Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10389. The contractual start date was in October 2008. The final report began editorial review in January 2016 and was accepted for publication in November 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Richard Morriss received personal fees for chairing the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guideline Development Group for bipolar disorder from 2012 to 2014.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Jones et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a life-long condition that has an impact on the individual, carers and wider society. 1,2 As such, it presents a serious public health problem; it is the sixth leading cause of disability among people aged 15–44 years3 and costs the UK £5.2B per annum. 4 It affects approximately 2% of the population according to recent estimates5 and is typically characterised by a recurring relapse course. Although the number of episodes experienced varies substantially, many individuals experience 7–10 episodes, or more, over the course of their disorder. 6,7 There is also increasing evidence that many individuals experience a significant impact from mood symptoms between episodes of mania and depression. Studies over follow-up periods of > 13 years by Judd et al. 8,9 indicate that individuals with BD spend 47–54% of their time experiencing significant mood symptoms, in particular depression. Furthermore, a significant factor contributing to the cost of BD to society is the high rates of unemployment as a result of indaequate treament. 10

Bipolar disorder is also highly comorbid with anxiety disorders (93% lifetime11), with 32% experiencing current comorbid anxiety12 and substance misuse (40–60% comorbidity across psychiatric and community settings13–16). Both of these comorbidities are associated with significantly worse clincal course and outcomes, including negative impacts on engagement with care. For instance, comorbid BD and anxiety is associated with poor treatment response,17 increases in suicidality,18 earlier age at onset of BD19 (which is also associated with higher levels of suicidality)20 and greater relapse risk. 12 Similarly, substance use can have profound effects on mood and behaviour and may have an adverse impact on the course, outcome and morbidity of BD,21,22 including disrupting sleep and circadian rhythms. This, in turn, worsens prodromal symptoms, increases the risk of relapse23,24 and increases impulsive behaviour, including self-harm, aggression25 and suicide. 26

Bipolar disorder in general is further associated with a particularly high risk of suicide,1 a major public health problem and a leading cause of death among young people in England,25 with one-quarter of those dying by suicide having had recent contact with Mental Health Services (MHS). 26 In addition, during acute periods of mania or depression, individuals with BD can sometimes lose capacity under the Mental Health Act (MHA). 27 The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), implemented in October 2007,28 provides a statutory framework to assess whether or not a person has the capacity to make decisions, and defines how others can make decisions on behalf of someone who lacks capacity.

Psychological treatment to delay episodes and optimise function is efficacious, cost-effective and popular with service users (SUs),1 but difficult to implement owing to a lack of both experienced therapists and service structure in NHS trusts to deliver these treatments. 29 Recent evidence supports group psychoeducation (PEd) as a clinically effective and cost-effective approach30–33 that may be a cheaper, more sustainable and generalisable means to deliver effective psychological treatment of BD in the NHS. The provision of psychological treatment is a key National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendation for BD and is cost-effective by preventing hospitalisation. 1,2 PEd increases return to work,34 a current Department of Health priority, and builds on the Expert Patients Programme, a current NHS priority. 35 SUs with BD have already delivered PEd successfully in some parts of the UK.

Effective time-limited interventions for anxiety already exist and would, therefore, have the potential to improve a range of adverse outcomes in BD. NICE guidelines for both BD and for substance misuse highlight the importance of psychosocial interventions in changing patterns of substance use and address comorbid affective symptoms. 1,23 Despite the evidence for the effectiveness of psychological interventions for anxiety,36 there have been no systematic efforts to apply these to those with BD. Similarly, BD is characterised by high rates of substance misuse. The investigation of psychological interventions for this comorbidity has been neglected, despite increasing evidence for effective integrated treatments in related disorders37 and for the efficacy of psychological interventions for substance misuse in non-bipolar populations. 23 A recent small trial of group cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) indicated some improvements in substance use but a deterioration in bipolar symptoms. 38 Uncontrolled data indicate that dual diagnosis BD patients who received generic dual disorders treatment (including motivational interventions) had increased remission from substance misuse compared with baseline, but the impact of this treatment on bipolar relapse was not assessed. 39

Suicide makes a major contribution to premature mortality:40 every year, 4500 people in England and Wales take their own life. Suicide is a major burden on health services and can devastate surviving family members. Suicide prevention is a health service priority,41 and a key goal of the English Suicide Prevention Strategy is to reduce suicide in high-risk groups, such as individuals with BD. 25 However, there is little current understanding of the factors associated with suicide risk in BD or how to ameliorate these. The MCA has been in effect since 1 October 2007. It is unclear what attempts NHS trusts have made to involve SUs and staff in ensuring that the Act is implemented. We have a unique opportunity to assess the extent and nature of its impact in BD, for which readmission, including temporary loss of capacity, is a key feature, and where mood can adversely affect decision-making,42 especially as research in BD indicates that joint planning in advance is clinically effective and cost-effective29 but is rarely implemented. 43

Key research areas for this programme

Bipolar disorder and suicide research have received only 1% of research spend, compared with 9% on schizophrenia, a disorder of similar prevalence and morbidity. 44 This programme encompasses five key areas neglected to date.

-

Group PEd jointly delivered by clinicians and service user facilitators (SUFs) has not been evaluated against group peer support (PS) controlling for the natural history of the condition, for duration and length of treatment, that both types of intervention have the same aim of treatment and for therapist effects in the NHS. The study will tell us whether the specific conduct and content of PEd provides added clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness or whether PS carried out for the same duration, time and conditions would be equally clinically effective and cost-effective. Such interventions may be particularly effective, as SUs and SUFs can share similar experiences. 35 In addition, joint working ensures that action plans are owned by SUs and services and are integrated into care plans, which is clinically effective and cost-effective in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of implementing advanced directives for mental illness. 45,46

-

Although psychological interventions for anxiety are effective36 and NICE BD guidelines1 recommend psychological interventions for treatment of comorbid anxiety, no research has evaluated such interventions in those with BD. In addition, antidepressant therapies, prescribed to treat symptoms of anxiety may be problematic because of the risk of manic switch. 47

-

Research has yet to clarify relationships between BD, substance misuse and poor outcomes,48 although the ‘self-medication’ hypothesis indicates a role for amelioration of distressing symptoms. 49,50 Recent data indicate the complex and dynamic relationship between BD and substance use. 51 Reasons for substance use include attempting to manipulate mood changes and responding to triggers common to all substance users, such as stress, interpersonal conflict and social pressures. 52

-

Suicide occurs in 10% of individuals hospitalised with BD. 53 A number of risk factors for suicide attempts have been identified, but we understand little about the risk factors for completed suicide. 54 It is unclear how poor clinical management might influence suicide risk or how risk factors may link together to precipitate episodes of suicidal behaviour.

-

The MCA may promote SUs’ involvement in decision-making when they lose capacity, but, as such loss is temporary in those with BD, the assessment of their capacity may be poor,42 the implementation of the MCA may be over-ridden by the MHA, and SUs may experience difficulties regaining their rights once they have recovered capacity. Although early-warning sign interventions are effective for those with BD,29 the MCA applies when capacity is lost, so joint action plans might not be implemented until a crisis and harm have already occurred. 55

Aims

To conduct a series of linked projects to evaluate practical approaches to understanding recurrence, comorbidity, capacity and suicide risk, including the potential for enhancing SU involvement in care planning and delivery to improve clinical outcomes for SUs with BD.

Objectives and research questions

The Psychoeducation, Anxiety, Relapse, Advance Directive Evaluation and Suicidality (PARADES) programme comprised five linked workstreams (WSs) to achieve the aims described above. The corresponding objectives for each theme were to:

-

develop a service model for delivery of evidence-based PEd by:

-

evaluating whether or not group PEd is feasible and sustainable across different NHS sites

-

determining whether or not group PEd is clinically effective and cost-effective compared with group PS

-

identifying barriers, to and potential solutions of barriers, to the implementation of effective group PEd

-

-

evaluate the feasibility of individual psychological interventions to address comorbid anxiety to help enhance recovery and reduce relapse and morbidity by:

-

understanding more about the impact that anxiety has on the lives of people with BD

-

understanding what psychological help is required and by whom in relation to anxiety

-

developing and evaluating the feasibility of CBT-informed time-limited therapy for people with anxiety and BD

-

-

evaluate the feasibility of individual psychological interventions to address comorbid substance misuse to help enhance recovery and reduce relapse and morbidity by:

-

exploring the reasons for substance use and cessation and the links between substance use, stabilisation and impulsivity

-

developing a psychological therapy to reduce substance use, increase stabilisation and reduce impulsiveness informed by findings from the reasons-for-use study

-

conducting an exploratory trial to evaluate feasibility and acceptability of this therapy and to provide preliminary estimates of therapy effect size

-

-

identify and explore factors associated with risk of suicide and self-harm in BD by:

-

understanding the risk of suicide in BD in a NHS service setting

-

understanding the demographic-, clinical- and management-related risk factors for suicidal behaviour in BD

-

understanding how factors associated with suicide and self-harm in BD link together to precipitate episodes of suicidal behaviour

-

-

test the application and impact of advance directives on clinical practice by:

-

determining whether or not the MCA promotes joint care planning in the event of capacity being lost

-

examining the barriers to, and drivers of use of, the MCA in general at SU and staff levels, and specifically in relation to the assessment of capacity in affective disorder and to joint care planning in an emergency when capacity is lost for a period of time but then regained and whether or not advance directives are considered in SUs detained under the 1983 MHA.

-

Structure of this report

Workstreams 1–5 are presented in Chapters 2–6. Each chapter provides an introduction to the WS topic and an overview of methods across each phase (multiple phases for WSs 2–4, single phase for WSs 1 and 5). This is followed by methodology and results sections, and a discussion of the WS results. The final chapter integrates the findings across the programme as a whole and considers the significance of this work for future developments in clinical practice and clinical research.

Chapter 2a Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of group psychoeducation versus group peer support in the maintenance of bipolar disorder: main clinical outcomes

Abstract

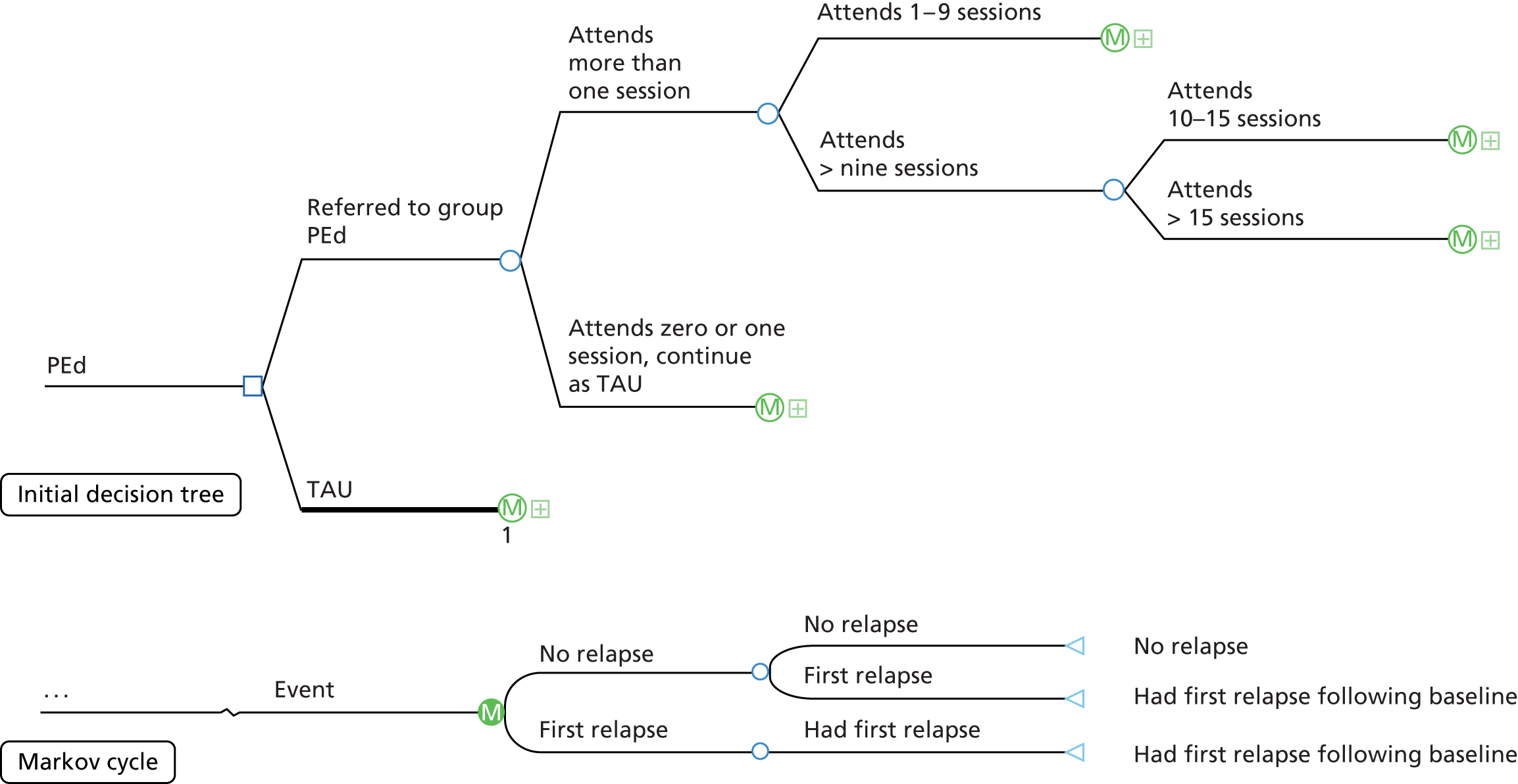

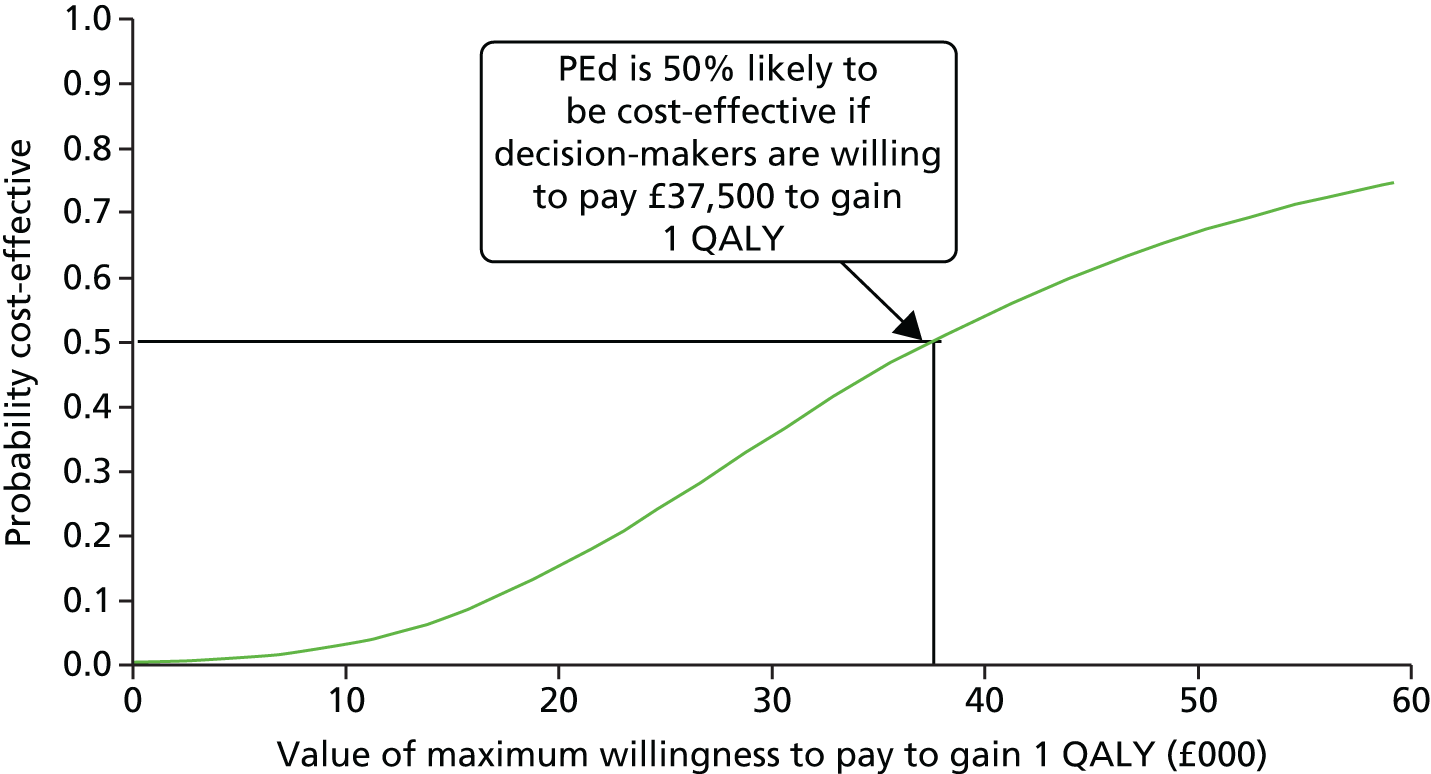

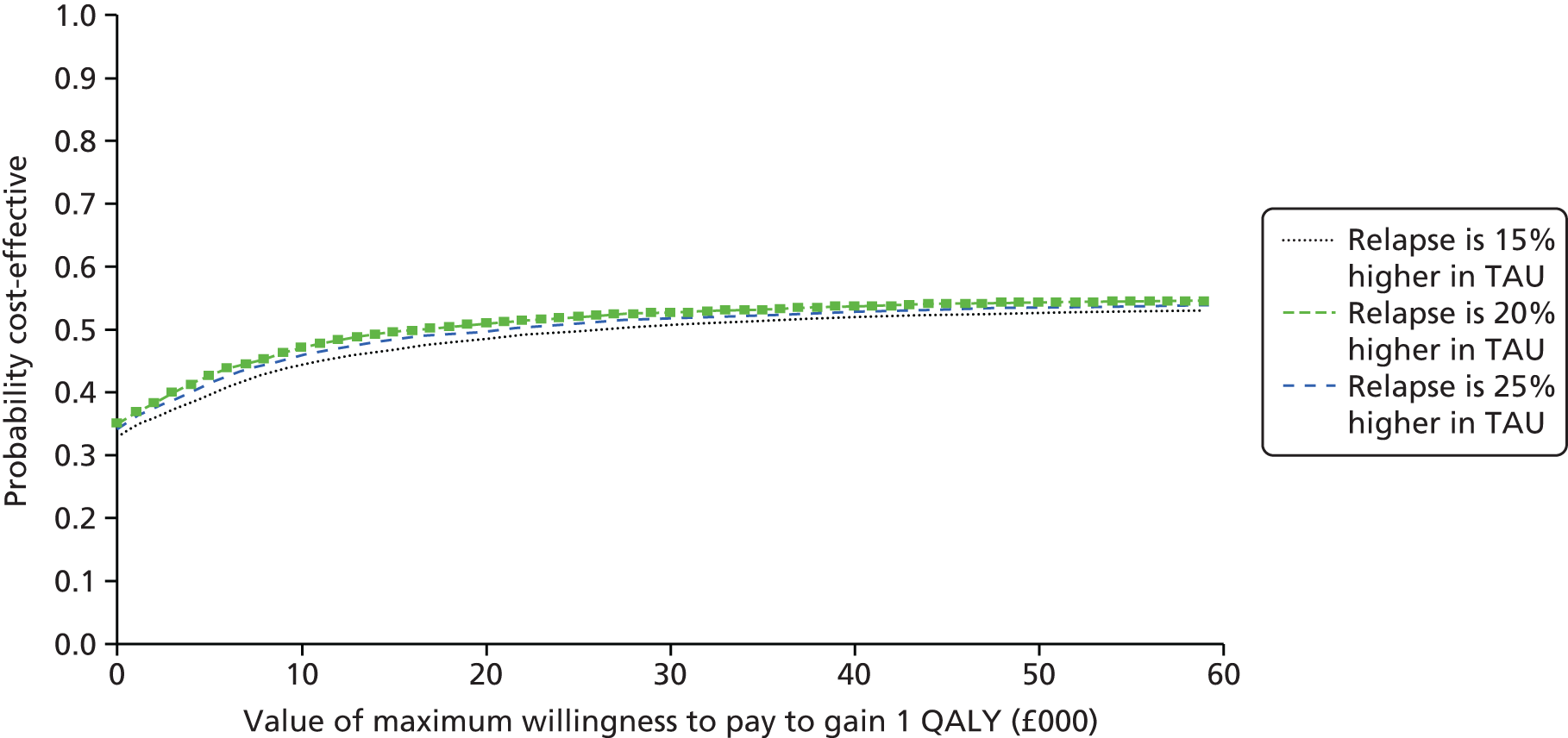

Group PEd for BD is a cheap (£447 per participant) and easy-to-implement NICE-recommended treatment. This chapter reports the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 21 sessions of group PEd versus group PS in which topics were selected by participants. The groups were matched for the duration, delivery and aim of treatment in a multicentre pragmatic RCT in England. Twenty-two groups facilitated by two health professionals and a SUF were delivered to 304 patients with BD, with a 24-month follow-up. The results showed that, overall, there was no significant difference in time to first bipolar episode [hazard ratio (HR) 0.83; p = 0.22], but group PEd reduced time to first bipolar episodes in those with seven or fewer previous bipolar episodes (HR 0.28; p = 0.034), and overall in relation to time to first mania episode (HR 0.66; p = 0.049) and interpersonal function (p = 0.012). There were no differences between the groups in bipolar symptoms, quality of life or other function. Group PEd was associated with better attendance (p = 0.026), while qualitative research showed that its structured approach was more acceptable to participants, although both group treatments increased knowledge and reduced isolation. Applying NICE thresholds for cost-effectiveness, group PEd was not more cost-effective than group PS using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), but was more cost-effective than using relapse-free years. Group PEd did not have the large clinical benefits first reported from Barcelona, but it has a small number of specific clinically important and economic benefits over group PS.

Chapter overview

This chapter describes the adaptation and evaluation of group PEd compared with group PS with a primary aim of reducing relapse in established BD. The chapter provides information on why PEd is a promising potential intervention for this group and then describes both PEd and PS interventions evaluated in the current research. Clinical and functional outcomes of the definitive RCT are described. This is followed by a discussion of the strengths, limitations and research and clinical implications of the trial. A health economic analysis of the trial is described in Chapter 2b.

Background

Bipolar disorder is a severe mental disorder characterised by recurrent episodes of mania and depression. It is the 19th leading cause of years lived with disability for any health problem. 56 The median age at onset is around 19 years. 5 Traditionally, medications such as lithium carbonate have been used to prevent episodes of illness and are still recommended for this purpose. 57 However, since 2006, clinical guidelines for the management of BD have also recommended psychological treatment for the prevention of relapse in addition to pharmacotherapy. 58,59 The most recently published guidelines from England and Wales recommend manualised evidence-based psychological interventions developed specifically for BD as a component of long-term management of BD. 57

Previous research in psychoeducation

Group PEd for BD is a manualised, evidence-based intervention. As relatively large groups of 10–18 people can undertake treatment together, group PEd is an efficient and easy-to-set-up option for MHS to deliver psychological treatment to improve longer-term outcomes. Although therapists need to be trained to run the groups, the training is less intensive than that for other psychological approaches such as individual CBT. 60 The first RCTs of group PEd versus group PS showed the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of group PEd for all types of bipolar relapse, with better outcomes maintained for 5 years. 33,61,62 However, these trials were carried out in a specialist BD service in Spain, which bears little resemblance to the UK NHS. Additionally, the relapse rates in the control arm of this Spanish trial were significantly higher than expected, with 92% of the sample who attended support groups experiencing a further bipolar episode within 2 years. This level of relapse was cited as an outlier in a recent meta-analysis of eight RCTs of PEd,32 which showed, in contrast, an unweighted mean of 70% relapse in treatment as usual (TAU) or attention control studies over follow-up periods ranging from 52 to 104 weeks. 32 Overall, in this meta-analysis, group PEd was effective in relation to all relapses [odds ratio (OR) 1.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09 to 3.58; p = 0.024; I2 = 54%; seven studies, 493 participants], almost significant for mania relapse (OR 1.68, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.85; p = 0.06; I2 = 55%; eight studies, 562 participants), but not significant for depression relapse (OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.48; p = 0.26; I2 = 63%; eight studies, 562 participants).

In another meta-analysis of RCTs for development of the NICE clinical guideline, the evidence base was reviewed for group psychological treatments overall, including CBT, mindfulness therapy, social cognition and interaction training, and dialectical behaviour therapy. 57,63 Up to 26 weeks, group psychological interventions showed a trend towards reducing overall relapse [relative risk (RR) 0.48, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.04; I2 = 59%; eight studies, 532 participants], reducing mania relapses (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.82; I2 = 0%; six studies, 564 participants) and reducing depression relapses (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.78; I2 = 0%; seven studies, 616 participants), compared with TAU or attentional controls. By 52 to 104 weeks’ follow-up, the benefits of group psychological treatments were confined to a reduction in depression relapses (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.88; I2 = 44%; five studies, 333 participants), with no effects on mania relapses (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.57; I2 = 69%; five studies, 328 participants) or on overall relapse (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.20; I2 = 81%; five studies, 395 participants).

Limitations of research to date

As observed by NICE, the evidence base for group psychological treatments in preventing relapses for BD is inconsistent and imprecise. 63 The vast majority of RCTs were small (with around 100 participants or fewer), single-centre trials, sometimes in specialist settings and often with only 12-month follow-up, and the meta-analysis shows high heterogeneity. Some trials were not pre-registered on trial databases, few reported functional, quality-of-life and economic outcomes, and there was evidence of selective reporting of outcomes. Furthermore, most RCTs did not control for the clustering effect of group treatments in their analysis, thereby overestimating the effectiveness of their treatments. 64 Furthermore, none of the trials of group PEd to date has occurred within a UK setting. In addition, there are concerns in relation to RCTs of psychological interventions that they are often carried out by the developers of the treatment approach, and that there is lack of blinding and of appropriate control groups that control for expectancy of effect as well as frequency, length and duration of treatment. 65 Thus, there is a need for a large multicentre RCT of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of group PEd carried out in non-specialist service settings in the UK that addresses all of these methodological issues.

In both the UK and other countries, people with BD often have the opportunity to access support groups, such as those run by Bipolar UK, as well as receiving medication and follow-up from health professionals. People with BD value such support,66 and PS groups run by expert patients improve self-efficacy and are effective for many health conditions. 67 The nature of the group PS in the first trials of PEd in Barcelona is unclear. 61,62 NICE57 could not find any RCT of support groups run by peers versus TAU for BD.

Aims of the current study

The primary aim of this RCT was to determine whether or not the content of a group PEd programme, as outlined by Colom et al. 60,68,69 but contextualised to UK practice, was clinically effective and cost-effective compared with group PS, the most frequently available form of group psychological treatment in the UK, with over 120 groups run by Bipolar UK (www.bipolaruk.org/find-a-support-group, accessed 9 October 2017). To ensure that groups were acceptable to participants and that participants benefited from both professional expertise and lived experience,70 both group interventions were co-facilitated by two health professionals and a trained SU. To ensure generalisability, health professionals currently working in NHS services were recruited to run the groups, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants were designed to be as inclusive as possible.

To ensure that group PS was an effective control, both groups received the same number of sessions of the same duration; each set of sessions involved two health professionals and a SUF and started off with the same number of participants with BD, and each meeting was held at the same place but on a different day that was not disclosed to the blinded assessor of outcome. Each group intervention had a manual and had the same aim of treatment, which was to use the resources of the group to develop a plan to prevent further bipolar episodes and improve overall function. Both groups were supervised by senior clinical academics and both groups were closed. Therefore, although this group PS was similar to the group PS offered by Bipolar UK, in that the participants determined the content of the group, it was also a long-term supervised closed group with a more specific aim, so in many important ways it was quite different from the usual group PS offered in the UK. We also addressed many of the issues highlighted by NICE58,63 as key problems with previous group psychological treatment and PEd RCTs for BD by ensuring that our trial was multicentre and pre-registered, and had relapse, symptom, function, quality-of-life and economic outcomes (reported in the next chapter). The trial was carried out in routine secondary care mental health settings. (A protocol paper has already been published. 71)

Aims

-

To determine whether or not it was feasible to run group PEd for BD across many different settings in the NHS (urban and more rural, teaching and non-teaching hospital, different parts of England) to explore its generalisability.

-

To determine whether or not group PEd is clinically effective compared with group PS in increasing time to first bipolar relapse.

-

To determine whether or not group PEd is clinically effective compared with group PS in relation to secondary outcomes of time to the next mania and depression relapse, severity of mania and depression symptoms, function, quality of life, health status and costs.

-

To identify the barriers to, and potential solutions of barriers to, the implementation of effective group PEd.

Methods

Design

A single-blind RCT compared the effectiveness of:

-

21 weekly bipolar group PEd sessions delivered by two health professionals (nurse, psychiatrist, psychologist or occupational therapist) and a SUF, plus TAU

-

21 weekly unstructured bipolar group PS sessions delivered by two health professionals and a SUF plus TAU71 (see Table 3).

The trial was located in two centres in England (East Midlands and North West), with four clinical sites in each centre. Overall, 11 groups of PEd were compared with 11 groups of PS, with some sites running two waves of groups. The intervention was taken to different locations in each regional centre to improve access for those people who wanted to participate but for whom travelling distance was a practical barrier to engagement.

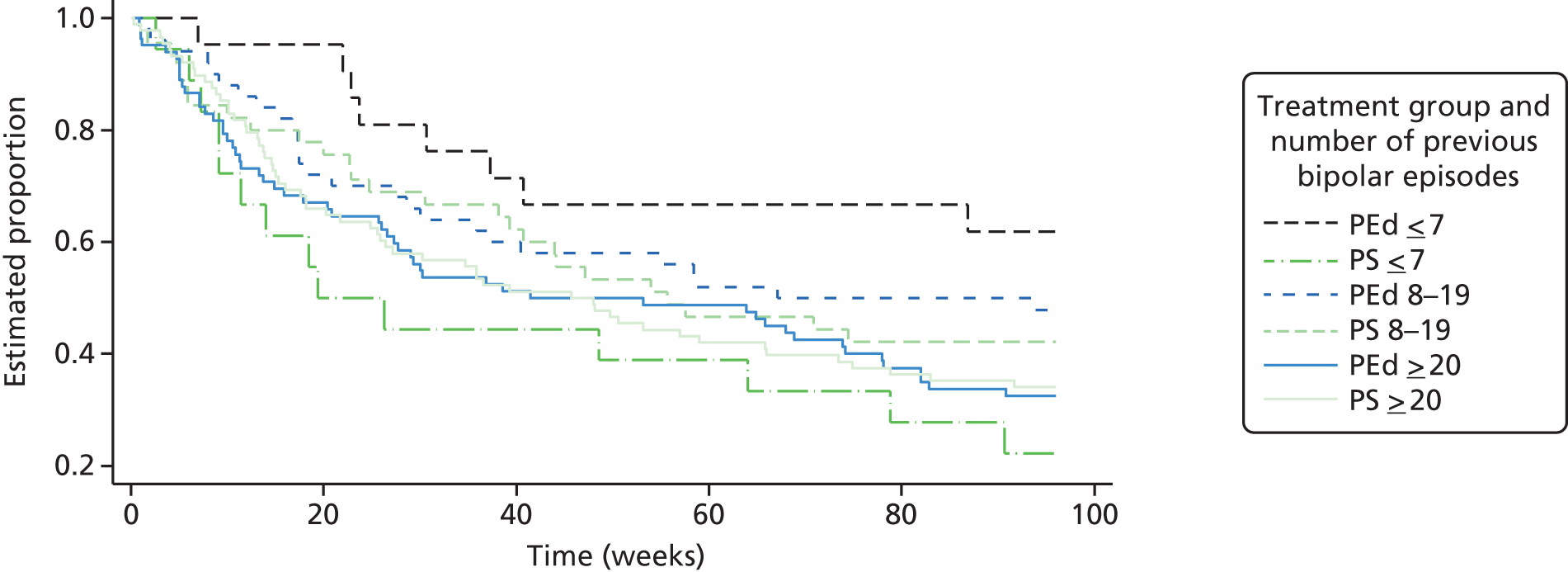

Consecutively eligible patients were individually randomised to either intervention, with stratification by clinical site and minimisation in terms of number of previous bipolar episodes (1–7, 8–19, ≥ 20). The latter was to control for the effect of rate of bipolar episodes: relapse is up to three times more likely in those with more than 20 episodes than in those with fewer than seven bipolar episodes. 72 There is also increasing evidence that psychological interventions may be particularly effective in people with fewer bipolar episodes or admissions to hospital,73,74 whereas one psychological intervention for unipolar depression, mindfulness CBT, may be more effective in people with three or more previous depression episodes than in those with fewer episodes. 75

Qualitative interviews were used to investigate the experiences of the group participants in order to identify facilitators of, and barriers to, the widespread delivery of the intervention across the NHS.

Setting and target population

The recruitment strategy was deliberately broad to ensure that targets were met and that the sample reflected a diversity of people with BD. Community mental health team bases at a number of NHS trusts located in two distinct geographical centres (East Midlands and North West) were encouraged to invite potentially relevant participants. The study was also promoted at a primary care level, with local family doctors being asked to display posters about the trial, and through SU-run local BD networks and the general media, allowing people to self-refer. The target population was patients with bipolar 1 or bipolar 2 affective disorder at increased risk of further relapse (defined as having had an episode in the last 24 months), as preventing relapse was the key aim of the intervention.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants were included if they:

-

had a Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-verified diagnosis of primary bipolar 1 or bipolar 2 disorder76,77

-

were at increased risk of relapse (at least one episode in the last 24 months)

-

were aged ≥ 18 years.

Participants were excluded if they had any of the following:

-

presence of a manic, hypomanic, mixed affective or major depressive episode currently or within the previous 4 weeks

-

current suicide plans or high suicide intent

-

inability or unwillingness to give written informed consent to the study

-

inability to communicate in written and verbal English to a sufficient level to allow them to complete the measures and take part in the groups.

Baseline and outcome measures

At baseline interview, the SCID was used to assess sociodemographic features, the presence of axis 1 comorbid psychopathology,76,77 the presence of borderline or antisocial personality disorder78 and the number of previous bipolar episodes. 79 Participants were also asked if they had any preference as to which group they were allocated to.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was time to next bipolar episode using 16-weekly SCID Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE) interviews80 to generate weekly scores of mania and depression on a 1–6 scale of severity, as we have previously used. 71,78 Specifically, we recorded the time from randomisation to the first week of recurrence of an episode of mania, hypomania, a mixed episode for 1 week, or a major depression for 2 consecutive weeks, satisfying DSM-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria76 (both coded as a 5 or 6 on SCID LIFE). The 16-weekly SCID LIFE interviews (alternating between telephone and face-to-face interviews) were used to generate weekly scores for mania and depression, both on a 1–6 scale of severity (1 = no symptoms; 2 = minor symptoms; 3 = partial remission; 4 = does not meet DSM-IV criteria but major symptoms of the disorder; 5 = DSM-IV definite, but no prominent psychotic symptoms and no extreme impairment in functioning; and 6 = DSM-IV definite, severe and either prominent psychotic symptoms or extreme impairment in functioning).

Those with a score of 5 or 6 on LIFE satisfied DSM-IV criteria. If a participant consented but did not complete the follow-up interview, the case notes (up to 96 weeks) were used to determine the time to recurrence, if applicable. Participants under the care of a NHS trust had their electronic and paper notes reviewed, whereas those participants seen only by their general practitioner (GP) had their GP notes reviewed. As previously outlined,71,78 a bipolar episode was recorded when there was a description of symptoms of a manic-type or a depression-type episode with symptoms of sufficient duration to meet episode criteria76 and there was a change of medication, care setting (inpatient or crisis team) or urgency of being reviewed because of these symptoms. When necessary, the same criteria were used to extract data from primary and secondary care records using assessors blinded to treatment group allocation.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures were:

-

time to next manic-type episode (mania, hypomania or mixed affective episode) and time to next depressive episode72,79

-

assessment of mean weekly symptoms of mania-type symptoms and depression symptoms using the LIFE72,79

-

assessment of function using the Social Adjustment Scale (SAS)29 and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS)81

-

observer- and self-rated measures of mood: 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D),82,83 Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Scale (MAS)84 and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)85

-

the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12),86 a 12-item self-completed questionnaire evaluating eight domains of overall health (general health, role–physical, physical function, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, role–emotional and mental health) in the preceding 4 weeks summarised as physical component scores and mental component scores.

The SCID LIFE, HAM-D and MAS efficacy outcome measures were recorded by interview at baseline and every 16 weeks up to 96 weeks. The remaining outcomes were recorded at baseline and at follow-up weeks 32, 64 and 96. Participants were given the option of returning self-rated outcomes by stamped, addressed envelope to the trial office.

Interventions

Group psychoeducation

The bipolar group PEd programme was run by three facilitators, two health professionals (usually one experienced and one in training as a facilitator), specially trained for the purpose, and a SUF with a diagnosis of BD35 and trained for the purpose. The SUF in the role of therapist working with a health professional was not part of the trials run in Spain60 (where they used three therapists), but was successfully piloted in Newcastle upon Tyne, England,70 before the start of the current trial. In the latter study, feedback suggested that the SUF ensures that the SU perspective is integral to the programme and provides additional credibility to the programme in the eyes of the participants. The SUF also served as a role model for the participants in tasks set out in the PEd manual. 70

In accordance with the trials of group PEd conducted in Spain,60 the PEd programme consisted of 21 sessions delivered over 26 weeks. 71 The group sessions used a closed group format; the sessions started with a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 18 participants in order to capture a variety of SU experience in relation to the topics covered at each session. A manual was produced, along with a handout for each session covering the content of that session. The groups were run as a collaborative workshop with a brief didactic introduction of the topic for the session, and the rest of the work taking the form of active interaction using the collective experience of the participants. 60 However, as recommended,60 the content of both the manual and the sessions themselves had been brought up to date to reflect recent research evidence,58,87 and the content was adapted to expectations of English SUs as determined by a panel of SUs working with the trial. For example, there was a greater emphasis on the role of family and the carer, there were changes to the wording of the manual and handouts so that they were written using more recovery-based language,57,88 and examples were given that were meaningful to English people and to the English context of service provision. Embedded in the PEd programme is the acquisition of specific skills by each individual, including life charting, recognition of early warning signs, problem-solving and other forms of coping, sleep hygiene and care planning, as well as general skills of actively participating and working collaboratively in the groups. Table 1 shows the sessional content of the programme. Any participant who missed a session was provided with printed materials for the session and an opportunity to discuss these before the next session.

| Session number | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to the group and defining BD |

| 2 | What causes and triggers BD |

| 3 | Symptoms 1: mania and hypomania |

| 4 | Symptoms 2: depression and mixed episodes |

| 5 | Evolution of BD and the future |

| 6 | Treatment 1: mood stabilisers |

| 7 | Treatment 2: antimanic drugs |

| 8 | Treatment 3: antidepressants |

| 9 | Pregnancy, genetic counselling and effects on families |

| 10 | Prescribed drugs and alternative therapies |

| 11 | Risks associated with treatment withdrawal |

| 12 | Alcohol, smoking, diet and street drugs |

| 13 | Early detection of mania and hypomania 1 |

| 14 | Early detection of mania and hypomania 2 |

| 15 | Early detection of depression and mixed episodes 1 |

| 16 | Early detection of depression and mixed episodes 2 |

| 17 | What to do when a new phase is detected |

| 18 | Regularity of habits |

| 19 | Stress control techniques |

| 20 | Problem-solving strategies |

| 21 | Finalisation of stay well plan and closure |

At the point of consent to the study, and at the first and subsequent sessions, participants were told that the purpose of this intervention was to develop their own personalised and tailored ‘staying well plan’ using the information given by the group facilitators, their own experience made more explicit through life charting, and the collective experience of the group. They were told that the plan should fit into their personalised goals for recovery and had two elements: (1) those actions they take every day to stay well, such as taking medication and keeping a regular early morning routine, and (2) those actions that they would take if they started to become unwell with mania or depression. They were encouraged to share this information with the health professionals with whom they had continuing care relationships [e.g. community psychiatric nurse (CPN), psychiatrist, GP] and other people who were personally important to them. However, participants did not have to do this and were in control of how information was shared. Thus, many participants chose to write down detailed ‘staying well plans’ for themselves; some chose to share these with health professionals and other key significant people in their life, and others did not. Some groups chose to actively rehearse strategies for communicating this kind of information to health professionals and other close people.

Group peer support

The purpose of the PS intervention was to provide an active control for the bipolar PEd group, reflecting the most commonly available group PS offered by support groups for BD in England. The PS groups aimed to enable the group participants to devise ways of remaining well through discussion of collective experience, mutual information sharing and support. Although the groups were unstructured, participants collectively decided on an agenda for discussion at each session. Explicitly, participants were told at the point of consent to the study, and at the first and subsequent sessions, that the purpose of this intervention was that they used the resources of the group to generate their own personalised and tailored ‘staying well plan’. However, instead of having a session-by-session curriculum to follow, the group collectively decided what they would talk about and how they were going to help each other to stay well. They decided whether or not they told health professionals or other significant people in their life about their plans to stay well. Thus, these groups did not merely provide a meeting place where people with BD could meet other people with shared experiences, but also they gave people a shared sense of purpose to actively seek ways of learning from the group, and to remain well in the future. Therefore, the PS group provided a control for the processes of delivering a group intervention that was also consistent with the overall aim of the intervention for each participant, namely to stay well over time. As a result, the groups differ only in terms of the content and style of delivery. The two health professionals and one SUF met with the groups of up to 18 participants, but were there to facilitate discussion, encourage participation, prevent unhelpful group behaviour, such as bullying or scapegoating, prevent factual misinformation and, if directly asked, to clear up factual uncertainty. A manual on the conduct of the PS group was produced for the therapists and given as a handout in the first session. The supervision arrangements and recording of the conduct and content of the sessions were the same as for the group PEd sessions.

The content of the PS group sessions is shown in Table 2. In almost all PS groups participants chose to introduce themselves and discuss the causes and triggers of BD, mania, depression, prescribed drugs and alternative therapies, regularity of habits, stress control techniques, problem-solving strategies that overlapped with PEd, as well as services, benefits and welfare, emotions, relationships and personal experience that were not main topics in PEd. Just over half of the PS groups discussed early warning signs of mania and depression relapse, although they did so in one session, and also finalised a ‘staying well plan’. Hardly any PS groups discussed medication and the longitudinal course of BD in any detail.

| Topics covered | Number of groups (n = 11) (% groups) |

|---|---|

| Topic covered also by PEd programme | |

| Introduction to the group and defining BD | 10 (91) |

| What causes and triggers BD | 10 (91) |

| Symptoms 1: mania and hypomania | 11 (100) |

| Symptoms 2: depression and mixed episodes | 11 (100) |

| Evolution of BD and the future | 1 (9) |

| Treatment 1: mood stabilisers | 0 |

| Treatment 2: antimanic drugs | 0 |

| Treatment 3: antidepressants | 0 |

| Pregnancy, genetic counselling and effects on families | 5 (45) |

| Prescribed drugs and alternative therapies | 8 (73) |

| Risks associated with treatment withdrawal | 3 (27) |

| Alcohol, smoking, diet and street drugs | 5 (45) |

| Early detection of mania and hypomania | 6 (55) |

| Early detection of depression and mixed episodes | 6 (55) |

| What to do when a new phase is detected | 6 (55) |

| Regularity of habits | 8 (73) |

| Stress control techniques | 9 (82) |

| Problem-solving strategies | 9 (82) |

| Finalisation of stay well plan and closure | 7 (64) |

| Additional topics covered by PS | |

| Services | 9 (82) |

| Hospital | 5 (45) |

| Benefits and welfare | 9 (82) |

| Finances and debt | 4 (36) |

| Emotions | 8 (73) |

| Relationships (family and friends) | 8 (73) |

| Positivity | 5 (45) |

| The self (personal experience/life stories) | 8 (73) |

| The self (identity and perception) | 5 (45) |

| Stigma | 5 (45) |

| Anxiety (including panic attacks, social anxiety, health anxiety) | 4 (36) |

| Non-anxiety mental comorbidity and physical health | 4 (36) |

| Religion and spirituality | 4 (36) |

| Media | 4 (36) |

In both trial arms, participants received the trial group therapies in addition to their usual treatment. They did not attend any other group, family or individual psychological treatment for BD at the same time as attending the groups in the study. Otherwise, TAU was unconstrained and recorded through interviews and from case notes.

Randomisation and treatment allocation

Randomisation was conducted by a clinical trials unit that was given the participant information by the trial manager or by the trial administrator working under the direct supervision of the trial manager. Randomisation was undertaken only once a group of 20 participants in a wave had been identified at one geographical site close to where both groups would be held, as 10 was the minimum number of participants that would constitute a viable group size. The maximum number allocated to a group was 36. The allocation of participants to treatment was based on stochastic minimisation using number of previous episodes banded as 1–7, 8–19 and ≥ 20, and clinical site. The clinical trials unit conveyed the allocation to the trial manager, who then informed both the participants and the therapists conducting the group. The research assistants (RAs) conducting the interview assessments were blind to group allocation. All information regarding attendance at the groups was collected by the therapists so that RAs remained blind. Any instances of unblindings were recorded by the trial office. On the rare occasion that a RA was unblinded, an alternative RA at that site collected the remainder of that participant’s follow-up data. At baseline, before attending either group, participants were asked whether they had a preference for PEd or PS.

Ethics and research governance approval

The trial received national multicentre research ethics approval (09/H0408/33) and research governance approval and permission at each participating health service delivery organisation. The University of Nottingham sponsored and indemnified the trial. Each participant gave written informed consent to take part in the trial and, separately, gave written informed consent to take part in qualitative interviews, exploring in depth their experience of the trial. The trial was overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee organised by the research investigators for the purpose. The members of the committees were drawn from outside the institutions in which the research team worked and were not involved in other currently funded research with the investigators to ensure their independence from the research team.

Sample size

When patients receive treatment in groups, interactions between patients may lead to correlation of outcomes of patients in the same group,89 sometimes referred to as cluster. As with cluster randomised trials, sample size calculation needs to consider the possibility of intracluster correlation. 64 As there are no previous trials of group interventions for BD that have considered clustering, we considered empirical evidence regarding the magnitude of clustering from cluster randomised trials. A previous trial90 found a very variable clustering effect, ranging from 0 to 0.27 with a median of 0, but this was from a small sample and so would be imprecisely estimated. We therefore assumed a small, but not zero, intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for group therapy of 5% for the purpose of sample size calculation. Based on the outcomes from the two previous Barcelona protocol PEd RCTs,61,62 a differential treatment effect of 0.22 was estimated (60% recurrence in the control group and 38% in the PEd group at 12-month follow-up, as one of these studies reported only 12-month follow-up). The power for 80% probability of detecting a difference at 0.05 level using two-tailed testing required 82 patients per arm. Assuming a mean group size of 18 and an ICC equal to 0.05, the design effect will be 1.85, giving a sample size of 152 in each arm. An 85% follow-up rate was assumed, giving a target of 360 SUs randomised, with 10 therapy groups planned in each treatment arm to achieve 80% power. During the initial waves of the study, the therapy group size was smaller than planned (approximately 14 participants per group owing to a slightly slower rate of accrual of each wave). In consultation with the Programme Steering Committee, the number of waves was increased from 10 to 11. Owing to the smaller therapy group size, with a reduced target sample size of 308, the study retained 80% power under the same assumptions about the ICC and follow-up rate.

Statistical methods

The quantitative trial outcome data included time-to-event data and longitudinal quantitative data that could be considered continuous.

Time-to-event analyses

A Cox model with robust standard errors for therapy group effect was fitted to the primary outcome measure incorporating the clinical notes data. To assess the clustering effect, a standard Cox model with the same baseline covariates without robust standard errors was fitted. When there is a clustering effect by therapy group, the robust standard errors will be larger. If the robust standard errors are smaller, this suggests no clustering and inference based on the robust standard errors will be non-conservative, and so the standard Cox model results are presented instead. The treatment effect (PEd compared with PS) was adjusted for sex, number of previous bipolar episodes and recruitment wave. The model assumptions were assessed and found to be acceptable. The same approach was used for the two secondary outcomes of time to first mania-type and depression episode.

Continuous longitudinal data

Longitudinal statistical models were fitted across follow-up time points to the secondary outcome scale data. The main statistical analysis used to compare the two interventions was a linear random-effects model (LME). This may be thought of as fitting regression lines of outcome against time for each patient, with variation between patients represented by differences in the intercept and gradient of these lines. It should be noted that these models incorporate time as a continuous variable rather than assuming a number of discrete assessment points. In the resulting statistical model, random effects are included to account for between-patient variation in the intercept and the gradient of the patient-specific lines. In addition, models were fitted that included random effects for wave and arm (nested within wave) to take account of therapy group clustering effects.

Fixed covariates were included to model systematic differences due to treatment, assessment time point and participant characteristics. Time since randomisation was calculated in months and was centred by subtracting the overall (grand) mean of assessment times for each outcome measure. Centring makes the intercept interpretable when there is a treatment by time interaction.

Rather than fitting a model across baseline and follow-up responses, the baseline value of the outcome measure was included as a covariate. This is usually more efficient than including the baseline as a response variable and simplifies interpretation when there are several follow-up assessments. Using baseline as a covariate also reduces the problem of non-linearity that can occur if the change from baseline to the first follow-up assessment tends to be large compared with the change between subsequent assessments. In addition to treatment group and baseline measure, models included the fixed-effect covariates: centred time from randomisation to each assessment at 16-week intervals, sex and number of previous bipolar episodes. In addition to the covariates specified in the statistical analysis plan, region and the interaction between baseline value and centred time were also included to increase the precision of the treatment effect. Including the fixed effects given above, up to four models were fitted to each outcome: both fixed-effect treatment by time interaction (F) and random effects for wave and arm (R) included for model 1; only R included for model 2; only F for model 3; and neither were used for model 4.

For those scales (or subscales) on which higher scores represent a ‘worse state’, a negative gradient over time represents improvement. When higher scores represent a ‘better state’, a positive gradient represents improvement over time. A non-zero time–treatment interaction corresponds to differences between treatments in the rate of improvement or worsening over time. To test for a time–treatment interaction, the selected model with the interaction (model 1 or 3) was compared with the corresponding model without the term (model 2 or 4, respectively) using a likelihood ratio test (LRT). If the interaction was not significant, then this term was omitted and differences in mean level over time were reported corresponding to a systematic difference between treatments in the follow-up.

The following sequence of steps was followed to select a model for each continuous outcome:

-

If the treatment by time interaction from model 1 was statistically significant at the 5% level using a LRT, then this model was selected.

-

Otherwise, model 2 was selected.

-

If model 2 could not be fitted (SCID mania), then models 3 and 4 were compared using a LRT; if the treatment by time interaction from model 3 was statistically significant at the 5% level using a LRT, then this model was selected.

For each outcome, the ICC was calculated using the random-effect variances and residual variance estimates. Based on the selected model, normal probability plots and histograms were used to check the distributional assumptions for residuals of within- and between-subject variance terms. Statistical analyses were carried out using Stata® release 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Qualitative methods

A nested qualitative study was conducted to explore the experiences of group participants and identify facilitators of, and barriers to, the widespread delivery of the intervention. A maximum variance sample of SUs who had been randomised to either the PEd or PS groups was recruited, including participants who had taken part in the full programme and those who had dropped out at different stages. We sought to ensure that the final qualitative sample had a varied range of clinical and demographic variables (sex, age, number of previous bipolar episodes, geographical location of group), thereby likely to include the range of experiences from participants in the trial.

Service users were approached following the completion of the programme and invited to take part in a single semistructured interview at a time and location of their choice. A researcher then interviewed consenting participants. The interviews followed a topic guide that provided a flexible framework for questioning and explored a number of areas including participants’ experiences and views of the groups, their expectations and motivations for participating, group content and process, key points of learning or interest, and any issues or challenges experienced. The topic guide was developed following a literature search and discussion with the PARADES SU research group and amended following pilot interviews with members of this group.

The interviewing researcher used a combination of open questions to elicit free responses, and focused questions to probe and prompt as necessary. The interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber. The interviewer checked the quality and accuracy of the transcripts against the original audio-recording. At this stage, any identifying information (e.g. names and places) was removed.

The analysis proceeded in parallel with the interviews. Coding was informed by accumulating data and continuing thematic analysis. 91,92 An inductive and emergent approach was taken to the analysis, guided by the study’s core questions about participants’ experiences of the groups. The interviewing researcher open-coded the interview transcripts as they became available using an inductive approach, and researchers from different backgrounds (health and clinical psychology, psychiatry and SU) discussed the developing coding scheme. All team members read and coded a selection of transcripts, and at least two members of the team read all of the transcripts. Hence, all authors undertook the interpretation and coding of data and agreed the themes through discussion. Using a multidisciplinary team is a recognised method for increasing the trustworthiness of the analysis. 93 The thematic categories identified in the initial interviews were then tested or explored in subsequent interviews in which disconfirmatory evidence was sought. Themes were continuously compared against the data using a constant comparative approach. 94 The final sample size was determined by thematic saturation: the point at which new data are no longer contributing to the findings owing to participants’ repetition of themes and comments. 95 At this point, data generation was terminated.

Of the 304 participants in the trial, 68 were identified for interview, of whom 37 consented and completed an interview (18 from the PEd arm and 19 from the PS arm). Of the 31 participants who were not interviewed, all initially agreed to be contacted, were in receipt of the participant information sheet and had the opportunity to discuss the interview with the interviewing researcher. Seven participants decided at this point not to take part, 20 were unable to be contacted and four did not attend their arranged interview. Twenty-eight interviews were completed face to face and eight interviews were completed by telephone. Owing to an unavoidable interruption, one participant was interviewed in two parts, initially by telephone and subsequently face to face. The mean duration of SU interviews was 47.2 minutes (range 29–103 minutes). Interviews were also conducted with health professional facilitators (n = 14/15) and SUFs (n = 9/10) to explore their experiences of the groups; however, these are not reported here.

Quantitative results

Recruitment into the trial

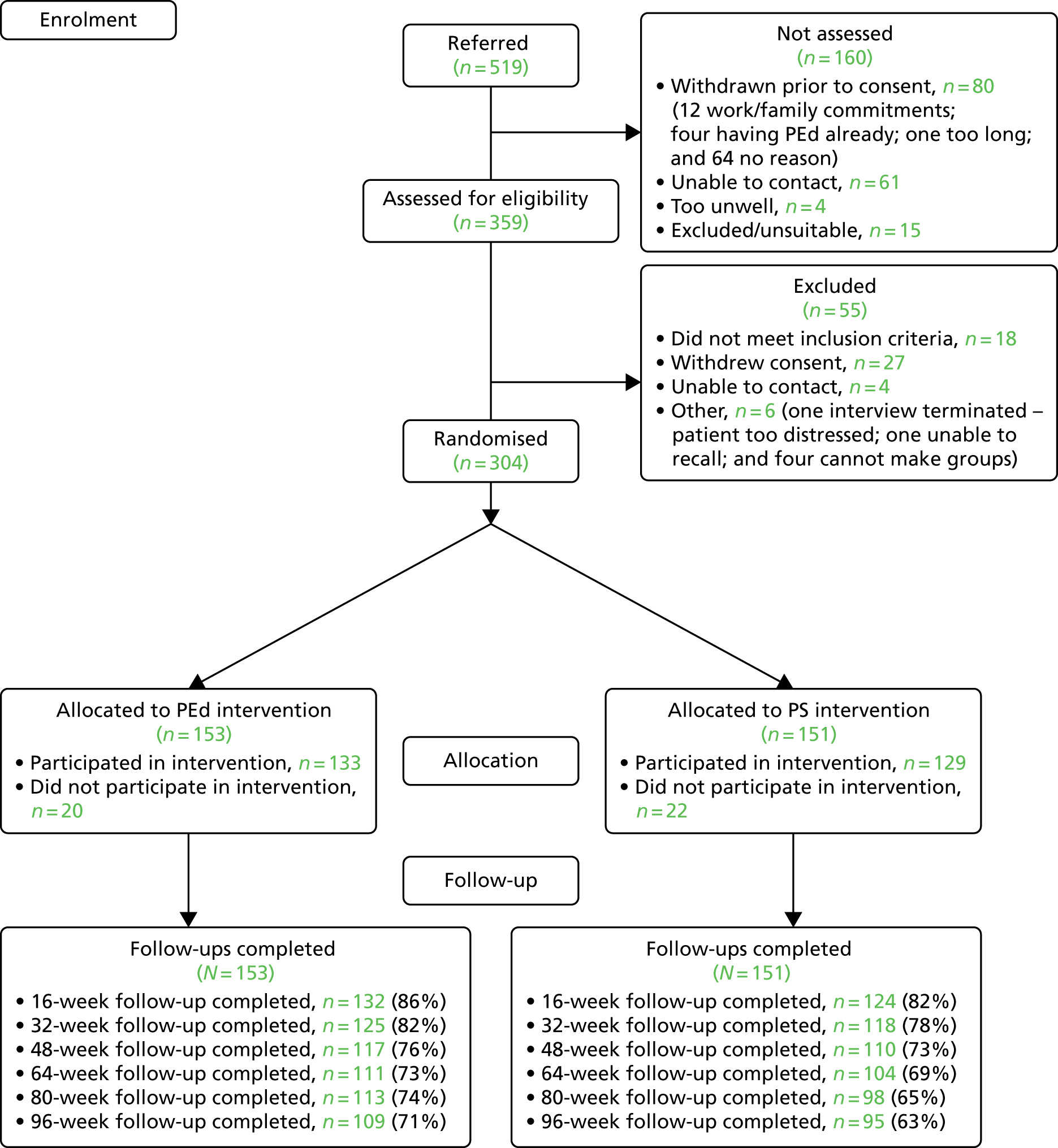

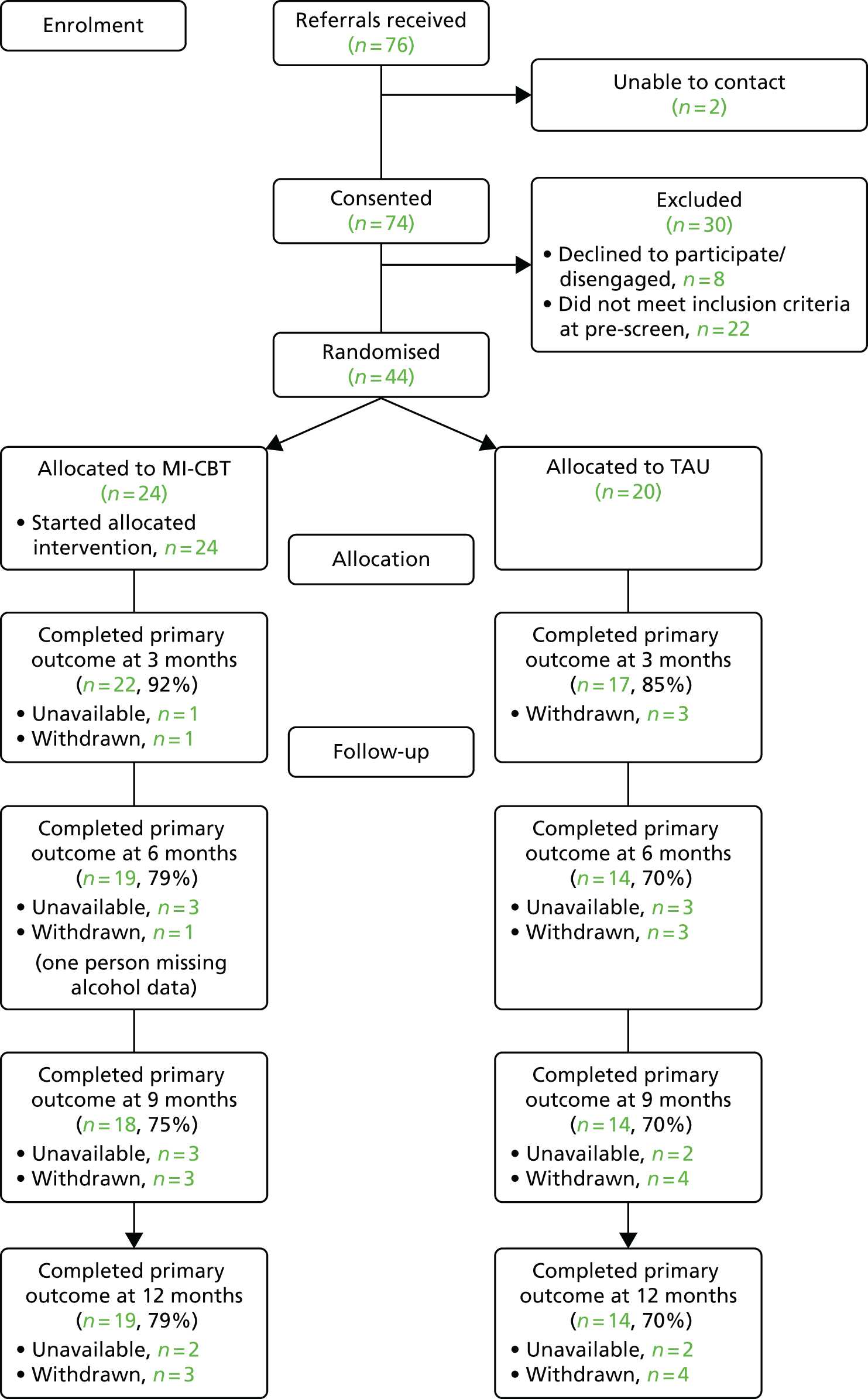

Table 3 and Figure 1 show the flow of participants through the trial, with six waves of recruitment in the North West (at four different geographical sites) and five in the East Midlands (at four different geographical sites). The additional wave in the North West was required to meet the total sample size of 308 participants estimated by our power calculation; we recruited 304 participants, four participants short of the revised target, between June 2009 and January 2012. In each wave the total numbers of participants were individually randomised so that they had an equal chance of attending PEd or PS, and the procedure for recruitment, treatment and assessment were the same in both the North West and the East Midlands. Recruitment was carried out in two inner-city sites, three rural sites and three urban sites.

| Wave | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| East Midlands | |||||

| Group PEd (number randomised = 14) | Group PEd (number randomised = 11) | Group PEd (number randomised = 11) | Group PEd (number randomised = 14) | Group PEd (number randomised = 17) | |

| Group PS (number randomised = 11) | Group PS (number randomised = 10) | Group PS (number randomised = 13) | Group PS (number randomised = 14) | Group PS (number randomised = 17) | |

| Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | |

| North West | |||||

| Group PEd (number randomised = 12) | Group PEd (number randomised = 17) | Group PEd (number randomised = 10) | Group PEd (number randomised = 17) | Group PEd (number randomised = 16) | Group PEd (number randomised = 14) |

| Group PS (number randomised = 12) | Group PS (number randomised = 15) | Group PS (number randomised = 11) | Group PS (number randomised = 17) | Group PS (number randomised = 16) | Group PS (number randomised = 15) |

| Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) | Minimise for number of previous bipolar episodes (≤ 7, 8–19 and ≥ 20) |

| 49 recruited in total in wave 1 | 53 recruited in total in wave 2 | 45 recruited in total in wave 3 | 62 recruited in total in wave 4 | 66 recruited in total in wave 5 | 29 recruited in total in wave 6 |

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of participants into the study from all sites and waves combined.

Three hundred and four (84.7%) participants were recruited into the study. In addition, 27 people who otherwise met the inclusion criteria of the study refused to give consent and six further people were unable to commit to the groups for practical reasons (e.g. time off work); 22 people were either not contactable or did not meet inclusion criteria on assessment. Two hundred and forty-three (79.9%) people completed the first follow-up point after completing treatment; and 204 (67.1%) completed interview assessments at the 96-week follow-up. Three participants were missing baseline assessments, although they had an assessment of eligibility and consented to take part. A further four subjects had baseline assessments taken after randomisation, so these data are not included in the summary statistics and analyses. Data on all bipolar relapses, mania and depression relapses were completed using primary care and secondary care records.

Four participants died during the follow-up period of the study from natural causes that were deemed by an independent TSC and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee to be unrelated to the interventions or procedures in the trial.

Baseline characteristics of treatment groups

Table 4 shows the baseline characteristics by treatment group. The study recruited a predominantly white British sample that contained more women than men, and a wide age range from 21 to 73 years. There were some baseline differences between the groups, with the PEd group being, on average, slightly younger [PEd mean age = 44.2 years, standard deviation (SD) = 11.1 years; PS mean age = 46.5 years, SD = 11.4 years] and more likely to be married and including fewer people with bipolar 1 disorder. Only 24 (7.9%) participants were not white British; 10 were black, seven were of mixed race, three were South Asian, three were white non-British and one was Chinese. Ethnicity was unavailable for two participants. Also of note was that the majority of participants had children. Just over one-quarter of participants were employed. Forty per cent of the sample expressed no preference for either treatment group, but more people expressed a preference for PEd over PS, although all were willing to be randomised to either group. Table 4 also shows that the groups did not differ on psychiatric comorbidity, with around 70% reporting psychotic symptoms in their lifetime, 40% describing a current anxiety disorder, just over 40% reporting an alcohol abuse or dependence problem in their lifetime and just under 10% with a borderline or antisocial personality disorder. Nearly three-quarters of the participants in both groups were taking mood-stabilising medication, although the proportion doing so was slightly higher in the PS group than in the PEd group. Similar numbers from both groups were receiving antipsychotic (54–55%) and antidepressant (46–47%) medication.

| Characteristic | Treatment group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| PEd (N = 153) | PS (N = 151) | |

| Sex: female | 92 (60.1) | 85 (56.3) |

| Number of previous bipolar episodes | ||

| 1–7 | 21 (13.7) | 18 (11.9) |

| 8–19 | 50 (32.7) | 45 (29.8) |

| ≥ 20 | 82 (53.6) | 88 (58.3) |

| Bipolar 1 | 114 (74.5) | 129 (85.4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living as married | 63 (41.2) | 46 (30.5) |

| Never married | 46 (30.1) | 53 (35.1) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 44 (28.7) | 52 (34.4) |

| With children, one or more | 90 (58.8) | 93 (61.6) |

| Employment | ||

| In full-time/part-time work | 45 (29) | 37 (24) |

| Unemployed/sickness/retired | 108 (71) | 114 (76) |

| Ethnicity: white British | 140 (91.5) | 138 (91.4) |

| Region | ||

| North West | 86 (56.2) | 86 (56.9) |

| East Midlands | 67 (43.8) | 65 (43.1) |

| Group preference | ||

| Prefer PEd | 55 (35.9) | 54 (35.8) |

| No preference | 66 (43.1) | 57 (37.7) |

| Prefer PS | 29 (19.0) | 35 (23.2) |

| Missing | 3 (2.0) | 5 (3.3) |

| Psychosis, lifetime | 97 (63.3) | 114 (75.5) |

| Any anxiety disorder | ||

| Lifetime | 87 (56.9) | 75 (49.7) |

| Past month | 68 (44.4) | 57 (37.7) |

| Any alcohol abuse/dependence | ||

| Lifetime | 56 (36.6) | 61 (40.3) |

| Past month | 4 (2.6) | 12 (7.9) |

| Any drug abuse/dependence | ||

| Lifetime | 10 (6.5) | 21 (13.9) |

| Past month | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) |

| Borderline/antisocial personality disorder | 12 (7.8) | 13 (9) |

| Baseline medication | ||

| Mood stabiliser | 108 (70.5) | 118 (78.1) |

| Antipsychotic drugs | 83 (54.2) | 84 (55.6) |

| Antidepressant drugs | 71 (46.4) | 71 (47.0) |

| Hypnotic/antianxiety | 21 (13.7) | 19 (12.6) |

| Baseline medication equivalences (mg/d) | ||

| Chlorpromazine | 188.2 | 182.8 |

| Imipramine | 83.6 | 80.4 |

| Diazepam | 2.25 | 2.43 |

Tables 5–7 summarise the trial secondary outcome measures at baseline and follow-up assessments. These show that, symptomatically and functionally, there were no clinically important differences between the groups at baseline. Symptomatically, participants scored on average just below the clinical threshold for observed depression symptoms on the HAM-D, slightly above the minimum clinical threshold for depression and anxiety symptoms on self-rated measures, with more severe anxiety than depression, and minimal mania symptoms at baseline. Consistent with the inclusion criteria, although a few participants scored above the symptomatic threshold score for depression for 1 week, the duration of symptoms meant that they did not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode. No participants met the criteria for a mania-type episode at baseline. On average, participants showed no more than slight impairment in social and occupational functioning overall (SOFAS and overall SAS) and across all domains (performance, interpersonal, friction and dependency).

| Time from baseline (weeks) | Treatment group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEd (n = 153) | PS (n = 151) | |||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | n | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | n | |

| SCID LIFE weekly mean score for depression over 16-week period | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.83 | 0.85 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 152 | 1.84 | 0.87 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 4.25 | 148 |

| 16 | 1.84 | 0.88 | 1.58 | 1.00 | 4.87 | 131 | 2.00 | 1.08 | 1.59 | 1.00 | 5.92 | 123 |

| 32 | 2.18 | 1.14 | 1.91 | 1.00 | 5.18 | 124 | 2.00 | 1.01 | 1.80 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 118 |

| 48 | 1.89 | 1.07 | 1.56 | 1.00 | 5.88 | 117 | 1.94 | 1.03 | 1.69 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 111 |

| 64 | 1.83 | 1.05 | 1.44 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 113 | 2.00 | 1.05 | 1.73 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 105 |

| 80 | 1.85 | 1.05 | 1.41 | 1.00 | 5.50 | 114 | 2.06 | 1.00 | 1.82 | 1.00 | 4.75 | 98 |

| 96 | 1.84 | 1.15 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 5.39 | 107 | 1.94 | 1.00 | 1.59 | 1.00 | 5.24 | 98 |

| SCID LIFE weekly mean score for mania over 16-week period | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.20 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.50 | 152 | 1.28 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 148 |

| 16 | 1.24 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.63 | 131 | 1.27 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 123 |

| 32 | 1.22 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.63 | 124 | 1.28 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 118 |

| 48 | 1.17 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.88 | 117 | 1.24 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.33 | 111 |

| 64 | 1.22 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.60 | 113 | 1.30 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 105 |

| 80 | 1.23 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 114 | 1.16 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.78 | 98 |

| 96 | 1.21 | 0.46 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 107 | 1.36 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.36 | 98 |

| HAM-D | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 6.59 | 5.18 | 7.00 | 0 | 27 | 152 | 6.17 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 0 | 26 | 145 |

| 16 | 7.04 | 7.15 | 4.50 | 0 | 30 | 131 | 7.58 | 6.29 | 6.63 | 0 | 24 | 123 |

| 32 | 7.00 | 7.17 | 5.00 | 0 | 35 | 122 | 8.18 | 7.26 | 6.00 | 0 | 33 | 119 |

| 48 | 6.09 | 6.91 | 4.00 | 0 | 32 | 117 | 7.19 | 7.71 | 5.00 | 0 | 36 | 111 |

| 64 | 6.73 | 6.71 | 4.38 | 0 | 29 | 111 | 7.62 | 6.49 | 6.00 | 0 | 34 | 104 |

| 80 | 5.69 | 6.09 | 3.63 | 0 | 32 | 112 | 7.08 | 7.25 | 5.00 | 0 | 30 | 98 |

| 96 | 6.39 | 6.04 | 5.00 | 0 | 28 | 107 | 7.07 | 7.33 | 5.00 | 0 | 36 | 98 |

| MAS | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.84 | 2.40 | 1.00 | 0 | 13 | 152 | 2.38 | 2.84 | 1.00 | 0 | 13 | 145 |

| 16 | 2.14 | 3.08 | 1.00 | 0 | 15 | 131 | 2.16 | 3.25 | 1.00 | 0 | 17 | 123 |

| 32 | 1.80 | 2.82 | 1.00 | 0 | 18 | 122 | 1.80 | 2.61 | 1.00 | 0 | 14 | 119 |

| 48 | 1.21 | 2.12 | 0.00 | 0 | 11 | 117 | 2.17 | 3.50 | 1.00 | 0 | 20 | 111 |

| 64 | 1.83 | 2.77 | 1.00 | 0 | 15 | 111 | 2.03 | 3.39 | 1.00 | 0 | 18 | 104 |

| 80 | 1.84 | 3.02 | 1.00 | 0 | 16 | 112 | 1.33 | 1.84 | 1.00 | 0 | 11 | 98 |

| 96 | 1.88 | 3.53 | 1.00 | 0 | 18 | 107 | 1.84 | 4.14 | 0.00 | 0 | 30 | 98 |

| Time from baseline (weeks) | Treatment group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEd (n = 153) | PS (n = 151) | |||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | n | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | n | |

| SOFAS | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 75.8 | 12.2 | 80 | 40 | 91 | 143 | 76.5 | 12.3 | 80 | 41 | 91 | 137 |

| 32 | 72.5 | 13.2 | 71 | 41 | 94 | 121 | 71.9 | 13.1 | 71 | 21 | 94 | 113 |

| 64 | 74.1 | 14.3 | 80 | 11 | 91 | 110 | 74.0 | 12.3 | 80 | 40 | 95 | 99 |

| 96 | 75.4 | 13.5 | 80 | 41 | 100 | 106 | 73.1 | 14.5 | 72 | 32 | 95 | 96 |

| SAS: overall | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.92 | 0.55 | 1.83 | 1.00 | 4.25 | 146 | 1.94 | 0.53 | 1.83 | 1.00 | 3.86 | 139 |

| 32 | 2.00 | 0.66 | 1.86 | 1.08 | 3.86 | 121 | 1.98 | 0.52 | 1.86 | 1.14 | 3.45 | 114 |

| 64 | 1.97 | 0.74 | 1.80 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 109 | 2.05 | 0.55 | 2.00 | 1.10 | 3.67 | 102 |

| 96 | 1.91 | 0.63 | 1.83 | 1.00 | 4.14 | 104 | 2.09 | 0.73 | 2.00 | 1.11 | 4.71 | 96 |

| SAS: performance | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 2.23 | 0.80 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 146 | 2.31 | 0.82 | 2.17 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 139 |

| 32 | 2.36 | 0.85 | 2.33 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 121 | 2.38 | 0.89 | 2.15 | 1.00 | 4.50 | 114 |

| 64 | 2.30 | 0.88 | 2.14 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 109 | 2.37 | 0.83 | 2.27 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 102 |

| 96 | 2.31 | 0.94 | 2.15 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 104 | 2.42 | 0.96 | 2.21 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 96 |

| SAS: interpersonal | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.70 | 0.60 | 1.62 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 146 | 1.77 | 0.58 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 3.33 | 139 |

| 32 | 1.81 | 0.70 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 121 | 1.73 | 0.69 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 114 |

| 64 | 1.64 | 0.61 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 4.67 | 109 | 1.73 | 0.63 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 3.33 | 102 |

| 96 | 1.52 | 0.55 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 104 | 1.75 | 0.76 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 96 |

| SAS: friction | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.51 | 0.59 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 146 | 1.54 | 0.54 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 139 |

| 32 | 1.59 | 0.72 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 121 | 1.57 | 0.61 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 114 |

| 64 | 1.56 | 0.78 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 109 | 1.61 | 0.58 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 102 |

| 96 | 1.50 | 0.67 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 104 | 1.70 | 0.75 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 4.50 | 96 |

| SAS: dependency | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.86 | 0.92 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 146 | 2.05 | 1.08 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 138 |

| 32 | 2.07 | 1.12 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 120 | 2.03 | 1.25 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 112 |

| 64 | 1.80 | 0.98 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 107 | 2.04 | 1.17 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 102 |

| 96 | 1.49 | 0.62 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 103 | 1.62 | 0.74 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 95 |

| Time from baseline (weeks) | Treatment group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEd (N = 153) | PS (N = 151) | |||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | n | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | n | |

| HADS-A | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 9.63 | 4.93 | 9.50 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 130 | 9.70 | 4.86 | 10.00 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 125 |

| 32 | 9.20 | 5.10 | 9.00 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 66 | 10.35 | 4.57 | 10.00 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 75 |

| 64 | 9.38 | 5.41 | 10.00 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 66 | 10.75 | 4.95 | 11.00 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 60 |

| 96 | 9.67 | 4.84 | 9.00 | 1.00 | 18.00 | 51 | 9.21 | 5.14 | 8.08 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 52 |

| HADS: depression | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 8.24 | 4.78 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 19.00 | 130 | 8.22 | 5.29 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 125 |

| 32 | 7.12 | 4.92 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 66 | 8.37 | 4.81 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 19.00 | 75 |

| 64 | 6.98 | 5.13 | 6.50 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 66 | 8.85 | 4.98 | 9.00 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 60 |

| 96 | 7.46 | 5.68 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 51 | 7.58 | 5.40 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 19.00 | 52 |

| SF-12: mental component score | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 37.0 | 12.1 | 34.8 | 13.6 | 63.2 | 128 | 36.1 | 12.1 | 33.4 | 12.8 | 63.7 | 120 |

| 32 | 37.5 | 11.7 | 37.6 | 15.3 | 62.8 | 66 | 36.6 | 10.9 | 34.0 | 14.1 | 57.3 | 75 |

| 64 | 37.9 | 13.2 | 35.4 | 13.0 | 66.7 | 66 | 35.0 | 11.1 | 33.5 | 16.1 | 61.0 | 60 |

| 96 | 38.9 | 12.8 | 36.6 | 12.1 | 60.3 | 49 | 37.1 | 11.4 | 34.1 | 19.2 | 60.6 | 52 |

| SF-12: physical component score | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 43.8 | 11.0 | 43.8 | 17.6 | 63.4 | 128 | 46.1 | 11.5 | 47.2 | 18.6 | 65.9 | 120 |

| 32 | 43.1 | 12.3 | 43.6 | 18.0 | 62.7 | 66 | 43.0 | 12.3 | 44.8 | 15.8 | 64.5 | 75 |

| 64 | 43.4 | 11.6 | 44.8 | 15.5 | 62.1 | 66 | 42.0 | 12.0 | 42.6 | 13.3 | 64.4 | 60 |

| 96 | 44.2 | 12.3 | 44.4 | 16.8 | 62.0 | 49 | 42.1 | 11.5 | 40.8 | 21.8 | 63.8 | 52 |

Attendance at the groups

The distribution of the number of sessions attended by PEd and PS group is presented in Table 8. The proportions who did not attend any group sessions of PEd and PS were similar (13% and 15%, respectively). The median number of sessions attended was 14 in the PEd group, compared with nine in the PS group. Overall, rates of attendance were higher for PEd groups than for the PS groups (Mann–Whitney U test z = 2.23; p = 0.026). With evidence of overdispersion, a negative binomial model for count data was used to investigate selected baseline factors that could potentially influence attendance. The following variables were included in the model (p-values given in brackets): sex (p = 0.888); number of previous episodes (1–7 vs. ≥ 20, p = 0.761; 8–19 vs. ≥ 20, p = 0.926); bipolar 1 disorder versus bipolar 2 disorder status (p = 0.289); group preference (none vs. prefer PEd; p = 0.779; prefer PS vs. prefer PEd p = 0.517); arm (p = 0.223); and wave (p-values ranged from 0.415 to 0.974). As shown from the above, none of these differences was significant.

| Sessions attended | Treatment group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEd (N = 153) | PS (N = 151) | |||||

| n | % each category | Cumulative % | n | % each category | Cumulative % | |

| 0 | 20 | 13.1 | – | 22 | 14.6 | – |

| 1–5 | 25 | 16.3 | 86.9 | 41 | 27.2 | 85.4 |

| 6–10 | 12 | 7.8 | 70.6 | 17 | 11.3 | 58.2 |

| 11–15 | 29 | 19.0 | 62.8 | 25 | 16.6 | 46.9 |

| 16–21 | 67 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 46 | 30.5 | 30.5 |

Response rates and missing data

Logistic models with a random effect for wave and arm (nested within wave) to take account of therapy group clustering effects were fitted to examine factors potentially predictive of missing primary depression outcome data at weeks 32 (over the treatment period) and 96 (over the whole follow-up period). The same covariates (i.e. sex, number of previous episodes, arm, baseline mania score and baseline depression score) were used for each model. None of these factors was predictive of non-response on the SCID LIFE at weeks 32 and 96. Sex, number of previous episodes and baseline score were specified as covariates in the statistical analysis plan for the LME analyses to increase the precision of estimates. No follow-up SCID LIFE data were available for a total of 14 (9%) participants in the PEd arm, compared with 21 (14%) in the PS arm.

Reliability and quality assurance

Ten unblindings occurred because the participant divulged their group allocation to their RA (three in PEd group and seven in the PS group). In seven cases this occurred during follow-up interview. One participant wrote their group allocation on self-completion paperwork, one telephoned the RA to change their assessment date and divulged their group allocation, and one RA overheard a conversation from the therapy team that unblinded them. When unblinding occurred during an interview, an alternative RA rated the SCID LIFE codings to avoid bias. For all seven participants, an unblinded RA was assigned for their remaining follow-ups.

An inter-rater reliability (IRR) study was carried out of the weekly SCID LIFE assessment in which scores of 1–6 were assigned for each of mania and depression. An ICC was determined for the depression and mania scores separately and percentile CIs were determined using a bootstrap resampling by subject. Six raters made 292 assessments of 17 subjects, with a mean of 17.2 assessments of each subject and 2.35 assessments per time point. The ICC was 0.71 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.85) for depression scores and 0.57 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.83) for mania scores, indicating a moderate level of inter-rater agreement. 96 There were 24 bipolar relapses in the IRR exercise (18 with depression-type and six with mania-type relapses). For the combined depression and mania outcomes, the ICC was 0.56 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.89).

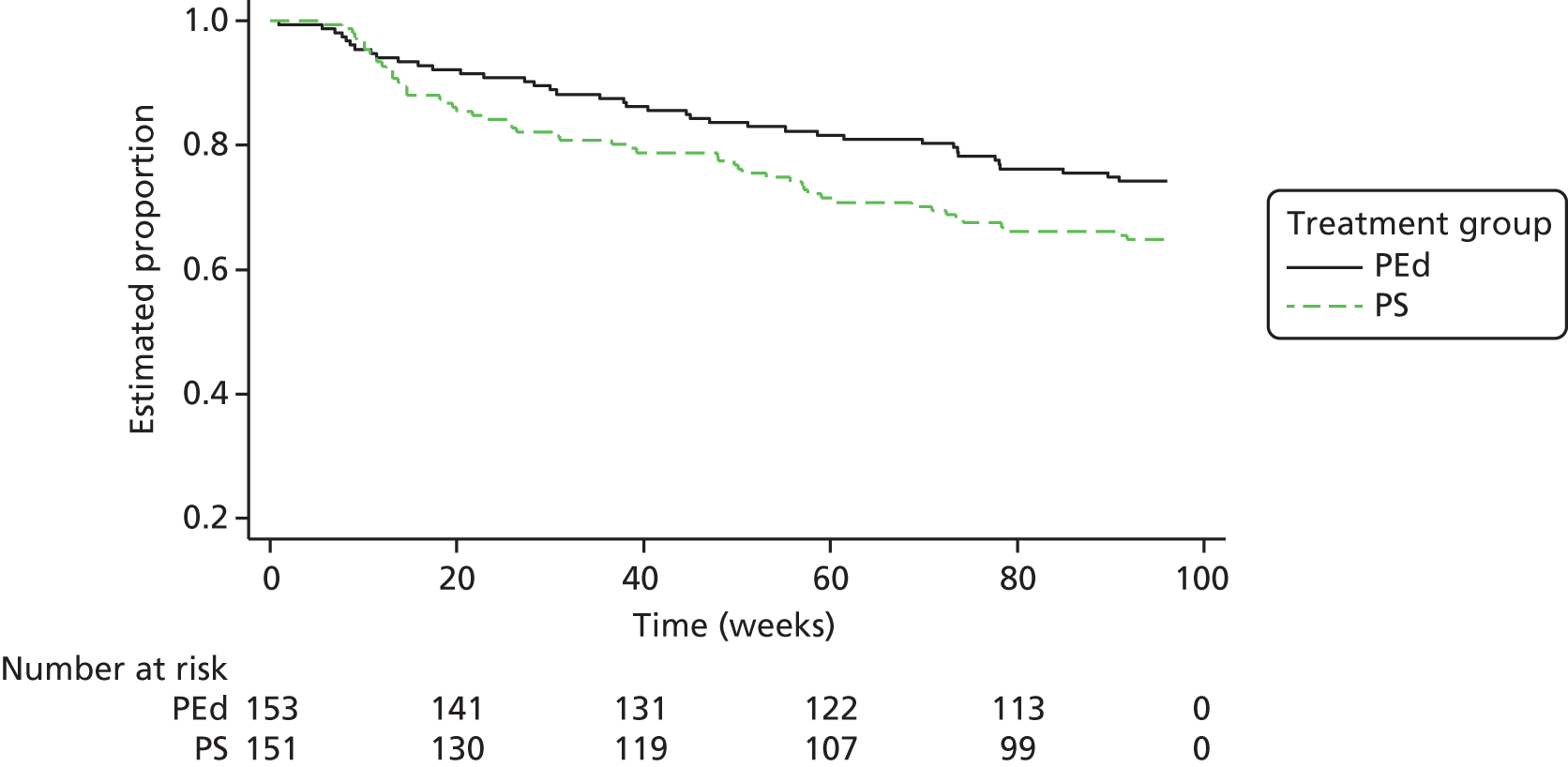

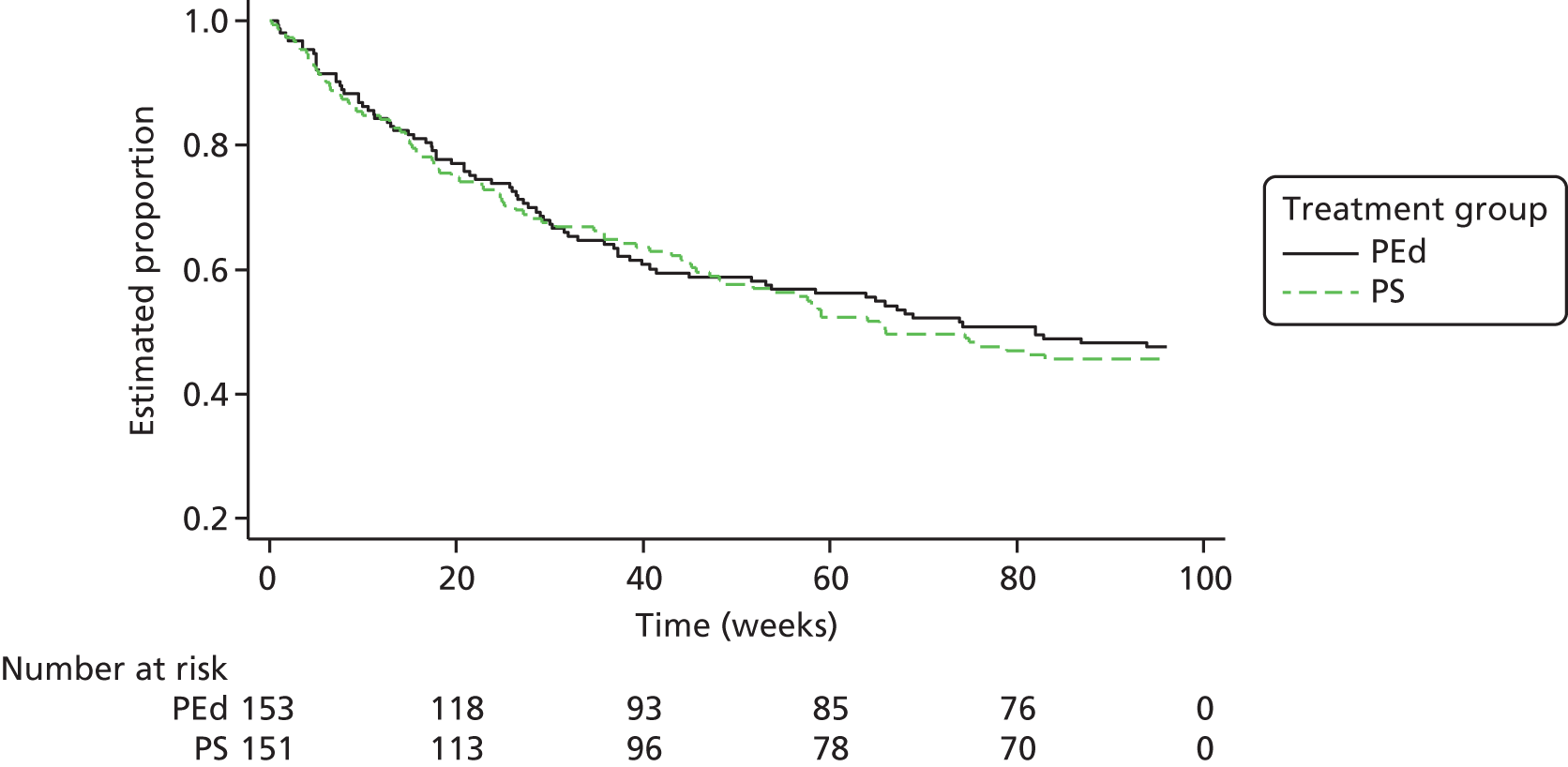

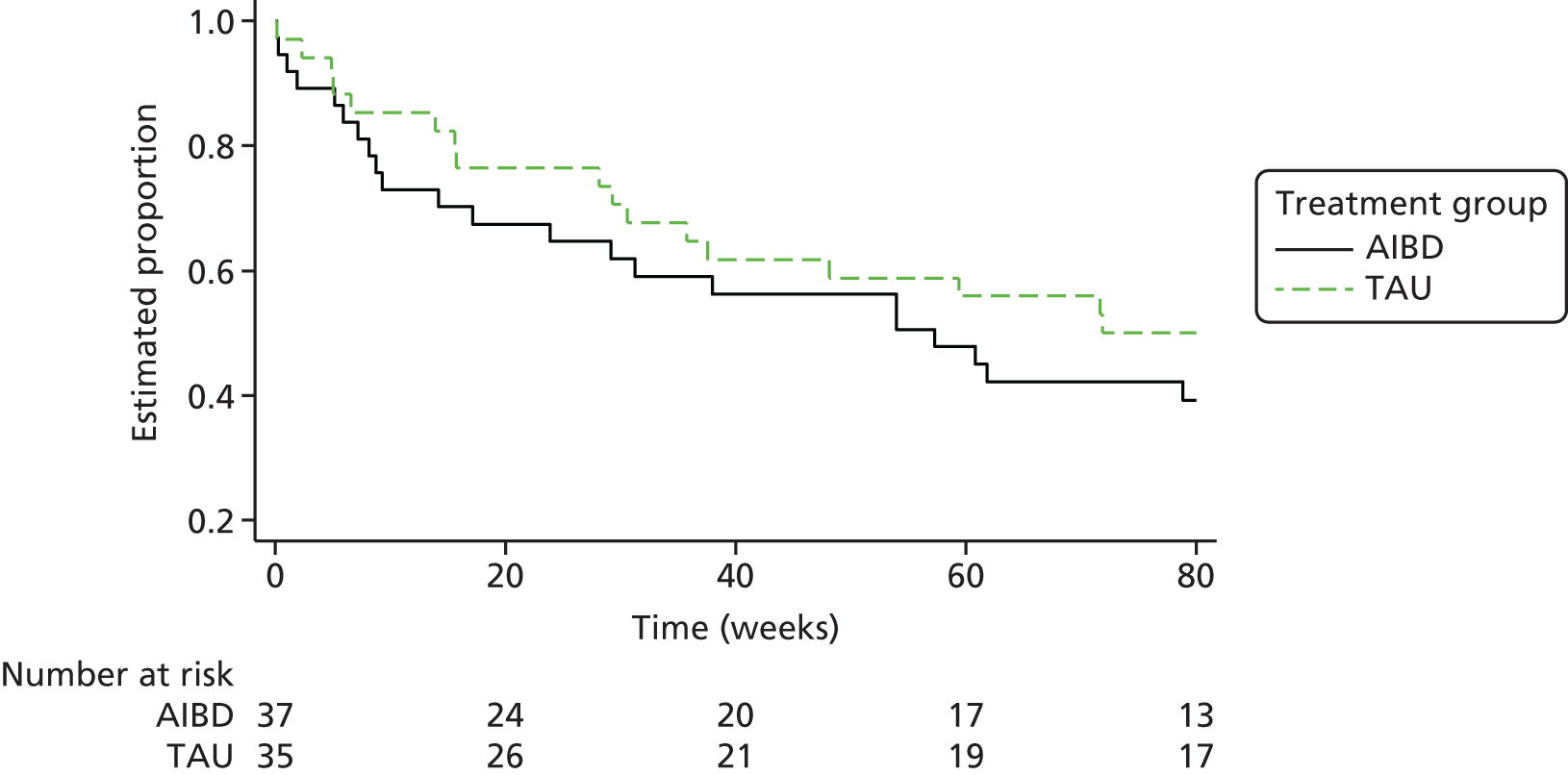

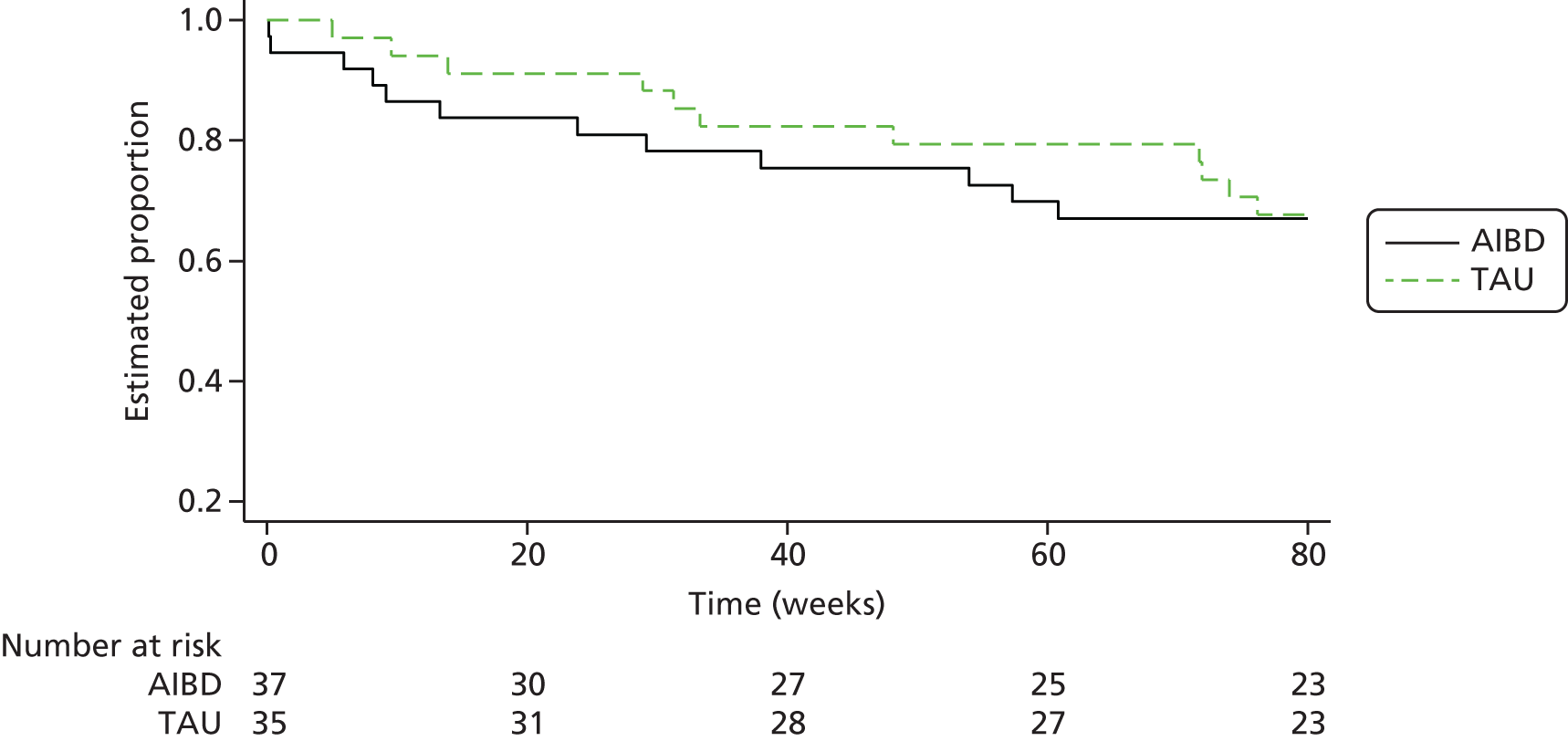

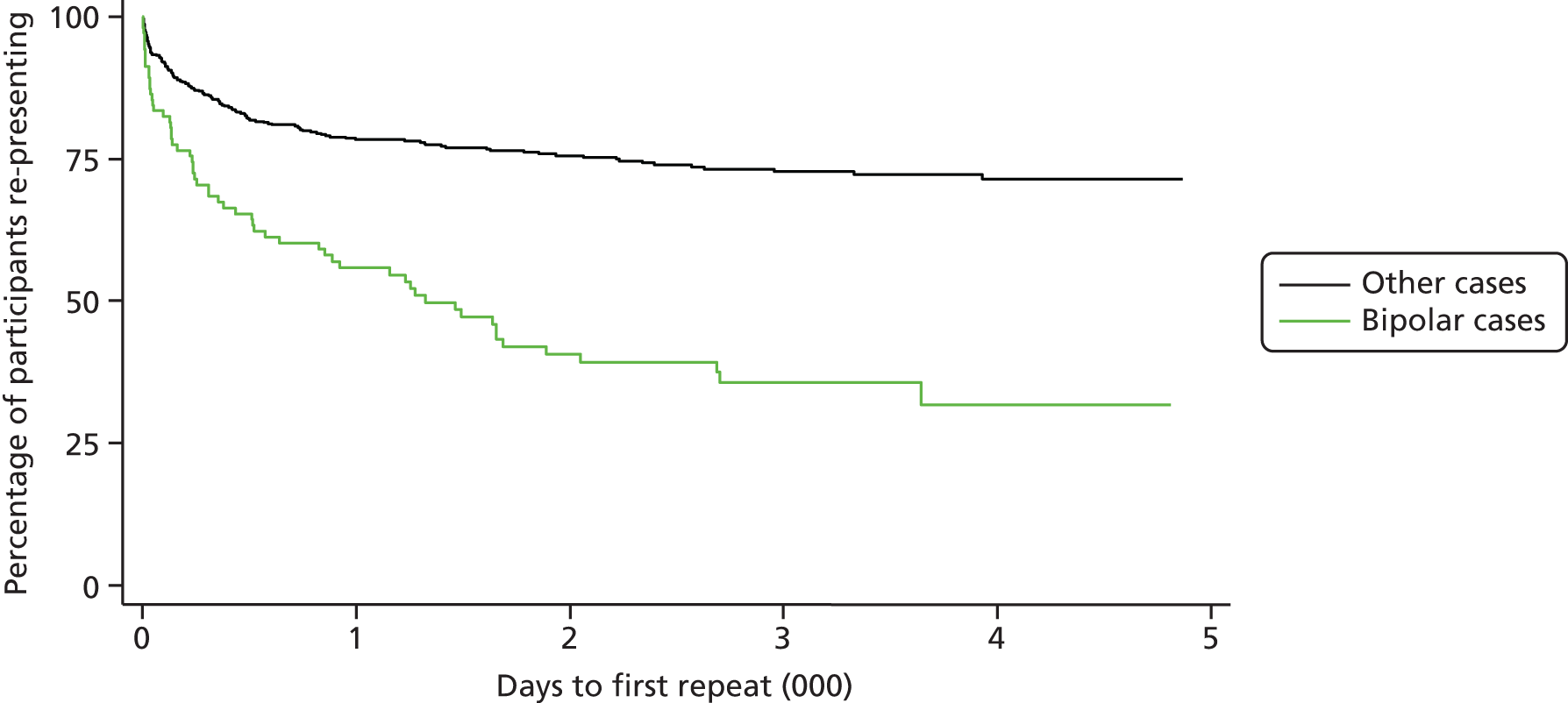

Episode recurrence

Of the 153 participants in the PEd arm, 89 (58%) had a recurrence of an episode of depression or mania type during the 96-week follow-up. In the PS arm, 98 (65%) had a recurrent episode. Of the first recurrences, 75% in the PEd arm and 63% in the PS arm were depressive episodes. When the Cox models with and without robust standard errors were compared, there was no evidence of a clustering effect (as the ratio of the square of the standard errors of the models with and without a cluster term was less than one), and so the latter are presented. A Kaplan–Meier plot for time to first recurrence in the two groups is shown in Figure 2. The estimated median time to first bipolar relapse was 67.1 (95% CI 37.3 to 90.9) weeks in the PEd group, compared with 48.0 (95% CI 30.6 to 65.9) weeks in the PS group, a difference of 19.1 weeks. When the Cox model was fitted, the adjusted HR was 0.83 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.11; LRT p = 0.217). Male participants tended to show a greater improvement than female participants in terms of time to relapse (HR 0.74; p = 0.052). There was also a non-significant (p = 0.094) trend for greater beneficial effects among SUs, with few bipolar episodes prior to joining the trial (8–19 vs. ≥ 20, HR 0.74; p = 0.073; 1–7 vs. ≥ 20 HR, 0.67; p = 0.105). The moderating effect of episode pre trial is considered below.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to first depression- or mania-type bipolar episode.