Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1050. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in February 2014 and was accepted for publication in January 2017. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Wykes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Overview of the programme

Mental health, including inpatient mental health, is in the news. In 2011, the government released a strategy entitled No Health Without Mental Health to close the gap between physical and mental health services. 1 It stated ‘We are clear that we expect parity of esteem between mental and physical health services’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0). 1 More recently, the 5-year forward plan now includes parity between mental and physical health2 and a policy document now promises to remedy the crisis in mental health care. 3 The Guardian4 also ran a feature in the same week describing the deleterious effects of bed closures on mental health inpatient services. These problems, although highlighted in 2014, were on the horizon when this research programme was developed and its results are now even more relevant with the recognition of further problems and the political support for parity between mental and physical health services.

In this chapter we describe the background, rationale and aims of our programme, which investigates the inpatient experience of mental health service users. We do this from a stakeholder perspective by involving both mental health services users and clinicians in all phases of the study. Throughout the report we refer to the programme as PERCEIVE which refers to Patient Involvement in Improving Patient Care. PERCEIVE consists of four work packages (WPs), two methodological and two investigating innovations into inpatient mental health care. PERCEIVE’s overarching aim is to investigate and improve the delivery of inpatient mental health services. This descriptive information can also be found on www.perceive.iop.kcl.ac.uk/about.html. 5

Background

In the UK, as well as internationally, there has been a gradual move to treating mental health service users in the community and a reduction in the number of mental health hospital beds. Alongside this there has been an unceasing pressure on mental health services to reduce costs. Inpatient care is the costliest component and so has been at the forefront of these cost-saving exercises. A great deal of effort, time and money has gone into improving mental health services over the past 50 years, often without any rigorous evaluation. This project seeks to examine the costs, the effects of innovative organisational changes made to service delivery, what activities service users engage in while inpatients and, most importantly, the experience of inpatient care from a stakeholder perspective.

Pressure on the number of inpatient beds available

Advances in psychopharmacology, changing attitudes towards mental illness and institutionalisation and the growing concerns about the quality of life in asylums have led to the gradual transition from the long-term hospitalisation of those with mental health problems to an increase in community treatment. However, hospitalisation for working-age adults is still an indispensable feature of mental health care and in 2011/12 accounted for around 40% of the NHS budget on mental health care for this group. 6 Bed numbers have continued to fall over the past 50 years, although the need for them to provide respite for the acutely ill remains the same. This reduction in the number of beds means that wards are now generally reserved for the most acutely ill. Consequently, there is an increase in the proportion of inpatients who are compulsorily detained and in the levels of behavioural disturbance. 7–9 In turn, this fraught environment can lead to difficulties in staff recruitment and retention. Taken together, this often brings about ward environments that appear to be more custodial than therapeutic.

Therapeutic activities and positive interactions on wards

Despite heavy investment, service users and front-line staff continue to complain about the quality of inpatient care. 10 More than 50 years ago, when institutionalism was being re-evaluated, Wing and Brown carried out their well-known Three Hospitals study which confirmed that the hospitals that provided richer social environments and social opportunities had markedly less disturbance in verbal and social behaviours. 11 Over the 5 years of the Wing and Brown study, the social environment improved in all participating hospitals and the clinical condition of patients improved alongside it. Those patients with the least access to the outside world, the least amount of social interaction and with the fewest interesting activities to take part in and who spent the majority of their time doing nothing were the most unwell. However, the study found that as their environments became more stimulating, they too showed some improvements.

All inpatient wards strive to provide an environment that is conducive to recovery and the importance of the social environment and therapeutic activities is recognised not just by those providing services, but also by those who use the services. For instance, a Mind report10 examining acute wards across England and Wales found that service users often complained about the intense boredom they experienced. The lack of therapeutic activities (or the cancellation of those on offer) is often as a result of staff shortages and/or too many demands being placed on staff. Service users are aware of this dilemma. 10 Nurses are often blamed for being immersed in the crisis management for a minority of patients or for spending time on administrative duties; both of these problems have increased as the acuity on wards increases. Nurses are therefore much less able to spend time on therapeutic activities or in direct patient contact. 12,13 Another reason often given by staff for not providing or running groups on acute wards is that service users are too ill to appreciate or take part in structured activities. However, it is not obvious that this is the case and it is the subject of some of our studies. This is not borne out in empirical studies. For instance, Kavanagh et al. 14 showed that education groups for individuals on a psychiatric intensive care ward were beneficial in improving knowledge of medication and the side effects of medication, and were appreciated by service users despite high levels of acuity in this group. A further barrier to the regular provision of therapeutic activities might be that the nurses lack the skills or confidence to run them. Hence, we included training and increasing skills for all staff on the ward. Although the majority of research in this area has originated in the UK, a recent review of the literature on patient activities and interaction encompassed international perspectives and found that this lack of service user engagement seems to hold true across North America, Australia and Europe. 15

A Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health report16 provided a more optimistic view of inpatient care, finding that nearly three-quarters of ward managers across England reported that both practical activities (e.g. cooking skills) and talking therapies occurred regularly on their wards, and 64% reported that leisure activities (e.g. bingo) occurred regularly. However, therapies with a strong evidence base, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), occurred only on 20% of wards. The recommendations included increasing the availability of training in therapeutic activities that have an evidence base. 16 What remains unknown from the report is how often therapeutic activities happen because, although activities may be something the wards aspire to provide and schedule into the ward timetables, how often they happen in practice may be a different matter.

Innovations in the service pathway have also been suggested to improve the therapeutic atmosphere of wards by reducing the patient flux where recovery-oriented approaches might be made. Hence, we included a comparison of two different service systems that might show how changes in patient flow could affect service user views. The innovative change was the introduction into one system of a triage ward where service users were assessed for longer-term care or a return to the community with the support of the home treatment team (HTT).

Stakeholder involvement

Our programme of research sought to involve relevant stakeholders in all aspects of the programme, not only in the WPs themselves but also in the analysis and publications from the programme. PERCEIVE was proposed by a group of clinicians, NHS managers, clinical academics and service users. Our stakeholders were represented on the steering and management committees. A senior service user researcher (DR) who spent time on inpatient wards contributed to the overall design of the programme as a whole. WP1 was wholly dedicated to stakeholder involvement and was co-ordinated and run from the Service User Research Enterprise (SURE). This is a research unit which is co-directed by a service user researcher and employs people who are skilled researchers and who also have experience of using mental health services. WP1 [Lasting Improvements for Acute Inpatient SEttings (LIAISE)] researchers were situated in SURE, supervised by DR, making LIAISE a user-led programme of work.

We involved service users and nurses in developments in each WP. The largest input was to WP1, which involved producing both a service user and nurse measure of perceptions of inpatient wards. To do this, a participatory model was used,17 such that service user researchers facilitated the production of the service user measure and nurse researchers the generation of the nurse measure. It was made clear to participants that the researchers themselves were like them and that it was their experience that counted, something that is not always the case in health services research. At all stages of the measure development, including the measure developed in WP2, researchers met with service users for feedback at various stages and changes were made based on their suggestions. In all WPs, we also employed service user and nurse researchers to collect data and to develop the programme of activity. At the completion of WP3, we returned to the wards involved and sought feedback from service users and nurses on the impact the project had and what we could have done better.

Additional studies that flowed from the programme were nearly all the result of service user suggestions (see Appendices 1–4 for details).

Involving service users as researchers and seeking to focus on the patient experience is a vital component of this project. The Francis report18 has highlighted patient experience as important in terms of both clinical outcomes and safety and quality, something which has been a key part of our project from the start.

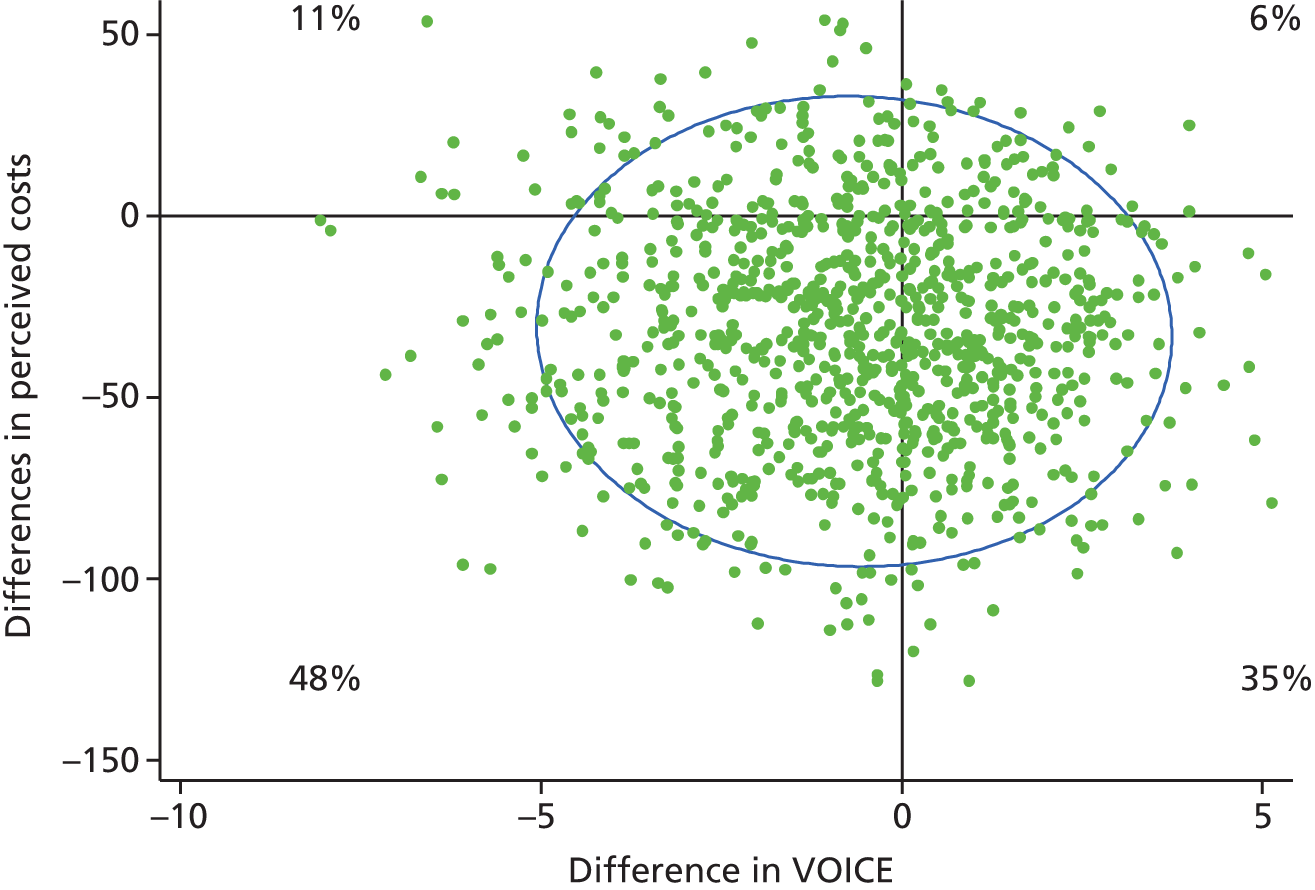

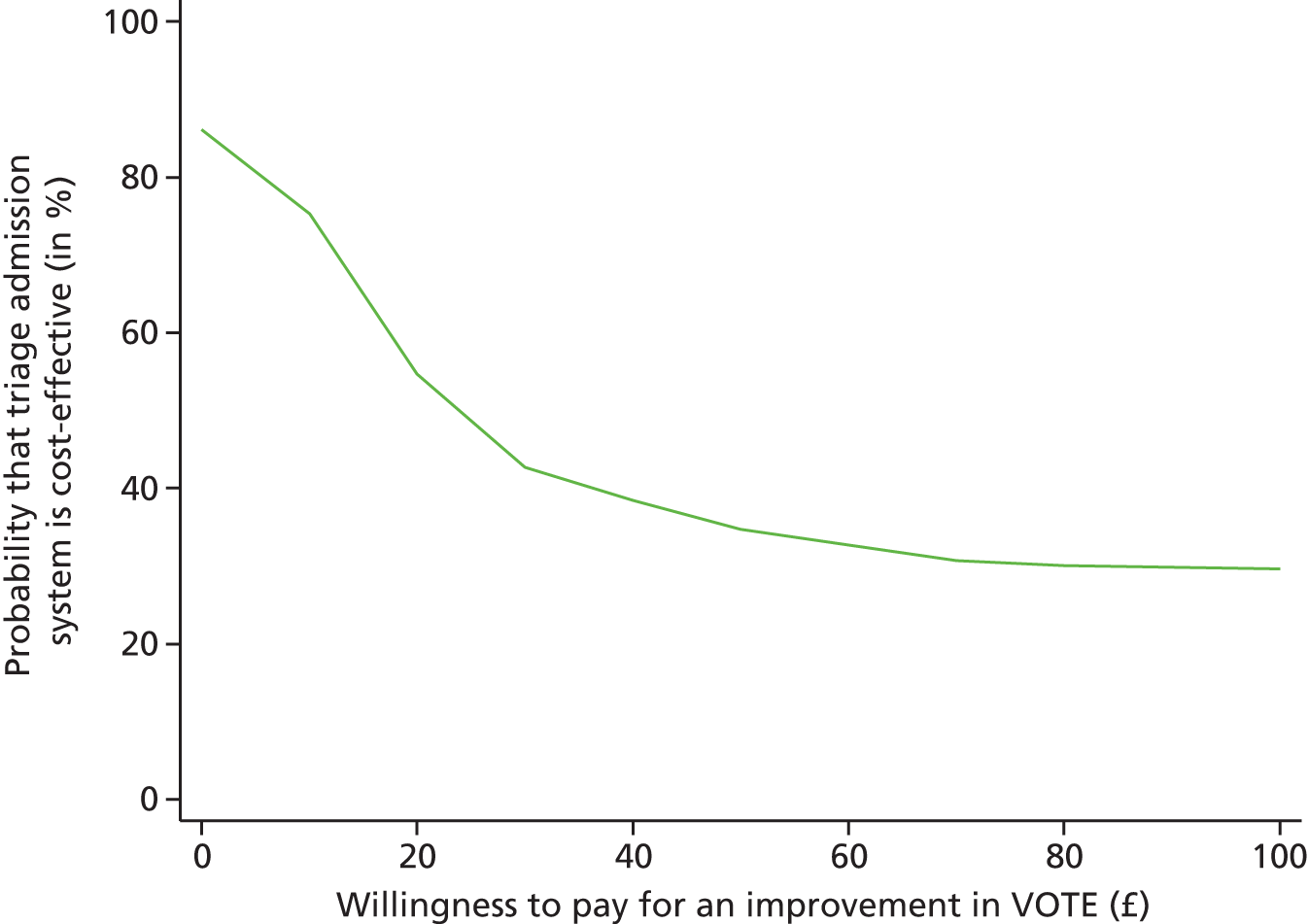

Health economic considerations

Given the high cost of inpatient care and, in particular, the context of limited health-care resources, it is essential to consider issues of cost-effectiveness in evaluations of new and existing interventions. However, there is a paucity of cost-effectiveness evidence pertaining to interventions focused on psychiatric inpatient wards such as increased therapeutic activities or triage models. Indeed, the methods used in most economic evaluations may actually be deficient in evaluating inpatient care because these frequently just record the number of days an individual spends as an inpatient and combines this with a standard unit cost. This ignores the fact that there will be heterogeneity in the number of staff who inpatients are in contact with and the uptake they have of activities irrespective of length of stay. The health economic component of the programme addressed these shortcomings by (1) developing an inpatient-focused resource use questionnaire and (2) using this questionnaire in the evaluations described in WP3 and WP4.

Work package 1

The first WP has the acronym LIAISE standing for Lasting Improvements for Acute Inpatient Settings. This was the WP that constituted service user-led research and extended that model to nurse research. The aim of the WP was to produce two measures capturing the experience of living and working in acute inpatient settings. The measures were generated using focus groups, expert panels and a feasibility study. The researchers for the service user measure were service user researchers [Views On Inpatient CarE (VOICE)] and the researchers for the nurse measure were nurse researchers [Views On Therapeutic Environment (VOTE)]. Both measures underwent psychometric testing and showed sound properties.

Work package 2

This WP was called Client Services Receipt Inventory – Inpatient (CITRINE) and had as the main aim the development of a measure of staff contacts and use of therapeutic activities on inpatient wards. As a precursor to this we conducted a systematic review of the literature to establish how inpatient activities had been measured in previous studies. This was then followed by the development of a draft questionnaire to record contacts and activities over a 1-week retrospective period. Consultation with clinical staff was crucial in this process and the questionnaire was piloted to determine its validity, reliability and acceptance from service users. The final version was then used in WP3 to evaluate the introduction of therapeutic activities to the wards and WP4 to evaluate the triage model.

Alongside the development and use of the questionnaire, we also reviewed the literature to identify economic evaluations of inpatient-based interventions. Our expectation was that these would be limited in number and, as an alternative to trial or observational methods, provide a demonstration of a decision modelling approach to conducting such evaluations.

Work package 3

The third WP [Delivering Opportunities for Recovery (DOORWAYS)] aimed to increase staff training and thereby increase the number of therapeutic activities occurring on the wards. Nurses working on the participating wards were offered training in a number of evidence-based therapeutic activities. After extensive discussion with nursing staff and their managers, a menu of therapies was chosen, from which each ward could choose the activities best suited to their needs. A stepped-wedge design was used to investigate the effect of the intervention on staff and service user perceptions of the wards. Nurses on all wards were offered the training, with two wards receiving training in each 6-month period. The order in which the wards were offered the training was determined by randomisation.

The wards randomised to the intervention would then receive the training. This consisted of a series of workshops involving a service user trainer and a clinical psychologist. For psychological activities, the clinical psychologist then demonstrated the group on the ward to the nurses, who then co-facilitated the group with the psychologist until ward staff were able to run them independently. Data collection on service user and nurse perceptions of the wards were completed before and after each randomisation and are the main outcomes in this WP.

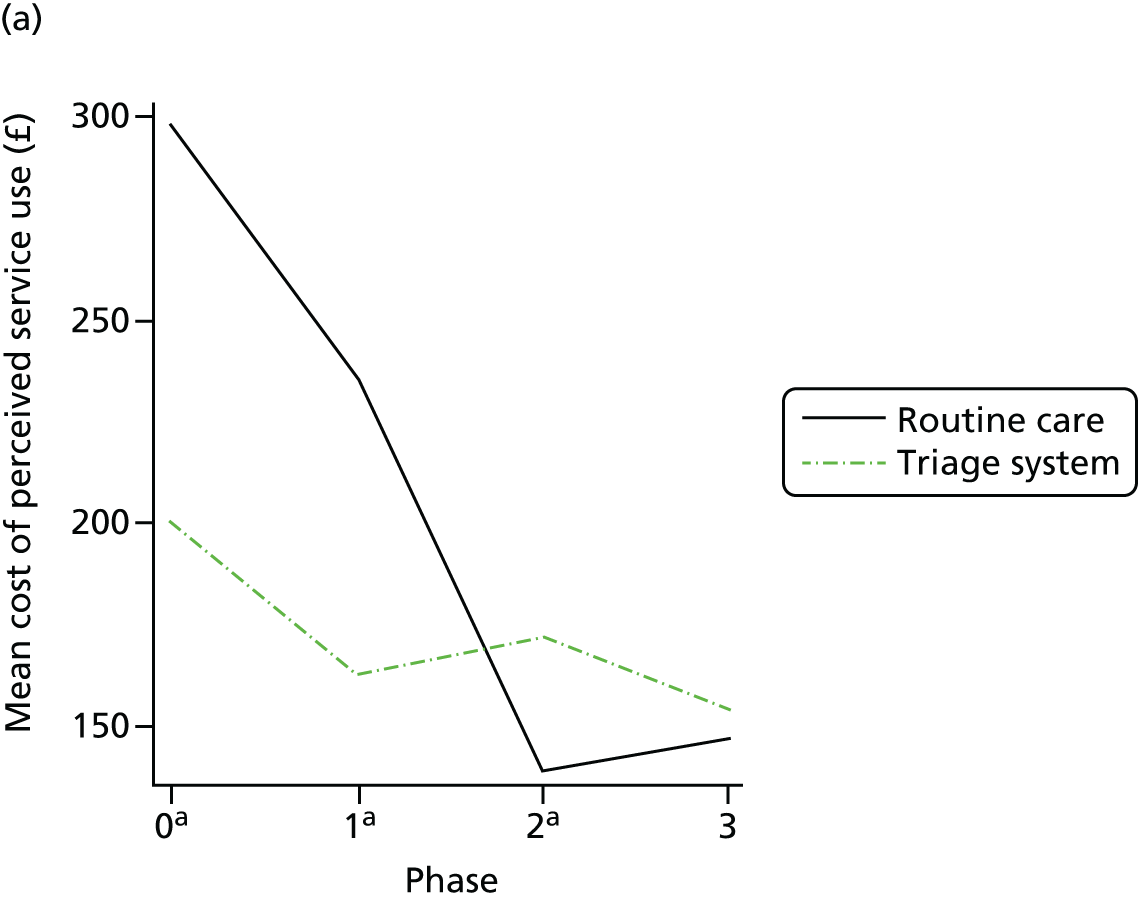

Work package 4

The final WP [Bringing Emergency TreatmenT to Early Resolution (BETTER PATHWAYS)] involved evaluating a unique admission system with a traditional admission system. One service within our catchment area developed a novel approach to solving the overcrowding and long admissions problems usually associated with inpatient care. They designated a specific ‘triage’ ward to accept all acute admissions in the catchment areas with immediate discharge planning beginning at admission, a guarantee to be assessed by senior members of the team and a tight working relationship with their HTTs. At the end of 7 days, service users were either discharged back into the community or transferred to one of three locality wards providing longer-term, more rehabilitative care. Initial reports suggested that it was working well but whether or not this has been maintained has not been evaluated. We undertook this WP in order to investigate whether or not the triage system does indeed reduce lengths of stay in inpatient care and whether or not it leads to a greater number of re-admissions than a more traditional system of inpatient care. Furthermore, we also investigated service users’ and nurses’ perception of these two systems to see if there were any clear preferences.

Objectives

We had six principal objectives:

-

To use methodology throughout the project which involved stakeholder participants.

-

To use stakeholder participatory methodology to develop and validate a measure of service user views of inpatient care.

-

To use stakeholder participatory methodology to develop and validate a measure of nurse views of inpatient care.

-

To develop and validate a patient-reported measure of staff contacts and uptake of activities while on inpatient wards.

-

To develop a training programme for nurses to increase their skills in running therapeutic activities and evaluate its effects on nurses’ and service users’ views of the wards.

-

To evaluate and compare a novel admission system to a traditional one on the perceptions of nurses and service users.

Chapter 2 Work package 1: LIAISE

Participatory research methods

The VOICE and VOTE measures were generated using a model of stakeholder involvement which holds at its core the concept of empowering under-represented groups in order to create well-balanced, responsive services. This method, pioneered in service user research,17,19–21 is novel because a researcher from the same group as the participants guides the process and the data are allowed to emerge by following the themes that the participants feel are the most important. This was also adapted for a nursing setting, with the emphasis being on a shared professional understanding, which fostered a non-judgemental research forum on which staff could express their experiences safely. A more balanced power dynamic between the researcher and the researched led to data and, subsequently, items on the scales that more accurately represented the views of services users and staff.

Background

In the UK and across the world, mental health hospitals have seen nursing staff shortages, bed shortages and an increase in complex presentations, especially in urban areas of high demand. 22–24 Indeed, mental health nurses perceive these issues as barriers to change in acute ward settings as well as poor/indeterminate leadership and incidents. 25,26 The effects of current working practices and the ward environment on the well-being of both staff and service users should be explored in more detail because an untherapeutic environment may negatively affect service user satisfaction and staff morale, may have a direct impact on the quality of the interactions between service users and staff and, moreover, may be detrimental to the overall quality of care. 27

Dissatisfaction with adult acute inpatient care is not a new issue and is well documented both in Britain and internationally. Negative service user reports of acute inpatient settings have emerged, describing the experience of hospital care as non-therapeutic and coercive. 28–30 Limited interaction between staff and service users is commonly reported and users express a need for good interpersonal relationships and support that is sensitive to individual needs. 31–33 Poor levels of involvement and a lack of information associated with medication, care and treatment have also been identified. 34 On many wards, there is little organised activity and service users experience intense boredom. 10 Security is of particular concern as many service users feel that they are not treated with respect or dignity, have significant safety concerns and report high levels of verbal and physical violence. 10

There is a rather sparse literature written by service user researchers themselves on acute inpatient settings, but it is important because information given to academic or clinical researchers may be influenced by the differential status of the two parties. Both Walsh and Boyle34 and Rose19 report that service users experience low levels of involvement and a lack of information about their care and treatment. This mirrors the nursing literature. Rose’s19 participants reported a lack of activities leading to crushing boredom and, like Mind’s Ward Watch campaign, patients reported feeling unsafe. 10

Alison Faulkner, a service user-researcher who spent time in acute wards, combines her systemic knowledge of mental health services with her own experience and that she has witnessed of others. 35,36 Drawing on the grey literature,30 she confirms the ‘shabbiness’ of wards, the intense boredom felt by the inpatients and the ‘petty’ rules and regulations. 35 She further concludes that in the inpatient wards she has frequented she was treated as ‘less than human’ and witnessed other patients also being treated as if they were a different species.

Studies in which the researcher was a user37,38 found that what was most important to service users was the quality of the therapeutic relationship. This is entirely in line with both UK policy and some of the nursing literature. Interestingly, good therapeutic relationships were prized whether the user was in a traditional acute ward or an alternative style of service, such as a crisis house.

Turning to the work environment for nurses, a growing body of literature links the stress of working on a ward to low morale, often measured as ‘burnout’ and poor job satisfaction. 39–41 Stress, burnout and lack of social support have been described as symptoms of a negative work environment. 26,42–44 Stressors such as high caseloads of patients, high volume of work, violence on wards45 and management issues such as poor leadership and low staffing levels42,46,47 have been linked to low morale. Different staff groups also seem to respond differently to work-related stressors. Jenkins and Elliott43 reported differences in perceptions of work-related stressors according to the occupational status of nursing staff. In their study, qualified staff cited poor staffing levels as the main stressor, while nursing assistants reported the main stressor as difficult interactions with distressed clients. Burnout was common to both groups. Cushway et al. 48 noted that occupational stress led to poorer mental health outcomes in male nursing staff than in females, perhaps because male staff are more likely to respond to violent situations. Burnout has also been described as affecting job performance and contributing to poor-quality care. 46,47,49 Both low morale and low job satisfaction result in poor staff retention, which again affects care quality. 50

The methods through which organisational outcomes are decided and the effects of these methods on the perceptions of the workforce may also be implicated in this negative trend. Organisational change in the NHS is often imposed via a top-down approach, which may not take into consideration the views of nursing staff. Indeed, change process issues, such as poor involvement in planning, implementation and control of a project, have been highlighted as potential barriers to success. 51 An inequitable stance to decision-making, perhaps as a result of poor staff involvement, may shape attitudes to planned changes if staff feel such changes are unfair to them or do not meet the needs of their client group. 52 This argument is supported by evidence from both the nursing and wider literature, which shows that staff who are in leadership roles may view changes more optimistically than staff who are involved in direct care with service users because they form part of the consultation process for the proposed changes. 53,54 The emotional response of staff to proposed changes may be an important barrier to the success of implementation.

Therefore, we propose a model where negative staff perceptions of the daily pressures of working on an acute ward and negative staff perceptions of barriers to change lead to burnout and low job satisfaction, and this affects the quality of care delivered. However, in order to test this model, the specific pressures for mental health nursing staff in maintaining a therapeutic environment and high-quality client relationships and the quality of care as perceived by service users must first be given more detailed consideration because, to date, these constructs remain underexplored. This is perhaps because the ward milieu is responsive to continuous organisational and social changes, that is, the client group and staff mix change on a daily basis and so this is a complex construct to measure. This model was considered in an add-on study carried out by a nurse researcher as part of her PhD and is presented in the appendix (see Appendix 3).

Objective measures of inpatient care, reviewed by Sharac et al. ,15 have many drawbacks. They neither capture the complexity of ward dynamics nor reflect the quality of inpatient care. Measures of perceptions have an important role to play in evaluating complex situations because they allow for objective stressors and their appraisal by subjects within the social environment, as well as linking cognitions with affective and behavioural components. 55

Recently there has been a focus on patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) as a measure of quality and appropriateness of services and therapies. Despite service user involvement being considered an essential element in improving mental health services,56 PROMs are rarely developed using an inclusive methodology and research suggests user dissatisfaction with many outcome measures currently in use. 57 Service users can often have different perspectives to professionals and can provide insight into how services and treatments feel. 58 Redefining outcomes according to users’ priorities can help to make greater sense of clinical research and develop a more valid evidence base. 36,59 Studies comparing the impact of traditional and user researchers in conducting research show some differences in qualitative data analysis60 but none on quantitative research findings. 17,61 Given this, we believe that research methodologies should aim to be as inclusive as possible.

There are also some staff measures in existence that address attitudes to occupational stress (e.g. The Mental Health Professionals Stress Scale48 and occupational stress indicator62) that highlight staff reactions to organisational pressures and team and client relationships. The well-known Daily Hassles Scale63 has also been used to appraise these stressors. However, these measures neither adequately explore whether staff view daily pressures as having an impact on the therapeutic milieu (and, therefore, on the quality of the therapeutic relationship) nor have they been developed using qualitative data generated by staff working within those areas.

In nursing studies, there has been limited focus on assessing how social, emotional and psychological barriers affect the implementation of new innovations. The relationship between psychological well-being and the acute ward setting in relation to planned changes may, in nursing, be distinct from other professions because nurses remain on the ward for the duration of their shift and are often expected to play a key role in delivering changes. There are several measures developed in health care that focus on the uptake of evidence-based practice in clinical areas by mental health providers and nurses. 64–71 However, there are no measures that focus on general changes in a mental health setting.

What is needed in the literature on acute care are psychometrically robust, brief, self-report measures reflecting service users’ experiences of receiving care and staff experiences of delivering/innovating that care. Measures of this type would allow a clear assessment of changes to inpatient care following specific interventions to improve the environment and therapy provided. Our study was designed to generate such measures.

The purpose of this section is to:

-

describe a model of service user and nurse involvement in developing two psychometrically sound measures. The service user measure captures service user perceptions of acute inpatient wards (VOICE) and the nurse measures capture staff perceptions of the daily pressures working on an acute ward (VOTE)

-

provide a secondary qualitative analysis of the data from VOICE and VOTE.

Methods

This study was designed to develop and test two self-report measures. The measures were generated through a process of stakeholder (service user and nursing staff) involvement. 17,19–21,59 This approach directly involved users of the mental health services and nursing staff in order to ensure measures were produced that captured an accurate picture of an acute care ward from both perspectives. Following the measure generation phase that used qualitative methods, prototypes of the new measures were assessed for their content validity, acceptability and feasibility prior to psychometric testing on two separate large samples of inpatient nurses and service users. Ethics approval was awarded by Bexley and Greenwich NHS Research Ethics Committee (07/H0809/49) for the study to be carried out in four boroughs within a London NHS Mental Health Trust.

Focus groups were conducted to generate data for VOICE and VOTE.

Phase 1: mapping out the dimensions of inpatient care

In this initial phase, three stakeholder/reference groups were held to map out the dimensions of inpatient care as a topic guide. In developing VOICE, the stakeholders were service users with experience of research and inpatient care who were not currently using local services. National voluntary organisations were also represented. In developing VOTE, the stakeholders consisted of senior nursing staff. Each group built a topic guide that was flexible in order to encourage as creative a list as possible. Members of these two groups also then constituted the reference groups for the user-led and staff parts of the study.

Phase 2: measure generation

For both VOICE and VOTE, purposive sampling was used to reflect local inpatient demographics with regard to gender, age and ethnicity when recruiting participants who were either staff or service users of an inner London UK mental health trust.

VOICE sample

The sample consisted of people who had used inpatient services within the previous 2 years. One of the groups was specifically for participants who had been detained under the Mental Health Act (2007)72 as it was anticipated that they may have had different experiences.

VOTE samples

Nursing staff from all grades (health-care assistants, entry-level qualified staff, clinical charge nurses and team leaders) were asked to participate in the development of VOTE. They were purposively sampled from acute inpatient mental health wards in an inner London UK mental health trust.

Focus groups

A pilot focus group was used to test the items on the topic guide. Then four two-part focus groups were run to enable respondent validation. This meant that the data from the first focus groups were analysed and results presented back to respondents in the second wave of focus groups to see if they agreed with the analyses or wished to amend, add to or change them. The aim was to ensure that the analyses were an accurate representation of the participants’ views.

The service user and nurse researchers then refined the thematic analyses and constructed the draft measure.

Expert panels

As a penultimate step, two expert panels met to discuss the design of the new measures and to inform the ‘instructions for use’. For the service users, one expert panel was made up of focus group members and the second was independent. Changes were made to the items, the layout of the measure and the language on the basis of this feedback.

Final consultation

The draft measure was finally presented back to the original reference group for their comments.

Psychometric assessment

The framework for psychometric assessment was that reported for the Health Technology Assessment on adequacy of outcome measures which used 10 criteria, including feasibility and acceptability as well as the usual categories of reliability and validity. 73

Samples

Service user participants for the feasibility study were recruited from acute wards and psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs), and test–retest participants were engaged on acute wards. For the larger psychometric testing phase, participants were recruited from acute wards. Service users were eligible if they could provide informed consent and they had been present on the ward for at least 7 days during the 4-week data collection phase. All nursing staff from all grades (health-care assistants, entry-level qualified staff, clinical charge nurses and team leaders) were asked to participate in the psychometric testing of VOTE. All potential participants gave written informed consent following an explanation of the study.

Phase 3: feasibility and acceptability

The final measures were intended as self-report tools, so studies of feasibility and acceptability were conducted to evaluate the burden of administering and completing the measure. In the feasibility study, participants completed the measure including two additional questions assessing whether or not the measure was easy to complete and understand. Acceptability was assessed using two additional questions collected from participants. Two tests which indicate readability, the Flesch reading ease test (the recommended score is between 60% and 70%), were assessed.

Phase 4: psychometric assessment

Scoring

Scoring methods for each measure were decided at this stage.

Reliability

Test–retest reliability was assessed with participants who completed the measures on two occasions with an interval of 6–10 days. The test–retest reliability was assessed by Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient,74 kappa and proportion of maximum kappa75 to measure the level of agreement between total scores and individual item responses at times one and two.

Generally, kappa scores of 0.21–0.4 indicate fair agreement, scores of 0.41–0.60 indicate ‘moderate’ agreement and scores > 0.60 indicate substantial agreement. 76 Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient can be interpreted similarly to a correlation coefficient.

Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, which refers to the correlation between items on the scale. Low scores would suggest that the items are not contributing to the same latent construct, those with a score of ≥ 0.7 are considered acceptable. 77

Face and content validity

Whether or not the new measures truly reflected the experiences of those receiving care (VOICE) and working (VOTE) in the acute inpatient services (face validity) and covered the full spectrum of views (content validity) was explored through participatory methodology during the instrument development phase.

Criterion validity

Criterion validity was assessed by testing hypothesised criteria against other relevant measures.

VOICE

We hypothesised that those with positive perceptions of acute inpatient services would also be satisfied with services. This was tested using the Service Satisfaction Scale – Residential Services Evaluation (SSS-RES). 78 This is adapted from the Service Satisfaction Scale-30 (SSS-30),79 designed to evaluate residential services for people with serious mental illness. The original SSS-30 has been used in a variety of settings and demonstrates sound psychometric properties. 80

VOTE

We hypothesised that those with negative perceptions of the daily ward pressures (VOTE) would have low levels of job satisfaction. This was tested using the Index of Work Satisfaction (IWS). This is a 44-item scale that can be totalled to produce a score that measures the level of job satisfaction for health professionals. Each item is answered on a seven-point Likert scale. 81

Construct validity

The construct under study for each measure was explored using factor analysis, with both orthogonal rotation using varimax and oblique rotation using promax. The final solution was chosen from the scree plot and the factor structure was chosen from the analysis that produced the highest loading. This analysis followed preliminary checks on the strength of the pairwise correlations between items and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. 82 The subscales produced were explored for internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. 83

Exploratory analyses

VOICE: Do demographic characteristics affect service user perceptions of the quality of acute ward care?

We expected differences in views between service users from different populations and clinical settings. Using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), we assessed whether or not service users’ perceptions differed by borough, gender, ethnicity, age, diagnosis, admission and legal status. The majority of the analyses were exploratory. However, we had specific hypotheses relating to ethnicity and legal status, for which we expected poorer perceptions from participants who were compulsorily admitted and those from minority ethnic communities.

VOTE: Do demographic characteristics affect staff perceptions of the daily pressures of working on an acute ward?

A regression analysis with the VOTE total score as the dependent variable and all demographic characteristics as the key independent variables was carried out using random-effects regression modelling (clustering on ward) to take into account the multilevel nature of the data. The purpose of this model was to identify any significant demographic predictors of negative staff perceptions of the daily stressors in the working environment (VOTE). The demographic variables were length of employment (> 3 years or < 3 years), qualified nurse or not, education (degree level or not), ethnicity [white, or black or minority ethnicity (BME)], country of origin (UK or not), gender and age (median split at age 39 years).

Results

Phase 1: mapping out the dimensions of inpatient care

VOICE

The stakeholder group recommended five core topics:

-

the effect of acuity on service users

-

security issues

-

medication

-

the experience of admission and discharge

-

how ward routine is experienced.

VOTE

The stakeholder group recommended six core headings for the topic guide:

-

patient care

-

core interventions

-

teamworking

-

change

-

safety

-

ethical issues.

Phase 2: measure generation

VOICE sample

As Table 1 shows, a total of 397 participants were recruited for the study: 37 for the measure generation phase and 360 for the feasibility study and psychometric testing. Schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders were the most frequent diagnoses for both groups and approximately half of each set of participants was from the BME community. In the measure development phase, 43% of participants were men and the median age was 45 (range 20–66). In the psychometric phase, 60% of participants were men and the mean age was 40 (range 18–75).

| Sociodemographic and clinical variable | Measure generation group, n (%) (N = 37) | Feasibility and psychometric assessment phase, n (%) (N = 360) |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 18 (48.6) | 168 (47) |

| BME | 19 (51.4) | 185 (51) |

| Not disclosed | 0 (0) | 7 (2) |

| Legal status | ||

| Formal | 20 (54.1) | 222 (62) |

| Informal | 12 (32.4) | 106 (29) |

| Not disclosed | 5 (13.5) | 32 (9) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Schizophrenia/psychosis | 18 (48.7) | 183 (51) |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 7 (18.9) | 51 (14) |

| Depression/anxiety | 6 (16.2) | 38 (11) |

| Personality disorder | 2 (5.4) | 19 (5) |

| Substance misuse | 0 (0) | 16 (4) |

| Other | 4 (10.8) | 46 (13) |

| Not disclosed | 0 (0) | 7 (2) |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 0 (0) | 62 (17.3) |

| Unemployed | 0 (0) | 248 (68.9) |

| Student | 0 (0) | 13 (3.6) |

| Retired | 0 (0) | 25 (6.9) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 5 (1.4) |

| Not disclosed | 37 (100) | 7 (1.9) |

| Admission | ||

| First admission | 0 (0) | 65 (18.1) |

| Previous admissions | 0 (0) | 260 (72.2) |

| Not disclosed | 37 (100) | 35 (9.7) |

VOTE sample

A total of 376 nursing staff participated in the measure development (Table 2). The majority of nurses were qualified nursing staff, while approximately one-third were health-care assistants. In the psychometric testing phase, 47% of participants were women and the median age was 39 years (range 20–67 years).

| Focus/reference group, n (%) (N = 48) | Feasibility group, n (%) (N = 40) | Test–retest group, n (%) (N = 43) | Psychometric group, n (%) (N = 245) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff | ||||

| Health-care assistants | 16 (33) | 23 (33) | 14 (33) | 72 (29) |

| Staff nurses | 23 (48) | 18 (45) | 16 (37) | 100 (41) |

| Clinical charge nurses | 9 (19) | 7 (18) | 8 (19) | 44 (18) |

| Team leaders | 0 | 2 (5) | 5 (12) | 17 (7) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White British | 13 (27) | 15 (38) | 16 (37) | 67 (27) |

| BME | 35 (73) | 25 (63) | 27 (63) | 178 (73) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 33 (69) | 19 (48) | 23 (54) | 116 (47) |

| Male | 15 (31 | 21 (53) | 20 (48) | 111 (45) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 37 (9.8) | 38 (8.9) | 38 (8.9) | 39 (9.6) |

| Range | 21–58 | 22–55 | 24–61 | 20–67 |

Thematic analysis of the full data set resulted in an initial bank of 34 items, which were formed into brief statements and grouped into domains. A six-point Likert scale was chosen, ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ and optional free-text sections were included to capture additional qualitative data. The items were unweighted and one question was reverse scored. The self-report measure was designed to provide a final total score, with a higher score indicating a more negative perception. The inter-rater reliability of the focus group data coding was assessed using an NVivo 7 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) coding comparison report and showed between 97% and 99% agreement. Item reduction based on relevance and preventing duplication produced 22 items.

The pilot study, which comprised a mixed group of health-care assistants and qualified staff, agreed that these topics were broad enough to allow flexibility in bringing in new ideas. Interim analysis of the pilot focus group suggested that occupational seniority might interfere with a full discussion so, in order to allow for the maximum emergence of key themes, one ‘health-care assistant only’ group was included.

Thematic analysis revealed that the staff participants found the following core themes the most important for inclusion on the measure: teamworking, patient care, core interventions, safety, bed management and continuing professional development. These themes provided the structure for the measure. The individual items were developed from sub-themes within these broader domains. A five-point Likert scale was reviewed at the expert panel stage, but those staff participants felt that a wider range of response options would provide more scope and reduce omissions. At this stage there were 26 items.

Themes from the focus groups

The main themes identified in the focus group data were staff/patient interaction and coercion. Often, staff and service users conceived these differently.

Staff and service users’ interactions on acute wards

In terms of the focus of group discussions, the overwhelming perception of service users was that the ward was ‘untherapeutic’. A crucial contributor was the lack of available staff and helpful staff. For patients, it appears that staff are ‘stuck in the office’ and cannot help even when the situation is urgent, the situation is escalating or the service user is in crisis. This lack of availability was compounded by the use of ‘bank’ or ‘agency’ staff who were brought onto the ward in times of staff shortage but were usually unfamiliar with the ward and did not know the patients. They were described as ‘sitting and staring’ and not prepared to have a conversation with users or even ask them how they were feeling.

In the UK, every service user should have a care plan and documented notes on meeting that care plan. In fact, this is the main form of ‘structured interaction’ that is meant to take place on wards. But even care planning was low in reference density in the data. One of our participants had been given his discharge summary which included this documentation. It implied that he had one-to-one conversations with a named nurse every day throughout his stay; however, this was not his memory of events.

Many of the service users understood that work pressures such as under-staffing, paperwork and work-related stress impacted on staff’s lack of interaction. Nevertheless, this resulted in an untherapeutic climate where emotional distress was suppressed rather than explored.

It is evident in the accounts that routine and therapeutic interaction was rare in ward life. Participants were more positive about talking therapies, although they gave instances of them being unhelpful, especially groups in which everyone, including the facilitator, sat mute for an hour. Although talking therapies were described as being helpful, very few people had actual experience of such therapy while on the ward. They reported in prospect that talking therapies would be a good way to deal with distress. One participant had observed a suicidal fellow patient and thought that if there had been group therapy available she might have got better. Another favourably contrasted talking therapies with the ever-present use of medication.

Nevertheless, there were instances when the service user recognised that the ward had done them some good or, at least, were ambivalent about it.

The nurse participants were aware that the care they were providing was less than perfect and that they did not spend enough time with patients. They perceived both administrative tasks and bed management as a barrier to interaction and the ‘pressure’ of these daily tasks was very frequently referenced. Instability as a result of both the distress of individual service users and the overall ward milieu were of concern.

Bed management, which involved early discharge, making space and moving clients around, provoked a strong emotional response among nurse participants as they knew it led to poor interactions with patients. The practice of ‘sleeping out’ when a patient spent the day on the ward and then was sent to another ward, or even a bed and breakfast, to sleep evoked angry responses. Using periods of leave to free up beds also provoked feelings of guilt and anxiety alongside the view that senior management did not care.

Nurses had complex emotional responses to the fact that they could not spend enough time with service users. They expressed frustration and concern that they were becoming deskilled. Anxiety, arising from the lack of interaction, was a common response. Explicitly, staff remained committed to the need for interaction despite the daily pressures of working in an acute setting. Implicitly, there was an underlying theme of avoidance or interaction anxiety which suggested that many staff had withdrawn from interaction with the service users. The main cause of this ‘burnout’ appeared to arise from limited internal coping skills and from the need for staff to protect themselves emotionally from the complexities of individual service users in their care.

Coercion and control

As a barrier to therapeutic interaction and within the wider theme of violence, we will illustrate how service users and staff perceive their own power to be manifested on the ward. The two groups have differing perspectives: users feel coerced, whereas staff feel they are delivering a legitimate response to violence.

For service users, coercion is a complex concept. Here we focus on control, restraint and forced medication (rapid tranquillisation), which had high reference density in the data and our patient participants devoted much time to this theme. Medication was the main (or sole) treatment but here we are concerned with medication that is given by force. Other countries use mechanical restraint but this is not deployed in the UK.

One of the main reasons given by patient participants for behaviour that might elicit restraint or forced medication was that users were cooped up in the ward and not allowed to go outside and get fresh air. Even those granted time off the ward would often find themselves without a suitable escort. Others put it more strongly, likening the environment to a prison or a cage for an animal. This, they said, provoked extreme frustration and anger which was responded to by nurses in a way they thought aggressive and unnecessary. Our participants conceptualised forced medication as violence and had a whole vernacular to describe it: ‘jump on you with the needle’ or ‘pound on you with the needle’. However, they did not see their own behaviour as unnatural. For these participants, forced medication was not medical treatment but control.

Coercion can be experienced in more subtle ways and examples were common in the data. Medication does not always have to be given forcibly, there can be pressure to take medication under the threat that if the patient does not then it will be given by force.

There is a dichotomy in our data. Inpatient wards were routinely described as unsafe, fearful places where users felt unprotected by staff. Perceptions of coercion regarding control, restraint and medication resulted mainly from ‘being done to’. However, within the context of an often chaotic ward, coercion was sometimes perceived as an appropriate staff response to other violent service users.

Both service users and nurses reported a sense of ‘them and us’ on the ward. In the management of violence, nurses used interventions that were perceived as coercive by service users. However, nurses expressed some awareness and sympathy towards service users around this issue and referred to the therapeutic relationship as a protective factor in the management of violence.

At the same time, it was clear that control was not absolutely one sided in favour of nurses. They reported that violence as well as intimidation was a tool that service users could use to express their resentment at their situation on the ward. The lack of support felt by nurses in the face of violence was strongly expressed in the data. This is despite the provider trust having a ‘zero tolerance’ policy with respect to abuse, which would imply that police intervention was sometimes warranted. Nonetheless, many felt that they had to cope alone.

There is no doubt that some nurse participants had experienced very serious incidents. As well as physical assault, two nurses had been taken hostage and locked in the nursing office for many hours. Attempts to have the police intervene were of no avail as the police saw it as a ‘mental health issue’. We asked the nurses about logging incidents and their response was that they logged only the most serious ones otherwise they would spend the whole day filling out incident reports.

Official documents from the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) in the UK emphasise that the initial response to an imminent incident should be one of de-escalation where the staff member tries to ‘talk down’ the patient. 86 The reference density of de-escalation in our data was tiny with only two chunks of text coded. One person tried to explain why de-escalation was impossible owing to lack of staff; however, there was one instance where de-escalation was highlighted as best practice.

The perceptions of users, nurses and doctors on the issues of managing aggression and violence have been compared. 87,88 Staff attributed some violent incidents to factors ‘internal’ to service users, such as their illness or demographic characteristics. Service users, on the other hand, found responses to ‘incidents’ to be unsympathetic, containing and controlling. This is consistent with other findings. 89

Expert panels

VOTE

The expert panels (n = 13) confirmed that the measure allowed a good range of staff perceptions of acute inpatient wards to be expressed. A five-point Likert scale was reviewed at the expert panel stage, but those staff participants felt that a wider range of response options would provide more scope and reduce omissions. At this stage there were 26 items.

VOICE

The expert panels considered the measure to be an appropriate length and breadth and, following some minor changes in wording, concluded that the measure was appropriate for use by service users in hospital.

Final consultation

The service user reference group requested that the wording of several items be clarified, that all statements should be made positive, that staff responses to emergencies and personal crises should be differentiated and that the measure should not begin with items about the staff. There were no changes to the nurses’ measure as a result of the final consultation.

Psychometric assessment

VOICE: feasibility and acceptability

Feasibility took place in two waves (n = 40 and n = 106). In the first wave, 98% of participants found the measure both easy to understand and complete, and in the second wave, 82% of participants considered the measure to be an appropriate length. Two participants (2%) disliked completing the measure and six (6%) found some of the questions upsetting. VOICE took between 5 and 15 minutes to complete and was easy to administer. The measure was found to be suitable for completion by participants with a range of diagnoses and at levels of acute illness found on inpatient units. The Flesch reading ease score was 78.8 (reading ages 9 and 10 years) indicating the measure was easy to understand. 90 Following the feasibility study, one item was removed as it was considered to be a duplicate. This left the measure with 21 items.

VOTE: feasibility and acceptability

The feasibility study (n = 40) revealed that 95% of staff agreed that VOTE was easy to complete and easy to understand. Generally, staff found that, with minimal explanation, the measure could be completed by self-report in approximately 15 minutes. Items identified as having confused phrasing were changed and those showing poor consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) or poor variability or poor reliability were dropped, leaving 20 items.

The acceptability study showed that 76% of staff thought that the length was about right and 91% that it was enjoyable and not upsetting. The Flesch reading ease score for the measure was 64%. The Flesch–Kincaid91 grade level score was 7.6, which means that the measure can be read by a 12-year-old who is of average ability.

Phase 4: psychometric assessment

VOICE scoring

Total scores were calculated by totalling all items with no missing data. For participants responding to at least 80% of the items, a pro-rated score was calculated. Less than an 80% response was considered as a missing total VOICE score. Negatively phrased items were reverse scored so that high scores indicated a more negative perception of the quality of care.

VOTE scoring

Total scores were calculated by totalling all items with no missing data. For participants responding to at least 80% of the items, a pro-rated score was calculated. Less than an 80% response was considered as a missing total VOTE score. Negatively phrased items were reverse scored so that higher scores indicated a more negative perception of the ward. When comparisons to other measures were made, the same rule was applied to their scoring, that is, high scores indicate poorer satisfaction.

VOICE reliability

The test–retest reliability (n = 40) was high [ρ 0.88, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 0.95] and there was no difference in scores between the two assessments. A total of 192 participants had complete data on the VOICE scale and were used in assessing the internal consistency. After removing items with poor reliability, this left a 19-item scale with high internal consistency (α = 0.92).

VOTE reliability

Group 2 (n = 43) participated in the test–retest study using the final 20-item measure. As items tended to be skewed towards ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’, the kappa coefficient is expressed as a proportion of the maximum possible value. Six items showed substantial agreement (kappa maximum ranged from 0.60 to 0.73). Moderate agreement was shown in 14 items with kappa maximum ranging between 0.41 and 0.59. These results indicated moderate and substantial reliability. Concordance between the total scores (n = 34) was good (total score: ρ 0.77, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.89). The internal consistency of the measure, assessed using data from group 3 (n = 200), was good with the overall alpha at 0.82.

VOICE validity

The measure has high face validity. The wide range of items was determined by service users during the focus groups and the measure reflected the domains that they considered most important. The feasibility study participants felt that the measure was comprehensive and, therefore, had high content validity. Pearson’s correlation coefficient showed a significant association between the total scores on VOICE and the SSS-RES (r = 0.82; p < 0.001), indicating high criterion validity.

The data were suitable for factor analysis for construct validity [Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure was high (0.9), Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.001)]. The exploratory factor analysis was conducted on 192 fully completed responses to the 19-item measure. A promax rotation, allowing the subscales to correlate, revealed two factors (Table 3) that accounted for 95% of the total variance. The item groupings indicated by the factors were used to determine subscales by summing the scores of the items. Items with a factor loading of > 0.4 were considered to load significantly. When items loaded onto both subscales, a decision was made to include them on the subscale with the closest conceptual fit. Subscale 1 was labelled security and subscale 2 was labelled care. Both factors were significantly correlated (r = 0.73; p < 0.001). One item (‘Staff give me medication instead of talking to me’) did not load highly onto either scale and so was not included in the subscales.

| Item | Item description | Subscale 1: security | Subscale 2: care |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | I feel safe on the ward | 0.797 | –0.11 |

| 21 | I think staff respect my ethnic background | 0.788 | –0.026 |

| 9 | I trust the staff to do a good job | 0.765 | 0.065 |

| 11 | I feel that staff treat me with respect | 0.705 | 0.152 |

| 18 | I feel staff respond well when the panic alarm goes off | 0.641 | –0.053 |

| 19 | I feel staff respond well when I tell them I’m in crisis | 0.592 | 0.223 |

| 20 | I feel able to practice my religion whilst I’m in hospital | 0.585 | 0.042 |

| 1 | I was made to feel welcome when I arrived on this ward | 0.414 | 0.343 |

| 15 | I find it easy to keep in contact with family and friends | 0.403 | 0.165 |

| 3 | Ward rounds are useful for me | –0.095 | 0.855 |

| 5 | I have the opportunity to discuss my medication and side effects | 0.099 | 0.661 |

| 2 | I have a say in my care and treatment | 0.079 | 0.659 |

| 13 | I find one-to-one time with staff useful | –0.078 | 0.634 |

| 4 | I feel my medication helps me | 0.072 | 0.623 |

| 12 | I think the activities on the ward meet my needs | 0.102 | 0.565 |

| 7 | Staff take an interest in me | 0.209 | 0.499 |

| 10 | I feel that staff understand how my illness affects me | 0.325 | 0.486 |

| 8 | Staff are available to talk to when I need them | 0.378 | 0.426 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.88 | 0.88 | |

| Mean (SD) | 23.6 (9.8) | 25.7 (9.7) | |

VOTE validity

A high level of staff involvement throughout the process of measure development ensured good face and content validity. This was achieved because staff participants provided feedback on the content of the themes arising from the qualitative data and on the language used in the item generation phase. Staff agreed that the results did capture what they had reported. The use of a flexible topic guide/interview schedule maximised exploration of the construct under study and minimised omissions in the data set. A t-test examining whether or not VOTE scores were associated with an a priori criterion of job satisfaction, as measured by the IWS, showed that those with negative perceptions of the daily pressures of working on an acute ward also had poor job satisfaction [t(157) = –10.34; p = 0.001 (n = 159)]. The mean VOTE score in the low job satisfaction group was 76.5 [standard deviation (SD) 10.4] and the mean VOTE score in high job satisfaction group was 60.4 (SD 10.1). The VOTE measure was strongly and significantly correlated with the IWS [r = 0.77; p < 0.001 (n = 159)]. Overall, the mean satisfaction of the group was 163.6 (SD 31.3).

An exploratory factor analysis for construct validity was carried out (n = 200). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was good (0.8) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p ≤ 0.001). The scree plot92 indicated three factors with an eigenvalue of > 1. The orthogonal rotation produced the most coherent solution because it had consistently higher factor loadings and this is presented in Table 4.

| VOTE items | Factor loadings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue 4.18 | Eigenvalue 1.22 | Eigenvalue 0.98 | ||

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | ||

| 1 | It is easy to balance documentation/paperwork and spending time with the patients on my ward | 0.56 | ||

| 2 | I feel pressured to complete tasks in my job | 0.46 | ||

| 3 | Other than mandatory training, staff development opportunities are limited | 0.3 | ||

| 4 | I think that the senior managers (above ward managers) understand the current realities of working on acute wards | 0.62 | ||

| 5 | Finding enough staff to cover shifts is easy on my ward | 0.57 | ||

| 6 | On my ward there is immense pressure to create bed space | 0.31 | ||

| 7 | When it comes to bed management the clinical perspective of my team is always considered | 0.54 | ||

| 8 | There are enough staff to maintain safety on my ward | 0.62 | ||

| 9 | Patients are provided with enough information about their medication on my ward | 0.59 | ||

| 10 | If I have concerns about patient care I am happy to address it with colleagues | 0.54 | ||

| 11 | I benefit from regular supervision | 0.41 | ||

| 12 | I benefit from strong leadership on my ward | 0.51 | ||

| 13 | When it comes to patient care there are staff in my team who have a ‘can’t do, won’t do’ attitude | 0.34 | ||

| 14 | I find that communication between the different Multi-Disciplinary Team professionals is consistently good | 0.41 | ||

| 15 | There is a strong emphasis on promoting a sense of team spirit on my ward | 0.58 | ||

| 16 | Patients can feel that there is a sense of ‘them and us’ on my ward | 0.47 | ||

| 17 | When I ask patients’ to join in with activities, they say they are not interested in those on offer | 0.4 | ||

| 18 | I worry about violence and aggression when at work | 0.68 | ||

| 19 | Decisions that are made on one shift are changed on the next which makes consistency difficult in my team | 0.39 | ||

| 20 | I’d rather not address relationship issues between teammates because it will create a bad atmosphere | 0.37 | ||

Factor 1 reflected staff perceptions of ‘workload intensity’ and appeared to be tapping issues relating to work pressures, administrative intensity and feeling unsupported (either through weak leadership or inadequate staffing). Factor 2 related to ‘team dynamics’ linking concepts such as staff confidence in their leadership and in the dynamics of their team. Factor 3 identified ‘interaction anxiety’, associated with powerlessness and a lack of confidence in the uncertain ward situation. Evaluations of the internal consistency of the subscales: factor 1 ‘workload intensity’ (Cronbach’s alpha 0.74), factor 2 ‘team dynamics’ (Cronbach’s alpha 0.75) and factor 3 ‘interaction anxiety’ (Cronbach’s alpha 0.60).

Exploratory analyses: how effective are the new measures in discriminating between groups?

VOICE: do demographic characteristics affect service user perceptions of the quality of care on an acute ward?

The ability of VOICE to discriminate between groups is indicated in Table 5. Bivariate analyses showed significant differences for legal status. Participants who had been compulsorily admitted had significantly worse perceptions (t = –3.82; p < 0.001). A multivariate analysis revealed that legal status remains significant even when adjusted for the other factors (p = 0.001).

| Variables considered | Number | Mean score | SD | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 199 | 55.5 | 19.2 | 52.8 to 58.1 | 0.15 |

| Female | 147 | 52.5 | 17.8 | 49.6 to 55.4 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 162 | 55.6 | 19.1 | 52.6 to 58.5 | 0.22 |

| BME | 180 | 53.1 | 18.1 | 50.4 to 55.7 | |

| Legal status | |||||

| Informal | 102 | 48.9 | 16 | 45.7 to 52.0 | < 0.001 |

| Formal | 215 | 57.4 | 19.6 | 54.7 to 60.0 | |

| Borough | |||||

| Borough 1 | 132 | 54.5 | 19.5 | 51.2 to 57.8 | 0.15 |

| Borough 2 | 100 | 52.7 | 18.5 | 49.1 to 56.4 | |

| Borough 3 | 75 | 57.8 | 17.7 | 53.8 to 61.8 | |

| Borough 4 | 40 | 50.1 | 16.9 | 44.9 to 55.4 | |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Schizophrenia/psychosis | 179 | 54.8 | 18.2 | 52.2 to 57.5 | 0.40 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 51 | 56.1 | 21.5 | 50.2 to 62.1 | |

| Depression/anxiety | 38 | 50.9 | 13.8 | 46.5 to 55.3 | |

| Personality disorder | 18 | 59.3 | 16.6 | 51.6 to 67.0 | |

| Substance misuse | 13 | 53.7 | 18.9 | 43.4 to 64.0 | |

| Other | 42 | 50.3 | 21.3 | 43.8 to 56.8 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤ 20 | 15 | 61 | 23.7 | 49.0 to 73.1 | 0.29 |

| 21–30 | 77 | 51.6 | 15.5 | 48.1 to 55.1 | |

| 31–40 | 93 | 53.5 | 16.7 | 50.1 to 56.9 | |

| 41–50 | 87 | 55.6 | 21.9 | 50.0 to 60.2 | |

| 51–60 | 45 | 57.2 | 19.1 | 51.6 to 62.8 | |

| ≥ 61 | 25 | 50.6 | 18.3 | 43.4 to 57.9 | |

| Admission | |||||

| First admission | 62 | 50.7 | 17.6 | 46.3 to 55.2 | 0.11 |

| Previous admissions | 255 | 55 | 18.9 | 52.6 to 57.3 | |

We assessed any independent demographic predictors of VOTE using random-effects modelling and a forward selection procedure with the level of significance set at 0.05. The results showed that one variable was a significant predictor: country of birth (n = 180, groups = 17).

Staff who were born in countries outside the UK had more positive perceptions of the daily pressures of working on an acute ward than those who were UK born (Tables 6 and 7).

| Variables considered | Mean VOTE scores (SD) |

|---|---|

| Staff | |

| Whole sample | 68.54 (12.77) |

| Health-care assistants | 67.25 (12.55) |

| Qualified nurses | 70.81 (13.33) |

| Clinical charge nurses | 66.55 (11.46) |

| Team leaders | 64.23 (10.51) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White British | 70.43 (13.53) |

| Other | – |

| BME | 67.74 (12.57) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 67.63 (12.18) |

| Female | 69.58 (12.93) |

| Age (years) | |

| ≤ 39 | 67.93 (13.94) |

| ≥ 40 | 69.17 (11.69) |

| Country of origin | |

| UK | 70.01 (13.00) |

| Non-UK | 66.96 (12.95) |

| Length of employment | |

| ≥ 3 years | 69.26 (12.98) |

| < 3 years | 67.25 (12.93) |

| Variables | Coefficient | SE | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of birth not UK (baseline = UK) | –4.03 | 1.82 | 0.03 | –7.59 to 0.46 |

| Between-ward variability (SD) | 5.08 | |||

| Residual variance (SD) | 11.61 | |||

| Intraclass correlation | 0.16 |

The final measures are available are in Appendices 7 and 8.

Discussion

Using a participatory methodology, we have developed both service user- and staff-generated, self-report measures of perceptions of acute care. VOICE encompasses the issues that service users consider most important, namely their care and treatment and feelings of security, and is suitable for use in research settings. VOTE identifies the daily hassles of staff that affect staff engagement with service users, colleagues and their professional identity, which are all areas that are important to stakeholders. Both measures have promising psychometric properties. In both measures, the internal consistency and criterion validity are high and test–retest data show stability over time. The full involvement of service users and staff throughout the development of each measure has ensured that VOICE and VOTE have good face and content validity and are accessible to the intended recipients.

Can VOICE and VOTE distinguish differences in views?

Detained participants were shown to hold more negative perceptions of inpatient services. This is similar to the satisfaction studies showing that service users who are admitted involuntarily are less satisfied with their care. 93 More recently, research has identified that lower levels of satisfaction are linked with the accumulation of coercive events and perceived coercion. 94,95 Our findings from the focus groups present a more complex picture and one that is worth further analysis.

We anticipated, but did not find, any differences on either VOICE or SSS-RES scores for ethnicity. Previous quantitative studies have shown differences for legal status but not ethnicity,96,97 whereas qualitative research has revealed that BME users hold relatively poor perceptions of acute care. 16,98 Our study was set in areas of London with high proportions of people from BME groups. 99,100 Staff demographics tended to mirror those of inpatients and it may be that services were better tailored towards BME groups. In addition, asking users for their perceptions while they were in hospital may have inhibited openness and honesty, particularly on sensitive issues.

In this study, staff had slightly more positive perceptions of job satisfaction than staff in other studies. 101–103 Staff with negative perceptions of the daily pressures of working on an acute ward and barriers to change also had poor job satisfaction.

In previous studies, work stressors have differed between groups including occupational status and gender. 43,48 Of all the demographic characteristics included in this study, only country of birth showed a significant effect on staff perceptions of the daily pressures of acute ward working, with staff born outside the UK showing more positive perceptions than those born within the UK. This may be a direct result of the inner London location of the trust under study, as a large percentage of the client group and the nursing workforce are not UK born.

However, the mean VOTE scores were most negative overall in the direct care staff groups (staff nurses/nursing assistants) compared with more positive scores in those who occupied more managerial roles (clinical charge nurses and team leaders). Although we did not address whether or not the stressors differed significantly between these groups, it is true that both nursing assistants and staff nurses spend the most time in direct client contact. Therefore, their more negative perceptions might be one of the inevitable aspects of delivering therapeutic acute care for patients with severe mental illness at their most distressed. Furthermore, staff in leadership roles are more likely to be involved in the planning stages of new changes and, therefore, have an increased sense of control and responsibility over them, while those in direct care roles are more likely to be involved in delivering changes. These important issues, revealed through stakeholder involvement, require further exploration to discover key drivers for these perceptions that might then be subjected to management and other interventions.

Are VOICE and VOTE different from other measures?

The benefits of the participatory model used to develop VOICE and VOTE are visible in both the breadth of the construct investigated and the rich content of the items. Although the VOICE total scores were correlated, there were also distinct differences in content between VOICE and the comparison satisfaction measure. We believe that this is because of the use of a participatory methodology. The factor analysis of VOICE discovered two main factors: security and care. In particular, the safety and security issues were given more weight in VOICE and items on diversity were included that did not appear in the conventionally generated measure. Although items regarding the physical environment and office procedures featured in the SSS-RES,78 these issues were not deemed as important by the service users in our study and, therefore, were not included in VOICE. However, other items referred to ‘care received’ overlapped with some items in SSS-RES.

It is often assumed that the only construct to measure is satisfaction with acute care. However, there are difficulties in encapsulating complex sets of beliefs, expectations and evaluations in satisfaction measures. Caution should be taken when making inferences from the results of such measures, as they may not accurately reflect the views of service users. 104 VOICE is unique in that it captures service users’ perceptions and we anticipate that this will depict the inpatient experience more accurately.

The factor analysis conducted during the development of VOTE revealed three novel factors. Factor 1, ‘workload intensity’, seems consistent with previous work identifying the effects of poor resources such as inadequate staffing and too few beds on occupational stress for nurses. 9 Factor 2, ‘teamwork’, is similar in content to the concept of ‘job satisfaction’ characterised by leadership, educational attainment, pay and stress. Factor 3 represents a new subscale that explains the lower correlations to the IWS and Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) subscales. It crystallises two ideas. First, it reflects some issues relating to burnout. 46 Second, it draws together some of the feelings of fear and uncertainty that are associated with working with distressed clients in an unstable environment. This complex issue was revealed through stakeholder involvement and adds a new and unique aspect to the current library of measures that capture staff perceptions of stressors in acute inpatient settings. This issue clearly requires further exploration in the field, as one of the fundamental aspects of delivering therapeutic acute care is in the ability to work with clients with severe mental illness at their most distressed.

Further developments

Three further measures grew out of this WP; please refer to Appendices 1–3.

Strengths and limitations

This study was conducted in London boroughs with high levels of deprivation, ethnic minority populations and psychiatric morbidity99,100 and, therefore, may not be directly generalisable to other settings. In addition, our focus groups and expert panels included a high proportion of participants from BME communities. Although this is a strength, it may be that different items would have been produced by other groups. Furthermore, as recruitment for VOTE was limited to staff from acute wards it is not clear whether or not VOTE would be suitable for other settings such as forensic or rehabilitation wards.

It is impossible to accurately assess inpatient care without involving the people directly affected by that service. Developing outcome measures that are valued by service users and staff is essential in evaluating and developing inpatient services. The main strength of this piece of research is that it fully exploits a participatory methodology: staff and service users were involved in a collaborative way throughout the whole research process. VOICE and VOTE are the only robust measures of acute inpatient services designed in such a way. This method has resulted in measures that encompass the issues that staff and service users consider most important and that are acceptable, easy to understand and complete by a diverse staff group and service users with a range of diagnoses and severity of illness.

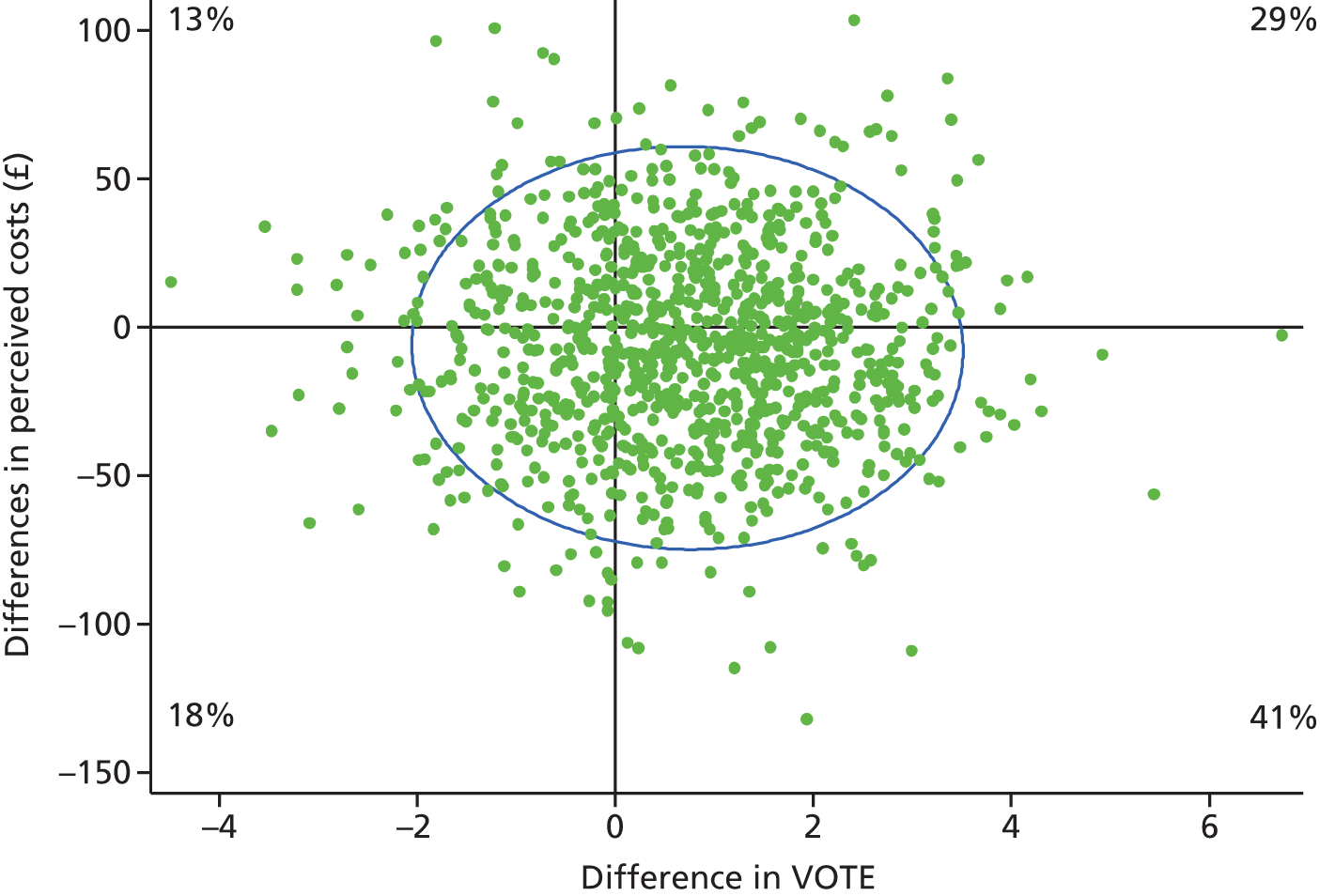

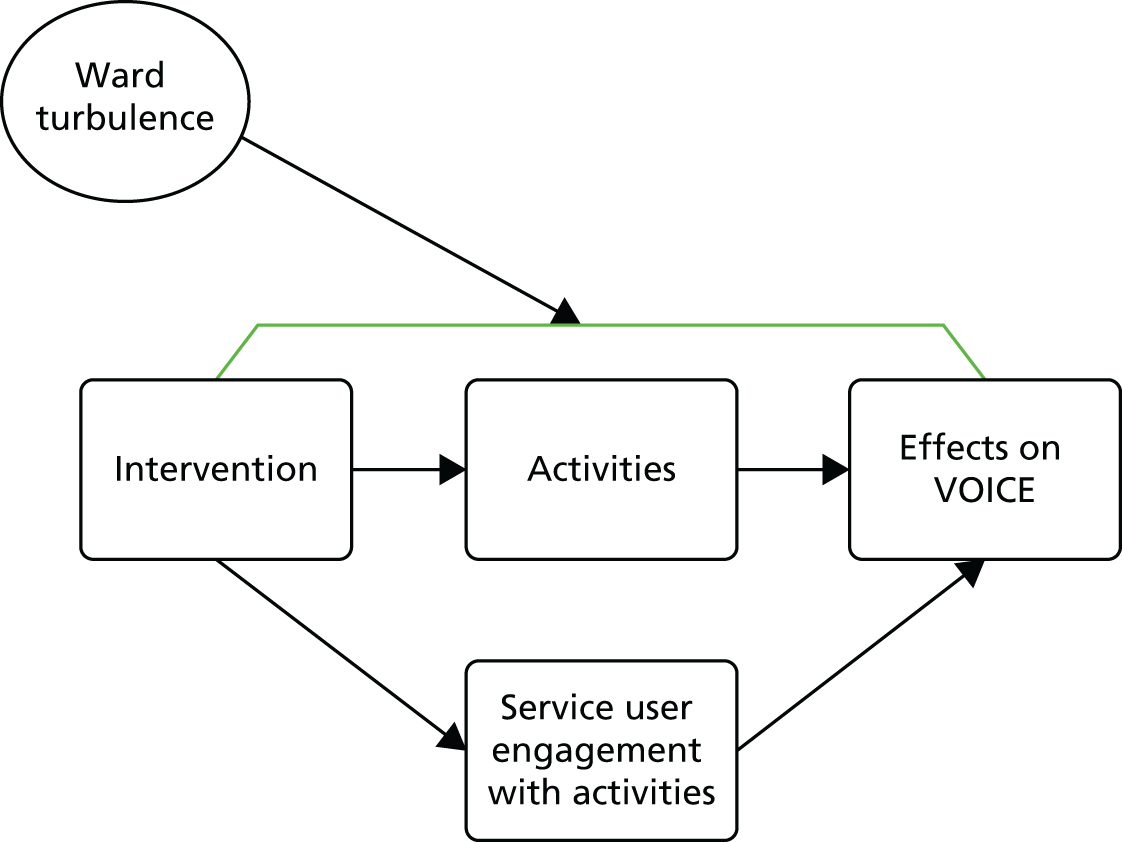

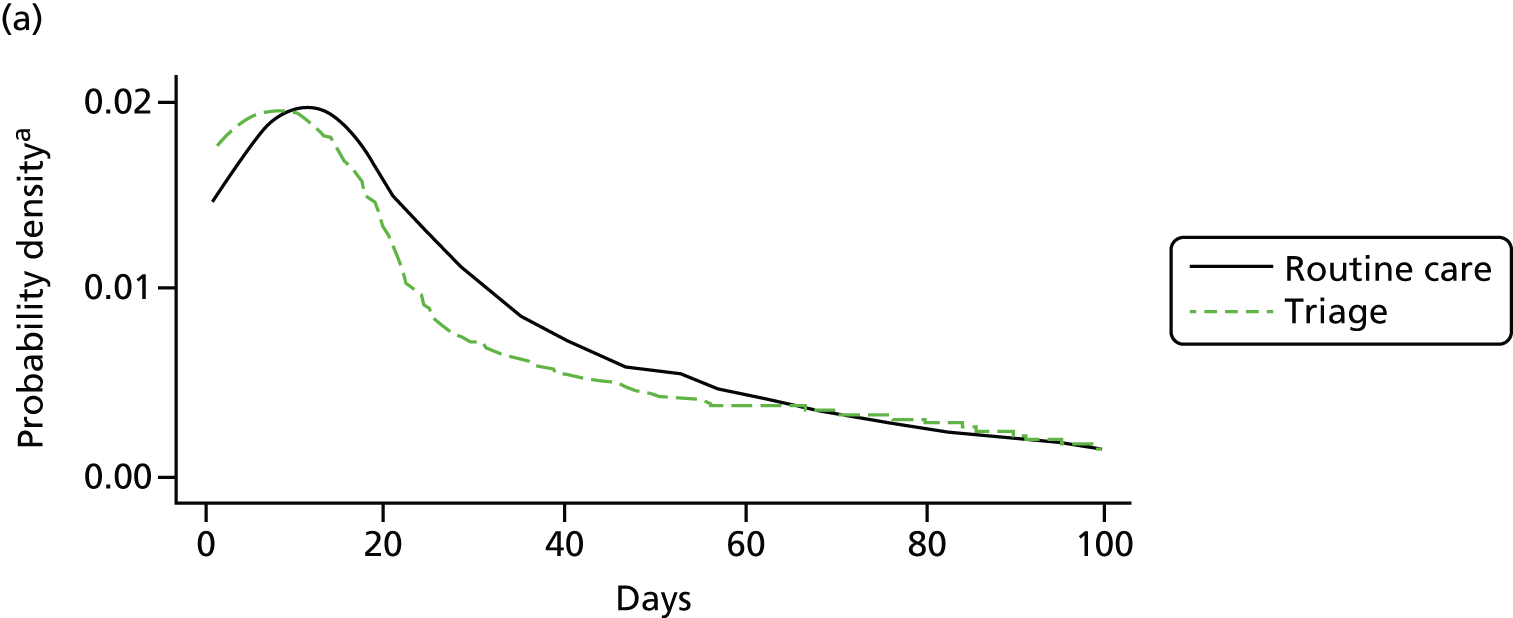

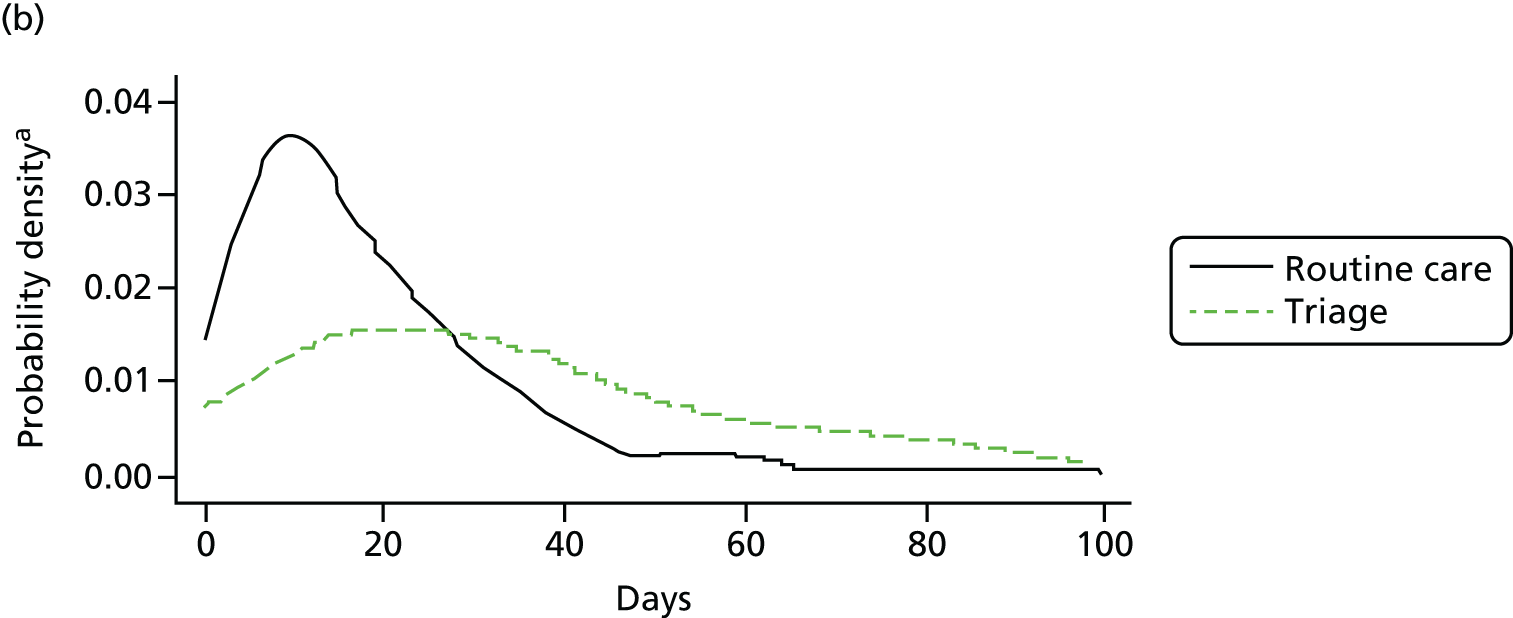

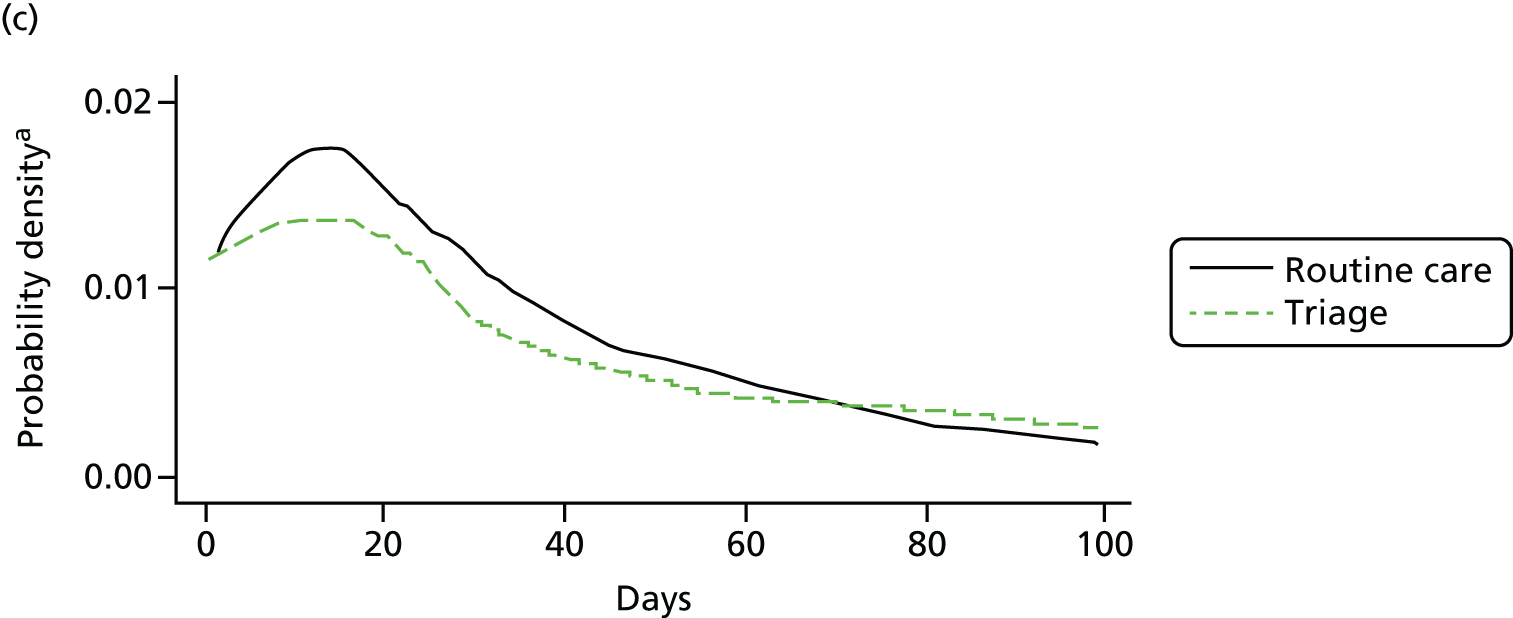

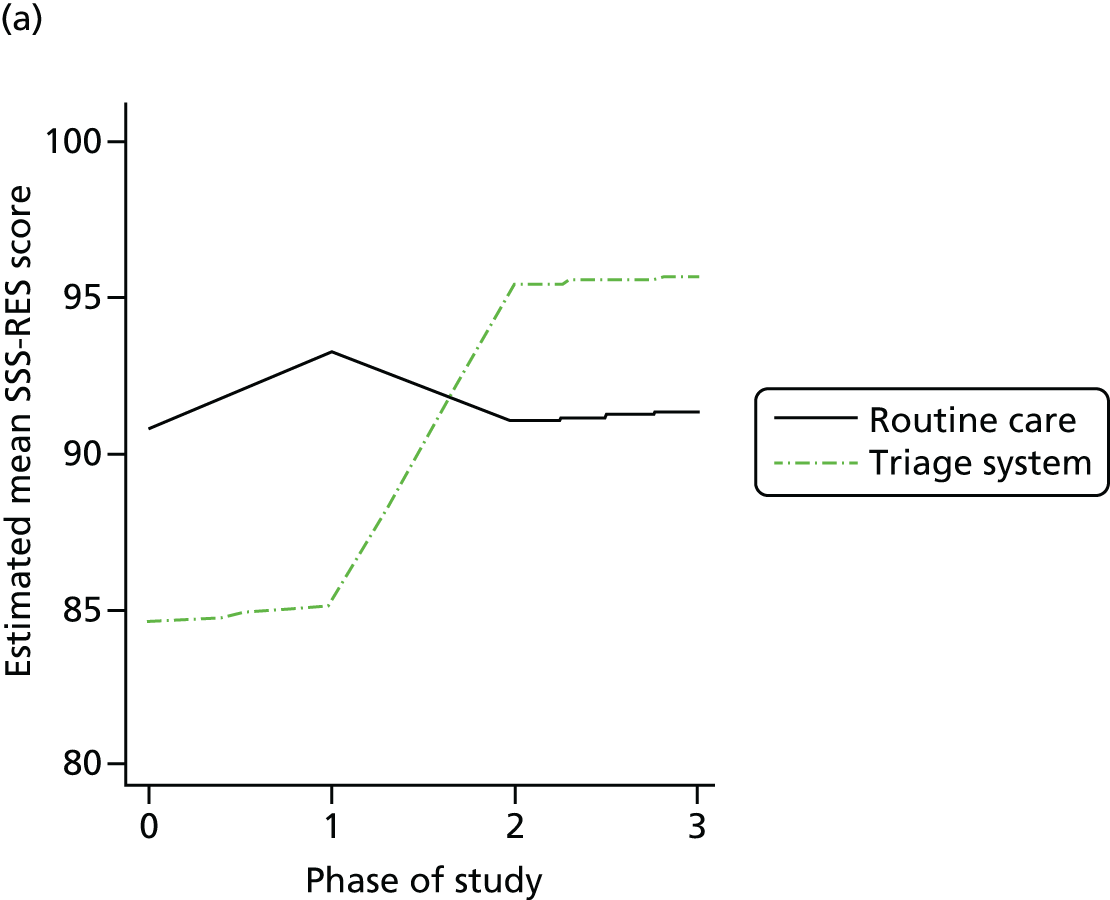

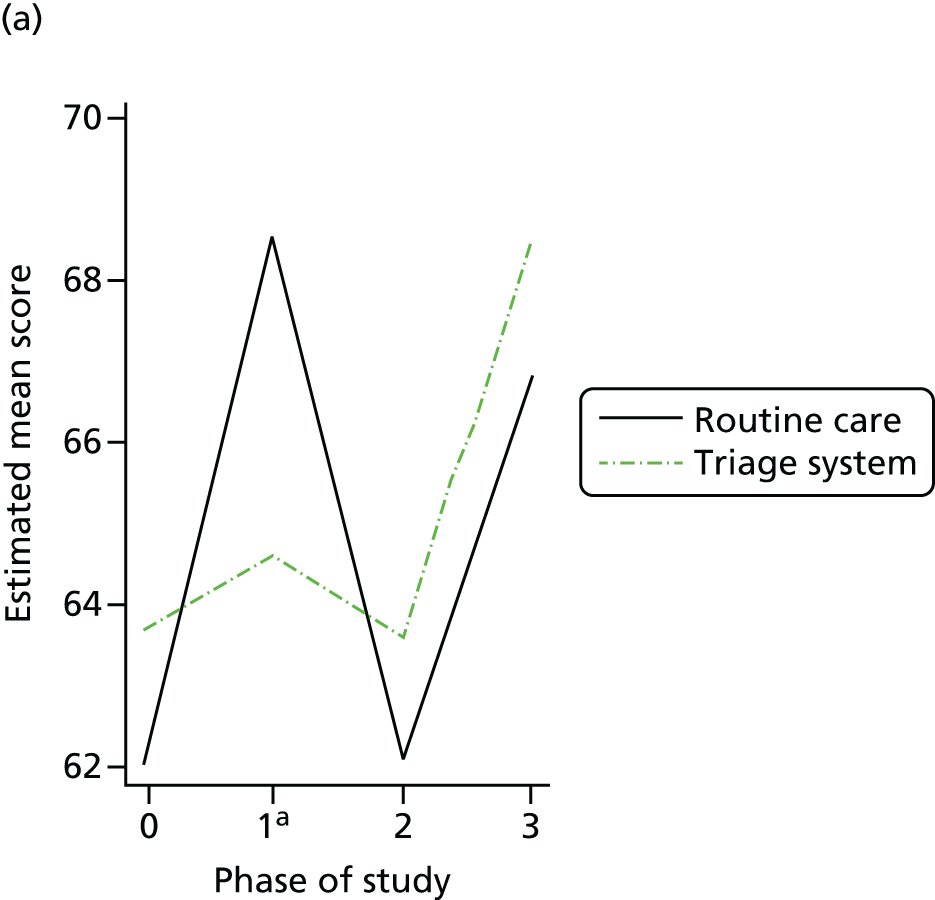

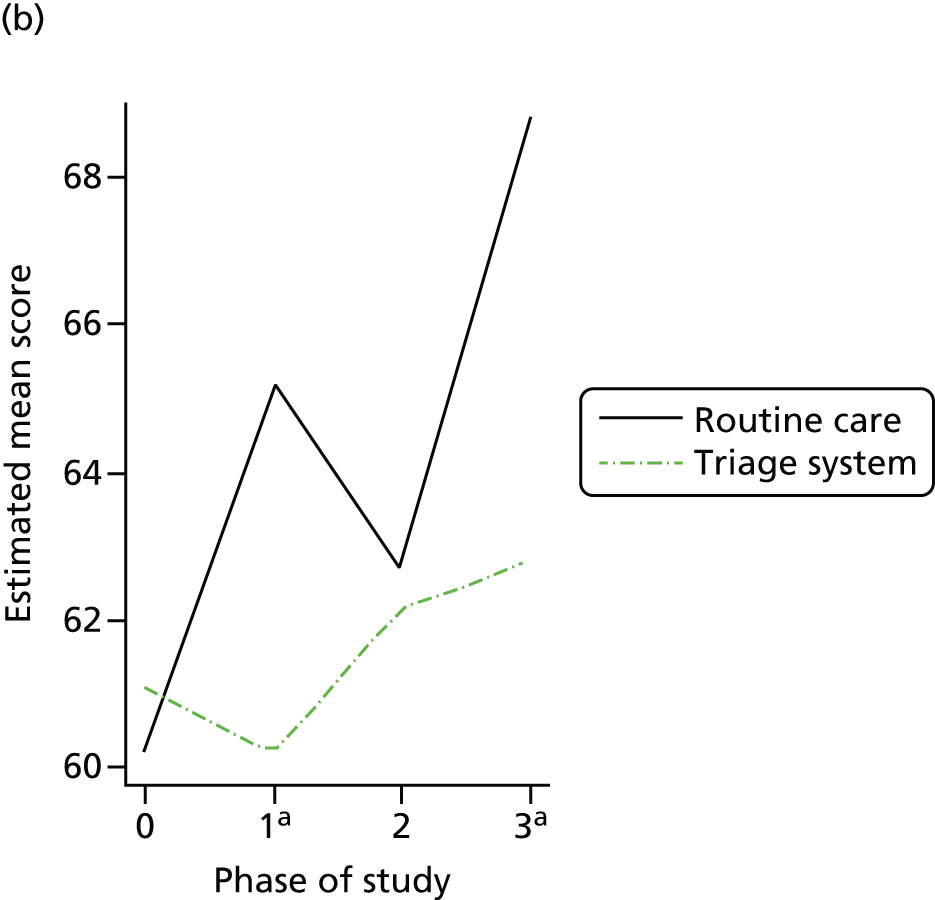

Conclusion