Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0610-10112. The contractual start date was in May 2012. The final report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Luke Vale was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research programme panel from 2008 to 2016, a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme Clinical Evaluation and Trials panel from 2014 to 2018, and Director of the NIHR Research Design Service North East and North Cumbria from 2012 to 2018.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Colver et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Setting the scene

All young people – defined by the World Health Organization as any person between the ages of 10 and 24 years1 – experience transformations in their lives and their understanding of the world as they grow older. Although it may not be possible for all, young people need to achieve four crucial developmental tasks: (1) consolidate their identity, (2) achieve independence from their parents, (3) establish adult relationships outside their families, and (4) find a vocation. 2 A fundamental principle is that when young people have a need for health care, this care must be provided in a manner that is appropriate to their stage of development. The term used to describe this principle is developmentally appropriate health care (DAH). DAH should underpin all health care for young people and in particular for those with a long-term condition. However, the term has been ill-defined and used inconsistently; in turn, this has made it difficult to assess whether or not it has been implemented in reported studies. 3,4

Furthermore, a young person with a long-term condition has to move from children’s to adults’ services. This process is called ‘transition’ and is defined as the purposeful, planned process that addresses the medical, psychosocial, educational and vocational needs of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical, neurodevelopmental and medical conditions as they move from child-centred to adult-oriented health care systems. 5 ‘Transfer’ is the formal ‘event’ when the medical care of a young person is moved from children’s to adults’ services.

The UK and Australia are the only two high-income countries with national guidance on transition, although academies and specialty groups also make recommendations. 7–9 The need for improved transitional health care is set out in recent policy and recommendations, such as advice from the Department of Health and Social Care in 200610 and 2008,11 recommendation 23 from the 2010 Kennedy Report,12 the 2015 Care Quality Commission report From the Pond to the Sea13 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on transition in 2016. 14 Commissioners, provider organisations and clinicians have a role to play in such improvements.

The number of young people surviving to adulthood is increasing; many children with long-term conditions that once commonly caused death in childhood now live into adulthood. In a typical NHS Trust serving a population of 270,000, about 100 young people with chronic illness, a complex physical impairment or a neurodevelopmental disorder reach the age of 16 years each year. 15 As transition takes place over about 7 years, the number in transition at any time in a typical trust is approximately 700.

New understanding of adolescent and young adult brain development and its associations with behaviour16 further reinforce the need for transitional health care to be set in a developmental context.

Transition is important because:

-

Many young people with a range of long-term conditions have poor social outcomes, following transition, in areas of social participation, employment or further education. For example, young adults with long-term conditions, such as cancer, congenital bowel anomalies and renal disease,17 congenital heart disease18 and chronic physical disability,19 and those with chronic illness,20,21 have demonstrated delays in autonomy, psychosexual and social development. Furthermore, few young adults with neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attain their potential for participation in society. 22

-

Chronic illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus and renal disease,23 are prone to deteriorate during the adolescent years; they need frequent medical monitoring and treatment optimisation. Young people reported finding it difficult to negotiate transition in services for haematology,24 type 1 diabetes mellitus,25 epilepsy,26,27 physical disability28,29 and rheumatology. 30 Conditions such as cerebral palsy give rise to symptoms that interfere with daily living, such as pain, spasticity and seizures. Most mental health disorders of adults develop during adolescence just at the time when the commissioning and provision of services is most likely to move from child- and family-focused to adult symptom-orientated mental health services. There are concerning rejection rates after solid organ transplants. 31

-

Some adults’ services are not routinely provided (e.g. for adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder32 or ASD). Other adults’ services, such as physiotherapy and mental health services,33 have different, and usually narrower, entry criteria. Some services that require multidisciplinary co-ordination (e.g. for those with cerebral palsy) are provided in childhood but are rarely provided in adulthood. 34

Central government guidance and direction has sought to improve services for transitional health care but there remains a need to improve services. 13,14 In 2017, a national CQUIN (Commissioning for Quality and Innovation National Goals)35 was introduced around transitions from children to young people’s mental health services.

Developments in health-care transition during the period of the research programme

Since the start of the programme in 2012, there have been developments in the field of transition of which we have taken account.

Results of published evaluative studies remain difficult to generalise from because they are usually about an intervention in one clinical setting, for one condition and using a locally designed intervention. The Cochrane review36 of interventions to improve transition, published in 2016, confirmed the lack of good evidence. Studies with more rigorous protocols have since been conducted. 37–40 A systematic review41 in 2017 reported the limitations of methods used in comparative studies of transition interventions. It found, for example, that most were small, single-condition studies, used unvalidated questionnaires, and did not report the age of transfer or the age at and time of questionnaire completion. In designing our research, we had anticipated such methodological limitations and addressed them in the methods we used for the longitudinal study [work packages (WPs) 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3].

Two Delphi studies proposed a suite of outcomes42 and process measures43 for evaluating transition. Our choice of outcomes in the longitudinal study is in line with these international studies.

A synthesis of qualitative studies of young people’s views about transition44 confirmed that there is much literature about the issues and difficulties encountered, and supported our decision not to undertake further exploratory work with young people.

As anticipated, arrangements for commissioning NHS services have continued to change during the research programme. However, the commissioning focus of our research concerns ‘what’ and ‘how’ to commission. We intended that our findings would be relevant to any commissioning structure, including whether or not commissioning and service provision are brought together in the same organisation.

Aims and objectives of the research programme

The overall aim of the programme was to promote the subjective well-being and health of young people with long-term conditions by generating evidence to enable NHS commissioners and trusts to facilitate the successful transition of young people from children’s to adults’ health care, thereby improving health and social outcomes.

To address this aim, the programme had three objectives:

-

to work with young people with long-term conditions to determine what successful transition means to them and what is important in their transitional health care

-

to identify the features of transitional health care that are effective and efficient

-

to determine how transitional health care should be organised, provided and commissioned.

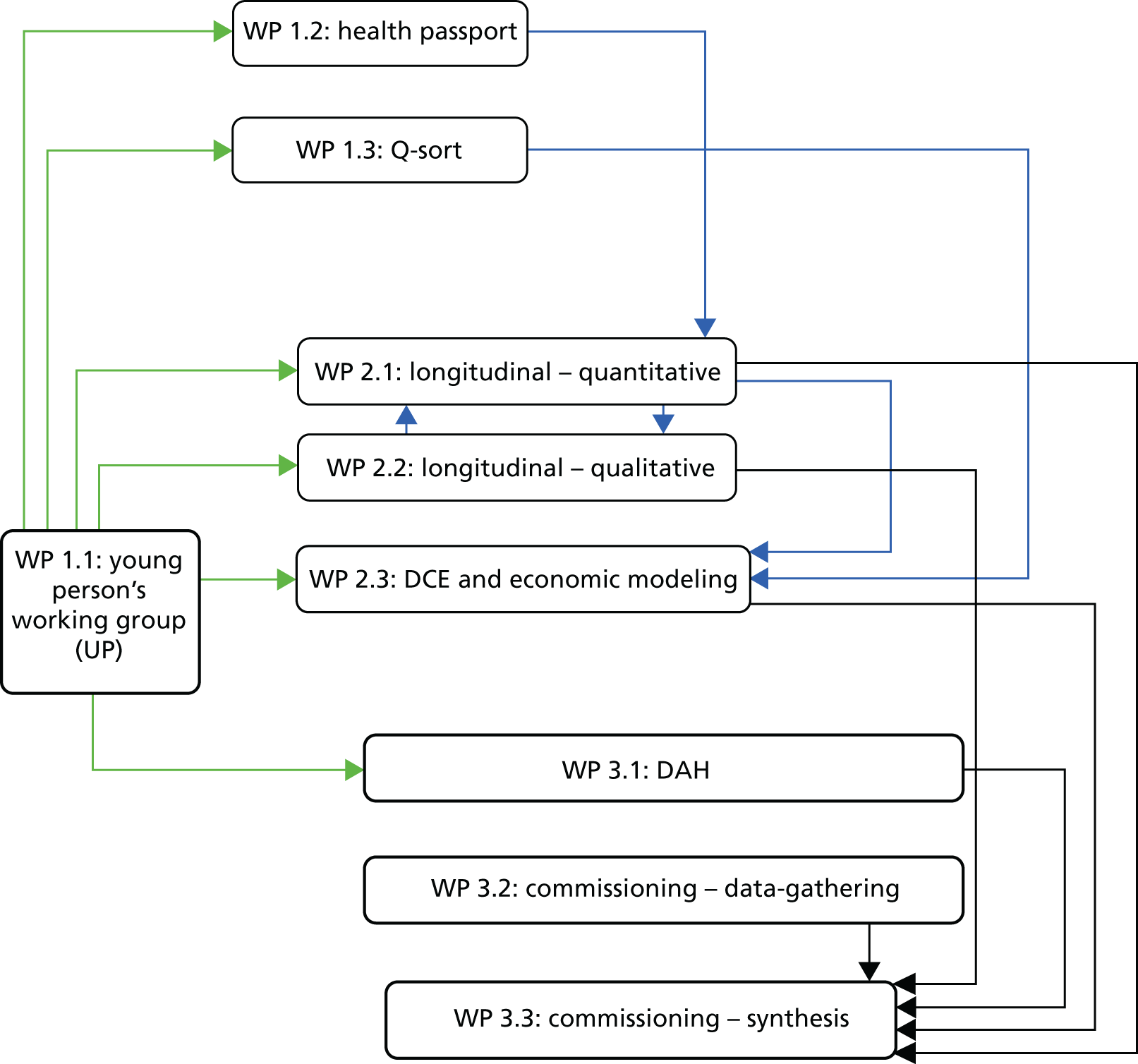

Three separate WPs addressed each of these objectives. We present a summary of each WP and then bring together the results of all nine strands to inform our conclusions and their implications. As an overview, and to aid orientation, the WPs are summarised in Box 1, followed by Figure 1, which shows how the WPs influenced each other.

-

To form and maintain a young people’s advisory group for the programme.

-

To consult with the young people’s advisory group on all aspects of the programme.

-

To explore the usefulness of a ‘health passport’ through research co-led by the young people’s advisory group.

-

To explore the importance that young people attach to different components of successful transition.

-

To examine whether or not the proposed beneficial features of services predict outcomes for young people with type 1 diabetes mellitus, cerebral palsy or ASD and an associated mental health problem.

-

To determine the resource use and costs of care.

-

To investigate the factors that promote or inhibit the introduction of the proposed beneficial features of services.

-

To assess the relative efficiency of illustrative models of transition.

-

To identify, describe and understand the factors that enable or inhibit the introduction of organisation-wide DAH for young people.

-

To identify the structures, processes and relationships between commissioning entities in the NHS and other agencies relevant to transitional health care.

-

To identify the facilitators of and barriers to commissioning for transitional health care.

-

To identify how transitional health care could be better commissioned.

-

To synthesise learning from the research programme on ‘what’ and ‘how’ to commission.

-

To learn about the most useful way to provide research-based evidence to inform commissioners.

FIGURE 1.

How the WPs influenced each other. DCE, discrete choice experiment; UP, United Progression.

At the end of the account of each WP, we indicate its links to the other WPs and how each WP contributed to the seven main implications of our work.

In Appendix 1 is a summary of work we completed before applying for a Programme Grant.

In Appendix 2 are the management arrangements for the programme and a diagram showing how key groups interacted.

Work package 1.1: work of the United Progression group

Addressing objective 1: to work with young people with long-term conditions to determine what successful transition means to them and what is important in their transitional health care

We ensured that the contributions of the young people were integrated with the research programme in meaningful ways for the young people and the research. Funds from the programme ensured that enough staff time was available to facilitate meaningful involvement of young people throughout the 5-year programme.

The young people called their group United Progression (UP; the term UP will be used in the remainder of this report).

Aims

-

To form and maintain UP.

-

To consult with UP throughout the duration of the programme.

Method

Preliminary work during the development of the grant application

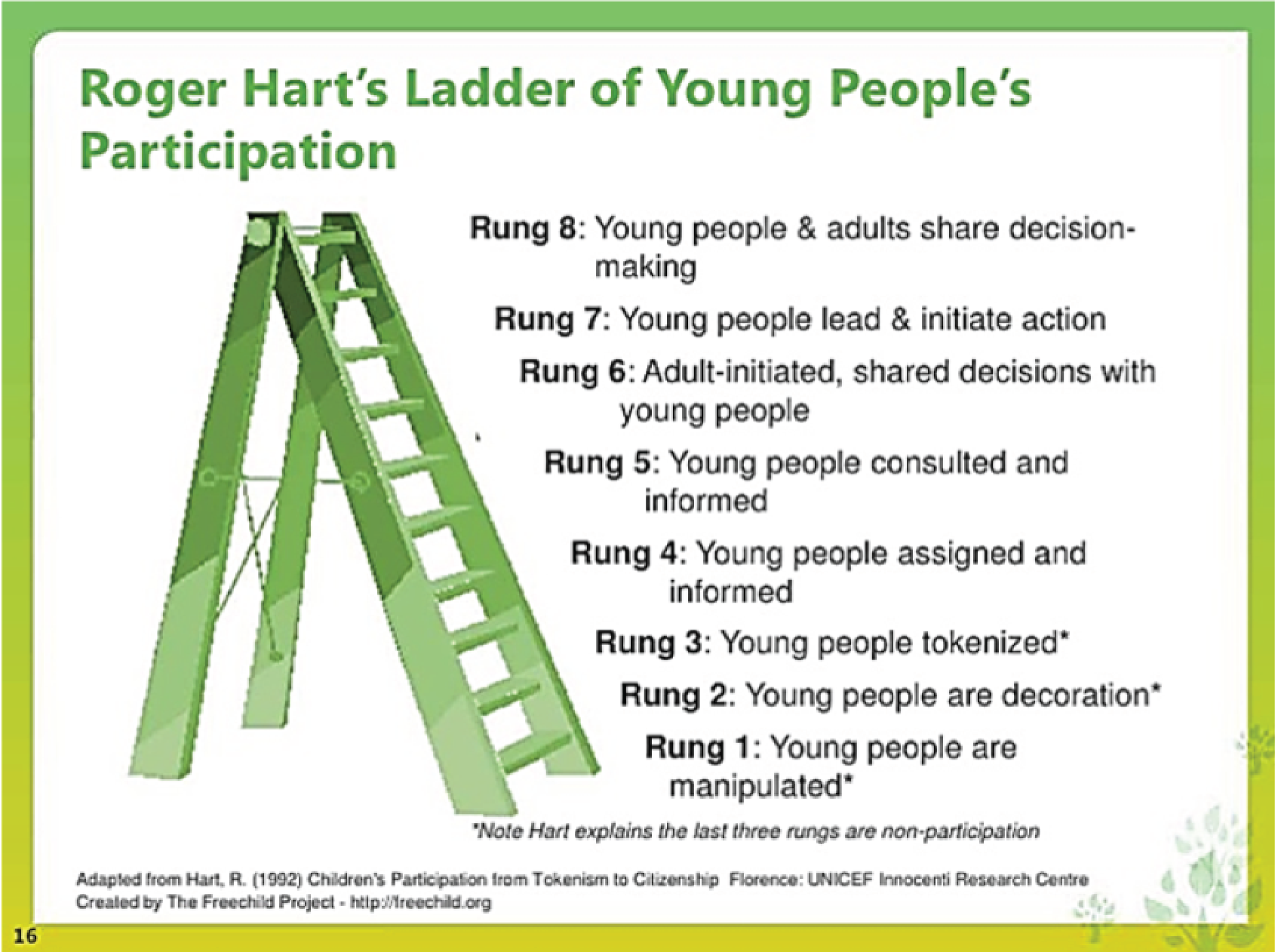

Discussion between a time-limited young person’s group and co-applicants concluded that a ‘partnership’ approach to involvement should be the fundamental value. Development of skills and confidence would be required to enable young people to contribute to a research programme. Peer support workers would be recruited to facilitate the induction and skills development of the advisory group.

Development of and recruitment to UP

Three part-time peer support workers were appointed. Recruitment to UP was undertaken by the programme’s patient and public involvement (PPI) lead.

At the start of the programme, UP members were aged between 15 and 20 years. All had experience of accessing a range of health-care services. Recruitment occurred in a range of ways: via young people’s health services, local schools and local young people’s health action groups. With membership growing steadily in the early months, the group consisted of over 20 members, and active participation fluctuated over time in line with exams, family events and other commitments. Most meetings had around eight members present. UP had 26 members over the 5 years. By the end of the programme, eight of the original members still attended regularly; this was crucial, as they brought their 5-year insights to the final research outputs.

UP met monthly over the 5-year programme. UP members had a hot meal and socialised before meetings began.

UP members were involved in advisory, consultative and dissemination roles – not as research participants.

Maintaining and sustaining the engagement of UP

Induction for UP members included a description of the project, a meeting with members of the management team, a glossary of research terminology, and attending and presenting at the programme’s launch.

Each monthly meeting was planned to be enjoyable for UP, and to ensure that there was enough guidance and support for the tasks that UP had agreed to do. Careful planning was needed for communication between UP and the programme management board to ensure fruitful interaction. The PPI lead was the link between UP and the board. The board set out timely, structured commissioning briefs for the PPI lead, rather than sending direct requests to UP. The PPI lead ensured that tasks were relevant and achievable and that young people had the skills to deliver them.

Impact on the programme

UP provided input to many WPs. For example, UP piloted the Q-sort tool in WP 1.3. UP commented on the ‘proposed beneficial features’ (PBFs) that were central to the longitudinal research described in WP 2.1; subsequently, two features (‘transfer readiness’ and ‘direct payments’) were dropped as they were unclear or not relevant to health-care transition. UP designed recruitment and retention materials for the longitudinal research of WP 2.1. UP responded to the findings of WPs; for example, they made a training DVD (digital versatile disc) on the importance and implementation of DAH for WP 3.1.

UP contributed directly to dissemination activities throughout the programme. They presented at the launch in Newcastle upon Tyne in October 2012, and ran a session at the final dissemination conference in London in October 2017. They wrote blogs for the programme’s website. UP representatives sat on the interview panels for the research associates and contributed to their induction, and sat on the external advisory board.

UP advocated for the programme and offered their skills and expertise to local and national groups. UP helped to develop training materials for doctors in partnership with the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, MindEd and the Association for Young People’s Health. This generated several videos. UP represented the Transition programme at the Department of Health and Social Care’s ‘Takeover Day’ in London in 2015.

Finally, UP worked with the Council for Disabled Children to disseminate their experiences and present early results of the programme to other young people’s groups between autumn 2015 and spring 2017. These meetings also enabled young people involved in research elsewhere to share their experiences with UP. In these meetings, UP disseminated results of the programme relating to the Q-sort study (WP 1.3), health passport work (WP 1.2) and the concept of DAH (WP 3.1). Meetings took place with Child Health Action Team (CHAT) North Tyneside; two Croydon groups; Together for Short Lives young person group; St Oswald’s Hospice, Newcastle upon Tyne; Transition2 group in Derby; and the Chatterboxes youth group in Bournemouth. Three facilitator guides (one example is given in Appendix 10) were developed for other groups to use, especially voluntary organisations.

In Appendix 3 are the certificate UP designed for participants in the longitudinal study (WP 2.1); UP’s Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentation for the programme’s launch; and one of the conference posters prepared by UP.

Key findings

-

UP influenced many of the WPs of the programme, and was involved in a wide range of dissemination and advocacy activities.

-

As the members of UP grew in confidence, their contributions became increasingly useful to the programme. The support and training offered to UP were very important, although they were resource intensive.

-

Members of UP reported that they enjoyed the challenges, the relationships they formed with other young people and their greater understanding of research.

Inter-relationships with other parts of the programme

UP influenced many aspects of the programme through their input to several WPs. The only two WPs they did not influence directly were those (WPs 3.2 and 3.3) on commissioning for transition.

Further analysis and discussion of the role of UP is presented in Involvement of patients, the voluntary sector and the public. This section also summarises the internal evaluation of the work UP undertook and points to our published paper. 45

Although not unique to our programme, when professionals, managers and commissioners attend meetings where young people contribute and have been closely involved in the work presented, such young-person involvement strengthens the assurance that the audience attaches to the work.

UP thoughts and opinions directly influenced implication 2 on DAH and the toolkit we developed to assist with introduction of such care across an organisation. By advising on questionnaire content, wording and feasibility, UP directly influenced both what research participants were asked to complete and the key implications of our work, namely implication 4 concerning joint planning, implication 5 concerning young people’s approaches to transition, implication 6 concerning features associated with better outcomes and implication 7 concerning features likely to optimise service uptake.

Work package 1.2: health passport

Addressing objective 1: to work with young people with long-term conditions to determine what successful transition means to them and what is important in their transitional health care

We determined that engaging UP in a research study co-led by them would help them better understand research processes and generate knowledge important to the programme. UP chose ‘health passports’ as the focus of their work. These are usually a portable means of recording health information. 46,47

Aim

-

To explore the usefulness of health passports in a project co-led by UP.

Methods

UP examined a range of passports designed to help young people navigate health services and concluded that there was no clear definition of what a ‘health passport’ was. As there were many health passports already available, UP decided that it would not be useful to develop another one. However, as no robust analysis of health passport use has been undertaken, UP aimed to examine the use and usefulness of some health passports already used by young people with long-term conditions.

UP contacted health-care professionals from a children’s hospital, a physical disabilities team, an adolescent rheumatology team and a voluntary organisation. UP asked professionals about their experience of health passports and this helped to identify questions and issues to explore with young people, such as:

-

What kind of passports are used and what are their essential components?

-

Who uses health passports and who benefits from them?

-

How are they used and how are young people supported to use them?

UP then worked with the patient satisfaction team in the lead trust to devise a questionnaire to assess the views of young people about health passports. Then the professionals in the above organisations helped UP link to young people who used health passports. However, this proved difficult as ethics and research governance permissions were required; it was impossible to achieve this across several organisations within the available time.

Analysis

Young people from one service returned questionnaires (n = 13) and, although the response rate was low (20%), interesting findings emerged. None of the 13 participants said that they completed the health passport alone; the majority said that they thought passports were ‘useful’, but half of them never took them to health-care appointments. The passports were considered more useful to health professionals than to young people themselves.

Strengths and limitations

This work identified some qualitative findings about health passports. However, the work did not generate, as intended, enough quantitative data from which to draw definitive conclusions. It was difficult to obtain all of the research governance permissions in a timely manner to enable UP to approach as many young people as they had intended. The approaches also depended on the willingness and time of local health professionals to approach young people. For other parts of the programme, all such preliminary contacts and undertakings had been formalised before the programme started. For this work, co-generated by UP, planning could not begin until UP had worked through its ideas, which was at least 1 year into the programme.

Such challenges have been reported before. A Dutch group undertook participatory research with young people with chronic illness48 and concluded that, although the activity benefited the young people, it was an inefficient and unreliable way to gather research data. Similar benefits to young people were reported in a study in Vancouver. 49

Key findings

-

There is a lack of conceptual clarity and no clear definition about what is meant by ‘health passport’.

-

The work raises questions about whether or not a health passport is a tool truly held by young people. Who should complete it and when? Do young people really want it to ‘travel’ with them to appointments and between services?

-

Even studies by enthusiasts for health passports found difficulties. Participants used their document only occasionally and its perceived utility was modest;50 only one-quarter completed a survey, and, of those who then agreed to a telephone discussion, only one-third had used their passport. 46

Inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

This WP contributed directly to the longitudinal study WP 2.1. A health passport was discussed as a candidate PBF of transitional health care. However, the initial work that UP undertook indicated that ‘health passport’ meant different things to different people, and although it was considered useful by some professionals, young people appeared to value it much less. We therefore decided not to include health passport as a PBF. This decision was vindicated by the subsequent survey work that UP undertook.

The confidence that members of UP gained by carrying out their research and their greater appreciation of research methodology enhanced the quality of all of their contributions to the programme, which were set out in the earlier account of WP 1.1. It also increased their self-confidence, and this is discussed in Involvement of patients, the voluntary sector and the public and in our associated published paper. 45

UP presented the health passport work at the Department of Health and Social Care’s ‘Takeover Day’, where interest was expressed in taking the passport work forward nationally.

UP presented their work as a poster at several meetings, including the final dissemination meeting at The King’s Fund, London, in October 2017. UP’s poster presentation is in Appendix 4.

Work package 1.3: Q-sort study

Addressing objective 1: to work with young people with long-term conditions to determine what successful transition means to them and what is important in their transitional health care

Qualitative research undertaken with young people during and after transition has been systematically reviewed. The first review51 identified four main issues: young people’s feelings and concerns, young people’s recommendations about components of transition services, outcomes after transfer and mode of transfer. The second review44 examined the point of transfer and identified four themes: facing changes in significant relationships, moving from a familiar to an unknown ward culture, being prepared for transfer and achieving responsibility.

The work of this WP has been published in Hislop et al. 52 and material in this section is based on that paper. Reprinted from Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 59, Hislop J, Mason H, Parr IR, Vale L, Colver A, Views of young people with chronic conditions on transition from pediatric to adult health services, 245–53, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier.

Aims

-

To explore the views of young people about transition.

-

To identify and describe these views using Q-methodology.

Methods

Q-methodology combines quantitative and qualitative methods to investigate the range of possible views on a subject. It involves the rank ordering (Q-sort) by participants of a set of statements (Q-set) about a topic, after which a by-person factor analysis of the Q-sorts is used to reveal shared perspectives on the topic. Further details are in our published paper. 52

The Q-set of statements relevant to young people in transition was generated using quotations from two reviews of qualitative studies44,51 and our own mapping review of service models. 53 These were coded into a set of emergent themes, ‘planning’, ‘staff related’, ‘maturity’, ‘parent-related’ and ‘other’, which were then recategorised into several subthemes. One representative statement from each subtheme was selected. Following consultation with UP, the wording was adjusted and each final statement was prepared for sorting by participants onto a triangular grid. The statements are set out in table 1 of the published article. 52

Q-methodology requires that individuals in the sample are likely to hold different views. Therefore, maximum variation sampling was used, by age, gender, health condition and whether or not the young person had transferred. We sought 45 young people, aged 14–22 years, with a long-term condition that would soon require or had recently required them to transfer from children’s to adults’ services. Those with intellectual disability who could not complete the Q-sort were excluded. The number of participants is usually, but not necessarily, smaller than the Q-set. 54 The aim is to have four or five persons defining each anticipated viewpoint; there are often two to four, and rarely more than six. Accordingly, the breadth and diversity of viewpoints is probably best achieved when a participant group contains between 40 and 60 participants. 55

Clinicians from 10 adults’ and children’s specialties in a NHS Trust with tertiary and secondary care responsibilities invited young people with long-term conditions to participate. Q-sorts were administered face to face by the researcher.

Analysis

The degree to which an individual’s Q-sort corresponds to each factor derived from the factor analysis is given by their ‘factor loading’. This is a correlation coefficient between +1 and –1; the closer to 1, the more similar an individual’s Q-sort is to the factor. Individuals are ‘exemplars’ for a factor if they have a significant factor loading on that factor alone (p ≤ 0.01). We used PQMethod software (version 2.11; Peter Schmolck, University of the Bundeswehr, Munich, Germany) with centroid factor analysis followed by varimax rotation. 56 Outputs include the number of exemplars per factor, eigenvalues and factor variance, which provide information on the proportion of variance for the entire study explained by each factor. These are used alongside the postsort qualitative information to determine the ‘factor solution’: the final number of factors identified.

For each factor, an idealised ‘composite’ Q-sort is computed, illustrating how a person with a factor loading of 1 would have laid out their statement cards. Attention is paid to statements that characterise each factor, for example those placed in the +3 and –3 position on the grid, and those statements that distinguish between factors.

We found that a four-factor solution was optimal from a statistical viewpoint and most meaningful in clinical terms.

Factor 1: young people with a ‘laid back’ approach to transition

These young people were not particularly worried about transition. They did not think that transition would make much difference to them and expected their new health team to provide similar care to that which they had experienced in children’s services. They were happy to be guided by staff on how to manage their condition and wanted continued involvement of their parents in their care. They also wanted to be well informed about their condition.

Factor 2: young people with an anxious approach to transition

For these individuals, transition mattered very much; it worried them, they did not want transfer to happen at a set age, and they wanted a written plan in place for this. They wanted to be able to say goodbye to their current doctors, and they thought that the post-transfer service would provide different care, and that seeing different staff might not help build trust. They thought that their condition was difficult to live with and all areas of their life were affected by it. They did not know what kinds of support would be available to them in future. They wanted their parents involved in their care.

Factor 3: young people with an autonomy-seeking approach to transition

These young people wanted independence and autonomy during transition and were characterised by their wish for the withdrawal of parental involvement in their care. They wanted doctors to speak to them, rather than to their parents. They wanted doctors to offer suggestions and choices but allow them to make decisions. They were more developmentally mature in terms of their responses to statements about leaving home and living independently. They preferred flexible timings for clinics and wanted to leave the paediatric environment. They showed that they wanted to meet adult staff before transfer, and then see the same doctors in order to develop trust.

Factor 4: young people with a socially oriented approach to transition

These young people valued social interaction with family, peers and professionals to assist transition. They thought that it was important to interact with those involved in their care. They wanted to meet others in a similar situation and wanted their parents to remain involved in their care. They were comfortable with other staff being present at consultations and, for example, did not find it difficult if students were present. They felt attached to doctors (wanting a chance to say goodbye before transfer) and wanted a particular person at the clinic to help them plan the practical side of managing their condition.

There is more discussion of these factors in our published paper. 52

Strengths and limitations

Owing to the purposive sampling, claims cannot be made about how many individuals hold each point of view. Nor can inferences be made about subgroup sizes based on gender, age or condition.

We do not know if the four styles are stable over time. The views of some young people might relate to underlying personality characteristics and, therefore, might not change substantially. Alternatively, preferences may change as young people develop or as their health or health care changes.

Key findings

-

Reviews of qualitative studies44,51 of transition have not revealed how individuals approach the dilemmas they face. Our results add a new dimension.

-

Four factors or interaction styles of approaching transition were identified: ‘laid back’, ‘anxious’, ‘autonomy-seeking’ and ‘socially oriented’.

-

These four diverse styles show that there is not one view on transition. Thus, a ‘one size fits all’ approach is inappropriate and tailoring care to each to each young person is crucial.

Inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

The recognition of these four interaction styles for approaching transition is a new finding and yields one of the seven key implications of the programme: implication 5.

The Q-sort study contributed to the design of the discrete choice experiment (DCE) (WP 2.3), which identified aspects of transitional health care that young people are more likely to take up. This in turn informed the economic analyses (WP 2.3).

Work package 2.1: longitudinal study (quantitative)

Addressing objective 2: to identify the features of transitional health care that are effective and efficient

Although there is some preliminary evidence of the benefit of transition programmes in diabetes care,57,58 there has been little research with young people with complex physical impairments. 59 Furthermore, the lack of planned transfer to adult mental health services for young people with neurodevelopmental disorders has been highlighted. 60 Therefore, to be as generalisable as possible across long-term conditions, a cohort of young people with one of three very different conditions was recruited: individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus as an exemplar of chronic illness; with cerebral palsy as an exemplar of complex physical impairment; and with ASD who continued to access children’s services for an associated mental health problem as an exemplar of neurodevelopmental disorder.

Following examination of published policy documents and research literature, nine proposed PBFs of services were identified and defined for the study. These were age-banded clinic, meet adult team before transfer, promotion of health self-efficacy, written transition plan, appropriate parent involvement, key worker, co-ordinated team, holistic life-skills training, and transition manager for clinical team. The Glossary provides the definitions of the features. Table 2 of the published protocol61 gives the details of the policy documents and tabulation of the research literature justifying their inclusion.

The following papers have been published from this WP:

-

Protocol61

-

Analysis of baseline data62

-

Young people’s experience of the PBFs63

-

Unmet needs of those with cerebral palsy64

-

Clinical course in diabetes mellitus65

-

Longitudinal analysis identifying that only three of the PBFs are associated with better outcomes. 66

Aims

To examine whether or not the PBFs of services are associated with better outcomes for young people with type 1 diabetes mellitus, cerebral palsy, or ASD and an associated mental health problem.

Hypothesis

In combination, and separately for type 1 diabetes mellitus, cerebral palsy and ASD, access to PBFs during the transition from children’s to adults’ health care predicts better health and social outcomes.

Methods

Sampling frame and site selection

In the UK, all young people with type 1 diabetes mellitus aged < 15 years attend secondary hospital care. Between June 2012 and October 2013, young people with type 1 diabetes mellitus were recruited from children’s services in five UK health-care provider NHS Trusts that were at different stages of development of transitional health care. These five NHS Trusts were in Greater London and north, south-west and south-east England. Young people with ASD and an associated mental health problem were recruited from four NHS Trusts, two of which claimed to have a readily available adults’ service to which to transfer young people. Similarly, all young people with ASD and an identified mental health problem attend specialised secondary care services. These four NHS Trusts were in north and south-west England. Young people with cerebral palsy were recruited from one NHS Trust in south-east England and randomly sampled from two regional population registers, the North of England Collaborative Cerebral Palsy Survey67 and the Northern Ireland Cerebral Palsy Register,68 that covered 17 NHS Trusts.

We conducted a survey, before submitting our application, that showed that the trusts varied greatly in the extent to which they provided PBFs; this was confirmed by the formal survey in all the trusts described in the previous paragraph undertaken during the study (see Proposed beneficial features).

All participants were aged 14–18 years 11 months at recruitment and had not transferred to adults’ services. Participants had no significant learning disabilities.

Procedures

Young people and their parent(s) were visited on four occasions, 1 year apart, by a locally based research assistant at home or at a clinic.

Information on date approached, date of birth, gender and postcode was collected. Postcodes were used in England to calculate the Index of Multiple Deprivation,69 and in Northern Ireland to calculate the Multiple Deprivation Measure. 70 The Index of Multiple Deprivation and the Multiple Deprivation Measure are markers of community-level socioeconomic status; higher scores indicate more socioeconomic deprivation.

We defined ‘date of transfer’ as the date of the final appointment with a paediatrician or principal children’s health specialist. This included when a young person saw a paediatrician and adult physician jointly to introduce a member of the adult team. If there was not a letter stating the transfer date, the date when the young person turned 18 years of age was recorded. At the study’s end, the young person’s status was recorded as still in children’s services, transferred to adults’ services, transferred to primary care, or left study.

To maximise the use of data, we carried out longitudinal analyses on the ‘final’ visit, defined as visit 4 unless there was a visit 3 that was not followed by a fourth visit, in which case visit 3 was used as the ‘final’ visit. At the ‘final’ visit, 274 young people (73.3%) had valid follow-up data for analysis (112 with diabetes mellitus, 74 with cerebral palsy and 88 with ASD).

Measures

We captured generic outcome measures about satisfaction with services, participation in life situations and well-being.

Parents and young people completed the Mind the Gap scale71 about their satisfaction with services. Satisfaction is conceptualised as the ‘gap’ between ratings of ‘ideal’ and ‘current’ care: the greater the ‘gap’ score, the lower the satisfaction. It yields an overall score and three subdomain scores.

Young people completed the Rotterdam Transition Profile,72 a nine-domain questionnaire on participation, defined as involvement in life situations. 73 For each domain, participants select the statement that best describes their current situation. Each statement represents one of three phases of transition: phase 1, childhood/dependence on parents; phase 2, experimenting and orienting to the future; and phase 3, adulthood/independence.

A three-item questionnaire captured the young person’s independence in appointments, and had a score range of 3–15 (15 being the most independent). 74

At visits 3 and 4, young people completed a frequency of social participation questionnaire,75 especially developed for adolescents; it has UK general population data available for comparison. Two ‘factors’ are captured: ‘getting on with people’ and ‘community recreation’. 76

Young people completed the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS), a 14-item questionnaire developed in the UK and valid in the age range 13–21 years. 77 It has UK general population data available for comparison.

No further psychometric analyses were carried out on the Mind the Gap scale and the Rotterdam Transition Profile because they have been validated and used with young people with a variety of long-term conditions. 71,72,78 However, for the WEMWBS, internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha with 95% confidence intervals to check that it was an appropriate measure to use in all three groups, particularly the group with ASD and an associated mental health problem.

In addition, the following condition-specific outcomes and process measures were captured.

-

Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Participants were assigned to a ‘satisfactory’ or ‘suboptimal’ clinical course at visits 2, 3 and 4. Following consultation with specialists in adult and paediatric diabetes, participants were deemed to have a satisfactory clinical course if, for each year of the study, HbA1c (glycated haemoglobin) level was < 7% above baseline, there were no hospital admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis, clinic attendance was > 75% and attendance for retinal screening was 100%. 65

-

Cerebral palsy. An unmet-needs questionnaire was developed based on a model widely used in disability research. 79 The questionnaire was completed separately by the young person and the parent. Categorical principal components analysis identified two domains: daily activity health care and medical care. 64

-

ASD and an associated mental health problem. Young people completed the self-report Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which has subscales for anxiety and depression. 80 The psychometric properties of this scale have been shown to be valid for use with young people with ASD. 81

Proposed beneficial features

A summary checklist about the PBFs was discussed by the research assistant with each young person at the first (baseline) visit. Then, at the second, third and fourth home visits, the checklist of PBFs experienced by the young person over each preceding 12 months was completed by the research assistants, in discussion with the young person (and with parents). This was supported by diary information recorded by the young person about their consultations. The research assistants also consulted health records to extract information about provision of PBFs; this included whether or not there was evidence that the clinic had a staff member with the role of transition manager for the clinical team (which was not directly asked to young people). Each PBF was recorded as received (or not) at least once during the year before the visit. For each PBF, we also established a trajectory of exposure, over the course of the study, deemed optimal or suboptimal according to whether or not:

-

In at least 1 of the 3 years there was exposure to the feature. This applied to the features ‘age-banded clinic’, ‘meet the adult team before transfer’, ‘written transition plan, ‘holistic life-skills training’ and ‘transition manager for clinical team’.

-

In at least 2 of the 3 years there was exposure to the feature. This applied to the features ‘key worker’ and ‘co-ordinated team’.

-

In each of the 3 years there was exposure to the feature. This applied to the features ‘promotion of health self-efficacy’ and ‘young person and/or parent satisfied with level of parent involvement’.

-

When visit(s) had been missed, and the trajectory could not be assessed, the trajectory was recorded as missing.

After the first year of the study, a questionnaire was sent to each of the 35 services attended by the young people recruited to ask whether or not their service aimed to provide each of the PBFs.

Analysis

Recruitment

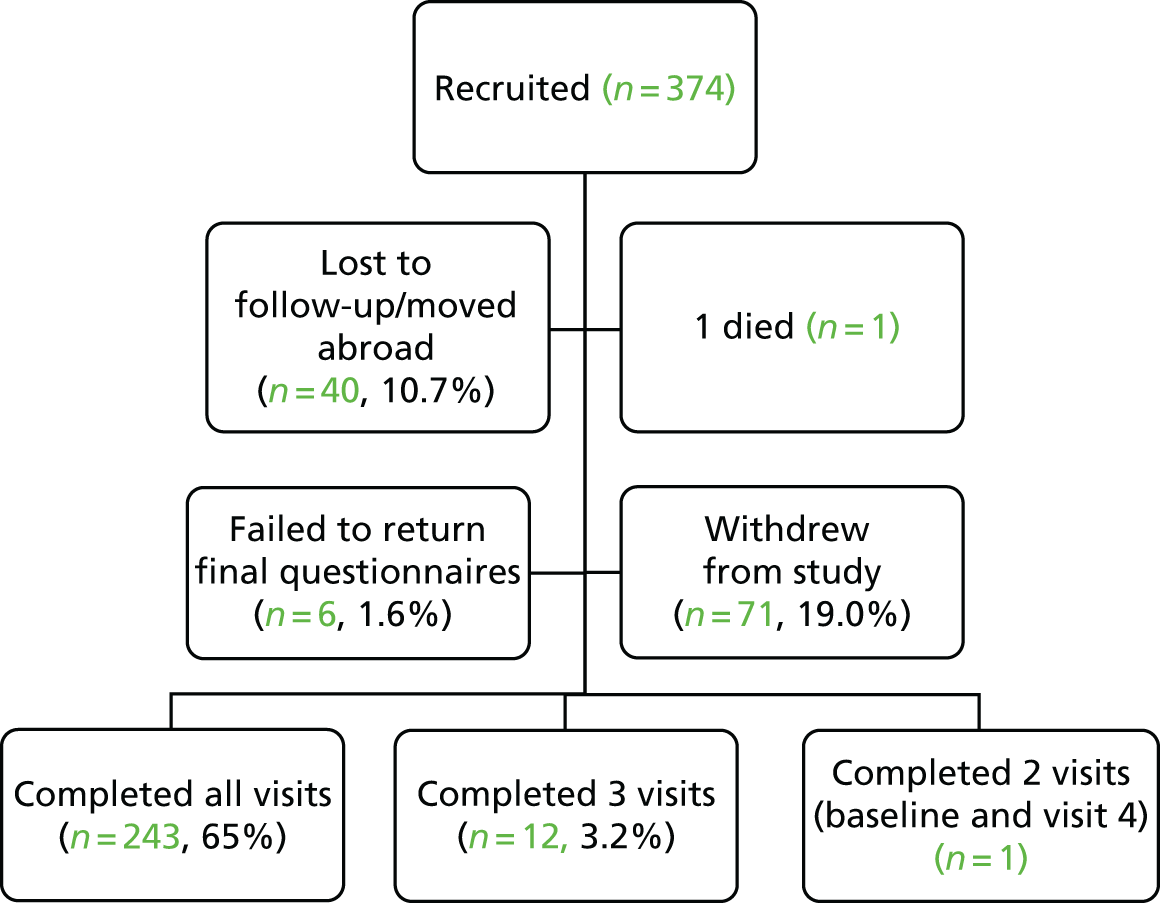

Eight hundred and seventy-eight young people were approached and 374 were recruited to the study; 118 with ASD, 106 with cerebral palsy and 150 with diabetes mellitus. Further details and a flow diagram are in figure 1 of our published paper on baseline characteristics. 62 Whereas recruitment rates were reasonably good for the ASD group (50.9% of those approached) and diabetes mellitus group (64.7%), the rate of recruitment of those with cerebral palsy was lower (25.6%). This may be due to the method of recruitment, which was to send letters of invitation rather than for their clinician to approach young people and their families directly.

As described in our baseline characteristics paper,62 participants with diabetes mellitus or cerebral palsy were comparable, in terms of condition severity, with larger population samples. However, for those with ASD this was more difficult to assess because we recruited individuals who also had an associated mental health problem.

The target of 150 in each group was achieved for young people with diabetes mellitus but not for those with ASD who were in contact with mental health services (n = 118) or for those with cerebral palsy (n = 106) (see Appendix 5, Figure 12). For each young person, a parent or carer was invited to participate; 369 agreed (367 parents, one grandparent and one foster parent). Thus, data from a parent or carer were available for 98.6% of the young people.

Participants did not differ significantly from non-participants by age or gender, as shown in table 1 of our published paper on baseline characteristics. 62 Overall, participants had significantly (p < 0.001) lower scores on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (i.e. they were less deprived) than non-participants; however, the difference in overall Index of Multiple Deprivation score, on a continuous scale ranging from 0.5 to 87.8, was only 6.1.

Retention

Most of this analysis is reported in our published paper on the longitudinal analysis. 66 A total of 304 (81.3%) young people remained in the study by visit 2, with 259 (69.3%) by visit 3 and 243 (65%) by visit 4 (see Appendix 5, Figure 13). Forty young people became uncontactable (see Appendix 6, Figure 13). Among the 71 who told us that they wanted to leave the study, the main reason (n = 22) was ‘no longer being interested’. Another 19 had other commitments that came with being older, such as sitting exams, university work, or part- or full-time jobs. Furthermore, some young people’s mental health was too poor to allow visits. This highlights the natural challenges of undertaking longitudinal research during a life stage when so much change is happening.

A total of 274 (73%) young people had data for the ‘final’ visit (defined in Methods as visit 4 unless there was a visit 3 that was not followed by a fourth visit, in which case visit 3 was used). Of these 274 young people, 58% were male, and 112 had diabetes mellitus, 74 had cerebral palsy and 88 had ASD.

Text in the following paragraph is from our published paper. 66 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

The mean time between the baseline and final visits was 2.9 years [standard deviation (SD) 0.4 years, range 1.8–3.9 years]. There were no significant differences between those remaining in the study and those not remaining with respect to sex (p = 0.6), age (p = 0.6), condition (p = 0.6), diabetes sites (p = 0.4) or ASD sites (p = 0.6) or condition severity (diabetes mellitus, p = 0.7; cerebral palsy, p = 0.9; ASD, p = 0.7). However, in Northern Ireland, those with cerebral palsy who were lost to follow-up came from areas with, on average, greater socioeconomic deprivation (p = 0.03) than did those remaining in the study. On examining socioeconomic factors, based on actual circumstances rather than on area of residence, there was more loss to follow-up in families with single parents.

To where did young people transfer?

For the 274 young people with a ‘final’ visit, Table 1 shows whether they remained in children’s services or transferred to adults’ services or primary care, by condition.

| Status | Total, N (%)a | Condition, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitusa | Cerebral palsy | ASD | ||

| Remained in children’s service | 49 (18) | 19 (17) | 10 (14) | 20 (23) |

| Transferred to adults’ service | 148 (54) | 89 (80) | 35 (47) | 24 (27) |

| Transferred to primary care | 76 (28) | 3 (3) | 29 (39) | 44 (50) |

Of those with diabetes mellitus, almost all transferred to an adults’ service, whereas the proportion of those with cerebral palsy who transferred to primary care was substantial, and this was even greater for those with ASD.

Baseline and subsequent changes in the outcome measures

A total of 304 (81.3%) of the young people took part in the second visit (diabetes mellitus, n = 128; cerebral palsy, n = 85; ASD, n = 91); 259 took part in the third visit and 243 took part in the fourth visit.

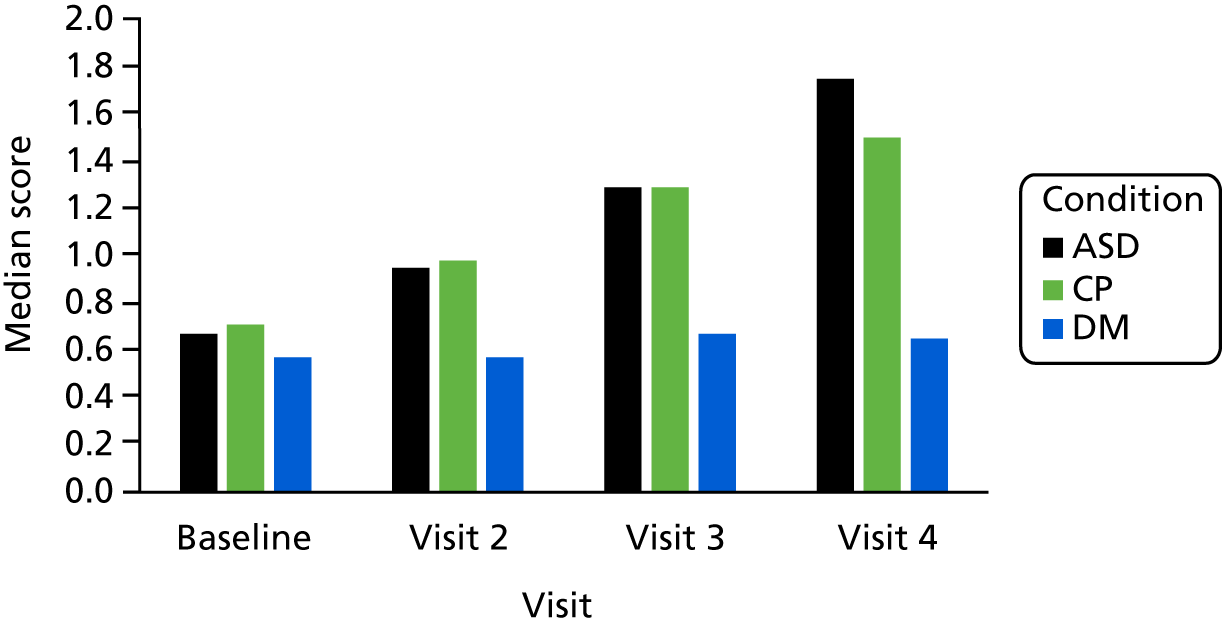

Satisfaction with services

Satisfaction with services was generally good, as the ‘gap’ scores (the difference between the respondent’s ideal and current care) were small. Parents’ satisfaction was significantly lower than their children’s. Over the four visits, satisfaction with services did not change for those with diabetes mellitus, but for those with cerebral palsy or ASD it steadily worsened (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Mind the Gap median score, young person reported: change over time by condition. CP, cerebral palsy; DM, diabetes mellitus.

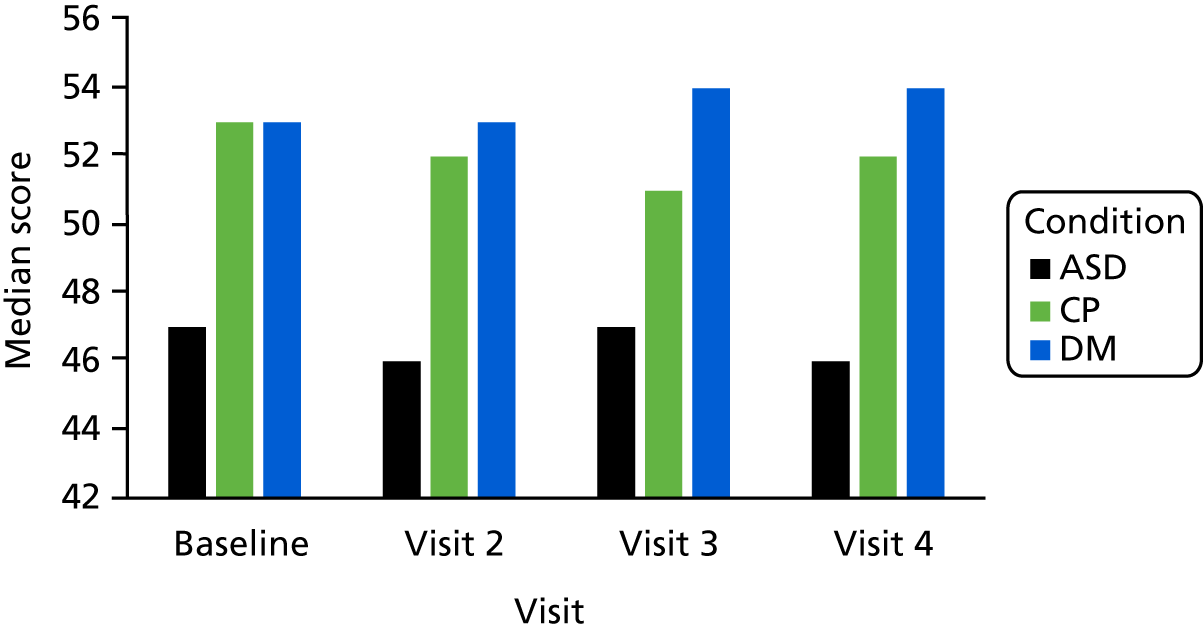

Well-being

The median baseline well-being scores of those with diabetes mellitus or cerebral palsy were similar to each other and to those in the general population, and significantly higher (p < 0.001) than the scores of those with ASD. In the general population of 13- to 16-year-olds, the median score on the WEMWBS was 48.8. 77 In those aged > 16 years in the general population in England, the median was 50.7. 82

Over the four visits, the well-being scores of those with diabetes mellitus, cerebral palsy or ASD were steady. Those with ASD continued to have significantly lower well-being scores (p < 0.001) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The WEMWBS: change over time by condition group. CP, cerebral palsy; DM, diabetes mellitus.

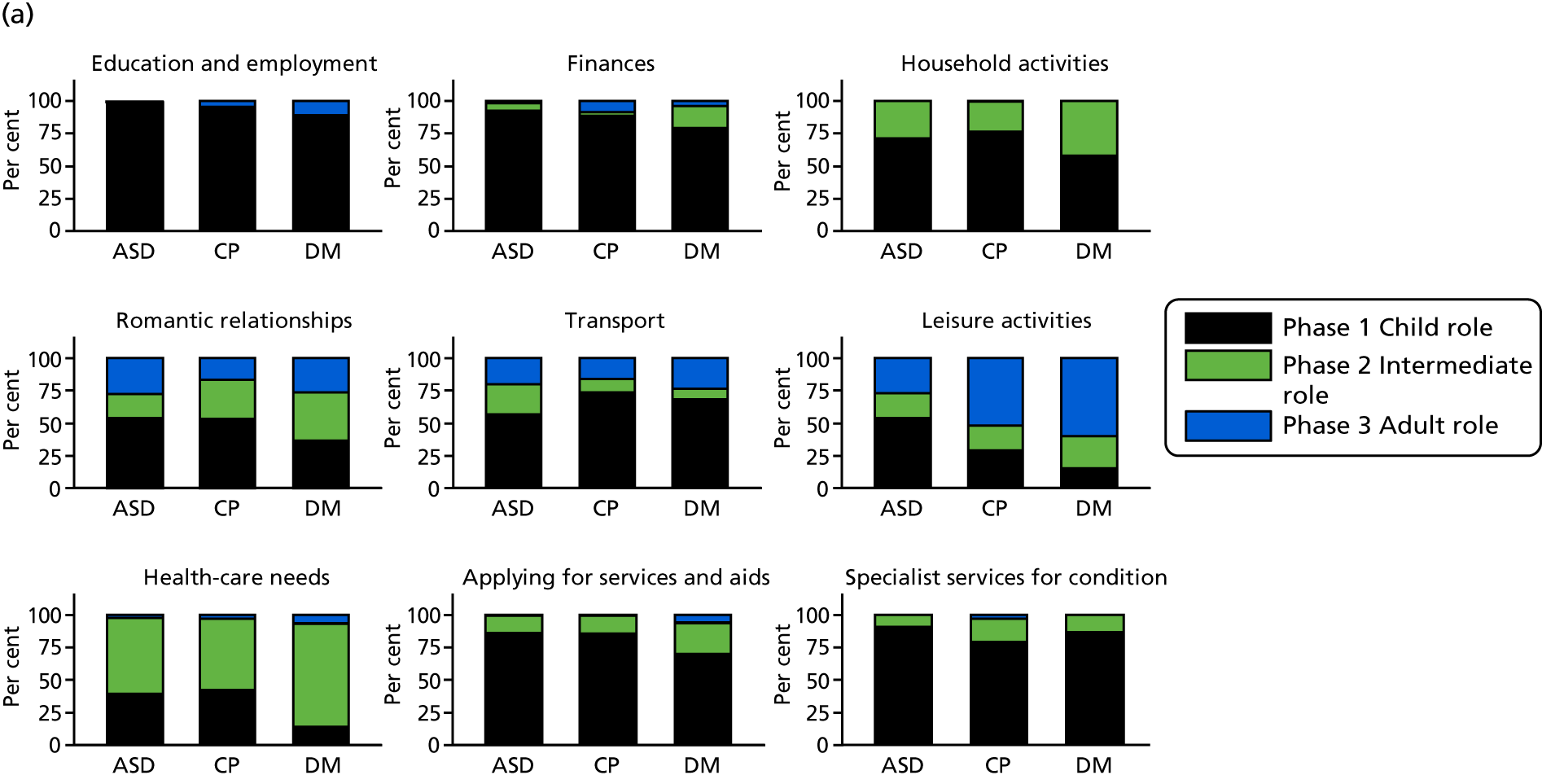

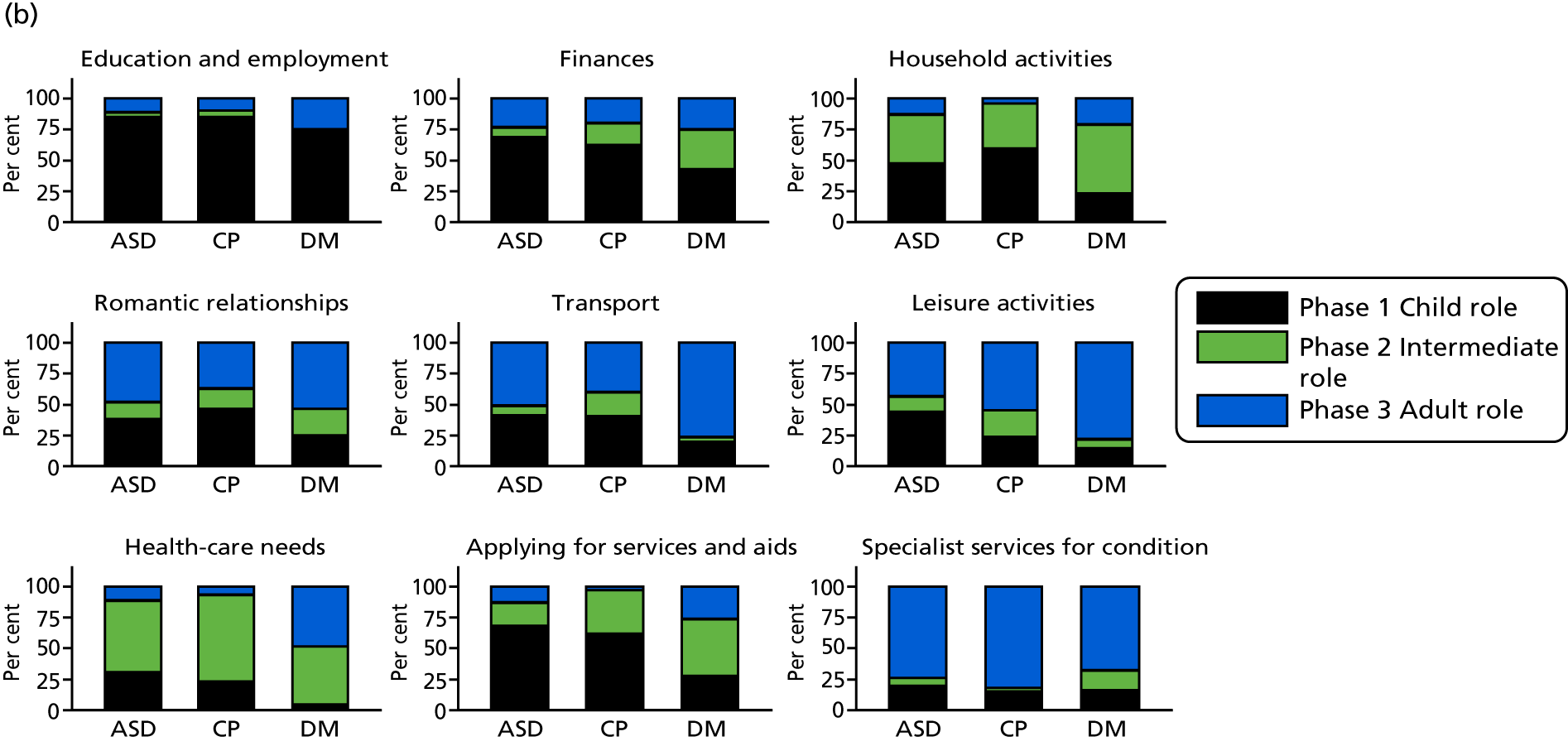

Rotterdam Transition Profile

On every domain of the Rotterdam Transition Profile, except ‘education and employment’, significant differences were found between the three conditions (most p-values were < 0.01). A larger proportion of young people with diabetes mellitus were in a more independent phase of participation than those with ASD or cerebral palsy. Over the four visits, young people steadily moved to a more independent phase of transition on every domain. Those with diabetes mellitus remained further ahead than those with ASD or cerebral palsy (Figure 4). As the phase for the domain ‘using specialist services for condition’ was determined entirely by the structure of the services and could not be influenced by the young person, we dropped it from this and further analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Rotterdam Transition Profile. Percentages of participants per phase at (a) baseline and (b) visit 4, by condition. CP, cerebral palsy; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Social participation

The mean score for the ‘getting on with people’ domain was significantly lower (p < 0.001) for participants than in the general population, whereas the score for the ‘community recreation’ domain was similar (Table 2). Those with diabetes mellitus had higher mean scores than those with ASD or cerebral palsy for ‘getting on with people’, and higher scores than those with ASD for ‘community recreation’. Scores for ‘getting on with people’ improved by visit 4 for all three conditions but remained lower than in the general population.

| Domain | General population | Study population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Mean (SD) | Number | Mean (SD) | |

| Getting on with people | 478 | 0.004 (1.37) | 253 | –1.09 (1.79) |

| Community recreation | 479 | 0.27 (0.15) | 253 | 0.26 (0.17) |

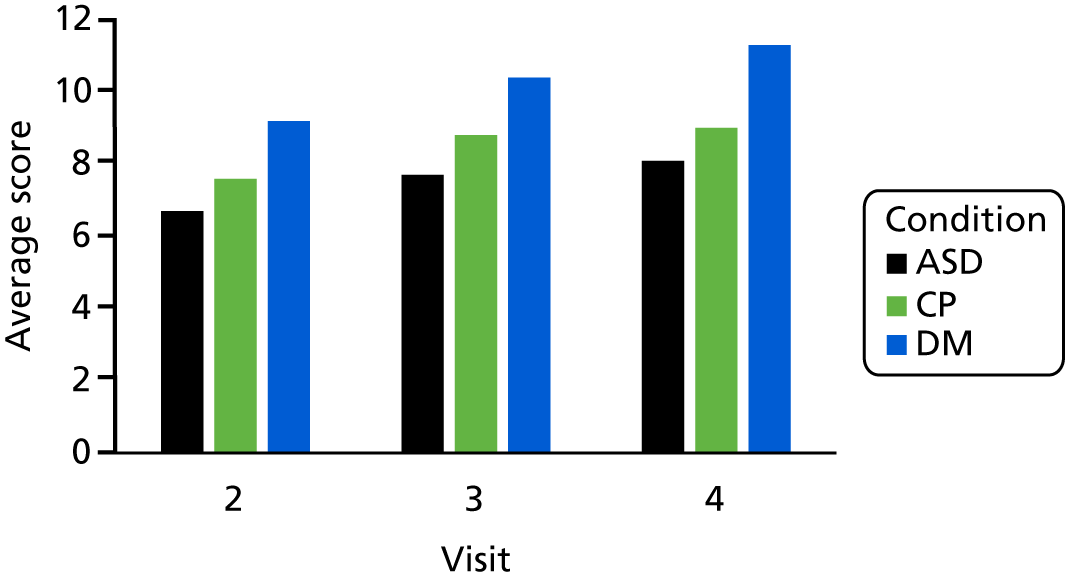

Independence in Appointments

The Independence in Appointments questionnaire was added from visit 2 onwards. At visit 2, the average score was 8. Those with diabetes mellitus had higher scores than those with ASD or cerebral palsy, and these differences persisted even though all scores increased, indicating more independence (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Independence in Appointments scale: change over time, by condition. CP, cerebral palsy; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Time from final paediatric appointment to first appointment in adults’ service

We could examine this only for young people with diabetes mellitus. For those with cerebral palsy, it was usually unclear with which professional the first appointment should be. For example, sometimes a young person had transferred to an adult physiotherapist but was still seeing a paediatrician.

For those with diabetes mellitus who had transferred, the mean time to adult appointment was 5.2 months (SD 4.9 months). The median time was 3.7 months [interquartile range (IQR) 3–6 months]. The proportion seen by adults’ services within 6 months of final paediatric appointment was 75%.

Diabetes mellitus condition-specific measure of clinical course

The proportion of young people with diabetes mellitus with satisfactory clinical course reduced over the study period (clinical course was determined from a composite score from HbA1c value, eye screening, clinic attendance and no diabetic ketoacidosis):65

-

by visit 2, 65 out of 128 (51%) had a satisfactory clinical course

-

by visit 3, 49 out of 112 (43%) had a satisfactory clinical course

-

by visit 4, 32 out of 108 (29%) had a satisfactory clinical course.

These results, and further reporting in our published paper65 (in which we report only on the 108 who had full data to visit 4), indicate that the well-being of young people with diabetes mellitus and their satisfaction with transition services were not closely related to the condition’s clinical course.

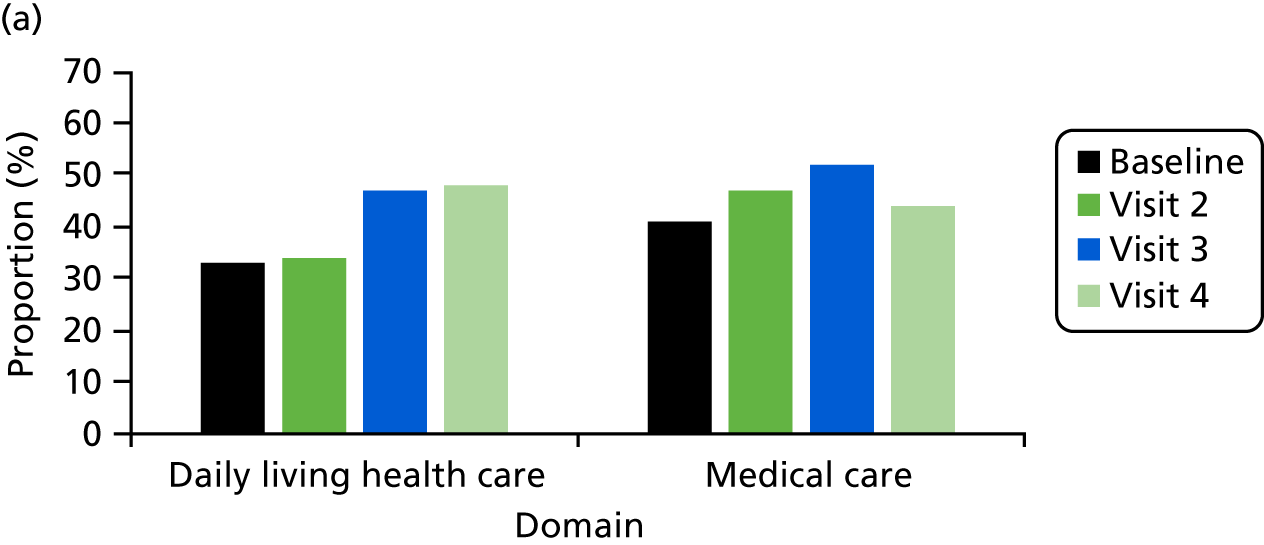

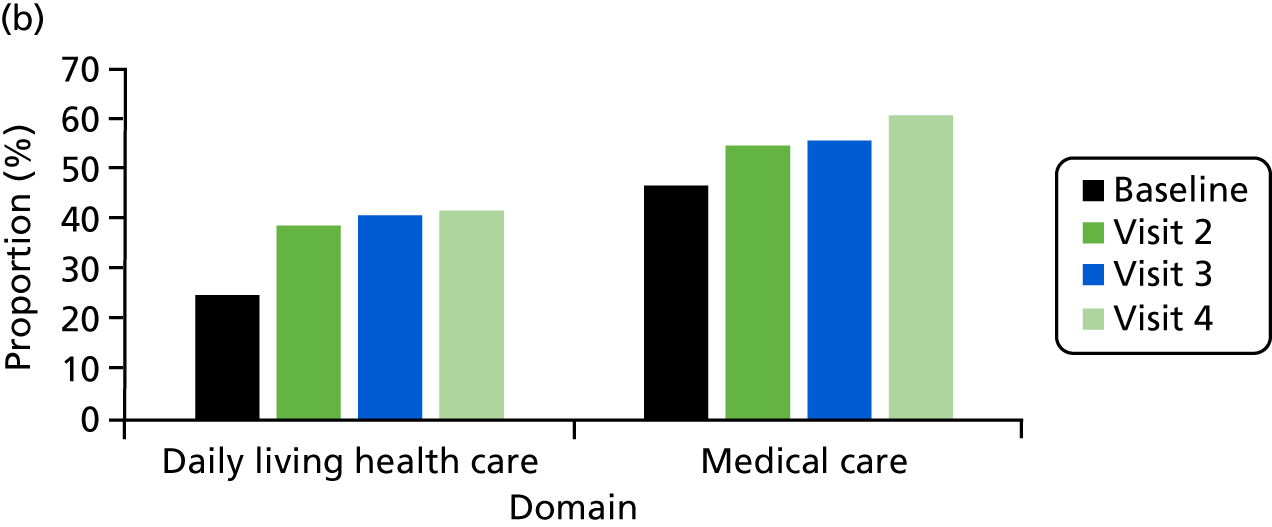

Cerebral palsy condition-specific measure of unmet need

As reported by parents, the proportion of young people with cerebral palsy with some unmet needs increased during the follow-up on the ‘daily living health care’ and ‘medical care’ domains. 64 As reported by the young person, an increase in unmet needs was seen only in the ‘daily living health care’ domain (Figure 6). When considering only those with some unmet needs, mean scores decreased slightly for the ‘daily living health care’ domain and remained the same for the ‘medical care’ domain, as reported by both young people and parents. These results were for the 64 young people who provided data at every visit. The results were similar when we examined data from each visit, whether or not data were available from other visits.

FIGURE 6.

Needs reported by (a) young person; and (b) parent.

These results draw attention to the need for more co-ordinated care in adults’ services for those with cerebral palsy. We discuss this further in our published paper64 and compare UK practice with that of other countries.

Autism spectrum disorder condition-specific measure of anxiety and depression

The proportion of young people with ASD and an associated mental health problem with an ‘abnormal’ score on the ‘anxiety’ and ‘depression’ domains (as measured by the HADS) remained similar between baseline and visit 4 (‘abnormal’ means above the recommended threshold score for a likely disorder) (Figure 7). The results were similar if analysed for the participants with data at baseline or visit 4, or if analysed for only those participants with data at baseline and visit 4.

FIGURE 7.

Proportions of normal, borderline and abnormal scores from the HADS at baseline and visit 4.

Further analysis of those with ASD is provided in Appendix 5. Having an additional diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or taking medication were predictors of a transfer to adult mental health services. Overall, the young people in our sample appeared to be doing reasonably well, with 67.5% in full-time education (either school or college) at the end of the study. Under one-third were in neither education nor employment. Analysis of HADS trajectories found that some young people were doing well, managing their mental health and able to engage successfully with services. However, the majority were experiencing episodes or continued levels of high anxiety. Qualitative data revealed that many young people struggled when faced with more challenging academic and social environments.

Proposed beneficial features

Some material in this section is from Colver et al. 63 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

The proposed beneficial features that services reported that they provided over the first year (i.e. before visit 2)

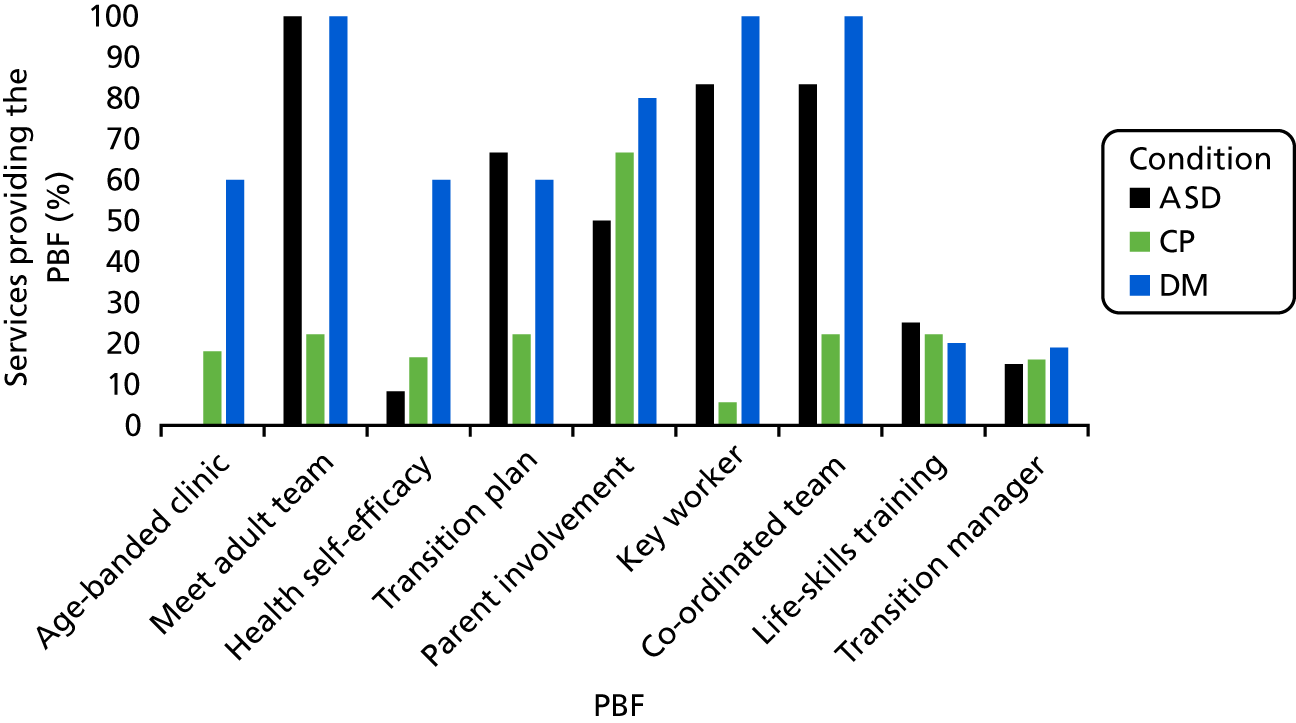

The following paragraph is covered in more detail in our published paper. 63 Overall, the nine PBFs of services for transitional health care were often not offered to young people in our study by NHS services. Fewer than half of the 35 services stated that they provided an ‘age-banded clinic’, ‘written transition plan’, ‘transition manager for clinical team’, ‘protocol for promotion of health self-efficacy’ or ‘holistic life-skills training’. Features were offered by services most often for young people with diabetes mellitus and least often for those with cerebral palsy (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Percentage of ‘yes’ responses from each service by condition, stating whether or not the PBF was offered. CP, cerebral palsy; DM, diabetes mellitus.

The proposed beneficial features that young people reported that they experienced over the first year (i.e. before visit 2)

The content of the following paragraph is covered in more detail in our published paper,63 which integrates the findings from this WP and the qualitative work of WP 2.2. At visit 2, young people often reported that they had not experienced the features that services said they provided. Agreement between the young person’s report and what the service said it offered was 30% for ‘written transition plan’, 43% for ‘holistic life-skills training’ and 49% for ‘key worker’. Agreement was better for ‘appropriate parent involvement’, at 77%; for ’age-banded clinic’, at 77%; for ‘promotion of health self-efficacy‘, at 80%; and for ‘co-ordinated team’, at 69%.

Associations of proposed beneficial features with outcomes

Two approaches were adopted to assessing the associations of PBFs with outcomes. In both, we used the young person’s account of whether or not they had experienced a PBF, rather than what the service reported that it provided or aspired to provide.

In the first approach, it was established at each research visit whether or not the young person had experienced each PBF at least once in the previous year, and this was recorded as yes or no. A separate analysis was then conducted for each PBF (as the independent variable) against the outcomes. This was undertaken for each annual period. Thus, this approach is a series of analyses that examine associations over 1 year, directly related to what the young person is experiencing at the time.

In the second approach, a consolidated indicator was compiled for each PBF for the duration of the study. The criteria for being optimal or suboptimal varied by PBF and was calculated as outlined in Methods. The proportions of young people experiencing optimal or suboptimal consolidated indicators are shown in Table 3. In the analyses, the independent variable was whether the consolidated indicator was optimal or suboptimal for each PBF; the dependent variables were the outcomes captured at the ‘final’ visit.

| PBF | Consolidated indicator | All, n (%) | Diabetes, n (%) | Cerebral palsy, n (%) | ASD, n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-banded clinic | Optimal | 145 (53) | 109 (97) | 16 (22) | 20 (23) | < 0.001 |

| Suboptimal | 111 (40) | 2 (2) | 54 (73) | 55 (62) | ||

| Missing | 18 (7) | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | 13 (15) | ||

| Meet adult team before transfer | Optimal | 111 (40) | 73 (65) | 16 (22) | 22 (25) | < 0.001 |

| Suboptimal | 133 (49) | 31 (28) | 54 (73) | 48 (55) | ||

| Missing | 30 (11) | 8 (7) | 4 (5) | 18 (20) | ||

| Promotion of health self-efficacy | Optimal | 116 (42) | 76 (68) | 18 (24) | 22 (25) | < 0.001 |

| Suboptimal | 151 (55) | 29 (26) | 56 (76) | 66 (75) | ||

| Missing | 7 (3) | 7 (6) | ||||

| Written transition plan | Optimal | 48 (17) | 32 (29) | 11 (15) | 5 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Suboptimal | 185 (68) | 62 (55) | 59 (80) | 64 (73) | ||

| Missing | 41 (15) | 18 (16) | 4 (5) | 19 (21) | ||

| N/A | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |||

| Both young person and parent happy with parent involvement | Optimal | 93 (34) | 36 (32) | 28 (38) | 29 (33) | 0.444 |

| Suboptimal | 141 (51) | 55 (49) | 33 (45) | 53 (60) | ||

| Missing | 38 (14) | 21 (19) | 12 (16) | 5 (6) | ||

| N/A | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |||

| Key worker | Optimal | 79 (29) | 56 (50) | 3 (4) | 20 (23) | < 0.001 |

| Suboptimal | 170 (62) | 47 (42) | 68 (92) | 55 (62) | ||

| Missing | 25 (9) | 9 (8) | 3 (4) | 13 (15) | ||

| Co-ordinated team | Optimal | 167 (61) | 104 (93) | 25 (34) | 38 (43) | < 0.001 |

| Suboptimal | 66 (24) | 2 (2) | 40 (54) | 24 (27) | ||

| Missing | 25 (9) | 6 (5) | 4 (5) | 15 (17) | ||

| N/A | 16 (6) | 5 (7) | 11 (13) | |||

| Holistic life-skills training | Optimal | 132 (48) | 74 (66) | 18 (24) | 40 (45) | < 0.001 |

| Suboptimal | 117 (43) | 28 (25) | 52 (70) | 37 (42) | ||

| Missing | 25 (9) | 10 (9) | 4 (6) | 11 (13) | ||

| Transition manager for clinical team | Optimal | 60 (22) | 27 (24) | 14 (19) | 19 (21) | 0.947 |

| Suboptimal | 143 (52) | 67 (60) | 34 (46) | 42 (48) | ||

| Missing | 71 (26) | 18 (16) | 26 (35) | 27 (31) | ||

| Total (n) | 274 | 112 | 74 | 88 |

All models were adjusted for age, sex, condition and potential for clustering by site. Significant associations (p < 0.05) from these models were further adjusted for transfer status, time since transfer to final visit (if applicable) and time to first adult appointment (if applicable).

Examining the Rotterdam Transition Profile, we performed the logistic regression by comparing phases 1 and 2 with phase 3.

Table 4 sets out the effect sizes for all associations that reached significance of p ≤ 0.05.

| PBF | PBFs by ‘year-by-year’ visits | Consolidated PBF indicator at final visit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Outcome | Whether regression b-coefficient or odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value | Outcome | Whether regression b-coefficient or odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value | |

| Appropriate parent involvement | 1 | MTG: total | −0.48 | −0.76 to −0.19 | 0.001 | MTG: total | −0.67 | −0.97 to −0.37 | < 0.001 |

| 1 | MTG: environment | −0.57 | −0.92 to −0.21 | 0.001 | MTG: environment | −0.71 | −1.17 to −0.26 | 0.006 | |

| 1 | MTG: provider | −0.52 | −0.82 to −0.22 | 0.001 | MTG: provider | −0.75 | −0.99 to −0.52 | < 0.001 | |

| 1 | RTP: domestic | [0.14a] | 0.03 to 0.67 | 0.01 | RTP: finances | [0.6a] | 0.92 to 0.39 | 0.02 | |

| 1 | RTP: health care | [0.35a] | 0.17 to 0.72 | 0.004 | WEMWBS | 2.18 | 0.21 to 4.15 | 0.03 | |

| 1 | RTP: services and aids | [0.42a] | 0.18 to 0.97 | 0.04 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: total | −0.60 | −1.00 to −0.21 | 0.003 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: environment | −0.65 | −1.08 to −0.21 | 0.004 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: provider | −0.48 | −0.90 to −0.06 | 0.03 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: process | −0.82 | −1.32 to −0.31 | 0.002 | |||||

| 3 | WEMWBS | 4.47 | 1.96 to 6.97 | 0.001 | |||||

| 3 | MTG: total | −0.87 | 0.45 to 1.29 | 0.001 | |||||

| 3 | MTG: environment | −0.91 | −1.44 to −0.37 | < 0.001 | |||||

| 3 | MTG: provider | −0.95 | −1.37 to −0.52 | < 0.001 | |||||

| 3 | MTG: process | −0.63 | −1.18 to −0.07 | 0.03 | |||||

| 3 | WEMWBS | 3.45 | 0.92 to 5.99 | 0.008 | |||||

| Promotion of health self-efficacy | 1 | MTG: total | −0.51 | −0.87 to −0.15 | 0.006 | MTG: total | −0.32 | −0.62 to −0.03 | 0.04 |

| 1 | MTG: environment | −0.63 | −1.06 to −0.18 | 0.005 | MTG: environment | −0.57 | −1.03 to −0.11 | 0.02 | |

| 1 | MTG: provider | −0.47 | −0.85 to −0.09 | 0.02 | MTG: process | −0.37 | −0.70 to −0.04 | 0.03 | |

| 1 | MTG: process | −0.46 | −0.91 to −0.01 | 0.04 | |||||

| 1 | RTP: finances | [0.26a] | 0.07 to 0.93 | 0.04 | |||||

| 1 | RTP: domestic | [0.04a] | 0.01 to 0.21 | 0.001 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: total | −0.51 | −0.91 to −0.11 | 0.01 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: provider | −0.49 | −0.90 to −0.08 | 0.02 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: process | −0.70 | −1.21 to −0.19 | 0.007 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: total | −0.60 | −1.01 to −0.20 | 0.004 | |||||

| 3 | MTG: environment | −0.90 | −1.40 to −0.40 | < 0.001 | |||||

| 3 | MTG: provider | −0.52 | −0.95 to −0.11 | 0.01 | |||||

| Meet adult team before transfer | 1 | RTP: domestic | 6.29a | 1.60 to 24.80 | 0.009 | RTP: education/employment | 2.33a | 1.21 to 4.55 | 0.01 |

| 1 | RTP: health care | 2.71a | 1.24 to 5.90 | 0.01 | RTP: finances | 2.78a | 1.10 to 7.14 | 0.03 | |

| 1 | RTP: services and aids | 5.15a | 2.08 to 12.78 | < 0.001 | RTP: services and aids | 2.50a | 1.06 to 5.88 | 0.04 | |

| 1 | RTP: transport | 2.01a | 1.06 to 3.79 | 0.03 | Autonomy in appointments | 1.60 | 0.32 to 2.87 | 0.02 | |

| 1 | RTP: education/employment | 3.24a | 1.09 to 9.65 | 0.04 | |||||

| Meet adult team before transfer (continued) | 1 | Autonomy in appointments | 1.69 | 0.80 to 2.58 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 2 | RTP: finances | 2.64a | 0.92 to 6.62 | 0.02 | |||||

| 2 | RTP: transport | 2.08a | 1.11 to 3.90 | 0.02 | |||||

| 2 | Autonomy in appointments | 1.00 | 0.01 to 2.0 | 0.05 | |||||

| 3 | RTP: health care | 2.11a | 1.03 to 4.34 | 0.004 | |||||

| 3 | Autonomy in appointments | 1.46 | 0.34 to 2.59 | 0.01 | |||||

| Key worker | 1 | RTP: leisure | [0.56a] | 0.32 to 0.96 | 0.04 | ||||

| 2 | MTG: provider | −0.66 | −1.04 to −0.28 | 0.001 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: process | −0.69 | −1.17 to −0.21 | 0.005 | |||||

| 3 | RTP: education/employment | [0.40a] | 0.20 to 0.95 | 0.02 | |||||

| Holistic life-skills training | 1 | RTP: domestic | [0.19a] | 0.04 to 0.93 | 0.04 | ||||

| 1 | RTP: services and aids | [0.34a] | 0.12 to 0.94 | 0.04 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: provider | [0.43] | 0.03 to 0.84 | 0.04 | |||||

| 3 | MTG: total | −0.46 | −0.87 to −0.05 | 0.03 | |||||

| 3 | MTG: provider | −0.57 | −0.99 to −0.14 | 0.009 | |||||

| 3 | RTP: domestic | 2.47a | 1.10 to 5.58 | 0.003 | |||||

| 3 | RTP: romantic relationships | [0.52a] | 0.26 to 0.98 | 0.04 | |||||

| Written transition plan | 1 | RTP: romantic relationships | [0.43a] | 0.19 to 0.96 | 0.04 | ||||

| 2 | MTG: total | −0.72 | −1.39 to −0.04 | 0.04 | |||||

| 2 | MTG: process | −1.19 | −1.39 to −0.04 | 0.007 | |||||

| Co-ordinated team | 1 | RTP: domestic | [0.19a] | 0.04 to 0.93 | 0.04 | MTG: provider | −0.67 | −1.25 to −0.09 | 0.03 |

| 3 | RTP: health care | [0.17a] | 0.04 to 0.82 | 0.03 | RTP: education/employment | [0.31a] | 0.11 to 0.82 | 0.02 | |

| 3 | RTP: services and aids | [0.22a] | 0.06 to 0.81 | 0.02 | RTP: domestic | [0.41a] | 0.19 to 0.91 | 0.03 | |

| Transition manager for clinical team | No associations | RTP: domestic | 2.63a | 1.16 to 5.88 | 0.02 | ||||

| RTP: services and aids | [0.41a] | 0.20 to 0.86 | 0.02 | ||||||

| RTP: romantic relationships | [0.52a] | 0.31 to 0.89 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Age-banded clinic | 1 | WEMWBS | 3.08 | 0.18 to 5.98 | 0.04 | ||||

| 1 | Autonomy in appointments | 1.44 | 0.48 to 2.4 | 0.003 | |||||

| 2 | RTP: education/employment | 5.22a | 1.21 to 22.53 | 0.03 | |||||

Interpretation of the associations of proposed beneficial features with outcomes

This is presented in more detail in our published paper. 66 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Three PBFs of transitional health care had significant (p ≤ 0.01) positive associations with better outcomes, namely ‘appropriate parent involvement’, ‘promotion of health self-efficacy’ and ‘meeting the adult team before transfer’. The b-coefficients indicated changes of approximately 0.5 SDs with respect to the satisfaction with services scale (SD 1.5 in our population), well-being (SD 7.0 in our population) and autonomy in appointments (SD 3.0 in our population). The odds ratios indicated increased likelihoods of being in a more independent phase of transition.

The other six PBFs had few statistically significant positive associations (p ≤ 0.01) with better outcomes in the year-by-year analysis, had a number of negative associations and had no positive associations with the consolidated indicator of exposure to PBFs.

‘Appropriate parent involvement’ and ‘promotion of health self-efficacy’ were reported to have been experienced satisfactorily by fewer than half of participants across transition across the three conditions. However, they were experienced by more young people with diabetes mellitus than those with cerebral palsy or ASD. For ‘meeting the adult team before transfer’, around two-thirds of young people with diabetes mellitus reported that they had met a member of the adult team, but fewer than one-quarter of those with cerebral palsy or ASD had done so. Thus, we found a different quality of experience of transitional health care between young people with a long-term illness (diabetes mellitus) and those with a long-term disability.

Strengths and limitations

Looking first at the strengths, our study drew 374 young people from across the UK and from many NHS Trusts. This is the largest sample for research in the UK in terms of examining transition longitudinally and collecting hypothesis-driven data from young people at home visits (compared with data-linkage studies from administrative data sets). Although we cannot be certain of representativeness and, therefore, generalisability across UK regions and NHS Trusts, we studied individuals from Greater London; north, south-east and south-west England; and Northern Ireland. Furthermore, we drew individuals from 27 NHS Trusts, and the trusts varied greatly in the number and variety of the PBFs they offered (see Figure 8).

We recruited from all young people with cerebral palsy in two population registers and all young people with diabetes mellitus or ASD and an associated mental health problem in nine NHS Trusts widely distributed across England (all such young people are seen in secondary care). Thus, complete populations of individuals with one of the three conditions were sampled from (e.g. rather than those attending particular schools, specialised tertiary health-care services or voluntary support groups).

The three conditions chosen were exemplars of chronic illness (diabetes mellitus), complex physical impairment (cerebral palsy) and neurodevelopmental impairment (ASD); they were deliberately chosen because they varied in terms of health needs, psychosocial complexity and availability of adults’ services. Thus, we consider that generalisability to other conditions is likely.

The 374 participants did not differ significantly from those declining to take part, other than for a small effect of deprivation. The distribution of severity of the three conditions was similar to that in national samples. 62 Those with the conditions had a wide range of severity; for example, the young people with cerebral palsy ranged from wheelchair users to those with independent ambulation. Attrition did not appear to create bias, as there were no significant differences between those remaining and those not remaining in the study with respect to sex, age, condition, diabetes site or ASD site. In Northern Ireland, there was a small effect of deprivation on the attrition of those with cerebral palsy. Thus, we think that, after non-participation and attrition, our study group continued to be representative of those we aimed to recruit.

Turning to the limitations, our study did not include young people with a learning disability because in the UK there is already a lifespan service for such individuals, and we would not have been able to base our quantitative studies on self-completed questionnaires, nor our qualitative work on interviews with young people. However, the exclusion of such individuals means that our results cannot be generalised to them.

Recruitment, especially of those with cerebral palsy, was more difficult than we expected. A possible explanation may be the method of recruitment, which was letters of invitation, rather than the young people’s clinician approaching them directly, as was undertaken for those with diabetes mellitus or ASD. Overall retention at 70% was acceptable in comparison with other longitudinal studies of adolescent populations. 32

It might be desirable to follow up young people for longer in adults’ services to assess later outcomes of transitional health care, but this is unlikely to be feasible. The fact that some young people were still in children’s services does not invalidate analyses; our study was about transition, not specifically health-care transfer. Table 1 shows the number still in children’s services.

Because of their personal circumstances, there was variability in precisely when the young people were seen by researchers. This is one reason why we chose the ‘final visit’ to be visit 4 or visit 3 (if the young person did not have a visit 4). Some of the visit 3s were considerably delayed and too close to a fourth visit to justify further data collection during the study. We examined the association of exposure to a PBF over the previous year in relation to outcomes. However, what constitutes optimal exposure over 3 years when, for instance, exposure occurs in one year but not the others? We made a clinical judgement about this for each feature for the consolidated longitudinal analysis. The decisions were agreed among our group, but others might have made different judgements.

Some PBFs, such as ‘written transition plan’, were infrequently provided and therefore we had less statistical power to detect associations with outcomes.

Key findings

-

There were striking mismatches between the PBFs of transitional health care that a service said it provided and the features that young people reported to have experienced.

-

PBFs were both provided and experienced less often in services for those with cerebral palsy and ASD than for those with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

-

Average satisfaction with services was reasonable at baseline (rating of ideal service only slightly higher than rating of actual service). It remained steady for those with type 1 diabetes mellitus but worsened significantly over the study period for those with ASD or cerebral palsy.

-

The well-being scores for each group remained similar over time. Those with type 1 diabetes mellitus or cerebral palsy had an average subjective well-being at baseline similar to that of the general population. Those with ASD and an associated mental health problem reported significantly lower well-being than those in the other two groups, and this difference persisted over the course of the study.

-