. UK-based data on the prevalence of T2DM are currently unclear. 32 Current estimates for diabetes prevalence in the UK are based on routinely reported data rather than on population-based studies. The suggested prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in people with ID in England is around 6–7%, but estimates are unable to distinguish between T2DM and other forms of diabetes. 13,51 Similarly, the prevalence of CVD among people with ID is reported to be greater than that among the general population, but the overall prevalence is unclear. 52

Further information on the current prevalence of T2DM, CVD and related risk factors in the ID population is presented in the systematic review in Chapter 2.

Diabetes screening

Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes, and the conferred risk of developing CVD, early identification and intervention through screening has been shown to be a useful approach in the general population. 53,54 The value of screening for IGR has also been demonstrated.

It is currently unknown if screening for asymptomatic glucose disorders is viable within UK populations with ID; there is a lack of evidence on feasibility, acceptability, outcomes and benefits. People with ID have been recommended by NICE as being an important group to consider in terms of diabetes prevention strategies, given their supposed high risk of developing diabetes. 27

General practitioners (GPs) in England have been incentivised to provide annual health checks to adults with ID since 2008–9 (for those aged ≥ 14 years since 2014). Recent data suggest that, nationally, the uptake of checks is around 44%. 55 However, the proportion who additionally have bloods taken as part of the health check, including HbA1c (7%) and cholesterol (30%), is extremely low. 13

Risk scores for the early identification of impaired glucose regulation and type 2 diabetes

A staged approach to screening is recommended by NICE for those at risk of diabetes in the general population. 56 This involves using a risk score to pre-screen for individuals at the greatest risk of T2DM followed by a blood test in those at the highest risk. However, this approach has not been tried with populations with ID.

Risk scores are a non-invasive way of stratifying a population for targeted screening. They use information data from non-invasive risk factors to calculate an individual’s score: a higher score reflects a higher risk. Risk scores can be applied to (1) an individual as a questionnaire (these scores generally require data from only non-invasive risk factors, which would be known by members of the public) or (2) a population (e.g. in primary care, for which software is used to calculate the score using routine data from electronic medical records) and then screening invitations can be sent to those at highest risk. A number of diabetes risk scores have been developed and validated for use in the UK general population. 56–60 One such score is the Leicester Self-Assessment risk score (see Appendix 2), which allows people to easily assess their own risk of having undiagnosed IGR or T2DM and then self-refer for screening with a HCP. 58 The score contains seven questions that ask about age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, waist circumference, family history of diabetes and high blood pressure (BP). The score has been validated for use in a multiethnic UK population58,61 and is specifically recommended by NICE for identifying people who are at risk opportunistically. 56

To date, we are not aware of any risk scores that have been specifically assessed for use in populations with ID. However, it cannot be assumed that a risk score that is developed for a specific population will work well in another;62 for people with ID, there may be different risk factors, or weightings for specific risk factors may change, when compared with the general population. Therefore, this programme of work will seek to validate the Leicester Self-Assessment risk score in a population with ID (this work is presented as part of the screening study; see Chapters 5 and 6).

Diabetes prevention in adults with intellectual disabilities

People with ID experience a disproportionate burden of health inequalities compared with the general population, including poorer mental and physical health and higher rates of mortality. 63–66 Despite their increased health needs, they often find it difficult to access primary care services and to participate in health promotion activities. 67–69

Given the health inequalities among people with ID, and the possible increased risk of developing diabetes, people with ID have the potential to benefit from lifestyle changes (with appropriate support) that are addressed in lifestyle education programmes. However, the evidence base for diabetes prevention relates to the general adult population; literature focusing on ID is scarce. Details of the key literature on lifestyle behaviour change interventions aimed at modifying risk factors for T2DM and CVD in people with ID are presented in the systematic review in Chapter 3.

Current evidence from studies conducted in the general population suggest that intensive multicomponent lifestyle interventions aimed at weight loss, a healthy diet and increased physical activity can successfully reduce the risk of diabetes by 30–60% in those with IGR, and are likely to be cost-effective in the long term. 54,70

Increasing physical activity is fundamental to diabetes prevention initiatives, as research suggests that inactivity may have more impact than increased body weight in the development of insulin resistance. 71

For both obesity management72 and prevention of T2DM,27 NICE recommends that lifestyle interventions should be multicomponent, involving both dietary and physical activity advice, and incorporating behaviour change techniques. However, at present there are no national prevention programmes that suitable for people with ID, despite ongoing recommendations to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to health-care services to address inequities in provision. 73

Education, exercise and leisure pursuits are often determined or influenced by carers (paid or family carers), who may have a range of competing time demands and a number of people for whom to provide support. For people with limited carer support, difficulties in understanding health risks could also influence motivation to change lifestyles. Therefore, there is the potential for this group to benefit from the development of a lifestyle education programme that is targeted at both people with ID and their carers in order to encourage changes in lifestyle behaviours that could reduce the long-term chances of this high-risk group developing diabetes.

Concluding remarks

This chapter has provided the rationale and aims for the research programme, and an overview of the programme of work undertaken. The next chapter presents a systematic review conducted to consolidate the evidence on rates of T2DM, CVD and associated risk factors in adults with ID.

Chapter 2 Systematic review and meta-analysis: rates of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and associated risk factors in populations with intellectual disability

Overview

In this chapter, we describe the first of two systematic reviews carried out for the research programme. We present the existing evidence in relation to the prevalence of T2DM, CVD and associated risk factors among people with ID. We have used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist74 as a guide to reporting the methods and findings from the review.

Rationale

It is recognised in the literature that ID populations may be at increased risk of developing T2DM and subsequent CVD through increased risk factors, such as obesity. The global increase in the prevalence of obesity, CVD and T2DM, and current discrepancies between studies focusing on prevalence of such conditions in those with ID, suggested a need for a systematic review of literature in this area.

Two recent reviews75,76 have focused on diabetes prevalence among people with ID. The reviews were unable to distinguish between T2DM and other types of diabetes. Similarly, the prevalence of CVD among people with ID is reported to be greater than that among the general population, but the overall prevalence is unclear. 52

The overall aim of this component of the research programme was to consolidate the evidence for current rates of T2DM, CVD and associated risk factors, restricting to population-based studies of adults with ID. If sufficient data were available, we also intended to conduct a meta-analysis. A secondary aim was to compare these data with the general population, when possible.

Objectives

The objectives of this review were to establish the prevalence of:

-

T2DM in a population with ID

-

CVD in a population with ID

-

risk factors for T2DM and/or CVD (obesity, adverse lipid profiles, IGR and hypertension) in a population with ID.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42015019048). 77

Eligibility criteria

The review was guided by the population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, study design (PICOS) model. 78 We defined the population as adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with ID (whole study population or a defined subsample). The items of interest were defined as T2DM, CVD and their associated risk factors. Context was defined as population-based studies. We defined the outcomes as prevalence and/or incidence rates (or data to enable this calculation). Study designs included cross-sectional, retrospective and prospective cohort studies (Table 2).

| PICOS elements | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Whole study population or defined subsample of adults (aged ≥ 18 years)a | Restrictively selected cohort, based on outcome (e.g. all of the participants were obese at time of data collection) |

| Items of interest | T2DM/diabetes | |

| CVD (atherosclerotic) | ||

| Overweight/obesity | ||

| Hypertension | ||

| Hyperlipidaemia | ||

| Elevated glucose level/IGR | ||

| Metabolic syndrome | ||

| Context | Population-based studies | |

| Outcomes | Prevalence | |

| Incidence | ||

| Study designs | Cross-sectional | |

| Retrospective cohort | ||

| Prospective cohort |

All studies published since 1 January 2000 (until 21 April 2015) and in the English language were eligible. We contacted lead authors for further information when inclusion/exclusion could not be determined.

We chose to limit studies to those published in and after the year 2000 so that the current prevalence of T2DM and CVD could be estimated accurately; it is known that the prevalence of both of these conditions has increased substantially in recent decades.

Information sources

For this review, we searched the databases EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO. The last date of the search was 21 April 2015. We also searched the reference lists of relevant articles for possible additional studies.

Search

We combined medical subject heading terms and key words for T2DM, CVD, overweight/obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, elevated glucose level/impaired glucose tolerance, metabolic syndrome and ID (MEDLINE search strategy; Box 1). The search was limited to English-language studies with cohorts of adults aged ≥ 18 years, depending on the database.

-

exp Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/

-

(diabet* adj3 type adj ‘2’).ti,ab.

-

T2DM.ti,ab.

-

(diabet* adj3 type adj ii).ti,ab.

-

niddm.ti,ab.

-

(non-insulin-dependent adj2 diabet*).ti,ab.

-

(adult-onset adj2 diabet*).ti,ab.

-

Or/1–7

-

exp Hypertension/

-

hypertens*.ti,ab.

-

(blood adj pressure adj3 (high or elevated or increased or raised)).ti,ab.

-

or/9–11

-

exp Metabolic syndrome x/

-

(metabolic adj syndrome).ti,ab.

-

(cardiometabolic adj syndrome).ti,ab.

-

(Insulin adj resistance adj syndrome).ti,ab.

-

MetSyn.ti,ab.

-

MetS.ti,ab.

-

or/13-18

-

exp. Hyperlipidemias/

-

Hyperlipid*.ti,ab.

-

dyslipid*.ti,ab.

-

hypercholes*.ti,ab.

-

hypertriglycer*.ti,ab.

-

(cholesterol* adj2(high or elevated or raised or increased)).ti,ab.

-

(triglcerid* adj2(high or elevated or raised or increased)).ti,ab.

-

(lipid adj profile adj2(adverse or abnormal)).ti,ab.

-

or/20-27

-

exp. Glucose intolerance/

-

(impaired adj glucose adj(tolerance or regulation)).ti,ab.

-

(impaired adj fasting adj glucose).ti,ab.

-

IGT.ti,ab.

-

IFG.ti,ab.

-

IGR.ti,ab.

-

exp Prediabetic state/

-

prediabet*.ti,ab.

-

pre-diabet*.ti,ab.

-

or/29–37

-

(cardiovascular adj diseas*).ti,ab.

-

CVD.ti,ab.

-

CHD.ti,ab.

-

exp. MI/

-

(infarct* adj2 myocardial).ti,ab.

-

exp Coronary disease/

-

(coronary adj2 diseas*).ti,ab.

-

(acute adj coronary adj syndrom*).ti,ab.

-

exp angina pectoris/

-

angina.ti,ab.

-

exp myocardial ischemia/

-

(isch* adj2 heart adj2 diseas*).ti,ab.

-

(Myocardial adj2 isch*).ti,ab.

-

exp. Stroke/

-

strok*.ti,ab.

-

(cerebrovascular adj2 diseas*).ti,ab.

-

(cerebrovascular adj2 accident*).ti,ab.

-

(cerebral adj2 diseas*).ti,ab.

-

(cerebral adj2 accident*).ti,ab.

-

CVA.ti,ab.

-

TIA.ti,ab.

-

(brain adj1 infarc*).ti,ab.

-

(brainstem adj1 infarc*).ti,ab.

-

exp ischemic attack, transient/

-

(isch* adj2 attac* adj2 transient).ti,ab.

-

exp Atherosclerosis/

-

atheroscle*.ti,ab.

-

(arteriosclerotic adj vascular adj diseas*).ti,ab.

-

exp Peripheral Arterial Disease/or exp Peripheral Vascular Diseases/

-

(peripheral adj2 arter* adj2 diseas*).ti,ab.

-

(peripheral adj2 vascular adj2 diseas*).ti,ab.

-

(peripheral adj1 angiopath*).ti,ab.

-

or/39-70

-

exp obesity/

-

obes*.ti,ab.

-

overweight.ti,ab.

-

(body adj weight adj2 (high or elevated or increase*)).ti,ab.

-

(bodyweight adj2 (high or elevated or increase*)).ti,ab.

-

(body adj mass adj3 (high or elevated or increase*)).ti,ab.

-

(waist adj2 (large or elevated or increas*)).ti,ab.

-

exp body mass index/

-

(BMI adj2 (high or elevated or increase*)).ti,ab.

-

or/72-80

-

exp Intellectual disability/

-

(learning adj1 disabilit*).ti,ab.

-

(developmental adj1 disabilit*).ti,ab.

-

(intellectual adj1 disabilit*).ti,ab.

-

(impair* adj2 intellectual adj2 function*).ti,ab.

-

(mental* adj1 impair*).ti,ab.

-

(mental* adj1 handicap*).ti,ab

-

exp mentally disabled persons/

-

(mental* adj1 disabl*).ti, ab

-

(mental* adj2 retard*).ti, ab

-

Or/82-91

-

8 or 12 or 19 or 28 or 38 or 71 or 81

-

92 and 93

-

limit 94 to yr=2000-current

-

limit 95 to English language

-

(animals not humans.mp) [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier]

-

96 not 97

Study selection

Full texts were identified after titles and abstracts were read separately by two investigators (TC and AD) who discussed discrepancies in selection at a later meeting. Only full-length articles were included; review articles were removed after being examined for references. Once we had retrieved the full texts of the articles, these were examined separately (by TC and AD) to check their suitability for inclusion.

Data collection process

We designed a data extraction form specifically for this review. Data were extracted by one investigator (TC) and verified for accuracy by another investigator (AD).

Data items

For each study, the first author’s name, title of the paper, year of publication, country of the cohort, study type, sampling method, dates of data collection and inclusion/exclusion criteria were extracted. We also extracted total sample size or subpopulation size, mean ages, proportion of male/female, severity of ID and ethnicity. For each of the outcomes, we also extracted how it was defined, how it was measured and the total number, and proportion, of people for whom it was measured. We extracted data separately for males and females, when reported. When framing the research question and designing the search strategy, we did not consider physical activity/sedentary behaviour, dietary factors or smoking; however, we extracted this information for studies that reported it. We also extracted information on general population data.

Risk of bias in individual studies

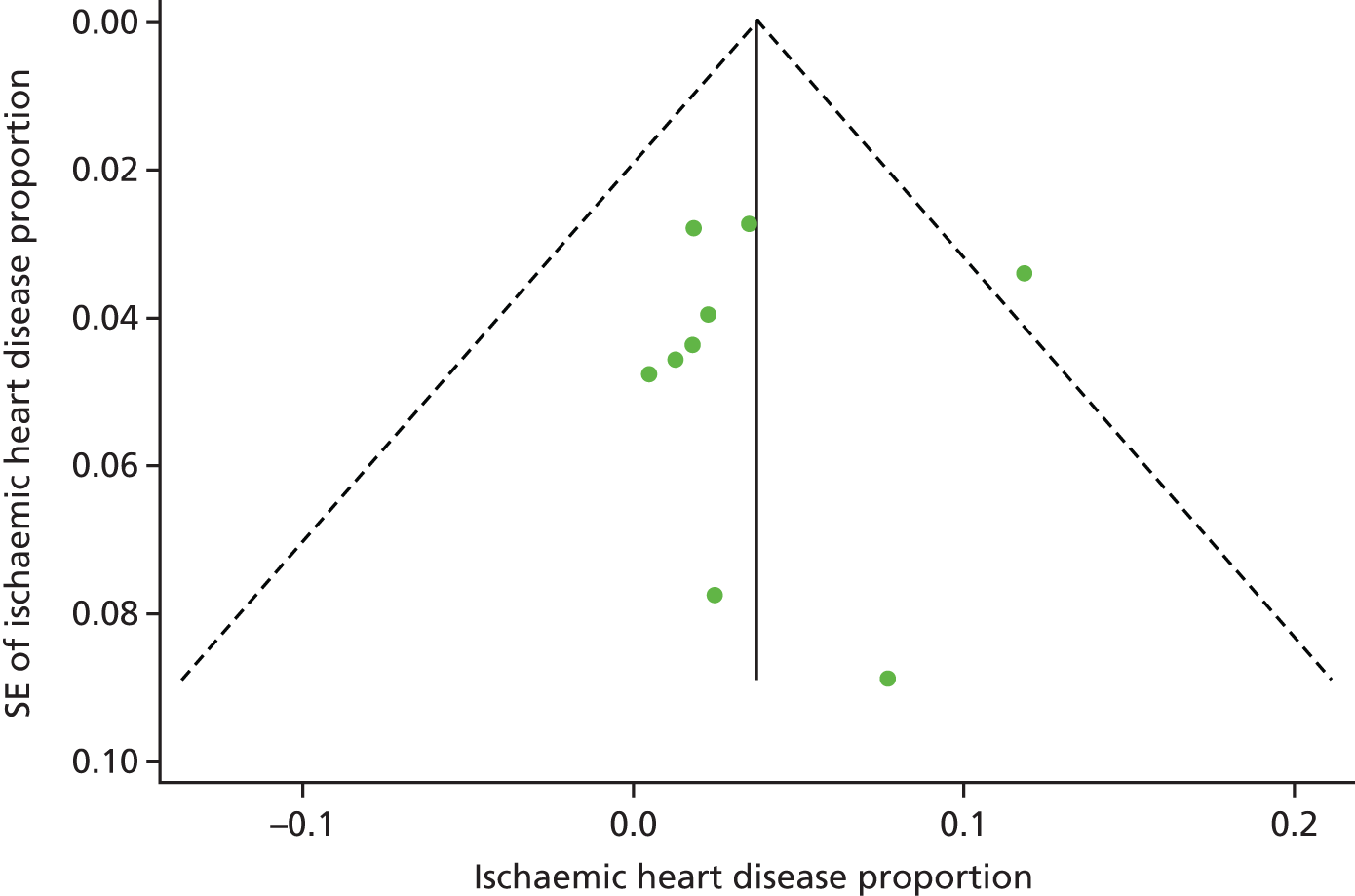

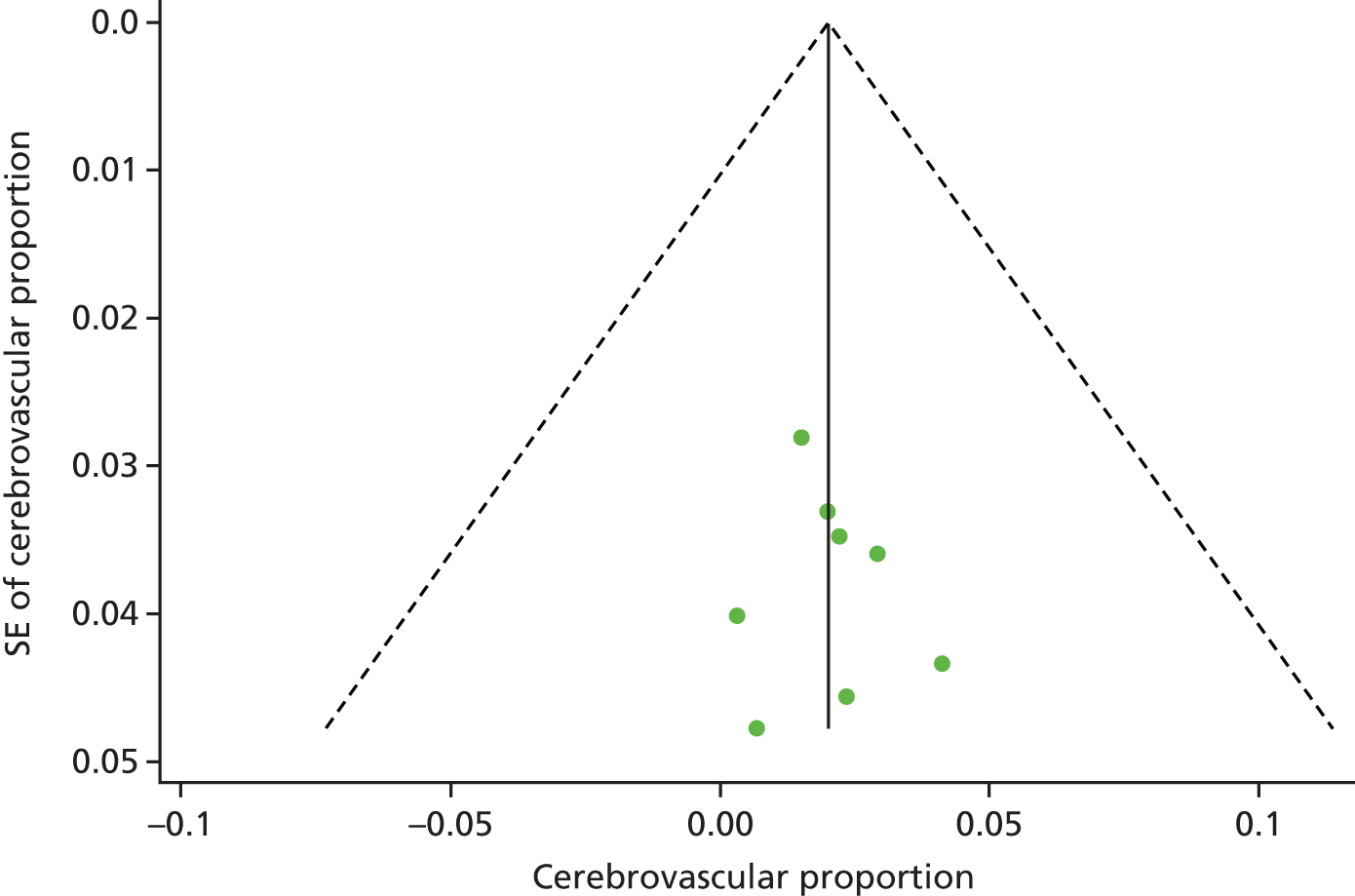

We used funnel plots79 and the Egger’s test80 to examine potential publication bias in the literature for the outcomes T2DM, ischaemic heart disease, obesity, hypertension and undefined CVD.

Summary measures

The main outcome measure for the meta-analysis was the prevalence of T2DM and CVD. The secondary outcome measures were the prevalence of:

-

overweight/obesity

-

hypertension

-

hyperlipidaemia

-

elevated glucose level/impaired glucose tolerance

-

metabolic syndrome.

Synthesis of results

Owing to the variation in reporting of outcomes, we extracted descriptions and definitions of each outcome for analytic purposes and subcategorised for meta-analyses. We subcategorised circulatory disease outcomes as ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and undefined CVD. We subcategorised diabetes outcomes as T2DM and pooled diabetes. BMI outcomes were labelled as obese (BMI of > 30 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2). In some articles, overweight and above (BMI of > 25 kg/m2) was used as an outcome. We combined papers reporting both obese and overweight data to create an overweight and above outcome. The outcome definitions can be seen in Appendix 3 (see Table 60).

Owing to the large amount of variability between studies, we used a random-effects model to pool the point prevalence for each outcome. We conducted a secondary meta-analysis including data from a subset of 10 papers,81–90 which additionally reported general population comparison data (from the same population and time period). We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 test. 80

Additional analysis

After the meta-analysis, metaregression was used to determine if study characteristics could explain heterogeneity (as measured using the I2 test). These study characteristics were severity of ID, mean age and method of data collection (self-/carer reported, researcher collected, retrospective records/database). We conducted all of the analyses using Stata® statistical software, version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Significance was set at the 5% level (p < 0.05) and 95% CIs are presented throughout.

Results

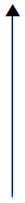

Study selection

In total, we identified 4513 articles via the literature searches. After duplicates were removed, 3645 articles remained to be screened. We reviewed the full texts of 148 articles once seven articles from other sources had been added (Figure 3). The authors of seven studies91–97 were contacted for information regarding their studies; five authors replied and two studies94,95 were deemed suitable to be included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. We also included a study93 by one of the authors who did not reply, after we had reread and discussed the article collectively in more depth.

FIGURE 3.

Study selection.

After review, 62 articles50,81–90,93–95,98–145 were included. Four of these articles90,102–104 reported findings from the same study and a further two articles109,125 reported findings from the same study, leaving 58 studies (see Table 3) remaining for the final systematic review and meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

The 58 studies included in the quantitative synthesis presented data on > 47,000 individuals. The characteristics of each of the studies are presented in Table 3.

| First author (year) | Country | ID severity | Data source/collection method | Total n | Male (%) | Mean age (years) | Outcomes reported | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molteno (2000)131 | South Africa | MILD 0.3%, MOD 18.7%, SEV 37.7%, PROF 33.5%, missing data | Researcher-collected data | 615 | 51 | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Robertson (2000)50 | UK | NR | Secondary data analysis | 500 | 60.3 | 44.4 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Janicki (2002)114 | USA | MILD 1.3%, MOD 50.3%, SEV/PROF 47% | Postal questionnaire | 1373 | 53.0 | 53.5 | CVD, undiagnosed diabetes, overweight, obese, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia | Cross-sectional observational |

| Lewis (2002)119 | USA | MILD 37.1%, MOD 16.4%, SEV 14.7%, PROF 15.3% | Medical review/researcher-collected data | 353 | 49.9 | 35.8 | Overweight, obese, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia | Cross-sectional observational |

| Marshall (2003)124 | UK | NR | Baseline data from health screening programme | 728 | NR | NR | Overweight, obese, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia | Cross-sectional observational (baseline) |

| Havercamp (2004)83 | USA | MILD 39.4%, MOD 26.6%, SEV 14.7%, PROF 10.6% | Database/medical records | 477 | 56.1 | NR | CVD, undefined diabetes, overweight, obese, hypertension | Cross-sectional, retrospective |

| Hove (2004)111 | Norway | MILD 39.2%, MOD 42.1%, SEV 15.5% | Postal questionnaire | 274 | 52.0 | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Merrick (2004)129 | Israel | NR | Postal questionnaire | 2282 | 51 | 49.8 | Heart disease, T2DM, overweight+, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia | Cross-sectional observational |

| Moore (2004)132 | Australia | NR | Researcher-collected data | 93 | NR | 32.5 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Emerson (2005)105 | UK | NR | Secondary data analysis | 1304 | 54.0 | 49.3 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Yen (2005)144 | Taiwan | MILD 22.2%, MOD 34.9%, SEV 28.1%, PROF 14.8% | Secondary data analysis | 516 | NR | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Ito (2006)89 | Japan | NR | Database/medical records | 526 | NR | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Lennox (2006)116 | Australia | NR | Medical history chart/GP examination | 25 | NR | 45.0 | Overweight, obese, hypertension | Cross-sectional observational |

| Levy (2006)117 | USA | MILD 47.6%, MOD 31.1%, SEV 14.6%, PROF 6.8% | Database/medical records | 103 | 52.4 | 38.2 | Hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, overweight, obese, undefined diabetes | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| McDermott (2006)86 | USA | NR | Database/medical records | 618 | NR | NR | Ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, obese, T1&T2DM | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Rurangirwa (2006)93 | USA | NR | Secondary data analysis | 173 | 58.0 | 23.3 | Overweight+ | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Shah (2006)135 | UK | NR | Postal questionnaire | 119 | NR | NR | Undefined diabetes | Cross-sectional observational |

| Van Den Akker (2006)140 | Netherlands | MILD 11%, MOD 53%, SEV 28%, PROF 8% | Database/medical records | 436 | 52 | NR | Ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Levy (2007)118 | USA | SEV 65.4%, PROF 34.6% | Database/medical records | 52 | 52.0 | NR | Overweight+ hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, undefined diabetes | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| McDermott (2007)87 | USA | NR | Database/medical records | 585 | NR | NR | Undefined diabetes | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| McGuire (2007)127 | Ireland | MILD 14.1%, MOD 63.5%, SEV 12.8%, PROF 9% | Postal questionnaire | 155 | 53.5 | 37.0 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Wang (2007)142 | Taiwan | NR | Face-to-face interview questionnaire | 1128 | 57.6 | NR | Heart disease, overweight+ | Cross-sectional observational |

| Bhaumik (2008)99 | UK | NR | Questionnaire data register | 1119 | 59.0 | NR | Overweight, obese, hypertension | Cross-sectional, retrospective |

| Henderson (2008)84 | USA | NR | Database/medical records | 100 | NR | T2DM, overweight, obese hypertension, dyslipidaemia | Cross-sectional, Retrospective | |

| Melville (2008)128 | UK | MILD 40.9%, MOD 25.1%, SEV 18.2%, PROF 15.8% | Researcher-collected data | 945 | 55.6 | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Wallace (2008)141 | Australia | NR | Database/medical records | 155 | 52 | NR | CVD, elevated glucose level, T1&T2DM, overweight, obese, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| de Winter (2009)81 | Netherlands | MILD 12.1%, MOD 33.2%, SEV 34.3%, PROF 20.4% | GP screened/medical chart/structured interview | 470 | NR | NR | MI, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, elevated glucose level, obese, hypercholesterolaemia | Cross-sectional observational |

| Gale (2009)107 | UK | NR | GP survey data | 1097 | 58.0 | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Henderson (2009)110 | USA | MILD/MOD 53%, SEV/PROF 47% | Health questionnaire data | 1196 | 53.0 | NR | Overweight+ | Cross-sectional observational |

| Maaskant (2009)123 | Netherlands | NR | Database/medical records (2007 data) | 336 | 55.1 | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional retrospective (2007 data) |

| Moss (2009)134 | South Africa | NR | Questionnaire/researcher-collected data | 100 | 47 | NR | Elevated glucose level, overweight+, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia | Cross-sectional observational |

| Sohler (2009)136 | USA | NR | Database/medical records | 5930 | NR | NR | Undefined diabetes, overweight, obese, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Van de Louw (2009)139 | Netherlands | MILD 10%, MOD 38%, SEV/PROF 52% | Researcher-collected data | 258 | 51.6 | 47 | Hypertension | Cross-sectional observational |

| Shireman (2010)95 | USA | NR | Database/medical records | 291 | 52.6 | NR | Undefined diabetes | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Stedman (2010)138 | New Zealand | NR | Database/medical records | 98 | NR | 43 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Tyler (2010)88 | USA | NR | Database/medical records | 1267 | 53.8 | 38.8 | Ischaemic heart disease, undiagnosed diabetes, obese, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Chen (2011)101 | China | NR | Physical examination (2008) | 117 | NR | NR | Heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, elevated glucose level, hypercholesterolaemia | Cross-sectional observational |

| Frighi (2011)106 | UK | MILD 48%, MOD 30.2%, SEV/PROF 21.8% | Researcher-collected data | 202 | 52.0 | 42.1 | Overweight+, T2DM | Cross-sectional observational |

| Haveman (2011) POMONA II study109 | 14 European countries | MILD 22.7%, MOD 28.2%, SEV 20.7%, PROF 11.8% | Interview survey data | 1253 | 51.0 | 41.0 | Undefined diabetes, hypertension, MI, cerebrovascular disease | Cross-sectional observational |

| Lee (2011)115 | Australia | MILD 33%, MOD 22%, SEV 23%, PROF 21% | Database/medical records | 162 | 52.0 | 44.0 | Ischaemic heart disease, overweight, obese, undefined diabetes, hypertension | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Martínez-Leal (2011) POMONA II study125 | 14 European countries | MILD 21.8%, MOD 27.7%, SEV 19.7%, PROF 11.4% | Interview survey data | 1257 | 50.5 | 41.4 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Stancliffe (2011)137 | USA | NR | Consumer survey interview | 8911 | NR | 43.5 | Overweight, obese, overweight+ | Cross-sectional observational |

| Wong (2011)143 | Hong Kong | MILD 4.9%, MOD 41.8%, SEV/PROF 51.9% | Postal questionnaire | 811 | 53.3 | 44 | Heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, undefined diabetes, overweight+, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia | Cross-sectional observational |

| Chang (2012)100 | Taiwan | MILD 65%, MOD 16%, SEV 9%, PROF 10% | Annual health checks | 129 | 56.6 | 33.0 | Overweight, obese, hypertension, elevated glucose level, hypercholesterolaemia, metabolic syndrome | Cross-sectional observational |

| De Winter (2012)_1 HA-ID study103 | Netherlands | MILD 24.8%, MOD 48%, SEV 16%, PROF 8.9% | Medical records/physical examination | 945 | 51.0 | 61.5 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| De Winter (2012)_2 HA-ID study102 | Netherlands | MILD 24.5% MOD 48.6%, SEV 16%, PROF 8.7% | Medical records/physical examination | 980 | 51.3 | 61.5 | Hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, metabolic syndrome, diabetes | Cross-sectional observational |

| Gazizova (2012)82 | UK | MILD 61%, MOD 24%, SEV 15% | Routine health assessment of people within a service | 100 | 67.0 | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Hsu (2012)113 | Taiwan | MILD/MOD 47%, SEV/PROF 53% | Health examination charts | 164 | NR | 33.0 | Overweight+, metabolic syndrome | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Lin (2012)122 | Taiwan | NR | Annual health examination chart | 184 | 62.5 | NR | Hypertension | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Morin (2012)133 | Canada | MILD 32.9%, MOD 46.4%, SEV 11.2%, PROF 5.2% | Postal questionnaire | 789 | NR | NR | Heart disease, undefined diabetes | Cross-sectional observational |

| Bégarie (2013)98 | France | NR | Questionnaire data | 255 | NR | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| De Winter (2013)104 HA-ID study | Netherlands | MILD 24.9%, MOD 53%, SEV 13.4%, PROF 4.6% | Medical records/physical examination | 629 | 53.6 | 61.5 | Peripheral arterial disease | Cross-sectional observational |

| Haider (2013)108 | Australia | NR | Telephone interview | 897 | NR | 38.4 | Heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, T2DM, overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Jansen (2013)85 | Netherlands | MILD 6.9%, MOD 37.8%, SEV 29%, PROF 26.3% | Database/medical records | 510 | 55.7 | 65.5 | MI, cerebrovascular disease | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Lin (2013)120 | Taiwan | NR | Annual health examination chart | 215 | NR | NR | Hypercholesterolaemia hypertension, elevated glucose level | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| McCarron (2013)126 | Ireland | NR | Face-to-face questionnaire – first wave data for a longitudinal study | 753 | 45.0 | 54.8 | Ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension | Cross-sectional observational (first wave) |

| Vacek (2013)94 | USA | NR | Database/medical records | 3079 | NR | NR | Hypertension | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Hsieh (2014)112 | USA | MILD 44.9%, MOD 23.7%, SEV/PROF 8.4% | Secondary data analysis | 1450 | 55.2 | 37.1 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional retrospective |

| Mikulovic (2014)130 | France | NR | Face-to-face interview questionnaire | 570 | NR | 38.1 | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| de Winter (2015)90 | Netherlands | MILD 21.3%, MOD 47.6%, SEV 16.7%, PROF 9.0% | Medical records/physical examination | 990 | 51.3 | 61.1 | Hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, T1DM, T2DM, diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, elevated glucose level, obese, metabolic syndrome | Cross-sectional observational |

| Lin (2015)121 | Taiwan | MILD 6.5%, MOD 32.6%, SEV 34.8%, PROF 26.1% | Researcher-collected data | 67 | NR | NR | Overweight, obese | Cross-sectional observational |

| Zaal-Schuller (2015)145 | Netherlands | MILD/MOD 51.1%, SEV/PROF 48.9% | Researcher-collected data | 407 | NR | NR | Peripheral arterial disease | Cross-sectional observational |

Ten of the studies81–89,102,103 included in the systematic review also presented as general population comparison data for inclusion in the secondary meta-analysis.

The studies represented 23 countries on five continents. One study109 covered 14 European countries. Most studies were conducted in the USA/Canada (n = 1783,84,86–88,93–95,110,112,114,117–119,133,136,137). The remaining studies were conducted in Europe [the Netherlands (n = 781,85,102,123,139,140,145), the UK (n = 950,82,89,105–107,124,128,135), France (n = 298,130), Norway (n = 1111) and Ireland (n = 2126,127)], Israel (n = 1129), Asia (n = 1089,100,101,113,120–122,142–144), Australia/New Zealand (n = 6108,115,116,132,138,141) and South Africa (n = 2131,134). Primarily, the included studies were cross-sectional observational (n = 3181,82,98,100–102,104,106,109–111,114,116,119,121,124,126–135,137,139,142,143,145). The remaining studies involved retrospective database or medical records data (n = 2283–89,94,95,99,107,113,115,117,118,120,122,123,136,138,140,141) or secondary data analysis (n = 550,93,105,112,144).

All studies were published in the years 2000–15. The average mean age of participants was 42.8 years, with an average mean age range of 23.3–65.5 years. The average mean percentage of male participants was 52.4%. The number of people included in the studies ranged from 25 to 8911, with a mean of 824.

Risk of bias within studies

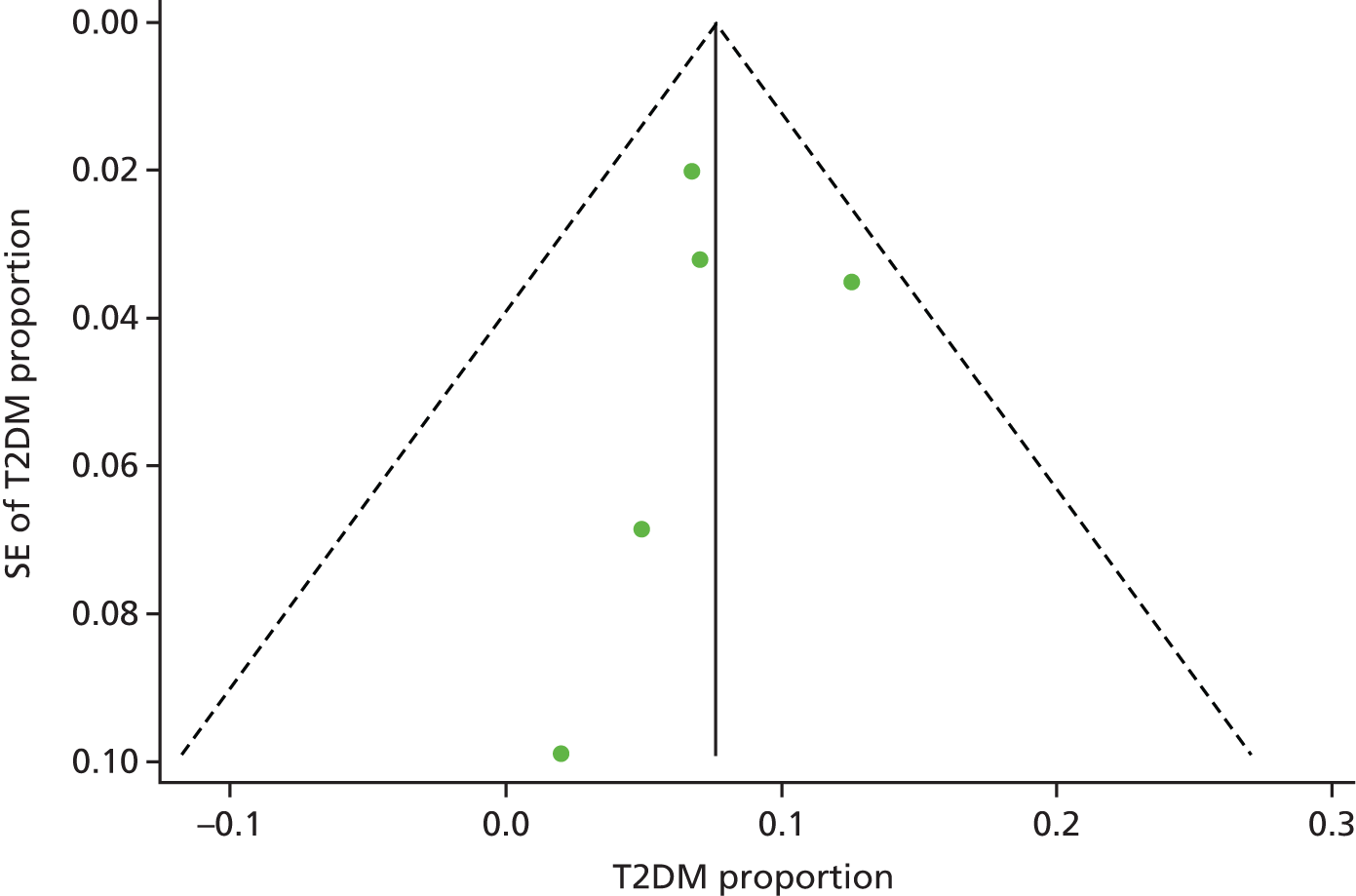

The funnel plots did not show any obvious asymmetry, and Egger’s test was not statistically significant for any of the outcome measures (specifically T2DM, t = –0.22; p = 0.84; ischaemic heart disease, t = –0.13; p = 0.91; cerebrovascular disease, t = 0.35; p = 0.58) (see Appendices 4–6, Figures 27–29, for funnel plots).

Results of individual studies and synthesis of results

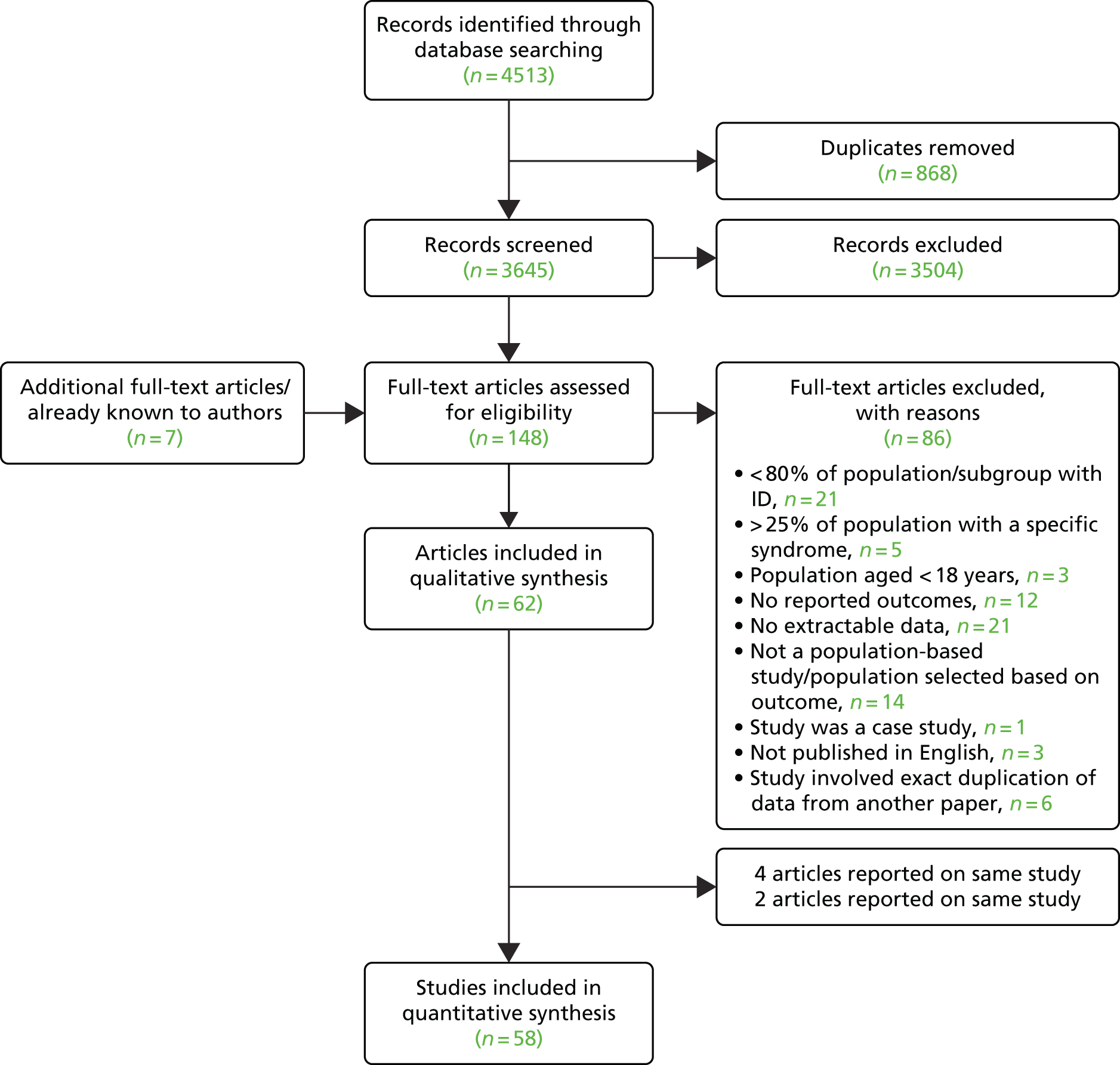

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes

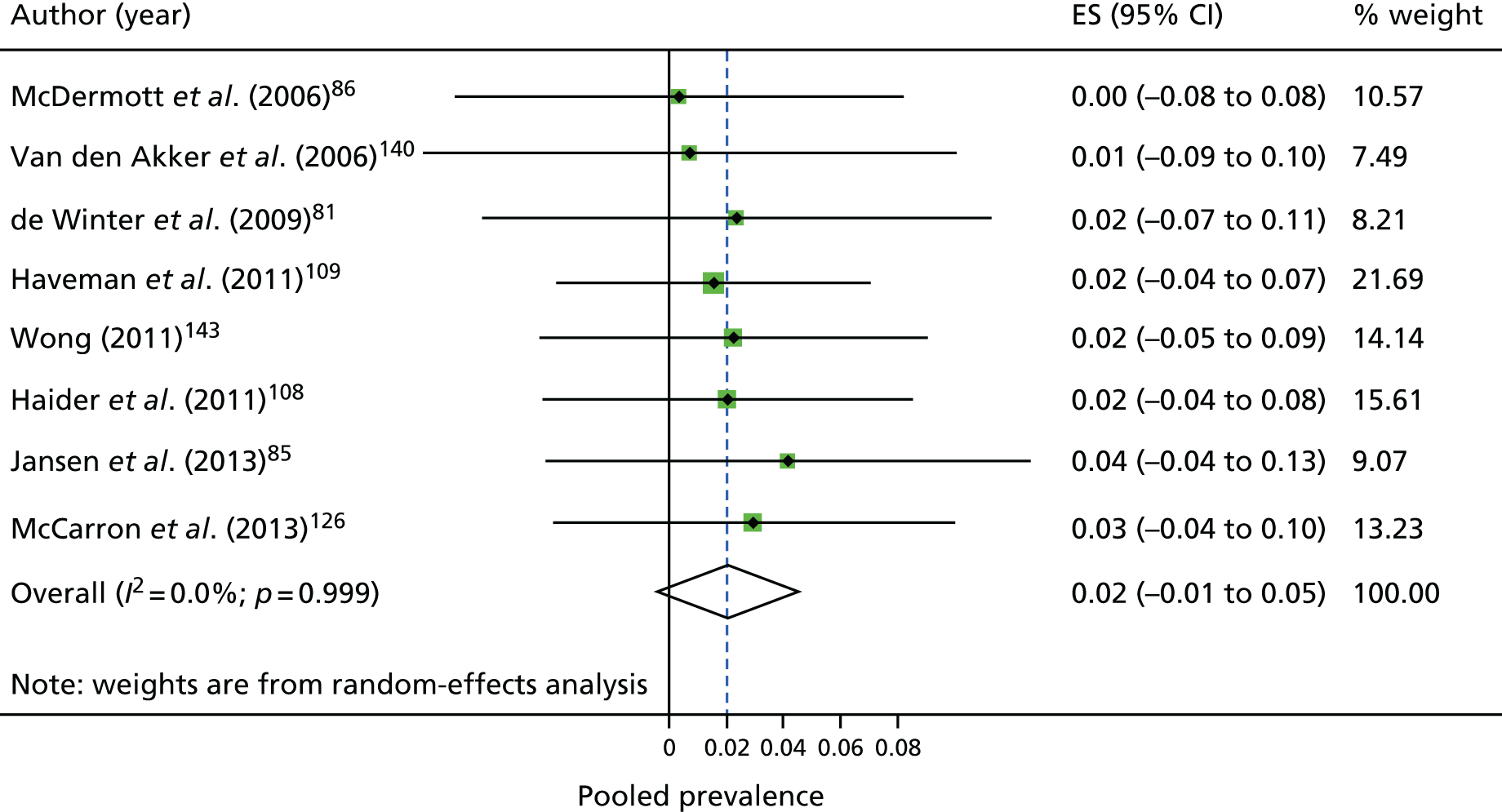

Figure 4 shows the individual studies reporting on the prevalence of T2DM and overall pooled prevalence. The prevalence estimates ranged from 2%84 to 13%. 90 The pooled prevalence of T2DM was 7.6%. The prevalence of any diabetes was 8.7%; this ranged from 2%84 to 11%95,102,117 (data not presented).

FIGURE 4.

Individual studies and pooled prevalence of T2DM. ES, effect size.

Prevalence of cardiovascular disease

Figure 5 shows the individual studies reporting on the prevalence of ischaemic heart disease. The prevalence estimates for ischaemic heart disease ranged from 0%140 to 12%. 126 The pooled prevalence of ischaemic heart disease was 3.7%.

FIGURE 5.

Individual studies and pooled prevalence of ischaemic heart disease. ES, effect size.

Similarly, Figure 6 shows the individual studies reporting on the prevalence of cerebrovascular disease. The estimates were fairly consistently in the < 1–4% range. The pooled prevalence of cerebrovascular disease was 2.2%. The pooled prevalence for undefined CVD was 10.6%, but ranged by individual study from 4%143 to 22%,114 reflecting the diverse case definitions.

FIGURE 6.

Individual studies and pooled prevalence of cerebrovascular disease. ES, effect size.

Prevalence of other risk factors

Table 4 summarises the findings from the individual meta-analyses. The overall estimated prevalence of hypertension was 18.5%. The estimated prevalence of overweight was 29.2%, the prevalence of obesity was 27.3% and the prevalence of BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 was 53.4%.

| Outcome | Study, n | Total, N | Total n with outcome | Pooled estimate (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic heart disease | 9 | 5586 | 200 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.06) | 0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 | 5748 | 114 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.05) | 0 |

| Undefined CVD | 8 | 7773 | 881 | 0.10 (0.05 to 0.15) | 77.5 |

| T2DM | 5 | 4183 | 317 | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.11) | 0 |

| Any diabetes | 23 | 19,133 | 1636 | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.10) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 28 | 17,161 | 3008 | 0.19 (0.13 to 0.24) | 93.2 |

| Overweight | 32 | 24,923 | 7434 | 0.29 (0.26 to 0.33) | 89.5 |

| Obese | 35 | 27,274 | 7741 | 0.27 (0.23 to 0.32) | 93.6 |

| Overweight and above | 41 | 31,172 | 16,525 | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.58) | 96.4 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 9 | 3892 | 491 | 0.17 (0.08 to 0.26) | 86.9 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 3 | 821 | 287 | 0.23 (0.00 to 0.50) | 91.7 |

On making comparisons with the general population, we found that the population with ID had decreased odds of having ischaemic heart disease [odds ratio (OR) 0.44, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.58; p < 0.01]. No other statistically significant results were found, but we observed high heterogeneity for the other outcomes (Table 5).

| Outcomes | Study, n | ID total, N | ID total, n with outcome | GP total, N | GP total, n with outcome | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic heart disease | 3 | 2395 | 67 | 5441 | 335 | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.58)* | 0 |

| Any diabetes | 6 | 4014 | 411 | 13,404 | 1371 | 0.96 (0.61 to 1.5) | 92.2 |

| Hypertension | 6 | 3588 | 1097 | 14,262 | 4598 | 0.76 (0.58 to 0.99) | 86.9 |

| Overweight | 4 | 1487 | 477 | 17,819 | 5986 | 1.31 (0.47 to 3.66) | 96.5 |

| Obese | 7 | 3838 | 1004 | 23,230 | 6824 | 1.09 (0.65 to 1.82) | 95.3 |

Discussion

Summary of evidence

In this systematic review, we found that the prevalence of T2DM was 8% and of any diabetes was 9%. For CVD, the prevalences of ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and undefined CVD were 4%, 2% and 10%, respectively.

The current prevalences of T2DM and CVD and associated risk factors in the population with ID were found to be similar to those in the general population. However, we found that ischaemic heart disease was significantly lower in the ID population. The metaregression showed that the method of data collection had minor effects on pooled diabetes and obesity. Mean age had minor effects on hypertension.

Strengths and limitations

A particular strength of this review is that we used robust methods. We wrote to authors to clarify and obtain additional data rather than excluding the articles. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of T2DM, CVD and associated risk factors in adults with ID. In addition, it is the first review of its kind to make comparisons with the general population.

However, we had limited data to separate T2DM from other diabetes, and we were sometimes restricted to unclear or poorly defined outcome measure definitions.

There were also limited data available to make comparisons with the general population. We would have benefited from additional general population data alongside the population with ID data to make more valid, generalisable comparisons.

Findings in relation to other studies

Two recent reviews75,76 have been conducted that have focused on diabetes prevalence among people with ID. The reviews found mean prevalences of 8.7%75 and 8.3%76 for combined gestational, type 1 diabetes mellitus and T2DM, respectively, but the reviews were unable to report on specific types of diabetes. The overall prevalence of CVD among people with ID is unclear. 52 However, our finding that ischaemic heart disease was significantly lower in the population with ID differs somewhat from the literature, which suggests that the prevalence of CVD among people with ID is greater than the general population. 52

Conclusions

Findings from the systematic review and meta-analysis presented in this chapter suggest that T2DM is at least as common in people with ID as in the general population. The findings also identify a gap in knowledge in relation to the prevalence of T2DM as many studies did not report this separately. In addition, none of the studies in our review reported on screen-detected T2DM in the population with ID.

Chapter 3 Systematic review of the effectiveness of multicomponent behaviour change interventions aimed at reducing modifiable risk factors

Overview

In this chapter, we describe the second of two systematic reviews conducted as part of the research programme. We present the existing evidence in relation to multicomponent behaviour change interventions that modify risk factors for T2DM and CVD in people with ID. The PRISMA checklist74 has been used to guide the reporting of this systematic review.

Rationale

Non-communicable diseases are on the rise globally and there is increasing demand for lifestyle behaviour change interventions to reduce morbidity, mortality and rising health costs. 146 The suggested mechanisms for this rise are increased availability of energy-rich foods and more sedentary lifestyles. 147 T2DM and CVD, and shared associated risk factors, are major contributors to morbidity and mortality. 148

Conditions such as CVD and T2DM share similar risk factors, including dyslipidaemia, hypertension, obesity and IGR. In the general population, these risk factors can be effectively lowered through interventions focusing on changes in nutrition and physical activity. 149–151 With a suggested increased risk of non-communicable diseases within populations with ID, special attention needs to be paid to the efficacy and effectiveness of multicomponent behaviour change interventions to reduce this disparity. However, there is a lack of quality evidence on the health and health care of people with ID, including the effectiveness of health interventions. 152 Previous systematic reviews of lifestyle behaviour change interventions in ID153–155 have generally been unable to make specific recommendations because of inadequacies in study design and conduct, a lack of theory basis for intervention and/or unclear reporting.

For the current review, we aimed to consolidate the evidence for the reduction of risk of T2DM and/or CVD through the delivery of multicomponent behaviour change interventions in the population with ID.

Objectives

The objectives were to establish the effectiveness of multicomponent behaviour change interventions:

-

in promoting weight loss in the population with ID

-

in reducing other modifiable risk factors for T2DM and/or CVD in the population with ID

-

aimed at primary prevention of T2DM or CVD, or reducing associated risk factors in the population with ID.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO 2015: CRD42015020758). 156

Eligibility criteria

The review was guided by the PICOS model. 78 We defined the population as adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with ID (whole study population or a defined subsample). We defined the intervention as any multicomponent lifestyle behaviour change intervention aimed at primary prevention of T2DM or CVD, or a reduction in associated risk factors for people with ID and/or their carers. We included studies with and without comparison groups. We defined outcome measures as changes in anthropometric measures (weight, BMI, waist circumference), BP, lipid levels, glucose levels, physical activity levels, sedentary behaviour and dietary habits. The study design was defined as an experimental study [before-and-after study, randomised controlled trial (RCT) or non-RCT] with a follow-up period of at least 24 weeks or 6 months from baseline (to allow for the initiation and maintenance of medium- and longer-term behaviour change)157 (Table 6).

| PICOS elements | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Whole study population or defined subsample of adults (aged ≥ 18 years)a | |

| Intervention | Multicomponent lifestyle behaviour change intervention aimed at primary prevention of T2DM or CVD, or a reduction in associated risk factors (weight management, increasing physical activity/reducing sedentary behaviour, dietary improvement) | Interventions involving meal replacements or those aimed at increasing physical fitness (in isolation) as opposed to changes in levels of physical activity |

| Comparison | Studies without comparison groups were included | |

| Outcomes | Changes in anthropometric measures (e.g. weight, BMI, body fat, waist circumference), BP, lipid levels, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, dietary habits | |

| Study designs | Before-and-after study, RCT, non-RCT | Follow-up period of < 24 weeks/< 6 months from baseline |

All studies that had been published on or after 1 January 2000 (until 21 April 2015) and in the English language were eligible. Studies were limited to those published in or after the year 2000, when most large diabetes prevention trials were first published in the general population. 70

We contacted lead authors for further information when inclusion/exclusion could not be determined.

Information sources

We searched the electronic databases EMBASE, MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and PsycINFO for this systematic review. The last date of the search was 21 April 2015. We searched the references lists of relevant systematic reviews and included papers within those for additional studies.

Search

We combined medical subject heading terms and key words for multicomponent lifestyle interventions and outcome measures and ID. The search was limited to English-language studies with cohorts of adults aged ≥ 18 years, depending on the database. Box 2 shows the MEDLINE search strategy.

-

(Behav* adj1 (Modif* or therap*)).ti,ab.

-

Cognitive* therap*.ti,ab.

-

(Health* adj2 (Educat* or promot* or behav*)).ti,ab.

-

Educat* adj2 program*.ti,ab.

-

(Diet* adj2 (Intervention* or modif* or therap*)).ti,ab.

-

(Health* adj2 Eating).ti,ab.

-

(Nutrition* adj2 (intervention* or modif* or counsel* or therap*)).ti,ab.

-

(Exercis* adj2 (intervention* or therap*)).ti,ab.

-

(Physical adj (education or fitness or activit* or training or exercise)).ti,ab.

-

(Lifestyle adj2 (advice or guidance or modif* program* or interven*)).ti,ab.

-

(Weight adj2 (control* or los* or reduc* or maintenance or management)).ti,ab.

-

Weight adj loss adj program*.ti,ab.

-

Exercise*.ti,ab.

-

Sport*.ti,ab.

-

exp Health Promotion/

-

exp Nutrition Therapy/

-

exp Exercise Therapy/

-

(Sedentary adj (behav* or lifestyle* or individual* or population*)).ti,ab.

-

or/1-18

-

exp Intellectual disability/

-

((learning or development* or intellectua* or mental*) adj1 disabilit*).ti,ab.

-

(impair* adj2 intellectual adj2 function*).ti,ab.

-

(mental* adj1 (impair* or handicap*)).ti,ab.

-

Exp mentally disabled persons/

-

(mental* adj2 retard*).ti,ab.

-

Or/20–25

-

19 and 26

-

animal/not (animal/and human/)

-

27 not 28

-

limit 29 to english language

-

limit 30 to yr=2000-current

Study selection

Full texts were identified after titles and abstracts were read separately by two investigators (TC and AD), who discussed discrepancies in selection at a later meeting.

After retrieval of the full-text articles, the papers were again examined separately by two investigators (TC and AD) to check their suitability for inclusion.

Data collection process

We created a data extraction form for this review. The data were extracted by one investigator (TC) and verified for accuracy by another investigator (AD).

Data items

For each study, we collected the first author’s name, title of paper, year of publication, country of the cohort, study design, sampling method, intervention details, dates of data collection and the intended recipient of the intervention. For the whole study population (and for each group, if applicable), we extracted data on total sample size or subpopulation size, mean ages, proportion of males/females, severity of ID, ethnicity and withdrawals.

For each reported outcome, we extracted information on how outcomes were defined and measured, the total number measured for each outcome, length of follow-up, mean baseline and post-intervention value, mean between-group change and/or change baseline to follow-up along with a measure of variability [standard deviation (SD), standard error (SE), etc.]. We extracted data separately for males and females, when reported.

Quality assessment

The NICE quality appraisal checklist for quantitative intervention studies158 was used to assess the quality of the selected studies. The checklist included criteria for assessing the internal and external validity of experimental and observational quantitative studies (RCTs, non-RCTs, before-and-after studies) and allowed assignment of an overall quality grade (categories ++, + or –). Studies were assessed by one reviewer (TC) and verified for accuracy by a second reviewer (RS).

Risk of bias in individual studies

Prior to carrying out this systematic review, we anticipated using funnel plots79 and the Egger’s test80 to examine potential publication bias in the literature for the collected outcomes. However, owing to the small number of studies included in this review resulting in low power to detect bias, these methods were not used.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis for this review involved describing the study characteristics (country, population size, age, percentage male, ethnicity, severity of ID, eligibility criteria, outcomes report and follow-up period) of the included articles. We then described the details and behavioural strategies of each of the multicomponent lifestyle behaviour change interventions, including their structure and delivery, and the underlying theory behind each of the interventions. Finally, we described the outcome measures and study findings. Given the low number of studies included, a formal evidence synthesis was not undertaken.

Results

Study selection

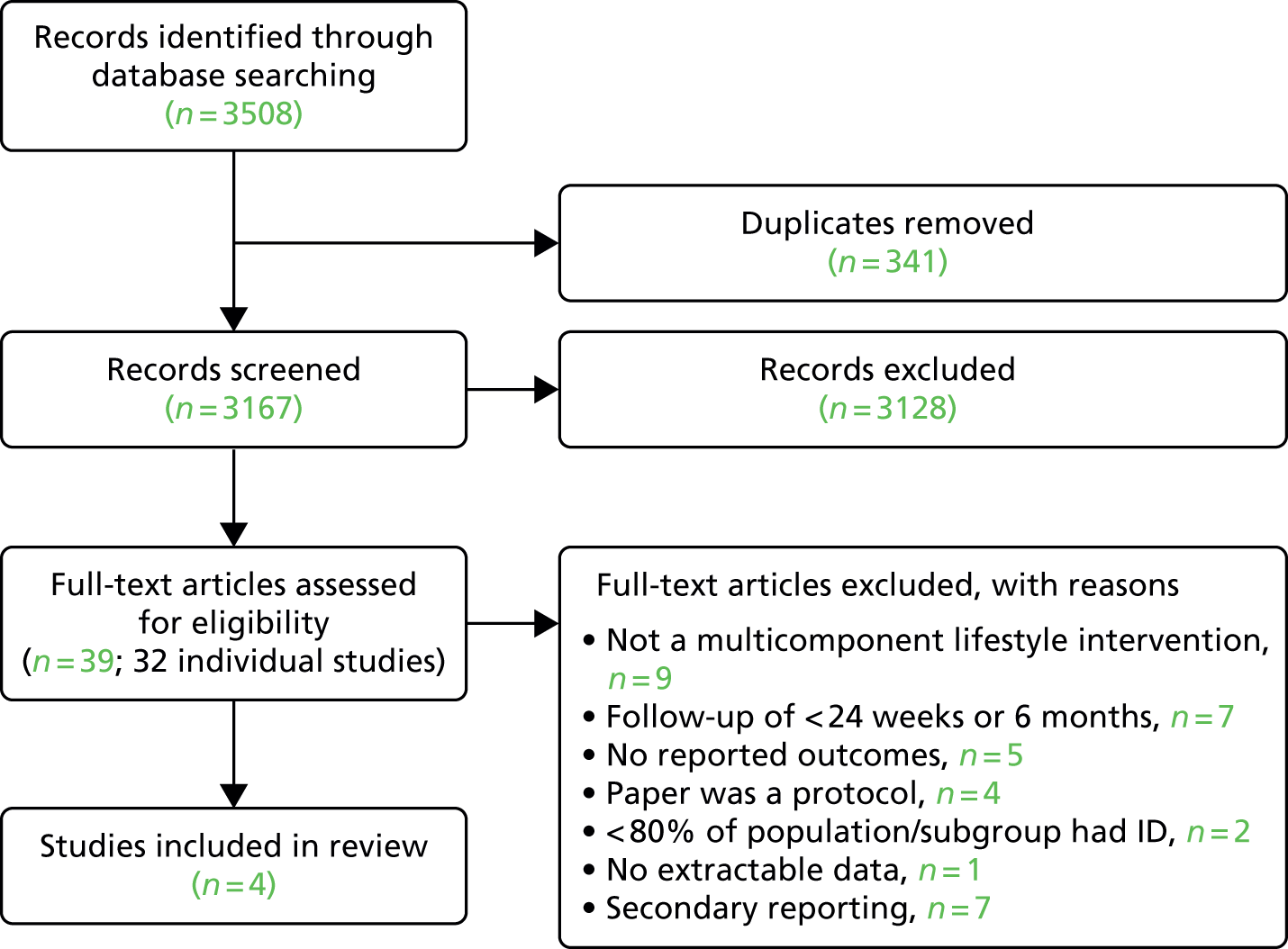

The literature searches yielded 3508 articles. After duplicates were removed, 3167 articles remained to be screened. We retrieved and reviewed the full text of 39 articles for 32 studies (Figure 7). Most potentially relevant studies were noted to have small sample size, short follow-up, high attrition rates and/or incomplete data for key outcomes. We contacted the authors of four study protocols159–162 for further information. One of the authors did not reply, and we were informed by the remaining three that their study results were still awaiting publication and could not be included in the review. In total, we identified only four studies163–166 for inclusion in this review.

FIGURE 7.

Study selection.

Study characteristics

The four studies163–166 included in the systematic review presented data on 700 individuals. The characteristics of each of the studies163–166 are presented in Table 7.

| First author (year) | Country | N (n after dropout) | Mean age (SD), years | Male (%) | Ethnic group (%) | Mean BMI (kg/m2) | Eligibility criteria | Severity of ID | Key outcomes reported | Follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazzano (2009)163 ‘Healthy Lifestyle Change Program (HLCP)’ | USA | 68 (44) | 44.0 | 38.6 | White (64), black African (21), other (16) | 33.3 | Aged 18–65 years High-functioning ID, BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2, diabetes or risk factors for diabetes [including hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, family history, hyperglycaemia, ethnicity (non-white), aged > 45 years] |

NR | BMI, weight, waist circumference, physical activity (frequency and duration) | 7 months |

| Melville (2011)164 ‘TAKE-5 STUDY’ | UK | 54 (47) | 48.3 | 40.7 | White (97), Pakistani (2), other Asian (2) | 40.0 | Aged ≥ 18 years, BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2, ambulatory Excluded: Prader–Willi syndrome |

MILD 31.5%, MOD 31.5%, SEV 35.2%, PROF 1.9% | BMI, weight, waist circumference, sedentary and, physical activity (minutes/day, accelerometer) | 24 weeks |

| McDermott (2012)165 ‘Steps To Your Health (STYH)’ | USA | 443 (196) | 38.8 | 49.2 | White (42), black (57), Hispanic (1), other (1) | 32.4 | Aged 18–65 years, voluntary participation, ambulatory and communicative, mild to moderate ID, residence in independent or supported settings Excluded: underweight (BMI of < 18.5 kg/m2) |

NR | BMI, MVPA (accelerometer) | 12 months |

| Bergström (2013)166 | Sweden | 130 (129) | Intervention, 36.2 (10.1); control, 39.4 (11.3) | 43.1 | NR | Intervention, 30.0; control, 28.5 | Adults: mild to moderate ID; three or more residents | NR | BMI, weight, waist circumference, physical activity (steps/day pedometer) | 12–16 months |

The studies163–166 covered three countries (USA, UK and Sweden). Two studies163,164 were single arm, and two studies165,166 had a control group. All of the four studies163–166 reported data for physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour.

The mean age was 42.2 years and the mean percentage of male participants was 42.9%. The mean group size was 174 before dropout and 104 after dropout. Group sizes ranged from 54 to 443 before dropout, and from 44 to 196 after dropout. The majority of participants were white (68% where known); approximately one-quarter (26%) were black and the remaining 7% were from other ethnic groups. Only one study164 provided information on severity of ID, but, based on eligibility criteria, the remaining studies were likely to comprise adults in the mild to moderate ID range. Other descriptive information for each study is presented in Table 7.

Study quality

A breakdown of study quality is presented in Table 8. The studies163–166 were generally of high quality; in particular, all of the studies achieved at least a good quality rating for internal and external validity. However, two163,165 of the four studies failed to account for all of the participants when concluding the study, and three163–165 of the four studies did not report on whether or not the studies were sufficiently powered to detect differences.

| Section | Bazzano (2009)163 | Melville (2011)164 | McDermott (2012)165 | Bergström (2013)166 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Population | ||||

| Source population/area well described? | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Eligible population/area representative of source population/area? | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Selected participants/areas represent eligible population? | + | ++ | ++ | + |

| 2. Method of allocation to intervention (or comparison) | ||||

| Allocation to intervention (or comparison). Was selection bias minimised? | NA | NA | ++ | ++ |

| Interventions (and comparisons) well described and appropriate? | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Was allocation concealed? | NA | NA | NR | ++ |

| Participants or investigators blind to exposure and comparison? | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Exposure to intervention appropriate? | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Contamination acceptably low? | NA | NA | ++ | ++ |

| Other interventions similar in both groups? | NA | NA | ++ | ++ |

| Participants accounted for at study conclusion? | – | ++ | – | ++ |

| Did setting reflect usual UK practice? | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Did intervention or control comparison reflect usual UK practice? | ++ | + | + | ++ |

| 3. Outcomes | ||||

| Outcome measures reliable? | + | + | ++ | + |

| All outcome measurements complete? | ++ | ++ | + | – |

| All important outcomes assessed? | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Outcomes relevant? | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Similar follow-up times in exposure and comparison groups? | NA | NA | ++ | + |

| Follow-up time meaningful? | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 4. Analyses | ||||

| Exposure and comparison groups similar at baseline? If not, were these adjusted? | NA | NA | NR | ++ |

| ITT analysis conducted? | – | – | ++ | ++ |

| Sufficiently powered to detect an intervention effect (if one exists)? | NR | NR | NR | ++ |

| Estimates of effect size given or can be calculated? | NR | ++ | ++ | + |

| Analytical methods appropriate? | + | – | ++ | + |

| Precision of intervention effects given or able to be calculated? Were they meaningful? | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 5. Summary | ||||

| Study results internally valid? (i.e. unbiased) | + | + | ++ | + |

| Findings generalisable to the source population? (i.e. externally valid) | ++ | + | ++ | + |

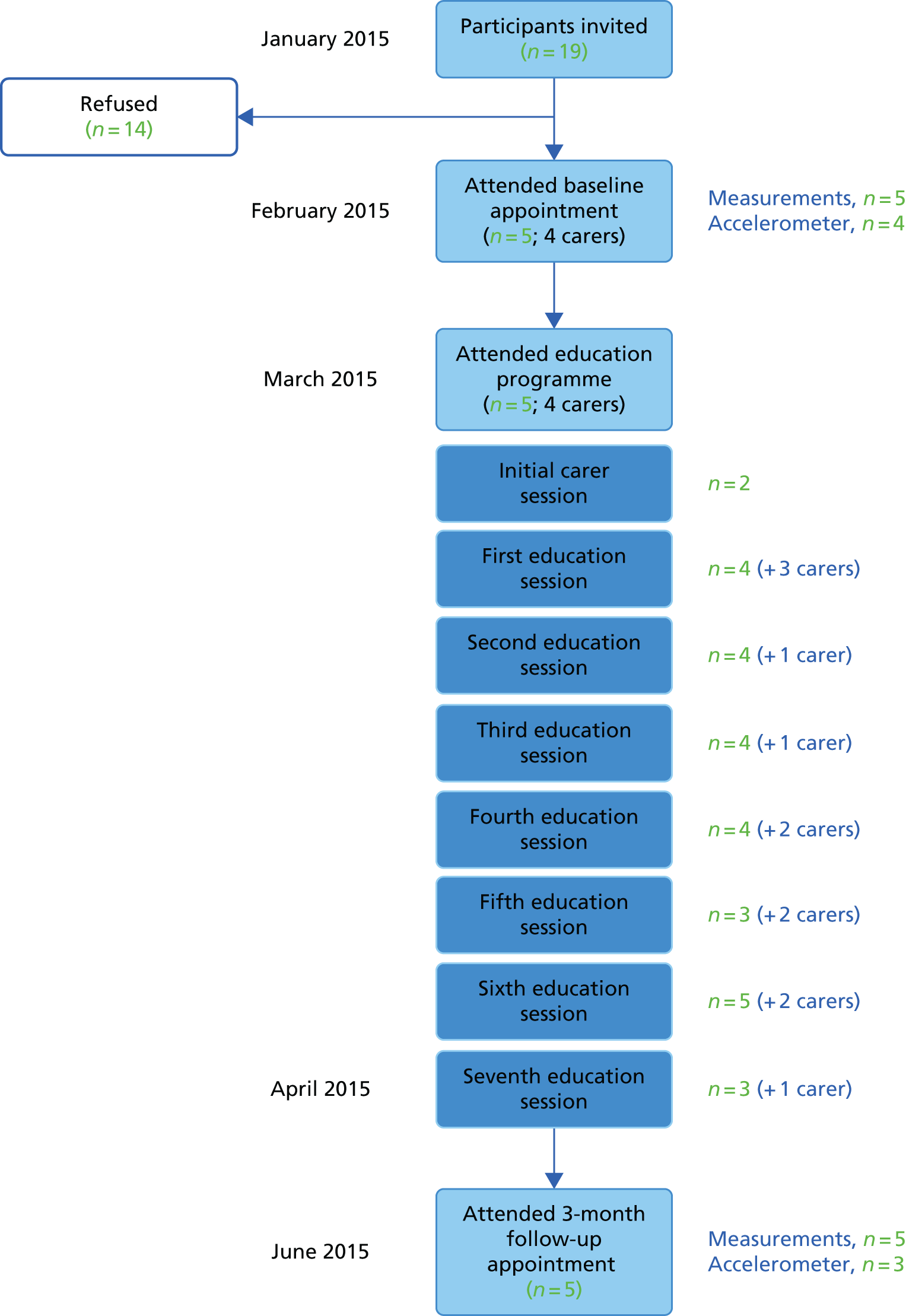

Results of individual studies and descriptive data synthesis